User login

European College of Neuropsychopharmacology (ECNP): Annual Congress

New psychoactive drug nomenclature system devised

BARCELONA – Neuropsychopharmacologists want to change the way you describe psychoactive drugs.

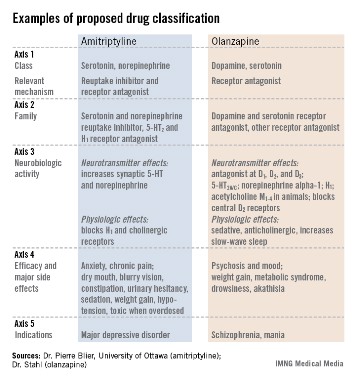

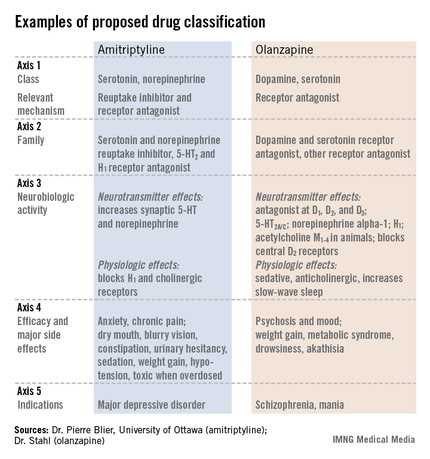

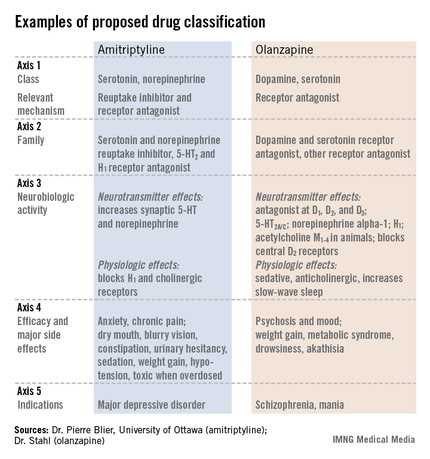

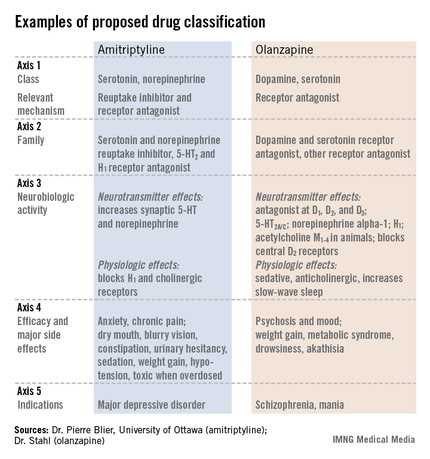

A team of representatives from four international neuropsychopharmacology groups is finishing a first draft of its proposed new system for drug classification and nomenclature that – in its current form – describes each of approximately 120 psychoactive drugs by five different parameters, or axes, including neurobiologic activity, efficacy, and approved indications worldwide. The goal is a new, Web-based framework for classifying and identifying drugs that is more consistent, informative, and transparent than the existing nomenclature.

"We expect drug nomenclature to reflect current scientific knowledge, give useful pharmacologic information to clinicians, and give patients a rationale for using a drug," but the existing nomenclature does not accomplish those goals, said Dr. Joseph Zohar, director of psychiatry at Sheba Medical Center in Tel Hashomer, Israel, and a member of the nomenclature group. "Existing nomenclature dates from the 1960s; no wonder it does not reflect current understanding. Drugs called antidepressants are often prescribed to patients with anxiety disorders. Patients ask, why give me an antidepressant if I have anxiety? Antipsychotics are prescribed to patients with depression, and they ask why they are getting an antipsychotic? The nomenclature is confusing," Dr. Zohar said at a session at the annual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology devoted to presenting the new nomenclature system to congress participants.

"We want to rationalize classification and have it better reflect science. We want to focus on mechanisms; knowing the entire profile of medications will help make more informed choices," he said.

"It’s getting people to think more about what drugs do. If people understood drugs better, they would use them better," said Dr. David J. Nutt, professor of neuropsychopharmacology at Imperial College London and another member of the nomenclature group. "The shorthands we currently use [for classifying psychoactive drugs] may be useful, but we need to determine what’s not useful" and get rid of it.

Leadership from the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology (ECNP) arranged for a panel with two representatives each from the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology, the International College of Neuropsychopharmacology, the Asian College of Neuropsychopharmacology, and the ECNP. A draft version of the nomenclature document should appear for comment on the ECNP website by early next year, and the current plan is to publish a finalized version before the end of next year. But the panel members stressed that since the document will primarily be Web-based, it will be open to frequent revision.

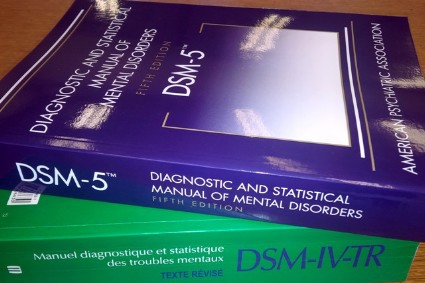

"This is the first step in a long process. We’re trying to wake up a 50-year-old nomenclature into a living document that will be used over the next decades and may someday merge with DSM [Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders]," said Dr. Stephen M. Stahl, a panel member and psychiatrist affiliated with the University of California, San Diego.

The format the panel has in place currently describes every psychoactive drug in terms of five axes: class and relevant mechanisms; family; neurobiologic activity, neurotransmitter effects, and physiologic effects; efficacy and major side effects; and approved and licenses indications in the major countries and regions that perform drug licensing. Some of the collaborators on the panel published an explanation of the five axes template online in September (Euro. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013 [doi:10.1016/j.euroneuro.2013.08.004]).

All this information for each drug "should tell you everything you need to know to make a rational decision about what to do with the drug," Dr. Nutt said.

"We need to be very humble about these medications and what they do. You have multiple things going on simultaneously," said Dr. Stahl, also founder of the Neuroscience Education Institute in San Diego. "The second-generation antipsychotics are the most complicated drugs in medicine; one patient’s side effect is another’s therapeutic effect.

"We propose that it is no longer appropriate to name all drugs that treat psychosis as ‘antipsychotics.’ We propose a multiaxial classification system based on pharmacologic mechanisms of action. A mechanism-based nomenclature may clarify the differing mechanisms of individual agents, especially actions in psychosis versus mood disorders. This approach has the potential to better inform those who work with drugs that treat depression, and prevent confusion with other drugs that treat both psychosis and multiple additional disorders such as depression and mania. This approach is also a strategy for naming drugs yet to be discovered that target novel mechanisms of action."

"What we don’t want is industry or a regulator to define a new glycine-reuptake blocker as an antipsychotic," Dr. Nutt said.

Several panel members stressed that the five-axis format will allow a diverse list of useful information.

"We don’t want to be constrained by the approved indications," Dr. Nutt said. "This is an opportunity to document off-label indications and to link to the evidence for off-label uses," said Dr. Guy Goodwin, chairman of psychiatry at the University of Oxford (England) and another collaborator on the panel.

The audience of about 150 congress attendees at the session seemed persuaded by the speakers. At the session’s end, in an electronic vote, 67% said they fully agreed, and another 26% said they partly agreed, that the existing nomenclature needs revision. Asked whether the proposed nomenclature was a step in the right direction, 48% said they fully agreed, and another 39% said they partly agreed. Another question asked what feature should drive a drug’s top-line definition. Sixty percent of the audience said pharmacologic action, and an additional 29% voted in favor of clinical indication.

Dr. Zohar said he has been an adviser or consultant to or received research support from eight drug companies. Dr. Nutt said he has been an adviser or consultant to eight drug companies. Dr. Stahl said he has been an adviser or consultant to more than 30 drug companies. Dr. Goodwin said he had been an adviser or consultant to 12 drug companies.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

BARCELONA – Neuropsychopharmacologists want to change the way you describe psychoactive drugs.

A team of representatives from four international neuropsychopharmacology groups is finishing a first draft of its proposed new system for drug classification and nomenclature that – in its current form – describes each of approximately 120 psychoactive drugs by five different parameters, or axes, including neurobiologic activity, efficacy, and approved indications worldwide. The goal is a new, Web-based framework for classifying and identifying drugs that is more consistent, informative, and transparent than the existing nomenclature.

