User login

European Society of Cardiology (ESC): Annual Congress

NHLBI hands off hypertension guidelines to ACC, AHA

The two U.S. groups most active in issuing guidelines and recommendations for cardiovascular disease diagnosis and management, the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association, received a surprise in June when the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute suddenly announced that it would shift to these and other "partner organizations" primary responsibility for the next updates of U.S. hypertension guidelines, national cholesterol-management guidelines, and the other cardiovascular disease–related management recommendations that the institute has had in the works.

The NHLBI launched "a collaborative relationship with the ACC, AHA, and other organizations because they said they are not in a position to endorse guidelines, they must be endorsed by other organizations," said Dr. Sidney C. Smith Jr., professor of medicine at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill. Dr. Smith is a member of the panel that’s been writing the Eighth Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC 8), and has been active for a long time in the ACC and AHA guidelines-development process.

On June 19, Dr. Gary H. Gibbons, NHLBI director, and his associates announced that effective immediately the institute was getting out of the guidelines-issuing business (Circulation 2013; doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.004587).

"Just over the past couple of months we began to look at how this will be done. Everyone wants the process to move quickly. How quickly can these organizations put it together? That’s the limiting factor right now," Dr. Smith said in an interview in early September.

While the ACC and AHA have on record some 20 sets of practice guidelines that cover most facets of cardiology, their list omits areas that the NHLBI covered in the past, notably hypertension and hypercholesterolemia assessment and management.

"The ACC and AHA guideline process is very expensive, and we wouldn’t dream of duplicating something when people you trust were commissioned by someone else [NHLBI] to do the work," said Dr. Kim Allan Williams Sr. of Wayne State University, Detroit. Dr. Williams will take the position of professor of medicine and chief of cardiovascular services at Rush University Medical Center in Chicago on Nov. 1. He serves as vice-president of the ACC. "We have all been under the impression that JNC 8 was being put together and getting published soon," he said in an interview.

Dr. Williams stressed that he and other ACC officials have pledged not to talk about the JNC 8 process until transition from the NHLBI works itself out, but he offered this succinct observation: The ACC "has made a commitment to go forward with the JNC process. There will be a publication from that panel, although it may not have that name."

Dr. Smith and Dr. Williams said that they had no relevant disclosures.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

The two U.S. groups most active in issuing guidelines and recommendations for cardiovascular disease diagnosis and management, the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association, received a surprise in June when the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute suddenly announced that it would shift to these and other "partner organizations" primary responsibility for the next updates of U.S. hypertension guidelines, national cholesterol-management guidelines, and the other cardiovascular disease–related management recommendations that the institute has had in the works.

The NHLBI launched "a collaborative relationship with the ACC, AHA, and other organizations because they said they are not in a position to endorse guidelines, they must be endorsed by other organizations," said Dr. Sidney C. Smith Jr., professor of medicine at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill. Dr. Smith is a member of the panel that’s been writing the Eighth Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC 8), and has been active for a long time in the ACC and AHA guidelines-development process.

On June 19, Dr. Gary H. Gibbons, NHLBI director, and his associates announced that effective immediately the institute was getting out of the guidelines-issuing business (Circulation 2013; doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.004587).

"Just over the past couple of months we began to look at how this will be done. Everyone wants the process to move quickly. How quickly can these organizations put it together? That’s the limiting factor right now," Dr. Smith said in an interview in early September.

While the ACC and AHA have on record some 20 sets of practice guidelines that cover most facets of cardiology, their list omits areas that the NHLBI covered in the past, notably hypertension and hypercholesterolemia assessment and management.

"The ACC and AHA guideline process is very expensive, and we wouldn’t dream of duplicating something when people you trust were commissioned by someone else [NHLBI] to do the work," said Dr. Kim Allan Williams Sr. of Wayne State University, Detroit. Dr. Williams will take the position of professor of medicine and chief of cardiovascular services at Rush University Medical Center in Chicago on Nov. 1. He serves as vice-president of the ACC. "We have all been under the impression that JNC 8 was being put together and getting published soon," he said in an interview.

Dr. Williams stressed that he and other ACC officials have pledged not to talk about the JNC 8 process until transition from the NHLBI works itself out, but he offered this succinct observation: The ACC "has made a commitment to go forward with the JNC process. There will be a publication from that panel, although it may not have that name."

Dr. Smith and Dr. Williams said that they had no relevant disclosures.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

The two U.S. groups most active in issuing guidelines and recommendations for cardiovascular disease diagnosis and management, the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association, received a surprise in June when the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute suddenly announced that it would shift to these and other "partner organizations" primary responsibility for the next updates of U.S. hypertension guidelines, national cholesterol-management guidelines, and the other cardiovascular disease–related management recommendations that the institute has had in the works.

The NHLBI launched "a collaborative relationship with the ACC, AHA, and other organizations because they said they are not in a position to endorse guidelines, they must be endorsed by other organizations," said Dr. Sidney C. Smith Jr., professor of medicine at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill. Dr. Smith is a member of the panel that’s been writing the Eighth Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC 8), and has been active for a long time in the ACC and AHA guidelines-development process.

On June 19, Dr. Gary H. Gibbons, NHLBI director, and his associates announced that effective immediately the institute was getting out of the guidelines-issuing business (Circulation 2013; doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.004587).

"Just over the past couple of months we began to look at how this will be done. Everyone wants the process to move quickly. How quickly can these organizations put it together? That’s the limiting factor right now," Dr. Smith said in an interview in early September.

While the ACC and AHA have on record some 20 sets of practice guidelines that cover most facets of cardiology, their list omits areas that the NHLBI covered in the past, notably hypertension and hypercholesterolemia assessment and management.

"The ACC and AHA guideline process is very expensive, and we wouldn’t dream of duplicating something when people you trust were commissioned by someone else [NHLBI] to do the work," said Dr. Kim Allan Williams Sr. of Wayne State University, Detroit. Dr. Williams will take the position of professor of medicine and chief of cardiovascular services at Rush University Medical Center in Chicago on Nov. 1. He serves as vice-president of the ACC. "We have all been under the impression that JNC 8 was being put together and getting published soon," he said in an interview.

Dr. Williams stressed that he and other ACC officials have pledged not to talk about the JNC 8 process until transition from the NHLBI works itself out, but he offered this succinct observation: The ACC "has made a commitment to go forward with the JNC process. There will be a publication from that panel, although it may not have that name."

Dr. Smith and Dr. Williams said that they had no relevant disclosures.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

Inherently low triglycerides may lower mortality

AMSTERDAM – People with congenitally reduced triglyceride levels had about a 20% reduced risk of all-cause death compared with people without inherently low triglyceride levels during more than 30-years follow-up of nearly 14,000 people enrolled in the Copenhagen City Heart Study.

Data from the study also showed that people with higher triglyceride (TG) levels at the time they entered the study had significantly higher all-cause mortality during more than 30 years of follow-up than did people who entered with lower TG levels, Dr. Børge G. Nordestgaard said at the European Society of Cardiology annual congress.

But the result from the genetic analysis provided even more persuasive evidence that it is time to run a large, prospective intervention trial aimed at testing the preventive efficacy of TG lowering in patients selected based on elevated TGs, he said.

The genetic analysis "took advantage of nature’s randomized trial," said Dr. Nordestgaard, professor and chief of clinical biochemistry at Copenhagen University Hospital. The genetic analysis looked at long-term survival relative to the number of TG-lowering alleles each person had in their lipoprotein lipase genes. "These data suggest a causal relationship between low TGs and improved survival. Lots of drugs are available to lower triglycerides, such as atorvastatin and rosuvastatin, but so far all the trials only focused on high LDL or low HDL cholesterol. No trial enrolled patients on the basis of high triglycerides.

"A lot of people have normal LDL levels and high TGs, and right now they are ignored," he said. "Before statins, everyone talked about high LDL and high TGs as being equal risk factors, but now TGs are completely forgotten. A big mistake has been interpreting results from the statin trials, because the participants in those studies did not enter the trials because of their TG levels."

