User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

Tense Bullae With Widespread Erosions

The Diagnosis: Linear IgA Bullous Dermatosis

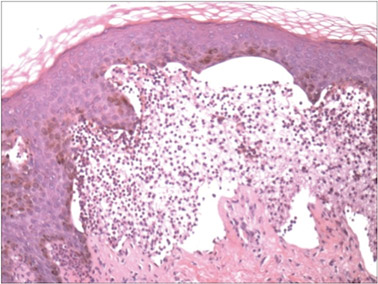

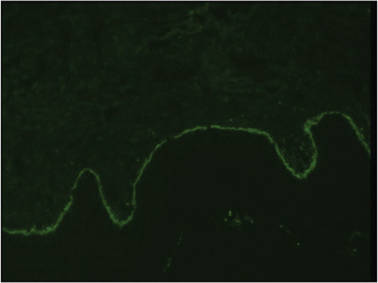

A biopsy specimen from an intact vesicle was obtained. Histologic findings showed a basket weave stratum corneum suggestive of an acute process. There was subepidermal separation with an inflammatory infiltrate of neutrophils (Figure 1). Direct immunofluorescence yielded a pattern of IgA deposition along the dermoepidermal junction (Figure 2). A diagnosis of linear IgA bullous dermatosis (LABD) was made. The patient was started on 100 mg daily of dapsone. The dose was subsequently increased to 175 mg twice daily, resulting in complete clearance. He became dermatologically disease free after 10 months and the dapsone was successfully tapered.

|

Linear IgA bullous dermatosis is an autoimmune subepidermal blistering disease with linear IgA deposits found along the basement membrane of the skin. There are 3 major categories of LABD: drug induced, systemic disorder related, and idiopathic.1 Patients with LABD present with a pruritic vesicobullous eruption that tends to favor the trunk, proximal extremities, and acral regions of the body. Mucous membrane lesions are present in less than 50% of patients.2 Linear IgA bullous dermatosis may resemble bullous pemphigoid, erythema multiforme, dermatitis herpetiformis, or toxic epidermal necrolysis. The gold standard for diagnosis is immunofluorescence staining that shows linear IgA deposition along the skin’s basement membrane.1 Prognosis for LABD is variable; there is risk for persistence and scarring.2 The drug-induced form of LABD is associated with clearance with the removal of the inciting agent.1

There are several autoimmune disorders that have been described in association with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).3 Autoimmune bullous dermatoses, while described, are very uncommon in the setting of HIV infection. Previously reported cases include bullous pemphigoid, epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, pemphigus herpetiformis, pemphigus vegetans, pemphigus vulgaris, and cicatricial pemphigoid.4-12 The presentation of LABD in an HIV-positive patient is extremely rare.

There are 3 proposed mechanisms by which HIV and autoimmune bullous dermatoses coexist: unregulated B-cell activation, loss of T-suppressor cell regulation, and molecular mimicry. In patients with HIV, infected macrophages increase production of IL-1 and IL-6, causing nonspecific stimulation of B cells. Further production of tumor necrosis factor and other lymphotoxins may kill CD8+ T-suppressor cells, which further reduces B-cell regulation and production of nonspecific antibodies. Unregulated B-cell activation could lead to proliferation of antiself-specific B cells and autoantibodies. Additionally, various autoantibodies may arise due to mimicry between HIV antigens and human proteins. Some of the antibodies produced may be cytotoxic antilymphocyte antibodies that further disrupt B-cell regulation.13,14

Zandman-Goddard and Shoenfeld14 proposed a staging system of autoimmune disease and HIV with respect to CD4 count and viral load. Stage I is clinical latency of HIV, with a high CD4 count (>500 cells/mm3) and high viral load, which correlates with an acute infection of HIV and an intact immune system. Autoimmune disease can be seen in this stage. Stage II is cellular response, a quiescent period without overt manifestations of AIDS. The CD4 count is declining (200–499 cells/mm3), indicating immunosuppression, and the viral count is high. Autoimmune disease can occur and typically includes immune complex–mediated disease and vasculitis. Stage III is immune deficiency. The CD4 count is low (<200 cells/mm3), viral load is high, and AIDS develops. Autoimmune disease is not seen during this stage. Stage IV is the period of immune restoration following the advent of highly active antiretroviral therapy. There is a high CD4 count (>500 cells/mm3) and low viral load. There is a resurgence of autoimmune disease in this stage. Autoimmune disease can occur with an immune system capable of B- and T-cell interactions and a normal CD4 count. Autoimmunity is possible in stages I, II, and IV.14 Our patient developed bullous disease in stage II.

Although uncommon, autoimmune disease is possible in the setting of immune deficiency. The presence of autoimmune disease in a patient with HIV can only be seen during certain stages of infection. Knowledge of the possible scenarios of autoimmune disease can assist the clinician with monitoring status of the HIV infection or immune reconstitution.

1. Bouldin MB, Clowers-Webb HE, Davis JL, et al. Naproxen-associated linear IgA bullous dermatosis: case report and review. Mayo Clin Proc. 2000;75:967-970.

2. Nousari HC, Kimyai-Asadi A, Caeiro JP, et al. Clinical, demographic, and immunohistologic features of vancomycin-induced linear IgA bullous disease of the skin: report of 2 cases and review of the literature. Medicine. 1999;78:1-8.

3. Gala S, Fulcher DA. How HIV leads to autoimmune disorders. Med J Aust. 1996;164:224-226.

4. Lateef A, Packles MR, White SM, et al. Pemphigus vegetans in association with human immunodeficiency virus. Int J Dermatol. 1999;38:778-781.

5. Levy PM, Balavoine JF, Salomon D, et al. Ritodrine-responsive bullous pemphigoing in a patient with AIDS-related complex. Br J Dermatol. 1986;114:635-636.

6. Bull RH, Fallowfield ME, Marsden RA. Autoimmune blistering diseases associated with HIV infection. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19:47-50.

7. Chou K, Kauh YC, Jacoby RA, et al. Autoimmune bullous disease in a patient with HIV infection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;24:1022-1023.

8. Mahé A, Flageul B, Prost C, et al. Pemphigus vegetans in an HIV-1-infected man. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19:447.

9. Capizzi R, Marasca G, De Luca A, et al. Pemphigus vulgaris in a human-immunodeficiency-virus-infected patient. Dermatology. 1998;197:97-98.

10. Splaver A, Silos S, Lowell B, et al. Case report: pemphigus vulgaris in a patient infected with HIV. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2000;14:295-296.

11. Hodgson TA, Fidler SJ, Speight PM, et al. Oral pemphigus vulgaris associated with HIV infection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:313-315.

12. Demathé A, Arede LT, Miyahara GI. Mucous membrane pemphigoid in HIV patient: a case report. Cases J. 2008;1:345.

13. Etzioni A. Immune deficiency and autoimmunity. Autoimmun Rev. 2003;2:364-369.

14. Zandman-Goddard G, Shoenfeld Y. HIV and autoimmunity. Autoimmun Rev. 2002;1:329-337.

The Diagnosis: Linear IgA Bullous Dermatosis

A biopsy specimen from an intact vesicle was obtained. Histologic findings showed a basket weave stratum corneum suggestive of an acute process. There was subepidermal separation with an inflammatory infiltrate of neutrophils (Figure 1). Direct immunofluorescence yielded a pattern of IgA deposition along the dermoepidermal junction (Figure 2). A diagnosis of linear IgA bullous dermatosis (LABD) was made. The patient was started on 100 mg daily of dapsone. The dose was subsequently increased to 175 mg twice daily, resulting in complete clearance. He became dermatologically disease free after 10 months and the dapsone was successfully tapered.

|

Linear IgA bullous dermatosis is an autoimmune subepidermal blistering disease with linear IgA deposits found along the basement membrane of the skin. There are 3 major categories of LABD: drug induced, systemic disorder related, and idiopathic.1 Patients with LABD present with a pruritic vesicobullous eruption that tends to favor the trunk, proximal extremities, and acral regions of the body. Mucous membrane lesions are present in less than 50% of patients.2 Linear IgA bullous dermatosis may resemble bullous pemphigoid, erythema multiforme, dermatitis herpetiformis, or toxic epidermal necrolysis. The gold standard for diagnosis is immunofluorescence staining that shows linear IgA deposition along the skin’s basement membrane.1 Prognosis for LABD is variable; there is risk for persistence and scarring.2 The drug-induced form of LABD is associated with clearance with the removal of the inciting agent.1

There are several autoimmune disorders that have been described in association with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).3 Autoimmune bullous dermatoses, while described, are very uncommon in the setting of HIV infection. Previously reported cases include bullous pemphigoid, epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, pemphigus herpetiformis, pemphigus vegetans, pemphigus vulgaris, and cicatricial pemphigoid.4-12 The presentation of LABD in an HIV-positive patient is extremely rare.

