User login

Health Systems Education Leadership: Learning From the VA Designated Education Officer Role

The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) operates the largest integrated health care system in the United States, providing physical and mental health care to more than 9 million veterans enrolled each year through a national system of inpatient, outpatient, and long-term care settings.1 As 1 of 4 statutory missions, the VA conducts the largest training effort for health professionals in cooperation with affiliated academic institutions. From 2016 through 2020, an average of 123,000 trainees from various professions received training at the VA.2 Physician residents comprised the largest trainee group (37%), followed by associated health students and residents (20%), and nursing professionals (21%).2 In VA, associated health professions include all health care disciplines other than allopathic and osteopathic medicine, dentistry, and nursing. The associated health professions encompass about 40 specialties, including audiology, dietetics, physical and occupational therapy, optometry, pharmacy, podiatry, psychology, and social work.

The VA also trains a smaller number of advanced fellows to address specialties important to the nation and veterans health that are not sufficiently addressed by standard accredited professional training.3 The VA Advanced Fellowship programs include 22 postresidency, postdoctoral, and postmasters fellowships to physicians and dentists, and associated health professions, including psychologists, social workers, and pharmacists. 3 From 2015 to 2019, 57 to 61% of medical school students reported having a VA clinical training experience during medical school.4 Of current VA employees, 20% of registered nurses, 64% of physicians, 73% of podiatrists and optometrists, and 81% of psychologists reported VA training prior to employment.5

Health professions education is led by the designated education officer (DEO) at each VA facility.6 Also known as the associate chief of staff for education (ACOS/E), the DEO is a leadership position that is accountable to local VA facility executive leadership as well as the national Office of Academic Affiliations (OAA), which directs all VA health professions training across the US.6 At most VA facilities, the DEO oversees clinical training and education reporting directly to the facility chief of staff. At the same time, the ACOS/E is accountable to the OAA to ensure adherence with national education directives and policy. The DEO oversees trainee programs through collaboration with training program directors, faculty, academic affiliates, and accreditation agencies across > 40 health professions.

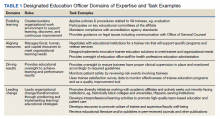

The DEO is expected to possess expertise in leadership attributes identified by the US Office of Personnel Management as essential to build a federal corporate culture that drives results, serves customers, and builds successful teams and coalitions within and outside the VA.7 These leadership attributes include leading change, leading people, driving results, business acumen, and building coalitions.7 They are operationalized by OAA as 4 domains of expertise required to lead education across multiple professions, including: (1) creating and sustaining an organizational work environment that supports learning, discovery, and continuous improvement; (2) aligning and managing fiscal, human, and capital resources to meet organizational learning needs; (3) driving learning and performance results to impact organizational success; and (4) leading change and transformation through positioning and implementing innovative learning and education strategies (Table 1).6

In this article we describe the VA DEO leadership role and the tasks required to lead education across multiple professions within the VA health care system. Given the broad scope of leading educational programs across multiple clinical professions and the interprofessional backgrounds of DEOs across the VA, we evaluated DEO self-perceived effectiveness to impact educational decisions and behavior by professional discipline. Our evaluation question is: Are different professional education and practice backgrounds functionally capable of providing leadership over all education of health professions training programs? Finally, we describe DEOs perceptions of facilitators and barriers to performing their DEO role within the VA.

Methods

We conducted a mixed methods analysis of data collected by OAA to assess DEO needs within a multiprofessional clinical learning environment. The needs assessment was conducted by an OAA evaluator (NH) with input on instrument development and data analysis from OAA leadership (KS, MB). This evaluation is categorized as an operations activity based on VA Handbook 1200 where information generated is used for business operations and quality improvement. 8 The overall project was subject to administrative rather than institutional review board oversight.

A needs assessment tool was developed based on the OAA domains of expertise.6 Prior to its administration, the tool was piloted with 8 DEOs in the field and the survey shortened based on their feedback. DEOs were asked about individual professional characteristics (eg, clinical profession, academic appointment, type of health professions training programs at the VA site) and their self-perceived effectiveness in impacting educational decisions and behaviors on general and profession-specific tasks within each of the 4 domains of expertise on a 5-point Likert scale (1, not effective; 5, very effective). 6,9 The needs assessment also included an open-ended question asking respondents to comment on any issues they felt important to understanding DEO role effectiveness.

The needs assessment was administered online via SurveyMonkey to 132 DEOs via email in September and October 2019. The DEOs represented 148 of 160 VA facilities with health professions education; 14 DEOs covered > 1 VA facility, and 12 positions were vacant. Email reminders were sent to nonresponders after 1 week. At 2 weeks, nonresponders received telephone reminders and personalized follow-up emails from OAA staff. The response rate at the end of 3 weeks was 96%.

Data Analysis

Mixed methods analyses included quantitative analyses to identify differences in general and profession-specific self-ratings of effectiveness in influencing educational decisions and behaviors by DEO profession, and qualitative analyses to further understand DEO’s perceptions of facilitators and barriers to DEO task effectiveness.10,11 Quantitative analyses included descriptive statistics for all variables followed by nonparametric tests including χ2 and Mann- Whitney U tests to assess differences between physician and other professional DEOs in descriptive characteristics and selfperceived effectiveness on general and profession- specific tasks. Quantitative analyses were conducted using SPSS software, version 26. Qualitative analyses consisted of rapid assessment procedures to identify facilitators and barriers to DEO effectiveness by profession using Atlas.ti version 8, which involved reviewing responses to the open-ended question and assigning each response to predetermined categories based on the organizational level it applied to (eg, individual DEO, VA facility, or external to the organization).12,13 Responses within categories were then summarized to identify the main themes.

Results

Completed surveys were received from 127 respondents representing 139 VA facilities. Eighty percent were physicians and 20% were other professionals, including psychologists, pharmacists, dentists, dieticians, nurses, and nonclinicians. There were no statistically significant differences between physician and other professional DEOs in the percent working full time or length of time spent working in the position. About one-third of the sample had been in the position for < 2 years, one-third had been in the position for 2 to < 5 years, and one-third had been in the role for ≥ 5 years. Eighty percent reported having a faculty appointment with an academic affiliate. While 92% of physician DEOs had a faculty appointment, only 40% of other professional DEOs did (P < .001). Most faculty appointments for both groups were with a school of medicine. More physician DEOs than other professionals had training programs at their site for physicians (P = .003) and dentists (P < .001), but there were no statistically significant differences for having associated health, nursing, or advanced fellowship training programs at their sites. Across all DEOs, 98% reported training programs at their site for associated health professions, 95% for physician training, 93% for nursing training, 59% for dental training, and 48% for advanced fellowships.

Self-Perceived Effectiveness

There were no statistically significant differences between physician and other professional DEOs on self-perceived effectiveness in impacting educational decisions or behaviors for general tasks applicable across professions (Table 2). This result held even after controlling for length of time in the position and whether the DEO had an academic appointment. Generally, both groups reported being effective on tasks in the enabling learning domain, including applying policies and procedures related to trainees who rotate through the VA and maintaining adherence with accreditation agency standards across health professions. Mean score ranges for both physician and other professional DEOs reported moderate effectiveness in aligning resources effectiveness questions (2.45-3.72 vs 2.75-3.76), driving results questions (3.02-3.60 vs 3.39-3.48), and leading change questions (3.12-3.50 vs 3.42-3.80).

