User login

THE CASE

Paul F* is a 16-year-old White boy who lives with his mother and spends some weekends with his father who has shared custody. He recently presented to the clinic for treatment due to an arrest for disorderly conduct at school. He and a friend were found drinking liquor outside the school building when they were scheduled to be in class. Paul reported that he and his friends often drink at school and at extracurricular functions. He has been using alcohol for the past 2 years, with escalating consumption (5 or more drinks per episode) in the past year. Paul has been drinking most days of the week and has even driven under the influence at times. He said, “I just feel happier when I am drinking.” An accomplished soccer player recruited by colleges, Paul recently was suspended from the team due to his poor grades. His response was, “It’s stupid anyway. What’s the point of playing?”

●

* The patient’s name and some personal details have been changed to protect his identity.

Alcohol is the number 1 substance of abuse for adolescents, used more than tobacco or drugs.1-3 In 2007 and again in 2016, the Surgeon General of the United States issued reports to highlight this important topic,1,2 noting that early and repeated exposure to alcohol during this crucial time of brain development increases the risk for future problems, including addiction.2

Adolescent alcohol use is often underestimated by parents and physicians, including misjudging how much, how often, and how young children are when they begin to drink.1 Boys and girls tend to start drinking at similar ages (13.9 and 14.4 years, respectively),3 but as girls age, they tend to drink more and binge more.4 In 2019, 1 in 4 adolescents reported drinking and more than 4 million reported at least 1 episode of binge drinking in the prior month.4 These numbers have further ramifications: early drinking is associated with alcohol dependence, relapse, use of other substances, risky sexual behaviors, injurious behaviors, suicide, motor vehicle accidents, and dating violence.4-6

