User login

Youth e-cigarette use: Assessing for, and halting, the hidden habit

THE CASE

Joe, an 18-year-old, has been your patient for many years and has an uncomplicated medical history. He presents for his preparticipation sports examination for the upcoming high school baseball season. Joe’s mother, who arrives at the office with him, tells you she’s worried because she found an e-cigarette in his backpack last week. Joe says that many of the kids at his school vape and he tried it a while back and now vapes “a lot.”

After talking further with Joe, you realize that he is vaping every day, using a 5% nicotine pod. Based on previous consults with the behavioral health counselor in your clinic, you know that this level of vaping is about the same as smoking 1 pack of cigarettes per day in terms of nicotine exposure. Joe states that he often vapes in the bathroom at school because he cannot concentrate in class if he doesn’t vape. He also reports that he had previously used 1 pod per week but had recently started vaping more to help with his cravings.

You assess his withdrawal symptoms and learn that he feels on edge when he is not able to vape and that he vapes heavily before going into school because he knows he will not be able to vape again until his third passing period.

●

Electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes; also called “vapes”) are electronic nicotine delivery systems that heat and aerosolize e-liquid or “e-juice” that is inhaled by the user. The e-liquid is made up primarily of propylene glycol, vegetable glycerin, and flavorings, and often includes nicotine. Nicotine levels in e-cigarettes can range from 0 mg/mL to 60 mg/mL (regular cigarettes contain ~12 mg of nicotine). The nicotine level of the pod available from e-cigarette company JUUL (50 mg/mL e-liquid) is equivalent to about 1 pack of cigarettes.1 E-cigarette devices are relatively affordable; popular brands cost $10 to $20, while the replacement pods or e-liquid are typically about $4 each.

The e-cigarette market is quickly evolving and diversifying. Originally, e-cigarettes looked similar to cigarettes (cig-a-likes) but did not efficiently deliver nicotine to the user.2 E-cigarettes have evolved and some now deliver cigarette-like levels of nicotine to the user.3,4 Youth and young adults primarily use pod-mod e-cigarettes, which have a sleek design and produce less vapor than older e-cigarettes, making them easier to conceal. They can look like a USB flash-drive or have a teardrop shape. Pod-mod e-cigarettes dominate the current market, led by companies such as JUUL, NJOY, and Vuse.5

E-cigarette use is proliferating in the United States, particularly among young people and facilitated by the introduction of pod-based e-cigarettes in appealing flavors.6,7 While rates of current e-cigarette use by US adults is around 5.5%,8 recent data show that 32.7% of US high school students say they’ve used an e-cigarette in the past 30 days.9

Continue to: A double-edged sword

A double-edged sword. E-cigarettes are less harmful than traditional cigarettes in the short term and likely benefit adult smokers who completely substitute e-cigarettes for their tobacco cigarettes.10 In randomized trials of adult smokers, e-cigarette use resulted in moderate combustible-cigarette cessation rates that rival or exceed rates achieved with traditional nicotine replacement therapy (NRT).11-13 However, most e-cigarettes contain addictive nicotine, can facilitate transitions to more harmful forms of tobacco use,10,14,15 and have unknown long-term health effects. Therefore, youth, young adults, and those who are otherwise tobacco naïve should not initiate e-cigarette use.

Moreover, cases of e-cigarette or vaping product use–associated lung injury (EVALI)—a disease linked to vaping that causes cough, fever, shortness of breath, and death—were first identified in August 2019 and peaked in September 2019 before new cases decreased dramatically through January 2020.16 Since the initial cases of EVALI arose, product testing has shown that tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and vitamin E acetate are the main ingredients linked to EVALI cases.17 For this reason, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and others strongly recommend against use of THC-containing e-cigarettes.18

Given the high rates of e-cigarette use among youth and young adults and its potential health harms, it is critical to inquire about e-cigarette use at primary care visits, and, as appropriate, to assess frequency and quantity of use. Patients who require intervention will be more likely to succeed in quitting if they are connected with behavioral health counseling and prescribed medication. This article offers evidence-based guidance to assess and advise teens and young adults regarding the potential health impact of e-cigarettes.

A NEW ICD-10-CM CODE AND A BRIEF ASSESSMENT TOOL

According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition (DSM-5)19 and the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10-CM),20 a tobacco use disorder is a problematic pattern of use leading to clinically significant impairment or distress. Associated features and behavioral markers of frequency and quantity include use within 30 minutes of waking, daily use, and increasing use. However, with youth, consider intervention for use of any nicotine or tobacco product, including e-cigarettes, regardless of whether it meets the threshold for diagnosis.21

The new code.

Continue to: As with other tobacco use...

As with other tobacco use, assess e-cigarette use patterns by asking questions about the frequency, duration, and quantity of use. Additionally, determine the level of nicotine in the e-liquid (discussed earlier) and evaluate whether the individual displays signs of physiologic dependence (eg, failed attempts to reduce or quit e-cigarette use, increased use, nicotine withdrawal symptoms).

