User login

Delays in Pediatric Discharge

Inpatient pediatrics is undergoing a paradigm shift in at least 3 ways. First, more children with chronic disease are being cared for in the hospital over time.1 Second, previous inpatient conditions are treated at home with advancing technology such as peripherally‐inserted catheters.2 Third, there are new areas of growing specialization, such as hospital medicine, in which the practitioners deliver more efficient care.3, 4

Nationwide, there is increasing pressure to improve inpatient quality of care. The Institute of Medicine defines 6 aims for improvement, including timeliness (reducing waits and sometimes harmful delays for both those who receive and those who give care) and efficiency of care (avoiding waste, including waste of equipment, supplies, ideas, and energy).5 Reducing unnecessary stays in the hospital is a potential quality measure that hospitals may use to address the timeliness and efficiency of care delivered to hospitalized children.

Delays in discharge have been used as markers of unnecessary stays in the hospital for inpatient adult and pediatric care,6, 7 but these are limited to inpatient systems from almost 20 years ago. Current reasons why patients are delayed from discharge, if at all, are not well described. We undertook this study to describe delays in hospital discharges at a tertiary‐care children's hospital in terms of number of patients, length of days of delay, and type of delay. In addition, we sought to characterize the impact of discharge delays on overall length of stay (LOS) and costs.

Methods

Patient Population/Study Design

All children cared for on 2 pediatric medical teams at Primary Children's Medical Center during the month of August 2004 were eligible for the study. Two research assistants independently attended team rounds and collected data relating to: the reasons for ongoing hospitalization, pending items (eg, consultations, tests), and the plan of care for that day. The research assistants each attended daily team rounds for the entire month of August (1 for each team, switching to the opposite team after 2 weeks). This was combined with information available in the Patient Tracker, a software tool developed to improve communication between caregivers and improve discharge efficiency.8 This software tool details diagnoses, daily medical care plans, discharge criteria, and ongoing medical interventions while tracking daily changes in interventions and the medical care plan for each patient cared for on a pediatric medical team.

The research assistants subsequently presented their observations along with information from Patient Tracker to 2 experienced physicians (R.S. and B.S.) who independently determined if a delay occurred, the number of delay days extending discharge, and the cause of the delay, if present, categorized according to the taxonomy of the Delay Tool.6, 7 If there was not enough information for either of the physicians to identify and classify a delay, the electronic medical record of the patient was also reviewed. Discrepancies between physicians assigning delays were discussed until consensus was reached.

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Utah Health Sciences Center and Primary Children's Medical Center (PCMC).

Setting

PCMC is a 233‐bed tertiary‐care children's hospital, owned and operated by Intermountain Healthcare (a not‐for‐profit vertically integrated managed care organization) in the Intermountain West, which serves as both the primary hospital for Salt Lake County and as a tertiary‐care children's hospital for 5 states (UT, MT, WY, ID, and NV).9

Study Definitions

Delay and Length of Delay

Delays in discharge were measured using a validated and reliable instrument, the Delay Tool.6, 7 A discharge was classified as delayed if there was no medical reason for the patient to be in the hospital on a given day, identical to the definition used in the original studies to validate the tool. Delays were recorded as whole days, not fractions of days or hours, as described in the original validation of the tool. For example, if the medical team requested a consultation, and the consultant's opinion was rendered late, but the patient would have remained in the hospital anyway, then this period of time would not count as a delay. However, if the medical team did not receive a consultant's opinion within the standard time (24 hours as defined for this study and in validating studies for the Delay Tool), and the patient's sole reason for being in the hospital during that day was waiting for that opinion, then that period of time would count toward a delay due to a late consultative opinion. Delays of less than 1 day, due to the mechanics of discharging a patient from the hospital (providing prescriptions, follow up, communication, arranging home health, and transportation) were not measured in this study, to match the original methodology of the Delay Tool.

Type of Delay

Primary reason for delay was assigned according to the taxonomy of the Delay Tool.6, 7 Delays were categorized to 1 of the following: (1) test scheduling; (2) obtaining test results; (3) surgery; (4) consultation; (5) patient (eg, family unavailable for decision‐making); (6) physician responsibility; (7) education, training. or research; (8) discharge planning or scheduling; and (9) availability of outside care and resources. There are 166 subcategories that clarify why a delay occurred. For example, within the main category of obtaining test results (2), there are 3 subcategories of delays related to problem in executing the test (2.1), return of results is delayed (2.2), and test results not reviewed within standard time of return (2.3). Subcategories are further divided to provide detail on the cause of delay. For example, a delay categorized as a 2.1:1 [(2) obtaining test results; (2.1) problem in executing the test; and 2.1:1 test to be done by MD is delayed beyond day desired], or 2.3:1 [(2) obtaining test results; (2.3) test results not reviewed within standard time of return; and 2.3:1 delay because physician did not review results]) both relate to physician causes of delays within the general category of obtaining test results. Some delays had more than 1 cause. A secondary cause of delay was assigned if applicable; however, the number of days delayed was attributed to the primary cause for analysis purposes.

Exemptions to Delay and Special Populations

Certain subpopulations of patients presented unique issues that led to them being unlikely to be classified as having a delay. For example, patients with a diagnosis of new onset of type 1 diabetes are historically admitted for 3 days at our hospital, which includes a specific education program; delays were not considered until this minimum period had passed. Children with medically complex care (eg, multisystem disease, multiple specialists involved, multiple medications) were included in this study.10 However, these children with frequent hospital admission were often fragile at discharge, and could meet criteria for readmission even on the date of their discharge, hence assigning a delay day was usually not indicated because of easily justified ongoing medical need for hospitalization.

Study Variables

The LOS, total costs, and routine demographic and administrative data for each study patient were extracted from Intermountain Healthcare's Enterprise Data Warehouse (EDW). The EDW contains detailed data about the cost of providing health care. Costs were derived from the hospital's cost accounting program, the Standard Cost Master, which is a transaction‐based microcosting accounting system.1113

For patients whose LOS extended before August 1 or after August 31, total hospital costs were averaged per day, and only days falling inside the month of August were counted in calculating the impact the delays in discharge had on the total costs of hospitalization. Hospital days that extended outside of August were not counted in either the numerator for potential days of delay or in the denominator for total days in the hospital.

Analyses

Descriptive statistics were calculated for the number, length of days of delay, and type of delay. Interrater reliability to assign a delay was ascertained for the 2 physicians. Mean LOS, mean total costs, and standard deviations (SDs) were calculated. All analyses were performed using Statistical Analytical Software version 9.13 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

During the 31 days of the study, 171 patients occupied hospital beds an average of 7.3 days on the 2 inpatient medical teams, for a total of 911 inpatient days. Seven patients were admitted prior to August 1; 6 of these were discharged during the month of August and 1 stayed through the entire month and was discharged in September. Three additional patients were admitted in August and discharged in September. There were 6 readmissions during the month of August, and 1 patient was excluded from the study because of lack of sufficient information. All patients with delays were able to be classified according to the Delay Tool taxonomy. Interrater reliability for the 2 study physicians was 98%.

