User login

Death of pig heart transplant patient is more a beginning than an end

The genetically altered pig’s heart “worked like a rock star, beautifully functioning,” the surgeon who performed the pioneering Jan. 7 xenotransplant procedure said in a press statement on the death of the patient, David Bennett Sr.

“He wasn’t able to overcome what turned out to be devastating – the debilitation from his previous period of heart failure, which was extreme,” said Bartley P. Griffith, MD, clinical director of the cardiac xenotransplantation program at the University of Maryland, Baltimore.

Representatives of the institution aren’t offering many details on the cause of Mr. Bennett’s death on March 8, 60 days after his operation, but said they will elaborate when their findings are formally published. But their comments seem to downplay the unique nature of the implanted heart itself as a culprit and instead implicate the patient’s diminished overall clinical condition and what grew into an ongoing battle with infections.

The 57-year-old Bennett, bedridden with end-stage heart failure, judged a poor candidate for a ventricular assist device, and on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), reportedly was offered the extraordinary surgery after being turned down for a conventional transplant at several major centers.

“Until day 45 or 50, he was doing very well,” Muhammad M. Mohiuddin, MD, the xenotransplantation program’s scientific director, observed in the statement. But infections soon took advantage of his hobbled immune system.

Given his “preexisting condition and how frail his body was,” Dr. Mohiuddin said, “we were having difficulty maintaining a balance between his immunosuppression and controlling his infection.” Mr. Bennett went into multiple organ failure and “I think that resulted in his passing away.”

Beyond wildest dreams

The surgeons confidently framed Mr. Bennett’s experience as a milestone for heart xenotransplantation. “The demonstration that it was possible, beyond the wildest dreams of most people in the field, even, at this point – that we were able to take a genetically engineered organ and watch it function flawlessly for 9 weeks – is pretty positive in terms of the potential of this therapy,” Dr. Griffith said.

But enough questions linger that others were more circumspect, even as they praised the accomplishment. “There’s no question that this is a historic event,” Mandeep R. Mehra, MD, of Harvard Medical School, and director of the Center for Advanced Heart Disease at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, both in Boston, said in an interview.

Still, “I don’t think we should just conclude that it was the patient’s frailty or death from infection,” Dr. Mehra said. With so few details available, “I would be very careful in prematurely concluding that the problem did not reside with the heart but with the patient. We cannot be sure.”

For example, he noted, “6 to 8 weeks is right around the time when some cardiac complications, like accelerated forms of vasculopathy, could become evident.” Immune-mediated cardiac allograft vasculopathy is a common cause of heart transplant failure.

Or, “it could as easily have been the fact that immunosuppression was modified at 6 to 7 weeks in response to potential infection, which could have led to a cardiac compromise,” Dr. Mehra said. “We just don’t know.”

“It’s really important that this be reported in a scientifically accurate way, because we will all learn from this,” Lori J. West, MD, DPhil, said in an interview.

Little seems to be known for sure about the actual cause of death, “but the fact there was not hyperacute rejection is itself a big step forward. And we know, at least from the limited information we have, that it did not occur,” observed Dr. West, who directs the Alberta Transplant Institute, Edmonton, and the Canadian Donation and Transplantation Research Program. She is a professor of pediatrics with adjunct positions in the departments of surgery and microbiology/immunology.

Dr. West also sees Mr. Bennett’s struggle with infections and adjustments to his unique immunosuppressive regimen, at least as characterized by his care team, as in line with the experience of many heart transplant recipients facing the same threat.

“We already walk this tightrope with every transplant patient,” she said. Typically, they’re put on a somewhat standardized immunosuppressant regimen, “and then we modify it a bit, either increasing or decreasing it, depending on the posttransplant course.” The regimen can become especially intense in response to new signs of rejection, “and you know that that’s going to have an impact on susceptibility to all kinds of infections.”

Full circle

The porcine heart was protected along two fronts against assault from Mr. Bennett’s immune system and other inhospitable aspects of his physiology, either of which could also have been obstacles to success: Genetic modification (Revivicor) of the pig that provided the heart, and a singularly aggressive antirejection drug regimen for the patient.

The knockout of three genes targeting specific porcine cell-surface carbohydrates that provoke a strong human antibody response reportedly averted a hyperacute rejection response that would have caused the graft to fail almost immediately.

Other genetic manipulations, some using CRISPR technology, silenced genes encoded for porcine endogenous retroviruses. Others were aimed at controlling myocardial growth and stemming graft microangiopathy.

Mr. Bennett himself was treated with powerful immunosuppressants, including an investigational anti-CD40 monoclonal antibody (KPL-404, Kiniksa Pharmaceuticals) that, according to UMSOM, inhibits a well-recognized pathway critical to B-cell proliferation, T-cell activation, and antibody production.

“I suspect the patient may not have had rejection, but unfortunately, that intense immunosuppression really set him up – even if he had been half that age – for a very difficult time,” David A. Baran, MD, a cardiologist from Sentara Advanced Heart Failure Center, Norfolk, Va., who studies transplant immunology, said in an interview.

“This is in some ways like the original heart transplant in 1967, when the ability to do the surgery evolved before understanding of the immunosuppression needed. Four or 5 years later, heart transplantation almost died out, before the development of better immunosuppressants like cyclosporine and later tacrolimus,” Dr. Baran said.

“The current age, when we use less immunosuppression than ever, is based on 30 years of progressive success,” he noted. This landmark xenotransplantation “basically turns back the clock to a time when the intensity of immunosuppression by definition had to be extremely high, because we really didn’t know what to expect.”

Emerging role of xeno-organs

Xenotransplantation has been touted as potential strategy for expanding the pool of organs available for transplantation. Mr. Bennett’s “breakthrough surgery” takes the world “one step closer to solving the organ shortage crisis,” his surgeon, Dr. Griffith, announced soon after the procedure. “There are simply not enough donor human hearts available to meet the long list of potential recipients.”

But it’s not the only proposed approach. Measures could be taken, for example, to make more efficient use of the human organs that become available, partly by opening the field to additional less-than-ideal hearts and loosening regulatory mandates for projected graft survival.

“Every year, more than two-thirds of donor organs in the United States are discarded. So it’s not actually that we don’t have enough organs, it’s that we don’t have enough organs that people are willing to take,” Dr. Baran said. Still, it’s important to pursue all promising avenues, and “the genetic manipulation pathway is remarkable.”

But “honestly, organs such as kidneys probably make the most sense” for early study of xenotransplantation from pigs, he said. “The waiting list for kidneys is also very long, but if the kidney graft were to fail, the patient wouldn’t die. It would allow us to work out the immunosuppression without putting patients’ lives at risk.”

Often overlooked in assessments of organ demand, Dr. West said, is that “a lot of patients who could benefit from a transplant will never even be listed for a transplant.” It’s not clear why; perhaps they have multiple comorbidities, live too far from a transplant center, “or they’re too big or too small. Even if there were unlimited organs, you could never meet the needs of people who could benefit from transplantation.”

So even if more available donor organs were used, she said, there would still be a gap that xenotransplantation could help fill. “I’m very much in favor of research that allows us to continue to try to find a pathway to xenotransplantation. I think it’s critically important.”

Unquestionably, “we now need to have a dialogue to entertain how a technology like this, using modern medicine with gene editing, is really going to be utilized,” Dr. Mehra said. The Bennett case “does open up the field, but it also raises caution.” There should be broad participation to move the field forward, “coordinated through either societies or nationally allocated advisory committees that oversee the movement of this technology, to the next step.”

Ideally, that next step “would be to do a safety clinical trial in the right patient,” he said. “And the right patient, by definition, would be one who does not have a life-prolonging option, either mechanical circulatory support or allograft transplantation. That would be the goal.”

Dr. Mehra has reported receiving payments to his institution from Abbott for consulting; consulting fees from Janssen, Mesoblast, Broadview Ventures, Natera, Paragonix, Moderna, and the Baim Institute for Clinical Research; and serving on a scientific advisory board NuPulseCV, Leviticus, and FineHeart. Dr. Baran disclosed consulting for Getinge and LivaNova; speaking for Pfizer; and serving on trial steering committees for CareDx and Procyrion, all unrelated to xenotransplantation. Dr. West has declared no relevant conflicts.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The genetically altered pig’s heart “worked like a rock star, beautifully functioning,” the surgeon who performed the pioneering Jan. 7 xenotransplant procedure said in a press statement on the death of the patient, David Bennett Sr.

