User login

Suicidal and paranoid thoughts after starting hepatitis C virus treatment

CASE Suicidal and paranoid

Ms. B, age 53, has a 30-year history of bipolar disorder, a 1-year history of hepatitis C virus (HCV), and previous inpatient psychiatric hospitalizations secondary to acute mania. She presents to our hospital describing her symptoms as the “worst depression ever” and reports suicidal ideation and paranoid thoughts of people watching and following her. Ms. B describes significant neurovegetative symptoms of depression, including poor sleep, poor appetite, low energy and concentration, and chronic feelings of hopelessness with thoughts of “ending it all.” Ms. B reports that her symptoms started 3 weeks ago, a few days after she started taking sofosbuvir and ribavirin for refractory HCV.

Ms. B’s medication regimen consisted of quetiapine, 400 mg at bedtime, fluoxetine, 40 mg/d, and lamotrigine, 150 mg/d, for bipolar disorder, when she started taking sofosbuvir and ribavirin. Ms. B admits she stopped taking her psychotropic and antiviral medications after she noticed progressively worsening depression with intrusive suicidal thoughts, including ruminative thoughts of overdosing on them.

At evaluation, Ms. B is casually dressed, pleasant, with fair hygiene and poor eye contact. Her speech is decreased in rate, volume, and tone; mood is “devastated and depressed”; affect is labile and tearful. Her thought process reveals occasional thought blocking and her thought content includes suicidal ideations and paranoid thoughts. Her cognition is intact; insight and judgment are poor. During evaluation, Ms. B reveals a history of alcohol and marijuana use, but reports that she has not used either for the past 15 years. She further states that she had agreed to a trial of medication first for her liver disease and had deferred any discussion of liver transplant at the time of her diagnosis with HCV.

Laboratory tests reveal a normal complete blood count, creatinine, and electrolytes. However, liver functions were elevated, including aspartate aminotransferase (AST) of 107 U/L (reference range, 8 to 48 U/L) and alanine aminotransferase of 117 U/L (reference range, 7 to 55 U/L). Although increased, the levels of AST and ALT were slightly less than her levels pre-sofosbuvir–ribavirin trial, indicating some response to the medication.

[polldaddy:9777325]

The authors’ observations

Approximately 170 million people worldwide suffer from chronic HCV infection, affecting 2.7 to 5.2 million people in the United States, with 350,000 deaths attributed to liver disease caused by HCV.1

The standard treatment of HCV genotype 1, which represents 70% of all cases of chronic HCV in the United States, is 12 to 32 weeks of an oral protease inhibitor combined with 24 to 48 weeks of peg-interferon (IFN)–alpha-2a plus ribavirin, with the duration of therapy guided by the on-treatment response and the stage of hepatic fibrosis.1

In 2013, the FDA approved sofosbuvir, a direct-acting antiviral drug for chronic HCV. It is a nucleotide analogue HCV NS5B polymerase inhibitor with similar in vitro activity against all HCV genotypes.1 This medication is efficient when used with an antiviral regimen in adults with HCV with liver disease, cirrhosis, HIV coinfection, and hepatocellular carcinoma awaiting liver transplant.2

TREATMENT Medication restarted

Ms. B is admitted to the psychiatric unit for management of severe depression and suicidal thoughts, and quetiapine, 400 mg at bedtime, fluoxetine, 40 mg/d, and lamotrigine, 150 mg/d, are restarted. The hepatology team is consulted for further evaluation and management of her liver disease.

She receives supportive psychotherapy, art therapy, and group therapy to develop better coping skills for her depression and suicidal thoughts and psychoeducation about her medical and psychiatric illness to understand the importance of treatment adherence for symptom improvement. Over the course of her hospital stay, Ms. B has subjective and objective improvements of her depressive symptoms.

The authors’ observations

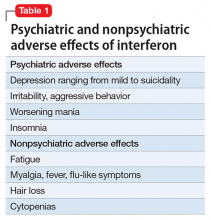

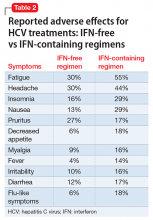

Psychiatric adverse effects associated with IFN-α therapy in chronic HCV patients are the main cause of antiviral treatment discontinuation, resulting in a decreased rate of sustained viral response.3 Chronic HCV is a major health burden; therefore there is a need for treatment options that are more efficient, safer, simpler, more convenient, and preferably IFN-free.

Sofosbuvir has met many of these criteria and has been found to be safe and well tolerated when administered alone or with ribavirin. Sofosbuvir represents a major breakthrough in HCV care to achieve cures and prevent IFN-associated morbidity and mortality.4,5

Our case report highlights, however, that significant depressive symptoms may be associated with sofosbuvir. Hepatologists should be cautious when prescribing sofosbuvir in patients with comorbid psychiatric illness to avoid exacerbating depressive symptoms and increasing the risk of suicidality.

[polldaddy:9777328]

OUTCOME Refuses treatment

Ms. B is seen by the hepatology team who discuss the best treatment options for HCV, including ledipasvir/sofosbuvir, daclatasvir and ribavirin, and ombitasvir/paritaprevir/ritonavir plus dasabuvir. However, she refuses treatment for HCV stating, “I would rather have no depression with hepatitis C than feel depressed and suicidal while getting treatment for hepatitis C.”

Ms. B is discharged with referral to the outpatient psychiatry clinic and hepatology clinic for monitoring her liver function and restarting sofosbuvir and ribavirin for HCV once her mood symptoms improved.

