User login

ObGyn compensation: Strides in the gender wage gap indicate closure possible

The gender wage gap in physician compensation persists but is narrowing. According to information gleaned from self-reported compensation surveys, collected by Doximity and completed by 90,000 full-time, US-licensed physicians, while wages for men idled between 2017 and 2018, they increased for women by 2%.1 So, whereas the gender wage gap was 27.7% in 2017, it dropped to 25.2% in 2018. This translates to female physicians making $90,490 less than male counterparts in 2018 vs $105,000 less in 2017.1

Gender wage gap and geography. Metropolitan areas with the smallest gender wage gaps according to the Doximity report include Birmingham, Alabama (9%); Bridgeport, Connecticut (10%); and Seattle, Washington (15%). Areas with the largest gender wage gap include Louisville/Jefferson County, Kentucky-Indiana (40%); New Orleans, Louisiana (32%); and Austin, Texas (31%).1

Gender wage gap and specialty. Specialties with the widest gender wage gaps are pediatric pulmonology (23%), otolaryngology (22%), and urology (22%). Those with the narrowest gaps are hematology (4%), rheumatology (8%), and radiation oncology (9%).1

Interestingly, although female physicians continue to earn less than men across the board, women were the slight majority of US medical school applicants (50.9%) and matriculants (51.6%) in 2018.2

What are physicians earning?

The overall average salary for physicians in 2019 is $313,000, according to a Medscape report, and the average annual compensation for ObGyns is $303,000, up from $300,000 in 2018.3 Doximity’s figure was slightly different; it reported average annual compensation for ObGyns to be $335,000 in 2018, ranking ObGyns 20th in specialties with the highest annual compensation.1

Compensation by specialty. The specialties with the highest average annual compensation in 2018 according to the Doximity report were neurosurgery ($617K), thoracic surgery ($584K), and orthopedic surgery ($526K). Those with the lowest were pediatric infectious disease ($186K), pediatric endocrinology ($201K), and general pediatrics ($223K).1

While women make up 61% of the ObGyn workforce, fewer than 15% of cardiologists, urologists, and orthopedists—some of the highest paying specialties—are women, although this alone does not explain the gender wage gap.3

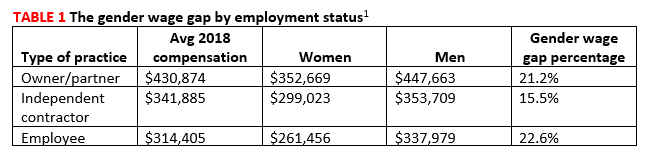

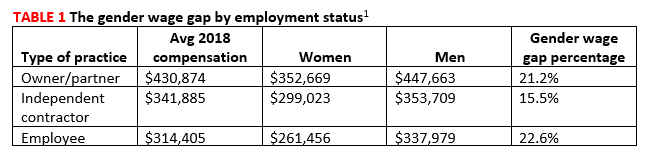

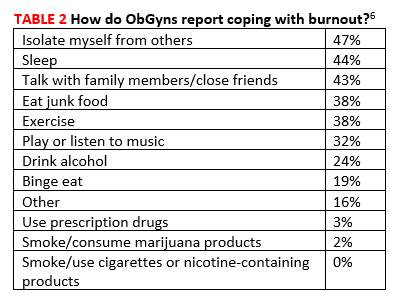

Compensation by employment type. While average annual compensation increased from 2017 to 2018 for physicians working in single specialty groups (1%), multispecialty groups (1%), solo practices (3%), and industry/pharmaceutical (17%), compensation decreased for those working in health maintenance organizations (-1%), hospitals (-7%), and academia (-9%).1 Only 14% of private practices are owned by female physicians (TABLE 1).1

Satisfaction with compensation. Exactly half (50%) of ObGyns report feeling fairly compensated.3 Those physicians working in public health and preventive medicine are the most likely to feel fairly compensated (73%), while those working in infectious disease are least likely (42%).3

Location matters and may surprise you

Contrary to what many believe, less populated metropolitan areas tend to pay better than larger, more populated cities.1 This may be because metropolitan areas without academic institutions or nationally renowned health systems tend to offer slightly higher compensation than those with such facilities. The reason? The presence of large or prestigious medical schools ensures a pipeline of viable physician candidates for limited jobs, resulting in institutions and practices needing to pay less for qualified applicants.1

The 5 markets paying the highest physician salaries in 2018 were (from highest to lowest) Milwaukee; New Orleans; Riverside, California; Minneapolis; and Charlotte, North Carolina. Those paying the lowest were Durham, North Carolina; Providence, Rhode Island; San Antonio; Virginia Beach; and New Haven, Connecticut.1 Rural areas continue to have problems luring physicians (see “Cures for the famine of rural physicians?”3,4).

