User login

How to protect patients’ confidentiality

Psychiatrist reveals patients’ information to another patient

Alameda County (CA) Superior Court

For several years 2 female patients were treated by the same psychiatrist. Jane Doe, age 56, read a breach of confidentiality report alleging sexual abuse filed by another patient of the psychiatrist. Jane Doe contacted the alleged victim, who informed her that the psychiatrist had disclosed information to her (the victim) regarding Jane Doe’s treatment, emotional problems, sexual preferences, and medication regimen.

Susan Doe, age 64, learned of the sexual abuse accusations against the psychiatrist in the same way and also contacted the alleged victim. She told Susan Doe that the psychiatrist had disclosed to her Susan Doe’s personal information regarding her dificult relationship with her daughter, depression, and instances when she stormed out of counseling sessions.

The patients brought separate claims, and their cases were later consolidated. The psychiatrist denied that he told the alleged sexual abuse victim details of the 2 patients’ treatments. The patients claimed that the victim could not have known their personal details unless the psychiatrist had told her.

- A jury returned a verdict in favor of the 2 patients. Jane Doe was awarded $225,000, and Susan Doe was awarded $47,000.

Dr. Grant’s observations

In the case of Jane Doe and Susan Doe, disclosing a patient’s personal information to another patient violates confidentiality. Patients must consent to the disclosure of information to third parties, and in this case these 2 patients apparently did not provide consent.

Medical practice—and particularly psychiatric practice—is based on the principle that communications between clinicians and patients are private. The Hippocratic oath states, “Whatever I see or hear in the lives of my patients, whether in connection with my professional practice or not, which ought not to be spoken of outside, I will keep secret, as considering all such things to be private.”1

According to the American Psychiatric Association’s (APA) code of ethics, “Psychiatric records, including even the identification of a person as a patient, must be protected with extreme care. Confidentiality is essential to psychiatric treatment, in part because of the special nature of psychiatric therapy. A psychiatrist may release confidential information only with the patient’s authorization or under proper legal compulsion.”2

Doctor-patient confidentiality is rooted in the belief that potential disclosure of information communicated during psychiatric diagnosis and treatment would discourage patients from seeking medical and mental health care (Table)

Table

Underlying values of confidentiality

| Proper doctor-patient confidentiality aims to: |

|

| Source: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General—Executive Summary. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Mental Health Services, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Mental Health, 1999. |

When to disclose

There are circumstances, however, that override the requirement to maintain confidentiality and do not need a patient’s consent. Examples include:3

Duty to protect third parties. In 1976 the California Supreme Court ruled in the landmark Tarasoff case4 that a psychiatrist has a duty to do what is reasonably necessary to protect third parties if a patient presents a serious risk of violence to another person. The specific applications of this principle are governed by other states’ laws, which have extended or limited this duty.5 Be familiar with the law in your jurisdiction before disclosing confidential information to third parties who may be at risk of violence.

The APA’s position on this exception is consistent with legal standards. Its code of ethics states, “When, in the clinical judgment of the treating psychiatrist, the risk of danger is deemed to be significant, the psychiatrist may reveal confidential information disclosed by the patient.”6

Emergency release of information. Psychiatrists can release confidential information during a medical emergency. Releasing the information must be in the patient’s best interests, and the patient’s inability to consent to the release should be the result of a potentially reversible condition that leads the clinician to question the patient’s capacity to consent.3

For example, if a patient in an emergency room is delirious because of ingesting an unknown substance and is unable to consent, a physician can call family members to ask about the patient’s medical problems. Notifying family that the patient is in the hospital could violate confidentiality, however.

Reporting abuse. All clinicians are obligated to report suspected child abuse or neglect. Some state laws also may require physicians to disclose abuse of vulnerable groups such as the elderly or the disabled and report to the local department of health diagnosis of communicable diseases such as HIV.3

Circle of confidentiality. Certain parties— including clinical staff on an inpatient unit or a psychiatrist supervising a resident— are considered to be within a circle of confidentiality.3 You do not need a patient’s consent to share clinical information with those within the circle of confidentiality. Do not release a patient’s information to parties who are not in the circle of confidentiality—such as family members, attorneys representing the patient, and law enforcement personnel—unless you’ve first obtained the patient’s consent.

Document the reasoning behind your decision to disclose your patient’s personal information without the patient’s consent. Show that you engaged in a reasonable clinical decision-making process.3 For example, record the risks and benefits of your decision and how you arrived at your conclusion.3

Other scenarios

Multidisciplinary teams. Members of a multidisciplinary treatment team—such as physicians, nurses, or social workers—should only receive confidential information that is relevant to the patient’s care. Other clinicians who are not involved in the case—although they may be seeing other patients on the same unit—should not have access to the patient’s confidential information. Discussions with these team members must be private so that others do not overhear confidential information.

Insurance companies generally are not party to the patient’s records unless the patient agrees to allow access by signing a release. If the patient’s refusal to allow disclosure results in the insurance company’s refusal to pay, then the patient is responsible for resolving the issue.7

Scientific publications and presentations. When you present a case report for a scientific publication or at a meeting, alter the patient’s biographical data so that someone who knows the patient would be unable to identify him or her based on the information in the case report. If the information is so specific that you cannot prevent patient identification, either do not publish the case or offer the patient the right to veto the manuscript’s distribution. If necessary, have the patient sign a consent form to allow publication or presentation of the case report.

Confidentiality violations

Breach of confidentiality may be intentional, such as disclosing a patient’s personal information to a third party as in this case, or unintentional, such as talking about a patient to a colleague and having someone overhear your discussion.8 Violating confidentiality may result in litigation for malpractice (negligence), invasion of privacy, or breach of contract, and ethical sanctions.8

No aspect of psychiatric practice seems to generate stronger emotions than the potential legal repercussions of our work. Keeping up with patients’ needs, billing issues, and advancements in medicine leaves little time for tracking changing state and federal laws or case precedents. For the past 4 years it has been my pleasure to provide information on the legal issues psychiatrists face and provide possible means of avoiding legal pitfalls.

Although I have decided to pursue other projects, I wish to give readers my thanks and to suggest resources—only a few among many great ones—that may be useful guides for a variety of legal issues.

Jon E. Grant, JD, MD, MPH

- Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law.

- Appelbaum PS, Gutheil TG. Clinical handbook of psychiatry and the law. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006.

- Lifson LE, Simon RI, eds. The mental health practitioner and the law. Cambridge, MA:Harvard University Press; 1998.

- Simon RI, Shuman DW.Clinical manual of psychiatry and the law. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc. ; 2007.

Editor’s note

Current Psychiatry thanks Dr. Grant for writing the Malpractice Verdicts column since 2004. The column will continue in a new format in the February 2008 issue.

1. National Institutes of Health. The Hippocratic oath. Available at: http://www.nlm.nih.gov/hmd/greek/greek_oath.html. Accessed October 30, 2007.

2. Principles of medical ethics with annotations especially applicable to psychiatry. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2006: 6. Availableat: http://www.psych.org/psych_pract/ethics/ppaethics.pdf. Accessed October 30, 2007.

3. Lowenthal D. Case studies in confidentiality. J Psychiatr Prac 2002;8:151-9.

4. Tarasoff vs Regents of the University of California 551P 2d 334 (Cal 1976).

5. Appelbaum PS Taras off and the clinician: problems in fulfilling the duty to protect. Am J Psychiatry 1985;142:425-9.

6. Principles of medical ethics with annotations especially applicable to psychiatry. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2006:7. Availableat: http://www.psych.org/psych_pract/ethics/ppaethics.pdf. Accessed October 30, 2007.

