User login

European Society of Cardiology (ESC): Annual Congress

Prophylactic beta-blockers and noncardiac surgery: It's complicated!

AMSTERDAM – Results of a new Danish national study suggest the effects of prophylactic beta-blocker therapy in patients with ischemic heart disease undergoing noncardiac surgery are considerably more heterogeneous than portrayed in current pro-prophylaxis practice guidelines or, at the opposite extreme, in a recent highly critical meta-analysis.

"This is an extraordinarily confusing area at the moment," Dr. Charlotte Andersson observed in presenting the Danish national registry findings at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

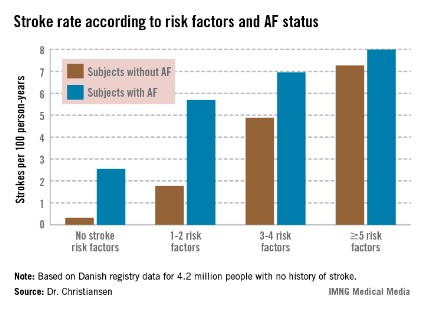

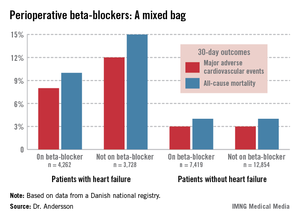

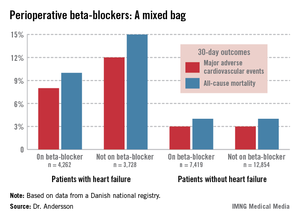

She reported on 28,263 adults with ischemic heart disease who underwent noncardiac surgery during 2004-2009. Hip or knee replacements were the most common operations, accounting for roughly one-third of the total. Patients were followed for 30 days postoperatively for the composite endpoint of acute myocardial infarction, ischemic stroke, or cardiovascular death, as well as for 30-day all-cause mortality.

In short, the effects of prophylactic beta-blocker therapy depended upon the type of background ischemic heart disease a surgical patient had.

"Our data suggest a beneficial effect of beta-blockers among patients with heart failure, perhaps a beneficial effect as well among patients with an MI within the previous 2 years, but no beneficial effect among patients with a more distant MI, and perhaps even harm associated with beta-blocker therapy among patients with neither heart failure nor a history of MI," according to Dr. Andersson of the University of Copenhagen.

The study population included 7,990 patients with heart failure, 53% of whom were on beta-blockers when they underwent noncardiac surgery. Those on beta-blockers fared significantly better in terms of the study endpoints (see graphic).

In contrast, 30-day outcomes in the 37% of patients without heart failure were identical regardless of whether or not they were on beta-blockers at surgery.

In a multivariate analysis, the use of beta-blockers in noncardiac surgery patients with heart failure was associated with a 22% reduction in major adverse cardiovascular events (MACEs) and an 18% reduction in all-cause mortality compared with no use of beta-blockers, both of which were statistically significant advantages. The analysis was adjusted for patient demographics, acute versus elective surgery, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes, atrial fibrillation, peripheral artery disease, cancer, anemia, smoking, alcohol consumption, cerebrovascular disease, and American Society of Anesthesiologists score.

Among the 1,664 patients with an MI within the past 2 years, being on a beta-blocker at the time of surgery was associated with an adjusted highly significant 46% reduction in MACE and a 20% decrease in all-cause mortality, compared with no use of beta-blockers.

For the 1,679 patients with an MI 2-5 years prior to surgery, being on a beta-blocker was associated with a 29% reduction in the risk of MACE and a 26% reduction in 30-day all-cause mortality.

Among the 5,018 patients with an MI more than 5 years earlier, the use of beta-blockers at surgery was associated with a 35% greater risk of MACE than in nonusers of beta-blockers as well as a 33% increase in all-cause mortality. These differences in adverse outcomes rates barely missed achieving statistical significance.

Perhaps the most striking study finding was that patients with no prior MI or heart failure who were on a beta-blocker at the time of noncardiac surgery had a 44% increased risk of 30-day MACE and a 30% higher all-cause mortality, compared with those not on a beta-blocker, with both differences being significant.

Session cochair Dr. Elmir Omerovic thanked Dr. Andersson for a presentation that "really adds important new information" and asked whether she had been surprised by the findings.

"Yes, I have to say I was surprised by the increased risk in patients without prior MI or heart failure, because the ESC [European Society of Cardiology] guidelines state as a class I recommendation that all patients with ischemic heart disease undergoing noncardiac surgery should be on a beta-blocker. Perhaps we should reevaluate beta-blockers in noncardiac surgery," Dr. Andersson replied.

Current American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines also endorse perioperative beta-blockade in patients with coronary artery disease undergoing vascular or intermediate-risk noncardiac surgery.

She noted that in drawing up the current guidelines, the ESC and ACC/AHA committees relied heavily on strongly positive randomized clinical trials whose validity has recently been called into question in a major research scandal. Indeed, the lead investigator in those studies, Dr. Don Poldermans – who also happened to be chairperson of the ESC guidelines-writing task force – has been dismissed from the faculty at Erasmus University in Rotterdam.

Dr. Omerovic, of Sahlgrenska University, Gothenburg, Sweden, asked for Dr. Andersson’s thoughts regarding a new meta-analysis by investigators at Imperial College London which excluded the suspect Dutch clinical trials. The investigators concluded that initiation of perioperative beta-blocker therapy was associated with a 27% increase in 30-day all-cause mortality, a 27% reduction in nonfatal MI, a 73% increase in stroke, and a 51% increase in hypotension.

"Patient safety being paramount, guidelines for perioperative beta-blocker initiation should be retracted without further delay," the meta-analysts argued (Heart 2013 July 31 [doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2013-304262]).

"I read that meta-analysis with great interest," Dr. Andersson said. "I think there definitely is a heterogeneity in the effects of perioperative beta-blockers, and it depends on your baseline risk. Most of the studies in the meta-analysis included many patients at lower risk."

Dr. Andersson’s study was funded by the Danish Medical Research Foundation. She reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

Dr. Jun Chiong, FCCP, comments: There are similar studies published regarding preoperative beta-blockers. Most studies are from large databases and not randomized. The results are varied. Important factors such as severity of comorbid conditions prior to surgery (eg, uncontrolled diabetic, noncompliance), amount of blood loss, and surgical technique (not just the organ involved) are often not factored in. I applaud the authors for reporting a significant finding from such a large database. I hope this will encourage investigators to initiate a large, well-controlled, randomized study.

Dr. Jun Chiong, FCCP, comments: There are similar studies published regarding preoperative beta-blockers. Most studies are from large databases and not randomized. The results are varied. Important factors such as severity of comorbid conditions prior to surgery (eg, uncontrolled diabetic, noncompliance), amount of blood loss, and surgical technique (not just the organ involved) are often not factored in. I applaud the authors for reporting a significant finding from such a large database. I hope this will encourage investigators to initiate a large, well-controlled, randomized study.

Dr. Jun Chiong, FCCP, comments: There are similar studies published regarding preoperative beta-blockers. Most studies are from large databases and not randomized. The results are varied. Important factors such as severity of comorbid conditions prior to surgery (eg, uncontrolled diabetic, noncompliance), amount of blood loss, and surgical technique (not just the organ involved) are often not factored in. I applaud the authors for reporting a significant finding from such a large database. I hope this will encourage investigators to initiate a large, well-controlled, randomized study.

AMSTERDAM – Results of a new Danish national study suggest the effects of prophylactic beta-blocker therapy in patients with ischemic heart disease undergoing noncardiac surgery are considerably more heterogeneous than portrayed in current pro-prophylaxis practice guidelines or, at the opposite extreme, in a recent highly critical meta-analysis.

"This is an extraordinarily confusing area at the moment," Dr. Charlotte Andersson observed in presenting the Danish national registry findings at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

She reported on 28,263 adults with ischemic heart disease who underwent noncardiac surgery during 2004-2009. Hip or knee replacements were the most common operations, accounting for roughly one-third of the total. Patients were followed for 30 days postoperatively for the composite endpoint of acute myocardial infarction, ischemic stroke, or cardiovascular death, as well as for 30-day all-cause mortality.

