User login

New Therapeutic Frontiers in the Treatment of Eosinophilic Esophagitis

New Therapeutic Frontiers in the Treatment of Eosinophilic Esophagitis

Rossi CM, Santacroce G, Lenti MV, di Sabatino A. Eosinophilic esophagitis in the era of biologics. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024;18(6):271-281. doi:10.1080/17474124.2024.2374471

Dellon ES, Liacouras CA, Molina-Infante J, et al. Updated International Consensus Diagnostic Criteria for Eosinophilic Esophagitis: Proceedings of the AGREE Conference. Gastroenterology. 2018;155(4):1022-1033.e10. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2018.07.009

Geow R, Arena G, Siah C, Picardo S. A retrospective real-world study on the safety and efficacy of budesonide orodispersible tablets for the induction therapy of eosinophilic oesophagitis. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2024;17:17562848241290346. doi:10.1177/17562848241290346

Sato H, Dellon ES, Aceves SS, et al. Clinical and molecular correlates of the Index of Severity for Eosinophilic Esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2024;154(2):375-386.e4. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2024.04.025

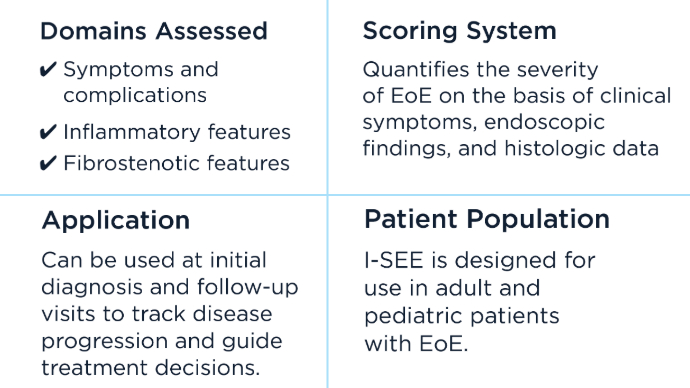

Dellon ES, Khoury P, Muir AB, et al. A Clinical Severity Index for Eosinophilic Esophagitis: Development, Consensus, and Future Directions. Gastroenterology. 2022;163(1):59-76. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2022.03.025

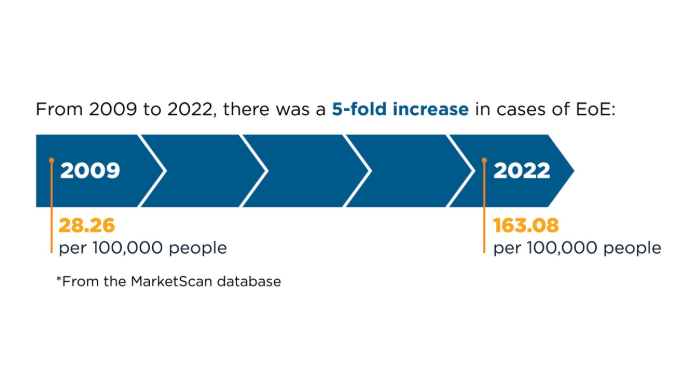

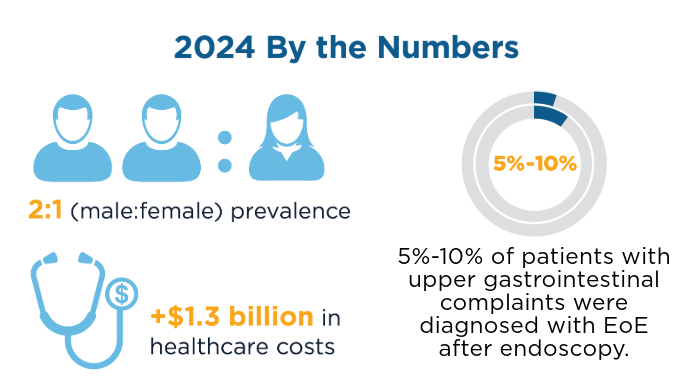

Thel HL, Anderson C, Xue AZ, Jensen ET, Dellon ES. Prevalence and Costs of Eosinophilic Esophagitis in the United States. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2025;23(2)272-280. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2024.09.031

Yang E-J, Jung KW. Role of endoscopy in eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Endosc. 2025;58(1):1-9. doi.org/10.5946/ce.2024.023

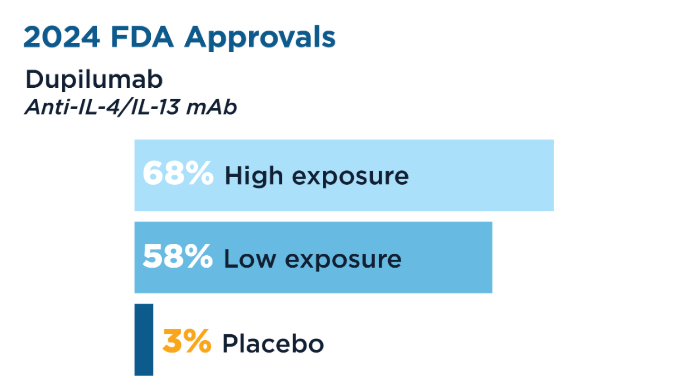

Chehade M, Dellon ES, Spergel JM, et al. Dupilumab for Eosinophilic Esophagitis in Patients 1 to 11 Years of Age. N Engl J Med. 2024;390(24):2239-2251. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2312282

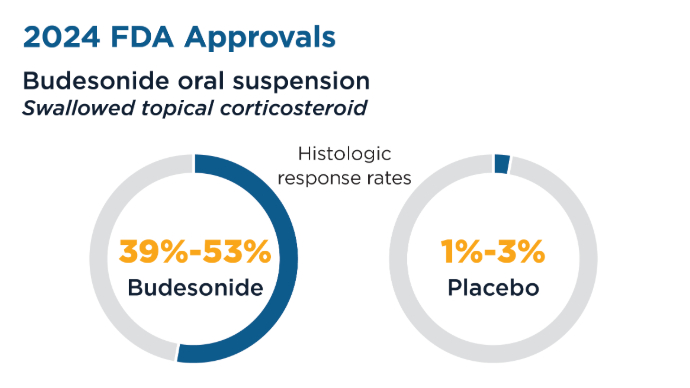

Hirano I, Collins MH, Katzka DA, et al; ORBIT1/SHP621-301 Investigators. Budesonide Oral Suspension Improves Outcomes in Patients With Eosinophilic Esophagitis: Results from a Phase 3 Trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20(3):525-534.e10. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2021.04.022

Dellon ES, Katzka DA, Collins MH, et al; MP-101-06 Investigators. Budesonide Oral Suspension Improves Symptomatic, Endoscopic, and Histologic Parameters Compared With Placebo in Patients With Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2017;152(4):776-786.e5. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2016.11.021

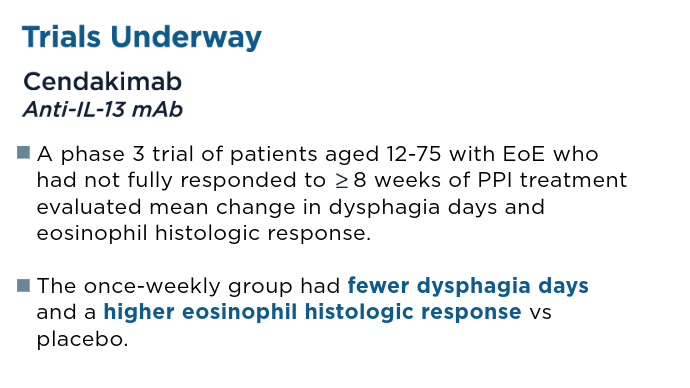

Dellon ES, Charriez CM, Zhang S, et al. Cendakimab efficacy and safety in adult and adolescent patients with eosinophilic esophagitis 48-week results from the randomized, placebo-controlled, phase 3 study (late-breaking abstract). Paper presented at: ACG 2024 Annual Scientific Meeting. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. October 25-30, 2024.

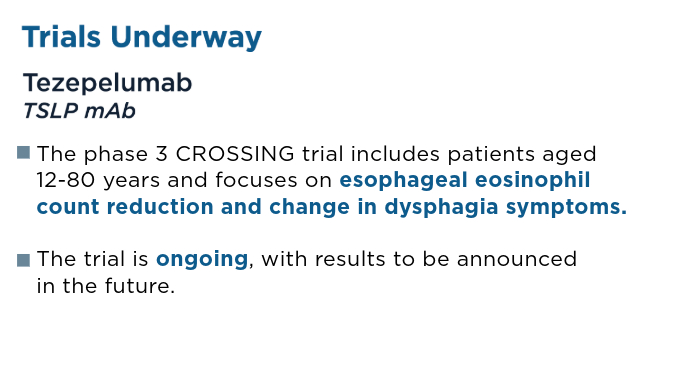

National Institutes of Health, National Library of Medicine, Cinicaltrials.gov website. Efficacy and Safety of Tezepelumab in Patients With Eosinophilic Esophagitis (CROSSING). ClinicalTrials.gov ID NCT05583227. Published December 2024. Accessed February 3, 2025. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05583227

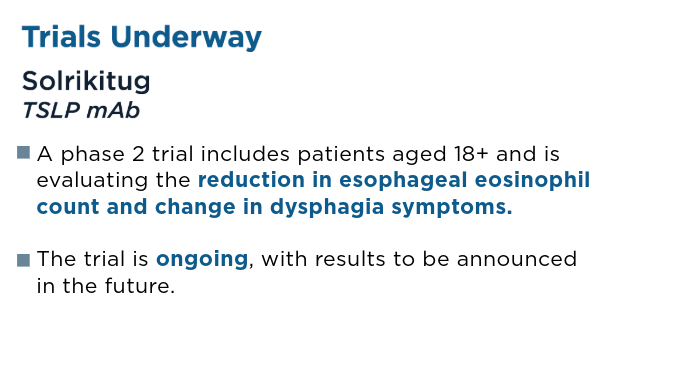

National Institutes of Health, National Library of Medicine, Cinicaltrials.gov website. A Study to Investigate the Efficacy and Safety of NSI-8226 in Adults with Eosinophilic Esophagitis. ClinicalTrials.gov ID NCT06598462. Published November 2024. Accessed February 3, 2025. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT06598462

