User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

Atypical Localized Scleroderma Development During Nivolumab Therapy for Metastatic Lung Adenocarcinoma

To the Editor:

Immune checkpoint inhibitors such as anti–programmed cell death protein 1 (anti–PD-1) and anticytotoxic T lymphocyte–associated protein 4 therapies are a promising class of cancer therapeutics. However, they are associated with a variety of immune-related adverse events (irAEs), including cutaneous toxicity.1 The PD-1/programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) pathway is important for the maintenance of immune tolerance, and a blockade has been shown to lead to development of various autoimmune diseases.2 We present the case of a patient who developed new-onset localized scleroderma during treatment with the PD-1 inhibitor nivolumab.

A 65-year-old woman presented with a rash on the left thigh that was associated with pruritus, pain, and a pulling sensation. She had a history of stage IV lung adenocarcinoma, with a mass in the right upper lobe with metastatic foci to the left femur, right humerus, right hilar, and pretracheal lymph nodes. She received palliative radiation to the left femur and was started on carboplatin and pemetrexed. Metastasis to the liver was noted after completion of 6 cycles of therapy, and the patient’s treatment was changed to nivolumab. After 17 months on nivolumab therapy (2 years after initial diagnosis and 20 months after radiation therapy), she presented to our dermatology clinic with a cutaneous eruption on the buttocks that spread to the left thigh. The rash failed to improve after 1 month of treatment with emollients and triamcinolone cream 0.1%.

