User login

The angry disciple

CASE Disorganized thoughts and grandiose delusions

Mr. J, age 54, presents to the psychiatric emergency department (ED) with agitation and disruptive behavior. He claims that he is “the son of Jesus Christ” and has to travel to the Middle East to be baptized. Mr. J is irritable, shouting, and threatening staff members. He receives

The next day, he is calm and cooperative, but continues to express the same religious delusions. Mr. J is admitted to the psychiatric inpatient unit for further evaluation.

On the unit, Mr. J is pleasant and cooperative, but tangential in thought process. He reports he was “saved” by God 4 years ago, and that God communicates with him through music. Despite this, he denies having auditory or visual hallucinations.

Approximately 3 months earlier, Mr. J had stopped working and left his home and family in another state to pursue his “mission” of being baptized in the Middle East. Mr. J has been homeless since then. Despite that, he reports that his mood is “great” and denies any recent changes in mood, sleep, appetite, energy level, or psychomotor agitation. Although no formal cognitive testing is performed, Mr. J is alert and oriented to person, place, and time with intact remote and recent memory, no language deficits, and no lapses in concentration or attention throughout interview.

Mr. J says he has been drinking alcohol regularly throughout his adult life, often a few times per week, up to “a case and a half” of beer at times. He claims he’s had multiple periods of sobriety but denies having experienced withdrawal symptoms during those times. Mr. J reports 1 prior psychiatric hospitalization 25 years ago after attempting suicide by overdose following the loss of a loved one. At that time, he was diagnosed with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). During this admission, he denies having any symptoms of PTSD or periods of mania or depression, and he has not undergone psychiatric treatment since he had been diagnosed with PTSD. He denies any family history of psychiatric illness as well as any medical comorbidities or medication use.

[polldaddy:10279202]

The authors’ observations

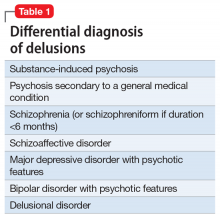

Mr. J’s presentation had a wide differential diagnosis (Table 1). The initial agitation Mr. J displayed in the psychiatric ED was likely secondary to acute alcohol intoxication, given that he was subsequently pleasant, calm, and cooperative after the alcohol was metabolized. Despite this, Mr. J continued to demonstrate delusions of a religious and somewhat grandiose nature with tangential thought processes, which made substance-induced psychosis less likely to be the sole diagnosis. Although it is possible to develop psychotic symptoms due to severe alcohol withdrawal (alcoholic hallucinosis), Mr. J’s vital signs remained stable, and he demonstrated no other signs or symptoms of withdrawal throughout his hospitalization. His presentation also did not fit that of delirium tremens because he was not confused or disoriented, and did not demonstrate perceptual disturbance.

While delusions were the most prominent feature of Mr. J’s apparent psychosis, the presence of disorganized thought processes and impaired functioning, as evidenced by Mr. J’s unemployment and recent homelessness, were more consistent with a primary psychotic disorder than a delusional disorder.1

Continue to: Mr. J began to exhibit...

Mr. J began to exhibit these psychotic symptoms in his early 50s; because the average age of onset of schizophrenia for males is approximately age 20 to 25, the likelihood of his presentation being the result of a primary psychotic disorder was low.1 Although less common, it was possible that Mr. J had developed late-onset schizophrenia, where the first episode typically occurs after approximately age 40 to 45. Mr. J also described that he was in a “great” mood but had grandiose delusions and had made recent impulsive decisions, which suggests there was a possible mood component to his presentation and a potential diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder or bipolar disorder with psychotic symptoms. However, before any of these diagnoses could be made, a medical or neurologic condition that could cause his symptoms needed to be investigated and ruled out. Further collateral information regarding Mr. J’s history and timeline of symptoms was required.

EVALUATION Family history reveals clues

All laboratory studies completed during Mr. J’s hospitalization are unremarkable, including complete blood count, basic metabolic panel, hepatic function panel, gamma-glutamyl transferase test, magnesium, phosphate, thyroid-stimulating hormone, vitamin B12, thiamine, folate, urinalysis, and urine drug screen. Mr. J does not undergo any head imaging.

Mr. J has not been in touch with his family since leaving his home approximately 3 months before he presented to the ED, and he gives consent for the inpatient team to attempt to contact them. One week into hospitalization, Mr. J’s sibling informs the team of a family history of genetically confirmed Huntington’s disease (HD), with psychiatric symptoms preceding the onset of motor symptoms in multiple first-degree relatives. His family says that before Mr. J first developed delusions 4 years ago, he had not exhibited any psychotic symptoms during periods of alcohol use or sobriety.

Mr. J does not demonstrate any overt movement symptoms on the unit and denies noting any rigidity, change in gait, or abnormal/uncontrolled movements. The inpatient psychiatric team consults neurology and a full neurologic evaluation is performed. The results are unremarkable outside of his psychiatric symptoms; specifically, Mr. J does not demonstrate even subtle motor signs or cognitive impairment. Given Mr. J’s family history, unremarkable lab findings, and age at presentation, the neurology team and inpatient psychiatry team suspect that his psychosis is likely an early presentation of HD.

[polldaddy:10279212]

The authors’ observations

Genetics of Huntington’s disease

Huntington’s disease is an autosomal dominant neurodegenerative disorder caused by expansion of cytosine-adenine-guanine (CAG) trinucleotide repeats within the Huntingtin (HTT) gene on chromosome 4, which codes for the huntingtin protein.2,3 While the function of “normal” huntingtin protein is not fully understood, it is known that CAG repeat expansion in the HTT gene of >35 repeats codes for a mutant huntingtin protein.2,3 The mutant huntingtin protein causes progressive neuronal loss in the basal ganglia and striatum, resulting in the clinical Huntington’s phenotype.3 Notably, the patient’s age at disease onset is inversely correlated with the number of repeats. For example, expansions of approximately 40 to 50 CAG repeats often result in adult-onset HD, while expansions of >60 repeats are typically associated with juvenile-onset HD (before age 20). CAG repeat lengths of approximately 36 to 39 demonstrate reduced penetrance, with some individuals developing symptomatic HD while others do not.2 Instability of the CAG repeat expansion can result in genetic “anticipation,” wherein repeat length increases between generations, causing earlier age of onset in affected offspring. Genetic anticipation in HD occurs more frequently in paternal transmission—approximately 80% to 90% of juvenile HD cases are inherited paternally, at times with the number of CAG repeats exceeding 200.3

