User login

Preauthorization for medications: Who oversees placement of the hoops?

The letter from the insurance company was addressed to my patient. The two pages of information boiled down to one simple sentence: “After a thorough review, our decision to not cover the medication Provigil (modafinil) is unchanged.” The letter went on to explain that there was no further recourse, and that the medication would not be approved because it was not Food and Drug Administration–approved for the condition my patient had: major depression. If she chose to take it, there would be no reimbursement. In many psychiatric conditions, the FDA-approved options are very limited; for some disorders, there simply are no approved medications, despite the fact that research has shown medications to be helpful. For a medication that now has a generic, there is no reason for the pharmaceutical agency to incur the cost of getting a medication approved by the FDA for a specific use.

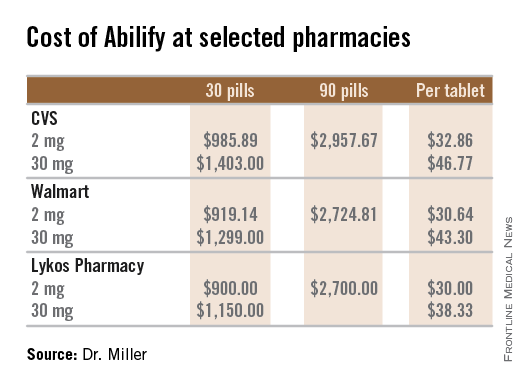

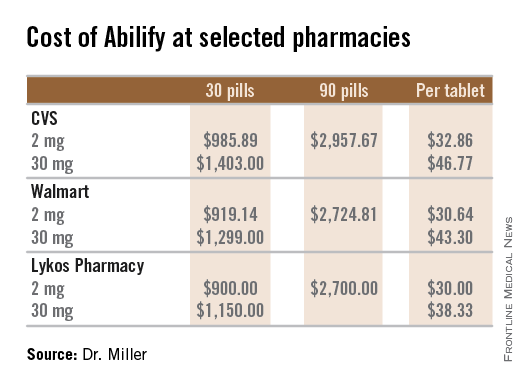

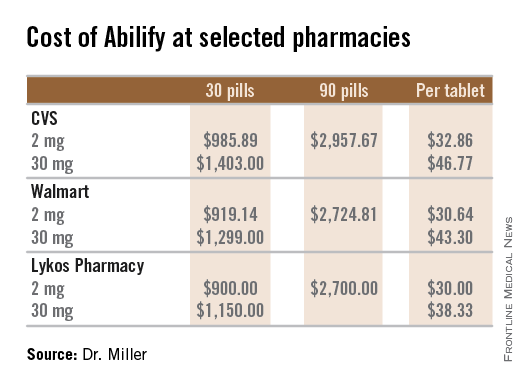

Psychiatrists are all familiar with the process of medication preauthorization. Insurance companies require the physician to make an extra effort in order to prescribe certain medications. Often, as in the case of modafinil, the medications are expensive, and one might wonder why a generic medication costs $25 a pill. The name-brand medication, Provigil, costs more than $33 for a single dose. Sometimes, however, a preauthorization process is put in place for very inexpensive medications that might cost only a few dollars a month. Preauthorization requirements waste enormous amounts of physician time and don’t necessarily save money for insurers.

What many physicians don’t realize is that there is no national oversight to this process. In some arenas, the insurers can set the hoops as high as they want and in perpetual motion, thereby making the process a long and miserable adventure – all while the patient suffers.

Nothing about my patient’s depression has been easy to treat. We started working together 8 years ago; her suffering at that time was extreme and her presentation was unusual. I arranged for her admission to a specialty unit in a psychiatric hospital, and she remained under their care for several months – an astounding period of time in an era where the average length of stay is 7 to 10 days. She was discharged – very much improved – on an unusual cocktail of medications.

Over time, we tapered some of the medications because of side effects. Five years ago, her insurance changed and after I answered a 13-question prior authorization form, the medication was denied because she did not have narcolepsy or any of the sleep disorders for which the FDA does approve the use of Provigil. An appeal was denied, and I prescribed stimulants instead. It wasn’t until recently, when the patient’s depression returned full-force, and every medication option I could think of had been tried, that I decided to try modafinil again, especially since I have found it helpful in another patient with a treatment-resistant depression.

I wrote a prescription and heard from the pharmacy that Provigil required preauthorization. I prescribed Nuvigil instead, but that too required preauthorization. A 20-minute phone call resulted in directions on how to find a form and fax a request for the medication. It contained many of the same questions from years ago, and the request was denied.

Several more phone calls led me to a reviewer with the pharmacy benefits company in Nevada, who told me I could find a form on the website, send in an appeal to the insurance company in Iowa, and I would hear within 15 business days if my patient could get the medication. When I said that was not acceptable – the patient was suffering and needed the medication now – I was told I would receive a call from a peer reviewer within 48 hours. A week later, a pharmacist called and asked the exact same questions that I had already answered. When I said that no, I had not ordered polysomnography or multiple sleep latency tests because they were not medically indicated, she denied approval of the medication and said she had no leeway to approve its use if the questions were not answered correctly. I found it curious that this step was called a “peer-to-peer” review. By this point, I had spent about an hour in a two-step process where the second step was exactly the same as the first step. It’s okay; the insurance company doesn’t mind the inefficient use of everyone’s time.

I was told that to file an appeal, I would need more forms off the website, and I was given (at my request) directions on where to find those forms. But first, I needed to get the patient to sign a form to authorize to release information on her behalf. The patient lives a 90-minute drive from my office and does not have a fax machine, and this delayed the process. It remained unclear to me why the patient’s permission was needed when it had not been needed for the first two steps of the process. The authorization was to be mailed or faxed to one location, while the appeal letter was to be mailed (fax or electronic submissions were not options) to another address.

In the appeal letter, I discussed her past history of a lengthy hospitalization, a long list of other medications that had been tried, and a study that documented the efficacy of modafinil as an adjunct agent in the treatment of depression.

As the weeks ticked by, I contacted the chief medical officer of the insurance company and complained; I had spent hours on an arbitrary, repetitive, and inefficient process that was yielding no results. I asked how he sleeps at night.

The response was infuriating: “I know that the appeal is being set up in the queue. I am sorry that this process has been drawn out for you and your patient.” In the queue? Had he ever sat with a sobbing, depressed patient who couldn’t get out of bed all day? A family member was taking off work to stay with her, and her life was on hold. The chief medical officer didn’t give any indication as to how long this queue might be. The family was hurting both emotionally and financially.

I tried one of my U.S. senators. His office replied that preauthorization oversight was not a legislative issue. I spoke with the insurance commission in Maryland where I practice, and I filed a formal complaint with the insurance commissioner in Iowa. I was told it could take up to 45 days for a response, but the next day, I heard back: The plan is funded through a family member’s employer and is not under the jurisdiction of the insurance commissioner. Simply put, the insurance company can set up as many hurdles as they like and take as long as they want to respond, regardless of the patient’s need.

Eight weeks after I wrote the prescription, a copy of the denial letter arrived in my mail. A physician in Iowa has determined that the medication is not medically necessary for a patient he or she had never seen in Maryland. I’ve turned to the American Psychiatric Association. With so many psychiatrists complaining about the burdens of preauthorization, this case would be a good example; one of its attorneys has agreed to write a letter to the Department of Labor. Perhaps that will help, but as of this writing, I have not yet seen that letter. All in all, it has been hours of my time, and lots of waiting, all without regard to the person who could possibly find some relief with a medication that is available to some, but not to her.

Dr. Miller is a coauthor of “Shrink Rap: Three Psychiatrists Explain Their Work” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2011).

