User login

Leadership hacks: structural tension

My leadership experience was limited when I became department chair 6 years ago. Recognizing the deficit immediately, I began reading self-help and leadership books, sought training in coaching techniques, and have attended innumerable leadership courses. I still have a lot to learn, but I am a lot more comfortable with my leadership skills than I was. Since I am often asked for advice with regard to advancing into administrative leadership positions, I want to share what I have learned with others.

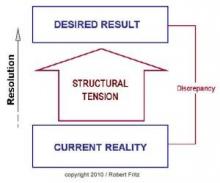

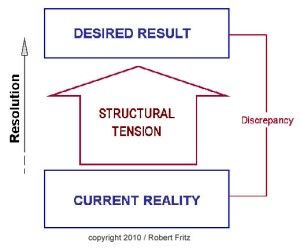

In one of my previous columns, I reviewed the concept of drama triangles and introduced structural tension as a model for addressing and breaking them. The structural tension model is attributed to Robert Fritz and is presented in Figure 1. I have found this model very helpful for coaching toward desired change.

Kelly, the supervisor/manager/director/chairman, expects all physicians to carry a heavy clinical load while also conducting research, writing papers, and securing as many grants as possible. Of course, the expected clinical load encroaches on the time required for academic pursuits. Tension increases among the faculty as the clinical load prohibits academic work resulting in unmet expectations for Kelly and dissatisfaction and disengagement for everyone else. A staff meeting is called to address the worsening workplace environment.

Since Kelly is at a loss, the administrator, Pat, offers to run the meeting in an attempt to address the problem. Pat asks the assembled team to describe the ideal state, or desired result, for the department. Eagerly, the participants begin to list the components of their ideal state including error-free scheduling, adequate staffing, an efficient electronic medical record, uninterrupted administrative time, sufficient research support, and several other important requirements to successfully meet department expectations.

Next, Pat asks the staff to list the current state. Once again, the participants are more than happy to call out the current situation as they see it, including patients arriving without records, slow rooming times, add-on appointments outside clinic schedules, poor statistical support, and several other impediments to optimal efficiency.

Critically, Pat resists the temptation to recount and defend all the efforts being made to address each of these difficult issues. Instead, Pat asks the team what they can do to begin moving from the current state to the ideal state. In contrast to the other questions, the team hesitates to answer this one. The administration is supposed to fix the problems, not them. Pat persists, though, and is willing to wait in awkward silence for someone to offer a suggestion. Finally, a junior faculty member speaks up and recommends that the physician staff meet with the schedulers to reconfigure their clinic templates to more realistically reflect their available time. As murmurs flow across the room, another physician offers that perhaps they could cross cover for each other to allow uninterrupted administrative time. More and more physicians then join in suggesting more and more opportunities to streamline processes to create efficiencies.

Reflecting on the meeting afterward, Kelly was astounded not only at the process, but at the engagement of the faculty. Kelly was under the impression that the faculty was too frustrated to effectively participate. Pat was thrilled to have so many good ideas to work on. Importantly, these ideas came from the staff (bottom-up) rather than from administration (top-down), which increases staff involvement in the projects already set up in addition to creating new ones. The staff, in turn, felt that their concerns were heard and were inspired to take on the new challenges they created for themselves.

The structural tension model is more nuanced than my illustrative example suggests, but it does provide a useful framework to address problems and create solutions. Different problems, though, lend themselves to different solutions and structural tension cannot address every problem a leader faces. It is just one more tool in the leadership toolbox.

For more reading: Fritz R, “The Path of Least Resistance” (New York: Random House, 1984).

My leadership experience was limited when I became department chair 6 years ago. Recognizing the deficit immediately, I began reading self-help and leadership books, sought training in coaching techniques, and have attended innumerable leadership courses. I still have a lot to learn, but I am a lot more comfortable with my leadership skills than I was. Since I am often asked for advice with regard to advancing into administrative leadership positions, I want to share what I have learned with others.

In one of my previous columns, I reviewed the concept of drama triangles and introduced structural tension as a model for addressing and breaking them. The structural tension model is attributed to Robert Fritz and is presented in Figure 1. I have found this model very helpful for coaching toward desired change.

Kelly, the supervisor/manager/director/chairman, expects all physicians to carry a heavy clinical load while also conducting research, writing papers, and securing as many grants as possible. Of course, the expected clinical load encroaches on the time required for academic pursuits. Tension increases among the faculty as the clinical load prohibits academic work resulting in unmet expectations for Kelly and dissatisfaction and disengagement for everyone else. A staff meeting is called to address the worsening workplace environment.

Since Kelly is at a loss, the administrator, Pat, offers to run the meeting in an attempt to address the problem. Pat asks the assembled team to describe the ideal state, or desired result, for the department. Eagerly, the participants begin to list the components of their ideal state including error-free scheduling, adequate staffing, an efficient electronic medical record, uninterrupted administrative time, sufficient research support, and several other important requirements to successfully meet department expectations.

Next, Pat asks the staff to list the current state. Once again, the participants are more than happy to call out the current situation as they see it, including patients arriving without records, slow rooming times, add-on appointments outside clinic schedules, poor statistical support, and several other impediments to optimal efficiency.

Critically, Pat resists the temptation to recount and defend all the efforts being made to address each of these difficult issues. Instead, Pat asks the team what they can do to begin moving from the current state to the ideal state. In contrast to the other questions, the team hesitates to answer this one. The administration is supposed to fix the problems, not them. Pat persists, though, and is willing to wait in awkward silence for someone to offer a suggestion. Finally, a junior faculty member speaks up and recommends that the physician staff meet with the schedulers to reconfigure their clinic templates to more realistically reflect their available time. As murmurs flow across the room, another physician offers that perhaps they could cross cover for each other to allow uninterrupted administrative time. More and more physicians then join in suggesting more and more opportunities to streamline processes to create efficiencies.

Reflecting on the meeting afterward, Kelly was astounded not only at the process, but at the engagement of the faculty. Kelly was under the impression that the faculty was too frustrated to effectively participate. Pat was thrilled to have so many good ideas to work on. Importantly, these ideas came from the staff (bottom-up) rather than from administration (top-down), which increases staff involvement in the projects already set up in addition to creating new ones. The staff, in turn, felt that their concerns were heard and were inspired to take on the new challenges they created for themselves.

The structural tension model is more nuanced than my illustrative example suggests, but it does provide a useful framework to address problems and create solutions. Different problems, though, lend themselves to different solutions and structural tension cannot address every problem a leader faces. It is just one more tool in the leadership toolbox.

For more reading: Fritz R, “The Path of Least Resistance” (New York: Random House, 1984).

My leadership experience was limited when I became department chair 6 years ago. Recognizing the deficit immediately, I began reading self-help and leadership books, sought training in coaching techniques, and have attended innumerable leadership courses. I still have a lot to learn, but I am a lot more comfortable with my leadership skills than I was. Since I am often asked for advice with regard to advancing into administrative leadership positions, I want to share what I have learned with others.

In one of my previous columns, I reviewed the concept of drama triangles and introduced structural tension as a model for addressing and breaking them. The structural tension model is attributed to Robert Fritz and is presented in Figure 1. I have found this model very helpful for coaching toward desired change.

Kelly, the supervisor/manager/director/chairman, expects all physicians to carry a heavy clinical load while also conducting research, writing papers, and securing as many grants as possible. Of course, the expected clinical load encroaches on the time required for academic pursuits. Tension increases among the faculty as the clinical load prohibits academic work resulting in unmet expectations for Kelly and dissatisfaction and disengagement for everyone else. A staff meeting is called to address the worsening workplace environment.

Since Kelly is at a loss, the administrator, Pat, offers to run the meeting in an attempt to address the problem. Pat asks the assembled team to describe the ideal state, or desired result, for the department. Eagerly, the participants begin to list the components of their ideal state including error-free scheduling, adequate staffing, an efficient electronic medical record, uninterrupted administrative time, sufficient research support, and several other important requirements to successfully meet department expectations.

Next, Pat asks the staff to list the current state. Once again, the participants are more than happy to call out the current situation as they see it, including patients arriving without records, slow rooming times, add-on appointments outside clinic schedules, poor statistical support, and several other impediments to optimal efficiency.