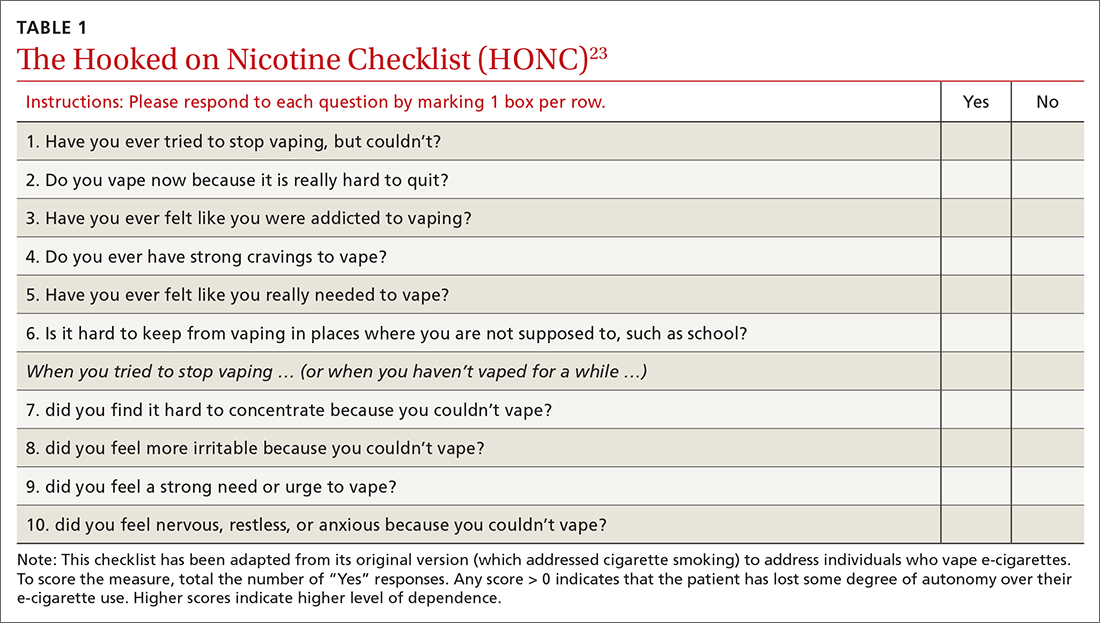

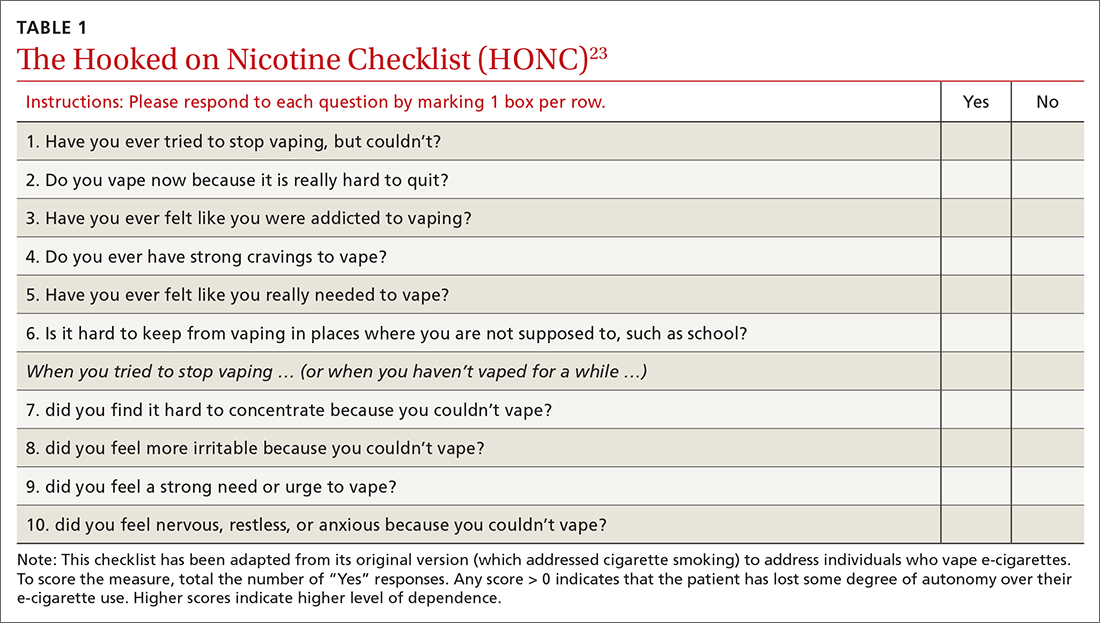

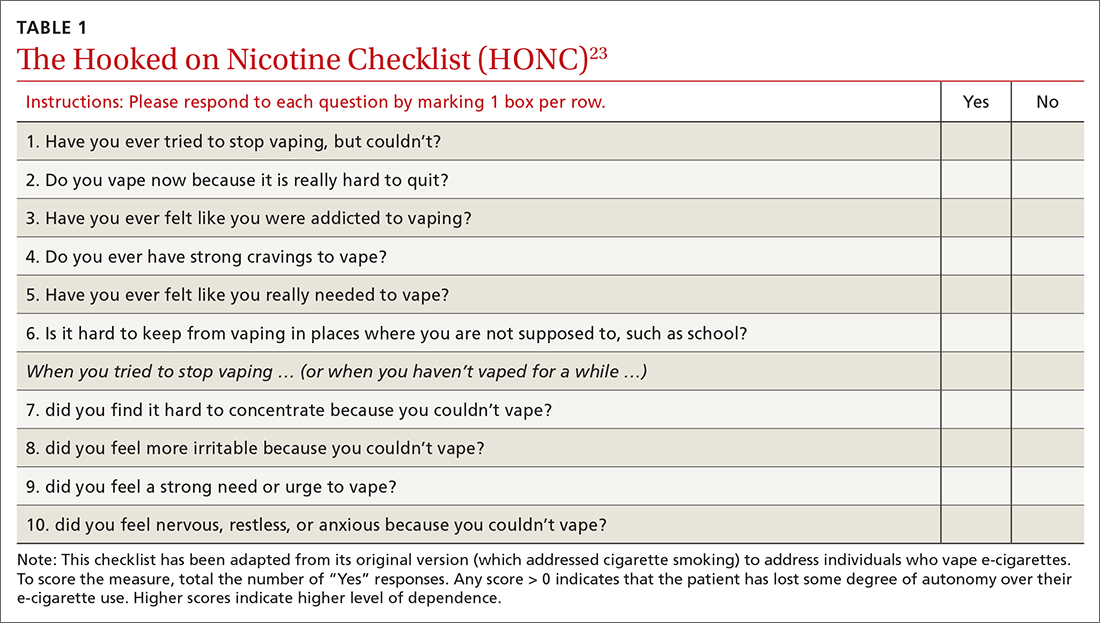

A useful assessment tool. While e-cigarette use is not often included on current substance use screening measures, the above questions can be added to the end of measures such as the CRAFFT (Car-Relax-Alone-Forget-Family and Friends-Trouble) test.22 Additionally, if an adolescent reports vaping, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends using a brief screening tool such as the Hooked on Nicotine Checklist (HONC) to establish his or her level of dependence (TABLE 1).23

The HONC is ideal for a primary care setting because it is brief and has a high level of sensitivity, minimizing false-negative reports24; a patient’s acknowledgement of any item indicates a loss of autonomy over nicotine. Establishing the level of nicotine dependence is particularly pertinent when making decisions regarding the course of treatment and whether to prescribe NRT (eg, nicotine patch, gum, lozenge). Alternatively, you can quickly assess level of dependence by determining the time to first e-cigarette use in the morning. Tobacco guidelines suggest that if time to first use is > 30 minutes, the individual is “moderately dependent”; if time to first use is < 30 minutes after waking, the individual is “severely dependent.”25

COMBINATION TREATMENT IS MOST SUCCESSFUL

Studies have shown that the most effective treatment for tobacco cessation is pairing behavioral treatment with combination NRT (eg, nicotine gum + patch).25,26 The literature on e-cigarette cessation remains in its infancy, but techniques from traditional smoking cessation can be applied because the behaviors differ only in their mode of nicotine delivery.

Behavioral treatment. There are several options for behavioral treatment for tobacco cessation—and thus, e-cigarette cessation. The first step will depend on the patient’s level of motivation. If the patient is not yet ready to quit, consider using brief motivational interviewing. Once the patient is willing to engage in treatment, options include setting a mutually agreed upon quit date or planning for a reduction in the frequency and duration of vaping.

Continue to: Referrals to the Quitline...

Referrals to the Quitline (800-QUIT-NOW) have long been standard practice and can be used to extend primary care treatment.25 Studies show that it is more effective to connect patients directly to the Quitline at their primary care appointment27 than asking them to call after the visit.28,29 We suggest providing direct assistance in the office to patients as they initiate treatment with the Quitline.

Finally, if the level of dependence is severe or the patient is not motivated to quit, connect them with a behavioral health provider in your clinic or with an outside therapist skilled in cognitive behavioral techniques related to tobacco cessation. Discuss with the patient that quitting nicotine use is difficult for many people and that the best option for success is the combination of counseling and medication.25

Nicotine replacement therapy for e-cigarette use. While over-the-counter NRT (nicotine gum, patches, lozenges) is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration only for sale to adults ≥ 18 years, the AAP issued guidance on prescribing NRT for those < 18 years who use e-cigarettes.30 While the AAP does not suggest a lower age limit for prescribing NRT, national data show that < 6% of middle schoolers report e-cigarette use and that e-cigarette use does not become common (~20% current use) until high school.31 It is therefore unlikely that a child < 14 years would require pharmacotherapy. On their fact sheet, the AAP includes the following guidance:

“Patients who are motivated to quit should use as much safe, FDA-approved NRT as needed to avoid smoking or vaping. When assessing a patient’s current level of nicotine use, it may be helpful to understand that using one JUUL pod per day is equivalent to one pack of cigarettes per day …. Pediatricians and other healthcare providers should work with each patient to determine a starting dosage of NRT that is most likely to help them quit successfully. Dosing is based on the patient’s level of nicotine dependence, which can be measured using a screening tool” (TABLE 123).32

The AAP NRT dosing guidelines can be found at downloads.aap.org/RCE/NRT_and_Adolescents_Pediatrician_Guidance_factsheet.pdf.32 Of note, the dosing guidelines for adolescents are the same as those for adults and are based on level of use and dependence. Moreover, the clinician and patient should work together to choose the initial dose and the plan for weaning NRT over time.

Continue to: THE CASE

Based on your conversation with Joe, you administer the HONC screening tool. He scores 9 out of 10, indicating significant loss of autonomy over nicotine. You consult with a behavioral health counselor, who believes that Joe would benefit from counseling and NRT. You discuss this treatment plan with Joe, who says he is ready to quit because he does not like feeling as if he depends on vaping. Your shared decision is to start the 21-mg patch and 4-mg gum with plans to step down from there.

Joe agrees to set a quit date in the following week. The behavioral health counselor then meets with Joe and they develop a quit plan, which is shared with you so you can follow up at the next visit. Joe also agrees to talk with his parents, who are unaware of his level of use and dependence. Everyone agrees on the quit plan, and a follow-up visit is scheduled.

At the follow-up visit 1 month later, Joe and his parents report that he has quit vaping but is still using the patch and gum. You instruct Joe to reduce his NRT use to the 14-mg patch and 2-mg gum and to stop using them over the next 2 to 3 weeks. Everyone is in agreement with the treatment plan. You also re-administer the HONC screening tool and see that Joe’s score has reduced by 7 points to just 2 out of 10. You recommend that Joe continue to see the behavioral health counselor and follow up as needed. (A noted benefit of having a behavioral health counselor in your clinic is the opportunity for informal briefings on patient progress.33,34)

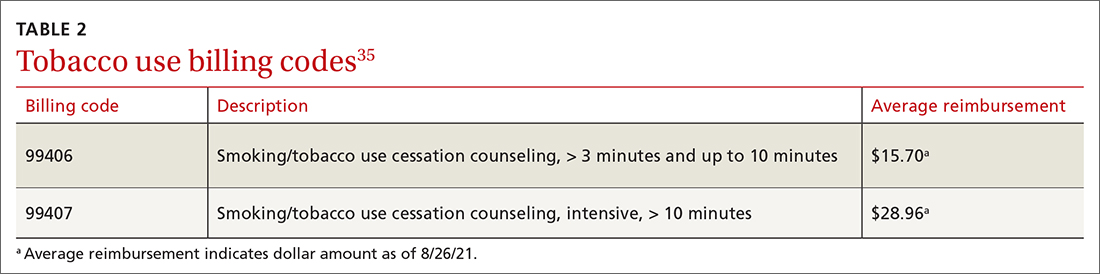

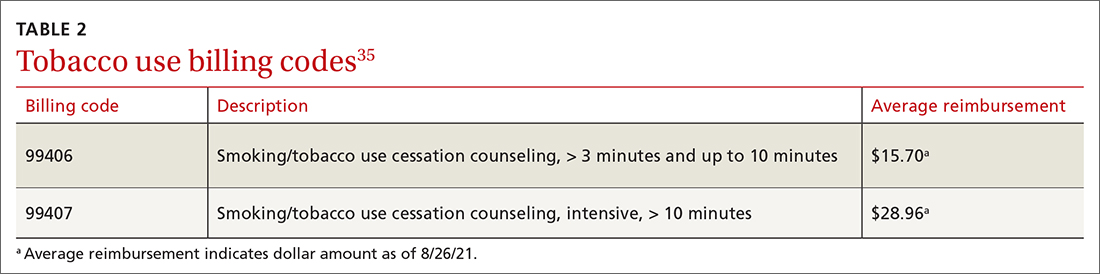

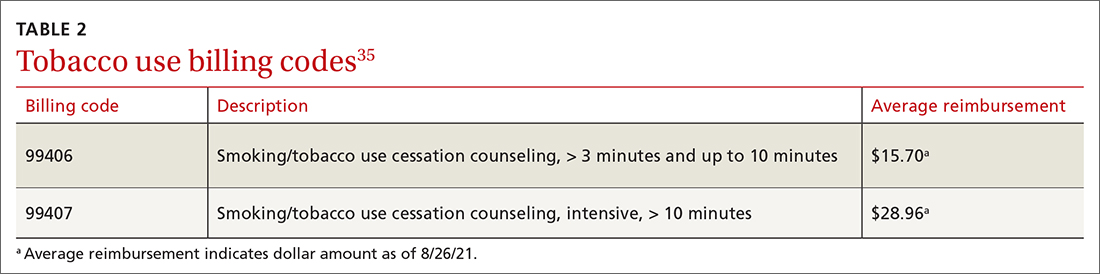

Following each visit with Joe, you make sure to complete documentation on (1) tobacco/e-cigarette use assessment, (2) diagnoses, (3) discussion of benefits of quitting,(4) assessment of readiness to quit, (5) creation and support of a quit plan, and (6) connection with a behavioral health counselor and planned follow-up. (See TABLE 235 for details onbilling codes.)

