User login

‘Self-anesthetizing’ to cope with grief

CASE Grieving, delusional

Mr. M, age 51, is brought to the emergency department (ED) because of new-onset delusions and decreased self-care over the last 2 weeks following the sudden death of his wife. He has become expansive and grandiose, with pressured speech, increased energy, and markedly reduced sleep. Mr. M is preoccupied with the idea that he is “the first to survive a human reboot process” and says that his and his wife’s bodies and brains had been “split apart.” Mr. M has limited his food and fluid intake and lost 15 lb within the past 2 to 3 weeks.

Mr. M has no history of any affective, psychotic, or other major mental disorders or treatment. He reports that he has regularly used Cannabis over the last 10 years, and a few years ago, he started occasionally using nitrous oxide (N2O). He says that in the week following his wife’s death, he used N2O almost daily and in copious amounts. In an attempt to “self-anesthetize” himself after his wife’s funeral, he isolated himself in his bedroom and used escalating amounts of Cannabis and N2O, while continually working on a book about their life together.

At first, Mr. M shows little emotion and describes his situation as “interesting and fascinating.” He mentions that he thinks he might have been “psychotic” the week after his wife’s death, but he shows no sustained insight and immediately relapses into psychotic thinking. Over several hours in the ED, he is tearful and sad about his wife’s death. Mr. M recalls a similar experience of grief after his mother died when he was a teenager, but at that time he did not abuse substances or have psychotic symptoms. He is fully alert, fully oriented, and has no significant deficits of attention or memory.

[polldaddy:9859135]

The authors’ observations

Grief was a precipitating event, but by itself grief cannot explain psychosis. Psychotic depression is a possibility, but Mr. M’s psychotic features are incongruent with his mood. Mania would be a diagnosis of exclusion. Mr. M had no prior history of major affective illness. Mr. M was abusing Cannabis, which might independently contribute to psychosis1; however, he had been using it recreationally for 10 years without psychiatric problems. N2O, however, can cause symptoms consistent with Mr. M’s presentation.

[polldaddy:9859140]

EVALUATION Laboratory tests

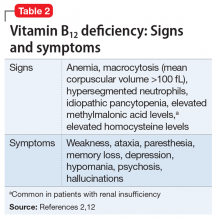

Mr. M’s physical examination is notable only for an elevated blood pressure of 196/120 mm Hg. Neurologic examination is normal. Toxicology is positive for cannabinoids and negative for amphetamines, cocaine, opiates, and phencyclidine. Chemistries are normal except for a potassium of 3.4 mEq/L (reference range, 3.7 to 5.2 mEq/L) and a blood urine nitrogen of 25 mg/dL (reference range, 6 to 20 mg/dL), which are consistent with reduced food and fluid intake. Mr. M shows no signs of anemia. Hematocrit is 42% and mean corpuscular volume is 90 fL. Syphilis screen is negative; a head CT scan is unremarkable.

The authors’ observations

N2O, also known as “laughing gas,” is routinely used by dentists and pediatric anesthesiologists, and has other medical uses. Some studies have examined an adjunctive use of N2O for pain control in the ED and during colonoscopies.3,4

In the 2013 U.S. National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 16% of respondents reported lifetime illicit use of N2O.5,6 It is readily available in tanks used in medicine and industry and in small dispensers called “whippits” that can be legally purchased. Acute effects of N2O include euphoric mood, numbness, feeling of warmth, dizziness, and auditory hallucinations.7 The anesthetic effects of N2O are linked to endogenous release of opiates, and recent research links its anxiolytic activity to the facilitation of GABAergic inhibitory and N-methyl-

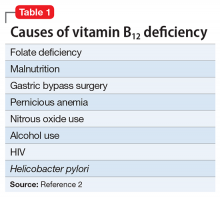

Beginning with a 1960 report of a series of patients with “megaloblastic madness,”17 there have been calls for increased awareness of the potential for vitamin B12 deficiency–induced psychiatric disorders, even in the absence of other hematologic or neurologic sequelae that would alert clinicians of the deficiency. In a case series of 141 patients with a broad array of neurologic and psychiatric symptoms associated with vitamin B12 deficiency, 40 (28%) patients had no anemia or macrocytosis.2

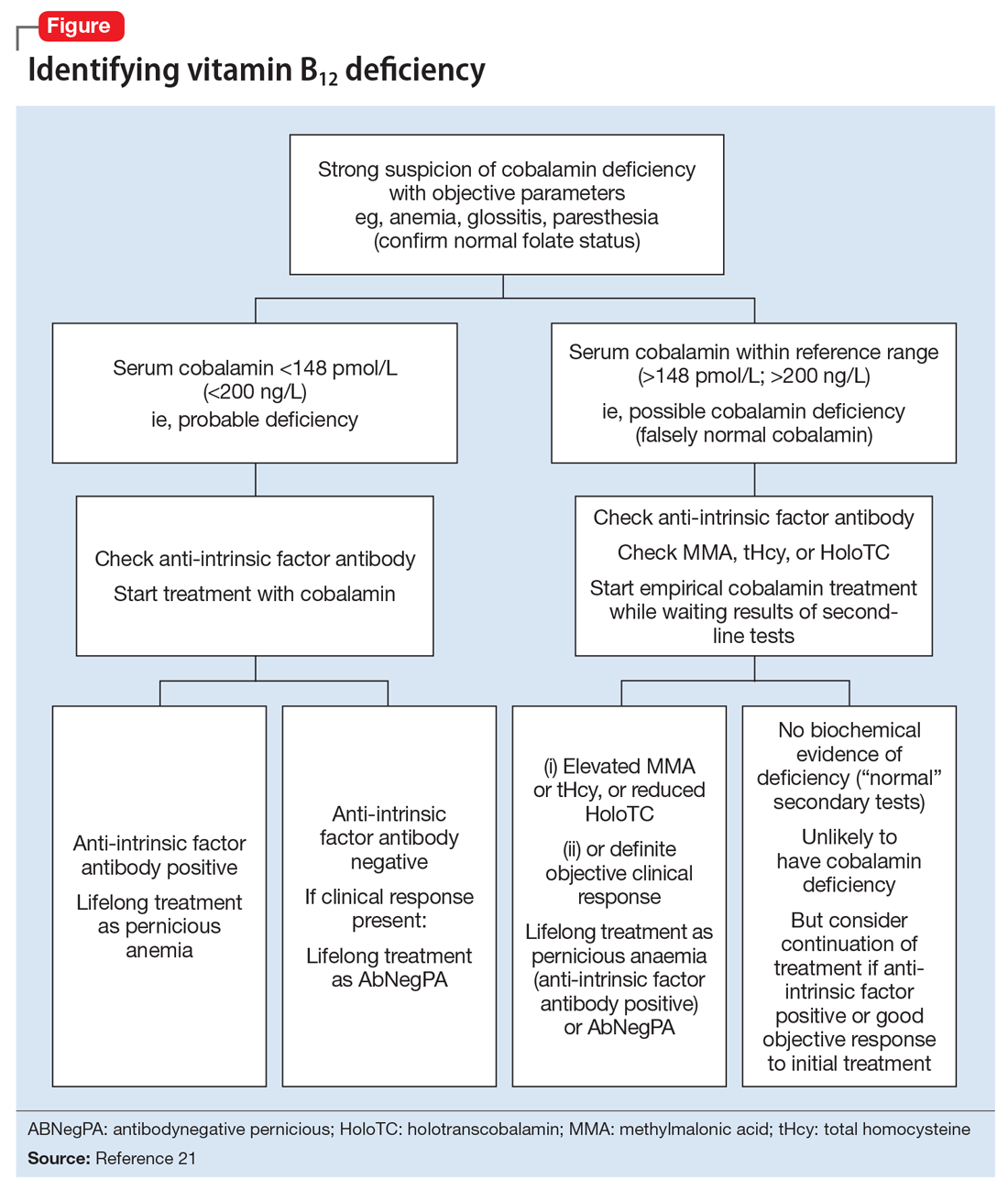

Vitamin B12-responsive psychosis has been reported as the sole manifestation of illness, without associated neurologic or hematologic symptoms, in only a few case reports. Vitamin B12 levels in these cases ranged from 75 to 236 pg/mL (reference range, 160 to 950 pg/mL).18-20 In all of these cases, the vitamin B12 deficiency was traced to dietary causes. The clinical evaluation of suspected vitamin B12 deficiency is outlined in the Figure.21 Mr. M had used Cannabis recreationally for a long time, and his Cannabis use acutely escalated with use of N2O. Long-term use of Cannabis alone is a risk factor for psychotic illness.22 Combined abuse of Cannabis and N2O has been reported to provoke psychotic illness. In a case report of a 22-year-old male who was treated for paranoid delusions, using Cannabis and 100 cartridges of N2O daily was associated with low vitamin B12 and elevated homocysteine and methylmalonic acid levels.23

Cannabis use may have played a role in Mr. M’s escalating N2O use. In a study comparing 9 active Cannabis users with 9 non-using controls, users rated the subjective effects of N2O as more intense than non-users.24 In our patient’s case, Cannabis may have played a role in both sustaining his escalating N2O abuse and potentiating its psychotomimetic effects.

It also is possible that Mr. M may have been “self-medicating” his grief with N2O. In a recent placebo-controlled crossover trial of 20 patients with treatment-resistant depression, Nagele et al25 found a significant rapid and week-long antidepressant effect of subanesthetic N2O use. A model involving NMDA receptor activation has been proposed.25,26 Zorumski et al26 further reviewed possible antidepressant mechanisms of N2O. They compared N2O with ketamine as an NMDA receptor antagonist, but also noted its distinct effects on glutaminergic and GABAergic neurotransmitter systems as well as other receptors and channels.26 However, illicit use of N2O poses toxicity dangers and has no current indication for psychiatric treatment.