For profession-specific tasks, effectiveness ratings between the 2 groups were generally not statistically significant for medical, dental, and advanced fellowship training programs (Table 3). There was a pattern of statistically significant differences between physician and other professional DEOs for associated health and nursing training programs on tasks across the 4 domains of expertise with physicians having lower mean ratings compared with other professionals. Generally, physician DEOs had higher task effectiveness when compared with other professionals for medical training programs, and other professionals had higher task effectiveness ratings than did physicians for associated health or nursing training programs.

Facilitators and Barriers

Seventy responses related to facilitators and barriers to DEO effectiveness were received (59 from physicians and 11 from other professionals). Most responses were categorized as individual level facilitators or barriers (53% for physician and 64% for other professionals). Only 3% of comments were categorized as external to the organization (all made by physicians). The themes were similar for both groups and were aggregated in Table 4. Facilitators included continuing education, having a mentor who works at a similar type of facility, maintaining balance and time management when working with different training programs, learning to work and develop relationships with training program directors, developing an overall picture of each type of health professions training program, holding regular meetings with all health training programs and academic affiliates, having a formal education service line with budget and staffing, facility executive leadership who are knowledgeable of the education mission and DEO role, having a national oversight body, and the DEO’s relationships with academic affiliates.

Barriers to role effectiveness at the individual DEO level included assignment of multiple roles and a focus on regulation and monitoring with little time for development of new programs and strategic planning. The organizational level barriers included difficulty getting core services to engage with health professions trainees and siloed education leadership.

Discussion

DEOs oversee multiple health professions training programs within local facilities. The DEO is accountable to local VA facility leadership and a national education office to lead local health professions education at local facilities and integrate these educational activities across the national VA system.

The VA DEO role is similar to the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education designated institutional official (DIO) except that the VA DEO provides oversight of > 40 health professions training programs.14,15 The VA DEO, therefore, has broader oversight than the DIO role that focuses only on graduate physician education. Similar to the DIO, the VA DEO role initially emphasized the enabling learning and aligning resources domains to provide oversight and administration of health professions training programs. Over time, both roles have expanded to include defining and ensuring healthy clinical learning environments, aligning educational resources and training with the institutional mission, workforce, and societal needs, and creating continuous educational improvement models.6,16,17 To accomplish these expanded goals, both the DEO and the DIO work closely with other educational leaders at the academic affiliate and the VA facility. As health professions education advances, there will be increased emphasis placed on delivering educational programs to improve clinical practice and health care outcomes.18

Our findings that DEO profession did not influence self-ratings of effectiveness to influence educational decisions or behaviors on general tasks applicable across health professions suggest that education and practice background are not factors influencing selfratings. Nor were self-ratings influenced by other factors. Since the DEO is a senior leadership position, candidates for the position already may possess managerial and leadership skills. In our sample, several individuals commented that they had prior education leadership positions, eg, training program director or had years of experience working in the VA. Similarly, having an academic appointment may not be important for the performance of general administrative tasks. However, an academic appointment may be important for effective performance of educational tasks, such as clinical teaching, didactic training, and curriculum development, which were not measured in this study.

The finding of differences in self-ratings between physicians and other professionals on profession-specific tasks for associated health and nursing suggests that physicians may require additional curriculum to enhance their knowledge in managing other professional educational programs. For nursing specifically, this finding could also reflect substantial input from the lead nurse executive in the facility. DEOs also identified practical ways to facilitate their work with multiple health professions that could immediately be put into practice, including developing relationships and enhancing communication with training program directors, faculty, and academic affiliates of each profession.

Taken together, the quantitative and qualitative findings indicate that despite differences in professional backgrounds, DEOs have high self-ratings of their own effectiveness to influence educational decisions and behaviors on general tasks they are expected to accomplish. There are some professionspecific tasks where professional background does influence self-perceived effectiveness, ie, physicians have higher self-ratings on physician-specific tasks and other professionals have higher self-ratings on associated health or nursing tasks. These perceived differences may be mitigated by increasing facilitators and decreasing barriers identified for the individual DEO, within the organization, and external to the organization.

Limitations Our findings should be interpreted with the following limitations in mind. The selfreport nature of the data opens the possibility of self-report bias or Dunning-Kruger effects where effectiveness ratings could have been overestimated by respondents.21 Although respondents were assured of their anonymity and that results would only be reported in the aggregate, there is potential for providing more positive responses on a needs assessment administered by the national education program office. We recommend further work be conducted to validate the needs assessment tool against other data collection methods, such as actual outcomes of educational effectiveness. Our study did not incorporate measures of educational effectiveness to determine whether self-perceived DEO effectiveness is translated to better trainee or learning outcomes. Before this can happen, educational policymakers must identify the most important facility-level learning outcomes. Since the DEO is a facility level educational administrator, learning efeffectiveness must be defined at the facility level. The qualitative findings could also be expanded through the application of more detailed qualitative methods, such as indepth interviews. The tasks rated by DEOs were based on OAA’s current definition of the DEO role.6 As the field advances, DEO tasks will also evolve.22-24

Conclusions

The DEO is a senior educational leadership role that oversees all health professions training in the VA. Our findings are supportive of individuals from various health disciplines serving in the VA DEO role with responsibilities that span multiple health profession training programs. We recommend further work to validate the instrument used in this study, as well as the application of qualitative methods like indepth interviews to further our understanding of the DEO role.

1. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration. Updated April 18, 2022. Accessed May 6, 2022. https://www.va.gov/health/aboutvha.asp

2. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Academic Affiliations. Health professions education: academic Year 2019-2020. Published 2020. Accessed May 6, 2022. https://www.va.gov/OAA/docs /OAA_Statistics_2020.pdf

3. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Academic Affiliations. Advanced Fellowships and Professional Development. Updated November 26, 2021. Accessed May 6, 2022. https://www.va.gov/oaa /advancedfellowships/advanced-fellowships.asp

4. Association of American Medical Colleges. Medical school graduation questionnaire, 2019 all schools summary report. Published July 2019. Accessed May 6, 2022. https://www.aamc.org/system/files/2019-08/2019-gq-all-schools -summary-report.pdf

5. US Department of Veterans Affairs, National Center for Organization Development. VA all employee survey. Published 2019. Accessed May 6, 2022. https://www.va.gov /NCOD/VAworkforcesurveys.asp

6. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Academic Affiliations. Education leaders in the VA: the role of the designated education officer (DEO). Published December 2019. Accessed May 6, 2022. https://www.va.gov/OAA/docs/DEO_Learning _Leader_2019.pdf

7. US Office of Personnel Management. Policy, data oversight: guide to senior executive service qualifications. Published 2010. Accessed May 6, 2022. https://www.opm .gov/policy-data-oversight/senior-executive-service /executive-core-qualifications/

8. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Research and Development. Program guide: 1200.21 VHA operations activities that may constitute research. Published January 9, 2019. Accessed May 6, 2022. https://www.research .va.gov/resources/policies/ProgramGuide-1200-21-VHA -Operations-Activities.pdf

9. Riesenberg LA, Rosenbaum PF, Stick SL. Competencies, essential training, and resources viewed by designated institutional officials as important to the position in graduate medical education [published correction appears in Acad Med. 2006 Dec;81(12):1025]. Acad Med. 2006;81(5):426- 431. doi:10.1097/01.ACM.0000222279.28824.f5

10. Palinkas LA, Mendon SJ, Hamilton AB. Inn o v a t i o n s i n M i x e d M e t h o d s E v a l u a - tions. Annu Rev Public Health. 2019;40:423-442. doi:10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040218-044215

11. Tashakkori A, Creswell JW. Exploring the nature of research questions in mixed methods research. J Mix Methods Res. 2007;1(3):207-211. doi:10.1177/1558689807302814

12. Averill JB. Matrix analysis as a complementary analytic strategy in qualitative inquiry. Qual Health Res. 2002;12(6):855-866. doi:10.1177/104973230201200611

13. Hamilton AB, Finley EP. Qualitative methods in implementation research: An introduction. Psychiatry Res. 2019;280:112516.

