User login

Anticoagulation Hub contains news and clinical review articles for physicians seeking the most up-to-date information on the rapidly evolving treatment options for preventing stroke, acute coronary events, deep vein thrombosis, and pulmonary embolism in at-risk patients. The Anticoagulation Hub is powered by Frontline Medical Communications.

Warfarin therapy highly unpredictable in real-world practice

Only a minority of patients with atrial fibrillation or venous thromboembolism achieved good anticoagulation control while on warfarin, according to a population-based data analysis by Ana Filipa Macedo and her colleagues at Boehringer Ingelheim in the United Kingdom. In fact, only 44% of 140,078 AF patients and 36% of 70,371 VTE patients assessed had an optimal International Normalized Ratio (INR) time in therapeutic range (TTR) more than 70% of the time while on warfarin.

Patient characteristics associated with a significant increase in time spent above or below the recommended INR range of 2.0-3.0 were current smoking, the use of NSAIDs, age less than 45 years, and a body mass index less than 18.5 kg/m2 in both AF and VTE patients, whereas patients with VTE alone had predictors of poor control that included chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or asthma, heart failure, and active cancer.

“The study provides evidence that in the first 12 months of warfarin use, there is a high amount of unpredictable variability in an individual’s TTR,” the researchers summarized. “These findings confirm the difficulty of achieving high-quality anticoagulation with warfarin in real-world clinical practice and can be used to identify patients who require closer monitoring or innovative management strategies,” the authors added.

More of the study can be read here (Thromb Res. 2015 Aug; 136(2):250-260.).

The study received funding from Boehringer Ingelheim, and the authors disclosed that they were all employees of the company, which makes a variety of cardiovascular therapies, including anticoagulants.

Only a minority of patients with atrial fibrillation or venous thromboembolism achieved good anticoagulation control while on warfarin, according to a population-based data analysis by Ana Filipa Macedo and her colleagues at Boehringer Ingelheim in the United Kingdom. In fact, only 44% of 140,078 AF patients and 36% of 70,371 VTE patients assessed had an optimal International Normalized Ratio (INR) time in therapeutic range (TTR) more than 70% of the time while on warfarin.

Patient characteristics associated with a significant increase in time spent above or below the recommended INR range of 2.0-3.0 were current smoking, the use of NSAIDs, age less than 45 years, and a body mass index less than 18.5 kg/m2 in both AF and VTE patients, whereas patients with VTE alone had predictors of poor control that included chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or asthma, heart failure, and active cancer.

“The study provides evidence that in the first 12 months of warfarin use, there is a high amount of unpredictable variability in an individual’s TTR,” the researchers summarized. “These findings confirm the difficulty of achieving high-quality anticoagulation with warfarin in real-world clinical practice and can be used to identify patients who require closer monitoring or innovative management strategies,” the authors added.

More of the study can be read here (Thromb Res. 2015 Aug; 136(2):250-260.).

The study received funding from Boehringer Ingelheim, and the authors disclosed that they were all employees of the company, which makes a variety of cardiovascular therapies, including anticoagulants.

Only a minority of patients with atrial fibrillation or venous thromboembolism achieved good anticoagulation control while on warfarin, according to a population-based data analysis by Ana Filipa Macedo and her colleagues at Boehringer Ingelheim in the United Kingdom. In fact, only 44% of 140,078 AF patients and 36% of 70,371 VTE patients assessed had an optimal International Normalized Ratio (INR) time in therapeutic range (TTR) more than 70% of the time while on warfarin.

Patient characteristics associated with a significant increase in time spent above or below the recommended INR range of 2.0-3.0 were current smoking, the use of NSAIDs, age less than 45 years, and a body mass index less than 18.5 kg/m2 in both AF and VTE patients, whereas patients with VTE alone had predictors of poor control that included chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or asthma, heart failure, and active cancer.

“The study provides evidence that in the first 12 months of warfarin use, there is a high amount of unpredictable variability in an individual’s TTR,” the researchers summarized. “These findings confirm the difficulty of achieving high-quality anticoagulation with warfarin in real-world clinical practice and can be used to identify patients who require closer monitoring or innovative management strategies,” the authors added.

More of the study can be read here (Thromb Res. 2015 Aug; 136(2):250-260.).

The study received funding from Boehringer Ingelheim, and the authors disclosed that they were all employees of the company, which makes a variety of cardiovascular therapies, including anticoagulants.

FROM THROMBOSIS RESEARCH

Combined ablation–mitral surgery safe for atrial fib

NEW YORK – Patients with both mitral valve regurgitation and atrial fibrillation who undergo concurrent mitral valve surgery and surgical ablation are more than twice as likely to be free of AF a year after surgery than are their counterparts who have mitral valve surgery alone, according to results of a randomized trial.

“About a quarter to a half of our your patients coming for mitral valve surgery also have AF,” Dr. A. Marc Gillinov said at the 2015 Mitral Valve Conclave sponsored by the American Association for Thoracic Surgery. “A great mitral valve repair is your first priority, but you also want to treat the AF.” Currently, cardiac surgeons perform concurrent mitral valve surgery and surgical ablation about 60% of the time in patients eligible for both procedures, he said.

The American College of Cardiology/American Health Association Guidelines state that surgical ablation in patients with AF having cardiac surgery for other indications is “reasonable” – “not very strong language,” he noted, and the level of evidence for concurrent procedures is C.

That led the Cardiothoracic Surgical Trials Network to pursue the clinical trial. The investigators randomized 260 patients with persistent or long-standing persistent atrial fibrillation who needed mitral valve surgery to also undergo either surgical ablation (133) or no ablation (127). The primary endpoint was freedom from AF at both 6 months and 12 months as assessed by 3-day Holter monitoring.

Almost two-thirds (63%) of patients in the ablation group were free from atrial fibrillation at both 6 and 12 months, compared with 29% of those who had mitral valve surgery only, a highly significant difference. Dr. Gillinov described the trial population as “tougher patients” with persistent AF whose average age was around 70 years, and most had organic mitral valve regurgitation.

Results were similar whether the patients underwent pulmonary vein isolation or biatrial maze procedure (61% and 66%, respectively). One-year mortality was 6.8% in the ablation group and 8.7% in the control group, reported Dr. Gillinov, who is surgical director of the Center for Atrial Fibrillation at Cleveland Clinic.

The trial found no significant differences between the ablation and nonablation groups in major cardiac or cerebrovascular adverse events, overall serious adverse events, or hospital readmissions. The results were published prior to the Dr. Gillinov’s presentation (N. Engl. J. Med. 2015;372:1399-409).

These results debunk findings from a survey a few years ago that found cardiac surgeons avoided doing surgical ablation during mitral valve surgery because it makes the operation too complex, requires longer pump times, and raises the risk of surgery, said Dr. Gillinov. “Does ablation improve rhythm control? Yes. Does ablation increase risk? No. Does ablation improve clinical outcomes? It probably does,” he said.

The trial had some limitations, Dr. Gillinov said. Its endpoint was not a clinical outcome, although looking at stroke risk or mortality would have required thousands of patients. Also, 20% of patients did not have follow-up with the 3-day Holter test. However, previous studies have shown a strong association between surgical ablation and a reduced risk of stroke. When Dr. Jolanda Kluin of Utrecht (the Netherlands) University asked if a patient would be better off with AF or a pacemaker, Dr. Gillinov replied, “I think it’s better to have an AV sequential rhythm, but the truth is no one can answer that question without clinical data.”

The bottom line is, “if you have a patient who’s having mitral valve surgery who also has AF, do an ablation,” he said.

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Dr. Gillinov disclosed relationships with AtriCure, Medtronic, Edwards Lifesciences, On-X Life Technologies, Abbott, Tendyne, and Clear Catheter.

NEW YORK – Patients with both mitral valve regurgitation and atrial fibrillation who undergo concurrent mitral valve surgery and surgical ablation are more than twice as likely to be free of AF a year after surgery than are their counterparts who have mitral valve surgery alone, according to results of a randomized trial.

“About a quarter to a half of our your patients coming for mitral valve surgery also have AF,” Dr. A. Marc Gillinov said at the 2015 Mitral Valve Conclave sponsored by the American Association for Thoracic Surgery. “A great mitral valve repair is your first priority, but you also want to treat the AF.” Currently, cardiac surgeons perform concurrent mitral valve surgery and surgical ablation about 60% of the time in patients eligible for both procedures, he said.

