User login

GERD in the School-Age Child

General pediatricians can take care of a great number of children with reflux disease. I recommend a step-up approach employing lifestyle modifications and/or medication prior to specialist referral in most cases. When symptoms become more troublesome or there is no response to therapeutic interventions, consultation with a pediatric gastroenterologist may be appropriate.

Begin with a thorough patient history, which is instrumental to distinguishing gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) from other conditions. Family medical and medication history also are important because of compelling evidence demonstrating a family link with GERD.

Advise school-age children with GERD to eat smaller meals throughout the day and not to eat too close to bedtime. Tomato-containing products, caffeine-containing products, citrus, and—believe it or not—chocolate are commonly implicated as evoking or exacerbating symptoms of GERD. Foods with high-fat content also are associated with the disorder, as they delay the ability of the stomach to empty quickly, thus potentially worsening GERD.

Sleep disturbances may be the sole symptom for a lot of older children with reflux. Microburps or microaspirations that occur when children are supine at night wake some; they do not wake others, so keep in mind that some children might be unaware of their GERD. A good question to ask is how many pillows they sleep on at night; some children already self-manage their symptoms by elevating their upper torso at night without realizing why.

Early morning nausea also can occur after a night of continuous reflux. Therefore, the presentation of a child who says he or she routinely does not want to eat in the morning, particularly if he or she complains of nausea, raises clinical suspicion for GERD. Also, some children can report regurgitating and re-swallowing all day as they sit in class.

In addition to lifestyle changes, a trial of acid-suppressing medication, such as an H2 blocker or a proton pump inhibitor, can be tried. Limit initial treatment to 6-8 weeks for most children. If a child reports respiratory symptoms associated with GERD, consider a longer course of acid suppression therapy. It is important to discuss the specific GERD-related symptoms you expect the medication to resolve prior to initiation of therapy.

A referral to a pediatric gastroenterologist is warranted after lifestyle modifications and pharmacotherapy fail, or if symptoms return after therapy is discontinued. Sometimes patients do not improve with these interventions or they get better but you cannot get patients off the medication without symptoms returning. Also, other warning signs or symptoms such as anemia or occult blood in the stool or vomit require a referral.

Frequently, children, particularly those of school age, with GERD complain of a stomachache. However, GERD is more of a burning pain versus a cramping pain. Pain that is associated with GERD or due to another “organic” cause tends to be pain that localizes away from the belly button and is more epigastric, versus periumbilical pain, which tends to be more functional. In addition, abdominal pain that awakens children at night tends to be more organic in nature. Some children with GERD are misdiagnosed and actually have a functional GI disorder or vice versa. Definitions of pediatric functional GI disorders can aid in the differential diagnosis; these are outlined in Rome III criteria (www.romecriteria.org

There is no diagnostic test that is 100% accurate for the diagnosis of GERD. Thus, it is important to avoid too much testing or inappropriate treatment. For example, pediatricians tend to do an upper gastrointestinal series using barium and x-ray fluoroscopy, which is not good for ruling GERD in or out, but can be beneficial in identifying upper GI anatomic abnormalities. Nuclear scintigraphy can be employed to assess gastric emptying and aspiration of reflux contents.

Pediatricians can order a pH probe to ascertain the degree of acid exposure to the esophagus, although some centers require a GI consultation first. Endoscopic studies require a referral to a specialist. Specialists also may perform a newer modality called multichannel intraluminal impedance, which, when combined with the pH probe, can measure both acid reflux and nonacid or weakly acid reflux.

In a survey of 6,000 American Academy of Pediatrics members, 82% of the 1,245 responding pediatricians and pediatric specialists said they treat GERD based on clinical suspicion (J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2007;45:56-64). Such empiric therapy is still appropriate in the pediatric patient. However, there is a need for future research on the optimal therapy type, dose, and duration in these patients with clinically suspected GERD.

To promote a more standardized approach to pediatric GERD, I participated on an international committee that released an evidence-based set of definitions for reflux and GERD in the pediatric population (Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2009;104:1278-95). Additional guidance on GERD is available from the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition (www.naspghan.orgwww.cdhnf.org

General pediatricians can take care of a great number of children with reflux disease. I recommend a step-up approach employing lifestyle modifications and/or medication prior to specialist referral in most cases. When symptoms become more troublesome or there is no response to therapeutic interventions, consultation with a pediatric gastroenterologist may be appropriate.

Begin with a thorough patient history, which is instrumental to distinguishing gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) from other conditions. Family medical and medication history also are important because of compelling evidence demonstrating a family link with GERD.

Advise school-age children with GERD to eat smaller meals throughout the day and not to eat too close to bedtime. Tomato-containing products, caffeine-containing products, citrus, and—believe it or not—chocolate are commonly implicated as evoking or exacerbating symptoms of GERD. Foods with high-fat content also are associated with the disorder, as they delay the ability of the stomach to empty quickly, thus potentially worsening GERD.

Sleep disturbances may be the sole symptom for a lot of older children with reflux. Microburps or microaspirations that occur when children are supine at night wake some; they do not wake others, so keep in mind that some children might be unaware of their GERD. A good question to ask is how many pillows they sleep on at night; some children already self-manage their symptoms by elevating their upper torso at night without realizing why.

Early morning nausea also can occur after a night of continuous reflux. Therefore, the presentation of a child who says he or she routinely does not want to eat in the morning, particularly if he or she complains of nausea, raises clinical suspicion for GERD. Also, some children can report regurgitating and re-swallowing all day as they sit in class.

In addition to lifestyle changes, a trial of acid-suppressing medication, such as an H2 blocker or a proton pump inhibitor, can be tried. Limit initial treatment to 6-8 weeks for most children. If a child reports respiratory symptoms associated with GERD, consider a longer course of acid suppression therapy. It is important to discuss the specific GERD-related symptoms you expect the medication to resolve prior to initiation of therapy.

A referral to a pediatric gastroenterologist is warranted after lifestyle modifications and pharmacotherapy fail, or if symptoms return after therapy is discontinued. Sometimes patients do not improve with these interventions or they get better but you cannot get patients off the medication without symptoms returning. Also, other warning signs or symptoms such as anemia or occult blood in the stool or vomit require a referral.

Frequently, children, particularly those of school age, with GERD complain of a stomachache. However, GERD is more of a burning pain versus a cramping pain. Pain that is associated with GERD or due to another “organic” cause tends to be pain that localizes away from the belly button and is more epigastric, versus periumbilical pain, which tends to be more functional. In addition, abdominal pain that awakens children at night tends to be more organic in nature. Some children with GERD are misdiagnosed and actually have a functional GI disorder or vice versa. Definitions of pediatric functional GI disorders can aid in the differential diagnosis; these are outlined in Rome III criteria (www.romecriteria.org

There is no diagnostic test that is 100% accurate for the diagnosis of GERD. Thus, it is important to avoid too much testing or inappropriate treatment. For example, pediatricians tend to do an upper gastrointestinal series using barium and x-ray fluoroscopy, which is not good for ruling GERD in or out, but can be beneficial in identifying upper GI anatomic abnormalities. Nuclear scintigraphy can be employed to assess gastric emptying and aspiration of reflux contents.

Pediatricians can order a pH probe to ascertain the degree of acid exposure to the esophagus, although some centers require a GI consultation first. Endoscopic studies require a referral to a specialist. Specialists also may perform a newer modality called multichannel intraluminal impedance, which, when combined with the pH probe, can measure both acid reflux and nonacid or weakly acid reflux.

In a survey of 6,000 American Academy of Pediatrics members, 82% of the 1,245 responding pediatricians and pediatric specialists said they treat GERD based on clinical suspicion (J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2007;45:56-64). Such empiric therapy is still appropriate in the pediatric patient. However, there is a need for future research on the optimal therapy type, dose, and duration in these patients with clinically suspected GERD.

To promote a more standardized approach to pediatric GERD, I participated on an international committee that released an evidence-based set of definitions for reflux and GERD in the pediatric population (Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2009;104:1278-95). Additional guidance on GERD is available from the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition (www.naspghan.orgwww.cdhnf.org

General pediatricians can take care of a great number of children with reflux disease. I recommend a step-up approach employing lifestyle modifications and/or medication prior to specialist referral in most cases. When symptoms become more troublesome or there is no response to therapeutic interventions, consultation with a pediatric gastroenterologist may be appropriate.

Begin with a thorough patient history, which is instrumental to distinguishing gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) from other conditions. Family medical and medication history also are important because of compelling evidence demonstrating a family link with GERD.

Advise school-age children with GERD to eat smaller meals throughout the day and not to eat too close to bedtime. Tomato-containing products, caffeine-containing products, citrus, and—believe it or not—chocolate are commonly implicated as evoking or exacerbating symptoms of GERD. Foods with high-fat content also are associated with the disorder, as they delay the ability of the stomach to empty quickly, thus potentially worsening GERD.