The letter from the insurance company was addressed to my patient. The two pages of information boiled down to one simple sentence: “After a thorough review, our decision to not cover the medication Provigil (modafinil) is unchanged.” The letter went on to explain that there was no further recourse, and that the medication would not be approved because it was not Food and Drug Administration–approved for the condition my patient had: major depression. If she chose to take it, there would be no reimbursement. In many psychiatric conditions, the FDA-approved options are very limited; for some disorders, there simply are no approved medications, despite the fact that research has shown medications to be helpful. For a medication that now has a generic, there is no reason for the pharmaceutical agency to incur the cost of getting a medication approved by the FDA for a specific use.

Psychiatrists are all familiar with the process of medication preauthorization. Insurance companies require the physician to make an extra effort in order to prescribe certain medications. Often, as in the case of modafinil, the medications are expensive, and one might wonder why a generic medication costs $25 a pill. The name-brand medication, Provigil, costs more than $33 for a single dose. Sometimes, however, a preauthorization process is put in place for very inexpensive medications that might cost only a few dollars a month. Preauthorization requirements waste enormous amounts of physician time and don’t necessarily save money for insurers.

What many physicians don’t realize is that there is no national oversight to this process. In some arenas, the insurers can set the hoops as high as they want and in perpetual motion, thereby making the process a long and miserable adventure – all while the patient suffers.

Nothing about my patient’s depression has been easy to treat. We started working together 8 years ago; her suffering at that time was extreme and her presentation was unusual. I arranged for her admission to a specialty unit in a psychiatric hospital, and she remained under their care for several months – an astounding period of time in an era where the average length of stay is 7 to 10 days. She was discharged – very much improved – on an unusual cocktail of medications.

Over time, we tapered some of the medications because of side effects. Five years ago, her insurance changed and after I answered a 13-question prior authorization form, the medication was denied because she did not have narcolepsy or any of the sleep disorders for which the FDA does approve the use of Provigil. An appeal was denied, and I prescribed stimulants instead. It wasn’t until recently, when the patient’s depression returned full-force, and every medication option I could think of had been tried, that I decided to try modafinil again, especially since I have found it helpful in another patient with a treatment-resistant depression.

I wrote a prescription and heard from the pharmacy that Provigil required preauthorization. I prescribed Nuvigil instead, but that too required preauthorization. A 20-minute phone call resulted in directions on how to find a form and fax a request for the medication. It contained many of the same questions from years ago, and the request was denied.

Several more phone calls led me to a reviewer with the pharmacy benefits company in Nevada, who told me I could find a form on the website, send in an appeal to the insurance company in Iowa, and I would hear within 15 business days if my patient could get the medication. When I said that was not acceptable – the patient was suffering and needed the medication now – I was told I would receive a call from a peer reviewer within 48 hours. A week later, a pharmacist called and asked the exact same questions that I had already answered. When I said that no, I had not ordered polysomnography or multiple sleep latency tests because they were not medically indicated, she denied approval of the medication and said she had no leeway to approve its use if the questions were not answered correctly. I found it curious that this step was called a “peer-to-peer” review. By this point, I had spent about an hour in a two-step process where the second step was exactly the same as the first step. It’s okay; the insurance company doesn’t mind the inefficient use of everyone’s time.

I was told that to file an appeal, I would need more forms off the website, and I was given (at my request) directions on where to find those forms. But first, I needed to get the patient to sign a form to authorize to release information on her behalf. The patient lives a 90-minute drive from my office and does not have a fax machine, and this delayed the process. It remained unclear to me why the patient’s permission was needed when it had not been needed for the first two steps of the process. The authorization was to be mailed or faxed to one location, while the appeal letter was to be mailed (fax or electronic submissions were not options) to another address.

In the appeal letter, I discussed her past history of a lengthy hospitalization, a long list of other medications that had been tried, and a study that documented the efficacy of modafinil as an adjunct agent in the treatment of depression.

As the weeks ticked by, I contacted the chief medical officer of the insurance company and complained; I had spent hours on an arbitrary, repetitive, and inefficient process that was yielding no results. I asked how he sleeps at night.

The response was infuriating: “I know that the appeal is being set up in the queue. I am sorry that this process has been drawn out for you and your patient.” In the queue? Had he ever sat with a sobbing, depressed patient who couldn’t get out of bed all day? A family member was taking off work to stay with her, and her life was on hold. The chief medical officer didn’t give any indication as to how long this queue might be. The family was hurting both emotionally and financially.

I tried one of my U.S. senators. His office replied that preauthorization oversight was not a legislative issue. I spoke with the insurance commission in Maryland where I practice, and I filed a formal complaint with the insurance commissioner in Iowa. I was told it could take up to 45 days for a response, but the next day, I heard back: The plan is funded through a family member’s employer and is not under the jurisdiction of the insurance commissioner. Simply put, the insurance company can set up as many hurdles as they like and take as long as they want to respond, regardless of the patient’s need.

Eight weeks after I wrote the prescription, a copy of the denial letter arrived in my mail. A physician in Iowa has determined that the medication is not medically necessary for a patient he or she had never seen in Maryland. I’ve turned to the American Psychiatric Association. With so many psychiatrists complaining about the burdens of preauthorization, this case would be a good example; one of its attorneys has agreed to write a letter to the Department of Labor. Perhaps that will help, but as of this writing, I have not yet seen that letter. All in all, it has been hours of my time, and lots of waiting, all without regard to the person who could possibly find some relief with a medication that is available to some, but not to her.

Dr. Miller is a coauthor of “Shrink Rap: Three Psychiatrists Explain Their Work” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2011).

The letter from the insurance company was addressed to my patient. The two pages of information boiled down to one simple sentence: “After a thorough review, our decision to not cover the medication Provigil (modafinil) is unchanged.” The letter went on to explain that there was no further recourse, and that the medication would not be approved because it was not Food and Drug Administration–approved for the condition my patient had: major depression. If she chose to take it, there would be no reimbursement. In many psychiatric conditions, the FDA-approved options are very limited; for some disorders, there simply are no approved medications, despite the fact that research has shown medications to be helpful. For a medication that now has a generic, there is no reason for the pharmaceutical agency to incur the cost of getting a medication approved by the FDA for a specific use.

Psychiatrists are all familiar with the process of medication preauthorization. Insurance companies require the physician to make an extra effort in order to prescribe certain medications. Often, as in the case of modafinil, the medications are expensive, and one might wonder why a generic medication costs $25 a pill. The name-brand medication, Provigil, costs more than $33 for a single dose. Sometimes, however, a preauthorization process is put in place for very inexpensive medications that might cost only a few dollars a month. Preauthorization requirements waste enormous amounts of physician time and don’t necessarily save money for insurers.

What many physicians don’t realize is that there is no national oversight to this process. In some arenas, the insurers can set the hoops as high as they want and in perpetual motion, thereby making the process a long and miserable adventure – all while the patient suffers.

Nothing about my patient’s depression has been easy to treat. We started working together 8 years ago; her suffering at that time was extreme and her presentation was unusual. I arranged for her admission to a specialty unit in a psychiatric hospital, and she remained under their care for several months – an astounding period of time in an era where the average length of stay is 7 to 10 days. She was discharged – very much improved – on an unusual cocktail of medications.

Over time, we tapered some of the medications because of side effects. Five years ago, her insurance changed and after I answered a 13-question prior authorization form, the medication was denied because she did not have narcolepsy or any of the sleep disorders for which the FDA does approve the use of Provigil. An appeal was denied, and I prescribed stimulants instead. It wasn’t until recently, when the patient’s depression returned full-force, and every medication option I could think of had been tried, that I decided to try modafinil again, especially since I have found it helpful in another patient with a treatment-resistant depression.

I wrote a prescription and heard from the pharmacy that Provigil required preauthorization. I prescribed Nuvigil instead, but that too required preauthorization. A 20-minute phone call resulted in directions on how to find a form and fax a request for the medication. It contained many of the same questions from years ago, and the request was denied.