The American College of Cardiology/American Health Association Guidelines state that surgical ablation in patients with AF having cardiac surgery for other indications is “reasonable” – “not very strong language,” he noted, and the level of evidence for concurrent procedures is C.

That led the Cardiothoracic Surgical Trials Network to pursue the clinical trial. The investigators randomized 260 patients with persistent or long-standing persistent atrial fibrillation who needed mitral valve surgery to also undergo either surgical ablation (133) or no ablation (127). The primary endpoint was freedom from AF at both 6 months and 12 months as assessed by 3-day Holter monitoring.

Almost two-thirds (63%) of patients in the ablation group were free from atrial fibrillation at both 6 and 12 months, compared with 29% of those who had mitral valve surgery only, a highly significant difference. Dr. Gillinov described the trial population as “tougher patients” with persistent AF whose average age was around 70 years, and most had organic mitral valve regurgitation.

Results were similar whether the patients underwent pulmonary vein isolation or biatrial maze procedure (61% and 66%, respectively). One-year mortality was 6.8% in the ablation group and 8.7% in the control group, reported Dr. Gillinov, who is surgical director of the Center for Atrial Fibrillation at Cleveland Clinic.

The trial found no significant differences between the ablation and nonablation groups in major cardiac or cerebrovascular adverse events, overall serious adverse events, or hospital readmissions. The results were published prior to the Dr. Gillinov’s presentation (N. Engl. J. Med. 2015;372:1399-409).

These results debunk findings from a survey a few years ago that found cardiac surgeons avoided doing surgical ablation during mitral valve surgery because it makes the operation too complex, requires longer pump times, and raises the risk of surgery, said Dr. Gillinov. “Does ablation improve rhythm control? Yes. Does ablation increase risk? No. Does ablation improve clinical outcomes? It probably does,” he said.

The trial had some limitations, Dr. Gillinov said. Its endpoint was not a clinical outcome, although looking at stroke risk or mortality would have required thousands of patients. Also, 20% of patients did not have follow-up with the 3-day Holter test. However, previous studies have shown a strong association between surgical ablation and a reduced risk of stroke. When Dr. Jolanda Kluin of Utrecht (the Netherlands) University asked if a patient would be better off with AF or a pacemaker, Dr. Gillinov replied, “I think it’s better to have an AV sequential rhythm, but the truth is no one can answer that question without clinical data.”

The bottom line is, “if you have a patient who’s having mitral valve surgery who also has AF, do an ablation,” he said.

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Dr. Gillinov disclosed relationships with AtriCure, Medtronic, Edwards Lifesciences, On-X Life Technologies, Abbott, Tendyne, and Clear Catheter.

NEW YORK – Patients with both mitral valve regurgitation and atrial fibrillation who undergo concurrent mitral valve surgery and surgical ablation are more than twice as likely to be free of AF a year after surgery than are their counterparts who have mitral valve surgery alone, according to results of a randomized trial.

“About a quarter to a half of our your patients coming for mitral valve surgery also have AF,” Dr. A. Marc Gillinov said at the 2015 Mitral Valve Conclave sponsored by the American Association for Thoracic Surgery. “A great mitral valve repair is your first priority, but you also want to treat the AF.” Currently, cardiac surgeons perform concurrent mitral valve surgery and surgical ablation about 60% of the time in patients eligible for both procedures, he said.

The American College of Cardiology/American Health Association Guidelines state that surgical ablation in patients with AF having cardiac surgery for other indications is “reasonable” – “not very strong language,” he noted, and the level of evidence for concurrent procedures is C.

That led the Cardiothoracic Surgical Trials Network to pursue the clinical trial. The investigators randomized 260 patients with persistent or long-standing persistent atrial fibrillation who needed mitral valve surgery to also undergo either surgical ablation (133) or no ablation (127). The primary endpoint was freedom from AF at both 6 months and 12 months as assessed by 3-day Holter monitoring.

Almost two-thirds (63%) of patients in the ablation group were free from atrial fibrillation at both 6 and 12 months, compared with 29% of those who had mitral valve surgery only, a highly significant difference. Dr. Gillinov described the trial population as “tougher patients” with persistent AF whose average age was around 70 years, and most had organic mitral valve regurgitation.

Results were similar whether the patients underwent pulmonary vein isolation or biatrial maze procedure (61% and 66%, respectively). One-year mortality was 6.8% in the ablation group and 8.7% in the control group, reported Dr. Gillinov, who is surgical director of the Center for Atrial Fibrillation at Cleveland Clinic.

The trial found no significant differences between the ablation and nonablation groups in major cardiac or cerebrovascular adverse events, overall serious adverse events, or hospital readmissions. The results were published prior to the Dr. Gillinov’s presentation (N. Engl. J. Med. 2015;372:1399-409).

These results debunk findings from a survey a few years ago that found cardiac surgeons avoided doing surgical ablation during mitral valve surgery because it makes the operation too complex, requires longer pump times, and raises the risk of surgery, said Dr. Gillinov. “Does ablation improve rhythm control? Yes. Does ablation increase risk? No. Does ablation improve clinical outcomes? It probably does,” he said.

The trial had some limitations, Dr. Gillinov said. Its endpoint was not a clinical outcome, although looking at stroke risk or mortality would have required thousands of patients. Also, 20% of patients did not have follow-up with the 3-day Holter test. However, previous studies have shown a strong association between surgical ablation and a reduced risk of stroke. When Dr. Jolanda Kluin of Utrecht (the Netherlands) University asked if a patient would be better off with AF or a pacemaker, Dr. Gillinov replied, “I think it’s better to have an AV sequential rhythm, but the truth is no one can answer that question without clinical data.”

The bottom line is, “if you have a patient who’s having mitral valve surgery who also has AF, do an ablation,” he said.

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Dr. Gillinov disclosed relationships with AtriCure, Medtronic, Edwards Lifesciences, On-X Life Technologies, Abbott, Tendyne, and Clear Catheter.

AT THE 2015 MITRAL VALVE CONCLAVE

Key clinical point: Patients with atrial fibrillation who have mitral valve surgery would benefit from surgical ablation at the same time.

Major finding: People with AF who had surgical ablation along with mitral valve surgery were more than twice as likely to be free of AF afterwards than were those who had mitral valve surgery only (63.2% vs. 29.4%).

Data source: A clinical trial in 260 patients with AF undergoing mitral valve surgery that randomized 127 to mitral valve surgery alone and 133 to mitral valve surgery with surgical ablation.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Dr. Gillinov disclosed relationships with AtriCure, Medtronic, Edwards Lifesciences, On-X Life Technologies, Abbott, Tendyne, and Clear Catheter.

Most hospitals overestimate their door-to-needle performance

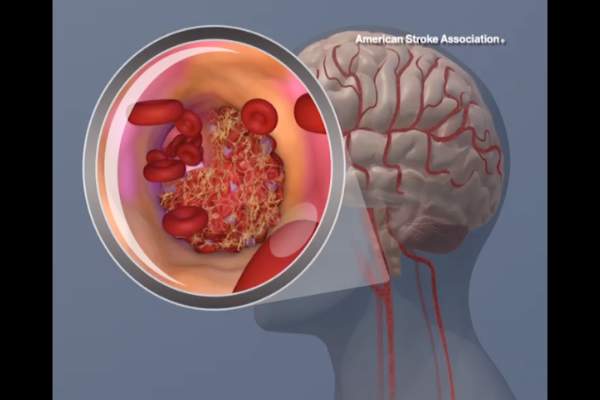

Personnel at most hospitals that treat acute stroke, particularly the lowest-performing hospitals, greatly overestimate their ability to deliver TPA to eligible patients within 1 hour, according to a report published online July 22 in Journal of the American Heart Association.

Overestimating the quality of care they actually provide may perpetuate this suboptimal performance, “whereas accurate measurements of current performance and realistic comparison to other, more successful, sites might provide the needed motivation to fuel quality improvement,” said Dr. Cheryl B. Lin of Tufts Medical Center Floating Hospital for Children, Boston, and her associates.

