User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

AWaRDS Study Examines Services for Adults With Rare Disorders

NORD is partnering with researchers at Oregon State University to conduct the first large-scale study of information and psychosocial support needs of people living with rare disorders. The purpose is to assess the needs and find similarities and differences across the spectrum of disorders. An online survey is now open for adults living with rare diseases. The principal investigator is Kathleen Bogart, PhD, Assistant Professor of Psychology at Oregon State. Co-investigator is Veronica Irvin, PhD, MPH, also of OSU.

NORD is partnering with researchers at Oregon State University to conduct the first large-scale study of information and psychosocial support needs of people living with rare disorders. The purpose is to assess the needs and find similarities and differences across the spectrum of disorders. An online survey is now open for adults living with rare diseases. The principal investigator is Kathleen Bogart, PhD, Assistant Professor of Psychology at Oregon State. Co-investigator is Veronica Irvin, PhD, MPH, also of OSU.

NORD is partnering with researchers at Oregon State University to conduct the first large-scale study of information and psychosocial support needs of people living with rare disorders. The purpose is to assess the needs and find similarities and differences across the spectrum of disorders. An online survey is now open for adults living with rare diseases. The principal investigator is Kathleen Bogart, PhD, Assistant Professor of Psychology at Oregon State. Co-investigator is Veronica Irvin, PhD, MPH, also of OSU.

Join Others Around the World in Observing Rare Disease Day

The last day of February is observed in more than 90 countries worldwide as Rare Disease Day to promote better understanding of the more than 7,000 diseases classified as rare. In the US, a disease is considered rare if it is believed to affect fewer than 200,000 Americans. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) lists all known rare diseases on its website.

As the national sponsor of Rare Disease Day in the US, NORD is working with other national alliances around the world to plan a global theme and educational outreach each year. This year’s theme is Research. Events will focus on the importance of research and the need for expanded research on rare diseases.

On the national Rare Disease Day website, which is hosted by NORD, a state-by-state listing of planned events makes it easy to find out what is happening in your state and/or to promote awareness of events you are planning. Many teaching hospitals and academic centers host special programs or lobby tabling events on or around Rare Disease Day.

If you are interested in organizing a program, tabling event, or literature display at your institution, you can download resources from NORD’s Rare Disease Day US website. NORD also can provide speakers for Rare Disease Day (or other) educational events through its Patient/Caregiver Speakers Bureau.

Medical professionals and students can also show their support for Rare Disease Day by submitting a photo to NORD’s “Handprints Across America” campaign, which will be displayed on the Rare Disease Day US website. Questions related to Rare Disease Day events or requests for speakers or other resources may be directed to education@rarediseases.org.

The last day of February is observed in more than 90 countries worldwide as Rare Disease Day to promote better understanding of the more than 7,000 diseases classified as rare. In the US, a disease is considered rare if it is believed to affect fewer than 200,000 Americans. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) lists all known rare diseases on its website.

As the national sponsor of Rare Disease Day in the US, NORD is working with other national alliances around the world to plan a global theme and educational outreach each year. This year’s theme is Research. Events will focus on the importance of research and the need for expanded research on rare diseases.

On the national Rare Disease Day website, which is hosted by NORD, a state-by-state listing of planned events makes it easy to find out what is happening in your state and/or to promote awareness of events you are planning. Many teaching hospitals and academic centers host special programs or lobby tabling events on or around Rare Disease Day.

If you are interested in organizing a program, tabling event, or literature display at your institution, you can download resources from NORD’s Rare Disease Day US website. NORD also can provide speakers for Rare Disease Day (or other) educational events through its Patient/Caregiver Speakers Bureau.

Medical professionals and students can also show their support for Rare Disease Day by submitting a photo to NORD’s “Handprints Across America” campaign, which will be displayed on the Rare Disease Day US website. Questions related to Rare Disease Day events or requests for speakers or other resources may be directed to education@rarediseases.org.

The last day of February is observed in more than 90 countries worldwide as Rare Disease Day to promote better understanding of the more than 7,000 diseases classified as rare. In the US, a disease is considered rare if it is believed to affect fewer than 200,000 Americans. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) lists all known rare diseases on its website.

As the national sponsor of Rare Disease Day in the US, NORD is working with other national alliances around the world to plan a global theme and educational outreach each year. This year’s theme is Research. Events will focus on the importance of research and the need for expanded research on rare diseases.

On the national Rare Disease Day website, which is hosted by NORD, a state-by-state listing of planned events makes it easy to find out what is happening in your state and/or to promote awareness of events you are planning. Many teaching hospitals and academic centers host special programs or lobby tabling events on or around Rare Disease Day.

If you are interested in organizing a program, tabling event, or literature display at your institution, you can download resources from NORD’s Rare Disease Day US website. NORD also can provide speakers for Rare Disease Day (or other) educational events through its Patient/Caregiver Speakers Bureau.

Medical professionals and students can also show their support for Rare Disease Day by submitting a photo to NORD’s “Handprints Across America” campaign, which will be displayed on the Rare Disease Day US website. Questions related to Rare Disease Day events or requests for speakers or other resources may be directed to education@rarediseases.org.

Painful Oral and Genital Ulcers

The Diagnosis: Pemphigus Vegetans

Pemphigus vegetans is a rare variant of pemphigus vulgaris. Clinically, pemphigus vegetans is characterized by vegetative lesions over the flexures, but any area of the skin may be involved. There have been case reports involving the scalp,1,2 mouth,3 and foot.4 There are 2 clinical subtypes: the Neumann type and the Hallopeau type.5 The Hallopeau type is relatively benign, requires lower doses of systemic corticosteroids, and has a prolonged remission, while the Neumann type necessitates higher doses of systemic corticosteroids and often presents with relapses and remissions.

The diagnosis of pemphigus vegetans is based on clinical suspicion and confirmed by histological examination and immunological findings. The diagnosis may be difficult, as its presentation varies and histopathological findings may resemble other conditions.

Systemic corticosteroids are the well-established drug of choice for treating pemphigus vegetans to induce remission and maintain healing before cautiously tapering down the dosage approximately 50% every 2 weeks.6 Adjuvant drugs used in conjunction with steroids for steroid-sparing purpose include azathioprine, cyclophosphamide, mycophenolate mofetil, methotrexate, and cyclosporine.6 Pulsed intravenous steroids,7 intravenous immunoglobulins,8 pulsed dexamethasone cyclophosphamide,9 and extracorporeal photopheresis10 are given for severe and recalcitrant disease.

Laboratory investigations of our patient showed a normal complete blood cell count and a normal renal and liver profile. Herpes simplex virus serology was positive for type 1 and type 2 IgM and IgG. Urethral swab was dry and negative for gonorrhea. Serology for chlamydia, toxoplasma, amoebiasis, and leishmaniasis was negative. Human immunodeficiency virus serology, hepatitis screening, rapid plasma reagin, Treponema pallidum hemagglutination, rheumatoid factor, and antinuclear antibody all were negative. The patient was given a course of oral acyclovir 400 mg 3 times daily and empirical treatment with oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for a week with no clinical response.

Two biopsies from the perianal ulcers showed inflamed squamous papillomata with no Donovan bodies. A third biopsy from an intact blister showed acantholytic cells in the suprabasal bullae with eosinophilic and lymphocytic infiltrates at the upper dermis. Direct immunofluorescence demonstrated intercellular C3 and IgG deposits.

The patient was started on oral prednisolone at 1 mg/kg daily and oral azathioprine 50 mg daily with resolution of the perianal, penile, and oral ulcers (Figures 1 and 2). He achieved good suppression of further eruption. At the patient's most recent follow-up (2.5 years after the initial presentation), he was in remission and was currently taking oral azathioprine 100 mg once daily and no oral corticosteroids.

- Danopoulou I, Stavropoulos P, Stratigos A, et al. Pemphigus vegetans confined to the scalp. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1008-1009.

- Mori M, Mariotti G, Grandi V, et al. Pemphigus vegetans of the scalp [published online October 22,2014]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:368-370.

- Augusto de Oliveira M, Martins E Martins F, Lourenço S, et al. Oral pemphigus vegetans: a case report. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:10.

- Ma DL, Fang K. Hallopeau type of pemphigus vegetans confined to the right foot: case report. Chin Med J (Engl). 2009;122:588-590.

- Ahmed AR, Blose DA. Pemphigus vegetans. Neumann type and Hallopeau type. Int J Dermatol. 1984;23:135-141.

- Harman KE, Albert S, Black MM, et al. Guidelines for the management of pemphigus vulgaris. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149:926-937.

- Chryssomallis F, Dimitriades A, Chaidemenos GC, et al. Steroid-pulse therapy in pemphigus vulgaris long term follow-up. Int J Dermatol. 1995;34:438-442.