Several more phone calls led me to a reviewer with the pharmacy benefits company in Nevada, who told me I could find a form on the website, send in an appeal to the insurance company in Iowa, and I would hear within 15 business days if my patient could get the medication. When I said that was not acceptable – the patient was suffering and needed the medication now – I was told I would receive a call from a peer reviewer within 48 hours. A week later, a pharmacist called and asked the exact same questions that I had already answered. When I said that no, I had not ordered polysomnography or multiple sleep latency tests because they were not medically indicated, she denied approval of the medication and said she had no leeway to approve its use if the questions were not answered correctly. I found it curious that this step was called a “peer-to-peer” review. By this point, I had spent about an hour in a two-step process where the second step was exactly the same as the first step. It’s okay; the insurance company doesn’t mind the inefficient use of everyone’s time.

I was told that to file an appeal, I would need more forms off the website, and I was given (at my request) directions on where to find those forms. But first, I needed to get the patient to sign a form to authorize to release information on her behalf. The patient lives a 90-minute drive from my office and does not have a fax machine, and this delayed the process. It remained unclear to me why the patient’s permission was needed when it had not been needed for the first two steps of the process. The authorization was to be mailed or faxed to one location, while the appeal letter was to be mailed (fax or electronic submissions were not options) to another address.

In the appeal letter, I discussed her past history of a lengthy hospitalization, a long list of other medications that had been tried, and a study that documented the efficacy of modafinil as an adjunct agent in the treatment of depression.

As the weeks ticked by, I contacted the chief medical officer of the insurance company and complained; I had spent hours on an arbitrary, repetitive, and inefficient process that was yielding no results. I asked how he sleeps at night.

The response was infuriating: “I know that the appeal is being set up in the queue. I am sorry that this process has been drawn out for you and your patient.” In the queue? Had he ever sat with a sobbing, depressed patient who couldn’t get out of bed all day? A family member was taking off work to stay with her, and her life was on hold. The chief medical officer didn’t give any indication as to how long this queue might be. The family was hurting both emotionally and financially.

I tried one of my U.S. senators. His office replied that preauthorization oversight was not a legislative issue. I spoke with the insurance commission in Maryland where I practice, and I filed a formal complaint with the insurance commissioner in Iowa. I was told it could take up to 45 days for a response, but the next day, I heard back: The plan is funded through a family member’s employer and is not under the jurisdiction of the insurance commissioner. Simply put, the insurance company can set up as many hurdles as they like and take as long as they want to respond, regardless of the patient’s need.

Eight weeks after I wrote the prescription, a copy of the denial letter arrived in my mail. A physician in Iowa has determined that the medication is not medically necessary for a patient he or she had never seen in Maryland. I’ve turned to the American Psychiatric Association. With so many psychiatrists complaining about the burdens of preauthorization, this case would be a good example; one of its attorneys has agreed to write a letter to the Department of Labor. Perhaps that will help, but as of this writing, I have not yet seen that letter. All in all, it has been hours of my time, and lots of waiting, all without regard to the person who could possibly find some relief with a medication that is available to some, but not to her.

Dr. Miller is a coauthor of “Shrink Rap: Three Psychiatrists Explain Their Work” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2011).

Does psychiatric treatment prevent suicide?

Over the past 2 decades, more and more people have been treated with antidepressant medications. In the same period of time, suicide rates have gone up – not down. To those of us who treat patients, this fact is both surprising and perplexing. It seems that suicidal thoughts are a common feature of major depression, and when the depressive symptoms abate with treatment, the suicidal thoughts dissipate. Intuitively, it seems that treating depression on a larger scale should prevent suicides, but we still don’t know that conclusively.

According to the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), 11% percent of Americans over the age of 12 are taking an antidepressant medication. In women aged 40-59, this number is 23%. Of those taking antidepressants, only one-third have seen a mental health professional in the past 12 months. What also is striking is that for people surveyed with symptoms of severe depression, only one-third were on medication.

In 2013, just over 40,000 Americans died of suicide. From 2000 to 2013, the suicide rate per 100,000 Americans has steadily increased from 10.4 to 12.6 per 100,000 people. While we know that people with psychiatric illnesses have higher rates of suicide compared with the general population, what we don’t know is whether the people dying are the same people who are getting treatment.

Thinking about this gets very difficult. It has been estimated that 90% of those who die of suicide have suffered from a mental illness. This figure includes those who were treated, untreated, and previously treated, but the studies have methodologic inconsistencies and that 90% estimate may not be accurate. Certainly, however, people die of suicide for reasons that have nothing to do with psychiatric illness, and we do know that impulsive responses to distressing circumstances are a factor, especially when a lethal method is easily available.

Several studies have shown that antidepressant use, particularly in older adults, may be associated with a decrease in suicidality. The studies often combine suicide attempts and completions. The issues with younger patients are more complicated, and in recent weeks, the reanalysis of the 2001 Paxil 329 study has again raised issues about the safety of certain antidepressants in children and adolescents. The data for all these studies are both confusing and contradictory, and are not easy to examine or interpret.

We also don’t know what role psychotherapy plays. A study done at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health looked at the follow-up for 65,000 people in Denmark who had attempted suicide and found that the rates for completed suicide dropped if the patient received a short course of psychosocial therapy at a suicide prevention center. But again, this study looked at a select group of people who had already attempted suicide.

I began to think it might help to ask these questions in a closed system where patients could be tallied with regard to requests for treatment, what type of treatment was provided, and even access to autopsy results. The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs seemed to be a source where such answers might be found. It has been reported that 22 veterans a day die by suicide, and many veterans get their care in VA facilities, with VA pharmacy benefits, and treatment effects can, in theory, be studied.

Hoping to get a better sense of the relationship between treatment and suicide, I met with Robert Bossarte, Ph.D., director of the Epidemiology Program in the VA’s Office of Public Health. His career has been focused on suicide prevention.

The first thing Dr. Bossarte did was dissuade me of the idea that the VA is a closed system. Not all veterans receive lifelong benefits from the VA, and the formulas for determining who is entitled to what benefits, and for how long, is rather complicated. Dr. Bossarte also noted that some patients go outside of the system for their care.

“What we do know is that among those who have used VA services in the previous year, about 2,000 veterans a year die from suicide. It’s been hovering around that for the past decade,” Dr. Bossarte explained, again emphasizing that many veterans do not receive care at VA facilities. “We published a report in 2012 where we estimated 22 veterans a day die by suicide and that caught fire, but it is purely an estimate. The truth is we have no idea what the real count is, because until we began working on the Suicide Data Repository there was no national register of veteran mortality and there has been no way for us to know.”

Dr. Bossarte anticipates that the VA will have the data necessary to calculate more accurate statistics by the end of the year. “More than 70% of veteran suicide are in people over age 50; but the rates are going up most among the youngest.”

A notable drop in veteran suicide rates for those who used services occurred between 2001 and 2003, and that decrease remains unexplained; it preceded later changes in mental health services and enhanced suicide prevention programs. Dr. Bossarte also pointed out that just under half of veterans who die from suicide have no mental health diagnosis, despite yearly screening to identify people who may be suffering from posttraumatic stress disorder, alcohol-related disorders, and depression.

“The attention on veteran suicide started around 2007,” Dr. Bossarte explained. “Mark Kaplan published a study using publicly available mortality data; those who reported they were veterans were twice as likely to die of suicide as those who were not.”

While this sparked interest in veteran suicide, it’s important to note that a replication of that study in 2012 by Matthew Miller did not have the same findings.

“Then, in 2008, for the first time in recent history,” Dr. Bossarte continued, “the suicide rate among active duty military personnel exceeded that of the general population. Traditionally, rates of suicide in this population have been 40%-50% lower than in the general population. The increased rate was seen primarily in the Army and Marines. Serious mental illness may make people ineligible for military service, as can violent and disruptive behavior – things that are associated with suicide – so you tended to get a healthier population in the military.”

