User login

Graduate Medical Education Financing in the US Department of Veterans Affairs

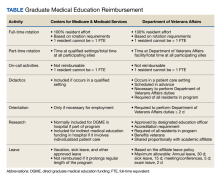

The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) has partnered with academic medical centers and programs since 1946 to provide clinical training for physician residents. Ranking second in federal graduate medical education (GME) funding to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), the $850 million VA GME budget annually reimburses > 250 GME-sponsoring institutions (affiliates) of 8000 GME programs for the clinical training of 49,000 individual residents rotating through > 11,000 full-time equivalent (FTE) positions.1 The VA also distributes $1.6 billion to VA facilities to offset the costs of conducting health professions education (HPE) (eg, facility infrastructure, salary support for VA instructors and preceptors, education office administration, and instructional equipment).2 The VA financial and educational contributions account for payment of 11% of resident positions nationally and allow academic medical centers to be less reliant on CMS GME funding.3,4 The VA contributions also provide opportunities for GME expansion,1,5,6 educational innovations,5,7 interprofessional and team-based care,8,9 and quality and safety training.10,11 The Table provides a comparison of CMS and VA GME reimbursability based on activity.

GME financing is complex, particularly the formulaic approach used by CMS, the details of which are often obscured in federal regulations. Due to this complexity and the $16 billion CMS GME budget, academic publications have focused on CMS GME financing while not fully explaining the VA GME policies and processes.4,12-14 By comparison, the VA GME financing model is relatively straightforward and governed by different statues and VA regulations, yet sharing some of the same principles as CMS regulations. Given the challenges in CMS reimbursement to fully support the cost of resident education, as well as the educational opportunities at the VA, the VA designs its reimbursement model to assure that affiliates receive appropriate payments.4,12,15 To ensure the continued success of VA GME partnerships, knowledge of VA GME financing has become increasingly important for designated institutional officers (DIOs) and residency program directors, particularly in light of recent investigations into oversight of the VA’s reimbursement to academic affiliates.

VA AUTHORITY

While the VA’s primary mission is “to provide a complete hospital medical service for the medical care and treatment of veterans,” early VA leaders recognized the importance of affiliating with the nation’s academic institutions.19 In 1946, the VA Policy Memorandum Number 2 established a partnership between the VA and the academic medical community.20 Additional legislation authorized specific agreements with academic affiliates for the central administration of salary and benefits for residents rotating at VA facilities. This process, known as disbursement, is an alternative payroll mechanism whereby the VA reimburses the academic affiliate for resident salary and benefits and the affiliate acts as the disbursing agent, issuing paychecks to residents.21,22

Resident FUNDING

By policy, with rare exceptions, the VA does not sponsor residency programs due to the challenges of providing an appropriate patient mix of age, sex, and medical conditions to meet accreditation standards.4 Nearly all VA reimbursements are for residents in affiliate-sponsored programs, while just 1% pays for residents in legacy, VA-sponsored residency programs at 2 VA facilities. The VA budget for resident (including fellows) salary and benefits is managed by the VA Office of Academic Affiliations (OAA), the national VA office responsible for oversight, policy, and funding of VA HPE programs.

Resident Salaries and Benefits

VA funding of resident salary and benefits are analogous with CMS direct GME (DGME), which is designed to cover resident salary and benefits costs.4,14,23 CMS DGME payments depend on a hospital’s volume of CMS inpatients and are based on a statutory formula, which uses the hospital’s resident FTE positions, the per-resident amount, and Medicare’s share of inpatient beds (Medicare patient load) to determine payments.12 The per-resident amount is set by statute, varies geographically, and is calculated by dividing the hospital’s allowable costs of GME (percentage of CMS inpatient days) divided by the number of residents.12,24

By comparison, the VA GME payment reimburses for each FTE based on the salary and benefits rate set by the academic affiliate. Reimbursement is calculated based on resident time spent at the VA multiplied by a daily salary rate. The daily salary rate is determined by dividing the resident’s total compensation (salary and benefits) by the number of calendar days in an academic year. Resident time spent at the VA facility is determined by obtaining rotation schedules provided by the academic affiliate and verifying resident clinical and educational activity during scheduled rotations.

Indirect Medical Education Funding

In addition to resident salary and benefits, funds to offset the cost of conducting HPE are provided to VA facilities. These funds are intended to improve and maintain necessary infrastructure for all HPE programs not just GME, including education office administration needs, teaching costs (ie, a portion of VA preceptors salary), and instructional equipment.

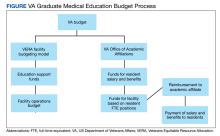

The Veterans Equitable Resource Allocation (VERA) is a national budgeting process for VA medical facilities that funds facility operational needs such as staff salary and benefits, infrastructure, and equipment.2 The education portion of the VERA, the VERA Education Support Component (VESC), is not managed by the OAA, but rather is distributed through the VERA model to the general budget of VA facilities hosting HPE (Figure). VESC funding in the VA budget is based on labor mapping of physician time spent in education; other labor mapping categories include clinical care, research, and administration. VA facility VESC funding is calculated based on the number of paid health profession trainees (HPTs) from all professions, apportioned according to the number of FTEs for physician residents and VA-paid HPTs in other disciplines. In fiscal year 2024, VA facilities received $115,812 for each physician resident FTE position and $84,906 for each VA-paid, non-GME FTE position.

The VESC is like CMS's indirect GME funding, termed Indirect Medical Education (IME), an additional payment for each Medicare patient discharged reflecting teaching hospitals’ higher patient care costs relative to nonteaching hospitals. Described elsewhere, IME is calculated using a resident-to-bed ratio and a multiplier, which is set by statute.4,25 While IME can be used for reimbursement for some resident clinical and educational activities(eg, research), VA VESC funds cannot be used for such activities and are part of the general facility budget and appropriated per the discretion of the medical facility director.

ESTABLISHING GME PARTNERSHIPS

An affiliation agreement establishes the administrative and legal requirements for educational relationships with academic affiliates and includes standards for conducting HPE, responsibilities for accreditation standards, program leadership, faculty, resources, supervision, academic policies, and procedures. The VA uses standardized affiliation agreement templates that have been vetted with accrediting bodies and the VA Office of General Counsel.

A disbursement agreement authorizes the VA to reimburse affiliates for resident salary and benefits for VA clinical and educational activities. The disbursement agreement details the fiscal arrangements (eg, payment in advance vs arrears, salary, and benefit rates, leave) for the reimbursement payments. Veterans Health Administration (VHA) Directive 1400.05 provides the policy and procedures for calculating reimbursement for HPT educational activities.26

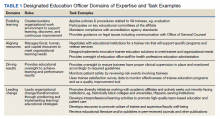

The VA facility designated education officer (DEO) oversees all HPE programs and coordinates the affiliation and disbursement agreement processes.27 The DEO, affiliate DIO, residency program director, and VA residency site director determine the physician resident FTE positions assigned to a VA facility based on educational objectives and availability of educational resources at the VA facility, such as patient care opportunities, faculty supervisors, space, and equipment. The VA facility requests for resident FTE positions are submitted to the OAA by the facility DEO.

Once GME FTE positions are approved by the OAA, VA facilities work with their academic affiliate to submit the physician resident salary and benefit rate. Affiliate DIOs attest to the accuracy of the salary rate schedule and the local DEO submits the budget request to the OAA. Upon approval, the funds are transferred to the VA facility each fiscal year, which begins October 1. DEOs report quarterly to the OAA both budget needs and excesses based on variations in the approved FTEs due to additional VA rotations, physician resident attrition, or reassignment.