- Ahmed AR. Intravenous immunoglobulin therapy in the treatment of patients with pemphigus vulgaris unresponsive to conventional immunosuppressive treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:679-690.

- Pasricha JS, Khaitan BK, Raman RS, et al. Dexamethasone-cyclophosphamide pulse therapy for pemphigus. Int J Dermatol. 1995;34:875-882.

- Rook AH, Jegasothy BV, Heald P, et al. Extracorporeal photochemotherapy for drug-resistant pemphigus vulgaris. Ann Int Med. 1990;112:303-305.

The Diagnosis: Pemphigus Vegetans

Pemphigus vegetans is a rare variant of pemphigus vulgaris. Clinically, pemphigus vegetans is characterized by vegetative lesions over the flexures, but any area of the skin may be involved. There have been case reports involving the scalp,1,2 mouth,3 and foot.4 There are 2 clinical subtypes: the Neumann type and the Hallopeau type.5 The Hallopeau type is relatively benign, requires lower doses of systemic corticosteroids, and has a prolonged remission, while the Neumann type necessitates higher doses of systemic corticosteroids and often presents with relapses and remissions.

The diagnosis of pemphigus vegetans is based on clinical suspicion and confirmed by histological examination and immunological findings. The diagnosis may be difficult, as its presentation varies and histopathological findings may resemble other conditions.

Systemic corticosteroids are the well-established drug of choice for treating pemphigus vegetans to induce remission and maintain healing before cautiously tapering down the dosage approximately 50% every 2 weeks.6 Adjuvant drugs used in conjunction with steroids for steroid-sparing purpose include azathioprine, cyclophosphamide, mycophenolate mofetil, methotrexate, and cyclosporine.6 Pulsed intravenous steroids,7 intravenous immunoglobulins,8 pulsed dexamethasone cyclophosphamide,9 and extracorporeal photopheresis10 are given for severe and recalcitrant disease.

Laboratory investigations of our patient showed a normal complete blood cell count and a normal renal and liver profile. Herpes simplex virus serology was positive for type 1 and type 2 IgM and IgG. Urethral swab was dry and negative for gonorrhea. Serology for chlamydia, toxoplasma, amoebiasis, and leishmaniasis was negative. Human immunodeficiency virus serology, hepatitis screening, rapid plasma reagin, Treponema pallidum hemagglutination, rheumatoid factor, and antinuclear antibody all were negative. The patient was given a course of oral acyclovir 400 mg 3 times daily and empirical treatment with oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for a week with no clinical response.

Two biopsies from the perianal ulcers showed inflamed squamous papillomata with no Donovan bodies. A third biopsy from an intact blister showed acantholytic cells in the suprabasal bullae with eosinophilic and lymphocytic infiltrates at the upper dermis. Direct immunofluorescence demonstrated intercellular C3 and IgG deposits.

The patient was started on oral prednisolone at 1 mg/kg daily and oral azathioprine 50 mg daily with resolution of the perianal, penile, and oral ulcers (Figures 1 and 2). He achieved good suppression of further eruption. At the patient's most recent follow-up (2.5 years after the initial presentation), he was in remission and was currently taking oral azathioprine 100 mg once daily and no oral corticosteroids.

The Diagnosis: Pemphigus Vegetans

Pemphigus vegetans is a rare variant of pemphigus vulgaris. Clinically, pemphigus vegetans is characterized by vegetative lesions over the flexures, but any area of the skin may be involved. There have been case reports involving the scalp,1,2 mouth,3 and foot.4 There are 2 clinical subtypes: the Neumann type and the Hallopeau type.5 The Hallopeau type is relatively benign, requires lower doses of systemic corticosteroids, and has a prolonged remission, while the Neumann type necessitates higher doses of systemic corticosteroids and often presents with relapses and remissions.

The diagnosis of pemphigus vegetans is based on clinical suspicion and confirmed by histological examination and immunological findings. The diagnosis may be difficult, as its presentation varies and histopathological findings may resemble other conditions.

Systemic corticosteroids are the well-established drug of choice for treating pemphigus vegetans to induce remission and maintain healing before cautiously tapering down the dosage approximately 50% every 2 weeks.6 Adjuvant drugs used in conjunction with steroids for steroid-sparing purpose include azathioprine, cyclophosphamide, mycophenolate mofetil, methotrexate, and cyclosporine.6 Pulsed intravenous steroids,7 intravenous immunoglobulins,8 pulsed dexamethasone cyclophosphamide,9 and extracorporeal photopheresis10 are given for severe and recalcitrant disease.

Laboratory investigations of our patient showed a normal complete blood cell count and a normal renal and liver profile. Herpes simplex virus serology was positive for type 1 and type 2 IgM and IgG. Urethral swab was dry and negative for gonorrhea. Serology for chlamydia, toxoplasma, amoebiasis, and leishmaniasis was negative. Human immunodeficiency virus serology, hepatitis screening, rapid plasma reagin, Treponema pallidum hemagglutination, rheumatoid factor, and antinuclear antibody all were negative. The patient was given a course of oral acyclovir 400 mg 3 times daily and empirical treatment with oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for a week with no clinical response.

Two biopsies from the perianal ulcers showed inflamed squamous papillomata with no Donovan bodies. A third biopsy from an intact blister showed acantholytic cells in the suprabasal bullae with eosinophilic and lymphocytic infiltrates at the upper dermis. Direct immunofluorescence demonstrated intercellular C3 and IgG deposits.

The patient was started on oral prednisolone at 1 mg/kg daily and oral azathioprine 50 mg daily with resolution of the perianal, penile, and oral ulcers (Figures 1 and 2). He achieved good suppression of further eruption. At the patient's most recent follow-up (2.5 years after the initial presentation), he was in remission and was currently taking oral azathioprine 100 mg once daily and no oral corticosteroids.

- Danopoulou I, Stavropoulos P, Stratigos A, et al. Pemphigus vegetans confined to the scalp. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1008-1009.

- Mori M, Mariotti G, Grandi V, et al. Pemphigus vegetans of the scalp [published online October 22,2014]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:368-370.

- Augusto de Oliveira M, Martins E Martins F, Lourenço S, et al. Oral pemphigus vegetans: a case report. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:10.

- Ma DL, Fang K. Hallopeau type of pemphigus vegetans confined to the right foot: case report. Chin Med J (Engl). 2009;122:588-590.

- Ahmed AR, Blose DA. Pemphigus vegetans. Neumann type and Hallopeau type. Int J Dermatol. 1984;23:135-141.

- Harman KE, Albert S, Black MM, et al. Guidelines for the management of pemphigus vulgaris. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149:926-937.

- Chryssomallis F, Dimitriades A, Chaidemenos GC, et al. Steroid-pulse therapy in pemphigus vulgaris long term follow-up. Int J Dermatol. 1995;34:438-442.

- Ahmed AR. Intravenous immunoglobulin therapy in the treatment of patients with pemphigus vulgaris unresponsive to conventional immunosuppressive treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:679-690.

- Pasricha JS, Khaitan BK, Raman RS, et al. Dexamethasone-cyclophosphamide pulse therapy for pemphigus. Int J Dermatol. 1995;34:875-882.

- Rook AH, Jegasothy BV, Heald P, et al. Extracorporeal photochemotherapy for drug-resistant pemphigus vulgaris. Ann Int Med. 1990;112:303-305.

- Danopoulou I, Stavropoulos P, Stratigos A, et al. Pemphigus vegetans confined to the scalp. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1008-1009.

- Mori M, Mariotti G, Grandi V, et al. Pemphigus vegetans of the scalp [published online October 22,2014]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:368-370.

- Augusto de Oliveira M, Martins E Martins F, Lourenço S, et al. Oral pemphigus vegetans: a case report. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:10.

- Ma DL, Fang K. Hallopeau type of pemphigus vegetans confined to the right foot: case report. Chin Med J (Engl). 2009;122:588-590.

- Ahmed AR, Blose DA. Pemphigus vegetans. Neumann type and Hallopeau type. Int J Dermatol. 1984;23:135-141.

- Harman KE, Albert S, Black MM, et al. Guidelines for the management of pemphigus vulgaris. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149:926-937.

- Chryssomallis F, Dimitriades A, Chaidemenos GC, et al. Steroid-pulse therapy in pemphigus vulgaris long term follow-up. Int J Dermatol. 1995;34:438-442.

- Ahmed AR. Intravenous immunoglobulin therapy in the treatment of patients with pemphigus vulgaris unresponsive to conventional immunosuppressive treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:679-690.

- Pasricha JS, Khaitan BK, Raman RS, et al. Dexamethasone-cyclophosphamide pulse therapy for pemphigus. Int J Dermatol. 1995;34:875-882.

- Rook AH, Jegasothy BV, Heald P, et al. Extracorporeal photochemotherapy for drug-resistant pemphigus vulgaris. Ann Int Med. 1990;112:303-305.