Dr. Bossarte noted that there was conjecture that increased suicide rates among active military might be related to more waivers that allowed people to enlist who would not ordinarily be eligible, and/or to higher rates of deployment. He went on to talk about Army STARRS (Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers).

“STARRS devoted $50 million over 5 years to the largest suicide study and did not find an effect of waivers. They did report a higher suicide rate among those who were deployed, however. But then Tim Bullman in my office looked at suicide rates 7 years after separation from service, and he reported a higher suicide rate among those who were never deployed.” The VA studies, I quickly realized, were also confusing and contradictory.

The VA has greatly expanded its mental health and suicide prevention services. For veterans overall, suicide rates have stabilized, but they have not decreased. For those veterans with psychiatric disorders, however, the suicide rates have gone down.

“When you ask ‘does treatment matter?’ it’s so hard to disentangle psychotherapy from pharmacotherapy. Over the past decade, we’ve seen a significant decrease in the suicide rate among those veterans with mental health disorders. We’ve looked at suicide rates every way you can think of. One thing we do know is that the better the relationship with the clinician, the lower the suicide risk.”

We talked about the role of hospitalization in preventing suicide, and Dr. Bossarte noted that the highest risk for suicide is immediately following hospital discharge.

“We are looking at people hospitalized after their first-ever suicide attempts and rates of mortality, including suicidal behavior, for 1 year after discharge. In very preliminary findings, we didn’t see any difference in the outcome for either all-cause mortality or repeat suicide attempts in those who were hospitalized, compared to those who were not. We don’t yet know about completed suicide.”

I left my discussion with Dr. Bossarte with more questions than answers. We have reason to believe that treatment helps, but we still don’t know which treatments help which people, and we do know that treatment doesn’t prevent suicide in every patient. In a culture where “treatment” has come to be equated with “prescribing” and is often based on a checklist of symptoms done by a primary care clinician, one might wonder if combining psychotherapy and medication – an increasingly rare offering – might have a better outcome. Simply put, for a problem that prematurely takes more than 40,000 lives a year, we know much too little.

Dr. Miller is a coauthor of “Shrink Rap: Three Psychiatrists Explain Their Work” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2011).

Over the past 2 decades, more and more people have been treated with antidepressant medications. In the same period of time, suicide rates have gone up – not down. To those of us who treat patients, this fact is both surprising and perplexing. It seems that suicidal thoughts are a common feature of major depression, and when the depressive symptoms abate with treatment, the suicidal thoughts dissipate. Intuitively, it seems that treating depression on a larger scale should prevent suicides, but we still don’t know that conclusively.

According to the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), 11% percent of Americans over the age of 12 are taking an antidepressant medication. In women aged 40-59, this number is 23%. Of those taking antidepressants, only one-third have seen a mental health professional in the past 12 months. What also is striking is that for people surveyed with symptoms of severe depression, only one-third were on medication.

In 2013, just over 40,000 Americans died of suicide. From 2000 to 2013, the suicide rate per 100,000 Americans has steadily increased from 10.4 to 12.6 per 100,000 people. While we know that people with psychiatric illnesses have higher rates of suicide compared with the general population, what we don’t know is whether the people dying are the same people who are getting treatment.

Thinking about this gets very difficult. It has been estimated that 90% of those who die of suicide have suffered from a mental illness. This figure includes those who were treated, untreated, and previously treated, but the studies have methodologic inconsistencies and that 90% estimate may not be accurate. Certainly, however, people die of suicide for reasons that have nothing to do with psychiatric illness, and we do know that impulsive responses to distressing circumstances are a factor, especially when a lethal method is easily available.

Several studies have shown that antidepressant use, particularly in older adults, may be associated with a decrease in suicidality. The studies often combine suicide attempts and completions. The issues with younger patients are more complicated, and in recent weeks, the reanalysis of the 2001 Paxil 329 study has again raised issues about the safety of certain antidepressants in children and adolescents. The data for all these studies are both confusing and contradictory, and are not easy to examine or interpret.

We also don’t know what role psychotherapy plays. A study done at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health looked at the follow-up for 65,000 people in Denmark who had attempted suicide and found that the rates for completed suicide dropped if the patient received a short course of psychosocial therapy at a suicide prevention center. But again, this study looked at a select group of people who had already attempted suicide.

I began to think it might help to ask these questions in a closed system where patients could be tallied with regard to requests for treatment, what type of treatment was provided, and even access to autopsy results. The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs seemed to be a source where such answers might be found. It has been reported that 22 veterans a day die by suicide, and many veterans get their care in VA facilities, with VA pharmacy benefits, and treatment effects can, in theory, be studied.

Hoping to get a better sense of the relationship between treatment and suicide, I met with Robert Bossarte, Ph.D., director of the Epidemiology Program in the VA’s Office of Public Health. His career has been focused on suicide prevention.

The first thing Dr. Bossarte did was dissuade me of the idea that the VA is a closed system. Not all veterans receive lifelong benefits from the VA, and the formulas for determining who is entitled to what benefits, and for how long, is rather complicated. Dr. Bossarte also noted that some patients go outside of the system for their care.

“What we do know is that among those who have used VA services in the previous year, about 2,000 veterans a year die from suicide. It’s been hovering around that for the past decade,” Dr. Bossarte explained, again emphasizing that many veterans do not receive care at VA facilities. “We published a report in 2012 where we estimated 22 veterans a day die by suicide and that caught fire, but it is purely an estimate. The truth is we have no idea what the real count is, because until we began working on the Suicide Data Repository there was no national register of veteran mortality and there has been no way for us to know.”

Dr. Bossarte anticipates that the VA will have the data necessary to calculate more accurate statistics by the end of the year. “More than 70% of veteran suicide are in people over age 50; but the rates are going up most among the youngest.”

A notable drop in veteran suicide rates for those who used services occurred between 2001 and 2003, and that decrease remains unexplained; it preceded later changes in mental health services and enhanced suicide prevention programs. Dr. Bossarte also pointed out that just under half of veterans who die from suicide have no mental health diagnosis, despite yearly screening to identify people who may be suffering from posttraumatic stress disorder, alcohol-related disorders, and depression.

“The attention on veteran suicide started around 2007,” Dr. Bossarte explained. “Mark Kaplan published a study using publicly available mortality data; those who reported they were veterans were twice as likely to die of suicide as those who were not.”

While this sparked interest in veteran suicide, it’s important to note that a replication of that study in 2012 by Matthew Miller did not have the same findings.

“Then, in 2008, for the first time in recent history,” Dr. Bossarte continued, “the suicide rate among active duty military personnel exceeded that of the general population. Traditionally, rates of suicide in this population have been 40%-50% lower than in the general population. The increased rate was seen primarily in the Army and Marines. Serious mental illness may make people ineligible for military service, as can violent and disruptive behavior – things that are associated with suicide – so you tended to get a healthier population in the military.”

Dr. Bossarte noted that there was conjecture that increased suicide rates among active military might be related to more waivers that allowed people to enlist who would not ordinarily be eligible, and/or to higher rates of deployment. He went on to talk about Army STARRS (Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers).

“STARRS devoted $50 million over 5 years to the largest suicide study and did not find an effect of waivers. They did report a higher suicide rate among those who were deployed, however. But then Tim Bullman in my office looked at suicide rates 7 years after separation from service, and he reported a higher suicide rate among those who were never deployed.” The VA studies, I quickly realized, were also confusing and contradictory.

The VA has greatly expanded its mental health and suicide prevention services. For veterans overall, suicide rates have stabilized, but they have not decreased. For those veterans with psychiatric disorders, however, the suicide rates have gone down.

“When you ask ‘does treatment matter?’ it’s so hard to disentangle psychotherapy from pharmacotherapy. Over the past decade, we’ve seen a significant decrease in the suicide rate among those veterans with mental health disorders. We’ve looked at suicide rates every way you can think of. One thing we do know is that the better the relationship with the clinician, the lower the suicide risk.”

