User login

Changing trends in diet pill use, from weight loss agent to recreational drug

The prevalence of obesity and obesity-related conditions in the United States is increasing. Many weight-loss products and dietary supplements are used in an attempt to combat this epidemic, but little evidence exists of their efficacy and safety.

We present a case report of a middle-age woman who developed severe psychotic symptoms while taking phentermine hydrochloride (HCl), a psychostimulant similar to amphetamine that is used as a weight-loss agent and for recreational purposes. Phentermine has been associated with mood and psychotic symptoms and has a tendency to cause psychological dependence and tolerance.

To investigate the risks and potential effects of using this drug, we searched OVID and PubMed databases using the search string “phentermine + psychosis.” We conclude that there is a need for awareness about early detection and treatment of reversible psychotic and mood symptoms caused by what might appear to be harmless weight-loss and energy pills.

Obesity epidemic, wide-ranging weight-loss effortsThere has been a dramatic increase in obesity in the United States in the past 20 years: More than one-third of adults and approximately 17% of children and adolescents are obese. Obesity-related conditions, such as heart disease, stroke, and type 2 diabetes mellitus, are leading causes of preventable death.1 Weight monitoring, a healthy lifestyle, surgical intervention, traditional herbs, and diet-pill supplements are some of the modalities used to address this epidemic.

Most so-called supplements for weight loss are exempt from FDA regulation. They do not undergo rigorous testing for safety. Furthermore, many contain controlled substances; some supplements are anti-seizure medications or other prescription drugs; and some are drugs not approved in the United States.2 Since the 1930s, such drugs as dinitrophenol, ephedrine, amphetamine, fenfluramine, and phentermine have flooded the market with the promise of quick weight loss.3,4

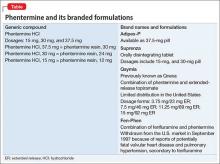

Phentermine, a contraction of “phenyltertiary-butylamine,” and its various types (Table) is a psychostimulant of the phenethylamine class, with a pharmacologic profile similar to that of amphetamine. It is known to yield false-positive immunoassay screening results for amphetamines.

CASE REPORT Acute psychotic break

Ms. B, age 37, with a history of postpartum depression, arrives at the emergency room reporting auditory hallucinations of her son and boyfriend; vivid visual hallucinations; and persecutory ideas toward her boyfriend, whom she believes had kidnapped her son. She also complains of insomnia and intermittent confusion for the past week.

Speech is pressured, fast, and difficult to comprehend at times; affect is labile and irritable. Ms. B denies suicidal ideation and is oriented to time, place, and person.

A urine drug screen is positive for amphetamine.

Pre-admission medications include alprazolam, 1 mg as needed, and zolpidem, 10 mg at bedtime, prescribed by Ms. B’s primary care physician for anxiety and insomnia. She discontinued these medications 3 weeks ago because of increased drowsiness at work. She denies other substance use and is unable to account for the positive urine drug screen.

Her medical history, physical examination, and a CT scan of the head are unremarkable. The components of a comprehensive metabolic panel and complete blood count are within normal limits.

After admission, in-depth assessment reveals that Ms. B has been taking phentermine, 37.5 mg (under the brand name Adipex-P), once daily since age 16 for weight loss. She recently discontinued the drug, abruptly, for 1 month, then resumed taking it at an unspecified higher dosage 1 week before she came to the emergency room, for what she said was recreational use and to meet the demands of her job, which required shift work and long hours.

Over the next few days in the hospital, Ms. B’s symptoms resolve as the drug is eliminated from her body. Speech becomes comprehensible and sleep improves. Affective distress diminishes considerably after admission; slight mood lability persists. She no longer reports perceptual disturbances or distress secondary to intrusive thoughts.

Ms. B is discharged 1 week after admission, with instructions to follow up at a dual-diagnosis outpatient program.

