User login

Karen Appold is a seasoned writer and editor, with more than 20 years of editorial experience and started Write Now Services in 2003. Her scope of work includes writing, editing, and proofreading scholarly peer-reviewed journal content, consumer articles, white papers, and company reports for a variety of medical organizations, businesses, and media. Karen, who holds a BA in English from Penn State University, resides in Lehigh Valley, Pa.

Why Hospitalists Should Embrace Population Health

Population health focuses on the specific health needs of an individual within a defined population.

“In order to truly measure a patient’s health outcomes and identify best practices, providers must evaluate a group of people with similar health needs,” explains Joseph Damore, vice president of population health management for Charlotte-N.C.-based Premier, Inc. “Once we understand a population’s outcomes, we can then target the individual.”

Fundamentally, population health is about individualized care and intervening earlier in order to get a better outcome based on what generally works for the population. It’s also about identifying populations that need specific, targeted care, such as diabetic and oncology patients.

Back in 2003, David A. Kindig MD, PhD, and Greg Stoddart, PhD, defined population health as “the health outcomes of a group of individuals, including the distribution of such outcomes within the group.”1

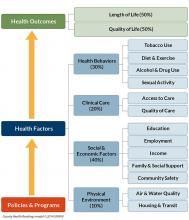

In order to achieve population health, according to Nick Fitterman, MD, SFHM, vice chair of hospital medicine for the Hofstra North Shore-LIJ School of Medicine in Hempstead, N.Y., “it is necessary to reduce health inequities or disparities among different populations due to, among other factors, the social determinants of health, which include social, environmental, cultural, and physical factors.”

Even though the concept of population health emerged more than 25 years ago, Dr. Fitterman points out that, until recently, the U.S. healthcare system has looked at an individual’s episodic illness rather than at population health, which focuses on wellness, prevention, and coordinated care across the continuum.

Marianne McPherson, PhD, MS, senior director of programs, research, and evaluation for the National Institute for Children’s Health Quality in Boston, says it is important for hospitalists to focus on both the patient and the population.

“You need to understand the particular factors facing the patient in front of you and understand that that individual is a product of a variety of different circumstances,” she says. “If you only look at an individual’s health, you can miss important trends across a group of patients within a population or community.

“By looking at both the individual and entire population, you can provide the most effective healthcare and health promotion.”

Government Spearheads Initiatives

With passage of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) of 2010, the U.S. government helped accelerate the movement toward population health. According to Joshua D. Lenchus, DO, RPh, FACP, SFHM, a veteran hospitalist, president of Jackson Health System Medical Staff, and associate professor of clinical medicine and anesthesiology at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, the act’s provisions aim to improve the quality of care and create accountable care organizations (ACOs).

“The idea was to provide patients with insurance coverage, which would improve the access to care of which they were previously deprived,” he says. “With better access, they may receive quality healthcare and the identification and mitigation of disease at an early stage, thereby reducing overall healthcare costs, with the commensurate benefit of a healthy patient population.

“Of course, this is fraught with naïveté, because it explicitly dismisses nonmedical health determinants (i.e., socioeconomic status, education, literacy rate, transportation availability, employment status, individual patient responsibility, and so forth).”

Now, with ACOs, a hospital or healthcare system can manage patient risk with a potential financial gain—if they manage it well. The government shifts the episodic cost of care to an ACO, charges it with achieving health outcome metrics, and allows it to reap the reward of doing so in a cost-effective manner. More risk equals more reward, potentially. But to affect positive change in patient outcomes (e.g. health) in this manner requires acknowledging such external determinants. Hospitals, hospitalists, and physician leaders must seriously consider health determinants and how they impact patients if they are going to adequately address population health.

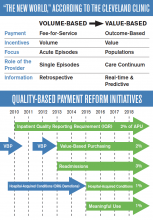

David Nash, MD, MBA, founding dean of the Jefferson College of Population Health at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia, sees the ACA as the major driver of population health, with the payment structure moving from a world of volume to one of value.

“It’s all about demonstrating an improvement in the population’s health,” he says.

In January 2015, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Secretary Sylvia Mathews Burwell announced that by 2018, 50 cents of every Medicare dollar will be attached to some measure of outcome.2

“So this move, from volume to value, will be the underpinning of the entire population health movement,” Dr. Nash says, “and we will be rewarded based on an improvement in a population’s health, instead of rewards for using resources on a per person basis.”

What’s a Hospitalist to Do?

Hospitalists typically are focused on inpatient care, managing a patient stay and coordinating discharge. Population health is an area, experts say, where hospitalists can extend their expertise in patient care and take a leadership role beyond the hospital.

“Hospitalists need to be aware of population health, embrace it, and help to develop structures within their programs that allow them to more closely partner with social services and case managers,” Dr. Fitterman says. “[You can] coordinate this type of care.”

Listen to more of our interview with Dr. Fitterman.

Dr. Lenchus agrees, noting that hospitalists intersect with population health most at discharge.

“The time point during which we must reconcile our discharge plan with the realities of the patient’s everyday life,” he says. “As we encourage an increasingly active lifestyle, we must pause to ascertain whether or not the patient lives in a neighborhood that is safe for outdoor activity.

As better nutrition is suggested, we must understand that the cost of a meal at a fast food chain is likely cheaper than one at a health food store. And, when arranging for a follow-up appointment, we must account for the bus schedule if a patient depends on that mode of transportation, as well as the potential to be released from work if employed.

“All of these external health determinants play a significant role in patients’ ability to adhere to instructions. Failure to [consider them in the discharge plan] will inevitably result in worsened health outcomes for the patient, and possibly hospital readmission.”

Hospitalists should be aware of the community-based organizations and services that exist, maintaining a working knowledge of who can provide volunteers, aid, food, and clothing to patients in need.

“Hospitalists should help lead or coordinate efforts to catalog these services in a community in which we practice, so we can steer patients toward these facilities,” Dr. Fitterman says. “In the past, we would treat acute medical issues and walk away. Now we need to be involved in patients’ needs, and those of their families.”

Establish a Team

A team-based approach is key to improving patient outcomes upon discharge, Dr. Lenchus says. Hospitalists should interact with social workers and case managers in anticipation of discharge; include the pharmacist in discharge medication counseling sessions. Are there relevant pharmaceutical industry-sponsored programs that can help the patient obtain prescription medications? Does the patient already qualify for some assistance? If the patient is insured, is the medication being prescribed on the formulary, or can it be modified so that it is covered? Could a generic version be prescribed? Does the patient understand the reason for hospitalization, have a follow-up appointment, and know how to take his medications?

Dr. Nash sees physicians as the team captains; physicians know how the system works, because they see it up close every day. The team includes key personnel, such as nurse practitioners, physician assistants, pharmacists, patient navigators, social workers, and patient educators.

“A physician, who might be a hospitalist, ideally will have additional training in both leadership and in population health,” Dr. Nash says.

He also encourages hospitalists to become patient advocates and educators, even though this is not their traditional role.

“They can do a lot to help a hospitalized patient face their challenges,” he says. “Encourage patients to stop smoking, go on a diet, and exercise. When a physician engages in this conversation, it aids in a patient’s ability to tackle challenges.”

For hospitalists who already feel overstretched with demands and overwhelmed with taking on the task of managing population health, Dr. McPherson suggests they learn more about the trend by studying it as part of their continuing education requirements. In addition, many hospitals have a department dedicated to patient safety or quality assurance.