A 52-year-old man presented with persistent painful oral ulcers and penile and perianal erosions of 6 months' duration. He strongly denied engaging in high-risk sexual activities and had lost 10 kg over the last 6 months. He did not report taking any over-the-counter or alternative medications. On physical examination there were multiple fissures on the lower lip with erosive white plaques on the tongue and buccal mucosa. There were erosions over the foreskin and glans penis and a few erosive plaques on the perianal skin. Bilateral inguinal lymph nodes were enlarged.

A Rare Association in Down Syndrome: Milialike Idiopathic Calcinosis Cutis and Palpebral Syringoma

To the Editor:

Down syndrome (DS) is associated with rare dermatological disorders, and the prevalence of some common dermatoses is greater in patients with DS. We report a case of milialike idiopathic calcinosis cutis (MICC) associated with syringomas in a patient with DS. We emphasize that MICC is one of the rare dermatoses associated with DS.

A 4-year-old girl with DS presented with a 4-mm, flesh-colored, regular-bordered, exophytic papular lesion on the left upper eyelid of 8 months' duration (Figure 1). It was clinically recognized as syringoma. On dermatologic examination of the patient, there also were 1- to 3-mm, round, whitish, painless, milialike papules on the dorsal surface of the hands and wrists (Figure 2). Some of these papules were surrounded by erythema. There was no sign of perforation. Her personal and family history were unremarkable.

Histopathologic examination of a biopsy from a milialike lesion on the hand showed a hyperkeratotic epidermis. In the dermis there was a roundish calcific nodule surrounded by a fibrovascular rim. The patient's guardians refused a biopsy from the lesion on the eyelid.

Laboratory tests including serum vitamin D, thyroid and parathyroid hormone, calcium, phosphorus, and urinary calcium levels, as well as renal function tests, were within reference range. On the basis of these clinical and histopathological findings, the patient was diagnosed with MICC and palpebral syringoma.

Many dermatoses associated with DS have been reported including elastosis perforans serpiginosa, alopecia areata, and syringomas.1-3 Sano et al4 first described MICC and syringomas in a patient with DS in 1978. Milialike idiopathic calcinosis cutis is characterized by asymptomatic, millimetric, firm, round, whitish papules that are sometimes surrounded by erythema. These papules may show perforation leading to transepidermal elimination of calcium, similar to the transdermal elimination of elastic fibrils in elastosis perforans serpiginosa. Although MICC usually is described in acral sites of children with DS, it also is reported in adults without DS and on other parts of the body.5-7

The cause of MICC is unknown. One hypothesis of the development of MICC is an increase of the calcium content in the sweat leading to calcification of the acrosyringium.8 Milia are small keratin cysts that usually develop by occlusion of the hair follicle, sweat duct, or sebaceous duct. However, milia also can occur from occlusion of the eccrine ducts where syringomas originate.9 Therefore, syringomas can be seen in association with milia and calcium deposits.5,9-11

We believe that MICC in DS may be more common than usually recognized, as the lesions often are asymptomatic. It is important to differentiate MICC from other dermatological diseases such as molluscum contagiosum, verruca plana, milia, and inclusion cysts. Histopathology and dermoscopy could aid in the accurate diagnosis of MICC.

- Dourmishev A, Miteva L, Mitev V, et al. Cutaneous aspects of Down syndrome. Cutis. 2000;66:420-424.

- Madan V, Williams J, Lear JT. Dermatological manifestations of Down's syndrome. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2006;31:623-629.

- Schepis C, Barone C, Siragusa M, et al. An updated survey on skin conditions in Down syndrome. Dermatology. 2002;205:234-238.

- Sano T, Tate S, Ishikawa C. A case of Down's syndrome associated with syringoma, milia, and subepidermal calcified nodule. Jpn J Dermatol. 1978;88:740.

- Schepis C, Siragusa M, Palazzo R, et al. Perforating milia-like idiopathic calcinosis cutis and periorbital syringomas in a girl with Down syndrome. Pediatr Dermatol. 1994;11:258-260.

- Schepis C, Siragusa M, Palazzo R, et al. Milia like idiopathic calcinosis cutis: an unusual dermatosis associated with Down syndrome. Br J Dermatol. 1996;134:143-146.

- Houtappel M, Leguit R, Sigurdsson V. Milia-like idiopathic calcinosis cutis in an adult without Down's syndrome. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2007;1:16-19.

- Eng AM, Mandrea E. Perforating calcinosis cutis presenting as milia. J Cutan Pathol. 1981;8:247-250.

- Wang KH, Chu JS, Lin YH, et al. Milium-like syringoma: a case study on histogenesis. J Cutan Pathol. 2004;31:336-340.

- Weiss E, Paez E, Greenberg AS, et al. Eruptive syringomas associated with milia. Int J Dermatol. 1995;34:193-195.

- Kim SJ, Won YH, Chun IK. Subepidermal calcified nodules and syringoma. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 1997;8:51-52.

To the Editor:

Down syndrome (DS) is associated with rare dermatological disorders, and the prevalence of some common dermatoses is greater in patients with DS. We report a case of milialike idiopathic calcinosis cutis (MICC) associated with syringomas in a patient with DS. We emphasize that MICC is one of the rare dermatoses associated with DS.

A 4-year-old girl with DS presented with a 4-mm, flesh-colored, regular-bordered, exophytic papular lesion on the left upper eyelid of 8 months' duration (Figure 1). It was clinically recognized as syringoma. On dermatologic examination of the patient, there also were 1- to 3-mm, round, whitish, painless, milialike papules on the dorsal surface of the hands and wrists (Figure 2). Some of these papules were surrounded by erythema. There was no sign of perforation. Her personal and family history were unremarkable.

Histopathologic examination of a biopsy from a milialike lesion on the hand showed a hyperkeratotic epidermis. In the dermis there was a roundish calcific nodule surrounded by a fibrovascular rim. The patient's guardians refused a biopsy from the lesion on the eyelid.

Laboratory tests including serum vitamin D, thyroid and parathyroid hormone, calcium, phosphorus, and urinary calcium levels, as well as renal function tests, were within reference range. On the basis of these clinical and histopathological findings, the patient was diagnosed with MICC and palpebral syringoma.

Many dermatoses associated with DS have been reported including elastosis perforans serpiginosa, alopecia areata, and syringomas.1-3 Sano et al4 first described MICC and syringomas in a patient with DS in 1978. Milialike idiopathic calcinosis cutis is characterized by asymptomatic, millimetric, firm, round, whitish papules that are sometimes surrounded by erythema. These papules may show perforation leading to transepidermal elimination of calcium, similar to the transdermal elimination of elastic fibrils in elastosis perforans serpiginosa. Although MICC usually is described in acral sites of children with DS, it also is reported in adults without DS and on other parts of the body.5-7

The cause of MICC is unknown. One hypothesis of the development of MICC is an increase of the calcium content in the sweat leading to calcification of the acrosyringium.8 Milia are small keratin cysts that usually develop by occlusion of the hair follicle, sweat duct, or sebaceous duct. However, milia also can occur from occlusion of the eccrine ducts where syringomas originate.9 Therefore, syringomas can be seen in association with milia and calcium deposits.5,9-11

We believe that MICC in DS may be more common than usually recognized, as the lesions often are asymptomatic. It is important to differentiate MICC from other dermatological diseases such as molluscum contagiosum, verruca plana, milia, and inclusion cysts. Histopathology and dermoscopy could aid in the accurate diagnosis of MICC.

To the Editor:

Down syndrome (DS) is associated with rare dermatological disorders, and the prevalence of some common dermatoses is greater in patients with DS. We report a case of milialike idiopathic calcinosis cutis (MICC) associated with syringomas in a patient with DS. We emphasize that MICC is one of the rare dermatoses associated with DS.

A 4-year-old girl with DS presented with a 4-mm, flesh-colored, regular-bordered, exophytic papular lesion on the left upper eyelid of 8 months' duration (Figure 1). It was clinically recognized as syringoma. On dermatologic examination of the patient, there also were 1- to 3-mm, round, whitish, painless, milialike papules on the dorsal surface of the hands and wrists (Figure 2). Some of these papules were surrounded by erythema. There was no sign of perforation. Her personal and family history were unremarkable.

Histopathologic examination of a biopsy from a milialike lesion on the hand showed a hyperkeratotic epidermis. In the dermis there was a roundish calcific nodule surrounded by a fibrovascular rim. The patient's guardians refused a biopsy from the lesion on the eyelid.

Laboratory tests including serum vitamin D, thyroid and parathyroid hormone, calcium, phosphorus, and urinary calcium levels, as well as renal function tests, were within reference range. On the basis of these clinical and histopathological findings, the patient was diagnosed with MICC and palpebral syringoma.