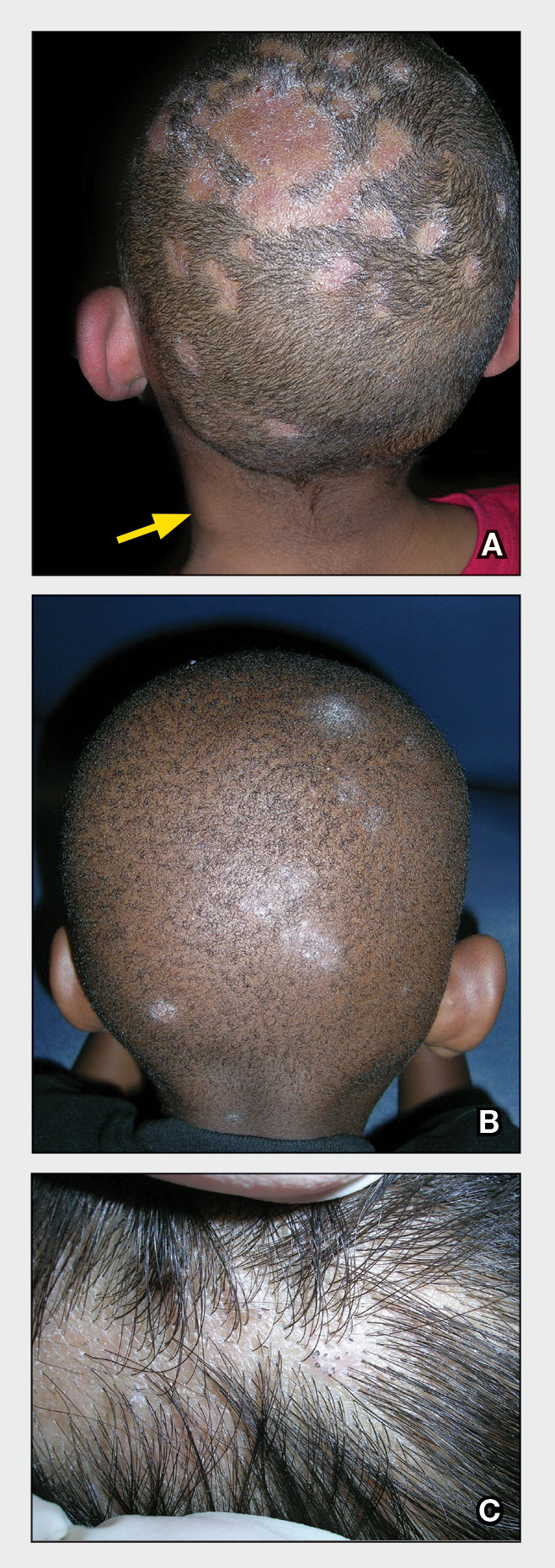

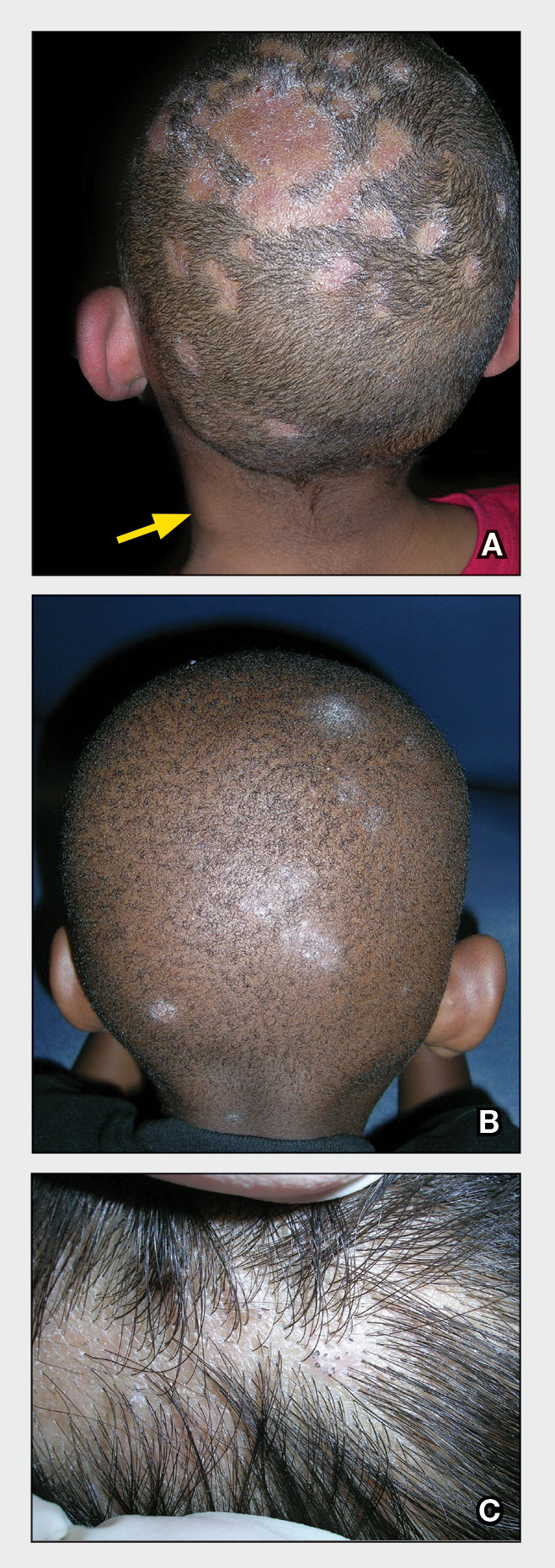

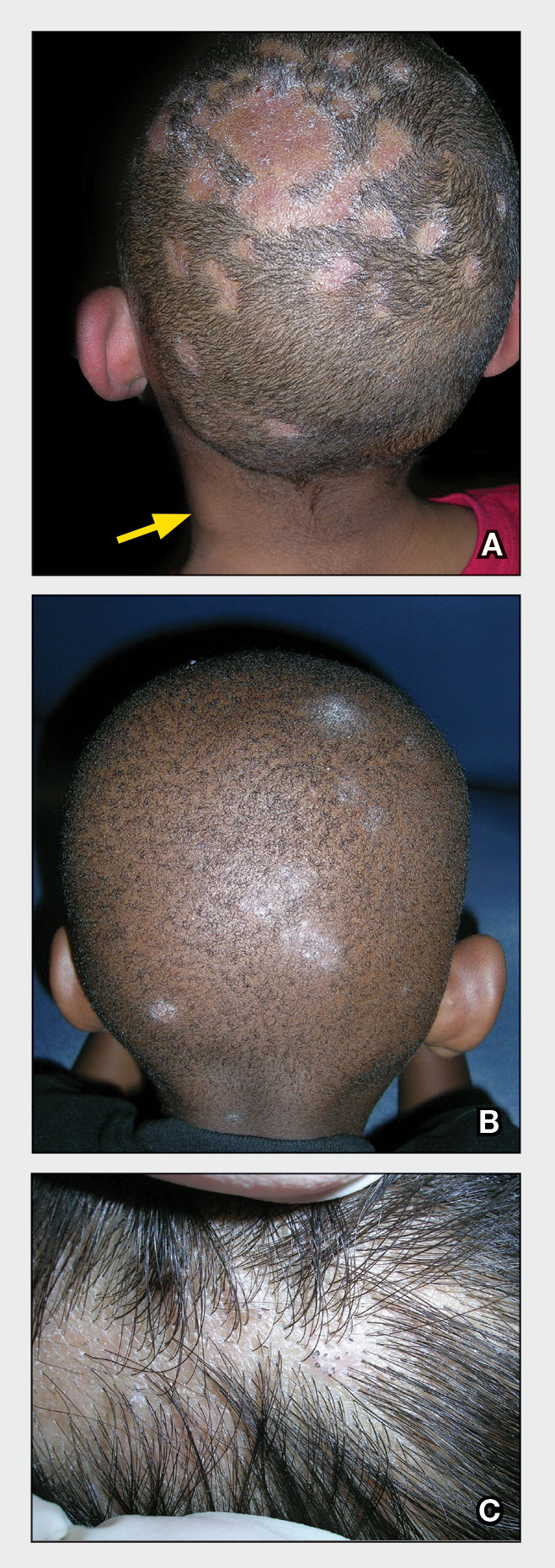

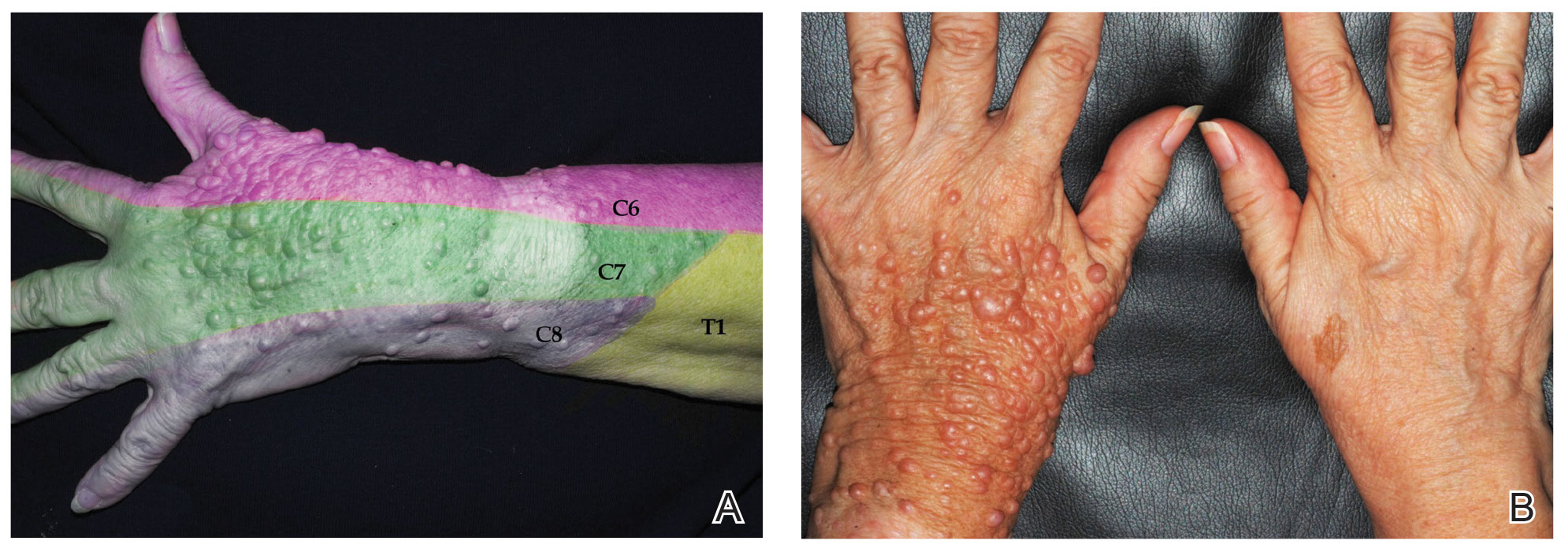

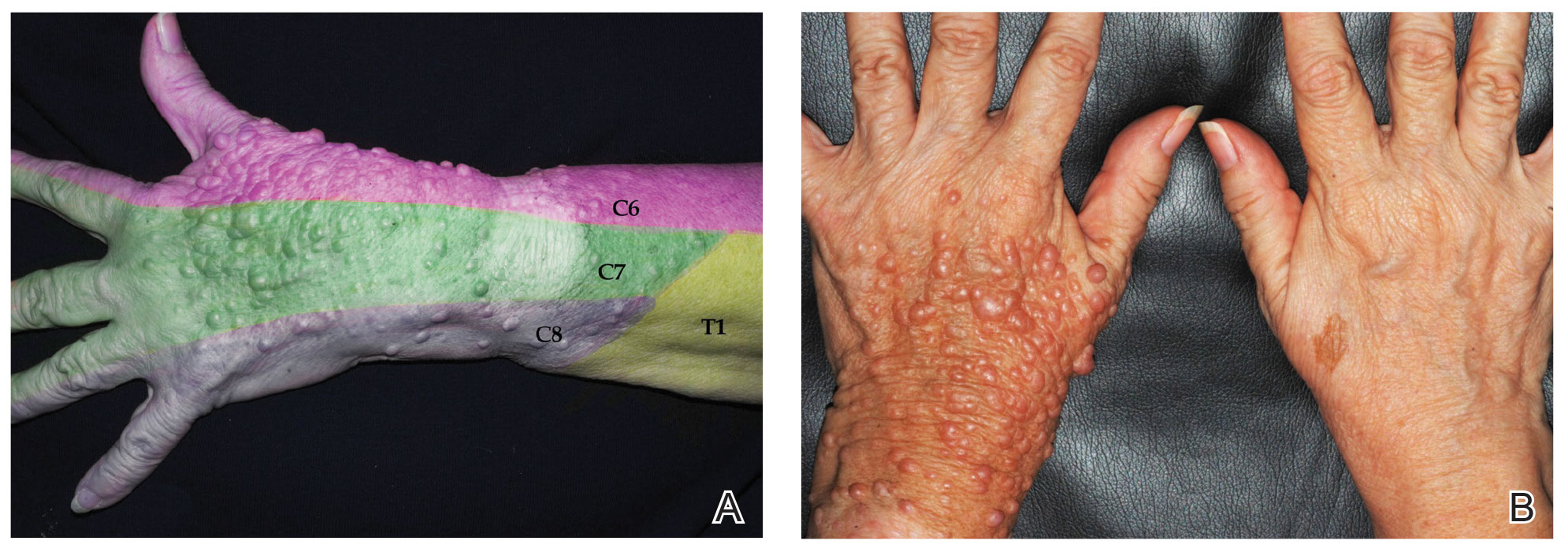

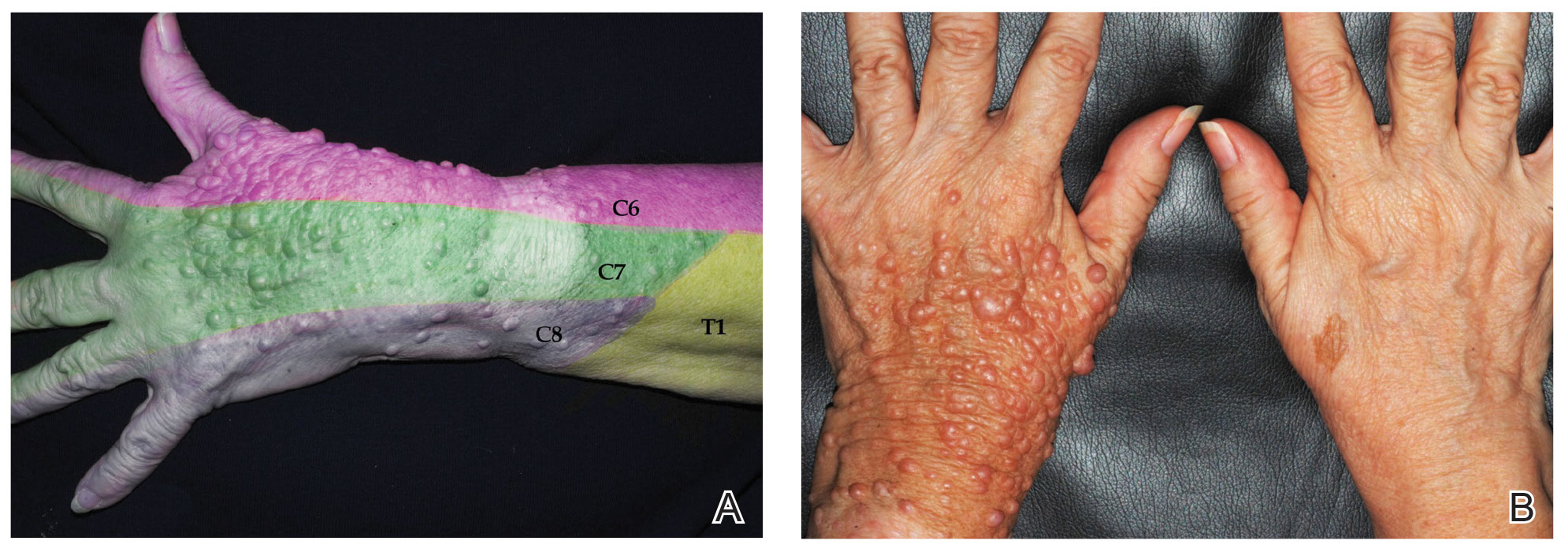

At the current presentation, which was 2 months after she initially presented to our clinic, dermatologic examination revealed erythematous and sclerotic plaques on the left lateral thigh (Figure 1A). Betamethasone cream 0.05% was prescribed, and nivolumab was discontinued due to progression of cutaneous symptoms. A punch biopsy from the left thigh demonstrated superficial dermal sclerosis that was suggestive of chronic radiation dermatitis; direct immunofluorescence testing was negative. The patient was started on prednisone 50 mg daily, which resulted in mild improvement in symptoms.