Dr. Nordestgaard and his associates performed an analysis of the hazard ratio for all-cause death among 13,957 people enrolled in the Copenhagen study. Compared with people who entered the study with a nonfasting serum triglyceride level of 266-442 mg/dL, 8% of everyone enrolled, those with a level of 177-265 mg/dL, 17% of enrollees, had an all-cause mortality rate that was relatively reduced by 10%, a statistically significant difference. People who entered with a TG level of 89-176 mg/dL, about half of the enrollees, had their relative mortality rate cut by 25% compared with the reference group, and those who entered with a level of less than 89 mg/dL, 22% of the enrollees, had a mortality rate that ran half that of the reference group, also statistically significant differences.

To better document an effect from reduced TG levels, the investigators used data that had been collected on six different genetic alleles in the gene coding for lipoprotein lipase linked to reduced TG levels. Data on allele numbers were available for 10,208 of the study participants, and those with 0-3 of the alleles were used as the reference group. People with four, five, or six of these alleles showed progressively larger drops in TG level; those with 4 of the alleles had a level about 10% below the reference group, those with five alleles were about 20% below, and those with six alleles had a TG level that averaged 30% below the reference group.

Mortality during follow-up tracked with TG levels at baseline and the number of TG-lowering alleles. People with 4 alleles had a mortality rate 15% below the rate among those with 0-3 alleles. People with five TG-lowering alleles had a 20% cut in mortality, and those with six alleles had a 22% reduction.

Dr. Nordestgaard said that he has been a consultant to 11 drug companies, including AstraZeneca, Merck, and Pfizer.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AMSTERDAM – People with congenitally reduced triglyceride levels had about a 20% reduced risk of all-cause death compared with people without inherently low triglyceride levels during more than 30-years follow-up of nearly 14,000 people enrolled in the Copenhagen City Heart Study.

Data from the study also showed that people with higher triglyceride (TG) levels at the time they entered the study had significantly higher all-cause mortality during more than 30 years of follow-up than did people who entered with lower TG levels, Dr. Børge G. Nordestgaard said at the European Society of Cardiology annual congress.

But the result from the genetic analysis provided even more persuasive evidence that it is time to run a large, prospective intervention trial aimed at testing the preventive efficacy of TG lowering in patients selected based on elevated TGs, he said.

The genetic analysis "took advantage of nature’s randomized trial," said Dr. Nordestgaard, professor and chief of clinical biochemistry at Copenhagen University Hospital. The genetic analysis looked at long-term survival relative to the number of TG-lowering alleles each person had in their lipoprotein lipase genes. "These data suggest a causal relationship between low TGs and improved survival. Lots of drugs are available to lower triglycerides, such as atorvastatin and rosuvastatin, but so far all the trials only focused on high LDL or low HDL cholesterol. No trial enrolled patients on the basis of high triglycerides.

"A lot of people have normal LDL levels and high TGs, and right now they are ignored," he said. "Before statins, everyone talked about high LDL and high TGs as being equal risk factors, but now TGs are completely forgotten. A big mistake has been interpreting results from the statin trials, because the participants in those studies did not enter the trials because of their TG levels."

Dr. Nordestgaard and his associates performed an analysis of the hazard ratio for all-cause death among 13,957 people enrolled in the Copenhagen study. Compared with people who entered the study with a nonfasting serum triglyceride level of 266-442 mg/dL, 8% of everyone enrolled, those with a level of 177-265 mg/dL, 17% of enrollees, had an all-cause mortality rate that was relatively reduced by 10%, a statistically significant difference. People who entered with a TG level of 89-176 mg/dL, about half of the enrollees, had their relative mortality rate cut by 25% compared with the reference group, and those who entered with a level of less than 89 mg/dL, 22% of the enrollees, had a mortality rate that ran half that of the reference group, also statistically significant differences.

To better document an effect from reduced TG levels, the investigators used data that had been collected on six different genetic alleles in the gene coding for lipoprotein lipase linked to reduced TG levels. Data on allele numbers were available for 10,208 of the study participants, and those with 0-3 of the alleles were used as the reference group. People with four, five, or six of these alleles showed progressively larger drops in TG level; those with 4 of the alleles had a level about 10% below the reference group, those with five alleles were about 20% below, and those with six alleles had a TG level that averaged 30% below the reference group.

Mortality during follow-up tracked with TG levels at baseline and the number of TG-lowering alleles. People with 4 alleles had a mortality rate 15% below the rate among those with 0-3 alleles. People with five TG-lowering alleles had a 20% cut in mortality, and those with six alleles had a 22% reduction.

Dr. Nordestgaard said that he has been a consultant to 11 drug companies, including AstraZeneca, Merck, and Pfizer.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AMSTERDAM – People with congenitally reduced triglyceride levels had about a 20% reduced risk of all-cause death compared with people without inherently low triglyceride levels during more than 30-years follow-up of nearly 14,000 people enrolled in the Copenhagen City Heart Study.

Data from the study also showed that people with higher triglyceride (TG) levels at the time they entered the study had significantly higher all-cause mortality during more than 30 years of follow-up than did people who entered with lower TG levels, Dr. Børge G. Nordestgaard said at the European Society of Cardiology annual congress.

But the result from the genetic analysis provided even more persuasive evidence that it is time to run a large, prospective intervention trial aimed at testing the preventive efficacy of TG lowering in patients selected based on elevated TGs, he said.

The genetic analysis "took advantage of nature’s randomized trial," said Dr. Nordestgaard, professor and chief of clinical biochemistry at Copenhagen University Hospital. The genetic analysis looked at long-term survival relative to the number of TG-lowering alleles each person had in their lipoprotein lipase genes. "These data suggest a causal relationship between low TGs and improved survival. Lots of drugs are available to lower triglycerides, such as atorvastatin and rosuvastatin, but so far all the trials only focused on high LDL or low HDL cholesterol. No trial enrolled patients on the basis of high triglycerides.

"A lot of people have normal LDL levels and high TGs, and right now they are ignored," he said. "Before statins, everyone talked about high LDL and high TGs as being equal risk factors, but now TGs are completely forgotten. A big mistake has been interpreting results from the statin trials, because the participants in those studies did not enter the trials because of their TG levels."

Dr. Nordestgaard and his associates performed an analysis of the hazard ratio for all-cause death among 13,957 people enrolled in the Copenhagen study. Compared with people who entered the study with a nonfasting serum triglyceride level of 266-442 mg/dL, 8% of everyone enrolled, those with a level of 177-265 mg/dL, 17% of enrollees, had an all-cause mortality rate that was relatively reduced by 10%, a statistically significant difference. People who entered with a TG level of 89-176 mg/dL, about half of the enrollees, had their relative mortality rate cut by 25% compared with the reference group, and those who entered with a level of less than 89 mg/dL, 22% of the enrollees, had a mortality rate that ran half that of the reference group, also statistically significant differences.

To better document an effect from reduced TG levels, the investigators used data that had been collected on six different genetic alleles in the gene coding for lipoprotein lipase linked to reduced TG levels. Data on allele numbers were available for 10,208 of the study participants, and those with 0-3 of the alleles were used as the reference group. People with four, five, or six of these alleles showed progressively larger drops in TG level; those with 4 of the alleles had a level about 10% below the reference group, those with five alleles were about 20% below, and those with six alleles had a TG level that averaged 30% below the reference group.

Mortality during follow-up tracked with TG levels at baseline and the number of TG-lowering alleles. People with 4 alleles had a mortality rate 15% below the rate among those with 0-3 alleles. People with five TG-lowering alleles had a 20% cut in mortality, and those with six alleles had a 22% reduction.

Dr. Nordestgaard said that he has been a consultant to 11 drug companies, including AstraZeneca, Merck, and Pfizer.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AT THE ESC CONGRESS 2013

Major finding:. People with five triglyceride-lowering alleles had 20% fewer long-term deaths compared with those who carried 0-3 alleles.

Data source: The Copenhagen City Heart Study, which enrolled 13,957 people in 1976-1978 and followed them for more than 30 years.

Disclosures: Dr. Nordestgaard said that he has been a consultant to 11 drug companies, including AstraZeneca, Merck, and Pfizer.