Critically, Pat resists the temptation to recount and defend all the efforts being made to address each of these difficult issues. Instead, Pat asks the team what they can do to begin moving from the current state to the ideal state. In contrast to the other questions, the team hesitates to answer this one. The administration is supposed to fix the problems, not them. Pat persists, though, and is willing to wait in awkward silence for someone to offer a suggestion. Finally, a junior faculty member speaks up and recommends that the physician staff meet with the schedulers to reconfigure their clinic templates to more realistically reflect their available time. As murmurs flow across the room, another physician offers that perhaps they could cross cover for each other to allow uninterrupted administrative time. More and more physicians then join in suggesting more and more opportunities to streamline processes to create efficiencies.

Reflecting on the meeting afterward, Kelly was astounded not only at the process, but at the engagement of the faculty. Kelly was under the impression that the faculty was too frustrated to effectively participate. Pat was thrilled to have so many good ideas to work on. Importantly, these ideas came from the staff (bottom-up) rather than from administration (top-down), which increases staff involvement in the projects already set up in addition to creating new ones. The staff, in turn, felt that their concerns were heard and were inspired to take on the new challenges they created for themselves.

The structural tension model is more nuanced than my illustrative example suggests, but it does provide a useful framework to address problems and create solutions. Different problems, though, lend themselves to different solutions and structural tension cannot address every problem a leader faces. It is just one more tool in the leadership toolbox.

For more reading: Fritz R, “The Path of Least Resistance” (New York: Random House, 1984).

ECT patients do better when families attend sessions

NEW ORLEANS – In 2001, a patient at the Menninger Clinic, Houston, asked whether her husband could be with her during ECT treatments, so she’d feel safer.

He declined, but then she told her care team “the fact that you would allow that makes me feel entirely safe now,” recalled M. Justin Coffey, MD, medical director of Menninger’s Center for Brain Stimulation.

“She made her request partly in jest, but it was a great idea,” he said. Fast-forward 16 years, and it’s now standard practice at Menninger for patients to invite loved ones to ECT sessions. Sometimes they pick family members, other times a neighbor or even a pastor.

“One of the most powerful benefits we’ve seen is that the loved ones observing the treatment become thoroughly underwhelmed by what they see,” not much more than the patient under anesthesia. “At the same time, they are incredibly impressed by the expertise and competence of the team. They become ambassadors against stigma; I’ve got family members and patients now that join me in workshops talking about why ECT should be [used] more,” Dr. Coffey said at the American Psychiatric Association’s Institute on Psychiatric Services.

The approach is catching on, including at the New York Community Hospital, Brooklyn, where it was implemented a few years ago. “It’s a wonderful thing to decrease patient anxiety and the stigma of treatment. You ask the patient’s permission, of course, and discuss with the family members what they are going to see. It demystifies the whole thing,” said Charles H. Kellner, MD, chief of electroconvulsive therapy at the hospital and a well-known ECT researcher.

Another benefit they’ve seen at Menninger is that patients come out of their postictal confusion sooner when there’s a familiar, comforting person in the room. That’s important, because the quicker patients reorient, the less likely they are to have retrograde memory problems, Dr. Coffey said.

Memory loss is perhaps the top fear people have about ECT, and it leads to the underuse of an otherwise safe and effective treatment for severe, refractory depression. Anterograde memory problems generally clear up in a few days, but retrograde problems can linger; memories formed within 3-6 months of ECT are the most vulnerable. It’s tough to pin down exactly how great the risk is because of variations in how ECT is performed from one center to the next.

“It’s always a risk-benefit decision,” Dr. Kellner said. “The vast majority of patients do not have profound memory trouble with ECT; it’s a temporary nuisance. I’d say maybe 10% or fewer have memory problems significant enough to stop treatment, or that really bother them.”

“The most important thing” when counseling patients “is not to promise anything, because you really don’t know how an individual is going to respond to ECT,” said Adriana P. Hermida, MD, a geriatric psychiatrist and ECT practitioner at Emory University, Atlanta.

In general, cognitive problems and memory loss are less likely with unilateral treatment than with bilateral, and least likely with ultra-brief unilateral treatment. Two sessions per week are less likely to cause problems than are the usual three, but treatment response isn’t as rapid. Also, giving more than two seizures per session increases the risk of medical and cognitive side effects, and isn’t recommended.

To manage the memory risk, cognitive function should be assessed before each session, not just by objective measures and patient report, but also by asking family members what they’ve noticed. “Many times patient do not report memory issues, but family members will,” Dr. Hermida said.

If there’s a problem, patients can switch to two sessions per week, for instance, or to ultra-brief unilateral ECT.

A few studies have suggested that cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine (Namenda) might attenuate cognitive side effects, but there’s not enough evidence to recommend their use, she said.

The speakers had no relevant industry disclosures.

NEW ORLEANS – In 2001, a patient at the Menninger Clinic, Houston, asked whether her husband could be with her during ECT treatments, so she’d feel safer.

He declined, but then she told her care team “the fact that you would allow that makes me feel entirely safe now,” recalled M. Justin Coffey, MD, medical director of Menninger’s Center for Brain Stimulation.

“She made her request partly in jest, but it was a great idea,” he said. Fast-forward 16 years, and it’s now standard practice at Menninger for patients to invite loved ones to ECT sessions. Sometimes they pick family members, other times a neighbor or even a pastor.

“One of the most powerful benefits we’ve seen is that the loved ones observing the treatment become thoroughly underwhelmed by what they see,” not much more than the patient under anesthesia. “At the same time, they are incredibly impressed by the expertise and competence of the team. They become ambassadors against stigma; I’ve got family members and patients now that join me in workshops talking about why ECT should be [used] more,” Dr. Coffey said at the American Psychiatric Association’s Institute on Psychiatric Services.

The approach is catching on, including at the New York Community Hospital, Brooklyn, where it was implemented a few years ago. “It’s a wonderful thing to decrease patient anxiety and the stigma of treatment. You ask the patient’s permission, of course, and discuss with the family members what they are going to see. It demystifies the whole thing,” said Charles H. Kellner, MD, chief of electroconvulsive therapy at the hospital and a well-known ECT researcher.

Another benefit they’ve seen at Menninger is that patients come out of their postictal confusion sooner when there’s a familiar, comforting person in the room. That’s important, because the quicker patients reorient, the less likely they are to have retrograde memory problems, Dr. Coffey said.

Memory loss is perhaps the top fear people have about ECT, and it leads to the underuse of an otherwise safe and effective treatment for severe, refractory depression. Anterograde memory problems generally clear up in a few days, but retrograde problems can linger; memories formed within 3-6 months of ECT are the most vulnerable. It’s tough to pin down exactly how great the risk is because of variations in how ECT is performed from one center to the next.

“It’s always a risk-benefit decision,” Dr. Kellner said. “The vast majority of patients do not have profound memory trouble with ECT; it’s a temporary nuisance. I’d say maybe 10% or fewer have memory problems significant enough to stop treatment, or that really bother them.”

“The most important thing” when counseling patients “is not to promise anything, because you really don’t know how an individual is going to respond to ECT,” said Adriana P. Hermida, MD, a geriatric psychiatrist and ECT practitioner at Emory University, Atlanta.

In general, cognitive problems and memory loss are less likely with unilateral treatment than with bilateral, and least likely with ultra-brief unilateral treatment. Two sessions per week are less likely to cause problems than are the usual three, but treatment response isn’t as rapid. Also, giving more than two seizures per session increases the risk of medical and cognitive side effects, and isn’t recommended.

To manage the memory risk, cognitive function should be assessed before each session, not just by objective measures and patient report, but also by asking family members what they’ve noticed. “Many times patient do not report memory issues, but family members will,” Dr. Hermida said.

If there’s a problem, patients can switch to two sessions per week, for instance, or to ultra-brief unilateral ECT.

A few studies have suggested that cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine (Namenda) might attenuate cognitive side effects, but there’s not enough evidence to recommend their use, she said.

The speakers had no relevant industry disclosures.