There are 3 proposed mechanisms by which HIV and autoimmune bullous dermatoses coexist: unregulated B-cell activation, loss of T-suppressor cell regulation, and molecular mimicry. In patients with HIV, infected macrophages increase production of IL-1 and IL-6, causing nonspecific stimulation of B cells. Further production of tumor necrosis factor and other lymphotoxins may kill CD8+ T-suppressor cells, which further reduces B-cell regulation and production of nonspecific antibodies. Unregulated B-cell activation could lead to proliferation of antiself-specific B cells and autoantibodies. Additionally, various autoantibodies may arise due to mimicry between HIV antigens and human proteins. Some of the antibodies produced may be cytotoxic antilymphocyte antibodies that further disrupt B-cell regulation.13,14

Zandman-Goddard and Shoenfeld14 proposed a staging system of autoimmune disease and HIV with respect to CD4 count and viral load. Stage I is clinical latency of HIV, with a high CD4 count (>500 cells/mm3) and high viral load, which correlates with an acute infection of HIV and an intact immune system. Autoimmune disease can be seen in this stage. Stage II is cellular response, a quiescent period without overt manifestations of AIDS. The CD4 count is declining (200–499 cells/mm3), indicating immunosuppression, and the viral count is high. Autoimmune disease can occur and typically includes immune complex–mediated disease and vasculitis. Stage III is immune deficiency. The CD4 count is low (<200 cells/mm3), viral load is high, and AIDS develops. Autoimmune disease is not seen during this stage. Stage IV is the period of immune restoration following the advent of highly active antiretroviral therapy. There is a high CD4 count (>500 cells/mm3) and low viral load. There is a resurgence of autoimmune disease in this stage. Autoimmune disease can occur with an immune system capable of B- and T-cell interactions and a normal CD4 count. Autoimmunity is possible in stages I, II, and IV.14 Our patient developed bullous disease in stage II.

Although uncommon, autoimmune disease is possible in the setting of immune deficiency. The presence of autoimmune disease in a patient with HIV can only be seen during certain stages of infection. Knowledge of the possible scenarios of autoimmune disease can assist the clinician with monitoring status of the HIV infection or immune reconstitution.

The Diagnosis: Linear IgA Bullous Dermatosis

A biopsy specimen from an intact vesicle was obtained. Histologic findings showed a basket weave stratum corneum suggestive of an acute process. There was subepidermal separation with an inflammatory infiltrate of neutrophils (Figure 1). Direct immunofluorescence yielded a pattern of IgA deposition along the dermoepidermal junction (Figure 2). A diagnosis of linear IgA bullous dermatosis (LABD) was made. The patient was started on 100 mg daily of dapsone. The dose was subsequently increased to 175 mg twice daily, resulting in complete clearance. He became dermatologically disease free after 10 months and the dapsone was successfully tapered.

|

Linear IgA bullous dermatosis is an autoimmune subepidermal blistering disease with linear IgA deposits found along the basement membrane of the skin. There are 3 major categories of LABD: drug induced, systemic disorder related, and idiopathic.1 Patients with LABD present with a pruritic vesicobullous eruption that tends to favor the trunk, proximal extremities, and acral regions of the body. Mucous membrane lesions are present in less than 50% of patients.2 Linear IgA bullous dermatosis may resemble bullous pemphigoid, erythema multiforme, dermatitis herpetiformis, or toxic epidermal necrolysis. The gold standard for diagnosis is immunofluorescence staining that shows linear IgA deposition along the skin’s basement membrane.1 Prognosis for LABD is variable; there is risk for persistence and scarring.2 The drug-induced form of LABD is associated with clearance with the removal of the inciting agent.1

There are several autoimmune disorders that have been described in association with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).3 Autoimmune bullous dermatoses, while described, are very uncommon in the setting of HIV infection. Previously reported cases include bullous pemphigoid, epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, pemphigus herpetiformis, pemphigus vegetans, pemphigus vulgaris, and cicatricial pemphigoid.4-12 The presentation of LABD in an HIV-positive patient is extremely rare.

There are 3 proposed mechanisms by which HIV and autoimmune bullous dermatoses coexist: unregulated B-cell activation, loss of T-suppressor cell regulation, and molecular mimicry. In patients with HIV, infected macrophages increase production of IL-1 and IL-6, causing nonspecific stimulation of B cells. Further production of tumor necrosis factor and other lymphotoxins may kill CD8+ T-suppressor cells, which further reduces B-cell regulation and production of nonspecific antibodies. Unregulated B-cell activation could lead to proliferation of antiself-specific B cells and autoantibodies. Additionally, various autoantibodies may arise due to mimicry between HIV antigens and human proteins. Some of the antibodies produced may be cytotoxic antilymphocyte antibodies that further disrupt B-cell regulation.13,14

Zandman-Goddard and Shoenfeld14 proposed a staging system of autoimmune disease and HIV with respect to CD4 count and viral load. Stage I is clinical latency of HIV, with a high CD4 count (>500 cells/mm3) and high viral load, which correlates with an acute infection of HIV and an intact immune system. Autoimmune disease can be seen in this stage. Stage II is cellular response, a quiescent period without overt manifestations of AIDS. The CD4 count is declining (200–499 cells/mm3), indicating immunosuppression, and the viral count is high. Autoimmune disease can occur and typically includes immune complex–mediated disease and vasculitis. Stage III is immune deficiency. The CD4 count is low (<200 cells/mm3), viral load is high, and AIDS develops. Autoimmune disease is not seen during this stage. Stage IV is the period of immune restoration following the advent of highly active antiretroviral therapy. There is a high CD4 count (>500 cells/mm3) and low viral load. There is a resurgence of autoimmune disease in this stage. Autoimmune disease can occur with an immune system capable of B- and T-cell interactions and a normal CD4 count. Autoimmunity is possible in stages I, II, and IV.14 Our patient developed bullous disease in stage II.

Although uncommon, autoimmune disease is possible in the setting of immune deficiency. The presence of autoimmune disease in a patient with HIV can only be seen during certain stages of infection. Knowledge of the possible scenarios of autoimmune disease can assist the clinician with monitoring status of the HIV infection or immune reconstitution.

1. Bouldin MB, Clowers-Webb HE, Davis JL, et al. Naproxen-associated linear IgA bullous dermatosis: case report and review. Mayo Clin Proc. 2000;75:967-970.

2. Nousari HC, Kimyai-Asadi A, Caeiro JP, et al. Clinical, demographic, and immunohistologic features of vancomycin-induced linear IgA bullous disease of the skin: report of 2 cases and review of the literature. Medicine. 1999;78:1-8.

3. Gala S, Fulcher DA. How HIV leads to autoimmune disorders. Med J Aust. 1996;164:224-226.

4. Lateef A, Packles MR, White SM, et al. Pemphigus vegetans in association with human immunodeficiency virus. Int J Dermatol. 1999;38:778-781.

5. Levy PM, Balavoine JF, Salomon D, et al. Ritodrine-responsive bullous pemphigoing in a patient with AIDS-related complex. Br J Dermatol. 1986;114:635-636.

6. Bull RH, Fallowfield ME, Marsden RA. Autoimmune blistering diseases associated with HIV infection. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19:47-50.

7. Chou K, Kauh YC, Jacoby RA, et al. Autoimmune bullous disease in a patient with HIV infection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;24:1022-1023.

8. Mahé A, Flageul B, Prost C, et al. Pemphigus vegetans in an HIV-1-infected man. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19:447.

9. Capizzi R, Marasca G, De Luca A, et al. Pemphigus vulgaris in a human-immunodeficiency-virus-infected patient. Dermatology. 1998;197:97-98.

10. Splaver A, Silos S, Lowell B, et al. Case report: pemphigus vulgaris in a patient infected with HIV. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2000;14:295-296.

11. Hodgson TA, Fidler SJ, Speight PM, et al. Oral pemphigus vulgaris associated with HIV infection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:313-315.

12. Demathé A, Arede LT, Miyahara GI. Mucous membrane pemphigoid in HIV patient: a case report. Cases J. 2008;1:345.

13. Etzioni A. Immune deficiency and autoimmunity. Autoimmun Rev. 2003;2:364-369.

14. Zandman-Goddard G, Shoenfeld Y. HIV and autoimmunity. Autoimmun Rev. 2002;1:329-337.

1. Bouldin MB, Clowers-Webb HE, Davis JL, et al. Naproxen-associated linear IgA bullous dermatosis: case report and review. Mayo Clin Proc. 2000;75:967-970.

