User login

Suicidal and paranoid thoughts after starting hepatitis C virus treatment

CASE Suicidal and paranoid

Ms. B, age 53, has a 30-year history of bipolar disorder, a 1-year history of hepatitis C virus (HCV), and previous inpatient psychiatric hospitalizations secondary to acute mania. She presents to our hospital describing her symptoms as the “worst depression ever” and reports suicidal ideation and paranoid thoughts of people watching and following her. Ms. B describes significant neurovegetative symptoms of depression, including poor sleep, poor appetite, low energy and concentration, and chronic feelings of hopelessness with thoughts of “ending it all.” Ms. B reports that her symptoms started 3 weeks ago, a few days after she started taking sofosbuvir and ribavirin for refractory HCV.

Ms. B’s medication regimen consisted of quetiapine, 400 mg at bedtime, fluoxetine, 40 mg/d, and lamotrigine, 150 mg/d, for bipolar disorder, when she started taking sofosbuvir and ribavirin. Ms. B admits she stopped taking her psychotropic and antiviral medications after she noticed progressively worsening depression with intrusive suicidal thoughts, including ruminative thoughts of overdosing on them.

At evaluation, Ms. B is casually dressed, pleasant, with fair hygiene and poor eye contact. Her speech is decreased in rate, volume, and tone; mood is “devastated and depressed”; affect is labile and tearful. Her thought process reveals occasional thought blocking and her thought content includes suicidal ideations and paranoid thoughts. Her cognition is intact; insight and judgment are poor. During evaluation, Ms. B reveals a history of alcohol and marijuana use, but reports that she has not used either for the past 15 years. She further states that she had agreed to a trial of medication first for her liver disease and had deferred any discussion of liver transplant at the time of her diagnosis with HCV.

Laboratory tests reveal a normal complete blood count, creatinine, and electrolytes. However, liver functions were elevated, including aspartate aminotransferase (AST) of 107 U/L (reference range, 8 to 48 U/L) and alanine aminotransferase of 117 U/L (reference range, 7 to 55 U/L). Although increased, the levels of AST and ALT were slightly less than her levels pre-sofosbuvir–ribavirin trial, indicating some response to the medication.

[polldaddy:9777325]

The authors’ observations

Approximately 170 million people worldwide suffer from chronic HCV infection, affecting 2.7 to 5.2 million people in the United States, with 350,000 deaths attributed to liver disease caused by HCV.1

The standard treatment of HCV genotype 1, which represents 70% of all cases of chronic HCV in the United States, is 12 to 32 weeks of an oral protease inhibitor combined with 24 to 48 weeks of peg-interferon (IFN)–alpha-2a plus ribavirin, with the duration of therapy guided by the on-treatment response and the stage of hepatic fibrosis.1

In 2013, the FDA approved sofosbuvir, a direct-acting antiviral drug for chronic HCV. It is a nucleotide analogue HCV NS5B polymerase inhibitor with similar in vitro activity against all HCV genotypes.1 This medication is efficient when used with an antiviral regimen in adults with HCV with liver disease, cirrhosis, HIV coinfection, and hepatocellular carcinoma awaiting liver transplant.2

TREATMENT Medication restarted

Ms. B is admitted to the psychiatric unit for management of severe depression and suicidal thoughts, and quetiapine, 400 mg at bedtime, fluoxetine, 40 mg/d, and lamotrigine, 150 mg/d, are restarted. The hepatology team is consulted for further evaluation and management of her liver disease.

She receives supportive psychotherapy, art therapy, and group therapy to develop better coping skills for her depression and suicidal thoughts and psychoeducation about her medical and psychiatric illness to understand the importance of treatment adherence for symptom improvement. Over the course of her hospital stay, Ms. B has subjective and objective improvements of her depressive symptoms.

The authors’ observations

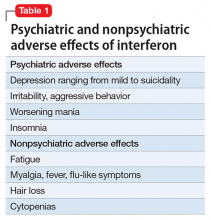

Psychiatric adverse effects associated with IFN-α therapy in chronic HCV patients are the main cause of antiviral treatment discontinuation, resulting in a decreased rate of sustained viral response.3 Chronic HCV is a major health burden; therefore there is a need for treatment options that are more efficient, safer, simpler, more convenient, and preferably IFN-free.

