User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

Updated celiac disease guideline addresses common clinical questions

The American College of Gastroenterology issued updated guidelines for celiac disease diagnosis, management, and screening that incorporates research conducted since the last update in 2013.

The guidelines offer evidence-based recommendations for common clinical questions on topics that include nonbiopsy diagnosis, gluten-free oats, probiotic use, and gluten-detection devices. They also point to areas for ongoing research.

“The main message of the guideline is all about quality of care,” Alberto Rubio-Tapia, MD, a gastroenterologist at the Cleveland Clinic, said in an interview.

“A precise celiac disease diagnosis is just the beginning of the role of the gastroenterologist,” he said. “But most importantly, we need to take care of our patients’ needs with good goal-directed follow-up using a multidisciplinary approach, with experienced dietitians playing an important role.”

The update was published in the American Journal of Gastroenterology.

Diagnosis recommendations

The ACG assembled a team of celiac disease experts and expert guideline methodologists to develop an update with high-quality evidence, Dr. Rubio-Tapia said. The authors made recommendations and suggestions for future research regarding eight questions concerning diagnosis, disease management, and screening.

For diagnosis, the guidelines recommend esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) with multiple duodenal biopsies – one or two from the bulb and four from the distal duodenum – for confirmation in children and adults with suspicion of celiac disease. EGD and duodenal biopsies can also be useful for the differential diagnosis of other malabsorptive disorders or enteropathies, the authors wrote.

For children, a nonbiopsy option may be considered to be reliable for diagnosis. This option includes a combination of high-level tissue transglutaminase (TTG) IgA – at greater than 10 times the upper limit of normal – and a positive endomysial antibody finding in a second blood sample. The same criteria may be considered after the fact for symptomatic adults who are unwilling or unable to undergo upper GI endoscopy.

For children younger than 2 years, the TTG-IgA is the preferred test for those who are not IgA deficient. For children with IgA deficiency, testing should be performed using IgG-based antibodies.

Disease management guidance

After diagnosis, intestinal healing should be the endpoint for a gluten-free diet, the guidelines recommended. Clinicians and patients should discuss individualized goals of the gluten-free diet beyond clinical and serologic remission.

The standard of care for assessing patients’ diet adherence is an interview with a dietician who has expertise in gluten-free diets, the recommendations stated. Subsequent visits should be encouraged as needed to reinforce adherence.

During disease management, upper endoscopy with intestinal biopsies can be helpful for monitoring cases in which there is a lack of clinical response or in which symptoms relapse despite a gluten-free diet, the authors noted.

In addition, after a shared decision-making conversation between the patient and provider, a follow-up biopsy could be considered for assessment of mucosal healing in adults who don’t have symptoms 2 years after starting a gluten-free diet, they wrote.

“Although most patients do well on a gluten-free diet, it’s a heavy burden of care and an important issue that impacts patients,” Joseph Murray, MD, a gastroenterologist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., said in an interview.

Dr. Murray, who wasn’t involved with this guideline update, contributed to the 2013 guidelines and the 2019 American Gastroenterological Association practice update on diagnosing and monitoring celiac disease. He agreed with many of the recommendations in this update.

“The goal of achieving healing is a good goal to reach. We do that routinely in my practice,” he said. “The older the patient, perhaps the more important it is to discuss, including the risk for complications. There’s a nuance involved with shared decision-making.”

Nutrition advice

The guidelines recommended against routine use of gluten-detection devices for food or biospecimens for patients with celiac disease. Although multiple devices have become commercially available in recent years, they are not regulated by the Food and Drug Administration and have sensitivity problems that can lead to false positive and false negative results, the authors noted. There’s also a lack of evidence that the devices enhance diet adherence or quality of life.

The evidence is insufficient to recommend for or against the use of probiotics for the treatment of celiac disease, the recommendations stated. Although dysbiosis is a feature of celiac disease, its role in disease pathogenesis and symptomatology is uncertain, the authors wrote.

Probiotics may help with functional disorders, such as irritable bowel syndrome, but because probiotics are marketed as supplements and regulations are lax, some products may contain detectable gluten despite being labeled gluten free, they added.

On the other hand, the authors recommended gluten-free oats as part of a gluten-free diet. Oat consumption appears to be safe for most patients with celiac disease, but it may be immunogenic in a subset of patients, depending on the products or quantity consumed. Given the small risk for an immune reaction to the oat protein avenin, monitoring for oat tolerance through symptoms and serology should be conducted, although the intervals for monitoring remain unknown.

Vaccination and screening

The guidelines also support vaccination against pneumococcal disease, since adults with celiac disease are at significantly increased risk of infection and complications. Vaccination is widely recommended for people aged 65 and older, for smokers aged 19-64, and for adults with underlying conditions that place them at higher risk, the authors noted.

Overall, the guidelines recommended case findings to increase detection of celiac disease in clinical practice but recommend against mass screening in the community. Patients with symptoms for whom there is lab evidence of malabsorption should be tested, as well as those for whom celiac disease could be a treatable cause of symptoms, the authors wrote. Those with a first-degree family member who has a confirmed diagnosis should also be tested if they have possible symptoms, and asymptomatic relatives should consider testing as well.

The updated guidelines include changes that are important for patients and patient care, and they emphasize the need for continued research on key questions, Isabel Hujoel, MD, a gastroenterologist at the University of Washington Medical Center, Seattle, told this news organization.

“In particular, the discussion on the lack of evidence behind gluten-detection devices and probiotic use in celiac disease addresses conversations that come up frequently in clinic,” said Dr. Hujoel, who wasn’t involved with the update. “The guidelines also include a new addition below each recommendation where future research questions are raised. Many of these questions address gaps in our understanding on celiac disease, such as the possibility of a nonbiopsy diagnosis in adults, which will potentially dramatically impact patient care if addressed.”

The update received no funding. The authors, Dr. Murray, and Dr. Hujoel have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The American College of Gastroenterology issued updated guidelines for celiac disease diagnosis, management, and screening that incorporates research conducted since the last update in 2013.

The guidelines offer evidence-based recommendations for common clinical questions on topics that include nonbiopsy diagnosis, gluten-free oats, probiotic use, and gluten-detection devices. They also point to areas for ongoing research.

“The main message of the guideline is all about quality of care,” Alberto Rubio-Tapia, MD, a gastroenterologist at the Cleveland Clinic, said in an interview.

“A precise celiac disease diagnosis is just the beginning of the role of the gastroenterologist,” he said. “But most importantly, we need to take care of our patients’ needs with good goal-directed follow-up using a multidisciplinary approach, with experienced dietitians playing an important role.”

The update was published in the American Journal of Gastroenterology.

Diagnosis recommendations

The ACG assembled a team of celiac disease experts and expert guideline methodologists to develop an update with high-quality evidence, Dr. Rubio-Tapia said. The authors made recommendations and suggestions for future research regarding eight questions concerning diagnosis, disease management, and screening.

For diagnosis, the guidelines recommend esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) with multiple duodenal biopsies – one or two from the bulb and four from the distal duodenum – for confirmation in children and adults with suspicion of celiac disease. EGD and duodenal biopsies can also be useful for the differential diagnosis of other malabsorptive disorders or enteropathies, the authors wrote.

For children, a nonbiopsy option may be considered to be reliable for diagnosis. This option includes a combination of high-level tissue transglutaminase (TTG) IgA – at greater than 10 times the upper limit of normal – and a positive endomysial antibody finding in a second blood sample. The same criteria may be considered after the fact for symptomatic adults who are unwilling or unable to undergo upper GI endoscopy.

For children younger than 2 years, the TTG-IgA is the preferred test for those who are not IgA deficient. For children with IgA deficiency, testing should be performed using IgG-based antibodies.

Disease management guidance

After diagnosis, intestinal healing should be the endpoint for a gluten-free diet, the guidelines recommended. Clinicians and patients should discuss individualized goals of the gluten-free diet beyond clinical and serologic remission.

The standard of care for assessing patients’ diet adherence is an interview with a dietician who has expertise in gluten-free diets, the recommendations stated. Subsequent visits should be encouraged as needed to reinforce adherence.

During disease management, upper endoscopy with intestinal biopsies can be helpful for monitoring cases in which there is a lack of clinical response or in which symptoms relapse despite a gluten-free diet, the authors noted.

In addition, after a shared decision-making conversation between the patient and provider, a follow-up biopsy could be considered for assessment of mucosal healing in adults who don’t have symptoms 2 years after starting a gluten-free diet, they wrote.