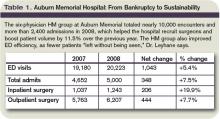

The characteristics between the patients who did and did not experience a delay in discharge are shown in Table 1. Thirty‐nine of 171 patients (22.8%), experienced at least 1 delay day. Eighteen of 39 patients had only 1 delay day (46.2%) and 11 patients experienced 2 delayed days (28.2%) (Figure 1). The average length of delay was 2.1 days.

| Nondelayed Patients (N = 132) | Delayed Patients (N = 39) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Age (months), mean (SD)* | 22.6 (14.4) | 15.0 (14.6) | 0.009 |

| LOS during August (days), mean (SD)* | 4.64 (6.1) | 7.64 (7.15) | <0.001 |

| Total costs during August ($), mean (SD)* | 10,451 (19,254) | 14,341 (16,241) | 0.002 |

| Number of ICD‐9 CM diagnoses codes, mean (SD)* | 7.1 (7.4) | 8.5 (7.3) | 0.056 |

| Number of ICD‐9 CM procedure codes, mean (SD)* | 1.7 (3.8) | 1.6 (2.6) | 0.068 |

| Number of Patients with APR‐DRG SOI 3 (%) | 59 (44.7%) | 19 (48.7%) | 0.65 |

Delays attributed to physician responsibility accounted for 42.3% (16.5/39) of patient delays (conservative management or clinical decision‐making), with discharge planning delays accounting for 21.8% (family‐related, patient‐related, and hospital‐related problems), consultation for 14.1% (delay in obtaining or lack of follow‐up), test scheduling for 12.8%, and obtaining test results for 5.1% (ordering and weekend scheduling). There were no primary delays due to surgery, education and research, or unavailability of outside resources such as a skilled nursing bed. Four patients had a single additional secondary cause of delay assigned to them, related to physician responsibility, consultation, surgery and test scheduling; these were split, attributing 0.5 patients to each delay type (thus, the 17/39 patients delayed for physician responsibility was analyzed as 16.5/39) (Table 2).

| Delay Category | Number of Patients Experiencing Delays* | Percentage of All Patients Experiencing Delays (%) | Percentage of Study Patients Observed (%) | Total Delay Days | Average Length of Delays (days) | Percentage of Hospital Days That Were Delay Days (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||

| 1. Scheduling | 5 | 12.8 | 2.92 | 16 | 3.20 | 1.76 |

| 2. Obtaining results | 2 | 5.1 | 1.17 | 3 | 1.50 | 0.33 |

| 3. Surgery | 0.5 | 1.3 | 0.29 | 1.5 | 3.00 | 0.16 |

| 4. Consultation | 5.5 | 14.1 | 3.22 | 10.5 | 1.91 | 1.15 |

| 5. Patient | 1 | 2.6 | 0.58 | 2 | 2.00 | 0.22 |

| 6. Physician | 16.5 | 42.3 | 9.65 | 33.5 | 2.03 | 3.68 |

| 7. Education | 0 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0 | 0.00 |

| 8. Discharge | 8.5 | 21.8 | 4.97 | 15.5 | 1.82 | 1.70 |

| 9. Outside | 0 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Total | 39 | 100 | 22.81 | 82 | 2.10 | 9.00 |

There were 82 delay‐related hospital days of 911 total inpatient days on the 2 medical teams for August 2004 (9%). More than $170,000 in excess costs was incurred due to delay days from a total of approximately 1.9 million dollars in patient costs for the month (8.9%).

Discussion

This study finds that discharge delays in a tertiary care children's hospital are common; almost 1 in 4 patients experienced a medically unnecessary excess hospital stay of at least 1 day. The average length of a delay was 2.1 days, and overall, delays consumed 9% of pediatric hospital days and 8.9% of total costs. The most common reason for a delay was related to physician clinical care, including excessively conservative management and variability in clinical decision‐making.

Our study results are similar to the other 2 published studies that use the Delay Tool. In the adult and pediatric studies, between 10% and 30% of patients experienced a delay in discharge, with the average length of delay between 2.9 and 3 days.6, 7 Although both studies were conducted at teaching hospitals, what is particularly interesting is that they were conducted almost 20 years ago. During this period of time, there has been a shift in the inpatient pediatric patient population. In recent years, children who are cared for in the hospital have more chronic illnesses.1 In addition, there has been a shift in the types of conditions that may be cared for at home and those that now require inpatient stay.2 Despite this, delays continue at a similar proportion, but the cause of delays have shifted from scheduling and consultation to physician responsibility.

There is another tool in the literature which is more widely used, the Pediatric Appropriateness Evaluation Protocol (PAEP), which is based on the Appropriateness Evaluation Protocol for adults.1417 This tool is used to determine the appropriateness of ongoing hospitalization, not the cause of delay if ongoing hospitalization is inappropriate. The 3 areas that are evaluated (medical services, nursing and ancillary services, and patient's condition) have objective criteria that dictate if the hospitalization is appropriate or not (eg, parenteral (intravenous) therapy for at least 8 hours on that day, under nursing and ancillary services). The PAEP may be less sensitive given today's healthcare resource utilization climate. Many clinicians and families would agree that insertion of a peripheral central catheter is an acceptable form of outpatient treatment for many pediatric conditions. In conjunction with the Delay Tool, the PAEP could be used to determine if a delay occurred, then the Delay Tool used to categorize the cause of the delay. We choose to use expert clinician judgment to determine if a delay had occurred. We were more interested in why patients who are admitted (appropriately or inappropriately) cannot be discharged sooner, thus allowing for future intervention studies targeted to impact delays in discharge, as elucidated in this study. The Delay Tool specifically allowed us to categorize the reasons for delays. Given that the average LOS for patients in the nondelayed group was over 4 days, despite not using a tool such as the PAEP, we believe that these were likely to be appropriate admissions.

A recent study reported the first use of the Medical Care Appropriateness Protocol (MCAP) in a tertiary‐care children's hospital. The authors used the MCAP to determine the impact of an intervention on reducing inappropriate hospitals days for children. This tool is similarly labor‐intensive to the Delay Tool. Interestingly, this Canadian study found a high rate of inappropriate hospital days (47%), which may be in part attributable to a different outcome measurement tool and/or a different health care system.18

There are several limitations to our study that deserve mention. The Delay Tool requires clinician judgment regarding whether or not there was a delay in discharge for that day. We may have introduced some bias in our study, as hospitalist investigators assigned the delay and blinding to the attending physician specialty of record was not feasible. However, our results are similar to the other 2 published studies that have used this tool, and we specifically chose not to analyze or report results in terms of hospitalist and nonhospitalist attending physicians. The Delay Tool is not designed to differentiate shorter delays in terms of hours instead of days (eg, due to the inability for the patient to get a ride home). Shorter delays may be of particular importance depending on the occupancy rate of the hospital, the demand for beds, and other patient and hospital factors. We could not capture these shorter delays (although they did occur frequently) due to the original description of the Delay Tool. In addition, we would not have been able to report data on the impact on LOS and costs, as these are attributed to whole days in the hospital. However, if we had been able to differentiate shorter delays, this would bias our results to show a greater percentage of delays over smaller increments of time. Generalizability is an issue, given that this was a single‐center study. This study sample included over 80 different attending physicians participating in community pediatrician, subspecialty, and hospitalist practice groups. However, the patient population at PCMC is similar to other medium and large children's hospitals in the United States. The month observed may not reflect the entire year of hospitalizationsthere may be seasonal variations with delays depending on the volume and type of illness seen. The study was conducted in August, when there are newer house staff present. However, physician responsibility, which was the largest source of delays in our study, had little attribution to house staff. Most of the decisions were those of attending physicians, which would largely be unaffected by the time of year of the study. Finally, we were unable to assess the safety of the potential earlier discharge, as this was an observational study. However, in any future intervention studies examining processes to discharge patients sooner, measures of safety to the patient are a necessity. Finally, given the potential of ongoing admission, even on the date of discharge of our most fragile patients, this approach to discovering causes of delay may not apply to this important group, which is responsible for significant and growing resource utilization.

Despite these limitations, our findings demonstrate that in an era of children staying in the hospital less, and more medically‐complex children being admitted,10 a substantial number of children who are hospitalized at a children's hospital may have been discharged sooner. The majority of these decisions were directly related to physician responsibility. As consumers, providers, and hospitals work together to develop quality measures that are reflective of inpatient pediatric care, the Delay Tool may be able to highlight 2 aims of quality (ie, timeliness and efficiency of care) that could be used to assess the impact of interventions designed to safely discharge patients sooner. Interventions such as audit‐feedback,18 clinical guideline deployment,19 and hospitalist systems of care4 continue to hold the promise of earlier discharge; however, tools designed to measure inappropriate use of hospital days should be employed to demonstrate their effectiveness. Our study demonstrates ongoing waste in children's hospitals.

Conclusions

Almost 1 out of 4 patients in this 1‐month period could have been discharged sooner than they were. The impact of delays on costs and LOS are substantial and should provide strong incentives to develop effective interventions. Such interventions will need to address variations in physician criteria for discharge, more efficient discharge planning, and timely scheduling of consultation and diagnostic testing.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Joni R. Beshanky and Harry Selker for their help and training in the use of the Delay Tool.

