User login

Polypharmacy in an Aging HIV Population

PORTLAND—“We are now working with an HIV population that is aging, and along with aging comes a lot of other diseases, such as heart and lung disease, that often result in the use of medications,” began Jennifer Cocohoba, PharmD, AAHIP, Professor of Clinical Pharmacy, UCSF School of Pharmacy. She explained that “the growing problem of having too many medications applies to all, but is particularly important among those living with HIV.”

Polypharmacy, as often defined in research studies, is the taking of at least 5 prescription medications. About 40% of US adults fall into this category, “and it’s not much different for people with HIV,” Cocohoba said. “Persons living with HIV experience polypharmacy at about the same rate.” But people living with HIV may reach that number faster, given that 2 to 3 of the 5 drugs may be for HIV. In addition, those living with HIV are potentially at greater risk for drug interactions.

Quality, not just quantity

Cocohoba explained that it’s important to pay attention to the number of medications a patient is taking because the greater the number, the greater the likelihood of interactions and adverse effects and the more difficult it is for patients to adhere to their medication regimens.

“But we should be looking also at appropriateness of using those medications in a particular person,” she continued, which moves into the realm of quality. She reviewed some criteria that can be used to evaluate the quality of prescribing.

The BEERS Criteria, published by the American Geriatric Society, present classes and specific medications that may be inappropriate in certain elderly persons. Benzodiazepines, for example, commonly used to treat anxiety, are not metabolized as efficiently in the elderly as they are in younger patients. As a result, older adults may experience sedation, falls, or other potentially harmful sequelae. “If a patient age 65 or older is taking a benzodiazepine, that’s a red flag for a clinician to look at that medication and see if it’s really the best choice or whether alternatives might be more appropriate,” explained Cocohoba.

START/STOPP Criteria. Other criteria include the Screening Tool To Alert To Right Treatment (START) and the Screening Tool Of Older People's Prescriptions (STOPP). START focuses on looking for medications that would be appropriate for a particular patient but that are missing from the patient’s medication list, while STOPP focuses on looking for medications that are on the list that might be inappropriate, much like the BEERS Criteria.

The Good Palliative Geriatric Practice Algorithm is a clinical decision-making tool that aids clinicians in thinking through whether a medication is appropriate or inappropriate and whether to maintain, alter, or discontinue the therapy. Cocohoba said it’s often used as a partner to BEERS.

Continue to: Reducing polypharmacy in HIV treatment

Reducing polypharmacy in HIV treatment

Cocohoba explained that there are essentially 2 frameworks for reducing polypharmacy that can be applied to HIV treatment regimens.

Consolidation. With consolidation, the focus is on reducing pill burden—but not by omitting medications. “It’s about looking into simpler dosage forms or combination medications to improve adherence and make life easier,” Cocohoba explained. “Same regimen, fewer pills.”

Simplification, on the other hand, is removing, and thus reducing the number of, agents a patient is taking. The question clinicians should be asking is, according to Cocohoba, “In what situations is it safe to strip down therapy to the bare essentials for the purposes of exposing people to fewer medications, reducing adverse effects, and keeping treatment as manageable as possible to optimize adherence?”

Simplification may be applied to either treatment-naïve or treatment-experienced patients. With the former, clinicians consider, for example, whether patients can be started on HIV treatment consisting of 2 rather than 3 medications. In the latter, “Clinicians may be dealing with patients who are fully virally suppressed on certain regimens and have been for a while; here we see if we can subtract medications, reducing say from triple to double therapy, while maintaining suppression,” explained Cocohoba.

“We want to offer people robust HIV treatment that is going to maintain viral suppression and prevent sequelae of HIV disease,” Cocohoba said, “but we need to balance that with safety, tolerability, and adherence.”

Continue to: An ongoing discussion and multidisciplinary effort

An ongoing discussion and multidisciplinary effort

“Medications can easily pile [up],” Cocohoba said, “so it’s important for clinicians to regularly review medication lists with patients to see if maybe they aren’t using certain agents anymore.” Another reason for clinicians to periodically review medication lists is to make certain they are aware of agents being prescribed by the patient’s other health care providers.

Polypharmacy is the responsibility of everyone on the health care team, both prescribers and nonprescribers, such as social workers and case managers, explained Cocohoba. “If ever there was a health care problem that could use an interdisciplinary approach, polypharmacy is it.”

PORTLAND—“We are now working with an HIV population that is aging, and along with aging comes a lot of other diseases, such as heart and lung disease, that often result in the use of medications,” began Jennifer Cocohoba, PharmD, AAHIP, Professor of Clinical Pharmacy, UCSF School of Pharmacy. She explained that “the growing problem of having too many medications applies to all, but is particularly important among those living with HIV.”

Polypharmacy, as often defined in research studies, is the taking of at least 5 prescription medications. About 40% of US adults fall into this category, “and it’s not much different for people with HIV,” Cocohoba said. “Persons living with HIV experience polypharmacy at about the same rate.” But people living with HIV may reach that number faster, given that 2 to 3 of the 5 drugs may be for HIV. In addition, those living with HIV are potentially at greater risk for drug interactions.

Quality, not just quantity

Cocohoba explained that it’s important to pay attention to the number of medications a patient is taking because the greater the number, the greater the likelihood of interactions and adverse effects and the more difficult it is for patients to adhere to their medication regimens.

“But we should be looking also at appropriateness of using those medications in a particular person,” she continued, which moves into the realm of quality. She reviewed some criteria that can be used to evaluate the quality of prescribing.

The BEERS Criteria, published by the American Geriatric Society, present classes and specific medications that may be inappropriate in certain elderly persons. Benzodiazepines, for example, commonly used to treat anxiety, are not metabolized as efficiently in the elderly as they are in younger patients. As a result, older adults may experience sedation, falls, or other potentially harmful sequelae. “If a patient age 65 or older is taking a benzodiazepine, that’s a red flag for a clinician to look at that medication and see if it’s really the best choice or whether alternatives might be more appropriate,” explained Cocohoba.

START/STOPP Criteria. Other criteria include the Screening Tool To Alert To Right Treatment (START) and the Screening Tool Of Older People's Prescriptions (STOPP). START focuses on looking for medications that would be appropriate for a particular patient but that are missing from the patient’s medication list, while STOPP focuses on looking for medications that are on the list that might be inappropriate, much like the BEERS Criteria.

The Good Palliative Geriatric Practice Algorithm is a clinical decision-making tool that aids clinicians in thinking through whether a medication is appropriate or inappropriate and whether to maintain, alter, or discontinue the therapy. Cocohoba said it’s often used as a partner to BEERS.

Continue to: Reducing polypharmacy in HIV treatment

Reducing polypharmacy in HIV treatment

Cocohoba explained that there are essentially 2 frameworks for reducing polypharmacy that can be applied to HIV treatment regimens.

Consolidation. With consolidation, the focus is on reducing pill burden—but not by omitting medications. “It’s about looking into simpler dosage forms or combination medications to improve adherence and make life easier,” Cocohoba explained. “Same regimen, fewer pills.”

Simplification, on the other hand, is removing, and thus reducing the number of, agents a patient is taking. The question clinicians should be asking is, according to Cocohoba, “In what situations is it safe to strip down therapy to the bare essentials for the purposes of exposing people to fewer medications, reducing adverse effects, and keeping treatment as manageable as possible to optimize adherence?”

Simplification may be applied to either treatment-naïve or treatment-experienced patients. With the former, clinicians consider, for example, whether patients can be started on HIV treatment consisting of 2 rather than 3 medications. In the latter, “Clinicians may be dealing with patients who are fully virally suppressed on certain regimens and have been for a while; here we see if we can subtract medications, reducing say from triple to double therapy, while maintaining suppression,” explained Cocohoba.

“We want to offer people robust HIV treatment that is going to maintain viral suppression and prevent sequelae of HIV disease,” Cocohoba said, “but we need to balance that with safety, tolerability, and adherence.”

Continue to: An ongoing discussion and multidisciplinary effort

An ongoing discussion and multidisciplinary effort

“Medications can easily pile [up],” Cocohoba said, “so it’s important for clinicians to regularly review medication lists with patients to see if maybe they aren’t using certain agents anymore.” Another reason for clinicians to periodically review medication lists is to make certain they are aware of agents being prescribed by the patient’s other health care providers.

Polypharmacy is the responsibility of everyone on the health care team, both prescribers and nonprescribers, such as social workers and case managers, explained Cocohoba. “If ever there was a health care problem that could use an interdisciplinary approach, polypharmacy is it.”

