User login

New blood test may detect preclinical Alzheimer’s years in advance

, early research suggests.

Analysis of two studies showed the test (AlzoSure Predict), which uses less than 1 ml of blood, had numerous benefits compared with other blood tests that track AD pathology.

“We believe this has the potential to radically improve early stratification and identification of patients for trials 6 years in advance of a diagnosis, which can potentially enable more rapid and efficient approvals of therapies,” Paul Kinnon, CEO of Diadem, the test’s manufacturer, said in an interview.

The findings were presented at the 14th Clinical Trials on Alzheimer’s Disease (CTAD) conference.

Positive “discovery” results

P53, which is present in both the brain and elsewhere in the body, “is one of the most targeted proteins” for drug development in cancer and other conditions, said Mr. Kinnon.

The current blood test measures a derivative of P53 (U-p53AZ). Previous research suggests this derivative, which affects amyloid and oxidative stress, is also implicated in AD pathogenesis.

Researchers used blood samples from patients aged 60 years and older from the Australia Imaging, Biomarkers, and Lifestyles (AIBL) study who had various levels of cognitive function.

They analyzed samples at multiple timepoints over a 10-year period, “so we know when the marker is most accurate at predicting decline,” Mr. Kinnon said.

The first of two studies was considered a “discovery” study and included blood samples from 224 patients.

Results showed the test predicted decline from mild cognitive impairment (MCI) to AD at the end of 6 years, with an area under the curve (AUC) greater than 90%.

These results are “massive,” said Mr. Kinnon. “It’s the most accurate test I’ve seen anywhere for predicting decline of a patient.”

The test can also accurately classify a patient’s stage of cognition, he added. “Not only does it allow us to predict 6 years in advance, it also tells us if the patient has SMC [subjective memory complaints], MCI, or AD with a 95% certainty,” Mr. Kinnon said.

He noted that test sensitivity was higher than results found from traditional methods that are currently being used. The positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV), which were at 90% or more, were “absolutely fantastic,” said Mr. Kinnon.

“Better than expected” results

In the second “validation” study, investigators examined samples from a completely different group of 482 patients. The “very compelling” results showed AUCs over 90%, PPVs over 90%, and “very high” NPVs, Mr. Kinnon said.

“These are great data, better than we expected,” he added.

However, he noted the test is “very specific” for decline to AD and not to other dementias.

In addition, Mr. Kinnon noted the test does not monitor levels of amyloid beta or tau, which accumulate at a later stage of AD. “Amyloid and tau tell you you’ve got it. We’re there way before those concentrations become detectable,” he said.

Identifying patients who will progress to AD years before they have symptoms gives them time to make medical decisions. These patients may also try treatments at an earlier stage of the disease, when these therapies are most likely to be helpful, said Mr. Kinnon.

In addition, using the test could speed up the approval of prospective drug treatments for AD. Currently, pharmaceutical companies enroll thousands of patients into a clinical study “and they don’t know which ones will have AD,” Mr. Kinnon noted.

“This test tells you these are the ones who are going to progress and should go into the study, and these are the ones that aren’t. So it makes the studies statistically relevant and accurate,” he said.

Investigators can also use the test to monitor patients during a study instead of relying on expensive PET scans and painful and costly spinal fluid taps, he added.

Previous surveys and market research have shown that neurologists and general practitioners “want a blood test to screen patients early, to help educate and inform patients,” said Mr. Kinnon.

Further results that will include biobank data on more than 1,000 patients in the United States and Europe are due for completion toward the end of this year.

The company is currently in negotiations to bring the product to North America, Europe, and elsewhere. “Our goal is to have it on the market by the middle of next year in multiple regions,” Mr. Kinnon said.

Encouraging, preliminary

Commenting on the findings, Percy Griffin, PhD, MSc, director of scientific engagement at the Alzheimer’s Association, said “it’s exciting” to see development of novel ways for detecting or predicting AD.

“There is an urgent need for simple, inexpensive, noninvasive, and accessible early detection tools for Alzheimer’s, such as a blood test,” he said.

However, Dr. Griffin cautioned the test is still in the early stages of development and has not been tested extensively in large, diverse clinical trials.

In addition, although the test predicts whether a person will progress, it does not predict when the person will progress, he added.

“These preliminary results are encouraging, but further validation is needed before this test can be implemented widely,” he said.

Technologies that facilitate the early detection and intervention before significant loss of brain cells from AD “would be game-changing” for individuals, families, and the healthcare system, Dr. Griffin concluded.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, early research suggests.

Analysis of two studies showed the test (AlzoSure Predict), which uses less than 1 ml of blood, had numerous benefits compared with other blood tests that track AD pathology.

“We believe this has the potential to radically improve early stratification and identification of patients for trials 6 years in advance of a diagnosis, which can potentially enable more rapid and efficient approvals of therapies,” Paul Kinnon, CEO of Diadem, the test’s manufacturer, said in an interview.

The findings were presented at the 14th Clinical Trials on Alzheimer’s Disease (CTAD) conference.

Positive “discovery” results

P53, which is present in both the brain and elsewhere in the body, “is one of the most targeted proteins” for drug development in cancer and other conditions, said Mr. Kinnon.

The current blood test measures a derivative of P53 (U-p53AZ). Previous research suggests this derivative, which affects amyloid and oxidative stress, is also implicated in AD pathogenesis.

Researchers used blood samples from patients aged 60 years and older from the Australia Imaging, Biomarkers, and Lifestyles (AIBL) study who had various levels of cognitive function.

They analyzed samples at multiple timepoints over a 10-year period, “so we know when the marker is most accurate at predicting decline,” Mr. Kinnon said.

The first of two studies was considered a “discovery” study and included blood samples from 224 patients.

Results showed the test predicted decline from mild cognitive impairment (MCI) to AD at the end of 6 years, with an area under the curve (AUC) greater than 90%.

These results are “massive,” said Mr. Kinnon. “It’s the most accurate test I’ve seen anywhere for predicting decline of a patient.”

The test can also accurately classify a patient’s stage of cognition, he added. “Not only does it allow us to predict 6 years in advance, it also tells us if the patient has SMC [subjective memory complaints], MCI, or AD with a 95% certainty,” Mr. Kinnon said.

He noted that test sensitivity was higher than results found from traditional methods that are currently being used. The positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV), which were at 90% or more, were “absolutely fantastic,” said Mr. Kinnon.

“Better than expected” results

In the second “validation” study, investigators examined samples from a completely different group of 482 patients. The “very compelling” results showed AUCs over 90%, PPVs over 90%, and “very high” NPVs, Mr. Kinnon said.

“These are great data, better than we expected,” he added.

However, he noted the test is “very specific” for decline to AD and not to other dementias.

In addition, Mr. Kinnon noted the test does not monitor levels of amyloid beta or tau, which accumulate at a later stage of AD. “Amyloid and tau tell you you’ve got it. We’re there way before those concentrations become detectable,” he said.

Identifying patients who will progress to AD years before they have symptoms gives them time to make medical decisions. These patients may also try treatments at an earlier stage of the disease, when these therapies are most likely to be helpful, said Mr. Kinnon.

In addition, using the test could speed up the approval of prospective drug treatments for AD. Currently, pharmaceutical companies enroll thousands of patients into a clinical study “and they don’t know which ones will have AD,” Mr. Kinnon noted.

“This test tells you these are the ones who are going to progress and should go into the study, and these are the ones that aren’t. So it makes the studies statistically relevant and accurate,” he said.

Investigators can also use the test to monitor patients during a study instead of relying on expensive PET scans and painful and costly spinal fluid taps, he added.

Previous surveys and market research have shown that neurologists and general practitioners “want a blood test to screen patients early, to help educate and inform patients,” said Mr. Kinnon.

Further results that will include biobank data on more than 1,000 patients in the United States and Europe are due for completion toward the end of this year.

The company is currently in negotiations to bring the product to North America, Europe, and elsewhere. “Our goal is to have it on the market by the middle of next year in multiple regions,” Mr. Kinnon said.

Encouraging, preliminary

Commenting on the findings, Percy Griffin, PhD, MSc, director of scientific engagement at the Alzheimer’s Association, said “it’s exciting” to see development of novel ways for detecting or predicting AD.

“There is an urgent need for simple, inexpensive, noninvasive, and accessible early detection tools for Alzheimer’s, such as a blood test,” he said.