They compared stroke teams’ perceptions of their door-to-needle performance, as measured on survey questionnaires answered by nurses, neurologists, and other staff members, against the hospitals’ actual performance, which was recorded in a large stroke registry. The investigators focused on 141 hospitals that treated 48,201 stroke patients during a 1-year period. This included 49 top-performing, 52 average-performing, and 40 low-performing hospitals. The top category had door-to-needle rates of 45%-93%, while the bottom category had consistent door-to-needle rates of 0%. The middle category had door-to-needle rates of 16%-25%.

Regardless of their hospital’s performance category, 61% of the respondents overestimated how many eligible patients there actually received TPA within 1 hour. The lowest-performing hospitals had the most unrealistic estimates, with 68% of them guessing that 20% of their patients received timely TPA when in fact 0% of patients did so. Low-performing hospitals also overestimated their performance in comparison with other hospitals, with 85% of them characterizing their performance as average, above average, or even superior relative to other hospitals, when in fact it was very poor, Dr. Lin and her associates wrote (J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2015 July 22 [doi:10.1161/JAHA.114.001298]).

“Addressing misperceptions that one’s performance is average or above average when it actually is not is an important step in addressing motivation for change,” they added.

The study was supported by the U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Dr. Lin reported having no relevant financial disclosures; her associates reported ties to Genentech, Lilly, Johnson & Johnson, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Sanofi-Aventis, and Merck Schering-Plough.

Personnel at most hospitals that treat acute stroke, particularly the lowest-performing hospitals, greatly overestimate their ability to deliver TPA to eligible patients within 1 hour, according to a report published online July 22 in Journal of the American Heart Association.

Overestimating the quality of care they actually provide may perpetuate this suboptimal performance, “whereas accurate measurements of current performance and realistic comparison to other, more successful, sites might provide the needed motivation to fuel quality improvement,” said Dr. Cheryl B. Lin of Tufts Medical Center Floating Hospital for Children, Boston, and her associates.

They compared stroke teams’ perceptions of their door-to-needle performance, as measured on survey questionnaires answered by nurses, neurologists, and other staff members, against the hospitals’ actual performance, which was recorded in a large stroke registry. The investigators focused on 141 hospitals that treated 48,201 stroke patients during a 1-year period. This included 49 top-performing, 52 average-performing, and 40 low-performing hospitals. The top category had door-to-needle rates of 45%-93%, while the bottom category had consistent door-to-needle rates of 0%. The middle category had door-to-needle rates of 16%-25%.

Regardless of their hospital’s performance category, 61% of the respondents overestimated how many eligible patients there actually received TPA within 1 hour. The lowest-performing hospitals had the most unrealistic estimates, with 68% of them guessing that 20% of their patients received timely TPA when in fact 0% of patients did so. Low-performing hospitals also overestimated their performance in comparison with other hospitals, with 85% of them characterizing their performance as average, above average, or even superior relative to other hospitals, when in fact it was very poor, Dr. Lin and her associates wrote (J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2015 July 22 [doi:10.1161/JAHA.114.001298]).

“Addressing misperceptions that one’s performance is average or above average when it actually is not is an important step in addressing motivation for change,” they added.

The study was supported by the U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Dr. Lin reported having no relevant financial disclosures; her associates reported ties to Genentech, Lilly, Johnson & Johnson, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Sanofi-Aventis, and Merck Schering-Plough.

Personnel at most hospitals that treat acute stroke, particularly the lowest-performing hospitals, greatly overestimate their ability to deliver TPA to eligible patients within 1 hour, according to a report published online July 22 in Journal of the American Heart Association.

Overestimating the quality of care they actually provide may perpetuate this suboptimal performance, “whereas accurate measurements of current performance and realistic comparison to other, more successful, sites might provide the needed motivation to fuel quality improvement,” said Dr. Cheryl B. Lin of Tufts Medical Center Floating Hospital for Children, Boston, and her associates.

They compared stroke teams’ perceptions of their door-to-needle performance, as measured on survey questionnaires answered by nurses, neurologists, and other staff members, against the hospitals’ actual performance, which was recorded in a large stroke registry. The investigators focused on 141 hospitals that treated 48,201 stroke patients during a 1-year period. This included 49 top-performing, 52 average-performing, and 40 low-performing hospitals. The top category had door-to-needle rates of 45%-93%, while the bottom category had consistent door-to-needle rates of 0%. The middle category had door-to-needle rates of 16%-25%.

Regardless of their hospital’s performance category, 61% of the respondents overestimated how many eligible patients there actually received TPA within 1 hour. The lowest-performing hospitals had the most unrealistic estimates, with 68% of them guessing that 20% of their patients received timely TPA when in fact 0% of patients did so. Low-performing hospitals also overestimated their performance in comparison with other hospitals, with 85% of them characterizing their performance as average, above average, or even superior relative to other hospitals, when in fact it was very poor, Dr. Lin and her associates wrote (J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2015 July 22 [doi:10.1161/JAHA.114.001298]).

“Addressing misperceptions that one’s performance is average or above average when it actually is not is an important step in addressing motivation for change,” they added.

The study was supported by the U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Dr. Lin reported having no relevant financial disclosures; her associates reported ties to Genentech, Lilly, Johnson & Johnson, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Sanofi-Aventis, and Merck Schering-Plough.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN HEART ASSOCIATION

Key clinical point: Personnel at most hospitals, particularly the lowest-performing hospitals, greatly overestimate their performance at giving stroke patients TPA within 1 hour of arrival.

Major finding: The lowest-performing hospitals had the most unrealistic estimates of their door-to-needle times, with 68% of them guessing that 20% of their patients received timely TPA when in fact 0% of their patients did so.

Data source: An analysis of data in a stroke registry regarding 141 hospitals that treated 48,201 patients during a 1-year period, plus a survey of stroke personnel at those hospitals.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Dr. Lin reported having no relevant financial disclosures; her associates reported ties to Genentech, Lilly, Johnson & Johnson, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Sanofi-Aventis and Merck Schering-Plough.

Dicloxacillin may cut INR levels in warfarin users

The antibiotic dicloxacillin appears to markedly decrease INR levels in patients taking warfarin, reducing the mean INR to subtherapeutic ranges in the majority who take both drugs concomitantly, according to a research letter to the editor published online July 20 in JAMA.

Adverse interactions between warfarin and other drugs are often suspected, but solid data are lacking. Case reports have suggested that the commonly used antibiotic dicloxacillin reduces warfarin’s anticoagulant effects, but no studies have examined the issue, said Anton Pottegård, Ph.D., of the department of clinical pharmacology, University of Southern Denmark, Odense, and his associates (JAMA 2015;314:296-7).

To further investigate that possibility, the investigators analyzed information in an anticoagulant database covering 7,400 patients treated by three outpatient clinics and 50 general practitioners during a 15-year period. They focused on weekly INR levels recorded for 236 patients (median age, 68 years), most of whom took warfarin because of atrial fibrillation or heart valve replacement.

The mean INR level before dicloxacillin exposure was 2.59, compared with 1.97 after dicloxacillin exposure (P < .001). A total of 144 patients (61%) had subtherapeutic INR levels (< 2.0) during the 2-4 weeks following a course of dicloxacillin, Dr. Pottegård and his associates said.

A similar but less drastic decrease was observed among the 64 patients taking a different anticoagulant, phenprocoumon, who were given dicloxacillin. Mean INR levels dropped from 2.61 before exposure to 2.30 afterward (P = .003), and 41% of the group had subtherapeutic INR levels after taking the antibiotic.

No sponsor was reported for this study. Dr. Pottegård and his associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

The antibiotic dicloxacillin appears to markedly decrease INR levels in patients taking warfarin, reducing the mean INR to subtherapeutic ranges in the majority who take both drugs concomitantly, according to a research letter to the editor published online July 20 in JAMA.

Adverse interactions between warfarin and other drugs are often suspected, but solid data are lacking. Case reports have suggested that the commonly used antibiotic dicloxacillin reduces warfarin’s anticoagulant effects, but no studies have examined the issue, said Anton Pottegård, Ph.D., of the department of clinical pharmacology, University of Southern Denmark, Odense, and his associates (JAMA 2015;314:296-7).

To further investigate that possibility, the investigators analyzed information in an anticoagulant database covering 7,400 patients treated by three outpatient clinics and 50 general practitioners during a 15-year period. They focused on weekly INR levels recorded for 236 patients (median age, 68 years), most of whom took warfarin because of atrial fibrillation or heart valve replacement.

