User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

Successful Treatment of Refractory Extensive Pityriasis Rubra Pilaris With Risankizumab and Acitretin

To the Editor:

Pityriasis rubra pilaris (PRP) is a rare papulosquamous condition with an unknown pathogenesis and limited efficacy data, which can make treatment challenging. Some cases of PRP spontaneously resolve in a few months, which is most common in the pediatric population.1 Pityriasis rubra pilaris in adults is likely to persist for years, and spontaneous resolution is unpredictable. Randomized clinical trials are difficult to perform due to the rarity of PRP.

Although there is no cure and no standard protocol for treating PRP, systemic retinoids historically are considered first-line therapy for moderate to severe cases.2 Additional management approaches include symptomatic control with moisturizers and psychological support. Alternative systemic treatments for moderate to severe cases include methotrexate, phototherapy, and cyclosporine.2

Pityriasis rubra pilaris demonstrates a favorable response to methotrexate treatment, especially in type I cases; however, patients on this alternative therapy should be monitored for severe adverse effects (eg, hepatotoxicity, pancytopenia, pneumonitis).2 Phototherapy should be approached with caution. Narrowband UVB, UVA1, and psoralen plus UVA therapy have successfully treated PRP; however, the response is variable. In some cases, the opposite effect can occur, in which the condition is photoaggravated. Phototherapy is a valid alternative form of treatment when used in combination with acitretin, and a phototest should be performed prior to starting this regimen. Cyclosporine is another immunosuppressant that can be considered for PRP treatment, though there are limited data demonstrating its efficacy.2

The introduction of biologic agents has changed the treatment approach for many dermatologic diseases, including PRP. Given the similar features between psoriasis and PRP, the biologics prescribed for psoriasis therapy also are used for patients with PRP that is challenging to treat, such as anti–tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors and IL inhibitors—specifically IL-17 and IL-23. Remission has been achieved with the use of biologics in combination with retinoid therapy.2

Biologic therapies used for PRP effectively inhibit cytokines and reduce the overall inflammatory processes involved in the development of the scaly patches and plaques seen in this condition. However, most reported clinical experiences are case studies, and more research in the form of randomized clinical trials is needed to understand the efficacy and long-term effects of this form of treatment in PRP. We present a case of a patient with refractory adult subtype I PRP that was successfully treated with the IL-23 inhibitor risankizumab.

