User login

Karen Appold is a seasoned writer and editor, with more than 20 years of editorial experience and started Write Now Services in 2003. Her scope of work includes writing, editing, and proofreading scholarly peer-reviewed journal content, consumer articles, white papers, and company reports for a variety of medical organizations, businesses, and media. Karen, who holds a BA in English from Penn State University, resides in Lehigh Valley, Pa.

10 Choosing Wisely Recommendations by Specialists for Hospitalists

When diagnosing a patient, it can be tempting to run all types of tests to expedite the process—and protect yourself from litigation. Patients may push for more tests, too, thinking “the more the better.” But that may not be the best course of action. In fact, according to recommendations of the ABIM Foundations’ Choosing Wisely campaign, more tests can actually bring a host of negative consequences.

In an effort to help hospitalists decide which tests to perform and which to forgo, The Hospitalist asked medical societies that contributed to the Choosing Wisely campaign to tell us which one of their recommendations was the most applicable to hospitalists. Then, we asked some hospitalists to discuss how they might implement each recommendation.

1 American Gastroenterological Association (AGA)

Recommendation: For a patient with functional abdominal pain syndrome (as per Rome criteria), computed tomography (CT) scans should not be repeated unless there is a major change in clinical findings or symptoms.

When a patient first complains of abdominal pain, a CT scan usually is done prior to a gastroenterological consultation. Despite this initial scan, many patients with chronic abdominal pain receive unnecessary repeated CT scans to evaluate their pain even if they have previous negative studies.

“It is important for the hospitalist to know that functional abdominal pain can be managed without additional diagnostic studies,” says John M. Inadomi, MD, head of the division of gastroenterology at the University of Washington School of Medicine in Seattle. “Some doctors are uncomfortable with the uncertainty of a diagnosis of chronic abdominal pain without evidence of biochemical or structural disease [functional abdominal pain syndrome] and fear litigation.”

An abdominal CT scan is one of the higher radiation exposure tests, equivalent to three years of natural background radiation.1

“Due to this risk and the high costs of this procedure, CT scans should be limited to situations in which they are likely to provide useful information that changes patient management,” Dr. Inadomi says.

According to Moises Auron, MD, FAAP, FACP, SFHM, assistant professor of medicine and pediatrics at Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine of Case Western University in Cleveland, Ohio, it should not be a difficult choice for hospitalists, “as the clinical context provides a safeguard to justify the rationale for a conservative approach. Hospitalists must be educated on the appropriate use of Rome criteria, as well as how to appropriately document it in the chart to justify a decision to avoid unnecessary testing.”

2 American College of Rheumatology (ACR)

Recommendation: Don’t test anti-nuclear antibody (ANA) sub-serologies without a positive ANA and clinical suspicion of immune-mediated disease.

“A fever of unknown origin is among the most common diagnoses the hospitalist encounters,” Dr. Auron says. “Nowadays, given the ease to order tests, as well as the increased awareness of patients with immune-mediated diseases, it may be tempting to order large panels of immunologic tests to minimize the risk of missing a diagnosis; however, because ANA has high sensitivity and poor specificity, it should only be ordered if the clinical context supports its use.”

Jinoos Yazdany, MD, MPH, assistant professor of medicine at the University of California at San Francisco and co-chair of the task force that developed the ACR’s Choosing Wisely list, points out that if you use ANAs as a broad screening test when the pretest probability of specific ANA-associated diseases is low, there is an increased chance of a false positive ANA result. This can lead to unnecessary further testing and additional costs. Furthermore, ANA sub-serologies are usually negative if the ANA (done by immunofluorescence) is negative.

“So it is recommended to order sub-serologies only once it is known that the ANA is positive,” she says. The exceptions to this are anti-SSA and anti-Jo-1 antibodies, which can sometimes be positive when the ANA is negative.

Mangla S. Gulati, MD, FACP, FHM, medical director for clinical effectiveness at the University of Maryland School of Medicine in Baltimore, says a positive ANA in conjunction with clinical information “will help to guide appropriate and cost-conscious testing. Hospitalists could implement this through a clinical decision support approach if using an electronic medical record.”

3 American College of Physicians (ACP)

Recommendation: In patients with low pretest probability of venous thromboembolism (VTE), obtain a high-sensitive D-dimer measurement as the initial diagnostic test; don’t obtain imaging studies as the initial diagnostic test.

VTE, a common problem in hospitalized patients, has high mortality rates. “However, recent statistics suggest that we may be overdiagnosing non-clinically significant disease and exposing large numbers of patients to high doses of radiation unnecessarily in an attempt to rule out VTE disease,” says Cynthia D. Smith, MD, FACP, ACP senior medical associate for content development and adjunct associate professor of medicine at the Perelman School of Medicine in Philadelphia.

Instead, physicians should estimate pretest probability of disease using a validated risk assessment tool (i.e., Wells score). For patients with low clinical probability of VTE, hospitalists should use a negative high-sensitive D-dimer measurement as the initial diagnostic test.

Dr. Auron says the litigious environment of American medicine may trigger clinicians to order testing to minimize the risk of missing potential conditions; however, an adequate, evidence-based approach with appropriate documentation should be sufficient. In this case, that would entail using D-dimer testing to outline the low pretest probability of VTE and explaining to the patient the rationale for not pursuing further imaging.

Dr. Gulati adds that hospitalists should have little difficulty implementing this cost-effective approach.

—Moises Auron, MD, FAAP, FACP, SFHM, assistant professor of medicine and pediatrics, Cleveland Clinic

4 American Geriatrics Society (AGS)

Recommendation: Don’t use antimicrobials to treat bacteriuria in older adults unless specific urinary tract symptoms are present.

Older adults with asymptomatic bacteriuria who received antimicrobial treatment show no benefit, according to multiple studies.2 In fact, increased adverse antimicrobial effects occurred, such as greater resistance patterns and super-infections (e.g. Clostridium difficile).

The truth is that as many as 30% of frail elders (particularly women) have bacterial colonization of the urinary tract without infection, also known as asymptomatic bacteriuria, says Heidi Wald, MD, MSPH, associate professor of medicine and vice chair for quality in the department of medicine at the University of Colorado School of Medicine in Aurora. Therefore, before being prescribed antimicrobials, a patient should exhibit symptoms of urinary tract infection such as fever, frequent urination, urgency to urinate, painful urination, or suprapubic tenderness.

“Without localizing symptoms, you can’t assume bacteriuria equals infection,” Dr. Wald adds. “Too often, we make the urine a scapegoat for unrelated presentations, such as mild confusion.”

If the patient is stable and doesn’t have UTI symptoms, Dr. Wald says hospitalists should consider hydration and monitor the patient without antibiotics.

“This should not be difficult to implement,” Dr. Auron says, “as hospitalists are on the front lines of antibiotic stewardship in hospitals.”

5 American Society of Echocardiography (ASE)

Recommendation: Avoid echocardiograms for pre-operative/peri-operative assessment of patients with no history or symptoms of heart disease.

Echocardiography can diagnose all types of heart disease while being completely safe, inexpensive, and available at the bedside.

“These features may logically lead hospitalists to think, ‘Why not?’ Maybe there’s something going on and an echo can’t hurt,” says James D. Thomas, MD, FASE, FACC, FAHA, FESC, Moore Chair of Cardiovascular Imaging at Cleveland Clinic and ASE past president. “Unfortunately, tests can have false positive findings that lead to other, potentially more hazardous and invasive, tests downstream, as well as unnecessary delays.”

If a patient has no history of heart disease, no positive physical findings, or no symptoms, then an echo probably won’t be helpful. Hospitalists need to be aware of the lack of value of a presumed normal study, Dr. Auron says.

“Having appropriate standards of care allows clinicians in pre-operative areas to use risk stratification tools in an adequate fashion,” he notes.

6 American Society of Nephrology (ASN)

Recommendation: Do not place peripherally inserted central venous catheters (PICC) in stage three to five chronic kidney disease (CKD) patients without consulting nephrology.

Given the increase in patients with CKD in the later stages, as well as end-stage renal disease, clinicians need to protect patients’ upper extremity veins in order to be able to have an adequate vascular substrate for subsequent creation of an arteriovenous fistula (AVF), Dr. Auron maintains.