CORRESPONDENCE

Eleanor L. S. Leavens, PhD, 3901 Rainbow Boulevard, Mail Stop 1008, Kansas City, KS 66160; eleavens@kumc.edu

1. Prochaska JJ, Vogel EA, Benowitz N. Nicotine delivery and cigarette equivalents from vaping a JUULpod. Tob Control. Published online March 24, 2021. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol- 2020-056367

2. Rüther T, Hagedorn D, Schiela K, et al. Nicotine delivery efficiency of first-and second-generation e-cigarettes and its impact on relief of craving during the acute phase of use. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2018;221:191-198. doi: 10.1016/j.ijheh.2017.10.012

3. Hajek P, Pittaccio K, Pesola F, et al. Nicotine delivery and users’ reactions to Juul compared with cigarettes and other e‐cigarette products. Addiction. 2020;115:1141-1148. doi: 10.1111/add.14936

4. Wagener TL, Floyd EL, Stepanov I, et al. Have combustible cigarettes met their match? The nicotine delivery profiles and harmful constituent exposures of second-generation and third-generation electronic cigarette users. Tob control. 2017;26:e23-e28. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2016-053041

5. Herzog B, Kanada P. Nielsen: Tobacco all channel data thru 8/11 - cig vol decelerates. Published August 21, 2018. Accessed August 19, 2021. https://athra.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Wells-Fargo-Nielsen-Tobacco-All-Channel-Report-Period-Ending-8.11.18.pdf

6. Harrell MB, Weaver SR, Loukas A, et al. Flavored e-cigarette use: characterizing youth, young adult, and adult users. Prev Med Rep. 2017;5:33-40. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2016.11.001

7. Morean ME, Butler ER, Bold KW, et al. Preferring more e-cigarette flavors is associated with e-cigarette use frequency among adolescents but not adults. PloS One. 2018;13:e0189015. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0189015

8. Obisesan OH, Osei AD, Iftekhar Uddin SM, et al. Trends in e-cigarette use in adults in the United States, 2016-2018. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180:1394-1398. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.2817

9. Creamer MR, Wang TW, Babb S, et al. Tobacco product use and cessation indicators among adults—United States, 2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68:1013-1019. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6845a2

10. NASEM. Public health consequences of e-cigarettes. National Academies Press; 2018. Accessed August 19, 2021. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507171/

11. Hajek P, Phillips-Waller A, Przulj D, et al. A randomized trial of e-cigarettes versus nicotine-replacement therapy. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:629-637. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1808779

12. Pulvers K, Nollen NL, Rice M, et al. Effect of pod e-cigarettes vs cigarettes on carcinogen exposure among African American and Latinx smokers: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e2026324. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.26324

13. Wang RJ, Bhadriraju S, Glantz SA. E-cigarette use and adult cigarette smoking cessation: a meta-analysis. Am J Public Health. 2021;111:230-246. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2020.305999

14. Barrington-Trimis JL, Urman R, Berhane K, et al. E-cigarettes and future cigarette use. Pediatrics. 2016;138:e20160379. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-0379

15. Soneji S, Barrington-Trimis JL, Wills TA, et al. Association between initial use of e-cigarettes and subsequent cigarette smoking among adolescents and young adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171:788-797. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.1488

16. Krishnasamy VP, Hallowell BD, Ko JY, et al. Update: characteristics of a nationwide outbreak of e-cigarette, or vaping, product use–associated lung injury—United States, August 2019–January 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:90-94. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6903e2

17. Blount BC, Karwowski MP, Shields PG, et al. Vitamin E acetate in bronchoalveolar-lavage fluid associated with EVALI. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:697-705. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1916433

18. CDC. Outbreak of lung injury associated with use of e-cigarette, or vaping, products. Updated February 25, 2020. Accessed August 19, 2021. www.cdc.gov/tobacco/basic_information/e-cigarettes/severe-lung-disease.html

19. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th edition (DSM-5). American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013.

20. CDC. International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision. Updated July 30, 2021. Accessed August 31, 2021. www.cdc.gov/nchs/icd/icd10cm.htm

21. CDC. Surgeon General’s advisory on e-cigarette use among youth. Reviewed April 9, 2019. Accessed August 19, 2021. www.cdc.gov/tobacco/basic_information/e-cigarettes/surgeon-general-advisory/index.html

22. Knight JR, Sherritt L, Shrier LA, et al. Validity of the CRAFFT substance abuse screening test among adolescent clinic patients. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156:607-614. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.156.6.607

23. DiFranza JR, Savageau JA, Fletcher K, et al. Measuring the loss of autonomy over nicotine use in adolescents: the DANDY (Development and Assessment of Nicotine Dependence in Youths) study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156:397-403. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.156.4.397

24. Wellman RJ, Savageau JA, Godiwala S, et al. A comparison of the Hooked on Nicotine Checklist and the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence in adult smokers. Nicotine Tob Res. 2006;8:575-580. doi: 10.1080/14622200600789965

25. Fiore MC, Jaén CR, Baker TB, et al. Treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update. Published May 2008. Accessed August 19, 2021. www.aafp.org/dam/AAFP/documents/patient_care/clinical_recommendations/TreatingTobaccoUseandDependence-2008Update.pdf

26. Shah SD, Wilken LA, Winkler SR, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of combination therapy for smoking cessation. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2008;48:659-665. doi: 10.1331/JAPhA.2008.07063

27. Vidrine JI, Shete S, Cao Y, et al. Ask-Advise-Connect: a new approach to smoking treatment delivery in health care settings. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:458-464. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.3751

28. Bentz CJ, Bayley KB, Bonin KE, et al. The feasibility of connecting physician offices to a state-level tobacco quit line. Am J Prev Med. 2006;30:31-37. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.08.043

29. Borland R, Segan CJ. The potential of quitlines to increase smoking cessation. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2006;25:73-78. doi: 10.1080/09595230500459537

30. Farber HJ, Walley SC, Groner JA, et al. Clinical practice policy to protect children from tobacco, nicotine, and tobacco smoke. Pediatrics. 2015;136:1008-1017. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-3108

31. Gentzke AS, Wang TW, Jamal A, et al. Tobacco product use among middle and high school students—United States, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:1881-1888. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6950a1

32. AAP. Nicotine replacement therapy and adolescent patients: information for pediatricians. Updated November 2019. Accessed August 19, 2021. https://downloads.aap.org/RCE/NRT_and_Adolescents_Pediatrician_Guidance_factsheet.pdf

33. Blasi PR, Cromp D, McDonald S, et al. Approaches to behavioral health integration at high performing primary care practices. J Am Board Fam Med. 2018;31:691-701. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2018.05.170468

34. Jacobs C, Brieler JA, Salas J, et al. Integrated behavioral health care in family medicine residencies a CERA survey. Fam Med. 2018;50:380-384. doi: 10.22454/FamMed.2018.639260

35. Oliverez M. Quick guide: billing for smoking cessation services. Capture Billing. Accessed August 26, 2021. https://capturebilling.com/how-bill-smoking-cessation-counseling-99406-99407/

THE CASE

Joe, an 18-year-old, has been your patient for many years and has an uncomplicated medical history. He presents for his preparticipation sports examination for the upcoming high school baseball season. Joe’s mother, who arrives at the office with him, tells you she’s worried because she found an e-cigarette in his backpack last week. Joe says that many of the kids at his school vape and he tried it a while back and now vapes “a lot.”

After talking further with Joe, you realize that he is vaping every day, using a 5% nicotine pod. Based on previous consults with the behavioral health counselor in your clinic, you know that this level of vaping is about the same as smoking 1 pack of cigarettes per day in terms of nicotine exposure. Joe states that he often vapes in the bathroom at school because he cannot concentrate in class if he doesn’t vape. He also reports that he had previously used 1 pod per week but had recently started vaping more to help with his cravings.

You assess his withdrawal symptoms and learn that he feels on edge when he is not able to vape and that he vapes heavily before going into school because he knows he will not be able to vape again until his third passing period.

●

Electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes; also called “vapes”) are electronic nicotine delivery systems that heat and aerosolize e-liquid or “e-juice” that is inhaled by the user. The e-liquid is made up primarily of propylene glycol, vegetable glycerin, and flavorings, and often includes nicotine. Nicotine levels in e-cigarettes can range from 0 mg/mL to 60 mg/mL (regular cigarettes contain ~12 mg of nicotine). The nicotine level of the pod available from e-cigarette company JUUL (50 mg/mL e-liquid) is equivalent to about 1 pack of cigarettes.1 E-cigarette devices are relatively affordable; popular brands cost $10 to $20, while the replacement pods or e-liquid are typically about $4 each.

The e-cigarette market is quickly evolving and diversifying. Originally, e-cigarettes looked similar to cigarettes (cig-a-likes) but did not efficiently deliver nicotine to the user.2 E-cigarettes have evolved and some now deliver cigarette-like levels of nicotine to the user.3,4 Youth and young adults primarily use pod-mod e-cigarettes, which have a sleek design and produce less vapor than older e-cigarettes, making them easier to conceal. They can look like a USB flash-drive or have a teardrop shape. Pod-mod e-cigarettes dominate the current market, led by companies such as JUUL, NJOY, and Vuse.5

E-cigarette use is proliferating in the United States, particularly among young people and facilitated by the introduction of pod-based e-cigarettes in appealing flavors.6,7 While rates of current e-cigarette use by US adults is around 5.5%,8 recent data show that 32.7% of US high school students say they’ve used an e-cigarette in the past 30 days.9

Continue to: A double-edged sword

A double-edged sword. E-cigarettes are less harmful than traditional cigarettes in the short term and likely benefit adult smokers who completely substitute e-cigarettes for their tobacco cigarettes.10 In randomized trials of adult smokers, e-cigarette use resulted in moderate combustible-cigarette cessation rates that rival or exceed rates achieved with traditional nicotine replacement therapy (NRT).11-13 However, most e-cigarettes contain addictive nicotine, can facilitate transitions to more harmful forms of tobacco use,10,14,15 and have unknown long-term health effects. Therefore, youth, young adults, and those who are otherwise tobacco naïve should not initiate e-cigarette use.