The mean INR level before dicloxacillin exposure was 2.59, compared with 1.97 after dicloxacillin exposure (P < .001). A total of 144 patients (61%) had subtherapeutic INR levels (< 2.0) during the 2-4 weeks following a course of dicloxacillin, Dr. Pottegård and his associates said.

A similar but less drastic decrease was observed among the 64 patients taking a different anticoagulant, phenprocoumon, who were given dicloxacillin. Mean INR levels dropped from 2.61 before exposure to 2.30 afterward (P = .003), and 41% of the group had subtherapeutic INR levels after taking the antibiotic.

No sponsor was reported for this study. Dr. Pottegård and his associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

The antibiotic dicloxacillin appears to markedly decrease INR levels in patients taking warfarin, reducing the mean INR to subtherapeutic ranges in the majority who take both drugs concomitantly, according to a research letter to the editor published online July 20 in JAMA.

Adverse interactions between warfarin and other drugs are often suspected, but solid data are lacking. Case reports have suggested that the commonly used antibiotic dicloxacillin reduces warfarin’s anticoagulant effects, but no studies have examined the issue, said Anton Pottegård, Ph.D., of the department of clinical pharmacology, University of Southern Denmark, Odense, and his associates (JAMA 2015;314:296-7).

To further investigate that possibility, the investigators analyzed information in an anticoagulant database covering 7,400 patients treated by three outpatient clinics and 50 general practitioners during a 15-year period. They focused on weekly INR levels recorded for 236 patients (median age, 68 years), most of whom took warfarin because of atrial fibrillation or heart valve replacement.

The mean INR level before dicloxacillin exposure was 2.59, compared with 1.97 after dicloxacillin exposure (P < .001). A total of 144 patients (61%) had subtherapeutic INR levels (< 2.0) during the 2-4 weeks following a course of dicloxacillin, Dr. Pottegård and his associates said.

A similar but less drastic decrease was observed among the 64 patients taking a different anticoagulant, phenprocoumon, who were given dicloxacillin. Mean INR levels dropped from 2.61 before exposure to 2.30 afterward (P = .003), and 41% of the group had subtherapeutic INR levels after taking the antibiotic.

No sponsor was reported for this study. Dr. Pottegård and his associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM JAMA

Key clinical point: The antibiotic dicloxacillin appears to markedly decrease INR levels in patients using warfarin.

Major finding: 144 patients taking warfarin (61%) had subtherapeutic international normalized ratio levels during the 2-4 weeks following a course of dicloxacillin.

Data source: An analysis of INR levels before and after antibiotic use from a Danish database of 7,400 patients taking anticoagulants.

Disclosures: No sponsor was reported for this study. Dr. Pottegard and his associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

SVS: Stroke reduction outweighs bleeding risk of dual antiplatelet therapy in CEA

CHICAGO – Don’t automatically discontinue dual antiplatelet therapy for carotid endarterectomy because the neuroprotective effects may outweigh the bleeding risks, researchers concluded after a review of more than 28,000 patients who underwent the procedure during 2003-2014.

They found in the study that the 7,059 patients on perioperative dual antiplatelet therapy with clopidogrel (Plavix) and aspirin had about a 40% reduction in transient ischemic attacks (TIAs), strokes, and stroke-related deaths when compared with the 21,624 patients on aspirin alone.

The investigators found on multivariate analysis that bleeding bad enough for a return trip to the operating room was more common in their dual antiplatelet group (odds ratio, 1.73; P < .01), but they felt the neuroprotective effect was probably worth the “slightly increased bleeding risk.” Earlier research suggests that about half of vascular surgeons will discontinue clopidogrel a week or so before carotid endarterectomy (CEA) because of bleeding risks (Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2009;38:402-7).

“Although dual therapy increases perioperative bleeding, it confers an overall benefit by reducing stroke and death. Patients taking dual therapy at the time of CEA should continue treatment preoperatively. This study also suggests that initiating dual therapy is beneficial for asymptomatic patients,” lead investigator Dr. Douglas Jones of the New York Presbyterian Hospital in New York said at the meeting hosted by the Society for Vascular Surgery.

The team used the Society for Vascular Surgery’s (SVS) Vascular Quality Initiative database. Patients were about 70 years old on average and about 60% were men. Dual-therapy patients had more coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and diabetes.

On multivariate analysis to control for those differences, dual therapy was protective against TIA or stroke (OR, 0.60; P < .01); ipsilateral TIA or stroke (OR, 0.68; P = .05); stroke (OR, 0.62; P = .04); and stroke death (OR, 0.65; P = .03). It did not protect against myocardial infarction.

“More than 95% of patients received heparin for these cases,” said Dr. Jones, noting that protamine-reversal after the case “had the greatest protective effect” against major bleeding, which is consistent with previous reports. Protamine reversal reduced it by more than 50% (OR, 0.44; P < .01).

The results, for the most part, were similar on propensity matching of 4,548 patients on dual therapy to 4,548 on aspirin alone, all of whom had CEA after 2010. Dual-therapy patients were about twice as likely to return to the operating room for bleeding (1.3% vs. 0.7%), but also had fewer thrombotic complications (for instance, stroke 0.6% vs. 1.0% in the aspirin cohort).

Asymptomatic patients on dual therapy were again about twice as likely to return to surgery for major bleeding, but half as likely to have a stroke. Bleeding was more common in symptomatic dual therapy patients, as well, but for reasons that aren’t clear, a trend toward fewer thrombotic events in symptomatic patients on propensity matching did not reach statistical significance. “The protective effect was greatest among asymptomatic patients,” Dr. Jones said.

Patients on dual therapy were also more likely to have a drain placed, but drain placement did not protect against reoperation for bleeding (OR, 1.06; P = .75).

Dr. Jones has no disclosures. Other investigators disclosed consulting fees from Medtronic, Volcano, Bard, and AnGes.

CHICAGO – Don’t automatically discontinue dual antiplatelet therapy for carotid endarterectomy because the neuroprotective effects may outweigh the bleeding risks, researchers concluded after a review of more than 28,000 patients who underwent the procedure during 2003-2014.

They found in the study that the 7,059 patients on perioperative dual antiplatelet therapy with clopidogrel (Plavix) and aspirin had about a 40% reduction in transient ischemic attacks (TIAs), strokes, and stroke-related deaths when compared with the 21,624 patients on aspirin alone.

The investigators found on multivariate analysis that bleeding bad enough for a return trip to the operating room was more common in their dual antiplatelet group (odds ratio, 1.73; P < .01), but they felt the neuroprotective effect was probably worth the “slightly increased bleeding risk.” Earlier research suggests that about half of vascular surgeons will discontinue clopidogrel a week or so before carotid endarterectomy (CEA) because of bleeding risks (Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2009;38:402-7).

“Although dual therapy increases perioperative bleeding, it confers an overall benefit by reducing stroke and death. Patients taking dual therapy at the time of CEA should continue treatment preoperatively. This study also suggests that initiating dual therapy is beneficial for asymptomatic patients,” lead investigator Dr. Douglas Jones of the New York Presbyterian Hospital in New York said at the meeting hosted by the Society for Vascular Surgery.

The team used the Society for Vascular Surgery’s (SVS) Vascular Quality Initiative database. Patients were about 70 years old on average and about 60% were men. Dual-therapy patients had more coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and diabetes.

On multivariate analysis to control for those differences, dual therapy was protective against TIA or stroke (OR, 0.60; P < .01); ipsilateral TIA or stroke (OR, 0.68; P = .05); stroke (OR, 0.62; P = .04); and stroke death (OR, 0.65; P = .03). It did not protect against myocardial infarction.

“More than 95% of patients received heparin for these cases,” said Dr. Jones, noting that protamine-reversal after the case “had the greatest protective effect” against major bleeding, which is consistent with previous reports. Protamine reversal reduced it by more than 50% (OR, 0.44; P < .01).

The results, for the most part, were similar on propensity matching of 4,548 patients on dual therapy to 4,548 on aspirin alone, all of whom had CEA after 2010. Dual-therapy patients were about twice as likely to return to the operating room for bleeding (1.3% vs. 0.7%), but also had fewer thrombotic complications (for instance, stroke 0.6% vs. 1.0% in the aspirin cohort).