NEW ORLEANS – In 2001, a patient at the Menninger Clinic, Houston, asked whether her husband could be with her during ECT treatments, so she’d feel safer.

He declined, but then she told her care team “the fact that you would allow that makes me feel entirely safe now,” recalled M. Justin Coffey, MD, medical director of Menninger’s Center for Brain Stimulation.

“She made her request partly in jest, but it was a great idea,” he said. Fast-forward 16 years, and it’s now standard practice at Menninger for patients to invite loved ones to ECT sessions. Sometimes they pick family members, other times a neighbor or even a pastor.

“One of the most powerful benefits we’ve seen is that the loved ones observing the treatment become thoroughly underwhelmed by what they see,” not much more than the patient under anesthesia. “At the same time, they are incredibly impressed by the expertise and competence of the team. They become ambassadors against stigma; I’ve got family members and patients now that join me in workshops talking about why ECT should be [used] more,” Dr. Coffey said at the American Psychiatric Association’s Institute on Psychiatric Services.

The approach is catching on, including at the New York Community Hospital, Brooklyn, where it was implemented a few years ago. “It’s a wonderful thing to decrease patient anxiety and the stigma of treatment. You ask the patient’s permission, of course, and discuss with the family members what they are going to see. It demystifies the whole thing,” said Charles H. Kellner, MD, chief of electroconvulsive therapy at the hospital and a well-known ECT researcher.

Another benefit they’ve seen at Menninger is that patients come out of their postictal confusion sooner when there’s a familiar, comforting person in the room. That’s important, because the quicker patients reorient, the less likely they are to have retrograde memory problems, Dr. Coffey said.

Memory loss is perhaps the top fear people have about ECT, and it leads to the underuse of an otherwise safe and effective treatment for severe, refractory depression. Anterograde memory problems generally clear up in a few days, but retrograde problems can linger; memories formed within 3-6 months of ECT are the most vulnerable. It’s tough to pin down exactly how great the risk is because of variations in how ECT is performed from one center to the next.

“It’s always a risk-benefit decision,” Dr. Kellner said. “The vast majority of patients do not have profound memory trouble with ECT; it’s a temporary nuisance. I’d say maybe 10% or fewer have memory problems significant enough to stop treatment, or that really bother them.”

“The most important thing” when counseling patients “is not to promise anything, because you really don’t know how an individual is going to respond to ECT,” said Adriana P. Hermida, MD, a geriatric psychiatrist and ECT practitioner at Emory University, Atlanta.

In general, cognitive problems and memory loss are less likely with unilateral treatment than with bilateral, and least likely with ultra-brief unilateral treatment. Two sessions per week are less likely to cause problems than are the usual three, but treatment response isn’t as rapid. Also, giving more than two seizures per session increases the risk of medical and cognitive side effects, and isn’t recommended.

To manage the memory risk, cognitive function should be assessed before each session, not just by objective measures and patient report, but also by asking family members what they’ve noticed. “Many times patient do not report memory issues, but family members will,” Dr. Hermida said.

If there’s a problem, patients can switch to two sessions per week, for instance, or to ultra-brief unilateral ECT.

A few studies have suggested that cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine (Namenda) might attenuate cognitive side effects, but there’s not enough evidence to recommend their use, she said.

The speakers had no relevant industry disclosures.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM IPS 2017

New narcolepsy drug passes phase 3 test

SAN DIEGO – The selective dopamine and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor solriamfetol is effective in reducing sleepiness in patients with narcolepsy, according to results of a phase 3 study.

At 150-mg and 300-mg doses, the drug had statistically significant effects on objective and subjective measures.

There are wake-promoting drugs available, such as amphetamine-related drugs that are often used off label, but addiction liability is a concern. The nonamphetamine modafinil has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration since 1998.

Jazz Pharmaceuticals is in the process of submitting solriamfetol for FDA evaluation. If approved, the drug will add to the options available for narcolepsy patients. “All of the available drugs have some limitations. Some have more abuse liability than others. Some have more robust wake-promoting properties than others. We haven’t done any head-to-head comparisons, so I can’t tell you how we will stack up,” Philip Jochelson, MD, said in an interview. Dr. Jochelson is vice president of clinical development at Jazz Pharmaceuticals and presented the results of the study at a poster session at the annual meeting of the American Neurological Association.

An earlier study showed the drug had less abuse potential than the schedule IV stimulant phentermine. That’s not surprising given the drug’s mechanism of action, Dr. Jochelson said. Amphetamine-based drugs stimulate dopamine release, which can prompt a dopamine surge that people equate with a high, he said. Solriamfetol also affects dopamine, but it is a reuptake inhibitor, so it doesn’t produce a surge.

If the drug gains approval, it remains to be seen how it will be classified on the Drug Enforcement Agency Controlled Substance scale. “Where it will fall in that spectrum is speculative at this point,” said Dr. Jochelson.

In the current study, 236 adults (aged 18-75 years) with type 1 narcolepsy were randomized to once-daily placebo, 75 mg solriamfetol, 150 mg solriamfetol, or 300 mg solriamfetol; 27.1% of patients in the 300-mg group discontinued, compared with 7.3% in the 150-mg group, 16.9% in the 75-mg group, and 10.3% in the placebo group. The mean change from baseline on the Maintenance of Wakefulness Test was statistically significant in the 300-mg group (12.3 minutes vs. 2.1 minutes for placebo, P less than .0001) and the 150-mg group (9.8 minutes vs. 2.1 minutes, P less than .0001) but not the 75-mg group (4.7 minutes vs. 2.1 minutes).

The drug also outperformed placebo at week 12 on the Epworth Sleepiness Scale. The mean change in the 300-mg group was –6.4 vs. –1.6 for placebo (P less than .001), –5.4 in the 150-mg group (P less than .0001), and –3.8 in the 75-mg group (P less than .05).

By both Maintenance of Wakefulness Test and Epworth Sleepiness Scale measures, the 150-mg and 300-mg solriamfetol groups had statistically significant differences as early as week 1.

The drug had some adverse effects, which were expected based on its pharmacologic profile. These included increases in headache (5.1% with placebo, 10.2% with 75 mg, 23.7% with 150 mg, 30.5% with 300 mg), nausea (1.7% for placebo, 5.1% for 75 mg, 10.2% for 150 mg, 16.9% for 300 mg), anxiety (1.7% with placebo, 1.7% with 75 mg, 5.1% with 150 mg, 8.5% with 300 mg), and insomnia (0% for placebo, 3.4% for 75 mg, 0% for 150 mg, 5.1% for 300 mg). Other adverse events occurring in at least 5% of patients were decreased appetite, nasopharyngitis, and dry mouth.

The study was funded by Jazz Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Jochelson is an employee of Jazz.

SAN DIEGO – The selective dopamine and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor solriamfetol is effective in reducing sleepiness in patients with narcolepsy, according to results of a phase 3 study.

At 150-mg and 300-mg doses, the drug had statistically significant effects on objective and subjective measures.

There are wake-promoting drugs available, such as amphetamine-related drugs that are often used off label, but addiction liability is a concern. The nonamphetamine modafinil has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration since 1998.

Jazz Pharmaceuticals is in the process of submitting solriamfetol for FDA evaluation. If approved, the drug will add to the options available for narcolepsy patients. “All of the available drugs have some limitations. Some have more abuse liability than others. Some have more robust wake-promoting properties than others. We haven’t done any head-to-head comparisons, so I can’t tell you how we will stack up,” Philip Jochelson, MD, said in an interview. Dr. Jochelson is vice president of clinical development at Jazz Pharmaceuticals and presented the results of the study at a poster session at the annual meeting of the American Neurological Association.

An earlier study showed the drug had less abuse potential than the schedule IV stimulant phentermine. That’s not surprising given the drug’s mechanism of action, Dr. Jochelson said. Amphetamine-based drugs stimulate dopamine release, which can prompt a dopamine surge that people equate with a high, he said. Solriamfetol also affects dopamine, but it is a reuptake inhibitor, so it doesn’t produce a surge.

If the drug gains approval, it remains to be seen how it will be classified on the Drug Enforcement Agency Controlled Substance scale. “Where it will fall in that spectrum is speculative at this point,” said Dr. Jochelson.