However, Dr. Griffin cautioned the test is still in the early stages of development and has not been tested extensively in large, diverse clinical trials.

In addition, although the test predicts whether a person will progress, it does not predict when the person will progress, he added.

“These preliminary results are encouraging, but further validation is needed before this test can be implemented widely,” he said.

Technologies that facilitate the early detection and intervention before significant loss of brain cells from AD “would be game-changing” for individuals, families, and the healthcare system, Dr. Griffin concluded.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, early research suggests.

Analysis of two studies showed the test (AlzoSure Predict), which uses less than 1 ml of blood, had numerous benefits compared with other blood tests that track AD pathology.

“We believe this has the potential to radically improve early stratification and identification of patients for trials 6 years in advance of a diagnosis, which can potentially enable more rapid and efficient approvals of therapies,” Paul Kinnon, CEO of Diadem, the test’s manufacturer, said in an interview.

The findings were presented at the 14th Clinical Trials on Alzheimer’s Disease (CTAD) conference.

Positive “discovery” results

P53, which is present in both the brain and elsewhere in the body, “is one of the most targeted proteins” for drug development in cancer and other conditions, said Mr. Kinnon.

The current blood test measures a derivative of P53 (U-p53AZ). Previous research suggests this derivative, which affects amyloid and oxidative stress, is also implicated in AD pathogenesis.

Researchers used blood samples from patients aged 60 years and older from the Australia Imaging, Biomarkers, and Lifestyles (AIBL) study who had various levels of cognitive function.

They analyzed samples at multiple timepoints over a 10-year period, “so we know when the marker is most accurate at predicting decline,” Mr. Kinnon said.

The first of two studies was considered a “discovery” study and included blood samples from 224 patients.

Results showed the test predicted decline from mild cognitive impairment (MCI) to AD at the end of 6 years, with an area under the curve (AUC) greater than 90%.

These results are “massive,” said Mr. Kinnon. “It’s the most accurate test I’ve seen anywhere for predicting decline of a patient.”

The test can also accurately classify a patient’s stage of cognition, he added. “Not only does it allow us to predict 6 years in advance, it also tells us if the patient has SMC [subjective memory complaints], MCI, or AD with a 95% certainty,” Mr. Kinnon said.

He noted that test sensitivity was higher than results found from traditional methods that are currently being used. The positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV), which were at 90% or more, were “absolutely fantastic,” said Mr. Kinnon.

“Better than expected” results

In the second “validation” study, investigators examined samples from a completely different group of 482 patients. The “very compelling” results showed AUCs over 90%, PPVs over 90%, and “very high” NPVs, Mr. Kinnon said.

“These are great data, better than we expected,” he added.

However, he noted the test is “very specific” for decline to AD and not to other dementias.

In addition, Mr. Kinnon noted the test does not monitor levels of amyloid beta or tau, which accumulate at a later stage of AD. “Amyloid and tau tell you you’ve got it. We’re there way before those concentrations become detectable,” he said.

Identifying patients who will progress to AD years before they have symptoms gives them time to make medical decisions. These patients may also try treatments at an earlier stage of the disease, when these therapies are most likely to be helpful, said Mr. Kinnon.

In addition, using the test could speed up the approval of prospective drug treatments for AD. Currently, pharmaceutical companies enroll thousands of patients into a clinical study “and they don’t know which ones will have AD,” Mr. Kinnon noted.

“This test tells you these are the ones who are going to progress and should go into the study, and these are the ones that aren’t. So it makes the studies statistically relevant and accurate,” he said.

Investigators can also use the test to monitor patients during a study instead of relying on expensive PET scans and painful and costly spinal fluid taps, he added.

Previous surveys and market research have shown that neurologists and general practitioners “want a blood test to screen patients early, to help educate and inform patients,” said Mr. Kinnon.

Further results that will include biobank data on more than 1,000 patients in the United States and Europe are due for completion toward the end of this year.

The company is currently in negotiations to bring the product to North America, Europe, and elsewhere. “Our goal is to have it on the market by the middle of next year in multiple regions,” Mr. Kinnon said.

Encouraging, preliminary

Commenting on the findings, Percy Griffin, PhD, MSc, director of scientific engagement at the Alzheimer’s Association, said “it’s exciting” to see development of novel ways for detecting or predicting AD.

“There is an urgent need for simple, inexpensive, noninvasive, and accessible early detection tools for Alzheimer’s, such as a blood test,” he said.

However, Dr. Griffin cautioned the test is still in the early stages of development and has not been tested extensively in large, diverse clinical trials.

In addition, although the test predicts whether a person will progress, it does not predict when the person will progress, he added.

“These preliminary results are encouraging, but further validation is needed before this test can be implemented widely,” he said.

Technologies that facilitate the early detection and intervention before significant loss of brain cells from AD “would be game-changing” for individuals, families, and the healthcare system, Dr. Griffin concluded.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM CTAD21

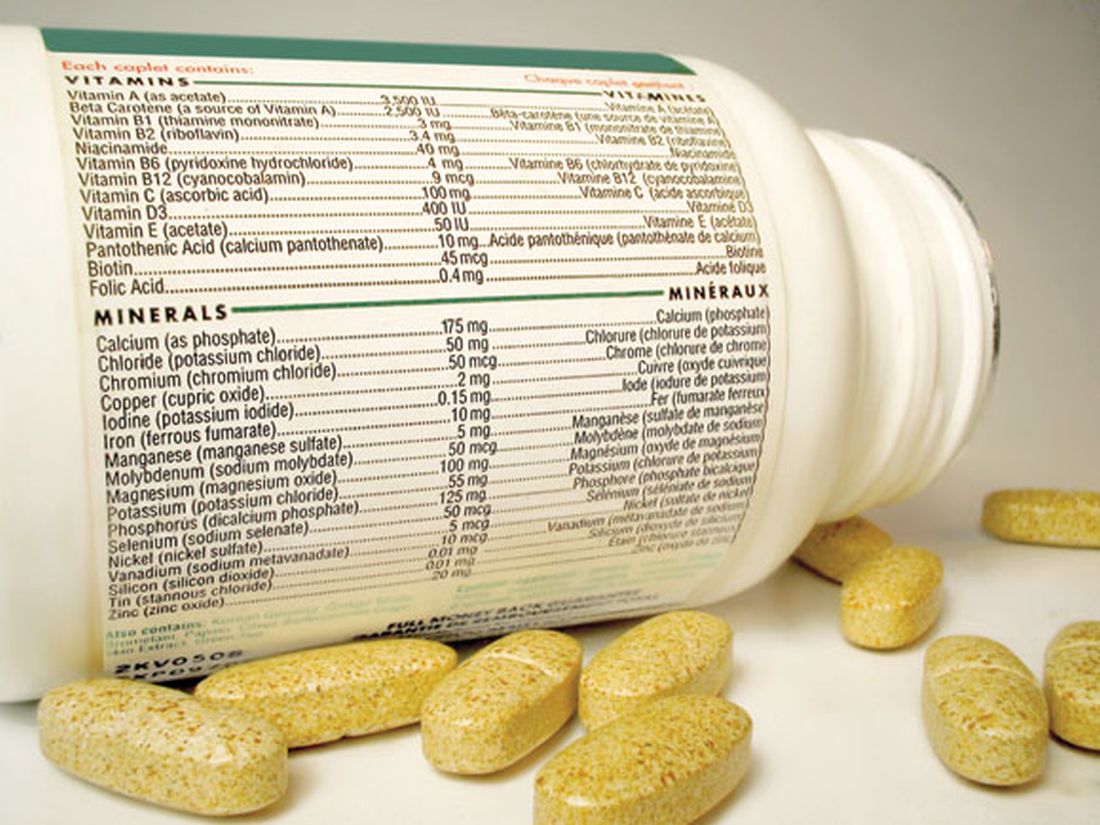

Multivitamins, but not cocoa, tied to slowed brain aging

, with the effects especially pronounced in patients with cardiovascular (CVD) disease, new research suggests.

In addition to testing the effect of a daily multivitamin on cognition, the COSMOS-Mind study examined the effect of cocoa flavanols, but showed no beneficial effect.

The findings “may have important public health implications, particularly for brain health, given the accessibility of multivitamins and minerals, and their low cost and safety,” said study investigator Laura D. Baker, PhD, professor, gerontology and geriatric medicine, Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, N.C.