“Ask how they can help the hospital to provide better patient care,” Dr. McPherson says. “Ask patients about their concerns or those of their neighbors. You may start to see trends.”

For example, if you suspect a trend of children who live in a certain housing development having difficulty breathing, try to find out if other hospital units are aware of this. Also try to ascertain whether or not any community groups connected to the hospital are already working to make the housing safer.

Population Health Challenges

The transition to being accountable for the health of a population will most likely be challenging for all providers. It involves significant risk, especially during the transition period, when an organization must live in both worlds (fee-for-service and value-based payment), says Damore, Premier’s vice president of population health management. He says it also requires:

- Enlightened and supportive leadership;

- Information technology to analyze claims and other infrastructure;

- New care management programs to coordinate care across the continuum;

- Agreements that align payment with population health management; and

- Skills and ability to transform a culture to a new value-based model.

To overcome the challenge of incorporating population health, Dr. McPherson suggests hospitals look to their large network of peers and learn from those already doing this, rather than reinventing the wheel. Look for champions to spearhead such initiatives.

“Identify folks who are already oriented in this direction and took steps in this vein,” she says.

Time and money are potential concerns, especially if embarking on a population health initiative will be an additional expense.

“A potential solution would be to look at ways to shift the focus, so that population health becomes integral to proper patient care, from promoting health and well-being to treating illness,” Dr. McPherson says. For example, by minimizing environmentally associated risks, hospitalists might be able to decrease the number of admissions, which will result in a return on your investment and improve population health.

Population health is here to stay, as payment models shift from fee-for-service to the value-based model. Hospitalists should embrace the movement and spearhead initiatives to get others on board. A hospital-wide team approach is advised. And, to save time and money, seek guidance from others who have already been successful. TH

Karen Appold is a medical writer in Pennsylvania.

References

1. Kindig D, Stoddart G. What is population health? Am J Public Health. 2003:93(3):380-383. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.93.3.380

2. Mathews Burwell S. Progress towards achieving better care, smarter spending, healthier people. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services website. January 26, 2015. Available at: http://www.hhs.gov/blog/2015/01/26/progress-towards-better-care-smarter-spending-healthier-people.html. Accessed November 8, 2015.

Population health focuses on the specific health needs of an individual within a defined population.

“In order to truly measure a patient’s health outcomes and identify best practices, providers must evaluate a group of people with similar health needs,” explains Joseph Damore, vice president of population health management for Charlotte-N.C.-based Premier, Inc. “Once we understand a population’s outcomes, we can then target the individual.”

Fundamentally, population health is about individualized care and intervening earlier in order to get a better outcome based on what generally works for the population. It’s also about identifying populations that need specific, targeted care, such as diabetic and oncology patients.

Back in 2003, David A. Kindig MD, PhD, and Greg Stoddart, PhD, defined population health as “the health outcomes of a group of individuals, including the distribution of such outcomes within the group.”1

In order to achieve population health, according to Nick Fitterman, MD, SFHM, vice chair of hospital medicine for the Hofstra North Shore-LIJ School of Medicine in Hempstead, N.Y., “it is necessary to reduce health inequities or disparities among different populations due to, among other factors, the social determinants of health, which include social, environmental, cultural, and physical factors.”

Even though the concept of population health emerged more than 25 years ago, Dr. Fitterman points out that, until recently, the U.S. healthcare system has looked at an individual’s episodic illness rather than at population health, which focuses on wellness, prevention, and coordinated care across the continuum.

Marianne McPherson, PhD, MS, senior director of programs, research, and evaluation for the National Institute for Children’s Health Quality in Boston, says it is important for hospitalists to focus on both the patient and the population.

“You need to understand the particular factors facing the patient in front of you and understand that that individual is a product of a variety of different circumstances,” she says. “If you only look at an individual’s health, you can miss important trends across a group of patients within a population or community.

“By looking at both the individual and entire population, you can provide the most effective healthcare and health promotion.”

Government Spearheads Initiatives

With passage of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) of 2010, the U.S. government helped accelerate the movement toward population health. According to Joshua D. Lenchus, DO, RPh, FACP, SFHM, a veteran hospitalist, president of Jackson Health System Medical Staff, and associate professor of clinical medicine and anesthesiology at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, the act’s provisions aim to improve the quality of care and create accountable care organizations (ACOs).

“The idea was to provide patients with insurance coverage, which would improve the access to care of which they were previously deprived,” he says. “With better access, they may receive quality healthcare and the identification and mitigation of disease at an early stage, thereby reducing overall healthcare costs, with the commensurate benefit of a healthy patient population.

“Of course, this is fraught with naïveté, because it explicitly dismisses nonmedical health determinants (i.e., socioeconomic status, education, literacy rate, transportation availability, employment status, individual patient responsibility, and so forth).”

Now, with ACOs, a hospital or healthcare system can manage patient risk with a potential financial gain—if they manage it well. The government shifts the episodic cost of care to an ACO, charges it with achieving health outcome metrics, and allows it to reap the reward of doing so in a cost-effective manner. More risk equals more reward, potentially. But to affect positive change in patient outcomes (e.g. health) in this manner requires acknowledging such external determinants. Hospitals, hospitalists, and physician leaders must seriously consider health determinants and how they impact patients if they are going to adequately address population health.

David Nash, MD, MBA, founding dean of the Jefferson College of Population Health at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia, sees the ACA as the major driver of population health, with the payment structure moving from a world of volume to one of value.

“It’s all about demonstrating an improvement in the population’s health,” he says.

In January 2015, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Secretary Sylvia Mathews Burwell announced that by 2018, 50 cents of every Medicare dollar will be attached to some measure of outcome.2

“So this move, from volume to value, will be the underpinning of the entire population health movement,” Dr. Nash says, “and we will be rewarded based on an improvement in a population’s health, instead of rewards for using resources on a per person basis.”

What’s a Hospitalist to Do?

Hospitalists typically are focused on inpatient care, managing a patient stay and coordinating discharge. Population health is an area, experts say, where hospitalists can extend their expertise in patient care and take a leadership role beyond the hospital.

“Hospitalists need to be aware of population health, embrace it, and help to develop structures within their programs that allow them to more closely partner with social services and case managers,” Dr. Fitterman says. “[You can] coordinate this type of care.”

Listen to more of our interview with Dr. Fitterman.

Dr. Lenchus agrees, noting that hospitalists intersect with population health most at discharge.

“The time point during which we must reconcile our discharge plan with the realities of the patient’s everyday life,” he says. “As we encourage an increasingly active lifestyle, we must pause to ascertain whether or not the patient lives in a neighborhood that is safe for outdoor activity.

As better nutrition is suggested, we must understand that the cost of a meal at a fast food chain is likely cheaper than one at a health food store. And, when arranging for a follow-up appointment, we must account for the bus schedule if a patient depends on that mode of transportation, as well as the potential to be released from work if employed.

“All of these external health determinants play a significant role in patients’ ability to adhere to instructions. Failure to [consider them in the discharge plan] will inevitably result in worsened health outcomes for the patient, and possibly hospital readmission.”

Hospitalists should be aware of the community-based organizations and services that exist, maintaining a working knowledge of who can provide volunteers, aid, food, and clothing to patients in need.

“Hospitalists should help lead or coordinate efforts to catalog these services in a community in which we practice, so we can steer patients toward these facilities,” Dr. Fitterman says. “In the past, we would treat acute medical issues and walk away. Now we need to be involved in patients’ needs, and those of their families.”

