User login

Population health focuses on the specific health needs of an individual within a defined population.

“In order to truly measure a patient’s health outcomes and identify best practices, providers must evaluate a group of people with similar health needs,” explains Joseph Damore, vice president of population health management for Charlotte-N.C.-based Premier, Inc. “Once we understand a population’s outcomes, we can then target the individual.”

Fundamentally, population health is about individualized care and intervening earlier in order to get a better outcome based on what generally works for the population. It’s also about identifying populations that need specific, targeted care, such as diabetic and oncology patients.

Back in 2003, David A. Kindig MD, PhD, and Greg Stoddart, PhD, defined population health as “the health outcomes of a group of individuals, including the distribution of such outcomes within the group.”1

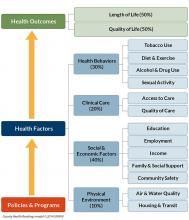

In order to achieve population health, according to Nick Fitterman, MD, SFHM, vice chair of hospital medicine for the Hofstra North Shore-LIJ School of Medicine in Hempstead, N.Y., “it is necessary to reduce health inequities or disparities among different populations due to, among other factors, the social determinants of health, which include social, environmental, cultural, and physical factors.”

Even though the concept of population health emerged more than 25 years ago, Dr. Fitterman points out that, until recently, the U.S. healthcare system has looked at an individual’s episodic illness rather than at population health, which focuses on wellness, prevention, and coordinated care across the continuum.

Marianne McPherson, PhD, MS, senior director of programs, research, and evaluation for the National Institute for Children’s Health Quality in Boston, says it is important for hospitalists to focus on both the patient and the population.

“You need to understand the particular factors facing the patient in front of you and understand that that individual is a product of a variety of different circumstances,” she says. “If you only look at an individual’s health, you can miss important trends across a group of patients within a population or community.

“By looking at both the individual and entire population, you can provide the most effective healthcare and health promotion.”

Government Spearheads Initiatives

With passage of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) of 2010, the U.S. government helped accelerate the movement toward population health. According to Joshua D. Lenchus, DO, RPh, FACP, SFHM, a veteran hospitalist, president of Jackson Health System Medical Staff, and associate professor of clinical medicine and anesthesiology at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, the act’s provisions aim to improve the quality of care and create accountable care organizations (ACOs).

“The idea was to provide patients with insurance coverage, which would improve the access to care of which they were previously deprived,” he says. “With better access, they may receive quality healthcare and the identification and mitigation of disease at an early stage, thereby reducing overall healthcare costs, with the commensurate benefit of a healthy patient population.

“Of course, this is fraught with naïveté, because it explicitly dismisses nonmedical health determinants (i.e., socioeconomic status, education, literacy rate, transportation availability, employment status, individual patient responsibility, and so forth).”

Now, with ACOs, a hospital or healthcare system can manage patient risk with a potential financial gain—if they manage it well. The government shifts the episodic cost of care to an ACO, charges it with achieving health outcome metrics, and allows it to reap the reward of doing so in a cost-effective manner. More risk equals more reward, potentially. But to affect positive change in patient outcomes (e.g. health) in this manner requires acknowledging such external determinants. Hospitals, hospitalists, and physician leaders must seriously consider health determinants and how they impact patients if they are going to adequately address population health.

David Nash, MD, MBA, founding dean of the Jefferson College of Population Health at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia, sees the ACA as the major driver of population health, with the payment structure moving from a world of volume to one of value.

“It’s all about demonstrating an improvement in the population’s health,” he says.

In January 2015, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Secretary Sylvia Mathews Burwell announced that by 2018, 50 cents of every Medicare dollar will be attached to some measure of outcome.2

“So this move, from volume to value, will be the underpinning of the entire population health movement,” Dr. Nash says, “and we will be rewarded based on an improvement in a population’s health, instead of rewards for using resources on a per person basis.”

What’s a Hospitalist to Do?