14. Bellini L, Hartmann D, Opas L. Beyond must: supporting the evolving role of the designated institutional official. J Grad Med Educ. 2010;2(2):147-150. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-10-00073.1

15. Riesenberg LA, Rosenbaum P, Stick SL. Characteristics, roles, and responsibilities of the Designated Institutional Official (DIO) position in graduate medical education education [published correction appears in Acad Med. 2006 Dec;81(12):1025] [published correction appears in Acad Med. 2006 Mar;81(3):274]. Acad Med. 2006;81(1):8-19. doi:10.1097/00001888-200601000-00005

16. Group on Resident Affairs Core Competency Task Force. Institutional GME leadership competencies. 2015. Accessed May 6, 2022. https://www.aamc.org/system /files/c/2/441248-institutionalgmeleadershipcompetencies .pdf

17. Weiss KB, Bagian JP, Nasca TJ. The clinical learning environment: the foundation of graduate medical education. JAMA. 2013;309(16):1687-1688. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.1931

18. Beliveau ME, Warnes CA, Harrington RA, et al. Organizational change, leadership, and the transformation of continuing professional development: lessons learned from the American College of Cardiology. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2015;35(3):201-210. doi:10.1002/chp.21301

19. World Health Organization. Framework for Action on Interprofessional Education and Collaborative Practice. Published September 1, 2020. Accessed May 10, 2022. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/framework -for-action-on-interprofessional-education-collaborative -practice

20. Weiss K, Passiment M, Riordan L, Wagner R for the National Collaborative for Improving the Clinical Learning Environment IP-CLE Report Work Group. Achieving the optimal interprofessional clinical learning environment: proceedings from an NCICLE symposium. Published January 18, 2019. Accessed May 6, 2022. doi:10.33385/NCICLE.0002

21. Althubaiti A. Information bias in health research: definition, pitfalls, and adjustment methods. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2016;9:211-217. Published 2016 May 4. doi:10.2147/JMDH.S104807

22. Gilman SC, Chokshi DA, Bowen JL, Rugen KW, Cox M. Connecting the dots: interprofessional health education and delivery system redesign at the Veterans Health Administration. Acad Med. 2014;89(8):1113-1116. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000312

23. Health Professions Accreditors Collaborative. Guidance on developing quality interprofessional education for the health professions. Published February 1, 2019. Accessed May 6, 2022. https://healthprofessionsaccreditors.org/wp -content/uploads/2019/02/HPACGuidance02-01-19.pdf

24. Watts BV, Paull DE, Williams LC, Neily J, Hemphill RR, Brannen JL. Department of Veterans Affairs Chief Resident in Quality and Patient Safety Program: a model to spread change. Am J Med Qual. 2016;31(6):598-600. doi:10.1177/1062860616643403

The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) operates the largest integrated health care system in the United States, providing physical and mental health care to more than 9 million veterans enrolled each year through a national system of inpatient, outpatient, and long-term care settings.1 As 1 of 4 statutory missions, the VA conducts the largest training effort for health professionals in cooperation with affiliated academic institutions. From 2016 through 2020, an average of 123,000 trainees from various professions received training at the VA.2 Physician residents comprised the largest trainee group (37%), followed by associated health students and residents (20%), and nursing professionals (21%).2 In VA, associated health professions include all health care disciplines other than allopathic and osteopathic medicine, dentistry, and nursing. The associated health professions encompass about 40 specialties, including audiology, dietetics, physical and occupational therapy, optometry, pharmacy, podiatry, psychology, and social work.

The VA also trains a smaller number of advanced fellows to address specialties important to the nation and veterans health that are not sufficiently addressed by standard accredited professional training.3 The VA Advanced Fellowship programs include 22 postresidency, postdoctoral, and postmasters fellowships to physicians and dentists, and associated health professions, including psychologists, social workers, and pharmacists. 3 From 2015 to 2019, 57 to 61% of medical school students reported having a VA clinical training experience during medical school.4 Of current VA employees, 20% of registered nurses, 64% of physicians, 73% of podiatrists and optometrists, and 81% of psychologists reported VA training prior to employment.5

Health professions education is led by the designated education officer (DEO) at each VA facility.6 Also known as the associate chief of staff for education (ACOS/E), the DEO is a leadership position that is accountable to local VA facility executive leadership as well as the national Office of Academic Affiliations (OAA), which directs all VA health professions training across the US.6 At most VA facilities, the DEO oversees clinical training and education reporting directly to the facility chief of staff. At the same time, the ACOS/E is accountable to the OAA to ensure adherence with national education directives and policy. The DEO oversees trainee programs through collaboration with training program directors, faculty, academic affiliates, and accreditation agencies across > 40 health professions.

The DEO is expected to possess expertise in leadership attributes identified by the US Office of Personnel Management as essential to build a federal corporate culture that drives results, serves customers, and builds successful teams and coalitions within and outside the VA.7 These leadership attributes include leading change, leading people, driving results, business acumen, and building coalitions.7 They are operationalized by OAA as 4 domains of expertise required to lead education across multiple professions, including: (1) creating and sustaining an organizational work environment that supports learning, discovery, and continuous improvement; (2) aligning and managing fiscal, human, and capital resources to meet organizational learning needs; (3) driving learning and performance results to impact organizational success; and (4) leading change and transformation through positioning and implementing innovative learning and education strategies (Table 1).6

In this article we describe the VA DEO leadership role and the tasks required to lead education across multiple professions within the VA health care system. Given the broad scope of leading educational programs across multiple clinical professions and the interprofessional backgrounds of DEOs across the VA, we evaluated DEO self-perceived effectiveness to impact educational decisions and behavior by professional discipline. Our evaluation question is: Are different professional education and practice backgrounds functionally capable of providing leadership over all education of health professions training programs? Finally, we describe DEOs perceptions of facilitators and barriers to performing their DEO role within the VA.

Methods

We conducted a mixed methods analysis of data collected by OAA to assess DEO needs within a multiprofessional clinical learning environment. The needs assessment was conducted by an OAA evaluator (NH) with input on instrument development and data analysis from OAA leadership (KS, MB). This evaluation is categorized as an operations activity based on VA Handbook 1200 where information generated is used for business operations and quality improvement. 8 The overall project was subject to administrative rather than institutional review board oversight.

A needs assessment tool was developed based on the OAA domains of expertise.6 Prior to its administration, the tool was piloted with 8 DEOs in the field and the survey shortened based on their feedback. DEOs were asked about individual professional characteristics (eg, clinical profession, academic appointment, type of health professions training programs at the VA site) and their self-perceived effectiveness in impacting educational decisions and behaviors on general and profession-specific tasks within each of the 4 domains of expertise on a 5-point Likert scale (1, not effective; 5, very effective). 6,9 The needs assessment also included an open-ended question asking respondents to comment on any issues they felt important to understanding DEO role effectiveness.

The needs assessment was administered online via SurveyMonkey to 132 DEOs via email in September and October 2019. The DEOs represented 148 of 160 VA facilities with health professions education; 14 DEOs covered > 1 VA facility, and 12 positions were vacant. Email reminders were sent to nonresponders after 1 week. At 2 weeks, nonresponders received telephone reminders and personalized follow-up emails from OAA staff. The response rate at the end of 3 weeks was 96%.

