User login

Karen Appold is a seasoned writer and editor, with more than 20 years of editorial experience and started Write Now Services in 2003. Her scope of work includes writing, editing, and proofreading scholarly peer-reviewed journal content, consumer articles, white papers, and company reports for a variety of medical organizations, businesses, and media. Karen, who holds a BA in English from Penn State University, resides in Lehigh Valley, Pa.

LISTEN NOW: Monal Shah, MD, discusses exceptions for VTE admissions

Although patients with blood clots are oftentimes not admitted to the hospital, there are some exceptions. Monal Shah, MD, physician advisor for Parkland Hospital in Dallas, Texas, and the former section head of hospital medicine at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, discusses some exceptions.

Although patients with blood clots are oftentimes not admitted to the hospital, there are some exceptions. Monal Shah, MD, physician advisor for Parkland Hospital in Dallas, Texas, and the former section head of hospital medicine at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, discusses some exceptions.

Although patients with blood clots are oftentimes not admitted to the hospital, there are some exceptions. Monal Shah, MD, physician advisor for Parkland Hospital in Dallas, Texas, and the former section head of hospital medicine at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, discusses some exceptions.

Tip-Top Tactics for Bedside Procedure Training

David Lichtman, PA, director of the Johns Hopkins Central Procedure Service in Baltimore, Md., says bedside procedure training should be consistent and thorough, regardless of whether the trainee is a medical student, a resident, a fellow, or an established physician. He is a strong advocate for training that includes well-designed computer coursework, evaluates practitioners from start to finish, and demonstrates that they are meeting established benchmarks.

“That’s what keeps patients safe,” he says.

Experienced, capable, and proven educators are also critical.

“Let’s face it: Not everybody is a very good teacher,” he adds.

Currently, many medical residents can do rotations that will give them hands-on experience. But some physicians question why certain procedures are still being taught to internal medicine residents if the ABIM no longer requires hands-on experience. Other programs may simply lack the resources, including experienced supervisors, to provide proper training.

The demand for more training is clearly there, however. Sally Wang, MD, FHM, director of procedure education at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and a clinical instructor at Harvard Medical School in Boston, co-leads the procedures pre-course at the SHM annual meeting. She compares the logistically complicated event to throwing a wedding. It consistently sells out despite having doubled in size, to 60 slots for a basic procedure course and 60 slots for a second course that emphasizes ultrasound. At the HM14 pre-course in Las Vegas, Dr. Wang counted enough people on the waiting list to fill an additional course.

“It was mind-boggling,” she says.

Several companies have taken notice of the pent-up demand and are offering their own courses and workshops. Joshua Lenchus, DO, RPh, FACP, SFHM, medical director of the University of Miami-Jackson Memorial Hospital’s procedure service, and others see many of these offerings as introductions only, however. At the University of Miami, he says, his rigorous, simulation-based invasive bedside procedures curriculum is mandatory for all internal medicine residents. The curriculum includes central line, thoracentesis, paracentesis, lumbar puncture, and sometimes arthrocentesis as its core procedures, though Dr. Lenchus says others can easily be added. This fall, for instance, he plans to add chest tube and arterial line placement.

He notes a dramatic reduction in central line placement and thoracentesis complications after his team began performing them to the “four pillars” of his program. Rigorous simulation-based training, strict adherence to a critical skills checklist, consistent use of ultrasound, and direct supervision can form a very effective bundle of safety measures, he says, just like a combination of seat belts, speed reduction, and other precautions can lead to fewer automobile-associated injuries and deaths. TH

David Lichtman, PA, director of the Johns Hopkins Central Procedure Service in Baltimore, Md., says bedside procedure training should be consistent and thorough, regardless of whether the trainee is a medical student, a resident, a fellow, or an established physician. He is a strong advocate for training that includes well-designed computer coursework, evaluates practitioners from start to finish, and demonstrates that they are meeting established benchmarks.

“That’s what keeps patients safe,” he says.

Experienced, capable, and proven educators are also critical.

“Let’s face it: Not everybody is a very good teacher,” he adds.

Currently, many medical residents can do rotations that will give them hands-on experience. But some physicians question why certain procedures are still being taught to internal medicine residents if the ABIM no longer requires hands-on experience. Other programs may simply lack the resources, including experienced supervisors, to provide proper training.

The demand for more training is clearly there, however. Sally Wang, MD, FHM, director of procedure education at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and a clinical instructor at Harvard Medical School in Boston, co-leads the procedures pre-course at the SHM annual meeting. She compares the logistically complicated event to throwing a wedding. It consistently sells out despite having doubled in size, to 60 slots for a basic procedure course and 60 slots for a second course that emphasizes ultrasound. At the HM14 pre-course in Las Vegas, Dr. Wang counted enough people on the waiting list to fill an additional course.

“It was mind-boggling,” she says.

Several companies have taken notice of the pent-up demand and are offering their own courses and workshops. Joshua Lenchus, DO, RPh, FACP, SFHM, medical director of the University of Miami-Jackson Memorial Hospital’s procedure service, and others see many of these offerings as introductions only, however. At the University of Miami, he says, his rigorous, simulation-based invasive bedside procedures curriculum is mandatory for all internal medicine residents. The curriculum includes central line, thoracentesis, paracentesis, lumbar puncture, and sometimes arthrocentesis as its core procedures, though Dr. Lenchus says others can easily be added. This fall, for instance, he plans to add chest tube and arterial line placement.

He notes a dramatic reduction in central line placement and thoracentesis complications after his team began performing them to the “four pillars” of his program. Rigorous simulation-based training, strict adherence to a critical skills checklist, consistent use of ultrasound, and direct supervision can form a very effective bundle of safety measures, he says, just like a combination of seat belts, speed reduction, and other precautions can lead to fewer automobile-associated injuries and deaths. TH

David Lichtman, PA, director of the Johns Hopkins Central Procedure Service in Baltimore, Md., says bedside procedure training should be consistent and thorough, regardless of whether the trainee is a medical student, a resident, a fellow, or an established physician. He is a strong advocate for training that includes well-designed computer coursework, evaluates practitioners from start to finish, and demonstrates that they are meeting established benchmarks.

“That’s what keeps patients safe,” he says.

Experienced, capable, and proven educators are also critical.

“Let’s face it: Not everybody is a very good teacher,” he adds.

Currently, many medical residents can do rotations that will give them hands-on experience. But some physicians question why certain procedures are still being taught to internal medicine residents if the ABIM no longer requires hands-on experience. Other programs may simply lack the resources, including experienced supervisors, to provide proper training.

The demand for more training is clearly there, however. Sally Wang, MD, FHM, director of procedure education at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and a clinical instructor at Harvard Medical School in Boston, co-leads the procedures pre-course at the SHM annual meeting. She compares the logistically complicated event to throwing a wedding. It consistently sells out despite having doubled in size, to 60 slots for a basic procedure course and 60 slots for a second course that emphasizes ultrasound. At the HM14 pre-course in Las Vegas, Dr. Wang counted enough people on the waiting list to fill an additional course.

“It was mind-boggling,” she says.

Several companies have taken notice of the pent-up demand and are offering their own courses and workshops. Joshua Lenchus, DO, RPh, FACP, SFHM, medical director of the University of Miami-Jackson Memorial Hospital’s procedure service, and others see many of these offerings as introductions only, however. At the University of Miami, he says, his rigorous, simulation-based invasive bedside procedures curriculum is mandatory for all internal medicine residents. The curriculum includes central line, thoracentesis, paracentesis, lumbar puncture, and sometimes arthrocentesis as its core procedures, though Dr. Lenchus says others can easily be added. This fall, for instance, he plans to add chest tube and arterial line placement.

He notes a dramatic reduction in central line placement and thoracentesis complications after his team began performing them to the “four pillars” of his program. Rigorous simulation-based training, strict adherence to a critical skills checklist, consistent use of ultrasound, and direct supervision can form a very effective bundle of safety measures, he says, just like a combination of seat belts, speed reduction, and other precautions can lead to fewer automobile-associated injuries and deaths. TH

Hospitalists Are Frontline Providers in Treating Venous Thromboembolism

“While VTE may not be the No. 1 reason for hospitalization, hospitalists very frequently care for patients with VTE,” says Sowmya Kanikkannan, MD, FACP, SFHM, hospitalist medical director and assistant professor of medicine at Rowan University School of Osteopathic Medicine in Stratford, N.J. “Hospitalists usually are the frontline providers that diagnose and manage hospital-acquired VTEs in hospitalized patients.”

