User login

The Journal of Clinical Outcomes Management® is an independent, peer-reviewed journal offering evidence-based, practical information for improving the quality, safety, and value of health care.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

Lp(a) tied to more early CV events than familial hypercholesterolemia

Many more people are at risk for early cardiovascular events because of raised lipoprotein(a) levels than from having familial hypercholesterolemia (FH), a new study suggests.

The Danish study set out to try and establish a level of Lp(a) that would be associated with a cardiovascular risk similar to that seen with FH. As there are many different definitions of FH, results showed a large range of Lp(a) values that corresponded to risk levels of the different FH definitions.

However, if considering one of the broadest FH definitions (from MEDPED – Make Early Diagnoses, Prevent Early Deaths), which is the one most commonly used in the United States, results showed that the level of cardiovascular risk in patients with this definition of FH is similar to that associated with Lp(a) levels of around 70 mg/dL (0.7 g/L).

“While FH is fairly unusual, occurring in less than 1% of the population, levels of Lp(a) of 70 mg/dL or above are much more common, occurring in around 10% of the White population,” Børge Nordestgaard, MD, Copenhagen University Hospital, said in an interview. Around 20% of the Black population have such high levels, while levels in Hispanics are in between.

“Our results suggest that there will be many more individuals at risk of premature MI or cardiovascular death because of raised Lp(a) levels than because of FH,” added Dr. Nordestgaard, the senior author of the current study.

Dr. Nordestgaard explained that FH is well established to be a serious condition. “We consider FH to be the genetic disease that causes the most cases of early heart disease and early death worldwide.”

“But we know now that raised levels of Lp(a), which is also genetically determined, can also lead to an increased risk of cardiovascular events relatively early in life, and when you look into the numbers, it seems like high levels of Lp(a) could be more common than FH. We wanted to try and find the levels of Lp(a) that corresponded to similar cardiovascular risk as FH.”

The Danish study was published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

The authors note that the 2019 joint European Society of Cardiology and European Atherosclerosis Society guidelines suggested that an Lp(a) level greater than 180 mg/dL (0.8 g/L) may confer a lifetime risk for heart disease equivalent to the risk associated with heterozygous FH, but they point out that this value was speculative and not based on a direct comparison of risk associated with the two conditions in the same population.

For their study, Dr. Nordestgaard and colleagues analyzed information from a large database of the Danish population, the Copenhagen General Population Study, including 69,644 individuals for whom data on FH and Lp(a) levels were available. As these conditions are genetically determined, and the study held records on individuals going back several decades, the researchers were able to analyze event rates over a median follow up time of 42 years. During this time, there were 4,166 cases of myocardial infarction and 11,464 cases of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD).

Results showed that Lp(a) levels associated with MI risk equivalent to that of clinical FH ranged from 67 to 402 mg/dL depending on the definition used for FH. The Lp(a) level corresponding to the MI risk of genetically determined FH was 180 mg/dL.

In terms of risk of ASCVD events, the levels of Lp(a) corresponding to the risk associated with clinical FH ranged from 130 to 391 mg/dL, and the Lp(a) level corresponding to the ASCVD risk of genetically determined FH was 175 mg/dL.

“All these different definitions of FH may cause some confusion, but basically we are saying that if an individual is found to have an Lp(a) above 70 mg/dL, then they have a similar level of cardiovascular risk as that associated with the broadest definition of FH, and they should be taken as seriously as a patient diagnosed with FH,” Dr. Nordestgaard said.

He estimated that these individuals have approximately a doubling of cardiovascular risk, compared with the general population, and risk increases further with rising Lp(a) levels.

The researchers also found that if an individual has both FH and raised Lp(a) they are at very high risk, as these two conditions are independent of each other.

Although a specific treatment for lowering Lp(a) levels is not yet available, Dr. Nordestgaard stresses that it is still worth identifying individuals with raised Lp(a) as efforts can be made to address other cardiovascular risk factors.

“We know raised Lp(a) increases cardiovascular risk, but there are also many other factors that likewise increase this risk, and they are all additive. So, it is very important that individuals with raised Lp(a) levels address these other risk factors,” he said. “These include stopping smoking, being at healthy weight, exercising regularly, eating a heart-healthy diet, and aggressive treatment of raised LDL, hypertension, and diabetes. All these things will lower their overall risk of cardiovascular disease.”

And there is the promise of new drugs to lower Lp(a) on the horizon, with several such products now in clinical development.

Dr. Nordestgaard also points out that as Lp(a) is genetically determined, cascade screening of close relatives of the individual with raised Lp(a) should also take place to detect others who may be at risk.

Although a level of Lp(a) of around 70 mg/dL confers similar cardiovascular risk than some definitions of FH, Dr. Nordestgaard says lower levels than this should also be a signal for concern.

“We usually say Lp(a) levels of 50 mg/dL are when we need to start to take this seriously. And it’s estimated that about 20% of the White population will have levels of 50 mg/dL or over and even more in the Black population,” he added.

‘Screen for both conditions’

In an accompanying editorial, Pamela Morris, MD, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston; Jagat Narula, MD, Icahn School of Medicine, New York; and Sotirios Tsimikas, MD, University of California, San Diego, say “the weight of evidence strongly supports that both genetic lipid disorders, elevated Lp(a) levels and FH, are causally associated with an increased risk of premature ASCVD and should be carefully considered in risk assessment and management for ASCVD risk reduction.”

Dr. Morris told this news organization that the current study found a very large range of Lp(a) levels that conferred a similar cardiovascular risk to FH, because of the many different definitions of FH in use.

“But this should not take away the importance of screening for raised Lp(a) levels,” she stressed.

“We know that increased Lp(a) levels signal a high risk of cardiovascular disease. A diagnosis of FH is also a high-risk condition,” she said. “Both are important, and we need to screen for both, but it is difficult to directly compare the two conditions because the different definitions of FH get in the way.”

Dr. Morris agrees with Dr. Nordestgaard that raised levels of Lp(a) may actually be more important for the population risk of cardiovascular disease than FH, as the prevalence of increased Lp(a) levels is higher.

“Because raised Lp(a) levels are more prevalent than confirmed FH, the risk to the population is greater,” she said.

Dr. Morris points out that cardiovascular risk starts to increase at Lp(a) levels of 30 mg/dL (75 nmol/L).

The editorialists recommend that “in addition to performing a lipid panel periodically according to evidence-based guidelines, measurement of Lp(a) levels should also be performed at least once in an individual’s lifetime for ASCVD risk assessment.”

They conclude that “it is vital to continue to raise awareness among clinicians and patients of these high-risk genetic lipid disorders. Our understanding of both disorders is rapidly expanding, and promising novel therapeutics may offer hope for prevention of cardiovascular disease in patients with elevated Lp(a) levels in the future.”

This work was supported by Copenhagen University Hospital – Herlev Gentofte, Denmark, and the Danish Beckett-Foundation. The Copenhagen General Population Study is supported by the Copenhagen County Foundation and Copenhagen University Hospital – Herlev Gentofte. Dr. Nordestgaard has been a consultant and a speaker for AstraZeneca, Sanofi, Regeneron, Akcea, Amgen, Kowa, Denka, Amarin, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Silence Therapeutics, Abbott, and Esperion.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Many more people are at risk for early cardiovascular events because of raised lipoprotein(a) levels than from having familial hypercholesterolemia (FH), a new study suggests.

The Danish study set out to try and establish a level of Lp(a) that would be associated with a cardiovascular risk similar to that seen with FH. As there are many different definitions of FH, results showed a large range of Lp(a) values that corresponded to risk levels of the different FH definitions.

However, if considering one of the broadest FH definitions (from MEDPED – Make Early Diagnoses, Prevent Early Deaths), which is the one most commonly used in the United States, results showed that the level of cardiovascular risk in patients with this definition of FH is similar to that associated with Lp(a) levels of around 70 mg/dL (0.7 g/L).

“While FH is fairly unusual, occurring in less than 1% of the population, levels of Lp(a) of 70 mg/dL or above are much more common, occurring in around 10% of the White population,” Børge Nordestgaard, MD, Copenhagen University Hospital, said in an interview. Around 20% of the Black population have such high levels, while levels in Hispanics are in between.

“Our results suggest that there will be many more individuals at risk of premature MI or cardiovascular death because of raised Lp(a) levels than because of FH,” added Dr. Nordestgaard, the senior author of the current study.

Dr. Nordestgaard explained that FH is well established to be a serious condition. “We consider FH to be the genetic disease that causes the most cases of early heart disease and early death worldwide.”

“But we know now that raised levels of Lp(a), which is also genetically determined, can also lead to an increased risk of cardiovascular events relatively early in life, and when you look into the numbers, it seems like high levels of Lp(a) could be more common than FH. We wanted to try and find the levels of Lp(a) that corresponded to similar cardiovascular risk as FH.”

The Danish study was published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

The authors note that the 2019 joint European Society of Cardiology and European Atherosclerosis Society guidelines suggested that an Lp(a) level greater than 180 mg/dL (0.8 g/L) may confer a lifetime risk for heart disease equivalent to the risk associated with heterozygous FH, but they point out that this value was speculative and not based on a direct comparison of risk associated with the two conditions in the same population.

For their study, Dr. Nordestgaard and colleagues analyzed information from a large database of the Danish population, the Copenhagen General Population Study, including 69,644 individuals for whom data on FH and Lp(a) levels were available. As these conditions are genetically determined, and the study held records on individuals going back several decades, the researchers were able to analyze event rates over a median follow up time of 42 years. During this time, there were 4,166 cases of myocardial infarction and 11,464 cases of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD).

Results showed that Lp(a) levels associated with MI risk equivalent to that of clinical FH ranged from 67 to 402 mg/dL depending on the definition used for FH. The Lp(a) level corresponding to the MI risk of genetically determined FH was 180 mg/dL.

In terms of risk of ASCVD events, the levels of Lp(a) corresponding to the risk associated with clinical FH ranged from 130 to 391 mg/dL, and the Lp(a) level corresponding to the ASCVD risk of genetically determined FH was 175 mg/dL.

“All these different definitions of FH may cause some confusion, but basically we are saying that if an individual is found to have an Lp(a) above 70 mg/dL, then they have a similar level of cardiovascular risk as that associated with the broadest definition of FH, and they should be taken as seriously as a patient diagnosed with FH,” Dr. Nordestgaard said.