“Although most patients do well on a gluten-free diet, it’s a heavy burden of care and an important issue that impacts patients,” Joseph Murray, MD, a gastroenterologist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., said in an interview.

Dr. Murray, who wasn’t involved with this guideline update, contributed to the 2013 guidelines and the 2019 American Gastroenterological Association practice update on diagnosing and monitoring celiac disease. He agreed with many of the recommendations in this update.

“The goal of achieving healing is a good goal to reach. We do that routinely in my practice,” he said. “The older the patient, perhaps the more important it is to discuss, including the risk for complications. There’s a nuance involved with shared decision-making.”

Nutrition advice

The guidelines recommended against routine use of gluten-detection devices for food or biospecimens for patients with celiac disease. Although multiple devices have become commercially available in recent years, they are not regulated by the Food and Drug Administration and have sensitivity problems that can lead to false positive and false negative results, the authors noted. There’s also a lack of evidence that the devices enhance diet adherence or quality of life.

The evidence is insufficient to recommend for or against the use of probiotics for the treatment of celiac disease, the recommendations stated. Although dysbiosis is a feature of celiac disease, its role in disease pathogenesis and symptomatology is uncertain, the authors wrote.

Probiotics may help with functional disorders, such as irritable bowel syndrome, but because probiotics are marketed as supplements and regulations are lax, some products may contain detectable gluten despite being labeled gluten free, they added.

On the other hand, the authors recommended gluten-free oats as part of a gluten-free diet. Oat consumption appears to be safe for most patients with celiac disease, but it may be immunogenic in a subset of patients, depending on the products or quantity consumed. Given the small risk for an immune reaction to the oat protein avenin, monitoring for oat tolerance through symptoms and serology should be conducted, although the intervals for monitoring remain unknown.

Vaccination and screening

The guidelines also support vaccination against pneumococcal disease, since adults with celiac disease are at significantly increased risk of infection and complications. Vaccination is widely recommended for people aged 65 and older, for smokers aged 19-64, and for adults with underlying conditions that place them at higher risk, the authors noted.

Overall, the guidelines recommended case findings to increase detection of celiac disease in clinical practice but recommend against mass screening in the community. Patients with symptoms for whom there is lab evidence of malabsorption should be tested, as well as those for whom celiac disease could be a treatable cause of symptoms, the authors wrote. Those with a first-degree family member who has a confirmed diagnosis should also be tested if they have possible symptoms, and asymptomatic relatives should consider testing as well.

The updated guidelines include changes that are important for patients and patient care, and they emphasize the need for continued research on key questions, Isabel Hujoel, MD, a gastroenterologist at the University of Washington Medical Center, Seattle, told this news organization.

“In particular, the discussion on the lack of evidence behind gluten-detection devices and probiotic use in celiac disease addresses conversations that come up frequently in clinic,” said Dr. Hujoel, who wasn’t involved with the update. “The guidelines also include a new addition below each recommendation where future research questions are raised. Many of these questions address gaps in our understanding on celiac disease, such as the possibility of a nonbiopsy diagnosis in adults, which will potentially dramatically impact patient care if addressed.”

The update received no funding. The authors, Dr. Murray, and Dr. Hujoel have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The American College of Gastroenterology issued updated guidelines for celiac disease diagnosis, management, and screening that incorporates research conducted since the last update in 2013.

The guidelines offer evidence-based recommendations for common clinical questions on topics that include nonbiopsy diagnosis, gluten-free oats, probiotic use, and gluten-detection devices. They also point to areas for ongoing research.

“The main message of the guideline is all about quality of care,” Alberto Rubio-Tapia, MD, a gastroenterologist at the Cleveland Clinic, said in an interview.

“A precise celiac disease diagnosis is just the beginning of the role of the gastroenterologist,” he said. “But most importantly, we need to take care of our patients’ needs with good goal-directed follow-up using a multidisciplinary approach, with experienced dietitians playing an important role.”

The update was published in the American Journal of Gastroenterology.

Diagnosis recommendations

The ACG assembled a team of celiac disease experts and expert guideline methodologists to develop an update with high-quality evidence, Dr. Rubio-Tapia said. The authors made recommendations and suggestions for future research regarding eight questions concerning diagnosis, disease management, and screening.

For diagnosis, the guidelines recommend esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) with multiple duodenal biopsies – one or two from the bulb and four from the distal duodenum – for confirmation in children and adults with suspicion of celiac disease. EGD and duodenal biopsies can also be useful for the differential diagnosis of other malabsorptive disorders or enteropathies, the authors wrote.

For children, a nonbiopsy option may be considered to be reliable for diagnosis. This option includes a combination of high-level tissue transglutaminase (TTG) IgA – at greater than 10 times the upper limit of normal – and a positive endomysial antibody finding in a second blood sample. The same criteria may be considered after the fact for symptomatic adults who are unwilling or unable to undergo upper GI endoscopy.

For children younger than 2 years, the TTG-IgA is the preferred test for those who are not IgA deficient. For children with IgA deficiency, testing should be performed using IgG-based antibodies.

Disease management guidance

After diagnosis, intestinal healing should be the endpoint for a gluten-free diet, the guidelines recommended. Clinicians and patients should discuss individualized goals of the gluten-free diet beyond clinical and serologic remission.

The standard of care for assessing patients’ diet adherence is an interview with a dietician who has expertise in gluten-free diets, the recommendations stated. Subsequent visits should be encouraged as needed to reinforce adherence.

During disease management, upper endoscopy with intestinal biopsies can be helpful for monitoring cases in which there is a lack of clinical response or in which symptoms relapse despite a gluten-free diet, the authors noted.

In addition, after a shared decision-making conversation between the patient and provider, a follow-up biopsy could be considered for assessment of mucosal healing in adults who don’t have symptoms 2 years after starting a gluten-free diet, they wrote.

“Although most patients do well on a gluten-free diet, it’s a heavy burden of care and an important issue that impacts patients,” Joseph Murray, MD, a gastroenterologist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., said in an interview.

Dr. Murray, who wasn’t involved with this guideline update, contributed to the 2013 guidelines and the 2019 American Gastroenterological Association practice update on diagnosing and monitoring celiac disease. He agreed with many of the recommendations in this update.

“The goal of achieving healing is a good goal to reach. We do that routinely in my practice,” he said. “The older the patient, perhaps the more important it is to discuss, including the risk for complications. There’s a nuance involved with shared decision-making.”

Nutrition advice

The guidelines recommended against routine use of gluten-detection devices for food or biospecimens for patients with celiac disease. Although multiple devices have become commercially available in recent years, they are not regulated by the Food and Drug Administration and have sensitivity problems that can lead to false positive and false negative results, the authors noted. There’s also a lack of evidence that the devices enhance diet adherence or quality of life.

The evidence is insufficient to recommend for or against the use of probiotics for the treatment of celiac disease, the recommendations stated. Although dysbiosis is a feature of celiac disease, its role in disease pathogenesis and symptomatology is uncertain, the authors wrote.

Probiotics may help with functional disorders, such as irritable bowel syndrome, but because probiotics are marketed as supplements and regulations are lax, some products may contain detectable gluten despite being labeled gluten free, they added.

On the other hand, the authors recommended gluten-free oats as part of a gluten-free diet. Oat consumption appears to be safe for most patients with celiac disease, but it may be immunogenic in a subset of patients, depending on the products or quantity consumed. Given the small risk for an immune reaction to the oat protein avenin, monitoring for oat tolerance through symptoms and serology should be conducted, although the intervals for monitoring remain unknown.

Vaccination and screening

The guidelines also support vaccination against pneumococcal disease, since adults with celiac disease are at significantly increased risk of infection and complications. Vaccination is widely recommended for people aged 65 and older, for smokers aged 19-64, and for adults with underlying conditions that place them at higher risk, the authors noted.

Overall, the guidelines recommended case findings to increase detection of celiac disease in clinical practice but recommend against mass screening in the community. Patients with symptoms for whom there is lab evidence of malabsorption should be tested, as well as those for whom celiac disease could be a treatable cause of symptoms, the authors wrote. Those with a first-degree family member who has a confirmed diagnosis should also be tested if they have possible symptoms, and asymptomatic relatives should consider testing as well.

The updated guidelines include changes that are important for patients and patient care, and they emphasize the need for continued research on key questions, Isabel Hujoel, MD, a gastroenterologist at the University of Washington Medical Center, Seattle, told this news organization.