Diagnosing alcohol use disorder

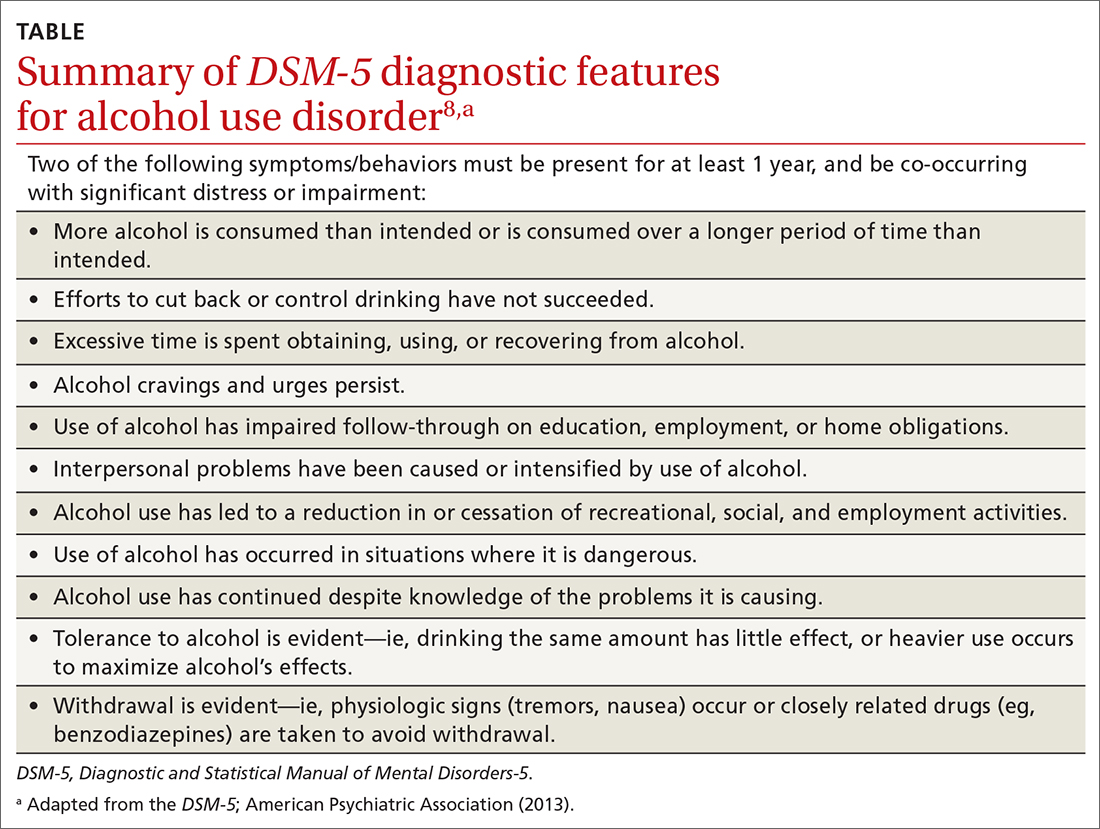

The range of alcohol use includes consumption, bingeing, abuse, and dependence.7,8 Consumption is defined as the drinking of alcoholic beverages. Bingeing is the consumption of more than 5 drinks for men or 4 drinks for women in 2 hours, according to the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism.7 However, the criterion is slightly different for the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, which broadens the timeframe to “on the same occasion.”9 While previously known as separate disorders, alcohol abuse (or misuse) and alcohol dependence are now diagnostically classified together as alcohol use disorders (AUDs), per the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-5 (DSM-5).8 AUD is further stratified as mild, moderate, or severe, depending on the number of criteria that are met by the patient (TABLE).8,10

Alcohol screening

Currently, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) does not recommend screening adolescents ages 12 to 17 for AUD, and has instead issued an “I” statement (insufficient evidence).11 While the USPSTF recognizes the potential burdens of adolescent alcohol use, the potential harms of screening include “stigma, anxiety, labeling, discrimination, privacy concerns, and interference with the patient–clinician relationship.”11 The USPSTF also notes that it “did not find any evidence that specifically examined the harms of screening for alcohol use in adolescents.”11

This is at odds with recommendations from the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), which in 2011 released a policy statement advocating screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment for adolescent substance use.12 In the United States, even though 83% of adolescents see a physician at least once each year,12,13 alcohol misuse screening still varies, occurring in the range of 50% to 86% of office visits.12 When screening does occur, it is often based on clinical impression only.12 Studies have shown that when a screening tool is not used, up to two-thirds of substance use disorders may be missed.12-15

Continue to: A full and complete biopsychosocial interview

A full and complete biopsychosocial interview with adolescents is a necessity, and should include queries about alcohol, drugs, and other substances. Acknowledgment of use should trigger further investigation into the substance use areas. Interviews may start with open-ended questions about alcohol use at home or at school before moving to more personalized and detailed questioning and use of screening tools.16

While various screening instruments exist, for the sake of brevity we provide as an example the Screening to Brief Intervention (S2BI) tool. It is an efficient, single-page tool that can help clinicians in their routine care of adolescents to quickly stratify the patient risk of substance use disorder as none/low, moderate, or severe.12 It can be found here: www.mcpap.com/pdf/S2Bi%20Toolkit.pdf (see page 10).

For all patients, but particularly for adolescents, confidentiality is important, and many specialty societies have created language to address this issue.12 Discuss confidentiality with both the adolescent patient and the patient’s caregiver simultaneously, with dialogue that includes: (a) the need to speak with adolescents alone during the office visit, (b) the benefits of confidentiality in the physician–patient relationship, and (c) the need to disclose selected information to keep patients safe.12 Describing the process for required disclosures is essential. Benefits of disclosure include further support for the adolescent patient as well as appropriate parental participation and support for possible referrals.12

Treating AUD

Treatment for AUD should be multifaceted. Screen for comorbid mood disorders, such as generalized anxiety,17,18 social anxiety,18 and depression,19 as well as for insomnia.18 Studies have demonstrated a strong link between insomnia and anxiety, and again between anxiety and AUD.17-19 Finally, screen for adverse childhood events such as trauma, victimization, and abuse.20 Addressing issues discovered in screening allows for more targeted and personalized treatment of AUD.

The National Institute on Drug Abuse categorizes evidence-based treatment into 3 areas: behavioral therapies, family therapies, and medications.21

Continue to: Behavioral therapies

Behavioral therapies can include group therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), motivational enhancement therapy, 12-Step facilitation, and contingency management, in which small rewards or incentives are given for participation in treatment to reinforce positive behaviors.21

Family-based therapies, such as brief strategic family therapy, functional family therapy, and multisystem therapy recognize that adolescents exist in systems of families in communities, and that the patient’s success in treatment may be supported by these relationships.21

Some medications may achieve modest benefit for treatment of adolescents with AUD. Naltrexone, acamprosate, and disulfiram have all been used successfully to treat AUD in adults21; some physicians may choose to use these medications “off label” in adolescents. Bupropion has been used successfully in the treatment of nicotine use disorder,21 and a small study in 2005 showed some success with bupropion in treating adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, comorbid depression, and substance use disorder.22 Naltrexone has also been studied in adolescents with opioid use disorder, although these were not large studies.23

Adolescents with serious, sustained issues with AUD may require more in-depth treatments such as an intensive outpatient program, a partial hospitalization program, or a residential treatment program.15 The least-restrictive environment is preferable.15 Families are generally included as part of the treatment and recovery process in those settings.21 Some patients may require detoxification prior to referral to residential treatment settings; the American Society of Addiction Medicine has published a comprehensive guideline on alcohol withdrawal.24

Paul’s family physician diagnosed his condition as AUD and referred him for CBT with a psychologist, who treated him for both the AUD and an underlying depressive disorder that was later identified. CBT focused on cognitive restructuring of depressive thoughts as well as support for continued abstinence from alcohol. The patient, with family support, declined antidepressant medication.