Establish a Team

A team-based approach is key to improving patient outcomes upon discharge, Dr. Lenchus says. Hospitalists should interact with social workers and case managers in anticipation of discharge; include the pharmacist in discharge medication counseling sessions. Are there relevant pharmaceutical industry-sponsored programs that can help the patient obtain prescription medications? Does the patient already qualify for some assistance? If the patient is insured, is the medication being prescribed on the formulary, or can it be modified so that it is covered? Could a generic version be prescribed? Does the patient understand the reason for hospitalization, have a follow-up appointment, and know how to take his medications?

Dr. Nash sees physicians as the team captains; physicians know how the system works, because they see it up close every day. The team includes key personnel, such as nurse practitioners, physician assistants, pharmacists, patient navigators, social workers, and patient educators.

“A physician, who might be a hospitalist, ideally will have additional training in both leadership and in population health,” Dr. Nash says.

He also encourages hospitalists to become patient advocates and educators, even though this is not their traditional role.

“They can do a lot to help a hospitalized patient face their challenges,” he says. “Encourage patients to stop smoking, go on a diet, and exercise. When a physician engages in this conversation, it aids in a patient’s ability to tackle challenges.”

For hospitalists who already feel overstretched with demands and overwhelmed with taking on the task of managing population health, Dr. McPherson suggests they learn more about the trend by studying it as part of their continuing education requirements. In addition, many hospitals have a department dedicated to patient safety or quality assurance.

“Ask how they can help the hospital to provide better patient care,” Dr. McPherson says. “Ask patients about their concerns or those of their neighbors. You may start to see trends.”

For example, if you suspect a trend of children who live in a certain housing development having difficulty breathing, try to find out if other hospital units are aware of this. Also try to ascertain whether or not any community groups connected to the hospital are already working to make the housing safer.

Population Health Challenges

The transition to being accountable for the health of a population will most likely be challenging for all providers. It involves significant risk, especially during the transition period, when an organization must live in both worlds (fee-for-service and value-based payment), says Damore, Premier’s vice president of population health management. He says it also requires:

- Enlightened and supportive leadership;

- Information technology to analyze claims and other infrastructure;

- New care management programs to coordinate care across the continuum;

- Agreements that align payment with population health management; and

- Skills and ability to transform a culture to a new value-based model.

To overcome the challenge of incorporating population health, Dr. McPherson suggests hospitals look to their large network of peers and learn from those already doing this, rather than reinventing the wheel. Look for champions to spearhead such initiatives.

“Identify folks who are already oriented in this direction and took steps in this vein,” she says.

Time and money are potential concerns, especially if embarking on a population health initiative will be an additional expense.

“A potential solution would be to look at ways to shift the focus, so that population health becomes integral to proper patient care, from promoting health and well-being to treating illness,” Dr. McPherson says. For example, by minimizing environmentally associated risks, hospitalists might be able to decrease the number of admissions, which will result in a return on your investment and improve population health.

Population health is here to stay, as payment models shift from fee-for-service to the value-based model. Hospitalists should embrace the movement and spearhead initiatives to get others on board. A hospital-wide team approach is advised. And, to save time and money, seek guidance from others who have already been successful. TH

Karen Appold is a medical writer in Pennsylvania.

References

1. Kindig D, Stoddart G. What is population health? Am J Public Health. 2003:93(3):380-383. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.93.3.380

2. Mathews Burwell S. Progress towards achieving better care, smarter spending, healthier people. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services website. January 26, 2015. Available at: http://www.hhs.gov/blog/2015/01/26/progress-towards-better-care-smarter-spending-healthier-people.html. Accessed November 8, 2015.

Population health focuses on the specific health needs of an individual within a defined population.

“In order to truly measure a patient’s health outcomes and identify best practices, providers must evaluate a group of people with similar health needs,” explains Joseph Damore, vice president of population health management for Charlotte-N.C.-based Premier, Inc. “Once we understand a population’s outcomes, we can then target the individual.”

Fundamentally, population health is about individualized care and intervening earlier in order to get a better outcome based on what generally works for the population. It’s also about identifying populations that need specific, targeted care, such as diabetic and oncology patients.

Back in 2003, David A. Kindig MD, PhD, and Greg Stoddart, PhD, defined population health as “the health outcomes of a group of individuals, including the distribution of such outcomes within the group.”1

In order to achieve population health, according to Nick Fitterman, MD, SFHM, vice chair of hospital medicine for the Hofstra North Shore-LIJ School of Medicine in Hempstead, N.Y., “it is necessary to reduce health inequities or disparities among different populations due to, among other factors, the social determinants of health, which include social, environmental, cultural, and physical factors.”

Even though the concept of population health emerged more than 25 years ago, Dr. Fitterman points out that, until recently, the U.S. healthcare system has looked at an individual’s episodic illness rather than at population health, which focuses on wellness, prevention, and coordinated care across the continuum.

Marianne McPherson, PhD, MS, senior director of programs, research, and evaluation for the National Institute for Children’s Health Quality in Boston, says it is important for hospitalists to focus on both the patient and the population.

“You need to understand the particular factors facing the patient in front of you and understand that that individual is a product of a variety of different circumstances,” she says. “If you only look at an individual’s health, you can miss important trends across a group of patients within a population or community.

“By looking at both the individual and entire population, you can provide the most effective healthcare and health promotion.”

Government Spearheads Initiatives

With passage of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) of 2010, the U.S. government helped accelerate the movement toward population health. According to Joshua D. Lenchus, DO, RPh, FACP, SFHM, a veteran hospitalist, president of Jackson Health System Medical Staff, and associate professor of clinical medicine and anesthesiology at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, the act’s provisions aim to improve the quality of care and create accountable care organizations (ACOs).

“The idea was to provide patients with insurance coverage, which would improve the access to care of which they were previously deprived,” he says. “With better access, they may receive quality healthcare and the identification and mitigation of disease at an early stage, thereby reducing overall healthcare costs, with the commensurate benefit of a healthy patient population.

“Of course, this is fraught with naïveté, because it explicitly dismisses nonmedical health determinants (i.e., socioeconomic status, education, literacy rate, transportation availability, employment status, individual patient responsibility, and so forth).”

Now, with ACOs, a hospital or healthcare system can manage patient risk with a potential financial gain—if they manage it well. The government shifts the episodic cost of care to an ACO, charges it with achieving health outcome metrics, and allows it to reap the reward of doing so in a cost-effective manner. More risk equals more reward, potentially. But to affect positive change in patient outcomes (e.g. health) in this manner requires acknowledging such external determinants. Hospitals, hospitalists, and physician leaders must seriously consider health determinants and how they impact patients if they are going to adequately address population health.

David Nash, MD, MBA, founding dean of the Jefferson College of Population Health at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia, sees the ACA as the major driver of population health, with the payment structure moving from a world of volume to one of value.

“It’s all about demonstrating an improvement in the population’s health,” he says.

In January 2015, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Secretary Sylvia Mathews Burwell announced that by 2018, 50 cents of every Medicare dollar will be attached to some measure of outcome.2

“So this move, from volume to value, will be the underpinning of the entire population health movement,” Dr. Nash says, “and we will be rewarded based on an improvement in a population’s health, instead of rewards for using resources on a per person basis.”

What’s a Hospitalist to Do?

Hospitalists typically are focused on inpatient care, managing a patient stay and coordinating discharge. Population health is an area, experts say, where hospitalists can extend their expertise in patient care and take a leadership role beyond the hospital.

“Hospitalists need to be aware of population health, embrace it, and help to develop structures within their programs that allow them to more closely partner with social services and case managers,” Dr. Fitterman says. “[You can] coordinate this type of care.”