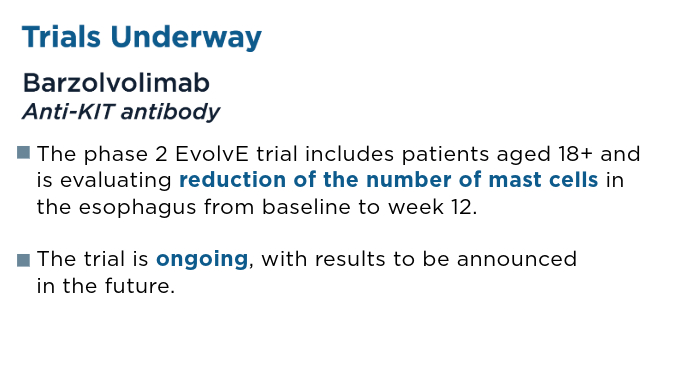

National Institutes of Health, National Library of Medicine, Cinicaltrials.gov website. A Study of CDX-0519 in Patients With Eosinophilic Esophagitis (EvolvE). ClinicalTrials.gov ID NCT05774184. Published June 2024. Accessed February 3, 2025. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05774184

Rossi CM, Santacroce G, Lenti MV, di Sabatino A. Eosinophilic esophagitis in the era of biologics. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024;18(6):271-281. doi:10.1080/17474124.2024.2374471

Dellon ES, Liacouras CA, Molina-Infante J, et al. Updated International Consensus Diagnostic Criteria for Eosinophilic Esophagitis: Proceedings of the AGREE Conference. Gastroenterology. 2018;155(4):1022-1033.e10. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2018.07.009

Geow R, Arena G, Siah C, Picardo S. A retrospective real-world study on the safety and efficacy of budesonide orodispersible tablets for the induction therapy of eosinophilic oesophagitis. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2024;17:17562848241290346. doi:10.1177/17562848241290346

Sato H, Dellon ES, Aceves SS, et al. Clinical and molecular correlates of the Index of Severity for Eosinophilic Esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2024;154(2):375-386.e4. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2024.04.025

Dellon ES, Khoury P, Muir AB, et al. A Clinical Severity Index for Eosinophilic Esophagitis: Development, Consensus, and Future Directions. Gastroenterology. 2022;163(1):59-76. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2022.03.025

Thel HL, Anderson C, Xue AZ, Jensen ET, Dellon ES. Prevalence and Costs of Eosinophilic Esophagitis in the United States. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2025;23(2)272-280. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2024.09.031

Yang E-J, Jung KW. Role of endoscopy in eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Endosc. 2025;58(1):1-9. doi.org/10.5946/ce.2024.023

Chehade M, Dellon ES, Spergel JM, et al. Dupilumab for Eosinophilic Esophagitis in Patients 1 to 11 Years of Age. N Engl J Med. 2024;390(24):2239-2251. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2312282

Hirano I, Collins MH, Katzka DA, et al; ORBIT1/SHP621-301 Investigators. Budesonide Oral Suspension Improves Outcomes in Patients With Eosinophilic Esophagitis: Results from a Phase 3 Trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20(3):525-534.e10. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2021.04.022

Dellon ES, Katzka DA, Collins MH, et al; MP-101-06 Investigators. Budesonide Oral Suspension Improves Symptomatic, Endoscopic, and Histologic Parameters Compared With Placebo in Patients With Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2017;152(4):776-786.e5. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2016.11.021

Dellon ES, Charriez CM, Zhang S, et al. Cendakimab efficacy and safety in adult and adolescent patients with eosinophilic esophagitis 48-week results from the randomized, placebo-controlled, phase 3 study (late-breaking abstract). Paper presented at: ACG 2024 Annual Scientific Meeting. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. October 25-30, 2024.

National Institutes of Health, National Library of Medicine, Cinicaltrials.gov website. Efficacy and Safety of Tezepelumab in Patients With Eosinophilic Esophagitis (CROSSING). ClinicalTrials.gov ID NCT05583227. Published December 2024. Accessed February 3, 2025. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05583227

National Institutes of Health, National Library of Medicine, Cinicaltrials.gov website. A Study to Investigate the Efficacy and Safety of NSI-8226 in Adults with Eosinophilic Esophagitis. ClinicalTrials.gov ID NCT06598462. Published November 2024. Accessed February 3, 2025. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT06598462

National Institutes of Health, National Library of Medicine, Cinicaltrials.gov website. A Study of CDX-0519 in Patients With Eosinophilic Esophagitis (EvolvE). ClinicalTrials.gov ID NCT05774184. Published June 2024. Accessed February 3, 2025. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05774184

Rossi CM, Santacroce G, Lenti MV, di Sabatino A. Eosinophilic esophagitis in the era of biologics. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024;18(6):271-281. doi:10.1080/17474124.2024.2374471

Dellon ES, Liacouras CA, Molina-Infante J, et al. Updated International Consensus Diagnostic Criteria for Eosinophilic Esophagitis: Proceedings of the AGREE Conference. Gastroenterology. 2018;155(4):1022-1033.e10. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2018.07.009

Geow R, Arena G, Siah C, Picardo S. A retrospective real-world study on the safety and efficacy of budesonide orodispersible tablets for the induction therapy of eosinophilic oesophagitis. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2024;17:17562848241290346. doi:10.1177/17562848241290346

Sato H, Dellon ES, Aceves SS, et al. Clinical and molecular correlates of the Index of Severity for Eosinophilic Esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2024;154(2):375-386.e4. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2024.04.025

Dellon ES, Khoury P, Muir AB, et al. A Clinical Severity Index for Eosinophilic Esophagitis: Development, Consensus, and Future Directions. Gastroenterology. 2022;163(1):59-76. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2022.03.025

Thel HL, Anderson C, Xue AZ, Jensen ET, Dellon ES. Prevalence and Costs of Eosinophilic Esophagitis in the United States. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2025;23(2)272-280. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2024.09.031

Yang E-J, Jung KW. Role of endoscopy in eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Endosc. 2025;58(1):1-9. doi.org/10.5946/ce.2024.023

Chehade M, Dellon ES, Spergel JM, et al. Dupilumab for Eosinophilic Esophagitis in Patients 1 to 11 Years of Age. N Engl J Med. 2024;390(24):2239-2251. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2312282

Hirano I, Collins MH, Katzka DA, et al; ORBIT1/SHP621-301 Investigators. Budesonide Oral Suspension Improves Outcomes in Patients With Eosinophilic Esophagitis: Results from a Phase 3 Trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20(3):525-534.e10. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2021.04.022

Dellon ES, Katzka DA, Collins MH, et al; MP-101-06 Investigators. Budesonide Oral Suspension Improves Symptomatic, Endoscopic, and Histologic Parameters Compared With Placebo in Patients With Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2017;152(4):776-786.e5. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2016.11.021

Dellon ES, Charriez CM, Zhang S, et al. Cendakimab efficacy and safety in adult and adolescent patients with eosinophilic esophagitis 48-week results from the randomized, placebo-controlled, phase 3 study (late-breaking abstract). Paper presented at: ACG 2024 Annual Scientific Meeting. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. October 25-30, 2024.

National Institutes of Health, National Library of Medicine, Cinicaltrials.gov website. Efficacy and Safety of Tezepelumab in Patients With Eosinophilic Esophagitis (CROSSING). ClinicalTrials.gov ID NCT05583227. Published December 2024. Accessed February 3, 2025. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05583227

National Institutes of Health, National Library of Medicine, Cinicaltrials.gov website. A Study to Investigate the Efficacy and Safety of NSI-8226 in Adults with Eosinophilic Esophagitis. ClinicalTrials.gov ID NCT06598462. Published November 2024. Accessed February 3, 2025. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT06598462

National Institutes of Health, National Library of Medicine, Cinicaltrials.gov website. A Study of CDX-0519 in Patients With Eosinophilic Esophagitis (EvolvE). ClinicalTrials.gov ID NCT05774184. Published June 2024. Accessed February 3, 2025. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05774184

New Therapeutic Frontiers in the Treatment of Eosinophilic Esophagitis

New Therapeutic Frontiers in the Treatment of Eosinophilic Esophagitis

A Practical Approach to Diagnosis and Management of Eosinophilic Esophagitis

Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) can be considered a “young” disease, with initial case series reported only about 30 years ago. Since that time, it has become a commonly encountered condition in both emergency and clinic settings. The most recent prevalence study estimates that 1 in 700 people in the U.S. have EoE,1 the volume of EoE-associated ED visits tripped between 2009 and 2019 and is projected to double again by 2030,2 and “new” gastroenterologists undoubtedly have learned about and seen this condition. As a chronic disease, EoE necessitates longitudinal follow-up and optimization of care to prevent complications. With increasing diagnostic delay, EoE progresses in most, but not all, patients from an inflammatory- to fibrostenotic-predominant condition.3

Diagnosis of EoE

The most likely area that you will encounter EoE is during an emergent middle-of-the-night endoscopy for food impaction. If called in for this, EoE will be the cause in more than 50% of patients.4 However, the diagnosis can only be made if esophageal biopsies are obtained at the time of the procedure. This is a critical time to decrease diagnostic delay, as half of patients are lost to follow-up after a food impaction.5 Unfortunately, although taking biopsies during index food impaction is guideline-recommended, a quality metric, and safe to obtain after the food bolus is cleared, this is infrequently done in practice.6, 7

The next most likely area for EoE detection is in the endoscopy suite where 15-23% of patients with dysphagia and 5-7% of patients undergoing upper endoscopy for any indication will have EoE.4 Sometimes EoE will be detected “incidentally” during an open-access case (for example, in a patient with diarrhea undergoing evaluation for celiac). In these cases, it is important to perform a careful history (as noted below) as subtle EoE symptoms can frequently be identified. Finally, when patients are seen in clinic for solid food dysphagia, EoE is clearly on the differential. A few percent of patients with refractory heartburn or chest pain will have EoE causing the symptoms rather than reflux,4 and all patients under consideration for antireflux surgery should have an endoscopy to assess for EoE.

When talking to patients with known or suspected EoE, the history must go beyond general questions about dysphagia or trouble swallowing. Many patients with EoE have overtly or subconsciously modified their eating behaviors over many years to minimize symptoms, may have adapted to chronic dysphagia, and will answer “no” when asked if they have trouble swallowing. Instead, use the acronym “IMPACT” to delve deeper into possible symptoms.8 Do they “Imbibe” fluids or liquids between each bite to help get food down? Do they “Modify” the way they eat (cut food into small bites; puree foods)? Do they “Prolong” mealtimes? Do they “Avoid” certain foods that stick? Do they “Chew’ until their food is a mush to get it down? And do they “Turn away” tablets or pills? Pill dysphagia is often a subtle symptom, and sometimes the only symptom elicited.

Additionally, it may be important to ask a partner or family member (if present) about their observations. They may provide insight (e.g. “yes – he chokes with every bite but never says it bothers him”) that the patient might not otherwise provide. The suspicion for EoE should also be increased in patients with concomitant atopic diseases and in those with a family history of dysphagia or who have family members needing esophageal dilation. It is important to remember that EoE can be seen across all ages, sexes, and races/ethnicities.