"We expect drug nomenclature to reflect current scientific knowledge, give useful pharmacologic information to clinicians, and give patients a rationale for using a drug," but the existing nomenclature does not accomplish those goals, said Dr. Joseph Zohar, director of psychiatry at Sheba Medical Center in Tel Hashomer, Israel, and a member of the nomenclature group. "Existing nomenclature dates from the 1960s; no wonder it does not reflect current understanding. Drugs called antidepressants are often prescribed to patients with anxiety disorders. Patients ask, why give me an antidepressant if I have anxiety? Antipsychotics are prescribed to patients with depression, and they ask why they are getting an antipsychotic? The nomenclature is confusing," Dr. Zohar said at a session at the annual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology devoted to presenting the new nomenclature system to congress participants.

"We want to rationalize classification and have it better reflect science. We want to focus on mechanisms; knowing the entire profile of medications will help make more informed choices," he said.

"It’s getting people to think more about what drugs do. If people understood drugs better, they would use them better," said Dr. David J. Nutt, professor of neuropsychopharmacology at Imperial College London and another member of the nomenclature group. "The shorthands we currently use [for classifying psychoactive drugs] may be useful, but we need to determine what’s not useful" and get rid of it.

Leadership from the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology (ECNP) arranged for a panel with two representatives each from the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology, the International College of Neuropsychopharmacology, the Asian College of Neuropsychopharmacology, and the ECNP. A draft version of the nomenclature document should appear for comment on the ECNP website by early next year, and the current plan is to publish a finalized version before the end of next year. But the panel members stressed that since the document will primarily be Web-based, it will be open to frequent revision.

"This is the first step in a long process. We’re trying to wake up a 50-year-old nomenclature into a living document that will be used over the next decades and may someday merge with DSM [Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders]," said Dr. Stephen M. Stahl, a panel member and psychiatrist affiliated with the University of California, San Diego.

The format the panel has in place currently describes every psychoactive drug in terms of five axes: class and relevant mechanisms; family; neurobiologic activity, neurotransmitter effects, and physiologic effects; efficacy and major side effects; and approved and licenses indications in the major countries and regions that perform drug licensing. Some of the collaborators on the panel published an explanation of the five axes template online in September (Euro. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013 [doi:10.1016/j.euroneuro.2013.08.004]).

All this information for each drug "should tell you everything you need to know to make a rational decision about what to do with the drug," Dr. Nutt said.

"We need to be very humble about these medications and what they do. You have multiple things going on simultaneously," said Dr. Stahl, also founder of the Neuroscience Education Institute in San Diego. "The second-generation antipsychotics are the most complicated drugs in medicine; one patient’s side effect is another’s therapeutic effect.

"We propose that it is no longer appropriate to name all drugs that treat psychosis as ‘antipsychotics.’ We propose a multiaxial classification system based on pharmacologic mechanisms of action. A mechanism-based nomenclature may clarify the differing mechanisms of individual agents, especially actions in psychosis versus mood disorders. This approach has the potential to better inform those who work with drugs that treat depression, and prevent confusion with other drugs that treat both psychosis and multiple additional disorders such as depression and mania. This approach is also a strategy for naming drugs yet to be discovered that target novel mechanisms of action."

"What we don’t want is industry or a regulator to define a new glycine-reuptake blocker as an antipsychotic," Dr. Nutt said.

Several panel members stressed that the five-axis format will allow a diverse list of useful information.

"We don’t want to be constrained by the approved indications," Dr. Nutt said. "This is an opportunity to document off-label indications and to link to the evidence for off-label uses," said Dr. Guy Goodwin, chairman of psychiatry at the University of Oxford (England) and another collaborator on the panel.

The audience of about 150 congress attendees at the session seemed persuaded by the speakers. At the session’s end, in an electronic vote, 67% said they fully agreed, and another 26% said they partly agreed, that the existing nomenclature needs revision. Asked whether the proposed nomenclature was a step in the right direction, 48% said they fully agreed, and another 39% said they partly agreed. Another question asked what feature should drive a drug’s top-line definition. Sixty percent of the audience said pharmacologic action, and an additional 29% voted in favor of clinical indication.

Dr. Zohar said he has been an adviser or consultant to or received research support from eight drug companies. Dr. Nutt said he has been an adviser or consultant to eight drug companies. Dr. Stahl said he has been an adviser or consultant to more than 30 drug companies. Dr. Goodwin said he had been an adviser or consultant to 12 drug companies.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

BARCELONA – Neuropsychopharmacologists want to change the way you describe psychoactive drugs.

A team of representatives from four international neuropsychopharmacology groups is finishing a first draft of its proposed new system for drug classification and nomenclature that – in its current form – describes each of approximately 120 psychoactive drugs by five different parameters, or axes, including neurobiologic activity, efficacy, and approved indications worldwide. The goal is a new, Web-based framework for classifying and identifying drugs that is more consistent, informative, and transparent than the existing nomenclature.

"We expect drug nomenclature to reflect current scientific knowledge, give useful pharmacologic information to clinicians, and give patients a rationale for using a drug," but the existing nomenclature does not accomplish those goals, said Dr. Joseph Zohar, director of psychiatry at Sheba Medical Center in Tel Hashomer, Israel, and a member of the nomenclature group. "Existing nomenclature dates from the 1960s; no wonder it does not reflect current understanding. Drugs called antidepressants are often prescribed to patients with anxiety disorders. Patients ask, why give me an antidepressant if I have anxiety? Antipsychotics are prescribed to patients with depression, and they ask why they are getting an antipsychotic? The nomenclature is confusing," Dr. Zohar said at a session at the annual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology devoted to presenting the new nomenclature system to congress participants.

"We want to rationalize classification and have it better reflect science. We want to focus on mechanisms; knowing the entire profile of medications will help make more informed choices," he said.

"It’s getting people to think more about what drugs do. If people understood drugs better, they would use them better," said Dr. David J. Nutt, professor of neuropsychopharmacology at Imperial College London and another member of the nomenclature group. "The shorthands we currently use [for classifying psychoactive drugs] may be useful, but we need to determine what’s not useful" and get rid of it.

Leadership from the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology (ECNP) arranged for a panel with two representatives each from the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology, the International College of Neuropsychopharmacology, the Asian College of Neuropsychopharmacology, and the ECNP. A draft version of the nomenclature document should appear for comment on the ECNP website by early next year, and the current plan is to publish a finalized version before the end of next year. But the panel members stressed that since the document will primarily be Web-based, it will be open to frequent revision.

"This is the first step in a long process. We’re trying to wake up a 50-year-old nomenclature into a living document that will be used over the next decades and may someday merge with DSM [Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders]," said Dr. Stephen M. Stahl, a panel member and psychiatrist affiliated with the University of California, San Diego.

The format the panel has in place currently describes every psychoactive drug in terms of five axes: class and relevant mechanisms; family; neurobiologic activity, neurotransmitter effects, and physiologic effects; efficacy and major side effects; and approved and licenses indications in the major countries and regions that perform drug licensing. Some of the collaborators on the panel published an explanation of the five axes template online in September (Euro. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013 [doi:10.1016/j.euroneuro.2013.08.004]).

All this information for each drug "should tell you everything you need to know to make a rational decision about what to do with the drug," Dr. Nutt said.

"We need to be very humble about these medications and what they do. You have multiple things going on simultaneously," said Dr. Stahl, also founder of the Neuroscience Education Institute in San Diego. "The second-generation antipsychotics are the most complicated drugs in medicine; one patient’s side effect is another’s therapeutic effect.

"We propose that it is no longer appropriate to name all drugs that treat psychosis as ‘antipsychotics.’ We propose a multiaxial classification system based on pharmacologic mechanisms of action. A mechanism-based nomenclature may clarify the differing mechanisms of individual agents, especially actions in psychosis versus mood disorders. This approach has the potential to better inform those who work with drugs that treat depression, and prevent confusion with other drugs that treat both psychosis and multiple additional disorders such as depression and mania. This approach is also a strategy for naming drugs yet to be discovered that target novel mechanisms of action."

"What we don’t want is industry or a regulator to define a new glycine-reuptake blocker as an antipsychotic," Dr. Nutt said.