Pharmacologic profilePhentermine acts through sympathomimetic pathways by increasing brain noradrenaline and dopamine. The drug has no effect on serotonin.4,5 Phentermine can lead to elevated blood pressure and heart rate, palpitations, restlessness, and insomnia, and can suppress appetite. Increased sympathomimetic activity has been implicated in the ability of phentermine to induce psychotic symptoms.

The literature. Our PubMed search of “phentermine + psychosis” produced 13 results, including 6 case reports of phentermine use. Five citations were more than 4 decades old5-12; only 1 could be considered recent (2011).13

Patients in these reports developed psychotic or manic features after chronic or acute phentermine use, mainly for weight reduction. The most recent article13 mentioned 4 patients who were abusing diet pills recreationally (including “for lethargy”). As with Ms. B, in all 4 of those patients, phentermine precipitated the primary pathology (mania in bipolar disorder; depression in postpartum depression and substance abuse) or revealed underlying illness.

Changing landscape of use and abuseThere has been a trend observed in the pattern of diet pill use: Initially marketed as an appetite suppressant, these pills are now being abused across ethnic, racial, and socioeconomic groups, by males and females.14 There is also a scarcity of useful guidance for clinicians.

Not only are diet pills used by people with an eating disorder; their recreational use is an emerging problem. If reports12,13 continue to reveal that phentermine is a substance of abuse and has catastrophic effects on the user’s psyche, the need for stronger warnings and guidelines might be warranted to allow consumers to make an informed choice about using the drug.

Call for awarenessThe case we presented here exemplifies the importance of tighter regulation of both over-the-counter and prescription stimulant analogs. There is a need for awareness among practitioners about early detection and treatment of reversible psychotic and mood symptoms secondary to what might be promoted as, or appear to be, “harmless” weight loss and energy pills.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

This unfunded study was presented as a case report poster at the Annual Meeting of the Academy of Psychosomatic Medicine, November 2013, Tucson, Arizona, and at the Colloquium of Scholars of the Philadelphia Psychiatric Society, March 2014, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Drug Brand Names

Alprazolam • Xanax

Fenfluramine • Pondimin

Phentermine HCl • Adipex-P, Fen-Phen, Qsymia, Suprenza

Topiramate • Topamax, Trokendi XR

Zolpidem • Ambien

1. Center for Disease Control. Division of nutrition, physical activity, and obesity. http://www.cdc.gov/obesity/data/adult. html. Updated September 14, 2015. Accessed October 27, 2015.

2. Retamero C, Rivera T, Murphy K. “Ephedra-free” diet pill-induced psychosis. Psychosomatics. 2011;52(6):579-582.

3. Cohen PA, Goday A, Swann JP. The return of rainbow diet pills. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(9):1676-1686.

4. Wellman PJ. Overview of adrenergic anorectic agents. Am J Clin Nutr. 1992;55(suppl 1):193S-198S.

5. Devan GS. Phentermine and psychosis. Br J Psychiatry. 1990;156:442-443.

6. Hoffman BF. Diet pill psychosis. Can Med Assoc J. 1977;116(4):351-355.

7. Hoffman BF. Diet pill psychosis: follow-up after 6 years. Can Med Assoc J. 1983;129(10):1077-1078.

8. Rubin RT. Acute psychotic reaction following ingestion of phentermine. Am J Psychiatry. 1964;120:1124-1125.

9. Schaffer CB, Pauli MW. Psychotic reaction caused by proprietary oral diet agent. Am J Psychiatry. 1980;137(10):1256-12567.

10. Lee SH, Liu CY, Yang YY. Schizophreniform-like psychotic disorder induced by phentermine: a case report. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi (Taipei). 1998;61(1):44-47.

11. Zimmer JE, Gregory RJ. Bipolar depression associated with fenfluramine and phentermine. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(7):383-384.

12. Bagri S, Reddy G. Delirium with manic symptoms induced by diet pills. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(2):83.

13. Alexander J, Cheng Y, Choudhary J, et al. Phentermine (Duromine) precipitated psychosis. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2011;45(8):684-685.