The findings were presented at the 14th Clinical Trials on Alzheimer’s Disease (CTAD) conference.

Placebo-controlled study

The study is a substudy of a large parent trial that compared the effects of cocoa extract (500 mg/day cocoa flavanols) and a standard multivitamin-mineral (MVM) to placebo on cardiovascular and cancer outcomes in more than 21,000 older participants.

COSMOS-Mind included 2,262 adults aged 65 and over without dementia who underwent cognitive testing at baseline and annually for 3 years. The mean age at baseline was 73 years, and 40.4% were men. Most participants (88.7%) were non-Hispanic White and almost half (49.2%) had some post-college education.

All study groups were balanced with respect to demographics, CVD history, diabetes, depression, smoking status, alcohol intake, chocolate intake, and prior multivitamin use. Baseline cognitive scores were similar between study groups. Researchers had complete data on 77% of study participants.

The primary endpoint was the effect of cocoa extract (CE) vs. placebo on Global Cognitive Function composite score. The secondary outcome was the effect of MVM vs. placebo on global cognitive function.

Additional outcomes included the impact of supplements on executive function and memory and the treatment effects for prespecified subgroups, including subjects with a history of CVD.

Using a graph of change over time, Dr. Baker showed there was no effect of cocoa on global cognitive function (effect: 0.03; 95% confidence interval, –0.02 to 0.08; P = .28). “We see the to-be-expected practice effects, but there’s no separation between the active and placebo groups,” she said.

It was a different story for MVM. Here, there was the same practice effect, but the graph showed the lines separated for global cognitive function composite score (effect: 0.07; 95% CI, 0.02-0.12; P = .007).

“We see a positive effect of multivitamins for the active group relative to placebo, peaking at 2 years and then remaining stable over time,” said Dr. Baker.

There were similar findings with MVM for the memory composite score, and the executive function composite score. “We have significance in all three, where the two lines do separate over and above the practice effects,” said Dr. Baker.

New evidence

Investigators found a baseline history of CVD, including transient ischemic attack, heart failure, coronary artery bypass graft, percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty, and stent, but not myocardial infarction or stroke as these were excluded in the parent trial because they affected the response to multivitamins.

As expected, those with CVD had lower cognitive scores at baseline. “But after an initial bump due to practice effect, at year 1, the cardiovascular disease history folks continue to benefit from multivitamins, whereas those who got placebo multivitamins continue to decline over time,” said Dr. Baker.

Based on information from a baseline scatter plot of cognitive function scores by age, the study’s modeling estimated the multivitamin treatment effect had a positive benefit of .028 standard deviations (SD) per year.

“Daily multivitamin-mineral supplementation appears to slow cognitive aging by 60% or by 1.8 years,” Dr. Baker added.

To date, the effect of MVM supplementation on cognition has been tested in only one large randomized clinical trial – the Physicians Health Study II. That study did not show an effect, but included only older male physicians – and cognitive testing began 2.5 years after randomization, said Dr. Baker.

“Our study provides new evidence that daily multivitamin supplementation may benefit cognitive function in older women and men, and the multivitamin effects may be more pronounced in participants with cardiovascular disease,” she noted.

For effects of multivitamins on Alzheimer’s disease prevalence and progression, “stay tuned,” Dr. Baker concluded.

Following the presentation, session cochair Suzanne Schindler, MD, PhD, instructor in the department of neurology at Washington University, St. Louis, said she and her colleagues “always check vitamin B12 levels” in patients with memory and cognitive difficulties and wondered if study subjects with a low level or deficiency of vitamin B12 benefited from the intervention.

“We are asking ourselves that as well,” said Dr. Baker.

“Some of this is a work in progress,” Dr. Baker added. “We still need to look at that more in-depth to understand whether it might be a mechanism for improvement. I think the results are still out on that topic.”

The study received support from the National Institute on Aging. Pfizer Consumer Healthcare (now GSK Consumer Healthcare) provided study pills and packaging. Dr. Baker has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, with the effects especially pronounced in patients with cardiovascular (CVD) disease, new research suggests.

In addition to testing the effect of a daily multivitamin on cognition, the COSMOS-Mind study examined the effect of cocoa flavanols, but showed no beneficial effect.

The findings “may have important public health implications, particularly for brain health, given the accessibility of multivitamins and minerals, and their low cost and safety,” said study investigator Laura D. Baker, PhD, professor, gerontology and geriatric medicine, Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, N.C.

The findings were presented at the 14th Clinical Trials on Alzheimer’s Disease (CTAD) conference.

Placebo-controlled study

The study is a substudy of a large parent trial that compared the effects of cocoa extract (500 mg/day cocoa flavanols) and a standard multivitamin-mineral (MVM) to placebo on cardiovascular and cancer outcomes in more than 21,000 older participants.

COSMOS-Mind included 2,262 adults aged 65 and over without dementia who underwent cognitive testing at baseline and annually for 3 years. The mean age at baseline was 73 years, and 40.4% were men. Most participants (88.7%) were non-Hispanic White and almost half (49.2%) had some post-college education.

All study groups were balanced with respect to demographics, CVD history, diabetes, depression, smoking status, alcohol intake, chocolate intake, and prior multivitamin use. Baseline cognitive scores were similar between study groups. Researchers had complete data on 77% of study participants.

The primary endpoint was the effect of cocoa extract (CE) vs. placebo on Global Cognitive Function composite score. The secondary outcome was the effect of MVM vs. placebo on global cognitive function.

Additional outcomes included the impact of supplements on executive function and memory and the treatment effects for prespecified subgroups, including subjects with a history of CVD.

Using a graph of change over time, Dr. Baker showed there was no effect of cocoa on global cognitive function (effect: 0.03; 95% confidence interval, –0.02 to 0.08; P = .28). “We see the to-be-expected practice effects, but there’s no separation between the active and placebo groups,” she said.

It was a different story for MVM. Here, there was the same practice effect, but the graph showed the lines separated for global cognitive function composite score (effect: 0.07; 95% CI, 0.02-0.12; P = .007).

“We see a positive effect of multivitamins for the active group relative to placebo, peaking at 2 years and then remaining stable over time,” said Dr. Baker.

There were similar findings with MVM for the memory composite score, and the executive function composite score. “We have significance in all three, where the two lines do separate over and above the practice effects,” said Dr. Baker.

New evidence

Investigators found a baseline history of CVD, including transient ischemic attack, heart failure, coronary artery bypass graft, percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty, and stent, but not myocardial infarction or stroke as these were excluded in the parent trial because they affected the response to multivitamins.

As expected, those with CVD had lower cognitive scores at baseline. “But after an initial bump due to practice effect, at year 1, the cardiovascular disease history folks continue to benefit from multivitamins, whereas those who got placebo multivitamins continue to decline over time,” said Dr. Baker.

Based on information from a baseline scatter plot of cognitive function scores by age, the study’s modeling estimated the multivitamin treatment effect had a positive benefit of .028 standard deviations (SD) per year.

“Daily multivitamin-mineral supplementation appears to slow cognitive aging by 60% or by 1.8 years,” Dr. Baker added.

To date, the effect of MVM supplementation on cognition has been tested in only one large randomized clinical trial – the Physicians Health Study II. That study did not show an effect, but included only older male physicians – and cognitive testing began 2.5 years after randomization, said Dr. Baker.

“Our study provides new evidence that daily multivitamin supplementation may benefit cognitive function in older women and men, and the multivitamin effects may be more pronounced in participants with cardiovascular disease,” she noted.

For effects of multivitamins on Alzheimer’s disease prevalence and progression, “stay tuned,” Dr. Baker concluded.

Following the presentation, session cochair Suzanne Schindler, MD, PhD, instructor in the department of neurology at Washington University, St. Louis, said she and her colleagues “always check vitamin B12 levels” in patients with memory and cognitive difficulties and wondered if study subjects with a low level or deficiency of vitamin B12 benefited from the intervention.

“We are asking ourselves that as well,” said Dr. Baker.

“Some of this is a work in progress,” Dr. Baker added. “We still need to look at that more in-depth to understand whether it might be a mechanism for improvement. I think the results are still out on that topic.”