Several panel members stressed that the five-axis format will allow a diverse list of useful information.

"We don’t want to be constrained by the approved indications," Dr. Nutt said. "This is an opportunity to document off-label indications and to link to the evidence for off-label uses," said Dr. Guy Goodwin, chairman of psychiatry at the University of Oxford (England) and another collaborator on the panel.

The audience of about 150 congress attendees at the session seemed persuaded by the speakers. At the session’s end, in an electronic vote, 67% said they fully agreed, and another 26% said they partly agreed, that the existing nomenclature needs revision. Asked whether the proposed nomenclature was a step in the right direction, 48% said they fully agreed, and another 39% said they partly agreed. Another question asked what feature should drive a drug’s top-line definition. Sixty percent of the audience said pharmacologic action, and an additional 29% voted in favor of clinical indication.

Dr. Zohar said he has been an adviser or consultant to or received research support from eight drug companies. Dr. Nutt said he has been an adviser or consultant to eight drug companies. Dr. Stahl said he has been an adviser or consultant to more than 30 drug companies. Dr. Goodwin said he had been an adviser or consultant to 12 drug companies.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE ECNP CONGRESS

Second-generation antipsychotics cause modest extrapyramidal symptoms

BARCELONA – The greatest risk that patients with schizophrenia will develop extrapyramidal symptoms while on treatment with a second-generation antipsychotic drug comes during the first few weeks of treatment, and then substantially resolves during the rest of the first year on treatment, according to findings from a multicenter European trial with 498 patients.

In addition, the risk level varies from drug to drug, and some extrapyramidal symptoms are rare, with no treatment-related episodes of dystonia and dyskinesia, including tardive dyskinesia, during the year on treatment, Dr. Janusz K. Rybakowski said at the annual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology.

"Generally, it can be stated that extrapyramidal symptoms are not much of a problem for patients taking second-generation antipsychotic drugs except for the problem of akathisia with ziprasidone treatment, which should be taken into account" when considering which drug to prescribe, said Dr. Rybakowski, professor and head of adult psychiatry at Poznañ (Poland) University.

In the study, 24% of newly diagnosed schizophrenia patients who received ziprasidone as their initial treatment developed akathisia by 1 month after starting treatment. However, among patients who remained in the study and on ziprasidone treatment for 1 year, the prevalence of akathisia fell to less than 9%, he reported. The analysis also documented the rates at which patients developed parkinsonian symptoms.

Second-generation antipsychotics "have to be looked at for their risk-benefit profile," commented Dr. W. Wolfgang Fleischhacker, professor and director of psychiatry at the Medical University of Innsbruck, Austria, and a EUFEST (European First Episode of Schizophrenia Trial) coinvestigator. "Some of these drugs have problems, but they are also effective. Some may have problems causing metabolic syndrome but not extrapyramidal symptoms, and vise versa. And we lack good predictors" for which patients will develop significant adverse effects on treatment. "Even if olanzapine is the biggest offender with regard to metabolic disturbances, probably only 40% of patients are affected. So we can’t judge these drugs generally; we need to closely monitor patients" to see which ones actually develop a significant adverse effect on treatment, Dr. Fleischhacker said.

Dr. Rybakowski and his associates used data collected in EUFEST, which enrolled 498 patients at 50 centers in Europe and in Israel (Lancet 2008;371:1085-97). The investigators randomized patients to treatment with olanzapine, quetiapine, amisulpride, ziprasidone, or to the first-generation antipsychotic haloperidol.

After 1 month, the incidence of parkinsonian symptoms ranged from 4% among those on olanzapine to 13% of those on ziprasidone (and 26% for those on haloperidol). But by 12 months, the rate had dropped to zero among patients on olanzapine and also dropped among all other patients. At 1 year, the highest rate, 9%, was among patients on haloperidol. After 1 month, the incidence of akathisia ranged from 3% among those on olanzapine to 24% for those on ziprasidone (and 21% for patients on haloperidol); after 12 months, the rate fell to zero in patients on olanzapine or amisulpride and was highest, at 7%, among patients on quetiapine.

Although no patients on any second-generation drug developed new symptoms of dystonia or dyskinesia, a few on haloperidol developed dyskinesia.

The percent of patients receiving an anticholinergic drug at 1 month to treat their extrapyramidal symptoms ranged from 13% of those on ziprasidone, 10% on amisulpride, 3% on olanzapine, 2% on quetiapine, and 24% on haloperidol. After 12 months, the rate of anticholinergic drug use fell to a high of 11% on haloperidol and 6% for amisulpride. Patients on all the other second-generation antipsychotics had lower rates of anticholinergic drug use.

EUFEST was sponsored by AstraZeneca, Sanofi-Aventis, and Pfizer. Dr. Rybakowski said he has been a consultant to Adamed, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Janssen-Cilag, Lundbeck, Sanofi-Aventis, and Servier. Dr. Fleischhacker has received honoraria as a speaker or consultant to Bristol-Myers Squibb, Janssen, Lundbeck, MedAvante, Merck, Otsuka, Pfizer, and Roche.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

BARCELONA – The greatest risk that patients with schizophrenia will develop extrapyramidal symptoms while on treatment with a second-generation antipsychotic drug comes during the first few weeks of treatment, and then substantially resolves during the rest of the first year on treatment, according to findings from a multicenter European trial with 498 patients.

In addition, the risk level varies from drug to drug, and some extrapyramidal symptoms are rare, with no treatment-related episodes of dystonia and dyskinesia, including tardive dyskinesia, during the year on treatment, Dr. Janusz K. Rybakowski said at the annual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology.

"Generally, it can be stated that extrapyramidal symptoms are not much of a problem for patients taking second-generation antipsychotic drugs except for the problem of akathisia with ziprasidone treatment, which should be taken into account" when considering which drug to prescribe, said Dr. Rybakowski, professor and head of adult psychiatry at Poznañ (Poland) University.

In the study, 24% of newly diagnosed schizophrenia patients who received ziprasidone as their initial treatment developed akathisia by 1 month after starting treatment. However, among patients who remained in the study and on ziprasidone treatment for 1 year, the prevalence of akathisia fell to less than 9%, he reported. The analysis also documented the rates at which patients developed parkinsonian symptoms.

Second-generation antipsychotics "have to be looked at for their risk-benefit profile," commented Dr. W. Wolfgang Fleischhacker, professor and director of psychiatry at the Medical University of Innsbruck, Austria, and a EUFEST (European First Episode of Schizophrenia Trial) coinvestigator. "Some of these drugs have problems, but they are also effective. Some may have problems causing metabolic syndrome but not extrapyramidal symptoms, and vise versa. And we lack good predictors" for which patients will develop significant adverse effects on treatment. "Even if olanzapine is the biggest offender with regard to metabolic disturbances, probably only 40% of patients are affected. So we can’t judge these drugs generally; we need to closely monitor patients" to see which ones actually develop a significant adverse effect on treatment, Dr. Fleischhacker said.

Dr. Rybakowski and his associates used data collected in EUFEST, which enrolled 498 patients at 50 centers in Europe and in Israel (Lancet 2008;371:1085-97). The investigators randomized patients to treatment with olanzapine, quetiapine, amisulpride, ziprasidone, or to the first-generation antipsychotic haloperidol.

After 1 month, the incidence of parkinsonian symptoms ranged from 4% among those on olanzapine to 13% of those on ziprasidone (and 26% for those on haloperidol). But by 12 months, the rate had dropped to zero among patients on olanzapine and also dropped among all other patients. At 1 year, the highest rate, 9%, was among patients on haloperidol. After 1 month, the incidence of akathisia ranged from 3% among those on olanzapine to 24% for those on ziprasidone (and 21% for patients on haloperidol); after 12 months, the rate fell to zero in patients on olanzapine or amisulpride and was highest, at 7%, among patients on quetiapine.

Although no patients on any second-generation drug developed new symptoms of dystonia or dyskinesia, a few on haloperidol developed dyskinesia.

The percent of patients receiving an anticholinergic drug at 1 month to treat their extrapyramidal symptoms ranged from 13% of those on ziprasidone, 10% on amisulpride, 3% on olanzapine, 2% on quetiapine, and 24% on haloperidol. After 12 months, the rate of anticholinergic drug use fell to a high of 11% on haloperidol and 6% for amisulpride. Patients on all the other second-generation antipsychotics had lower rates of anticholinergic drug use.