He estimated that these individuals have approximately a doubling of cardiovascular risk, compared with the general population, and risk increases further with rising Lp(a) levels.

The researchers also found that if an individual has both FH and raised Lp(a) they are at very high risk, as these two conditions are independent of each other.

Although a specific treatment for lowering Lp(a) levels is not yet available, Dr. Nordestgaard stresses that it is still worth identifying individuals with raised Lp(a) as efforts can be made to address other cardiovascular risk factors.

“We know raised Lp(a) increases cardiovascular risk, but there are also many other factors that likewise increase this risk, and they are all additive. So, it is very important that individuals with raised Lp(a) levels address these other risk factors,” he said. “These include stopping smoking, being at healthy weight, exercising regularly, eating a heart-healthy diet, and aggressive treatment of raised LDL, hypertension, and diabetes. All these things will lower their overall risk of cardiovascular disease.”

And there is the promise of new drugs to lower Lp(a) on the horizon, with several such products now in clinical development.

Dr. Nordestgaard also points out that as Lp(a) is genetically determined, cascade screening of close relatives of the individual with raised Lp(a) should also take place to detect others who may be at risk.

Although a level of Lp(a) of around 70 mg/dL confers similar cardiovascular risk than some definitions of FH, Dr. Nordestgaard says lower levels than this should also be a signal for concern.

“We usually say Lp(a) levels of 50 mg/dL are when we need to start to take this seriously. And it’s estimated that about 20% of the White population will have levels of 50 mg/dL or over and even more in the Black population,” he added.

‘Screen for both conditions’

In an accompanying editorial, Pamela Morris, MD, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston; Jagat Narula, MD, Icahn School of Medicine, New York; and Sotirios Tsimikas, MD, University of California, San Diego, say “the weight of evidence strongly supports that both genetic lipid disorders, elevated Lp(a) levels and FH, are causally associated with an increased risk of premature ASCVD and should be carefully considered in risk assessment and management for ASCVD risk reduction.”

Dr. Morris told this news organization that the current study found a very large range of Lp(a) levels that conferred a similar cardiovascular risk to FH, because of the many different definitions of FH in use.

“But this should not take away the importance of screening for raised Lp(a) levels,” she stressed.

“We know that increased Lp(a) levels signal a high risk of cardiovascular disease. A diagnosis of FH is also a high-risk condition,” she said. “Both are important, and we need to screen for both, but it is difficult to directly compare the two conditions because the different definitions of FH get in the way.”

Dr. Morris agrees with Dr. Nordestgaard that raised levels of Lp(a) may actually be more important for the population risk of cardiovascular disease than FH, as the prevalence of increased Lp(a) levels is higher.

“Because raised Lp(a) levels are more prevalent than confirmed FH, the risk to the population is greater,” she said.

Dr. Morris points out that cardiovascular risk starts to increase at Lp(a) levels of 30 mg/dL (75 nmol/L).

The editorialists recommend that “in addition to performing a lipid panel periodically according to evidence-based guidelines, measurement of Lp(a) levels should also be performed at least once in an individual’s lifetime for ASCVD risk assessment.”

They conclude that “it is vital to continue to raise awareness among clinicians and patients of these high-risk genetic lipid disorders. Our understanding of both disorders is rapidly expanding, and promising novel therapeutics may offer hope for prevention of cardiovascular disease in patients with elevated Lp(a) levels in the future.”

This work was supported by Copenhagen University Hospital – Herlev Gentofte, Denmark, and the Danish Beckett-Foundation. The Copenhagen General Population Study is supported by the Copenhagen County Foundation and Copenhagen University Hospital – Herlev Gentofte. Dr. Nordestgaard has been a consultant and a speaker for AstraZeneca, Sanofi, Regeneron, Akcea, Amgen, Kowa, Denka, Amarin, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Silence Therapeutics, Abbott, and Esperion.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Many more people are at risk for early cardiovascular events because of raised lipoprotein(a) levels than from having familial hypercholesterolemia (FH), a new study suggests.

The Danish study set out to try and establish a level of Lp(a) that would be associated with a cardiovascular risk similar to that seen with FH. As there are many different definitions of FH, results showed a large range of Lp(a) values that corresponded to risk levels of the different FH definitions.

However, if considering one of the broadest FH definitions (from MEDPED – Make Early Diagnoses, Prevent Early Deaths), which is the one most commonly used in the United States, results showed that the level of cardiovascular risk in patients with this definition of FH is similar to that associated with Lp(a) levels of around 70 mg/dL (0.7 g/L).

“While FH is fairly unusual, occurring in less than 1% of the population, levels of Lp(a) of 70 mg/dL or above are much more common, occurring in around 10% of the White population,” Børge Nordestgaard, MD, Copenhagen University Hospital, said in an interview. Around 20% of the Black population have such high levels, while levels in Hispanics are in between.

“Our results suggest that there will be many more individuals at risk of premature MI or cardiovascular death because of raised Lp(a) levels than because of FH,” added Dr. Nordestgaard, the senior author of the current study.

Dr. Nordestgaard explained that FH is well established to be a serious condition. “We consider FH to be the genetic disease that causes the most cases of early heart disease and early death worldwide.”

“But we know now that raised levels of Lp(a), which is also genetically determined, can also lead to an increased risk of cardiovascular events relatively early in life, and when you look into the numbers, it seems like high levels of Lp(a) could be more common than FH. We wanted to try and find the levels of Lp(a) that corresponded to similar cardiovascular risk as FH.”

The Danish study was published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

The authors note that the 2019 joint European Society of Cardiology and European Atherosclerosis Society guidelines suggested that an Lp(a) level greater than 180 mg/dL (0.8 g/L) may confer a lifetime risk for heart disease equivalent to the risk associated with heterozygous FH, but they point out that this value was speculative and not based on a direct comparison of risk associated with the two conditions in the same population.

For their study, Dr. Nordestgaard and colleagues analyzed information from a large database of the Danish population, the Copenhagen General Population Study, including 69,644 individuals for whom data on FH and Lp(a) levels were available. As these conditions are genetically determined, and the study held records on individuals going back several decades, the researchers were able to analyze event rates over a median follow up time of 42 years. During this time, there were 4,166 cases of myocardial infarction and 11,464 cases of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD).

Results showed that Lp(a) levels associated with MI risk equivalent to that of clinical FH ranged from 67 to 402 mg/dL depending on the definition used for FH. The Lp(a) level corresponding to the MI risk of genetically determined FH was 180 mg/dL.

In terms of risk of ASCVD events, the levels of Lp(a) corresponding to the risk associated with clinical FH ranged from 130 to 391 mg/dL, and the Lp(a) level corresponding to the ASCVD risk of genetically determined FH was 175 mg/dL.

“All these different definitions of FH may cause some confusion, but basically we are saying that if an individual is found to have an Lp(a) above 70 mg/dL, then they have a similar level of cardiovascular risk as that associated with the broadest definition of FH, and they should be taken as seriously as a patient diagnosed with FH,” Dr. Nordestgaard said.

He estimated that these individuals have approximately a doubling of cardiovascular risk, compared with the general population, and risk increases further with rising Lp(a) levels.

The researchers also found that if an individual has both FH and raised Lp(a) they are at very high risk, as these two conditions are independent of each other.

Although a specific treatment for lowering Lp(a) levels is not yet available, Dr. Nordestgaard stresses that it is still worth identifying individuals with raised Lp(a) as efforts can be made to address other cardiovascular risk factors.

“We know raised Lp(a) increases cardiovascular risk, but there are also many other factors that likewise increase this risk, and they are all additive. So, it is very important that individuals with raised Lp(a) levels address these other risk factors,” he said. “These include stopping smoking, being at healthy weight, exercising regularly, eating a heart-healthy diet, and aggressive treatment of raised LDL, hypertension, and diabetes. All these things will lower their overall risk of cardiovascular disease.”

And there is the promise of new drugs to lower Lp(a) on the horizon, with several such products now in clinical development.

Dr. Nordestgaard also points out that as Lp(a) is genetically determined, cascade screening of close relatives of the individual with raised Lp(a) should also take place to detect others who may be at risk.

Although a level of Lp(a) of around 70 mg/dL confers similar cardiovascular risk than some definitions of FH, Dr. Nordestgaard says lower levels than this should also be a signal for concern.

“We usually say Lp(a) levels of 50 mg/dL are when we need to start to take this seriously. And it’s estimated that about 20% of the White population will have levels of 50 mg/dL or over and even more in the Black population,” he added.

‘Screen for both conditions’

In an accompanying editorial, Pamela Morris, MD, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston; Jagat Narula, MD, Icahn School of Medicine, New York; and Sotirios Tsimikas, MD, University of California, San Diego, say “the weight of evidence strongly supports that both genetic lipid disorders, elevated Lp(a) levels and FH, are causally associated with an increased risk of premature ASCVD and should be carefully considered in risk assessment and management for ASCVD risk reduction.”

Dr. Morris told this news organization that the current study found a very large range of Lp(a) levels that conferred a similar cardiovascular risk to FH, because of the many different definitions of FH in use.

“But this should not take away the importance of screening for raised Lp(a) levels,” she stressed.

“We know that increased Lp(a) levels signal a high risk of cardiovascular disease. A diagnosis of FH is also a high-risk condition,” she said. “Both are important, and we need to screen for both, but it is difficult to directly compare the two conditions because the different definitions of FH get in the way.”

Dr. Morris agrees with Dr. Nordestgaard that raised levels of Lp(a) may actually be more important for the population risk of cardiovascular disease than FH, as the prevalence of increased Lp(a) levels is higher.

“Because raised Lp(a) levels are more prevalent than confirmed FH, the risk to the population is greater,” she said.

Dr. Morris points out that cardiovascular risk starts to increase at Lp(a) levels of 30 mg/dL (75 nmol/L).

The editorialists recommend that “in addition to performing a lipid panel periodically according to evidence-based guidelines, measurement of Lp(a) levels should also be performed at least once in an individual’s lifetime for ASCVD risk assessment.”

They conclude that “it is vital to continue to raise awareness among clinicians and patients of these high-risk genetic lipid disorders. Our understanding of both disorders is rapidly expanding, and promising novel therapeutics may offer hope for prevention of cardiovascular disease in patients with elevated Lp(a) levels in the future.”