Data Analysis

Mixed methods analyses included quantitative analyses to identify differences in general and profession-specific self-ratings of effectiveness in influencing educational decisions and behaviors by DEO profession, and qualitative analyses to further understand DEO’s perceptions of facilitators and barriers to DEO task effectiveness.10,11 Quantitative analyses included descriptive statistics for all variables followed by nonparametric tests including χ2 and Mann- Whitney U tests to assess differences between physician and other professional DEOs in descriptive characteristics and selfperceived effectiveness on general and profession- specific tasks. Quantitative analyses were conducted using SPSS software, version 26. Qualitative analyses consisted of rapid assessment procedures to identify facilitators and barriers to DEO effectiveness by profession using Atlas.ti version 8, which involved reviewing responses to the open-ended question and assigning each response to predetermined categories based on the organizational level it applied to (eg, individual DEO, VA facility, or external to the organization).12,13 Responses within categories were then summarized to identify the main themes.

Results

Completed surveys were received from 127 respondents representing 139 VA facilities. Eighty percent were physicians and 20% were other professionals, including psychologists, pharmacists, dentists, dieticians, nurses, and nonclinicians. There were no statistically significant differences between physician and other professional DEOs in the percent working full time or length of time spent working in the position. About one-third of the sample had been in the position for < 2 years, one-third had been in the position for 2 to < 5 years, and one-third had been in the role for ≥ 5 years. Eighty percent reported having a faculty appointment with an academic affiliate. While 92% of physician DEOs had a faculty appointment, only 40% of other professional DEOs did (P < .001). Most faculty appointments for both groups were with a school of medicine. More physician DEOs than other professionals had training programs at their site for physicians (P = .003) and dentists (P < .001), but there were no statistically significant differences for having associated health, nursing, or advanced fellowship training programs at their sites. Across all DEOs, 98% reported training programs at their site for associated health professions, 95% for physician training, 93% for nursing training, 59% for dental training, and 48% for advanced fellowships.

Self-Perceived Effectiveness

There were no statistically significant differences between physician and other professional DEOs on self-perceived effectiveness in impacting educational decisions or behaviors for general tasks applicable across professions (Table 2). This result held even after controlling for length of time in the position and whether the DEO had an academic appointment. Generally, both groups reported being effective on tasks in the enabling learning domain, including applying policies and procedures related to trainees who rotate through the VA and maintaining adherence with accreditation agency standards across health professions. Mean score ranges for both physician and other professional DEOs reported moderate effectiveness in aligning resources effectiveness questions (2.45-3.72 vs 2.75-3.76), driving results questions (3.02-3.60 vs 3.39-3.48), and leading change questions (3.12-3.50 vs 3.42-3.80).

For profession-specific tasks, effectiveness ratings between the 2 groups were generally not statistically significant for medical, dental, and advanced fellowship training programs (Table 3). There was a pattern of statistically significant differences between physician and other professional DEOs for associated health and nursing training programs on tasks across the 4 domains of expertise with physicians having lower mean ratings compared with other professionals. Generally, physician DEOs had higher task effectiveness when compared with other professionals for medical training programs, and other professionals had higher task effectiveness ratings than did physicians for associated health or nursing training programs.

Facilitators and Barriers

Seventy responses related to facilitators and barriers to DEO effectiveness were received (59 from physicians and 11 from other professionals). Most responses were categorized as individual level facilitators or barriers (53% for physician and 64% for other professionals). Only 3% of comments were categorized as external to the organization (all made by physicians). The themes were similar for both groups and were aggregated in Table 4. Facilitators included continuing education, having a mentor who works at a similar type of facility, maintaining balance and time management when working with different training programs, learning to work and develop relationships with training program directors, developing an overall picture of each type of health professions training program, holding regular meetings with all health training programs and academic affiliates, having a formal education service line with budget and staffing, facility executive leadership who are knowledgeable of the education mission and DEO role, having a national oversight body, and the DEO’s relationships with academic affiliates.

Barriers to role effectiveness at the individual DEO level included assignment of multiple roles and a focus on regulation and monitoring with little time for development of new programs and strategic planning. The organizational level barriers included difficulty getting core services to engage with health professions trainees and siloed education leadership.

Discussion

DEOs oversee multiple health professions training programs within local facilities. The DEO is accountable to local VA facility leadership and a national education office to lead local health professions education at local facilities and integrate these educational activities across the national VA system.

The VA DEO role is similar to the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education designated institutional official (DIO) except that the VA DEO provides oversight of > 40 health professions training programs.14,15 The VA DEO, therefore, has broader oversight than the DIO role that focuses only on graduate physician education. Similar to the DIO, the VA DEO role initially emphasized the enabling learning and aligning resources domains to provide oversight and administration of health professions training programs. Over time, both roles have expanded to include defining and ensuring healthy clinical learning environments, aligning educational resources and training with the institutional mission, workforce, and societal needs, and creating continuous educational improvement models.6,16,17 To accomplish these expanded goals, both the DEO and the DIO work closely with other educational leaders at the academic affiliate and the VA facility. As health professions education advances, there will be increased emphasis placed on delivering educational programs to improve clinical practice and health care outcomes.18

Our findings that DEO profession did not influence self-ratings of effectiveness to influence educational decisions or behaviors on general tasks applicable across health professions suggest that education and practice background are not factors influencing selfratings. Nor were self-ratings influenced by other factors. Since the DEO is a senior leadership position, candidates for the position already may possess managerial and leadership skills. In our sample, several individuals commented that they had prior education leadership positions, eg, training program director or had years of experience working in the VA. Similarly, having an academic appointment may not be important for the performance of general administrative tasks. However, an academic appointment may be important for effective performance of educational tasks, such as clinical teaching, didactic training, and curriculum development, which were not measured in this study.

The finding of differences in self-ratings between physicians and other professionals on profession-specific tasks for associated health and nursing suggests that physicians may require additional curriculum to enhance their knowledge in managing other professional educational programs. For nursing specifically, this finding could also reflect substantial input from the lead nurse executive in the facility. DEOs also identified practical ways to facilitate their work with multiple health professions that could immediately be put into practice, including developing relationships and enhancing communication with training program directors, faculty, and academic affiliates of each profession.

Taken together, the quantitative and qualitative findings indicate that despite differences in professional backgrounds, DEOs have high self-ratings of their own effectiveness to influence educational decisions and behaviors on general tasks they are expected to accomplish. There are some professionspecific tasks where professional background does influence self-perceived effectiveness, ie, physicians have higher self-ratings on physician-specific tasks and other professionals have higher self-ratings on associated health or nursing tasks. These perceived differences may be mitigated by increasing facilitators and decreasing barriers identified for the individual DEO, within the organization, and external to the organization.

Limitations Our findings should be interpreted with the following limitations in mind. The selfreport nature of the data opens the possibility of self-report bias or Dunning-Kruger effects where effectiveness ratings could have been overestimated by respondents.21 Although respondents were assured of their anonymity and that results would only be reported in the aggregate, there is potential for providing more positive responses on a needs assessment administered by the national education program office. We recommend further work be conducted to validate the needs assessment tool against other data collection methods, such as actual outcomes of educational effectiveness. Our study did not incorporate measures of educational effectiveness to determine whether self-perceived DEO effectiveness is translated to better trainee or learning outcomes. Before this can happen, educational policymakers must identify the most important facility-level learning outcomes. Since the DEO is a facility level educational administrator, learning efeffectiveness must be defined at the facility level. The qualitative findings could also be expanded through the application of more detailed qualitative methods, such as indepth interviews. The tasks rated by DEOs were based on OAA’s current definition of the DEO role.6 As the field advances, DEO tasks will also evolve.22-24

Conclusions

The DEO is a senior educational leadership role that oversees all health professions training in the VA. Our findings are supportive of individuals from various health disciplines serving in the VA DEO role with responsibilities that span multiple health profession training programs. We recommend further work to validate the instrument used in this study, as well as the application of qualitative methods like indepth interviews to further our understanding of the DEO role.