Hospitalists typically are focused on inpatient care, managing a patient stay and coordinating discharge. Population health is an area, experts say, where hospitalists can extend their expertise in patient care and take a leadership role beyond the hospital.

“Hospitalists need to be aware of population health, embrace it, and help to develop structures within their programs that allow them to more closely partner with social services and case managers,” Dr. Fitterman says. “[You can] coordinate this type of care.”

Listen to more of our interview with Dr. Fitterman.

Dr. Lenchus agrees, noting that hospitalists intersect with population health most at discharge.

“The time point during which we must reconcile our discharge plan with the realities of the patient’s everyday life,” he says. “As we encourage an increasingly active lifestyle, we must pause to ascertain whether or not the patient lives in a neighborhood that is safe for outdoor activity.

As better nutrition is suggested, we must understand that the cost of a meal at a fast food chain is likely cheaper than one at a health food store. And, when arranging for a follow-up appointment, we must account for the bus schedule if a patient depends on that mode of transportation, as well as the potential to be released from work if employed.

“All of these external health determinants play a significant role in patients’ ability to adhere to instructions. Failure to [consider them in the discharge plan] will inevitably result in worsened health outcomes for the patient, and possibly hospital readmission.”

Hospitalists should be aware of the community-based organizations and services that exist, maintaining a working knowledge of who can provide volunteers, aid, food, and clothing to patients in need.

“Hospitalists should help lead or coordinate efforts to catalog these services in a community in which we practice, so we can steer patients toward these facilities,” Dr. Fitterman says. “In the past, we would treat acute medical issues and walk away. Now we need to be involved in patients’ needs, and those of their families.”

Establish a Team

A team-based approach is key to improving patient outcomes upon discharge, Dr. Lenchus says. Hospitalists should interact with social workers and case managers in anticipation of discharge; include the pharmacist in discharge medication counseling sessions. Are there relevant pharmaceutical industry-sponsored programs that can help the patient obtain prescription medications? Does the patient already qualify for some assistance? If the patient is insured, is the medication being prescribed on the formulary, or can it be modified so that it is covered? Could a generic version be prescribed? Does the patient understand the reason for hospitalization, have a follow-up appointment, and know how to take his medications?

Dr. Nash sees physicians as the team captains; physicians know how the system works, because they see it up close every day. The team includes key personnel, such as nurse practitioners, physician assistants, pharmacists, patient navigators, social workers, and patient educators.

“A physician, who might be a hospitalist, ideally will have additional training in both leadership and in population health,” Dr. Nash says.

He also encourages hospitalists to become patient advocates and educators, even though this is not their traditional role.

“They can do a lot to help a hospitalized patient face their challenges,” he says. “Encourage patients to stop smoking, go on a diet, and exercise. When a physician engages in this conversation, it aids in a patient’s ability to tackle challenges.”

For hospitalists who already feel overstretched with demands and overwhelmed with taking on the task of managing population health, Dr. McPherson suggests they learn more about the trend by studying it as part of their continuing education requirements. In addition, many hospitals have a department dedicated to patient safety or quality assurance.

“Ask how they can help the hospital to provide better patient care,” Dr. McPherson says. “Ask patients about their concerns or those of their neighbors. You may start to see trends.”

For example, if you suspect a trend of children who live in a certain housing development having difficulty breathing, try to find out if other hospital units are aware of this. Also try to ascertain whether or not any community groups connected to the hospital are already working to make the housing safer.

Population Health Challenges

The transition to being accountable for the health of a population will most likely be challenging for all providers. It involves significant risk, especially during the transition period, when an organization must live in both worlds (fee-for-service and value-based payment), says Damore, Premier’s vice president of population health management. He says it also requires:

- Enlightened and supportive leadership;

- Information technology to analyze claims and other infrastructure;

- New care management programs to coordinate care across the continuum;

- Agreements that align payment with population health management; and

- Skills and ability to transform a culture to a new value-based model.