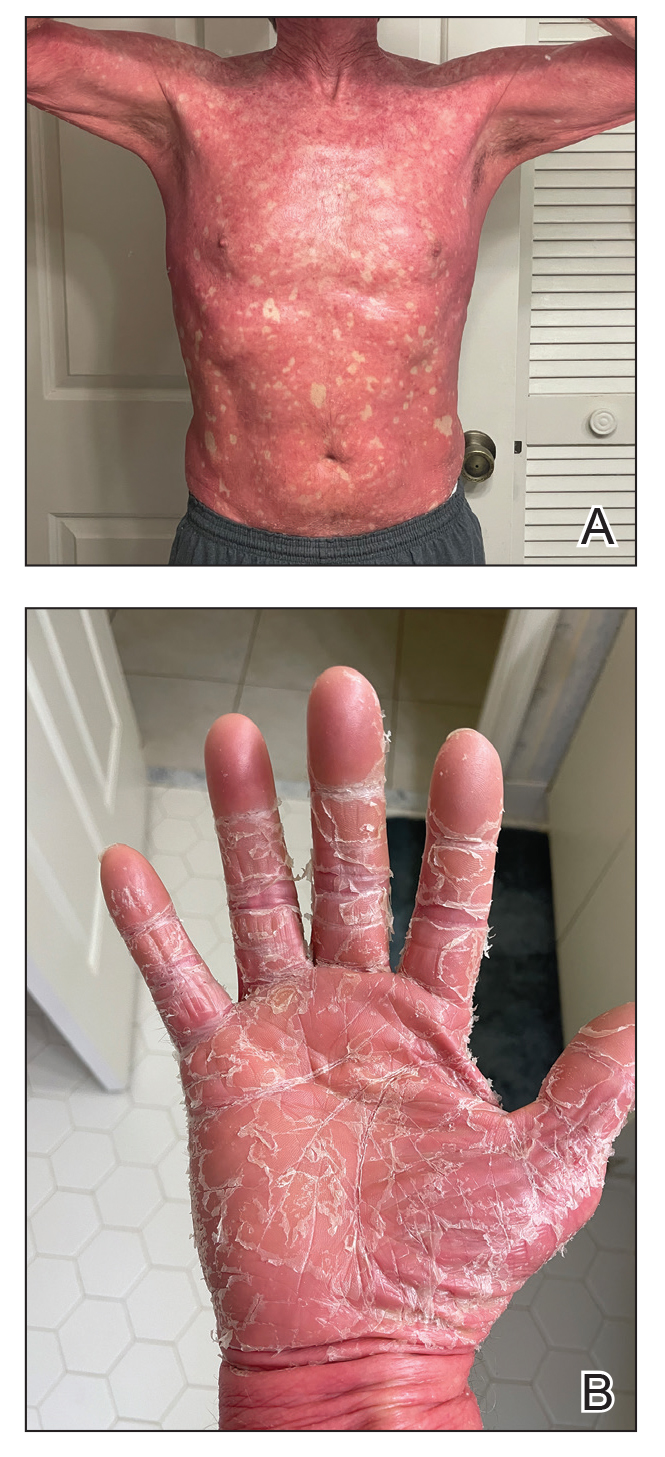

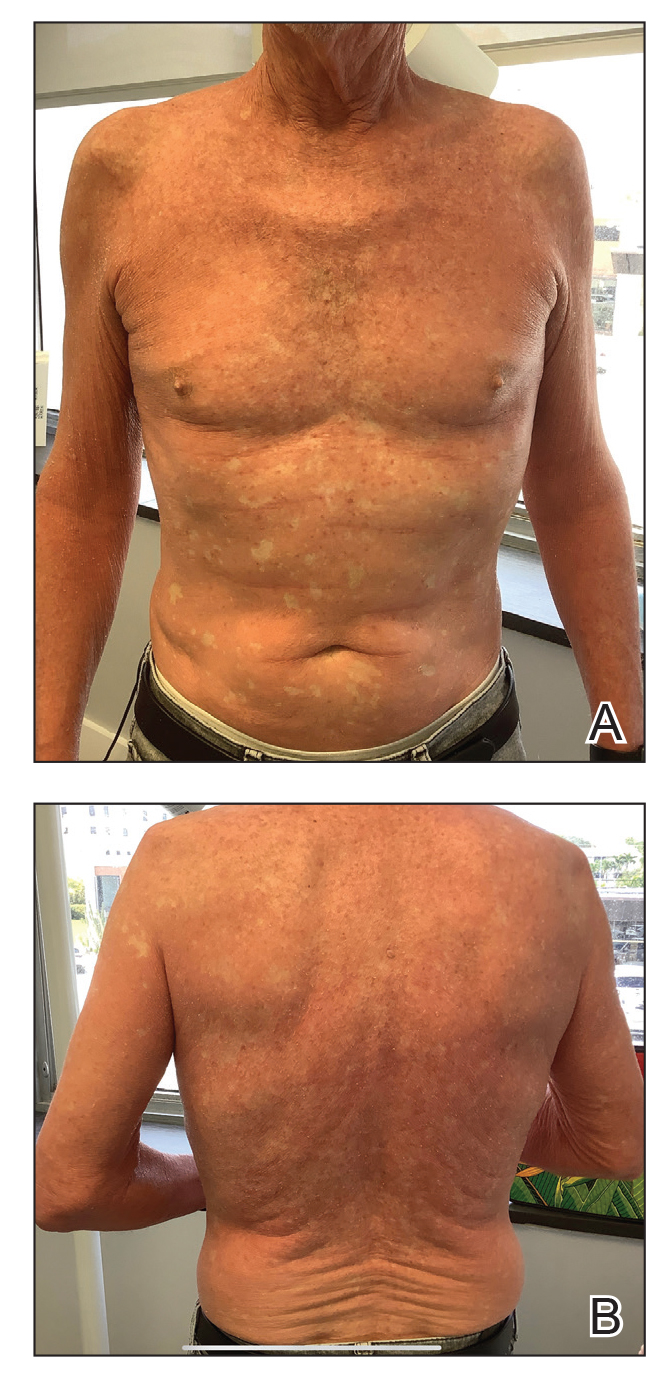

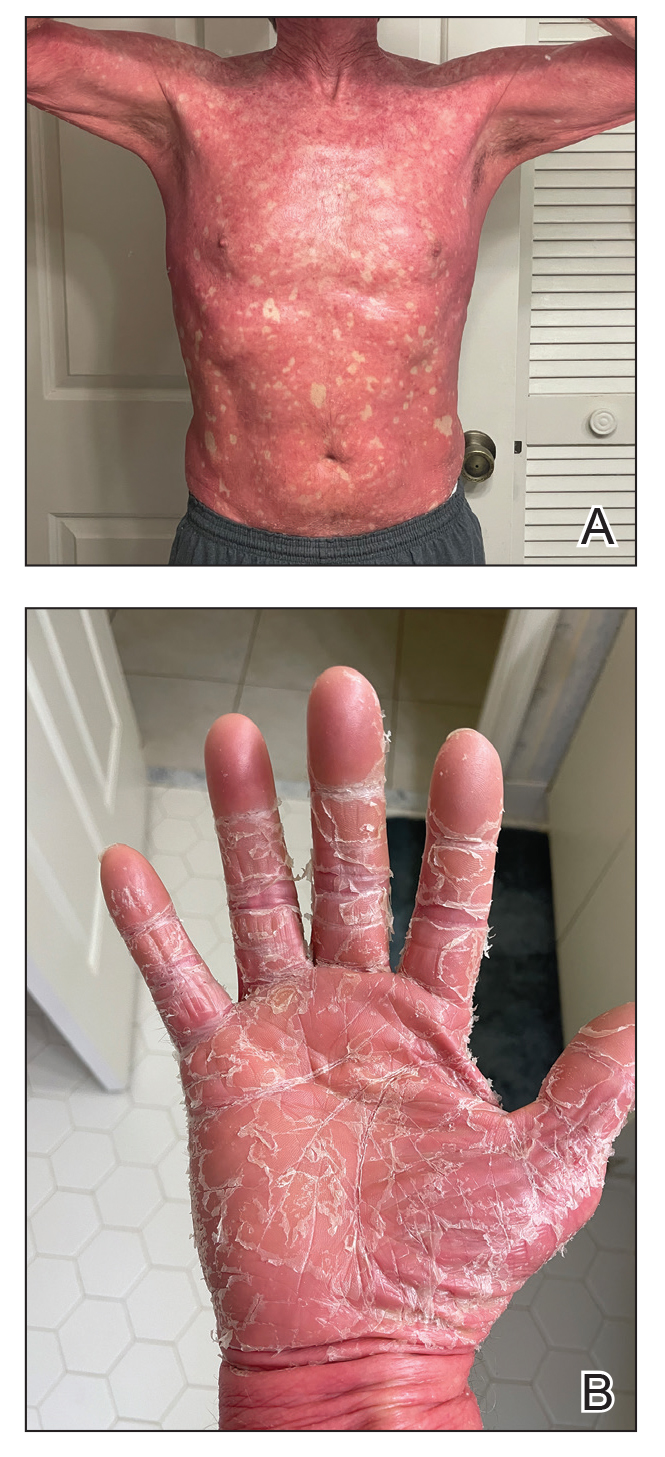

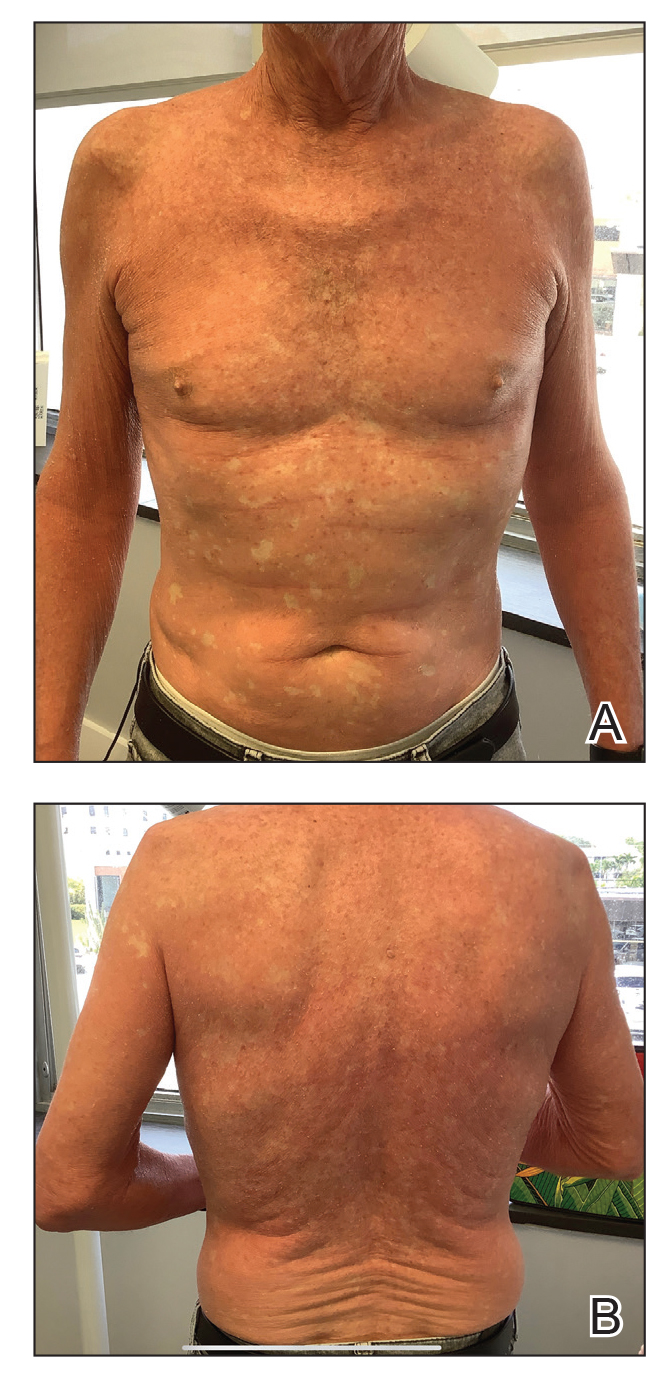

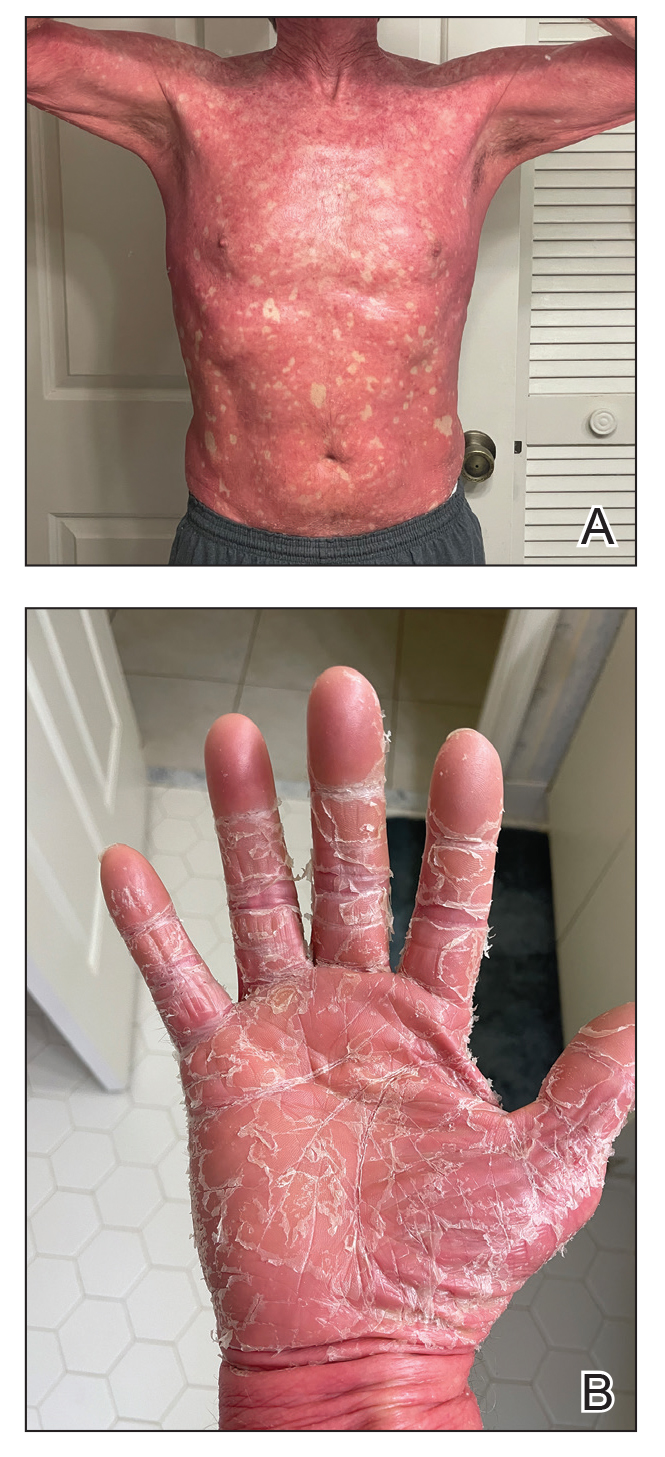

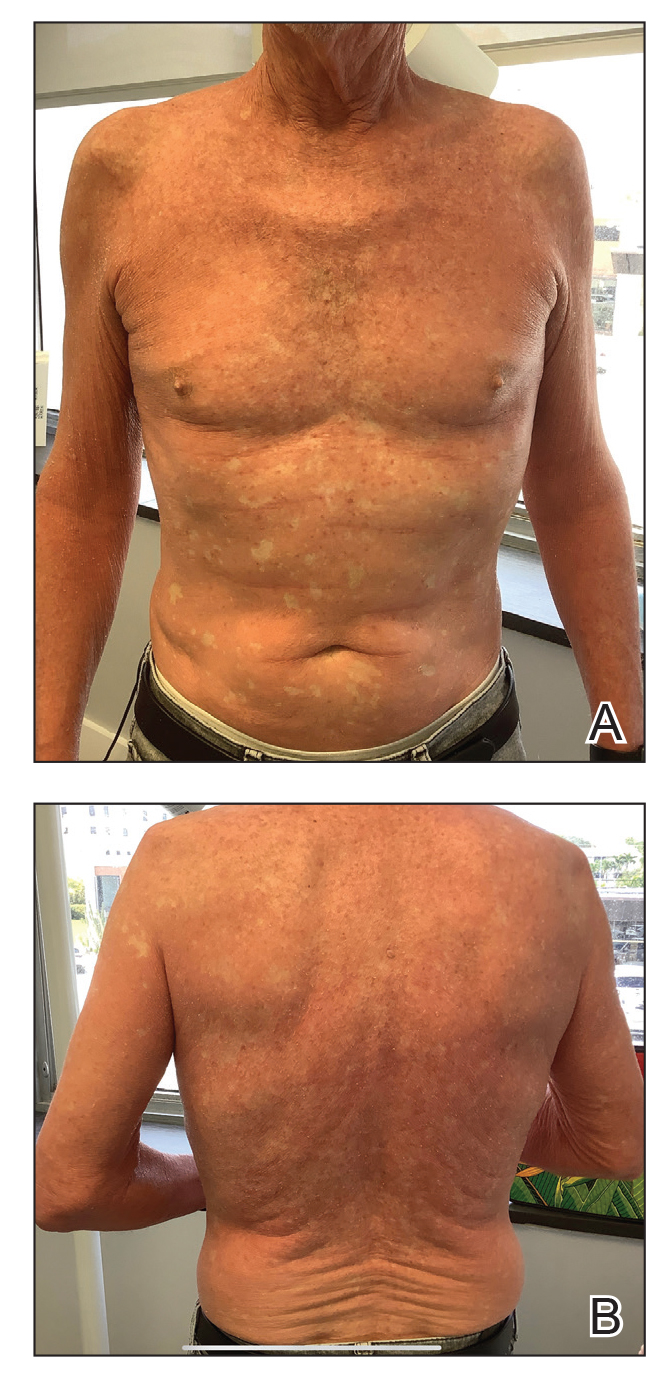

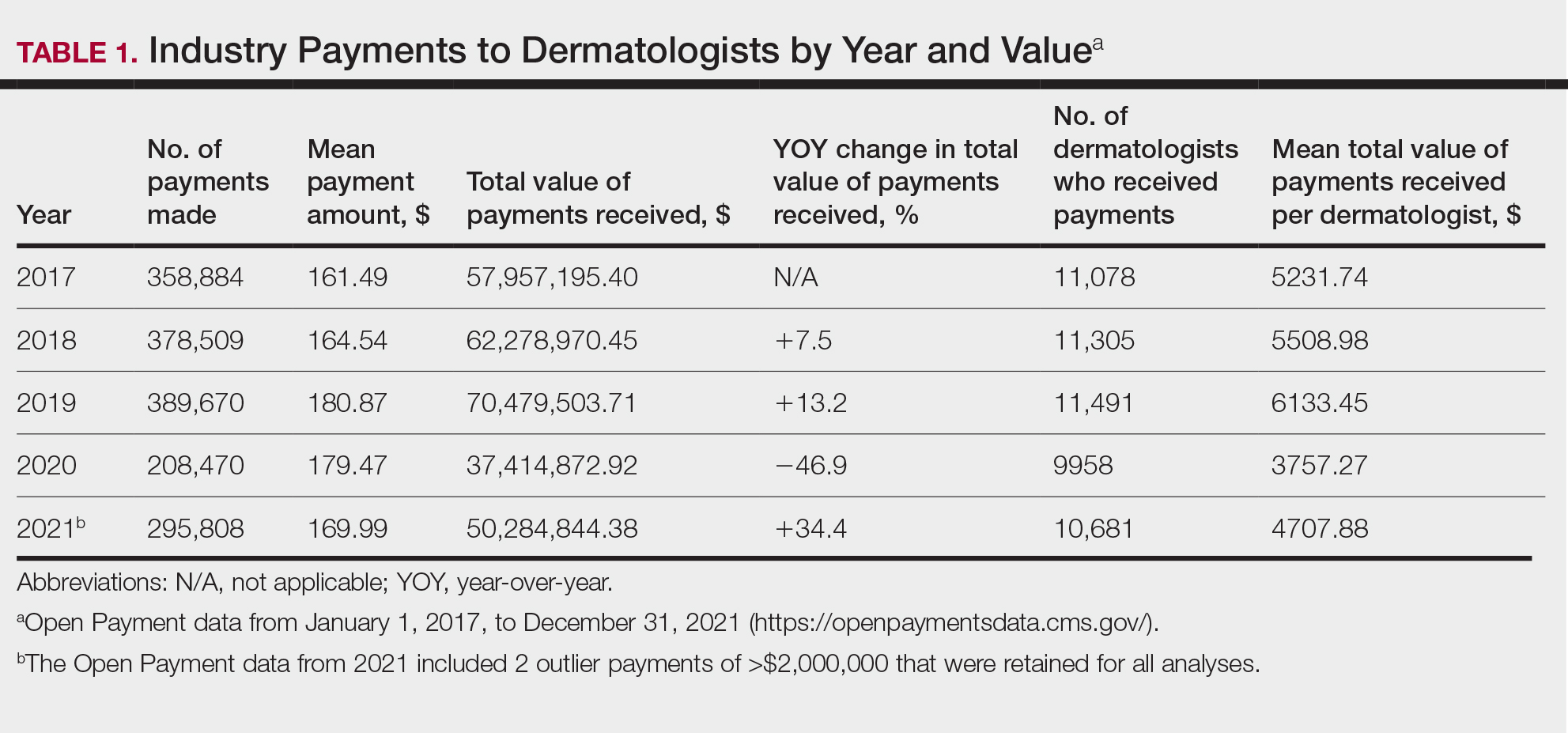

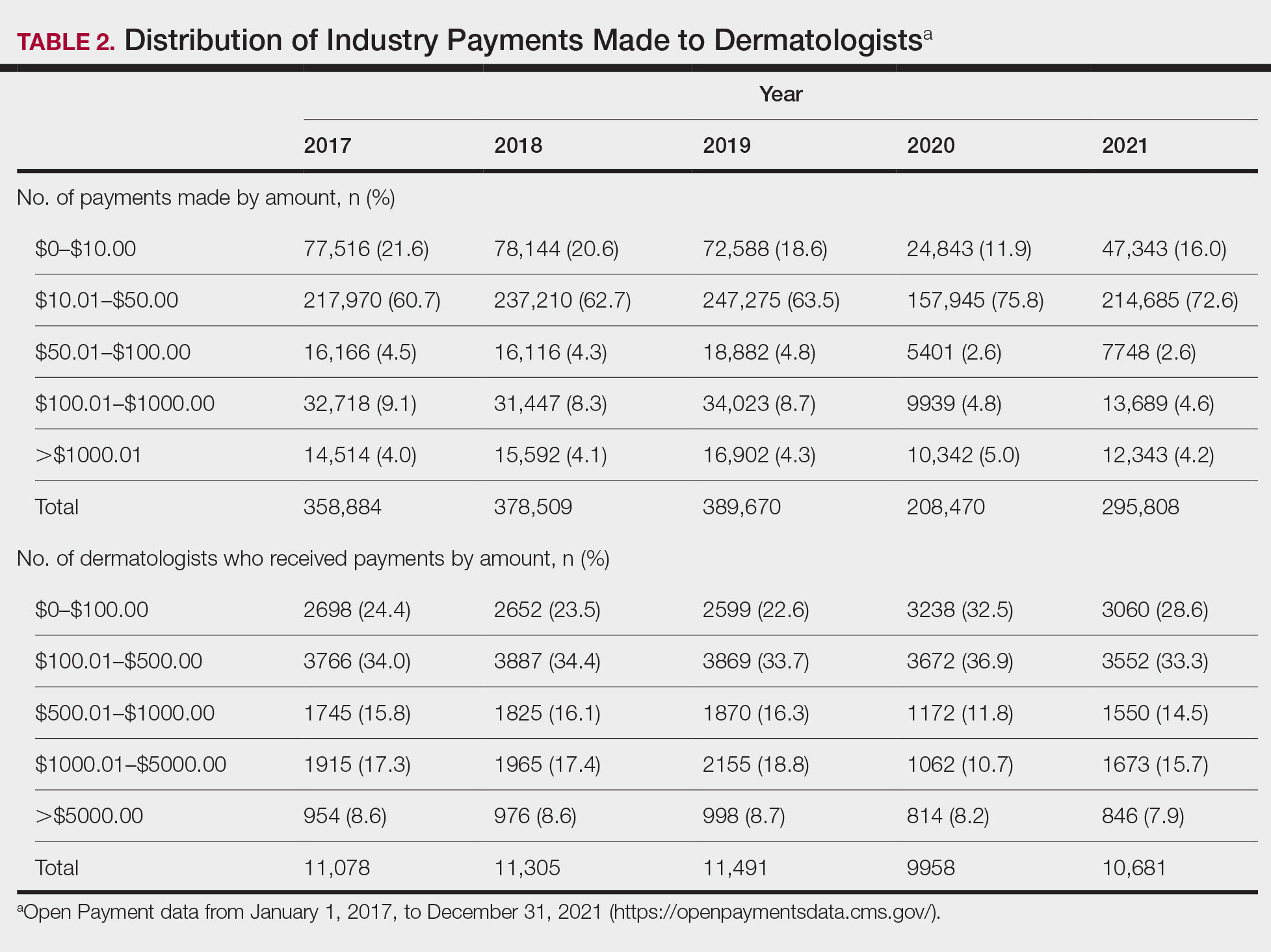

A 65-year-old man was referred to Florida Academic Dermatology Center (Coral Gables, Florida) with biopsy-proven PRP diagnosed 1 year prior. The patient reported experiencing a debilitating quality of life in the year since diagnosis (Figure 1). Treatment attempts with dupilumab, tralokinumab, intramuscular steroid injections, and topical corticosteroids had failed (Figure 2). Following evaluation at Florida Academic Dermatology Center, the patient was started on acitretin 25 mg every other day and received an initial subcutaneous injection of ixekizumab 160 mg (an IL-17 inhibitor) followed 2 weeks later by a second injection of 80 mg. After the 2 doses of ixekizumab, the patient’s condition worsened with the development of pinpoint hemorrhagic lesions. The medication was discontinued, and he was started on risankizumab 150 mg at the approved dosing regimen for plaque psoriasis in combination with the acitretin therapy. Prior to starting risankizumab, the affected body surface area (BSA) was 80%. At 1-month follow-up, he showed improvement with reduction in scaling and erythema and an affected BSA of 30% (Figure 3). At 4-month follow-up, he continued showing improvement with an affected BSA of 10% (Figure 4). Acitretin was discontinued, and the patient has been successfully maintained on risankizumab 150 mg/mL subcutaneous injections every 12 weeks since.

Oral retinoid therapy historically was considered first-line therapy for moderate to severe PRP. A systematic review (N=105) of retinoid therapies showed 83% of patients with PRP who were treated with acitretin plus biologic therapy had a favorable response, whereas only 36% of patients treated with acitretin as monotherapy had the same response, highlighting the importance of dual therapy.3 The use of ustekinumab, ixekizumab, and secukinumab (IL-17 inhibitors) for refractory PRP has been well documented, but a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the search terms risankizumab and pityriasis rubra pilaris yielded only 8 published cases of risankizumab for treatment of PRP.4-8 All patients were diagnosed with refractory PRP, and multiple treatment modalities failed.

Ustekinumab has been shown to create a rapid response and maintain it long term, especially in patients with type 1 PRP who did not respond to systemic therapies or anti–tumor necrosis factor α agents.2 An open-label, single-arm clinical trial found secukinumab was an effective therapy for PRP and demonstrated transcription heterogeneity of this dermatologic condition.9 The researchers proposed that some patients may respond to IL-17 inhibitors but others may not due to the differences in RNA molecules transcribed.9 Our patient demonstrated worsening of his condition with an IL-17 inhibitor but experienced remarkable improvement with risankizumab, an IL-23 inhibitor.