7. Hilliard J. Liability issues with managed care. In: Lifson LE, Simon RI, eds. The mental health practitioner and the law. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1998:44-51.

8. Berner M. Write smarter, not longer. In: Lifson LE, Simon RI, eds. The mental health practitioner and the law. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1998:54-71.

Cases are selected by Current Psychiatry fromMedical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements & Experts, with permission of its editor, Lewis Laska of Nashville, TN (www.verdictslaska.com). Information may be incomplete in some instances, but these cases represent clinical situations that typically result in litigation.

Psychiatrist reveals patients’ information to another patient

Alameda County (CA) Superior Court

For several years 2 female patients were treated by the same psychiatrist. Jane Doe, age 56, read a breach of confidentiality report alleging sexual abuse filed by another patient of the psychiatrist. Jane Doe contacted the alleged victim, who informed her that the psychiatrist had disclosed information to her (the victim) regarding Jane Doe’s treatment, emotional problems, sexual preferences, and medication regimen.

Susan Doe, age 64, learned of the sexual abuse accusations against the psychiatrist in the same way and also contacted the alleged victim. She told Susan Doe that the psychiatrist had disclosed to her Susan Doe’s personal information regarding her dificult relationship with her daughter, depression, and instances when she stormed out of counseling sessions.

The patients brought separate claims, and their cases were later consolidated. The psychiatrist denied that he told the alleged sexual abuse victim details of the 2 patients’ treatments. The patients claimed that the victim could not have known their personal details unless the psychiatrist had told her.

- A jury returned a verdict in favor of the 2 patients. Jane Doe was awarded $225,000, and Susan Doe was awarded $47,000.

Dr. Grant’s observations

In the case of Jane Doe and Susan Doe, disclosing a patient’s personal information to another patient violates confidentiality. Patients must consent to the disclosure of information to third parties, and in this case these 2 patients apparently did not provide consent.

Medical practice—and particularly psychiatric practice—is based on the principle that communications between clinicians and patients are private. The Hippocratic oath states, “Whatever I see or hear in the lives of my patients, whether in connection with my professional practice or not, which ought not to be spoken of outside, I will keep secret, as considering all such things to be private.”1

According to the American Psychiatric Association’s (APA) code of ethics, “Psychiatric records, including even the identification of a person as a patient, must be protected with extreme care. Confidentiality is essential to psychiatric treatment, in part because of the special nature of psychiatric therapy. A psychiatrist may release confidential information only with the patient’s authorization or under proper legal compulsion.”2

Doctor-patient confidentiality is rooted in the belief that potential disclosure of information communicated during psychiatric diagnosis and treatment would discourage patients from seeking medical and mental health care (Table)

Table

Underlying values of confidentiality

| Proper doctor-patient confidentiality aims to: |

|

| Source: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General—Executive Summary. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Mental Health Services, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Mental Health, 1999. |

When to disclose

There are circumstances, however, that override the requirement to maintain confidentiality and do not need a patient’s consent. Examples include:3

Duty to protect third parties. In 1976 the California Supreme Court ruled in the landmark Tarasoff case4 that a psychiatrist has a duty to do what is reasonably necessary to protect third parties if a patient presents a serious risk of violence to another person. The specific applications of this principle are governed by other states’ laws, which have extended or limited this duty.5 Be familiar with the law in your jurisdiction before disclosing confidential information to third parties who may be at risk of violence.

The APA’s position on this exception is consistent with legal standards. Its code of ethics states, “When, in the clinical judgment of the treating psychiatrist, the risk of danger is deemed to be significant, the psychiatrist may reveal confidential information disclosed by the patient.”6

Emergency release of information. Psychiatrists can release confidential information during a medical emergency. Releasing the information must be in the patient’s best interests, and the patient’s inability to consent to the release should be the result of a potentially reversible condition that leads the clinician to question the patient’s capacity to consent.3

For example, if a patient in an emergency room is delirious because of ingesting an unknown substance and is unable to consent, a physician can call family members to ask about the patient’s medical problems. Notifying family that the patient is in the hospital could violate confidentiality, however.

Reporting abuse. All clinicians are obligated to report suspected child abuse or neglect. Some state laws also may require physicians to disclose abuse of vulnerable groups such as the elderly or the disabled and report to the local department of health diagnosis of communicable diseases such as HIV.3

Circle of confidentiality. Certain parties— including clinical staff on an inpatient unit or a psychiatrist supervising a resident— are considered to be within a circle of confidentiality.3 You do not need a patient’s consent to share clinical information with those within the circle of confidentiality. Do not release a patient’s information to parties who are not in the circle of confidentiality—such as family members, attorneys representing the patient, and law enforcement personnel—unless you’ve first obtained the patient’s consent.

Document the reasoning behind your decision to disclose your patient’s personal information without the patient’s consent. Show that you engaged in a reasonable clinical decision-making process.3 For example, record the risks and benefits of your decision and how you arrived at your conclusion.3

Other scenarios

Multidisciplinary teams. Members of a multidisciplinary treatment team—such as physicians, nurses, or social workers—should only receive confidential information that is relevant to the patient’s care. Other clinicians who are not involved in the case—although they may be seeing other patients on the same unit—should not have access to the patient’s confidential information. Discussions with these team members must be private so that others do not overhear confidential information.

Insurance companies generally are not party to the patient’s records unless the patient agrees to allow access by signing a release. If the patient’s refusal to allow disclosure results in the insurance company’s refusal to pay, then the patient is responsible for resolving the issue.7

Scientific publications and presentations. When you present a case report for a scientific publication or at a meeting, alter the patient’s biographical data so that someone who knows the patient would be unable to identify him or her based on the information in the case report. If the information is so specific that you cannot prevent patient identification, either do not publish the case or offer the patient the right to veto the manuscript’s distribution. If necessary, have the patient sign a consent form to allow publication or presentation of the case report.

Confidentiality violations

Breach of confidentiality may be intentional, such as disclosing a patient’s personal information to a third party as in this case, or unintentional, such as talking about a patient to a colleague and having someone overhear your discussion.8 Violating confidentiality may result in litigation for malpractice (negligence), invasion of privacy, or breach of contract, and ethical sanctions.8

No aspect of psychiatric practice seems to generate stronger emotions than the potential legal repercussions of our work. Keeping up with patients’ needs, billing issues, and advancements in medicine leaves little time for tracking changing state and federal laws or case precedents. For the past 4 years it has been my pleasure to provide information on the legal issues psychiatrists face and provide possible means of avoiding legal pitfalls.

Although I have decided to pursue other projects, I wish to give readers my thanks and to suggest resources—only a few among many great ones—that may be useful guides for a variety of legal issues.

Jon E. Grant, JD, MD, MPH

- Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law.

- Appelbaum PS, Gutheil TG. Clinical handbook of psychiatry and the law. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006.

- Lifson LE, Simon RI, eds. The mental health practitioner and the law. Cambridge, MA:Harvard University Press; 1998.

- Simon RI, Shuman DW.Clinical manual of psychiatry and the law. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc. ; 2007.

Editor’s note

Current Psychiatry thanks Dr. Grant for writing the Malpractice Verdicts column since 2004. The column will continue in a new format in the February 2008 issue.