Resident Position Allocation

VA GME financing provides flexibility through periodic needs assessments and expansion initiatives. In August and December, DEOs collaborate with an academic affiliate to submit reports to the OAA confirming their projected GME needs for the next academic year. Additional positions requests are reviewed by the OAA; funding depends on budget and the educational justification. The OAA periodically issues GME expansion requests for proposal, which typically arise from legislation to address specific VA workforce needs. The VA facility DEO and affiliate GME leaders collaborate to apply for additional positions. For example, a VA GME expansion under the Veterans Access, Choice, and Accountability Act of 2014 added 1500 GME positions in 8 years for critically needed specialties and in rural and underserved areas.5 The Maintaining Internal Systems and Strengthening Outside Networks (MISSION) Act of 2018 authorized a pilot program for VA to fund residents at non-VA facilities with priority for Indian Health Services, Tribes and Tribal Organizations, Federally Qualified Health Centers, and US Department of Defense facilities to provide access to veterans in underserved areas.6

The VA GME financing system has flexibility to meet local needs for additional resident positions and to address broader VA workforce gaps through targeted expansion. Generally, CMS does not fund positions to address workforce needs, place residents in specific geographic areas, or require the training of certain types of residents.4 However, the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2021 has provided the opportunity to address rural workforce needs.28

Reimbursement

The VA provides reimbursement for clinical and educational activities performed in VA facilities for the benefit of veterans as well as research, didactics, meetings and conferences, annual and sick leave, and orientation. The VA also may provide reimbursement for educational activities that occur off VA grounds (eg, the VA proportional share of a residency program’s didactic sessions). The VA does not reimburse for affiliate clinical duties or administrative costs, although a national policy allows VA facilities to reimburse affiliates for some GME overhead costs.29

CMS similarly reimburses for residency training time spent in patient care activities as well as orientation activities, didactics, leave, and, in some cases, research.4,30,31 CMS makes payments to hospitals, which may include sponsoring institutions and Medicare-eligible participating training sites.4,30,31 For both the VA and CMS, residents may not be counted twice for reimbursement by 2 federal agencies; in other words, a resident may not count for > 1 FTE.4,30-32

GME Oversight

VA GME funding came under significant scrutiny. At a 2016 House Veterans Affairs Committee hearing, Representative Phil Roe, MD (R-Tennessee), noted that no process existed at many VA facilities for “determining trainee presence” and that many VA medical centers had “difficulty tracking resident rotations”16 A VA Office of the Inspector General investigation recommended that the VA implement policies and procedures to improve oversight to “ensure residents are fully participating in educational activities” and that the VA is “paying the correct amount” to the affiliate.17 A 2020 General Accountability Office report outlined unclear policy guidance, incomplete tracking of resident activities, and improper fiscal processes for reimbursement and reconciliation of affiliate invoices.18

In response, the OAA created an oversight and compliance unit, revised VHA Directive 1400.05 (the policy for disbursement), and improved resident tracking procedures.26 The standard operating procedure that accompanied VHA Directive 1400.05 provides detailed information for the DEO and VA facility staff for tracking resident clinical and educational activities. FTE counts are essential to both VA and CMS for accurate reimbursement. The eAppendix and the Table provide a guide to reimbursable activities in the VA for the calculation of reimbursement, with a comparison to CMS.33,34 The OAA in cooperation with other VA staff and officers periodically conducts audits to assess compliance with disbursement policy and affiliate reimbursement accuracy.

In the VA, resident activities are captured on the VA Educational Activity Record, a standardized spreadsheet to track activities and calculate reimbursement. Each VA facility hosting resident physicians manually records resident activity by the half-day. This process is labor intensive, involving both VA and affiliate staff to accurately reconcile payments. To address the workload demands, the OAA is developing an online tool that will automate aspects of the tracking process. Also, to ensure adequate staffing, the OAA is in the process of implementing an office optimization project, providing standardized position descriptions, an organizational chart, and staffing levels for DEO offices in VA facilities.

Conclusions

This report describes the key policies and principles of VA GME financing, highlighting the essential similarities and differences between VA and CMS. Neither the VA nor CMS regulations allow for reimbursement for > 1 FTE position per resident, a principle that underpins the assignment of resident rotations and federal funding for GME and are similar with respect to reimbursement for patient care activities, didactics, research, orientation, and scholarly activity. While reimbursable activities in the VA require physical presence and care of veteran patients, CMS also limits reimbursement to resident activities in the hospital and approved other settings if the hospital is paying for resident salary and benefits in these settings. The VA provides some flexibility for offsite activities including didactics and, in specific circumstances, remote care of veteran patients (eg, teleradiology).

The VA and CMS use different GME financing models. For example, the CMS calculations for resident FTEs are complex, whereas VA calculations reimburse the salary and benefits as set by the academic affiliate. The VA process accounts for local variation in salary rates, whereas the per-resident amount set by CMS varies regionally and does not fully account for differences in the cost of living.24 Because all patients in VA facilities are veterans, VA calculations for reimbursement do not involve ratios of beds like the CMS calculations to determine a proportional share of reimbursement. The VA GME expansion tends to be more directed to VA health workforce needs than CMS, specifying the types of programs and geographic locations to address these needs.

The VA regularly reevaluates how affiliates are reimbursed for VA resident activity, balancing compliance with VA policies and the workload for VA and its affiliates. The VA obtains input from key stakeholders including DEOs, DIOs, and professional organizations such as the Association of American Medical Colleges and the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education.35,36

Looking ahead, the VA is developing an online tool to improve the accuracy of affiliate reimbursement. The VA will also implement a standardized staffing model, organizational structure, and position descriptions for DEO offices. These initiatives will help reduce the burden of tracking and verifying resident activity and continue to support the 77-year partnership between VA and its affiliated institutions.

1. Klink KA, Albanese AP, Bope ET, Sanders KM. Veterans Affairs graduate medical education expansion addresses US physician workforce needs. Acad Med. 2022;97(8):1144-1150. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000004545

2. Andrus CH, Johnson K, Pierce E, Romito PJ, Hartel P, Berrios‐Guccione S, Best W. Finance modeling in the delivery of medical care in tertiary‐care hospitals in the Department of Veterans Affairs. J Surg Res. 2001;96(2):152-157. doi:10.1006/jsre.1999.5728

3. Petrakis IL, Kozal M. Academic medical centers and the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs: a 75-year partnership influences medical education, scientific discovery, and clinical care. Acad Med. 2022;97(8):1110-1113. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000004734

4. Heisler EJ, Mendez BH, Mitchell A, Panangala SV, Villagrana MA. Federal support for graduate medical education: an overview (R44376). Congressional Research Service report R44376; version 11. Updated December 27, 2018. Accessed March 2, 2024. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R44376/11

5. Chang BK, Brannen JL. The Veterans Access, Choice, and Accountability Act of 2014: examining graduate medical education enhancement in the Department of Veterans Affairs. Acad Med. 2015;90(9):1196-1198. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000795

6. Albanese AP, Bope ET, Sanders KM, Bowman M. The VA MISSION Act of 2018: a potential game changer for rural GME expansion and veteran health care. J Rural Health. 2020;36(1):133-136. doi:10.1111/jrh.12360

7. Lypson ML, Roberts LW. Valuing the partnership between the Veterans Health Administration and academic medicine. Acad Med. 2022;97(8):1091-1093. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000004748

8. Harada ND, Traylor L, Rugen KW, et al. Interprofessional transformation of clinical education: the first six years of the Veterans Affairs Centers of Excellence in Primary Care Education. J Interprof Care. 2023;37(suppl 1):S86-S94. doi:10.1080/13561820.2018.1433642

9. Harada ND, Rajashekara S, Sansgiry S, et al. Developing interprofessional primary care teams: alumni evaluation of the Department of Veterans Affairs Centers of Excellence in Primary Care Education Program. J Med Educ Curric Dev. 2019;6:2382120519875455. doi:10.1177/2382120519875455

10. Splaine ME, Ogrinc G, Gilman SC, et al. The Department of Veterans Affairs National Quality Scholars Fellowship Program: experience from 10 years of training quality scholars. Acad Med. 2009;84(12):1741-1748. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181bfdcef

11. Watts BV, Paull DE, Williams LC, Neily J, Hemphill RR, Brannen JL. Department of Veterans Affairs chief resident in quality and patient safety program: a model to spread change. Am J Med Qual. 2016;31(6):598-600. doi:10.1177/1062860616643403

12. He K, Whang E, Kristo G. Graduate medical education funding mechanisms, challenges, and solutions: a narrative review. Am J Surg. 2021;221(1):65-71. doi:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2020.06.007

13. Villagrana M. Medicare graduate medical education payments: an overview. Congressional Research Service report IF10960. Updated September 29, 2022. Accessed March 2, 2024. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF10960