To overcome the challenge of incorporating population health, Dr. McPherson suggests hospitals look to their large network of peers and learn from those already doing this, rather than reinventing the wheel. Look for champions to spearhead such initiatives.

“Identify folks who are already oriented in this direction and took steps in this vein,” she says.

Time and money are potential concerns, especially if embarking on a population health initiative will be an additional expense.

“A potential solution would be to look at ways to shift the focus, so that population health becomes integral to proper patient care, from promoting health and well-being to treating illness,” Dr. McPherson says. For example, by minimizing environmentally associated risks, hospitalists might be able to decrease the number of admissions, which will result in a return on your investment and improve population health.

Population health is here to stay, as payment models shift from fee-for-service to the value-based model. Hospitalists should embrace the movement and spearhead initiatives to get others on board. A hospital-wide team approach is advised. And, to save time and money, seek guidance from others who have already been successful. TH

Karen Appold is a medical writer in Pennsylvania.

References

1. Kindig D, Stoddart G. What is population health? Am J Public Health. 2003:93(3):380-383. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.93.3.380

2. Mathews Burwell S. Progress towards achieving better care, smarter spending, healthier people. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services website. January 26, 2015. Available at: http://www.hhs.gov/blog/2015/01/26/progress-towards-better-care-smarter-spending-healthier-people.html. Accessed November 8, 2015.

Population health focuses on the specific health needs of an individual within a defined population.

“In order to truly measure a patient’s health outcomes and identify best practices, providers must evaluate a group of people with similar health needs,” explains Joseph Damore, vice president of population health management for Charlotte-N.C.-based Premier, Inc. “Once we understand a population’s outcomes, we can then target the individual.”

Fundamentally, population health is about individualized care and intervening earlier in order to get a better outcome based on what generally works for the population. It’s also about identifying populations that need specific, targeted care, such as diabetic and oncology patients.

Back in 2003, David A. Kindig MD, PhD, and Greg Stoddart, PhD, defined population health as “the health outcomes of a group of individuals, including the distribution of such outcomes within the group.”1

In order to achieve population health, according to Nick Fitterman, MD, SFHM, vice chair of hospital medicine for the Hofstra North Shore-LIJ School of Medicine in Hempstead, N.Y., “it is necessary to reduce health inequities or disparities among different populations due to, among other factors, the social determinants of health, which include social, environmental, cultural, and physical factors.”

Even though the concept of population health emerged more than 25 years ago, Dr. Fitterman points out that, until recently, the U.S. healthcare system has looked at an individual’s episodic illness rather than at population health, which focuses on wellness, prevention, and coordinated care across the continuum.

Marianne McPherson, PhD, MS, senior director of programs, research, and evaluation for the National Institute for Children’s Health Quality in Boston, says it is important for hospitalists to focus on both the patient and the population.

“You need to understand the particular factors facing the patient in front of you and understand that that individual is a product of a variety of different circumstances,” she says. “If you only look at an individual’s health, you can miss important trends across a group of patients within a population or community.

“By looking at both the individual and entire population, you can provide the most effective healthcare and health promotion.”

Government Spearheads Initiatives

With passage of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) of 2010, the U.S. government helped accelerate the movement toward population health. According to Joshua D. Lenchus, DO, RPh, FACP, SFHM, a veteran hospitalist, president of Jackson Health System Medical Staff, and associate professor of clinical medicine and anesthesiology at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, the act’s provisions aim to improve the quality of care and create accountable care organizations (ACOs).

“The idea was to provide patients with insurance coverage, which would improve the access to care of which they were previously deprived,” he says. “With better access, they may receive quality healthcare and the identification and mitigation of disease at an early stage, thereby reducing overall healthcare costs, with the commensurate benefit of a healthy patient population.