PORTLAND—“We are now working with an HIV population that is aging, and along with aging comes a lot of other diseases, such as heart and lung disease, that often result in the use of medications,” began Jennifer Cocohoba, PharmD, AAHIP, Professor of Clinical Pharmacy, UCSF School of Pharmacy. She explained that “the growing problem of having too many medications applies to all, but is particularly important among those living with HIV.”

Polypharmacy, as often defined in research studies, is the taking of at least 5 prescription medications. About 40% of US adults fall into this category, “and it’s not much different for people with HIV,” Cocohoba said. “Persons living with HIV experience polypharmacy at about the same rate.” But people living with HIV may reach that number faster, given that 2 to 3 of the 5 drugs may be for HIV. In addition, those living with HIV are potentially at greater risk for drug interactions.

Quality, not just quantity

Cocohoba explained that it’s important to pay attention to the number of medications a patient is taking because the greater the number, the greater the likelihood of interactions and adverse effects and the more difficult it is for patients to adhere to their medication regimens.

“But we should be looking also at appropriateness of using those medications in a particular person,” she continued, which moves into the realm of quality. She reviewed some criteria that can be used to evaluate the quality of prescribing.

The BEERS Criteria, published by the American Geriatric Society, present classes and specific medications that may be inappropriate in certain elderly persons. Benzodiazepines, for example, commonly used to treat anxiety, are not metabolized as efficiently in the elderly as they are in younger patients. As a result, older adults may experience sedation, falls, or other potentially harmful sequelae. “If a patient age 65 or older is taking a benzodiazepine, that’s a red flag for a clinician to look at that medication and see if it’s really the best choice or whether alternatives might be more appropriate,” explained Cocohoba.

START/STOPP Criteria. Other criteria include the Screening Tool To Alert To Right Treatment (START) and the Screening Tool Of Older People's Prescriptions (STOPP). START focuses on looking for medications that would be appropriate for a particular patient but that are missing from the patient’s medication list, while STOPP focuses on looking for medications that are on the list that might be inappropriate, much like the BEERS Criteria.

The Good Palliative Geriatric Practice Algorithm is a clinical decision-making tool that aids clinicians in thinking through whether a medication is appropriate or inappropriate and whether to maintain, alter, or discontinue the therapy. Cocohoba said it’s often used as a partner to BEERS.

Continue to: Reducing polypharmacy in HIV treatment

Reducing polypharmacy in HIV treatment

Cocohoba explained that there are essentially 2 frameworks for reducing polypharmacy that can be applied to HIV treatment regimens.

Consolidation. With consolidation, the focus is on reducing pill burden—but not by omitting medications. “It’s about looking into simpler dosage forms or combination medications to improve adherence and make life easier,” Cocohoba explained. “Same regimen, fewer pills.”

Simplification, on the other hand, is removing, and thus reducing the number of, agents a patient is taking. The question clinicians should be asking is, according to Cocohoba, “In what situations is it safe to strip down therapy to the bare essentials for the purposes of exposing people to fewer medications, reducing adverse effects, and keeping treatment as manageable as possible to optimize adherence?”

Simplification may be applied to either treatment-naïve or treatment-experienced patients. With the former, clinicians consider, for example, whether patients can be started on HIV treatment consisting of 2 rather than 3 medications. In the latter, “Clinicians may be dealing with patients who are fully virally suppressed on certain regimens and have been for a while; here we see if we can subtract medications, reducing say from triple to double therapy, while maintaining suppression,” explained Cocohoba.

“We want to offer people robust HIV treatment that is going to maintain viral suppression and prevent sequelae of HIV disease,” Cocohoba said, “but we need to balance that with safety, tolerability, and adherence.”

Continue to: An ongoing discussion and multidisciplinary effort

An ongoing discussion and multidisciplinary effort

“Medications can easily pile [up],” Cocohoba said, “so it’s important for clinicians to regularly review medication lists with patients to see if maybe they aren’t using certain agents anymore.” Another reason for clinicians to periodically review medication lists is to make certain they are aware of agents being prescribed by the patient’s other health care providers.

Polypharmacy is the responsibility of everyone on the health care team, both prescribers and nonprescribers, such as social workers and case managers, explained Cocohoba. “If ever there was a health care problem that could use an interdisciplinary approach, polypharmacy is it.”

Association of Nurses in AIDS Care 2019

Physical Therapists as Pain Specialists in HIV Care

PORTLAND—A lot of health care providers involved in the care of patients with HIV/AIDS think physical therapists (PTs) have a very narrow role to play in chronic pain when in actuality, "we have a very big footprint," says Michael DeArman, DPT, Fellow of the American Association of Orthopedic Manual Therapists.

In his session, "Physical therapy alternatives for people living with HIV and persistent pain," he reviewed how his role in the care of patients with HIV has evolved over the years. He explained that the emphasis in physical therapy used to be on exercises that would help to maintain lean body mass, because it was a predictor of survivability and helped patients avoid opportunistic infections.

After that, the role of the PT focused largely on helping patients deal with the adverse effects of medications. DeArman explained that back in the days of azathioprine (AZT), for example, many patients developed peripheral neuropathy, lipodystrophy, and low cervical fat deposition leading to neck pain. PTs also helped patients deal with the complications of surviving with HIV, including the effects of meningitis and stroke. "But we don't see much of that anymore because the medications are so much better,” DeArman said. “That's not the profile for HIV anymore."

But now patients are dealing with chronic pain

DeArman reported that 80% to 90% of people with HIV/AIDS have chronic pain for at least 2 months, if not much longer. He said, "PT can be an alternative to opioids," and explained that his efforts are twofold. "Graded activity to slowly build peoples' ability to do aerobic exercise is a really good way to manage pain,” he said, “but the other half of it is a lot of counseling and education, talking about how pain works and doesn't work, and how what you're told and what you believe and experience and your expectations can affect the experience of pain and the level of pain at any given moment."

He remarked that now about 60% of this professional time is devoted to the counseling and educational aspects of pain and 40% to movement and exercise: "It's not really the kind of therapist I trained to be, and it's not what most people think of as physical therapy work, but it's falling in our lap."

He said that as a society, we rely heavily on more formal counseling by psychotherapists and counselors, for example, to manage depression and anxiety, but that few others in the medical realm are picking up the slack when it comes to pain education for patients with HIV.

Tools for talking

DeArman discussed some of the tools and techniques he uses when talking to patients about their pain, such as motivational interviewing and assessing readiness for change. He uses the Fear-Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire (FABQ) to uncover how a patient's fear-avoidance beliefs about physical activity may be affecting their pain. He also assesses levels of catastrophization, or how seriously a patient interprets a physical symptom; a high level correlates with greater pain states. Similarly, those with low self-efficacy—feelings about how well you can control your destiny and situations—are more likely to experience chronic pain states than those with high self-efficacy.

Continue to: He said that using...

He said that using these tools has made a huge difference in the way he and others in his field approach pain and its outcomes. He says that not only are they helping people get better, but "we are giving patients a way to manage their pain before they go down the road of pharmacologic solutions."

DeArman said his main message is "to think about physical therapy for your patients with chronic pain." He pointed out that there's a new generation of PTs coming out of school that have a much better understanding of how to manage chronic pain, so "expect [this type of treatment] to be available from those PTs to whom you refer patients. Just realize it may still take a little looking to find it."

PORTLAND—A lot of health care providers involved in the care of patients with HIV/AIDS think physical therapists (PTs) have a very narrow role to play in chronic pain when in actuality, "we have a very big footprint," says Michael DeArman, DPT, Fellow of the American Association of Orthopedic Manual Therapists.

In his session, "Physical therapy alternatives for people living with HIV and persistent pain," he reviewed how his role in the care of patients with HIV has evolved over the years. He explained that the emphasis in physical therapy used to be on exercises that would help to maintain lean body mass, because it was a predictor of survivability and helped patients avoid opportunistic infections.

After that, the role of the PT focused largely on helping patients deal with the adverse effects of medications. DeArman explained that back in the days of azathioprine (AZT), for example, many patients developed peripheral neuropathy, lipodystrophy, and low cervical fat deposition leading to neck pain. PTs also helped patients deal with the complications of surviving with HIV, including the effects of meningitis and stroke. "But we don't see much of that anymore because the medications are so much better,” DeArman said. “That's not the profile for HIV anymore."

