User login

Intimate partner violence: Opening the door to a safer future

THE CASE

Louise T* is a 42-year-old woman who presented to her family medicine office for a routine annual visit. During the exam, her physician noticed bruises on Ms. T’s arms and back. Upon further inquiry, Ms. T reported that she and her husband had argued the night before the appointment. With some hesitancy, she went on to say that this was not the first time this had happened. She said that she and her husband had been arguing frequently for several years and that 6 months earlier, when he lost his job, he began hitting and pushing her.

●

*The patient’s name has been changed to protect her identity.

Intimate partner violence (IPV) includes physical, sexual, or psychological aggression or stalking perpetrated by a current or former relationship partner.1 IPV affects more than 12 million men and women living in the United States each year.2 According to a national survey of IPV, approximately one-third (35.6%) of women and one-quarter (28.5%) of men living in the United States experience rape, physical violence, or stalking by an intimate partner during their lifetime.2 Lifetime exposure to psychological IPV is even more prevalent, affecting nearly half of women and men (48.4% and 48.8%, respectively).2

Lifetime prevalence of any form of IPV is higher among women who identify as bisexual (59.8%) and lesbian (46.3%) compared with those who identify as heterosexual (37.2%); rates are comparable among men who identify as heterosexual (31.9%), bisexual (35.3%), and gay (35.1%).3 Preliminary data suggest that IPV may have increased in frequency and severity during the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly in the context of mandated shelter-in-place and stay-at-home orders.4-6

IPV is associated with numerous negative health consequences. They include fear and concern for safety, mental health disorders such as posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and physical health problems including physical injury, chronic pain, sleep disturbance, and frequent headaches.2 IPV is also associated with a greater number of missed days from school and work and increased utilization of legal, health care, and housing services.2,7 The overall annual cost of IPV against women is estimated at $5.8 billion, with health care costs accounting for approximately $4.1 billion.7 Family physicians can play an important role in curbing the devastating effects of IPV by screening patients and providing resources when needed.

Facilitate disclosure using screening tools and protocol

In Ms. T’s case, evidence of violence was clearly visible. However, not all instances of IPV leave physical marks. The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends that all women of childbearing age be screened for IPV, whether or not they exhibit signs of violence.8 While the USPSTF has only published recommendations regarding screening women for IPV, there has been a recent push to screen all patients given that men also experience high rates of IPV.9

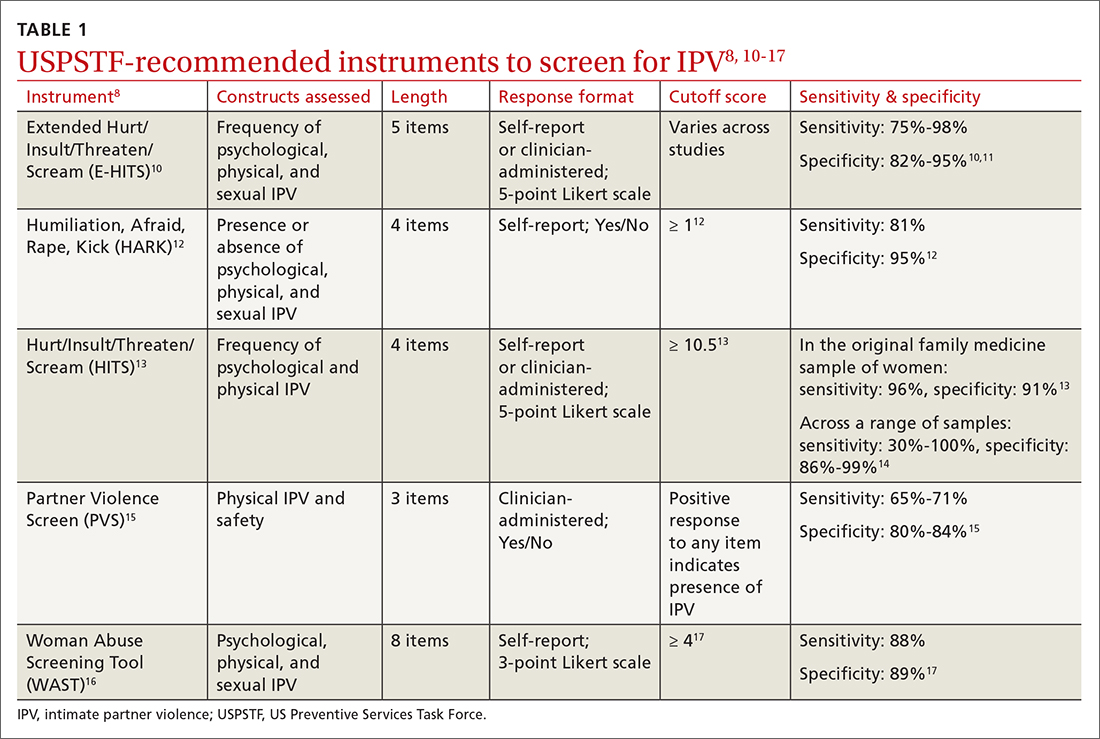

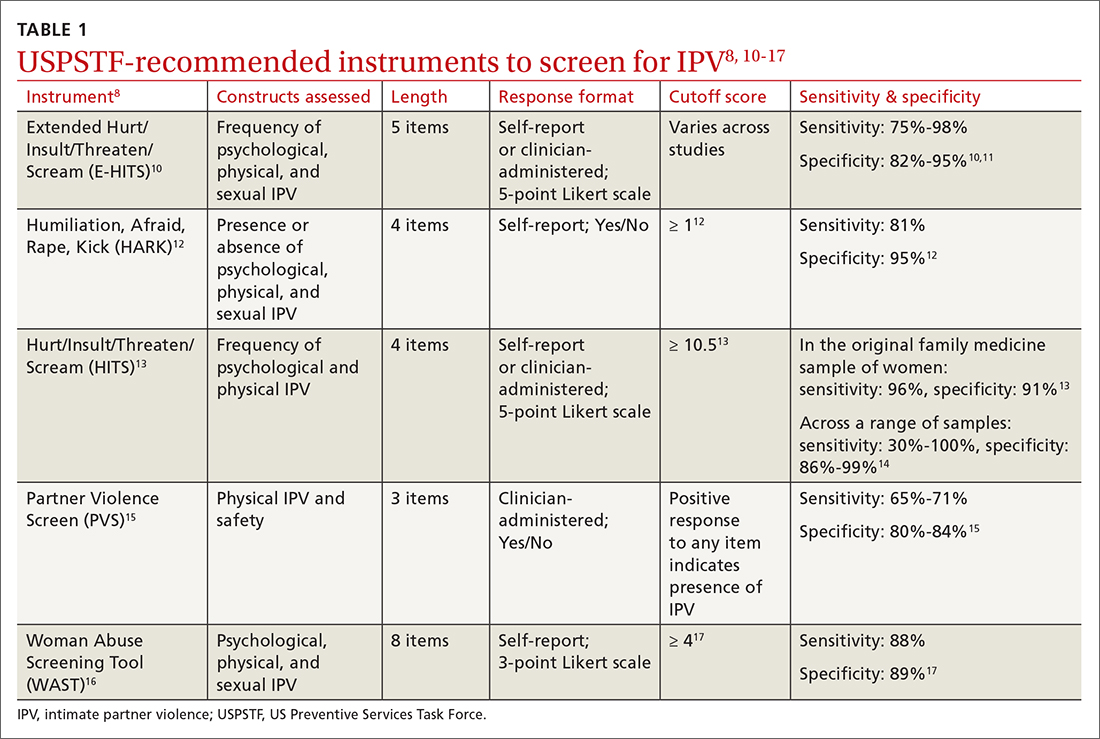

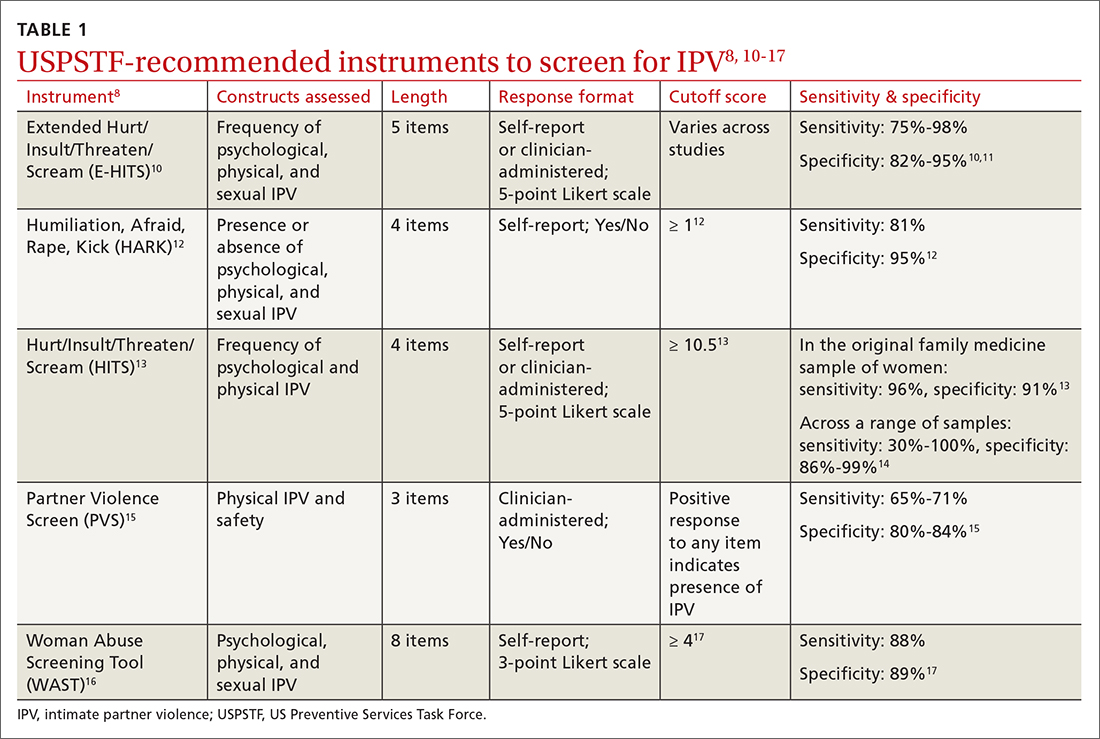

Utilize a brief screening tool. Directly ask patients about IPV; this can help reduce stigma, facilitate disclosure, and initiate the process of connecting patients to potentially lifesaving resources. The USPSTF lists several brief screening measures that can be used in primary care settings to assess exposure to IPV (TABLE 18,10-17). The brevity of these screening tools makes them well suited for busy physicians; cutoff scores facilitate the rapid identification of positive screens. While the USPSTF has not made specific recommendations regarding a screening interval, many studies examining the utility of these measures have reported on annual screenings.8 While there is limited evidence that brief screening alone leads to reductions in IPV,8 discussing IPV in a supportive and empathic manner and connecting patients to resources, such as supportive counseling, does have an important benefit: It can reduce symptoms of depression.18

Continue to: Screen patients in private; this protocol can help

Screen patients in private; this protocol can help. Given the sensitive nature of IPV and the potential danger some patients may be facing, it is important to screen patients in a safe and supportive environment.19,20 Screening should be conducted by the primary care clinician, ideally when a trusting relationship already has been formed. Screen patients only when they are alone in a private room; avoid screening in public spaces such as clinic waiting rooms or in the vicinity of the patient’s partner or children older than age 2 years.19,20