“In particular, the discussion on the lack of evidence behind gluten-detection devices and probiotic use in celiac disease addresses conversations that come up frequently in clinic,” said Dr. Hujoel, who wasn’t involved with the update. “The guidelines also include a new addition below each recommendation where future research questions are raised. Many of these questions address gaps in our understanding on celiac disease, such as the possibility of a nonbiopsy diagnosis in adults, which will potentially dramatically impact patient care if addressed.”

The update received no funding. The authors, Dr. Murray, and Dr. Hujoel have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF GASTROENTEROLOGY

AD outcomes improved with lebrikizumab and topical steroids

, according to results of the 16-week phase 3 ADhere trial.

“Lebrikizumab, a monoclonal antibody inhibiting interleukin-13, combined with TCS was associated with reduced overall disease severity of moderate to severe AD in adolescents and adults, and had a safety profile consistent with previous lebrikizumab AD studies,” noted lead author Eric L. Simpson, MD, professor of dermatology at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, and coauthors in their article on the study, which was published in JAMA Dermatology.

The double-blind trial, conducted at 54 sites across Germany, Poland, Canada, and the United States, included 211 patients, mean age 37.2 years, of whom 48.8% were female and roughly 22% were adolescents. Almost 15% were Asian, and about 13% were Black.

At baseline, participants had a score of 16 or higher on the Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI), a score of 3 or higher on the Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA) scale, AD covering a body surface area of 10% or greater, and a history of inadequate response to treatment with topical medications.

After a minimum 1-week washout period from topical and systemic therapy, participants were randomized in a 2:1 ratio to receive lebrikizumab plus TCS (n = 145) or placebo plus TCS (n = 66) for 16 weeks.

Lebrikizumab or placebo was administered by subcutaneous injection every 2 weeks; the loading and week-2 doses of lebrikizumab were 500 mg, followed by 250 mg thereafter. All patients were instructed to use low- to mid-potency TCS at their own discretion. Study sites provided a mid-potency TCS (triamcinolone acetonide 0.1% cream) and a low-potency TCS (hydrocortisone 1% cream), with topical calcineurin inhibitors permitted for sensitive skin areas.

Primary outcomes at 16 weeks included a 2-point or more reduction in IGA score from baseline and EASI-75 response. Patients in the lebrikizumab arm had superior responses on both of these outcomes, with statistical significance achieved as early as week 8 and week 4, respectively, and maintained through week 16. Specifically, 41.2% of those treated with lebrikizumab had an IGA reduction of 2 points or more, compared with 22.1% of those receiving placebo plus TCS (P = .01), and the proportion of patients achieving EASI-75 responses was 69.5% vs. 42.2%, respectively (P < .001).

Patients treated with lebrikizumab also showed statistically significant improvements, compared with TCS alone in all key secondary endpoints, “including skin clearance, improvement in itch, itch interference on sleep, and enhanced QoL [quality of life],” noted the authors. “This study captured the clinical benefit of lebrikizumab through the combined end point of physician-assessed clinical sign of skin clearance (EASI-75) and patient-reported outcome of improvement in itch (Pruritus NRS).”

The percentage of patients who achieved the combined endpoint was more than double for the lebrikizumab plus TCS group vs. the group on TCS alone, indicating that patients treated with lebrikizumab plus TCS “were more likely to experience improvement in skin symptoms and itch,” the investigators added.

The authors noted that most treatment-emergent adverse events “were nonserious, mild, or moderate in severity, and did not lead to study discontinuation.” These included conjunctivitis (4.8%), headache (4.8%), hypertension (2.8%), injection-site reactions (2.8%), and herpes infection (3.4%) – all of which occurred in 1.5% or less of patients in the placebo group.

“The higher incidence of conjunctivitis has also been reported in other biologics inhibiting IL [interleukin]–13 and/or IL-4 signaling, as well as lebrikizumab monotherapy studies,” they noted. The 4.8% rate of conjunctivitis reported in the combination study, they added, is “compared with 7.5% frequency in 16-week data from the lebrikizumab monotherapy studies. Although the mechanism remains unclear, it has been reported that conjunctival goblet cell scarcity due to IL-13 and IL-4 inhibition, and subsequent effects on the homeostasis of the conjunctival mucosal surface, results in ocular AEs [adverse events].”

“This truly is a time of great hope and promise for our patients with AD,” commented Zelma Chiesa Fuxench, MD, who was not involved in the study. “The advent of newer, targeted therapeutic agents for AD continues to revolutionize the treatment experience for our patients, offering the possibility of greater AD disease control with a favorable risk profile and less need for blood work monitoring compared to traditional systemic agents.”

On the basis of the study results, Dr. Chiesa Fuxench, of the department of dermatology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said in an interview that “lebrikizumab represents an additional option in the treatment armamentarium for providers who care for patients with AD.” She added that, “while head-to-head trials comparing lebrikizumab to dupilumab, the first FDA-approved biologic for AD, would be beneficial, to the best of my knowledge this data is currently lacking. However, based on the results of this study, we would expect lebrikizumab to work at least similarly to dupilumab, based on the reported improvements in IGA and EASI score.”

Additionally, lebrikizumab showed a favorable safety profile, “with most treatment-emergent adverse effects reported as nonserious and not leading to drug discontinuation,” she said. “Of interest to clinicians may be the reported rates of conjunctivitis in this study. Rates of conjunctivitis for lebrikizumab appear to be lower than those reported in the LIBERTY AD CHRONOS study for dupilumab – a finding that merits further scrutiny in my opinion, as this one of the most frequent treatment-emergent adverse events that I encounter in my clinical practice.”

The study was funded by Dermira, a subsidiary of Eli Lilly. Dr. Simpson reported personal fees and grants from multiple sources, including Dermira and Eli Lilly, the companies developing lebrikizumab. Several authors were employees of Eli Lilly. Dr. Fuxench disclosed serving as a consultant for the Asthma and Allergy Foundation of America, National Eczema Association, Pfizer, AbbVie, and Incyte, for which she has received honoraria for AD-related work. She is the recipient of research grants through Regeneron, Sanofi, Tioga, Vanda, Menlo Therapeutics, Leo Pharma, and Eli Lilly for work related to AD as well as honoraria for continuing medical education work related to AD sponsored through educational grants from Regeneron/Sanofi and Pfizer.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, according to results of the 16-week phase 3 ADhere trial.

“Lebrikizumab, a monoclonal antibody inhibiting interleukin-13, combined with TCS was associated with reduced overall disease severity of moderate to severe AD in adolescents and adults, and had a safety profile consistent with previous lebrikizumab AD studies,” noted lead author Eric L. Simpson, MD, professor of dermatology at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, and coauthors in their article on the study, which was published in JAMA Dermatology.

The double-blind trial, conducted at 54 sites across Germany, Poland, Canada, and the United States, included 211 patients, mean age 37.2 years, of whom 48.8% were female and roughly 22% were adolescents. Almost 15% were Asian, and about 13% were Black.

At baseline, participants had a score of 16 or higher on the Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI), a score of 3 or higher on the Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA) scale, AD covering a body surface area of 10% or greater, and a history of inadequate response to treatment with topical medications.

After a minimum 1-week washout period from topical and systemic therapy, participants were randomized in a 2:1 ratio to receive lebrikizumab plus TCS (n = 145) or placebo plus TCS (n = 66) for 16 weeks.

Lebrikizumab or placebo was administered by subcutaneous injection every 2 weeks; the loading and week-2 doses of lebrikizumab were 500 mg, followed by 250 mg thereafter. All patients were instructed to use low- to mid-potency TCS at their own discretion. Study sites provided a mid-potency TCS (triamcinolone acetonide 0.1% cream) and a low-potency TCS (hydrocortisone 1% cream), with topical calcineurin inhibitors permitted for sensitive skin areas.

Primary outcomes at 16 weeks included a 2-point or more reduction in IGA score from baseline and EASI-75 response. Patients in the lebrikizumab arm had superior responses on both of these outcomes, with statistical significance achieved as early as week 8 and week 4, respectively, and maintained through week 16. Specifically, 41.2% of those treated with lebrikizumab had an IGA reduction of 2 points or more, compared with 22.1% of those receiving placebo plus TCS (P = .01), and the proportion of patients achieving EASI-75 responses was 69.5% vs. 42.2%, respectively (P < .001).

