User login

Sulfonylureas as street drugs: Hidden hypoglycemia cause

SEATTLE – .

“Physicians should be aware of this possibility and consider intentional or unintentional sulfonylurea abuse, with or without other drugs,” Amanda McKenna, MD, a first-year endocrinology fellow at the Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, Fla., and colleagues say in a poster presented at the annual scientific & clinical congress of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinology.

The new case, seen in Florida, involves a 33-year-old man with a history of narcotic dependence and anxiety but not diabetes. At the time of presentation, the patient was unconscious and diaphoretic. The patient’s blood glucose level was 18 mg/dL. He had purchased two unmarked, light blue pills on the street which he thought were Valiums but turned out to be glyburide.

Sulfonylureas have no potential for abuse, but they physically resemble Valiums and are easier for illicit drug dealers to obtain because they’re not a controlled substance, and they can be sold for considerably more money, Dr. McKenna said in an interview.

“He thought he was getting Valium, but what he really purchased was glyburide. ... When he took it, he developed sweating and weakness. He probably thought he was having a bad trip, but it was really low blood sugar,” she said.

Similar cases go back nearly two decades

Similar cases have been reported as far back as 2004 in different parts of the United States. A 2004 article reports five cases in which people in San Francisco were “admitted to the hospital for hypoglycemia as a result of a drug purchased on the streets as a presumed benzodiazepine.”

Two more cases of “glyburide poisoning by ingestion of ‘street Valium,’ ” also from San Francisco, were reported in 2012. And in another case presented at the 2022 Endocrine Society meeting, sulfonylurea had been cut with cocaine, presumably to increase the volume.

The lead author of the 2012 article, Craig Smollin, MD, medical director of the California Poison Control System, San Francisco Division, and professor of emergency medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, told this news organization that his team has seen “a handful of cases over the years” but that “it is hard to say how common it is because hypoglycemia is common in this patient population for a variety of reasons.”

Persistent hypoglycemia led to the source

In the current case, paramedics treated the patient with D50W, and his blood glucose level increased from 18 mg/dL to 109 mg/dL. He regained consciousness but then developed recurrent hypoglycemia, and his blood glucose level dropped back to 15 mg/dL in the ED. Urine toxicology results were positive for benzodiazepines, cannabis, and cocaine.

Laboratory results showed elevations in levels of insulin (47.4 mIU/mL), C-peptide (5.4 ng/mL), and glucose (44 mg/dL). He was again treated with D50W, and his blood glucose level returned to normal over 20 hours. Once alert and oriented, he reported no personal or family history of diabetes. A 72-hour fast showed no evidence of insulinoma. A sulfonylurea screen was positive for glyburide. He was discharged home in stable condition. How many more cases have been missed?

Dr. McKenna pointed out that a typical urine toxicology screen for drugs wouldn’t detect a sulfonylurea. “The screen for hypoglycemic agents is a blood test, not a urine screen, so it’s completely different in the workup, and you really have to be thinking about that. It typically takes a while to come back,” she said.

She added that if the hypoglycemia resolves and testing isn’t conducted, the cause of the low blood sugar level might be missed. “If the hypoglycemia doesn’t persist, the [ED] physician wouldn’t consult endocrine. ... Is this happening more than we think?”

Ocreotide: A ‘unique antidote’

In their article, Dr. Smollin and colleagues describe the use of ocreotide, a long-acting somatostatin agonist that reverses the insulin-releasing effect of sulfonylureas on pancreatic beta cells, resulting in diminished insulin secretion. Unlike glucose supplementation, ocreotide doesn’t stimulate additional insulin release. It is of longer duration than glucagon, the authors say.

“The management of sulfonylurea overdose includes administration of glucose but also may include the use of octreotide, a unique antidote for sulfonylurea induced hypoglycemia,” Dr. Smollin said.

However, he also cautioned, “there is a broad differential diagnosis for hypoglycemia, and clinicians must consider many alternative diagnoses.”

Dr. McKenna and Dr. Smollin have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

SEATTLE – .

“Physicians should be aware of this possibility and consider intentional or unintentional sulfonylurea abuse, with or without other drugs,” Amanda McKenna, MD, a first-year endocrinology fellow at the Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, Fla., and colleagues say in a poster presented at the annual scientific & clinical congress of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinology.

The new case, seen in Florida, involves a 33-year-old man with a history of narcotic dependence and anxiety but not diabetes. At the time of presentation, the patient was unconscious and diaphoretic. The patient’s blood glucose level was 18 mg/dL. He had purchased two unmarked, light blue pills on the street which he thought were Valiums but turned out to be glyburide.