EUFEST was sponsored by AstraZeneca, Sanofi-Aventis, and Pfizer. Dr. Rybakowski said he has been a consultant to Adamed, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Janssen-Cilag, Lundbeck, Sanofi-Aventis, and Servier. Dr. Fleischhacker has received honoraria as a speaker or consultant to Bristol-Myers Squibb, Janssen, Lundbeck, MedAvante, Merck, Otsuka, Pfizer, and Roche.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

BARCELONA – The greatest risk that patients with schizophrenia will develop extrapyramidal symptoms while on treatment with a second-generation antipsychotic drug comes during the first few weeks of treatment, and then substantially resolves during the rest of the first year on treatment, according to findings from a multicenter European trial with 498 patients.

In addition, the risk level varies from drug to drug, and some extrapyramidal symptoms are rare, with no treatment-related episodes of dystonia and dyskinesia, including tardive dyskinesia, during the year on treatment, Dr. Janusz K. Rybakowski said at the annual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology.

"Generally, it can be stated that extrapyramidal symptoms are not much of a problem for patients taking second-generation antipsychotic drugs except for the problem of akathisia with ziprasidone treatment, which should be taken into account" when considering which drug to prescribe, said Dr. Rybakowski, professor and head of adult psychiatry at Poznañ (Poland) University.

In the study, 24% of newly diagnosed schizophrenia patients who received ziprasidone as their initial treatment developed akathisia by 1 month after starting treatment. However, among patients who remained in the study and on ziprasidone treatment for 1 year, the prevalence of akathisia fell to less than 9%, he reported. The analysis also documented the rates at which patients developed parkinsonian symptoms.

Second-generation antipsychotics "have to be looked at for their risk-benefit profile," commented Dr. W. Wolfgang Fleischhacker, professor and director of psychiatry at the Medical University of Innsbruck, Austria, and a EUFEST (European First Episode of Schizophrenia Trial) coinvestigator. "Some of these drugs have problems, but they are also effective. Some may have problems causing metabolic syndrome but not extrapyramidal symptoms, and vise versa. And we lack good predictors" for which patients will develop significant adverse effects on treatment. "Even if olanzapine is the biggest offender with regard to metabolic disturbances, probably only 40% of patients are affected. So we can’t judge these drugs generally; we need to closely monitor patients" to see which ones actually develop a significant adverse effect on treatment, Dr. Fleischhacker said.

Dr. Rybakowski and his associates used data collected in EUFEST, which enrolled 498 patients at 50 centers in Europe and in Israel (Lancet 2008;371:1085-97). The investigators randomized patients to treatment with olanzapine, quetiapine, amisulpride, ziprasidone, or to the first-generation antipsychotic haloperidol.

After 1 month, the incidence of parkinsonian symptoms ranged from 4% among those on olanzapine to 13% of those on ziprasidone (and 26% for those on haloperidol). But by 12 months, the rate had dropped to zero among patients on olanzapine and also dropped among all other patients. At 1 year, the highest rate, 9%, was among patients on haloperidol. After 1 month, the incidence of akathisia ranged from 3% among those on olanzapine to 24% for those on ziprasidone (and 21% for patients on haloperidol); after 12 months, the rate fell to zero in patients on olanzapine or amisulpride and was highest, at 7%, among patients on quetiapine.

Although no patients on any second-generation drug developed new symptoms of dystonia or dyskinesia, a few on haloperidol developed dyskinesia.

The percent of patients receiving an anticholinergic drug at 1 month to treat their extrapyramidal symptoms ranged from 13% of those on ziprasidone, 10% on amisulpride, 3% on olanzapine, 2% on quetiapine, and 24% on haloperidol. After 12 months, the rate of anticholinergic drug use fell to a high of 11% on haloperidol and 6% for amisulpride. Patients on all the other second-generation antipsychotics had lower rates of anticholinergic drug use.

EUFEST was sponsored by AstraZeneca, Sanofi-Aventis, and Pfizer. Dr. Rybakowski said he has been a consultant to Adamed, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Janssen-Cilag, Lundbeck, Sanofi-Aventis, and Servier. Dr. Fleischhacker has received honoraria as a speaker or consultant to Bristol-Myers Squibb, Janssen, Lundbeck, MedAvante, Merck, Otsuka, Pfizer, and Roche.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AT THE ECNP CONGRESS

Major finding: Ziprasidone caused the highest incidence of extrapyramidal symptoms: a 24% akathisia rate and 13% parkinsonian-symptom rate after 1 month.

Data source: EUFEST, a multicenter, randomized study with 498 patients with first-episode schizophrenia.

Disclosures: EUFEST was sponsored by AstraZeneca, Sanofi-Aventis, and Pfizer. Dr. Rybakowski said that he has been a consultant to Adamed, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Janssen-Cilag, Lundbeck, Sanofi-Aventis, and Servier. Dr. Fleischhacker has received honoraria as a speaker or consultant to Bristol-Myers Squibb, Janssen, Lundbeck, MedAvante, Merck, Otsuka, Pfizer, and Roche.

Fibromyalgia patients may harbor fewer small-nerve fibers

BARCELONA – Many patients with fibromyalgia syndrome have an unusually low number of small-nerve fibers in their skin, a finding that may provide important new insights into the pathology, etiology, and possible treatment of what has been a poorly understood disorder, according to Dr. Claudia Sommer.

"With three different methods, we showed pathologic changes in small-nerve fibers" in the skin of patients diagnosed with fibromyalgia, she said at the annual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology. These somatic findings are too strong to allow classification of these patients with fibromyalgia as having a "somatoform pain disorder." She suggested that the nerve deficits in patients’ skin could reflect systemic nerve damage that causes the deep pain that fibromyalgia patients have in muscles, tendons, and joints. "What we see in the skin may also exist elsewhere," said Dr. Sommer, professor of neurology at the University Clinic of Würzburg (Germany).

Three other, independent research groups have recently made similar findings of small-nerve deficits in the skin of fibromyalgia patients, including researchers at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston (Pain 2013;154:2310-6), further boosting the likelihood that impaired small-nerve function is real and a key feature of at least some fibromyalgia patients, Dr. Sommer said.

The finding led her to develop a new model for the pathogenesis of these cases: An adverse life event or other predisposing factor leads to a more proinflammatory cytokine profile that causes small-nerve fiber damage and ongoing pain system activity that produces central sensitization and changes in central pain processing.

"This is just a model, but we can work on this and test hypotheses," she said. "We are a long way from finding new treatments, but trying to understand what causes damage to nerve fibers may give a start, something a new treatment could be directed against."

Dr. Sommer and her associates studied 25 patients who had been diagnosed with fibromyalgia, 10 diagnosed with unipolar depression, and 25 healthy controls who were matched by age and sex with the fibromyalgia patients. The participants ranged from 39 to 75 years old, and those with either depression or fibromyalgia had been diagnosed for an average of more than 20 years.

Compared with the controls, patients with fibromyalgia had significantly increased detection thresholds to warm and cold when quantitative sensory testing was used, while the depressed patients had no significant difference compared with the controls. Measurement of pain-related evoked potentials showed increased latency on stimulation of the feet and reduced amplitudes on stimulation of the feet, hands, and face in fibromyalgia patients compared with both the controls and the patients with depression.

The researchers also found reduced numbers of total and regenerating intraepidermal, unmyelinated nerve fibers in skin biopsies from the lower leg and upper thigh of the patients with fibromyalgia compared with the controls and the patients with depression. The nerve fiber count averaged 5 fibers/mm2 in the patients with fibromyalgia, about 7/mm2 in patients with depression, and about 8/mm2 in the controls. The difference between the fibromyalgia patients and the controls was statistically significant.

Dr. Sommer and her associates also published these results in Brain (2013;136:1857-67).

Dr. Sommer said she has received honoraria for being a speaker on behalf of Allergan, Astella, Baxter, CSL Behring, Eli Lilly, Genzyme, GlaxoSmithKline, and Pfizer.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

BARCELONA – Many patients with fibromyalgia syndrome have an unusually low number of small-nerve fibers in their skin, a finding that may provide important new insights into the pathology, etiology, and possible treatment of what has been a poorly understood disorder, according to Dr. Claudia Sommer.