Job satisfaction

ObGyns rank 16th in terms of specialists who are happiest at work; 27% responded that they were very or extremely happy. Plastic surgeons ranked first in happiness on the job (41%), while those in physical medicine and rehabilitation ranked last (19%).5

Physicians as a whole report that the most rewarding part of the job is the gratitude from and relationships with patients, followed by “being good at a what I do”/finding answers/diagnoses, and “knowing that I’m making the world a better place.”3 Three-quarters (74%) of ObGyns would choose medicine again, and 75% would choose the same specialty. Those most likely to choose medicine again are those in infectious disease (84%), while those least likely work in physical medicine and rehabilitation (62%). Those most satisfied with their chosen specialty are ophthalmologists; 96% would choose the specialty again, whereas only 62% of internists would do so.3

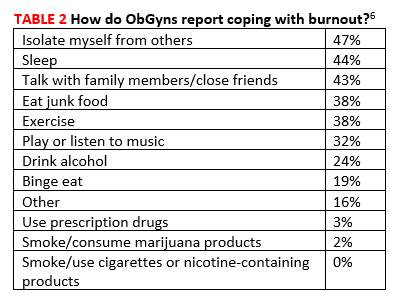

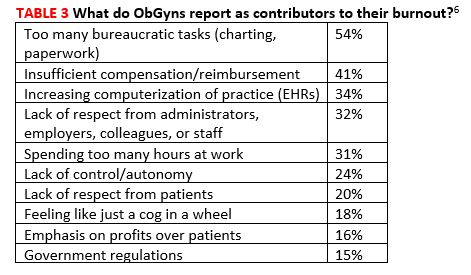

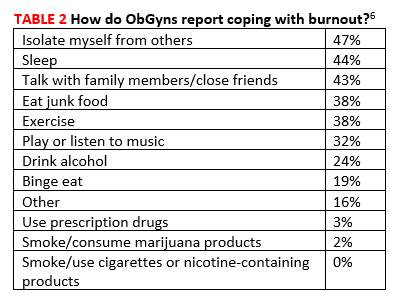

Burnout. In a Medscape survey of 15,000 physicians in 29 specialties, 45% of ObGyns reported being burned out.5 Another 15% reported being “colloquially” depressed (sad, despondent, but not clinically depressed), and 7% reported clinical depression. While physicians overall most frequently engage in exercise as a coping mechanism, ObGyns most frequently report isolating themselves from others (47%)(TABLE 2).6

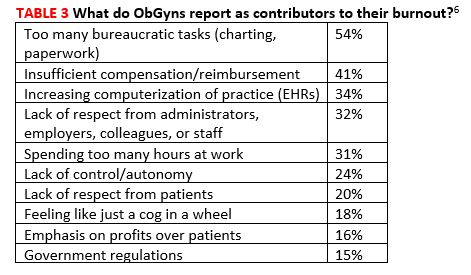

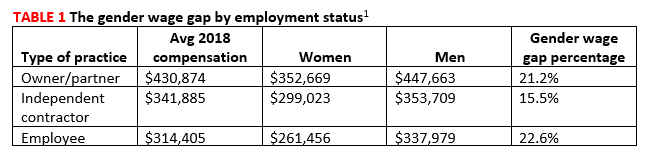

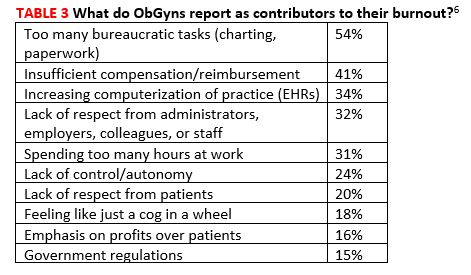

Across all specialties, more female physicians report being burned out than men (50% vs 39%). The 3 highest contributors to burnout are too many bureaucratic tasks (charting, paperwork), spending too many hours at work/insufficient compensation, and the increasing computerization of practices (electronic health records [EHRs])(TABLE 3).6 While 44% of ObGyns report that their feelings of being burned out or depressed do not affect their interactions with patients, 39% say such feelings make them easily exasperated with their patients.6 One in five (20%) responding ObGyns reported having had thoughts of suicide (vs 14% for physicians as a whole).5,6