Risankizumab is indicated for the treatment of adults with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. This humanized IgG1 monoclonal antibody targets the p19 subunit of IL-23, inhibiting its role in the pathogenic helper T cell (TH17) pathway. Research has shown that it is an efficacious and well-tolerated treatment modality for psoriatic conditions.10 It is well known that PRP and psoriasis have similar cytokine activations; therefore, we propose that combination therapy with risankizumab and acitretin may show promise for refractory PRP.

- Gelmetti C, Schiuma AA, Cerri D, et al. Pityriasis rubra pilaris in childhood: a long-term study of 29 cases. Pediatr Dermatol. 1986;3:446-451. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.1986.tb00648.x

- Moretta G, De Luca EV, Di Stefani A. Management of refractory pityriasis rubra pilaris: challenges and solutions. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2017;10:451-457. doi:10.2147/CCID.S124351

- Engelmann C, Elsner P, Miguel D. Treatment of pityriasis rubra pilaris type I: a systematic review. Eur J Dermatol. 2019;29:524-537. doi:10.1684/ejd.2019.3641

- Ricar J, Cetkovska P. Successful treatment of refractory extensive pityriasis rubra pilaris with risankizumab. Br J Dermatol. 2021;184:E148. doi:10.1111/bjd.19681

- Brocco E, Laffitte E. Risankizumab for pityriasis rubra pilaris. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2021;46:1322-1324. doi:10.1111/ced.14715

- Duarte B, Paiva Lopes MJ. Response to: ‘Successful treatment of refractory extensive pityriasis rubra pilaris with risankizumab.’ Br J Dermatol. 2021;185:235-236. doi:10.1111/bjd.20061

- Kromer C, Schön MP, Mössner R. Treatment of pityriasis rubra pilaris with risankizumab in two cases. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2021;19:1207-1209. doi:10.1111/ddg.14504

- Kołt-Kamińska M, Osińska A, Kaznowska E, et al. Successful treatment of pityriasis rubra pilaris with risankizumab in children. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2023;13:2431-2441. doi:10.1007/s13555-023-01005-y

- Boudreaux BW, Pincelli TP, Bhullar PK, et al. Secukinumab for the treatment of adult-onset pityriasis rubra pilaris: a single-arm clinical trial with transcriptomic analysis. Br J Dermatol. 2022;187:650-658. doi:10.1111/bjd.21708

- Blauvelt A, Leonardi CL, Gooderham M, et al. Efficacy and safety of continuous risankizumab therapy vs treatment withdrawal in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: a phase 3 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:649-658. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.0723

To the Editor:

Pityriasis rubra pilaris (PRP) is a rare papulosquamous condition with an unknown pathogenesis and limited efficacy data, which can make treatment challenging. Some cases of PRP spontaneously resolve in a few months, which is most common in the pediatric population.1 Pityriasis rubra pilaris in adults is likely to persist for years, and spontaneous resolution is unpredictable. Randomized clinical trials are difficult to perform due to the rarity of PRP.