Diagnosis of EoE is based on the AGREE consensus,9 which is also echoed in the recently updated American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) guidelines.10 Diagnosis requires three steps. First, symptoms of esophageal dysfunction must be present. This will most typically be dysphagia in adolescents and adults, but symptoms are non-specific in children (e.g. poor growth and feeding, abdominal pain, vomiting, regurgitation, heartburn).

Second, at least 15 eosinophils per high-power field (eos/hpf) are required on esophageal biopsy, which implies that an endoscopy be performed. A high-quality endoscopic exam in EoE is of the utmost importance. The approach has been described elsewhere,11 but enough time on insertion should be taken to fully insufflate and examine the esophagus, including the areas of the gastroesophageal junction and upper esophageal sphincter where strictures can be missed, to gently wash debris, and to assess the endoscopic findings of EoE. Endoscopic findings should be reported using the validated EoE Endoscopy Reference Score (EREFS),12 which grades five key features. EREFS is reproducible, is responsive to treatment, and is guideline-recommended (see Figure 1).6, 10 The features are edema (present=1), rings (mild=1; moderate=2; severe=3), exudates (mild=1; severe=2), furrows (mild=1; severe=2), and stricture (present=1; also estimate diameter in mm) and are incorporated into many endoscopic reporting programs. Additionally, diffuse luminal narrowing and mucosal fragility (“crepe-paper” mucosa) should be assessed.

After this, biopsies should be obtained with at least 6 biopsy fragments from different locations in the esophagus. Any visible endoscopic abnormalities should be targeted (the highest yield is in exudates and furrows). The rationale is that EoE is patchy and at least 6 biopsies will maximize diagnostic yield.10 Ideally the initial endoscopy for EoE should be done off of treatments (like PPI or diet restriction) as these could mask the diagnosis. If a patient with suspected EoE has an endoscopy while on PPI, and the endoscopy is normal, a diagnosis of EoE cannot be made. In this case, consideration should be given as to stopping the PPI, allowing a wash out period (at least 1-2 months), and then repeating the endoscopy to confirm the diagnosis. This is important as EoE is a chronic condition necessitating life-long treatment and monitoring, so a definitive diagnosis is critical.

The third and final step in diagnosis is assessing for other conditions that could cause esophageal eosinophilia.9 The most common differential diagnosis is gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). In some cases, EoE and GERD overlap or can have a complex relationship.13 Unfortunately the location of the eosinophilia (i.e. distal only) and the level of the eosinophil counts are not useful in making this distinction, so all clinical features (symptoms, presence of erosive esophagitis, or a hiatal hernia endoscopically), and ancillary reflex testing when indicated may be required prior to a formal EoE diagnosis. After the diagnosis is established, there should be direct communication with the patient to review the diagnosis and select treatments. While it is possible to convey results electronically in a messaging portal or with a letter, a more formal interaction, such as a clinic visit, is recommended because this is a new diagnosis of a chronic condition. Similarly, a new diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease would never be made in a pathology follow-up letter alone.

Treatment of EoE

When it comes to treatment, the new guidelines emphasize several points.10 First, there is the concept that anti-inflammatory treatment should be paired with assessment of fibrostenosis and esophageal dilation; to do either in isolation is incomplete treatment. It is safe to perform dilation both prior to anti-inflammatory treatment (for example, with a critical stricture in a patient with dysphagia) and after anti-inflammatory treatment has been prescribed (for example, during an endoscopy to assess treatment response).

Second, proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), swallowed topical corticosteroids (tCS), or dietary elimination are all acceptable first-line treatment options for EoE. A shared decision-making framework should be used for this discussion. If dietary elimination is selected,14 based on new clinical trial data, guidelines recommend using empiric elimination and starting with a less restrictive diet (either a one-food elimination diet with dairy alone or a two-food elimination with dairy and wheat elimination). If PPIs are selected, the dose should be double the standard reflux dose. Data are mixed as to whether to use twice daily dosing (i.e., omeprazole 20 mg twice daily) or once a day dosing (i.e., omeprazole 40 mg daily), but total dose and adherence may be more important than frequency.10

For tCS use, either budesonide or fluticasone can be selected, but budesonide oral suspension is the only FDA-approved tCS for EoE.15 Initial treatment length is usually 6-8 weeks for diet elimination and, 12 weeks for PPI and tCS. In general, it is best to pick a single treatment to start, and reserve combining therapies for patients who do not have a complete response to a single modality as there are few data to support combination therapy.

After initial treatment, it is critical to assess for treatment response.16 Goals of EoE treatment include improvement in symptoms, but also improvement in endoscopic and histologic features to prevent complications. Symptoms in EoE do not always correlate with underlying biologic disease activity: patients can minimize symptoms with careful eating; they may perceive no difference in symptoms despite histologic improvement if a stricture persists; and they may have minimal symptoms after esophageal dilation despite ongoing inflammation. Because of this, performing a follow-up endoscopy after initial treatment is guideline-recommended.10, 17 This allows assessing for endoscopic improvement, re-assessing for fibrostenosis and performing dilation if indicated, and obtaining esophageal biopsies. If there is non-response, options include switching between other first line treatments or considering “stepping-up” to dupilumab which is also an FDA-approved option for EoE that is recommended in the guidelines.10, 18 In some cases where patients have multiple severe atopic conditions such as asthma or eczema that would warrant dupilumab use, or if patients are intolerant to PPIs or tCS, dupilumab could be considered as an earlier treatment for EoE.

Long-Term Maintenance

If a patient has a good response (for example, improved symptoms, improved endoscopic features, and <15 eos/hpf on biopsy), treatment can be maintained long-term. In almost all cases, if treatment is stopped, EoE disease activity recurs.19 Patients could be seen back in clinic in 6-12 months, and then a discussion can be conducted about a follow-up endoscopy, with timing to be determined based on their individual disease features and severity.17

Patients with more severe strictures, however, may have to be seen in endoscopy for serial dilations. Continued follow-up is essential for optimal care. Just as patients can progress in their disease course with diagnostic delay, there are data that show they can also progress after diagnosis when there are gaps in care without regular follow-up.20 Unlike other chronic esophageal disorders such as GERD and Barrett’s esophagus and other chronic GI inflammatory conditions like inflammatory bowel disease, however, EoE is not associated with an increased risk of esophageal cancer.21, 22

Given its increasing frequency, EoE will be commonly encountered by gastroenterologists both new and established. Having a systematic approach for diagnosis, understanding how to elicit subtle symptoms, implementing a shared decision-making framework for treatment with a structured algorithm for assessing response, performing follow-up, maintaining treatment, and monitoring patients long-term will allow the large majority of EoE patients to be successfully managed.

Dr. Dellon is based at the Center for Esophageal Diseases and Swallowing, Center for Gastrointestinal Biology and Disease, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, University of North Carolina School of Medicine, Chapel Hill. He disclosed research funding, consultant fees, and educational grants from multiple companies.

References

1. Thel HL, et al. Prevalence and Costs of Eosinophilic Esophagitis in the United States. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2025 Feb. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2024.09.031.

2. Lam AY, et al. Epidemiologic Burden and Projections for Eosinophilic Esophagitis-Associated Emergency Department Visits in the United States: 2009-2030. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023 Nov. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2023.04.028.

3. Schoepfer AM, et al. Delay in diagnosis of eosinophilic esophagitis increases risk for stricture formation in a time-dependent manner. Gastroenterology. 2013 Dec. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.08.015.

4. Dellon ES, Hirano I. Epidemiology and Natural History of Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2018 Jan. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.06.067.

5. Chang JW, et al. Loss to follow-up after food impaction among patients with and without eosinophilic esophagitis. Dis Esophagus. 2019 Dec. doi: 10.1093/dote/doz056.

6. Aceves SS, et al. Endoscopic approach to eosinophilic esophagitis: American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Consensus Conference. Gastrointest Endosc. 2022 Aug. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2022.05.013.

7. Leiman DA, et al. Quality Indicators for the Diagnosis and Management of Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2023 Jun. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000002138.

8. Hirano I, Furuta GT. Approaches and Challenges to Management of Pediatric and Adult Patients With Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2020 Mar. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.09.052.

9. Dellon ES, et al. Updated international consensus diagnostic criteria for eosinophilic esophagitis: Proceedings of the AGREE conference. Gastroenterology. 2018 Oct. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.07.009.

10. Dellon ES, et al. ACG Clinical Guideline: Diagnosis and Management of Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2025 Jan. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000003194.

11. Dellon ES. Optimizing the Endoscopic Examination in Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Dec. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.07.011.

12. Hirano I, et al. Endoscopic assessment of the oesophageal features of eosinophilic oesophagitis: validation of a novel classification and grading system. Gut. 2012 May. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301817.

13. Spechler SJ, et al. Thoughts on the complex relationship between gastroesophageal reflux disease and eosinophilic esophagitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007 Jun. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01179.x.

14. Chang JW, et al. Development of a Practical Guide to Implement and Monitor Diet Therapy for Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023 Jul. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2023.03.006.

15. Hirano I, et al. Budesonide Oral Suspension Improves Outcomes in Patients With Eosinophilic Esophagitis: Results from a Phase 3 Trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Mar. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.04.022.

16. Dellon ES, Gupta SK. A conceptual approach to understanding treatment response in eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 Oct. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.01.030.

17. von Arnim U, et al. Monitoring Patients With Eosinophilic Esophagitis in Routine Clinical Practice - International Expert Recommendations. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023 Sep. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.12.018.

18. Dellon ES, et al. Dupilumab in Adults and Adolescents with Eosinophilic Esophagitis. N Engl J Med. 2022 Dec. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa220598.

19. Dellon ES, et al. Rapid Recurrence of Eosinophilic Esophagitis Activity After Successful Treatment in the Observation Phase of a Randomized, Double-Blind, Double-Dummy Trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020 Jun. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.08.050.

20. Chang NC, et al. A Gap in Care Leads to Progression of Fibrosis in Eosinophilic Esophagitis Patients. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Aug. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.10.028.

21. Syed A, et al. The relationship between eosinophilic esophagitis and esophageal cancer. Dis Esophagus. 2017 Jul. doi: 10.1093/dote/dox050.

22. Albaneze N, et al. No Association Between Eosinophilic Oesophagitis and Oesophageal Cancer in US Adults: A Case-Control Study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2025 Jan. doi: 10.1111/apt.18431.

Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) can be considered a “young” disease, with initial case series reported only about 30 years ago. Since that time, it has become a commonly encountered condition in both emergency and clinic settings. The most recent prevalence study estimates that 1 in 700 people in the U.S. have EoE,1 the volume of EoE-associated ED visits tripped between 2009 and 2019 and is projected to double again by 2030,2 and “new” gastroenterologists undoubtedly have learned about and seen this condition. As a chronic disease, EoE necessitates longitudinal follow-up and optimization of care to prevent complications. With increasing diagnostic delay, EoE progresses in most, but not all, patients from an inflammatory- to fibrostenotic-predominant condition.3

Diagnosis of EoE

The most likely area that you will encounter EoE is during an emergent middle-of-the-night endoscopy for food impaction. If called in for this, EoE will be the cause in more than 50% of patients.4 However, the diagnosis can only be made if esophageal biopsies are obtained at the time of the procedure. This is a critical time to decrease diagnostic delay, as half of patients are lost to follow-up after a food impaction.5 Unfortunately, although taking biopsies during index food impaction is guideline-recommended, a quality metric, and safe to obtain after the food bolus is cleared, this is infrequently done in practice.6, 7

The next most likely area for EoE detection is in the endoscopy suite where 15-23% of patients with dysphagia and 5-7% of patients undergoing upper endoscopy for any indication will have EoE.4 Sometimes EoE will be detected “incidentally” during an open-access case (for example, in a patient with diarrhea undergoing evaluation for celiac). In these cases, it is important to perform a careful history (as noted below) as subtle EoE symptoms can frequently be identified. Finally, when patients are seen in clinic for solid food dysphagia, EoE is clearly on the differential. A few percent of patients with refractory heartburn or chest pain will have EoE causing the symptoms rather than reflux,4 and all patients under consideration for antireflux surgery should have an endoscopy to assess for EoE.

When talking to patients with known or suspected EoE, the history must go beyond general questions about dysphagia or trouble swallowing. Many patients with EoE have overtly or subconsciously modified their eating behaviors over many years to minimize symptoms, may have adapted to chronic dysphagia, and will answer “no” when asked if they have trouble swallowing. Instead, use the acronym “IMPACT” to delve deeper into possible symptoms.8 Do they “Imbibe” fluids or liquids between each bite to help get food down? Do they “Modify” the way they eat (cut food into small bites; puree foods)? Do they “Prolong” mealtimes? Do they “Avoid” certain foods that stick? Do they “Chew’ until their food is a mush to get it down? And do they “Turn away” tablets or pills? Pill dysphagia is often a subtle symptom, and sometimes the only symptom elicited.

Additionally, it may be important to ask a partner or family member (if present) about their observations. They may provide insight (e.g. “yes – he chokes with every bite but never says it bothers him”) that the patient might not otherwise provide. The suspicion for EoE should also be increased in patients with concomitant atopic diseases and in those with a family history of dysphagia or who have family members needing esophageal dilation. It is important to remember that EoE can be seen across all ages, sexes, and races/ethnicities.

Diagnosis of EoE is based on the AGREE consensus,9 which is also echoed in the recently updated American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) guidelines.10 Diagnosis requires three steps. First, symptoms of esophageal dysfunction must be present. This will most typically be dysphagia in adolescents and adults, but symptoms are non-specific in children (e.g. poor growth and feeding, abdominal pain, vomiting, regurgitation, heartburn).

Second, at least 15 eosinophils per high-power field (eos/hpf) are required on esophageal biopsy, which implies that an endoscopy be performed. A high-quality endoscopic exam in EoE is of the utmost importance. The approach has been described elsewhere,11 but enough time on insertion should be taken to fully insufflate and examine the esophagus, including the areas of the gastroesophageal junction and upper esophageal sphincter where strictures can be missed, to gently wash debris, and to assess the endoscopic findings of EoE. Endoscopic findings should be reported using the validated EoE Endoscopy Reference Score (EREFS),12 which grades five key features. EREFS is reproducible, is responsive to treatment, and is guideline-recommended (see Figure 1).6, 10 The features are edema (present=1), rings (mild=1; moderate=2; severe=3), exudates (mild=1; severe=2), furrows (mild=1; severe=2), and stricture (present=1; also estimate diameter in mm) and are incorporated into many endoscopic reporting programs. Additionally, diffuse luminal narrowing and mucosal fragility (“crepe-paper” mucosa) should be assessed.

After this, biopsies should be obtained with at least 6 biopsy fragments from different locations in the esophagus. Any visible endoscopic abnormalities should be targeted (the highest yield is in exudates and furrows). The rationale is that EoE is patchy and at least 6 biopsies will maximize diagnostic yield.10 Ideally the initial endoscopy for EoE should be done off of treatments (like PPI or diet restriction) as these could mask the diagnosis. If a patient with suspected EoE has an endoscopy while on PPI, and the endoscopy is normal, a diagnosis of EoE cannot be made. In this case, consideration should be given as to stopping the PPI, allowing a wash out period (at least 1-2 months), and then repeating the endoscopy to confirm the diagnosis. This is important as EoE is a chronic condition necessitating life-long treatment and monitoring, so a definitive diagnosis is critical.

The third and final step in diagnosis is assessing for other conditions that could cause esophageal eosinophilia.9 The most common differential diagnosis is gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). In some cases, EoE and GERD overlap or can have a complex relationship.13 Unfortunately the location of the eosinophilia (i.e. distal only) and the level of the eosinophil counts are not useful in making this distinction, so all clinical features (symptoms, presence of erosive esophagitis, or a hiatal hernia endoscopically), and ancillary reflex testing when indicated may be required prior to a formal EoE diagnosis. After the diagnosis is established, there should be direct communication with the patient to review the diagnosis and select treatments. While it is possible to convey results electronically in a messaging portal or with a letter, a more formal interaction, such as a clinic visit, is recommended because this is a new diagnosis of a chronic condition. Similarly, a new diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease would never be made in a pathology follow-up letter alone.

Treatment of EoE

When it comes to treatment, the new guidelines emphasize several points.10 First, there is the concept that anti-inflammatory treatment should be paired with assessment of fibrostenosis and esophageal dilation; to do either in isolation is incomplete treatment. It is safe to perform dilation both prior to anti-inflammatory treatment (for example, with a critical stricture in a patient with dysphagia) and after anti-inflammatory treatment has been prescribed (for example, during an endoscopy to assess treatment response).

Second, proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), swallowed topical corticosteroids (tCS), or dietary elimination are all acceptable first-line treatment options for EoE. A shared decision-making framework should be used for this discussion. If dietary elimination is selected,14 based on new clinical trial data, guidelines recommend using empiric elimination and starting with a less restrictive diet (either a one-food elimination diet with dairy alone or a two-food elimination with dairy and wheat elimination). If PPIs are selected, the dose should be double the standard reflux dose. Data are mixed as to whether to use twice daily dosing (i.e., omeprazole 20 mg twice daily) or once a day dosing (i.e., omeprazole 40 mg daily), but total dose and adherence may be more important than frequency.10

For tCS use, either budesonide or fluticasone can be selected, but budesonide oral suspension is the only FDA-approved tCS for EoE.15 Initial treatment length is usually 6-8 weeks for diet elimination and, 12 weeks for PPI and tCS. In general, it is best to pick a single treatment to start, and reserve combining therapies for patients who do not have a complete response to a single modality as there are few data to support combination therapy.

After initial treatment, it is critical to assess for treatment response.16 Goals of EoE treatment include improvement in symptoms, but also improvement in endoscopic and histologic features to prevent complications. Symptoms in EoE do not always correlate with underlying biologic disease activity: patients can minimize symptoms with careful eating; they may perceive no difference in symptoms despite histologic improvement if a stricture persists; and they may have minimal symptoms after esophageal dilation despite ongoing inflammation. Because of this, performing a follow-up endoscopy after initial treatment is guideline-recommended.10, 17 This allows assessing for endoscopic improvement, re-assessing for fibrostenosis and performing dilation if indicated, and obtaining esophageal biopsies. If there is non-response, options include switching between other first line treatments or considering “stepping-up” to dupilumab which is also an FDA-approved option for EoE that is recommended in the guidelines.10, 18 In some cases where patients have multiple severe atopic conditions such as asthma or eczema that would warrant dupilumab use, or if patients are intolerant to PPIs or tCS, dupilumab could be considered as an earlier treatment for EoE.

Long-Term Maintenance

If a patient has a good response (for example, improved symptoms, improved endoscopic features, and <15 eos/hpf on biopsy), treatment can be maintained long-term. In almost all cases, if treatment is stopped, EoE disease activity recurs.19 Patients could be seen back in clinic in 6-12 months, and then a discussion can be conducted about a follow-up endoscopy, with timing to be determined based on their individual disease features and severity.17

Patients with more severe strictures, however, may have to be seen in endoscopy for serial dilations. Continued follow-up is essential for optimal care. Just as patients can progress in their disease course with diagnostic delay, there are data that show they can also progress after diagnosis when there are gaps in care without regular follow-up.20 Unlike other chronic esophageal disorders such as GERD and Barrett’s esophagus and other chronic GI inflammatory conditions like inflammatory bowel disease, however, EoE is not associated with an increased risk of esophageal cancer.21, 22

Given its increasing frequency, EoE will be commonly encountered by gastroenterologists both new and established. Having a systematic approach for diagnosis, understanding how to elicit subtle symptoms, implementing a shared decision-making framework for treatment with a structured algorithm for assessing response, performing follow-up, maintaining treatment, and monitoring patients long-term will allow the large majority of EoE patients to be successfully managed.

Dr. Dellon is based at the Center for Esophageal Diseases and Swallowing, Center for Gastrointestinal Biology and Disease, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, University of North Carolina School of Medicine, Chapel Hill. He disclosed research funding, consultant fees, and educational grants from multiple companies.

References

1. Thel HL, et al. Prevalence and Costs of Eosinophilic Esophagitis in the United States. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2025 Feb. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2024.09.031.

2. Lam AY, et al. Epidemiologic Burden and Projections for Eosinophilic Esophagitis-Associated Emergency Department Visits in the United States: 2009-2030. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023 Nov. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2023.04.028.

3. Schoepfer AM, et al. Delay in diagnosis of eosinophilic esophagitis increases risk for stricture formation in a time-dependent manner. Gastroenterology. 2013 Dec. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.08.015.

4. Dellon ES, Hirano I. Epidemiology and Natural History of Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2018 Jan. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.06.067.

5. Chang JW, et al. Loss to follow-up after food impaction among patients with and without eosinophilic esophagitis. Dis Esophagus. 2019 Dec. doi: 10.1093/dote/doz056.

6. Aceves SS, et al. Endoscopic approach to eosinophilic esophagitis: American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Consensus Conference. Gastrointest Endosc. 2022 Aug. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2022.05.013.