PICCs, along with other central venous catheters, damage veins and destroy sites for future hemodialysis vascular access, explains Amy W. Williams, MD, medical director of hospital operations and consultant in the division of nephrology and hypertension at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. If there are no options for AVF or grafts, patients starting or being maintained on hemodialysis will need a tunneled central venous catheter for dialysis access.

Studies have shown that AVFs have better patency rates and fewer complications compared to catheters, and there is a direct correlation of increased mortality and inadequate dialysis with tunneled central catheters.3 In addition, dialysis patients with a tunneled central venous catheter have a five-fold increase of infection compared to those with an AVF.4 The incidence of central venous stenosis associated with PICC lines has been shown to be 42% and the incidence of thrombosis 38%.5,6 There is no significant difference in the rate of central venous complications based on the duration of catheter use or catheter size. In addition, prior PICC use has been shown to be an independent predictor of lack of a functioning AVF (odds ratio 2.8 [95 % CI, 1.5 to 5.5]).7

A better choice for extended venous access in patients with advanced CKD is a tunneled internal jugular vein catheter, which is associated with a lower risk of permanent vascular damage, says Dr. Williams, who is chair of the ASN’s Quality and Patient Safety Task Force.

—James J. O’Callaghan, MD, FAAP, FHM, clinical assistant professor of pediatrics, Seattle Children’s Hospital at the University of Washington, Team Hospitalist member

7 The Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS)

Recommendation: Patients who have no cardiac history and good functional status do not require pre-operative stress testing prior to non-cardiac thoracic surgery.

By eliminating routine stress testing prior to non-cardiac thoracic surgery for patients without a history of cardiac symptoms, hospitalists can reduce the burden of costs on patients and eliminate the possibility of adverse outcomes due to inappropriate testing.

“Functional status has been shown to be reliable to predict peri-operative and long-term cardiac events,” says Douglas E. Wood, MD, chief of the division of cardiothoracic surgery at the University of Washington in Seattle and president of the STS. “In highly functional asymptomatic patients, management is rarely changed by pre-operative stress testing. Furthermore, abnormalities identified in testing often require additional investigation, with negative consequences related to the risks of more procedures or tests, delays in therapies, and additional costs.”

Pre-operative stress testing should be reserved for patients with low functional capacity or clinical risk factors for cardiac complications. It is important to identify patients pre-operatively who are at risk for these complications by doing a thorough history, physical examination, and resting electrocardiogram.

8 Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging (SNMMI)

Recommendation: Avoid using a CT angiogram to diagnose pulmonary embolism (PE) in young women with a normal chest radiograph; consider a radionuclide lung (V/Q) study instead.

Hospitalists should be knowledgeable of the diagnostic options that will result in the lowest radiation exposure when evaluating young women for PE.

“When a chest radiograph is normal or nearly normal, a computed tomography angiogram or a V/Q lung scan can be used to evaluate these patients. While both exams have low radiation exposure, the V/Q lung scan results in less radiation to the breast tissue,” says society president Gary L. Dillehay, MD, FACNM, FACR, professor of radiology at Northwestern Memorial Hospital in Chicago. “Recent literature cites concerns over radiation exposure from mammography; therefore, reducing radiation exposure to breast tissue, when evaluating patients for suspected PE, is desirable.”

Hospitalists might have difficulty obtaining a V/Q lung scan when nuclear medicine departments are closed.

“The caveat is that CT scans are much more readily available,” Dr. Auron says. In addition, a CT scan provides additional information. But unless the differential diagnosis is much higher for PE than other possibilities, just having a V/Q scan should suffice.

Hospitalists could help implement protocols for chest pain evaluation in premenopausal women by having checklists for risk factors for coronary artery disease, connective tissue disease (essentially aortic dissection), and VTE (e.g. Wells and Geneva scores, use of oral contraceptives, smoking), Dr. Auron says. If the diagnostic branch supports the risk of PE, then nuclear imaging should be available.

“A reasonable way to justify the increased availability of the nuclear medicine department would be to document the number of CT chest scans done after hours in patients who would have instead had a V/Q scan,” he says.

LISTEN NOW to Rahul Shah, MD, FACS, FAAP, associate professor of otolaryngology and pediatrics at Children's National Medical Center in Washington, D.C, and co-chair of the American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery Foundation’s Patient Safety Quality Improvement Committee, explain why hospitalists should avoid routine radiographic imaging for patients who meet diagnostic criteria for uncomplicated acute rhinosinusitis.

9 American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP)

Recommendation: Antibiotics should not be used for apparent viral respiratory illnesses (sinusitis, pharyngitis, bronchitis).

Respiratory illnesses are the most common reason for hospitalization in pediatrics. Recent studies and surveys continue to demonstrate antibiotic overuse in the pediatric population, especially when prescribed for apparent viral respiratory illnesses.8,9

“Hospitalists who care for pediatric patients have the potential to significantly impact antibiotic overuse, as hospitalizations for respiratory illnesses due to viruses such as bronchiolitis and croup remain a leading cause of admission,” says James J. O’Callaghan, MD, FAAP, FHM, clinical assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Washington School of Medicine in Seattle.

Many respiratory problems, such as bronchiolitis, asthma, and even some pneumonias are caused or exacerbated by viruses, points out Ricardo Quiñonez, MD, FAAP, FHM, section head of pediatric hospital medicine at the Children’s Hospital of San Antonio and the Baylor College of Medicine, and chair of the AAP’s section on hospital medicine. In particular, there are national guidelines for bronchiolitis and asthma that recommend against the use of systemic antibiotics.

This recommendation may be difficult for hospitalists to implement, because antibiotics are frequently started by other providers (PCP or ED), Dr. O’Callaghan admits. It can be tricky to change or stop therapy without undermining patients’ or parents’ confidence in their medical decision-making. Hospitalists may need to collaborate with new partners, such as community-wide antibiotic reduction campaigns, in order to affect this culture change.

—James D. Thomas, MD, FASE, FACC, FAHA, FESC, Moore Chair of Cardiovascular Imaging at the Cleveland Clinic in Ohio and past president of the American Society of Echocardiography.

10 American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOB)

Recommendation: Don’t schedule elective inductions prior to 39 weeks, and don’t schedule elective inductions of labor after 39 weeks without a favorable cervix.

Studies show an increased risk to newborns that are electively inducted between 37 and 39 weeks. Complications include increased admission to the neonatal intensive care unit, increased risk of respiratory distress and need for respiratory support, and increased incidence of infection and sepsis.

This recommendation may be difficult for hospitalists to implement, because obstetrical providers typically schedule elective inductions. Implementation of this recommendation would involve collaboration with obstetrical providers, with possible support from maternal-fetal and neonatal providers.

“Recent quality measures and initiatives from such organizations such as CMS and the National Quality Forum … may help to galvanize institutional support for its successful implementation,” says Dr. O’Callaghan, a Team Hospitalist member.

Elective surgeries should only be done in cases where there is a medical necessity, such as when the mother is diabetic or has hypertension, adds Rob Olson, MD, FACOG, an OB/GYN hospitalist for PeaceHealth at St. Joseph Medical Center in Bellingham, Wash. “Hospitalists should not give in to pressures from patients who are either tired of the discomforts of pregnancy or have family pressure to end the pregnancy early.”

Karen Appold is a freelance writer in Pennsylvania.

References

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Reducing radiation from medical X-rays. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/ForConsumers/ConsumerUpdates/ucm095505.htm. Accessed May 12, 2014.

- Nicolle LE, Bradley S, Colgan R, et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria in adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40(5):643-654.

- Hoggard J, Saad T, Schon D, et al. Guidelines for venous access in patients with chronic kidney disease. A position statement from the American Society of Diagnostic and Interventional Nephrology, Clinical Practice Committee and the Association for Vascular Access. Semin Dial. 2008;21(2):186-191.

- Rayner HC, Besarab A, Brown WW, Disney A, Saito A, Pisoni RL. Vascular access results from the dialysis outcomes and practice patterns study (DOPPS): Performance against kidney disease outcomes quality initiative (K/DOQI)clinical practice guidelines. Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;44(5 Suppl 2):22-26.

- Gonsalves CF, Eschelman DJ, Sullivan KL, DuBois N, Bonn J. Incidence of central vein stenosis and occlusion following upper extremity PICC and port placement. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2003;26(2):123-127.

