User login

Tips for treating patients with late-life depression

Late-life depression is the onset of a major depressive disorder in an individual ≥ 60 years of age. Depressive illness compromises quality of life and is especially troublesome for older people. The prevalence of depression among individuals > 65 years of age is about 4% in women and 3% in men.1 The estimated lifetime prevalence is approximately 24% for women and 10% for men.2 Three factors account for this disparity: women exhibit greater susceptibility to depression; the illness persists longer in women than it does in men; and the probability of death related to depression is lower in women.2

Beyond its direct mental and emotional impacts, depression takes a financial toll; health care costs are higher for those with depression than for those without depression.3 Unpaid caregiver expense is the largest indirect financial burden with late-life depression.4 Additional indirect costs include less work productivity, early retirement, and diminished financial security.4

Many individuals with depression never receive treatment. Fortunately, there are many interventions in the primary care arsenal that can be used to treat older patients with depression and dramatically improve mood, comfort, and function.

The interactions of emotional and physical health

The pathophysiology of depression remains unclear. However, numerous factors are known to contribute to, exacerbate, or prolong depression among elderly populations. Insufficient social engagement and support is strongly associated with depressive mood.5 The loss of independence in giving up automobile driving can compromise self-confidence.6 Sleep difficulties predispose to, and predict, the emergence of a mood disorder, independent of other symptoms.7 Age-related hearing deficits also are associated with depression.8

There is a close relationship between emotional and physical health.9 Depression adds to the likelihood of medical illness, and somatic pathology increases the risk for mood disorders.9 Depression has been linked with obesity, frailty, diabetes, cognitive impairment, and terminal illness.9

Inflammatory markers and depression may also be related. Plasma levels of interleukin-6 and C-reactive protein were measured in a longitudinal aging study.14 A high level of interleukin-6, but not C-reactive protein, correlated with an increased prevalence of depression in older people.

Chronic cerebral ischemia can result in a “vascular depression”13 in which disruption of prefrontal systems by ischemic lesions is hypothesized to be an important factor in developing despair. Psychomotor retardation, executive dysfunction, severe disability, and a heightened risk for relapse are common features of vascular depression.15 Poststroke depression often follows a cerebrovascular episode16; the exact pathogenic mechanism is unknown.17

Continue to: A summation of common risk factors

A summation of common risk factors. A personal or family history of depression increases the risk for late-life depression. Other risk factors are female gender, bereavement, sleep disturbance, and disability.18 Poor general health, chronic pain, cognitive impairment, poor social support, and medical comorbidities with impaired functioning increase the likelihood of resultant mood disorders.18

Somatic complaints may overshadow diagnostic symptoms

Manifestations of depression include disturbed sleep and reductions in appetite, concentration, activity, and energy for daily function.19 These features, of course, may accompany medical disorders and some normal physiologic changes among elderly people. We find that while older individuals may report a sad mood, disturbed sleep, or other dysfunctions, they frequently emphasize their somatic complaints much more prominently than their emotions. This can make it difficult to recognize clinical depression.

For a diagnosis of major depression, 5 of the following 9 symptoms must be present for most of the day or nearly every day over a period of at least 2 weeks19: depressed mood; diminished interest in most activities; significant weight loss or decreased appetite; insomnia or hypersomnia; agitation or retardation; fatigue or loss of energy; feelings of worthlessness or guilt; diminished concentration; and recurrent thoughts of death or suicide.19

Planning difficulties, apathy, disability, and anhedonia frequently occur. Executive dysfunction and inefficacy of antidepressant pharmacotherapy are related to compromised frontal-striatal-limbic pathways.20 Since difficulties with planning and organization are associated with suboptimal response to antidepressant medications, a psychotherapeutic focus on these executive functions can augment drug-induced benefit.

Rule out these alternative diagnoses

Dementias can manifest as depression. Other brain pathologies, particularly Parkinson disease or stroke, also should be ruled out. Overmedication can simulate depression, so be sure to review the prescription and over-the-counter agents a patient is taking. Some medications can occasionally precipitate a clinical depression; these include stimulants, steroids, methyldopa, triptans, chemotherapeutic agents, and immunologic drugs, to name a few.19

Continue to: Pharmacotherapy, Yes, but first, consider these factors

Pharmacotherapy, Yes, but first, consider these factors

Maintaining a close patient–doctor relationship augments all therapeutic interventions. Good eye contact when listening to and counseling patients is key, as is providing close follow-up appointments.

Encourage social interactions with family and friends, which can be particularly productive. Encouraging spiritual endeavors, such as attendance at religious services, can be beneficial.21

Recommend exercise. Physical exercise yields positive outcomes22; it can enhance mood, improve sleep, and help to diminish anxiety. Encourage patients with depression to take a daily walk during the day; doing so can enhance emotional outlook, health, and even socialization.

What treatment will best serve your patient?

It’s important when caring for patients with depression to assess and address suicidal ideation. Depression with a previous suicide attempt is a strong risk factor for suicide. Inquire about suicidal intent or death wishes, access to guns, and other life-ending behaviors. Whenever suicide is an active issue, immediate crisis management is required. Psychiatric referral is an option, and hospitalization may be indicated. Advise family members to remove firearms or restrict access, be with the patient as much as possible, and assist at intervention planning and implementation.

It is worth mentioning, here, the connection between chronic pain and suicidal ideation. Pain management reduces suicidal ideation, regardless of depression severity.23

Continue to: Psychotherapy and pharmacotherapies...

Psychotherapy and pharmacotherapies offered for the treatment of depression in geriatric practices are both effective, without much difference seen in efficacy.24 Psychotherapy might include direct physician and family support to the patient or referral to a mental health professional. Base treatment choices on clinical access, patient preference, and medical contraindications and other illnesses.

Pros and cons of various pharmacotherapies

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are commonly prescribed first for elderly patients with depression.25 Escitalopram is often better tolerated than paroxetine, which exhibits muscarinic antagonism and enzyme inhibition of cytochrome P450-2D6.26 Escitalopram also has fewer pharmaceutical interactions compared with sertraline.26

Generally, when prescribing an antidepressant drug, stay with the initial choice, gradually increasing the dose as clinically needed to its maximum limit. Suicidal ideation may be worsened by too quickly switching from one antidepressant to another or by co-prescribing anxiolytic or hypnotic medicines. Benzodiazepines have addictive and disinhibiting properties and should be avoided, if possible.27 For patients with insomnia, consider initially selecting a sedating antidepressant medication such as paroxetine or mirtazapine to augment sleep.

Alternatives to SSRIs. Nonselective serotonin reuptake inhibitors have similar efficacy as SSRIs. However, escitalopram is as effective as venlafaxine (a selective serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor [SSNRI]) and is better tolerated.28 Duloxetine, another SSNRI, improves mood and often diminishes chronic pain.29 Mirtazapine, an alpha-2 antagonist, might cause fewer drug-drug interactions and is effective, well tolerated, and especially helpful for patients with anxiety or insomnia.30 Dry mouth, sedation, and weight gain are common adverse effects of mirtazapine. Obesity precautions are often necessary during mirtazapine therapy; this includes monitoring body weight and metabolic profiles, instituting dietary changes, and recommending an exercise regimen. In contrast to SSRIs, mirtazapine might induce less sexual dysfunction.31

Tricyclic antidepressant drugs can also be effective but may worsen cardiac conduction abnormalities, prostatic hypertrophy, or narrow angle glaucoma. Tricyclic antidepressants may be useful in patients without cardiac disease who have not responded to an SSRI or an SSNRI.

Continue to: The role of aripiprazole

The role of aripiprazole. Elderly patients not achieving remission from depression with antidepressant agents alone may benefit from co-prescribing aripiprazole.32 As an adjunct, aripiprazole is effective in achieving and sustaining remission

Minimize risks and maximize benefits of antidepressants by following these recommendations:

- Ascertain whether any antidepressant treatments have worked well in the past.

- Start with an SSRI if no other antidepressant treatment has worked in the past.

- Counsel patients about the need for treatment adherence. Antidepressants may take 2 weeks to 2 months to provide noticeable improvement.

- Prescribe up to the maximum drug dose if needed to enhance benefit.

- Use a mood measurement tool (eg, the Patient Health Questionnaire-9) to help evaluate treatment response.

Try a different class of drugs for patients who do not respond to treatment. For patients who have a partial response, augment with bupropion XL, mirtazapine, aripiprazole, or quetiapine.33 Sertraline and nortriptyline are similarly effective on a population-wide basis, with sertraline having less-problematic adverse effects.34 Trial-and-error treatments in practice may find one patient responding only to sertraline and another patient only to nortriptyline.

Combinations of different drug classes may provide benefit for patients not responding to a single antidepressant. In geriatric patients, combined treatment with methylphenidate and citalopram enhances mood and well-being.35 Compared with either drug alone, the combination yielded an augmented clinical response profile and a higher rate of remission. Cognitive functioning, energy, and mood improve even with methylphenidate alone, especially when fatigue is an issue. However, addictive properties limit its use to cases in which conventional antidepressant medications are not effective or indicated, and only when drug refills are closely monitored.

The challenges of advancing age. Antidepressant treatment needs increase with advanced age.36 As mentioned earlier, elderly people often have medical illnesses complicating their depression and frequently are dealing with pain from the medical illness. When dementia coexists with depression, the efficacy of pharmacotherapies is compromised.