In short, the effects of prophylactic beta-blocker therapy depended upon the type of background ischemic heart disease a surgical patient had.

"Our data suggest a beneficial effect of beta-blockers among patients with heart failure, perhaps a beneficial effect as well among patients with an MI within the previous 2 years, but no beneficial effect among patients with a more distant MI, and perhaps even harm associated with beta-blocker therapy among patients with neither heart failure nor a history of MI," according to Dr. Andersson of the University of Copenhagen.

The study population included 7,990 patients with heart failure, 53% of whom were on beta-blockers when they underwent noncardiac surgery. Those on beta-blockers fared significantly better in terms of the study endpoints (see graphic).

In contrast, 30-day outcomes in the 37% of patients without heart failure were identical regardless of whether or not they were on beta-blockers at surgery.

In a multivariate analysis, the use of beta-blockers in noncardiac surgery patients with heart failure was associated with a 22% reduction in major adverse cardiovascular events (MACEs) and an 18% reduction in all-cause mortality compared with no use of beta-blockers, both of which were statistically significant advantages. The analysis was adjusted for patient demographics, acute versus elective surgery, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes, atrial fibrillation, peripheral artery disease, cancer, anemia, smoking, alcohol consumption, cerebrovascular disease, and American Society of Anesthesiologists score.

Among the 1,664 patients with an MI within the past 2 years, being on a beta-blocker at the time of surgery was associated with an adjusted highly significant 46% reduction in MACE and a 20% decrease in all-cause mortality, compared with no use of beta-blockers.

For the 1,679 patients with an MI 2-5 years prior to surgery, being on a beta-blocker was associated with a 29% reduction in the risk of MACE and a 26% reduction in 30-day all-cause mortality.

Among the 5,018 patients with an MI more than 5 years earlier, the use of beta-blockers at surgery was associated with a 35% greater risk of MACE than in nonusers of beta-blockers as well as a 33% increase in all-cause mortality. These differences in adverse outcomes rates barely missed achieving statistical significance.

Perhaps the most striking study finding was that patients with no prior MI or heart failure who were on a beta-blocker at the time of noncardiac surgery had a 44% increased risk of 30-day MACE and a 30% higher all-cause mortality, compared with those not on a beta-blocker, with both differences being significant.

Session cochair Dr. Elmir Omerovic thanked Dr. Andersson for a presentation that "really adds important new information" and asked whether she had been surprised by the findings.

"Yes, I have to say I was surprised by the increased risk in patients without prior MI or heart failure, because the ESC [European Society of Cardiology] guidelines state as a class I recommendation that all patients with ischemic heart disease undergoing noncardiac surgery should be on a beta-blocker. Perhaps we should reevaluate beta-blockers in noncardiac surgery," Dr. Andersson replied.

Current American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines also endorse perioperative beta-blockade in patients with coronary artery disease undergoing vascular or intermediate-risk noncardiac surgery.

She noted that in drawing up the current guidelines, the ESC and ACC/AHA committees relied heavily on strongly positive randomized clinical trials whose validity has recently been called into question in a major research scandal. Indeed, the lead investigator in those studies, Dr. Don Poldermans – who also happened to be chairperson of the ESC guidelines-writing task force – has been dismissed from the faculty at Erasmus University in Rotterdam.

Dr. Omerovic, of Sahlgrenska University, Gothenburg, Sweden, asked for Dr. Andersson’s thoughts regarding a new meta-analysis by investigators at Imperial College London which excluded the suspect Dutch clinical trials. The investigators concluded that initiation of perioperative beta-blocker therapy was associated with a 27% increase in 30-day all-cause mortality, a 27% reduction in nonfatal MI, a 73% increase in stroke, and a 51% increase in hypotension.

"Patient safety being paramount, guidelines for perioperative beta-blocker initiation should be retracted without further delay," the meta-analysts argued (Heart 2013 July 31 [doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2013-304262]).

"I read that meta-analysis with great interest," Dr. Andersson said. "I think there definitely is a heterogeneity in the effects of perioperative beta-blockers, and it depends on your baseline risk. Most of the studies in the meta-analysis included many patients at lower risk."

Dr. Andersson’s study was funded by the Danish Medical Research Foundation. She reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

AMSTERDAM – Results of a new Danish national study suggest the effects of prophylactic beta-blocker therapy in patients with ischemic heart disease undergoing noncardiac surgery are considerably more heterogeneous than portrayed in current pro-prophylaxis practice guidelines or, at the opposite extreme, in a recent highly critical meta-analysis.

"This is an extraordinarily confusing area at the moment," Dr. Charlotte Andersson observed in presenting the Danish national registry findings at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

She reported on 28,263 adults with ischemic heart disease who underwent noncardiac surgery during 2004-2009. Hip or knee replacements were the most common operations, accounting for roughly one-third of the total. Patients were followed for 30 days postoperatively for the composite endpoint of acute myocardial infarction, ischemic stroke, or cardiovascular death, as well as for 30-day all-cause mortality.

In short, the effects of prophylactic beta-blocker therapy depended upon the type of background ischemic heart disease a surgical patient had.

"Our data suggest a beneficial effect of beta-blockers among patients with heart failure, perhaps a beneficial effect as well among patients with an MI within the previous 2 years, but no beneficial effect among patients with a more distant MI, and perhaps even harm associated with beta-blocker therapy among patients with neither heart failure nor a history of MI," according to Dr. Andersson of the University of Copenhagen.

The study population included 7,990 patients with heart failure, 53% of whom were on beta-blockers when they underwent noncardiac surgery. Those on beta-blockers fared significantly better in terms of the study endpoints (see graphic).

In contrast, 30-day outcomes in the 37% of patients without heart failure were identical regardless of whether or not they were on beta-blockers at surgery.

In a multivariate analysis, the use of beta-blockers in noncardiac surgery patients with heart failure was associated with a 22% reduction in major adverse cardiovascular events (MACEs) and an 18% reduction in all-cause mortality compared with no use of beta-blockers, both of which were statistically significant advantages. The analysis was adjusted for patient demographics, acute versus elective surgery, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes, atrial fibrillation, peripheral artery disease, cancer, anemia, smoking, alcohol consumption, cerebrovascular disease, and American Society of Anesthesiologists score.

Among the 1,664 patients with an MI within the past 2 years, being on a beta-blocker at the time of surgery was associated with an adjusted highly significant 46% reduction in MACE and a 20% decrease in all-cause mortality, compared with no use of beta-blockers.

For the 1,679 patients with an MI 2-5 years prior to surgery, being on a beta-blocker was associated with a 29% reduction in the risk of MACE and a 26% reduction in 30-day all-cause mortality.

Among the 5,018 patients with an MI more than 5 years earlier, the use of beta-blockers at surgery was associated with a 35% greater risk of MACE than in nonusers of beta-blockers as well as a 33% increase in all-cause mortality. These differences in adverse outcomes rates barely missed achieving statistical significance.

Perhaps the most striking study finding was that patients with no prior MI or heart failure who were on a beta-blocker at the time of noncardiac surgery had a 44% increased risk of 30-day MACE and a 30% higher all-cause mortality, compared with those not on a beta-blocker, with both differences being significant.

Session cochair Dr. Elmir Omerovic thanked Dr. Andersson for a presentation that "really adds important new information" and asked whether she had been surprised by the findings.

"Yes, I have to say I was surprised by the increased risk in patients without prior MI or heart failure, because the ESC [European Society of Cardiology] guidelines state as a class I recommendation that all patients with ischemic heart disease undergoing noncardiac surgery should be on a beta-blocker. Perhaps we should reevaluate beta-blockers in noncardiac surgery," Dr. Andersson replied.

Current American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines also endorse perioperative beta-blockade in patients with coronary artery disease undergoing vascular or intermediate-risk noncardiac surgery.

She noted that in drawing up the current guidelines, the ESC and ACC/AHA committees relied heavily on strongly positive randomized clinical trials whose validity has recently been called into question in a major research scandal. Indeed, the lead investigator in those studies, Dr. Don Poldermans – who also happened to be chairperson of the ESC guidelines-writing task force – has been dismissed from the faculty at Erasmus University in Rotterdam.

