User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

Approach to Diagnosing and Managing Sporotrichosis

Approach to Diagnosing and Managing Sporotrichosis

Sporotrichosis is an implantation mycosis that classically manifests as a localized skin and subcutaneous fungal infection but may disseminate to other parts of the body.1 It is caused by several species within the Sporothrix genus2 and is associated with varying clinical manifestations, geographic distributions, virulence profiles, and antifungal susceptibility patterns.3,4 Transmission of the fungus can involve inoculation from wild or domestic animals (eg, cats).5,6 Occupations such as landscaping and gardening or elements in the environment (eg, soil, plant fragments) also can be sources of exposure.7,8

Sporotrichosis is recognized by the World Health Organization as a neglected tropical disease that warrants global advocacy to prevent infections and improve patient outcomes.9,10 It carries substantial stigma and socioeconomic burden.11,12 Diagnostics, species identification, and antifungal susceptibility testing often are limited, particularly in resource-limited settings.13 In this article, we outline steps to diagnose and manage sporotrichosis to improve care for affected patients globally.

Epidemiology

Sporotrichosis occurs worldwide but is most common in tropical and subtropical regions.14,15 Outbreaks and clusters of sporotrichosis have been observed across North, Central, and South America as well as in southern Africa and Asia. The estimated annual incidence is 40,000 cases worldwide,16-20 but global case counts likely are underestimated due to limited surveillance data and diagnostic capability.21

On the Asian subcontinent, Sporothrix globosa is the predominant causative species of sporotrichosis, typically via contaminated plant material22; however, at least 1 outbreak has been associated with severe flooding.23 In Africa, infections are most commonly caused by Sporothrix schenckii sensu stricto through a similar transmission route. Across Central America, S schenckii sensu stricto is the predominant causative species; however, Sporothrix brasiliensis is the predominant species in some countries in South America, particularly Brazil.20

Data describing the current geographic distribution and prevalence of sporotrichosis in the United States are limited. Historically, the disease was reported most commonly in Midwestern states and was associated with outbreaks related to handling Sphagnum moss.24,25 Epidemiologic studies using health insurance data indicate an average annual incidence of 2.0 cases per million individuals in the United States, with a higher prevalence among women and a median age at diagnosis of 54 years.26 A review of sporotrichosis-associated hospitalizations across the United States from 2000 to 2013 indicated an average hospitalization rate of 0.35 cases per 1 million individuals; rates were higher (0.45 cases per million) in the West and lower (0.15 per million) in the Northeast and in men (0.40 per million).27 Type 2 diabetes, immune-mediated inflammatory disease, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease are associated with an increased risk for infection and hospitalization.27

Causative Organisms

Sporothrix species are thermally dimorphic fungi that can grow as mold in the environment and as yeast in human tissue. Sporothrix brasiliensis is the only thermodimorphic fungus known to be transmitted directly in its yeast form.28 In other species, inoculation usually occurs after contact with contaminated soil or plant material during gardening, carpentry, or agricultural practices.7

Zoonotic transmission of sporotrichosis from animals to humans has been reported from a range of domestic and wild animals and birds but historically has been rare.5,7,29,30 Recently, the importance of both cat-to-cat (epizootic) and cat-to-human (zoonotic) transmission of S brasiliensis has been recognized, with infection typically following traumatic inoculation after a scratch or bite; less frequently, transmission occurs due to exposure to respiratory droplets or contact with feline exudates.5,29,31 Sporothrix brasiliensis is responsible for zoonotic epidemics in South America, primarily in Brazil. Transmission occurs among humans, cats, and canines, with felines serving as the primary vector.32 Transmission of this species is particularly common in stray and unneutered male cats that exhibit aggressive behaviors.33 This species also is thought to be the most virulent Sporothrix species.21

Sporothrix brasiliensis can persist on nondisinfected inanimate surfaces, which suggests that fomite transmission can lead to human infection.31 The epidemiology of sporotrichosis has transformed in regions where S brasiliensis circulates, with epidemic spread resulting in thousands of cases, whereas in other areas without S brasilinesis, sporotrichosis predominantly occurs sporadically with rare clusters.1,2,7,15

Sporotrichosis has been the subject of a taxonomic debate in the mycology community.21 Sporothrix schenckii sensu lato originally was believed to be the sole fungal pathogen causing sporotrichosis34 but was later divided into S schenckii sensu stricto, Sporothrix globosa, and S brasiliensis.35 More than 60 distinct species now have been described within the Sporothrix genus,36,37 but the primary species causing human sporotrichosis include S schenckii sensu stricto, S brasiliensis, S globosa, Sporothrix mexicana, and Sporothrix luriei.35 Both S schenckii and S brasiliensis have greater virulence than other Sporothrix species4; however, S schenckii causes infections that typically are localized and are milder, while S brasiliensis can lead to more atypical, severe, and disseminated infections38,39 and can spread epidemically.