Sleep disturbances may be the sole symptom for a lot of older children with reflux. Microburps or microaspirations that occur when children are supine at night wake some; they do not wake others, so keep in mind that some children might be unaware of their GERD. A good question to ask is how many pillows they sleep on at night; some children already self-manage their symptoms by elevating their upper torso at night without realizing why.

Early morning nausea also can occur after a night of continuous reflux. Therefore, the presentation of a child who says he or she routinely does not want to eat in the morning, particularly if he or she complains of nausea, raises clinical suspicion for GERD. Also, some children can report regurgitating and re-swallowing all day as they sit in class.

In addition to lifestyle changes, a trial of acid-suppressing medication, such as an H2 blocker or a proton pump inhibitor, can be tried. Limit initial treatment to 6-8 weeks for most children. If a child reports respiratory symptoms associated with GERD, consider a longer course of acid suppression therapy. It is important to discuss the specific GERD-related symptoms you expect the medication to resolve prior to initiation of therapy.

A referral to a pediatric gastroenterologist is warranted after lifestyle modifications and pharmacotherapy fail, or if symptoms return after therapy is discontinued. Sometimes patients do not improve with these interventions or they get better but you cannot get patients off the medication without symptoms returning. Also, other warning signs or symptoms such as anemia or occult blood in the stool or vomit require a referral.

Frequently, children, particularly those of school age, with GERD complain of a stomachache. However, GERD is more of a burning pain versus a cramping pain. Pain that is associated with GERD or due to another “organic” cause tends to be pain that localizes away from the belly button and is more epigastric, versus periumbilical pain, which tends to be more functional. In addition, abdominal pain that awakens children at night tends to be more organic in nature. Some children with GERD are misdiagnosed and actually have a functional GI disorder or vice versa. Definitions of pediatric functional GI disorders can aid in the differential diagnosis; these are outlined in Rome III criteria (www.romecriteria.org

There is no diagnostic test that is 100% accurate for the diagnosis of GERD. Thus, it is important to avoid too much testing or inappropriate treatment. For example, pediatricians tend to do an upper gastrointestinal series using barium and x-ray fluoroscopy, which is not good for ruling GERD in or out, but can be beneficial in identifying upper GI anatomic abnormalities. Nuclear scintigraphy can be employed to assess gastric emptying and aspiration of reflux contents.

Pediatricians can order a pH probe to ascertain the degree of acid exposure to the esophagus, although some centers require a GI consultation first. Endoscopic studies require a referral to a specialist. Specialists also may perform a newer modality called multichannel intraluminal impedance, which, when combined with the pH probe, can measure both acid reflux and nonacid or weakly acid reflux.

In a survey of 6,000 American Academy of Pediatrics members, 82% of the 1,245 responding pediatricians and pediatric specialists said they treat GERD based on clinical suspicion (J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2007;45:56-64). Such empiric therapy is still appropriate in the pediatric patient. However, there is a need for future research on the optimal therapy type, dose, and duration in these patients with clinically suspected GERD.

To promote a more standardized approach to pediatric GERD, I participated on an international committee that released an evidence-based set of definitions for reflux and GERD in the pediatric population (Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2009;104:1278-95). Additional guidance on GERD is available from the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition (www.naspghan.orgwww.cdhnf.org

HM's Watershed Moment

John Nelson, MD, FACP, FHM, hasn't taken a medical test in more than 20 years. So when news began to spread last week that the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) soon will be offering a Recognition of Focused Practice (RFP) in Hospital Medicine certification, he started to get a little nervous.

"I will lose sleep the week before I take this test," says Dr. Nelson, co-founder and past president of SHM, and a principal in the practice management firm Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. "This exam will help identify those who see this as a career. … Boy, there is nothing like a test to demonstrate professional centeredness."

The exam, likely to be available in the fall of 2010, will identify physicians who have "maintained their internal medicine certification focused in hospital medicine," according to the ABIM Web site.

"For those individuals [whose certificate] will be expiring in 2010 or 2011, this is a viable pathway for re-certification," says Eric Holmbloe, MD, senior vice president and chief medical officer at ABIM. "Interested diplomats should be able to begin the application process in early 2010. We are feverishly working to complete the test and build the technology infrastructure. We should have more information available in about six weeks."

HM pioneers like Dr. Nelson consider the RFP designation a validation of decades-long efforts to carve a niche in medicine. The test will symbolize dedication to the specialty and provide HM physicians with professional self-regulation.

Scott Flanders, MD, FHM, president of SHM, terms the announcement a "watershed moment" for the field.

"I think this is a major, major moment for HM," says Dr. Flanders, who practices at the University of Michigan Medical Center in Ann Arbor. "We've been looking at this for a long time. This validates the field, and the belief that HM is a positive [for the field of medicine]."

Dr. Nelson couldn't agree more. "This test is the first way hospitalists will be able to show their competence," he says. "I think it's a great opportunity. This will help people take our field more seriously."

John Nelson, MD, FACP, FHM, hasn't taken a medical test in more than 20 years. So when news began to spread last week that the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) soon will be offering a Recognition of Focused Practice (RFP) in Hospital Medicine certification, he started to get a little nervous.

"I will lose sleep the week before I take this test," says Dr. Nelson, co-founder and past president of SHM, and a principal in the practice management firm Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. "This exam will help identify those who see this as a career. … Boy, there is nothing like a test to demonstrate professional centeredness."

The exam, likely to be available in the fall of 2010, will identify physicians who have "maintained their internal medicine certification focused in hospital medicine," according to the ABIM Web site.

"For those individuals [whose certificate] will be expiring in 2010 or 2011, this is a viable pathway for re-certification," says Eric Holmbloe, MD, senior vice president and chief medical officer at ABIM. "Interested diplomats should be able to begin the application process in early 2010. We are feverishly working to complete the test and build the technology infrastructure. We should have more information available in about six weeks."

HM pioneers like Dr. Nelson consider the RFP designation a validation of decades-long efforts to carve a niche in medicine. The test will symbolize dedication to the specialty and provide HM physicians with professional self-regulation.

Scott Flanders, MD, FHM, president of SHM, terms the announcement a "watershed moment" for the field.

"I think this is a major, major moment for HM," says Dr. Flanders, who practices at the University of Michigan Medical Center in Ann Arbor. "We've been looking at this for a long time. This validates the field, and the belief that HM is a positive [for the field of medicine]."

Dr. Nelson couldn't agree more. "This test is the first way hospitalists will be able to show their competence," he says. "I think it's a great opportunity. This will help people take our field more seriously."

John Nelson, MD, FACP, FHM, hasn't taken a medical test in more than 20 years. So when news began to spread last week that the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) soon will be offering a Recognition of Focused Practice (RFP) in Hospital Medicine certification, he started to get a little nervous.

"I will lose sleep the week before I take this test," says Dr. Nelson, co-founder and past president of SHM, and a principal in the practice management firm Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. "This exam will help identify those who see this as a career. … Boy, there is nothing like a test to demonstrate professional centeredness."

The exam, likely to be available in the fall of 2010, will identify physicians who have "maintained their internal medicine certification focused in hospital medicine," according to the ABIM Web site.

"For those individuals [whose certificate] will be expiring in 2010 or 2011, this is a viable pathway for re-certification," says Eric Holmbloe, MD, senior vice president and chief medical officer at ABIM. "Interested diplomats should be able to begin the application process in early 2010. We are feverishly working to complete the test and build the technology infrastructure. We should have more information available in about six weeks."

HM pioneers like Dr. Nelson consider the RFP designation a validation of decades-long efforts to carve a niche in medicine. The test will symbolize dedication to the specialty and provide HM physicians with professional self-regulation.

Scott Flanders, MD, FHM, president of SHM, terms the announcement a "watershed moment" for the field.

"I think this is a major, major moment for HM," says Dr. Flanders, who practices at the University of Michigan Medical Center in Ann Arbor. "We've been looking at this for a long time. This validates the field, and the belief that HM is a positive [for the field of medicine]."

Dr. Nelson couldn't agree more. "This test is the first way hospitalists will be able to show their competence," he says. "I think it's a great opportunity. This will help people take our field more seriously."

Social Distortion?

A presentation at last week's 13th annual Management of the Hospitalized Patient conference in San Francisco described various ways that hospitals, hospitalists, and HM groups can incorporate new social media into their practice routines.

Hospitalist Russell Cucina, MD, MS, associate medical director of information technology at the University of California at San Francisco, says some physicians mistakenly disclose unprofessional content through social networks. He points to a recent article in the Journal of the American Medical Association (2009;302(12):1309-1315), which shows some physicians inadvertently violate Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act privacy rules by accepting e-mails from patients that contain protected personal health information.