Fortunately, ObGyns are the third most likely type of specialists to seek help for burnout or depression (37%), following psychiatrists (45%) and public health and preventive medicine specialists (45%).6 Those least likely to seek help are allergists/immunologists (13%).5

Sources of frustration on the job

Long hours. Physicians responding to the Medscape survey say that the most frustrating part of their job is having so many rules and regulations, followed by having to work with an EHR, and having to work long hours.3

As for the latter, 60% of responding ObGyns reported working long hours, which places obstetrics/gynecology in the 11th position on a list of specialties with physicians reporting working too many hours.5 Surgeons were number 1 with 77% reporting working long hours, and emergency medicine physicians were last with only 13% reporting working long hours.

Paper and administrative tasks. Thirty-eight percent of the physicians responding to the Medscape survey report spending 10 to 19 hours per week on paperwork; another 36% report spending 20 hours or more.3 This is almost identical to last year when the figures were 38% and 32%, respectively. However, the trend in the last few years has been dramatic. In 2017, the total percentage of physicians spending 10 of more hours on paperwork per week was 57%, compared with this year’s 74%.3

According to the latest Medscape report, 50% of responding physicians employ nurse practitioners (NPs) and 36% employ physician assistants (PAs); 38% employ neither. Almost half (47%) of respondents report increased profitability as a result of employing NPs/PAs.1

NPs and PAs may be increasingly important in rural America, suggests Skinner and colleagues in an article in New England Journal of Medicine.2,3 They report that the total number of rural physicians grew only 3% between 2000 and 2017 (from 61,000 to 62,700) and that the number of physicians under 50 years of age living in rural areas decreased by 25% during the same time period (from 39,200 to 29,600). As a result, the rural physician workforce is aging. In 2017, only about 25% of rural physicians were under the age of 50 years. Without a sizeable influx of younger physicians, the size of the rural physician workforce will decrease by 23% by 2030, as all of the current rural physicians retire.

To help offset the difference, the authors suggest that the rapidly growing NP workforce is poised to help. NPs provide cost-effective, high-quality care, and many more go into primary care in rural areas than do physicians. The authors suggest that sites training primary care clinicians, particularly those in or near rural areas, should work with programs educating NPs to develop ways to make it conducive for rural NPs to consult with physicians and other rural health specialists, and, in this way, help to stave off the coming dearth of physicians in rural America.

In addition to utilizing an NP workforce, Skinner and colleagues suggest that further strategies will be needed to address the rural physician shortfall and greater patient workload. Although certain actions instituted in the past have been helpful, including physician loan repayment, expansion of the national health service corps, medical school grants, and funding of rural teaching clinics, they have not done enough to address the growing needs of rural patient populations. The authors additionally suggest2:

- expansion of graduate medical education programs in rural hospitals

- higher payments for physicians in rural areas

- expanding use of mobile health vans equipped with diagnostic and treatment technology

- overcoming barriers that have slowed adoption of telehealth services.

References

- Kane L. Medscape physician compensation report 2019. Color/Word_R0_G0_B255https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2019-compensation-overview-6011286#30. Accessed August 19, 2019.

- Skinner L, Staiger DO, Auerbach DI, Buerhaus PI. Implications of an aging rural physician workforce. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(4):299-300. https://www.nejm.org/doi/pdf/10.1056/NEJMp1900808?articleTools=true. Accessed August 19, 2019.

- Morr M. Nurse practitioners may alleviate dwindling physician workforce in rural populations. Clinical Advisor.

- Doximity. 2019 Physician Compensation Report. Third annual study. https://s3.amazonaws.com/s3.doximity.com/press/doximity_third_annual_physician_compensation_report_round4.pdf Color/Word_R0_G0_B255 March 2019. Accessed August 19, 2019.

- Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC). Women were majority of US medical school applicants in 2018. Press release, December 4, 2018. Color/Word_R0_G0_B255https://news.aamc.org/press-releases/article/applicant-data-2018/. Accessed August 19, 2019.

- Kane L. Medscape physician compensation report 2019. Color/Word_R0_G0_B255https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2019-compensation-overview-6011286#30. Accessed August 19, 2019.

- Skinner L, Staiger DO, Auerbach DI, et al. Implications of an aging rural physician workforce. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:299-300. https://www.nejm.org/doi/pdf/10.1056/NEJMp1900808?articleTools=true. Accessed August 19, 2019.

- Kane L. Medscape national physician burnout, depression and suicide report 2019. January 16, 2019. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2019-lifestyle-burnout-depression-6011056. Accessed August 19, 2019.

- Kane L. Medscape obstetrician and gynecologist lifestyle, happiness and burnout report 2019. February 20, 2019. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2019-lifestyle-obgyn-6011131Color/Word_R0_G0_B255. Accessed August 20, 2019.

The gender wage gap in physician compensation persists but is narrowing. According to information gleaned from self-reported compensation surveys, collected by Doximity and completed by 90,000 full-time, US-licensed physicians, while wages for men idled between 2017 and 2018, they increased for women by 2%.1 So, whereas the gender wage gap was 27.7% in 2017, it dropped to 25.2% in 2018. This translates to female physicians making $90,490 less than male counterparts in 2018 vs $105,000 less in 2017.1

Gender wage gap and geography. Metropolitan areas with the smallest gender wage gaps according to the Doximity report include Birmingham, Alabama (9%); Bridgeport, Connecticut (10%); and Seattle, Washington (15%). Areas with the largest gender wage gap include Louisville/Jefferson County, Kentucky-Indiana (40%); New Orleans, Louisiana (32%); and Austin, Texas (31%).1

Gender wage gap and specialty. Specialties with the widest gender wage gaps are pediatric pulmonology (23%), otolaryngology (22%), and urology (22%). Those with the narrowest gaps are hematology (4%), rheumatology (8%), and radiation oncology (9%).1

Interestingly, although female physicians continue to earn less than men across the board, women were the slight majority of US medical school applicants (50.9%) and matriculants (51.6%) in 2018.2

What are physicians earning?

The overall average salary for physicians in 2019 is $313,000, according to a Medscape report, and the average annual compensation for ObGyns is $303,000, up from $300,000 in 2018.3 Doximity’s figure was slightly different; it reported average annual compensation for ObGyns to be $335,000 in 2018, ranking ObGyns 20th in specialties with the highest annual compensation.1

Compensation by specialty. The specialties with the highest average annual compensation in 2018 according to the Doximity report were neurosurgery ($617K), thoracic surgery ($584K), and orthopedic surgery ($526K). Those with the lowest were pediatric infectious disease ($186K), pediatric endocrinology ($201K), and general pediatrics ($223K).1

While women make up 61% of the ObGyn workforce, fewer than 15% of cardiologists, urologists, and orthopedists—some of the highest paying specialties—are women, although this alone does not explain the gender wage gap.3

Compensation by employment type. While average annual compensation increased from 2017 to 2018 for physicians working in single specialty groups (1%), multispecialty groups (1%), solo practices (3%), and industry/pharmaceutical (17%), compensation decreased for those working in health maintenance organizations (-1%), hospitals (-7%), and academia (-9%).1 Only 14% of private practices are owned by female physicians (TABLE 1).1

Satisfaction with compensation. Exactly half (50%) of ObGyns report feeling fairly compensated.3 Those physicians working in public health and preventive medicine are the most likely to feel fairly compensated (73%), while those working in infectious disease are least likely (42%).3

Location matters and may surprise you

Contrary to what many believe, less populated metropolitan areas tend to pay better than larger, more populated cities.1 This may be because metropolitan areas without academic institutions or nationally renowned health systems tend to offer slightly higher compensation than those with such facilities. The reason? The presence of large or prestigious medical schools ensures a pipeline of viable physician candidates for limited jobs, resulting in institutions and practices needing to pay less for qualified applicants.1

The 5 markets paying the highest physician salaries in 2018 were (from highest to lowest) Milwaukee; New Orleans; Riverside, California; Minneapolis; and Charlotte, North Carolina. Those paying the lowest were Durham, North Carolina; Providence, Rhode Island; San Antonio; Virginia Beach; and New Haven, Connecticut.1 Rural areas continue to have problems luring physicians (see “Cures for the famine of rural physicians?”3,4).