Sulfonylureas have no potential for abuse, but they physically resemble Valiums and are easier for illicit drug dealers to obtain because they’re not a controlled substance, and they can be sold for considerably more money, Dr. McKenna said in an interview.

“He thought he was getting Valium, but what he really purchased was glyburide. ... When he took it, he developed sweating and weakness. He probably thought he was having a bad trip, but it was really low blood sugar,” she said.

Similar cases go back nearly two decades

Similar cases have been reported as far back as 2004 in different parts of the United States. A 2004 article reports five cases in which people in San Francisco were “admitted to the hospital for hypoglycemia as a result of a drug purchased on the streets as a presumed benzodiazepine.”

Two more cases of “glyburide poisoning by ingestion of ‘street Valium,’ ” also from San Francisco, were reported in 2012. And in another case presented at the 2022 Endocrine Society meeting, sulfonylurea had been cut with cocaine, presumably to increase the volume.

The lead author of the 2012 article, Craig Smollin, MD, medical director of the California Poison Control System, San Francisco Division, and professor of emergency medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, told this news organization that his team has seen “a handful of cases over the years” but that “it is hard to say how common it is because hypoglycemia is common in this patient population for a variety of reasons.”

Persistent hypoglycemia led to the source

In the current case, paramedics treated the patient with D50W, and his blood glucose level increased from 18 mg/dL to 109 mg/dL. He regained consciousness but then developed recurrent hypoglycemia, and his blood glucose level dropped back to 15 mg/dL in the ED. Urine toxicology results were positive for benzodiazepines, cannabis, and cocaine.

Laboratory results showed elevations in levels of insulin (47.4 mIU/mL), C-peptide (5.4 ng/mL), and glucose (44 mg/dL). He was again treated with D50W, and his blood glucose level returned to normal over 20 hours. Once alert and oriented, he reported no personal or family history of diabetes. A 72-hour fast showed no evidence of insulinoma. A sulfonylurea screen was positive for glyburide. He was discharged home in stable condition. How many more cases have been missed?

Dr. McKenna pointed out that a typical urine toxicology screen for drugs wouldn’t detect a sulfonylurea. “The screen for hypoglycemic agents is a blood test, not a urine screen, so it’s completely different in the workup, and you really have to be thinking about that. It typically takes a while to come back,” she said.

She added that if the hypoglycemia resolves and testing isn’t conducted, the cause of the low blood sugar level might be missed. “If the hypoglycemia doesn’t persist, the [ED] physician wouldn’t consult endocrine. ... Is this happening more than we think?”

Ocreotide: A ‘unique antidote’

In their article, Dr. Smollin and colleagues describe the use of ocreotide, a long-acting somatostatin agonist that reverses the insulin-releasing effect of sulfonylureas on pancreatic beta cells, resulting in diminished insulin secretion. Unlike glucose supplementation, ocreotide doesn’t stimulate additional insulin release. It is of longer duration than glucagon, the authors say.

“The management of sulfonylurea overdose includes administration of glucose but also may include the use of octreotide, a unique antidote for sulfonylurea induced hypoglycemia,” Dr. Smollin said.

However, he also cautioned, “there is a broad differential diagnosis for hypoglycemia, and clinicians must consider many alternative diagnoses.”

Dr. McKenna and Dr. Smollin have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

SEATTLE – .

“Physicians should be aware of this possibility and consider intentional or unintentional sulfonylurea abuse, with or without other drugs,” Amanda McKenna, MD, a first-year endocrinology fellow at the Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, Fla., and colleagues say in a poster presented at the annual scientific & clinical congress of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinology.

The new case, seen in Florida, involves a 33-year-old man with a history of narcotic dependence and anxiety but not diabetes. At the time of presentation, the patient was unconscious and diaphoretic. The patient’s blood glucose level was 18 mg/dL. He had purchased two unmarked, light blue pills on the street which he thought were Valiums but turned out to be glyburide.

Sulfonylureas have no potential for abuse, but they physically resemble Valiums and are easier for illicit drug dealers to obtain because they’re not a controlled substance, and they can be sold for considerably more money, Dr. McKenna said in an interview.

“He thought he was getting Valium, but what he really purchased was glyburide. ... When he took it, he developed sweating and weakness. He probably thought he was having a bad trip, but it was really low blood sugar,” she said.

Similar cases go back nearly two decades

Similar cases have been reported as far back as 2004 in different parts of the United States. A 2004 article reports five cases in which people in San Francisco were “admitted to the hospital for hypoglycemia as a result of a drug purchased on the streets as a presumed benzodiazepine.”