This work was supported by Copenhagen University Hospital – Herlev Gentofte, Denmark, and the Danish Beckett-Foundation. The Copenhagen General Population Study is supported by the Copenhagen County Foundation and Copenhagen University Hospital – Herlev Gentofte. Dr. Nordestgaard has been a consultant and a speaker for AstraZeneca, Sanofi, Regeneron, Akcea, Amgen, Kowa, Denka, Amarin, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Silence Therapeutics, Abbott, and Esperion.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

‘Modest’ benefit for lecanemab in Alzheimer’s disease, but adverse events are common

SAN FRANCISCO –

In the CLARITY AD trial, adverse events (AEs) were common compared with placebo, including amyloid-related edema and effusions; and a recent news report linked a second death to the drug.

Moving forward, “longer trials are warranted to determine the efficacy and safety of lecanemab in early Alzheimer’s disease,” wrote Christopher H. van Dyck, MD, Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and colleagues.

The full trial findings were presented at the Clinical Trials on Alzheimer’s Disease (CTAD) conference, with simultaneous publication on Nov. 29 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Complications in the field

The phase 3 trial of lecanemab has been closely watched in AD circles, especially considering positive early data released in September and reported by this news organization at that time.

The Food and Drug Administration is expected to make a decision about possible approval of the drug in January 2023. Only one other antiamyloid treatment, the highly controversial and expensive aducanumab (Aduhelm), is currently approved by the FDA.

For the new 18-month, randomized, double-blind CLARITY AD trial, researchers enrolled 1,795 patients aged 50-90 years (average age, 71 years) with early AD. All were randomly assigned to receive either a placebo (n = 898) or intravenous lecanemab, a humanized immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1) monoclonal antibody that selectively targets amyloid beta (A-beta) protofibrils, at 10 mg/kg of body weight every 2 weeks (n = 897).

The study ran from 2019 to 2021. The participants (52% women, 20% non-White) were recruited in North America, Europe, and Asia. Safety data included all participants, and the modified intention-to-treat group included 1,734 participants, with 859 receiving lecanemab and 875 receiving placebo.

The primary endpoint was the Clinical Dementia Rating–Sum of Boxes (CDR-SB). Scores from 0.5 to 6 are signs of early AD, according to the study. The mean baseline score for both groups was 3.2. The adjusted mean change at 18 months was 1.21 for lecanemab versus 1.66 for placebo (difference, –0.45; 95% confidence interval [CI], –0.67 to –0.23; P < .001).

As Dr. van Dyck noted in his presentation at the CTAD meting, this represents a 27% slowing of the decline in the lecanemab group.

The published findings do not speculate about how this difference would affect the day-to-day life of participants who took the drug, although it does refer to “modestly less decline” of cognition/function in the lecanemab group.

Other measurements that suggest cognitive improvements in the lecanemab group versus placebo include the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale–Cognitive Subscale score (mean difference, –1.44; 95% CI, –2.27 to –0.61), the Alzheimer’s Disease Composite Score (mean difference, –0.05; 95% CI, –.074 to –.027,), and the Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study–Activities of Daily Living Scale for Mild Cognitive Impairment score (mean difference, 2.0; 95% CI, 1.2-2.8; all, P < .001).

Overall, Dr. van Dyck said, “Lecanemab met the primary and secondary endpoints versus placebo at 18 months, with highly significant differences starting at 6 months.”

In a substudy of 698 participants, results showed that amyloid burden fell at a higher rate in the lecanemab group than in the placebo group (difference, –59.1 centiloids; 95% CI, –62.6 to –55.6).

“Lecanemab has high selectivity for soluble aggregated species of A-beta as compared with monomeric amyloid, with moderate selectivity for fibrillar amyloid; this profile is considered to target the most toxic pathologic amyloid species,” the researchers wrote.

Concerning AE data

With respect to AEs, deaths occurred in both groups (0.7% in those who took lecanemab and 0.8% in those who took the placebo). The researchers did not attribute any deaths to the drug. However, according to a report in the journal Science published Nov. 27, a 65-year-old woman who was taking the drug as part of a clinical trial “recently died from a massive brain hemorrhage that some researchers link to the drug.”

The woman, the second person “whose death was linked to lecanemab,” died after suffering a stroke. Researchers summarized a case report as saying that the drug “contributed to her brain hemorrhage after biweekly infusions of lecanemab inflamed and weakened the blood vessels.”

Eisai, which sponsored the new trial, told Science that “all the available safety information indicates that lecanemab therapy is not associated with an increased risk of death overall or from any specific cause.”

In a CTAD presentation, study coauthor Marwan Sabbagh, MD, Barrow Neurological Institute, Phoenix, said two hemorrhage-related deaths occurred in an open-label extension. One was in the context of a tissue plasminogen activator treatment for a stroke, which fits with the description of the case in the Science report. “Causality with lecanemab is a little difficult ...,” he said. “Patients on anticoagulation might need further consideration.”

In the CLARITY AD Trial, serious AEs occurred in 14% of the lecanemab group, leading to discontinuation 6.9% of the time, and in 11.3% of the placebo group, leading to discontinuation 2.9% of the time, the investigators reported.

They added that, in the lecanemab group, the most common AEs, defined as affecting more than 10% of participants, were infusion-related reactions (26.4% vs. 7.4% for placebo); amyloid-related imaging abnormalities with cerebral microhemorrhages, cerebral macrohemorrhages, or superficial siderosis (17.3% vs. 9%, respectively); amyloid-related imaging abnormalities with edema or effusions (12.6% vs. 1.7%); headache (11.1% vs. 8.1%); and falls (10.4% vs. 9.6%).

In addition, macrohemorrhage was reported in 0.6% of the lecanemab group and 0.1% of the placebo group.

Cautious optimism

In separate interviews, two Alzheimer’s specialists who weren’t involved in the study praised the trial and described the findings as “exciting.” But they also highlighted its limitations.

Alvaro Pascual-Leone, MD, PhD, professor of neurology at Harvard Medical School and chief medical officer of Linus Health, said the study represents impressive progress after 60-plus trials examining anti-amyloid monoclonal antibodies. “This is the first trial that shows a clinical benefit that can be measured,” he said.

However, it’s unclear whether the changes “are really going to make a difference in people’s lives,” he said. The drug is likely to be expensive, owing to the large investment needed for research, he added, and patients will have to undergo costly testing, such as PET scans and spinal taps.

Still, “this could be a valuable adjunct to the armamentarium we have,” which includes interventions such as lifestyle changes, he said.

Howard Fillit, MD, cofounder and chief science officer at the Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation, noted that the trial reached its primary and secondary endpoints and that the drug had what he called a “modest” effect on cognition.

However, the drugmaker will need to explore the adverse effects, he said, especially among patients with atrial fibrillation who take anticoagulants. And, he said, medicine is still far from the ultimate goal – fully reversing cognitive decline.

Michael Weiner, MD, president of the CTAD22 Scientific Committee, noted in a press release that there is “growing evidence” that some antiamyloid therapies, “especially lecanemab and donanemab” have shown promising results.

“Unfortunately, these treatments are also associated with abnormal differences seen in imaging, including brain swelling and bleeding in the brain,” said Dr. Weiner, professor of radiology, medicine, and neurology at the University of California, San Francisco.

“There is considerable controversy concerning the significance and impact of these findings, including whether or not governments and medical insurance will provide financial coverage for such treatments,” he added.

Rave reviews from the Alzheimer’s Association

In a statement, the Alzheimer’s Association raved about lecanemab and declared that the FDA should approve lecanemab on an accelerated basis. The study “confirms this treatment can meaningfully change the course of the disease for people in the earliest stages of Alzheimer’s disease ...” the association said, adding that “it could mean many months more of recognizing their spouse, children and grandchildren.”

The association, which is a staunch supporter of aducanumab, called on the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to cover the drug if the FDA approves it. The association’s statement did not address the drug’s potential high cost, the adverse effects, or the two reported deaths.

The trial was supported by Eisai (regulatory sponsor) with partial funding from Biogen. Dr. van Dyck reports having received research grants from Biogen, Eisai, Biohaven, Cerevel Therapeutics, Eli Lilly, Genentech, Janssen, Novartis, and UCB. He has been a consultant to Cerevel, Eisai, Ono Pharmaceutical, and Roche. Relevant financial relationships for the other investigators are fully listed in the original article.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

SAN FRANCISCO –

In the CLARITY AD trial, adverse events (AEs) were common compared with placebo, including amyloid-related edema and effusions; and a recent news report linked a second death to the drug.

Moving forward, “longer trials are warranted to determine the efficacy and safety of lecanemab in early Alzheimer’s disease,” wrote Christopher H. van Dyck, MD, Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and colleagues.

The full trial findings were presented at the Clinical Trials on Alzheimer’s Disease (CTAD) conference, with simultaneous publication on Nov. 29 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Complications in the field

The phase 3 trial of lecanemab has been closely watched in AD circles, especially considering positive early data released in September and reported by this news organization at that time.

The Food and Drug Administration is expected to make a decision about possible approval of the drug in January 2023. Only one other antiamyloid treatment, the highly controversial and expensive aducanumab (Aduhelm), is currently approved by the FDA.

For the new 18-month, randomized, double-blind CLARITY AD trial, researchers enrolled 1,795 patients aged 50-90 years (average age, 71 years) with early AD. All were randomly assigned to receive either a placebo (n = 898) or intravenous lecanemab, a humanized immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1) monoclonal antibody that selectively targets amyloid beta (A-beta) protofibrils, at 10 mg/kg of body weight every 2 weeks (n = 897).

The study ran from 2019 to 2021. The participants (52% women, 20% non-White) were recruited in North America, Europe, and Asia. Safety data included all participants, and the modified intention-to-treat group included 1,734 participants, with 859 receiving lecanemab and 875 receiving placebo.

The primary endpoint was the Clinical Dementia Rating–Sum of Boxes (CDR-SB). Scores from 0.5 to 6 are signs of early AD, according to the study. The mean baseline score for both groups was 3.2. The adjusted mean change at 18 months was 1.21 for lecanemab versus 1.66 for placebo (difference, –0.45; 95% confidence interval [CI], –0.67 to –0.23; P < .001).

As Dr. van Dyck noted in his presentation at the CTAD meting, this represents a 27% slowing of the decline in the lecanemab group.

The published findings do not speculate about how this difference would affect the day-to-day life of participants who took the drug, although it does refer to “modestly less decline” of cognition/function in the lecanemab group.