The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) operates the largest integrated health care system in the United States, providing physical and mental health care to more than 9 million veterans enrolled each year through a national system of inpatient, outpatient, and long-term care settings.1 As 1 of 4 statutory missions, the VA conducts the largest training effort for health professionals in cooperation with affiliated academic institutions. From 2016 through 2020, an average of 123,000 trainees from various professions received training at the VA.2 Physician residents comprised the largest trainee group (37%), followed by associated health students and residents (20%), and nursing professionals (21%).2 In VA, associated health professions include all health care disciplines other than allopathic and osteopathic medicine, dentistry, and nursing. The associated health professions encompass about 40 specialties, including audiology, dietetics, physical and occupational therapy, optometry, pharmacy, podiatry, psychology, and social work.

The VA also trains a smaller number of advanced fellows to address specialties important to the nation and veterans health that are not sufficiently addressed by standard accredited professional training.3 The VA Advanced Fellowship programs include 22 postresidency, postdoctoral, and postmasters fellowships to physicians and dentists, and associated health professions, including psychologists, social workers, and pharmacists. 3 From 2015 to 2019, 57 to 61% of medical school students reported having a VA clinical training experience during medical school.4 Of current VA employees, 20% of registered nurses, 64% of physicians, 73% of podiatrists and optometrists, and 81% of psychologists reported VA training prior to employment.5

Health professions education is led by the designated education officer (DEO) at each VA facility.6 Also known as the associate chief of staff for education (ACOS/E), the DEO is a leadership position that is accountable to local VA facility executive leadership as well as the national Office of Academic Affiliations (OAA), which directs all VA health professions training across the US.6 At most VA facilities, the DEO oversees clinical training and education reporting directly to the facility chief of staff. At the same time, the ACOS/E is accountable to the OAA to ensure adherence with national education directives and policy. The DEO oversees trainee programs through collaboration with training program directors, faculty, academic affiliates, and accreditation agencies across > 40 health professions.

The DEO is expected to possess expertise in leadership attributes identified by the US Office of Personnel Management as essential to build a federal corporate culture that drives results, serves customers, and builds successful teams and coalitions within and outside the VA.7 These leadership attributes include leading change, leading people, driving results, business acumen, and building coalitions.7 They are operationalized by OAA as 4 domains of expertise required to lead education across multiple professions, including: (1) creating and sustaining an organizational work environment that supports learning, discovery, and continuous improvement; (2) aligning and managing fiscal, human, and capital resources to meet organizational learning needs; (3) driving learning and performance results to impact organizational success; and (4) leading change and transformation through positioning and implementing innovative learning and education strategies (Table 1).6

In this article we describe the VA DEO leadership role and the tasks required to lead education across multiple professions within the VA health care system. Given the broad scope of leading educational programs across multiple clinical professions and the interprofessional backgrounds of DEOs across the VA, we evaluated DEO self-perceived effectiveness to impact educational decisions and behavior by professional discipline. Our evaluation question is: Are different professional education and practice backgrounds functionally capable of providing leadership over all education of health professions training programs? Finally, we describe DEOs perceptions of facilitators and barriers to performing their DEO role within the VA.

Methods

We conducted a mixed methods analysis of data collected by OAA to assess DEO needs within a multiprofessional clinical learning environment. The needs assessment was conducted by an OAA evaluator (NH) with input on instrument development and data analysis from OAA leadership (KS, MB). This evaluation is categorized as an operations activity based on VA Handbook 1200 where information generated is used for business operations and quality improvement. 8 The overall project was subject to administrative rather than institutional review board oversight.

A needs assessment tool was developed based on the OAA domains of expertise.6 Prior to its administration, the tool was piloted with 8 DEOs in the field and the survey shortened based on their feedback. DEOs were asked about individual professional characteristics (eg, clinical profession, academic appointment, type of health professions training programs at the VA site) and their self-perceived effectiveness in impacting educational decisions and behaviors on general and profession-specific tasks within each of the 4 domains of expertise on a 5-point Likert scale (1, not effective; 5, very effective). 6,9 The needs assessment also included an open-ended question asking respondents to comment on any issues they felt important to understanding DEO role effectiveness.

The needs assessment was administered online via SurveyMonkey to 132 DEOs via email in September and October 2019. The DEOs represented 148 of 160 VA facilities with health professions education; 14 DEOs covered > 1 VA facility, and 12 positions were vacant. Email reminders were sent to nonresponders after 1 week. At 2 weeks, nonresponders received telephone reminders and personalized follow-up emails from OAA staff. The response rate at the end of 3 weeks was 96%.

Data Analysis

Mixed methods analyses included quantitative analyses to identify differences in general and profession-specific self-ratings of effectiveness in influencing educational decisions and behaviors by DEO profession, and qualitative analyses to further understand DEO’s perceptions of facilitators and barriers to DEO task effectiveness.10,11 Quantitative analyses included descriptive statistics for all variables followed by nonparametric tests including χ2 and Mann- Whitney U tests to assess differences between physician and other professional DEOs in descriptive characteristics and selfperceived effectiveness on general and profession- specific tasks. Quantitative analyses were conducted using SPSS software, version 26. Qualitative analyses consisted of rapid assessment procedures to identify facilitators and barriers to DEO effectiveness by profession using Atlas.ti version 8, which involved reviewing responses to the open-ended question and assigning each response to predetermined categories based on the organizational level it applied to (eg, individual DEO, VA facility, or external to the organization).12,13 Responses within categories were then summarized to identify the main themes.

Results

Completed surveys were received from 127 respondents representing 139 VA facilities. Eighty percent were physicians and 20% were other professionals, including psychologists, pharmacists, dentists, dieticians, nurses, and nonclinicians. There were no statistically significant differences between physician and other professional DEOs in the percent working full time or length of time spent working in the position. About one-third of the sample had been in the position for < 2 years, one-third had been in the position for 2 to < 5 years, and one-third had been in the role for ≥ 5 years. Eighty percent reported having a faculty appointment with an academic affiliate. While 92% of physician DEOs had a faculty appointment, only 40% of other professional DEOs did (P < .001). Most faculty appointments for both groups were with a school of medicine. More physician DEOs than other professionals had training programs at their site for physicians (P = .003) and dentists (P < .001), but there were no statistically significant differences for having associated health, nursing, or advanced fellowship training programs at their sites. Across all DEOs, 98% reported training programs at their site for associated health professions, 95% for physician training, 93% for nursing training, 59% for dental training, and 48% for advanced fellowships.

Self-Perceived Effectiveness

There were no statistically significant differences between physician and other professional DEOs on self-perceived effectiveness in impacting educational decisions or behaviors for general tasks applicable across professions (Table 2). This result held even after controlling for length of time in the position and whether the DEO had an academic appointment. Generally, both groups reported being effective on tasks in the enabling learning domain, including applying policies and procedures related to trainees who rotate through the VA and maintaining adherence with accreditation agency standards across health professions. Mean score ranges for both physician and other professional DEOs reported moderate effectiveness in aligning resources effectiveness questions (2.45-3.72 vs 2.75-3.76), driving results questions (3.02-3.60 vs 3.39-3.48), and leading change questions (3.12-3.50 vs 3.42-3.80).