Two more cases of “glyburide poisoning by ingestion of ‘street Valium,’ ” also from San Francisco, were reported in 2012. And in another case presented at the 2022 Endocrine Society meeting, sulfonylurea had been cut with cocaine, presumably to increase the volume.

The lead author of the 2012 article, Craig Smollin, MD, medical director of the California Poison Control System, San Francisco Division, and professor of emergency medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, told this news organization that his team has seen “a handful of cases over the years” but that “it is hard to say how common it is because hypoglycemia is common in this patient population for a variety of reasons.”

Persistent hypoglycemia led to the source

In the current case, paramedics treated the patient with D50W, and his blood glucose level increased from 18 mg/dL to 109 mg/dL. He regained consciousness but then developed recurrent hypoglycemia, and his blood glucose level dropped back to 15 mg/dL in the ED. Urine toxicology results were positive for benzodiazepines, cannabis, and cocaine.

Laboratory results showed elevations in levels of insulin (47.4 mIU/mL), C-peptide (5.4 ng/mL), and glucose (44 mg/dL). He was again treated with D50W, and his blood glucose level returned to normal over 20 hours. Once alert and oriented, he reported no personal or family history of diabetes. A 72-hour fast showed no evidence of insulinoma. A sulfonylurea screen was positive for glyburide. He was discharged home in stable condition. How many more cases have been missed?

Dr. McKenna pointed out that a typical urine toxicology screen for drugs wouldn’t detect a sulfonylurea. “The screen for hypoglycemic agents is a blood test, not a urine screen, so it’s completely different in the workup, and you really have to be thinking about that. It typically takes a while to come back,” she said.

She added that if the hypoglycemia resolves and testing isn’t conducted, the cause of the low blood sugar level might be missed. “If the hypoglycemia doesn’t persist, the [ED] physician wouldn’t consult endocrine. ... Is this happening more than we think?”

Ocreotide: A ‘unique antidote’

In their article, Dr. Smollin and colleagues describe the use of ocreotide, a long-acting somatostatin agonist that reverses the insulin-releasing effect of sulfonylureas on pancreatic beta cells, resulting in diminished insulin secretion. Unlike glucose supplementation, ocreotide doesn’t stimulate additional insulin release. It is of longer duration than glucagon, the authors say.

“The management of sulfonylurea overdose includes administration of glucose but also may include the use of octreotide, a unique antidote for sulfonylurea induced hypoglycemia,” Dr. Smollin said.

However, he also cautioned, “there is a broad differential diagnosis for hypoglycemia, and clinicians must consider many alternative diagnoses.”

Dr. McKenna and Dr. Smollin have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

AT AACE 2023

‘Shocking’ data on what’s really in melatonin gummies

New data may explain the recent massive jump in pediatric hospitalizations.

Thenvestigators found that consuming some products as directed could expose consumers, including children, to doses that are 40-130 times greater than what’s recommended.

“The results were quite shocking,” lead researcher Pieter Cohen, MD, with Harvard Medical School, Boston, and Cambridge Health Alliance, Somerville, Mass., said in an interview.

“Melatonin gummies contained up to 347% more melatonin than what was listed on the label, and some products also contained cannabidiol; in one brand of melatonin gummies, there was zero melatonin, just CBD,” Dr. Cohen said.

The study was published online in JAMA.

530% jump in pediatric hospitalizations

Melatonin products are not approved by the Food and Drug Administration but are sold over the counter or online.

Previous research from JAMA has shown the use of melatonin has increased over the past 2 decades among people of all ages.

With increased use has come a spike in reports of melatonin overdose, calls to poison control centers, and related ED visits for children.

Federal data show the number of U.S. children who unintentionally ingested melatonin supplements jumped 530% from 2012 to 2021. More than 4,000 of the reported ingestions led to a hospital stay; 287 children required intensive care, and two children died.

It was unclear why melatonin supplements were causing these harms, which led Dr. Cohen’s team to analyze 25 unique brands of “melatonin” gummies purchased online.

One product didn’t contain any melatonin but did contain 31.3 mg of CBD.

In the remaining products, the quantity of melatonin ranged from 1.3 mg to 13.1 mg per serving. The actual quantity of melatonin ranged from 74% to 347% of the labeled quantity, the researchers found.

They note that for a young adult who takes as little as 0.1-0.3 mg of melatonin, plasma concentrations can increase into the normal night-time range.

Of the 25 products (88%) analyzed, 22 were inaccurately labeled, and only 3 (12%) contained a quantity of melatonin that was within 10% (plus or minus) of the declared quantity.