To provide all patients with an opportunity for private and safe IPV screening, clinics are encouraged to develop a clinic-wide policy whereby patients are routinely escorted to the exam room alone for the first portion of their visit, after which any accompanying individuals may be invited to join.21 Clinic staff can inform patients and accompanying individuals of this policy when they first arrive. Once in the exam room, and before the screening process begins, clearly state reporting requirements to ensure that patients can make an informed decision about whether to disclose IPV.19

Set a receptive tone. The manner in which clinicians discuss IPV with their patients is just as important as the setting. Demonstrating sensitivity and genuine concern for the patient’s safety and well-being may increase the patient’s comfort level throughout the screening process and may facilitate disclosures of IPV.19,22 When screening patients for IPV, sit face to face rather than standing over them, maintain warm and open body language, and speak in a soft tone of voice.22

Patients may feel more comfortable if you ask screening questions in a straightforward, nonjudgmental manner, as this helps to normalize the screening experience. We also recommend using behaviorally specific language (eg, “Do arguments [with your partner] ever result in hitting, kicking, or pushing?”16 or “How often does your partner scream or curse at you?”),13 as some patients who have experienced IPV will not label their experiences as “abuse” or “violence.” Not every patient who experiences IPV will be ready to disclose these events; however, maintaining a positive and supportive relationship during routine IPV screening and throughout the remainder of the medical visit may help facilitate future disclosures if, and when, a patient is ready to seek support.19

CRITICAL INTERVENTION ELEMENTS: EMPATHY AND SAFETY

A physician’s response to an IPV disclosure can have a lasting impact on the patient. We encourage family physicians to respond to IPV disclosures with empathy. Maintain eye contact and warm body language, validate the patient’s experiences (“I am sorry this happened to you,” “that must have been terrifying”), tell the patient that the violence was not their fault, and thank the patient for disclosing.23

Continue to: Assess patient safety

Assess patient safety. Another critical component of intervention is to assess the patient’s safety and engage in safety planning. If the patient agrees to this next step, you may wish to provide a warm handoff to a trained social worker, nurse, or psychologist in the clinic who can spend more time covering this information with the patient. Some key components of a safety assessment include determining whether the violence or threat of violence is ongoing and identifying who lives in the home (eg, the partner, children, and any pets). You and the patient can also discuss red flags that would indicate elevated risk. You should discuss red flags that are unique to the patient’s relationship as well as common factors that have been found to heighten risk for IPV (eg, partner engaging in heavy alcohol use).1