Continue to: Psychiatric manifestations of Huntington's disease

Psychiatric manifestations of Huntington’s disease

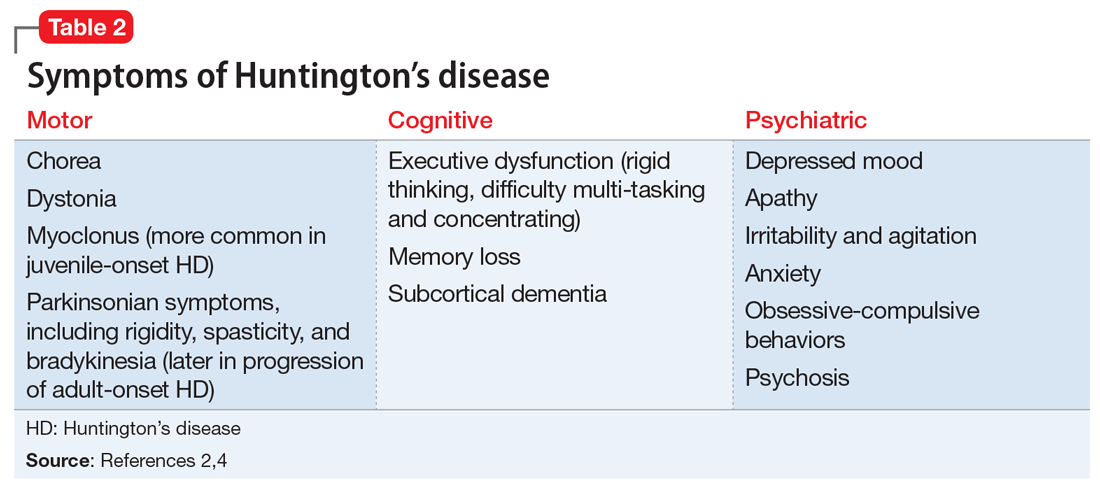

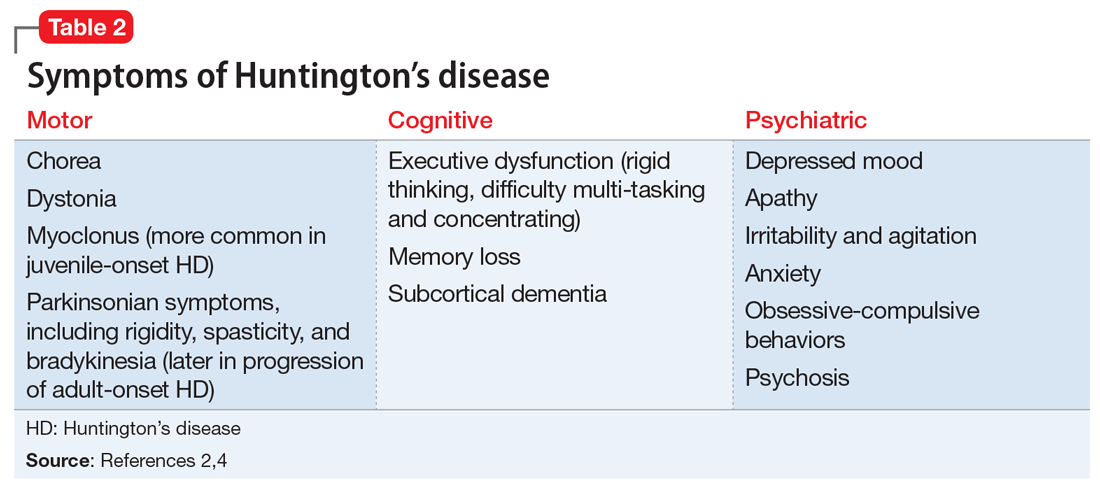

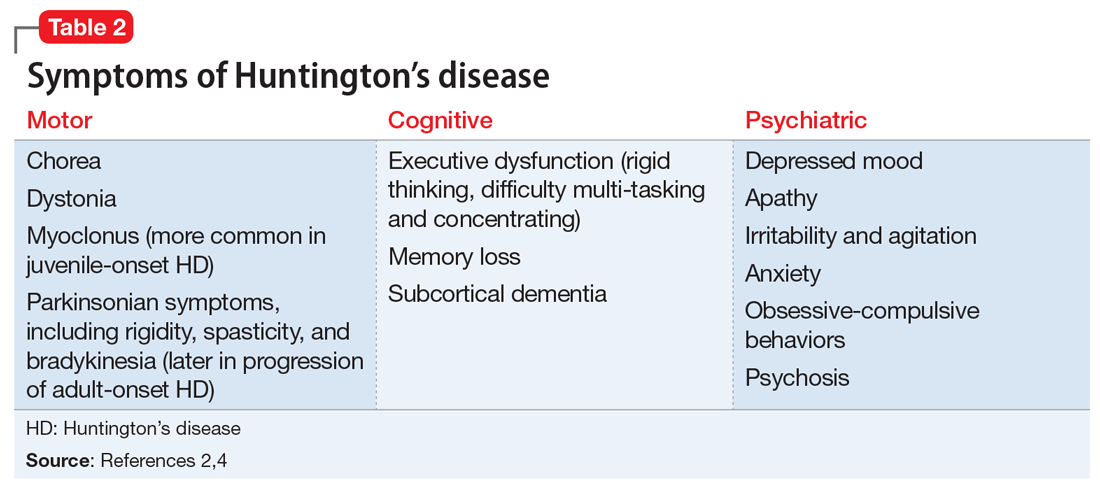

Huntington’s disease is characterized by motor, cognitive, and behavioral disturbances (Table 22,4). Motor symptoms include a characteristic and well-recognized chorea, often predominating earlier in HD, that progresses to rigidity, spasticity, and bradykinesia later in the disease course.2 Cognitive impairments develop in a similar progressive manner and can often precede the onset of motor symptoms, beginning with early executive dysfunction. Thinking often becomes more rigid and less efficient, causing difficulty with multi-tasking and concentration, and often progressing to subcortical dementia.2

Psychiatric symptoms have long been recognized as a feature of HD; the estimated lifetime prevalence in patients with HD ranges from approximately 33% to 76%.4 Depressed mood, anxiety, irritability, and apathy are the most commonly reported symptoms, while a smaller percentage of patients with HD can experience obsessive-compulsive disorder (10% to 52%) or psychotic symptoms (3% to 11%).4 A more specific schizophrenia-like psychosis occurs in approximately 3% to 6% of patients, and often is a paranoid type.5,6 Positive psychotic symptoms, such as hallucinations and delusions, typically become less overt as HD progresses and cognitive impairments worsen.7

Although the onset of motor symptoms leads to diagnosis in the majority of patients with HD, many patients present with psychiatric symptoms—most commonly depression—prior to motor symptoms.8 An increasing body of literature details instances of psychosis preceding motor symptom onset by up to 10 years.6,9-12 In many of these cases, the patient has a family history of HD-associated psychosis. Family history is a major risk factor for HD-associated psychosis, as is early-onset HD.7,9

TREATMENT Antipsychotics result in some improvement

On Day 1 or 2, Mr. J is started on risperidone, 1 mg twice daily, to manage his symptoms. He shows incremental improvement in thought organization. Although his religious and grandiose delusions persist, they become less fixed, and he is able to take the team’s suggestion that he reconnect with his family.

Mr. J is aware of his family history of HD and acknowledges that multiple relatives had early psychiatric manifestations of HD. Despite this, he still has difficulty recognizing any connection between other family members’ presentation and his own. The psychiatry and neurology teams discuss the process, ethics, and implications of genetic testing for HD with Mr. J; however, he is ambivalent regarding genetic testing, and states he would consider it after discussing it with his family.

Continue to: The neurology team recommends...

The neurology team recommends against imaging for Mr. J because HD-related changes are not typically seen until later in the disease progression. On Day 9, they recommend changing from risperidone to quetiapine (50 mg every night at bedtime) due to evidence of its effectiveness specifically for treating behavioral symptoms of HD.13

While receiving quetiapine, Mr. J experiences significant drowsiness. Because he had experienced improvement in thought organization while he was receiving risperidone, he is switched back to risperidone.

[polldaddy:10279220]

The authors’ observations

Currently, no treatments are available to prevent the development or progression of HD. However, symptomatic treatment of motor and behavioral disturbances can lead to functional improvement and improved quality of life for individuals affected by HD.

There are no extensive clinical trials to date, but multiple case reports and studies have shown second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs), including quetiapine, olanzapine,

OUTCOME Discharge despite persistent delusions

Mr. J’s religious and grandiose delusions continue throughout hospitalization despite treatment with antipsychotics. However, because he remains calm and cooperative and demonstrates improvement in thought organization, he is deemed safe for discharge and instructed to continue risperidone. The team coordinates with Mr. J’s family to arrange transportation home and outpatient neurology follow-up.

Bottom Line

Psychiatric manifestations, including psychosis, are prominent symptoms of Huntington’s disease (HD) and may precede the onset of more readily recognized motor symptoms. This poses a diagnostic challenge, and clinicians should remain cognizant of this possibility, especially in patients with a family history of HD-associated psychosis.

Related Resources

- Huntington’s Disease Society of America. http://hdsa.org.

- National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Huntington’s disease information page: What research is being done? https://www.ninds.nih.gov/Disorders/All-Disorders/Huntingtons-Disease-Information-Page.

- Scher LM. How to target psychiatric symptoms of Huntington’s disease. Current Psychiatry. 2012;11(9):34-39.

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Clozapine • Clozaril

Haloperidol • Haldol

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Risperidone • Risperdal

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013.

2. Novak MJ, Tabrizi SJ. Huntington’s disease: clinical presentation and treatment. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2011;98:297-323.

3. Reiner A, Dragatsis I, Dietrich P. Genetics and neuropathology of Huntington’s disease. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2011;98:325-372.

4. van Duijn E, Kingma EM, Van der mast RC. Psychopathology in verified Huntington’s disease gene carriers. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2007;19(4):441-448.

5. Naarding P, Kremer HP, Zitman FG. Huntington’s disease: a review of the literature on prevalence and treatment of neuropsychiatric phenomena. Eur Psychiatry. 2001;16(8):439-445.

6. Xu C, Yogaratnam J, Tan N, et al. Psychosis, treatment emergent extrapyramidal events, and subsequent onset of Huntington’s disease: a case report and review of the literature. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci. 2016;14(3):302-304.

7. Mendez MF. Huntington’s disease: update and review of neuropsychiatric aspects. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1994;24(3):189-208.

8. Di Maio L, Squitieri F, Napolitano G, et al. Onset symptoms in 510 patients with Huntington’s disease. J Med Genet. 1993;30(4):289-292.

9. Jauhar S, Ritchie S. Psychiatric and behavioural manifestations of Huntington’s disease. Adv Psychiatr Treat. 2010;16(3):168-175.

10. Nagel M, Rumpf HJ, Kasten M. Acute psychosis in a verified Huntington disease gene carrier with subtle motor signs: psychiatric criteria should be considered for the diagnosis. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2014;36(3):361.e3-e4. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2014.01.008.

11. Corrêa BB, Xavier M, Guimarães J. Association of Huntington’s disease and schizophrenia-like psychosis in a Huntington’s disease pedigree. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2006;2:1.

12. Ding J, Gadit AM. Psychosis with Huntington’s disease: role of antipsychotic medications. BMJ Case Rep. 2014: bcr2013202625. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2013-202625.

13. Alpay M, Koroshetz WJ. Quetiapine in the treatment of behavioral disturbances in patients with Huntington’s disease. Psychosomatics. 2006;47(1):70-72.

14. Duff K, Beglinger LJ, O’Rourke ME, et al. Risperidone and the treatment of psychiatric, motor, and cognitive symptoms in Huntington’s disease. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2008;20(1):1-3.

15. Paleacu D, Anca M, Giladi N. Olanzapine in Huntington’s disease. Acta Neurol Scand. 2002;105(6):441-444.

16. Lin W, Chou Y. Aripiprazole effects on psychosis and chorea in a patient with Huntington’s disease. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(9):1207-1208.

17. van Vugt JP, Siesling S, Vergeer M, et al. Clozapine versus placebo in Huntington’s disease: a double blind randomized comparative study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatr. 1997;63(1):35-39.

CASE Disorganized thoughts and grandiose delusions

Mr. J, age 54, presents to the psychiatric emergency department (ED) with agitation and disruptive behavior. He claims that he is “the son of Jesus Christ” and has to travel to the Middle East to be baptized. Mr. J is irritable, shouting, and threatening staff members. He receives

The next day, he is calm and cooperative, but continues to express the same religious delusions. Mr. J is admitted to the psychiatric inpatient unit for further evaluation.

On the unit, Mr. J is pleasant and cooperative, but tangential in thought process. He reports he was “saved” by God 4 years ago, and that God communicates with him through music. Despite this, he denies having auditory or visual hallucinations.

Approximately 3 months earlier, Mr. J had stopped working and left his home and family in another state to pursue his “mission” of being baptized in the Middle East. Mr. J has been homeless since then. Despite that, he reports that his mood is “great” and denies any recent changes in mood, sleep, appetite, energy level, or psychomotor agitation. Although no formal cognitive testing is performed, Mr. J is alert and oriented to person, place, and time with intact remote and recent memory, no language deficits, and no lapses in concentration or attention throughout interview.

Mr. J says he has been drinking alcohol regularly throughout his adult life, often a few times per week, up to “a case and a half” of beer at times. He claims he’s had multiple periods of sobriety but denies having experienced withdrawal symptoms during those times. Mr. J reports 1 prior psychiatric hospitalization 25 years ago after attempting suicide by overdose following the loss of a loved one. At that time, he was diagnosed with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). During this admission, he denies having any symptoms of PTSD or periods of mania or depression, and he has not undergone psychiatric treatment since he had been diagnosed with PTSD. He denies any family history of psychiatric illness as well as any medical comorbidities or medication use.

[polldaddy:10279202]

The authors’ observations

Mr. J’s presentation had a wide differential diagnosis (Table 1). The initial agitation Mr. J displayed in the psychiatric ED was likely secondary to acute alcohol intoxication, given that he was subsequently pleasant, calm, and cooperative after the alcohol was metabolized. Despite this, Mr. J continued to demonstrate delusions of a religious and somewhat grandiose nature with tangential thought processes, which made substance-induced psychosis less likely to be the sole diagnosis. Although it is possible to develop psychotic symptoms due to severe alcohol withdrawal (alcoholic hallucinosis), Mr. J’s vital signs remained stable, and he demonstrated no other signs or symptoms of withdrawal throughout his hospitalization. His presentation also did not fit that of delirium tremens because he was not confused or disoriented, and did not demonstrate perceptual disturbance.