Sofosbuvir has met many of these criteria and has been found to be safe and well tolerated when administered alone or with ribavirin. Sofosbuvir represents a major breakthrough in HCV care to achieve cures and prevent IFN-associated morbidity and mortality.4,5

Our case report highlights, however, that significant depressive symptoms may be associated with sofosbuvir. Hepatologists should be cautious when prescribing sofosbuvir in patients with comorbid psychiatric illness to avoid exacerbating depressive symptoms and increasing the risk of suicidality.

[polldaddy:9777328]

OUTCOME Refuses treatment

Ms. B is seen by the hepatology team who discuss the best treatment options for HCV, including ledipasvir/sofosbuvir, daclatasvir and ribavirin, and ombitasvir/paritaprevir/ritonavir plus dasabuvir. However, she refuses treatment for HCV stating, “I would rather have no depression with hepatitis C than feel depressed and suicidal while getting treatment for hepatitis C.”

Ms. B is discharged with referral to the outpatient psychiatry clinic and hepatology clinic for monitoring her liver function and restarting sofosbuvir and ribavirin for HCV once her mood symptoms improved.

The authors’ observations

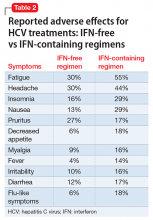

A robust psychiatric evaluation is required before initiating the previously mentioned antiviral therapy to identify high-risk patients to prevent emergence or exacerbation of new psychiatric symptoms, including depression and mania, when treating with IFN-free or IFN-containing regimens. Collaborative care involving a hepatologist and psychiatrist is necessary for comprehensive monitoring of a patient’s psychiatric symptoms and management with medication and psychotherapy. This will limit psychiatric morbidity in patients receiving antiviral treatment with sofosbuvir and ribavirin.

It’s imperative to improve medication adherence for patients by adopting strategies, such as:

- identifying factors leading to noncompliance

- establishing a strong rapport with the patients

- providing psychoeducation about the illness, discussing the benefits and risks of medications and the importance of maintenance treatment

- simplifying medication regimen.6

More research on medication management of HCV in patients with comorbid psychiatric illness should be encouraged and focused on initiating and monitoring non-IFN treatment regimens for patients with HCV and preexisting bipolar disorder or other mood disorders.

1. Lawitz E, Mangia A, Wyles D, et al. Sofosbuvir for previously untreated chronic hepatitis C infection. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(20):1878-1887.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Hepatitis C FAQ for health professionals. http://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/HCV/HCVfaq.htm#section4. Updated January 27, 2017. Accessed June 2, 2017.

3. Lucaciu LA, Dumitrascu DL. Depression and suicide ideation in chronic hepatitis C patients untreated and treated with interferon: prevalence, prevention, and treatment. Ann Gastroenterol. 2015;28(4):440-447.

4. Lam B, Henry L, Younossi Z. Sofosbuvir (Sovaldi) for the treatment of hepatitis C. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2014;7(5):555-566.

5. Lawitz E, Poordad FF, Pang PS, et al. Sofosbuvir and ledipasvir fixed-dose combination with and without ribavirin in treatment-naive and previously treated patients with genotype 1 hepatitis C virus infection (LONESTAR): an open-label, randomized, phase 2 trial. Lancet 2014;383(9916):515-523.

6. Balon R. Managing compliance. Psychiatric Times. www.psychiatrictimes.com/articles/managing-compliance. Published May 1, 2002. Accessed June 14, 2017.

CASE Suicidal and paranoid

Ms. B, age 53, has a 30-year history of bipolar disorder, a 1-year history of hepatitis C virus (HCV), and previous inpatient psychiatric hospitalizations secondary to acute mania. She presents to our hospital describing her symptoms as the “worst depression ever” and reports suicidal ideation and paranoid thoughts of people watching and following her. Ms. B describes significant neurovegetative symptoms of depression, including poor sleep, poor appetite, low energy and concentration, and chronic feelings of hopelessness with thoughts of “ending it all.” Ms. B reports that her symptoms started 3 weeks ago, a few days after she started taking sofosbuvir and ribavirin for refractory HCV.

Ms. B’s medication regimen consisted of quetiapine, 400 mg at bedtime, fluoxetine, 40 mg/d, and lamotrigine, 150 mg/d, for bipolar disorder, when she started taking sofosbuvir and ribavirin. Ms. B admits she stopped taking her psychotropic and antiviral medications after she noticed progressively worsening depression with intrusive suicidal thoughts, including ruminative thoughts of overdosing on them.