After 6 months of treatment, Paul and his parents were pleased with his progress. His grades improved to the point that he was permitted to play soccer again, and he was seriously looking at his future college options.

CORRESPONDENCE

Scott A. Fields, PhD, 3200 MacCorkle Avenue Southeast, 5th Floor, Robert C. Byrd Clinical Teaching Center, Department of Family Medicine, Charleston, WV 25304; sfields@hsc.wvu.edu

1. US Department of Health and Human Services. The Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Prevent and Reduce Underage Drinking. Washington, DC; US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General. 2007.

2. US Department of Health and Human Services. Facing Addiction in America: The Surgeon General’s Report on Alcohol, Drugs, and Health. Washington, DC; US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General. 2016.

3. Hingson R, White A. New research findings since the 2007 Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Prevent and Reduce Underage Drinking: A review. J Stud Alcohol Drugs Suppl. 2014; 75:158-169.

4. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Underage drinking. National Institute of Health. Accessed December 22, 2021. www.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/brochures-and-fact-sheets/underage-drinking.

5. Hingson R, Zha W, Iannotti R, et al. Physician advice to adolescents about drinking and other health behaviors. Pediatrics. 2013;131:249-257.

6. Schaus JF, Sole ML, McCoy TP, et al. Screening for high-risk drinking in a college student health center: characterizing students based on quantity, frequency, and harms. J Stud Alcohol Drugs Suppl. 2009;16:34-44.

7. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Drinking levels defined. Accessed December 27, 2021. www.niaaa.nih.gov/alcohol-health/overview-alcohol-consumption/moderate-binge-drinking

8. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5). Arlington, VA; American Psychiatric Association. 2013.

9. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Bringing down binge drinking. Accessed December 27, 2021. www.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/programs_campaigns/nation_prevention_week/data-binge-drinking.pdf

10. Grant BF, Goldstein RB, Saha TD, et al. Epidemiology of DSM-5 Alcohol Use Disorder: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions III. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72:757-766.

11. USPSTF. Screening and behavioral counseling interventions to reduce unhealthy alcohol use in adolescents and adults: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2018;320:1899-1909.

12. Levy SJ, Williams JF, Committee on Substance Use and Prevention. Substance use screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment. Pediatrics. 2016;138:e20161211.

13. MacKay AP, Duran CP. Adolescent Health in the United States. National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2007.

14. Haller DM, Meynard A, Lefebvre D, et al. Effectiveness of training family physicians to deliver a brief intervention to address excessive substance use among young patients: a cluster randomized controlled trial. CMAJ. 2014;186:E263-E272.

15. Borus J, Parhami I, Levy S. Screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment. Child Adolesc Psychiatric Clin N Am. 2016;25:579-601.

16. Knight J, Roberts T, Gabrielli J, et al. Adolescent alcohol and substance use and abuse. Performing preventive services: A bright futures handbook. Accessed December 22, 2021. American Academy of Pediatrics. https://ocfcpacourts.us/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Adolescent_Alcohol_and_Substance_Abuse_001005.pdf

17. Dyer ML, Heron J, Hickman M, et al. Alcohol use in late adolescence and early adulthood: the role of generalized anxiety disorder and drinking to cope motives. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;204:107480.

18. Blumenthal H, Taylor DJ, Cloutier RM, et al. The links between social anxiety disorder, insomnia symptoms, and alcohol use disorders: findings from a large sample of adolescents in the United States. Behav Ther. 2019;50:50-59.

19. Pedrelli P, Shapero B, Archibald A, et al. Alcohol use and depression during adolescence and young adulthood: a summary and interpretation of mixed findings. Curr Addict Rep. 2016;3:91-97.

20. Davis JP, Dworkin ER, Helton J, et al. Extending poly-victimization theory: differential effects of adolescents’ experiences of victimization on substance use disorder diagnoses upon treatment entry. Child Abuse Negl. 2019; 89:165-177.

21. NIDA. Principles of adolescent substance use disorder treatment: a research-based guide. Accessed December 22, 2021. www.drugabuse.gov/publications/principles-adolescent-substance-use-disorder-treatment-research-based-guide

22. Solhkhah R, Wilens TE, Daly J, et al. Bupropion SR for the treatment of substance-abusing outpatient adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and mood disorders. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2005:15:777-786.