Moreover, cases of e-cigarette or vaping product use–associated lung injury (EVALI)—a disease linked to vaping that causes cough, fever, shortness of breath, and death—were first identified in August 2019 and peaked in September 2019 before new cases decreased dramatically through January 2020.16 Since the initial cases of EVALI arose, product testing has shown that tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and vitamin E acetate are the main ingredients linked to EVALI cases.17 For this reason, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and others strongly recommend against use of THC-containing e-cigarettes.18

Given the high rates of e-cigarette use among youth and young adults and its potential health harms, it is critical to inquire about e-cigarette use at primary care visits, and, as appropriate, to assess frequency and quantity of use. Patients who require intervention will be more likely to succeed in quitting if they are connected with behavioral health counseling and prescribed medication. This article offers evidence-based guidance to assess and advise teens and young adults regarding the potential health impact of e-cigarettes.

A NEW ICD-10-CM CODE AND A BRIEF ASSESSMENT TOOL

According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition (DSM-5)19 and the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10-CM),20 a tobacco use disorder is a problematic pattern of use leading to clinically significant impairment or distress. Associated features and behavioral markers of frequency and quantity include use within 30 minutes of waking, daily use, and increasing use. However, with youth, consider intervention for use of any nicotine or tobacco product, including e-cigarettes, regardless of whether it meets the threshold for diagnosis.21

The new code.

Continue to: As with other tobacco use...

As with other tobacco use, assess e-cigarette use patterns by asking questions about the frequency, duration, and quantity of use. Additionally, determine the level of nicotine in the e-liquid (discussed earlier) and evaluate whether the individual displays signs of physiologic dependence (eg, failed attempts to reduce or quit e-cigarette use, increased use, nicotine withdrawal symptoms).

A useful assessment tool. While e-cigarette use is not often included on current substance use screening measures, the above questions can be added to the end of measures such as the CRAFFT (Car-Relax-Alone-Forget-Family and Friends-Trouble) test.22 Additionally, if an adolescent reports vaping, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends using a brief screening tool such as the Hooked on Nicotine Checklist (HONC) to establish his or her level of dependence (TABLE 1).23

The HONC is ideal for a primary care setting because it is brief and has a high level of sensitivity, minimizing false-negative reports24; a patient’s acknowledgement of any item indicates a loss of autonomy over nicotine. Establishing the level of nicotine dependence is particularly pertinent when making decisions regarding the course of treatment and whether to prescribe NRT (eg, nicotine patch, gum, lozenge). Alternatively, you can quickly assess level of dependence by determining the time to first e-cigarette use in the morning. Tobacco guidelines suggest that if time to first use is > 30 minutes, the individual is “moderately dependent”; if time to first use is < 30 minutes after waking, the individual is “severely dependent.”25

COMBINATION TREATMENT IS MOST SUCCESSFUL

Studies have shown that the most effective treatment for tobacco cessation is pairing behavioral treatment with combination NRT (eg, nicotine gum + patch).25,26 The literature on e-cigarette cessation remains in its infancy, but techniques from traditional smoking cessation can be applied because the behaviors differ only in their mode of nicotine delivery.

Behavioral treatment. There are several options for behavioral treatment for tobacco cessation—and thus, e-cigarette cessation. The first step will depend on the patient’s level of motivation. If the patient is not yet ready to quit, consider using brief motivational interviewing. Once the patient is willing to engage in treatment, options include setting a mutually agreed upon quit date or planning for a reduction in the frequency and duration of vaping.

Continue to: Referrals to the Quitline...

Referrals to the Quitline (800-QUIT-NOW) have long been standard practice and can be used to extend primary care treatment.25 Studies show that it is more effective to connect patients directly to the Quitline at their primary care appointment27 than asking them to call after the visit.28,29 We suggest providing direct assistance in the office to patients as they initiate treatment with the Quitline.

Finally, if the level of dependence is severe or the patient is not motivated to quit, connect them with a behavioral health provider in your clinic or with an outside therapist skilled in cognitive behavioral techniques related to tobacco cessation. Discuss with the patient that quitting nicotine use is difficult for many people and that the best option for success is the combination of counseling and medication.25

Nicotine replacement therapy for e-cigarette use. While over-the-counter NRT (nicotine gum, patches, lozenges) is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration only for sale to adults ≥ 18 years, the AAP issued guidance on prescribing NRT for those < 18 years who use e-cigarettes.30 While the AAP does not suggest a lower age limit for prescribing NRT, national data show that < 6% of middle schoolers report e-cigarette use and that e-cigarette use does not become common (~20% current use) until high school.31 It is therefore unlikely that a child < 14 years would require pharmacotherapy. On their fact sheet, the AAP includes the following guidance:

“Patients who are motivated to quit should use as much safe, FDA-approved NRT as needed to avoid smoking or vaping. When assessing a patient’s current level of nicotine use, it may be helpful to understand that using one JUUL pod per day is equivalent to one pack of cigarettes per day …. Pediatricians and other healthcare providers should work with each patient to determine a starting dosage of NRT that is most likely to help them quit successfully. Dosing is based on the patient’s level of nicotine dependence, which can be measured using a screening tool” (TABLE 123).32

The AAP NRT dosing guidelines can be found at downloads.aap.org/RCE/NRT_and_Adolescents_Pediatrician_Guidance_factsheet.pdf.32 Of note, the dosing guidelines for adolescents are the same as those for adults and are based on level of use and dependence. Moreover, the clinician and patient should work together to choose the initial dose and the plan for weaning NRT over time.

Continue to: THE CASE

Based on your conversation with Joe, you administer the HONC screening tool. He scores 9 out of 10, indicating significant loss of autonomy over nicotine. You consult with a behavioral health counselor, who believes that Joe would benefit from counseling and NRT. You discuss this treatment plan with Joe, who says he is ready to quit because he does not like feeling as if he depends on vaping. Your shared decision is to start the 21-mg patch and 4-mg gum with plans to step down from there.

Joe agrees to set a quit date in the following week. The behavioral health counselor then meets with Joe and they develop a quit plan, which is shared with you so you can follow up at the next visit. Joe also agrees to talk with his parents, who are unaware of his level of use and dependence. Everyone agrees on the quit plan, and a follow-up visit is scheduled.

At the follow-up visit 1 month later, Joe and his parents report that he has quit vaping but is still using the patch and gum. You instruct Joe to reduce his NRT use to the 14-mg patch and 2-mg gum and to stop using them over the next 2 to 3 weeks. Everyone is in agreement with the treatment plan. You also re-administer the HONC screening tool and see that Joe’s score has reduced by 7 points to just 2 out of 10. You recommend that Joe continue to see the behavioral health counselor and follow up as needed. (A noted benefit of having a behavioral health counselor in your clinic is the opportunity for informal briefings on patient progress.33,34)

Following each visit with Joe, you make sure to complete documentation on (1) tobacco/e-cigarette use assessment, (2) diagnoses, (3) discussion of benefits of quitting,(4) assessment of readiness to quit, (5) creation and support of a quit plan, and (6) connection with a behavioral health counselor and planned follow-up. (See TABLE 235 for details onbilling codes.)

CORRESPONDENCE

Eleanor L. S. Leavens, PhD, 3901 Rainbow Boulevard, Mail Stop 1008, Kansas City, KS 66160; eleavens@kumc.edu

THE CASE

Joe, an 18-year-old, has been your patient for many years and has an uncomplicated medical history. He presents for his preparticipation sports examination for the upcoming high school baseball season. Joe’s mother, who arrives at the office with him, tells you she’s worried because she found an e-cigarette in his backpack last week. Joe says that many of the kids at his school vape and he tried it a while back and now vapes “a lot.”

After talking further with Joe, you realize that he is vaping every day, using a 5% nicotine pod. Based on previous consults with the behavioral health counselor in your clinic, you know that this level of vaping is about the same as smoking 1 pack of cigarettes per day in terms of nicotine exposure. Joe states that he often vapes in the bathroom at school because he cannot concentrate in class if he doesn’t vape. He also reports that he had previously used 1 pod per week but had recently started vaping more to help with his cravings.

You assess his withdrawal symptoms and learn that he feels on edge when he is not able to vape and that he vapes heavily before going into school because he knows he will not be able to vape again until his third passing period.

●

Electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes; also called “vapes”) are electronic nicotine delivery systems that heat and aerosolize e-liquid or “e-juice” that is inhaled by the user. The e-liquid is made up primarily of propylene glycol, vegetable glycerin, and flavorings, and often includes nicotine. Nicotine levels in e-cigarettes can range from 0 mg/mL to 60 mg/mL (regular cigarettes contain ~12 mg of nicotine). The nicotine level of the pod available from e-cigarette company JUUL (50 mg/mL e-liquid) is equivalent to about 1 pack of cigarettes.1 E-cigarette devices are relatively affordable; popular brands cost $10 to $20, while the replacement pods or e-liquid are typically about $4 each.

The e-cigarette market is quickly evolving and diversifying. Originally, e-cigarettes looked similar to cigarettes (cig-a-likes) but did not efficiently deliver nicotine to the user.2 E-cigarettes have evolved and some now deliver cigarette-like levels of nicotine to the user.3,4 Youth and young adults primarily use pod-mod e-cigarettes, which have a sleek design and produce less vapor than older e-cigarettes, making them easier to conceal. They can look like a USB flash-drive or have a teardrop shape. Pod-mod e-cigarettes dominate the current market, led by companies such as JUUL, NJOY, and Vuse.5

E-cigarette use is proliferating in the United States, particularly among young people and facilitated by the introduction of pod-based e-cigarettes in appealing flavors.6,7 While rates of current e-cigarette use by US adults is around 5.5%,8 recent data show that 32.7% of US high school students say they’ve used an e-cigarette in the past 30 days.9

Continue to: A double-edged sword

A double-edged sword. E-cigarettes are less harmful than traditional cigarettes in the short term and likely benefit adult smokers who completely substitute e-cigarettes for their tobacco cigarettes.10 In randomized trials of adult smokers, e-cigarette use resulted in moderate combustible-cigarette cessation rates that rival or exceed rates achieved with traditional nicotine replacement therapy (NRT).11-13 However, most e-cigarettes contain addictive nicotine, can facilitate transitions to more harmful forms of tobacco use,10,14,15 and have unknown long-term health effects. Therefore, youth, young adults, and those who are otherwise tobacco naïve should not initiate e-cigarette use.