Five products listed CBD as an ingredient. The listed quantity ranged from 10.6 mg to 31.3 mg per serving, although the actual quantity of CBD ranged from 104% to 118% of the labeled quantity.

Inquire about use in kids

A limitation of the study is that only one sample of each brand was analyzed, and only gummies were analyzed. It is not known whether the results are generalizable to melatonin products sold as tablets and capsules in the United States or whether the quantity of melatonin within an individual brand may vary from batch to batch.

A recent study from Canada showed similar results. In an analysis of 16 Canadian melatonin brands, the actual dose of melatonin ranged from 17% to 478% of the declared quantity.

It’s estimated that more than 1% of all U.S. children use melatonin supplements, most commonly for sleep, stress, and relaxation.

“Given new research as to the excessive quantities of melatonin in gummies, caution should be used if considering their use,” said Dr. Cohen.

“It’s important to inquire about melatonin use when caring for children, particularly when parents express concerns about their child’s sleep,” he added.

The American Academy of Sleep Medicine recently issued a health advisory encouraging parents to talk to a health care professional before giving melatonin or any supplement to children.

Children don’t need melatonin

Commenting on the study, Michael Breus, PhD, clinical psychologist and founder of TheSleepDoctor.com, agreed that analyzing only one sample of each brand is a key limitation “because supplements are made in batches, and gummies in particular are difficult to distribute the active ingredient evenly.

“But even with that being said, 88% of them were labeled incorrectly, so even if there were a few single-sample issues, I kind of doubt its all of them,” Dr. Breus said.

“Kids as a general rule do not need melatonin. Their brains make almost four times the necessary amount already. If you start giving kids pills to help them sleep, then they start to have a pill problem, causing another issue,” Dr. Breus added.

“Most children’s falling asleep and staying sleep issues can be treated with behavioral measures like cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia,” he said.

The study had no specific funding. Dr. Cohen has received research support from Consumers Union and PEW Charitable Trusts and royalties from UptoDate. Dr. Breus disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

New data may explain the recent massive jump in pediatric hospitalizations.

Thenvestigators found that consuming some products as directed could expose consumers, including children, to doses that are 40-130 times greater than what’s recommended.

“The results were quite shocking,” lead researcher Pieter Cohen, MD, with Harvard Medical School, Boston, and Cambridge Health Alliance, Somerville, Mass., said in an interview.

“Melatonin gummies contained up to 347% more melatonin than what was listed on the label, and some products also contained cannabidiol; in one brand of melatonin gummies, there was zero melatonin, just CBD,” Dr. Cohen said.

The study was published online in JAMA.

530% jump in pediatric hospitalizations

Melatonin products are not approved by the Food and Drug Administration but are sold over the counter or online.

Previous research from JAMA has shown the use of melatonin has increased over the past 2 decades among people of all ages.

With increased use has come a spike in reports of melatonin overdose, calls to poison control centers, and related ED visits for children.

Federal data show the number of U.S. children who unintentionally ingested melatonin supplements jumped 530% from 2012 to 2021. More than 4,000 of the reported ingestions led to a hospital stay; 287 children required intensive care, and two children died.

It was unclear why melatonin supplements were causing these harms, which led Dr. Cohen’s team to analyze 25 unique brands of “melatonin” gummies purchased online.

One product didn’t contain any melatonin but did contain 31.3 mg of CBD.

In the remaining products, the quantity of melatonin ranged from 1.3 mg to 13.1 mg per serving. The actual quantity of melatonin ranged from 74% to 347% of the labeled quantity, the researchers found.

They note that for a young adult who takes as little as 0.1-0.3 mg of melatonin, plasma concentrations can increase into the normal night-time range.

Of the 25 products (88%) analyzed, 22 were inaccurately labeled, and only 3 (12%) contained a quantity of melatonin that was within 10% (plus or minus) of the declared quantity.

Five products listed CBD as an ingredient. The listed quantity ranged from 10.6 mg to 31.3 mg per serving, although the actual quantity of CBD ranged from 104% to 118% of the labeled quantity.

Inquire about use in kids

A limitation of the study is that only one sample of each brand was analyzed, and only gummies were analyzed. It is not known whether the results are generalizable to melatonin products sold as tablets and capsules in the United States or whether the quantity of melatonin within an individual brand may vary from batch to batch.

A recent study from Canada showed similar results. In an analysis of 16 Canadian melatonin brands, the actual dose of melatonin ranged from 17% to 478% of the declared quantity.

It’s estimated that more than 1% of all U.S. children use melatonin supplements, most commonly for sleep, stress, and relaxation.

“Given new research as to the excessive quantities of melatonin in gummies, caution should be used if considering their use,” said Dr. Cohen.