But now patients are dealing with chronic pain

DeArman reported that 80% to 90% of people with HIV/AIDS have chronic pain for at least 2 months, if not much longer. He said, "PT can be an alternative to opioids," and explained that his efforts are twofold. "Graded activity to slowly build peoples' ability to do aerobic exercise is a really good way to manage pain,” he said, “but the other half of it is a lot of counseling and education, talking about how pain works and doesn't work, and how what you're told and what you believe and experience and your expectations can affect the experience of pain and the level of pain at any given moment."

He remarked that now about 60% of this professional time is devoted to the counseling and educational aspects of pain and 40% to movement and exercise: "It's not really the kind of therapist I trained to be, and it's not what most people think of as physical therapy work, but it's falling in our lap."

He said that as a society, we rely heavily on more formal counseling by psychotherapists and counselors, for example, to manage depression and anxiety, but that few others in the medical realm are picking up the slack when it comes to pain education for patients with HIV.

Tools for talking

DeArman discussed some of the tools and techniques he uses when talking to patients about their pain, such as motivational interviewing and assessing readiness for change. He uses the Fear-Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire (FABQ) to uncover how a patient's fear-avoidance beliefs about physical activity may be affecting their pain. He also assesses levels of catastrophization, or how seriously a patient interprets a physical symptom; a high level correlates with greater pain states. Similarly, those with low self-efficacy—feelings about how well you can control your destiny and situations—are more likely to experience chronic pain states than those with high self-efficacy.

Continue to: He said that using...

He said that using these tools has made a huge difference in the way he and others in his field approach pain and its outcomes. He says that not only are they helping people get better, but "we are giving patients a way to manage their pain before they go down the road of pharmacologic solutions."

DeArman said his main message is "to think about physical therapy for your patients with chronic pain." He pointed out that there's a new generation of PTs coming out of school that have a much better understanding of how to manage chronic pain, so "expect [this type of treatment] to be available from those PTs to whom you refer patients. Just realize it may still take a little looking to find it."

PORTLAND—A lot of health care providers involved in the care of patients with HIV/AIDS think physical therapists (PTs) have a very narrow role to play in chronic pain when in actuality, "we have a very big footprint," says Michael DeArman, DPT, Fellow of the American Association of Orthopedic Manual Therapists.

In his session, "Physical therapy alternatives for people living with HIV and persistent pain," he reviewed how his role in the care of patients with HIV has evolved over the years. He explained that the emphasis in physical therapy used to be on exercises that would help to maintain lean body mass, because it was a predictor of survivability and helped patients avoid opportunistic infections.

After that, the role of the PT focused largely on helping patients deal with the adverse effects of medications. DeArman explained that back in the days of azathioprine (AZT), for example, many patients developed peripheral neuropathy, lipodystrophy, and low cervical fat deposition leading to neck pain. PTs also helped patients deal with the complications of surviving with HIV, including the effects of meningitis and stroke. "But we don't see much of that anymore because the medications are so much better,” DeArman said. “That's not the profile for HIV anymore."

But now patients are dealing with chronic pain

DeArman reported that 80% to 90% of people with HIV/AIDS have chronic pain for at least 2 months, if not much longer. He said, "PT can be an alternative to opioids," and explained that his efforts are twofold. "Graded activity to slowly build peoples' ability to do aerobic exercise is a really good way to manage pain,” he said, “but the other half of it is a lot of counseling and education, talking about how pain works and doesn't work, and how what you're told and what you believe and experience and your expectations can affect the experience of pain and the level of pain at any given moment."

He remarked that now about 60% of this professional time is devoted to the counseling and educational aspects of pain and 40% to movement and exercise: "It's not really the kind of therapist I trained to be, and it's not what most people think of as physical therapy work, but it's falling in our lap."

He said that as a society, we rely heavily on more formal counseling by psychotherapists and counselors, for example, to manage depression and anxiety, but that few others in the medical realm are picking up the slack when it comes to pain education for patients with HIV.

Tools for talking

DeArman discussed some of the tools and techniques he uses when talking to patients about their pain, such as motivational interviewing and assessing readiness for change. He uses the Fear-Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire (FABQ) to uncover how a patient's fear-avoidance beliefs about physical activity may be affecting their pain. He also assesses levels of catastrophization, or how seriously a patient interprets a physical symptom; a high level correlates with greater pain states. Similarly, those with low self-efficacy—feelings about how well you can control your destiny and situations—are more likely to experience chronic pain states than those with high self-efficacy.

Continue to: He said that using...

He said that using these tools has made a huge difference in the way he and others in his field approach pain and its outcomes. He says that not only are they helping people get better, but "we are giving patients a way to manage their pain before they go down the road of pharmacologic solutions."

DeArman said his main message is "to think about physical therapy for your patients with chronic pain." He pointed out that there's a new generation of PTs coming out of school that have a much better understanding of how to manage chronic pain, so "expect [this type of treatment] to be available from those PTs to whom you refer patients. Just realize it may still take a little looking to find it."

Association of Nurses in AIDS Care 2019

ARV Therapy: Current Issues and Controversies

PORTLAND—The investigational drug islatravir “could be a game changer in the field of HIV," said David H. Spach, MD, Professor of Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases, University of Washington, Seattle, in a session called, "Antiretroviral therapy 2019 update: Mechanism of action, new medications, current guidelines, and controversies."

Dr. Spach reported that islatravir, a nucleoside reverse transcriptase translocation inhibitor (NRTTI), is highly potent, is well tolerated, has a high genetic barrier to resistance, and has an extremely long half-life, according to the findings of preliminary studies. Its long half-life enables subdermal implantation and maintenance of therapeutic levels even after a year in place. Researchers are studying the compound in combination with other agents for treatment and independently for preexposure prophylaxis.

Another noteworthy investigational agent, according to Dr. Spach, is cabotegravir, an integrase strand transfer inhibitor (INSTI) with the potential for intramuscular administration every 4 to 8 weeks. Dr. Spach explained that researchers are studying the agent in 3 different clinical situations: oral cabotegravir in combination with rilpivirine for lead-in therapy; an extended-release injectable of cabotegravir and rilpivirine for maintenance antiretroviral (ARV) treatment every 4 weeks; and an extended-release cabotegravir injectable for preexposure prophylaxis every 8 weeks. The agent is highly potent, with a high genetic barrier to resistance.

ARV: The current state of affairs

"We are in an era now where everyone who is living with HIV ideally should be receiving fully suppressive antiretroviral therapy," remarked Dr. Spach. He explained that not only does this benefit the person living with HIV by reducing the onset and progression of chronic inflammatory disease states that occur along with HIV, such as cardiovascular disease, stroke, and cancer, but also "fully suppressive ARV therapy virtually eliminates sexual transmission of HIV to another person."

Spach explained that the most recent (2018) Health and Human Services ARV therapy guidelines have greatly simplified the choices for ARV therapy. The current recommendations for initial ARV therapy for most people are to use a 2-drug backbone regimen, consisting of 2 nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs), combined with a single anchor drug, which should be an INSTI. The INSTI should have the highest potency and highest genetic barrier to resistance available, which effectively means using a regimen that contains either dolutegravir or bictegravir. The latter is available only in combination with emtricitabine and tenofovir alafenamide as a single-tablet regimen.

Spach also explained that "the guidelines have moved away from using boosted regimens for initial therapy, so elvitegravir boosted with cobicistat and protease inhibitors (PIs) boosted with ritonavir or cobicistat are no longer recommended as preferred initial therapy, although boosted PIs are still very useful as second- or third-line therapies."

Newer medications

Doravirine, a nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI), was approved by the FDA in 2018. "It probably won't have a big impact on initial therapy, but it is likely to have a significant effect on second- and third-line therapy," Dr. Spach said. "Because of its high potency and high genetic barrier to resistance, those taking etravirine twice a day, for example, may be able to simplify to once-a-day doravirine." In addition, "Doravirine may have advantages over rilpivirine in that it has no restrictions when used with acid-suppressing agents such as H2 blockers or proton pump inhibitors."

Continue to: Ibalizumab

Ibalizumab. Another newer agent “worth mentioning,” according to Dr. Spach, is ibalizumab. This monoclonal antibody has a unique mechanism of action. It is 1 of only 2 drugs used for HIV treatment that targets human receptors (all of the others work by inhibiting either an HIV enzyme or binding to the HIV virus itself). Ibalizumab targets the D2 region of the CD4 receptor. It is an injectable (intravenous) compound administered with an initial loading dose and then every 2 weeks thereafter. Dr. Spach reported that the data surrounding ibalizumab show that it is effective as an add-on medication in more advanced resistant settings. Also, it provides an option for people who can't take oral drugs, such as those who have had major surgery or trauma.