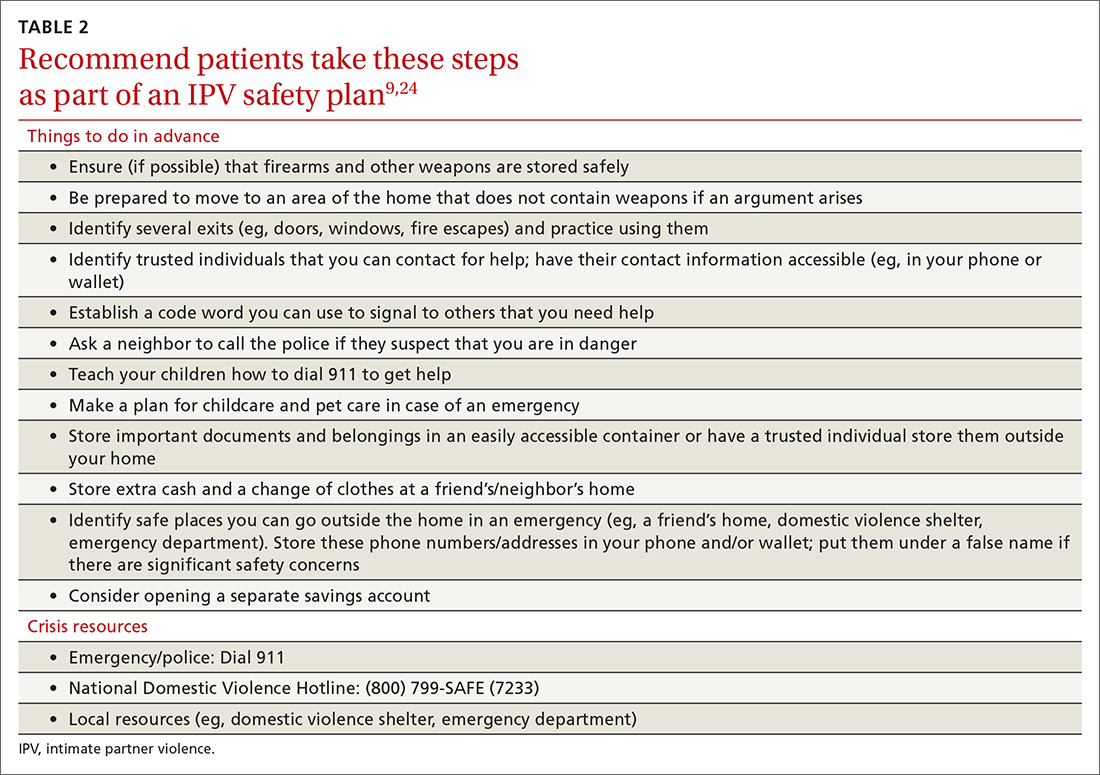

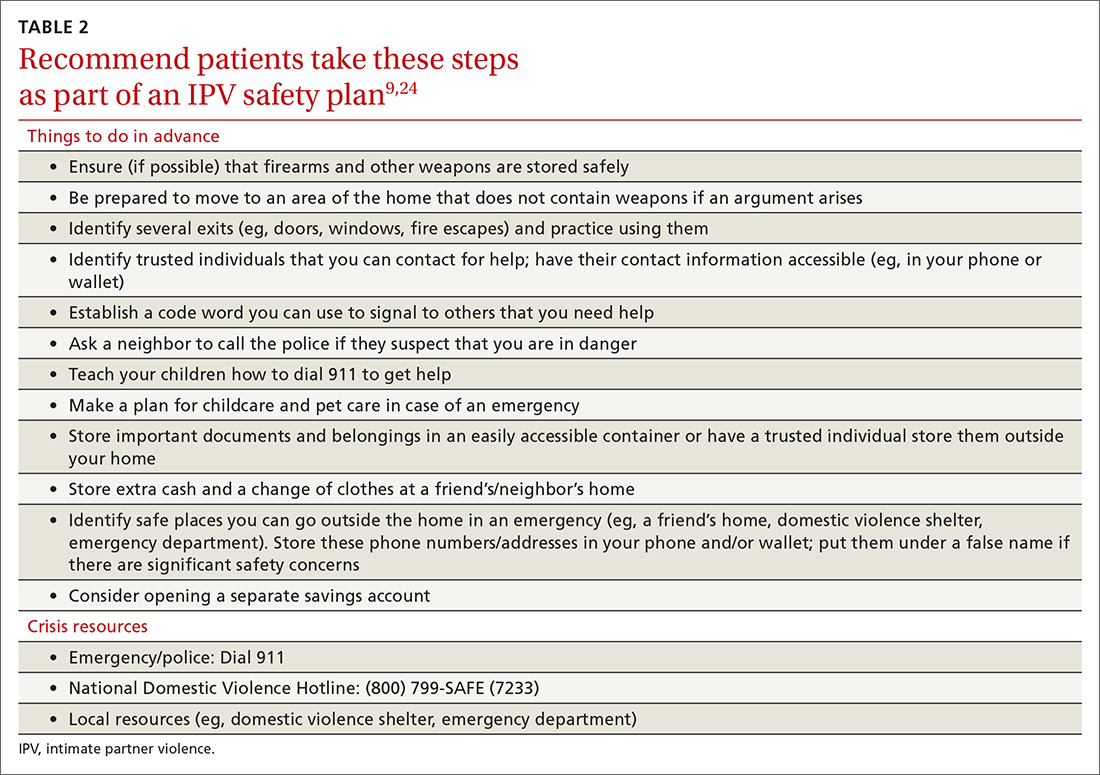

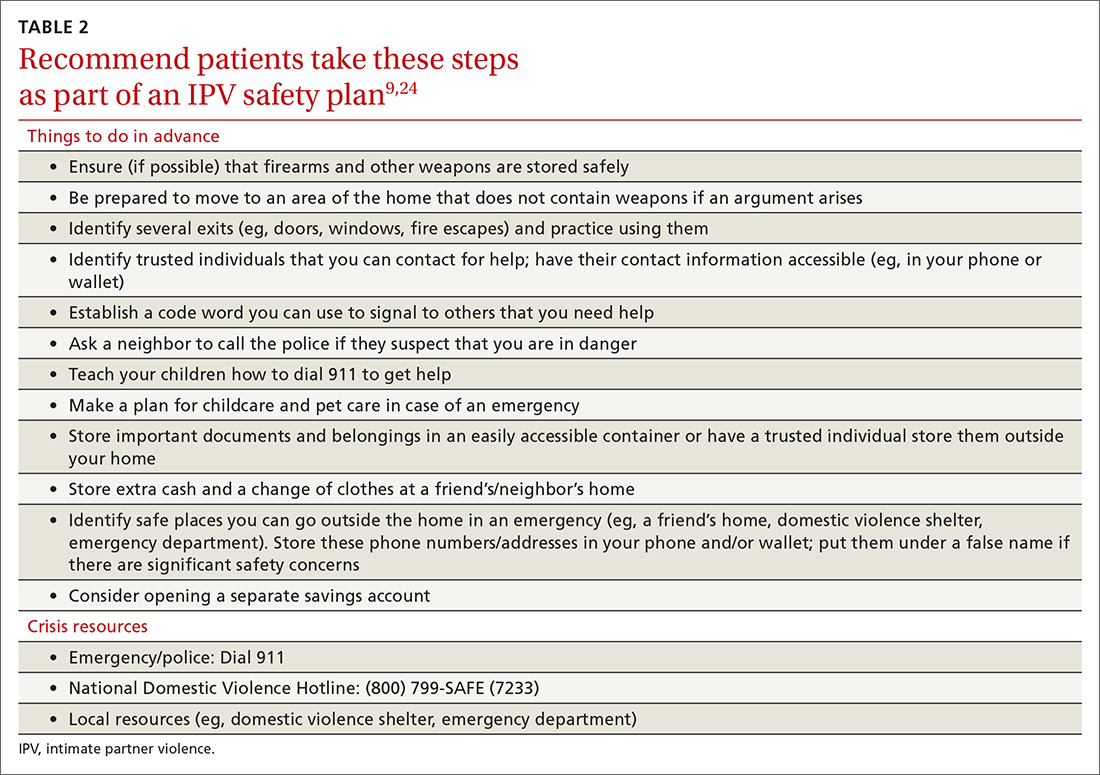

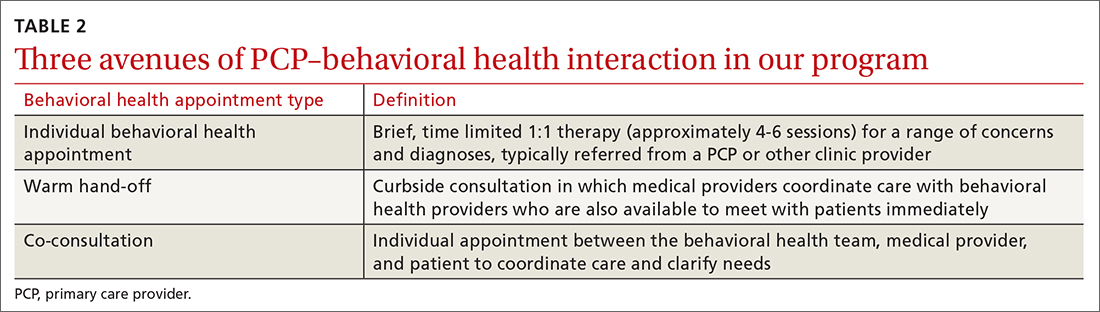

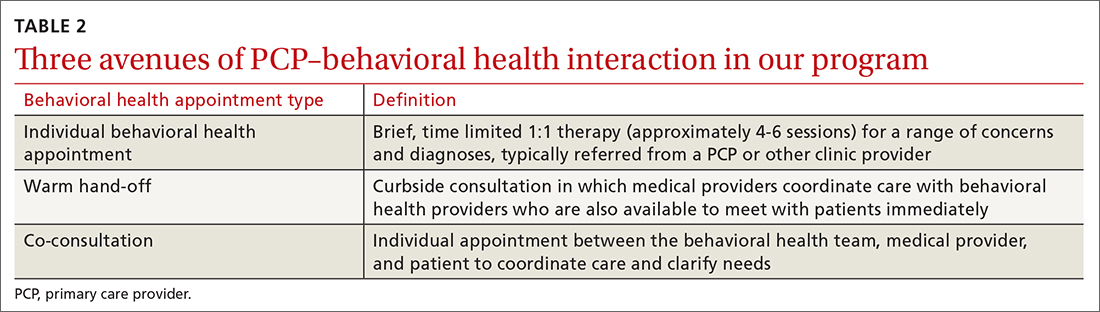

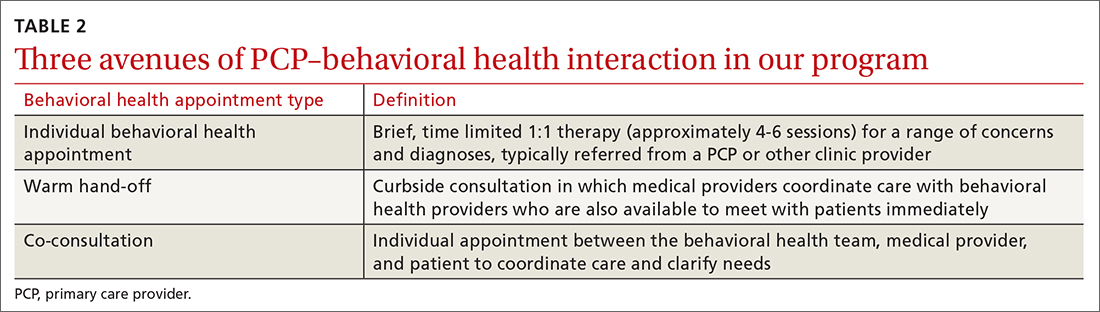

With the patient’s permission, collaboratively construct a safety plan that details how the patient can stay safe on a daily basis and how to safely leave should a dangerous situation arise (TABLE 29,24). The interactive safety planning tool available on the National Domestic Violence Hotline’s website can be a valuable resource (www.thehotline.org/plan-for-safety/).24 Finally, if a patient is experiencing mental health concerns associated with IPV (eg, PTSD, depression, substance misuse, suicidal ideation), consider a referral to a domestic violence counseling center or mental health provider.

Move at the patient’s pace. Even if patients are willing to disclose IPV, they will differ in their readiness to discuss psychoeducation, safety planning, and referrals. Similarly, even if a patient is experiencing severe violence, they may not be ready to leave the relationship. Thus, it’s important to ask the patient for permission before initiating each successive step of the follow-up intervention. You and the patient may wish to schedule additional appointments to discuss this information at a pace the patient finds appropriate.

You may need to spend some time helping the patient recognize the severity of their situation and to feel empowered to take action. In addition, offer information and resources to all patients, even those who do not disclose IPV. Some patients may want to receive this information even if they do not feel comfortable sharing their experiences during the appointment.20 You can also inform patients that they are welcome to bring up issues related to IPV at any future appointments in order to leave the door open to future disclosures.

THE CASE

The physician determined that Ms. T had been experiencing physical and psychological IPV in her current relationship. After responding empathically and obtaining the patient’s consent, the physician provided a warm handoff to the psychologist in the clinic. With Ms. T’s permission, the psychologist provided psychoeducation about IPV, and they discussed Ms. T’s current situation and risk level. They determined that Ms. T was at risk for subsequent episodes of IPV and they collaborated on a safety plan, making sure to discuss contact information for local and national crisis resources.

Continue to: Ms. T saved the phone number...

Ms. T saved the phone number for her local domestic violence shelter in her phone under a false name in case her husband looked through her phone. She said she planned to work on several safety plan items when her husband was away from the house and it was safe to do so. For example, she planned to identify additional ways to exit the house in an emergency and she was going to put together a bag with a change of clothes and some money and drop it off at a trusted friend’s house.

Ms. T and the psychologist agreed to follow up with an office visit in 1 week to discuss any additional safety concerns and to determine whether Ms. T could benefit from a referral to domestic violence counseling services or mental health treatment. The psychologist provided a summary of the topics she and Ms. T had discussed to the physician. The physician scheduled a follow-up appointment with Ms. T in 3 weeks to assess her current safety, troubleshoot any difficulties in implementing her safety plan, and offer additional resources, as needed.

CORRESPONDENCE

Andrea Massa, PhD, 125 Doughty Street, Suite 300, Charleston, SC 29403; massa@musc.edu

1. CDC. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. Preventing intimate partner violence. 2021. Accessed June 27, 2022. www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/intimatepartnerviolence/fastfact.html

2. CDC. Black MC, Basile KC, Breiding MJ, et al. The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey: 2010 Summary Report. Accessed June 27, 2022. www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/nisvs_executive_summary-a.pdf

3. Chen J, Walters ML, Gilbert LK, et al. Sexual violence, stalking, and intimate partner violence by sexual orientation, United States. Psychol Violence. 2020;10:110-119. doi:10.1037/vio0000252

4. Kofman YB, Garfin DR. Home is not always a haven: the domestic violence crisis amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol Trauma. 2020;12:S199-S201. doi:10.1037/tra0000866

5. Lyons M, Brewer G. Experiences of intimate partner violence during lockdown and the COVID-19 pandemic. J Fam Violence. 2021:1-9. doi:10.1007/s10896-021-00260-x

6. Parrott DJ, Halmos MB, Stappenbeck CA, et al. Intimate partner aggression during the COVID-19 pandemic: associations with stress and heavy drinking. Psychol Violence. 2021;12:95-103. doi:10.1037/vio0000395

7. CDC. National Center for Injury Prevention and

8. US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for intimate partner violence, elder abuse, and abuse of vulnerable adults: US Preventive Services Task Force final recommendation statement. JAMA. 2018;320:1678-1687. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.14741

9. Sprunger JG, Schumacher JA, Coffey SF, et al. It’s time to start asking all patients about intimate partner violence. J Fam Pract. 2019;68:152-161.

10. Chan CC, Chan YC, Au A, et al. Reliability and validity of the “Extended - Hurt, Insult, Threaten, Scream” (E-HITS) screening tool in detecting intimate partner violence in hospital emergency departments in Hong Kong. Hong Kong J Emerg Med. 2010;17:109-117. doi:10.1177/102490791001700202

11. Iverson KM, King MW, Gerber MR, et al. Accuracy of an intimate partner violence screening tool for female VHA patients: a replication and extension. J Trauma Stress. 2015;28:79-82. doi:10.1002/jts.21985

12. Sohal H, Eldridge S, Feder G. The sensitivity and specificity of four questions (HARK) to identify intimate partner violence: a diagnostic accuracy study in general practice. BMC Fam Pract. 2007;8:49. doi:10.1186/1471-2296-8-49

13. Sherin KM, Sinacore JM, Li X, et al. HITS: a short domestic violence screening tool for use in a family practice setting. Fam Med. 1998;30:508-512.

14. Rabin RF, Jennings JM, Campbell JC, et al. Intimate partner violence screening tools: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2009;36:439-445.e4. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2009.01.024

15. Feldhaus KM, Koziol-McLain J, Amsbury HL, et al. Accuracy of 3 brief screening questions for detecting partner violence in the emergency department. JAMA. 1997;277:1357-1361. doi:10.1001/jama.1997.03540410035027

16. Brown JB, Lent B, Schmidt G, et al. Application of the Woman Abuse Screening Tool (WAST) and WAST-short in the family practice setting. J Fam Pract. 2000;49:896-903.

17. Wathen CN, Jamieson E, MacMillan HL, MVAWRG. Who is identified by screening for intimate partner violence? Womens Health Issues. 2008;18:423-432. doi:10.1016/j.whi.2008.08.003

18. Hegarty K, O’Doherty L, Taft A, et al. Screening and counselling in the primary care setting for women who have experienced intimate partner violence (WEAVE): a cluster randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2013;382:249-258. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60052-5

19. Correa NP, Cain CM, Bertenthal M, et al. Women’s experiences of being screened for intimate partner violence in the health care setting. Nurs Womens Health. 2020;24:185-196. doi:10.1016/j.nwh.2020.04.002

20. Chang JC, Decker MR, Moracco KE, et al. Asking about intimate partner violence: advice from female survivors to health care providers. Patient Educ Couns. 2005;59:141-147. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2004.10.008

21. Paterno MT, Draughon JE. Screening for intimate partner violence. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2016;61:370-375. doi:10.1111/jmwh.12443

22. Iverson KM, Huang K, Wells SY, et al. Women veterans’ preferences for intimate partner violence screening and response procedures within the Veterans Health Administration. Res Nurs Health. 2014;37:302-311. doi:10.1002/nur.21602

23. National Sexual Violence Research Center. Assessing patients for sexual violence: A guide for health care providers. 2011. Accessed June 28, 2022. www.nsvrc.org/publications/assessing-patients-sexual-violence-guide-health-care-providers

24. National Domestic Violence Hotline. Interactive guide to safety planning. Accessed August 22, 2022. https://www.thehotline.org/plan-for-safety/create-a-safety-plan/

THE CASE

Louise T* is a 42-year-old woman who presented to her family medicine office for a routine annual visit. During the exam, her physician noticed bruises on Ms. T’s arms and back. Upon further inquiry, Ms. T reported that she and her husband had argued the night before the appointment. With some hesitancy, she went on to say that this was not the first time this had happened. She said that she and her husband had been arguing frequently for several years and that 6 months earlier, when he lost his job, he began hitting and pushing her.

●

*The patient’s name has been changed to protect her identity.