14. Pomeranz JL, Taylor LM, Austin SB. Over-the-counter and out-of-control: legal strategies to protect youths from abusing products for weight control. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(2):222-2253.

The prevalence of obesity and obesity-related conditions in the United States is increasing. Many weight-loss products and dietary supplements are used in an attempt to combat this epidemic, but little evidence exists of their efficacy and safety.

We present a case report of a middle-age woman who developed severe psychotic symptoms while taking phentermine hydrochloride (HCl), a psychostimulant similar to amphetamine that is used as a weight-loss agent and for recreational purposes. Phentermine has been associated with mood and psychotic symptoms and has a tendency to cause psychological dependence and tolerance.

To investigate the risks and potential effects of using this drug, we searched OVID and PubMed databases using the search string “phentermine + psychosis.” We conclude that there is a need for awareness about early detection and treatment of reversible psychotic and mood symptoms caused by what might appear to be harmless weight-loss and energy pills.

Obesity epidemic, wide-ranging weight-loss effortsThere has been a dramatic increase in obesity in the United States in the past 20 years: More than one-third of adults and approximately 17% of children and adolescents are obese. Obesity-related conditions, such as heart disease, stroke, and type 2 diabetes mellitus, are leading causes of preventable death.1 Weight monitoring, a healthy lifestyle, surgical intervention, traditional herbs, and diet-pill supplements are some of the modalities used to address this epidemic.

Most so-called supplements for weight loss are exempt from FDA regulation. They do not undergo rigorous testing for safety. Furthermore, many contain controlled substances; some supplements are anti-seizure medications or other prescription drugs; and some are drugs not approved in the United States.2 Since the 1930s, such drugs as dinitrophenol, ephedrine, amphetamine, fenfluramine, and phentermine have flooded the market with the promise of quick weight loss.3,4

Phentermine, a contraction of “phenyltertiary-butylamine,” and its various types (Table) is a psychostimulant of the phenethylamine class, with a pharmacologic profile similar to that of amphetamine. It is known to yield false-positive immunoassay screening results for amphetamines.

CASE REPORT Acute psychotic break

Ms. B, age 37, with a history of postpartum depression, arrives at the emergency room reporting auditory hallucinations of her son and boyfriend; vivid visual hallucinations; and persecutory ideas toward her boyfriend, whom she believes had kidnapped her son. She also complains of insomnia and intermittent confusion for the past week.

Speech is pressured, fast, and difficult to comprehend at times; affect is labile and irritable. Ms. B denies suicidal ideation and is oriented to time, place, and person.

A urine drug screen is positive for amphetamine.

Pre-admission medications include alprazolam, 1 mg as needed, and zolpidem, 10 mg at bedtime, prescribed by Ms. B’s primary care physician for anxiety and insomnia. She discontinued these medications 3 weeks ago because of increased drowsiness at work. She denies other substance use and is unable to account for the positive urine drug screen.

Her medical history, physical examination, and a CT scan of the head are unremarkable. The components of a comprehensive metabolic panel and complete blood count are within normal limits.

After admission, in-depth assessment reveals that Ms. B has been taking phentermine, 37.5 mg (under the brand name Adipex-P), once daily since age 16 for weight loss. She recently discontinued the drug, abruptly, for 1 month, then resumed taking it at an unspecified higher dosage 1 week before she came to the emergency room, for what she said was recreational use and to meet the demands of her job, which required shift work and long hours.

Over the next few days in the hospital, Ms. B’s symptoms resolve as the drug is eliminated from her body. Speech becomes comprehensible and sleep improves. Affective distress diminishes considerably after admission; slight mood lability persists. She no longer reports perceptual disturbances or distress secondary to intrusive thoughts.

Ms. B is discharged 1 week after admission, with instructions to follow up at a dual-diagnosis outpatient program.

Pharmacologic profilePhentermine acts through sympathomimetic pathways by increasing brain noradrenaline and dopamine. The drug has no effect on serotonin.4,5 Phentermine can lead to elevated blood pressure and heart rate, palpitations, restlessness, and insomnia, and can suppress appetite. Increased sympathomimetic activity has been implicated in the ability of phentermine to induce psychotic symptoms.

