User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

Medicare Part D Prescription Claims for Brodalumab: Analysis of Annual Trends for 2017-2019

To the Editor:

Brodalumab, a monoclonal antibody targeting IL-17RA, was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2017 for the treatment of moderate to severe chronic plaque psoriasis. The drug is the only biologic agent available for the treatment of psoriasis for which a psoriasis area severity index score of 100 is a primary end point.1,2 Brodalumab is associated with an FDA boxed warning due to an increased risk for suicidal ideation and behavior (SIB), including completed suicides, during clinical trials.

We sought to characterize national utilization of this effective yet underutilized drug among Medicare beneficiaries by surveying the Medicare Part D Prescriber dataset.3 We tabulated brodalumab utilization statistics and characteristics of high-volume prescribers who had 11 or more annual claims for brodalumab.

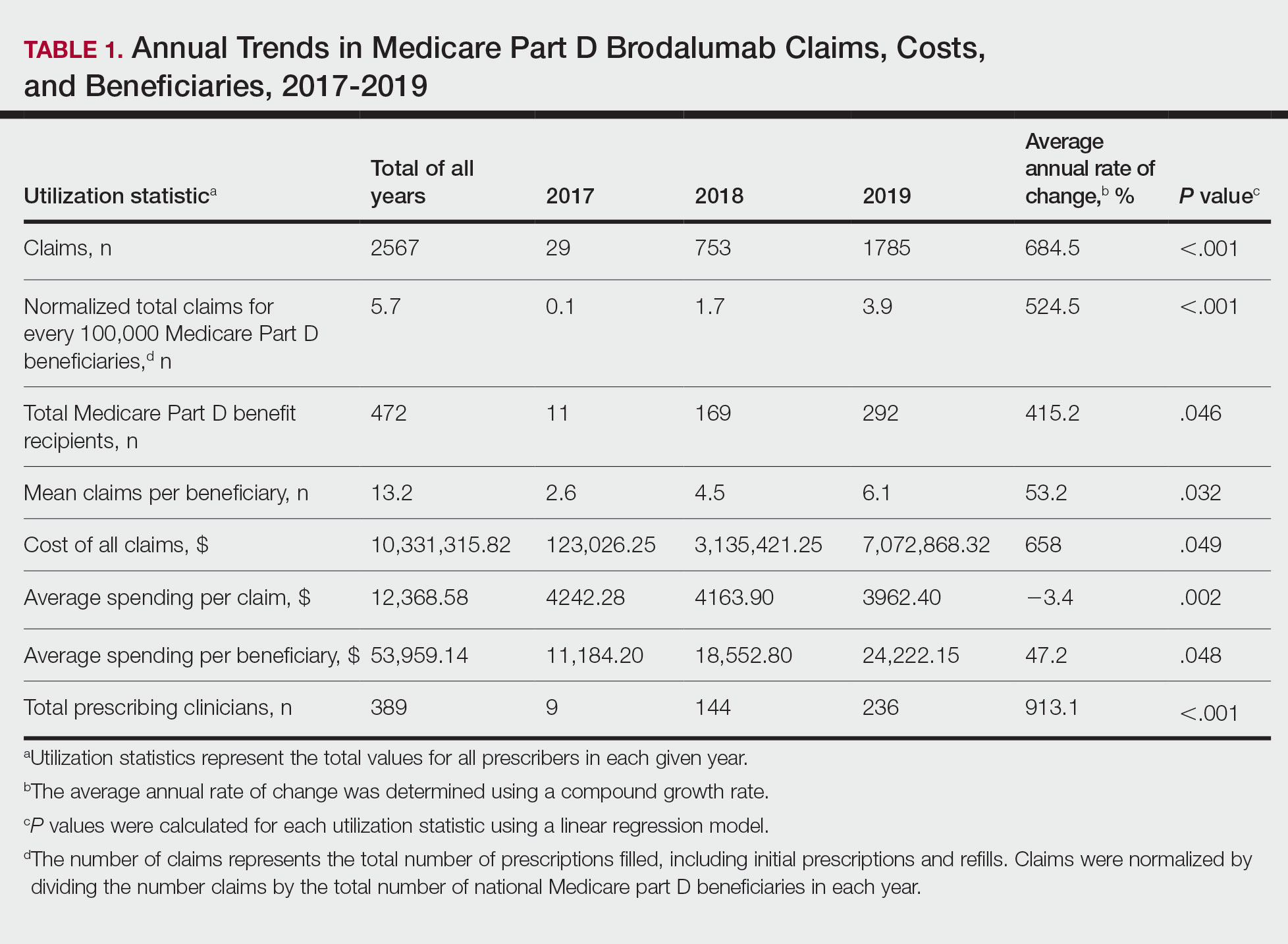

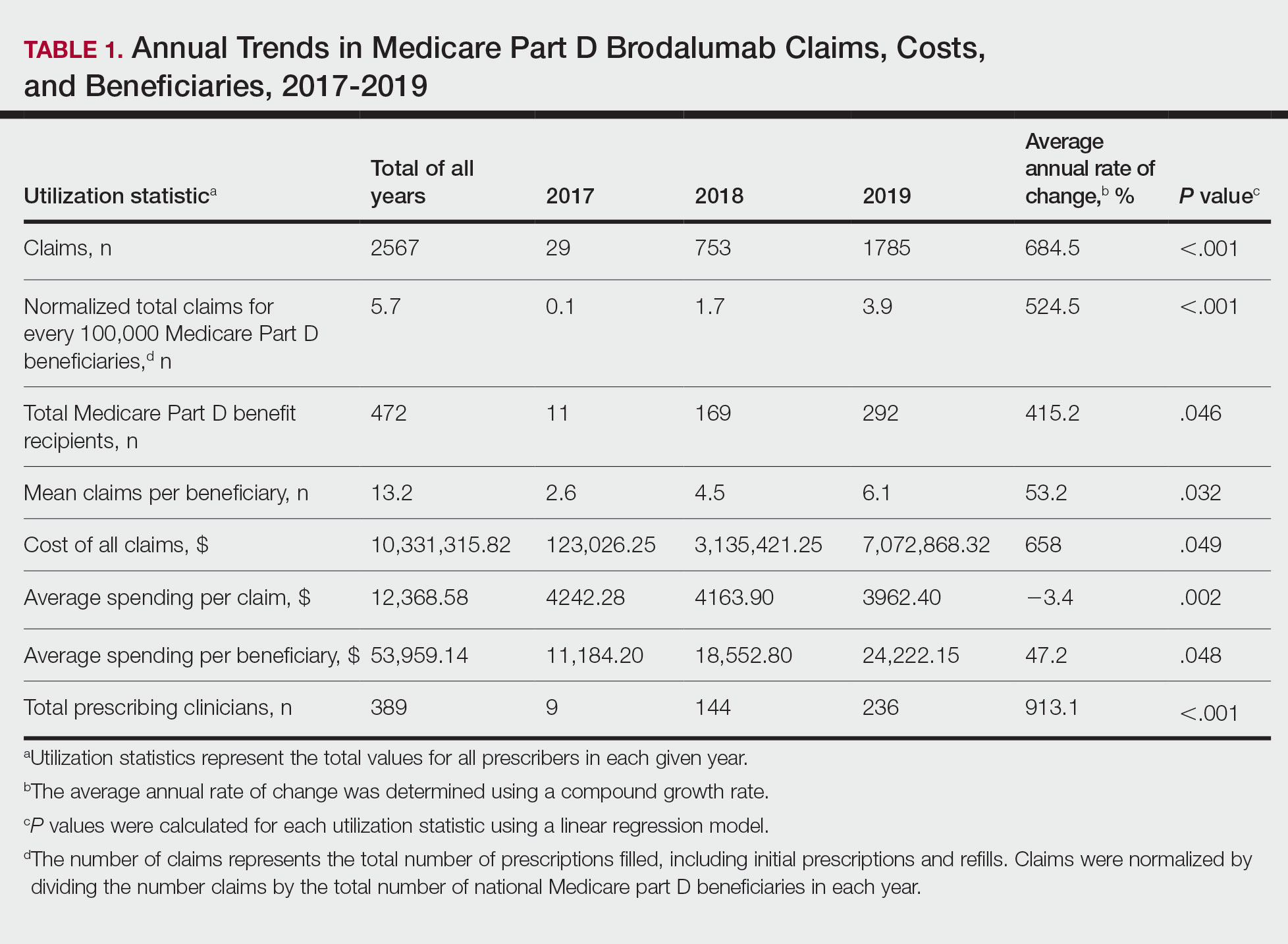

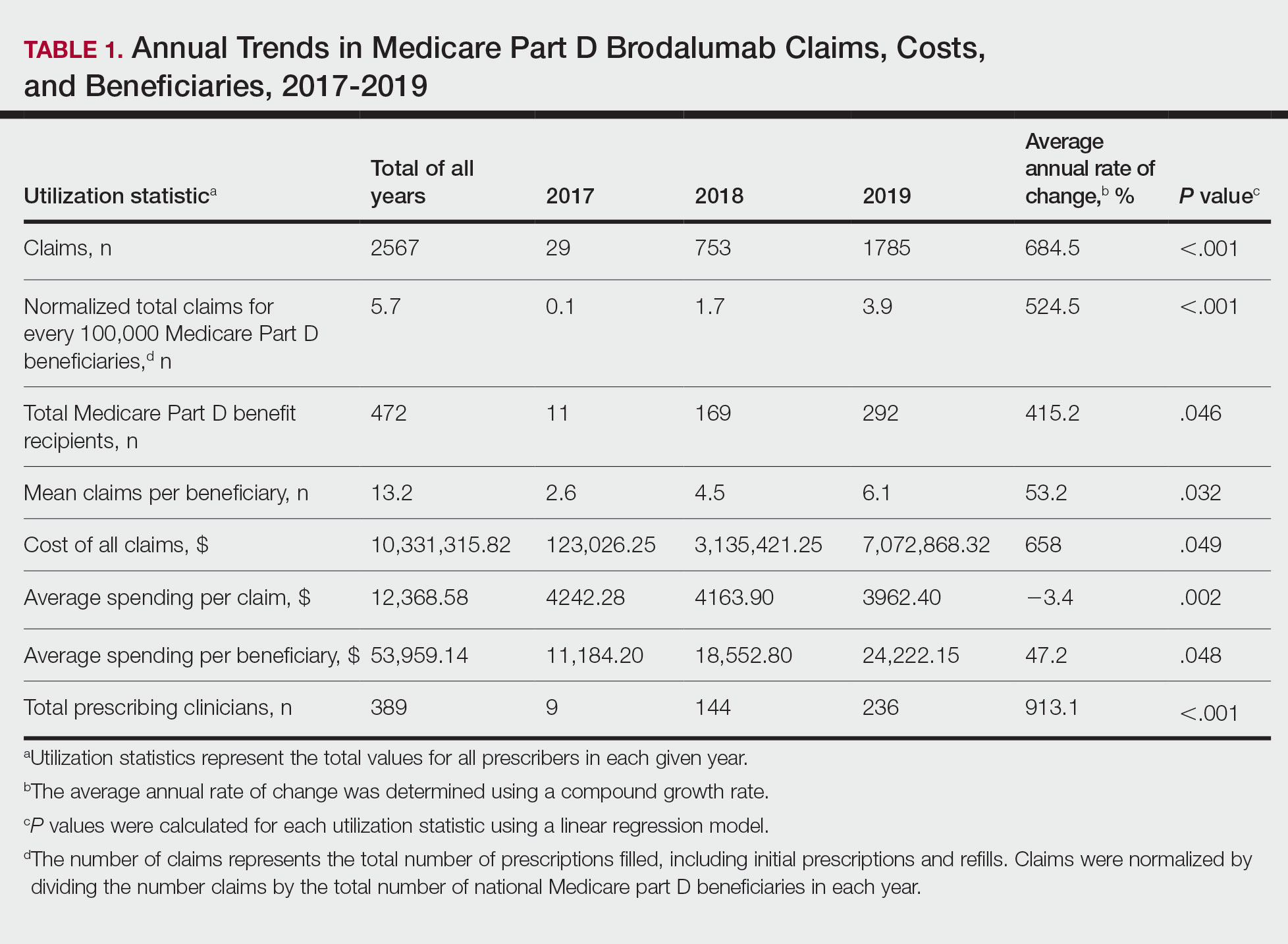

Despite its associated boxed warning, the number of Medicare D claims for brodalumab increased by 1756 from 2017 to 2019, surpassing $7 million in costs by 2019. The number of beneficiaries also increased from 11 to 292—a 415.2% annual increase in beneficiaries for whom brodalumab was prescribed (Table 1).

