User login

In Case You Missed It: COVID

New Data on Mild COVID’s Risk for Neurologic, Psychiatric Disorders

While severe COVID-19 is associated with a significantly higher risk for psychiatric and neurologic disorders a year after infection, mild does not carry the same risk, a new study shows.

However, less severe COVID-19 was not linked to a higher incidence of psychiatric diagnoses and was associated with only a slightly higher risk for neurologic disorders.

The new research challenges previous findings of long-term risk for psychiatric and neurologic disorders associated with SARS-CoV-2 in patients who had not been hospitalized for the condition.

“Our study does not support previous findings of substantial post-acute neurologic and psychiatric morbidities among the general population of SARS-CoV-2-infected individuals but does corroborate an elevated risk among the most severe cases with COVID-19,” the authors wrote.

The study was published online on February 21 in Neurology.

‘Alarming’ Findings

Previous studies have reported nervous system symptoms in patients who have experienced COVID-19, which may persist for several weeks or months after the acute phase, even in milder cases.

But these findings haven’t been consistent across all studies, and few studies have addressed the potential effect of different viral variants and vaccination status on post-acute psychiatric and neurologic morbidities.

“Our study was partly motivated by our strong research interest in the associations between infectious disease and later chronic disease and partly by international studies, such as those conducted in the US Veterans Health databases, that have suggested substantial risks of psychiatric and neurological conditions associated with infection,” senior author Anders Hviid, MSc, DrMedSci, head of the department and professor of pharmacoepidemiology, Statens Serum Institut, Copenhagen, Denmark, told this news organization.

Investigators drew on data from the Danish National Patient Registry to compare the risk for neurologic and psychiatric disorders during the 12 months after acute COVID-19 infection to risk among people who never tested positive.

They examined data on all recorded hospital contacts between January 2005 and January 2023 for a discharge diagnosis of at least one of 11 psychiatric illnesses or at least one of 30 neurologic disorders.

The researchers compared the incidence of each disorder within 1-12 months after infection with those of COVID-naive individuals and stratified analyses according to time since infection, vaccination status, variant period, age, sex, and infection severity.

The final study cohort included 1.8 million individuals who tested positive during the study period and 1.5 who didn’t. Three quarters of those who tested positive were infected primarily with the Omicron variant.

Hospitalized vs Nonhospitalized

Overall, individuals who tested positive had a 24% lower risk for psychiatric disorders during the post-acute period (incident rate ratio [IRR], 0.76; 95% CI, 0.74-0.78) compared with the control group, but a 5% higher risk for any neurologic disorder (IRR, 1.05; 95% CI, 1.04-1.07).

Age, sex, and variant had less influence on risk than infection severity, where the differences between hospitalized and nonhospitalized patients were significant.

Compared with COVID-negative individuals, the risk for any psychiatric disorder was double for hospitalized patients (IRR, 2.05; 95% CI, 1.78-2.37) but was 25% lower among nonhospitalized patients (IRR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.73-0.77).

For neurologic disorders, the IRR for hospitalized patients was 2.44 (95% CI, 2.29-2.60) compared with COVID-negative individuals vs an IRR of only 1.02 (95% CI, 1.01-1.04) among nonhospitalized patients.

“In a general population, there was little support for clinically relevant post-acute risk increases of psychiatric and neurologic disorders associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection without hospitalization. This was particularly true for vaccinated individuals and for the more recent variants,” the authors wrote, adding that the only exception was for change in sense and smell.

‘Flaws’ in Previous Studies?

The findings in hospitalized patients were in line with previous findings, but those in nonhospitalized patients stand out, they added.

Previous studies were done predominantly in older males with comorbidities and those who were more socioeconomically disadvantaged, which could lead to a bias, Dr. Hviid said.

Those other studies “had a number of fundamental flaws that we do not believe our study has,” Dr. Hviid said. “Our study was conducted in the general population, with free and universal testing and healthcare.”

Researchers stress that sequelae after infection are predominantly associated with severe illness.

“Today, a healthy vaccinated adult having an asymptomatic or mild bout of COVID-19 with the current variants shouldn’t fear developing serious psychiatric or neurologic disorders in the months or years after infection.”

One limitation is that only hospital contacts were included, omitting possible diagnoses given outside hospital settings.

‘Extreme Caution’ Required

The link between COVID-19 and brain health is “complex,” and the new findings should be viewed cautiously, said Maxime Taquet, MRCPsych, PhD, National Institute for Health and Care Research clinical lecturer and specialty registrar in Psychiatry, Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust, England, who commented on the findings.

Previous research by Dr. Taquet, who was not involved in the current study, found an increased risk for neurologic and psychiatric diagnoses during the first 6 months after COVID-19 diagnosis.

The current study “contributes to better understanding this link by providing data from another country with a different organization of healthcare provision than the US, where most of the existing data come from,” Dr. Taquet said.

However, “some observations — for example, that COVID-19 is associated with a 50% reduction in the risk of autism, a condition present from very early in life — call for extreme caution in the interpretation of the findings, as they suggest that residual bias has not been accounted for,” Dr. Taquet continued.

Authors of an accompanying editorial, Eric Chow, MD, MS, MPH, of the Division of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, University of Washington, School of Public Health, and Anita Chopra, MD, of the post-COVID Clinic, University of Washington, Seattle, called the study a “critical contribution to the published literature.”

The association of neurologic and psychiatric diagnoses with severe disease “is a reminder of the importance of risk reduction by combining vaccinations with improved indoor ventilation and masking,” they concluded.

The study was supported by a grant from the Independent Research Fund Denmark. Dr. Hviid and coauthors, Dr. Chopra, and Dr. Taquet reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Chow received a travel award from the Infectious Diseases Society of America to attend ID Week 2022.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

While severe COVID-19 is associated with a significantly higher risk for psychiatric and neurologic disorders a year after infection, mild does not carry the same risk, a new study shows.

However, less severe COVID-19 was not linked to a higher incidence of psychiatric diagnoses and was associated with only a slightly higher risk for neurologic disorders.

The new research challenges previous findings of long-term risk for psychiatric and neurologic disorders associated with SARS-CoV-2 in patients who had not been hospitalized for the condition.

“Our study does not support previous findings of substantial post-acute neurologic and psychiatric morbidities among the general population of SARS-CoV-2-infected individuals but does corroborate an elevated risk among the most severe cases with COVID-19,” the authors wrote.

The study was published online on February 21 in Neurology.

‘Alarming’ Findings

Previous studies have reported nervous system symptoms in patients who have experienced COVID-19, which may persist for several weeks or months after the acute phase, even in milder cases.

But these findings haven’t been consistent across all studies, and few studies have addressed the potential effect of different viral variants and vaccination status on post-acute psychiatric and neurologic morbidities.

“Our study was partly motivated by our strong research interest in the associations between infectious disease and later chronic disease and partly by international studies, such as those conducted in the US Veterans Health databases, that have suggested substantial risks of psychiatric and neurological conditions associated with infection,” senior author Anders Hviid, MSc, DrMedSci, head of the department and professor of pharmacoepidemiology, Statens Serum Institut, Copenhagen, Denmark, told this news organization.

Investigators drew on data from the Danish National Patient Registry to compare the risk for neurologic and psychiatric disorders during the 12 months after acute COVID-19 infection to risk among people who never tested positive.

They examined data on all recorded hospital contacts between January 2005 and January 2023 for a discharge diagnosis of at least one of 11 psychiatric illnesses or at least one of 30 neurologic disorders.

The researchers compared the incidence of each disorder within 1-12 months after infection with those of COVID-naive individuals and stratified analyses according to time since infection, vaccination status, variant period, age, sex, and infection severity.

The final study cohort included 1.8 million individuals who tested positive during the study period and 1.5 who didn’t. Three quarters of those who tested positive were infected primarily with the Omicron variant.

Hospitalized vs Nonhospitalized

Overall, individuals who tested positive had a 24% lower risk for psychiatric disorders during the post-acute period (incident rate ratio [IRR], 0.76; 95% CI, 0.74-0.78) compared with the control group, but a 5% higher risk for any neurologic disorder (IRR, 1.05; 95% CI, 1.04-1.07).

Age, sex, and variant had less influence on risk than infection severity, where the differences between hospitalized and nonhospitalized patients were significant.

Compared with COVID-negative individuals, the risk for any psychiatric disorder was double for hospitalized patients (IRR, 2.05; 95% CI, 1.78-2.37) but was 25% lower among nonhospitalized patients (IRR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.73-0.77).

For neurologic disorders, the IRR for hospitalized patients was 2.44 (95% CI, 2.29-2.60) compared with COVID-negative individuals vs an IRR of only 1.02 (95% CI, 1.01-1.04) among nonhospitalized patients.

“In a general population, there was little support for clinically relevant post-acute risk increases of psychiatric and neurologic disorders associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection without hospitalization. This was particularly true for vaccinated individuals and for the more recent variants,” the authors wrote, adding that the only exception was for change in sense and smell.

‘Flaws’ in Previous Studies?

The findings in hospitalized patients were in line with previous findings, but those in nonhospitalized patients stand out, they added.

Previous studies were done predominantly in older males with comorbidities and those who were more socioeconomically disadvantaged, which could lead to a bias, Dr. Hviid said.

Those other studies “had a number of fundamental flaws that we do not believe our study has,” Dr. Hviid said. “Our study was conducted in the general population, with free and universal testing and healthcare.”

Researchers stress that sequelae after infection are predominantly associated with severe illness.

“Today, a healthy vaccinated adult having an asymptomatic or mild bout of COVID-19 with the current variants shouldn’t fear developing serious psychiatric or neurologic disorders in the months or years after infection.”

One limitation is that only hospital contacts were included, omitting possible diagnoses given outside hospital settings.

‘Extreme Caution’ Required

The link between COVID-19 and brain health is “complex,” and the new findings should be viewed cautiously, said Maxime Taquet, MRCPsych, PhD, National Institute for Health and Care Research clinical lecturer and specialty registrar in Psychiatry, Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust, England, who commented on the findings.

Previous research by Dr. Taquet, who was not involved in the current study, found an increased risk for neurologic and psychiatric diagnoses during the first 6 months after COVID-19 diagnosis.

The current study “contributes to better understanding this link by providing data from another country with a different organization of healthcare provision than the US, where most of the existing data come from,” Dr. Taquet said.

However, “some observations — for example, that COVID-19 is associated with a 50% reduction in the risk of autism, a condition present from very early in life — call for extreme caution in the interpretation of the findings, as they suggest that residual bias has not been accounted for,” Dr. Taquet continued.

Authors of an accompanying editorial, Eric Chow, MD, MS, MPH, of the Division of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, University of Washington, School of Public Health, and Anita Chopra, MD, of the post-COVID Clinic, University of Washington, Seattle, called the study a “critical contribution to the published literature.”

The association of neurologic and psychiatric diagnoses with severe disease “is a reminder of the importance of risk reduction by combining vaccinations with improved indoor ventilation and masking,” they concluded.

The study was supported by a grant from the Independent Research Fund Denmark. Dr. Hviid and coauthors, Dr. Chopra, and Dr. Taquet reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Chow received a travel award from the Infectious Diseases Society of America to attend ID Week 2022.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

While severe COVID-19 is associated with a significantly higher risk for psychiatric and neurologic disorders a year after infection, mild does not carry the same risk, a new study shows.

However, less severe COVID-19 was not linked to a higher incidence of psychiatric diagnoses and was associated with only a slightly higher risk for neurologic disorders.

The new research challenges previous findings of long-term risk for psychiatric and neurologic disorders associated with SARS-CoV-2 in patients who had not been hospitalized for the condition.

“Our study does not support previous findings of substantial post-acute neurologic and psychiatric morbidities among the general population of SARS-CoV-2-infected individuals but does corroborate an elevated risk among the most severe cases with COVID-19,” the authors wrote.

The study was published online on February 21 in Neurology.

‘Alarming’ Findings

Previous studies have reported nervous system symptoms in patients who have experienced COVID-19, which may persist for several weeks or months after the acute phase, even in milder cases.

But these findings haven’t been consistent across all studies, and few studies have addressed the potential effect of different viral variants and vaccination status on post-acute psychiatric and neurologic morbidities.

“Our study was partly motivated by our strong research interest in the associations between infectious disease and later chronic disease and partly by international studies, such as those conducted in the US Veterans Health databases, that have suggested substantial risks of psychiatric and neurological conditions associated with infection,” senior author Anders Hviid, MSc, DrMedSci, head of the department and professor of pharmacoepidemiology, Statens Serum Institut, Copenhagen, Denmark, told this news organization.

Investigators drew on data from the Danish National Patient Registry to compare the risk for neurologic and psychiatric disorders during the 12 months after acute COVID-19 infection to risk among people who never tested positive.

They examined data on all recorded hospital contacts between January 2005 and January 2023 for a discharge diagnosis of at least one of 11 psychiatric illnesses or at least one of 30 neurologic disorders.

The researchers compared the incidence of each disorder within 1-12 months after infection with those of COVID-naive individuals and stratified analyses according to time since infection, vaccination status, variant period, age, sex, and infection severity.

The final study cohort included 1.8 million individuals who tested positive during the study period and 1.5 who didn’t. Three quarters of those who tested positive were infected primarily with the Omicron variant.

Hospitalized vs Nonhospitalized

Overall, individuals who tested positive had a 24% lower risk for psychiatric disorders during the post-acute period (incident rate ratio [IRR], 0.76; 95% CI, 0.74-0.78) compared with the control group, but a 5% higher risk for any neurologic disorder (IRR, 1.05; 95% CI, 1.04-1.07).

Age, sex, and variant had less influence on risk than infection severity, where the differences between hospitalized and nonhospitalized patients were significant.

Compared with COVID-negative individuals, the risk for any psychiatric disorder was double for hospitalized patients (IRR, 2.05; 95% CI, 1.78-2.37) but was 25% lower among nonhospitalized patients (IRR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.73-0.77).

For neurologic disorders, the IRR for hospitalized patients was 2.44 (95% CI, 2.29-2.60) compared with COVID-negative individuals vs an IRR of only 1.02 (95% CI, 1.01-1.04) among nonhospitalized patients.