- .The transformation of child health in the United States: social disparities in child health persistent despite dramatic improvement in child health overall.Health Aff (Millwood).2004;23(5):9–25.

- , , , .Hospitalist care of medically complex children.Pediatr Res.2004;55(4):314A–315A.

- , , , .Pediatric hospitalists: a systematic review of the literature.Pediatrics.2006;117(5):1736–1744.

- , , , et al.Pediatric hospitalists: report of a leadership conference.Pediatrics.2006;117(4):1122–1130.

- Institute of Medicine.Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the Twenty‐first Century.Washington, DC:National Academy Press;2001.

- , , .Using the Delay Tool to attribute causes for unnecessary pediatric hospital days.Med Care.1990;28(10):982–989.

- , , , .The epidemiology of delays in a teaching hospital. The development and use of a tool that detects unnecessary hospital days.Med Care.1989;27(2):112–129.

- , , , , .A tool for improving patient discharge process and hospital communication practices: the Patient Tracker.AMIA Annu Symp Proc.2007;11:493–497.

- , .Organizational responses to managed care: issues for academic health centers and implications for pediatric programs.Pediatrics.1998;101(4 Pt 2):805–811; discussion 811–802.

- , , .Hospitalist care of the medically complex child.Pediatr Clin North Am.2005;52(4):1165–1187.

- , , , et al.Epidemiology, complications, and cost of hospitalization in children with laboratory‐confirmed influenza infection.Pediatrics.2006;118(6):2409–2417.

- , , , , , .Clinical and economic outcomes of conventional amphotericin B‐associated nephrotoxicity.Clin Infect Dis.2002;35(12):e120–e127.

- , , , et al.Using a hospital information system to assess the effects of adverse drug events.Proc Annu Symp Comput Appl Med Care.1993;1993:161–165.

- , , .Appropriateness of hospitalization in a Canadian pediatric hospital.Pediatrics.1993;91(1):70–74.

- , , , .The appropriateness evaluation protocol: application in an Australian children's hospital.Aust Clin Rev.1991;11(4):123–131.

- , .Assessing the need to hospitalize children: pediatric appropriateness evaluation protocol.Pediatrics.1989;84(2):242–247.

- .Medically inappropriate hospital use in a pediatric population.N Engl J Med.1988;318(16):1033–1037.

- , , , , .Reducing inappropriate hospital use on a general pediatric inpatient unit.Pediatrics.2008;121(5):e1068–e1073.

- , .Reliable implementation of clinical pathways: what will it take—that is the question.J Pediatr.2008;152(3):303–304.

Inpatient pediatrics is undergoing a paradigm shift in at least 3 ways. First, more children with chronic disease are being cared for in the hospital over time.1 Second, previous inpatient conditions are treated at home with advancing technology such as peripherally‐inserted catheters.2 Third, there are new areas of growing specialization, such as hospital medicine, in which the practitioners deliver more efficient care.3, 4

Nationwide, there is increasing pressure to improve inpatient quality of care. The Institute of Medicine defines 6 aims for improvement, including timeliness (reducing waits and sometimes harmful delays for both those who receive and those who give care) and efficiency of care (avoiding waste, including waste of equipment, supplies, ideas, and energy).5 Reducing unnecessary stays in the hospital is a potential quality measure that hospitals may use to address the timeliness and efficiency of care delivered to hospitalized children.

Delays in discharge have been used as markers of unnecessary stays in the hospital for inpatient adult and pediatric care,6, 7 but these are limited to inpatient systems from almost 20 years ago. Current reasons why patients are delayed from discharge, if at all, are not well described. We undertook this study to describe delays in hospital discharges at a tertiary‐care children's hospital in terms of number of patients, length of days of delay, and type of delay. In addition, we sought to characterize the impact of discharge delays on overall length of stay (LOS) and costs.

Methods

Patient Population/Study Design

All children cared for on 2 pediatric medical teams at Primary Children's Medical Center during the month of August 2004 were eligible for the study. Two research assistants independently attended team rounds and collected data relating to: the reasons for ongoing hospitalization, pending items (eg, consultations, tests), and the plan of care for that day. The research assistants each attended daily team rounds for the entire month of August (1 for each team, switching to the opposite team after 2 weeks). This was combined with information available in the Patient Tracker, a software tool developed to improve communication between caregivers and improve discharge efficiency.8 This software tool details diagnoses, daily medical care plans, discharge criteria, and ongoing medical interventions while tracking daily changes in interventions and the medical care plan for each patient cared for on a pediatric medical team.

The research assistants subsequently presented their observations along with information from Patient Tracker to 2 experienced physicians (R.S. and B.S.) who independently determined if a delay occurred, the number of delay days extending discharge, and the cause of the delay, if present, categorized according to the taxonomy of the Delay Tool.6, 7 If there was not enough information for either of the physicians to identify and classify a delay, the electronic medical record of the patient was also reviewed. Discrepancies between physicians assigning delays were discussed until consensus was reached.

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Utah Health Sciences Center and Primary Children's Medical Center (PCMC).

Setting

PCMC is a 233‐bed tertiary‐care children's hospital, owned and operated by Intermountain Healthcare (a not‐for‐profit vertically integrated managed care organization) in the Intermountain West, which serves as both the primary hospital for Salt Lake County and as a tertiary‐care children's hospital for 5 states (UT, MT, WY, ID, and NV).9

Study Definitions

Delay and Length of Delay

Delays in discharge were measured using a validated and reliable instrument, the Delay Tool.6, 7 A discharge was classified as delayed if there was no medical reason for the patient to be in the hospital on a given day, identical to the definition used in the original studies to validate the tool. Delays were recorded as whole days, not fractions of days or hours, as described in the original validation of the tool. For example, if the medical team requested a consultation, and the consultant's opinion was rendered late, but the patient would have remained in the hospital anyway, then this period of time would not count as a delay. However, if the medical team did not receive a consultant's opinion within the standard time (24 hours as defined for this study and in validating studies for the Delay Tool), and the patient's sole reason for being in the hospital during that day was waiting for that opinion, then that period of time would count toward a delay due to a late consultative opinion. Delays of less than 1 day, due to the mechanics of discharging a patient from the hospital (providing prescriptions, follow up, communication, arranging home health, and transportation) were not measured in this study, to match the original methodology of the Delay Tool.

Type of Delay

Primary reason for delay was assigned according to the taxonomy of the Delay Tool.6, 7 Delays were categorized to 1 of the following: (1) test scheduling; (2) obtaining test results; (3) surgery; (4) consultation; (5) patient (eg, family unavailable for decision‐making); (6) physician responsibility; (7) education, training. or research; (8) discharge planning or scheduling; and (9) availability of outside care and resources. There are 166 subcategories that clarify why a delay occurred. For example, within the main category of obtaining test results (2), there are 3 subcategories of delays related to problem in executing the test (2.1), return of results is delayed (2.2), and test results not reviewed within standard time of return (2.3). Subcategories are further divided to provide detail on the cause of delay. For example, a delay categorized as a 2.1:1 [(2) obtaining test results; (2.1) problem in executing the test; and 2.1:1 test to be done by MD is delayed beyond day desired], or 2.3:1 [(2) obtaining test results; (2.3) test results not reviewed within standard time of return; and 2.3:1 delay because physician did not review results]) both relate to physician causes of delays within the general category of obtaining test results. Some delays had more than 1 cause. A secondary cause of delay was assigned if applicable; however, the number of days delayed was attributed to the primary cause for analysis purposes.

Exemptions to Delay and Special Populations

Certain subpopulations of patients presented unique issues that led to them being unlikely to be classified as having a delay. For example, patients with a diagnosis of new onset of type 1 diabetes are historically admitted for 3 days at our hospital, which includes a specific education program; delays were not considered until this minimum period had passed. Children with medically complex care (eg, multisystem disease, multiple specialists involved, multiple medications) were included in this study.10 However, these children with frequent hospital admission were often fragile at discharge, and could meet criteria for readmission even on the date of their discharge, hence assigning a delay day was usually not indicated because of easily justified ongoing medical need for hospitalization.