Although there is no cure and no standard protocol for treating PRP, systemic retinoids historically are considered first-line therapy for moderate to severe cases.2 Additional management approaches include symptomatic control with moisturizers and psychological support. Alternative systemic treatments for moderate to severe cases include methotrexate, phototherapy, and cyclosporine.2

Pityriasis rubra pilaris demonstrates a favorable response to methotrexate treatment, especially in type I cases; however, patients on this alternative therapy should be monitored for severe adverse effects (eg, hepatotoxicity, pancytopenia, pneumonitis).2 Phototherapy should be approached with caution. Narrowband UVB, UVA1, and psoralen plus UVA therapy have successfully treated PRP; however, the response is variable. In some cases, the opposite effect can occur, in which the condition is photoaggravated. Phototherapy is a valid alternative form of treatment when used in combination with acitretin, and a phototest should be performed prior to starting this regimen. Cyclosporine is another immunosuppressant that can be considered for PRP treatment, though there are limited data demonstrating its efficacy.2

The introduction of biologic agents has changed the treatment approach for many dermatologic diseases, including PRP. Given the similar features between psoriasis and PRP, the biologics prescribed for psoriasis therapy also are used for patients with PRP that is challenging to treat, such as anti–tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors and IL inhibitors—specifically IL-17 and IL-23. Remission has been achieved with the use of biologics in combination with retinoid therapy.2

Biologic therapies used for PRP effectively inhibit cytokines and reduce the overall inflammatory processes involved in the development of the scaly patches and plaques seen in this condition. However, most reported clinical experiences are case studies, and more research in the form of randomized clinical trials is needed to understand the efficacy and long-term effects of this form of treatment in PRP. We present a case of a patient with refractory adult subtype I PRP that was successfully treated with the IL-23 inhibitor risankizumab.

A 65-year-old man was referred to Florida Academic Dermatology Center (Coral Gables, Florida) with biopsy-proven PRP diagnosed 1 year prior. The patient reported experiencing a debilitating quality of life in the year since diagnosis (Figure 1). Treatment attempts with dupilumab, tralokinumab, intramuscular steroid injections, and topical corticosteroids had failed (Figure 2). Following evaluation at Florida Academic Dermatology Center, the patient was started on acitretin 25 mg every other day and received an initial subcutaneous injection of ixekizumab 160 mg (an IL-17 inhibitor) followed 2 weeks later by a second injection of 80 mg. After the 2 doses of ixekizumab, the patient’s condition worsened with the development of pinpoint hemorrhagic lesions. The medication was discontinued, and he was started on risankizumab 150 mg at the approved dosing regimen for plaque psoriasis in combination with the acitretin therapy. Prior to starting risankizumab, the affected body surface area (BSA) was 80%. At 1-month follow-up, he showed improvement with reduction in scaling and erythema and an affected BSA of 30% (Figure 3). At 4-month follow-up, he continued showing improvement with an affected BSA of 10% (Figure 4). Acitretin was discontinued, and the patient has been successfully maintained on risankizumab 150 mg/mL subcutaneous injections every 12 weeks since.

Oral retinoid therapy historically was considered first-line therapy for moderate to severe PRP. A systematic review (N=105) of retinoid therapies showed 83% of patients with PRP who were treated with acitretin plus biologic therapy had a favorable response, whereas only 36% of patients treated with acitretin as monotherapy had the same response, highlighting the importance of dual therapy.3 The use of ustekinumab, ixekizumab, and secukinumab (IL-17 inhibitors) for refractory PRP has been well documented, but a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the search terms risankizumab and pityriasis rubra pilaris yielded only 8 published cases of risankizumab for treatment of PRP.4-8 All patients were diagnosed with refractory PRP, and multiple treatment modalities failed.

Ustekinumab has been shown to create a rapid response and maintain it long term, especially in patients with type 1 PRP who did not respond to systemic therapies or anti–tumor necrosis factor α agents.2 An open-label, single-arm clinical trial found secukinumab was an effective therapy for PRP and demonstrated transcription heterogeneity of this dermatologic condition.9 The researchers proposed that some patients may respond to IL-17 inhibitors but others may not due to the differences in RNA molecules transcribed.9 Our patient demonstrated worsening of his condition with an IL-17 inhibitor but experienced remarkable improvement with risankizumab, an IL-23 inhibitor.

Risankizumab is indicated for the treatment of adults with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. This humanized IgG1 monoclonal antibody targets the p19 subunit of IL-23, inhibiting its role in the pathogenic helper T cell (TH17) pathway. Research has shown that it is an efficacious and well-tolerated treatment modality for psoriatic conditions.10 It is well known that PRP and psoriasis have similar cytokine activations; therefore, we propose that combination therapy with risankizumab and acitretin may show promise for refractory PRP.

To the Editor:

Pityriasis rubra pilaris (PRP) is a rare papulosquamous condition with an unknown pathogenesis and limited efficacy data, which can make treatment challenging. Some cases of PRP spontaneously resolve in a few months, which is most common in the pediatric population.1 Pityriasis rubra pilaris in adults is likely to persist for years, and spontaneous resolution is unpredictable. Randomized clinical trials are difficult to perform due to the rarity of PRP.

Although there is no cure and no standard protocol for treating PRP, systemic retinoids historically are considered first-line therapy for moderate to severe cases.2 Additional management approaches include symptomatic control with moisturizers and psychological support. Alternative systemic treatments for moderate to severe cases include methotrexate, phototherapy, and cyclosporine.2

Pityriasis rubra pilaris demonstrates a favorable response to methotrexate treatment, especially in type I cases; however, patients on this alternative therapy should be monitored for severe adverse effects (eg, hepatotoxicity, pancytopenia, pneumonitis).2 Phototherapy should be approached with caution. Narrowband UVB, UVA1, and psoralen plus UVA therapy have successfully treated PRP; however, the response is variable. In some cases, the opposite effect can occur, in which the condition is photoaggravated. Phototherapy is a valid alternative form of treatment when used in combination with acitretin, and a phototest should be performed prior to starting this regimen. Cyclosporine is another immunosuppressant that can be considered for PRP treatment, though there are limited data demonstrating its efficacy.2

The introduction of biologic agents has changed the treatment approach for many dermatologic diseases, including PRP. Given the similar features between psoriasis and PRP, the biologics prescribed for psoriasis therapy also are used for patients with PRP that is challenging to treat, such as anti–tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors and IL inhibitors—specifically IL-17 and IL-23. Remission has been achieved with the use of biologics in combination with retinoid therapy.2

Biologic therapies used for PRP effectively inhibit cytokines and reduce the overall inflammatory processes involved in the development of the scaly patches and plaques seen in this condition. However, most reported clinical experiences are case studies, and more research in the form of randomized clinical trials is needed to understand the efficacy and long-term effects of this form of treatment in PRP. We present a case of a patient with refractory adult subtype I PRP that was successfully treated with the IL-23 inhibitor risankizumab.

A 65-year-old man was referred to Florida Academic Dermatology Center (Coral Gables, Florida) with biopsy-proven PRP diagnosed 1 year prior. The patient reported experiencing a debilitating quality of life in the year since diagnosis (Figure 1). Treatment attempts with dupilumab, tralokinumab, intramuscular steroid injections, and topical corticosteroids had failed (Figure 2). Following evaluation at Florida Academic Dermatology Center, the patient was started on acitretin 25 mg every other day and received an initial subcutaneous injection of ixekizumab 160 mg (an IL-17 inhibitor) followed 2 weeks later by a second injection of 80 mg. After the 2 doses of ixekizumab, the patient’s condition worsened with the development of pinpoint hemorrhagic lesions. The medication was discontinued, and he was started on risankizumab 150 mg at the approved dosing regimen for plaque psoriasis in combination with the acitretin therapy. Prior to starting risankizumab, the affected body surface area (BSA) was 80%. At 1-month follow-up, he showed improvement with reduction in scaling and erythema and an affected BSA of 30% (Figure 3). At 4-month follow-up, he continued showing improvement with an affected BSA of 10% (Figure 4). Acitretin was discontinued, and the patient has been successfully maintained on risankizumab 150 mg/mL subcutaneous injections every 12 weeks since.

Oral retinoid therapy historically was considered first-line therapy for moderate to severe PRP. A systematic review (N=105) of retinoid therapies showed 83% of patients with PRP who were treated with acitretin plus biologic therapy had a favorable response, whereas only 36% of patients treated with acitretin as monotherapy had the same response, highlighting the importance of dual therapy.3 The use of ustekinumab, ixekizumab, and secukinumab (IL-17 inhibitors) for refractory PRP has been well documented, but a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the search terms risankizumab and pityriasis rubra pilaris yielded only 8 published cases of risankizumab for treatment of PRP.4-8 All patients were diagnosed with refractory PRP, and multiple treatment modalities failed.

Ustekinumab has been shown to create a rapid response and maintain it long term, especially in patients with type 1 PRP who did not respond to systemic therapies or anti–tumor necrosis factor α agents.2 An open-label, single-arm clinical trial found secukinumab was an effective therapy for PRP and demonstrated transcription heterogeneity of this dermatologic condition.9 The researchers proposed that some patients may respond to IL-17 inhibitors but others may not due to the differences in RNA molecules transcribed.9 Our patient demonstrated worsening of his condition with an IL-17 inhibitor but experienced remarkable improvement with risankizumab, an IL-23 inhibitor.

Risankizumab is indicated for the treatment of adults with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. This humanized IgG1 monoclonal antibody targets the p19 subunit of IL-23, inhibiting its role in the pathogenic helper T cell (TH17) pathway. Research has shown that it is an efficacious and well-tolerated treatment modality for psoriatic conditions.10 It is well known that PRP and psoriasis have similar cytokine activations; therefore, we propose that combination therapy with risankizumab and acitretin may show promise for refractory PRP.