“In a general population, there was little support for clinically relevant post-acute risk increases of psychiatric and neurologic disorders associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection without hospitalization. This was particularly true for vaccinated individuals and for the more recent variants,” the authors wrote, adding that the only exception was for change in sense and smell.

‘Flaws’ in Previous Studies?

The findings in hospitalized patients were in line with previous findings, but those in nonhospitalized patients stand out, they added.

Previous studies were done predominantly in older males with comorbidities and those who were more socioeconomically disadvantaged, which could lead to a bias, Dr. Hviid said.

Those other studies “had a number of fundamental flaws that we do not believe our study has,” Dr. Hviid said. “Our study was conducted in the general population, with free and universal testing and healthcare.”

Researchers stress that sequelae after infection are predominantly associated with severe illness.

“Today, a healthy vaccinated adult having an asymptomatic or mild bout of COVID-19 with the current variants shouldn’t fear developing serious psychiatric or neurologic disorders in the months or years after infection.”

One limitation is that only hospital contacts were included, omitting possible diagnoses given outside hospital settings.

‘Extreme Caution’ Required

The link between COVID-19 and brain health is “complex,” and the new findings should be viewed cautiously, said Maxime Taquet, MRCPsych, PhD, National Institute for Health and Care Research clinical lecturer and specialty registrar in Psychiatry, Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust, England, who commented on the findings.

Previous research by Dr. Taquet, who was not involved in the current study, found an increased risk for neurologic and psychiatric diagnoses during the first 6 months after COVID-19 diagnosis.

The current study “contributes to better understanding this link by providing data from another country with a different organization of healthcare provision than the US, where most of the existing data come from,” Dr. Taquet said.

However, “some observations — for example, that COVID-19 is associated with a 50% reduction in the risk of autism, a condition present from very early in life — call for extreme caution in the interpretation of the findings, as they suggest that residual bias has not been accounted for,” Dr. Taquet continued.

Authors of an accompanying editorial, Eric Chow, MD, MS, MPH, of the Division of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, University of Washington, School of Public Health, and Anita Chopra, MD, of the post-COVID Clinic, University of Washington, Seattle, called the study a “critical contribution to the published literature.”

The association of neurologic and psychiatric diagnoses with severe disease “is a reminder of the importance of risk reduction by combining vaccinations with improved indoor ventilation and masking,” they concluded.

The study was supported by a grant from the Independent Research Fund Denmark. Dr. Hviid and coauthors, Dr. Chopra, and Dr. Taquet reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Chow received a travel award from the Infectious Diseases Society of America to attend ID Week 2022.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

COVID-19 Is a Very Weird Virus

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

In the early days of the pandemic, before we really understood what COVID was, two specialties in the hospital had a foreboding sense that something was very strange about this virus. The first was the pulmonologists, who noticed the striking levels of hypoxemia — low oxygen in the blood — and the rapidity with which patients who had previously been stable would crash in the intensive care unit.

The second, and I mark myself among this group, were the nephrologists. The dialysis machines stopped working right. I remember rounding on patients in the hospital who were on dialysis for kidney failure in the setting of severe COVID infection and seeing clots forming on the dialysis filters. Some patients could barely get in a full treatment because the filters would clog so quickly.

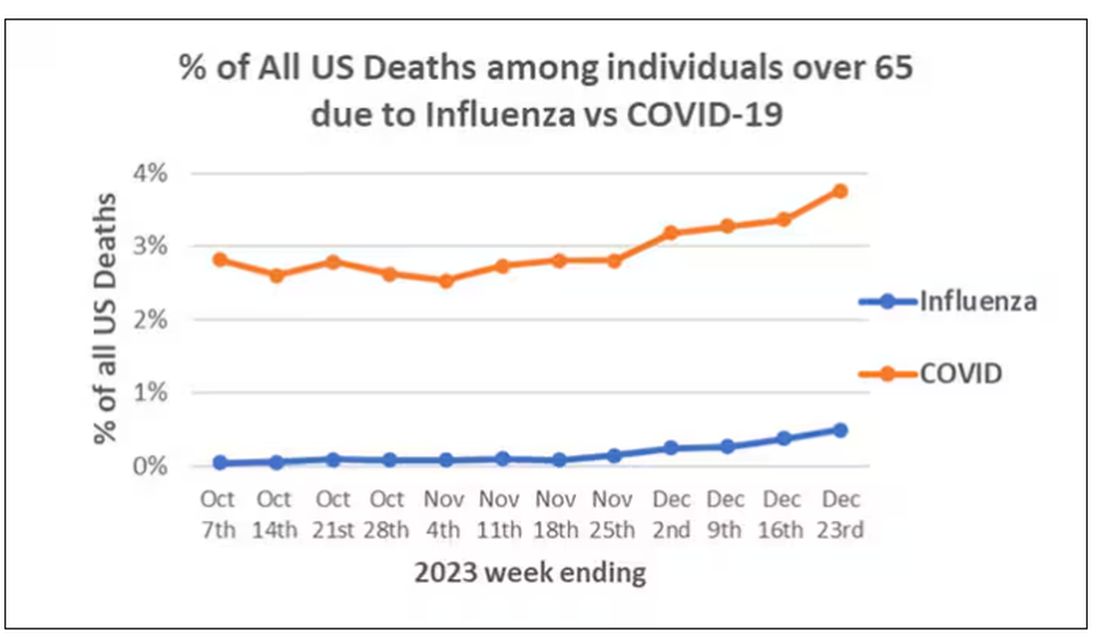

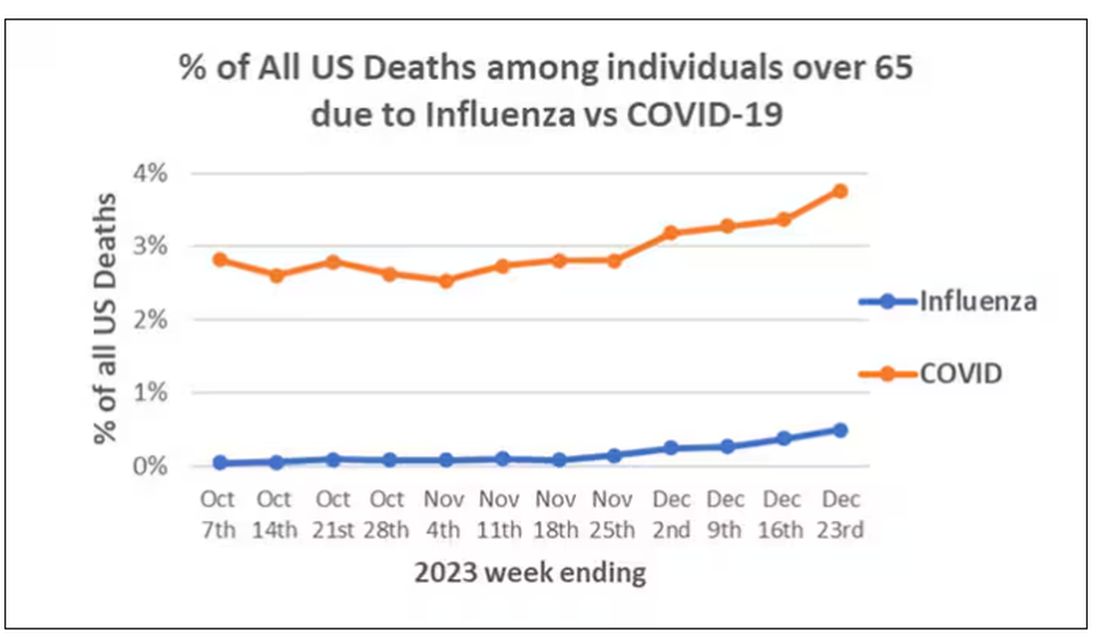

We knew it was worse than flu because of the mortality rates, but these oddities made us realize that it was different too — not just a particularly nasty respiratory virus but one that had effects on the body that we hadn’t really seen before.

That’s why I’ve always been interested in studies that compare what happens to patients after COVID infection vs what happens to patients after other respiratory infections. This week, we’ll look at an intriguing study that suggests that COVID may lead to autoimmune diseases like rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, and vasculitis.

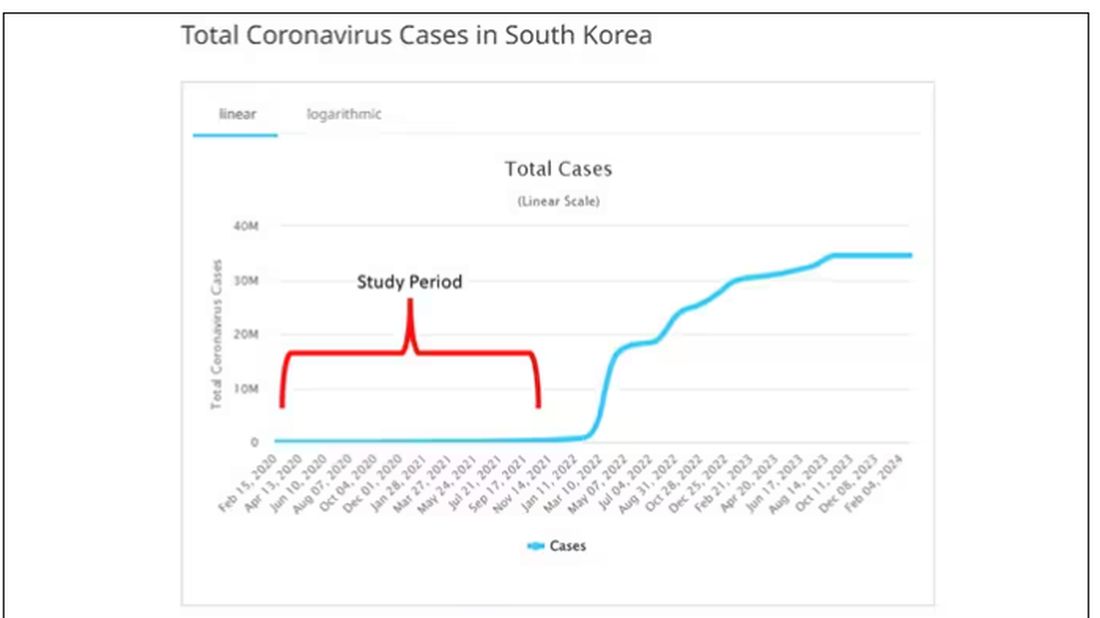

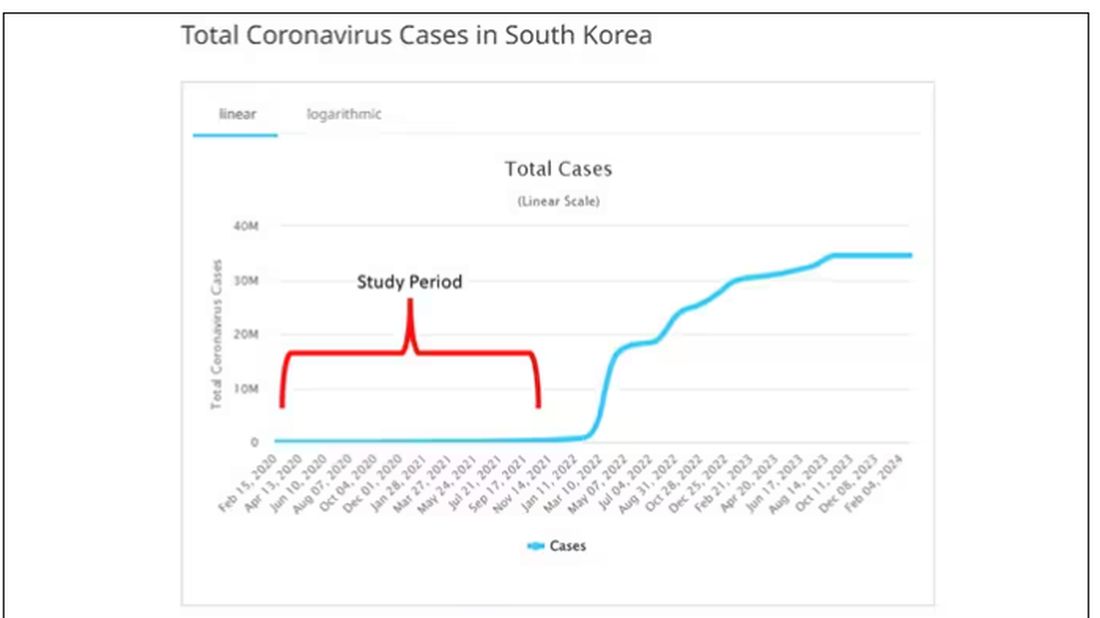

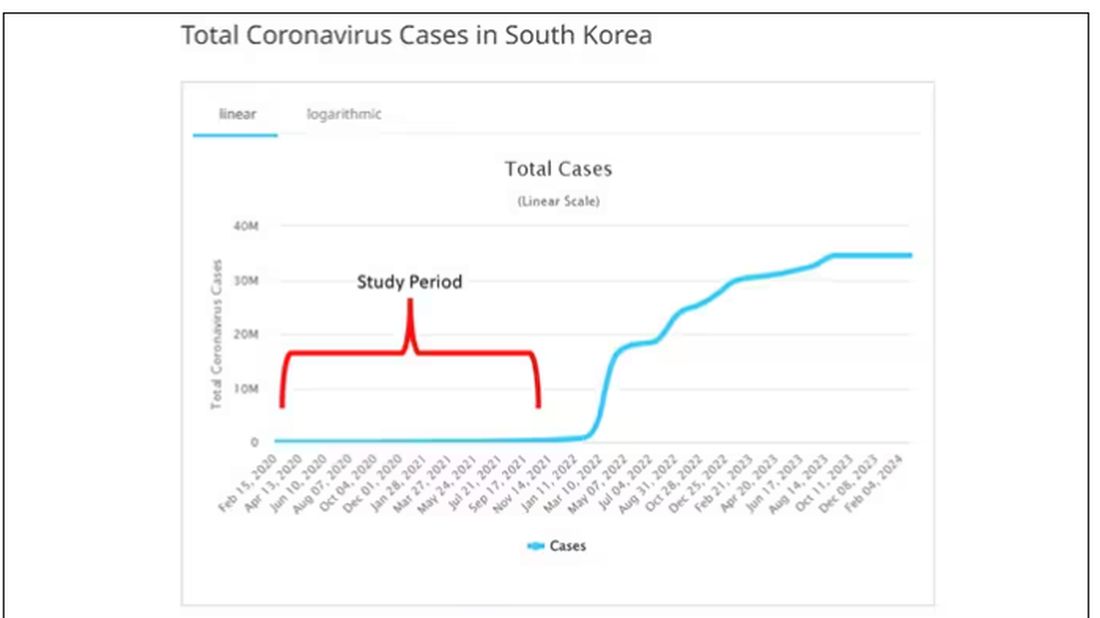

The study appears in the Annals of Internal Medicine and is made possible by the universal electronic health record systems of South Korea and Japan, who collaborated to create a truly staggering cohort of more than 20 million individuals living in those countries from 2020 to 2021.