7. Leiman DA, et al. Quality Indicators for the Diagnosis and Management of Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2023 Jun. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000002138.

8. Hirano I, Furuta GT. Approaches and Challenges to Management of Pediatric and Adult Patients With Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2020 Mar. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.09.052.

9. Dellon ES, et al. Updated international consensus diagnostic criteria for eosinophilic esophagitis: Proceedings of the AGREE conference. Gastroenterology. 2018 Oct. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.07.009.

10. Dellon ES, et al. ACG Clinical Guideline: Diagnosis and Management of Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2025 Jan. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000003194.

11. Dellon ES. Optimizing the Endoscopic Examination in Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Dec. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.07.011.

12. Hirano I, et al. Endoscopic assessment of the oesophageal features of eosinophilic oesophagitis: validation of a novel classification and grading system. Gut. 2012 May. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301817.

13. Spechler SJ, et al. Thoughts on the complex relationship between gastroesophageal reflux disease and eosinophilic esophagitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007 Jun. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01179.x.

14. Chang JW, et al. Development of a Practical Guide to Implement and Monitor Diet Therapy for Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023 Jul. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2023.03.006.

15. Hirano I, et al. Budesonide Oral Suspension Improves Outcomes in Patients With Eosinophilic Esophagitis: Results from a Phase 3 Trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Mar. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.04.022.

16. Dellon ES, Gupta SK. A conceptual approach to understanding treatment response in eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 Oct. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.01.030.

17. von Arnim U, et al. Monitoring Patients With Eosinophilic Esophagitis in Routine Clinical Practice - International Expert Recommendations. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023 Sep. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.12.018.

18. Dellon ES, et al. Dupilumab in Adults and Adolescents with Eosinophilic Esophagitis. N Engl J Med. 2022 Dec. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa220598.

19. Dellon ES, et al. Rapid Recurrence of Eosinophilic Esophagitis Activity After Successful Treatment in the Observation Phase of a Randomized, Double-Blind, Double-Dummy Trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020 Jun. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.08.050.

20. Chang NC, et al. A Gap in Care Leads to Progression of Fibrosis in Eosinophilic Esophagitis Patients. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Aug. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.10.028.

21. Syed A, et al. The relationship between eosinophilic esophagitis and esophageal cancer. Dis Esophagus. 2017 Jul. doi: 10.1093/dote/dox050.

22. Albaneze N, et al. No Association Between Eosinophilic Oesophagitis and Oesophageal Cancer in US Adults: A Case-Control Study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2025 Jan. doi: 10.1111/apt.18431.

Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) can be considered a “young” disease, with initial case series reported only about 30 years ago. Since that time, it has become a commonly encountered condition in both emergency and clinic settings. The most recent prevalence study estimates that 1 in 700 people in the U.S. have EoE,1 the volume of EoE-associated ED visits tripped between 2009 and 2019 and is projected to double again by 2030,2 and “new” gastroenterologists undoubtedly have learned about and seen this condition. As a chronic disease, EoE necessitates longitudinal follow-up and optimization of care to prevent complications. With increasing diagnostic delay, EoE progresses in most, but not all, patients from an inflammatory- to fibrostenotic-predominant condition.3

Diagnosis of EoE

The most likely area that you will encounter EoE is during an emergent middle-of-the-night endoscopy for food impaction. If called in for this, EoE will be the cause in more than 50% of patients.4 However, the diagnosis can only be made if esophageal biopsies are obtained at the time of the procedure. This is a critical time to decrease diagnostic delay, as half of patients are lost to follow-up after a food impaction.5 Unfortunately, although taking biopsies during index food impaction is guideline-recommended, a quality metric, and safe to obtain after the food bolus is cleared, this is infrequently done in practice.6, 7

The next most likely area for EoE detection is in the endoscopy suite where 15-23% of patients with dysphagia and 5-7% of patients undergoing upper endoscopy for any indication will have EoE.4 Sometimes EoE will be detected “incidentally” during an open-access case (for example, in a patient with diarrhea undergoing evaluation for celiac). In these cases, it is important to perform a careful history (as noted below) as subtle EoE symptoms can frequently be identified. Finally, when patients are seen in clinic for solid food dysphagia, EoE is clearly on the differential. A few percent of patients with refractory heartburn or chest pain will have EoE causing the symptoms rather than reflux,4 and all patients under consideration for antireflux surgery should have an endoscopy to assess for EoE.

When talking to patients with known or suspected EoE, the history must go beyond general questions about dysphagia or trouble swallowing. Many patients with EoE have overtly or subconsciously modified their eating behaviors over many years to minimize symptoms, may have adapted to chronic dysphagia, and will answer “no” when asked if they have trouble swallowing. Instead, use the acronym “IMPACT” to delve deeper into possible symptoms.8 Do they “Imbibe” fluids or liquids between each bite to help get food down? Do they “Modify” the way they eat (cut food into small bites; puree foods)? Do they “Prolong” mealtimes? Do they “Avoid” certain foods that stick? Do they “Chew’ until their food is a mush to get it down? And do they “Turn away” tablets or pills? Pill dysphagia is often a subtle symptom, and sometimes the only symptom elicited.

Additionally, it may be important to ask a partner or family member (if present) about their observations. They may provide insight (e.g. “yes – he chokes with every bite but never says it bothers him”) that the patient might not otherwise provide. The suspicion for EoE should also be increased in patients with concomitant atopic diseases and in those with a family history of dysphagia or who have family members needing esophageal dilation. It is important to remember that EoE can be seen across all ages, sexes, and races/ethnicities.

Diagnosis of EoE is based on the AGREE consensus,9 which is also echoed in the recently updated American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) guidelines.10 Diagnosis requires three steps. First, symptoms of esophageal dysfunction must be present. This will most typically be dysphagia in adolescents and adults, but symptoms are non-specific in children (e.g. poor growth and feeding, abdominal pain, vomiting, regurgitation, heartburn).

Second, at least 15 eosinophils per high-power field (eos/hpf) are required on esophageal biopsy, which implies that an endoscopy be performed. A high-quality endoscopic exam in EoE is of the utmost importance. The approach has been described elsewhere,11 but enough time on insertion should be taken to fully insufflate and examine the esophagus, including the areas of the gastroesophageal junction and upper esophageal sphincter where strictures can be missed, to gently wash debris, and to assess the endoscopic findings of EoE. Endoscopic findings should be reported using the validated EoE Endoscopy Reference Score (EREFS),12 which grades five key features. EREFS is reproducible, is responsive to treatment, and is guideline-recommended (see Figure 1).6, 10 The features are edema (present=1), rings (mild=1; moderate=2; severe=3), exudates (mild=1; severe=2), furrows (mild=1; severe=2), and stricture (present=1; also estimate diameter in mm) and are incorporated into many endoscopic reporting programs. Additionally, diffuse luminal narrowing and mucosal fragility (“crepe-paper” mucosa) should be assessed.

After this, biopsies should be obtained with at least 6 biopsy fragments from different locations in the esophagus. Any visible endoscopic abnormalities should be targeted (the highest yield is in exudates and furrows). The rationale is that EoE is patchy and at least 6 biopsies will maximize diagnostic yield.10 Ideally the initial endoscopy for EoE should be done off of treatments (like PPI or diet restriction) as these could mask the diagnosis. If a patient with suspected EoE has an endoscopy while on PPI, and the endoscopy is normal, a diagnosis of EoE cannot be made. In this case, consideration should be given as to stopping the PPI, allowing a wash out period (at least 1-2 months), and then repeating the endoscopy to confirm the diagnosis. This is important as EoE is a chronic condition necessitating life-long treatment and monitoring, so a definitive diagnosis is critical.

The third and final step in diagnosis is assessing for other conditions that could cause esophageal eosinophilia.9 The most common differential diagnosis is gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). In some cases, EoE and GERD overlap or can have a complex relationship.13 Unfortunately the location of the eosinophilia (i.e. distal only) and the level of the eosinophil counts are not useful in making this distinction, so all clinical features (symptoms, presence of erosive esophagitis, or a hiatal hernia endoscopically), and ancillary reflex testing when indicated may be required prior to a formal EoE diagnosis. After the diagnosis is established, there should be direct communication with the patient to review the diagnosis and select treatments. While it is possible to convey results electronically in a messaging portal or with a letter, a more formal interaction, such as a clinic visit, is recommended because this is a new diagnosis of a chronic condition. Similarly, a new diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease would never be made in a pathology follow-up letter alone.

Treatment of EoE

When it comes to treatment, the new guidelines emphasize several points.10 First, there is the concept that anti-inflammatory treatment should be paired with assessment of fibrostenosis and esophageal dilation; to do either in isolation is incomplete treatment. It is safe to perform dilation both prior to anti-inflammatory treatment (for example, with a critical stricture in a patient with dysphagia) and after anti-inflammatory treatment has been prescribed (for example, during an endoscopy to assess treatment response).

Second, proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), swallowed topical corticosteroids (tCS), or dietary elimination are all acceptable first-line treatment options for EoE. A shared decision-making framework should be used for this discussion. If dietary elimination is selected,14 based on new clinical trial data, guidelines recommend using empiric elimination and starting with a less restrictive diet (either a one-food elimination diet with dairy alone or a two-food elimination with dairy and wheat elimination). If PPIs are selected, the dose should be double the standard reflux dose. Data are mixed as to whether to use twice daily dosing (i.e., omeprazole 20 mg twice daily) or once a day dosing (i.e., omeprazole 40 mg daily), but total dose and adherence may be more important than frequency.10

For tCS use, either budesonide or fluticasone can be selected, but budesonide oral suspension is the only FDA-approved tCS for EoE.15 Initial treatment length is usually 6-8 weeks for diet elimination and, 12 weeks for PPI and tCS. In general, it is best to pick a single treatment to start, and reserve combining therapies for patients who do not have a complete response to a single modality as there are few data to support combination therapy.

After initial treatment, it is critical to assess for treatment response.16 Goals of EoE treatment include improvement in symptoms, but also improvement in endoscopic and histologic features to prevent complications. Symptoms in EoE do not always correlate with underlying biologic disease activity: patients can minimize symptoms with careful eating; they may perceive no difference in symptoms despite histologic improvement if a stricture persists; and they may have minimal symptoms after esophageal dilation despite ongoing inflammation. Because of this, performing a follow-up endoscopy after initial treatment is guideline-recommended.10, 17 This allows assessing for endoscopic improvement, re-assessing for fibrostenosis and performing dilation if indicated, and obtaining esophageal biopsies. If there is non-response, options include switching between other first line treatments or considering “stepping-up” to dupilumab which is also an FDA-approved option for EoE that is recommended in the guidelines.10, 18 In some cases where patients have multiple severe atopic conditions such as asthma or eczema that would warrant dupilumab use, or if patients are intolerant to PPIs or tCS, dupilumab could be considered as an earlier treatment for EoE.