"With three different methods, we showed pathologic changes in small-nerve fibers" in the skin of patients diagnosed with fibromyalgia, she said at the annual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology. These somatic findings are too strong to allow classification of these patients with fibromyalgia as having a "somatoform pain disorder." She suggested that the nerve deficits in patients’ skin could reflect systemic nerve damage that causes the deep pain that fibromyalgia patients have in muscles, tendons, and joints. "What we see in the skin may also exist elsewhere," said Dr. Sommer, professor of neurology at the University Clinic of Würzburg (Germany).

Three other, independent research groups have recently made similar findings of small-nerve deficits in the skin of fibromyalgia patients, including researchers at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston (Pain 2013;154:2310-6), further boosting the likelihood that impaired small-nerve function is real and a key feature of at least some fibromyalgia patients, Dr. Sommer said.

The finding led her to develop a new model for the pathogenesis of these cases: An adverse life event or other predisposing factor leads to a more proinflammatory cytokine profile that causes small-nerve fiber damage and ongoing pain system activity that produces central sensitization and changes in central pain processing.

"This is just a model, but we can work on this and test hypotheses," she said. "We are a long way from finding new treatments, but trying to understand what causes damage to nerve fibers may give a start, something a new treatment could be directed against."

Dr. Sommer and her associates studied 25 patients who had been diagnosed with fibromyalgia, 10 diagnosed with unipolar depression, and 25 healthy controls who were matched by age and sex with the fibromyalgia patients. The participants ranged from 39 to 75 years old, and those with either depression or fibromyalgia had been diagnosed for an average of more than 20 years.

Compared with the controls, patients with fibromyalgia had significantly increased detection thresholds to warm and cold when quantitative sensory testing was used, while the depressed patients had no significant difference compared with the controls. Measurement of pain-related evoked potentials showed increased latency on stimulation of the feet and reduced amplitudes on stimulation of the feet, hands, and face in fibromyalgia patients compared with both the controls and the patients with depression.

The researchers also found reduced numbers of total and regenerating intraepidermal, unmyelinated nerve fibers in skin biopsies from the lower leg and upper thigh of the patients with fibromyalgia compared with the controls and the patients with depression. The nerve fiber count averaged 5 fibers/mm2 in the patients with fibromyalgia, about 7/mm2 in patients with depression, and about 8/mm2 in the controls. The difference between the fibromyalgia patients and the controls was statistically significant.

Dr. Sommer and her associates also published these results in Brain (2013;136:1857-67).

Dr. Sommer said she has received honoraria for being a speaker on behalf of Allergan, Astella, Baxter, CSL Behring, Eli Lilly, Genzyme, GlaxoSmithKline, and Pfizer.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

BARCELONA – Many patients with fibromyalgia syndrome have an unusually low number of small-nerve fibers in their skin, a finding that may provide important new insights into the pathology, etiology, and possible treatment of what has been a poorly understood disorder, according to Dr. Claudia Sommer.

"With three different methods, we showed pathologic changes in small-nerve fibers" in the skin of patients diagnosed with fibromyalgia, she said at the annual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology. These somatic findings are too strong to allow classification of these patients with fibromyalgia as having a "somatoform pain disorder." She suggested that the nerve deficits in patients’ skin could reflect systemic nerve damage that causes the deep pain that fibromyalgia patients have in muscles, tendons, and joints. "What we see in the skin may also exist elsewhere," said Dr. Sommer, professor of neurology at the University Clinic of Würzburg (Germany).

Three other, independent research groups have recently made similar findings of small-nerve deficits in the skin of fibromyalgia patients, including researchers at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston (Pain 2013;154:2310-6), further boosting the likelihood that impaired small-nerve function is real and a key feature of at least some fibromyalgia patients, Dr. Sommer said.

The finding led her to develop a new model for the pathogenesis of these cases: An adverse life event or other predisposing factor leads to a more proinflammatory cytokine profile that causes small-nerve fiber damage and ongoing pain system activity that produces central sensitization and changes in central pain processing.

"This is just a model, but we can work on this and test hypotheses," she said. "We are a long way from finding new treatments, but trying to understand what causes damage to nerve fibers may give a start, something a new treatment could be directed against."

Dr. Sommer and her associates studied 25 patients who had been diagnosed with fibromyalgia, 10 diagnosed with unipolar depression, and 25 healthy controls who were matched by age and sex with the fibromyalgia patients. The participants ranged from 39 to 75 years old, and those with either depression or fibromyalgia had been diagnosed for an average of more than 20 years.

Compared with the controls, patients with fibromyalgia had significantly increased detection thresholds to warm and cold when quantitative sensory testing was used, while the depressed patients had no significant difference compared with the controls. Measurement of pain-related evoked potentials showed increased latency on stimulation of the feet and reduced amplitudes on stimulation of the feet, hands, and face in fibromyalgia patients compared with both the controls and the patients with depression.

The researchers also found reduced numbers of total and regenerating intraepidermal, unmyelinated nerve fibers in skin biopsies from the lower leg and upper thigh of the patients with fibromyalgia compared with the controls and the patients with depression. The nerve fiber count averaged 5 fibers/mm2 in the patients with fibromyalgia, about 7/mm2 in patients with depression, and about 8/mm2 in the controls. The difference between the fibromyalgia patients and the controls was statistically significant.

Dr. Sommer and her associates also published these results in Brain (2013;136:1857-67).

Dr. Sommer said she has received honoraria for being a speaker on behalf of Allergan, Astella, Baxter, CSL Behring, Eli Lilly, Genzyme, GlaxoSmithKline, and Pfizer.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AT THE ECNP CONGRESS

Major finding: Skin biopsies from patients with fibromyalgia averaged 5 fibers/mm2 compared with 8 fibers/mm2 in matched control patients.

Data source: A single-center study of 25 adults diagnosed with fibromyalgia syndrome and 25 healthy controls matched by age and sex.

Disclosures: Dr. Sommer that she has received honoraria for being a speaker on behalf of Allergan, Astella, Baxter, CSL Behring, Eli Lilly, Genzyme, GlaxoSmithKline, and Pfizer.

Did the DSM-5 pathologize what’s normal?

Some elements of the DSM-5, released nearly 6 months ago now, follow a tricky path between giving the psychiatric community useful, new diagnostic tools and pathologizing what is part of the normal range of human behavior, but despite that, the manual seems to generally succeed in "better classifying the patients who come to psychiatrists," said Dr. Guy Goodwin, head of the psychiatry department at the University of Oxford (England).

Dr. Goodwin spoke in an unusual press conference during the annual Congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology (ECNP) in Barcelona in October. The topic was the still somewhat new Fifth Edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), and the role of diagnosis in psychiatry, which did not link to any report or talk at the meeting. The press conference seemed mostly a way for Dr. Goodwin, who became president of the ECNP during the meeting, and two other participants to give their thoughts on the DSM-5 and shifting views on psychiatric diagnoses, especially in children.

Dr. Goodwin ultimately called himself "sort of pro-DSM-5" and said that the key test of whether the diagnostic changes made by the DSM-5 were a step forward or not will come with time, as psychiatrists determine whether following the DSM-5 results in better diagnosis and patient care.

He offered an example of what he said some have characterized as a disorder "invented" by the DSM-5, disruptive mood dysregulation disorder (DMDD). It was an interesting choice for Dr. Goodwin to highlight, as he is not a pediatric specialist, although he noted it ties to his practice of treating patients with bipolar disorder because DMDD was designed as a replacement diagnosis for many children previously diagnosed with bipolar disorder. DMDD also has a history of controversy going back several years to when the DSM-5 writing group struggled with how to deal with what many saw as overdiagnosis of bipolar disease in children.

The DSM-5 "is trying to stop" the diagnosis of bipolar disease by U.S. psychiatrists in children as young as 3 years old "by inventing a disorder that describes these problematic children." DMDD is "a diagnosis that takes you into areas of judgment that many people are uncomfortable with," such as deciding whether outbursts by children are "grossly out of proportion" to the situation, Dr. Goodwin said. "It’s specific to the United States, and I think the rest of the world has difficulty with this. You’ve added another diagnosis that’s carved out of normal childhood experience. This is the difficulty for people with the perspective that all diagnoses are bad labels."

But Dr. Goodwin also noted that the DSM-5 "set the bar high" when designing the diagnosis. "U.S. psychiatrists see this as a way to stop the pathologizing of normal life" by creating a high threshold for diagnosis that is rarely met.