While delusions were the most prominent feature of Mr. J’s apparent psychosis, the presence of disorganized thought processes and impaired functioning, as evidenced by Mr. J’s unemployment and recent homelessness, were more consistent with a primary psychotic disorder than a delusional disorder.1

Continue to: Mr. J began to exhibit...

Mr. J began to exhibit these psychotic symptoms in his early 50s; because the average age of onset of schizophrenia for males is approximately age 20 to 25, the likelihood of his presentation being the result of a primary psychotic disorder was low.1 Although less common, it was possible that Mr. J had developed late-onset schizophrenia, where the first episode typically occurs after approximately age 40 to 45. Mr. J also described that he was in a “great” mood but had grandiose delusions and had made recent impulsive decisions, which suggests there was a possible mood component to his presentation and a potential diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder or bipolar disorder with psychotic symptoms. However, before any of these diagnoses could be made, a medical or neurologic condition that could cause his symptoms needed to be investigated and ruled out. Further collateral information regarding Mr. J’s history and timeline of symptoms was required.

EVALUATION Family history reveals clues

All laboratory studies completed during Mr. J’s hospitalization are unremarkable, including complete blood count, basic metabolic panel, hepatic function panel, gamma-glutamyl transferase test, magnesium, phosphate, thyroid-stimulating hormone, vitamin B12, thiamine, folate, urinalysis, and urine drug screen. Mr. J does not undergo any head imaging.

Mr. J has not been in touch with his family since leaving his home approximately 3 months before he presented to the ED, and he gives consent for the inpatient team to attempt to contact them. One week into hospitalization, Mr. J’s sibling informs the team of a family history of genetically confirmed Huntington’s disease (HD), with psychiatric symptoms preceding the onset of motor symptoms in multiple first-degree relatives. His family says that before Mr. J first developed delusions 4 years ago, he had not exhibited any psychotic symptoms during periods of alcohol use or sobriety.

Mr. J does not demonstrate any overt movement symptoms on the unit and denies noting any rigidity, change in gait, or abnormal/uncontrolled movements. The inpatient psychiatric team consults neurology and a full neurologic evaluation is performed. The results are unremarkable outside of his psychiatric symptoms; specifically, Mr. J does not demonstrate even subtle motor signs or cognitive impairment. Given Mr. J’s family history, unremarkable lab findings, and age at presentation, the neurology team and inpatient psychiatry team suspect that his psychosis is likely an early presentation of HD.

[polldaddy:10279212]

The authors’ observations

Genetics of Huntington’s disease

Huntington’s disease is an autosomal dominant neurodegenerative disorder caused by expansion of cytosine-adenine-guanine (CAG) trinucleotide repeats within the Huntingtin (HTT) gene on chromosome 4, which codes for the huntingtin protein.2,3 While the function of “normal” huntingtin protein is not fully understood, it is known that CAG repeat expansion in the HTT gene of >35 repeats codes for a mutant huntingtin protein.2,3 The mutant huntingtin protein causes progressive neuronal loss in the basal ganglia and striatum, resulting in the clinical Huntington’s phenotype.3 Notably, the patient’s age at disease onset is inversely correlated with the number of repeats. For example, expansions of approximately 40 to 50 CAG repeats often result in adult-onset HD, while expansions of >60 repeats are typically associated with juvenile-onset HD (before age 20). CAG repeat lengths of approximately 36 to 39 demonstrate reduced penetrance, with some individuals developing symptomatic HD while others do not.2 Instability of the CAG repeat expansion can result in genetic “anticipation,” wherein repeat length increases between generations, causing earlier age of onset in affected offspring. Genetic anticipation in HD occurs more frequently in paternal transmission—approximately 80% to 90% of juvenile HD cases are inherited paternally, at times with the number of CAG repeats exceeding 200.3

Continue to: Psychiatric manifestations of Huntington's disease

Psychiatric manifestations of Huntington’s disease

Huntington’s disease is characterized by motor, cognitive, and behavioral disturbances (Table 22,4). Motor symptoms include a characteristic and well-recognized chorea, often predominating earlier in HD, that progresses to rigidity, spasticity, and bradykinesia later in the disease course.2 Cognitive impairments develop in a similar progressive manner and can often precede the onset of motor symptoms, beginning with early executive dysfunction. Thinking often becomes more rigid and less efficient, causing difficulty with multi-tasking and concentration, and often progressing to subcortical dementia.2

Psychiatric symptoms have long been recognized as a feature of HD; the estimated lifetime prevalence in patients with HD ranges from approximately 33% to 76%.4 Depressed mood, anxiety, irritability, and apathy are the most commonly reported symptoms, while a smaller percentage of patients with HD can experience obsessive-compulsive disorder (10% to 52%) or psychotic symptoms (3% to 11%).4 A more specific schizophrenia-like psychosis occurs in approximately 3% to 6% of patients, and often is a paranoid type.5,6 Positive psychotic symptoms, such as hallucinations and delusions, typically become less overt as HD progresses and cognitive impairments worsen.7

Although the onset of motor symptoms leads to diagnosis in the majority of patients with HD, many patients present with psychiatric symptoms—most commonly depression—prior to motor symptoms.8 An increasing body of literature details instances of psychosis preceding motor symptom onset by up to 10 years.6,9-12 In many of these cases, the patient has a family history of HD-associated psychosis. Family history is a major risk factor for HD-associated psychosis, as is early-onset HD.7,9

TREATMENT Antipsychotics result in some improvement

On Day 1 or 2, Mr. J is started on risperidone, 1 mg twice daily, to manage his symptoms. He shows incremental improvement in thought organization. Although his religious and grandiose delusions persist, they become less fixed, and he is able to take the team’s suggestion that he reconnect with his family.

Mr. J is aware of his family history of HD and acknowledges that multiple relatives had early psychiatric manifestations of HD. Despite this, he still has difficulty recognizing any connection between other family members’ presentation and his own. The psychiatry and neurology teams discuss the process, ethics, and implications of genetic testing for HD with Mr. J; however, he is ambivalent regarding genetic testing, and states he would consider it after discussing it with his family.

Continue to: The neurology team recommends...

The neurology team recommends against imaging for Mr. J because HD-related changes are not typically seen until later in the disease progression. On Day 9, they recommend changing from risperidone to quetiapine (50 mg every night at bedtime) due to evidence of its effectiveness specifically for treating behavioral symptoms of HD.13

While receiving quetiapine, Mr. J experiences significant drowsiness. Because he had experienced improvement in thought organization while he was receiving risperidone, he is switched back to risperidone.

[polldaddy:10279220]

The authors’ observations

Currently, no treatments are available to prevent the development or progression of HD. However, symptomatic treatment of motor and behavioral disturbances can lead to functional improvement and improved quality of life for individuals affected by HD.

There are no extensive clinical trials to date, but multiple case reports and studies have shown second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs), including quetiapine, olanzapine,

OUTCOME Discharge despite persistent delusions

Mr. J’s religious and grandiose delusions continue throughout hospitalization despite treatment with antipsychotics. However, because he remains calm and cooperative and demonstrates improvement in thought organization, he is deemed safe for discharge and instructed to continue risperidone. The team coordinates with Mr. J’s family to arrange transportation home and outpatient neurology follow-up.

Bottom Line

Psychiatric manifestations, including psychosis, are prominent symptoms of Huntington’s disease (HD) and may precede the onset of more readily recognized motor symptoms. This poses a diagnostic challenge, and clinicians should remain cognizant of this possibility, especially in patients with a family history of HD-associated psychosis.

Related Resources

- Huntington’s Disease Society of America. http://hdsa.org.

- National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Huntington’s disease information page: What research is being done? https://www.ninds.nih.gov/Disorders/All-Disorders/Huntingtons-Disease-Information-Page.

- Scher LM. How to target psychiatric symptoms of Huntington’s disease. Current Psychiatry. 2012;11(9):34-39.

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Clozapine • Clozaril

Haloperidol • Haldol

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Risperidone • Risperdal

CASE Disorganized thoughts and grandiose delusions

Mr. J, age 54, presents to the psychiatric emergency department (ED) with agitation and disruptive behavior. He claims that he is “the son of Jesus Christ” and has to travel to the Middle East to be baptized. Mr. J is irritable, shouting, and threatening staff members. He receives

The next day, he is calm and cooperative, but continues to express the same religious delusions. Mr. J is admitted to the psychiatric inpatient unit for further evaluation.

On the unit, Mr. J is pleasant and cooperative, but tangential in thought process. He reports he was “saved” by God 4 years ago, and that God communicates with him through music. Despite this, he denies having auditory or visual hallucinations.

Approximately 3 months earlier, Mr. J had stopped working and left his home and family in another state to pursue his “mission” of being baptized in the Middle East. Mr. J has been homeless since then. Despite that, he reports that his mood is “great” and denies any recent changes in mood, sleep, appetite, energy level, or psychomotor agitation. Although no formal cognitive testing is performed, Mr. J is alert and oriented to person, place, and time with intact remote and recent memory, no language deficits, and no lapses in concentration or attention throughout interview.

Mr. J says he has been drinking alcohol regularly throughout his adult life, often a few times per week, up to “a case and a half” of beer at times. He claims he’s had multiple periods of sobriety but denies having experienced withdrawal symptoms during those times. Mr. J reports 1 prior psychiatric hospitalization 25 years ago after attempting suicide by overdose following the loss of a loved one. At that time, he was diagnosed with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). During this admission, he denies having any symptoms of PTSD or periods of mania or depression, and he has not undergone psychiatric treatment since he had been diagnosed with PTSD. He denies any family history of psychiatric illness as well as any medical comorbidities or medication use.

[polldaddy:10279202]

The authors’ observations

Mr. J’s presentation had a wide differential diagnosis (Table 1). The initial agitation Mr. J displayed in the psychiatric ED was likely secondary to acute alcohol intoxication, given that he was subsequently pleasant, calm, and cooperative after the alcohol was metabolized. Despite this, Mr. J continued to demonstrate delusions of a religious and somewhat grandiose nature with tangential thought processes, which made substance-induced psychosis less likely to be the sole diagnosis. Although it is possible to develop psychotic symptoms due to severe alcohol withdrawal (alcoholic hallucinosis), Mr. J’s vital signs remained stable, and he demonstrated no other signs or symptoms of withdrawal throughout his hospitalization. His presentation also did not fit that of delirium tremens because he was not confused or disoriented, and did not demonstrate perceptual disturbance.