Psychiatrist reveals patients’ information to another patient

Alameda County (CA) Superior Court

For several years 2 female patients were treated by the same psychiatrist. Jane Doe, age 56, read a breach of confidentiality report alleging sexual abuse filed by another patient of the psychiatrist. Jane Doe contacted the alleged victim, who informed her that the psychiatrist had disclosed information to her (the victim) regarding Jane Doe’s treatment, emotional problems, sexual preferences, and medication regimen.

Susan Doe, age 64, learned of the sexual abuse accusations against the psychiatrist in the same way and also contacted the alleged victim. She told Susan Doe that the psychiatrist had disclosed to her Susan Doe’s personal information regarding her dificult relationship with her daughter, depression, and instances when she stormed out of counseling sessions.

The patients brought separate claims, and their cases were later consolidated. The psychiatrist denied that he told the alleged sexual abuse victim details of the 2 patients’ treatments. The patients claimed that the victim could not have known their personal details unless the psychiatrist had told her.

- A jury returned a verdict in favor of the 2 patients. Jane Doe was awarded $225,000, and Susan Doe was awarded $47,000.

Dr. Grant’s observations

In the case of Jane Doe and Susan Doe, disclosing a patient’s personal information to another patient violates confidentiality. Patients must consent to the disclosure of information to third parties, and in this case these 2 patients apparently did not provide consent.

Medical practice—and particularly psychiatric practice—is based on the principle that communications between clinicians and patients are private. The Hippocratic oath states, “Whatever I see or hear in the lives of my patients, whether in connection with my professional practice or not, which ought not to be spoken of outside, I will keep secret, as considering all such things to be private.”1

According to the American Psychiatric Association’s (APA) code of ethics, “Psychiatric records, including even the identification of a person as a patient, must be protected with extreme care. Confidentiality is essential to psychiatric treatment, in part because of the special nature of psychiatric therapy. A psychiatrist may release confidential information only with the patient’s authorization or under proper legal compulsion.”2

Doctor-patient confidentiality is rooted in the belief that potential disclosure of information communicated during psychiatric diagnosis and treatment would discourage patients from seeking medical and mental health care (Table)

Table

Underlying values of confidentiality

| Proper doctor-patient confidentiality aims to: |

|

| Source: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General—Executive Summary. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Mental Health Services, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Mental Health, 1999. |

When to disclose

There are circumstances, however, that override the requirement to maintain confidentiality and do not need a patient’s consent. Examples include:3

Duty to protect third parties. In 1976 the California Supreme Court ruled in the landmark Tarasoff case4 that a psychiatrist has a duty to do what is reasonably necessary to protect third parties if a patient presents a serious risk of violence to another person. The specific applications of this principle are governed by other states’ laws, which have extended or limited this duty.5 Be familiar with the law in your jurisdiction before disclosing confidential information to third parties who may be at risk of violence.

The APA’s position on this exception is consistent with legal standards. Its code of ethics states, “When, in the clinical judgment of the treating psychiatrist, the risk of danger is deemed to be significant, the psychiatrist may reveal confidential information disclosed by the patient.”6

Emergency release of information. Psychiatrists can release confidential information during a medical emergency. Releasing the information must be in the patient’s best interests, and the patient’s inability to consent to the release should be the result of a potentially reversible condition that leads the clinician to question the patient’s capacity to consent.3

For example, if a patient in an emergency room is delirious because of ingesting an unknown substance and is unable to consent, a physician can call family members to ask about the patient’s medical problems. Notifying family that the patient is in the hospital could violate confidentiality, however.

Reporting abuse. All clinicians are obligated to report suspected child abuse or neglect. Some state laws also may require physicians to disclose abuse of vulnerable groups such as the elderly or the disabled and report to the local department of health diagnosis of communicable diseases such as HIV.3

Circle of confidentiality. Certain parties— including clinical staff on an inpatient unit or a psychiatrist supervising a resident— are considered to be within a circle of confidentiality.3 You do not need a patient’s consent to share clinical information with those within the circle of confidentiality. Do not release a patient’s information to parties who are not in the circle of confidentiality—such as family members, attorneys representing the patient, and law enforcement personnel—unless you’ve first obtained the patient’s consent.

Document the reasoning behind your decision to disclose your patient’s personal information without the patient’s consent. Show that you engaged in a reasonable clinical decision-making process.3 For example, record the risks and benefits of your decision and how you arrived at your conclusion.3

Other scenarios

Multidisciplinary teams. Members of a multidisciplinary treatment team—such as physicians, nurses, or social workers—should only receive confidential information that is relevant to the patient’s care. Other clinicians who are not involved in the case—although they may be seeing other patients on the same unit—should not have access to the patient’s confidential information. Discussions with these team members must be private so that others do not overhear confidential information.

Insurance companies generally are not party to the patient’s records unless the patient agrees to allow access by signing a release. If the patient’s refusal to allow disclosure results in the insurance company’s refusal to pay, then the patient is responsible for resolving the issue.7

Scientific publications and presentations. When you present a case report for a scientific publication or at a meeting, alter the patient’s biographical data so that someone who knows the patient would be unable to identify him or her based on the information in the case report. If the information is so specific that you cannot prevent patient identification, either do not publish the case or offer the patient the right to veto the manuscript’s distribution. If necessary, have the patient sign a consent form to allow publication or presentation of the case report.

Confidentiality violations

Breach of confidentiality may be intentional, such as disclosing a patient’s personal information to a third party as in this case, or unintentional, such as talking about a patient to a colleague and having someone overhear your discussion.8 Violating confidentiality may result in litigation for malpractice (negligence), invasion of privacy, or breach of contract, and ethical sanctions.8

No aspect of psychiatric practice seems to generate stronger emotions than the potential legal repercussions of our work. Keeping up with patients’ needs, billing issues, and advancements in medicine leaves little time for tracking changing state and federal laws or case precedents. For the past 4 years it has been my pleasure to provide information on the legal issues psychiatrists face and provide possible means of avoiding legal pitfalls.

Although I have decided to pursue other projects, I wish to give readers my thanks and to suggest resources—only a few among many great ones—that may be useful guides for a variety of legal issues.

Jon E. Grant, JD, MD, MPH

- Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law.

- Appelbaum PS, Gutheil TG. Clinical handbook of psychiatry and the law. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006.

- Lifson LE, Simon RI, eds. The mental health practitioner and the law. Cambridge, MA:Harvard University Press; 1998.

- Simon RI, Shuman DW.Clinical manual of psychiatry and the law. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc. ; 2007.

Editor’s note

Current Psychiatry thanks Dr. Grant for writing the Malpractice Verdicts column since 2004. The column will continue in a new format in the February 2008 issue.

1. National Institutes of Health. The Hippocratic oath. Available at: http://www.nlm.nih.gov/hmd/greek/greek_oath.html. Accessed October 30, 2007.

2. Principles of medical ethics with annotations especially applicable to psychiatry. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2006: 6. Availableat: http://www.psych.org/psych_pract/ethics/ppaethics.pdf. Accessed October 30, 2007.

3. Lowenthal D. Case studies in confidentiality. J Psychiatr Prac 2002;8:151-9.

4. Tarasoff vs Regents of the University of California 551P 2d 334 (Cal 1976).

5. Appelbaum PS Taras off and the clinician: problems in fulfilling the duty to protect. Am J Psychiatry 1985;142:425-9.

6. Principles of medical ethics with annotations especially applicable to psychiatry. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2006:7. Availableat: http://www.psych.org/psych_pract/ethics/ppaethics.pdf. Accessed October 30, 2007.