- Gelmetti C, Schiuma AA, Cerri D, et al. Pityriasis rubra pilaris in childhood: a long-term study of 29 cases. Pediatr Dermatol. 1986;3:446-451. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.1986.tb00648.x

- Moretta G, De Luca EV, Di Stefani A. Management of refractory pityriasis rubra pilaris: challenges and solutions. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2017;10:451-457. doi:10.2147/CCID.S124351

- Engelmann C, Elsner P, Miguel D. Treatment of pityriasis rubra pilaris type I: a systematic review. Eur J Dermatol. 2019;29:524-537. doi:10.1684/ejd.2019.3641

- Ricar J, Cetkovska P. Successful treatment of refractory extensive pityriasis rubra pilaris with risankizumab. Br J Dermatol. 2021;184:E148. doi:10.1111/bjd.19681

- Brocco E, Laffitte E. Risankizumab for pityriasis rubra pilaris. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2021;46:1322-1324. doi:10.1111/ced.14715

- Duarte B, Paiva Lopes MJ. Response to: ‘Successful treatment of refractory extensive pityriasis rubra pilaris with risankizumab.’ Br J Dermatol. 2021;185:235-236. doi:10.1111/bjd.20061

- Kromer C, Schön MP, Mössner R. Treatment of pityriasis rubra pilaris with risankizumab in two cases. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2021;19:1207-1209. doi:10.1111/ddg.14504

- Kołt-Kamińska M, Osińska A, Kaznowska E, et al. Successful treatment of pityriasis rubra pilaris with risankizumab in children. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2023;13:2431-2441. doi:10.1007/s13555-023-01005-y

- Boudreaux BW, Pincelli TP, Bhullar PK, et al. Secukinumab for the treatment of adult-onset pityriasis rubra pilaris: a single-arm clinical trial with transcriptomic analysis. Br J Dermatol. 2022;187:650-658. doi:10.1111/bjd.21708

- Blauvelt A, Leonardi CL, Gooderham M, et al. Efficacy and safety of continuous risankizumab therapy vs treatment withdrawal in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: a phase 3 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:649-658. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.0723

- Gelmetti C, Schiuma AA, Cerri D, et al. Pityriasis rubra pilaris in childhood: a long-term study of 29 cases. Pediatr Dermatol. 1986;3:446-451. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.1986.tb00648.x

- Moretta G, De Luca EV, Di Stefani A. Management of refractory pityriasis rubra pilaris: challenges and solutions. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2017;10:451-457. doi:10.2147/CCID.S124351

- Engelmann C, Elsner P, Miguel D. Treatment of pityriasis rubra pilaris type I: a systematic review. Eur J Dermatol. 2019;29:524-537. doi:10.1684/ejd.2019.3641

- Ricar J, Cetkovska P. Successful treatment of refractory extensive pityriasis rubra pilaris with risankizumab. Br J Dermatol. 2021;184:E148. doi:10.1111/bjd.19681

- Brocco E, Laffitte E. Risankizumab for pityriasis rubra pilaris. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2021;46:1322-1324. doi:10.1111/ced.14715

- Duarte B, Paiva Lopes MJ. Response to: ‘Successful treatment of refractory extensive pityriasis rubra pilaris with risankizumab.’ Br J Dermatol. 2021;185:235-236. doi:10.1111/bjd.20061

- Kromer C, Schön MP, Mössner R. Treatment of pityriasis rubra pilaris with risankizumab in two cases. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2021;19:1207-1209. doi:10.1111/ddg.14504

- Kołt-Kamińska M, Osińska A, Kaznowska E, et al. Successful treatment of pityriasis rubra pilaris with risankizumab in children. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2023;13:2431-2441. doi:10.1007/s13555-023-01005-y

- Boudreaux BW, Pincelli TP, Bhullar PK, et al. Secukinumab for the treatment of adult-onset pityriasis rubra pilaris: a single-arm clinical trial with transcriptomic analysis. Br J Dermatol. 2022;187:650-658. doi:10.1111/bjd.21708

- Blauvelt A, Leonardi CL, Gooderham M, et al. Efficacy and safety of continuous risankizumab therapy vs treatment withdrawal in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: a phase 3 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:649-658. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.0723

Practice Points

- Pityriasis rubra pilaris (PRP) is a rare condition that is challenging to treat due to its unknown pathogenesis and limited efficacy data. Systemic retinoids historically were considered first-line therapy for moderate to severe cases of PRP.

- Biologics may be useful for refractory cases of PRP.

- Risankizumab is approved for moderate to severe plaque psoriasis and can be considered off-label for refractory PRP.

A Roadmap to Research Opportunities for Dermatology Residents

Dermatology remains one of the most competitive specialties in the residency match, with successful applicants demonstrating a well-rounded application reflecting not only their academic excellence but also their dedication to research, community service, and hands-on clinical experience.1 A growing emphasis on scholarly activities has made it crucial for applicants to stand out, with an increasing number opting to take gap years to engage in focused research endeavors.2 In highly competitive specialties such as dermatology, successful applicants now report more than 20 research items on average.3,4 This trend also is evident in primary care specialties, which have seen a 2- to 3-fold increase in reported research activities. The average unmatched applicant today lists more research items than the average matched applicant did a decade ago, underscoring the growing emphasis on scholarly activity.3

Ideally, graduate medical education should foster an environment of inquiry and scholarship, where residents develop new knowledge, evaluate research findings, and cultivate lifelong habits of inquiry. The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education requires residents to engage in scholarship, such as case reports, research reviews, and original research.5 Research during residency has been linked to several benefits, including enhanced patient care through improved critical appraisal skills, clinical reasoning, and lifelong learning.6,7 Additionally, students and residents who publish research are more likely to achieve higher rank during residency and pursue careers in academic medicine, potentially helping to address the decline in clinician investigators.8,9 Publishing and presenting research also can enhance a residency program’s reputation, making it more attractive to competitive applicants, and may be beneficial for residents seeking jobs or fellowships.6

Dermatology residency programs vary in their structure and support for resident research. One survey revealed that many programs lack the necessary support, structure, and resources to effectively promote and maintain research training.1 Additionally, residents have less exposure to researchers who could serve as mentors due to the growing demands placed on attending physicians in teaching hospitals.10

The Research Arms Race

The growing emphasis on scholarly activity for residency and fellowship applicants coupled with the use of research productivity to differentiate candidates has led some to declare a “research arms race” in residency selection.3 As one author stated, “We need less research, better research, and research done for the right reasons.”11 Indeed, most articles authored by medical students are short reviews or case reports, with the majority (59% [207/350]) being cited zero times, according to one analysis.12 Given the variable research infrastructure between programs and the decreasing availability of research mentors despite the growing emphasis on scholarly activity, applicants face an unfortunate dilemma. Until the system changes, those who protest this research arms race by not engaging in substantial scholarly activity are less likely to match into competitive specialties. Thus, the race continues.

The Value of Mentorship

Resident research success is impacted by having an effective faculty research mentor.13 Although all medical research at the student or resident levels should be conducted with a faculty mentor to oversee it, finding a mentor can be challenging. If a resident’s program boasts a strong research infrastructure or prolific faculty, building relationships with potential mentors is a logical first step for residents wishing to engage in research; however, if suitable mentors are lacking, efforts should be made by residents to establish these connections elsewhere, such as attending society meetings to network with potential mentors and applying to formal mentorship programs (eg, the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery’s Preceptor Program, the Women’s Dermatologic Society’s Mentorship Award). Unsolicited email inquiries asking, “Hi Dr. X, my name is Y, and I was wondering if you have any research projects I could help with?” often go unanswered. Instead, consider emailing or approaching potential mentors with a more developed proposition, such as the following example:

Hello Dr. X, my name is Y. I have enjoyed reading your publications on A, which inspired me to think about B. I reviewed the literature and noticed a potential to enhance our current understanding on the topic. My team and I conducted a systematic review of the available literature and drafted a manuscript summarizing our findings. Given your expertise in this field, would you be willing to collaborate on this paper? We would be grateful for your critical eye, suggestions for improvement, and overall thoughts.

This approach demonstrates initiative, provides a clear plan, and shows respect for the mentor’s expertise, increasing the likelihood of a positive response and fruitful collaboration. Assuming the resident’s working draft meets the potential mentor’s basic expectations, such a display of initiative is likely to impress them, and they may then offer opportunities to engage in meaningful research projects in the future. Everyone benefits! These efforts to establish connections with mentors can pave the way to further collaboration and meaningful research opportunities for dermatology residents.

The Systematic Review: An Attractive Option For Residents

There are several potential avenues for students or residents interested in pursuing research. Case reports and case series are relatively easy to compile, can be completed quickly, and often require minimal guidance from a faculty mentor; however, case reports rank low in the research hierarchy. Conversely, prospective blinded clinical trials provide some of the highest-quality evidence available but are challenging to conduct without a practicing faculty member to provide a patient cohort, often require extensive funding, and may involve complex statistical analyses beyond the expertise of most students or residents. Additionally, they may take years to complete, often extending beyond residency or fellowship application deadlines.

Most medical applicants likely hold at least some hesitation in churning out vast amounts of low-quality research merely to boost their publication count for the match process. Ideally, those who pursue scholarly activity should be driven by a genuine desire to contribute meaningfully to the medical literature. One particularly valuable avenue for trainees wishing to engage in research is the systematic review, which aims to identify, evaluate, and summarize the findings of all relevant individual studies regarding a research topic and answer a focused question. If performed thoughtfully, a systematic review can meaningfully contribute to the medical literature without requiring access to a prospectively followed cohort of patients or the constant supervision of a faculty mentor. Sure, systematic reviews may not be as robust as prospective cohort clinical trials, but they often provide comprehensive insights and are considered valuable contributions to evidence-based medicine. With the help of co-residents or medical students, a medical reference librarian, and a statistician—along with a working understanding of universally accepted quality measures—a resident physician and their team can produce a systematic review that ultimately may merit publication in a top-tier medical journal.

The remainder of this column will outline a streamlined approach to the systematic review writing process, specifically tailored for medical residents who may not have affiliations to a prolific research department or established relationships with faculty mentors in their field of interest. The aim is to offer a basic framework to help residents navigate the complexities of conducting and writing a high-quality, impactful systematic review. It is important to emphasize that resident research should always be conducted under the guidance of a faculty mentor, and this approach is not intended to encourage independent research and publication by residents. Instead, it provides steps that can be undertaken with a foundational understanding of accepted principles, allowing residents to compile a working draft of a manuscript in collaboration with a trusted faculty mentor.

The Systematic Review: A Simple Approach

Step 1: Choose a Topic—Once a resident has decided to embark on conducting a systematic review, the first step is to choose a topic, which requires consideration of several factors to ensure relevance, feasibility, and impact. Begin by identifying areas of clinical uncertainty or controversy in which a comprehensive synthesis of the literature could provide valuable insights. Often, such a topic can be gleaned from the conclusion section of other primary studies; statements such as “further study is needed to determine the efficacy of X” or “systematic reviews would be beneficial to ascertaining the impact of Y” may be a great place to start.