Patients treated with lebrikizumab also showed statistically significant improvements, compared with TCS alone in all key secondary endpoints, “including skin clearance, improvement in itch, itch interference on sleep, and enhanced QoL [quality of life],” noted the authors. “This study captured the clinical benefit of lebrikizumab through the combined end point of physician-assessed clinical sign of skin clearance (EASI-75) and patient-reported outcome of improvement in itch (Pruritus NRS).”

The percentage of patients who achieved the combined endpoint was more than double for the lebrikizumab plus TCS group vs. the group on TCS alone, indicating that patients treated with lebrikizumab plus TCS “were more likely to experience improvement in skin symptoms and itch,” the investigators added.

The authors noted that most treatment-emergent adverse events “were nonserious, mild, or moderate in severity, and did not lead to study discontinuation.” These included conjunctivitis (4.8%), headache (4.8%), hypertension (2.8%), injection-site reactions (2.8%), and herpes infection (3.4%) – all of which occurred in 1.5% or less of patients in the placebo group.

“The higher incidence of conjunctivitis has also been reported in other biologics inhibiting IL [interleukin]–13 and/or IL-4 signaling, as well as lebrikizumab monotherapy studies,” they noted. The 4.8% rate of conjunctivitis reported in the combination study, they added, is “compared with 7.5% frequency in 16-week data from the lebrikizumab monotherapy studies. Although the mechanism remains unclear, it has been reported that conjunctival goblet cell scarcity due to IL-13 and IL-4 inhibition, and subsequent effects on the homeostasis of the conjunctival mucosal surface, results in ocular AEs [adverse events].”

“This truly is a time of great hope and promise for our patients with AD,” commented Zelma Chiesa Fuxench, MD, who was not involved in the study. “The advent of newer, targeted therapeutic agents for AD continues to revolutionize the treatment experience for our patients, offering the possibility of greater AD disease control with a favorable risk profile and less need for blood work monitoring compared to traditional systemic agents.”

On the basis of the study results, Dr. Chiesa Fuxench, of the department of dermatology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said in an interview that “lebrikizumab represents an additional option in the treatment armamentarium for providers who care for patients with AD.” She added that, “while head-to-head trials comparing lebrikizumab to dupilumab, the first FDA-approved biologic for AD, would be beneficial, to the best of my knowledge this data is currently lacking. However, based on the results of this study, we would expect lebrikizumab to work at least similarly to dupilumab, based on the reported improvements in IGA and EASI score.”

Additionally, lebrikizumab showed a favorable safety profile, “with most treatment-emergent adverse effects reported as nonserious and not leading to drug discontinuation,” she said. “Of interest to clinicians may be the reported rates of conjunctivitis in this study. Rates of conjunctivitis for lebrikizumab appear to be lower than those reported in the LIBERTY AD CHRONOS study for dupilumab – a finding that merits further scrutiny in my opinion, as this one of the most frequent treatment-emergent adverse events that I encounter in my clinical practice.”

The study was funded by Dermira, a subsidiary of Eli Lilly. Dr. Simpson reported personal fees and grants from multiple sources, including Dermira and Eli Lilly, the companies developing lebrikizumab. Several authors were employees of Eli Lilly. Dr. Fuxench disclosed serving as a consultant for the Asthma and Allergy Foundation of America, National Eczema Association, Pfizer, AbbVie, and Incyte, for which she has received honoraria for AD-related work. She is the recipient of research grants through Regeneron, Sanofi, Tioga, Vanda, Menlo Therapeutics, Leo Pharma, and Eli Lilly for work related to AD as well as honoraria for continuing medical education work related to AD sponsored through educational grants from Regeneron/Sanofi and Pfizer.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, according to results of the 16-week phase 3 ADhere trial.

“Lebrikizumab, a monoclonal antibody inhibiting interleukin-13, combined with TCS was associated with reduced overall disease severity of moderate to severe AD in adolescents and adults, and had a safety profile consistent with previous lebrikizumab AD studies,” noted lead author Eric L. Simpson, MD, professor of dermatology at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, and coauthors in their article on the study, which was published in JAMA Dermatology.

The double-blind trial, conducted at 54 sites across Germany, Poland, Canada, and the United States, included 211 patients, mean age 37.2 years, of whom 48.8% were female and roughly 22% were adolescents. Almost 15% were Asian, and about 13% were Black.

At baseline, participants had a score of 16 or higher on the Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI), a score of 3 or higher on the Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA) scale, AD covering a body surface area of 10% or greater, and a history of inadequate response to treatment with topical medications.

After a minimum 1-week washout period from topical and systemic therapy, participants were randomized in a 2:1 ratio to receive lebrikizumab plus TCS (n = 145) or placebo plus TCS (n = 66) for 16 weeks.

Lebrikizumab or placebo was administered by subcutaneous injection every 2 weeks; the loading and week-2 doses of lebrikizumab were 500 mg, followed by 250 mg thereafter. All patients were instructed to use low- to mid-potency TCS at their own discretion. Study sites provided a mid-potency TCS (triamcinolone acetonide 0.1% cream) and a low-potency TCS (hydrocortisone 1% cream), with topical calcineurin inhibitors permitted for sensitive skin areas.

Primary outcomes at 16 weeks included a 2-point or more reduction in IGA score from baseline and EASI-75 response. Patients in the lebrikizumab arm had superior responses on both of these outcomes, with statistical significance achieved as early as week 8 and week 4, respectively, and maintained through week 16. Specifically, 41.2% of those treated with lebrikizumab had an IGA reduction of 2 points or more, compared with 22.1% of those receiving placebo plus TCS (P = .01), and the proportion of patients achieving EASI-75 responses was 69.5% vs. 42.2%, respectively (P < .001).

Patients treated with lebrikizumab also showed statistically significant improvements, compared with TCS alone in all key secondary endpoints, “including skin clearance, improvement in itch, itch interference on sleep, and enhanced QoL [quality of life],” noted the authors. “This study captured the clinical benefit of lebrikizumab through the combined end point of physician-assessed clinical sign of skin clearance (EASI-75) and patient-reported outcome of improvement in itch (Pruritus NRS).”

The percentage of patients who achieved the combined endpoint was more than double for the lebrikizumab plus TCS group vs. the group on TCS alone, indicating that patients treated with lebrikizumab plus TCS “were more likely to experience improvement in skin symptoms and itch,” the investigators added.

The authors noted that most treatment-emergent adverse events “were nonserious, mild, or moderate in severity, and did not lead to study discontinuation.” These included conjunctivitis (4.8%), headache (4.8%), hypertension (2.8%), injection-site reactions (2.8%), and herpes infection (3.4%) – all of which occurred in 1.5% or less of patients in the placebo group.

“The higher incidence of conjunctivitis has also been reported in other biologics inhibiting IL [interleukin]–13 and/or IL-4 signaling, as well as lebrikizumab monotherapy studies,” they noted. The 4.8% rate of conjunctivitis reported in the combination study, they added, is “compared with 7.5% frequency in 16-week data from the lebrikizumab monotherapy studies. Although the mechanism remains unclear, it has been reported that conjunctival goblet cell scarcity due to IL-13 and IL-4 inhibition, and subsequent effects on the homeostasis of the conjunctival mucosal surface, results in ocular AEs [adverse events].”

“This truly is a time of great hope and promise for our patients with AD,” commented Zelma Chiesa Fuxench, MD, who was not involved in the study. “The advent of newer, targeted therapeutic agents for AD continues to revolutionize the treatment experience for our patients, offering the possibility of greater AD disease control with a favorable risk profile and less need for blood work monitoring compared to traditional systemic agents.”

On the basis of the study results, Dr. Chiesa Fuxench, of the department of dermatology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said in an interview that “lebrikizumab represents an additional option in the treatment armamentarium for providers who care for patients with AD.” She added that, “while head-to-head trials comparing lebrikizumab to dupilumab, the first FDA-approved biologic for AD, would be beneficial, to the best of my knowledge this data is currently lacking. However, based on the results of this study, we would expect lebrikizumab to work at least similarly to dupilumab, based on the reported improvements in IGA and EASI score.”

Additionally, lebrikizumab showed a favorable safety profile, “with most treatment-emergent adverse effects reported as nonserious and not leading to drug discontinuation,” she said. “Of interest to clinicians may be the reported rates of conjunctivitis in this study. Rates of conjunctivitis for lebrikizumab appear to be lower than those reported in the LIBERTY AD CHRONOS study for dupilumab – a finding that merits further scrutiny in my opinion, as this one of the most frequent treatment-emergent adverse events that I encounter in my clinical practice.”