- Allen AW, Megargell JL, Brown DB, et al. Venous thrombosis associated with the placement of peripherally inserted central catheters. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2000;11(10):1309-1314.

- El Ters M, Schears GJ, Taler SJ, et al. Association between prior peripherally inserted central catheters and lack of functioning ateriovenous fistulas: A case control study in hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;60(4):601-608.

- Hersh AL, Shapiro DJ, Pavia AT, Shah SS. Antibiotic prescribing in ambulatory pediatrics in the United States. Pediatrics. 2011;128(6):1053-1061.

- Knapp JF, Simon SD, Sharma V. Quality of care for common pediatric respiratory illnesses in United States emergency departments: Analysis of 2005 National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey data. Pediatrics. 2008;122(6):1165-1170.

When diagnosing a patient, it can be tempting to run all types of tests to expedite the process—and protect yourself from litigation. Patients may push for more tests, too, thinking “the more the better.” But that may not be the best course of action. In fact, according to recommendations of the ABIM Foundations’ Choosing Wisely campaign, more tests can actually bring a host of negative consequences.

In an effort to help hospitalists decide which tests to perform and which to forgo, The Hospitalist asked medical societies that contributed to the Choosing Wisely campaign to tell us which one of their recommendations was the most applicable to hospitalists. Then, we asked some hospitalists to discuss how they might implement each recommendation.

1 American Gastroenterological Association (AGA)

Recommendation: For a patient with functional abdominal pain syndrome (as per Rome criteria), computed tomography (CT) scans should not be repeated unless there is a major change in clinical findings or symptoms.

When a patient first complains of abdominal pain, a CT scan usually is done prior to a gastroenterological consultation. Despite this initial scan, many patients with chronic abdominal pain receive unnecessary repeated CT scans to evaluate their pain even if they have previous negative studies.

“It is important for the hospitalist to know that functional abdominal pain can be managed without additional diagnostic studies,” says John M. Inadomi, MD, head of the division of gastroenterology at the University of Washington School of Medicine in Seattle. “Some doctors are uncomfortable with the uncertainty of a diagnosis of chronic abdominal pain without evidence of biochemical or structural disease [functional abdominal pain syndrome] and fear litigation.”

An abdominal CT scan is one of the higher radiation exposure tests, equivalent to three years of natural background radiation.1

“Due to this risk and the high costs of this procedure, CT scans should be limited to situations in which they are likely to provide useful information that changes patient management,” Dr. Inadomi says.

According to Moises Auron, MD, FAAP, FACP, SFHM, assistant professor of medicine and pediatrics at Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine of Case Western University in Cleveland, Ohio, it should not be a difficult choice for hospitalists, “as the clinical context provides a safeguard to justify the rationale for a conservative approach. Hospitalists must be educated on the appropriate use of Rome criteria, as well as how to appropriately document it in the chart to justify a decision to avoid unnecessary testing.”

2 American College of Rheumatology (ACR)

Recommendation: Don’t test anti-nuclear antibody (ANA) sub-serologies without a positive ANA and clinical suspicion of immune-mediated disease.

“A fever of unknown origin is among the most common diagnoses the hospitalist encounters,” Dr. Auron says. “Nowadays, given the ease to order tests, as well as the increased awareness of patients with immune-mediated diseases, it may be tempting to order large panels of immunologic tests to minimize the risk of missing a diagnosis; however, because ANA has high sensitivity and poor specificity, it should only be ordered if the clinical context supports its use.”

Jinoos Yazdany, MD, MPH, assistant professor of medicine at the University of California at San Francisco and co-chair of the task force that developed the ACR’s Choosing Wisely list, points out that if you use ANAs as a broad screening test when the pretest probability of specific ANA-associated diseases is low, there is an increased chance of a false positive ANA result. This can lead to unnecessary further testing and additional costs. Furthermore, ANA sub-serologies are usually negative if the ANA (done by immunofluorescence) is negative.

“So it is recommended to order sub-serologies only once it is known that the ANA is positive,” she says. The exceptions to this are anti-SSA and anti-Jo-1 antibodies, which can sometimes be positive when the ANA is negative.

Mangla S. Gulati, MD, FACP, FHM, medical director for clinical effectiveness at the University of Maryland School of Medicine in Baltimore, says a positive ANA in conjunction with clinical information “will help to guide appropriate and cost-conscious testing. Hospitalists could implement this through a clinical decision support approach if using an electronic medical record.”

3 American College of Physicians (ACP)

Recommendation: In patients with low pretest probability of venous thromboembolism (VTE), obtain a high-sensitive D-dimer measurement as the initial diagnostic test; don’t obtain imaging studies as the initial diagnostic test.

VTE, a common problem in hospitalized patients, has high mortality rates. “However, recent statistics suggest that we may be overdiagnosing non-clinically significant disease and exposing large numbers of patients to high doses of radiation unnecessarily in an attempt to rule out VTE disease,” says Cynthia D. Smith, MD, FACP, ACP senior medical associate for content development and adjunct associate professor of medicine at the Perelman School of Medicine in Philadelphia.

Instead, physicians should estimate pretest probability of disease using a validated risk assessment tool (i.e., Wells score). For patients with low clinical probability of VTE, hospitalists should use a negative high-sensitive D-dimer measurement as the initial diagnostic test.

Dr. Auron says the litigious environment of American medicine may trigger clinicians to order testing to minimize the risk of missing potential conditions; however, an adequate, evidence-based approach with appropriate documentation should be sufficient. In this case, that would entail using D-dimer testing to outline the low pretest probability of VTE and explaining to the patient the rationale for not pursuing further imaging.

Dr. Gulati adds that hospitalists should have little difficulty implementing this cost-effective approach.

—Moises Auron, MD, FAAP, FACP, SFHM, assistant professor of medicine and pediatrics, Cleveland Clinic

4 American Geriatrics Society (AGS)

Recommendation: Don’t use antimicrobials to treat bacteriuria in older adults unless specific urinary tract symptoms are present.

Older adults with asymptomatic bacteriuria who received antimicrobial treatment show no benefit, according to multiple studies.2 In fact, increased adverse antimicrobial effects occurred, such as greater resistance patterns and super-infections (e.g. Clostridium difficile).

The truth is that as many as 30% of frail elders (particularly women) have bacterial colonization of the urinary tract without infection, also known as asymptomatic bacteriuria, says Heidi Wald, MD, MSPH, associate professor of medicine and vice chair for quality in the department of medicine at the University of Colorado School of Medicine in Aurora. Therefore, before being prescribed antimicrobials, a patient should exhibit symptoms of urinary tract infection such as fever, frequent urination, urgency to urinate, painful urination, or suprapubic tenderness.

“Without localizing symptoms, you can’t assume bacteriuria equals infection,” Dr. Wald adds. “Too often, we make the urine a scapegoat for unrelated presentations, such as mild confusion.”

If the patient is stable and doesn’t have UTI symptoms, Dr. Wald says hospitalists should consider hydration and monitor the patient without antibiotics.

“This should not be difficult to implement,” Dr. Auron says, “as hospitalists are on the front lines of antibiotic stewardship in hospitals.”

5 American Society of Echocardiography (ASE)

Recommendation: Avoid echocardiograms for pre-operative/peri-operative assessment of patients with no history or symptoms of heart disease.

Echocardiography can diagnose all types of heart disease while being completely safe, inexpensive, and available at the bedside.

“These features may logically lead hospitalists to think, ‘Why not?’ Maybe there’s something going on and an echo can’t hurt,” says James D. Thomas, MD, FASE, FACC, FAHA, FESC, Moore Chair of Cardiovascular Imaging at Cleveland Clinic and ASE past president. “Unfortunately, tests can have false positive findings that lead to other, potentially more hazardous and invasive, tests downstream, as well as unnecessary delays.”

If a patient has no history of heart disease, no positive physical findings, or no symptoms, then an echo probably won’t be helpful. Hospitalists need to be aware of the lack of value of a presumed normal study, Dr. Auron says.

“Having appropriate standards of care allows clinicians in pre-operative areas to use risk stratification tools in an adequate fashion,” he notes.

6 American Society of Nephrology (ASN)

Recommendation: Do not place peripherally inserted central venous catheters (PICC) in stage three to five chronic kidney disease (CKD) patients without consulting nephrology.