At evaluation, Ms. B is casually dressed, pleasant, with fair hygiene and poor eye contact. Her speech is decreased in rate, volume, and tone; mood is “devastated and depressed”; affect is labile and tearful. Her thought process reveals occasional thought blocking and her thought content includes suicidal ideations and paranoid thoughts. Her cognition is intact; insight and judgment are poor. During evaluation, Ms. B reveals a history of alcohol and marijuana use, but reports that she has not used either for the past 15 years. She further states that she had agreed to a trial of medication first for her liver disease and had deferred any discussion of liver transplant at the time of her diagnosis with HCV.

Laboratory tests reveal a normal complete blood count, creatinine, and electrolytes. However, liver functions were elevated, including aspartate aminotransferase (AST) of 107 U/L (reference range, 8 to 48 U/L) and alanine aminotransferase of 117 U/L (reference range, 7 to 55 U/L). Although increased, the levels of AST and ALT were slightly less than her levels pre-sofosbuvir–ribavirin trial, indicating some response to the medication.

[polldaddy:9777325]

The authors’ observations

Approximately 170 million people worldwide suffer from chronic HCV infection, affecting 2.7 to 5.2 million people in the United States, with 350,000 deaths attributed to liver disease caused by HCV.1

The standard treatment of HCV genotype 1, which represents 70% of all cases of chronic HCV in the United States, is 12 to 32 weeks of an oral protease inhibitor combined with 24 to 48 weeks of peg-interferon (IFN)–alpha-2a plus ribavirin, with the duration of therapy guided by the on-treatment response and the stage of hepatic fibrosis.1

In 2013, the FDA approved sofosbuvir, a direct-acting antiviral drug for chronic HCV. It is a nucleotide analogue HCV NS5B polymerase inhibitor with similar in vitro activity against all HCV genotypes.1 This medication is efficient when used with an antiviral regimen in adults with HCV with liver disease, cirrhosis, HIV coinfection, and hepatocellular carcinoma awaiting liver transplant.2

TREATMENT Medication restarted

Ms. B is admitted to the psychiatric unit for management of severe depression and suicidal thoughts, and quetiapine, 400 mg at bedtime, fluoxetine, 40 mg/d, and lamotrigine, 150 mg/d, are restarted. The hepatology team is consulted for further evaluation and management of her liver disease.

She receives supportive psychotherapy, art therapy, and group therapy to develop better coping skills for her depression and suicidal thoughts and psychoeducation about her medical and psychiatric illness to understand the importance of treatment adherence for symptom improvement. Over the course of her hospital stay, Ms. B has subjective and objective improvements of her depressive symptoms.

The authors’ observations

Psychiatric adverse effects associated with IFN-α therapy in chronic HCV patients are the main cause of antiviral treatment discontinuation, resulting in a decreased rate of sustained viral response.3 Chronic HCV is a major health burden; therefore there is a need for treatment options that are more efficient, safer, simpler, more convenient, and preferably IFN-free.

Sofosbuvir has met many of these criteria and has been found to be safe and well tolerated when administered alone or with ribavirin. Sofosbuvir represents a major breakthrough in HCV care to achieve cures and prevent IFN-associated morbidity and mortality.4,5

Our case report highlights, however, that significant depressive symptoms may be associated with sofosbuvir. Hepatologists should be cautious when prescribing sofosbuvir in patients with comorbid psychiatric illness to avoid exacerbating depressive symptoms and increasing the risk of suicidality.

[polldaddy:9777328]

OUTCOME Refuses treatment

Ms. B is seen by the hepatology team who discuss the best treatment options for HCV, including ledipasvir/sofosbuvir, daclatasvir and ribavirin, and ombitasvir/paritaprevir/ritonavir plus dasabuvir. However, she refuses treatment for HCV stating, “I would rather have no depression with hepatitis C than feel depressed and suicidal while getting treatment for hepatitis C.”

Ms. B is discharged with referral to the outpatient psychiatry clinic and hepatology clinic for monitoring her liver function and restarting sofosbuvir and ribavirin for HCV once her mood symptoms improved.

The authors’ observations

A robust psychiatric evaluation is required before initiating the previously mentioned antiviral therapy to identify high-risk patients to prevent emergence or exacerbation of new psychiatric symptoms, including depression and mania, when treating with IFN-free or IFN-containing regimens. Collaborative care involving a hepatologist and psychiatrist is necessary for comprehensive monitoring of a patient’s psychiatric symptoms and management with medication and psychotherapy. This will limit psychiatric morbidity in patients receiving antiviral treatment with sofosbuvir and ribavirin.