The exposure of interest? COVID infection, experienced by just under 5% of that cohort over the study period. (Remember, there was a time when COVID infections were relatively controlled, particularly in some countries.)

The researchers wanted to compare the risk for autoimmune disease among COVID-infected individuals against two control groups. The first control group was the general population. This is interesting but a difficult analysis, because people who become infected with COVID might be very different from the general population. The second control group was people infected with influenza. I like this a lot better; the risk factors for COVID and influenza are quite similar, and the fact that this group was diagnosed with flu means at least that they are getting medical care and are sort of “in the system,” so to speak.

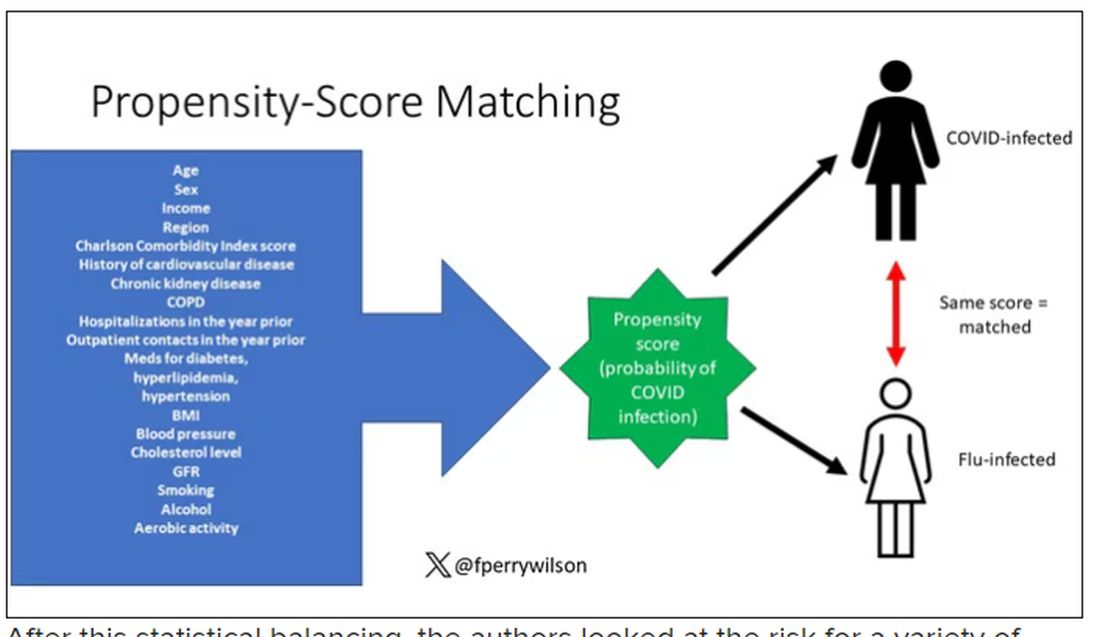

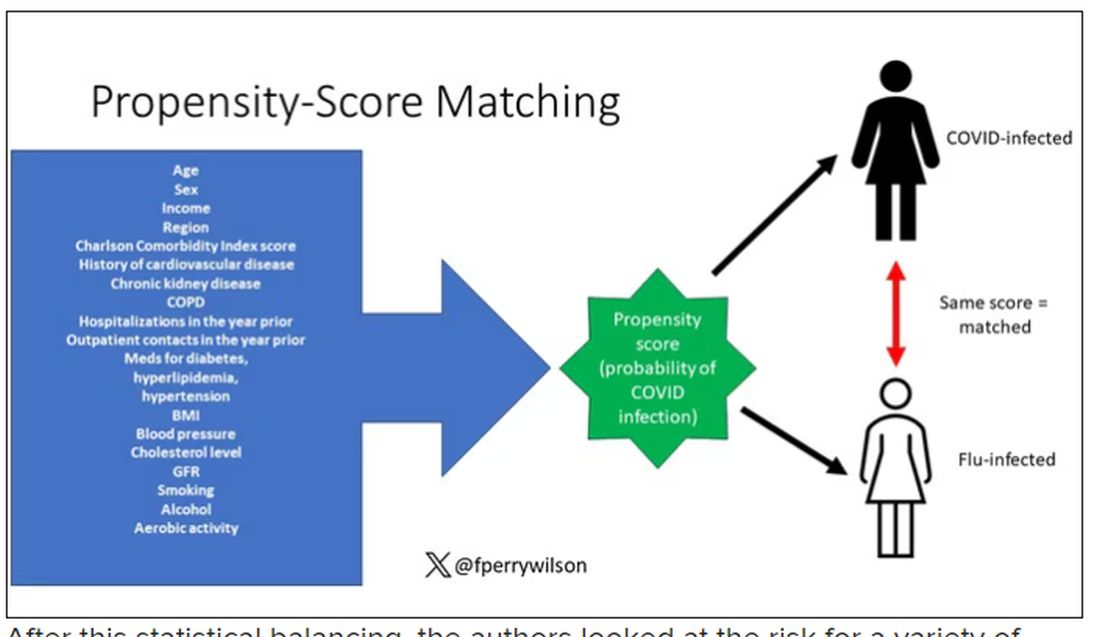

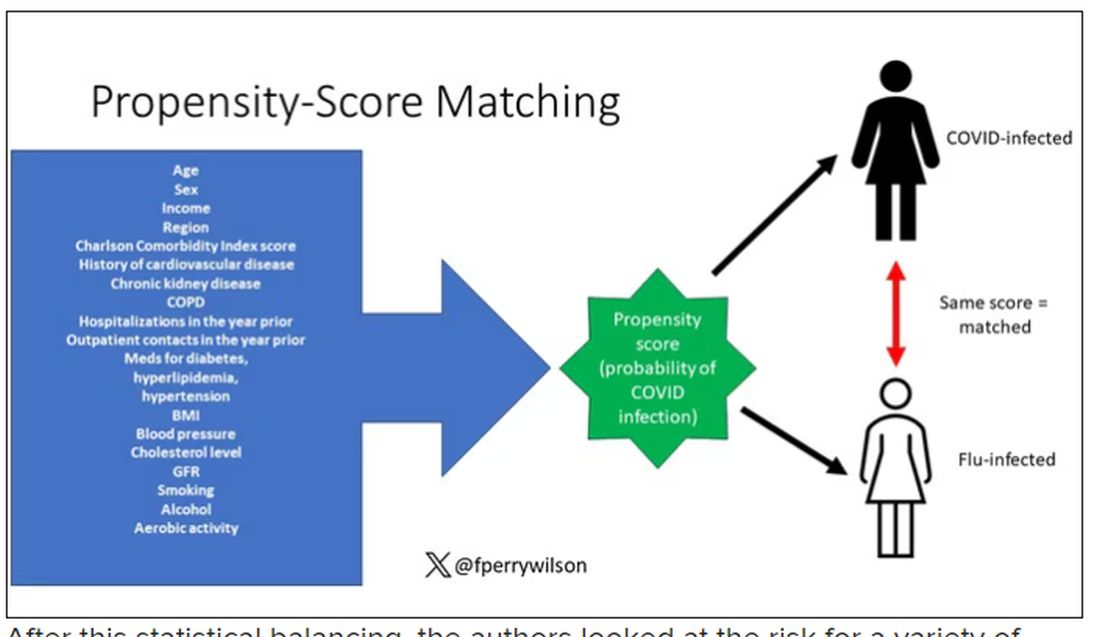

But it’s not enough to simply identify these folks and see who ends up with more autoimmune disease. The authors used propensity score matching to pair individuals infected with COVID with individuals from the control groups who were very similar to them. I’ve talked about this strategy before, but the basic idea is that you build a model predicting the likelihood of infection with COVID, based on a slew of factors — and the slew these authors used is pretty big, as shown below — and then stick people with similar risk for COVID together, with one member of the pair having had COVID and the other having eluded it (at least for the study period).

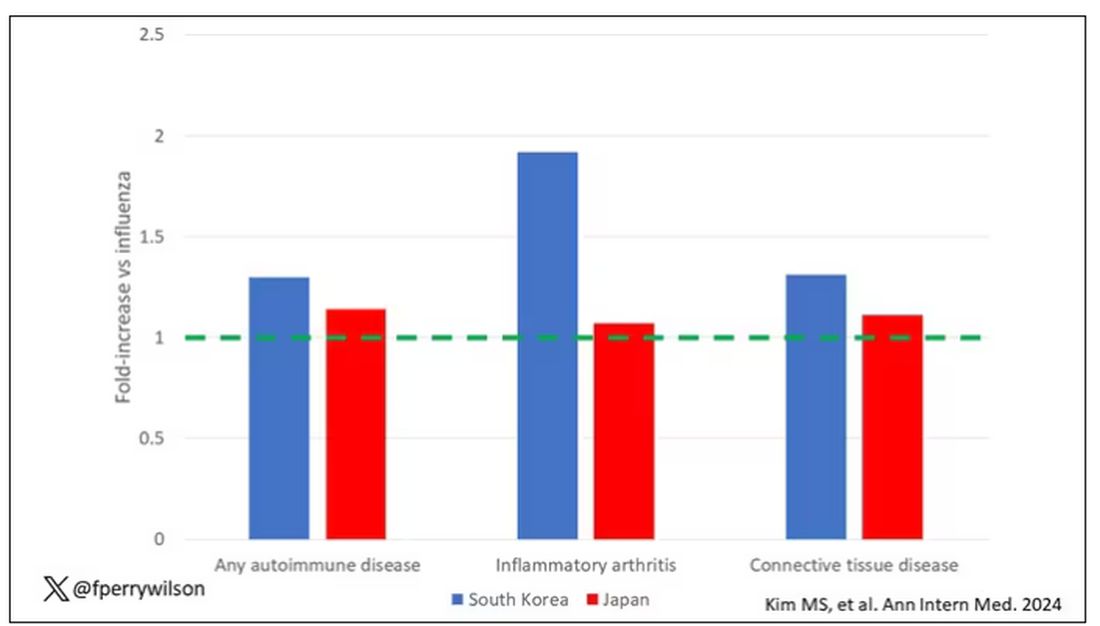

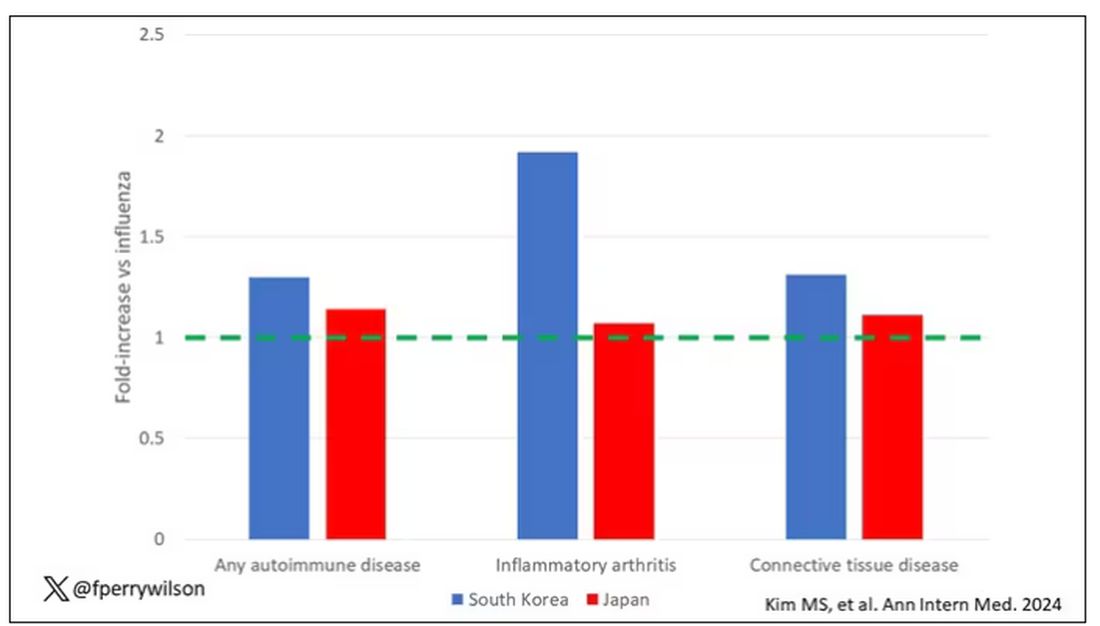

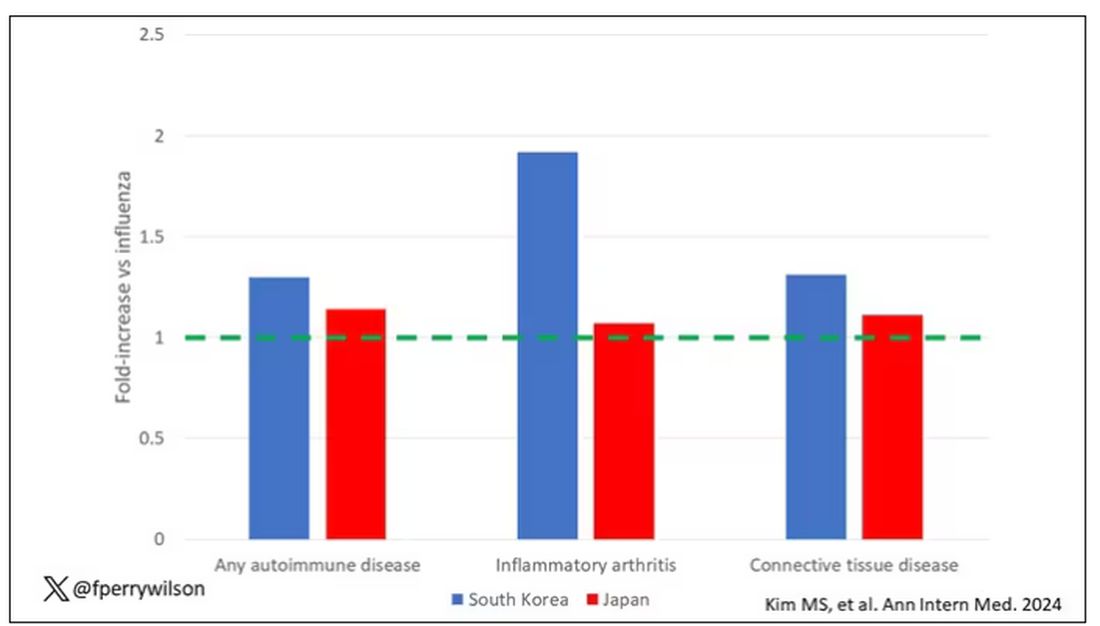

After this statistical balancing, the authors looked at the risk for a variety of autoimmune diseases.