Long-Term Maintenance

If a patient has a good response (for example, improved symptoms, improved endoscopic features, and <15 eos/hpf on biopsy), treatment can be maintained long-term. In almost all cases, if treatment is stopped, EoE disease activity recurs.19 Patients could be seen back in clinic in 6-12 months, and then a discussion can be conducted about a follow-up endoscopy, with timing to be determined based on their individual disease features and severity.17

Patients with more severe strictures, however, may have to be seen in endoscopy for serial dilations. Continued follow-up is essential for optimal care. Just as patients can progress in their disease course with diagnostic delay, there are data that show they can also progress after diagnosis when there are gaps in care without regular follow-up.20 Unlike other chronic esophageal disorders such as GERD and Barrett’s esophagus and other chronic GI inflammatory conditions like inflammatory bowel disease, however, EoE is not associated with an increased risk of esophageal cancer.21, 22

Given its increasing frequency, EoE will be commonly encountered by gastroenterologists both new and established. Having a systematic approach for diagnosis, understanding how to elicit subtle symptoms, implementing a shared decision-making framework for treatment with a structured algorithm for assessing response, performing follow-up, maintaining treatment, and monitoring patients long-term will allow the large majority of EoE patients to be successfully managed.

Dr. Dellon is based at the Center for Esophageal Diseases and Swallowing, Center for Gastrointestinal Biology and Disease, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, University of North Carolina School of Medicine, Chapel Hill. He disclosed research funding, consultant fees, and educational grants from multiple companies.

References

1. Thel HL, et al. Prevalence and Costs of Eosinophilic Esophagitis in the United States. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2025 Feb. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2024.09.031.

2. Lam AY, et al. Epidemiologic Burden and Projections for Eosinophilic Esophagitis-Associated Emergency Department Visits in the United States: 2009-2030. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023 Nov. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2023.04.028.

3. Schoepfer AM, et al. Delay in diagnosis of eosinophilic esophagitis increases risk for stricture formation in a time-dependent manner. Gastroenterology. 2013 Dec. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.08.015.

4. Dellon ES, Hirano I. Epidemiology and Natural History of Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2018 Jan. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.06.067.

5. Chang JW, et al. Loss to follow-up after food impaction among patients with and without eosinophilic esophagitis. Dis Esophagus. 2019 Dec. doi: 10.1093/dote/doz056.

6. Aceves SS, et al. Endoscopic approach to eosinophilic esophagitis: American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Consensus Conference. Gastrointest Endosc. 2022 Aug. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2022.05.013.

7. Leiman DA, et al. Quality Indicators for the Diagnosis and Management of Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2023 Jun. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000002138.

8. Hirano I, Furuta GT. Approaches and Challenges to Management of Pediatric and Adult Patients With Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2020 Mar. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.09.052.

9. Dellon ES, et al. Updated international consensus diagnostic criteria for eosinophilic esophagitis: Proceedings of the AGREE conference. Gastroenterology. 2018 Oct. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.07.009.

10. Dellon ES, et al. ACG Clinical Guideline: Diagnosis and Management of Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2025 Jan. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000003194.

11. Dellon ES. Optimizing the Endoscopic Examination in Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Dec. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.07.011.

12. Hirano I, et al. Endoscopic assessment of the oesophageal features of eosinophilic oesophagitis: validation of a novel classification and grading system. Gut. 2012 May. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301817.

13. Spechler SJ, et al. Thoughts on the complex relationship between gastroesophageal reflux disease and eosinophilic esophagitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007 Jun. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01179.x.

14. Chang JW, et al. Development of a Practical Guide to Implement and Monitor Diet Therapy for Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023 Jul. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2023.03.006.

15. Hirano I, et al. Budesonide Oral Suspension Improves Outcomes in Patients With Eosinophilic Esophagitis: Results from a Phase 3 Trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Mar. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.04.022.

16. Dellon ES, Gupta SK. A conceptual approach to understanding treatment response in eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 Oct. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.01.030.

17. von Arnim U, et al. Monitoring Patients With Eosinophilic Esophagitis in Routine Clinical Practice - International Expert Recommendations. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023 Sep. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.12.018.

18. Dellon ES, et al. Dupilumab in Adults and Adolescents with Eosinophilic Esophagitis. N Engl J Med. 2022 Dec. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa220598.

19. Dellon ES, et al. Rapid Recurrence of Eosinophilic Esophagitis Activity After Successful Treatment in the Observation Phase of a Randomized, Double-Blind, Double-Dummy Trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020 Jun. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.08.050.

20. Chang NC, et al. A Gap in Care Leads to Progression of Fibrosis in Eosinophilic Esophagitis Patients. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Aug. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.10.028.

21. Syed A, et al. The relationship between eosinophilic esophagitis and esophageal cancer. Dis Esophagus. 2017 Jul. doi: 10.1093/dote/dox050.

22. Albaneze N, et al. No Association Between Eosinophilic Oesophagitis and Oesophageal Cancer in US Adults: A Case-Control Study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2025 Jan. doi: 10.1111/apt.18431.

Patient-reported outcomes in esophageal diseases

In my introductory comments to the practice management section last year, I wrote about cultivating competencies for value-based care. One of the key competencies was patient centeredness. Patient-reported outcomes (PROs) and patient experience measures specifically were highlighted as examples of meaningful tools for achieving patient centeredness. Starting with this month’s contribution by Drs Reed and Dellon on PROs in esophageal disease, we begin a series of articles focused on this important construct. We will follow this article with reports focused on PRO for patients with irritable bowel syndrome, inflammatory bowel disease, and chronic liver disease. These reports will not only review the importance of PROs, but also highlight the most practical approaches to measuring disease-specific PROs in clinical practice all with the goal of improving the care of our patients.

Ziad Gellad, MD, MPH, AGAF, Special Section Editor

Patients seek medical care for symptoms affecting their quality of life,1 and this is particularly true of digestive diseases, in which many common conditions are symptom predominant. However, clinician and patient perception of symptoms often conflict,2 and formalized measurement tools may have a role for optimizing symptom assessment. Patient-reported outcomes (PROs) directly capture patients’ health status from their own perspectives and can bridge the divide between patient and provider interpretation. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) defines PROs as “any report of the status of a patient’s health condition that comes directly from the patient without interpretation of the patient’s response by a clinician or anyone else.”3

For the clinical assessment of esophageal diseases, existing physiologic and structural testing modalities cannot ascertain patient disease perception or measure the impact of symptoms on health care–associated quality of life. In contrast, by capturing patient-centric data, PROs can provide insight into the psychosocial aspects of patient disease perceptions; capture health-related quality of life (HRQL); improve provider understanding; highlight discordance between physiologic, symptom, and HRQL measures; and formalize follow-up evaluation of treatment response.1,4 Following up symptoms such as dysphagia or heartburn over time in a structured way allows clinically obtained data to be used in pragmatic or comparative effectiveness studies. PROs are now an integral part of the FDA’s drug approval process.

In this article, we review the available PROs capturing esophageal symptoms with a focus on dysphagia and heartburn measures that were developed with rigorous methodology; it is beyond the scope of this article to perform a thorough review of all upper gastrointestinal (GI) PROs or quality-of-life PROs. We then discuss how esophageal PROs may be incorporated into clinical practice now, as well as opportunities for PRO use in the future.

