User login

“While VTE may not be the No. 1 reason for hospitalization, hospitalists very frequently care for patients with VTE,” says Sowmya Kanikkannan, MD, FACP, SFHM, hospitalist medical director and assistant professor of medicine at Rowan University School of Osteopathic Medicine in Stratford, N.J. “Hospitalists usually are the frontline providers that diagnose and manage hospital-acquired VTEs in hospitalized patients.”

Dr. Kanikkannan, a member of Team Hospitalist, sees a wide range of VTE cases caused by two related conditions—deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE).

“Some patients present with a straightforward diagnosis of DVT, while others have extensive DVT,” she says. “In other instances, patients present with acute PE with or without hemodynamic compromise. I’ve also diagnosed and managed hospital-acquired VTEs in medical patients, as well as post-operatively in surgical co-management.”

It is estimated that between 350,000 to 900,000 Americans are affected by DVT or PE each year, with up to 100,000 dying as a result. Twenty to 50% of people who experience DVT develop long-term complications.1VTE costs the U.S. healthcare system more than $1.5 billion annually.2

As lieutenants in the war against VTE, hospitalists are finding that new treatments, continued efforts to standardize VTE prophylaxis, and increased transparency in performance reporting are the tools needed to combat these common conditions—and hospitalists are being held accountable for optimal patient care.

New Treatments Show Promise

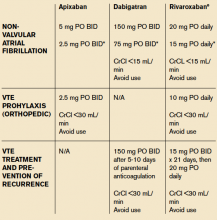

Diagnosing and treating VTE early helps to prevent progression and hemodynamic instability. Although the accepted treatment for VTE used to be heparin, or a low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) (Fragmin, Innohep and Lovenox) with a transition to warfarin, three target-specific oral anticoagulants (TSOACs)—dabigatran, rivaroxaban, and apixaban—are now being prescribed. The FDA has approved rivaroxaban and apixaban for the prevention of VTE after knee and hip surgery and for treatment of VTE, while dabigatran is FDA approved only for the treatment of VTE. All three are approved for use in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (Afib). A fourth TSOAC, edoxaban, received FDA approval in January for VTE treatment and nonvalvular atrial fibrillation.

“The drawback of warfarin is that patients need frequent international normalized ratio (INR) monitoring,” Dr. Kanikkannan says. “Discharge planning is time consuming because patients need to be educated on warfarin, and follow-up appointments need to be arranged before discharge to ensure patient safety.”

“Their [TSOACs] ease of administration and easy dosing helps hospitalists to manage patients with VTE more efficiently,” Dr. Kanikkannan says. “Patients like having lab testing less frequently but equal efficacy in treatment.”

Rivaroxaban used to have the most approved indications by the FDA; however, based on three clinical trials—ADVANCE-1, 2, and 3—apixaban has the same six FDA indications as rivaroxaban.

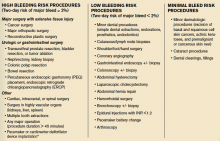

The majority of clinical trials suggest noninferiority or superiority of the oral agents compared to LMWH, and safety appears to be similar across treatment groups, other than an increased risk in bleeding with oral agents (see Table 1).

“The increased risk of bleeding seen in trials is something hospitalists need to consider,” says Yong Lee, PharmD, BCPS, clinical pharmacy specialist at Parkland Health and Hospital System in Dallas, Texas. Warfarin is easily reversed; the new anticoagulants don’t have any specific reversal agent (see new table about reversal options). Consequently, the American College of Chest Physicians still recommends unfractionated heparin or a LMWH for VTE prophylaxis. “These agents will still likely remain the best available options to hospitalists for VTE prevention,” he adds.

Julianna Lindsey, MD, MBA, FACP, FHM, chief of staff and hospitalist at Victory Medical Center in McKinney, Texas, says there are instances when it would be helpful to know what the therapeutic level of a TSOAC’s anticoagulation effect is, such as in a patient with active bleeding or one who requires major emergent surgery. But there is no coagulation assay to date that is readily available to test the effect of apixaban; the anticoagulation effect for dabigatran can be roughly estimated by the activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) and thrombin time (TT), and the anticoagulation effect for rivaroxaban can be roughly estimated by the prothrombin time (PT).

Dr. Lee expects the new FDA approvals to expand the utilization of oral anti-Xa inhibitors in practice. “This will, hopefully, make the new oral anticoagulant market more competitive, driving down their costs,” he says, referring to one of the biggest barriers to current use of these agents. Warfarin still remains the most cost-effective option, despite the need for regular INR monitoring.