TREATMENT Supplementation

Mr. M is diagnosed with substance-induced psychotic disorder. His symptoms were precipitated by an acute increase in N2O use, which has been shown to cause vitamin B12 deficiency, which we consider was likely a primary contributor to his presentation. Other potential contributing factors are premorbid hyperthymic temperament, a possible propensity to psychotic thinking under stress, the sudden death of his wife, acute grief, the potentiating role of Cannabis, dehydration, and general malnutrition. The death of a loved one is associated with an increased risk of developing substance use disorders.27

During a 15-day psychiatric hospitalization, Mr. M is given olanzapine, increased to 15 mg/d and oral vitamin B12, 1,000 mcg/d for 4 days, then IM cyanocobalamin for 7 days. Mr. M’s symptoms steadily improve, with normalization of sleep and near-total resolution of delusions. On hospital Day 14, his vitamin B12 levels are within normal limits (844 pg/mL). At discharge, Mr. M shows residual mild grandiosity, with limited insight into his illness and what caused it, but frank delusional ideation has clearly receded. He still shows some signs of grief. Mr. M is advised to stop using Cannabis and N2O and about the potential consequences of continued use.

The authors’ observations

For patients with vitamin B12 deficiency, guidelines from the National Health Service in the United Kingdom and the British Society for Haematology recommend treatment with IM hydroxocobalamin, 1,000 IU, 3 times weekly, for 2 weeks.21,28 For patients with neurologic symptoms, the British National Foundation recommends treatment with IM hydroxocobalamin, 1,000 IU, on alternative days until there is no further improvement.21

This case is a reminder for clinicians to screen for inhalant use, specifically N2O, which can precipitate vitamin B12 deficiency with psychiatric symptoms as the only presenting concern. Clinicians should consider measuring vitamin B12 levels in psychiatric patients at risk of deficiency of this nutrient, including older adults, vegetarians, and those with alimentary disorders.29,30 Dietary sources of vitamin B12 include meat, milk, egg, fish, and shellfish.31 The body can store a total of 2 to 5 mg of vitamin B12; thus, it takes 2 to 5 years to develop vitamin B12 deficiency from malabsorption and can take as long as 20 years to develop vitamin B12 deficiency from vegetarianism.32 However, by chemically inactivating vitamin B12, N2O causes a rapid functional deficiency, as was seen in our patient.

OUTCOME Improved insight

At a 1-week follow-up appointment with a psychiatrist, Mr. M has no evident psychotic symptoms. He reports that he has not used Cannabis or N2O, and he discontinues olanzapine following this visit. Two weeks later, Mr. M shows no psychotic or affective symptoms other than grief, which is appropriately expressed. His insight has improved. He commits to not using Cannabis, N2O, or any other illicit substances. Mr. M is referred back to his long-standing primary care provider with the understanding that if any psychiatric symptoms recur he will see a psychiatrist again.

1. Semple DM, McIntosh AM, Lawrie SM. Cannabis as a risk factor for psychosis: systematic review. J Psychopharmacol. 2005;19(2):187-194.

2. Lindenbaum J, Healton EB, Savage DG, et al. Neuropsychiatric disorders caused by cobalamin deficiency in the absence of anemia or macrocytosis. N Engl J Med. 1988;318(26)1720-1728.

3. Herres J, Chudnofsky CR, Manur R, et al. The use of inhaled nitrous oxide for analgesia in adult ED patients: a pilot study. Am J Emerg Med. 2016;34(2):269-273.

4. Aboumarzouk OM, Agarwal T, Syed Nong Chek SA, et al. Nitrous oxide for colonoscopy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(8):CD008506.

5. National Institute on Drug Abuse. Drug facts: inhalants. http://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/drugfacts/inhalants. Updated February 2017. Accessed September 30, 2017.

6. SAMHSA, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, National Survey on Drug Use and Health 2012 and 2013: Table 1.88C. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-DetTabs2013.pdf. Published September 4, 2017. Accessed September 30, 2017.

7. Brouette T, Anton R. Clinical review of inhalants. Am J Addict. 2001;10(1):79-94.

8. Emmanouil DE, Quock RM. Advances in understanding the actions of nitrous oxide. Anesth Prog. 2007;54(1):9-18.

9. Garakani A, Jaffe RJ, Savla D, et al. Neurologic, psychiatric, and other medical manifestations of nitrous oxide abuse: a systematic review of the case literature. Am J Addict. 2016;25(5):358-369.

10. Hathout L, El-Saden S. Nitrous oxide-induced B12 deficiency myelopathy: perspectives on the clinical biochemistry of vitamin B12. J Neurol Sci. 2011;301(1-2):1-8.

11. van Tonder SV, Ruck A, van der Westhuyzen J, et al. Dissociation of methionine synthetase (EC 2.1.1.13) activity and impairment of DNA synthesis in fruit bats (Rousettus aegyptiacus) with nitrous oxide-induced vitamin B12 deficiency. Br J Nutr. 1986;55(1):187-192.

12. Schrier SL, Mentzer WC, Tirnauer JS. Diagnosis and treatment of vitamin B12 and folate deficiency. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/clinical-manifestations-and-diagnosis-of-vitamin-b12-and-folate-deficiency. Updated September 30, 2011. Accessed September 8, 2015.

13. Sethi NK, Mullin P, Torgovnick J, et al. Nitrous oxide “whippit” abuse presenting with cobalamin responsive psychosis. J Med Toxicol. 2006;2(2):71-74.

14. Cousaert C, Heylens G, Audenaert K. Laughing gas abuse is no joke. An overview of the implications for psychiatric practice. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2013;115(7):859-862.

15. Brodsky L, Zuniga J. Nitrous oxide: a psychotogenic agent. Compr Psychiatry. 1975;16(2):185-188.

16. Wong SL, Harrison R, Mattman A, et al. Nitrous oxide (N2O)-induced acute psychosis. Can J Neurol Sci. 2014;41(5):672-674.

17. Smith AD. Megaloblastic madness. Br Med J. 1960;2(5216):1840-1845.

18. Masalha R, Chudakov B, Muhamad M, et al. Cobalamin-responsive psychosis as the sole manifestation of vitamin B12 deficiency. Isr Med Associ J. 2001;3(9):701-703.

19. Kuo SC, Yeh SB, Yeh YW, et al. Schizophrenia-like psychotic episode precipitated by cobalamin deficiency. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2009;31(6):586-588.

20. Raveendranathan D, Shiva L, Venkatasubramanian G, et al. Vitamin B12 deficiency masquerading as clozapine-resistant psychotic symptoms in schizophrenia. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2013;25(2):E34-E35.

21. Devalia V, Hamilton MS, Molloy AM; British Committee for Standards in Haematology. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of cobalamin and folate disorders. Br J Haematol. 2014;166(4):496-513.

22. Moore THM, Zammit S, Lingford-Hughes A, et al. Cannabis use and risk of psychotic or affective mental health outcomes: a systematic review. Lancet. 2007;370:319-328.

23. Garakani A, Welch AK, Jaffe RJ, et al. Psychosis and low cyanocobalamin in a patient abusing nitrous oxide and cannabis. Psychosomatics. 2014;55(6):715-719.

24. Yajnik S, Thapar P, Lichtor JL, et al. Effects of marijuana history on the subjective, psychomotor, and reinforcing effects of nitrous oxide in human. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1994;36(3):227-236.

25. Nagele P, Duma A, Kopec M, et al. Nitrous oxide for treatment-resistant major depression: a proof-of-concept trial. Biol Psychiatry. 2015;78(1):10-18.

26. Zorumski CF, Nagele P, Mennerick S, et al. Treatment-resistant major depression: rationale for NMDA receptors as targets and nitrous oxide as therapy. Front Psychiatry. 2015;6:172.

27. Shear MK. Clinical practice. Complicated grief. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(2):153-160.

28. Knechtli CJC, Crowe JN. Guidelines for the investigation & management of vitamin B12 deficiency. Royal United Hospital Bath, National Health Service. http://www.ruh.nhs.uk/For_Clinicians/departments_ruh/Pathology/documents/haematology/B12_-_advice_on_investigation_management.pdf. Accessed June 14, 2016.

29. Jayaram N, Rao MG, Narashima A, et al. Vitamin B12 levels and psychiatric symptomatology: a case series. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2013;25(2):150-152.

30. Marks PW, Zukerberg LR. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Weekly clinicopathological exercises. Case 30-2004. A 37-year-old woman with paresthesias of the arms and legs. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(13):1333-1341.

31. Watanabe F. Vitamin B12 sources and bioavailablility. Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 2007;232(10):1266-1274.

32. Green R, Kinsella LJ. Current concepts in the diagnosis of cobalamin deficiency. Neurology. 1995;45(8):1435-1440.

CASE Grieving, delusional

Mr. M, age 51, is brought to the emergency department (ED) because of new-onset delusions and decreased self-care over the last 2 weeks following the sudden death of his wife. He has become expansive and grandiose, with pressured speech, increased energy, and markedly reduced sleep. Mr. M is preoccupied with the idea that he is “the first to survive a human reboot process” and says that his and his wife’s bodies and brains had been “split apart.” Mr. M has limited his food and fluid intake and lost 15 lb within the past 2 to 3 weeks.

Mr. M has no history of any affective, psychotic, or other major mental disorders or treatment. He reports that he has regularly used Cannabis over the last 10 years, and a few years ago, he started occasionally using nitrous oxide (N2O). He says that in the week following his wife’s death, he used N2O almost daily and in copious amounts. In an attempt to “self-anesthetize” himself after his wife’s funeral, he isolated himself in his bedroom and used escalating amounts of Cannabis and N2O, while continually working on a book about their life together.

At first, Mr. M shows little emotion and describes his situation as “interesting and fascinating.” He mentions that he thinks he might have been “psychotic” the week after his wife’s death, but he shows no sustained insight and immediately relapses into psychotic thinking. Over several hours in the ED, he is tearful and sad about his wife’s death. Mr. M recalls a similar experience of grief after his mother died when he was a teenager, but at that time he did not abuse substances or have psychotic symptoms. He is fully alert, fully oriented, and has no significant deficits of attention or memory.

[polldaddy:9859135]

The authors’ observations

Grief was a precipitating event, but by itself grief cannot explain psychosis. Psychotic depression is a possibility, but Mr. M’s psychotic features are incongruent with his mood. Mania would be a diagnosis of exclusion. Mr. M had no prior history of major affective illness. Mr. M was abusing Cannabis, which might independently contribute to psychosis1; however, he had been using it recreationally for 10 years without psychiatric problems. N2O, however, can cause symptoms consistent with Mr. M’s presentation.