Intimate partner violence (IPV) includes physical, sexual, or psychological aggression or stalking perpetrated by a current or former relationship partner.1 IPV affects more than 12 million men and women living in the United States each year.2 According to a national survey of IPV, approximately one-third (35.6%) of women and one-quarter (28.5%) of men living in the United States experience rape, physical violence, or stalking by an intimate partner during their lifetime.2 Lifetime exposure to psychological IPV is even more prevalent, affecting nearly half of women and men (48.4% and 48.8%, respectively).2

Lifetime prevalence of any form of IPV is higher among women who identify as bisexual (59.8%) and lesbian (46.3%) compared with those who identify as heterosexual (37.2%); rates are comparable among men who identify as heterosexual (31.9%), bisexual (35.3%), and gay (35.1%).3 Preliminary data suggest that IPV may have increased in frequency and severity during the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly in the context of mandated shelter-in-place and stay-at-home orders.4-6

IPV is associated with numerous negative health consequences. They include fear and concern for safety, mental health disorders such as posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and physical health problems including physical injury, chronic pain, sleep disturbance, and frequent headaches.2 IPV is also associated with a greater number of missed days from school and work and increased utilization of legal, health care, and housing services.2,7 The overall annual cost of IPV against women is estimated at $5.8 billion, with health care costs accounting for approximately $4.1 billion.7 Family physicians can play an important role in curbing the devastating effects of IPV by screening patients and providing resources when needed.

Facilitate disclosure using screening tools and protocol

In Ms. T’s case, evidence of violence was clearly visible. However, not all instances of IPV leave physical marks. The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends that all women of childbearing age be screened for IPV, whether or not they exhibit signs of violence.8 While the USPSTF has only published recommendations regarding screening women for IPV, there has been a recent push to screen all patients given that men also experience high rates of IPV.9

Utilize a brief screening tool. Directly ask patients about IPV; this can help reduce stigma, facilitate disclosure, and initiate the process of connecting patients to potentially lifesaving resources. The USPSTF lists several brief screening measures that can be used in primary care settings to assess exposure to IPV (TABLE 18,10-17). The brevity of these screening tools makes them well suited for busy physicians; cutoff scores facilitate the rapid identification of positive screens. While the USPSTF has not made specific recommendations regarding a screening interval, many studies examining the utility of these measures have reported on annual screenings.8 While there is limited evidence that brief screening alone leads to reductions in IPV,8 discussing IPV in a supportive and empathic manner and connecting patients to resources, such as supportive counseling, does have an important benefit: It can reduce symptoms of depression.18

Continue to: Screen patients in private; this protocol can help

Screen patients in private; this protocol can help. Given the sensitive nature of IPV and the potential danger some patients may be facing, it is important to screen patients in a safe and supportive environment.19,20 Screening should be conducted by the primary care clinician, ideally when a trusting relationship already has been formed. Screen patients only when they are alone in a private room; avoid screening in public spaces such as clinic waiting rooms or in the vicinity of the patient’s partner or children older than age 2 years.19,20

To provide all patients with an opportunity for private and safe IPV screening, clinics are encouraged to develop a clinic-wide policy whereby patients are routinely escorted to the exam room alone for the first portion of their visit, after which any accompanying individuals may be invited to join.21 Clinic staff can inform patients and accompanying individuals of this policy when they first arrive. Once in the exam room, and before the screening process begins, clearly state reporting requirements to ensure that patients can make an informed decision about whether to disclose IPV.19

Set a receptive tone. The manner in which clinicians discuss IPV with their patients is just as important as the setting. Demonstrating sensitivity and genuine concern for the patient’s safety and well-being may increase the patient’s comfort level throughout the screening process and may facilitate disclosures of IPV.19,22 When screening patients for IPV, sit face to face rather than standing over them, maintain warm and open body language, and speak in a soft tone of voice.22

Patients may feel more comfortable if you ask screening questions in a straightforward, nonjudgmental manner, as this helps to normalize the screening experience. We also recommend using behaviorally specific language (eg, “Do arguments [with your partner] ever result in hitting, kicking, or pushing?”16 or “How often does your partner scream or curse at you?”),13 as some patients who have experienced IPV will not label their experiences as “abuse” or “violence.” Not every patient who experiences IPV will be ready to disclose these events; however, maintaining a positive and supportive relationship during routine IPV screening and throughout the remainder of the medical visit may help facilitate future disclosures if, and when, a patient is ready to seek support.19

CRITICAL INTERVENTION ELEMENTS: EMPATHY AND SAFETY

A physician’s response to an IPV disclosure can have a lasting impact on the patient. We encourage family physicians to respond to IPV disclosures with empathy. Maintain eye contact and warm body language, validate the patient’s experiences (“I am sorry this happened to you,” “that must have been terrifying”), tell the patient that the violence was not their fault, and thank the patient for disclosing.23

Continue to: Assess patient safety

Assess patient safety. Another critical component of intervention is to assess the patient’s safety and engage in safety planning. If the patient agrees to this next step, you may wish to provide a warm handoff to a trained social worker, nurse, or psychologist in the clinic who can spend more time covering this information with the patient. Some key components of a safety assessment include determining whether the violence or threat of violence is ongoing and identifying who lives in the home (eg, the partner, children, and any pets). You and the patient can also discuss red flags that would indicate elevated risk. You should discuss red flags that are unique to the patient’s relationship as well as common factors that have been found to heighten risk for IPV (eg, partner engaging in heavy alcohol use).1

With the patient’s permission, collaboratively construct a safety plan that details how the patient can stay safe on a daily basis and how to safely leave should a dangerous situation arise (TABLE 29,24). The interactive safety planning tool available on the National Domestic Violence Hotline’s website can be a valuable resource (www.thehotline.org/plan-for-safety/).24 Finally, if a patient is experiencing mental health concerns associated with IPV (eg, PTSD, depression, substance misuse, suicidal ideation), consider a referral to a domestic violence counseling center or mental health provider.

Move at the patient’s pace. Even if patients are willing to disclose IPV, they will differ in their readiness to discuss psychoeducation, safety planning, and referrals. Similarly, even if a patient is experiencing severe violence, they may not be ready to leave the relationship. Thus, it’s important to ask the patient for permission before initiating each successive step of the follow-up intervention. You and the patient may wish to schedule additional appointments to discuss this information at a pace the patient finds appropriate.

You may need to spend some time helping the patient recognize the severity of their situation and to feel empowered to take action. In addition, offer information and resources to all patients, even those who do not disclose IPV. Some patients may want to receive this information even if they do not feel comfortable sharing their experiences during the appointment.20 You can also inform patients that they are welcome to bring up issues related to IPV at any future appointments in order to leave the door open to future disclosures.

THE CASE

The physician determined that Ms. T had been experiencing physical and psychological IPV in her current relationship. After responding empathically and obtaining the patient’s consent, the physician provided a warm handoff to the psychologist in the clinic. With Ms. T’s permission, the psychologist provided psychoeducation about IPV, and they discussed Ms. T’s current situation and risk level. They determined that Ms. T was at risk for subsequent episodes of IPV and they collaborated on a safety plan, making sure to discuss contact information for local and national crisis resources.

Continue to: Ms. T saved the phone number...

Ms. T saved the phone number for her local domestic violence shelter in her phone under a false name in case her husband looked through her phone. She said she planned to work on several safety plan items when her husband was away from the house and it was safe to do so. For example, she planned to identify additional ways to exit the house in an emergency and she was going to put together a bag with a change of clothes and some money and drop it off at a trusted friend’s house.

Ms. T and the psychologist agreed to follow up with an office visit in 1 week to discuss any additional safety concerns and to determine whether Ms. T could benefit from a referral to domestic violence counseling services or mental health treatment. The psychologist provided a summary of the topics she and Ms. T had discussed to the physician. The physician scheduled a follow-up appointment with Ms. T in 3 weeks to assess her current safety, troubleshoot any difficulties in implementing her safety plan, and offer additional resources, as needed.

CORRESPONDENCE

Andrea Massa, PhD, 125 Doughty Street, Suite 300, Charleston, SC 29403; massa@musc.edu

THE CASE

Louise T* is a 42-year-old woman who presented to her family medicine office for a routine annual visit. During the exam, her physician noticed bruises on Ms. T’s arms and back. Upon further inquiry, Ms. T reported that she and her husband had argued the night before the appointment. With some hesitancy, she went on to say that this was not the first time this had happened. She said that she and her husband had been arguing frequently for several years and that 6 months earlier, when he lost his job, he began hitting and pushing her.

●

*The patient’s name has been changed to protect her identity.

Intimate partner violence (IPV) includes physical, sexual, or psychological aggression or stalking perpetrated by a current or former relationship partner.1 IPV affects more than 12 million men and women living in the United States each year.2 According to a national survey of IPV, approximately one-third (35.6%) of women and one-quarter (28.5%) of men living in the United States experience rape, physical violence, or stalking by an intimate partner during their lifetime.2 Lifetime exposure to psychological IPV is even more prevalent, affecting nearly half of women and men (48.4% and 48.8%, respectively).2

Lifetime prevalence of any form of IPV is higher among women who identify as bisexual (59.8%) and lesbian (46.3%) compared with those who identify as heterosexual (37.2%); rates are comparable among men who identify as heterosexual (31.9%), bisexual (35.3%), and gay (35.1%).3 Preliminary data suggest that IPV may have increased in frequency and severity during the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly in the context of mandated shelter-in-place and stay-at-home orders.4-6

IPV is associated with numerous negative health consequences. They include fear and concern for safety, mental health disorders such as posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and physical health problems including physical injury, chronic pain, sleep disturbance, and frequent headaches.2 IPV is also associated with a greater number of missed days from school and work and increased utilization of legal, health care, and housing services.2,7 The overall annual cost of IPV against women is estimated at $5.8 billion, with health care costs accounting for approximately $4.1 billion.7 Family physicians can play an important role in curbing the devastating effects of IPV by screening patients and providing resources when needed.

Facilitate disclosure using screening tools and protocol

In Ms. T’s case, evidence of violence was clearly visible. However, not all instances of IPV leave physical marks. The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends that all women of childbearing age be screened for IPV, whether or not they exhibit signs of violence.8 While the USPSTF has only published recommendations regarding screening women for IPV, there has been a recent push to screen all patients given that men also experience high rates of IPV.9

Utilize a brief screening tool. Directly ask patients about IPV; this can help reduce stigma, facilitate disclosure, and initiate the process of connecting patients to potentially lifesaving resources. The USPSTF lists several brief screening measures that can be used in primary care settings to assess exposure to IPV (TABLE 18,10-17). The brevity of these screening tools makes them well suited for busy physicians; cutoff scores facilitate the rapid identification of positive screens. While the USPSTF has not made specific recommendations regarding a screening interval, many studies examining the utility of these measures have reported on annual screenings.8 While there is limited evidence that brief screening alone leads to reductions in IPV,8 discussing IPV in a supportive and empathic manner and connecting patients to resources, such as supportive counseling, does have an important benefit: It can reduce symptoms of depression.18

Continue to: Screen patients in private; this protocol can help

Screen patients in private; this protocol can help. Given the sensitive nature of IPV and the potential danger some patients may be facing, it is important to screen patients in a safe and supportive environment.19,20 Screening should be conducted by the primary care clinician, ideally when a trusting relationship already has been formed. Screen patients only when they are alone in a private room; avoid screening in public spaces such as clinic waiting rooms or in the vicinity of the patient’s partner or children older than age 2 years.19,20

To provide all patients with an opportunity for private and safe IPV screening, clinics are encouraged to develop a clinic-wide policy whereby patients are routinely escorted to the exam room alone for the first portion of their visit, after which any accompanying individuals may be invited to join.21 Clinic staff can inform patients and accompanying individuals of this policy when they first arrive. Once in the exam room, and before the screening process begins, clearly state reporting requirements to ensure that patients can make an informed decision about whether to disclose IPV.19