It’s imperative to improve medication adherence for patients by adopting strategies, such as:

- identifying factors leading to noncompliance

- establishing a strong rapport with the patients

- providing psychoeducation about the illness, discussing the benefits and risks of medications and the importance of maintenance treatment

- simplifying medication regimen.6

More research on medication management of HCV in patients with comorbid psychiatric illness should be encouraged and focused on initiating and monitoring non-IFN treatment regimens for patients with HCV and preexisting bipolar disorder or other mood disorders.

CASE Suicidal and paranoid

Ms. B, age 53, has a 30-year history of bipolar disorder, a 1-year history of hepatitis C virus (HCV), and previous inpatient psychiatric hospitalizations secondary to acute mania. She presents to our hospital describing her symptoms as the “worst depression ever” and reports suicidal ideation and paranoid thoughts of people watching and following her. Ms. B describes significant neurovegetative symptoms of depression, including poor sleep, poor appetite, low energy and concentration, and chronic feelings of hopelessness with thoughts of “ending it all.” Ms. B reports that her symptoms started 3 weeks ago, a few days after she started taking sofosbuvir and ribavirin for refractory HCV.

Ms. B’s medication regimen consisted of quetiapine, 400 mg at bedtime, fluoxetine, 40 mg/d, and lamotrigine, 150 mg/d, for bipolar disorder, when she started taking sofosbuvir and ribavirin. Ms. B admits she stopped taking her psychotropic and antiviral medications after she noticed progressively worsening depression with intrusive suicidal thoughts, including ruminative thoughts of overdosing on them.

At evaluation, Ms. B is casually dressed, pleasant, with fair hygiene and poor eye contact. Her speech is decreased in rate, volume, and tone; mood is “devastated and depressed”; affect is labile and tearful. Her thought process reveals occasional thought blocking and her thought content includes suicidal ideations and paranoid thoughts. Her cognition is intact; insight and judgment are poor. During evaluation, Ms. B reveals a history of alcohol and marijuana use, but reports that she has not used either for the past 15 years. She further states that she had agreed to a trial of medication first for her liver disease and had deferred any discussion of liver transplant at the time of her diagnosis with HCV.

Laboratory tests reveal a normal complete blood count, creatinine, and electrolytes. However, liver functions were elevated, including aspartate aminotransferase (AST) of 107 U/L (reference range, 8 to 48 U/L) and alanine aminotransferase of 117 U/L (reference range, 7 to 55 U/L). Although increased, the levels of AST and ALT were slightly less than her levels pre-sofosbuvir–ribavirin trial, indicating some response to the medication.

[polldaddy:9777325]

The authors’ observations

Approximately 170 million people worldwide suffer from chronic HCV infection, affecting 2.7 to 5.2 million people in the United States, with 350,000 deaths attributed to liver disease caused by HCV.1

The standard treatment of HCV genotype 1, which represents 70% of all cases of chronic HCV in the United States, is 12 to 32 weeks of an oral protease inhibitor combined with 24 to 48 weeks of peg-interferon (IFN)–alpha-2a plus ribavirin, with the duration of therapy guided by the on-treatment response and the stage of hepatic fibrosis.1

In 2013, the FDA approved sofosbuvir, a direct-acting antiviral drug for chronic HCV. It is a nucleotide analogue HCV NS5B polymerase inhibitor with similar in vitro activity against all HCV genotypes.1 This medication is efficient when used with an antiviral regimen in adults with HCV with liver disease, cirrhosis, HIV coinfection, and hepatocellular carcinoma awaiting liver transplant.2

TREATMENT Medication restarted

Ms. B is admitted to the psychiatric unit for management of severe depression and suicidal thoughts, and quetiapine, 400 mg at bedtime, fluoxetine, 40 mg/d, and lamotrigine, 150 mg/d, are restarted. The hepatology team is consulted for further evaluation and management of her liver disease.

She receives supportive psychotherapy, art therapy, and group therapy to develop better coping skills for her depression and suicidal thoughts and psychoeducation about her medical and psychiatric illness to understand the importance of treatment adherence for symptom improvement. Over the course of her hospital stay, Ms. B has subjective and objective improvements of her depressive symptoms.

The authors’ observations

Psychiatric adverse effects associated with IFN-α therapy in chronic HCV patients are the main cause of antiviral treatment discontinuation, resulting in a decreased rate of sustained viral response.3 Chronic HCV is a major health burden; therefore there is a need for treatment options that are more efficient, safer, simpler, more convenient, and preferably IFN-free.