Dr. Kanikkannan, a member of Team Hospitalist, sees a wide range of VTE cases caused by two related conditions—deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE).

“Some patients present with a straightforward diagnosis of DVT, while others have extensive DVT,” she says. “In other instances, patients present with acute PE with or without hemodynamic compromise. I’ve also diagnosed and managed hospital-acquired VTEs in medical patients, as well as post-operatively in surgical co-management.”

It is estimated that between 350,000 to 900,000 Americans are affected by DVT or PE each year, with up to 100,000 dying as a result. Twenty to 50% of people who experience DVT develop long-term complications.1VTE costs the U.S. healthcare system more than $1.5 billion annually.2

As lieutenants in the war against VTE, hospitalists are finding that new treatments, continued efforts to standardize VTE prophylaxis, and increased transparency in performance reporting are the tools needed to combat these common conditions—and hospitalists are being held accountable for optimal patient care.

New Treatments Show Promise

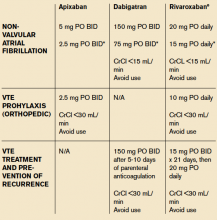

Diagnosing and treating VTE early helps to prevent progression and hemodynamic instability. Although the accepted treatment for VTE used to be heparin, or a low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) (Fragmin, Innohep and Lovenox) with a transition to warfarin, three target-specific oral anticoagulants (TSOACs)—dabigatran, rivaroxaban, and apixaban—are now being prescribed. The FDA has approved rivaroxaban and apixaban for the prevention of VTE after knee and hip surgery and for treatment of VTE, while dabigatran is FDA approved only for the treatment of VTE. All three are approved for use in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (Afib). A fourth TSOAC, edoxaban, received FDA approval in January for VTE treatment and nonvalvular atrial fibrillation.

“The drawback of warfarin is that patients need frequent international normalized ratio (INR) monitoring,” Dr. Kanikkannan says. “Discharge planning is time consuming because patients need to be educated on warfarin, and follow-up appointments need to be arranged before discharge to ensure patient safety.”

“Their [TSOACs] ease of administration and easy dosing helps hospitalists to manage patients with VTE more efficiently,” Dr. Kanikkannan says. “Patients like having lab testing less frequently but equal efficacy in treatment.”

Rivaroxaban used to have the most approved indications by the FDA; however, based on three clinical trials—ADVANCE-1, 2, and 3—apixaban has the same six FDA indications as rivaroxaban.

The majority of clinical trials suggest noninferiority or superiority of the oral agents compared to LMWH, and safety appears to be similar across treatment groups, other than an increased risk in bleeding with oral agents (see Table 1).

“The increased risk of bleeding seen in trials is something hospitalists need to consider,” says Yong Lee, PharmD, BCPS, clinical pharmacy specialist at Parkland Health and Hospital System in Dallas, Texas. Warfarin is easily reversed; the new anticoagulants don’t have any specific reversal agent (see new table about reversal options). Consequently, the American College of Chest Physicians still recommends unfractionated heparin or a LMWH for VTE prophylaxis. “These agents will still likely remain the best available options to hospitalists for VTE prevention,” he adds.

Julianna Lindsey, MD, MBA, FACP, FHM, chief of staff and hospitalist at Victory Medical Center in McKinney, Texas, says there are instances when it would be helpful to know what the therapeutic level of a TSOAC’s anticoagulation effect is, such as in a patient with active bleeding or one who requires major emergent surgery. But there is no coagulation assay to date that is readily available to test the effect of apixaban; the anticoagulation effect for dabigatran can be roughly estimated by the activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) and thrombin time (TT), and the anticoagulation effect for rivaroxaban can be roughly estimated by the prothrombin time (PT).

Dr. Lee expects the new FDA approvals to expand the utilization of oral anti-Xa inhibitors in practice. “This will, hopefully, make the new oral anticoagulant market more competitive, driving down their costs,” he says, referring to one of the biggest barriers to current use of these agents. Warfarin still remains the most cost-effective option, despite the need for regular INR monitoring.

“Studies are looking not only at effectiveness but also the safety profile of these anticoagulants,” Dr. Kanikkannan says, as long-term safety data is not yet available on these oral agents.8,9

Researchers also are looking at the comparative effects of other medications. For example, a Journal of Hospital Medicine study concluded that, compared with other anticoagulants, aspirin is associated with a higher risk of DVT following hip fracture repair but similar rates of DVT risk following hip-knee arthroplasty. Bleeding rates with aspirin, however, were substantially lower.10

Improvement Efforts

In an effort to improve VTE prophylaxis in hospitalized patients, The Joint Commission developed a VTE standardized performance measure set in 2009, which has been reported on www.qualitycheck.org since then. The VTE measure set comprises six different measures evaluating the prophylaxis of VTE, treatment of VTE, warfarin discharge education, and hospital-acquired VTE. Since reporting started, most hospitals have implemented VTE risk assessment models and VTE process improvement programs; data trends have shown improvement, says Denise Krusenoski, MSN, RN, CMSRN, CHTS-CP, associate project director at The Joint Commission, which is based in Oakbrook Terrace, Ill.

“While a lot of good, evidence-based data is available, no single VTE risk assessment tool has been prospectively validated as superior,” she says. “Involving key members of medical staff to create and approve protocols based on proven data will increase the buy-in and adoption for using these tools.”

E-Measures Promote Excellence

Many hospitals are now moving from traditional chart abstracting for VTE measures to electronic measures (e-measures), which allow for more rapid and automated reporting of these quality metrics. In order for e-measures to be accurate, documentation necessary for measure computation must be present in defined standardized fields in the medical record. “With no human interpretation, data must be documented in a precise fashion,” Krusenoski says. “Providers will need to be flexible in learning new documentation skills.”

Dr. Lindsey, a member of Team Hospitalist, cautions that e-measures have the potential to increase unwanted events by overutilization of pharmacologic VTE prophylaxis and associated hemorrhagic events.

“We have to continue to make sure that our practice of medicine remains based in evidence and not succumb to the pull of getting a check-box ticked,” she warns.

VTE remains a significant problem in hospitalized patients today. Hospitalists should consider the pros and cons of using newer treatment methods over traditional agents. Efforts are under way to improve VTE prophylaxis by standardizing best practice and moving from traditional chart abstracting to using e-measures for performance reporting.

Karen Appold is a freelance medical writer in Pennsylvania.

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Public Health Grand Rounds. Preventing venous thromboembolism. January 15, 2013. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/cdcgrandrounds/archives/2013/january2013.htm. Accessed February 12, 2015.

- Dobesh PP. Economic burden of venous thromboembolism in hospitalized patients. Pharmacotherapy. 2009;29(8):943-953.

- Lassen MR, Raskob GE, Gallus A, Pineo G, Chen D, Portman RJ. Apixaban or enoxaparin for thromboprophylaxis after knee replacement. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(6):594-604.

- Lassen MR, Raskob GE, Gallus A, Pineo G, Chen D, Hornick P; ADVANCE-2 Investigators. Apixaban versus enoxaparin for thromboprophylaxis after knee replacement (ADVANCE-2): a randomised double-blind trial. Lancet. 2010;375(9717):807-815.

- Lassen MR, Gallus A, Raskob GE, Pineo G, Chen D, Ramirez LM; ADVANCE-3 Investigators. Apixaban versus enoxaparin for thromboprophylaxis after hip replacement. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(26):2487-2498.

- Cohen AT, Spiro TE, Büller HR, et al. Rivaroxaban for thromboprophylaxis in acutely ill medical patients. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(6):513-523.

- Goldhaber SZ, Leizorovicz A, Kakkar AK, et al. Apixaban versus enoxaparin for thromboprophylaxis in medically ill patients. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(23):2167-2177.

- Gonsalves WI, Pruthi RK, Patnaik MM. The new oral anticoagulants in clinical practice. Mayo Clin Proc. 2013;88(5):495-511.

- Holster IL, Valkoff VE, Kuipers EJ, Tjwa ET. New oral anticoagulants increase risk for gastrointestinal bleeding: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2013;145(1):105-112.