Other measurements that suggest cognitive improvements in the lecanemab group versus placebo include the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale–Cognitive Subscale score (mean difference, –1.44; 95% CI, –2.27 to –0.61), the Alzheimer’s Disease Composite Score (mean difference, –0.05; 95% CI, –.074 to –.027,), and the Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study–Activities of Daily Living Scale for Mild Cognitive Impairment score (mean difference, 2.0; 95% CI, 1.2-2.8; all, P < .001).

Overall, Dr. van Dyck said, “Lecanemab met the primary and secondary endpoints versus placebo at 18 months, with highly significant differences starting at 6 months.”

In a substudy of 698 participants, results showed that amyloid burden fell at a higher rate in the lecanemab group than in the placebo group (difference, –59.1 centiloids; 95% CI, –62.6 to –55.6).

“Lecanemab has high selectivity for soluble aggregated species of A-beta as compared with monomeric amyloid, with moderate selectivity for fibrillar amyloid; this profile is considered to target the most toxic pathologic amyloid species,” the researchers wrote.

Concerning AE data

With respect to AEs, deaths occurred in both groups (0.7% in those who took lecanemab and 0.8% in those who took the placebo). The researchers did not attribute any deaths to the drug. However, according to a report in the journal Science published Nov. 27, a 65-year-old woman who was taking the drug as part of a clinical trial “recently died from a massive brain hemorrhage that some researchers link to the drug.”

The woman, the second person “whose death was linked to lecanemab,” died after suffering a stroke. Researchers summarized a case report as saying that the drug “contributed to her brain hemorrhage after biweekly infusions of lecanemab inflamed and weakened the blood vessels.”

Eisai, which sponsored the new trial, told Science that “all the available safety information indicates that lecanemab therapy is not associated with an increased risk of death overall or from any specific cause.”

In a CTAD presentation, study coauthor Marwan Sabbagh, MD, Barrow Neurological Institute, Phoenix, said two hemorrhage-related deaths occurred in an open-label extension. One was in the context of a tissue plasminogen activator treatment for a stroke, which fits with the description of the case in the Science report. “Causality with lecanemab is a little difficult ...,” he said. “Patients on anticoagulation might need further consideration.”

In the CLARITY AD Trial, serious AEs occurred in 14% of the lecanemab group, leading to discontinuation 6.9% of the time, and in 11.3% of the placebo group, leading to discontinuation 2.9% of the time, the investigators reported.

They added that, in the lecanemab group, the most common AEs, defined as affecting more than 10% of participants, were infusion-related reactions (26.4% vs. 7.4% for placebo); amyloid-related imaging abnormalities with cerebral microhemorrhages, cerebral macrohemorrhages, or superficial siderosis (17.3% vs. 9%, respectively); amyloid-related imaging abnormalities with edema or effusions (12.6% vs. 1.7%); headache (11.1% vs. 8.1%); and falls (10.4% vs. 9.6%).

In addition, macrohemorrhage was reported in 0.6% of the lecanemab group and 0.1% of the placebo group.

Cautious optimism

In separate interviews, two Alzheimer’s specialists who weren’t involved in the study praised the trial and described the findings as “exciting.” But they also highlighted its limitations.

Alvaro Pascual-Leone, MD, PhD, professor of neurology at Harvard Medical School and chief medical officer of Linus Health, said the study represents impressive progress after 60-plus trials examining anti-amyloid monoclonal antibodies. “This is the first trial that shows a clinical benefit that can be measured,” he said.

However, it’s unclear whether the changes “are really going to make a difference in people’s lives,” he said. The drug is likely to be expensive, owing to the large investment needed for research, he added, and patients will have to undergo costly testing, such as PET scans and spinal taps.

Still, “this could be a valuable adjunct to the armamentarium we have,” which includes interventions such as lifestyle changes, he said.

Howard Fillit, MD, cofounder and chief science officer at the Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation, noted that the trial reached its primary and secondary endpoints and that the drug had what he called a “modest” effect on cognition.

However, the drugmaker will need to explore the adverse effects, he said, especially among patients with atrial fibrillation who take anticoagulants. And, he said, medicine is still far from the ultimate goal – fully reversing cognitive decline.

Michael Weiner, MD, president of the CTAD22 Scientific Committee, noted in a press release that there is “growing evidence” that some antiamyloid therapies, “especially lecanemab and donanemab” have shown promising results.

“Unfortunately, these treatments are also associated with abnormal differences seen in imaging, including brain swelling and bleeding in the brain,” said Dr. Weiner, professor of radiology, medicine, and neurology at the University of California, San Francisco.

“There is considerable controversy concerning the significance and impact of these findings, including whether or not governments and medical insurance will provide financial coverage for such treatments,” he added.

Rave reviews from the Alzheimer’s Association

In a statement, the Alzheimer’s Association raved about lecanemab and declared that the FDA should approve lecanemab on an accelerated basis. The study “confirms this treatment can meaningfully change the course of the disease for people in the earliest stages of Alzheimer’s disease ...” the association said, adding that “it could mean many months more of recognizing their spouse, children and grandchildren.”

The association, which is a staunch supporter of aducanumab, called on the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to cover the drug if the FDA approves it. The association’s statement did not address the drug’s potential high cost, the adverse effects, or the two reported deaths.

The trial was supported by Eisai (regulatory sponsor) with partial funding from Biogen. Dr. van Dyck reports having received research grants from Biogen, Eisai, Biohaven, Cerevel Therapeutics, Eli Lilly, Genentech, Janssen, Novartis, and UCB. He has been a consultant to Cerevel, Eisai, Ono Pharmaceutical, and Roche. Relevant financial relationships for the other investigators are fully listed in the original article.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

SAN FRANCISCO –

In the CLARITY AD trial, adverse events (AEs) were common compared with placebo, including amyloid-related edema and effusions; and a recent news report linked a second death to the drug.

Moving forward, “longer trials are warranted to determine the efficacy and safety of lecanemab in early Alzheimer’s disease,” wrote Christopher H. van Dyck, MD, Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and colleagues.

The full trial findings were presented at the Clinical Trials on Alzheimer’s Disease (CTAD) conference, with simultaneous publication on Nov. 29 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Complications in the field

The phase 3 trial of lecanemab has been closely watched in AD circles, especially considering positive early data released in September and reported by this news organization at that time.

The Food and Drug Administration is expected to make a decision about possible approval of the drug in January 2023. Only one other antiamyloid treatment, the highly controversial and expensive aducanumab (Aduhelm), is currently approved by the FDA.

For the new 18-month, randomized, double-blind CLARITY AD trial, researchers enrolled 1,795 patients aged 50-90 years (average age, 71 years) with early AD. All were randomly assigned to receive either a placebo (n = 898) or intravenous lecanemab, a humanized immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1) monoclonal antibody that selectively targets amyloid beta (A-beta) protofibrils, at 10 mg/kg of body weight every 2 weeks (n = 897).

The study ran from 2019 to 2021. The participants (52% women, 20% non-White) were recruited in North America, Europe, and Asia. Safety data included all participants, and the modified intention-to-treat group included 1,734 participants, with 859 receiving lecanemab and 875 receiving placebo.

The primary endpoint was the Clinical Dementia Rating–Sum of Boxes (CDR-SB). Scores from 0.5 to 6 are signs of early AD, according to the study. The mean baseline score for both groups was 3.2. The adjusted mean change at 18 months was 1.21 for lecanemab versus 1.66 for placebo (difference, –0.45; 95% confidence interval [CI], –0.67 to –0.23; P < .001).

As Dr. van Dyck noted in his presentation at the CTAD meting, this represents a 27% slowing of the decline in the lecanemab group.

The published findings do not speculate about how this difference would affect the day-to-day life of participants who took the drug, although it does refer to “modestly less decline” of cognition/function in the lecanemab group.

Other measurements that suggest cognitive improvements in the lecanemab group versus placebo include the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale–Cognitive Subscale score (mean difference, –1.44; 95% CI, –2.27 to –0.61), the Alzheimer’s Disease Composite Score (mean difference, –0.05; 95% CI, –.074 to –.027,), and the Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study–Activities of Daily Living Scale for Mild Cognitive Impairment score (mean difference, 2.0; 95% CI, 1.2-2.8; all, P < .001).

Overall, Dr. van Dyck said, “Lecanemab met the primary and secondary endpoints versus placebo at 18 months, with highly significant differences starting at 6 months.”

In a substudy of 698 participants, results showed that amyloid burden fell at a higher rate in the lecanemab group than in the placebo group (difference, –59.1 centiloids; 95% CI, –62.6 to –55.6).

“Lecanemab has high selectivity for soluble aggregated species of A-beta as compared with monomeric amyloid, with moderate selectivity for fibrillar amyloid; this profile is considered to target the most toxic pathologic amyloid species,” the researchers wrote.

Concerning AE data

With respect to AEs, deaths occurred in both groups (0.7% in those who took lecanemab and 0.8% in those who took the placebo). The researchers did not attribute any deaths to the drug. However, according to a report in the journal Science published Nov. 27, a 65-year-old woman who was taking the drug as part of a clinical trial “recently died from a massive brain hemorrhage that some researchers link to the drug.”

The woman, the second person “whose death was linked to lecanemab,” died after suffering a stroke. Researchers summarized a case report as saying that the drug “contributed to her brain hemorrhage after biweekly infusions of lecanemab inflamed and weakened the blood vessels.”

Eisai, which sponsored the new trial, told Science that “all the available safety information indicates that lecanemab therapy is not associated with an increased risk of death overall or from any specific cause.”

In a CTAD presentation, study coauthor Marwan Sabbagh, MD, Barrow Neurological Institute, Phoenix, said two hemorrhage-related deaths occurred in an open-label extension. One was in the context of a tissue plasminogen activator treatment for a stroke, which fits with the description of the case in the Science report. “Causality with lecanemab is a little difficult ...,” he said. “Patients on anticoagulation might need further consideration.”

In the CLARITY AD Trial, serious AEs occurred in 14% of the lecanemab group, leading to discontinuation 6.9% of the time, and in 11.3% of the placebo group, leading to discontinuation 2.9% of the time, the investigators reported.

They added that, in the lecanemab group, the most common AEs, defined as affecting more than 10% of participants, were infusion-related reactions (26.4% vs. 7.4% for placebo); amyloid-related imaging abnormalities with cerebral microhemorrhages, cerebral macrohemorrhages, or superficial siderosis (17.3% vs. 9%, respectively); amyloid-related imaging abnormalities with edema or effusions (12.6% vs. 1.7%); headache (11.1% vs. 8.1%); and falls (10.4% vs. 9.6%).