Listen to more of our interview with Dr. Fitterman.

Dr. Lenchus agrees, noting that hospitalists intersect with population health most at discharge.

“The time point during which we must reconcile our discharge plan with the realities of the patient’s everyday life,” he says. “As we encourage an increasingly active lifestyle, we must pause to ascertain whether or not the patient lives in a neighborhood that is safe for outdoor activity.

As better nutrition is suggested, we must understand that the cost of a meal at a fast food chain is likely cheaper than one at a health food store. And, when arranging for a follow-up appointment, we must account for the bus schedule if a patient depends on that mode of transportation, as well as the potential to be released from work if employed.

“All of these external health determinants play a significant role in patients’ ability to adhere to instructions. Failure to [consider them in the discharge plan] will inevitably result in worsened health outcomes for the patient, and possibly hospital readmission.”

Hospitalists should be aware of the community-based organizations and services that exist, maintaining a working knowledge of who can provide volunteers, aid, food, and clothing to patients in need.

“Hospitalists should help lead or coordinate efforts to catalog these services in a community in which we practice, so we can steer patients toward these facilities,” Dr. Fitterman says. “In the past, we would treat acute medical issues and walk away. Now we need to be involved in patients’ needs, and those of their families.”

Establish a Team

A team-based approach is key to improving patient outcomes upon discharge, Dr. Lenchus says. Hospitalists should interact with social workers and case managers in anticipation of discharge; include the pharmacist in discharge medication counseling sessions. Are there relevant pharmaceutical industry-sponsored programs that can help the patient obtain prescription medications? Does the patient already qualify for some assistance? If the patient is insured, is the medication being prescribed on the formulary, or can it be modified so that it is covered? Could a generic version be prescribed? Does the patient understand the reason for hospitalization, have a follow-up appointment, and know how to take his medications?

Dr. Nash sees physicians as the team captains; physicians know how the system works, because they see it up close every day. The team includes key personnel, such as nurse practitioners, physician assistants, pharmacists, patient navigators, social workers, and patient educators.

“A physician, who might be a hospitalist, ideally will have additional training in both leadership and in population health,” Dr. Nash says.

He also encourages hospitalists to become patient advocates and educators, even though this is not their traditional role.

“They can do a lot to help a hospitalized patient face their challenges,” he says. “Encourage patients to stop smoking, go on a diet, and exercise. When a physician engages in this conversation, it aids in a patient’s ability to tackle challenges.”

For hospitalists who already feel overstretched with demands and overwhelmed with taking on the task of managing population health, Dr. McPherson suggests they learn more about the trend by studying it as part of their continuing education requirements. In addition, many hospitals have a department dedicated to patient safety or quality assurance.

“Ask how they can help the hospital to provide better patient care,” Dr. McPherson says. “Ask patients about their concerns or those of their neighbors. You may start to see trends.”

For example, if you suspect a trend of children who live in a certain housing development having difficulty breathing, try to find out if other hospital units are aware of this. Also try to ascertain whether or not any community groups connected to the hospital are already working to make the housing safer.

Population Health Challenges

The transition to being accountable for the health of a population will most likely be challenging for all providers. It involves significant risk, especially during the transition period, when an organization must live in both worlds (fee-for-service and value-based payment), says Damore, Premier’s vice president of population health management. He says it also requires:

- Enlightened and supportive leadership;

- Information technology to analyze claims and other infrastructure;

- New care management programs to coordinate care across the continuum;

- Agreements that align payment with population health management; and

- Skills and ability to transform a culture to a new value-based model.

To overcome the challenge of incorporating population health, Dr. McPherson suggests hospitals look to their large network of peers and learn from those already doing this, rather than reinventing the wheel. Look for champions to spearhead such initiatives.

“Identify folks who are already oriented in this direction and took steps in this vein,” she says.

Time and money are potential concerns, especially if embarking on a population health initiative will be an additional expense.

“A potential solution would be to look at ways to shift the focus, so that population health becomes integral to proper patient care, from promoting health and well-being to treating illness,” Dr. McPherson says. For example, by minimizing environmentally associated risks, hospitalists might be able to decrease the number of admissions, which will result in a return on your investment and improve population health.

Population health is here to stay, as payment models shift from fee-for-service to the value-based model. Hospitalists should embrace the movement and spearhead initiatives to get others on board. A hospital-wide team approach is advised. And, to save time and money, seek guidance from others who have already been successful. TH

Karen Appold is a medical writer in Pennsylvania.

References

1. Kindig D, Stoddart G. What is population health? Am J Public Health. 2003:93(3):380-383. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.93.3.380

2. Mathews Burwell S. Progress towards achieving better care, smarter spending, healthier people. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services website. January 26, 2015. Available at: http://www.hhs.gov/blog/2015/01/26/progress-towards-better-care-smarter-spending-healthier-people.html. Accessed November 8, 2015.

Population Health Prevails at Two Institutions

Population health—a movement to improve the health of an entire population—is a growing trend driven by the U.S. government. Many health systems are already on board, as healthcare shifts from a fee-for-service system to a value-based system.

One group of Premier Health hospitals and health systems has been collaborating since 2011 to build capabilities to become clinically integrated care networks that are accountable for the health of defined populations within their communities, according to Joseph Damore, vice president of population health management for the Charlotte, N.C-based company.

Damore says Premier has developed a comprehensive framework for the activities and capabilities necessary for successful population health management. Building blocks include:

- Patient-centered foundation (greater patient engagement and involvement in clinical decisions);

- Health home (a primary care medical home);

- High-value network (a set of providers who deliver quality care at an efficient price and whose performance is measured in the areas of cost, quality, and satisfaction);

- Payer partnership (care delivery network providers working with payers to create aligned financial incentives consistent with providing high-value care);

- Population health data management (collecting, analyzing, and reporting data covering all of the care the network’s patient population receives); and

- Network leadership (systematic governance and administration) focused on improving health, managing and coordinating care, and managing per capita cost.

“We’re also working with health systems on initiatives to establish patient-centered foundations and medical homes and create clinically integrated networks, providing our members with a direct roadmap to follow to successfully transition to this new value-based model,” Damore says.

At Jackson Memorial Hospital, one of the nation’s largest safety net hospitals, managing population health is ingrained in staff from day one. Nonetheless, Joshua D. Lenchus, DO, RPh, FACP, SFHM, president of Jackson Health System Medical Staff, says there are opportunities for improvement.

“A more team-based, collaborative approach is being piloted on some floors of our hospital, with specific physician groups,” he says. “Armed with the knowledge of these interventions, we can work on bolstering the pearls and rectifying the pitfalls as we move forward.

“One of our biggest obstacles to success is our patients’ general socioeconomic status.”

A current initiative at Jackson includes piloting a physician-led, multidisciplinary approach to address some of the health determinants. Furthermore, the health system is building additional satellite community clinics and urgent care centers, as it attempts to address disease earlier in the process. Additionally, there is a renewed emphasis on reinforcing the primary care infrastructure to facilitate patient appointment needs, Dr. Lenchus says. TH

Population health—a movement to improve the health of an entire population—is a growing trend driven by the U.S. government. Many health systems are already on board, as healthcare shifts from a fee-for-service system to a value-based system.

One group of Premier Health hospitals and health systems has been collaborating since 2011 to build capabilities to become clinically integrated care networks that are accountable for the health of defined populations within their communities, according to Joseph Damore, vice president of population health management for the Charlotte, N.C-based company.