But in many cases, hospitals and physicians use blogs, Twitter, Facebook, LinkedIn, and other networking sites to exchange information with colleagues, promote their practice in their communities, or recruit new physicians. Such organizations as the Mayo Clinic and SHM use Facebook to reach targeted audiences, while the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) uses Twitter to quickly disseminate influenza updates. Dr. Cucina says he knows of 167 U.S. hospitals using the much-hyped Twitter, but he could not find an HM group that uses the quick-hit network. He also reports that Ozmosis and Sermo, networking sites reserved for physicians, have yet to catch on in a big way.

Christine Roed, MD, a hospitalist at El Camino Hospital in Mountain View, Calif., says she sees great potential for communicating within her small medical group and for tapping into public health information. "I also feel it might be quite overwhelming. I think we have to look quite carefully at which information sources are reliable and, in turn, advise the public," Dr. Roed says. "I think a lot of physicians don't really have time to sit down and figure out what they're going to do with these things."

A presentation at last week's 13th annual Management of the Hospitalized Patient conference in San Francisco described various ways that hospitals, hospitalists, and HM groups can incorporate new social media into their practice routines.

Hospitalist Russell Cucina, MD, MS, associate medical director of information technology at the University of California at San Francisco, says some physicians mistakenly disclose unprofessional content through social networks. He points to a recent article in the Journal of the American Medical Association (2009;302(12):1309-1315), which shows some physicians inadvertently violate Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act privacy rules by accepting e-mails from patients that contain protected personal health information.

But in many cases, hospitals and physicians use blogs, Twitter, Facebook, LinkedIn, and other networking sites to exchange information with colleagues, promote their practice in their communities, or recruit new physicians. Such organizations as the Mayo Clinic and SHM use Facebook to reach targeted audiences, while the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) uses Twitter to quickly disseminate influenza updates. Dr. Cucina says he knows of 167 U.S. hospitals using the much-hyped Twitter, but he could not find an HM group that uses the quick-hit network. He also reports that Ozmosis and Sermo, networking sites reserved for physicians, have yet to catch on in a big way.

Christine Roed, MD, a hospitalist at El Camino Hospital in Mountain View, Calif., says she sees great potential for communicating within her small medical group and for tapping into public health information. "I also feel it might be quite overwhelming. I think we have to look quite carefully at which information sources are reliable and, in turn, advise the public," Dr. Roed says. "I think a lot of physicians don't really have time to sit down and figure out what they're going to do with these things."

A presentation at last week's 13th annual Management of the Hospitalized Patient conference in San Francisco described various ways that hospitals, hospitalists, and HM groups can incorporate new social media into their practice routines.

Hospitalist Russell Cucina, MD, MS, associate medical director of information technology at the University of California at San Francisco, says some physicians mistakenly disclose unprofessional content through social networks. He points to a recent article in the Journal of the American Medical Association (2009;302(12):1309-1315), which shows some physicians inadvertently violate Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act privacy rules by accepting e-mails from patients that contain protected personal health information.

But in many cases, hospitals and physicians use blogs, Twitter, Facebook, LinkedIn, and other networking sites to exchange information with colleagues, promote their practice in their communities, or recruit new physicians. Such organizations as the Mayo Clinic and SHM use Facebook to reach targeted audiences, while the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) uses Twitter to quickly disseminate influenza updates. Dr. Cucina says he knows of 167 U.S. hospitals using the much-hyped Twitter, but he could not find an HM group that uses the quick-hit network. He also reports that Ozmosis and Sermo, networking sites reserved for physicians, have yet to catch on in a big way.

Christine Roed, MD, a hospitalist at El Camino Hospital in Mountain View, Calif., says she sees great potential for communicating within her small medical group and for tapping into public health information. "I also feel it might be quite overwhelming. I think we have to look quite carefully at which information sources are reliable and, in turn, advise the public," Dr. Roed says. "I think a lot of physicians don't really have time to sit down and figure out what they're going to do with these things."

Baucus Plan Lends Clarity to Healthcare Debate

Last week’s release of the “chairman’s mark” of the America’s Healthy Future Act from Senate Finance Committee Chairman Max Baucus (D-Mont.) opened the latest chapter in the debate over healthcare reform. Beyond the hot-button issues, several Medicare-related proposals could directly impact hospitalists. Here’s a look at four of them, with observations from Eric Siegal, MD, FHM, chair of SHM’s Public Policy Committee.

Addition of a hospital value-based purchasing (VBP) program to Medicare beginning in 2012. The program would tie incentive payments to performance on quality measures related to such conditions as heart failure, pneumonia, surgical care, and patient perceptions of care. So far, the program’s rough outlines have been well received. “We fundamentally support hospital value-based purchasing,” Dr. Siegal says. “We think it’s a necessary step in the evolution to higher-value health care in general.”

Expansion of the Physician’s Quality Reporting Initiative, with a 1% payment penalty by 2012 for nonparticipants. The bill also would direct the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) to improve the appeals process and feedback mechanism. Although the Baucus plan’s “mark” doesn’t discuss transitioning to pay-for-performance, Dr. Siegal says the shift likely is inevitable. In the meantime, pay-for-reporting can encourage better outcomes through a public reporting mechanism and “grease the skids” for a pay-for-performance initiative.

Creation of a CMS Payment Innovation Center “authorized to test, evaluate, and expand different payment structures and methodologies,” with a goal of improving quality and reducing Medicare costs. Dr. Siegal says the proposal is consistent with SHM’s aims. “We have for a long time advocated for a robust capability to test new payment models and to figure out what works better than what we have right now,” he says.

Establishment of a three-year Medicare pilot called the Community Care Transitions Program. The program would spend $500 million over 10 years on efforts to reduce preventable rehospitalizations. SHM’s Project BOOST (Better Outcomes for Older Adults through Safe Transitions) likely would qualify. “We’re very positive about that,” Dr. Siegal says. “I think there is a huge amount of scrutiny now on avoidable rehospitalizations. We think BOOST is a step in the right direction, and we’d love to see greater funding to roll this out on a much larger basis.”

For more information on the current healthcare reform debate, visit SHM’s advocacy portal.

Last week’s release of the “chairman’s mark” of the America’s Healthy Future Act from Senate Finance Committee Chairman Max Baucus (D-Mont.) opened the latest chapter in the debate over healthcare reform. Beyond the hot-button issues, several Medicare-related proposals could directly impact hospitalists. Here’s a look at four of them, with observations from Eric Siegal, MD, FHM, chair of SHM’s Public Policy Committee.

Addition of a hospital value-based purchasing (VBP) program to Medicare beginning in 2012. The program would tie incentive payments to performance on quality measures related to such conditions as heart failure, pneumonia, surgical care, and patient perceptions of care. So far, the program’s rough outlines have been well received. “We fundamentally support hospital value-based purchasing,” Dr. Siegal says. “We think it’s a necessary step in the evolution to higher-value health care in general.”

Expansion of the Physician’s Quality Reporting Initiative, with a 1% payment penalty by 2012 for nonparticipants. The bill also would direct the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) to improve the appeals process and feedback mechanism. Although the Baucus plan’s “mark” doesn’t discuss transitioning to pay-for-performance, Dr. Siegal says the shift likely is inevitable. In the meantime, pay-for-reporting can encourage better outcomes through a public reporting mechanism and “grease the skids” for a pay-for-performance initiative.

Creation of a CMS Payment Innovation Center “authorized to test, evaluate, and expand different payment structures and methodologies,” with a goal of improving quality and reducing Medicare costs. Dr. Siegal says the proposal is consistent with SHM’s aims. “We have for a long time advocated for a robust capability to test new payment models and to figure out what works better than what we have right now,” he says.

Establishment of a three-year Medicare pilot called the Community Care Transitions Program. The program would spend $500 million over 10 years on efforts to reduce preventable rehospitalizations. SHM’s Project BOOST (Better Outcomes for Older Adults through Safe Transitions) likely would qualify. “We’re very positive about that,” Dr. Siegal says. “I think there is a huge amount of scrutiny now on avoidable rehospitalizations. We think BOOST is a step in the right direction, and we’d love to see greater funding to roll this out on a much larger basis.”

For more information on the current healthcare reform debate, visit SHM’s advocacy portal.

Last week’s release of the “chairman’s mark” of the America’s Healthy Future Act from Senate Finance Committee Chairman Max Baucus (D-Mont.) opened the latest chapter in the debate over healthcare reform. Beyond the hot-button issues, several Medicare-related proposals could directly impact hospitalists. Here’s a look at four of them, with observations from Eric Siegal, MD, FHM, chair of SHM’s Public Policy Committee.

Addition of a hospital value-based purchasing (VBP) program to Medicare beginning in 2012. The program would tie incentive payments to performance on quality measures related to such conditions as heart failure, pneumonia, surgical care, and patient perceptions of care. So far, the program’s rough outlines have been well received. “We fundamentally support hospital value-based purchasing,” Dr. Siegal says. “We think it’s a necessary step in the evolution to higher-value health care in general.”