Given the increase in patients with CKD in the later stages, as well as end-stage renal disease, clinicians need to protect patients’ upper extremity veins in order to be able to have an adequate vascular substrate for subsequent creation of an arteriovenous fistula (AVF), Dr. Auron maintains.

PICCs, along with other central venous catheters, damage veins and destroy sites for future hemodialysis vascular access, explains Amy W. Williams, MD, medical director of hospital operations and consultant in the division of nephrology and hypertension at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. If there are no options for AVF or grafts, patients starting or being maintained on hemodialysis will need a tunneled central venous catheter for dialysis access.

Studies have shown that AVFs have better patency rates and fewer complications compared to catheters, and there is a direct correlation of increased mortality and inadequate dialysis with tunneled central catheters.3 In addition, dialysis patients with a tunneled central venous catheter have a five-fold increase of infection compared to those with an AVF.4 The incidence of central venous stenosis associated with PICC lines has been shown to be 42% and the incidence of thrombosis 38%.5,6 There is no significant difference in the rate of central venous complications based on the duration of catheter use or catheter size. In addition, prior PICC use has been shown to be an independent predictor of lack of a functioning AVF (odds ratio 2.8 [95 % CI, 1.5 to 5.5]).7

A better choice for extended venous access in patients with advanced CKD is a tunneled internal jugular vein catheter, which is associated with a lower risk of permanent vascular damage, says Dr. Williams, who is chair of the ASN’s Quality and Patient Safety Task Force.

—James J. O’Callaghan, MD, FAAP, FHM, clinical assistant professor of pediatrics, Seattle Children’s Hospital at the University of Washington, Team Hospitalist member

7 The Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS)

Recommendation: Patients who have no cardiac history and good functional status do not require pre-operative stress testing prior to non-cardiac thoracic surgery.

By eliminating routine stress testing prior to non-cardiac thoracic surgery for patients without a history of cardiac symptoms, hospitalists can reduce the burden of costs on patients and eliminate the possibility of adverse outcomes due to inappropriate testing.

“Functional status has been shown to be reliable to predict peri-operative and long-term cardiac events,” says Douglas E. Wood, MD, chief of the division of cardiothoracic surgery at the University of Washington in Seattle and president of the STS. “In highly functional asymptomatic patients, management is rarely changed by pre-operative stress testing. Furthermore, abnormalities identified in testing often require additional investigation, with negative consequences related to the risks of more procedures or tests, delays in therapies, and additional costs.”

Pre-operative stress testing should be reserved for patients with low functional capacity or clinical risk factors for cardiac complications. It is important to identify patients pre-operatively who are at risk for these complications by doing a thorough history, physical examination, and resting electrocardiogram.

8 Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging (SNMMI)

Recommendation: Avoid using a CT angiogram to diagnose pulmonary embolism (PE) in young women with a normal chest radiograph; consider a radionuclide lung (V/Q) study instead.

Hospitalists should be knowledgeable of the diagnostic options that will result in the lowest radiation exposure when evaluating young women for PE.

“When a chest radiograph is normal or nearly normal, a computed tomography angiogram or a V/Q lung scan can be used to evaluate these patients. While both exams have low radiation exposure, the V/Q lung scan results in less radiation to the breast tissue,” says society president Gary L. Dillehay, MD, FACNM, FACR, professor of radiology at Northwestern Memorial Hospital in Chicago. “Recent literature cites concerns over radiation exposure from mammography; therefore, reducing radiation exposure to breast tissue, when evaluating patients for suspected PE, is desirable.”

Hospitalists might have difficulty obtaining a V/Q lung scan when nuclear medicine departments are closed.

“The caveat is that CT scans are much more readily available,” Dr. Auron says. In addition, a CT scan provides additional information. But unless the differential diagnosis is much higher for PE than other possibilities, just having a V/Q scan should suffice.

Hospitalists could help implement protocols for chest pain evaluation in premenopausal women by having checklists for risk factors for coronary artery disease, connective tissue disease (essentially aortic dissection), and VTE (e.g. Wells and Geneva scores, use of oral contraceptives, smoking), Dr. Auron says. If the diagnostic branch supports the risk of PE, then nuclear imaging should be available.

“A reasonable way to justify the increased availability of the nuclear medicine department would be to document the number of CT chest scans done after hours in patients who would have instead had a V/Q scan,” he says.

LISTEN NOW to Rahul Shah, MD, FACS, FAAP, associate professor of otolaryngology and pediatrics at Children's National Medical Center in Washington, D.C, and co-chair of the American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery Foundation’s Patient Safety Quality Improvement Committee, explain why hospitalists should avoid routine radiographic imaging for patients who meet diagnostic criteria for uncomplicated acute rhinosinusitis.

9 American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP)

Recommendation: Antibiotics should not be used for apparent viral respiratory illnesses (sinusitis, pharyngitis, bronchitis).

Respiratory illnesses are the most common reason for hospitalization in pediatrics. Recent studies and surveys continue to demonstrate antibiotic overuse in the pediatric population, especially when prescribed for apparent viral respiratory illnesses.8,9

“Hospitalists who care for pediatric patients have the potential to significantly impact antibiotic overuse, as hospitalizations for respiratory illnesses due to viruses such as bronchiolitis and croup remain a leading cause of admission,” says James J. O’Callaghan, MD, FAAP, FHM, clinical assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Washington School of Medicine in Seattle.

Many respiratory problems, such as bronchiolitis, asthma, and even some pneumonias are caused or exacerbated by viruses, points out Ricardo Quiñonez, MD, FAAP, FHM, section head of pediatric hospital medicine at the Children’s Hospital of San Antonio and the Baylor College of Medicine, and chair of the AAP’s section on hospital medicine. In particular, there are national guidelines for bronchiolitis and asthma that recommend against the use of systemic antibiotics.

This recommendation may be difficult for hospitalists to implement, because antibiotics are frequently started by other providers (PCP or ED), Dr. O’Callaghan admits. It can be tricky to change or stop therapy without undermining patients’ or parents’ confidence in their medical decision-making. Hospitalists may need to collaborate with new partners, such as community-wide antibiotic reduction campaigns, in order to affect this culture change.

—James D. Thomas, MD, FASE, FACC, FAHA, FESC, Moore Chair of Cardiovascular Imaging at the Cleveland Clinic in Ohio and past president of the American Society of Echocardiography.

10 American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOB)

Recommendation: Don’t schedule elective inductions prior to 39 weeks, and don’t schedule elective inductions of labor after 39 weeks without a favorable cervix.

Studies show an increased risk to newborns that are electively inducted between 37 and 39 weeks. Complications include increased admission to the neonatal intensive care unit, increased risk of respiratory distress and need for respiratory support, and increased incidence of infection and sepsis.

This recommendation may be difficult for hospitalists to implement, because obstetrical providers typically schedule elective inductions. Implementation of this recommendation would involve collaboration with obstetrical providers, with possible support from maternal-fetal and neonatal providers.

“Recent quality measures and initiatives from such organizations such as CMS and the National Quality Forum … may help to galvanize institutional support for its successful implementation,” says Dr. O’Callaghan, a Team Hospitalist member.

Elective surgeries should only be done in cases where there is a medical necessity, such as when the mother is diabetic or has hypertension, adds Rob Olson, MD, FACOG, an OB/GYN hospitalist for PeaceHealth at St. Joseph Medical Center in Bellingham, Wash. “Hospitalists should not give in to pressures from patients who are either tired of the discomforts of pregnancy or have family pressure to end the pregnancy early.”

Karen Appold is a freelance writer in Pennsylvania.

References

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Reducing radiation from medical X-rays. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/ForConsumers/ConsumerUpdates/ucm095505.htm. Accessed May 12, 2014.

- Nicolle LE, Bradley S, Colgan R, et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria in adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40(5):643-654.

- Hoggard J, Saad T, Schon D, et al. Guidelines for venous access in patients with chronic kidney disease. A position statement from the American Society of Diagnostic and Interventional Nephrology, Clinical Practice Committee and the Association for Vascular Access. Semin Dial. 2008;21(2):186-191.