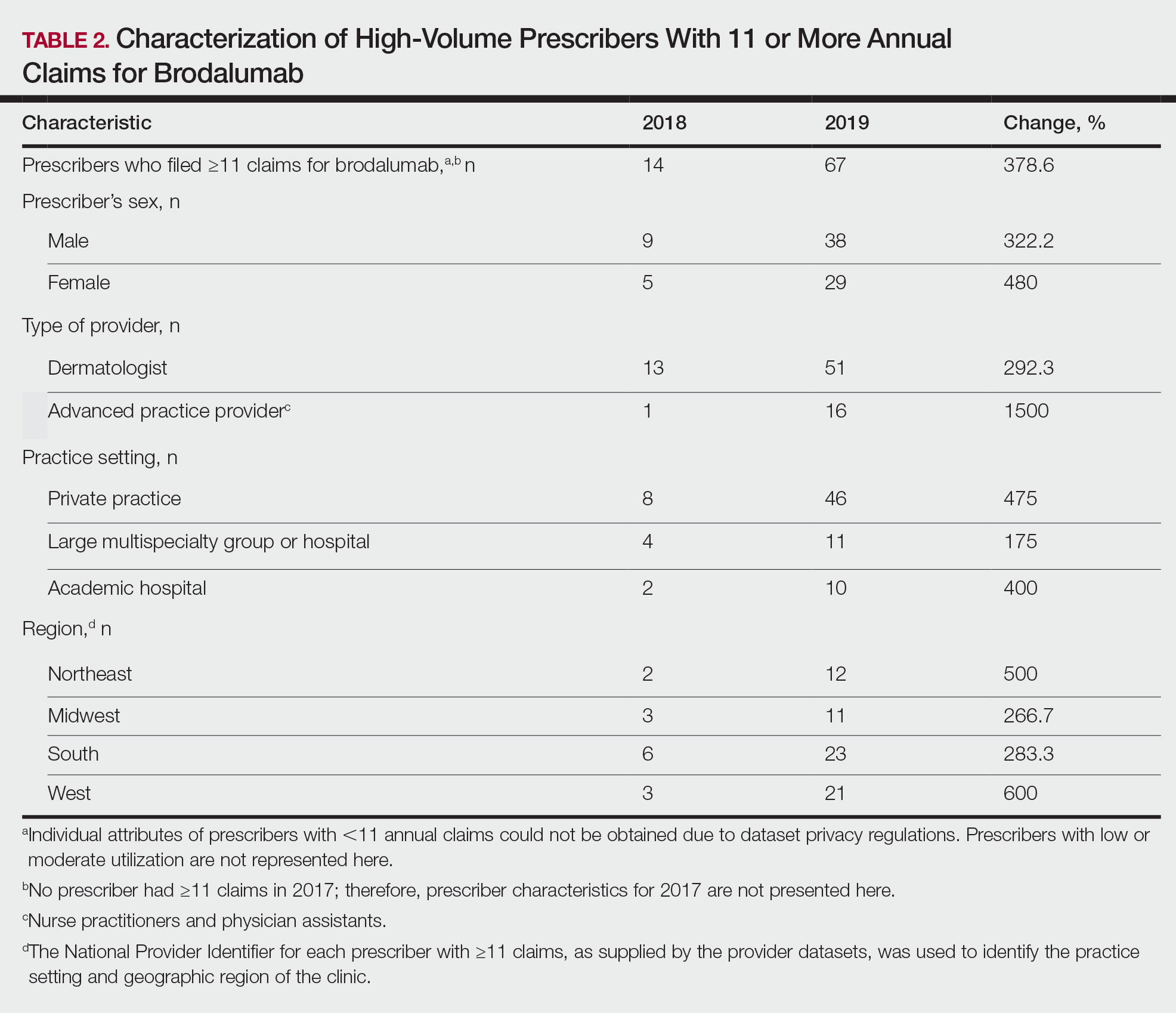

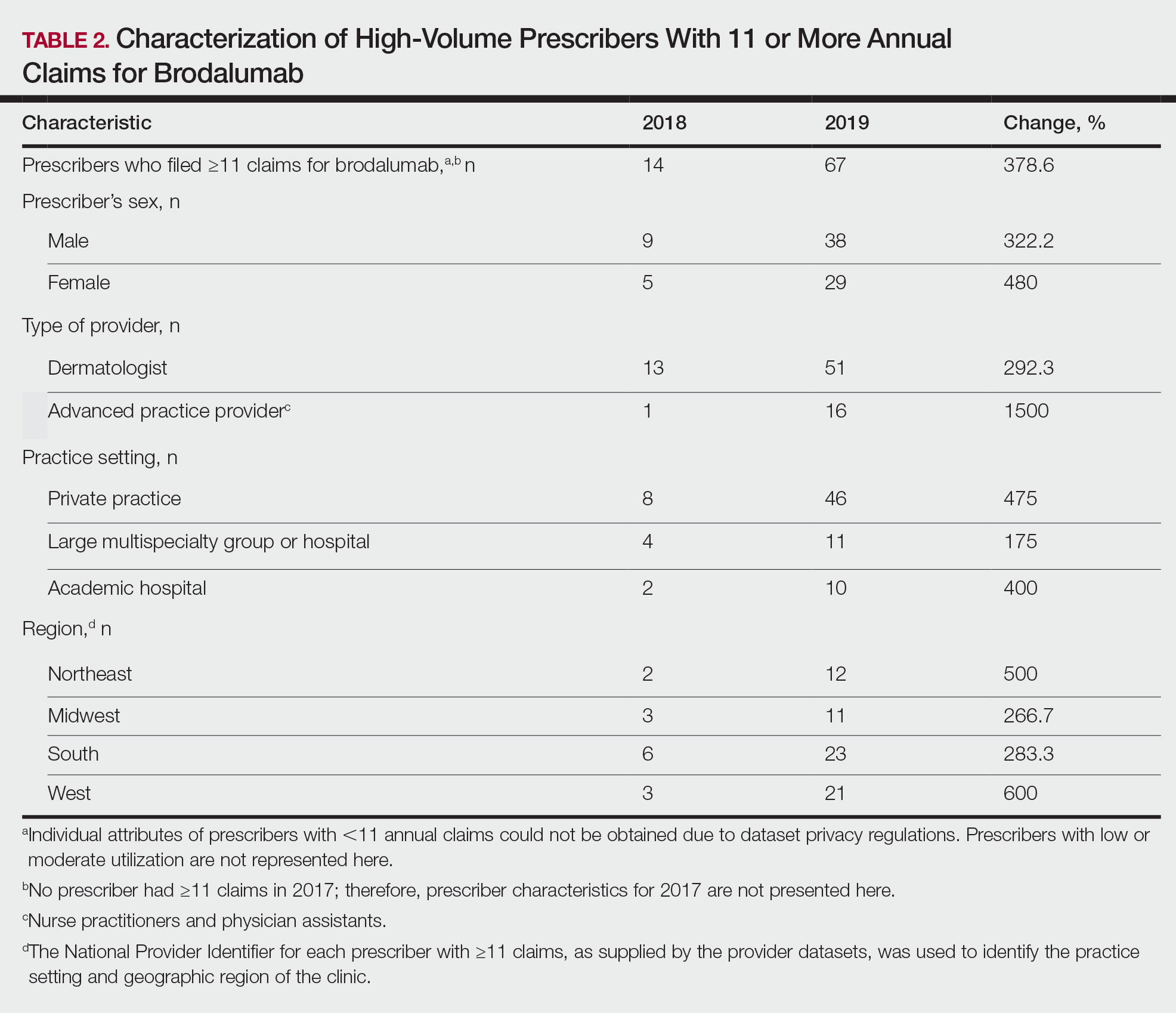

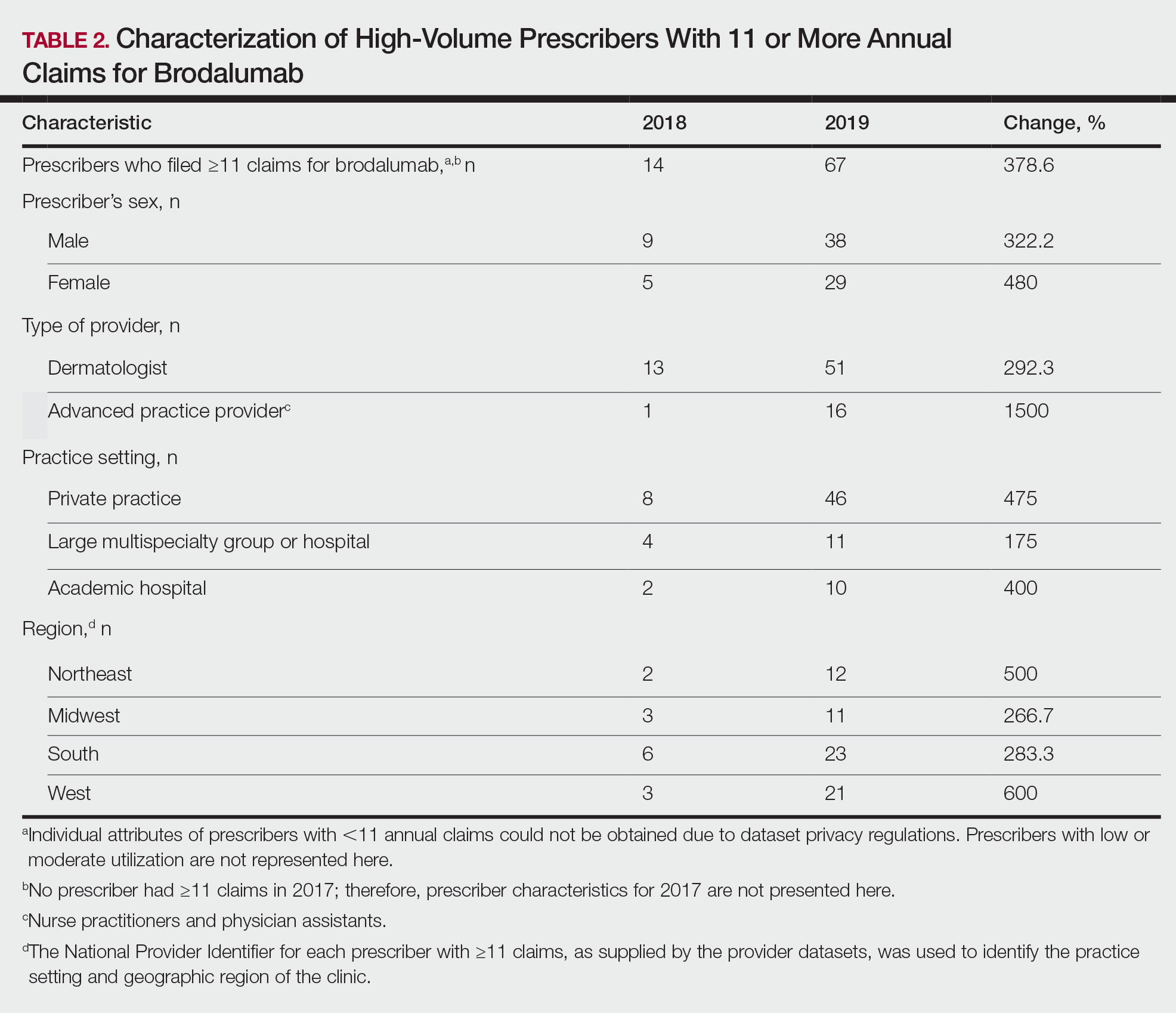

In addition, states in the West and South had the highest utilization rates of brodalumab in 2019. There also was an increasing trend toward high-volume prescribers of brodalumab, with private practice clinicians constituting the majority (Table 2).

There was a substantial increase in advanced practice providers including nurse practitioners and physician assistants who were brodalumab prescribers. Although this trend might promote greater access to brodalumab, it is vital to ensure that advanced practice providers receive targeted training to properly understand the complexities of treatment with brodalumab.