In the current study, 236 adults (aged 18-75 years) with type 1 narcolepsy were randomized to once-daily placebo, 75 mg solriamfetol, 150 mg solriamfetol, or 300 mg solriamfetol; 27.1% of patients in the 300-mg group discontinued, compared with 7.3% in the 150-mg group, 16.9% in the 75-mg group, and 10.3% in the placebo group. The mean change from baseline on the Maintenance of Wakefulness Test was statistically significant in the 300-mg group (12.3 minutes vs. 2.1 minutes for placebo, P less than .0001) and the 150-mg group (9.8 minutes vs. 2.1 minutes, P less than .0001) but not the 75-mg group (4.7 minutes vs. 2.1 minutes).

The drug also outperformed placebo at week 12 on the Epworth Sleepiness Scale. The mean change in the 300-mg group was –6.4 vs. –1.6 for placebo (P less than .001), –5.4 in the 150-mg group (P less than .0001), and –3.8 in the 75-mg group (P less than .05).

By both Maintenance of Wakefulness Test and Epworth Sleepiness Scale measures, the 150-mg and 300-mg solriamfetol groups had statistically significant differences as early as week 1.

The drug had some adverse effects, which were expected based on its pharmacologic profile. These included increases in headache (5.1% with placebo, 10.2% with 75 mg, 23.7% with 150 mg, 30.5% with 300 mg), nausea (1.7% for placebo, 5.1% for 75 mg, 10.2% for 150 mg, 16.9% for 300 mg), anxiety (1.7% with placebo, 1.7% with 75 mg, 5.1% with 150 mg, 8.5% with 300 mg), and insomnia (0% for placebo, 3.4% for 75 mg, 0% for 150 mg, 5.1% for 300 mg). Other adverse events occurring in at least 5% of patients were decreased appetite, nasopharyngitis, and dry mouth.

The study was funded by Jazz Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Jochelson is an employee of Jazz.

SAN DIEGO – The selective dopamine and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor solriamfetol is effective in reducing sleepiness in patients with narcolepsy, according to results of a phase 3 study.

At 150-mg and 300-mg doses, the drug had statistically significant effects on objective and subjective measures.

There are wake-promoting drugs available, such as amphetamine-related drugs that are often used off label, but addiction liability is a concern. The nonamphetamine modafinil has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration since 1998.

Jazz Pharmaceuticals is in the process of submitting solriamfetol for FDA evaluation. If approved, the drug will add to the options available for narcolepsy patients. “All of the available drugs have some limitations. Some have more abuse liability than others. Some have more robust wake-promoting properties than others. We haven’t done any head-to-head comparisons, so I can’t tell you how we will stack up,” Philip Jochelson, MD, said in an interview. Dr. Jochelson is vice president of clinical development at Jazz Pharmaceuticals and presented the results of the study at a poster session at the annual meeting of the American Neurological Association.

An earlier study showed the drug had less abuse potential than the schedule IV stimulant phentermine. That’s not surprising given the drug’s mechanism of action, Dr. Jochelson said. Amphetamine-based drugs stimulate dopamine release, which can prompt a dopamine surge that people equate with a high, he said. Solriamfetol also affects dopamine, but it is a reuptake inhibitor, so it doesn’t produce a surge.

If the drug gains approval, it remains to be seen how it will be classified on the Drug Enforcement Agency Controlled Substance scale. “Where it will fall in that spectrum is speculative at this point,” said Dr. Jochelson.

In the current study, 236 adults (aged 18-75 years) with type 1 narcolepsy were randomized to once-daily placebo, 75 mg solriamfetol, 150 mg solriamfetol, or 300 mg solriamfetol; 27.1% of patients in the 300-mg group discontinued, compared with 7.3% in the 150-mg group, 16.9% in the 75-mg group, and 10.3% in the placebo group. The mean change from baseline on the Maintenance of Wakefulness Test was statistically significant in the 300-mg group (12.3 minutes vs. 2.1 minutes for placebo, P less than .0001) and the 150-mg group (9.8 minutes vs. 2.1 minutes, P less than .0001) but not the 75-mg group (4.7 minutes vs. 2.1 minutes).

The drug also outperformed placebo at week 12 on the Epworth Sleepiness Scale. The mean change in the 300-mg group was –6.4 vs. –1.6 for placebo (P less than .001), –5.4 in the 150-mg group (P less than .0001), and –3.8 in the 75-mg group (P less than .05).

By both Maintenance of Wakefulness Test and Epworth Sleepiness Scale measures, the 150-mg and 300-mg solriamfetol groups had statistically significant differences as early as week 1.

The drug had some adverse effects, which were expected based on its pharmacologic profile. These included increases in headache (5.1% with placebo, 10.2% with 75 mg, 23.7% with 150 mg, 30.5% with 300 mg), nausea (1.7% for placebo, 5.1% for 75 mg, 10.2% for 150 mg, 16.9% for 300 mg), anxiety (1.7% with placebo, 1.7% with 75 mg, 5.1% with 150 mg, 8.5% with 300 mg), and insomnia (0% for placebo, 3.4% for 75 mg, 0% for 150 mg, 5.1% for 300 mg). Other adverse events occurring in at least 5% of patients were decreased appetite, nasopharyngitis, and dry mouth.

The study was funded by Jazz Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Jochelson is an employee of Jazz.

AT ANA 2017

Key clinical point: Solriamfetol outperformed placebo on both objective and subjective sleep measures.

Major finding: At 12 weeks, 150 mg increased Maintenance of Wakefulness Test score to 9.8 minutes, compared with 2.1 minutes in the placebo group.

Data source: A randomized, controlled trial (n = 236).

Disclosures: The study was funded by Jazz Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Jochelson is an employee of Jazz.

ADMIRE CD trial: Stem cells promote long-term fistula remission

ORLANDO – A single treatment with a suspension of allogeneic expanded adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells, or Cx601, promotes long-term combined remission of complex perianal fistulas in patients with Crohn’s disease, according to 52-week results from the phase 3 ADMIRE CD trial.

Combined remission – a stringent endpoint consisting of closure of all treated external openings that were draining at baseline and of an absence of collections more than 2 cm of treated perianal fistulas as confirmed by blinded central MRI – was achieved in 56.3% of 103 treated patients, compared with 38.6% of 101 patients who received placebo (P = .010), Daniel C. Baumgart, MD, reported at the World Congress of Gastroenterology at ACG 2017.

This parallel-group, double-blind, multicenter study included patients who had draining, treatment-refractory, complex perianal fistulas and inactive or mildly active luminal Crohn’s disease (Crohn’s Disease Activity Index scores of 220 or less) at baseline. Those randomized to the Cx601 group received a single intralesional injection of 120 million expanded adipose-derived stem cells and standard of care. Those in the control arm received a placebo injection plus standard of care, said Dr. Baumgart of Charité Medical School, which is affiliated with both Humboldt University in Berlin and the Free University of Berlin.

Prior to receiving treatment or placebo, the patients underwent fistula curettage and, if indicated, seton placement and subsequent removal, he noted, adding that baseline concomitant medications, including immunosuppressants and anti–tumor necrosis factors, were continued without dose or regimen modification and that antibiotics were allowed for up to 4 weeks.

The 52-week findings were evaluated in the modified intention-to-treat population of patients who were randomized, were treated, and had at least one postbaseline efficacy assessment (61.8% of the study population). These findings showed that Cx601 is associated with even better outcomes at 1 year than those reported at 24 weeks; those prior results, published in The Lancet in July 2016, showed combined remission rates in the modified intention-to-treat population of 51% vs. 36% for placebo.

Furthermore, 75% of treated patients who achieved combined remission at 24 weeks maintained that remission at 52 weeks, compared with 55.9% of those in the placebo group (P = .052), Dr. Baumgart said.

Sensitivity analyses in this long-term assessment supported the long-term effectiveness of Cx601 over that of the control treatment, which provided evidence on the robustness of its advantage, he said, noting that safety results were also encouraging.

“The safety profile was similar to week 24; there were no new safety signals there at all,” he said.