23. Camenga DR, Colon-Rivera HA, Muvvala SB. Medications for maintenance treatment of opioid use disorder in adolescents. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2019;80:393-402.

24. American Society of Addiction Medicine. The ASAM clinical practice guideline on alcohol withdrawal management. Accessed December 22, 2021. www.asam.org/quality-care/clinical-guidelines/alcohol-withdrawal-management-guideline

THE CASE

Paul F* is a 16-year-old White boy who lives with his mother and spends some weekends with his father who has shared custody. He recently presented to the clinic for treatment due to an arrest for disorderly conduct at school. He and a friend were found drinking liquor outside the school building when they were scheduled to be in class. Paul reported that he and his friends often drink at school and at extracurricular functions. He has been using alcohol for the past 2 years, with escalating consumption (5 or more drinks per episode) in the past year. Paul has been drinking most days of the week and has even driven under the influence at times. He said, “I just feel happier when I am drinking.” An accomplished soccer player recruited by colleges, Paul recently was suspended from the team due to his poor grades. His response was, “It’s stupid anyway. What’s the point of playing?”

●

* The patient’s name and some personal details have been changed to protect his identity.

Alcohol is the number 1 substance of abuse for adolescents, used more than tobacco or drugs.1-3 In 2007 and again in 2016, the Surgeon General of the United States issued reports to highlight this important topic,1,2 noting that early and repeated exposure to alcohol during this crucial time of brain development increases the risk for future problems, including addiction.2

Adolescent alcohol use is often underestimated by parents and physicians, including misjudging how much, how often, and how young children are when they begin to drink.1 Boys and girls tend to start drinking at similar ages (13.9 and 14.4 years, respectively),3 but as girls age, they tend to drink more and binge more.4 In 2019, 1 in 4 adolescents reported drinking and more than 4 million reported at least 1 episode of binge drinking in the prior month.4 These numbers have further ramifications: early drinking is associated with alcohol dependence, relapse, use of other substances, risky sexual behaviors, injurious behaviors, suicide, motor vehicle accidents, and dating violence.4-6

Diagnosing alcohol use disorder

The range of alcohol use includes consumption, bingeing, abuse, and dependence.7,8 Consumption is defined as the drinking of alcoholic beverages. Bingeing is the consumption of more than 5 drinks for men or 4 drinks for women in 2 hours, according to the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism.7 However, the criterion is slightly different for the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, which broadens the timeframe to “on the same occasion.”9 While previously known as separate disorders, alcohol abuse (or misuse) and alcohol dependence are now diagnostically classified together as alcohol use disorders (AUDs), per the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-5 (DSM-5).8 AUD is further stratified as mild, moderate, or severe, depending on the number of criteria that are met by the patient (TABLE).8,10

Alcohol screening

Currently, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) does not recommend screening adolescents ages 12 to 17 for AUD, and has instead issued an “I” statement (insufficient evidence).11 While the USPSTF recognizes the potential burdens of adolescent alcohol use, the potential harms of screening include “stigma, anxiety, labeling, discrimination, privacy concerns, and interference with the patient–clinician relationship.”11 The USPSTF also notes that it “did not find any evidence that specifically examined the harms of screening for alcohol use in adolescents.”11

This is at odds with recommendations from the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), which in 2011 released a policy statement advocating screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment for adolescent substance use.12 In the United States, even though 83% of adolescents see a physician at least once each year,12,13 alcohol misuse screening still varies, occurring in the range of 50% to 86% of office visits.12 When screening does occur, it is often based on clinical impression only.12 Studies have shown that when a screening tool is not used, up to two-thirds of substance use disorders may be missed.12-15

Continue to: A full and complete biopsychosocial interview

A full and complete biopsychosocial interview with adolescents is a necessity, and should include queries about alcohol, drugs, and other substances. Acknowledgment of use should trigger further investigation into the substance use areas. Interviews may start with open-ended questions about alcohol use at home or at school before moving to more personalized and detailed questioning and use of screening tools.16

While various screening instruments exist, for the sake of brevity we provide as an example the Screening to Brief Intervention (S2BI) tool. It is an efficient, single-page tool that can help clinicians in their routine care of adolescents to quickly stratify the patient risk of substance use disorder as none/low, moderate, or severe.12 It can be found here: www.mcpap.com/pdf/S2Bi%20Toolkit.pdf (see page 10).