Compared with those infected with flu, those infected with COVID were more likely to be diagnosed with any autoimmune condition, connective tissue disease, and, in Japan at least, inflammatory arthritis.

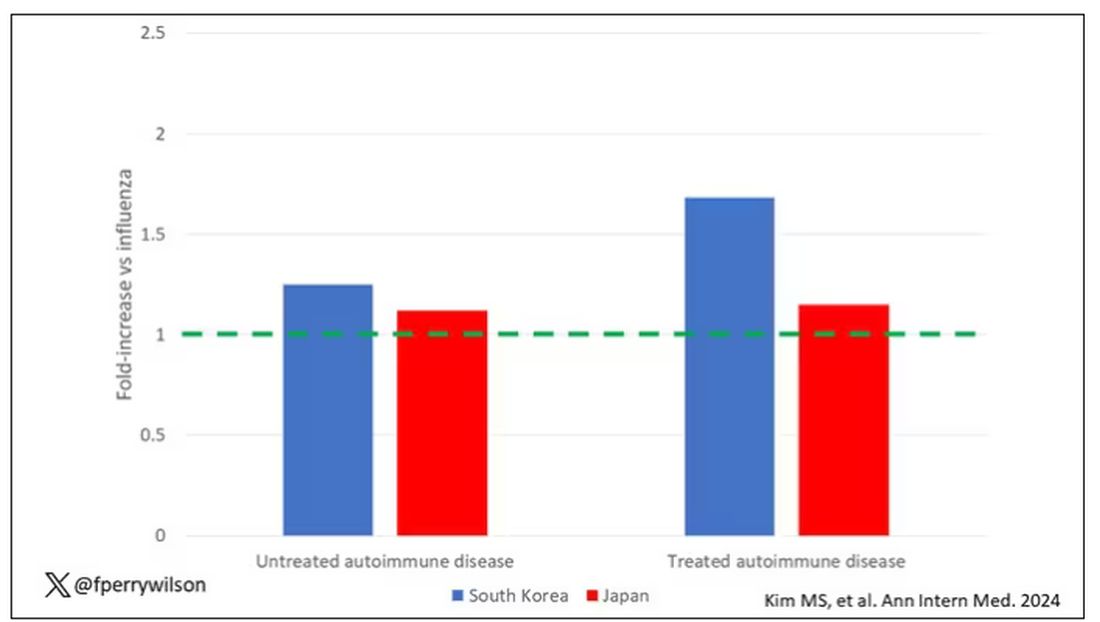

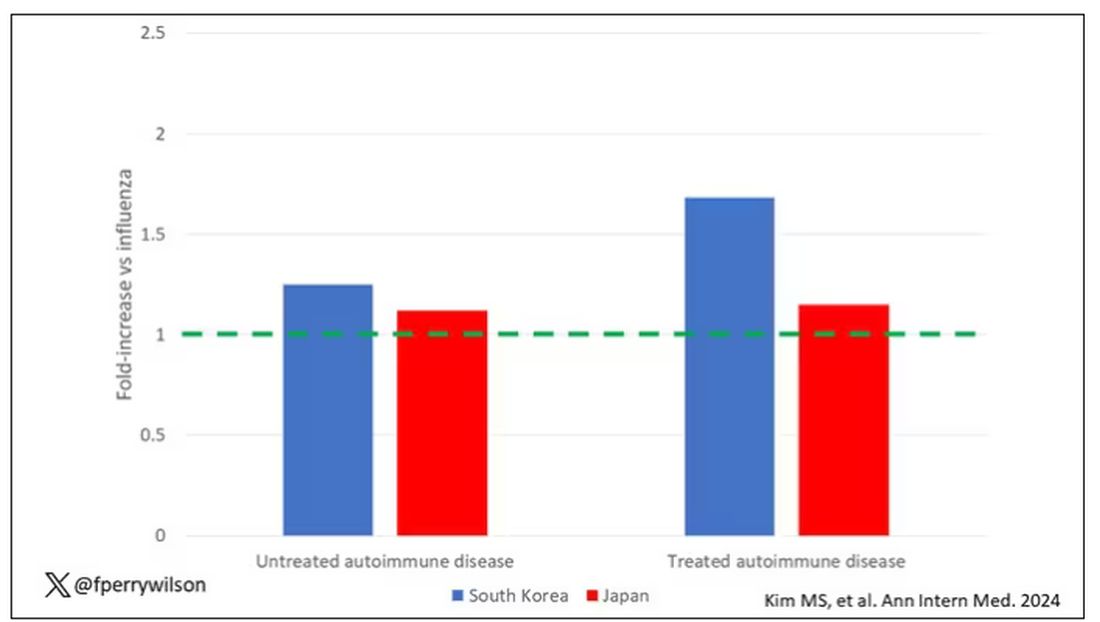

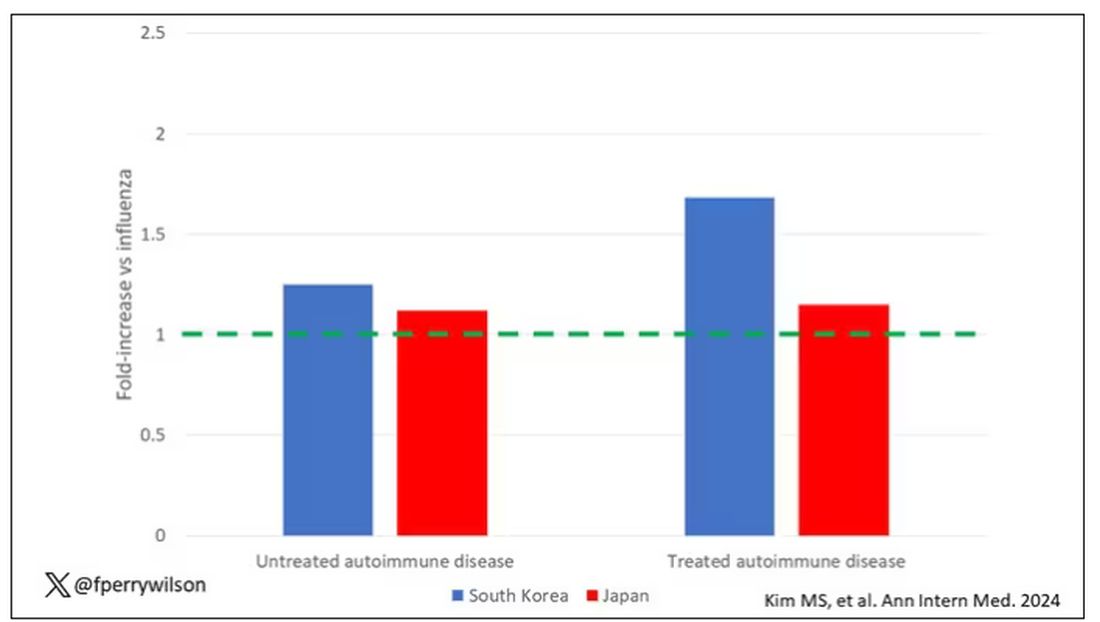

The authors acknowledge that being diagnosed with a disease might not be the same as actually having the disease, so in another analysis they looked only at people who received treatment for the autoimmune conditions, and the signals were even stronger in that group.

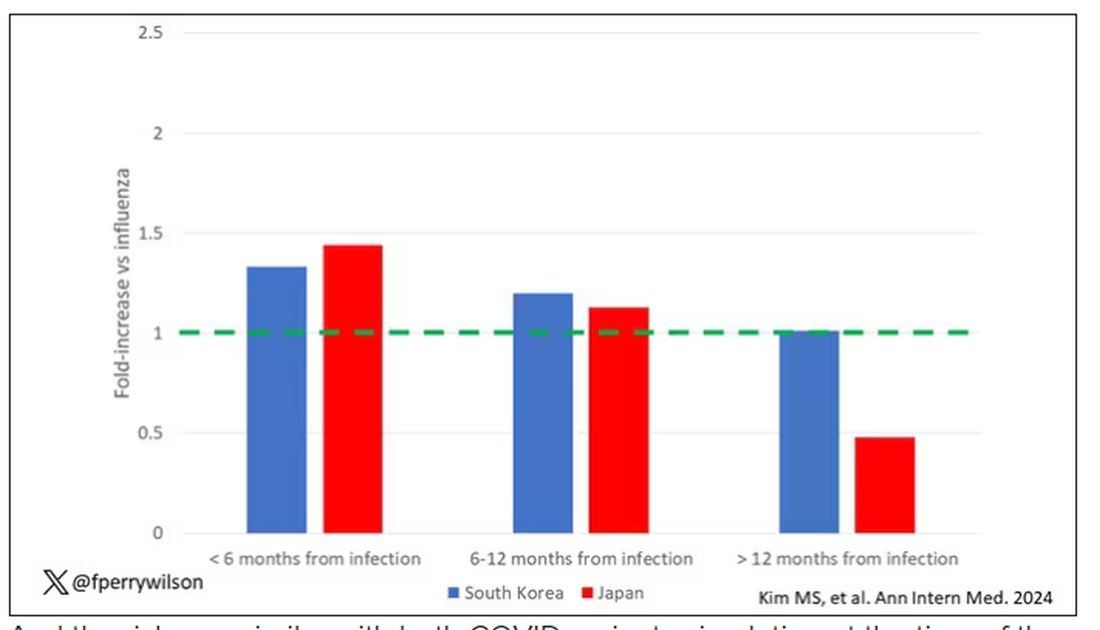

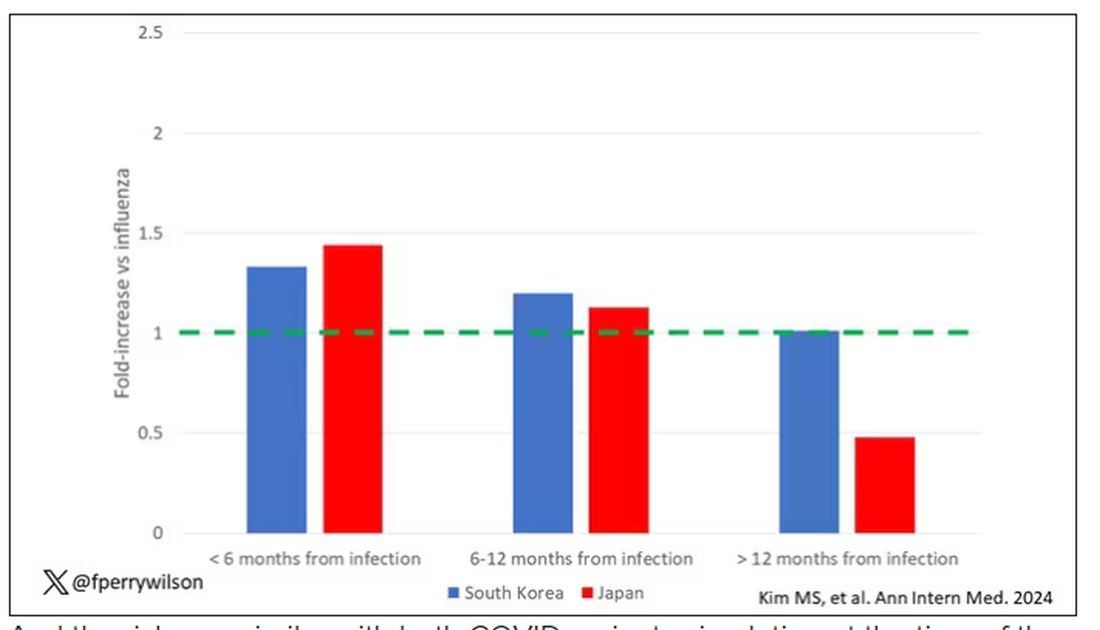

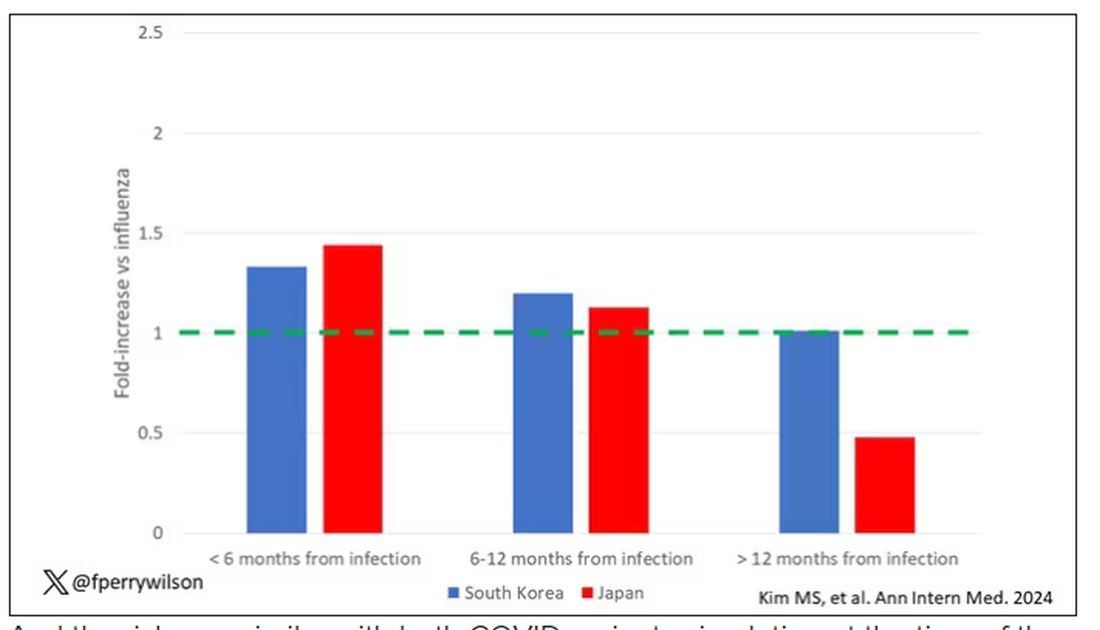

This risk seemed to be highest in the 6 months following the COVID infection, which makes sense biologically if we think that the infection is somehow screwing up the immune system.