The study received support from the National Institute on Aging. Pfizer Consumer Healthcare (now GSK Consumer Healthcare) provided study pills and packaging. Dr. Baker has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, with the effects especially pronounced in patients with cardiovascular (CVD) disease, new research suggests.

In addition to testing the effect of a daily multivitamin on cognition, the COSMOS-Mind study examined the effect of cocoa flavanols, but showed no beneficial effect.

The findings “may have important public health implications, particularly for brain health, given the accessibility of multivitamins and minerals, and their low cost and safety,” said study investigator Laura D. Baker, PhD, professor, gerontology and geriatric medicine, Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, N.C.

The findings were presented at the 14th Clinical Trials on Alzheimer’s Disease (CTAD) conference.

Placebo-controlled study

The study is a substudy of a large parent trial that compared the effects of cocoa extract (500 mg/day cocoa flavanols) and a standard multivitamin-mineral (MVM) to placebo on cardiovascular and cancer outcomes in more than 21,000 older participants.

COSMOS-Mind included 2,262 adults aged 65 and over without dementia who underwent cognitive testing at baseline and annually for 3 years. The mean age at baseline was 73 years, and 40.4% were men. Most participants (88.7%) were non-Hispanic White and almost half (49.2%) had some post-college education.

All study groups were balanced with respect to demographics, CVD history, diabetes, depression, smoking status, alcohol intake, chocolate intake, and prior multivitamin use. Baseline cognitive scores were similar between study groups. Researchers had complete data on 77% of study participants.

The primary endpoint was the effect of cocoa extract (CE) vs. placebo on Global Cognitive Function composite score. The secondary outcome was the effect of MVM vs. placebo on global cognitive function.

Additional outcomes included the impact of supplements on executive function and memory and the treatment effects for prespecified subgroups, including subjects with a history of CVD.

Using a graph of change over time, Dr. Baker showed there was no effect of cocoa on global cognitive function (effect: 0.03; 95% confidence interval, –0.02 to 0.08; P = .28). “We see the to-be-expected practice effects, but there’s no separation between the active and placebo groups,” she said.

It was a different story for MVM. Here, there was the same practice effect, but the graph showed the lines separated for global cognitive function composite score (effect: 0.07; 95% CI, 0.02-0.12; P = .007).

“We see a positive effect of multivitamins for the active group relative to placebo, peaking at 2 years and then remaining stable over time,” said Dr. Baker.

There were similar findings with MVM for the memory composite score, and the executive function composite score. “We have significance in all three, where the two lines do separate over and above the practice effects,” said Dr. Baker.

New evidence

Investigators found a baseline history of CVD, including transient ischemic attack, heart failure, coronary artery bypass graft, percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty, and stent, but not myocardial infarction or stroke as these were excluded in the parent trial because they affected the response to multivitamins.

As expected, those with CVD had lower cognitive scores at baseline. “But after an initial bump due to practice effect, at year 1, the cardiovascular disease history folks continue to benefit from multivitamins, whereas those who got placebo multivitamins continue to decline over time,” said Dr. Baker.

Based on information from a baseline scatter plot of cognitive function scores by age, the study’s modeling estimated the multivitamin treatment effect had a positive benefit of .028 standard deviations (SD) per year.

“Daily multivitamin-mineral supplementation appears to slow cognitive aging by 60% or by 1.8 years,” Dr. Baker added.

To date, the effect of MVM supplementation on cognition has been tested in only one large randomized clinical trial – the Physicians Health Study II. That study did not show an effect, but included only older male physicians – and cognitive testing began 2.5 years after randomization, said Dr. Baker.

“Our study provides new evidence that daily multivitamin supplementation may benefit cognitive function in older women and men, and the multivitamin effects may be more pronounced in participants with cardiovascular disease,” she noted.

For effects of multivitamins on Alzheimer’s disease prevalence and progression, “stay tuned,” Dr. Baker concluded.

Following the presentation, session cochair Suzanne Schindler, MD, PhD, instructor in the department of neurology at Washington University, St. Louis, said she and her colleagues “always check vitamin B12 levels” in patients with memory and cognitive difficulties and wondered if study subjects with a low level or deficiency of vitamin B12 benefited from the intervention.

“We are asking ourselves that as well,” said Dr. Baker.

“Some of this is a work in progress,” Dr. Baker added. “We still need to look at that more in-depth to understand whether it might be a mechanism for improvement. I think the results are still out on that topic.”

The study received support from the National Institute on Aging. Pfizer Consumer Healthcare (now GSK Consumer Healthcare) provided study pills and packaging. Dr. Baker has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Antihypertensives tied to lower Alzheimer’s disease pathology

new research shows.

Investigators found that use of any antihypertensive was associated with an 18% decrease in Alzheimer’s disease neuropathology, a 22% decrease in Lewy bodies, and a 40% decrease in TAR DNA-binding protein 43 (TDP-43), a protein relevant to several neurodegenerative diseases. Diuretics in particular appear to be driving the association.

Although diuretics might be a better option for preventing brain neuropathology, it’s too early to make firm recommendations solely on the basis of these results as to what blood pressure–lowering agent to prescribe a particular patient, said study investigator Ahmad Sajjadi, MD, assistant professor of neurology, University of California, Irvine.

“This is early stages and preliminary results,” said Dr. Sajjadi, “but it’s food for thought.”

The findings were presented at the 2021 annual meeting of the American Neurological Association.

Autopsy data

The study included 3,315 individuals who had donated their brains to research. The National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center maintains a database that includes data from 32 Alzheimer’s disease research centers in the United States. Participants in the study must have visited one of these centers within 4 years of death. Each person whose brain was included in the study underwent two or more BP measurements on at least 50% of visits.

The mean age at death was 81.7 years, and the mean time between last visit and death was 13.1 months. About 44.4% of participants were women, 57.0% had at least a college degree, and 84.7% had cognitive impairment.

Researchers defined hypertension as systolic BP of at least 130 mm Hg, diastolic BP of at least 80 mm Hg, mean arterial pressure of at least 100 mm Hg, and pulse pressure of at least 60 mm Hg.

Antihypertensive medications that were evaluated included antiadrenergic agents, ACE inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor blockers, beta blockers, calcium channel blockers, diuretics, vasodilators, and combination therapies.

The investigators assessed the number of neuropathologies. In addition to Alzheimer’s disease neuropathology, which included amyloid-beta, tau, Lewy bodies, and TDP-43, they also assessed for atherosclerosis, arteriolosclerosis, cerebral amyloid angiopathy, frontotemporal lobar degeneration, and hippocampal sclerosis.

Results showed that use of any antihypertensive was associated with a lower likelihood of Alzheimer’s disease neuropathology (odds ratio, 0.822), Lewy bodies (OR, 0.786), and TDP 43 (OR, 0.597). Use of antihypertensives was also associated with increased odds of atherosclerosis (OR, 1.217) (all P < .5.)

The study showed that hypertensive systolic BP was associated with higher odds of Alzheimer’s disease neuropathology (OR, 1.28; P < .5).

Differences by drug type

Results differed in accordance with antihypertensive class. Angiotensin II receptor blockers decreased the odds of Alzheimer’s disease neuropathology by 40% (OR, 0.60; P < .5). Diuretics decreased the odds of Alzheimer’s disease by 36% (OR, 0.64; P < .001) and of hippocampal sclerosis by 32% (OR, 0.68; P < .5).

“We see diuretics are a main driver, especially for lower odds of Alzheimer’s disease and lower odds of hippocampal sclerosis,” said lead author Hanna L. Nguyen, a first-year medical student at the University of California, Irvine.

The results indicate that it is the medications, not BP levels, that account for these associations, she added.

One potential mechanism linking antihypertensives to brain pathology is that with these agents, BP is maintained in the target zone. Blood pressure that’s too high can damage blood vessels, whereas BP that’s too low may result in less than adequate perfusion, said Ms. Nguyen.

These medications may also alter pathways leading to degeneration and could, for example, affect the apo E mechanism of Alzheimer’s disease, she added.

The researchers plan to conduct subset analyses using apo E genetic status and age of death.

Although this is a “massive database,” it has limitations. For example, said Dr. Sajjadi, it does not reveal when patients started taking BP medication, how long they had been taking it, or why.

“We don’t know the exact the reason they were taking these medications. Was it just hypertension, or did they also have heart disease, stroke, a kidney problem, or was there another explanation,” he said.