14. Committee on the Governance and Financing of Graduate Medical Education; Board on Health Care Services; Institute of Medicine. Graduate Medical Education That Meets the Nation’s Health Needs. Eden J, Berwick DM, Wilensky GR, eds. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2014. doi:10.17226/18754

15. Physician workforce: caps on Medicare-funded graduate medical education at teaching hospitals. Report to congressional requesters. GAO-21-391. May 21, 2021. Accessed March 1, 2024. https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-21-391.pdf

16. VA and Academic Affiliates: Who Benefits? Hearing Before the Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations of the Committee on Veterans’ Affairs, 114th Cong, 2nd Sess (2016). Accessed March 1, 2024. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CHRG-115hhrg29685/html/CHRG-115hhrg29685.htm

17. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Inspector General (OIG). Veterans Health Administration. Review of resident and part-time physician time and attendance at the Oklahoma City VA Health Care System. OIG report 17-00253-93. March 28, 2018. Accessed March 1, 2024. https://www.oversight.gov/sites/default/files/oig-reports/VAOIG-17-00253-93.pdf

18. VA health care: actions needed to improve oversight of graduate medical education reimbursement. Report to the ranking member, Committee on Veterans’ Affairs, House of Representatives. GAO-20-553. July 2020. Accessed March 1, 2024. https://www.gao.gov/assets/710/708275.pdf

19. Functions of Veterans Health Administration: in general, 38 USC §7301 (2022). Accessed March 1, 2024. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/USCODE-2022-title38/pdf/USCODE-2022-title38-partV-chap73-subchapI-sec7301.pdf

20. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Policy memorandum no. 2, policy in association of veterans’ hospitals with medical schools. January 30, 1946.

21. Veterans Health Care Expansion Act of 1973, Public Law 93-82. August 2, 1973. Accessed March 1, 2024. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/STATUTE-87/pdf/STATUTE-87-Pg179.pdf

22. Residencies and internships, 38 USC § 7406 (2022). Accessed March 1, 2024. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/USCODE-2022-title38/pdf/USCODE-2022-title38-partV-chap74-subchapI-sec7406.pdf

23. Direct graduate medical education (DGME). Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services. Updated December 5, 2023. Accessed March 1, 2024. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/DGME

24. Drezdzon MK, Cowley NJ, Sweeney DP, et al. Going for broke: the impact of cost of living on surgery resident stipend value. Ann Surg. 2023;278(6):1053-1059. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000005923

25. Special treatment: hospitals that incur indirect costs for graduate medical education programs, 42 CFR § 412.105 (2023). Accessed March 1, 2024. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CFR-2023-title42-vol2/pdf/CFR-2023-title42-vol2-sec412-105.pdf

26. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration. VHA Directive 1400.05, Disbursement agreements for health professions trainees appointed under 38 U.S.C. § 7406. June 2, 2021. Accessed March 1, 2024. https://www.va.gov/vhapublications/ViewPublication.asp?pub_ID=9293

27. Harada ND, Sanders KM, Bowman MA. Health systems education leadership: learning from the VA designated education officer role. Fed Pract. 2022;39(6):266-273. doi:10.12788/fp.0278

28. Schleiter Hitchell K, Johnson L. CMS finalizes rules for distribution of 1000 new Medicare-funded residency positions and changes to rural training track programs. J Grad Med Educ. 2022;14(2):245-249. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-22-00193.1

29. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration. VHA Directive 1400.10, Educational cost contracts for health professions education. September 25, 2023. Accessed March 1, 2024. https://www.va.gov/VHAPUBLICATIONS/ViewPublication.asp?pub_ID=11480

30. Direct GME payments: general requirements, 42 CFR § 413.75 (2023). Accessed March 1, 2024. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CFR-2023-title42-vol2/pdf/CFR-2023-title42-vol2-sec413-75.pdf

31. Direct GME payments: determination of the total number of FTE residents, 42 CFR § 413.78 (2023). Accessed March 1, 2024. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CFR-2023-title42-vol2/pdf/CFR-2023-title42-vol2-sec413-78.pdf

32. US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare financial management manual, chapter 8. Contractor procedures for provider audits. Accessed March 1, 2024. https://www.cms.gov/regulations-and-guidance/guidance/manuals/downloads/fin106c08.pdf

33. US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Inspector General. CMS did not always ensure hospitals complied with Medicare reimbursement requirements for graduate medical education. OIG report A-02-17-01017. November 2018. Accessed March 1, 2024. https://oig.hhs.gov/oas/reports/region2/21701017.pdf

34. US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Interns and Residents Information System (IRIS) XML format. Publication 100-20. Transmittal 11418. Change request 12724. May 19, 2022. Accessed March 1, 2024. https://www.hhs.gov/guidance/sites/default/files/hhs-guidance-documents/R11418OTN.pdf

35. Birnbaum AD, Byrne J, on behalf of the VA Office of Academic Affiliations. VHA Updates: Disbursement Policy and Education Cost Contracts. Presented at: American Association of Medical Colleges Webinar; June 2021. Accessed March 1, 2024. https://vimeo.com/644415670

36. Byrne JM, on behalf of the VA Office of Academic Affiliations. Disbursement procedures update for AY 23-24. Accessed March 1, 2024. https://www.va.gov/oaa/Videos/AffiliatePresentationDisbursementandEARsAY23-24.pptx

The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) has partnered with academic medical centers and programs since 1946 to provide clinical training for physician residents. Ranking second in federal graduate medical education (GME) funding to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), the $850 million VA GME budget annually reimburses > 250 GME-sponsoring institutions (affiliates) of 8000 GME programs for the clinical training of 49,000 individual residents rotating through > 11,000 full-time equivalent (FTE) positions.1 The VA also distributes $1.6 billion to VA facilities to offset the costs of conducting health professions education (HPE) (eg, facility infrastructure, salary support for VA instructors and preceptors, education office administration, and instructional equipment).2 The VA financial and educational contributions account for payment of 11% of resident positions nationally and allow academic medical centers to be less reliant on CMS GME funding.3,4 The VA contributions also provide opportunities for GME expansion,1,5,6 educational innovations,5,7 interprofessional and team-based care,8,9 and quality and safety training.10,11 The Table provides a comparison of CMS and VA GME reimbursability based on activity.

GME financing is complex, particularly the formulaic approach used by CMS, the details of which are often obscured in federal regulations. Due to this complexity and the $16 billion CMS GME budget, academic publications have focused on CMS GME financing while not fully explaining the VA GME policies and processes.4,12-14 By comparison, the VA GME financing model is relatively straightforward and governed by different statues and VA regulations, yet sharing some of the same principles as CMS regulations. Given the challenges in CMS reimbursement to fully support the cost of resident education, as well as the educational opportunities at the VA, the VA designs its reimbursement model to assure that affiliates receive appropriate payments.4,12,15 To ensure the continued success of VA GME partnerships, knowledge of VA GME financing has become increasingly important for designated institutional officers (DIOs) and residency program directors, particularly in light of recent investigations into oversight of the VA’s reimbursement to academic affiliates.

VA AUTHORITY

While the VA’s primary mission is “to provide a complete hospital medical service for the medical care and treatment of veterans,” early VA leaders recognized the importance of affiliating with the nation’s academic institutions.19 In 1946, the VA Policy Memorandum Number 2 established a partnership between the VA and the academic medical community.20 Additional legislation authorized specific agreements with academic affiliates for the central administration of salary and benefits for residents rotating at VA facilities. This process, known as disbursement, is an alternative payroll mechanism whereby the VA reimburses the academic affiliate for resident salary and benefits and the affiliate acts as the disbursing agent, issuing paychecks to residents.21,22

Resident FUNDING

By policy, with rare exceptions, the VA does not sponsor residency programs due to the challenges of providing an appropriate patient mix of age, sex, and medical conditions to meet accreditation standards.4 Nearly all VA reimbursements are for residents in affiliate-sponsored programs, while just 1% pays for residents in legacy, VA-sponsored residency programs at 2 VA facilities. The VA budget for resident (including fellows) salary and benefits is managed by the VA Office of Academic Affiliations (OAA), the national VA office responsible for oversight, policy, and funding of VA HPE programs.