Esophageal symptom-specific patient-reported outcomes

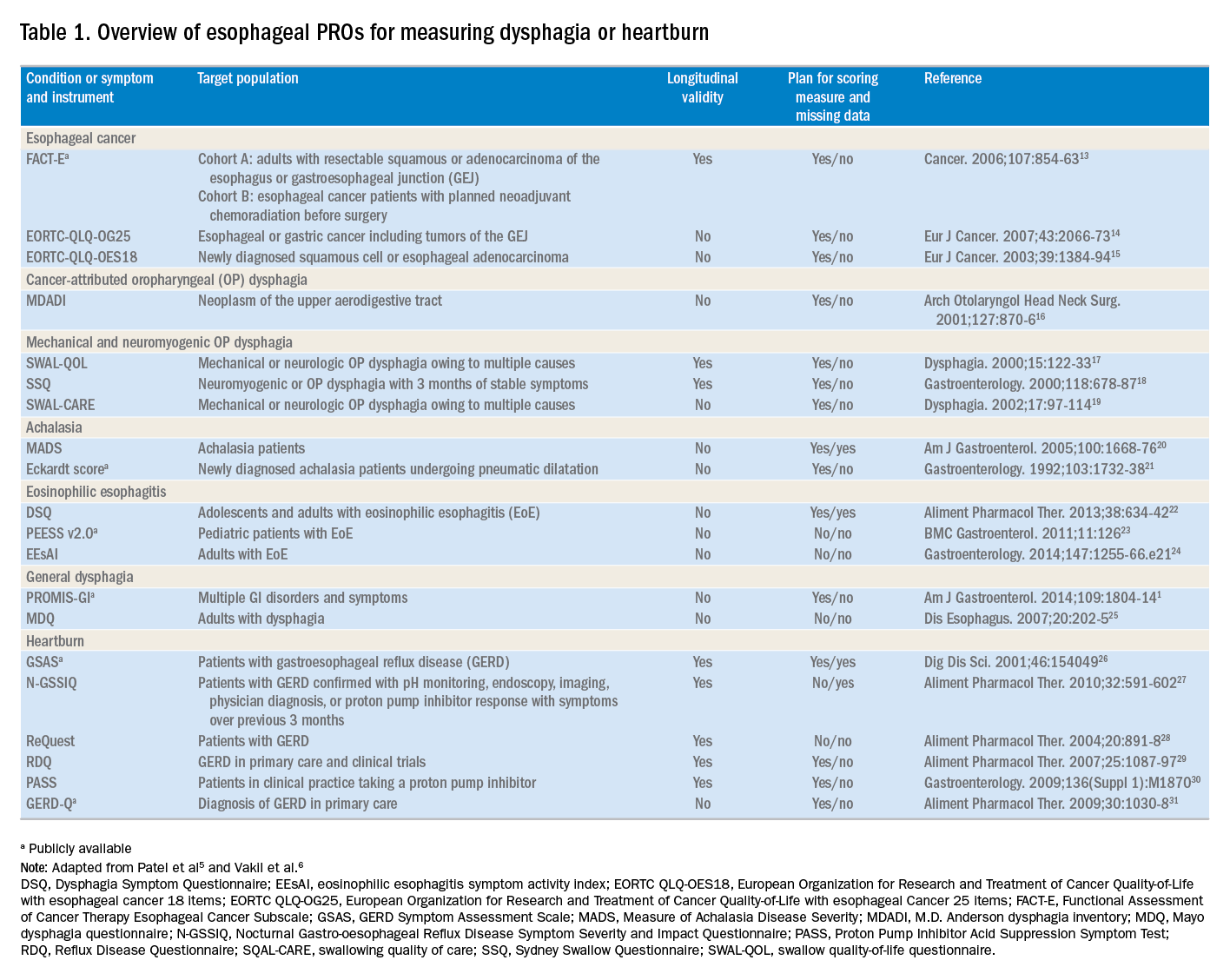

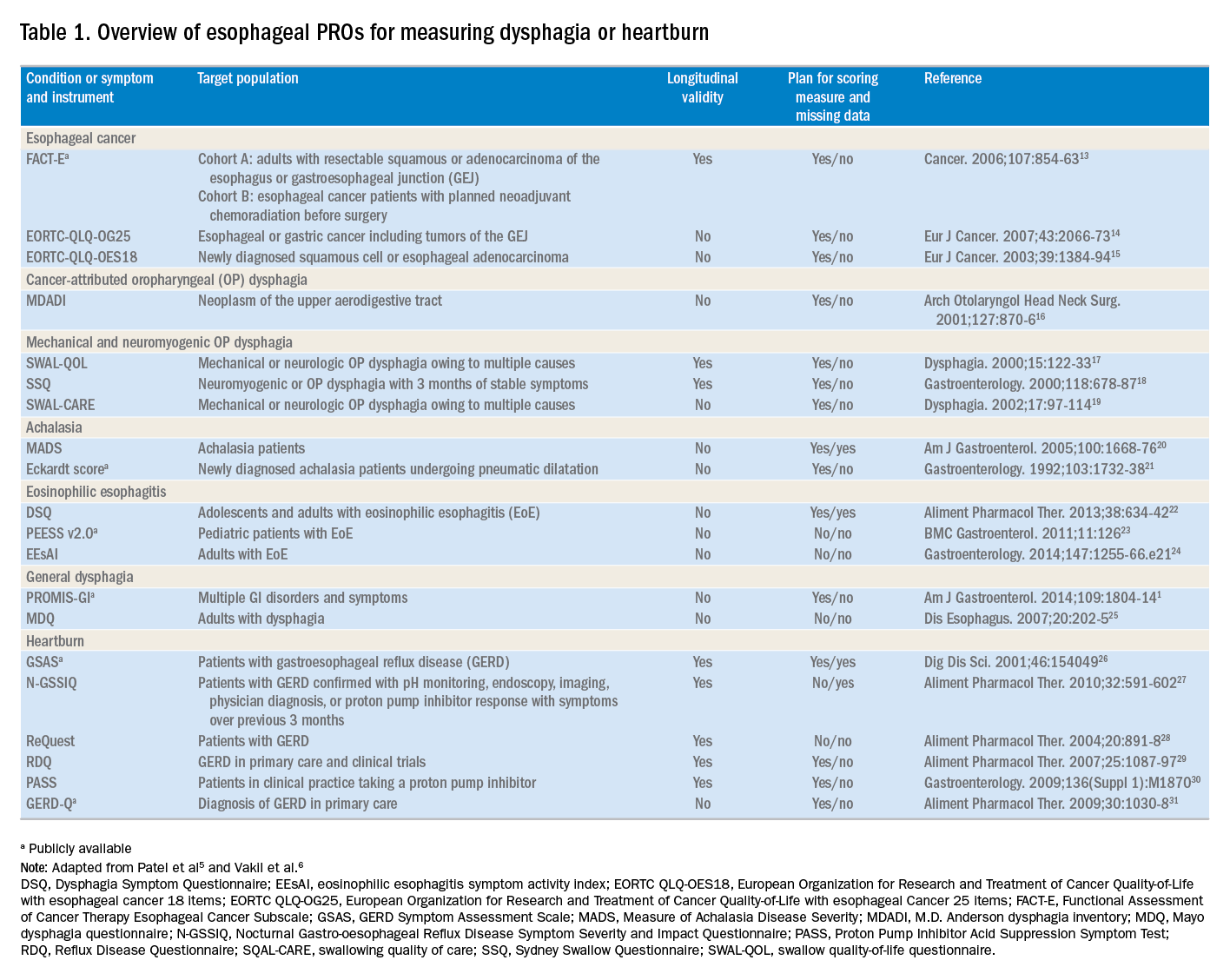

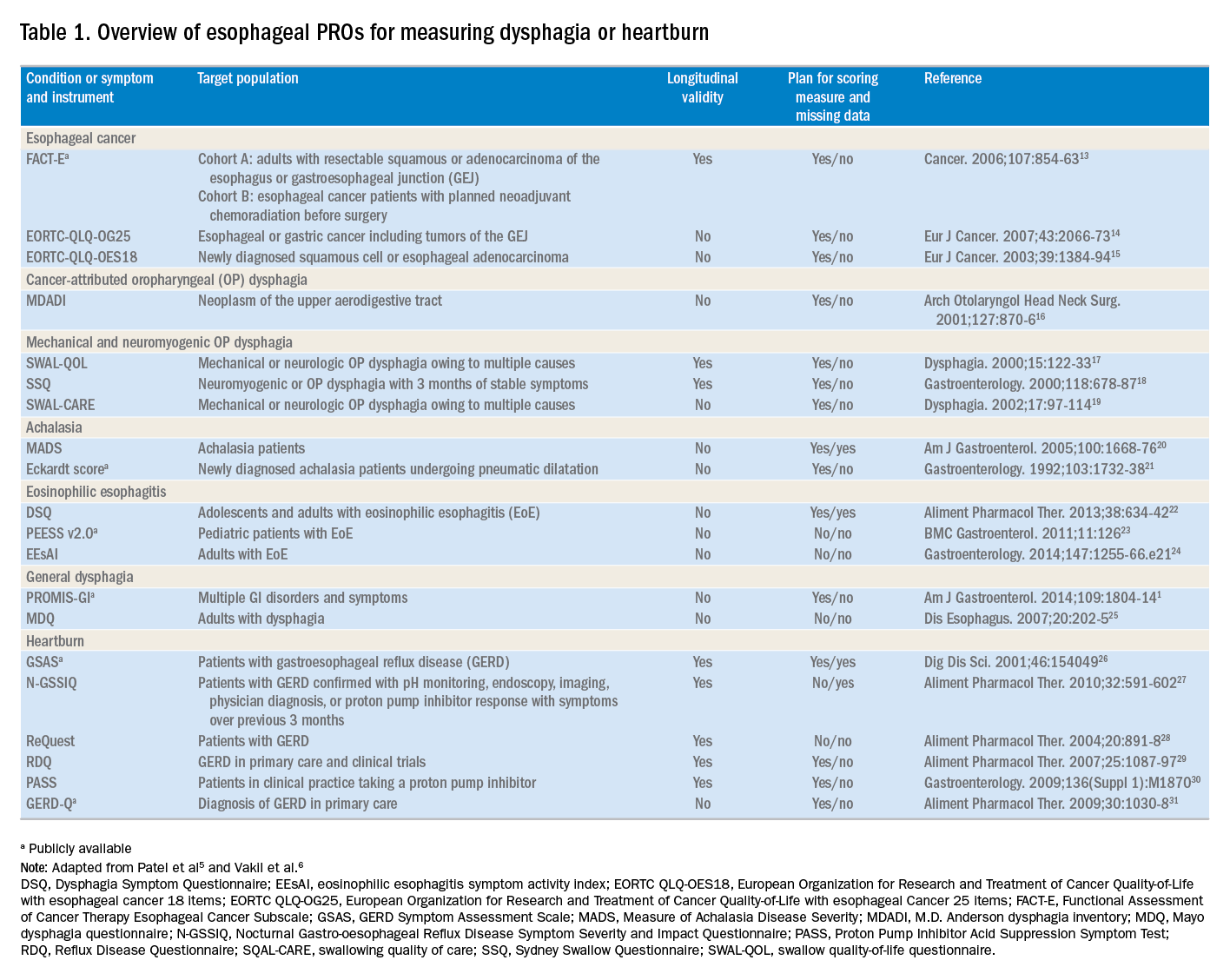

The literature pertinent to upper GI and esophageal-specific PROs is heterogeneous, and the development of PROs has been variable in rigor. Two recent systematic reviews identified PROs pertinent to dysphagia and heartburn (Table 1) and both emphasized rigorous measures developed in accordance with FDA guidance.3

Patel et al5 identified 34 dysphagia-specific PRO measures, of which 10 were rigorously developed (Table 1). These measures encompassed multiple conditions including esophageal cancer (Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy Esophageal Cancer Subscale, European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality-of-Life with esophageal Cancer 25 items, European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality-of-Life with esophageal cancer 18 items, upper aerodigestive neoplasm-attributable oropharyngeal dysphagia [M.D. Anderson dysphagia inventory], mechanical and neuromyogenic oropharyngeal dysphagia [swallow quality-of-life questionnaire], Sydney Swallow Questionnaire, [swallowing quality of care], achalasia [Measure of Achalasia Disease Severity], eosinophilic esophagitis [Dysphagia Symptom Questionnaire], and general dysphagia symptoms and gastroesophageal reflux [Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System Gastrointestinal Symptom Scales (PROMIS-GI)]. PROMIS-GI, produced as part of the National Institutes of Health PROMIS program, includes rigorous measures for general dysphagia symptoms and gastroesophageal reflux in addition to lower gastrointestinal symptom measures.

The systematic review by Vakil et al6 found 15 PRO measures for gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) symptoms that underwent psychometric evaluation (Table 1). Of these, 5 measures were devised according to the developmental steps stipulated by the US FDA and the European Medicines Agency, and each measure has been used as an end point for a clinical trial. The 5 measures include the GERD Symptom Assessment Scale, the Nocturnal Gastro-oesophageal Reflux Disease Symptom Severity and Impact Questionnaire, the Reflux Questionnaire, the Reflux Disease Questionnaire, and the Proton Pump Inhibitor Acid Suppression Symptom Test (Table 1). Additional PROs capturing esophageal symptoms include the eosinophilic esophagitis symptom activity index, Eckardt score (used for achalasia), Mayo dysphagia questionnaire, and GERD-Q (Table 1).