“Of course, this is fraught with naïveté, because it explicitly dismisses nonmedical health determinants (i.e., socioeconomic status, education, literacy rate, transportation availability, employment status, individual patient responsibility, and so forth).”

Now, with ACOs, a hospital or healthcare system can manage patient risk with a potential financial gain—if they manage it well. The government shifts the episodic cost of care to an ACO, charges it with achieving health outcome metrics, and allows it to reap the reward of doing so in a cost-effective manner. More risk equals more reward, potentially. But to affect positive change in patient outcomes (e.g. health) in this manner requires acknowledging such external determinants. Hospitals, hospitalists, and physician leaders must seriously consider health determinants and how they impact patients if they are going to adequately address population health.

David Nash, MD, MBA, founding dean of the Jefferson College of Population Health at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia, sees the ACA as the major driver of population health, with the payment structure moving from a world of volume to one of value.

“It’s all about demonstrating an improvement in the population’s health,” he says.

In January 2015, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Secretary Sylvia Mathews Burwell announced that by 2018, 50 cents of every Medicare dollar will be attached to some measure of outcome.2

“So this move, from volume to value, will be the underpinning of the entire population health movement,” Dr. Nash says, “and we will be rewarded based on an improvement in a population’s health, instead of rewards for using resources on a per person basis.”

What’s a Hospitalist to Do?

Hospitalists typically are focused on inpatient care, managing a patient stay and coordinating discharge. Population health is an area, experts say, where hospitalists can extend their expertise in patient care and take a leadership role beyond the hospital.

“Hospitalists need to be aware of population health, embrace it, and help to develop structures within their programs that allow them to more closely partner with social services and case managers,” Dr. Fitterman says. “[You can] coordinate this type of care.”

Listen to more of our interview with Dr. Fitterman.

Dr. Lenchus agrees, noting that hospitalists intersect with population health most at discharge.

“The time point during which we must reconcile our discharge plan with the realities of the patient’s everyday life,” he says. “As we encourage an increasingly active lifestyle, we must pause to ascertain whether or not the patient lives in a neighborhood that is safe for outdoor activity.

As better nutrition is suggested, we must understand that the cost of a meal at a fast food chain is likely cheaper than one at a health food store. And, when arranging for a follow-up appointment, we must account for the bus schedule if a patient depends on that mode of transportation, as well as the potential to be released from work if employed.

“All of these external health determinants play a significant role in patients’ ability to adhere to instructions. Failure to [consider them in the discharge plan] will inevitably result in worsened health outcomes for the patient, and possibly hospital readmission.”

Hospitalists should be aware of the community-based organizations and services that exist, maintaining a working knowledge of who can provide volunteers, aid, food, and clothing to patients in need.

“Hospitalists should help lead or coordinate efforts to catalog these services in a community in which we practice, so we can steer patients toward these facilities,” Dr. Fitterman says. “In the past, we would treat acute medical issues and walk away. Now we need to be involved in patients’ needs, and those of their families.”

Establish a Team

A team-based approach is key to improving patient outcomes upon discharge, Dr. Lenchus says. Hospitalists should interact with social workers and case managers in anticipation of discharge; include the pharmacist in discharge medication counseling sessions. Are there relevant pharmaceutical industry-sponsored programs that can help the patient obtain prescription medications? Does the patient already qualify for some assistance? If the patient is insured, is the medication being prescribed on the formulary, or can it be modified so that it is covered? Could a generic version be prescribed? Does the patient understand the reason for hospitalization, have a follow-up appointment, and know how to take his medications?

Dr. Nash sees physicians as the team captains; physicians know how the system works, because they see it up close every day. The team includes key personnel, such as nurse practitioners, physician assistants, pharmacists, patient navigators, social workers, and patient educators.

“A physician, who might be a hospitalist, ideally will have additional training in both leadership and in population health,” Dr. Nash says.

He also encourages hospitalists to become patient advocates and educators, even though this is not their traditional role.