7. Hilliard J. Liability issues with managed care. In: Lifson LE, Simon RI, eds. The mental health practitioner and the law. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1998:44-51.

8. Berner M. Write smarter, not longer. In: Lifson LE, Simon RI, eds. The mental health practitioner and the law. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1998:54-71.

Cases are selected by Current Psychiatry fromMedical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements & Experts, with permission of its editor, Lewis Laska of Nashville, TN (www.verdictslaska.com). Information may be incomplete in some instances, but these cases represent clinical situations that typically result in litigation.

1. National Institutes of Health. The Hippocratic oath. Available at: http://www.nlm.nih.gov/hmd/greek/greek_oath.html. Accessed October 30, 2007.

2. Principles of medical ethics with annotations especially applicable to psychiatry. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2006: 6. Availableat: http://www.psych.org/psych_pract/ethics/ppaethics.pdf. Accessed October 30, 2007.

3. Lowenthal D. Case studies in confidentiality. J Psychiatr Prac 2002;8:151-9.

4. Tarasoff vs Regents of the University of California 551P 2d 334 (Cal 1976).

5. Appelbaum PS Taras off and the clinician: problems in fulfilling the duty to protect. Am J Psychiatry 1985;142:425-9.

6. Principles of medical ethics with annotations especially applicable to psychiatry. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2006:7. Availableat: http://www.psych.org/psych_pract/ethics/ppaethics.pdf. Accessed October 30, 2007.

7. Hilliard J. Liability issues with managed care. In: Lifson LE, Simon RI, eds. The mental health practitioner and the law. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1998:44-51.

8. Berner M. Write smarter, not longer. In: Lifson LE, Simon RI, eds. The mental health practitioner and the law. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1998:54-71.

Cases are selected by Current Psychiatry fromMedical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements & Experts, with permission of its editor, Lewis Laska of Nashville, TN (www.verdictslaska.com). Information may be incomplete in some instances, but these cases represent clinical situations that typically result in litigation.

SHM: BEHIND THE SCENES

Enter text here

Enter text here

Enter text here

Salary Stress

Question: I am working too hard and getting paid too little. Is there any easy to figure out if I am getting paid what I am worth?

Show Me the Money, Austin, Texas

Dr. Hospitalist responds: I suspect you may have already asked hospitalists you know about how much they make and compared schedules. Although this may be sadistically fun (alas, misery loves company), there are problems with this approach.

Your perspective is limited to friends and colleagues willing to share this information. Some people are reluctant to talk money, others have a tendency to embellish their productivity. I am not saying folks would intentionally lie to you (wink, nod), but who would tell you they feel overpaid and do not work hard?

What you need are objective data. You and a couple of colleagues could develop a survey, send it to every hospitalist you know, and hope they respond. But even if you did, how often could you muster the energy to do this to keep your data up to date?

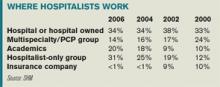

Remember, you are doing this survey to demonstrate you are compensated appropriately for how much work you produce. Lucky for you, several organizations collect physician productivity and compensation data, including SHM and the Medical Group Management Association (MGMA). But there are differences in the data.

Some believe the MGMA data set may include information from primary care groups with inpatient rounders in addition to full-time hospitalists. Meanwhile, SHM data were last collected in November 2005. SHM collects updated information from hospitalists around the country. They will make those findings available at the next SHM annual meeting in San Diego in April 2008.

This will also be the first survey done since Medicare moved to the new 2007 relative value unit (RVU) values. Hospitalists who contribute to the survey can access the data for free. I suppose critics could argue that the approach taken by these groups is subject to bias because individuals could submit false data. This is all the more reason I would encourage you to submit data to the SHM survey. The larger the sample size, the more difficult it will be for any one individual’s data to warp the survey.

Speak Up

Question: I know hospitalists should communicate with primary care physicians (PCPs) about their patients, but I find it takes a lot of time for me to call their offices. Is there an easier way to do this? I am also not completely sure of when I should communicate. Any suggestions?

No Time to Talk, Atlanta

Dr. Hospitalist responds: Let me guess. Your “communication” with the PCP goes something like this: You pick up the telephone to call a patient’s PCP. After sitting on hold for what seems like eternity (your pager rings repeatedly during this time), a voice on the other end of line tells you that the doctor is in an exam room. “Do you want me to interrupt him?”

Do you say yes and run the risk of sitting on hold another five minutes? Or do you decide whatever you had to say really isn’t that important? But don’t you need that outpatient medication list? Do you really have to tell the PCP about the ongoing end of life discussions with the patient? What’s a hospitalist to do?

This method of communication may have worked when you were a resident in training, when your workload was capped and your attending physician had to make time for your calls. But try this as a hospitalist and you’ll quickly discover you don’t have enough hours each day.

When working out a relationship with a PCP, hospitalists should engage the PCP in a discussion about how they should communicate. For example, the hospitalist and PCP may agree that each time a patient presents for admission, the hospitalist will ask the hospitalist administrative assistant to fax the PCP office. A fax with admission diagnoses will not only serve as notification of admission but also as a request for information from the PCP.

As important as it is for the hospitalist to get his staff to fax the request in a timely manner, the PCP will have to do the same with his/her office staff. In such a system, the hospitalist and the PCP communicate about admissions via their administrative staff. If the PCP or hospitalist has further questions, the expectation may be that a page will be in order. But for the majority of admissions, that won’t be necessary.

I have seen hospitalists and PCPs handle routine communication in a variety of ways: phone calls, face-to-face discussion, e-mail, voicemail, discharge summaries/letters, fax notification of admission, pages. No single method works well with all groups all the time. To succeed, communication:

- Must be timely, easy to understand, and concise;

- Must be efficient for the communicator and the recipient, not labor intensive;

- Should occur at each transition in care; and

- Should meet privacy guidelines.

Communicators must understand the rules of engagement and share common expectations. Ideally, there should be a paper trail or other record.

Hiring is Work

Question: My group is having a hard time recruiting physicians. How can we do better?

Need Help, Richmond, Va.

Dr. Hospitalist responds: If it’s any consolation, you’re not alone. Look at the number of pages devoted to job ads in this issue of The Hospitalist and you’ll understand the high demand for hospitalists. There are about 20,000 hospitalists in the country, and many believe there is room for double that number. Advertising and hiring qualified staff is not a challenge unique to hospital medicine, but most hospitalists received no training on how to do it. Most hospitalists underestimate the time and resources it takes to recruit and hire staff.

Here are some hiring hints to help you and your hospitalist program maximize your success.

The first step is to create a job description. Before you can describe the job to prospective hospitalists, you need a clear understanding yourself. I would expect applicants to ask some of the following questions:

- Do your hospitalists to work days, nights or a combination of both?

- What about weekdays versus weekends?

- How does your group handle admissions versus daily rounding?

- Do your hospitalists provide consultative services?

- Are there teaching responsibilities?

- How many patients do you expect each hospitalists to see daily?

Based on your job description, how do you expect to compensate your hospitalists? Do your homework and find out what competitors are paying for similar job descriptions. While there are many reasons prospective hospitalists might accept an offer, salary is often not the only reason. What else is part of your compensation package? It might include some of the following:

- A retirement plan, like a 401k/ 403b or a pension;

- Paid parking;

- Continuing-education stipend;

- Productivity incentive;

- Access to health, life and/or disability insurance;

- Paid malpractice insurance; and

- Ownership/equity opportunity.