For profession-specific tasks, effectiveness ratings between the 2 groups were generally not statistically significant for medical, dental, and advanced fellowship training programs (Table 3). There was a pattern of statistically significant differences between physician and other professional DEOs for associated health and nursing training programs on tasks across the 4 domains of expertise with physicians having lower mean ratings compared with other professionals. Generally, physician DEOs had higher task effectiveness when compared with other professionals for medical training programs, and other professionals had higher task effectiveness ratings than did physicians for associated health or nursing training programs.

Facilitators and Barriers

Seventy responses related to facilitators and barriers to DEO effectiveness were received (59 from physicians and 11 from other professionals). Most responses were categorized as individual level facilitators or barriers (53% for physician and 64% for other professionals). Only 3% of comments were categorized as external to the organization (all made by physicians). The themes were similar for both groups and were aggregated in Table 4. Facilitators included continuing education, having a mentor who works at a similar type of facility, maintaining balance and time management when working with different training programs, learning to work and develop relationships with training program directors, developing an overall picture of each type of health professions training program, holding regular meetings with all health training programs and academic affiliates, having a formal education service line with budget and staffing, facility executive leadership who are knowledgeable of the education mission and DEO role, having a national oversight body, and the DEO’s relationships with academic affiliates.

Barriers to role effectiveness at the individual DEO level included assignment of multiple roles and a focus on regulation and monitoring with little time for development of new programs and strategic planning. The organizational level barriers included difficulty getting core services to engage with health professions trainees and siloed education leadership.

Discussion

DEOs oversee multiple health professions training programs within local facilities. The DEO is accountable to local VA facility leadership and a national education office to lead local health professions education at local facilities and integrate these educational activities across the national VA system.

The VA DEO role is similar to the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education designated institutional official (DIO) except that the VA DEO provides oversight of > 40 health professions training programs.14,15 The VA DEO, therefore, has broader oversight than the DIO role that focuses only on graduate physician education. Similar to the DIO, the VA DEO role initially emphasized the enabling learning and aligning resources domains to provide oversight and administration of health professions training programs. Over time, both roles have expanded to include defining and ensuring healthy clinical learning environments, aligning educational resources and training with the institutional mission, workforce, and societal needs, and creating continuous educational improvement models.6,16,17 To accomplish these expanded goals, both the DEO and the DIO work closely with other educational leaders at the academic affiliate and the VA facility. As health professions education advances, there will be increased emphasis placed on delivering educational programs to improve clinical practice and health care outcomes.18

Our findings that DEO profession did not influence self-ratings of effectiveness to influence educational decisions or behaviors on general tasks applicable across health professions suggest that education and practice background are not factors influencing selfratings. Nor were self-ratings influenced by other factors. Since the DEO is a senior leadership position, candidates for the position already may possess managerial and leadership skills. In our sample, several individuals commented that they had prior education leadership positions, eg, training program director or had years of experience working in the VA. Similarly, having an academic appointment may not be important for the performance of general administrative tasks. However, an academic appointment may be important for effective performance of educational tasks, such as clinical teaching, didactic training, and curriculum development, which were not measured in this study.

The finding of differences in self-ratings between physicians and other professionals on profession-specific tasks for associated health and nursing suggests that physicians may require additional curriculum to enhance their knowledge in managing other professional educational programs. For nursing specifically, this finding could also reflect substantial input from the lead nurse executive in the facility. DEOs also identified practical ways to facilitate their work with multiple health professions that could immediately be put into practice, including developing relationships and enhancing communication with training program directors, faculty, and academic affiliates of each profession.

Taken together, the quantitative and qualitative findings indicate that despite differences in professional backgrounds, DEOs have high self-ratings of their own effectiveness to influence educational decisions and behaviors on general tasks they are expected to accomplish. There are some professionspecific tasks where professional background does influence self-perceived effectiveness, ie, physicians have higher self-ratings on physician-specific tasks and other professionals have higher self-ratings on associated health or nursing tasks. These perceived differences may be mitigated by increasing facilitators and decreasing barriers identified for the individual DEO, within the organization, and external to the organization.

Limitations Our findings should be interpreted with the following limitations in mind. The selfreport nature of the data opens the possibility of self-report bias or Dunning-Kruger effects where effectiveness ratings could have been overestimated by respondents.21 Although respondents were assured of their anonymity and that results would only be reported in the aggregate, there is potential for providing more positive responses on a needs assessment administered by the national education program office. We recommend further work be conducted to validate the needs assessment tool against other data collection methods, such as actual outcomes of educational effectiveness. Our study did not incorporate measures of educational effectiveness to determine whether self-perceived DEO effectiveness is translated to better trainee or learning outcomes. Before this can happen, educational policymakers must identify the most important facility-level learning outcomes. Since the DEO is a facility level educational administrator, learning efeffectiveness must be defined at the facility level. The qualitative findings could also be expanded through the application of more detailed qualitative methods, such as indepth interviews. The tasks rated by DEOs were based on OAA’s current definition of the DEO role.6 As the field advances, DEO tasks will also evolve.22-24

Conclusions

The DEO is a senior educational leadership role that oversees all health professions training in the VA. Our findings are supportive of individuals from various health disciplines serving in the VA DEO role with responsibilities that span multiple health profession training programs. We recommend further work to validate the instrument used in this study, as well as the application of qualitative methods like indepth interviews to further our understanding of the DEO role.

1. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration. Updated April 18, 2022. Accessed May 6, 2022. https://www.va.gov/health/aboutvha.asp

2. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Academic Affiliations. Health professions education: academic Year 2019-2020. Published 2020. Accessed May 6, 2022. https://www.va.gov/OAA/docs /OAA_Statistics_2020.pdf

3. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Academic Affiliations. Advanced Fellowships and Professional Development. Updated November 26, 2021. Accessed May 6, 2022. https://www.va.gov/oaa /advancedfellowships/advanced-fellowships.asp

4. Association of American Medical Colleges. Medical school graduation questionnaire, 2019 all schools summary report. Published July 2019. Accessed May 6, 2022. https://www.aamc.org/system/files/2019-08/2019-gq-all-schools -summary-report.pdf

5. US Department of Veterans Affairs, National Center for Organization Development. VA all employee survey. Published 2019. Accessed May 6, 2022. https://www.va.gov /NCOD/VAworkforcesurveys.asp

6. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Academic Affiliations. Education leaders in the VA: the role of the designated education officer (DEO). Published December 2019. Accessed May 6, 2022. https://www.va.gov/OAA/docs/DEO_Learning _Leader_2019.pdf

7. US Office of Personnel Management. Policy, data oversight: guide to senior executive service qualifications. Published 2010. Accessed May 6, 2022. https://www.opm .gov/policy-data-oversight/senior-executive-service /executive-core-qualifications/

8. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Research and Development. Program guide: 1200.21 VHA operations activities that may constitute research. Published January 9, 2019. Accessed May 6, 2022. https://www.research .va.gov/resources/policies/ProgramGuide-1200-21-VHA -Operations-Activities.pdf

9. Riesenberg LA, Rosenbaum PF, Stick SL. Competencies, essential training, and resources viewed by designated institutional officials as important to the position in graduate medical education [published correction appears in Acad Med. 2006 Dec;81(12):1025]. Acad Med. 2006;81(5):426- 431. doi:10.1097/01.ACM.0000222279.28824.f5

10. Palinkas LA, Mendon SJ, Hamilton AB. Inn o v a t i o n s i n M i x e d M e t h o d s E v a l u a - tions. Annu Rev Public Health. 2019;40:423-442. doi:10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040218-044215

11. Tashakkori A, Creswell JW. Exploring the nature of research questions in mixed methods research. J Mix Methods Res. 2007;1(3):207-211. doi:10.1177/1558689807302814

12. Averill JB. Matrix analysis as a complementary analytic strategy in qualitative inquiry. Qual Health Res. 2002;12(6):855-866. doi:10.1177/104973230201200611

13. Hamilton AB, Finley EP. Qualitative methods in implementation research: An introduction. Psychiatry Res. 2019;280:112516.