Dr. Omerovic, of Sahlgrenska University, Gothenburg, Sweden, asked for Dr. Andersson’s thoughts regarding a new meta-analysis by investigators at Imperial College London which excluded the suspect Dutch clinical trials. The investigators concluded that initiation of perioperative beta-blocker therapy was associated with a 27% increase in 30-day all-cause mortality, a 27% reduction in nonfatal MI, a 73% increase in stroke, and a 51% increase in hypotension.

"Patient safety being paramount, guidelines for perioperative beta-blocker initiation should be retracted without further delay," the meta-analysts argued (Heart 2013 July 31 [doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2013-304262]).

"I read that meta-analysis with great interest," Dr. Andersson said. "I think there definitely is a heterogeneity in the effects of perioperative beta-blockers, and it depends on your baseline risk. Most of the studies in the meta-analysis included many patients at lower risk."

Dr. Andersson’s study was funded by the Danish Medical Research Foundation. She reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

AT THE ESC CONGRESS 2013

Major finding: Patients with heart failure who were on beta-blocker therapy at the time of noncardiac surgery had a 22% reduction in 30-day major adverse cardiovascular events, compared with those not on a beta-blocker perioperatively. In stark contrast, patients with ischemic heart disease but no history of heart failure or MI had a 44% greater risk of such events if they were on a perioperative beta-blocker.

Data source: This was a Danish national registry study that included more than 28,000 patients with ischemic heart disease who underwent noncardiac surgery.

Disclosures: Dr. Andersson’s study was funded by the Danish Medical Research Foundation. She reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

Psoriasis linked to increased heart failure risk

AMSTERDAM – Psoriasis proved to be independently associated with an increased risk for new-onset heart failure in the first nationwide study to look at a possible relationship.

As word of the newly identified psoriasis/heart failure link spreads, it’s likely cardiologists will receive a growing number of referrals from dermatologists and primary care physicians for evaluation of possible heart failure in psoriasis patients who develop shortness of breath or other symptoms suggestive of ventricular dysfunction, Dr. Usman Khalid said at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

"Our results underlie the importance of considering the psoriatic population as a high-risk patient group in terms of cardiovascular risk. We encourage early screening for cardiovascular risk factors in psoriasis patients," he said.

Psoriasis is known to be associated with an increased cardiovascular event rate, presumably due to shared systemic inflammatory pathways, but the association between the dermatologic disease and heart failure, specifically, hadn’t been looked at in depth prior to Dr. Khalid’s presentation of a Danish study involving all 5.85 million Danish adults, who were followed from 1997 through 2009.

Among the Danish population without known heart failure at baseline were 57,049 individuals with mild psoriasis – identified by their use of prescription topical agents – and 11,638 others with severe psoriasis. The incidence of new-onset heart failure during follow-up was 2.27 cases per 1,000 person-years in subjects without psoriasis and a significantly greater 4.02 per 1,000 person-years in those with mild psoriasis and 4.50 per 1,000 person-years in individuals with severe psoriasis, reported Dr. Khalid of the University of Copenhagen.

In a multivariate regression analysis adjusted for demographic and socioeconomic factors, comorbid conditions, and use of cardiovascular medications, the likelihood of developing new-onset heart failure during follow-up was 64% greater among individuals with mild psoriasis and 85% greater in those with severe psoriasis than in psoriasis-free subjects.

Because of limitations in the registry database, it is not possible to determine the proportion of new-onset heart failure among psoriasis patients that involved systolic as opposed to diastolic dysfunction, or ischemic versus nonischemic etiology, Dr. Khalid said in response to audience questions.

This study was supported by a research grant from Leo Pharma. Dr. Khalid reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

AMSTERDAM – Psoriasis proved to be independently associated with an increased risk for new-onset heart failure in the first nationwide study to look at a possible relationship.

As word of the newly identified psoriasis/heart failure link spreads, it’s likely cardiologists will receive a growing number of referrals from dermatologists and primary care physicians for evaluation of possible heart failure in psoriasis patients who develop shortness of breath or other symptoms suggestive of ventricular dysfunction, Dr. Usman Khalid said at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

"Our results underlie the importance of considering the psoriatic population as a high-risk patient group in terms of cardiovascular risk. We encourage early screening for cardiovascular risk factors in psoriasis patients," he said.

Psoriasis is known to be associated with an increased cardiovascular event rate, presumably due to shared systemic inflammatory pathways, but the association between the dermatologic disease and heart failure, specifically, hadn’t been looked at in depth prior to Dr. Khalid’s presentation of a Danish study involving all 5.85 million Danish adults, who were followed from 1997 through 2009.

Among the Danish population without known heart failure at baseline were 57,049 individuals with mild psoriasis – identified by their use of prescription topical agents – and 11,638 others with severe psoriasis. The incidence of new-onset heart failure during follow-up was 2.27 cases per 1,000 person-years in subjects without psoriasis and a significantly greater 4.02 per 1,000 person-years in those with mild psoriasis and 4.50 per 1,000 person-years in individuals with severe psoriasis, reported Dr. Khalid of the University of Copenhagen.

In a multivariate regression analysis adjusted for demographic and socioeconomic factors, comorbid conditions, and use of cardiovascular medications, the likelihood of developing new-onset heart failure during follow-up was 64% greater among individuals with mild psoriasis and 85% greater in those with severe psoriasis than in psoriasis-free subjects.

Because of limitations in the registry database, it is not possible to determine the proportion of new-onset heart failure among psoriasis patients that involved systolic as opposed to diastolic dysfunction, or ischemic versus nonischemic etiology, Dr. Khalid said in response to audience questions.

This study was supported by a research grant from Leo Pharma. Dr. Khalid reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

AMSTERDAM – Psoriasis proved to be independently associated with an increased risk for new-onset heart failure in the first nationwide study to look at a possible relationship.

As word of the newly identified psoriasis/heart failure link spreads, it’s likely cardiologists will receive a growing number of referrals from dermatologists and primary care physicians for evaluation of possible heart failure in psoriasis patients who develop shortness of breath or other symptoms suggestive of ventricular dysfunction, Dr. Usman Khalid said at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

"Our results underlie the importance of considering the psoriatic population as a high-risk patient group in terms of cardiovascular risk. We encourage early screening for cardiovascular risk factors in psoriasis patients," he said.

Psoriasis is known to be associated with an increased cardiovascular event rate, presumably due to shared systemic inflammatory pathways, but the association between the dermatologic disease and heart failure, specifically, hadn’t been looked at in depth prior to Dr. Khalid’s presentation of a Danish study involving all 5.85 million Danish adults, who were followed from 1997 through 2009.

Among the Danish population without known heart failure at baseline were 57,049 individuals with mild psoriasis – identified by their use of prescription topical agents – and 11,638 others with severe psoriasis. The incidence of new-onset heart failure during follow-up was 2.27 cases per 1,000 person-years in subjects without psoriasis and a significantly greater 4.02 per 1,000 person-years in those with mild psoriasis and 4.50 per 1,000 person-years in individuals with severe psoriasis, reported Dr. Khalid of the University of Copenhagen.

In a multivariate regression analysis adjusted for demographic and socioeconomic factors, comorbid conditions, and use of cardiovascular medications, the likelihood of developing new-onset heart failure during follow-up was 64% greater among individuals with mild psoriasis and 85% greater in those with severe psoriasis than in psoriasis-free subjects.

Because of limitations in the registry database, it is not possible to determine the proportion of new-onset heart failure among psoriasis patients that involved systolic as opposed to diastolic dysfunction, or ischemic versus nonischemic etiology, Dr. Khalid said in response to audience questions.

This study was supported by a research grant from Leo Pharma. Dr. Khalid reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

AT THE ESC CONGRESS 2013

Major finding: Danish patients with mild psoriasis developed new-onset heart failure at the rate of 4.02 cases per 1,000 person-years of follow-up, while those with severe psoriasis did so at a pace of 4.50 cases per 1,000 person-years, both significantly higher rates than the 2.27 per 1,000 person-years in the general psoriasis-free population.

Data source: This was a Danish nationwide registry study that included all 5.85 million Danish adults. They were followed during 1997-2009 for development of heart failure.