“He wasn’t able to overcome what turned out to be devastating – the debilitation from his previous period of heart failure, which was extreme,” said Bartley P. Griffith, MD, clinical director of the cardiac xenotransplantation program at the University of Maryland, Baltimore.

Representatives of the institution aren’t offering many details on the cause of Mr. Bennett’s death on March 8, 60 days after his operation, but said they will elaborate when their findings are formally published. But their comments seem to downplay the unique nature of the implanted heart itself as a culprit and instead implicate the patient’s diminished overall clinical condition and what grew into an ongoing battle with infections.

The 57-year-old Bennett, bedridden with end-stage heart failure, judged a poor candidate for a ventricular assist device, and on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), reportedly was offered the extraordinary surgery after being turned down for a conventional transplant at several major centers.

“Until day 45 or 50, he was doing very well,” Muhammad M. Mohiuddin, MD, the xenotransplantation program’s scientific director, observed in the statement. But infections soon took advantage of his hobbled immune system.

Given his “preexisting condition and how frail his body was,” Dr. Mohiuddin said, “we were having difficulty maintaining a balance between his immunosuppression and controlling his infection.” Mr. Bennett went into multiple organ failure and “I think that resulted in his passing away.”

Beyond wildest dreams

The surgeons confidently framed Mr. Bennett’s experience as a milestone for heart xenotransplantation. “The demonstration that it was possible, beyond the wildest dreams of most people in the field, even, at this point – that we were able to take a genetically engineered organ and watch it function flawlessly for 9 weeks – is pretty positive in terms of the potential of this therapy,” Dr. Griffith said.

But enough questions linger that others were more circumspect, even as they praised the accomplishment. “There’s no question that this is a historic event,” Mandeep R. Mehra, MD, of Harvard Medical School, and director of the Center for Advanced Heart Disease at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, both in Boston, said in an interview.

Still, “I don’t think we should just conclude that it was the patient’s frailty or death from infection,” Dr. Mehra said. With so few details available, “I would be very careful in prematurely concluding that the problem did not reside with the heart but with the patient. We cannot be sure.”

For example, he noted, “6 to 8 weeks is right around the time when some cardiac complications, like accelerated forms of vasculopathy, could become evident.” Immune-mediated cardiac allograft vasculopathy is a common cause of heart transplant failure.

Or, “it could as easily have been the fact that immunosuppression was modified at 6 to 7 weeks in response to potential infection, which could have led to a cardiac compromise,” Dr. Mehra said. “We just don’t know.”

“It’s really important that this be reported in a scientifically accurate way, because we will all learn from this,” Lori J. West, MD, DPhil, said in an interview.

Little seems to be known for sure about the actual cause of death, “but the fact there was not hyperacute rejection is itself a big step forward. And we know, at least from the limited information we have, that it did not occur,” observed Dr. West, who directs the Alberta Transplant Institute, Edmonton, and the Canadian Donation and Transplantation Research Program. She is a professor of pediatrics with adjunct positions in the departments of surgery and microbiology/immunology.

Dr. West also sees Mr. Bennett’s struggle with infections and adjustments to his unique immunosuppressive regimen, at least as characterized by his care team, as in line with the experience of many heart transplant recipients facing the same threat.

“We already walk this tightrope with every transplant patient,” she said. Typically, they’re put on a somewhat standardized immunosuppressant regimen, “and then we modify it a bit, either increasing or decreasing it, depending on the posttransplant course.” The regimen can become especially intense in response to new signs of rejection, “and you know that that’s going to have an impact on susceptibility to all kinds of infections.”

Full circle

The porcine heart was protected along two fronts against assault from Mr. Bennett’s immune system and other inhospitable aspects of his physiology, either of which could also have been obstacles to success: Genetic modification (Revivicor) of the pig that provided the heart, and a singularly aggressive antirejection drug regimen for the patient.

The knockout of three genes targeting specific porcine cell-surface carbohydrates that provoke a strong human antibody response reportedly averted a hyperacute rejection response that would have caused the graft to fail almost immediately.

Other genetic manipulations, some using CRISPR technology, silenced genes encoded for porcine endogenous retroviruses. Others were aimed at controlling myocardial growth and stemming graft microangiopathy.

Mr. Bennett himself was treated with powerful immunosuppressants, including an investigational anti-CD40 monoclonal antibody (KPL-404, Kiniksa Pharmaceuticals) that, according to UMSOM, inhibits a well-recognized pathway critical to B-cell proliferation, T-cell activation, and antibody production.

“I suspect the patient may not have had rejection, but unfortunately, that intense immunosuppression really set him up – even if he had been half that age – for a very difficult time,” David A. Baran, MD, a cardiologist from Sentara Advanced Heart Failure Center, Norfolk, Va., who studies transplant immunology, said in an interview.

“This is in some ways like the original heart transplant in 1967, when the ability to do the surgery evolved before understanding of the immunosuppression needed. Four or 5 years later, heart transplantation almost died out, before the development of better immunosuppressants like cyclosporine and later tacrolimus,” Dr. Baran said.

“The current age, when we use less immunosuppression than ever, is based on 30 years of progressive success,” he noted. This landmark xenotransplantation “basically turns back the clock to a time when the intensity of immunosuppression by definition had to be extremely high, because we really didn’t know what to expect.”

Emerging role of xeno-organs

Xenotransplantation has been touted as potential strategy for expanding the pool of organs available for transplantation. Mr. Bennett’s “breakthrough surgery” takes the world “one step closer to solving the organ shortage crisis,” his surgeon, Dr. Griffith, announced soon after the procedure. “There are simply not enough donor human hearts available to meet the long list of potential recipients.”

But it’s not the only proposed approach. Measures could be taken, for example, to make more efficient use of the human organs that become available, partly by opening the field to additional less-than-ideal hearts and loosening regulatory mandates for projected graft survival.

“Every year, more than two-thirds of donor organs in the United States are discarded. So it’s not actually that we don’t have enough organs, it’s that we don’t have enough organs that people are willing to take,” Dr. Baran said. Still, it’s important to pursue all promising avenues, and “the genetic manipulation pathway is remarkable.”

But “honestly, organs such as kidneys probably make the most sense” for early study of xenotransplantation from pigs, he said. “The waiting list for kidneys is also very long, but if the kidney graft were to fail, the patient wouldn’t die. It would allow us to work out the immunosuppression without putting patients’ lives at risk.”

Often overlooked in assessments of organ demand, Dr. West said, is that “a lot of patients who could benefit from a transplant will never even be listed for a transplant.” It’s not clear why; perhaps they have multiple comorbidities, live too far from a transplant center, “or they’re too big or too small. Even if there were unlimited organs, you could never meet the needs of people who could benefit from transplantation.”

So even if more available donor organs were used, she said, there would still be a gap that xenotransplantation could help fill. “I’m very much in favor of research that allows us to continue to try to find a pathway to xenotransplantation. I think it’s critically important.”

Unquestionably, “we now need to have a dialogue to entertain how a technology like this, using modern medicine with gene editing, is really going to be utilized,” Dr. Mehra said. The Bennett case “does open up the field, but it also raises caution.” There should be broad participation to move the field forward, “coordinated through either societies or nationally allocated advisory committees that oversee the movement of this technology, to the next step.”

Ideally, that next step “would be to do a safety clinical trial in the right patient,” he said. “And the right patient, by definition, would be one who does not have a life-prolonging option, either mechanical circulatory support or allograft transplantation. That would be the goal.”

Dr. Mehra has reported receiving payments to his institution from Abbott for consulting; consulting fees from Janssen, Mesoblast, Broadview Ventures, Natera, Paragonix, Moderna, and the Baim Institute for Clinical Research; and serving on a scientific advisory board NuPulseCV, Leviticus, and FineHeart. Dr. Baran disclosed consulting for Getinge and LivaNova; speaking for Pfizer; and serving on trial steering committees for CareDx and Procyrion, all unrelated to xenotransplantation. Dr. West has declared no relevant conflicts.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The genetically altered pig’s heart “worked like a rock star, beautifully functioning,” the surgeon who performed the pioneering Jan. 7 xenotransplant procedure said in a press statement on the death of the patient, David Bennett Sr.