Asymptomatic patients on dual therapy were again about twice as likely to return to surgery for major bleeding, but half as likely to have a stroke. Bleeding was more common in symptomatic dual therapy patients, as well, but for reasons that aren’t clear, a trend toward fewer thrombotic events in symptomatic patients on propensity matching did not reach statistical significance. “The protective effect was greatest among asymptomatic patients,” Dr. Jones said.

Patients on dual therapy were also more likely to have a drain placed, but drain placement did not protect against reoperation for bleeding (OR, 1.06; P = .75).

Dr. Jones has no disclosures. Other investigators disclosed consulting fees from Medtronic, Volcano, Bard, and AnGes.

CHICAGO – Don’t automatically discontinue dual antiplatelet therapy for carotid endarterectomy because the neuroprotective effects may outweigh the bleeding risks, researchers concluded after a review of more than 28,000 patients who underwent the procedure during 2003-2014.

They found in the study that the 7,059 patients on perioperative dual antiplatelet therapy with clopidogrel (Plavix) and aspirin had about a 40% reduction in transient ischemic attacks (TIAs), strokes, and stroke-related deaths when compared with the 21,624 patients on aspirin alone.

The investigators found on multivariate analysis that bleeding bad enough for a return trip to the operating room was more common in their dual antiplatelet group (odds ratio, 1.73; P < .01), but they felt the neuroprotective effect was probably worth the “slightly increased bleeding risk.” Earlier research suggests that about half of vascular surgeons will discontinue clopidogrel a week or so before carotid endarterectomy (CEA) because of bleeding risks (Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2009;38:402-7).

“Although dual therapy increases perioperative bleeding, it confers an overall benefit by reducing stroke and death. Patients taking dual therapy at the time of CEA should continue treatment preoperatively. This study also suggests that initiating dual therapy is beneficial for asymptomatic patients,” lead investigator Dr. Douglas Jones of the New York Presbyterian Hospital in New York said at the meeting hosted by the Society for Vascular Surgery.

The team used the Society for Vascular Surgery’s (SVS) Vascular Quality Initiative database. Patients were about 70 years old on average and about 60% were men. Dual-therapy patients had more coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and diabetes.

On multivariate analysis to control for those differences, dual therapy was protective against TIA or stroke (OR, 0.60; P < .01); ipsilateral TIA or stroke (OR, 0.68; P = .05); stroke (OR, 0.62; P = .04); and stroke death (OR, 0.65; P = .03). It did not protect against myocardial infarction.

“More than 95% of patients received heparin for these cases,” said Dr. Jones, noting that protamine-reversal after the case “had the greatest protective effect” against major bleeding, which is consistent with previous reports. Protamine reversal reduced it by more than 50% (OR, 0.44; P < .01).

The results, for the most part, were similar on propensity matching of 4,548 patients on dual therapy to 4,548 on aspirin alone, all of whom had CEA after 2010. Dual-therapy patients were about twice as likely to return to the operating room for bleeding (1.3% vs. 0.7%), but also had fewer thrombotic complications (for instance, stroke 0.6% vs. 1.0% in the aspirin cohort).

Asymptomatic patients on dual therapy were again about twice as likely to return to surgery for major bleeding, but half as likely to have a stroke. Bleeding was more common in symptomatic dual therapy patients, as well, but for reasons that aren’t clear, a trend toward fewer thrombotic events in symptomatic patients on propensity matching did not reach statistical significance. “The protective effect was greatest among asymptomatic patients,” Dr. Jones said.

Patients on dual therapy were also more likely to have a drain placed, but drain placement did not protect against reoperation for bleeding (OR, 1.06; P = .75).

Dr. Jones has no disclosures. Other investigators disclosed consulting fees from Medtronic, Volcano, Bard, and AnGes.

AT THE 2015 VASCULAR ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: Strokes are less likely after CEA if patients are on perioperative clopidogrel and aspirin.

Major finding: On multivariate analysis, dual therapy was protective against TIA or stroke (OR, 0.60; P < .01); ipsilateral TIA or stroke (OR, 0.68; P = .05); stroke (OR, 0.62, P = .04); and stroke death (OR, 0.65; P = .03).

Data source: Review of more than 28,000 carotid endarterectomy patients

Disclosures: The presenter has no disclosures. Other investigators disclosed consulting fees from Medtronic, Volcano, Bard, and AnGes.

Bivalirudin in STEMI has low real-world stent thrombosis rate

PARIS – Antithrombotic therapy with bivalirudin for primary percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction may have been unfairly tarnished as having a high stent thrombosis rate, according to a large, prospective, observational cohort study.

A new analysis from the Swedish Coronary Angiography and Angioplasty Registry (SCAAR) showed similarly low stent thrombosis rates within 30 days following primary PCI for STEMI regardless of whether the antithrombotic regimen involved bivalirudin (Angiomax), heparin only, or a glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor, Dr. Per Grimfjard reported at the annual congress of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions.

The SCAAR analysis captured all STEMI patients undergoing primary PCI in Sweden from 2007 through mid-2014. These data reflect real-world interventional practice in Sweden and elsewhere, where bivalirudin is typically administered in a prolonged infusion to protect against early stent thrombosis. In contrast, the randomized trials that linked bivalirudin to high stent thrombosis rates featured protocols in which the drug was stopped immediately after the procedure, noted Dr. Grimfjard, an interventional cardiologist at Uppsala (Sweden) University.

“These are nationwide Swedish numbers, and they are complete. We think the numbers are reassuring in that respect,” he said.

Session chair Dr. Andreas Baumbach said the Swedish data are consistent with his own experience in using bivalirudin in primary PCI for STEMI.

“The headline last year was that bivalirudin has a high stent thrombosis rate. It made the newspapers everywhere. But we never saw that, and we always thought that the difference might be in how we used the drug. There’s a new headline now, that this high stent thrombosis rate is not seen in clinical practice. The practice differs from the randomized trials, and the outcomes differ as well,” observed Dr. Baumbach, professor of interventional cardiology at the University of Bristol (England).

In SCAAR, the 30-day rate of definite, angiographically proven stent thrombosis was 0.84% in 16,860 bivalirudin-treated patients, 0.94% in 3,182 who got heparin only, and 0.83% in 11,216 glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor recipients. These numeric differences weren’t statistically significant.

All-cause mortality 1 year post-PCI was 9.1% in patients with no stent thrombosis, 16.1% in those who experienced stent thrombosis within 1 day post PCI, and 23.0% in those whose stent thrombosis occurred on days 2-30. Dr. Grimfjard speculated that the explanation for the numerically higher 1-year all-cause mortality rate in patients whose stent thrombosis occurred on days 2-30 as opposed to day 0-1 is probably that they were more likely to have left the hospital when stent thrombosis occurred. That would translate to a longer time to repeat revascularization, hence a larger MI, more heart failure and arrhythmia, and thus a higher long-term risk of death.

Several audience members commented that they weren’t sure what to make of the observational Swedish data because of the looming presence of several potential confounders. For one, clinical practice trends changed considerably during the 7-year time frame of the study, as evidenced by the fact that the use of drug-eluting stents was far more common in bivalirudin-treated patients than in the glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor group. Also, Swedish cardiologists who put their STEMI patients on bivalirudin were more likely to utilize the more modern radial artery access in performing primary PCI; their practice may have differed from their colleagues’ in other, unrecorded ways as well, it was noted.

Dr. Grimfjard reported having no financial conflicts regarding the study, which was conducted free of commercial support.

PARIS – Antithrombotic therapy with bivalirudin for primary percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction may have been unfairly tarnished as having a high stent thrombosis rate, according to a large, prospective, observational cohort study.

A new analysis from the Swedish Coronary Angiography and Angioplasty Registry (SCAAR) showed similarly low stent thrombosis rates within 30 days following primary PCI for STEMI regardless of whether the antithrombotic regimen involved bivalirudin (Angiomax), heparin only, or a glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor, Dr. Per Grimfjard reported at the annual congress of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions.

The SCAAR analysis captured all STEMI patients undergoing primary PCI in Sweden from 2007 through mid-2014. These data reflect real-world interventional practice in Sweden and elsewhere, where bivalirudin is typically administered in a prolonged infusion to protect against early stent thrombosis. In contrast, the randomized trials that linked bivalirudin to high stent thrombosis rates featured protocols in which the drug was stopped immediately after the procedure, noted Dr. Grimfjard, an interventional cardiologist at Uppsala (Sweden) University.

“These are nationwide Swedish numbers, and they are complete. We think the numbers are reassuring in that respect,” he said.