Sofosbuvir has met many of these criteria and has been found to be safe and well tolerated when administered alone or with ribavirin. Sofosbuvir represents a major breakthrough in HCV care to achieve cures and prevent IFN-associated morbidity and mortality.4,5

Our case report highlights, however, that significant depressive symptoms may be associated with sofosbuvir. Hepatologists should be cautious when prescribing sofosbuvir in patients with comorbid psychiatric illness to avoid exacerbating depressive symptoms and increasing the risk of suicidality.

[polldaddy:9777328]

OUTCOME Refuses treatment

Ms. B is seen by the hepatology team who discuss the best treatment options for HCV, including ledipasvir/sofosbuvir, daclatasvir and ribavirin, and ombitasvir/paritaprevir/ritonavir plus dasabuvir. However, she refuses treatment for HCV stating, “I would rather have no depression with hepatitis C than feel depressed and suicidal while getting treatment for hepatitis C.”

Ms. B is discharged with referral to the outpatient psychiatry clinic and hepatology clinic for monitoring her liver function and restarting sofosbuvir and ribavirin for HCV once her mood symptoms improved.

The authors’ observations

A robust psychiatric evaluation is required before initiating the previously mentioned antiviral therapy to identify high-risk patients to prevent emergence or exacerbation of new psychiatric symptoms, including depression and mania, when treating with IFN-free or IFN-containing regimens. Collaborative care involving a hepatologist and psychiatrist is necessary for comprehensive monitoring of a patient’s psychiatric symptoms and management with medication and psychotherapy. This will limit psychiatric morbidity in patients receiving antiviral treatment with sofosbuvir and ribavirin.

It’s imperative to improve medication adherence for patients by adopting strategies, such as:

- identifying factors leading to noncompliance

- establishing a strong rapport with the patients

- providing psychoeducation about the illness, discussing the benefits and risks of medications and the importance of maintenance treatment

- simplifying medication regimen.6

More research on medication management of HCV in patients with comorbid psychiatric illness should be encouraged and focused on initiating and monitoring non-IFN treatment regimens for patients with HCV and preexisting bipolar disorder or other mood disorders.

1. Lawitz E, Mangia A, Wyles D, et al. Sofosbuvir for previously untreated chronic hepatitis C infection. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(20):1878-1887.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Hepatitis C FAQ for health professionals. http://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/HCV/HCVfaq.htm#section4. Updated January 27, 2017. Accessed June 2, 2017.

3. Lucaciu LA, Dumitrascu DL. Depression and suicide ideation in chronic hepatitis C patients untreated and treated with interferon: prevalence, prevention, and treatment. Ann Gastroenterol. 2015;28(4):440-447.

4. Lam B, Henry L, Younossi Z. Sofosbuvir (Sovaldi) for the treatment of hepatitis C. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2014;7(5):555-566.

5. Lawitz E, Poordad FF, Pang PS, et al. Sofosbuvir and ledipasvir fixed-dose combination with and without ribavirin in treatment-naive and previously treated patients with genotype 1 hepatitis C virus infection (LONESTAR): an open-label, randomized, phase 2 trial. Lancet 2014;383(9916):515-523.

6. Balon R. Managing compliance. Psychiatric Times. www.psychiatrictimes.com/articles/managing-compliance. Published May 1, 2002. Accessed June 14, 2017.

1. Lawitz E, Mangia A, Wyles D, et al. Sofosbuvir for previously untreated chronic hepatitis C infection. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(20):1878-1887.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Hepatitis C FAQ for health professionals. http://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/HCV/HCVfaq.htm#section4. Updated January 27, 2017. Accessed June 2, 2017.

3. Lucaciu LA, Dumitrascu DL. Depression and suicide ideation in chronic hepatitis C patients untreated and treated with interferon: prevalence, prevention, and treatment. Ann Gastroenterol. 2015;28(4):440-447.

4. Lam B, Henry L, Younossi Z. Sofosbuvir (Sovaldi) for the treatment of hepatitis C. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2014;7(5):555-566.

5. Lawitz E, Poordad FF, Pang PS, et al. Sofosbuvir and ledipasvir fixed-dose combination with and without ribavirin in treatment-naive and previously treated patients with genotype 1 hepatitis C virus infection (LONESTAR): an open-label, randomized, phase 2 trial. Lancet 2014;383(9916):515-523.

6. Balon R. Managing compliance. Psychiatric Times. www.psychiatrictimes.com/articles/managing-compliance. Published May 1, 2002. Accessed June 14, 2017.