In addition, macrohemorrhage was reported in 0.6% of the lecanemab group and 0.1% of the placebo group.

Cautious optimism

In separate interviews, two Alzheimer’s specialists who weren’t involved in the study praised the trial and described the findings as “exciting.” But they also highlighted its limitations.

Alvaro Pascual-Leone, MD, PhD, professor of neurology at Harvard Medical School and chief medical officer of Linus Health, said the study represents impressive progress after 60-plus trials examining anti-amyloid monoclonal antibodies. “This is the first trial that shows a clinical benefit that can be measured,” he said.

However, it’s unclear whether the changes “are really going to make a difference in people’s lives,” he said. The drug is likely to be expensive, owing to the large investment needed for research, he added, and patients will have to undergo costly testing, such as PET scans and spinal taps.

Still, “this could be a valuable adjunct to the armamentarium we have,” which includes interventions such as lifestyle changes, he said.

Howard Fillit, MD, cofounder and chief science officer at the Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation, noted that the trial reached its primary and secondary endpoints and that the drug had what he called a “modest” effect on cognition.

However, the drugmaker will need to explore the adverse effects, he said, especially among patients with atrial fibrillation who take anticoagulants. And, he said, medicine is still far from the ultimate goal – fully reversing cognitive decline.

Michael Weiner, MD, president of the CTAD22 Scientific Committee, noted in a press release that there is “growing evidence” that some antiamyloid therapies, “especially lecanemab and donanemab” have shown promising results.

“Unfortunately, these treatments are also associated with abnormal differences seen in imaging, including brain swelling and bleeding in the brain,” said Dr. Weiner, professor of radiology, medicine, and neurology at the University of California, San Francisco.

“There is considerable controversy concerning the significance and impact of these findings, including whether or not governments and medical insurance will provide financial coverage for such treatments,” he added.

Rave reviews from the Alzheimer’s Association

In a statement, the Alzheimer’s Association raved about lecanemab and declared that the FDA should approve lecanemab on an accelerated basis. The study “confirms this treatment can meaningfully change the course of the disease for people in the earliest stages of Alzheimer’s disease ...” the association said, adding that “it could mean many months more of recognizing their spouse, children and grandchildren.”

The association, which is a staunch supporter of aducanumab, called on the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to cover the drug if the FDA approves it. The association’s statement did not address the drug’s potential high cost, the adverse effects, or the two reported deaths.

The trial was supported by Eisai (regulatory sponsor) with partial funding from Biogen. Dr. van Dyck reports having received research grants from Biogen, Eisai, Biohaven, Cerevel Therapeutics, Eli Lilly, Genentech, Janssen, Novartis, and UCB. He has been a consultant to Cerevel, Eisai, Ono Pharmaceutical, and Roche. Relevant financial relationships for the other investigators are fully listed in the original article.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

AT CTAD 2022

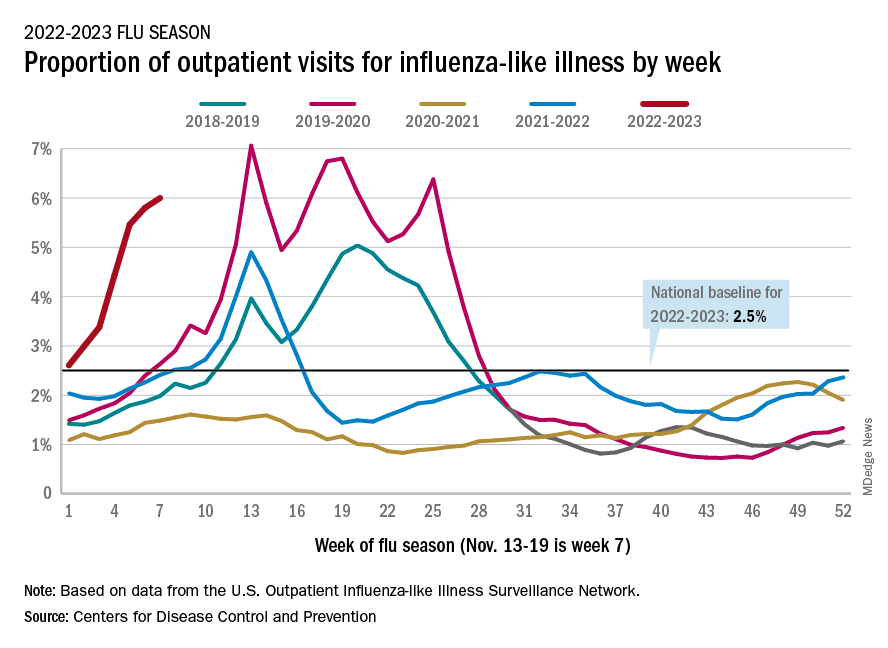

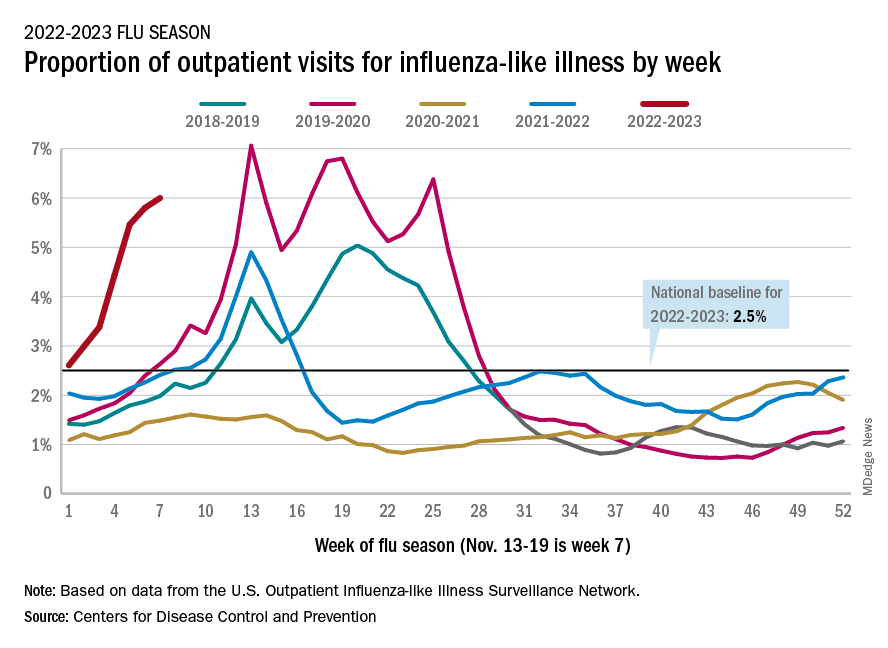

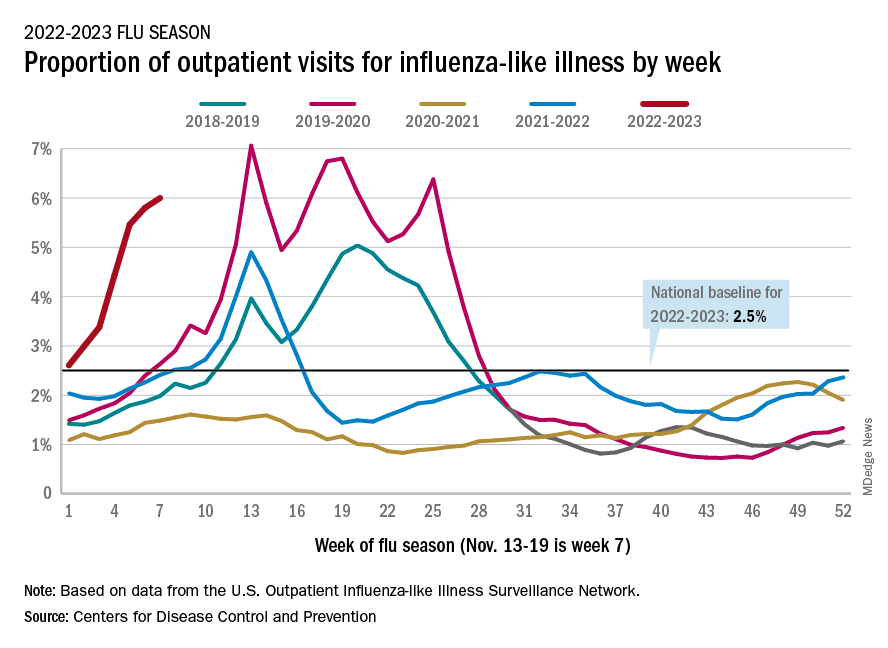

U.S. flu activity already at mid-season levels

according to the Centers of Disease Control and Prevention.

Nationally, 6% of all outpatient visits were because of flu or flu-like illness for the week of Nov. 13-19, up from 5.8% the previous week, the CDC’s Influenza Division said in its weekly FluView report.

Those figures are the highest recorded in November since 2009, but the peak of the 2009-10 flu season occurred even earlier – the week of Oct. 18-24 – and the rate of flu-like illness had already dropped to just over 4.0% by Nov. 15-21 that year and continued to drop thereafter.

Although COVID-19 and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) are included in the data from the CDC’s Outpatient Influenza-like Illness Surveillance Network, the agency did note that “seasonal influenza activity is elevated across the country” and estimated that “there have been at least 6.2 million illnesses, 53,000 hospitalizations, and 2,900 deaths from flu” during the 2022-23 season.

Total flu deaths include 11 reported in children as of Nov. 19, and children ages 0-4 had a higher proportion of visits for flu like-illness than other age groups.

The agency also said the cumulative hospitalization rate of 11.3 per 100,000 population “is higher than the rate observed in [the corresponding week of] every previous season since 2010-2011.” Adults 65 years and older have the highest cumulative rate, 25.9 per 100,000, for this year, compared with 20.7 for children 0-4; 11.1 for adults 50-64; 10.3 for children 5-17; and 5.6 for adults 18-49 years old, the CDC said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

according to the Centers of Disease Control and Prevention.

Nationally, 6% of all outpatient visits were because of flu or flu-like illness for the week of Nov. 13-19, up from 5.8% the previous week, the CDC’s Influenza Division said in its weekly FluView report.

Those figures are the highest recorded in November since 2009, but the peak of the 2009-10 flu season occurred even earlier – the week of Oct. 18-24 – and the rate of flu-like illness had already dropped to just over 4.0% by Nov. 15-21 that year and continued to drop thereafter.