Disclosures: The study was supported by a research grant from Leo Pharma. The presenter reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

Statins cut limb events in PAD patients

AMSTERDAM – Treatment with a statin cut the relative rate of worsening peripheral artery disease by roughly 20% in a registry with nearly 6,000 peripheral artery disease patients.

But the registry data also showed that more than a third of patients with peripheral artery disease (PAD) failed to receive statin treatment, Dr. Dharam Kumbhani said at the annual Congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

"This is one of the first, and largest, studies to demonstrate an impact [of statin treatment] on adverse limb outcomes in patients with PAD, including worsening claudication, new critical limb ischemia, need for revascularization, and notably need for ischemic amputations. But despite having a class I recommendation for use in patients with PAD, data from this large, international registry suggest that statin use remains suboptimal," said Dr. Kumbhani, an interventional cardiologist at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas.

"Future research should focus on improving patient and physician compliance with statin use across the entire spectrum of PAD patients," he said.

Concomitant coronary artery disease, as well as the specialty of the treating physician, seemed to link with statin use in these patients, Dr. Kumbhani added. "In PAD patients with CAD, statin use occurred in about 75%; in PAD patients without CAD, it was less than 50%."

Statins were most reliably prescribed to PAD patients by cardiologists, who administered the drugs to about 80% of all their PAD patients, regardless of concomitant CAD. In contrast, vascular surgeons prescribed statins to fewer than half their PAD patients, and in those who did not have concomitant CAD, statin use fell to less than a third. About 70% of all patients enrolled in the registry received their treatment from a primary care physician.

The data came from the Reduction of Atherothrombosis for Continued Health (REACH) registry, which followed more than 45,000 enrolled patients for at least 4 years at more than 3,600 centers in 29 countries; more than a quarter were U.S. patients (JAMA 2010;304:1350-7). Enrolled patients were at least 45 years old and had at least three atherosclerosis risk factors or established vascular disease in the coronary, cerebral, or peripheral domains. The enrolled patients included 5,861 with established, symptomatic PAD, of whom 3,643 (62%) were on statin treatment at the time they entered the registry.

During 4-year follow-up the rate of the primary systemic outcome – a composite of cardiovascular death, nonfatal myocardial infarction, and nonfatal stroke – decreased by a statistically significant, relative 15% among patients on a statin compared with those not on a statin at baseline, in a propensity-score adjusted analysis.

Statin use linked with a statistically significant, 21% relative drop in worsening PAD events, compared with nonuse, in the propensity-score adjusted model. Adjusted analyses also showed statistically significant reductions for most of the individual outcomes that formed the composites, including a 27% relative reduction in nonfatal strokes and a 43% relative drop in limb amputations.

The systemic benefits seen in the registry from statin use in patients with PAD are consistent with results from randomized, controlled trials, but finding statin use also linked with decreased adverse limb outcomes is new, Dr. Kumbhani said.

The REACH registry is funded by Sanofi and Bristol-Myers Squibb. Dr. Kumbhani reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AMSTERDAM – Treatment with a statin cut the relative rate of worsening peripheral artery disease by roughly 20% in a registry with nearly 6,000 peripheral artery disease patients.

But the registry data also showed that more than a third of patients with peripheral artery disease (PAD) failed to receive statin treatment, Dr. Dharam Kumbhani said at the annual Congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

"This is one of the first, and largest, studies to demonstrate an impact [of statin treatment] on adverse limb outcomes in patients with PAD, including worsening claudication, new critical limb ischemia, need for revascularization, and notably need for ischemic amputations. But despite having a class I recommendation for use in patients with PAD, data from this large, international registry suggest that statin use remains suboptimal," said Dr. Kumbhani, an interventional cardiologist at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas.

"Future research should focus on improving patient and physician compliance with statin use across the entire spectrum of PAD patients," he said.

Concomitant coronary artery disease, as well as the specialty of the treating physician, seemed to link with statin use in these patients, Dr. Kumbhani added. "In PAD patients with CAD, statin use occurred in about 75%; in PAD patients without CAD, it was less than 50%."

Statins were most reliably prescribed to PAD patients by cardiologists, who administered the drugs to about 80% of all their PAD patients, regardless of concomitant CAD. In contrast, vascular surgeons prescribed statins to fewer than half their PAD patients, and in those who did not have concomitant CAD, statin use fell to less than a third. About 70% of all patients enrolled in the registry received their treatment from a primary care physician.

The data came from the Reduction of Atherothrombosis for Continued Health (REACH) registry, which followed more than 45,000 enrolled patients for at least 4 years at more than 3,600 centers in 29 countries; more than a quarter were U.S. patients (JAMA 2010;304:1350-7). Enrolled patients were at least 45 years old and had at least three atherosclerosis risk factors or established vascular disease in the coronary, cerebral, or peripheral domains. The enrolled patients included 5,861 with established, symptomatic PAD, of whom 3,643 (62%) were on statin treatment at the time they entered the registry.

During 4-year follow-up the rate of the primary systemic outcome – a composite of cardiovascular death, nonfatal myocardial infarction, and nonfatal stroke – decreased by a statistically significant, relative 15% among patients on a statin compared with those not on a statin at baseline, in a propensity-score adjusted analysis.

Statin use linked with a statistically significant, 21% relative drop in worsening PAD events, compared with nonuse, in the propensity-score adjusted model. Adjusted analyses also showed statistically significant reductions for most of the individual outcomes that formed the composites, including a 27% relative reduction in nonfatal strokes and a 43% relative drop in limb amputations.

The systemic benefits seen in the registry from statin use in patients with PAD are consistent with results from randomized, controlled trials, but finding statin use also linked with decreased adverse limb outcomes is new, Dr. Kumbhani said.

The REACH registry is funded by Sanofi and Bristol-Myers Squibb. Dr. Kumbhani reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AMSTERDAM – Treatment with a statin cut the relative rate of worsening peripheral artery disease by roughly 20% in a registry with nearly 6,000 peripheral artery disease patients.

But the registry data also showed that more than a third of patients with peripheral artery disease (PAD) failed to receive statin treatment, Dr. Dharam Kumbhani said at the annual Congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

"This is one of the first, and largest, studies to demonstrate an impact [of statin treatment] on adverse limb outcomes in patients with PAD, including worsening claudication, new critical limb ischemia, need for revascularization, and notably need for ischemic amputations. But despite having a class I recommendation for use in patients with PAD, data from this large, international registry suggest that statin use remains suboptimal," said Dr. Kumbhani, an interventional cardiologist at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas.

"Future research should focus on improving patient and physician compliance with statin use across the entire spectrum of PAD patients," he said.

Concomitant coronary artery disease, as well as the specialty of the treating physician, seemed to link with statin use in these patients, Dr. Kumbhani added. "In PAD patients with CAD, statin use occurred in about 75%; in PAD patients without CAD, it was less than 50%."

Statins were most reliably prescribed to PAD patients by cardiologists, who administered the drugs to about 80% of all their PAD patients, regardless of concomitant CAD. In contrast, vascular surgeons prescribed statins to fewer than half their PAD patients, and in those who did not have concomitant CAD, statin use fell to less than a third. About 70% of all patients enrolled in the registry received their treatment from a primary care physician.

The data came from the Reduction of Atherothrombosis for Continued Health (REACH) registry, which followed more than 45,000 enrolled patients for at least 4 years at more than 3,600 centers in 29 countries; more than a quarter were U.S. patients (JAMA 2010;304:1350-7). Enrolled patients were at least 45 years old and had at least three atherosclerosis risk factors or established vascular disease in the coronary, cerebral, or peripheral domains. The enrolled patients included 5,861 with established, symptomatic PAD, of whom 3,643 (62%) were on statin treatment at the time they entered the registry.

During 4-year follow-up the rate of the primary systemic outcome – a composite of cardiovascular death, nonfatal myocardial infarction, and nonfatal stroke – decreased by a statistically significant, relative 15% among patients on a statin compared with those not on a statin at baseline, in a propensity-score adjusted analysis.

Statin use linked with a statistically significant, 21% relative drop in worsening PAD events, compared with nonuse, in the propensity-score adjusted model. Adjusted analyses also showed statistically significant reductions for most of the individual outcomes that formed the composites, including a 27% relative reduction in nonfatal strokes and a 43% relative drop in limb amputations.