Session chair Dr. Andreas Baumbach said the Swedish data are consistent with his own experience in using bivalirudin in primary PCI for STEMI.

“The headline last year was that bivalirudin has a high stent thrombosis rate. It made the newspapers everywhere. But we never saw that, and we always thought that the difference might be in how we used the drug. There’s a new headline now, that this high stent thrombosis rate is not seen in clinical practice. The practice differs from the randomized trials, and the outcomes differ as well,” observed Dr. Baumbach, professor of interventional cardiology at the University of Bristol (England).

In SCAAR, the 30-day rate of definite, angiographically proven stent thrombosis was 0.84% in 16,860 bivalirudin-treated patients, 0.94% in 3,182 who got heparin only, and 0.83% in 11,216 glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor recipients. These numeric differences weren’t statistically significant.

All-cause mortality 1 year post-PCI was 9.1% in patients with no stent thrombosis, 16.1% in those who experienced stent thrombosis within 1 day post PCI, and 23.0% in those whose stent thrombosis occurred on days 2-30. Dr. Grimfjard speculated that the explanation for the numerically higher 1-year all-cause mortality rate in patients whose stent thrombosis occurred on days 2-30 as opposed to day 0-1 is probably that they were more likely to have left the hospital when stent thrombosis occurred. That would translate to a longer time to repeat revascularization, hence a larger MI, more heart failure and arrhythmia, and thus a higher long-term risk of death.

Several audience members commented that they weren’t sure what to make of the observational Swedish data because of the looming presence of several potential confounders. For one, clinical practice trends changed considerably during the 7-year time frame of the study, as evidenced by the fact that the use of drug-eluting stents was far more common in bivalirudin-treated patients than in the glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor group. Also, Swedish cardiologists who put their STEMI patients on bivalirudin were more likely to utilize the more modern radial artery access in performing primary PCI; their practice may have differed from their colleagues’ in other, unrecorded ways as well, it was noted.

Dr. Grimfjard reported having no financial conflicts regarding the study, which was conducted free of commercial support.

PARIS – Antithrombotic therapy with bivalirudin for primary percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction may have been unfairly tarnished as having a high stent thrombosis rate, according to a large, prospective, observational cohort study.

A new analysis from the Swedish Coronary Angiography and Angioplasty Registry (SCAAR) showed similarly low stent thrombosis rates within 30 days following primary PCI for STEMI regardless of whether the antithrombotic regimen involved bivalirudin (Angiomax), heparin only, or a glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor, Dr. Per Grimfjard reported at the annual congress of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions.

The SCAAR analysis captured all STEMI patients undergoing primary PCI in Sweden from 2007 through mid-2014. These data reflect real-world interventional practice in Sweden and elsewhere, where bivalirudin is typically administered in a prolonged infusion to protect against early stent thrombosis. In contrast, the randomized trials that linked bivalirudin to high stent thrombosis rates featured protocols in which the drug was stopped immediately after the procedure, noted Dr. Grimfjard, an interventional cardiologist at Uppsala (Sweden) University.

“These are nationwide Swedish numbers, and they are complete. We think the numbers are reassuring in that respect,” he said.

Session chair Dr. Andreas Baumbach said the Swedish data are consistent with his own experience in using bivalirudin in primary PCI for STEMI.

“The headline last year was that bivalirudin has a high stent thrombosis rate. It made the newspapers everywhere. But we never saw that, and we always thought that the difference might be in how we used the drug. There’s a new headline now, that this high stent thrombosis rate is not seen in clinical practice. The practice differs from the randomized trials, and the outcomes differ as well,” observed Dr. Baumbach, professor of interventional cardiology at the University of Bristol (England).

In SCAAR, the 30-day rate of definite, angiographically proven stent thrombosis was 0.84% in 16,860 bivalirudin-treated patients, 0.94% in 3,182 who got heparin only, and 0.83% in 11,216 glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor recipients. These numeric differences weren’t statistically significant.

All-cause mortality 1 year post-PCI was 9.1% in patients with no stent thrombosis, 16.1% in those who experienced stent thrombosis within 1 day post PCI, and 23.0% in those whose stent thrombosis occurred on days 2-30. Dr. Grimfjard speculated that the explanation for the numerically higher 1-year all-cause mortality rate in patients whose stent thrombosis occurred on days 2-30 as opposed to day 0-1 is probably that they were more likely to have left the hospital when stent thrombosis occurred. That would translate to a longer time to repeat revascularization, hence a larger MI, more heart failure and arrhythmia, and thus a higher long-term risk of death.

Several audience members commented that they weren’t sure what to make of the observational Swedish data because of the looming presence of several potential confounders. For one, clinical practice trends changed considerably during the 7-year time frame of the study, as evidenced by the fact that the use of drug-eluting stents was far more common in bivalirudin-treated patients than in the glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor group. Also, Swedish cardiologists who put their STEMI patients on bivalirudin were more likely to utilize the more modern radial artery access in performing primary PCI; their practice may have differed from their colleagues’ in other, unrecorded ways as well, it was noted.

Dr. Grimfjard reported having no financial conflicts regarding the study, which was conducted free of commercial support.

AT EUROPCR 2015

Key clinical point: The 30-day incidence of stent thrombosis following primary PCI in a large, real-world STEMI population was reassuringly low regardless of the antithrombotic regimen.

Major finding: The stent thrombosis rate within 30 days after primary PCI for STEMI was 0.84% in patients who received bivalirudin for antithrombotic therapy, 0.94% with heparin only, and 0.83% with a glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor in this real-world nationwide Swedish registry.

Data source: A prospective observational cohort study which included all patients who underwent primary PCI for STEMI in Sweden during 2007-2014.

Disclosures: The presenter reported having no financial conflicts regarding the study, which was conducted free of commercial support.

Routine screening sufficient for detecting occult cancer in patients with VTE

TORONTO – The prevalence of occult cancer is low in patients with a first unprovoked venous thromboembolism, according to results from a multicenter, randomized study presented at the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis congress.

In addition, routine screening with the addition of a comprehensive CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis was no better than routine screening alone in detecting occult cancer in this population.

Those are key findings that Dr. Marc Carrier of the University of Ottawa presented from the Screening for Occult Malignancy in Patients with Idiopathic Venous Thromboembolism (SOME) trial, a multicenter, open-label, randomized controlled trial that compared the efficacy of conventional screening with or without comprehensive CT of the abdomen/pelvis for detecting occult cancers in patients with unprovoked venous thromboembolism (VTE). The results of this study were published the same day as his presentation in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“It has been described that up to 10% of patients with unprovoked VTE are diagnosed with cancer in the year following their VTE diagnosis,” Dr. Carrier said. “Therefore, it’s appealing for clinicians to screen these patients for occult cancer but it has led to a lot of great diversity in practices. Some clinicians prefer to use a limited screening strategy that would include a history, physical examination, routine blood tests, and a chest X-ray. Other clinicians prefer to use the limited screening strategy in combination with additional tests. That could be CT of the abdomen and pelvis, ultrasound, or tumor marker, or [computed axial tomography] scan. It’s hard for a physician to know what to use.”

For the SOME trial, a total of 854 patients with unprovoked VTE were randomized to two groups: 431 to limited occult cancer screening (basic blood work, chest X-ray, and breast/cervical/prostate cancer screening) and 423 to limited screening in combination with a comprehensive CT of the abdomen/pelvis. The comprehensive CT included a virtual colonoscopy and gastroscopy, a biphasic enhanced CT, a parenchymal pancreatogram, and a uniphasic enhanced CT of distended bladder. The primary outcome was confirmed cancer that was missed by the screening strategy and detected by the end of the 1-year follow-up period.

Dr. Carrier reported that 33 patients (3.9%) had a new diagnosis of cancer in the interval between randomization and 1-year follow-up: 14 in the limited-screening group and 19 in the limited-screening-plus-CT group, a difference that was not statistically significant (P = .28). In addition, the number of occult cancers missed by the end of the 1-year follow-up period was similar between the two groups: four in the limited-screening group and five in the limited-screening-plus-CT group.

He and his associates also found no significant differences between the limited-screening group and the limited-screening-plus-CT group in the rate of detection of early cancers (0.23% vs. 0.71%, respectively; P = .37), in overall mortality (1.4% vs. 1.2%; P > 0.99), or in cancer-related mortality (1.4% vs. 0.95%; P = .75).