And the risk was similar with both COVID variants circulating at the time of the study.

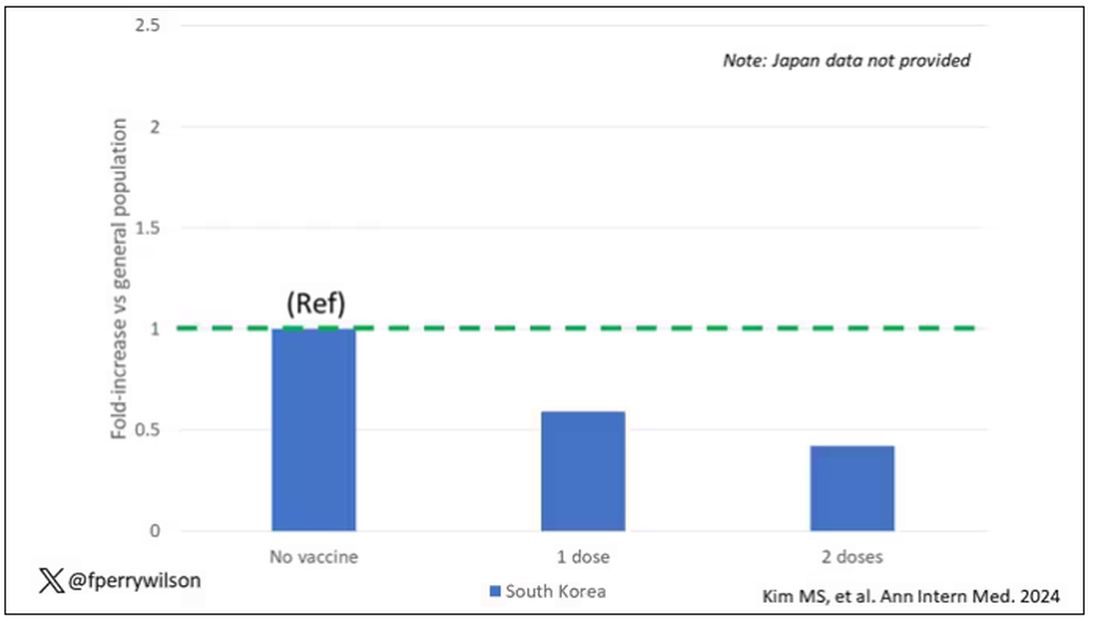

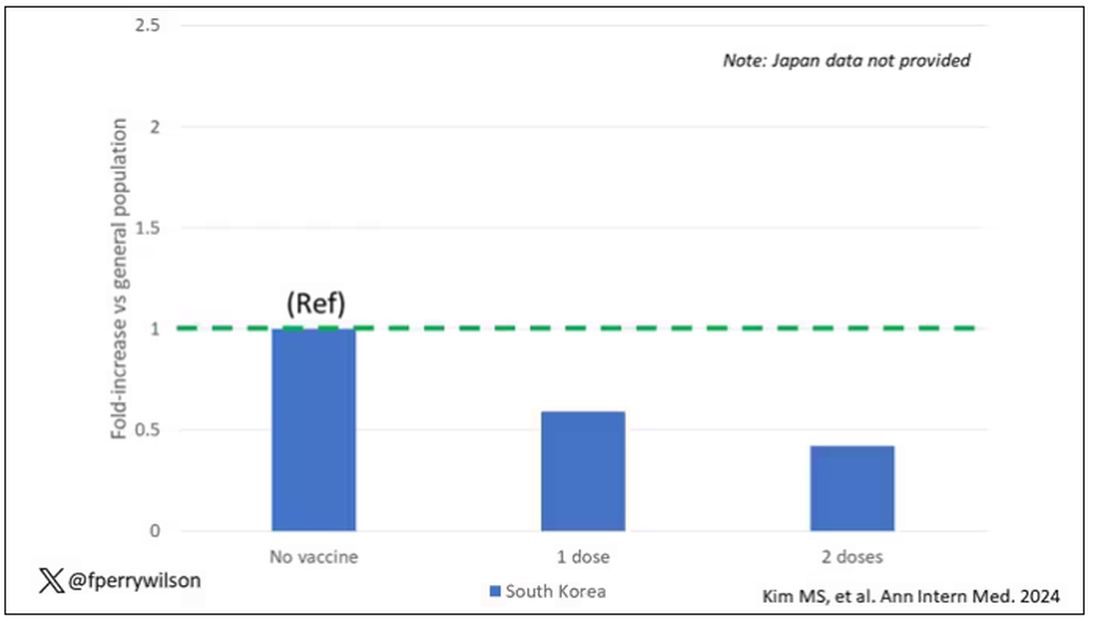

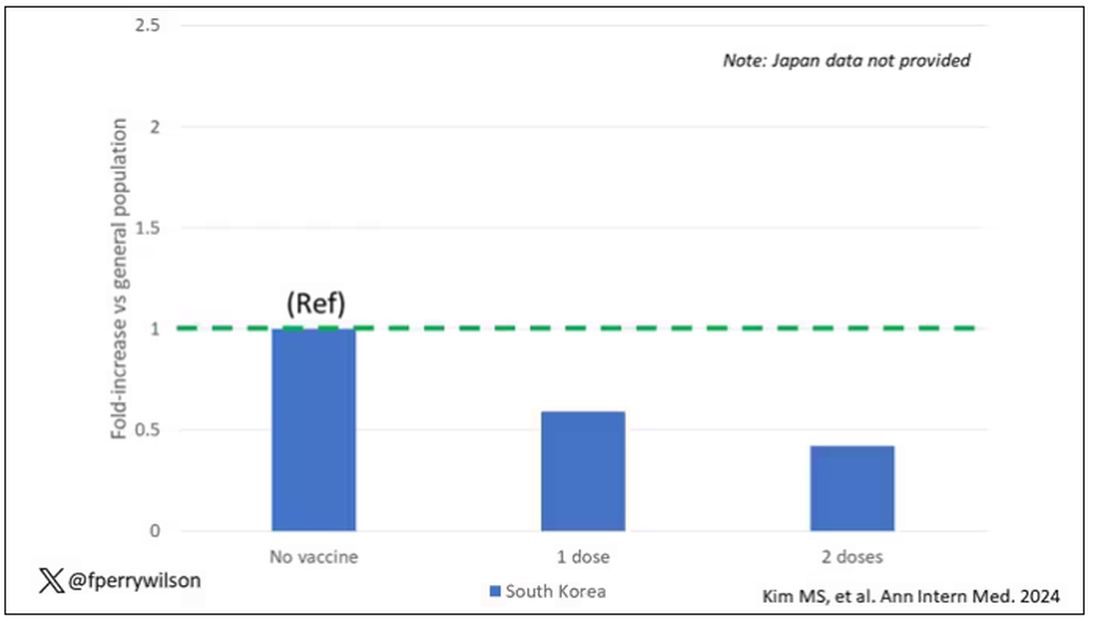

The only factor that reduced the risk? You guessed it: vaccination. This is a particularly interesting finding because the exposure cohort was defined by having been infected with COVID. Therefore, the mechanism of protection is not prevention of infection; it’s something else. Perhaps vaccination helps to get the immune system in a state to respond to COVID infection more… appropriately?

Yes, this study is observational. We can’t draw causal conclusions here. But it does reinforce my long-held belief that COVID is a weird virus, one with effects that are different from the respiratory viruses we are used to. I can’t say for certain whether COVID causes immune system dysfunction that puts someone at risk for autoimmunity — not from this study. But I can say it wouldn’t surprise me.

Dr. F. Perry Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

In the early days of the pandemic, before we really understood what COVID was, two specialties in the hospital had a foreboding sense that something was very strange about this virus. The first was the pulmonologists, who noticed the striking levels of hypoxemia — low oxygen in the blood — and the rapidity with which patients who had previously been stable would crash in the intensive care unit.

The second, and I mark myself among this group, were the nephrologists. The dialysis machines stopped working right. I remember rounding on patients in the hospital who were on dialysis for kidney failure in the setting of severe COVID infection and seeing clots forming on the dialysis filters. Some patients could barely get in a full treatment because the filters would clog so quickly.

We knew it was worse than flu because of the mortality rates, but these oddities made us realize that it was different too — not just a particularly nasty respiratory virus but one that had effects on the body that we hadn’t really seen before.

That’s why I’ve always been interested in studies that compare what happens to patients after COVID infection vs what happens to patients after other respiratory infections. This week, we’ll look at an intriguing study that suggests that COVID may lead to autoimmune diseases like rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, and vasculitis.

The study appears in the Annals of Internal Medicine and is made possible by the universal electronic health record systems of South Korea and Japan, who collaborated to create a truly staggering cohort of more than 20 million individuals living in those countries from 2020 to 2021.

The exposure of interest? COVID infection, experienced by just under 5% of that cohort over the study period. (Remember, there was a time when COVID infections were relatively controlled, particularly in some countries.)

The researchers wanted to compare the risk for autoimmune disease among COVID-infected individuals against two control groups. The first control group was the general population. This is interesting but a difficult analysis, because people who become infected with COVID might be very different from the general population. The second control group was people infected with influenza. I like this a lot better; the risk factors for COVID and influenza are quite similar, and the fact that this group was diagnosed with flu means at least that they are getting medical care and are sort of “in the system,” so to speak.

But it’s not enough to simply identify these folks and see who ends up with more autoimmune disease. The authors used propensity score matching to pair individuals infected with COVID with individuals from the control groups who were very similar to them. I’ve talked about this strategy before, but the basic idea is that you build a model predicting the likelihood of infection with COVID, based on a slew of factors — and the slew these authors used is pretty big, as shown below — and then stick people with similar risk for COVID together, with one member of the pair having had COVID and the other having eluded it (at least for the study period).

After this statistical balancing, the authors looked at the risk for a variety of autoimmune diseases.

Compared with those infected with flu, those infected with COVID were more likely to be diagnosed with any autoimmune condition, connective tissue disease, and, in Japan at least, inflammatory arthritis.

The authors acknowledge that being diagnosed with a disease might not be the same as actually having the disease, so in another analysis they looked only at people who received treatment for the autoimmune conditions, and the signals were even stronger in that group.

This risk seemed to be highest in the 6 months following the COVID infection, which makes sense biologically if we think that the infection is somehow screwing up the immune system.

And the risk was similar with both COVID variants circulating at the time of the study.

The only factor that reduced the risk? You guessed it: vaccination. This is a particularly interesting finding because the exposure cohort was defined by having been infected with COVID. Therefore, the mechanism of protection is not prevention of infection; it’s something else. Perhaps vaccination helps to get the immune system in a state to respond to COVID infection more… appropriately?

Yes, this study is observational. We can’t draw causal conclusions here. But it does reinforce my long-held belief that COVID is a weird virus, one with effects that are different from the respiratory viruses we are used to. I can’t say for certain whether COVID causes immune system dysfunction that puts someone at risk for autoimmunity — not from this study. But I can say it wouldn’t surprise me.

Dr. F. Perry Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

In the early days of the pandemic, before we really understood what COVID was, two specialties in the hospital had a foreboding sense that something was very strange about this virus. The first was the pulmonologists, who noticed the striking levels of hypoxemia — low oxygen in the blood — and the rapidity with which patients who had previously been stable would crash in the intensive care unit.

The second, and I mark myself among this group, were the nephrologists. The dialysis machines stopped working right. I remember rounding on patients in the hospital who were on dialysis for kidney failure in the setting of severe COVID infection and seeing clots forming on the dialysis filters. Some patients could barely get in a full treatment because the filters would clog so quickly.

We knew it was worse than flu because of the mortality rates, but these oddities made us realize that it was different too — not just a particularly nasty respiratory virus but one that had effects on the body that we hadn’t really seen before.

That’s why I’ve always been interested in studies that compare what happens to patients after COVID infection vs what happens to patients after other respiratory infections. This week, we’ll look at an intriguing study that suggests that COVID may lead to autoimmune diseases like rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, and vasculitis.

The study appears in the Annals of Internal Medicine and is made possible by the universal electronic health record systems of South Korea and Japan, who collaborated to create a truly staggering cohort of more than 20 million individuals living in those countries from 2020 to 2021.

The exposure of interest? COVID infection, experienced by just under 5% of that cohort over the study period. (Remember, there was a time when COVID infections were relatively controlled, particularly in some countries.)