Expansion of the Physician’s Quality Reporting Initiative, with a 1% payment penalty by 2012 for nonparticipants. The bill also would direct the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) to improve the appeals process and feedback mechanism. Although the Baucus plan’s “mark” doesn’t discuss transitioning to pay-for-performance, Dr. Siegal says the shift likely is inevitable. In the meantime, pay-for-reporting can encourage better outcomes through a public reporting mechanism and “grease the skids” for a pay-for-performance initiative.

Creation of a CMS Payment Innovation Center “authorized to test, evaluate, and expand different payment structures and methodologies,” with a goal of improving quality and reducing Medicare costs. Dr. Siegal says the proposal is consistent with SHM’s aims. “We have for a long time advocated for a robust capability to test new payment models and to figure out what works better than what we have right now,” he says.

Establishment of a three-year Medicare pilot called the Community Care Transitions Program. The program would spend $500 million over 10 years on efforts to reduce preventable rehospitalizations. SHM’s Project BOOST (Better Outcomes for Older Adults through Safe Transitions) likely would qualify. “We’re very positive about that,” Dr. Siegal says. “I think there is a huge amount of scrutiny now on avoidable rehospitalizations. We think BOOST is a step in the right direction, and we’d love to see greater funding to roll this out on a much larger basis.”

For more information on the current healthcare reform debate, visit SHM’s advocacy portal.

1,200 Satisfied Customers and Counting

Another SHM Leadership Academy just ended, with introductory and advanced courses presented at the Fontainebleau resort, complete with the backdrop of Miami Beach. These four-day courses are aimed at hospitalist leaders, and have trained more than 1,200 participants to date. The faculty includes nationally recognized experts in their respective fields, as well as experienced HM leaders.

Level I courses are designed to help new leaders in HM, and focus on communication skills, hospital business drivers, leadership, strategic planning, and conflict resolution. Harjit Bhogal, MD, a hospitalist at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore, found the Level I course addressed many of the roles she has as a new hospitalist. “The session on strategic planning was interactive and extremely informative,” Dr. Bhogal says. She also says the academy is an ideal place for networking, as attendees have access to more than 100 practicing hospitalist leaders with whom to connect.

Level II takes concepts introduced in Level I and refines them. Communication and negotiation, “meta-leadership,” financial storytelling, and a leadership roundtable help more advanced leaders tackle more complex issues. The session on meta-leadership was “terrific,” according to hospitalist Darlene Tad-y, MD, of Johns Hopkins. “One of the best days I have spent as an adult learner,” she says. “Lenny [Marcus] was absolutely amazing; his walk-in-the-woods approach was a terrific method to discuss leadership.”

Many see hospitalists as the future leaders of the hospital and throughout healthcare. “In addition to helping train leaders for hospital medicine, we believe that SHM has the obligation to train hospitalists to be the next hospital CMOs and CEOs,” says Larry Wellikson, MD, FHM, CEO of SHM.

Apparently, 1,200 academy graduates agree with him.

Another SHM Leadership Academy just ended, with introductory and advanced courses presented at the Fontainebleau resort, complete with the backdrop of Miami Beach. These four-day courses are aimed at hospitalist leaders, and have trained more than 1,200 participants to date. The faculty includes nationally recognized experts in their respective fields, as well as experienced HM leaders.

Level I courses are designed to help new leaders in HM, and focus on communication skills, hospital business drivers, leadership, strategic planning, and conflict resolution. Harjit Bhogal, MD, a hospitalist at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore, found the Level I course addressed many of the roles she has as a new hospitalist. “The session on strategic planning was interactive and extremely informative,” Dr. Bhogal says. She also says the academy is an ideal place for networking, as attendees have access to more than 100 practicing hospitalist leaders with whom to connect.

Level II takes concepts introduced in Level I and refines them. Communication and negotiation, “meta-leadership,” financial storytelling, and a leadership roundtable help more advanced leaders tackle more complex issues. The session on meta-leadership was “terrific,” according to hospitalist Darlene Tad-y, MD, of Johns Hopkins. “One of the best days I have spent as an adult learner,” she says. “Lenny [Marcus] was absolutely amazing; his walk-in-the-woods approach was a terrific method to discuss leadership.”

Many see hospitalists as the future leaders of the hospital and throughout healthcare. “In addition to helping train leaders for hospital medicine, we believe that SHM has the obligation to train hospitalists to be the next hospital CMOs and CEOs,” says Larry Wellikson, MD, FHM, CEO of SHM.

Apparently, 1,200 academy graduates agree with him.

Another SHM Leadership Academy just ended, with introductory and advanced courses presented at the Fontainebleau resort, complete with the backdrop of Miami Beach. These four-day courses are aimed at hospitalist leaders, and have trained more than 1,200 participants to date. The faculty includes nationally recognized experts in their respective fields, as well as experienced HM leaders.

Level I courses are designed to help new leaders in HM, and focus on communication skills, hospital business drivers, leadership, strategic planning, and conflict resolution. Harjit Bhogal, MD, a hospitalist at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore, found the Level I course addressed many of the roles she has as a new hospitalist. “The session on strategic planning was interactive and extremely informative,” Dr. Bhogal says. She also says the academy is an ideal place for networking, as attendees have access to more than 100 practicing hospitalist leaders with whom to connect.

Level II takes concepts introduced in Level I and refines them. Communication and negotiation, “meta-leadership,” financial storytelling, and a leadership roundtable help more advanced leaders tackle more complex issues. The session on meta-leadership was “terrific,” according to hospitalist Darlene Tad-y, MD, of Johns Hopkins. “One of the best days I have spent as an adult learner,” she says. “Lenny [Marcus] was absolutely amazing; his walk-in-the-woods approach was a terrific method to discuss leadership.”

Many see hospitalists as the future leaders of the hospital and throughout healthcare. “In addition to helping train leaders for hospital medicine, we believe that SHM has the obligation to train hospitalists to be the next hospital CMOs and CEOs,” says Larry Wellikson, MD, FHM, CEO of SHM.

Apparently, 1,200 academy graduates agree with him.

Sleep Disruptions and Sedative Use

Adequate sleep is important for health, yet the hospital environment commonly disrupts sleep.13 Sleep improves after several days in the hospital.3, 4 Sleep deprivation increases cortisol levels5 and sleep loss of greater than 4 hours may be hyperalgesic.6 Even a few days' suppression of slow‐wave sleep worsens glucose tolerance.7 Sleep disruption may cause irritability and aggressiveness,8 impaired memory consolidation, and delirium.2

Noise may disrupt sleep. The World Health Organization recommends a maximum of 30 to 40 dBA in patients' rooms at night.9, 10 Normal conversation occurs at 60 dBA. Medical equipment alarms are about 80 dBA.

Sedative use is common in the hospital.3 Sedatives typically shorten sleep latency and suppress rapid eye movement (REM) sleep. However, some sedatives cause delirium, falls, amnesia, and confusion, particularly in the elderly.1113

Most research on sleep in hospitalized patients has been done in the critical care setting, often in sedated ventilated patients, where sleep disruption is well‐described.1416 Only a few small studies have assessed the sleep of hospitalized patients outside critical care.17, 18

A single blinded interventional trial assessed sedative use, but was a nonrandomized study.19, 20 As‐needed sedative use was measured among hospitalized elderly patients as a secondary endpoint. The intervention, known as the Hospital Elder Life Program (HELP), included a protocol with noise reduction, massage, music, and warm drinks, as well as rescheduling of medications and procedures; it resulted in a 24% reduction in as‐needed sedative use. Another trial decreased noise and reduced overnight X‐rays on a surgical unit, then measured staff and patient attitudes.21 Two interventional studies in nursing homes reduced noise and light, and/or increased daytime activity and found no effect on most objective measures of sleep.22, 23 One descriptive study found most sleep disturbances in medical‐surgical patients came from noise and sleeping in an unfamiliar bed.4

We hypothesized that an intervention designed to improve patient sleep through changes in staff behavior would decrease sedative use among unselected patients in a medical‐surgical unit. We measured sedative use as our primary endpoint as a marker for effective sleep, and because decreased sedative use is desirable. We also hypothesized that the intervention would lead to improved sleep experiences, as measured by a questionnaire and Verran Snyder‐Halpern (VSH) sleep scores as secondary endpoints.24

Materials And Methods

Study Design

This was a pre‐post study assessing the effect of the intervention on as‐needed sedative use, questionnaire responses, and sleep quality. It was an intention‐to‐treat analysis, and was blinded in terms of measurement of sedative use. The Institutional Review Board of Cambridge Health Alliance approved the study.