Moreover, cases of e-cigarette or vaping product use–associated lung injury (EVALI)—a disease linked to vaping that causes cough, fever, shortness of breath, and death—were first identified in August 2019 and peaked in September 2019 before new cases decreased dramatically through January 2020.16 Since the initial cases of EVALI arose, product testing has shown that tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and vitamin E acetate are the main ingredients linked to EVALI cases.17 For this reason, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and others strongly recommend against use of THC-containing e-cigarettes.18

Given the high rates of e-cigarette use among youth and young adults and its potential health harms, it is critical to inquire about e-cigarette use at primary care visits, and, as appropriate, to assess frequency and quantity of use. Patients who require intervention will be more likely to succeed in quitting if they are connected with behavioral health counseling and prescribed medication. This article offers evidence-based guidance to assess and advise teens and young adults regarding the potential health impact of e-cigarettes.

A NEW ICD-10-CM CODE AND A BRIEF ASSESSMENT TOOL

According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition (DSM-5)19 and the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10-CM),20 a tobacco use disorder is a problematic pattern of use leading to clinically significant impairment or distress. Associated features and behavioral markers of frequency and quantity include use within 30 minutes of waking, daily use, and increasing use. However, with youth, consider intervention for use of any nicotine or tobacco product, including e-cigarettes, regardless of whether it meets the threshold for diagnosis.21

The new code.

Continue to: As with other tobacco use...

As with other tobacco use, assess e-cigarette use patterns by asking questions about the frequency, duration, and quantity of use. Additionally, determine the level of nicotine in the e-liquid (discussed earlier) and evaluate whether the individual displays signs of physiologic dependence (eg, failed attempts to reduce or quit e-cigarette use, increased use, nicotine withdrawal symptoms).

A useful assessment tool. While e-cigarette use is not often included on current substance use screening measures, the above questions can be added to the end of measures such as the CRAFFT (Car-Relax-Alone-Forget-Family and Friends-Trouble) test.22 Additionally, if an adolescent reports vaping, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends using a brief screening tool such as the Hooked on Nicotine Checklist (HONC) to establish his or her level of dependence (TABLE 1).23

The HONC is ideal for a primary care setting because it is brief and has a high level of sensitivity, minimizing false-negative reports24; a patient’s acknowledgement of any item indicates a loss of autonomy over nicotine. Establishing the level of nicotine dependence is particularly pertinent when making decisions regarding the course of treatment and whether to prescribe NRT (eg, nicotine patch, gum, lozenge). Alternatively, you can quickly assess level of dependence by determining the time to first e-cigarette use in the morning. Tobacco guidelines suggest that if time to first use is > 30 minutes, the individual is “moderately dependent”; if time to first use is < 30 minutes after waking, the individual is “severely dependent.”25

COMBINATION TREATMENT IS MOST SUCCESSFUL

Studies have shown that the most effective treatment for tobacco cessation is pairing behavioral treatment with combination NRT (eg, nicotine gum + patch).25,26 The literature on e-cigarette cessation remains in its infancy, but techniques from traditional smoking cessation can be applied because the behaviors differ only in their mode of nicotine delivery.

Behavioral treatment. There are several options for behavioral treatment for tobacco cessation—and thus, e-cigarette cessation. The first step will depend on the patient’s level of motivation. If the patient is not yet ready to quit, consider using brief motivational interviewing. Once the patient is willing to engage in treatment, options include setting a mutually agreed upon quit date or planning for a reduction in the frequency and duration of vaping.

Continue to: Referrals to the Quitline...

Referrals to the Quitline (800-QUIT-NOW) have long been standard practice and can be used to extend primary care treatment.25 Studies show that it is more effective to connect patients directly to the Quitline at their primary care appointment27 than asking them to call after the visit.28,29 We suggest providing direct assistance in the office to patients as they initiate treatment with the Quitline.

Finally, if the level of dependence is severe or the patient is not motivated to quit, connect them with a behavioral health provider in your clinic or with an outside therapist skilled in cognitive behavioral techniques related to tobacco cessation. Discuss with the patient that quitting nicotine use is difficult for many people and that the best option for success is the combination of counseling and medication.25

Nicotine replacement therapy for e-cigarette use. While over-the-counter NRT (nicotine gum, patches, lozenges) is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration only for sale to adults ≥ 18 years, the AAP issued guidance on prescribing NRT for those < 18 years who use e-cigarettes.30 While the AAP does not suggest a lower age limit for prescribing NRT, national data show that < 6% of middle schoolers report e-cigarette use and that e-cigarette use does not become common (~20% current use) until high school.31 It is therefore unlikely that a child < 14 years would require pharmacotherapy. On their fact sheet, the AAP includes the following guidance:

“Patients who are motivated to quit should use as much safe, FDA-approved NRT as needed to avoid smoking or vaping. When assessing a patient’s current level of nicotine use, it may be helpful to understand that using one JUUL pod per day is equivalent to one pack of cigarettes per day …. Pediatricians and other healthcare providers should work with each patient to determine a starting dosage of NRT that is most likely to help them quit successfully. Dosing is based on the patient’s level of nicotine dependence, which can be measured using a screening tool” (TABLE 123).32

The AAP NRT dosing guidelines can be found at downloads.aap.org/RCE/NRT_and_Adolescents_Pediatrician_Guidance_factsheet.pdf.32 Of note, the dosing guidelines for adolescents are the same as those for adults and are based on level of use and dependence. Moreover, the clinician and patient should work together to choose the initial dose and the plan for weaning NRT over time.

Continue to: THE CASE

Based on your conversation with Joe, you administer the HONC screening tool. He scores 9 out of 10, indicating significant loss of autonomy over nicotine. You consult with a behavioral health counselor, who believes that Joe would benefit from counseling and NRT. You discuss this treatment plan with Joe, who says he is ready to quit because he does not like feeling as if he depends on vaping. Your shared decision is to start the 21-mg patch and 4-mg gum with plans to step down from there.

Joe agrees to set a quit date in the following week. The behavioral health counselor then meets with Joe and they develop a quit plan, which is shared with you so you can follow up at the next visit. Joe also agrees to talk with his parents, who are unaware of his level of use and dependence. Everyone agrees on the quit plan, and a follow-up visit is scheduled.

At the follow-up visit 1 month later, Joe and his parents report that he has quit vaping but is still using the patch and gum. You instruct Joe to reduce his NRT use to the 14-mg patch and 2-mg gum and to stop using them over the next 2 to 3 weeks. Everyone is in agreement with the treatment plan. You also re-administer the HONC screening tool and see that Joe’s score has reduced by 7 points to just 2 out of 10. You recommend that Joe continue to see the behavioral health counselor and follow up as needed. (A noted benefit of having a behavioral health counselor in your clinic is the opportunity for informal briefings on patient progress.33,34)

Following each visit with Joe, you make sure to complete documentation on (1) tobacco/e-cigarette use assessment, (2) diagnoses, (3) discussion of benefits of quitting,(4) assessment of readiness to quit, (5) creation and support of a quit plan, and (6) connection with a behavioral health counselor and planned follow-up. (See TABLE 235 for details onbilling codes.)

CORRESPONDENCE

Eleanor L. S. Leavens, PhD, 3901 Rainbow Boulevard, Mail Stop 1008, Kansas City, KS 66160; eleavens@kumc.edu

1. Prochaska JJ, Vogel EA, Benowitz N. Nicotine delivery and cigarette equivalents from vaping a JUULpod. Tob Control. Published online March 24, 2021. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol- 2020-056367

2. Rüther T, Hagedorn D, Schiela K, et al. Nicotine delivery efficiency of first-and second-generation e-cigarettes and its impact on relief of craving during the acute phase of use. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2018;221:191-198. doi: 10.1016/j.ijheh.2017.10.012

3. Hajek P, Pittaccio K, Pesola F, et al. Nicotine delivery and users’ reactions to Juul compared with cigarettes and other e‐cigarette products. Addiction. 2020;115:1141-1148. doi: 10.1111/add.14936

4. Wagener TL, Floyd EL, Stepanov I, et al. Have combustible cigarettes met their match? The nicotine delivery profiles and harmful constituent exposures of second-generation and third-generation electronic cigarette users. Tob control. 2017;26:e23-e28. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2016-053041

5. Herzog B, Kanada P. Nielsen: Tobacco all channel data thru 8/11 - cig vol decelerates. Published August 21, 2018. Accessed August 19, 2021. https://athra.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Wells-Fargo-Nielsen-Tobacco-All-Channel-Report-Period-Ending-8.11.18.pdf

6. Harrell MB, Weaver SR, Loukas A, et al. Flavored e-cigarette use: characterizing youth, young adult, and adult users. Prev Med Rep. 2017;5:33-40. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2016.11.001

7. Morean ME, Butler ER, Bold KW, et al. Preferring more e-cigarette flavors is associated with e-cigarette use frequency among adolescents but not adults. PloS One. 2018;13:e0189015. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0189015

8. Obisesan OH, Osei AD, Iftekhar Uddin SM, et al. Trends in e-cigarette use in adults in the United States, 2016-2018. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180:1394-1398. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.2817

9. Creamer MR, Wang TW, Babb S, et al. Tobacco product use and cessation indicators among adults—United States, 2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68:1013-1019. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6845a2

10. NASEM. Public health consequences of e-cigarettes. National Academies Press; 2018. Accessed August 19, 2021. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507171/