Study Variables

The LOS, total costs, and routine demographic and administrative data for each study patient were extracted from Intermountain Healthcare's Enterprise Data Warehouse (EDW). The EDW contains detailed data about the cost of providing health care. Costs were derived from the hospital's cost accounting program, the Standard Cost Master, which is a transaction‐based microcosting accounting system.1113

For patients whose LOS extended before August 1 or after August 31, total hospital costs were averaged per day, and only days falling inside the month of August were counted in calculating the impact the delays in discharge had on the total costs of hospitalization. Hospital days that extended outside of August were not counted in either the numerator for potential days of delay or in the denominator for total days in the hospital.

Analyses

Descriptive statistics were calculated for the number, length of days of delay, and type of delay. Interrater reliability to assign a delay was ascertained for the 2 physicians. Mean LOS, mean total costs, and standard deviations (SDs) were calculated. All analyses were performed using Statistical Analytical Software version 9.13 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

During the 31 days of the study, 171 patients occupied hospital beds an average of 7.3 days on the 2 inpatient medical teams, for a total of 911 inpatient days. Seven patients were admitted prior to August 1; 6 of these were discharged during the month of August and 1 stayed through the entire month and was discharged in September. Three additional patients were admitted in August and discharged in September. There were 6 readmissions during the month of August, and 1 patient was excluded from the study because of lack of sufficient information. All patients with delays were able to be classified according to the Delay Tool taxonomy. Interrater reliability for the 2 study physicians was 98%.

The characteristics between the patients who did and did not experience a delay in discharge are shown in Table 1. Thirty‐nine of 171 patients (22.8%), experienced at least 1 delay day. Eighteen of 39 patients had only 1 delay day (46.2%) and 11 patients experienced 2 delayed days (28.2%) (Figure 1). The average length of delay was 2.1 days.

| Nondelayed Patients (N = 132) | Delayed Patients (N = 39) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Age (months), mean (SD)* | 22.6 (14.4) | 15.0 (14.6) | 0.009 |

| LOS during August (days), mean (SD)* | 4.64 (6.1) | 7.64 (7.15) | <0.001 |

| Total costs during August ($), mean (SD)* | 10,451 (19,254) | 14,341 (16,241) | 0.002 |

| Number of ICD‐9 CM diagnoses codes, mean (SD)* | 7.1 (7.4) | 8.5 (7.3) | 0.056 |

| Number of ICD‐9 CM procedure codes, mean (SD)* | 1.7 (3.8) | 1.6 (2.6) | 0.068 |

| Number of Patients with APR‐DRG SOI 3 (%) | 59 (44.7%) | 19 (48.7%) | 0.65 |

Delays attributed to physician responsibility accounted for 42.3% (16.5/39) of patient delays (conservative management or clinical decision‐making), with discharge planning delays accounting for 21.8% (family‐related, patient‐related, and hospital‐related problems), consultation for 14.1% (delay in obtaining or lack of follow‐up), test scheduling for 12.8%, and obtaining test results for 5.1% (ordering and weekend scheduling). There were no primary delays due to surgery, education and research, or unavailability of outside resources such as a skilled nursing bed. Four patients had a single additional secondary cause of delay assigned to them, related to physician responsibility, consultation, surgery and test scheduling; these were split, attributing 0.5 patients to each delay type (thus, the 17/39 patients delayed for physician responsibility was analyzed as 16.5/39) (Table 2).

| Delay Category | Number of Patients Experiencing Delays* | Percentage of All Patients Experiencing Delays (%) | Percentage of Study Patients Observed (%) | Total Delay Days | Average Length of Delays (days) | Percentage of Hospital Days That Were Delay Days (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||

| 1. Scheduling | 5 | 12.8 | 2.92 | 16 | 3.20 | 1.76 |

| 2. Obtaining results | 2 | 5.1 | 1.17 | 3 | 1.50 | 0.33 |

| 3. Surgery | 0.5 | 1.3 | 0.29 | 1.5 | 3.00 | 0.16 |

| 4. Consultation | 5.5 | 14.1 | 3.22 | 10.5 | 1.91 | 1.15 |

| 5. Patient | 1 | 2.6 | 0.58 | 2 | 2.00 | 0.22 |

| 6. Physician | 16.5 | 42.3 | 9.65 | 33.5 | 2.03 | 3.68 |

| 7. Education | 0 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0 | 0.00 |

| 8. Discharge | 8.5 | 21.8 | 4.97 | 15.5 | 1.82 | 1.70 |

| 9. Outside | 0 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Total | 39 | 100 | 22.81 | 82 | 2.10 | 9.00 |

There were 82 delay‐related hospital days of 911 total inpatient days on the 2 medical teams for August 2004 (9%). More than $170,000 in excess costs was incurred due to delay days from a total of approximately 1.9 million dollars in patient costs for the month (8.9%).

Discussion

This study finds that discharge delays in a tertiary care children's hospital are common; almost 1 in 4 patients experienced a medically unnecessary excess hospital stay of at least 1 day. The average length of a delay was 2.1 days, and overall, delays consumed 9% of pediatric hospital days and 8.9% of total costs. The most common reason for a delay was related to physician clinical care, including excessively conservative management and variability in clinical decision‐making.

Our study results are similar to the other 2 published studies that use the Delay Tool. In the adult and pediatric studies, between 10% and 30% of patients experienced a delay in discharge, with the average length of delay between 2.9 and 3 days.6, 7 Although both studies were conducted at teaching hospitals, what is particularly interesting is that they were conducted almost 20 years ago. During this period of time, there has been a shift in the inpatient pediatric patient population. In recent years, children who are cared for in the hospital have more chronic illnesses.1 In addition, there has been a shift in the types of conditions that may be cared for at home and those that now require inpatient stay.2 Despite this, delays continue at a similar proportion, but the cause of delays have shifted from scheduling and consultation to physician responsibility.

There is another tool in the literature which is more widely used, the Pediatric Appropriateness Evaluation Protocol (PAEP), which is based on the Appropriateness Evaluation Protocol for adults.1417 This tool is used to determine the appropriateness of ongoing hospitalization, not the cause of delay if ongoing hospitalization is inappropriate. The 3 areas that are evaluated (medical services, nursing and ancillary services, and patient's condition) have objective criteria that dictate if the hospitalization is appropriate or not (eg, parenteral (intravenous) therapy for at least 8 hours on that day, under nursing and ancillary services). The PAEP may be less sensitive given today's healthcare resource utilization climate. Many clinicians and families would agree that insertion of a peripheral central catheter is an acceptable form of outpatient treatment for many pediatric conditions. In conjunction with the Delay Tool, the PAEP could be used to determine if a delay occurred, then the Delay Tool used to categorize the cause of the delay. We choose to use expert clinician judgment to determine if a delay had occurred. We were more interested in why patients who are admitted (appropriately or inappropriately) cannot be discharged sooner, thus allowing for future intervention studies targeted to impact delays in discharge, as elucidated in this study. The Delay Tool specifically allowed us to categorize the reasons for delays. Given that the average LOS for patients in the nondelayed group was over 4 days, despite not using a tool such as the PAEP, we believe that these were likely to be appropriate admissions.