The findings are of note because existing therapies for complex perianal fistulas in Crohn’s disease are often ineffective, he said, adding that fistulas occur in up to 50% of Crohn’s disease patients and that 70%-80% are complex and difficult to treat. Most are refractory to conventional anti–tumor necrosis factor therapies, and 60%-70% of patients relapse, he explained.

“If we’re honest, very few medications have been properly studied,” he said, adding that fistula patients often are excluded from industry trials.

“So [the ADMIRE CD trial] is new, design-wise, and has addressed a true medical need,” he said.

He attributed the good placebo response in this trial to the ongoing standard of care treatment in both groups, as well as to the team approach to care used in the trial. He also noted that a number of questions regarding the use of Cx601 remain to be answered, including the when the ideal retreatment time point should be, whether the treatment can be used for rectovaginal fistulas, and which patients should not receive treatment.

“So there is a lot to learn still, but I think it’s a revolutionary step forward, compared to what we have today, due to the trial design, which I think is robust, and also the encouraging outcomes,” he said.

The ADMIRE CD trial was sponsored by TiGenix SAU. Dr. Baumgart has received consulting fees and nonfinancial support from AbbVie, Biogen, and BMS.

ORLANDO – A single treatment with a suspension of allogeneic expanded adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells, or Cx601, promotes long-term combined remission of complex perianal fistulas in patients with Crohn’s disease, according to 52-week results from the phase 3 ADMIRE CD trial.

Combined remission – a stringent endpoint consisting of closure of all treated external openings that were draining at baseline and of an absence of collections more than 2 cm of treated perianal fistulas as confirmed by blinded central MRI – was achieved in 56.3% of 103 treated patients, compared with 38.6% of 101 patients who received placebo (P = .010), Daniel C. Baumgart, MD, reported at the World Congress of Gastroenterology at ACG 2017.

This parallel-group, double-blind, multicenter study included patients who had draining, treatment-refractory, complex perianal fistulas and inactive or mildly active luminal Crohn’s disease (Crohn’s Disease Activity Index scores of 220 or less) at baseline. Those randomized to the Cx601 group received a single intralesional injection of 120 million expanded adipose-derived stem cells and standard of care. Those in the control arm received a placebo injection plus standard of care, said Dr. Baumgart of Charité Medical School, which is affiliated with both Humboldt University in Berlin and the Free University of Berlin.

Prior to receiving treatment or placebo, the patients underwent fistula curettage and, if indicated, seton placement and subsequent removal, he noted, adding that baseline concomitant medications, including immunosuppressants and anti–tumor necrosis factors, were continued without dose or regimen modification and that antibiotics were allowed for up to 4 weeks.

The 52-week findings were evaluated in the modified intention-to-treat population of patients who were randomized, were treated, and had at least one postbaseline efficacy assessment (61.8% of the study population). These findings showed that Cx601 is associated with even better outcomes at 1 year than those reported at 24 weeks; those prior results, published in The Lancet in July 2016, showed combined remission rates in the modified intention-to-treat population of 51% vs. 36% for placebo.

Furthermore, 75% of treated patients who achieved combined remission at 24 weeks maintained that remission at 52 weeks, compared with 55.9% of those in the placebo group (P = .052), Dr. Baumgart said.

Sensitivity analyses in this long-term assessment supported the long-term effectiveness of Cx601 over that of the control treatment, which provided evidence on the robustness of its advantage, he said, noting that safety results were also encouraging.

“The safety profile was similar to week 24; there were no new safety signals there at all,” he said.

The findings are of note because existing therapies for complex perianal fistulas in Crohn’s disease are often ineffective, he said, adding that fistulas occur in up to 50% of Crohn’s disease patients and that 70%-80% are complex and difficult to treat. Most are refractory to conventional anti–tumor necrosis factor therapies, and 60%-70% of patients relapse, he explained.

“If we’re honest, very few medications have been properly studied,” he said, adding that fistula patients often are excluded from industry trials.

“So [the ADMIRE CD trial] is new, design-wise, and has addressed a true medical need,” he said.

He attributed the good placebo response in this trial to the ongoing standard of care treatment in both groups, as well as to the team approach to care used in the trial. He also noted that a number of questions regarding the use of Cx601 remain to be answered, including the when the ideal retreatment time point should be, whether the treatment can be used for rectovaginal fistulas, and which patients should not receive treatment.

“So there is a lot to learn still, but I think it’s a revolutionary step forward, compared to what we have today, due to the trial design, which I think is robust, and also the encouraging outcomes,” he said.

The ADMIRE CD trial was sponsored by TiGenix SAU. Dr. Baumgart has received consulting fees and nonfinancial support from AbbVie, Biogen, and BMS.

ORLANDO – A single treatment with a suspension of allogeneic expanded adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells, or Cx601, promotes long-term combined remission of complex perianal fistulas in patients with Crohn’s disease, according to 52-week results from the phase 3 ADMIRE CD trial.

Combined remission – a stringent endpoint consisting of closure of all treated external openings that were draining at baseline and of an absence of collections more than 2 cm of treated perianal fistulas as confirmed by blinded central MRI – was achieved in 56.3% of 103 treated patients, compared with 38.6% of 101 patients who received placebo (P = .010), Daniel C. Baumgart, MD, reported at the World Congress of Gastroenterology at ACG 2017.

This parallel-group, double-blind, multicenter study included patients who had draining, treatment-refractory, complex perianal fistulas and inactive or mildly active luminal Crohn’s disease (Crohn’s Disease Activity Index scores of 220 or less) at baseline. Those randomized to the Cx601 group received a single intralesional injection of 120 million expanded adipose-derived stem cells and standard of care. Those in the control arm received a placebo injection plus standard of care, said Dr. Baumgart of Charité Medical School, which is affiliated with both Humboldt University in Berlin and the Free University of Berlin.

Prior to receiving treatment or placebo, the patients underwent fistula curettage and, if indicated, seton placement and subsequent removal, he noted, adding that baseline concomitant medications, including immunosuppressants and anti–tumor necrosis factors, were continued without dose or regimen modification and that antibiotics were allowed for up to 4 weeks.

The 52-week findings were evaluated in the modified intention-to-treat population of patients who were randomized, were treated, and had at least one postbaseline efficacy assessment (61.8% of the study population). These findings showed that Cx601 is associated with even better outcomes at 1 year than those reported at 24 weeks; those prior results, published in The Lancet in July 2016, showed combined remission rates in the modified intention-to-treat population of 51% vs. 36% for placebo.

Furthermore, 75% of treated patients who achieved combined remission at 24 weeks maintained that remission at 52 weeks, compared with 55.9% of those in the placebo group (P = .052), Dr. Baumgart said.

Sensitivity analyses in this long-term assessment supported the long-term effectiveness of Cx601 over that of the control treatment, which provided evidence on the robustness of its advantage, he said, noting that safety results were also encouraging.

“The safety profile was similar to week 24; there were no new safety signals there at all,” he said.

The findings are of note because existing therapies for complex perianal fistulas in Crohn’s disease are often ineffective, he said, adding that fistulas occur in up to 50% of Crohn’s disease patients and that 70%-80% are complex and difficult to treat. Most are refractory to conventional anti–tumor necrosis factor therapies, and 60%-70% of patients relapse, he explained.

“If we’re honest, very few medications have been properly studied,” he said, adding that fistula patients often are excluded from industry trials.

“So [the ADMIRE CD trial] is new, design-wise, and has addressed a true medical need,” he said.

He attributed the good placebo response in this trial to the ongoing standard of care treatment in both groups, as well as to the team approach to care used in the trial. He also noted that a number of questions regarding the use of Cx601 remain to be answered, including the when the ideal retreatment time point should be, whether the treatment can be used for rectovaginal fistulas, and which patients should not receive treatment.

“So there is a lot to learn still, but I think it’s a revolutionary step forward, compared to what we have today, due to the trial design, which I think is robust, and also the encouraging outcomes,” he said.

The ADMIRE CD trial was sponsored by TiGenix SAU. Dr. Baumgart has received consulting fees and nonfinancial support from AbbVie, Biogen, and BMS.

AT THE WORLD CONGRESS OF GASTROENTEROLOGY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Combined remission was achieved in 56.3% of treated patients, compared with 38.6% of controls.