The authors’ observations

A robust psychiatric evaluation is required before initiating the previously mentioned antiviral therapy to identify high-risk patients to prevent emergence or exacerbation of new psychiatric symptoms, including depression and mania, when treating with IFN-free or IFN-containing regimens. Collaborative care involving a hepatologist and psychiatrist is necessary for comprehensive monitoring of a patient’s psychiatric symptoms and management with medication and psychotherapy. This will limit psychiatric morbidity in patients receiving antiviral treatment with sofosbuvir and ribavirin.

It’s imperative to improve medication adherence for patients by adopting strategies, such as:

- identifying factors leading to noncompliance

- establishing a strong rapport with the patients

- providing psychoeducation about the illness, discussing the benefits and risks of medications and the importance of maintenance treatment

- simplifying medication regimen.6

More research on medication management of HCV in patients with comorbid psychiatric illness should be encouraged and focused on initiating and monitoring non-IFN treatment regimens for patients with HCV and preexisting bipolar disorder or other mood disorders.

1. Lawitz E, Mangia A, Wyles D, et al. Sofosbuvir for previously untreated chronic hepatitis C infection. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(20):1878-1887.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Hepatitis C FAQ for health professionals. http://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/HCV/HCVfaq.htm#section4. Updated January 27, 2017. Accessed June 2, 2017.

3. Lucaciu LA, Dumitrascu DL. Depression and suicide ideation in chronic hepatitis C patients untreated and treated with interferon: prevalence, prevention, and treatment. Ann Gastroenterol. 2015;28(4):440-447.

4. Lam B, Henry L, Younossi Z. Sofosbuvir (Sovaldi) for the treatment of hepatitis C. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2014;7(5):555-566.

5. Lawitz E, Poordad FF, Pang PS, et al. Sofosbuvir and ledipasvir fixed-dose combination with and without ribavirin in treatment-naive and previously treated patients with genotype 1 hepatitis C virus infection (LONESTAR): an open-label, randomized, phase 2 trial. Lancet 2014;383(9916):515-523.

6. Balon R. Managing compliance. Psychiatric Times. www.psychiatrictimes.com/articles/managing-compliance. Published May 1, 2002. Accessed June 14, 2017.

CASE Suicidal and paranoid

Ms. B, age 53, has a 30-year history of bipolar disorder, a 1-year history of hepatitis C virus (HCV), and previous inpatient psychiatric hospitalizations secondary to acute mania. She presents to our hospital describing her symptoms as the “worst depression ever” and reports suicidal ideation and paranoid thoughts of people watching and following her. Ms. B describes significant neurovegetative symptoms of depression, including poor sleep, poor appetite, low energy and concentration, and chronic feelings of hopelessness with thoughts of “ending it all.” Ms. B reports that her symptoms started 3 weeks ago, a few days after she started taking sofosbuvir and ribavirin for refractory HCV.

Ms. B’s medication regimen consisted of quetiapine, 400 mg at bedtime, fluoxetine, 40 mg/d, and lamotrigine, 150 mg/d, for bipolar disorder, when she started taking sofosbuvir and ribavirin. Ms. B admits she stopped taking her psychotropic and antiviral medications after she noticed progressively worsening depression with intrusive suicidal thoughts, including ruminative thoughts of overdosing on them.

At evaluation, Ms. B is casually dressed, pleasant, with fair hygiene and poor eye contact. Her speech is decreased in rate, volume, and tone; mood is “devastated and depressed”; affect is labile and tearful. Her thought process reveals occasional thought blocking and her thought content includes suicidal ideations and paranoid thoughts. Her cognition is intact; insight and judgment are poor. During evaluation, Ms. B reveals a history of alcohol and marijuana use, but reports that she has not used either for the past 15 years. She further states that she had agreed to a trial of medication first for her liver disease and had deferred any discussion of liver transplant at the time of her diagnosis with HCV.

Laboratory tests reveal a normal complete blood count, creatinine, and electrolytes. However, liver functions were elevated, including aspartate aminotransferase (AST) of 107 U/L (reference range, 8 to 48 U/L) and alanine aminotransferase of 117 U/L (reference range, 7 to 55 U/L). Although increased, the levels of AST and ALT were slightly less than her levels pre-sofosbuvir–ribavirin trial, indicating some response to the medication.

[polldaddy:9777325]

The authors’ observations

Approximately 170 million people worldwide suffer from chronic HCV infection, affecting 2.7 to 5.2 million people in the United States, with 350,000 deaths attributed to liver disease caused by HCV.1

The standard treatment of HCV genotype 1, which represents 70% of all cases of chronic HCV in the United States, is 12 to 32 weeks of an oral protease inhibitor combined with 24 to 48 weeks of peg-interferon (IFN)–alpha-2a plus ribavirin, with the duration of therapy guided by the on-treatment response and the stage of hepatic fibrosis.1

In 2013, the FDA approved sofosbuvir, a direct-acting antiviral drug for chronic HCV. It is a nucleotide analogue HCV NS5B polymerase inhibitor with similar in vitro activity against all HCV genotypes.1 This medication is efficient when used with an antiviral regimen in adults with HCV with liver disease, cirrhosis, HIV coinfection, and hepatocellular carcinoma awaiting liver transplant.2

TREATMENT Medication restarted

Ms. B is admitted to the psychiatric unit for management of severe depression and suicidal thoughts, and quetiapine, 400 mg at bedtime, fluoxetine, 40 mg/d, and lamotrigine, 150 mg/d, are restarted. The hepatology team is consulted for further evaluation and management of her liver disease.

She receives supportive psychotherapy, art therapy, and group therapy to develop better coping skills for her depression and suicidal thoughts and psychoeducation about her medical and psychiatric illness to understand the importance of treatment adherence for symptom improvement. Over the course of her hospital stay, Ms. B has subjective and objective improvements of her depressive symptoms.