Clinical Manifestations

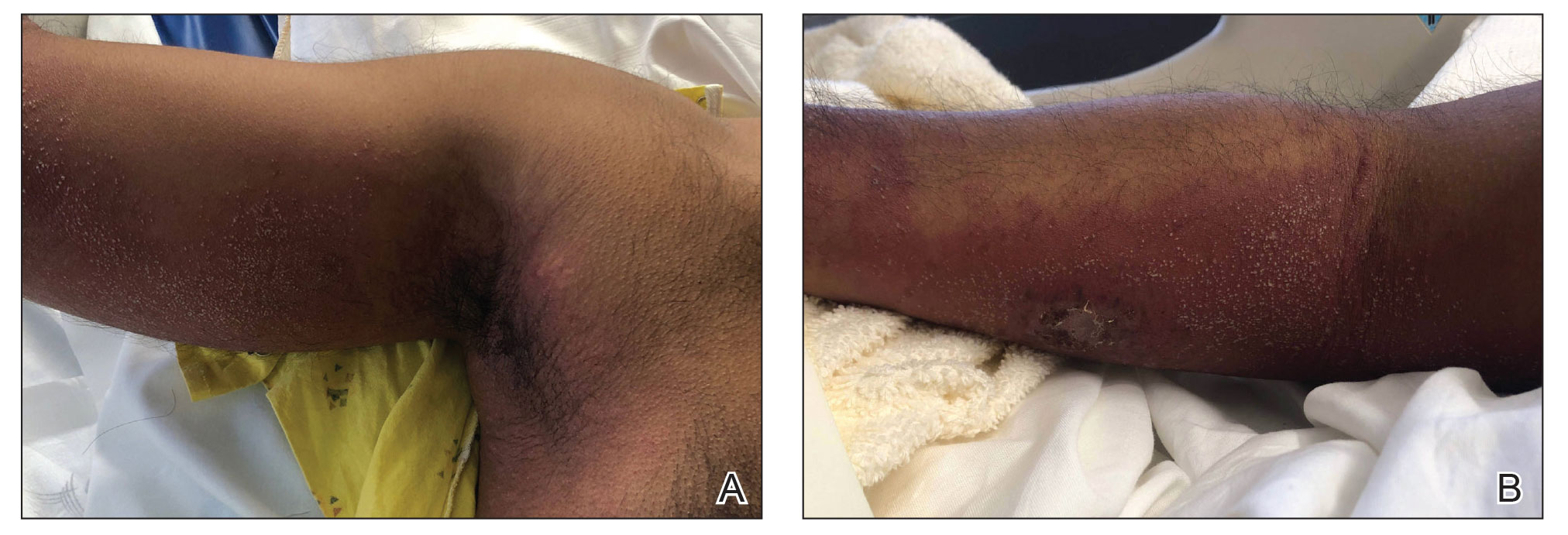

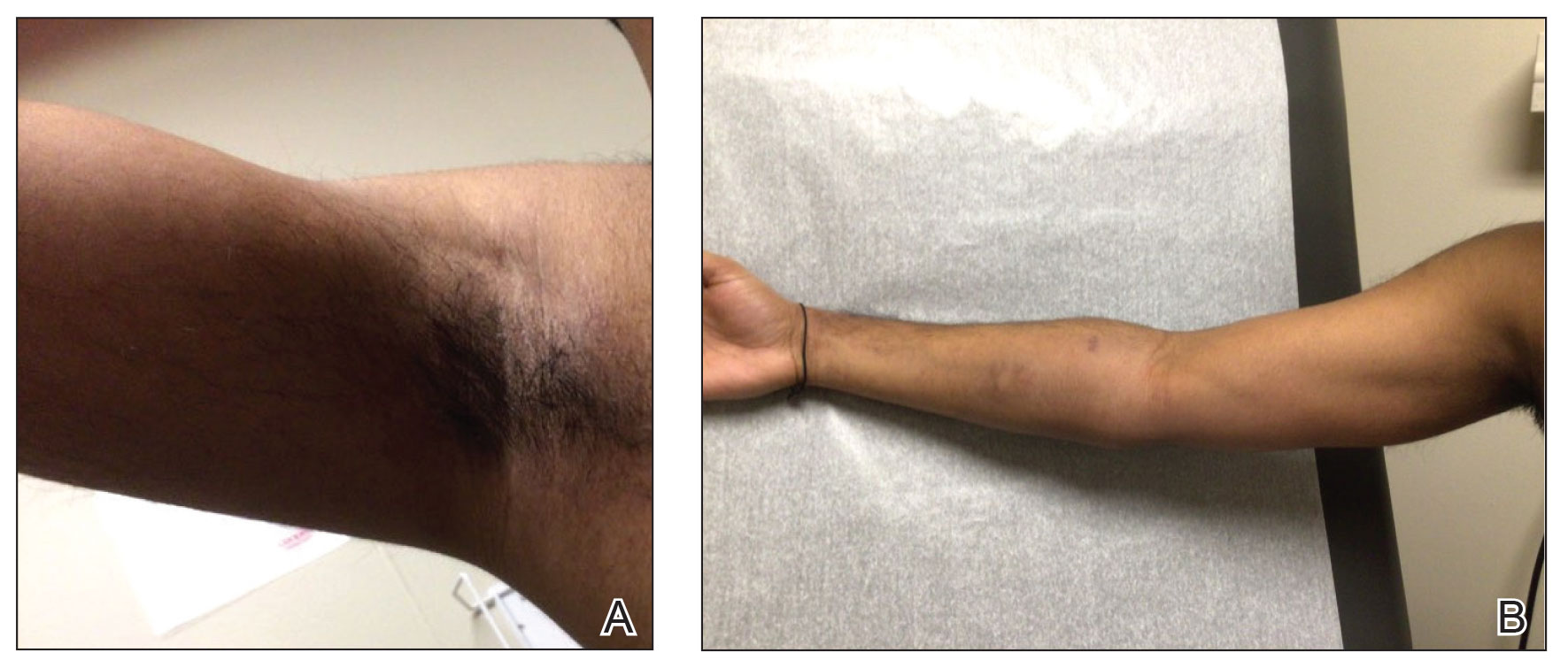

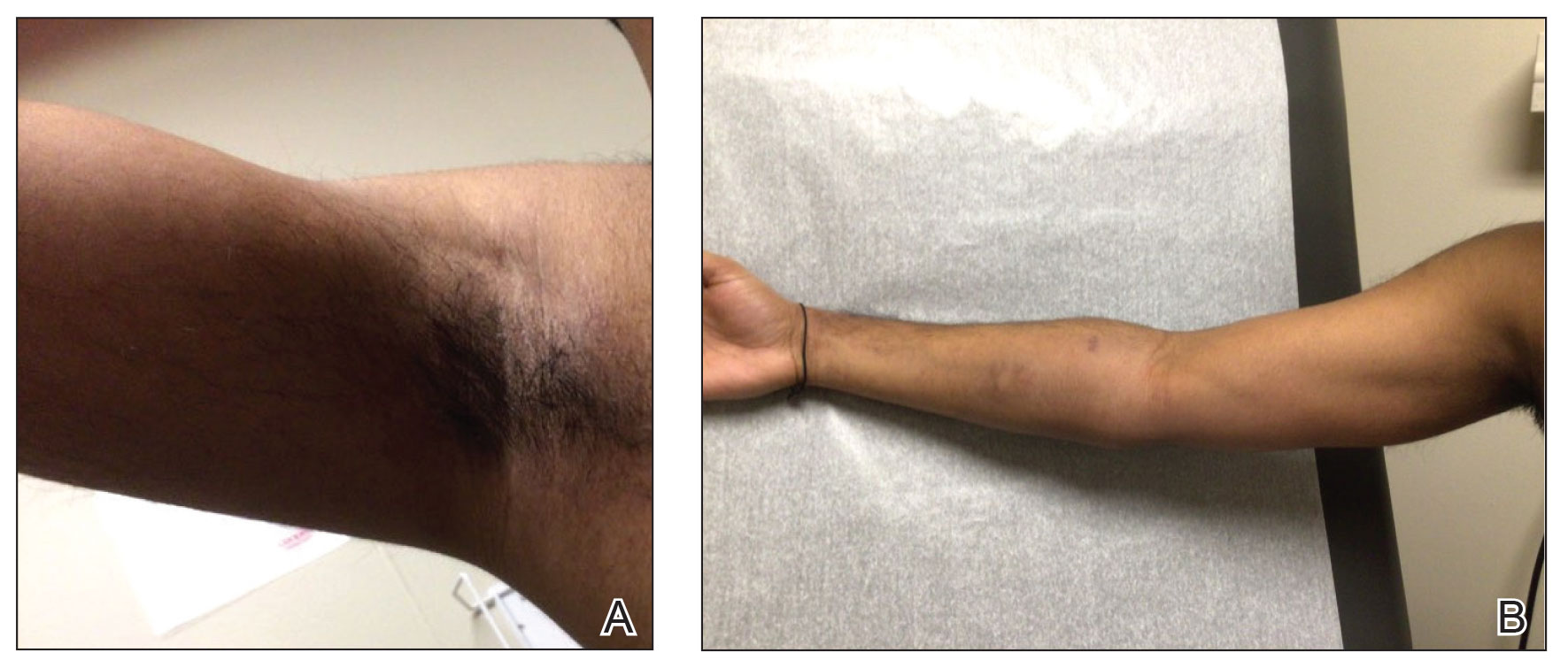

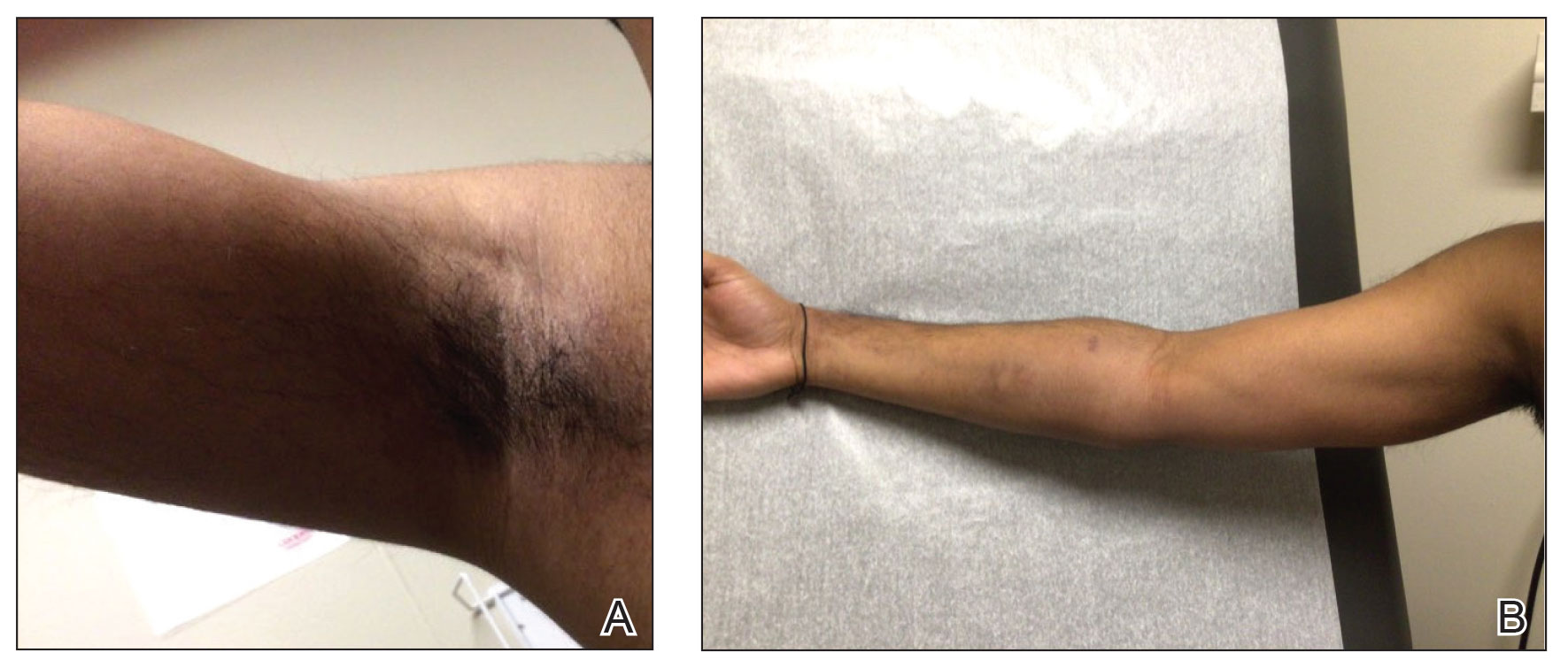

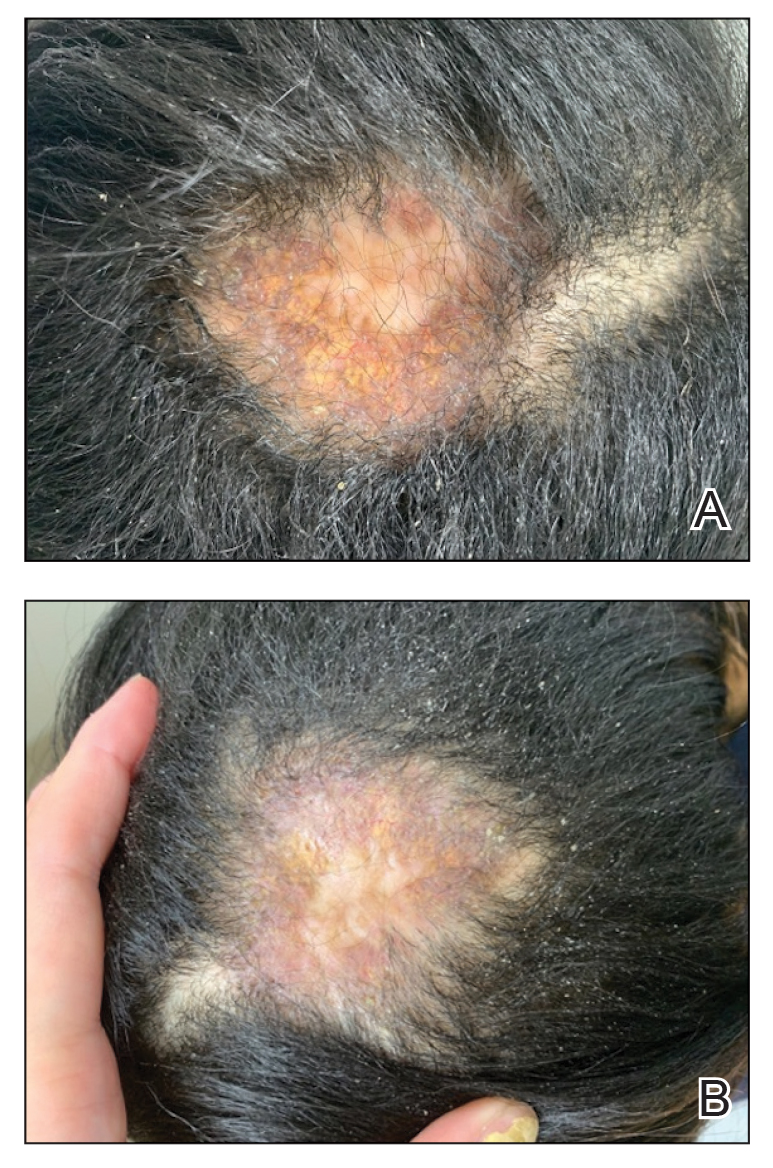

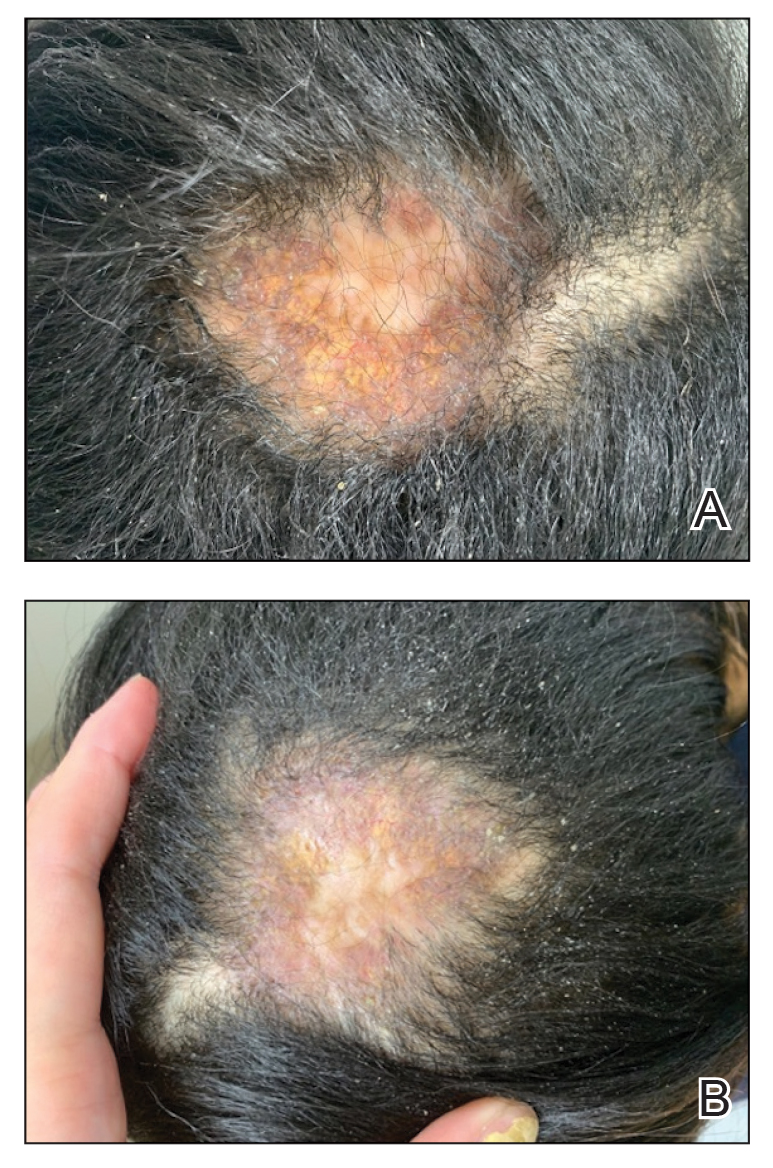

Sporotrichosis has 4 main clinical presentations: cutaneous lymphatic, fixed cutaneous, cutaneous or systemic disseminated, and extracutaneous.40,41 The most common clinical manifestation is the cutaneous lymphatic form, which predominantly affects the hands and forearms in adults and the face in children.7 The primary lesion usually manifests as a unilateral papule, nodule, or pustule that may ulcerate (sporotrichotic chancre), but multiple sites of inoculation are possible. Subsequent lesions may appear in a linear distribution along a regional lymphatic path (sporotrichoid spread). Systemic symptoms and regional lymphadenopathy are uncommon and usually are mild.

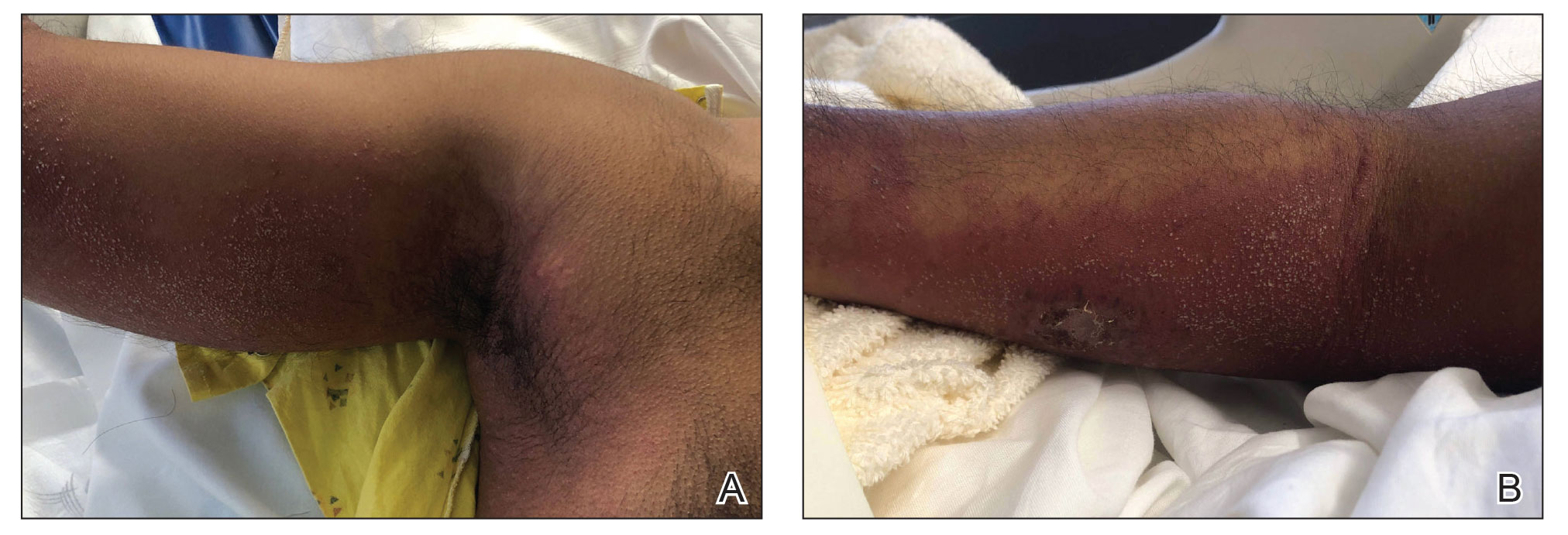

The second most common clinical manifestation is the fixed cutaneous form, typically affecting the face, neck, trunk, or legs with a single papule, nodule, or verrucous lesion with no lymphangitic spread.7 Usually confined to the inoculation site, the primary lesion may be accompanied by satellite lesions and often presents a diagnostic challenge.

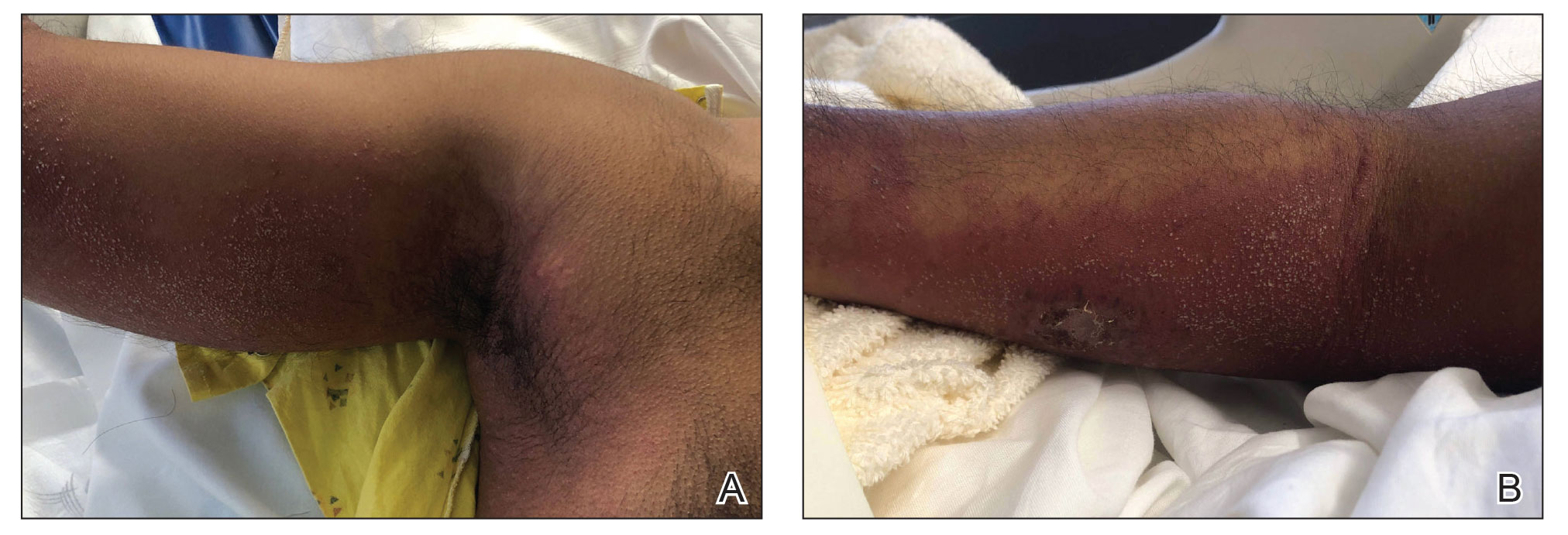

Disseminated sporotrichosis (either cutaneous or systemic) is rare. Disseminated cutaneous sporotrichosis manifests with multiple noncontiguous skin lesions caused by lymphatic and possible hematogenous spread. Lesions may include a combination of papules, pustules, follicular eruptions, crusted plaques, and ulcers that may mimic other systemic infections. Immunoreactive changes such as erythema nodosum, erythema multiforme, or arthritis may accompany skin lesions, most commonly with S brasiliensis infections. Nearly 10% of S brasiliensis infections involve the ocular adnexa, and Parinaud oculoglandular syndrome is commonly described in cases reported in Brazil.42,43 Disseminated disease usually occurs in immunocompromised hosts; however, despite a focus on HIV co-infection,8,44 prior epidemiologic research has suggested that diabetes and alcoholism are the most common predisposing factors.45 Systemic disseminated sporotrichosis by definition affects at least 2 body systems, most commonly the central nervous system, lungs, and musculoskeletal system (including joints and bone marrow).45

Extracutaneous sporotrichosis is rare and often is difficult to diagnose. Risk factors include chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, alcoholism, use of steroid medications, AIDS, solid organ transplantation, and use of tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors. It usually affects bony structures through hematogenous spread in immunocompromised hosts and is associated with a high risk for osteomyelitis due to delayed diagnosis.2

Clinical progression of sporotrichosis usually is slow, and lesions may persist for months or years if untreated. Sporotrichosis should always be considered for atypical, persistent, or treatment-resistant manifestations of nodular or ulcerated skin lesions in endemic regions or acute illness with these symptoms following exposure. Preventing secondary bacterial infection is an important consideration as it can exacerbate disease severity, extend the treatment duration, prolong hospitalization, and increase mortality risk.46