Although the utilization of brodalumab has increased since 2017 (P<.001), it is still underutilized compared to the other IL-17 inhibitors secukinumab and ixekizumab. Secukinumab was FDA approved for the treatment of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis in 2015, followed by ixekizumab in 2016.4

According to the Medicare Part D database, both secukinumab and ixekizumab had a higher number of total claims and prescribers compared to brodalumab in the years of their debut.3 In 2015, there were 3593 claims for and 862 prescribers of secukinumab; in 2016, there were 1731 claims for and 681 prescribers of ixekizumab. In contrast, there were only 29 claims for and 11 prescribers of brodalumab in 2017, the year that the drug was approved by the FDA. During the same 3-year period, secukinumab and ixekizumab had a substantially greater number of claims—totals of 176,823 and 55,289, respectively—than brodalumab. The higher number of claims for secukinumab and ixekizumab compared to brodalumab may reflect clinicians’ increasing confidence in prescribing those drugs, given their long-term safety and efficacy. In addition, secukinumab and ixekizumab do not require completion of a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) program, which makes them more readily prescribable.3

Overall, most experts agree that there is no increase in the risk for suicide associated with brodalumab compared to the general population. A 2-year pharmacovigilance report on brodalumab supports the safety of this drug.5 All participants who completed suicide during the clinical trials harbored an underlying psychiatric disorder or stressor(s).6

Although causation between brodalumab and SIB has not been demonstrated, it remains imperative that prescribers diligently assess patients’ risk of SIB and subsequently their access to appropriate psychiatric services as a precaution, if necessary. This is particularly important for private practice prescribers, who constitute the majority of Medicare D brodalumab claims, because they must ensure collaboration with a multidisciplinary team involving mental health providers. Lastly, considering that the highest number of brodalumab Medicare D claims were in western and southern states, it is critical to note that those 2 regions also harbor comparatively fewer mental health facilities that accept Medicare than other regions of the country.7 Prescribers in western and southern states must be mindful of mental health coverage limitations when treating psoriasis patients with brodalumab.

The increase in the number of claims, beneficiaries, and prescribers of brodalumab during its first 3 years of availability might be attributed to its efficacy and safety. On the other hand, the boxed warning and REMS associated with brodalumab might have led to underutilization of this drug compared to other IL-17 inhibitors.

Our analysis is limited by its representative restriction to Medicare patients. There also are limited data on brodalumab given its novelty. Individual attributes of prescribers with fewer than 11 annual claims for brodalumab could not be obtained because of dataset regulations; however, aggregated utilization statistics provide an indication of brodalumab prescribing patterns among all providers. Furthermore, during this analysis, data on the Medicare D database were limited to 2013 through 2020. Studies are needed to determine prescribing patterns of brodalumab since this study period.

- Foulkes AC, Warren RB. Brodalumab in psoriasis: evidence to date and clinical potential. Drugs Context. 2019;8:212570. doi:10.7573/dic.212570

- Beck KM, Koo J. Brodalumab for the treatment of plaque psoriasis: up-to-date. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2019;19:287-292. doi:10.1080/14712598.2019.1579794

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare Part D Prescribers. Updated July 27, 2022. Accessed September 23, 2022. https://data.cms.gov/provider-summary-by-type-of-service/medicare-part-d-prescribers/medicare-part-d-prescribers-by-provider

- Drugs. US Food and Drug Administration website. Accessed September 23, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/drugs

- Lebwohl M, Leonardi C, Wu JJ, et al. Two-year US pharmacovigilance report on brodalumab. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2021;11:173-180. doi:10.1007/s13555-020-00472-x

- Lebwohl MG, Papp KA, Marangell LB, et al. Psychiatric adverse events during treatment with brodalumab: analysis of psoriasis clinical trials. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:81-89.e5. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.08.024

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. National Mental Health Services Survey (N-MHSS): 2019, Data On Mental Health Treatment Facilities. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; August 13, 2020. Accessed September 21, 2022. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/report/national-mental-health-services-survey-n-mhss-2019-data-mental-health-treatment-facilities

To the Editor:

Brodalumab, a monoclonal antibody targeting IL-17RA, was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2017 for the treatment of moderate to severe chronic plaque psoriasis. The drug is the only biologic agent available for the treatment of psoriasis for which a psoriasis area severity index score of 100 is a primary end point.1,2 Brodalumab is associated with an FDA boxed warning due to an increased risk for suicidal ideation and behavior (SIB), including completed suicides, during clinical trials.

We sought to characterize national utilization of this effective yet underutilized drug among Medicare beneficiaries by surveying the Medicare Part D Prescriber dataset.3 We tabulated brodalumab utilization statistics and characteristics of high-volume prescribers who had 11 or more annual claims for brodalumab.

Despite its associated boxed warning, the number of Medicare D claims for brodalumab increased by 1756 from 2017 to 2019, surpassing $7 million in costs by 2019. The number of beneficiaries also increased from 11 to 292—a 415.2% annual increase in beneficiaries for whom brodalumab was prescribed (Table 1).

In addition, states in the West and South had the highest utilization rates of brodalumab in 2019. There also was an increasing trend toward high-volume prescribers of brodalumab, with private practice clinicians constituting the majority (Table 2).

There was a substantial increase in advanced practice providers including nurse practitioners and physician assistants who were brodalumab prescribers. Although this trend might promote greater access to brodalumab, it is vital to ensure that advanced practice providers receive targeted training to properly understand the complexities of treatment with brodalumab.

Although the utilization of brodalumab has increased since 2017 (P<.001), it is still underutilized compared to the other IL-17 inhibitors secukinumab and ixekizumab. Secukinumab was FDA approved for the treatment of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis in 2015, followed by ixekizumab in 2016.4

According to the Medicare Part D database, both secukinumab and ixekizumab had a higher number of total claims and prescribers compared to brodalumab in the years of their debut.3 In 2015, there were 3593 claims for and 862 prescribers of secukinumab; in 2016, there were 1731 claims for and 681 prescribers of ixekizumab. In contrast, there were only 29 claims for and 11 prescribers of brodalumab in 2017, the year that the drug was approved by the FDA. During the same 3-year period, secukinumab and ixekizumab had a substantially greater number of claims—totals of 176,823 and 55,289, respectively—than brodalumab. The higher number of claims for secukinumab and ixekizumab compared to brodalumab may reflect clinicians’ increasing confidence in prescribing those drugs, given their long-term safety and efficacy. In addition, secukinumab and ixekizumab do not require completion of a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) program, which makes them more readily prescribable.3

Overall, most experts agree that there is no increase in the risk for suicide associated with brodalumab compared to the general population. A 2-year pharmacovigilance report on brodalumab supports the safety of this drug.5 All participants who completed suicide during the clinical trials harbored an underlying psychiatric disorder or stressor(s).6

Although causation between brodalumab and SIB has not been demonstrated, it remains imperative that prescribers diligently assess patients’ risk of SIB and subsequently their access to appropriate psychiatric services as a precaution, if necessary. This is particularly important for private practice prescribers, who constitute the majority of Medicare D brodalumab claims, because they must ensure collaboration with a multidisciplinary team involving mental health providers. Lastly, considering that the highest number of brodalumab Medicare D claims were in western and southern states, it is critical to note that those 2 regions also harbor comparatively fewer mental health facilities that accept Medicare than other regions of the country.7 Prescribers in western and southern states must be mindful of mental health coverage limitations when treating psoriasis patients with brodalumab.

The increase in the number of claims, beneficiaries, and prescribers of brodalumab during its first 3 years of availability might be attributed to its efficacy and safety. On the other hand, the boxed warning and REMS associated with brodalumab might have led to underutilization of this drug compared to other IL-17 inhibitors.

Our analysis is limited by its representative restriction to Medicare patients. There also are limited data on brodalumab given its novelty. Individual attributes of prescribers with fewer than 11 annual claims for brodalumab could not be obtained because of dataset regulations; however, aggregated utilization statistics provide an indication of brodalumab prescribing patterns among all providers. Furthermore, during this analysis, data on the Medicare D database were limited to 2013 through 2020. Studies are needed to determine prescribing patterns of brodalumab since this study period.

To the Editor:

Brodalumab, a monoclonal antibody targeting IL-17RA, was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2017 for the treatment of moderate to severe chronic plaque psoriasis. The drug is the only biologic agent available for the treatment of psoriasis for which a psoriasis area severity index score of 100 is a primary end point.1,2 Brodalumab is associated with an FDA boxed warning due to an increased risk for suicidal ideation and behavior (SIB), including completed suicides, during clinical trials.

We sought to characterize national utilization of this effective yet underutilized drug among Medicare beneficiaries by surveying the Medicare Part D Prescriber dataset.3 We tabulated brodalumab utilization statistics and characteristics of high-volume prescribers who had 11 or more annual claims for brodalumab.

Despite its associated boxed warning, the number of Medicare D claims for brodalumab increased by 1756 from 2017 to 2019, surpassing $7 million in costs by 2019. The number of beneficiaries also increased from 11 to 292—a 415.2% annual increase in beneficiaries for whom brodalumab was prescribed (Table 1).

In addition, states in the West and South had the highest utilization rates of brodalumab in 2019. There also was an increasing trend toward high-volume prescribers of brodalumab, with private practice clinicians constituting the majority (Table 2).

There was a substantial increase in advanced practice providers including nurse practitioners and physician assistants who were brodalumab prescribers. Although this trend might promote greater access to brodalumab, it is vital to ensure that advanced practice providers receive targeted training to properly understand the complexities of treatment with brodalumab.

Although the utilization of brodalumab has increased since 2017 (P<.001), it is still underutilized compared to the other IL-17 inhibitors secukinumab and ixekizumab. Secukinumab was FDA approved for the treatment of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis in 2015, followed by ixekizumab in 2016.4

According to the Medicare Part D database, both secukinumab and ixekizumab had a higher number of total claims and prescribers compared to brodalumab in the years of their debut.3 In 2015, there were 3593 claims for and 862 prescribers of secukinumab; in 2016, there were 1731 claims for and 681 prescribers of ixekizumab. In contrast, there were only 29 claims for and 11 prescribers of brodalumab in 2017, the year that the drug was approved by the FDA. During the same 3-year period, secukinumab and ixekizumab had a substantially greater number of claims—totals of 176,823 and 55,289, respectively—than brodalumab. The higher number of claims for secukinumab and ixekizumab compared to brodalumab may reflect clinicians’ increasing confidence in prescribing those drugs, given their long-term safety and efficacy. In addition, secukinumab and ixekizumab do not require completion of a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) program, which makes them more readily prescribable.3

Overall, most experts agree that there is no increase in the risk for suicide associated with brodalumab compared to the general population. A 2-year pharmacovigilance report on brodalumab supports the safety of this drug.5 All participants who completed suicide during the clinical trials harbored an underlying psychiatric disorder or stressor(s).6

Although causation between brodalumab and SIB has not been demonstrated, it remains imperative that prescribers diligently assess patients’ risk of SIB and subsequently their access to appropriate psychiatric services as a precaution, if necessary. This is particularly important for private practice prescribers, who constitute the majority of Medicare D brodalumab claims, because they must ensure collaboration with a multidisciplinary team involving mental health providers. Lastly, considering that the highest number of brodalumab Medicare D claims were in western and southern states, it is critical to note that those 2 regions also harbor comparatively fewer mental health facilities that accept Medicare than other regions of the country.7 Prescribers in western and southern states must be mindful of mental health coverage limitations when treating psoriasis patients with brodalumab.

The increase in the number of claims, beneficiaries, and prescribers of brodalumab during its first 3 years of availability might be attributed to its efficacy and safety. On the other hand, the boxed warning and REMS associated with brodalumab might have led to underutilization of this drug compared to other IL-17 inhibitors.

Our analysis is limited by its representative restriction to Medicare patients. There also are limited data on brodalumab given its novelty. Individual attributes of prescribers with fewer than 11 annual claims for brodalumab could not be obtained because of dataset regulations; however, aggregated utilization statistics provide an indication of brodalumab prescribing patterns among all providers. Furthermore, during this analysis, data on the Medicare D database were limited to 2013 through 2020. Studies are needed to determine prescribing patterns of brodalumab since this study period.