Study hints at obesity paradox in older women with coronary artery disease

AMSTERDAM – Older women with coronary artery disease who lost weight had an increased risk of death regardless of their body mass index, a finding that hints at the presence of an obesity paradox in this population, according to a registry-based retrospective study.

The unpublished abstract, which was presented at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology, also showed that, among patients who maintained their weight, underweight women had a twofold increase in risk of all-cause mortality while obese and overweight women had a nonsignificant but reduced risk of death, compared with normal-weight patients.

Although studies have shown that obesity is a risk factor for developing cardiovascular disease, and guidelines recommend weight loss for patients who are overweight and obese, the study’s key message is that advising weight loss to patients with heart disease is not so simple and straightforward, said Dr. Diethelm Tschoepe of Ruhr University in Bochum, Germany, who commented on the study.

Researchers analyzed data for 1,685 women with an average age of 64 years who were diagnosed with coronary artery disease (CAD) based on angiography between 2005 and 2011.

They stratified the cohort into three weight-change groups: no change (gain or loss of less than 2 kg/year), weight loss (loss of more than 2 kg/year), and weight gain (gain of more than 2 kg/year.)

Each group was then divided into four weight classes based on body mass index: underweight (BMI less than 20 kg/m2), normal weight (BMI 20-24.9 kg/m2), overweight (BMI 25-29.9 kg/m2), and obese (BMI more than 30 kg/m2).

The normal-weight group was used as reference to calculate the hazard ratios. Data were adjusted for age, smoking, diabetes, previous heart surgery, use of statins and antihypertensive drugs, degree of CAD, and previous percutaneous coronary intervention.

When comparing the BMI in weight-change groups, women who were underweight and maintained their weight had a twofold increase in death (hazard ratio, 2.15; P = .03), compared with normal-weight women. Also, when these women lost weight, their risk was increased by almost twofold, although it didn’t reach statistical significance.

Among the different BMI groups, obese women who lost weight had an eightfold increase in the risk of all-cause mortality, and obese women who gained weight had a more than fourfold risk increase, compared with obese women who maintained their weight.

Meanwhile, overweight and normal-weight women who lost weight had sixfold and threefold increases in risk of death, respectively, compared with their stable-weight counterparts.

Dr. Aziza Azimi of Gentofte Hospital, Copenhagen, who presented the study, said that the findings highlight the importance of individual-based weight management.

Researchers said that, since the study subjects had comorbidities, their weight management should be handled differently from the general population. They added that, because of the retrospective design of the study, it’s not clear why the women lost weight, although, given their condition, it was most probably unintentional and due to comorbidities or medications.

Dr. Azimi and Dr. Tschoepe had no disclosures.

On Twitter @NaseemSMiller

AMSTERDAM – Older women with coronary artery disease who lost weight had an increased risk of death regardless of their body mass index, a finding that hints at the presence of an obesity paradox in this population, according to a registry-based retrospective study.

The unpublished abstract, which was presented at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology, also showed that, among patients who maintained their weight, underweight women had a twofold increase in risk of all-cause mortality while obese and overweight women had a nonsignificant but reduced risk of death, compared with normal-weight patients.

Although studies have shown that obesity is a risk factor for developing cardiovascular disease, and guidelines recommend weight loss for patients who are overweight and obese, the study’s key message is that advising weight loss to patients with heart disease is not so simple and straightforward, said Dr. Diethelm Tschoepe of Ruhr University in Bochum, Germany, who commented on the study.

Researchers analyzed data for 1,685 women with an average age of 64 years who were diagnosed with coronary artery disease (CAD) based on angiography between 2005 and 2011.

They stratified the cohort into three weight-change groups: no change (gain or loss of less than 2 kg/year), weight loss (loss of more than 2 kg/year), and weight gain (gain of more than 2 kg/year.)

Each group was then divided into four weight classes based on body mass index: underweight (BMI less than 20 kg/m2), normal weight (BMI 20-24.9 kg/m2), overweight (BMI 25-29.9 kg/m2), and obese (BMI more than 30 kg/m2).

The normal-weight group was used as reference to calculate the hazard ratios. Data were adjusted for age, smoking, diabetes, previous heart surgery, use of statins and antihypertensive drugs, degree of CAD, and previous percutaneous coronary intervention.

When comparing the BMI in weight-change groups, women who were underweight and maintained their weight had a twofold increase in death (hazard ratio, 2.15; P = .03), compared with normal-weight women. Also, when these women lost weight, their risk was increased by almost twofold, although it didn’t reach statistical significance.

Among the different BMI groups, obese women who lost weight had an eightfold increase in the risk of all-cause mortality, and obese women who gained weight had a more than fourfold risk increase, compared with obese women who maintained their weight.

Meanwhile, overweight and normal-weight women who lost weight had sixfold and threefold increases in risk of death, respectively, compared with their stable-weight counterparts.

Dr. Aziza Azimi of Gentofte Hospital, Copenhagen, who presented the study, said that the findings highlight the importance of individual-based weight management.

Researchers said that, since the study subjects had comorbidities, their weight management should be handled differently from the general population. They added that, because of the retrospective design of the study, it’s not clear why the women lost weight, although, given their condition, it was most probably unintentional and due to comorbidities or medications.

Dr. Azimi and Dr. Tschoepe had no disclosures.

On Twitter @NaseemSMiller

AMSTERDAM – Older women with coronary artery disease who lost weight had an increased risk of death regardless of their body mass index, a finding that hints at the presence of an obesity paradox in this population, according to a registry-based retrospective study.

The unpublished abstract, which was presented at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology, also showed that, among patients who maintained their weight, underweight women had a twofold increase in risk of all-cause mortality while obese and overweight women had a nonsignificant but reduced risk of death, compared with normal-weight patients.

Although studies have shown that obesity is a risk factor for developing cardiovascular disease, and guidelines recommend weight loss for patients who are overweight and obese, the study’s key message is that advising weight loss to patients with heart disease is not so simple and straightforward, said Dr. Diethelm Tschoepe of Ruhr University in Bochum, Germany, who commented on the study.

Researchers analyzed data for 1,685 women with an average age of 64 years who were diagnosed with coronary artery disease (CAD) based on angiography between 2005 and 2011.

They stratified the cohort into three weight-change groups: no change (gain or loss of less than 2 kg/year), weight loss (loss of more than 2 kg/year), and weight gain (gain of more than 2 kg/year.)

Each group was then divided into four weight classes based on body mass index: underweight (BMI less than 20 kg/m2), normal weight (BMI 20-24.9 kg/m2), overweight (BMI 25-29.9 kg/m2), and obese (BMI more than 30 kg/m2).

The normal-weight group was used as reference to calculate the hazard ratios. Data were adjusted for age, smoking, diabetes, previous heart surgery, use of statins and antihypertensive drugs, degree of CAD, and previous percutaneous coronary intervention.

When comparing the BMI in weight-change groups, women who were underweight and maintained their weight had a twofold increase in death (hazard ratio, 2.15; P = .03), compared with normal-weight women. Also, when these women lost weight, their risk was increased by almost twofold, although it didn’t reach statistical significance.

Among the different BMI groups, obese women who lost weight had an eightfold increase in the risk of all-cause mortality, and obese women who gained weight had a more than fourfold risk increase, compared with obese women who maintained their weight.

Meanwhile, overweight and normal-weight women who lost weight had sixfold and threefold increases in risk of death, respectively, compared with their stable-weight counterparts.

Dr. Aziza Azimi of Gentofte Hospital, Copenhagen, who presented the study, said that the findings highlight the importance of individual-based weight management.

Researchers said that, since the study subjects had comorbidities, their weight management should be handled differently from the general population. They added that, because of the retrospective design of the study, it’s not clear why the women lost weight, although, given their condition, it was most probably unintentional and due to comorbidities or medications.

Dr. Azimi and Dr. Tschoepe had no disclosures.

On Twitter @NaseemSMiller

ESC CONGRESS 2013

Major finding: Women who were underweight and maintained their weight had a significant, 2.15-fold increase in mortality, compared with normal-weight women.