While delusions were the most prominent feature of Mr. J’s apparent psychosis, the presence of disorganized thought processes and impaired functioning, as evidenced by Mr. J’s unemployment and recent homelessness, were more consistent with a primary psychotic disorder than a delusional disorder.1

Continue to: Mr. J began to exhibit...

Mr. J began to exhibit these psychotic symptoms in his early 50s; because the average age of onset of schizophrenia for males is approximately age 20 to 25, the likelihood of his presentation being the result of a primary psychotic disorder was low.1 Although less common, it was possible that Mr. J had developed late-onset schizophrenia, where the first episode typically occurs after approximately age 40 to 45. Mr. J also described that he was in a “great” mood but had grandiose delusions and had made recent impulsive decisions, which suggests there was a possible mood component to his presentation and a potential diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder or bipolar disorder with psychotic symptoms. However, before any of these diagnoses could be made, a medical or neurologic condition that could cause his symptoms needed to be investigated and ruled out. Further collateral information regarding Mr. J’s history and timeline of symptoms was required.

EVALUATION Family history reveals clues

All laboratory studies completed during Mr. J’s hospitalization are unremarkable, including complete blood count, basic metabolic panel, hepatic function panel, gamma-glutamyl transferase test, magnesium, phosphate, thyroid-stimulating hormone, vitamin B12, thiamine, folate, urinalysis, and urine drug screen. Mr. J does not undergo any head imaging.

Mr. J has not been in touch with his family since leaving his home approximately 3 months before he presented to the ED, and he gives consent for the inpatient team to attempt to contact them. One week into hospitalization, Mr. J’s sibling informs the team of a family history of genetically confirmed Huntington’s disease (HD), with psychiatric symptoms preceding the onset of motor symptoms in multiple first-degree relatives. His family says that before Mr. J first developed delusions 4 years ago, he had not exhibited any psychotic symptoms during periods of alcohol use or sobriety.

Mr. J does not demonstrate any overt movement symptoms on the unit and denies noting any rigidity, change in gait, or abnormal/uncontrolled movements. The inpatient psychiatric team consults neurology and a full neurologic evaluation is performed. The results are unremarkable outside of his psychiatric symptoms; specifically, Mr. J does not demonstrate even subtle motor signs or cognitive impairment. Given Mr. J’s family history, unremarkable lab findings, and age at presentation, the neurology team and inpatient psychiatry team suspect that his psychosis is likely an early presentation of HD.

[polldaddy:10279212]

The authors’ observations

Genetics of Huntington’s disease

Huntington’s disease is an autosomal dominant neurodegenerative disorder caused by expansion of cytosine-adenine-guanine (CAG) trinucleotide repeats within the Huntingtin (HTT) gene on chromosome 4, which codes for the huntingtin protein.2,3 While the function of “normal” huntingtin protein is not fully understood, it is known that CAG repeat expansion in the HTT gene of >35 repeats codes for a mutant huntingtin protein.2,3 The mutant huntingtin protein causes progressive neuronal loss in the basal ganglia and striatum, resulting in the clinical Huntington’s phenotype.3 Notably, the patient’s age at disease onset is inversely correlated with the number of repeats. For example, expansions of approximately 40 to 50 CAG repeats often result in adult-onset HD, while expansions of >60 repeats are typically associated with juvenile-onset HD (before age 20). CAG repeat lengths of approximately 36 to 39 demonstrate reduced penetrance, with some individuals developing symptomatic HD while others do not.2 Instability of the CAG repeat expansion can result in genetic “anticipation,” wherein repeat length increases between generations, causing earlier age of onset in affected offspring. Genetic anticipation in HD occurs more frequently in paternal transmission—approximately 80% to 90% of juvenile HD cases are inherited paternally, at times with the number of CAG repeats exceeding 200.3

Continue to: Psychiatric manifestations of Huntington's disease

Psychiatric manifestations of Huntington’s disease

Huntington’s disease is characterized by motor, cognitive, and behavioral disturbances (Table 22,4). Motor symptoms include a characteristic and well-recognized chorea, often predominating earlier in HD, that progresses to rigidity, spasticity, and bradykinesia later in the disease course.2 Cognitive impairments develop in a similar progressive manner and can often precede the onset of motor symptoms, beginning with early executive dysfunction. Thinking often becomes more rigid and less efficient, causing difficulty with multi-tasking and concentration, and often progressing to subcortical dementia.2

Psychiatric symptoms have long been recognized as a feature of HD; the estimated lifetime prevalence in patients with HD ranges from approximately 33% to 76%.4 Depressed mood, anxiety, irritability, and apathy are the most commonly reported symptoms, while a smaller percentage of patients with HD can experience obsessive-compulsive disorder (10% to 52%) or psychotic symptoms (3% to 11%).4 A more specific schizophrenia-like psychosis occurs in approximately 3% to 6% of patients, and often is a paranoid type.5,6 Positive psychotic symptoms, such as hallucinations and delusions, typically become less overt as HD progresses and cognitive impairments worsen.7

Although the onset of motor symptoms leads to diagnosis in the majority of patients with HD, many patients present with psychiatric symptoms—most commonly depression—prior to motor symptoms.8 An increasing body of literature details instances of psychosis preceding motor symptom onset by up to 10 years.6,9-12 In many of these cases, the patient has a family history of HD-associated psychosis. Family history is a major risk factor for HD-associated psychosis, as is early-onset HD.7,9

TREATMENT Antipsychotics result in some improvement

On Day 1 or 2, Mr. J is started on risperidone, 1 mg twice daily, to manage his symptoms. He shows incremental improvement in thought organization. Although his religious and grandiose delusions persist, they become less fixed, and he is able to take the team’s suggestion that he reconnect with his family.

Mr. J is aware of his family history of HD and acknowledges that multiple relatives had early psychiatric manifestations of HD. Despite this, he still has difficulty recognizing any connection between other family members’ presentation and his own. The psychiatry and neurology teams discuss the process, ethics, and implications of genetic testing for HD with Mr. J; however, he is ambivalent regarding genetic testing, and states he would consider it after discussing it with his family.

Continue to: The neurology team recommends...

The neurology team recommends against imaging for Mr. J because HD-related changes are not typically seen until later in the disease progression. On Day 9, they recommend changing from risperidone to quetiapine (50 mg every night at bedtime) due to evidence of its effectiveness specifically for treating behavioral symptoms of HD.13

While receiving quetiapine, Mr. J experiences significant drowsiness. Because he had experienced improvement in thought organization while he was receiving risperidone, he is switched back to risperidone.

[polldaddy:10279220]

The authors’ observations

Currently, no treatments are available to prevent the development or progression of HD. However, symptomatic treatment of motor and behavioral disturbances can lead to functional improvement and improved quality of life for individuals affected by HD.

There are no extensive clinical trials to date, but multiple case reports and studies have shown second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs), including quetiapine, olanzapine,

OUTCOME Discharge despite persistent delusions

Mr. J’s religious and grandiose delusions continue throughout hospitalization despite treatment with antipsychotics. However, because he remains calm and cooperative and demonstrates improvement in thought organization, he is deemed safe for discharge and instructed to continue risperidone. The team coordinates with Mr. J’s family to arrange transportation home and outpatient neurology follow-up.

Bottom Line

Psychiatric manifestations, including psychosis, are prominent symptoms of Huntington’s disease (HD) and may precede the onset of more readily recognized motor symptoms. This poses a diagnostic challenge, and clinicians should remain cognizant of this possibility, especially in patients with a family history of HD-associated psychosis.

Related Resources

- Huntington’s Disease Society of America. http://hdsa.org.

- National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Huntington’s disease information page: What research is being done? https://www.ninds.nih.gov/Disorders/All-Disorders/Huntingtons-Disease-Information-Page.

- Scher LM. How to target psychiatric symptoms of Huntington’s disease. Current Psychiatry. 2012;11(9):34-39.

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Clozapine • Clozaril

Haloperidol • Haldol

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Risperidone • Risperdal

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013.

2. Novak MJ, Tabrizi SJ. Huntington’s disease: clinical presentation and treatment. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2011;98:297-323.

3. Reiner A, Dragatsis I, Dietrich P. Genetics and neuropathology of Huntington’s disease. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2011;98:325-372.

4. van Duijn E, Kingma EM, Van der mast RC. Psychopathology in verified Huntington’s disease gene carriers. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2007;19(4):441-448.

5. Naarding P, Kremer HP, Zitman FG. Huntington’s disease: a review of the literature on prevalence and treatment of neuropsychiatric phenomena. Eur Psychiatry. 2001;16(8):439-445.

6. Xu C, Yogaratnam J, Tan N, et al. Psychosis, treatment emergent extrapyramidal events, and subsequent onset of Huntington’s disease: a case report and review of the literature. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci. 2016;14(3):302-304.

7. Mendez MF. Huntington’s disease: update and review of neuropsychiatric aspects. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1994;24(3):189-208.

8. Di Maio L, Squitieri F, Napolitano G, et al. Onset symptoms in 510 patients with Huntington’s disease. J Med Genet. 1993;30(4):289-292.

9. Jauhar S, Ritchie S. Psychiatric and behavioural manifestations of Huntington’s disease. Adv Psychiatr Treat. 2010;16(3):168-175.

10. Nagel M, Rumpf HJ, Kasten M. Acute psychosis in a verified Huntington disease gene carrier with subtle motor signs: psychiatric criteria should be considered for the diagnosis. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2014;36(3):361.e3-e4. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2014.01.008.

11. Corrêa BB, Xavier M, Guimarães J. Association of Huntington’s disease and schizophrenia-like psychosis in a Huntington’s disease pedigree. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2006;2:1.

12. Ding J, Gadit AM. Psychosis with Huntington’s disease: role of antipsychotic medications. BMJ Case Rep. 2014: bcr2013202625. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2013-202625.

13. Alpay M, Koroshetz WJ. Quetiapine in the treatment of behavioral disturbances in patients with Huntington’s disease. Psychosomatics. 2006;47(1):70-72.

14. Duff K, Beglinger LJ, O’Rourke ME, et al. Risperidone and the treatment of psychiatric, motor, and cognitive symptoms in Huntington’s disease. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2008;20(1):1-3.

15. Paleacu D, Anca M, Giladi N. Olanzapine in Huntington’s disease. Acta Neurol Scand. 2002;105(6):441-444.

16. Lin W, Chou Y. Aripiprazole effects on psychosis and chorea in a patient with Huntington’s disease. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(9):1207-1208.

17. van Vugt JP, Siesling S, Vergeer M, et al. Clozapine versus placebo in Huntington’s disease: a double blind randomized comparative study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatr. 1997;63(1):35-39.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013.