Many dermatoses associated with DS have been reported including elastosis perforans serpiginosa, alopecia areata, and syringomas.1-3 Sano et al4 first described MICC and syringomas in a patient with DS in 1978. Milialike idiopathic calcinosis cutis is characterized by asymptomatic, millimetric, firm, round, whitish papules that are sometimes surrounded by erythema. These papules may show perforation leading to transepidermal elimination of calcium, similar to the transdermal elimination of elastic fibrils in elastosis perforans serpiginosa. Although MICC usually is described in acral sites of children with DS, it also is reported in adults without DS and on other parts of the body.5-7

The cause of MICC is unknown. One hypothesis of the development of MICC is an increase of the calcium content in the sweat leading to calcification of the acrosyringium.8 Milia are small keratin cysts that usually develop by occlusion of the hair follicle, sweat duct, or sebaceous duct. However, milia also can occur from occlusion of the eccrine ducts where syringomas originate.9 Therefore, syringomas can be seen in association with milia and calcium deposits.5,9-11

We believe that MICC in DS may be more common than usually recognized, as the lesions often are asymptomatic. It is important to differentiate MICC from other dermatological diseases such as molluscum contagiosum, verruca plana, milia, and inclusion cysts. Histopathology and dermoscopy could aid in the accurate diagnosis of MICC.

- Dourmishev A, Miteva L, Mitev V, et al. Cutaneous aspects of Down syndrome. Cutis. 2000;66:420-424.

- Madan V, Williams J, Lear JT. Dermatological manifestations of Down's syndrome. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2006;31:623-629.

- Schepis C, Barone C, Siragusa M, et al. An updated survey on skin conditions in Down syndrome. Dermatology. 2002;205:234-238.

- Sano T, Tate S, Ishikawa C. A case of Down's syndrome associated with syringoma, milia, and subepidermal calcified nodule. Jpn J Dermatol. 1978;88:740.

- Schepis C, Siragusa M, Palazzo R, et al. Perforating milia-like idiopathic calcinosis cutis and periorbital syringomas in a girl with Down syndrome. Pediatr Dermatol. 1994;11:258-260.

- Schepis C, Siragusa M, Palazzo R, et al. Milia like idiopathic calcinosis cutis: an unusual dermatosis associated with Down syndrome. Br J Dermatol. 1996;134:143-146.

- Houtappel M, Leguit R, Sigurdsson V. Milia-like idiopathic calcinosis cutis in an adult without Down's syndrome. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2007;1:16-19.

- Eng AM, Mandrea E. Perforating calcinosis cutis presenting as milia. J Cutan Pathol. 1981;8:247-250.

- Wang KH, Chu JS, Lin YH, et al. Milium-like syringoma: a case study on histogenesis. J Cutan Pathol. 2004;31:336-340.

- Weiss E, Paez E, Greenberg AS, et al. Eruptive syringomas associated with milia. Int J Dermatol. 1995;34:193-195.

- Kim SJ, Won YH, Chun IK. Subepidermal calcified nodules and syringoma. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 1997;8:51-52.

- Dourmishev A, Miteva L, Mitev V, et al. Cutaneous aspects of Down syndrome. Cutis. 2000;66:420-424.

- Madan V, Williams J, Lear JT. Dermatological manifestations of Down's syndrome. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2006;31:623-629.

- Schepis C, Barone C, Siragusa M, et al. An updated survey on skin conditions in Down syndrome. Dermatology. 2002;205:234-238.

- Sano T, Tate S, Ishikawa C. A case of Down's syndrome associated with syringoma, milia, and subepidermal calcified nodule. Jpn J Dermatol. 1978;88:740.

- Schepis C, Siragusa M, Palazzo R, et al. Perforating milia-like idiopathic calcinosis cutis and periorbital syringomas in a girl with Down syndrome. Pediatr Dermatol. 1994;11:258-260.

- Schepis C, Siragusa M, Palazzo R, et al. Milia like idiopathic calcinosis cutis: an unusual dermatosis associated with Down syndrome. Br J Dermatol. 1996;134:143-146.

- Houtappel M, Leguit R, Sigurdsson V. Milia-like idiopathic calcinosis cutis in an adult without Down's syndrome. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2007;1:16-19.

- Eng AM, Mandrea E. Perforating calcinosis cutis presenting as milia. J Cutan Pathol. 1981;8:247-250.

- Wang KH, Chu JS, Lin YH, et al. Milium-like syringoma: a case study on histogenesis. J Cutan Pathol. 2004;31:336-340.

- Weiss E, Paez E, Greenberg AS, et al. Eruptive syringomas associated with milia. Int J Dermatol. 1995;34:193-195.

- Kim SJ, Won YH, Chun IK. Subepidermal calcified nodules and syringoma. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 1997;8:51-52.

Practice Points

- Down syndrome is associated with rare dermatological disorders and an increased prevalence of common dermatoses.

- It is important to differentiate milialike idiopathic calcinosis cutis from other dermatological diseases using histopathology and dermoscopy.

Nominate a Patient or Colleague for a NORD Rare Impact Award

Do you have a patient or colleague who has demonstrated extraordinary commitment to advancing understanding of rare diseases or improving the lives of those affected by rare diseases? January 13th is the deadline to nominate individuals for NORD’s Rare Impact Awards. Nominations can be submitted through the NORD website.

NORD’s Rare Impact Awards ceremony will take place on May 18, 2017, in the amphitheater of the Ronald Reagan Building and International Trade Center, the largest structure in Washington, DC, and the first and only federal building dedicated to both federal and private use. More than 500 distinguished guests are expected to attend. Registration will be available soon on the NORD website.

The Rare Impact Awards honor individuals and organizations for commitment to improving the lives of patients and families affected by rare diseases. Nominees may include patients, caregivers, clinicians, researchers, advocates, and others who in some way have contributed to the greater good of the community. Nominations are also being sought for organizations that have helped drive better understanding of rare diseases and/or improved care for those affected.

Do you have a patient or colleague who has demonstrated extraordinary commitment to advancing understanding of rare diseases or improving the lives of those affected by rare diseases? January 13th is the deadline to nominate individuals for NORD’s Rare Impact Awards. Nominations can be submitted through the NORD website.

NORD’s Rare Impact Awards ceremony will take place on May 18, 2017, in the amphitheater of the Ronald Reagan Building and International Trade Center, the largest structure in Washington, DC, and the first and only federal building dedicated to both federal and private use. More than 500 distinguished guests are expected to attend. Registration will be available soon on the NORD website.

The Rare Impact Awards honor individuals and organizations for commitment to improving the lives of patients and families affected by rare diseases. Nominees may include patients, caregivers, clinicians, researchers, advocates, and others who in some way have contributed to the greater good of the community. Nominations are also being sought for organizations that have helped drive better understanding of rare diseases and/or improved care for those affected.

Do you have a patient or colleague who has demonstrated extraordinary commitment to advancing understanding of rare diseases or improving the lives of those affected by rare diseases? January 13th is the deadline to nominate individuals for NORD’s Rare Impact Awards. Nominations can be submitted through the NORD website.

NORD’s Rare Impact Awards ceremony will take place on May 18, 2017, in the amphitheater of the Ronald Reagan Building and International Trade Center, the largest structure in Washington, DC, and the first and only federal building dedicated to both federal and private use. More than 500 distinguished guests are expected to attend. Registration will be available soon on the NORD website.

The Rare Impact Awards honor individuals and organizations for commitment to improving the lives of patients and families affected by rare diseases. Nominees may include patients, caregivers, clinicians, researchers, advocates, and others who in some way have contributed to the greater good of the community. Nominations are also being sought for organizations that have helped drive better understanding of rare diseases and/or improved care for those affected.

Transient Benign Neonatal Skin Findings

Review the PDF of the fact sheet on transient benign neonatal skin findings with board-relevant, easy-to-review material. This fact sheet lists benign findings that can be seen in neonates and infants.