[polldaddy:9859140]

EVALUATION Laboratory tests

Mr. M’s physical examination is notable only for an elevated blood pressure of 196/120 mm Hg. Neurologic examination is normal. Toxicology is positive for cannabinoids and negative for amphetamines, cocaine, opiates, and phencyclidine. Chemistries are normal except for a potassium of 3.4 mEq/L (reference range, 3.7 to 5.2 mEq/L) and a blood urine nitrogen of 25 mg/dL (reference range, 6 to 20 mg/dL), which are consistent with reduced food and fluid intake. Mr. M shows no signs of anemia. Hematocrit is 42% and mean corpuscular volume is 90 fL. Syphilis screen is negative; a head CT scan is unremarkable.

The authors’ observations

N2O, also known as “laughing gas,” is routinely used by dentists and pediatric anesthesiologists, and has other medical uses. Some studies have examined an adjunctive use of N2O for pain control in the ED and during colonoscopies.3,4

In the 2013 U.S. National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 16% of respondents reported lifetime illicit use of N2O.5,6 It is readily available in tanks used in medicine and industry and in small dispensers called “whippits” that can be legally purchased. Acute effects of N2O include euphoric mood, numbness, feeling of warmth, dizziness, and auditory hallucinations.7 The anesthetic effects of N2O are linked to endogenous release of opiates, and recent research links its anxiolytic activity to the facilitation of GABAergic inhibitory and N-methyl-

Beginning with a 1960 report of a series of patients with “megaloblastic madness,”17 there have been calls for increased awareness of the potential for vitamin B12 deficiency–induced psychiatric disorders, even in the absence of other hematologic or neurologic sequelae that would alert clinicians of the deficiency. In a case series of 141 patients with a broad array of neurologic and psychiatric symptoms associated with vitamin B12 deficiency, 40 (28%) patients had no anemia or macrocytosis.2

Vitamin B12-responsive psychosis has been reported as the sole manifestation of illness, without associated neurologic or hematologic symptoms, in only a few case reports. Vitamin B12 levels in these cases ranged from 75 to 236 pg/mL (reference range, 160 to 950 pg/mL).18-20 In all of these cases, the vitamin B12 deficiency was traced to dietary causes. The clinical evaluation of suspected vitamin B12 deficiency is outlined in the Figure.21 Mr. M had used Cannabis recreationally for a long time, and his Cannabis use acutely escalated with use of N2O. Long-term use of Cannabis alone is a risk factor for psychotic illness.22 Combined abuse of Cannabis and N2O has been reported to provoke psychotic illness. In a case report of a 22-year-old male who was treated for paranoid delusions, using Cannabis and 100 cartridges of N2O daily was associated with low vitamin B12 and elevated homocysteine and methylmalonic acid levels.23

Cannabis use may have played a role in Mr. M’s escalating N2O use. In a study comparing 9 active Cannabis users with 9 non-using controls, users rated the subjective effects of N2O as more intense than non-users.24 In our patient’s case, Cannabis may have played a role in both sustaining his escalating N2O abuse and potentiating its psychotomimetic effects.

It also is possible that Mr. M may have been “self-medicating” his grief with N2O. In a recent placebo-controlled crossover trial of 20 patients with treatment-resistant depression, Nagele et al25 found a significant rapid and week-long antidepressant effect of subanesthetic N2O use. A model involving NMDA receptor activation has been proposed.25,26 Zorumski et al26 further reviewed possible antidepressant mechanisms of N2O. They compared N2O with ketamine as an NMDA receptor antagonist, but also noted its distinct effects on glutaminergic and GABAergic neurotransmitter systems as well as other receptors and channels.26 However, illicit use of N2O poses toxicity dangers and has no current indication for psychiatric treatment.

TREATMENT Supplementation

Mr. M is diagnosed with substance-induced psychotic disorder. His symptoms were precipitated by an acute increase in N2O use, which has been shown to cause vitamin B12 deficiency, which we consider was likely a primary contributor to his presentation. Other potential contributing factors are premorbid hyperthymic temperament, a possible propensity to psychotic thinking under stress, the sudden death of his wife, acute grief, the potentiating role of Cannabis, dehydration, and general malnutrition. The death of a loved one is associated with an increased risk of developing substance use disorders.27

During a 15-day psychiatric hospitalization, Mr. M is given olanzapine, increased to 15 mg/d and oral vitamin B12, 1,000 mcg/d for 4 days, then IM cyanocobalamin for 7 days. Mr. M’s symptoms steadily improve, with normalization of sleep and near-total resolution of delusions. On hospital Day 14, his vitamin B12 levels are within normal limits (844 pg/mL). At discharge, Mr. M shows residual mild grandiosity, with limited insight into his illness and what caused it, but frank delusional ideation has clearly receded. He still shows some signs of grief. Mr. M is advised to stop using Cannabis and N2O and about the potential consequences of continued use.

The authors’ observations

For patients with vitamin B12 deficiency, guidelines from the National Health Service in the United Kingdom and the British Society for Haematology recommend treatment with IM hydroxocobalamin, 1,000 IU, 3 times weekly, for 2 weeks.21,28 For patients with neurologic symptoms, the British National Foundation recommends treatment with IM hydroxocobalamin, 1,000 IU, on alternative days until there is no further improvement.21

This case is a reminder for clinicians to screen for inhalant use, specifically N2O, which can precipitate vitamin B12 deficiency with psychiatric symptoms as the only presenting concern. Clinicians should consider measuring vitamin B12 levels in psychiatric patients at risk of deficiency of this nutrient, including older adults, vegetarians, and those with alimentary disorders.29,30 Dietary sources of vitamin B12 include meat, milk, egg, fish, and shellfish.31 The body can store a total of 2 to 5 mg of vitamin B12; thus, it takes 2 to 5 years to develop vitamin B12 deficiency from malabsorption and can take as long as 20 years to develop vitamin B12 deficiency from vegetarianism.32 However, by chemically inactivating vitamin B12, N2O causes a rapid functional deficiency, as was seen in our patient.

OUTCOME Improved insight

At a 1-week follow-up appointment with a psychiatrist, Mr. M has no evident psychotic symptoms. He reports that he has not used Cannabis or N2O, and he discontinues olanzapine following this visit. Two weeks later, Mr. M shows no psychotic or affective symptoms other than grief, which is appropriately expressed. His insight has improved. He commits to not using Cannabis, N2O, or any other illicit substances. Mr. M is referred back to his long-standing primary care provider with the understanding that if any psychiatric symptoms recur he will see a psychiatrist again.

CASE Grieving, delusional

Mr. M, age 51, is brought to the emergency department (ED) because of new-onset delusions and decreased self-care over the last 2 weeks following the sudden death of his wife. He has become expansive and grandiose, with pressured speech, increased energy, and markedly reduced sleep. Mr. M is preoccupied with the idea that he is “the first to survive a human reboot process” and says that his and his wife’s bodies and brains had been “split apart.” Mr. M has limited his food and fluid intake and lost 15 lb within the past 2 to 3 weeks.

Mr. M has no history of any affective, psychotic, or other major mental disorders or treatment. He reports that he has regularly used Cannabis over the last 10 years, and a few years ago, he started occasionally using nitrous oxide (N2O). He says that in the week following his wife’s death, he used N2O almost daily and in copious amounts. In an attempt to “self-anesthetize” himself after his wife’s funeral, he isolated himself in his bedroom and used escalating amounts of Cannabis and N2O, while continually working on a book about their life together.

At first, Mr. M shows little emotion and describes his situation as “interesting and fascinating.” He mentions that he thinks he might have been “psychotic” the week after his wife’s death, but he shows no sustained insight and immediately relapses into psychotic thinking. Over several hours in the ED, he is tearful and sad about his wife’s death. Mr. M recalls a similar experience of grief after his mother died when he was a teenager, but at that time he did not abuse substances or have psychotic symptoms. He is fully alert, fully oriented, and has no significant deficits of attention or memory.

[polldaddy:9859135]

The authors’ observations

Grief was a precipitating event, but by itself grief cannot explain psychosis. Psychotic depression is a possibility, but Mr. M’s psychotic features are incongruent with his mood. Mania would be a diagnosis of exclusion. Mr. M had no prior history of major affective illness. Mr. M was abusing Cannabis, which might independently contribute to psychosis1; however, he had been using it recreationally for 10 years without psychiatric problems. N2O, however, can cause symptoms consistent with Mr. M’s presentation.

[polldaddy:9859140]

EVALUATION Laboratory tests

Mr. M’s physical examination is notable only for an elevated blood pressure of 196/120 mm Hg. Neurologic examination is normal. Toxicology is positive for cannabinoids and negative for amphetamines, cocaine, opiates, and phencyclidine. Chemistries are normal except for a potassium of 3.4 mEq/L (reference range, 3.7 to 5.2 mEq/L) and a blood urine nitrogen of 25 mg/dL (reference range, 6 to 20 mg/dL), which are consistent with reduced food and fluid intake. Mr. M shows no signs of anemia. Hematocrit is 42% and mean corpuscular volume is 90 fL. Syphilis screen is negative; a head CT scan is unremarkable.

The authors’ observations

N2O, also known as “laughing gas,” is routinely used by dentists and pediatric anesthesiologists, and has other medical uses. Some studies have examined an adjunctive use of N2O for pain control in the ED and during colonoscopies.3,4

In the 2013 U.S. National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 16% of respondents reported lifetime illicit use of N2O.5,6 It is readily available in tanks used in medicine and industry and in small dispensers called “whippits” that can be legally purchased. Acute effects of N2O include euphoric mood, numbness, feeling of warmth, dizziness, and auditory hallucinations.7 The anesthetic effects of N2O are linked to endogenous release of opiates, and recent research links its anxiolytic activity to the facilitation of GABAergic inhibitory and N-methyl-

Beginning with a 1960 report of a series of patients with “megaloblastic madness,”17 there have been calls for increased awareness of the potential for vitamin B12 deficiency–induced psychiatric disorders, even in the absence of other hematologic or neurologic sequelae that would alert clinicians of the deficiency. In a case series of 141 patients with a broad array of neurologic and psychiatric symptoms associated with vitamin B12 deficiency, 40 (28%) patients had no anemia or macrocytosis.2

Vitamin B12-responsive psychosis has been reported as the sole manifestation of illness, without associated neurologic or hematologic symptoms, in only a few case reports. Vitamin B12 levels in these cases ranged from 75 to 236 pg/mL (reference range, 160 to 950 pg/mL).18-20 In all of these cases, the vitamin B12 deficiency was traced to dietary causes. The clinical evaluation of suspected vitamin B12 deficiency is outlined in the Figure.21 Mr. M had used Cannabis recreationally for a long time, and his Cannabis use acutely escalated with use of N2O. Long-term use of Cannabis alone is a risk factor for psychotic illness.22 Combined abuse of Cannabis and N2O has been reported to provoke psychotic illness. In a case report of a 22-year-old male who was treated for paranoid delusions, using Cannabis and 100 cartridges of N2O daily was associated with low vitamin B12 and elevated homocysteine and methylmalonic acid levels.23

Cannabis use may have played a role in Mr. M’s escalating N2O use. In a study comparing 9 active Cannabis users with 9 non-using controls, users rated the subjective effects of N2O as more intense than non-users.24 In our patient’s case, Cannabis may have played a role in both sustaining his escalating N2O abuse and potentiating its psychotomimetic effects.