Data source: Danish registry data on 1,685 women with an average age of 64 years, diagnosed with CAD between 2005 and 2011.

Disclosures: Dr. Azimi and Dr. Tschoepe had no disclosures.

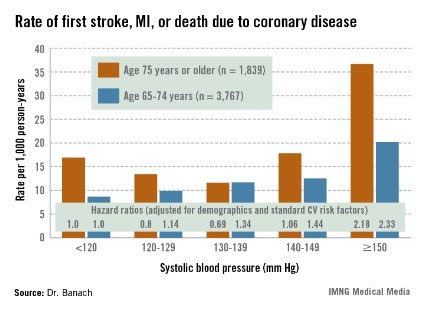

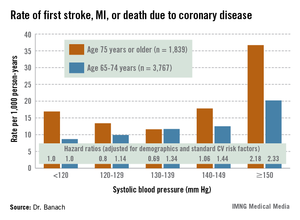

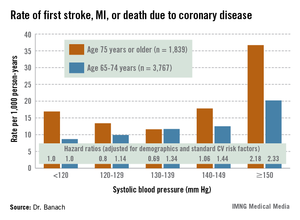

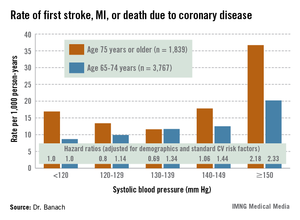

REGARDS study suggests optimal elderly SBP of 120-139 mm Hg

AMSTERDAM – The optimal level of systolic blood pressure in all patients above age 55 appears to be 120-139 mm Hg, according to controversial data from a large, observational, U.S. population–based cohort study.

Results from the REGARDS (Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke) study suggest that a systolic blood pressure (SBP) in that range is associated with the lowest rates of cardiovascular events, stroke, and all-cause mortality, even in individuals aged 75 years and up. Since REGARDS is an observational study, this proposed target SBP range should be viewed as a testable hypothesis worthy of confirmation in a large, randomized, antihypertensive treatment study in the elderly, Dr. Maciej Banach said at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC).

REGARDS also turned up evidence supportive of the existence of the long-controversial J-curve, with an increased rate of adverse events noted in subjects with an SBP below 120 mm Hg, added Dr. Banach, professor and head of the department of hypertension at the Medical University of Lodz (Poland).

But discussant Christi Deaton, Ph.D., was quick to slam on the brakes in response to Dr. Banach’s suggestion that 120-139 mm Hg looks like the new optimal in older patients. She noted that the REGARDS proposal is at odds with the latest ESC hypertension guidelines, issued just a couple of months ago.

The evidence-based ESC guidelines (J. Hypertens. 2013;31:1281-357) offer as a class I recommendation an SBP target of 140-150 mm Hg for elderly patients under age 80, with consideration of a target below 140 mm Hg for the subgroup of elderly patients who are fit, noted Dr. Deaton, professor of nursing at the University of Manchester (U.K.), and a member of the ESC Guidelines Committee.

The American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines, in contrast, recommend a target of less than 140/90 in 65- to 79-year-olds, and an SBP of 140-145 mm Hg, if tolerated, in those aged 80 years and up (Circulation 2011;123:2434-506).

"The hypothesis from this REGARDS analysis is a bold one," she observed. "But we need large, well-designed intervention trials in older patients, particularly in underrepresented groups, before we can set lower blood pressure targets than are currently recommended in our guidelines."

The REGARDS study is a National Institutes of Health–sponsored observational study of 30,329 U.S. subjects aged 45 years or older, with overrepresentation of blacks and residents of the nation’s southeastern "stroke belt." Dr. Banach presented an analysis of 13,948 REGARDS participants aged 55 years or older who were taking antihypertensive medications at baseline. They have thus far been followed for a median of 6 years for all-cause mortality, and slightly less for first occurrence of stroke or coronary heart disease.

The suggestion of a J-curve was strongest for the composite endpoint of a first stroke, nonfatal myocardial infarction (MI), or death due to coronary heart disease in subjects aged 75 years or older (see graphic). There was no significant relationship between stroke and SBP category for subjects under age 75; however, over age 75, stroke rates were highest in those with an SBP less than 120 or more than 150 mm Hg.

All-cause mortality showed a linear relationship with increasing SBP in subjects aged 55-74 years, but no relationship in those over age 75.

Dr. Deaton applauded the REGARDS investigators for focusing on a high-risk population that’s "certainly underrepresented in our clinical intervention trials," but she cited several major study limitations. One is that only baseline blood pressure measurements were available.

"Importantly," she observed, "we don’t know what happened to blood pressure control during these years of follow-up."

In addition, the incidence rates of stroke, MI, and other major adverse events were relatively low in some subgroups. The planned further follow-up in REGARDS should bring greater clarity, Dr. Deaton added.

Dr. Banach and Dr. Deaton reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

AMSTERDAM – The optimal level of systolic blood pressure in all patients above age 55 appears to be 120-139 mm Hg, according to controversial data from a large, observational, U.S. population–based cohort study.

Results from the REGARDS (Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke) study suggest that a systolic blood pressure (SBP) in that range is associated with the lowest rates of cardiovascular events, stroke, and all-cause mortality, even in individuals aged 75 years and up. Since REGARDS is an observational study, this proposed target SBP range should be viewed as a testable hypothesis worthy of confirmation in a large, randomized, antihypertensive treatment study in the elderly, Dr. Maciej Banach said at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC).

REGARDS also turned up evidence supportive of the existence of the long-controversial J-curve, with an increased rate of adverse events noted in subjects with an SBP below 120 mm Hg, added Dr. Banach, professor and head of the department of hypertension at the Medical University of Lodz (Poland).

But discussant Christi Deaton, Ph.D., was quick to slam on the brakes in response to Dr. Banach’s suggestion that 120-139 mm Hg looks like the new optimal in older patients. She noted that the REGARDS proposal is at odds with the latest ESC hypertension guidelines, issued just a couple of months ago.

The evidence-based ESC guidelines (J. Hypertens. 2013;31:1281-357) offer as a class I recommendation an SBP target of 140-150 mm Hg for elderly patients under age 80, with consideration of a target below 140 mm Hg for the subgroup of elderly patients who are fit, noted Dr. Deaton, professor of nursing at the University of Manchester (U.K.), and a member of the ESC Guidelines Committee.

The American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines, in contrast, recommend a target of less than 140/90 in 65- to 79-year-olds, and an SBP of 140-145 mm Hg, if tolerated, in those aged 80 years and up (Circulation 2011;123:2434-506).

"The hypothesis from this REGARDS analysis is a bold one," she observed. "But we need large, well-designed intervention trials in older patients, particularly in underrepresented groups, before we can set lower blood pressure targets than are currently recommended in our guidelines."

The REGARDS study is a National Institutes of Health–sponsored observational study of 30,329 U.S. subjects aged 45 years or older, with overrepresentation of blacks and residents of the nation’s southeastern "stroke belt." Dr. Banach presented an analysis of 13,948 REGARDS participants aged 55 years or older who were taking antihypertensive medications at baseline. They have thus far been followed for a median of 6 years for all-cause mortality, and slightly less for first occurrence of stroke or coronary heart disease.

The suggestion of a J-curve was strongest for the composite endpoint of a first stroke, nonfatal myocardial infarction (MI), or death due to coronary heart disease in subjects aged 75 years or older (see graphic). There was no significant relationship between stroke and SBP category for subjects under age 75; however, over age 75, stroke rates were highest in those with an SBP less than 120 or more than 150 mm Hg.

All-cause mortality showed a linear relationship with increasing SBP in subjects aged 55-74 years, but no relationship in those over age 75.

Dr. Deaton applauded the REGARDS investigators for focusing on a high-risk population that’s "certainly underrepresented in our clinical intervention trials," but she cited several major study limitations. One is that only baseline blood pressure measurements were available.

"Importantly," she observed, "we don’t know what happened to blood pressure control during these years of follow-up."

In addition, the incidence rates of stroke, MI, and other major adverse events were relatively low in some subgroups. The planned further follow-up in REGARDS should bring greater clarity, Dr. Deaton added.