A recent study reported the first use of the Medical Care Appropriateness Protocol (MCAP) in a tertiary‐care children's hospital. The authors used the MCAP to determine the impact of an intervention on reducing inappropriate hospitals days for children. This tool is similarly labor‐intensive to the Delay Tool. Interestingly, this Canadian study found a high rate of inappropriate hospital days (47%), which may be in part attributable to a different outcome measurement tool and/or a different health care system.18

There are several limitations to our study that deserve mention. The Delay Tool requires clinician judgment regarding whether or not there was a delay in discharge for that day. We may have introduced some bias in our study, as hospitalist investigators assigned the delay and blinding to the attending physician specialty of record was not feasible. However, our results are similar to the other 2 published studies that have used this tool, and we specifically chose not to analyze or report results in terms of hospitalist and nonhospitalist attending physicians. The Delay Tool is not designed to differentiate shorter delays in terms of hours instead of days (eg, due to the inability for the patient to get a ride home). Shorter delays may be of particular importance depending on the occupancy rate of the hospital, the demand for beds, and other patient and hospital factors. We could not capture these shorter delays (although they did occur frequently) due to the original description of the Delay Tool. In addition, we would not have been able to report data on the impact on LOS and costs, as these are attributed to whole days in the hospital. However, if we had been able to differentiate shorter delays, this would bias our results to show a greater percentage of delays over smaller increments of time. Generalizability is an issue, given that this was a single‐center study. This study sample included over 80 different attending physicians participating in community pediatrician, subspecialty, and hospitalist practice groups. However, the patient population at PCMC is similar to other medium and large children's hospitals in the United States. The month observed may not reflect the entire year of hospitalizationsthere may be seasonal variations with delays depending on the volume and type of illness seen. The study was conducted in August, when there are newer house staff present. However, physician responsibility, which was the largest source of delays in our study, had little attribution to house staff. Most of the decisions were those of attending physicians, which would largely be unaffected by the time of year of the study. Finally, we were unable to assess the safety of the potential earlier discharge, as this was an observational study. However, in any future intervention studies examining processes to discharge patients sooner, measures of safety to the patient are a necessity. Finally, given the potential of ongoing admission, even on the date of discharge of our most fragile patients, this approach to discovering causes of delay may not apply to this important group, which is responsible for significant and growing resource utilization.

Despite these limitations, our findings demonstrate that in an era of children staying in the hospital less, and more medically‐complex children being admitted,10 a substantial number of children who are hospitalized at a children's hospital may have been discharged sooner. The majority of these decisions were directly related to physician responsibility. As consumers, providers, and hospitals work together to develop quality measures that are reflective of inpatient pediatric care, the Delay Tool may be able to highlight 2 aims of quality (ie, timeliness and efficiency of care) that could be used to assess the impact of interventions designed to safely discharge patients sooner. Interventions such as audit‐feedback,18 clinical guideline deployment,19 and hospitalist systems of care4 continue to hold the promise of earlier discharge; however, tools designed to measure inappropriate use of hospital days should be employed to demonstrate their effectiveness. Our study demonstrates ongoing waste in children's hospitals.

Conclusions

Almost 1 out of 4 patients in this 1‐month period could have been discharged sooner than they were. The impact of delays on costs and LOS are substantial and should provide strong incentives to develop effective interventions. Such interventions will need to address variations in physician criteria for discharge, more efficient discharge planning, and timely scheduling of consultation and diagnostic testing.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Joni R. Beshanky and Harry Selker for their help and training in the use of the Delay Tool.

Inpatient pediatrics is undergoing a paradigm shift in at least 3 ways. First, more children with chronic disease are being cared for in the hospital over time.1 Second, previous inpatient conditions are treated at home with advancing technology such as peripherally‐inserted catheters.2 Third, there are new areas of growing specialization, such as hospital medicine, in which the practitioners deliver more efficient care.3, 4

Nationwide, there is increasing pressure to improve inpatient quality of care. The Institute of Medicine defines 6 aims for improvement, including timeliness (reducing waits and sometimes harmful delays for both those who receive and those who give care) and efficiency of care (avoiding waste, including waste of equipment, supplies, ideas, and energy).5 Reducing unnecessary stays in the hospital is a potential quality measure that hospitals may use to address the timeliness and efficiency of care delivered to hospitalized children.

Delays in discharge have been used as markers of unnecessary stays in the hospital for inpatient adult and pediatric care,6, 7 but these are limited to inpatient systems from almost 20 years ago. Current reasons why patients are delayed from discharge, if at all, are not well described. We undertook this study to describe delays in hospital discharges at a tertiary‐care children's hospital in terms of number of patients, length of days of delay, and type of delay. In addition, we sought to characterize the impact of discharge delays on overall length of stay (LOS) and costs.

Methods

Patient Population/Study Design

All children cared for on 2 pediatric medical teams at Primary Children's Medical Center during the month of August 2004 were eligible for the study. Two research assistants independently attended team rounds and collected data relating to: the reasons for ongoing hospitalization, pending items (eg, consultations, tests), and the plan of care for that day. The research assistants each attended daily team rounds for the entire month of August (1 for each team, switching to the opposite team after 2 weeks). This was combined with information available in the Patient Tracker, a software tool developed to improve communication between caregivers and improve discharge efficiency.8 This software tool details diagnoses, daily medical care plans, discharge criteria, and ongoing medical interventions while tracking daily changes in interventions and the medical care plan for each patient cared for on a pediatric medical team.

The research assistants subsequently presented their observations along with information from Patient Tracker to 2 experienced physicians (R.S. and B.S.) who independently determined if a delay occurred, the number of delay days extending discharge, and the cause of the delay, if present, categorized according to the taxonomy of the Delay Tool.6, 7 If there was not enough information for either of the physicians to identify and classify a delay, the electronic medical record of the patient was also reviewed. Discrepancies between physicians assigning delays were discussed until consensus was reached.

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Utah Health Sciences Center and Primary Children's Medical Center (PCMC).

Setting

PCMC is a 233‐bed tertiary‐care children's hospital, owned and operated by Intermountain Healthcare (a not‐for‐profit vertically integrated managed care organization) in the Intermountain West, which serves as both the primary hospital for Salt Lake County and as a tertiary‐care children's hospital for 5 states (UT, MT, WY, ID, and NV).9

Study Definitions

Delay and Length of Delay

Delays in discharge were measured using a validated and reliable instrument, the Delay Tool.6, 7 A discharge was classified as delayed if there was no medical reason for the patient to be in the hospital on a given day, identical to the definition used in the original studies to validate the tool. Delays were recorded as whole days, not fractions of days or hours, as described in the original validation of the tool. For example, if the medical team requested a consultation, and the consultant's opinion was rendered late, but the patient would have remained in the hospital anyway, then this period of time would not count as a delay. However, if the medical team did not receive a consultant's opinion within the standard time (24 hours as defined for this study and in validating studies for the Delay Tool), and the patient's sole reason for being in the hospital during that day was waiting for that opinion, then that period of time would count toward a delay due to a late consultative opinion. Delays of less than 1 day, due to the mechanics of discharging a patient from the hospital (providing prescriptions, follow up, communication, arranging home health, and transportation) were not measured in this study, to match the original methodology of the Delay Tool.

Type of Delay

Primary reason for delay was assigned according to the taxonomy of the Delay Tool.6, 7 Delays were categorized to 1 of the following: (1) test scheduling; (2) obtaining test results; (3) surgery; (4) consultation; (5) patient (eg, family unavailable for decision‐making); (6) physician responsibility; (7) education, training. or research; (8) discharge planning or scheduling; and (9) availability of outside care and resources. There are 166 subcategories that clarify why a delay occurred. For example, within the main category of obtaining test results (2), there are 3 subcategories of delays related to problem in executing the test (2.1), return of results is delayed (2.2), and test results not reviewed within standard time of return (2.3). Subcategories are further divided to provide detail on the cause of delay. For example, a delay categorized as a 2.1:1 [(2) obtaining test results; (2.1) problem in executing the test; and 2.1:1 test to be done by MD is delayed beyond day desired], or 2.3:1 [(2) obtaining test results; (2.3) test results not reviewed within standard time of return; and 2.3:1 delay because physician did not review results]) both relate to physician causes of delays within the general category of obtaining test results. Some delays had more than 1 cause. A secondary cause of delay was assigned if applicable; however, the number of days delayed was attributed to the primary cause for analysis purposes.

Exemptions to Delay and Special Populations

Certain subpopulations of patients presented unique issues that led to them being unlikely to be classified as having a delay. For example, patients with a diagnosis of new onset of type 1 diabetes are historically admitted for 3 days at our hospital, which includes a specific education program; delays were not considered until this minimum period had passed. Children with medically complex care (eg, multisystem disease, multiple specialists involved, multiple medications) were included in this study.10 However, these children with frequent hospital admission were often fragile at discharge, and could meet criteria for readmission even on the date of their discharge, hence assigning a delay day was usually not indicated because of easily justified ongoing medical need for hospitalization.