Damore says Premier has developed a comprehensive framework for the activities and capabilities necessary for successful population health management. Building blocks include:

- Patient-centered foundation (greater patient engagement and involvement in clinical decisions);

- Health home (a primary care medical home);

- High-value network (a set of providers who deliver quality care at an efficient price and whose performance is measured in the areas of cost, quality, and satisfaction);

- Payer partnership (care delivery network providers working with payers to create aligned financial incentives consistent with providing high-value care);

- Population health data management (collecting, analyzing, and reporting data covering all of the care the network’s patient population receives); and

- Network leadership (systematic governance and administration) focused on improving health, managing and coordinating care, and managing per capita cost.

“We’re also working with health systems on initiatives to establish patient-centered foundations and medical homes and create clinically integrated networks, providing our members with a direct roadmap to follow to successfully transition to this new value-based model,” Damore says.

At Jackson Memorial Hospital, one of the nation’s largest safety net hospitals, managing population health is ingrained in staff from day one. Nonetheless, Joshua D. Lenchus, DO, RPh, FACP, SFHM, president of Jackson Health System Medical Staff, says there are opportunities for improvement.

“A more team-based, collaborative approach is being piloted on some floors of our hospital, with specific physician groups,” he says. “Armed with the knowledge of these interventions, we can work on bolstering the pearls and rectifying the pitfalls as we move forward.

“One of our biggest obstacles to success is our patients’ general socioeconomic status.”

A current initiative at Jackson includes piloting a physician-led, multidisciplinary approach to address some of the health determinants. Furthermore, the health system is building additional satellite community clinics and urgent care centers, as it attempts to address disease earlier in the process. Additionally, there is a renewed emphasis on reinforcing the primary care infrastructure to facilitate patient appointment needs, Dr. Lenchus says. TH

Population health—a movement to improve the health of an entire population—is a growing trend driven by the U.S. government. Many health systems are already on board, as healthcare shifts from a fee-for-service system to a value-based system.

One group of Premier Health hospitals and health systems has been collaborating since 2011 to build capabilities to become clinically integrated care networks that are accountable for the health of defined populations within their communities, according to Joseph Damore, vice president of population health management for the Charlotte, N.C-based company.

Damore says Premier has developed a comprehensive framework for the activities and capabilities necessary for successful population health management. Building blocks include:

- Patient-centered foundation (greater patient engagement and involvement in clinical decisions);

- Health home (a primary care medical home);

- High-value network (a set of providers who deliver quality care at an efficient price and whose performance is measured in the areas of cost, quality, and satisfaction);

- Payer partnership (care delivery network providers working with payers to create aligned financial incentives consistent with providing high-value care);

- Population health data management (collecting, analyzing, and reporting data covering all of the care the network’s patient population receives); and

- Network leadership (systematic governance and administration) focused on improving health, managing and coordinating care, and managing per capita cost.

“We’re also working with health systems on initiatives to establish patient-centered foundations and medical homes and create clinically integrated networks, providing our members with a direct roadmap to follow to successfully transition to this new value-based model,” Damore says.

At Jackson Memorial Hospital, one of the nation’s largest safety net hospitals, managing population health is ingrained in staff from day one. Nonetheless, Joshua D. Lenchus, DO, RPh, FACP, SFHM, president of Jackson Health System Medical Staff, says there are opportunities for improvement.

“A more team-based, collaborative approach is being piloted on some floors of our hospital, with specific physician groups,” he says. “Armed with the knowledge of these interventions, we can work on bolstering the pearls and rectifying the pitfalls as we move forward.

“One of our biggest obstacles to success is our patients’ general socioeconomic status.”

A current initiative at Jackson includes piloting a physician-led, multidisciplinary approach to address some of the health determinants. Furthermore, the health system is building additional satellite community clinics and urgent care centers, as it attempts to address disease earlier in the process. Additionally, there is a renewed emphasis on reinforcing the primary care infrastructure to facilitate patient appointment needs, Dr. Lenchus says. TH

Unassigned, Undocumented Patients Take a Toll on Healthcare and Hospitalists

When a patient must remain in the acute care hospital setting—despite being well enough to transition to a lower level of care, costs continue to mount as the patient receives care at the most expensive level.

“But policymakers must understand that reducing support for essential hospitals might save dollars in the short term but ultimately threatens access to care and creates greater costs in the long run,” says Beth Feldpush, DrPH, senior vice president of policy and advocacy for America’s Essential Hospitals in Washington, D.C. The group represents more than 250 essential hospitals, which fill a safety net role and provide communitywide services, such as trauma, neonatal intensive care, and disaster response.

“Our hospitals, which already operate at a loss on average, cannot continue to sustain federal and state funding cuts,” Dr. Feldpush says. “Access to care for vulnerable patients and entire communities will suffer if we continue to chip away at crucial sources of support, such as Medicaid and Medicare disproportionate share hospital funding and payment for outpatient services.”

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) makes many changes to the healthcare system that are designed to improve the quality, value of, and access to healthcare services.

“While many are good in theory, they have faced challenges in practice,” Dr. Feldpush says.

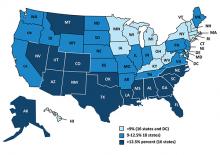

For example, the law’s authors included deep cuts to Medicaid and Medicare disproportionate share hospital (DSH) payments, which support hospitals that provide a large volume of uncompensated care. They made these cuts with the assumption that Medicare expansion and the ACA health insurance marketplace would significantly increase coverage, lessening the need for DSH payments. The U.S. Supreme Court’s decision to give states the option of expanding Medicaid has resulted in expansion in only about half of the states, however.

“But the DSH cuts remain, meaning our hospitals are getting significantly less support for the same or more uncompensated care,” Dr. Feldpush says.

Likewise, the ACA put into place many quality incentive programs for Medicare, including those designed to reduce preventable readmissions and hospital-acquired conditions and to encourage more value-based purchasing.

“The goals are obviously good ones, but the quality measures used to calculate incentive payments or penalties fail to account for the sociodemographic challenges our patients face—and that our hospitals can’t control,” she says. “So, these programs disproportionately penalize our hospitals, which, in turn, creates a vicious circle that reduces the funding they need to make improvements.”

Access to equitable healthcare for low-income, uninsured, and other vulnerable patients is a national problem, Dr. Feldpush continues. But the severity of the problem can vary by community and region—in states that have chosen not to expand their Medicaid programs, for example, or in economically depressed areas. TH

When a patient must remain in the acute care hospital setting—despite being well enough to transition to a lower level of care, costs continue to mount as the patient receives care at the most expensive level.

“But policymakers must understand that reducing support for essential hospitals might save dollars in the short term but ultimately threatens access to care and creates greater costs in the long run,” says Beth Feldpush, DrPH, senior vice president of policy and advocacy for America’s Essential Hospitals in Washington, D.C. The group represents more than 250 essential hospitals, which fill a safety net role and provide communitywide services, such as trauma, neonatal intensive care, and disaster response.

“Our hospitals, which already operate at a loss on average, cannot continue to sustain federal and state funding cuts,” Dr. Feldpush says. “Access to care for vulnerable patients and entire communities will suffer if we continue to chip away at crucial sources of support, such as Medicaid and Medicare disproportionate share hospital funding and payment for outpatient services.”

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) makes many changes to the healthcare system that are designed to improve the quality, value of, and access to healthcare services.

“While many are good in theory, they have faced challenges in practice,” Dr. Feldpush says.