Diagnosis

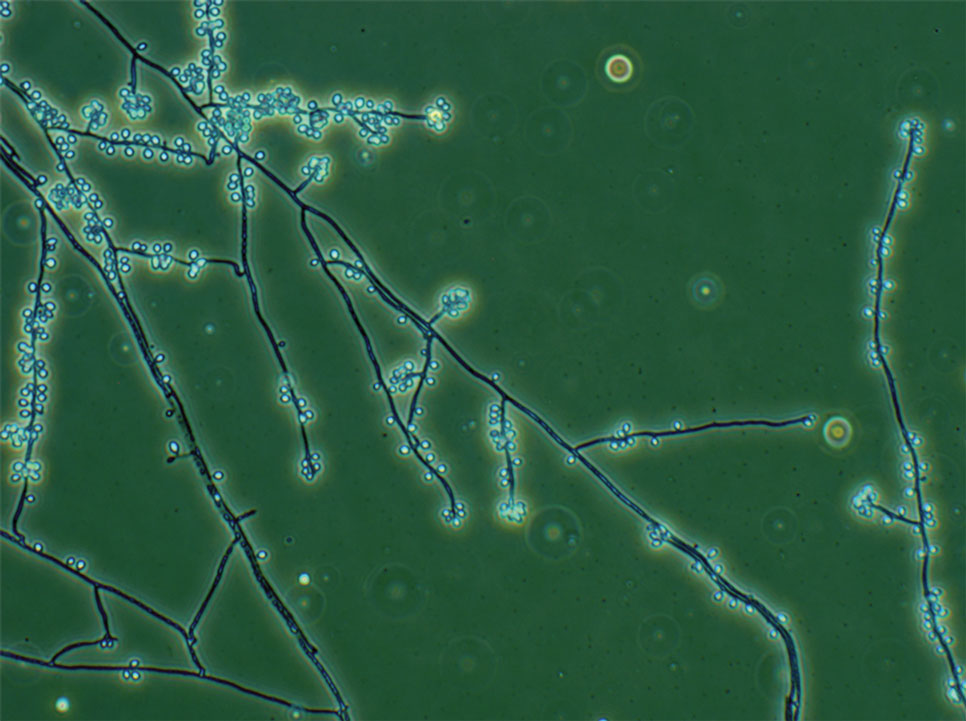

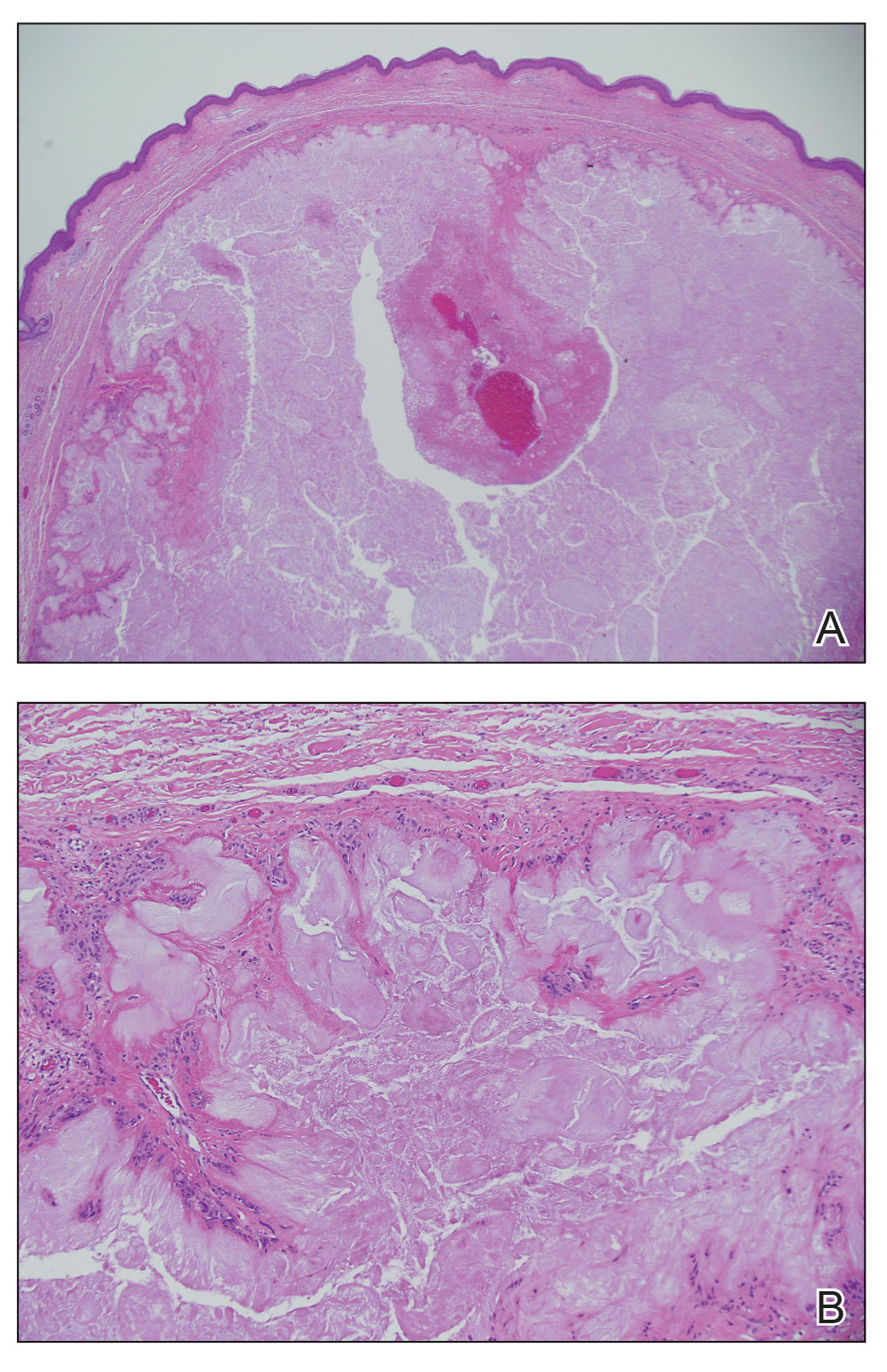

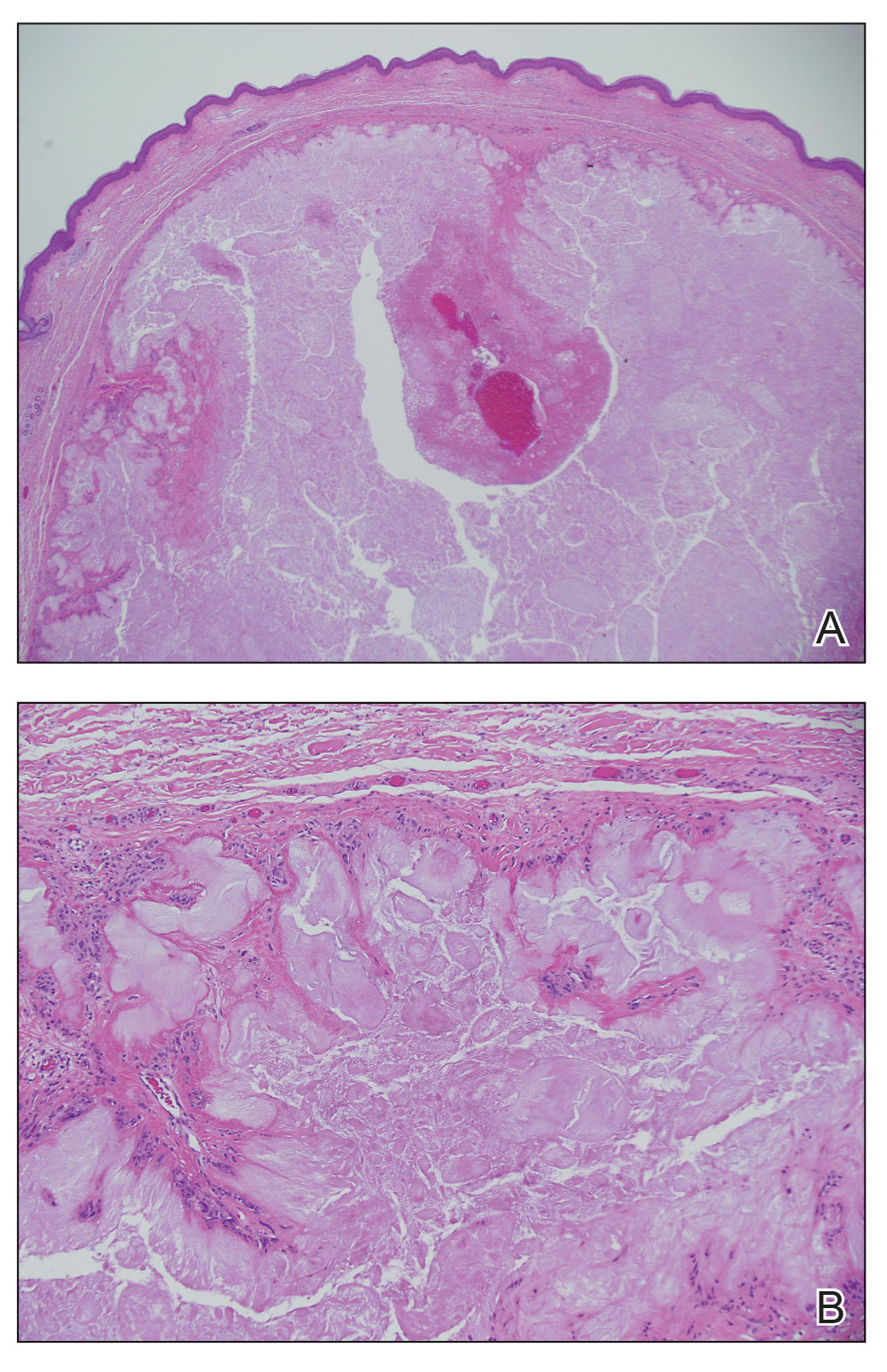

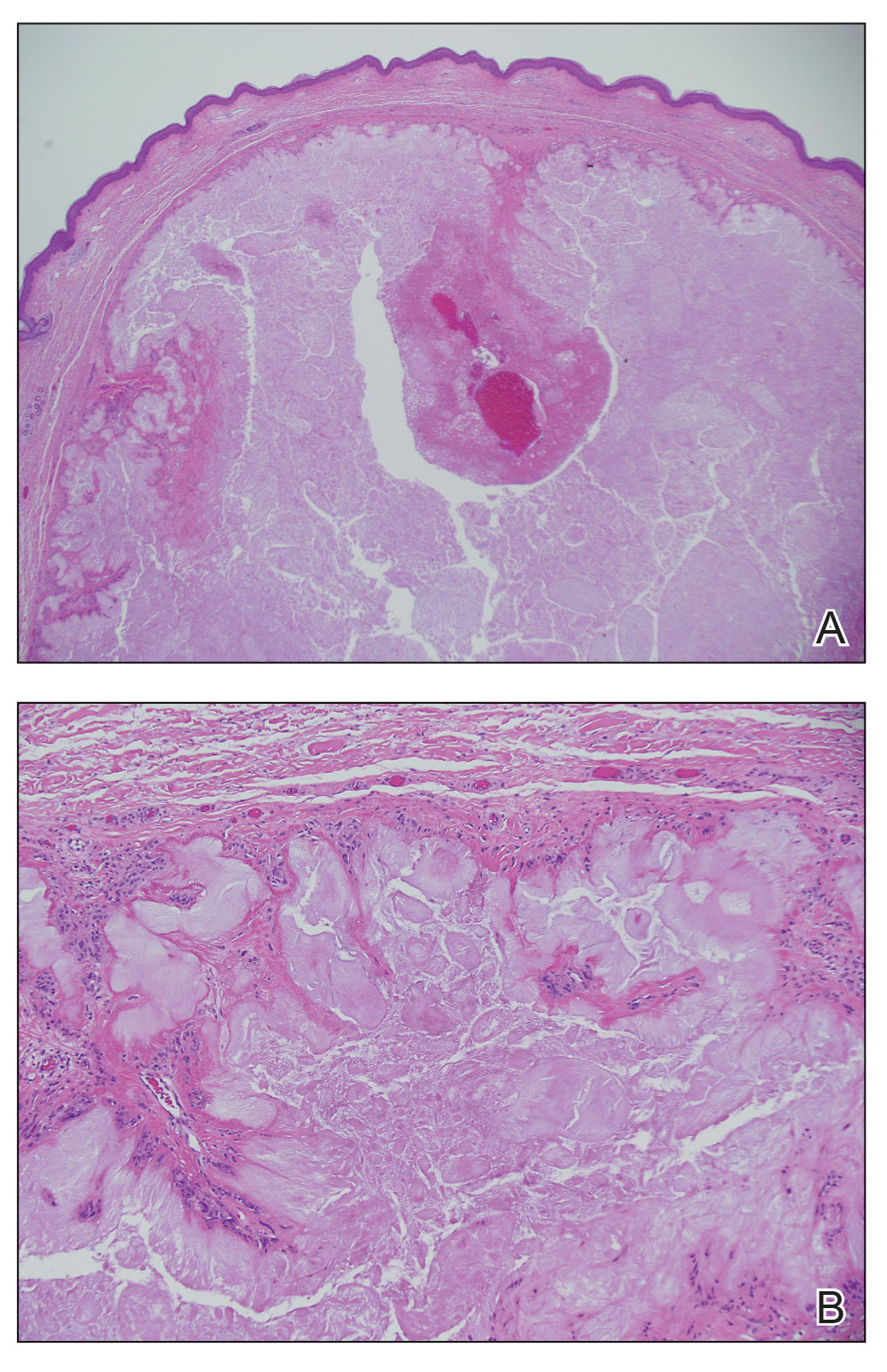

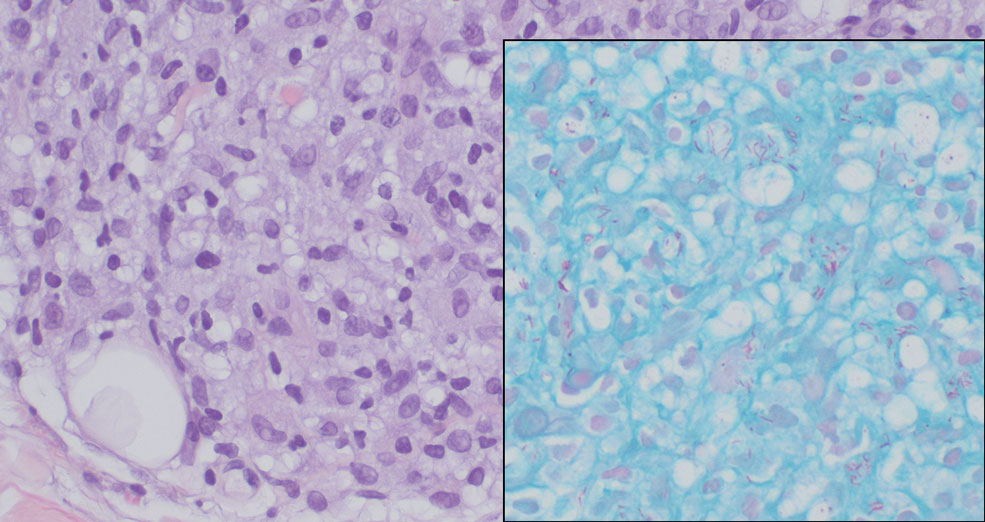

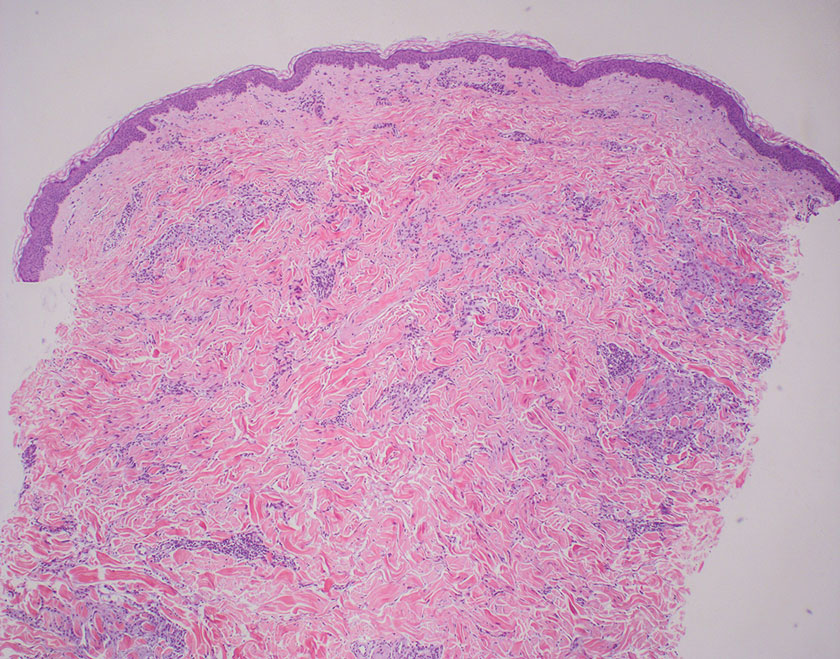

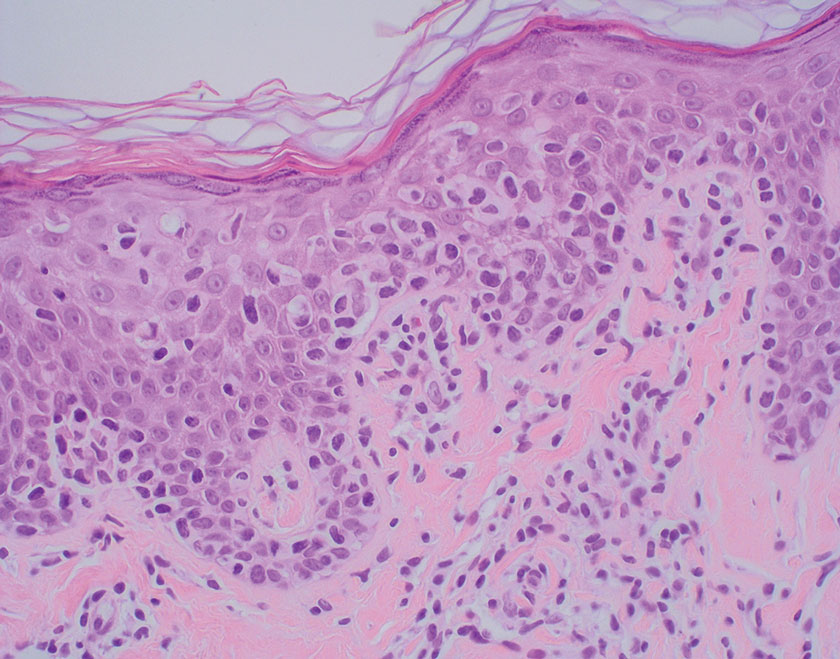

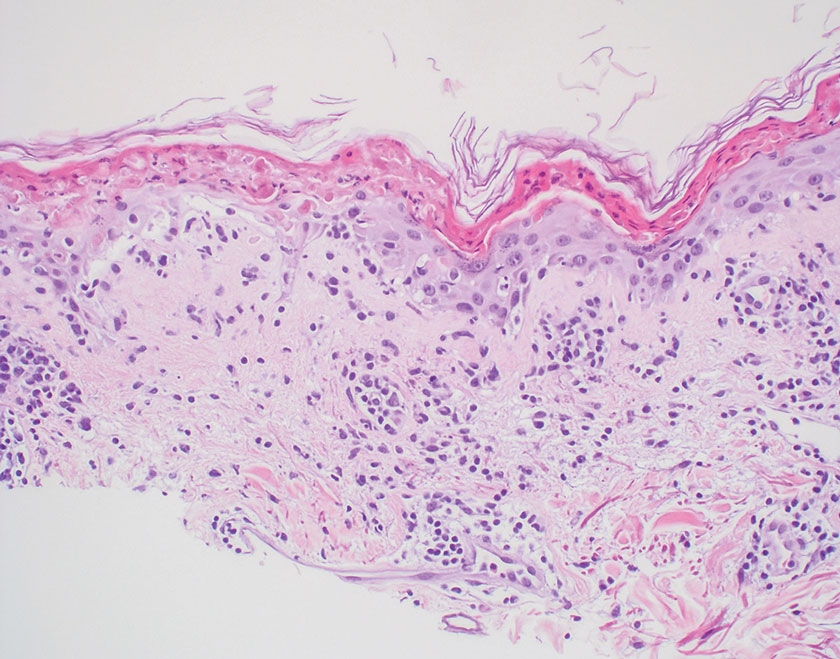

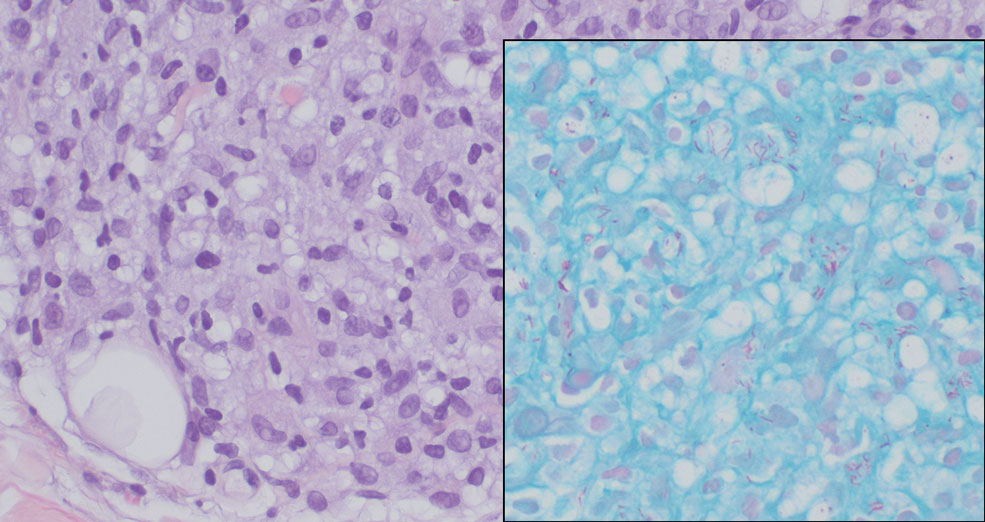

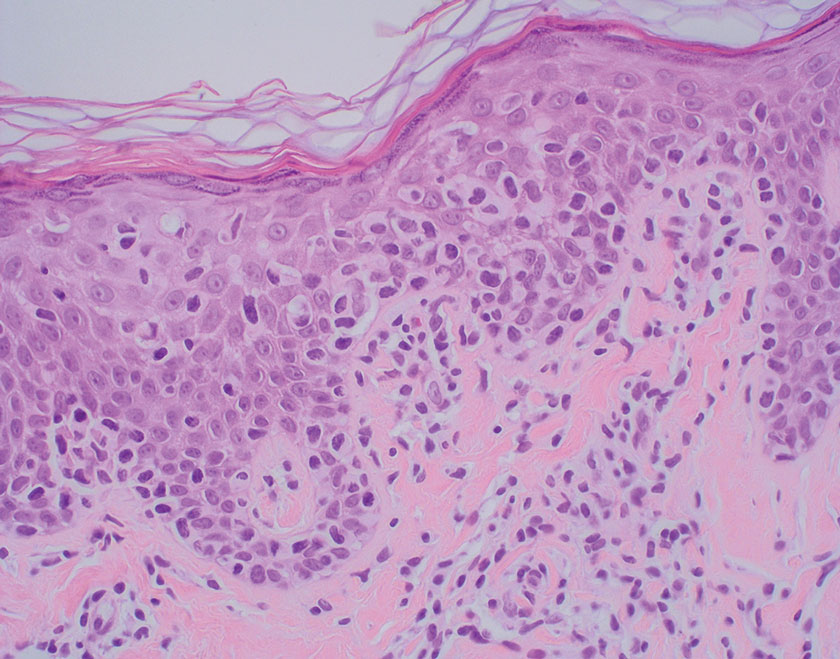

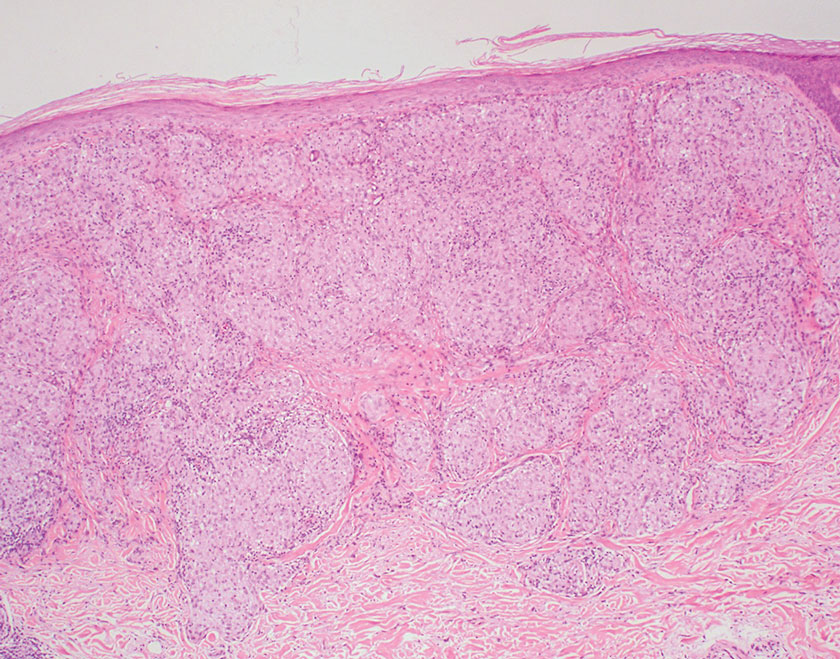

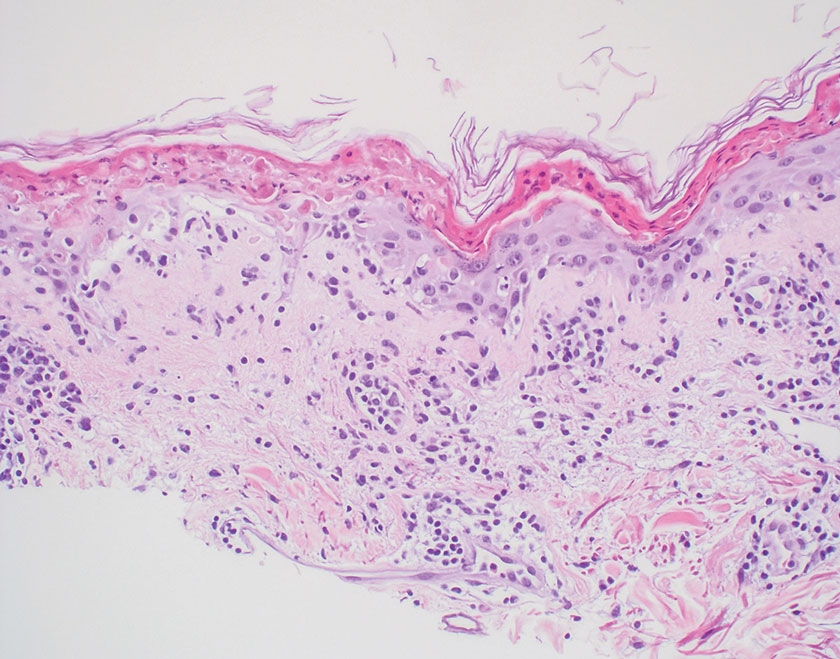

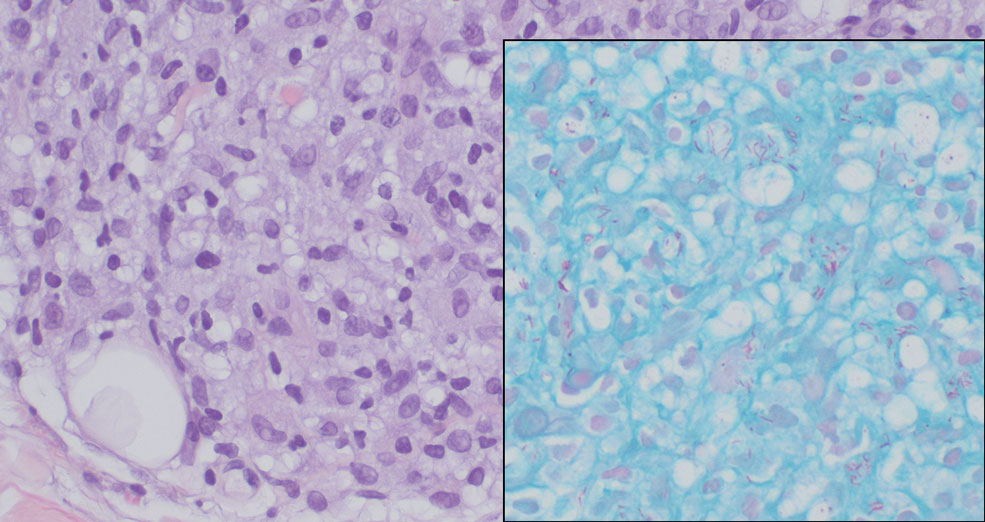

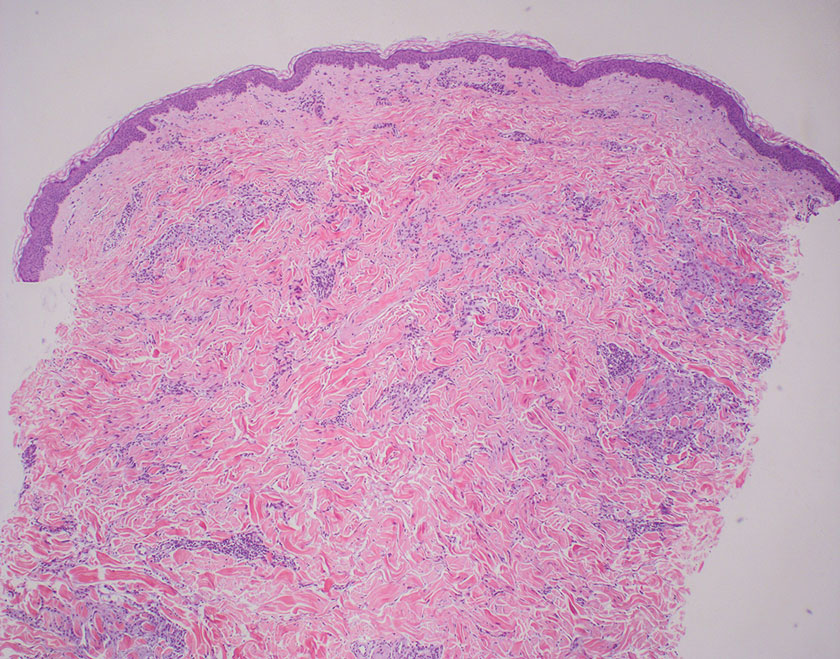

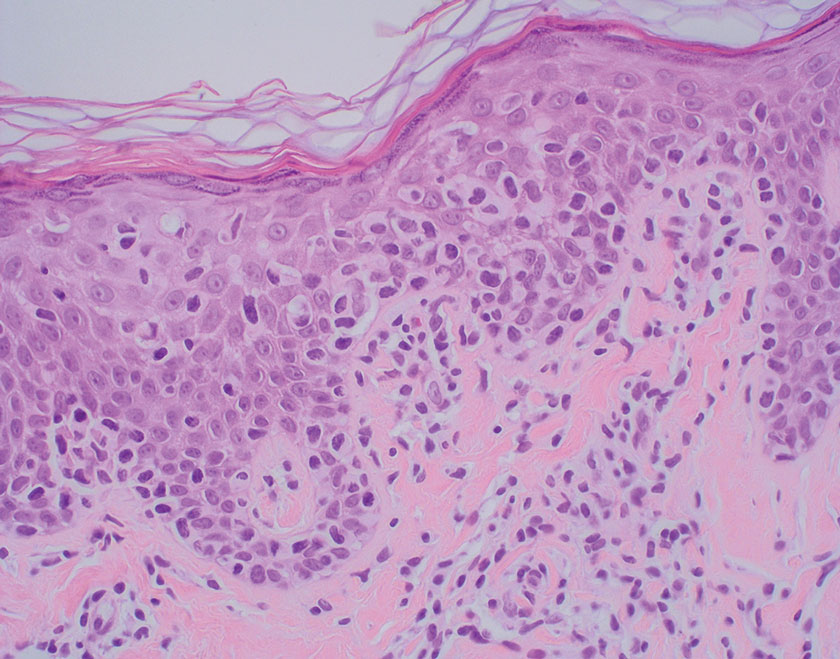

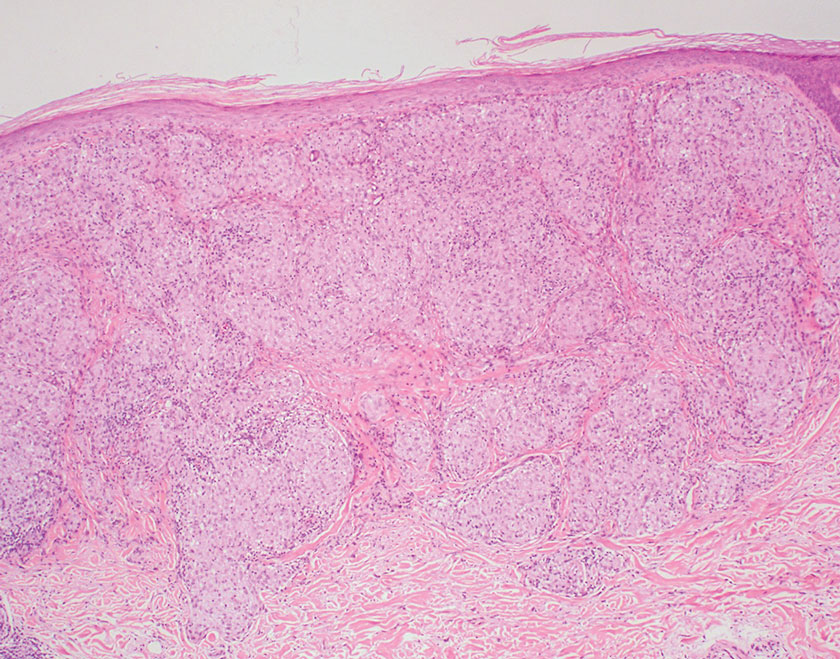

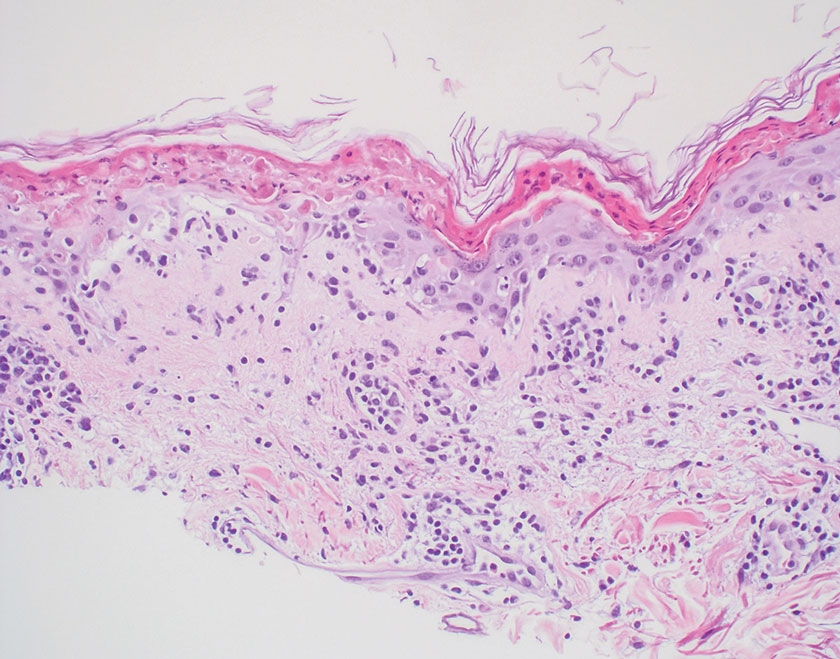

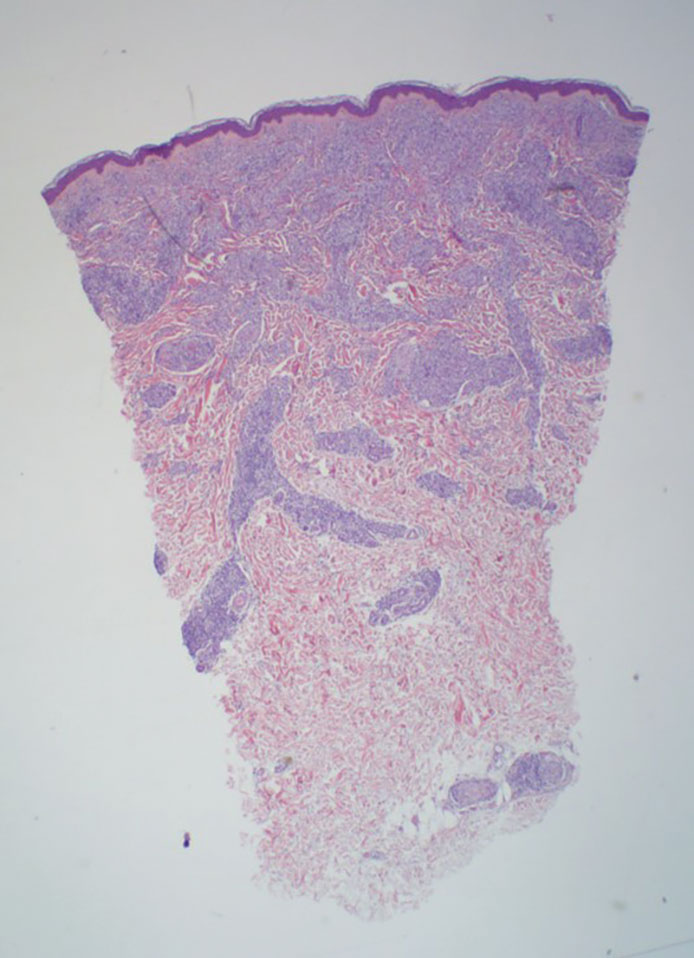

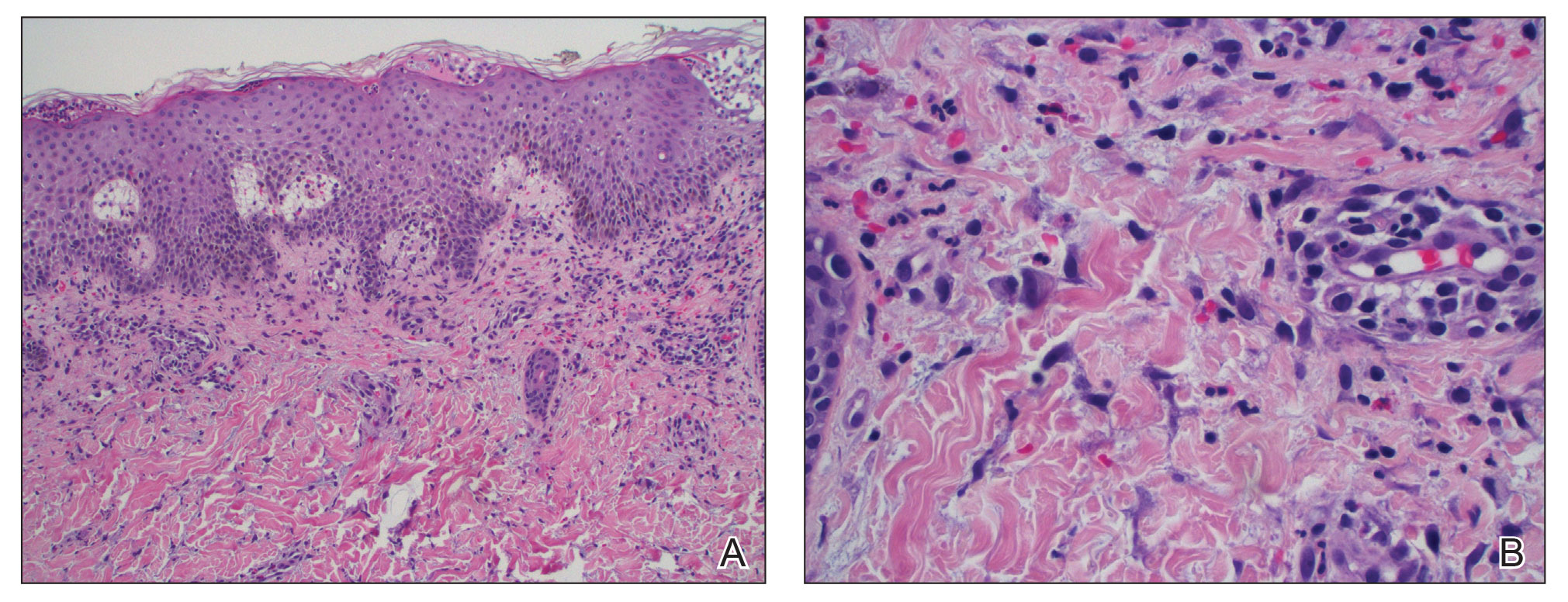

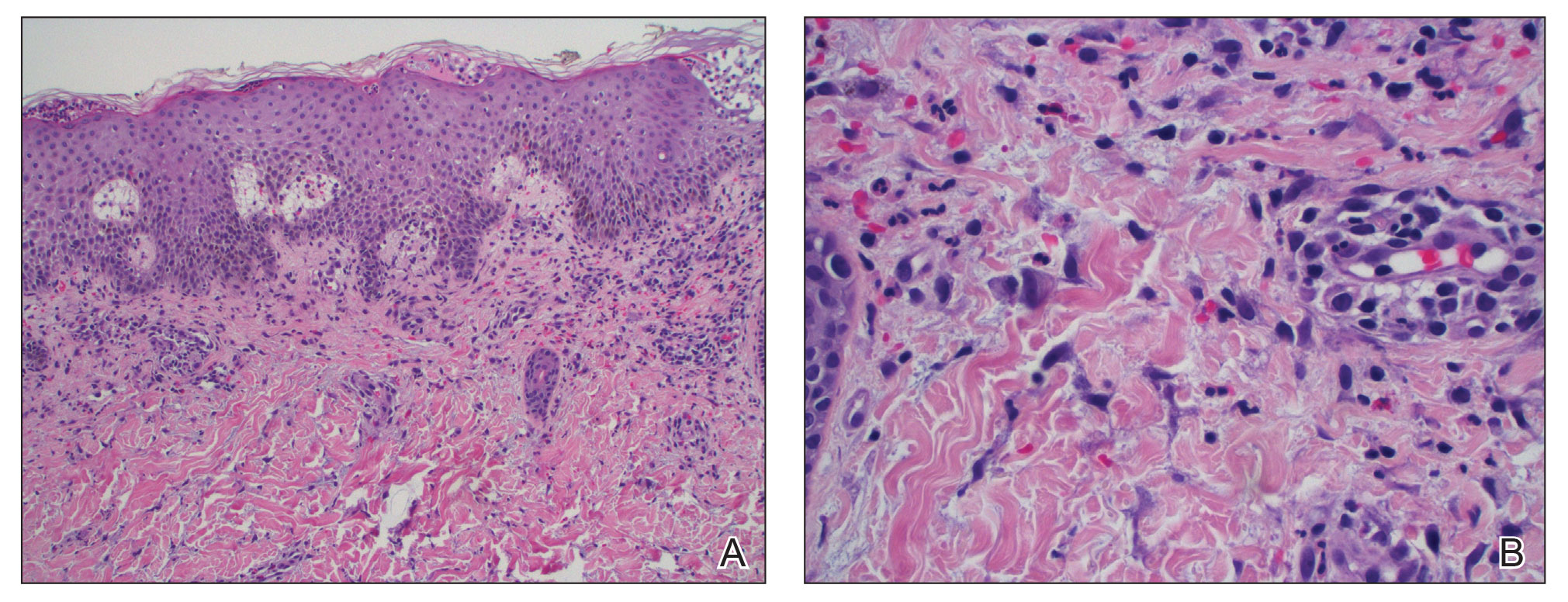

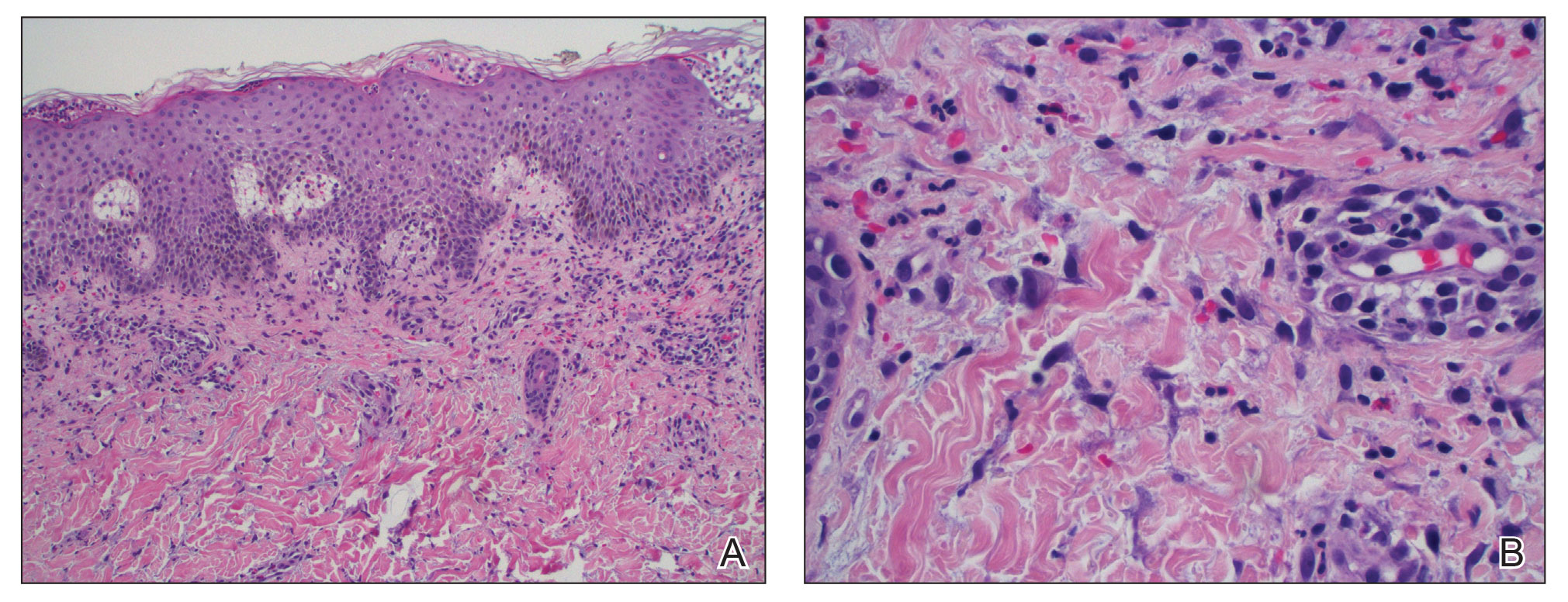

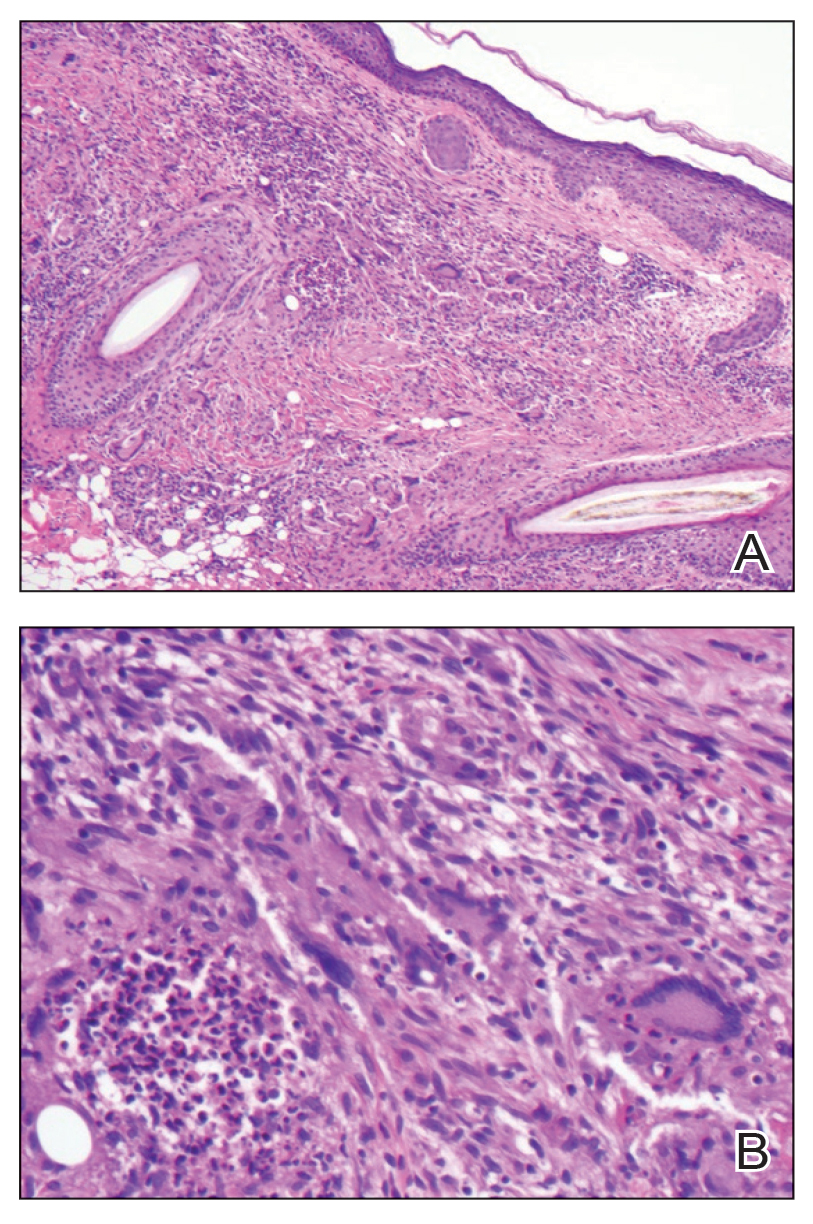

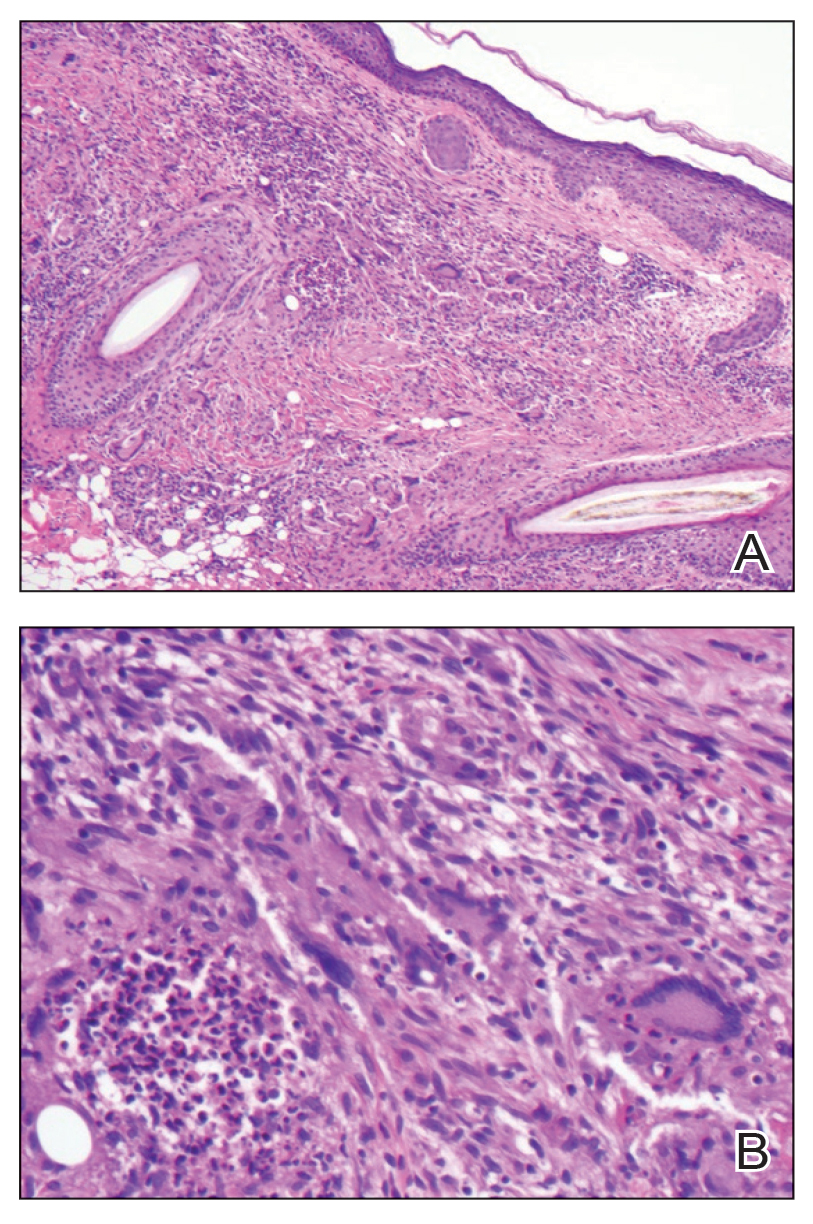

In regions endemic for S brasiliensis, it may be acceptable to commence treatment on clinical suspicion without a definitive diagnosis,21 but caution is necessary, as lesions easily can be mistaken for other conditions such as Mycobacterium marinum infections (sporotrichoid lesions) or cutaneous leishmaniasis. Limited availability of molecular diagnostic tools in routine clinical laboratories affects the diagnosis of sporotrichosis and species identification. Direct microscopy on a 10% to 30% potassium hydroxide wet mount has low diagnostic sensitivity and is not recommended47; findings typically include cigar-shaped yeast cells (eFigure 1). Biopsy and histopathology also are useful, although in many infections (other than those due to S brasiliensis) there are very few detectable organisms in the tissue. Fluorescent staining of fungi with optical brighteners (eg, Calcofluor, Blankophor) is a useful technique with high sensitivity in clinical specimens on histopathologic and direct examination.48

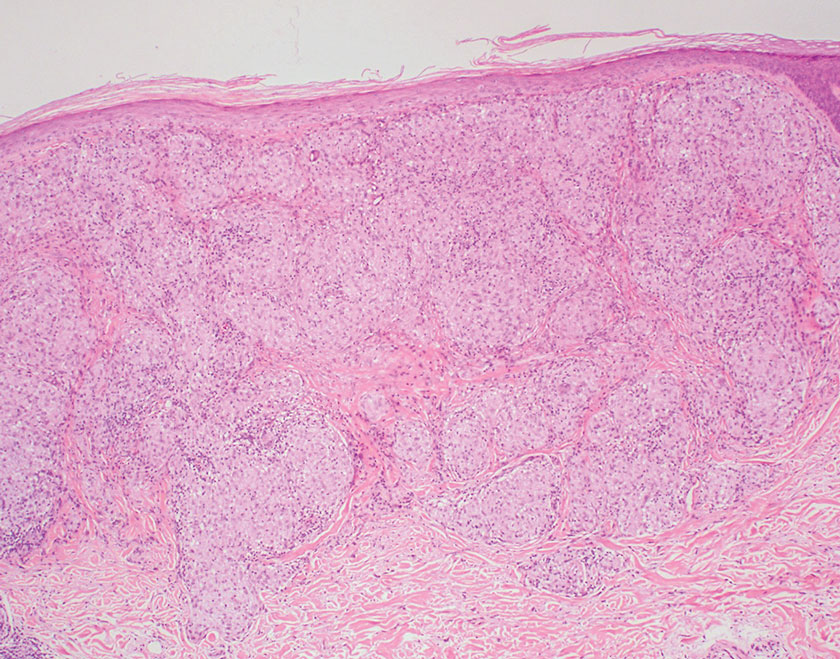

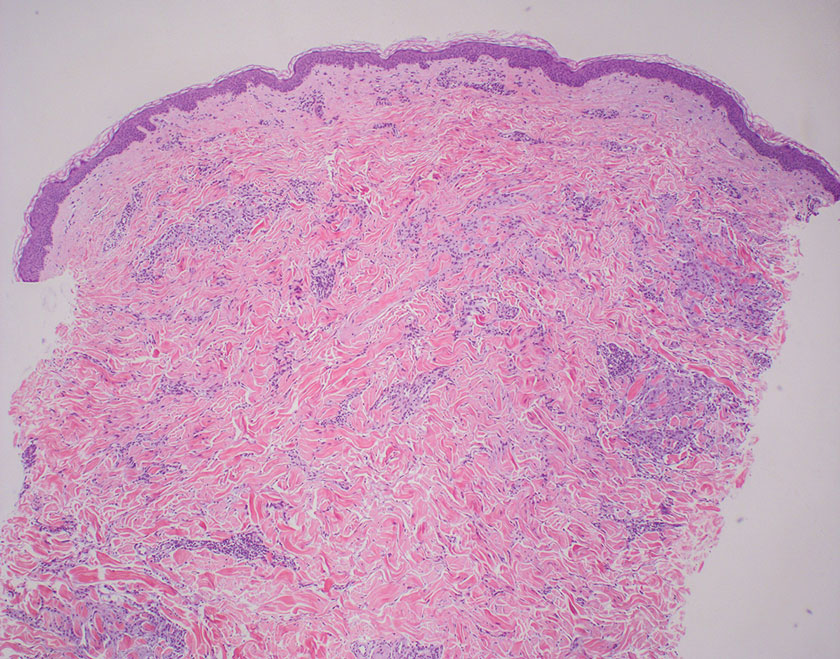

Fungal culture has higher sensitivity and specificity than microscopy and is the gold-standard approach for diagnosis of sporotrichosis (eFigure 2); however, culture cannot differentiate between Sporothrix species and may take more than a month to yield a positive result.7 No reliable serologic test for sporotrichosis has been validated, and a standardized antigen assay currently is unavailable.49 Serology may be more useful for patients who present with systemic disease or have persistently negative culture results despite a high index of suspicion.

A recent study evaluated the effectiveness of a lateral flow assay for detecting anti-Sporothrix antibodies, demonstrating the potential for its use as a rapid diagnostic test.50 Investigating different molecular methods to increase the sensitivity and specificity of diagnosis and distinguish Sporothrix species has been a focus of recent research, with a preference for polymerase chain reaction (PCR)–based genotypic methods.13,51 Recent advances in diagnostic testing include the development of multiplex PCR,52 culture-independent PCR techniques,53 and matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization–time of flight mass spectrometry,54 each with varying clinical and practical applicability. Specialized testing can be beneficial for patients who have a poor therapeutic response to standard treatment, guide antifungal treatment choices, and identify epidemiologic disease and transmission patterns.21

Although rarely performed, antifungal susceptibility testing may be useful in guiding therapy to improve patient outcomes, particularly in the context of treatment failure, which has been documented with isolates exhibiting high minimal inhibitory concentrations (MICs) to first-line therapy and a poor clinical response.55,56 Proposed mechanisms of resistance include increased cellular melanin production, which protects against oxidative stress and reduces antifungal activity.56 Antifungal susceptibility profiles for therapeutics vary across Sporothrix species; for example, S brasiliensis generally shows lower MICs to itraconazole and terbinafine compared with S schenckii and S globosa, and S schenckii has shown a high MIC to itraconazole, as reflected in MIC distribution studies and epidemiologic cutoff values for antifungal agents.55,57-59 However, specific breakpoints for different Sporothrix species have not been determined.60 Robust clinical studies are needed to determine the correlation of in vitro MICs to clinical outcomes to assess the utility of antifungal susceptibility testing for Sporothrix species.