The study was funded by Dermira, a subsidiary of Eli Lilly. Dr. Simpson reported personal fees and grants from multiple sources, including Dermira and Eli Lilly, the companies developing lebrikizumab. Several authors were employees of Eli Lilly. Dr. Fuxench disclosed serving as a consultant for the Asthma and Allergy Foundation of America, National Eczema Association, Pfizer, AbbVie, and Incyte, for which she has received honoraria for AD-related work. She is the recipient of research grants through Regeneron, Sanofi, Tioga, Vanda, Menlo Therapeutics, Leo Pharma, and Eli Lilly for work related to AD as well as honoraria for continuing medical education work related to AD sponsored through educational grants from Regeneron/Sanofi and Pfizer.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA DERMATOLOGY

Children and COVID: ED visits and hospitalizations start to fall again

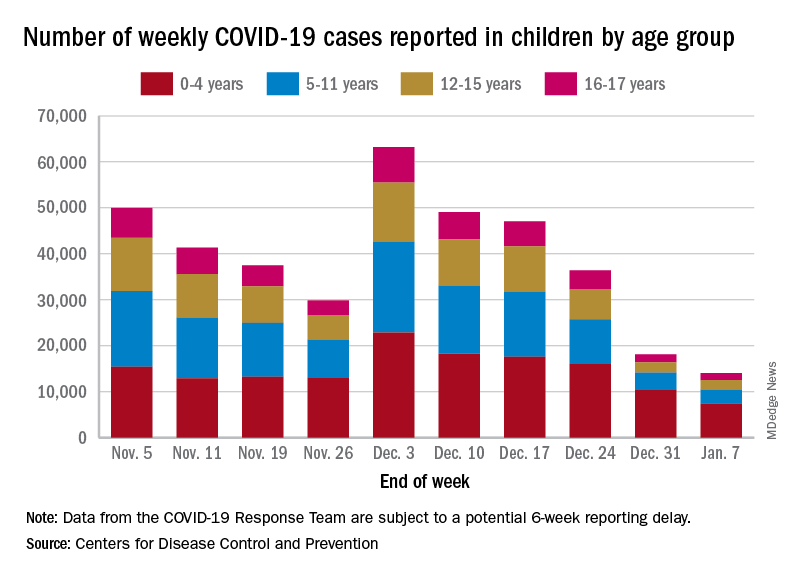

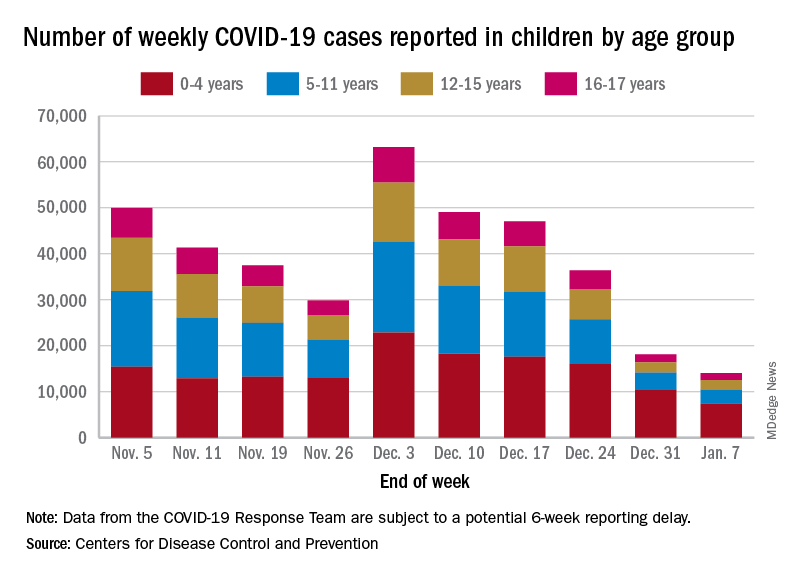

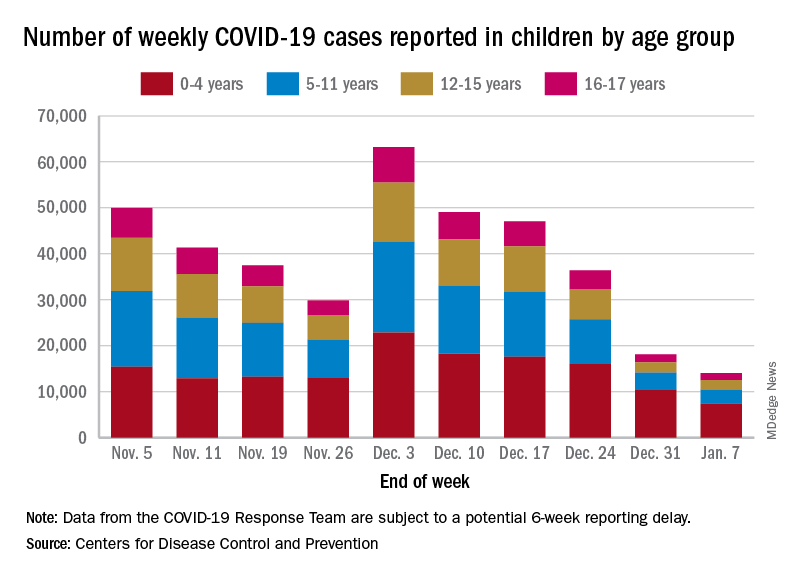

Emergency department visits and hospitalizations for COVID-19 in children appear to be following the declining trend set by weekly cases since early December, based on data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

. New cases took a different path that had the weekly total falling through November before taking a big jump during the week of Nov. 27 to Dec. 3 – the count doubled from 30,000 the previous week to 63,000 – and then decreased again, the CDC reported.

The proportion of ED visits with COVID, which was down to 1.0% of all ED visits (7-day average) for children aged 0-4 years on Nov. 4, was up to 3.2% on Jan. 3 but slipped to 2.5% as of Jan. 10. The patterns for older children are similar, with some differences in timing and lower peaks (1.7% for 12- to 15-year-olds and 1.9% for those aged 16-17), according to the CDC’s COVID Data Tracker.

The trend for new hospital admissions of children with confirmed COVID showed a similar rise through December, and the latest data for the very beginning of January suggest an even faster drop, although there is more of a reporting lag with hospitalization data, compared with ED visits, the CDC noted.

The most current data (Dec. 30 to Jan. 5) available from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association show less volatility in the number of weekly cases through November and December, with the peak being about 48,000 in mid-December. The AAP/CHA totals for the last 2 weeks, however, were both higher than the CDC’s corresponding counts, which are more preliminary and subject to revision.

The CDC puts the total number of COVID cases in children at 16.7 million – about 17.2% of all cases – as of Jan. 11, with 1,981 deaths reported so far. The AAP and CHA are not tracking deaths, but their case total as of Jan. 5 was 15.2 million, which represents 18.1% of cases in all ages. The AAP/CHA report is based on data reported publicly by an ever-decreasing number of states and territories.

Emergency department visits and hospitalizations for COVID-19 in children appear to be following the declining trend set by weekly cases since early December, based on data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

. New cases took a different path that had the weekly total falling through November before taking a big jump during the week of Nov. 27 to Dec. 3 – the count doubled from 30,000 the previous week to 63,000 – and then decreased again, the CDC reported.

The proportion of ED visits with COVID, which was down to 1.0% of all ED visits (7-day average) for children aged 0-4 years on Nov. 4, was up to 3.2% on Jan. 3 but slipped to 2.5% as of Jan. 10. The patterns for older children are similar, with some differences in timing and lower peaks (1.7% for 12- to 15-year-olds and 1.9% for those aged 16-17), according to the CDC’s COVID Data Tracker.

The trend for new hospital admissions of children with confirmed COVID showed a similar rise through December, and the latest data for the very beginning of January suggest an even faster drop, although there is more of a reporting lag with hospitalization data, compared with ED visits, the CDC noted.

The most current data (Dec. 30 to Jan. 5) available from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association show less volatility in the number of weekly cases through November and December, with the peak being about 48,000 in mid-December. The AAP/CHA totals for the last 2 weeks, however, were both higher than the CDC’s corresponding counts, which are more preliminary and subject to revision.

The CDC puts the total number of COVID cases in children at 16.7 million – about 17.2% of all cases – as of Jan. 11, with 1,981 deaths reported so far. The AAP and CHA are not tracking deaths, but their case total as of Jan. 5 was 15.2 million, which represents 18.1% of cases in all ages. The AAP/CHA report is based on data reported publicly by an ever-decreasing number of states and territories.