14. Bellini L, Hartmann D, Opas L. Beyond must: supporting the evolving role of the designated institutional official. J Grad Med Educ. 2010;2(2):147-150. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-10-00073.1

15. Riesenberg LA, Rosenbaum P, Stick SL. Characteristics, roles, and responsibilities of the Designated Institutional Official (DIO) position in graduate medical education education [published correction appears in Acad Med. 2006 Dec;81(12):1025] [published correction appears in Acad Med. 2006 Mar;81(3):274]. Acad Med. 2006;81(1):8-19. doi:10.1097/00001888-200601000-00005

16. Group on Resident Affairs Core Competency Task Force. Institutional GME leadership competencies. 2015. Accessed May 6, 2022. https://www.aamc.org/system /files/c/2/441248-institutionalgmeleadershipcompetencies .pdf

17. Weiss KB, Bagian JP, Nasca TJ. The clinical learning environment: the foundation of graduate medical education. JAMA. 2013;309(16):1687-1688. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.1931

18. Beliveau ME, Warnes CA, Harrington RA, et al. Organizational change, leadership, and the transformation of continuing professional development: lessons learned from the American College of Cardiology. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2015;35(3):201-210. doi:10.1002/chp.21301

19. World Health Organization. Framework for Action on Interprofessional Education and Collaborative Practice. Published September 1, 2020. Accessed May 10, 2022. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/framework -for-action-on-interprofessional-education-collaborative -practice

20. Weiss K, Passiment M, Riordan L, Wagner R for the National Collaborative for Improving the Clinical Learning Environment IP-CLE Report Work Group. Achieving the optimal interprofessional clinical learning environment: proceedings from an NCICLE symposium. Published January 18, 2019. Accessed May 6, 2022. doi:10.33385/NCICLE.0002

21. Althubaiti A. Information bias in health research: definition, pitfalls, and adjustment methods. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2016;9:211-217. Published 2016 May 4. doi:10.2147/JMDH.S104807

22. Gilman SC, Chokshi DA, Bowen JL, Rugen KW, Cox M. Connecting the dots: interprofessional health education and delivery system redesign at the Veterans Health Administration. Acad Med. 2014;89(8):1113-1116. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000312

23. Health Professions Accreditors Collaborative. Guidance on developing quality interprofessional education for the health professions. Published February 1, 2019. Accessed May 6, 2022. https://healthprofessionsaccreditors.org/wp -content/uploads/2019/02/HPACGuidance02-01-19.pdf

24. Watts BV, Paull DE, Williams LC, Neily J, Hemphill RR, Brannen JL. Department of Veterans Affairs Chief Resident in Quality and Patient Safety Program: a model to spread change. Am J Med Qual. 2016;31(6):598-600. doi:10.1177/1062860616643403

1. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration. Updated April 18, 2022. Accessed May 6, 2022. https://www.va.gov/health/aboutvha.asp

2. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Academic Affiliations. Health professions education: academic Year 2019-2020. Published 2020. Accessed May 6, 2022. https://www.va.gov/OAA/docs /OAA_Statistics_2020.pdf

3. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Academic Affiliations. Advanced Fellowships and Professional Development. Updated November 26, 2021. Accessed May 6, 2022. https://www.va.gov/oaa /advancedfellowships/advanced-fellowships.asp

4. Association of American Medical Colleges. Medical school graduation questionnaire, 2019 all schools summary report. Published July 2019. Accessed May 6, 2022. https://www.aamc.org/system/files/2019-08/2019-gq-all-schools -summary-report.pdf

5. US Department of Veterans Affairs, National Center for Organization Development. VA all employee survey. Published 2019. Accessed May 6, 2022. https://www.va.gov /NCOD/VAworkforcesurveys.asp

6. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Academic Affiliations. Education leaders in the VA: the role of the designated education officer (DEO). Published December 2019. Accessed May 6, 2022. https://www.va.gov/OAA/docs/DEO_Learning _Leader_2019.pdf

7. US Office of Personnel Management. Policy, data oversight: guide to senior executive service qualifications. Published 2010. Accessed May 6, 2022. https://www.opm .gov/policy-data-oversight/senior-executive-service /executive-core-qualifications/

8. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Research and Development. Program guide: 1200.21 VHA operations activities that may constitute research. Published January 9, 2019. Accessed May 6, 2022. https://www.research .va.gov/resources/policies/ProgramGuide-1200-21-VHA -Operations-Activities.pdf

9. Riesenberg LA, Rosenbaum PF, Stick SL. Competencies, essential training, and resources viewed by designated institutional officials as important to the position in graduate medical education [published correction appears in Acad Med. 2006 Dec;81(12):1025]. Acad Med. 2006;81(5):426- 431. doi:10.1097/01.ACM.0000222279.28824.f5

10. Palinkas LA, Mendon SJ, Hamilton AB. Inn o v a t i o n s i n M i x e d M e t h o d s E v a l u a - tions. Annu Rev Public Health. 2019;40:423-442. doi:10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040218-044215

11. Tashakkori A, Creswell JW. Exploring the nature of research questions in mixed methods research. J Mix Methods Res. 2007;1(3):207-211. doi:10.1177/1558689807302814

12. Averill JB. Matrix analysis as a complementary analytic strategy in qualitative inquiry. Qual Health Res. 2002;12(6):855-866. doi:10.1177/104973230201200611

13. Hamilton AB, Finley EP. Qualitative methods in implementation research: An introduction. Psychiatry Res. 2019;280:112516.

14. Bellini L, Hartmann D, Opas L. Beyond must: supporting the evolving role of the designated institutional official. J Grad Med Educ. 2010;2(2):147-150. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-10-00073.1

15. Riesenberg LA, Rosenbaum P, Stick SL. Characteristics, roles, and responsibilities of the Designated Institutional Official (DIO) position in graduate medical education education [published correction appears in Acad Med. 2006 Dec;81(12):1025] [published correction appears in Acad Med. 2006 Mar;81(3):274]. Acad Med. 2006;81(1):8-19. doi:10.1097/00001888-200601000-00005

16. Group on Resident Affairs Core Competency Task Force. Institutional GME leadership competencies. 2015. Accessed May 6, 2022. https://www.aamc.org/system /files/c/2/441248-institutionalgmeleadershipcompetencies .pdf

17. Weiss KB, Bagian JP, Nasca TJ. The clinical learning environment: the foundation of graduate medical education. JAMA. 2013;309(16):1687-1688. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.1931

18. Beliveau ME, Warnes CA, Harrington RA, et al. Organizational change, leadership, and the transformation of continuing professional development: lessons learned from the American College of Cardiology. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2015;35(3):201-210. doi:10.1002/chp.21301

19. World Health Organization. Framework for Action on Interprofessional Education and Collaborative Practice. Published September 1, 2020. Accessed May 10, 2022. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/framework -for-action-on-interprofessional-education-collaborative -practice

20. Weiss K, Passiment M, Riordan L, Wagner R for the National Collaborative for Improving the Clinical Learning Environment IP-CLE Report Work Group. Achieving the optimal interprofessional clinical learning environment: proceedings from an NCICLE symposium. Published January 18, 2019. Accessed May 6, 2022. doi:10.33385/NCICLE.0002