Job satisfaction

ObGyns rank 16th in terms of specialists who are happiest at work; 27% responded that they were very or extremely happy. Plastic surgeons ranked first in happiness on the job (41%), while those in physical medicine and rehabilitation ranked last (19%).5

Physicians as a whole report that the most rewarding part of the job is the gratitude from and relationships with patients, followed by “being good at a what I do”/finding answers/diagnoses, and “knowing that I’m making the world a better place.”3 Three-quarters (74%) of ObGyns would choose medicine again, and 75% would choose the same specialty. Those most likely to choose medicine again are those in infectious disease (84%), while those least likely work in physical medicine and rehabilitation (62%). Those most satisfied with their chosen specialty are ophthalmologists; 96% would choose the specialty again, whereas only 62% of internists would do so.3

Burnout. In a Medscape survey of 15,000 physicians in 29 specialties, 45% of ObGyns reported being burned out.5 Another 15% reported being “colloquially” depressed (sad, despondent, but not clinically depressed), and 7% reported clinical depression. While physicians overall most frequently engage in exercise as a coping mechanism, ObGyns most frequently report isolating themselves from others (47%)(TABLE 2).6

Across all specialties, more female physicians report being burned out than men (50% vs 39%). The 3 highest contributors to burnout are too many bureaucratic tasks (charting, paperwork), spending too many hours at work/insufficient compensation, and the increasing computerization of practices (electronic health records [EHRs])(TABLE 3).6 While 44% of ObGyns report that their feelings of being burned out or depressed do not affect their interactions with patients, 39% say such feelings make them easily exasperated with their patients.6 One in five (20%) responding ObGyns reported having had thoughts of suicide (vs 14% for physicians as a whole).5,6

Fortunately, ObGyns are the third most likely type of specialists to seek help for burnout or depression (37%), following psychiatrists (45%) and public health and preventive medicine specialists (45%).6 Those least likely to seek help are allergists/immunologists (13%).5

Sources of frustration on the job

Long hours. Physicians responding to the Medscape survey say that the most frustrating part of their job is having so many rules and regulations, followed by having to work with an EHR, and having to work long hours.3

As for the latter, 60% of responding ObGyns reported working long hours, which places obstetrics/gynecology in the 11th position on a list of specialties with physicians reporting working too many hours.5 Surgeons were number 1 with 77% reporting working long hours, and emergency medicine physicians were last with only 13% reporting working long hours.

Paper and administrative tasks. Thirty-eight percent of the physicians responding to the Medscape survey report spending 10 to 19 hours per week on paperwork; another 36% report spending 20 hours or more.3 This is almost identical to last year when the figures were 38% and 32%, respectively. However, the trend in the last few years has been dramatic. In 2017, the total percentage of physicians spending 10 of more hours on paperwork per week was 57%, compared with this year’s 74%.3

According to the latest Medscape report, 50% of responding physicians employ nurse practitioners (NPs) and 36% employ physician assistants (PAs); 38% employ neither. Almost half (47%) of respondents report increased profitability as a result of employing NPs/PAs.1

NPs and PAs may be increasingly important in rural America, suggests Skinner and colleagues in an article in New England Journal of Medicine.2,3 They report that the total number of rural physicians grew only 3% between 2000 and 2017 (from 61,000 to 62,700) and that the number of physicians under 50 years of age living in rural areas decreased by 25% during the same time period (from 39,200 to 29,600). As a result, the rural physician workforce is aging. In 2017, only about 25% of rural physicians were under the age of 50 years. Without a sizeable influx of younger physicians, the size of the rural physician workforce will decrease by 23% by 2030, as all of the current rural physicians retire.