2. Nousari HC, Kimyai-Asadi A, Caeiro JP, et al. Clinical, demographic, and immunohistologic features of vancomycin-induced linear IgA bullous disease of the skin: report of 2 cases and review of the literature. Medicine. 1999;78:1-8.

3. Gala S, Fulcher DA. How HIV leads to autoimmune disorders. Med J Aust. 1996;164:224-226.

4. Lateef A, Packles MR, White SM, et al. Pemphigus vegetans in association with human immunodeficiency virus. Int J Dermatol. 1999;38:778-781.

5. Levy PM, Balavoine JF, Salomon D, et al. Ritodrine-responsive bullous pemphigoing in a patient with AIDS-related complex. Br J Dermatol. 1986;114:635-636.

6. Bull RH, Fallowfield ME, Marsden RA. Autoimmune blistering diseases associated with HIV infection. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19:47-50.

7. Chou K, Kauh YC, Jacoby RA, et al. Autoimmune bullous disease in a patient with HIV infection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;24:1022-1023.

8. Mahé A, Flageul B, Prost C, et al. Pemphigus vegetans in an HIV-1-infected man. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19:447.

9. Capizzi R, Marasca G, De Luca A, et al. Pemphigus vulgaris in a human-immunodeficiency-virus-infected patient. Dermatology. 1998;197:97-98.

10. Splaver A, Silos S, Lowell B, et al. Case report: pemphigus vulgaris in a patient infected with HIV. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2000;14:295-296.

11. Hodgson TA, Fidler SJ, Speight PM, et al. Oral pemphigus vulgaris associated with HIV infection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:313-315.

12. Demathé A, Arede LT, Miyahara GI. Mucous membrane pemphigoid in HIV patient: a case report. Cases J. 2008;1:345.

13. Etzioni A. Immune deficiency and autoimmunity. Autoimmun Rev. 2003;2:364-369.

14. Zandman-Goddard G, Shoenfeld Y. HIV and autoimmunity. Autoimmun Rev. 2002;1:329-337.

A 50-year-old black man presented with a new-onset widespread pruritic bullous eruption 7 months after being diagnosed with human immunodeficiency virus. The CD4 lymphocyte count was 421 cells/mm3 and viral load was 7818 copies/mL. Results of a viral culture were negative for herpes simplex virus. Dermatologic examination revealed numerous intact tense bullae as well as scattered erosions on the trunk and extremities. Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation was prominent, with some areas of hypopigmentation and depigmentation.

The Role of Diet in Acne: We Get It, But What Should We Do About It?

The role of diet in acne, both as a causative agent and therapeutic intervention, has been the topic of discussion in both the dermatology community as well as the laypress for decades. There is ample evidence highlighting the association of acne and high glycemic loads, certain dairy products, and refined sugar product ingestion. In the most recent edition to the repository, Grossi et al (J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. doi:10.1111/jdv.12878) reanalyzed data from their case-control study among young patients (age range, 10–24 years; N=563) with a diagnosis of moderate to severe acne versus control (participants with no or mild acne) between March 2009 and February 2010 that was originally published in 2012 (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:1129-1135). The unique element was how they evaluated the data. The investigators utilized a semantic connectivity map approach derived from artificial neural network computational models, which allowed for a better understanding of the complex connections between all of the studied variables. (The assumption of a given relation between any variables would not influence the results.) The data were presented on an Auto Semantic Connectivity Map that resembled a 4-leaf clover, representing “explanatory” information pertaining to the cases and controls and “residual” information of less importance. It is worth seeing in the manuscript to better appreciate the data.

What did they find? There is a close association between moderate to severe acne and a high intake of milk, other dairy products, sweets, and chocolate. Obesity and the low consumption of fish were linked to the presence of moderate to severe acne, while high consumption of fish (1 d/wk or more), high intake of fruits and vegetables, and body mass index lower than 18.5 were all associated with limited or no acne.

What’s the issue?

By adopting a different analytic approach, it was shown once again that diet plays a substantial role in acne, indicating that some food items may stimulate selected acne-promoting pathways. But what now? Here is the evidence yet again, but where is the medicine of “evidence-based medicine”? It is time to recommend guidelines for screening and counseling. In a recent article, Bronsnick et al (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:1039.e1-1039.e12) found that the level of evidence supporting the benefit of a low-glycemic, low-carbohydrate diet was sufficient to recommend to acne patients. How many dermatologists feel comfortable providing dietary guidance to their acne patients? A consensus statement from relevant organizations such as the American Academy of Dermatology, the Society for Investigative Dermatology, and the American Acne & Rosacea Society that provides tangible and realistic screening tools to identify those who would benefit from dietary intervention and implementation and practice guidelines for Dr. Derm seeing 40 to 50 patients a day in Springfield, USA (homage to The Simpsons) based on the level of evidence available would be useful. What are your thoughts?

We want to know your views! Tell us what you think.

Suggested Readings

- Bowe WP, Joshi SS, Shalita AR. Diet and acne. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:124-141.

- Ferdowsian HR, Levin S. Does diet really affect acne? Skin Therapy Lett. 2010;15:1-2, 5.

- Melnik B. Dietary intervention in acne: attenuation of increased mTORC1 signaling promoted by Western diet. Dermatoendocrinol. 2012;4:20-32.

- Veith WB, Silverberg NB. The association of acne vulgaris with diet. Cutis. 2011;88:84-91.

The role of diet in acne, both as a causative agent and therapeutic intervention, has been the topic of discussion in both the dermatology community as well as the laypress for decades. There is ample evidence highlighting the association of acne and high glycemic loads, certain dairy products, and refined sugar product ingestion. In the most recent edition to the repository, Grossi et al (J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. doi:10.1111/jdv.12878) reanalyzed data from their case-control study among young patients (age range, 10–24 years; N=563) with a diagnosis of moderate to severe acne versus control (participants with no or mild acne) between March 2009 and February 2010 that was originally published in 2012 (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:1129-1135). The unique element was how they evaluated the data. The investigators utilized a semantic connectivity map approach derived from artificial neural network computational models, which allowed for a better understanding of the complex connections between all of the studied variables. (The assumption of a given relation between any variables would not influence the results.) The data were presented on an Auto Semantic Connectivity Map that resembled a 4-leaf clover, representing “explanatory” information pertaining to the cases and controls and “residual” information of less importance. It is worth seeing in the manuscript to better appreciate the data.

What did they find? There is a close association between moderate to severe acne and a high intake of milk, other dairy products, sweets, and chocolate. Obesity and the low consumption of fish were linked to the presence of moderate to severe acne, while high consumption of fish (1 d/wk or more), high intake of fruits and vegetables, and body mass index lower than 18.5 were all associated with limited or no acne.

What’s the issue?

By adopting a different analytic approach, it was shown once again that diet plays a substantial role in acne, indicating that some food items may stimulate selected acne-promoting pathways. But what now? Here is the evidence yet again, but where is the medicine of “evidence-based medicine”? It is time to recommend guidelines for screening and counseling. In a recent article, Bronsnick et al (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:1039.e1-1039.e12) found that the level of evidence supporting the benefit of a low-glycemic, low-carbohydrate diet was sufficient to recommend to acne patients. How many dermatologists feel comfortable providing dietary guidance to their acne patients? A consensus statement from relevant organizations such as the American Academy of Dermatology, the Society for Investigative Dermatology, and the American Acne & Rosacea Society that provides tangible and realistic screening tools to identify those who would benefit from dietary intervention and implementation and practice guidelines for Dr. Derm seeing 40 to 50 patients a day in Springfield, USA (homage to The Simpsons) based on the level of evidence available would be useful. What are your thoughts?

We want to know your views! Tell us what you think.

Suggested Readings

- Bowe WP, Joshi SS, Shalita AR. Diet and acne. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:124-141.

- Ferdowsian HR, Levin S. Does diet really affect acne? Skin Therapy Lett. 2010;15:1-2, 5.

- Melnik B. Dietary intervention in acne: attenuation of increased mTORC1 signaling promoted by Western diet. Dermatoendocrinol. 2012;4:20-32.

- Veith WB, Silverberg NB. The association of acne vulgaris with diet. Cutis. 2011;88:84-91.