Resident Salaries and Benefits

VA funding of resident salary and benefits are analogous with CMS direct GME (DGME), which is designed to cover resident salary and benefits costs.4,14,23 CMS DGME payments depend on a hospital’s volume of CMS inpatients and are based on a statutory formula, which uses the hospital’s resident FTE positions, the per-resident amount, and Medicare’s share of inpatient beds (Medicare patient load) to determine payments.12 The per-resident amount is set by statute, varies geographically, and is calculated by dividing the hospital’s allowable costs of GME (percentage of CMS inpatient days) divided by the number of residents.12,24

By comparison, the VA GME payment reimburses for each FTE based on the salary and benefits rate set by the academic affiliate. Reimbursement is calculated based on resident time spent at the VA multiplied by a daily salary rate. The daily salary rate is determined by dividing the resident’s total compensation (salary and benefits) by the number of calendar days in an academic year. Resident time spent at the VA facility is determined by obtaining rotation schedules provided by the academic affiliate and verifying resident clinical and educational activity during scheduled rotations.

Indirect Medical Education Funding

In addition to resident salary and benefits, funds to offset the cost of conducting HPE are provided to VA facilities. These funds are intended to improve and maintain necessary infrastructure for all HPE programs not just GME, including education office administration needs, teaching costs (ie, a portion of VA preceptors salary), and instructional equipment.

The Veterans Equitable Resource Allocation (VERA) is a national budgeting process for VA medical facilities that funds facility operational needs such as staff salary and benefits, infrastructure, and equipment.2 The education portion of the VERA, the VERA Education Support Component (VESC), is not managed by the OAA, but rather is distributed through the VERA model to the general budget of VA facilities hosting HPE (Figure). VESC funding in the VA budget is based on labor mapping of physician time spent in education; other labor mapping categories include clinical care, research, and administration. VA facility VESC funding is calculated based on the number of paid health profession trainees (HPTs) from all professions, apportioned according to the number of FTEs for physician residents and VA-paid HPTs in other disciplines. In fiscal year 2024, VA facilities received $115,812 for each physician resident FTE position and $84,906 for each VA-paid, non-GME FTE position.

The VESC is like CMS's indirect GME funding, termed Indirect Medical Education (IME), an additional payment for each Medicare patient discharged reflecting teaching hospitals’ higher patient care costs relative to nonteaching hospitals. Described elsewhere, IME is calculated using a resident-to-bed ratio and a multiplier, which is set by statute.4,25 While IME can be used for reimbursement for some resident clinical and educational activities(eg, research), VA VESC funds cannot be used for such activities and are part of the general facility budget and appropriated per the discretion of the medical facility director.

ESTABLISHING GME PARTNERSHIPS

An affiliation agreement establishes the administrative and legal requirements for educational relationships with academic affiliates and includes standards for conducting HPE, responsibilities for accreditation standards, program leadership, faculty, resources, supervision, academic policies, and procedures. The VA uses standardized affiliation agreement templates that have been vetted with accrediting bodies and the VA Office of General Counsel.

A disbursement agreement authorizes the VA to reimburse affiliates for resident salary and benefits for VA clinical and educational activities. The disbursement agreement details the fiscal arrangements (eg, payment in advance vs arrears, salary, and benefit rates, leave) for the reimbursement payments. Veterans Health Administration (VHA) Directive 1400.05 provides the policy and procedures for calculating reimbursement for HPT educational activities.26

The VA facility designated education officer (DEO) oversees all HPE programs and coordinates the affiliation and disbursement agreement processes.27 The DEO, affiliate DIO, residency program director, and VA residency site director determine the physician resident FTE positions assigned to a VA facility based on educational objectives and availability of educational resources at the VA facility, such as patient care opportunities, faculty supervisors, space, and equipment. The VA facility requests for resident FTE positions are submitted to the OAA by the facility DEO.

Once GME FTE positions are approved by the OAA, VA facilities work with their academic affiliate to submit the physician resident salary and benefit rate. Affiliate DIOs attest to the accuracy of the salary rate schedule and the local DEO submits the budget request to the OAA. Upon approval, the funds are transferred to the VA facility each fiscal year, which begins October 1. DEOs report quarterly to the OAA both budget needs and excesses based on variations in the approved FTEs due to additional VA rotations, physician resident attrition, or reassignment.

Resident Position Allocation

VA GME financing provides flexibility through periodic needs assessments and expansion initiatives. In August and December, DEOs collaborate with an academic affiliate to submit reports to the OAA confirming their projected GME needs for the next academic year. Additional positions requests are reviewed by the OAA; funding depends on budget and the educational justification. The OAA periodically issues GME expansion requests for proposal, which typically arise from legislation to address specific VA workforce needs. The VA facility DEO and affiliate GME leaders collaborate to apply for additional positions. For example, a VA GME expansion under the Veterans Access, Choice, and Accountability Act of 2014 added 1500 GME positions in 8 years for critically needed specialties and in rural and underserved areas.5 The Maintaining Internal Systems and Strengthening Outside Networks (MISSION) Act of 2018 authorized a pilot program for VA to fund residents at non-VA facilities with priority for Indian Health Services, Tribes and Tribal Organizations, Federally Qualified Health Centers, and US Department of Defense facilities to provide access to veterans in underserved areas.6

The VA GME financing system has flexibility to meet local needs for additional resident positions and to address broader VA workforce gaps through targeted expansion. Generally, CMS does not fund positions to address workforce needs, place residents in specific geographic areas, or require the training of certain types of residents.4 However, the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2021 has provided the opportunity to address rural workforce needs.28

Reimbursement

The VA provides reimbursement for clinical and educational activities performed in VA facilities for the benefit of veterans as well as research, didactics, meetings and conferences, annual and sick leave, and orientation. The VA also may provide reimbursement for educational activities that occur off VA grounds (eg, the VA proportional share of a residency program’s didactic sessions). The VA does not reimburse for affiliate clinical duties or administrative costs, although a national policy allows VA facilities to reimburse affiliates for some GME overhead costs.29

CMS similarly reimburses for residency training time spent in patient care activities as well as orientation activities, didactics, leave, and, in some cases, research.4,30,31 CMS makes payments to hospitals, which may include sponsoring institutions and Medicare-eligible participating training sites.4,30,31 For both the VA and CMS, residents may not be counted twice for reimbursement by 2 federal agencies; in other words, a resident may not count for > 1 FTE.4,30-32

GME Oversight

VA GME funding came under significant scrutiny. At a 2016 House Veterans Affairs Committee hearing, Representative Phil Roe, MD (R-Tennessee), noted that no process existed at many VA facilities for “determining trainee presence” and that many VA medical centers had “difficulty tracking resident rotations”16 A VA Office of the Inspector General investigation recommended that the VA implement policies and procedures to improve oversight to “ensure residents are fully participating in educational activities” and that the VA is “paying the correct amount” to the affiliate.17 A 2020 General Accountability Office report outlined unclear policy guidance, incomplete tracking of resident activities, and improper fiscal processes for reimbursement and reconciliation of affiliate invoices.18

In response, the OAA created an oversight and compliance unit, revised VHA Directive 1400.05 (the policy for disbursement), and improved resident tracking procedures.26 The standard operating procedure that accompanied VHA Directive 1400.05 provides detailed information for the DEO and VA facility staff for tracking resident clinical and educational activities. FTE counts are essential to both VA and CMS for accurate reimbursement. The eAppendix and the Table provide a guide to reimbursable activities in the VA for the calculation of reimbursement, with a comparison to CMS.33,34 The OAA in cooperation with other VA staff and officers periodically conducts audits to assess compliance with disbursement policy and affiliate reimbursement accuracy.

In the VA, resident activities are captured on the VA Educational Activity Record, a standardized spreadsheet to track activities and calculate reimbursement. Each VA facility hosting resident physicians manually records resident activity by the half-day. This process is labor intensive, involving both VA and affiliate staff to accurately reconcile payments. To address the workload demands, the OAA is developing an online tool that will automate aspects of the tracking process. Also, to ensure adequate staffing, the OAA is in the process of implementing an office optimization project, providing standardized position descriptions, an organizational chart, and staffing levels for DEO offices in VA facilities.