The researchers wanted to compare the risk for autoimmune disease among COVID-infected individuals against two control groups. The first control group was the general population. This is interesting but a difficult analysis, because people who become infected with COVID might be very different from the general population. The second control group was people infected with influenza. I like this a lot better; the risk factors for COVID and influenza are quite similar, and the fact that this group was diagnosed with flu means at least that they are getting medical care and are sort of “in the system,” so to speak.

But it’s not enough to simply identify these folks and see who ends up with more autoimmune disease. The authors used propensity score matching to pair individuals infected with COVID with individuals from the control groups who were very similar to them. I’ve talked about this strategy before, but the basic idea is that you build a model predicting the likelihood of infection with COVID, based on a slew of factors — and the slew these authors used is pretty big, as shown below — and then stick people with similar risk for COVID together, with one member of the pair having had COVID and the other having eluded it (at least for the study period).

After this statistical balancing, the authors looked at the risk for a variety of autoimmune diseases.

Compared with those infected with flu, those infected with COVID were more likely to be diagnosed with any autoimmune condition, connective tissue disease, and, in Japan at least, inflammatory arthritis.

The authors acknowledge that being diagnosed with a disease might not be the same as actually having the disease, so in another analysis they looked only at people who received treatment for the autoimmune conditions, and the signals were even stronger in that group.

This risk seemed to be highest in the 6 months following the COVID infection, which makes sense biologically if we think that the infection is somehow screwing up the immune system.

And the risk was similar with both COVID variants circulating at the time of the study.

The only factor that reduced the risk? You guessed it: vaccination. This is a particularly interesting finding because the exposure cohort was defined by having been infected with COVID. Therefore, the mechanism of protection is not prevention of infection; it’s something else. Perhaps vaccination helps to get the immune system in a state to respond to COVID infection more… appropriately?

Yes, this study is observational. We can’t draw causal conclusions here. But it does reinforce my long-held belief that COVID is a weird virus, one with effects that are different from the respiratory viruses we are used to. I can’t say for certain whether COVID causes immune system dysfunction that puts someone at risk for autoimmunity — not from this study. But I can say it wouldn’t surprise me.

Dr. F. Perry Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Increased Risk of New Rheumatic Disease Follows COVID-19 Infection

The risk of developing a new autoimmune inflammatory rheumatic disease (AIRD) is greater following a COVID-19 infection than after an influenza infection or in the general population, according to a study published March 5 in Annals of Internal Medicine. More severe COVID-19 infections were linked to a greater risk of incident rheumatic disease, but vaccination appeared protective against development of a new AIRD.

“Importantly, this study shows the value of vaccination to prevent severe disease and these types of sequelae,” Anne Davidson, MBBS, a professor in the Institute of Molecular Medicine at The Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research in Manhasset, New York, who was not involved in the study, said in an interview.

Previous research had already identified the likelihood of an association between SARS-CoV-2 infection and subsequent development of a new AIRD. This new study, however, includes much larger cohorts from two different countries and relies on more robust methodology than previous studies, experts said.

“Unique steps were taken by the study authors to make sure that what they were looking at in terms of signal was most likely true,” Alfred Kim, MD, PhD, assistant professor of medicine in rheumatology at Washington University in St. Louis, who was not involved in the study, said in an interview. Dr. Davidson agreed, noting that these authors “were a bit more rigorous with ascertainment of the autoimmune diagnosis, using two codes and also checking that appropriate medications were administered.”

More Robust and Rigorous Research

Past cohort studies finding an increased risk of rheumatic disease after COVID-19 “based their findings solely on comparisons between infected and uninfected groups, which could be influenced by ascertainment bias due to disparities in care, differences in health-seeking tendencies, and inherent risks among the groups,” Min Seo Kim, MD, of the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, Cambridge, Massachusetts, and his colleagues reported. Their study, however, required at least two claims with codes for rheumatic disease and compared patients with COVID-19 to those with flu “to adjust for the potentially heightened detection of AIRD in SARS-CoV-2–infected persons owing to their interactions with the health care system.”

Dr. Alfred Kim said the fact that they used at least two claims codes “gives a little more credence that the patients were actually experiencing some sort of autoimmune inflammatory condition as opposed to a very transient issue post COVID that just went away on its own.”

He acknowledged that the previous research was reasonably strong, “especially in light of the fact that there has been so much work done on a molecular level demonstrating that COVID-19 is associated with a substantial increase in autoantibodies in a significant proportion of patients, so this always opened up the possibility that this could associate with some sort of autoimmune disease downstream.”

While the study is well done with a large population, “it still has limitations that might overestimate the effect,” Kevin W. Byram, MD, associate professor of medicine in rheumatology and immunology at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tennessee, who was not involved in the study, said in an interview. “We certainly have seen individual cases of new rheumatic disease where COVID-19 infection is likely the trigger,” but the phenomenon is not new, he added.

“Many autoimmune diseases are spurred by a loss of tolerance that might be induced by a pathogen of some sort,” Dr. Byram said. “The study is right to point out different forms of bias that might be at play. One in particular that is important to consider in a study like this is the lack of case-level adjudication regarding the diagnosis of rheumatic disease” since the study relied on available ICD-10 codes and medication prescriptions.

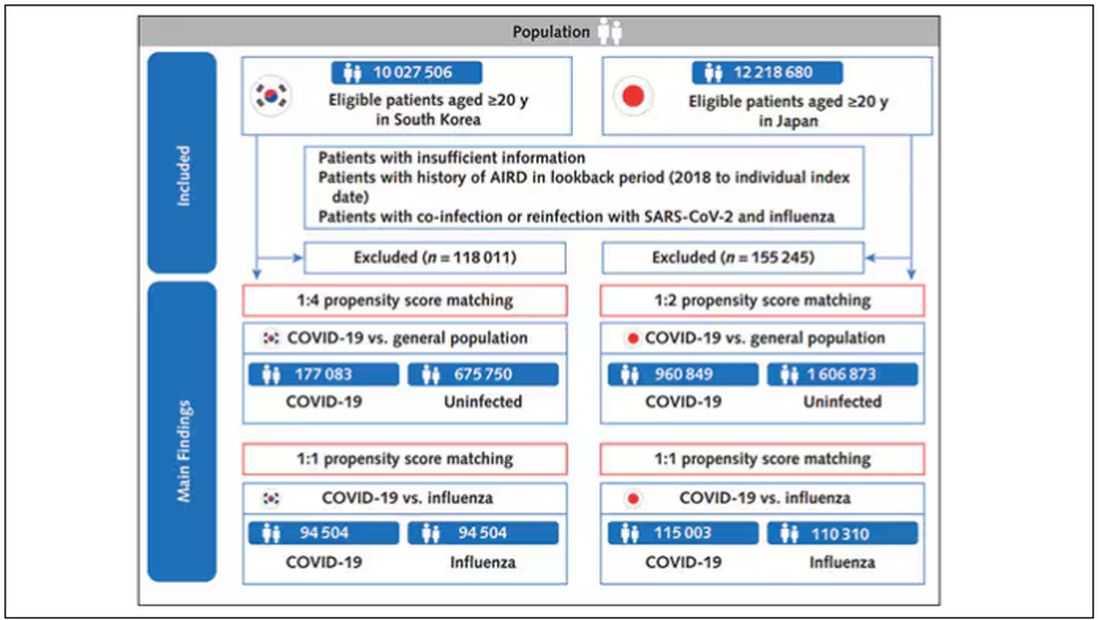

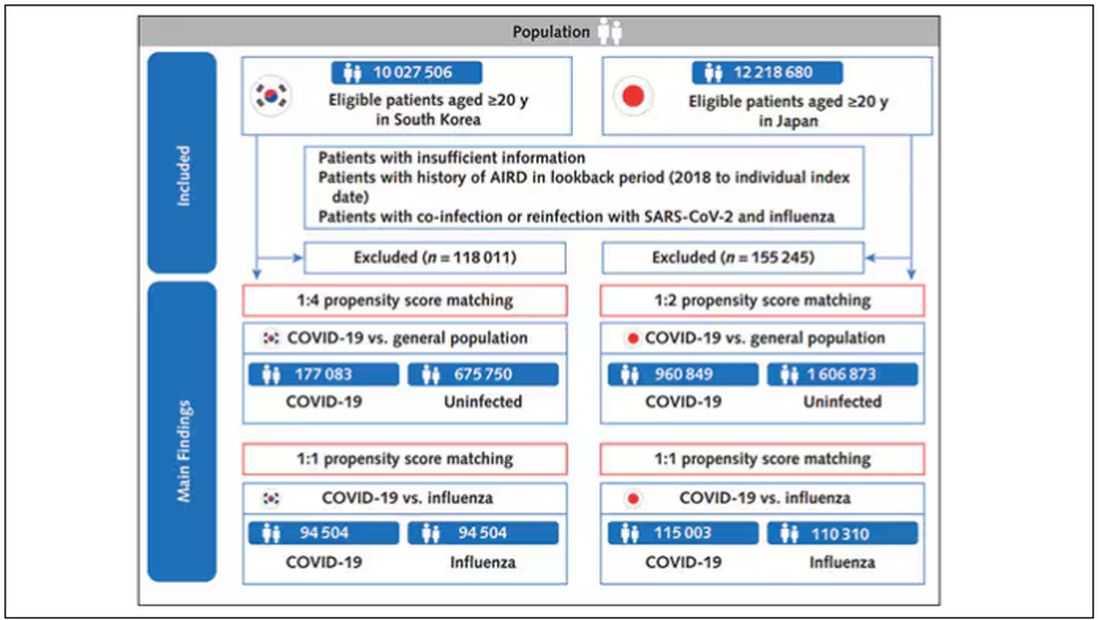

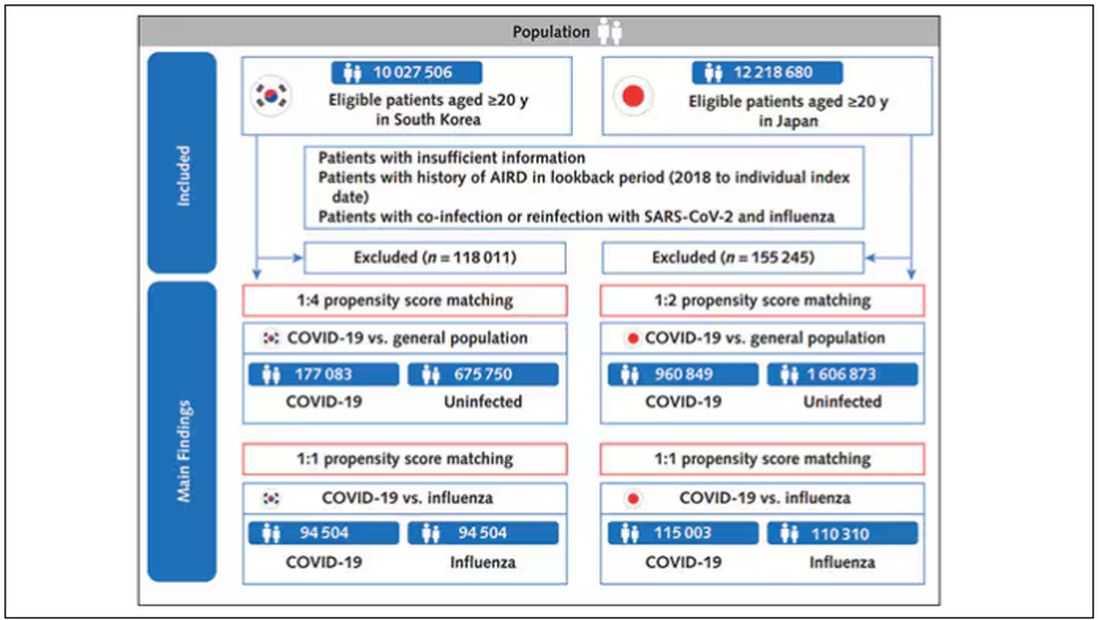

The researchers used national claims data to compare risk of incident AIRD in 10,027,506 South Korean and 12,218,680 Japanese adults, aged 20 and older, at 1 month, 6 months, and 12 months after COVID-19 infection, influenza infection, or a matched index date for uninfected control participants. Only patients with at least two claims for AIRD were considered to have a new diagnosis.

Patients who had COVID-19 between January 2020 and December 2021, confirmed by PCR or antigen testing, were matched 1:1 with patients who had test-confirmed influenza during that time and 1:4 with uninfected control participants, whose index date was set to the infection date of their matched COVID-19 patient.

The propensity score matching was based on age, sex, household income, urban versus rural residence, and various clinical characteristics and history: body mass index; blood pressure; fasting blood glucose; glomerular filtration rate; smoking status; alcohol consumption; weekly aerobic physical activity; comorbidity index; hospitalizations and outpatient visits in the previous year; past use of diabetes, hyperlipidemia, or hypertension medication; and history of cardiovascular disease, chronic kidney disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or respiratory infectious disease.

Patients with a history of AIRD or with coinfection or reinfection of COVID-19 and influenza were excluded, as were patients diagnosed with rheumatic disease within a month of COVID-19 infection.

Risk Varied With Disease Severity and Vaccination Status

Among the Korean patients, 3.9% had a COVID-19 infection and 0.98% had an influenza infection. After matching, the comparison populations included 94,504 patients with COVID-19 versus 94,504 patients with flu, and 177,083 patients with COVID-19 versus 675,750 uninfected controls.

The risk of developing an AIRD at least 1 month after infection in South Korean patients with COVID-19 was 25% higher than in uninfected control participants (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 1.25; 95% CI, 1.18–1.31; P < .05) and 30% higher than in influenza patients (aHR, 1.3; 95% CI, 1.02–1.59; P < .05). Specifically, risk in South Korean patients with COVID-19 was significantly increased for connective tissue disease and both treated and untreated AIRD but not for inflammatory arthritis.