The role of diet in acne, both as a causative agent and therapeutic intervention, has been the topic of discussion in both the dermatology community as well as the laypress for decades. There is ample evidence highlighting the association of acne and high glycemic loads, certain dairy products, and refined sugar product ingestion. In the most recent edition to the repository, Grossi et al (J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. doi:10.1111/jdv.12878) reanalyzed data from their case-control study among young patients (age range, 10–24 years; N=563) with a diagnosis of moderate to severe acne versus control (participants with no or mild acne) between March 2009 and February 2010 that was originally published in 2012 (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:1129-1135). The unique element was how they evaluated the data. The investigators utilized a semantic connectivity map approach derived from artificial neural network computational models, which allowed for a better understanding of the complex connections between all of the studied variables. (The assumption of a given relation between any variables would not influence the results.) The data were presented on an Auto Semantic Connectivity Map that resembled a 4-leaf clover, representing “explanatory” information pertaining to the cases and controls and “residual” information of less importance. It is worth seeing in the manuscript to better appreciate the data.

What did they find? There is a close association between moderate to severe acne and a high intake of milk, other dairy products, sweets, and chocolate. Obesity and the low consumption of fish were linked to the presence of moderate to severe acne, while high consumption of fish (1 d/wk or more), high intake of fruits and vegetables, and body mass index lower than 18.5 were all associated with limited or no acne.

What’s the issue?

By adopting a different analytic approach, it was shown once again that diet plays a substantial role in acne, indicating that some food items may stimulate selected acne-promoting pathways. But what now? Here is the evidence yet again, but where is the medicine of “evidence-based medicine”? It is time to recommend guidelines for screening and counseling. In a recent article, Bronsnick et al (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:1039.e1-1039.e12) found that the level of evidence supporting the benefit of a low-glycemic, low-carbohydrate diet was sufficient to recommend to acne patients. How many dermatologists feel comfortable providing dietary guidance to their acne patients? A consensus statement from relevant organizations such as the American Academy of Dermatology, the Society for Investigative Dermatology, and the American Acne & Rosacea Society that provides tangible and realistic screening tools to identify those who would benefit from dietary intervention and implementation and practice guidelines for Dr. Derm seeing 40 to 50 patients a day in Springfield, USA (homage to The Simpsons) based on the level of evidence available would be useful. What are your thoughts?

We want to know your views! Tell us what you think.

Suggested Readings

- Bowe WP, Joshi SS, Shalita AR. Diet and acne. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:124-141.

- Ferdowsian HR, Levin S. Does diet really affect acne? Skin Therapy Lett. 2010;15:1-2, 5.

- Melnik B. Dietary intervention in acne: attenuation of increased mTORC1 signaling promoted by Western diet. Dermatoendocrinol. 2012;4:20-32.

- Veith WB, Silverberg NB. The association of acne vulgaris with diet. Cutis. 2011;88:84-91.

The Redness Remover

Tanghetti et al (J Drugs Dermatol. 2015;14:33-40) discuss the use of topical brimonidine for the redness associated with rosacea. Brimonidine is the newest therapeutic to combat the erythema associated with rosacea of all subtypes. It is a topical α2-adrenergic agonist that causes peripheral vasoconstriction via a direct effect on smooth muscle receptors. The authors describe 2 large studies that studied the safety and efficacy of topical brimonidine and also give consensus recommendations regarding optimal utilization while minimizing adverse effects, such as the “rebound” phenomena described. It is important to note that it is not a traditional rebound effect, as it does not occur once the medication has stopped; however, it is a worsening of the erythema during active treatment with brimonidine. The authors discuss the various cases reported to the manufacturer after the medication was released. The most frequently associated side effects reported were erythema in almost all cases, flushing, feeling of heat or burning sensation, and rarely pain. Other issues such as dermatitis, pruritus, facial swelling, and pallor were seen in less than 10% of reports each.

These rebound effects were most likely to occur in the first 15 days after initiation of therapy, mainly in the first week. They also were noticed at 2 other time points—3 to 6 hours and 10 to 12 hours after application—which allowed the identification of 2 types of reactions based on the time to onset postapplication: appearing within 3 to 6 hours and observed after 10 to 12 hours. These events have been given new names. “Paradoxical erythema” is the redness appearing within 3 to 6 hours after application, which can be worse than baseline. “Exaggerated recurrence of erythema” is the redness that is greater than baseline and occurs as therapy wears off, approximately 10 to 12 hours after application. Allergic contact dermatitis also has been associated with the medication and can therefore be a source of redness 3 to 4 months after initiation.

What’s the issue?

The erythema associated with rosacea can be a distressing symptom for both the patient and the dermatologist. It can be difficult to treat and quite often recalcitrant to multiple treatments. Although pulsed dye laser is an effective therapy for treating telangiectases and dilated blood vessels, it can be expensive for many patients. Topical brimonidine represents a novel therapeutic to combat one of the most remarkable symptoms of rosacea. However, because of the possibility of this increased redness after use, Tanghetti et al suggest the following treatment algorithm:

- “Assess” the patient and rule out other causes of redness or associated conditions, such as seborrheic dermatitis or lupus.

- “Educate” the patient regarding the known triggers of rosacea flair and how they can be best avoided. Also educate that brimonidine only treats redness and not the papules, pustules, or other symptoms of rosacea.

- “Inhibit” inflammation that is currently present using gentle skin care practices, mild cleansers, and barrier-restoring emollients.

- “Optimize” the application of brimonidine. Instruct how to apply a pea-sized amount in the morning or how patients can best time the application to coincide with daily events or social events.

- “Understand” that worsening redness may occur, which can be key to patient satisfaction. Patients should be made aware that there is a risk for worsening redness in 10% to 20% of patients. It usually occurs within the first 2 weeks of starting the medication and it may be seen soon after application (3–6 hours) or after treatment has subsided (10–12 hours). Generally this worsening will subside within 12 to 24 hours after discontinuation. Also symptoms can be treated throughout with the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications, antihistamines, topical calcineurin inhibitors, and topical steroids, if necessary.

What has been your experience with brimonidine gel and how do you manage these patients?

Tanghetti et al (J Drugs Dermatol. 2015;14:33-40) discuss the use of topical brimonidine for the redness associated with rosacea. Brimonidine is the newest therapeutic to combat the erythema associated with rosacea of all subtypes. It is a topical α2-adrenergic agonist that causes peripheral vasoconstriction via a direct effect on smooth muscle receptors. The authors describe 2 large studies that studied the safety and efficacy of topical brimonidine and also give consensus recommendations regarding optimal utilization while minimizing adverse effects, such as the “rebound” phenomena described. It is important to note that it is not a traditional rebound effect, as it does not occur once the medication has stopped; however, it is a worsening of the erythema during active treatment with brimonidine. The authors discuss the various cases reported to the manufacturer after the medication was released. The most frequently associated side effects reported were erythema in almost all cases, flushing, feeling of heat or burning sensation, and rarely pain. Other issues such as dermatitis, pruritus, facial swelling, and pallor were seen in less than 10% of reports each.

These rebound effects were most likely to occur in the first 15 days after initiation of therapy, mainly in the first week. They also were noticed at 2 other time points—3 to 6 hours and 10 to 12 hours after application—which allowed the identification of 2 types of reactions based on the time to onset postapplication: appearing within 3 to 6 hours and observed after 10 to 12 hours. These events have been given new names. “Paradoxical erythema” is the redness appearing within 3 to 6 hours after application, which can be worse than baseline. “Exaggerated recurrence of erythema” is the redness that is greater than baseline and occurs as therapy wears off, approximately 10 to 12 hours after application. Allergic contact dermatitis also has been associated with the medication and can therefore be a source of redness 3 to 4 months after initiation.

What’s the issue?

The erythema associated with rosacea can be a distressing symptom for both the patient and the dermatologist. It can be difficult to treat and quite often recalcitrant to multiple treatments. Although pulsed dye laser is an effective therapy for treating telangiectases and dilated blood vessels, it can be expensive for many patients. Topical brimonidine represents a novel therapeutic to combat one of the most remarkable symptoms of rosacea. However, because of the possibility of this increased redness after use, Tanghetti et al suggest the following treatment algorithm:

- “Assess” the patient and rule out other causes of redness or associated conditions, such as seborrheic dermatitis or lupus.

- “Educate” the patient regarding the known triggers of rosacea flair and how they can be best avoided. Also educate that brimonidine only treats redness and not the papules, pustules, or other symptoms of rosacea.

- “Inhibit” inflammation that is currently present using gentle skin care practices, mild cleansers, and barrier-restoring emollients.

- “Optimize” the application of brimonidine. Instruct how to apply a pea-sized amount in the morning or how patients can best time the application to coincide with daily events or social events.