Although COVID-19 and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) are included in the data from the CDC’s Outpatient Influenza-like Illness Surveillance Network, the agency did note that “seasonal influenza activity is elevated across the country” and estimated that “there have been at least 6.2 million illnesses, 53,000 hospitalizations, and 2,900 deaths from flu” during the 2022-23 season.

Total flu deaths include 11 reported in children as of Nov. 19, and children ages 0-4 had a higher proportion of visits for flu like-illness than other age groups.

The agency also said the cumulative hospitalization rate of 11.3 per 100,000 population “is higher than the rate observed in [the corresponding week of] every previous season since 2010-2011.” Adults 65 years and older have the highest cumulative rate, 25.9 per 100,000, for this year, compared with 20.7 for children 0-4; 11.1 for adults 50-64; 10.3 for children 5-17; and 5.6 for adults 18-49 years old, the CDC said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

according to the Centers of Disease Control and Prevention.

Nationally, 6% of all outpatient visits were because of flu or flu-like illness for the week of Nov. 13-19, up from 5.8% the previous week, the CDC’s Influenza Division said in its weekly FluView report.

Those figures are the highest recorded in November since 2009, but the peak of the 2009-10 flu season occurred even earlier – the week of Oct. 18-24 – and the rate of flu-like illness had already dropped to just over 4.0% by Nov. 15-21 that year and continued to drop thereafter.

Although COVID-19 and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) are included in the data from the CDC’s Outpatient Influenza-like Illness Surveillance Network, the agency did note that “seasonal influenza activity is elevated across the country” and estimated that “there have been at least 6.2 million illnesses, 53,000 hospitalizations, and 2,900 deaths from flu” during the 2022-23 season.

Total flu deaths include 11 reported in children as of Nov. 19, and children ages 0-4 had a higher proportion of visits for flu like-illness than other age groups.

The agency also said the cumulative hospitalization rate of 11.3 per 100,000 population “is higher than the rate observed in [the corresponding week of] every previous season since 2010-2011.” Adults 65 years and older have the highest cumulative rate, 25.9 per 100,000, for this year, compared with 20.7 for children 0-4; 11.1 for adults 50-64; 10.3 for children 5-17; and 5.6 for adults 18-49 years old, the CDC said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Yellow Nodule on the Scalp