Setting and Patients

The site was the only medical‐surgical unit of Somerville Hospital, a small urban community teaching hospital that is part of Cambridge Health Alliance. The hospital unit was chosen for its architectural characteristics, and is organized spatially as 3 U‐shaped pods surrounding nursing workstations. Hence, patient rooms were nearly equidistant from the nurses' stations, unlike a hallway design where distant rooms are quieter. Six rooms were private; 11 were semiprivate. Most of the unit's 28 beds are used for medical patients covered by the hospitalist service. Residents see a minority of patients. A hospitalist is available around the clock. Few agency nurses are used.

Preintervention patients were recruited between April and August 2007. The intervention was planned and implemented from September 2007 to January 2008. Intervention patients were recruited between February and June 2008. The most common principle diagnoses on the unit were chest pain (11%), pneumonia (8%), congestive heart failure (CHF) (5.1%), and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) flare (3%). Exclusion criteria ensured that no patient was ill enough to require intensive care unit (ICU)‐level care or was actively dying. All consecutive hospitalized patients on the unit on Tuesdays through Fridays were potentially eligible and invited to participate unless they met exclusion criteria. The limited days of the week ensured that technical support would be available during the intervention phase.

Exclusion criteria were: known sleep disorders; language other than English, Spanish, Portuguese, or Haitian Creole; surgery the prior day; arrival on the floor after 10 PM the prior evening; residence on the unit for more than 4 days; alcohol or drug withdrawal; end‐of‐life morphine drip; significant hearing loss; and blindness.

Study Protocol

A single investigator surveyed patients in the morning about the prior night's sleep experience. The surveys consisted of the VSH sleep scale, as well as an 8‐item questionnaire developed from informal pilot interviews with about 18 patients conducted by 1 of the investigators (M.B.) (Supporting Information Figure 1). The VSH scale is a visual analog scale using a 100‐cm line,24 which we modified with a 100‐mm line to make it easier to collect data. The questionnaire and VSH scores of patients with cognitive impairment were not included in the final analysis. Cognitive impairment was determined by diagnoses present in chart review. Surveys and consent forms were available in 4 languages and trained interpreters were used as needed. Nurses, providers, and patients were blinded to the measurement of as‐needed sedative use, and staff were unaware of which patients were study subjects.

Measurements

Nighttime administration of any medication ordered prn sleep or insomnia was measured using the pharmacy dispensing equipment (Pyxis; Cardinal Health, Dublin, OH), then verified by reviewing the patients' medication administration records. VSH sleep scores were created by measuring the distance in millimeters from the lower end of the scale (0) to the location marked.

We also tracked adherence to some aspects of the intervention. The questionnaire recorded door closing. Chart audits measured the numbers of different prescribers, and the frequency of medication orders using flexible timing.

Data Analysis

Medication use was analyzed as any as‐needed sedative use vs. none. The proportions of patients who used sedatives preintervention and postintervention were compared using a 2‐sample Z statistic, as were survey items. Mean VSH scores were compared with 2‐sample t tests. The study had greater than 80% power to detect a difference in proportion of at least 0.14 at alpha = 0.05.

Design and Implementation of the Intervention

Preintervention, routine vital signs were taken every 8 hours: 8 AM, 4 PM, and midnight. Night nurses arrived at 11 PM, and typically turned off the hallway lights, but the practice was variable and occurred at no set time.

Patients in our informal pilot interviews identified vital signs, medication administration, noise, and evening diuretic administration as disrupting their sleep. After the preintervention phase, we spent 4 months designing and implementing the intervention. We solicited opinions from staff, who identified inflexible timing of medications as disruptive. The plan was discussed at routine staff meetings of all shifts.

The intervention, called the Somerville Protocol (Figure 1) created an 8‐hour Quiet Time from 10 PM to 6 AM, when disruptions were minimized. Vital signs were taken 2 hours earlier (6 AM, 2 PM, and 10 PM); routine medication administration was avoided; and noise was reduced. As before, telemetry patients required vital signs every 4 hours. At 10 PM, hallway lights were turned off by a timer while the Lullaby by Brahms played overhead, signaling the start of Quiet Time to staff and patients. Inexpensive sound meters were installed in each nursing area. They flashed warning lights when 60 dBA was exceeded.

A physician and nurse served as champions. Educational signs were posted in the hospitalists' call room and in the nursing areas. The champions used e‐mail and detailed the intervention to staff. Because the staff played an active role in intervention planning, implementation went smoothly.

Results

During the preintervention phase, 334 patients were screened, 294 were eligible, and 54.7% of eligible subjects were enrolled (n = 161). During the intervention phase, 211 patients were screened, 188 were eligible, and 56.3% of eligible patients were enrolled (n = 106). The mean patient age was 60.6 years. The preintervention and intervention groups did not differ significantly in enrollment rate, age, gender, cognitive impairment, surgical status, or hearing deficiencies (Table 1). Over 93% of patients were nonsurgical.

| Preintervention Patients (n = 161) | Intervention Patients (n = 106) | P Values for Difference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (years) | 59.1 | 62.95 | P = 0.146 |

| Males, n (%) | 79 (49.1%) | 46 (43.4%) | P = 0.38 |

| Hard of hearing, n (%) (self‐report) | 33/157 (21.0%) | 14/103 (13.6%) | P = 0.128 |

| English‐speaking, n (%) | 134 (83%) | 83 (78.3%) | P = 0.34 |

| Cognitive impairment, n (%) | 4 (2.5%) | 3 (2.8%) | P = 0.88 |

| Surgical patients, n (%) | 10 (6.2%) | 2 (1.8%) | P = 0.089 |

Sedative Use

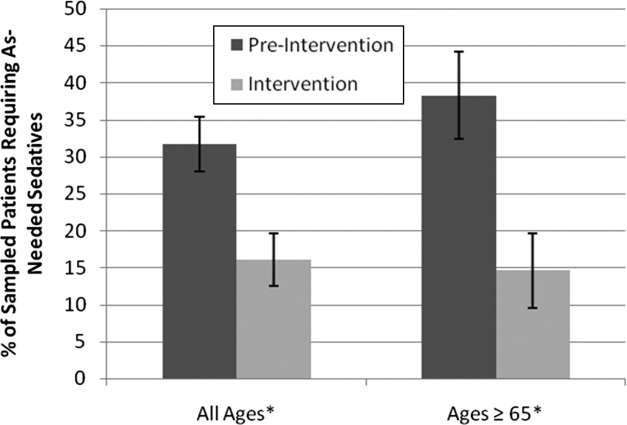

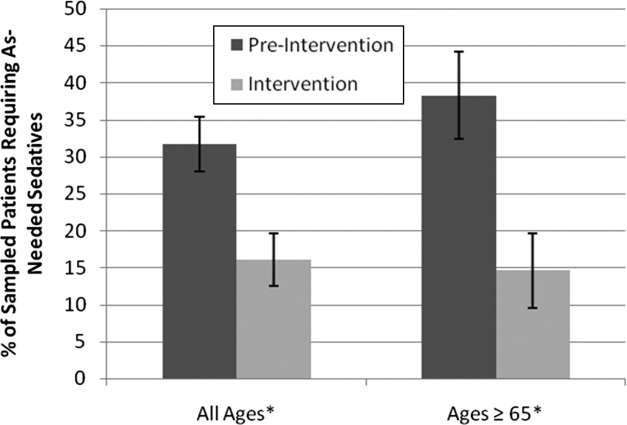

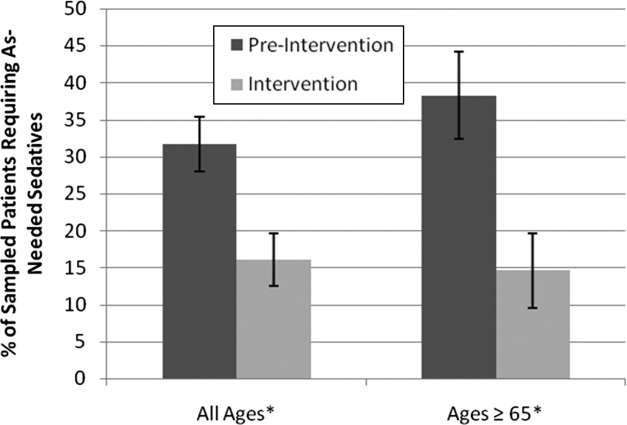

Preintervention, 31.7% of patients received nighttime as‐needed sedatives, versus 16.0% of the intervention group, a 49.4% reduction (P = 0.0041; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.056‐0.26) (Figure 2). In patients aged 65 years or older, 38.2% received nighttime as‐needed sedatives preintervention, and 14.6% did postintervention, a 61.2% reduction (P = 0.0054; 95% CI: 0.084‐0.39).