- Rayner HC, Besarab A, Brown WW, Disney A, Saito A, Pisoni RL. Vascular access results from the dialysis outcomes and practice patterns study (DOPPS): Performance against kidney disease outcomes quality initiative (K/DOQI)clinical practice guidelines. Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;44(5 Suppl 2):22-26.

- Gonsalves CF, Eschelman DJ, Sullivan KL, DuBois N, Bonn J. Incidence of central vein stenosis and occlusion following upper extremity PICC and port placement. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2003;26(2):123-127.

- Allen AW, Megargell JL, Brown DB, et al. Venous thrombosis associated with the placement of peripherally inserted central catheters. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2000;11(10):1309-1314.

- El Ters M, Schears GJ, Taler SJ, et al. Association between prior peripherally inserted central catheters and lack of functioning ateriovenous fistulas: A case control study in hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;60(4):601-608.

- Hersh AL, Shapiro DJ, Pavia AT, Shah SS. Antibiotic prescribing in ambulatory pediatrics in the United States. Pediatrics. 2011;128(6):1053-1061.

- Knapp JF, Simon SD, Sharma V. Quality of care for common pediatric respiratory illnesses in United States emergency departments: Analysis of 2005 National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey data. Pediatrics. 2008;122(6):1165-1170.

When diagnosing a patient, it can be tempting to run all types of tests to expedite the process—and protect yourself from litigation. Patients may push for more tests, too, thinking “the more the better.” But that may not be the best course of action. In fact, according to recommendations of the ABIM Foundations’ Choosing Wisely campaign, more tests can actually bring a host of negative consequences.

In an effort to help hospitalists decide which tests to perform and which to forgo, The Hospitalist asked medical societies that contributed to the Choosing Wisely campaign to tell us which one of their recommendations was the most applicable to hospitalists. Then, we asked some hospitalists to discuss how they might implement each recommendation.

1 American Gastroenterological Association (AGA)

Recommendation: For a patient with functional abdominal pain syndrome (as per Rome criteria), computed tomography (CT) scans should not be repeated unless there is a major change in clinical findings or symptoms.

When a patient first complains of abdominal pain, a CT scan usually is done prior to a gastroenterological consultation. Despite this initial scan, many patients with chronic abdominal pain receive unnecessary repeated CT scans to evaluate their pain even if they have previous negative studies.

“It is important for the hospitalist to know that functional abdominal pain can be managed without additional diagnostic studies,” says John M. Inadomi, MD, head of the division of gastroenterology at the University of Washington School of Medicine in Seattle. “Some doctors are uncomfortable with the uncertainty of a diagnosis of chronic abdominal pain without evidence of biochemical or structural disease [functional abdominal pain syndrome] and fear litigation.”

An abdominal CT scan is one of the higher radiation exposure tests, equivalent to three years of natural background radiation.1

“Due to this risk and the high costs of this procedure, CT scans should be limited to situations in which they are likely to provide useful information that changes patient management,” Dr. Inadomi says.

According to Moises Auron, MD, FAAP, FACP, SFHM, assistant professor of medicine and pediatrics at Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine of Case Western University in Cleveland, Ohio, it should not be a difficult choice for hospitalists, “as the clinical context provides a safeguard to justify the rationale for a conservative approach. Hospitalists must be educated on the appropriate use of Rome criteria, as well as how to appropriately document it in the chart to justify a decision to avoid unnecessary testing.”

2 American College of Rheumatology (ACR)

Recommendation: Don’t test anti-nuclear antibody (ANA) sub-serologies without a positive ANA and clinical suspicion of immune-mediated disease.

“A fever of unknown origin is among the most common diagnoses the hospitalist encounters,” Dr. Auron says. “Nowadays, given the ease to order tests, as well as the increased awareness of patients with immune-mediated diseases, it may be tempting to order large panels of immunologic tests to minimize the risk of missing a diagnosis; however, because ANA has high sensitivity and poor specificity, it should only be ordered if the clinical context supports its use.”

Jinoos Yazdany, MD, MPH, assistant professor of medicine at the University of California at San Francisco and co-chair of the task force that developed the ACR’s Choosing Wisely list, points out that if you use ANAs as a broad screening test when the pretest probability of specific ANA-associated diseases is low, there is an increased chance of a false positive ANA result. This can lead to unnecessary further testing and additional costs. Furthermore, ANA sub-serologies are usually negative if the ANA (done by immunofluorescence) is negative.

“So it is recommended to order sub-serologies only once it is known that the ANA is positive,” she says. The exceptions to this are anti-SSA and anti-Jo-1 antibodies, which can sometimes be positive when the ANA is negative.

Mangla S. Gulati, MD, FACP, FHM, medical director for clinical effectiveness at the University of Maryland School of Medicine in Baltimore, says a positive ANA in conjunction with clinical information “will help to guide appropriate and cost-conscious testing. Hospitalists could implement this through a clinical decision support approach if using an electronic medical record.”

3 American College of Physicians (ACP)

Recommendation: In patients with low pretest probability of venous thromboembolism (VTE), obtain a high-sensitive D-dimer measurement as the initial diagnostic test; don’t obtain imaging studies as the initial diagnostic test.

VTE, a common problem in hospitalized patients, has high mortality rates. “However, recent statistics suggest that we may be overdiagnosing non-clinically significant disease and exposing large numbers of patients to high doses of radiation unnecessarily in an attempt to rule out VTE disease,” says Cynthia D. Smith, MD, FACP, ACP senior medical associate for content development and adjunct associate professor of medicine at the Perelman School of Medicine in Philadelphia.

Instead, physicians should estimate pretest probability of disease using a validated risk assessment tool (i.e., Wells score). For patients with low clinical probability of VTE, hospitalists should use a negative high-sensitive D-dimer measurement as the initial diagnostic test.

Dr. Auron says the litigious environment of American medicine may trigger clinicians to order testing to minimize the risk of missing potential conditions; however, an adequate, evidence-based approach with appropriate documentation should be sufficient. In this case, that would entail using D-dimer testing to outline the low pretest probability of VTE and explaining to the patient the rationale for not pursuing further imaging.

Dr. Gulati adds that hospitalists should have little difficulty implementing this cost-effective approach.

—Moises Auron, MD, FAAP, FACP, SFHM, assistant professor of medicine and pediatrics, Cleveland Clinic

4 American Geriatrics Society (AGS)

Recommendation: Don’t use antimicrobials to treat bacteriuria in older adults unless specific urinary tract symptoms are present.

Older adults with asymptomatic bacteriuria who received antimicrobial treatment show no benefit, according to multiple studies.2 In fact, increased adverse antimicrobial effects occurred, such as greater resistance patterns and super-infections (e.g. Clostridium difficile).

The truth is that as many as 30% of frail elders (particularly women) have bacterial colonization of the urinary tract without infection, also known as asymptomatic bacteriuria, says Heidi Wald, MD, MSPH, associate professor of medicine and vice chair for quality in the department of medicine at the University of Colorado School of Medicine in Aurora. Therefore, before being prescribed antimicrobials, a patient should exhibit symptoms of urinary tract infection such as fever, frequent urination, urgency to urinate, painful urination, or suprapubic tenderness.

“Without localizing symptoms, you can’t assume bacteriuria equals infection,” Dr. Wald adds. “Too often, we make the urine a scapegoat for unrelated presentations, such as mild confusion.”

If the patient is stable and doesn’t have UTI symptoms, Dr. Wald says hospitalists should consider hydration and monitor the patient without antibiotics.

“This should not be difficult to implement,” Dr. Auron says, “as hospitalists are on the front lines of antibiotic stewardship in hospitals.”

5 American Society of Echocardiography (ASE)

Recommendation: Avoid echocardiograms for pre-operative/peri-operative assessment of patients with no history or symptoms of heart disease.

Echocardiography can diagnose all types of heart disease while being completely safe, inexpensive, and available at the bedside.

“These features may logically lead hospitalists to think, ‘Why not?’ Maybe there’s something going on and an echo can’t hurt,” says James D. Thomas, MD, FASE, FACC, FAHA, FESC, Moore Chair of Cardiovascular Imaging at Cleveland Clinic and ASE past president. “Unfortunately, tests can have false positive findings that lead to other, potentially more hazardous and invasive, tests downstream, as well as unnecessary delays.”