2. Novak MJ, Tabrizi SJ. Huntington’s disease: clinical presentation and treatment. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2011;98:297-323.

3. Reiner A, Dragatsis I, Dietrich P. Genetics and neuropathology of Huntington’s disease. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2011;98:325-372.

4. van Duijn E, Kingma EM, Van der mast RC. Psychopathology in verified Huntington’s disease gene carriers. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2007;19(4):441-448.

5. Naarding P, Kremer HP, Zitman FG. Huntington’s disease: a review of the literature on prevalence and treatment of neuropsychiatric phenomena. Eur Psychiatry. 2001;16(8):439-445.

6. Xu C, Yogaratnam J, Tan N, et al. Psychosis, treatment emergent extrapyramidal events, and subsequent onset of Huntington’s disease: a case report and review of the literature. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci. 2016;14(3):302-304.

7. Mendez MF. Huntington’s disease: update and review of neuropsychiatric aspects. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1994;24(3):189-208.

8. Di Maio L, Squitieri F, Napolitano G, et al. Onset symptoms in 510 patients with Huntington’s disease. J Med Genet. 1993;30(4):289-292.

9. Jauhar S, Ritchie S. Psychiatric and behavioural manifestations of Huntington’s disease. Adv Psychiatr Treat. 2010;16(3):168-175.

10. Nagel M, Rumpf HJ, Kasten M. Acute psychosis in a verified Huntington disease gene carrier with subtle motor signs: psychiatric criteria should be considered for the diagnosis. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2014;36(3):361.e3-e4. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2014.01.008.

11. Corrêa BB, Xavier M, Guimarães J. Association of Huntington’s disease and schizophrenia-like psychosis in a Huntington’s disease pedigree. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2006;2:1.

12. Ding J, Gadit AM. Psychosis with Huntington’s disease: role of antipsychotic medications. BMJ Case Rep. 2014: bcr2013202625. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2013-202625.

13. Alpay M, Koroshetz WJ. Quetiapine in the treatment of behavioral disturbances in patients with Huntington’s disease. Psychosomatics. 2006;47(1):70-72.

14. Duff K, Beglinger LJ, O’Rourke ME, et al. Risperidone and the treatment of psychiatric, motor, and cognitive symptoms in Huntington’s disease. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2008;20(1):1-3.

15. Paleacu D, Anca M, Giladi N. Olanzapine in Huntington’s disease. Acta Neurol Scand. 2002;105(6):441-444.

16. Lin W, Chou Y. Aripiprazole effects on psychosis and chorea in a patient with Huntington’s disease. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(9):1207-1208.

17. van Vugt JP, Siesling S, Vergeer M, et al. Clozapine versus placebo in Huntington’s disease: a double blind randomized comparative study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatr. 1997;63(1):35-39.

Sudden-onset memory problems, visual hallucinations, and odd behaviors

CASE A rapid decline

Ms. D, age 62, presents to a psychiatric emergency room (ER) after experiencing visual hallucinations, exhibiting odd behaviors, and having memory problems. On interview, she is disoriented, distractible, tearful, and tangential. She plays with her shirt and glasses, and occasionally shouts. She perseverates on “the aerialists,” acrobatic children she has been seeing in her apartment. She becomes distressed and shouts, “I would love to just get them!”

Ms. D is unable to provide an account of her history. Collateral information is obtained from her daughter, who has brought Ms. D to the ER for evaluation. She reports that her mother has no relevant medical or psychiatric history, and does not take any medications, except a mixture of Chinese herbs that she brews into a tea.

Ms. D’s daughter says that her mother began to deteriorate 5 months ago, after she traveled to California to care for her sister, who was seriously ill and passed away. After Ms. D returned, she would cry frequently. She also appeared “spaced out,” complained of feeling dizzy, and frequently misplaced belongings. Three months before presenting to the ER, she began to experience weakness, fatigue, and difficulty walking. Her daughter became more worried 2 months ago, when Ms. D began sleeping with her purse and hiding her belongings around their house. When asked about these odd behaviors, Ms. D claimed that “the aerialists” were climbing through her windows at night and stealing her things.

A week before seeking treatment at the ER, Ms. D’s daughter had taken her to a neurologist at another facility for clinical evaluation. An MRI of the brain showed minimal dilation in the subarachnoid space and a focal 1 cm lipoma in the anterior falx cerebri, but was otherwise unremarkable. However, Ms. D’s symptoms continued to worsen, and began to interfere with her ability to care for herself.

The team in the psychiatric ER attributes Ms. D’s symptoms to a severe, psychotic depressive episode. They admit her to the psychiatric inpatient unit for further evaluation.

[polldaddy:10012742]

Continue to: The authors' observations

The authors’ observations

Ms. D was plagued by several mood and psychotic symptoms. Such symptoms can arise from many different psychiatric or organic etiologies. In Ms. D’s case, several aspects of her presentation suggest that her illness was psychiatric. The severe illness of a beloved family member is a significant stressor that could cause a great deal of grief and devastation, possibly leading to depression. Indeed, Ms. D’s daughter noticed that her mother was crying frequently, which is consistent with grief or depression.

Memory problems, which might manifest as misplacing belongings, can also indicate a depressive illness, especially in older patients. Moreover, impaired concentration, which can cause one to appear “spaced out” or distractible, is a core symptom of major depressive disorder. Sadness and grief also can be appropriate during bereavement and in response to significant losses. Therefore, in Ms. D’s case, it is possible her frequent crying, “spaced out” appearance, and other mood symptoms she experienced immediately after caring for her sister were an appropriate response to her sister’s illness and death.

However, other aspects of Ms. D’s presentation suggested an organic etiology. Her rapid deterioration and symptom onset relatively late in life were consistent with dementia and malignancy. Her complaint of feeling dizzy suggested a neurologic process was affecting her vestibular system. Finally, while psychiatric disorders can certainly cause visual hallucinations, they occur in only a small percentage of cases.1 Visual hallucinations are commonly associated with delirium, intoxication, and neurologic illness.

Continue to: EVALUATION Severe impairment

EVALUATION Severe impairment

On the psychiatric inpatient unit, Ms. D remains unable to give a coherent account of her illness or recent events. During interviews, she abruptly shifts from laughing to crying for no apparent reason. While answering questions, her responses trail off and she appears to forget what she had been saying. However, she continues to speak at length about “the aerialists,” stating that she sees them living in her wardrobe and jumping from rooftop to rooftop in her neighborhood.

A mental status examination finds evidence of severe cognitive impairment. Ms. D is unable to identify the correct date, time, or place, and appears surprised when told she is in a hospital. She can repeat the names of 3 objects but cannot recall them a few minutes later. Finally, she scores a 14 on the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) and a 5 on the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), indicating severe impairment.

On the unit, Ms. D cannot remember the location of her room or bathroom, and even when given directions, she needs to be escorted to her destination. Her gait is unsteady and wide-spaced, and she walks on her toes at times. When food is placed before her, she needs to be shown how to take the lids off containers, pick up utensils, and start eating.

All laboratory results are unremarkable, including a complete blood count, basic metabolic panel, liver function tests, gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase, magnesium, phosphate, thyroid-stimulating hormone, vitamin B12, methylmalonic acid, homocysteine, folate, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, antinuclear antibodies, rapid plasma reagin, human immunodeficiency virus, and Lyme titers. The team also considers Ms. D’s history of herbal medicine use, because herbal mixtures can contain heavy metals and other contaminants. However, all toxicology results are normal, including arsenic, mercury, lead, copper, and zinc.

To address her symptoms, Ms. D is given risperidone, 0.5 mg twice a day, and donepezil, 5 mg/d.

[polldaddy:10012743]

Continue to: The authors' observations

The authors’ observations

Despite her persistent psychiatric symptoms, Ms. D had several neurologic symptoms that warranted further investigation. Her abrupt shifts from laughter to tears for no apparent reason were consistent with pseudobulbar affect. Her inability to remember how to use utensils during meals was consistent with apraxia. Finally, her abnormal gait raised concern for a process affecting her motor system.

OUTCOME A rare disorder

Given the psychiatry team’s suspicions for a neurologic etiology of Ms. D’s symptoms, an MRI of her brain is repeated. The results are notable for abnormal restricted diffusion in the caudate and putamen bilaterally, which is consistent with Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD). EEG shows moderate diffuse cerebral dysfunction, frontal intermittent delta activity, and diffuse cortical hyperexcitability, consistent with early- to mid-onset prion disease. Upon evaluation by the neurology team, Ms. D appears fearful, suspicious, and disorganized, but her examination does not reveal additional significant sensorimotor findings.

Ms. D is transferred to the neurology service for further workup and management. A lumbar puncture is positive for real-time quaking-induced conversion (RT-QuIC) and 14-3-3 protein with elevated tau proteins; these findings also are consistent with CJD. She develops transaminitis, with an alanine transaminase (ALT) of 127 and aspartate transaminase (AST) of 355, and a malignancy is suspected. However, CT scans of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis show no evidence of malignancy, and an extensive gastrointestinal workup is unremarkable, including anti-smooth muscle antibodies, anti-liver-kidney microsomal antibody, antimitochondrial antibodies, gliadin antibody, alpha-1 antitrypsin, liver/kidney microsomal antibody, and hepatitis serologies. While on the neurology service, risperidone and donepezil are discontinued because

After discontinuing these medications, she is evaluated by the psychiatry consult team for mood lability. The psychiatry consult team recommends quetiapine, which is later started at 25 mg nightly at bedtime.

Clinically, Ms. D’s mental status continues to deteriorate. She becomes nonverbal and minimally able to follow commands. She is ultimately discharged to an inpatient hospice for end-of-life care and the team recommends that she continue with quetiapine once there.