The systemic benefits seen in the registry from statin use in patients with PAD are consistent with results from randomized, controlled trials, but finding statin use also linked with decreased adverse limb outcomes is new, Dr. Kumbhani said.

The REACH registry is funded by Sanofi and Bristol-Myers Squibb. Dr. Kumbhani reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AT THE ESC CONGRESS 2013

Major finding: In patients with peripheral artery disease, statin use was linked with an adjusted, relative 21% cut in adverse limb outcomes.

Data source: Four-year follow-up in the REACH registry, which enrolled more than 45,000 patients with atherothrombotic disease in 29 countries.

Disclosures: The REACH registry is funded by Sanofi and Bristol-Myers Squibb. Dr. Kumbhani reported having no relevant financial conflicts.

Registry-based randomized clinical trials are here

The results from the TASTE trial reported last week at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology and in the New England Journal of Medicine – which showed no 30-day survival benefit for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction patients treated with thrombus aspiration compared with conventional stenting – received more kudos for the study’s design than for its primary finding.

A big reason was that the study design was so unprecedented. Called a "registry-based randomized clinical trial" (RRCT), the Thrombus Aspiration in ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction in Scandinavia (TASTE) trial enrolled STEMI patients as they entered the long-standing, pan–Sweden and Iceland Swedish Web System for Enhancement and Development of Evidence-Based Care in Heart Disease Evaluated According to Recommended Therapies (SWEDEHEART) registry.

On the SWEDEHEART registry backbone, which automatically provided comprehensive data collection and follow-up, the researchers who collaborated on TASTE built in a web-based randomization that allocated more than 7,200 patients to either treatment by thrombus aspiration followed by percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) or to PCI only.

The main result was clear, but several experts who heard it hedged on the immediate impact of the TASTE results on use of thrombus aspiration.

This treatment "is still logical, feasible, and relatively easy, and will continue to be attractive to many," especially until the results of a more conventionally designed, similarly-sized trial, TOTAL, are available, commented Dr. Raffaele De Caterina, the designated discussant for the report at the meeting.

Despite their skepticism on what the TASTE findings mean for current practice, Dr. De Caterina and others had unbridled enthusiasm for the new RRCT. The design "allowed completeness of follow-up and a much lower cost," and with no commercial involvement, he said.

"This is an exciting and innovative approach. Automatic collection of outcomes makes it incredibly cost effective, and a number of countries have large registry programs," said Dr. Keith A.A. Fox, a professor of cardiology at the University of Edinburgh.

A commentary that ran with the published report on TASTE called the RRCT concept "a disruptive technology" that "transforms existing standards, procedures, and cost structures." The commentary, cowritten by Dr. Michael S. Lauer, director of cardiovascular sciences at the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, noted that the incremental cost to run TASTE was about $300,000, roughly the size of an average research grant from the National Institutes of Health to an academic laboratory.

The RRCT model inaugurated by TASTE produced enough interest to have the TASTE investigators give a second talk at the ESC meeting focused just on their study’s design and its implications. Dr. Stefan James, a TASTE researcher, highlighted several other clinical questions that he and his colleagues are addressing in ongoing RRCTS: the role of supplemental oxygen in acute MI patients, a comparison of bivalirudin (Angiomax) and heparin in acute MI patients on contemporary antiplatelet treatment, the value of drug-eluting technologies for treating peripheral artery disease, and the ability of bioabsorbable vascular scaffolds to prevent events.

The RRCT is "ideal for one clinically important hypothesis with reliable, hard endpoints," Dr. James said.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

The results from the TASTE trial reported last week at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology and in the New England Journal of Medicine – which showed no 30-day survival benefit for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction patients treated with thrombus aspiration compared with conventional stenting – received more kudos for the study’s design than for its primary finding.

A big reason was that the study design was so unprecedented. Called a "registry-based randomized clinical trial" (RRCT), the Thrombus Aspiration in ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction in Scandinavia (TASTE) trial enrolled STEMI patients as they entered the long-standing, pan–Sweden and Iceland Swedish Web System for Enhancement and Development of Evidence-Based Care in Heart Disease Evaluated According to Recommended Therapies (SWEDEHEART) registry.

On the SWEDEHEART registry backbone, which automatically provided comprehensive data collection and follow-up, the researchers who collaborated on TASTE built in a web-based randomization that allocated more than 7,200 patients to either treatment by thrombus aspiration followed by percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) or to PCI only.

The main result was clear, but several experts who heard it hedged on the immediate impact of the TASTE results on use of thrombus aspiration.

This treatment "is still logical, feasible, and relatively easy, and will continue to be attractive to many," especially until the results of a more conventionally designed, similarly-sized trial, TOTAL, are available, commented Dr. Raffaele De Caterina, the designated discussant for the report at the meeting.

Despite their skepticism on what the TASTE findings mean for current practice, Dr. De Caterina and others had unbridled enthusiasm for the new RRCT. The design "allowed completeness of follow-up and a much lower cost," and with no commercial involvement, he said.

"This is an exciting and innovative approach. Automatic collection of outcomes makes it incredibly cost effective, and a number of countries have large registry programs," said Dr. Keith A.A. Fox, a professor of cardiology at the University of Edinburgh.

A commentary that ran with the published report on TASTE called the RRCT concept "a disruptive technology" that "transforms existing standards, procedures, and cost structures." The commentary, cowritten by Dr. Michael S. Lauer, director of cardiovascular sciences at the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, noted that the incremental cost to run TASTE was about $300,000, roughly the size of an average research grant from the National Institutes of Health to an academic laboratory.

The RRCT model inaugurated by TASTE produced enough interest to have the TASTE investigators give a second talk at the ESC meeting focused just on their study’s design and its implications. Dr. Stefan James, a TASTE researcher, highlighted several other clinical questions that he and his colleagues are addressing in ongoing RRCTS: the role of supplemental oxygen in acute MI patients, a comparison of bivalirudin (Angiomax) and heparin in acute MI patients on contemporary antiplatelet treatment, the value of drug-eluting technologies for treating peripheral artery disease, and the ability of bioabsorbable vascular scaffolds to prevent events.

The RRCT is "ideal for one clinically important hypothesis with reliable, hard endpoints," Dr. James said.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

The results from the TASTE trial reported last week at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology and in the New England Journal of Medicine – which showed no 30-day survival benefit for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction patients treated with thrombus aspiration compared with conventional stenting – received more kudos for the study’s design than for its primary finding.

A big reason was that the study design was so unprecedented. Called a "registry-based randomized clinical trial" (RRCT), the Thrombus Aspiration in ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction in Scandinavia (TASTE) trial enrolled STEMI patients as they entered the long-standing, pan–Sweden and Iceland Swedish Web System for Enhancement and Development of Evidence-Based Care in Heart Disease Evaluated According to Recommended Therapies (SWEDEHEART) registry.

On the SWEDEHEART registry backbone, which automatically provided comprehensive data collection and follow-up, the researchers who collaborated on TASTE built in a web-based randomization that allocated more than 7,200 patients to either treatment by thrombus aspiration followed by percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) or to PCI only.

The main result was clear, but several experts who heard it hedged on the immediate impact of the TASTE results on use of thrombus aspiration.

This treatment "is still logical, feasible, and relatively easy, and will continue to be attractive to many," especially until the results of a more conventionally designed, similarly-sized trial, TOTAL, are available, commented Dr. Raffaele De Caterina, the designated discussant for the report at the meeting.

Despite their skepticism on what the TASTE findings mean for current practice, Dr. De Caterina and others had unbridled enthusiasm for the new RRCT. The design "allowed completeness of follow-up and a much lower cost," and with no commercial involvement, he said.

"This is an exciting and innovative approach. Automatic collection of outcomes makes it incredibly cost effective, and a number of countries have large registry programs," said Dr. Keith A.A. Fox, a professor of cardiology at the University of Edinburgh.

A commentary that ran with the published report on TASTE called the RRCT concept "a disruptive technology" that "transforms existing standards, procedures, and cost structures." The commentary, cowritten by Dr. Michael S. Lauer, director of cardiovascular sciences at the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, noted that the incremental cost to run TASTE was about $300,000, roughly the size of an average research grant from the National Institutes of Health to an academic laboratory.