If a patient has no history of heart disease, no positive physical findings, or no symptoms, then an echo probably won’t be helpful. Hospitalists need to be aware of the lack of value of a presumed normal study, Dr. Auron says.

“Having appropriate standards of care allows clinicians in pre-operative areas to use risk stratification tools in an adequate fashion,” he notes.

6 American Society of Nephrology (ASN)

Recommendation: Do not place peripherally inserted central venous catheters (PICC) in stage three to five chronic kidney disease (CKD) patients without consulting nephrology.

Given the increase in patients with CKD in the later stages, as well as end-stage renal disease, clinicians need to protect patients’ upper extremity veins in order to be able to have an adequate vascular substrate for subsequent creation of an arteriovenous fistula (AVF), Dr. Auron maintains.

PICCs, along with other central venous catheters, damage veins and destroy sites for future hemodialysis vascular access, explains Amy W. Williams, MD, medical director of hospital operations and consultant in the division of nephrology and hypertension at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. If there are no options for AVF or grafts, patients starting or being maintained on hemodialysis will need a tunneled central venous catheter for dialysis access.

Studies have shown that AVFs have better patency rates and fewer complications compared to catheters, and there is a direct correlation of increased mortality and inadequate dialysis with tunneled central catheters.3 In addition, dialysis patients with a tunneled central venous catheter have a five-fold increase of infection compared to those with an AVF.4 The incidence of central venous stenosis associated with PICC lines has been shown to be 42% and the incidence of thrombosis 38%.5,6 There is no significant difference in the rate of central venous complications based on the duration of catheter use or catheter size. In addition, prior PICC use has been shown to be an independent predictor of lack of a functioning AVF (odds ratio 2.8 [95 % CI, 1.5 to 5.5]).7

A better choice for extended venous access in patients with advanced CKD is a tunneled internal jugular vein catheter, which is associated with a lower risk of permanent vascular damage, says Dr. Williams, who is chair of the ASN’s Quality and Patient Safety Task Force.

—James J. O’Callaghan, MD, FAAP, FHM, clinical assistant professor of pediatrics, Seattle Children’s Hospital at the University of Washington, Team Hospitalist member

7 The Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS)

Recommendation: Patients who have no cardiac history and good functional status do not require pre-operative stress testing prior to non-cardiac thoracic surgery.

By eliminating routine stress testing prior to non-cardiac thoracic surgery for patients without a history of cardiac symptoms, hospitalists can reduce the burden of costs on patients and eliminate the possibility of adverse outcomes due to inappropriate testing.

“Functional status has been shown to be reliable to predict peri-operative and long-term cardiac events,” says Douglas E. Wood, MD, chief of the division of cardiothoracic surgery at the University of Washington in Seattle and president of the STS. “In highly functional asymptomatic patients, management is rarely changed by pre-operative stress testing. Furthermore, abnormalities identified in testing often require additional investigation, with negative consequences related to the risks of more procedures or tests, delays in therapies, and additional costs.”

Pre-operative stress testing should be reserved for patients with low functional capacity or clinical risk factors for cardiac complications. It is important to identify patients pre-operatively who are at risk for these complications by doing a thorough history, physical examination, and resting electrocardiogram.

8 Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging (SNMMI)

Recommendation: Avoid using a CT angiogram to diagnose pulmonary embolism (PE) in young women with a normal chest radiograph; consider a radionuclide lung (V/Q) study instead.

Hospitalists should be knowledgeable of the diagnostic options that will result in the lowest radiation exposure when evaluating young women for PE.

“When a chest radiograph is normal or nearly normal, a computed tomography angiogram or a V/Q lung scan can be used to evaluate these patients. While both exams have low radiation exposure, the V/Q lung scan results in less radiation to the breast tissue,” says society president Gary L. Dillehay, MD, FACNM, FACR, professor of radiology at Northwestern Memorial Hospital in Chicago. “Recent literature cites concerns over radiation exposure from mammography; therefore, reducing radiation exposure to breast tissue, when evaluating patients for suspected PE, is desirable.”

Hospitalists might have difficulty obtaining a V/Q lung scan when nuclear medicine departments are closed.

“The caveat is that CT scans are much more readily available,” Dr. Auron says. In addition, a CT scan provides additional information. But unless the differential diagnosis is much higher for PE than other possibilities, just having a V/Q scan should suffice.

Hospitalists could help implement protocols for chest pain evaluation in premenopausal women by having checklists for risk factors for coronary artery disease, connective tissue disease (essentially aortic dissection), and VTE (e.g. Wells and Geneva scores, use of oral contraceptives, smoking), Dr. Auron says. If the diagnostic branch supports the risk of PE, then nuclear imaging should be available.

“A reasonable way to justify the increased availability of the nuclear medicine department would be to document the number of CT chest scans done after hours in patients who would have instead had a V/Q scan,” he says.

LISTEN NOW to Rahul Shah, MD, FACS, FAAP, associate professor of otolaryngology and pediatrics at Children's National Medical Center in Washington, D.C, and co-chair of the American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery Foundation’s Patient Safety Quality Improvement Committee, explain why hospitalists should avoid routine radiographic imaging for patients who meet diagnostic criteria for uncomplicated acute rhinosinusitis.

9 American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP)

Recommendation: Antibiotics should not be used for apparent viral respiratory illnesses (sinusitis, pharyngitis, bronchitis).

Respiratory illnesses are the most common reason for hospitalization in pediatrics. Recent studies and surveys continue to demonstrate antibiotic overuse in the pediatric population, especially when prescribed for apparent viral respiratory illnesses.8,9

“Hospitalists who care for pediatric patients have the potential to significantly impact antibiotic overuse, as hospitalizations for respiratory illnesses due to viruses such as bronchiolitis and croup remain a leading cause of admission,” says James J. O’Callaghan, MD, FAAP, FHM, clinical assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Washington School of Medicine in Seattle.

Many respiratory problems, such as bronchiolitis, asthma, and even some pneumonias are caused or exacerbated by viruses, points out Ricardo Quiñonez, MD, FAAP, FHM, section head of pediatric hospital medicine at the Children’s Hospital of San Antonio and the Baylor College of Medicine, and chair of the AAP’s section on hospital medicine. In particular, there are national guidelines for bronchiolitis and asthma that recommend against the use of systemic antibiotics.

This recommendation may be difficult for hospitalists to implement, because antibiotics are frequently started by other providers (PCP or ED), Dr. O’Callaghan admits. It can be tricky to change or stop therapy without undermining patients’ or parents’ confidence in their medical decision-making. Hospitalists may need to collaborate with new partners, such as community-wide antibiotic reduction campaigns, in order to affect this culture change.

—James D. Thomas, MD, FASE, FACC, FAHA, FESC, Moore Chair of Cardiovascular Imaging at the Cleveland Clinic in Ohio and past president of the American Society of Echocardiography.

10 American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOB)

Recommendation: Don’t schedule elective inductions prior to 39 weeks, and don’t schedule elective inductions of labor after 39 weeks without a favorable cervix.

Studies show an increased risk to newborns that are electively inducted between 37 and 39 weeks. Complications include increased admission to the neonatal intensive care unit, increased risk of respiratory distress and need for respiratory support, and increased incidence of infection and sepsis.

This recommendation may be difficult for hospitalists to implement, because obstetrical providers typically schedule elective inductions. Implementation of this recommendation would involve collaboration with obstetrical providers, with possible support from maternal-fetal and neonatal providers.

“Recent quality measures and initiatives from such organizations such as CMS and the National Quality Forum … may help to galvanize institutional support for its successful implementation,” says Dr. O’Callaghan, a Team Hospitalist member.

Elective surgeries should only be done in cases where there is a medical necessity, such as when the mother is diabetic or has hypertension, adds Rob Olson, MD, FACOG, an OB/GYN hospitalist for PeaceHealth at St. Joseph Medical Center in Bellingham, Wash. “Hospitalists should not give in to pressures from patients who are either tired of the discomforts of pregnancy or have family pressure to end the pregnancy early.”

Karen Appold is a freelance writer in Pennsylvania.

References

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Reducing radiation from medical X-rays. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/ForConsumers/ConsumerUpdates/ucm095505.htm. Accessed May 12, 2014.

- Nicolle LE, Bradley S, Colgan R, et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria in adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40(5):643-654.