“He wasn’t able to overcome what turned out to be devastating – the debilitation from his previous period of heart failure, which was extreme,” said Bartley P. Griffith, MD, clinical director of the cardiac xenotransplantation program at the University of Maryland, Baltimore.

Representatives of the institution aren’t offering many details on the cause of Mr. Bennett’s death on March 8, 60 days after his operation, but said they will elaborate when their findings are formally published. But their comments seem to downplay the unique nature of the implanted heart itself as a culprit and instead implicate the patient’s diminished overall clinical condition and what grew into an ongoing battle with infections.

The 57-year-old Bennett, bedridden with end-stage heart failure, judged a poor candidate for a ventricular assist device, and on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), reportedly was offered the extraordinary surgery after being turned down for a conventional transplant at several major centers.

“Until day 45 or 50, he was doing very well,” Muhammad M. Mohiuddin, MD, the xenotransplantation program’s scientific director, observed in the statement. But infections soon took advantage of his hobbled immune system.

Given his “preexisting condition and how frail his body was,” Dr. Mohiuddin said, “we were having difficulty maintaining a balance between his immunosuppression and controlling his infection.” Mr. Bennett went into multiple organ failure and “I think that resulted in his passing away.”

Beyond wildest dreams

The surgeons confidently framed Mr. Bennett’s experience as a milestone for heart xenotransplantation. “The demonstration that it was possible, beyond the wildest dreams of most people in the field, even, at this point – that we were able to take a genetically engineered organ and watch it function flawlessly for 9 weeks – is pretty positive in terms of the potential of this therapy,” Dr. Griffith said.

But enough questions linger that others were more circumspect, even as they praised the accomplishment. “There’s no question that this is a historic event,” Mandeep R. Mehra, MD, of Harvard Medical School, and director of the Center for Advanced Heart Disease at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, both in Boston, said in an interview.

Still, “I don’t think we should just conclude that it was the patient’s frailty or death from infection,” Dr. Mehra said. With so few details available, “I would be very careful in prematurely concluding that the problem did not reside with the heart but with the patient. We cannot be sure.”

For example, he noted, “6 to 8 weeks is right around the time when some cardiac complications, like accelerated forms of vasculopathy, could become evident.” Immune-mediated cardiac allograft vasculopathy is a common cause of heart transplant failure.

Or, “it could as easily have been the fact that immunosuppression was modified at 6 to 7 weeks in response to potential infection, which could have led to a cardiac compromise,” Dr. Mehra said. “We just don’t know.”

“It’s really important that this be reported in a scientifically accurate way, because we will all learn from this,” Lori J. West, MD, DPhil, said in an interview.

Little seems to be known for sure about the actual cause of death, “but the fact there was not hyperacute rejection is itself a big step forward. And we know, at least from the limited information we have, that it did not occur,” observed Dr. West, who directs the Alberta Transplant Institute, Edmonton, and the Canadian Donation and Transplantation Research Program. She is a professor of pediatrics with adjunct positions in the departments of surgery and microbiology/immunology.

Dr. West also sees Mr. Bennett’s struggle with infections and adjustments to his unique immunosuppressive regimen, at least as characterized by his care team, as in line with the experience of many heart transplant recipients facing the same threat.

“We already walk this tightrope with every transplant patient,” she said. Typically, they’re put on a somewhat standardized immunosuppressant regimen, “and then we modify it a bit, either increasing or decreasing it, depending on the posttransplant course.” The regimen can become especially intense in response to new signs of rejection, “and you know that that’s going to have an impact on susceptibility to all kinds of infections.”

Full circle

The porcine heart was protected along two fronts against assault from Mr. Bennett’s immune system and other inhospitable aspects of his physiology, either of which could also have been obstacles to success: Genetic modification (Revivicor) of the pig that provided the heart, and a singularly aggressive antirejection drug regimen for the patient.

The knockout of three genes targeting specific porcine cell-surface carbohydrates that provoke a strong human antibody response reportedly averted a hyperacute rejection response that would have caused the graft to fail almost immediately.

Other genetic manipulations, some using CRISPR technology, silenced genes encoded for porcine endogenous retroviruses. Others were aimed at controlling myocardial growth and stemming graft microangiopathy.

Mr. Bennett himself was treated with powerful immunosuppressants, including an investigational anti-CD40 monoclonal antibody (KPL-404, Kiniksa Pharmaceuticals) that, according to UMSOM, inhibits a well-recognized pathway critical to B-cell proliferation, T-cell activation, and antibody production.

“I suspect the patient may not have had rejection, but unfortunately, that intense immunosuppression really set him up – even if he had been half that age – for a very difficult time,” David A. Baran, MD, a cardiologist from Sentara Advanced Heart Failure Center, Norfolk, Va., who studies transplant immunology, said in an interview.

“This is in some ways like the original heart transplant in 1967, when the ability to do the surgery evolved before understanding of the immunosuppression needed. Four or 5 years later, heart transplantation almost died out, before the development of better immunosuppressants like cyclosporine and later tacrolimus,” Dr. Baran said.

“The current age, when we use less immunosuppression than ever, is based on 30 years of progressive success,” he noted. This landmark xenotransplantation “basically turns back the clock to a time when the intensity of immunosuppression by definition had to be extremely high, because we really didn’t know what to expect.”

Emerging role of xeno-organs

Xenotransplantation has been touted as potential strategy for expanding the pool of organs available for transplantation. Mr. Bennett’s “breakthrough surgery” takes the world “one step closer to solving the organ shortage crisis,” his surgeon, Dr. Griffith, announced soon after the procedure. “There are simply not enough donor human hearts available to meet the long list of potential recipients.”

But it’s not the only proposed approach. Measures could be taken, for example, to make more efficient use of the human organs that become available, partly by opening the field to additional less-than-ideal hearts and loosening regulatory mandates for projected graft survival.

“Every year, more than two-thirds of donor organs in the United States are discarded. So it’s not actually that we don’t have enough organs, it’s that we don’t have enough organs that people are willing to take,” Dr. Baran said. Still, it’s important to pursue all promising avenues, and “the genetic manipulation pathway is remarkable.”

But “honestly, organs such as kidneys probably make the most sense” for early study of xenotransplantation from pigs, he said. “The waiting list for kidneys is also very long, but if the kidney graft were to fail, the patient wouldn’t die. It would allow us to work out the immunosuppression without putting patients’ lives at risk.”

Often overlooked in assessments of organ demand, Dr. West said, is that “a lot of patients who could benefit from a transplant will never even be listed for a transplant.” It’s not clear why; perhaps they have multiple comorbidities, live too far from a transplant center, “or they’re too big or too small. Even if there were unlimited organs, you could never meet the needs of people who could benefit from transplantation.”

So even if more available donor organs were used, she said, there would still be a gap that xenotransplantation could help fill. “I’m very much in favor of research that allows us to continue to try to find a pathway to xenotransplantation. I think it’s critically important.”

Unquestionably, “we now need to have a dialogue to entertain how a technology like this, using modern medicine with gene editing, is really going to be utilized,” Dr. Mehra said. The Bennett case “does open up the field, but it also raises caution.” There should be broad participation to move the field forward, “coordinated through either societies or nationally allocated advisory committees that oversee the movement of this technology, to the next step.”

Ideally, that next step “would be to do a safety clinical trial in the right patient,” he said. “And the right patient, by definition, would be one who does not have a life-prolonging option, either mechanical circulatory support or allograft transplantation. That would be the goal.”

Dr. Mehra has reported receiving payments to his institution from Abbott for consulting; consulting fees from Janssen, Mesoblast, Broadview Ventures, Natera, Paragonix, Moderna, and the Baim Institute for Clinical Research; and serving on a scientific advisory board NuPulseCV, Leviticus, and FineHeart. Dr. Baran disclosed consulting for Getinge and LivaNova; speaking for Pfizer; and serving on trial steering committees for CareDx and Procyrion, all unrelated to xenotransplantation. Dr. West has declared no relevant conflicts.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Man who received first modified pig heart transplant dies

He passed away March 8, according to a statement from the University of Maryland Medical Center (UMMC), Baltimore, where the transplant was performed.