Continue to: When drug-related interventions fail

When drug-related interventions fail, therapy ought to be more psychologically focused.37 Psychotherapy is usually helpful and is particularly indicated when recovery is suboptimal. Counseling might come from the treating physician or referral to a psychotherapist.

Nasal esketamine can be efficacious when supplementing antidepressant pharmacotherapy among older patients with treatment-resistant depression.38 Elderly individuals responding to antidepressants do not benefit from adjunctive donepezil to correct mild cognitive impairment.39 There is no advantage to off-label cholinesterase inhibitor prescribing for patients with both depression and dementia.

Other options. Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) does not cause long-term cognitive problems and is reserved for treatment-resistant cases.40 Patients with depression who also have had previous cognitive impairment often improve in mental ability following ECT.41

A promising new option. Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) is a promising, relatively new therapeutic option for treating refractory cases of depressive mood disorders. In TMS, an electromagnetic coil that creates a magnetic field is placed over the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (which is responsible for mood regulation). Referral for TMS administration may offer new hope for older patients with treatment-resistant depression.42

Keep comorbidities in mind as you address depression

Coexisting psychiatric illnesses worsen emotions. Geriatric patients are susceptible to psychiatric comorbidities that include substance abuse, obsessive-compulsive characteristics, dysfunctional eating, and panic disorder.19 Myocardial and cerebral infarctions are detrimental to mental health, especially soon after such events.43 Poststroke depression magnifies the risk for disability and mortality,16,17 yet antidepressant pharmacotherapy often enhances prognoses. Along with early intervention algorithm-based plans and inclusion of a depression care manager, antidepressants often diminish poststroke depression severity.44 Even when cancer is present, depression care reduces mortality.44 So with this in mind, persist with antidepressant treatment, which will often benefit an elderly individual with depression.

Continue to: When possible, get ahead of depression before it sets in

When possible, get ahead of depression before it sets in

Social participation and employment help to sustain an optimistic, euthymic mood.45 Maintaining good physical health, in part through consistent activity levels (including exercise), can help prevent depression. Since persistent sleep disturbance predicts depression among those with a depression history, optimizing sleep among geriatric adults can avoid or alleviate depression.46

Sleep hygiene education for patients is also helpful. A regular waking time often promotes a better sleeping schedule. Restful sleep also is more likely when an individual avoids excess caffeine, exercises during the day, and uses the bed only for sleeping (not for listening to music or watching television).

Because inflammation may precede depression, anti-inflammatory medications have been proposed as potential treatment, but such pharmacotherapies are often ineffective. Older adults generally do not benefit from low-dose aspirin administration to prevent depression.47 Low vitamin D levels can contribute to depression, yet vitamin D supplementation may not improve mood.48

Offering hope. Tell your patients that if they are feeling depressed, they should make an appointment with you, their primary care physician, because there are medications they can take and counseling they can avail themselves of that could help.

CORRESPONDENCE

Steven Lippmann, MD, University of Louisville-Psychiatry, 401 East Chestnut Street, Suite 610, Louisville, KY 40202; steven.lippmann@louisville.edu.

1. Steffens DC, Skoog I, Norton MC, et al. Prevalence of depression and its treatment in an elderly population: the Cache County study. Arch Gen Psych. 2000;57:601-607. doi: 10.1001/ archpsyc.57.6.601

2. Barry LC, Allore HG, Guo Z, et al. Higher burden of depression among older women: the effect of onset, persistence, and mortality over time. Arch Gen Psych. 2008;65:172-178. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2007.17

3. Katon WJ, Lin E, Russo J, et al. Increased medical costs of a population-based sample of depressed elderly patients. Arch Gen Psych. 2003;60:897-903. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.9.897

4. Snow CE, Abrams RC. The indirect costs of late-life depression in the United States: a literature review and perspective. Geriatrics. 2016;1,30. doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics/1040030

5. George LK, Blazer DG, Hughes D, et al. Social support and the outcome of major depression. Br J Psych. 1989;154:478-485. doi: 10.1192/bjp.154.4.478

6. Fonda SJ, Wallace RB, Herzog AR. Changes in driving patterns and worsening depressive symptoms among older adults. J Gerontol Psychol Soc Sci. 2001;56:S343-S351. doi: 10.1093/geronb/56.6.s343

7. Cho HJ, Lavretsky H, Olmstead R, et al. Sleep disturbance and depression recurrence in community dwelling older adults—a prospective study. Am J Psych. 2008;165:1543-1550. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07121882

8. Golub JS, Brewster KK, Brickman AM, et al. Subclinical hearing loss is associated with depressive symptoms. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2020;28:545-556. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2019.12.008

9. Alexopoulos GS. Mechanisms and treatment of late-life depression. Focus (Am Psychiatr Publ). 2021;19:340-354. doi: 10.1176/appi.focus.19304

10. Starkstein SE, Preziosi TJ, Bolduc PL, et al. Depression in Parkinson’s disease. J Nerv Ment Disord. 1990;178:27-31. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199001000-00005

11. Gilman SE, Abraham HE. A longitudinal study of the order of onset of alcohol dependence and major depression. Drug Alco Depend. 2001;63:277-286. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(00)00216-7

12. Parmelee PA, Katz IR, Lawton MP. The relation of pain to depression among institutionalized aged. J Gerontol. 1991;46:P15-P21. doi: 10.1093/geronj/46.1.p15

13. Alexopoulos GS, Meyers BS, Young RC, et al. ‘Vascular depression’ hypothesis. Arch Gen Psych. 1997;54:915-922. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830220033006

14. Bremmer MA, Beekman AT, Deeg DJ, et al. Inflammatory markers in late-life depression: results from a population-based study. J Affect Disord. 2008;106:249-255. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.07.002

15. Taylor WD, Aizenstein HJ, Alexopoulos GS. The vascular depression hypothesis: mechanisms linking vascular disease with depression. Mol Psych. 2013;18:963-974. doi: 10.1038/mp.2013.20

16. Robinson RG, Jorge RE. Post-stroke depression: a review. Am J Psych. 2016;173:221-231. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.15030363

17. Cai W, Mueller C, Li YJ, et al. Post stroke depression and risk of stroke recurrence and mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res Rev. 2019;50:102-109. doi: 10.1016/ j.arr.2019.01.013

18. Cole MG, Dendukuri N. Risk factors for depression among elderly community subjects: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Psych. 2003;160:1147-1156. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.6.1147

19. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5). 2013:160-168.

20. Pimontel MA, Rindskopf D, Rutherford BR, et al. A meta-analysis of executive dysfunction and antidepressant treatment response in late-life depression. Am J Geriatr Psych. 2016;24:31-34. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2015.05.010

21. Koenig HG, Cohen HJ, Blazer DG, et al. Religious coping and depression in elderly hospitalized medically ill men. Am J Psychiatry. 1992;149:1693-1700. doi: 10.1176/ajp.149.12.1693

22. Blake H, Mo P, Malik S, et al. How effective are physical activity interventions for alleviating depressive symptoms in older people? A systematic review. Clin Rehabil. 2009;10:873-887. doi: 10.1177/0269215509337449

23. Bruce ML, Ten Have TR, Reynolds CF, et al. Reducing suicidal and depressive symptoms in depressed older primary care patients: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291:1081-1091. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.9.1081

24. Pinquart M, Duberstein PR, Lyness JM. Treatments for later-life depressive conditions: a meta-analytic comparison of pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:1493-1501. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.9.1493

25. Solai LK, Mulsant BH, Pollack BG. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for late-life depression: a comparative review. Drugs Aging. 2001;18:355-368. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200118050-00006

26. Sanchez C, Reines EH, Montgomery SA. A comparative review of escitalopram, paroxetine, and sertraline. Are they all alike? Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2014;29:185-196. doi: 10.1097/YIC.0000000000000023

27. Hedna K, Sundell KA, Hamidi A, et al. Antidepressants and suicidal behaviour in late life: a prospective population-based study of use patterns in new users aged 75 and above. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2018;74:201-208. doi: 10.1007/s00228-017-2360-x

28. Bielski RJ, Ventura D, Chang CC. A double-blind comparison of escitalopram and venlafaxine extended release in the treatment of major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65:1190-1196. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n0906

29. Robinson M, Oakes TM, Raskin J, et al. Acute and long-term treatment of late-life major depressive disorder: duloxetine versus placebo. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2014;22:34-45. doi: 10.1016/ j.jagp.2013.01.019

30. Holm KJ, Markham A. Mirtazapine: a review of its use in major depression. Drugs. 1999;57:607-631. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199957040-00010

31. Anttila SA, Leinonen EV. A review of the pharmacological and clinical profile of mirtazapine. CNS Drug Rev. 2001;7:249-264. doi: 10.1111/j.1527-3458.2001.tb00198.x

32. Lenze EJ, Mulsant BH, Blumberger DM, et al. Efficacy, safety and tolerability of augmentation pharmacotherapy with aripiprazole for treatment-resistant depression in late life: a randomised double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;386:2404-2412. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00308-6

33. Lenze EJ, Oughli HA. Antidepressant treatment for late-life depression: considering risks and benefits. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67:1555-1556. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15964