Remaining questions

Dr. Spach explained that 1 of the questions that remains is whether to prescribe ARV therapy for patients who are viremic controllers (those who inherently control HIV through their own immunologic response to a level < 200 copies) or elite controllers (those whose own immunologic response controls the virus to a level < 50 copies, which is in the undetectable range). Both of these groups still have a higher risk for hospitalization and for HIV-related inflammatory conditions such as heart disease, according to Dr. Spach. Current thinking among most experts is to initiate and maintain therapy as long as it is tolerated well.

3 drugs to 2? Another question that remains is whether to switch patients who are doing well on 3-drug maintenance therapy to 2-drug maintenance therapy. According to Dr Spach, studies involving the combination dolutegravir/rilpivirine indicate that patients who have suppressed HIV RNA levels for at least 6 months on a 3-drug maintenance regimen do well after switching to the 2-drug combination dolutegravir/rilpivirine, as long as they do not have baseline resistance to either dolutegravir or rilpivirine. But he questioned the need for the change if the individual is tolerating a 3-drug regimen well, saying that given the safety of current regimens, the only broader motivating force may be cost savings. For now, he said, if patients are without complaints or tolerability issues on 3 drugs, leave them alone.

INSTIs and weight gain. The last issue is weight gain with the use of INSTIs. Preliminary data suggest disproportionate weight gain with these drugs (on the order of about 6 kg over a year and half, which may be 2-3 kg greater than that which occurs with PI-based and NNRTI-based regimens). At this point, experts do not recommend avoiding these agents, mainly because of the tremendous benefits that have been observed with INSTIs. Dr. Spach concluded, "Although we will continue to use INSTIs widely in clinical practice, there may be a subset of individuals taking an INSTI who have pronounced weight gain and may need to switch to another regimen that does not contain an INSTI.”

PORTLAND—The investigational drug islatravir “could be a game changer in the field of HIV," said David H. Spach, MD, Professor of Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases, University of Washington, Seattle, in a session called, "Antiretroviral therapy 2019 update: Mechanism of action, new medications, current guidelines, and controversies."

Dr. Spach reported that islatravir, a nucleoside reverse transcriptase translocation inhibitor (NRTTI), is highly potent, is well tolerated, has a high genetic barrier to resistance, and has an extremely long half-life, according to the findings of preliminary studies. Its long half-life enables subdermal implantation and maintenance of therapeutic levels even after a year in place. Researchers are studying the compound in combination with other agents for treatment and independently for preexposure prophylaxis.

Another noteworthy investigational agent, according to Dr. Spach, is cabotegravir, an integrase strand transfer inhibitor (INSTI) with the potential for intramuscular administration every 4 to 8 weeks. Dr. Spach explained that researchers are studying the agent in 3 different clinical situations: oral cabotegravir in combination with rilpivirine for lead-in therapy; an extended-release injectable of cabotegravir and rilpivirine for maintenance antiretroviral (ARV) treatment every 4 weeks; and an extended-release cabotegravir injectable for preexposure prophylaxis every 8 weeks. The agent is highly potent, with a high genetic barrier to resistance.

ARV: The current state of affairs

"We are in an era now where everyone who is living with HIV ideally should be receiving fully suppressive antiretroviral therapy," remarked Dr. Spach. He explained that not only does this benefit the person living with HIV by reducing the onset and progression of chronic inflammatory disease states that occur along with HIV, such as cardiovascular disease, stroke, and cancer, but also "fully suppressive ARV therapy virtually eliminates sexual transmission of HIV to another person."

Spach explained that the most recent (2018) Health and Human Services ARV therapy guidelines have greatly simplified the choices for ARV therapy. The current recommendations for initial ARV therapy for most people are to use a 2-drug backbone regimen, consisting of 2 nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs), combined with a single anchor drug, which should be an INSTI. The INSTI should have the highest potency and highest genetic barrier to resistance available, which effectively means using a regimen that contains either dolutegravir or bictegravir. The latter is available only in combination with emtricitabine and tenofovir alafenamide as a single-tablet regimen.

Spach also explained that "the guidelines have moved away from using boosted regimens for initial therapy, so elvitegravir boosted with cobicistat and protease inhibitors (PIs) boosted with ritonavir or cobicistat are no longer recommended as preferred initial therapy, although boosted PIs are still very useful as second- or third-line therapies."

Newer medications

Doravirine, a nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI), was approved by the FDA in 2018. "It probably won't have a big impact on initial therapy, but it is likely to have a significant effect on second- and third-line therapy," Dr. Spach said. "Because of its high potency and high genetic barrier to resistance, those taking etravirine twice a day, for example, may be able to simplify to once-a-day doravirine." In addition, "Doravirine may have advantages over rilpivirine in that it has no restrictions when used with acid-suppressing agents such as H2 blockers or proton pump inhibitors."

Continue to: Ibalizumab

Ibalizumab. Another newer agent “worth mentioning,” according to Dr. Spach, is ibalizumab. This monoclonal antibody has a unique mechanism of action. It is 1 of only 2 drugs used for HIV treatment that targets human receptors (all of the others work by inhibiting either an HIV enzyme or binding to the HIV virus itself). Ibalizumab targets the D2 region of the CD4 receptor. It is an injectable (intravenous) compound administered with an initial loading dose and then every 2 weeks thereafter. Dr. Spach reported that the data surrounding ibalizumab show that it is effective as an add-on medication in more advanced resistant settings. Also, it provides an option for people who can't take oral drugs, such as those who have had major surgery or trauma.

Remaining questions

Dr. Spach explained that 1 of the questions that remains is whether to prescribe ARV therapy for patients who are viremic controllers (those who inherently control HIV through their own immunologic response to a level < 200 copies) or elite controllers (those whose own immunologic response controls the virus to a level < 50 copies, which is in the undetectable range). Both of these groups still have a higher risk for hospitalization and for HIV-related inflammatory conditions such as heart disease, according to Dr. Spach. Current thinking among most experts is to initiate and maintain therapy as long as it is tolerated well.

3 drugs to 2? Another question that remains is whether to switch patients who are doing well on 3-drug maintenance therapy to 2-drug maintenance therapy. According to Dr Spach, studies involving the combination dolutegravir/rilpivirine indicate that patients who have suppressed HIV RNA levels for at least 6 months on a 3-drug maintenance regimen do well after switching to the 2-drug combination dolutegravir/rilpivirine, as long as they do not have baseline resistance to either dolutegravir or rilpivirine. But he questioned the need for the change if the individual is tolerating a 3-drug regimen well, saying that given the safety of current regimens, the only broader motivating force may be cost savings. For now, he said, if patients are without complaints or tolerability issues on 3 drugs, leave them alone.

INSTIs and weight gain. The last issue is weight gain with the use of INSTIs. Preliminary data suggest disproportionate weight gain with these drugs (on the order of about 6 kg over a year and half, which may be 2-3 kg greater than that which occurs with PI-based and NNRTI-based regimens). At this point, experts do not recommend avoiding these agents, mainly because of the tremendous benefits that have been observed with INSTIs. Dr. Spach concluded, "Although we will continue to use INSTIs widely in clinical practice, there may be a subset of individuals taking an INSTI who have pronounced weight gain and may need to switch to another regimen that does not contain an INSTI.”

PORTLAND—The investigational drug islatravir “could be a game changer in the field of HIV," said David H. Spach, MD, Professor of Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases, University of Washington, Seattle, in a session called, "Antiretroviral therapy 2019 update: Mechanism of action, new medications, current guidelines, and controversies."

Dr. Spach reported that islatravir, a nucleoside reverse transcriptase translocation inhibitor (NRTTI), is highly potent, is well tolerated, has a high genetic barrier to resistance, and has an extremely long half-life, according to the findings of preliminary studies. Its long half-life enables subdermal implantation and maintenance of therapeutic levels even after a year in place. Researchers are studying the compound in combination with other agents for treatment and independently for preexposure prophylaxis.

Another noteworthy investigational agent, according to Dr. Spach, is cabotegravir, an integrase strand transfer inhibitor (INSTI) with the potential for intramuscular administration every 4 to 8 weeks. Dr. Spach explained that researchers are studying the agent in 3 different clinical situations: oral cabotegravir in combination with rilpivirine for lead-in therapy; an extended-release injectable of cabotegravir and rilpivirine for maintenance antiretroviral (ARV) treatment every 4 weeks; and an extended-release cabotegravir injectable for preexposure prophylaxis every 8 weeks. The agent is highly potent, with a high genetic barrier to resistance.