The RRCT model inaugurated by TASTE produced enough interest to have the TASTE investigators give a second talk at the ESC meeting focused just on their study’s design and its implications. Dr. Stefan James, a TASTE researcher, highlighted several other clinical questions that he and his colleagues are addressing in ongoing RRCTS: the role of supplemental oxygen in acute MI patients, a comparison of bivalirudin (Angiomax) and heparin in acute MI patients on contemporary antiplatelet treatment, the value of drug-eluting technologies for treating peripheral artery disease, and the ability of bioabsorbable vascular scaffolds to prevent events.

The RRCT is "ideal for one clinically important hypothesis with reliable, hard endpoints," Dr. James said.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

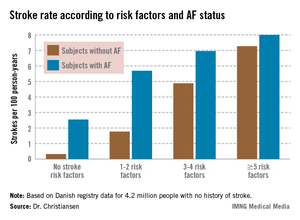

Stroke risk climbs sharply with more risk factors, even without AF

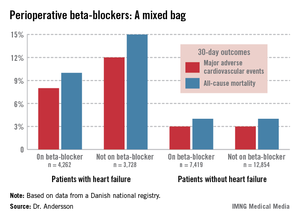

AMSTERDAM – The presence of three or more ischemic stroke risk factors in patients with no history of atrial fibrillation or stroke spells high stroke risk, comparable with that seen in patients who do have atrial fibrillation, according to a Danish national study.

Moreover, individuals with five or more stroke risk factors have essentially the same high stroke risk – roughly 8% per year – regardless of whether they have a history of atrial fibrillation (AF) or not, Dr. Christine Benn Christiansen reported at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

"The stroke risk increases with the number of risk factors. This has not been shown before in patients without prior stroke or atrial fibrillation," said Dr. Christiansen of Gentofte Hospital, Hellerup, Denmark.

"The main message here is there’s a great potential for reducing stroke risk in patients without atrial fibrillation," she added.

The impetus for the Danish national study lies in the fact that 80% of ischemic strokes occur in individuals without AF. The majority of these are first-time strokes. Yet the well-known guideline-recommended stroke-risk scores CHADS2 and CHA2DS2-VASc apply only to patients with AF.

"In patients without prior stroke, without AF, there is no systematic risk approach to deciding whether such people should receive any kind of antithrombotic medication to prevent ischemic strokes," Dr. Christiansen observed.

She and her coinvestigators analyzed comprehensive Danish national health care registries and identified 4.2 million adult Danes with no history of stroke. The investigators then followed these subjects, including 31,716 with a baseline diagnosis of AF, through the registries for 11 years, during which 130,336 patients were diagnosed with new-onset AF. The main goal was to compare 11-year stroke rates between patients with and without baseline AF based upon the number of stroke risk factors present.

The investigators cast a wide net in terms of stroke risk factors. They included epilepsy, heart failure, chronic systemic inflammatory conditions, hypertension, chronic renal disease, prior MI, diabetes, and peripheral artery disease. They also took into account venous thromboembolism, migraine, arterial embolism, carotid stenosis, and retinal vascular occlusion.

The stroke rate in subjects without baseline AF maxed out at 7.27 cases per 100 patient-years, or 7.27% annually, with five or more stroke risk factors present. Notably, the stroke rate was similar at 8.0% per year in patients with five or more baseline stroke risk factors plus AF (see graph).

ESC spokesperson Dr. Güenter Breithardt, emeritus professor of medicine at the University of Münster (Germany), said that he suspects the mechanism underlying the high stroke rate seen in patients with large numbers of stroke risk factors but no AF is that many of these individuals actually had silent AF that went unrecognized. Many of these stroke risk factors are also risk factors for development of AF, he observed.

Arguing against that hypothesis, Dr. Christiansen replied, is that each of the stroke risk factors as well as the development of AF were analyzed as time-dependent variables adjusted for age, gender, and the remaining stroke risk factors. Thus, patients with silent and unrecognized AF at baseline whose arrhythmia became symptomatic and got diagnosed during 11 years of follow-up were removed from the no-baseline-AF group for the data analysis, she said.

Dr. Harry Crijns, session cochair, summarized the central study findings as follows: "For patients who do not have a lot of accumulated risk factors, the additional presence of atrial fibrillation has a significant impact. On the other hand, in patients who have a lot of risk factors, atrial fibrillation doesn’t seem to have an impact. However, I would say searching for atrial fibrillation in such patients might differentiate a subgroup with even higher risk, although that wasn’t looked at in this study. That would be a good topic for future research."

In an interview, he said he doesn’t consider the Danish results practice changing. Patients with a large accumulation of the stroke risk factors used in the study, especially patients with established vascular disease, should already be on daily aspirin, yet at this point the Danish investigators aren’t able to say how many such patients were. However, he granted that in everyday practice today many such patients aren’t on aspirin, which is how the organizers of the ongoing, 5-year ARRIVE (Aspirin to Reduce Risk of Initial Vascular Events) trial were able to enroll roughly 12,000 high-risk patients who weren’t on aspirin to randomize them to daily aspirin or placebo.

No expert would recommend oral anticoagulant therapy for stroke prevention in patients without AF or prior stroke at this time, no matter how many stroke risk factors they have, because there are as yet no randomized trial data to support such a step. There will need to be evidence that the preventive benefit outstrips the increased bleeding risk.

"It would be marvelous if we knew how to fine-tune stroke risk, but the data are not there," added Dr. Crijns, professor and head of the department of cardiology at Maastricht (the Netherlands) University.

The study was funded by the University of Copenhagen and national research grants. None of the physicians had any financial conflicts of interest to disclose.

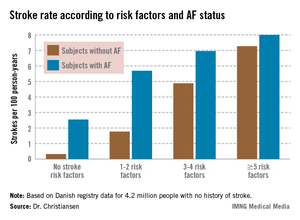

AMSTERDAM – The presence of three or more ischemic stroke risk factors in patients with no history of atrial fibrillation or stroke spells high stroke risk, comparable with that seen in patients who do have atrial fibrillation, according to a Danish national study.

Moreover, individuals with five or more stroke risk factors have essentially the same high stroke risk – roughly 8% per year – regardless of whether they have a history of atrial fibrillation (AF) or not, Dr. Christine Benn Christiansen reported at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

"The stroke risk increases with the number of risk factors. This has not been shown before in patients without prior stroke or atrial fibrillation," said Dr. Christiansen of Gentofte Hospital, Hellerup, Denmark.

"The main message here is there’s a great potential for reducing stroke risk in patients without atrial fibrillation," she added.

The impetus for the Danish national study lies in the fact that 80% of ischemic strokes occur in individuals without AF. The majority of these are first-time strokes. Yet the well-known guideline-recommended stroke-risk scores CHADS2 and CHA2DS2-VASc apply only to patients with AF.

"In patients without prior stroke, without AF, there is no systematic risk approach to deciding whether such people should receive any kind of antithrombotic medication to prevent ischemic strokes," Dr. Christiansen observed.

She and her coinvestigators analyzed comprehensive Danish national health care registries and identified 4.2 million adult Danes with no history of stroke. The investigators then followed these subjects, including 31,716 with a baseline diagnosis of AF, through the registries for 11 years, during which 130,336 patients were diagnosed with new-onset AF. The main goal was to compare 11-year stroke rates between patients with and without baseline AF based upon the number of stroke risk factors present.

The investigators cast a wide net in terms of stroke risk factors. They included epilepsy, heart failure, chronic systemic inflammatory conditions, hypertension, chronic renal disease, prior MI, diabetes, and peripheral artery disease. They also took into account venous thromboembolism, migraine, arterial embolism, carotid stenosis, and retinal vascular occlusion.

The stroke rate in subjects without baseline AF maxed out at 7.27 cases per 100 patient-years, or 7.27% annually, with five or more stroke risk factors present. Notably, the stroke rate was similar at 8.0% per year in patients with five or more baseline stroke risk factors plus AF (see graph).

ESC spokesperson Dr. Güenter Breithardt, emeritus professor of medicine at the University of Münster (Germany), said that he suspects the mechanism underlying the high stroke rate seen in patients with large numbers of stroke risk factors but no AF is that many of these individuals actually had silent AF that went unrecognized. Many of these stroke risk factors are also risk factors for development of AF, he observed.