We talked about the role of hospitalization in preventing suicide, and Dr. Bossarte noted that the highest risk for suicide is immediately following hospital discharge.

“We are looking at people hospitalized after their first-ever suicide attempts and rates of mortality, including suicidal behavior, for 1 year after discharge. In very preliminary findings, we didn’t see any difference in the outcome for either all-cause mortality or repeat suicide attempts in those who were hospitalized, compared to those who were not. We don’t yet know about completed suicide.”

I left my discussion with Dr. Bossarte with more questions than answers. We have reason to believe that treatment helps, but we still don’t know which treatments help which people, and we do know that treatment doesn’t prevent suicide in every patient. In a culture where “treatment” has come to be equated with “prescribing” and is often based on a checklist of symptoms done by a primary care clinician, one might wonder if combining psychotherapy and medication – an increasingly rare offering – might have a better outcome. Simply put, for a problem that prematurely takes more than 40,000 lives a year, we know much too little.

Dr. Miller is a coauthor of “Shrink Rap: Three Psychiatrists Explain Their Work” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2011).

Over the past 2 decades, more and more people have been treated with antidepressant medications. In the same period of time, suicide rates have gone up – not down. To those of us who treat patients, this fact is both surprising and perplexing. It seems that suicidal thoughts are a common feature of major depression, and when the depressive symptoms abate with treatment, the suicidal thoughts dissipate. Intuitively, it seems that treating depression on a larger scale should prevent suicides, but we still don’t know that conclusively.

According to the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), 11% percent of Americans over the age of 12 are taking an antidepressant medication. In women aged 40-59, this number is 23%. Of those taking antidepressants, only one-third have seen a mental health professional in the past 12 months. What also is striking is that for people surveyed with symptoms of severe depression, only one-third were on medication.

In 2013, just over 40,000 Americans died of suicide. From 2000 to 2013, the suicide rate per 100,000 Americans has steadily increased from 10.4 to 12.6 per 100,000 people. While we know that people with psychiatric illnesses have higher rates of suicide compared with the general population, what we don’t know is whether the people dying are the same people who are getting treatment.

Thinking about this gets very difficult. It has been estimated that 90% of those who die of suicide have suffered from a mental illness. This figure includes those who were treated, untreated, and previously treated, but the studies have methodologic inconsistencies and that 90% estimate may not be accurate. Certainly, however, people die of suicide for reasons that have nothing to do with psychiatric illness, and we do know that impulsive responses to distressing circumstances are a factor, especially when a lethal method is easily available.

Several studies have shown that antidepressant use, particularly in older adults, may be associated with a decrease in suicidality. The studies often combine suicide attempts and completions. The issues with younger patients are more complicated, and in recent weeks, the reanalysis of the 2001 Paxil 329 study has again raised issues about the safety of certain antidepressants in children and adolescents. The data for all these studies are both confusing and contradictory, and are not easy to examine or interpret.

We also don’t know what role psychotherapy plays. A study done at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health looked at the follow-up for 65,000 people in Denmark who had attempted suicide and found that the rates for completed suicide dropped if the patient received a short course of psychosocial therapy at a suicide prevention center. But again, this study looked at a select group of people who had already attempted suicide.

I began to think it might help to ask these questions in a closed system where patients could be tallied with regard to requests for treatment, what type of treatment was provided, and even access to autopsy results. The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs seemed to be a source where such answers might be found. It has been reported that 22 veterans a day die by suicide, and many veterans get their care in VA facilities, with VA pharmacy benefits, and treatment effects can, in theory, be studied.

Hoping to get a better sense of the relationship between treatment and suicide, I met with Robert Bossarte, Ph.D., director of the Epidemiology Program in the VA’s Office of Public Health. His career has been focused on suicide prevention.

The first thing Dr. Bossarte did was dissuade me of the idea that the VA is a closed system. Not all veterans receive lifelong benefits from the VA, and the formulas for determining who is entitled to what benefits, and for how long, is rather complicated. Dr. Bossarte also noted that some patients go outside of the system for their care.

“What we do know is that among those who have used VA services in the previous year, about 2,000 veterans a year die from suicide. It’s been hovering around that for the past decade,” Dr. Bossarte explained, again emphasizing that many veterans do not receive care at VA facilities. “We published a report in 2012 where we estimated 22 veterans a day die by suicide and that caught fire, but it is purely an estimate. The truth is we have no idea what the real count is, because until we began working on the Suicide Data Repository there was no national register of veteran mortality and there has been no way for us to know.”

Dr. Bossarte anticipates that the VA will have the data necessary to calculate more accurate statistics by the end of the year. “More than 70% of veteran suicide are in people over age 50; but the rates are going up most among the youngest.”

A notable drop in veteran suicide rates for those who used services occurred between 2001 and 2003, and that decrease remains unexplained; it preceded later changes in mental health services and enhanced suicide prevention programs. Dr. Bossarte also pointed out that just under half of veterans who die from suicide have no mental health diagnosis, despite yearly screening to identify people who may be suffering from posttraumatic stress disorder, alcohol-related disorders, and depression.

“The attention on veteran suicide started around 2007,” Dr. Bossarte explained. “Mark Kaplan published a study using publicly available mortality data; those who reported they were veterans were twice as likely to die of suicide as those who were not.”

While this sparked interest in veteran suicide, it’s important to note that a replication of that study in 2012 by Matthew Miller did not have the same findings.

“Then, in 2008, for the first time in recent history,” Dr. Bossarte continued, “the suicide rate among active duty military personnel exceeded that of the general population. Traditionally, rates of suicide in this population have been 40%-50% lower than in the general population. The increased rate was seen primarily in the Army and Marines. Serious mental illness may make people ineligible for military service, as can violent and disruptive behavior – things that are associated with suicide – so you tended to get a healthier population in the military.”

Dr. Bossarte noted that there was conjecture that increased suicide rates among active military might be related to more waivers that allowed people to enlist who would not ordinarily be eligible, and/or to higher rates of deployment. He went on to talk about Army STARRS (Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers).

“STARRS devoted $50 million over 5 years to the largest suicide study and did not find an effect of waivers. They did report a higher suicide rate among those who were deployed, however. But then Tim Bullman in my office looked at suicide rates 7 years after separation from service, and he reported a higher suicide rate among those who were never deployed.” The VA studies, I quickly realized, were also confusing and contradictory.

The VA has greatly expanded its mental health and suicide prevention services. For veterans overall, suicide rates have stabilized, but they have not decreased. For those veterans with psychiatric disorders, however, the suicide rates have gone down.

“When you ask ‘does treatment matter?’ it’s so hard to disentangle psychotherapy from pharmacotherapy. Over the past decade, we’ve seen a significant decrease in the suicide rate among those veterans with mental health disorders. We’ve looked at suicide rates every way you can think of. One thing we do know is that the better the relationship with the clinician, the lower the suicide risk.”

We talked about the role of hospitalization in preventing suicide, and Dr. Bossarte noted that the highest risk for suicide is immediately following hospital discharge.

“We are looking at people hospitalized after their first-ever suicide attempts and rates of mortality, including suicidal behavior, for 1 year after discharge. In very preliminary findings, we didn’t see any difference in the outcome for either all-cause mortality or repeat suicide attempts in those who were hospitalized, compared to those who were not. We don’t yet know about completed suicide.”

I left my discussion with Dr. Bossarte with more questions than answers. We have reason to believe that treatment helps, but we still don’t know which treatments help which people, and we do know that treatment doesn’t prevent suicide in every patient. In a culture where “treatment” has come to be equated with “prescribing” and is often based on a checklist of symptoms done by a primary care clinician, one might wonder if combining psychotherapy and medication – an increasingly rare offering – might have a better outcome. Simply put, for a problem that prematurely takes more than 40,000 lives a year, we know much too little.

Dr. Miller is a coauthor of “Shrink Rap: Three Psychiatrists Explain Their Work” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2011).