Dr. Goodwin also stressed that psychiatric diagnoses are not inherently bad for patients. Research findings, including work he collaborated on, showed that patients generally welcome a diagnosis and don’t feel stigmatized by it.

"Diagnoses are useful, because they give patients a starting point for understanding their problems and give clinicians a starting point for understanding" the best way to manage each patient, he said. "What patients want is an explanation of their situation."

A second speaker at the press conference, Dr. Celso Arango, head of child and adolescent psychiatry at a university hospital in Madrid and president-elect of ECNP, offered his own take on diagnosing psychiatric disorders in children that indirectly added another dimension to questions about DMDD’s validity and role.

Although psychiatric disorders are usually first diagnosed in adults, "they start much earlier. More than 70% of mental illnesses present first symptoms during childhood," said Dr. Arango. "The earlier we intervene, the lower the risk of a more severe disorder." He cited recent study results documenting the cost effectiveness of early intervention in children diagnosed with psychosis.

The DMDD diagnosis "may or may not be useful. If you count kids with this new diagnosis and find that it’s useful, that it’s a precursor for later problems, and is something we need to take seriously and treat, then it may be a prelude to successful intervention," Dr. Goodwin said.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

Some elements of the DSM-5, released nearly 6 months ago now, follow a tricky path between giving the psychiatric community useful, new diagnostic tools and pathologizing what is part of the normal range of human behavior, but despite that, the manual seems to generally succeed in "better classifying the patients who come to psychiatrists," said Dr. Guy Goodwin, head of the psychiatry department at the University of Oxford (England).

Dr. Goodwin spoke in an unusual press conference during the annual Congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology (ECNP) in Barcelona in October. The topic was the still somewhat new Fifth Edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), and the role of diagnosis in psychiatry, which did not link to any report or talk at the meeting. The press conference seemed mostly a way for Dr. Goodwin, who became president of the ECNP during the meeting, and two other participants to give their thoughts on the DSM-5 and shifting views on psychiatric diagnoses, especially in children.

Dr. Goodwin ultimately called himself "sort of pro-DSM-5" and said that the key test of whether the diagnostic changes made by the DSM-5 were a step forward or not will come with time, as psychiatrists determine whether following the DSM-5 results in better diagnosis and patient care.

He offered an example of what he said some have characterized as a disorder "invented" by the DSM-5, disruptive mood dysregulation disorder (DMDD). It was an interesting choice for Dr. Goodwin to highlight, as he is not a pediatric specialist, although he noted it ties to his practice of treating patients with bipolar disorder because DMDD was designed as a replacement diagnosis for many children previously diagnosed with bipolar disorder. DMDD also has a history of controversy going back several years to when the DSM-5 writing group struggled with how to deal with what many saw as overdiagnosis of bipolar disease in children.

The DSM-5 "is trying to stop" the diagnosis of bipolar disease by U.S. psychiatrists in children as young as 3 years old "by inventing a disorder that describes these problematic children." DMDD is "a diagnosis that takes you into areas of judgment that many people are uncomfortable with," such as deciding whether outbursts by children are "grossly out of proportion" to the situation, Dr. Goodwin said. "It’s specific to the United States, and I think the rest of the world has difficulty with this. You’ve added another diagnosis that’s carved out of normal childhood experience. This is the difficulty for people with the perspective that all diagnoses are bad labels."

But Dr. Goodwin also noted that the DSM-5 "set the bar high" when designing the diagnosis. "U.S. psychiatrists see this as a way to stop the pathologizing of normal life" by creating a high threshold for diagnosis that is rarely met.

Dr. Goodwin also stressed that psychiatric diagnoses are not inherently bad for patients. Research findings, including work he collaborated on, showed that patients generally welcome a diagnosis and don’t feel stigmatized by it.

"Diagnoses are useful, because they give patients a starting point for understanding their problems and give clinicians a starting point for understanding" the best way to manage each patient, he said. "What patients want is an explanation of their situation."

A second speaker at the press conference, Dr. Celso Arango, head of child and adolescent psychiatry at a university hospital in Madrid and president-elect of ECNP, offered his own take on diagnosing psychiatric disorders in children that indirectly added another dimension to questions about DMDD’s validity and role.

Although psychiatric disorders are usually first diagnosed in adults, "they start much earlier. More than 70% of mental illnesses present first symptoms during childhood," said Dr. Arango. "The earlier we intervene, the lower the risk of a more severe disorder." He cited recent study results documenting the cost effectiveness of early intervention in children diagnosed with psychosis.

The DMDD diagnosis "may or may not be useful. If you count kids with this new diagnosis and find that it’s useful, that it’s a precursor for later problems, and is something we need to take seriously and treat, then it may be a prelude to successful intervention," Dr. Goodwin said.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

Some elements of the DSM-5, released nearly 6 months ago now, follow a tricky path between giving the psychiatric community useful, new diagnostic tools and pathologizing what is part of the normal range of human behavior, but despite that, the manual seems to generally succeed in "better classifying the patients who come to psychiatrists," said Dr. Guy Goodwin, head of the psychiatry department at the University of Oxford (England).

Dr. Goodwin spoke in an unusual press conference during the annual Congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology (ECNP) in Barcelona in October. The topic was the still somewhat new Fifth Edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), and the role of diagnosis in psychiatry, which did not link to any report or talk at the meeting. The press conference seemed mostly a way for Dr. Goodwin, who became president of the ECNP during the meeting, and two other participants to give their thoughts on the DSM-5 and shifting views on psychiatric diagnoses, especially in children.

Dr. Goodwin ultimately called himself "sort of pro-DSM-5" and said that the key test of whether the diagnostic changes made by the DSM-5 were a step forward or not will come with time, as psychiatrists determine whether following the DSM-5 results in better diagnosis and patient care.

He offered an example of what he said some have characterized as a disorder "invented" by the DSM-5, disruptive mood dysregulation disorder (DMDD). It was an interesting choice for Dr. Goodwin to highlight, as he is not a pediatric specialist, although he noted it ties to his practice of treating patients with bipolar disorder because DMDD was designed as a replacement diagnosis for many children previously diagnosed with bipolar disorder. DMDD also has a history of controversy going back several years to when the DSM-5 writing group struggled with how to deal with what many saw as overdiagnosis of bipolar disease in children.

The DSM-5 "is trying to stop" the diagnosis of bipolar disease by U.S. psychiatrists in children as young as 3 years old "by inventing a disorder that describes these problematic children." DMDD is "a diagnosis that takes you into areas of judgment that many people are uncomfortable with," such as deciding whether outbursts by children are "grossly out of proportion" to the situation, Dr. Goodwin said. "It’s specific to the United States, and I think the rest of the world has difficulty with this. You’ve added another diagnosis that’s carved out of normal childhood experience. This is the difficulty for people with the perspective that all diagnoses are bad labels."

But Dr. Goodwin also noted that the DSM-5 "set the bar high" when designing the diagnosis. "U.S. psychiatrists see this as a way to stop the pathologizing of normal life" by creating a high threshold for diagnosis that is rarely met.

Dr. Goodwin also stressed that psychiatric diagnoses are not inherently bad for patients. Research findings, including work he collaborated on, showed that patients generally welcome a diagnosis and don’t feel stigmatized by it.

"Diagnoses are useful, because they give patients a starting point for understanding their problems and give clinicians a starting point for understanding" the best way to manage each patient, he said. "What patients want is an explanation of their situation."

A second speaker at the press conference, Dr. Celso Arango, head of child and adolescent psychiatry at a university hospital in Madrid and president-elect of ECNP, offered his own take on diagnosing psychiatric disorders in children that indirectly added another dimension to questions about DMDD’s validity and role.

Although psychiatric disorders are usually first diagnosed in adults, "they start much earlier. More than 70% of mental illnesses present first symptoms during childhood," said Dr. Arango. "The earlier we intervene, the lower the risk of a more severe disorder." He cited recent study results documenting the cost effectiveness of early intervention in children diagnosed with psychosis.

The DMDD diagnosis "may or may not be useful. If you count kids with this new diagnosis and find that it’s useful, that it’s a precursor for later problems, and is something we need to take seriously and treat, then it may be a prelude to successful intervention," Dr. Goodwin said.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

NMDA blocker lanicemine safely reduces depression

BARCELONA – Lanicemine, a new drug active in the glutamate neurotransmitter system, showed safety and efficacy for treating major depressive disorder during 3 weeks of treatment in a multicenter, U.S. phase II study with 152 patients.