Practice Questions

1. The parents of a 2-month-old infant present with their child. They are worried because the infant has “acne” that is not going away. Friends told them to try gentle cleansers and they have avoided using lotions or cream on her face. However, the bumps will not go away. On examination she has papules and pustules. Comedones cannot be identified. What are your next steps?

a. adapalene cream 0.1% every night at bedtime

b. benzoyl peroxide cream 4%

c. benzoyl peroxide wash 2.5%

d. erythromycin gel 2%

e. ketoconazole cream 2% twice daily

2. While in the newborn nursery prior to discharge, the attending pediatrician notices a rash on a 2-day-old neonate who is otherwise completely healthy. The pediatrician consults a dermatologist for his/her opinion. The dermatologist sees erythematous macules with central pustules located predominately on the trunk and proximal extremities. A pustule is unroofed with a blade, the contents smeared on a glass slide, and a Giemsa stain is performed. What is the predominant cell type you would expect to see on histological examination?

a. eosinophils

b. Langerhans cells

c. lymphocytes

d. neutrophils

e. no cells are visualized

3. Shortly after delivery, the pediatricians notice that the baby has numerous hyperpigmented macules on the back. No other primary lesions are seen. The neonate is otherwise normal in appearance and nontoxic appearing. A dermatologist is consulted for a recommendation for further workup or potential biopsy. The dermatologist examines the newborn. He is a well-appearing black boy with skin that is otherwise intact. A few pustules on the back are present that have a collarette of scale. The dermatologist reviews the mother’s prenatal history and the review shows that she was screened for syphilis and had a negative screening test with no other history of infectious diseases. What is the most appropriate next step to confirm your suspicions?

a. do a swab of a pustule and send it for viral culture

b. have his blood drawn and check for signs of neonatal herpes simplex virus infection

c. perform a biopsy of a pustule

d. perform a Giemsa stain on a smear of the pustule

e. start treatment with permethrin

4. Which intraoral cysts occur on the alveolar ridge of a neonate?

a. Bohn nodule

b. branchial cleft cyst

c. Epstein pearls

d. median raphe cyst

e. palatal cysts of the newborn

5. Miliaria rubra is associated with inflammation of the sweat glands in what portion of the skin?

a. basement membrane zone

b. dermis

c. dermoepidermal junction

d. intraepidermal

e. subcutis

Answers to practice questions provided on next page

Practice Question Answers

1. The parents of a 2-month-old infant present with their child. They are worried because the infant has “acne” that is not going away. Friends told them to try gentle cleansers and they have avoided using lotions or cream on her face. However, the bumps will not go away. On examination she has papules and pustules. Comedones cannot be identified. What are your next steps?

a. adapalene cream 0.1% every night at bedtime

b. benzoyl peroxide cream 4%

c. benzoyl peroxide wash 2.5%

d. erythromycin gel 2%

e. ketoconazole cream 2% twice daily

2. While in the newborn nursery prior to discharge, the attending pediatrician notices a rash on a 2-day-old neonate who is otherwise completely healthy. The pediatrician consults a dermatologist for his/her opinion. The dermatologist sees erythematous macules with central pustules located predominately on the trunk and proximal extremities. A pustule is unroofed with a blade, the contents smeared on a glass slide, and a Giemsa stain is performed. What is the predominant cell type you would expect to see on histological examination?

a. eosinophils

b. Langerhans cells

c. lymphocytes

d. neutrophils

e. no cells are visualized

3. Shortly after delivery, the pediatricians notice that the baby has numerous hyperpigmented macules on the back. No other primary lesions are seen. The neonate is otherwise normal in appearance and nontoxic appearing. A dermatologist is consulted for a recommendation for further workup or potential biopsy. The dermatologist examines the newborn. He is a well-appearing black boy with skin that is otherwise intact. A few pustules on the back are present that have a collarette of scale. The dermatologist reviews the mother’s prenatal history and the review shows that she was screened for syphilis and had a negative screening test with no other history of infectious diseases. What is the most appropriate next step to confirm your suspicions?

a. do a swab of a pustule and send it for viral culture

b. have his blood drawn and check for signs of neonatal herpes simplex virus infection

c. perform a biopsy of a pustule

d. perform a Giemsa stain on a smear of the pustule

e. start treatment with permethrin

4. Which intraoral cysts occur on the alveolar ridge of a neonate?

a. Bohn nodule

b. branchial cleft cyst

c. Epstein pearls

d. median raphe cyst

e. palatal cysts of the newborn

5. Miliaria rubra is associated with inflammation of the sweat glands in what portion of the skin?

a. basement membrane zone

b. dermis

c. dermoepidermal junction

d. intraepidermal

e. subcutis

Review the PDF of the fact sheet on transient benign neonatal skin findings with board-relevant, easy-to-review material. This fact sheet lists benign findings that can be seen in neonates and infants.

Practice Questions

1. The parents of a 2-month-old infant present with their child. They are worried because the infant has “acne” that is not going away. Friends told them to try gentle cleansers and they have avoided using lotions or cream on her face. However, the bumps will not go away. On examination she has papules and pustules. Comedones cannot be identified. What are your next steps?

a. adapalene cream 0.1% every night at bedtime

b. benzoyl peroxide cream 4%

c. benzoyl peroxide wash 2.5%

d. erythromycin gel 2%

e. ketoconazole cream 2% twice daily

2. While in the newborn nursery prior to discharge, the attending pediatrician notices a rash on a 2-day-old neonate who is otherwise completely healthy. The pediatrician consults a dermatologist for his/her opinion. The dermatologist sees erythematous macules with central pustules located predominately on the trunk and proximal extremities. A pustule is unroofed with a blade, the contents smeared on a glass slide, and a Giemsa stain is performed. What is the predominant cell type you would expect to see on histological examination?

a. eosinophils

b. Langerhans cells

c. lymphocytes

d. neutrophils

e. no cells are visualized

3. Shortly after delivery, the pediatricians notice that the baby has numerous hyperpigmented macules on the back. No other primary lesions are seen. The neonate is otherwise normal in appearance and nontoxic appearing. A dermatologist is consulted for a recommendation for further workup or potential biopsy. The dermatologist examines the newborn. He is a well-appearing black boy with skin that is otherwise intact. A few pustules on the back are present that have a collarette of scale. The dermatologist reviews the mother’s prenatal history and the review shows that she was screened for syphilis and had a negative screening test with no other history of infectious diseases. What is the most appropriate next step to confirm your suspicions?

a. do a swab of a pustule and send it for viral culture

b. have his blood drawn and check for signs of neonatal herpes simplex virus infection

c. perform a biopsy of a pustule

d. perform a Giemsa stain on a smear of the pustule

e. start treatment with permethrin

4. Which intraoral cysts occur on the alveolar ridge of a neonate?

a. Bohn nodule

b. branchial cleft cyst

c. Epstein pearls

d. median raphe cyst

e. palatal cysts of the newborn

5. Miliaria rubra is associated with inflammation of the sweat glands in what portion of the skin?

a. basement membrane zone

b. dermis

c. dermoepidermal junction

d. intraepidermal

e. subcutis

Answers to practice questions provided on next page

Practice Question Answers

1. The parents of a 2-month-old infant present with their child. They are worried because the infant has “acne” that is not going away. Friends told them to try gentle cleansers and they have avoided using lotions or cream on her face. However, the bumps will not go away. On examination she has papules and pustules. Comedones cannot be identified. What are your next steps?

a. adapalene cream 0.1% every night at bedtime

b. benzoyl peroxide cream 4%

c. benzoyl peroxide wash 2.5%

d. erythromycin gel 2%

e. ketoconazole cream 2% twice daily

2. While in the newborn nursery prior to discharge, the attending pediatrician notices a rash on a 2-day-old neonate who is otherwise completely healthy. The pediatrician consults a dermatologist for his/her opinion. The dermatologist sees erythematous macules with central pustules located predominately on the trunk and proximal extremities. A pustule is unroofed with a blade, the contents smeared on a glass slide, and a Giemsa stain is performed. What is the predominant cell type you would expect to see on histological examination?

a. eosinophils

b. Langerhans cells

c. lymphocytes

d. neutrophils

e. no cells are visualized

3. Shortly after delivery, the pediatricians notice that the baby has numerous hyperpigmented macules on the back. No other primary lesions are seen. The neonate is otherwise normal in appearance and nontoxic appearing. A dermatologist is consulted for a recommendation for further workup or potential biopsy. The dermatologist examines the newborn. He is a well-appearing black boy with skin that is otherwise intact. A few pustules on the back are present that have a collarette of scale. The dermatologist reviews the mother’s prenatal history and the review shows that she was screened for syphilis and had a negative screening test with no other history of infectious diseases. What is the most appropriate next step to confirm your suspicions?

a. do a swab of a pustule and send it for viral culture

b. have his blood drawn and check for signs of neonatal herpes simplex virus infection

c. perform a biopsy of a pustule

d. perform a Giemsa stain on a smear of the pustule

e. start treatment with permethrin

4. Which intraoral cysts occur on the alveolar ridge of a neonate?

a. Bohn nodule

b. branchial cleft cyst

c. Epstein pearls

d. median raphe cyst

e. palatal cysts of the newborn

5. Miliaria rubra is associated with inflammation of the sweat glands in what portion of the skin?

a. basement membrane zone

b. dermis

c. dermoepidermal junction

d. intraepidermal

e. subcutis

Review the PDF of the fact sheet on transient benign neonatal skin findings with board-relevant, easy-to-review material. This fact sheet lists benign findings that can be seen in neonates and infants.