- Hoggard J, Saad T, Schon D, et al. Guidelines for venous access in patients with chronic kidney disease. A position statement from the American Society of Diagnostic and Interventional Nephrology, Clinical Practice Committee and the Association for Vascular Access. Semin Dial. 2008;21(2):186-191.

- Rayner HC, Besarab A, Brown WW, Disney A, Saito A, Pisoni RL. Vascular access results from the dialysis outcomes and practice patterns study (DOPPS): Performance against kidney disease outcomes quality initiative (K/DOQI)clinical practice guidelines. Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;44(5 Suppl 2):22-26.

- Gonsalves CF, Eschelman DJ, Sullivan KL, DuBois N, Bonn J. Incidence of central vein stenosis and occlusion following upper extremity PICC and port placement. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2003;26(2):123-127.

- Allen AW, Megargell JL, Brown DB, et al. Venous thrombosis associated with the placement of peripherally inserted central catheters. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2000;11(10):1309-1314.

- El Ters M, Schears GJ, Taler SJ, et al. Association between prior peripherally inserted central catheters and lack of functioning ateriovenous fistulas: A case control study in hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;60(4):601-608.

- Hersh AL, Shapiro DJ, Pavia AT, Shah SS. Antibiotic prescribing in ambulatory pediatrics in the United States. Pediatrics. 2011;128(6):1053-1061.

- Knapp JF, Simon SD, Sharma V. Quality of care for common pediatric respiratory illnesses in United States emergency departments: Analysis of 2005 National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey data. Pediatrics. 2008;122(6):1165-1170.

LISTEN NOW! ABIM Foundation EVP/COO Explains How the Choosing Wisely Campaign Got Started, and Its Impact on the U.S. Healthcare System

Listen to Daniel Wolfson explain how the Choosing Wisely campaign got started and its significance in U.S. healthcare

Listen to Daniel Wolfson explain how the Choosing Wisely campaign got started and its significance in U.S. healthcare

Listen to Daniel Wolfson explain how the Choosing Wisely campaign got started and its significance in U.S. healthcare

LISTEN NOW! Two Additional Choosing Wisely Recommendations from Specialty Societies

Listen to Dr. Cox, owner of Allergy and Asthma Center in Ft. Lauderdale, Fla., discuss why it's important for hospitalists to avoid diagnosing or managing asthma without spirometry.

Click here to listen to Dr. Shah, associate professor of otolaryngology and pediatrics at Children's National Medical Center in Washington, D.C, tell hospitalists why they should avoid routine radiographic imaging for patients who meet diagnostic criteria for uncomplicated acute rhinosinusitis.

Listen to Dr. Cox, owner of Allergy and Asthma Center in Ft. Lauderdale, Fla., discuss why it's important for hospitalists to avoid diagnosing or managing asthma without spirometry.

Click here to listen to Dr. Shah, associate professor of otolaryngology and pediatrics at Children's National Medical Center in Washington, D.C, tell hospitalists why they should avoid routine radiographic imaging for patients who meet diagnostic criteria for uncomplicated acute rhinosinusitis.

Listen to Dr. Cox, owner of Allergy and Asthma Center in Ft. Lauderdale, Fla., discuss why it's important for hospitalists to avoid diagnosing or managing asthma without spirometry.

Click here to listen to Dr. Shah, associate professor of otolaryngology and pediatrics at Children's National Medical Center in Washington, D.C, tell hospitalists why they should avoid routine radiographic imaging for patients who meet diagnostic criteria for uncomplicated acute rhinosinusitis.

Copper Considered Safe, Effective in Preventing Hospital-Acquired Infections

Concern about Copper’s Effectiveness in Preventing Hospital-Acquired Infections

As public knowledge about the benefits of antimicrobial copper touch surfaces in healthcare facilities continues to grow, questions about this tool naturally arise. Can this copper surface really continuously kill up to 83% of bacteria it comes in contact with? Can it really reduce patient infections by more than half? Can this metal really keep people safer? The answer is “yes,” as has been reported in the Journal of Infection Control, in Hospital Epidemiology, and in the Journal of Clinical Microbiology.

In his “Letter to the Editor (“Concern about Copper’s Effectiveness in Preventing Hospital-Acquired Infections,” November 2013), Dr. Rod Duraski voices cautions about human sensitivity to copper—noting that implanted copper-nickel alloy devices have the potential for severe allergic reactions; however, implanted devices are not part of the EPA-approved products list of antimicrobial copper and, therefore, are not being proposed for use in the fight against hospital infections. Although some patients might experience sensitivity to jewelry, zippers, or buttons, if made from nickel-containing copper alloys, these reactions will be the result of prolonged skin contact, and when removed, the sensitivity will dissipate. The touch-surface components proposed in Karen Appold’s story, “Copper,” (September 2013) come into very brief and intermittent contact with the skin. And, sensitivities are not life-threatening; hospital-acquired infections are.

In fact, three of the four major coin denominations (nickel, dime, quarter) are made from copper-nickel alloys. If these metals are suitable for the everyday exposure we all experience with coinage, they are just as safe when it comes to touch surface components in hospitals. In many instances, the benefits of copper outweigh the relative risk of a rash caused by nickel sensitivity.

Like any surface, copper alloys should be cleaned regularly—especially in hospitals. Copper alloys are compatible with all hospital grade cleaners and disinfectants when the cleaners are used according to manufacturer label instructions. But more importantly, the antimicrobial effect of this metal is not inhibited if the surfaces tarnish. In 2005, a study (www.antimicrobialcopper.com/media/69850/infectious_disease.pdf) found tarnish to be a non-issue when researchers tested the bacterial load on three separate copper alloys, all of which had developed tarnish over time. Additionally, manufacturers are offering components made from tarnish-resistant alloys.

—Harold Michels, PhD, senior vice president of technology and technical services, Copper Development Association, Inc.

Correction: April 4, 2014

A version of this article appeared in print in the April 2014 issue of The Hospitalist. Changes have since been made to the online article per the request of the author.

Concern about Copper’s Effectiveness in Preventing Hospital-Acquired Infections

As public knowledge about the benefits of antimicrobial copper touch surfaces in healthcare facilities continues to grow, questions about this tool naturally arise. Can this copper surface really continuously kill up to 83% of bacteria it comes in contact with? Can it really reduce patient infections by more than half? Can this metal really keep people safer? The answer is “yes,” as has been reported in the Journal of Infection Control, in Hospital Epidemiology, and in the Journal of Clinical Microbiology.

In his “Letter to the Editor (“Concern about Copper’s Effectiveness in Preventing Hospital-Acquired Infections,” November 2013), Dr. Rod Duraski voices cautions about human sensitivity to copper—noting that implanted copper-nickel alloy devices have the potential for severe allergic reactions; however, implanted devices are not part of the EPA-approved products list of antimicrobial copper and, therefore, are not being proposed for use in the fight against hospital infections. Although some patients might experience sensitivity to jewelry, zippers, or buttons, if made from nickel-containing copper alloys, these reactions will be the result of prolonged skin contact, and when removed, the sensitivity will dissipate. The touch-surface components proposed in Karen Appold’s story, “Copper,” (September 2013) come into very brief and intermittent contact with the skin. And, sensitivities are not life-threatening; hospital-acquired infections are.

In fact, three of the four major coin denominations (nickel, dime, quarter) are made from copper-nickel alloys. If these metals are suitable for the everyday exposure we all experience with coinage, they are just as safe when it comes to touch surface components in hospitals. In many instances, the benefits of copper outweigh the relative risk of a rash caused by nickel sensitivity.

Like any surface, copper alloys should be cleaned regularly—especially in hospitals. Copper alloys are compatible with all hospital grade cleaners and disinfectants when the cleaners are used according to manufacturer label instructions. But more importantly, the antimicrobial effect of this metal is not inhibited if the surfaces tarnish. In 2005, a study (www.antimicrobialcopper.com/media/69850/infectious_disease.pdf) found tarnish to be a non-issue when researchers tested the bacterial load on three separate copper alloys, all of which had developed tarnish over time. Additionally, manufacturers are offering components made from tarnish-resistant alloys.

—Harold Michels, PhD, senior vice president of technology and technical services, Copper Development Association, Inc.