“Occult cancers are not nearly as common as we thought they were, which is reassuring for clinicians and patients because then we don’t have to do a lot of investigations to try and find them, and often scare patients and expose them to radiation and additional procedures,” Dr. Carrier said in an interview. “Limited screening alone, which is what is recommended in Canada and in the United States for age- and gender-specific screening, is more than reasonable for these patients.”

The SOME trial was funded by the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada. Dr. Carrier had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

Therese Borden contributed to this article.

TORONTO – The prevalence of occult cancer is low in patients with a first unprovoked venous thromboembolism, according to results from a multicenter, randomized study presented at the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis congress.

In addition, routine screening with the addition of a comprehensive CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis was no better than routine screening alone in detecting occult cancer in this population.

Those are key findings that Dr. Marc Carrier of the University of Ottawa presented from the Screening for Occult Malignancy in Patients with Idiopathic Venous Thromboembolism (SOME) trial, a multicenter, open-label, randomized controlled trial that compared the efficacy of conventional screening with or without comprehensive CT of the abdomen/pelvis for detecting occult cancers in patients with unprovoked venous thromboembolism (VTE). The results of this study were published the same day as his presentation in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“It has been described that up to 10% of patients with unprovoked VTE are diagnosed with cancer in the year following their VTE diagnosis,” Dr. Carrier said. “Therefore, it’s appealing for clinicians to screen these patients for occult cancer but it has led to a lot of great diversity in practices. Some clinicians prefer to use a limited screening strategy that would include a history, physical examination, routine blood tests, and a chest X-ray. Other clinicians prefer to use the limited screening strategy in combination with additional tests. That could be CT of the abdomen and pelvis, ultrasound, or tumor marker, or [computed axial tomography] scan. It’s hard for a physician to know what to use.”

For the SOME trial, a total of 854 patients with unprovoked VTE were randomized to two groups: 431 to limited occult cancer screening (basic blood work, chest X-ray, and breast/cervical/prostate cancer screening) and 423 to limited screening in combination with a comprehensive CT of the abdomen/pelvis. The comprehensive CT included a virtual colonoscopy and gastroscopy, a biphasic enhanced CT, a parenchymal pancreatogram, and a uniphasic enhanced CT of distended bladder. The primary outcome was confirmed cancer that was missed by the screening strategy and detected by the end of the 1-year follow-up period.

Dr. Carrier reported that 33 patients (3.9%) had a new diagnosis of cancer in the interval between randomization and 1-year follow-up: 14 in the limited-screening group and 19 in the limited-screening-plus-CT group, a difference that was not statistically significant (P = .28). In addition, the number of occult cancers missed by the end of the 1-year follow-up period was similar between the two groups: four in the limited-screening group and five in the limited-screening-plus-CT group.

He and his associates also found no significant differences between the limited-screening group and the limited-screening-plus-CT group in the rate of detection of early cancers (0.23% vs. 0.71%, respectively; P = .37), in overall mortality (1.4% vs. 1.2%; P > 0.99), or in cancer-related mortality (1.4% vs. 0.95%; P = .75).

“Occult cancers are not nearly as common as we thought they were, which is reassuring for clinicians and patients because then we don’t have to do a lot of investigations to try and find them, and often scare patients and expose them to radiation and additional procedures,” Dr. Carrier said in an interview. “Limited screening alone, which is what is recommended in Canada and in the United States for age- and gender-specific screening, is more than reasonable for these patients.”

The SOME trial was funded by the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada. Dr. Carrier had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

Therese Borden contributed to this article.

TORONTO – The prevalence of occult cancer is low in patients with a first unprovoked venous thromboembolism, according to results from a multicenter, randomized study presented at the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis congress.

In addition, routine screening with the addition of a comprehensive CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis was no better than routine screening alone in detecting occult cancer in this population.

Those are key findings that Dr. Marc Carrier of the University of Ottawa presented from the Screening for Occult Malignancy in Patients with Idiopathic Venous Thromboembolism (SOME) trial, a multicenter, open-label, randomized controlled trial that compared the efficacy of conventional screening with or without comprehensive CT of the abdomen/pelvis for detecting occult cancers in patients with unprovoked venous thromboembolism (VTE). The results of this study were published the same day as his presentation in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“It has been described that up to 10% of patients with unprovoked VTE are diagnosed with cancer in the year following their VTE diagnosis,” Dr. Carrier said. “Therefore, it’s appealing for clinicians to screen these patients for occult cancer but it has led to a lot of great diversity in practices. Some clinicians prefer to use a limited screening strategy that would include a history, physical examination, routine blood tests, and a chest X-ray. Other clinicians prefer to use the limited screening strategy in combination with additional tests. That could be CT of the abdomen and pelvis, ultrasound, or tumor marker, or [computed axial tomography] scan. It’s hard for a physician to know what to use.”

For the SOME trial, a total of 854 patients with unprovoked VTE were randomized to two groups: 431 to limited occult cancer screening (basic blood work, chest X-ray, and breast/cervical/prostate cancer screening) and 423 to limited screening in combination with a comprehensive CT of the abdomen/pelvis. The comprehensive CT included a virtual colonoscopy and gastroscopy, a biphasic enhanced CT, a parenchymal pancreatogram, and a uniphasic enhanced CT of distended bladder. The primary outcome was confirmed cancer that was missed by the screening strategy and detected by the end of the 1-year follow-up period.

Dr. Carrier reported that 33 patients (3.9%) had a new diagnosis of cancer in the interval between randomization and 1-year follow-up: 14 in the limited-screening group and 19 in the limited-screening-plus-CT group, a difference that was not statistically significant (P = .28). In addition, the number of occult cancers missed by the end of the 1-year follow-up period was similar between the two groups: four in the limited-screening group and five in the limited-screening-plus-CT group.

He and his associates also found no significant differences between the limited-screening group and the limited-screening-plus-CT group in the rate of detection of early cancers (0.23% vs. 0.71%, respectively; P = .37), in overall mortality (1.4% vs. 1.2%; P > 0.99), or in cancer-related mortality (1.4% vs. 0.95%; P = .75).

“Occult cancers are not nearly as common as we thought they were, which is reassuring for clinicians and patients because then we don’t have to do a lot of investigations to try and find them, and often scare patients and expose them to radiation and additional procedures,” Dr. Carrier said in an interview. “Limited screening alone, which is what is recommended in Canada and in the United States for age- and gender-specific screening, is more than reasonable for these patients.”

The SOME trial was funded by the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada. Dr. Carrier had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

Therese Borden contributed to this article.

AT THE 2015 ISTH CONGRESS

Key clinical point: Occult cancers in patients with a first unprovoked VTE are not nearly as common as previously thought, and limited screening for such cancers is appropriate.

Major finding: There were no significant differences between the limited-screening group and the limited-screening-plus-CT group in the rate of detection of early cancers (0.23% vs. 0.71%); in overall mortality (1.4% vs. 1.2%), or in cancer-related mortality (1.4% vs. 0.95%).

Data source: A multicenter, open-label, randomized controlled trial of 854 patients with unprovoked VTE.

Disclosures: The trial was funded by the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada. Dr. Carrier reported having no financial disclosures.

In PCI, switching clopidogrel nonresponders to prasugrel halved 2-year cardiac mortality

PARIS – Clopidogrel nonresponsiveness is a modifiable cardiovascular risk factor in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention, according to the results of the third Responsiveness to Clopidogrel and Stent-Related Events (RECLOSE-3) study.

High residual platelet activity following a loading dose of clopidogrel in patients undergoing PCI was shown in the earlier RECLOSE-2 study to be a potent predictor of an increased 2-year cardiovascular event rate (JAMA 2011;306:1215-23). This left open the question of whether switching to a different antiplatelet drug would reduce that elevated 2-year risk.

The new RECLOSE-3 study shows that this clopidogrel nonresponsiveness is indeed a modifiable risk factor. All that’s necessary is to identify affected patients via a commercially available in vitro assay, switch them to prasugrel, and their long-term cardiac outcomes become markedly better than if they stayed on clopidogrel, Dr. David Antoniucci reported at the annual congress of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions.