- “Understand” that worsening redness may occur, which can be key to patient satisfaction. Patients should be made aware that there is a risk for worsening redness in 10% to 20% of patients. It usually occurs within the first 2 weeks of starting the medication and it may be seen soon after application (3–6 hours) or after treatment has subsided (10–12 hours). Generally this worsening will subside within 12 to 24 hours after discontinuation. Also symptoms can be treated throughout with the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications, antihistamines, topical calcineurin inhibitors, and topical steroids, if necessary.

What has been your experience with brimonidine gel and how do you manage these patients?

Tanghetti et al (J Drugs Dermatol. 2015;14:33-40) discuss the use of topical brimonidine for the redness associated with rosacea. Brimonidine is the newest therapeutic to combat the erythema associated with rosacea of all subtypes. It is a topical α2-adrenergic agonist that causes peripheral vasoconstriction via a direct effect on smooth muscle receptors. The authors describe 2 large studies that studied the safety and efficacy of topical brimonidine and also give consensus recommendations regarding optimal utilization while minimizing adverse effects, such as the “rebound” phenomena described. It is important to note that it is not a traditional rebound effect, as it does not occur once the medication has stopped; however, it is a worsening of the erythema during active treatment with brimonidine. The authors discuss the various cases reported to the manufacturer after the medication was released. The most frequently associated side effects reported were erythema in almost all cases, flushing, feeling of heat or burning sensation, and rarely pain. Other issues such as dermatitis, pruritus, facial swelling, and pallor were seen in less than 10% of reports each.

These rebound effects were most likely to occur in the first 15 days after initiation of therapy, mainly in the first week. They also were noticed at 2 other time points—3 to 6 hours and 10 to 12 hours after application—which allowed the identification of 2 types of reactions based on the time to onset postapplication: appearing within 3 to 6 hours and observed after 10 to 12 hours. These events have been given new names. “Paradoxical erythema” is the redness appearing within 3 to 6 hours after application, which can be worse than baseline. “Exaggerated recurrence of erythema” is the redness that is greater than baseline and occurs as therapy wears off, approximately 10 to 12 hours after application. Allergic contact dermatitis also has been associated with the medication and can therefore be a source of redness 3 to 4 months after initiation.

What’s the issue?

The erythema associated with rosacea can be a distressing symptom for both the patient and the dermatologist. It can be difficult to treat and quite often recalcitrant to multiple treatments. Although pulsed dye laser is an effective therapy for treating telangiectases and dilated blood vessels, it can be expensive for many patients. Topical brimonidine represents a novel therapeutic to combat one of the most remarkable symptoms of rosacea. However, because of the possibility of this increased redness after use, Tanghetti et al suggest the following treatment algorithm:

- “Assess” the patient and rule out other causes of redness or associated conditions, such as seborrheic dermatitis or lupus.

- “Educate” the patient regarding the known triggers of rosacea flair and how they can be best avoided. Also educate that brimonidine only treats redness and not the papules, pustules, or other symptoms of rosacea.

- “Inhibit” inflammation that is currently present using gentle skin care practices, mild cleansers, and barrier-restoring emollients.

- “Optimize” the application of brimonidine. Instruct how to apply a pea-sized amount in the morning or how patients can best time the application to coincide with daily events or social events.

- “Understand” that worsening redness may occur, which can be key to patient satisfaction. Patients should be made aware that there is a risk for worsening redness in 10% to 20% of patients. It usually occurs within the first 2 weeks of starting the medication and it may be seen soon after application (3–6 hours) or after treatment has subsided (10–12 hours). Generally this worsening will subside within 12 to 24 hours after discontinuation. Also symptoms can be treated throughout with the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications, antihistamines, topical calcineurin inhibitors, and topical steroids, if necessary.

What has been your experience with brimonidine gel and how do you manage these patients?

The Rosacea Patient Journey

For more information, access Dr. Feldman's article from the January 2015 issue, "The Rosacea Patient Journey: A Novel Approach to Conceptualizing Patient Experiences."

For more information, access Dr. Feldman's article from the January 2015 issue, "The Rosacea Patient Journey: A Novel Approach to Conceptualizing Patient Experiences."

For more information, access Dr. Feldman's article from the January 2015 issue, "The Rosacea Patient Journey: A Novel Approach to Conceptualizing Patient Experiences."

Manage Your Dermatology Practice: Managing Difficult Patient Encounters

Difficult patient encounters in the dermatology office can be navigated through honest physician-patient communication regarding problems within the office and insurance coverage. Dr. Gary Goldenberg provides tips on communicating with patients about cosmetic procedures that may be noncovered services as well as diagnoses such as melanoma and psoriasis. He also advises how to work through a long list of questions patients may bring to their visit.

Difficult patient encounters in the dermatology office can be navigated through honest physician-patient communication regarding problems within the office and insurance coverage. Dr. Gary Goldenberg provides tips on communicating with patients about cosmetic procedures that may be noncovered services as well as diagnoses such as melanoma and psoriasis. He also advises how to work through a long list of questions patients may bring to their visit.

Difficult patient encounters in the dermatology office can be navigated through honest physician-patient communication regarding problems within the office and insurance coverage. Dr. Gary Goldenberg provides tips on communicating with patients about cosmetic procedures that may be noncovered services as well as diagnoses such as melanoma and psoriasis. He also advises how to work through a long list of questions patients may bring to their visit.

Tonsillectomy and Psoriasis

We are all aware that infections, particularly streptococcal infection, can be associated with psoriasis, especially the guttate variety. A logical question emanating from this fact is: Would tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy have any impact on psoriasis and its symptoms?

In a November 2014 article published online in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, Rachakonda et al (doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2014.10.013) performed an extensive literature review to evaluate if tonsillectomy reduces psoriasis severity. The authors searched the following sources: MEDLINE, CINAHL, Cochrane, Embase, Web of Science, and Ovid databases (August 1, 1960, to September 12, 2013). In addition, they executed a manual search of selected references. Through this process, they identified observational studies and clinical trials examining psoriasis after tonsillectomy.

In the analysis, the authors included data from 20 articles from the 53 years they examined. From this literature, they included 545 patients with psoriasis who were either evaluated for or underwent tonsillectomy. Of 410 patients with psoriasis who actually underwent tonsillectomy, 290 experienced improvement in their psoriasis. Although some individuals who underwent tonsillectomy experienced sustained improvement in their disease, others experienced relapse following the procedure. The authors noted that their study was limited. Fifteen of 20 analyzed publications were case reports or series that lacked control groups. In addition, they noted that a publication bias that favored the reporting of improved cases needs to be considered.

Based on this comprehensive systematic review on the effect of tonsillectomy on psoriasis, the authors concluded that although tonsillectomy is effective in ameliorating psoriasis in a subpopulation of patients, there are insufficient data to describe the differences in clinical characteristics between responders versus nonresponders. Tonsillectomy may be a potential option for patients with recalcitrant psoriasis that is associated with occurrences of tonsillitis. Studies with long-term follow-up are needed to elucidate more clearly the extent and persistence of benefit of tonsillectomy in psoriasis.

What’s the issue?

Tonsillectomy represents an intriguing option not commonly considered for those with resistant disease. Based on the current data, will you discuss tonsillectomy with your patients?

We want to know your views! Tell us what you think.

Reader Comment

This concept so intrigued me when I heard Dr. Susan Katz discuss it at the NYU Advances in Medicine conference last June that I had the discussion with one of my patients, and she opted to have tonsillectomy this past fall. So far, she seems to improving, but I have not yet discontinued her long-term biologic therapy. At the same conference, Dr. Katz presented the idea that delaying antibiotic treatment of streptococcal pharyngitis by a few days might actually improve strep clearance rates by allowing the immune system to mount a greater response to the infection. Waiting for culture results before initiating antibiotic therapy might be prudent not only because it might reduce the unnecessary use of antibiotics in non-streptococcal pharyngitis, but because it might actually improve the long-term prognosis of patients (with or without psoriasis) who do have strep by reducing the odds of a chronic carrier state. Thanks for highlighting this area of study. Fascinating to consider that there might be a surgical cure for some psoriatic patients.

—Jennifer Goldwasser, MD (Scarsdale, New York)

We are all aware that infections, particularly streptococcal infection, can be associated with psoriasis, especially the guttate variety. A logical question emanating from this fact is: Would tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy have any impact on psoriasis and its symptoms?

In a November 2014 article published online in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, Rachakonda et al (doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2014.10.013) performed an extensive literature review to evaluate if tonsillectomy reduces psoriasis severity. The authors searched the following sources: MEDLINE, CINAHL, Cochrane, Embase, Web of Science, and Ovid databases (August 1, 1960, to September 12, 2013). In addition, they executed a manual search of selected references. Through this process, they identified observational studies and clinical trials examining psoriasis after tonsillectomy.