It also is possible that Mr. M may have been “self-medicating” his grief with N2O. In a recent placebo-controlled crossover trial of 20 patients with treatment-resistant depression, Nagele et al25 found a significant rapid and week-long antidepressant effect of subanesthetic N2O use. A model involving NMDA receptor activation has been proposed.25,26 Zorumski et al26 further reviewed possible antidepressant mechanisms of N2O. They compared N2O with ketamine as an NMDA receptor antagonist, but also noted its distinct effects on glutaminergic and GABAergic neurotransmitter systems as well as other receptors and channels.26 However, illicit use of N2O poses toxicity dangers and has no current indication for psychiatric treatment.

TREATMENT Supplementation

Mr. M is diagnosed with substance-induced psychotic disorder. His symptoms were precipitated by an acute increase in N2O use, which has been shown to cause vitamin B12 deficiency, which we consider was likely a primary contributor to his presentation. Other potential contributing factors are premorbid hyperthymic temperament, a possible propensity to psychotic thinking under stress, the sudden death of his wife, acute grief, the potentiating role of Cannabis, dehydration, and general malnutrition. The death of a loved one is associated with an increased risk of developing substance use disorders.27

During a 15-day psychiatric hospitalization, Mr. M is given olanzapine, increased to 15 mg/d and oral vitamin B12, 1,000 mcg/d for 4 days, then IM cyanocobalamin for 7 days. Mr. M’s symptoms steadily improve, with normalization of sleep and near-total resolution of delusions. On hospital Day 14, his vitamin B12 levels are within normal limits (844 pg/mL). At discharge, Mr. M shows residual mild grandiosity, with limited insight into his illness and what caused it, but frank delusional ideation has clearly receded. He still shows some signs of grief. Mr. M is advised to stop using Cannabis and N2O and about the potential consequences of continued use.

The authors’ observations

For patients with vitamin B12 deficiency, guidelines from the National Health Service in the United Kingdom and the British Society for Haematology recommend treatment with IM hydroxocobalamin, 1,000 IU, 3 times weekly, for 2 weeks.21,28 For patients with neurologic symptoms, the British National Foundation recommends treatment with IM hydroxocobalamin, 1,000 IU, on alternative days until there is no further improvement.21

This case is a reminder for clinicians to screen for inhalant use, specifically N2O, which can precipitate vitamin B12 deficiency with psychiatric symptoms as the only presenting concern. Clinicians should consider measuring vitamin B12 levels in psychiatric patients at risk of deficiency of this nutrient, including older adults, vegetarians, and those with alimentary disorders.29,30 Dietary sources of vitamin B12 include meat, milk, egg, fish, and shellfish.31 The body can store a total of 2 to 5 mg of vitamin B12; thus, it takes 2 to 5 years to develop vitamin B12 deficiency from malabsorption and can take as long as 20 years to develop vitamin B12 deficiency from vegetarianism.32 However, by chemically inactivating vitamin B12, N2O causes a rapid functional deficiency, as was seen in our patient.

OUTCOME Improved insight

At a 1-week follow-up appointment with a psychiatrist, Mr. M has no evident psychotic symptoms. He reports that he has not used Cannabis or N2O, and he discontinues olanzapine following this visit. Two weeks later, Mr. M shows no psychotic or affective symptoms other than grief, which is appropriately expressed. His insight has improved. He commits to not using Cannabis, N2O, or any other illicit substances. Mr. M is referred back to his long-standing primary care provider with the understanding that if any psychiatric symptoms recur he will see a psychiatrist again.

1. Semple DM, McIntosh AM, Lawrie SM. Cannabis as a risk factor for psychosis: systematic review. J Psychopharmacol. 2005;19(2):187-194.

2. Lindenbaum J, Healton EB, Savage DG, et al. Neuropsychiatric disorders caused by cobalamin deficiency in the absence of anemia or macrocytosis. N Engl J Med. 1988;318(26)1720-1728.

3. Herres J, Chudnofsky CR, Manur R, et al. The use of inhaled nitrous oxide for analgesia in adult ED patients: a pilot study. Am J Emerg Med. 2016;34(2):269-273.

4. Aboumarzouk OM, Agarwal T, Syed Nong Chek SA, et al. Nitrous oxide for colonoscopy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(8):CD008506.

5. National Institute on Drug Abuse. Drug facts: inhalants. http://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/drugfacts/inhalants. Updated February 2017. Accessed September 30, 2017.

6. SAMHSA, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, National Survey on Drug Use and Health 2012 and 2013: Table 1.88C. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-DetTabs2013.pdf. Published September 4, 2017. Accessed September 30, 2017.

7. Brouette T, Anton R. Clinical review of inhalants. Am J Addict. 2001;10(1):79-94.

8. Emmanouil DE, Quock RM. Advances in understanding the actions of nitrous oxide. Anesth Prog. 2007;54(1):9-18.

9. Garakani A, Jaffe RJ, Savla D, et al. Neurologic, psychiatric, and other medical manifestations of nitrous oxide abuse: a systematic review of the case literature. Am J Addict. 2016;25(5):358-369.

10. Hathout L, El-Saden S. Nitrous oxide-induced B12 deficiency myelopathy: perspectives on the clinical biochemistry of vitamin B12. J Neurol Sci. 2011;301(1-2):1-8.

11. van Tonder SV, Ruck A, van der Westhuyzen J, et al. Dissociation of methionine synthetase (EC 2.1.1.13) activity and impairment of DNA synthesis in fruit bats (Rousettus aegyptiacus) with nitrous oxide-induced vitamin B12 deficiency. Br J Nutr. 1986;55(1):187-192.

12. Schrier SL, Mentzer WC, Tirnauer JS. Diagnosis and treatment of vitamin B12 and folate deficiency. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/clinical-manifestations-and-diagnosis-of-vitamin-b12-and-folate-deficiency. Updated September 30, 2011. Accessed September 8, 2015.

13. Sethi NK, Mullin P, Torgovnick J, et al. Nitrous oxide “whippit” abuse presenting with cobalamin responsive psychosis. J Med Toxicol. 2006;2(2):71-74.

14. Cousaert C, Heylens G, Audenaert K. Laughing gas abuse is no joke. An overview of the implications for psychiatric practice. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2013;115(7):859-862.

15. Brodsky L, Zuniga J. Nitrous oxide: a psychotogenic agent. Compr Psychiatry. 1975;16(2):185-188.

16. Wong SL, Harrison R, Mattman A, et al. Nitrous oxide (N2O)-induced acute psychosis. Can J Neurol Sci. 2014;41(5):672-674.

17. Smith AD. Megaloblastic madness. Br Med J. 1960;2(5216):1840-1845.

18. Masalha R, Chudakov B, Muhamad M, et al. Cobalamin-responsive psychosis as the sole manifestation of vitamin B12 deficiency. Isr Med Associ J. 2001;3(9):701-703.

19. Kuo SC, Yeh SB, Yeh YW, et al. Schizophrenia-like psychotic episode precipitated by cobalamin deficiency. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2009;31(6):586-588.

20. Raveendranathan D, Shiva L, Venkatasubramanian G, et al. Vitamin B12 deficiency masquerading as clozapine-resistant psychotic symptoms in schizophrenia. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2013;25(2):E34-E35.

21. Devalia V, Hamilton MS, Molloy AM; British Committee for Standards in Haematology. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of cobalamin and folate disorders. Br J Haematol. 2014;166(4):496-513.

22. Moore THM, Zammit S, Lingford-Hughes A, et al. Cannabis use and risk of psychotic or affective mental health outcomes: a systematic review. Lancet. 2007;370:319-328.

23. Garakani A, Welch AK, Jaffe RJ, et al. Psychosis and low cyanocobalamin in a patient abusing nitrous oxide and cannabis. Psychosomatics. 2014;55(6):715-719.

24. Yajnik S, Thapar P, Lichtor JL, et al. Effects of marijuana history on the subjective, psychomotor, and reinforcing effects of nitrous oxide in human. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1994;36(3):227-236.

25. Nagele P, Duma A, Kopec M, et al. Nitrous oxide for treatment-resistant major depression: a proof-of-concept trial. Biol Psychiatry. 2015;78(1):10-18.

26. Zorumski CF, Nagele P, Mennerick S, et al. Treatment-resistant major depression: rationale for NMDA receptors as targets and nitrous oxide as therapy. Front Psychiatry. 2015;6:172.

27. Shear MK. Clinical practice. Complicated grief. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(2):153-160.

28. Knechtli CJC, Crowe JN. Guidelines for the investigation & management of vitamin B12 deficiency. Royal United Hospital Bath, National Health Service. http://www.ruh.nhs.uk/For_Clinicians/departments_ruh/Pathology/documents/haematology/B12_-_advice_on_investigation_management.pdf. Accessed June 14, 2016.

29. Jayaram N, Rao MG, Narashima A, et al. Vitamin B12 levels and psychiatric symptomatology: a case series. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2013;25(2):150-152.

30. Marks PW, Zukerberg LR. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Weekly clinicopathological exercises. Case 30-2004. A 37-year-old woman with paresthesias of the arms and legs. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(13):1333-1341.

31. Watanabe F. Vitamin B12 sources and bioavailablility. Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 2007;232(10):1266-1274.

32. Green R, Kinsella LJ. Current concepts in the diagnosis of cobalamin deficiency. Neurology. 1995;45(8):1435-1440.

1. Semple DM, McIntosh AM, Lawrie SM. Cannabis as a risk factor for psychosis: systematic review. J Psychopharmacol. 2005;19(2):187-194.