Practice Questions

1. The parents of a 2-month-old infant present with their child. They are worried because the infant has “acne” that is not going away. Friends told them to try gentle cleansers and they have avoided using lotions or cream on her face. However, the bumps will not go away. On examination she has papules and pustules. Comedones cannot be identified. What are your next steps?

a. adapalene cream 0.1% every night at bedtime

b. benzoyl peroxide cream 4%

c. benzoyl peroxide wash 2.5%

d. erythromycin gel 2%

e. ketoconazole cream 2% twice daily

2. While in the newborn nursery prior to discharge, the attending pediatrician notices a rash on a 2-day-old neonate who is otherwise completely healthy. The pediatrician consults a dermatologist for his/her opinion. The dermatologist sees erythematous macules with central pustules located predominately on the trunk and proximal extremities. A pustule is unroofed with a blade, the contents smeared on a glass slide, and a Giemsa stain is performed. What is the predominant cell type you would expect to see on histological examination?

a. eosinophils

b. Langerhans cells

c. lymphocytes

d. neutrophils

e. no cells are visualized

3. Shortly after delivery, the pediatricians notice that the baby has numerous hyperpigmented macules on the back. No other primary lesions are seen. The neonate is otherwise normal in appearance and nontoxic appearing. A dermatologist is consulted for a recommendation for further workup or potential biopsy. The dermatologist examines the newborn. He is a well-appearing black boy with skin that is otherwise intact. A few pustules on the back are present that have a collarette of scale. The dermatologist reviews the mother’s prenatal history and the review shows that she was screened for syphilis and had a negative screening test with no other history of infectious diseases. What is the most appropriate next step to confirm your suspicions?

a. do a swab of a pustule and send it for viral culture

b. have his blood drawn and check for signs of neonatal herpes simplex virus infection

c. perform a biopsy of a pustule

d. perform a Giemsa stain on a smear of the pustule

e. start treatment with permethrin

4. Which intraoral cysts occur on the alveolar ridge of a neonate?

a. Bohn nodule

b. branchial cleft cyst

c. Epstein pearls

d. median raphe cyst

e. palatal cysts of the newborn

5. Miliaria rubra is associated with inflammation of the sweat glands in what portion of the skin?

a. basement membrane zone

b. dermis

c. dermoepidermal junction

d. intraepidermal

e. subcutis

Answers to practice questions provided on next page

Practice Question Answers

1. The parents of a 2-month-old infant present with their child. They are worried because the infant has “acne” that is not going away. Friends told them to try gentle cleansers and they have avoided using lotions or cream on her face. However, the bumps will not go away. On examination she has papules and pustules. Comedones cannot be identified. What are your next steps?

a. adapalene cream 0.1% every night at bedtime

b. benzoyl peroxide cream 4%

c. benzoyl peroxide wash 2.5%

d. erythromycin gel 2%

e. ketoconazole cream 2% twice daily

2. While in the newborn nursery prior to discharge, the attending pediatrician notices a rash on a 2-day-old neonate who is otherwise completely healthy. The pediatrician consults a dermatologist for his/her opinion. The dermatologist sees erythematous macules with central pustules located predominately on the trunk and proximal extremities. A pustule is unroofed with a blade, the contents smeared on a glass slide, and a Giemsa stain is performed. What is the predominant cell type you would expect to see on histological examination?

a. eosinophils

b. Langerhans cells

c. lymphocytes

d. neutrophils

e. no cells are visualized

3. Shortly after delivery, the pediatricians notice that the baby has numerous hyperpigmented macules on the back. No other primary lesions are seen. The neonate is otherwise normal in appearance and nontoxic appearing. A dermatologist is consulted for a recommendation for further workup or potential biopsy. The dermatologist examines the newborn. He is a well-appearing black boy with skin that is otherwise intact. A few pustules on the back are present that have a collarette of scale. The dermatologist reviews the mother’s prenatal history and the review shows that she was screened for syphilis and had a negative screening test with no other history of infectious diseases. What is the most appropriate next step to confirm your suspicions?

a. do a swab of a pustule and send it for viral culture

b. have his blood drawn and check for signs of neonatal herpes simplex virus infection

c. perform a biopsy of a pustule

d. perform a Giemsa stain on a smear of the pustule

e. start treatment with permethrin

4. Which intraoral cysts occur on the alveolar ridge of a neonate?

a. Bohn nodule

b. branchial cleft cyst

c. Epstein pearls

d. median raphe cyst

e. palatal cysts of the newborn

5. Miliaria rubra is associated with inflammation of the sweat glands in what portion of the skin?

a. basement membrane zone

b. dermis

c. dermoepidermal junction

d. intraepidermal

e. subcutis

Red-Blue Nodule on the Scalp

Metastatic Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma

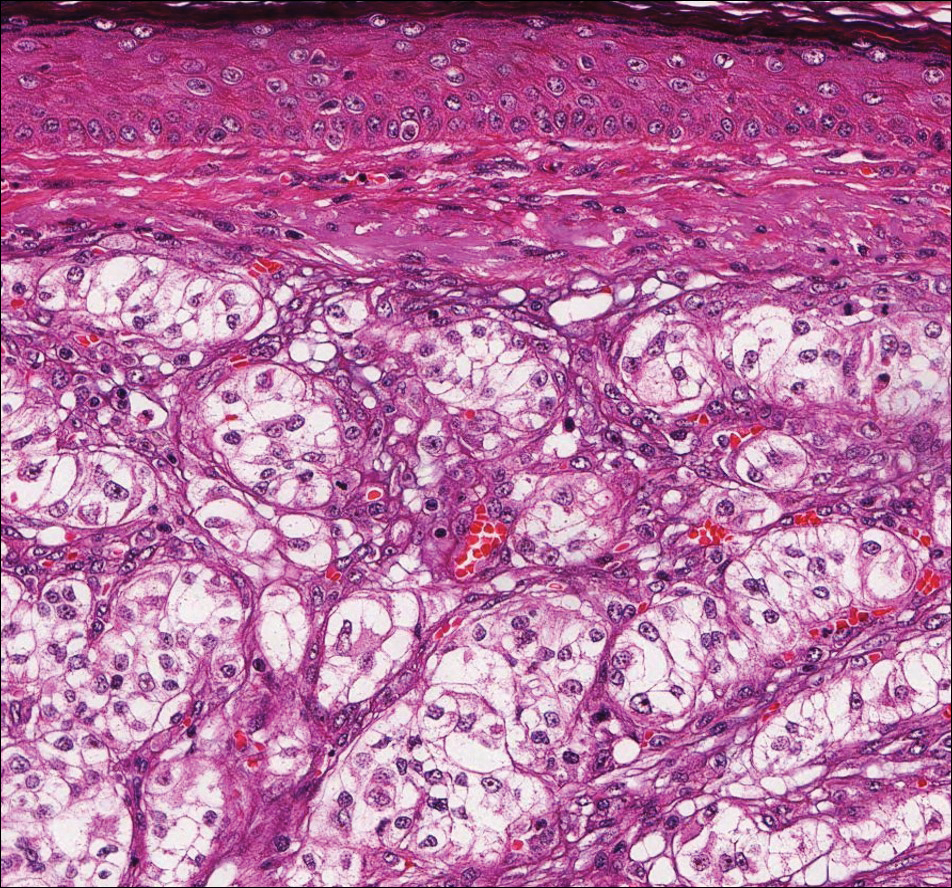

The differential diagnosis of cutaneous neoplasms with clear cells is broad. Clear cell features can be seen in primary tumors arising from the epidermis and cutaneous adnexa as well as in mesenchymal and melanocytic neoplasms. Furthermore, metastatic disease should be considered in the histologic differential diagnosis, as many visceral malignancies have clear cell features. This patient was subsequently found to have a large renal mass with metastasis to the lungs, spleen, and bone. The histologic findings support the diagnosis of metastatic clear cell renal cell carcinoma (RCC) to the skin.