“Studies are looking not only at effectiveness but also the safety profile of these anticoagulants,” Dr. Kanikkannan says, as long-term safety data is not yet available on these oral agents.8,9

Researchers also are looking at the comparative effects of other medications. For example, a Journal of Hospital Medicine study concluded that, compared with other anticoagulants, aspirin is associated with a higher risk of DVT following hip fracture repair but similar rates of DVT risk following hip-knee arthroplasty. Bleeding rates with aspirin, however, were substantially lower.10

Improvement Efforts

In an effort to improve VTE prophylaxis in hospitalized patients, The Joint Commission developed a VTE standardized performance measure set in 2009, which has been reported on www.qualitycheck.org since then. The VTE measure set comprises six different measures evaluating the prophylaxis of VTE, treatment of VTE, warfarin discharge education, and hospital-acquired VTE. Since reporting started, most hospitals have implemented VTE risk assessment models and VTE process improvement programs; data trends have shown improvement, says Denise Krusenoski, MSN, RN, CMSRN, CHTS-CP, associate project director at The Joint Commission, which is based in Oakbrook Terrace, Ill.

“While a lot of good, evidence-based data is available, no single VTE risk assessment tool has been prospectively validated as superior,” she says. “Involving key members of medical staff to create and approve protocols based on proven data will increase the buy-in and adoption for using these tools.”

E-Measures Promote Excellence

Many hospitals are now moving from traditional chart abstracting for VTE measures to electronic measures (e-measures), which allow for more rapid and automated reporting of these quality metrics. In order for e-measures to be accurate, documentation necessary for measure computation must be present in defined standardized fields in the medical record. “With no human interpretation, data must be documented in a precise fashion,” Krusenoski says. “Providers will need to be flexible in learning new documentation skills.”

Dr. Lindsey, a member of Team Hospitalist, cautions that e-measures have the potential to increase unwanted events by overutilization of pharmacologic VTE prophylaxis and associated hemorrhagic events.

“We have to continue to make sure that our practice of medicine remains based in evidence and not succumb to the pull of getting a check-box ticked,” she warns.

VTE remains a significant problem in hospitalized patients today. Hospitalists should consider the pros and cons of using newer treatment methods over traditional agents. Efforts are under way to improve VTE prophylaxis by standardizing best practice and moving from traditional chart abstracting to using e-measures for performance reporting.

Karen Appold is a freelance medical writer in Pennsylvania.

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Public Health Grand Rounds. Preventing venous thromboembolism. January 15, 2013. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/cdcgrandrounds/archives/2013/january2013.htm. Accessed February 12, 2015.

- Dobesh PP. Economic burden of venous thromboembolism in hospitalized patients. Pharmacotherapy. 2009;29(8):943-953.

- Lassen MR, Raskob GE, Gallus A, Pineo G, Chen D, Portman RJ. Apixaban or enoxaparin for thromboprophylaxis after knee replacement. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(6):594-604.

- Lassen MR, Raskob GE, Gallus A, Pineo G, Chen D, Hornick P; ADVANCE-2 Investigators. Apixaban versus enoxaparin for thromboprophylaxis after knee replacement (ADVANCE-2): a randomised double-blind trial. Lancet. 2010;375(9717):807-815.

- Lassen MR, Gallus A, Raskob GE, Pineo G, Chen D, Ramirez LM; ADVANCE-3 Investigators. Apixaban versus enoxaparin for thromboprophylaxis after hip replacement. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(26):2487-2498.

- Cohen AT, Spiro TE, Büller HR, et al. Rivaroxaban for thromboprophylaxis in acutely ill medical patients. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(6):513-523.

- Goldhaber SZ, Leizorovicz A, Kakkar AK, et al. Apixaban versus enoxaparin for thromboprophylaxis in medically ill patients. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(23):2167-2177.

- Gonsalves WI, Pruthi RK, Patnaik MM. The new oral anticoagulants in clinical practice. Mayo Clin Proc. 2013;88(5):495-511.

- Holster IL, Valkoff VE, Kuipers EJ, Tjwa ET. New oral anticoagulants increase risk for gastrointestinal bleeding: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2013;145(1):105-112.

- Drescher FS, Sirovich BE, Lee A, Morrison DH, Chiang WH, Larson RJ. Aspirin versus anticoagulation for prevention of venous thromboembolism major lower extremity orthopedic surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(9):579-585.