Catching up on brain stimulation with Dr. Irving Reti

Psychiatry is a field where the treatment of our disorders remains perplexing: We’re still trying to figure out if the best way to treat psychiatric conditions is through psychotherapy, with medications, or for more resistant conditions, by stimulating activity in the brain in several different ways.

The field of brain stimulation includes electroconvulsive therapy, as well as transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), direct transcranial current stimulation (tDCS), and deep brain stimulation (DBS), all of which are examples of treatments that are still just coming into their own.

In search of an update on brain stimulation, I met with Dr. Irving Reti, director of the Johns Hopkins Hospital Brain Stimulation Program and editor of “Brain Stimulation: Methodologies and Interventions” (Hoboken, N.J.: Wiley-Blackwell, 2015). We met at a Starbucks in Baltimore, and I’ll tell you that a one-on-one conversation with an expert is a wonderful way to learn about state-of-the-art treatments, the only downside being that Starbucks does not offer CME credit.

Dr. Reti, who went to medical school at the University of Sydney and speaks with a charming Australian accent, trained in psychiatry at Johns Hopkins, and then did a neuroscience fellowship.

“I’d just finished residency training, and I was giving ECT to rats. We were looking at the expression of immediate-early genes. At the same time, I started doing consults in the mood disorders clinic.”

In 2006, Dr. Reti took over as director of ECT at Hopkins, and that same year, Dr. Jimmy Potash got funding to study TMS. Dr. Potash has since moved to the University of Iowa, and Dr. Reti took over TMS administration at Hopkins. Dr. Reti was flattered to be approached by Wiley to edit “Brain Stimulation,” and he talked about how he was pleased with the final edition of the book.

“I ended up getting the top people to write the chapters, people like Sarah Lisanby, Michael Nitsche, John Rothwell, and Mark George. These are the leaders in the field of brain stimulation.”

I asked Dr. Reti to walk me through what was happening in each brain stimulation area.

“In ECT,” he said, “we know a lot more now about how both the settings and the anesthesia regimen affect the outcomes. We didn’t know this when I trained in the ’90s.” Dr. Reti estimated that he’s administered ECT to close to 2,000 patients.

TMS is done less often at Hopkins; he estimated that 10-20 patients receive the treatment, and each patient comes 30-40 times, with each session lasting 40 minutes.

“It’s better than medicine but not as effective as ECT. We’re seeing an efficacy rate around 50%-60%,” and he noted that some patients have trouble tolerating the procedure as the magnetic stimulation can be uncomfortable. “The TMS coil stimulates the scalp nerves and muscles immediately under the coil, which causes discomfort.” He noted that some patients need to premedicate with over-the-counter pain medicines.

“We’re also finding that low-frequency stimulation on the right can be helpful for anxiety,” Dr. Reti said.

He talked about treating patients with psychotherapy along with TMS. The brain changes are thought to increase the brain’s plasticity and perhaps make psychotherapy more effective.

“It’s being studied in drug treatment. You can show someone with an addiction stimuli to trigger cravings, and doing this with TMS may block the response,” he said.

He talked for a while about direct transcranial brain stimulation, which I was not very familiar with. Because it is being used to improve focus-playing video games, the equipment is not being marketed as a psychiatric treatment and doesn’t fall under the domain of the Food and Drug Administration.

“Kids are using it to improve their concentration and performance with video games; all you need is a 9-volt battery and some electrodes that are attached to the scalp. The kits cost about $250, but you can burn your scalp,” he said.

Dr. Reti referred me to an article in the New Yorker on tDCS, “Electrified: Adventures in transcranial direct-current stimulation” by Elif Batuman. He noted that there are studies in progress to look at therapeutic uses for tDCS, including one at Johns Hopkins where neuropsychologist David Schretlen is looking at improving cognition in schizophrenia. Dr. Reti is interested in seeing if tDCS might be helpful in decreasing self-injurious behaviors in autistic children, as ECT has been effective in severe cases. He noted that while ECT and TMS stimulate neurons in the brain to fire, tDCS changes the stimulation threshold without directly causing the neurons to discharge.

Finally, we talked a little about deep brain stimulation. Thin electrodes directly target nodes in brain circuits that can modulate the activity of those circuits. He noted that deep brain stimulation was being used at Johns Hopkins to treat Parkinson’s disease, and other centers have looked at its use for severe obsessive-compulsive disorder and treatment-resistant depression.

“We know that the response habituates; now they are trying on-demand DBS,” Dr. Reti noted.

So, although I got no continuing medical education credits, I did get to try a new Starbucks drink while having a very stimulating discussion on the latest convulsive and nonconvulsive psychiatric brain research.

Dr. Miller is a coauthor of “Shrink Rap: Three Psychiatrists Explain Their Work” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2011).

Psychiatry is a field where the treatment of our disorders remains perplexing: We’re still trying to figure out if the best way to treat psychiatric conditions is through psychotherapy, with medications, or for more resistant conditions, by stimulating activity in the brain in several different ways.

The field of brain stimulation includes electroconvulsive therapy, as well as transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), direct transcranial current stimulation (tDCS), and deep brain stimulation (DBS), all of which are examples of treatments that are still just coming into their own.

In search of an update on brain stimulation, I met with Dr. Irving Reti, director of the Johns Hopkins Hospital Brain Stimulation Program and editor of “Brain Stimulation: Methodologies and Interventions” (Hoboken, N.J.: Wiley-Blackwell, 2015). We met at a Starbucks in Baltimore, and I’ll tell you that a one-on-one conversation with an expert is a wonderful way to learn about state-of-the-art treatments, the only downside being that Starbucks does not offer CME credit.

Dr. Reti, who went to medical school at the University of Sydney and speaks with a charming Australian accent, trained in psychiatry at Johns Hopkins, and then did a neuroscience fellowship.

“I’d just finished residency training, and I was giving ECT to rats. We were looking at the expression of immediate-early genes. At the same time, I started doing consults in the mood disorders clinic.”

In 2006, Dr. Reti took over as director of ECT at Hopkins, and that same year, Dr. Jimmy Potash got funding to study TMS. Dr. Potash has since moved to the University of Iowa, and Dr. Reti took over TMS administration at Hopkins. Dr. Reti was flattered to be approached by Wiley to edit “Brain Stimulation,” and he talked about how he was pleased with the final edition of the book.

“I ended up getting the top people to write the chapters, people like Sarah Lisanby, Michael Nitsche, John Rothwell, and Mark George. These are the leaders in the field of brain stimulation.”

I asked Dr. Reti to walk me through what was happening in each brain stimulation area.

“In ECT,” he said, “we know a lot more now about how both the settings and the anesthesia regimen affect the outcomes. We didn’t know this when I trained in the ’90s.” Dr. Reti estimated that he’s administered ECT to close to 2,000 patients.

TMS is done less often at Hopkins; he estimated that 10-20 patients receive the treatment, and each patient comes 30-40 times, with each session lasting 40 minutes.

“It’s better than medicine but not as effective as ECT. We’re seeing an efficacy rate around 50%-60%,” and he noted that some patients have trouble tolerating the procedure as the magnetic stimulation can be uncomfortable. “The TMS coil stimulates the scalp nerves and muscles immediately under the coil, which causes discomfort.” He noted that some patients need to premedicate with over-the-counter pain medicines.

“We’re also finding that low-frequency stimulation on the right can be helpful for anxiety,” Dr. Reti said.

He talked about treating patients with psychotherapy along with TMS. The brain changes are thought to increase the brain’s plasticity and perhaps make psychotherapy more effective.

“It’s being studied in drug treatment. You can show someone with an addiction stimuli to trigger cravings, and doing this with TMS may block the response,” he said.

He talked for a while about direct transcranial brain stimulation, which I was not very familiar with. Because it is being used to improve focus-playing video games, the equipment is not being marketed as a psychiatric treatment and doesn’t fall under the domain of the Food and Drug Administration.