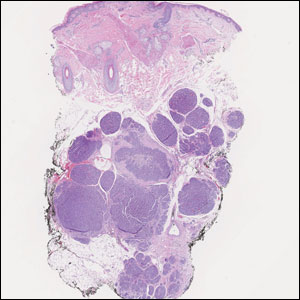

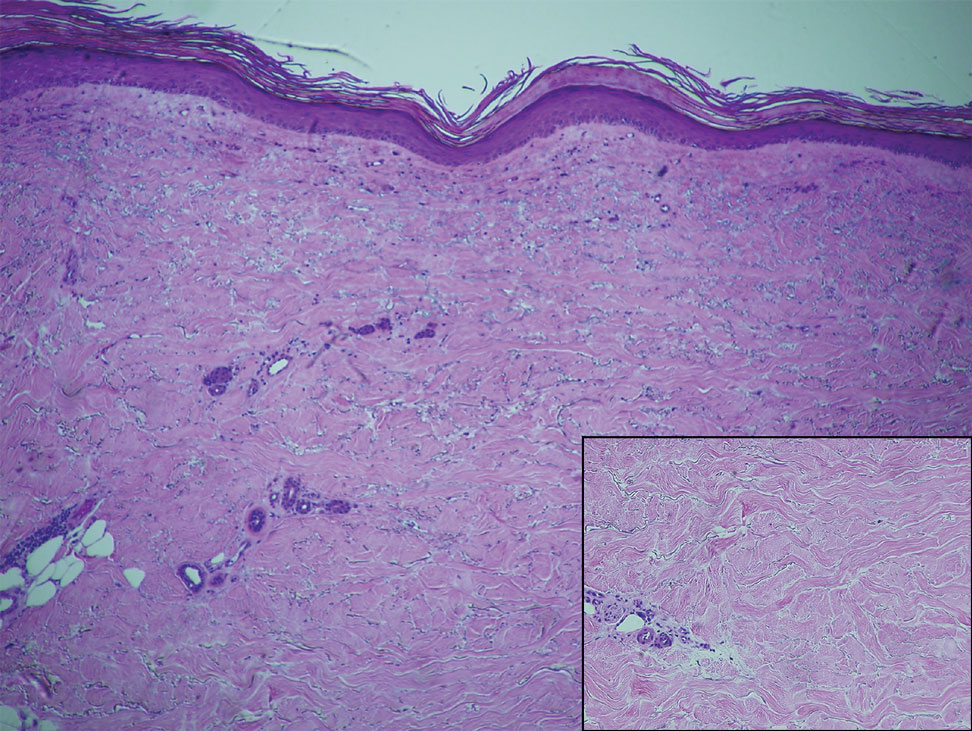

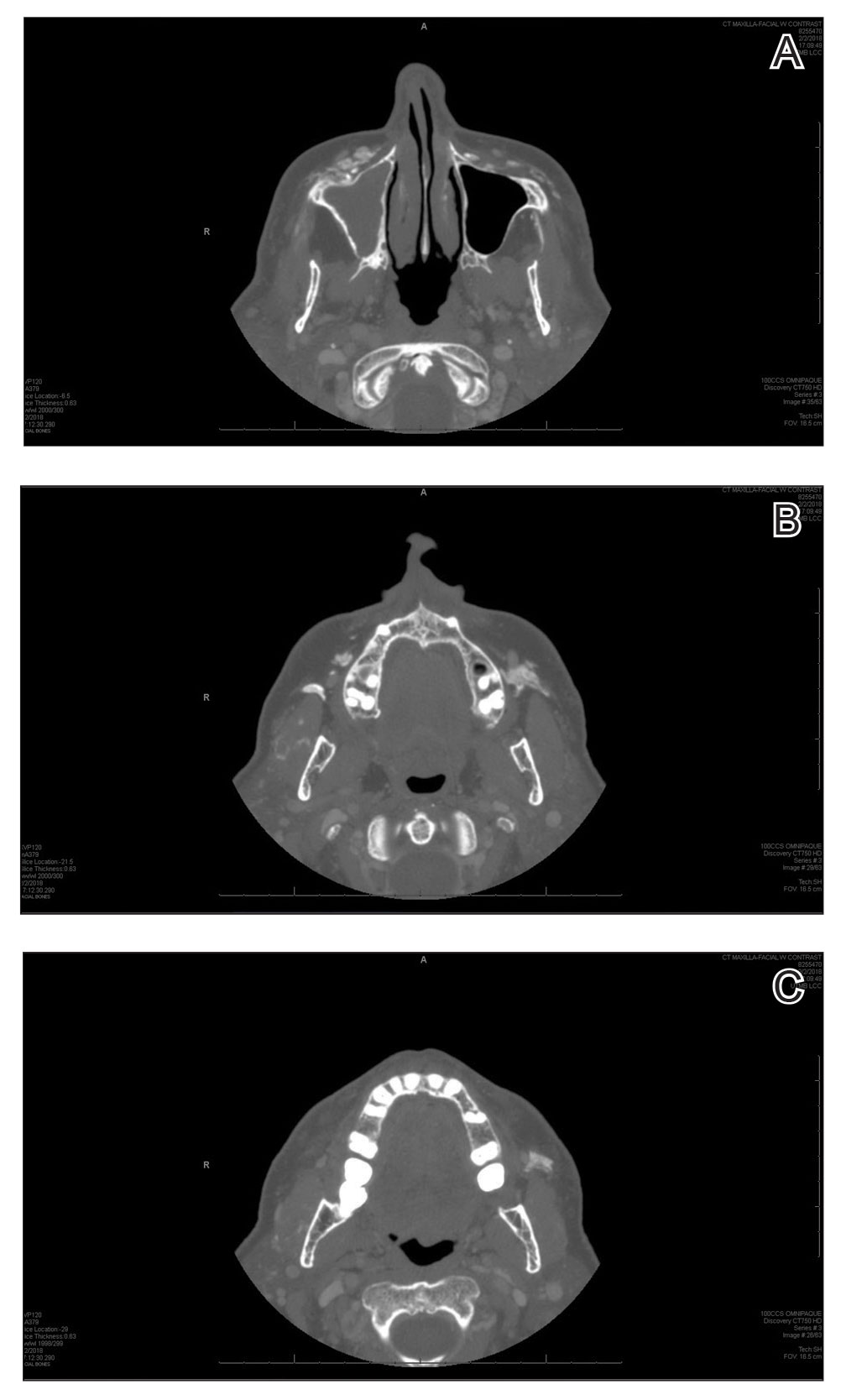

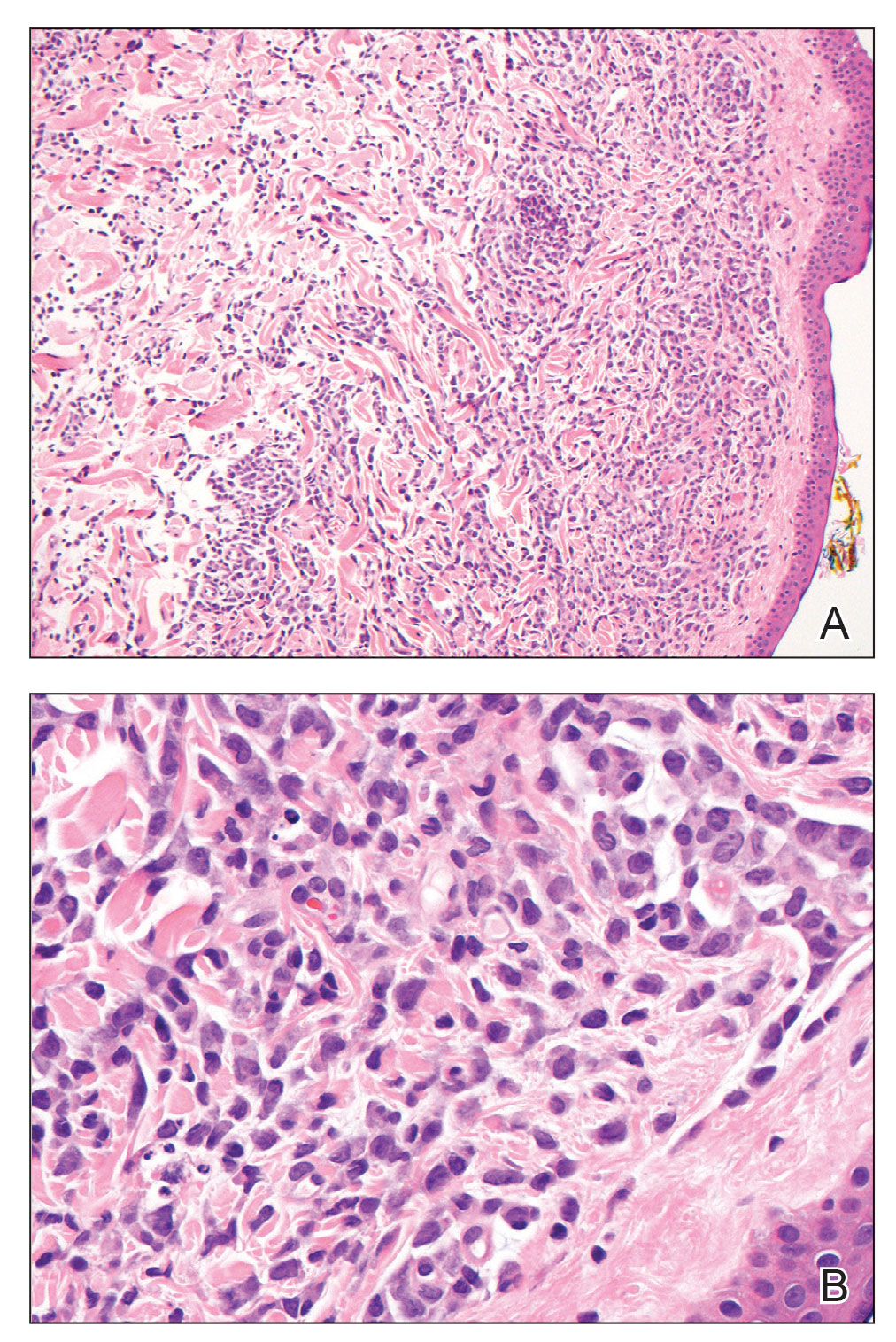

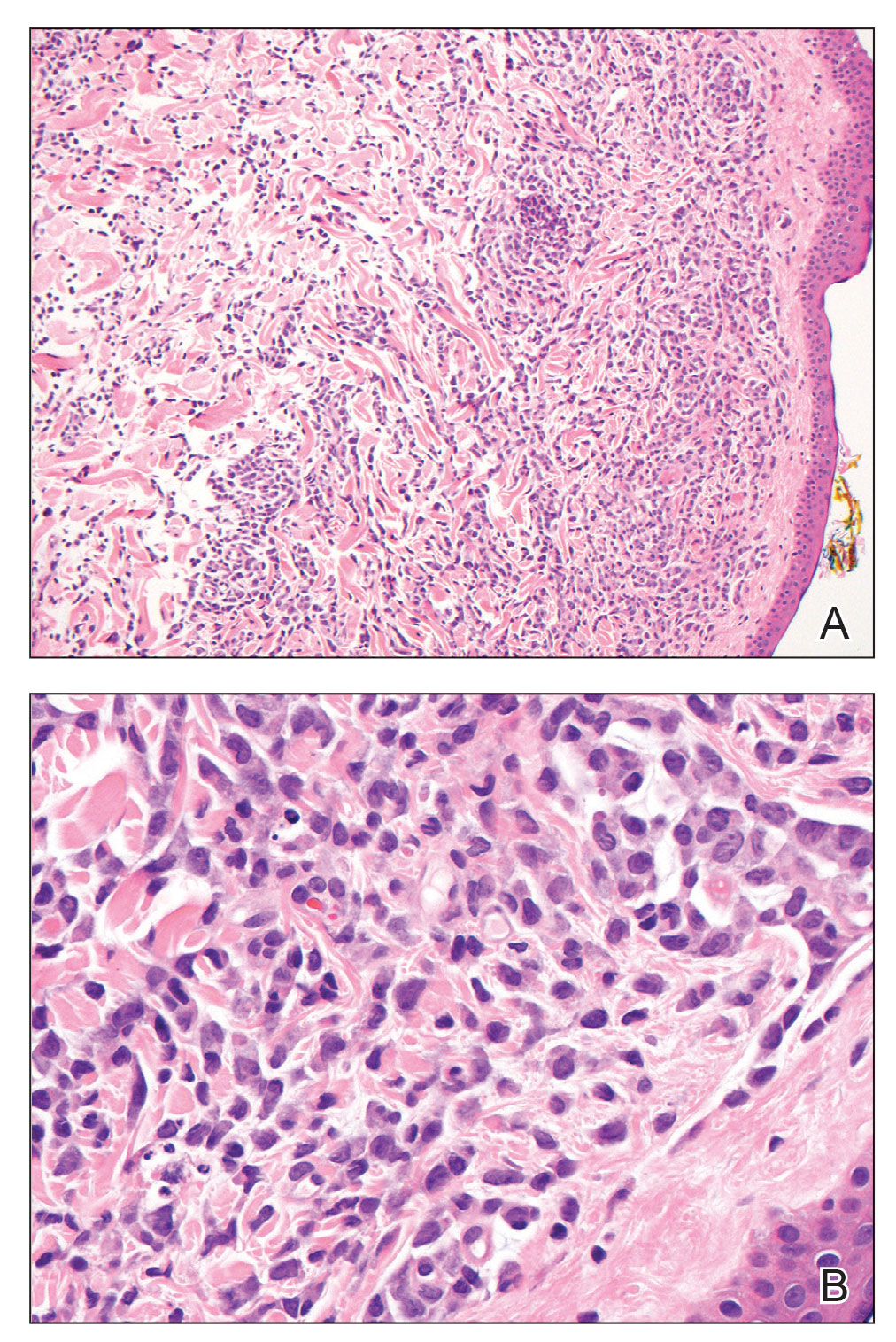

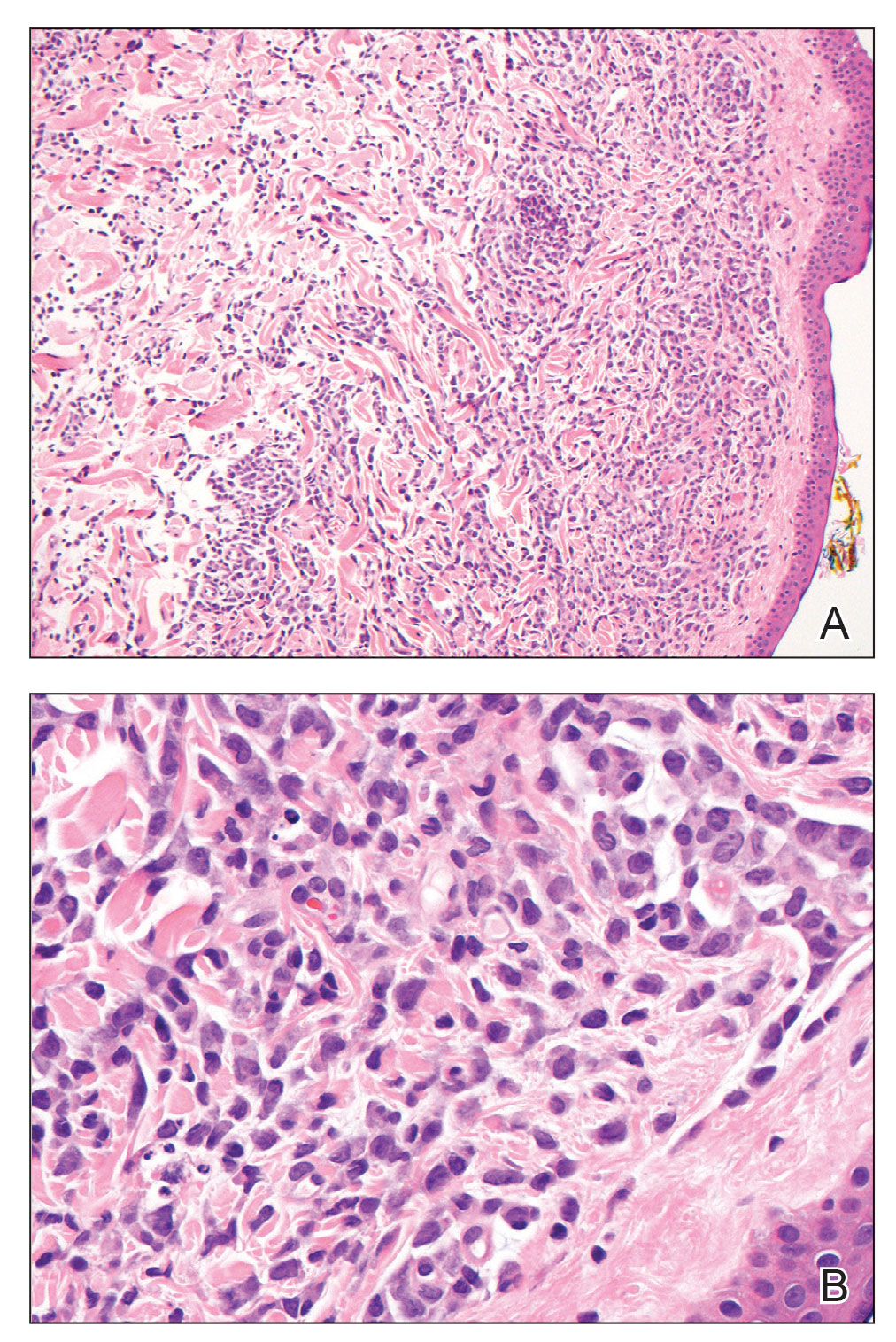

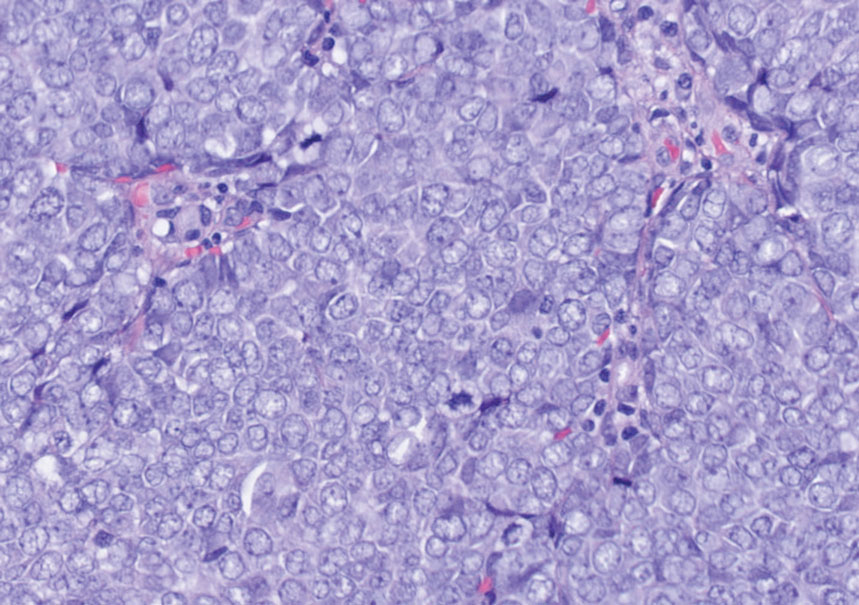

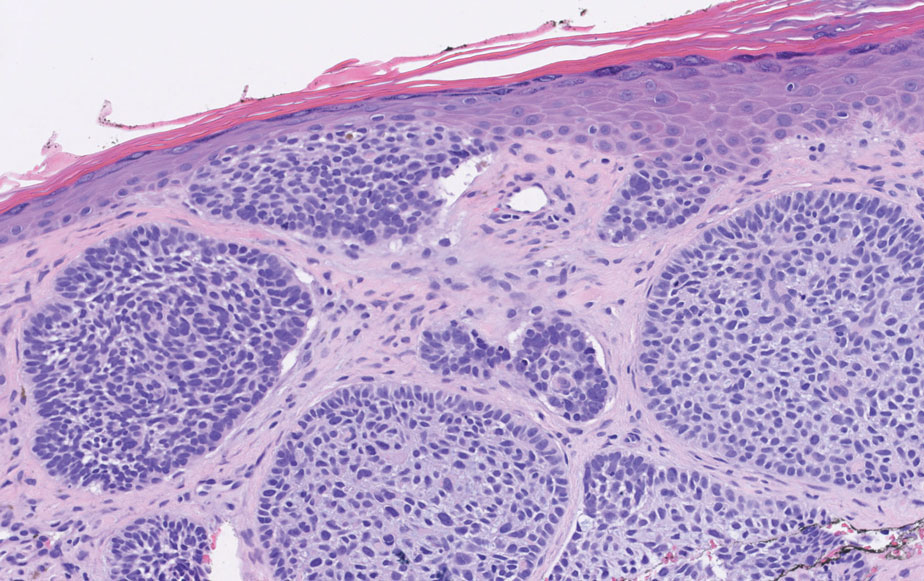

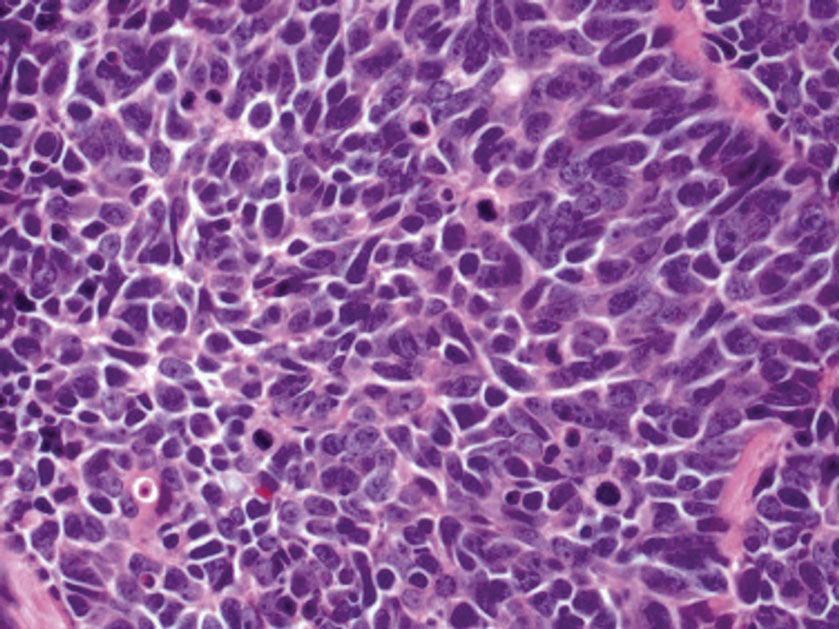

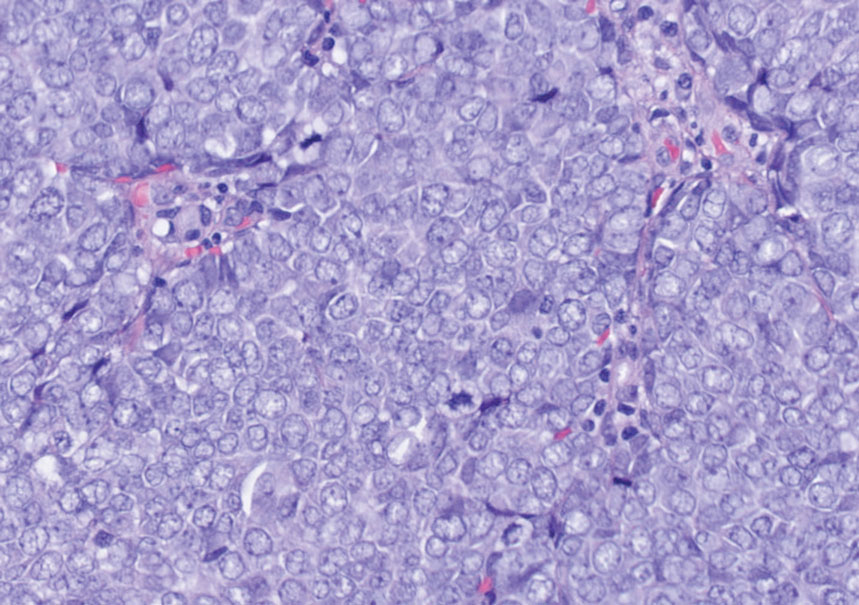

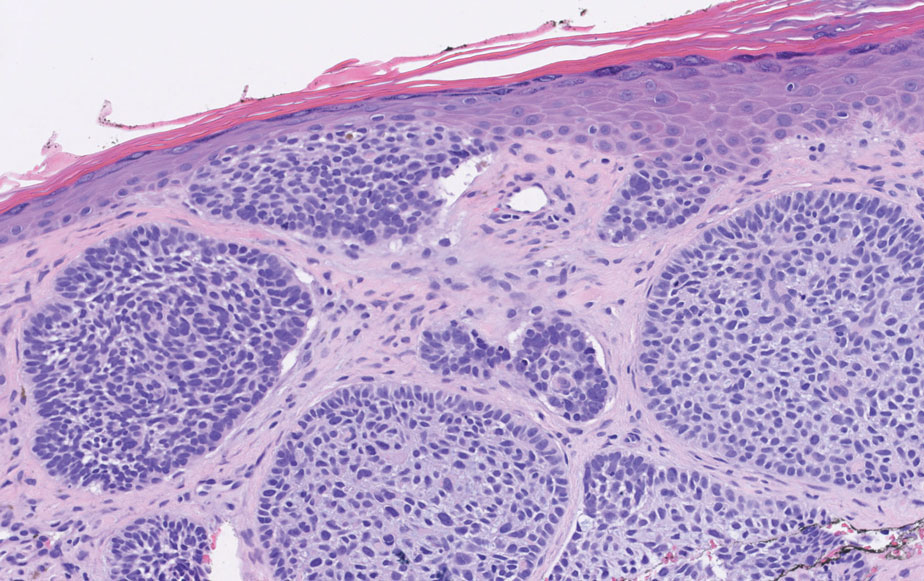

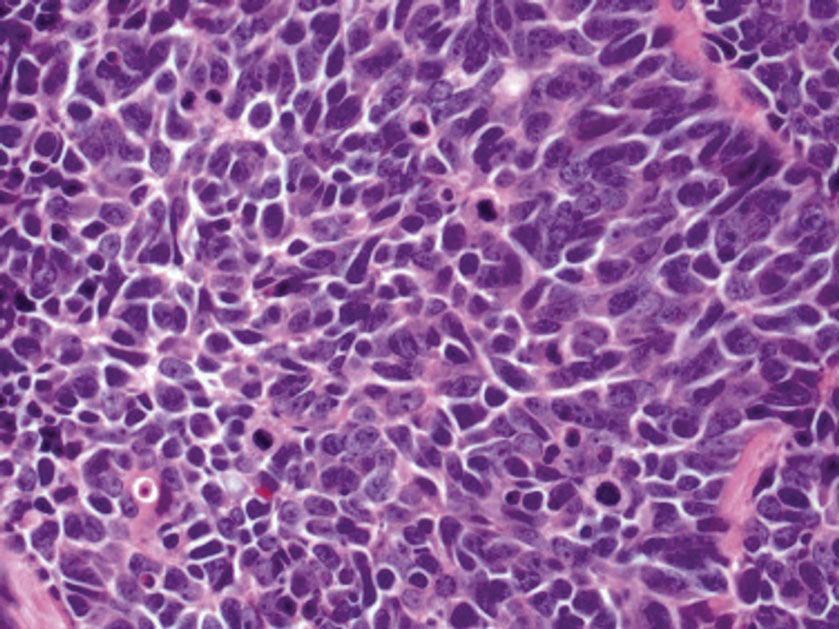

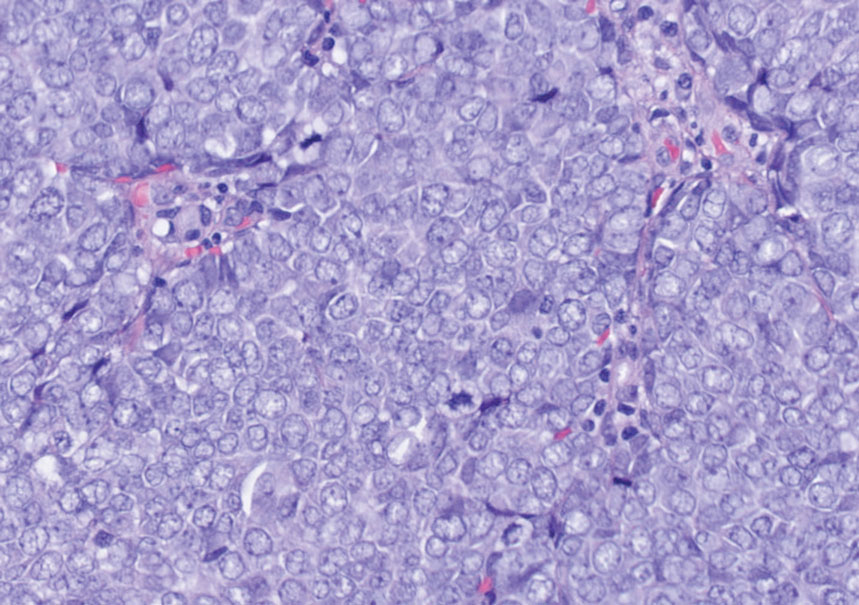

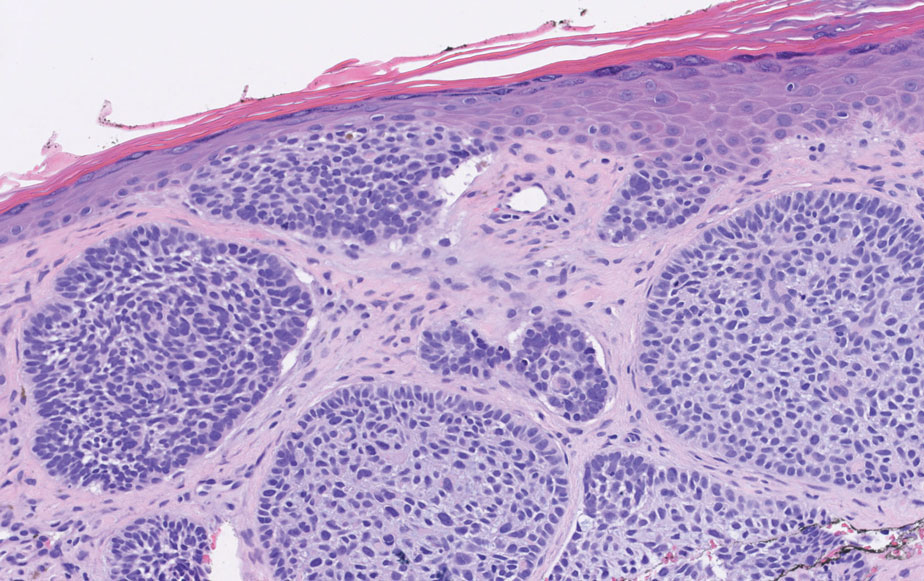

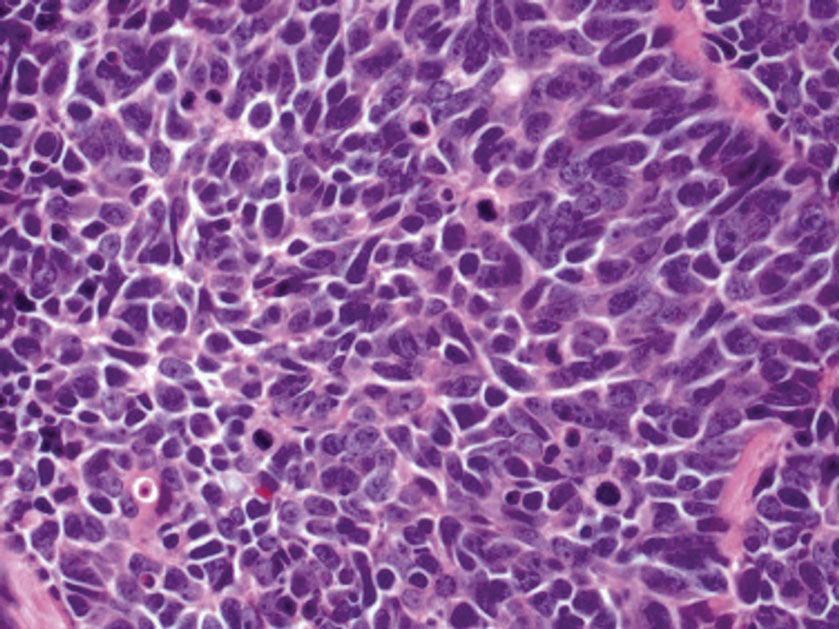

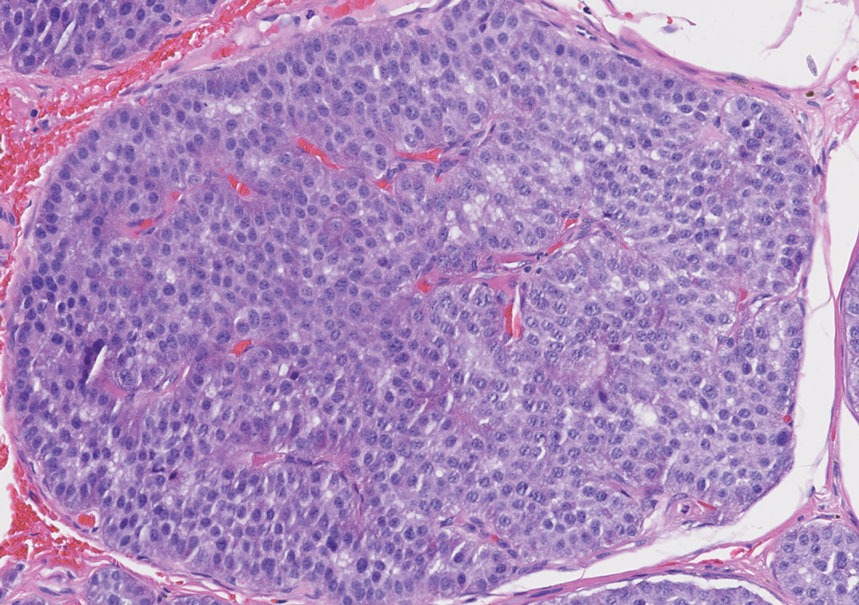

Within 6 months, new sclerotic plaques developed on the patient’s back and right thigh (Figure 1B). Because the lesions were located outside the radiation field of the left femur, a second biopsy was obtained from the right thigh. Histopathology revealed extensive dermal sclerosis and a perivascular lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate (Figure 2). An antinuclear antibody test was weakly positive (1:40, nucleolar pattern) with a negative extractable nuclear antigen panel result. Anti–double-stranded DNA, anti–topoisomerase 1, anti-Smith, antiribonucleoprotein, anti–Sjögren syndrome type A, anti–Sjögren syndrome type B, and anticentromere serology test results were negative. The patient denied decreased oral aperture, difficulty swallowing, or Raynaud phenomenon. Due to the atypical clinical presentation in the setting of PD-1 inhibitor therapy, the etiology of the eruption was potentially attributable to nivolumab. She was started on treatment with methotrexate 20 mg weekly and clobetasol cream 0.05% twice daily; she continued taking prednisone 5 mg daily. The cutaneous manifestations on the patient’s back completely resolved, and the legs continued to gradually improve on this regimen. Immunotherapy continued to be held due to skin toxicity.

Localized scleroderma is an autoimmune disorder characterized by inflammation and skin thickening. Overactive fibroblasts produce excess collagen, leading to the clinical symptoms of skin thickening, hardening, and discoloration.3 Lesions frequently develop on the arms, face, or legs and can present as patches or linear bands. Unlike systemic sclerosis, the internal organs typically are uninvolved; however, sclerotic lesions can be disfiguring and cause notable disability if they impede joint movement.

The PD-1/PD-L1 pathway is a negative regulator of the immune response that inactivates T cells and helps maintain self-tolerance. Modulation of the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway and overexpression of PD-L1 are seen in various cancers as a mechanism to help malignant cells avoid immune destruction.4 Conversely, inhibition of this pathway can be used to stimulate an antitumor immune response. This checkpoint inhibition strategy has been highly successful for the treatment of various cancers including melanoma and non–small cell lung carcinoma. There are several checkpoint inhibitors approved in the United States that are used for cancer therapy and target the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway, such as nivolumab, pembrolizumab, atezolizumab, durvalumab, and avelumab.4 A downside of checkpoint inhibitor treatment is that uncontrolled T-cell activation can lead to irAEs, including cutaneous eruptions, pruritus, diarrhea, colitis, hepatitis, endocrinopathies, pneumonitis, and renal insufficiency.5 These toxicities are reversible if treated appropriately but can cause notable morbidity and mortality if left unrecognized. Cutaneous eruption is one of the most common irAEs associated with anti–PD-1 and anti–PD-L1 therapies and can limit therapeutic efficacy, as the drug may need to be held or discontinued due to the severity of the eruption.6 Mid-potency to high-potency topical corticosteroids and systemic antihistamines are first-line treatments of grades 1 and 2 skin toxicities associated with PD-1 inhibitor therapy. For eruptions classified as grades 3 or 4 or refractory grade 2, discontinuation of the drug and systemic corticosteroids is recommended.7

The cutaneous eruption in immunotherapy-mediated dermatitis is thought to be largely mediated by activated T cells infiltrating the dermis.8 In localized scleroderma, increased tumor necrosis factor α, IFN-γ, IFN-γ–induced protein 10, and granulocyte macrophage colony stimulating factor activity have been shown to correlate with disease activity.9,10 Interestingly, increased tumor necrosis factor α and IFN-γ correlate with better response and increased overall survival in PD-1 inhibition therapy, suggesting a correlation between PD-1 inhibition and T helper activation as noted by the etiology of sclerosis in our patient.11 Additionally, history of radiation was a confounding factor in the diagnosis of our patient, as both sclerodermoid reactions and chronic radiation dermatitis can present with dermal sclerosis. However, the progression of disease outside of the radiation field excluded this etiology. Although new-onset sclerodermoid reactions have been reported with PD-1 inhibitors, they have been described secondary to sclerodermoid reactions from treatment with pembrolizumab.12,13 One case series reported a case of diffuse sclerodermoid reaction and a limited reaction in response to pembrolizumab treatment, while another case report described a relapse of generalized morphea in response to pembrolizumab treatment.12,13 One case of relapsing morphea in response to nivolumab treatment for stage IV lung adenocarcinoma also has been reported.14