- Bullock-Palmer RP, Weiss S, Hyman C. Innovative approaches to increase deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis rate resulting in a decrease in hospital-acquired deep vein thrombosis at a tertiary-care teaching hospital. J Hosp Med. 2008;3(2):148-155.

“While VTE may not be the No. 1 reason for hospitalization, hospitalists very frequently care for patients with VTE,” says Sowmya Kanikkannan, MD, FACP, SFHM, hospitalist medical director and assistant professor of medicine at Rowan University School of Osteopathic Medicine in Stratford, N.J. “Hospitalists usually are the frontline providers that diagnose and manage hospital-acquired VTEs in hospitalized patients.”

Dr. Kanikkannan, a member of Team Hospitalist, sees a wide range of VTE cases caused by two related conditions—deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE).

“Some patients present with a straightforward diagnosis of DVT, while others have extensive DVT,” she says. “In other instances, patients present with acute PE with or without hemodynamic compromise. I’ve also diagnosed and managed hospital-acquired VTEs in medical patients, as well as post-operatively in surgical co-management.”

It is estimated that between 350,000 to 900,000 Americans are affected by DVT or PE each year, with up to 100,000 dying as a result. Twenty to 50% of people who experience DVT develop long-term complications.1VTE costs the U.S. healthcare system more than $1.5 billion annually.2

As lieutenants in the war against VTE, hospitalists are finding that new treatments, continued efforts to standardize VTE prophylaxis, and increased transparency in performance reporting are the tools needed to combat these common conditions—and hospitalists are being held accountable for optimal patient care.

New Treatments Show Promise

Diagnosing and treating VTE early helps to prevent progression and hemodynamic instability. Although the accepted treatment for VTE used to be heparin, or a low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) (Fragmin, Innohep and Lovenox) with a transition to warfarin, three target-specific oral anticoagulants (TSOACs)—dabigatran, rivaroxaban, and apixaban—are now being prescribed. The FDA has approved rivaroxaban and apixaban for the prevention of VTE after knee and hip surgery and for treatment of VTE, while dabigatran is FDA approved only for the treatment of VTE. All three are approved for use in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (Afib). A fourth TSOAC, edoxaban, received FDA approval in January for VTE treatment and nonvalvular atrial fibrillation.

“The drawback of warfarin is that patients need frequent international normalized ratio (INR) monitoring,” Dr. Kanikkannan says. “Discharge planning is time consuming because patients need to be educated on warfarin, and follow-up appointments need to be arranged before discharge to ensure patient safety.”

“Their [TSOACs] ease of administration and easy dosing helps hospitalists to manage patients with VTE more efficiently,” Dr. Kanikkannan says. “Patients like having lab testing less frequently but equal efficacy in treatment.”

Rivaroxaban used to have the most approved indications by the FDA; however, based on three clinical trials—ADVANCE-1, 2, and 3—apixaban has the same six FDA indications as rivaroxaban.

The majority of clinical trials suggest noninferiority or superiority of the oral agents compared to LMWH, and safety appears to be similar across treatment groups, other than an increased risk in bleeding with oral agents (see Table 1).

“The increased risk of bleeding seen in trials is something hospitalists need to consider,” says Yong Lee, PharmD, BCPS, clinical pharmacy specialist at Parkland Health and Hospital System in Dallas, Texas. Warfarin is easily reversed; the new anticoagulants don’t have any specific reversal agent (see new table about reversal options). Consequently, the American College of Chest Physicians still recommends unfractionated heparin or a LMWH for VTE prophylaxis. “These agents will still likely remain the best available options to hospitalists for VTE prevention,” he adds.

Julianna Lindsey, MD, MBA, FACP, FHM, chief of staff and hospitalist at Victory Medical Center in McKinney, Texas, says there are instances when it would be helpful to know what the therapeutic level of a TSOAC’s anticoagulation effect is, such as in a patient with active bleeding or one who requires major emergent surgery. But there is no coagulation assay to date that is readily available to test the effect of apixaban; the anticoagulation effect for dabigatran can be roughly estimated by the activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) and thrombin time (TT), and the anticoagulation effect for rivaroxaban can be roughly estimated by the prothrombin time (PT).

Dr. Lee expects the new FDA approvals to expand the utilization of oral anti-Xa inhibitors in practice. “This will, hopefully, make the new oral anticoagulant market more competitive, driving down their costs,” he says, referring to one of the biggest barriers to current use of these agents. Warfarin still remains the most cost-effective option, despite the need for regular INR monitoring.