34. Bondareff W, Alpert M, Friedhoff AJ, et al: Comparison of sertraline and nortriptyline in the treatment of major depressive disorder in late life. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:729-736. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.5.729

35. Lavretsky H, Reinlieb M, St Cyr N. Citalopram, methylphenidate, or their combination in geriatric depression: a randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled trial. Am J Psych. 2015;72:561-569. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.14070889

36. Arthur A, Savva GM, Barnes LE, et al. Changing prevalence and treatment of depression among older people over two decades. Br J Psychiatry. 2020;21:49-54. doi: 10.1192/bjp.2019.193

37. Zuidersma M, Chua K-C, Hellier J, et al. Sertraline and mirtazapine versus placebo in subgroups of depression in dementia: findings from the HTA-SADD randomized controlled trial. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2019;27:920-931. doi: 10.1016/ j.jagp.2019.03.021

38. Ochs-Ross R, Wajs E, Daly EJ, et al. Comparison of long-term efficacy and safety of esketamine nasal spray plus oral antidepressant in younger versus older patients with treatment-resistant depression: post-hoc analysis of SUSTAIN-2, a long-term open-label phase 3 safety and efficacy study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2022;30:541-556. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2021.09.014

39. Devanand DP, Pelton GH, D’Antonio K, et al. Donepezil treatment in patients with depression and cognitive impairment on stable antidepressant treatment: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2018;26:1050-1060. doi: 10.1016/ j.jagp.2018.05.008

40. Obbels J, Vansteelandt K, Verwijk E, et al. MMSE changes during and after ECT in late life depression: a prospective study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2019;27:934-944. doi: 10.1016/ j.jagp.2019.04.006

41. Wagenmakers MJ, Vansteelandt K, van Exel E, et al. Transient cognitive impairment and white matter hyperintensities in severely depressed older patients treated with electroconvulsive therapy. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2021:29:1117-1128. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2020.12.028

42. Trevizol AP, Goldberger KW, Mulsant BH, et al. Unilateral and bilateral repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation for treatment-resistant late-life depression. Int J Ger Psychiatry. 2019;34:822-827. doi: 10.1002/gps.5091

43. Aben I, Verhey F, Stik J, et al. A comparative study into the one year cumulative incidence of depression after stroke and myocardial infarction. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2003;74:581-585. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.74.5.581

44. Gallo JJ, Bogner HR, Morales KH, et al. The effect of a primary care practice-based depression intervention on mortality in older adults: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:689-698. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-10-200705150-00002

45. Lee J, Jang SN, Cho SL. Gender differences in the trajectories and the risk factors of depressive symptoms in later life. Int Psychogeriatr. 2017;29:1495-1505. doi: 10.1017/S1041610217000709

46. Lee E, Cho HJ, Olmstead R, et al. Persistent sleep disturbance: a risk factor for recurrent depression in community-dwelling older adults. Sleep. 2013;36:1685-1691. doi: 10.5665/sleep.3128

47. Berk M, Woods RL, Nelson MR, et al. Effect of aspirin vs placebo on the prevention of depression in older people: a randomized clinical trial. J Am Med A Psych. 2020;77:1012-1020. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.1214

48. Okereke OI, Reynolds CF, Mischoulon D, et al. Effect of long-term vitamin D3 supplementation vs placebo on risk of depression or clinically relevant depressive symptoms and on change in mood scores: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2020;324:471-480. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.10224

Late-life depression is the onset of a major depressive disorder in an individual ≥ 60 years of age. Depressive illness compromises quality of life and is especially troublesome for older people. The prevalence of depression among individuals > 65 years of age is about 4% in women and 3% in men.1 The estimated lifetime prevalence is approximately 24% for women and 10% for men.2 Three factors account for this disparity: women exhibit greater susceptibility to depression; the illness persists longer in women than it does in men; and the probability of death related to depression is lower in women.2

Beyond its direct mental and emotional impacts, depression takes a financial toll; health care costs are higher for those with depression than for those without depression.3 Unpaid caregiver expense is the largest indirect financial burden with late-life depression.4 Additional indirect costs include less work productivity, early retirement, and diminished financial security.4

Many individuals with depression never receive treatment. Fortunately, there are many interventions in the primary care arsenal that can be used to treat older patients with depression and dramatically improve mood, comfort, and function.

The interactions of emotional and physical health

The pathophysiology of depression remains unclear. However, numerous factors are known to contribute to, exacerbate, or prolong depression among elderly populations. Insufficient social engagement and support is strongly associated with depressive mood.5 The loss of independence in giving up automobile driving can compromise self-confidence.6 Sleep difficulties predispose to, and predict, the emergence of a mood disorder, independent of other symptoms.7 Age-related hearing deficits also are associated with depression.8

There is a close relationship between emotional and physical health.9 Depression adds to the likelihood of medical illness, and somatic pathology increases the risk for mood disorders.9 Depression has been linked with obesity, frailty, diabetes, cognitive impairment, and terminal illness.9

Inflammatory markers and depression may also be related. Plasma levels of interleukin-6 and C-reactive protein were measured in a longitudinal aging study.14 A high level of interleukin-6, but not C-reactive protein, correlated with an increased prevalence of depression in older people.

Chronic cerebral ischemia can result in a “vascular depression”13 in which disruption of prefrontal systems by ischemic lesions is hypothesized to be an important factor in developing despair. Psychomotor retardation, executive dysfunction, severe disability, and a heightened risk for relapse are common features of vascular depression.15 Poststroke depression often follows a cerebrovascular episode16; the exact pathogenic mechanism is unknown.17

Continue to: A summation of common risk factors

A summation of common risk factors. A personal or family history of depression increases the risk for late-life depression. Other risk factors are female gender, bereavement, sleep disturbance, and disability.18 Poor general health, chronic pain, cognitive impairment, poor social support, and medical comorbidities with impaired functioning increase the likelihood of resultant mood disorders.18

Somatic complaints may overshadow diagnostic symptoms

Manifestations of depression include disturbed sleep and reductions in appetite, concentration, activity, and energy for daily function.19 These features, of course, may accompany medical disorders and some normal physiologic changes among elderly people. We find that while older individuals may report a sad mood, disturbed sleep, or other dysfunctions, they frequently emphasize their somatic complaints much more prominently than their emotions. This can make it difficult to recognize clinical depression.

For a diagnosis of major depression, 5 of the following 9 symptoms must be present for most of the day or nearly every day over a period of at least 2 weeks19: depressed mood; diminished interest in most activities; significant weight loss or decreased appetite; insomnia or hypersomnia; agitation or retardation; fatigue or loss of energy; feelings of worthlessness or guilt; diminished concentration; and recurrent thoughts of death or suicide.19

Planning difficulties, apathy, disability, and anhedonia frequently occur. Executive dysfunction and inefficacy of antidepressant pharmacotherapy are related to compromised frontal-striatal-limbic pathways.20 Since difficulties with planning and organization are associated with suboptimal response to antidepressant medications, a psychotherapeutic focus on these executive functions can augment drug-induced benefit.

Rule out these alternative diagnoses

Dementias can manifest as depression. Other brain pathologies, particularly Parkinson disease or stroke, also should be ruled out. Overmedication can simulate depression, so be sure to review the prescription and over-the-counter agents a patient is taking. Some medications can occasionally precipitate a clinical depression; these include stimulants, steroids, methyldopa, triptans, chemotherapeutic agents, and immunologic drugs, to name a few.19

Continue to: Pharmacotherapy, Yes, but first, consider these factors

Pharmacotherapy, Yes, but first, consider these factors

Maintaining a close patient–doctor relationship augments all therapeutic interventions. Good eye contact when listening to and counseling patients is key, as is providing close follow-up appointments.

Encourage social interactions with family and friends, which can be particularly productive. Encouraging spiritual endeavors, such as attendance at religious services, can be beneficial.21

Recommend exercise. Physical exercise yields positive outcomes22; it can enhance mood, improve sleep, and help to diminish anxiety. Encourage patients with depression to take a daily walk during the day; doing so can enhance emotional outlook, health, and even socialization.

What treatment will best serve your patient?

It’s important when caring for patients with depression to assess and address suicidal ideation. Depression with a previous suicide attempt is a strong risk factor for suicide. Inquire about suicidal intent or death wishes, access to guns, and other life-ending behaviors. Whenever suicide is an active issue, immediate crisis management is required. Psychiatric referral is an option, and hospitalization may be indicated. Advise family members to remove firearms or restrict access, be with the patient as much as possible, and assist at intervention planning and implementation.

It is worth mentioning, here, the connection between chronic pain and suicidal ideation. Pain management reduces suicidal ideation, regardless of depression severity.23

Continue to: Psychotherapy and pharmacotherapies...

Psychotherapy and pharmacotherapies offered for the treatment of depression in geriatric practices are both effective, without much difference seen in efficacy.24 Psychotherapy might include direct physician and family support to the patient or referral to a mental health professional. Base treatment choices on clinical access, patient preference, and medical contraindications and other illnesses.