Cutaneous toxicities are one of the most common irAEs associated with checkpoint inhibitors and are seen in more than one-third of treated patients. Most frequently, these irAEs manifest as spongiotic dermatitis on histopathology, but a broad spectrum of cutaneous reactions have been observed.15 Although sclerodermoid reactions have been reported with PD-1 inhibitors, most are described secondary to sclerodermoid reactions with pembrolizumab and involve relapse of previously diagnosed morphea rather than new-onset disease.12-14

Our case highlights new-onset localized scleroderma in the setting of nivolumab therapy that showed clinical improvement with methotrexate and topical and systemic steroids. This reaction pattern should be considered in all patients who develop cutaneous eruptions when treated with a PD-1 inhibitor. There should be a high index of suspicion for the potential occurrence of irAEs to ensure early recognition and treatment to minimize morbidity and maximize adherence to therapy for the underlying malignancy.

- Baxi S, Yang A, Gennarelli RL, et al. Immune-related adverse events for anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 drugs: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2018;360:k793.

- Dai S, Jia R, Zhang X, et al. The PD-1/PD-Ls pathway and autoimmune diseases. Cell Immunol. 2014;290:72-79.

- Badea I, Taylor M, Rosenberg A, et al. Pathogenesis and therapeutic approaches for improved topical treatment in localized scleroderma and systemic sclerosis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2009;48:213-221.

- Constantinidou A, Alifieris C, Trafalis DT. Targeting programmed cell death-1 (PD-1) and ligand (PD-L1): a new era in cancer active immunotherapy. Pharmacol Ther. 2019;194:84-106.

- Villadolid J, Asim A. Immune checkpoint inhibitors in clinical practice: update on management of immune-related toxicities. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2015;4:560-575.

- Naidoo J, Page DB, Li BT, et al. Toxicities of the anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 immune checkpoint antibodies. Ann Oncol. 2016;27:1362.

- O’Kane GM, Labbé C, Doherty MK, et al. Monitoring and management of immune-related adverse events associated with programmed cell death protein-1 axis inhibitors in lung cancer. Oncologist. 2017;22:70-80.

- Shi VJ, Rodic N, Gettinger S, et al. Clinical and histologic features of lichenoid mucocutaneous eruptions due to anti-programmed celldeath 1 and anti-programmed cell death ligand 1 immunotherapy. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:1128-1136.

- Torok KS, Kurzinski K, Kelsey C, et al. Peripheral blood cytokine and chemokine profiles in juvenile localized scleroderma: T-helper cell-associated cytokine profiles. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2015;45:284-293.

- Guo X, Higgs BW, Bay-Jensen AC, et al. Suppression of T cell activation and collagen accumulation by an anti-IFNAR1 mAb, anifrolumab, in adult patients with systemic sclerosis. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135:2402-2409.

- Boutsikou E, Domvri K, Hardavella G, et al. Tumor necrosis factor, interferon-gamma and interleukins as predictive markers of antiprogrammed cell-death protein-1 treatment in advanced non-small cell lung cancer: a pragmatic approach in clinical practice. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2018;10:1758835918768238.

- Barbosa NS, Wetter DA, Wieland CN, et al. Scleroderma induced by pembrolizumab: a case series. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92:1158-1163.

- Cheng MW, Hisaw LD, Bernet L. Generalized morphea in the setting of pembrolizumab. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:736-738.

- Alegre-Sánchez A, Fonda-Pascual P, Saceda-Corralo D, et al. Relapse of morphea during nivolumab therapy for lung adenocarcinoma. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2017;108:69-70.

- Sibaud V. Dermatologic reactions to immune checkpoint inhibitors: skin toxicities and immunotherapy. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2018;19:345-361.

To the Editor:

Immune checkpoint inhibitors such as anti–programmed cell death protein 1 (anti–PD-1) and anticytotoxic T lymphocyte–associated protein 4 therapies are a promising class of cancer therapeutics. However, they are associated with a variety of immune-related adverse events (irAEs), including cutaneous toxicity.1 The PD-1/programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) pathway is important for the maintenance of immune tolerance, and a blockade has been shown to lead to development of various autoimmune diseases.2 We present the case of a patient who developed new-onset localized scleroderma during treatment with the PD-1 inhibitor nivolumab.