Among the Japanese patients, 8.2% had COVID-19 and 0.99% had flu, resulting in matched populations of 115,003 with COVID-19 versus 110,310 with flu, and 960,849 with COVID-19 versus 1,606,873 uninfected patients. The effect size was larger in Japanese patients, with a 79% increased risk for AIRD in patients with COVID-19, compared with the general population (aHR, 1.79; 95% CI, 1.77–1.82; P < .05) and a 14% increased risk, compared with patients with influenza infection (aHR, 1.14; 95% CI, 1.10–1.17; P < .05). In Japanese patients, risk was increased across all four categories, including a doubled risk for inflammatory arthritis (aHR, 2.02; 95% CI, 1.96–2.07; P < .05), compared with the general population.

The researchers had data only from the South Korean cohort to calculate risk based on vaccination status, SARS-CoV-2 variant (wild type versus Delta), and COVID-19 severity. Researchers determined a COVID-19 infection to be moderate-to-severe based on billing codes for ICU admission or requiring oxygen therapy, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, renal replacement, or CPR.

Infection with both the original strain and the Delta variant were linked to similar increased risks for AIRD, but moderate to severe COVID-19 infections had greater risk of subsequent AIRD (aHR, 1.42; P < .05) than mild infections (aHR, 1.22; P < .05). Vaccination was linked to a lower risk of AIRD within the COVID-19 patient population: One dose was linked to a 41% reduced risk (HR, 0.59; P < .05) and two doses were linked to a 58% reduced risk (HR, 0.42; P < .05), regardless of the vaccine type, compared with unvaccinated patients with COVID-19. The apparent protective effect of vaccination was true only for patients with mild COVID-19, not those with moderate to severe infection.

“One has to wonder whether or not these people were at much higher risk of developing autoimmune disease that just got exposed because they got COVID, so that a fraction of these would have gotten an autoimmune disease downstream,” Dr. Alfred Kim said. Regardless, one clinical implication of the findings is the reduced risk in vaccinated patients, regardless of the vaccine type, given the fact that “mRNA vaccination in particular has not been associated with any autoantibody development,” he said.

Though the correlations in the study cannot translate to causation, several mechanisms might be at play in a viral infection contributing to autoimmune risk, Dr. Davidson said. Given that viral nucleic acids also recognize self-nucleic acids, “a large load of viral nucleic acid may break tolerance,” or “viral proteins could also mimic self-proteins,” she said. “In addition, tolerance may be broken by a highly inflammatory environment associated with the release of cytokines and other inflammatory mediators.”

The association between new-onset autoimmune disease and severe COVID-19 infection suggests multiple mechanisms may be involved in excess immune stimulation, Dr. Davidson said. But she added that it’s unclear how these findings, involving the original strain and Delta variant of SARS-CoV-2, might relate to currently circulating variants.

The research was funded by the National Research Foundation of Korea, the Korea Health Industry Development Institute, and the Ministry of Food and Drug Safety of the Republic of Korea. The authors reported no relevant financial relationships with industry. Dr. Alfred Kim has sponsored research agreements with AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Novartis; receives royalties from a patent with Kypha Inc.; and has done consulting or speaking for Amgen, ANI Pharmaceuticals, Aurinia Pharmaceuticals, Exagen Diagnostics, GlaxoSmithKline, Kypha, Miltenyi Biotech, Pfizer, Rheumatology & Arthritis Learning Network, Synthekine, Techtonic Therapeutics, and UpToDate. Dr. Byram reported consulting for TenSixteen Bio. Dr. Davidson had no disclosures.

The risk of developing a new autoimmune inflammatory rheumatic disease (AIRD) is greater following a COVID-19 infection than after an influenza infection or in the general population, according to a study published March 5 in Annals of Internal Medicine. More severe COVID-19 infections were linked to a greater risk of incident rheumatic disease, but vaccination appeared protective against development of a new AIRD.

“Importantly, this study shows the value of vaccination to prevent severe disease and these types of sequelae,” Anne Davidson, MBBS, a professor in the Institute of Molecular Medicine at The Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research in Manhasset, New York, who was not involved in the study, said in an interview.

Previous research had already identified the likelihood of an association between SARS-CoV-2 infection and subsequent development of a new AIRD. This new study, however, includes much larger cohorts from two different countries and relies on more robust methodology than previous studies, experts said.

“Unique steps were taken by the study authors to make sure that what they were looking at in terms of signal was most likely true,” Alfred Kim, MD, PhD, assistant professor of medicine in rheumatology at Washington University in St. Louis, who was not involved in the study, said in an interview. Dr. Davidson agreed, noting that these authors “were a bit more rigorous with ascertainment of the autoimmune diagnosis, using two codes and also checking that appropriate medications were administered.”

More Robust and Rigorous Research

Past cohort studies finding an increased risk of rheumatic disease after COVID-19 “based their findings solely on comparisons between infected and uninfected groups, which could be influenced by ascertainment bias due to disparities in care, differences in health-seeking tendencies, and inherent risks among the groups,” Min Seo Kim, MD, of the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, Cambridge, Massachusetts, and his colleagues reported. Their study, however, required at least two claims with codes for rheumatic disease and compared patients with COVID-19 to those with flu “to adjust for the potentially heightened detection of AIRD in SARS-CoV-2–infected persons owing to their interactions with the health care system.”

Dr. Alfred Kim said the fact that they used at least two claims codes “gives a little more credence that the patients were actually experiencing some sort of autoimmune inflammatory condition as opposed to a very transient issue post COVID that just went away on its own.”

He acknowledged that the previous research was reasonably strong, “especially in light of the fact that there has been so much work done on a molecular level demonstrating that COVID-19 is associated with a substantial increase in autoantibodies in a significant proportion of patients, so this always opened up the possibility that this could associate with some sort of autoimmune disease downstream.”

While the study is well done with a large population, “it still has limitations that might overestimate the effect,” Kevin W. Byram, MD, associate professor of medicine in rheumatology and immunology at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tennessee, who was not involved in the study, said in an interview. “We certainly have seen individual cases of new rheumatic disease where COVID-19 infection is likely the trigger,” but the phenomenon is not new, he added.

“Many autoimmune diseases are spurred by a loss of tolerance that might be induced by a pathogen of some sort,” Dr. Byram said. “The study is right to point out different forms of bias that might be at play. One in particular that is important to consider in a study like this is the lack of case-level adjudication regarding the diagnosis of rheumatic disease” since the study relied on available ICD-10 codes and medication prescriptions.

The researchers used national claims data to compare risk of incident AIRD in 10,027,506 South Korean and 12,218,680 Japanese adults, aged 20 and older, at 1 month, 6 months, and 12 months after COVID-19 infection, influenza infection, or a matched index date for uninfected control participants. Only patients with at least two claims for AIRD were considered to have a new diagnosis.

Patients who had COVID-19 between January 2020 and December 2021, confirmed by PCR or antigen testing, were matched 1:1 with patients who had test-confirmed influenza during that time and 1:4 with uninfected control participants, whose index date was set to the infection date of their matched COVID-19 patient.

The propensity score matching was based on age, sex, household income, urban versus rural residence, and various clinical characteristics and history: body mass index; blood pressure; fasting blood glucose; glomerular filtration rate; smoking status; alcohol consumption; weekly aerobic physical activity; comorbidity index; hospitalizations and outpatient visits in the previous year; past use of diabetes, hyperlipidemia, or hypertension medication; and history of cardiovascular disease, chronic kidney disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or respiratory infectious disease.

Patients with a history of AIRD or with coinfection or reinfection of COVID-19 and influenza were excluded, as were patients diagnosed with rheumatic disease within a month of COVID-19 infection.

Risk Varied With Disease Severity and Vaccination Status

Among the Korean patients, 3.9% had a COVID-19 infection and 0.98% had an influenza infection. After matching, the comparison populations included 94,504 patients with COVID-19 versus 94,504 patients with flu, and 177,083 patients with COVID-19 versus 675,750 uninfected controls.

The risk of developing an AIRD at least 1 month after infection in South Korean patients with COVID-19 was 25% higher than in uninfected control participants (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 1.25; 95% CI, 1.18–1.31; P < .05) and 30% higher than in influenza patients (aHR, 1.3; 95% CI, 1.02–1.59; P < .05). Specifically, risk in South Korean patients with COVID-19 was significantly increased for connective tissue disease and both treated and untreated AIRD but not for inflammatory arthritis.

Among the Japanese patients, 8.2% had COVID-19 and 0.99% had flu, resulting in matched populations of 115,003 with COVID-19 versus 110,310 with flu, and 960,849 with COVID-19 versus 1,606,873 uninfected patients. The effect size was larger in Japanese patients, with a 79% increased risk for AIRD in patients with COVID-19, compared with the general population (aHR, 1.79; 95% CI, 1.77–1.82; P < .05) and a 14% increased risk, compared with patients with influenza infection (aHR, 1.14; 95% CI, 1.10–1.17; P < .05). In Japanese patients, risk was increased across all four categories, including a doubled risk for inflammatory arthritis (aHR, 2.02; 95% CI, 1.96–2.07; P < .05), compared with the general population.

The researchers had data only from the South Korean cohort to calculate risk based on vaccination status, SARS-CoV-2 variant (wild type versus Delta), and COVID-19 severity. Researchers determined a COVID-19 infection to be moderate-to-severe based on billing codes for ICU admission or requiring oxygen therapy, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, renal replacement, or CPR.

Infection with both the original strain and the Delta variant were linked to similar increased risks for AIRD, but moderate to severe COVID-19 infections had greater risk of subsequent AIRD (aHR, 1.42; P < .05) than mild infections (aHR, 1.22; P < .05). Vaccination was linked to a lower risk of AIRD within the COVID-19 patient population: One dose was linked to a 41% reduced risk (HR, 0.59; P < .05) and two doses were linked to a 58% reduced risk (HR, 0.42; P < .05), regardless of the vaccine type, compared with unvaccinated patients with COVID-19. The apparent protective effect of vaccination was true only for patients with mild COVID-19, not those with moderate to severe infection.

“One has to wonder whether or not these people were at much higher risk of developing autoimmune disease that just got exposed because they got COVID, so that a fraction of these would have gotten an autoimmune disease downstream,” Dr. Alfred Kim said. Regardless, one clinical implication of the findings is the reduced risk in vaccinated patients, regardless of the vaccine type, given the fact that “mRNA vaccination in particular has not been associated with any autoantibody development,” he said.

Though the correlations in the study cannot translate to causation, several mechanisms might be at play in a viral infection contributing to autoimmune risk, Dr. Davidson said. Given that viral nucleic acids also recognize self-nucleic acids, “a large load of viral nucleic acid may break tolerance,” or “viral proteins could also mimic self-proteins,” she said. “In addition, tolerance may be broken by a highly inflammatory environment associated with the release of cytokines and other inflammatory mediators.”

The association between new-onset autoimmune disease and severe COVID-19 infection suggests multiple mechanisms may be involved in excess immune stimulation, Dr. Davidson said. But she added that it’s unclear how these findings, involving the original strain and Delta variant of SARS-CoV-2, might relate to currently circulating variants.

The research was funded by the National Research Foundation of Korea, the Korea Health Industry Development Institute, and the Ministry of Food and Drug Safety of the Republic of Korea. The authors reported no relevant financial relationships with industry. Dr. Alfred Kim has sponsored research agreements with AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Novartis; receives royalties from a patent with Kypha Inc.; and has done consulting or speaking for Amgen, ANI Pharmaceuticals, Aurinia Pharmaceuticals, Exagen Diagnostics, GlaxoSmithKline, Kypha, Miltenyi Biotech, Pfizer, Rheumatology & Arthritis Learning Network, Synthekine, Techtonic Therapeutics, and UpToDate. Dr. Byram reported consulting for TenSixteen Bio. Dr. Davidson had no disclosures.

The risk of developing a new autoimmune inflammatory rheumatic disease (AIRD) is greater following a COVID-19 infection than after an influenza infection or in the general population, according to a study published March 5 in Annals of Internal Medicine. More severe COVID-19 infections were linked to a greater risk of incident rheumatic disease, but vaccination appeared protective against development of a new AIRD.

“Importantly, this study shows the value of vaccination to prevent severe disease and these types of sequelae,” Anne Davidson, MBBS, a professor in the Institute of Molecular Medicine at The Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research in Manhasset, New York, who was not involved in the study, said in an interview.

Previous research had already identified the likelihood of an association between SARS-CoV-2 infection and subsequent development of a new AIRD. This new study, however, includes much larger cohorts from two different countries and relies on more robust methodology than previous studies, experts said.

“Unique steps were taken by the study authors to make sure that what they were looking at in terms of signal was most likely true,” Alfred Kim, MD, PhD, assistant professor of medicine in rheumatology at Washington University in St. Louis, who was not involved in the study, said in an interview. Dr. Davidson agreed, noting that these authors “were a bit more rigorous with ascertainment of the autoimmune diagnosis, using two codes and also checking that appropriate medications were administered.”

More Robust and Rigorous Research

Past cohort studies finding an increased risk of rheumatic disease after COVID-19 “based their findings solely on comparisons between infected and uninfected groups, which could be influenced by ascertainment bias due to disparities in care, differences in health-seeking tendencies, and inherent risks among the groups,” Min Seo Kim, MD, of the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, Cambridge, Massachusetts, and his colleagues reported. Their study, however, required at least two claims with codes for rheumatic disease and compared patients with COVID-19 to those with flu “to adjust for the potentially heightened detection of AIRD in SARS-CoV-2–infected persons owing to their interactions with the health care system.”

Dr. Alfred Kim said the fact that they used at least two claims codes “gives a little more credence that the patients were actually experiencing some sort of autoimmune inflammatory condition as opposed to a very transient issue post COVID that just went away on its own.”

He acknowledged that the previous research was reasonably strong, “especially in light of the fact that there has been so much work done on a molecular level demonstrating that COVID-19 is associated with a substantial increase in autoantibodies in a significant proportion of patients, so this always opened up the possibility that this could associate with some sort of autoimmune disease downstream.”

While the study is well done with a large population, “it still has limitations that might overestimate the effect,” Kevin W. Byram, MD, associate professor of medicine in rheumatology and immunology at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tennessee, who was not involved in the study, said in an interview. “We certainly have seen individual cases of new rheumatic disease where COVID-19 infection is likely the trigger,” but the phenomenon is not new, he added.