Conclusions

This report describes the key policies and principles of VA GME financing, highlighting the essential similarities and differences between VA and CMS. Neither the VA nor CMS regulations allow for reimbursement for > 1 FTE position per resident, a principle that underpins the assignment of resident rotations and federal funding for GME and are similar with respect to reimbursement for patient care activities, didactics, research, orientation, and scholarly activity. While reimbursable activities in the VA require physical presence and care of veteran patients, CMS also limits reimbursement to resident activities in the hospital and approved other settings if the hospital is paying for resident salary and benefits in these settings. The VA provides some flexibility for offsite activities including didactics and, in specific circumstances, remote care of veteran patients (eg, teleradiology).

The VA and CMS use different GME financing models. For example, the CMS calculations for resident FTEs are complex, whereas VA calculations reimburse the salary and benefits as set by the academic affiliate. The VA process accounts for local variation in salary rates, whereas the per-resident amount set by CMS varies regionally and does not fully account for differences in the cost of living.24 Because all patients in VA facilities are veterans, VA calculations for reimbursement do not involve ratios of beds like the CMS calculations to determine a proportional share of reimbursement. The VA GME expansion tends to be more directed to VA health workforce needs than CMS, specifying the types of programs and geographic locations to address these needs.

The VA regularly reevaluates how affiliates are reimbursed for VA resident activity, balancing compliance with VA policies and the workload for VA and its affiliates. The VA obtains input from key stakeholders including DEOs, DIOs, and professional organizations such as the Association of American Medical Colleges and the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education.35,36

Looking ahead, the VA is developing an online tool to improve the accuracy of affiliate reimbursement. The VA will also implement a standardized staffing model, organizational structure, and position descriptions for DEO offices. These initiatives will help reduce the burden of tracking and verifying resident activity and continue to support the 77-year partnership between VA and its affiliated institutions.

The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) has partnered with academic medical centers and programs since 1946 to provide clinical training for physician residents. Ranking second in federal graduate medical education (GME) funding to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), the $850 million VA GME budget annually reimburses > 250 GME-sponsoring institutions (affiliates) of 8000 GME programs for the clinical training of 49,000 individual residents rotating through > 11,000 full-time equivalent (FTE) positions.1 The VA also distributes $1.6 billion to VA facilities to offset the costs of conducting health professions education (HPE) (eg, facility infrastructure, salary support for VA instructors and preceptors, education office administration, and instructional equipment).2 The VA financial and educational contributions account for payment of 11% of resident positions nationally and allow academic medical centers to be less reliant on CMS GME funding.3,4 The VA contributions also provide opportunities for GME expansion,1,5,6 educational innovations,5,7 interprofessional and team-based care,8,9 and quality and safety training.10,11 The Table provides a comparison of CMS and VA GME reimbursability based on activity.

GME financing is complex, particularly the formulaic approach used by CMS, the details of which are often obscured in federal regulations. Due to this complexity and the $16 billion CMS GME budget, academic publications have focused on CMS GME financing while not fully explaining the VA GME policies and processes.4,12-14 By comparison, the VA GME financing model is relatively straightforward and governed by different statues and VA regulations, yet sharing some of the same principles as CMS regulations. Given the challenges in CMS reimbursement to fully support the cost of resident education, as well as the educational opportunities at the VA, the VA designs its reimbursement model to assure that affiliates receive appropriate payments.4,12,15 To ensure the continued success of VA GME partnerships, knowledge of VA GME financing has become increasingly important for designated institutional officers (DIOs) and residency program directors, particularly in light of recent investigations into oversight of the VA’s reimbursement to academic affiliates.

VA AUTHORITY

While the VA’s primary mission is “to provide a complete hospital medical service for the medical care and treatment of veterans,” early VA leaders recognized the importance of affiliating with the nation’s academic institutions.19 In 1946, the VA Policy Memorandum Number 2 established a partnership between the VA and the academic medical community.20 Additional legislation authorized specific agreements with academic affiliates for the central administration of salary and benefits for residents rotating at VA facilities. This process, known as disbursement, is an alternative payroll mechanism whereby the VA reimburses the academic affiliate for resident salary and benefits and the affiliate acts as the disbursing agent, issuing paychecks to residents.21,22

Resident FUNDING

By policy, with rare exceptions, the VA does not sponsor residency programs due to the challenges of providing an appropriate patient mix of age, sex, and medical conditions to meet accreditation standards.4 Nearly all VA reimbursements are for residents in affiliate-sponsored programs, while just 1% pays for residents in legacy, VA-sponsored residency programs at 2 VA facilities. The VA budget for resident (including fellows) salary and benefits is managed by the VA Office of Academic Affiliations (OAA), the national VA office responsible for oversight, policy, and funding of VA HPE programs.

Resident Salaries and Benefits

VA funding of resident salary and benefits are analogous with CMS direct GME (DGME), which is designed to cover resident salary and benefits costs.4,14,23 CMS DGME payments depend on a hospital’s volume of CMS inpatients and are based on a statutory formula, which uses the hospital’s resident FTE positions, the per-resident amount, and Medicare’s share of inpatient beds (Medicare patient load) to determine payments.12 The per-resident amount is set by statute, varies geographically, and is calculated by dividing the hospital’s allowable costs of GME (percentage of CMS inpatient days) divided by the number of residents.12,24

By comparison, the VA GME payment reimburses for each FTE based on the salary and benefits rate set by the academic affiliate. Reimbursement is calculated based on resident time spent at the VA multiplied by a daily salary rate. The daily salary rate is determined by dividing the resident’s total compensation (salary and benefits) by the number of calendar days in an academic year. Resident time spent at the VA facility is determined by obtaining rotation schedules provided by the academic affiliate and verifying resident clinical and educational activity during scheduled rotations.

Indirect Medical Education Funding

In addition to resident salary and benefits, funds to offset the cost of conducting HPE are provided to VA facilities. These funds are intended to improve and maintain necessary infrastructure for all HPE programs not just GME, including education office administration needs, teaching costs (ie, a portion of VA preceptors salary), and instructional equipment.

The Veterans Equitable Resource Allocation (VERA) is a national budgeting process for VA medical facilities that funds facility operational needs such as staff salary and benefits, infrastructure, and equipment.2 The education portion of the VERA, the VERA Education Support Component (VESC), is not managed by the OAA, but rather is distributed through the VERA model to the general budget of VA facilities hosting HPE (Figure). VESC funding in the VA budget is based on labor mapping of physician time spent in education; other labor mapping categories include clinical care, research, and administration. VA facility VESC funding is calculated based on the number of paid health profession trainees (HPTs) from all professions, apportioned according to the number of FTEs for physician residents and VA-paid HPTs in other disciplines. In fiscal year 2024, VA facilities received $115,812 for each physician resident FTE position and $84,906 for each VA-paid, non-GME FTE position.

The VESC is like CMS's indirect GME funding, termed Indirect Medical Education (IME), an additional payment for each Medicare patient discharged reflecting teaching hospitals’ higher patient care costs relative to nonteaching hospitals. Described elsewhere, IME is calculated using a resident-to-bed ratio and a multiplier, which is set by statute.4,25 While IME can be used for reimbursement for some resident clinical and educational activities(eg, research), VA VESC funds cannot be used for such activities and are part of the general facility budget and appropriated per the discretion of the medical facility director.

ESTABLISHING GME PARTNERSHIPS

An affiliation agreement establishes the administrative and legal requirements for educational relationships with academic affiliates and includes standards for conducting HPE, responsibilities for accreditation standards, program leadership, faculty, resources, supervision, academic policies, and procedures. The VA uses standardized affiliation agreement templates that have been vetted with accrediting bodies and the VA Office of General Counsel.

A disbursement agreement authorizes the VA to reimburse affiliates for resident salary and benefits for VA clinical and educational activities. The disbursement agreement details the fiscal arrangements (eg, payment in advance vs arrears, salary, and benefit rates, leave) for the reimbursement payments. Veterans Health Administration (VHA) Directive 1400.05 provides the policy and procedures for calculating reimbursement for HPT educational activities.26

The VA facility designated education officer (DEO) oversees all HPE programs and coordinates the affiliation and disbursement agreement processes.27 The DEO, affiliate DIO, residency program director, and VA residency site director determine the physician resident FTE positions assigned to a VA facility based on educational objectives and availability of educational resources at the VA facility, such as patient care opportunities, faculty supervisors, space, and equipment. The VA facility requests for resident FTE positions are submitted to the OAA by the facility DEO.