Management

Treatment of sporotrichosis is guided by clinical presentation, host immune status, and species identification. Management can be challenging in cases with an atypical or delayed diagnosis and limited access to molecular testing methods. Itraconazole is the first-line therapy for management of cutaneous sporotrichosis. It is regarded as safe, effective, well tolerated, and easily administered, with doses ranging from 100 mg in mild cases to 400 mg (with daily or twice-daily dosing).61 Treatment usually is for 3 to 6 months and should continue for 1 month after complete clinical resolution is achieved62; however, some cases of S brasiliensis infection require longer treatment, and complex or disseminated cases may require therapy for up to 12 months.61 Itraconazole is contraindicated in pregnancy and has many drug interactions (through cytochrome P450 inhibition) that may preclude administration, particularly in elderly populations. Therapeutic drug monitoring is recommended for prolonged or high-dose therapy, with periodic liver function testing to reduce the risk for toxicity. Itraconazole should be administered with food, and concurrent use of antacids or proton pump inhibitors should be avoided.61

Oral terbinafine (250 mg daily) can be considered as an effective alternative to treat cutaneous disease.63 Particularly in resource-limited settings, potassium iodide is an affordable and effective treatment for cutaneous sporotrichosis, administered as a saturated oral solution,64 but due to adverse effects such as severe nausea, the daily dose should be increased slowly each day to ensure tolerance.

Amphotericin B is the treatment of choice for severe and treatment-resistant cases of sporotrichosis as well as for immunocompromised patients.21,61 In patients with HIV, a longer treatment course is recommended with oversight from an infectious diseases specialist and usually is followed by a 12-month course of itraconazole after completion of initial therapy.61 Surgical excision infrequently is recommended but can be used in combination with another treatment modality and may be useful with a slow or incomplete response to medical therapy. Thermotherapy involves direct application of heat to cutaneous lesions and may be considered for small and localized lesions, particularly if antifungal agents are contraindicated or poorly tolerated.61 Public health measures include promoting case detection through practitioner education and patient awareness in endemic regions, as well as zoonotic control of infected animals to manage sporotrichosis.

Final Thoughts

Sporotrichosis is a fungal infection with growing public health significance. While the global disease burden is unknown, rising case numbers and geographic spread likely reflect a complex interaction between humans, the environment, and animals, exemplified by the spread of feline-associated infection due to S brasiliensis in South America.28 Cases of S brasiliensis infection after importation of an affected cat have been detected outside South America, and clinicians should be alert for introduction to the United States. Strengthening genotypic and phenotypic diagnostic capabilities will allow species identification and guide treatment and management. Disease surveillance and operational research will inform public health approaches to control sporotrichosis worldwide.

- Queiroz-Telles F, Nucci M, Colombo AL, et al. Mycoses of implantation in Latin America: an overview of epidemiology, clinical manifestations, diagnosis and treatment. Med Mycol. 2011;49:225-236.

- Orofino-Costa R, de Macedo PM, Rodrigues AM, et al. Sporotrichosis: an update on epidemiology, etiopathogenesis, laboratory and clinical therapeutics. An Bras Dermatol. 2017;92:606-620.

- Almeida-Paes R, de Oliveira MM, Freitas DF, et al. Sporotrichosis in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: Sporothrix brasiliensis is associated with atypical clinical presentations. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8:E3094.

- Arrillaga-Moncrieff I, Capilla J, Mayayo E, et al. Different virulence levels of the species of Sporothrix in a murine model. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2009;15:651-655.