11. Hajek P, Phillips-Waller A, Przulj D, et al. A randomized trial of e-cigarettes versus nicotine-replacement therapy. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:629-637. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1808779

12. Pulvers K, Nollen NL, Rice M, et al. Effect of pod e-cigarettes vs cigarettes on carcinogen exposure among African American and Latinx smokers: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e2026324. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.26324

13. Wang RJ, Bhadriraju S, Glantz SA. E-cigarette use and adult cigarette smoking cessation: a meta-analysis. Am J Public Health. 2021;111:230-246. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2020.305999

14. Barrington-Trimis JL, Urman R, Berhane K, et al. E-cigarettes and future cigarette use. Pediatrics. 2016;138:e20160379. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-0379

15. Soneji S, Barrington-Trimis JL, Wills TA, et al. Association between initial use of e-cigarettes and subsequent cigarette smoking among adolescents and young adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171:788-797. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.1488

16. Krishnasamy VP, Hallowell BD, Ko JY, et al. Update: characteristics of a nationwide outbreak of e-cigarette, or vaping, product use–associated lung injury—United States, August 2019–January 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:90-94. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6903e2

17. Blount BC, Karwowski MP, Shields PG, et al. Vitamin E acetate in bronchoalveolar-lavage fluid associated with EVALI. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:697-705. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1916433

18. CDC. Outbreak of lung injury associated with use of e-cigarette, or vaping, products. Updated February 25, 2020. Accessed August 19, 2021. www.cdc.gov/tobacco/basic_information/e-cigarettes/severe-lung-disease.html

19. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th edition (DSM-5). American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013.

20. CDC. International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision. Updated July 30, 2021. Accessed August 31, 2021. www.cdc.gov/nchs/icd/icd10cm.htm

21. CDC. Surgeon General’s advisory on e-cigarette use among youth. Reviewed April 9, 2019. Accessed August 19, 2021. www.cdc.gov/tobacco/basic_information/e-cigarettes/surgeon-general-advisory/index.html

22. Knight JR, Sherritt L, Shrier LA, et al. Validity of the CRAFFT substance abuse screening test among adolescent clinic patients. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156:607-614. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.156.6.607

23. DiFranza JR, Savageau JA, Fletcher K, et al. Measuring the loss of autonomy over nicotine use in adolescents: the DANDY (Development and Assessment of Nicotine Dependence in Youths) study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156:397-403. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.156.4.397

24. Wellman RJ, Savageau JA, Godiwala S, et al. A comparison of the Hooked on Nicotine Checklist and the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence in adult smokers. Nicotine Tob Res. 2006;8:575-580. doi: 10.1080/14622200600789965

25. Fiore MC, Jaén CR, Baker TB, et al. Treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update. Published May 2008. Accessed August 19, 2021. www.aafp.org/dam/AAFP/documents/patient_care/clinical_recommendations/TreatingTobaccoUseandDependence-2008Update.pdf

26. Shah SD, Wilken LA, Winkler SR, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of combination therapy for smoking cessation. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2008;48:659-665. doi: 10.1331/JAPhA.2008.07063

27. Vidrine JI, Shete S, Cao Y, et al. Ask-Advise-Connect: a new approach to smoking treatment delivery in health care settings. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:458-464. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.3751

28. Bentz CJ, Bayley KB, Bonin KE, et al. The feasibility of connecting physician offices to a state-level tobacco quit line. Am J Prev Med. 2006;30:31-37. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.08.043

29. Borland R, Segan CJ. The potential of quitlines to increase smoking cessation. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2006;25:73-78. doi: 10.1080/09595230500459537

30. Farber HJ, Walley SC, Groner JA, et al. Clinical practice policy to protect children from tobacco, nicotine, and tobacco smoke. Pediatrics. 2015;136:1008-1017. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-3108

31. Gentzke AS, Wang TW, Jamal A, et al. Tobacco product use among middle and high school students—United States, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:1881-1888. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6950a1

32. AAP. Nicotine replacement therapy and adolescent patients: information for pediatricians. Updated November 2019. Accessed August 19, 2021. https://downloads.aap.org/RCE/NRT_and_Adolescents_Pediatrician_Guidance_factsheet.pdf

33. Blasi PR, Cromp D, McDonald S, et al. Approaches to behavioral health integration at high performing primary care practices. J Am Board Fam Med. 2018;31:691-701. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2018.05.170468

34. Jacobs C, Brieler JA, Salas J, et al. Integrated behavioral health care in family medicine residencies a CERA survey. Fam Med. 2018;50:380-384. doi: 10.22454/FamMed.2018.639260

35. Oliverez M. Quick guide: billing for smoking cessation services. Capture Billing. Accessed August 26, 2021. https://capturebilling.com/how-bill-smoking-cessation-counseling-99406-99407/

1. Prochaska JJ, Vogel EA, Benowitz N. Nicotine delivery and cigarette equivalents from vaping a JUULpod. Tob Control. Published online March 24, 2021. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol- 2020-056367

2. Rüther T, Hagedorn D, Schiela K, et al. Nicotine delivery efficiency of first-and second-generation e-cigarettes and its impact on relief of craving during the acute phase of use. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2018;221:191-198. doi: 10.1016/j.ijheh.2017.10.012

3. Hajek P, Pittaccio K, Pesola F, et al. Nicotine delivery and users’ reactions to Juul compared with cigarettes and other e‐cigarette products. Addiction. 2020;115:1141-1148. doi: 10.1111/add.14936

4. Wagener TL, Floyd EL, Stepanov I, et al. Have combustible cigarettes met their match? The nicotine delivery profiles and harmful constituent exposures of second-generation and third-generation electronic cigarette users. Tob control. 2017;26:e23-e28. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2016-053041

5. Herzog B, Kanada P. Nielsen: Tobacco all channel data thru 8/11 - cig vol decelerates. Published August 21, 2018. Accessed August 19, 2021. https://athra.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Wells-Fargo-Nielsen-Tobacco-All-Channel-Report-Period-Ending-8.11.18.pdf

6. Harrell MB, Weaver SR, Loukas A, et al. Flavored e-cigarette use: characterizing youth, young adult, and adult users. Prev Med Rep. 2017;5:33-40. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2016.11.001

7. Morean ME, Butler ER, Bold KW, et al. Preferring more e-cigarette flavors is associated with e-cigarette use frequency among adolescents but not adults. PloS One. 2018;13:e0189015. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0189015

8. Obisesan OH, Osei AD, Iftekhar Uddin SM, et al. Trends in e-cigarette use in adults in the United States, 2016-2018. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180:1394-1398. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.2817

9. Creamer MR, Wang TW, Babb S, et al. Tobacco product use and cessation indicators among adults—United States, 2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68:1013-1019. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6845a2

10. NASEM. Public health consequences of e-cigarettes. National Academies Press; 2018. Accessed August 19, 2021. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507171/

11. Hajek P, Phillips-Waller A, Przulj D, et al. A randomized trial of e-cigarettes versus nicotine-replacement therapy. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:629-637. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1808779

12. Pulvers K, Nollen NL, Rice M, et al. Effect of pod e-cigarettes vs cigarettes on carcinogen exposure among African American and Latinx smokers: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e2026324. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.26324

13. Wang RJ, Bhadriraju S, Glantz SA. E-cigarette use and adult cigarette smoking cessation: a meta-analysis. Am J Public Health. 2021;111:230-246. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2020.305999

14. Barrington-Trimis JL, Urman R, Berhane K, et al. E-cigarettes and future cigarette use. Pediatrics. 2016;138:e20160379. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-0379

15. Soneji S, Barrington-Trimis JL, Wills TA, et al. Association between initial use of e-cigarettes and subsequent cigarette smoking among adolescents and young adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171:788-797. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.1488

16. Krishnasamy VP, Hallowell BD, Ko JY, et al. Update: characteristics of a nationwide outbreak of e-cigarette, or vaping, product use–associated lung injury—United States, August 2019–January 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:90-94. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6903e2

17. Blount BC, Karwowski MP, Shields PG, et al. Vitamin E acetate in bronchoalveolar-lavage fluid associated with EVALI. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:697-705. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1916433

18. CDC. Outbreak of lung injury associated with use of e-cigarette, or vaping, products. Updated February 25, 2020. Accessed August 19, 2021. www.cdc.gov/tobacco/basic_information/e-cigarettes/severe-lung-disease.html

19. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th edition (DSM-5). American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013.

20. CDC. International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision. Updated July 30, 2021. Accessed August 31, 2021. www.cdc.gov/nchs/icd/icd10cm.htm

21. CDC. Surgeon General’s advisory on e-cigarette use among youth. Reviewed April 9, 2019. Accessed August 19, 2021. www.cdc.gov/tobacco/basic_information/e-cigarettes/surgeon-general-advisory/index.html

22. Knight JR, Sherritt L, Shrier LA, et al. Validity of the CRAFFT substance abuse screening test among adolescent clinic patients. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156:607-614. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.156.6.607

23. DiFranza JR, Savageau JA, Fletcher K, et al. Measuring the loss of autonomy over nicotine use in adolescents: the DANDY (Development and Assessment of Nicotine Dependence in Youths) study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156:397-403. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.156.4.397

24. Wellman RJ, Savageau JA, Godiwala S, et al. A comparison of the Hooked on Nicotine Checklist and the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence in adult smokers. Nicotine Tob Res. 2006;8:575-580. doi: 10.1080/14622200600789965

25. Fiore MC, Jaén CR, Baker TB, et al. Treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update. Published May 2008. Accessed August 19, 2021. www.aafp.org/dam/AAFP/documents/patient_care/clinical_recommendations/TreatingTobaccoUseandDependence-2008Update.pdf

26. Shah SD, Wilken LA, Winkler SR, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of combination therapy for smoking cessation. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2008;48:659-665. doi: 10.1331/JAPhA.2008.07063

27. Vidrine JI, Shete S, Cao Y, et al. Ask-Advise-Connect: a new approach to smoking treatment delivery in health care settings. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:458-464. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.3751