ARV: The current state of affairs

"We are in an era now where everyone who is living with HIV ideally should be receiving fully suppressive antiretroviral therapy," remarked Dr. Spach. He explained that not only does this benefit the person living with HIV by reducing the onset and progression of chronic inflammatory disease states that occur along with HIV, such as cardiovascular disease, stroke, and cancer, but also "fully suppressive ARV therapy virtually eliminates sexual transmission of HIV to another person."

Spach explained that the most recent (2018) Health and Human Services ARV therapy guidelines have greatly simplified the choices for ARV therapy. The current recommendations for initial ARV therapy for most people are to use a 2-drug backbone regimen, consisting of 2 nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs), combined with a single anchor drug, which should be an INSTI. The INSTI should have the highest potency and highest genetic barrier to resistance available, which effectively means using a regimen that contains either dolutegravir or bictegravir. The latter is available only in combination with emtricitabine and tenofovir alafenamide as a single-tablet regimen.

Spach also explained that "the guidelines have moved away from using boosted regimens for initial therapy, so elvitegravir boosted with cobicistat and protease inhibitors (PIs) boosted with ritonavir or cobicistat are no longer recommended as preferred initial therapy, although boosted PIs are still very useful as second- or third-line therapies."

Newer medications

Doravirine, a nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI), was approved by the FDA in 2018. "It probably won't have a big impact on initial therapy, but it is likely to have a significant effect on second- and third-line therapy," Dr. Spach said. "Because of its high potency and high genetic barrier to resistance, those taking etravirine twice a day, for example, may be able to simplify to once-a-day doravirine." In addition, "Doravirine may have advantages over rilpivirine in that it has no restrictions when used with acid-suppressing agents such as H2 blockers or proton pump inhibitors."

Continue to: Ibalizumab

Ibalizumab. Another newer agent “worth mentioning,” according to Dr. Spach, is ibalizumab. This monoclonal antibody has a unique mechanism of action. It is 1 of only 2 drugs used for HIV treatment that targets human receptors (all of the others work by inhibiting either an HIV enzyme or binding to the HIV virus itself). Ibalizumab targets the D2 region of the CD4 receptor. It is an injectable (intravenous) compound administered with an initial loading dose and then every 2 weeks thereafter. Dr. Spach reported that the data surrounding ibalizumab show that it is effective as an add-on medication in more advanced resistant settings. Also, it provides an option for people who can't take oral drugs, such as those who have had major surgery or trauma.

Remaining questions

Dr. Spach explained that 1 of the questions that remains is whether to prescribe ARV therapy for patients who are viremic controllers (those who inherently control HIV through their own immunologic response to a level < 200 copies) or elite controllers (those whose own immunologic response controls the virus to a level < 50 copies, which is in the undetectable range). Both of these groups still have a higher risk for hospitalization and for HIV-related inflammatory conditions such as heart disease, according to Dr. Spach. Current thinking among most experts is to initiate and maintain therapy as long as it is tolerated well.

3 drugs to 2? Another question that remains is whether to switch patients who are doing well on 3-drug maintenance therapy to 2-drug maintenance therapy. According to Dr Spach, studies involving the combination dolutegravir/rilpivirine indicate that patients who have suppressed HIV RNA levels for at least 6 months on a 3-drug maintenance regimen do well after switching to the 2-drug combination dolutegravir/rilpivirine, as long as they do not have baseline resistance to either dolutegravir or rilpivirine. But he questioned the need for the change if the individual is tolerating a 3-drug regimen well, saying that given the safety of current regimens, the only broader motivating force may be cost savings. For now, he said, if patients are without complaints or tolerability issues on 3 drugs, leave them alone.

INSTIs and weight gain. The last issue is weight gain with the use of INSTIs. Preliminary data suggest disproportionate weight gain with these drugs (on the order of about 6 kg over a year and half, which may be 2-3 kg greater than that which occurs with PI-based and NNRTI-based regimens). At this point, experts do not recommend avoiding these agents, mainly because of the tremendous benefits that have been observed with INSTIs. Dr. Spach concluded, "Although we will continue to use INSTIs widely in clinical practice, there may be a subset of individuals taking an INSTI who have pronounced weight gain and may need to switch to another regimen that does not contain an INSTI.”

Association of Nurses in AIDS Care 2019

ObGyn compensation: Strides in the gender wage gap indicate closure possible

The gender wage gap in physician compensation persists but is narrowing. According to information gleaned from self-reported compensation surveys, collected by Doximity and completed by 90,000 full-time, US-licensed physicians, while wages for men idled between 2017 and 2018, they increased for women by 2%.1 So, whereas the gender wage gap was 27.7% in 2017, it dropped to 25.2% in 2018. This translates to female physicians making $90,490 less than male counterparts in 2018 vs $105,000 less in 2017.1

Gender wage gap and geography. Metropolitan areas with the smallest gender wage gaps according to the Doximity report include Birmingham, Alabama (9%); Bridgeport, Connecticut (10%); and Seattle, Washington (15%). Areas with the largest gender wage gap include Louisville/Jefferson County, Kentucky-Indiana (40%); New Orleans, Louisiana (32%); and Austin, Texas (31%).1

Gender wage gap and specialty. Specialties with the widest gender wage gaps are pediatric pulmonology (23%), otolaryngology (22%), and urology (22%). Those with the narrowest gaps are hematology (4%), rheumatology (8%), and radiation oncology (9%).1

Interestingly, although female physicians continue to earn less than men across the board, women were the slight majority of US medical school applicants (50.9%) and matriculants (51.6%) in 2018.2

What are physicians earning?

The overall average salary for physicians in 2019 is $313,000, according to a Medscape report, and the average annual compensation for ObGyns is $303,000, up from $300,000 in 2018.3 Doximity’s figure was slightly different; it reported average annual compensation for ObGyns to be $335,000 in 2018, ranking ObGyns 20th in specialties with the highest annual compensation.1

Compensation by specialty. The specialties with the highest average annual compensation in 2018 according to the Doximity report were neurosurgery ($617K), thoracic surgery ($584K), and orthopedic surgery ($526K). Those with the lowest were pediatric infectious disease ($186K), pediatric endocrinology ($201K), and general pediatrics ($223K).1

While women make up 61% of the ObGyn workforce, fewer than 15% of cardiologists, urologists, and orthopedists—some of the highest paying specialties—are women, although this alone does not explain the gender wage gap.3

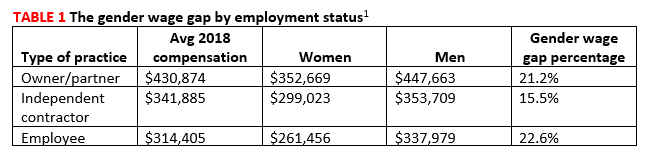

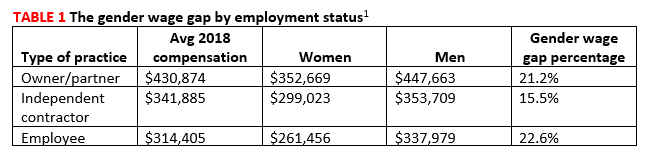

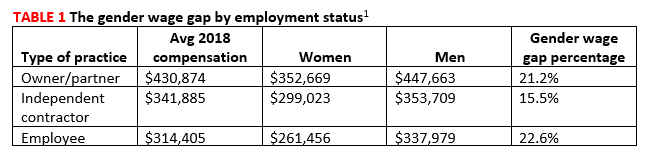

Compensation by employment type. While average annual compensation increased from 2017 to 2018 for physicians working in single specialty groups (1%), multispecialty groups (1%), solo practices (3%), and industry/pharmaceutical (17%), compensation decreased for those working in health maintenance organizations (-1%), hospitals (-7%), and academia (-9%).1 Only 14% of private practices are owned by female physicians (TABLE 1).1

Satisfaction with compensation. Exactly half (50%) of ObGyns report feeling fairly compensated.3 Those physicians working in public health and preventive medicine are the most likely to feel fairly compensated (73%), while those working in infectious disease are least likely (42%).3

Location matters and may surprise you

Contrary to what many believe, less populated metropolitan areas tend to pay better than larger, more populated cities.1 This may be because metropolitan areas without academic institutions or nationally renowned health systems tend to offer slightly higher compensation than those with such facilities. The reason? The presence of large or prestigious medical schools ensures a pipeline of viable physician candidates for limited jobs, resulting in institutions and practices needing to pay less for qualified applicants.1

The 5 markets paying the highest physician salaries in 2018 were (from highest to lowest) Milwaukee; New Orleans; Riverside, California; Minneapolis; and Charlotte, North Carolina. Those paying the lowest were Durham, North Carolina; Providence, Rhode Island; San Antonio; Virginia Beach; and New Haven, Connecticut.1 Rural areas continue to have problems luring physicians (see “Cures for the famine of rural physicians?”3,4).