The authors’ observations

Psychiatric adverse effects associated with IFN-α therapy in chronic HCV patients are the main cause of antiviral treatment discontinuation, resulting in a decreased rate of sustained viral response.3 Chronic HCV is a major health burden; therefore there is a need for treatment options that are more efficient, safer, simpler, more convenient, and preferably IFN-free.

Sofosbuvir has met many of these criteria and has been found to be safe and well tolerated when administered alone or with ribavirin. Sofosbuvir represents a major breakthrough in HCV care to achieve cures and prevent IFN-associated morbidity and mortality.4,5

Our case report highlights, however, that significant depressive symptoms may be associated with sofosbuvir. Hepatologists should be cautious when prescribing sofosbuvir in patients with comorbid psychiatric illness to avoid exacerbating depressive symptoms and increasing the risk of suicidality.

[polldaddy:9777328]

OUTCOME Refuses treatment

Ms. B is seen by the hepatology team who discuss the best treatment options for HCV, including ledipasvir/sofosbuvir, daclatasvir and ribavirin, and ombitasvir/paritaprevir/ritonavir plus dasabuvir. However, she refuses treatment for HCV stating, “I would rather have no depression with hepatitis C than feel depressed and suicidal while getting treatment for hepatitis C.”

Ms. B is discharged with referral to the outpatient psychiatry clinic and hepatology clinic for monitoring her liver function and restarting sofosbuvir and ribavirin for HCV once her mood symptoms improved.

The authors’ observations

A robust psychiatric evaluation is required before initiating the previously mentioned antiviral therapy to identify high-risk patients to prevent emergence or exacerbation of new psychiatric symptoms, including depression and mania, when treating with IFN-free or IFN-containing regimens. Collaborative care involving a hepatologist and psychiatrist is necessary for comprehensive monitoring of a patient’s psychiatric symptoms and management with medication and psychotherapy. This will limit psychiatric morbidity in patients receiving antiviral treatment with sofosbuvir and ribavirin.

It’s imperative to improve medication adherence for patients by adopting strategies, such as:

- identifying factors leading to noncompliance

- establishing a strong rapport with the patients

- providing psychoeducation about the illness, discussing the benefits and risks of medications and the importance of maintenance treatment

- simplifying medication regimen.6

More research on medication management of HCV in patients with comorbid psychiatric illness should be encouraged and focused on initiating and monitoring non-IFN treatment regimens for patients with HCV and preexisting bipolar disorder or other mood disorders.

CASE Suicidal and paranoid

Ms. B, age 53, has a 30-year history of bipolar disorder, a 1-year history of hepatitis C virus (HCV), and previous inpatient psychiatric hospitalizations secondary to acute mania. She presents to our hospital describing her symptoms as the “worst depression ever” and reports suicidal ideation and paranoid thoughts of people watching and following her. Ms. B describes significant neurovegetative symptoms of depression, including poor sleep, poor appetite, low energy and concentration, and chronic feelings of hopelessness with thoughts of “ending it all.” Ms. B reports that her symptoms started 3 weeks ago, a few days after she started taking sofosbuvir and ribavirin for refractory HCV.

Ms. B’s medication regimen consisted of quetiapine, 400 mg at bedtime, fluoxetine, 40 mg/d, and lamotrigine, 150 mg/d, for bipolar disorder, when she started taking sofosbuvir and ribavirin. Ms. B admits she stopped taking her psychotropic and antiviral medications after she noticed progressively worsening depression with intrusive suicidal thoughts, including ruminative thoughts of overdosing on them.

At evaluation, Ms. B is casually dressed, pleasant, with fair hygiene and poor eye contact. Her speech is decreased in rate, volume, and tone; mood is “devastated and depressed”; affect is labile and tearful. Her thought process reveals occasional thought blocking and her thought content includes suicidal ideations and paranoid thoughts. Her cognition is intact; insight and judgment are poor. During evaluation, Ms. B reveals a history of alcohol and marijuana use, but reports that she has not used either for the past 15 years. She further states that she had agreed to a trial of medication first for her liver disease and had deferred any discussion of liver transplant at the time of her diagnosis with HCV.

Laboratory tests reveal a normal complete blood count, creatinine, and electrolytes. However, liver functions were elevated, including aspartate aminotransferase (AST) of 107 U/L (reference range, 8 to 48 U/L) and alanine aminotransferase of 117 U/L (reference range, 7 to 55 U/L). Although increased, the levels of AST and ALT were slightly less than her levels pre-sofosbuvir–ribavirin trial, indicating some response to the medication.

[polldaddy:9777325]

The authors’ observations

Approximately 170 million people worldwide suffer from chronic HCV infection, affecting 2.7 to 5.2 million people in the United States, with 350,000 deaths attributed to liver disease caused by HCV.1

The standard treatment of HCV genotype 1, which represents 70% of all cases of chronic HCV in the United States, is 12 to 32 weeks of an oral protease inhibitor combined with 24 to 48 weeks of peg-interferon (IFN)–alpha-2a plus ribavirin, with the duration of therapy guided by the on-treatment response and the stage of hepatic fibrosis.1

In 2013, the FDA approved sofosbuvir, a direct-acting antiviral drug for chronic HCV. It is a nucleotide analogue HCV NS5B polymerase inhibitor with similar in vitro activity against all HCV genotypes.1 This medication is efficient when used with an antiviral regimen in adults with HCV with liver disease, cirrhosis, HIV coinfection, and hepatocellular carcinoma awaiting liver transplant.2

TREATMENT Medication restarted

Ms. B is admitted to the psychiatric unit for management of severe depression and suicidal thoughts, and quetiapine, 400 mg at bedtime, fluoxetine, 40 mg/d, and lamotrigine, 150 mg/d, are restarted. The hepatology team is consulted for further evaluation and management of her liver disease.