Set a receptive tone. The manner in which clinicians discuss IPV with their patients is just as important as the setting. Demonstrating sensitivity and genuine concern for the patient’s safety and well-being may increase the patient’s comfort level throughout the screening process and may facilitate disclosures of IPV.19,22 When screening patients for IPV, sit face to face rather than standing over them, maintain warm and open body language, and speak in a soft tone of voice.22

Patients may feel more comfortable if you ask screening questions in a straightforward, nonjudgmental manner, as this helps to normalize the screening experience. We also recommend using behaviorally specific language (eg, “Do arguments [with your partner] ever result in hitting, kicking, or pushing?”16 or “How often does your partner scream or curse at you?”),13 as some patients who have experienced IPV will not label their experiences as “abuse” or “violence.” Not every patient who experiences IPV will be ready to disclose these events; however, maintaining a positive and supportive relationship during routine IPV screening and throughout the remainder of the medical visit may help facilitate future disclosures if, and when, a patient is ready to seek support.19

CRITICAL INTERVENTION ELEMENTS: EMPATHY AND SAFETY

A physician’s response to an IPV disclosure can have a lasting impact on the patient. We encourage family physicians to respond to IPV disclosures with empathy. Maintain eye contact and warm body language, validate the patient’s experiences (“I am sorry this happened to you,” “that must have been terrifying”), tell the patient that the violence was not their fault, and thank the patient for disclosing.23

Continue to: Assess patient safety

Assess patient safety. Another critical component of intervention is to assess the patient’s safety and engage in safety planning. If the patient agrees to this next step, you may wish to provide a warm handoff to a trained social worker, nurse, or psychologist in the clinic who can spend more time covering this information with the patient. Some key components of a safety assessment include determining whether the violence or threat of violence is ongoing and identifying who lives in the home (eg, the partner, children, and any pets). You and the patient can also discuss red flags that would indicate elevated risk. You should discuss red flags that are unique to the patient’s relationship as well as common factors that have been found to heighten risk for IPV (eg, partner engaging in heavy alcohol use).1

With the patient’s permission, collaboratively construct a safety plan that details how the patient can stay safe on a daily basis and how to safely leave should a dangerous situation arise (TABLE 29,24). The interactive safety planning tool available on the National Domestic Violence Hotline’s website can be a valuable resource (www.thehotline.org/plan-for-safety/).24 Finally, if a patient is experiencing mental health concerns associated with IPV (eg, PTSD, depression, substance misuse, suicidal ideation), consider a referral to a domestic violence counseling center or mental health provider.

Move at the patient’s pace. Even if patients are willing to disclose IPV, they will differ in their readiness to discuss psychoeducation, safety planning, and referrals. Similarly, even if a patient is experiencing severe violence, they may not be ready to leave the relationship. Thus, it’s important to ask the patient for permission before initiating each successive step of the follow-up intervention. You and the patient may wish to schedule additional appointments to discuss this information at a pace the patient finds appropriate.

You may need to spend some time helping the patient recognize the severity of their situation and to feel empowered to take action. In addition, offer information and resources to all patients, even those who do not disclose IPV. Some patients may want to receive this information even if they do not feel comfortable sharing their experiences during the appointment.20 You can also inform patients that they are welcome to bring up issues related to IPV at any future appointments in order to leave the door open to future disclosures.

THE CASE

The physician determined that Ms. T had been experiencing physical and psychological IPV in her current relationship. After responding empathically and obtaining the patient’s consent, the physician provided a warm handoff to the psychologist in the clinic. With Ms. T’s permission, the psychologist provided psychoeducation about IPV, and they discussed Ms. T’s current situation and risk level. They determined that Ms. T was at risk for subsequent episodes of IPV and they collaborated on a safety plan, making sure to discuss contact information for local and national crisis resources.

Continue to: Ms. T saved the phone number...

Ms. T saved the phone number for her local domestic violence shelter in her phone under a false name in case her husband looked through her phone. She said she planned to work on several safety plan items when her husband was away from the house and it was safe to do so. For example, she planned to identify additional ways to exit the house in an emergency and she was going to put together a bag with a change of clothes and some money and drop it off at a trusted friend’s house.

Ms. T and the psychologist agreed to follow up with an office visit in 1 week to discuss any additional safety concerns and to determine whether Ms. T could benefit from a referral to domestic violence counseling services or mental health treatment. The psychologist provided a summary of the topics she and Ms. T had discussed to the physician. The physician scheduled a follow-up appointment with Ms. T in 3 weeks to assess her current safety, troubleshoot any difficulties in implementing her safety plan, and offer additional resources, as needed.

CORRESPONDENCE

Andrea Massa, PhD, 125 Doughty Street, Suite 300, Charleston, SC 29403; massa@musc.edu

1. CDC. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. Preventing intimate partner violence. 2021. Accessed June 27, 2022. www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/intimatepartnerviolence/fastfact.html

2. CDC. Black MC, Basile KC, Breiding MJ, et al. The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey: 2010 Summary Report. Accessed June 27, 2022. www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/nisvs_executive_summary-a.pdf

3. Chen J, Walters ML, Gilbert LK, et al. Sexual violence, stalking, and intimate partner violence by sexual orientation, United States. Psychol Violence. 2020;10:110-119. doi:10.1037/vio0000252

4. Kofman YB, Garfin DR. Home is not always a haven: the domestic violence crisis amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol Trauma. 2020;12:S199-S201. doi:10.1037/tra0000866

5. Lyons M, Brewer G. Experiences of intimate partner violence during lockdown and the COVID-19 pandemic. J Fam Violence. 2021:1-9. doi:10.1007/s10896-021-00260-x

6. Parrott DJ, Halmos MB, Stappenbeck CA, et al. Intimate partner aggression during the COVID-19 pandemic: associations with stress and heavy drinking. Psychol Violence. 2021;12:95-103. doi:10.1037/vio0000395

7. CDC. National Center for Injury Prevention and

8. US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for intimate partner violence, elder abuse, and abuse of vulnerable adults: US Preventive Services Task Force final recommendation statement. JAMA. 2018;320:1678-1687. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.14741

9. Sprunger JG, Schumacher JA, Coffey SF, et al. It’s time to start asking all patients about intimate partner violence. J Fam Pract. 2019;68:152-161.

10. Chan CC, Chan YC, Au A, et al. Reliability and validity of the “Extended - Hurt, Insult, Threaten, Scream” (E-HITS) screening tool in detecting intimate partner violence in hospital emergency departments in Hong Kong. Hong Kong J Emerg Med. 2010;17:109-117. doi:10.1177/102490791001700202

11. Iverson KM, King MW, Gerber MR, et al. Accuracy of an intimate partner violence screening tool for female VHA patients: a replication and extension. J Trauma Stress. 2015;28:79-82. doi:10.1002/jts.21985

12. Sohal H, Eldridge S, Feder G. The sensitivity and specificity of four questions (HARK) to identify intimate partner violence: a diagnostic accuracy study in general practice. BMC Fam Pract. 2007;8:49. doi:10.1186/1471-2296-8-49

13. Sherin KM, Sinacore JM, Li X, et al. HITS: a short domestic violence screening tool for use in a family practice setting. Fam Med. 1998;30:508-512.

14. Rabin RF, Jennings JM, Campbell JC, et al. Intimate partner violence screening tools: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2009;36:439-445.e4. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2009.01.024

15. Feldhaus KM, Koziol-McLain J, Amsbury HL, et al. Accuracy of 3 brief screening questions for detecting partner violence in the emergency department. JAMA. 1997;277:1357-1361. doi:10.1001/jama.1997.03540410035027

16. Brown JB, Lent B, Schmidt G, et al. Application of the Woman Abuse Screening Tool (WAST) and WAST-short in the family practice setting. J Fam Pract. 2000;49:896-903.

17. Wathen CN, Jamieson E, MacMillan HL, MVAWRG. Who is identified by screening for intimate partner violence? Womens Health Issues. 2008;18:423-432. doi:10.1016/j.whi.2008.08.003

18. Hegarty K, O’Doherty L, Taft A, et al. Screening and counselling in the primary care setting for women who have experienced intimate partner violence (WEAVE): a cluster randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2013;382:249-258. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60052-5

19. Correa NP, Cain CM, Bertenthal M, et al. Women’s experiences of being screened for intimate partner violence in the health care setting. Nurs Womens Health. 2020;24:185-196. doi:10.1016/j.nwh.2020.04.002

20. Chang JC, Decker MR, Moracco KE, et al. Asking about intimate partner violence: advice from female survivors to health care providers. Patient Educ Couns. 2005;59:141-147. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2004.10.008

21. Paterno MT, Draughon JE. Screening for intimate partner violence. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2016;61:370-375. doi:10.1111/jmwh.12443

22. Iverson KM, Huang K, Wells SY, et al. Women veterans’ preferences for intimate partner violence screening and response procedures within the Veterans Health Administration. Res Nurs Health. 2014;37:302-311. doi:10.1002/nur.21602

23. National Sexual Violence Research Center. Assessing patients for sexual violence: A guide for health care providers. 2011. Accessed June 28, 2022. www.nsvrc.org/publications/assessing-patients-sexual-violence-guide-health-care-providers

24. National Domestic Violence Hotline. Interactive guide to safety planning. Accessed August 22, 2022. https://www.thehotline.org/plan-for-safety/create-a-safety-plan/

1. CDC. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. Preventing intimate partner violence. 2021. Accessed June 27, 2022. www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/intimatepartnerviolence/fastfact.html

2. CDC. Black MC, Basile KC, Breiding MJ, et al. The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey: 2010 Summary Report. Accessed June 27, 2022. www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/nisvs_executive_summary-a.pdf

3. Chen J, Walters ML, Gilbert LK, et al. Sexual violence, stalking, and intimate partner violence by sexual orientation, United States. Psychol Violence. 2020;10:110-119. doi:10.1037/vio0000252

4. Kofman YB, Garfin DR. Home is not always a haven: the domestic violence crisis amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol Trauma. 2020;12:S199-S201. doi:10.1037/tra0000866

5. Lyons M, Brewer G. Experiences of intimate partner violence during lockdown and the COVID-19 pandemic. J Fam Violence. 2021:1-9. doi:10.1007/s10896-021-00260-x

6. Parrott DJ, Halmos MB, Stappenbeck CA, et al. Intimate partner aggression during the COVID-19 pandemic: associations with stress and heavy drinking. Psychol Violence. 2021;12:95-103. doi:10.1037/vio0000395

7. CDC. National Center for Injury Prevention and

8. US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for intimate partner violence, elder abuse, and abuse of vulnerable adults: US Preventive Services Task Force final recommendation statement. JAMA. 2018;320:1678-1687. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.14741

9. Sprunger JG, Schumacher JA, Coffey SF, et al. It’s time to start asking all patients about intimate partner violence. J Fam Pract. 2019;68:152-161.