For example, the law’s authors included deep cuts to Medicaid and Medicare disproportionate share hospital (DSH) payments, which support hospitals that provide a large volume of uncompensated care. They made these cuts with the assumption that Medicare expansion and the ACA health insurance marketplace would significantly increase coverage, lessening the need for DSH payments. The U.S. Supreme Court’s decision to give states the option of expanding Medicaid has resulted in expansion in only about half of the states, however.

“But the DSH cuts remain, meaning our hospitals are getting significantly less support for the same or more uncompensated care,” Dr. Feldpush says.

Likewise, the ACA put into place many quality incentive programs for Medicare, including those designed to reduce preventable readmissions and hospital-acquired conditions and to encourage more value-based purchasing.

“The goals are obviously good ones, but the quality measures used to calculate incentive payments or penalties fail to account for the sociodemographic challenges our patients face—and that our hospitals can’t control,” she says. “So, these programs disproportionately penalize our hospitals, which, in turn, creates a vicious circle that reduces the funding they need to make improvements.”

Access to equitable healthcare for low-income, uninsured, and other vulnerable patients is a national problem, Dr. Feldpush continues. But the severity of the problem can vary by community and region—in states that have chosen not to expand their Medicaid programs, for example, or in economically depressed areas. TH

When a patient must remain in the acute care hospital setting—despite being well enough to transition to a lower level of care, costs continue to mount as the patient receives care at the most expensive level.

“But policymakers must understand that reducing support for essential hospitals might save dollars in the short term but ultimately threatens access to care and creates greater costs in the long run,” says Beth Feldpush, DrPH, senior vice president of policy and advocacy for America’s Essential Hospitals in Washington, D.C. The group represents more than 250 essential hospitals, which fill a safety net role and provide communitywide services, such as trauma, neonatal intensive care, and disaster response.

“Our hospitals, which already operate at a loss on average, cannot continue to sustain federal and state funding cuts,” Dr. Feldpush says. “Access to care for vulnerable patients and entire communities will suffer if we continue to chip away at crucial sources of support, such as Medicaid and Medicare disproportionate share hospital funding and payment for outpatient services.”

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) makes many changes to the healthcare system that are designed to improve the quality, value of, and access to healthcare services.

“While many are good in theory, they have faced challenges in practice,” Dr. Feldpush says.

For example, the law’s authors included deep cuts to Medicaid and Medicare disproportionate share hospital (DSH) payments, which support hospitals that provide a large volume of uncompensated care. They made these cuts with the assumption that Medicare expansion and the ACA health insurance marketplace would significantly increase coverage, lessening the need for DSH payments. The U.S. Supreme Court’s decision to give states the option of expanding Medicaid has resulted in expansion in only about half of the states, however.

“But the DSH cuts remain, meaning our hospitals are getting significantly less support for the same or more uncompensated care,” Dr. Feldpush says.

Likewise, the ACA put into place many quality incentive programs for Medicare, including those designed to reduce preventable readmissions and hospital-acquired conditions and to encourage more value-based purchasing.

“The goals are obviously good ones, but the quality measures used to calculate incentive payments or penalties fail to account for the sociodemographic challenges our patients face—and that our hospitals can’t control,” she says. “So, these programs disproportionately penalize our hospitals, which, in turn, creates a vicious circle that reduces the funding they need to make improvements.”

Access to equitable healthcare for low-income, uninsured, and other vulnerable patients is a national problem, Dr. Feldpush continues. But the severity of the problem can vary by community and region—in states that have chosen not to expand their Medicaid programs, for example, or in economically depressed areas. TH

Unassigned, Undocumented Inpatients Present Challenges; Some Hospitalists Have Solutions

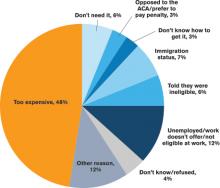

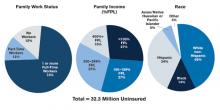

Hospitalists are charged with giving the best of care and treatment, regardless of whether or not a patient is insured or has a PCP to transition to after discharge. But patients who do not have insurance or a PCP pose many challenges to hospitalists, as well as the healthcare systems they work in. Although some hospitals and health systems have found ways to address these challenges, issues persist, with high costs to care for these patients topping the list. In 2013, the cost of community hospitals’ uncompensated care climbed to $46.4 billion.1

Typically, undocumented and unassigned patients face many social and economic challenges. Many of these patients are unemployed or work as independent contractors without employer-offered health insurance. Some have multiple jobs, can’t take time off from work for doctor appointments, or are undocumented workers.

More patients have acquired health insurance in recent years as a result of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) and Medicaid expansion; however, some eligible people never complete the necessary forms.

With or without insurance, some patients don’t establish primary care because they have been healthy, have difficulty navigating the healthcare system, lack transportation, or desire more culturally tailored care. Some Medicare and Medicaid patients don’t have a PCP in their community who accepts these programs.

Treatment Challenges

Uninsured patients often are sicker and have more complex conditions than those with insurance, according to Beth Feldpush, DrPH, senior vice president of policy and advocacy at the nonprofit trade group America’s Essential Hospitals, which is based in Washington, D.C., and represents 250 safety net hospitals throughout the U.S.

“Because they can’t afford regular preventive and primary care, they forgo needed healthcare services until their conditions worsen and they require costly hospital care,” says Dr. Feldpush. Uninsured patients often lack the resources for follow-up care to help them recover and stay well. She says more than half of all inpatient discharges and outpatient visits at her groups’ hospitals are for uninsured or Medicaid patients.

When an uninsured patient is discharged from the hospital, finding follow-up care can be difficult.

“Their ability to get an appointment to see a PCP is extremely limited, because many providers don’t see patients without health insurance,” says Scott Sears, MD, MBA, chief clinical officer of Tacoma, Wash.-based Sound Physicians. Dr. Sears notes that in some hospitalist programs, as many as 40% of hospitalized patients lack insurance. “But without secured follow-up care, hospitalists are hesitant to send patients home, because they could relapse.”

Typically, these patients are not completely well and should be transferred to a skilled nursing or hospice facility; however, many facilities won’t accept them without insurance. Often, these patients need a PCP to monitor them with laboratory tests and other follow-up tests, to prescribe and monitor medications, and to ensure that they are following their plan of care.

At some medical facilities, subspecialists who consult on patients may screen them and refuse to see anyone without health insurance.

“So even though some patients may need subspecialty support, they may not have access to it,” Dr. Sears says. “While some patients without insurance qualify for Medicaid or other programs, due to the amount of paperwork and time to enroll, they end up staying in the hospital even though they are ready for discharge.”

Transitional Challenges

Most patients admitted to the hospital either have exacerbations of chronic conditions or a new diagnosis. “It’s rare to hospitalize a patient with a discrete illness that wouldn’t need care after discharge, so having a robust PCP partner is critical to a patient’s health,” says Honora Englander, MD, medical director of the Care Transitions Innovation (C-TRAIN) program at Oregon Health and Science University (OHSU) in Portland. For many patients, psychosocial complexity complicates their transition out of the hospital. An effective system needs to address a patient’s mental health, housing, and other social needs.

It may take four to six weeks for a patient without an established PCP to get a new patient appointment. “This is a huge impediment, as the patient won’t have anyone to ensure that he or she continues along the proper care path,” Dr. Sears says.

“Studies estimate that more than half of medication errors that patients experience occur during transitions and after discharge,” Dr. Sears says.2 “Intervention with a healthcare provider who can review proper use after discharge can dramatically reduce errors and [improve] patient outcomes.”