The literature. Our PubMed search of “phentermine + psychosis” produced 13 results, including 6 case reports of phentermine use. Five citations were more than 4 decades old5-12; only 1 could be considered recent (2011).13

Patients in these reports developed psychotic or manic features after chronic or acute phentermine use, mainly for weight reduction. The most recent article13 mentioned 4 patients who were abusing diet pills recreationally (including “for lethargy”). As with Ms. B, in all 4 of those patients, phentermine precipitated the primary pathology (mania in bipolar disorder; depression in postpartum depression and substance abuse) or revealed underlying illness.

Changing landscape of use and abuseThere has been a trend observed in the pattern of diet pill use: Initially marketed as an appetite suppressant, these pills are now being abused across ethnic, racial, and socioeconomic groups, by males and females.14 There is also a scarcity of useful guidance for clinicians.

Not only are diet pills used by people with an eating disorder; their recreational use is an emerging problem. If reports12,13 continue to reveal that phentermine is a substance of abuse and has catastrophic effects on the user’s psyche, the need for stronger warnings and guidelines might be warranted to allow consumers to make an informed choice about using the drug.

Call for awarenessThe case we presented here exemplifies the importance of tighter regulation of both over-the-counter and prescription stimulant analogs. There is a need for awareness among practitioners about early detection and treatment of reversible psychotic and mood symptoms secondary to what might be promoted as, or appear to be, “harmless” weight loss and energy pills.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

This unfunded study was presented as a case report poster at the Annual Meeting of the Academy of Psychosomatic Medicine, November 2013, Tucson, Arizona, and at the Colloquium of Scholars of the Philadelphia Psychiatric Society, March 2014, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Drug Brand Names

Alprazolam • Xanax

Fenfluramine • Pondimin

Phentermine HCl • Adipex-P, Fen-Phen, Qsymia, Suprenza

Topiramate • Topamax, Trokendi XR

Zolpidem • Ambien

The prevalence of obesity and obesity-related conditions in the United States is increasing. Many weight-loss products and dietary supplements are used in an attempt to combat this epidemic, but little evidence exists of their efficacy and safety.

We present a case report of a middle-age woman who developed severe psychotic symptoms while taking phentermine hydrochloride (HCl), a psychostimulant similar to amphetamine that is used as a weight-loss agent and for recreational purposes. Phentermine has been associated with mood and psychotic symptoms and has a tendency to cause psychological dependence and tolerance.

To investigate the risks and potential effects of using this drug, we searched OVID and PubMed databases using the search string “phentermine + psychosis.” We conclude that there is a need for awareness about early detection and treatment of reversible psychotic and mood symptoms caused by what might appear to be harmless weight-loss and energy pills.

Obesity epidemic, wide-ranging weight-loss effortsThere has been a dramatic increase in obesity in the United States in the past 20 years: More than one-third of adults and approximately 17% of children and adolescents are obese. Obesity-related conditions, such as heart disease, stroke, and type 2 diabetes mellitus, are leading causes of preventable death.1 Weight monitoring, a healthy lifestyle, surgical intervention, traditional herbs, and diet-pill supplements are some of the modalities used to address this epidemic.

Most so-called supplements for weight loss are exempt from FDA regulation. They do not undergo rigorous testing for safety. Furthermore, many contain controlled substances; some supplements are anti-seizure medications or other prescription drugs; and some are drugs not approved in the United States.2 Since the 1930s, such drugs as dinitrophenol, ephedrine, amphetamine, fenfluramine, and phentermine have flooded the market with the promise of quick weight loss.3,4

Phentermine, a contraction of “phenyltertiary-butylamine,” and its various types (Table) is a psychostimulant of the phenethylamine class, with a pharmacologic profile similar to that of amphetamine. It is known to yield false-positive immunoassay screening results for amphetamines.