Once you create an attractive job description with a competitive compensation package, it’s time to get the word out. There are many options for reaching prospective candidates:

- Advertise in journals and online;

- Advertise at meetings;

- Tell friends, colleagues and nurses;

- Work with your hospital’s recruiter;

- Send targeted mailings; and

- Be seen at local hospitalist events.

Once you have an applicant interested, it’s time to close the deal. Qualified applicants are likely going to field offers from several groups. Why should the applicant accept your offer over another? Here are several incentives:

- Signing bonus;

- Relocation package;

- Loan forgiveness;

- Title for an administrative role; and

- Opportunity for advancement.

Don’t underestimate the effect of a simple phone call or e-mail to your candidate after the interview. I can’t emphasize how often I hear people say they joined a group because they felt as though they fit in well.

Hiring is a year-round group effort. The most important resource in any hospitalist program is staff. Recruitment, hiring, and retention should be a primary goal of any hospitalist medical director. TH

Question: I am working too hard and getting paid too little. Is there any easy to figure out if I am getting paid what I am worth?

Show Me the Money, Austin, Texas

Dr. Hospitalist responds: I suspect you may have already asked hospitalists you know about how much they make and compared schedules. Although this may be sadistically fun (alas, misery loves company), there are problems with this approach.

Your perspective is limited to friends and colleagues willing to share this information. Some people are reluctant to talk money, others have a tendency to embellish their productivity. I am not saying folks would intentionally lie to you (wink, nod), but who would tell you they feel overpaid and do not work hard?

What you need are objective data. You and a couple of colleagues could develop a survey, send it to every hospitalist you know, and hope they respond. But even if you did, how often could you muster the energy to do this to keep your data up to date?

Remember, you are doing this survey to demonstrate you are compensated appropriately for how much work you produce. Lucky for you, several organizations collect physician productivity and compensation data, including SHM and the Medical Group Management Association (MGMA). But there are differences in the data.

Some believe the MGMA data set may include information from primary care groups with inpatient rounders in addition to full-time hospitalists. Meanwhile, SHM data were last collected in November 2005. SHM collects updated information from hospitalists around the country. They will make those findings available at the next SHM annual meeting in San Diego in April 2008.

This will also be the first survey done since Medicare moved to the new 2007 relative value unit (RVU) values. Hospitalists who contribute to the survey can access the data for free. I suppose critics could argue that the approach taken by these groups is subject to bias because individuals could submit false data. This is all the more reason I would encourage you to submit data to the SHM survey. The larger the sample size, the more difficult it will be for any one individual’s data to warp the survey.

Speak Up

Question: I know hospitalists should communicate with primary care physicians (PCPs) about their patients, but I find it takes a lot of time for me to call their offices. Is there an easier way to do this? I am also not completely sure of when I should communicate. Any suggestions?

No Time to Talk, Atlanta

Dr. Hospitalist responds: Let me guess. Your “communication” with the PCP goes something like this: You pick up the telephone to call a patient’s PCP. After sitting on hold for what seems like eternity (your pager rings repeatedly during this time), a voice on the other end of line tells you that the doctor is in an exam room. “Do you want me to interrupt him?”

Do you say yes and run the risk of sitting on hold another five minutes? Or do you decide whatever you had to say really isn’t that important? But don’t you need that outpatient medication list? Do you really have to tell the PCP about the ongoing end of life discussions with the patient? What’s a hospitalist to do?

This method of communication may have worked when you were a resident in training, when your workload was capped and your attending physician had to make time for your calls. But try this as a hospitalist and you’ll quickly discover you don’t have enough hours each day.

When working out a relationship with a PCP, hospitalists should engage the PCP in a discussion about how they should communicate. For example, the hospitalist and PCP may agree that each time a patient presents for admission, the hospitalist will ask the hospitalist administrative assistant to fax the PCP office. A fax with admission diagnoses will not only serve as notification of admission but also as a request for information from the PCP.

As important as it is for the hospitalist to get his staff to fax the request in a timely manner, the PCP will have to do the same with his/her office staff. In such a system, the hospitalist and the PCP communicate about admissions via their administrative staff. If the PCP or hospitalist has further questions, the expectation may be that a page will be in order. But for the majority of admissions, that won’t be necessary.

I have seen hospitalists and PCPs handle routine communication in a variety of ways: phone calls, face-to-face discussion, e-mail, voicemail, discharge summaries/letters, fax notification of admission, pages. No single method works well with all groups all the time. To succeed, communication:

- Must be timely, easy to understand, and concise;

- Must be efficient for the communicator and the recipient, not labor intensive;

- Should occur at each transition in care; and

- Should meet privacy guidelines.

Communicators must understand the rules of engagement and share common expectations. Ideally, there should be a paper trail or other record.

Hiring is Work

Question: My group is having a hard time recruiting physicians. How can we do better?

Need Help, Richmond, Va.

Dr. Hospitalist responds: If it’s any consolation, you’re not alone. Look at the number of pages devoted to job ads in this issue of The Hospitalist and you’ll understand the high demand for hospitalists. There are about 20,000 hospitalists in the country, and many believe there is room for double that number. Advertising and hiring qualified staff is not a challenge unique to hospital medicine, but most hospitalists received no training on how to do it. Most hospitalists underestimate the time and resources it takes to recruit and hire staff.

Here are some hiring hints to help you and your hospitalist program maximize your success.

The first step is to create a job description. Before you can describe the job to prospective hospitalists, you need a clear understanding yourself. I would expect applicants to ask some of the following questions:

- Do your hospitalists to work days, nights or a combination of both?

- What about weekdays versus weekends?

- How does your group handle admissions versus daily rounding?

- Do your hospitalists provide consultative services?

- Are there teaching responsibilities?

- How many patients do you expect each hospitalists to see daily?

Based on your job description, how do you expect to compensate your hospitalists? Do your homework and find out what competitors are paying for similar job descriptions. While there are many reasons prospective hospitalists might accept an offer, salary is often not the only reason. What else is part of your compensation package? It might include some of the following:

- A retirement plan, like a 401k/ 403b or a pension;

- Paid parking;

- Continuing-education stipend;

- Productivity incentive;

- Access to health, life and/or disability insurance;

- Paid malpractice insurance; and

- Ownership/equity opportunity.

Once you create an attractive job description with a competitive compensation package, it’s time to get the word out. There are many options for reaching prospective candidates:

- Advertise in journals and online;

- Advertise at meetings;

- Tell friends, colleagues and nurses;

- Work with your hospital’s recruiter;

- Send targeted mailings; and

- Be seen at local hospitalist events.

Once you have an applicant interested, it’s time to close the deal. Qualified applicants are likely going to field offers from several groups. Why should the applicant accept your offer over another? Here are several incentives:

- Signing bonus;

- Relocation package;

- Loan forgiveness;

- Title for an administrative role; and

- Opportunity for advancement.

Don’t underestimate the effect of a simple phone call or e-mail to your candidate after the interview. I can’t emphasize how often I hear people say they joined a group because they felt as though they fit in well.

Hiring is a year-round group effort. The most important resource in any hospitalist program is staff. Recruitment, hiring, and retention should be a primary goal of any hospitalist medical director. TH

Question: I am working too hard and getting paid too little. Is there any easy to figure out if I am getting paid what I am worth?

Show Me the Money, Austin, Texas

Dr. Hospitalist responds: I suspect you may have already asked hospitalists you know about how much they make and compared schedules. Although this may be sadistically fun (alas, misery loves company), there are problems with this approach.