Emergency department visits and hospitalizations for COVID-19 in children appear to be following the declining trend set by weekly cases since early December, based on data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

. New cases took a different path that had the weekly total falling through November before taking a big jump during the week of Nov. 27 to Dec. 3 – the count doubled from 30,000 the previous week to 63,000 – and then decreased again, the CDC reported.

The proportion of ED visits with COVID, which was down to 1.0% of all ED visits (7-day average) for children aged 0-4 years on Nov. 4, was up to 3.2% on Jan. 3 but slipped to 2.5% as of Jan. 10. The patterns for older children are similar, with some differences in timing and lower peaks (1.7% for 12- to 15-year-olds and 1.9% for those aged 16-17), according to the CDC’s COVID Data Tracker.

The trend for new hospital admissions of children with confirmed COVID showed a similar rise through December, and the latest data for the very beginning of January suggest an even faster drop, although there is more of a reporting lag with hospitalization data, compared with ED visits, the CDC noted.

The most current data (Dec. 30 to Jan. 5) available from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association show less volatility in the number of weekly cases through November and December, with the peak being about 48,000 in mid-December. The AAP/CHA totals for the last 2 weeks, however, were both higher than the CDC’s corresponding counts, which are more preliminary and subject to revision.

The CDC puts the total number of COVID cases in children at 16.7 million – about 17.2% of all cases – as of Jan. 11, with 1,981 deaths reported so far. The AAP and CHA are not tracking deaths, but their case total as of Jan. 5 was 15.2 million, which represents 18.1% of cases in all ages. The AAP/CHA report is based on data reported publicly by an ever-decreasing number of states and territories.

Manicure gone wrong leads to cancer diagnosis

. Now, she and her doctor are spreading the word about her ordeal as a lesson that speed and persistence in seeking treatment are the keys that make her type of cancer – squamous cell carcinoma – completely curable.

“She cut me, and the cut wasn’t just a regular cuticle cut. She cut me deep, and that was one of the first times that happened to me,” Grace Garcia, 50, told TODAY.com, recalling the November 2021 incident.

Ms. Garcia had been getting her nails done regularly for 20 years, she said, but happened to go to a different salon than her usual spot because she couldn’t get an appointment during the busy pre-Thanksgiving season. She doesn’t recall whether the technician opened packaging that signals unused tools.

She put antibiotic ointment on the cut, but it didn’t heal after a few days. Eventually, the skin closed and a darkened bump formed. It was painful. She went to her doctor, who said it was a “callus from writing,” she told TODAY.com. But it was on her ring finger, which didn’t seem connected to writing. Her doctor said to keep an eye on it.

Five months after the cut occurred, she mentioned it during a gynecology appointment and was referred to a dermatologist, who also advised keeping an eye on it. A wart developed. She went back to her primary care physician and then to another dermatologist. The spot was biopsied.

Squamous cell carcinoma is a common type of skin cancer, according to the American Academy of Dermatology. It can have many causes, but the cause in Ms. Garcia’s case was both very common and very rare: human papillomavirus, or HPV. HPV is a virus that infects millions of people every year, but it’s not a typical cause of skin cancer.

“It’s pretty rare for several reasons. Generally speaking, the strains that cause cancer from an HPV standpoint tend to be more sexually transmitted,” dermatologist Teo Soleymani told TODAY.com. “In Grace’s case, she had an injury, which became the portal of entry. So that thick skin that we have on our hands and feet that acts as a natural barrier against infections and things like that was no longer the case, and the virus was able to infect her skin.”

Dr. Soleymani said Ms. Garcia’s persistence to get answers likely saved her from losing a finger.

“Your outcomes are entirely dictated by how early you catch them, and very often they’re completely curable,” he said. “Her persistence – not only was she able to have a great outcome, she probably saved herself from having her finger amputated.”

. Now, she and her doctor are spreading the word about her ordeal as a lesson that speed and persistence in seeking treatment are the keys that make her type of cancer – squamous cell carcinoma – completely curable.

“She cut me, and the cut wasn’t just a regular cuticle cut. She cut me deep, and that was one of the first times that happened to me,” Grace Garcia, 50, told TODAY.com, recalling the November 2021 incident.

Ms. Garcia had been getting her nails done regularly for 20 years, she said, but happened to go to a different salon than her usual spot because she couldn’t get an appointment during the busy pre-Thanksgiving season. She doesn’t recall whether the technician opened packaging that signals unused tools.

She put antibiotic ointment on the cut, but it didn’t heal after a few days. Eventually, the skin closed and a darkened bump formed. It was painful. She went to her doctor, who said it was a “callus from writing,” she told TODAY.com. But it was on her ring finger, which didn’t seem connected to writing. Her doctor said to keep an eye on it.

Five months after the cut occurred, she mentioned it during a gynecology appointment and was referred to a dermatologist, who also advised keeping an eye on it. A wart developed. She went back to her primary care physician and then to another dermatologist. The spot was biopsied.

Squamous cell carcinoma is a common type of skin cancer, according to the American Academy of Dermatology. It can have many causes, but the cause in Ms. Garcia’s case was both very common and very rare: human papillomavirus, or HPV. HPV is a virus that infects millions of people every year, but it’s not a typical cause of skin cancer.

“It’s pretty rare for several reasons. Generally speaking, the strains that cause cancer from an HPV standpoint tend to be more sexually transmitted,” dermatologist Teo Soleymani told TODAY.com. “In Grace’s case, she had an injury, which became the portal of entry. So that thick skin that we have on our hands and feet that acts as a natural barrier against infections and things like that was no longer the case, and the virus was able to infect her skin.”

Dr. Soleymani said Ms. Garcia’s persistence to get answers likely saved her from losing a finger.

“Your outcomes are entirely dictated by how early you catch them, and very often they’re completely curable,” he said. “Her persistence – not only was she able to have a great outcome, she probably saved herself from having her finger amputated.”

. Now, she and her doctor are spreading the word about her ordeal as a lesson that speed and persistence in seeking treatment are the keys that make her type of cancer – squamous cell carcinoma – completely curable.

“She cut me, and the cut wasn’t just a regular cuticle cut. She cut me deep, and that was one of the first times that happened to me,” Grace Garcia, 50, told TODAY.com, recalling the November 2021 incident.

Ms. Garcia had been getting her nails done regularly for 20 years, she said, but happened to go to a different salon than her usual spot because she couldn’t get an appointment during the busy pre-Thanksgiving season. She doesn’t recall whether the technician opened packaging that signals unused tools.

She put antibiotic ointment on the cut, but it didn’t heal after a few days. Eventually, the skin closed and a darkened bump formed. It was painful. She went to her doctor, who said it was a “callus from writing,” she told TODAY.com. But it was on her ring finger, which didn’t seem connected to writing. Her doctor said to keep an eye on it.

Five months after the cut occurred, she mentioned it during a gynecology appointment and was referred to a dermatologist, who also advised keeping an eye on it. A wart developed. She went back to her primary care physician and then to another dermatologist. The spot was biopsied.

Squamous cell carcinoma is a common type of skin cancer, according to the American Academy of Dermatology. It can have many causes, but the cause in Ms. Garcia’s case was both very common and very rare: human papillomavirus, or HPV. HPV is a virus that infects millions of people every year, but it’s not a typical cause of skin cancer.

“It’s pretty rare for several reasons. Generally speaking, the strains that cause cancer from an HPV standpoint tend to be more sexually transmitted,” dermatologist Teo Soleymani told TODAY.com. “In Grace’s case, she had an injury, which became the portal of entry. So that thick skin that we have on our hands and feet that acts as a natural barrier against infections and things like that was no longer the case, and the virus was able to infect her skin.”

Dr. Soleymani said Ms. Garcia’s persistence to get answers likely saved her from losing a finger.

“Your outcomes are entirely dictated by how early you catch them, and very often they’re completely curable,” he said. “Her persistence – not only was she able to have a great outcome, she probably saved herself from having her finger amputated.”

Scaly facial plaques

This patient was experiencing a flare of his psoriasis. Three factors contributed to the flare: noncompliance with his treatment regimen, decreased sunlight in the winter, and his lithium therapy. Though carcinogenic, certain wavelengths of UV light are beneficial for psoriasis, and the shorter days of winter can cause flaring of psoriasis (or relative flaring). In addition, lithium—the most effective therapy for this patient’s bipolar disorder—can worsen psoriasis.