- de Lima Barros MB, Schubach TM, Gutierrez-Galhardo MC, et al. Sporotrichosis: an emergent zoonosis in Rio de Janeiro. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2001;96:777-779.

- Bao F, Huai P, Chen C, et al. An outbreak of sporotrichosis associated with tying crabs. JAMA Dermatol. 2025;161:883-885.

- de Lima Barros MB, de Almeida Paes R, Schubach AO. Sporothrix schenckii and sporotrichosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2011;24:633-654.

- Queiroz-Telles F, Buccheri R, Benard G. Sporotrichosis in immunocompromised hosts. J Fungi. 2019;5:8.

- World Health Organization. Generic Framework for Control, Elimination and Eradication of Neglected Tropical Diseases. World Health Organization; 2016.

- Smith DJ, Soebono H, Parajuli N, et al. South-East Asia regional neglected tropical disease framework: improving control of mycetoma, chromoblastomycosis, and sporotrichosis. Lancet Reg Health Southeast Asia. 2025;35:100561.

- Winck GR, Raimundo RL, Fernandes-Ferreira H, et al. Socioecological vulnerability and the risk of zoonotic disease emergence in Brazil. Sci Adv. 2022;8:eabo5774.

- Jenks JD, Prattes J, Wurster S, et al. Social determinants of health as drivers of fungal disease. EClinicalMedicine. 2023;66:102325.

- Rodrigues AM, Gonçalves SS, de Carvalho JA, et al. Current progress on epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment of sporotrichosis and their future trends. J Fungi. 2022;8:776.

- Evans EGV, Ashbee HR, Frankland JC, et al. Tropical mycoses: hazards to travellers. In: Evans EGV, Ashbee HR, eds. Tropical Mycology. Vol 2. CABI Publishing; 2002:145-163.

- Matute DR, Teixeira MM. Sporothrix is neglected among the neglected. PLoS Pathog. 2025;21:E1012898.

- Matruchot L. Sur un nouveau groupe de champignons pathogenes, agents des sporotrichoses. Comptes Rendus De L’Académie Des Sci. 1910;150:543-545.

- Dangerfield LF. Sporotriehosis among miners on the Witwatersrand gold mines. S Afr Med J. 1941;15:128-131.

- Fukushiro R. Epidemiology and ecology of sporotrichosis in Japan. Zentralbl Bakteriol Mikrobiol Hyg. 1984;257:228-233.

- Dixon DM, Salkin IF, Duncan RA, et al. Isolation and characterization of Sporothrix schenckii from clinical and environmental sources associated with the largest US epidemic of sporotrichosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:1106-1113.

- dos Santos AR, Misas E, Min B, et al. Emergence of zoonotic sporotrichosis in Brazil: a genomic epidemiology study. Lancet Microbe. 2024;5:E282-E290.

- Schechtman RC, Falcão EM, Carard M, et al. Sporotrichosis: hyperendemic by zoonotic transmission, with atypical presentations, hypersensitivity reactions and greater severity. An Bras Dermatol. 2022;97:1-13.

- Rodrigues AM, de Hoog GS, de Camargo ZP. Sporothrix species causing outbreaks in animals and humans driven by animal-animal transmission. PLoS Pathog. 2016;12:E1005638.

- Li HY, Song J, Zhang Y. Epidemiological survey of sporotrichosis in Zhaodong, Heilongjiang. Chin J Dermatol. 1995;28:401-402.

- Hajjeh R, McDonnell S, Reef S, et al. Outbreak of sporotrichosis among tree nursery workers. J Infect Dis. 1997;176:499-504.

- Coles FB, Schuchat A, Hibbs JR, et al. A multistate outbreak of sporotrichosis associated with sphagnum moss. Am J Epidemiol. 1992;136:475-487.

- Benedict K, Jackson BR. Sporotrichosis cases in commercial insurance data, United States, 2012-2018. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26:2783-2785.

- Gold JAW, Derado G, Mody RK, et al. Sporotrichosis-associated hospitalizations, United States, 2000-2013. Emerg Infect Dis. 2016;22:1817-1820.

- Rossow JA, Queiroz-Telles F, Caceres DH, et al. A One Health approach to combatting Sporothrix brasiliensis: narrative review of an emerging zoonotic fungal pathogen in South America. J Fungi. 2020;6:247-274.

- Madrid IM, Mattei AS, Fernandes CG, et al. Epidemiological findings and laboratory evaluation of sporotrichosis: a description of 103 cases in cats and dogs in southern Brazil. Mycopathologia. 2012;173:265-273.

- Fichman V, Gremião ID, Mendes-Júnior AA, et al. Sporotrichosis transmitted by a cockatiel (Nymphicus hollandicus). J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:E157-E158.

- Cognialli RC, Queiroz-Telles F, Cavanaugh AM, et al. New insights on transmission of Sporothrix brasiliensis. Mycoses. 2025;68:E70047.