Mr. Bennett received the transplant on January 7 and lived for 2 months following the surgery.

Although not providing the exact cause of his death, UMMC said Mr. Bennett’s condition began deteriorating several days before his death.

When it became clear that he would not recover, he was given compassionate palliative care and was able to communicate with his family during his final hours.

“We are devastated by the loss of Mr. Bennett. He proved to be a brave and noble patient who fought all the way to the end. We extend our sincerest condolences to his family,” Bartley P. Griffith, MD, who performed the transplant, said in the statement.

“We are grateful to Mr. Bennett for his unique and historic role in helping to contribute to a vast array of knowledge to the field of xenotransplantation,” added Muhammad M. Mohiuddin, MD, director of the cardiac xenotransplantation program at University of Maryland School of Medicine.

Before receiving the genetically modified pig heart, Mr. Bennett had required mechanical circulatory support to stay alive but was rejected for standard heart transplantation at UMMC and other centers. He was ineligible for an implanted ventricular assist device due to ventricular arrhythmias.

Following surgery, the transplanted pig heart performed well for several weeks without any signs of rejection. The patient was able to spend time with his family and participate in physical therapy to help regain strength.

“This organ transplant demonstrated for the first time that a genetically modified animal heart can function like a human heart without immediate rejection by the body,” UMMC said in a statement issued 3 days after the surgery.

Thanks to Mr. Bennett, “we have gained invaluable insights learning that the genetically modified pig heart can function well within the human body while the immune system is adequately suppressed,” said Dr. Mohiuddin. “We remain optimistic and plan on continuing our work in future clinical trials.”

The patient’s son, David Bennett Jr, said the family is “profoundly grateful for the life-extending opportunity” provided to his father by the “stellar team” at the University of Maryland School of Medicine and the University of Maryland Medical Center.

“We were able to spend some precious weeks together while he recovered from the transplant surgery, weeks we would not have had without this miraculous effort,” he said.

“We also hope that what was learned from his surgery will benefit future patients and hopefully, one day, end the organ shortage that costs so many lives each year,” he added.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

He passed away March 8, according to a statement from the University of Maryland Medical Center (UMMC), Baltimore, where the transplant was performed.

Mr. Bennett received the transplant on January 7 and lived for 2 months following the surgery.

Although not providing the exact cause of his death, UMMC said Mr. Bennett’s condition began deteriorating several days before his death.

When it became clear that he would not recover, he was given compassionate palliative care and was able to communicate with his family during his final hours.

“We are devastated by the loss of Mr. Bennett. He proved to be a brave and noble patient who fought all the way to the end. We extend our sincerest condolences to his family,” Bartley P. Griffith, MD, who performed the transplant, said in the statement.

“We are grateful to Mr. Bennett for his unique and historic role in helping to contribute to a vast array of knowledge to the field of xenotransplantation,” added Muhammad M. Mohiuddin, MD, director of the cardiac xenotransplantation program at University of Maryland School of Medicine.

Before receiving the genetically modified pig heart, Mr. Bennett had required mechanical circulatory support to stay alive but was rejected for standard heart transplantation at UMMC and other centers. He was ineligible for an implanted ventricular assist device due to ventricular arrhythmias.

Following surgery, the transplanted pig heart performed well for several weeks without any signs of rejection. The patient was able to spend time with his family and participate in physical therapy to help regain strength.

“This organ transplant demonstrated for the first time that a genetically modified animal heart can function like a human heart without immediate rejection by the body,” UMMC said in a statement issued 3 days after the surgery.

Thanks to Mr. Bennett, “we have gained invaluable insights learning that the genetically modified pig heart can function well within the human body while the immune system is adequately suppressed,” said Dr. Mohiuddin. “We remain optimistic and plan on continuing our work in future clinical trials.”

The patient’s son, David Bennett Jr, said the family is “profoundly grateful for the life-extending opportunity” provided to his father by the “stellar team” at the University of Maryland School of Medicine and the University of Maryland Medical Center.

“We were able to spend some precious weeks together while he recovered from the transplant surgery, weeks we would not have had without this miraculous effort,” he said.

“We also hope that what was learned from his surgery will benefit future patients and hopefully, one day, end the organ shortage that costs so many lives each year,” he added.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

He passed away March 8, according to a statement from the University of Maryland Medical Center (UMMC), Baltimore, where the transplant was performed.

Mr. Bennett received the transplant on January 7 and lived for 2 months following the surgery.

Although not providing the exact cause of his death, UMMC said Mr. Bennett’s condition began deteriorating several days before his death.

When it became clear that he would not recover, he was given compassionate palliative care and was able to communicate with his family during his final hours.

“We are devastated by the loss of Mr. Bennett. He proved to be a brave and noble patient who fought all the way to the end. We extend our sincerest condolences to his family,” Bartley P. Griffith, MD, who performed the transplant, said in the statement.

“We are grateful to Mr. Bennett for his unique and historic role in helping to contribute to a vast array of knowledge to the field of xenotransplantation,” added Muhammad M. Mohiuddin, MD, director of the cardiac xenotransplantation program at University of Maryland School of Medicine.

Before receiving the genetically modified pig heart, Mr. Bennett had required mechanical circulatory support to stay alive but was rejected for standard heart transplantation at UMMC and other centers. He was ineligible for an implanted ventricular assist device due to ventricular arrhythmias.

Following surgery, the transplanted pig heart performed well for several weeks without any signs of rejection. The patient was able to spend time with his family and participate in physical therapy to help regain strength.

“This organ transplant demonstrated for the first time that a genetically modified animal heart can function like a human heart without immediate rejection by the body,” UMMC said in a statement issued 3 days after the surgery.

Thanks to Mr. Bennett, “we have gained invaluable insights learning that the genetically modified pig heart can function well within the human body while the immune system is adequately suppressed,” said Dr. Mohiuddin. “We remain optimistic and plan on continuing our work in future clinical trials.”

The patient’s son, David Bennett Jr, said the family is “profoundly grateful for the life-extending opportunity” provided to his father by the “stellar team” at the University of Maryland School of Medicine and the University of Maryland Medical Center.

“We were able to spend some precious weeks together while he recovered from the transplant surgery, weeks we would not have had without this miraculous effort,” he said.

“We also hope that what was learned from his surgery will benefit future patients and hopefully, one day, end the organ shortage that costs so many lives each year,” he added.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Organ transplantation: Unvaccinated need not apply

I agree with most advice given by the affable TV character Ted Lasso. “Every choice is a chance,” he said. Pandemic-era physicians must now consider whether a politically motivated choice to decline COVID-19 vaccination should negatively affect the chance to receive an organ donation.

And in confronting these choices, we have a chance to educate the public on the complexities of the organ allocation process.

A well-informed patient’s personal choice should be honored, even if clinicians disagree, if it does not affect the well-being of others. For example, I once had a patient in acute leukemic crisis who declined blood products because she was a Jehovah’s Witness. She died. Her choice affected her longevity only.

Compare that decision with awarding an organ to an individual who has declined readily available protection of that organ. Weigh that choice against the fact that said protection is against an infectious disease that has killed over 5.5 million worldwide.

Some institutions stand strong, others hedge their bets

Admirably, Loyola University Health System understands that difference. They published a firm stand on transplant candidacy and COVID-19 vaccination status in the Journal of Heart and Lung Transplant. Daniel Dilling, MD, medical director of the lung transplantation program , and Mark Kuczewski, PhD, a professor of medical ethics at Loyola University Chicago, Maywood, Ill., wrote that: “We believe that requiring vaccination against COVID-19 should not be controversial when we focus strictly on established frameworks and practices surrounding eligibility for wait-listing to receive a solid organ transplant.”

The Cleveland Clinic apparently agrees. In October 2021, they denied a liver transplant to Michelle Vitullo of Ohio, whose daughter had been deemed “a perfect match.” Her daughter, also unvaccinated, stated: “Being denied for a nonmedical reason for someone’s beliefs that are different to yours, I mean that’s not how that should be.”