“They can do a lot to help a hospitalized patient face their challenges,” he says. “Encourage patients to stop smoking, go on a diet, and exercise. When a physician engages in this conversation, it aids in a patient’s ability to tackle challenges.”

For hospitalists who already feel overstretched with demands and overwhelmed with taking on the task of managing population health, Dr. McPherson suggests they learn more about the trend by studying it as part of their continuing education requirements. In addition, many hospitals have a department dedicated to patient safety or quality assurance.

“Ask how they can help the hospital to provide better patient care,” Dr. McPherson says. “Ask patients about their concerns or those of their neighbors. You may start to see trends.”

For example, if you suspect a trend of children who live in a certain housing development having difficulty breathing, try to find out if other hospital units are aware of this. Also try to ascertain whether or not any community groups connected to the hospital are already working to make the housing safer.

Population Health Challenges

The transition to being accountable for the health of a population will most likely be challenging for all providers. It involves significant risk, especially during the transition period, when an organization must live in both worlds (fee-for-service and value-based payment), says Damore, Premier’s vice president of population health management. He says it also requires:

- Enlightened and supportive leadership;

- Information technology to analyze claims and other infrastructure;

- New care management programs to coordinate care across the continuum;

- Agreements that align payment with population health management; and

- Skills and ability to transform a culture to a new value-based model.

To overcome the challenge of incorporating population health, Dr. McPherson suggests hospitals look to their large network of peers and learn from those already doing this, rather than reinventing the wheel. Look for champions to spearhead such initiatives.

“Identify folks who are already oriented in this direction and took steps in this vein,” she says.

Time and money are potential concerns, especially if embarking on a population health initiative will be an additional expense.

“A potential solution would be to look at ways to shift the focus, so that population health becomes integral to proper patient care, from promoting health and well-being to treating illness,” Dr. McPherson says. For example, by minimizing environmentally associated risks, hospitalists might be able to decrease the number of admissions, which will result in a return on your investment and improve population health.

Population health is here to stay, as payment models shift from fee-for-service to the value-based model. Hospitalists should embrace the movement and spearhead initiatives to get others on board. A hospital-wide team approach is advised. And, to save time and money, seek guidance from others who have already been successful. TH

Karen Appold is a medical writer in Pennsylvania.

References

1. Kindig D, Stoddart G. What is population health? Am J Public Health. 2003:93(3):380-383. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.93.3.380

2. Mathews Burwell S. Progress towards achieving better care, smarter spending, healthier people. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services website. January 26, 2015. Available at: http://www.hhs.gov/blog/2015/01/26/progress-towards-better-care-smarter-spending-healthier-people.html. Accessed November 8, 2015.

Population health focuses on the specific health needs of an individual within a defined population.

“In order to truly measure a patient’s health outcomes and identify best practices, providers must evaluate a group of people with similar health needs,” explains Joseph Damore, vice president of population health management for Charlotte-N.C.-based Premier, Inc. “Once we understand a population’s outcomes, we can then target the individual.”

Fundamentally, population health is about individualized care and intervening earlier in order to get a better outcome based on what generally works for the population. It’s also about identifying populations that need specific, targeted care, such as diabetic and oncology patients.

Back in 2003, David A. Kindig MD, PhD, and Greg Stoddart, PhD, defined population health as “the health outcomes of a group of individuals, including the distribution of such outcomes within the group.”1

In order to achieve population health, according to Nick Fitterman, MD, SFHM, vice chair of hospital medicine for the Hofstra North Shore-LIJ School of Medicine in Hempstead, N.Y., “it is necessary to reduce health inequities or disparities among different populations due to, among other factors, the social determinants of health, which include social, environmental, cultural, and physical factors.”

Even though the concept of population health emerged more than 25 years ago, Dr. Fitterman points out that, until recently, the U.S. healthcare system has looked at an individual’s episodic illness rather than at population health, which focuses on wellness, prevention, and coordinated care across the continuum.