Job satisfaction

ObGyns rank 16th in terms of specialists who are happiest at work; 27% responded that they were very or extremely happy. Plastic surgeons ranked first in happiness on the job (41%), while those in physical medicine and rehabilitation ranked last (19%).5

Physicians as a whole report that the most rewarding part of the job is the gratitude from and relationships with patients, followed by “being good at a what I do”/finding answers/diagnoses, and “knowing that I’m making the world a better place.”3 Three-quarters (74%) of ObGyns would choose medicine again, and 75% would choose the same specialty. Those most likely to choose medicine again are those in infectious disease (84%), while those least likely work in physical medicine and rehabilitation (62%). Those most satisfied with their chosen specialty are ophthalmologists; 96% would choose the specialty again, whereas only 62% of internists would do so.3

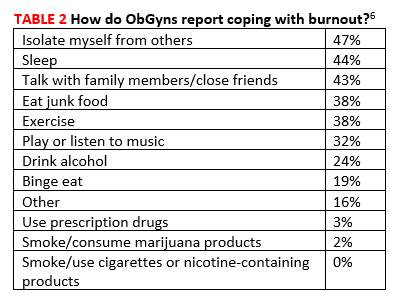

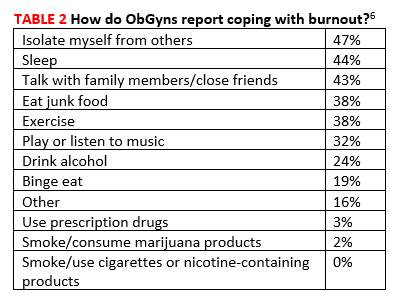

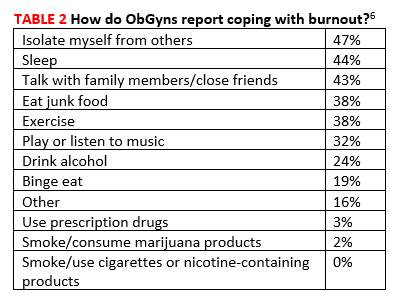

Burnout. In a Medscape survey of 15,000 physicians in 29 specialties, 45% of ObGyns reported being burned out.5 Another 15% reported being “colloquially” depressed (sad, despondent, but not clinically depressed), and 7% reported clinical depression. While physicians overall most frequently engage in exercise as a coping mechanism, ObGyns most frequently report isolating themselves from others (47%)(TABLE 2).6

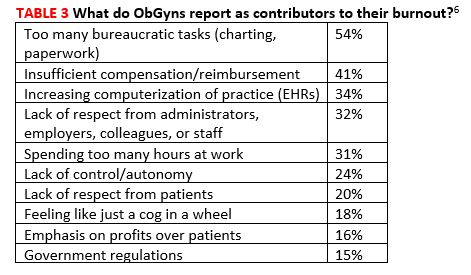

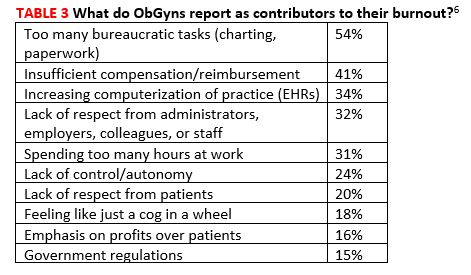

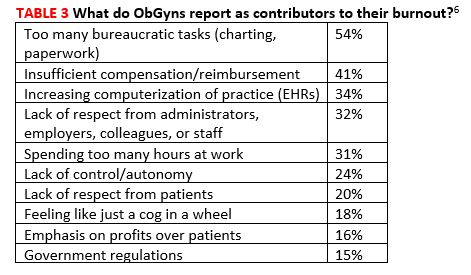

Across all specialties, more female physicians report being burned out than men (50% vs 39%). The 3 highest contributors to burnout are too many bureaucratic tasks (charting, paperwork), spending too many hours at work/insufficient compensation, and the increasing computerization of practices (electronic health records [EHRs])(TABLE 3).6 While 44% of ObGyns report that their feelings of being burned out or depressed do not affect their interactions with patients, 39% say such feelings make them easily exasperated with their patients.6 One in five (20%) responding ObGyns reported having had thoughts of suicide (vs 14% for physicians as a whole).5,6

Fortunately, ObGyns are the third most likely type of specialists to seek help for burnout or depression (37%), following psychiatrists (45%) and public health and preventive medicine specialists (45%).6 Those least likely to seek help are allergists/immunologists (13%).5

Sources of frustration on the job

Long hours. Physicians responding to the Medscape survey say that the most frustrating part of their job is having so many rules and regulations, followed by having to work with an EHR, and having to work long hours.3

As for the latter, 60% of responding ObGyns reported working long hours, which places obstetrics/gynecology in the 11th position on a list of specialties with physicians reporting working too many hours.5 Surgeons were number 1 with 77% reporting working long hours, and emergency medicine physicians were last with only 13% reporting working long hours.

Paper and administrative tasks. Thirty-eight percent of the physicians responding to the Medscape survey report spending 10 to 19 hours per week on paperwork; another 36% report spending 20 hours or more.3 This is almost identical to last year when the figures were 38% and 32%, respectively. However, the trend in the last few years has been dramatic. In 2017, the total percentage of physicians spending 10 of more hours on paperwork per week was 57%, compared with this year’s 74%.3

According to the latest Medscape report, 50% of responding physicians employ nurse practitioners (NPs) and 36% employ physician assistants (PAs); 38% employ neither. Almost half (47%) of respondents report increased profitability as a result of employing NPs/PAs.1

NPs and PAs may be increasingly important in rural America, suggests Skinner and colleagues in an article in New England Journal of Medicine.2,3 They report that the total number of rural physicians grew only 3% between 2000 and 2017 (from 61,000 to 62,700) and that the number of physicians under 50 years of age living in rural areas decreased by 25% during the same time period (from 39,200 to 29,600). As a result, the rural physician workforce is aging. In 2017, only about 25% of rural physicians were under the age of 50 years. Without a sizeable influx of younger physicians, the size of the rural physician workforce will decrease by 23% by 2030, as all of the current rural physicians retire.

To help offset the difference, the authors suggest that the rapidly growing NP workforce is poised to help. NPs provide cost-effective, high-quality care, and many more go into primary care in rural areas than do physicians. The authors suggest that sites training primary care clinicians, particularly those in or near rural areas, should work with programs educating NPs to develop ways to make it conducive for rural NPs to consult with physicians and other rural health specialists, and, in this way, help to stave off the coming dearth of physicians in rural America.

In addition to utilizing an NP workforce, Skinner and colleagues suggest that further strategies will be needed to address the rural physician shortfall and greater patient workload. Although certain actions instituted in the past have been helpful, including physician loan repayment, expansion of the national health service corps, medical school grants, and funding of rural teaching clinics, they have not done enough to address the growing needs of rural patient populations. The authors additionally suggest2:

- expansion of graduate medical education programs in rural hospitals

- higher payments for physicians in rural areas

- expanding use of mobile health vans equipped with diagnostic and treatment technology

- overcoming barriers that have slowed adoption of telehealth services.

References

- Kane L. Medscape physician compensation report 2019. Color/Word_R0_G0_B255https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2019-compensation-overview-6011286#30. Accessed August 19, 2019.

- Skinner L, Staiger DO, Auerbach DI, Buerhaus PI. Implications of an aging rural physician workforce. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(4):299-300. https://www.nejm.org/doi/pdf/10.1056/NEJMp1900808?articleTools=true. Accessed August 19, 2019.

- Morr M. Nurse practitioners may alleviate dwindling physician workforce in rural populations. Clinical Advisor.

- Doximity. 2019 Physician Compensation Report. Third annual study. https://s3.amazonaws.com/s3.doximity.com/press/doximity_third_annual_physician_compensation_report_round4.pdf Color/Word_R0_G0_B255 March 2019. Accessed August 19, 2019.

- Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC). Women were majority of US medical school applicants in 2018. Press release, December 4, 2018. Color/Word_R0_G0_B255https://news.aamc.org/press-releases/article/applicant-data-2018/. Accessed August 19, 2019.

- Kane L. Medscape physician compensation report 2019. Color/Word_R0_G0_B255https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2019-compensation-overview-6011286#30. Accessed August 19, 2019.

- Skinner L, Staiger DO, Auerbach DI, et al. Implications of an aging rural physician workforce. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:299-300. https://www.nejm.org/doi/pdf/10.1056/NEJMp1900808?articleTools=true. Accessed August 19, 2019.

- Kane L. Medscape national physician burnout, depression and suicide report 2019. January 16, 2019. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2019-lifestyle-burnout-depression-6011056. Accessed August 19, 2019.

- Kane L. Medscape obstetrician and gynecologist lifestyle, happiness and burnout report 2019. February 20, 2019. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2019-lifestyle-obgyn-6011131Color/Word_R0_G0_B255. Accessed August 20, 2019.

The gender wage gap in physician compensation persists but is narrowing. According to information gleaned from self-reported compensation surveys, collected by Doximity and completed by 90,000 full-time, US-licensed physicians, while wages for men idled between 2017 and 2018, they increased for women by 2%.1 So, whereas the gender wage gap was 27.7% in 2017, it dropped to 25.2% in 2018. This translates to female physicians making $90,490 less than male counterparts in 2018 vs $105,000 less in 2017.1

Gender wage gap and geography. Metropolitan areas with the smallest gender wage gaps according to the Doximity report include Birmingham, Alabama (9%); Bridgeport, Connecticut (10%); and Seattle, Washington (15%). Areas with the largest gender wage gap include Louisville/Jefferson County, Kentucky-Indiana (40%); New Orleans, Louisiana (32%); and Austin, Texas (31%).1

Gender wage gap and specialty. Specialties with the widest gender wage gaps are pediatric pulmonology (23%), otolaryngology (22%), and urology (22%). Those with the narrowest gaps are hematology (4%), rheumatology (8%), and radiation oncology (9%).1

Interestingly, although female physicians continue to earn less than men across the board, women were the slight majority of US medical school applicants (50.9%) and matriculants (51.6%) in 2018.2

What are physicians earning?

The overall average salary for physicians in 2019 is $313,000, according to a Medscape report, and the average annual compensation for ObGyns is $303,000, up from $300,000 in 2018.3 Doximity’s figure was slightly different; it reported average annual compensation for ObGyns to be $335,000 in 2018, ranking ObGyns 20th in specialties with the highest annual compensation.1

Compensation by specialty. The specialties with the highest average annual compensation in 2018 according to the Doximity report were neurosurgery ($617K), thoracic surgery ($584K), and orthopedic surgery ($526K). Those with the lowest were pediatric infectious disease ($186K), pediatric endocrinology ($201K), and general pediatrics ($223K).1

While women make up 61% of the ObGyn workforce, fewer than 15% of cardiologists, urologists, and orthopedists—some of the highest paying specialties—are women, although this alone does not explain the gender wage gap.3

Compensation by employment type. While average annual compensation increased from 2017 to 2018 for physicians working in single specialty groups (1%), multispecialty groups (1%), solo practices (3%), and industry/pharmaceutical (17%), compensation decreased for those working in health maintenance organizations (-1%), hospitals (-7%), and academia (-9%).1 Only 14% of private practices are owned by female physicians (TABLE 1).1

Satisfaction with compensation. Exactly half (50%) of ObGyns report feeling fairly compensated.3 Those physicians working in public health and preventive medicine are the most likely to feel fairly compensated (73%), while those working in infectious disease are least likely (42%).3

Location matters and may surprise you

Contrary to what many believe, less populated metropolitan areas tend to pay better than larger, more populated cities.1 This may be because metropolitan areas without academic institutions or nationally renowned health systems tend to offer slightly higher compensation than those with such facilities. The reason? The presence of large or prestigious medical schools ensures a pipeline of viable physician candidates for limited jobs, resulting in institutions and practices needing to pay less for qualified applicants.1

The 5 markets paying the highest physician salaries in 2018 were (from highest to lowest) Milwaukee; New Orleans; Riverside, California; Minneapolis; and Charlotte, North Carolina. Those paying the lowest were Durham, North Carolina; Providence, Rhode Island; San Antonio; Virginia Beach; and New Haven, Connecticut.1 Rural areas continue to have problems luring physicians (see “Cures for the famine of rural physicians?”3,4).

Job satisfaction

ObGyns rank 16th in terms of specialists who are happiest at work; 27% responded that they were very or extremely happy. Plastic surgeons ranked first in happiness on the job (41%), while those in physical medicine and rehabilitation ranked last (19%).5

Physicians as a whole report that the most rewarding part of the job is the gratitude from and relationships with patients, followed by “being good at a what I do”/finding answers/diagnoses, and “knowing that I’m making the world a better place.”3 Three-quarters (74%) of ObGyns would choose medicine again, and 75% would choose the same specialty. Those most likely to choose medicine again are those in infectious disease (84%), while those least likely work in physical medicine and rehabilitation (62%). Those most satisfied with their chosen specialty are ophthalmologists; 96% would choose the specialty again, whereas only 62% of internists would do so.3

Burnout. In a Medscape survey of 15,000 physicians in 29 specialties, 45% of ObGyns reported being burned out.5 Another 15% reported being “colloquially” depressed (sad, despondent, but not clinically depressed), and 7% reported clinical depression. While physicians overall most frequently engage in exercise as a coping mechanism, ObGyns most frequently report isolating themselves from others (47%)(TABLE 2).6

Across all specialties, more female physicians report being burned out than men (50% vs 39%). The 3 highest contributors to burnout are too many bureaucratic tasks (charting, paperwork), spending too many hours at work/insufficient compensation, and the increasing computerization of practices (electronic health records [EHRs])(TABLE 3).6 While 44% of ObGyns report that their feelings of being burned out or depressed do not affect their interactions with patients, 39% say such feelings make them easily exasperated with their patients.6 One in five (20%) responding ObGyns reported having had thoughts of suicide (vs 14% for physicians as a whole).5,6

Fortunately, ObGyns are the third most likely type of specialists to seek help for burnout or depression (37%), following psychiatrists (45%) and public health and preventive medicine specialists (45%).6 Those least likely to seek help are allergists/immunologists (13%).5

Sources of frustration on the job

Long hours. Physicians responding to the Medscape survey say that the most frustrating part of their job is having so many rules and regulations, followed by having to work with an EHR, and having to work long hours.3

As for the latter, 60% of responding ObGyns reported working long hours, which places obstetrics/gynecology in the 11th position on a list of specialties with physicians reporting working too many hours.5 Surgeons were number 1 with 77% reporting working long hours, and emergency medicine physicians were last with only 13% reporting working long hours.

Paper and administrative tasks. Thirty-eight percent of the physicians responding to the Medscape survey report spending 10 to 19 hours per week on paperwork; another 36% report spending 20 hours or more.3 This is almost identical to last year when the figures were 38% and 32%, respectively. However, the trend in the last few years has been dramatic. In 2017, the total percentage of physicians spending 10 of more hours on paperwork per week was 57%, compared with this year’s 74%.3

According to the latest Medscape report, 50% of responding physicians employ nurse practitioners (NPs) and 36% employ physician assistants (PAs); 38% employ neither. Almost half (47%) of respondents report increased profitability as a result of employing NPs/PAs.1

NPs and PAs may be increasingly important in rural America, suggests Skinner and colleagues in an article in New England Journal of Medicine.2,3 They report that the total number of rural physicians grew only 3% between 2000 and 2017 (from 61,000 to 62,700) and that the number of physicians under 50 years of age living in rural areas decreased by 25% during the same time period (from 39,200 to 29,600). As a result, the rural physician workforce is aging. In 2017, only about 25% of rural physicians were under the age of 50 years. Without a sizeable influx of younger physicians, the size of the rural physician workforce will decrease by 23% by 2030, as all of the current rural physicians retire.

To help offset the difference, the authors suggest that the rapidly growing NP workforce is poised to help. NPs provide cost-effective, high-quality care, and many more go into primary care in rural areas than do physicians. The authors suggest that sites training primary care clinicians, particularly those in or near rural areas, should work with programs educating NPs to develop ways to make it conducive for rural NPs to consult with physicians and other rural health specialists, and, in this way, help to stave off the coming dearth of physicians in rural America.