Data source: The phase 3 ADMIRE CD trial of 204 patients.

Disclosures: The ADMIRE CD trial was sponsored by TiGenix SAU. Dr. Baumgart has received consulting fees and nonfinancial support from AbbVie, Biogen, and Bristol-Myers Squibb.

Sneak Peek: The Hospital Leader blog – Oct. 2017

You Have Lowered Length of Stay. Congratulations: You’re Fired.

For several decades, providers working within hospitals have had incentives to reduce stay durations and keep patient flow tip-top. Diagnosis Related Group (DRG)–based and capitated payments expedited that shift.

Accompanying the change, physicians became more aware of the potential repercussions of sicker and quicker discharges. They began to monitor their care and, as best as possible, use what measures they could as a proxy for quality (readmissions and hospital-acquired conditions). Providers balanced the harms of a continued stay with the benefits of added days, not to mention the need for cost savings.

I recognize this because of the cognitive dissonance providers now experience because of the mixed messages delivered by hospital leaders.

On the one hand, the DRG-driven system that we have binds the hospital’s bottom line – and that is not going away. On the other, we are paying more attention to excessive costs in post-acute settings, that is, subacute facilities when home health will do or more intense acute rehabilitation rather than the subacute route.

Making determinations as to whether a certain course is proper, whether a patient will be safe, whether families can provide adequate agency and backing, and whether we can avail community services takes time. Sicker and quicker; mindful of short-term outcomes; worked when we had postdischarge blinders on. As we remove such obstacles, and payment incentives change to cover broader intervals of time, we have to adapt. And that means leadership must realize that the practices that held hospitals in sound financial stead in years past are heading toward extinction – or, at best, falling out of favor.

Compare the costs of routine hospital care with the added expense of post-acute care, then multiply that extra expense times an aging, dependent population, and you add billions of dollars to the recovery tab. Some of these expenses are necessary, and some are not; a stay at a skilled nursing facility, for example, doubles the cost of an episode.

Read the full post at hospitalleader.org.

Also on The Hospital Leader …

- Why 7 On/7 Off Doesn’t Meet the Needs of Long-Stay Hospital Patients by Lauren Doctoroff, MD, FHM

- Is It Time for Health Policy M&Ms? by Chris Moriates, MD

- George Carlin Predicts Hospital Planning Strategy by Jordan Messler, MD, SFHM

- Many Paths to a Richer Job by Leslie Flores, MHA, MPH, SFHM

- A New Face for Online Modules by Chris Moriates, MD

You Have Lowered Length of Stay. Congratulations: You’re Fired.

For several decades, providers working within hospitals have had incentives to reduce stay durations and keep patient flow tip-top. Diagnosis Related Group (DRG)–based and capitated payments expedited that shift.

Accompanying the change, physicians became more aware of the potential repercussions of sicker and quicker discharges. They began to monitor their care and, as best as possible, use what measures they could as a proxy for quality (readmissions and hospital-acquired conditions). Providers balanced the harms of a continued stay with the benefits of added days, not to mention the need for cost savings.

I recognize this because of the cognitive dissonance providers now experience because of the mixed messages delivered by hospital leaders.

On the one hand, the DRG-driven system that we have binds the hospital’s bottom line – and that is not going away. On the other, we are paying more attention to excessive costs in post-acute settings, that is, subacute facilities when home health will do or more intense acute rehabilitation rather than the subacute route.

Making determinations as to whether a certain course is proper, whether a patient will be safe, whether families can provide adequate agency and backing, and whether we can avail community services takes time. Sicker and quicker; mindful of short-term outcomes; worked when we had postdischarge blinders on. As we remove such obstacles, and payment incentives change to cover broader intervals of time, we have to adapt. And that means leadership must realize that the practices that held hospitals in sound financial stead in years past are heading toward extinction – or, at best, falling out of favor.

Compare the costs of routine hospital care with the added expense of post-acute care, then multiply that extra expense times an aging, dependent population, and you add billions of dollars to the recovery tab. Some of these expenses are necessary, and some are not; a stay at a skilled nursing facility, for example, doubles the cost of an episode.

Read the full post at hospitalleader.org.

Also on The Hospital Leader …

- Why 7 On/7 Off Doesn’t Meet the Needs of Long-Stay Hospital Patients by Lauren Doctoroff, MD, FHM

- Is It Time for Health Policy M&Ms? by Chris Moriates, MD

- George Carlin Predicts Hospital Planning Strategy by Jordan Messler, MD, SFHM

- Many Paths to a Richer Job by Leslie Flores, MHA, MPH, SFHM

- A New Face for Online Modules by Chris Moriates, MD

You Have Lowered Length of Stay. Congratulations: You’re Fired.

For several decades, providers working within hospitals have had incentives to reduce stay durations and keep patient flow tip-top. Diagnosis Related Group (DRG)–based and capitated payments expedited that shift.

Accompanying the change, physicians became more aware of the potential repercussions of sicker and quicker discharges. They began to monitor their care and, as best as possible, use what measures they could as a proxy for quality (readmissions and hospital-acquired conditions). Providers balanced the harms of a continued stay with the benefits of added days, not to mention the need for cost savings.

I recognize this because of the cognitive dissonance providers now experience because of the mixed messages delivered by hospital leaders.

On the one hand, the DRG-driven system that we have binds the hospital’s bottom line – and that is not going away. On the other, we are paying more attention to excessive costs in post-acute settings, that is, subacute facilities when home health will do or more intense acute rehabilitation rather than the subacute route.

Making determinations as to whether a certain course is proper, whether a patient will be safe, whether families can provide adequate agency and backing, and whether we can avail community services takes time. Sicker and quicker; mindful of short-term outcomes; worked when we had postdischarge blinders on. As we remove such obstacles, and payment incentives change to cover broader intervals of time, we have to adapt. And that means leadership must realize that the practices that held hospitals in sound financial stead in years past are heading toward extinction – or, at best, falling out of favor.

Compare the costs of routine hospital care with the added expense of post-acute care, then multiply that extra expense times an aging, dependent population, and you add billions of dollars to the recovery tab. Some of these expenses are necessary, and some are not; a stay at a skilled nursing facility, for example, doubles the cost of an episode.

Read the full post at hospitalleader.org.

Also on The Hospital Leader …

- Why 7 On/7 Off Doesn’t Meet the Needs of Long-Stay Hospital Patients by Lauren Doctoroff, MD, FHM

- Is It Time for Health Policy M&Ms? by Chris Moriates, MD

- George Carlin Predicts Hospital Planning Strategy by Jordan Messler, MD, SFHM

- Many Paths to a Richer Job by Leslie Flores, MHA, MPH, SFHM

- A New Face for Online Modules by Chris Moriates, MD

How Does Cladribine Compare With Other MS Therapies?

New data confirm cladribine’s efficacy as a treatment for relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (MS), according to results published online ahead of print August 1 in Multiple Sclerosis Journal. The drug’s effect on relapses is comparable to that of fingolimod, and its effect on disability accumulation is comparable to those of interferon β and fingolimod. Compared with interferon, fingolimod, and natalizumab, cladribine may be associated with superior recovery from disability.

A phase III trial demonstrated that, compared with placebo, cladribine reduced relapse rate and increased the likelihood of remaining free from three-month confirmed disability progression in patients with relapsing-remitting MS. The European Medicines Agency approved the therapy in August 2017. Cladribine’s potential position in the treatment landscape is unclear, however, because no direct comparisons of cladribine with other MS therapies are available.

An Analysis of Matched Cohorts

Tomas Kalincik, MD, PhD, Professor of Medicine at Royal Melbourne Hospital in Australia, and colleagues conducted a propensity score–matched analysis of observational data from MSBase, including patients from the Australian Cladribine Product Familiarization Program, to compare the effectiveness of cladribine to that of interferon β, fingolimod, and natalizumab. Eligible participants had relapsing-remitting MS, received one of the study medications as monotherapy for one or more years, and had no prior exposure to alemtuzumab, mitoxantrone, rituximab, or hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

Patients received 3.5 mg/kg of oral cladribine, 44 μg of subcutaneous interferon β-1a three times weekly, 0.5 mg/day of oral fingolimod, or 300 μg of IV natalizumab every four weeks. Data were recorded during routine clinical practice. The primary end points were the proportion of patients free from relapses, disability accumulation, and disability improvement while on study therapy.