Psoriasis is a chronic multisystem inflammatory disorder with characteristic skin findings that include well-demarcated micaceous plaques, nail pitting, and sometimes tendon pain and inflammatory arthritis. Severity can range from small, thin plaques that are intermittently noticeable on the elbows or knees to widespread ash-like plaques covering most of the body.

Good topical choices for facial skin include hydrocortisone 2.5% cream or desonide 0.05%. Nonsteroidal topical therapies that are safe for facial skin include tacrolimus 0.1% ointment or pimecrolimus 1% cream.1 These options may be used twice daily until the disease is controlled.

In many cases (as in this one), the patient’s previous psoriasis outbreaks could not be controlled with topical therapy alone. The patient had not responded to a previous methotrexate regimen, and more recently had been clear for several years on systemic ustekinumab, a monoclonal antibody. Dosed every 12 weeks, or sometimes every 8 weeks, ustekinumab is given by subcutaneous injection, usually in the abdomen, through normal skin. Ustekinumab was recently approved for home use with just 4 injections per year for maintenance therapy. However, the infrequency of the injections sometimes leads to noncompliance, as occurred with this patient. He had missed 2 doses since taking over his own dosing regimen.

Ultimately, the patient’s flare resolved when he was transitioned back to in-office treatment with ustekinumab.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

1. Woo SM, Choi JW, Yoon HS, et al. Classification of facial psoriasis based on the distributions of facial lesions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:959-63. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.02.006

This patient was experiencing a flare of his psoriasis. Three factors contributed to the flare: noncompliance with his treatment regimen, decreased sunlight in the winter, and his lithium therapy. Though carcinogenic, certain wavelengths of UV light are beneficial for psoriasis, and the shorter days of winter can cause flaring of psoriasis (or relative flaring). In addition, lithium—the most effective therapy for this patient’s bipolar disorder—can worsen psoriasis.

Psoriasis is a chronic multisystem inflammatory disorder with characteristic skin findings that include well-demarcated micaceous plaques, nail pitting, and sometimes tendon pain and inflammatory arthritis. Severity can range from small, thin plaques that are intermittently noticeable on the elbows or knees to widespread ash-like plaques covering most of the body.

Good topical choices for facial skin include hydrocortisone 2.5% cream or desonide 0.05%. Nonsteroidal topical therapies that are safe for facial skin include tacrolimus 0.1% ointment or pimecrolimus 1% cream.1 These options may be used twice daily until the disease is controlled.

In many cases (as in this one), the patient’s previous psoriasis outbreaks could not be controlled with topical therapy alone. The patient had not responded to a previous methotrexate regimen, and more recently had been clear for several years on systemic ustekinumab, a monoclonal antibody. Dosed every 12 weeks, or sometimes every 8 weeks, ustekinumab is given by subcutaneous injection, usually in the abdomen, through normal skin. Ustekinumab was recently approved for home use with just 4 injections per year for maintenance therapy. However, the infrequency of the injections sometimes leads to noncompliance, as occurred with this patient. He had missed 2 doses since taking over his own dosing regimen.

Ultimately, the patient’s flare resolved when he was transitioned back to in-office treatment with ustekinumab.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

This patient was experiencing a flare of his psoriasis. Three factors contributed to the flare: noncompliance with his treatment regimen, decreased sunlight in the winter, and his lithium therapy. Though carcinogenic, certain wavelengths of UV light are beneficial for psoriasis, and the shorter days of winter can cause flaring of psoriasis (or relative flaring). In addition, lithium—the most effective therapy for this patient’s bipolar disorder—can worsen psoriasis.

Psoriasis is a chronic multisystem inflammatory disorder with characteristic skin findings that include well-demarcated micaceous plaques, nail pitting, and sometimes tendon pain and inflammatory arthritis. Severity can range from small, thin plaques that are intermittently noticeable on the elbows or knees to widespread ash-like plaques covering most of the body.

Good topical choices for facial skin include hydrocortisone 2.5% cream or desonide 0.05%. Nonsteroidal topical therapies that are safe for facial skin include tacrolimus 0.1% ointment or pimecrolimus 1% cream.1 These options may be used twice daily until the disease is controlled.

In many cases (as in this one), the patient’s previous psoriasis outbreaks could not be controlled with topical therapy alone. The patient had not responded to a previous methotrexate regimen, and more recently had been clear for several years on systemic ustekinumab, a monoclonal antibody. Dosed every 12 weeks, or sometimes every 8 weeks, ustekinumab is given by subcutaneous injection, usually in the abdomen, through normal skin. Ustekinumab was recently approved for home use with just 4 injections per year for maintenance therapy. However, the infrequency of the injections sometimes leads to noncompliance, as occurred with this patient. He had missed 2 doses since taking over his own dosing regimen.

Ultimately, the patient’s flare resolved when he was transitioned back to in-office treatment with ustekinumab.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

1. Woo SM, Choi JW, Yoon HS, et al. Classification of facial psoriasis based on the distributions of facial lesions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:959-63. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.02.006

1. Woo SM, Choi JW, Yoon HS, et al. Classification of facial psoriasis based on the distributions of facial lesions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:959-63. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.02.006

Add this to the list of long COVID symptoms: Stigma

Most people with long COVID find they’re facing stigma due to their condition, according to a new report from researchers in the United Kingdom. In short: Relatives and friends may not believe they’re truly sick.

The U.K. team found that more than three-quarters of people studied had experienced stigma often or always.

In fact, 95% of people with long COVID faced at least one type of stigma at least sometimes, according to the study, published in November in the journal PLOS One.

Those conclusions had surprised the study’s lead researcher, Marija Pantelic, PhD, a public health lecturer at Brighton and Sussex Medical School, England.

“After years of working on HIV-related stigma, I was shocked to see how many people were turning a blind eye to and dismissing the difficulties experienced by people with long COVID,” Dr. Pantelic says. “It has also been clear to me from the start that this stigma is detrimental not just for people’s dignity, but also public health.”

Even some doctors argue that the growing attention paid to long COVID is excessive.

“It’s often normal to experience mild fatigue or weaknesses for weeks after being sick and inactive and not eating well. Calling these cases long COVID is the medicalization of modern life,” Marty Makary, MD, a surgeon and public policy researcher at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, wrote in a commentary in the Wall Street Journal.

Other doctors strongly disagree, including Alba Azola, MD, codirector of the Johns Hopkins Post-Acute COVID-19 Team and an expert in the stigma surrounding long COVID.

“Putting that spin on things, it’s just hurting people,” she says.

One example is people who cannot return to work.

“A lot of their family members tell me that they’re being lazy,” Dr. Azola says. “That’s part of the public stigma, that these are people just trying to get out of work.”

Some experts say the U.K. study represents a landmark.

“When you have data like this on long COVID stigma, it becomes more difficult to deny its existence or address it,” says Naomi Torres-Mackie, PhD, a clinical psychologist at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York. She also is head of research at the New York–based Mental Health Coalition, a group of experts working to end the stigma surrounding mental health.

She recalls her first patient with long COVID.

“She experienced the discomfort and pain itself, and then she had this crushing feeling that it wasn’t valid, or real. She felt very alone in it,” Dr. Torres-Mackie says.

Another one of her patients is working at her job from home but facing doubt about her condition from her employers.

“Every month, her medical doctor has to produce a letter confirming her medical condition,” Dr. Torres-Mackie says.

Taking part in the British stigma survey were 1,166 people, including 966 residents of the United Kingdom, with the average age of 48. Nearly 85% were female, and more than three-quarters were educated at the university level or higher.

Half of them said they had a clinical diagnosis of long COVID.

More than 60% of them said that at least some of the time, they were cautious about who they talked to about their condition. And fully 34% of those who did disclose their diagnosis said that they regretted having done so.

That’s a difficult experience for those with long COVID, says Leonard Jason, PhD, a professor of psychology at DePaul University in Chicago.

“It’s like they’re traumatized by the initial experience of being sick, and retraumatized by the response of others to them,” he says.

Unexplained illnesses are not well-regarded by the general public, Dr. Jason says.

He gave the example of multiple sclerosis. Before the 1980s, those with MS were considered to have a psychological illness, he says. “Then, in the 1980s, there were biomarkers that said, ‘Here’s the evidence.’ ”

The British study described three types of stigma stemming from the long COVID diagnosis of those questioned:

- Enacted stigma: People were directly treated unfairly because of their condition.