Rates of patients without a PCP vary by region for Sound Physicians. In the northwest region, about 25% of admitted patients lack a PCP; in the gulf region, the figure can be as high as 60%.

“In Texas, there is a large number of patients and not as many PCPs,” he adds. “There is also a larger percentage of patients without health insurance. Sometimes patients have coverage but have never established care with a PCP.”

As a result of not having a PCP to transition to, some patients return to the hospital soon after discharge, Dr. Feldpush notes.

Tips for Treating Uninsured Patients

Some facilities have found successful ways to help hospitalized patients without health insurance. Dr. Sears says that hospitalists can investigate which clinics accept uninsured patients or which local physician groups are willing to see them after discharge, in exchange for hospitalists taking care of them in the hospital. They also can investigate the community-based insurance programs that are available.

Teresa Coker, MSN, ARNP, FNP-BC, a Sound Physicians program manager at Mercy Medical Center in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, says that when patients lack insurance at her hospital, an organization will review the patient’s case, determine insurance eligibility, and assist the patient in completing the appropriate paperwork. When patients are not eligible, they are instructed to inquire about the hospital’s charity care program if they receive a bill they are unable to pay.

In addition, the community has a free health clinic that serves those without insurance. “Patients are given the address and hours prior to discharge, because it is walk-in only,” Coker says. “All patients are recommended to follow up within one week, or sooner if medications are needed.”

Dr. Englander advocates that physicians take into account medication costs, transportation, and other social considerations when planning care after hospitalization. The team at OHSU developed a low-cost formulary (based in part on widely available $4 plans from national pharmacy chains), and OHSU provides medications for uninsured patients in the program for up to 30 days following discharge.

For patients who can’t afford the $4 drug plan, case managers offer coupons for $4 prescriptions, says Malik Merchant, MD, area medical officer for the Schumachergroup in Harker Heights, Texas. He says that as many as 30% of the patients in his area are undocumented or unassigned. For more expensive medications, a social worker offers pharmaceutical company coupons when they are available. The institution also has a small budget to pay for drugs.

Dr. Merchant has found the biggest challenge to be the transition of care from inpatient to outpatient.

“Case managers and social workers prepare a financial worksheet that provides the possibility of overall cost savings for the institution, if patients are willing to participate in some upfront cost,” he says. “When our parent institution came on board, we developed contracts with local pharmacies, [a] skilled nursing facility, and PCPs to take these patients until they recovered from an acute illness. Our institution paid for these services at a reduced rate but saved money by reducing the length of their hospital stay.”

Dr. Feldpush says her group’s hospitals work hard to reach the uninsured. South Florida’s Memorial Healthcare System (MHS) created the Health Intervention with Targeted Services (HITS) Program, an outreach initiative that links patients with insurance programs or medical homes.3 The HITS team used a geographic information system map to target 15 neighborhoods with the highest rates of hospitalized, uninsured patients. Over a six-month period, the team approached these neighborhoods using various outreach strategies, such as health fairs, educational workshops, and door-to-door visits.3

Approximately 6,910 HITS participants have been enrolled in Medicaid, Florida’s children’s health insurance program, or an MHS community health center. Over a three-year study period, MHS saved $284,856 in the ED, about $2.8 million in inpatient costs, and roughly $4 million overall.3

Barriers to Follow-Up Care

Whether you are looking to help uninsured patients, those without a PCP, or both, the key is to try to fill in the gaps.

“As hospitalists, we need to work with pharmacists, case managers and social workers, and others to identify affordable and effective ways to provide care,” Dr. Englander says. “Interprofessional team members, community partners, and family members can help hospitalists understand patient and population health needs and available resources.”

In an effort to close transitional care gaps, OHSU developed the C-TRAIN program, a multi-component transitional care intervention that includes four main elements:

- Transitional care nurse who sees patients in the hospital, makes home visits, and helps coordinate care 30 days post-discharge;

- Inpatient pharmacy consultation and prescription medications at discharge from a low-cost, value-based formulary;

- Medical home linkages, whereby OHSU partners with and provides payment to three community clinics to provide primary care for uninsured patients; and

- Monthly implementation team meetings that convene diverse healthcare stakeholders to integrate elements of the healthcare system and engage in ongoing quality improvement.

The Schumachergroup has also found an effective solution.

“The department head of our case managers and social workers made an agreement with a local multispecialty group,” Dr. Merchant says. “The group agreed to take all discharged patients and be their PCP for 30 days, even if the patient couldn’t pay, in exchange for receiving all patients who had good insurance but did not have an established PCP.

“This has worked well. Every patient discharged from our facility has a PCP listed at discharge, and the unit clerk makes an appointment and documents it in the electronic medical record.”

Sound Physicians has set up a service line, called transitional care services, to smooth transitions of care after discharge for up to 90 days, depending on their clinical needs. It hires providers who work in post-acute facilities and who can also visit patients at home. After discharge, a nurse practitioner will visit the patient, connect him or her with a PCP, and get the patient access to care.

“Smaller hospitalist groups could set up post-discharge clinics,” Dr. Sears suggests, “so when they discharge a patient without a PCP, [the patient] could return to see one of the hospitalists there.”

Mount Carmel East Hospital, a Sound Physicians’ hospital in Columbus, Ohio, has a financial assistance program.

“The case management department provides community health resources to patients who are insured but have no PCP,” says Shelli Morris, RN. “We also have a hotline that patients can call for a list of PCPs that are accepting new patients.”

When a patient lacks insurance or a PCP, Morris is contacted by the physician or case management to provide a referral to a neighborhood health clinic. “Then, as a courtesy, we set up a post-hospital follow-up appointment,” she says.

By working with other care team members at facilities such as outpatient clinics and pharmacies, hospitalists and other staff have been able to improve care for patients without insurance or a PCP after discharge. Knowing the funding that is available, as well as programs to help these patients, is also integral.

Karen Appold is a medical writer in Pennsylvania.

References

- American Hospital Association. American Hospital Association Uncompensated Hospital Care Cost Fact Sheet. Accessed October 8, 2015.

- The Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology. Health IT in long-term and post acute care: issue brief. March 15, 2013. Accessed October 8, 2015.

- Addison E. Gage award winner HITS the streets to connect with the uninsured. America’s Essential Hospitals. July 22, 2014. Accessed October 8, 2015.

- DeNavas C, Proctor BD, Smith JC. Income, poverty, and health insurance coverage in the United States: 2010. United States Census Bureau. September 2011. Accessed October 8, 2015.

- United States Census Bureau. People without health insurance coverage by selected characteristics: 2010 and 2011. Accessed October 8, 2015.

- Coughlin TA, Holahan J, Caswell K, McGrath M. Uncompensated care for the uninsured in 2013: a detailed examination. The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. May 30, 2014. Accessed October 8, 2015.

Hospitalists are charged with giving the best of care and treatment, regardless of whether or not a patient is insured or has a PCP to transition to after discharge. But patients who do not have insurance or a PCP pose many challenges to hospitalists, as well as the healthcare systems they work in. Although some hospitals and health systems have found ways to address these challenges, issues persist, with high costs to care for these patients topping the list. In 2013, the cost of community hospitals’ uncompensated care climbed to $46.4 billion.1

Typically, undocumented and unassigned patients face many social and economic challenges. Many of these patients are unemployed or work as independent contractors without employer-offered health insurance. Some have multiple jobs, can’t take time off from work for doctor appointments, or are undocumented workers.