In the analysis, the authors included data from 20 articles from the 53 years they examined. From this literature, they included 545 patients with psoriasis who were either evaluated for or underwent tonsillectomy. Of 410 patients with psoriasis who actually underwent tonsillectomy, 290 experienced improvement in their psoriasis. Although some individuals who underwent tonsillectomy experienced sustained improvement in their disease, others experienced relapse following the procedure. The authors noted that their study was limited. Fifteen of 20 analyzed publications were case reports or series that lacked control groups. In addition, they noted that a publication bias that favored the reporting of improved cases needs to be considered.

Based on this comprehensive systematic review on the effect of tonsillectomy on psoriasis, the authors concluded that although tonsillectomy is effective in ameliorating psoriasis in a subpopulation of patients, there are insufficient data to describe the differences in clinical characteristics between responders versus nonresponders. Tonsillectomy may be a potential option for patients with recalcitrant psoriasis that is associated with occurrences of tonsillitis. Studies with long-term follow-up are needed to elucidate more clearly the extent and persistence of benefit of tonsillectomy in psoriasis.

What’s the issue?

Tonsillectomy represents an intriguing option not commonly considered for those with resistant disease. Based on the current data, will you discuss tonsillectomy with your patients?

We want to know your views! Tell us what you think.

Reader Comment

This concept so intrigued me when I heard Dr. Susan Katz discuss it at the NYU Advances in Medicine conference last June that I had the discussion with one of my patients, and she opted to have tonsillectomy this past fall. So far, she seems to improving, but I have not yet discontinued her long-term biologic therapy. At the same conference, Dr. Katz presented the idea that delaying antibiotic treatment of streptococcal pharyngitis by a few days might actually improve strep clearance rates by allowing the immune system to mount a greater response to the infection. Waiting for culture results before initiating antibiotic therapy might be prudent not only because it might reduce the unnecessary use of antibiotics in non-streptococcal pharyngitis, but because it might actually improve the long-term prognosis of patients (with or without psoriasis) who do have strep by reducing the odds of a chronic carrier state. Thanks for highlighting this area of study. Fascinating to consider that there might be a surgical cure for some psoriatic patients.

—Jennifer Goldwasser, MD (Scarsdale, New York)

We are all aware that infections, particularly streptococcal infection, can be associated with psoriasis, especially the guttate variety. A logical question emanating from this fact is: Would tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy have any impact on psoriasis and its symptoms?

In a November 2014 article published online in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, Rachakonda et al (doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2014.10.013) performed an extensive literature review to evaluate if tonsillectomy reduces psoriasis severity. The authors searched the following sources: MEDLINE, CINAHL, Cochrane, Embase, Web of Science, and Ovid databases (August 1, 1960, to September 12, 2013). In addition, they executed a manual search of selected references. Through this process, they identified observational studies and clinical trials examining psoriasis after tonsillectomy.

In the analysis, the authors included data from 20 articles from the 53 years they examined. From this literature, they included 545 patients with psoriasis who were either evaluated for or underwent tonsillectomy. Of 410 patients with psoriasis who actually underwent tonsillectomy, 290 experienced improvement in their psoriasis. Although some individuals who underwent tonsillectomy experienced sustained improvement in their disease, others experienced relapse following the procedure. The authors noted that their study was limited. Fifteen of 20 analyzed publications were case reports or series that lacked control groups. In addition, they noted that a publication bias that favored the reporting of improved cases needs to be considered.

Based on this comprehensive systematic review on the effect of tonsillectomy on psoriasis, the authors concluded that although tonsillectomy is effective in ameliorating psoriasis in a subpopulation of patients, there are insufficient data to describe the differences in clinical characteristics between responders versus nonresponders. Tonsillectomy may be a potential option for patients with recalcitrant psoriasis that is associated with occurrences of tonsillitis. Studies with long-term follow-up are needed to elucidate more clearly the extent and persistence of benefit of tonsillectomy in psoriasis.

What’s the issue?

Tonsillectomy represents an intriguing option not commonly considered for those with resistant disease. Based on the current data, will you discuss tonsillectomy with your patients?

We want to know your views! Tell us what you think.

Reader Comment

This concept so intrigued me when I heard Dr. Susan Katz discuss it at the NYU Advances in Medicine conference last June that I had the discussion with one of my patients, and she opted to have tonsillectomy this past fall. So far, she seems to improving, but I have not yet discontinued her long-term biologic therapy. At the same conference, Dr. Katz presented the idea that delaying antibiotic treatment of streptococcal pharyngitis by a few days might actually improve strep clearance rates by allowing the immune system to mount a greater response to the infection. Waiting for culture results before initiating antibiotic therapy might be prudent not only because it might reduce the unnecessary use of antibiotics in non-streptococcal pharyngitis, but because it might actually improve the long-term prognosis of patients (with or without psoriasis) who do have strep by reducing the odds of a chronic carrier state. Thanks for highlighting this area of study. Fascinating to consider that there might be a surgical cure for some psoriatic patients.

—Jennifer Goldwasser, MD (Scarsdale, New York)

Practice Question Answers: AIDS-Related Noninfectious Dermatoses

1. What is considered to be the most common skin finding in human immunodeficiency virus/AIDS patients?

a. atopic dermatitis

b. atypical nevi

c. basal cell carcinoma

d. psoriasis

e. seborrheic dermatitis

2. You are treating a patient with widespread psoriasis who also has human immunodeficiency virus and is currently on highly active antiretroviral therapy. What would not be the best option for treatment?

a. acitretin

b. adalimumab

c. cyclosporine

d. infliximab

e. topical steroids

3. Which of the following conditions is seen in human immunodeficiency virus patients and is associated with the human papillomavirus?

a. basal cell carcinoma

b. cervical intraepithelial neoplasia

c. eosinophilic folliculitis

d. Kaposi sarcoma

e. squamous cell carcinoma

4. Which of the following cosmetic products is US Food and Drug Administration approved for treatment of AIDS-associated lipodystrophy?

a. abobotulinumtoxin

b. calcium hydroxylapatite

c. hyaluronic acid

d. incobotulinumtoxin

e. silicone

5. Which of the following dermatologic conditions typically does not present until the CD4 count is less than 200 cells/mm3?

a. atopic dermatitis

b. basal cell carcinoma

c. Kaposi sarcoma

d. pruritic papular eruption

e. psoriasis

1. What is considered to be the most common skin finding in human immunodeficiency virus/AIDS patients?

a. atopic dermatitis

b. atypical nevi

c. basal cell carcinoma

d. psoriasis

e. seborrheic dermatitis

2. You are treating a patient with widespread psoriasis who also has human immunodeficiency virus and is currently on highly active antiretroviral therapy. What would not be the best option for treatment?

a. acitretin

b. adalimumab

c. cyclosporine

d. infliximab

e. topical steroids

3. Which of the following conditions is seen in human immunodeficiency virus patients and is associated with the human papillomavirus?

a. basal cell carcinoma

b. cervical intraepithelial neoplasia

c. eosinophilic folliculitis

d. Kaposi sarcoma

e. squamous cell carcinoma

4. Which of the following cosmetic products is US Food and Drug Administration approved for treatment of AIDS-associated lipodystrophy?

a. abobotulinumtoxin

b. calcium hydroxylapatite

c. hyaluronic acid

d. incobotulinumtoxin

e. silicone

5. Which of the following dermatologic conditions typically does not present until the CD4 count is less than 200 cells/mm3?

a. atopic dermatitis

b. basal cell carcinoma

c. Kaposi sarcoma

d. pruritic papular eruption

e. psoriasis

1. What is considered to be the most common skin finding in human immunodeficiency virus/AIDS patients?

a. atopic dermatitis

b. atypical nevi

c. basal cell carcinoma

d. psoriasis

e. seborrheic dermatitis

2. You are treating a patient with widespread psoriasis who also has human immunodeficiency virus and is currently on highly active antiretroviral therapy. What would not be the best option for treatment?

a. acitretin

b. adalimumab

c. cyclosporine

d. infliximab

e. topical steroids

3. Which of the following conditions is seen in human immunodeficiency virus patients and is associated with the human papillomavirus?

a. basal cell carcinoma

b. cervical intraepithelial neoplasia

c. eosinophilic folliculitis

d. Kaposi sarcoma

e. squamous cell carcinoma

4. Which of the following cosmetic products is US Food and Drug Administration approved for treatment of AIDS-associated lipodystrophy?