10. Chan CC, Chan YC, Au A, et al. Reliability and validity of the “Extended - Hurt, Insult, Threaten, Scream” (E-HITS) screening tool in detecting intimate partner violence in hospital emergency departments in Hong Kong. Hong Kong J Emerg Med. 2010;17:109-117. doi:10.1177/102490791001700202

11. Iverson KM, King MW, Gerber MR, et al. Accuracy of an intimate partner violence screening tool for female VHA patients: a replication and extension. J Trauma Stress. 2015;28:79-82. doi:10.1002/jts.21985

12. Sohal H, Eldridge S, Feder G. The sensitivity and specificity of four questions (HARK) to identify intimate partner violence: a diagnostic accuracy study in general practice. BMC Fam Pract. 2007;8:49. doi:10.1186/1471-2296-8-49

13. Sherin KM, Sinacore JM, Li X, et al. HITS: a short domestic violence screening tool for use in a family practice setting. Fam Med. 1998;30:508-512.

14. Rabin RF, Jennings JM, Campbell JC, et al. Intimate partner violence screening tools: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2009;36:439-445.e4. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2009.01.024

15. Feldhaus KM, Koziol-McLain J, Amsbury HL, et al. Accuracy of 3 brief screening questions for detecting partner violence in the emergency department. JAMA. 1997;277:1357-1361. doi:10.1001/jama.1997.03540410035027

16. Brown JB, Lent B, Schmidt G, et al. Application of the Woman Abuse Screening Tool (WAST) and WAST-short in the family practice setting. J Fam Pract. 2000;49:896-903.

17. Wathen CN, Jamieson E, MacMillan HL, MVAWRG. Who is identified by screening for intimate partner violence? Womens Health Issues. 2008;18:423-432. doi:10.1016/j.whi.2008.08.003

18. Hegarty K, O’Doherty L, Taft A, et al. Screening and counselling in the primary care setting for women who have experienced intimate partner violence (WEAVE): a cluster randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2013;382:249-258. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60052-5

19. Correa NP, Cain CM, Bertenthal M, et al. Women’s experiences of being screened for intimate partner violence in the health care setting. Nurs Womens Health. 2020;24:185-196. doi:10.1016/j.nwh.2020.04.002

20. Chang JC, Decker MR, Moracco KE, et al. Asking about intimate partner violence: advice from female survivors to health care providers. Patient Educ Couns. 2005;59:141-147. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2004.10.008

21. Paterno MT, Draughon JE. Screening for intimate partner violence. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2016;61:370-375. doi:10.1111/jmwh.12443

22. Iverson KM, Huang K, Wells SY, et al. Women veterans’ preferences for intimate partner violence screening and response procedures within the Veterans Health Administration. Res Nurs Health. 2014;37:302-311. doi:10.1002/nur.21602

23. National Sexual Violence Research Center. Assessing patients for sexual violence: A guide for health care providers. 2011. Accessed June 28, 2022. www.nsvrc.org/publications/assessing-patients-sexual-violence-guide-health-care-providers

24. National Domestic Violence Hotline. Interactive guide to safety planning. Accessed August 22, 2022. https://www.thehotline.org/plan-for-safety/create-a-safety-plan/

Helping patients move forward following traumatic brain injury

THE CASE

Declan M*, a 42-year-old man, presents as a new patient for general medical care. One year ago, he sustained a severe frontal traumatic brain injury (TBI) when he was hit by a car while crossing a street. He developed a subdural hematoma and was in a coma for 6 days. He also had fractured ribs and a fractured left foot. When he regained consciousness, he had posttraumatic amnesia. He also had executive function deficits and memory difficulties, so a guardian was appointed.

Mr. M no longer works as an auto mechanic, a career he once greatly enjoyed. Mr. M’s guardian reports that recently, Mr. M has lost interest in activities he’d previously enjoyed, is frequently irritable, has poor sleep, is socially isolated, and is spending increasing amounts of time at home. When his new primary care physician (PCP) enters the examining room, Mr. M is seated in a chair with his arms folded across his chest. He states that he is “fine” and just needs to “get a doctor.”

●

*This patient is an amalgam of patients for whom the author has provided care.

TBI ranges from mild to severe and can produce a number of profound effects that are a direct—or indirect—result of the physical injury.1 The location and the severity of the injury affect symptoms.2 Even mild TBI can cause impairment, and severe TBI can lead to broad cognitive, behavioral, and physical difficulties. As numbers of TBI cases increase globally, primary care providers need to recognize the symptoms and assess accordingly.1 The Acute Concussion Evaluation (ACE; Physician/Clinician Office Version) facilitates a structured evaluation for patients presenting with possible TBI symptoms. It can easily be accessed on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website.3

Direct effects of TBI include impulsivity, depression, reduced frustration tolerance, reduced motivation, low awareness, and insomnia and other sleep difficulties.4,5 Depression may also result indirectly from, or be exacerbated by, new posttraumatic limitations and lifestyle changes as well as loss of career and community.4 Both direct and indirect depression often manifest as feelings of hopelessness and worthlessness and a lack of interest in once enjoyable activities. Depression can worsen other TBI sequelae such as difficulty concentrating, lack of initiation, flat affect, irritability, reduced independence, reduced functional performance, loss of inhibition, and physical pain.6

Nationwide, most mental health concerns continue to be addressed in the primary care setting.7 Individuals with TBI experience major depression at a rate 5 to 6 times higher than those in the general population, with a prevalence rate of 45%.8

Suicide. The subject of suicide must be explored with survivors of TBI; evidence suggests a correlation between TBI, depression, and increased risk for suicide.9 Among those who have TBI, as many as 22% experience suicidal ideation; the risk of suicide in survivors of severe TBI is 3 to 4 times the risk in the general population.10 Additionally, suicidality in this context appears to be a chronic concern; therefore, carefully assess for its presence no matter how long ago the TBI occurred.10

Additional TBI-associated health concerns

Grief and loss. We so often focus on death as the only cause for grief, but grief can occur for other types of loss, as well. Individuals with TBI often experience a radical negative change in self-concept after their injury, which is associated with feelings of grief.11 Helping patients recognize that they are grieving the loss of the person they once were can help set a framework for their experience.

Continue to: Relationship loss

Relationship loss. Many people with TBI lose close relationships.12 This can be due to life changes such as job loss, loss of function or ability to do previously enjoyed activities, or personality changes. These relationship losses can affect a person profoundly.12 Going forward, they may have difficulty trusting others, for example.

Existential issues. Many people with TBI also find that cognitive deficits prevent them from engaging in formerly meaningful work. For example, Mr. M lost his longstanding career as an auto mechanic and therefore part of his identity. Not being able to find purpose and meaning can be a strong contributor to coping difficulties in those with TBI.13

Chronic pain. More than half of people with TBI experience chronic pain. Headaches are the most common pain condition among all TBI survivors.14

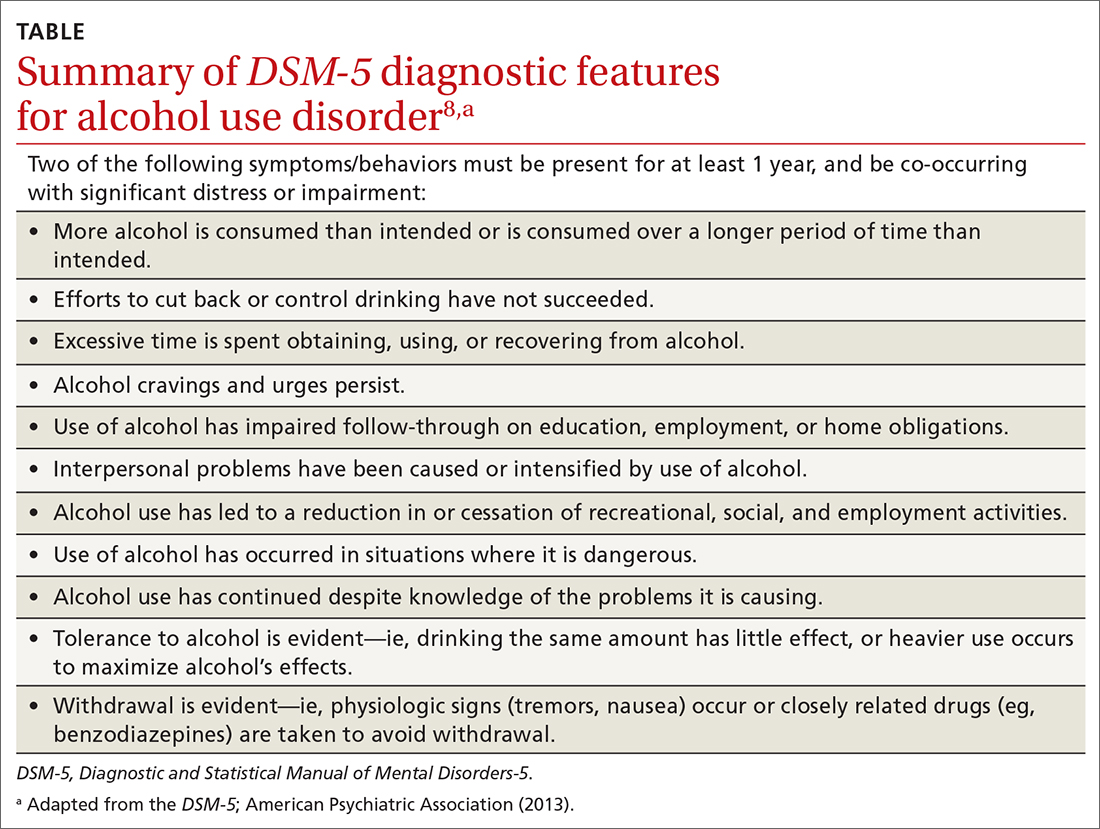

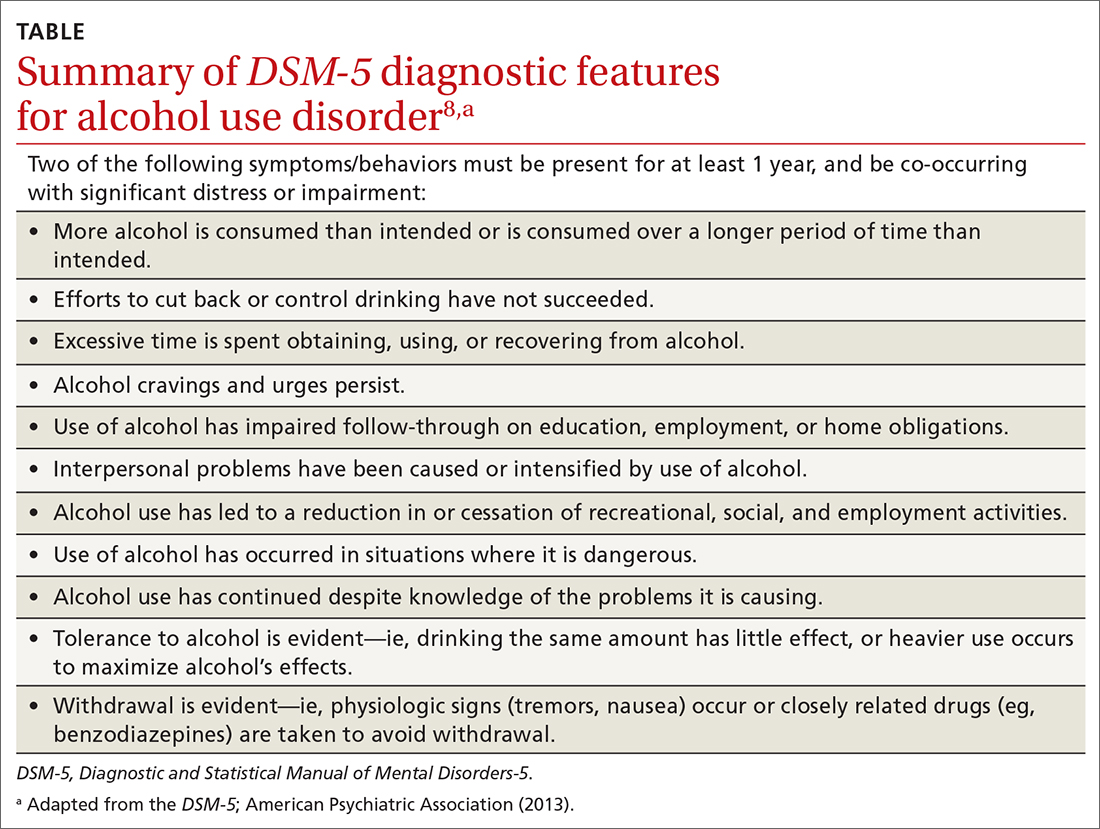

Substance use disorders. The directionality of substance use disorders and TBI is not always clear; however, most evidence suggests that substance abuse is highly prevalent, premorbid, and often a contributing factor in TBI (eg, car accidents).15 Alcohol abuse is the most common risk factor, followed by drug abuse.16 Substance abuse may be exacerbated after TBI when it becomes a coping mechanism under worsening stressors; additionally, executive function deficits or other neurologic problems may result in poor decision-making with regard to substance use.15 While substance abuse may decline in the immediate post-TBI period, it can return to pre-injury levels within a year.17