In addition, 3 weeks of lanicemine treatment did not result in any marked psychomimetic effects such as those produced by ketamine, an anesthetic and related drug that first showed clinical antidepressant effects more than a decade ago and led to lanicemine’s testing, Dr. Gerard Sanacora said at the annual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology.

With the new lanicemine results, "I think we’re getting closer to a proof of concept that an NMDA [N-methyl-D-aspartate] receptor antagonist could be useful for development of antidepressant drugs," said Dr. Sanacora, professor of psychiatry and director of the depression research program at Yale University in New Haven, Conn.

"The results are encouraging. The study adds a lot" to addressing whether treatments targeted at the NMDA receptor can help patients with mood disorder, he said in an interview.

The study enrolled 152 patients diagnosed with major depressive disorder and poor responses to at least two antidepressants at 30 U.S. centers. While patients remained on their entry drugs, the researchers administered 100 or 150 mg lanicemine or placebo as an intravenous infusion three times a week for 3 weeks. At 3 weeks, the change from baseline in total Montgomery Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) score, the primary endpoint, was about a 13-point decline with either dosage of lanicemine and a decline of about 8 points with placebo, a 5-point increased reduction with either lanicemine dosage that was statistically significant for each dosage.

The 100-mg dosage showed more consistent efficacy than the higher dosage. The 100-mg dosage produced significantly greater reductions from baseline, compared with placebo after 2 weeks on treatment, and also at 4 and 5 weeks after treatment began, when patients no longer received infusions. The higher lanicemine dosage did not show significant effects compared with placebo at these other time points.

Lanicemine treatment, especially the 100-mg dosage, also showed efficacy by several secondary measures. For example, the proportion of patients who recorded a clinical global impression of much improved or very much improved was 65% with the 100-mg dosage at weeks 3, 4, and 5 after treatment began, significantly better than the 25%-30% rates at the same time points in the placebo group. Dr. Sanacora and his associates also published their results online (Mol. Psychiatry 2013 [doi:10.1038/mp.2013.130]).

During the study, neither lanicemine dosage produced any clinically meaningful difference compared with placebo for dissociative symptoms, and lanicemine was generally well tolerated. The most common adverse effect was dizziness around the time of infusion, which occurred in a third to half of the lanicemine patients, compared with 12% of those on placebo. Lanicemine "looked dramatically different from ketamine," Dr. Sanacora said.

He also downplayed the barrier that treatment by infusion presents. "There is such an unmet need" for patients with severe depression who fail to respond to existing drugs that infusion is not a major issue, he said. But "several companies are trying to develop novel formulations of NMDA receptor–targeted drugs" that might be active orally or intranasally.

The study was funded by AstraZeneca, the company developing lanicemine. Dr. Sanacora said he has been a consultant to and has received research support from AstraZeneca and several other drug companies. Some of Dr. Sanacora’s associates on this study were AstraZeneca employees.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

BARCELONA – Lanicemine, a new drug active in the glutamate neurotransmitter system, showed safety and efficacy for treating major depressive disorder during 3 weeks of treatment in a multicenter, U.S. phase II study with 152 patients.

In addition, 3 weeks of lanicemine treatment did not result in any marked psychomimetic effects such as those produced by ketamine, an anesthetic and related drug that first showed clinical antidepressant effects more than a decade ago and led to lanicemine’s testing, Dr. Gerard Sanacora said at the annual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology.

With the new lanicemine results, "I think we’re getting closer to a proof of concept that an NMDA [N-methyl-D-aspartate] receptor antagonist could be useful for development of antidepressant drugs," said Dr. Sanacora, professor of psychiatry and director of the depression research program at Yale University in New Haven, Conn.

"The results are encouraging. The study adds a lot" to addressing whether treatments targeted at the NMDA receptor can help patients with mood disorder, he said in an interview.

The study enrolled 152 patients diagnosed with major depressive disorder and poor responses to at least two antidepressants at 30 U.S. centers. While patients remained on their entry drugs, the researchers administered 100 or 150 mg lanicemine or placebo as an intravenous infusion three times a week for 3 weeks. At 3 weeks, the change from baseline in total Montgomery Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) score, the primary endpoint, was about a 13-point decline with either dosage of lanicemine and a decline of about 8 points with placebo, a 5-point increased reduction with either lanicemine dosage that was statistically significant for each dosage.

The 100-mg dosage showed more consistent efficacy than the higher dosage. The 100-mg dosage produced significantly greater reductions from baseline, compared with placebo after 2 weeks on treatment, and also at 4 and 5 weeks after treatment began, when patients no longer received infusions. The higher lanicemine dosage did not show significant effects compared with placebo at these other time points.

Lanicemine treatment, especially the 100-mg dosage, also showed efficacy by several secondary measures. For example, the proportion of patients who recorded a clinical global impression of much improved or very much improved was 65% with the 100-mg dosage at weeks 3, 4, and 5 after treatment began, significantly better than the 25%-30% rates at the same time points in the placebo group. Dr. Sanacora and his associates also published their results online (Mol. Psychiatry 2013 [doi:10.1038/mp.2013.130]).

During the study, neither lanicemine dosage produced any clinically meaningful difference compared with placebo for dissociative symptoms, and lanicemine was generally well tolerated. The most common adverse effect was dizziness around the time of infusion, which occurred in a third to half of the lanicemine patients, compared with 12% of those on placebo. Lanicemine "looked dramatically different from ketamine," Dr. Sanacora said.

He also downplayed the barrier that treatment by infusion presents. "There is such an unmet need" for patients with severe depression who fail to respond to existing drugs that infusion is not a major issue, he said. But "several companies are trying to develop novel formulations of NMDA receptor–targeted drugs" that might be active orally or intranasally.

The study was funded by AstraZeneca, the company developing lanicemine. Dr. Sanacora said he has been a consultant to and has received research support from AstraZeneca and several other drug companies. Some of Dr. Sanacora’s associates on this study were AstraZeneca employees.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

BARCELONA – Lanicemine, a new drug active in the glutamate neurotransmitter system, showed safety and efficacy for treating major depressive disorder during 3 weeks of treatment in a multicenter, U.S. phase II study with 152 patients.

In addition, 3 weeks of lanicemine treatment did not result in any marked psychomimetic effects such as those produced by ketamine, an anesthetic and related drug that first showed clinical antidepressant effects more than a decade ago and led to lanicemine’s testing, Dr. Gerard Sanacora said at the annual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology.

With the new lanicemine results, "I think we’re getting closer to a proof of concept that an NMDA [N-methyl-D-aspartate] receptor antagonist could be useful for development of antidepressant drugs," said Dr. Sanacora, professor of psychiatry and director of the depression research program at Yale University in New Haven, Conn.

"The results are encouraging. The study adds a lot" to addressing whether treatments targeted at the NMDA receptor can help patients with mood disorder, he said in an interview.

The study enrolled 152 patients diagnosed with major depressive disorder and poor responses to at least two antidepressants at 30 U.S. centers. While patients remained on their entry drugs, the researchers administered 100 or 150 mg lanicemine or placebo as an intravenous infusion three times a week for 3 weeks. At 3 weeks, the change from baseline in total Montgomery Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) score, the primary endpoint, was about a 13-point decline with either dosage of lanicemine and a decline of about 8 points with placebo, a 5-point increased reduction with either lanicemine dosage that was statistically significant for each dosage.

The 100-mg dosage showed more consistent efficacy than the higher dosage. The 100-mg dosage produced significantly greater reductions from baseline, compared with placebo after 2 weeks on treatment, and also at 4 and 5 weeks after treatment began, when patients no longer received infusions. The higher lanicemine dosage did not show significant effects compared with placebo at these other time points.

Lanicemine treatment, especially the 100-mg dosage, also showed efficacy by several secondary measures. For example, the proportion of patients who recorded a clinical global impression of much improved or very much improved was 65% with the 100-mg dosage at weeks 3, 4, and 5 after treatment began, significantly better than the 25%-30% rates at the same time points in the placebo group. Dr. Sanacora and his associates also published their results online (Mol. Psychiatry 2013 [doi:10.1038/mp.2013.130]).