a. abobotulinumtoxin

b. calcium hydroxylapatite

c. hyaluronic acid

d. incobotulinumtoxin

e. silicone

5. Which of the following dermatologic conditions typically does not present until the CD4 count is less than 200 cells/mm3?

a. atopic dermatitis

b. basal cell carcinoma

c. Kaposi sarcoma

d. pruritic papular eruption

e. psoriasis

AIDS-Related Noninfectious Dermatoses

Lobular-Appearing Nodule on the Scalp

The Diagnosis: Dermal Cylindroma

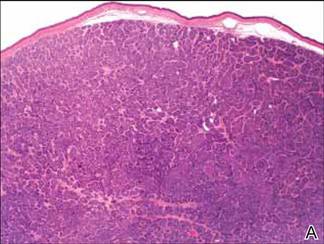

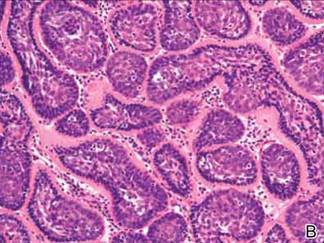

Microsopic evaluation of a tangential biopsy revealed findings of a dermal process consisting of well-circumscribed islands of pale and darker blue cells with little cytoplasm outlined by a hyaline basement membrane (Figure). These cellular islands were arranged in a jigsawlike configuration. These findings were thought to be consistent with a diagnosis of cylindroma.

|

Cylindromas are benign appendageal neoplasms with a somewhat controversial histogenesis. Munger and colleagues1 investigated the pattern of acid mucopolysaccharide secretion by these tumors in association with prosecretory vacuoles in proximity to the Golgi apparatus, which led to their impression that cylindromas most resemble eccrine rather than apocrine sweat glands. Other researchers, however, have concluded that cylindromas are of apocrine derivation.2

Clinically, cylindromas appear most often in 2 settings: isolated or as a manifestation of one of several inherited familial syndromes. One such syndrome is familial cylindromatosis, a rare autosomal-dominant disorder in which affected individuals develop multiple cylindromas, usually on the head and neck. The merging of multiple lesions gives rise to the often-employed term turban tumor.3 This syndrome has been linked to mutations in the cylindromatosis gene, CYLD.4 Brooke-Spiegler syndrome also has been associated with the development of multiple cylindromas. Similar to familial cylindromatosis, it is inherited in an autosomal-dominant fashion. Brooke-Spiegler syndrome is typified by the appearance of multiple cylindromas, trichoepitheliomas, and less commonly spiradenomas. Mutations in the CYLD gene also have been linked to Brooke-Spiegler syndrome in some cases.5

Although considered a benign entity, in rare cases cylindromas have shown evidence of malignant transformation to cylindrocarcinoma. This more aggressive tumor may occur in the setting of isolated cylindromas or more commonly in individuals with numerous lesions, as with both familial cylindromatosis and Brooke-Spiegler syndrome. These lesions may appear to grow rapidly, ulcerate, or bleed, traits that are not associated with their benign counterparts.

Diagnosis of cylindromas rests on histopathologic confirmation, which demonstrates well-defined dermal islands of epithelial cells comprised of dark- and pale-staining nuclei. These tumor islands are surrounded by a hyaline basement membrane and often take on the appearance of a jigsaw puzzle. Cylindrocarcinomas exhibit greater cellular pleomorphism and higher mitotic rates.

Dermal cylindromas require no further treatment but can be electively excised, while treatment of cylindrocarcinoma with excision is curative.6 Definitive excision was offered to our patient, but she declined treatment.

1. Munger BL, Graham JH, Helwig EB. Ultrastructure and histochemical characteristics of dermal eccrine cylindroma (turban tumor). J Invest Dermatol. 1962;39:577-595.

2. Tellechea O, Reis JP, Ilheu O, et al. Dermal cylindroma. an immunohistochemical study of thirteen cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 1995;17:260-265.

3. Biggs PJ, Wooster R, Ford D, et al. Familial cylindromatosis (turban tumour syndrome) gene localised to chromosome 16q12-q13: evidence for its role as a tumour suppressor gene. Nat Genet. 1995;11:441-443.

4. Bignell GR, Warren W, Seal S, et al. Identification of the familial cylindromatosis tumour-suppressor gene. Nat Genet. 2000;25:160-165.

5. Bowen S, Gill M, Lee DA, et al. Mutations in the CYLD gene in Brooke-Spiegler syndrome, familial cylindromatosis, and multiple familial trichoepithelioma: lack of genotype-phenotype correlation. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;124:919-920.

6. Gerretsen AL, van der Putte SC, Deenstra W, et al. Cutaneous cylindroma with malignant transformation. Cancer. 1993;72:1618-1623.

The Diagnosis: Dermal Cylindroma

Microsopic evaluation of a tangential biopsy revealed findings of a dermal process consisting of well-circumscribed islands of pale and darker blue cells with little cytoplasm outlined by a hyaline basement membrane (Figure). These cellular islands were arranged in a jigsawlike configuration. These findings were thought to be consistent with a diagnosis of cylindroma.

|

Cylindromas are benign appendageal neoplasms with a somewhat controversial histogenesis. Munger and colleagues1 investigated the pattern of acid mucopolysaccharide secretion by these tumors in association with prosecretory vacuoles in proximity to the Golgi apparatus, which led to their impression that cylindromas most resemble eccrine rather than apocrine sweat glands. Other researchers, however, have concluded that cylindromas are of apocrine derivation.2

Clinically, cylindromas appear most often in 2 settings: isolated or as a manifestation of one of several inherited familial syndromes. One such syndrome is familial cylindromatosis, a rare autosomal-dominant disorder in which affected individuals develop multiple cylindromas, usually on the head and neck. The merging of multiple lesions gives rise to the often-employed term turban tumor.3 This syndrome has been linked to mutations in the cylindromatosis gene, CYLD.4 Brooke-Spiegler syndrome also has been associated with the development of multiple cylindromas. Similar to familial cylindromatosis, it is inherited in an autosomal-dominant fashion. Brooke-Spiegler syndrome is typified by the appearance of multiple cylindromas, trichoepitheliomas, and less commonly spiradenomas. Mutations in the CYLD gene also have been linked to Brooke-Spiegler syndrome in some cases.5

Although considered a benign entity, in rare cases cylindromas have shown evidence of malignant transformation to cylindrocarcinoma. This more aggressive tumor may occur in the setting of isolated cylindromas or more commonly in individuals with numerous lesions, as with both familial cylindromatosis and Brooke-Spiegler syndrome. These lesions may appear to grow rapidly, ulcerate, or bleed, traits that are not associated with their benign counterparts.

Diagnosis of cylindromas rests on histopathologic confirmation, which demonstrates well-defined dermal islands of epithelial cells comprised of dark- and pale-staining nuclei. These tumor islands are surrounded by a hyaline basement membrane and often take on the appearance of a jigsaw puzzle. Cylindrocarcinomas exhibit greater cellular pleomorphism and higher mitotic rates.

Dermal cylindromas require no further treatment but can be electively excised, while treatment of cylindrocarcinoma with excision is curative.6 Definitive excision was offered to our patient, but she declined treatment.

The Diagnosis: Dermal Cylindroma

Microsopic evaluation of a tangential biopsy revealed findings of a dermal process consisting of well-circumscribed islands of pale and darker blue cells with little cytoplasm outlined by a hyaline basement membrane (Figure). These cellular islands were arranged in a jigsawlike configuration. These findings were thought to be consistent with a diagnosis of cylindroma.

|

Cylindromas are benign appendageal neoplasms with a somewhat controversial histogenesis. Munger and colleagues1 investigated the pattern of acid mucopolysaccharide secretion by these tumors in association with prosecretory vacuoles in proximity to the Golgi apparatus, which led to their impression that cylindromas most resemble eccrine rather than apocrine sweat glands. Other researchers, however, have concluded that cylindromas are of apocrine derivation.2

Clinically, cylindromas appear most often in 2 settings: isolated or as a manifestation of one of several inherited familial syndromes. One such syndrome is familial cylindromatosis, a rare autosomal-dominant disorder in which affected individuals develop multiple cylindromas, usually on the head and neck. The merging of multiple lesions gives rise to the often-employed term turban tumor.3 This syndrome has been linked to mutations in the cylindromatosis gene, CYLD.4 Brooke-Spiegler syndrome also has been associated with the development of multiple cylindromas. Similar to familial cylindromatosis, it is inherited in an autosomal-dominant fashion. Brooke-Spiegler syndrome is typified by the appearance of multiple cylindromas, trichoepitheliomas, and less commonly spiradenomas. Mutations in the CYLD gene also have been linked to Brooke-Spiegler syndrome in some cases.5

Although considered a benign entity, in rare cases cylindromas have shown evidence of malignant transformation to cylindrocarcinoma. This more aggressive tumor may occur in the setting of isolated cylindromas or more commonly in individuals with numerous lesions, as with both familial cylindromatosis and Brooke-Spiegler syndrome. These lesions may appear to grow rapidly, ulcerate, or bleed, traits that are not associated with their benign counterparts.