More patients have acquired health insurance in recent years as a result of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) and Medicaid expansion; however, some eligible people never complete the necessary forms.

With or without insurance, some patients don’t establish primary care because they have been healthy, have difficulty navigating the healthcare system, lack transportation, or desire more culturally tailored care. Some Medicare and Medicaid patients don’t have a PCP in their community who accepts these programs.

Treatment Challenges

Uninsured patients often are sicker and have more complex conditions than those with insurance, according to Beth Feldpush, DrPH, senior vice president of policy and advocacy at the nonprofit trade group America’s Essential Hospitals, which is based in Washington, D.C., and represents 250 safety net hospitals throughout the U.S.

“Because they can’t afford regular preventive and primary care, they forgo needed healthcare services until their conditions worsen and they require costly hospital care,” says Dr. Feldpush. Uninsured patients often lack the resources for follow-up care to help them recover and stay well. She says more than half of all inpatient discharges and outpatient visits at her groups’ hospitals are for uninsured or Medicaid patients.

When an uninsured patient is discharged from the hospital, finding follow-up care can be difficult.

“Their ability to get an appointment to see a PCP is extremely limited, because many providers don’t see patients without health insurance,” says Scott Sears, MD, MBA, chief clinical officer of Tacoma, Wash.-based Sound Physicians. Dr. Sears notes that in some hospitalist programs, as many as 40% of hospitalized patients lack insurance. “But without secured follow-up care, hospitalists are hesitant to send patients home, because they could relapse.”

Typically, these patients are not completely well and should be transferred to a skilled nursing or hospice facility; however, many facilities won’t accept them without insurance. Often, these patients need a PCP to monitor them with laboratory tests and other follow-up tests, to prescribe and monitor medications, and to ensure that they are following their plan of care.

At some medical facilities, subspecialists who consult on patients may screen them and refuse to see anyone without health insurance.

“So even though some patients may need subspecialty support, they may not have access to it,” Dr. Sears says. “While some patients without insurance qualify for Medicaid or other programs, due to the amount of paperwork and time to enroll, they end up staying in the hospital even though they are ready for discharge.”

Transitional Challenges

Most patients admitted to the hospital either have exacerbations of chronic conditions or a new diagnosis. “It’s rare to hospitalize a patient with a discrete illness that wouldn’t need care after discharge, so having a robust PCP partner is critical to a patient’s health,” says Honora Englander, MD, medical director of the Care Transitions Innovation (C-TRAIN) program at Oregon Health and Science University (OHSU) in Portland. For many patients, psychosocial complexity complicates their transition out of the hospital. An effective system needs to address a patient’s mental health, housing, and other social needs.

It may take four to six weeks for a patient without an established PCP to get a new patient appointment. “This is a huge impediment, as the patient won’t have anyone to ensure that he or she continues along the proper care path,” Dr. Sears says.

“Studies estimate that more than half of medication errors that patients experience occur during transitions and after discharge,” Dr. Sears says.2 “Intervention with a healthcare provider who can review proper use after discharge can dramatically reduce errors and [improve] patient outcomes.”

Rates of patients without a PCP vary by region for Sound Physicians. In the northwest region, about 25% of admitted patients lack a PCP; in the gulf region, the figure can be as high as 60%.

“In Texas, there is a large number of patients and not as many PCPs,” he adds. “There is also a larger percentage of patients without health insurance. Sometimes patients have coverage but have never established care with a PCP.”

As a result of not having a PCP to transition to, some patients return to the hospital soon after discharge, Dr. Feldpush notes.

Tips for Treating Uninsured Patients

Some facilities have found successful ways to help hospitalized patients without health insurance. Dr. Sears says that hospitalists can investigate which clinics accept uninsured patients or which local physician groups are willing to see them after discharge, in exchange for hospitalists taking care of them in the hospital. They also can investigate the community-based insurance programs that are available.

Teresa Coker, MSN, ARNP, FNP-BC, a Sound Physicians program manager at Mercy Medical Center in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, says that when patients lack insurance at her hospital, an organization will review the patient’s case, determine insurance eligibility, and assist the patient in completing the appropriate paperwork. When patients are not eligible, they are instructed to inquire about the hospital’s charity care program if they receive a bill they are unable to pay.

In addition, the community has a free health clinic that serves those without insurance. “Patients are given the address and hours prior to discharge, because it is walk-in only,” Coker says. “All patients are recommended to follow up within one week, or sooner if medications are needed.”

Dr. Englander advocates that physicians take into account medication costs, transportation, and other social considerations when planning care after hospitalization. The team at OHSU developed a low-cost formulary (based in part on widely available $4 plans from national pharmacy chains), and OHSU provides medications for uninsured patients in the program for up to 30 days following discharge.

For patients who can’t afford the $4 drug plan, case managers offer coupons for $4 prescriptions, says Malik Merchant, MD, area medical officer for the Schumachergroup in Harker Heights, Texas. He says that as many as 30% of the patients in his area are undocumented or unassigned. For more expensive medications, a social worker offers pharmaceutical company coupons when they are available. The institution also has a small budget to pay for drugs.

Dr. Merchant has found the biggest challenge to be the transition of care from inpatient to outpatient.

“Case managers and social workers prepare a financial worksheet that provides the possibility of overall cost savings for the institution, if patients are willing to participate in some upfront cost,” he says. “When our parent institution came on board, we developed contracts with local pharmacies, [a] skilled nursing facility, and PCPs to take these patients until they recovered from an acute illness. Our institution paid for these services at a reduced rate but saved money by reducing the length of their hospital stay.”

Dr. Feldpush says her group’s hospitals work hard to reach the uninsured. South Florida’s Memorial Healthcare System (MHS) created the Health Intervention with Targeted Services (HITS) Program, an outreach initiative that links patients with insurance programs or medical homes.3 The HITS team used a geographic information system map to target 15 neighborhoods with the highest rates of hospitalized, uninsured patients. Over a six-month period, the team approached these neighborhoods using various outreach strategies, such as health fairs, educational workshops, and door-to-door visits.3

Approximately 6,910 HITS participants have been enrolled in Medicaid, Florida’s children’s health insurance program, or an MHS community health center. Over a three-year study period, MHS saved $284,856 in the ED, about $2.8 million in inpatient costs, and roughly $4 million overall.3

Barriers to Follow-Up Care

Whether you are looking to help uninsured patients, those without a PCP, or both, the key is to try to fill in the gaps.

“As hospitalists, we need to work with pharmacists, case managers and social workers, and others to identify affordable and effective ways to provide care,” Dr. Englander says. “Interprofessional team members, community partners, and family members can help hospitalists understand patient and population health needs and available resources.”

In an effort to close transitional care gaps, OHSU developed the C-TRAIN program, a multi-component transitional care intervention that includes four main elements:

- Transitional care nurse who sees patients in the hospital, makes home visits, and helps coordinate care 30 days post-discharge;

- Inpatient pharmacy consultation and prescription medications at discharge from a low-cost, value-based formulary;

- Medical home linkages, whereby OHSU partners with and provides payment to three community clinics to provide primary care for uninsured patients; and

- Monthly implementation team meetings that convene diverse healthcare stakeholders to integrate elements of the healthcare system and engage in ongoing quality improvement.

The Schumachergroup has also found an effective solution.

“The department head of our case managers and social workers made an agreement with a local multispecialty group,” Dr. Merchant says. “The group agreed to take all discharged patients and be their PCP for 30 days, even if the patient couldn’t pay, in exchange for receiving all patients who had good insurance but did not have an established PCP.