To help offset the difference, the authors suggest that the rapidly growing NP workforce is poised to help. NPs provide cost-effective, high-quality care, and many more go into primary care in rural areas than do physicians. The authors suggest that sites training primary care clinicians, particularly those in or near rural areas, should work with programs educating NPs to develop ways to make it conducive for rural NPs to consult with physicians and other rural health specialists, and, in this way, help to stave off the coming dearth of physicians in rural America.

In addition to utilizing an NP workforce, Skinner and colleagues suggest that further strategies will be needed to address the rural physician shortfall and greater patient workload. Although certain actions instituted in the past have been helpful, including physician loan repayment, expansion of the national health service corps, medical school grants, and funding of rural teaching clinics, they have not done enough to address the growing needs of rural patient populations. The authors additionally suggest2:

- expansion of graduate medical education programs in rural hospitals

- higher payments for physicians in rural areas

- expanding use of mobile health vans equipped with diagnostic and treatment technology

- overcoming barriers that have slowed adoption of telehealth services.

References

- Kane L. Medscape physician compensation report 2019. Color/Word_R0_G0_B255https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2019-compensation-overview-6011286#30. Accessed August 19, 2019.

- Skinner L, Staiger DO, Auerbach DI, Buerhaus PI. Implications of an aging rural physician workforce. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(4):299-300. https://www.nejm.org/doi/pdf/10.1056/NEJMp1900808?articleTools=true. Accessed August 19, 2019.

- Morr M. Nurse practitioners may alleviate dwindling physician workforce in rural populations. Clinical Advisor.

The gender wage gap in physician compensation persists but is narrowing. According to information gleaned from self-reported compensation surveys, collected by Doximity and completed by 90,000 full-time, US-licensed physicians, while wages for men idled between 2017 and 2018, they increased for women by 2%.1 So, whereas the gender wage gap was 27.7% in 2017, it dropped to 25.2% in 2018. This translates to female physicians making $90,490 less than male counterparts in 2018 vs $105,000 less in 2017.1

Gender wage gap and geography. Metropolitan areas with the smallest gender wage gaps according to the Doximity report include Birmingham, Alabama (9%); Bridgeport, Connecticut (10%); and Seattle, Washington (15%). Areas with the largest gender wage gap include Louisville/Jefferson County, Kentucky-Indiana (40%); New Orleans, Louisiana (32%); and Austin, Texas (31%).1

Gender wage gap and specialty. Specialties with the widest gender wage gaps are pediatric pulmonology (23%), otolaryngology (22%), and urology (22%). Those with the narrowest gaps are hematology (4%), rheumatology (8%), and radiation oncology (9%).1

Interestingly, although female physicians continue to earn less than men across the board, women were the slight majority of US medical school applicants (50.9%) and matriculants (51.6%) in 2018.2

What are physicians earning?

The overall average salary for physicians in 2019 is $313,000, according to a Medscape report, and the average annual compensation for ObGyns is $303,000, up from $300,000 in 2018.3 Doximity’s figure was slightly different; it reported average annual compensation for ObGyns to be $335,000 in 2018, ranking ObGyns 20th in specialties with the highest annual compensation.1

Compensation by specialty. The specialties with the highest average annual compensation in 2018 according to the Doximity report were neurosurgery ($617K), thoracic surgery ($584K), and orthopedic surgery ($526K). Those with the lowest were pediatric infectious disease ($186K), pediatric endocrinology ($201K), and general pediatrics ($223K).1

While women make up 61% of the ObGyn workforce, fewer than 15% of cardiologists, urologists, and orthopedists—some of the highest paying specialties—are women, although this alone does not explain the gender wage gap.3

Compensation by employment type. While average annual compensation increased from 2017 to 2018 for physicians working in single specialty groups (1%), multispecialty groups (1%), solo practices (3%), and industry/pharmaceutical (17%), compensation decreased for those working in health maintenance organizations (-1%), hospitals (-7%), and academia (-9%).1 Only 14% of private practices are owned by female physicians (TABLE 1).1

Satisfaction with compensation. Exactly half (50%) of ObGyns report feeling fairly compensated.3 Those physicians working in public health and preventive medicine are the most likely to feel fairly compensated (73%), while those working in infectious disease are least likely (42%).3