Study Variables

The LOS, total costs, and routine demographic and administrative data for each study patient were extracted from Intermountain Healthcare's Enterprise Data Warehouse (EDW). The EDW contains detailed data about the cost of providing health care. Costs were derived from the hospital's cost accounting program, the Standard Cost Master, which is a transaction‐based microcosting accounting system.1113

For patients whose LOS extended before August 1 or after August 31, total hospital costs were averaged per day, and only days falling inside the month of August were counted in calculating the impact the delays in discharge had on the total costs of hospitalization. Hospital days that extended outside of August were not counted in either the numerator for potential days of delay or in the denominator for total days in the hospital.

Analyses

Descriptive statistics were calculated for the number, length of days of delay, and type of delay. Interrater reliability to assign a delay was ascertained for the 2 physicians. Mean LOS, mean total costs, and standard deviations (SDs) were calculated. All analyses were performed using Statistical Analytical Software version 9.13 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

During the 31 days of the study, 171 patients occupied hospital beds an average of 7.3 days on the 2 inpatient medical teams, for a total of 911 inpatient days. Seven patients were admitted prior to August 1; 6 of these were discharged during the month of August and 1 stayed through the entire month and was discharged in September. Three additional patients were admitted in August and discharged in September. There were 6 readmissions during the month of August, and 1 patient was excluded from the study because of lack of sufficient information. All patients with delays were able to be classified according to the Delay Tool taxonomy. Interrater reliability for the 2 study physicians was 98%.

The characteristics between the patients who did and did not experience a delay in discharge are shown in Table 1. Thirty‐nine of 171 patients (22.8%), experienced at least 1 delay day. Eighteen of 39 patients had only 1 delay day (46.2%) and 11 patients experienced 2 delayed days (28.2%) (Figure 1). The average length of delay was 2.1 days.

| Nondelayed Patients (N = 132) | Delayed Patients (N = 39) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Age (months), mean (SD)* | 22.6 (14.4) | 15.0 (14.6) | 0.009 |

| LOS during August (days), mean (SD)* | 4.64 (6.1) | 7.64 (7.15) | <0.001 |

| Total costs during August ($), mean (SD)* | 10,451 (19,254) | 14,341 (16,241) | 0.002 |

| Number of ICD‐9 CM diagnoses codes, mean (SD)* | 7.1 (7.4) | 8.5 (7.3) | 0.056 |

| Number of ICD‐9 CM procedure codes, mean (SD)* | 1.7 (3.8) | 1.6 (2.6) | 0.068 |

| Number of Patients with APR‐DRG SOI 3 (%) | 59 (44.7%) | 19 (48.7%) | 0.65 |

Delays attributed to physician responsibility accounted for 42.3% (16.5/39) of patient delays (conservative management or clinical decision‐making), with discharge planning delays accounting for 21.8% (family‐related, patient‐related, and hospital‐related problems), consultation for 14.1% (delay in obtaining or lack of follow‐up), test scheduling for 12.8%, and obtaining test results for 5.1% (ordering and weekend scheduling). There were no primary delays due to surgery, education and research, or unavailability of outside resources such as a skilled nursing bed. Four patients had a single additional secondary cause of delay assigned to them, related to physician responsibility, consultation, surgery and test scheduling; these were split, attributing 0.5 patients to each delay type (thus, the 17/39 patients delayed for physician responsibility was analyzed as 16.5/39) (Table 2).

| Delay Category | Number of Patients Experiencing Delays* | Percentage of All Patients Experiencing Delays (%) | Percentage of Study Patients Observed (%) | Total Delay Days | Average Length of Delays (days) | Percentage of Hospital Days That Were Delay Days (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||

| 1. Scheduling | 5 | 12.8 | 2.92 | 16 | 3.20 | 1.76 |

| 2. Obtaining results | 2 | 5.1 | 1.17 | 3 | 1.50 | 0.33 |

| 3. Surgery | 0.5 | 1.3 | 0.29 | 1.5 | 3.00 | 0.16 |

| 4. Consultation | 5.5 | 14.1 | 3.22 | 10.5 | 1.91 | 1.15 |

| 5. Patient | 1 | 2.6 | 0.58 | 2 | 2.00 | 0.22 |

| 6. Physician | 16.5 | 42.3 | 9.65 | 33.5 | 2.03 | 3.68 |

| 7. Education | 0 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0 | 0.00 |

| 8. Discharge | 8.5 | 21.8 | 4.97 | 15.5 | 1.82 | 1.70 |

| 9. Outside | 0 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Total | 39 | 100 | 22.81 | 82 | 2.10 | 9.00 |

There were 82 delay‐related hospital days of 911 total inpatient days on the 2 medical teams for August 2004 (9%). More than $170,000 in excess costs was incurred due to delay days from a total of approximately 1.9 million dollars in patient costs for the month (8.9%).

Discussion

This study finds that discharge delays in a tertiary care children's hospital are common; almost 1 in 4 patients experienced a medically unnecessary excess hospital stay of at least 1 day. The average length of a delay was 2.1 days, and overall, delays consumed 9% of pediatric hospital days and 8.9% of total costs. The most common reason for a delay was related to physician clinical care, including excessively conservative management and variability in clinical decision‐making.

Our study results are similar to the other 2 published studies that use the Delay Tool. In the adult and pediatric studies, between 10% and 30% of patients experienced a delay in discharge, with the average length of delay between 2.9 and 3 days.6, 7 Although both studies were conducted at teaching hospitals, what is particularly interesting is that they were conducted almost 20 years ago. During this period of time, there has been a shift in the inpatient pediatric patient population. In recent years, children who are cared for in the hospital have more chronic illnesses.1 In addition, there has been a shift in the types of conditions that may be cared for at home and those that now require inpatient stay.2 Despite this, delays continue at a similar proportion, but the cause of delays have shifted from scheduling and consultation to physician responsibility.

There is another tool in the literature which is more widely used, the Pediatric Appropriateness Evaluation Protocol (PAEP), which is based on the Appropriateness Evaluation Protocol for adults.1417 This tool is used to determine the appropriateness of ongoing hospitalization, not the cause of delay if ongoing hospitalization is inappropriate. The 3 areas that are evaluated (medical services, nursing and ancillary services, and patient's condition) have objective criteria that dictate if the hospitalization is appropriate or not (eg, parenteral (intravenous) therapy for at least 8 hours on that day, under nursing and ancillary services). The PAEP may be less sensitive given today's healthcare resource utilization climate. Many clinicians and families would agree that insertion of a peripheral central catheter is an acceptable form of outpatient treatment for many pediatric conditions. In conjunction with the Delay Tool, the PAEP could be used to determine if a delay occurred, then the Delay Tool used to categorize the cause of the delay. We choose to use expert clinician judgment to determine if a delay had occurred. We were more interested in why patients who are admitted (appropriately or inappropriately) cannot be discharged sooner, thus allowing for future intervention studies targeted to impact delays in discharge, as elucidated in this study. The Delay Tool specifically allowed us to categorize the reasons for delays. Given that the average LOS for patients in the nondelayed group was over 4 days, despite not using a tool such as the PAEP, we believe that these were likely to be appropriate admissions.