A 65-year-old woman presented with a rash on the left thigh that was associated with pruritus, pain, and a pulling sensation. She had a history of stage IV lung adenocarcinoma, with a mass in the right upper lobe with metastatic foci to the left femur, right humerus, right hilar, and pretracheal lymph nodes. She received palliative radiation to the left femur and was started on carboplatin and pemetrexed. Metastasis to the liver was noted after completion of 6 cycles of therapy, and the patient’s treatment was changed to nivolumab. After 17 months on nivolumab therapy (2 years after initial diagnosis and 20 months after radiation therapy), she presented to our dermatology clinic with a cutaneous eruption on the buttocks that spread to the left thigh. The rash failed to improve after 1 month of treatment with emollients and triamcinolone cream 0.1%.

At the current presentation, which was 2 months after she initially presented to our clinic, dermatologic examination revealed erythematous and sclerotic plaques on the left lateral thigh (Figure 1A). Betamethasone cream 0.05% was prescribed, and nivolumab was discontinued due to progression of cutaneous symptoms. A punch biopsy from the left thigh demonstrated superficial dermal sclerosis that was suggestive of chronic radiation dermatitis; direct immunofluorescence testing was negative. The patient was started on prednisone 50 mg daily, which resulted in mild improvement in symptoms.

Within 6 months, new sclerotic plaques developed on the patient’s back and right thigh (Figure 1B). Because the lesions were located outside the radiation field of the left femur, a second biopsy was obtained from the right thigh. Histopathology revealed extensive dermal sclerosis and a perivascular lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate (Figure 2). An antinuclear antibody test was weakly positive (1:40, nucleolar pattern) with a negative extractable nuclear antigen panel result. Anti–double-stranded DNA, anti–topoisomerase 1, anti-Smith, antiribonucleoprotein, anti–Sjögren syndrome type A, anti–Sjögren syndrome type B, and anticentromere serology test results were negative. The patient denied decreased oral aperture, difficulty swallowing, or Raynaud phenomenon. Due to the atypical clinical presentation in the setting of PD-1 inhibitor therapy, the etiology of the eruption was potentially attributable to nivolumab. She was started on treatment with methotrexate 20 mg weekly and clobetasol cream 0.05% twice daily; she continued taking prednisone 5 mg daily. The cutaneous manifestations on the patient’s back completely resolved, and the legs continued to gradually improve on this regimen. Immunotherapy continued to be held due to skin toxicity.

Localized scleroderma is an autoimmune disorder characterized by inflammation and skin thickening. Overactive fibroblasts produce excess collagen, leading to the clinical symptoms of skin thickening, hardening, and discoloration.3 Lesions frequently develop on the arms, face, or legs and can present as patches or linear bands. Unlike systemic sclerosis, the internal organs typically are uninvolved; however, sclerotic lesions can be disfiguring and cause notable disability if they impede joint movement.

The PD-1/PD-L1 pathway is a negative regulator of the immune response that inactivates T cells and helps maintain self-tolerance. Modulation of the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway and overexpression of PD-L1 are seen in various cancers as a mechanism to help malignant cells avoid immune destruction.4 Conversely, inhibition of this pathway can be used to stimulate an antitumor immune response. This checkpoint inhibition strategy has been highly successful for the treatment of various cancers including melanoma and non–small cell lung carcinoma. There are several checkpoint inhibitors approved in the United States that are used for cancer therapy and target the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway, such as nivolumab, pembrolizumab, atezolizumab, durvalumab, and avelumab.4 A downside of checkpoint inhibitor treatment is that uncontrolled T-cell activation can lead to irAEs, including cutaneous eruptions, pruritus, diarrhea, colitis, hepatitis, endocrinopathies, pneumonitis, and renal insufficiency.5 These toxicities are reversible if treated appropriately but can cause notable morbidity and mortality if left unrecognized. Cutaneous eruption is one of the most common irAEs associated with anti–PD-1 and anti–PD-L1 therapies and can limit therapeutic efficacy, as the drug may need to be held or discontinued due to the severity of the eruption.6 Mid-potency to high-potency topical corticosteroids and systemic antihistamines are first-line treatments of grades 1 and 2 skin toxicities associated with PD-1 inhibitor therapy. For eruptions classified as grades 3 or 4 or refractory grade 2, discontinuation of the drug and systemic corticosteroids is recommended.7

The cutaneous eruption in immunotherapy-mediated dermatitis is thought to be largely mediated by activated T cells infiltrating the dermis.8 In localized scleroderma, increased tumor necrosis factor α, IFN-γ, IFN-γ–induced protein 10, and granulocyte macrophage colony stimulating factor activity have been shown to correlate with disease activity.9,10 Interestingly, increased tumor necrosis factor α and IFN-γ correlate with better response and increased overall survival in PD-1 inhibition therapy, suggesting a correlation between PD-1 inhibition and T helper activation as noted by the etiology of sclerosis in our patient.11 Additionally, history of radiation was a confounding factor in the diagnosis of our patient, as both sclerodermoid reactions and chronic radiation dermatitis can present with dermal sclerosis. However, the progression of disease outside of the radiation field excluded this etiology. Although new-onset sclerodermoid reactions have been reported with PD-1 inhibitors, they have been described secondary to sclerodermoid reactions from treatment with pembrolizumab.12,13 One case series reported a case of diffuse sclerodermoid reaction and a limited reaction in response to pembrolizumab treatment, while another case report described a relapse of generalized morphea in response to pembrolizumab treatment.12,13 One case of relapsing morphea in response to nivolumab treatment for stage IV lung adenocarcinoma also has been reported.14

Cutaneous toxicities are one of the most common irAEs associated with checkpoint inhibitors and are seen in more than one-third of treated patients. Most frequently, these irAEs manifest as spongiotic dermatitis on histopathology, but a broad spectrum of cutaneous reactions have been observed.15 Although sclerodermoid reactions have been reported with PD-1 inhibitors, most are described secondary to sclerodermoid reactions with pembrolizumab and involve relapse of previously diagnosed morphea rather than new-onset disease.12-14

Our case highlights new-onset localized scleroderma in the setting of nivolumab therapy that showed clinical improvement with methotrexate and topical and systemic steroids. This reaction pattern should be considered in all patients who develop cutaneous eruptions when treated with a PD-1 inhibitor. There should be a high index of suspicion for the potential occurrence of irAEs to ensure early recognition and treatment to minimize morbidity and maximize adherence to therapy for the underlying malignancy.

To the Editor:

Immune checkpoint inhibitors such as anti–programmed cell death protein 1 (anti–PD-1) and anticytotoxic T lymphocyte–associated protein 4 therapies are a promising class of cancer therapeutics. However, they are associated with a variety of immune-related adverse events (irAEs), including cutaneous toxicity.1 The PD-1/programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) pathway is important for the maintenance of immune tolerance, and a blockade has been shown to lead to development of various autoimmune diseases.2 We present the case of a patient who developed new-onset localized scleroderma during treatment with the PD-1 inhibitor nivolumab.

A 65-year-old woman presented with a rash on the left thigh that was associated with pruritus, pain, and a pulling sensation. She had a history of stage IV lung adenocarcinoma, with a mass in the right upper lobe with metastatic foci to the left femur, right humerus, right hilar, and pretracheal lymph nodes. She received palliative radiation to the left femur and was started on carboplatin and pemetrexed. Metastasis to the liver was noted after completion of 6 cycles of therapy, and the patient’s treatment was changed to nivolumab. After 17 months on nivolumab therapy (2 years after initial diagnosis and 20 months after radiation therapy), she presented to our dermatology clinic with a cutaneous eruption on the buttocks that spread to the left thigh. The rash failed to improve after 1 month of treatment with emollients and triamcinolone cream 0.1%.

At the current presentation, which was 2 months after she initially presented to our clinic, dermatologic examination revealed erythematous and sclerotic plaques on the left lateral thigh (Figure 1A). Betamethasone cream 0.05% was prescribed, and nivolumab was discontinued due to progression of cutaneous symptoms. A punch biopsy from the left thigh demonstrated superficial dermal sclerosis that was suggestive of chronic radiation dermatitis; direct immunofluorescence testing was negative. The patient was started on prednisone 50 mg daily, which resulted in mild improvement in symptoms.

Within 6 months, new sclerotic plaques developed on the patient’s back and right thigh (Figure 1B). Because the lesions were located outside the radiation field of the left femur, a second biopsy was obtained from the right thigh. Histopathology revealed extensive dermal sclerosis and a perivascular lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate (Figure 2). An antinuclear antibody test was weakly positive (1:40, nucleolar pattern) with a negative extractable nuclear antigen panel result. Anti–double-stranded DNA, anti–topoisomerase 1, anti-Smith, antiribonucleoprotein, anti–Sjögren syndrome type A, anti–Sjögren syndrome type B, and anticentromere serology test results were negative. The patient denied decreased oral aperture, difficulty swallowing, or Raynaud phenomenon. Due to the atypical clinical presentation in the setting of PD-1 inhibitor therapy, the etiology of the eruption was potentially attributable to nivolumab. She was started on treatment with methotrexate 20 mg weekly and clobetasol cream 0.05% twice daily; she continued taking prednisone 5 mg daily. The cutaneous manifestations on the patient’s back completely resolved, and the legs continued to gradually improve on this regimen. Immunotherapy continued to be held due to skin toxicity.

Localized scleroderma is an autoimmune disorder characterized by inflammation and skin thickening. Overactive fibroblasts produce excess collagen, leading to the clinical symptoms of skin thickening, hardening, and discoloration.3 Lesions frequently develop on the arms, face, or legs and can present as patches or linear bands. Unlike systemic sclerosis, the internal organs typically are uninvolved; however, sclerotic lesions can be disfiguring and cause notable disability if they impede joint movement.

The PD-1/PD-L1 pathway is a negative regulator of the immune response that inactivates T cells and helps maintain self-tolerance. Modulation of the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway and overexpression of PD-L1 are seen in various cancers as a mechanism to help malignant cells avoid immune destruction.4 Conversely, inhibition of this pathway can be used to stimulate an antitumor immune response. This checkpoint inhibition strategy has been highly successful for the treatment of various cancers including melanoma and non–small cell lung carcinoma. There are several checkpoint inhibitors approved in the United States that are used for cancer therapy and target the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway, such as nivolumab, pembrolizumab, atezolizumab, durvalumab, and avelumab.4 A downside of checkpoint inhibitor treatment is that uncontrolled T-cell activation can lead to irAEs, including cutaneous eruptions, pruritus, diarrhea, colitis, hepatitis, endocrinopathies, pneumonitis, and renal insufficiency.5 These toxicities are reversible if treated appropriately but can cause notable morbidity and mortality if left unrecognized. Cutaneous eruption is one of the most common irAEs associated with anti–PD-1 and anti–PD-L1 therapies and can limit therapeutic efficacy, as the drug may need to be held or discontinued due to the severity of the eruption.6 Mid-potency to high-potency topical corticosteroids and systemic antihistamines are first-line treatments of grades 1 and 2 skin toxicities associated with PD-1 inhibitor therapy. For eruptions classified as grades 3 or 4 or refractory grade 2, discontinuation of the drug and systemic corticosteroids is recommended.7

The cutaneous eruption in immunotherapy-mediated dermatitis is thought to be largely mediated by activated T cells infiltrating the dermis.8 In localized scleroderma, increased tumor necrosis factor α, IFN-γ, IFN-γ–induced protein 10, and granulocyte macrophage colony stimulating factor activity have been shown to correlate with disease activity.9,10 Interestingly, increased tumor necrosis factor α and IFN-γ correlate with better response and increased overall survival in PD-1 inhibition therapy, suggesting a correlation between PD-1 inhibition and T helper activation as noted by the etiology of sclerosis in our patient.11 Additionally, history of radiation was a confounding factor in the diagnosis of our patient, as both sclerodermoid reactions and chronic radiation dermatitis can present with dermal sclerosis. However, the progression of disease outside of the radiation field excluded this etiology. Although new-onset sclerodermoid reactions have been reported with PD-1 inhibitors, they have been described secondary to sclerodermoid reactions from treatment with pembrolizumab.12,13 One case series reported a case of diffuse sclerodermoid reaction and a limited reaction in response to pembrolizumab treatment, while another case report described a relapse of generalized morphea in response to pembrolizumab treatment.12,13 One case of relapsing morphea in response to nivolumab treatment for stage IV lung adenocarcinoma also has been reported.14

Cutaneous toxicities are one of the most common irAEs associated with checkpoint inhibitors and are seen in more than one-third of treated patients. Most frequently, these irAEs manifest as spongiotic dermatitis on histopathology, but a broad spectrum of cutaneous reactions have been observed.15 Although sclerodermoid reactions have been reported with PD-1 inhibitors, most are described secondary to sclerodermoid reactions with pembrolizumab and involve relapse of previously diagnosed morphea rather than new-onset disease.12-14

Our case highlights new-onset localized scleroderma in the setting of nivolumab therapy that showed clinical improvement with methotrexate and topical and systemic steroids. This reaction pattern should be considered in all patients who develop cutaneous eruptions when treated with a PD-1 inhibitor. There should be a high index of suspicion for the potential occurrence of irAEs to ensure early recognition and treatment to minimize morbidity and maximize adherence to therapy for the underlying malignancy.

- Baxi S, Yang A, Gennarelli RL, et al. Immune-related adverse events for anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 drugs: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2018;360:k793.

- Dai S, Jia R, Zhang X, et al. The PD-1/PD-Ls pathway and autoimmune diseases. Cell Immunol. 2014;290:72-79.

- Badea I, Taylor M, Rosenberg A, et al. Pathogenesis and therapeutic approaches for improved topical treatment in localized scleroderma and systemic sclerosis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2009;48:213-221.

- Constantinidou A, Alifieris C, Trafalis DT. Targeting programmed cell death-1 (PD-1) and ligand (PD-L1): a new era in cancer active immunotherapy. Pharmacol Ther. 2019;194:84-106.

- Villadolid J, Asim A. Immune checkpoint inhibitors in clinical practice: update on management of immune-related toxicities. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2015;4:560-575.

- Naidoo J, Page DB, Li BT, et al. Toxicities of the anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 immune checkpoint antibodies. Ann Oncol. 2016;27:1362.

- O’Kane GM, Labbé C, Doherty MK, et al. Monitoring and management of immune-related adverse events associated with programmed cell death protein-1 axis inhibitors in lung cancer. Oncologist. 2017;22:70-80.

- Shi VJ, Rodic N, Gettinger S, et al. Clinical and histologic features of lichenoid mucocutaneous eruptions due to anti-programmed celldeath 1 and anti-programmed cell death ligand 1 immunotherapy. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:1128-1136.

- Torok KS, Kurzinski K, Kelsey C, et al. Peripheral blood cytokine and chemokine profiles in juvenile localized scleroderma: T-helper cell-associated cytokine profiles. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2015;45:284-293.

- Guo X, Higgs BW, Bay-Jensen AC, et al. Suppression of T cell activation and collagen accumulation by an anti-IFNAR1 mAb, anifrolumab, in adult patients with systemic sclerosis. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135:2402-2409.

- Boutsikou E, Domvri K, Hardavella G, et al. Tumor necrosis factor, interferon-gamma and interleukins as predictive markers of antiprogrammed cell-death protein-1 treatment in advanced non-small cell lung cancer: a pragmatic approach in clinical practice. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2018;10:1758835918768238.

- Barbosa NS, Wetter DA, Wieland CN, et al. Scleroderma induced by pembrolizumab: a case series. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92:1158-1163.

- Cheng MW, Hisaw LD, Bernet L. Generalized morphea in the setting of pembrolizumab. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:736-738.