“Kids are using it to improve their concentration and performance with video games; all you need is a 9-volt battery and some electrodes that are attached to the scalp. The kits cost about $250, but you can burn your scalp,” he said.

Dr. Reti referred me to an article in the New Yorker on tDCS, “Electrified: Adventures in transcranial direct-current stimulation” by Elif Batuman. He noted that there are studies in progress to look at therapeutic uses for tDCS, including one at Johns Hopkins where neuropsychologist David Schretlen is looking at improving cognition in schizophrenia. Dr. Reti is interested in seeing if tDCS might be helpful in decreasing self-injurious behaviors in autistic children, as ECT has been effective in severe cases. He noted that while ECT and TMS stimulate neurons in the brain to fire, tDCS changes the stimulation threshold without directly causing the neurons to discharge.

Finally, we talked a little about deep brain stimulation. Thin electrodes directly target nodes in brain circuits that can modulate the activity of those circuits. He noted that deep brain stimulation was being used at Johns Hopkins to treat Parkinson’s disease, and other centers have looked at its use for severe obsessive-compulsive disorder and treatment-resistant depression.

“We know that the response habituates; now they are trying on-demand DBS,” Dr. Reti noted.

So, although I got no continuing medical education credits, I did get to try a new Starbucks drink while having a very stimulating discussion on the latest convulsive and nonconvulsive psychiatric brain research.

Dr. Miller is a coauthor of “Shrink Rap: Three Psychiatrists Explain Their Work” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2011).

Psychiatry is a field where the treatment of our disorders remains perplexing: We’re still trying to figure out if the best way to treat psychiatric conditions is through psychotherapy, with medications, or for more resistant conditions, by stimulating activity in the brain in several different ways.

The field of brain stimulation includes electroconvulsive therapy, as well as transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), direct transcranial current stimulation (tDCS), and deep brain stimulation (DBS), all of which are examples of treatments that are still just coming into their own.

In search of an update on brain stimulation, I met with Dr. Irving Reti, director of the Johns Hopkins Hospital Brain Stimulation Program and editor of “Brain Stimulation: Methodologies and Interventions” (Hoboken, N.J.: Wiley-Blackwell, 2015). We met at a Starbucks in Baltimore, and I’ll tell you that a one-on-one conversation with an expert is a wonderful way to learn about state-of-the-art treatments, the only downside being that Starbucks does not offer CME credit.

Dr. Reti, who went to medical school at the University of Sydney and speaks with a charming Australian accent, trained in psychiatry at Johns Hopkins, and then did a neuroscience fellowship.

“I’d just finished residency training, and I was giving ECT to rats. We were looking at the expression of immediate-early genes. At the same time, I started doing consults in the mood disorders clinic.”

In 2006, Dr. Reti took over as director of ECT at Hopkins, and that same year, Dr. Jimmy Potash got funding to study TMS. Dr. Potash has since moved to the University of Iowa, and Dr. Reti took over TMS administration at Hopkins. Dr. Reti was flattered to be approached by Wiley to edit “Brain Stimulation,” and he talked about how he was pleased with the final edition of the book.

“I ended up getting the top people to write the chapters, people like Sarah Lisanby, Michael Nitsche, John Rothwell, and Mark George. These are the leaders in the field of brain stimulation.”

I asked Dr. Reti to walk me through what was happening in each brain stimulation area.

“In ECT,” he said, “we know a lot more now about how both the settings and the anesthesia regimen affect the outcomes. We didn’t know this when I trained in the ’90s.” Dr. Reti estimated that he’s administered ECT to close to 2,000 patients.

TMS is done less often at Hopkins; he estimated that 10-20 patients receive the treatment, and each patient comes 30-40 times, with each session lasting 40 minutes.

“It’s better than medicine but not as effective as ECT. We’re seeing an efficacy rate around 50%-60%,” and he noted that some patients have trouble tolerating the procedure as the magnetic stimulation can be uncomfortable. “The TMS coil stimulates the scalp nerves and muscles immediately under the coil, which causes discomfort.” He noted that some patients need to premedicate with over-the-counter pain medicines.

“We’re also finding that low-frequency stimulation on the right can be helpful for anxiety,” Dr. Reti said.

He talked about treating patients with psychotherapy along with TMS. The brain changes are thought to increase the brain’s plasticity and perhaps make psychotherapy more effective.

“It’s being studied in drug treatment. You can show someone with an addiction stimuli to trigger cravings, and doing this with TMS may block the response,” he said.

He talked for a while about direct transcranial brain stimulation, which I was not very familiar with. Because it is being used to improve focus-playing video games, the equipment is not being marketed as a psychiatric treatment and doesn’t fall under the domain of the Food and Drug Administration.

“Kids are using it to improve their concentration and performance with video games; all you need is a 9-volt battery and some electrodes that are attached to the scalp. The kits cost about $250, but you can burn your scalp,” he said.

Dr. Reti referred me to an article in the New Yorker on tDCS, “Electrified: Adventures in transcranial direct-current stimulation” by Elif Batuman. He noted that there are studies in progress to look at therapeutic uses for tDCS, including one at Johns Hopkins where neuropsychologist David Schretlen is looking at improving cognition in schizophrenia. Dr. Reti is interested in seeing if tDCS might be helpful in decreasing self-injurious behaviors in autistic children, as ECT has been effective in severe cases. He noted that while ECT and TMS stimulate neurons in the brain to fire, tDCS changes the stimulation threshold without directly causing the neurons to discharge.

Finally, we talked a little about deep brain stimulation. Thin electrodes directly target nodes in brain circuits that can modulate the activity of those circuits. He noted that deep brain stimulation was being used at Johns Hopkins to treat Parkinson’s disease, and other centers have looked at its use for severe obsessive-compulsive disorder and treatment-resistant depression.

“We know that the response habituates; now they are trying on-demand DBS,” Dr. Reti noted.

So, although I got no continuing medical education credits, I did get to try a new Starbucks drink while having a very stimulating discussion on the latest convulsive and nonconvulsive psychiatric brain research.

Dr. Miller is a coauthor of “Shrink Rap: Three Psychiatrists Explain Their Work” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2011).

Single-session psychiatry at 11,000 feet

The woman sitting across from me talked, through two translators (Quechua to Spanish to English) about how sad she had been since the death of her husband last year. “I eat alone,” she said, and my Spanish translator, a native Peruvian, explained the cultural significance of such a phrase to me. Eating alone is not a good thing; sometimes it’s how people are shunned. The woman talked about her adult children and how little contact she had with them, a continual disappointment in a poor rural area where the younger generation often flocked to the city and the hope of a better life.

She was in her 60s and dressed in the traditional attire of the indigenous people of the Andes: a high bowler hat, layers of sweaters, a long skirt, and woolen stockings. Her long black braids remained ageless in a land where somehow hair does not turn gray, but her bronze skin was leathery from generations in the sun. Her problems – grief and loneliness – are universal issues, and while she had moments where she longed for death, she felt her animals, and her cow in particular, needed her now.

Months ago, a friend – an internist – asked if my husband and I would join him, his wife, and some other families we knew on a volunteer medical mission to Peru. Hands Across the Americas is an organization founded by Jennifer Diamond and it has sent 27 medical and surgical missions to Latin America to serve those with limited access to medical treatments. I hesitated when I heard the request, and in case I wasn’t entranced by the idea of spending a week addressing the mental health needs of indigenous people in remote Andean villages, he added that another friend of ours, Patricia Poppe, a native of Peru and an expert on health communications at the Johns Hopkins School of Public Health, was eager to show our group of friends around her homeland before we all joined the mission. With this, I was sold on the whole adventure. I will spare you the details of our wonderful vacation, but will share with you, instead, what I learned about psychiatry in the Andes.