Dr. Banach and Dr. Deaton reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

AMSTERDAM – The optimal level of systolic blood pressure in all patients above age 55 appears to be 120-139 mm Hg, according to controversial data from a large, observational, U.S. population–based cohort study.

Results from the REGARDS (Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke) study suggest that a systolic blood pressure (SBP) in that range is associated with the lowest rates of cardiovascular events, stroke, and all-cause mortality, even in individuals aged 75 years and up. Since REGARDS is an observational study, this proposed target SBP range should be viewed as a testable hypothesis worthy of confirmation in a large, randomized, antihypertensive treatment study in the elderly, Dr. Maciej Banach said at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC).

REGARDS also turned up evidence supportive of the existence of the long-controversial J-curve, with an increased rate of adverse events noted in subjects with an SBP below 120 mm Hg, added Dr. Banach, professor and head of the department of hypertension at the Medical University of Lodz (Poland).

But discussant Christi Deaton, Ph.D., was quick to slam on the brakes in response to Dr. Banach’s suggestion that 120-139 mm Hg looks like the new optimal in older patients. She noted that the REGARDS proposal is at odds with the latest ESC hypertension guidelines, issued just a couple of months ago.

The evidence-based ESC guidelines (J. Hypertens. 2013;31:1281-357) offer as a class I recommendation an SBP target of 140-150 mm Hg for elderly patients under age 80, with consideration of a target below 140 mm Hg for the subgroup of elderly patients who are fit, noted Dr. Deaton, professor of nursing at the University of Manchester (U.K.), and a member of the ESC Guidelines Committee.

The American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines, in contrast, recommend a target of less than 140/90 in 65- to 79-year-olds, and an SBP of 140-145 mm Hg, if tolerated, in those aged 80 years and up (Circulation 2011;123:2434-506).

"The hypothesis from this REGARDS analysis is a bold one," she observed. "But we need large, well-designed intervention trials in older patients, particularly in underrepresented groups, before we can set lower blood pressure targets than are currently recommended in our guidelines."

The REGARDS study is a National Institutes of Health–sponsored observational study of 30,329 U.S. subjects aged 45 years or older, with overrepresentation of blacks and residents of the nation’s southeastern "stroke belt." Dr. Banach presented an analysis of 13,948 REGARDS participants aged 55 years or older who were taking antihypertensive medications at baseline. They have thus far been followed for a median of 6 years for all-cause mortality, and slightly less for first occurrence of stroke or coronary heart disease.

The suggestion of a J-curve was strongest for the composite endpoint of a first stroke, nonfatal myocardial infarction (MI), or death due to coronary heart disease in subjects aged 75 years or older (see graphic). There was no significant relationship between stroke and SBP category for subjects under age 75; however, over age 75, stroke rates were highest in those with an SBP less than 120 or more than 150 mm Hg.

All-cause mortality showed a linear relationship with increasing SBP in subjects aged 55-74 years, but no relationship in those over age 75.

Dr. Deaton applauded the REGARDS investigators for focusing on a high-risk population that’s "certainly underrepresented in our clinical intervention trials," but she cited several major study limitations. One is that only baseline blood pressure measurements were available.

"Importantly," she observed, "we don’t know what happened to blood pressure control during these years of follow-up."

In addition, the incidence rates of stroke, MI, and other major adverse events were relatively low in some subgroups. The planned further follow-up in REGARDS should bring greater clarity, Dr. Deaton added.

Dr. Banach and Dr. Deaton reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

AT THE ESC CONGRESS 2013

Major finding: The adjusted risk of a first stroke, MI, or cardiovascular death in individuals aged 75 years or older on antihypertensive therapy was 20% lower in those with a systolic blood pressure of 120-129 mm Hg than in those with an SBP less than 120, and 31% lower in those with an SBP of 130-139 mm Hg. In contrast, the risk was 2.2-fold greater in those with an SBP of 150 mm Hg or more than in subjects with an SBP below 120 mm Hg.

Data source: This was a secondary analysis involving nearly 14,000 participants in the prospective observational REGARDS study, all at least 55 years old and on antihypertensive medication at baseline.

Disclosures: Dr. Banach and Dr. Deaton reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

TAVR shows large survival benefit in diabetes patients

AMSTERDAM – Transcatheter aortic valve replacement produced dramatically better 1-year survival, compared with surgical valve replacement, among high-risk patients with diabetes in a new, post hoc analysis of data collected in the first PARTNER trial.

The 145 patients with any type of diabetes who underwent transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) in the operable, cohort A of the first Placement of Aortic Transcatheter Valves (PARTNER) trial had an 18% all-cause mortality rate during 1-year follow-up, compared with a 27% rate among the 130 patients who underwent surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR), a difference in this post hoc analysis that reached statistical significance.

The finding of a 9-percentage-point difference in mortality in the diabetic subgroup treated with TAVR, a 40% relative risk reduction compared with SAVR, contrasts with the overall, primary finding of the PARTNER I cohort A trial, which showed that TAVR and SAVR produced similar mortality rates in high surgical-risk patients after 1 year (N. Engl. J. Med. 2011;364:2187-98).

TAVR use in patients with diabetes also resulted in a statistically significant reduction in the 1-year incidence of renal failure requiring dialysis, a 4% rate compared with an 11% among the SAVR patients, Dr. Brian R. Lindman reported at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology. This also contrasted with the overall PARTNER results when patients without diabetes were included, which showed no difference in renal outcomes between TAVR and SAVR.

The results "raise the possibility that TAVR may be the preferred approach for patients with diabetes," said Dr. Lindman. But he cautioned that because this was a post hoc analysis, the results need confirmation in a prospective study.

Despite this caveat, Dr. Lindman said that the finding can’t be completely ignored when treatment options are discussed with patients who have severe aortic stenosis. "Going forward, I think this is something we’ll need to think about, and we might lean more toward TAVR for patients with diabetes. But we’d like to see some confirmatory evidence in the PARTNER II cohort A trial," he said in an interview. Investigators from the PARTNER II trial, which is randomizing patients with moderate surgical risk, have said that the cohort A results are expected in 2015.

"Although hypothesis-generating only, this result is good news for patients with diabetes," said Dr. William Wijns, codirector of the cardiovascular center at O.L.V. Hospital in Aalst, Belgium.

Dr. Lindman also cautioned that investigators collected limited data on patients’ diabetes status in PARTNER I. The data did not include information on diabetes type, hemoglobin A1c or blood glucose levels, or treatment received. He also acknowledged that the 42% prevalence of diabetes in the study cohort was unexpectedly high, but noted that if this meant that some patients with a questionable diabetes diagnosis entered the analysis, this should have diminished the mortality difference between TAVR and SAVR.

The 275 patients with diabetes in PARTNER I cohort A averaged 82 years of age, and just over a third were women. The subgroups of patients with diabetes randomized to TAVR and to SAVR showed no significant differences for any physiologic or cardiovascular measure or in the prevalence of various comorbidities.

The analysis also showed a statistically significant reduced rate of 1-year mortality in the subgroup treated with transfemoral TAVR compared with SAVR, and in the subgroup of patients with diabetes treated with transapical TAVR compared with SAVR. The 1-year rate of stroke was an identical 3.5% in the patients with diabetes treated with TAVR and in those treated with SAVR. Patients treated with SAVR had a higher incidence of a major bleeding event during follow-up compared with the TAVR patients, while the TAVR patients had a significantly higher rate of major vascular complications during follow-up. Both findings were consistent with the overall PARTNER I cohort A results, said Dr. Lindman, a cardiologist at Washington University in St. Louis.

The diabetes patients who underwent TAVR showed their striking reduction in 1-year mortality despite having the same problem with postprocedural aortic regurgitation as seen in the overall PARTNER I trial. At 6 months after treatment, 9% of the TAVR patients had moderate or severe aortic regurgitation, and 54% had mild regurgitation, compared with rates of 1% moderate or severe and 6% mild in the SAVR patients.

Dr. Lindman speculated that increased inflammation and oxidative stress in patients with diabetes may interact with the stresses of heart surgery to produce the excess mortality seen after SAVR in patients with diabetes. Results from prior studies had documented worsened survival in patients with diabetes who undergo heart surgery, he said.