The Diagnosis: Solitary Sclerotic Fibroma

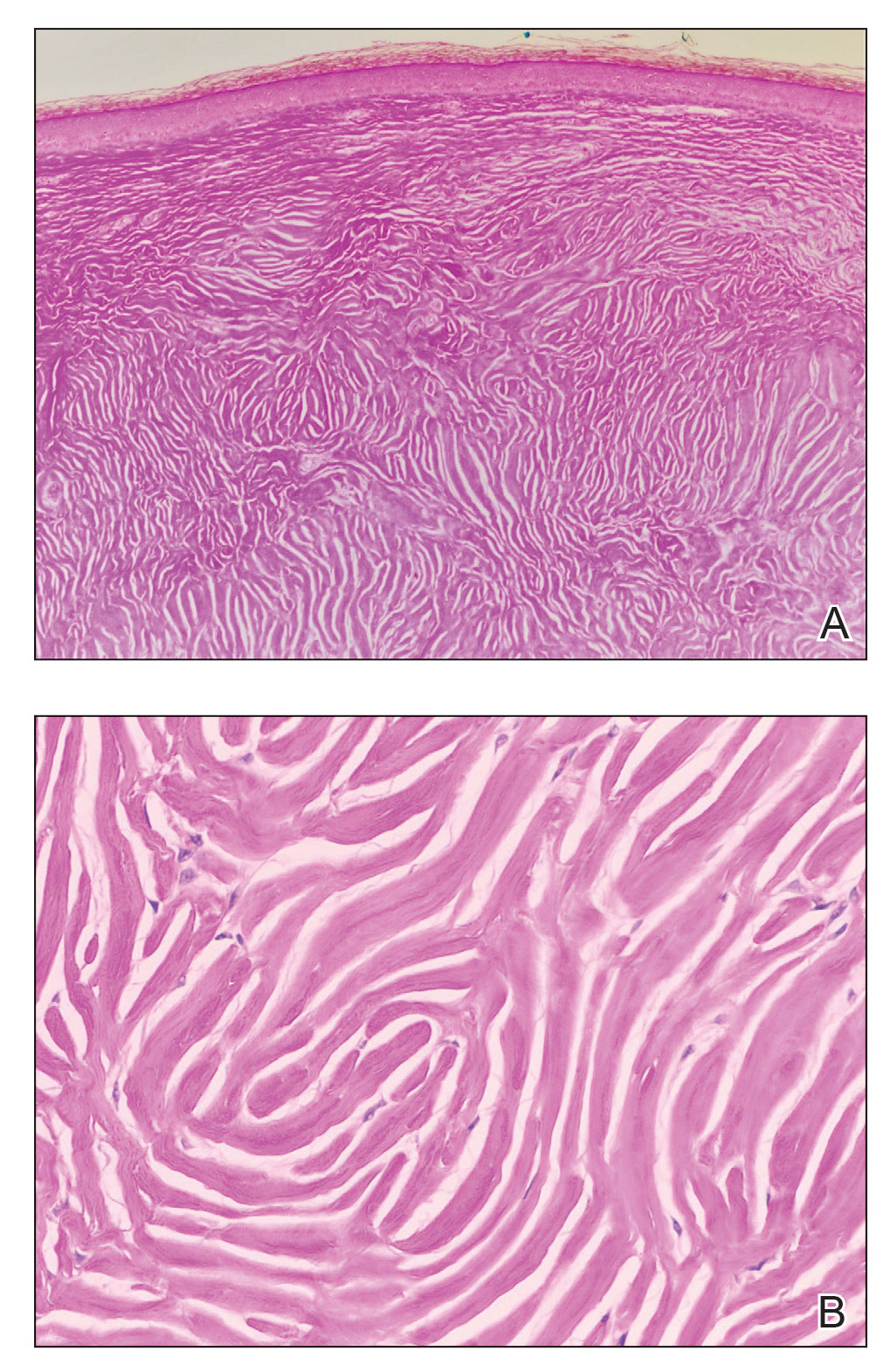

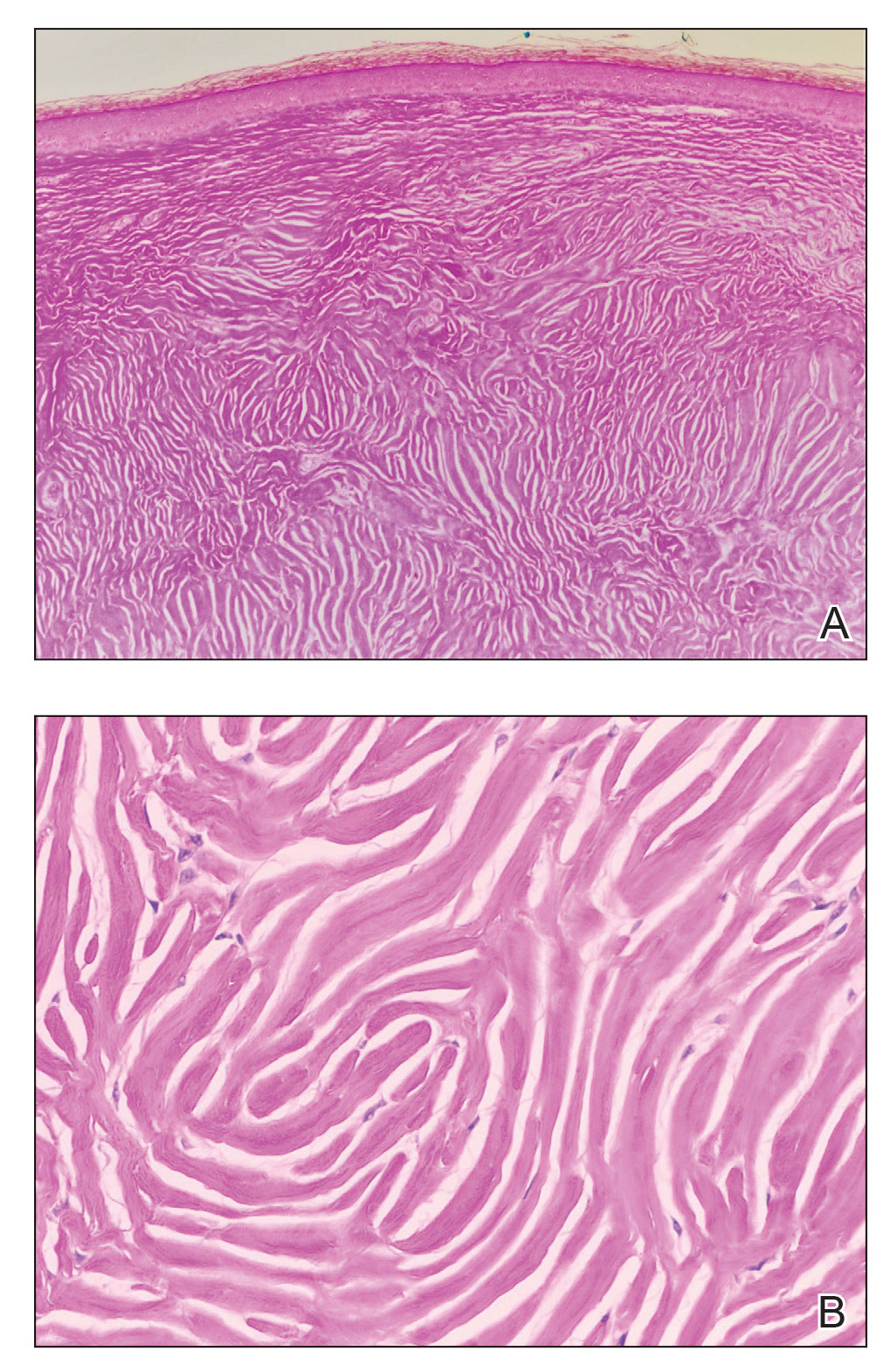

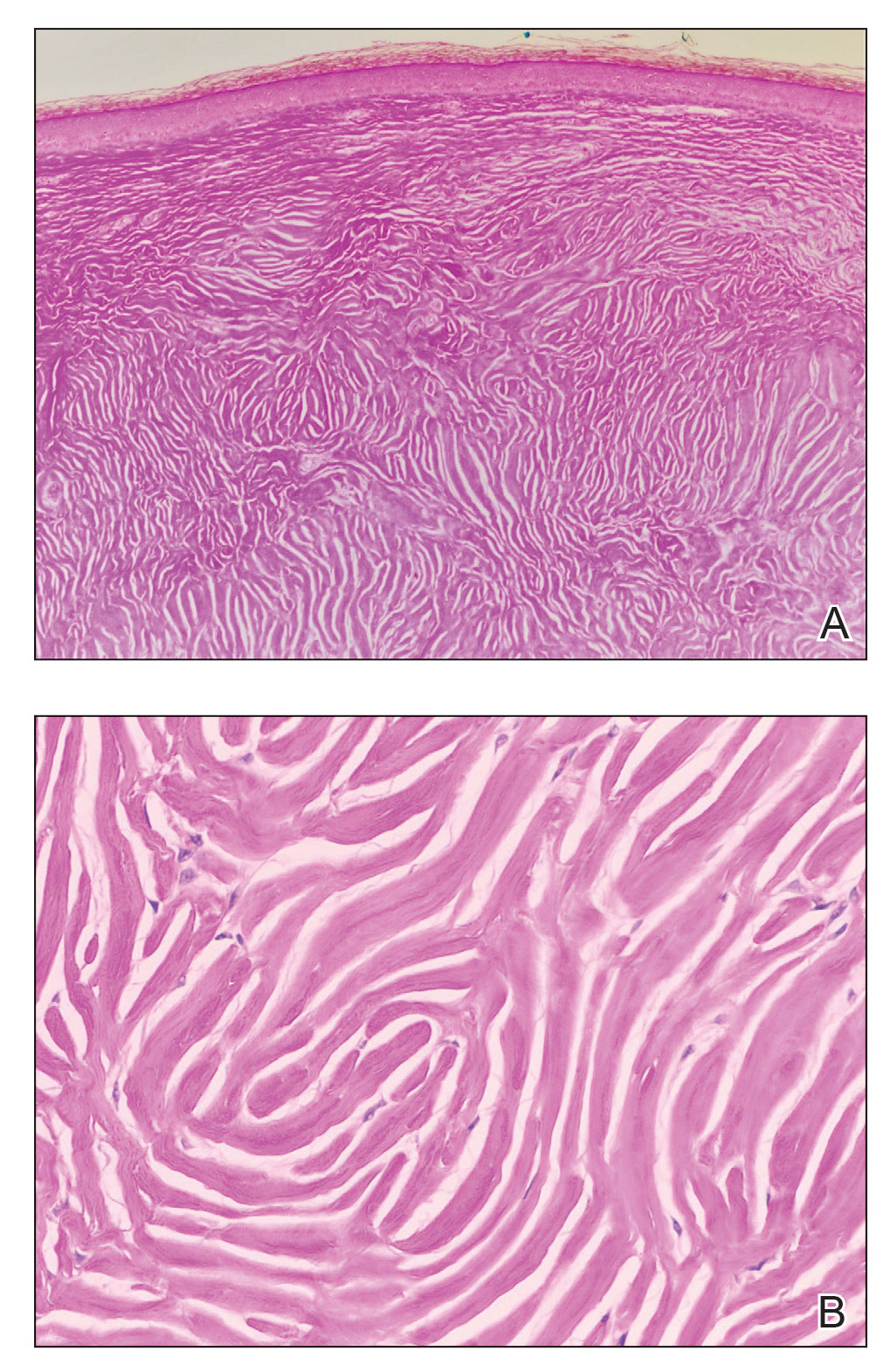

Based on the clinical and histologic findings, the patient was diagnosed with solitary sclerotic fibroma (SF). Sclerotic fibroma is a rare benign tumor that first was described in 1972 by Weary et al1 in the oral mucosa of a patient with Cowden syndrome, a genodermatosis associated with multiple benign and malignant tumors. Rapini and Golitz2 reported solitary SF in 11 otherwise-healthy individuals with no signs of multiple hamartoma syndrome. Solitary SF is a sporadic benign condition, whereas multiple lesions are suggestive of Cowden syndrome. Solitary SF most commonly appears as an asymptomatic white-yellow papule or nodule on the head or neck, though larger tumors have been reported on the trunk and extremities.3 Histologic features of solitary SF include a well-circumscribed dermal nodule composed of eosinophilic dense collagen bundles arranged in a plywoodlike pattern (Figure). Immunohistochemistry is positive for CD34 and vimentin but negative for S-100, epithelial membrane antigen, and neuron-specific enolase.4

The differential diagnosis of solitary SF of the head and neck includes sebaceous adenoma, pilar cyst, nodular basal cell carcinoma, and giant molluscum contagiosum. Sebaceous adenomas usually are solitary yellow nodules less than 1 cm in diameter and located on the head and neck. They are the most common sebaceous neoplasm associated with Muir-Torre syndrome, an autosomal-dominant disorder characterized by sebaceous adenoma or carcinoma and colorectal cancer. Histopathology demonstrates well-circumscribed, round aggregations of mature lipid-filled sebocytes with a rim of basaloid germinative cells at the periphery. Pilar cysts typically are flesh-colored subcutaneous nodules on the scalp that are freely mobile over underlying tissue. Histopathology shows stratified squamous epithelium lining and trichilemmal keratinization. Nodular basal cell carcinoma has a pearly translucent appearance and arborizing telangiectases. Histopathology demonstrates nests of basaloid cells with palisading of the cells at the periphery. Giant solitary molluscum contagiosum is a dome-shaped, flesh-colored nodule with central umbilication. Histopathology reveals hyperplastic squamous epithelium with characteristic eosinophilic inclusion bodies above the basal layer.

Solitary SF can be difficult to diagnose based solely on the clinical presentation; thus biopsy with histologic evaluation is recommended. If SF is confirmed, the clinician should inquire about a family history of Cowden syndrome and then perform a total-body skin examination to check for multiple SF and other clinical hamartomas of Cowden syndrome such as trichilemmomas, acral keratosis, and oral papillomas.

- Weary PE, Gorlin RJ, Gentry Jr WC, et al. Multiple hamartoma syndrome (Cowden’s disease). Arch Dermatol. 1972;106:682-690.

- Rapini RP, Golitz LE. Sclerotic fibromas of the skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;20(2 pt 1):266-271.

- Tosa M, Ansai S, Kuwahara H, et al. Two cases of sclerotic fibroma of the skin that mimicked keloids clinically. J Nippon Med Sch. 2018;85:283-286.

- High WA, Stewart D, Essary LR, et al. Sclerotic fibroma-like changes in various neoplastic and inflammatory skin lesions: is sclerotic fibroma a distinct entity? J Cutan Pathol. 2004;31:373-378.

The Diagnosis: Solitary Sclerotic Fibroma

Based on the clinical and histologic findings, the patient was diagnosed with solitary sclerotic fibroma (SF). Sclerotic fibroma is a rare benign tumor that first was described in 1972 by Weary et al1 in the oral mucosa of a patient with Cowden syndrome, a genodermatosis associated with multiple benign and malignant tumors. Rapini and Golitz2 reported solitary SF in 11 otherwise-healthy individuals with no signs of multiple hamartoma syndrome. Solitary SF is a sporadic benign condition, whereas multiple lesions are suggestive of Cowden syndrome. Solitary SF most commonly appears as an asymptomatic white-yellow papule or nodule on the head or neck, though larger tumors have been reported on the trunk and extremities.3 Histologic features of solitary SF include a well-circumscribed dermal nodule composed of eosinophilic dense collagen bundles arranged in a plywoodlike pattern (Figure). Immunohistochemistry is positive for CD34 and vimentin but negative for S-100, epithelial membrane antigen, and neuron-specific enolase.4

The differential diagnosis of solitary SF of the head and neck includes sebaceous adenoma, pilar cyst, nodular basal cell carcinoma, and giant molluscum contagiosum. Sebaceous adenomas usually are solitary yellow nodules less than 1 cm in diameter and located on the head and neck. They are the most common sebaceous neoplasm associated with Muir-Torre syndrome, an autosomal-dominant disorder characterized by sebaceous adenoma or carcinoma and colorectal cancer. Histopathology demonstrates well-circumscribed, round aggregations of mature lipid-filled sebocytes with a rim of basaloid germinative cells at the periphery. Pilar cysts typically are flesh-colored subcutaneous nodules on the scalp that are freely mobile over underlying tissue. Histopathology shows stratified squamous epithelium lining and trichilemmal keratinization. Nodular basal cell carcinoma has a pearly translucent appearance and arborizing telangiectases. Histopathology demonstrates nests of basaloid cells with palisading of the cells at the periphery. Giant solitary molluscum contagiosum is a dome-shaped, flesh-colored nodule with central umbilication. Histopathology reveals hyperplastic squamous epithelium with characteristic eosinophilic inclusion bodies above the basal layer.

Solitary SF can be difficult to diagnose based solely on the clinical presentation; thus biopsy with histologic evaluation is recommended. If SF is confirmed, the clinician should inquire about a family history of Cowden syndrome and then perform a total-body skin examination to check for multiple SF and other clinical hamartomas of Cowden syndrome such as trichilemmomas, acral keratosis, and oral papillomas.