Continue to: The authors' observations

The authors’ observations

CJD is a rare, rapidly progressive, fatal form of dementia. In the United States, the incidence is approximately 1 to 1.5 cases per 1 million people each year.2 There are various forms of the disease. Sporadic CJD is the most common, representing 85% of cases.3 Sporadic CJD typically occurs in patients in their 60s and quickly leads to death—50% of patients die within 5 months, and 90% of patients die within 1 year.2,3 The illness is hypothesized to arise from the production of misfolded prion proteins, ultimately leading to vacuolation, neuronal loss, and the spongiform appearance characteristic of CJD.3,4

Psychiatric symptoms have long been acknowledged as a feature of CJD. Recent data indicates that psychiatric symptoms occur in 90% to 92% of cases.5,6 Sleep disturbances and depressive symptoms, including vegetative symptoms, anhedonia, and tearfulness, appear to be most common.5 Psychotic symptoms occur in approximately 42% of cases and may include persecutory and paranoid delusions, as well as an array of vivid auditory, visual, and tactile hallucinations.5,7

There is also evidence that psychiatric symptoms may be an early marker of CJD.5,8 A Mayo Clinic study found that psychiatric symptoms occurred within the prodromal phase of CJD in 26% of cases, and psychiatric symptoms occurred within the first 100 days of illness in 86% of cases.5

Case reports have described patients with CJD who initially presented with depression, psychosis, and other psychiatric symptoms.9-11 Interestingly, there have been cases with only psychiatric symptoms, and no neurologic symptoms until relatively late in the illness.10,11 Several patients with CJD have been evaluated in psychiatric ERs, admitted to psychiatric hospitals, and treated with psychiatric medications and ECT.5,9 In one study, 44% of CJD cases were misdiagnosed as “psychiatric patients” due to the prominence of their psychiatric symptomatology.8