CASE REPORT Acute psychotic break

Ms. B, age 37, with a history of postpartum depression, arrives at the emergency room reporting auditory hallucinations of her son and boyfriend; vivid visual hallucinations; and persecutory ideas toward her boyfriend, whom she believes had kidnapped her son. She also complains of insomnia and intermittent confusion for the past week.

Speech is pressured, fast, and difficult to comprehend at times; affect is labile and irritable. Ms. B denies suicidal ideation and is oriented to time, place, and person.

A urine drug screen is positive for amphetamine.

Pre-admission medications include alprazolam, 1 mg as needed, and zolpidem, 10 mg at bedtime, prescribed by Ms. B’s primary care physician for anxiety and insomnia. She discontinued these medications 3 weeks ago because of increased drowsiness at work. She denies other substance use and is unable to account for the positive urine drug screen.

Her medical history, physical examination, and a CT scan of the head are unremarkable. The components of a comprehensive metabolic panel and complete blood count are within normal limits.

After admission, in-depth assessment reveals that Ms. B has been taking phentermine, 37.5 mg (under the brand name Adipex-P), once daily since age 16 for weight loss. She recently discontinued the drug, abruptly, for 1 month, then resumed taking it at an unspecified higher dosage 1 week before she came to the emergency room, for what she said was recreational use and to meet the demands of her job, which required shift work and long hours.

Over the next few days in the hospital, Ms. B’s symptoms resolve as the drug is eliminated from her body. Speech becomes comprehensible and sleep improves. Affective distress diminishes considerably after admission; slight mood lability persists. She no longer reports perceptual disturbances or distress secondary to intrusive thoughts.

Ms. B is discharged 1 week after admission, with instructions to follow up at a dual-diagnosis outpatient program.

Pharmacologic profilePhentermine acts through sympathomimetic pathways by increasing brain noradrenaline and dopamine. The drug has no effect on serotonin.4,5 Phentermine can lead to elevated blood pressure and heart rate, palpitations, restlessness, and insomnia, and can suppress appetite. Increased sympathomimetic activity has been implicated in the ability of phentermine to induce psychotic symptoms.

The literature. Our PubMed search of “phentermine + psychosis” produced 13 results, including 6 case reports of phentermine use. Five citations were more than 4 decades old5-12; only 1 could be considered recent (2011).13

Patients in these reports developed psychotic or manic features after chronic or acute phentermine use, mainly for weight reduction. The most recent article13 mentioned 4 patients who were abusing diet pills recreationally (including “for lethargy”). As with Ms. B, in all 4 of those patients, phentermine precipitated the primary pathology (mania in bipolar disorder; depression in postpartum depression and substance abuse) or revealed underlying illness.

Changing landscape of use and abuseThere has been a trend observed in the pattern of diet pill use: Initially marketed as an appetite suppressant, these pills are now being abused across ethnic, racial, and socioeconomic groups, by males and females.14 There is also a scarcity of useful guidance for clinicians.

Not only are diet pills used by people with an eating disorder; their recreational use is an emerging problem. If reports12,13 continue to reveal that phentermine is a substance of abuse and has catastrophic effects on the user’s psyche, the need for stronger warnings and guidelines might be warranted to allow consumers to make an informed choice about using the drug.

Call for awarenessThe case we presented here exemplifies the importance of tighter regulation of both over-the-counter and prescription stimulant analogs. There is a need for awareness among practitioners about early detection and treatment of reversible psychotic and mood symptoms secondary to what might be promoted as, or appear to be, “harmless” weight loss and energy pills.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

This unfunded study was presented as a case report poster at the Annual Meeting of the Academy of Psychosomatic Medicine, November 2013, Tucson, Arizona, and at the Colloquium of Scholars of the Philadelphia Psychiatric Society, March 2014, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Drug Brand Names

Alprazolam • Xanax

Fenfluramine • Pondimin

Phentermine HCl • Adipex-P, Fen-Phen, Qsymia, Suprenza

Topiramate • Topamax, Trokendi XR

Zolpidem • Ambien

1. Center for Disease Control. Division of nutrition, physical activity, and obesity. http://www.cdc.gov/obesity/data/adult. html. Updated September 14, 2015. Accessed October 27, 2015.