“Studies are looking not only at effectiveness but also the safety profile of these anticoagulants,” Dr. Kanikkannan says, as long-term safety data is not yet available on these oral agents.8,9

Researchers also are looking at the comparative effects of other medications. For example, a Journal of Hospital Medicine study concluded that, compared with other anticoagulants, aspirin is associated with a higher risk of DVT following hip fracture repair but similar rates of DVT risk following hip-knee arthroplasty. Bleeding rates with aspirin, however, were substantially lower.10

Improvement Efforts

In an effort to improve VTE prophylaxis in hospitalized patients, The Joint Commission developed a VTE standardized performance measure set in 2009, which has been reported on www.qualitycheck.org since then. The VTE measure set comprises six different measures evaluating the prophylaxis of VTE, treatment of VTE, warfarin discharge education, and hospital-acquired VTE. Since reporting started, most hospitals have implemented VTE risk assessment models and VTE process improvement programs; data trends have shown improvement, says Denise Krusenoski, MSN, RN, CMSRN, CHTS-CP, associate project director at The Joint Commission, which is based in Oakbrook Terrace, Ill.

“While a lot of good, evidence-based data is available, no single VTE risk assessment tool has been prospectively validated as superior,” she says. “Involving key members of medical staff to create and approve protocols based on proven data will increase the buy-in and adoption for using these tools.”

E-Measures Promote Excellence

Many hospitals are now moving from traditional chart abstracting for VTE measures to electronic measures (e-measures), which allow for more rapid and automated reporting of these quality metrics. In order for e-measures to be accurate, documentation necessary for measure computation must be present in defined standardized fields in the medical record. “With no human interpretation, data must be documented in a precise fashion,” Krusenoski says. “Providers will need to be flexible in learning new documentation skills.”

Dr. Lindsey, a member of Team Hospitalist, cautions that e-measures have the potential to increase unwanted events by overutilization of pharmacologic VTE prophylaxis and associated hemorrhagic events.

“We have to continue to make sure that our practice of medicine remains based in evidence and not succumb to the pull of getting a check-box ticked,” she warns.

VTE remains a significant problem in hospitalized patients today. Hospitalists should consider the pros and cons of using newer treatment methods over traditional agents. Efforts are under way to improve VTE prophylaxis by standardizing best practice and moving from traditional chart abstracting to using e-measures for performance reporting.

Karen Appold is a freelance medical writer in Pennsylvania.

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Public Health Grand Rounds. Preventing venous thromboembolism. January 15, 2013. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/cdcgrandrounds/archives/2013/january2013.htm. Accessed February 12, 2015.

- Dobesh PP. Economic burden of venous thromboembolism in hospitalized patients. Pharmacotherapy. 2009;29(8):943-953.

- Lassen MR, Raskob GE, Gallus A, Pineo G, Chen D, Portman RJ. Apixaban or enoxaparin for thromboprophylaxis after knee replacement. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(6):594-604.

- Lassen MR, Raskob GE, Gallus A, Pineo G, Chen D, Hornick P; ADVANCE-2 Investigators. Apixaban versus enoxaparin for thromboprophylaxis after knee replacement (ADVANCE-2): a randomised double-blind trial. Lancet. 2010;375(9717):807-815.

- Lassen MR, Gallus A, Raskob GE, Pineo G, Chen D, Ramirez LM; ADVANCE-3 Investigators. Apixaban versus enoxaparin for thromboprophylaxis after hip replacement. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(26):2487-2498.

- Cohen AT, Spiro TE, Büller HR, et al. Rivaroxaban for thromboprophylaxis in acutely ill medical patients. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(6):513-523.

- Goldhaber SZ, Leizorovicz A, Kakkar AK, et al. Apixaban versus enoxaparin for thromboprophylaxis in medically ill patients. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(23):2167-2177.

- Gonsalves WI, Pruthi RK, Patnaik MM. The new oral anticoagulants in clinical practice. Mayo Clin Proc. 2013;88(5):495-511.

- Holster IL, Valkoff VE, Kuipers EJ, Tjwa ET. New oral anticoagulants increase risk for gastrointestinal bleeding: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2013;145(1):105-112.

- Drescher FS, Sirovich BE, Lee A, Morrison DH, Chiang WH, Larson RJ. Aspirin versus anticoagulation for prevention of venous thromboembolism major lower extremity orthopedic surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(9):579-585.

- Bullock-Palmer RP, Weiss S, Hyman C. Innovative approaches to increase deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis rate resulting in a decrease in hospital-acquired deep vein thrombosis at a tertiary-care teaching hospital. J Hosp Med. 2008;3(2):148-155.