Your perspective is limited to friends and colleagues willing to share this information. Some people are reluctant to talk money, others have a tendency to embellish their productivity. I am not saying folks would intentionally lie to you (wink, nod), but who would tell you they feel overpaid and do not work hard?

What you need are objective data. You and a couple of colleagues could develop a survey, send it to every hospitalist you know, and hope they respond. But even if you did, how often could you muster the energy to do this to keep your data up to date?

Remember, you are doing this survey to demonstrate you are compensated appropriately for how much work you produce. Lucky for you, several organizations collect physician productivity and compensation data, including SHM and the Medical Group Management Association (MGMA). But there are differences in the data.

Some believe the MGMA data set may include information from primary care groups with inpatient rounders in addition to full-time hospitalists. Meanwhile, SHM data were last collected in November 2005. SHM collects updated information from hospitalists around the country. They will make those findings available at the next SHM annual meeting in San Diego in April 2008.

This will also be the first survey done since Medicare moved to the new 2007 relative value unit (RVU) values. Hospitalists who contribute to the survey can access the data for free. I suppose critics could argue that the approach taken by these groups is subject to bias because individuals could submit false data. This is all the more reason I would encourage you to submit data to the SHM survey. The larger the sample size, the more difficult it will be for any one individual’s data to warp the survey.

Speak Up

Question: I know hospitalists should communicate with primary care physicians (PCPs) about their patients, but I find it takes a lot of time for me to call their offices. Is there an easier way to do this? I am also not completely sure of when I should communicate. Any suggestions?

No Time to Talk, Atlanta

Dr. Hospitalist responds: Let me guess. Your “communication” with the PCP goes something like this: You pick up the telephone to call a patient’s PCP. After sitting on hold for what seems like eternity (your pager rings repeatedly during this time), a voice on the other end of line tells you that the doctor is in an exam room. “Do you want me to interrupt him?”

Do you say yes and run the risk of sitting on hold another five minutes? Or do you decide whatever you had to say really isn’t that important? But don’t you need that outpatient medication list? Do you really have to tell the PCP about the ongoing end of life discussions with the patient? What’s a hospitalist to do?

This method of communication may have worked when you were a resident in training, when your workload was capped and your attending physician had to make time for your calls. But try this as a hospitalist and you’ll quickly discover you don’t have enough hours each day.

When working out a relationship with a PCP, hospitalists should engage the PCP in a discussion about how they should communicate. For example, the hospitalist and PCP may agree that each time a patient presents for admission, the hospitalist will ask the hospitalist administrative assistant to fax the PCP office. A fax with admission diagnoses will not only serve as notification of admission but also as a request for information from the PCP.

As important as it is for the hospitalist to get his staff to fax the request in a timely manner, the PCP will have to do the same with his/her office staff. In such a system, the hospitalist and the PCP communicate about admissions via their administrative staff. If the PCP or hospitalist has further questions, the expectation may be that a page will be in order. But for the majority of admissions, that won’t be necessary.

I have seen hospitalists and PCPs handle routine communication in a variety of ways: phone calls, face-to-face discussion, e-mail, voicemail, discharge summaries/letters, fax notification of admission, pages. No single method works well with all groups all the time. To succeed, communication:

- Must be timely, easy to understand, and concise;

- Must be efficient for the communicator and the recipient, not labor intensive;

- Should occur at each transition in care; and

- Should meet privacy guidelines.

Communicators must understand the rules of engagement and share common expectations. Ideally, there should be a paper trail or other record.

Hiring is Work

Question: My group is having a hard time recruiting physicians. How can we do better?

Need Help, Richmond, Va.

Dr. Hospitalist responds: If it’s any consolation, you’re not alone. Look at the number of pages devoted to job ads in this issue of The Hospitalist and you’ll understand the high demand for hospitalists. There are about 20,000 hospitalists in the country, and many believe there is room for double that number. Advertising and hiring qualified staff is not a challenge unique to hospital medicine, but most hospitalists received no training on how to do it. Most hospitalists underestimate the time and resources it takes to recruit and hire staff.

Here are some hiring hints to help you and your hospitalist program maximize your success.

The first step is to create a job description. Before you can describe the job to prospective hospitalists, you need a clear understanding yourself. I would expect applicants to ask some of the following questions:

- Do your hospitalists to work days, nights or a combination of both?

- What about weekdays versus weekends?

- How does your group handle admissions versus daily rounding?

- Do your hospitalists provide consultative services?

- Are there teaching responsibilities?

- How many patients do you expect each hospitalists to see daily?

Based on your job description, how do you expect to compensate your hospitalists? Do your homework and find out what competitors are paying for similar job descriptions. While there are many reasons prospective hospitalists might accept an offer, salary is often not the only reason. What else is part of your compensation package? It might include some of the following:

- A retirement plan, like a 401k/ 403b or a pension;

- Paid parking;

- Continuing-education stipend;

- Productivity incentive;

- Access to health, life and/or disability insurance;

- Paid malpractice insurance; and

- Ownership/equity opportunity.

Once you create an attractive job description with a competitive compensation package, it’s time to get the word out. There are many options for reaching prospective candidates:

- Advertise in journals and online;

- Advertise at meetings;

- Tell friends, colleagues and nurses;

- Work with your hospital’s recruiter;

- Send targeted mailings; and

- Be seen at local hospitalist events.

Once you have an applicant interested, it’s time to close the deal. Qualified applicants are likely going to field offers from several groups. Why should the applicant accept your offer over another? Here are several incentives:

- Signing bonus;

- Relocation package;

- Loan forgiveness;

- Title for an administrative role; and

- Opportunity for advancement.

Don’t underestimate the effect of a simple phone call or e-mail to your candidate after the interview. I can’t emphasize how often I hear people say they joined a group because they felt as though they fit in well.

Hiring is a year-round group effort. The most important resource in any hospitalist program is staff. Recruitment, hiring, and retention should be a primary goal of any hospitalist medical director. TH

A Surgical Surge

Many or most specialties in medicine are adopting a hospitalist model, at least to a limited extent. In fact, hospital care of adult medical patients wasn’t even the first place the idea was adopted.

In talking with people from hundreds of institutions it seems clear the idea appeared earlier and grew more quickly in pediatrics than adult medicine. And in the past 10 to 15 years, fields like obstetrics (“laborists”), psychiatry, gastroenterology, and many others have slowly begun to adopt the hospitalist model.

One of the most recent disciplines to join the parade is general surgery. And when comparing the forces in play for hospitalists in the early 1990s to the current situation for surgical hospitalists, I think we may be close to a surge in surgical hospitalists similar to what we’ve seen with medical hospitalists in the past 10 years.

When I say surgical hospitalists, I’m referring to surgeons with a nearly exclusive inpatient practice. Other terms such as surgicalist, acute care surgeon, and traumatologist overlap to some degree but have ambiguous meanings.

Generalizations

For some months I have contacted all the surgical hospitalist practices I can find to learn what forces led to their creation and how they are structured. Several common themes are emerging:

Prevalence: There are probably no more than 20 to 40 surgical hospitalist practices, but many institutions are considering the idea. This is similar to the situation for medical hospitalists in the early to mid-1990s.