- Bastos FA, De Farias MR, Gremião ID, et al. Cat-transmitted sporotrichosis by Sporothrix brasiliensis: focus on its potential transmission routes and epidemiological profile. Med Mycol. 2025;63.

- Gremiao ID, Menezes RC, Schubach TM, et al. Feline sporotrichosis: epidemiological and clinical aspects. Med Mycol. 2015;53:15-21.

- Hektoen L, Perkins CF. Refractory subcutaneous abscesses caused by Sporothrix schenckii: a new pathogenic fungus. J Exp Med. 1900;5:77-89.

- Marimon R, Cano J, Gené J, et al. Sporothrix brasiliensis, S. globosa, and S. mexicana, three new Sporothrix species of clinical interest. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45:3198-3206.

- Rodrigues AM, Della Terra PP, Gremião ID, et al. The threat of emerging and re-emerging pathogenic Sporothrix species. Mycopathologia. 2020;185:813-842.

- Morgado DS, Castro R, Ribeiro-Alves M, et al. Global distribution of animal sporotrichosis: a systematic review of Sporothrix sp. identified using molecular tools. Curr Res Microbial Sci. 2022;3:100140.

- de Lima IM, Ferraz CE, Lima-Neto RG, et al. Case report: Sweet syndrome in patients with sporotrichosis: a 10-case series. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2020;103:2533-2538.

- Xavier MO, Bittencourt LR, da Silva CM, et al. Atypical presentation of sporotrichosis: report of three cases. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2013;46:116-118.

- Ramos-e-Silva M, Vasconcelos C, Carneiro S, et al. Sporotrichosis. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:181-187.

- Sampaio SA, Lacaz CS. Klinische und statische Untersuchungen uber Sporotrichose in Sao Paulo. Der Hautarzt. 1959;10:490-493.

- Arinelli A, Aleixo L, Freitas DF, et al. Ocular manifestations of sporotrichosis in a hyperendemic region in Brazil: description of a series of 120 cases. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2023;31:329-337.

- Cognialli RC, Cáceres DH, Bastos FA, et al. Rising incidence of Sporothrix brasiliensis infections, Curitiba, Brazil, 2011-2022. Emerg Infect Dis. 2023;29:1330-1339.

- Freitas DF, Valle AC, da Silva MB, et al. Sporotrichosis: an emerging neglected opportunistic infection in HIV-infected patients in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8:E3110.

- Bonifaz A, Tirado-Sánchez A. Cutaneous disseminated and extracutaneous sporotrichosis: current status of a complex disease. J Fungi. 2017;3:6.

- Falcão EM, de Lima Filho JB, Campos DP, et al. Hospitalizações e óbitos relacionados à esporotricose no Brasil (1992-2015). Cad Saude Publica. 2019;35:4.

- Mahajan VK, Burkhart CG. Sporotrichosis: an overview and therapeutic options. Dermatol Res Pract. 2014;2014:32-44.

- Hamer EC, Moore CB, Denning DW. Comparison of two fluorescent whiteners, Calcofluor and Blankophor, for the detection of fungal elements in clinical specimens in the diagnostic laboratory. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2006;12:181-184.

- Bernardes-Engemann AR, Orofino Costa RC, Miguens BP, et al. Development of an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for the serodiagnosis of several clinical forms of sporotrichosis. Med Mycol. 2005;43:487-493.

- Cognialli R, Bloss K, Weiss I, et al. A lateral flow assay for the immunodiagnosis of human cat-transmitted sporotrichosis. Mycoses. 2022;65:926-934.

- Rodrigues AM, de Hoog GS, de Camargo ZP. Molecular diagnosis of pathogenic Sporothrix species. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9:E0004190.

- Della Terra PP, Gonsales FF, de Carvalho JA, et al. Development and evaluation of a multiplex qPCR assay for rapid diagnostics of emerging sporotrichosis. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2022;69.

- Kano R, Nakamura Y, Watanabe S, et al. Identification of Sporothrix schenckii based on sequences of the chitin synthase 1 gene. Mycoses. 2001;44:261-265.

- Oliveira MM, Santos C, Sampaio P, et al. Development and optimization of a new MALDI-TOF protocol for identification of the Sporothrix species complex. Res Microbiol. 2015;166:102-110.

- Bernardes-Engemann AR, Tomki GF, Rabello VBS, et al. Sporotrichosis caused by non-wild type Sporothrix brasiliensis strains. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2022;12:893501.

- Waller SB, Dalla Lana DF, Quatrin PM, et al. Antifungal resistance on Sporothrix species: an overview. Braz J Microbiol. 2021;52:73-80.

- Marimon R, Serena C, Gene J. In vitro antifungal susceptibilities of five species of sporothrix. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52:732-734.

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Reference Method for Broth Dilution Antifungal Susceptibility Testing of Yeasts (M27, 4th edition). 4th ed. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI); 2017.

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Reference Method for Broth Dilution Antifungal Susceptibility Testing of Filamentous Fungi (Approved Standard, M38, 3rd edition). Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI); 2017

- Oliveira DC, Lopes PG, Spader TB, et al. Antifungal susceptibilities of Sporothrix albicans, S. brasiliensis, and S. luriei of the S. schenckii complex identified in Brazil. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49:3047-3049.

- Kauffman CA, Bustamante B, Chapman SW, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of sporotrichosis: 2007 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45:1255-1265.

- Thompson GR, Le T, Chindamporn A, et al. Global guideline for the diagnosis and management of the endemic mycoses: an initiative of the European Confederation of Medical Mycology in cooperation with the International Society for Human and Animal Mycology. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021;21:E364-E374.

- Francesconi G, Valle AC, Passos S, et al. Terbinafine (250 mg/day): an effective and safe treatment of cutaneous sporotrichosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23:1273-1276.

- Macedo PM, Lopes-Bezerra LM, Bernardes-Engemann AR, et al. New posology of potassium iodide for the treatment of cutaneous sporotrichosis: study of efficacy and safety in 102 patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:719-724.

Sporotrichosis is an implantation mycosis that classically manifests as a localized skin and subcutaneous fungal infection but may disseminate to other parts of the body.1 It is caused by several species within the Sporothrix genus2 and is associated with varying clinical manifestations, geographic distributions, virulence profiles, and antifungal susceptibility patterns.3,4 Transmission of the fungus can involve inoculation from wild or domestic animals (eg, cats).5,6 Occupations such as landscaping and gardening or elements in the environment (eg, soil, plant fragments) also can be sources of exposure.7,8

Sporotrichosis is recognized by the World Health Organization as a neglected tropical disease that warrants global advocacy to prevent infections and improve patient outcomes.9,10 It carries substantial stigma and socioeconomic burden.11,12 Diagnostics, species identification, and antifungal susceptibility testing often are limited, particularly in resource-limited settings.13 In this article, we outline steps to diagnose and manage sporotrichosis to improve care for affected patients globally.

Epidemiology

Sporotrichosis occurs worldwide but is most common in tropical and subtropical regions.14,15 Outbreaks and clusters of sporotrichosis have been observed across North, Central, and South America as well as in southern Africa and Asia. The estimated annual incidence is 40,000 cases worldwide,16-20 but global case counts likely are underestimated due to limited surveillance data and diagnostic capability.21

On the Asian subcontinent, Sporothrix globosa is the predominant causative species of sporotrichosis, typically via contaminated plant material22; however, at least 1 outbreak has been associated with severe flooding.23 In Africa, infections are most commonly caused by Sporothrix schenckii sensu stricto through a similar transmission route. Across Central America, S schenckii sensu stricto is the predominant causative species; however, Sporothrix brasiliensis is the predominant species in some countries in South America, particularly Brazil.20

Data describing the current geographic distribution and prevalence of sporotrichosis in the United States are limited. Historically, the disease was reported most commonly in Midwestern states and was associated with outbreaks related to handling Sphagnum moss.24,25 Epidemiologic studies using health insurance data indicate an average annual incidence of 2.0 cases per million individuals in the United States, with a higher prevalence among women and a median age at diagnosis of 54 years.26 A review of sporotrichosis-associated hospitalizations across the United States from 2000 to 2013 indicated an average hospitalization rate of 0.35 cases per 1 million individuals; rates were higher (0.45 cases per million) in the West and lower (0.15 per million) in the Northeast and in men (0.40 per million).27 Type 2 diabetes, immune-mediated inflammatory disease, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease are associated with an increased risk for infection and hospitalization.27

Causative Organisms

Sporothrix species are thermally dimorphic fungi that can grow as mold in the environment and as yeast in human tissue. Sporothrix brasiliensis is the only thermodimorphic fungus known to be transmitted directly in its yeast form.28 In other species, inoculation usually occurs after contact with contaminated soil or plant material during gardening, carpentry, or agricultural practices.7

Zoonotic transmission of sporotrichosis from animals to humans has been reported from a range of domestic and wild animals and birds but historically has been rare.5,7,29,30 Recently, the importance of both cat-to-cat (epizootic) and cat-to-human (zoonotic) transmission of S brasiliensis has been recognized, with infection typically following traumatic inoculation after a scratch or bite; less frequently, transmission occurs due to exposure to respiratory droplets or contact with feline exudates.5,29,31 Sporothrix brasiliensis is responsible for zoonotic epidemics in South America, primarily in Brazil. Transmission occurs among humans, cats, and canines, with felines serving as the primary vector.32 Transmission of this species is particularly common in stray and unneutered male cats that exhibit aggressive behaviors.33 This species also is thought to be the most virulent Sporothrix species.21

Sporothrix brasiliensis can persist on nondisinfected inanimate surfaces, which suggests that fomite transmission can lead to human infection.31 The epidemiology of sporotrichosis has transformed in regions where S brasiliensis circulates, with epidemic spread resulting in thousands of cases, whereas in other areas without S brasilinesis, sporotrichosis predominantly occurs sporadically with rare clusters.1,2,7,15

Sporotrichosis has been the subject of a taxonomic debate in the mycology community.21 Sporothrix schenckii sensu lato originally was believed to be the sole fungal pathogen causing sporotrichosis34 but was later divided into S schenckii sensu stricto, Sporothrix globosa, and S brasiliensis.35 More than 60 distinct species now have been described within the Sporothrix genus,36,37 but the primary species causing human sporotrichosis include S schenckii sensu stricto, S brasiliensis, S globosa, Sporothrix mexicana, and Sporothrix luriei.35 Both S schenckii and S brasiliensis have greater virulence than other Sporothrix species4; however, S schenckii causes infections that typically are localized and are milder, while S brasiliensis can lead to more atypical, severe, and disseminated infections38,39 and can spread epidemically.

Clinical Manifestations

Sporotrichosis has 4 main clinical presentations: cutaneous lymphatic, fixed cutaneous, cutaneous or systemic disseminated, and extracutaneous.40,41 The most common clinical manifestation is the cutaneous lymphatic form, which predominantly affects the hands and forearms in adults and the face in children.7 The primary lesion usually manifests as a unilateral papule, nodule, or pustule that may ulcerate (sporotrichotic chancre), but multiple sites of inoculation are possible. Subsequent lesions may appear in a linear distribution along a regional lymphatic path (sporotrichoid spread). Systemic symptoms and regional lymphadenopathy are uncommon and usually are mild.

The second most common clinical manifestation is the fixed cutaneous form, typically affecting the face, neck, trunk, or legs with a single papule, nodule, or verrucous lesion with no lymphangitic spread.7 Usually confined to the inoculation site, the primary lesion may be accompanied by satellite lesions and often presents a diagnostic challenge.

Disseminated sporotrichosis (either cutaneous or systemic) is rare. Disseminated cutaneous sporotrichosis manifests with multiple noncontiguous skin lesions caused by lymphatic and possible hematogenous spread. Lesions may include a combination of papules, pustules, follicular eruptions, crusted plaques, and ulcers that may mimic other systemic infections. Immunoreactive changes such as erythema nodosum, erythema multiforme, or arthritis may accompany skin lesions, most commonly with S brasiliensis infections. Nearly 10% of S brasiliensis infections involve the ocular adnexa, and Parinaud oculoglandular syndrome is commonly described in cases reported in Brazil.42,43 Disseminated disease usually occurs in immunocompromised hosts; however, despite a focus on HIV co-infection,8,44 prior epidemiologic research has suggested that diabetes and alcoholism are the most common predisposing factors.45 Systemic disseminated sporotrichosis by definition affects at least 2 body systems, most commonly the central nervous system, lungs, and musculoskeletal system (including joints and bone marrow).45

Extracutaneous sporotrichosis is rare and often is difficult to diagnose. Risk factors include chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, alcoholism, use of steroid medications, AIDS, solid organ transplantation, and use of tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors. It usually affects bony structures through hematogenous spread in immunocompromised hosts and is associated with a high risk for osteomyelitis due to delayed diagnosis.2

Clinical progression of sporotrichosis usually is slow, and lesions may persist for months or years if untreated. Sporotrichosis should always be considered for atypical, persistent, or treatment-resistant manifestations of nodular or ulcerated skin lesions in endemic regions or acute illness with these symptoms following exposure. Preventing secondary bacterial infection is an important consideration as it can exacerbate disease severity, extend the treatment duration, prolong hospitalization, and increase mortality risk.46

Diagnosis

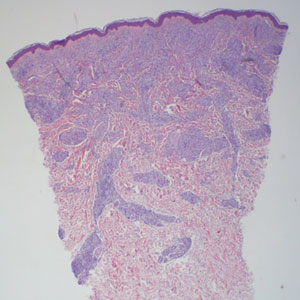

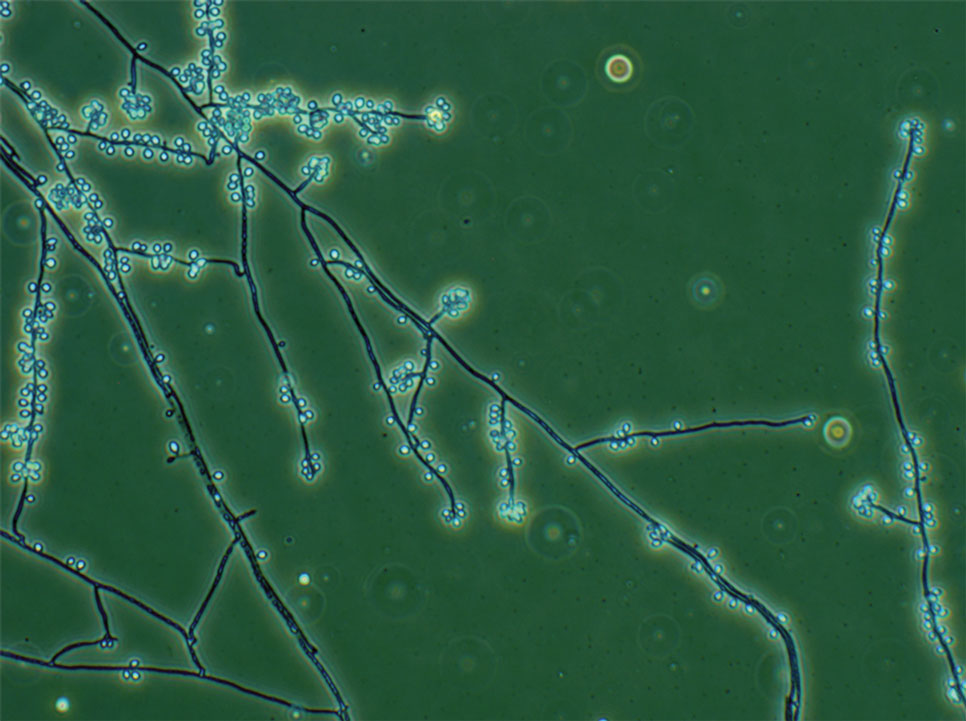

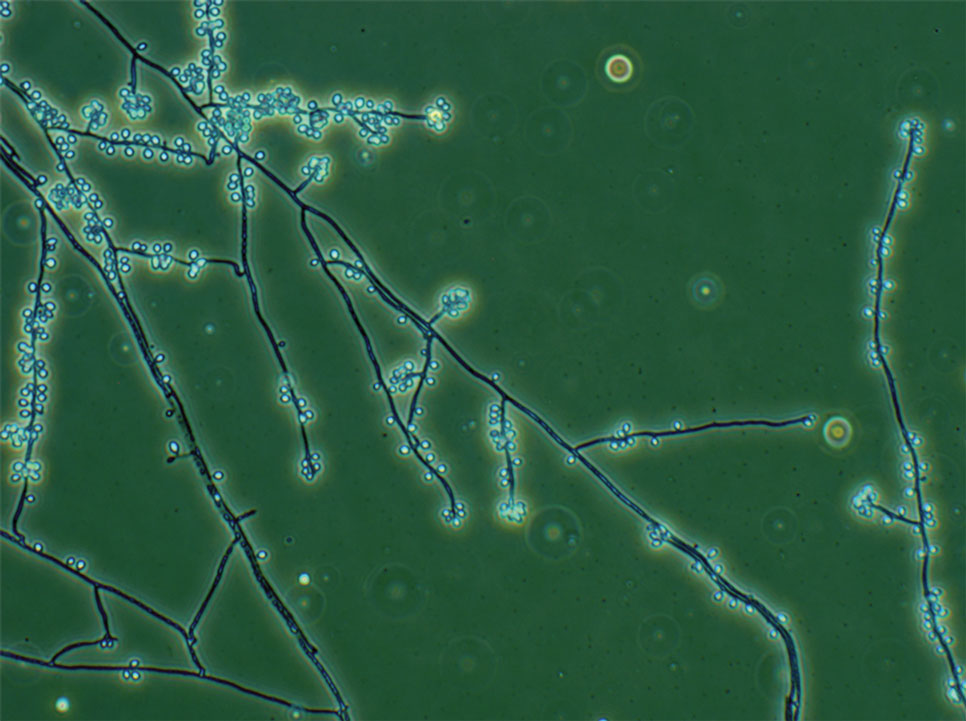

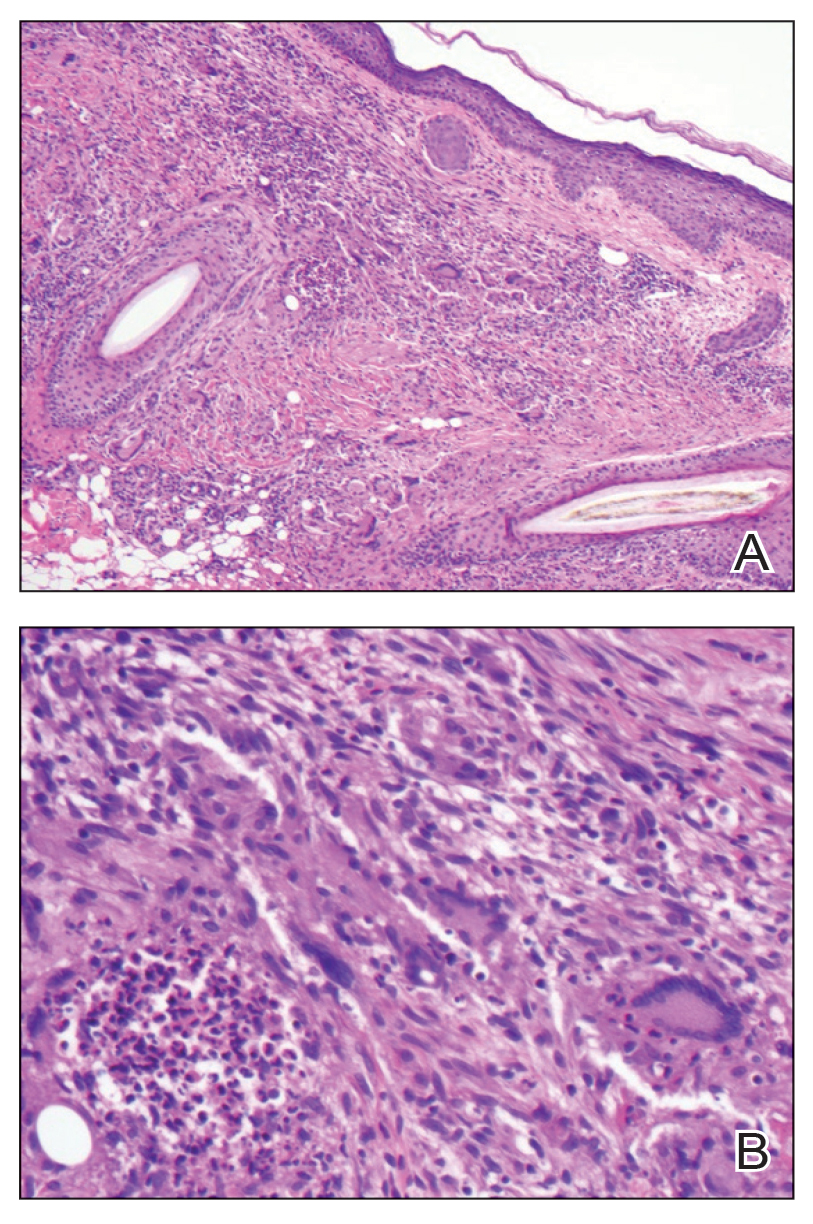

In regions endemic for S brasiliensis, it may be acceptable to commence treatment on clinical suspicion without a definitive diagnosis,21 but caution is necessary, as lesions easily can be mistaken for other conditions such as Mycobacterium marinum infections (sporotrichoid lesions) or cutaneous leishmaniasis. Limited availability of molecular diagnostic tools in routine clinical laboratories affects the diagnosis of sporotrichosis and species identification. Direct microscopy on a 10% to 30% potassium hydroxide wet mount has low diagnostic sensitivity and is not recommended47; findings typically include cigar-shaped yeast cells (eFigure 1). Biopsy and histopathology also are useful, although in many infections (other than those due to S brasiliensis) there are very few detectable organisms in the tissue. Fluorescent staining of fungi with optical brighteners (eg, Calcofluor, Blankophor) is a useful technique with high sensitivity in clinical specimens on histopathologic and direct examination.48

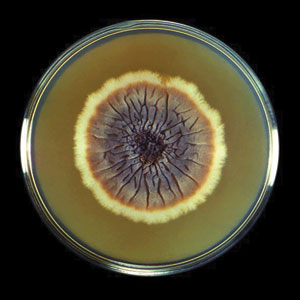

Fungal culture has higher sensitivity and specificity than microscopy and is the gold-standard approach for diagnosis of sporotrichosis (eFigure 2); however, culture cannot differentiate between Sporothrix species and may take more than a month to yield a positive result.7 No reliable serologic test for sporotrichosis has been validated, and a standardized antigen assay currently is unavailable.49 Serology may be more useful for patients who present with systemic disease or have persistently negative culture results despite a high index of suspicion.