Approximately 30% of patients with clear cell RCC present with metastatic disease with approximately 8% of those involving the skin.1,2 Cutaneous RCC metastases show a predilection for the head, especially the scalp. The clinical presentation is variable, but there often is a history of a rapidly growing brown, black, or purple nodule or plaque. A thorough review of the patient's history should be conducted if metastatic RCC is in the differential diagnosis, as it has been reported to occur up to 20 years after initial diagnosis.3

Histologically, clear cell RCC (quiz image) is composed of nests of tumor cells with clear cytoplasm and centrally located nuclei with prominent nucleoli. The clear cell features result from abundant cytoplasmic glycogen and lipid but may not be present in every case. One of the most important histologic features is the presence of delicate branching blood vessels (Figure 1). Numerous extravasated red blood cells also may be present. Positive immunohistochemical staining for PAX8, CD10, and RCC antigens support the diagnosis.4

Balloon cell nevi (Figure 2) most commonly occur on the head and neck in adolescents and young adults but clinically are indistinguishable from other banal nevi. The nevus cells are large with foamy to finely vacuolated cytoplasm and lack atypia. The clear cell change is the result of melanosome degeneration and may be extensive. The presence of melanin pigment, nests of typical nevus cells, and positive staining with MART-1 can help distinguish the tumor from xanthomas and RCC.5

Clear cell hidradenoma (Figure 3) is a well-circumscribed tumor of sweat gland origin that arises in the dermis. The architecture usually is solid, cystic, or a combination of both. The cytology is classically bland with poroid, squamoid, or clear cell morphology. Clear cells that are positive on periodic acid-Schiff staining predominate in up to one-third of cases. Carcinoembryonic antigen and epithelial membrane antigen can be used to highlight the eosinophilic cuticles of ducts within solid areas.6

Sebaceous carcinoma (Figure 4) most frequently arises in a periorbital distribution, although extraocular lesions are known to occur. Histologically, there is a proliferation of both mature sebocytes and basaloid cells in the dermis, occasionally involving the epidermis. The mature sebocytes demonstrate clear cell features with foamy to vacuolated cytoplasm and large nuclei with scalloped borders. The clear cells may vary greatly in number and often are sparse in poorly differentiated tumors in which pleomorphic basaloid cells may predominate. The basaloid cells may resemble those of squamous or basal cell carcinoma, leading to a diagnostic dilemma in some cases. Special staining with Sudan black B and oil red O highlights the cytoplasmic lipid but must be performed on frozen section specimens. Although not entirely specific, immunohistochemical expression of epithelial membrane antigen, androgen receptor, and membranous vesicular adipophilin staining in sebaceous carcinoma can assist in the diagnosis.7

Cutaneous xanthomas (Figure 5) may arise in patients of any age and represent deposition of lipid-laden macrophages. Classification often is dependent on the clinical presentation; however, some subtypes demonstrate unique morphologic features (eg, verruciform xanthomas). Xanthomas classically arise in association with elevated serum lipids, but they also may occur in normolipemic patients. Individuals with Erdheim-Chester disease have an increased propensity to develop xanthelasma. Similarly, plane xanthomas have been associated with monoclonal gammopathy. Histologically, xanthomas are characterized by sheets of foamy macrophages within the dermis and subcutis. Positive immunohistochemical staining for CD68 highlighting the histiocytic nature of the cells and the absence of a delicate vascular network aid in the differentiation from RCC.

- Patterson JW, Hosler GA. Weedon's Skin Pathology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier; 2016.

- Alcaraz I, Cerroni L, Rutten A, et al. Cutaneous metastases from internal malignancies: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:347-393.

- Calonje E, McKee PH. McKee's Pathology of the Skin. 4th ed. Edinburgh, Scotland: Elsevier/Saunders; 2012.

- Lin F, Prichard J. Handbook of Practical Immunohistochemistry: Frequently Asked Questions. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Springer; 2015.

- McKee PH, Calonje E. Diagnostic Atlas of Melanocytic Pathology. Edinburgh, Scotland: Mosby/Elsevier; 2009.

- Elston DM, Ferringer T, Ko CJ. Dermatopathology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2014.

- Ansai S, Takeichi H, Arase S, et al. Sebaceous carcinoma: an immunohistochemical reappraisal. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011;33:579-587.

Metastatic Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma

The differential diagnosis of cutaneous neoplasms with clear cells is broad. Clear cell features can be seen in primary tumors arising from the epidermis and cutaneous adnexa as well as in mesenchymal and melanocytic neoplasms. Furthermore, metastatic disease should be considered in the histologic differential diagnosis, as many visceral malignancies have clear cell features. This patient was subsequently found to have a large renal mass with metastasis to the lungs, spleen, and bone. The histologic findings support the diagnosis of metastatic clear cell renal cell carcinoma (RCC) to the skin.

Approximately 30% of patients with clear cell RCC present with metastatic disease with approximately 8% of those involving the skin.1,2 Cutaneous RCC metastases show a predilection for the head, especially the scalp. The clinical presentation is variable, but there often is a history of a rapidly growing brown, black, or purple nodule or plaque. A thorough review of the patient's history should be conducted if metastatic RCC is in the differential diagnosis, as it has been reported to occur up to 20 years after initial diagnosis.3

Histologically, clear cell RCC (quiz image) is composed of nests of tumor cells with clear cytoplasm and centrally located nuclei with prominent nucleoli. The clear cell features result from abundant cytoplasmic glycogen and lipid but may not be present in every case. One of the most important histologic features is the presence of delicate branching blood vessels (Figure 1). Numerous extravasated red blood cells also may be present. Positive immunohistochemical staining for PAX8, CD10, and RCC antigens support the diagnosis.4

Balloon cell nevi (Figure 2) most commonly occur on the head and neck in adolescents and young adults but clinically are indistinguishable from other banal nevi. The nevus cells are large with foamy to finely vacuolated cytoplasm and lack atypia. The clear cell change is the result of melanosome degeneration and may be extensive. The presence of melanin pigment, nests of typical nevus cells, and positive staining with MART-1 can help distinguish the tumor from xanthomas and RCC.5

Clear cell hidradenoma (Figure 3) is a well-circumscribed tumor of sweat gland origin that arises in the dermis. The architecture usually is solid, cystic, or a combination of both. The cytology is classically bland with poroid, squamoid, or clear cell morphology. Clear cells that are positive on periodic acid-Schiff staining predominate in up to one-third of cases. Carcinoembryonic antigen and epithelial membrane antigen can be used to highlight the eosinophilic cuticles of ducts within solid areas.6

Sebaceous carcinoma (Figure 4) most frequently arises in a periorbital distribution, although extraocular lesions are known to occur. Histologically, there is a proliferation of both mature sebocytes and basaloid cells in the dermis, occasionally involving the epidermis. The mature sebocytes demonstrate clear cell features with foamy to vacuolated cytoplasm and large nuclei with scalloped borders. The clear cells may vary greatly in number and often are sparse in poorly differentiated tumors in which pleomorphic basaloid cells may predominate. The basaloid cells may resemble those of squamous or basal cell carcinoma, leading to a diagnostic dilemma in some cases. Special staining with Sudan black B and oil red O highlights the cytoplasmic lipid but must be performed on frozen section specimens. Although not entirely specific, immunohistochemical expression of epithelial membrane antigen, androgen receptor, and membranous vesicular adipophilin staining in sebaceous carcinoma can assist in the diagnosis.7

Cutaneous xanthomas (Figure 5) may arise in patients of any age and represent deposition of lipid-laden macrophages. Classification often is dependent on the clinical presentation; however, some subtypes demonstrate unique morphologic features (eg, verruciform xanthomas). Xanthomas classically arise in association with elevated serum lipids, but they also may occur in normolipemic patients. Individuals with Erdheim-Chester disease have an increased propensity to develop xanthelasma. Similarly, plane xanthomas have been associated with monoclonal gammopathy. Histologically, xanthomas are characterized by sheets of foamy macrophages within the dermis and subcutis. Positive immunohistochemical staining for CD68 highlighting the histiocytic nature of the cells and the absence of a delicate vascular network aid in the differentiation from RCC.

Metastatic Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma

The differential diagnosis of cutaneous neoplasms with clear cells is broad. Clear cell features can be seen in primary tumors arising from the epidermis and cutaneous adnexa as well as in mesenchymal and melanocytic neoplasms. Furthermore, metastatic disease should be considered in the histologic differential diagnosis, as many visceral malignancies have clear cell features. This patient was subsequently found to have a large renal mass with metastasis to the lungs, spleen, and bone. The histologic findings support the diagnosis of metastatic clear cell renal cell carcinoma (RCC) to the skin.

Approximately 30% of patients with clear cell RCC present with metastatic disease with approximately 8% of those involving the skin.1,2 Cutaneous RCC metastases show a predilection for the head, especially the scalp. The clinical presentation is variable, but there often is a history of a rapidly growing brown, black, or purple nodule or plaque. A thorough review of the patient's history should be conducted if metastatic RCC is in the differential diagnosis, as it has been reported to occur up to 20 years after initial diagnosis.3

Histologically, clear cell RCC (quiz image) is composed of nests of tumor cells with clear cytoplasm and centrally located nuclei with prominent nucleoli. The clear cell features result from abundant cytoplasmic glycogen and lipid but may not be present in every case. One of the most important histologic features is the presence of delicate branching blood vessels (Figure 1). Numerous extravasated red blood cells also may be present. Positive immunohistochemical staining for PAX8, CD10, and RCC antigens support the diagnosis.4

Balloon cell nevi (Figure 2) most commonly occur on the head and neck in adolescents and young adults but clinically are indistinguishable from other banal nevi. The nevus cells are large with foamy to finely vacuolated cytoplasm and lack atypia. The clear cell change is the result of melanosome degeneration and may be extensive. The presence of melanin pigment, nests of typical nevus cells, and positive staining with MART-1 can help distinguish the tumor from xanthomas and RCC.5