- Alegre-Sánchez A, Fonda-Pascual P, Saceda-Corralo D, et al. Relapse of morphea during nivolumab therapy for lung adenocarcinoma. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2017;108:69-70.

- Sibaud V. Dermatologic reactions to immune checkpoint inhibitors: skin toxicities and immunotherapy. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2018;19:345-361.

- Baxi S, Yang A, Gennarelli RL, et al. Immune-related adverse events for anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 drugs: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2018;360:k793.

- Dai S, Jia R, Zhang X, et al. The PD-1/PD-Ls pathway and autoimmune diseases. Cell Immunol. 2014;290:72-79.

- Badea I, Taylor M, Rosenberg A, et al. Pathogenesis and therapeutic approaches for improved topical treatment in localized scleroderma and systemic sclerosis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2009;48:213-221.

- Constantinidou A, Alifieris C, Trafalis DT. Targeting programmed cell death-1 (PD-1) and ligand (PD-L1): a new era in cancer active immunotherapy. Pharmacol Ther. 2019;194:84-106.

- Villadolid J, Asim A. Immune checkpoint inhibitors in clinical practice: update on management of immune-related toxicities. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2015;4:560-575.

- Naidoo J, Page DB, Li BT, et al. Toxicities of the anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 immune checkpoint antibodies. Ann Oncol. 2016;27:1362.

- O’Kane GM, Labbé C, Doherty MK, et al. Monitoring and management of immune-related adverse events associated with programmed cell death protein-1 axis inhibitors in lung cancer. Oncologist. 2017;22:70-80.

- Shi VJ, Rodic N, Gettinger S, et al. Clinical and histologic features of lichenoid mucocutaneous eruptions due to anti-programmed celldeath 1 and anti-programmed cell death ligand 1 immunotherapy. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:1128-1136.

- Torok KS, Kurzinski K, Kelsey C, et al. Peripheral blood cytokine and chemokine profiles in juvenile localized scleroderma: T-helper cell-associated cytokine profiles. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2015;45:284-293.

- Guo X, Higgs BW, Bay-Jensen AC, et al. Suppression of T cell activation and collagen accumulation by an anti-IFNAR1 mAb, anifrolumab, in adult patients with systemic sclerosis. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135:2402-2409.

- Boutsikou E, Domvri K, Hardavella G, et al. Tumor necrosis factor, interferon-gamma and interleukins as predictive markers of antiprogrammed cell-death protein-1 treatment in advanced non-small cell lung cancer: a pragmatic approach in clinical practice. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2018;10:1758835918768238.

- Barbosa NS, Wetter DA, Wieland CN, et al. Scleroderma induced by pembrolizumab: a case series. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92:1158-1163.

- Cheng MW, Hisaw LD, Bernet L. Generalized morphea in the setting of pembrolizumab. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:736-738.

- Alegre-Sánchez A, Fonda-Pascual P, Saceda-Corralo D, et al. Relapse of morphea during nivolumab therapy for lung adenocarcinoma. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2017;108:69-70.

- Sibaud V. Dermatologic reactions to immune checkpoint inhibitors: skin toxicities and immunotherapy. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2018;19:345-361.

Practice Points

- Immune checkpoint inhibitors such as nivolumab, a programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) inhibitor, are associated with immune-related adverse events (irAEs) such as skin toxicity.

- Scleroderma should be considered in the differential diagnosis of patients who develop cutaneous eruptions during treatment with PD-1 inhibitors.

- To ensure prompt recognition and treatment, health care providers should maintain a high index of suspicion for development of cutaneous irAEs in patients using checkpoint inhibitors.

Transitioning From an Intern to a Dermatology Resident

The transition from medical school to residency is a rewarding milestone but involves a steep learning curve wrought with new responsibilities, new colleagues, and a new schedule, often all within a new setting. This transition period has been a longstanding focus of graduate medical education research, and a recent study identified 6 key areas that residency programs need to address to better facilitate this transition: (1) a sense of community within the residency program, (2) relocation resources, (3) residency preparation courses in medical school, (4) readiness to address racism and bias, (5) connecting with peers, and (6) open communication with program leadership.1 There is considerable interest in ensuring that this transition is smooth for all graduates, as nearly all US medical schools feature some variety of a residency preparation course during the fourth year of medical school, which, alongside the subinternships, serves to better prepare their graduates for the healthcare workforce.2

What about the transition from intern to dermatology resident? Near the end of intern year, my categorical medicine colleagues experienced a crescendo of responsibilities, all in preparation for junior year. The senior medicine residents, themselves having previously experienced the graduated responsibilities, knew to ease their grip on the reins and provide the late spring interns an opportunity to lead rounds or run a code. This was not the case for the preliminary interns for whom there was no preview available for what was to come; little guidance exists on how to best transform from a preliminary or transitional postgraduate year (PGY) 1 to a dermatology PGY-2. A survey of 44 dermatology residents and 33 dermatology program directors found electives such as rheumatology, infectious diseases, and allergy and immunology to be helpful for this transition, and residents most often cited friendly and supportive senior and fellow residents as the factor that eased their transition to PGY-2.3 Notably, less than half of the residents (40%) surveyed stated that team-building exercises and dedicated time to meet colleagues were helpful for this transition. They identified studying principles of dermatologic disease, learning new clinical duties, and adjusting to new coworkers and supervisors as the greatest work-related stressors during entry to PGY-2.3

My transition from intern year to dermatology was shrouded in uncertainty, and I was fortunate to have supportive seniors and co-residents to ease the process. There is much about starting dermatology residency that cannot be prepared for by reading a book, and a natural metamorphosis into the new role is hard to articulate. Still, the following are pieces of information I wish I knew as a graduating intern, which I hope will prove useful for those graduating to their PGY-2 dermatology year.

The Pace of Outpatient Dermatology

If the preliminary or transitional year did not have an ambulatory component, the switch from wards to clinic can be jarring. An outpatient encounter can be as short as 10 to 15 minutes, necessitating an efficient interview and examination to avoid a backup of patients. Unlike a hospital admission where the history of present illness can expound on multiple concerns and organ systems, the general dermatology visit must focus on the chief concern, with priority given to the clinical examination of the skin. For total-body skin examinations, a formulaic approach to assessing all areas of the body, with fluent transitions and minimal repositioning of the patient, is critical for patient comfort and to save time. Of course, accuracy and thoroughness are paramount, but the constant mindfulness of time and efficiency is uniquely emphasized in the outpatient setting.

Continuity of Care

On the wards, patients are admitted with an acute problem and discharged with the aim to prevent re-admission. However, in the dermatology clinic, the conditions encountered often are chronic, requiring repeated follow-ups that involve dosage tapers, laboratory monitoring, and trial and error. Unlike the rigid algorithm-based treatments utilized in the inpatient setting, the management of the same chronic disease can vary, as it is tailored to the patient based on their comorbidities and response. This longitudinal relationship with patients, whereby many disorders are managed rather than treated, stands in stark contrast to inpatient medicine, and learning to value symptom management rather than focusing on a cure is critical in a largely outpatient specialty such as dermatology.

Consulter to Consultant

Calling a consultation as an intern is challenging and requires succinct delivery of pertinent information while fearing pushback from the consultant. In a survey of 50 hospitalist attendings, only 11% responded that interns could be entrusted to call an effective consultation without supervision.4 When undertaking the role of a consultant, the goals should be to identify the team’s main question and to obtain key information necessary to formulate a differential diagnosis. The quality of the consultation will inevitably fluctuate; try to remember what it was like for you as a member of the primary team and remain patient and courteous during the exchange.5 In 1983, Goldman et al6 published a guideline on effective consultations that often is cited to this day, dubbed the “Ten Commandments for Effective Consultations,” which consists of the following: (1) determine the question that is being asked, (2) establish the urgency of the consultation, (3) gather primary data, (4) communicate as briefly as appropriate, (5) make specific recommendations, (6) provide contingency plans, (7) understand your own role in the process, (8) offer educational information, (9) communicate recommendations directly to the requesting physician, and (10) provide appropriate follow-up.

Consider Your Future

Frequently reflect on what you most enjoy about your job. Although it can be easy to passively engage with intern year as a mere stepping-stone to dermatology residency, the years in PGY-2 and onward require active introspection to find a future niche. What made you gravitate to the specialty of dermatology? Try to identify your predilections for dermatopathology, pediatric dermatology, dermatologic surgery, cosmetic dermatology, and academia. Be consistently cognizant of your life after residency, as some fellowships such as dermatopathology require applications to be submitted at the conclusion of the PGY-2 year. Seek out faculty mentors or alumni who are walking a path similar to the one you want to embark on, as the next stop after graduation may be your forever job.

Depth, Not Breadth

The practice of medicine changes when narrowing the focus to one organ system. In both medical school and intern year, my study habits and history-taking of patients cast a wide net across multiple organ systems, aiming to know just enough about any one specialty to address all chief concerns and to know when it was appropriate to consult a specialist. This paradigm inevitably shifts in dermatology residency, as residents are tasked with memorizing the endless number of diagnoses of the skin alone, comprehending the many shades of “erythematous,” including pink, salmon, red, and purple. Both on the wards and in clinics, I had to grow comfortable with telling patients that I did not have an answer for many of their nondermatologic concerns and directing them to the right specialist. As medicine continues trending to specialization, subspecialization, and sub-subspecialization, the scope of any given physician likely will continue to narrow,7 as evidenced by specialty clinics within dermatology such as those focusing on hair loss or immunobullous disease. In this health care system, it is imperative to remember that you are only one physician within a team of care providers—understand your own role in the process and become comfortable with not having the answer to all the questions.

Final Thoughts

In a study of 44 dermatology residents, 35 (83%) indicated zero to less than 1 hour per week of independent preparation for dermatology residency during PGY-1.3 Although the usefulness of preparing is debatable, this figure likely reflects the absence of any insight on how to best prepare for the transition. Recognizing the many contrasts between internal medicine and dermatology and embracing the changes will enable a seamless promotion from a medicine PGY-1 to a dermatology PGY-2.

- Staples H, Frank S, Mullen M, et al. Improving the medical school to residency transition: narrative experiences from first-year residents.J Surg Educ. 2022;S1931-7204(22)00146-5. doi:10.1016/j.jsurg.2022.06.001

- Heidemann LA, Walford E, Mack J, et al. Is there a role for internal medicine residency preparation courses in the fourth year curriculum? a single-center experience. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33:2048-2050.

- Hopkins C, Jalali O, Guffey D, et al. A survey of dermatology residents and program directors assessing the transition to dermatology residency. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2020;34:59-62.

- Marcus CH, Winn AS, Sectish TC, et al. How much supervision is required is the beginning of intern year? Acad Pediatr. 2016;16:E3-E4.

- Bly RA, Bly EG. Consult courtesy. J Grad Med Educ. 2013;5:533-534.

- Goldman L, Lee T, Rudd P. Ten commandments for effective consultations. Arch Intern Med. 1983;143:1753-1755.

- Oren O, Gersh BJ, Bhatt DL. On the pearls and perils of sub-subspecialization. Am J Med. 2020;133:158-159.

The transition from medical school to residency is a rewarding milestone but involves a steep learning curve wrought with new responsibilities, new colleagues, and a new schedule, often all within a new setting. This transition period has been a longstanding focus of graduate medical education research, and a recent study identified 6 key areas that residency programs need to address to better facilitate this transition: (1) a sense of community within the residency program, (2) relocation resources, (3) residency preparation courses in medical school, (4) readiness to address racism and bias, (5) connecting with peers, and (6) open communication with program leadership.1 There is considerable interest in ensuring that this transition is smooth for all graduates, as nearly all US medical schools feature some variety of a residency preparation course during the fourth year of medical school, which, alongside the subinternships, serves to better prepare their graduates for the healthcare workforce.2

What about the transition from intern to dermatology resident? Near the end of intern year, my categorical medicine colleagues experienced a crescendo of responsibilities, all in preparation for junior year. The senior medicine residents, themselves having previously experienced the graduated responsibilities, knew to ease their grip on the reins and provide the late spring interns an opportunity to lead rounds or run a code. This was not the case for the preliminary interns for whom there was no preview available for what was to come; little guidance exists on how to best transform from a preliminary or transitional postgraduate year (PGY) 1 to a dermatology PGY-2. A survey of 44 dermatology residents and 33 dermatology program directors found electives such as rheumatology, infectious diseases, and allergy and immunology to be helpful for this transition, and residents most often cited friendly and supportive senior and fellow residents as the factor that eased their transition to PGY-2.3 Notably, less than half of the residents (40%) surveyed stated that team-building exercises and dedicated time to meet colleagues were helpful for this transition. They identified studying principles of dermatologic disease, learning new clinical duties, and adjusting to new coworkers and supervisors as the greatest work-related stressors during entry to PGY-2.3

My transition from intern year to dermatology was shrouded in uncertainty, and I was fortunate to have supportive seniors and co-residents to ease the process. There is much about starting dermatology residency that cannot be prepared for by reading a book, and a natural metamorphosis into the new role is hard to articulate. Still, the following are pieces of information I wish I knew as a graduating intern, which I hope will prove useful for those graduating to their PGY-2 dermatology year.

The Pace of Outpatient Dermatology

If the preliminary or transitional year did not have an ambulatory component, the switch from wards to clinic can be jarring. An outpatient encounter can be as short as 10 to 15 minutes, necessitating an efficient interview and examination to avoid a backup of patients. Unlike a hospital admission where the history of present illness can expound on multiple concerns and organ systems, the general dermatology visit must focus on the chief concern, with priority given to the clinical examination of the skin. For total-body skin examinations, a formulaic approach to assessing all areas of the body, with fluent transitions and minimal repositioning of the patient, is critical for patient comfort and to save time. Of course, accuracy and thoroughness are paramount, but the constant mindfulness of time and efficiency is uniquely emphasized in the outpatient setting.

Continuity of Care

On the wards, patients are admitted with an acute problem and discharged with the aim to prevent re-admission. However, in the dermatology clinic, the conditions encountered often are chronic, requiring repeated follow-ups that involve dosage tapers, laboratory monitoring, and trial and error. Unlike the rigid algorithm-based treatments utilized in the inpatient setting, the management of the same chronic disease can vary, as it is tailored to the patient based on their comorbidities and response. This longitudinal relationship with patients, whereby many disorders are managed rather than treated, stands in stark contrast to inpatient medicine, and learning to value symptom management rather than focusing on a cure is critical in a largely outpatient specialty such as dermatology.

Consulter to Consultant

Calling a consultation as an intern is challenging and requires succinct delivery of pertinent information while fearing pushback from the consultant. In a survey of 50 hospitalist attendings, only 11% responded that interns could be entrusted to call an effective consultation without supervision.4 When undertaking the role of a consultant, the goals should be to identify the team’s main question and to obtain key information necessary to formulate a differential diagnosis. The quality of the consultation will inevitably fluctuate; try to remember what it was like for you as a member of the primary team and remain patient and courteous during the exchange.5 In 1983, Goldman et al6 published a guideline on effective consultations that often is cited to this day, dubbed the “Ten Commandments for Effective Consultations,” which consists of the following: (1) determine the question that is being asked, (2) establish the urgency of the consultation, (3) gather primary data, (4) communicate as briefly as appropriate, (5) make specific recommendations, (6) provide contingency plans, (7) understand your own role in the process, (8) offer educational information, (9) communicate recommendations directly to the requesting physician, and (10) provide appropriate follow-up.