Next, ensure that sufficient primary studies exist to support a robust review or meta-analysis by conducting a preliminary literature search, which will confirm that the chosen topic is both researchable and relevant. A narrow, focused, well-defined topic likely will prove more feasible to review than a broad, ill-defined one. Once a topic is selected, it is advisable to discuss it with a faculty mentor before starting the literature search to ensure the topic’s feasibility and clinical relevance, helping to guide your research in a meaningful direction.

When deciding between a systematic review and a meta-analysis, the nature of the research question is an influential factor. A systematic review is particularly suitable for addressing broad questions or topics when the aim is to summarize and synthesize all relevant research studies; for example, a systematic review may investigate the various treatment options for atopic dermatitis and their efficacy, which allows for a comprehensive overview of the available treatments—both the interventions and the outcomes. In contrast, a meta-analysis is ideal for collecting and statistically combining quantitative data from multiple primary studies, provided there are enough relevant studies available in the literature.

Step 2: Build a Team—Recruiting a skilled librarian to assist with Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms and retrieving relevant papers is crucial for conducting a high-quality systematic review or meta-analysis. Medical librarians specializing in health sciences enhance the efficiency, comprehensiveness, and reliability of your literature search, substantially boosting your work’s credibility. These librarians are well versed in medical databases such as PubMed and Embase. Begin by contacting your institution’s library services, as there often are valuable resources and personnel available to assist you. Personally, I was surprised to find a librarian at my institution specifically dedicated to helping medical residents with such projects! These professionals are eager to help, and if provided with the scope and goal of your project, they can deliver literature search results in a digestible format. Similarly, seeking the expertise of a medical statistician is crucial to the accuracy and legitimacy of your study. In your final paper, it is important to recognize the contributions of the librarian and statistician, either as co-authors or in the acknowledgments section.

In addition, recruiting colleagues or medical students can be an effective strategy to make the project more feasible and offer collaborative benefits for all parties involved. Given the growing emphasis on research for residency and fellowship admissions, there usually is no shortage of motivated volunteers.

Next, identify the software tool you will use for your systematic review. Options range from simple spreadsheets such as Microsoft Excel to reference managers such as EndNote or Mendeley or dedicated systematic review tools. Academic institutions may subscribe to paid services such as Covidence (https://www.covidence.org), or you can utilize free alternatives such as Rayyan (https://www.rayyan.ai). Investing time in learning to navigate dedicated systematic review software can greatly enhance efficiency and reduce frustrations compared to more basic methods. Ultimately, staying organized, thorough, and committed is key.

Step 3: Conduct the Literature Review—At this point, your research topic has been decided, a medical reference librarian has provided the results of a comprehensive literature search, and a software tool has been chosen. The next task is to read hundreds or thousands of papers—easy, right? With your dedicated team assembled, the workload can be divided and conquered. The first step involves screening out duplicate and irrelevant studies based on titles and abstracts. Next, review the remaining papers in more detail. Those that pass this preliminary screen should be read in their entirety, and only the papers relevant to the research topic should be included in the final synthesis. If there are uncertainties about a study’s relevance, consulting a faculty mentor is advisable. To ensure the systematic review is as thorough as possible, pay special attention to the references section of each paper, as cited references can reveal relevant studies that may have been missed in the literature search.

Once all relevant papers are compiled and read, the relevant data points should be extracted and imputed into a data sheet. Collaborating with a medical statistician is crucial at this stage, as they can provide guidance on the most effective ways to structure and input data. After all studies are included, the relevant statistical analyses on the resultant dataset can be run.

Step 4: Write the Paper—In 2020, the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement was developed to ensure transparent and complete reporting of systematic reviews. A full discussion of PRISMA guidelines is beyond the scope of this paper; Page et al14 provided a summary, checklist, and flow diagram that is available online (https://www.prisma-statement.org). Following the PRISMA checklist and guidelines ensures a high-quality, transparent, and reliable systematic review. These guidelines not only help streamline and simplify the writing process but also enhance its efficiency and effectiveness. Discovering the PRISMA checklist can be transformative, providing a valuable roadmap that guides the author through each step of the reporting process, helping to avoid common pitfalls. This structured approach ultimately leads to a more comprehensive and trustworthy review.

Step 5: Make Finishing Touches—At this stage in the systematic review process, the studies have been compiled and thoroughly analyzed and the statistical analysis has been conducted. The results have been organized within a structured framework following the PRISMA checklist. With these steps completed, the next task is to finalize the manuscript and seek a final review from the senior author or faculty mentor. To streamline this process, it is beneficial to adhere to the formatting guidelines of the specific medical journal you intend to submit to. Check the author guidelines on the journal’s website and review recent systematic reviews published there as a reference. Even if you have not chosen a journal yet, formatting your manuscript according to a prestigious journal’s general style provides a strong foundation that can be easily adapted to fit another journal’s requirements if necessary.

Final Thoughts

Designing and conducting a systematic review is no easy task, but it can be a valuable skill for dermatology residents aiming to contribute meaningfully to the medical literature. The process of compiling a systematic review offers an opportunity for developing critical research skills, from formulating a research question to synthesizing evidence and presenting findings in a clear methodical way. Engaging in systematic review writing not only enhances the resident’s understanding of a particular topic but also demonstrates a commitment to scholarly activity—a key factor in an increasingly competitive residency and fellowship application environment.

The basic steps outlined in this article are just one way in which residents can begin to navigate the complexities of medical research, specifically the systematic review process. By assembling a supportive team, utilizing available resources, and adhering to established guidelines such as PRISMA, one can produce a high-quality, impactful review. Ultimately, the systematic review process is not just about publication—it is about fostering a habit of inquiry, improving patient care, and contributing to the ever-evolving field of medicine. With dedication and collaboration, even the most challenging aspects of research can be tackled, paving the way for future opportunities and professional growth. In this way, perhaps one day the spirit of the “research race” can shift from a frantic sprint to a graceful marathon, where each mile is run with heart and every step is filled with purpose.

- Anand P, Szeto MD, Flaten H, et al. Dermatology residency research policies: a 2021 national survey. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2021;7:787-792.

- Costello CM, Harvey JA, Besch-Stokes JG, et al. The role research gap years play in a successful dermatology match. Int J Dermatol. 2022;61:226-230.

- Elliott B, Carmody JB. Publish or perish: the research arms race in residency selection. J Grad Med Educ. 2023;15:524-527.

- MedSchoolCoach. How competitive is a dermatology residency? Updated in 2023. ProspectiveDoctor website. Accessed August 22, 2024. https://www.prospectivedoctor.com/how-competitive-is-a-dermatology-residency/#:~:text=Statistics%20on%20the%20Dermatology%20Match,applied%2C%20169%20did%20not%20match

- ACGME program requirements for graduate medical education in dermatology. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education Updated July 1, 2023. Accessed August 22, 2024. https://www.acgme.org/globalassets/pfassets/programrequirements/080_dermatology_2023.pdf

- Bhuiya T, Makaryus AN. The importance of engaging in scientific research during medical training. Int J Angiol. 2023;32:153-157.

- Seaburg LA, Wang AT, West CP, et al. Associations between resident physicians’ publications and clinical performance during residency training. BMC Med Educ. 2016;16:22.

- West CP, Halvorsen AJ, McDonald FS. Scholarship during residency training: a controlled comparison study. Am J Med. 2011;124:983-987.e1.

- Bhattacharya SD, Williams JB, De La Fuente SG, et al. Does protected research time during general surgery training contribute to graduates’ career choice? Am Surg. 2011;77:907-910.

- Kralovec PD, Miller JA, Wellikson L, et al. The status of hospital medicine groups in the United States. J Hosp Med. 2006;1:75-80.

- Altman DG. The scandal of poor medical research. BMJ. 1994;308:283-284.

- Wickramasinghe DP, Perera CS, Senarathna S, et al. Patterns and trends of medical student research. BMC Med Educ. 2013;13:175.

- Ercan-Fang NG, Mahmoud MA, Cottrell C, et al. Best practices in resident research—a national survey of high functioning internal medicine residency programs in resident research in USA. Am J Med Sci. 2021;361:23-29.

- Page MJ, Moher D, Bossuyt PM, et al. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372.

Dermatology remains one of the most competitive specialties in the residency match, with successful applicants demonstrating a well-rounded application reflecting not only their academic excellence but also their dedication to research, community service, and hands-on clinical experience.1 A growing emphasis on scholarly activities has made it crucial for applicants to stand out, with an increasing number opting to take gap years to engage in focused research endeavors.2 In highly competitive specialties such as dermatology, successful applicants now report more than 20 research items on average.3,4 This trend also is evident in primary care specialties, which have seen a 2- to 3-fold increase in reported research activities. The average unmatched applicant today lists more research items than the average matched applicant did a decade ago, underscoring the growing emphasis on scholarly activity.3

Ideally, graduate medical education should foster an environment of inquiry and scholarship, where residents develop new knowledge, evaluate research findings, and cultivate lifelong habits of inquiry. The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education requires residents to engage in scholarship, such as case reports, research reviews, and original research.5 Research during residency has been linked to several benefits, including enhanced patient care through improved critical appraisal skills, clinical reasoning, and lifelong learning.6,7 Additionally, students and residents who publish research are more likely to achieve higher rank during residency and pursue careers in academic medicine, potentially helping to address the decline in clinician investigators.8,9 Publishing and presenting research also can enhance a residency program’s reputation, making it more attractive to competitive applicants, and may be beneficial for residents seeking jobs or fellowships.6

Dermatology residency programs vary in their structure and support for resident research. One survey revealed that many programs lack the necessary support, structure, and resources to effectively promote and maintain research training.1 Additionally, residents have less exposure to researchers who could serve as mentors due to the growing demands placed on attending physicians in teaching hospitals.10

The Research Arms Race

The growing emphasis on scholarly activity for residency and fellowship applicants coupled with the use of research productivity to differentiate candidates has led some to declare a “research arms race” in residency selection.3 As one author stated, “We need less research, better research, and research done for the right reasons.”11 Indeed, most articles authored by medical students are short reviews or case reports, with the majority (59% [207/350]) being cited zero times, according to one analysis.12 Given the variable research infrastructure between programs and the decreasing availability of research mentors despite the growing emphasis on scholarly activity, applicants face an unfortunate dilemma. Until the system changes, those who protest this research arms race by not engaging in substantial scholarly activity are less likely to match into competitive specialties. Thus, the race continues.