2. Retamero C, Rivera T, Murphy K. “Ephedra-free” diet pill-induced psychosis. Psychosomatics. 2011;52(6):579-582.

3. Cohen PA, Goday A, Swann JP. The return of rainbow diet pills. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(9):1676-1686.

4. Wellman PJ. Overview of adrenergic anorectic agents. Am J Clin Nutr. 1992;55(suppl 1):193S-198S.

5. Devan GS. Phentermine and psychosis. Br J Psychiatry. 1990;156:442-443.

6. Hoffman BF. Diet pill psychosis. Can Med Assoc J. 1977;116(4):351-355.

7. Hoffman BF. Diet pill psychosis: follow-up after 6 years. Can Med Assoc J. 1983;129(10):1077-1078.

8. Rubin RT. Acute psychotic reaction following ingestion of phentermine. Am J Psychiatry. 1964;120:1124-1125.

9. Schaffer CB, Pauli MW. Psychotic reaction caused by proprietary oral diet agent. Am J Psychiatry. 1980;137(10):1256-12567.

10. Lee SH, Liu CY, Yang YY. Schizophreniform-like psychotic disorder induced by phentermine: a case report. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi (Taipei). 1998;61(1):44-47.

11. Zimmer JE, Gregory RJ. Bipolar depression associated with fenfluramine and phentermine. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(7):383-384.

12. Bagri S, Reddy G. Delirium with manic symptoms induced by diet pills. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(2):83.

13. Alexander J, Cheng Y, Choudhary J, et al. Phentermine (Duromine) precipitated psychosis. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2011;45(8):684-685.

14. Pomeranz JL, Taylor LM, Austin SB. Over-the-counter and out-of-control: legal strategies to protect youths from abusing products for weight control. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(2):222-2253.

1. Center for Disease Control. Division of nutrition, physical activity, and obesity. http://www.cdc.gov/obesity/data/adult. html. Updated September 14, 2015. Accessed October 27, 2015.

2. Retamero C, Rivera T, Murphy K. “Ephedra-free” diet pill-induced psychosis. Psychosomatics. 2011;52(6):579-582.

3. Cohen PA, Goday A, Swann JP. The return of rainbow diet pills. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(9):1676-1686.

4. Wellman PJ. Overview of adrenergic anorectic agents. Am J Clin Nutr. 1992;55(suppl 1):193S-198S.

5. Devan GS. Phentermine and psychosis. Br J Psychiatry. 1990;156:442-443.

6. Hoffman BF. Diet pill psychosis. Can Med Assoc J. 1977;116(4):351-355.

7. Hoffman BF. Diet pill psychosis: follow-up after 6 years. Can Med Assoc J. 1983;129(10):1077-1078.

8. Rubin RT. Acute psychotic reaction following ingestion of phentermine. Am J Psychiatry. 1964;120:1124-1125.

9. Schaffer CB, Pauli MW. Psychotic reaction caused by proprietary oral diet agent. Am J Psychiatry. 1980;137(10):1256-12567.

10. Lee SH, Liu CY, Yang YY. Schizophreniform-like psychotic disorder induced by phentermine: a case report. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi (Taipei). 1998;61(1):44-47.

11. Zimmer JE, Gregory RJ. Bipolar depression associated with fenfluramine and phentermine. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(7):383-384.

12. Bagri S, Reddy G. Delirium with manic symptoms induced by diet pills. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(2):83.

13. Alexander J, Cheng Y, Choudhary J, et al. Phentermine (Duromine) precipitated psychosis. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2011;45(8):684-685.

14. Pomeranz JL, Taylor LM, Austin SB. Over-the-counter and out-of-control: legal strategies to protect youths from abusing products for weight control. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(2):222-2253.