Following the study presentation, session comoderator Krish Sathian, MBBS, PhD, professor of neurology, neural, and behavioral sciences, and psychology and director of the Neuroscience Institute, Penn State University, Hershey, called this work “fascinating. It provides a lot of data that really touches on everyday practice,” inasmuch as clinicians often prescribe antihypertensive medications and see patients with these kinds of brain disorders.

The investigators and Dr. Sathian reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

new research shows.

Investigators found that use of any antihypertensive was associated with an 18% decrease in Alzheimer’s disease neuropathology, a 22% decrease in Lewy bodies, and a 40% decrease in TAR DNA-binding protein 43 (TDP-43), a protein relevant to several neurodegenerative diseases. Diuretics in particular appear to be driving the association.

Although diuretics might be a better option for preventing brain neuropathology, it’s too early to make firm recommendations solely on the basis of these results as to what blood pressure–lowering agent to prescribe a particular patient, said study investigator Ahmad Sajjadi, MD, assistant professor of neurology, University of California, Irvine.

“This is early stages and preliminary results,” said Dr. Sajjadi, “but it’s food for thought.”

The findings were presented at the 2021 annual meeting of the American Neurological Association.

Autopsy data

The study included 3,315 individuals who had donated their brains to research. The National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center maintains a database that includes data from 32 Alzheimer’s disease research centers in the United States. Participants in the study must have visited one of these centers within 4 years of death. Each person whose brain was included in the study underwent two or more BP measurements on at least 50% of visits.

The mean age at death was 81.7 years, and the mean time between last visit and death was 13.1 months. About 44.4% of participants were women, 57.0% had at least a college degree, and 84.7% had cognitive impairment.

Researchers defined hypertension as systolic BP of at least 130 mm Hg, diastolic BP of at least 80 mm Hg, mean arterial pressure of at least 100 mm Hg, and pulse pressure of at least 60 mm Hg.

Antihypertensive medications that were evaluated included antiadrenergic agents, ACE inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor blockers, beta blockers, calcium channel blockers, diuretics, vasodilators, and combination therapies.

The investigators assessed the number of neuropathologies. In addition to Alzheimer’s disease neuropathology, which included amyloid-beta, tau, Lewy bodies, and TDP-43, they also assessed for atherosclerosis, arteriolosclerosis, cerebral amyloid angiopathy, frontotemporal lobar degeneration, and hippocampal sclerosis.

Results showed that use of any antihypertensive was associated with a lower likelihood of Alzheimer’s disease neuropathology (odds ratio, 0.822), Lewy bodies (OR, 0.786), and TDP 43 (OR, 0.597). Use of antihypertensives was also associated with increased odds of atherosclerosis (OR, 1.217) (all P < .5.)

The study showed that hypertensive systolic BP was associated with higher odds of Alzheimer’s disease neuropathology (OR, 1.28; P < .5).

Differences by drug type

Results differed in accordance with antihypertensive class. Angiotensin II receptor blockers decreased the odds of Alzheimer’s disease neuropathology by 40% (OR, 0.60; P < .5). Diuretics decreased the odds of Alzheimer’s disease by 36% (OR, 0.64; P < .001) and of hippocampal sclerosis by 32% (OR, 0.68; P < .5).

“We see diuretics are a main driver, especially for lower odds of Alzheimer’s disease and lower odds of hippocampal sclerosis,” said lead author Hanna L. Nguyen, a first-year medical student at the University of California, Irvine.

The results indicate that it is the medications, not BP levels, that account for these associations, she added.

One potential mechanism linking antihypertensives to brain pathology is that with these agents, BP is maintained in the target zone. Blood pressure that’s too high can damage blood vessels, whereas BP that’s too low may result in less than adequate perfusion, said Ms. Nguyen.

These medications may also alter pathways leading to degeneration and could, for example, affect the apo E mechanism of Alzheimer’s disease, she added.

The researchers plan to conduct subset analyses using apo E genetic status and age of death.

Although this is a “massive database,” it has limitations. For example, said Dr. Sajjadi, it does not reveal when patients started taking BP medication, how long they had been taking it, or why.

“We don’t know the exact the reason they were taking these medications. Was it just hypertension, or did they also have heart disease, stroke, a kidney problem, or was there another explanation,” he said.

Following the study presentation, session comoderator Krish Sathian, MBBS, PhD, professor of neurology, neural, and behavioral sciences, and psychology and director of the Neuroscience Institute, Penn State University, Hershey, called this work “fascinating. It provides a lot of data that really touches on everyday practice,” inasmuch as clinicians often prescribe antihypertensive medications and see patients with these kinds of brain disorders.

The investigators and Dr. Sathian reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

new research shows.

Investigators found that use of any antihypertensive was associated with an 18% decrease in Alzheimer’s disease neuropathology, a 22% decrease in Lewy bodies, and a 40% decrease in TAR DNA-binding protein 43 (TDP-43), a protein relevant to several neurodegenerative diseases. Diuretics in particular appear to be driving the association.

Although diuretics might be a better option for preventing brain neuropathology, it’s too early to make firm recommendations solely on the basis of these results as to what blood pressure–lowering agent to prescribe a particular patient, said study investigator Ahmad Sajjadi, MD, assistant professor of neurology, University of California, Irvine.

“This is early stages and preliminary results,” said Dr. Sajjadi, “but it’s food for thought.”

The findings were presented at the 2021 annual meeting of the American Neurological Association.

Autopsy data

The study included 3,315 individuals who had donated their brains to research. The National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center maintains a database that includes data from 32 Alzheimer’s disease research centers in the United States. Participants in the study must have visited one of these centers within 4 years of death. Each person whose brain was included in the study underwent two or more BP measurements on at least 50% of visits.

The mean age at death was 81.7 years, and the mean time between last visit and death was 13.1 months. About 44.4% of participants were women, 57.0% had at least a college degree, and 84.7% had cognitive impairment.

Researchers defined hypertension as systolic BP of at least 130 mm Hg, diastolic BP of at least 80 mm Hg, mean arterial pressure of at least 100 mm Hg, and pulse pressure of at least 60 mm Hg.

Antihypertensive medications that were evaluated included antiadrenergic agents, ACE inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor blockers, beta blockers, calcium channel blockers, diuretics, vasodilators, and combination therapies.

The investigators assessed the number of neuropathologies. In addition to Alzheimer’s disease neuropathology, which included amyloid-beta, tau, Lewy bodies, and TDP-43, they also assessed for atherosclerosis, arteriolosclerosis, cerebral amyloid angiopathy, frontotemporal lobar degeneration, and hippocampal sclerosis.

Results showed that use of any antihypertensive was associated with a lower likelihood of Alzheimer’s disease neuropathology (odds ratio, 0.822), Lewy bodies (OR, 0.786), and TDP 43 (OR, 0.597). Use of antihypertensives was also associated with increased odds of atherosclerosis (OR, 1.217) (all P < .5.)

The study showed that hypertensive systolic BP was associated with higher odds of Alzheimer’s disease neuropathology (OR, 1.28; P < .5).

Differences by drug type

Results differed in accordance with antihypertensive class. Angiotensin II receptor blockers decreased the odds of Alzheimer’s disease neuropathology by 40% (OR, 0.60; P < .5). Diuretics decreased the odds of Alzheimer’s disease by 36% (OR, 0.64; P < .001) and of hippocampal sclerosis by 32% (OR, 0.68; P < .5).

“We see diuretics are a main driver, especially for lower odds of Alzheimer’s disease and lower odds of hippocampal sclerosis,” said lead author Hanna L. Nguyen, a first-year medical student at the University of California, Irvine.

The results indicate that it is the medications, not BP levels, that account for these associations, she added.

One potential mechanism linking antihypertensives to brain pathology is that with these agents, BP is maintained in the target zone. Blood pressure that’s too high can damage blood vessels, whereas BP that’s too low may result in less than adequate perfusion, said Ms. Nguyen.

These medications may also alter pathways leading to degeneration and could, for example, affect the apo E mechanism of Alzheimer’s disease, she added.

The researchers plan to conduct subset analyses using apo E genetic status and age of death.

Although this is a “massive database,” it has limitations. For example, said Dr. Sajjadi, it does not reveal when patients started taking BP medication, how long they had been taking it, or why.