- Foulkes AC, Warren RB. Brodalumab in psoriasis: evidence to date and clinical potential. Drugs Context. 2019;8:212570. doi:10.7573/dic.212570

- Beck KM, Koo J. Brodalumab for the treatment of plaque psoriasis: up-to-date. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2019;19:287-292. doi:10.1080/14712598.2019.1579794

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare Part D Prescribers. Updated July 27, 2022. Accessed September 23, 2022. https://data.cms.gov/provider-summary-by-type-of-service/medicare-part-d-prescribers/medicare-part-d-prescribers-by-provider

- Drugs. US Food and Drug Administration website. Accessed September 23, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/drugs

- Lebwohl M, Leonardi C, Wu JJ, et al. Two-year US pharmacovigilance report on brodalumab. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2021;11:173-180. doi:10.1007/s13555-020-00472-x

- Lebwohl MG, Papp KA, Marangell LB, et al. Psychiatric adverse events during treatment with brodalumab: analysis of psoriasis clinical trials. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:81-89.e5. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.08.024

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. National Mental Health Services Survey (N-MHSS): 2019, Data On Mental Health Treatment Facilities. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; August 13, 2020. Accessed September 21, 2022. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/report/national-mental-health-services-survey-n-mhss-2019-data-mental-health-treatment-facilities

- Foulkes AC, Warren RB. Brodalumab in psoriasis: evidence to date and clinical potential. Drugs Context. 2019;8:212570. doi:10.7573/dic.212570

- Beck KM, Koo J. Brodalumab for the treatment of plaque psoriasis: up-to-date. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2019;19:287-292. doi:10.1080/14712598.2019.1579794

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare Part D Prescribers. Updated July 27, 2022. Accessed September 23, 2022. https://data.cms.gov/provider-summary-by-type-of-service/medicare-part-d-prescribers/medicare-part-d-prescribers-by-provider

- Drugs. US Food and Drug Administration website. Accessed September 23, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/drugs

- Lebwohl M, Leonardi C, Wu JJ, et al. Two-year US pharmacovigilance report on brodalumab. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2021;11:173-180. doi:10.1007/s13555-020-00472-x

- Lebwohl MG, Papp KA, Marangell LB, et al. Psychiatric adverse events during treatment with brodalumab: analysis of psoriasis clinical trials. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:81-89.e5. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.08.024

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. National Mental Health Services Survey (N-MHSS): 2019, Data On Mental Health Treatment Facilities. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; August 13, 2020. Accessed September 21, 2022. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/report/national-mental-health-services-survey-n-mhss-2019-data-mental-health-treatment-facilities

Practice Points

- Brodalumab is associated with a boxed warning due to increased suicidal ideation and behavior (SIB), including completed suicides, during clinical trials.

- Brodalumab is underutilized compared to the other US Food and Drug Administration–approved IL-17 inhibitors used to treat psoriasis.

- Most experts agree that there is no increased risk for suicide associated with brodalumab. However, it remains imperative that prescribers assess patients’ risk of SIB and subsequently their access to appropriate psychiatric services prior to initiating and during treatment with brodalumab.

Glucocorticoid-Induced Bone Loss: Dietary Supplementation Recommendations to Reduce the Risk for Osteoporosis and Osteoporotic Fractures

Glucocorticoids (GCs) are among the most widely prescribed medications in dermatologic practice. Although GCs are highly effective anti-inflammatory agents, long-term systemic therapy can result in dangerous adverse effects, including GC-induced osteoporosis (GIO), a bone disease associated with a heightened risk for fragility fractures.1,2 In the United States, an estimated 10.2 million adults have osteoporosis—defined as a T-score lower than −2.5 measured via a bone densitometry scan—and 43.4 million adults have low bone mineral density (BMD).3,4 The prevalence of osteoporosis is increasing, and the diagnosis is more common in females and adults 55 years and older.2 More than 2 million individuals have osteoporosis-related fractures annually, and the mortality risk is increased at 5 and 10 years following low-energy osteoporosis-related fractures.3-5

Glucocorticoid therapy is the leading iatrogenic cause of secondary osteoporosis. As many as 30% of all patients treated with systemic GCs for more than 6 months develop GIO.1,6,7 Glucocorticoid-induced BMD loss occurs at a rate of 6% to 12% of total BMD during the first year, slowing to approximately 3% per year during subsequent therapy.1 The risk for insufficiency fractures increases by as much as 75% from baseline in adults with rheumatic, pulmonary, and skin disorders within the first 3 months of therapy and peaks at approximately 12 months.1,2

Despite the risks, many long-term GC users never receive therapy to prevent bone loss; others are only started on therapy once they have sustained an insufficiency fracture. A 5-year international observational study including more than 40,000 postmenopausal women found that only 51% of patients who were on continuous GC therapy were undergoing BMD testing and appropriate medical management.8 This review highlights the existing evidence on the risks of osteoporosis and osteoporotic (OP) fractures in the setting of topical, intralesional, intramuscular, and systemic GC treatment, as well as recommendations for nutritional supplementation to reduce these risks.

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of GIO is multifactorial and occurs in both early and late phases.9,10 The early phase is characterized by rapid BMD reduction due to excessive bone resorption. The late phase is characterized by slower and more progressive BMD reduction due to impaired bone formation.9 At the osteocyte level, GCs decrease cell viability and induce apoptosis.11 At the osteoblast level, GCs impair cell replication and differentiation and have proapoptotic effects, resulting in decreased cell numbers and subsequent bone formation.10 At the osteoclast level, GCs increase expression of pro-osteoclastic cytokines and decrease mature osteoclast apoptosis, resulting in an expanded osteoclastic life span and prolonged bone resorption.12,13 Indirectly, GCs alter calcium metabolism by decreasing gastrointestinal calcium absorption and impairing renal absorption.14,15