Pros and cons of various pharmacotherapies

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are commonly prescribed first for elderly patients with depression.25 Escitalopram is often better tolerated than paroxetine, which exhibits muscarinic antagonism and enzyme inhibition of cytochrome P450-2D6.26 Escitalopram also has fewer pharmaceutical interactions compared with sertraline.26

Generally, when prescribing an antidepressant drug, stay with the initial choice, gradually increasing the dose as clinically needed to its maximum limit. Suicidal ideation may be worsened by too quickly switching from one antidepressant to another or by co-prescribing anxiolytic or hypnotic medicines. Benzodiazepines have addictive and disinhibiting properties and should be avoided, if possible.27 For patients with insomnia, consider initially selecting a sedating antidepressant medication such as paroxetine or mirtazapine to augment sleep.

Alternatives to SSRIs. Nonselective serotonin reuptake inhibitors have similar efficacy as SSRIs. However, escitalopram is as effective as venlafaxine (a selective serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor [SSNRI]) and is better tolerated.28 Duloxetine, another SSNRI, improves mood and often diminishes chronic pain.29 Mirtazapine, an alpha-2 antagonist, might cause fewer drug-drug interactions and is effective, well tolerated, and especially helpful for patients with anxiety or insomnia.30 Dry mouth, sedation, and weight gain are common adverse effects of mirtazapine. Obesity precautions are often necessary during mirtazapine therapy; this includes monitoring body weight and metabolic profiles, instituting dietary changes, and recommending an exercise regimen. In contrast to SSRIs, mirtazapine might induce less sexual dysfunction.31

Tricyclic antidepressant drugs can also be effective but may worsen cardiac conduction abnormalities, prostatic hypertrophy, or narrow angle glaucoma. Tricyclic antidepressants may be useful in patients without cardiac disease who have not responded to an SSRI or an SSNRI.

Continue to: The role of aripiprazole

The role of aripiprazole. Elderly patients not achieving remission from depression with antidepressant agents alone may benefit from co-prescribing aripiprazole.32 As an adjunct, aripiprazole is effective in achieving and sustaining remission

Minimize risks and maximize benefits of antidepressants by following these recommendations:

- Ascertain whether any antidepressant treatments have worked well in the past.

- Start with an SSRI if no other antidepressant treatment has worked in the past.

- Counsel patients about the need for treatment adherence. Antidepressants may take 2 weeks to 2 months to provide noticeable improvement.

- Prescribe up to the maximum drug dose if needed to enhance benefit.

- Use a mood measurement tool (eg, the Patient Health Questionnaire-9) to help evaluate treatment response.

Try a different class of drugs for patients who do not respond to treatment. For patients who have a partial response, augment with bupropion XL, mirtazapine, aripiprazole, or quetiapine.33 Sertraline and nortriptyline are similarly effective on a population-wide basis, with sertraline having less-problematic adverse effects.34 Trial-and-error treatments in practice may find one patient responding only to sertraline and another patient only to nortriptyline.

Combinations of different drug classes may provide benefit for patients not responding to a single antidepressant. In geriatric patients, combined treatment with methylphenidate and citalopram enhances mood and well-being.35 Compared with either drug alone, the combination yielded an augmented clinical response profile and a higher rate of remission. Cognitive functioning, energy, and mood improve even with methylphenidate alone, especially when fatigue is an issue. However, addictive properties limit its use to cases in which conventional antidepressant medications are not effective or indicated, and only when drug refills are closely monitored.

The challenges of advancing age. Antidepressant treatment needs increase with advanced age.36 As mentioned earlier, elderly people often have medical illnesses complicating their depression and frequently are dealing with pain from the medical illness. When dementia coexists with depression, the efficacy of pharmacotherapies is compromised.

Continue to: When drug-related interventions fail

When drug-related interventions fail, therapy ought to be more psychologically focused.37 Psychotherapy is usually helpful and is particularly indicated when recovery is suboptimal. Counseling might come from the treating physician or referral to a psychotherapist.

Nasal esketamine can be efficacious when supplementing antidepressant pharmacotherapy among older patients with treatment-resistant depression.38 Elderly individuals responding to antidepressants do not benefit from adjunctive donepezil to correct mild cognitive impairment.39 There is no advantage to off-label cholinesterase inhibitor prescribing for patients with both depression and dementia.

Other options. Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) does not cause long-term cognitive problems and is reserved for treatment-resistant cases.40 Patients with depression who also have had previous cognitive impairment often improve in mental ability following ECT.41

A promising new option. Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) is a promising, relatively new therapeutic option for treating refractory cases of depressive mood disorders. In TMS, an electromagnetic coil that creates a magnetic field is placed over the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (which is responsible for mood regulation). Referral for TMS administration may offer new hope for older patients with treatment-resistant depression.42

Keep comorbidities in mind as you address depression

Coexisting psychiatric illnesses worsen emotions. Geriatric patients are susceptible to psychiatric comorbidities that include substance abuse, obsessive-compulsive characteristics, dysfunctional eating, and panic disorder.19 Myocardial and cerebral infarctions are detrimental to mental health, especially soon after such events.43 Poststroke depression magnifies the risk for disability and mortality,16,17 yet antidepressant pharmacotherapy often enhances prognoses. Along with early intervention algorithm-based plans and inclusion of a depression care manager, antidepressants often diminish poststroke depression severity.44 Even when cancer is present, depression care reduces mortality.44 So with this in mind, persist with antidepressant treatment, which will often benefit an elderly individual with depression.

Continue to: When possible, get ahead of depression before it sets in

When possible, get ahead of depression before it sets in

Social participation and employment help to sustain an optimistic, euthymic mood.45 Maintaining good physical health, in part through consistent activity levels (including exercise), can help prevent depression. Since persistent sleep disturbance predicts depression among those with a depression history, optimizing sleep among geriatric adults can avoid or alleviate depression.46

Sleep hygiene education for patients is also helpful. A regular waking time often promotes a better sleeping schedule. Restful sleep also is more likely when an individual avoids excess caffeine, exercises during the day, and uses the bed only for sleeping (not for listening to music or watching television).

Because inflammation may precede depression, anti-inflammatory medications have been proposed as potential treatment, but such pharmacotherapies are often ineffective. Older adults generally do not benefit from low-dose aspirin administration to prevent depression.47 Low vitamin D levels can contribute to depression, yet vitamin D supplementation may not improve mood.48

Offering hope. Tell your patients that if they are feeling depressed, they should make an appointment with you, their primary care physician, because there are medications they can take and counseling they can avail themselves of that could help.

CORRESPONDENCE

Steven Lippmann, MD, University of Louisville-Psychiatry, 401 East Chestnut Street, Suite 610, Louisville, KY 40202; steven.lippmann@louisville.edu.

Late-life depression is the onset of a major depressive disorder in an individual ≥ 60 years of age. Depressive illness compromises quality of life and is especially troublesome for older people. The prevalence of depression among individuals > 65 years of age is about 4% in women and 3% in men.1 The estimated lifetime prevalence is approximately 24% for women and 10% for men.2 Three factors account for this disparity: women exhibit greater susceptibility to depression; the illness persists longer in women than it does in men; and the probability of death related to depression is lower in women.2

Beyond its direct mental and emotional impacts, depression takes a financial toll; health care costs are higher for those with depression than for those without depression.3 Unpaid caregiver expense is the largest indirect financial burden with late-life depression.4 Additional indirect costs include less work productivity, early retirement, and diminished financial security.4

Many individuals with depression never receive treatment. Fortunately, there are many interventions in the primary care arsenal that can be used to treat older patients with depression and dramatically improve mood, comfort, and function.

The interactions of emotional and physical health

The pathophysiology of depression remains unclear. However, numerous factors are known to contribute to, exacerbate, or prolong depression among elderly populations. Insufficient social engagement and support is strongly associated with depressive mood.5 The loss of independence in giving up automobile driving can compromise self-confidence.6 Sleep difficulties predispose to, and predict, the emergence of a mood disorder, independent of other symptoms.7 Age-related hearing deficits also are associated with depression.8

There is a close relationship between emotional and physical health.9 Depression adds to the likelihood of medical illness, and somatic pathology increases the risk for mood disorders.9 Depression has been linked with obesity, frailty, diabetes, cognitive impairment, and terminal illness.9

Inflammatory markers and depression may also be related. Plasma levels of interleukin-6 and C-reactive protein were measured in a longitudinal aging study.14 A high level of interleukin-6, but not C-reactive protein, correlated with an increased prevalence of depression in older people.

Chronic cerebral ischemia can result in a “vascular depression”13 in which disruption of prefrontal systems by ischemic lesions is hypothesized to be an important factor in developing despair. Psychomotor retardation, executive dysfunction, severe disability, and a heightened risk for relapse are common features of vascular depression.15 Poststroke depression often follows a cerebrovascular episode16; the exact pathogenic mechanism is unknown.17

Continue to: A summation of common risk factors

A summation of common risk factors. A personal or family history of depression increases the risk for late-life depression. Other risk factors are female gender, bereavement, sleep disturbance, and disability.18 Poor general health, chronic pain, cognitive impairment, poor social support, and medical comorbidities with impaired functioning increase the likelihood of resultant mood disorders.18

Somatic complaints may overshadow diagnostic symptoms

Manifestations of depression include disturbed sleep and reductions in appetite, concentration, activity, and energy for daily function.19 These features, of course, may accompany medical disorders and some normal physiologic changes among elderly people. We find that while older individuals may report a sad mood, disturbed sleep, or other dysfunctions, they frequently emphasize their somatic complaints much more prominently than their emotions. This can make it difficult to recognize clinical depression.