A recent study evaluated the effectiveness of a lateral flow assay for detecting anti-Sporothrix antibodies, demonstrating the potential for its use as a rapid diagnostic test.50 Investigating different molecular methods to increase the sensitivity and specificity of diagnosis and distinguish Sporothrix species has been a focus of recent research, with a preference for polymerase chain reaction (PCR)–based genotypic methods.13,51 Recent advances in diagnostic testing include the development of multiplex PCR,52 culture-independent PCR techniques,53 and matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization–time of flight mass spectrometry,54 each with varying clinical and practical applicability. Specialized testing can be beneficial for patients who have a poor therapeutic response to standard treatment, guide antifungal treatment choices, and identify epidemiologic disease and transmission patterns.21

Although rarely performed, antifungal susceptibility testing may be useful in guiding therapy to improve patient outcomes, particularly in the context of treatment failure, which has been documented with isolates exhibiting high minimal inhibitory concentrations (MICs) to first-line therapy and a poor clinical response.55,56 Proposed mechanisms of resistance include increased cellular melanin production, which protects against oxidative stress and reduces antifungal activity.56 Antifungal susceptibility profiles for therapeutics vary across Sporothrix species; for example, S brasiliensis generally shows lower MICs to itraconazole and terbinafine compared with S schenckii and S globosa, and S schenckii has shown a high MIC to itraconazole, as reflected in MIC distribution studies and epidemiologic cutoff values for antifungal agents.55,57-59 However, specific breakpoints for different Sporothrix species have not been determined.60 Robust clinical studies are needed to determine the correlation of in vitro MICs to clinical outcomes to assess the utility of antifungal susceptibility testing for Sporothrix species.

Management

Treatment of sporotrichosis is guided by clinical presentation, host immune status, and species identification. Management can be challenging in cases with an atypical or delayed diagnosis and limited access to molecular testing methods. Itraconazole is the first-line therapy for management of cutaneous sporotrichosis. It is regarded as safe, effective, well tolerated, and easily administered, with doses ranging from 100 mg in mild cases to 400 mg (with daily or twice-daily dosing).61 Treatment usually is for 3 to 6 months and should continue for 1 month after complete clinical resolution is achieved62; however, some cases of S brasiliensis infection require longer treatment, and complex or disseminated cases may require therapy for up to 12 months.61 Itraconazole is contraindicated in pregnancy and has many drug interactions (through cytochrome P450 inhibition) that may preclude administration, particularly in elderly populations. Therapeutic drug monitoring is recommended for prolonged or high-dose therapy, with periodic liver function testing to reduce the risk for toxicity. Itraconazole should be administered with food, and concurrent use of antacids or proton pump inhibitors should be avoided.61

Oral terbinafine (250 mg daily) can be considered as an effective alternative to treat cutaneous disease.63 Particularly in resource-limited settings, potassium iodide is an affordable and effective treatment for cutaneous sporotrichosis, administered as a saturated oral solution,64 but due to adverse effects such as severe nausea, the daily dose should be increased slowly each day to ensure tolerance.

Amphotericin B is the treatment of choice for severe and treatment-resistant cases of sporotrichosis as well as for immunocompromised patients.21,61 In patients with HIV, a longer treatment course is recommended with oversight from an infectious diseases specialist and usually is followed by a 12-month course of itraconazole after completion of initial therapy.61 Surgical excision infrequently is recommended but can be used in combination with another treatment modality and may be useful with a slow or incomplete response to medical therapy. Thermotherapy involves direct application of heat to cutaneous lesions and may be considered for small and localized lesions, particularly if antifungal agents are contraindicated or poorly tolerated.61 Public health measures include promoting case detection through practitioner education and patient awareness in endemic regions, as well as zoonotic control of infected animals to manage sporotrichosis.

Final Thoughts

Sporotrichosis is a fungal infection with growing public health significance. While the global disease burden is unknown, rising case numbers and geographic spread likely reflect a complex interaction between humans, the environment, and animals, exemplified by the spread of feline-associated infection due to S brasiliensis in South America.28 Cases of S brasiliensis infection after importation of an affected cat have been detected outside South America, and clinicians should be alert for introduction to the United States. Strengthening genotypic and phenotypic diagnostic capabilities will allow species identification and guide treatment and management. Disease surveillance and operational research will inform public health approaches to control sporotrichosis worldwide.

Sporotrichosis is an implantation mycosis that classically manifests as a localized skin and subcutaneous fungal infection but may disseminate to other parts of the body.1 It is caused by several species within the Sporothrix genus2 and is associated with varying clinical manifestations, geographic distributions, virulence profiles, and antifungal susceptibility patterns.3,4 Transmission of the fungus can involve inoculation from wild or domestic animals (eg, cats).5,6 Occupations such as landscaping and gardening or elements in the environment (eg, soil, plant fragments) also can be sources of exposure.7,8

Sporotrichosis is recognized by the World Health Organization as a neglected tropical disease that warrants global advocacy to prevent infections and improve patient outcomes.9,10 It carries substantial stigma and socioeconomic burden.11,12 Diagnostics, species identification, and antifungal susceptibility testing often are limited, particularly in resource-limited settings.13 In this article, we outline steps to diagnose and manage sporotrichosis to improve care for affected patients globally.

Epidemiology

Sporotrichosis occurs worldwide but is most common in tropical and subtropical regions.14,15 Outbreaks and clusters of sporotrichosis have been observed across North, Central, and South America as well as in southern Africa and Asia. The estimated annual incidence is 40,000 cases worldwide,16-20 but global case counts likely are underestimated due to limited surveillance data and diagnostic capability.21

On the Asian subcontinent, Sporothrix globosa is the predominant causative species of sporotrichosis, typically via contaminated plant material22; however, at least 1 outbreak has been associated with severe flooding.23 In Africa, infections are most commonly caused by Sporothrix schenckii sensu stricto through a similar transmission route. Across Central America, S schenckii sensu stricto is the predominant causative species; however, Sporothrix brasiliensis is the predominant species in some countries in South America, particularly Brazil.20

Data describing the current geographic distribution and prevalence of sporotrichosis in the United States are limited. Historically, the disease was reported most commonly in Midwestern states and was associated with outbreaks related to handling Sphagnum moss.24,25 Epidemiologic studies using health insurance data indicate an average annual incidence of 2.0 cases per million individuals in the United States, with a higher prevalence among women and a median age at diagnosis of 54 years.26 A review of sporotrichosis-associated hospitalizations across the United States from 2000 to 2013 indicated an average hospitalization rate of 0.35 cases per 1 million individuals; rates were higher (0.45 cases per million) in the West and lower (0.15 per million) in the Northeast and in men (0.40 per million).27 Type 2 diabetes, immune-mediated inflammatory disease, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease are associated with an increased risk for infection and hospitalization.27

Causative Organisms

Sporothrix species are thermally dimorphic fungi that can grow as mold in the environment and as yeast in human tissue. Sporothrix brasiliensis is the only thermodimorphic fungus known to be transmitted directly in its yeast form.28 In other species, inoculation usually occurs after contact with contaminated soil or plant material during gardening, carpentry, or agricultural practices.7

Zoonotic transmission of sporotrichosis from animals to humans has been reported from a range of domestic and wild animals and birds but historically has been rare.5,7,29,30 Recently, the importance of both cat-to-cat (epizootic) and cat-to-human (zoonotic) transmission of S brasiliensis has been recognized, with infection typically following traumatic inoculation after a scratch or bite; less frequently, transmission occurs due to exposure to respiratory droplets or contact with feline exudates.5,29,31 Sporothrix brasiliensis is responsible for zoonotic epidemics in South America, primarily in Brazil. Transmission occurs among humans, cats, and canines, with felines serving as the primary vector.32 Transmission of this species is particularly common in stray and unneutered male cats that exhibit aggressive behaviors.33 This species also is thought to be the most virulent Sporothrix species.21

Sporothrix brasiliensis can persist on nondisinfected inanimate surfaces, which suggests that fomite transmission can lead to human infection.31 The epidemiology of sporotrichosis has transformed in regions where S brasiliensis circulates, with epidemic spread resulting in thousands of cases, whereas in other areas without S brasilinesis, sporotrichosis predominantly occurs sporadically with rare clusters.1,2,7,15

Sporotrichosis has been the subject of a taxonomic debate in the mycology community.21 Sporothrix schenckii sensu lato originally was believed to be the sole fungal pathogen causing sporotrichosis34 but was later divided into S schenckii sensu stricto, Sporothrix globosa, and S brasiliensis.35 More than 60 distinct species now have been described within the Sporothrix genus,36,37 but the primary species causing human sporotrichosis include S schenckii sensu stricto, S brasiliensis, S globosa, Sporothrix mexicana, and Sporothrix luriei.35 Both S schenckii and S brasiliensis have greater virulence than other Sporothrix species4; however, S schenckii causes infections that typically are localized and are milder, while S brasiliensis can lead to more atypical, severe, and disseminated infections38,39 and can spread epidemically.

Clinical Manifestations

Sporotrichosis has 4 main clinical presentations: cutaneous lymphatic, fixed cutaneous, cutaneous or systemic disseminated, and extracutaneous.40,41 The most common clinical manifestation is the cutaneous lymphatic form, which predominantly affects the hands and forearms in adults and the face in children.7 The primary lesion usually manifests as a unilateral papule, nodule, or pustule that may ulcerate (sporotrichotic chancre), but multiple sites of inoculation are possible. Subsequent lesions may appear in a linear distribution along a regional lymphatic path (sporotrichoid spread). Systemic symptoms and regional lymphadenopathy are uncommon and usually are mild.

The second most common clinical manifestation is the fixed cutaneous form, typically affecting the face, neck, trunk, or legs with a single papule, nodule, or verrucous lesion with no lymphangitic spread.7 Usually confined to the inoculation site, the primary lesion may be accompanied by satellite lesions and often presents a diagnostic challenge.

Disseminated sporotrichosis (either cutaneous or systemic) is rare. Disseminated cutaneous sporotrichosis manifests with multiple noncontiguous skin lesions caused by lymphatic and possible hematogenous spread. Lesions may include a combination of papules, pustules, follicular eruptions, crusted plaques, and ulcers that may mimic other systemic infections. Immunoreactive changes such as erythema nodosum, erythema multiforme, or arthritis may accompany skin lesions, most commonly with S brasiliensis infections. Nearly 10% of S brasiliensis infections involve the ocular adnexa, and Parinaud oculoglandular syndrome is commonly described in cases reported in Brazil.42,43 Disseminated disease usually occurs in immunocompromised hosts; however, despite a focus on HIV co-infection,8,44 prior epidemiologic research has suggested that diabetes and alcoholism are the most common predisposing factors.45 Systemic disseminated sporotrichosis by definition affects at least 2 body systems, most commonly the central nervous system, lungs, and musculoskeletal system (including joints and bone marrow).45

Extracutaneous sporotrichosis is rare and often is difficult to diagnose. Risk factors include chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, alcoholism, use of steroid medications, AIDS, solid organ transplantation, and use of tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors. It usually affects bony structures through hematogenous spread in immunocompromised hosts and is associated with a high risk for osteomyelitis due to delayed diagnosis.2

Clinical progression of sporotrichosis usually is slow, and lesions may persist for months or years if untreated. Sporotrichosis should always be considered for atypical, persistent, or treatment-resistant manifestations of nodular or ulcerated skin lesions in endemic regions or acute illness with these symptoms following exposure. Preventing secondary bacterial infection is an important consideration as it can exacerbate disease severity, extend the treatment duration, prolong hospitalization, and increase mortality risk.46

Diagnosis

In regions endemic for S brasiliensis, it may be acceptable to commence treatment on clinical suspicion without a definitive diagnosis,21 but caution is necessary, as lesions easily can be mistaken for other conditions such as Mycobacterium marinum infections (sporotrichoid lesions) or cutaneous leishmaniasis. Limited availability of molecular diagnostic tools in routine clinical laboratories affects the diagnosis of sporotrichosis and species identification. Direct microscopy on a 10% to 30% potassium hydroxide wet mount has low diagnostic sensitivity and is not recommended47; findings typically include cigar-shaped yeast cells (eFigure 1). Biopsy and histopathology also are useful, although in many infections (other than those due to S brasiliensis) there are very few detectable organisms in the tissue. Fluorescent staining of fungi with optical brighteners (eg, Calcofluor, Blankophor) is a useful technique with high sensitivity in clinical specimens on histopathologic and direct examination.48

Fungal culture has higher sensitivity and specificity than microscopy and is the gold-standard approach for diagnosis of sporotrichosis (eFigure 2); however, culture cannot differentiate between Sporothrix species and may take more than a month to yield a positive result.7 No reliable serologic test for sporotrichosis has been validated, and a standardized antigen assay currently is unavailable.49 Serology may be more useful for patients who present with systemic disease or have persistently negative culture results despite a high index of suspicion.

A recent study evaluated the effectiveness of a lateral flow assay for detecting anti-Sporothrix antibodies, demonstrating the potential for its use as a rapid diagnostic test.50 Investigating different molecular methods to increase the sensitivity and specificity of diagnosis and distinguish Sporothrix species has been a focus of recent research, with a preference for polymerase chain reaction (PCR)–based genotypic methods.13,51 Recent advances in diagnostic testing include the development of multiplex PCR,52 culture-independent PCR techniques,53 and matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization–time of flight mass spectrometry,54 each with varying clinical and practical applicability. Specialized testing can be beneficial for patients who have a poor therapeutic response to standard treatment, guide antifungal treatment choices, and identify epidemiologic disease and transmission patterns.21

Although rarely performed, antifungal susceptibility testing may be useful in guiding therapy to improve patient outcomes, particularly in the context of treatment failure, which has been documented with isolates exhibiting high minimal inhibitory concentrations (MICs) to first-line therapy and a poor clinical response.55,56 Proposed mechanisms of resistance include increased cellular melanin production, which protects against oxidative stress and reduces antifungal activity.56 Antifungal susceptibility profiles for therapeutics vary across Sporothrix species; for example, S brasiliensis generally shows lower MICs to itraconazole and terbinafine compared with S schenckii and S globosa, and S schenckii has shown a high MIC to itraconazole, as reflected in MIC distribution studies and epidemiologic cutoff values for antifungal agents.55,57-59 However, specific breakpoints for different Sporothrix species have not been determined.60 Robust clinical studies are needed to determine the correlation of in vitro MICs to clinical outcomes to assess the utility of antifungal susceptibility testing for Sporothrix species.

Management

Treatment of sporotrichosis is guided by clinical presentation, host immune status, and species identification. Management can be challenging in cases with an atypical or delayed diagnosis and limited access to molecular testing methods. Itraconazole is the first-line therapy for management of cutaneous sporotrichosis. It is regarded as safe, effective, well tolerated, and easily administered, with doses ranging from 100 mg in mild cases to 400 mg (with daily or twice-daily dosing).61 Treatment usually is for 3 to 6 months and should continue for 1 month after complete clinical resolution is achieved62; however, some cases of S brasiliensis infection require longer treatment, and complex or disseminated cases may require therapy for up to 12 months.61 Itraconazole is contraindicated in pregnancy and has many drug interactions (through cytochrome P450 inhibition) that may preclude administration, particularly in elderly populations. Therapeutic drug monitoring is recommended for prolonged or high-dose therapy, with periodic liver function testing to reduce the risk for toxicity. Itraconazole should be administered with food, and concurrent use of antacids or proton pump inhibitors should be avoided.61

Oral terbinafine (250 mg daily) can be considered as an effective alternative to treat cutaneous disease.63 Particularly in resource-limited settings, potassium iodide is an affordable and effective treatment for cutaneous sporotrichosis, administered as a saturated oral solution,64 but due to adverse effects such as severe nausea, the daily dose should be increased slowly each day to ensure tolerance.

Amphotericin B is the treatment of choice for severe and treatment-resistant cases of sporotrichosis as well as for immunocompromised patients.21,61 In patients with HIV, a longer treatment course is recommended with oversight from an infectious diseases specialist and usually is followed by a 12-month course of itraconazole after completion of initial therapy.61 Surgical excision infrequently is recommended but can be used in combination with another treatment modality and may be useful with a slow or incomplete response to medical therapy. Thermotherapy involves direct application of heat to cutaneous lesions and may be considered for small and localized lesions, particularly if antifungal agents are contraindicated or poorly tolerated.61 Public health measures include promoting case detection through practitioner education and patient awareness in endemic regions, as well as zoonotic control of infected animals to manage sporotrichosis.

Final Thoughts

Sporotrichosis is a fungal infection with growing public health significance. While the global disease burden is unknown, rising case numbers and geographic spread likely reflect a complex interaction between humans, the environment, and animals, exemplified by the spread of feline-associated infection due to S brasiliensis in South America.28 Cases of S brasiliensis infection after importation of an affected cat have been detected outside South America, and clinicians should be alert for introduction to the United States. Strengthening genotypic and phenotypic diagnostic capabilities will allow species identification and guide treatment and management. Disease surveillance and operational research will inform public health approaches to control sporotrichosis worldwide.

- Queiroz-Telles F, Nucci M, Colombo AL, et al. Mycoses of implantation in Latin America: an overview of epidemiology, clinical manifestations, diagnosis and treatment. Med Mycol. 2011;49:225-236.