Marianne McPherson, PhD, MS, senior director of programs, research, and evaluation for the National Institute for Children’s Health Quality in Boston, says it is important for hospitalists to focus on both the patient and the population.

“You need to understand the particular factors facing the patient in front of you and understand that that individual is a product of a variety of different circumstances,” she says. “If you only look at an individual’s health, you can miss important trends across a group of patients within a population or community.

“By looking at both the individual and entire population, you can provide the most effective healthcare and health promotion.”

Government Spearheads Initiatives

With passage of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) of 2010, the U.S. government helped accelerate the movement toward population health. According to Joshua D. Lenchus, DO, RPh, FACP, SFHM, a veteran hospitalist, president of Jackson Health System Medical Staff, and associate professor of clinical medicine and anesthesiology at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, the act’s provisions aim to improve the quality of care and create accountable care organizations (ACOs).

“The idea was to provide patients with insurance coverage, which would improve the access to care of which they were previously deprived,” he says. “With better access, they may receive quality healthcare and the identification and mitigation of disease at an early stage, thereby reducing overall healthcare costs, with the commensurate benefit of a healthy patient population.

“Of course, this is fraught with naïveté, because it explicitly dismisses nonmedical health determinants (i.e., socioeconomic status, education, literacy rate, transportation availability, employment status, individual patient responsibility, and so forth).”

Now, with ACOs, a hospital or healthcare system can manage patient risk with a potential financial gain—if they manage it well. The government shifts the episodic cost of care to an ACO, charges it with achieving health outcome metrics, and allows it to reap the reward of doing so in a cost-effective manner. More risk equals more reward, potentially. But to affect positive change in patient outcomes (e.g. health) in this manner requires acknowledging such external determinants. Hospitals, hospitalists, and physician leaders must seriously consider health determinants and how they impact patients if they are going to adequately address population health.

David Nash, MD, MBA, founding dean of the Jefferson College of Population Health at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia, sees the ACA as the major driver of population health, with the payment structure moving from a world of volume to one of value.

“It’s all about demonstrating an improvement in the population’s health,” he says.

In January 2015, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Secretary Sylvia Mathews Burwell announced that by 2018, 50 cents of every Medicare dollar will be attached to some measure of outcome.2

“So this move, from volume to value, will be the underpinning of the entire population health movement,” Dr. Nash says, “and we will be rewarded based on an improvement in a population’s health, instead of rewards for using resources on a per person basis.”

What’s a Hospitalist to Do?

Hospitalists typically are focused on inpatient care, managing a patient stay and coordinating discharge. Population health is an area, experts say, where hospitalists can extend their expertise in patient care and take a leadership role beyond the hospital.

“Hospitalists need to be aware of population health, embrace it, and help to develop structures within their programs that allow them to more closely partner with social services and case managers,” Dr. Fitterman says. “[You can] coordinate this type of care.”

Listen to more of our interview with Dr. Fitterman.

Dr. Lenchus agrees, noting that hospitalists intersect with population health most at discharge.

“The time point during which we must reconcile our discharge plan with the realities of the patient’s everyday life,” he says. “As we encourage an increasingly active lifestyle, we must pause to ascertain whether or not the patient lives in a neighborhood that is safe for outdoor activity.

As better nutrition is suggested, we must understand that the cost of a meal at a fast food chain is likely cheaper than one at a health food store. And, when arranging for a follow-up appointment, we must account for the bus schedule if a patient depends on that mode of transportation, as well as the potential to be released from work if employed.

“All of these external health determinants play a significant role in patients’ ability to adhere to instructions. Failure to [consider them in the discharge plan] will inevitably result in worsened health outcomes for the patient, and possibly hospital readmission.”

Hospitalists should be aware of the community-based organizations and services that exist, maintaining a working knowledge of who can provide volunteers, aid, food, and clothing to patients in need.