The PARTNER trial was sponsored by Edwards Lifesciences, which markets the TAVR device used in the study. Dr. Lindman was an investigator in PARTNER and said that he had no disclosures.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AMSTERDAM – Transcatheter aortic valve replacement produced dramatically better 1-year survival, compared with surgical valve replacement, among high-risk patients with diabetes in a new, post hoc analysis of data collected in the first PARTNER trial.

The 145 patients with any type of diabetes who underwent transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) in the operable, cohort A of the first Placement of Aortic Transcatheter Valves (PARTNER) trial had an 18% all-cause mortality rate during 1-year follow-up, compared with a 27% rate among the 130 patients who underwent surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR), a difference in this post hoc analysis that reached statistical significance.

The finding of a 9-percentage-point difference in mortality in the diabetic subgroup treated with TAVR, a 40% relative risk reduction compared with SAVR, contrasts with the overall, primary finding of the PARTNER I cohort A trial, which showed that TAVR and SAVR produced similar mortality rates in high surgical-risk patients after 1 year (N. Engl. J. Med. 2011;364:2187-98).

TAVR use in patients with diabetes also resulted in a statistically significant reduction in the 1-year incidence of renal failure requiring dialysis, a 4% rate compared with an 11% among the SAVR patients, Dr. Brian R. Lindman reported at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology. This also contrasted with the overall PARTNER results when patients without diabetes were included, which showed no difference in renal outcomes between TAVR and SAVR.

The results "raise the possibility that TAVR may be the preferred approach for patients with diabetes," said Dr. Lindman. But he cautioned that because this was a post hoc analysis, the results need confirmation in a prospective study.

Despite this caveat, Dr. Lindman said that the finding can’t be completely ignored when treatment options are discussed with patients who have severe aortic stenosis. "Going forward, I think this is something we’ll need to think about, and we might lean more toward TAVR for patients with diabetes. But we’d like to see some confirmatory evidence in the PARTNER II cohort A trial," he said in an interview. Investigators from the PARTNER II trial, which is randomizing patients with moderate surgical risk, have said that the cohort A results are expected in 2015.

"Although hypothesis-generating only, this result is good news for patients with diabetes," said Dr. William Wijns, codirector of the cardiovascular center at O.L.V. Hospital in Aalst, Belgium.

Dr. Lindman also cautioned that investigators collected limited data on patients’ diabetes status in PARTNER I. The data did not include information on diabetes type, hemoglobin A1c or blood glucose levels, or treatment received. He also acknowledged that the 42% prevalence of diabetes in the study cohort was unexpectedly high, but noted that if this meant that some patients with a questionable diabetes diagnosis entered the analysis, this should have diminished the mortality difference between TAVR and SAVR.

The 275 patients with diabetes in PARTNER I cohort A averaged 82 years of age, and just over a third were women. The subgroups of patients with diabetes randomized to TAVR and to SAVR showed no significant differences for any physiologic or cardiovascular measure or in the prevalence of various comorbidities.

The analysis also showed a statistically significant reduced rate of 1-year mortality in the subgroup treated with transfemoral TAVR compared with SAVR, and in the subgroup of patients with diabetes treated with transapical TAVR compared with SAVR. The 1-year rate of stroke was an identical 3.5% in the patients with diabetes treated with TAVR and in those treated with SAVR. Patients treated with SAVR had a higher incidence of a major bleeding event during follow-up compared with the TAVR patients, while the TAVR patients had a significantly higher rate of major vascular complications during follow-up. Both findings were consistent with the overall PARTNER I cohort A results, said Dr. Lindman, a cardiologist at Washington University in St. Louis.

The diabetes patients who underwent TAVR showed their striking reduction in 1-year mortality despite having the same problem with postprocedural aortic regurgitation as seen in the overall PARTNER I trial. At 6 months after treatment, 9% of the TAVR patients had moderate or severe aortic regurgitation, and 54% had mild regurgitation, compared with rates of 1% moderate or severe and 6% mild in the SAVR patients.

Dr. Lindman speculated that increased inflammation and oxidative stress in patients with diabetes may interact with the stresses of heart surgery to produce the excess mortality seen after SAVR in patients with diabetes. Results from prior studies had documented worsened survival in patients with diabetes who undergo heart surgery, he said.

The PARTNER trial was sponsored by Edwards Lifesciences, which markets the TAVR device used in the study. Dr. Lindman was an investigator in PARTNER and said that he had no disclosures.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AMSTERDAM – Transcatheter aortic valve replacement produced dramatically better 1-year survival, compared with surgical valve replacement, among high-risk patients with diabetes in a new, post hoc analysis of data collected in the first PARTNER trial.

The 145 patients with any type of diabetes who underwent transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) in the operable, cohort A of the first Placement of Aortic Transcatheter Valves (PARTNER) trial had an 18% all-cause mortality rate during 1-year follow-up, compared with a 27% rate among the 130 patients who underwent surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR), a difference in this post hoc analysis that reached statistical significance.

The finding of a 9-percentage-point difference in mortality in the diabetic subgroup treated with TAVR, a 40% relative risk reduction compared with SAVR, contrasts with the overall, primary finding of the PARTNER I cohort A trial, which showed that TAVR and SAVR produced similar mortality rates in high surgical-risk patients after 1 year (N. Engl. J. Med. 2011;364:2187-98).

TAVR use in patients with diabetes also resulted in a statistically significant reduction in the 1-year incidence of renal failure requiring dialysis, a 4% rate compared with an 11% among the SAVR patients, Dr. Brian R. Lindman reported at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology. This also contrasted with the overall PARTNER results when patients without diabetes were included, which showed no difference in renal outcomes between TAVR and SAVR.

The results "raise the possibility that TAVR may be the preferred approach for patients with diabetes," said Dr. Lindman. But he cautioned that because this was a post hoc analysis, the results need confirmation in a prospective study.

Despite this caveat, Dr. Lindman said that the finding can’t be completely ignored when treatment options are discussed with patients who have severe aortic stenosis. "Going forward, I think this is something we’ll need to think about, and we might lean more toward TAVR for patients with diabetes. But we’d like to see some confirmatory evidence in the PARTNER II cohort A trial," he said in an interview. Investigators from the PARTNER II trial, which is randomizing patients with moderate surgical risk, have said that the cohort A results are expected in 2015.

"Although hypothesis-generating only, this result is good news for patients with diabetes," said Dr. William Wijns, codirector of the cardiovascular center at O.L.V. Hospital in Aalst, Belgium.

Dr. Lindman also cautioned that investigators collected limited data on patients’ diabetes status in PARTNER I. The data did not include information on diabetes type, hemoglobin A1c or blood glucose levels, or treatment received. He also acknowledged that the 42% prevalence of diabetes in the study cohort was unexpectedly high, but noted that if this meant that some patients with a questionable diabetes diagnosis entered the analysis, this should have diminished the mortality difference between TAVR and SAVR.

The 275 patients with diabetes in PARTNER I cohort A averaged 82 years of age, and just over a third were women. The subgroups of patients with diabetes randomized to TAVR and to SAVR showed no significant differences for any physiologic or cardiovascular measure or in the prevalence of various comorbidities.

The analysis also showed a statistically significant reduced rate of 1-year mortality in the subgroup treated with transfemoral TAVR compared with SAVR, and in the subgroup of patients with diabetes treated with transapical TAVR compared with SAVR. The 1-year rate of stroke was an identical 3.5% in the patients with diabetes treated with TAVR and in those treated with SAVR. Patients treated with SAVR had a higher incidence of a major bleeding event during follow-up compared with the TAVR patients, while the TAVR patients had a significantly higher rate of major vascular complications during follow-up. Both findings were consistent with the overall PARTNER I cohort A results, said Dr. Lindman, a cardiologist at Washington University in St. Louis.