- Internalized stigma: People felt embarrassed by that condition.

- Anticipated stigma: People expected they would be treated poorly because of their diagnosis.

Dr. Azola calls the medical community a major problem when it comes to dealing with long COVID.

“What I see with my patients is medical trauma,” she says. They may have symptoms that send them to the emergency room, and then the tests come back negative. “Instead of tracking the patients’ symptoms, patients get told, ‘Everything looks good, you can go home, this is a panic attack,’ ” she says.

Some people go online to search for treatments, sometimes launching GoFundMe campaigns to raise money for unreliable treatments.

Long COVID patients may have gone through 5 to 10 doctors before they arrive for treatment with the Johns Hopkins Post-Acute COVID-19 Team. The clinic began in April 2020 remotely and in August of that year in person.

Today, the clinic staff spends an hour with a first-time long COVID patient, hearing their stories and helping relieve anxiety, Dr. Azola says.

The phenomenon of long COVID is similar to what patients have had with chronic fatigue syndrome, lupus, or fibromyalgia, where people have symptoms that are hard to explain, says Jennifer Chevinsky, MD, deputy public health officer for Riverside County, Calif.

“Stigma within medicine or health care is nothing new,” she says.

In Chicago, Dr. Jason notes that the federal government’s decision to invest hundreds of millions of dollars in long COVID research “shows the government is helping destigmatize it.”

Dr. Pantelic says she and her colleagues are continuing their research.

“We are interested in understanding the impacts of this stigma, and how to mitigate any adverse outcomes for patients and services,” she says.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Most people with long COVID find they’re facing stigma due to their condition, according to a new report from researchers in the United Kingdom. In short: Relatives and friends may not believe they’re truly sick.

The U.K. team found that more than three-quarters of people studied had experienced stigma often or always.

In fact, 95% of people with long COVID faced at least one type of stigma at least sometimes, according to the study, published in November in the journal PLOS One.

Those conclusions had surprised the study’s lead researcher, Marija Pantelic, PhD, a public health lecturer at Brighton and Sussex Medical School, England.

“After years of working on HIV-related stigma, I was shocked to see how many people were turning a blind eye to and dismissing the difficulties experienced by people with long COVID,” Dr. Pantelic says. “It has also been clear to me from the start that this stigma is detrimental not just for people’s dignity, but also public health.”

Even some doctors argue that the growing attention paid to long COVID is excessive.

“It’s often normal to experience mild fatigue or weaknesses for weeks after being sick and inactive and not eating well. Calling these cases long COVID is the medicalization of modern life,” Marty Makary, MD, a surgeon and public policy researcher at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, wrote in a commentary in the Wall Street Journal.

Other doctors strongly disagree, including Alba Azola, MD, codirector of the Johns Hopkins Post-Acute COVID-19 Team and an expert in the stigma surrounding long COVID.

“Putting that spin on things, it’s just hurting people,” she says.

One example is people who cannot return to work.

“A lot of their family members tell me that they’re being lazy,” Dr. Azola says. “That’s part of the public stigma, that these are people just trying to get out of work.”

Some experts say the U.K. study represents a landmark.

“When you have data like this on long COVID stigma, it becomes more difficult to deny its existence or address it,” says Naomi Torres-Mackie, PhD, a clinical psychologist at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York. She also is head of research at the New York–based Mental Health Coalition, a group of experts working to end the stigma surrounding mental health.

She recalls her first patient with long COVID.

“She experienced the discomfort and pain itself, and then she had this crushing feeling that it wasn’t valid, or real. She felt very alone in it,” Dr. Torres-Mackie says.

Another one of her patients is working at her job from home but facing doubt about her condition from her employers.

“Every month, her medical doctor has to produce a letter confirming her medical condition,” Dr. Torres-Mackie says.

Taking part in the British stigma survey were 1,166 people, including 966 residents of the United Kingdom, with the average age of 48. Nearly 85% were female, and more than three-quarters were educated at the university level or higher.

Half of them said they had a clinical diagnosis of long COVID.

More than 60% of them said that at least some of the time, they were cautious about who they talked to about their condition. And fully 34% of those who did disclose their diagnosis said that they regretted having done so.

That’s a difficult experience for those with long COVID, says Leonard Jason, PhD, a professor of psychology at DePaul University in Chicago.

“It’s like they’re traumatized by the initial experience of being sick, and retraumatized by the response of others to them,” he says.

Unexplained illnesses are not well-regarded by the general public, Dr. Jason says.

He gave the example of multiple sclerosis. Before the 1980s, those with MS were considered to have a psychological illness, he says. “Then, in the 1980s, there were biomarkers that said, ‘Here’s the evidence.’ ”

The British study described three types of stigma stemming from the long COVID diagnosis of those questioned:

- Enacted stigma: People were directly treated unfairly because of their condition.

- Internalized stigma: People felt embarrassed by that condition.

- Anticipated stigma: People expected they would be treated poorly because of their diagnosis.

Dr. Azola calls the medical community a major problem when it comes to dealing with long COVID.

“What I see with my patients is medical trauma,” she says. They may have symptoms that send them to the emergency room, and then the tests come back negative. “Instead of tracking the patients’ symptoms, patients get told, ‘Everything looks good, you can go home, this is a panic attack,’ ” she says.

Some people go online to search for treatments, sometimes launching GoFundMe campaigns to raise money for unreliable treatments.

Long COVID patients may have gone through 5 to 10 doctors before they arrive for treatment with the Johns Hopkins Post-Acute COVID-19 Team. The clinic began in April 2020 remotely and in August of that year in person.

Today, the clinic staff spends an hour with a first-time long COVID patient, hearing their stories and helping relieve anxiety, Dr. Azola says.

The phenomenon of long COVID is similar to what patients have had with chronic fatigue syndrome, lupus, or fibromyalgia, where people have symptoms that are hard to explain, says Jennifer Chevinsky, MD, deputy public health officer for Riverside County, Calif.

“Stigma within medicine or health care is nothing new,” she says.

In Chicago, Dr. Jason notes that the federal government’s decision to invest hundreds of millions of dollars in long COVID research “shows the government is helping destigmatize it.”

Dr. Pantelic says she and her colleagues are continuing their research.

“We are interested in understanding the impacts of this stigma, and how to mitigate any adverse outcomes for patients and services,” she says.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Most people with long COVID find they’re facing stigma due to their condition, according to a new report from researchers in the United Kingdom. In short: Relatives and friends may not believe they’re truly sick.

The U.K. team found that more than three-quarters of people studied had experienced stigma often or always.

In fact, 95% of people with long COVID faced at least one type of stigma at least sometimes, according to the study, published in November in the journal PLOS One.

Those conclusions had surprised the study’s lead researcher, Marija Pantelic, PhD, a public health lecturer at Brighton and Sussex Medical School, England.

“After years of working on HIV-related stigma, I was shocked to see how many people were turning a blind eye to and dismissing the difficulties experienced by people with long COVID,” Dr. Pantelic says. “It has also been clear to me from the start that this stigma is detrimental not just for people’s dignity, but also public health.”

Even some doctors argue that the growing attention paid to long COVID is excessive.

“It’s often normal to experience mild fatigue or weaknesses for weeks after being sick and inactive and not eating well. Calling these cases long COVID is the medicalization of modern life,” Marty Makary, MD, a surgeon and public policy researcher at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, wrote in a commentary in the Wall Street Journal.

Other doctors strongly disagree, including Alba Azola, MD, codirector of the Johns Hopkins Post-Acute COVID-19 Team and an expert in the stigma surrounding long COVID.

“Putting that spin on things, it’s just hurting people,” she says.

One example is people who cannot return to work.

“A lot of their family members tell me that they’re being lazy,” Dr. Azola says. “That’s part of the public stigma, that these are people just trying to get out of work.”

Some experts say the U.K. study represents a landmark.

“When you have data like this on long COVID stigma, it becomes more difficult to deny its existence or address it,” says Naomi Torres-Mackie, PhD, a clinical psychologist at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York. She also is head of research at the New York–based Mental Health Coalition, a group of experts working to end the stigma surrounding mental health.

She recalls her first patient with long COVID.

“She experienced the discomfort and pain itself, and then she had this crushing feeling that it wasn’t valid, or real. She felt very alone in it,” Dr. Torres-Mackie says.

Another one of her patients is working at her job from home but facing doubt about her condition from her employers.

“Every month, her medical doctor has to produce a letter confirming her medical condition,” Dr. Torres-Mackie says.