The Diagnosis: Solitary Sclerotic Fibroma

Based on the clinical and histologic findings, the patient was diagnosed with solitary sclerotic fibroma (SF). Sclerotic fibroma is a rare benign tumor that first was described in 1972 by Weary et al1 in the oral mucosa of a patient with Cowden syndrome, a genodermatosis associated with multiple benign and malignant tumors. Rapini and Golitz2 reported solitary SF in 11 otherwise-healthy individuals with no signs of multiple hamartoma syndrome. Solitary SF is a sporadic benign condition, whereas multiple lesions are suggestive of Cowden syndrome. Solitary SF most commonly appears as an asymptomatic white-yellow papule or nodule on the head or neck, though larger tumors have been reported on the trunk and extremities.3 Histologic features of solitary SF include a well-circumscribed dermal nodule composed of eosinophilic dense collagen bundles arranged in a plywoodlike pattern (Figure). Immunohistochemistry is positive for CD34 and vimentin but negative for S-100, epithelial membrane antigen, and neuron-specific enolase.4

The differential diagnosis of solitary SF of the head and neck includes sebaceous adenoma, pilar cyst, nodular basal cell carcinoma, and giant molluscum contagiosum. Sebaceous adenomas usually are solitary yellow nodules less than 1 cm in diameter and located on the head and neck. They are the most common sebaceous neoplasm associated with Muir-Torre syndrome, an autosomal-dominant disorder characterized by sebaceous adenoma or carcinoma and colorectal cancer. Histopathology demonstrates well-circumscribed, round aggregations of mature lipid-filled sebocytes with a rim of basaloid germinative cells at the periphery. Pilar cysts typically are flesh-colored subcutaneous nodules on the scalp that are freely mobile over underlying tissue. Histopathology shows stratified squamous epithelium lining and trichilemmal keratinization. Nodular basal cell carcinoma has a pearly translucent appearance and arborizing telangiectases. Histopathology demonstrates nests of basaloid cells with palisading of the cells at the periphery. Giant solitary molluscum contagiosum is a dome-shaped, flesh-colored nodule with central umbilication. Histopathology reveals hyperplastic squamous epithelium with characteristic eosinophilic inclusion bodies above the basal layer.

Solitary SF can be difficult to diagnose based solely on the clinical presentation; thus biopsy with histologic evaluation is recommended. If SF is confirmed, the clinician should inquire about a family history of Cowden syndrome and then perform a total-body skin examination to check for multiple SF and other clinical hamartomas of Cowden syndrome such as trichilemmomas, acral keratosis, and oral papillomas.

- Weary PE, Gorlin RJ, Gentry Jr WC, et al. Multiple hamartoma syndrome (Cowden’s disease). Arch Dermatol. 1972;106:682-690.

- Rapini RP, Golitz LE. Sclerotic fibromas of the skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;20(2 pt 1):266-271.

- Tosa M, Ansai S, Kuwahara H, et al. Two cases of sclerotic fibroma of the skin that mimicked keloids clinically. J Nippon Med Sch. 2018;85:283-286.

- High WA, Stewart D, Essary LR, et al. Sclerotic fibroma-like changes in various neoplastic and inflammatory skin lesions: is sclerotic fibroma a distinct entity? J Cutan Pathol. 2004;31:373-378.

- Weary PE, Gorlin RJ, Gentry Jr WC, et al. Multiple hamartoma syndrome (Cowden’s disease). Arch Dermatol. 1972;106:682-690.

- Rapini RP, Golitz LE. Sclerotic fibromas of the skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;20(2 pt 1):266-271.

- Tosa M, Ansai S, Kuwahara H, et al. Two cases of sclerotic fibroma of the skin that mimicked keloids clinically. J Nippon Med Sch. 2018;85:283-286.

- High WA, Stewart D, Essary LR, et al. Sclerotic fibroma-like changes in various neoplastic and inflammatory skin lesions: is sclerotic fibroma a distinct entity? J Cutan Pathol. 2004;31:373-378.

A 45-year-old woman was referred to dermatology by a primary care physician for evaluation of a raised skin lesion on the scalp. She was otherwise healthy. The lesion had been present for many years but recently grew in size. The patient reported that the lesion was subject to recurrent physical trauma and she wanted it removed. Physical examination revealed a 6×6-mm, domeshaped, yellow nodule on the left inferior parietal scalp. There were no similar lesions located elsewhere on the body. A shave removal was performed and sent for histopathologic evaluation.

Advancing health equity in neurology is essential to patient care

Black and Latinx older adults are up to three times as likely to develop Alzheimer’s disease than non-Latinx White adults and tend to experience onset at a younger age with more severe symptoms, according to Monica Rivera-Mindt, PhD, a professor of psychology at Fordham University and the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York. Looking ahead, that means by 2030, nearly 40% of the 8.4 million Americans affected by Alzheimer’s disease will be Black and/or Latinx, she said. These facts were among the stark disparities in health care outcomes Dr. Rivera-Mindt discussed in her presentation on brain health equity at the 2022 annual meeting of the American Neurological Association.

Dr. Rivera-Mindt’s presentation opened the ANA’s plenary session on health disparities and inequities. The plenary, “Advancing Neurologic Equity: Challenges and Paths Forward,” did not simply enumerate racial and ethnic disparities that exist with various neurological conditions. Rather it went beyond the discussion of what disparities exist into understanding the roots of them as well as tips, tools, and resources that can aid clinicians in addressing or ameliorating them.

Roy Hamilton, MD, an associate professor of neurology and physical medicine and rehabilitation at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said. “If clinicians are unaware of these disparities or don’t have any sense of how to start to address or think about them, then they’re really missing out on an important component of their education as persons who take care of patients with brain disorders.”

Dr. Hamilton, who organized the plenary, noted that awareness of these disparities is crucial to comprehensively caring for patients.

Missed opportunities

“We’re talking about disadvantages that are structural and large scale, but those disadvantages play themselves out in the individual encounter,” Dr. Hamilton said. “When physicians see patients, they have to treat the whole patient in front of them,” which means being aware of the risks and factors that could affect a patient’s clinical presentation. “Being aware of disparities has practical impacts on physician judgment,” he said.

For example, recent research in multiple sclerosis (MS) has highlighted how clinicians may be missing diagnosis of this condition in non-White populations because the condition has been regarded for so long as a “White person’s” disease, Dr. Hamilton said. In non-White patients exhibiting MS symptoms, then, clinicians may have been less likely to consider MS as a possibility, thereby delaying diagnosis and treatment.

Those patterns may partly explain why the mortality rate for MS is greater in Black patients, who also show more rapid neurodegeneration than White patients with MS, Lilyana Amezcua, MD, an associate professor of neurology at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, reported in the plenary’s second presentation.

Transgender issues

The third session, presented by Nicole Rosendale, MD, an assistant professor of neurology at the University of California, San Francisco, and director of the San Francisco General Hospital neurology inpatient services, examined disparities in neurology within the LGBTQ+ community through representative case studies and then offered specific ways that neurologists could make their practices more inclusive and equitable for sexual and gender minorities.

Her first case study was a 52-year-old man who presented with new-onset seizures, right hemiparesis, and aphasia. A brain biopsy consistent with adenocarcinoma eventually led his physician to discover he had metastatic breast cancer. It turned out the man was transgender and, despite a family history of breast cancer, hadn’t been advised to get breast cancer screenings.

“Breast cancer was not initially on the differential as no one had identified that the patient was transmasculine,” Dr. Rosendale said. A major challenge to providing care to transgender patients is a dearth of data on risks and screening recommendations. Another barrier is low knowledge of LGBTQ+ health among neurologists, Dr. Rosendale said while sharing findings from her 2019 study on the topic and calling for more research in LGBTQ+ populations.

Dr. Rosendale’s second case study dealt with a nonbinary patient who suffered from debilitating headaches for decades, first because they lacked access to health insurance and then because negative experiences with providers dissuaded them from seeking care. In data from the Center for American Progress she shared, 8% of LGB respondents and 22% of transgender respondents said they had avoided or delayed care because of fear of discrimination or mistreatment.

“So it’s not only access but also what experiences people are having when they go in and whether they’re actually even getting access to care or being taken care of,” Dr. Rosendale said. Other findings from the CAP found that:

- 8% of LGB patients and 29% of transgender patients reported having a clinician refuse to see them.

- 6% of LGB patients and 12% of transgender patients reported that a clinician refused to give them health care.

- 9% of LGB patients and 21% of transgender patients experienced harsh or abusive language during a health care experience.

- 7% of LGB patients and nearly a third (29%) of transgender patients experienced unwanted physical contact, such as fondling or sexual assault.

Reducing the disparities

Adys Mendizabal, MD, an assistant professor of neurology at the Institute of Society and Genetics at the University of California, Los Angeles, who attended the presentation, was grateful to see how the various lectures enriched the discussion beyond stating the fact of racial/ethnic disparities and dug into the nuances on how to think about and address these disparities. She particularly appreciated discussion about the need to go out of the way to recruit diverse patient populations for clinical trials while also providing them care.

“It is definitely complicated, but it’s not impossible for an individual neurologist or an individual department to do something to reduce some of the disparities,” Dr. Mendizabal said. “It starts with just knowing that they exist and being aware of some of the things that may be impacting care for a particular patient.”

Tools to counter disparity

In the final presentation, Amy Kind, MD, PhD, the associate dean for social health sciences and programs at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, rounded out the discussion by exploring social determinants of health and their influence on outcomes.

“Social determinants impact brain health, and brain health is not distributed equally,” Dr. Kind told attendees. “We have known this for decades, yet disparities persist.”

Dr. Kind described the “exposome,” a “measure of all the exposures of an individual in a lifetime and how those exposures relate to health,” according to the CDC, and then introduced a tool clinicians can use to better understand social determinants of health in specific geographic areas. The Neighborhood Atlas, which Dr. Kind described in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2018, measures 17 social determinants across small population-sensitive areas and provides an area deprivation index. A high area deprivation index is linked to a range of negative outcomes, including reshopitalization, later diagnoses, less comprehensive diagnostic evaluation, increased risk of postsurgical complications, and decreased life expectancy.

“One of the things that really stood out to me about Dr. Kind’s discussion of the use of the area deprivation index was the fact that understanding and quantifying these kinds of risks and exposures is the vehicle for creating the kinds of social changes, including policy changes, that will actually lead to addressing and mitigating some of these lifelong risks and exposures,” Dr. Hamilton said. “It is implausible to think that a specific group of people would be genetically more susceptible to basically every disease that we know,” he added. “It makes much more sense to think that groups of individuals have been subjected systematically to conditions that impair health in a variety of ways.”

Not just race, ethnicity, sex, and gender

Following the four presentations from researchers in health inequities was an Emerging Scholar presentation in which Jay B. Lusk, an MD/MBA candidate at Duke University, Durham, N.C., shared new research findings on the role of neighborhood disadvantage in predicting mortality from coma, stroke, and other neurologic conditions. His findings revealed that living in a neighborhood with greater deprivation substantially increased risk of mortality even after accounting for individual wealth and demographics.

Maria Eugenia Diaz-Ortiz, PhD, of the department of neurology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said she found the five presentations to be an excellent introduction to people like herself who are in the earlier stages of learning about health equity research.

“I think they introduced various important concepts and frameworks and provided tools for people who don’t know about them,” Dr. Diaz-Ortiz said. “Then they asked important questions and provided some solutions to them.”