For a diagnosis of major depression, 5 of the following 9 symptoms must be present for most of the day or nearly every day over a period of at least 2 weeks19: depressed mood; diminished interest in most activities; significant weight loss or decreased appetite; insomnia or hypersomnia; agitation or retardation; fatigue or loss of energy; feelings of worthlessness or guilt; diminished concentration; and recurrent thoughts of death or suicide.19

Planning difficulties, apathy, disability, and anhedonia frequently occur. Executive dysfunction and inefficacy of antidepressant pharmacotherapy are related to compromised frontal-striatal-limbic pathways.20 Since difficulties with planning and organization are associated with suboptimal response to antidepressant medications, a psychotherapeutic focus on these executive functions can augment drug-induced benefit.

Rule out these alternative diagnoses

Dementias can manifest as depression. Other brain pathologies, particularly Parkinson disease or stroke, also should be ruled out. Overmedication can simulate depression, so be sure to review the prescription and over-the-counter agents a patient is taking. Some medications can occasionally precipitate a clinical depression; these include stimulants, steroids, methyldopa, triptans, chemotherapeutic agents, and immunologic drugs, to name a few.19

Continue to: Pharmacotherapy, Yes, but first, consider these factors

Pharmacotherapy, Yes, but first, consider these factors

Maintaining a close patient–doctor relationship augments all therapeutic interventions. Good eye contact when listening to and counseling patients is key, as is providing close follow-up appointments.

Encourage social interactions with family and friends, which can be particularly productive. Encouraging spiritual endeavors, such as attendance at religious services, can be beneficial.21

Recommend exercise. Physical exercise yields positive outcomes22; it can enhance mood, improve sleep, and help to diminish anxiety. Encourage patients with depression to take a daily walk during the day; doing so can enhance emotional outlook, health, and even socialization.

What treatment will best serve your patient?

It’s important when caring for patients with depression to assess and address suicidal ideation. Depression with a previous suicide attempt is a strong risk factor for suicide. Inquire about suicidal intent or death wishes, access to guns, and other life-ending behaviors. Whenever suicide is an active issue, immediate crisis management is required. Psychiatric referral is an option, and hospitalization may be indicated. Advise family members to remove firearms or restrict access, be with the patient as much as possible, and assist at intervention planning and implementation.

It is worth mentioning, here, the connection between chronic pain and suicidal ideation. Pain management reduces suicidal ideation, regardless of depression severity.23

Continue to: Psychotherapy and pharmacotherapies...

Psychotherapy and pharmacotherapies offered for the treatment of depression in geriatric practices are both effective, without much difference seen in efficacy.24 Psychotherapy might include direct physician and family support to the patient or referral to a mental health professional. Base treatment choices on clinical access, patient preference, and medical contraindications and other illnesses.

Pros and cons of various pharmacotherapies

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are commonly prescribed first for elderly patients with depression.25 Escitalopram is often better tolerated than paroxetine, which exhibits muscarinic antagonism and enzyme inhibition of cytochrome P450-2D6.26 Escitalopram also has fewer pharmaceutical interactions compared with sertraline.26

Generally, when prescribing an antidepressant drug, stay with the initial choice, gradually increasing the dose as clinically needed to its maximum limit. Suicidal ideation may be worsened by too quickly switching from one antidepressant to another or by co-prescribing anxiolytic or hypnotic medicines. Benzodiazepines have addictive and disinhibiting properties and should be avoided, if possible.27 For patients with insomnia, consider initially selecting a sedating antidepressant medication such as paroxetine or mirtazapine to augment sleep.

Alternatives to SSRIs. Nonselective serotonin reuptake inhibitors have similar efficacy as SSRIs. However, escitalopram is as effective as venlafaxine (a selective serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor [SSNRI]) and is better tolerated.28 Duloxetine, another SSNRI, improves mood and often diminishes chronic pain.29 Mirtazapine, an alpha-2 antagonist, might cause fewer drug-drug interactions and is effective, well tolerated, and especially helpful for patients with anxiety or insomnia.30 Dry mouth, sedation, and weight gain are common adverse effects of mirtazapine. Obesity precautions are often necessary during mirtazapine therapy; this includes monitoring body weight and metabolic profiles, instituting dietary changes, and recommending an exercise regimen. In contrast to SSRIs, mirtazapine might induce less sexual dysfunction.31

Tricyclic antidepressant drugs can also be effective but may worsen cardiac conduction abnormalities, prostatic hypertrophy, or narrow angle glaucoma. Tricyclic antidepressants may be useful in patients without cardiac disease who have not responded to an SSRI or an SSNRI.

Continue to: The role of aripiprazole

The role of aripiprazole. Elderly patients not achieving remission from depression with antidepressant agents alone may benefit from co-prescribing aripiprazole.32 As an adjunct, aripiprazole is effective in achieving and sustaining remission

Minimize risks and maximize benefits of antidepressants by following these recommendations:

- Ascertain whether any antidepressant treatments have worked well in the past.

- Start with an SSRI if no other antidepressant treatment has worked in the past.

- Counsel patients about the need for treatment adherence. Antidepressants may take 2 weeks to 2 months to provide noticeable improvement.

- Prescribe up to the maximum drug dose if needed to enhance benefit.

- Use a mood measurement tool (eg, the Patient Health Questionnaire-9) to help evaluate treatment response.

Try a different class of drugs for patients who do not respond to treatment. For patients who have a partial response, augment with bupropion XL, mirtazapine, aripiprazole, or quetiapine.33 Sertraline and nortriptyline are similarly effective on a population-wide basis, with sertraline having less-problematic adverse effects.34 Trial-and-error treatments in practice may find one patient responding only to sertraline and another patient only to nortriptyline.

Combinations of different drug classes may provide benefit for patients not responding to a single antidepressant. In geriatric patients, combined treatment with methylphenidate and citalopram enhances mood and well-being.35 Compared with either drug alone, the combination yielded an augmented clinical response profile and a higher rate of remission. Cognitive functioning, energy, and mood improve even with methylphenidate alone, especially when fatigue is an issue. However, addictive properties limit its use to cases in which conventional antidepressant medications are not effective or indicated, and only when drug refills are closely monitored.

The challenges of advancing age. Antidepressant treatment needs increase with advanced age.36 As mentioned earlier, elderly people often have medical illnesses complicating their depression and frequently are dealing with pain from the medical illness. When dementia coexists with depression, the efficacy of pharmacotherapies is compromised.

Continue to: When drug-related interventions fail

When drug-related interventions fail, therapy ought to be more psychologically focused.37 Psychotherapy is usually helpful and is particularly indicated when recovery is suboptimal. Counseling might come from the treating physician or referral to a psychotherapist.

Nasal esketamine can be efficacious when supplementing antidepressant pharmacotherapy among older patients with treatment-resistant depression.38 Elderly individuals responding to antidepressants do not benefit from adjunctive donepezil to correct mild cognitive impairment.39 There is no advantage to off-label cholinesterase inhibitor prescribing for patients with both depression and dementia.

Other options. Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) does not cause long-term cognitive problems and is reserved for treatment-resistant cases.40 Patients with depression who also have had previous cognitive impairment often improve in mental ability following ECT.41

A promising new option. Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) is a promising, relatively new therapeutic option for treating refractory cases of depressive mood disorders. In TMS, an electromagnetic coil that creates a magnetic field is placed over the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (which is responsible for mood regulation). Referral for TMS administration may offer new hope for older patients with treatment-resistant depression.42

Keep comorbidities in mind as you address depression

Coexisting psychiatric illnesses worsen emotions. Geriatric patients are susceptible to psychiatric comorbidities that include substance abuse, obsessive-compulsive characteristics, dysfunctional eating, and panic disorder.19 Myocardial and cerebral infarctions are detrimental to mental health, especially soon after such events.43 Poststroke depression magnifies the risk for disability and mortality,16,17 yet antidepressant pharmacotherapy often enhances prognoses. Along with early intervention algorithm-based plans and inclusion of a depression care manager, antidepressants often diminish poststroke depression severity.44 Even when cancer is present, depression care reduces mortality.44 So with this in mind, persist with antidepressant treatment, which will often benefit an elderly individual with depression.

Continue to: When possible, get ahead of depression before it sets in

When possible, get ahead of depression before it sets in

Social participation and employment help to sustain an optimistic, euthymic mood.45 Maintaining good physical health, in part through consistent activity levels (including exercise), can help prevent depression. Since persistent sleep disturbance predicts depression among those with a depression history, optimizing sleep among geriatric adults can avoid or alleviate depression.46

Sleep hygiene education for patients is also helpful. A regular waking time often promotes a better sleeping schedule. Restful sleep also is more likely when an individual avoids excess caffeine, exercises during the day, and uses the bed only for sleeping (not for listening to music or watching television).

Because inflammation may precede depression, anti-inflammatory medications have been proposed as potential treatment, but such pharmacotherapies are often ineffective. Older adults generally do not benefit from low-dose aspirin administration to prevent depression.47 Low vitamin D levels can contribute to depression, yet vitamin D supplementation may not improve mood.48

Offering hope. Tell your patients that if they are feeling depressed, they should make an appointment with you, their primary care physician, because there are medications they can take and counseling they can avail themselves of that could help.