She receives supportive psychotherapy, art therapy, and group therapy to develop better coping skills for her depression and suicidal thoughts and psychoeducation about her medical and psychiatric illness to understand the importance of treatment adherence for symptom improvement. Over the course of her hospital stay, Ms. B has subjective and objective improvements of her depressive symptoms.

The authors’ observations

Psychiatric adverse effects associated with IFN-α therapy in chronic HCV patients are the main cause of antiviral treatment discontinuation, resulting in a decreased rate of sustained viral response.3 Chronic HCV is a major health burden; therefore there is a need for treatment options that are more efficient, safer, simpler, more convenient, and preferably IFN-free.

Sofosbuvir has met many of these criteria and has been found to be safe and well tolerated when administered alone or with ribavirin. Sofosbuvir represents a major breakthrough in HCV care to achieve cures and prevent IFN-associated morbidity and mortality.4,5

Our case report highlights, however, that significant depressive symptoms may be associated with sofosbuvir. Hepatologists should be cautious when prescribing sofosbuvir in patients with comorbid psychiatric illness to avoid exacerbating depressive symptoms and increasing the risk of suicidality.

[polldaddy:9777328]

OUTCOME Refuses treatment

Ms. B is seen by the hepatology team who discuss the best treatment options for HCV, including ledipasvir/sofosbuvir, daclatasvir and ribavirin, and ombitasvir/paritaprevir/ritonavir plus dasabuvir. However, she refuses treatment for HCV stating, “I would rather have no depression with hepatitis C than feel depressed and suicidal while getting treatment for hepatitis C.”

Ms. B is discharged with referral to the outpatient psychiatry clinic and hepatology clinic for monitoring her liver function and restarting sofosbuvir and ribavirin for HCV once her mood symptoms improved.

The authors’ observations

A robust psychiatric evaluation is required before initiating the previously mentioned antiviral therapy to identify high-risk patients to prevent emergence or exacerbation of new psychiatric symptoms, including depression and mania, when treating with IFN-free or IFN-containing regimens. Collaborative care involving a hepatologist and psychiatrist is necessary for comprehensive monitoring of a patient’s psychiatric symptoms and management with medication and psychotherapy. This will limit psychiatric morbidity in patients receiving antiviral treatment with sofosbuvir and ribavirin.

It’s imperative to improve medication adherence for patients by adopting strategies, such as:

- identifying factors leading to noncompliance

- establishing a strong rapport with the patients

- providing psychoeducation about the illness, discussing the benefits and risks of medications and the importance of maintenance treatment

- simplifying medication regimen.6

More research on medication management of HCV in patients with comorbid psychiatric illness should be encouraged and focused on initiating and monitoring non-IFN treatment regimens for patients with HCV and preexisting bipolar disorder or other mood disorders.

1. Lawitz E, Mangia A, Wyles D, et al. Sofosbuvir for previously untreated chronic hepatitis C infection. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(20):1878-1887.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Hepatitis C FAQ for health professionals. http://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/HCV/HCVfaq.htm#section4. Updated January 27, 2017. Accessed June 2, 2017.

3. Lucaciu LA, Dumitrascu DL. Depression and suicide ideation in chronic hepatitis C patients untreated and treated with interferon: prevalence, prevention, and treatment. Ann Gastroenterol. 2015;28(4):440-447.

4. Lam B, Henry L, Younossi Z. Sofosbuvir (Sovaldi) for the treatment of hepatitis C. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2014;7(5):555-566.

5. Lawitz E, Poordad FF, Pang PS, et al. Sofosbuvir and ledipasvir fixed-dose combination with and without ribavirin in treatment-naive and previously treated patients with genotype 1 hepatitis C virus infection (LONESTAR): an open-label, randomized, phase 2 trial. Lancet 2014;383(9916):515-523.

6. Balon R. Managing compliance. Psychiatric Times. www.psychiatrictimes.com/articles/managing-compliance. Published May 1, 2002. Accessed June 14, 2017.

1. Lawitz E, Mangia A, Wyles D, et al. Sofosbuvir for previously untreated chronic hepatitis C infection. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(20):1878-1887.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Hepatitis C FAQ for health professionals. http://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/HCV/HCVfaq.htm#section4. Updated January 27, 2017. Accessed June 2, 2017.

3. Lucaciu LA, Dumitrascu DL. Depression and suicide ideation in chronic hepatitis C patients untreated and treated with interferon: prevalence, prevention, and treatment. Ann Gastroenterol. 2015;28(4):440-447.

4. Lam B, Henry L, Younossi Z. Sofosbuvir (Sovaldi) for the treatment of hepatitis C. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2014;7(5):555-566.

5. Lawitz E, Poordad FF, Pang PS, et al. Sofosbuvir and ledipasvir fixed-dose combination with and without ribavirin in treatment-naive and previously treated patients with genotype 1 hepatitis C virus infection (LONESTAR): an open-label, randomized, phase 2 trial. Lancet 2014;383(9916):515-523.

6. Balon R. Managing compliance. Psychiatric Times. www.psychiatrictimes.com/articles/managing-compliance. Published May 1, 2002. Accessed June 14, 2017.

Changing trends in diet pill use, from weight loss agent to recreational drug

The prevalence of obesity and obesity-related conditions in the United States is increasing. Many weight-loss products and dietary supplements are used in an attempt to combat this epidemic, but little evidence exists of their efficacy and safety.

We present a case report of a middle-age woman who developed severe psychotic symptoms while taking phentermine hydrochloride (HCl), a psychostimulant similar to amphetamine that is used as a weight-loss agent and for recreational purposes. Phentermine has been associated with mood and psychotic symptoms and has a tendency to cause psychological dependence and tolerance.