“We don’t know the exact the reason they were taking these medications. Was it just hypertension, or did they also have heart disease, stroke, a kidney problem, or was there another explanation,” he said.

Following the study presentation, session comoderator Krish Sathian, MBBS, PhD, professor of neurology, neural, and behavioral sciences, and psychology and director of the Neuroscience Institute, Penn State University, Hershey, called this work “fascinating. It provides a lot of data that really touches on everyday practice,” inasmuch as clinicians often prescribe antihypertensive medications and see patients with these kinds of brain disorders.

The investigators and Dr. Sathian reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ANA 2021

Influenza tied to long-term increased risk for Parkinson’s disease

Influenza infection is linked to a subsequent diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease (PD) more than 10 years later, resurfacing a long-held debate about whether infection increases the risk for movement disorders over the long term.

In a large case-control study, investigators found and by more than 70% for PD occurring more than 10 years after the flu.

“This study is not definitive by any means, but it certainly suggests there are potential long-term consequences from influenza,” study investigator Noelle M. Cocoros, DSc, research scientist at Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute and Harvard Medical School, Boston, said in an interview.

The study was published online Oct. 25 in JAMA Neurology.

Ongoing debate

The debate about whether influenza is associated with PD has been going on as far back as the 1918 influenza pandemic, when experts documented parkinsonism in affected individuals.

Using data from the Danish patient registry, researchers identified 10,271 subjects diagnosed with PD during a 17-year period (2000-2016). Of these, 38.7% were female, and the mean age was 71.4 years.

They matched these subjects for age and sex to 51,355 controls without PD. Compared with controls, slightly fewer individuals with PD had chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or emphysema, but there was a similar distribution of cardiovascular disease and various other conditions.

Researchers collected data on influenza diagnoses from inpatient and outpatient hospital clinics from 1977 to 2016. They plotted these by month and year on a graph, calculated the median number of diagnoses per month, and identified peaks as those with more than threefold the median.

They categorized cases in groups related to the time between the infection and PD: More than 10 years, 10-15 years, and more than 15 years.

The time lapse accounts for a rather long “run-up” to PD, said Dr. Cocoros. There’s a sometimes decades-long preclinical phase before patients develop typical motor signs and a prodromal phase where they may present with nonmotor symptoms such as sleep disorders and constipation.

“We expected there would be at least 10 years between any infection and PD if there was an association present,” said Dr. Cocoros.

Investigators found an association between influenza exposure and PD diagnosis “that held up over time,” she said.

For more than 10 years before PD, the likelihood of a diagnosis for the infected compared with the unexposed was increased 73% (odds ratio [OR] 1.73; 95% confidence interval, 1.11-2.71; P = .02) after adjustment for cardiovascular disease, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, emphysema, lung cancer, Crohn’s disease, and ulcerative colitis.

The odds increased with more time from infection. For more than 15 years, the adjusted OR was 1.91 (95% CI, 1.14 - 3.19; P =.01).

However, for the 10- to 15-year time frame, the point estimate was reduced and the CI nonsignificant (OR, 1.33; 95% CI, 0.54-3.27; P = .53). This “is a little hard to interpret,” but could be a result of the small numbers, exposure misclassification, or because “the longer time interval is what’s meaningful,” said Dr. Cocoros.

Potential COVID-19–related PD surge?

In a sensitivity analysis, researchers looked at peak infection activity. “We wanted to increase the likelihood of these diagnoses representing actual infection,” Dr. Cocoros noted.

Here, the OR was still elevated at more than 10 years, but the CI was quite wide and included 1 (OR, 1.52; 95% CI, 0.80-2.89; P = .21). “So the association holds up, but the estimates are quite unstable,” said Dr. Cocoros.

Researchers examined associations with numerous other infection types, but did not see the same trend over time. Some infections – for example, gastrointestinal infections and septicemia – were associated with PD within 5 years, but most associations appeared to be null after more than 10 years.

“There seemed to be associations earlier between the infection and PD, which we interpret to suggest there’s actually not a meaningful association,” said Dr. Cocoros.

An exception might be urinary tract infections (UTIs), where after 10 years, the adjusted OR was 1.19 (95% CI, 1.01-1.40). Research suggests patients with PD often have UTIs and neurogenic bladder.

“It’s possible that UTIs could be an early symptom of PD rather than a causative factor,” said Dr. Cocoros.

It’s unclear how influenza might lead to PD but it could be that the virus gets into the central nervous system, resulting in neuroinflammation. Cytokines generated in response to the influenza infection might damage the brain.

“The infection could be a ‘primer’ or an initial ‘hit’ to the system, maybe setting people up for PD,” said Dr. Cocoros.

As for the current COVID-19 pandemic, some experts are concerned about a potential surge in PD cases in decades to come, and are calling for prospective monitoring of patients with this infection, said Dr. Cocoros.

However, she noted that infections don’t account for all PD cases and that genetic and environmental factors also influence risk.

Many individuals who contract influenza don’t seek medical care or get tested, so it’s possible the study counted those who had the infection as unexposed. Another potential study limitation was that small numbers for some infections, for example, Helicobacter pylori and hepatitis C, limited the ability to interpret results.

‘Exciting and important’ findings

Commenting on the research for this news organization, Aparna Wagle Shukla, MD, professor, Norman Fixel Institute for Neurological Diseases, University of Florida, Gainesville, said the results amid the current pandemic are “exciting and important” and “have reinvigorated interest” in the role of infection in PD.

However, the study had some limitations, an important one being lack of accounting for confounding factors, including environmental factors, she said. Exposure to pesticides, living in a rural area, drinking well water, and having had a head injury may increase PD risk, whereas high intake of caffeine, nicotine, alcohol, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs might lower the risk.

The researchers did not take into account exposure to multiple microbes or “infection burden,” said Dr. Wagle Shukla, who was not involved in the current study. In addition, as the data are from a single country with exposure to specific influenza strains, application of the findings elsewhere may be limited.

Dr. Wagle Shukla noted that a case-control design “isn’t ideal” from an epidemiological perspective. “Future studies should involve large cohorts followed longitudinally.”

The study was supported by grants from the Lundbeck Foundation and the Augustinus Foundation. Dr. Cocoros has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Several coauthors have disclosed relationships with industry. The full list can be found with the original article.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Influenza infection is linked to a subsequent diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease (PD) more than 10 years later, resurfacing a long-held debate about whether infection increases the risk for movement disorders over the long term.

In a large case-control study, investigators found and by more than 70% for PD occurring more than 10 years after the flu.

“This study is not definitive by any means, but it certainly suggests there are potential long-term consequences from influenza,” study investigator Noelle M. Cocoros, DSc, research scientist at Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute and Harvard Medical School, Boston, said in an interview.

The study was published online Oct. 25 in JAMA Neurology.

Ongoing debate

The debate about whether influenza is associated with PD has been going on as far back as the 1918 influenza pandemic, when experts documented parkinsonism in affected individuals.

Using data from the Danish patient registry, researchers identified 10,271 subjects diagnosed with PD during a 17-year period (2000-2016). Of these, 38.7% were female, and the mean age was 71.4 years.

They matched these subjects for age and sex to 51,355 controls without PD. Compared with controls, slightly fewer individuals with PD had chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or emphysema, but there was a similar distribution of cardiovascular disease and various other conditions.

Researchers collected data on influenza diagnoses from inpatient and outpatient hospital clinics from 1977 to 2016. They plotted these by month and year on a graph, calculated the median number of diagnoses per month, and identified peaks as those with more than threefold the median.

They categorized cases in groups related to the time between the infection and PD: More than 10 years, 10-15 years, and more than 15 years.

The time lapse accounts for a rather long “run-up” to PD, said Dr. Cocoros. There’s a sometimes decades-long preclinical phase before patients develop typical motor signs and a prodromal phase where they may present with nonmotor symptoms such as sleep disorders and constipation.

“We expected there would be at least 10 years between any infection and PD if there was an association present,” said Dr. Cocoros.

Investigators found an association between influenza exposure and PD diagnosis “that held up over time,” she said.

For more than 10 years before PD, the likelihood of a diagnosis for the infected compared with the unexposed was increased 73% (odds ratio [OR] 1.73; 95% confidence interval, 1.11-2.71; P = .02) after adjustment for cardiovascular disease, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, emphysema, lung cancer, Crohn’s disease, and ulcerative colitis.