Arguing against that hypothesis, Dr. Christiansen replied, is that each of the stroke risk factors as well as the development of AF were analyzed as time-dependent variables adjusted for age, gender, and the remaining stroke risk factors. Thus, patients with silent and unrecognized AF at baseline whose arrhythmia became symptomatic and got diagnosed during 11 years of follow-up were removed from the no-baseline-AF group for the data analysis, she said.

Dr. Harry Crijns, session cochair, summarized the central study findings as follows: "For patients who do not have a lot of accumulated risk factors, the additional presence of atrial fibrillation has a significant impact. On the other hand, in patients who have a lot of risk factors, atrial fibrillation doesn’t seem to have an impact. However, I would say searching for atrial fibrillation in such patients might differentiate a subgroup with even higher risk, although that wasn’t looked at in this study. That would be a good topic for future research."

In an interview, he said he doesn’t consider the Danish results practice changing. Patients with a large accumulation of the stroke risk factors used in the study, especially patients with established vascular disease, should already be on daily aspirin, yet at this point the Danish investigators aren’t able to say how many such patients were. However, he granted that in everyday practice today many such patients aren’t on aspirin, which is how the organizers of the ongoing, 5-year ARRIVE (Aspirin to Reduce Risk of Initial Vascular Events) trial were able to enroll roughly 12,000 high-risk patients who weren’t on aspirin to randomize them to daily aspirin or placebo.

No expert would recommend oral anticoagulant therapy for stroke prevention in patients without AF or prior stroke at this time, no matter how many stroke risk factors they have, because there are as yet no randomized trial data to support such a step. There will need to be evidence that the preventive benefit outstrips the increased bleeding risk.

"It would be marvelous if we knew how to fine-tune stroke risk, but the data are not there," added Dr. Crijns, professor and head of the department of cardiology at Maastricht (the Netherlands) University.

The study was funded by the University of Copenhagen and national research grants. None of the physicians had any financial conflicts of interest to disclose.

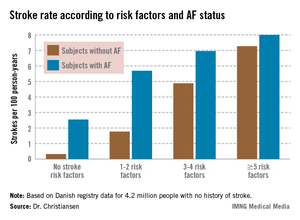

AMSTERDAM – The presence of three or more ischemic stroke risk factors in patients with no history of atrial fibrillation or stroke spells high stroke risk, comparable with that seen in patients who do have atrial fibrillation, according to a Danish national study.

Moreover, individuals with five or more stroke risk factors have essentially the same high stroke risk – roughly 8% per year – regardless of whether they have a history of atrial fibrillation (AF) or not, Dr. Christine Benn Christiansen reported at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

"The stroke risk increases with the number of risk factors. This has not been shown before in patients without prior stroke or atrial fibrillation," said Dr. Christiansen of Gentofte Hospital, Hellerup, Denmark.

"The main message here is there’s a great potential for reducing stroke risk in patients without atrial fibrillation," she added.

The impetus for the Danish national study lies in the fact that 80% of ischemic strokes occur in individuals without AF. The majority of these are first-time strokes. Yet the well-known guideline-recommended stroke-risk scores CHADS2 and CHA2DS2-VASc apply only to patients with AF.

"In patients without prior stroke, without AF, there is no systematic risk approach to deciding whether such people should receive any kind of antithrombotic medication to prevent ischemic strokes," Dr. Christiansen observed.

She and her coinvestigators analyzed comprehensive Danish national health care registries and identified 4.2 million adult Danes with no history of stroke. The investigators then followed these subjects, including 31,716 with a baseline diagnosis of AF, through the registries for 11 years, during which 130,336 patients were diagnosed with new-onset AF. The main goal was to compare 11-year stroke rates between patients with and without baseline AF based upon the number of stroke risk factors present.

The investigators cast a wide net in terms of stroke risk factors. They included epilepsy, heart failure, chronic systemic inflammatory conditions, hypertension, chronic renal disease, prior MI, diabetes, and peripheral artery disease. They also took into account venous thromboembolism, migraine, arterial embolism, carotid stenosis, and retinal vascular occlusion.

The stroke rate in subjects without baseline AF maxed out at 7.27 cases per 100 patient-years, or 7.27% annually, with five or more stroke risk factors present. Notably, the stroke rate was similar at 8.0% per year in patients with five or more baseline stroke risk factors plus AF (see graph).

ESC spokesperson Dr. Güenter Breithardt, emeritus professor of medicine at the University of Münster (Germany), said that he suspects the mechanism underlying the high stroke rate seen in patients with large numbers of stroke risk factors but no AF is that many of these individuals actually had silent AF that went unrecognized. Many of these stroke risk factors are also risk factors for development of AF, he observed.

Arguing against that hypothesis, Dr. Christiansen replied, is that each of the stroke risk factors as well as the development of AF were analyzed as time-dependent variables adjusted for age, gender, and the remaining stroke risk factors. Thus, patients with silent and unrecognized AF at baseline whose arrhythmia became symptomatic and got diagnosed during 11 years of follow-up were removed from the no-baseline-AF group for the data analysis, she said.

Dr. Harry Crijns, session cochair, summarized the central study findings as follows: "For patients who do not have a lot of accumulated risk factors, the additional presence of atrial fibrillation has a significant impact. On the other hand, in patients who have a lot of risk factors, atrial fibrillation doesn’t seem to have an impact. However, I would say searching for atrial fibrillation in such patients might differentiate a subgroup with even higher risk, although that wasn’t looked at in this study. That would be a good topic for future research."

In an interview, he said he doesn’t consider the Danish results practice changing. Patients with a large accumulation of the stroke risk factors used in the study, especially patients with established vascular disease, should already be on daily aspirin, yet at this point the Danish investigators aren’t able to say how many such patients were. However, he granted that in everyday practice today many such patients aren’t on aspirin, which is how the organizers of the ongoing, 5-year ARRIVE (Aspirin to Reduce Risk of Initial Vascular Events) trial were able to enroll roughly 12,000 high-risk patients who weren’t on aspirin to randomize them to daily aspirin or placebo.

No expert would recommend oral anticoagulant therapy for stroke prevention in patients without AF or prior stroke at this time, no matter how many stroke risk factors they have, because there are as yet no randomized trial data to support such a step. There will need to be evidence that the preventive benefit outstrips the increased bleeding risk.

"It would be marvelous if we knew how to fine-tune stroke risk, but the data are not there," added Dr. Crijns, professor and head of the department of cardiology at Maastricht (the Netherlands) University.

The study was funded by the University of Copenhagen and national research grants. None of the physicians had any financial conflicts of interest to disclose.

AT THE ESC CONGRESS 2013

Major finding: The ischemic stroke rate in patients with no history of stroke or atrial fibrillation who had five or more stroke risk factors at baseline was 7.27% annually, similar to the 8.0% rate in patients with five or more risk factors as well as atrial fibrillation.

Data source: A Danish national registry study of 4.2 million adults with no baseline history of stroke who were followed for 11 years.*

Disclosures: The study was funded by the University of Copenhagen and national research grants. The presenter reported having no financial conflicts.

* Correction, 9/24/2013: An earlier version of this story misstated the baseline history of people in the study.

RE-ALIGN reaction: Nix novel anticoagulants in mechanical valve patients

AMSTERDAM – The complete failure of the oral direct thrombin inhibitor dabigatran in the RE-ALIGN trial spells big trouble for efforts to use the novel oral factor Xa inhibitors for anticoagulation in patients with a mechanical heart valve, RE-ALIGN steering committee cochair Dr. Frans Van de Werf cautioned at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

"It would not be wise for a cardiologist to prescribe these agents for a patient with a mechanical heart valve," declared Dr. Van de Werf, professor and chairman of the department of cardiovascular medicine at the Catholic University at Leuven (Belgium).

Dabigatran (Pradaxa) is approved as a more effective and convenient alternative to warfarin for prevention of stroke and other systemic embolism in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. RE-ALIGN (the Randomized, Phase II Study to Evaluate the Safety and Pharmacokinetics of Oral Dabigatran Etexilate in Patients After Heart Valve Replacement) was an effort to expand the drug’s indications to include prevention of thromboembolic events in patients with mechanical heart valves.