Location matters and may surprise you

Contrary to what many believe, less populated metropolitan areas tend to pay better than larger, more populated cities.1 This may be because metropolitan areas without academic institutions or nationally renowned health systems tend to offer slightly higher compensation than those with such facilities. The reason? The presence of large or prestigious medical schools ensures a pipeline of viable physician candidates for limited jobs, resulting in institutions and practices needing to pay less for qualified applicants.1

The 5 markets paying the highest physician salaries in 2018 were (from highest to lowest) Milwaukee; New Orleans; Riverside, California; Minneapolis; and Charlotte, North Carolina. Those paying the lowest were Durham, North Carolina; Providence, Rhode Island; San Antonio; Virginia Beach; and New Haven, Connecticut.1 Rural areas continue to have problems luring physicians (see “Cures for the famine of rural physicians?”3,4).

Job satisfaction

ObGyns rank 16th in terms of specialists who are happiest at work; 27% responded that they were very or extremely happy. Plastic surgeons ranked first in happiness on the job (41%), while those in physical medicine and rehabilitation ranked last (19%).5

Physicians as a whole report that the most rewarding part of the job is the gratitude from and relationships with patients, followed by “being good at a what I do”/finding answers/diagnoses, and “knowing that I’m making the world a better place.”3 Three-quarters (74%) of ObGyns would choose medicine again, and 75% would choose the same specialty. Those most likely to choose medicine again are those in infectious disease (84%), while those least likely work in physical medicine and rehabilitation (62%). Those most satisfied with their chosen specialty are ophthalmologists; 96% would choose the specialty again, whereas only 62% of internists would do so.3

Burnout. In a Medscape survey of 15,000 physicians in 29 specialties, 45% of ObGyns reported being burned out.5 Another 15% reported being “colloquially” depressed (sad, despondent, but not clinically depressed), and 7% reported clinical depression. While physicians overall most frequently engage in exercise as a coping mechanism, ObGyns most frequently report isolating themselves from others (47%)(TABLE 2).6

Across all specialties, more female physicians report being burned out than men (50% vs 39%). The 3 highest contributors to burnout are too many bureaucratic tasks (charting, paperwork), spending too many hours at work/insufficient compensation, and the increasing computerization of practices (electronic health records [EHRs])(TABLE 3).6 While 44% of ObGyns report that their feelings of being burned out or depressed do not affect their interactions with patients, 39% say such feelings make them easily exasperated with their patients.6 One in five (20%) responding ObGyns reported having had thoughts of suicide (vs 14% for physicians as a whole).5,6

Fortunately, ObGyns are the third most likely type of specialists to seek help for burnout or depression (37%), following psychiatrists (45%) and public health and preventive medicine specialists (45%).6 Those least likely to seek help are allergists/immunologists (13%).5

Sources of frustration on the job

Long hours. Physicians responding to the Medscape survey say that the most frustrating part of their job is having so many rules and regulations, followed by having to work with an EHR, and having to work long hours.3

As for the latter, 60% of responding ObGyns reported working long hours, which places obstetrics/gynecology in the 11th position on a list of specialties with physicians reporting working too many hours.5 Surgeons were number 1 with 77% reporting working long hours, and emergency medicine physicians were last with only 13% reporting working long hours.

Paper and administrative tasks. Thirty-eight percent of the physicians responding to the Medscape survey report spending 10 to 19 hours per week on paperwork; another 36% report spending 20 hours or more.3 This is almost identical to last year when the figures were 38% and 32%, respectively. However, the trend in the last few years has been dramatic. In 2017, the total percentage of physicians spending 10 of more hours on paperwork per week was 57%, compared with this year’s 74%.3

According to the latest Medscape report, 50% of responding physicians employ nurse practitioners (NPs) and 36% employ physician assistants (PAs); 38% employ neither. Almost half (47%) of respondents report increased profitability as a result of employing NPs/PAs.1

NPs and PAs may be increasingly important in rural America, suggests Skinner and colleagues in an article in New England Journal of Medicine.2,3 They report that the total number of rural physicians grew only 3% between 2000 and 2017 (from 61,000 to 62,700) and that the number of physicians under 50 years of age living in rural areas decreased by 25% during the same time period (from 39,200 to 29,600). As a result, the rural physician workforce is aging. In 2017, only about 25% of rural physicians were under the age of 50 years. Without a sizeable influx of younger physicians, the size of the rural physician workforce will decrease by 23% by 2030, as all of the current rural physicians retire.