The odds increased with more time from infection. For more than 15 years, the adjusted OR was 1.91 (95% CI, 1.14 - 3.19; P =.01).

However, for the 10- to 15-year time frame, the point estimate was reduced and the CI nonsignificant (OR, 1.33; 95% CI, 0.54-3.27; P = .53). This “is a little hard to interpret,” but could be a result of the small numbers, exposure misclassification, or because “the longer time interval is what’s meaningful,” said Dr. Cocoros.

Potential COVID-19–related PD surge?

In a sensitivity analysis, researchers looked at peak infection activity. “We wanted to increase the likelihood of these diagnoses representing actual infection,” Dr. Cocoros noted.

Here, the OR was still elevated at more than 10 years, but the CI was quite wide and included 1 (OR, 1.52; 95% CI, 0.80-2.89; P = .21). “So the association holds up, but the estimates are quite unstable,” said Dr. Cocoros.

Researchers examined associations with numerous other infection types, but did not see the same trend over time. Some infections – for example, gastrointestinal infections and septicemia – were associated with PD within 5 years, but most associations appeared to be null after more than 10 years.

“There seemed to be associations earlier between the infection and PD, which we interpret to suggest there’s actually not a meaningful association,” said Dr. Cocoros.

An exception might be urinary tract infections (UTIs), where after 10 years, the adjusted OR was 1.19 (95% CI, 1.01-1.40). Research suggests patients with PD often have UTIs and neurogenic bladder.

“It’s possible that UTIs could be an early symptom of PD rather than a causative factor,” said Dr. Cocoros.

It’s unclear how influenza might lead to PD but it could be that the virus gets into the central nervous system, resulting in neuroinflammation. Cytokines generated in response to the influenza infection might damage the brain.

“The infection could be a ‘primer’ or an initial ‘hit’ to the system, maybe setting people up for PD,” said Dr. Cocoros.

As for the current COVID-19 pandemic, some experts are concerned about a potential surge in PD cases in decades to come, and are calling for prospective monitoring of patients with this infection, said Dr. Cocoros.

However, she noted that infections don’t account for all PD cases and that genetic and environmental factors also influence risk.

Many individuals who contract influenza don’t seek medical care or get tested, so it’s possible the study counted those who had the infection as unexposed. Another potential study limitation was that small numbers for some infections, for example, Helicobacter pylori and hepatitis C, limited the ability to interpret results.

‘Exciting and important’ findings

Commenting on the research for this news organization, Aparna Wagle Shukla, MD, professor, Norman Fixel Institute for Neurological Diseases, University of Florida, Gainesville, said the results amid the current pandemic are “exciting and important” and “have reinvigorated interest” in the role of infection in PD.

However, the study had some limitations, an important one being lack of accounting for confounding factors, including environmental factors, she said. Exposure to pesticides, living in a rural area, drinking well water, and having had a head injury may increase PD risk, whereas high intake of caffeine, nicotine, alcohol, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs might lower the risk.

The researchers did not take into account exposure to multiple microbes or “infection burden,” said Dr. Wagle Shukla, who was not involved in the current study. In addition, as the data are from a single country with exposure to specific influenza strains, application of the findings elsewhere may be limited.

Dr. Wagle Shukla noted that a case-control design “isn’t ideal” from an epidemiological perspective. “Future studies should involve large cohorts followed longitudinally.”

The study was supported by grants from the Lundbeck Foundation and the Augustinus Foundation. Dr. Cocoros has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Several coauthors have disclosed relationships with industry. The full list can be found with the original article.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Influenza infection is linked to a subsequent diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease (PD) more than 10 years later, resurfacing a long-held debate about whether infection increases the risk for movement disorders over the long term.

In a large case-control study, investigators found and by more than 70% for PD occurring more than 10 years after the flu.

“This study is not definitive by any means, but it certainly suggests there are potential long-term consequences from influenza,” study investigator Noelle M. Cocoros, DSc, research scientist at Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute and Harvard Medical School, Boston, said in an interview.

The study was published online Oct. 25 in JAMA Neurology.

Ongoing debate

The debate about whether influenza is associated with PD has been going on as far back as the 1918 influenza pandemic, when experts documented parkinsonism in affected individuals.

Using data from the Danish patient registry, researchers identified 10,271 subjects diagnosed with PD during a 17-year period (2000-2016). Of these, 38.7% were female, and the mean age was 71.4 years.

They matched these subjects for age and sex to 51,355 controls without PD. Compared with controls, slightly fewer individuals with PD had chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or emphysema, but there was a similar distribution of cardiovascular disease and various other conditions.

Researchers collected data on influenza diagnoses from inpatient and outpatient hospital clinics from 1977 to 2016. They plotted these by month and year on a graph, calculated the median number of diagnoses per month, and identified peaks as those with more than threefold the median.

They categorized cases in groups related to the time between the infection and PD: More than 10 years, 10-15 years, and more than 15 years.

The time lapse accounts for a rather long “run-up” to PD, said Dr. Cocoros. There’s a sometimes decades-long preclinical phase before patients develop typical motor signs and a prodromal phase where they may present with nonmotor symptoms such as sleep disorders and constipation.

“We expected there would be at least 10 years between any infection and PD if there was an association present,” said Dr. Cocoros.

Investigators found an association between influenza exposure and PD diagnosis “that held up over time,” she said.

For more than 10 years before PD, the likelihood of a diagnosis for the infected compared with the unexposed was increased 73% (odds ratio [OR] 1.73; 95% confidence interval, 1.11-2.71; P = .02) after adjustment for cardiovascular disease, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, emphysema, lung cancer, Crohn’s disease, and ulcerative colitis.

The odds increased with more time from infection. For more than 15 years, the adjusted OR was 1.91 (95% CI, 1.14 - 3.19; P =.01).

However, for the 10- to 15-year time frame, the point estimate was reduced and the CI nonsignificant (OR, 1.33; 95% CI, 0.54-3.27; P = .53). This “is a little hard to interpret,” but could be a result of the small numbers, exposure misclassification, or because “the longer time interval is what’s meaningful,” said Dr. Cocoros.

Potential COVID-19–related PD surge?

In a sensitivity analysis, researchers looked at peak infection activity. “We wanted to increase the likelihood of these diagnoses representing actual infection,” Dr. Cocoros noted.

Here, the OR was still elevated at more than 10 years, but the CI was quite wide and included 1 (OR, 1.52; 95% CI, 0.80-2.89; P = .21). “So the association holds up, but the estimates are quite unstable,” said Dr. Cocoros.

Researchers examined associations with numerous other infection types, but did not see the same trend over time. Some infections – for example, gastrointestinal infections and septicemia – were associated with PD within 5 years, but most associations appeared to be null after more than 10 years.

“There seemed to be associations earlier between the infection and PD, which we interpret to suggest there’s actually not a meaningful association,” said Dr. Cocoros.

An exception might be urinary tract infections (UTIs), where after 10 years, the adjusted OR was 1.19 (95% CI, 1.01-1.40). Research suggests patients with PD often have UTIs and neurogenic bladder.

“It’s possible that UTIs could be an early symptom of PD rather than a causative factor,” said Dr. Cocoros.

It’s unclear how influenza might lead to PD but it could be that the virus gets into the central nervous system, resulting in neuroinflammation. Cytokines generated in response to the influenza infection might damage the brain.

“The infection could be a ‘primer’ or an initial ‘hit’ to the system, maybe setting people up for PD,” said Dr. Cocoros.

As for the current COVID-19 pandemic, some experts are concerned about a potential surge in PD cases in decades to come, and are calling for prospective monitoring of patients with this infection, said Dr. Cocoros.

However, she noted that infections don’t account for all PD cases and that genetic and environmental factors also influence risk.

Many individuals who contract influenza don’t seek medical care or get tested, so it’s possible the study counted those who had the infection as unexposed. Another potential study limitation was that small numbers for some infections, for example, Helicobacter pylori and hepatitis C, limited the ability to interpret results.

‘Exciting and important’ findings

Commenting on the research for this news organization, Aparna Wagle Shukla, MD, professor, Norman Fixel Institute for Neurological Diseases, University of Florida, Gainesville, said the results amid the current pandemic are “exciting and important” and “have reinvigorated interest” in the role of infection in PD.