But vaccination status is a medical reason, given well-established data regarding increased mortality among the immunosuppressed. Ms. Vitullo then said: “We are trying to get to UPMC [University of Pittsburgh Medical Center] as they don’t require a vaccination.”

The public information page on transplant candidacy from UPMC reads (my italics): It is recommended that all transplant candidates, transplant recipients, and their household members receive COVID-19 vaccination when the vaccine is available to them. It is preferred that transplant candidates are vaccinated more than 2 weeks before transplantation.

I reached out to UPMC for clarification and was told by email that “we do not have a policy regarding COVID-19 vaccination requirement for current transplant candidates.” Houston Methodist shares the same agnostic stance.

Compare these opinions with Brigham and Women’s Hospital, where the requirements are resolute: “Like most other transplant programs across the country, the COVID-19 vaccine is one of several vaccines and lifestyle behaviors that are required for patients awaiting solid organ transplant.”

They add that “transplant candidates must also receive the seasonal influenza and hepatitis B vaccines, follow other healthy behaviors, and demonstrate they can commit to taking the required medications following transplant.”

In January 2022, Brigham and Women’s Hospital declared 31-year-old D.J. Ferguson ineligible for a heart transplant because he declined to be vaccinated against COVID-19. According to the New York Post and ABC News, his physicians resorted to left ventricular assist device support. His mother, Tracy Ferguson, is quoted as saying: “He’s not an antivaxxer. He has all of his vaccines.” I’ll just leave that right there.

Unfortunately, Michelle Vitullo’s obituary was published in December 2021. Regardless of whether she received her liver transplant, the outcome is tragic, and whatever you think of this family’s battle playing out in the glare of the national spotlight, their loss is no less devastating.

The directed-donation aspect of this case poses an interesting question. A news anchor asked the mother and daughter: “If you both accept the risks, why doesn’t the hospital just let you try?” The answers are obvious to us clinicians. Performing a transplantation in an unvaccinated patient could lead to their early death if they became infected because of their immunocompromised state, would open the door for transplantation of any patient who is unvaccinated for anything, including influenza and hepatitis B, which could result in the preventable waste of organs, and puts other vulnerable hospitalized patients at risk during the initial transplant stay and follow-up.

That’s not to mention the potential legal suit. Never has a consent form dissuaded any party from lodging an accusation of wrongful death or medical malpractice. In the face of strong data on higher mortality in unvaccinated, immunocompromised patients, a good lawyer could charge that the institution and transplant surgeons should have known better, regardless of the donor and recipient’s willingness to accept the risks.

The Vitullo and Ferguson cases are among many similar dilemmas surrounding transplant candidacy across the United States.

University of Virginia Health in Charlottesville denied 42-year-old Shamgar Connors a kidney transplant because he is unvaccinated, despite a previous COVID-19 infection. In October 2021, Leilani Lutali of Colorado was denied a kidney by UCHealth because she declined vaccination.

As Ted Lasso says: “There’s a bunch of crazy stuff on Twitter.”

Predictably, social media is full of public outcry. “Some cold-hearted people on here” tweeted one. “What if it was one of your loved ones who needed a transplant?” Another tweeted the Hippocratic oath with the comment that “They all swore under this noble ‘oat’, but I guess it’s been forgotten.” (This was followed with a photo of a box of Quaker Oats in a failed attempt at humor.) These discussions among the Twitterati highlight the depths of misunderstanding on organ transplantation.

To be fair, unless you have been personally involved in the decision-making process for transplant candidacy, there is little opportunity to be educated. I explain to my anxious patients and their families that a donor organ is like a fumbled football. There may be well over 100 patients at all levels of transplant status in many geographic locations diving for that same organ.

The transplant team is tasked with finding the best match, determining who is the sickest, assessing time for transport of that organ, and, above all, who will be the best steward of that organ.

Take heart transplantation, for instance. Approximately 3,500 patients in the United States are awaiting one each year. Instead of facing an almost certain death within 5 years, a transplant recipient has a chance at a median survival of 12-13 years. The cost of a heart transplant is approximately $1.38 million, according to Milliman, a consulting firm. This is “an incredibly resource intensive procedure,” including expenditures for transportation, antirejection medication, office visits, physician fees, ICU stays, rejection surveillance, and acute rejection therapies.

Transplant denial is nothing new

People get turned down for organ transplants all the time. My patient with end-stage dilated cardiomyopathy was denied a heart transplant when it was discovered that he had scores of outstanding parking tickets. This was seen as a surrogate for an inability to afford his antirejection medication.

Another patient swore that her positive cotinine levels were caused by endless hours at the bingo hall where second-hand smoke swirled. She was also denied. Many potential candidates who are in acute decline hold precariously to newfound sobriety. They are denied. A patient’s boyfriend told the transplant team that he couldn’t be relied upon to drive her to her appointments. She was denied.

Many people who engage in antisocial behaviors have no idea that these actions may result in the denial of an organ transplant should their future selves need one. These are hard lines, but everyone should agree that the odds of survival are heavily in favor of the consistently adherent.

We should take this opportunity to educate the public on how complicated obtaining an organ transplant can be. More than 6,000 people die each year waiting for an organ because of the supply-and-demand disparities in the transplantation arena. I’m willing to bet that many of the loudest protesters in favor of unvaccinated transplant recipients have not signed the organ donor box on the back of their driver’s license. This conversation is an opportunity to change that and remind people that organ donation may be their only opportunity to save a fellow human’s life.

Again, to quote Ted Lasso: “If you care about someone and you got a little love in your heart, there ain’t nothing you can’t get through together.” That philosophy should apply to the tasks of selecting the best organ donors as well as the best organ recipients.

And every organ should go to the one who will honor their donor and their donor’s family by taking the best care of that ultimate gift of life, including being vaccinated against COVID-19.

Dr. Walton-Shirley is a native Kentuckian who retired from full-time invasive cardiology. She enjoys locums work in Montana and is a champion of physician rights and patient safety. She disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

I agree with most advice given by the affable TV character Ted Lasso. “Every choice is a chance,” he said. Pandemic-era physicians must now consider whether a politically motivated choice to decline COVID-19 vaccination should negatively affect the chance to receive an organ donation.

And in confronting these choices, we have a chance to educate the public on the complexities of the organ allocation process.

A well-informed patient’s personal choice should be honored, even if clinicians disagree, if it does not affect the well-being of others. For example, I once had a patient in acute leukemic crisis who declined blood products because she was a Jehovah’s Witness. She died. Her choice affected her longevity only.

Compare that decision with awarding an organ to an individual who has declined readily available protection of that organ. Weigh that choice against the fact that said protection is against an infectious disease that has killed over 5.5 million worldwide.

Some institutions stand strong, others hedge their bets

Admirably, Loyola University Health System understands that difference. They published a firm stand on transplant candidacy and COVID-19 vaccination status in the Journal of Heart and Lung Transplant. Daniel Dilling, MD, medical director of the lung transplantation program , and Mark Kuczewski, PhD, a professor of medical ethics at Loyola University Chicago, Maywood, Ill., wrote that: “We believe that requiring vaccination against COVID-19 should not be controversial when we focus strictly on established frameworks and practices surrounding eligibility for wait-listing to receive a solid organ transplant.”

The Cleveland Clinic apparently agrees. In October 2021, they denied a liver transplant to Michelle Vitullo of Ohio, whose daughter had been deemed “a perfect match.” Her daughter, also unvaccinated, stated: “Being denied for a nonmedical reason for someone’s beliefs that are different to yours, I mean that’s not how that should be.”

But vaccination status is a medical reason, given well-established data regarding increased mortality among the immunosuppressed. Ms. Vitullo then said: “We are trying to get to UPMC [University of Pittsburgh Medical Center] as they don’t require a vaccination.”

The public information page on transplant candidacy from UPMC reads (my italics): It is recommended that all transplant candidates, transplant recipients, and their household members receive COVID-19 vaccination when the vaccine is available to them. It is preferred that transplant candidates are vaccinated more than 2 weeks before transplantation.