To investigate the risks and potential effects of using this drug, we searched OVID and PubMed databases using the search string “phentermine + psychosis.” We conclude that there is a need for awareness about early detection and treatment of reversible psychotic and mood symptoms caused by what might appear to be harmless weight-loss and energy pills.

Obesity epidemic, wide-ranging weight-loss effortsThere has been a dramatic increase in obesity in the United States in the past 20 years: More than one-third of adults and approximately 17% of children and adolescents are obese. Obesity-related conditions, such as heart disease, stroke, and type 2 diabetes mellitus, are leading causes of preventable death.1 Weight monitoring, a healthy lifestyle, surgical intervention, traditional herbs, and diet-pill supplements are some of the modalities used to address this epidemic.

Most so-called supplements for weight loss are exempt from FDA regulation. They do not undergo rigorous testing for safety. Furthermore, many contain controlled substances; some supplements are anti-seizure medications or other prescription drugs; and some are drugs not approved in the United States.2 Since the 1930s, such drugs as dinitrophenol, ephedrine, amphetamine, fenfluramine, and phentermine have flooded the market with the promise of quick weight loss.3,4

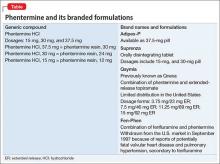

Phentermine, a contraction of “phenyltertiary-butylamine,” and its various types (Table) is a psychostimulant of the phenethylamine class, with a pharmacologic profile similar to that of amphetamine. It is known to yield false-positive immunoassay screening results for amphetamines.

CASE REPORT Acute psychotic break

Ms. B, age 37, with a history of postpartum depression, arrives at the emergency room reporting auditory hallucinations of her son and boyfriend; vivid visual hallucinations; and persecutory ideas toward her boyfriend, whom she believes had kidnapped her son. She also complains of insomnia and intermittent confusion for the past week.

Speech is pressured, fast, and difficult to comprehend at times; affect is labile and irritable. Ms. B denies suicidal ideation and is oriented to time, place, and person.

A urine drug screen is positive for amphetamine.

Pre-admission medications include alprazolam, 1 mg as needed, and zolpidem, 10 mg at bedtime, prescribed by Ms. B’s primary care physician for anxiety and insomnia. She discontinued these medications 3 weeks ago because of increased drowsiness at work. She denies other substance use and is unable to account for the positive urine drug screen.

Her medical history, physical examination, and a CT scan of the head are unremarkable. The components of a comprehensive metabolic panel and complete blood count are within normal limits.

After admission, in-depth assessment reveals that Ms. B has been taking phentermine, 37.5 mg (under the brand name Adipex-P), once daily since age 16 for weight loss. She recently discontinued the drug, abruptly, for 1 month, then resumed taking it at an unspecified higher dosage 1 week before she came to the emergency room, for what she said was recreational use and to meet the demands of her job, which required shift work and long hours.

Over the next few days in the hospital, Ms. B’s symptoms resolve as the drug is eliminated from her body. Speech becomes comprehensible and sleep improves. Affective distress diminishes considerably after admission; slight mood lability persists. She no longer reports perceptual disturbances or distress secondary to intrusive thoughts.

Ms. B is discharged 1 week after admission, with instructions to follow up at a dual-diagnosis outpatient program.

Pharmacologic profilePhentermine acts through sympathomimetic pathways by increasing brain noradrenaline and dopamine. The drug has no effect on serotonin.4,5 Phentermine can lead to elevated blood pressure and heart rate, palpitations, restlessness, and insomnia, and can suppress appetite. Increased sympathomimetic activity has been implicated in the ability of phentermine to induce psychotic symptoms.

The literature. Our PubMed search of “phentermine + psychosis” produced 13 results, including 6 case reports of phentermine use. Five citations were more than 4 decades old5-12; only 1 could be considered recent (2011).13

Patients in these reports developed psychotic or manic features after chronic or acute phentermine use, mainly for weight reduction. The most recent article13 mentioned 4 patients who were abusing diet pills recreationally (including “for lethargy”). As with Ms. B, in all 4 of those patients, phentermine precipitated the primary pathology (mania in bipolar disorder; depression in postpartum depression and substance abuse) or revealed underlying illness.

Changing landscape of use and abuseThere has been a trend observed in the pattern of diet pill use: Initially marketed as an appetite suppressant, these pills are now being abused across ethnic, racial, and socioeconomic groups, by males and females.14 There is also a scarcity of useful guidance for clinicians.

Not only are diet pills used by people with an eating disorder; their recreational use is an emerging problem. If reports12,13 continue to reveal that phentermine is a substance of abuse and has catastrophic effects on the user’s psyche, the need for stronger warnings and guidelines might be warranted to allow consumers to make an informed choice about using the drug.

Call for awarenessThe case we presented here exemplifies the importance of tighter regulation of both over-the-counter and prescription stimulant analogs. There is a need for awareness among practitioners about early detection and treatment of reversible psychotic and mood symptoms secondary to what might be promoted as, or appear to be, “harmless” weight loss and energy pills.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

This unfunded study was presented as a case report poster at the Annual Meeting of the Academy of Psychosomatic Medicine, November 2013, Tucson, Arizona, and at the Colloquium of Scholars of the Philadelphia Psychiatric Society, March 2014, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Drug Brand Names

Alprazolam • Xanax

Fenfluramine • Pondimin

Phentermine HCl • Adipex-P, Fen-Phen, Qsymia, Suprenza

Topiramate • Topamax, Trokendi XR

Zolpidem • Ambien

1. Center for Disease Control. Division of nutrition, physical activity, and obesity. http://www.cdc.gov/obesity/data/adult. html. Updated September 14, 2015. Accessed October 27, 2015.

2. Retamero C, Rivera T, Murphy K. “Ephedra-free” diet pill-induced psychosis. Psychosomatics. 2011;52(6):579-582.

3. Cohen PA, Goday A, Swann JP. The return of rainbow diet pills. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(9):1676-1686.