Diagnosis of cylindromas rests on histopathologic confirmation, which demonstrates well-defined dermal islands of epithelial cells comprised of dark- and pale-staining nuclei. These tumor islands are surrounded by a hyaline basement membrane and often take on the appearance of a jigsaw puzzle. Cylindrocarcinomas exhibit greater cellular pleomorphism and higher mitotic rates.

Dermal cylindromas require no further treatment but can be electively excised, while treatment of cylindrocarcinoma with excision is curative.6 Definitive excision was offered to our patient, but she declined treatment.

1. Munger BL, Graham JH, Helwig EB. Ultrastructure and histochemical characteristics of dermal eccrine cylindroma (turban tumor). J Invest Dermatol. 1962;39:577-595.

2. Tellechea O, Reis JP, Ilheu O, et al. Dermal cylindroma. an immunohistochemical study of thirteen cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 1995;17:260-265.

3. Biggs PJ, Wooster R, Ford D, et al. Familial cylindromatosis (turban tumour syndrome) gene localised to chromosome 16q12-q13: evidence for its role as a tumour suppressor gene. Nat Genet. 1995;11:441-443.

4. Bignell GR, Warren W, Seal S, et al. Identification of the familial cylindromatosis tumour-suppressor gene. Nat Genet. 2000;25:160-165.

5. Bowen S, Gill M, Lee DA, et al. Mutations in the CYLD gene in Brooke-Spiegler syndrome, familial cylindromatosis, and multiple familial trichoepithelioma: lack of genotype-phenotype correlation. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;124:919-920.

6. Gerretsen AL, van der Putte SC, Deenstra W, et al. Cutaneous cylindroma with malignant transformation. Cancer. 1993;72:1618-1623.

1. Munger BL, Graham JH, Helwig EB. Ultrastructure and histochemical characteristics of dermal eccrine cylindroma (turban tumor). J Invest Dermatol. 1962;39:577-595.

2. Tellechea O, Reis JP, Ilheu O, et al. Dermal cylindroma. an immunohistochemical study of thirteen cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 1995;17:260-265.

3. Biggs PJ, Wooster R, Ford D, et al. Familial cylindromatosis (turban tumour syndrome) gene localised to chromosome 16q12-q13: evidence for its role as a tumour suppressor gene. Nat Genet. 1995;11:441-443.

4. Bignell GR, Warren W, Seal S, et al. Identification of the familial cylindromatosis tumour-suppressor gene. Nat Genet. 2000;25:160-165.

5. Bowen S, Gill M, Lee DA, et al. Mutations in the CYLD gene in Brooke-Spiegler syndrome, familial cylindromatosis, and multiple familial trichoepithelioma: lack of genotype-phenotype correlation. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;124:919-920.

6. Gerretsen AL, van der Putte SC, Deenstra W, et al. Cutaneous cylindroma with malignant transformation. Cancer. 1993;72:1618-1623.

A 79-year-old woman presented with a lesion on the left side of the scalp of several years’ duration that had slowly increased in size. Despite its growth, the lesion remained asymptomatic. Physical examination revealed an exophytic, lobular-appearing nodule on the left side of the temporoparietal scalp, measuring 1.5 cm in size.

Cosmetic Corner: Dermatologists Weigh in on Eyelash Enhancers

To improve patient care and outcomes, leading dermatologists offered their recommendations on the eyelash enhancers. Consideration must be given to:

- Latisse

Allergan, Inc.

“It’s the only eyelash-enhancing product that is FDA approved and has been proven to increase eyelash size.”—Gary Goldenberg, MD, New York, New York

Recommended by Elizabeth K. Hale, MD, New York, New York

“It’s an excellent treatment for stimulating the length and diameter of eyelashes (as well as eyebrows). Most patients respond well to it and side effects are minimal and rare.”—Mark G. Rubin, MD, Beverly Hills, California

Recommended by Joel Schlessinger, MD, Omaha, Nebraska

“My choice is definitely Latisse, but inform patients that they should not stop abruptly as this can cause acute eyelash loss.”—Antonella Tosti, MD, Miami, Florida

- RapidLash

Rocasuba, Inc

“This active ingredient is proving to have good clinical results at a good price point for consumers.”—Anthony M. Rossi, MD, New York, New York

- RevitaLash Advanced

Athena Cosmetics

“A great alternative to Latisse or one that patients can transition to once they are satisfied with the growth that Latisse has brought them or if they are allergic/sensitive to Latisse.”—Joel Schlessinger, MD, Omaha, Nebraska

Cutis invites readers to send us their recommendations. Skin care products for babies, hair straighteners, aftershaves, and cleansing pads will be featured in upcoming editions of Cosmetic Corner. Please e-mail your recommendation(s) to the Editorial Office.

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect those of Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. and shall not be used for product endorsement purposes. Any reference made to a specific commercial product does not indicate or imply that Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. endorses, recommends, or favors the product mentioned. No guarantee is given to the effects of recommended products.

To improve patient care and outcomes, leading dermatologists offered their recommendations on the eyelash enhancers. Consideration must be given to:

- Latisse

Allergan, Inc.

“It’s the only eyelash-enhancing product that is FDA approved and has been proven to increase eyelash size.”—Gary Goldenberg, MD, New York, New York

Recommended by Elizabeth K. Hale, MD, New York, New York

“It’s an excellent treatment for stimulating the length and diameter of eyelashes (as well as eyebrows). Most patients respond well to it and side effects are minimal and rare.”—Mark G. Rubin, MD, Beverly Hills, California

Recommended by Joel Schlessinger, MD, Omaha, Nebraska

“My choice is definitely Latisse, but inform patients that they should not stop abruptly as this can cause acute eyelash loss.”—Antonella Tosti, MD, Miami, Florida

- RapidLash

Rocasuba, Inc

“This active ingredient is proving to have good clinical results at a good price point for consumers.”—Anthony M. Rossi, MD, New York, New York

- RevitaLash Advanced

Athena Cosmetics

“A great alternative to Latisse or one that patients can transition to once they are satisfied with the growth that Latisse has brought them or if they are allergic/sensitive to Latisse.”—Joel Schlessinger, MD, Omaha, Nebraska

Cutis invites readers to send us their recommendations. Skin care products for babies, hair straighteners, aftershaves, and cleansing pads will be featured in upcoming editions of Cosmetic Corner. Please e-mail your recommendation(s) to the Editorial Office.

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect those of Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. and shall not be used for product endorsement purposes. Any reference made to a specific commercial product does not indicate or imply that Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. endorses, recommends, or favors the product mentioned. No guarantee is given to the effects of recommended products.

To improve patient care and outcomes, leading dermatologists offered their recommendations on the eyelash enhancers. Consideration must be given to:

- Latisse

Allergan, Inc.

“It’s the only eyelash-enhancing product that is FDA approved and has been proven to increase eyelash size.”—Gary Goldenberg, MD, New York, New York

Recommended by Elizabeth K. Hale, MD, New York, New York

“It’s an excellent treatment for stimulating the length and diameter of eyelashes (as well as eyebrows). Most patients respond well to it and side effects are minimal and rare.”—Mark G. Rubin, MD, Beverly Hills, California

Recommended by Joel Schlessinger, MD, Omaha, Nebraska

“My choice is definitely Latisse, but inform patients that they should not stop abruptly as this can cause acute eyelash loss.”—Antonella Tosti, MD, Miami, Florida

- RapidLash

Rocasuba, Inc

“This active ingredient is proving to have good clinical results at a good price point for consumers.”—Anthony M. Rossi, MD, New York, New York

- RevitaLash Advanced

Athena Cosmetics

“A great alternative to Latisse or one that patients can transition to once they are satisfied with the growth that Latisse has brought them or if they are allergic/sensitive to Latisse.”—Joel Schlessinger, MD, Omaha, Nebraska

Cutis invites readers to send us their recommendations. Skin care products for babies, hair straighteners, aftershaves, and cleansing pads will be featured in upcoming editions of Cosmetic Corner. Please e-mail your recommendation(s) to the Editorial Office.