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors may help

Few studies have explored the efficacy of antidepressant medication in TBI survivors. In a controlled study of patients with TBI, Fann and colleagues18 found no significant improvement in depression symptoms between sertraline and a placebo. However, they did note some possibilities for this lack of significance: socially isolated TBI survivors in the placebo group may have demonstrated improvement in depression symptoms because of increased social interaction;

Continue to: Other research has found...

Other research has found that sertraline improved both depression and quality of life for men with post-TBI depression.19 In a meta-analysis of 4 studies, Paraschakis and Katsanos20 found that sertraline demonstrated a “trend toward significance” in the treatment of depression among patients with TBI. Silverberg and Panenka21 argue that selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors should be used as first-line treatment for depression in survivors of TBI. They note that in non-randomized studies, treatment effects with antidepressants are significant. Additionally, patients who do not respond to the first antidepressant prescribed will often respond to adjunctive or different medications. Finally, they argue that depression measures can capture symptoms related to the physical brain injury, in addition to symptoms of depression, thus confounding results.

THE CASE

Mr. M’s chart showed that he was not taking any medication and that he had no history of substance abuse or tobacco use. He refused to fill out the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ)-2. His guardian said that Mr. M was spending much of his time at home, and that he used to be an avid painter and guitar player but had not engaged in either activity for months. Furthermore, Mr. M used to enjoy working out but did so rarely now.

During the interview, the PCP was careful to make eye contact with Mr. M as well as his guardian, thereby making sure Mr. M was part of the conversation about his care. Pacing of questions was deliberate and unhurried; a return visit would be scheduled to further explore any concerns not covered in this visit. This collaborative, inclusive, patient-centered approach to the clinical interview seemed to place Mr. M at ease. When his guardian said he thought Mr. M was depressed, Mr. M agreed. Although Mr. M still refused to fill out the PHQ-2, he was now willing to answer questions about depression. He acknowledged that he was feeling hopeless and took little pleasure in activities he used to enjoy, thereby indicating a positive screen for depression.

The PCP opted to read the PHQ-9 questions aloud, and Mr. M agreed with most of the items but strongly denied suicidal ideation, citing his religious faith.

The PCP determined that Mr. M’s depression was likely a combination of the direct and indirect effects of his TBI. A quantitative estimate based on Mr. M’s report yielded a PHQ-9 score of 17, indicating moderately severe depression.

Continue to: In addition to building rapport...

In addition to building rapport, careful listening garnered important information about Mr. M. For example, until his accident and subsequent depression, Mr. M had long prioritized his physical health through diet and exercise. He followed a vegetarian diet but recently had little appetite and was eating one microwaveable meal a day. He had an irregular sleep schedule and struggled with insomnia. He lost his closest long-term relationship after his accident due to difficulties with affect regulation. He also lost his job as he could no longer cognitively handle the tasks required.

Hearing Mr. M’s story provided the opportunity to customize education about self-management skills including regular diet, exercise, and sleep hygiene. Due to limited visit time, the PCP elected to use this first visit to focus on sleep and depression. As cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) for insomnia is first-line treatment for both primary insomnia and insomnia due to a medical condition such as TBI,5 a sleep aid was not prescribed. Fortunately, the clinic psychologist who offered CBT was able to join the interview to meet Mr. M and explain the treatment.

Mr. M expressed some initial reluctance to try an antidepressant. However, acknowledging he “just hasn’t been the same” since his TBI, he agreed to a prescription for sertraline and said he hoped it could make him “more like [he] was.”

RETURN VISIT

Four weeks after Mr. M began taking sertraline and participating in weekly CBT sessions, he returned for a follow-up visit with his PCP. He had a noticeably brighter affect, and his guardian reported that he had been playing the guitar again. Mr. M said that he had more energy as a result of improved sleep and mood, and that he felt like his “thinking was clearer.” Mr. M noted that he never thought he would meet with a psychologist but was finding CBT for insomnia helpful.

The psychologist’s notes proposed a treatment plan that would also include targeted grief and existential therapies to address Mr. M’s sudden life changes. At this visit, Mr. M admitted that his reading comprehension and speed were negatively affected by the accident and said this is why he did not wish to fill out the PHQ-2. But he was again willing to have the PHQ-9 questions read to him with his guardian’s support. Results showed a score of 6, indicating mild depression.

A follow-up appointment with Mr. M was scheduled for 6 weeks later, and the team was confident he was getting the behavioral and mental health support he needed through medication and therapy.

CORRESPONDENCE

Elizabeth Imbesi, PhD, VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System, 2215 Fuller Road, Ann Arbor, MI 48105; elizabeth.imbesi@va.gov

1. CDC. Traumatic brain injury & concussion. 2020. Accessed May 19, 2022. www.cdc.gov/traumaticbraininjury/index.html

2. Finset A, Anderson S. Coping strategies in patients with acquired brain injury: relationships between coping, apathy, depression and lesion location. Brain Inj. 2009;14:887-905. doi: 10.1080/026990500445718

3. CDC. Gioia G, Collins M. Acute concussion evaluation. 2006. Accessed May 19, 2022. www.cdc.gov/headsup/pdfs/providers/ace_v2-a.pdf

4. Prigatano GP. Psychotherapy and the process of coping with a brain disorder. Oral presentation at: American Psychological Association annual convention. August 2015; Toronto, Canada.

5. Ouellet M, Beaulieu-Bonneau S, Savard J, Morin C. Insomnia and Fatigue After Traumatic Brain Injury: A CBT Approach to Assessment and Treatment. Elsevier Academic Press: 2019.

6. Lewis FD, Horn GH. Depression following traumatic brain injury: impact on post-hospital residential rehabilitation outcomes. NeuroRehabilitation. 2017;40:401-410. doi: 10.3233/NRE-161427

7. Barkil-Oteo A. Collaborative care for depression in primary care: how psychiatry could “troubleshoot” current treatments and practices. Yale J Bio Med. 2013;86:139-146.

8. Whelan-Goodinson R, Ponsford J, Johnston L, et al. Psychiatric disorders following traumatic brain injury: their nature and frequency. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2009;24:324-332. doi: 10.1097/HTR.0b013e3181a712aa

9. Reeves RR, Laizer JT. Traumatic brain injury and suicide. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 2012;50:32-38. doi: 10.3928/02793695-20120207-02

10. Simpson G, Tate R. Suicidality in people surviving a traumatic brain injury: Prevalence, risk factors and implications for clinical management. Brain Inj. 2007;21:1335-1351. doi: 10.1080/02699050701785542

11. Carroll E, Coetzer R. Identity, grief and self-awareness after traumatic brain injury. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2011;21:289-305. doi: 10.1080/09602011.2011.555972

12. Salas CE, Casassus M, Rowlands L, et al. “Relating through sameness”: a qualitative study of friendship and social isolation in chronic traumatic brain injury. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2018;28:1161-1178. doi: 10.1080/09602011.2016.1247730

13. Hinkebein JA, Stucky R. Coping with traumatic brain injury: existential challenges and managing hope. In: Martz E, Livneh H, eds. Coping with Chronic Illness and Disability: Theoretical, Empirical, and Clinical Aspects. Springer Science & Business Media; 2007:389-409.

14. Khoury S, Benavides R. Pain with traumatic brain injury and psychological disorders. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol and Biol Psychiatry. 2018;87:224-233. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2017.06.007

15. Bjork JM, Grant SJ. Does traumatic brain injury increase risk for substance abuse? J Neurotrauma. 2009;26:1077-1082. doi: 10.1089/neu.2008.0849

16. Unsworth DJ, Mathias JL. Traumatic brain injury and alcohol/substance abuse: a Bayesian meta-analysis comparing the outcomes of people with and without a history of abuse. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2017,39:547-562. doi: 10.1080/13803395.2016.1248812

17. Beaulieu-Bonneau S, St-Onge F, Blackburn M, et al. Alcohol and drug use before and during the first year after traumatic brain injury. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2018;33:E51-E60. doi: 10.1097/HTR.0000000000000341

18. Fann JR, Bombardier CH, Temkin N, et al. Sertraline for major depression during the year following traumatic brain injury: a randomized control trial. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2017;32:332-342. doi: 10.1097/HTR.0000000000000322

19. Ansari A, Jain A, Sharma A, et al. Role of sertraline in posttraumatic brain injury depression and quality of life in TBI. Asian J Neurosurg. 2014;9:182-188. doi: 10.4103/1793-5482.146597

20. Paraschakis A, Katsanos AH. Antidepressants for depression associated with traumatic brain injury: a meta-analytical study of randomized control trials. East Asian Arch Psychiatry. 2017;27:142-149.

21. Silverberg ND, Panenka WJ. Antidepressants for depression after concussion and traumatic brain injury are still best practice. BMC Psychiatry. 2019;19:100. doi: 10.1186/s12888-019-2076-9

THE CASE

Declan M*, a 42-year-old man, presents as a new patient for general medical care. One year ago, he sustained a severe frontal traumatic brain injury (TBI) when he was hit by a car while crossing a street. He developed a subdural hematoma and was in a coma for 6 days. He also had fractured ribs and a fractured left foot. When he regained consciousness, he had posttraumatic amnesia. He also had executive function deficits and memory difficulties, so a guardian was appointed.

Mr. M no longer works as an auto mechanic, a career he once greatly enjoyed. Mr. M’s guardian reports that recently, Mr. M has lost interest in activities he’d previously enjoyed, is frequently irritable, has poor sleep, is socially isolated, and is spending increasing amounts of time at home. When his new primary care physician (PCP) enters the examining room, Mr. M is seated in a chair with his arms folded across his chest. He states that he is “fine” and just needs to “get a doctor.”

●

*This patient is an amalgam of patients for whom the author has provided care.