Questionnaire Results

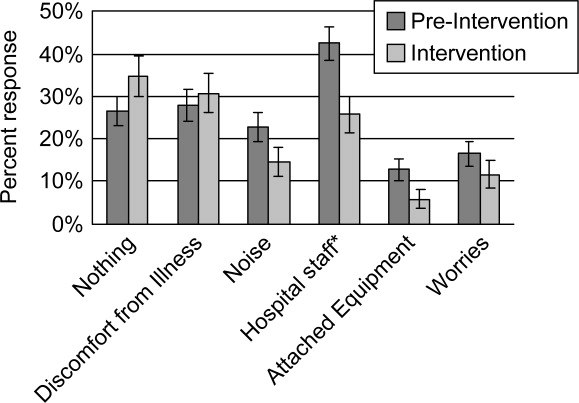

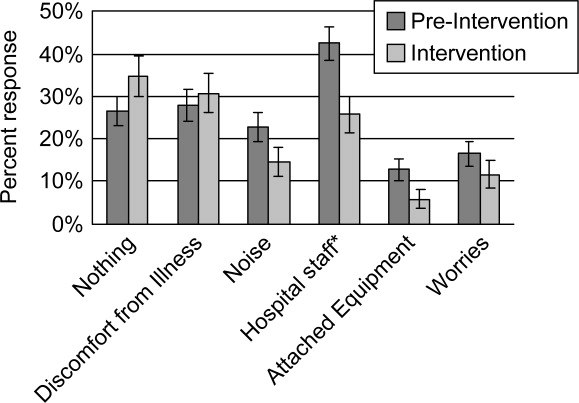

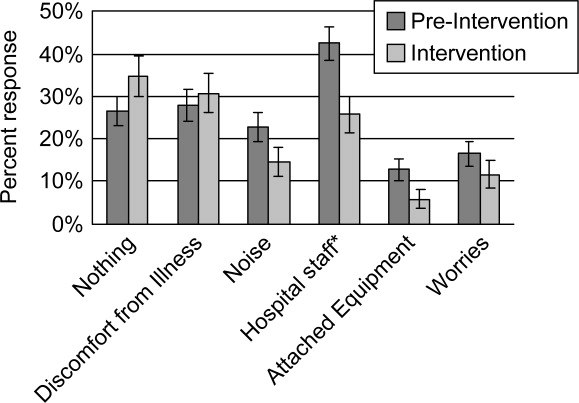

Preintervention, hospital staff was by far the biggest factor keeping patients awake, with 42.4% of patients reporting it (Figure 3). This dropped to only 25.7% with the intervention, a 39.3% decrease (P = 0.009; 95% CI: 0.0452‐0.2765). Preintervention, 19.2% of patients selected voices as the noise most likely to bother them at night, and this dropped to 9.9% with the intervention, a 48% decrease (P = 0.045; 95% CI: 0.0074‐0.1787). No other significant differences were found.

VSH Sleep Score Results

We found no improvement in any measure of the VSH sleep scale. However, 75% of our patients were unable to use the modified VSH scale, generally because they felt too ill, and were then prompted by the surveyor to choose a number between 1 and 10 that reflected their experience.

Protocol Adherence

Changes in unit routines resulted in complete adherence to the new vital signs schedule and avoidance of routine evening diuretics. The closing of patients' doors did not change. An audit of 40 charts found that the percentage of medication orders written with appropriate flexible timing increased from 82% (n = 228) to 95.5% (n = 200) (P = 0.001; 95% CI: 0.077‐0.192). From 20 to 30 different providers wrote orders during each phase.

Discussion

Our trial found that hospital staff was the factor most responsible for patient sleep disruption, and that behavioral interventions on hospital staff can reduce use of as‐needed sedatives. The only previously reported intervention to reduce sedative use, the HELP strategy, involved a complex intervention requiring extra staff, with adherence ranging from 10% to 75%.19, 20, 25 In contrast, our protocol can be easily replicated at minimal cost.

Our results are consistent with those of Freedman et al.,26 who found that noise was not the primary factor responsible for sleep disruption in ICU patients, and that staff activities were at least as important a factor. The study is also consistent with the nursing home studies in which decreases in noise and light did not improve sleep.22, 23 It refutes the study that showed that most sleep disturbance in medical‐surgical patients comes from noise and sleeping in an unfamiliar bed.4 Our results call into question the use of the VSH scale in hospitalized patients, which was designed for use in healthy subjects.

Limitations of this study were as follows: moderate size, lack of refined measures of disease severity, and, as in previous studies,19, 2123 the lack of randomized concurrent controls. Evaluation of secondary endpoints was limited by lack of validation of the questionnaire with objective observations, and inability to use the modified VSH scale. Self‐reports of sleep may correlate imperfectly with objective measures, such as polysomnography.27

A larger concurrent trial randomizing similar units at multiple hospitals would be ideal. Future research is needed to determine whether improving sleep in the hospital improves other outcomes, such as recovery times, delirium, falls, or cost.

The need to reduce as‐needed sedatives is an important safety issue and similar interventions in other hospitals may be helpful. Simple changes in staff routines and provider prescribing habits can yield significant reductions in sedative use.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Gertrude Gavin, Steffie Woolhandler, MD, Linda Borodkin, John Brusch, MD, Patricia Crombie, Priscilla Dasse, Glen Dawson, Ben Davenny, Linda Kasten, Judith Krempin, Mark Letzeisen, Carmen Mohan, and Arun Mohan. Linda Kasten, Timothy Schmidt, and Glen Dawson provided statistical analysis. The sound meters (Yacker Trackers, Creative Toys of Colorado) were donated by John Brusch, who has no financial conflict of interest.

- ,,,.Sleep in hospitalized medical patients, Part 1: Factors affecting sleep.J Hosp Med.2008;3:473–482.

- ,.Sleep‐dependent learning and memory consolidation.Neuron.2004;44:121–133.

- ,,,,,.An assessment of quality of sleep and the use of drugs with sedating properties in hospitalized adult patients.Health Qual Life Outcomes.2004;2:17.

- ,,,.The sleep experience of medical and surgical patients.Clin Nurs Res.2003;12:159–173.

- .Metabolic and endocrine effects of sleep deprivation.Essent Psychopharmacol.2005;6:341–347.

- ,,,,.Sleep loss and REM sleep loss are hyperalgesic.Sleep.2006;29:145–151.

- ,,,.Slow‐wave sleep and the risk of type 2 diabetes in humans.Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.2008;105:1044–1049.

- .Sleep inquiry: a look with fresh eyes.Image J Nurs Sch.1993;25:249–256.

- Berglund B, Lindvall T, Schwela D, eds.Guidelines for Community Noise.World Health Organization;1999:47.

- ,,,,,.Noise levels in Johns Hopkins Hospital.J Acoust Soc Am.2005;118:3629–3645.

- .Explicit criteria for determining potentially inappropriate medication use by the elderly. An update.Arch Intern Med.1997;157:1531–1536.

- .Delirium in older persons.N Engl J Med.2006;354:1157–1165.

- ,,,,.Sedative hypnotics in older people with insomnia: meta‐analysis of risks and benefits.BMJ.2005;331:1169.

- .Sleep in acute care units.Sleep Breath.2006;10:6–15.

- ,,,,.Quantity and quality of sleep in the surgical intensive care unit: are our patients sleeping?J Trauma.2007;63:1210–1214.

- ,.Sleep in the critically ill patient.Sleep.2006;29:707–716.

- ,,.Sleep quality in hospitalized patients.J Clin Nurs.2005;14:107–113.

- ,.Interactive relationships between hospital patients' noise‐induced stress and other stress with sleep.Heart Lung.2001;30:237–243.

- ,,, et al.A multicomponent intervention to prevent delirium in hospitalized older patients.N Engl J Med.1999;340:669–676.

- ,,,,.The Hospital Elder Life Program: a model of care to prevent cognitive and functional decline in older hospitalized patients. Hospital Elder Life Program.J Am Geriatr Soc.2000;48:1697–1706.

- ,,,,.Noise control: a nursing team's approach to sleep promotion.Am J Nurs.2004;104:40–48; quiz 48‐49.

- ,,,,,.A nonpharmacological intervention to improve sleep in nursing home patients: results of a controlled clinical trial.J Am Geriatr Soc.2006;54:38–47.

- ,,,,.The nursing home at night: effects of an intervention on noise, light, and sleep.J Am Geriatr Soc.1999;47:430–438.

- ,.Instrumentation to describe subjective sleep characteristics in healthy subjects.Res Nurs Health.1987;10:155–163.

- ,,,,.The role of adherence on the effectiveness of nonpharmacologic interventions: evidence from the delirium prevention trial.Arch Intern Med.2003;163:958–964.

- ,,.Patient perception of sleep quality and etiology of sleep disruption in the intensive care unit.Am J Respir Crit Care Med.1999;159:1155–1162.

- ,,.When sleep is perceived as wakefulness: an experimental study on state perception during physiological sleep.J Sleep Res.2007;16:346–353.