The prospective RECLOSE-3 study included 302 consecutive patients undergoing PCI who were determined to be clopidogrel nonresponders based upon residual platelet activity of 70% or more as measured by light transmittance aggregometry. All were switched to prasugrel and underwent repeat platelet activity measurement. The control group consisted of 248 clopidogrel nonresponders who stayed on the antiplatelet agent in RECLOSE-2.

It was necessary to rely on historical controls for ethical reasons; based upon the RECLOSE-2 results, it’s no longer appropriate to randomize clopidogrel nonresponders to continued use of clopidogrel, according to Dr. Antoniucci, head of the division of cardiology at Careggi Hospital in Florence, Italy.

Mean residual platelet reactivity improved from 78% in RECLOSE-3 participants on clopidogrel to 47% on prasugrel. All but 6% of clopidogrel nonresponders demonstrated acceptable suppression of platelet activity on prasugrel.

The primary study endpoint was 2-year cardiac mortality. With a follow-up rate of 99%, the rate was 4% in clopidogrel nonresponders switched to prasugrel, significantly better than the 9.7% in controls. Moreover, the rate of definite stent thrombosis – a key secondary endpoint – was 0.7% in the group switched to prasugrel, fourfold lower than in controls. Probable stent thrombosis was diagnosed in 1.6% of controls and none of the prasugrel group.

All patients in the control group from RECLOSE-2 had been admitted with an acute coronary syndrome. Restricting the analysis to the 126 RECLOSE-3 participants switched to prasugrel who had an acute coronary syndrome upon hospitalization, the 2-year cardiac death rate was 3.2%, still significantly lower than the 9.7% in controls.

In a multivariate analysis that controlled for potential confounders – including the more frequent use of drug-eluting stents and lower prevalence of a left ventricular ejection fraction of 40% or less in the RECLOSE-3 patients – switching clopidogrel nonresponders to prasugrel was associated with a highly significant 50% reduction in the risk of cardiac death at 2 years’ follow-up. The only other significant predictors were a baseline serum creatinine greater than 1.5 mg/dL and advanced age, both of which were associated with increased risk.

The RECLOSE-3 study was sponsored by the Italian Department of Health. Dr. Antoniucci reported having no financial conflicts.

bjancin@frontlinemedcom.com

PARIS – Clopidogrel nonresponsiveness is a modifiable cardiovascular risk factor in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention, according to the results of the third Responsiveness to Clopidogrel and Stent-Related Events (RECLOSE-3) study.

High residual platelet activity following a loading dose of clopidogrel in patients undergoing PCI was shown in the earlier RECLOSE-2 study to be a potent predictor of an increased 2-year cardiovascular event rate (JAMA 2011;306:1215-23). This left open the question of whether switching to a different antiplatelet drug would reduce that elevated 2-year risk.

The new RECLOSE-3 study shows that this clopidogrel nonresponsiveness is indeed a modifiable risk factor. All that’s necessary is to identify affected patients via a commercially available in vitro assay, switch them to prasugrel, and their long-term cardiac outcomes become markedly better than if they stayed on clopidogrel, Dr. David Antoniucci reported at the annual congress of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions.

The prospective RECLOSE-3 study included 302 consecutive patients undergoing PCI who were determined to be clopidogrel nonresponders based upon residual platelet activity of 70% or more as measured by light transmittance aggregometry. All were switched to prasugrel and underwent repeat platelet activity measurement. The control group consisted of 248 clopidogrel nonresponders who stayed on the antiplatelet agent in RECLOSE-2.

It was necessary to rely on historical controls for ethical reasons; based upon the RECLOSE-2 results, it’s no longer appropriate to randomize clopidogrel nonresponders to continued use of clopidogrel, according to Dr. Antoniucci, head of the division of cardiology at Careggi Hospital in Florence, Italy.

Mean residual platelet reactivity improved from 78% in RECLOSE-3 participants on clopidogrel to 47% on prasugrel. All but 6% of clopidogrel nonresponders demonstrated acceptable suppression of platelet activity on prasugrel.

The primary study endpoint was 2-year cardiac mortality. With a follow-up rate of 99%, the rate was 4% in clopidogrel nonresponders switched to prasugrel, significantly better than the 9.7% in controls. Moreover, the rate of definite stent thrombosis – a key secondary endpoint – was 0.7% in the group switched to prasugrel, fourfold lower than in controls. Probable stent thrombosis was diagnosed in 1.6% of controls and none of the prasugrel group.

All patients in the control group from RECLOSE-2 had been admitted with an acute coronary syndrome. Restricting the analysis to the 126 RECLOSE-3 participants switched to prasugrel who had an acute coronary syndrome upon hospitalization, the 2-year cardiac death rate was 3.2%, still significantly lower than the 9.7% in controls.

In a multivariate analysis that controlled for potential confounders – including the more frequent use of drug-eluting stents and lower prevalence of a left ventricular ejection fraction of 40% or less in the RECLOSE-3 patients – switching clopidogrel nonresponders to prasugrel was associated with a highly significant 50% reduction in the risk of cardiac death at 2 years’ follow-up. The only other significant predictors were a baseline serum creatinine greater than 1.5 mg/dL and advanced age, both of which were associated with increased risk.

The RECLOSE-3 study was sponsored by the Italian Department of Health. Dr. Antoniucci reported having no financial conflicts.

bjancin@frontlinemedcom.com

PARIS – Clopidogrel nonresponsiveness is a modifiable cardiovascular risk factor in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention, according to the results of the third Responsiveness to Clopidogrel and Stent-Related Events (RECLOSE-3) study.

High residual platelet activity following a loading dose of clopidogrel in patients undergoing PCI was shown in the earlier RECLOSE-2 study to be a potent predictor of an increased 2-year cardiovascular event rate (JAMA 2011;306:1215-23). This left open the question of whether switching to a different antiplatelet drug would reduce that elevated 2-year risk.

The new RECLOSE-3 study shows that this clopidogrel nonresponsiveness is indeed a modifiable risk factor. All that’s necessary is to identify affected patients via a commercially available in vitro assay, switch them to prasugrel, and their long-term cardiac outcomes become markedly better than if they stayed on clopidogrel, Dr. David Antoniucci reported at the annual congress of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions.

The prospective RECLOSE-3 study included 302 consecutive patients undergoing PCI who were determined to be clopidogrel nonresponders based upon residual platelet activity of 70% or more as measured by light transmittance aggregometry. All were switched to prasugrel and underwent repeat platelet activity measurement. The control group consisted of 248 clopidogrel nonresponders who stayed on the antiplatelet agent in RECLOSE-2.

It was necessary to rely on historical controls for ethical reasons; based upon the RECLOSE-2 results, it’s no longer appropriate to randomize clopidogrel nonresponders to continued use of clopidogrel, according to Dr. Antoniucci, head of the division of cardiology at Careggi Hospital in Florence, Italy.

Mean residual platelet reactivity improved from 78% in RECLOSE-3 participants on clopidogrel to 47% on prasugrel. All but 6% of clopidogrel nonresponders demonstrated acceptable suppression of platelet activity on prasugrel.

The primary study endpoint was 2-year cardiac mortality. With a follow-up rate of 99%, the rate was 4% in clopidogrel nonresponders switched to prasugrel, significantly better than the 9.7% in controls. Moreover, the rate of definite stent thrombosis – a key secondary endpoint – was 0.7% in the group switched to prasugrel, fourfold lower than in controls. Probable stent thrombosis was diagnosed in 1.6% of controls and none of the prasugrel group.

All patients in the control group from RECLOSE-2 had been admitted with an acute coronary syndrome. Restricting the analysis to the 126 RECLOSE-3 participants switched to prasugrel who had an acute coronary syndrome upon hospitalization, the 2-year cardiac death rate was 3.2%, still significantly lower than the 9.7% in controls.

In a multivariate analysis that controlled for potential confounders – including the more frequent use of drug-eluting stents and lower prevalence of a left ventricular ejection fraction of 40% or less in the RECLOSE-3 patients – switching clopidogrel nonresponders to prasugrel was associated with a highly significant 50% reduction in the risk of cardiac death at 2 years’ follow-up. The only other significant predictors were a baseline serum creatinine greater than 1.5 mg/dL and advanced age, both of which were associated with increased risk.

The RECLOSE-3 study was sponsored by the Italian Department of Health. Dr. Antoniucci reported having no financial conflicts.

bjancin@frontlinemedcom.com

AT EuroPCR 2015