- Orofino-Costa R, de Macedo PM, Rodrigues AM, et al. Sporotrichosis: an update on epidemiology, etiopathogenesis, laboratory and clinical therapeutics. An Bras Dermatol. 2017;92:606-620.

- Almeida-Paes R, de Oliveira MM, Freitas DF, et al. Sporotrichosis in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: Sporothrix brasiliensis is associated with atypical clinical presentations. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8:E3094.

- Arrillaga-Moncrieff I, Capilla J, Mayayo E, et al. Different virulence levels of the species of Sporothrix in a murine model. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2009;15:651-655.

- de Lima Barros MB, Schubach TM, Gutierrez-Galhardo MC, et al. Sporotrichosis: an emergent zoonosis in Rio de Janeiro. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2001;96:777-779.

- Bao F, Huai P, Chen C, et al. An outbreak of sporotrichosis associated with tying crabs. JAMA Dermatol. 2025;161:883-885.

- de Lima Barros MB, de Almeida Paes R, Schubach AO. Sporothrix schenckii and sporotrichosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2011;24:633-654.

- Queiroz-Telles F, Buccheri R, Benard G. Sporotrichosis in immunocompromised hosts. J Fungi. 2019;5:8.

- World Health Organization. Generic Framework for Control, Elimination and Eradication of Neglected Tropical Diseases. World Health Organization; 2016.

- Smith DJ, Soebono H, Parajuli N, et al. South-East Asia regional neglected tropical disease framework: improving control of mycetoma, chromoblastomycosis, and sporotrichosis. Lancet Reg Health Southeast Asia. 2025;35:100561.

- Winck GR, Raimundo RL, Fernandes-Ferreira H, et al. Socioecological vulnerability and the risk of zoonotic disease emergence in Brazil. Sci Adv. 2022;8:eabo5774.

- Jenks JD, Prattes J, Wurster S, et al. Social determinants of health as drivers of fungal disease. EClinicalMedicine. 2023;66:102325.

- Rodrigues AM, Gonçalves SS, de Carvalho JA, et al. Current progress on epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment of sporotrichosis and their future trends. J Fungi. 2022;8:776.

- Evans EGV, Ashbee HR, Frankland JC, et al. Tropical mycoses: hazards to travellers. In: Evans EGV, Ashbee HR, eds. Tropical Mycology. Vol 2. CABI Publishing; 2002:145-163.

- Matute DR, Teixeira MM. Sporothrix is neglected among the neglected. PLoS Pathog. 2025;21:E1012898.

- Matruchot L. Sur un nouveau groupe de champignons pathogenes, agents des sporotrichoses. Comptes Rendus De L’Académie Des Sci. 1910;150:543-545.

- Dangerfield LF. Sporotriehosis among miners on the Witwatersrand gold mines. S Afr Med J. 1941;15:128-131.

- Fukushiro R. Epidemiology and ecology of sporotrichosis in Japan. Zentralbl Bakteriol Mikrobiol Hyg. 1984;257:228-233.

- Dixon DM, Salkin IF, Duncan RA, et al. Isolation and characterization of Sporothrix schenckii from clinical and environmental sources associated with the largest US epidemic of sporotrichosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:1106-1113.

- dos Santos AR, Misas E, Min B, et al. Emergence of zoonotic sporotrichosis in Brazil: a genomic epidemiology study. Lancet Microbe. 2024;5:E282-E290.

- Schechtman RC, Falcão EM, Carard M, et al. Sporotrichosis: hyperendemic by zoonotic transmission, with atypical presentations, hypersensitivity reactions and greater severity. An Bras Dermatol. 2022;97:1-13.

- Rodrigues AM, de Hoog GS, de Camargo ZP. Sporothrix species causing outbreaks in animals and humans driven by animal-animal transmission. PLoS Pathog. 2016;12:E1005638.

- Li HY, Song J, Zhang Y. Epidemiological survey of sporotrichosis in Zhaodong, Heilongjiang. Chin J Dermatol. 1995;28:401-402.

- Hajjeh R, McDonnell S, Reef S, et al. Outbreak of sporotrichosis among tree nursery workers. J Infect Dis. 1997;176:499-504.

- Coles FB, Schuchat A, Hibbs JR, et al. A multistate outbreak of sporotrichosis associated with sphagnum moss. Am J Epidemiol. 1992;136:475-487.

- Benedict K, Jackson BR. Sporotrichosis cases in commercial insurance data, United States, 2012-2018. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26:2783-2785.

- Gold JAW, Derado G, Mody RK, et al. Sporotrichosis-associated hospitalizations, United States, 2000-2013. Emerg Infect Dis. 2016;22:1817-1820.

- Rossow JA, Queiroz-Telles F, Caceres DH, et al. A One Health approach to combatting Sporothrix brasiliensis: narrative review of an emerging zoonotic fungal pathogen in South America. J Fungi. 2020;6:247-274.

- Madrid IM, Mattei AS, Fernandes CG, et al. Epidemiological findings and laboratory evaluation of sporotrichosis: a description of 103 cases in cats and dogs in southern Brazil. Mycopathologia. 2012;173:265-273.

- Fichman V, Gremião ID, Mendes-Júnior AA, et al. Sporotrichosis transmitted by a cockatiel (Nymphicus hollandicus). J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:E157-E158.

- Cognialli RC, Queiroz-Telles F, Cavanaugh AM, et al. New insights on transmission of Sporothrix brasiliensis. Mycoses. 2025;68:E70047.

- Bastos FA, De Farias MR, Gremião ID, et al. Cat-transmitted sporotrichosis by Sporothrix brasiliensis: focus on its potential transmission routes and epidemiological profile. Med Mycol. 2025;63.

- Gremiao ID, Menezes RC, Schubach TM, et al. Feline sporotrichosis: epidemiological and clinical aspects. Med Mycol. 2015;53:15-21.

- Hektoen L, Perkins CF. Refractory subcutaneous abscesses caused by Sporothrix schenckii: a new pathogenic fungus. J Exp Med. 1900;5:77-89.

- Marimon R, Cano J, Gené J, et al. Sporothrix brasiliensis, S. globosa, and S. mexicana, three new Sporothrix species of clinical interest. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45:3198-3206.

- Rodrigues AM, Della Terra PP, Gremião ID, et al. The threat of emerging and re-emerging pathogenic Sporothrix species. Mycopathologia. 2020;185:813-842.

- Morgado DS, Castro R, Ribeiro-Alves M, et al. Global distribution of animal sporotrichosis: a systematic review of Sporothrix sp. identified using molecular tools. Curr Res Microbial Sci. 2022;3:100140.

- de Lima IM, Ferraz CE, Lima-Neto RG, et al. Case report: Sweet syndrome in patients with sporotrichosis: a 10-case series. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2020;103:2533-2538.

- Xavier MO, Bittencourt LR, da Silva CM, et al. Atypical presentation of sporotrichosis: report of three cases. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2013;46:116-118.

- Ramos-e-Silva M, Vasconcelos C, Carneiro S, et al. Sporotrichosis. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:181-187.

- Sampaio SA, Lacaz CS. Klinische und statische Untersuchungen uber Sporotrichose in Sao Paulo. Der Hautarzt. 1959;10:490-493.

- Arinelli A, Aleixo L, Freitas DF, et al. Ocular manifestations of sporotrichosis in a hyperendemic region in Brazil: description of a series of 120 cases. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2023;31:329-337.

- Cognialli RC, Cáceres DH, Bastos FA, et al. Rising incidence of Sporothrix brasiliensis infections, Curitiba, Brazil, 2011-2022. Emerg Infect Dis. 2023;29:1330-1339.

- Freitas DF, Valle AC, da Silva MB, et al. Sporotrichosis: an emerging neglected opportunistic infection in HIV-infected patients in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8:E3110.

- Bonifaz A, Tirado-Sánchez A. Cutaneous disseminated and extracutaneous sporotrichosis: current status of a complex disease. J Fungi. 2017;3:6.

- Falcão EM, de Lima Filho JB, Campos DP, et al. Hospitalizações e óbitos relacionados à esporotricose no Brasil (1992-2015). Cad Saude Publica. 2019;35:4.

- Mahajan VK, Burkhart CG. Sporotrichosis: an overview and therapeutic options. Dermatol Res Pract. 2014;2014:32-44.

- Hamer EC, Moore CB, Denning DW. Comparison of two fluorescent whiteners, Calcofluor and Blankophor, for the detection of fungal elements in clinical specimens in the diagnostic laboratory. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2006;12:181-184.

- Bernardes-Engemann AR, Orofino Costa RC, Miguens BP, et al. Development of an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for the serodiagnosis of several clinical forms of sporotrichosis. Med Mycol. 2005;43:487-493.

- Cognialli R, Bloss K, Weiss I, et al. A lateral flow assay for the immunodiagnosis of human cat-transmitted sporotrichosis. Mycoses. 2022;65:926-934.

- Rodrigues AM, de Hoog GS, de Camargo ZP. Molecular diagnosis of pathogenic Sporothrix species. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9:E0004190.

- Della Terra PP, Gonsales FF, de Carvalho JA, et al. Development and evaluation of a multiplex qPCR assay for rapid diagnostics of emerging sporotrichosis. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2022;69.

- Kano R, Nakamura Y, Watanabe S, et al. Identification of Sporothrix schenckii based on sequences of the chitin synthase 1 gene. Mycoses. 2001;44:261-265.

- Oliveira MM, Santos C, Sampaio P, et al. Development and optimization of a new MALDI-TOF protocol for identification of the Sporothrix species complex. Res Microbiol. 2015;166:102-110.

- Bernardes-Engemann AR, Tomki GF, Rabello VBS, et al. Sporotrichosis caused by non-wild type Sporothrix brasiliensis strains. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2022;12:893501.

- Waller SB, Dalla Lana DF, Quatrin PM, et al. Antifungal resistance on Sporothrix species: an overview. Braz J Microbiol. 2021;52:73-80.

- Marimon R, Serena C, Gene J. In vitro antifungal susceptibilities of five species of sporothrix. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52:732-734.

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Reference Method for Broth Dilution Antifungal Susceptibility Testing of Yeasts (M27, 4th edition). 4th ed. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI); 2017.

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Reference Method for Broth Dilution Antifungal Susceptibility Testing of Filamentous Fungi (Approved Standard, M38, 3rd edition). Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI); 2017

- Oliveira DC, Lopes PG, Spader TB, et al. Antifungal susceptibilities of Sporothrix albicans, S. brasiliensis, and S. luriei of the S. schenckii complex identified in Brazil. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49:3047-3049.

- Kauffman CA, Bustamante B, Chapman SW, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of sporotrichosis: 2007 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45:1255-1265.

- Thompson GR, Le T, Chindamporn A, et al. Global guideline for the diagnosis and management of the endemic mycoses: an initiative of the European Confederation of Medical Mycology in cooperation with the International Society for Human and Animal Mycology. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021;21:E364-E374.

- Francesconi G, Valle AC, Passos S, et al. Terbinafine (250 mg/day): an effective and safe treatment of cutaneous sporotrichosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23:1273-1276.

- Macedo PM, Lopes-Bezerra LM, Bernardes-Engemann AR, et al. New posology of potassium iodide for the treatment of cutaneous sporotrichosis: study of efficacy and safety in 102 patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:719-724.

- Queiroz-Telles F, Nucci M, Colombo AL, et al. Mycoses of implantation in Latin America: an overview of epidemiology, clinical manifestations, diagnosis and treatment. Med Mycol. 2011;49:225-236.

- Orofino-Costa R, de Macedo PM, Rodrigues AM, et al. Sporotrichosis: an update on epidemiology, etiopathogenesis, laboratory and clinical therapeutics. An Bras Dermatol. 2017;92:606-620.

- Almeida-Paes R, de Oliveira MM, Freitas DF, et al. Sporotrichosis in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: Sporothrix brasiliensis is associated with atypical clinical presentations. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8:E3094.

- Arrillaga-Moncrieff I, Capilla J, Mayayo E, et al. Different virulence levels of the species of Sporothrix in a murine model. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2009;15:651-655.

- de Lima Barros MB, Schubach TM, Gutierrez-Galhardo MC, et al. Sporotrichosis: an emergent zoonosis in Rio de Janeiro. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2001;96:777-779.

- Bao F, Huai P, Chen C, et al. An outbreak of sporotrichosis associated with tying crabs. JAMA Dermatol. 2025;161:883-885.

- de Lima Barros MB, de Almeida Paes R, Schubach AO. Sporothrix schenckii and sporotrichosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2011;24:633-654.

- Queiroz-Telles F, Buccheri R, Benard G. Sporotrichosis in immunocompromised hosts. J Fungi. 2019;5:8.

- World Health Organization. Generic Framework for Control, Elimination and Eradication of Neglected Tropical Diseases. World Health Organization; 2016.

- Smith DJ, Soebono H, Parajuli N, et al. South-East Asia regional neglected tropical disease framework: improving control of mycetoma, chromoblastomycosis, and sporotrichosis. Lancet Reg Health Southeast Asia. 2025;35:100561.

- Winck GR, Raimundo RL, Fernandes-Ferreira H, et al. Socioecological vulnerability and the risk of zoonotic disease emergence in Brazil. Sci Adv. 2022;8:eabo5774.

- Jenks JD, Prattes J, Wurster S, et al. Social determinants of health as drivers of fungal disease. EClinicalMedicine. 2023;66:102325.

- Rodrigues AM, Gonçalves SS, de Carvalho JA, et al. Current progress on epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment of sporotrichosis and their future trends. J Fungi. 2022;8:776.

- Evans EGV, Ashbee HR, Frankland JC, et al. Tropical mycoses: hazards to travellers. In: Evans EGV, Ashbee HR, eds. Tropical Mycology. Vol 2. CABI Publishing; 2002:145-163.

- Matute DR, Teixeira MM. Sporothrix is neglected among the neglected. PLoS Pathog. 2025;21:E1012898.

- Matruchot L. Sur un nouveau groupe de champignons pathogenes, agents des sporotrichoses. Comptes Rendus De L’Académie Des Sci. 1910;150:543-545.

- Dangerfield LF. Sporotriehosis among miners on the Witwatersrand gold mines. S Afr Med J. 1941;15:128-131.

- Fukushiro R. Epidemiology and ecology of sporotrichosis in Japan. Zentralbl Bakteriol Mikrobiol Hyg. 1984;257:228-233.

- Dixon DM, Salkin IF, Duncan RA, et al. Isolation and characterization of Sporothrix schenckii from clinical and environmental sources associated with the largest US epidemic of sporotrichosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:1106-1113.

- dos Santos AR, Misas E, Min B, et al. Emergence of zoonotic sporotrichosis in Brazil: a genomic epidemiology study. Lancet Microbe. 2024;5:E282-E290.

- Schechtman RC, Falcão EM, Carard M, et al. Sporotrichosis: hyperendemic by zoonotic transmission, with atypical presentations, hypersensitivity reactions and greater severity. An Bras Dermatol. 2022;97:1-13.

- Rodrigues AM, de Hoog GS, de Camargo ZP. Sporothrix species causing outbreaks in animals and humans driven by animal-animal transmission. PLoS Pathog. 2016;12:E1005638.

- Li HY, Song J, Zhang Y. Epidemiological survey of sporotrichosis in Zhaodong, Heilongjiang. Chin J Dermatol. 1995;28:401-402.

- Hajjeh R, McDonnell S, Reef S, et al. Outbreak of sporotrichosis among tree nursery workers. J Infect Dis. 1997;176:499-504.

- Coles FB, Schuchat A, Hibbs JR, et al. A multistate outbreak of sporotrichosis associated with sphagnum moss. Am J Epidemiol. 1992;136:475-487.

- Benedict K, Jackson BR. Sporotrichosis cases in commercial insurance data, United States, 2012-2018. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26:2783-2785.

- Gold JAW, Derado G, Mody RK, et al. Sporotrichosis-associated hospitalizations, United States, 2000-2013. Emerg Infect Dis. 2016;22:1817-1820.

- Rossow JA, Queiroz-Telles F, Caceres DH, et al. A One Health approach to combatting Sporothrix brasiliensis: narrative review of an emerging zoonotic fungal pathogen in South America. J Fungi. 2020;6:247-274.

- Madrid IM, Mattei AS, Fernandes CG, et al. Epidemiological findings and laboratory evaluation of sporotrichosis: a description of 103 cases in cats and dogs in southern Brazil. Mycopathologia. 2012;173:265-273.

- Fichman V, Gremião ID, Mendes-Júnior AA, et al. Sporotrichosis transmitted by a cockatiel (Nymphicus hollandicus). J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:E157-E158.

- Cognialli RC, Queiroz-Telles F, Cavanaugh AM, et al. New insights on transmission of Sporothrix brasiliensis. Mycoses. 2025;68:E70047.

- Bastos FA, De Farias MR, Gremião ID, et al. Cat-transmitted sporotrichosis by Sporothrix brasiliensis: focus on its potential transmission routes and epidemiological profile. Med Mycol. 2025;63.

- Gremiao ID, Menezes RC, Schubach TM, et al. Feline sporotrichosis: epidemiological and clinical aspects. Med Mycol. 2015;53:15-21.

- Hektoen L, Perkins CF. Refractory subcutaneous abscesses caused by Sporothrix schenckii: a new pathogenic fungus. J Exp Med. 1900;5:77-89.

- Marimon R, Cano J, Gené J, et al. Sporothrix brasiliensis, S. globosa, and S. mexicana, three new Sporothrix species of clinical interest. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45:3198-3206.

- Rodrigues AM, Della Terra PP, Gremião ID, et al. The threat of emerging and re-emerging pathogenic Sporothrix species. Mycopathologia. 2020;185:813-842.

- Morgado DS, Castro R, Ribeiro-Alves M, et al. Global distribution of animal sporotrichosis: a systematic review of Sporothrix sp. identified using molecular tools. Curr Res Microbial Sci. 2022;3:100140.

- de Lima IM, Ferraz CE, Lima-Neto RG, et al. Case report: Sweet syndrome in patients with sporotrichosis: a 10-case series. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2020;103:2533-2538.

- Xavier MO, Bittencourt LR, da Silva CM, et al. Atypical presentation of sporotrichosis: report of three cases. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2013;46:116-118.

- Ramos-e-Silva M, Vasconcelos C, Carneiro S, et al. Sporotrichosis. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:181-187.

- Sampaio SA, Lacaz CS. Klinische und statische Untersuchungen uber Sporotrichose in Sao Paulo. Der Hautarzt. 1959;10:490-493.

- Arinelli A, Aleixo L, Freitas DF, et al. Ocular manifestations of sporotrichosis in a hyperendemic region in Brazil: description of a series of 120 cases. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2023;31:329-337.

- Cognialli RC, Cáceres DH, Bastos FA, et al. Rising incidence of Sporothrix brasiliensis infections, Curitiba, Brazil, 2011-2022. Emerg Infect Dis. 2023;29:1330-1339.

- Freitas DF, Valle AC, da Silva MB, et al. Sporotrichosis: an emerging neglected opportunistic infection in HIV-infected patients in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8:E3110.

- Bonifaz A, Tirado-Sánchez A. Cutaneous disseminated and extracutaneous sporotrichosis: current status of a complex disease. J Fungi. 2017;3:6.

- Falcão EM, de Lima Filho JB, Campos DP, et al. Hospitalizações e óbitos relacionados à esporotricose no Brasil (1992-2015). Cad Saude Publica. 2019;35:4.

- Mahajan VK, Burkhart CG. Sporotrichosis: an overview and therapeutic options. Dermatol Res Pract. 2014;2014:32-44.

- Hamer EC, Moore CB, Denning DW. Comparison of two fluorescent whiteners, Calcofluor and Blankophor, for the detection of fungal elements in clinical specimens in the diagnostic laboratory. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2006;12:181-184.

- Bernardes-Engemann AR, Orofino Costa RC, Miguens BP, et al. Development of an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for the serodiagnosis of several clinical forms of sporotrichosis. Med Mycol. 2005;43:487-493.