In addition to utilizing an NP workforce, Skinner and colleagues suggest that further strategies will be needed to address the rural physician shortfall and greater patient workload. Although certain actions instituted in the past have been helpful, including physician loan repayment, expansion of the national health service corps, medical school grants, and funding of rural teaching clinics, they have not done enough to address the growing needs of rural patient populations. The authors additionally suggest2:

- expansion of graduate medical education programs in rural hospitals

- higher payments for physicians in rural areas

- expanding use of mobile health vans equipped with diagnostic and treatment technology

- overcoming barriers that have slowed adoption of telehealth services.

References

- Kane L. Medscape physician compensation report 2019. Color/Word_R0_G0_B255https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2019-compensation-overview-6011286#30. Accessed August 19, 2019.

- Skinner L, Staiger DO, Auerbach DI, Buerhaus PI. Implications of an aging rural physician workforce. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(4):299-300. https://www.nejm.org/doi/pdf/10.1056/NEJMp1900808?articleTools=true. Accessed August 19, 2019.

- Morr M. Nurse practitioners may alleviate dwindling physician workforce in rural populations. Clinical Advisor.

The gender wage gap in physician compensation persists but is narrowing. According to information gleaned from self-reported compensation surveys, collected by Doximity and completed by 90,000 full-time, US-licensed physicians, while wages for men idled between 2017 and 2018, they increased for women by 2%.1 So, whereas the gender wage gap was 27.7% in 2017, it dropped to 25.2% in 2018. This translates to female physicians making $90,490 less than male counterparts in 2018 vs $105,000 less in 2017.1

Gender wage gap and geography. Metropolitan areas with the smallest gender wage gaps according to the Doximity report include Birmingham, Alabama (9%); Bridgeport, Connecticut (10%); and Seattle, Washington (15%). Areas with the largest gender wage gap include Louisville/Jefferson County, Kentucky-Indiana (40%); New Orleans, Louisiana (32%); and Austin, Texas (31%).1

Gender wage gap and specialty. Specialties with the widest gender wage gaps are pediatric pulmonology (23%), otolaryngology (22%), and urology (22%). Those with the narrowest gaps are hematology (4%), rheumatology (8%), and radiation oncology (9%).1

Interestingly, although female physicians continue to earn less than men across the board, women were the slight majority of US medical school applicants (50.9%) and matriculants (51.6%) in 2018.2

What are physicians earning?

The overall average salary for physicians in 2019 is $313,000, according to a Medscape report, and the average annual compensation for ObGyns is $303,000, up from $300,000 in 2018.3 Doximity’s figure was slightly different; it reported average annual compensation for ObGyns to be $335,000 in 2018, ranking ObGyns 20th in specialties with the highest annual compensation.1

Compensation by specialty. The specialties with the highest average annual compensation in 2018 according to the Doximity report were neurosurgery ($617K), thoracic surgery ($584K), and orthopedic surgery ($526K). Those with the lowest were pediatric infectious disease ($186K), pediatric endocrinology ($201K), and general pediatrics ($223K).1

While women make up 61% of the ObGyn workforce, fewer than 15% of cardiologists, urologists, and orthopedists—some of the highest paying specialties—are women, although this alone does not explain the gender wage gap.3

Compensation by employment type. While average annual compensation increased from 2017 to 2018 for physicians working in single specialty groups (1%), multispecialty groups (1%), solo practices (3%), and industry/pharmaceutical (17%), compensation decreased for those working in health maintenance organizations (-1%), hospitals (-7%), and academia (-9%).1 Only 14% of private practices are owned by female physicians (TABLE 1).1

Satisfaction with compensation. Exactly half (50%) of ObGyns report feeling fairly compensated.3 Those physicians working in public health and preventive medicine are the most likely to feel fairly compensated (73%), while those working in infectious disease are least likely (42%).3

Location matters and may surprise you

Contrary to what many believe, less populated metropolitan areas tend to pay better than larger, more populated cities.1 This may be because metropolitan areas without academic institutions or nationally renowned health systems tend to offer slightly higher compensation than those with such facilities. The reason? The presence of large or prestigious medical schools ensures a pipeline of viable physician candidates for limited jobs, resulting in institutions and practices needing to pay less for qualified applicants.1

The 5 markets paying the highest physician salaries in 2018 were (from highest to lowest) Milwaukee; New Orleans; Riverside, California; Minneapolis; and Charlotte, North Carolina. Those paying the lowest were Durham, North Carolina; Providence, Rhode Island; San Antonio; Virginia Beach; and New Haven, Connecticut.1 Rural areas continue to have problems luring physicians (see “Cures for the famine of rural physicians?”3,4).

Job satisfaction

ObGyns rank 16th in terms of specialists who are happiest at work; 27% responded that they were very or extremely happy. Plastic surgeons ranked first in happiness on the job (41%), while those in physical medicine and rehabilitation ranked last (19%).5

Physicians as a whole report that the most rewarding part of the job is the gratitude from and relationships with patients, followed by “being good at a what I do”/finding answers/diagnoses, and “knowing that I’m making the world a better place.”3 Three-quarters (74%) of ObGyns would choose medicine again, and 75% would choose the same specialty. Those most likely to choose medicine again are those in infectious disease (84%), while those least likely work in physical medicine and rehabilitation (62%). Those most satisfied with their chosen specialty are ophthalmologists; 96% would choose the specialty again, whereas only 62% of internists would do so.3

Burnout. In a Medscape survey of 15,000 physicians in 29 specialties, 45% of ObGyns reported being burned out.5 Another 15% reported being “colloquially” depressed (sad, despondent, but not clinically depressed), and 7% reported clinical depression. While physicians overall most frequently engage in exercise as a coping mechanism, ObGyns most frequently report isolating themselves from others (47%)(TABLE 2).6

Across all specialties, more female physicians report being burned out than men (50% vs 39%). The 3 highest contributors to burnout are too many bureaucratic tasks (charting, paperwork), spending too many hours at work/insufficient compensation, and the increasing computerization of practices (electronic health records [EHRs])(TABLE 3).6 While 44% of ObGyns report that their feelings of being burned out or depressed do not affect their interactions with patients, 39% say such feelings make them easily exasperated with their patients.6 One in five (20%) responding ObGyns reported having had thoughts of suicide (vs 14% for physicians as a whole).5,6

Fortunately, ObGyns are the third most likely type of specialists to seek help for burnout or depression (37%), following psychiatrists (45%) and public health and preventive medicine specialists (45%).6 Those least likely to seek help are allergists/immunologists (13%).5

Sources of frustration on the job

Long hours. Physicians responding to the Medscape survey say that the most frustrating part of their job is having so many rules and regulations, followed by having to work with an EHR, and having to work long hours.3

As for the latter, 60% of responding ObGyns reported working long hours, which places obstetrics/gynecology in the 11th position on a list of specialties with physicians reporting working too many hours.5 Surgeons were number 1 with 77% reporting working long hours, and emergency medicine physicians were last with only 13% reporting working long hours.

Paper and administrative tasks. Thirty-eight percent of the physicians responding to the Medscape survey report spending 10 to 19 hours per week on paperwork; another 36% report spending 20 hours or more.3 This is almost identical to last year when the figures were 38% and 32%, respectively. However, the trend in the last few years has been dramatic. In 2017, the total percentage of physicians spending 10 of more hours on paperwork per week was 57%, compared with this year’s 74%.3

According to the latest Medscape report, 50% of responding physicians employ nurse practitioners (NPs) and 36% employ physician assistants (PAs); 38% employ neither. Almost half (47%) of respondents report increased profitability as a result of employing NPs/PAs.1

NPs and PAs may be increasingly important in rural America, suggests Skinner and colleagues in an article in New England Journal of Medicine.2,3 They report that the total number of rural physicians grew only 3% between 2000 and 2017 (from 61,000 to 62,700) and that the number of physicians under 50 years of age living in rural areas decreased by 25% during the same time period (from 39,200 to 29,600). As a result, the rural physician workforce is aging. In 2017, only about 25% of rural physicians were under the age of 50 years. Without a sizeable influx of younger physicians, the size of the rural physician workforce will decrease by 23% by 2030, as all of the current rural physicians retire.

To help offset the difference, the authors suggest that the rapidly growing NP workforce is poised to help. NPs provide cost-effective, high-quality care, and many more go into primary care in rural areas than do physicians. The authors suggest that sites training primary care clinicians, particularly those in or near rural areas, should work with programs educating NPs to develop ways to make it conducive for rural NPs to consult with physicians and other rural health specialists, and, in this way, help to stave off the coming dearth of physicians in rural America.