GCs and Osteoporosis

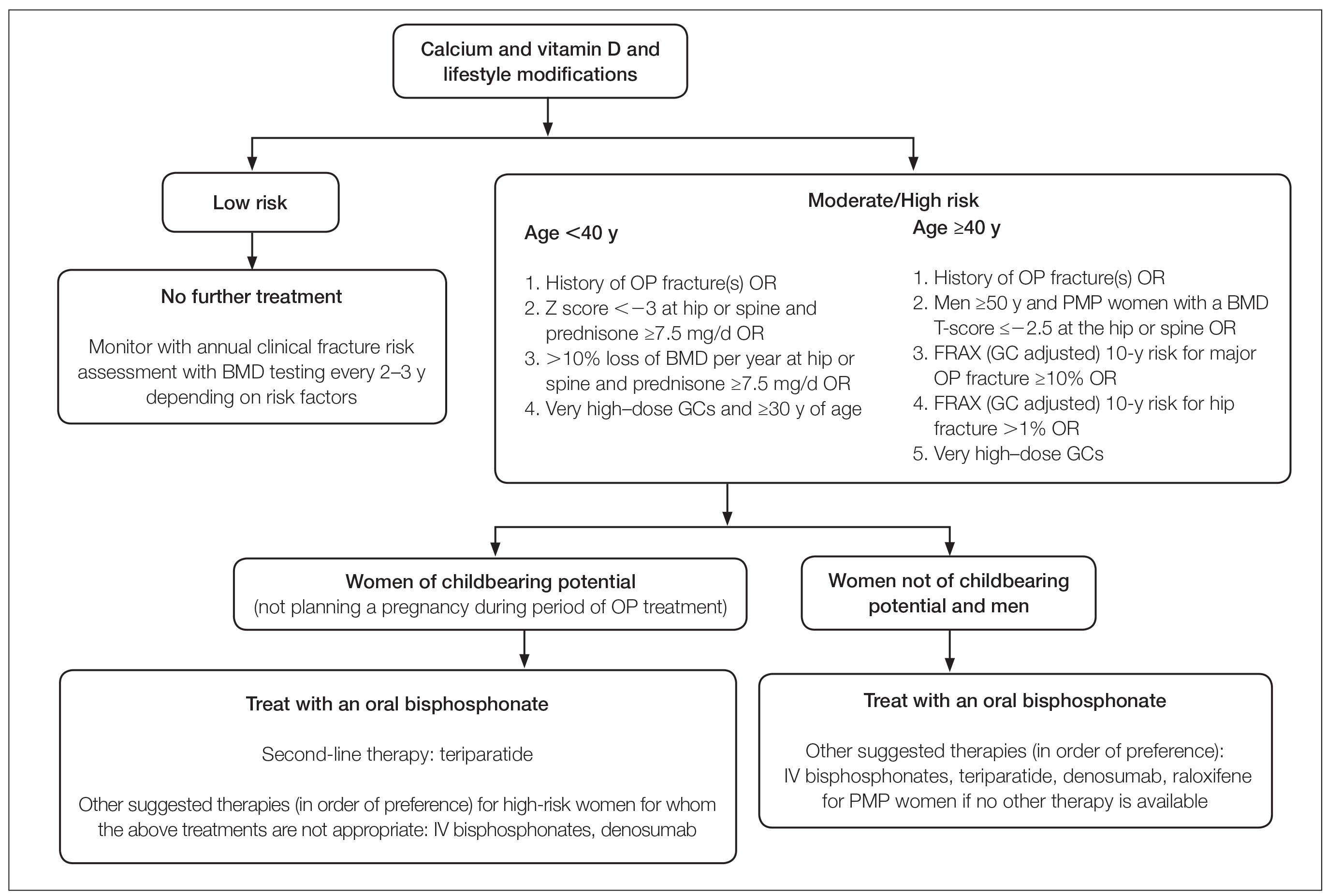

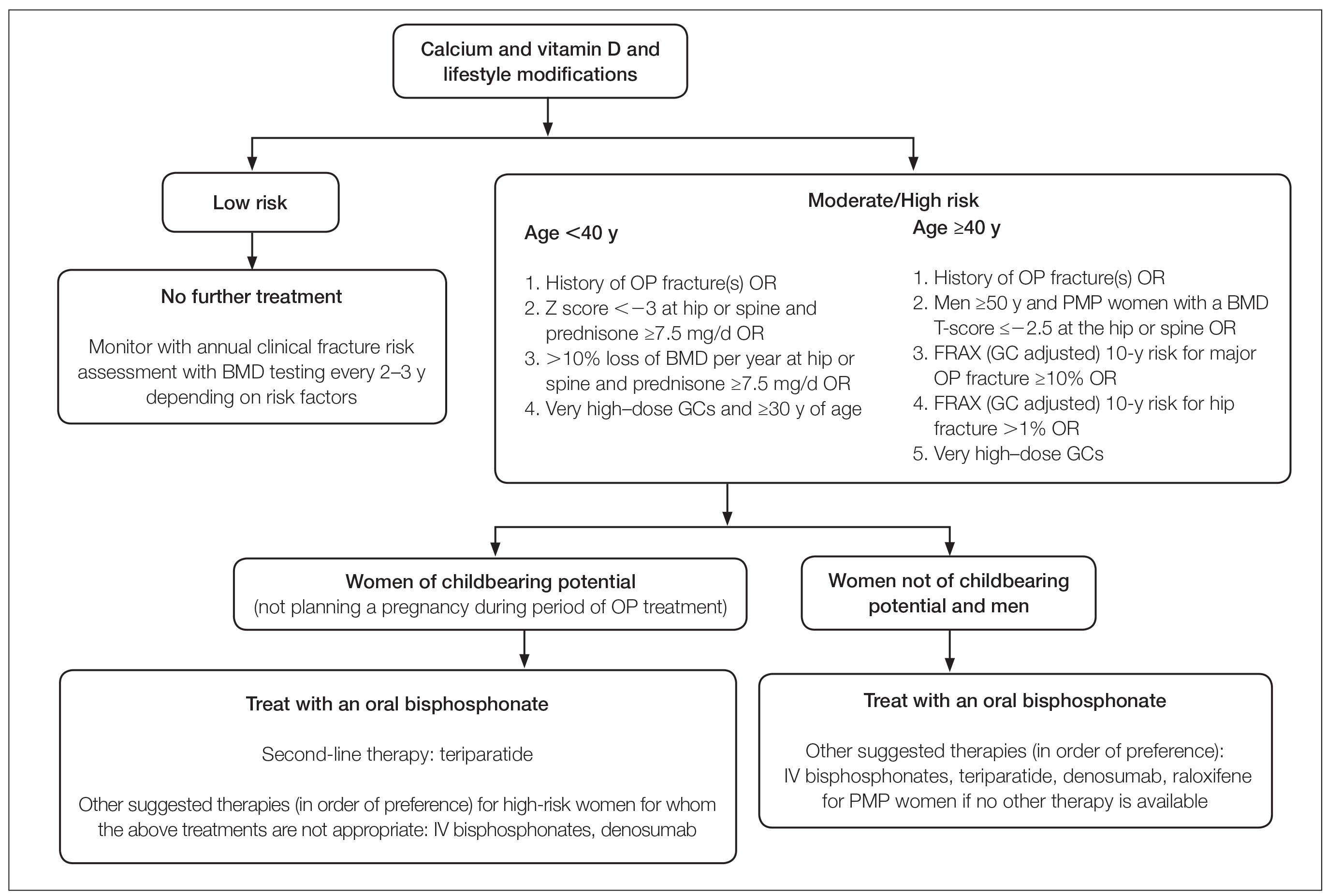

Oral GCs—Glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis and fracture risk are dose and duration dependent.6 A study of 244,235 patients taking GCs and 244,235 controls found the relative risk of vertebral fracture was 1.55 (range, 1.20–2.01) for daily prednisone use at less than 2.5 mg, 2.59 (range, 2.16–3.10) for daily prednisone use from 2.5 to 7.4 mg, and 5.18 (range, 4.25–6.31) for daily doses of 7.5 mg or higher; the relative risk for hip fractures was 0.99 (range, 0.82–1.20), 1.77 (range, 1.55–2.02), and 2.27 (range, 1.94–2.66), respectively.16 Another large retrospective cohort study found that continuous treatment with prednisone 10 mg/d for more than 90 days compared to no GC exposure increased the risk for hip fractures 7-fold and 17-fold for vertebral fractures.17 Although the minimum cumulative dose of GCs known to cause osteoporosis is not clearly established, the American College of Rheumatology has proposed an algorithm as a basic approach to anticipate, prevent, and treat GIO (Figure).18,19 Fracture risk should be assessed in all patients who are prescribed prednisone 2.5 mg/d for 3 months or longer or an anticipated cumulative dose of more than 1 g per year. Patients 40 years and older with anticipated GC use of 3 months or longer should have both a bone densitometry scan and a Fracture Risk Assessment (FRAX) score. The FRAX tool estimates the 10-year probability of fracture in patients aged 40 to 80 years, and those patients can be further risk stratified as low (FRAX <10%), moderate (FRAX 10%–19%), or high (FRAX ≥20%) risk. In patients with moderate to high risk of fracture (FRAX >10%), initiation of pharmacologic treatment or referral to a metabolic bone specialist should be considered.18,19 First-line therapy is an oral bisphosphonate, and second-line therapies include intravenous bisphosphonates, teriparatide, denosumab, or raloxifene for patients at high risk for GIO.19 Adults younger than 40 years with a history of OP fracture or considerable risk factors for OP fractures should have a bone densitometry scan, and, if results are abnormal, the patient should be referred to a metabolic bone specialist. Those with low fracture risk based on bone densitometry and FRAX and those with no risk factors should be assessed annually for bone health (additional risk factors, GC dose and duration, bone densitometry/FRAX if indicated).18 In addition to GC dose and duration, additional risk factors for GIO, which are factored into the FRAX tool, include advanced age, low body mass index, history of bone fracture, smoking, excessive alcohol use (≥3 drinks/d), history of falls, low BMD, family history of bone fracture, and hypovitaminosis D.6

Topical GCs—Although there is strong evidence and clear guidelines regarding oral GIO, there is a dearth of data surrounding OP risk due to treatment with topical GCs. A recent retrospective nationwide Danish study evaluating the risk of osteoporosis and major OP fracture in 723,251 adults treated with potent or very potent topical steroids sought to evaluate these risks.20 Patients were included if they had filled prescriptions of at least 500 g of topical mometasone or an equivalent alternative. The investigators reported a 3% increase in relative risk of osteoporosis and major OP fracture with doubling of the cumulative topical GC dose (hazard ratio [HR], 1.03 [95% CI, 1.02-1.04] for both). The overall population-attributable risk was 4.3% (95% CI, 2.7%-5.8%) for osteoporosis and 2.7% (95% CI, 1.7%-3.8%) for major OP fracture. Notably, at least 10,000 g of mometasone was required for 1 additional patient to have a major OP fracture.20 In a commentary based on this study, Jackson21 noted that the number of patient-years of topical GC use needed for 1 fracture was 4-fold higher than that for high-dose oral GCs (40 mg/d prednisolone for ≥30 days). Another study assessed the effects of topical GCs on BMD in adults with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis over a 2-year period.22 No significant difference in BMD assessed via bone densitometry of either the lumbar spine or total hip at baseline or at 2-year follow-up was reported for either group treated with corticosteroids (<75 g per month or ≥75 g per month). Of note, the authors did not account for steroid potency, which ranged from class 1 through class 4.22 Although limited data exist, these studies suggest topical GCs used at conventional doses with appropriate breaks in therapy will not substantially increase risk for GIO or OP fracture; however, in the small subset of patients requiring chronic use of superpotent topical corticosteroids with other OP risk factors, transitioning to non–GC-based therapy or initiating bone health therapy may be advised to improve patient outcomes. Risk assessment, as in cases of chronic topical GC use, may be beneficial.

Intralesional GCs—Intralesional GCs are indicated for numerous inflammatory conditions including alopecia areata, discoid lupus erythematosus, keloids, and granuloma annulare. It generally is accepted that doses of triamcinolone acetonide should not exceed 20 mg per session spaced at least 3 weeks apart or up to 40 mg per month.18 One study demonstrated that doses of triamcinolone diacetate of 25 mg or less were unlikely to produce systemic effects and were determined to be a safe dose for intralesional injections.23 A retrospective cross-sectional case series including 18 patients with alopecia areata reported decreased BMD in 9 patients receiving intralesional triamcinolone acetonide 10 mg/mL at 4- to 8-week intervals for at least 20 months, with cumulative doses greater than 500 mg. This was particularly notable in postmenopausal women and men older than 50 years; participants with a body mass index less than 18.5 kg/m2, history of a stress fracture, family history of osteopenia or osteoporosis, and history of smoking; and those who did not regularly engage in weight-bearing exercises.24 Patients receiving long-term (ie, >1 year) intralesional steroids should be evaluated for osteoporosis risk and preventative strategies should be considered (ie, regular weight-bearing exercises, calcium and vitamin D supplementation, bisphosphate therapy). As with topical GCs, there are no clear guidelines for risk assessment or treatment recommendations for GIO.

Intramuscular GCs—The data regarding intramuscular (IM) GCs and dermatologic disease is severely limited, and to the best of our knowledge, no studies specifically assess the risk for GIO or fracture secondary to intramuscular GCs; however, a retrospective study of 27 patients (4 female, 23 male; mean age, 33 years [range, 12–61 years]) with refractory alopecia areata receiving IM triamcinolone acetonide (40 mg every 4 weeks for 3–6 months) reported 1 patient (a 56-year-old woman) with notably decreased bone densitometry from baseline requiring treatment discontinuation.25 No other patients at risk for osteoporosis had decreased BMD from treatment with IM triamcinolone; however, it was noted that 1 month following treatment, 10 of 11 assessed patients demonstrated decreased levels of morning serum cortisol and plasma adrenocorticotropic hormone—despite baseline levels within reference range—that resolved 3 months after treatment completion,25 which suggests a prolonged release of IM triamcinolone and sustained systemic effect. One systematic review of 342 patients with dermatologic diseases treated with IM corticosteroids found the primary side effects included dysmenorrhea, injection-site lipoatrophy, and adrenocortical suppression, with only a single reported case of low BMD.26 Given the paucity of evidence, additional studies are required to assess the effect of IM triamcinolone on BMD and risk for major OP fractures with regard to dosing and frequency. As there are no clear guidelines for osteoporosis evaluation in the setting of intramuscular GCs, it may be prudent to follow the algorithmic model recommended for oral steroids when anticipating at least 3 months of intramuscular GCs.

Diet and Prevention of Bone Loss

Given the profound impact that systemic GCs have on osteoporosis and fracture risk and the sparse data regarding risk from topical, intralesional, or intramuscular GCs, diet and nutrition represent a simple, safe, and potentially preventative method of slowing BMD loss and minimizing fracture risk. In higher-risk patients, nutritional assessment in combination with medical therapy also is likely warranted.

Calcium and Vitamin D3—Patients treated with any GC dose longer than 3 months should undergo calcium and vitamin D optimization.19 Exceptions for supplementation include certain patients with sarcoidosis, which can be associated with high vitamin D levels; patients with a history of hypercalcemia or hypercalciuria; and patients with chronic kidney disease.6 In a meta-analysis including 30,970 patients in 8 randomized controlled trials, calcium (500–1200 mg/d) and vitamin D (400–800 IU/d) supplementation reduced the risk of total fractures by 15% (summary relative risk estimate, 0.85 [95% CI, 0.73-0.98]) and hip fractures by 30% (summary relative risk estimate, 0.70 [95% CI, 0.56-0.87]).4 One double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial conducted by the Women’s Health Initiative that included 36,282 postmenopausal women who were taking 1000 mg of calcium and 400 IU of vitamin D3 daily for more than 5 years reported an HR of 0.62 (95% CI, 0.38-1.00) for hip fracture for supplementation vs placebo.27 Lastly, a 2016 Cochrane Review including 12 randomized trials and 1343 participants reported a 43% lower risk of new vertebral fractures following supplementation with calcium, vitamin D, or both compared with controls.28

Specific recommendations for calcium and vitamin D3 supplementation vary based on age and sex. The US Preventive Services Task Force concluded that insufficient evidence exists to support calcium and vitamin D3 supplementation in asymptomatic men and premenopausal women.29 The National Osteoporosis Foundation (NOF) supports the use of calcium supplementation for fracture risk reduction in middle-aged and older adults.4 Furthermore, the NOF supports the Institute of Medicine recommendations31 that men aged 50 to 70 years consume 1000 mg/d of calcium and that women 51 years and older as well as men 71 years and older consume 1200 mg/d of calcium.30 The NOF recommends 800 to 1000 IU/d of vitamin D in adults 50 years and older, while the Institute of Medicine recommends 600 IU/d in adults 70 years and younger and 800 IU/d in adults 71 years and older.31 These recommendations are similar to both the Endocrine Society and the American Geriatric Society.32,33 Total calcium should not exceed 2000 mg/d due to risk of adverse effects.

Dietary sources of vitamin D include fatty fish, mushrooms, and fortified dairy products, though recommended doses rarely can be achieved through diet alone.34 Dairy products are the primary source of dietary calcium. Other high-calcium foods include green leafy vegetables, nuts and seeds, soft-boned fish, and fortified beverages and cereals.35

Probiotics—A growing body of evidence suggests that probiotics may be beneficial in promoting bone health by improving calcium homeostasis, reducing risk for hyperparathyroidism secondary to GC therapy, and decreasing age-related bone resorption.36 An animal study demonstrated that probiotics can regulate bone resorption and formation as well as reduce bone loss secondary to GC therapy.37 A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial randomly assigned 249 healthy, early postmenopausal women to receive probiotic treatment containing 3 lactobacillus strains (Lactobacillus paracasei DSM 13434, Lactobacillus plantarum DSM 15312, and L plantarum DSM 15313) or placebo once daily for 12 months.38 Bone mineral density was measured at baseline and at 12 months. Of the 234 participants who completed the study, lactobacillus treatment reduced lumbosacral BMD loss compared to the placebo group (mean difference, 0.71% [95% CI, 0.06-1.35]). They also reported significant lumbosacral BMD loss in the placebo group (−0.72% [95% CI, −1.22 to −0.22]) compared to no BMD loss in the group treated with lactobacillus (−0.01% [95% CI, −0.50 to 0.48]).38 Although the data may be encouraging, more studies are needed to determine if probiotics should be regarded as an adjuvant treatment to calcium, vitamin D, and pharmacologic therapy for long-term prevention of bone loss in the setting of GIO.39 Because existing studies on probiotics include varying compositions and doses, larger studies with consistent supplementation are required. Encouraging probiotic intake through fermented dairy products may represent a simple low-risk intervention to support bone health.