Consider Your Future

Frequently reflect on what you most enjoy about your job. Although it can be easy to passively engage with intern year as a mere stepping-stone to dermatology residency, the years in PGY-2 and onward require active introspection to find a future niche. What made you gravitate to the specialty of dermatology? Try to identify your predilections for dermatopathology, pediatric dermatology, dermatologic surgery, cosmetic dermatology, and academia. Be consistently cognizant of your life after residency, as some fellowships such as dermatopathology require applications to be submitted at the conclusion of the PGY-2 year. Seek out faculty mentors or alumni who are walking a path similar to the one you want to embark on, as the next stop after graduation may be your forever job.

Depth, Not Breadth

The practice of medicine changes when narrowing the focus to one organ system. In both medical school and intern year, my study habits and history-taking of patients cast a wide net across multiple organ systems, aiming to know just enough about any one specialty to address all chief concerns and to know when it was appropriate to consult a specialist. This paradigm inevitably shifts in dermatology residency, as residents are tasked with memorizing the endless number of diagnoses of the skin alone, comprehending the many shades of “erythematous,” including pink, salmon, red, and purple. Both on the wards and in clinics, I had to grow comfortable with telling patients that I did not have an answer for many of their nondermatologic concerns and directing them to the right specialist. As medicine continues trending to specialization, subspecialization, and sub-subspecialization, the scope of any given physician likely will continue to narrow,7 as evidenced by specialty clinics within dermatology such as those focusing on hair loss or immunobullous disease. In this health care system, it is imperative to remember that you are only one physician within a team of care providers—understand your own role in the process and become comfortable with not having the answer to all the questions.

Final Thoughts

In a study of 44 dermatology residents, 35 (83%) indicated zero to less than 1 hour per week of independent preparation for dermatology residency during PGY-1.3 Although the usefulness of preparing is debatable, this figure likely reflects the absence of any insight on how to best prepare for the transition. Recognizing the many contrasts between internal medicine and dermatology and embracing the changes will enable a seamless promotion from a medicine PGY-1 to a dermatology PGY-2.

The transition from medical school to residency is a rewarding milestone but involves a steep learning curve wrought with new responsibilities, new colleagues, and a new schedule, often all within a new setting. This transition period has been a longstanding focus of graduate medical education research, and a recent study identified 6 key areas that residency programs need to address to better facilitate this transition: (1) a sense of community within the residency program, (2) relocation resources, (3) residency preparation courses in medical school, (4) readiness to address racism and bias, (5) connecting with peers, and (6) open communication with program leadership.1 There is considerable interest in ensuring that this transition is smooth for all graduates, as nearly all US medical schools feature some variety of a residency preparation course during the fourth year of medical school, which, alongside the subinternships, serves to better prepare their graduates for the healthcare workforce.2

What about the transition from intern to dermatology resident? Near the end of intern year, my categorical medicine colleagues experienced a crescendo of responsibilities, all in preparation for junior year. The senior medicine residents, themselves having previously experienced the graduated responsibilities, knew to ease their grip on the reins and provide the late spring interns an opportunity to lead rounds or run a code. This was not the case for the preliminary interns for whom there was no preview available for what was to come; little guidance exists on how to best transform from a preliminary or transitional postgraduate year (PGY) 1 to a dermatology PGY-2. A survey of 44 dermatology residents and 33 dermatology program directors found electives such as rheumatology, infectious diseases, and allergy and immunology to be helpful for this transition, and residents most often cited friendly and supportive senior and fellow residents as the factor that eased their transition to PGY-2.3 Notably, less than half of the residents (40%) surveyed stated that team-building exercises and dedicated time to meet colleagues were helpful for this transition. They identified studying principles of dermatologic disease, learning new clinical duties, and adjusting to new coworkers and supervisors as the greatest work-related stressors during entry to PGY-2.3

My transition from intern year to dermatology was shrouded in uncertainty, and I was fortunate to have supportive seniors and co-residents to ease the process. There is much about starting dermatology residency that cannot be prepared for by reading a book, and a natural metamorphosis into the new role is hard to articulate. Still, the following are pieces of information I wish I knew as a graduating intern, which I hope will prove useful for those graduating to their PGY-2 dermatology year.

The Pace of Outpatient Dermatology

If the preliminary or transitional year did not have an ambulatory component, the switch from wards to clinic can be jarring. An outpatient encounter can be as short as 10 to 15 minutes, necessitating an efficient interview and examination to avoid a backup of patients. Unlike a hospital admission where the history of present illness can expound on multiple concerns and organ systems, the general dermatology visit must focus on the chief concern, with priority given to the clinical examination of the skin. For total-body skin examinations, a formulaic approach to assessing all areas of the body, with fluent transitions and minimal repositioning of the patient, is critical for patient comfort and to save time. Of course, accuracy and thoroughness are paramount, but the constant mindfulness of time and efficiency is uniquely emphasized in the outpatient setting.

Continuity of Care

On the wards, patients are admitted with an acute problem and discharged with the aim to prevent re-admission. However, in the dermatology clinic, the conditions encountered often are chronic, requiring repeated follow-ups that involve dosage tapers, laboratory monitoring, and trial and error. Unlike the rigid algorithm-based treatments utilized in the inpatient setting, the management of the same chronic disease can vary, as it is tailored to the patient based on their comorbidities and response. This longitudinal relationship with patients, whereby many disorders are managed rather than treated, stands in stark contrast to inpatient medicine, and learning to value symptom management rather than focusing on a cure is critical in a largely outpatient specialty such as dermatology.

Consulter to Consultant

Calling a consultation as an intern is challenging and requires succinct delivery of pertinent information while fearing pushback from the consultant. In a survey of 50 hospitalist attendings, only 11% responded that interns could be entrusted to call an effective consultation without supervision.4 When undertaking the role of a consultant, the goals should be to identify the team’s main question and to obtain key information necessary to formulate a differential diagnosis. The quality of the consultation will inevitably fluctuate; try to remember what it was like for you as a member of the primary team and remain patient and courteous during the exchange.5 In 1983, Goldman et al6 published a guideline on effective consultations that often is cited to this day, dubbed the “Ten Commandments for Effective Consultations,” which consists of the following: (1) determine the question that is being asked, (2) establish the urgency of the consultation, (3) gather primary data, (4) communicate as briefly as appropriate, (5) make specific recommendations, (6) provide contingency plans, (7) understand your own role in the process, (8) offer educational information, (9) communicate recommendations directly to the requesting physician, and (10) provide appropriate follow-up.

Consider Your Future

Frequently reflect on what you most enjoy about your job. Although it can be easy to passively engage with intern year as a mere stepping-stone to dermatology residency, the years in PGY-2 and onward require active introspection to find a future niche. What made you gravitate to the specialty of dermatology? Try to identify your predilections for dermatopathology, pediatric dermatology, dermatologic surgery, cosmetic dermatology, and academia. Be consistently cognizant of your life after residency, as some fellowships such as dermatopathology require applications to be submitted at the conclusion of the PGY-2 year. Seek out faculty mentors or alumni who are walking a path similar to the one you want to embark on, as the next stop after graduation may be your forever job.

Depth, Not Breadth

The practice of medicine changes when narrowing the focus to one organ system. In both medical school and intern year, my study habits and history-taking of patients cast a wide net across multiple organ systems, aiming to know just enough about any one specialty to address all chief concerns and to know when it was appropriate to consult a specialist. This paradigm inevitably shifts in dermatology residency, as residents are tasked with memorizing the endless number of diagnoses of the skin alone, comprehending the many shades of “erythematous,” including pink, salmon, red, and purple. Both on the wards and in clinics, I had to grow comfortable with telling patients that I did not have an answer for many of their nondermatologic concerns and directing them to the right specialist. As medicine continues trending to specialization, subspecialization, and sub-subspecialization, the scope of any given physician likely will continue to narrow,7 as evidenced by specialty clinics within dermatology such as those focusing on hair loss or immunobullous disease. In this health care system, it is imperative to remember that you are only one physician within a team of care providers—understand your own role in the process and become comfortable with not having the answer to all the questions.

Final Thoughts

In a study of 44 dermatology residents, 35 (83%) indicated zero to less than 1 hour per week of independent preparation for dermatology residency during PGY-1.3 Although the usefulness of preparing is debatable, this figure likely reflects the absence of any insight on how to best prepare for the transition. Recognizing the many contrasts between internal medicine and dermatology and embracing the changes will enable a seamless promotion from a medicine PGY-1 to a dermatology PGY-2.

- Staples H, Frank S, Mullen M, et al. Improving the medical school to residency transition: narrative experiences from first-year residents.J Surg Educ. 2022;S1931-7204(22)00146-5. doi:10.1016/j.jsurg.2022.06.001

- Heidemann LA, Walford E, Mack J, et al. Is there a role for internal medicine residency preparation courses in the fourth year curriculum? a single-center experience. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33:2048-2050.

- Hopkins C, Jalali O, Guffey D, et al. A survey of dermatology residents and program directors assessing the transition to dermatology residency. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2020;34:59-62.

- Marcus CH, Winn AS, Sectish TC, et al. How much supervision is required is the beginning of intern year? Acad Pediatr. 2016;16:E3-E4.

- Bly RA, Bly EG. Consult courtesy. J Grad Med Educ. 2013;5:533-534.

- Goldman L, Lee T, Rudd P. Ten commandments for effective consultations. Arch Intern Med. 1983;143:1753-1755.

- Oren O, Gersh BJ, Bhatt DL. On the pearls and perils of sub-subspecialization. Am J Med. 2020;133:158-159.

- Staples H, Frank S, Mullen M, et al. Improving the medical school to residency transition: narrative experiences from first-year residents.J Surg Educ. 2022;S1931-7204(22)00146-5. doi:10.1016/j.jsurg.2022.06.001

- Heidemann LA, Walford E, Mack J, et al. Is there a role for internal medicine residency preparation courses in the fourth year curriculum? a single-center experience. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33:2048-2050.

- Hopkins C, Jalali O, Guffey D, et al. A survey of dermatology residents and program directors assessing the transition to dermatology residency. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2020;34:59-62.

- Marcus CH, Winn AS, Sectish TC, et al. How much supervision is required is the beginning of intern year? Acad Pediatr. 2016;16:E3-E4.

- Bly RA, Bly EG. Consult courtesy. J Grad Med Educ. 2013;5:533-534.

- Goldman L, Lee T, Rudd P. Ten commandments for effective consultations. Arch Intern Med. 1983;143:1753-1755.

- Oren O, Gersh BJ, Bhatt DL. On the pearls and perils of sub-subspecialization. Am J Med. 2020;133:158-159.

Resident Pearl

- There is surprisingly little information on what to expect when transitioning from intern year to dermatology residency. Recognizing the unique aspects of a largely outpatient specialty and embracing the role of a specialist will help facilitate this transition.

Ossification and Migration of a Nodule Following Calcium Hydroxylapatite Injection

To the Editor:

Calcium hydroxylapatite is an injectable filler approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for moderate to severe rhytides of the face and the treatment of facial lipodystrophy in patients with HIV.1 This long-lasting filler generally is well tolerated with minimal side effects; however, there have been reports of nodules or granulomatous formation following injection.2 We present a case of a migrating nodule following injection of a calcium hydroxylapatite filler that appeared ossified on radiographic imaging. We highlight this rarely reported phenomenon to increase awareness of this complication.