Once GME FTE positions are approved by the OAA, VA facilities work with their academic affiliate to submit the physician resident salary and benefit rate. Affiliate DIOs attest to the accuracy of the salary rate schedule and the local DEO submits the budget request to the OAA. Upon approval, the funds are transferred to the VA facility each fiscal year, which begins October 1. DEOs report quarterly to the OAA both budget needs and excesses based on variations in the approved FTEs due to additional VA rotations, physician resident attrition, or reassignment.

Resident Position Allocation

VA GME financing provides flexibility through periodic needs assessments and expansion initiatives. In August and December, DEOs collaborate with an academic affiliate to submit reports to the OAA confirming their projected GME needs for the next academic year. Additional positions requests are reviewed by the OAA; funding depends on budget and the educational justification. The OAA periodically issues GME expansion requests for proposal, which typically arise from legislation to address specific VA workforce needs. The VA facility DEO and affiliate GME leaders collaborate to apply for additional positions. For example, a VA GME expansion under the Veterans Access, Choice, and Accountability Act of 2014 added 1500 GME positions in 8 years for critically needed specialties and in rural and underserved areas.5 The Maintaining Internal Systems and Strengthening Outside Networks (MISSION) Act of 2018 authorized a pilot program for VA to fund residents at non-VA facilities with priority for Indian Health Services, Tribes and Tribal Organizations, Federally Qualified Health Centers, and US Department of Defense facilities to provide access to veterans in underserved areas.6

The VA GME financing system has flexibility to meet local needs for additional resident positions and to address broader VA workforce gaps through targeted expansion. Generally, CMS does not fund positions to address workforce needs, place residents in specific geographic areas, or require the training of certain types of residents.4 However, the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2021 has provided the opportunity to address rural workforce needs.28

Reimbursement

The VA provides reimbursement for clinical and educational activities performed in VA facilities for the benefit of veterans as well as research, didactics, meetings and conferences, annual and sick leave, and orientation. The VA also may provide reimbursement for educational activities that occur off VA grounds (eg, the VA proportional share of a residency program’s didactic sessions). The VA does not reimburse for affiliate clinical duties or administrative costs, although a national policy allows VA facilities to reimburse affiliates for some GME overhead costs.29

CMS similarly reimburses for residency training time spent in patient care activities as well as orientation activities, didactics, leave, and, in some cases, research.4,30,31 CMS makes payments to hospitals, which may include sponsoring institutions and Medicare-eligible participating training sites.4,30,31 For both the VA and CMS, residents may not be counted twice for reimbursement by 2 federal agencies; in other words, a resident may not count for > 1 FTE.4,30-32

GME Oversight

VA GME funding came under significant scrutiny. At a 2016 House Veterans Affairs Committee hearing, Representative Phil Roe, MD (R-Tennessee), noted that no process existed at many VA facilities for “determining trainee presence” and that many VA medical centers had “difficulty tracking resident rotations”16 A VA Office of the Inspector General investigation recommended that the VA implement policies and procedures to improve oversight to “ensure residents are fully participating in educational activities” and that the VA is “paying the correct amount” to the affiliate.17 A 2020 General Accountability Office report outlined unclear policy guidance, incomplete tracking of resident activities, and improper fiscal processes for reimbursement and reconciliation of affiliate invoices.18

In response, the OAA created an oversight and compliance unit, revised VHA Directive 1400.05 (the policy for disbursement), and improved resident tracking procedures.26 The standard operating procedure that accompanied VHA Directive 1400.05 provides detailed information for the DEO and VA facility staff for tracking resident clinical and educational activities. FTE counts are essential to both VA and CMS for accurate reimbursement. The eAppendix and the Table provide a guide to reimbursable activities in the VA for the calculation of reimbursement, with a comparison to CMS.33,34 The OAA in cooperation with other VA staff and officers periodically conducts audits to assess compliance with disbursement policy and affiliate reimbursement accuracy.

In the VA, resident activities are captured on the VA Educational Activity Record, a standardized spreadsheet to track activities and calculate reimbursement. Each VA facility hosting resident physicians manually records resident activity by the half-day. This process is labor intensive, involving both VA and affiliate staff to accurately reconcile payments. To address the workload demands, the OAA is developing an online tool that will automate aspects of the tracking process. Also, to ensure adequate staffing, the OAA is in the process of implementing an office optimization project, providing standardized position descriptions, an organizational chart, and staffing levels for DEO offices in VA facilities.

Conclusions

This report describes the key policies and principles of VA GME financing, highlighting the essential similarities and differences between VA and CMS. Neither the VA nor CMS regulations allow for reimbursement for > 1 FTE position per resident, a principle that underpins the assignment of resident rotations and federal funding for GME and are similar with respect to reimbursement for patient care activities, didactics, research, orientation, and scholarly activity. While reimbursable activities in the VA require physical presence and care of veteran patients, CMS also limits reimbursement to resident activities in the hospital and approved other settings if the hospital is paying for resident salary and benefits in these settings. The VA provides some flexibility for offsite activities including didactics and, in specific circumstances, remote care of veteran patients (eg, teleradiology).

The VA and CMS use different GME financing models. For example, the CMS calculations for resident FTEs are complex, whereas VA calculations reimburse the salary and benefits as set by the academic affiliate. The VA process accounts for local variation in salary rates, whereas the per-resident amount set by CMS varies regionally and does not fully account for differences in the cost of living.24 Because all patients in VA facilities are veterans, VA calculations for reimbursement do not involve ratios of beds like the CMS calculations to determine a proportional share of reimbursement. The VA GME expansion tends to be more directed to VA health workforce needs than CMS, specifying the types of programs and geographic locations to address these needs.

The VA regularly reevaluates how affiliates are reimbursed for VA resident activity, balancing compliance with VA policies and the workload for VA and its affiliates. The VA obtains input from key stakeholders including DEOs, DIOs, and professional organizations such as the Association of American Medical Colleges and the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education.35,36

Looking ahead, the VA is developing an online tool to improve the accuracy of affiliate reimbursement. The VA will also implement a standardized staffing model, organizational structure, and position descriptions for DEO offices. These initiatives will help reduce the burden of tracking and verifying resident activity and continue to support the 77-year partnership between VA and its affiliated institutions.

1. Klink KA, Albanese AP, Bope ET, Sanders KM. Veterans Affairs graduate medical education expansion addresses US physician workforce needs. Acad Med. 2022;97(8):1144-1150. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000004545

2. Andrus CH, Johnson K, Pierce E, Romito PJ, Hartel P, Berrios‐Guccione S, Best W. Finance modeling in the delivery of medical care in tertiary‐care hospitals in the Department of Veterans Affairs. J Surg Res. 2001;96(2):152-157. doi:10.1006/jsre.1999.5728

3. Petrakis IL, Kozal M. Academic medical centers and the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs: a 75-year partnership influences medical education, scientific discovery, and clinical care. Acad Med. 2022;97(8):1110-1113. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000004734

4. Heisler EJ, Mendez BH, Mitchell A, Panangala SV, Villagrana MA. Federal support for graduate medical education: an overview (R44376). Congressional Research Service report R44376; version 11. Updated December 27, 2018. Accessed March 2, 2024. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R44376/11

5. Chang BK, Brannen JL. The Veterans Access, Choice, and Accountability Act of 2014: examining graduate medical education enhancement in the Department of Veterans Affairs. Acad Med. 2015;90(9):1196-1198. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000795

6. Albanese AP, Bope ET, Sanders KM, Bowman M. The VA MISSION Act of 2018: a potential game changer for rural GME expansion and veteran health care. J Rural Health. 2020;36(1):133-136. doi:10.1111/jrh.12360

7. Lypson ML, Roberts LW. Valuing the partnership between the Veterans Health Administration and academic medicine. Acad Med. 2022;97(8):1091-1093. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000004748