4. Wellman PJ. Overview of adrenergic anorectic agents. Am J Clin Nutr. 1992;55(suppl 1):193S-198S.

5. Devan GS. Phentermine and psychosis. Br J Psychiatry. 1990;156:442-443.

6. Hoffman BF. Diet pill psychosis. Can Med Assoc J. 1977;116(4):351-355.

7. Hoffman BF. Diet pill psychosis: follow-up after 6 years. Can Med Assoc J. 1983;129(10):1077-1078.

8. Rubin RT. Acute psychotic reaction following ingestion of phentermine. Am J Psychiatry. 1964;120:1124-1125.

9. Schaffer CB, Pauli MW. Psychotic reaction caused by proprietary oral diet agent. Am J Psychiatry. 1980;137(10):1256-12567.

10. Lee SH, Liu CY, Yang YY. Schizophreniform-like psychotic disorder induced by phentermine: a case report. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi (Taipei). 1998;61(1):44-47.

11. Zimmer JE, Gregory RJ. Bipolar depression associated with fenfluramine and phentermine. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(7):383-384.

12. Bagri S, Reddy G. Delirium with manic symptoms induced by diet pills. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(2):83.

13. Alexander J, Cheng Y, Choudhary J, et al. Phentermine (Duromine) precipitated psychosis. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2011;45(8):684-685.

14. Pomeranz JL, Taylor LM, Austin SB. Over-the-counter and out-of-control: legal strategies to protect youths from abusing products for weight control. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(2):222-2253.

The prevalence of obesity and obesity-related conditions in the United States is increasing. Many weight-loss products and dietary supplements are used in an attempt to combat this epidemic, but little evidence exists of their efficacy and safety.

We present a case report of a middle-age woman who developed severe psychotic symptoms while taking phentermine hydrochloride (HCl), a psychostimulant similar to amphetamine that is used as a weight-loss agent and for recreational purposes. Phentermine has been associated with mood and psychotic symptoms and has a tendency to cause psychological dependence and tolerance.

To investigate the risks and potential effects of using this drug, we searched OVID and PubMed databases using the search string “phentermine + psychosis.” We conclude that there is a need for awareness about early detection and treatment of reversible psychotic and mood symptoms caused by what might appear to be harmless weight-loss and energy pills.

Obesity epidemic, wide-ranging weight-loss effortsThere has been a dramatic increase in obesity in the United States in the past 20 years: More than one-third of adults and approximately 17% of children and adolescents are obese. Obesity-related conditions, such as heart disease, stroke, and type 2 diabetes mellitus, are leading causes of preventable death.1 Weight monitoring, a healthy lifestyle, surgical intervention, traditional herbs, and diet-pill supplements are some of the modalities used to address this epidemic.

Most so-called supplements for weight loss are exempt from FDA regulation. They do not undergo rigorous testing for safety. Furthermore, many contain controlled substances; some supplements are anti-seizure medications or other prescription drugs; and some are drugs not approved in the United States.2 Since the 1930s, such drugs as dinitrophenol, ephedrine, amphetamine, fenfluramine, and phentermine have flooded the market with the promise of quick weight loss.3,4

Phentermine, a contraction of “phenyltertiary-butylamine,” and its various types (Table) is a psychostimulant of the phenethylamine class, with a pharmacologic profile similar to that of amphetamine. It is known to yield false-positive immunoassay screening results for amphetamines.

CASE REPORT Acute psychotic break

Ms. B, age 37, with a history of postpartum depression, arrives at the emergency room reporting auditory hallucinations of her son and boyfriend; vivid visual hallucinations; and persecutory ideas toward her boyfriend, whom she believes had kidnapped her son. She also complains of insomnia and intermittent confusion for the past week.

Speech is pressured, fast, and difficult to comprehend at times; affect is labile and irritable. Ms. B denies suicidal ideation and is oriented to time, place, and person.

A urine drug screen is positive for amphetamine.

Pre-admission medications include alprazolam, 1 mg as needed, and zolpidem, 10 mg at bedtime, prescribed by Ms. B’s primary care physician for anxiety and insomnia. She discontinued these medications 3 weeks ago because of increased drowsiness at work. She denies other substance use and is unable to account for the positive urine drug screen.

Her medical history, physical examination, and a CT scan of the head are unremarkable. The components of a comprehensive metabolic panel and complete blood count are within normal limits.

After admission, in-depth assessment reveals that Ms. B has been taking phentermine, 37.5 mg (under the brand name Adipex-P), once daily since age 16 for weight loss. She recently discontinued the drug, abruptly, for 1 month, then resumed taking it at an unspecified higher dosage 1 week before she came to the emergency room, for what she said was recreational use and to meet the demands of her job, which required shift work and long hours.

Over the next few days in the hospital, Ms. B’s symptoms resolve as the drug is eliminated from her body. Speech becomes comprehensible and sleep improves. Affective distress diminishes considerably after admission; slight mood lability persists. She no longer reports perceptual disturbances or distress secondary to intrusive thoughts.

Ms. B is discharged 1 week after admission, with instructions to follow up at a dual-diagnosis outpatient program.

Pharmacologic profilePhentermine acts through sympathomimetic pathways by increasing brain noradrenaline and dopamine. The drug has no effect on serotonin.4,5 Phentermine can lead to elevated blood pressure and heart rate, palpitations, restlessness, and insomnia, and can suppress appetite. Increased sympathomimetic activity has been implicated in the ability of phentermine to induce psychotic symptoms.