Cladribine Was Associated With Superior Disability Improvement

The researchers included 37 patients treated with cladribine, 1,940 patients treated with interferon β, 1,892 patients treated with fingolimod, and 1,410 patients treated with natalizumab in their analysis. The investigators noted only small differences in baseline characteristics between the matched cohorts.

Compared with participants receiving interferon β, patients receiving cladribine were less likely to have a relapse during the first year of treatment (hazard ratio [HR], 0.6). The proportion of relapse-free patients was 86% in the cladribine group and 70% in the interferon β group. The probability of disability accumulation was similar for these drugs (HR, 0.41), but the cladribine group was more likely to have disability improvement (HR, 15).

The proportion of relapse-free patients at one year was 79% in the cladribine and fingolimod groups, and cumulative hazards of a relapse did not differ between the two groups (HR, 1.2). The probability of disability accumulation was similar for cladribine and fingolimod (HR, 1.8), but the probability of disability improvement was greater for cladribine (HR, 3.9).

The probability of relapse was higher with cladribine than with natalizumab (HR, 1.8), but the proportions of relapse-free patients at the end of year one were 80% and 81%, respectively. The probability of disability accumulation was greater in the cladribine group than in the natalizumab group (HR, 2.5). The probability of disability improvement was greater among patients receiving cladribine than among those receiving natalizumab (HR, 4). Sensitivity analyses largely confirmed the results of the primary analyses.

“Six-month confirmed improvement of disability was observed in 10%–20% of the cladribine cohort during the first year, which was superior to all three comparator therapies. This [finding] is of interest in the context of the comparison to natalizumab, which is known to be associated with a marked improvement in disability early after its commencement,” said Dr. Kalincik and colleagues. “Improvement in disability in a cohort with this profile is unexpected.”

The study’s main limitation is the small size of the cladribine cohort, said the authors. Another limitation is the brief duration of follow-up for the cladribine group, which precludes conclusions about long-term outcomes. Nevertheless, the comparative effectiveness results “represent timely information about the role of cladribine in the management of MS,” Dr. Kalincik concluded.

—Erik Greb

Suggested Reading

Kalincik T, Jokubaitis V, Spelman T, et al. Cladribine versus fingolimod, natalizumab and interferon β for multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2017 Aug 1 [Epub ahead of print].

New data confirm cladribine’s efficacy as a treatment for relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (MS), according to results published online ahead of print August 1 in Multiple Sclerosis Journal. The drug’s effect on relapses is comparable to that of fingolimod, and its effect on disability accumulation is comparable to those of interferon β and fingolimod. Compared with interferon, fingolimod, and natalizumab, cladribine may be associated with superior recovery from disability.

A phase III trial demonstrated that, compared with placebo, cladribine reduced relapse rate and increased the likelihood of remaining free from three-month confirmed disability progression in patients with relapsing-remitting MS. The European Medicines Agency approved the therapy in August 2017. Cladribine’s potential position in the treatment landscape is unclear, however, because no direct comparisons of cladribine with other MS therapies are available.

An Analysis of Matched Cohorts

Tomas Kalincik, MD, PhD, Professor of Medicine at Royal Melbourne Hospital in Australia, and colleagues conducted a propensity score–matched analysis of observational data from MSBase, including patients from the Australian Cladribine Product Familiarization Program, to compare the effectiveness of cladribine to that of interferon β, fingolimod, and natalizumab. Eligible participants had relapsing-remitting MS, received one of the study medications as monotherapy for one or more years, and had no prior exposure to alemtuzumab, mitoxantrone, rituximab, or hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

Patients received 3.5 mg/kg of oral cladribine, 44 μg of subcutaneous interferon β-1a three times weekly, 0.5 mg/day of oral fingolimod, or 300 μg of IV natalizumab every four weeks. Data were recorded during routine clinical practice. The primary end points were the proportion of patients free from relapses, disability accumulation, and disability improvement while on study therapy.

Cladribine Was Associated With Superior Disability Improvement

The researchers included 37 patients treated with cladribine, 1,940 patients treated with interferon β, 1,892 patients treated with fingolimod, and 1,410 patients treated with natalizumab in their analysis. The investigators noted only small differences in baseline characteristics between the matched cohorts.

Compared with participants receiving interferon β, patients receiving cladribine were less likely to have a relapse during the first year of treatment (hazard ratio [HR], 0.6). The proportion of relapse-free patients was 86% in the cladribine group and 70% in the interferon β group. The probability of disability accumulation was similar for these drugs (HR, 0.41), but the cladribine group was more likely to have disability improvement (HR, 15).

The proportion of relapse-free patients at one year was 79% in the cladribine and fingolimod groups, and cumulative hazards of a relapse did not differ between the two groups (HR, 1.2). The probability of disability accumulation was similar for cladribine and fingolimod (HR, 1.8), but the probability of disability improvement was greater for cladribine (HR, 3.9).

The probability of relapse was higher with cladribine than with natalizumab (HR, 1.8), but the proportions of relapse-free patients at the end of year one were 80% and 81%, respectively. The probability of disability accumulation was greater in the cladribine group than in the natalizumab group (HR, 2.5). The probability of disability improvement was greater among patients receiving cladribine than among those receiving natalizumab (HR, 4). Sensitivity analyses largely confirmed the results of the primary analyses.

“Six-month confirmed improvement of disability was observed in 10%–20% of the cladribine cohort during the first year, which was superior to all three comparator therapies. This [finding] is of interest in the context of the comparison to natalizumab, which is known to be associated with a marked improvement in disability early after its commencement,” said Dr. Kalincik and colleagues. “Improvement in disability in a cohort with this profile is unexpected.”

The study’s main limitation is the small size of the cladribine cohort, said the authors. Another limitation is the brief duration of follow-up for the cladribine group, which precludes conclusions about long-term outcomes. Nevertheless, the comparative effectiveness results “represent timely information about the role of cladribine in the management of MS,” Dr. Kalincik concluded.

—Erik Greb

Suggested Reading

Kalincik T, Jokubaitis V, Spelman T, et al. Cladribine versus fingolimod, natalizumab and interferon β for multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2017 Aug 1 [Epub ahead of print].

New data confirm cladribine’s efficacy as a treatment for relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (MS), according to results published online ahead of print August 1 in Multiple Sclerosis Journal. The drug’s effect on relapses is comparable to that of fingolimod, and its effect on disability accumulation is comparable to those of interferon β and fingolimod. Compared with interferon, fingolimod, and natalizumab, cladribine may be associated with superior recovery from disability.

A phase III trial demonstrated that, compared with placebo, cladribine reduced relapse rate and increased the likelihood of remaining free from three-month confirmed disability progression in patients with relapsing-remitting MS. The European Medicines Agency approved the therapy in August 2017. Cladribine’s potential position in the treatment landscape is unclear, however, because no direct comparisons of cladribine with other MS therapies are available.

An Analysis of Matched Cohorts

Tomas Kalincik, MD, PhD, Professor of Medicine at Royal Melbourne Hospital in Australia, and colleagues conducted a propensity score–matched analysis of observational data from MSBase, including patients from the Australian Cladribine Product Familiarization Program, to compare the effectiveness of cladribine to that of interferon β, fingolimod, and natalizumab. Eligible participants had relapsing-remitting MS, received one of the study medications as monotherapy for one or more years, and had no prior exposure to alemtuzumab, mitoxantrone, rituximab, or hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

Patients received 3.5 mg/kg of oral cladribine, 44 μg of subcutaneous interferon β-1a three times weekly, 0.5 mg/day of oral fingolimod, or 300 μg of IV natalizumab every four weeks. Data were recorded during routine clinical practice. The primary end points were the proportion of patients free from relapses, disability accumulation, and disability improvement while on study therapy.