For all patients, but particularly for adolescents, confidentiality is important, and many specialty societies have created language to address this issue.12 Discuss confidentiality with both the adolescent patient and the patient’s caregiver simultaneously, with dialogue that includes: (a) the need to speak with adolescents alone during the office visit, (b) the benefits of confidentiality in the physician–patient relationship, and (c) the need to disclose selected information to keep patients safe.12 Describing the process for required disclosures is essential. Benefits of disclosure include further support for the adolescent patient as well as appropriate parental participation and support for possible referrals.12

Treating AUD

Treatment for AUD should be multifaceted. Screen for comorbid mood disorders, such as generalized anxiety,17,18 social anxiety,18 and depression,19 as well as for insomnia.18 Studies have demonstrated a strong link between insomnia and anxiety, and again between anxiety and AUD.17-19 Finally, screen for adverse childhood events such as trauma, victimization, and abuse.20 Addressing issues discovered in screening allows for more targeted and personalized treatment of AUD.

The National Institute on Drug Abuse categorizes evidence-based treatment into 3 areas: behavioral therapies, family therapies, and medications.21

Continue to: Behavioral therapies

Behavioral therapies can include group therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), motivational enhancement therapy, 12-Step facilitation, and contingency management, in which small rewards or incentives are given for participation in treatment to reinforce positive behaviors.21

Family-based therapies, such as brief strategic family therapy, functional family therapy, and multisystem therapy recognize that adolescents exist in systems of families in communities, and that the patient’s success in treatment may be supported by these relationships.21

Some medications may achieve modest benefit for treatment of adolescents with AUD. Naltrexone, acamprosate, and disulfiram have all been used successfully to treat AUD in adults21; some physicians may choose to use these medications “off label” in adolescents. Bupropion has been used successfully in the treatment of nicotine use disorder,21 and a small study in 2005 showed some success with bupropion in treating adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, comorbid depression, and substance use disorder.22 Naltrexone has also been studied in adolescents with opioid use disorder, although these were not large studies.23

Adolescents with serious, sustained issues with AUD may require more in-depth treatments such as an intensive outpatient program, a partial hospitalization program, or a residential treatment program.15 The least-restrictive environment is preferable.15 Families are generally included as part of the treatment and recovery process in those settings.21 Some patients may require detoxification prior to referral to residential treatment settings; the American Society of Addiction Medicine has published a comprehensive guideline on alcohol withdrawal.24

Paul’s family physician diagnosed his condition as AUD and referred him for CBT with a psychologist, who treated him for both the AUD and an underlying depressive disorder that was later identified. CBT focused on cognitive restructuring of depressive thoughts as well as support for continued abstinence from alcohol. The patient, with family support, declined antidepressant medication.

After 6 months of treatment, Paul and his parents were pleased with his progress. His grades improved to the point that he was permitted to play soccer again, and he was seriously looking at his future college options.

CORRESPONDENCE

Scott A. Fields, PhD, 3200 MacCorkle Avenue Southeast, 5th Floor, Robert C. Byrd Clinical Teaching Center, Department of Family Medicine, Charleston, WV 25304; sfields@hsc.wvu.edu

THE CASE

Paul F* is a 16-year-old White boy who lives with his mother and spends some weekends with his father who has shared custody. He recently presented to the clinic for treatment due to an arrest for disorderly conduct at school. He and a friend were found drinking liquor outside the school building when they were scheduled to be in class. Paul reported that he and his friends often drink at school and at extracurricular functions. He has been using alcohol for the past 2 years, with escalating consumption (5 or more drinks per episode) in the past year. Paul has been drinking most days of the week and has even driven under the influence at times. He said, “I just feel happier when I am drinking.” An accomplished soccer player recruited by colleges, Paul recently was suspended from the team due to his poor grades. His response was, “It’s stupid anyway. What’s the point of playing?”

●

* The patient’s name and some personal details have been changed to protect his identity.

Alcohol is the number 1 substance of abuse for adolescents, used more than tobacco or drugs.1-3 In 2007 and again in 2016, the Surgeon General of the United States issued reports to highlight this important topic,1,2 noting that early and repeated exposure to alcohol during this crucial time of brain development increases the risk for future problems, including addiction.2

Adolescent alcohol use is often underestimated by parents and physicians, including misjudging how much, how often, and how young children are when they begin to drink.1 Boys and girls tend to start drinking at similar ages (13.9 and 14.4 years, respectively),3 but as girls age, they tend to drink more and binge more.4 In 2019, 1 in 4 adolescents reported drinking and more than 4 million reported at least 1 episode of binge drinking in the prior month.4 These numbers have further ramifications: early drinking is associated with alcohol dependence, relapse, use of other substances, risky sexual behaviors, injurious behaviors, suicide, motor vehicle accidents, and dating violence.4-6