Continue to: Making the diagnosis in psychiatric settings

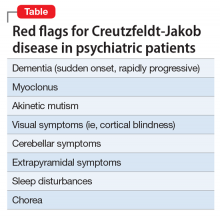

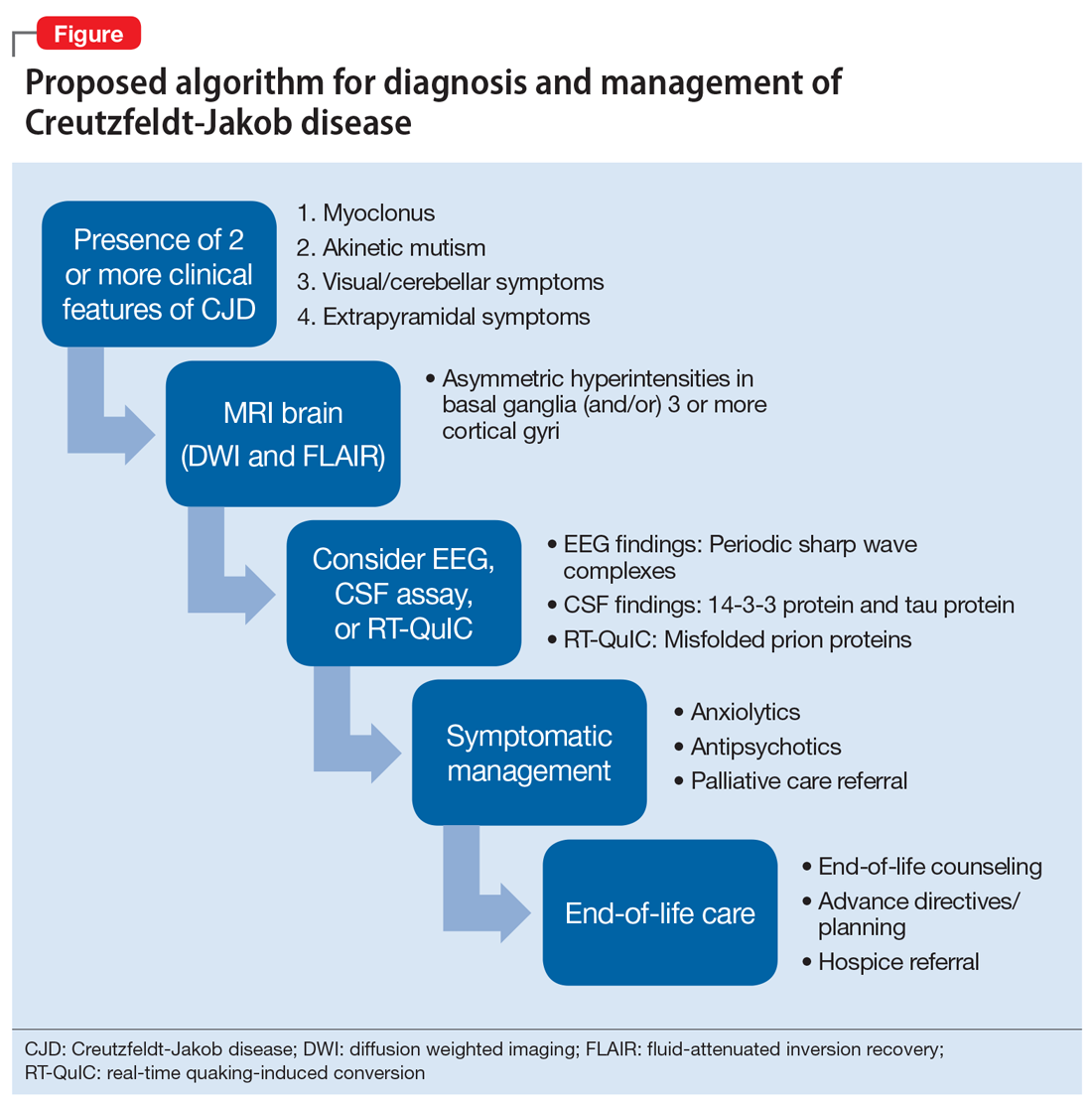

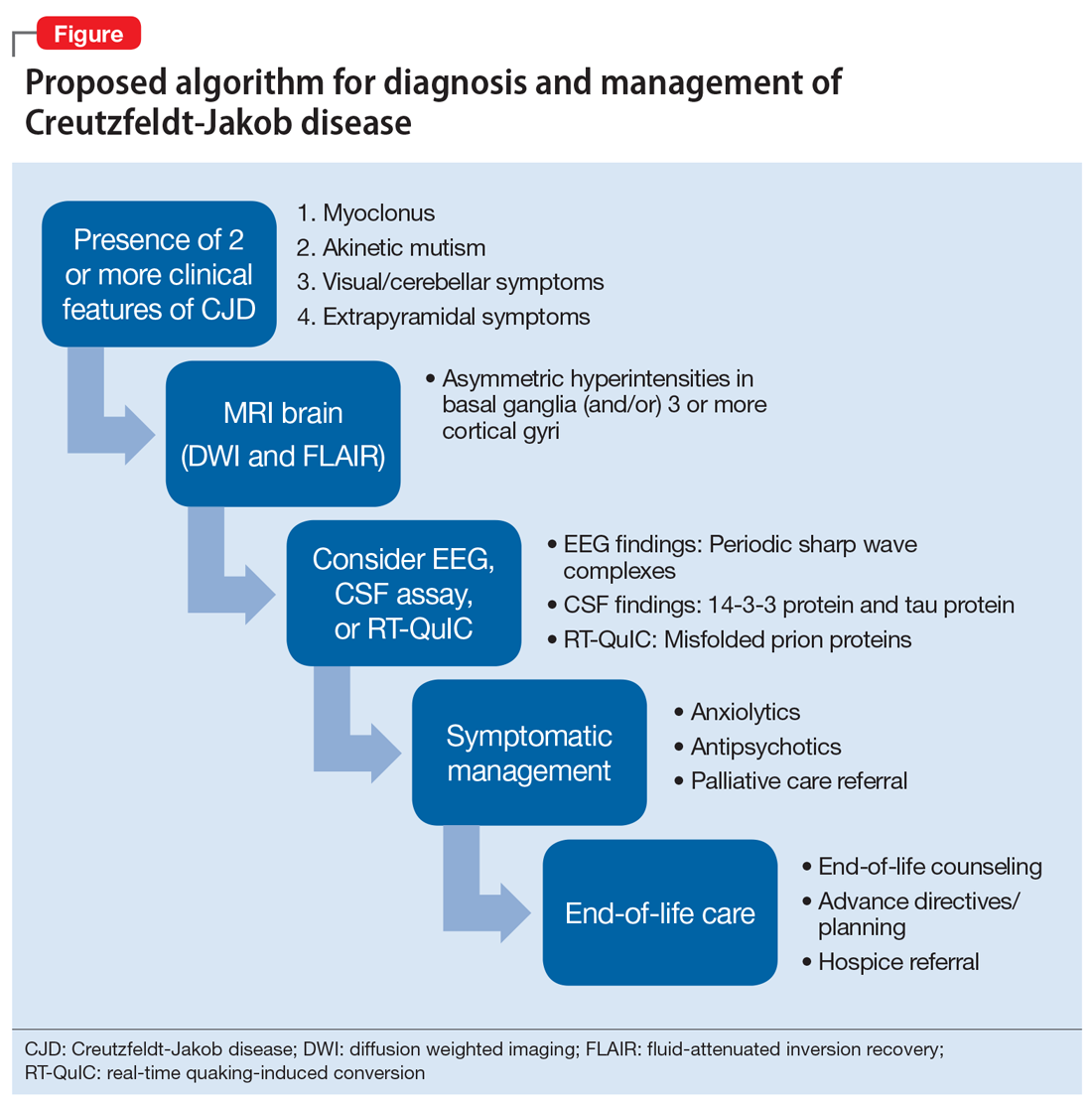

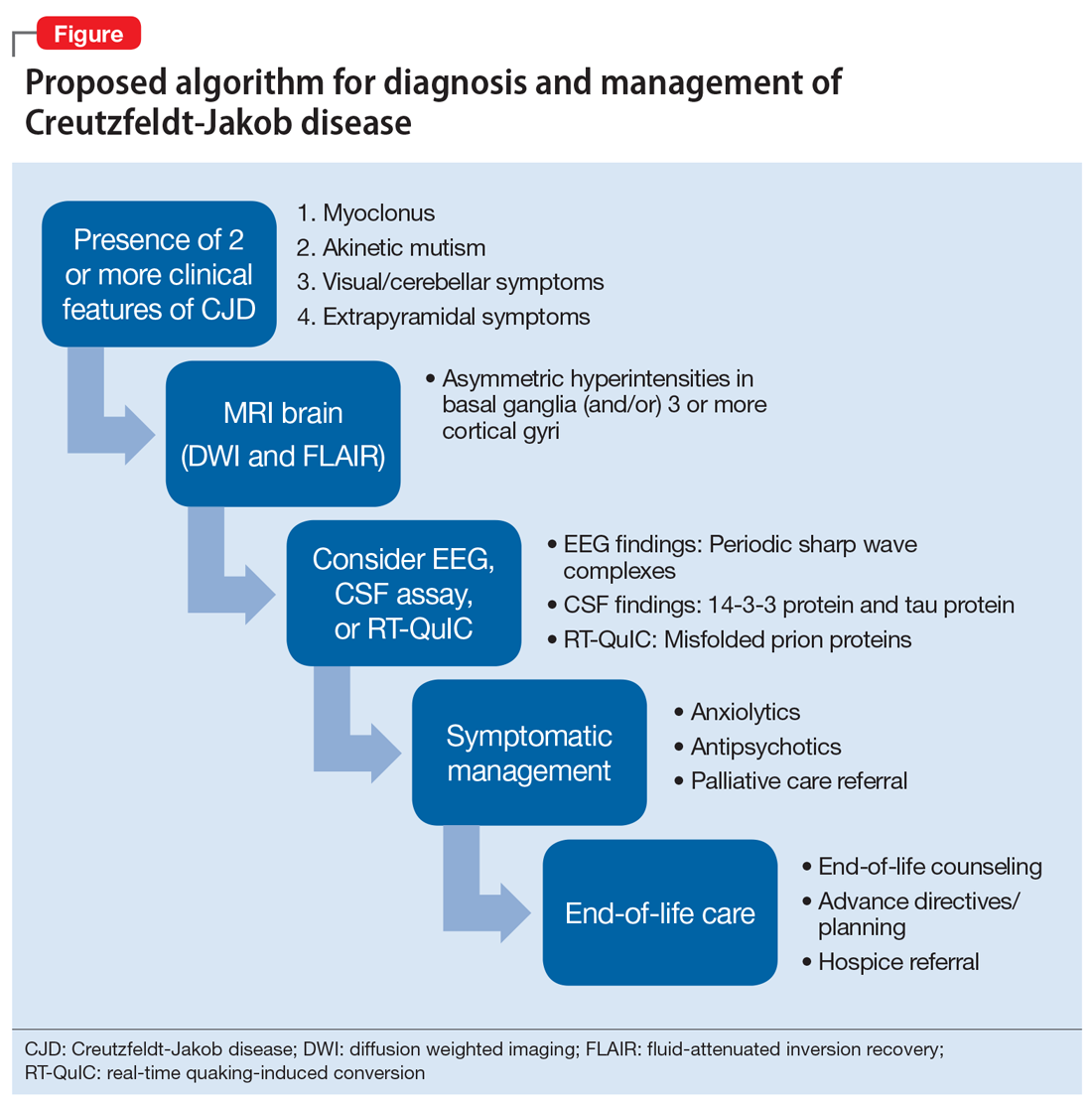

Making the diagnosis in psychiatric settings. Often, the most difficult aspect of CJD is making the diagnosis.3,12 Sporadic CJD in particular can vary widely in its clinical presentation.3 The core clinical feature of CJD is rapidly progressive dementia, so suspect CJD in these patients. However, CJD can be difficult to distinguish from other rapidly progressive dementias, such as autoimmune and paraneoplastic encephalopathies.2,3 The presence of neurologic features, specifically myoclonus, akinetic mutism, and visual, cerebellar, and extrapyramidal symptoms, should also be considered a red flag for the disorder3 (Table).

Finally, positive findings on MRI, EEG, or CSF assay can indicate a probable diagnosis of CJD.13 MRI, particularly diffusion weighted imaging (DWI) and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR), is recognized as the most studied, sensitive, and overall useful neuroimaging modality for detecting CJD.2,3,12 Although the appearance of CJD on MRI can vary widely, asymmetric hyperintensities in ≥3 cortical gyri, particularly in the frontal and parietal lobes, provide strong evidence of CJD and are observed in 80% to 81% of cases.4,12 Asymmetric hyperintensities in the basal ganglia, particularly the caudate and rostral putamen, are observed in 69% to 70% of cases.4,12,13

EEG and CSF assay also can be useful for making the diagnosis. While diffuse slowing and frontal rhythmic delta activity appear early in the course of CJD, periodic sharp wave complexes emerge later in the illness.4 However, EEG findings are not diagnostic, because periodic sharp wave complexes are seen in only two-thirds of CJD cases and also occur in other neurologic illnesses.3,4 In recent years, lumbar puncture with subsequent CSF testing has become increasingly useful in detecting the illness. The presence of the 14-3-3 protein and tau protein is highly sensitive, although not specific, for CJD.3 A definite diagnosis of CJD requires discovery of the misfolded prion proteins, such as by RT-QuIC or brain biopsy.2,3,13

Management of CJD in psychiatric patients. CJD is an invariably fatal disease for which there is no effective cure or disease modifying treatment.2 Therefore, supportive therapies are the mainstay of care. Psychotropic medications can be used to provide symptom relief. While the sleep disturbances, anxiety, and agitation/hallucinations associated with CJD appear to respond well to hypnotic, anxiolytic, and antipsychotic medications, respectively, antidepressants and mood-stabilizing medications appear to have little benefit for patients with CJD.5 During the final stages of the disease, patients may suffer from akinetic mutism and inability to swallow, which often leads to aspiration pneumonia.14 Patients should also be offered end-of-life counseling, planning, and care, and provided with other comfort measures wherever possible (Figure).

Continue to: Bottom Line

Bottom Line

Patients with Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD) may present to psychiatric settings, particularly to a psychiatric emergency room. Consider CJD as a possible etiology in patients with rapidly progressive dementia, depression, and psychosis. CJD is invariably fatal and there is no effective disease-modifying treatment. Supportive therapies are the mainstay of care.

Related Resources

- National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease fact sheet. http://www.ninds.nih.gov/disorders/cjd/detail_cjd.htm.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, classic (CJD). http://www.cdc.gov/prions/cjd.

Drug Brand Names

Donepezil • Aricept

Risperidone • Risperdal

Quetiapine • Seroquel

1. Resnick PJ. The detection of malingered psychosis. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1999;22(1):159-172.

2. Bucelli RC, Ances BM. Diagnosis and evaluation of a patient with rapidly progressive dementia. Mo Med. 2013;110(5):422-428.

3. Manix M, Kalakoti P, Henry M, et al. Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease: updated diagnostic criteria, treatment algorithm, and the utility of brain biopsy. Neurosurg Focus. 2015;39(5):E2.

4. Puoti G, Bizzi A, Forloni G, et al. Sporadic human prion diseases: molecular insights and diagnosis. Lancet Neurol. 2012;11(7):618-628.

5. Wall CA, Rummans TA, Aksamit AJ, et al. Psychiatric manifestations of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease: a 25-year analysis. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2005;17(4):489-495.

6. Krasnianski A, Bohling GT, Harden M, et al. Psychiatric symptoms in patients with sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease in Germany. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(9):1209-1215.

7. Javed Q, Alam F, Krishna S, et al. An unusual case of sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD). BMJ Case Rep. 2010;pii: bcr1220092576. doi:10.1136/bcr.12.2009.2576.

8. Abudy A, Juven-Wetzler A, Zohar J. The different faces of Creutzfeldt-Jacob disease CJD in psychiatry. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2014;36(3):245-248.

9. Jiang TT, Moses H, Gordon H, et al. Sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease presenting as major depression. South Med J. 1999;92(8):807-808.

10. Ali R, Baborie A, Larner AJ et al. Psychiatric presentation of sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease: a challenge to current diagnostic criteria. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2013;25(4):335-338.

11. Gençer AG, Pelin Z, Küçükali CI., et al. Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Psychogeriatrics. 2011;11(2):119-124.

12. Caobelli F, Cobelli M, Pizzocaro C, et al. The role of neuroimaging in evaluating patients affected by Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease: a systematic review of the literature. J Neuroimaging. 2015;25(1):2-13.

13. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC's diagnostic criteria for Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, 2010. http://www.cdc.gov/prions/cjd/diagnostic-criteria.html. Updated February 11, 2015. Accessed August 2, 2016.

14. Martindale JL, Geschwind MD, Miller BL. Psychiatric and neuroimaging findings in Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2003;5(1):43-46.

CASE A rapid decline

Ms. D, age 62, presents to a psychiatric emergency room (ER) after experiencing visual hallucinations, exhibiting odd behaviors, and having memory problems. On interview, she is disoriented, distractible, tearful, and tangential. She plays with her shirt and glasses, and occasionally shouts. She perseverates on “the aerialists,” acrobatic children she has been seeing in her apartment. She becomes distressed and shouts, “I would love to just get them!”

Ms. D is unable to provide an account of her history. Collateral information is obtained from her daughter, who has brought Ms. D to the ER for evaluation. She reports that her mother has no relevant medical or psychiatric history, and does not take any medications, except a mixture of Chinese herbs that she brews into a tea.

Ms. D’s daughter says that her mother began to deteriorate 5 months ago, after she traveled to California to care for her sister, who was seriously ill and passed away. After Ms. D returned, she would cry frequently. She also appeared “spaced out,” complained of feeling dizzy, and frequently misplaced belongings. Three months before presenting to the ER, she began to experience weakness, fatigue, and difficulty walking. Her daughter became more worried 2 months ago, when Ms. D began sleeping with her purse and hiding her belongings around their house. When asked about these odd behaviors, Ms. D claimed that “the aerialists” were climbing through her windows at night and stealing her things.

A week before seeking treatment at the ER, Ms. D’s daughter had taken her to a neurologist at another facility for clinical evaluation. An MRI of the brain showed minimal dilation in the subarachnoid space and a focal 1 cm lipoma in the anterior falx cerebri, but was otherwise unremarkable. However, Ms. D’s symptoms continued to worsen, and began to interfere with her ability to care for herself.

The team in the psychiatric ER attributes Ms. D’s symptoms to a severe, psychotic depressive episode. They admit her to the psychiatric inpatient unit for further evaluation.

[polldaddy:10012742]

Continue to: The authors' observations

The authors’ observations

Ms. D was plagued by several mood and psychotic symptoms. Such symptoms can arise from many different psychiatric or organic etiologies. In Ms. D’s case, several aspects of her presentation suggest that her illness was psychiatric. The severe illness of a beloved family member is a significant stressor that could cause a great deal of grief and devastation, possibly leading to depression. Indeed, Ms. D’s daughter noticed that her mother was crying frequently, which is consistent with grief or depression.

Memory problems, which might manifest as misplacing belongings, can also indicate a depressive illness, especially in older patients. Moreover, impaired concentration, which can cause one to appear “spaced out” or distractible, is a core symptom of major depressive disorder. Sadness and grief also can be appropriate during bereavement and in response to significant losses. Therefore, in Ms. D’s case, it is possible her frequent crying, “spaced out” appearance, and other mood symptoms she experienced immediately after caring for her sister were an appropriate response to her sister’s illness and death.

However, other aspects of Ms. D’s presentation suggested an organic etiology. Her rapid deterioration and symptom onset relatively late in life were consistent with dementia and malignancy. Her complaint of feeling dizzy suggested a neurologic process was affecting her vestibular system. Finally, while psychiatric disorders can certainly cause visual hallucinations, they occur in only a small percentage of cases.1 Visual hallucinations are commonly associated with delirium, intoxication, and neurologic illness.