Clear cell hidradenoma (Figure 3) is a well-circumscribed tumor of sweat gland origin that arises in the dermis. The architecture usually is solid, cystic, or a combination of both. The cytology is classically bland with poroid, squamoid, or clear cell morphology. Clear cells that are positive on periodic acid-Schiff staining predominate in up to one-third of cases. Carcinoembryonic antigen and epithelial membrane antigen can be used to highlight the eosinophilic cuticles of ducts within solid areas.6

Sebaceous carcinoma (Figure 4) most frequently arises in a periorbital distribution, although extraocular lesions are known to occur. Histologically, there is a proliferation of both mature sebocytes and basaloid cells in the dermis, occasionally involving the epidermis. The mature sebocytes demonstrate clear cell features with foamy to vacuolated cytoplasm and large nuclei with scalloped borders. The clear cells may vary greatly in number and often are sparse in poorly differentiated tumors in which pleomorphic basaloid cells may predominate. The basaloid cells may resemble those of squamous or basal cell carcinoma, leading to a diagnostic dilemma in some cases. Special staining with Sudan black B and oil red O highlights the cytoplasmic lipid but must be performed on frozen section specimens. Although not entirely specific, immunohistochemical expression of epithelial membrane antigen, androgen receptor, and membranous vesicular adipophilin staining in sebaceous carcinoma can assist in the diagnosis.7

Cutaneous xanthomas (Figure 5) may arise in patients of any age and represent deposition of lipid-laden macrophages. Classification often is dependent on the clinical presentation; however, some subtypes demonstrate unique morphologic features (eg, verruciform xanthomas). Xanthomas classically arise in association with elevated serum lipids, but they also may occur in normolipemic patients. Individuals with Erdheim-Chester disease have an increased propensity to develop xanthelasma. Similarly, plane xanthomas have been associated with monoclonal gammopathy. Histologically, xanthomas are characterized by sheets of foamy macrophages within the dermis and subcutis. Positive immunohistochemical staining for CD68 highlighting the histiocytic nature of the cells and the absence of a delicate vascular network aid in the differentiation from RCC.

- Patterson JW, Hosler GA. Weedon's Skin Pathology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier; 2016.

- Alcaraz I, Cerroni L, Rutten A, et al. Cutaneous metastases from internal malignancies: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:347-393.

- Calonje E, McKee PH. McKee's Pathology of the Skin. 4th ed. Edinburgh, Scotland: Elsevier/Saunders; 2012.

- Lin F, Prichard J. Handbook of Practical Immunohistochemistry: Frequently Asked Questions. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Springer; 2015.

- McKee PH, Calonje E. Diagnostic Atlas of Melanocytic Pathology. Edinburgh, Scotland: Mosby/Elsevier; 2009.

- Elston DM, Ferringer T, Ko CJ. Dermatopathology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2014.

- Ansai S, Takeichi H, Arase S, et al. Sebaceous carcinoma: an immunohistochemical reappraisal. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011;33:579-587.

- Patterson JW, Hosler GA. Weedon's Skin Pathology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier; 2016.

- Alcaraz I, Cerroni L, Rutten A, et al. Cutaneous metastases from internal malignancies: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:347-393.

- Calonje E, McKee PH. McKee's Pathology of the Skin. 4th ed. Edinburgh, Scotland: Elsevier/Saunders; 2012.

- Lin F, Prichard J. Handbook of Practical Immunohistochemistry: Frequently Asked Questions. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Springer; 2015.

- McKee PH, Calonje E. Diagnostic Atlas of Melanocytic Pathology. Edinburgh, Scotland: Mosby/Elsevier; 2009.

- Elston DM, Ferringer T, Ko CJ. Dermatopathology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2014.

- Ansai S, Takeichi H, Arase S, et al. Sebaceous carcinoma: an immunohistochemical reappraisal. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011;33:579-587.

A 59-year-old man presented with a 1.5×1.0-cm asymptomatic, smooth, red-blue nodule on the left parietal scalp. The nodule had been rapidly enlarging over the last 3 weeks. After resection, the cut surface was golden yellow and focally hemorrhagic.

Superficial Ulceration on the Vulva

Foscarnet-Induced Ulceration

Viral swabs were negative for herpes simplex virus. The diagnosis of foscarnet-induced ulceration was reached and the drug was discontinued. Symptomatic treatment with soap substitutes and lidocaine ointment was used.

Foscarnet is an antiviral agent used when resistance develops to first-line therapies.1 It is a pyrophosphate analogue that inhibits viral DNA polymerase, thereby preventing viral replication. It is used in treating cytomegalovirus and herpes simplex virus, which are resistant to first-line therapies, or patients who develop hematologic toxicity from antivirals. The main side effects of foscarnet include nephrotoxicity, alteration of calcium homeostasis, and malaise. Genital ulceration is a known side effect of therapy, though it is rare and more commonly seen in uncircumcised males. Approximately 94% of the drug is excreted unchanged in the urine, which causes an irritant dermatitis that is more pronounced in males as the urine stays in the subpreputial area.1

Vulval ulceration2 and penile ulceration3 has been reported in AIDS patients treated with foscarnet. In these patients, the onset of ulceration is temporally related to foscarnet therapy, occurring at approximately day 7 to 24 of treatment and resolving after discontinuation of therapy.

- Wagstaff AJ, Bryson HM. Foscarnet. a reappraisal of its antiviral activity, pharmacokinetic properties and therapeutic use in immunocompromised patients with viral infections. Drugs. 1994;48:199-226.

- Lacey HB, Ness A, Mandal BK. Vulval ulceration associated with foscarnet. Genitourin Med. 1992;68:182.

- Moyle G, Barton S, Gazzard BG. Penile ulceration with foscarnet therapy. AIDS. 1993;7:140-141.

Foscarnet-Induced Ulceration

Viral swabs were negative for herpes simplex virus. The diagnosis of foscarnet-induced ulceration was reached and the drug was discontinued. Symptomatic treatment with soap substitutes and lidocaine ointment was used.

Foscarnet is an antiviral agent used when resistance develops to first-line therapies.1 It is a pyrophosphate analogue that inhibits viral DNA polymerase, thereby preventing viral replication. It is used in treating cytomegalovirus and herpes simplex virus, which are resistant to first-line therapies, or patients who develop hematologic toxicity from antivirals. The main side effects of foscarnet include nephrotoxicity, alteration of calcium homeostasis, and malaise. Genital ulceration is a known side effect of therapy, though it is rare and more commonly seen in uncircumcised males. Approximately 94% of the drug is excreted unchanged in the urine, which causes an irritant dermatitis that is more pronounced in males as the urine stays in the subpreputial area.1

Vulval ulceration2 and penile ulceration3 has been reported in AIDS patients treated with foscarnet. In these patients, the onset of ulceration is temporally related to foscarnet therapy, occurring at approximately day 7 to 24 of treatment and resolving after discontinuation of therapy.

Foscarnet-Induced Ulceration

Viral swabs were negative for herpes simplex virus. The diagnosis of foscarnet-induced ulceration was reached and the drug was discontinued. Symptomatic treatment with soap substitutes and lidocaine ointment was used.

Foscarnet is an antiviral agent used when resistance develops to first-line therapies.1 It is a pyrophosphate analogue that inhibits viral DNA polymerase, thereby preventing viral replication. It is used in treating cytomegalovirus and herpes simplex virus, which are resistant to first-line therapies, or patients who develop hematologic toxicity from antivirals. The main side effects of foscarnet include nephrotoxicity, alteration of calcium homeostasis, and malaise. Genital ulceration is a known side effect of therapy, though it is rare and more commonly seen in uncircumcised males. Approximately 94% of the drug is excreted unchanged in the urine, which causes an irritant dermatitis that is more pronounced in males as the urine stays in the subpreputial area.1

Vulval ulceration2 and penile ulceration3 has been reported in AIDS patients treated with foscarnet. In these patients, the onset of ulceration is temporally related to foscarnet therapy, occurring at approximately day 7 to 24 of treatment and resolving after discontinuation of therapy.

- Wagstaff AJ, Bryson HM. Foscarnet. a reappraisal of its antiviral activity, pharmacokinetic properties and therapeutic use in immunocompromised patients with viral infections. Drugs. 1994;48:199-226.

- Lacey HB, Ness A, Mandal BK. Vulval ulceration associated with foscarnet. Genitourin Med. 1992;68:182.

- Moyle G, Barton S, Gazzard BG. Penile ulceration with foscarnet therapy. AIDS. 1993;7:140-141.

- Wagstaff AJ, Bryson HM. Foscarnet. a reappraisal of its antiviral activity, pharmacokinetic properties and therapeutic use in immunocompromised patients with viral infections. Drugs. 1994;48:199-226.

- Lacey HB, Ness A, Mandal BK. Vulval ulceration associated with foscarnet. Genitourin Med. 1992;68:182.

- Moyle G, Barton S, Gazzard BG. Penile ulceration with foscarnet therapy. AIDS. 1993;7:140-141.