- Drescher FS, Sirovich BE, Lee A, Morrison DH, Chiang WH, Larson RJ. Aspirin versus anticoagulation for prevention of venous thromboembolism major lower extremity orthopedic surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(9):579-585.

- Bullock-Palmer RP, Weiss S, Hyman C. Innovative approaches to increase deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis rate resulting in a decrease in hospital-acquired deep vein thrombosis at a tertiary-care teaching hospital. J Hosp Med. 2008;3(2):148-155.

“While VTE may not be the No. 1 reason for hospitalization, hospitalists very frequently care for patients with VTE,” says Sowmya Kanikkannan, MD, FACP, SFHM, hospitalist medical director and assistant professor of medicine at Rowan University School of Osteopathic Medicine in Stratford, N.J. “Hospitalists usually are the frontline providers that diagnose and manage hospital-acquired VTEs in hospitalized patients.”

Dr. Kanikkannan, a member of Team Hospitalist, sees a wide range of VTE cases caused by two related conditions—deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE).

“Some patients present with a straightforward diagnosis of DVT, while others have extensive DVT,” she says. “In other instances, patients present with acute PE with or without hemodynamic compromise. I’ve also diagnosed and managed hospital-acquired VTEs in medical patients, as well as post-operatively in surgical co-management.”

It is estimated that between 350,000 to 900,000 Americans are affected by DVT or PE each year, with up to 100,000 dying as a result. Twenty to 50% of people who experience DVT develop long-term complications.1VTE costs the U.S. healthcare system more than $1.5 billion annually.2

As lieutenants in the war against VTE, hospitalists are finding that new treatments, continued efforts to standardize VTE prophylaxis, and increased transparency in performance reporting are the tools needed to combat these common conditions—and hospitalists are being held accountable for optimal patient care.

New Treatments Show Promise

Diagnosing and treating VTE early helps to prevent progression and hemodynamic instability. Although the accepted treatment for VTE used to be heparin, or a low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) (Fragmin, Innohep and Lovenox) with a transition to warfarin, three target-specific oral anticoagulants (TSOACs)—dabigatran, rivaroxaban, and apixaban—are now being prescribed. The FDA has approved rivaroxaban and apixaban for the prevention of VTE after knee and hip surgery and for treatment of VTE, while dabigatran is FDA approved only for the treatment of VTE. All three are approved for use in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (Afib). A fourth TSOAC, edoxaban, received FDA approval in January for VTE treatment and nonvalvular atrial fibrillation.

“The drawback of warfarin is that patients need frequent international normalized ratio (INR) monitoring,” Dr. Kanikkannan says. “Discharge planning is time consuming because patients need to be educated on warfarin, and follow-up appointments need to be arranged before discharge to ensure patient safety.”

“Their [TSOACs] ease of administration and easy dosing helps hospitalists to manage patients with VTE more efficiently,” Dr. Kanikkannan says. “Patients like having lab testing less frequently but equal efficacy in treatment.”

Rivaroxaban used to have the most approved indications by the FDA; however, based on three clinical trials—ADVANCE-1, 2, and 3—apixaban has the same six FDA indications as rivaroxaban.

The majority of clinical trials suggest noninferiority or superiority of the oral agents compared to LMWH, and safety appears to be similar across treatment groups, other than an increased risk in bleeding with oral agents (see Table 1).

“The increased risk of bleeding seen in trials is something hospitalists need to consider,” says Yong Lee, PharmD, BCPS, clinical pharmacy specialist at Parkland Health and Hospital System in Dallas, Texas. Warfarin is easily reversed; the new anticoagulants don’t have any specific reversal agent (see new table about reversal options). Consequently, the American College of Chest Physicians still recommends unfractionated heparin or a LMWH for VTE prophylaxis. “These agents will still likely remain the best available options to hospitalists for VTE prevention,” he adds.

Julianna Lindsey, MD, MBA, FACP, FHM, chief of staff and hospitalist at Victory Medical Center in McKinney, Texas, says there are instances when it would be helpful to know what the therapeutic level of a TSOAC’s anticoagulation effect is, such as in a patient with active bleeding or one who requires major emergent surgery. But there is no coagulation assay to date that is readily available to test the effect of apixaban; the anticoagulation effect for dabigatran can be roughly estimated by the activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) and thrombin time (TT), and the anticoagulation effect for rivaroxaban can be roughly estimated by the prothrombin time (PT).

Dr. Lee expects the new FDA approvals to expand the utilization of oral anti-Xa inhibitors in practice. “This will, hopefully, make the new oral anticoagulant market more competitive, driving down their costs,” he says, referring to one of the biggest barriers to current use of these agents. Warfarin still remains the most cost-effective option, despite the need for regular INR monitoring.

“Studies are looking not only at effectiveness but also the safety profile of these anticoagulants,” Dr. Kanikkannan says, as long-term safety data is not yet available on these oral agents.8,9

Researchers also are looking at the comparative effects of other medications. For example, a Journal of Hospital Medicine study concluded that, compared with other anticoagulants, aspirin is associated with a higher risk of DVT following hip fracture repair but similar rates of DVT risk following hip-knee arthroplasty. Bleeding rates with aspirin, however, were substantially lower.10

Improvement Efforts

In an effort to improve VTE prophylaxis in hospitalized patients, The Joint Commission developed a VTE standardized performance measure set in 2009, which has been reported on www.qualitycheck.org since then. The VTE measure set comprises six different measures evaluating the prophylaxis of VTE, treatment of VTE, warfarin discharge education, and hospital-acquired VTE. Since reporting started, most hospitals have implemented VTE risk assessment models and VTE process improvement programs; data trends have shown improvement, says Denise Krusenoski, MSN, RN, CMSRN, CHTS-CP, associate project director at The Joint Commission, which is based in Oakbrook Terrace, Ill.

“While a lot of good, evidence-based data is available, no single VTE risk assessment tool has been prospectively validated as superior,” she says. “Involving key members of medical staff to create and approve protocols based on proven data will increase the buy-in and adoption for using these tools.”

E-Measures Promote Excellence

Many hospitals are now moving from traditional chart abstracting for VTE measures to electronic measures (e-measures), which allow for more rapid and automated reporting of these quality metrics. In order for e-measures to be accurate, documentation necessary for measure computation must be present in defined standardized fields in the medical record. “With no human interpretation, data must be documented in a precise fashion,” Krusenoski says. “Providers will need to be flexible in learning new documentation skills.”

Dr. Lindsey, a member of Team Hospitalist, cautions that e-measures have the potential to increase unwanted events by overutilization of pharmacologic VTE prophylaxis and associated hemorrhagic events.

“We have to continue to make sure that our practice of medicine remains based in evidence and not succumb to the pull of getting a check-box ticked,” she warns.

VTE remains a significant problem in hospitalized patients today. Hospitalists should consider the pros and cons of using newer treatment methods over traditional agents. Efforts are under way to improve VTE prophylaxis by standardizing best practice and moving from traditional chart abstracting to using e-measures for performance reporting.

Karen Appold is a freelance medical writer in Pennsylvania.

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Public Health Grand Rounds. Preventing venous thromboembolism. January 15, 2013. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/cdcgrandrounds/archives/2013/january2013.htm. Accessed February 12, 2015.

- Dobesh PP. Economic burden of venous thromboembolism in hospitalized patients. Pharmacotherapy. 2009;29(8):943-953.

- Lassen MR, Raskob GE, Gallus A, Pineo G, Chen D, Portman RJ. Apixaban or enoxaparin for thromboprophylaxis after knee replacement. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(6):594-604.

- Lassen MR, Raskob GE, Gallus A, Pineo G, Chen D, Hornick P; ADVANCE-2 Investigators. Apixaban versus enoxaparin for thromboprophylaxis after knee replacement (ADVANCE-2): a randomised double-blind trial. Lancet. 2010;375(9717):807-815.

- Lassen MR, Gallus A, Raskob GE, Pineo G, Chen D, Ramirez LM; ADVANCE-3 Investigators. Apixaban versus enoxaparin for thromboprophylaxis after hip replacement. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(26):2487-2498.

- Cohen AT, Spiro TE, Büller HR, et al. Rivaroxaban for thromboprophylaxis in acutely ill medical patients. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(6):513-523.