A recent study reported the first use of the Medical Care Appropriateness Protocol (MCAP) in a tertiary‐care children's hospital. The authors used the MCAP to determine the impact of an intervention on reducing inappropriate hospitals days for children. This tool is similarly labor‐intensive to the Delay Tool. Interestingly, this Canadian study found a high rate of inappropriate hospital days (47%), which may be in part attributable to a different outcome measurement tool and/or a different health care system.18

There are several limitations to our study that deserve mention. The Delay Tool requires clinician judgment regarding whether or not there was a delay in discharge for that day. We may have introduced some bias in our study, as hospitalist investigators assigned the delay and blinding to the attending physician specialty of record was not feasible. However, our results are similar to the other 2 published studies that have used this tool, and we specifically chose not to analyze or report results in terms of hospitalist and nonhospitalist attending physicians. The Delay Tool is not designed to differentiate shorter delays in terms of hours instead of days (eg, due to the inability for the patient to get a ride home). Shorter delays may be of particular importance depending on the occupancy rate of the hospital, the demand for beds, and other patient and hospital factors. We could not capture these shorter delays (although they did occur frequently) due to the original description of the Delay Tool. In addition, we would not have been able to report data on the impact on LOS and costs, as these are attributed to whole days in the hospital. However, if we had been able to differentiate shorter delays, this would bias our results to show a greater percentage of delays over smaller increments of time. Generalizability is an issue, given that this was a single‐center study. This study sample included over 80 different attending physicians participating in community pediatrician, subspecialty, and hospitalist practice groups. However, the patient population at PCMC is similar to other medium and large children's hospitals in the United States. The month observed may not reflect the entire year of hospitalizationsthere may be seasonal variations with delays depending on the volume and type of illness seen. The study was conducted in August, when there are newer house staff present. However, physician responsibility, which was the largest source of delays in our study, had little attribution to house staff. Most of the decisions were those of attending physicians, which would largely be unaffected by the time of year of the study. Finally, we were unable to assess the safety of the potential earlier discharge, as this was an observational study. However, in any future intervention studies examining processes to discharge patients sooner, measures of safety to the patient are a necessity. Finally, given the potential of ongoing admission, even on the date of discharge of our most fragile patients, this approach to discovering causes of delay may not apply to this important group, which is responsible for significant and growing resource utilization.

Despite these limitations, our findings demonstrate that in an era of children staying in the hospital less, and more medically‐complex children being admitted,10 a substantial number of children who are hospitalized at a children's hospital may have been discharged sooner. The majority of these decisions were directly related to physician responsibility. As consumers, providers, and hospitals work together to develop quality measures that are reflective of inpatient pediatric care, the Delay Tool may be able to highlight 2 aims of quality (ie, timeliness and efficiency of care) that could be used to assess the impact of interventions designed to safely discharge patients sooner. Interventions such as audit‐feedback,18 clinical guideline deployment,19 and hospitalist systems of care4 continue to hold the promise of earlier discharge; however, tools designed to measure inappropriate use of hospital days should be employed to demonstrate their effectiveness. Our study demonstrates ongoing waste in children's hospitals.

Conclusions

Almost 1 out of 4 patients in this 1‐month period could have been discharged sooner than they were. The impact of delays on costs and LOS are substantial and should provide strong incentives to develop effective interventions. Such interventions will need to address variations in physician criteria for discharge, more efficient discharge planning, and timely scheduling of consultation and diagnostic testing.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Joni R. Beshanky and Harry Selker for their help and training in the use of the Delay Tool.

- .The transformation of child health in the United States: social disparities in child health persistent despite dramatic improvement in child health overall.Health Aff (Millwood).2004;23(5):9–25.

- , , , .Hospitalist care of medically complex children.Pediatr Res.2004;55(4):314A–315A.

- , , , .Pediatric hospitalists: a systematic review of the literature.Pediatrics.2006;117(5):1736–1744.

- , , , et al.Pediatric hospitalists: report of a leadership conference.Pediatrics.2006;117(4):1122–1130.

- Institute of Medicine.Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the Twenty‐first Century.Washington, DC:National Academy Press;2001.

- , , .Using the Delay Tool to attribute causes for unnecessary pediatric hospital days.Med Care.1990;28(10):982–989.

- , , , .The epidemiology of delays in a teaching hospital. The development and use of a tool that detects unnecessary hospital days.Med Care.1989;27(2):112–129.

- , , , , .A tool for improving patient discharge process and hospital communication practices: the Patient Tracker.AMIA Annu Symp Proc.2007;11:493–497.

- , .Organizational responses to managed care: issues for academic health centers and implications for pediatric programs.Pediatrics.1998;101(4 Pt 2):805–811; discussion 811–802.

- , , .Hospitalist care of the medically complex child.Pediatr Clin North Am.2005;52(4):1165–1187.

- , , , et al.Epidemiology, complications, and cost of hospitalization in children with laboratory‐confirmed influenza infection.Pediatrics.2006;118(6):2409–2417.

- , , , , , .Clinical and economic outcomes of conventional amphotericin B‐associated nephrotoxicity.Clin Infect Dis.2002;35(12):e120–e127.

- , , , et al.Using a hospital information system to assess the effects of adverse drug events.Proc Annu Symp Comput Appl Med Care.1993;1993:161–165.

- , , .Appropriateness of hospitalization in a Canadian pediatric hospital.Pediatrics.1993;91(1):70–74.

- , , , .The appropriateness evaluation protocol: application in an Australian children's hospital.Aust Clin Rev.1991;11(4):123–131.

- , .Assessing the need to hospitalize children: pediatric appropriateness evaluation protocol.Pediatrics.1989;84(2):242–247.

- .Medically inappropriate hospital use in a pediatric population.N Engl J Med.1988;318(16):1033–1037.

- , , , , .Reducing inappropriate hospital use on a general pediatric inpatient unit.Pediatrics.2008;121(5):e1068–e1073.

- , .Reliable implementation of clinical pathways: what will it take—that is the question.J Pediatr.2008;152(3):303–304.

- .The transformation of child health in the United States: social disparities in child health persistent despite dramatic improvement in child health overall.Health Aff (Millwood).2004;23(5):9–25.

- , , , .Hospitalist care of medically complex children.Pediatr Res.2004;55(4):314A–315A.

- , , , .Pediatric hospitalists: a systematic review of the literature.Pediatrics.2006;117(5):1736–1744.

- , , , et al.Pediatric hospitalists: report of a leadership conference.Pediatrics.2006;117(4):1122–1130.

- Institute of Medicine.Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the Twenty‐first Century.Washington, DC:National Academy Press;2001.

- , , .Using the Delay Tool to attribute causes for unnecessary pediatric hospital days.Med Care.1990;28(10):982–989.

- , , , .The epidemiology of delays in a teaching hospital. The development and use of a tool that detects unnecessary hospital days.Med Care.1989;27(2):112–129.

- , , , , .A tool for improving patient discharge process and hospital communication practices: the Patient Tracker.AMIA Annu Symp Proc.2007;11:493–497.

- , .Organizational responses to managed care: issues for academic health centers and implications for pediatric programs.Pediatrics.1998;101(4 Pt 2):805–811; discussion 811–802.

- , , .Hospitalist care of the medically complex child.Pediatr Clin North Am.2005;52(4):1165–1187.

- , , , et al.Epidemiology, complications, and cost of hospitalization in children with laboratory‐confirmed influenza infection.Pediatrics.2006;118(6):2409–2417.

- , , , , , .Clinical and economic outcomes of conventional amphotericin B‐associated nephrotoxicity.Clin Infect Dis.2002;35(12):e120–e127.

- , , , et al.Using a hospital information system to assess the effects of adverse drug events.Proc Annu Symp Comput Appl Med Care.1993;1993:161–165.

- , , .Appropriateness of hospitalization in a Canadian pediatric hospital.Pediatrics.1993;91(1):70–74.

- , , , .The appropriateness evaluation protocol: application in an Australian children's hospital.Aust Clin Rev.1991;11(4):123–131.

- , .Assessing the need to hospitalize children: pediatric appropriateness evaluation protocol.Pediatrics.1989;84(2):242–247.

- .Medically inappropriate hospital use in a pediatric population.N Engl J Med.1988;318(16):1033–1037.

- , , , , .Reducing inappropriate hospital use on a general pediatric inpatient unit.Pediatrics.2008;121(5):e1068–e1073.

- , .Reliable implementation of clinical pathways: what will it take—that is the question.J Pediatr.2008;152(3):303–304.

Copyright © 2009 Society of Hospital Medicine

World Mental Health Day: Preventing suicide

Increased engagement of men in mental health services is needed

Each year, the World Federation of Mental Health chooses a theme for World Mental Health Day, which is Oct. 10. This year’s theme is “Mental Health Promotion and Suicide Prevention.”

About 800,000 people die by suicide every year, according to the World Health Organization. Suicide is the second-leading cause of death among people aged 15-29 years.1

Most suicide occurs in low- and middle-income countries, the WHO reports. In addition, almost two-thirds of those deaths around the world occur in males, a recent study shows.2 The study, conducted by Danah Alothman and Andrew Fogarty, MBBS, of the NIHR Biomedical Research Center at the University of Nottingham (England), looked at sex-specific suicide rates for 182 countries in 2015.