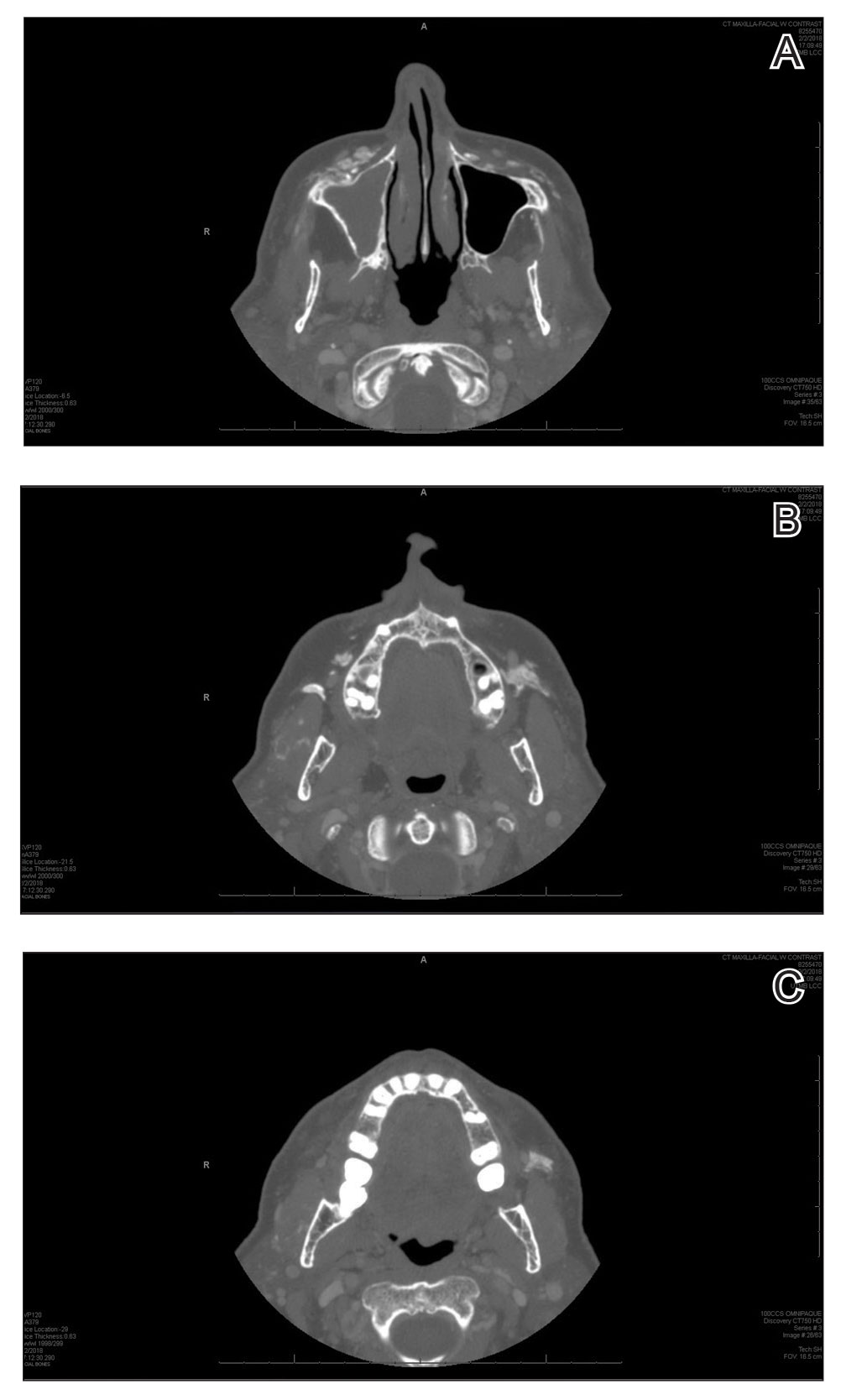

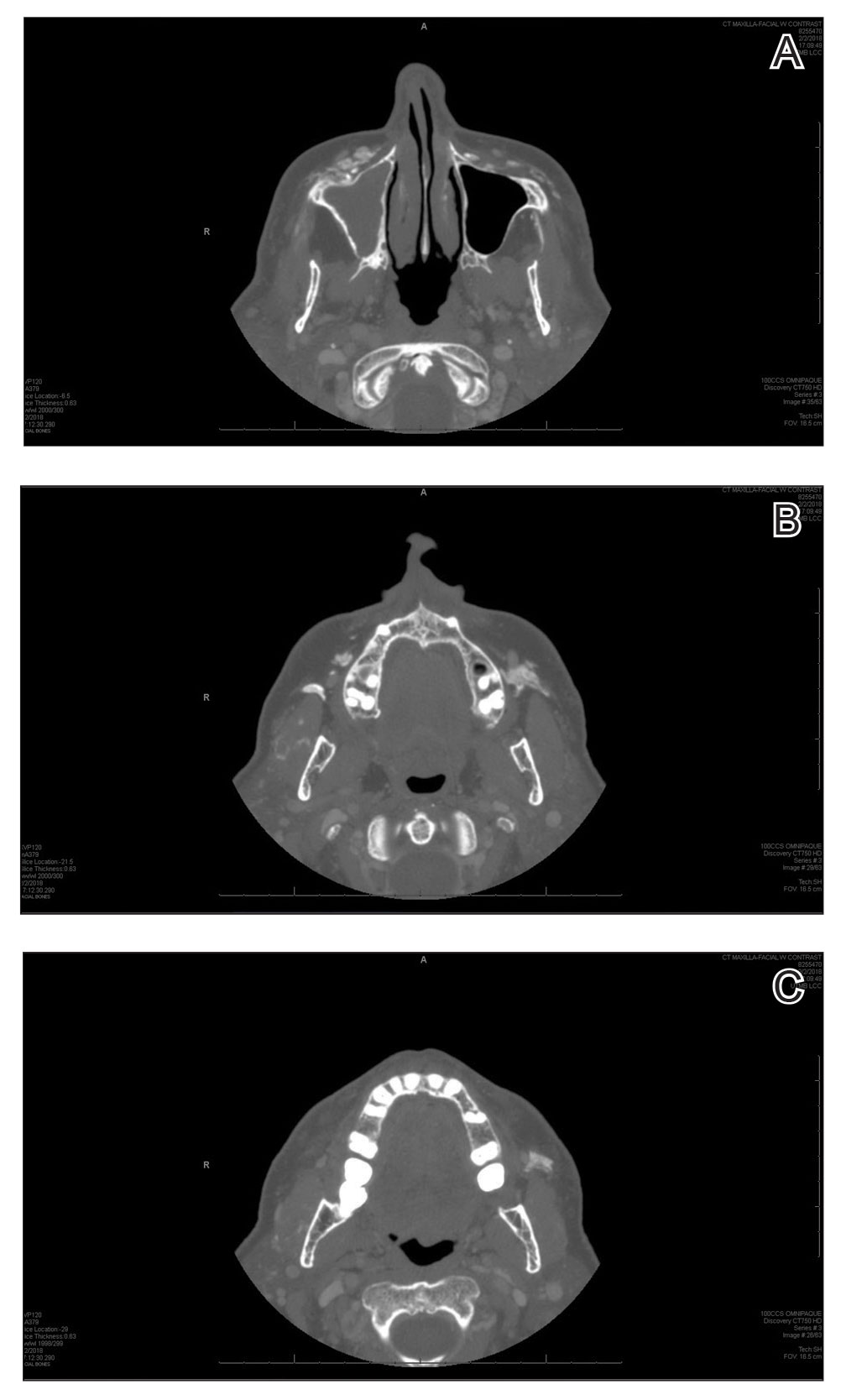

A 72-year-old woman presented to our clinic with a mass on the left cheek. The patient had a history of treatment with facial fillers but no notable medical conditions. She initially received hyaluronic acid injectable gel dermal filler twice—3 years apart—before switching to calcium hydroxylapatite injections twice—4 months apart—from an outside provider. One month after the second treatment, she noticed a mass on the left cheek and promptly returned to the provider who performed the calcium hydroxylapatite injections. The provider, who had originally injected in the infraorbital area, stated it was unlikely that the filler would have migrated to the mid cheek and referred the patient to a general dentist who suspected salivary gland pathology. The patient was referred to an oral and maxillofacial surgeon who suspected the mass was related to the parotid gland. Maxillofacial computed tomography (CT) revealed heterotopic ossification vs myositis ossificans, possibly related to the recent injection. The patient was eventually referred to the Division of Plastic Surgery, Department of Surgery, at the University of Texas Medical Branch (Galveston, Texas) for further evaluation. Physical examination revealed a 2×1-cm firm, mobile, nontender mass in the left cheek in the area of the buccinator muscles. The mass did not express any fluid and was most easily palpable from the oral cavity. Radiography findings showed that the calcium hydroxylapatite filler had migrated to this location and formed a nodule (Figure). Because calcium hydroxylapatite fillers generally last 12 to 18 months, we opted to observe the lesion for spontaneous resolution. Four months later, the patient presented to our clinic for follow-up and the mass had reduced in size and appeared to be spontaneously resolving.

We present a unique case of a migrating nodule that occurred after injection with calcium hydroxylapatite, which led to concern for neoplastic tumor formation. This complication is rare, and it is important for practitioners who inject calcium hydroxylapatite as well as those who these patients may be referred to for evaluation to be aware that migrating nodules can occur. This awareness can help reduce unnecessary referrals, medical procedures, and anxiety.

Calcium hydroxylapatite filler is composed of 30% calcium hydroxylapatite microspheres suspended in a 70% sodium carboxymethylcellulose gel. The water-soluble gel rapidly becomes absorbed upon injection; however, the microspheres form a scaffold for the production of newly synthesized collagen. The filling effect generally lasts 12 to 18 months.1

Calcium hydroxylapatite, similar to most fillers, generally is well tolerated with a low complication rate of 3%.1 Although nodule formation with calcium hydroxylapatite is rare, it is the most common adverse event and encompasses 96% of complications. The remaining 4% of complications include persistent inflammation, swelling, erythema, and technical mistakes leading to overcorrection.1 Migrating nodules are rare; however, Beer3 reported a similar case.

Treatment of calcium hydroxylapatite nodules depends on differentiating a cause based on the time of onset. Early nodules that occur within 1 to 2 weeks of the injection usually represent incorrect positioning of the filler and can be treated by massaging the nodule. Other more invasive techniques involve aspiration or injection of sterile water. Late-onset nodules have shown response to corticosteroid injections. For inflammatory nodules of infectious origin, antibiotics can be useful. Surgical excision of the nodule rarely is required, as most nodules will resolve spontaneously, even without intervention.1,2

Radiologic findings of calcium hydroxylapatite appear as high-attenuation linear streaks or masses on CT (280–700 HU) and as low to intermediate signal intensity on T1- or T2-weighted sequences on magnetic resonance imaging. Oftentimes, calcium hydroxylapatite has a similar radiographic appearance to bone and can persist for 2 years or more on radiographic imaging, longer than they are clinically visible.4 The nodule formation from injection with calcium hydroxylapatite can mimic pathologic conditions such as miliary osteomas, myositis ossificans, heterotrophic/dystrophic calcifications, and foreign bodies on CT. Our patient’s CT findings of high attenuation linear streaks and nodules of similar signal intensity to bone were consistent with those previously described in the radiographic literature.

Calcium hydroxylapatite fillers have a good safety profile, but it is important to recognize that nodule formation is a common adverse event and that migration of nodules can occur. Practitioners should recognize this possibility in patients presenting with new masses after filler injection before advocating for potentially invasive and costly procedures and diagnostic modalities.

- Kadouch JA. Calcium hydroxylapatite: a review on safety and complications. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2017;16:152-161.

- Moulinets I, Arnaud E, Bui P, et al. Foreign body reaction to Radiesse: 2 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35:e37-40.

- Beer KR. Radiesse nodule of the lips from a distant injection site: report of a case and consideration of etiology and management. J Drugs Dermatol. 2007;6:846-847.

- Ginat DT, Schatz CJ. Imaging features of midface injectable fillers and associated complications. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2013;34:1488-1495.

To the Editor:

Calcium hydroxylapatite is an injectable filler approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for moderate to severe rhytides of the face and the treatment of facial lipodystrophy in patients with HIV.1 This long-lasting filler generally is well tolerated with minimal side effects; however, there have been reports of nodules or granulomatous formation following injection.2 We present a case of a migrating nodule following injection of a calcium hydroxylapatite filler that appeared ossified on radiographic imaging. We highlight this rarely reported phenomenon to increase awareness of this complication.

A 72-year-old woman presented to our clinic with a mass on the left cheek. The patient had a history of treatment with facial fillers but no notable medical conditions. She initially received hyaluronic acid injectable gel dermal filler twice—3 years apart—before switching to calcium hydroxylapatite injections twice—4 months apart—from an outside provider. One month after the second treatment, she noticed a mass on the left cheek and promptly returned to the provider who performed the calcium hydroxylapatite injections. The provider, who had originally injected in the infraorbital area, stated it was unlikely that the filler would have migrated to the mid cheek and referred the patient to a general dentist who suspected salivary gland pathology. The patient was referred to an oral and maxillofacial surgeon who suspected the mass was related to the parotid gland. Maxillofacial computed tomography (CT) revealed heterotopic ossification vs myositis ossificans, possibly related to the recent injection. The patient was eventually referred to the Division of Plastic Surgery, Department of Surgery, at the University of Texas Medical Branch (Galveston, Texas) for further evaluation. Physical examination revealed a 2×1-cm firm, mobile, nontender mass in the left cheek in the area of the buccinator muscles. The mass did not express any fluid and was most easily palpable from the oral cavity. Radiography findings showed that the calcium hydroxylapatite filler had migrated to this location and formed a nodule (Figure). Because calcium hydroxylapatite fillers generally last 12 to 18 months, we opted to observe the lesion for spontaneous resolution. Four months later, the patient presented to our clinic for follow-up and the mass had reduced in size and appeared to be spontaneously resolving.

We present a unique case of a migrating nodule that occurred after injection with calcium hydroxylapatite, which led to concern for neoplastic tumor formation. This complication is rare, and it is important for practitioners who inject calcium hydroxylapatite as well as those who these patients may be referred to for evaluation to be aware that migrating nodules can occur. This awareness can help reduce unnecessary referrals, medical procedures, and anxiety.

Calcium hydroxylapatite filler is composed of 30% calcium hydroxylapatite microspheres suspended in a 70% sodium carboxymethylcellulose gel. The water-soluble gel rapidly becomes absorbed upon injection; however, the microspheres form a scaffold for the production of newly synthesized collagen. The filling effect generally lasts 12 to 18 months.1

Calcium hydroxylapatite, similar to most fillers, generally is well tolerated with a low complication rate of 3%.1 Although nodule formation with calcium hydroxylapatite is rare, it is the most common adverse event and encompasses 96% of complications. The remaining 4% of complications include persistent inflammation, swelling, erythema, and technical mistakes leading to overcorrection.1 Migrating nodules are rare; however, Beer3 reported a similar case.

Treatment of calcium hydroxylapatite nodules depends on differentiating a cause based on the time of onset. Early nodules that occur within 1 to 2 weeks of the injection usually represent incorrect positioning of the filler and can be treated by massaging the nodule. Other more invasive techniques involve aspiration or injection of sterile water. Late-onset nodules have shown response to corticosteroid injections. For inflammatory nodules of infectious origin, antibiotics can be useful. Surgical excision of the nodule rarely is required, as most nodules will resolve spontaneously, even without intervention.1,2

Radiologic findings of calcium hydroxylapatite appear as high-attenuation linear streaks or masses on CT (280–700 HU) and as low to intermediate signal intensity on T1- or T2-weighted sequences on magnetic resonance imaging. Oftentimes, calcium hydroxylapatite has a similar radiographic appearance to bone and can persist for 2 years or more on radiographic imaging, longer than they are clinically visible.4 The nodule formation from injection with calcium hydroxylapatite can mimic pathologic conditions such as miliary osteomas, myositis ossificans, heterotrophic/dystrophic calcifications, and foreign bodies on CT. Our patient’s CT findings of high attenuation linear streaks and nodules of similar signal intensity to bone were consistent with those previously described in the radiographic literature.

Calcium hydroxylapatite fillers have a good safety profile, but it is important to recognize that nodule formation is a common adverse event and that migration of nodules can occur. Practitioners should recognize this possibility in patients presenting with new masses after filler injection before advocating for potentially invasive and costly procedures and diagnostic modalities.

To the Editor:

Calcium hydroxylapatite is an injectable filler approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for moderate to severe rhytides of the face and the treatment of facial lipodystrophy in patients with HIV.1 This long-lasting filler generally is well tolerated with minimal side effects; however, there have been reports of nodules or granulomatous formation following injection.2 We present a case of a migrating nodule following injection of a calcium hydroxylapatite filler that appeared ossified on radiographic imaging. We highlight this rarely reported phenomenon to increase awareness of this complication.

A 72-year-old woman presented to our clinic with a mass on the left cheek. The patient had a history of treatment with facial fillers but no notable medical conditions. She initially received hyaluronic acid injectable gel dermal filler twice—3 years apart—before switching to calcium hydroxylapatite injections twice—4 months apart—from an outside provider. One month after the second treatment, she noticed a mass on the left cheek and promptly returned to the provider who performed the calcium hydroxylapatite injections. The provider, who had originally injected in the infraorbital area, stated it was unlikely that the filler would have migrated to the mid cheek and referred the patient to a general dentist who suspected salivary gland pathology. The patient was referred to an oral and maxillofacial surgeon who suspected the mass was related to the parotid gland. Maxillofacial computed tomography (CT) revealed heterotopic ossification vs myositis ossificans, possibly related to the recent injection. The patient was eventually referred to the Division of Plastic Surgery, Department of Surgery, at the University of Texas Medical Branch (Galveston, Texas) for further evaluation. Physical examination revealed a 2×1-cm firm, mobile, nontender mass in the left cheek in the area of the buccinator muscles. The mass did not express any fluid and was most easily palpable from the oral cavity. Radiography findings showed that the calcium hydroxylapatite filler had migrated to this location and formed a nodule (Figure). Because calcium hydroxylapatite fillers generally last 12 to 18 months, we opted to observe the lesion for spontaneous resolution. Four months later, the patient presented to our clinic for follow-up and the mass had reduced in size and appeared to be spontaneously resolving.

We present a unique case of a migrating nodule that occurred after injection with calcium hydroxylapatite, which led to concern for neoplastic tumor formation. This complication is rare, and it is important for practitioners who inject calcium hydroxylapatite as well as those who these patients may be referred to for evaluation to be aware that migrating nodules can occur. This awareness can help reduce unnecessary referrals, medical procedures, and anxiety.

Calcium hydroxylapatite filler is composed of 30% calcium hydroxylapatite microspheres suspended in a 70% sodium carboxymethylcellulose gel. The water-soluble gel rapidly becomes absorbed upon injection; however, the microspheres form a scaffold for the production of newly synthesized collagen. The filling effect generally lasts 12 to 18 months.1

Calcium hydroxylapatite, similar to most fillers, generally is well tolerated with a low complication rate of 3%.1 Although nodule formation with calcium hydroxylapatite is rare, it is the most common adverse event and encompasses 96% of complications. The remaining 4% of complications include persistent inflammation, swelling, erythema, and technical mistakes leading to overcorrection.1 Migrating nodules are rare; however, Beer3 reported a similar case.