Diagnosing alcohol use disorder

The range of alcohol use includes consumption, bingeing, abuse, and dependence.7,8 Consumption is defined as the drinking of alcoholic beverages. Bingeing is the consumption of more than 5 drinks for men or 4 drinks for women in 2 hours, according to the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism.7 However, the criterion is slightly different for the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, which broadens the timeframe to “on the same occasion.”9 While previously known as separate disorders, alcohol abuse (or misuse) and alcohol dependence are now diagnostically classified together as alcohol use disorders (AUDs), per the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-5 (DSM-5).8 AUD is further stratified as mild, moderate, or severe, depending on the number of criteria that are met by the patient (TABLE).8,10

Alcohol screening

Currently, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) does not recommend screening adolescents ages 12 to 17 for AUD, and has instead issued an “I” statement (insufficient evidence).11 While the USPSTF recognizes the potential burdens of adolescent alcohol use, the potential harms of screening include “stigma, anxiety, labeling, discrimination, privacy concerns, and interference with the patient–clinician relationship.”11 The USPSTF also notes that it “did not find any evidence that specifically examined the harms of screening for alcohol use in adolescents.”11

This is at odds with recommendations from the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), which in 2011 released a policy statement advocating screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment for adolescent substance use.12 In the United States, even though 83% of adolescents see a physician at least once each year,12,13 alcohol misuse screening still varies, occurring in the range of 50% to 86% of office visits.12 When screening does occur, it is often based on clinical impression only.12 Studies have shown that when a screening tool is not used, up to two-thirds of substance use disorders may be missed.12-15

Continue to: A full and complete biopsychosocial interview

A full and complete biopsychosocial interview with adolescents is a necessity, and should include queries about alcohol, drugs, and other substances. Acknowledgment of use should trigger further investigation into the substance use areas. Interviews may start with open-ended questions about alcohol use at home or at school before moving to more personalized and detailed questioning and use of screening tools.16

While various screening instruments exist, for the sake of brevity we provide as an example the Screening to Brief Intervention (S2BI) tool. It is an efficient, single-page tool that can help clinicians in their routine care of adolescents to quickly stratify the patient risk of substance use disorder as none/low, moderate, or severe.12 It can be found here: www.mcpap.com/pdf/S2Bi%20Toolkit.pdf (see page 10).

For all patients, but particularly for adolescents, confidentiality is important, and many specialty societies have created language to address this issue.12 Discuss confidentiality with both the adolescent patient and the patient’s caregiver simultaneously, with dialogue that includes: (a) the need to speak with adolescents alone during the office visit, (b) the benefits of confidentiality in the physician–patient relationship, and (c) the need to disclose selected information to keep patients safe.12 Describing the process for required disclosures is essential. Benefits of disclosure include further support for the adolescent patient as well as appropriate parental participation and support for possible referrals.12

Treating AUD

Treatment for AUD should be multifaceted. Screen for comorbid mood disorders, such as generalized anxiety,17,18 social anxiety,18 and depression,19 as well as for insomnia.18 Studies have demonstrated a strong link between insomnia and anxiety, and again between anxiety and AUD.17-19 Finally, screen for adverse childhood events such as trauma, victimization, and abuse.20 Addressing issues discovered in screening allows for more targeted and personalized treatment of AUD.

The National Institute on Drug Abuse categorizes evidence-based treatment into 3 areas: behavioral therapies, family therapies, and medications.21

Continue to: Behavioral therapies

Behavioral therapies can include group therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), motivational enhancement therapy, 12-Step facilitation, and contingency management, in which small rewards or incentives are given for participation in treatment to reinforce positive behaviors.21

Family-based therapies, such as brief strategic family therapy, functional family therapy, and multisystem therapy recognize that adolescents exist in systems of families in communities, and that the patient’s success in treatment may be supported by these relationships.21

Some medications may achieve modest benefit for treatment of adolescents with AUD. Naltrexone, acamprosate, and disulfiram have all been used successfully to treat AUD in adults21; some physicians may choose to use these medications “off label” in adolescents. Bupropion has been used successfully in the treatment of nicotine use disorder,21 and a small study in 2005 showed some success with bupropion in treating adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, comorbid depression, and substance use disorder.22 Naltrexone has also been studied in adolescents with opioid use disorder, although these were not large studies.23

Adolescents with serious, sustained issues with AUD may require more in-depth treatments such as an intensive outpatient program, a partial hospitalization program, or a residential treatment program.15 The least-restrictive environment is preferable.15 Families are generally included as part of the treatment and recovery process in those settings.21 Some patients may require detoxification prior to referral to residential treatment settings; the American Society of Addiction Medicine has published a comprehensive guideline on alcohol withdrawal.24

Paul’s family physician diagnosed his condition as AUD and referred him for CBT with a psychologist, who treated him for both the AUD and an underlying depressive disorder that was later identified. CBT focused on cognitive restructuring of depressive thoughts as well as support for continued abstinence from alcohol. The patient, with family support, declined antidepressant medication.