Driver to start program: In every program I’ve found, the main impetus to start it was to address the burden of emergency department (ED) call for existing general surgeons. Like primary care, ED call is regarded as unattractive because it is unpredictable (lots of night and weekend work), usually has a poor payer mix, and many general surgeons have seen the “center of gravity” of their practice move away from the hospital toward an ambulatory surgery center over the past 10 years or so. Additionally, many general surgeons are increasingly uncomfortable caring for trauma patients because of recent changes in that field. (For an excellent discussion of the changing nature of general surgery and trauma care see “The Acute Care Surgeon” in The Hospitalist, May 2006, p. 25.)

Case volume: General surgery case volume tends to go up at a hospital that puts a surgical hospitalist program in place. When existing surgeons are relieved of ED call they increase their volume of (mostly elective) surgery. The availability of surgical hospitalists may mean fewer emergency cases presenting to the ED are referred elsewhere (which may happen when non-hospitalist surgeons are required to take ED call). These changes in case volume and the timing of the operations (e.g., volume of night surgeries may go up) may require adjustments to operating room staffing and scheduling. Presumably this increased volume would not occur in an area oversupplied with surgeons.

Economics: Like nearly all medical hospitalist programs, surgical hospitalist practices are not viable without financial support in addition to collected professional fees. In all cases I am aware of, this support comes from the sponsoring hospital.

While the cost may be similar to what the hospital might have paid for existing surgeons to take ED call, hospitals seem to be getting a better return on that investment with surgical hospitalists. A small group of surgical hospitalists can handle the increased volume and all ED calls, improving clinical and service quality. Some institutions report that surgical hospitalists are much more attentive to billing for nonoperative work than their predecessors.

Structure: Programs should have an outpatient clinic where the surgical hospitalists can provide post-operative follow-up. In most cases, each surgeon spends only half a day a week in the clinic.

Scope of practice: All surgical hospitalist practices take most or all ED general surgery calls. In some institutions, the surgical hospitalist also leads the trauma team. Other duties at a few institutions include things like managing a wound-care clinic and being on-call to place lines.

Opinion of other surgeons: Community private practice surgeons tend to support these programs, but most institutions limit or prohibit surgical hospitalists from accepting elective referrals. Community surgeons are still offered the option of remaining on the ED call schedule—as might be the case for surgeons new to the community. At least one institution reported that the presence of surgical hospitalists improved recruitment of non-hospitalist general surgeons. However, I am also aware of one program put into place largely at the insistence of the existing surgeons. Those same surgeons later insisted it be dissolved because they saw it as unwanted competition.

Staff needs: Surgical hospitalist practices nearly always require fewer doctors than a medical hospitalist practice in the same institution. This can lead to a tension between having the right number of surgical hospitalists for the case volume (often just one or two doctors) and enough to provide for a reasonable call schedule. Existing groups have adopted a number of strategies.

Groups with only two doctors often have each work seven on/seven off. The doctor on-call for that week takes all night call him/herself. In some practices that have a medical hospitalist in-house all night, it could be reasonable to have routine calls on the surgical patients (e.g., sleeping pills, laxatives, low urine output, fever) first paged to the medical hospitalist, who refers the call to the surgical hospitalist only as needed.

At least one practice has hired enough surgeons so the call burden on each is reasonable. This might be more staff than required for the patient volume: Four surgical hospitalists each work 12-hour shifts in a seven on/seven off schedule. During the seven consecutive night shifts (worked by each surgeon one week in four), patient volume is low.

Some practices hire community surgeons as moonlighters or consider using nurse practitioners or physician’s assistants as first responders at night.

Demographics: Surgical hospitalists are usually midcareer doctors, not surgeons who have recently completed their training. Many say they have gotten burned out with the stress of operating a private practice and prefer hospital work to office work.

Where Will It All Lead?

In every institution I have made contact with, the medical and surgical hospitalists have a good working relationship. Each is available to the other for consults, and they work together so frequently that they can begin to build a greater sense of teamwork. It is important that both groups jointly develop guidelines, such as who admits which type of patients.

If, like primary care doctors, general surgeons and a handful of other specialties with significant hospital volume (such as obstetrics and gastroenterology) move largely to a hospitalist model, U.S. healthcare will have made a remarkable transformation. In the span of my career we will have gone from a system of most doctors seeing patients in and out of the hospital to a division of physician labor such that most doctors practice almost exclusively in only one setting or the other.

I can see how this could be a good thing for patients and medical professionals, but that isn’t a given. For it to turn out we must preserve the elements of the earlier system that worked well and mitigate new problems and complexities. We will need well-designed research to show the economic and quality effects of the hospitalist model on non-primary care fields such as general surgery. We face growing challenges in ensuring excellent communication between inpatient and outpatient caregivers—something that doesn’t work ideally in all medical hospitalist practices.

Let Me Hear From You

I’d like to hear about any surgical hospitalist program you know of so I can add it to my database of information about such programs. And if you’re thinking about becoming a surgical hospitalist or you’re an institution thinking about starting such a practice, feel free to contact me so we can compare notes. I can be reached at (425) 467-3316, or by e-mail: john@jnelson.net. TH

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988 and is co-founder and past president of SHM. He is a principal in Nelson/Flores Associates, a national hospitalist practice management-consulting firm. This column represents his views and is not intended to reflect an official position of SHM.

Many or most specialties in medicine are adopting a hospitalist model, at least to a limited extent. In fact, hospital care of adult medical patients wasn’t even the first place the idea was adopted.

In talking with people from hundreds of institutions it seems clear the idea appeared earlier and grew more quickly in pediatrics than adult medicine. And in the past 10 to 15 years, fields like obstetrics (“laborists”), psychiatry, gastroenterology, and many others have slowly begun to adopt the hospitalist model.

One of the most recent disciplines to join the parade is general surgery. And when comparing the forces in play for hospitalists in the early 1990s to the current situation for surgical hospitalists, I think we may be close to a surge in surgical hospitalists similar to what we’ve seen with medical hospitalists in the past 10 years.

When I say surgical hospitalists, I’m referring to surgeons with a nearly exclusive inpatient practice. Other terms such as surgicalist, acute care surgeon, and traumatologist overlap to some degree but have ambiguous meanings.

Generalizations

For some months I have contacted all the surgical hospitalist practices I can find to learn what forces led to their creation and how they are structured. Several common themes are emerging:

Prevalence: There are probably no more than 20 to 40 surgical hospitalist practices, but many institutions are considering the idea. This is similar to the situation for medical hospitalists in the early to mid-1990s.

Driver to start program: In every program I’ve found, the main impetus to start it was to address the burden of emergency department (ED) call for existing general surgeons. Like primary care, ED call is regarded as unattractive because it is unpredictable (lots of night and weekend work), usually has a poor payer mix, and many general surgeons have seen the “center of gravity” of their practice move away from the hospital toward an ambulatory surgery center over the past 10 years or so. Additionally, many general surgeons are increasingly uncomfortable caring for trauma patients because of recent changes in that field. (For an excellent discussion of the changing nature of general surgery and trauma care see “The Acute Care Surgeon” in The Hospitalist, May 2006, p. 25.)

Case volume: General surgery case volume tends to go up at a hospital that puts a surgical hospitalist program in place. When existing surgeons are relieved of ED call they increase their volume of (mostly elective) surgery. The availability of surgical hospitalists may mean fewer emergency cases presenting to the ED are referred elsewhere (which may happen when non-hospitalist surgeons are required to take ED call). These changes in case volume and the timing of the operations (e.g., volume of night surgeries may go up) may require adjustments to operating room staffing and scheduling. Presumably this increased volume would not occur in an area oversupplied with surgeons.