“Hospitalists should help lead or coordinate efforts to catalog these services in a community in which we practice, so we can steer patients toward these facilities,” Dr. Fitterman says. “In the past, we would treat acute medical issues and walk away. Now we need to be involved in patients’ needs, and those of their families.”

Establish a Team

A team-based approach is key to improving patient outcomes upon discharge, Dr. Lenchus says. Hospitalists should interact with social workers and case managers in anticipation of discharge; include the pharmacist in discharge medication counseling sessions. Are there relevant pharmaceutical industry-sponsored programs that can help the patient obtain prescription medications? Does the patient already qualify for some assistance? If the patient is insured, is the medication being prescribed on the formulary, or can it be modified so that it is covered? Could a generic version be prescribed? Does the patient understand the reason for hospitalization, have a follow-up appointment, and know how to take his medications?

Dr. Nash sees physicians as the team captains; physicians know how the system works, because they see it up close every day. The team includes key personnel, such as nurse practitioners, physician assistants, pharmacists, patient navigators, social workers, and patient educators.

“A physician, who might be a hospitalist, ideally will have additional training in both leadership and in population health,” Dr. Nash says.

He also encourages hospitalists to become patient advocates and educators, even though this is not their traditional role.

“They can do a lot to help a hospitalized patient face their challenges,” he says. “Encourage patients to stop smoking, go on a diet, and exercise. When a physician engages in this conversation, it aids in a patient’s ability to tackle challenges.”

For hospitalists who already feel overstretched with demands and overwhelmed with taking on the task of managing population health, Dr. McPherson suggests they learn more about the trend by studying it as part of their continuing education requirements. In addition, many hospitals have a department dedicated to patient safety or quality assurance.

“Ask how they can help the hospital to provide better patient care,” Dr. McPherson says. “Ask patients about their concerns or those of their neighbors. You may start to see trends.”

For example, if you suspect a trend of children who live in a certain housing development having difficulty breathing, try to find out if other hospital units are aware of this. Also try to ascertain whether or not any community groups connected to the hospital are already working to make the housing safer.

Population Health Challenges

The transition to being accountable for the health of a population will most likely be challenging for all providers. It involves significant risk, especially during the transition period, when an organization must live in both worlds (fee-for-service and value-based payment), says Damore, Premier’s vice president of population health management. He says it also requires:

- Enlightened and supportive leadership;

- Information technology to analyze claims and other infrastructure;

- New care management programs to coordinate care across the continuum;

- Agreements that align payment with population health management; and

- Skills and ability to transform a culture to a new value-based model.

To overcome the challenge of incorporating population health, Dr. McPherson suggests hospitals look to their large network of peers and learn from those already doing this, rather than reinventing the wheel. Look for champions to spearhead such initiatives.

“Identify folks who are already oriented in this direction and took steps in this vein,” she says.

Time and money are potential concerns, especially if embarking on a population health initiative will be an additional expense.

“A potential solution would be to look at ways to shift the focus, so that population health becomes integral to proper patient care, from promoting health and well-being to treating illness,” Dr. McPherson says. For example, by minimizing environmentally associated risks, hospitalists might be able to decrease the number of admissions, which will result in a return on your investment and improve population health.

Population health is here to stay, as payment models shift from fee-for-service to the value-based model. Hospitalists should embrace the movement and spearhead initiatives to get others on board. A hospital-wide team approach is advised. And, to save time and money, seek guidance from others who have already been successful. TH

Karen Appold is a medical writer in Pennsylvania.

References

1. Kindig D, Stoddart G. What is population health? Am J Public Health. 2003:93(3):380-383. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.93.3.380

2. Mathews Burwell S. Progress towards achieving better care, smarter spending, healthier people. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services website. January 26, 2015. Available at: http://www.hhs.gov/blog/2015/01/26/progress-towards-better-care-smarter-spending-healthier-people.html. Accessed November 8, 2015.