Continue to: EVALUATION Severe impairment

EVALUATION Severe impairment

On the psychiatric inpatient unit, Ms. D remains unable to give a coherent account of her illness or recent events. During interviews, she abruptly shifts from laughing to crying for no apparent reason. While answering questions, her responses trail off and she appears to forget what she had been saying. However, she continues to speak at length about “the aerialists,” stating that she sees them living in her wardrobe and jumping from rooftop to rooftop in her neighborhood.

A mental status examination finds evidence of severe cognitive impairment. Ms. D is unable to identify the correct date, time, or place, and appears surprised when told she is in a hospital. She can repeat the names of 3 objects but cannot recall them a few minutes later. Finally, she scores a 14 on the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) and a 5 on the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), indicating severe impairment.

On the unit, Ms. D cannot remember the location of her room or bathroom, and even when given directions, she needs to be escorted to her destination. Her gait is unsteady and wide-spaced, and she walks on her toes at times. When food is placed before her, she needs to be shown how to take the lids off containers, pick up utensils, and start eating.

All laboratory results are unremarkable, including a complete blood count, basic metabolic panel, liver function tests, gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase, magnesium, phosphate, thyroid-stimulating hormone, vitamin B12, methylmalonic acid, homocysteine, folate, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, antinuclear antibodies, rapid plasma reagin, human immunodeficiency virus, and Lyme titers. The team also considers Ms. D’s history of herbal medicine use, because herbal mixtures can contain heavy metals and other contaminants. However, all toxicology results are normal, including arsenic, mercury, lead, copper, and zinc.

To address her symptoms, Ms. D is given risperidone, 0.5 mg twice a day, and donepezil, 5 mg/d.

[polldaddy:10012743]

Continue to: The authors' observations

The authors’ observations

Despite her persistent psychiatric symptoms, Ms. D had several neurologic symptoms that warranted further investigation. Her abrupt shifts from laughter to tears for no apparent reason were consistent with pseudobulbar affect. Her inability to remember how to use utensils during meals was consistent with apraxia. Finally, her abnormal gait raised concern for a process affecting her motor system.

OUTCOME A rare disorder

Given the psychiatry team’s suspicions for a neurologic etiology of Ms. D’s symptoms, an MRI of her brain is repeated. The results are notable for abnormal restricted diffusion in the caudate and putamen bilaterally, which is consistent with Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD). EEG shows moderate diffuse cerebral dysfunction, frontal intermittent delta activity, and diffuse cortical hyperexcitability, consistent with early- to mid-onset prion disease. Upon evaluation by the neurology team, Ms. D appears fearful, suspicious, and disorganized, but her examination does not reveal additional significant sensorimotor findings.

Ms. D is transferred to the neurology service for further workup and management. A lumbar puncture is positive for real-time quaking-induced conversion (RT-QuIC) and 14-3-3 protein with elevated tau proteins; these findings also are consistent with CJD. She develops transaminitis, with an alanine transaminase (ALT) of 127 and aspartate transaminase (AST) of 355, and a malignancy is suspected. However, CT scans of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis show no evidence of malignancy, and an extensive gastrointestinal workup is unremarkable, including anti-smooth muscle antibodies, anti-liver-kidney microsomal antibody, antimitochondrial antibodies, gliadin antibody, alpha-1 antitrypsin, liver/kidney microsomal antibody, and hepatitis serologies. While on the neurology service, risperidone and donepezil are discontinued because

After discontinuing these medications, she is evaluated by the psychiatry consult team for mood lability. The psychiatry consult team recommends quetiapine, which is later started at 25 mg nightly at bedtime.

Clinically, Ms. D’s mental status continues to deteriorate. She becomes nonverbal and minimally able to follow commands. She is ultimately discharged to an inpatient hospice for end-of-life care and the team recommends that she continue with quetiapine once there.

Continue to: The authors' observations

The authors’ observations

CJD is a rare, rapidly progressive, fatal form of dementia. In the United States, the incidence is approximately 1 to 1.5 cases per 1 million people each year.2 There are various forms of the disease. Sporadic CJD is the most common, representing 85% of cases.3 Sporadic CJD typically occurs in patients in their 60s and quickly leads to death—50% of patients die within 5 months, and 90% of patients die within 1 year.2,3 The illness is hypothesized to arise from the production of misfolded prion proteins, ultimately leading to vacuolation, neuronal loss, and the spongiform appearance characteristic of CJD.3,4

Psychiatric symptoms have long been acknowledged as a feature of CJD. Recent data indicates that psychiatric symptoms occur in 90% to 92% of cases.5,6 Sleep disturbances and depressive symptoms, including vegetative symptoms, anhedonia, and tearfulness, appear to be most common.5 Psychotic symptoms occur in approximately 42% of cases and may include persecutory and paranoid delusions, as well as an array of vivid auditory, visual, and tactile hallucinations.5,7

There is also evidence that psychiatric symptoms may be an early marker of CJD.5,8 A Mayo Clinic study found that psychiatric symptoms occurred within the prodromal phase of CJD in 26% of cases, and psychiatric symptoms occurred within the first 100 days of illness in 86% of cases.5

Case reports have described patients with CJD who initially presented with depression, psychosis, and other psychiatric symptoms.9-11 Interestingly, there have been cases with only psychiatric symptoms, and no neurologic symptoms until relatively late in the illness.10,11 Several patients with CJD have been evaluated in psychiatric ERs, admitted to psychiatric hospitals, and treated with psychiatric medications and ECT.5,9 In one study, 44% of CJD cases were misdiagnosed as “psychiatric patients” due to the prominence of their psychiatric symptomatology.8

Continue to: Making the diagnosis in psychiatric settings

Making the diagnosis in psychiatric settings. Often, the most difficult aspect of CJD is making the diagnosis.3,12 Sporadic CJD in particular can vary widely in its clinical presentation.3 The core clinical feature of CJD is rapidly progressive dementia, so suspect CJD in these patients. However, CJD can be difficult to distinguish from other rapidly progressive dementias, such as autoimmune and paraneoplastic encephalopathies.2,3 The presence of neurologic features, specifically myoclonus, akinetic mutism, and visual, cerebellar, and extrapyramidal symptoms, should also be considered a red flag for the disorder3 (Table).

Finally, positive findings on MRI, EEG, or CSF assay can indicate a probable diagnosis of CJD.13 MRI, particularly diffusion weighted imaging (DWI) and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR), is recognized as the most studied, sensitive, and overall useful neuroimaging modality for detecting CJD.2,3,12 Although the appearance of CJD on MRI can vary widely, asymmetric hyperintensities in ≥3 cortical gyri, particularly in the frontal and parietal lobes, provide strong evidence of CJD and are observed in 80% to 81% of cases.4,12 Asymmetric hyperintensities in the basal ganglia, particularly the caudate and rostral putamen, are observed in 69% to 70% of cases.4,12,13

EEG and CSF assay also can be useful for making the diagnosis. While diffuse slowing and frontal rhythmic delta activity appear early in the course of CJD, periodic sharp wave complexes emerge later in the illness.4 However, EEG findings are not diagnostic, because periodic sharp wave complexes are seen in only two-thirds of CJD cases and also occur in other neurologic illnesses.3,4 In recent years, lumbar puncture with subsequent CSF testing has become increasingly useful in detecting the illness. The presence of the 14-3-3 protein and tau protein is highly sensitive, although not specific, for CJD.3 A definite diagnosis of CJD requires discovery of the misfolded prion proteins, such as by RT-QuIC or brain biopsy.2,3,13

Management of CJD in psychiatric patients. CJD is an invariably fatal disease for which there is no effective cure or disease modifying treatment.2 Therefore, supportive therapies are the mainstay of care. Psychotropic medications can be used to provide symptom relief. While the sleep disturbances, anxiety, and agitation/hallucinations associated with CJD appear to respond well to hypnotic, anxiolytic, and antipsychotic medications, respectively, antidepressants and mood-stabilizing medications appear to have little benefit for patients with CJD.5 During the final stages of the disease, patients may suffer from akinetic mutism and inability to swallow, which often leads to aspiration pneumonia.14 Patients should also be offered end-of-life counseling, planning, and care, and provided with other comfort measures wherever possible (Figure).

Continue to: Bottom Line

Bottom Line

Patients with Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD) may present to psychiatric settings, particularly to a psychiatric emergency room. Consider CJD as a possible etiology in patients with rapidly progressive dementia, depression, and psychosis. CJD is invariably fatal and there is no effective disease-modifying treatment. Supportive therapies are the mainstay of care.

Related Resources

- National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease fact sheet. http://www.ninds.nih.gov/disorders/cjd/detail_cjd.htm.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, classic (CJD). http://www.cdc.gov/prions/cjd.

Drug Brand Names

Donepezil • Aricept

Risperidone • Risperdal

Quetiapine • Seroquel

CASE A rapid decline

Ms. D, age 62, presents to a psychiatric emergency room (ER) after experiencing visual hallucinations, exhibiting odd behaviors, and having memory problems. On interview, she is disoriented, distractible, tearful, and tangential. She plays with her shirt and glasses, and occasionally shouts. She perseverates on “the aerialists,” acrobatic children she has been seeing in her apartment. She becomes distressed and shouts, “I would love to just get them!”

Ms. D is unable to provide an account of her history. Collateral information is obtained from her daughter, who has brought Ms. D to the ER for evaluation. She reports that her mother has no relevant medical or psychiatric history, and does not take any medications, except a mixture of Chinese herbs that she brews into a tea.

Ms. D’s daughter says that her mother began to deteriorate 5 months ago, after she traveled to California to care for her sister, who was seriously ill and passed away. After Ms. D returned, she would cry frequently. She also appeared “spaced out,” complained of feeling dizzy, and frequently misplaced belongings. Three months before presenting to the ER, she began to experience weakness, fatigue, and difficulty walking. Her daughter became more worried 2 months ago, when Ms. D began sleeping with her purse and hiding her belongings around their house. When asked about these odd behaviors, Ms. D claimed that “the aerialists” were climbing through her windows at night and stealing her things.

A week before seeking treatment at the ER, Ms. D’s daughter had taken her to a neurologist at another facility for clinical evaluation. An MRI of the brain showed minimal dilation in the subarachnoid space and a focal 1 cm lipoma in the anterior falx cerebri, but was otherwise unremarkable. However, Ms. D’s symptoms continued to worsen, and began to interfere with her ability to care for herself.

The team in the psychiatric ER attributes Ms. D’s symptoms to a severe, psychotic depressive episode. They admit her to the psychiatric inpatient unit for further evaluation.