CORRESPONDENCE

Steven Lippmann, MD, University of Louisville-Psychiatry, 401 East Chestnut Street, Suite 610, Louisville, KY 40202; steven.lippmann@louisville.edu.

1. Steffens DC, Skoog I, Norton MC, et al. Prevalence of depression and its treatment in an elderly population: the Cache County study. Arch Gen Psych. 2000;57:601-607. doi: 10.1001/ archpsyc.57.6.601

2. Barry LC, Allore HG, Guo Z, et al. Higher burden of depression among older women: the effect of onset, persistence, and mortality over time. Arch Gen Psych. 2008;65:172-178. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2007.17

3. Katon WJ, Lin E, Russo J, et al. Increased medical costs of a population-based sample of depressed elderly patients. Arch Gen Psych. 2003;60:897-903. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.9.897

4. Snow CE, Abrams RC. The indirect costs of late-life depression in the United States: a literature review and perspective. Geriatrics. 2016;1,30. doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics/1040030

5. George LK, Blazer DG, Hughes D, et al. Social support and the outcome of major depression. Br J Psych. 1989;154:478-485. doi: 10.1192/bjp.154.4.478

6. Fonda SJ, Wallace RB, Herzog AR. Changes in driving patterns and worsening depressive symptoms among older adults. J Gerontol Psychol Soc Sci. 2001;56:S343-S351. doi: 10.1093/geronb/56.6.s343

7. Cho HJ, Lavretsky H, Olmstead R, et al. Sleep disturbance and depression recurrence in community dwelling older adults—a prospective study. Am J Psych. 2008;165:1543-1550. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07121882

8. Golub JS, Brewster KK, Brickman AM, et al. Subclinical hearing loss is associated with depressive symptoms. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2020;28:545-556. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2019.12.008

9. Alexopoulos GS. Mechanisms and treatment of late-life depression. Focus (Am Psychiatr Publ). 2021;19:340-354. doi: 10.1176/appi.focus.19304

10. Starkstein SE, Preziosi TJ, Bolduc PL, et al. Depression in Parkinson’s disease. J Nerv Ment Disord. 1990;178:27-31. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199001000-00005

11. Gilman SE, Abraham HE. A longitudinal study of the order of onset of alcohol dependence and major depression. Drug Alco Depend. 2001;63:277-286. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(00)00216-7

12. Parmelee PA, Katz IR, Lawton MP. The relation of pain to depression among institutionalized aged. J Gerontol. 1991;46:P15-P21. doi: 10.1093/geronj/46.1.p15

13. Alexopoulos GS, Meyers BS, Young RC, et al. ‘Vascular depression’ hypothesis. Arch Gen Psych. 1997;54:915-922. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830220033006

14. Bremmer MA, Beekman AT, Deeg DJ, et al. Inflammatory markers in late-life depression: results from a population-based study. J Affect Disord. 2008;106:249-255. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.07.002

15. Taylor WD, Aizenstein HJ, Alexopoulos GS. The vascular depression hypothesis: mechanisms linking vascular disease with depression. Mol Psych. 2013;18:963-974. doi: 10.1038/mp.2013.20

16. Robinson RG, Jorge RE. Post-stroke depression: a review. Am J Psych. 2016;173:221-231. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.15030363

17. Cai W, Mueller C, Li YJ, et al. Post stroke depression and risk of stroke recurrence and mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res Rev. 2019;50:102-109. doi: 10.1016/ j.arr.2019.01.013

18. Cole MG, Dendukuri N. Risk factors for depression among elderly community subjects: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Psych. 2003;160:1147-1156. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.6.1147

19. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5). 2013:160-168.

20. Pimontel MA, Rindskopf D, Rutherford BR, et al. A meta-analysis of executive dysfunction and antidepressant treatment response in late-life depression. Am J Geriatr Psych. 2016;24:31-34. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2015.05.010

21. Koenig HG, Cohen HJ, Blazer DG, et al. Religious coping and depression in elderly hospitalized medically ill men. Am J Psychiatry. 1992;149:1693-1700. doi: 10.1176/ajp.149.12.1693

22. Blake H, Mo P, Malik S, et al. How effective are physical activity interventions for alleviating depressive symptoms in older people? A systematic review. Clin Rehabil. 2009;10:873-887. doi: 10.1177/0269215509337449

23. Bruce ML, Ten Have TR, Reynolds CF, et al. Reducing suicidal and depressive symptoms in depressed older primary care patients: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291:1081-1091. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.9.1081

24. Pinquart M, Duberstein PR, Lyness JM. Treatments for later-life depressive conditions: a meta-analytic comparison of pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:1493-1501. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.9.1493

25. Solai LK, Mulsant BH, Pollack BG. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for late-life depression: a comparative review. Drugs Aging. 2001;18:355-368. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200118050-00006

26. Sanchez C, Reines EH, Montgomery SA. A comparative review of escitalopram, paroxetine, and sertraline. Are they all alike? Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2014;29:185-196. doi: 10.1097/YIC.0000000000000023

27. Hedna K, Sundell KA, Hamidi A, et al. Antidepressants and suicidal behaviour in late life: a prospective population-based study of use patterns in new users aged 75 and above. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2018;74:201-208. doi: 10.1007/s00228-017-2360-x

28. Bielski RJ, Ventura D, Chang CC. A double-blind comparison of escitalopram and venlafaxine extended release in the treatment of major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65:1190-1196. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n0906

29. Robinson M, Oakes TM, Raskin J, et al. Acute and long-term treatment of late-life major depressive disorder: duloxetine versus placebo. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2014;22:34-45. doi: 10.1016/ j.jagp.2013.01.019

30. Holm KJ, Markham A. Mirtazapine: a review of its use in major depression. Drugs. 1999;57:607-631. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199957040-00010

31. Anttila SA, Leinonen EV. A review of the pharmacological and clinical profile of mirtazapine. CNS Drug Rev. 2001;7:249-264. doi: 10.1111/j.1527-3458.2001.tb00198.x

32. Lenze EJ, Mulsant BH, Blumberger DM, et al. Efficacy, safety and tolerability of augmentation pharmacotherapy with aripiprazole for treatment-resistant depression in late life: a randomised double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;386:2404-2412. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00308-6

33. Lenze EJ, Oughli HA. Antidepressant treatment for late-life depression: considering risks and benefits. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67:1555-1556. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15964

34. Bondareff W, Alpert M, Friedhoff AJ, et al: Comparison of sertraline and nortriptyline in the treatment of major depressive disorder in late life. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:729-736. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.5.729

35. Lavretsky H, Reinlieb M, St Cyr N. Citalopram, methylphenidate, or their combination in geriatric depression: a randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled trial. Am J Psych. 2015;72:561-569. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.14070889

36. Arthur A, Savva GM, Barnes LE, et al. Changing prevalence and treatment of depression among older people over two decades. Br J Psychiatry. 2020;21:49-54. doi: 10.1192/bjp.2019.193

37. Zuidersma M, Chua K-C, Hellier J, et al. Sertraline and mirtazapine versus placebo in subgroups of depression in dementia: findings from the HTA-SADD randomized controlled trial. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2019;27:920-931. doi: 10.1016/ j.jagp.2019.03.021

38. Ochs-Ross R, Wajs E, Daly EJ, et al. Comparison of long-term efficacy and safety of esketamine nasal spray plus oral antidepressant in younger versus older patients with treatment-resistant depression: post-hoc analysis of SUSTAIN-2, a long-term open-label phase 3 safety and efficacy study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2022;30:541-556. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2021.09.014

39. Devanand DP, Pelton GH, D’Antonio K, et al. Donepezil treatment in patients with depression and cognitive impairment on stable antidepressant treatment: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2018;26:1050-1060. doi: 10.1016/ j.jagp.2018.05.008

40. Obbels J, Vansteelandt K, Verwijk E, et al. MMSE changes during and after ECT in late life depression: a prospective study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2019;27:934-944. doi: 10.1016/ j.jagp.2019.04.006

41. Wagenmakers MJ, Vansteelandt K, van Exel E, et al. Transient cognitive impairment and white matter hyperintensities in severely depressed older patients treated with electroconvulsive therapy. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2021:29:1117-1128. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2020.12.028

42. Trevizol AP, Goldberger KW, Mulsant BH, et al. Unilateral and bilateral repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation for treatment-resistant late-life depression. Int J Ger Psychiatry. 2019;34:822-827. doi: 10.1002/gps.5091

43. Aben I, Verhey F, Stik J, et al. A comparative study into the one year cumulative incidence of depression after stroke and myocardial infarction. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2003;74:581-585. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.74.5.581

44. Gallo JJ, Bogner HR, Morales KH, et al. The effect of a primary care practice-based depression intervention on mortality in older adults: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:689-698. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-10-200705150-00002

45. Lee J, Jang SN, Cho SL. Gender differences in the trajectories and the risk factors of depressive symptoms in later life. Int Psychogeriatr. 2017;29:1495-1505. doi: 10.1017/S1041610217000709

46. Lee E, Cho HJ, Olmstead R, et al. Persistent sleep disturbance: a risk factor for recurrent depression in community-dwelling older adults. Sleep. 2013;36:1685-1691. doi: 10.5665/sleep.3128