They found that the highest difference between male:female suicide rates were in the Americas (median, 4:1/100,000), and the lowest were in Africa and Asia (median for both continents, 2.7:1/100,000).

“The implication is that as societies become richer and more educated, males have a higher risk of dying as a consequence of suicide relative to females,” they wrote in the Journal of Affective Disorders.

For clinicians who treat patients with mental illness, particularly those of us who practice in the Americas, this sex differential is concerning. We know that women are more likely to be diagnosed the depression.3 But perhaps this has something to do with the way men are socialized around the world. In other words, as John S. Ogrodniczuk, PhD, and John L. Oliffe, PhD, wrote,4 depression in men “often manifests as irritability; anger; hostile, aggressive, abusive behavior; risk taking, substance abuse; and escaping behavior.” They argue that the outward behavior shown by some men with depression might, in fact, “serve as a cover-up mechanism to hide the internal turmoil” they are experiencing. We certainly know that some men adhere to masculine norms such as stoicism, which in turn, heightens self-stigma. Unfortunately, men seek help for depression less often than do women.5 So one key question becomes: What can we as mental health professionals do to better meet the treatment needs of our male patients?

One example of a program that could hold promise in this area is one called Men at Risk. That program, developed by the nonprofit Centre for Suicide Prevention, in Grande Prairie, Alta., helps men who work in the oil, forestry, and agriculture sectors talk about their challenges and encourages them to let go of stigma.6

Factors other than male gender also might increase the likelihood of suicide. It has rightly been said that genetics and environment play a big role on the psyche of the individuals, and the act of suicide is no different when we discuss the etiologic factors that lead to perpetration of such an act. Genetic vulnerability is a factor that cannot be modified or altered in an easy way, hence, control of environmental factors is more pertinent.

Poverty and violence are two major detrimental factors that have reached alarming proportions and can lead people end their lives.

The developing countries, and now to a significant extent, developed countries, face terrorism that affect the human psyche and can lead to depression, psychosis, and substance abuse, and hence, increase the vulnerability toward the act of suicide. In our offices, we psychiatrists come across patients with borderline personality disorder, for example, who present to emergency departments with multiple and repeated suicidal attempts. There is a big role of genetics here – and role of specific interventions, such as dialectical behavior therapy. Pharmacologic treatment can play a vital role.

In order to make the world a safe place, joint global efforts are required. Enhanced security steps, improved immigration screening, and political will are essential to curb this heartbreaking act. Responsible reporting on the part of the media is needed to make suicide contagion less likely.7

Among other important measures are reducing access to guns and other firearms, and increasing health education about consumption of alcohol and other substances. We also need early identification and prompt treatment of mental illnesses; alleviation of poverty; mobilization of community supports; activation of multiple crisis lines; increased availability and affordability of psychotropic medications; reduction of waiting times for seeking treatment of mental illness; enhanced training of crisis workers; and refresher courses for psychiatrists, family physicians, and other allied mental health workers. Above all, strategies are needed to address the stigma associated with seeking help for mental health issues.

Suicide is a global public health issue, and it is of the utmost importance that a collaborative effort be placed in perspective by individual countries within their own health-related policies and parameters.

Good-quality data on suicide prevalence rates would be of the utmost help in understanding the magnitude of this grave problem. The WHO Mental Health Action Plan 2013-2020 indicates the commitment of member states to work toward the global target of reducing the suicide rate in countries by 10% by 2020.

Individual and collective efforts should become the priority to achieve this target going forward.

References

1. World Health Organization. Suicide. 2019 Sep 2.

2. Alothman D and A Fogarty. J Affect Disord. 2020 Jan 1. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2019.08.093.

3. Albert PR. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2015 Jul;40(4):219-21.

4. Ogrodniczuk JS and JL Oliffe. Can Fam Physician. 2011;57(2):153-5.

5. Seidler ZE et al. Clin Psychology Rev. 2016;49:106-18.

6. Ellwand O. Men at risk program helping men in Alberta trades, industry, agriculture struggling with mental health issues. Edmonton Sun. 2016 Mar 27.

7. American Association of Suicidology, et al. Recommendations for reporting on suicide.

Dr. Muhammad is clinical professor of psychiatry and consultant psychiatrist at Niagara Health Service, St. Catharines, Ont.

Increased engagement of men in mental health services is needed

Increased engagement of men in mental health services is needed

Each year, the World Federation of Mental Health chooses a theme for World Mental Health Day, which is Oct. 10. This year’s theme is “Mental Health Promotion and Suicide Prevention.”

About 800,000 people die by suicide every year, according to the World Health Organization. Suicide is the second-leading cause of death among people aged 15-29 years.1

Most suicide occurs in low- and middle-income countries, the WHO reports. In addition, almost two-thirds of those deaths around the world occur in males, a recent study shows.2 The study, conducted by Danah Alothman and Andrew Fogarty, MBBS, of the NIHR Biomedical Research Center at the University of Nottingham (England), looked at sex-specific suicide rates for 182 countries in 2015.

They found that the highest difference between male:female suicide rates were in the Americas (median, 4:1/100,000), and the lowest were in Africa and Asia (median for both continents, 2.7:1/100,000).

“The implication is that as societies become richer and more educated, males have a higher risk of dying as a consequence of suicide relative to females,” they wrote in the Journal of Affective Disorders.

For clinicians who treat patients with mental illness, particularly those of us who practice in the Americas, this sex differential is concerning. We know that women are more likely to be diagnosed the depression.3 But perhaps this has something to do with the way men are socialized around the world. In other words, as John S. Ogrodniczuk, PhD, and John L. Oliffe, PhD, wrote,4 depression in men “often manifests as irritability; anger; hostile, aggressive, abusive behavior; risk taking, substance abuse; and escaping behavior.” They argue that the outward behavior shown by some men with depression might, in fact, “serve as a cover-up mechanism to hide the internal turmoil” they are experiencing. We certainly know that some men adhere to masculine norms such as stoicism, which in turn, heightens self-stigma. Unfortunately, men seek help for depression less often than do women.5 So one key question becomes: What can we as mental health professionals do to better meet the treatment needs of our male patients?

One example of a program that could hold promise in this area is one called Men at Risk. That program, developed by the nonprofit Centre for Suicide Prevention, in Grande Prairie, Alta., helps men who work in the oil, forestry, and agriculture sectors talk about their challenges and encourages them to let go of stigma.6

Factors other than male gender also might increase the likelihood of suicide. It has rightly been said that genetics and environment play a big role on the psyche of the individuals, and the act of suicide is no different when we discuss the etiologic factors that lead to perpetration of such an act. Genetic vulnerability is a factor that cannot be modified or altered in an easy way, hence, control of environmental factors is more pertinent.

Poverty and violence are two major detrimental factors that have reached alarming proportions and can lead people end their lives.

The developing countries, and now to a significant extent, developed countries, face terrorism that affect the human psyche and can lead to depression, psychosis, and substance abuse, and hence, increase the vulnerability toward the act of suicide. In our offices, we psychiatrists come across patients with borderline personality disorder, for example, who present to emergency departments with multiple and repeated suicidal attempts. There is a big role of genetics here – and role of specific interventions, such as dialectical behavior therapy. Pharmacologic treatment can play a vital role.

In order to make the world a safe place, joint global efforts are required. Enhanced security steps, improved immigration screening, and political will are essential to curb this heartbreaking act. Responsible reporting on the part of the media is needed to make suicide contagion less likely.7

Among other important measures are reducing access to guns and other firearms, and increasing health education about consumption of alcohol and other substances. We also need early identification and prompt treatment of mental illnesses; alleviation of poverty; mobilization of community supports; activation of multiple crisis lines; increased availability and affordability of psychotropic medications; reduction of waiting times for seeking treatment of mental illness; enhanced training of crisis workers; and refresher courses for psychiatrists, family physicians, and other allied mental health workers. Above all, strategies are needed to address the stigma associated with seeking help for mental health issues.