Cladribine Was Associated With Superior Disability Improvement

The researchers included 37 patients treated with cladribine, 1,940 patients treated with interferon β, 1,892 patients treated with fingolimod, and 1,410 patients treated with natalizumab in their analysis. The investigators noted only small differences in baseline characteristics between the matched cohorts.

Compared with participants receiving interferon β, patients receiving cladribine were less likely to have a relapse during the first year of treatment (hazard ratio [HR], 0.6). The proportion of relapse-free patients was 86% in the cladribine group and 70% in the interferon β group. The probability of disability accumulation was similar for these drugs (HR, 0.41), but the cladribine group was more likely to have disability improvement (HR, 15).

The proportion of relapse-free patients at one year was 79% in the cladribine and fingolimod groups, and cumulative hazards of a relapse did not differ between the two groups (HR, 1.2). The probability of disability accumulation was similar for cladribine and fingolimod (HR, 1.8), but the probability of disability improvement was greater for cladribine (HR, 3.9).

The probability of relapse was higher with cladribine than with natalizumab (HR, 1.8), but the proportions of relapse-free patients at the end of year one were 80% and 81%, respectively. The probability of disability accumulation was greater in the cladribine group than in the natalizumab group (HR, 2.5). The probability of disability improvement was greater among patients receiving cladribine than among those receiving natalizumab (HR, 4). Sensitivity analyses largely confirmed the results of the primary analyses.

“Six-month confirmed improvement of disability was observed in 10%–20% of the cladribine cohort during the first year, which was superior to all three comparator therapies. This [finding] is of interest in the context of the comparison to natalizumab, which is known to be associated with a marked improvement in disability early after its commencement,” said Dr. Kalincik and colleagues. “Improvement in disability in a cohort with this profile is unexpected.”

The study’s main limitation is the small size of the cladribine cohort, said the authors. Another limitation is the brief duration of follow-up for the cladribine group, which precludes conclusions about long-term outcomes. Nevertheless, the comparative effectiveness results “represent timely information about the role of cladribine in the management of MS,” Dr. Kalincik concluded.

—Erik Greb

Suggested Reading

Kalincik T, Jokubaitis V, Spelman T, et al. Cladribine versus fingolimod, natalizumab and interferon β for multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2017 Aug 1 [Epub ahead of print].

Junior surgical trainees hew closer to surgery risk calculators than do faculty members

SAN DIEGO – Researchers say that they’ve developed an easy and inexpensive way to instantly track divergences in thinking by faculty and students as they ponder cases presented in Mortality and Morbidity (M&M) conferences. They’ve already produced an intriguing early finding: Interns and junior residents hew more closely than do their elders to estimates provided by a surgical risk calculator.

The research has the potential to shed light on problems in the much-maligned M&M, says study leader Ira Leeds, MD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. He presented the study findings at the annual Clinical Congress of the American College of Surgeons.

“This project demonstrates that educational technologies can reveal important gaps in surgical education,” said Dr. Leeds, who made comments during his presentation and in an interview.

At issue: The M&M conference, a mainstay of medical education. “This has been defined as the ‘golden hour’ of surgical education,” Dr. Leeds said. “By discussing someone else’s complications, you can learn how to handle your own in the future.”

However, he added, “there’s very little evidence that we’re currently learning from M&M.”

Dr. Leeds and his colleagues are studying the M&M’s role in medical education to see if it can be improved. The new study, a prospective time-series analysis of weekly M&M conferences, aims to understand the potential value of a real-time feedback system. The idea is to develop a way to alert participants to discrepancies in their perceptions about cases.

The researchers turned to a company called Poll Everywhere, whose technology allowed them to collect instant opinions about M&M cases from those in attendance. During 2016-2017, 110 faculty, residents, and interns used Poll Everywhere’s smartphone app to do two things – make guesses about the root causes of adverse events and estimate the risk of complications from surgical procedures over the next 30 days.

“We can see all the results streaming in real time,” said Dr. Leeds, noting that the service cost $600 per year.

The participants, about two-thirds of whom were male, included faculty (35%), fellows and senior residents (28%), and interns and junior residents (37%). They’d been trained an average of 9 years.

The 34 M&M cases represented a mixture of surgical specialties, including oncology, trauma, transplant, and others.

In terms of the root cause analysis, the technology allowed researchers to instantly detect if the guesses of faculty and students were far apart.

The researchers also compared the risk estimates from the participants to those provided by the NSQIP Risk Calculator. They found that the participants tended to boost their estimate of risk, compared with the calculator, by an absolute mean difference of 7.7 percentage points.

“They were overestimating risk by nearly 8 percentage points,” Dr. Leeds said. This isn’t surprising, since other research has revealed a trend toward overestimation of risk by physicians, compared with calculators, he added.

There wasn’t a major difference between the general level of higher estimation of risk among faculty and senior residents (mean of 8.6 and 7.2 percentage points higher than the calculator, respectively). But interns and junior residents estimated risk higher than the calculator by a mean of 4.9 percentage points.

What’s going on? Are the less experienced staff members outperforming their teachers? Another possibility, Dr. Leeds said, is that “the senior surgeons are better picking up on nuances that aren’t being captured by predictive models or the underdeveloped intuition of a junior trainee.”

Rachel Dawn Aufforth, MD, of Johns Hopkins Medicine, who served as discussant for the presentation by Dr. Leeds, said she looks forward to seeing if this technology can improve resident education. She also wondered why estimates via the risk calculator were chosen as a baseline, especially considering that surgeons tend to estimate higher levels of risk.

“One of the things we’ve been trying to do is look at time-series differences,” Dr. Leeds said. “Are they getting better over an academic year? And does that vary by faculty, especially for interns? The calculator isn’t changing or learning on its own.”

In the big picture, the study shows that “collecting real-time risk estimates and root cause assignment is feasible and can be performed as part of routine M&M conferences,” he said.

The study was funded in part by Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine Institute for Excellence in Education. Dr. Leeds reports no relevant disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Researchers say that they’ve developed an easy and inexpensive way to instantly track divergences in thinking by faculty and students as they ponder cases presented in Mortality and Morbidity (M&M) conferences. They’ve already produced an intriguing early finding: Interns and junior residents hew more closely than do their elders to estimates provided by a surgical risk calculator.

The research has the potential to shed light on problems in the much-maligned M&M, says study leader Ira Leeds, MD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. He presented the study findings at the annual Clinical Congress of the American College of Surgeons.

“This project demonstrates that educational technologies can reveal important gaps in surgical education,” said Dr. Leeds, who made comments during his presentation and in an interview.

At issue: The M&M conference, a mainstay of medical education. “This has been defined as the ‘golden hour’ of surgical education,” Dr. Leeds said. “By discussing someone else’s complications, you can learn how to handle your own in the future.”

However, he added, “there’s very little evidence that we’re currently learning from M&M.”

Dr. Leeds and his colleagues are studying the M&M’s role in medical education to see if it can be improved. The new study, a prospective time-series analysis of weekly M&M conferences, aims to understand the potential value of a real-time feedback system. The idea is to develop a way to alert participants to discrepancies in their perceptions about cases.

The researchers turned to a company called Poll Everywhere, whose technology allowed them to collect instant opinions about M&M cases from those in attendance. During 2016-2017, 110 faculty, residents, and interns used Poll Everywhere’s smartphone app to do two things – make guesses about the root causes of adverse events and estimate the risk of complications from surgical procedures over the next 30 days.

“We can see all the results streaming in real time,” said Dr. Leeds, noting that the service cost $600 per year.

The participants, about two-thirds of whom were male, included faculty (35%), fellows and senior residents (28%), and interns and junior residents (37%). They’d been trained an average of 9 years.

The 34 M&M cases represented a mixture of surgical specialties, including oncology, trauma, transplant, and others.

In terms of the root cause analysis, the technology allowed researchers to instantly detect if the guesses of faculty and students were far apart.

The researchers also compared the risk estimates from the participants to those provided by the NSQIP Risk Calculator. They found that the participants tended to boost their estimate of risk, compared with the calculator, by an absolute mean difference of 7.7 percentage points.

“They were overestimating risk by nearly 8 percentage points,” Dr. Leeds said. This isn’t surprising, since other research has revealed a trend toward overestimation of risk by physicians, compared with calculators, he added.