Utilization of esophageal patient-reported outcomes in practice

Before incorporating a PRO into clinical practice, providers must appreciate the construct(s), intent, developmental measurement properties, validation strategies, and responsiveness characteristics associated with the measure.4 PROs can be symptom- and/or condition-specific. For example, this could include dysphagia associated with achalasia or eosinophilic esophagitis, postoperative dysphagia from spine surgery, or general dysphagia symptoms regardless of the etiology (Table 1). Intent refers to the context in which a PRO should be used and generally is stratified into 3 areas: population surveillance, individual patient-clinician interactions, and research studies.4 A thorough analysis of PRO developmental properties exceeds the scope of this article. However, several key considerations are worth discussing. Each measure should clearly delineate the construct, or outcome, in addition to the population used to create the measure (eg, patients with achalasia). PROs should be assessed for reliability, construct validity, and content validity. Reliability pertains to the degree in which scores are free from measurement error, the extent to which items (ie, questions) correlate, and test–retest reliability. Construct validity includes dimensionality (evidence of whether a single or multiple subscales exist in the measure), responsiveness to change (longitudinal validity), and convergent validity (correlation with additional construct-specific measures). Central to the PRO development process is the involvement of patients and content experts (content validity). PRO measures should be readily interpretable, and the handling of missing items should be stipulated. The burden, or time required for administering and scoring the instrument, and the reading level of the PRO need to be considered.8 In short, a PRO should measure something important to patients, in a way that patients can understand, and in a way that accurately reflects the underlying symptom and disease.

Although PROs traditionally represent a method for gathering data for research, they also should be viewed as a means of improving clinical care. The monitoring of change in a particular construct represents a common application of PROs in clinical practice. This helps quantify the efficacy of an intervention and can provide insight into the comparative effectiveness of alternative therapies. For example, in a patient with an esophageal stricture, a dysphagia-specific measure could be used at baseline before an endoscopy and dilation, in follow-up evaluation after dilation, and then as a monitoring tool to determine when repeat dilation may be needed. Similarly, the Eckardt score has been used commonly to monitor response to achalasia treatments. Clinicians also may use PROs in real time to optimize patient management. The data gathered from PROs may help triage patients into treatment pathways, trigger follow-up appointments, supply patient education prompts, and produce patient and provider alerts.8 For providers engaging in clinical research, PROs administered at the point of patient intake, whether electronically through a patient portal or in the clinic, provide a means of gathering baseline data.9 A key question, however, is whether it is practical to use a PRO routinely in the clinic, esophageal function laboratory, or endoscopy suite.

These practical issues include cultivating a conducive environment for PRO utilization, considering the burden of the measure on the patient, and utilization of the results in an expedient manner.9 To promote seamless use of a PRO in clinical work-flows, a multimodal means of collecting PRO data should be arranged. Electronic PROs available through a patient portal, designed with a user-friendly and intuitive interface, facilitate patient completion of PROs at their convenience, and ideally before a clinical or procedure visit. For patients without access to the internet, tablets and/or computer terminals within the office are convenient options. Nurses or clinic staff also could help patients complete a PRO during check-in for clinic, esophageal testing, or endoscopy. The burden a PRO imposes on patients also limits the utility of a measure. For instance, PROs with a small number of questions are more likely to be completed, while scales consisting of 30 of more items are infrequently finished. Clinicians also should consider how they plan to use the results of a PRO before implementing one; if the data will not be used, then the effort to implement and collect it will be wasted. Moreover, patients will anticipate that the time required to complete a PRO will translate to an impact on their management plan and will more readily complete additional PROs if previous measures expediently affected their care.9

Barriers to patient-reported outcome implementation and future directions

Given the potential benefits to PRO use, why are they not implemented routinely? In practice, there are multiple barriers that thwart the adoption of PROs into both health care systems and individual practices. The integration of PROs into large health care systems languishes partly because of technological and operational barriers.9 For instance, the manual distribution, collection, and transcription of handwritten information requires substantial investitures of time, which is magnified by the number of patients whose care is provided within a large health system. One approach to the technological barrier includes the creation of an electronic platform integrating with patient portals. Such a platform would obviate the need to manually collect and transcribe documents, and could import data directly into provider documentation and flowsheets. However, the programming time and costs are substantial upfront, and without clear data that this could lead to improved outcomes or decreased costs downstream there may be reluctance to devote resources to this. In clinical practice, the already significant demands on providers’ time mitigates enthusiasm to add additional tasks. Providers also could face annual licensing agreements, fees on a per-study basis, or royalties associated with particular PROs, and at the individual practice level, there may not be appropriate expertise to select and implement routine PRO monitoring. To address this, efforts are being made to simplify the process of incorporating PROs. For example, given the relatively large number of heterogeneous PROs, the PROMIS project1 endeavors to clarify which PROs constitute the best measure for each construct and condition.9 The PROMIS measures also are provided publicly and are available without license or fee.

Areas particularly well situated for growth in the use of PRO measures include comparative effectiveness studies and pragmatic clinical trials. PRO-derived data may promote a shift from explanatory randomized controlled trials to pragmatic randomized controlled trials because these data emphasize patient-centered care and are more broadly generalizable to clinical settings. Furthermore, the derivation of data directly from the health care delivery system through PROs, such as two-way text messages, increases the relevance and cost effectiveness of clinical trials. Given the current medical climate, pressures continue to mount to identify cost-efficient and efficacious medical therapies.10 In this capacity, PROs facilitate the understanding of changes in HRQL domains subject to treatment choices. PROs further consider the comparative symptom burden and side effects associated with competing treatment strategies.11 Finally, PROs also have enabled the procurement of data from patient-powered research networks. Although this concept has not yet been applied to esophageal diseases, one example of this in the GI field is the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America Partners project, which has built an internet cohort consisting of approximately 14,200 inflammatory bowel disease patients who are monitored with a series of PROs.12 An endeavor such as this should be a model for esophageal conditions in the future.

Conclusions

PROs, as a structured means of directly assessing symptoms, help facilitate a provider’s understanding from a patient’s perspectives. Multiple PROs have been developed to characterize constructs pertinent to esophageal diseases and symptoms. These vary in methodologic rigor, but multiple well-constructed PROs exist for symptom domains such as dysphagia and heartburn, and can be used to monitor symptoms over time and assess treatment efficacy. Implementation of esophageal PROs, both in large health systems and in routine clinical practice, is not yet standard and faces a number of barriers. However, the potential benefits are substantial and include increased patient-centeredness, more accurate and timely disease monitoring, and applicability to comparative effectiveness studies, pragmatic clinical trials, and patient-powered research networks.

References

1. Spiegel B., Hays R., Bolus R., et al. Development of the NIH Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) gastrointestinal symptom scales. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:1804-14.

2. Chassany O., Shaheen N.J., Karlsson M., et al. Systematic review: symptom assessment using patient-reported outcomes in gastroesophageal reflux disease and dyspepsia. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2012;47:1412-21.

3. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services FDA Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services FDA Center for Devices and Radiological Health. Guidance for industry: patient-reported outcome measures: use in medical product development to support labeling claims: draft guidance. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2006;4:79. Available from:http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17034633%0Ahttp://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=PMC1629006

Accessed May 23, 2017

4. Lipscomb J. Cancer outcomes research and the arenas of application. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2004;2004:1-7.

5. Patel D.A., Sharda R., Hovis K.L., et al. Patient-reported outcome measures in dysphagia: a systematic review of instrument development and validation. Dis Esophagus. 2017;30:1-23.

6. Vakil N.B., Halling K., Becher A., et al. Systematic review of patient-reported outcome instruments for gastroesophageal reflux disease symptoms. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;25:2-14.

7. Bedell A., Taft T.H., Keefer L. Development of the Northwestern Esophageal Quality of Life Scale: a hybrid measure for use across esophageal conditions. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111:493-9.

8. Farnik M., Pierzchala W. Instrument development and evaluation for patient-related outcomes assessments. Patient Relat Outcome Meas. 2012;3:1-7.

9. Wagle N.W.. Implementing patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs). N Engl J Med Catal. 2016; :1-2. Available from:

http://catalyst.nejm.org/implementing-proms-patient-reported-outcome-measures/. Accessed July 14, 2017

10. Richesson R.L., Hammond W.E., Nahm M., et al. Electronic health records based phenotyping in next-generation clinical trials: a perspective from the NIH Health Care Systems Collaboratory. J Am Med Informatics Assoc. 2013;20: e226-e231.

11. Coon C.D., McLeod L.D. Patient-reported outcomes: current perspectives and future directions. Clin Ther. 2013;35:399-401.

12. Chung A.E., Sandler R.S., Long M.D., et al. Harnessing person-generated health data to accelerate patient-centered outcomes research: The Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America PCORnet Patient Powered Research Network (CCFA Partners)

J Am Med Informatics Assoc. 2016;23:485-90.

13. Darling G., Eton D.T., Sulman J., et al. Validation of the functional assessment of cancer therapy esophageal cancer subscale. Cancer. 2006;107:854-63.

14. Lagergren P., Fayers P., Conroy T., et al. Clinical and psychometric validation of a questionnaire module, the EORTC QLQ-OG25, to assess health-related quality of life in patients with cancer of the oesophagus, the oesophago-gastric junction and the stomach. Eur J Cancer. 2007;43:2066-73.

15. Blazeby J.M., Conroy T., Hammerlid E., et al. Clinical and psychometric validation of an EORTC questionnaire module, the EORTC QLQ-OES18, to assess quality of life in patients with oesophageal cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2003;39:1384-94.

16. Chen A.Y., Frankowski R., Bishop-Leone J., et al. The development and validation of a dysphagia-specific quality-of-life questionnaire for patients with head and neck cancer: the M. D. Anderson dysphagia inventory. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001;127:870-6.

17. McHorney C.A., Bricker D.E., Robbins J., et al. The SWAL-QOL outcomes tool for oropharyngeal dysphagia in adults: II. item reduction and preliminary scaling. Dysphagia. 2000;15:122-33.

18. Wallace K.L., Middleton S., Cook I.J. Development and validation of a self-report symptom inventory to assess the severity of oral-pharyngeal dysphagia. Gastroenterology. 2000;118:678-87.

19. McHorney C.A., Robbins J.A., Lomax K., et al. The SWAL-QOL and SWAL-CARE outcomes tool for oropharyngeal dysphagia in adults: III. Documentation of reliability and validity. Dysphagia. 2002;17:97-114.

20. Urbach D.R., Tomlinson G.A., Harnish J.L., et al. A measure of disease-specific health-related quality of life for achalasia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:1668-76.

21. Eckardt V., Aignherr C., Bernhard G. Predictors of outcome in patients with achalasia treated by pneumatic dilation. Gastroenterology. 1992;103:1732-8.

22. Dellon E.S., Irani A.M., Hill M.R., et al. Development and field testing of a novel patient-reported outcome measure of dysphagia in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;38:634-42.

23. Franciosi J.P., Hommel K., DeBrosse C.W., et al. Development of a validated patient-reported symptom metric for pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis: qualitative methods. BMC Gastroenterol. 2011;11:126.