I reached out to UPMC for clarification and was told by email that “we do not have a policy regarding COVID-19 vaccination requirement for current transplant candidates.” Houston Methodist shares the same agnostic stance.

Compare these opinions with Brigham and Women’s Hospital, where the requirements are resolute: “Like most other transplant programs across the country, the COVID-19 vaccine is one of several vaccines and lifestyle behaviors that are required for patients awaiting solid organ transplant.”

They add that “transplant candidates must also receive the seasonal influenza and hepatitis B vaccines, follow other healthy behaviors, and demonstrate they can commit to taking the required medications following transplant.”

In January 2022, Brigham and Women’s Hospital declared 31-year-old D.J. Ferguson ineligible for a heart transplant because he declined to be vaccinated against COVID-19. According to the New York Post and ABC News, his physicians resorted to left ventricular assist device support. His mother, Tracy Ferguson, is quoted as saying: “He’s not an antivaxxer. He has all of his vaccines.” I’ll just leave that right there.

Unfortunately, Michelle Vitullo’s obituary was published in December 2021. Regardless of whether she received her liver transplant, the outcome is tragic, and whatever you think of this family’s battle playing out in the glare of the national spotlight, their loss is no less devastating.

The directed-donation aspect of this case poses an interesting question. A news anchor asked the mother and daughter: “If you both accept the risks, why doesn’t the hospital just let you try?” The answers are obvious to us clinicians. Performing a transplantation in an unvaccinated patient could lead to their early death if they became infected because of their immunocompromised state, would open the door for transplantation of any patient who is unvaccinated for anything, including influenza and hepatitis B, which could result in the preventable waste of organs, and puts other vulnerable hospitalized patients at risk during the initial transplant stay and follow-up.

That’s not to mention the potential legal suit. Never has a consent form dissuaded any party from lodging an accusation of wrongful death or medical malpractice. In the face of strong data on higher mortality in unvaccinated, immunocompromised patients, a good lawyer could charge that the institution and transplant surgeons should have known better, regardless of the donor and recipient’s willingness to accept the risks.

The Vitullo and Ferguson cases are among many similar dilemmas surrounding transplant candidacy across the United States.

University of Virginia Health in Charlottesville denied 42-year-old Shamgar Connors a kidney transplant because he is unvaccinated, despite a previous COVID-19 infection. In October 2021, Leilani Lutali of Colorado was denied a kidney by UCHealth because she declined vaccination.

As Ted Lasso says: “There’s a bunch of crazy stuff on Twitter.”

Predictably, social media is full of public outcry. “Some cold-hearted people on here” tweeted one. “What if it was one of your loved ones who needed a transplant?” Another tweeted the Hippocratic oath with the comment that “They all swore under this noble ‘oat’, but I guess it’s been forgotten.” (This was followed with a photo of a box of Quaker Oats in a failed attempt at humor.) These discussions among the Twitterati highlight the depths of misunderstanding on organ transplantation.

To be fair, unless you have been personally involved in the decision-making process for transplant candidacy, there is little opportunity to be educated. I explain to my anxious patients and their families that a donor organ is like a fumbled football. There may be well over 100 patients at all levels of transplant status in many geographic locations diving for that same organ.

The transplant team is tasked with finding the best match, determining who is the sickest, assessing time for transport of that organ, and, above all, who will be the best steward of that organ.

Take heart transplantation, for instance. Approximately 3,500 patients in the United States are awaiting one each year. Instead of facing an almost certain death within 5 years, a transplant recipient has a chance at a median survival of 12-13 years. The cost of a heart transplant is approximately $1.38 million, according to Milliman, a consulting firm. This is “an incredibly resource intensive procedure,” including expenditures for transportation, antirejection medication, office visits, physician fees, ICU stays, rejection surveillance, and acute rejection therapies.

Transplant denial is nothing new

People get turned down for organ transplants all the time. My patient with end-stage dilated cardiomyopathy was denied a heart transplant when it was discovered that he had scores of outstanding parking tickets. This was seen as a surrogate for an inability to afford his antirejection medication.

Another patient swore that her positive cotinine levels were caused by endless hours at the bingo hall where second-hand smoke swirled. She was also denied. Many potential candidates who are in acute decline hold precariously to newfound sobriety. They are denied. A patient’s boyfriend told the transplant team that he couldn’t be relied upon to drive her to her appointments. She was denied.

Many people who engage in antisocial behaviors have no idea that these actions may result in the denial of an organ transplant should their future selves need one. These are hard lines, but everyone should agree that the odds of survival are heavily in favor of the consistently adherent.

We should take this opportunity to educate the public on how complicated obtaining an organ transplant can be. More than 6,000 people die each year waiting for an organ because of the supply-and-demand disparities in the transplantation arena. I’m willing to bet that many of the loudest protesters in favor of unvaccinated transplant recipients have not signed the organ donor box on the back of their driver’s license. This conversation is an opportunity to change that and remind people that organ donation may be their only opportunity to save a fellow human’s life.

Again, to quote Ted Lasso: “If you care about someone and you got a little love in your heart, there ain’t nothing you can’t get through together.” That philosophy should apply to the tasks of selecting the best organ donors as well as the best organ recipients.

And every organ should go to the one who will honor their donor and their donor’s family by taking the best care of that ultimate gift of life, including being vaccinated against COVID-19.

Dr. Walton-Shirley is a native Kentuckian who retired from full-time invasive cardiology. She enjoys locums work in Montana and is a champion of physician rights and patient safety. She disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

I agree with most advice given by the affable TV character Ted Lasso. “Every choice is a chance,” he said. Pandemic-era physicians must now consider whether a politically motivated choice to decline COVID-19 vaccination should negatively affect the chance to receive an organ donation.

And in confronting these choices, we have a chance to educate the public on the complexities of the organ allocation process.

A well-informed patient’s personal choice should be honored, even if clinicians disagree, if it does not affect the well-being of others. For example, I once had a patient in acute leukemic crisis who declined blood products because she was a Jehovah’s Witness. She died. Her choice affected her longevity only.

Compare that decision with awarding an organ to an individual who has declined readily available protection of that organ. Weigh that choice against the fact that said protection is against an infectious disease that has killed over 5.5 million worldwide.

Some institutions stand strong, others hedge their bets

Admirably, Loyola University Health System understands that difference. They published a firm stand on transplant candidacy and COVID-19 vaccination status in the Journal of Heart and Lung Transplant. Daniel Dilling, MD, medical director of the lung transplantation program , and Mark Kuczewski, PhD, a professor of medical ethics at Loyola University Chicago, Maywood, Ill., wrote that: “We believe that requiring vaccination against COVID-19 should not be controversial when we focus strictly on established frameworks and practices surrounding eligibility for wait-listing to receive a solid organ transplant.”

The Cleveland Clinic apparently agrees. In October 2021, they denied a liver transplant to Michelle Vitullo of Ohio, whose daughter had been deemed “a perfect match.” Her daughter, also unvaccinated, stated: “Being denied for a nonmedical reason for someone’s beliefs that are different to yours, I mean that’s not how that should be.”

But vaccination status is a medical reason, given well-established data regarding increased mortality among the immunosuppressed. Ms. Vitullo then said: “We are trying to get to UPMC [University of Pittsburgh Medical Center] as they don’t require a vaccination.”

The public information page on transplant candidacy from UPMC reads (my italics): It is recommended that all transplant candidates, transplant recipients, and their household members receive COVID-19 vaccination when the vaccine is available to them. It is preferred that transplant candidates are vaccinated more than 2 weeks before transplantation.

I reached out to UPMC for clarification and was told by email that “we do not have a policy regarding COVID-19 vaccination requirement for current transplant candidates.” Houston Methodist shares the same agnostic stance.

Compare these opinions with Brigham and Women’s Hospital, where the requirements are resolute: “Like most other transplant programs across the country, the COVID-19 vaccine is one of several vaccines and lifestyle behaviors that are required for patients awaiting solid organ transplant.”

They add that “transplant candidates must also receive the seasonal influenza and hepatitis B vaccines, follow other healthy behaviors, and demonstrate they can commit to taking the required medications following transplant.”