The mission orientation began in Cusco, Peru’s second-largest city and a way station for travelers headed to Machu Picchu. The tourist district of Cusco is a beautiful and fascinating city that reflects both Incan and pre-Incan Latin America and the heavy Spanish influence brought by the 16th- century conquistadors. While the city is beautiful, and the worlds have intertwined over the centuries, it remains a land where there is tension between the different cultures.

At just over 11,000 feet, the air is thin and visitors get easily winded just walking the hills. The villages we worked in were all about an hour outside of Cusco. They were impoverished and dilapidated, with some of the homes still constructed of bricks made from mud and straw. Dogs and farm animals roamed the streets. July is midwinter there, and it’s the dry season, so everything – and everyone – was covered in a layer of Andean grit. By the end of each day, we were as well.

I wish I could say that I wasn’t anxious about the work, but I was. What can a psychiatrist do in a single visit, much less a single session that requires one, and occasionally two, translators, in a population where I had no knowledge of their culture or resources? I didn’t know what types of patients I might see, if using medication would be reasonable, or if follow-up of any kind would be feasible. In the 27 missions of Hands Across the Americas, I was to be the first psychiatrist.

Four years earlier, a psychologist, Dr. David Doolittle, had gone with another psychologist, and when we spoke on the phone, he was very enthusiastic. He told me that this had been one of the best experiences of his professional life, and he was pleased to hear that mental health would continue to be a part of the agenda.

Finally, I should add that despite my hesitation about how helpful I might be as part of a medical team offering one-time services, I did have a similar experience in a different setting; In 2005, I volunteered for 2 weeks with the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s Katrina Assistance Project, and while I wondered then if my efforts were helpful to those I was trying to serve, I walked away feeling that I personally had gotten a great deal from the experience. I decided I would go to Peru with limited expectations and one simple agenda: I would try to be helpful.

The mission started with a brief orientation in Cusco, and it didn’t escape me when the medical director announced that patients could be seen by internal medicine, pediatrics, ENT, gynecology, and optometry. Psychiatry was strangely missing from the list, and when I pointed this out, he told me he had a special job for me: to run the pharmacy. While I was happy to help dispense medications, I had the sense that this population might have unmet mental health needs and suggested that it could be worthwhile to offer psychiatry as a specialty as well!

While the group came with an extensive supply of medications, vitamins, reading glasses, toothbrushes, and some wheelchairs, canes, and walkers, there were no psychotropic medications in the stash. I spoke with a local doctor who served as a liaison, and learned that he was familiar only with diazepam and alprazolam. Psychiatric patients were referred to doctors in Cusco, and local doctors did not prescribe antidepressants. For complex issues that required medical or surgical subspecialization, the referrals were even more complex: Patients traveled 18 hours by bus to be treated in Lima.

On the morning of our first clinic, I was given a small supply of fluoxetine (per my request) and alprazolam. Over 5 days we worked in three sites. On the first day, we were at the municipal center in Huarocondo, a little more than an hour outside of Cusco. Tents were set up inside the building, with the waiting room, triage, and pharmacy all stationed outside on the dirt. Inside, there was very little light, and like the other places we’d set up, no heat. My tent had a table and two chairs meant for primary school children, and I absconded with an adult-sized plastic chair for my interpreter. We had no access to medical records, no labs or radiographic equipment, and no clear place to send anyone for follow-up – this was true across all specialties, though the ENT who was working with us had come with suitcases full of his own equipment. Patients didn’t know what a psychiatrist or psychologist was, and some responded to questions about depression by saying that their blood pressure was just fine. Triage resorted to asking people if they felt sad and wanted to talk to a doctor about it.

The next 2 days, we worked in medical clinics in Ancahuasi and Anta, and while the conditions were more conducive to providing medical care, there was still no heat, the lighting was poor, and the buildings had not seen new coats of paint or furniture in many years. The clinics did not have psychiatrists, but they did each have a psychologist, and a couple of the people I saw had been seen. I was also told that fluoxetine could be obtained in Anta.

Hundreds of patients came each day, and all told, more than a thousand patients were seen by nine doctors in those 5 days. My official psychiatry tally was 79, but my personal count was less – I imagine some people became impatient with the long line and left without being seen – I recorded visits with 8-15 people each day.

First, let me say that I was surprised at the lack of pure psychopathology; the issues were more reactions to tremendous deprivation, violence, loneliness, medical and developmental disorders, and chronic struggles. I saw only two adult men, the rest of the patients were women and a few children. No one I saw had ever seen a psychiatrist before, and no one had taken psychotropic medications (not even the diazepam or alprazolam, which I was told could be obtained), and in fact, very few were on any medications of any kind. No one had ever been in a psychiatric hospital. Poverty was rampant, as was domestic violence: Men beat their wives, parents beat their children, and there seemed to be no societal means to interrupt this. One bruised woman said her husband had been released from jail in a day, and several women spoke of living in fear for their lives; still, their families encouraged them to stay with men who were abusive or unfaithful. I was told that the statistic for spousal abuse in Peru was 60%, in Cusco it was 75%; I suspect it was even higher in these outlying villages. Families were fractured; employment was physically very difficult; and stress was extreme. Low mood and poor sleep were pervasive, but given the fact that I was unsure if people could get follow-up or even afford to refill medications, I gave out very little in the way of medications, and used the fluoxetine only for a few people where I felt their mood and circumstances were so dire that perhaps it would help – and it seemed unlikely to hurt. I was able to hospitalize one 18-year-old mother who was suicidal and said she had tried to hang herself, though she was released early the next morning before she was ever seen by a doctor; she did note she felt much better and was grateful for the help.

Despite tremendous stresses and limited access to care, the suicide rate in Peru are quite low at 3.2 per 100,000 (as compared with nearly 14 per 100,000 in the United States), and despite the fact that some of the patients I saw had considered it, most said that their children or animals needed them, and there are religious prohibitions.

At moments, I wondered what I could possibly offer. One woman came in with a 5-year-old child with Down syndrome strapped to her, and another, older, developmentally delayed child in tow. There were other children at home, and while many women noted that their husbands beat them while they were drunk, this woman said her husband was calmer when he was drinking; he beat her when he was sober. I asked her what would help, and she said she needed money. Feeling I had nothing else to offer, I did something I have never done in my years as a psychiatrist: I gave her money. I hoped that she would spend it on something that might provide a moment of relief from her anguished life.

For the most part, it was interesting work, and often, it felt useful to make psychological interventions, to validate the distress the patients felt and to reorient them to seeing their own strengths. The people talked of holding their problems close, and of a relief and ease that came with sharing their difficulties.

In the end, I did feel helpful for at least some of the patients some of the time. At the very least, I felt appreciated – in one clinic, we were greeted by the mayor and a band – and patients expressed their thanks to both me and my cadre of interpreters, sometimes profusely. In the end, it was an adventure, from the vacation with 16 people to Lima, the Sacred Valley, and Machu Picchu, to my foray into high-volume, single-session psychiatry in a culture so vastly different from my own.

Dr. Miller is a coauthor of “Shrink Rap: Three Psychiatrists Explain Their Work” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2011).

The woman sitting across from me talked, through two translators (Quechua to Spanish to English) about how sad she had been since the death of her husband last year. “I eat alone,” she said, and my Spanish translator, a native Peruvian, explained the cultural significance of such a phrase to me. Eating alone is not a good thing; sometimes it’s how people are shunned. The woman talked about her adult children and how little contact she had with them, a continual disappointment in a poor rural area where the younger generation often flocked to the city and the hope of a better life.

She was in her 60s and dressed in the traditional attire of the indigenous people of the Andes: a high bowler hat, layers of sweaters, a long skirt, and woolen stockings. Her long black braids remained ageless in a land where somehow hair does not turn gray, but her bronze skin was leathery from generations in the sun. Her problems – grief and loneliness – are universal issues, and while she had moments where she longed for death, she felt her animals, and her cow in particular, needed her now.