Anti-inflammatory Diet—The traditional Mediterranean diet is rich in fruits, vegetables, fish, nuts, whole grains, legumes, and monounsaturated fats and low in meat and dairy products. The Mediterranean diet has been shown to be modestly protective against osteoporosis and fracture risk. A large US observational study including 93,676 women showed that those with the highest quintile of the alternate Mediterranean diet score had a lower risk for hip fracture (HR, 0.80 [95% CI, 0.66-0.97]), with an absolute risk reduction of 0.29% and number needed to treat at 342.40 A multicenter study involving adults from 8 European countries found that increased adherence to the Mediterranean diet was associated with a 7% reduction in hip fracture incidence (HR per 1 unit increase in Mediterranean diet, 0.93 [95% CI, 0.89-0.98]). High vegetable and fruit intake was associated with decreased hip fracture incidence (HR, 0.86 and 0.89 [95% CI, 0.79-0.94 and 0.82-0.97, respectively]), and high meat and excessive ethanol consumption were associated with increased fracture incidence (HR, 1.18 and 1.74 [95% CI, 1.06-1.31 and 1.32-2.31, respectively]).41 Similarly, a large observational study in Sweden that included 37,903 men and 33,403 women reported similar findings, noting a 6% lower hip fracture rate per one unit increase in alternate Mediterranean diet score (adjusted HR, 0.94 [95% CI, 0.92-0.96]).42 This is thought to be due in part to higher levels of dietary vitamin D present in many foods traditionally included in the Mediterranean diet.43 Additionally, olive oil, a staple in the Mediterranean diet, appears to reduce bone loss by promoting osteoblast proliferation and maturation, inhibiting bone resorption, suppressing oxidative stress and inflammation, and increasing calcium deposition in the extracellular matrix.44,45 Fruits, vegetables, legumes, and nuts also are rich in minerals including potassium and magnesium, which are important in bone health to promote osteoblast proliferation and vitamin D activation.36,46-48

Final Thoughts

Osteoporosis-related fractures are common and are associated with high morbidity and health care costs. Dermatologists using and prescribing corticosteroids must be aware of the risk for GIO, particularly in patients with a pre-existing diagnosis of osteopenia or osteoporosis. There likely is no oral corticosteroid dose that does not increase a patient’s risk for osteoporosis; therefore, oral GCs should be used at the lowest effective daily dose for the shortest duration possible. Patients with an anticipated duration of at least 3 months—regardless of dose—should be assessed for their risk for GIO. Patients using topical and intralesional corticosteroids are unlikely to develop GIO; however, those with risk factors and a considerable cumulative dose may warrant further evaluation. In all cases, we advocate for supplementing with calcium and vitamin D as well as promoting probiotic intake and the Mediterranean diet. Those at moderate to high risk for fracture may require additional medical therapy. Dermatologists are uniquely positioned to identify this at-risk population, and because osteoporosis is a chronic illness, primary care providers should be notified of prolonged GC therapy to help with risk assessment, initiation of vitamin and mineral supplementation, and follow-up with metabolic bone health specialists. Through a multidisciplinary approach and patient education, GIO and the potential risk for fracture can be successfully mitigated in most patients.

- Weinstein RS. Clinical practice. glucocorticoid-induced bone disease. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:62-70.

- Buckley L, Humphrey MB. Glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:2547-2556.

- Wright NC, Looker AC, Saag KG, et al. The recent prevalence of osteoporosis and low bone mass in the United States based on bone mineral density at the femoral neck or lumbar spine. J Bone Miner Res. 2014;29:2520-2526.

- Weaver CM, Alexander DD, Boushey CJ, et al. Calcium plus vitamin D supplementation and risk of fractures: an updated meta-analysis from the National Osteoporosis Foundation. Osteoporos Int. 2016;27:367-376.

- Bliuc D, Nguyen ND, Milch VE, et al. Mortality risk associated with low-trauma osteoporotic fracture and subsequent fracture in men and women. JAMA. 2009;301:513-521.

- Caplan A, Fett N, Rosenbach M, et al. Prevention and management of glucocorticoid-induced side effects: a comprehensive review: a review of glucocorticoid pharmacology and bone health. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:1-9.

- Gudbjornsson B, Juliusson UI, Gudjonsson FV. Prevalence of long term steroid treatment and the frequency of decision making to prevent steroid induced osteoporosis in daily clinical practice. Ann Rheum Dis. 2002;61:32-36.

- Silverman S, Curtis J, Saag K, et al. International management of bone health in glucocorticoid-exposed individuals in the observational GLOW study. Osteoporos Int. 2015;26:419-420.

- Canalis E, Bilezikian JP, Angeli A, et al. Perspectives on glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. Bone. 2004;34:593-598.

- Canalis E, Mazziotti G, Giustina A, et al. Glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis: pathophysiology and therapy. Osteoporos Int. 2007;18:1319-1328.

- Lane NE, Yao W, Balooch M, et al. Glucocorticoid-treated mice have localized changes in trabecular bone material properties and osteocyte lacunar size that are not observed in placebo-treated or estrogen-deficient mice. J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21:466-476.

- Hofbauer LC, Gori F, Riggs BL, et al. Stimulation of osteoprotegerin ligand and inhibition of osteoprotegerin production by glucocorticoids in human osteoblastic lineage cells: potential paracrine mechanisms of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. Endocrinology. 1999;140:4382-4389.

- Jia D, O’Brien CA, Stewart SA, et al. Glucocorticoids act directly on osteoclasts to increase their life span and reduce bone density. Endocrinology. 2006;147:5592-5599.

- Mazziotti G, Angeli A, Bilezikian JP, et al. Glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis: an update. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2006;17:144-149.

- Huybers S, Naber TH, Bindels RJ, et al. Prednisolone-induced Ca2+ malabsorption is caused by diminished expression of the epithelial Ca2+ channel TRPV6. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2007;292:G92-G97.

- Van Staa TP, Leufkens HG, Abenhaim L, et al. Use of oral corticosteroids and risk of fractures. J Bone Miner Res. 2000;15:993-1000.

- Steinbuch M, Youket TE, Cohen S. Oral glucocorticoid use is associated with an increased risk of fracture. Osteoporos Int. 2004;15:323-328.

- Lupsa BC, Insogna KL, Micheletti RG, et al. Corticosteroid use in chronic dermatologic disorders and osteoporosis. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2021;7:545-551.

- Buckley L, Guyatt G, Fink HA, et al. 2017 American College of Rheumatology guideline for the prevention and treatment of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2017;69:1095-1110.

- Egeberg A, Schwarz P, Harsløf T, et al. Association of potent and very potent topical corticosteroids and the risk of osteoporosis and major osteoporotic fractures. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:275-282.

- Jackson RD. Topical corticosteroids and glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis-cumulative dose and duration matter. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:269-270.

- van Velsen SG, Haeck IM, Knol MJ, et al. Two-year assessment of effect of topical corticosteroids on bone mineral density in adults with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:691-693.

- McGugan AD, Shuster S, Bottoms E. Adrenal suppression from intradermal triamcinolone. J Invest Dermatol. 1963;40:271-272.

- Samrao A, Fu JM, Harris ST, et al. Bone mineral density in patients with alopecia areata treated with long-term intralesional corticosteroids. J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12:E36-E40.

- Seo J, Lee YI, Hwang S, et al. Intramuscular triamcinolone acetonide: an undervalued option for refractory alopecia areata. J Dermatol. 2017;44:173-179.

- Thomas LW, Elsensohn A, Bergheim T, et al. Intramuscular steroids in the treatment of dermatologic disease: a systematic review. J Drugs Dermatol. 2018;17:323-329.

- Prentice RL, Pettinger MB, Jackson RD, et al. Health risks and benefits from calcium and vitamin D supplementation: Women’s Health Initiative clinical trial and cohort study. Osteoporos Int. 2013;24:567-580.

- Allen CS, Yeung JH, Vandermeer B, et al. Bisphosphonates for steroid-induced osteoporosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;10:CD001347. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001347.pub2

- US Preventive Services Task Force; Grossman DC, Curry SJ, Owens DK, et al. Vitamin D, calcium, or combined supplementation for the primary prevention of fractures in community-dwelling adults: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2018;319:1592-1599.

- Cosman F, de Beur SJ, LeBoff MS, et al. Clinician’s guide to prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2014;25:2359-2381.

- Institute of Medicine. Dietary reference intakes for calcium and vitamin D. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2011.

- Holick MF, Binkley NC, Bischoff-Ferrari HA, et al. Evaluation, treatment, and prevention of vitamin D deficiency: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:1911-1930.

- American Geriatrics Society Workgroup on Vitamin D Supplementation for Older Adults. Recommendations abstracted from the American Geriatrics Society Consensus Statement on vitamin D for prevention of falls and their consequences. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62:147-152.

- Vitamin D fact sheet for health professionals. National Institutes of Health Office of Dietary Supplements website. Updated August 12, 2022. Accessed September 16, 2022. https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/VitaminD-HealthProfessional/

- Calcium fact sheet for health professionals. National Institutes of Health Office of Dietary Supplements website. Updated June 2, 2022. Accessed September 16, 2022. https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/Calcium-HealthProfessional/

- Muñoz-Garach A, García-Fontana B, Muñoz-Torres M. Nutrients and dietary patterns related to osteoporosis. Nutrients. 2020;12:1986.

- Schepper JD, Collins F, Rios-Arce ND, et al. Involvement of the gut microbiota and barrier function in glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res. 2020;35:801-820.

- Jansson PA, Curiac D, Ahrén IL, et al. Probiotic treatment using a mix of three Lactobacillus strains for lumbar spine bone loss in postmenopausal women: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial. Lancet Rheumatol. 2019;1:E154-E162.

- Rizzoli R, Biver E. Are probiotics the new calcium and vitamin D for bone health? Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2020;18:273-284.

- Haring B, Crandall CJ, Wu C, et al. Dietary patterns and fractures in postmenopausal women: results from the Women’s Health Initiative. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176:645-652.

- Benetou V, Orfanos P, Pettersson-Kymmer U, et al. Mediterranean diet and incidence of hip fractures in a European cohort. Osteoporos Int. 2013;24:1587-1598.

- Byberg L, Bellavia A, Larsson SC, et al. Mediterranean diet and hip fracture in Swedish men and women. J Bone Miner Res. 2016;31:2098-2105.

- Zupo R, Lampignano L, Lattanzio A, et al. Association between adherence to the Mediterranean diet and circulating vitamin D levels. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2020;71:884-890.

- Chin KY, Ima-Nirwana S. Olives and bone: a green osteoporosis prevention option. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016;13:755.

- García-Martínez O, Rivas A, Ramos-Torrecillas J, et al. The effect of olive oil on osteoporosis prevention. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2014;65:834-840.

- Uwitonze AM, Razzaque MS. Role of magnesium in vitamin D activation and function. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2018;118:181-189.

- Veronese N, Stubbs B, Solmi M, et al. Dietary magnesium intake and fracture risk: data from a large prospective study. Br J Nutr. 2017;117:1570-1576.

- Kong SH, Kim JH, Hong AR, et al. Dietary potassium intake is beneficial to bone health in a low calcium intake population: the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES)(2008-2011). Osteoporos Int. 2017;28:1577-1585.