2. Lindenbaum J, Healton EB, Savage DG, et al. Neuropsychiatric disorders caused by cobalamin deficiency in the absence of anemia or macrocytosis. N Engl J Med. 1988;318(26)1720-1728.

3. Herres J, Chudnofsky CR, Manur R, et al. The use of inhaled nitrous oxide for analgesia in adult ED patients: a pilot study. Am J Emerg Med. 2016;34(2):269-273.

4. Aboumarzouk OM, Agarwal T, Syed Nong Chek SA, et al. Nitrous oxide for colonoscopy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(8):CD008506.

5. National Institute on Drug Abuse. Drug facts: inhalants. http://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/drugfacts/inhalants. Updated February 2017. Accessed September 30, 2017.

6. SAMHSA, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, National Survey on Drug Use and Health 2012 and 2013: Table 1.88C. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-DetTabs2013.pdf. Published September 4, 2017. Accessed September 30, 2017.

7. Brouette T, Anton R. Clinical review of inhalants. Am J Addict. 2001;10(1):79-94.

8. Emmanouil DE, Quock RM. Advances in understanding the actions of nitrous oxide. Anesth Prog. 2007;54(1):9-18.

9. Garakani A, Jaffe RJ, Savla D, et al. Neurologic, psychiatric, and other medical manifestations of nitrous oxide abuse: a systematic review of the case literature. Am J Addict. 2016;25(5):358-369.

10. Hathout L, El-Saden S. Nitrous oxide-induced B12 deficiency myelopathy: perspectives on the clinical biochemistry of vitamin B12. J Neurol Sci. 2011;301(1-2):1-8.

11. van Tonder SV, Ruck A, van der Westhuyzen J, et al. Dissociation of methionine synthetase (EC 2.1.1.13) activity and impairment of DNA synthesis in fruit bats (Rousettus aegyptiacus) with nitrous oxide-induced vitamin B12 deficiency. Br J Nutr. 1986;55(1):187-192.

12. Schrier SL, Mentzer WC, Tirnauer JS. Diagnosis and treatment of vitamin B12 and folate deficiency. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/clinical-manifestations-and-diagnosis-of-vitamin-b12-and-folate-deficiency. Updated September 30, 2011. Accessed September 8, 2015.

13. Sethi NK, Mullin P, Torgovnick J, et al. Nitrous oxide “whippit” abuse presenting with cobalamin responsive psychosis. J Med Toxicol. 2006;2(2):71-74.

14. Cousaert C, Heylens G, Audenaert K. Laughing gas abuse is no joke. An overview of the implications for psychiatric practice. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2013;115(7):859-862.

15. Brodsky L, Zuniga J. Nitrous oxide: a psychotogenic agent. Compr Psychiatry. 1975;16(2):185-188.

16. Wong SL, Harrison R, Mattman A, et al. Nitrous oxide (N2O)-induced acute psychosis. Can J Neurol Sci. 2014;41(5):672-674.

17. Smith AD. Megaloblastic madness. Br Med J. 1960;2(5216):1840-1845.

18. Masalha R, Chudakov B, Muhamad M, et al. Cobalamin-responsive psychosis as the sole manifestation of vitamin B12 deficiency. Isr Med Associ J. 2001;3(9):701-703.

19. Kuo SC, Yeh SB, Yeh YW, et al. Schizophrenia-like psychotic episode precipitated by cobalamin deficiency. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2009;31(6):586-588.

20. Raveendranathan D, Shiva L, Venkatasubramanian G, et al. Vitamin B12 deficiency masquerading as clozapine-resistant psychotic symptoms in schizophrenia. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2013;25(2):E34-E35.

21. Devalia V, Hamilton MS, Molloy AM; British Committee for Standards in Haematology. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of cobalamin and folate disorders. Br J Haematol. 2014;166(4):496-513.

22. Moore THM, Zammit S, Lingford-Hughes A, et al. Cannabis use and risk of psychotic or affective mental health outcomes: a systematic review. Lancet. 2007;370:319-328.

23. Garakani A, Welch AK, Jaffe RJ, et al. Psychosis and low cyanocobalamin in a patient abusing nitrous oxide and cannabis. Psychosomatics. 2014;55(6):715-719.

24. Yajnik S, Thapar P, Lichtor JL, et al. Effects of marijuana history on the subjective, psychomotor, and reinforcing effects of nitrous oxide in human. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1994;36(3):227-236.

25. Nagele P, Duma A, Kopec M, et al. Nitrous oxide for treatment-resistant major depression: a proof-of-concept trial. Biol Psychiatry. 2015;78(1):10-18.

26. Zorumski CF, Nagele P, Mennerick S, et al. Treatment-resistant major depression: rationale for NMDA receptors as targets and nitrous oxide as therapy. Front Psychiatry. 2015;6:172.

27. Shear MK. Clinical practice. Complicated grief. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(2):153-160.

28. Knechtli CJC, Crowe JN. Guidelines for the investigation & management of vitamin B12 deficiency. Royal United Hospital Bath, National Health Service. http://www.ruh.nhs.uk/For_Clinicians/departments_ruh/Pathology/documents/haematology/B12_-_advice_on_investigation_management.pdf. Accessed June 14, 2016.

29. Jayaram N, Rao MG, Narashima A, et al. Vitamin B12 levels and psychiatric symptomatology: a case series. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2013;25(2):150-152.

30. Marks PW, Zukerberg LR. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Weekly clinicopathological exercises. Case 30-2004. A 37-year-old woman with paresthesias of the arms and legs. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(13):1333-1341.

31. Watanabe F. Vitamin B12 sources and bioavailablility. Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 2007;232(10):1266-1274.

32. Green R, Kinsella LJ. Current concepts in the diagnosis of cobalamin deficiency. Neurology. 1995;45(8):1435-1440.

The girl who couldn’t stop stealing

CASE A lifelong habit

Ms. B, age 14, has diagnoses of attention-deficit/hyperactive disorder (ADHD) and oppositional defiant disorder, and is taking extended-release (ER) methylphenidate, 36 mg/d. Her mother brings her to the hospital with concerns that Ms. B has been stealing small objects, such as money, toys, and pencils from home, school, and her peers, even though she does not need them and her family can afford to buy them for her. Ms. B’s mother routinely searches her daughter when she leaves the house and when she returns and frequently finds things in Ms. B’s possession that do not belong to her.

The mother reports that Ms. B’s stealing has been a lifelong habit that worsened after Ms. B’s father died in a car accident last year.

Ms. B does not volunteer any information about her stealing. She is admitted to a partial hospitalization program for further evaluation and treatment.

[polldaddy:9837962]

EVALUATION Continued stealing

A week later, Ms. B remains reluctant to talk about her stealing habit. However, once a therapeutic alliance is established, she reveals that she experiences increased anxiety before stealing and feels pleasure during the theft. Her methylphenidate ER dosage is increased to 54 mg/d in an attempt to address poor impulse control and subsequent stealing behavior. Her ADHD symptoms are controlled, and she does not exhibit poor impulse control in any situation other than stealing.

However, Ms. B continues to have poor insight and impaired judgment about her behavior. During treatment, Ms. B steals markers from the psychiatrist’s office, which later are found in her bag. When the staff convinces Ms. B to return the markers to the psychiatrist, she denies knowing how they got there. Behavioral interventions, including covert sensitization, systemic desensitization, positive reinforcement, body and bag search, and reminders, occur consistently as part of treatment, but have little effect on her symptoms.

The author’s observations

Risk-taking and novelty-seeking behaviors are common in adolescent patients. Impulsivity, instant reward-seeking behavior, and poor judgment can lead to stealing in this population, but this behavior is not necessarily indicative of kleptomania.

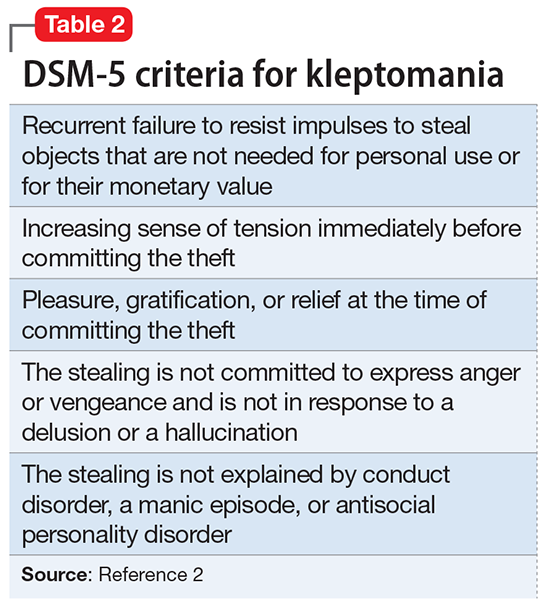

Kleptomania is the recurrent failure to resist impulses to steal objects.2 It differs from other forms of stealing in that the objects stolen by a patient with kleptomania are not needed for personal use or for their monetary value. Kleptomania usually begins in early adolescence, is found in about 0.5% of the general population, and is more common among females.3

There are 2 important theories to explain kleptomania:

- The psychoanalytical theory explains kleptomania as an immature defense against unconscious impulses, conflicts, and desires of destruction. By stealing, the individual protects the self from narcissistic injury and disintegration. The frantic search for objects helps to divert self-destructive aggressiveness and allows for the preservation of the self.4

- The biological model indicates that individuals with kleptomania have a significant deficit of white matter in inferior frontal regions and poor integrity of the tracts connecting the limbic system to the thalamus and to the prefrontal cortex.5 Reward system circuitry (ventral tegmental area–nucleus accumbens–orbital frontal cortex) is likely to be involved in impulse control disorders including kleptomania.6

Comorbidity. Kleptomania often is comorbid with substance use disorder (SUD), obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), and compulsive shopping, as well as depression, anxiety disorders, bulimia nervosa, and impulse control and conduct disorders.3,6

Kleptomania shares many characteristics with SUD, including continued engagement in a behavior despite negative consequences and the temporary reduction in urges after the behavior’s completion, followed by a return of the urge to steal. There also is a bidirectional relationship between OCD and kleptomania. Individuals with both disorders frequently engage in excessive and unnecessary rituals even when it is ego-dystonic. First-degree relatives of kleptomania patients have high rates of SUD and OCD.3

Serotonin, dopamine, and opioid pathways play a role in both kleptomania and other behavioral addictions.6 Clinicians should be cautious in treating comorbid disorders with stimulants. These agents may help patients with high impulsivity, but lead to disinhibition and worsen impulse control in patients with low impulsivity.7

TREATMENT Naltrexone

The psychiatrist discusses pharmacologic options to treat kleptomania with Ms. B and her mother. After considering the risks, benefits, adverse effects, and alternative treatments (including the option of no pharmacologic treatment), the mother consents and Ms. B assents to treatment with naltrexone, 25 mg/d. Before starting this medication, both the mother and Ms. B receive detailed psychoeducation describing naltrexone’s interactions with opioids. They are told that if Ms. B has a traumatic injury, they should inform the treatment team that she is taking naltrexone, which can acutely precipitate opiate withdrawal.