“Many autoimmune diseases are spurred by a loss of tolerance that might be induced by a pathogen of some sort,” Dr. Byram said. “The study is right to point out different forms of bias that might be at play. One in particular that is important to consider in a study like this is the lack of case-level adjudication regarding the diagnosis of rheumatic disease” since the study relied on available ICD-10 codes and medication prescriptions.

The researchers used national claims data to compare risk of incident AIRD in 10,027,506 South Korean and 12,218,680 Japanese adults, aged 20 and older, at 1 month, 6 months, and 12 months after COVID-19 infection, influenza infection, or a matched index date for uninfected control participants. Only patients with at least two claims for AIRD were considered to have a new diagnosis.

Patients who had COVID-19 between January 2020 and December 2021, confirmed by PCR or antigen testing, were matched 1:1 with patients who had test-confirmed influenza during that time and 1:4 with uninfected control participants, whose index date was set to the infection date of their matched COVID-19 patient.

The propensity score matching was based on age, sex, household income, urban versus rural residence, and various clinical characteristics and history: body mass index; blood pressure; fasting blood glucose; glomerular filtration rate; smoking status; alcohol consumption; weekly aerobic physical activity; comorbidity index; hospitalizations and outpatient visits in the previous year; past use of diabetes, hyperlipidemia, or hypertension medication; and history of cardiovascular disease, chronic kidney disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or respiratory infectious disease.

Patients with a history of AIRD or with coinfection or reinfection of COVID-19 and influenza were excluded, as were patients diagnosed with rheumatic disease within a month of COVID-19 infection.

Risk Varied With Disease Severity and Vaccination Status

Among the Korean patients, 3.9% had a COVID-19 infection and 0.98% had an influenza infection. After matching, the comparison populations included 94,504 patients with COVID-19 versus 94,504 patients with flu, and 177,083 patients with COVID-19 versus 675,750 uninfected controls.

The risk of developing an AIRD at least 1 month after infection in South Korean patients with COVID-19 was 25% higher than in uninfected control participants (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 1.25; 95% CI, 1.18–1.31; P < .05) and 30% higher than in influenza patients (aHR, 1.3; 95% CI, 1.02–1.59; P < .05). Specifically, risk in South Korean patients with COVID-19 was significantly increased for connective tissue disease and both treated and untreated AIRD but not for inflammatory arthritis.

Among the Japanese patients, 8.2% had COVID-19 and 0.99% had flu, resulting in matched populations of 115,003 with COVID-19 versus 110,310 with flu, and 960,849 with COVID-19 versus 1,606,873 uninfected patients. The effect size was larger in Japanese patients, with a 79% increased risk for AIRD in patients with COVID-19, compared with the general population (aHR, 1.79; 95% CI, 1.77–1.82; P < .05) and a 14% increased risk, compared with patients with influenza infection (aHR, 1.14; 95% CI, 1.10–1.17; P < .05). In Japanese patients, risk was increased across all four categories, including a doubled risk for inflammatory arthritis (aHR, 2.02; 95% CI, 1.96–2.07; P < .05), compared with the general population.

The researchers had data only from the South Korean cohort to calculate risk based on vaccination status, SARS-CoV-2 variant (wild type versus Delta), and COVID-19 severity. Researchers determined a COVID-19 infection to be moderate-to-severe based on billing codes for ICU admission or requiring oxygen therapy, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, renal replacement, or CPR.

Infection with both the original strain and the Delta variant were linked to similar increased risks for AIRD, but moderate to severe COVID-19 infections had greater risk of subsequent AIRD (aHR, 1.42; P < .05) than mild infections (aHR, 1.22; P < .05). Vaccination was linked to a lower risk of AIRD within the COVID-19 patient population: One dose was linked to a 41% reduced risk (HR, 0.59; P < .05) and two doses were linked to a 58% reduced risk (HR, 0.42; P < .05), regardless of the vaccine type, compared with unvaccinated patients with COVID-19. The apparent protective effect of vaccination was true only for patients with mild COVID-19, not those with moderate to severe infection.

“One has to wonder whether or not these people were at much higher risk of developing autoimmune disease that just got exposed because they got COVID, so that a fraction of these would have gotten an autoimmune disease downstream,” Dr. Alfred Kim said. Regardless, one clinical implication of the findings is the reduced risk in vaccinated patients, regardless of the vaccine type, given the fact that “mRNA vaccination in particular has not been associated with any autoantibody development,” he said.

Though the correlations in the study cannot translate to causation, several mechanisms might be at play in a viral infection contributing to autoimmune risk, Dr. Davidson said. Given that viral nucleic acids also recognize self-nucleic acids, “a large load of viral nucleic acid may break tolerance,” or “viral proteins could also mimic self-proteins,” she said. “In addition, tolerance may be broken by a highly inflammatory environment associated with the release of cytokines and other inflammatory mediators.”

The association between new-onset autoimmune disease and severe COVID-19 infection suggests multiple mechanisms may be involved in excess immune stimulation, Dr. Davidson said. But she added that it’s unclear how these findings, involving the original strain and Delta variant of SARS-CoV-2, might relate to currently circulating variants.

The research was funded by the National Research Foundation of Korea, the Korea Health Industry Development Institute, and the Ministry of Food and Drug Safety of the Republic of Korea. The authors reported no relevant financial relationships with industry. Dr. Alfred Kim has sponsored research agreements with AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Novartis; receives royalties from a patent with Kypha Inc.; and has done consulting or speaking for Amgen, ANI Pharmaceuticals, Aurinia Pharmaceuticals, Exagen Diagnostics, GlaxoSmithKline, Kypha, Miltenyi Biotech, Pfizer, Rheumatology & Arthritis Learning Network, Synthekine, Techtonic Therapeutics, and UpToDate. Dr. Byram reported consulting for TenSixteen Bio. Dr. Davidson had no disclosures.

FROM ANNALS OF INTERNAL MEDICINE

Biological Sex Differences: Key to Understanding Long COVID?

Letícia Soares was infected with COVID-19 in April 2020, in the final year of postdoctoral studies in disease ecology at a Canadian University. What started with piercing migraines and severe fatigue in 2020 soon spiraled into a myriad of long COVID symptoms: Gastrointestinal issues, sleep problems, joint and muscle pain, along with unexpected menstrual changes.

After an absence of menstrual bleeding and its usual signs, she later suffered from severe periods and symptoms that worsened her long COVID condition. “It just baffled me,” said Soares, now 39. “It was debilitating.”

Cases like Soares’s are leading scientists to spend more time trying to understand the biological sex disparity in chronic illnesses such as long COVID that until recently have all but been ignored. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, long COVID affects nearly twice as many women as men.

What’s more, up to two thirds of female patients with long COVID report an increase in symptoms related to menstruation, which suggests a possible link between sex hormone fluctuations and immune dysfunction in the illness.

“These illnesses are underfunded and understudied relative to their disease burdens,” said Beth Pollack, a research scientist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, Massachusetts, who studies complex chronic illnesses.

Addressing knowledge gaps, especially around sex differences, could significantly improve our understanding of complex chronic illnesses, said Pollack, who coauthored a 2023 literature review of female reproductive health impacts of long COVID.

Emerging ‘Menstrual Science’ Could Be Key

There is a critical need, she said, for studies on these illnesses to include considerations of sex differences, hormones, reproductive phases, and reproductive conditions. This research could potentially inform doctors and other clinicians or lead to treatments, both for reproductive symptoms and for the illnesses themselves.

Pollack noted that reproductive symptoms are prevalent across a group of infection-associated chronic illnesses she studies, all of which disproportionately affect women. These associated conditions, traditionally studied in isolation, share pathologies like reproductive health concerns, signaling a need for focused research on their shared mechanisms.

Recognizing this critical gap, “menstrual science” is emerging as a pivotal area of study, aiming to connect these dots through focused research on hormonal influences.

Researchers at the University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Australia, for example, are studying whether hormones play a role in causing or worsening the symptoms of long COVID. By comparing hormone levels in people with these conditions with those in healthy people and by tracking how symptoms change with hormone levels over time and across menstrual cycles, scientists hope to find patterns that could help diagnose these conditions more easily and lead to new treatments. They’re also examining how hormonal life phases such as puberty, pregnancy, or perimenopause and hormone treatments like birth control might affect these illnesses.

How Gender and Long COVID Intertwine

The pathologies of long COVID, affecting at least 65 million people worldwide, currently focus on four hypotheses: Persistent viral infection, reactivation of dormant viruses (such as common herpes viruses), inflammation-related damage to tissues and organs, and autoimmunity (the body attacking itself).

It’s this last reason that holds some of the most interesting clues on biological sex differences, said Akiko Iwasaki, PhD, a Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut, immunologist who has led numerous research breakthroughs on long COVID since the start of the pandemic. Women have two X chromosomes, for example, and although one is inactivated, the inactivation is incomplete.

Some cells still express genes from the “inactivated genes” on the X chromosome, Iwasaki said. Those include key immune genes, which trigger a more robust response to infections and vaccinations but also predispose them to autoimmune reactions. “It comes at the cost of triggering too much immune response,” Iwasaki said.

Sex hormones also factor in. Testosterone, which is higher in males, is immunosuppressive, so it can dampen immune responses, Iwasaki said. That may contribute to making males more likely to get severe acute infections of COVID-19 but have fewer long-term effects.

Estrogen, on the other hand, is known to enhance the immune response. It can increase the production of antibodies and the activation of T cells, which are critical for fighting off infections. This heightened immune response, however, might also contribute to the persistent inflammation observed in long COVID, where the immune system continues to react even after the acute infection has resolved.

Sex-Specific Symptoms and Marginalized Communities

Of the more than 200 symptoms long haulers experience, Iwasaki said, several are also sex-specific. A recent draft study by Iwasaki and another leading COVID researcher, David Putrino, PhD, at Mount Sinai Health System in New York City, shows hair loss as one of the most female-dominant symptoms and sexual dysfunction among males.

In examining sex differences, another question is why long COVID rates in the trans community are disproportionately high. One of the reasons Iwasaki’s lab is looking at testosterone closely is because anecdotal evidence from female-to-male trans individuals indicates that testosterone therapy improved their long COVID symptoms significantly. It also raises the possibility that hormone therapy could help.

However, patients and advocates say it’s also important to consider socioeconomic factors in the trans community. “We need to start at this population and social structure level to understand why trans people over and over are put in harm’s way,” said JD Davids, a trans patient-researcher with long COVID and the cofounder and codirector of Strategies for High Impact and its Long COVID Justice project.

For trans people, said Davids, risk factors for both severe COVID and long COVID include being part of low-income groups, belonging to marginalized racial and ethnic communities, and living in crowded environments such as shelters or prisons.

The disproportionate impact of long COVID on marginalized communities, especially when seen through the lens of historical medical neglect, also demands attention, said Iwasaki. “Women used to be labeled hysteric when they complained about these kinds of symptoms.”

Where It All Leads

The possibility of diagnosing long COVID with a simple blood test could radically change some doctors’ false perceptions that it is not a real condition, Iwasaki said, ensuring it is recognized and treated with the seriousness it deserves.

“I feel like we need to get there with long COVID. If we can order a blood test and say somebody has a long COVID because of these values, then suddenly the diseases become medically explainable,” Iwasaki added. This advancement is critical for propelling research forward, she said, refining treatment approaches — including those that target sex-specific hormone, immunity, and inflammation issues — and improving the well-being of those living with long COVID.

This hope resonates with scientists like Pollack, who recently led the first National Institutes of Health-sponsored research webinar on less studied pathologies in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) and long COVID, and with the experiences of individuals like Soares, who navigates through the unpredictable nature of both of these conditions with resilience.

“This illness never ceases to surprise me in how it changes my body. I feel like it’s a constant adaptation,” said Soares. Now living in Salvador, Brazil, her daily life has dramatically shifted to the confines of her home.

“It’s how I have more predictability in my symptoms,” she said, pointing out the pressing need for the scientific advancements that Iwasaki envisions and a deepening of our understanding of the disease’s impacts on patients’ lives.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Letícia Soares was infected with COVID-19 in April 2020, in the final year of postdoctoral studies in disease ecology at a Canadian University. What started with piercing migraines and severe fatigue in 2020 soon spiraled into a myriad of long COVID symptoms: Gastrointestinal issues, sleep problems, joint and muscle pain, along with unexpected menstrual changes.

After an absence of menstrual bleeding and its usual signs, she later suffered from severe periods and symptoms that worsened her long COVID condition. “It just baffled me,” said Soares, now 39. “It was debilitating.”

Cases like Soares’s are leading scientists to spend more time trying to understand the biological sex disparity in chronic illnesses such as long COVID that until recently have all but been ignored. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, long COVID affects nearly twice as many women as men.

What’s more, up to two thirds of female patients with long COVID report an increase in symptoms related to menstruation, which suggests a possible link between sex hormone fluctuations and immune dysfunction in the illness.

“These illnesses are underfunded and understudied relative to their disease burdens,” said Beth Pollack, a research scientist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, Massachusetts, who studies complex chronic illnesses.

Addressing knowledge gaps, especially around sex differences, could significantly improve our understanding of complex chronic illnesses, said Pollack, who coauthored a 2023 literature review of female reproductive health impacts of long COVID.

Emerging ‘Menstrual Science’ Could Be Key

There is a critical need, she said, for studies on these illnesses to include considerations of sex differences, hormones, reproductive phases, and reproductive conditions. This research could potentially inform doctors and other clinicians or lead to treatments, both for reproductive symptoms and for the illnesses themselves.

Pollack noted that reproductive symptoms are prevalent across a group of infection-associated chronic illnesses she studies, all of which disproportionately affect women. These associated conditions, traditionally studied in isolation, share pathologies like reproductive health concerns, signaling a need for focused research on their shared mechanisms.

Recognizing this critical gap, “menstrual science” is emerging as a pivotal area of study, aiming to connect these dots through focused research on hormonal influences.