Glucocorticoids (GCs) are among the most widely prescribed medications in dermatologic practice. Although GCs are highly effective anti-inflammatory agents, long-term systemic therapy can result in dangerous adverse effects, including GC-induced osteoporosis (GIO), a bone disease associated with a heightened risk for fragility fractures.1,2 In the United States, an estimated 10.2 million adults have osteoporosis—defined as a T-score lower than −2.5 measured via a bone densitometry scan—and 43.4 million adults have low bone mineral density (BMD).3,4 The prevalence of osteoporosis is increasing, and the diagnosis is more common in females and adults 55 years and older.2 More than 2 million individuals have osteoporosis-related fractures annually, and the mortality risk is increased at 5 and 10 years following low-energy osteoporosis-related fractures.3-5

Glucocorticoid therapy is the leading iatrogenic cause of secondary osteoporosis. As many as 30% of all patients treated with systemic GCs for more than 6 months develop GIO.1,6,7 Glucocorticoid-induced BMD loss occurs at a rate of 6% to 12% of total BMD during the first year, slowing to approximately 3% per year during subsequent therapy.1 The risk for insufficiency fractures increases by as much as 75% from baseline in adults with rheumatic, pulmonary, and skin disorders within the first 3 months of therapy and peaks at approximately 12 months.1,2

Despite the risks, many long-term GC users never receive therapy to prevent bone loss; others are only started on therapy once they have sustained an insufficiency fracture. A 5-year international observational study including more than 40,000 postmenopausal women found that only 51% of patients who were on continuous GC therapy were undergoing BMD testing and appropriate medical management.8 This review highlights the existing evidence on the risks of osteoporosis and osteoporotic (OP) fractures in the setting of topical, intralesional, intramuscular, and systemic GC treatment, as well as recommendations for nutritional supplementation to reduce these risks.

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of GIO is multifactorial and occurs in both early and late phases.9,10 The early phase is characterized by rapid BMD reduction due to excessive bone resorption. The late phase is characterized by slower and more progressive BMD reduction due to impaired bone formation.9 At the osteocyte level, GCs decrease cell viability and induce apoptosis.11 At the osteoblast level, GCs impair cell replication and differentiation and have proapoptotic effects, resulting in decreased cell numbers and subsequent bone formation.10 At the osteoclast level, GCs increase expression of pro-osteoclastic cytokines and decrease mature osteoclast apoptosis, resulting in an expanded osteoclastic life span and prolonged bone resorption.12,13 Indirectly, GCs alter calcium metabolism by decreasing gastrointestinal calcium absorption and impairing renal absorption.14,15

GCs and Osteoporosis

Oral GCs—Glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis and fracture risk are dose and duration dependent.6 A study of 244,235 patients taking GCs and 244,235 controls found the relative risk of vertebral fracture was 1.55 (range, 1.20–2.01) for daily prednisone use at less than 2.5 mg, 2.59 (range, 2.16–3.10) for daily prednisone use from 2.5 to 7.4 mg, and 5.18 (range, 4.25–6.31) for daily doses of 7.5 mg or higher; the relative risk for hip fractures was 0.99 (range, 0.82–1.20), 1.77 (range, 1.55–2.02), and 2.27 (range, 1.94–2.66), respectively.16 Another large retrospective cohort study found that continuous treatment with prednisone 10 mg/d for more than 90 days compared to no GC exposure increased the risk for hip fractures 7-fold and 17-fold for vertebral fractures.17 Although the minimum cumulative dose of GCs known to cause osteoporosis is not clearly established, the American College of Rheumatology has proposed an algorithm as a basic approach to anticipate, prevent, and treat GIO (Figure).18,19 Fracture risk should be assessed in all patients who are prescribed prednisone 2.5 mg/d for 3 months or longer or an anticipated cumulative dose of more than 1 g per year. Patients 40 years and older with anticipated GC use of 3 months or longer should have both a bone densitometry scan and a Fracture Risk Assessment (FRAX) score. The FRAX tool estimates the 10-year probability of fracture in patients aged 40 to 80 years, and those patients can be further risk stratified as low (FRAX <10%), moderate (FRAX 10%–19%), or high (FRAX ≥20%) risk. In patients with moderate to high risk of fracture (FRAX >10%), initiation of pharmacologic treatment or referral to a metabolic bone specialist should be considered.18,19 First-line therapy is an oral bisphosphonate, and second-line therapies include intravenous bisphosphonates, teriparatide, denosumab, or raloxifene for patients at high risk for GIO.19 Adults younger than 40 years with a history of OP fracture or considerable risk factors for OP fractures should have a bone densitometry scan, and, if results are abnormal, the patient should be referred to a metabolic bone specialist. Those with low fracture risk based on bone densitometry and FRAX and those with no risk factors should be assessed annually for bone health (additional risk factors, GC dose and duration, bone densitometry/FRAX if indicated).18 In addition to GC dose and duration, additional risk factors for GIO, which are factored into the FRAX tool, include advanced age, low body mass index, history of bone fracture, smoking, excessive alcohol use (≥3 drinks/d), history of falls, low BMD, family history of bone fracture, and hypovitaminosis D.6

Topical GCs—Although there is strong evidence and clear guidelines regarding oral GIO, there is a dearth of data surrounding OP risk due to treatment with topical GCs. A recent retrospective nationwide Danish study evaluating the risk of osteoporosis and major OP fracture in 723,251 adults treated with potent or very potent topical steroids sought to evaluate these risks.20 Patients were included if they had filled prescriptions of at least 500 g of topical mometasone or an equivalent alternative. The investigators reported a 3% increase in relative risk of osteoporosis and major OP fracture with doubling of the cumulative topical GC dose (hazard ratio [HR], 1.03 [95% CI, 1.02-1.04] for both). The overall population-attributable risk was 4.3% (95% CI, 2.7%-5.8%) for osteoporosis and 2.7% (95% CI, 1.7%-3.8%) for major OP fracture. Notably, at least 10,000 g of mometasone was required for 1 additional patient to have a major OP fracture.20 In a commentary based on this study, Jackson21 noted that the number of patient-years of topical GC use needed for 1 fracture was 4-fold higher than that for high-dose oral GCs (40 mg/d prednisolone for ≥30 days). Another study assessed the effects of topical GCs on BMD in adults with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis over a 2-year period.22 No significant difference in BMD assessed via bone densitometry of either the lumbar spine or total hip at baseline or at 2-year follow-up was reported for either group treated with corticosteroids (<75 g per month or ≥75 g per month). Of note, the authors did not account for steroid potency, which ranged from class 1 through class 4.22 Although limited data exist, these studies suggest topical GCs used at conventional doses with appropriate breaks in therapy will not substantially increase risk for GIO or OP fracture; however, in the small subset of patients requiring chronic use of superpotent topical corticosteroids with other OP risk factors, transitioning to non–GC-based therapy or initiating bone health therapy may be advised to improve patient outcomes. Risk assessment, as in cases of chronic topical GC use, may be beneficial.

Intralesional GCs—Intralesional GCs are indicated for numerous inflammatory conditions including alopecia areata, discoid lupus erythematosus, keloids, and granuloma annulare. It generally is accepted that doses of triamcinolone acetonide should not exceed 20 mg per session spaced at least 3 weeks apart or up to 40 mg per month.18 One study demonstrated that doses of triamcinolone diacetate of 25 mg or less were unlikely to produce systemic effects and were determined to be a safe dose for intralesional injections.23 A retrospective cross-sectional case series including 18 patients with alopecia areata reported decreased BMD in 9 patients receiving intralesional triamcinolone acetonide 10 mg/mL at 4- to 8-week intervals for at least 20 months, with cumulative doses greater than 500 mg. This was particularly notable in postmenopausal women and men older than 50 years; participants with a body mass index less than 18.5 kg/m2, history of a stress fracture, family history of osteopenia or osteoporosis, and history of smoking; and those who did not regularly engage in weight-bearing exercises.24 Patients receiving long-term (ie, >1 year) intralesional steroids should be evaluated for osteoporosis risk and preventative strategies should be considered (ie, regular weight-bearing exercises, calcium and vitamin D supplementation, bisphosphate therapy). As with topical GCs, there are no clear guidelines for risk assessment or treatment recommendations for GIO.

Intramuscular GCs—The data regarding intramuscular (IM) GCs and dermatologic disease is severely limited, and to the best of our knowledge, no studies specifically assess the risk for GIO or fracture secondary to intramuscular GCs; however, a retrospective study of 27 patients (4 female, 23 male; mean age, 33 years [range, 12–61 years]) with refractory alopecia areata receiving IM triamcinolone acetonide (40 mg every 4 weeks for 3–6 months) reported 1 patient (a 56-year-old woman) with notably decreased bone densitometry from baseline requiring treatment discontinuation.25 No other patients at risk for osteoporosis had decreased BMD from treatment with IM triamcinolone; however, it was noted that 1 month following treatment, 10 of 11 assessed patients demonstrated decreased levels of morning serum cortisol and plasma adrenocorticotropic hormone—despite baseline levels within reference range—that resolved 3 months after treatment completion,25 which suggests a prolonged release of IM triamcinolone and sustained systemic effect. One systematic review of 342 patients with dermatologic diseases treated with IM corticosteroids found the primary side effects included dysmenorrhea, injection-site lipoatrophy, and adrenocortical suppression, with only a single reported case of low BMD.26 Given the paucity of evidence, additional studies are required to assess the effect of IM triamcinolone on BMD and risk for major OP fractures with regard to dosing and frequency. As there are no clear guidelines for osteoporosis evaluation in the setting of intramuscular GCs, it may be prudent to follow the algorithmic model recommended for oral steroids when anticipating at least 3 months of intramuscular GCs.

Diet and Prevention of Bone Loss

Given the profound impact that systemic GCs have on osteoporosis and fracture risk and the sparse data regarding risk from topical, intralesional, or intramuscular GCs, diet and nutrition represent a simple, safe, and potentially preventative method of slowing BMD loss and minimizing fracture risk. In higher-risk patients, nutritional assessment in combination with medical therapy also is likely warranted.

Calcium and Vitamin D3—Patients treated with any GC dose longer than 3 months should undergo calcium and vitamin D optimization.19 Exceptions for supplementation include certain patients with sarcoidosis, which can be associated with high vitamin D levels; patients with a history of hypercalcemia or hypercalciuria; and patients with chronic kidney disease.6 In a meta-analysis including 30,970 patients in 8 randomized controlled trials, calcium (500–1200 mg/d) and vitamin D (400–800 IU/d) supplementation reduced the risk of total fractures by 15% (summary relative risk estimate, 0.85 [95% CI, 0.73-0.98]) and hip fractures by 30% (summary relative risk estimate, 0.70 [95% CI, 0.56-0.87]).4 One double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial conducted by the Women’s Health Initiative that included 36,282 postmenopausal women who were taking 1000 mg of calcium and 400 IU of vitamin D3 daily for more than 5 years reported an HR of 0.62 (95% CI, 0.38-1.00) for hip fracture for supplementation vs placebo.27 Lastly, a 2016 Cochrane Review including 12 randomized trials and 1343 participants reported a 43% lower risk of new vertebral fractures following supplementation with calcium, vitamin D, or both compared with controls.28

Specific recommendations for calcium and vitamin D3 supplementation vary based on age and sex. The US Preventive Services Task Force concluded that insufficient evidence exists to support calcium and vitamin D3 supplementation in asymptomatic men and premenopausal women.29 The National Osteoporosis Foundation (NOF) supports the use of calcium supplementation for fracture risk reduction in middle-aged and older adults.4 Furthermore, the NOF supports the Institute of Medicine recommendations31 that men aged 50 to 70 years consume 1000 mg/d of calcium and that women 51 years and older as well as men 71 years and older consume 1200 mg/d of calcium.30 The NOF recommends 800 to 1000 IU/d of vitamin D in adults 50 years and older, while the Institute of Medicine recommends 600 IU/d in adults 70 years and younger and 800 IU/d in adults 71 years and older.31 These recommendations are similar to both the Endocrine Society and the American Geriatric Society.32,33 Total calcium should not exceed 2000 mg/d due to risk of adverse effects.