“While VTE may not be the No. 1 reason for hospitalization, hospitalists very frequently care for patients with VTE,” says Sowmya Kanikkannan, MD, FACP, SFHM, hospitalist medical director and assistant professor of medicine at Rowan University School of Osteopathic Medicine in Stratford, N.J. “Hospitalists usually are the frontline providers that diagnose and manage hospital-acquired VTEs in hospitalized patients.”

Dr. Kanikkannan, a member of Team Hospitalist, sees a wide range of VTE cases caused by two related conditions—deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE).

“Some patients present with a straightforward diagnosis of DVT, while others have extensive DVT,” she says. “In other instances, patients present with acute PE with or without hemodynamic compromise. I’ve also diagnosed and managed hospital-acquired VTEs in medical patients, as well as post-operatively in surgical co-management.”

It is estimated that between 350,000 to 900,000 Americans are affected by DVT or PE each year, with up to 100,000 dying as a result. Twenty to 50% of people who experience DVT develop long-term complications.1VTE costs the U.S. healthcare system more than $1.5 billion annually.2

As lieutenants in the war against VTE, hospitalists are finding that new treatments, continued efforts to standardize VTE prophylaxis, and increased transparency in performance reporting are the tools needed to combat these common conditions—and hospitalists are being held accountable for optimal patient care.

New Treatments Show Promise

Diagnosing and treating VTE early helps to prevent progression and hemodynamic instability. Although the accepted treatment for VTE used to be heparin, or a low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) (Fragmin, Innohep and Lovenox) with a transition to warfarin, three target-specific oral anticoagulants (TSOACs)—dabigatran, rivaroxaban, and apixaban—are now being prescribed. The FDA has approved rivaroxaban and apixaban for the prevention of VTE after knee and hip surgery and for treatment of VTE, while dabigatran is FDA approved only for the treatment of VTE. All three are approved for use in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (Afib). A fourth TSOAC, edoxaban, received FDA approval in January for VTE treatment and nonvalvular atrial fibrillation.

“The drawback of warfarin is that patients need frequent international normalized ratio (INR) monitoring,” Dr. Kanikkannan says. “Discharge planning is time consuming because patients need to be educated on warfarin, and follow-up appointments need to be arranged before discharge to ensure patient safety.”

“Their [TSOACs] ease of administration and easy dosing helps hospitalists to manage patients with VTE more efficiently,” Dr. Kanikkannan says. “Patients like having lab testing less frequently but equal efficacy in treatment.”

Rivaroxaban used to have the most approved indications by the FDA; however, based on three clinical trials—ADVANCE-1, 2, and 3—apixaban has the same six FDA indications as rivaroxaban.

The majority of clinical trials suggest noninferiority or superiority of the oral agents compared to LMWH, and safety appears to be similar across treatment groups, other than an increased risk in bleeding with oral agents (see Table 1).

“The increased risk of bleeding seen in trials is something hospitalists need to consider,” says Yong Lee, PharmD, BCPS, clinical pharmacy specialist at Parkland Health and Hospital System in Dallas, Texas. Warfarin is easily reversed; the new anticoagulants don’t have any specific reversal agent (see new table about reversal options). Consequently, the American College of Chest Physicians still recommends unfractionated heparin or a LMWH for VTE prophylaxis. “These agents will still likely remain the best available options to hospitalists for VTE prevention,” he adds.

Julianna Lindsey, MD, MBA, FACP, FHM, chief of staff and hospitalist at Victory Medical Center in McKinney, Texas, says there are instances when it would be helpful to know what the therapeutic level of a TSOAC’s anticoagulation effect is, such as in a patient with active bleeding or one who requires major emergent surgery. But there is no coagulation assay to date that is readily available to test the effect of apixaban; the anticoagulation effect for dabigatran can be roughly estimated by the activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) and thrombin time (TT), and the anticoagulation effect for rivaroxaban can be roughly estimated by the prothrombin time (PT).

Dr. Lee expects the new FDA approvals to expand the utilization of oral anti-Xa inhibitors in practice. “This will, hopefully, make the new oral anticoagulant market more competitive, driving down their costs,” he says, referring to one of the biggest barriers to current use of these agents. Warfarin still remains the most cost-effective option, despite the need for regular INR monitoring.