21. Althubaiti A. Information bias in health research: definition, pitfalls, and adjustment methods. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2016;9:211-217. Published 2016 May 4. doi:10.2147/JMDH.S104807

22. Gilman SC, Chokshi DA, Bowen JL, Rugen KW, Cox M. Connecting the dots: interprofessional health education and delivery system redesign at the Veterans Health Administration. Acad Med. 2014;89(8):1113-1116. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000312

23. Health Professions Accreditors Collaborative. Guidance on developing quality interprofessional education for the health professions. Published February 1, 2019. Accessed May 6, 2022. https://healthprofessionsaccreditors.org/wp -content/uploads/2019/02/HPACGuidance02-01-19.pdf

24. Watts BV, Paull DE, Williams LC, Neily J, Hemphill RR, Brannen JL. Department of Veterans Affairs Chief Resident in Quality and Patient Safety Program: a model to spread change. Am J Med Qual. 2016;31(6):598-600. doi:10.1177/1062860616643403

The Expansion of Associated Health Training in the VA

The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) is the largest health care delivery system in the United States, comprising 1293 sites of care, including 171 medical centers.1 One of the 4 statutory missions of the VA is to train health care professionals (HCPs) to meet the needs of the VA and the nation.2 Through partnerships with more than 1800 accredited colleges, universities, and training programs, the VA provides training annually to nearly 118,000 health professions trainees (HPTs) across a variety of health care professions, and all of whom provide direct clinical care to veterans.3

In the VA, the Office of Academic Affiliations (OAA) is charged with overseeing health professions training and the VA’s partnership with medical and associated health (AH) professions schools, which was first codified in Policy Memorandum No. 2 in 1946.4,5 Given the scope and breadth of health professions education offered through the VA, OAA is in a unique position to address health care shortage areas as well as influence the educational standards for certain professions.

Many of these health care professions fall under the rubric of AH, which include mental health (MH) specialties, rehabilitative specialties, and others. These professions are critical to address in the expanding world of health care in the United States with its increased specialization and emphasis on coordination of care with interprofessional teams. During the 2019/2020 academic year, the VA provided clinical training to approximately 21,000 AH HPTs from > 40 professions with just over 20% receiving financial support through the OAA. Of the HPTs who train at VA without compensation, most spend shorter amounts of time in clinical rotations in the VA, are in pregraduate-degree education programs where payment for clinical rotations is not expected and may not be eligible for hire immediately on completion of their clinical training experience. The 17 funded professions have been strategically selected by the OAA to ensure a robust pipeline of HCPs to meet the needs of veterans and the nation.

To meet the demands of AH professionals (AHPs), the OAA implemented targeted expansion over the past 10 years. While not exhaustive, this paper describes several expansion efforts based on VA special initiatives, including enhancing clinical access in rural settings and shifting toward postgraduate-degree training and specialization. By aligning expansion with VA priorities as well as trends in health care more broadly, the OAA can ensure that there is a supply of well-trained AHPs who have developed the requisite competencies to contribute to our nation’s health care needs. Further, expansion can help train and recruit health professionals who can be hired into VA positions ready to care for the complex needs of veterans.

Associated Health Professionals

Overseen by the OAA, AH expansion is designed to address the specific needs of the VA and the US health care system. Data from the VA Workforce Management and Consulting (WMC) shows that the VA employment of AHPs has grown from 87,351 AHPs hired in fiscal year (FY) 2010 to 119,120 as of April 2020. This represents an average yearly growth rate of 3.4% and a total growth rate of 36%. The Bureau of Labor Statistics predictions for 2019/2029 suggest that certain AHPs are expected to have a 10-year growth rates of 20% or more to meet the changing health care needs of patients especially as the population ages; the growth rates for many AHPs far surpasses that of physicians, which is anticipated to be 4% (Table).6,7 The VA WMC expects an additional 52,283 AHPs will be hired by the VA by FY 2030 based on the 10-year average growth rate (Kali Clark, Veterans Health Administration Workforce Management and Consulting Office, email communication, May 28, 2020).

One of the driving forces behind the growth rate is the move toward using AHPs to supplement health care for a variety of health conditions.8,9 Examples include the integration of rehabilitation professionals, alternative care professionals (eg, massage therapists, practitioners who offer training in yoga and meditation), chiropractors, MH professionals, and pharmacists in the treatment of chronic pain, the use of a wider range of professionals in the treatment of MH conditions, and the integration of MH professionals into traditional medical settings, such as primary care. This intentional move to a more well-integrated model of interprofessional care is apparent in many other health care systems throughout the United States. Within the VA, this shift may be most evident through the introduction of the Whole Health model of care. The Whole Health model of care uses an interprofessional team to assess and care for veterans, using a personalized health plan addressing medical and MH conditions as well as behavioral, social, or spiritual concerns.10 The Whole Health model of care provides veterans with access to a variety of health care services, including but not limited to MH services, spiritual interventions, exercise-based programs, yoga, meditation, and nutrition counseling.

The OAA and AH education division have focused expansion to meet the increased need for MH and rehabilitation providers, to enhance interprofessional education, and to emphasize postgraduate-degree clinical training. This focus reflects the trends seen in health care training broadly throughout the nation and the intentional pivot is a model of these trends and a model for how to intentionally address these trends. Specific to the VA, focused expansion plans have allowed OAA to address VA strategic initiatives such as pain management and caring for rural veterans.

Funded Training Positions

As a result of recent AH expansion efforts, there has been a 33% increase in stipend-funded positions during the past 10 years, a rate that directly corresponds with the growth of AHPs in the VA. Recent AH expansion efforts can contribute to a particularly positive impact in highly rural and underserved areas where recruiting providers remains challenging.

The OAA launched the Mental Health Education Expansion (MHEE) initiative in 2012, which has now added 782 funded training slots across 10 health professions, 8 of which are psychology, pharmacy, chaplaincy, professional MH counseling, marriage and family therapy (MFT), social work (SW), occupational therapy (OT), and physician assistant (PA). Through the MHEE initiative, the VA has established funded internships for licensed professional mental health counselors and marriage and family therapists, as these professions are targeted for expanding the overall MH workforce in the VA. The OAA currently funds more than 50 total HPT positions for these 2 professions with an aim of increasing their recruitment to the VA MH workforce over the next decade. The MHEE is aligned with specified VA priorities to train a future VA workforce prepared for interprofessional collaboration and clinical care in an increasingly integrated and complex environment. This expansion effort also aligns with an increasing understanding of the importance of addressing the MH needs of our nation by ensuring there is an adequate supply of competent, well-trained clinicians entering the workforce.

The OAA has created and expanded residencies and fellowships in multiple rehabilitation professions, including chiropractic, physical therapy (PT), and OT. With the increased focus on the management of chronic pain in the nation combined with a specific emphasis on this clinical need in the VA, chiropractors have been deemed essential HCPs. In 2014, the VA established 5 chiropractic residency programs while partnering with the Council on Chiropractic Education to develop accreditation standards for residency training. OAA’s efforts have yielded 5 accredited residency programs, the first in the United States. In 2020, the VA doubled the number of available chiropractic residency programs, and future expansion is anticipated. Since 2010, PT residencies have expanded from 1 to 28 programs (42 funded positions) across 4 board certification specialties: cardiovascular-pulmonary, geriatric, neurologic, and orthopedic. Similarly, the VA was one of the first organizations to achieve accreditation for OT fellowships; there are currently 5 accredited OT fellowship programs across 3 areas of practice: assistive technology, MH, and physical rehabilitation. The VA OT fellowship program focused on assistive technology is the only program in the United States at this time.

Interprofessional Education