During the study, neither lanicemine dosage produced any clinically meaningful difference compared with placebo for dissociative symptoms, and lanicemine was generally well tolerated. The most common adverse effect was dizziness around the time of infusion, which occurred in a third to half of the lanicemine patients, compared with 12% of those on placebo. Lanicemine "looked dramatically different from ketamine," Dr. Sanacora said.

He also downplayed the barrier that treatment by infusion presents. "There is such an unmet need" for patients with severe depression who fail to respond to existing drugs that infusion is not a major issue, he said. But "several companies are trying to develop novel formulations of NMDA receptor–targeted drugs" that might be active orally or intranasally.

The study was funded by AstraZeneca, the company developing lanicemine. Dr. Sanacora said he has been a consultant to and has received research support from AstraZeneca and several other drug companies. Some of Dr. Sanacora’s associates on this study were AstraZeneca employees.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AT THE ANNUAL ENCP CONGRESS

Major finding: Treatment with lanicemine produced an average 5-point greater reduction in depression score from baseline, compared with placebo.

Data source: A phase II study that randomized 152 patients with major depressive disorder to either of two lanicemine dosages or placebo for 3 weeks at 30 U.S. centers.

Disclosures: The study was funded by AstraZeneca, the company developing lanicemine. Dr. Sanacora said he has been a consultant to and has received research support from AstraZeneca and several other drug companies. Some of Dr. Sanacora’s associates in the study were AstraZeneca employees.

Atomoxetine may lead to improved driving for adults with ADHD

BARCELONA – Adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder who undergo treatment for their most intrusive symptoms also might benefit by having their driving improve.

Most adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) do not seek treatment because of their driving; most usually want their disorder to intrude less into their work life, education, or relationships. However, a poor driving record is common among ADHD patients. In addition, driving performance improved significantly during treatment with atomoxetine in a controlled study with 43 patients.

These are the first study results to show that atomoxetine treatment can improve driving performance in real traffic in adults with ADHD, Dr. Esther Sobanski said at the annual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology.

Atomoxetine, which is approved in the United States and in Europe for treating ADHD in adults and children, also has shown efficacy in controlled studies for treating patients with ADHD and social anxiety disorder (Depress. Anxiety 2009;26:212-21), and partial efficacy for patients with ADHD and alcohol-use disorder (Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;96:145-54). The drug probably is similar in efficacy and safety to methylphenidate but without methylphenidate’s long clinical track record, Dr. Sobanski said.

"We are trying to figure out whom to treat with atomoxetine and whom to treat with methylphenidate," she said in an interview. "There is no evidence base now, so we are trying to figure out" whether certain types of ADHD patients respond better to one drug or the other.

The study enrolled adults diagnosed with ADHD at an outpatient mental health clinic in Mannheim, Germany, who were 18-50 years old and had a valid German driver’s license. After a 4-week tapering-dosage washout of entry medications, patients underwent baseline testing and then randomized to 18 mg/day atomoxetine or placebo. The atomoxetine dosage gradually ramped up over 4 weeks to 80 mg/day, which continued for 8 weeks until follow-up testing occurred. Enrolled patients averaged about 35 years old.

After 8 weeks of full treatment, the 22 atomoxetine patients showed statistically significant reductions in their average rates of false reactions for three different measures: orientation to traffic, attention to traffic, and driver skills. For each of these, the rate of false reactions fell by more than half, compared with the baseline rate, reported Dr. Sobanski, a psychiatrist at the Central Institute of Mental Health in Mannheim. False reactions by a fourth measure, risk-related self-control, also fell by more than half, but this trend was not statistically significant. In contrast, the placebo group showed virtually no change from baseline by all four measures. The rate of "critical traffic situations" recorded by participants in their daily diaries also fell by about half in the atomoxetine patients but not in the placebo group. Dr. Sobanski and her associates recently published their findings (Eur. Psychiatry 2013;28:379-85).

Prior research documented that adults with ADHD have three to four times more traffic accidents and double the traffic violations (especially speeding) than does the general adult population, Dr. Sobanski said. But driving problems usually are not what bring patients to treatment. "Most patients with ADHD get interventions for other reasons, but our findings show that their driving benefits, too."

The study was funded by Eli Lilly, which markets atomoxetine (Strattera). Dr. Sobanski said she has been an adviser to and received support from Eli Lilly and also from Medice, Shire, and Novartis.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

BARCELONA – Adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder who undergo treatment for their most intrusive symptoms also might benefit by having their driving improve.

Most adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) do not seek treatment because of their driving; most usually want their disorder to intrude less into their work life, education, or relationships. However, a poor driving record is common among ADHD patients. In addition, driving performance improved significantly during treatment with atomoxetine in a controlled study with 43 patients.

These are the first study results to show that atomoxetine treatment can improve driving performance in real traffic in adults with ADHD, Dr. Esther Sobanski said at the annual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology.

Atomoxetine, which is approved in the United States and in Europe for treating ADHD in adults and children, also has shown efficacy in controlled studies for treating patients with ADHD and social anxiety disorder (Depress. Anxiety 2009;26:212-21), and partial efficacy for patients with ADHD and alcohol-use disorder (Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;96:145-54). The drug probably is similar in efficacy and safety to methylphenidate but without methylphenidate’s long clinical track record, Dr. Sobanski said.

"We are trying to figure out whom to treat with atomoxetine and whom to treat with methylphenidate," she said in an interview. "There is no evidence base now, so we are trying to figure out" whether certain types of ADHD patients respond better to one drug or the other.

The study enrolled adults diagnosed with ADHD at an outpatient mental health clinic in Mannheim, Germany, who were 18-50 years old and had a valid German driver’s license. After a 4-week tapering-dosage washout of entry medications, patients underwent baseline testing and then randomized to 18 mg/day atomoxetine or placebo. The atomoxetine dosage gradually ramped up over 4 weeks to 80 mg/day, which continued for 8 weeks until follow-up testing occurred. Enrolled patients averaged about 35 years old.

After 8 weeks of full treatment, the 22 atomoxetine patients showed statistically significant reductions in their average rates of false reactions for three different measures: orientation to traffic, attention to traffic, and driver skills. For each of these, the rate of false reactions fell by more than half, compared with the baseline rate, reported Dr. Sobanski, a psychiatrist at the Central Institute of Mental Health in Mannheim. False reactions by a fourth measure, risk-related self-control, also fell by more than half, but this trend was not statistically significant. In contrast, the placebo group showed virtually no change from baseline by all four measures. The rate of "critical traffic situations" recorded by participants in their daily diaries also fell by about half in the atomoxetine patients but not in the placebo group. Dr. Sobanski and her associates recently published their findings (Eur. Psychiatry 2013;28:379-85).

Prior research documented that adults with ADHD have three to four times more traffic accidents and double the traffic violations (especially speeding) than does the general adult population, Dr. Sobanski said. But driving problems usually are not what bring patients to treatment. "Most patients with ADHD get interventions for other reasons, but our findings show that their driving benefits, too."

The study was funded by Eli Lilly, which markets atomoxetine (Strattera). Dr. Sobanski said she has been an adviser to and received support from Eli Lilly and also from Medice, Shire, and Novartis.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

BARCELONA – Adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder who undergo treatment for their most intrusive symptoms also might benefit by having their driving improve.

Most adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) do not seek treatment because of their driving; most usually want their disorder to intrude less into their work life, education, or relationships. However, a poor driving record is common among ADHD patients. In addition, driving performance improved significantly during treatment with atomoxetine in a controlled study with 43 patients.

These are the first study results to show that atomoxetine treatment can improve driving performance in real traffic in adults with ADHD, Dr. Esther Sobanski said at the annual congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology.

Atomoxetine, which is approved in the United States and in Europe for treating ADHD in adults and children, also has shown efficacy in controlled studies for treating patients with ADHD and social anxiety disorder (Depress. Anxiety 2009;26:212-21), and partial efficacy for patients with ADHD and alcohol-use disorder (Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;96:145-54). The drug probably is similar in efficacy and safety to methylphenidate but without methylphenidate’s long clinical track record, Dr. Sobanski said.

"We are trying to figure out whom to treat with atomoxetine and whom to treat with methylphenidate," she said in an interview. "There is no evidence base now, so we are trying to figure out" whether certain types of ADHD patients respond better to one drug or the other.