28. Bentz CJ, Bayley KB, Bonin KE, et al. The feasibility of connecting physician offices to a state-level tobacco quit line. Am J Prev Med. 2006;30:31-37. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.08.043

29. Borland R, Segan CJ. The potential of quitlines to increase smoking cessation. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2006;25:73-78. doi: 10.1080/09595230500459537

30. Farber HJ, Walley SC, Groner JA, et al. Clinical practice policy to protect children from tobacco, nicotine, and tobacco smoke. Pediatrics. 2015;136:1008-1017. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-3108

31. Gentzke AS, Wang TW, Jamal A, et al. Tobacco product use among middle and high school students—United States, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:1881-1888. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6950a1

32. AAP. Nicotine replacement therapy and adolescent patients: information for pediatricians. Updated November 2019. Accessed August 19, 2021. https://downloads.aap.org/RCE/NRT_and_Adolescents_Pediatrician_Guidance_factsheet.pdf

33. Blasi PR, Cromp D, McDonald S, et al. Approaches to behavioral health integration at high performing primary care practices. J Am Board Fam Med. 2018;31:691-701. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2018.05.170468

34. Jacobs C, Brieler JA, Salas J, et al. Integrated behavioral health care in family medicine residencies a CERA survey. Fam Med. 2018;50:380-384. doi: 10.22454/FamMed.2018.639260

35. Oliverez M. Quick guide: billing for smoking cessation services. Capture Billing. Accessed August 26, 2021. https://capturebilling.com/how-bill-smoking-cessation-counseling-99406-99407/

Difficult patient, or something else? A review of personality disorders

Specific behaviors or expressed thoughts may signal a need for screening. Take into account an individual’s strengths and limitations when designing a Tx approach.

THE CASES

Winston S* is a 23-year-old man referred by a psychiatrist colleague for primary care. He works delivering papers in the early morning hours and spends his day alone in his apartment mainly eating frozen pizza. He has worked solitary jobs his entire life and says he prefers it that way. His answers to questions lack emotion. He doesn’t seem to have any friends or regular contact with family. He follows the medical advice he receives but can’t seem to get out of the house to exercise or socialize. His psychiatrist was treating him with a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor for depression when he was referred.

Denise L* is a 37-year-old woman who transferred to your practice because she says the previous practice’s office manager was disrespectful and the doctor did not listen to her. She has been “very appreciative” of you and your “well-run office.” You have addressed her fibromyalgia and she has shared several personal details about her life. In the following weeks, you receive several phone calls and messages from her. At a follow-up visit, she asks questions about your family and seems agitated when you hesitate to answer. She questions whether you remember details of her history. She pushes, “Did you remember that, doctor?” She also mentions that your front desk staff seems rude to her.

Ruth B* is an 82-year-old woman whose blood pressure measured in your office is 176/94 mm Hg. When you recommend starting a medication and getting blood tests, she responds with a litany of fearful questions. She seems immobilized by worries about treatment and equally so about the risks of nontreatment. You can’t seem to get past the anxiety to decide on a satisfactory plan. She has to write everything down on a notepad and worries if she does not get every detail.

●

* This patient’s name has been changed to protect his identity. The other 2 patients are an amalgam of patients for whom the authors have provided care.

According to a survey of practicing primary care physicians, as many as 15% of patient encounters can be difficult.1 Demanding, intrusive, or angry patients who reject health care interventions are often-cited sources of these difficulties.2,3 While it is true that patient, physician, and environmental factors may contribute to challenging interactions, some patients who are “difficult” may actually have a personality disorder that requires a distinctive approach to care. Recognizing these patients can help empower physicians to provide compassionate and effective care, reduce team angst, and minimize burnout.

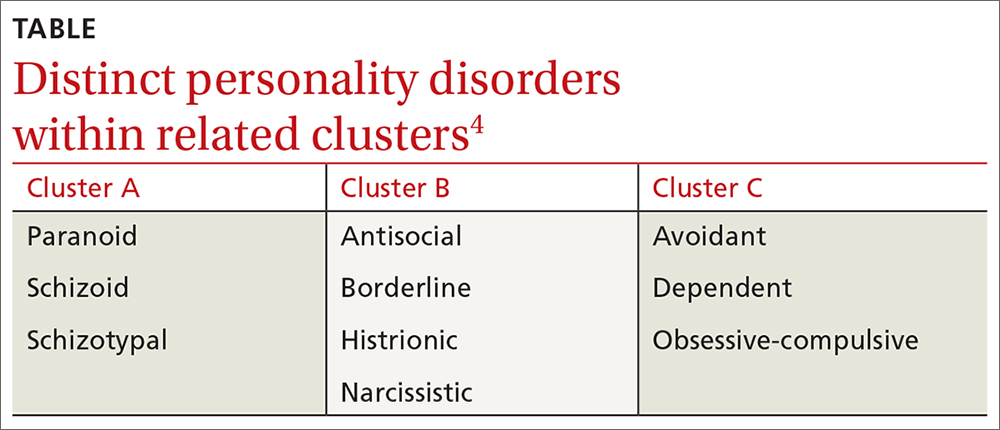

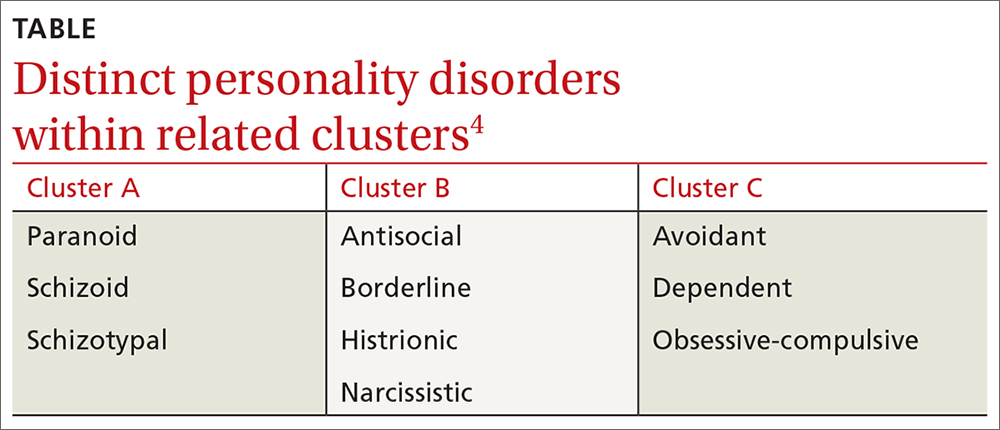

❚ What qualifies as a personality disorder? A personality disorder is an enduring pattern of inner experience and behavior that deviates markedly from the expectations of the individual’s culture, is pervasive and inflexible, has an onset in adolescence or early adulthood, is unchanging over time, and leads to distress or impairment in social or occupational functioning.4 The prevalence of any personality disorder seems to have increased over the past decade from 9.1%4 to 12.16%.5 The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) classifies personality disorders in 3 clusters—A, B, and C (TABLE4)—with prevalence rates at 7.23%, 5.53%, and 6.7%, respectively.5 The review below will focus on the distinct personality disorders exhibited by the patients described in the opening cases.

Continue to: A closer look at the clusters...

A closer look at the clusters

Cluster A disorders

Paranoid, schizoid, and schizotypal disorders are part of this cluster. These patients exhibit odd or eccentric thinking and behavior. Individuals with schizoid personality disorder, for instance, usually lack relationships and lack the desire to acquire and maintain relationships.4 They often organize their lives to remain isolated and will choose occupations that require little social interaction. They sometimes view themselves as observers rather than participants in their own lives.6

Cluster B disorders

Dramatic, overly emotional, or unpredictable thinking and behavior are characteristic of individuals who have antisocial, borderline, histrionic, or narcissistic disorders. Patients with borderline personality disorder (BPD), for example, demonstrate a longstanding pattern of instability in affect, self-image, and relationships.4 Patients with BPD often display extreme interpersonal hypersensitivity and make frantic efforts to avoid real or imagined abandonment. Identity disturbance, feelings of emptiness, and efforts to avoid abandonment have all been associated with increased suicide risk.7

In a primary care setting, such a patient may display extremely strong reactions to minor disappointments. When the physician is unavailable for a last-minute appointment or to authorize an unscheduled medication refill or to receive an after-hours phone call, the patient may become irate. The physician, who previously was idealized by the patient as “the only person who understands me,” is now devalued as “the worst doctor I’ve ever had.”8

Cluster C disorders

With these individuals, anxious or fearful thinking and behavior predominate. Avoidant, dependent, and obsessive-compulsive disorders are included in this cluster.

Dependent personality disorder (DPD) is characterized by a pervasive and extreme need to be taken care of. Submissive and clingy behavior and fear of separation are excessive. This patient may have difficulty making everyday decisions, being assertive, or expressing disagreement with others.4

Obsessive-compulsive personality disorder falls in this cluster and is typified by a pervasive preoccupation with orderliness, perfectionism, and control, at the price of flexibility and efficiency. This individual may be reluctant to get rid of sentimental objects, have rigid moral beliefs, and have significant difficulty working with others who do not follow their rules.4

Continue to: These clues may suggest...

These clues may suggest a personality disorder

If you find that encounters with a particular patient are growing increasingly difficult, consider whether the following behaviors, attitudes, and patterns of thinking are coming into play. If they are, you may want to consider using a screening tool, which we’ll discuss in a moment.

❚ Clues to cluster A disorders

- The patient has no peer relationships outside immediate family.

- The patient almost always chooses solitary activities for work and personal enjoyment.

❚ Cluster B clues

- Hypersensitivity to treatment disagreements or cancelled appointments are common (and likely experienced as rejection).

- Mood changes occur very quickly, even during a single visit.

- There is a history of many failed relationships with providers and others.

- The patient will describe an individual as both “wonderful” and “terrible” (ie, splitting) and may do so during the course of one visit.

- The patient may also split groups (eg, medical staff) by affective extremes (eg, adoration and hatred).