- Goldhaber SZ, Leizorovicz A, Kakkar AK, et al. Apixaban versus enoxaparin for thromboprophylaxis in medically ill patients. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(23):2167-2177.

- Gonsalves WI, Pruthi RK, Patnaik MM. The new oral anticoagulants in clinical practice. Mayo Clin Proc. 2013;88(5):495-511.

- Holster IL, Valkoff VE, Kuipers EJ, Tjwa ET. New oral anticoagulants increase risk for gastrointestinal bleeding: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2013;145(1):105-112.

- Drescher FS, Sirovich BE, Lee A, Morrison DH, Chiang WH, Larson RJ. Aspirin versus anticoagulation for prevention of venous thromboembolism major lower extremity orthopedic surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(9):579-585.

- Bullock-Palmer RP, Weiss S, Hyman C. Innovative approaches to increase deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis rate resulting in a decrease in hospital-acquired deep vein thrombosis at a tertiary-care teaching hospital. J Hosp Med. 2008;3(2):148-155.

“While VTE may not be the No. 1 reason for hospitalization, hospitalists very frequently care for patients with VTE,” says Sowmya Kanikkannan, MD, FACP, SFHM, hospitalist medical director and assistant professor of medicine at Rowan University School of Osteopathic Medicine in Stratford, N.J. “Hospitalists usually are the frontline providers that diagnose and manage hospital-acquired VTEs in hospitalized patients.”

Dr. Kanikkannan, a member of Team Hospitalist, sees a wide range of VTE cases caused by two related conditions—deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE).

“Some patients present with a straightforward diagnosis of DVT, while others have extensive DVT,” she says. “In other instances, patients present with acute PE with or without hemodynamic compromise. I’ve also diagnosed and managed hospital-acquired VTEs in medical patients, as well as post-operatively in surgical co-management.”

It is estimated that between 350,000 to 900,000 Americans are affected by DVT or PE each year, with up to 100,000 dying as a result. Twenty to 50% of people who experience DVT develop long-term complications.1VTE costs the U.S. healthcare system more than $1.5 billion annually.2

As lieutenants in the war against VTE, hospitalists are finding that new treatments, continued efforts to standardize VTE prophylaxis, and increased transparency in performance reporting are the tools needed to combat these common conditions—and hospitalists are being held accountable for optimal patient care.

New Treatments Show Promise

Diagnosing and treating VTE early helps to prevent progression and hemodynamic instability. Although the accepted treatment for VTE used to be heparin, or a low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) (Fragmin, Innohep and Lovenox) with a transition to warfarin, three target-specific oral anticoagulants (TSOACs)—dabigatran, rivaroxaban, and apixaban—are now being prescribed. The FDA has approved rivaroxaban and apixaban for the prevention of VTE after knee and hip surgery and for treatment of VTE, while dabigatran is FDA approved only for the treatment of VTE. All three are approved for use in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (Afib). A fourth TSOAC, edoxaban, received FDA approval in January for VTE treatment and nonvalvular atrial fibrillation.

“The drawback of warfarin is that patients need frequent international normalized ratio (INR) monitoring,” Dr. Kanikkannan says. “Discharge planning is time consuming because patients need to be educated on warfarin, and follow-up appointments need to be arranged before discharge to ensure patient safety.”

“Their [TSOACs] ease of administration and easy dosing helps hospitalists to manage patients with VTE more efficiently,” Dr. Kanikkannan says. “Patients like having lab testing less frequently but equal efficacy in treatment.”

Rivaroxaban used to have the most approved indications by the FDA; however, based on three clinical trials—ADVANCE-1, 2, and 3—apixaban has the same six FDA indications as rivaroxaban.

The majority of clinical trials suggest noninferiority or superiority of the oral agents compared to LMWH, and safety appears to be similar across treatment groups, other than an increased risk in bleeding with oral agents (see Table 1).

“The increased risk of bleeding seen in trials is something hospitalists need to consider,” says Yong Lee, PharmD, BCPS, clinical pharmacy specialist at Parkland Health and Hospital System in Dallas, Texas. Warfarin is easily reversed; the new anticoagulants don’t have any specific reversal agent (see new table about reversal options). Consequently, the American College of Chest Physicians still recommends unfractionated heparin or a LMWH for VTE prophylaxis. “These agents will still likely remain the best available options to hospitalists for VTE prevention,” he adds.

Julianna Lindsey, MD, MBA, FACP, FHM, chief of staff and hospitalist at Victory Medical Center in McKinney, Texas, says there are instances when it would be helpful to know what the therapeutic level of a TSOAC’s anticoagulation effect is, such as in a patient with active bleeding or one who requires major emergent surgery. But there is no coagulation assay to date that is readily available to test the effect of apixaban; the anticoagulation effect for dabigatran can be roughly estimated by the activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) and thrombin time (TT), and the anticoagulation effect for rivaroxaban can be roughly estimated by the prothrombin time (PT).

Dr. Lee expects the new FDA approvals to expand the utilization of oral anti-Xa inhibitors in practice. “This will, hopefully, make the new oral anticoagulant market more competitive, driving down their costs,” he says, referring to one of the biggest barriers to current use of these agents. Warfarin still remains the most cost-effective option, despite the need for regular INR monitoring.

“Studies are looking not only at effectiveness but also the safety profile of these anticoagulants,” Dr. Kanikkannan says, as long-term safety data is not yet available on these oral agents.8,9

Researchers also are looking at the comparative effects of other medications. For example, a Journal of Hospital Medicine study concluded that, compared with other anticoagulants, aspirin is associated with a higher risk of DVT following hip fracture repair but similar rates of DVT risk following hip-knee arthroplasty. Bleeding rates with aspirin, however, were substantially lower.10

Improvement Efforts

In an effort to improve VTE prophylaxis in hospitalized patients, The Joint Commission developed a VTE standardized performance measure set in 2009, which has been reported on www.qualitycheck.org since then. The VTE measure set comprises six different measures evaluating the prophylaxis of VTE, treatment of VTE, warfarin discharge education, and hospital-acquired VTE. Since reporting started, most hospitals have implemented VTE risk assessment models and VTE process improvement programs; data trends have shown improvement, says Denise Krusenoski, MSN, RN, CMSRN, CHTS-CP, associate project director at The Joint Commission, which is based in Oakbrook Terrace, Ill.

“While a lot of good, evidence-based data is available, no single VTE risk assessment tool has been prospectively validated as superior,” she says. “Involving key members of medical staff to create and approve protocols based on proven data will increase the buy-in and adoption for using these tools.”

E-Measures Promote Excellence

Many hospitals are now moving from traditional chart abstracting for VTE measures to electronic measures (e-measures), which allow for more rapid and automated reporting of these quality metrics. In order for e-measures to be accurate, documentation necessary for measure computation must be present in defined standardized fields in the medical record. “With no human interpretation, data must be documented in a precise fashion,” Krusenoski says. “Providers will need to be flexible in learning new documentation skills.”

Dr. Lindsey, a member of Team Hospitalist, cautions that e-measures have the potential to increase unwanted events by overutilization of pharmacologic VTE prophylaxis and associated hemorrhagic events.

“We have to continue to make sure that our practice of medicine remains based in evidence and not succumb to the pull of getting a check-box ticked,” she warns.

VTE remains a significant problem in hospitalized patients today. Hospitalists should consider the pros and cons of using newer treatment methods over traditional agents. Efforts are under way to improve VTE prophylaxis by standardizing best practice and moving from traditional chart abstracting to using e-measures for performance reporting.

Karen Appold is a freelance medical writer in Pennsylvania.

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Public Health Grand Rounds. Preventing venous thromboembolism. January 15, 2013. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/cdcgrandrounds/archives/2013/january2013.htm. Accessed February 12, 2015.

- Dobesh PP. Economic burden of venous thromboembolism in hospitalized patients. Pharmacotherapy. 2009;29(8):943-953.

- Lassen MR, Raskob GE, Gallus A, Pineo G, Chen D, Portman RJ. Apixaban or enoxaparin for thromboprophylaxis after knee replacement. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(6):594-604.

- Lassen MR, Raskob GE, Gallus A, Pineo G, Chen D, Hornick P; ADVANCE-2 Investigators. Apixaban versus enoxaparin for thromboprophylaxis after knee replacement (ADVANCE-2): a randomised double-blind trial. Lancet. 2010;375(9717):807-815.