Adequate sleep is important for health, yet the hospital environment commonly disrupts sleep.13 Sleep improves after several days in the hospital.3, 4 Sleep deprivation increases cortisol levels5 and sleep loss of greater than 4 hours may be hyperalgesic.6 Even a few days' suppression of slow‐wave sleep worsens glucose tolerance.7 Sleep disruption may cause irritability and aggressiveness,8 impaired memory consolidation, and delirium.2

Noise may disrupt sleep. The World Health Organization recommends a maximum of 30 to 40 dBA in patients' rooms at night.9, 10 Normal conversation occurs at 60 dBA. Medical equipment alarms are about 80 dBA.

Sedative use is common in the hospital.3 Sedatives typically shorten sleep latency and suppress rapid eye movement (REM) sleep. However, some sedatives cause delirium, falls, amnesia, and confusion, particularly in the elderly.1113

Most research on sleep in hospitalized patients has been done in the critical care setting, often in sedated ventilated patients, where sleep disruption is well‐described.1416 Only a few small studies have assessed the sleep of hospitalized patients outside critical care.17, 18

A single blinded interventional trial assessed sedative use, but was a nonrandomized study.19, 20 As‐needed sedative use was measured among hospitalized elderly patients as a secondary endpoint. The intervention, known as the Hospital Elder Life Program (HELP), included a protocol with noise reduction, massage, music, and warm drinks, as well as rescheduling of medications and procedures; it resulted in a 24% reduction in as‐needed sedative use. Another trial decreased noise and reduced overnight X‐rays on a surgical unit, then measured staff and patient attitudes.21 Two interventional studies in nursing homes reduced noise and light, and/or increased daytime activity and found no effect on most objective measures of sleep.22, 23 One descriptive study found most sleep disturbances in medical‐surgical patients came from noise and sleeping in an unfamiliar bed.4

We hypothesized that an intervention designed to improve patient sleep through changes in staff behavior would decrease sedative use among unselected patients in a medical‐surgical unit. We measured sedative use as our primary endpoint as a marker for effective sleep, and because decreased sedative use is desirable. We also hypothesized that the intervention would lead to improved sleep experiences, as measured by a questionnaire and Verran Snyder‐Halpern (VSH) sleep scores as secondary endpoints.24

Materials And Methods

Study Design

This was a pre‐post study assessing the effect of the intervention on as‐needed sedative use, questionnaire responses, and sleep quality. It was an intention‐to‐treat analysis, and was blinded in terms of measurement of sedative use. The Institutional Review Board of Cambridge Health Alliance approved the study.

Setting and Patients

The site was the only medical‐surgical unit of Somerville Hospital, a small urban community teaching hospital that is part of Cambridge Health Alliance. The hospital unit was chosen for its architectural characteristics, and is organized spatially as 3 U‐shaped pods surrounding nursing workstations. Hence, patient rooms were nearly equidistant from the nurses' stations, unlike a hallway design where distant rooms are quieter. Six rooms were private; 11 were semiprivate. Most of the unit's 28 beds are used for medical patients covered by the hospitalist service. Residents see a minority of patients. A hospitalist is available around the clock. Few agency nurses are used.

Preintervention patients were recruited between April and August 2007. The intervention was planned and implemented from September 2007 to January 2008. Intervention patients were recruited between February and June 2008. The most common principle diagnoses on the unit were chest pain (11%), pneumonia (8%), congestive heart failure (CHF) (5.1%), and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) flare (3%). Exclusion criteria ensured that no patient was ill enough to require intensive care unit (ICU)‐level care or was actively dying. All consecutive hospitalized patients on the unit on Tuesdays through Fridays were potentially eligible and invited to participate unless they met exclusion criteria. The limited days of the week ensured that technical support would be available during the intervention phase.

Exclusion criteria were: known sleep disorders; language other than English, Spanish, Portuguese, or Haitian Creole; surgery the prior day; arrival on the floor after 10 PM the prior evening; residence on the unit for more than 4 days; alcohol or drug withdrawal; end‐of‐life morphine drip; significant hearing loss; and blindness.

Study Protocol

A single investigator surveyed patients in the morning about the prior night's sleep experience. The surveys consisted of the VSH sleep scale, as well as an 8‐item questionnaire developed from informal pilot interviews with about 18 patients conducted by 1 of the investigators (M.B.) (Supporting Information Figure 1). The VSH scale is a visual analog scale using a 100‐cm line,24 which we modified with a 100‐mm line to make it easier to collect data. The questionnaire and VSH scores of patients with cognitive impairment were not included in the final analysis. Cognitive impairment was determined by diagnoses present in chart review. Surveys and consent forms were available in 4 languages and trained interpreters were used as needed. Nurses, providers, and patients were blinded to the measurement of as‐needed sedative use, and staff were unaware of which patients were study subjects.

Measurements

Nighttime administration of any medication ordered prn sleep or insomnia was measured using the pharmacy dispensing equipment (Pyxis; Cardinal Health, Dublin, OH), then verified by reviewing the patients' medication administration records. VSH sleep scores were created by measuring the distance in millimeters from the lower end of the scale (0) to the location marked.

We also tracked adherence to some aspects of the intervention. The questionnaire recorded door closing. Chart audits measured the numbers of different prescribers, and the frequency of medication orders using flexible timing.

Data Analysis

Medication use was analyzed as any as‐needed sedative use vs. none. The proportions of patients who used sedatives preintervention and postintervention were compared using a 2‐sample Z statistic, as were survey items. Mean VSH scores were compared with 2‐sample t tests. The study had greater than 80% power to detect a difference in proportion of at least 0.14 at alpha = 0.05.

Design and Implementation of the Intervention

Preintervention, routine vital signs were taken every 8 hours: 8 AM, 4 PM, and midnight. Night nurses arrived at 11 PM, and typically turned off the hallway lights, but the practice was variable and occurred at no set time.

Patients in our informal pilot interviews identified vital signs, medication administration, noise, and evening diuretic administration as disrupting their sleep. After the preintervention phase, we spent 4 months designing and implementing the intervention. We solicited opinions from staff, who identified inflexible timing of medications as disruptive. The plan was discussed at routine staff meetings of all shifts.

The intervention, called the Somerville Protocol (Figure 1) created an 8‐hour Quiet Time from 10 PM to 6 AM, when disruptions were minimized. Vital signs were taken 2 hours earlier (6 AM, 2 PM, and 10 PM); routine medication administration was avoided; and noise was reduced. As before, telemetry patients required vital signs every 4 hours. At 10 PM, hallway lights were turned off by a timer while the Lullaby by Brahms played overhead, signaling the start of Quiet Time to staff and patients. Inexpensive sound meters were installed in each nursing area. They flashed warning lights when 60 dBA was exceeded.

A physician and nurse served as champions. Educational signs were posted in the hospitalists' call room and in the nursing areas. The champions used e‐mail and detailed the intervention to staff. Because the staff played an active role in intervention planning, implementation went smoothly.

Results

During the preintervention phase, 334 patients were screened, 294 were eligible, and 54.7% of eligible subjects were enrolled (n = 161). During the intervention phase, 211 patients were screened, 188 were eligible, and 56.3% of eligible patients were enrolled (n = 106). The mean patient age was 60.6 years. The preintervention and intervention groups did not differ significantly in enrollment rate, age, gender, cognitive impairment, surgical status, or hearing deficiencies (Table 1). Over 93% of patients were nonsurgical.

| Preintervention Patients (n = 161) | Intervention Patients (n = 106) | P Values for Difference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (years) | 59.1 | 62.95 | P = 0.146 |

| Males, n (%) | 79 (49.1%) | 46 (43.4%) | P = 0.38 |

| Hard of hearing, n (%) (self‐report) | 33/157 (21.0%) | 14/103 (13.6%) | P = 0.128 |

| English‐speaking, n (%) | 134 (83%) | 83 (78.3%) | P = 0.34 |

| Cognitive impairment, n (%) | 4 (2.5%) | 3 (2.8%) | P = 0.88 |

| Surgical patients, n (%) | 10 (6.2%) | 2 (1.8%) | P = 0.089 |

Sedative Use

Preintervention, 31.7% of patients received nighttime as‐needed sedatives, versus 16.0% of the intervention group, a 49.4% reduction (P = 0.0041; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.056‐0.26) (Figure 2). In patients aged 65 years or older, 38.2% received nighttime as‐needed sedatives preintervention, and 14.6% did postintervention, a 61.2% reduction (P = 0.0054; 95% CI: 0.084‐0.39).

Questionnaire Results

Preintervention, hospital staff was by far the biggest factor keeping patients awake, with 42.4% of patients reporting it (Figure 3). This dropped to only 25.7% with the intervention, a 39.3% decrease (P = 0.009; 95% CI: 0.0452‐0.2765). Preintervention, 19.2% of patients selected voices as the noise most likely to bother them at night, and this dropped to 9.9% with the intervention, a 48% decrease (P = 0.045; 95% CI: 0.0074‐0.1787). No other significant differences were found.