The Value of Mentorship

Resident research success is impacted by having an effective faculty research mentor.13 Although all medical research at the student or resident levels should be conducted with a faculty mentor to oversee it, finding a mentor can be challenging. If a resident’s program boasts a strong research infrastructure or prolific faculty, building relationships with potential mentors is a logical first step for residents wishing to engage in research; however, if suitable mentors are lacking, efforts should be made by residents to establish these connections elsewhere, such as attending society meetings to network with potential mentors and applying to formal mentorship programs (eg, the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery’s Preceptor Program, the Women’s Dermatologic Society’s Mentorship Award). Unsolicited email inquiries asking, “Hi Dr. X, my name is Y, and I was wondering if you have any research projects I could help with?” often go unanswered. Instead, consider emailing or approaching potential mentors with a more developed proposition, such as the following example:

Hello Dr. X, my name is Y. I have enjoyed reading your publications on A, which inspired me to think about B. I reviewed the literature and noticed a potential to enhance our current understanding on the topic. My team and I conducted a systematic review of the available literature and drafted a manuscript summarizing our findings. Given your expertise in this field, would you be willing to collaborate on this paper? We would be grateful for your critical eye, suggestions for improvement, and overall thoughts.

This approach demonstrates initiative, provides a clear plan, and shows respect for the mentor’s expertise, increasing the likelihood of a positive response and fruitful collaboration. Assuming the resident’s working draft meets the potential mentor’s basic expectations, such a display of initiative is likely to impress them, and they may then offer opportunities to engage in meaningful research projects in the future. Everyone benefits! These efforts to establish connections with mentors can pave the way to further collaboration and meaningful research opportunities for dermatology residents.

The Systematic Review: An Attractive Option For Residents

There are several potential avenues for students or residents interested in pursuing research. Case reports and case series are relatively easy to compile, can be completed quickly, and often require minimal guidance from a faculty mentor; however, case reports rank low in the research hierarchy. Conversely, prospective blinded clinical trials provide some of the highest-quality evidence available but are challenging to conduct without a practicing faculty member to provide a patient cohort, often require extensive funding, and may involve complex statistical analyses beyond the expertise of most students or residents. Additionally, they may take years to complete, often extending beyond residency or fellowship application deadlines.

Most medical applicants likely hold at least some hesitation in churning out vast amounts of low-quality research merely to boost their publication count for the match process. Ideally, those who pursue scholarly activity should be driven by a genuine desire to contribute meaningfully to the medical literature. One particularly valuable avenue for trainees wishing to engage in research is the systematic review, which aims to identify, evaluate, and summarize the findings of all relevant individual studies regarding a research topic and answer a focused question. If performed thoughtfully, a systematic review can meaningfully contribute to the medical literature without requiring access to a prospectively followed cohort of patients or the constant supervision of a faculty mentor. Sure, systematic reviews may not be as robust as prospective cohort clinical trials, but they often provide comprehensive insights and are considered valuable contributions to evidence-based medicine. With the help of co-residents or medical students, a medical reference librarian, and a statistician—along with a working understanding of universally accepted quality measures—a resident physician and their team can produce a systematic review that ultimately may merit publication in a top-tier medical journal.

The remainder of this column will outline a streamlined approach to the systematic review writing process, specifically tailored for medical residents who may not have affiliations to a prolific research department or established relationships with faculty mentors in their field of interest. The aim is to offer a basic framework to help residents navigate the complexities of conducting and writing a high-quality, impactful systematic review. It is important to emphasize that resident research should always be conducted under the guidance of a faculty mentor, and this approach is not intended to encourage independent research and publication by residents. Instead, it provides steps that can be undertaken with a foundational understanding of accepted principles, allowing residents to compile a working draft of a manuscript in collaboration with a trusted faculty mentor.

The Systematic Review: A Simple Approach

Step 1: Choose a Topic—Once a resident has decided to embark on conducting a systematic review, the first step is to choose a topic, which requires consideration of several factors to ensure relevance, feasibility, and impact. Begin by identifying areas of clinical uncertainty or controversy in which a comprehensive synthesis of the literature could provide valuable insights. Often, such a topic can be gleaned from the conclusion section of other primary studies; statements such as “further study is needed to determine the efficacy of X” or “systematic reviews would be beneficial to ascertaining the impact of Y” may be a great place to start.

Next, ensure that sufficient primary studies exist to support a robust review or meta-analysis by conducting a preliminary literature search, which will confirm that the chosen topic is both researchable and relevant. A narrow, focused, well-defined topic likely will prove more feasible to review than a broad, ill-defined one. Once a topic is selected, it is advisable to discuss it with a faculty mentor before starting the literature search to ensure the topic’s feasibility and clinical relevance, helping to guide your research in a meaningful direction.

When deciding between a systematic review and a meta-analysis, the nature of the research question is an influential factor. A systematic review is particularly suitable for addressing broad questions or topics when the aim is to summarize and synthesize all relevant research studies; for example, a systematic review may investigate the various treatment options for atopic dermatitis and their efficacy, which allows for a comprehensive overview of the available treatments—both the interventions and the outcomes. In contrast, a meta-analysis is ideal for collecting and statistically combining quantitative data from multiple primary studies, provided there are enough relevant studies available in the literature.

Step 2: Build a Team—Recruiting a skilled librarian to assist with Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms and retrieving relevant papers is crucial for conducting a high-quality systematic review or meta-analysis. Medical librarians specializing in health sciences enhance the efficiency, comprehensiveness, and reliability of your literature search, substantially boosting your work’s credibility. These librarians are well versed in medical databases such as PubMed and Embase. Begin by contacting your institution’s library services, as there often are valuable resources and personnel available to assist you. Personally, I was surprised to find a librarian at my institution specifically dedicated to helping medical residents with such projects! These professionals are eager to help, and if provided with the scope and goal of your project, they can deliver literature search results in a digestible format. Similarly, seeking the expertise of a medical statistician is crucial to the accuracy and legitimacy of your study. In your final paper, it is important to recognize the contributions of the librarian and statistician, either as co-authors or in the acknowledgments section.

In addition, recruiting colleagues or medical students can be an effective strategy to make the project more feasible and offer collaborative benefits for all parties involved. Given the growing emphasis on research for residency and fellowship admissions, there usually is no shortage of motivated volunteers.

Next, identify the software tool you will use for your systematic review. Options range from simple spreadsheets such as Microsoft Excel to reference managers such as EndNote or Mendeley or dedicated systematic review tools. Academic institutions may subscribe to paid services such as Covidence (https://www.covidence.org), or you can utilize free alternatives such as Rayyan (https://www.rayyan.ai). Investing time in learning to navigate dedicated systematic review software can greatly enhance efficiency and reduce frustrations compared to more basic methods. Ultimately, staying organized, thorough, and committed is key.

Step 3: Conduct the Literature Review—At this point, your research topic has been decided, a medical reference librarian has provided the results of a comprehensive literature search, and a software tool has been chosen. The next task is to read hundreds or thousands of papers—easy, right? With your dedicated team assembled, the workload can be divided and conquered. The first step involves screening out duplicate and irrelevant studies based on titles and abstracts. Next, review the remaining papers in more detail. Those that pass this preliminary screen should be read in their entirety, and only the papers relevant to the research topic should be included in the final synthesis. If there are uncertainties about a study’s relevance, consulting a faculty mentor is advisable. To ensure the systematic review is as thorough as possible, pay special attention to the references section of each paper, as cited references can reveal relevant studies that may have been missed in the literature search.

Once all relevant papers are compiled and read, the relevant data points should be extracted and imputed into a data sheet. Collaborating with a medical statistician is crucial at this stage, as they can provide guidance on the most effective ways to structure and input data. After all studies are included, the relevant statistical analyses on the resultant dataset can be run.

Step 4: Write the Paper—In 2020, the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement was developed to ensure transparent and complete reporting of systematic reviews. A full discussion of PRISMA guidelines is beyond the scope of this paper; Page et al14 provided a summary, checklist, and flow diagram that is available online (https://www.prisma-statement.org). Following the PRISMA checklist and guidelines ensures a high-quality, transparent, and reliable systematic review. These guidelines not only help streamline and simplify the writing process but also enhance its efficiency and effectiveness. Discovering the PRISMA checklist can be transformative, providing a valuable roadmap that guides the author through each step of the reporting process, helping to avoid common pitfalls. This structured approach ultimately leads to a more comprehensive and trustworthy review.

Step 5: Make Finishing Touches—At this stage in the systematic review process, the studies have been compiled and thoroughly analyzed and the statistical analysis has been conducted. The results have been organized within a structured framework following the PRISMA checklist. With these steps completed, the next task is to finalize the manuscript and seek a final review from the senior author or faculty mentor. To streamline this process, it is beneficial to adhere to the formatting guidelines of the specific medical journal you intend to submit to. Check the author guidelines on the journal’s website and review recent systematic reviews published there as a reference. Even if you have not chosen a journal yet, formatting your manuscript according to a prestigious journal’s general style provides a strong foundation that can be easily adapted to fit another journal’s requirements if necessary.

Final Thoughts

Designing and conducting a systematic review is no easy task, but it can be a valuable skill for dermatology residents aiming to contribute meaningfully to the medical literature. The process of compiling a systematic review offers an opportunity for developing critical research skills, from formulating a research question to synthesizing evidence and presenting findings in a clear methodical way. Engaging in systematic review writing not only enhances the resident’s understanding of a particular topic but also demonstrates a commitment to scholarly activity—a key factor in an increasingly competitive residency and fellowship application environment.

The basic steps outlined in this article are just one way in which residents can begin to navigate the complexities of medical research, specifically the systematic review process. By assembling a supportive team, utilizing available resources, and adhering to established guidelines such as PRISMA, one can produce a high-quality, impactful review. Ultimately, the systematic review process is not just about publication—it is about fostering a habit of inquiry, improving patient care, and contributing to the ever-evolving field of medicine. With dedication and collaboration, even the most challenging aspects of research can be tackled, paving the way for future opportunities and professional growth. In this way, perhaps one day the spirit of the “research race” can shift from a frantic sprint to a graceful marathon, where each mile is run with heart and every step is filled with purpose.