In January 2022, Brigham and Women’s Hospital declared 31-year-old D.J. Ferguson ineligible for a heart transplant because he declined to be vaccinated against COVID-19. According to the New York Post and ABC News, his physicians resorted to left ventricular assist device support. His mother, Tracy Ferguson, is quoted as saying: “He’s not an antivaxxer. He has all of his vaccines.” I’ll just leave that right there.

Unfortunately, Michelle Vitullo’s obituary was published in December 2021. Regardless of whether she received her liver transplant, the outcome is tragic, and whatever you think of this family’s battle playing out in the glare of the national spotlight, their loss is no less devastating.

The directed-donation aspect of this case poses an interesting question. A news anchor asked the mother and daughter: “If you both accept the risks, why doesn’t the hospital just let you try?” The answers are obvious to us clinicians. Performing a transplantation in an unvaccinated patient could lead to their early death if they became infected because of their immunocompromised state, would open the door for transplantation of any patient who is unvaccinated for anything, including influenza and hepatitis B, which could result in the preventable waste of organs, and puts other vulnerable hospitalized patients at risk during the initial transplant stay and follow-up.

That’s not to mention the potential legal suit. Never has a consent form dissuaded any party from lodging an accusation of wrongful death or medical malpractice. In the face of strong data on higher mortality in unvaccinated, immunocompromised patients, a good lawyer could charge that the institution and transplant surgeons should have known better, regardless of the donor and recipient’s willingness to accept the risks.

The Vitullo and Ferguson cases are among many similar dilemmas surrounding transplant candidacy across the United States.

University of Virginia Health in Charlottesville denied 42-year-old Shamgar Connors a kidney transplant because he is unvaccinated, despite a previous COVID-19 infection. In October 2021, Leilani Lutali of Colorado was denied a kidney by UCHealth because she declined vaccination.

As Ted Lasso says: “There’s a bunch of crazy stuff on Twitter.”

Predictably, social media is full of public outcry. “Some cold-hearted people on here” tweeted one. “What if it was one of your loved ones who needed a transplant?” Another tweeted the Hippocratic oath with the comment that “They all swore under this noble ‘oat’, but I guess it’s been forgotten.” (This was followed with a photo of a box of Quaker Oats in a failed attempt at humor.) These discussions among the Twitterati highlight the depths of misunderstanding on organ transplantation.

To be fair, unless you have been personally involved in the decision-making process for transplant candidacy, there is little opportunity to be educated. I explain to my anxious patients and their families that a donor organ is like a fumbled football. There may be well over 100 patients at all levels of transplant status in many geographic locations diving for that same organ.

The transplant team is tasked with finding the best match, determining who is the sickest, assessing time for transport of that organ, and, above all, who will be the best steward of that organ.

Take heart transplantation, for instance. Approximately 3,500 patients in the United States are awaiting one each year. Instead of facing an almost certain death within 5 years, a transplant recipient has a chance at a median survival of 12-13 years. The cost of a heart transplant is approximately $1.38 million, according to Milliman, a consulting firm. This is “an incredibly resource intensive procedure,” including expenditures for transportation, antirejection medication, office visits, physician fees, ICU stays, rejection surveillance, and acute rejection therapies.

Transplant denial is nothing new

People get turned down for organ transplants all the time. My patient with end-stage dilated cardiomyopathy was denied a heart transplant when it was discovered that he had scores of outstanding parking tickets. This was seen as a surrogate for an inability to afford his antirejection medication.

Another patient swore that her positive cotinine levels were caused by endless hours at the bingo hall where second-hand smoke swirled. She was also denied. Many potential candidates who are in acute decline hold precariously to newfound sobriety. They are denied. A patient’s boyfriend told the transplant team that he couldn’t be relied upon to drive her to her appointments. She was denied.

Many people who engage in antisocial behaviors have no idea that these actions may result in the denial of an organ transplant should their future selves need one. These are hard lines, but everyone should agree that the odds of survival are heavily in favor of the consistently adherent.

We should take this opportunity to educate the public on how complicated obtaining an organ transplant can be. More than 6,000 people die each year waiting for an organ because of the supply-and-demand disparities in the transplantation arena. I’m willing to bet that many of the loudest protesters in favor of unvaccinated transplant recipients have not signed the organ donor box on the back of their driver’s license. This conversation is an opportunity to change that and remind people that organ donation may be their only opportunity to save a fellow human’s life.

Again, to quote Ted Lasso: “If you care about someone and you got a little love in your heart, there ain’t nothing you can’t get through together.” That philosophy should apply to the tasks of selecting the best organ donors as well as the best organ recipients.

And every organ should go to the one who will honor their donor and their donor’s family by taking the best care of that ultimate gift of life, including being vaccinated against COVID-19.

Dr. Walton-Shirley is a native Kentuckian who retired from full-time invasive cardiology. She enjoys locums work in Montana and is a champion of physician rights and patient safety. She disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

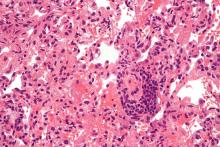

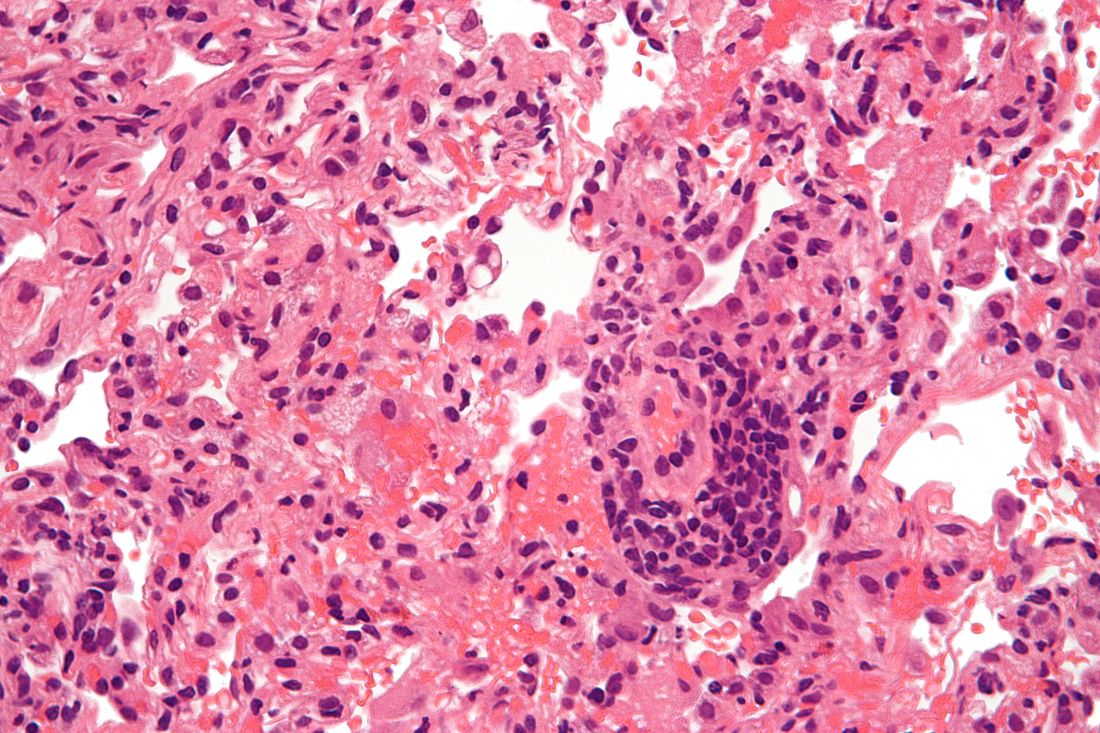

Real-world data reinforce stem cell transplant for progressive systemic sclerosis

Current selection criteria for autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplant (AHSCT) in patients with rapidly progressing systemic sclerosis were validated in a study presented at the annual meeting of the Canadian Rheumatology Association.

The study, which associated AHSCT with improvement in overall survival and an acceptable risk of adverse events, “provides valuable real-world, long-term data pertaining to key clinical outcomes to support the use of AHSCT in patients with rapidly progressing systemic sclerosis,” reported Nancy Maltez, MD, a rheumatologist and clinical investigator who is on the faculty of the University of Ottawa.