“Studies are looking not only at effectiveness but also the safety profile of these anticoagulants,” Dr. Kanikkannan says, as long-term safety data is not yet available on these oral agents.8,9

Researchers also are looking at the comparative effects of other medications. For example, a Journal of Hospital Medicine study concluded that, compared with other anticoagulants, aspirin is associated with a higher risk of DVT following hip fracture repair but similar rates of DVT risk following hip-knee arthroplasty. Bleeding rates with aspirin, however, were substantially lower.10

Improvement Efforts

In an effort to improve VTE prophylaxis in hospitalized patients, The Joint Commission developed a VTE standardized performance measure set in 2009, which has been reported on www.qualitycheck.org since then. The VTE measure set comprises six different measures evaluating the prophylaxis of VTE, treatment of VTE, warfarin discharge education, and hospital-acquired VTE. Since reporting started, most hospitals have implemented VTE risk assessment models and VTE process improvement programs; data trends have shown improvement, says Denise Krusenoski, MSN, RN, CMSRN, CHTS-CP, associate project director at The Joint Commission, which is based in Oakbrook Terrace, Ill.

“While a lot of good, evidence-based data is available, no single VTE risk assessment tool has been prospectively validated as superior,” she says. “Involving key members of medical staff to create and approve protocols based on proven data will increase the buy-in and adoption for using these tools.”

E-Measures Promote Excellence

Many hospitals are now moving from traditional chart abstracting for VTE measures to electronic measures (e-measures), which allow for more rapid and automated reporting of these quality metrics. In order for e-measures to be accurate, documentation necessary for measure computation must be present in defined standardized fields in the medical record. “With no human interpretation, data must be documented in a precise fashion,” Krusenoski says. “Providers will need to be flexible in learning new documentation skills.”

Dr. Lindsey, a member of Team Hospitalist, cautions that e-measures have the potential to increase unwanted events by overutilization of pharmacologic VTE prophylaxis and associated hemorrhagic events.

“We have to continue to make sure that our practice of medicine remains based in evidence and not succumb to the pull of getting a check-box ticked,” she warns.

VTE remains a significant problem in hospitalized patients today. Hospitalists should consider the pros and cons of using newer treatment methods over traditional agents. Efforts are under way to improve VTE prophylaxis by standardizing best practice and moving from traditional chart abstracting to using e-measures for performance reporting.

Karen Appold is a freelance medical writer in Pennsylvania.

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Public Health Grand Rounds. Preventing venous thromboembolism. January 15, 2013. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/cdcgrandrounds/archives/2013/january2013.htm. Accessed February 12, 2015.

- Dobesh PP. Economic burden of venous thromboembolism in hospitalized patients. Pharmacotherapy. 2009;29(8):943-953.

- Lassen MR, Raskob GE, Gallus A, Pineo G, Chen D, Portman RJ. Apixaban or enoxaparin for thromboprophylaxis after knee replacement. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(6):594-604.

- Lassen MR, Raskob GE, Gallus A, Pineo G, Chen D, Hornick P; ADVANCE-2 Investigators. Apixaban versus enoxaparin for thromboprophylaxis after knee replacement (ADVANCE-2): a randomised double-blind trial. Lancet. 2010;375(9717):807-815.

- Lassen MR, Gallus A, Raskob GE, Pineo G, Chen D, Ramirez LM; ADVANCE-3 Investigators. Apixaban versus enoxaparin for thromboprophylaxis after hip replacement. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(26):2487-2498.

- Cohen AT, Spiro TE, Büller HR, et al. Rivaroxaban for thromboprophylaxis in acutely ill medical patients. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(6):513-523.

- Goldhaber SZ, Leizorovicz A, Kakkar AK, et al. Apixaban versus enoxaparin for thromboprophylaxis in medically ill patients. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(23):2167-2177.

- Gonsalves WI, Pruthi RK, Patnaik MM. The new oral anticoagulants in clinical practice. Mayo Clin Proc. 2013;88(5):495-511.

- Holster IL, Valkoff VE, Kuipers EJ, Tjwa ET. New oral anticoagulants increase risk for gastrointestinal bleeding: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2013;145(1):105-112.

- Drescher FS, Sirovich BE, Lee A, Morrison DH, Chiang WH, Larson RJ. Aspirin versus anticoagulation for prevention of venous thromboembolism major lower extremity orthopedic surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(9):579-585.

- Bullock-Palmer RP, Weiss S, Hyman C. Innovative approaches to increase deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis rate resulting in a decrease in hospital-acquired deep vein thrombosis at a tertiary-care teaching hospital. J Hosp Med. 2008;3(2):148-155.