47. Berk M, Woods RL, Nelson MR, et al. Effect of aspirin vs placebo on the prevention of depression in older people: a randomized clinical trial. J Am Med A Psych. 2020;77:1012-1020. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.1214

48. Okereke OI, Reynolds CF, Mischoulon D, et al. Effect of long-term vitamin D3 supplementation vs placebo on risk of depression or clinically relevant depressive symptoms and on change in mood scores: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2020;324:471-480. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.10224

1. Steffens DC, Skoog I, Norton MC, et al. Prevalence of depression and its treatment in an elderly population: the Cache County study. Arch Gen Psych. 2000;57:601-607. doi: 10.1001/ archpsyc.57.6.601

2. Barry LC, Allore HG, Guo Z, et al. Higher burden of depression among older women: the effect of onset, persistence, and mortality over time. Arch Gen Psych. 2008;65:172-178. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2007.17

3. Katon WJ, Lin E, Russo J, et al. Increased medical costs of a population-based sample of depressed elderly patients. Arch Gen Psych. 2003;60:897-903. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.9.897

4. Snow CE, Abrams RC. The indirect costs of late-life depression in the United States: a literature review and perspective. Geriatrics. 2016;1,30. doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics/1040030

5. George LK, Blazer DG, Hughes D, et al. Social support and the outcome of major depression. Br J Psych. 1989;154:478-485. doi: 10.1192/bjp.154.4.478

6. Fonda SJ, Wallace RB, Herzog AR. Changes in driving patterns and worsening depressive symptoms among older adults. J Gerontol Psychol Soc Sci. 2001;56:S343-S351. doi: 10.1093/geronb/56.6.s343

7. Cho HJ, Lavretsky H, Olmstead R, et al. Sleep disturbance and depression recurrence in community dwelling older adults—a prospective study. Am J Psych. 2008;165:1543-1550. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07121882

8. Golub JS, Brewster KK, Brickman AM, et al. Subclinical hearing loss is associated with depressive symptoms. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2020;28:545-556. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2019.12.008

9. Alexopoulos GS. Mechanisms and treatment of late-life depression. Focus (Am Psychiatr Publ). 2021;19:340-354. doi: 10.1176/appi.focus.19304

10. Starkstein SE, Preziosi TJ, Bolduc PL, et al. Depression in Parkinson’s disease. J Nerv Ment Disord. 1990;178:27-31. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199001000-00005

11. Gilman SE, Abraham HE. A longitudinal study of the order of onset of alcohol dependence and major depression. Drug Alco Depend. 2001;63:277-286. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(00)00216-7

12. Parmelee PA, Katz IR, Lawton MP. The relation of pain to depression among institutionalized aged. J Gerontol. 1991;46:P15-P21. doi: 10.1093/geronj/46.1.p15

13. Alexopoulos GS, Meyers BS, Young RC, et al. ‘Vascular depression’ hypothesis. Arch Gen Psych. 1997;54:915-922. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830220033006

14. Bremmer MA, Beekman AT, Deeg DJ, et al. Inflammatory markers in late-life depression: results from a population-based study. J Affect Disord. 2008;106:249-255. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.07.002

15. Taylor WD, Aizenstein HJ, Alexopoulos GS. The vascular depression hypothesis: mechanisms linking vascular disease with depression. Mol Psych. 2013;18:963-974. doi: 10.1038/mp.2013.20

16. Robinson RG, Jorge RE. Post-stroke depression: a review. Am J Psych. 2016;173:221-231. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.15030363

17. Cai W, Mueller C, Li YJ, et al. Post stroke depression and risk of stroke recurrence and mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res Rev. 2019;50:102-109. doi: 10.1016/ j.arr.2019.01.013

18. Cole MG, Dendukuri N. Risk factors for depression among elderly community subjects: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Psych. 2003;160:1147-1156. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.6.1147

19. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5). 2013:160-168.

20. Pimontel MA, Rindskopf D, Rutherford BR, et al. A meta-analysis of executive dysfunction and antidepressant treatment response in late-life depression. Am J Geriatr Psych. 2016;24:31-34. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2015.05.010

21. Koenig HG, Cohen HJ, Blazer DG, et al. Religious coping and depression in elderly hospitalized medically ill men. Am J Psychiatry. 1992;149:1693-1700. doi: 10.1176/ajp.149.12.1693

22. Blake H, Mo P, Malik S, et al. How effective are physical activity interventions for alleviating depressive symptoms in older people? A systematic review. Clin Rehabil. 2009;10:873-887. doi: 10.1177/0269215509337449

23. Bruce ML, Ten Have TR, Reynolds CF, et al. Reducing suicidal and depressive symptoms in depressed older primary care patients: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291:1081-1091. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.9.1081

24. Pinquart M, Duberstein PR, Lyness JM. Treatments for later-life depressive conditions: a meta-analytic comparison of pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:1493-1501. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.9.1493

25. Solai LK, Mulsant BH, Pollack BG. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for late-life depression: a comparative review. Drugs Aging. 2001;18:355-368. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200118050-00006

26. Sanchez C, Reines EH, Montgomery SA. A comparative review of escitalopram, paroxetine, and sertraline. Are they all alike? Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2014;29:185-196. doi: 10.1097/YIC.0000000000000023

27. Hedna K, Sundell KA, Hamidi A, et al. Antidepressants and suicidal behaviour in late life: a prospective population-based study of use patterns in new users aged 75 and above. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2018;74:201-208. doi: 10.1007/s00228-017-2360-x

28. Bielski RJ, Ventura D, Chang CC. A double-blind comparison of escitalopram and venlafaxine extended release in the treatment of major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65:1190-1196. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n0906

29. Robinson M, Oakes TM, Raskin J, et al. Acute and long-term treatment of late-life major depressive disorder: duloxetine versus placebo. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2014;22:34-45. doi: 10.1016/ j.jagp.2013.01.019

30. Holm KJ, Markham A. Mirtazapine: a review of its use in major depression. Drugs. 1999;57:607-631. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199957040-00010

31. Anttila SA, Leinonen EV. A review of the pharmacological and clinical profile of mirtazapine. CNS Drug Rev. 2001;7:249-264. doi: 10.1111/j.1527-3458.2001.tb00198.x

32. Lenze EJ, Mulsant BH, Blumberger DM, et al. Efficacy, safety and tolerability of augmentation pharmacotherapy with aripiprazole for treatment-resistant depression in late life: a randomised double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;386:2404-2412. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00308-6

33. Lenze EJ, Oughli HA. Antidepressant treatment for late-life depression: considering risks and benefits. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67:1555-1556. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15964

34. Bondareff W, Alpert M, Friedhoff AJ, et al: Comparison of sertraline and nortriptyline in the treatment of major depressive disorder in late life. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:729-736. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.5.729

35. Lavretsky H, Reinlieb M, St Cyr N. Citalopram, methylphenidate, or their combination in geriatric depression: a randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled trial. Am J Psych. 2015;72:561-569. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.14070889

36. Arthur A, Savva GM, Barnes LE, et al. Changing prevalence and treatment of depression among older people over two decades. Br J Psychiatry. 2020;21:49-54. doi: 10.1192/bjp.2019.193

37. Zuidersma M, Chua K-C, Hellier J, et al. Sertraline and mirtazapine versus placebo in subgroups of depression in dementia: findings from the HTA-SADD randomized controlled trial. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2019;27:920-931. doi: 10.1016/ j.jagp.2019.03.021

38. Ochs-Ross R, Wajs E, Daly EJ, et al. Comparison of long-term efficacy and safety of esketamine nasal spray plus oral antidepressant in younger versus older patients with treatment-resistant depression: post-hoc analysis of SUSTAIN-2, a long-term open-label phase 3 safety and efficacy study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2022;30:541-556. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2021.09.014

39. Devanand DP, Pelton GH, D’Antonio K, et al. Donepezil treatment in patients with depression and cognitive impairment on stable antidepressant treatment: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2018;26:1050-1060. doi: 10.1016/ j.jagp.2018.05.008

40. Obbels J, Vansteelandt K, Verwijk E, et al. MMSE changes during and after ECT in late life depression: a prospective study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2019;27:934-944. doi: 10.1016/ j.jagp.2019.04.006

41. Wagenmakers MJ, Vansteelandt K, van Exel E, et al. Transient cognitive impairment and white matter hyperintensities in severely depressed older patients treated with electroconvulsive therapy. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2021:29:1117-1128. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2020.12.028

42. Trevizol AP, Goldberger KW, Mulsant BH, et al. Unilateral and bilateral repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation for treatment-resistant late-life depression. Int J Ger Psychiatry. 2019;34:822-827. doi: 10.1002/gps.5091

43. Aben I, Verhey F, Stik J, et al. A comparative study into the one year cumulative incidence of depression after stroke and myocardial infarction. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2003;74:581-585. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.74.5.581

44. Gallo JJ, Bogner HR, Morales KH, et al. The effect of a primary care practice-based depression intervention on mortality in older adults: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:689-698. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-10-200705150-00002

45. Lee J, Jang SN, Cho SL. Gender differences in the trajectories and the risk factors of depressive symptoms in later life. Int Psychogeriatr. 2017;29:1495-1505. doi: 10.1017/S1041610217000709