- Lassen MR, Gallus A, Raskob GE, Pineo G, Chen D, Ramirez LM; ADVANCE-3 Investigators. Apixaban versus enoxaparin for thromboprophylaxis after hip replacement. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(26):2487-2498.

- Cohen AT, Spiro TE, Büller HR, et al. Rivaroxaban for thromboprophylaxis in acutely ill medical patients. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(6):513-523.

- Goldhaber SZ, Leizorovicz A, Kakkar AK, et al. Apixaban versus enoxaparin for thromboprophylaxis in medically ill patients. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(23):2167-2177.

- Gonsalves WI, Pruthi RK, Patnaik MM. The new oral anticoagulants in clinical practice. Mayo Clin Proc. 2013;88(5):495-511.

- Holster IL, Valkoff VE, Kuipers EJ, Tjwa ET. New oral anticoagulants increase risk for gastrointestinal bleeding: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2013;145(1):105-112.

- Drescher FS, Sirovich BE, Lee A, Morrison DH, Chiang WH, Larson RJ. Aspirin versus anticoagulation for prevention of venous thromboembolism major lower extremity orthopedic surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(9):579-585.

- Bullock-Palmer RP, Weiss S, Hyman C. Innovative approaches to increase deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis rate resulting in a decrease in hospital-acquired deep vein thrombosis at a tertiary-care teaching hospital. J Hosp Med. 2008;3(2):148-155.

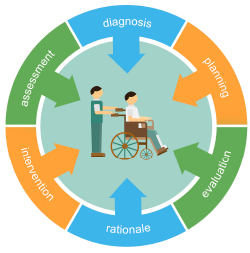

How to Initiate a VTE Quality Improvement Project

While VTE sometimes occurs in spite of the best available prophylaxis, there are many lost opportunities to optimize prevention and reduce VTE risk factors in virtually every hospital. Reaching a meaningful improvement in VTE prevention requires an empowered, interdisciplinary team approach supported by the institution to standardize processes, monitor, and measure VTE process and outcomes, implement institutional policies, and educate providers and patients.

In particular, Greg Maynard, MD, MSc, SFHM, director of the University of California San Diego Center for Innovation and Improvement Science, and senior medical officer of the Society of Hospital Medicine’s Center for Hospital Innovation and Improvement, suggests reviewing guidelines and regulatory materials that focus on the implications for implementation. Then, summarize the evidence into a VTE prevention protocol.

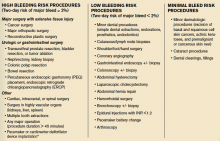

A VTE prevention protocol includes a VTE risk assessment, bleeding risk assessment, and clinical decision support (CDS) on prophylactic choices based on this combination of VTE and bleeding risk factors. The VTE protocol CDS must be available at crucial junctures of care, such as admission to the hospital, transfer to different levels of care, and post-operatively.

“This VTE protocol guidance is most often embedded in order sets that are commonly used [or mandated for use] in these settings, essentially ‘hard-wiring’ the VTE risk assessment into the process,” Dr. Maynard says.

Risk assessment is essential, as there are harms, costs, and discomfort associated with prophylactic methods. For some inpatients, the risk of anticoagulant prophylaxis may outweigh the risk

of hospital-acquired VTE. No perfect VTE risk assessment tool exists, and there is always inherent tension between the desire to provide comprehensive, detailed guidance and the need to keep the process simple to understand and measure.

Principles for the effective implementation of reliable interventions generally favor simple models, with more complicated models reserved for settings with advanced methods to make the models easier for the end user.

“Order sets with CDS are of no use if they are not used correctly and reliably, so monitoring this process is crucial,” Dr. Maynard says.

No matter which VTE risk assessment model is used, every effort should be made to enhance ease of use for the ordering provider. This may include carving out special populations such as obstetric patients and major orthopedic, trauma, cardiovascular surgery, and neurosurgery patients for modified VTE risk assessment and order sets, Dr. Maynard says, which allows for streamlining and simplification of VTE prevention order sets.

Successful integration of a VTE prevention protocol into heavily utilized admission and transfer order sets serves as a foundational beginning point for VTE prevention efforts, rather than the end point.

“Even if every patient has the best prophylaxis ordered on admission, other problems can lead to VTE during the hospital stay or after discharge,”

Dr. Maynard says.

For example:

- Bleeding and VTE risk factors can change several times during a hospital stay, but reassessment does not occur;

- Patients are not optimally mobilized;

- Adherence to ordered mechanical prophylaxis is notoriously low; and

- Overutilization of peripherally inserted central catheter lines or other central venous catheters contributes to upper extremity DVT.

VTE prevention programs should address these pitfalls, in addition to implementing order sets.

Publicly reported measures and the CMS core measures set a relatively low bar for performance and are inadequate to drive breakthrough levels of improvement, Dr. Maynard adds. The adequacy of VTE prophylaxis should be assessed not only on admission or transfer to the intensive care unit but also across the hospital stay. Month-to-month reporting is important to follow progress, but at least some measures should drive concurrent intervention to address deficits in prophylaxis in real time. This method of active surveillance (also known as measure-vention), along with multiple other measurement methods that go beyond the core measures, is often necessary to secure real improvement.

An extensive update and revision of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality/Society of Hospital Medicine VTE Prevention Implementation Guide will be released by early spring. It will provide comprehensive coverage of these concepts.

Karen Appold is a freelance medical writer in Pennsylvania.

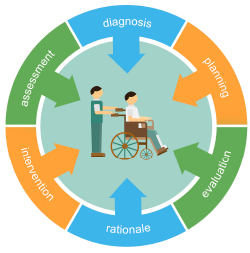

While VTE sometimes occurs in spite of the best available prophylaxis, there are many lost opportunities to optimize prevention and reduce VTE risk factors in virtually every hospital. Reaching a meaningful improvement in VTE prevention requires an empowered, interdisciplinary team approach supported by the institution to standardize processes, monitor, and measure VTE process and outcomes, implement institutional policies, and educate providers and patients.

In particular, Greg Maynard, MD, MSc, SFHM, director of the University of California San Diego Center for Innovation and Improvement Science, and senior medical officer of the Society of Hospital Medicine’s Center for Hospital Innovation and Improvement, suggests reviewing guidelines and regulatory materials that focus on the implications for implementation. Then, summarize the evidence into a VTE prevention protocol.

A VTE prevention protocol includes a VTE risk assessment, bleeding risk assessment, and clinical decision support (CDS) on prophylactic choices based on this combination of VTE and bleeding risk factors. The VTE protocol CDS must be available at crucial junctures of care, such as admission to the hospital, transfer to different levels of care, and post-operatively.

“This VTE protocol guidance is most often embedded in order sets that are commonly used [or mandated for use] in these settings, essentially ‘hard-wiring’ the VTE risk assessment into the process,” Dr. Maynard says.

Risk assessment is essential, as there are harms, costs, and discomfort associated with prophylactic methods. For some inpatients, the risk of anticoagulant prophylaxis may outweigh the risk

of hospital-acquired VTE. No perfect VTE risk assessment tool exists, and there is always inherent tension between the desire to provide comprehensive, detailed guidance and the need to keep the process simple to understand and measure.

Principles for the effective implementation of reliable interventions generally favor simple models, with more complicated models reserved for settings with advanced methods to make the models easier for the end user.

“Order sets with CDS are of no use if they are not used correctly and reliably, so monitoring this process is crucial,” Dr. Maynard says.

No matter which VTE risk assessment model is used, every effort should be made to enhance ease of use for the ordering provider. This may include carving out special populations such as obstetric patients and major orthopedic, trauma, cardiovascular surgery, and neurosurgery patients for modified VTE risk assessment and order sets, Dr. Maynard says, which allows for streamlining and simplification of VTE prevention order sets.

Successful integration of a VTE prevention protocol into heavily utilized admission and transfer order sets serves as a foundational beginning point for VTE prevention efforts, rather than the end point.

“Even if every patient has the best prophylaxis ordered on admission, other problems can lead to VTE during the hospital stay or after discharge,”

Dr. Maynard says.