- The patient may hint at suicide or acts of self-harm.7

❚ Cluster C clues

- There is an excessive dependency on family, friends, or providers.

- Significant anxiety is experienced when the patient has to make an independent decision.

- There is a fear of relationship loss and resultant vulnerability to exploitation or abuse.

- Pervasive perfectionism makes treatment planning or course changes difficult.

- Anxiety and fear are unrelieved despite support and ample information.

Consider these screening tools

Several screening tools for personality disorders can be used to follow up on your initial clinical impressions. We also highly recommend you consider concurrent screening for substance abuse, as addiction is a common comorbidity with personality disorders.

❚

❚ A sampling of screening tools. The Standardised Assessment of Personality Abbreviated Scale (SAPAS)9 is an 8-item measure that correlates well with disorders in clusters A and C.

BPD (cluster B) has many brief scale options, including the McLean Screening Instrument for Borderline Personality Disorder (MSI-BPD).10 This 10-item questionnaire demonstrates sensitivity and specificity for BPD.

The International Personality Disorder Examination (IPDE) includes a 15-minute screening tool to help identify patients who may have any personality disorder, regardless of cluster.11

Improve patient encounters with these Tx pearls

In the family medicine clinic, a collaborative primary care and behavioral health team can be extremely helpful in the diagnosis and management of patients with personality disorders.12 First-line treatment of these disorders is psychotherapy, whereas medications are mainly used for symptom management. See Black and colleagues’ work for a thorough discussion on psychopharmacology considerations with personality disorders. 13

The following tips can help you to improve your interactions with patients who have personality disorders.

❚ Cluster A approaches

- Recommend treatment that respects the patient’s need for relative isolation.14

- Don’t be personally offended by your patient’s flat or disinterested affect or concrete thinking; don’t let it diminish the emotional support you provide.6

- Consult with a health psychologist (who has expertise in physical health conditions, brief treatments, and the medical system) to connect the patient with a long-term therapist. It is better to focus on fundamental changes, rather than employing brief behavioral techniques, for symptom relief. Patients with personality disorders tend to have better outcomes with long-term psychological care.15

❚ Cluster B approaches

- Set boundaries—eg, specific time limits for visits—and keep them.8

- Schedule brief, more frequent, appointments to reduce perceived feelings of abandonment.

- Coordinate plans with the entire clinic team to avoid splitting and blaming.16

- Avoid providing patients with personal information, as it may provide fodder for splitting behavior. 8

- Do not take things personally. Let patients “own” their own distress. These patients often take an emotional toll on the provider.16

- Engage the help of a health psychologist to reduce burnout and for more long-term continuity of care. A health psychologist who specializes in dialectical behavioral therapy to work on emotion regulation, distress tolerance, and interpersonal effectiveness would be ideal.17

Continue to: Cluster C approaches...

❚

❚ Cluster C approaches

- Engage the help of family and other trusted individuals in supporting treatment plans.18,19

- Try to provide just 2 treatment choices to the patient and reinforce his or her responsibility to help make the decision collaboratively. This step is important since it is difficult to enhance autonomy in these patients.20

- Engage the help of a cognitive behavioral therapist who can work on assertiveness and problem-solving skills.19

- Be empathetic with the patient and patiently build a trusting relationship, rather than “arguing” with the patient about each specific worry.20

- Make only one change at a time. Give small assignments to the patient, such as monitoring symptoms or reading up on their condition. These can help the patient feel more in control.21

- Present information in brief, clear terms. Avoid “grey areas” to reduce anxiety.21

- Engage a behavioral health provider to reduce rigid expectations and ideally increase feelings of self-esteem; this has been shown to predict better treatment outcomes.22

CASES

Mr. S displays cluster-A characteristics of schizoid personality disorder in addition to the depression he is being treated for. His physician was not put off by his flat affect and respected his limitations with social activities. Use of a stationary bike was recommended for exercise rather than walks outdoors. He also preferred phone calls to in-person encounters, so his follow-up visits were conducted by phone.

Ms. L exhibits cluster-B characteristics of BPD. You begin the tricky dance of setting limits, keeping communication clear, and not blaming yourself or others on your team for Ms. L’s feelings. You schedule regular visits with explicit time limits and discuss with your entire team how to avoid splitting. You involve a psychologist, familiar with treating BPD, who helps the patient learn positive interpersonal coping skills.

Ms. B displays cluster-C characteristics of dependent and obsessive-compulsive personality disorders. At her follow-up visit, you provide a great deal of empathy and try not to argue her out of each worry that she brings up. You make one change at a time and enlist the help of her daughter in giving her pills at home and offering reassurance. You collaborate with a cognitive behavioral therapist who works on exposing her to moderately anxiety-provoking situations/decisions.

1. Hull SK, Broquet K. How to manage difficult patient encounters. Fam Pract Manag. 2007;14:30-34.

2. Groves JE. Taking care of the hateful patient. N Engl J Med.1978;298: 883-887.

3. O’Dowd TC. Five years of heartsink patients in primary care. BMJ. 1988;297:528-530.

4. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th edition (DSM-5). American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013.

5. Volkert J, Gablonski TC, Rabung S. Prevalence of personality disorders in the general adult population in Western countries: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2018;213:709-715.

6. Esterberg ML, Goulding SM, Walker EF. Cluster A personality disorders: schizotypal, schizoid and paranoid personality disorders in childhood and adolescence. J Psychopathol Behav Assess. 2010;32:515-528.

7. Yen S, Peters JR, Nishar S, et al. Association of borderline personality disorder criteria with suicide attempts: findings from the collaborative longitudinal study of personality disorders over 10 years of follow-up. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78:187-194.

8. Dubovsky AN, Kiefer MM. Borderline personality disorder in the primary care setting. Med Clin North Am. 2014;98:1049-1064.

9. Hesse M, Moran P. (2010). Screening for personality disorder with the Standardised Assessment of Personality: Abbreviated Scale (SAPAS): further evidence of concurrent validity. BMC Psychiatry. 2010;10:10.

10. Zanarini MC, Vujanovic AA, Parachini EA, et al. A screening measure for BPD: the McLean screening instrument for borderline personality disorder (MSI-BPD). J Pers Disord. 2003;17:568-573.

11. Loranger AW, Sartorius N, Andreoli A, et al. The International Personality Disorder Examination. The World Health Organization/Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration international pilot study of personality disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:215-224.12. Nelson KJ, Skodol A, Friedman M. Pharmacotherapy for personality disorders. UpToDate. Accessed April 22, 2021. www.uptodate.com/contents/pharmacotherapy-for-personality-disorders

13. Black D, Paris J, Schulz C. Evidence-based integrated biopsychosocial treatment of borderline personality disorder. In: Muse M (ed). Cognitive Behavioral Psychopharmacology: the Clinical Practice of Evidence-Based Biopsychosocial Integration. Wiley; 2017:137-166.

14. Beck AT, Davis DD, Freeman A. Cognitive Therapy of Personality Disorders. 3rd ed. The Guilford Press; 2015.

15. Thylstrup B, Hesse M. “I am not complaining”–ambivalence construct in schizoid personality disorder. Am J Psychother. 2009;63:147-167.

16. Ricke AK, Lee MJ, Chambers JE. The difficult patient: borderline personality disorder in the obstetrical and gynecological patient. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2012;67:495-502.

17. Seow LLY, Page AC, Hooke GR. Severity of borderline personality disorder symptoms as a moderator of the association between the use of dialectical behaviour therapy skills and treatment outcomes. Psychother Res. 2020;30:920-933.

18. Nichols WC. Integrative marital and family treatment of dependent personality disorders. In: MacFarlane MM (Ed.) Family Treatment of Personality Disorders: Advances in Clinical Practice. Haworth Clinical Practice Press; 2004:173-204.

19. Disney KL. Dependent personality disorder: a critical review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2013;33:1184-1196.

20. Bender DS. The therapeutic alliance in the treatment of personality disorders. J Psychiatr Pract. 2005;11:73-87.

21. Ward RK. Assessment and management of personality disorders. Am Fam Physician. 2004;70:1505-1512.

22. Cummings JA, Hayes AM, Cardaciotto L, et al. The dynamics of self-esteem in cognitive therapy for avoidant and obsessive-compulsive personality disorders: an adaptive role of self-esteem variability? Cognit Ther Res. 2012;36:272-281.

Specific behaviors or expressed thoughts may signal a need for screening. Take into account an individual’s strengths and limitations when designing a Tx approach.

Specific behaviors or expressed thoughts may signal a need for screening. Take into account an individual’s strengths and limitations when designing a Tx approach.

THE CASES

Winston S* is a 23-year-old man referred by a psychiatrist colleague for primary care. He works delivering papers in the early morning hours and spends his day alone in his apartment mainly eating frozen pizza. He has worked solitary jobs his entire life and says he prefers it that way. His answers to questions lack emotion. He doesn’t seem to have any friends or regular contact with family. He follows the medical advice he receives but can’t seem to get out of the house to exercise or socialize. His psychiatrist was treating him with a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor for depression when he was referred.

Denise L* is a 37-year-old woman who transferred to your practice because she says the previous practice’s office manager was disrespectful and the doctor did not listen to her. She has been “very appreciative” of you and your “well-run office.” You have addressed her fibromyalgia and she has shared several personal details about her life. In the following weeks, you receive several phone calls and messages from her. At a follow-up visit, she asks questions about your family and seems agitated when you hesitate to answer. She questions whether you remember details of her history. She pushes, “Did you remember that, doctor?” She also mentions that your front desk staff seems rude to her.

Ruth B* is an 82-year-old woman whose blood pressure measured in your office is 176/94 mm Hg. When you recommend starting a medication and getting blood tests, she responds with a litany of fearful questions. She seems immobilized by worries about treatment and equally so about the risks of nontreatment. You can’t seem to get past the anxiety to decide on a satisfactory plan. She has to write everything down on a notepad and worries if she does not get every detail.

●

* This patient’s name has been changed to protect his identity. The other 2 patients are an amalgam of patients for whom the authors have provided care.