Correction: April 4, 2014

A version of this article appeared in print in the April 2014 issue of The Hospitalist. Changes have since been made to the online article per the request of the author.

Concern about Copper’s Effectiveness in Preventing Hospital-Acquired Infections

As public knowledge about the benefits of antimicrobial copper touch surfaces in healthcare facilities continues to grow, questions about this tool naturally arise. Can this copper surface really continuously kill up to 83% of bacteria it comes in contact with? Can it really reduce patient infections by more than half? Can this metal really keep people safer? The answer is “yes,” as has been reported in the Journal of Infection Control, in Hospital Epidemiology, and in the Journal of Clinical Microbiology.

In his “Letter to the Editor (“Concern about Copper’s Effectiveness in Preventing Hospital-Acquired Infections,” November 2013), Dr. Rod Duraski voices cautions about human sensitivity to copper—noting that implanted copper-nickel alloy devices have the potential for severe allergic reactions; however, implanted devices are not part of the EPA-approved products list of antimicrobial copper and, therefore, are not being proposed for use in the fight against hospital infections. Although some patients might experience sensitivity to jewelry, zippers, or buttons, if made from nickel-containing copper alloys, these reactions will be the result of prolonged skin contact, and when removed, the sensitivity will dissipate. The touch-surface components proposed in Karen Appold’s story, “Copper,” (September 2013) come into very brief and intermittent contact with the skin. And, sensitivities are not life-threatening; hospital-acquired infections are.

In fact, three of the four major coin denominations (nickel, dime, quarter) are made from copper-nickel alloys. If these metals are suitable for the everyday exposure we all experience with coinage, they are just as safe when it comes to touch surface components in hospitals. In many instances, the benefits of copper outweigh the relative risk of a rash caused by nickel sensitivity.

Like any surface, copper alloys should be cleaned regularly—especially in hospitals. Copper alloys are compatible with all hospital grade cleaners and disinfectants when the cleaners are used according to manufacturer label instructions. But more importantly, the antimicrobial effect of this metal is not inhibited if the surfaces tarnish. In 2005, a study (www.antimicrobialcopper.com/media/69850/infectious_disease.pdf) found tarnish to be a non-issue when researchers tested the bacterial load on three separate copper alloys, all of which had developed tarnish over time. Additionally, manufacturers are offering components made from tarnish-resistant alloys.

—Harold Michels, PhD, senior vice president of technology and technical services, Copper Development Association, Inc.

Correction: April 4, 2014

A version of this article appeared in print in the April 2014 issue of The Hospitalist. Changes have since been made to the online article per the request of the author.

Concern about Copper's Effectiveness in Preventing Hospital-Acquired Infections

Karen Appold’s cover story, “Copper,” in the September 2013 issue, offers an exciting and encouraging development in the struggle to prevent hospital-acquired infections, but I have two concerns. As copper tarnishes, it forms a surface patina of copper hydroxide and copper carbonate. Would this patina act as a physical barrier, preventing bacteria from coming into contact with elemental copper and inhibiting the antimicrobial effect? If so, the obvious solution is to polish the surface frequently enough to prevent tarnishing.

The second concern regards the use of copper-nickel alloys. Many people are sensitive to nickel, [with reactions that] usually manifest as contact dermatitis. A study by the North American Contact Dermatitis Group (NACDG), conducted between 1992-2004 and involving 25,626 patients who were patch-tested, showed a prevalence of nickel sensitivity of 18.8% in 2004, increased from 14.5% in 1992.1

With a current U.S. population of approximately 317 million, a prevalence of 18.8% would mean nearly 60 million people with nickel sensitivity. Extrapolating from the NACDG study, the rate is probably actually higher. Medical devices made with copper-nickel alloys that contact the patient’s skin would cause contact dermatitis, and implanted devices would have the potential for more severe allergic reactions.

I simply urge foresight and caution in the use of various copper alloys for medical applications.

Rod Duraski, MD, MBA, FACP, medical director, WGH Hospital Medicine, LaGrange, Ga.

Reference

Karen Appold’s cover story, “Copper,” in the September 2013 issue, offers an exciting and encouraging development in the struggle to prevent hospital-acquired infections, but I have two concerns. As copper tarnishes, it forms a surface patina of copper hydroxide and copper carbonate. Would this patina act as a physical barrier, preventing bacteria from coming into contact with elemental copper and inhibiting the antimicrobial effect? If so, the obvious solution is to polish the surface frequently enough to prevent tarnishing.

The second concern regards the use of copper-nickel alloys. Many people are sensitive to nickel, [with reactions that] usually manifest as contact dermatitis. A study by the North American Contact Dermatitis Group (NACDG), conducted between 1992-2004 and involving 25,626 patients who were patch-tested, showed a prevalence of nickel sensitivity of 18.8% in 2004, increased from 14.5% in 1992.1

With a current U.S. population of approximately 317 million, a prevalence of 18.8% would mean nearly 60 million people with nickel sensitivity. Extrapolating from the NACDG study, the rate is probably actually higher. Medical devices made with copper-nickel alloys that contact the patient’s skin would cause contact dermatitis, and implanted devices would have the potential for more severe allergic reactions.

I simply urge foresight and caution in the use of various copper alloys for medical applications.

Rod Duraski, MD, MBA, FACP, medical director, WGH Hospital Medicine, LaGrange, Ga.

Reference

Karen Appold’s cover story, “Copper,” in the September 2013 issue, offers an exciting and encouraging development in the struggle to prevent hospital-acquired infections, but I have two concerns. As copper tarnishes, it forms a surface patina of copper hydroxide and copper carbonate. Would this patina act as a physical barrier, preventing bacteria from coming into contact with elemental copper and inhibiting the antimicrobial effect? If so, the obvious solution is to polish the surface frequently enough to prevent tarnishing.

The second concern regards the use of copper-nickel alloys. Many people are sensitive to nickel, [with reactions that] usually manifest as contact dermatitis. A study by the North American Contact Dermatitis Group (NACDG), conducted between 1992-2004 and involving 25,626 patients who were patch-tested, showed a prevalence of nickel sensitivity of 18.8% in 2004, increased from 14.5% in 1992.1

With a current U.S. population of approximately 317 million, a prevalence of 18.8% would mean nearly 60 million people with nickel sensitivity. Extrapolating from the NACDG study, the rate is probably actually higher. Medical devices made with copper-nickel alloys that contact the patient’s skin would cause contact dermatitis, and implanted devices would have the potential for more severe allergic reactions.

I simply urge foresight and caution in the use of various copper alloys for medical applications.

Rod Duraski, MD, MBA, FACP, medical director, WGH Hospital Medicine, LaGrange, Ga.

Reference

Copper-Surface Experiment Makes Immediate Impact

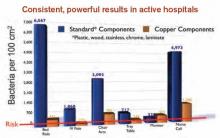

Given the encouraging results published in Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology regarding the effectiveness of copper-alloy surfaces in killing bacteria, one institution has decided to go full steam ahead with installing copper components.1

The Ronald McDonald House of Charleston, S.C. (RMHC), a home for families of critically ill children who are being treated at the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC), was the first nonprofit, temporary-residence facility in the U.S. to undertake an antimicrobial copper retrofit.

“We were the ideal public building site to test copper’s antimicrobial efficacy outside of ICUs,” says Robin Willis, RMHC’s antimicrobial project manager.

South Carolina Research Authority, which managed the study, approached RMHC about being the “guinea pig.”

“The families would get the benefits for a long time, and we would have additional data outside of a closed ICU,” Willis says. “Additionally, it gave vendors a testing ground for copper components.”

Surfaces that were identified in the study as having the highest bacteria counts (stair railings, sinks, faucets, tables, locksets, cabinet pulls, and chair arms) were replaced with solid, copper-based metals such as bronze and brass that are registered by the Environmental Protection Agency. The Copper Development Association donated the bulk of funds for the project. Copper manufacturers and installers donated their time and materials.

Initial discussions about the project began in 2010; copper installations started in November 2011. The facility remained open and fully functional throughout the project, which was completed in April 2012.

MUSC measured the amount of bacteria on touch surfaces prior to the copper retrofit, then compared the amount of bacteria on the new copper surfaces against their predecessors.

“Bacteria levels dropped more than 90 percent, around the clock, without cleaning agents,” Willis says.