However, the study had some limitations, an important one being lack of accounting for confounding factors, including environmental factors, she said. Exposure to pesticides, living in a rural area, drinking well water, and having had a head injury may increase PD risk, whereas high intake of caffeine, nicotine, alcohol, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs might lower the risk.

The researchers did not take into account exposure to multiple microbes or “infection burden,” said Dr. Wagle Shukla, who was not involved in the current study. In addition, as the data are from a single country with exposure to specific influenza strains, application of the findings elsewhere may be limited.

Dr. Wagle Shukla noted that a case-control design “isn’t ideal” from an epidemiological perspective. “Future studies should involve large cohorts followed longitudinally.”

The study was supported by grants from the Lundbeck Foundation and the Augustinus Foundation. Dr. Cocoros has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Several coauthors have disclosed relationships with industry. The full list can be found with the original article.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

DIY nerve stimulation effective in episodic migraine

results from a phase 3 study show.

This is great news for headache patients who want to explore nondrug treatment options, said study investigator Deena E. Kuruvilla, MD, neurologist and headache specialist at the Westport Headache Institute, Connecticut.

She added that such devices “aren’t always part of the conversation when we’re discussing preventive and acute treatments with our patients. Making this a regular part of the conversation might be helpful to patients.”

The findings were presented at ANA 2021: 146th Annual Meeting of the American Neurological Association (ANA), which was held online.

A key therapeutic target

The randomized, double-blind trial compared E-TNS with sham stimulation for the acute treatment of migraine.

The E-TNS device (Verum Cefaly Abortive Program) stimulates the supraorbital nerve in the forehead. “This nerve is a branch of the trigeminal nerve, which is thought to be the key player in migraine pathophysiology,” Dr. Kuruvilla noted.

The device has been cleared by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for acute and preventive treatment of migraine.

During a run-in period before randomization, patients were asked to keep a detailed headache diary and to become comfortable using the trial device to treat an acute migraine attack at home.

The study enrolled 538 adult patients at 10 centers. The patients were aged 18 to 65 years, and they had been having episodic migraines, with or without aura, for at least a year. The participants had to have received a migraine diagnosis before age 50, and they had to be experiencing an attack of migraine 2 to 8 days per month.

The patients used the device only for a migraine of at least moderate intensity that was accompanied by at least one migraine-associated symptom, such as photophobia, phonophobia, or nausea. They were asked not to take rescue medication prior to or during a therapy session.

Study participants applied either neurostimulation or sham stimulation for a continuous 2-hour period within 4 hours of a migraine attack over the 2-month study period.

The two primary endpoints were pain freedom and freedom from the most bothersome migraine-associated symptoms at 2 hours.

Compared to sham treatment, active stimulation was more effective in achieving pain freedom (P = .043) and freedom from the most bothersome migraine-associated symptom (P = .001) at 2 hours.

“So the study did meet both primary endpoints with statistical significance,” said Dr. Kuruvilla.

The five secondary endpoints included pain relief at 2 hours; absence of all migraine-associated symptoms at 2 hours; use of rescue medication within 24 hours; sustained pain freedom at 24 hours; and sustained pain relief at 24 hours.

All but one of these endpoints reached statistical significance, showing superiority for the active intervention. The only exception was in regard to use of rescue medication.

The most common adverse event (AE) was forehead paresthesia, discomfort, or burning, which was more common in the active-treatment group than in the sham-treatment group (P = .009). There were four cases of nausea or vomiting in the active-treatment group and none in the sham-treatment group. There were no serious AEs.

Available over the counter

Both moderators of the headache poster tour that featured this study – Justin C. McArthur, MBBS, from Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and Steven Galetta, MD, from NYU Grossman School of Medicine – praised the presentation.

Dr. Galetta questioned whether patients were receiving preventive therapies. Dr. Kuruvilla said that the patients were allowed to enter the trial while taking preventive therapies, including antiepileptic treatments, blood pressure medications, and antidepressants, but that they had to be receiving stable doses.

The investigators didn’t distinguish between participants who were taking preventive therapies and those who weren’t, she said. “The aim was really to look at acute treatment for migraine,” and patients taking such medication “had been stable on their regimen for a pretty prolonged period of time.”

Dr. McArthur asked about the origin of the nausea some patients experienced.

It was difficult to determine whether the nausea was an aspect of an individual patient’s migraine attack or was an effect of the stimulation, said Dr. Kuruvilla. She noted that some patients found the vibrating sensation from the device uncomfortable and that nausea could be associated with pain at the site.

The device costs $300 to $400 (U.S.) and is available over the counter.

Dr. Kuruvilla is a consultant for Cefaly, Neurolief, Theranica, Now What Media, and Kx Advisors. She is on the speakers bureau for AbbVie/Allergan, Amgen/Novartis, Lilly, the American Headache Society, Biohaven, and CME meeting, and she is on an advisory board at AbbVie/Allergan, Lilly, Theranica, and Amgen/Novartis. She is editor and associate editor of Healthline and is an author for WebMD/Medscape, Healthline.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

results from a phase 3 study show.

This is great news for headache patients who want to explore nondrug treatment options, said study investigator Deena E. Kuruvilla, MD, neurologist and headache specialist at the Westport Headache Institute, Connecticut.

She added that such devices “aren’t always part of the conversation when we’re discussing preventive and acute treatments with our patients. Making this a regular part of the conversation might be helpful to patients.”

The findings were presented at ANA 2021: 146th Annual Meeting of the American Neurological Association (ANA), which was held online.

A key therapeutic target

The randomized, double-blind trial compared E-TNS with sham stimulation for the acute treatment of migraine.

The E-TNS device (Verum Cefaly Abortive Program) stimulates the supraorbital nerve in the forehead. “This nerve is a branch of the trigeminal nerve, which is thought to be the key player in migraine pathophysiology,” Dr. Kuruvilla noted.

The device has been cleared by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for acute and preventive treatment of migraine.

During a run-in period before randomization, patients were asked to keep a detailed headache diary and to become comfortable using the trial device to treat an acute migraine attack at home.

The study enrolled 538 adult patients at 10 centers. The patients were aged 18 to 65 years, and they had been having episodic migraines, with or without aura, for at least a year. The participants had to have received a migraine diagnosis before age 50, and they had to be experiencing an attack of migraine 2 to 8 days per month.

The patients used the device only for a migraine of at least moderate intensity that was accompanied by at least one migraine-associated symptom, such as photophobia, phonophobia, or nausea. They were asked not to take rescue medication prior to or during a therapy session.

Study participants applied either neurostimulation or sham stimulation for a continuous 2-hour period within 4 hours of a migraine attack over the 2-month study period.

The two primary endpoints were pain freedom and freedom from the most bothersome migraine-associated symptoms at 2 hours.

Compared to sham treatment, active stimulation was more effective in achieving pain freedom (P = .043) and freedom from the most bothersome migraine-associated symptom (P = .001) at 2 hours.

“So the study did meet both primary endpoints with statistical significance,” said Dr. Kuruvilla.

The five secondary endpoints included pain relief at 2 hours; absence of all migraine-associated symptoms at 2 hours; use of rescue medication within 24 hours; sustained pain freedom at 24 hours; and sustained pain relief at 24 hours.

All but one of these endpoints reached statistical significance, showing superiority for the active intervention. The only exception was in regard to use of rescue medication.

The most common adverse event (AE) was forehead paresthesia, discomfort, or burning, which was more common in the active-treatment group than in the sham-treatment group (P = .009). There were four cases of nausea or vomiting in the active-treatment group and none in the sham-treatment group. There were no serious AEs.

Available over the counter

Both moderators of the headache poster tour that featured this study – Justin C. McArthur, MBBS, from Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and Steven Galetta, MD, from NYU Grossman School of Medicine – praised the presentation.

Dr. Galetta questioned whether patients were receiving preventive therapies. Dr. Kuruvilla said that the patients were allowed to enter the trial while taking preventive therapies, including antiepileptic treatments, blood pressure medications, and antidepressants, but that they had to be receiving stable doses.

The investigators didn’t distinguish between participants who were taking preventive therapies and those who weren’t, she said. “The aim was really to look at acute treatment for migraine,” and patients taking such medication “had been stable on their regimen for a pretty prolonged period of time.”

Dr. McArthur asked about the origin of the nausea some patients experienced.