46. Lee E, Cho HJ, Olmstead R, et al. Persistent sleep disturbance: a risk factor for recurrent depression in community-dwelling older adults. Sleep. 2013;36:1685-1691. doi: 10.5665/sleep.3128

47. Berk M, Woods RL, Nelson MR, et al. Effect of aspirin vs placebo on the prevention of depression in older people: a randomized clinical trial. J Am Med A Psych. 2020;77:1012-1020. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.1214

48. Okereke OI, Reynolds CF, Mischoulon D, et al. Effect of long-term vitamin D3 supplementation vs placebo on risk of depression or clinically relevant depressive symptoms and on change in mood scores: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2020;324:471-480. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.10224

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

› Begin treatment with a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) unless another antidepressant has worked well in the past. A

› Consider augmenting therapy with bupropion XL, mirtazapine, aripiprazole, or quetiapine for any patient who responds only partially to an SSRI. C

› Add psychotherapy to antidepressant pharmacotherapy, particularly for patients who have difficulties with executive functions such as planning and organization. B

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

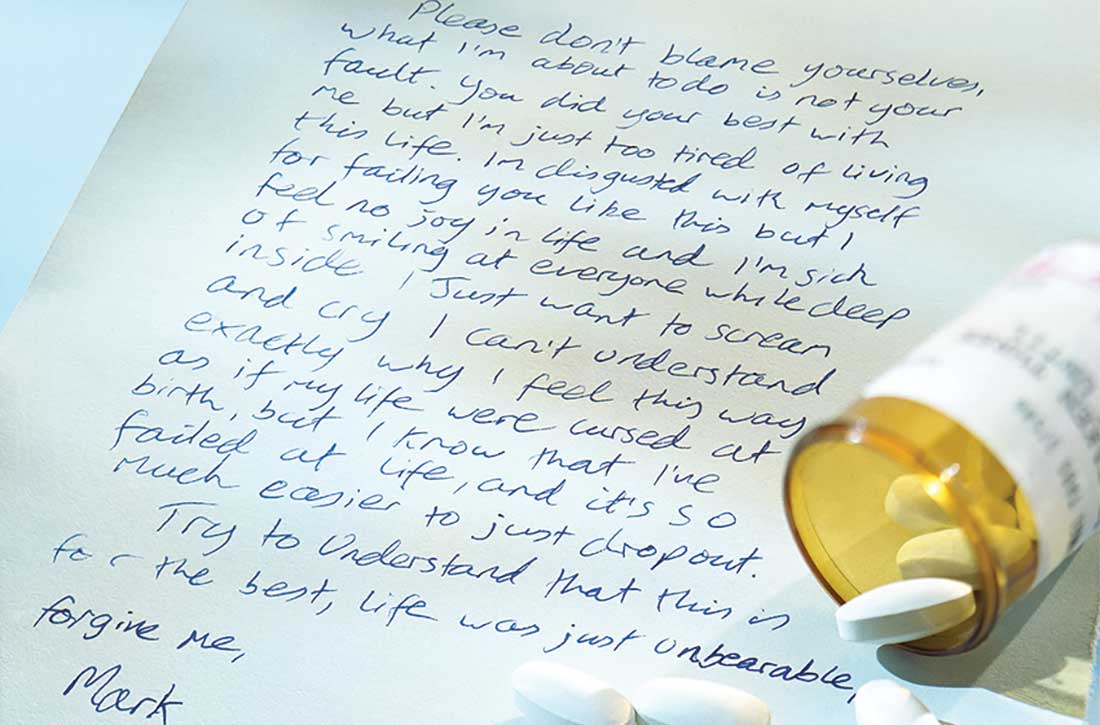

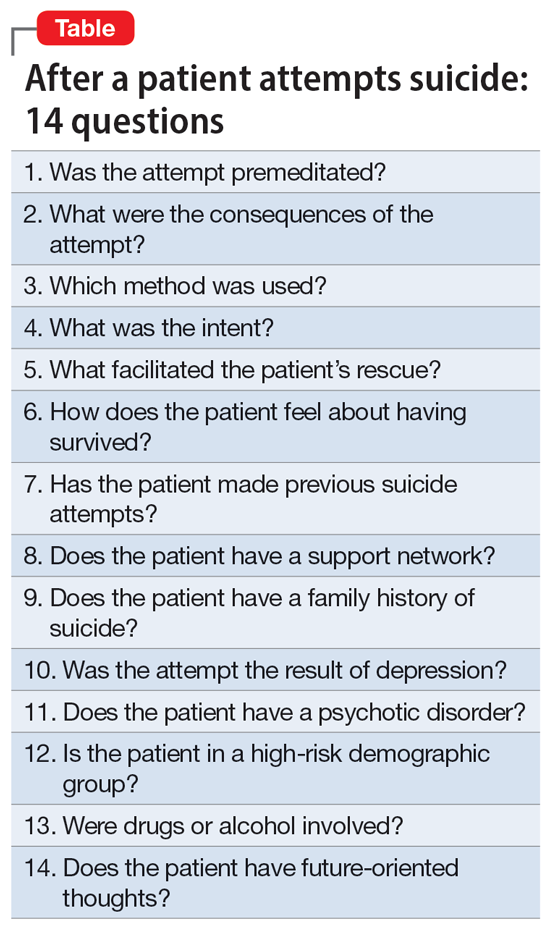

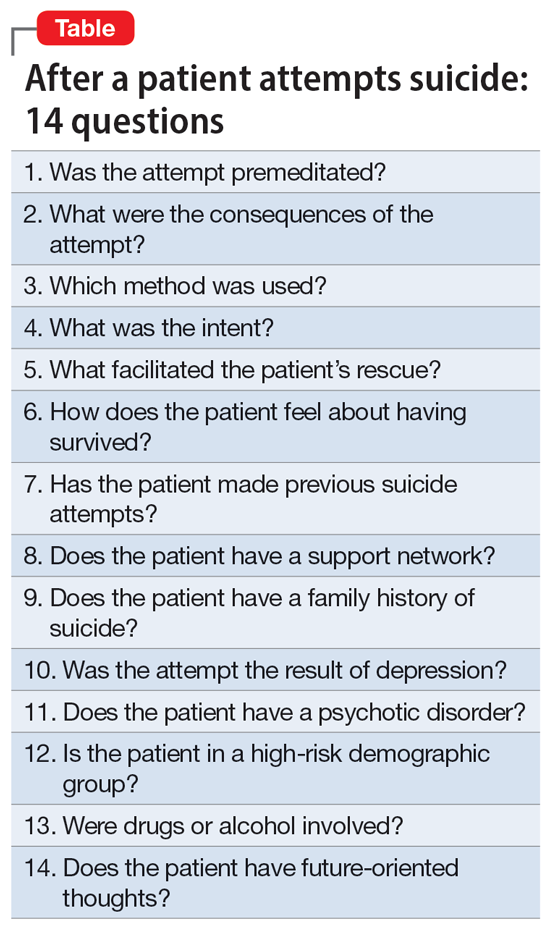

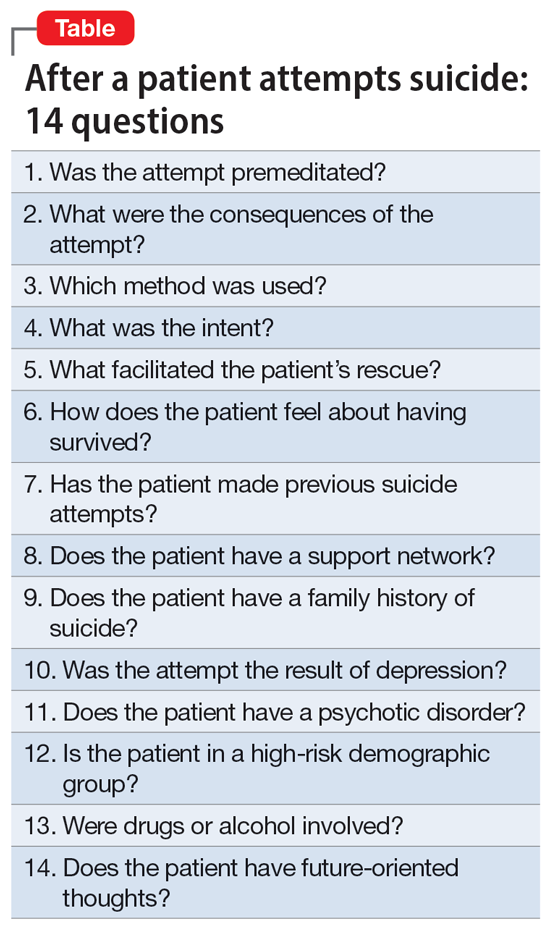

Evaluation after a suicide attempt: What to ask

In 2021, suicide was the 11th leading cause of death in the United States.1 Suicide resulted in 49,000 US deaths during 2021; it was the second most common cause of death in individuals age 10 to 34, and the fifth leading cause among children.1,2 Women are 3 to 4 times more likely than men to attempt suicide, but men are 4 times more likely to die by suicide.2

The evaluation of patients with suicidal ideation who have not made an attempt generally involves assessing 4 factors: the specific plan, access to lethal means, any recent social stressors, and the presence of a psychiatric disorder.3 The clinician should also assess which potential deterrents, such as religious beliefs or dependent children, might be present.