Before initiating pharmacotherapy, a comprehensive metabolic profile is obtained, and all values are within the normal range. After 1 week, naltrexone is increased to 50 mg/d. The medication is well tolerated, without any adverse effects.

[polldaddy:9837976]

The author’s observations

Behavioral interventions, such as covert sensitization and systemic desensitization, often are used to treat kleptomania.8 There are no FDA-approved medications for this condition. Opioid antagonists have been considered for the treatment of kleptomania.7

Mu-opioid receptors exist in highest concentrations in presynaptic neurons in the periaqueductal gray region and spinal cord and have high affinity for enkephalins and beta-endorphins. They also are involved in the reward and pleasure pathway. This neurocircuit is implicated in behavioral addiction.9

Naltrexone is an antagonist at μ-opioid receptors. It blocks the binding of endogenous and exogenous opioids at the receptors, particularly at the ventral tegmental area. By blocking the μ-receptor, naltrexone inhibits the processing of the reward and pleasure pathway involved in kleptomania. Naltrexone binds to these receptors, preventing the euphoric effects of behavioral addictions.10 This medication works best in conjunction with behavioral interventions.8

Naltrexone is a Schedule II drug. Use of naltrexone to treat kleptomania or other impulse control disorders is an off-label use of the medication. Naltrexone should not be prescribed to patients who are receiving opiates because it can cause acute opiate withdrawal.

Liver function tests should be monitored in all patients taking naltrexone. If liver function levels begin to rise, naltrexone should be discontinued. Naltrexone should be used with caution in patients with preexisting liver disease.11

OUTCOME Marked improvement

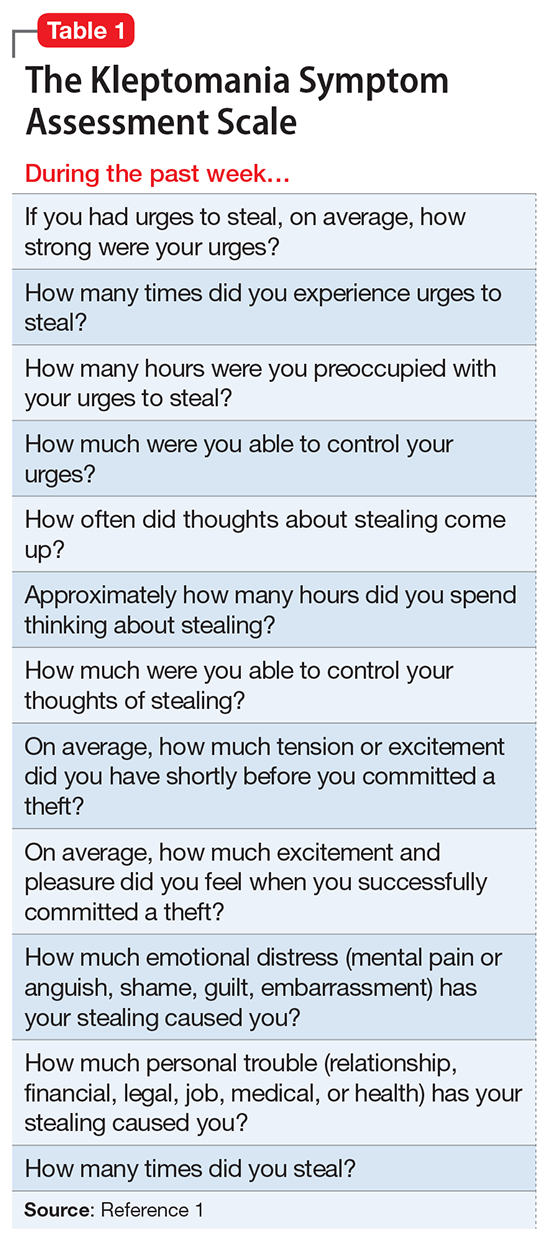

Ms. B’s K-SAS scores are evaluated 2 weeks after starting naltrexone. The results show a marked reduction in the urge to steal and in stealing behavior, and Ms. B’s mother reports no incidents of stealing in the previous week.

Ms. B is maintained on naltrexone, 50 mg/d, for 2 months. On repeated K-SAS scores, her mother rates Ms. B’s symptoms “very much improved” with “occasional” stealing. Ms. B is discharged from the intensive outpatient program.

1. Christianini AR, Conti MA, Hearst N, et al. Treating kleptomania: cross-cultural adaptation of the Kleptomania Symptom Assessment Scale and assessment of an outpatient program. Compr Psychiatry. 2015;56:289-294.

2. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

3. Talih FR. Kleptomania and potential exacerbating factors: a review and case report. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2011;8(10):35-39.

4. Cierpka M. Psychodynamics of neurotically-induced kleptomania [in German]. Psychiatr Prax. 1986;13(3):94-103.

5. Grant JE, Correia S, Brennan-Krohn T. White matter integrity in kleptomania: a pilot study. Psychiatry Res. 2006;147(2-3):233-237.

6. Grant JE, Odlaug BL, Kim SW. Kleptomania: clinical characteristics and relationship to substance use disorders. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2010;36(5):291-295.

7. Zack M, Poulos CX. Effects of the atypical stimulant modafinil on a brief gambling episode in pathological gamblers with high vs. low impulsivity. J Psychopharmacol. 2009;23(6):660-671.

8. Grant JE. Understanding and treating kleptomania: new models and new treatments. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci. 2006;43(2):81-87.

9. Potenza MN. Should addictive disorders include non-substance-related conditions? Addiction. 2006;101(suppl 1):142-151.

10. Grant JE, Kim SW. An open-label study of naltrexone in the treatment of kleptomania. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63(4):349-356.

11. Pfohl DN, Allen JI, Atkinson RL, et al. Naltrexone hydrochloride (Trexan): a review of serum transaminase elevations at high dosage. NIDA Res Monogr. 1986;67:66-72.

CASE A lifelong habit

Ms. B, age 14, has diagnoses of attention-deficit/hyperactive disorder (ADHD) and oppositional defiant disorder, and is taking extended-release (ER) methylphenidate, 36 mg/d. Her mother brings her to the hospital with concerns that Ms. B has been stealing small objects, such as money, toys, and pencils from home, school, and her peers, even though she does not need them and her family can afford to buy them for her. Ms. B’s mother routinely searches her daughter when she leaves the house and when she returns and frequently finds things in Ms. B’s possession that do not belong to her.

The mother reports that Ms. B’s stealing has been a lifelong habit that worsened after Ms. B’s father died in a car accident last year.

Ms. B does not volunteer any information about her stealing. She is admitted to a partial hospitalization program for further evaluation and treatment.

[polldaddy:9837962]

EVALUATION Continued stealing

A week later, Ms. B remains reluctant to talk about her stealing habit. However, once a therapeutic alliance is established, she reveals that she experiences increased anxiety before stealing and feels pleasure during the theft. Her methylphenidate ER dosage is increased to 54 mg/d in an attempt to address poor impulse control and subsequent stealing behavior. Her ADHD symptoms are controlled, and she does not exhibit poor impulse control in any situation other than stealing.

However, Ms. B continues to have poor insight and impaired judgment about her behavior. During treatment, Ms. B steals markers from the psychiatrist’s office, which later are found in her bag. When the staff convinces Ms. B to return the markers to the psychiatrist, she denies knowing how they got there. Behavioral interventions, including covert sensitization, systemic desensitization, positive reinforcement, body and bag search, and reminders, occur consistently as part of treatment, but have little effect on her symptoms.

The author’s observations

Risk-taking and novelty-seeking behaviors are common in adolescent patients. Impulsivity, instant reward-seeking behavior, and poor judgment can lead to stealing in this population, but this behavior is not necessarily indicative of kleptomania.

Kleptomania is the recurrent failure to resist impulses to steal objects.2 It differs from other forms of stealing in that the objects stolen by a patient with kleptomania are not needed for personal use or for their monetary value. Kleptomania usually begins in early adolescence, is found in about 0.5% of the general population, and is more common among females.3

There are 2 important theories to explain kleptomania:

- The psychoanalytical theory explains kleptomania as an immature defense against unconscious impulses, conflicts, and desires of destruction. By stealing, the individual protects the self from narcissistic injury and disintegration. The frantic search for objects helps to divert self-destructive aggressiveness and allows for the preservation of the self.4

- The biological model indicates that individuals with kleptomania have a significant deficit of white matter in inferior frontal regions and poor integrity of the tracts connecting the limbic system to the thalamus and to the prefrontal cortex.5 Reward system circuitry (ventral tegmental area–nucleus accumbens–orbital frontal cortex) is likely to be involved in impulse control disorders including kleptomania.6

Comorbidity. Kleptomania often is comorbid with substance use disorder (SUD), obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), and compulsive shopping, as well as depression, anxiety disorders, bulimia nervosa, and impulse control and conduct disorders.3,6

Kleptomania shares many characteristics with SUD, including continued engagement in a behavior despite negative consequences and the temporary reduction in urges after the behavior’s completion, followed by a return of the urge to steal. There also is a bidirectional relationship between OCD and kleptomania. Individuals with both disorders frequently engage in excessive and unnecessary rituals even when it is ego-dystonic. First-degree relatives of kleptomania patients have high rates of SUD and OCD.3

Serotonin, dopamine, and opioid pathways play a role in both kleptomania and other behavioral addictions.6 Clinicians should be cautious in treating comorbid disorders with stimulants. These agents may help patients with high impulsivity, but lead to disinhibition and worsen impulse control in patients with low impulsivity.7

TREATMENT Naltrexone

The psychiatrist discusses pharmacologic options to treat kleptomania with Ms. B and her mother. After considering the risks, benefits, adverse effects, and alternative treatments (including the option of no pharmacologic treatment), the mother consents and Ms. B assents to treatment with naltrexone, 25 mg/d. Before starting this medication, both the mother and Ms. B receive detailed psychoeducation describing naltrexone’s interactions with opioids. They are told that if Ms. B has a traumatic injury, they should inform the treatment team that she is taking naltrexone, which can acutely precipitate opiate withdrawal.