Dietary sources of vitamin D include fatty fish, mushrooms, and fortified dairy products, though recommended doses rarely can be achieved through diet alone.34 Dairy products are the primary source of dietary calcium. Other high-calcium foods include green leafy vegetables, nuts and seeds, soft-boned fish, and fortified beverages and cereals.35

Probiotics—A growing body of evidence suggests that probiotics may be beneficial in promoting bone health by improving calcium homeostasis, reducing risk for hyperparathyroidism secondary to GC therapy, and decreasing age-related bone resorption.36 An animal study demonstrated that probiotics can regulate bone resorption and formation as well as reduce bone loss secondary to GC therapy.37 A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial randomly assigned 249 healthy, early postmenopausal women to receive probiotic treatment containing 3 lactobacillus strains (Lactobacillus paracasei DSM 13434, Lactobacillus plantarum DSM 15312, and L plantarum DSM 15313) or placebo once daily for 12 months.38 Bone mineral density was measured at baseline and at 12 months. Of the 234 participants who completed the study, lactobacillus treatment reduced lumbosacral BMD loss compared to the placebo group (mean difference, 0.71% [95% CI, 0.06-1.35]). They also reported significant lumbosacral BMD loss in the placebo group (−0.72% [95% CI, −1.22 to −0.22]) compared to no BMD loss in the group treated with lactobacillus (−0.01% [95% CI, −0.50 to 0.48]).38 Although the data may be encouraging, more studies are needed to determine if probiotics should be regarded as an adjuvant treatment to calcium, vitamin D, and pharmacologic therapy for long-term prevention of bone loss in the setting of GIO.39 Because existing studies on probiotics include varying compositions and doses, larger studies with consistent supplementation are required. Encouraging probiotic intake through fermented dairy products may represent a simple low-risk intervention to support bone health.

Anti-inflammatory Diet—The traditional Mediterranean diet is rich in fruits, vegetables, fish, nuts, whole grains, legumes, and monounsaturated fats and low in meat and dairy products. The Mediterranean diet has been shown to be modestly protective against osteoporosis and fracture risk. A large US observational study including 93,676 women showed that those with the highest quintile of the alternate Mediterranean diet score had a lower risk for hip fracture (HR, 0.80 [95% CI, 0.66-0.97]), with an absolute risk reduction of 0.29% and number needed to treat at 342.40 A multicenter study involving adults from 8 European countries found that increased adherence to the Mediterranean diet was associated with a 7% reduction in hip fracture incidence (HR per 1 unit increase in Mediterranean diet, 0.93 [95% CI, 0.89-0.98]). High vegetable and fruit intake was associated with decreased hip fracture incidence (HR, 0.86 and 0.89 [95% CI, 0.79-0.94 and 0.82-0.97, respectively]), and high meat and excessive ethanol consumption were associated with increased fracture incidence (HR, 1.18 and 1.74 [95% CI, 1.06-1.31 and 1.32-2.31, respectively]).41 Similarly, a large observational study in Sweden that included 37,903 men and 33,403 women reported similar findings, noting a 6% lower hip fracture rate per one unit increase in alternate Mediterranean diet score (adjusted HR, 0.94 [95% CI, 0.92-0.96]).42 This is thought to be due in part to higher levels of dietary vitamin D present in many foods traditionally included in the Mediterranean diet.43 Additionally, olive oil, a staple in the Mediterranean diet, appears to reduce bone loss by promoting osteoblast proliferation and maturation, inhibiting bone resorption, suppressing oxidative stress and inflammation, and increasing calcium deposition in the extracellular matrix.44,45 Fruits, vegetables, legumes, and nuts also are rich in minerals including potassium and magnesium, which are important in bone health to promote osteoblast proliferation and vitamin D activation.36,46-48

Final Thoughts

Osteoporosis-related fractures are common and are associated with high morbidity and health care costs. Dermatologists using and prescribing corticosteroids must be aware of the risk for GIO, particularly in patients with a pre-existing diagnosis of osteopenia or osteoporosis. There likely is no oral corticosteroid dose that does not increase a patient’s risk for osteoporosis; therefore, oral GCs should be used at the lowest effective daily dose for the shortest duration possible. Patients with an anticipated duration of at least 3 months—regardless of dose—should be assessed for their risk for GIO. Patients using topical and intralesional corticosteroids are unlikely to develop GIO; however, those with risk factors and a considerable cumulative dose may warrant further evaluation. In all cases, we advocate for supplementing with calcium and vitamin D as well as promoting probiotic intake and the Mediterranean diet. Those at moderate to high risk for fracture may require additional medical therapy. Dermatologists are uniquely positioned to identify this at-risk population, and because osteoporosis is a chronic illness, primary care providers should be notified of prolonged GC therapy to help with risk assessment, initiation of vitamin and mineral supplementation, and follow-up with metabolic bone health specialists. Through a multidisciplinary approach and patient education, GIO and the potential risk for fracture can be successfully mitigated in most patients.

Glucocorticoids (GCs) are among the most widely prescribed medications in dermatologic practice. Although GCs are highly effective anti-inflammatory agents, long-term systemic therapy can result in dangerous adverse effects, including GC-induced osteoporosis (GIO), a bone disease associated with a heightened risk for fragility fractures.1,2 In the United States, an estimated 10.2 million adults have osteoporosis—defined as a T-score lower than −2.5 measured via a bone densitometry scan—and 43.4 million adults have low bone mineral density (BMD).3,4 The prevalence of osteoporosis is increasing, and the diagnosis is more common in females and adults 55 years and older.2 More than 2 million individuals have osteoporosis-related fractures annually, and the mortality risk is increased at 5 and 10 years following low-energy osteoporosis-related fractures.3-5

Glucocorticoid therapy is the leading iatrogenic cause of secondary osteoporosis. As many as 30% of all patients treated with systemic GCs for more than 6 months develop GIO.1,6,7 Glucocorticoid-induced BMD loss occurs at a rate of 6% to 12% of total BMD during the first year, slowing to approximately 3% per year during subsequent therapy.1 The risk for insufficiency fractures increases by as much as 75% from baseline in adults with rheumatic, pulmonary, and skin disorders within the first 3 months of therapy and peaks at approximately 12 months.1,2

Despite the risks, many long-term GC users never receive therapy to prevent bone loss; others are only started on therapy once they have sustained an insufficiency fracture. A 5-year international observational study including more than 40,000 postmenopausal women found that only 51% of patients who were on continuous GC therapy were undergoing BMD testing and appropriate medical management.8 This review highlights the existing evidence on the risks of osteoporosis and osteoporotic (OP) fractures in the setting of topical, intralesional, intramuscular, and systemic GC treatment, as well as recommendations for nutritional supplementation to reduce these risks.

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of GIO is multifactorial and occurs in both early and late phases.9,10 The early phase is characterized by rapid BMD reduction due to excessive bone resorption. The late phase is characterized by slower and more progressive BMD reduction due to impaired bone formation.9 At the osteocyte level, GCs decrease cell viability and induce apoptosis.11 At the osteoblast level, GCs impair cell replication and differentiation and have proapoptotic effects, resulting in decreased cell numbers and subsequent bone formation.10 At the osteoclast level, GCs increase expression of pro-osteoclastic cytokines and decrease mature osteoclast apoptosis, resulting in an expanded osteoclastic life span and prolonged bone resorption.12,13 Indirectly, GCs alter calcium metabolism by decreasing gastrointestinal calcium absorption and impairing renal absorption.14,15

GCs and Osteoporosis

Oral GCs—Glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis and fracture risk are dose and duration dependent.6 A study of 244,235 patients taking GCs and 244,235 controls found the relative risk of vertebral fracture was 1.55 (range, 1.20–2.01) for daily prednisone use at less than 2.5 mg, 2.59 (range, 2.16–3.10) for daily prednisone use from 2.5 to 7.4 mg, and 5.18 (range, 4.25–6.31) for daily doses of 7.5 mg or higher; the relative risk for hip fractures was 0.99 (range, 0.82–1.20), 1.77 (range, 1.55–2.02), and 2.27 (range, 1.94–2.66), respectively.16 Another large retrospective cohort study found that continuous treatment with prednisone 10 mg/d for more than 90 days compared to no GC exposure increased the risk for hip fractures 7-fold and 17-fold for vertebral fractures.17 Although the minimum cumulative dose of GCs known to cause osteoporosis is not clearly established, the American College of Rheumatology has proposed an algorithm as a basic approach to anticipate, prevent, and treat GIO (Figure).18,19 Fracture risk should be assessed in all patients who are prescribed prednisone 2.5 mg/d for 3 months or longer or an anticipated cumulative dose of more than 1 g per year. Patients 40 years and older with anticipated GC use of 3 months or longer should have both a bone densitometry scan and a Fracture Risk Assessment (FRAX) score. The FRAX tool estimates the 10-year probability of fracture in patients aged 40 to 80 years, and those patients can be further risk stratified as low (FRAX <10%), moderate (FRAX 10%–19%), or high (FRAX ≥20%) risk. In patients with moderate to high risk of fracture (FRAX >10%), initiation of pharmacologic treatment or referral to a metabolic bone specialist should be considered.18,19 First-line therapy is an oral bisphosphonate, and second-line therapies include intravenous bisphosphonates, teriparatide, denosumab, or raloxifene for patients at high risk for GIO.19 Adults younger than 40 years with a history of OP fracture or considerable risk factors for OP fractures should have a bone densitometry scan, and, if results are abnormal, the patient should be referred to a metabolic bone specialist. Those with low fracture risk based on bone densitometry and FRAX and those with no risk factors should be assessed annually for bone health (additional risk factors, GC dose and duration, bone densitometry/FRAX if indicated).18 In addition to GC dose and duration, additional risk factors for GIO, which are factored into the FRAX tool, include advanced age, low body mass index, history of bone fracture, smoking, excessive alcohol use (≥3 drinks/d), history of falls, low BMD, family history of bone fracture, and hypovitaminosis D.6

Topical GCs—Although there is strong evidence and clear guidelines regarding oral GIO, there is a dearth of data surrounding OP risk due to treatment with topical GCs. A recent retrospective nationwide Danish study evaluating the risk of osteoporosis and major OP fracture in 723,251 adults treated with potent or very potent topical steroids sought to evaluate these risks.20 Patients were included if they had filled prescriptions of at least 500 g of topical mometasone or an equivalent alternative. The investigators reported a 3% increase in relative risk of osteoporosis and major OP fracture with doubling of the cumulative topical GC dose (hazard ratio [HR], 1.03 [95% CI, 1.02-1.04] for both). The overall population-attributable risk was 4.3% (95% CI, 2.7%-5.8%) for osteoporosis and 2.7% (95% CI, 1.7%-3.8%) for major OP fracture. Notably, at least 10,000 g of mometasone was required for 1 additional patient to have a major OP fracture.20 In a commentary based on this study, Jackson21 noted that the number of patient-years of topical GC use needed for 1 fracture was 4-fold higher than that for high-dose oral GCs (40 mg/d prednisolone for ≥30 days). Another study assessed the effects of topical GCs on BMD in adults with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis over a 2-year period.22 No significant difference in BMD assessed via bone densitometry of either the lumbar spine or total hip at baseline or at 2-year follow-up was reported for either group treated with corticosteroids (<75 g per month or ≥75 g per month). Of note, the authors did not account for steroid potency, which ranged from class 1 through class 4.22 Although limited data exist, these studies suggest topical GCs used at conventional doses with appropriate breaks in therapy will not substantially increase risk for GIO or OP fracture; however, in the small subset of patients requiring chronic use of superpotent topical corticosteroids with other OP risk factors, transitioning to non–GC-based therapy or initiating bone health therapy may be advised to improve patient outcomes. Risk assessment, as in cases of chronic topical GC use, may be beneficial.

Intralesional GCs—Intralesional GCs are indicated for numerous inflammatory conditions including alopecia areata, discoid lupus erythematosus, keloids, and granuloma annulare. It generally is accepted that doses of triamcinolone acetonide should not exceed 20 mg per session spaced at least 3 weeks apart or up to 40 mg per month.18 One study demonstrated that doses of triamcinolone diacetate of 25 mg or less were unlikely to produce systemic effects and were determined to be a safe dose for intralesional injections.23 A retrospective cross-sectional case series including 18 patients with alopecia areata reported decreased BMD in 9 patients receiving intralesional triamcinolone acetonide 10 mg/mL at 4- to 8-week intervals for at least 20 months, with cumulative doses greater than 500 mg. This was particularly notable in postmenopausal women and men older than 50 years; participants with a body mass index less than 18.5 kg/m2, history of a stress fracture, family history of osteopenia or osteoporosis, and history of smoking; and those who did not regularly engage in weight-bearing exercises.24 Patients receiving long-term (ie, >1 year) intralesional steroids should be evaluated for osteoporosis risk and preventative strategies should be considered (ie, regular weight-bearing exercises, calcium and vitamin D supplementation, bisphosphate therapy). As with topical GCs, there are no clear guidelines for risk assessment or treatment recommendations for GIO.