VSH Sleep Score Results

We found no improvement in any measure of the VSH sleep scale. However, 75% of our patients were unable to use the modified VSH scale, generally because they felt too ill, and were then prompted by the surveyor to choose a number between 1 and 10 that reflected their experience.

Protocol Adherence

Changes in unit routines resulted in complete adherence to the new vital signs schedule and avoidance of routine evening diuretics. The closing of patients' doors did not change. An audit of 40 charts found that the percentage of medication orders written with appropriate flexible timing increased from 82% (n = 228) to 95.5% (n = 200) (P = 0.001; 95% CI: 0.077‐0.192). From 20 to 30 different providers wrote orders during each phase.

Discussion

Our trial found that hospital staff was the factor most responsible for patient sleep disruption, and that behavioral interventions on hospital staff can reduce use of as‐needed sedatives. The only previously reported intervention to reduce sedative use, the HELP strategy, involved a complex intervention requiring extra staff, with adherence ranging from 10% to 75%.19, 20, 25 In contrast, our protocol can be easily replicated at minimal cost.

Our results are consistent with those of Freedman et al.,26 who found that noise was not the primary factor responsible for sleep disruption in ICU patients, and that staff activities were at least as important a factor. The study is also consistent with the nursing home studies in which decreases in noise and light did not improve sleep.22, 23 It refutes the study that showed that most sleep disturbance in medical‐surgical patients comes from noise and sleeping in an unfamiliar bed.4 Our results call into question the use of the VSH scale in hospitalized patients, which was designed for use in healthy subjects.

Limitations of this study were as follows: moderate size, lack of refined measures of disease severity, and, as in previous studies,19, 2123 the lack of randomized concurrent controls. Evaluation of secondary endpoints was limited by lack of validation of the questionnaire with objective observations, and inability to use the modified VSH scale. Self‐reports of sleep may correlate imperfectly with objective measures, such as polysomnography.27

A larger concurrent trial randomizing similar units at multiple hospitals would be ideal. Future research is needed to determine whether improving sleep in the hospital improves other outcomes, such as recovery times, delirium, falls, or cost.

The need to reduce as‐needed sedatives is an important safety issue and similar interventions in other hospitals may be helpful. Simple changes in staff routines and provider prescribing habits can yield significant reductions in sedative use.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Gertrude Gavin, Steffie Woolhandler, MD, Linda Borodkin, John Brusch, MD, Patricia Crombie, Priscilla Dasse, Glen Dawson, Ben Davenny, Linda Kasten, Judith Krempin, Mark Letzeisen, Carmen Mohan, and Arun Mohan. Linda Kasten, Timothy Schmidt, and Glen Dawson provided statistical analysis. The sound meters (Yacker Trackers, Creative Toys of Colorado) were donated by John Brusch, who has no financial conflict of interest.

Adequate sleep is important for health, yet the hospital environment commonly disrupts sleep.13 Sleep improves after several days in the hospital.3, 4 Sleep deprivation increases cortisol levels5 and sleep loss of greater than 4 hours may be hyperalgesic.6 Even a few days' suppression of slow‐wave sleep worsens glucose tolerance.7 Sleep disruption may cause irritability and aggressiveness,8 impaired memory consolidation, and delirium.2

Noise may disrupt sleep. The World Health Organization recommends a maximum of 30 to 40 dBA in patients' rooms at night.9, 10 Normal conversation occurs at 60 dBA. Medical equipment alarms are about 80 dBA.

Sedative use is common in the hospital.3 Sedatives typically shorten sleep latency and suppress rapid eye movement (REM) sleep. However, some sedatives cause delirium, falls, amnesia, and confusion, particularly in the elderly.1113

Most research on sleep in hospitalized patients has been done in the critical care setting, often in sedated ventilated patients, where sleep disruption is well‐described.1416 Only a few small studies have assessed the sleep of hospitalized patients outside critical care.17, 18

A single blinded interventional trial assessed sedative use, but was a nonrandomized study.19, 20 As‐needed sedative use was measured among hospitalized elderly patients as a secondary endpoint. The intervention, known as the Hospital Elder Life Program (HELP), included a protocol with noise reduction, massage, music, and warm drinks, as well as rescheduling of medications and procedures; it resulted in a 24% reduction in as‐needed sedative use. Another trial decreased noise and reduced overnight X‐rays on a surgical unit, then measured staff and patient attitudes.21 Two interventional studies in nursing homes reduced noise and light, and/or increased daytime activity and found no effect on most objective measures of sleep.22, 23 One descriptive study found most sleep disturbances in medical‐surgical patients came from noise and sleeping in an unfamiliar bed.4

We hypothesized that an intervention designed to improve patient sleep through changes in staff behavior would decrease sedative use among unselected patients in a medical‐surgical unit. We measured sedative use as our primary endpoint as a marker for effective sleep, and because decreased sedative use is desirable. We also hypothesized that the intervention would lead to improved sleep experiences, as measured by a questionnaire and Verran Snyder‐Halpern (VSH) sleep scores as secondary endpoints.24

Materials And Methods

Study Design

This was a pre‐post study assessing the effect of the intervention on as‐needed sedative use, questionnaire responses, and sleep quality. It was an intention‐to‐treat analysis, and was blinded in terms of measurement of sedative use. The Institutional Review Board of Cambridge Health Alliance approved the study.

Setting and Patients

The site was the only medical‐surgical unit of Somerville Hospital, a small urban community teaching hospital that is part of Cambridge Health Alliance. The hospital unit was chosen for its architectural characteristics, and is organized spatially as 3 U‐shaped pods surrounding nursing workstations. Hence, patient rooms were nearly equidistant from the nurses' stations, unlike a hallway design where distant rooms are quieter. Six rooms were private; 11 were semiprivate. Most of the unit's 28 beds are used for medical patients covered by the hospitalist service. Residents see a minority of patients. A hospitalist is available around the clock. Few agency nurses are used.

Preintervention patients were recruited between April and August 2007. The intervention was planned and implemented from September 2007 to January 2008. Intervention patients were recruited between February and June 2008. The most common principle diagnoses on the unit were chest pain (11%), pneumonia (8%), congestive heart failure (CHF) (5.1%), and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) flare (3%). Exclusion criteria ensured that no patient was ill enough to require intensive care unit (ICU)‐level care or was actively dying. All consecutive hospitalized patients on the unit on Tuesdays through Fridays were potentially eligible and invited to participate unless they met exclusion criteria. The limited days of the week ensured that technical support would be available during the intervention phase.

Exclusion criteria were: known sleep disorders; language other than English, Spanish, Portuguese, or Haitian Creole; surgery the prior day; arrival on the floor after 10 PM the prior evening; residence on the unit for more than 4 days; alcohol or drug withdrawal; end‐of‐life morphine drip; significant hearing loss; and blindness.

Study Protocol

A single investigator surveyed patients in the morning about the prior night's sleep experience. The surveys consisted of the VSH sleep scale, as well as an 8‐item questionnaire developed from informal pilot interviews with about 18 patients conducted by 1 of the investigators (M.B.) (Supporting Information Figure 1). The VSH scale is a visual analog scale using a 100‐cm line,24 which we modified with a 100‐mm line to make it easier to collect data. The questionnaire and VSH scores of patients with cognitive impairment were not included in the final analysis. Cognitive impairment was determined by diagnoses present in chart review. Surveys and consent forms were available in 4 languages and trained interpreters were used as needed. Nurses, providers, and patients were blinded to the measurement of as‐needed sedative use, and staff were unaware of which patients were study subjects.

Measurements

Nighttime administration of any medication ordered prn sleep or insomnia was measured using the pharmacy dispensing equipment (Pyxis; Cardinal Health, Dublin, OH), then verified by reviewing the patients' medication administration records. VSH sleep scores were created by measuring the distance in millimeters from the lower end of the scale (0) to the location marked.

We also tracked adherence to some aspects of the intervention. The questionnaire recorded door closing. Chart audits measured the numbers of different prescribers, and the frequency of medication orders using flexible timing.

Data Analysis

Medication use was analyzed as any as‐needed sedative use vs. none. The proportions of patients who used sedatives preintervention and postintervention were compared using a 2‐sample Z statistic, as were survey items. Mean VSH scores were compared with 2‐sample t tests. The study had greater than 80% power to detect a difference in proportion of at least 0.14 at alpha = 0.05.

Design and Implementation of the Intervention

Preintervention, routine vital signs were taken every 8 hours: 8 AM, 4 PM, and midnight. Night nurses arrived at 11 PM, and typically turned off the hallway lights, but the practice was variable and occurred at no set time.

Patients in our informal pilot interviews identified vital signs, medication administration, noise, and evening diuretic administration as disrupting their sleep. After the preintervention phase, we spent 4 months designing and implementing the intervention. We solicited opinions from staff, who identified inflexible timing of medications as disruptive. The plan was discussed at routine staff meetings of all shifts.