Before initiating pharmacotherapy, a comprehensive metabolic profile is obtained, and all values are within the normal range. After 1 week, naltrexone is increased to 50 mg/d. The medication is well tolerated, without any adverse effects.

[polldaddy:9837976]

The author’s observations

Behavioral interventions, such as covert sensitization and systemic desensitization, often are used to treat kleptomania.8 There are no FDA-approved medications for this condition. Opioid antagonists have been considered for the treatment of kleptomania.7

Mu-opioid receptors exist in highest concentrations in presynaptic neurons in the periaqueductal gray region and spinal cord and have high affinity for enkephalins and beta-endorphins. They also are involved in the reward and pleasure pathway. This neurocircuit is implicated in behavioral addiction.9

Naltrexone is an antagonist at μ-opioid receptors. It blocks the binding of endogenous and exogenous opioids at the receptors, particularly at the ventral tegmental area. By blocking the μ-receptor, naltrexone inhibits the processing of the reward and pleasure pathway involved in kleptomania. Naltrexone binds to these receptors, preventing the euphoric effects of behavioral addictions.10 This medication works best in conjunction with behavioral interventions.8

Naltrexone is a Schedule II drug. Use of naltrexone to treat kleptomania or other impulse control disorders is an off-label use of the medication. Naltrexone should not be prescribed to patients who are receiving opiates because it can cause acute opiate withdrawal.

Liver function tests should be monitored in all patients taking naltrexone. If liver function levels begin to rise, naltrexone should be discontinued. Naltrexone should be used with caution in patients with preexisting liver disease.11

OUTCOME Marked improvement

Ms. B’s K-SAS scores are evaluated 2 weeks after starting naltrexone. The results show a marked reduction in the urge to steal and in stealing behavior, and Ms. B’s mother reports no incidents of stealing in the previous week.

Ms. B is maintained on naltrexone, 50 mg/d, for 2 months. On repeated K-SAS scores, her mother rates Ms. B’s symptoms “very much improved” with “occasional” stealing. Ms. B is discharged from the intensive outpatient program.

CASE A lifelong habit

Ms. B, age 14, has diagnoses of attention-deficit/hyperactive disorder (ADHD) and oppositional defiant disorder, and is taking extended-release (ER) methylphenidate, 36 mg/d. Her mother brings her to the hospital with concerns that Ms. B has been stealing small objects, such as money, toys, and pencils from home, school, and her peers, even though she does not need them and her family can afford to buy them for her. Ms. B’s mother routinely searches her daughter when she leaves the house and when she returns and frequently finds things in Ms. B’s possession that do not belong to her.

The mother reports that Ms. B’s stealing has been a lifelong habit that worsened after Ms. B’s father died in a car accident last year.

Ms. B does not volunteer any information about her stealing. She is admitted to a partial hospitalization program for further evaluation and treatment.

[polldaddy:9837962]

EVALUATION Continued stealing

A week later, Ms. B remains reluctant to talk about her stealing habit. However, once a therapeutic alliance is established, she reveals that she experiences increased anxiety before stealing and feels pleasure during the theft. Her methylphenidate ER dosage is increased to 54 mg/d in an attempt to address poor impulse control and subsequent stealing behavior. Her ADHD symptoms are controlled, and she does not exhibit poor impulse control in any situation other than stealing.

However, Ms. B continues to have poor insight and impaired judgment about her behavior. During treatment, Ms. B steals markers from the psychiatrist’s office, which later are found in her bag. When the staff convinces Ms. B to return the markers to the psychiatrist, she denies knowing how they got there. Behavioral interventions, including covert sensitization, systemic desensitization, positive reinforcement, body and bag search, and reminders, occur consistently as part of treatment, but have little effect on her symptoms.

The author’s observations

Risk-taking and novelty-seeking behaviors are common in adolescent patients. Impulsivity, instant reward-seeking behavior, and poor judgment can lead to stealing in this population, but this behavior is not necessarily indicative of kleptomania.

Kleptomania is the recurrent failure to resist impulses to steal objects.2 It differs from other forms of stealing in that the objects stolen by a patient with kleptomania are not needed for personal use or for their monetary value. Kleptomania usually begins in early adolescence, is found in about 0.5% of the general population, and is more common among females.3

There are 2 important theories to explain kleptomania:

- The psychoanalytical theory explains kleptomania as an immature defense against unconscious impulses, conflicts, and desires of destruction. By stealing, the individual protects the self from narcissistic injury and disintegration. The frantic search for objects helps to divert self-destructive aggressiveness and allows for the preservation of the self.4

- The biological model indicates that individuals with kleptomania have a significant deficit of white matter in inferior frontal regions and poor integrity of the tracts connecting the limbic system to the thalamus and to the prefrontal cortex.5 Reward system circuitry (ventral tegmental area–nucleus accumbens–orbital frontal cortex) is likely to be involved in impulse control disorders including kleptomania.6

Comorbidity. Kleptomania often is comorbid with substance use disorder (SUD), obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), and compulsive shopping, as well as depression, anxiety disorders, bulimia nervosa, and impulse control and conduct disorders.3,6

Kleptomania shares many characteristics with SUD, including continued engagement in a behavior despite negative consequences and the temporary reduction in urges after the behavior’s completion, followed by a return of the urge to steal. There also is a bidirectional relationship between OCD and kleptomania. Individuals with both disorders frequently engage in excessive and unnecessary rituals even when it is ego-dystonic. First-degree relatives of kleptomania patients have high rates of SUD and OCD.3

Serotonin, dopamine, and opioid pathways play a role in both kleptomania and other behavioral addictions.6 Clinicians should be cautious in treating comorbid disorders with stimulants. These agents may help patients with high impulsivity, but lead to disinhibition and worsen impulse control in patients with low impulsivity.7

TREATMENT Naltrexone

The psychiatrist discusses pharmacologic options to treat kleptomania with Ms. B and her mother. After considering the risks, benefits, adverse effects, and alternative treatments (including the option of no pharmacologic treatment), the mother consents and Ms. B assents to treatment with naltrexone, 25 mg/d. Before starting this medication, both the mother and Ms. B receive detailed psychoeducation describing naltrexone’s interactions with opioids. They are told that if Ms. B has a traumatic injury, they should inform the treatment team that she is taking naltrexone, which can acutely precipitate opiate withdrawal.

Before initiating pharmacotherapy, a comprehensive metabolic profile is obtained, and all values are within the normal range. After 1 week, naltrexone is increased to 50 mg/d. The medication is well tolerated, without any adverse effects.

[polldaddy:9837976]

The author’s observations

Behavioral interventions, such as covert sensitization and systemic desensitization, often are used to treat kleptomania.8 There are no FDA-approved medications for this condition. Opioid antagonists have been considered for the treatment of kleptomania.7

Mu-opioid receptors exist in highest concentrations in presynaptic neurons in the periaqueductal gray region and spinal cord and have high affinity for enkephalins and beta-endorphins. They also are involved in the reward and pleasure pathway. This neurocircuit is implicated in behavioral addiction.9

Naltrexone is an antagonist at μ-opioid receptors. It blocks the binding of endogenous and exogenous opioids at the receptors, particularly at the ventral tegmental area. By blocking the μ-receptor, naltrexone inhibits the processing of the reward and pleasure pathway involved in kleptomania. Naltrexone binds to these receptors, preventing the euphoric effects of behavioral addictions.10 This medication works best in conjunction with behavioral interventions.8

Naltrexone is a Schedule II drug. Use of naltrexone to treat kleptomania or other impulse control disorders is an off-label use of the medication. Naltrexone should not be prescribed to patients who are receiving opiates because it can cause acute opiate withdrawal.

Liver function tests should be monitored in all patients taking naltrexone. If liver function levels begin to rise, naltrexone should be discontinued. Naltrexone should be used with caution in patients with preexisting liver disease.11

OUTCOME Marked improvement

Ms. B’s K-SAS scores are evaluated 2 weeks after starting naltrexone. The results show a marked reduction in the urge to steal and in stealing behavior, and Ms. B’s mother reports no incidents of stealing in the previous week.

Ms. B is maintained on naltrexone, 50 mg/d, for 2 months. On repeated K-SAS scores, her mother rates Ms. B’s symptoms “very much improved” with “occasional” stealing. Ms. B is discharged from the intensive outpatient program.

1. Christianini AR, Conti MA, Hearst N, et al. Treating kleptomania: cross-cultural adaptation of the Kleptomania Symptom Assessment Scale and assessment of an outpatient program. Compr Psychiatry. 2015;56:289-294.

2. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

3. Talih FR. Kleptomania and potential exacerbating factors: a review and case report. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2011;8(10):35-39.

4. Cierpka M. Psychodynamics of neurotically-induced kleptomania [in German]. Psychiatr Prax. 1986;13(3):94-103.

5. Grant JE, Correia S, Brennan-Krohn T. White matter integrity in kleptomania: a pilot study. Psychiatry Res. 2006;147(2-3):233-237.

6. Grant JE, Odlaug BL, Kim SW. Kleptomania: clinical characteristics and relationship to substance use disorders. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2010;36(5):291-295.

7. Zack M, Poulos CX. Effects of the atypical stimulant modafinil on a brief gambling episode in pathological gamblers with high vs. low impulsivity. J Psychopharmacol. 2009;23(6):660-671.

8. Grant JE. Understanding and treating kleptomania: new models and new treatments. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci. 2006;43(2):81-87.

9. Potenza MN. Should addictive disorders include non-substance-related conditions? Addiction. 2006;101(suppl 1):142-151.

10. Grant JE, Kim SW. An open-label study of naltrexone in the treatment of kleptomania. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63(4):349-356.