After 6 months of treatment, Paul and his parents were pleased with his progress. His grades improved to the point that he was permitted to play soccer again, and he was seriously looking at his future college options.

CORRESPONDENCE

Scott A. Fields, PhD, 3200 MacCorkle Avenue Southeast, 5th Floor, Robert C. Byrd Clinical Teaching Center, Department of Family Medicine, Charleston, WV 25304; sfields@hsc.wvu.edu

1. US Department of Health and Human Services. The Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Prevent and Reduce Underage Drinking. Washington, DC; US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General. 2007.

2. US Department of Health and Human Services. Facing Addiction in America: The Surgeon General’s Report on Alcohol, Drugs, and Health. Washington, DC; US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General. 2016.

3. Hingson R, White A. New research findings since the 2007 Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Prevent and Reduce Underage Drinking: A review. J Stud Alcohol Drugs Suppl. 2014; 75:158-169.

4. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Underage drinking. National Institute of Health. Accessed December 22, 2021. www.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/brochures-and-fact-sheets/underage-drinking.

5. Hingson R, Zha W, Iannotti R, et al. Physician advice to adolescents about drinking and other health behaviors. Pediatrics. 2013;131:249-257.

6. Schaus JF, Sole ML, McCoy TP, et al. Screening for high-risk drinking in a college student health center: characterizing students based on quantity, frequency, and harms. J Stud Alcohol Drugs Suppl. 2009;16:34-44.

7. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Drinking levels defined. Accessed December 27, 2021. www.niaaa.nih.gov/alcohol-health/overview-alcohol-consumption/moderate-binge-drinking

8. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5). Arlington, VA; American Psychiatric Association. 2013.

9. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Bringing down binge drinking. Accessed December 27, 2021. www.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/programs_campaigns/nation_prevention_week/data-binge-drinking.pdf

10. Grant BF, Goldstein RB, Saha TD, et al. Epidemiology of DSM-5 Alcohol Use Disorder: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions III. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72:757-766.

11. USPSTF. Screening and behavioral counseling interventions to reduce unhealthy alcohol use in adolescents and adults: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2018;320:1899-1909.

12. Levy SJ, Williams JF, Committee on Substance Use and Prevention. Substance use screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment. Pediatrics. 2016;138:e20161211.

13. MacKay AP, Duran CP. Adolescent Health in the United States. National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2007.

14. Haller DM, Meynard A, Lefebvre D, et al. Effectiveness of training family physicians to deliver a brief intervention to address excessive substance use among young patients: a cluster randomized controlled trial. CMAJ. 2014;186:E263-E272.

15. Borus J, Parhami I, Levy S. Screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment. Child Adolesc Psychiatric Clin N Am. 2016;25:579-601.

16. Knight J, Roberts T, Gabrielli J, et al. Adolescent alcohol and substance use and abuse. Performing preventive services: A bright futures handbook. Accessed December 22, 2021. American Academy of Pediatrics. https://ocfcpacourts.us/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Adolescent_Alcohol_and_Substance_Abuse_001005.pdf

17. Dyer ML, Heron J, Hickman M, et al. Alcohol use in late adolescence and early adulthood: the role of generalized anxiety disorder and drinking to cope motives. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;204:107480.

18. Blumenthal H, Taylor DJ, Cloutier RM, et al. The links between social anxiety disorder, insomnia symptoms, and alcohol use disorders: findings from a large sample of adolescents in the United States. Behav Ther. 2019;50:50-59.

19. Pedrelli P, Shapero B, Archibald A, et al. Alcohol use and depression during adolescence and young adulthood: a summary and interpretation of mixed findings. Curr Addict Rep. 2016;3:91-97.

20. Davis JP, Dworkin ER, Helton J, et al. Extending poly-victimization theory: differential effects of adolescents’ experiences of victimization on substance use disorder diagnoses upon treatment entry. Child Abuse Negl. 2019; 89:165-177.

21. NIDA. Principles of adolescent substance use disorder treatment: a research-based guide. Accessed December 22, 2021. www.drugabuse.gov/publications/principles-adolescent-substance-use-disorder-treatment-research-based-guide

22. Solhkhah R, Wilens TE, Daly J, et al. Bupropion SR for the treatment of substance-abusing outpatient adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and mood disorders. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2005:15:777-786.