The literature. Our PubMed search of “phentermine + psychosis” produced 13 results, including 6 case reports of phentermine use. Five citations were more than 4 decades old5-12; only 1 could be considered recent (2011).13

Patients in these reports developed psychotic or manic features after chronic or acute phentermine use, mainly for weight reduction. The most recent article13 mentioned 4 patients who were abusing diet pills recreationally (including “for lethargy”). As with Ms. B, in all 4 of those patients, phentermine precipitated the primary pathology (mania in bipolar disorder; depression in postpartum depression and substance abuse) or revealed underlying illness.

Changing landscape of use and abuseThere has been a trend observed in the pattern of diet pill use: Initially marketed as an appetite suppressant, these pills are now being abused across ethnic, racial, and socioeconomic groups, by males and females.14 There is also a scarcity of useful guidance for clinicians.

Not only are diet pills used by people with an eating disorder; their recreational use is an emerging problem. If reports12,13 continue to reveal that phentermine is a substance of abuse and has catastrophic effects on the user’s psyche, the need for stronger warnings and guidelines might be warranted to allow consumers to make an informed choice about using the drug.

Call for awarenessThe case we presented here exemplifies the importance of tighter regulation of both over-the-counter and prescription stimulant analogs. There is a need for awareness among practitioners about early detection and treatment of reversible psychotic and mood symptoms secondary to what might be promoted as, or appear to be, “harmless” weight loss and energy pills.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

This unfunded study was presented as a case report poster at the Annual Meeting of the Academy of Psychosomatic Medicine, November 2013, Tucson, Arizona, and at the Colloquium of Scholars of the Philadelphia Psychiatric Society, March 2014, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Drug Brand Names

Alprazolam • Xanax

Fenfluramine • Pondimin

Phentermine HCl • Adipex-P, Fen-Phen, Qsymia, Suprenza

Topiramate • Topamax, Trokendi XR

Zolpidem • Ambien

The prevalence of obesity and obesity-related conditions in the United States is increasing. Many weight-loss products and dietary supplements are used in an attempt to combat this epidemic, but little evidence exists of their efficacy and safety.

We present a case report of a middle-age woman who developed severe psychotic symptoms while taking phentermine hydrochloride (HCl), a psychostimulant similar to amphetamine that is used as a weight-loss agent and for recreational purposes. Phentermine has been associated with mood and psychotic symptoms and has a tendency to cause psychological dependence and tolerance.

To investigate the risks and potential effects of using this drug, we searched OVID and PubMed databases using the search string “phentermine + psychosis.” We conclude that there is a need for awareness about early detection and treatment of reversible psychotic and mood symptoms caused by what might appear to be harmless weight-loss and energy pills.

Obesity epidemic, wide-ranging weight-loss effortsThere has been a dramatic increase in obesity in the United States in the past 20 years: More than one-third of adults and approximately 17% of children and adolescents are obese. Obesity-related conditions, such as heart disease, stroke, and type 2 diabetes mellitus, are leading causes of preventable death.1 Weight monitoring, a healthy lifestyle, surgical intervention, traditional herbs, and diet-pill supplements are some of the modalities used to address this epidemic.

Most so-called supplements for weight loss are exempt from FDA regulation. They do not undergo rigorous testing for safety. Furthermore, many contain controlled substances; some supplements are anti-seizure medications or other prescription drugs; and some are drugs not approved in the United States.2 Since the 1930s, such drugs as dinitrophenol, ephedrine, amphetamine, fenfluramine, and phentermine have flooded the market with the promise of quick weight loss.3,4

Phentermine, a contraction of “phenyltertiary-butylamine,” and its various types (Table) is a psychostimulant of the phenethylamine class, with a pharmacologic profile similar to that of amphetamine. It is known to yield false-positive immunoassay screening results for amphetamines.

CASE REPORT Acute psychotic break

Ms. B, age 37, with a history of postpartum depression, arrives at the emergency room reporting auditory hallucinations of her son and boyfriend; vivid visual hallucinations; and persecutory ideas toward her boyfriend, whom she believes had kidnapped her son. She also complains of insomnia and intermittent confusion for the past week.

Speech is pressured, fast, and difficult to comprehend at times; affect is labile and irritable. Ms. B denies suicidal ideation and is oriented to time, place, and person.

A urine drug screen is positive for amphetamine.

Pre-admission medications include alprazolam, 1 mg as needed, and zolpidem, 10 mg at bedtime, prescribed by Ms. B’s primary care physician for anxiety and insomnia. She discontinued these medications 3 weeks ago because of increased drowsiness at work. She denies other substance use and is unable to account for the positive urine drug screen.

Her medical history, physical examination, and a CT scan of the head are unremarkable. The components of a comprehensive metabolic panel and complete blood count are within normal limits.

After admission, in-depth assessment reveals that Ms. B has been taking phentermine, 37.5 mg (under the brand name Adipex-P), once daily since age 16 for weight loss. She recently discontinued the drug, abruptly, for 1 month, then resumed taking it at an unspecified higher dosage 1 week before she came to the emergency room, for what she said was recreational use and to meet the demands of her job, which required shift work and long hours.

Over the next few days in the hospital, Ms. B’s symptoms resolve as the drug is eliminated from her body. Speech becomes comprehensible and sleep improves. Affective distress diminishes considerably after admission; slight mood lability persists. She no longer reports perceptual disturbances or distress secondary to intrusive thoughts.

Ms. B is discharged 1 week after admission, with instructions to follow up at a dual-diagnosis outpatient program.

Pharmacologic profilePhentermine acts through sympathomimetic pathways by increasing brain noradrenaline and dopamine. The drug has no effect on serotonin.4,5 Phentermine can lead to elevated blood pressure and heart rate, palpitations, restlessness, and insomnia, and can suppress appetite. Increased sympathomimetic activity has been implicated in the ability of phentermine to induce psychotic symptoms.