TBI ranges from mild to severe and can produce a number of profound effects that are a direct—or indirect—result of the physical injury.1 The location and the severity of the injury affect symptoms.2 Even mild TBI can cause impairment, and severe TBI can lead to broad cognitive, behavioral, and physical difficulties. As numbers of TBI cases increase globally, primary care providers need to recognize the symptoms and assess accordingly.1 The Acute Concussion Evaluation (ACE; Physician/Clinician Office Version) facilitates a structured evaluation for patients presenting with possible TBI symptoms. It can easily be accessed on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website.3

Direct effects of TBI include impulsivity, depression, reduced frustration tolerance, reduced motivation, low awareness, and insomnia and other sleep difficulties.4,5 Depression may also result indirectly from, or be exacerbated by, new posttraumatic limitations and lifestyle changes as well as loss of career and community.4 Both direct and indirect depression often manifest as feelings of hopelessness and worthlessness and a lack of interest in once enjoyable activities. Depression can worsen other TBI sequelae such as difficulty concentrating, lack of initiation, flat affect, irritability, reduced independence, reduced functional performance, loss of inhibition, and physical pain.6

Nationwide, most mental health concerns continue to be addressed in the primary care setting.7 Individuals with TBI experience major depression at a rate 5 to 6 times higher than those in the general population, with a prevalence rate of 45%.8

Suicide. The subject of suicide must be explored with survivors of TBI; evidence suggests a correlation between TBI, depression, and increased risk for suicide.9 Among those who have TBI, as many as 22% experience suicidal ideation; the risk of suicide in survivors of severe TBI is 3 to 4 times the risk in the general population.10 Additionally, suicidality in this context appears to be a chronic concern; therefore, carefully assess for its presence no matter how long ago the TBI occurred.10

Additional TBI-associated health concerns

Grief and loss. We so often focus on death as the only cause for grief, but grief can occur for other types of loss, as well. Individuals with TBI often experience a radical negative change in self-concept after their injury, which is associated with feelings of grief.11 Helping patients recognize that they are grieving the loss of the person they once were can help set a framework for their experience.

Continue to: Relationship loss

Relationship loss. Many people with TBI lose close relationships.12 This can be due to life changes such as job loss, loss of function or ability to do previously enjoyed activities, or personality changes. These relationship losses can affect a person profoundly.12 Going forward, they may have difficulty trusting others, for example.

Existential issues. Many people with TBI also find that cognitive deficits prevent them from engaging in formerly meaningful work. For example, Mr. M lost his longstanding career as an auto mechanic and therefore part of his identity. Not being able to find purpose and meaning can be a strong contributor to coping difficulties in those with TBI.13

Chronic pain. More than half of people with TBI experience chronic pain. Headaches are the most common pain condition among all TBI survivors.14

Substance use disorders. The directionality of substance use disorders and TBI is not always clear; however, most evidence suggests that substance abuse is highly prevalent, premorbid, and often a contributing factor in TBI (eg, car accidents).15 Alcohol abuse is the most common risk factor, followed by drug abuse.16 Substance abuse may be exacerbated after TBI when it becomes a coping mechanism under worsening stressors; additionally, executive function deficits or other neurologic problems may result in poor decision-making with regard to substance use.15 While substance abuse may decline in the immediate post-TBI period, it can return to pre-injury levels within a year.17

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors may help

Few studies have explored the efficacy of antidepressant medication in TBI survivors. In a controlled study of patients with TBI, Fann and colleagues18 found no significant improvement in depression symptoms between sertraline and a placebo. However, they did note some possibilities for this lack of significance: socially isolated TBI survivors in the placebo group may have demonstrated improvement in depression symptoms because of increased social interaction;

Continue to: Other research has found...

Other research has found that sertraline improved both depression and quality of life for men with post-TBI depression.19 In a meta-analysis of 4 studies, Paraschakis and Katsanos20 found that sertraline demonstrated a “trend toward significance” in the treatment of depression among patients with TBI. Silverberg and Panenka21 argue that selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors should be used as first-line treatment for depression in survivors of TBI. They note that in non-randomized studies, treatment effects with antidepressants are significant. Additionally, patients who do not respond to the first antidepressant prescribed will often respond to adjunctive or different medications. Finally, they argue that depression measures can capture symptoms related to the physical brain injury, in addition to symptoms of depression, thus confounding results.

THE CASE

Mr. M’s chart showed that he was not taking any medication and that he had no history of substance abuse or tobacco use. He refused to fill out the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ)-2. His guardian said that Mr. M was spending much of his time at home, and that he used to be an avid painter and guitar player but had not engaged in either activity for months. Furthermore, Mr. M used to enjoy working out but did so rarely now.

During the interview, the PCP was careful to make eye contact with Mr. M as well as his guardian, thereby making sure Mr. M was part of the conversation about his care. Pacing of questions was deliberate and unhurried; a return visit would be scheduled to further explore any concerns not covered in this visit. This collaborative, inclusive, patient-centered approach to the clinical interview seemed to place Mr. M at ease. When his guardian said he thought Mr. M was depressed, Mr. M agreed. Although Mr. M still refused to fill out the PHQ-2, he was now willing to answer questions about depression. He acknowledged that he was feeling hopeless and took little pleasure in activities he used to enjoy, thereby indicating a positive screen for depression.

The PCP opted to read the PHQ-9 questions aloud, and Mr. M agreed with most of the items but strongly denied suicidal ideation, citing his religious faith.

The PCP determined that Mr. M’s depression was likely a combination of the direct and indirect effects of his TBI. A quantitative estimate based on Mr. M’s report yielded a PHQ-9 score of 17, indicating moderately severe depression.

Continue to: In addition to building rapport...

In addition to building rapport, careful listening garnered important information about Mr. M. For example, until his accident and subsequent depression, Mr. M had long prioritized his physical health through diet and exercise. He followed a vegetarian diet but recently had little appetite and was eating one microwaveable meal a day. He had an irregular sleep schedule and struggled with insomnia. He lost his closest long-term relationship after his accident due to difficulties with affect regulation. He also lost his job as he could no longer cognitively handle the tasks required.

Hearing Mr. M’s story provided the opportunity to customize education about self-management skills including regular diet, exercise, and sleep hygiene. Due to limited visit time, the PCP elected to use this first visit to focus on sleep and depression. As cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) for insomnia is first-line treatment for both primary insomnia and insomnia due to a medical condition such as TBI,5 a sleep aid was not prescribed. Fortunately, the clinic psychologist who offered CBT was able to join the interview to meet Mr. M and explain the treatment.

Mr. M expressed some initial reluctance to try an antidepressant. However, acknowledging he “just hasn’t been the same” since his TBI, he agreed to a prescription for sertraline and said he hoped it could make him “more like [he] was.”

RETURN VISIT

Four weeks after Mr. M began taking sertraline and participating in weekly CBT sessions, he returned for a follow-up visit with his PCP. He had a noticeably brighter affect, and his guardian reported that he had been playing the guitar again. Mr. M said that he had more energy as a result of improved sleep and mood, and that he felt like his “thinking was clearer.” Mr. M noted that he never thought he would meet with a psychologist but was finding CBT for insomnia helpful.

The psychologist’s notes proposed a treatment plan that would also include targeted grief and existential therapies to address Mr. M’s sudden life changes. At this visit, Mr. M admitted that his reading comprehension and speed were negatively affected by the accident and said this is why he did not wish to fill out the PHQ-2. But he was again willing to have the PHQ-9 questions read to him with his guardian’s support. Results showed a score of 6, indicating mild depression.

A follow-up appointment with Mr. M was scheduled for 6 weeks later, and the team was confident he was getting the behavioral and mental health support he needed through medication and therapy.

CORRESPONDENCE

Elizabeth Imbesi, PhD, VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System, 2215 Fuller Road, Ann Arbor, MI 48105; elizabeth.imbesi@va.gov

THE CASE

Declan M*, a 42-year-old man, presents as a new patient for general medical care. One year ago, he sustained a severe frontal traumatic brain injury (TBI) when he was hit by a car while crossing a street. He developed a subdural hematoma and was in a coma for 6 days. He also had fractured ribs and a fractured left foot. When he regained consciousness, he had posttraumatic amnesia. He also had executive function deficits and memory difficulties, so a guardian was appointed.

Mr. M no longer works as an auto mechanic, a career he once greatly enjoyed. Mr. M’s guardian reports that recently, Mr. M has lost interest in activities he’d previously enjoyed, is frequently irritable, has poor sleep, is socially isolated, and is spending increasing amounts of time at home. When his new primary care physician (PCP) enters the examining room, Mr. M is seated in a chair with his arms folded across his chest. He states that he is “fine” and just needs to “get a doctor.”

●

*This patient is an amalgam of patients for whom the author has provided care.

TBI ranges from mild to severe and can produce a number of profound effects that are a direct—or indirect—result of the physical injury.1 The location and the severity of the injury affect symptoms.2 Even mild TBI can cause impairment, and severe TBI can lead to broad cognitive, behavioral, and physical difficulties. As numbers of TBI cases increase globally, primary care providers need to recognize the symptoms and assess accordingly.1 The Acute Concussion Evaluation (ACE; Physician/Clinician Office Version) facilitates a structured evaluation for patients presenting with possible TBI symptoms. It can easily be accessed on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website.3

Direct effects of TBI include impulsivity, depression, reduced frustration tolerance, reduced motivation, low awareness, and insomnia and other sleep difficulties.4,5 Depression may also result indirectly from, or be exacerbated by, new posttraumatic limitations and lifestyle changes as well as loss of career and community.4 Both direct and indirect depression often manifest as feelings of hopelessness and worthlessness and a lack of interest in once enjoyable activities. Depression can worsen other TBI sequelae such as difficulty concentrating, lack of initiation, flat affect, irritability, reduced independence, reduced functional performance, loss of inhibition, and physical pain.6

Nationwide, most mental health concerns continue to be addressed in the primary care setting.7 Individuals with TBI experience major depression at a rate 5 to 6 times higher than those in the general population, with a prevalence rate of 45%.8

Suicide. The subject of suicide must be explored with survivors of TBI; evidence suggests a correlation between TBI, depression, and increased risk for suicide.9 Among those who have TBI, as many as 22% experience suicidal ideation; the risk of suicide in survivors of severe TBI is 3 to 4 times the risk in the general population.10 Additionally, suicidality in this context appears to be a chronic concern; therefore, carefully assess for its presence no matter how long ago the TBI occurred.10

Additional TBI-associated health concerns

Grief and loss. We so often focus on death as the only cause for grief, but grief can occur for other types of loss, as well. Individuals with TBI often experience a radical negative change in self-concept after their injury, which is associated with feelings of grief.11 Helping patients recognize that they are grieving the loss of the person they once were can help set a framework for their experience.

Continue to: Relationship loss

Relationship loss. Many people with TBI lose close relationships.12 This can be due to life changes such as job loss, loss of function or ability to do previously enjoyed activities, or personality changes. These relationship losses can affect a person profoundly.12 Going forward, they may have difficulty trusting others, for example.

Existential issues. Many people with TBI also find that cognitive deficits prevent them from engaging in formerly meaningful work. For example, Mr. M lost his longstanding career as an auto mechanic and therefore part of his identity. Not being able to find purpose and meaning can be a strong contributor to coping difficulties in those with TBI.13

Chronic pain. More than half of people with TBI experience chronic pain. Headaches are the most common pain condition among all TBI survivors.14