23. Camenga DR, Colon-Rivera HA, Muvvala SB. Medications for maintenance treatment of opioid use disorder in adolescents. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2019;80:393-402.

24. American Society of Addiction Medicine. The ASAM clinical practice guideline on alcohol withdrawal management. Accessed December 22, 2021. www.asam.org/quality-care/clinical-guidelines/alcohol-withdrawal-management-guideline

1. US Department of Health and Human Services. The Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Prevent and Reduce Underage Drinking. Washington, DC; US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General. 2007.

2. US Department of Health and Human Services. Facing Addiction in America: The Surgeon General’s Report on Alcohol, Drugs, and Health. Washington, DC; US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General. 2016.

3. Hingson R, White A. New research findings since the 2007 Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Prevent and Reduce Underage Drinking: A review. J Stud Alcohol Drugs Suppl. 2014; 75:158-169.

4. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Underage drinking. National Institute of Health. Accessed December 22, 2021. www.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/brochures-and-fact-sheets/underage-drinking.

5. Hingson R, Zha W, Iannotti R, et al. Physician advice to adolescents about drinking and other health behaviors. Pediatrics. 2013;131:249-257.

6. Schaus JF, Sole ML, McCoy TP, et al. Screening for high-risk drinking in a college student health center: characterizing students based on quantity, frequency, and harms. J Stud Alcohol Drugs Suppl. 2009;16:34-44.

7. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Drinking levels defined. Accessed December 27, 2021. www.niaaa.nih.gov/alcohol-health/overview-alcohol-consumption/moderate-binge-drinking

8. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5). Arlington, VA; American Psychiatric Association. 2013.

9. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Bringing down binge drinking. Accessed December 27, 2021. www.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/programs_campaigns/nation_prevention_week/data-binge-drinking.pdf

10. Grant BF, Goldstein RB, Saha TD, et al. Epidemiology of DSM-5 Alcohol Use Disorder: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions III. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72:757-766.

11. USPSTF. Screening and behavioral counseling interventions to reduce unhealthy alcohol use in adolescents and adults: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2018;320:1899-1909.

12. Levy SJ, Williams JF, Committee on Substance Use and Prevention. Substance use screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment. Pediatrics. 2016;138:e20161211.

13. MacKay AP, Duran CP. Adolescent Health in the United States. National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2007.

14. Haller DM, Meynard A, Lefebvre D, et al. Effectiveness of training family physicians to deliver a brief intervention to address excessive substance use among young patients: a cluster randomized controlled trial. CMAJ. 2014;186:E263-E272.

15. Borus J, Parhami I, Levy S. Screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment. Child Adolesc Psychiatric Clin N Am. 2016;25:579-601.

16. Knight J, Roberts T, Gabrielli J, et al. Adolescent alcohol and substance use and abuse. Performing preventive services: A bright futures handbook. Accessed December 22, 2021. American Academy of Pediatrics. https://ocfcpacourts.us/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Adolescent_Alcohol_and_Substance_Abuse_001005.pdf

17. Dyer ML, Heron J, Hickman M, et al. Alcohol use in late adolescence and early adulthood: the role of generalized anxiety disorder and drinking to cope motives. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;204:107480.

18. Blumenthal H, Taylor DJ, Cloutier RM, et al. The links between social anxiety disorder, insomnia symptoms, and alcohol use disorders: findings from a large sample of adolescents in the United States. Behav Ther. 2019;50:50-59.

19. Pedrelli P, Shapero B, Archibald A, et al. Alcohol use and depression during adolescence and young adulthood: a summary and interpretation of mixed findings. Curr Addict Rep. 2016;3:91-97.

20. Davis JP, Dworkin ER, Helton J, et al. Extending poly-victimization theory: differential effects of adolescents’ experiences of victimization on substance use disorder diagnoses upon treatment entry. Child Abuse Negl. 2019; 89:165-177.

21. NIDA. Principles of adolescent substance use disorder treatment: a research-based guide. Accessed December 22, 2021. www.drugabuse.gov/publications/principles-adolescent-substance-use-disorder-treatment-research-based-guide

22. Solhkhah R, Wilens TE, Daly J, et al. Bupropion SR for the treatment of substance-abusing outpatient adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and mood disorders. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2005:15:777-786.

23. Camenga DR, Colon-Rivera HA, Muvvala SB. Medications for maintenance treatment of opioid use disorder in adolescents. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2019;80:393-402.

24. American Society of Addiction Medicine. The ASAM clinical practice guideline on alcohol withdrawal management. Accessed December 22, 2021. www.asam.org/quality-care/clinical-guidelines/alcohol-withdrawal-management-guideline