The diabetes patients who underwent TAVR showed their striking reduction in 1-year mortality despite having the same problem with postprocedural aortic regurgitation as seen in the overall PARTNER I trial. At 6 months after treatment, 9% of the TAVR patients had moderate or severe aortic regurgitation, and 54% had mild regurgitation, compared with rates of 1% moderate or severe and 6% mild in the SAVR patients.

Dr. Lindman speculated that increased inflammation and oxidative stress in patients with diabetes may interact with the stresses of heart surgery to produce the excess mortality seen after SAVR in patients with diabetes. Results from prior studies had documented worsened survival in patients with diabetes who undergo heart surgery, he said.

The PARTNER trial was sponsored by Edwards Lifesciences, which markets the TAVR device used in the study. Dr. Lindman was an investigator in PARTNER and said that he had no disclosures.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AT THE ESC CONGRESS 2013

Major finding: In patients with diabetes, 1-year mortality was 18% after TAVR and 27% after SAVR in a post hoc analysis.

Data source: The PARTNER I cohort A study, which enrolled 699 high-risk patients with severe aortic stenosis to treatment with aortic valve replacement by the transcatheter or surgical approach, including 275 patients with diabetes.

Disclosures: The trial was sponsored by Edwards Lifesciences, which markets the TAVR device used in the study. Dr. Lindman was an investigator in PARTNER, and said that he had no disclosures.

Full-dose beta-blockers still show heart failure benefit

AMSTERDAM – Patients with heart failure appeared to continue to benefit from full-dose beta-blocker therapy against a background of optimal, contemporary treatment, based on an analysis of data collected from an 1,800-patient trial of cardiac resynchronization therapy.

Dr. L. Brent Mitchell, who presented this finding at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology, acknowledged that assessing the efficacy of drugs in a study that did not randomize patients based on their use of those drugs had questionable validity and was vulnerable to unidentified confounding, but he also noted that data on the role of beta-blockers in contemporary heart failure management were unlikely to come from any other source.

"You need some tool to ask whether beta-blockers are still useful," said Dr. Mitchell, professor of cardiac sciences at the University of Calgary (Alta.). "The purpose of this analysis was to ask if beta-blockers at full dosages are still better than not using a full-dose beta-blocker despite all the other treatments" that patients received while in the study during 2003-2009. The analysis showed that those receiving full-dosage or nearly full-dosage beta-blocker regimens had a one-third cut in all-cause death or heart failure hospitalization, compared with patients receiving less than half the recommended dosage, after adjustment for many baseline differences between these two subgroups.

The analysis also showed that just half of the nearly 1,500 patients who received treatment with a beta-blocker in this cohort received an adequate dosage, defined as at least 50% of the level recommended by the European Society of Cardiology in heart failure treatment guidelines issued last year (Euro. Heart J. 2012;33:1787-847). Two-thirds of the patients on carvedilol received at least half of the recommended target dosage of 50 mg/day. In contrast, about a third of patients being treated with either bisoprolol or metoprolol received a dosage that was at least half the target dosage (10 mg/day for bisoprolol, 200 mg/day for metoprolol).

The analysis used data collected in the Resynchronization-Defibrillation for Ambulatory Heart Failure Trial (RAFT), which enrolled 1,798 patients primarily with New York Heart Association class II heart failure at 34 centers worldwide. When the primary endpoint of RAFT was evaluated, treatment with cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) with defibrillator capability was more effective at preventing death or heart failure hospitalization in the study population than was an implanted defibrillator alone against a background of optimal medical treatment (N. Engl. J. Med. 2010;363:2385-95).

Dr. Mitchell and his associates focused on 1,474 patients who all received beta-blocker treatment while in RAFT. Like the entire RAFT population, 97% of these patients also received treatment with an ACE inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker, and 42% received treatment with spironolactone, and their average left ventricular ejection fraction was 23%.

The patients in this group who were undertreated with beta-blockers were significantly older and had a significantly greater prevalence of New York Heart Association class III heart failure and heart failure with an ischemic etiology compared with those who received at least 50% of the target dosage.

In a regression model that adjusted for all measured baseline differences, patients treated with at least half of the recommended dosage had an incidence of mortality or heart failure hospitalization during an average 40 months of follow-up that was 33% below the rate among patients on lower beta-blocker dosages, a statistically significant difference. This 33% relative risk reduction with adequate beta-blocker treatment is "indistinguishable" from the risk reductions seen with placebo in the major beta-blocker efficacy trials in heart failure patients during the 1990s, Dr. Mitchell noted. "This suggests that beta-blocker treatment still has potency," he said.

Other significant, independent predictors of the primary outcome in this model were prior coronary artery bypass, which boosted the risk by 63%; a history of ischemic heart disease, which raised the risk by 39%; having peripheral vascular disease, which increased the risk by 36%; and receiving CRT, which cut the risk by 33%. In addition, adverse outcomes rose 10% for each reduction of 5 mL/min per 1.73 m2 in estimated glomerular filtration rate.

The impact of underdosing was roughly similar across all three beta-blockers, bisoprolol, carvedilol, and metoprolol. The adverse effect of underdosing was mitigated to some extent when patients also received CRT.

RAFT was partially funded by Medtronic of Canada. Dr. Mitchell said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

A post hoc analysis of the nonrandomized interventions that patients receive during randomized clinical trials is generally discouraged. Patients treated with lower dosages of hemodynamically active drugs like beta-blockers are often sicker and have a worse prognosis. This problem can be seen in the baseline characteristics of the two subgroups in this analysis, which revealed many significant differences between the two. Performing statistical compensations to counterbalance these differences is very uncertain.

In addition, a few years ago, my associates and I ran the Systolic Heart Failure Treatment With the If inhibitor Ivabradine Trial (SHIFT) (Lancet 2010;376:875-85) to assess the efficacy and safety of ivabradine to lower heart rate and improve outcomes in optimally treated heart failure patients. In SHIFT we saw a relationship similar to the one seen in RAFT by the current investigators: Patients on lower dosages of beta-blockers were sicker and at higher risk than patients on higher beta-blocker dosages. In our analyses, adjusting for differences in heart rate eliminated the link between beta-blocker dosage and outcomes. We found that the entire treatment effect could be explained by differences in patient heart rate.

Dr. Karl Swedberg is a professor of medicine at the University of Gothenburg (Sweden). He was lead investigator for the SHIFT trial, which was funded by Servier, the company that markets ivabradine (Procoralan). He made these comments as designated discussant for Dr. Mitchell’s report.

A post hoc analysis of the nonrandomized interventions that patients receive during randomized clinical trials is generally discouraged. Patients treated with lower dosages of hemodynamically active drugs like beta-blockers are often sicker and have a worse prognosis. This problem can be seen in the baseline characteristics of the two subgroups in this analysis, which revealed many significant differences between the two. Performing statistical compensations to counterbalance these differences is very uncertain.

In addition, a few years ago, my associates and I ran the Systolic Heart Failure Treatment With the If inhibitor Ivabradine Trial (SHIFT) (Lancet 2010;376:875-85) to assess the efficacy and safety of ivabradine to lower heart rate and improve outcomes in optimally treated heart failure patients. In SHIFT we saw a relationship similar to the one seen in RAFT by the current investigators: Patients on lower dosages of beta-blockers were sicker and at higher risk than patients on higher beta-blocker dosages. In our analyses, adjusting for differences in heart rate eliminated the link between beta-blocker dosage and outcomes. We found that the entire treatment effect could be explained by differences in patient heart rate.

Dr. Karl Swedberg is a professor of medicine at the University of Gothenburg (Sweden). He was lead investigator for the SHIFT trial, which was funded by Servier, the company that markets ivabradine (Procoralan). He made these comments as designated discussant for Dr. Mitchell’s report.

A post hoc analysis of the nonrandomized interventions that patients receive during randomized clinical trials is generally discouraged. Patients treated with lower dosages of hemodynamically active drugs like beta-blockers are often sicker and have a worse prognosis. This problem can be seen in the baseline characteristics of the two subgroups in this analysis, which revealed many significant differences between the two. Performing statistical compensations to counterbalance these differences is very uncertain.