The prospective study enrolled 85 patients in Canada and 41 patients in France with rapidly progressing systemic sclerosis. The patients in both countries were enrolled with the same eligibility criteria for AHSCT, but patients in France underwent AHSCT while the patients in Canada were treated with conventional therapies, such as cyclophosphamide.

On the primary outcome of overall survival, the Kaplan-Meier curve split almost immediately in favor of AHSCT. At 4 years, more than 25% of patients in the conventional therapy group had died versus less than 5% of those who underwent AHSCT. Although the mortality curve did slope downwards in the AHSCT group over the subsequent 6 years of follow-up, it largely paralleled and remained superior to convention therapy.

About 50% survival advantage seen for AHSCT

In this nonrandomized study, the statistical survival advantage of AHSCT was not provided, but the survival graph showed about 75% survival at 8 years of follow-up in the AHSCT group, compared with about 50% survival in the conventional-therapy group.

Many of the secondary outcomes, including those evaluating skin involvement, preservation of lung function, and absence of renal complications also favored AHSCT, according to Dr. Maltez.

On the modified Rodnan skin score, a significant difference (P < .001) observed at 12 months was sustained at 36 months, when the score was 4.48 points lower among patients treated with AHSCT. The difference in forced vital capacity (FVC) was about 10% higher (P < .0001) in the AHSCT group.

Over long-term follow-up, the incidence of scleroderma renal crisis per 100 person-years was 6.02 cases in the conventional therapy group versus 0.58 cases (P < .001) in the AHSCT group. There was no significant difference in the proportion of patients in the two groups receiving a pacemaker over the course of follow-up, but the rate of new malignancies per 100 person-years was 3.71 in the conventional care group versus 0.58 (P < .001) in the AHSCT group.

Significant complications attributed to AHSCT were uncommon. This is important, because AHSCT was not uniformly well tolerated in the initial trials. The first of three randomized trials with AHSCT in progressive systemic sclerosis was published more than 10 years ago after a series of promising early phase trials. Each associated AHSCT with benefit, but patient selection appeared to be important.

In the ASSIST trial of 2011, AHSCT was associated with significant reductions in skin involvement and improvements in pulmonary function relative to cyclophosphamide, but enrollment was stopped after only 19 patients, and follow-up extended to only 2 years.

Substantial AHSCT-related mortality in ASTIS

In the second trial, called ASTIS, AHSCT was associated with a higher rate of mortality than cyclophosphamide after 1 year of follow-up, although there was a significantly greater long-term event-free survival for AHSCT when patients were followed out to 4 years. This study reinforced the need for cardiac screening because of because of concern that severe cardiac compromise contributed to the increased risk of AHSCT-related mortality.

The SCOT trial employed a high-intensity myeloablative conditioning regimen and total body irradiation prior to AHSCT. It is not clear that these contributed to improved survival, particularly because of the risk for irradiation to exacerbate complications in the lung and kidney, but AHSCT-related mortality was only 3% at 54 months. Patient enrollment criteria in this trial were also suspected of having played a role in the favorable results.

In the Canadian-French collaborative study, patients were considered eligible for AHSCT if they met the enrollment criteria used in the ASTIS trial, according to Dr. Maltez. She attributed the low rates of early mortality and relative absence of transplant-related death to the lessons learned in the published trials.

Overall, the data support the routine but selective use of AHSCT in rapidly progressing systemic sclerosis, Dr. Maltez concluded.

Maria Carolina Oliveira, MD, of the department of internal medicine at the University of São Paulo, generally agreed. A coauthor of a recent review of AHSCT for systemic sclerosis, Dr. Oliveira emphasized that patient selection is critical.

“AHSCT for systemic sclerosis has very specific inclusion criteria. Indeed, it is indicated for patients with severe and progressive disease but under two specific conditions: severe and progressive diffuse skin involvement and/or progressive interstitial lung disease,” she said in an interview.

Because of the thin line between benefit and risk according to disease subtypes and comorbidities, she said that it is important to be aware of relative contraindications and to recognize the risks of AHSCT.

At this time, and in the absence of better biomarkers to identify those most likely to benefit, “patients with other forms of severe scleroderma, such as those with pulmonary hypertension, scleroderma renal crisis, or severe cardiac involvement, for example, are not eligible,” she said.

Dr. Maltez and Dr. Oliveira reported having no potential conflicts of interest.

Current selection criteria for autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplant (AHSCT) in patients with rapidly progressing systemic sclerosis were validated in a study presented at the annual meeting of the Canadian Rheumatology Association.

The study, which associated AHSCT with improvement in overall survival and an acceptable risk of adverse events, “provides valuable real-world, long-term data pertaining to key clinical outcomes to support the use of AHSCT in patients with rapidly progressing systemic sclerosis,” reported Nancy Maltez, MD, a rheumatologist and clinical investigator who is on the faculty of the University of Ottawa.

The prospective study enrolled 85 patients in Canada and 41 patients in France with rapidly progressing systemic sclerosis. The patients in both countries were enrolled with the same eligibility criteria for AHSCT, but patients in France underwent AHSCT while the patients in Canada were treated with conventional therapies, such as cyclophosphamide.

On the primary outcome of overall survival, the Kaplan-Meier curve split almost immediately in favor of AHSCT. At 4 years, more than 25% of patients in the conventional therapy group had died versus less than 5% of those who underwent AHSCT. Although the mortality curve did slope downwards in the AHSCT group over the subsequent 6 years of follow-up, it largely paralleled and remained superior to convention therapy.

About 50% survival advantage seen for AHSCT

In this nonrandomized study, the statistical survival advantage of AHSCT was not provided, but the survival graph showed about 75% survival at 8 years of follow-up in the AHSCT group, compared with about 50% survival in the conventional-therapy group.

Many of the secondary outcomes, including those evaluating skin involvement, preservation of lung function, and absence of renal complications also favored AHSCT, according to Dr. Maltez.

On the modified Rodnan skin score, a significant difference (P < .001) observed at 12 months was sustained at 36 months, when the score was 4.48 points lower among patients treated with AHSCT. The difference in forced vital capacity (FVC) was about 10% higher (P < .0001) in the AHSCT group.

Over long-term follow-up, the incidence of scleroderma renal crisis per 100 person-years was 6.02 cases in the conventional therapy group versus 0.58 cases (P < .001) in the AHSCT group. There was no significant difference in the proportion of patients in the two groups receiving a pacemaker over the course of follow-up, but the rate of new malignancies per 100 person-years was 3.71 in the conventional care group versus 0.58 (P < .001) in the AHSCT group.

Significant complications attributed to AHSCT were uncommon. This is important, because AHSCT was not uniformly well tolerated in the initial trials. The first of three randomized trials with AHSCT in progressive systemic sclerosis was published more than 10 years ago after a series of promising early phase trials. Each associated AHSCT with benefit, but patient selection appeared to be important.

In the ASSIST trial of 2011, AHSCT was associated with significant reductions in skin involvement and improvements in pulmonary function relative to cyclophosphamide, but enrollment was stopped after only 19 patients, and follow-up extended to only 2 years.

Substantial AHSCT-related mortality in ASTIS

In the second trial, called ASTIS, AHSCT was associated with a higher rate of mortality than cyclophosphamide after 1 year of follow-up, although there was a significantly greater long-term event-free survival for AHSCT when patients were followed out to 4 years. This study reinforced the need for cardiac screening because of because of concern that severe cardiac compromise contributed to the increased risk of AHSCT-related mortality.

The SCOT trial employed a high-intensity myeloablative conditioning regimen and total body irradiation prior to AHSCT. It is not clear that these contributed to improved survival, particularly because of the risk for irradiation to exacerbate complications in the lung and kidney, but AHSCT-related mortality was only 3% at 54 months. Patient enrollment criteria in this trial were also suspected of having played a role in the favorable results.

In the Canadian-French collaborative study, patients were considered eligible for AHSCT if they met the enrollment criteria used in the ASTIS trial, according to Dr. Maltez. She attributed the low rates of early mortality and relative absence of transplant-related death to the lessons learned in the published trials.

Overall, the data support the routine but selective use of AHSCT in rapidly progressing systemic sclerosis, Dr. Maltez concluded.