To help offset the difference, the authors suggest that the rapidly growing NP workforce is poised to help. NPs provide cost-effective, high-quality care, and many more go into primary care in rural areas than do physicians. The authors suggest that sites training primary care clinicians, particularly those in or near rural areas, should work with programs educating NPs to develop ways to make it conducive for rural NPs to consult with physicians and other rural health specialists, and, in this way, help to stave off the coming dearth of physicians in rural America.

In addition to utilizing an NP workforce, Skinner and colleagues suggest that further strategies will be needed to address the rural physician shortfall and greater patient workload. Although certain actions instituted in the past have been helpful, including physician loan repayment, expansion of the national health service corps, medical school grants, and funding of rural teaching clinics, they have not done enough to address the growing needs of rural patient populations. The authors additionally suggest2:

- expansion of graduate medical education programs in rural hospitals

- higher payments for physicians in rural areas

- expanding use of mobile health vans equipped with diagnostic and treatment technology

- overcoming barriers that have slowed adoption of telehealth services.

References

- Kane L. Medscape physician compensation report 2019. Color/Word_R0_G0_B255https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2019-compensation-overview-6011286#30. Accessed August 19, 2019.

- Skinner L, Staiger DO, Auerbach DI, Buerhaus PI. Implications of an aging rural physician workforce. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(4):299-300. https://www.nejm.org/doi/pdf/10.1056/NEJMp1900808?articleTools=true. Accessed August 19, 2019.

- Morr M. Nurse practitioners may alleviate dwindling physician workforce in rural populations. Clinical Advisor.

- Doximity. 2019 Physician Compensation Report. Third annual study. https://s3.amazonaws.com/s3.doximity.com/press/doximity_third_annual_physician_compensation_report_round4.pdf Color/Word_R0_G0_B255 March 2019. Accessed August 19, 2019.

- Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC). Women were majority of US medical school applicants in 2018. Press release, December 4, 2018. Color/Word_R0_G0_B255https://news.aamc.org/press-releases/article/applicant-data-2018/. Accessed August 19, 2019.

- Kane L. Medscape physician compensation report 2019. Color/Word_R0_G0_B255https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2019-compensation-overview-6011286#30. Accessed August 19, 2019.

- Skinner L, Staiger DO, Auerbach DI, et al. Implications of an aging rural physician workforce. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:299-300. https://www.nejm.org/doi/pdf/10.1056/NEJMp1900808?articleTools=true. Accessed August 19, 2019.

- Kane L. Medscape national physician burnout, depression and suicide report 2019. January 16, 2019. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2019-lifestyle-burnout-depression-6011056. Accessed August 19, 2019.

- Kane L. Medscape obstetrician and gynecologist lifestyle, happiness and burnout report 2019. February 20, 2019. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2019-lifestyle-obgyn-6011131Color/Word_R0_G0_B255. Accessed August 20, 2019.

- Doximity. 2019 Physician Compensation Report. Third annual study. https://s3.amazonaws.com/s3.doximity.com/press/doximity_third_annual_physician_compensation_report_round4.pdf Color/Word_R0_G0_B255 March 2019. Accessed August 19, 2019.

- Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC). Women were majority of US medical school applicants in 2018. Press release, December 4, 2018. Color/Word_R0_G0_B255https://news.aamc.org/press-releases/article/applicant-data-2018/. Accessed August 19, 2019.

- Kane L. Medscape physician compensation report 2019. Color/Word_R0_G0_B255https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2019-compensation-overview-6011286#30. Accessed August 19, 2019.

- Skinner L, Staiger DO, Auerbach DI, et al. Implications of an aging rural physician workforce. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:299-300. https://www.nejm.org/doi/pdf/10.1056/NEJMp1900808?articleTools=true. Accessed August 19, 2019.

- Kane L. Medscape national physician burnout, depression and suicide report 2019. January 16, 2019. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2019-lifestyle-burnout-depression-6011056. Accessed August 19, 2019.

- Kane L. Medscape obstetrician and gynecologist lifestyle, happiness and burnout report 2019. February 20, 2019. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2019-lifestyle-obgyn-6011131Color/Word_R0_G0_B255. Accessed August 20, 2019.