The literature. Our PubMed search of “phentermine + psychosis” produced 13 results, including 6 case reports of phentermine use. Five citations were more than 4 decades old5-12; only 1 could be considered recent (2011).13

Patients in these reports developed psychotic or manic features after chronic or acute phentermine use, mainly for weight reduction. The most recent article13 mentioned 4 patients who were abusing diet pills recreationally (including “for lethargy”). As with Ms. B, in all 4 of those patients, phentermine precipitated the primary pathology (mania in bipolar disorder; depression in postpartum depression and substance abuse) or revealed underlying illness.

Changing landscape of use and abuseThere has been a trend observed in the pattern of diet pill use: Initially marketed as an appetite suppressant, these pills are now being abused across ethnic, racial, and socioeconomic groups, by males and females.14 There is also a scarcity of useful guidance for clinicians.

Not only are diet pills used by people with an eating disorder; their recreational use is an emerging problem. If reports12,13 continue to reveal that phentermine is a substance of abuse and has catastrophic effects on the user’s psyche, the need for stronger warnings and guidelines might be warranted to allow consumers to make an informed choice about using the drug.

Call for awarenessThe case we presented here exemplifies the importance of tighter regulation of both over-the-counter and prescription stimulant analogs. There is a need for awareness among practitioners about early detection and treatment of reversible psychotic and mood symptoms secondary to what might be promoted as, or appear to be, “harmless” weight loss and energy pills.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

This unfunded study was presented as a case report poster at the Annual Meeting of the Academy of Psychosomatic Medicine, November 2013, Tucson, Arizona, and at the Colloquium of Scholars of the Philadelphia Psychiatric Society, March 2014, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Drug Brand Names

Alprazolam • Xanax

Fenfluramine • Pondimin

Phentermine HCl • Adipex-P, Fen-Phen, Qsymia, Suprenza

Topiramate • Topamax, Trokendi XR

Zolpidem • Ambien

1. Center for Disease Control. Division of nutrition, physical activity, and obesity. http://www.cdc.gov/obesity/data/adult. html. Updated September 14, 2015. Accessed October 27, 2015.

2. Retamero C, Rivera T, Murphy K. “Ephedra-free” diet pill-induced psychosis. Psychosomatics. 2011;52(6):579-582.

3. Cohen PA, Goday A, Swann JP. The return of rainbow diet pills. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(9):1676-1686.

4. Wellman PJ. Overview of adrenergic anorectic agents. Am J Clin Nutr. 1992;55(suppl 1):193S-198S.

5. Devan GS. Phentermine and psychosis. Br J Psychiatry. 1990;156:442-443.

6. Hoffman BF. Diet pill psychosis. Can Med Assoc J. 1977;116(4):351-355.

7. Hoffman BF. Diet pill psychosis: follow-up after 6 years. Can Med Assoc J. 1983;129(10):1077-1078.

8. Rubin RT. Acute psychotic reaction following ingestion of phentermine. Am J Psychiatry. 1964;120:1124-1125.

9. Schaffer CB, Pauli MW. Psychotic reaction caused by proprietary oral diet agent. Am J Psychiatry. 1980;137(10):1256-12567.

10. Lee SH, Liu CY, Yang YY. Schizophreniform-like psychotic disorder induced by phentermine: a case report. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi (Taipei). 1998;61(1):44-47.

11. Zimmer JE, Gregory RJ. Bipolar depression associated with fenfluramine and phentermine. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(7):383-384.

12. Bagri S, Reddy G. Delirium with manic symptoms induced by diet pills. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(2):83.

13. Alexander J, Cheng Y, Choudhary J, et al. Phentermine (Duromine) precipitated psychosis. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2011;45(8):684-685.

14. Pomeranz JL, Taylor LM, Austin SB. Over-the-counter and out-of-control: legal strategies to protect youths from abusing products for weight control. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(2):222-2253.

1. Center for Disease Control. Division of nutrition, physical activity, and obesity. http://www.cdc.gov/obesity/data/adult. html. Updated September 14, 2015. Accessed October 27, 2015.

2. Retamero C, Rivera T, Murphy K. “Ephedra-free” diet pill-induced psychosis. Psychosomatics. 2011;52(6):579-582.

3. Cohen PA, Goday A, Swann JP. The return of rainbow diet pills. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(9):1676-1686.

4. Wellman PJ. Overview of adrenergic anorectic agents. Am J Clin Nutr. 1992;55(suppl 1):193S-198S.

5. Devan GS. Phentermine and psychosis. Br J Psychiatry. 1990;156:442-443.

6. Hoffman BF. Diet pill psychosis. Can Med Assoc J. 1977;116(4):351-355.

7. Hoffman BF. Diet pill psychosis: follow-up after 6 years. Can Med Assoc J. 1983;129(10):1077-1078.

8. Rubin RT. Acute psychotic reaction following ingestion of phentermine. Am J Psychiatry. 1964;120:1124-1125.

9. Schaffer CB, Pauli MW. Psychotic reaction caused by proprietary oral diet agent. Am J Psychiatry. 1980;137(10):1256-12567.

10. Lee SH, Liu CY, Yang YY. Schizophreniform-like psychotic disorder induced by phentermine: a case report. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi (Taipei). 1998;61(1):44-47.

11. Zimmer JE, Gregory RJ. Bipolar depression associated with fenfluramine and phentermine. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(7):383-384.

12. Bagri S, Reddy G. Delirium with manic symptoms induced by diet pills. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(2):83.

13. Alexander J, Cheng Y, Choudhary J, et al. Phentermine (Duromine) precipitated psychosis. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2011;45(8):684-685.

14. Pomeranz JL, Taylor LM, Austin SB. Over-the-counter and out-of-control: legal strategies to protect youths from abusing products for weight control. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(2):222-2253.