11. Pfohl DN, Allen JI, Atkinson RL, et al. Naltrexone hydrochloride (Trexan): a review of serum transaminase elevations at high dosage. NIDA Res Monogr. 1986;67:66-72.

1. Christianini AR, Conti MA, Hearst N, et al. Treating kleptomania: cross-cultural adaptation of the Kleptomania Symptom Assessment Scale and assessment of an outpatient program. Compr Psychiatry. 2015;56:289-294.

2. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

3. Talih FR. Kleptomania and potential exacerbating factors: a review and case report. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2011;8(10):35-39.

4. Cierpka M. Psychodynamics of neurotically-induced kleptomania [in German]. Psychiatr Prax. 1986;13(3):94-103.

5. Grant JE, Correia S, Brennan-Krohn T. White matter integrity in kleptomania: a pilot study. Psychiatry Res. 2006;147(2-3):233-237.

6. Grant JE, Odlaug BL, Kim SW. Kleptomania: clinical characteristics and relationship to substance use disorders. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2010;36(5):291-295.

7. Zack M, Poulos CX. Effects of the atypical stimulant modafinil on a brief gambling episode in pathological gamblers with high vs. low impulsivity. J Psychopharmacol. 2009;23(6):660-671.

8. Grant JE. Understanding and treating kleptomania: new models and new treatments. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci. 2006;43(2):81-87.

9. Potenza MN. Should addictive disorders include non-substance-related conditions? Addiction. 2006;101(suppl 1):142-151.

10. Grant JE, Kim SW. An open-label study of naltrexone in the treatment of kleptomania. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63(4):349-356.

11. Pfohl DN, Allen JI, Atkinson RL, et al. Naltrexone hydrochloride (Trexan): a review of serum transaminase elevations at high dosage. NIDA Res Monogr. 1986;67:66-72.

Suspicious, sleepless, and smoking

CASE Sleepless, hallucinating

Mr. F, age 30, is brought to the emergency department (ED) by his brother, with whom he has been living for the last 2 days; his brother says that Mr. F’s wife is afraid of her husband and concerned about her children’s safety. Mr. F has been talking to himself, saying “odd things,” and has an unpredictable temper. He claims that his long-deceased father is alive and telling him “to move to a land that he brought [sic] for him.” In order to follow his father’s instructions, Mr. F says he wants to “see the ambassador so he can get his passport ready.” He also believes his wife and children are intruders in his home. Although he had never smoked before, Mr. F has started smoking ≥2 packs of cigarettes per day, sometimes smoking a pack in 30 minutes. He has not eaten or slept for the last 2 days and lies awake in bed all night staring at the ceiling and smiling to himself.

On examination, Mr. F is short with a slight build and has large, dark eyes, disheveled, short, brown hair, and a scraggly beard. English is not his first language, and he speaks with a thick Eastern European accent. His speech is latent, monotonous, tangential, and illogical. He is alert, oriented only to his person, and says he is 21 or 27 years old and at the hospital for “smoking medication and that’s it.” Despite immigrating to the United States 8 years ago, Mr. F claims he has spent his whole life “here,” although he is unsure of exactly where that is. Cognition and memory are impaired. Regarding his wife and 5 children, he says, “I am a virgin. How then can I have children? That woman is abusing me by forcefully entering my house with 5 kids.” He is fidgety, appears anxious, and does not make eye contact with the examiner during the interview. He is suspicious and irritable. Initial medical workup in the ED is negative.

[polldaddy:9813268]

EVALUATION Labs and observation

Because Mr. F had delusions and hallucinations for the past 2 days and the initial medical workup was negative, brief psychotic disorder is suspected.1 He is admitted to a secure psychiatric floor for further evaluation. He has no documented medical history. A thorough medical workup for a cause of his hallucinations and delusions, including EEG and brain MRI, is negative. Additional collateral interviews with Mr. F’s wife and brother at a family meeting indicate Mr. F had a slow onset of symptoms that began 4 to 5 years ago. Initially, he became isolated, withdrawn, inactive, and had poor sleep. Recently, he also had become suspicious, irritable, delusional, and hallucinatory. Mr. F used to work full-time in construction, then began working intermittently in a warehouse as a day laborer, but has not worked for the last few months. He used to be an involved father and reliable partner, helping with household chores and caring for the children. However, for the last few months, he had become increasingly apathetic and isolated.

During the comprehensive workup for psychosis, Mr. F’s symptoms continue. He is disoriented; although it is 2015, he states it is “2007… I carry a cell phone so I don’t need to know.” On July 31, he is told the date, and for several days after that, he states that it is July 31. When asked his birth date, he looks at his hospital wrist ID. His affect is flat, but he states he feels “fine” and smiles at inappropriate times. He answers open-ended questions briefly, with irrelevant or illogical answers after long pauses, or not at all. His eye contact is poor; he seems preoccupied with internal stimuli, and it is difficult to keep his attention.

Mr. F says he is a “natural-born Bosnian gypsy translator,” and that he needs to finish “building the warehouse” with his father and grandfather (both are deceased). The nurses note that he is withdrawn, inactive, and suspicious; he spends most of the day lying in bed awake, and in the evening he paces in the hallway. Mr. F does not interact with other patients, is guarded when questioned, and does not eat much. He has minimal insight into his condition and says that he is at the hospital for “fevers and a cold,” “ESL treatment,” or because his “right side is thicker” than his left. It is unclear what Mr. F means by “ESL.” It may refer to English as a Second Language, given his apparent perseveration regarding his immigration status and language ability, but this is speculation.

[polldaddy:9813271]

TREATMENT Residual symptoms

With the additional collateral history and a negative medical workup, Mr. F meets DSM-5 criteria for acute, first-episode schizophrenia1 and is started on risperidone, 2 mg/d, titrated up to 2 mg twice daily, and trazodone, 50 mg, as needed, as a sleep aid. He shows significant improvement in his symptoms early in his treatment course. During visiting hours and at family meetings, he recognizes his wife, and during interviews he denies any continuing hallucinations. He initially says that he never failed to recognize his wife and kids, but later explains that he “woke up different…from a dream, and she was a different woman.” When asked specifically about hearing his father’s voice, he is uncertain, saying “No,” “I don’t know,” “I didn’t hear,” or “Not anymore.”

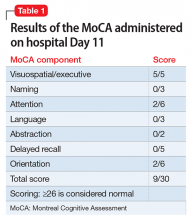

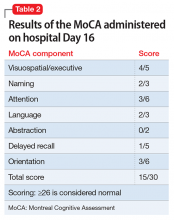

Despite his improvement, Mr. F continues to be disoriented and suspicious, and has minimal insight into his illness. He also continues to exhibit significant negative symptoms and cognitive impairment. Mr. F is withdrawn and has a flat affect, poverty of speech, delayed processing, and poor focus and attention.

On hospital Day 6, Mr. F reports feeling depressed. He misses his children and wants to go home. He has lost several pounds because he had a poor appetite and is now underweight. He is apathetic; interactions with staff and patients are minimal, he declines to attend group therapy sessions, and he still spends most of his time lying in bed awake or pacing the hallway. He also expresses a desire to quit smoking.

[polldaddy:9813273]

The authors’ observations

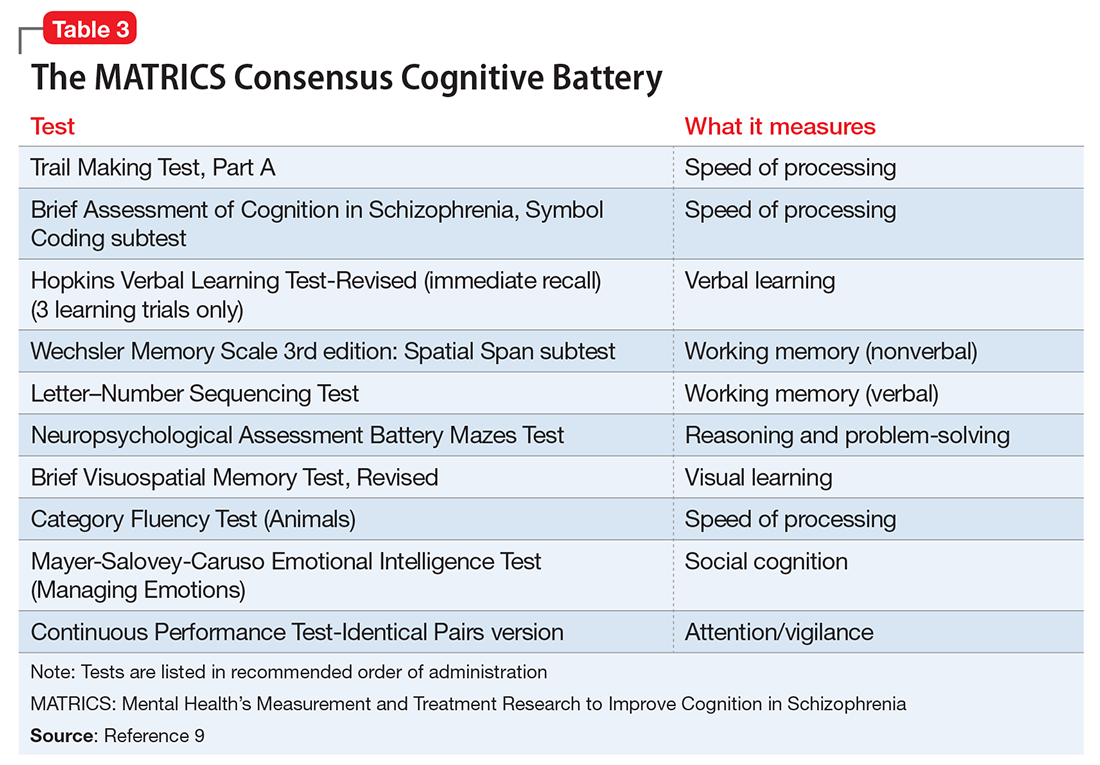

Despite its lack of specific inclusion in the DSM-5 criteria,1 cognitive impairment is a distinct, core, and nearly universal feature of schizophrenia. As demonstrated by Mr. F’s case, the severity of cognitive impairment in schizophrenia has no association with the positive symptoms of schizophrenia; it is a patient’s neurocognitive abilities—not the severity of his (her) psychotic symptoms—that most strongly predict functional outcomes.2