For example:

- Bleeding and VTE risk factors can change several times during a hospital stay, but reassessment does not occur;

- Patients are not optimally mobilized;

- Adherence to ordered mechanical prophylaxis is notoriously low; and

- Overutilization of peripherally inserted central catheter lines or other central venous catheters contributes to upper extremity DVT.

VTE prevention programs should address these pitfalls, in addition to implementing order sets.

Publicly reported measures and the CMS core measures set a relatively low bar for performance and are inadequate to drive breakthrough levels of improvement, Dr. Maynard adds. The adequacy of VTE prophylaxis should be assessed not only on admission or transfer to the intensive care unit but also across the hospital stay. Month-to-month reporting is important to follow progress, but at least some measures should drive concurrent intervention to address deficits in prophylaxis in real time. This method of active surveillance (also known as measure-vention), along with multiple other measurement methods that go beyond the core measures, is often necessary to secure real improvement.

An extensive update and revision of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality/Society of Hospital Medicine VTE Prevention Implementation Guide will be released by early spring. It will provide comprehensive coverage of these concepts.

Karen Appold is a freelance medical writer in Pennsylvania.

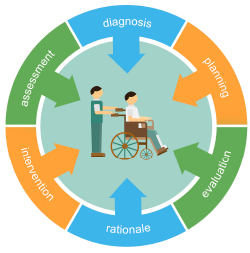

While VTE sometimes occurs in spite of the best available prophylaxis, there are many lost opportunities to optimize prevention and reduce VTE risk factors in virtually every hospital. Reaching a meaningful improvement in VTE prevention requires an empowered, interdisciplinary team approach supported by the institution to standardize processes, monitor, and measure VTE process and outcomes, implement institutional policies, and educate providers and patients.

In particular, Greg Maynard, MD, MSc, SFHM, director of the University of California San Diego Center for Innovation and Improvement Science, and senior medical officer of the Society of Hospital Medicine’s Center for Hospital Innovation and Improvement, suggests reviewing guidelines and regulatory materials that focus on the implications for implementation. Then, summarize the evidence into a VTE prevention protocol.

A VTE prevention protocol includes a VTE risk assessment, bleeding risk assessment, and clinical decision support (CDS) on prophylactic choices based on this combination of VTE and bleeding risk factors. The VTE protocol CDS must be available at crucial junctures of care, such as admission to the hospital, transfer to different levels of care, and post-operatively.

“This VTE protocol guidance is most often embedded in order sets that are commonly used [or mandated for use] in these settings, essentially ‘hard-wiring’ the VTE risk assessment into the process,” Dr. Maynard says.

Risk assessment is essential, as there are harms, costs, and discomfort associated with prophylactic methods. For some inpatients, the risk of anticoagulant prophylaxis may outweigh the risk

of hospital-acquired VTE. No perfect VTE risk assessment tool exists, and there is always inherent tension between the desire to provide comprehensive, detailed guidance and the need to keep the process simple to understand and measure.

Principles for the effective implementation of reliable interventions generally favor simple models, with more complicated models reserved for settings with advanced methods to make the models easier for the end user.

“Order sets with CDS are of no use if they are not used correctly and reliably, so monitoring this process is crucial,” Dr. Maynard says.

No matter which VTE risk assessment model is used, every effort should be made to enhance ease of use for the ordering provider. This may include carving out special populations such as obstetric patients and major orthopedic, trauma, cardiovascular surgery, and neurosurgery patients for modified VTE risk assessment and order sets, Dr. Maynard says, which allows for streamlining and simplification of VTE prevention order sets.

Successful integration of a VTE prevention protocol into heavily utilized admission and transfer order sets serves as a foundational beginning point for VTE prevention efforts, rather than the end point.

“Even if every patient has the best prophylaxis ordered on admission, other problems can lead to VTE during the hospital stay or after discharge,”

Dr. Maynard says.

For example:

- Bleeding and VTE risk factors can change several times during a hospital stay, but reassessment does not occur;

- Patients are not optimally mobilized;

- Adherence to ordered mechanical prophylaxis is notoriously low; and

- Overutilization of peripherally inserted central catheter lines or other central venous catheters contributes to upper extremity DVT.

VTE prevention programs should address these pitfalls, in addition to implementing order sets.

Publicly reported measures and the CMS core measures set a relatively low bar for performance and are inadequate to drive breakthrough levels of improvement, Dr. Maynard adds. The adequacy of VTE prophylaxis should be assessed not only on admission or transfer to the intensive care unit but also across the hospital stay. Month-to-month reporting is important to follow progress, but at least some measures should drive concurrent intervention to address deficits in prophylaxis in real time. This method of active surveillance (also known as measure-vention), along with multiple other measurement methods that go beyond the core measures, is often necessary to secure real improvement.

An extensive update and revision of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality/Society of Hospital Medicine VTE Prevention Implementation Guide will be released by early spring. It will provide comprehensive coverage of these concepts.

Karen Appold is a freelance medical writer in Pennsylvania.

De-Escalation Training Prepares Hospitalists to Calm Agitated Patients

If a patient shows signs of agitation, Aaron Gottesman, MD, SFHM, says the best way to handle it is to stay calm. It may sound simple, but, in the heat of the moment, people tend to become defensive and on guard rather than acting composed and sympathetic. He suggests trying to speak softly and evenly to the patient, make eye contact, keep your arms at your side, and ask opened-ended questions such as, “How can I help you?” in a genuine manner.

Dr. Gottesman, director of hospitalist services at Staten Island (N.Y.) University Hospital (SIUH), learned these strategies in a voluntary one-hour course on de-escalation training. Although he says he feels fortunate that he has never had to deal with a physically volatile patient, he has used the verbal de-escalation training. In some cases, he believes that employing it may have prevented a physically violent situation from occurring.

Specifically, de-escalation training teaches how to respond to individuals who are acting aggressive or agitated in a verbal or physical manner. The techniques focus on how to calm someone down, while also teaching basic self-defense skills.

Various companies offer this type of training; some will train staff onsite.

“It is money well-spent,” says Scott Zeller, MD, chief of psychiatric emergency services at Alameda Health System in Oakland, Calif. “This is truly a situation where an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure. It only takes one unfortunate episode to result in a serious injury, where a healthcare professional will have to miss work or go on disability, which results in a far greater cost than that of the training.”

Appropriate Responses

By the nature of their work, hospitalists regularly come into contact with agitated patients. “Knowing how to safely help a patient calm down will result in better outcomes for the patient, the physicians, and everyone nearby,” Dr. Zeller says.

“Hospitalists should focus on what they can control,” says Judith Schubert, president of Crisis Prevention Institute (CPI), a Milwaukee, Wis.-based company that offers de-escalation training in 400 cities annually. This includes physicians’ own behavior/demeanor, responsiveness, environmental factors, communication protocols, and a continuous assessment of risk and an understanding of how to balance duty of care with responsibilities to maintain safety.

Hospitalists should be aware of behaviors that could lead to volatility.

“Challenging or oppositional questions and emotional release or intimidating comments often mark the beginning stages of loss of rationality. These are behaviors that warrant specific, directive intervention aimed at stimulating a rational response and diffusing tension,” Schubert says. “Before it even gets to that point, empathy, demonstrated with the patient and family members, can reduce contagion of emotional displays that are likely rooted in fear and anxiety.”

Agitation usually doesn’t arise out of the blue.

“It is typically seen over a spectrum of behaviors, from merely restless and irritable up to sarcastic and demeaning, pacing, unable to sit still, all the way up to screaming, combative, and violent to persons and property,” Dr. Zeller says. “It is best to intervene in the earlier stages and help a person to calm before a situation gets out of hand.”

Thus, hospitalists should be wary of people who are increasingly hostile and energetic and should seek help or work to de-escalate promptly.

Although you may suspect that patients with mental illnesses are more prone to volatility, Dr. Zeller says that isn’t necessarily the case. The most common psychiatric illnesses that can lead to agitation are schizophrenia and bipolar mania. In addition, being intoxicated—especially with alcohol and stimulants—can predispose someone to agitation. Many other medical conditions can cause someone to become agitated, such as confusion, a postictal state, hypoglycemia, or a head injury.

How Bad Is It?