8. Harada ND, Traylor L, Rugen KW, et al. Interprofessional transformation of clinical education: the first six years of the Veterans Affairs Centers of Excellence in Primary Care Education. J Interprof Care. 2023;37(suppl 1):S86-S94. doi:10.1080/13561820.2018.1433642

9. Harada ND, Rajashekara S, Sansgiry S, et al. Developing interprofessional primary care teams: alumni evaluation of the Department of Veterans Affairs Centers of Excellence in Primary Care Education Program. J Med Educ Curric Dev. 2019;6:2382120519875455. doi:10.1177/2382120519875455

10. Splaine ME, Ogrinc G, Gilman SC, et al. The Department of Veterans Affairs National Quality Scholars Fellowship Program: experience from 10 years of training quality scholars. Acad Med. 2009;84(12):1741-1748. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181bfdcef

11. Watts BV, Paull DE, Williams LC, Neily J, Hemphill RR, Brannen JL. Department of Veterans Affairs chief resident in quality and patient safety program: a model to spread change. Am J Med Qual. 2016;31(6):598-600. doi:10.1177/1062860616643403

12. He K, Whang E, Kristo G. Graduate medical education funding mechanisms, challenges, and solutions: a narrative review. Am J Surg. 2021;221(1):65-71. doi:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2020.06.007

13. Villagrana M. Medicare graduate medical education payments: an overview. Congressional Research Service report IF10960. Updated September 29, 2022. Accessed March 2, 2024. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF10960

14. Committee on the Governance and Financing of Graduate Medical Education; Board on Health Care Services; Institute of Medicine. Graduate Medical Education That Meets the Nation’s Health Needs. Eden J, Berwick DM, Wilensky GR, eds. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2014. doi:10.17226/18754

15. Physician workforce: caps on Medicare-funded graduate medical education at teaching hospitals. Report to congressional requesters. GAO-21-391. May 21, 2021. Accessed March 1, 2024. https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-21-391.pdf

16. VA and Academic Affiliates: Who Benefits? Hearing Before the Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations of the Committee on Veterans’ Affairs, 114th Cong, 2nd Sess (2016). Accessed March 1, 2024. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CHRG-115hhrg29685/html/CHRG-115hhrg29685.htm

17. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Inspector General (OIG). Veterans Health Administration. Review of resident and part-time physician time and attendance at the Oklahoma City VA Health Care System. OIG report 17-00253-93. March 28, 2018. Accessed March 1, 2024. https://www.oversight.gov/sites/default/files/oig-reports/VAOIG-17-00253-93.pdf

18. VA health care: actions needed to improve oversight of graduate medical education reimbursement. Report to the ranking member, Committee on Veterans’ Affairs, House of Representatives. GAO-20-553. July 2020. Accessed March 1, 2024. https://www.gao.gov/assets/710/708275.pdf

19. Functions of Veterans Health Administration: in general, 38 USC §7301 (2022). Accessed March 1, 2024. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/USCODE-2022-title38/pdf/USCODE-2022-title38-partV-chap73-subchapI-sec7301.pdf

20. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Policy memorandum no. 2, policy in association of veterans’ hospitals with medical schools. January 30, 1946.

21. Veterans Health Care Expansion Act of 1973, Public Law 93-82. August 2, 1973. Accessed March 1, 2024. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/STATUTE-87/pdf/STATUTE-87-Pg179.pdf

22. Residencies and internships, 38 USC § 7406 (2022). Accessed March 1, 2024. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/USCODE-2022-title38/pdf/USCODE-2022-title38-partV-chap74-subchapI-sec7406.pdf

23. Direct graduate medical education (DGME). Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services. Updated December 5, 2023. Accessed March 1, 2024. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/DGME

24. Drezdzon MK, Cowley NJ, Sweeney DP, et al. Going for broke: the impact of cost of living on surgery resident stipend value. Ann Surg. 2023;278(6):1053-1059. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000005923

25. Special treatment: hospitals that incur indirect costs for graduate medical education programs, 42 CFR § 412.105 (2023). Accessed March 1, 2024. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CFR-2023-title42-vol2/pdf/CFR-2023-title42-vol2-sec412-105.pdf

26. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration. VHA Directive 1400.05, Disbursement agreements for health professions trainees appointed under 38 U.S.C. § 7406. June 2, 2021. Accessed March 1, 2024. https://www.va.gov/vhapublications/ViewPublication.asp?pub_ID=9293

27. Harada ND, Sanders KM, Bowman MA. Health systems education leadership: learning from the VA designated education officer role. Fed Pract. 2022;39(6):266-273. doi:10.12788/fp.0278

28. Schleiter Hitchell K, Johnson L. CMS finalizes rules for distribution of 1000 new Medicare-funded residency positions and changes to rural training track programs. J Grad Med Educ. 2022;14(2):245-249. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-22-00193.1

29. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration. VHA Directive 1400.10, Educational cost contracts for health professions education. September 25, 2023. Accessed March 1, 2024. https://www.va.gov/VHAPUBLICATIONS/ViewPublication.asp?pub_ID=11480

30. Direct GME payments: general requirements, 42 CFR § 413.75 (2023). Accessed March 1, 2024. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CFR-2023-title42-vol2/pdf/CFR-2023-title42-vol2-sec413-75.pdf

31. Direct GME payments: determination of the total number of FTE residents, 42 CFR § 413.78 (2023). Accessed March 1, 2024. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CFR-2023-title42-vol2/pdf/CFR-2023-title42-vol2-sec413-78.pdf

32. US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare financial management manual, chapter 8. Contractor procedures for provider audits. Accessed March 1, 2024. https://www.cms.gov/regulations-and-guidance/guidance/manuals/downloads/fin106c08.pdf

33. US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Inspector General. CMS did not always ensure hospitals complied with Medicare reimbursement requirements for graduate medical education. OIG report A-02-17-01017. November 2018. Accessed March 1, 2024. https://oig.hhs.gov/oas/reports/region2/21701017.pdf

34. US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Interns and Residents Information System (IRIS) XML format. Publication 100-20. Transmittal 11418. Change request 12724. May 19, 2022. Accessed March 1, 2024. https://www.hhs.gov/guidance/sites/default/files/hhs-guidance-documents/R11418OTN.pdf

35. Birnbaum AD, Byrne J, on behalf of the VA Office of Academic Affiliations. VHA Updates: Disbursement Policy and Education Cost Contracts. Presented at: American Association of Medical Colleges Webinar; June 2021. Accessed March 1, 2024. https://vimeo.com/644415670

36. Byrne JM, on behalf of the VA Office of Academic Affiliations. Disbursement procedures update for AY 23-24. Accessed March 1, 2024. https://www.va.gov/oaa/Videos/AffiliatePresentationDisbursementandEARsAY23-24.pptx

1. Klink KA, Albanese AP, Bope ET, Sanders KM. Veterans Affairs graduate medical education expansion addresses US physician workforce needs. Acad Med. 2022;97(8):1144-1150. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000004545

2. Andrus CH, Johnson K, Pierce E, Romito PJ, Hartel P, Berrios‐Guccione S, Best W. Finance modeling in the delivery of medical care in tertiary‐care hospitals in the Department of Veterans Affairs. J Surg Res. 2001;96(2):152-157. doi:10.1006/jsre.1999.5728

3. Petrakis IL, Kozal M. Academic medical centers and the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs: a 75-year partnership influences medical education, scientific discovery, and clinical care. Acad Med. 2022;97(8):1110-1113. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000004734

4. Heisler EJ, Mendez BH, Mitchell A, Panangala SV, Villagrana MA. Federal support for graduate medical education: an overview (R44376). Congressional Research Service report R44376; version 11. Updated December 27, 2018. Accessed March 2, 2024. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R44376/11

5. Chang BK, Brannen JL. The Veterans Access, Choice, and Accountability Act of 2014: examining graduate medical education enhancement in the Department of Veterans Affairs. Acad Med. 2015;90(9):1196-1198. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000795

6. Albanese AP, Bope ET, Sanders KM, Bowman M. The VA MISSION Act of 2018: a potential game changer for rural GME expansion and veteran health care. J Rural Health. 2020;36(1):133-136. doi:10.1111/jrh.12360