In addition, a few years ago, my associates and I ran the Systolic Heart Failure Treatment With the If inhibitor Ivabradine Trial (SHIFT) (Lancet 2010;376:875-85) to assess the efficacy and safety of ivabradine to lower heart rate and improve outcomes in optimally treated heart failure patients. In SHIFT we saw a relationship similar to the one seen in RAFT by the current investigators: Patients on lower dosages of beta-blockers were sicker and at higher risk than patients on higher beta-blocker dosages. In our analyses, adjusting for differences in heart rate eliminated the link between beta-blocker dosage and outcomes. We found that the entire treatment effect could be explained by differences in patient heart rate.

Dr. Karl Swedberg is a professor of medicine at the University of Gothenburg (Sweden). He was lead investigator for the SHIFT trial, which was funded by Servier, the company that markets ivabradine (Procoralan). He made these comments as designated discussant for Dr. Mitchell’s report.

AMSTERDAM – Patients with heart failure appeared to continue to benefit from full-dose beta-blocker therapy against a background of optimal, contemporary treatment, based on an analysis of data collected from an 1,800-patient trial of cardiac resynchronization therapy.

Dr. L. Brent Mitchell, who presented this finding at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology, acknowledged that assessing the efficacy of drugs in a study that did not randomize patients based on their use of those drugs had questionable validity and was vulnerable to unidentified confounding, but he also noted that data on the role of beta-blockers in contemporary heart failure management were unlikely to come from any other source.

"You need some tool to ask whether beta-blockers are still useful," said Dr. Mitchell, professor of cardiac sciences at the University of Calgary (Alta.). "The purpose of this analysis was to ask if beta-blockers at full dosages are still better than not using a full-dose beta-blocker despite all the other treatments" that patients received while in the study during 2003-2009. The analysis showed that those receiving full-dosage or nearly full-dosage beta-blocker regimens had a one-third cut in all-cause death or heart failure hospitalization, compared with patients receiving less than half the recommended dosage, after adjustment for many baseline differences between these two subgroups.

The analysis also showed that just half of the nearly 1,500 patients who received treatment with a beta-blocker in this cohort received an adequate dosage, defined as at least 50% of the level recommended by the European Society of Cardiology in heart failure treatment guidelines issued last year (Euro. Heart J. 2012;33:1787-847). Two-thirds of the patients on carvedilol received at least half of the recommended target dosage of 50 mg/day. In contrast, about a third of patients being treated with either bisoprolol or metoprolol received a dosage that was at least half the target dosage (10 mg/day for bisoprolol, 200 mg/day for metoprolol).

The analysis used data collected in the Resynchronization-Defibrillation for Ambulatory Heart Failure Trial (RAFT), which enrolled 1,798 patients primarily with New York Heart Association class II heart failure at 34 centers worldwide. When the primary endpoint of RAFT was evaluated, treatment with cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) with defibrillator capability was more effective at preventing death or heart failure hospitalization in the study population than was an implanted defibrillator alone against a background of optimal medical treatment (N. Engl. J. Med. 2010;363:2385-95).

Dr. Mitchell and his associates focused on 1,474 patients who all received beta-blocker treatment while in RAFT. Like the entire RAFT population, 97% of these patients also received treatment with an ACE inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker, and 42% received treatment with spironolactone, and their average left ventricular ejection fraction was 23%.

The patients in this group who were undertreated with beta-blockers were significantly older and had a significantly greater prevalence of New York Heart Association class III heart failure and heart failure with an ischemic etiology compared with those who received at least 50% of the target dosage.

In a regression model that adjusted for all measured baseline differences, patients treated with at least half of the recommended dosage had an incidence of mortality or heart failure hospitalization during an average 40 months of follow-up that was 33% below the rate among patients on lower beta-blocker dosages, a statistically significant difference. This 33% relative risk reduction with adequate beta-blocker treatment is "indistinguishable" from the risk reductions seen with placebo in the major beta-blocker efficacy trials in heart failure patients during the 1990s, Dr. Mitchell noted. "This suggests that beta-blocker treatment still has potency," he said.

Other significant, independent predictors of the primary outcome in this model were prior coronary artery bypass, which boosted the risk by 63%; a history of ischemic heart disease, which raised the risk by 39%; having peripheral vascular disease, which increased the risk by 36%; and receiving CRT, which cut the risk by 33%. In addition, adverse outcomes rose 10% for each reduction of 5 mL/min per 1.73 m2 in estimated glomerular filtration rate.

The impact of underdosing was roughly similar across all three beta-blockers, bisoprolol, carvedilol, and metoprolol. The adverse effect of underdosing was mitigated to some extent when patients also received CRT.

RAFT was partially funded by Medtronic of Canada. Dr. Mitchell said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AMSTERDAM – Patients with heart failure appeared to continue to benefit from full-dose beta-blocker therapy against a background of optimal, contemporary treatment, based on an analysis of data collected from an 1,800-patient trial of cardiac resynchronization therapy.

Dr. L. Brent Mitchell, who presented this finding at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology, acknowledged that assessing the efficacy of drugs in a study that did not randomize patients based on their use of those drugs had questionable validity and was vulnerable to unidentified confounding, but he also noted that data on the role of beta-blockers in contemporary heart failure management were unlikely to come from any other source.

"You need some tool to ask whether beta-blockers are still useful," said Dr. Mitchell, professor of cardiac sciences at the University of Calgary (Alta.). "The purpose of this analysis was to ask if beta-blockers at full dosages are still better than not using a full-dose beta-blocker despite all the other treatments" that patients received while in the study during 2003-2009. The analysis showed that those receiving full-dosage or nearly full-dosage beta-blocker regimens had a one-third cut in all-cause death or heart failure hospitalization, compared with patients receiving less than half the recommended dosage, after adjustment for many baseline differences between these two subgroups.

The analysis also showed that just half of the nearly 1,500 patients who received treatment with a beta-blocker in this cohort received an adequate dosage, defined as at least 50% of the level recommended by the European Society of Cardiology in heart failure treatment guidelines issued last year (Euro. Heart J. 2012;33:1787-847). Two-thirds of the patients on carvedilol received at least half of the recommended target dosage of 50 mg/day. In contrast, about a third of patients being treated with either bisoprolol or metoprolol received a dosage that was at least half the target dosage (10 mg/day for bisoprolol, 200 mg/day for metoprolol).

The analysis used data collected in the Resynchronization-Defibrillation for Ambulatory Heart Failure Trial (RAFT), which enrolled 1,798 patients primarily with New York Heart Association class II heart failure at 34 centers worldwide. When the primary endpoint of RAFT was evaluated, treatment with cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) with defibrillator capability was more effective at preventing death or heart failure hospitalization in the study population than was an implanted defibrillator alone against a background of optimal medical treatment (N. Engl. J. Med. 2010;363:2385-95).

Dr. Mitchell and his associates focused on 1,474 patients who all received beta-blocker treatment while in RAFT. Like the entire RAFT population, 97% of these patients also received treatment with an ACE inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker, and 42% received treatment with spironolactone, and their average left ventricular ejection fraction was 23%.

The patients in this group who were undertreated with beta-blockers were significantly older and had a significantly greater prevalence of New York Heart Association class III heart failure and heart failure with an ischemic etiology compared with those who received at least 50% of the target dosage.

In a regression model that adjusted for all measured baseline differences, patients treated with at least half of the recommended dosage had an incidence of mortality or heart failure hospitalization during an average 40 months of follow-up that was 33% below the rate among patients on lower beta-blocker dosages, a statistically significant difference. This 33% relative risk reduction with adequate beta-blocker treatment is "indistinguishable" from the risk reductions seen with placebo in the major beta-blocker efficacy trials in heart failure patients during the 1990s, Dr. Mitchell noted. "This suggests that beta-blocker treatment still has potency," he said.

Other significant, independent predictors of the primary outcome in this model were prior coronary artery bypass, which boosted the risk by 63%; a history of ischemic heart disease, which raised the risk by 39%; having peripheral vascular disease, which increased the risk by 36%; and receiving CRT, which cut the risk by 33%. In addition, adverse outcomes rose 10% for each reduction of 5 mL/min per 1.73 m2 in estimated glomerular filtration rate.