Economics: Like nearly all medical hospitalist programs, surgical hospitalist practices are not viable without financial support in addition to collected professional fees. In all cases I am aware of, this support comes from the sponsoring hospital.

While the cost may be similar to what the hospital might have paid for existing surgeons to take ED call, hospitals seem to be getting a better return on that investment with surgical hospitalists. A small group of surgical hospitalists can handle the increased volume and all ED calls, improving clinical and service quality. Some institutions report that surgical hospitalists are much more attentive to billing for nonoperative work than their predecessors.

Structure: Programs should have an outpatient clinic where the surgical hospitalists can provide post-operative follow-up. In most cases, each surgeon spends only half a day a week in the clinic.

Scope of practice: All surgical hospitalist practices take most or all ED general surgery calls. In some institutions, the surgical hospitalist also leads the trauma team. Other duties at a few institutions include things like managing a wound-care clinic and being on-call to place lines.

Opinion of other surgeons: Community private practice surgeons tend to support these programs, but most institutions limit or prohibit surgical hospitalists from accepting elective referrals. Community surgeons are still offered the option of remaining on the ED call schedule—as might be the case for surgeons new to the community. At least one institution reported that the presence of surgical hospitalists improved recruitment of non-hospitalist general surgeons. However, I am also aware of one program put into place largely at the insistence of the existing surgeons. Those same surgeons later insisted it be dissolved because they saw it as unwanted competition.

Staff needs: Surgical hospitalist practices nearly always require fewer doctors than a medical hospitalist practice in the same institution. This can lead to a tension between having the right number of surgical hospitalists for the case volume (often just one or two doctors) and enough to provide for a reasonable call schedule. Existing groups have adopted a number of strategies.

Groups with only two doctors often have each work seven on/seven off. The doctor on-call for that week takes all night call him/herself. In some practices that have a medical hospitalist in-house all night, it could be reasonable to have routine calls on the surgical patients (e.g., sleeping pills, laxatives, low urine output, fever) first paged to the medical hospitalist, who refers the call to the surgical hospitalist only as needed.

At least one practice has hired enough surgeons so the call burden on each is reasonable. This might be more staff than required for the patient volume: Four surgical hospitalists each work 12-hour shifts in a seven on/seven off schedule. During the seven consecutive night shifts (worked by each surgeon one week in four), patient volume is low.

Some practices hire community surgeons as moonlighters or consider using nurse practitioners or physician’s assistants as first responders at night.

Demographics: Surgical hospitalists are usually midcareer doctors, not surgeons who have recently completed their training. Many say they have gotten burned out with the stress of operating a private practice and prefer hospital work to office work.

Where Will It All Lead?

In every institution I have made contact with, the medical and surgical hospitalists have a good working relationship. Each is available to the other for consults, and they work together so frequently that they can begin to build a greater sense of teamwork. It is important that both groups jointly develop guidelines, such as who admits which type of patients.

If, like primary care doctors, general surgeons and a handful of other specialties with significant hospital volume (such as obstetrics and gastroenterology) move largely to a hospitalist model, U.S. healthcare will have made a remarkable transformation. In the span of my career we will have gone from a system of most doctors seeing patients in and out of the hospital to a division of physician labor such that most doctors practice almost exclusively in only one setting or the other.

I can see how this could be a good thing for patients and medical professionals, but that isn’t a given. For it to turn out we must preserve the elements of the earlier system that worked well and mitigate new problems and complexities. We will need well-designed research to show the economic and quality effects of the hospitalist model on non-primary care fields such as general surgery. We face growing challenges in ensuring excellent communication between inpatient and outpatient caregivers—something that doesn’t work ideally in all medical hospitalist practices.

Let Me Hear From You

I’d like to hear about any surgical hospitalist program you know of so I can add it to my database of information about such programs. And if you’re thinking about becoming a surgical hospitalist or you’re an institution thinking about starting such a practice, feel free to contact me so we can compare notes. I can be reached at (425) 467-3316, or by e-mail: john@jnelson.net. TH

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988 and is co-founder and past president of SHM. He is a principal in Nelson/Flores Associates, a national hospitalist practice management-consulting firm. This column represents his views and is not intended to reflect an official position of SHM.

Many or most specialties in medicine are adopting a hospitalist model, at least to a limited extent. In fact, hospital care of adult medical patients wasn’t even the first place the idea was adopted.

In talking with people from hundreds of institutions it seems clear the idea appeared earlier and grew more quickly in pediatrics than adult medicine. And in the past 10 to 15 years, fields like obstetrics (“laborists”), psychiatry, gastroenterology, and many others have slowly begun to adopt the hospitalist model.

One of the most recent disciplines to join the parade is general surgery. And when comparing the forces in play for hospitalists in the early 1990s to the current situation for surgical hospitalists, I think we may be close to a surge in surgical hospitalists similar to what we’ve seen with medical hospitalists in the past 10 years.

When I say surgical hospitalists, I’m referring to surgeons with a nearly exclusive inpatient practice. Other terms such as surgicalist, acute care surgeon, and traumatologist overlap to some degree but have ambiguous meanings.

Generalizations

For some months I have contacted all the surgical hospitalist practices I can find to learn what forces led to their creation and how they are structured. Several common themes are emerging:

Prevalence: There are probably no more than 20 to 40 surgical hospitalist practices, but many institutions are considering the idea. This is similar to the situation for medical hospitalists in the early to mid-1990s.

Driver to start program: In every program I’ve found, the main impetus to start it was to address the burden of emergency department (ED) call for existing general surgeons. Like primary care, ED call is regarded as unattractive because it is unpredictable (lots of night and weekend work), usually has a poor payer mix, and many general surgeons have seen the “center of gravity” of their practice move away from the hospital toward an ambulatory surgery center over the past 10 years or so. Additionally, many general surgeons are increasingly uncomfortable caring for trauma patients because of recent changes in that field. (For an excellent discussion of the changing nature of general surgery and trauma care see “The Acute Care Surgeon” in The Hospitalist, May 2006, p. 25.)

Case volume: General surgery case volume tends to go up at a hospital that puts a surgical hospitalist program in place. When existing surgeons are relieved of ED call they increase their volume of (mostly elective) surgery. The availability of surgical hospitalists may mean fewer emergency cases presenting to the ED are referred elsewhere (which may happen when non-hospitalist surgeons are required to take ED call). These changes in case volume and the timing of the operations (e.g., volume of night surgeries may go up) may require adjustments to operating room staffing and scheduling. Presumably this increased volume would not occur in an area oversupplied with surgeons.

Economics: Like nearly all medical hospitalist programs, surgical hospitalist practices are not viable without financial support in addition to collected professional fees. In all cases I am aware of, this support comes from the sponsoring hospital.

While the cost may be similar to what the hospital might have paid for existing surgeons to take ED call, hospitals seem to be getting a better return on that investment with surgical hospitalists. A small group of surgical hospitalists can handle the increased volume and all ED calls, improving clinical and service quality. Some institutions report that surgical hospitalists are much more attentive to billing for nonoperative work than their predecessors.

Structure: Programs should have an outpatient clinic where the surgical hospitalists can provide post-operative follow-up. In most cases, each surgeon spends only half a day a week in the clinic.

Scope of practice: All surgical hospitalist practices take most or all ED general surgery calls. In some institutions, the surgical hospitalist also leads the trauma team. Other duties at a few institutions include things like managing a wound-care clinic and being on-call to place lines.