7. Lypson ML, Roberts LW. Valuing the partnership between the Veterans Health Administration and academic medicine. Acad Med. 2022;97(8):1091-1093. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000004748

8. Harada ND, Traylor L, Rugen KW, et al. Interprofessional transformation of clinical education: the first six years of the Veterans Affairs Centers of Excellence in Primary Care Education. J Interprof Care. 2023;37(suppl 1):S86-S94. doi:10.1080/13561820.2018.1433642

9. Harada ND, Rajashekara S, Sansgiry S, et al. Developing interprofessional primary care teams: alumni evaluation of the Department of Veterans Affairs Centers of Excellence in Primary Care Education Program. J Med Educ Curric Dev. 2019;6:2382120519875455. doi:10.1177/2382120519875455

10. Splaine ME, Ogrinc G, Gilman SC, et al. The Department of Veterans Affairs National Quality Scholars Fellowship Program: experience from 10 years of training quality scholars. Acad Med. 2009;84(12):1741-1748. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181bfdcef

11. Watts BV, Paull DE, Williams LC, Neily J, Hemphill RR, Brannen JL. Department of Veterans Affairs chief resident in quality and patient safety program: a model to spread change. Am J Med Qual. 2016;31(6):598-600. doi:10.1177/1062860616643403

12. He K, Whang E, Kristo G. Graduate medical education funding mechanisms, challenges, and solutions: a narrative review. Am J Surg. 2021;221(1):65-71. doi:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2020.06.007

13. Villagrana M. Medicare graduate medical education payments: an overview. Congressional Research Service report IF10960. Updated September 29, 2022. Accessed March 2, 2024. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF10960

14. Committee on the Governance and Financing of Graduate Medical Education; Board on Health Care Services; Institute of Medicine. Graduate Medical Education That Meets the Nation’s Health Needs. Eden J, Berwick DM, Wilensky GR, eds. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2014. doi:10.17226/18754

15. Physician workforce: caps on Medicare-funded graduate medical education at teaching hospitals. Report to congressional requesters. GAO-21-391. May 21, 2021. Accessed March 1, 2024. https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-21-391.pdf

16. VA and Academic Affiliates: Who Benefits? Hearing Before the Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations of the Committee on Veterans’ Affairs, 114th Cong, 2nd Sess (2016). Accessed March 1, 2024. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CHRG-115hhrg29685/html/CHRG-115hhrg29685.htm

17. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Inspector General (OIG). Veterans Health Administration. Review of resident and part-time physician time and attendance at the Oklahoma City VA Health Care System. OIG report 17-00253-93. March 28, 2018. Accessed March 1, 2024. https://www.oversight.gov/sites/default/files/oig-reports/VAOIG-17-00253-93.pdf

18. VA health care: actions needed to improve oversight of graduate medical education reimbursement. Report to the ranking member, Committee on Veterans’ Affairs, House of Representatives. GAO-20-553. July 2020. Accessed March 1, 2024. https://www.gao.gov/assets/710/708275.pdf

19. Functions of Veterans Health Administration: in general, 38 USC §7301 (2022). Accessed March 1, 2024. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/USCODE-2022-title38/pdf/USCODE-2022-title38-partV-chap73-subchapI-sec7301.pdf

20. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Policy memorandum no. 2, policy in association of veterans’ hospitals with medical schools. January 30, 1946.

21. Veterans Health Care Expansion Act of 1973, Public Law 93-82. August 2, 1973. Accessed March 1, 2024. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/STATUTE-87/pdf/STATUTE-87-Pg179.pdf

22. Residencies and internships, 38 USC § 7406 (2022). Accessed March 1, 2024. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/USCODE-2022-title38/pdf/USCODE-2022-title38-partV-chap74-subchapI-sec7406.pdf

23. Direct graduate medical education (DGME). Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services. Updated December 5, 2023. Accessed March 1, 2024. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/DGME

24. Drezdzon MK, Cowley NJ, Sweeney DP, et al. Going for broke: the impact of cost of living on surgery resident stipend value. Ann Surg. 2023;278(6):1053-1059. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000005923

25. Special treatment: hospitals that incur indirect costs for graduate medical education programs, 42 CFR § 412.105 (2023). Accessed March 1, 2024. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CFR-2023-title42-vol2/pdf/CFR-2023-title42-vol2-sec412-105.pdf

26. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration. VHA Directive 1400.05, Disbursement agreements for health professions trainees appointed under 38 U.S.C. § 7406. June 2, 2021. Accessed March 1, 2024. https://www.va.gov/vhapublications/ViewPublication.asp?pub_ID=9293

27. Harada ND, Sanders KM, Bowman MA. Health systems education leadership: learning from the VA designated education officer role. Fed Pract. 2022;39(6):266-273. doi:10.12788/fp.0278

28. Schleiter Hitchell K, Johnson L. CMS finalizes rules for distribution of 1000 new Medicare-funded residency positions and changes to rural training track programs. J Grad Med Educ. 2022;14(2):245-249. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-22-00193.1

29. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration. VHA Directive 1400.10, Educational cost contracts for health professions education. September 25, 2023. Accessed March 1, 2024. https://www.va.gov/VHAPUBLICATIONS/ViewPublication.asp?pub_ID=11480

30. Direct GME payments: general requirements, 42 CFR § 413.75 (2023). Accessed March 1, 2024. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CFR-2023-title42-vol2/pdf/CFR-2023-title42-vol2-sec413-75.pdf

31. Direct GME payments: determination of the total number of FTE residents, 42 CFR § 413.78 (2023). Accessed March 1, 2024. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CFR-2023-title42-vol2/pdf/CFR-2023-title42-vol2-sec413-78.pdf

32. US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare financial management manual, chapter 8. Contractor procedures for provider audits. Accessed March 1, 2024. https://www.cms.gov/regulations-and-guidance/guidance/manuals/downloads/fin106c08.pdf

33. US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Inspector General. CMS did not always ensure hospitals complied with Medicare reimbursement requirements for graduate medical education. OIG report A-02-17-01017. November 2018. Accessed March 1, 2024. https://oig.hhs.gov/oas/reports/region2/21701017.pdf

34. US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Interns and Residents Information System (IRIS) XML format. Publication 100-20. Transmittal 11418. Change request 12724. May 19, 2022. Accessed March 1, 2024. https://www.hhs.gov/guidance/sites/default/files/hhs-guidance-documents/R11418OTN.pdf

35. Birnbaum AD, Byrne J, on behalf of the VA Office of Academic Affiliations. VHA Updates: Disbursement Policy and Education Cost Contracts. Presented at: American Association of Medical Colleges Webinar; June 2021. Accessed March 1, 2024. https://vimeo.com/644415670

36. Byrne JM, on behalf of the VA Office of Academic Affiliations. Disbursement procedures update for AY 23-24. Accessed March 1, 2024. https://www.va.gov/oaa/Videos/AffiliatePresentationDisbursementandEARsAY23-24.pptx

75 Years of the Historic Partnership Between the VA and Academic Medical Centers

The US government has a legacy of providing support for veterans. Pensions were offered to disabled veterans as early as 1776, and benefits were expanded to cover medical needs as the country grew and modernized.1,2 Enacted during the Civil War, the General Pension Act increased benefits for widows and dependents.2 Rehabilitation and vocational training assistance benefits were added after World War I, and the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) was created in 1930 to consolidate all benefits under one umbrella organization.2,3

Prior to World War II, the VA lacked the bed capacity for the 4 million veterans who were eligible for care. This shortage became more acute by the end of the war, when the number of eligible veterans increased by 15 million.4 Although the VA successfully built bed capacity through acquisition of military hospitals, VA hospitals struggled to recruit clinical staff.2 Physicians were hesitant to join the VA because civil service salaries were lower than comparable positions in the community, and the VA offered limited opportunities for research or continuing education. These limitations negatively impacted the overall reputation of the VA. The American Medical Association (AMA) was reluctant to directly admit VA physicians for membership because of a “lower” standard of care at VA hospitals.2 This review will describe how passage of 2 legislative actions, the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act and Public Law (PL)79-293, and a key policy memorandum set the foundation for the partnership between the VA and academic medical centers. This led to improved medical care for veterans and expansion of health professions education for VA and the nation.5,6

GI Bill of Rights