The study was halted prematurely late last year when an interim analysis showed that dabigatran was both less safe and less protective than standard warfarin therapy. Shortly afterwards, the Food and Drug Administration and the European regulatory agency warned that dabigatran is contraindicated in patients with mechanical heart valves. Dr. Van de Werf’s report in Amsterdam, however, was the first presentation of the actual data.

RE-ALIGN was stopped after 252 patients with mechanical heart valves had been randomized 2:1 to dabigatran or warfarin. Dabigatran dosing was adjusted on the basis of creatinine clearance to achieve a trough plasma level of at least 50 ng/mL.

The study halt came in response to an interim analysis showing a 5% stroke rate in the dabigatran group, compared with 0% with warfarin. This was accompanied by a 4% rate of major bleeding with dabigatran, compared with 2% with warfarin, and a 27% rate of any bleeding with dabigatran versus 12% with warfarin. All dabigatran-treated patients with major bleeding had pericardial bleeding and were in the subgroup of participants who started on the direct thrombin inhibitor within 7 days post surgery.

Other unwelcome outcomes in the interim analysis included a 2% MI rate and 3% rate of valve thrombosis without symptoms in the dabigatran group, versus no such events in the warfarin arm.

"Overall, this study was clearly negative: more thrombotic events and more bleeding complications in spite of adjusting the dose of dabigatran based upon renal function," Dr. Van de Werf observed.

Simultaneous with his presentation of the RE-ALIGN findings at the ESC congress in Amsterdam, the results were published online (N. Engl. J. Med. 2013 Sept. 1 [doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1300615].

In an accompanying editorial, Dr. Elaine M. Hylek of Boston University said the most likely explanation for the disappointing results in RE-ALIGN was that blood levels of dabigatran were inadequate (N. Engl. J. Med. 2013 Sept. 1 [doi:10.1056/NEJMe1310399]).

Dr. Van de Werf, however, rejected that as unlikely. Given that there were excesses of both thromboembolic and bleeding events, other dosing regimens would surely have sent rates of one type of complication or the other even higher, he argued.

Instead, he and his coinvestigators believe that the most likely explanation for the negative results lies in the differences in the mechanisms of action of dabigatran and warfarin. Dabigatran acts near the tail end of the coagulation cascade, on thrombin. In patients with a mechanical heart valve, thrombin is generated by exposure of blood to the artificial surface of the valve leaflets, activating what is known as the contact pathway of coagulation. Thrombin also is generated by the release of tissue factor from tissues injured during the valve surgery. Warfarin acts at both the contact pathway and tissue injury levels; dabigatran doesn’t address either.

The novel oral factor Xa inhibitors don’t act at the contact pathway and tissue injury levels, either, which is why Dr. Van de Werf cautioned against their off-label use in patients with a mechanical valve.

Discussant Dr. Alec Vahanian said that he "fully agrees" with Dr. Van de Werf’s interpretation that the negative results most likely stemmed from dabigatran’s absence of efficacy on the contact pathway.

"It sounds from this study that there is no future for dabigatran with this indication. We should not give this agent to a patient with a mechanical prosthesis, and personally I would extend that further and say we should not give this agent to patients with a bioprosthesis or other high-risk patients with severe valve disease. We don’t have the evidence for that yet," said Dr. Vahanian, head of cardiology at Bichat Hospital, Paris.

Patients with a mechanical heart valve constitute a challenging population at extreme thromboembolic risk, but Dr. Vahanian offered a comforting prediction: "We are nearing the end of the era of mechanical prosthetic valves," he declared. "Patients are getting older, bioprostheses are getting better, and valve repair techniques are improving."

Dr. Harry R. Buller took issue with Dr. Van de Werf’s blanket prediction that the factor Xa inhibitors will prove similarly unsafe and ineffective in patients with mechanical valves, as was dabigatran.

"We still need to find that out. One molecule of factor Xa generates about 1,000 thrombin molecules, so inhibiting coagulation at the level of Xa might actually be effective. What you see with dabigatran is inhibition at the very last stages of the whole coagulation cascade, when there are millions and millions of molecules of thrombin. That’s quite difficult. If you do it higher up in the cascade it might work," argued Dr. Buller, chairman of the department of vascular medicine at the Academic Medical Center, Amsterdam.

"Would you take that risk?" challenged Dr. Van de Werf.

"I know there are people taking that risk. I love studies; I would study it," Dr. Buller replied.

Session cochair Dr. Keith A.A. Fox of the University of Edinburgh posed a provocative question to Dr. Van de Werf: "Would you extrapolate these RE-ALIGN data to a patient in atrial fibrillation with a bioprosthetic valve?"

"It’s a difficult question," Dr. Van de Werf replied. "In principle, you could give one of the novel anticoagulants approved for atrial fibrillation, including dabigatran, because it is assumed there is no indication for oral anticoagulation for the bioprosthetic valve. I’m not saying you necessarily should do that. If the patient is doing well on warfarin, I don’t see the need to switch to one of the new anticoagulants."

RE-ALIGN was supported by Boehringer Ingelheim. Dr. Van de Werf reported receiving research grants and speakers’ fees from the company. Dr. Buller, Dr. Fox, and Dr. Vahanian reported no relevant financial interests.

AMSTERDAM – The complete failure of the oral direct thrombin inhibitor dabigatran in the RE-ALIGN trial spells big trouble for efforts to use the novel oral factor Xa inhibitors for anticoagulation in patients with a mechanical heart valve, RE-ALIGN steering committee cochair Dr. Frans Van de Werf cautioned at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

"It would not be wise for a cardiologist to prescribe these agents for a patient with a mechanical heart valve," declared Dr. Van de Werf, professor and chairman of the department of cardiovascular medicine at the Catholic University at Leuven (Belgium).

Dabigatran (Pradaxa) is approved as a more effective and convenient alternative to warfarin for prevention of stroke and other systemic embolism in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. RE-ALIGN (the Randomized, Phase II Study to Evaluate the Safety and Pharmacokinetics of Oral Dabigatran Etexilate in Patients After Heart Valve Replacement) was an effort to expand the drug’s indications to include prevention of thromboembolic events in patients with mechanical heart valves.

The study was halted prematurely late last year when an interim analysis showed that dabigatran was both less safe and less protective than standard warfarin therapy. Shortly afterwards, the Food and Drug Administration and the European regulatory agency warned that dabigatran is contraindicated in patients with mechanical heart valves. Dr. Van de Werf’s report in Amsterdam, however, was the first presentation of the actual data.

RE-ALIGN was stopped after 252 patients with mechanical heart valves had been randomized 2:1 to dabigatran or warfarin. Dabigatran dosing was adjusted on the basis of creatinine clearance to achieve a trough plasma level of at least 50 ng/mL.

The study halt came in response to an interim analysis showing a 5% stroke rate in the dabigatran group, compared with 0% with warfarin. This was accompanied by a 4% rate of major bleeding with dabigatran, compared with 2% with warfarin, and a 27% rate of any bleeding with dabigatran versus 12% with warfarin. All dabigatran-treated patients with major bleeding had pericardial bleeding and were in the subgroup of participants who started on the direct thrombin inhibitor within 7 days post surgery.

Other unwelcome outcomes in the interim analysis included a 2% MI rate and 3% rate of valve thrombosis without symptoms in the dabigatran group, versus no such events in the warfarin arm.

"Overall, this study was clearly negative: more thrombotic events and more bleeding complications in spite of adjusting the dose of dabigatran based upon renal function," Dr. Van de Werf observed.

Simultaneous with his presentation of the RE-ALIGN findings at the ESC congress in Amsterdam, the results were published online (N. Engl. J. Med. 2013 Sept. 1 [doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1300615].

In an accompanying editorial, Dr. Elaine M. Hylek of Boston University said the most likely explanation for the disappointing results in RE-ALIGN was that blood levels of dabigatran were inadequate (N. Engl. J. Med. 2013 Sept. 1 [doi:10.1056/NEJMe1310399]).

Dr. Van de Werf, however, rejected that as unlikely. Given that there were excesses of both thromboembolic and bleeding events, other dosing regimens would surely have sent rates of one type of complication or the other even higher, he argued.