Dermatology remains one of the most competitive specialties in the residency match, with successful applicants demonstrating a well-rounded application reflecting not only their academic excellence but also their dedication to research, community service, and hands-on clinical experience.1 A growing emphasis on scholarly activities has made it crucial for applicants to stand out, with an increasing number opting to take gap years to engage in focused research endeavors.2 In highly competitive specialties such as dermatology, successful applicants now report more than 20 research items on average.3,4 This trend also is evident in primary care specialties, which have seen a 2- to 3-fold increase in reported research activities. The average unmatched applicant today lists more research items than the average matched applicant did a decade ago, underscoring the growing emphasis on scholarly activity.3

Ideally, graduate medical education should foster an environment of inquiry and scholarship, where residents develop new knowledge, evaluate research findings, and cultivate lifelong habits of inquiry. The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education requires residents to engage in scholarship, such as case reports, research reviews, and original research.5 Research during residency has been linked to several benefits, including enhanced patient care through improved critical appraisal skills, clinical reasoning, and lifelong learning.6,7 Additionally, students and residents who publish research are more likely to achieve higher rank during residency and pursue careers in academic medicine, potentially helping to address the decline in clinician investigators.8,9 Publishing and presenting research also can enhance a residency program’s reputation, making it more attractive to competitive applicants, and may be beneficial for residents seeking jobs or fellowships.6

Dermatology residency programs vary in their structure and support for resident research. One survey revealed that many programs lack the necessary support, structure, and resources to effectively promote and maintain research training.1 Additionally, residents have less exposure to researchers who could serve as mentors due to the growing demands placed on attending physicians in teaching hospitals.10

The Research Arms Race

The growing emphasis on scholarly activity for residency and fellowship applicants coupled with the use of research productivity to differentiate candidates has led some to declare a “research arms race” in residency selection.3 As one author stated, “We need less research, better research, and research done for the right reasons.”11 Indeed, most articles authored by medical students are short reviews or case reports, with the majority (59% [207/350]) being cited zero times, according to one analysis.12 Given the variable research infrastructure between programs and the decreasing availability of research mentors despite the growing emphasis on scholarly activity, applicants face an unfortunate dilemma. Until the system changes, those who protest this research arms race by not engaging in substantial scholarly activity are less likely to match into competitive specialties. Thus, the race continues.

The Value of Mentorship

Resident research success is impacted by having an effective faculty research mentor.13 Although all medical research at the student or resident levels should be conducted with a faculty mentor to oversee it, finding a mentor can be challenging. If a resident’s program boasts a strong research infrastructure or prolific faculty, building relationships with potential mentors is a logical first step for residents wishing to engage in research; however, if suitable mentors are lacking, efforts should be made by residents to establish these connections elsewhere, such as attending society meetings to network with potential mentors and applying to formal mentorship programs (eg, the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery’s Preceptor Program, the Women’s Dermatologic Society’s Mentorship Award). Unsolicited email inquiries asking, “Hi Dr. X, my name is Y, and I was wondering if you have any research projects I could help with?” often go unanswered. Instead, consider emailing or approaching potential mentors with a more developed proposition, such as the following example:

Hello Dr. X, my name is Y. I have enjoyed reading your publications on A, which inspired me to think about B. I reviewed the literature and noticed a potential to enhance our current understanding on the topic. My team and I conducted a systematic review of the available literature and drafted a manuscript summarizing our findings. Given your expertise in this field, would you be willing to collaborate on this paper? We would be grateful for your critical eye, suggestions for improvement, and overall thoughts.

This approach demonstrates initiative, provides a clear plan, and shows respect for the mentor’s expertise, increasing the likelihood of a positive response and fruitful collaboration. Assuming the resident’s working draft meets the potential mentor’s basic expectations, such a display of initiative is likely to impress them, and they may then offer opportunities to engage in meaningful research projects in the future. Everyone benefits! These efforts to establish connections with mentors can pave the way to further collaboration and meaningful research opportunities for dermatology residents.

The Systematic Review: An Attractive Option For Residents

There are several potential avenues for students or residents interested in pursuing research. Case reports and case series are relatively easy to compile, can be completed quickly, and often require minimal guidance from a faculty mentor; however, case reports rank low in the research hierarchy. Conversely, prospective blinded clinical trials provide some of the highest-quality evidence available but are challenging to conduct without a practicing faculty member to provide a patient cohort, often require extensive funding, and may involve complex statistical analyses beyond the expertise of most students or residents. Additionally, they may take years to complete, often extending beyond residency or fellowship application deadlines.

Most medical applicants likely hold at least some hesitation in churning out vast amounts of low-quality research merely to boost their publication count for the match process. Ideally, those who pursue scholarly activity should be driven by a genuine desire to contribute meaningfully to the medical literature. One particularly valuable avenue for trainees wishing to engage in research is the systematic review, which aims to identify, evaluate, and summarize the findings of all relevant individual studies regarding a research topic and answer a focused question. If performed thoughtfully, a systematic review can meaningfully contribute to the medical literature without requiring access to a prospectively followed cohort of patients or the constant supervision of a faculty mentor. Sure, systematic reviews may not be as robust as prospective cohort clinical trials, but they often provide comprehensive insights and are considered valuable contributions to evidence-based medicine. With the help of co-residents or medical students, a medical reference librarian, and a statistician—along with a working understanding of universally accepted quality measures—a resident physician and their team can produce a systematic review that ultimately may merit publication in a top-tier medical journal.

The remainder of this column will outline a streamlined approach to the systematic review writing process, specifically tailored for medical residents who may not have affiliations to a prolific research department or established relationships with faculty mentors in their field of interest. The aim is to offer a basic framework to help residents navigate the complexities of conducting and writing a high-quality, impactful systematic review. It is important to emphasize that resident research should always be conducted under the guidance of a faculty mentor, and this approach is not intended to encourage independent research and publication by residents. Instead, it provides steps that can be undertaken with a foundational understanding of accepted principles, allowing residents to compile a working draft of a manuscript in collaboration with a trusted faculty mentor.

The Systematic Review: A Simple Approach

Step 1: Choose a Topic—Once a resident has decided to embark on conducting a systematic review, the first step is to choose a topic, which requires consideration of several factors to ensure relevance, feasibility, and impact. Begin by identifying areas of clinical uncertainty or controversy in which a comprehensive synthesis of the literature could provide valuable insights. Often, such a topic can be gleaned from the conclusion section of other primary studies; statements such as “further study is needed to determine the efficacy of X” or “systematic reviews would be beneficial to ascertaining the impact of Y” may be a great place to start.

Next, ensure that sufficient primary studies exist to support a robust review or meta-analysis by conducting a preliminary literature search, which will confirm that the chosen topic is both researchable and relevant. A narrow, focused, well-defined topic likely will prove more feasible to review than a broad, ill-defined one. Once a topic is selected, it is advisable to discuss it with a faculty mentor before starting the literature search to ensure the topic’s feasibility and clinical relevance, helping to guide your research in a meaningful direction.

When deciding between a systematic review and a meta-analysis, the nature of the research question is an influential factor. A systematic review is particularly suitable for addressing broad questions or topics when the aim is to summarize and synthesize all relevant research studies; for example, a systematic review may investigate the various treatment options for atopic dermatitis and their efficacy, which allows for a comprehensive overview of the available treatments—both the interventions and the outcomes. In contrast, a meta-analysis is ideal for collecting and statistically combining quantitative data from multiple primary studies, provided there are enough relevant studies available in the literature.

Step 2: Build a Team—Recruiting a skilled librarian to assist with Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms and retrieving relevant papers is crucial for conducting a high-quality systematic review or meta-analysis. Medical librarians specializing in health sciences enhance the efficiency, comprehensiveness, and reliability of your literature search, substantially boosting your work’s credibility. These librarians are well versed in medical databases such as PubMed and Embase. Begin by contacting your institution’s library services, as there often are valuable resources and personnel available to assist you. Personally, I was surprised to find a librarian at my institution specifically dedicated to helping medical residents with such projects! These professionals are eager to help, and if provided with the scope and goal of your project, they can deliver literature search results in a digestible format. Similarly, seeking the expertise of a medical statistician is crucial to the accuracy and legitimacy of your study. In your final paper, it is important to recognize the contributions of the librarian and statistician, either as co-authors or in the acknowledgments section.

In addition, recruiting colleagues or medical students can be an effective strategy to make the project more feasible and offer collaborative benefits for all parties involved. Given the growing emphasis on research for residency and fellowship admissions, there usually is no shortage of motivated volunteers.

Next, identify the software tool you will use for your systematic review. Options range from simple spreadsheets such as Microsoft Excel to reference managers such as EndNote or Mendeley or dedicated systematic review tools. Academic institutions may subscribe to paid services such as Covidence (https://www.covidence.org), or you can utilize free alternatives such as Rayyan (https://www.rayyan.ai). Investing time in learning to navigate dedicated systematic review software can greatly enhance efficiency and reduce frustrations compared to more basic methods. Ultimately, staying organized, thorough, and committed is key.

Step 3: Conduct the Literature Review—At this point, your research topic has been decided, a medical reference librarian has provided the results of a comprehensive literature search, and a software tool has been chosen. The next task is to read hundreds or thousands of papers—easy, right? With your dedicated team assembled, the workload can be divided and conquered. The first step involves screening out duplicate and irrelevant studies based on titles and abstracts. Next, review the remaining papers in more detail. Those that pass this preliminary screen should be read in their entirety, and only the papers relevant to the research topic should be included in the final synthesis. If there are uncertainties about a study’s relevance, consulting a faculty mentor is advisable. To ensure the systematic review is as thorough as possible, pay special attention to the references section of each paper, as cited references can reveal relevant studies that may have been missed in the literature search.

Once all relevant papers are compiled and read, the relevant data points should be extracted and imputed into a data sheet. Collaborating with a medical statistician is crucial at this stage, as they can provide guidance on the most effective ways to structure and input data. After all studies are included, the relevant statistical analyses on the resultant dataset can be run.

Step 4: Write the Paper—In 2020, the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement was developed to ensure transparent and complete reporting of systematic reviews. A full discussion of PRISMA guidelines is beyond the scope of this paper; Page et al14 provided a summary, checklist, and flow diagram that is available online (https://www.prisma-statement.org). Following the PRISMA checklist and guidelines ensures a high-quality, transparent, and reliable systematic review. These guidelines not only help streamline and simplify the writing process but also enhance its efficiency and effectiveness. Discovering the PRISMA checklist can be transformative, providing a valuable roadmap that guides the author through each step of the reporting process, helping to avoid common pitfalls. This structured approach ultimately leads to a more comprehensive and trustworthy review.

Step 5: Make Finishing Touches—At this stage in the systematic review process, the studies have been compiled and thoroughly analyzed and the statistical analysis has been conducted. The results have been organized within a structured framework following the PRISMA checklist. With these steps completed, the next task is to finalize the manuscript and seek a final review from the senior author or faculty mentor. To streamline this process, it is beneficial to adhere to the formatting guidelines of the specific medical journal you intend to submit to. Check the author guidelines on the journal’s website and review recent systematic reviews published there as a reference. Even if you have not chosen a journal yet, formatting your manuscript according to a prestigious journal’s general style provides a strong foundation that can be easily adapted to fit another journal’s requirements if necessary.

Final Thoughts

Designing and conducting a systematic review is no easy task, but it can be a valuable skill for dermatology residents aiming to contribute meaningfully to the medical literature. The process of compiling a systematic review offers an opportunity for developing critical research skills, from formulating a research question to synthesizing evidence and presenting findings in a clear methodical way. Engaging in systematic review writing not only enhances the resident’s understanding of a particular topic but also demonstrates a commitment to scholarly activity—a key factor in an increasingly competitive residency and fellowship application environment.