According to the Emergency Nurses Association’s Institute for Emergency Nursing Research, violence is especially prevalent in the ED; about 11% of ED nurses report being physically assaulted each week. The agency states that the data is most likely grossly underreported, since reporting is voluntary.1

Healthcare workers in psychiatric wards are the most likely to suffer an injury caused by an agitated patient, Dr. Zeller says. Of those, nurses are the ones most commonly affected, followed by physicians.

“But agitation-related assaults and injuries can happen just about anywhere in a hospital,” he adds.

According to a study conducted by the Emergency Nurses Association, pushing/grabbing and yelling/shouting were the most prevalent types of violence. Eighty percent of cases occurred in the patient’s room.2 Dr. Zeller says that the most common injuries are those resulting from being struck, kicked or punched, or knocked down. Injuries include heavy bruising, sprains, and broken bones.

Dr. Zeller says it’s difficult to quantify exactly what types and costs of injuries occur. Injuries related to agitation are known to cause staff to miss work frequently. “That can cost a lot in terms of lost hours and replacement wages, as well as medical care for the injured party,” he says.

The Most Dangerous Circumstances

According to a series of 2012 articles on best practices guidelines for the evaluation and treatment of agitation published in Western Journal of Emergency Medicine, two-thirds of all staff injuries occur during the “takedown,” which is when staff attempt to tackle and restrain an agitated patient.3

“If interactions with a patient could help the person to regain control without needing the takedown or restraints, there would be fewer injuries and better outcomes,” says Dr. Zeller, who co-authored the article. “To help these patients in a collaborative and noncoercive way, and avoid restraints, verbal de-escalation is the necessary approach.”

As part of the study, a team of more than 40 experts nationwide was established to create Project BETA (Best practices in Evaluation and Treatment of Agitation). Participants were divided into five workgroups: triage and medical evaluation, psychiatric evaluation, de-escalation techniques, psychopharmacology of agitation, and use and avoidance of seclusion and restraint.

The guidelines were intended to cover all aspects of working with an agitated individual, with a focus on safety and outcomes, but also had a goal of being as patient-centric, collaborative, and noncoercive as possible.

“Every part of Project BETA revolves around verbal de-escalation, which can be done in a very short amount of time while simultaneously doing an assessment and offering medications,” Dr. Zeller says.

As a result of incorporating the guidelines in Project BETA, the psychiatric emergency room at Alameda Health System—which deals with a highly acute, emergency population of patients with serious mental illnesses—restrains less than 0.5% of patients seen. Dr. Zeller points out that this is much lower than the numbers restrained at other institutions. For instance, an article published in October 2013 reported several studies showing that 8% to 24% of patients in psychiatric EDs were placed into physical restraints or seclusion.4

What’s Required of Hospital Administration?

Under its Environment of Care standards, The Joint Commission requires accredited healthcare facilities to address workplace violence risk. The requirements mandate facilities to maintain a written plan describing how the security of patients, staff, and facility visitors will be ensured, to conduct proactive risk assessments considering the potential for workplace violence, and to determine a means for identifying individuals on their premises and controlling access to and egress from security-sensitive areas.1

The standard states that “staff are trained in the use of nonphysical intervention skills,” says Cynthia Leslie, APRN, BC, MSN, associate director of the Standards Interpretation Group at The Joint Commission, which is based in Oakbrook Terrace, Ill. “These skills may assist the patient in calming down and prevent the use of restraints and/or seclusion.”

In addition, staff must be trained before they participate in a restraint or seclusion episode and must have periodic training thereafter.

Anyone who wants de-escalation training can contact a company like CPI directly or establish in-house training teams (CPI offers an Instructor Certification Program). “This allows a cost-effective way [approximately $10 per person] to cascade training to others within the hospital who are part of care teams,” Schubert says.

In Sum

Providing for the care and welfare of patients while maintaining a safe and secure environment for everyone is a balancing act that requires the involvement of a multidisciplinary hospital team, Schubert says.

“Coordination, communication, and continuity among all members of a hospital team are crucial to minimize conflict, avoid chaos, and reduce risks,” she explains. “By being armed with information and skills, hospitalists are less likely to isolate themselves from other team members or react in a nonproductive way when crisis situations emerge.

“Training will help staff to take steps to ensure that their behavior and attitudes don’t become part of the problem and increase risks for others involved. Care team perceptions of physician involvement in solution-focused interventions are important for hospitalists to fully understand so risks can be avoided.”

Karen Appold is a freelance medical writer in Pennsylvania.

References

- ECRI Institute. Healthcare Risk, Quality, and Safety Guidance. Violence in healthcare facilities. March 1, 2011. Available at: https://www.ecri.org/components/HRC/Pages/SafSec3.aspx?tab=1. Accessed February 11, 2015.

- Emergency Nurses Association. Emergency department violence surveillance study. November 2011. Available at: http://www.ena.org/practice-research/research/Documents/ENAEDVSReportNovember2011.pdf. Accessed February 11, 2015.

- Richmond JS, Berlin JS, Fishkind AB, et al. Verbal de-escalation of the agitated patient: consensus statement of the American Association for Emergency Psychiatry Project BETA De-escalation Workgroup. West J Emerg Med. 2012;13(1):17-25.

- Simpson SA, Joesch JM, West II, Pasic J. Risk for physical restraint or seclusion in the psychiatric emergency service (PES). Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2014;36(1):113-118.

If a patient shows signs of agitation, Aaron Gottesman, MD, SFHM, says the best way to handle it is to stay calm. It may sound simple, but, in the heat of the moment, people tend to become defensive and on guard rather than acting composed and sympathetic. He suggests trying to speak softly and evenly to the patient, make eye contact, keep your arms at your side, and ask opened-ended questions such as, “How can I help you?” in a genuine manner.

Dr. Gottesman, director of hospitalist services at Staten Island (N.Y.) University Hospital (SIUH), learned these strategies in a voluntary one-hour course on de-escalation training. Although he says he feels fortunate that he has never had to deal with a physically volatile patient, he has used the verbal de-escalation training. In some cases, he believes that employing it may have prevented a physically violent situation from occurring.

Specifically, de-escalation training teaches how to respond to individuals who are acting aggressive or agitated in a verbal or physical manner. The techniques focus on how to calm someone down, while also teaching basic self-defense skills.

Various companies offer this type of training; some will train staff onsite.

“It is money well-spent,” says Scott Zeller, MD, chief of psychiatric emergency services at Alameda Health System in Oakland, Calif. “This is truly a situation where an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure. It only takes one unfortunate episode to result in a serious injury, where a healthcare professional will have to miss work or go on disability, which results in a far greater cost than that of the training.”

Appropriate Responses

By the nature of their work, hospitalists regularly come into contact with agitated patients. “Knowing how to safely help a patient calm down will result in better outcomes for the patient, the physicians, and everyone nearby,” Dr. Zeller says.

“Hospitalists should focus on what they can control,” says Judith Schubert, president of Crisis Prevention Institute (CPI), a Milwaukee, Wis.-based company that offers de-escalation training in 400 cities annually. This includes physicians’ own behavior/demeanor, responsiveness, environmental factors, communication protocols, and a continuous assessment of risk and an understanding of how to balance duty of care with responsibilities to maintain safety.

Hospitalists should be aware of behaviors that could lead to volatility.

“Challenging or oppositional questions and emotional release or intimidating comments often mark the beginning stages of loss of rationality. These are behaviors that warrant specific, directive intervention aimed at stimulating a rational response and diffusing tension,” Schubert says. “Before it even gets to that point, empathy, demonstrated with the patient and family members, can reduce contagion of emotional displays that are likely rooted in fear and anxiety.”

Agitation usually doesn’t arise out of the blue.

“It is typically seen over a spectrum of behaviors, from merely restless and irritable up to sarcastic and demeaning, pacing, unable to sit still, all the way up to screaming, combative, and violent to persons and property,” Dr. Zeller says. “It is best to intervene in the earlier stages and help a person to calm before a situation gets out of hand.”

Thus, hospitalists should be wary of people who are increasingly hostile and energetic and should seek help or work to de-escalate promptly.

Although you may suspect that patients with mental illnesses are more prone to volatility, Dr. Zeller says that isn’t necessarily the case. The most common psychiatric illnesses that can lead to agitation are schizophrenia and bipolar mania. In addition, being intoxicated—especially with alcohol and stimulants—can predispose someone to agitation. Many other medical conditions can cause someone to become agitated, such as confusion, a postictal state, hypoglycemia, or a head injury.

How Bad Is It?

According to the Emergency Nurses Association’s Institute for Emergency Nursing Research, violence is especially prevalent in the ED; about 11% of ED nurses report being physically assaulted each week. The agency states that the data is most likely grossly underreported, since reporting is voluntary.1

Healthcare workers in psychiatric wards are the most likely to suffer an injury caused by an agitated patient, Dr. Zeller says. Of those, nurses are the ones most commonly affected, followed by physicians.

“But agitation-related assaults and injuries can happen just about anywhere in a hospital,” he adds.

According to a study conducted by the Emergency Nurses Association, pushing/grabbing and yelling/shouting were the most prevalent types of violence. Eighty percent of cases occurred in the patient’s room.2 Dr. Zeller says that the most common injuries are those resulting from being struck, kicked or punched, or knocked down. Injuries include heavy bruising, sprains, and broken bones.

Dr. Zeller says it’s difficult to quantify exactly what types and costs of injuries occur. Injuries related to agitation are known to cause staff to miss work frequently. “That can cost a lot in terms of lost hours and replacement wages, as well as medical care for the injured party,” he says.

The Most Dangerous Circumstances

According to a series of 2012 articles on best practices guidelines for the evaluation and treatment of agitation published in Western Journal of Emergency Medicine, two-thirds of all staff injuries occur during the “takedown,” which is when staff attempt to tackle and restrain an agitated patient.3

“If interactions with a patient could help the person to regain control without needing the takedown or restraints, there would be fewer injuries and better outcomes,” says Dr. Zeller, who co-authored the article. “To help these patients in a collaborative and noncoercive way, and avoid restraints, verbal de-escalation is the necessary approach.”

As part of the study, a team of more than 40 experts nationwide was established to create Project BETA (Best practices in Evaluation and Treatment of Agitation). Participants were divided into five workgroups: triage and medical evaluation, psychiatric evaluation, de-escalation techniques, psychopharmacology of agitation, and use and avoidance of seclusion and restraint.

The guidelines were intended to cover all aspects of working with an agitated individual, with a focus on safety and outcomes, but also had a goal of being as patient-centric, collaborative, and noncoercive as possible.

“Every part of Project BETA revolves around verbal de-escalation, which can be done in a very short amount of time while simultaneously doing an assessment and offering medications,” Dr. Zeller says.

As a result of incorporating the guidelines in Project BETA, the psychiatric emergency room at Alameda Health System—which deals with a highly acute, emergency population of patients with serious mental illnesses—restrains less than 0.5% of patients seen. Dr. Zeller points out that this is much lower than the numbers restrained at other institutions. For instance, an article published in October 2013 reported several studies showing that 8% to 24% of patients in psychiatric EDs were placed into physical restraints or seclusion.4

What’s Required of Hospital Administration?

Under its Environment of Care standards, The Joint Commission requires accredited healthcare facilities to address workplace violence risk. The requirements mandate facilities to maintain a written plan describing how the security of patients, staff, and facility visitors will be ensured, to conduct proactive risk assessments considering the potential for workplace violence, and to determine a means for identifying individuals on their premises and controlling access to and egress from security-sensitive areas.1

The standard states that “staff are trained in the use of nonphysical intervention skills,” says Cynthia Leslie, APRN, BC, MSN, associate director of the Standards Interpretation Group at The Joint Commission, which is based in Oakbrook Terrace, Ill. “These skills may assist the patient in calming down and prevent the use of restraints and/or seclusion.”

In addition, staff must be trained before they participate in a restraint or seclusion episode and must have periodic training thereafter.

Anyone who wants de-escalation training can contact a company like CPI directly or establish in-house training teams (CPI offers an Instructor Certification Program). “This allows a cost-effective way [approximately $10 per person] to cascade training to others within the hospital who are part of care teams,” Schubert says.

In Sum

Providing for the care and welfare of patients while maintaining a safe and secure environment for everyone is a balancing act that requires the involvement of a multidisciplinary hospital team, Schubert says.

“Coordination, communication, and continuity among all members of a hospital team are crucial to minimize conflict, avoid chaos, and reduce risks,” she explains. “By being armed with information and skills, hospitalists are less likely to isolate themselves from other team members or react in a nonproductive way when crisis situations emerge.

“Training will help staff to take steps to ensure that their behavior and attitudes don’t become part of the problem and increase risks for others involved. Care team perceptions of physician involvement in solution-focused interventions are important for hospitalists to fully understand so risks can be avoided.”

Karen Appold is a freelance medical writer in Pennsylvania.

References

- ECRI Institute. Healthcare Risk, Quality, and Safety Guidance. Violence in healthcare facilities. March 1, 2011. Available at: https://www.ecri.org/components/HRC/Pages/SafSec3.aspx?tab=1. Accessed February 11, 2015.

- Emergency Nurses Association. Emergency department violence surveillance study. November 2011. Available at: http://www.ena.org/practice-research/research/Documents/ENAEDVSReportNovember2011.pdf. Accessed February 11, 2015.

- Richmond JS, Berlin JS, Fishkind AB, et al. Verbal de-escalation of the agitated patient: consensus statement of the American Association for Emergency Psychiatry Project BETA De-escalation Workgroup. West J Emerg Med. 2012;13(1):17-25.

- Simpson SA, Joesch JM, West II, Pasic J. Risk for physical restraint or seclusion in the psychiatric emergency service (PES). Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2014;36(1):113-118.

If a patient shows signs of agitation, Aaron Gottesman, MD, SFHM, says the best way to handle it is to stay calm. It may sound simple, but, in the heat of the moment, people tend to become defensive and on guard rather than acting composed and sympathetic. He suggests trying to speak softly and evenly to the patient, make eye contact, keep your arms at your side, and ask opened-ended questions such as, “How can I help you?” in a genuine manner.

Dr. Gottesman, director of hospitalist services at Staten Island (N.Y.) University Hospital (SIUH), learned these strategies in a voluntary one-hour course on de-escalation training. Although he says he feels fortunate that he has never had to deal with a physically volatile patient, he has used the verbal de-escalation training. In some cases, he believes that employing it may have prevented a physically violent situation from occurring.

Specifically, de-escalation training teaches how to respond to individuals who are acting aggressive or agitated in a verbal or physical manner. The techniques focus on how to calm someone down, while also teaching basic self-defense skills.

Various companies offer this type of training; some will train staff onsite.

“It is money well-spent,” says Scott Zeller, MD, chief of psychiatric emergency services at Alameda Health System in Oakland, Calif. “This is truly a situation where an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure. It only takes one unfortunate episode to result in a serious injury, where a healthcare professional will have to miss work or go on disability, which results in a far greater cost than that of the training.”

Appropriate Responses

By the nature of their work, hospitalists regularly come into contact with agitated patients. “Knowing how to safely help a patient calm down will result in better outcomes for the patient, the physicians, and everyone nearby,” Dr. Zeller says.

“Hospitalists should focus on what they can control,” says Judith Schubert, president of Crisis Prevention Institute (CPI), a Milwaukee, Wis.-based company that offers de-escalation training in 400 cities annually. This includes physicians’ own behavior/demeanor, responsiveness, environmental factors, communication protocols, and a continuous assessment of risk and an understanding of how to balance duty of care with responsibilities to maintain safety.

Hospitalists should be aware of behaviors that could lead to volatility.

“Challenging or oppositional questions and emotional release or intimidating comments often mark the beginning stages of loss of rationality. These are behaviors that warrant specific, directive intervention aimed at stimulating a rational response and diffusing tension,” Schubert says. “Before it even gets to that point, empathy, demonstrated with the patient and family members, can reduce contagion of emotional displays that are likely rooted in fear and anxiety.”

Agitation usually doesn’t arise out of the blue.

“It is typically seen over a spectrum of behaviors, from merely restless and irritable up to sarcastic and demeaning, pacing, unable to sit still, all the way up to screaming, combative, and violent to persons and property,” Dr. Zeller says. “It is best to intervene in the earlier stages and help a person to calm before a situation gets out of hand.”

Thus, hospitalists should be wary of people who are increasingly hostile and energetic and should seek help or work to de-escalate promptly.