“It’s important to inquire about melatonin use when caring for children, particularly when parents express concerns about their child’s sleep,” he added.

The American Academy of Sleep Medicine recently issued a health advisory encouraging parents to talk to a health care professional before giving melatonin or any supplement to children.

Children don’t need melatonin

Commenting on the study, Michael Breus, PhD, clinical psychologist and founder of TheSleepDoctor.com, agreed that analyzing only one sample of each brand is a key limitation “because supplements are made in batches, and gummies in particular are difficult to distribute the active ingredient evenly.

“But even with that being said, 88% of them were labeled incorrectly, so even if there were a few single-sample issues, I kind of doubt its all of them,” Dr. Breus said.

“Kids as a general rule do not need melatonin. Their brains make almost four times the necessary amount already. If you start giving kids pills to help them sleep, then they start to have a pill problem, causing another issue,” Dr. Breus added.

“Most children’s falling asleep and staying sleep issues can be treated with behavioral measures like cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia,” he said.

The study had no specific funding. Dr. Cohen has received research support from Consumers Union and PEW Charitable Trusts and royalties from UptoDate. Dr. Breus disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

New data may explain the recent massive jump in pediatric hospitalizations.

Thenvestigators found that consuming some products as directed could expose consumers, including children, to doses that are 40-130 times greater than what’s recommended.

“The results were quite shocking,” lead researcher Pieter Cohen, MD, with Harvard Medical School, Boston, and Cambridge Health Alliance, Somerville, Mass., said in an interview.

“Melatonin gummies contained up to 347% more melatonin than what was listed on the label, and some products also contained cannabidiol; in one brand of melatonin gummies, there was zero melatonin, just CBD,” Dr. Cohen said.

The study was published online in JAMA.

530% jump in pediatric hospitalizations

Melatonin products are not approved by the Food and Drug Administration but are sold over the counter or online.

Previous research from JAMA has shown the use of melatonin has increased over the past 2 decades among people of all ages.

With increased use has come a spike in reports of melatonin overdose, calls to poison control centers, and related ED visits for children.

Federal data show the number of U.S. children who unintentionally ingested melatonin supplements jumped 530% from 2012 to 2021. More than 4,000 of the reported ingestions led to a hospital stay; 287 children required intensive care, and two children died.

It was unclear why melatonin supplements were causing these harms, which led Dr. Cohen’s team to analyze 25 unique brands of “melatonin” gummies purchased online.

One product didn’t contain any melatonin but did contain 31.3 mg of CBD.

In the remaining products, the quantity of melatonin ranged from 1.3 mg to 13.1 mg per serving. The actual quantity of melatonin ranged from 74% to 347% of the labeled quantity, the researchers found.

They note that for a young adult who takes as little as 0.1-0.3 mg of melatonin, plasma concentrations can increase into the normal night-time range.

Of the 25 products (88%) analyzed, 22 were inaccurately labeled, and only 3 (12%) contained a quantity of melatonin that was within 10% (plus or minus) of the declared quantity.

Five products listed CBD as an ingredient. The listed quantity ranged from 10.6 mg to 31.3 mg per serving, although the actual quantity of CBD ranged from 104% to 118% of the labeled quantity.

Inquire about use in kids

A limitation of the study is that only one sample of each brand was analyzed, and only gummies were analyzed. It is not known whether the results are generalizable to melatonin products sold as tablets and capsules in the United States or whether the quantity of melatonin within an individual brand may vary from batch to batch.

A recent study from Canada showed similar results. In an analysis of 16 Canadian melatonin brands, the actual dose of melatonin ranged from 17% to 478% of the declared quantity.

It’s estimated that more than 1% of all U.S. children use melatonin supplements, most commonly for sleep, stress, and relaxation.

“Given new research as to the excessive quantities of melatonin in gummies, caution should be used if considering their use,” said Dr. Cohen.

“It’s important to inquire about melatonin use when caring for children, particularly when parents express concerns about their child’s sleep,” he added.

The American Academy of Sleep Medicine recently issued a health advisory encouraging parents to talk to a health care professional before giving melatonin or any supplement to children.

Children don’t need melatonin

Commenting on the study, Michael Breus, PhD, clinical psychologist and founder of TheSleepDoctor.com, agreed that analyzing only one sample of each brand is a key limitation “because supplements are made in batches, and gummies in particular are difficult to distribute the active ingredient evenly.

“But even with that being said, 88% of them were labeled incorrectly, so even if there were a few single-sample issues, I kind of doubt its all of them,” Dr. Breus said.

“Kids as a general rule do not need melatonin. Their brains make almost four times the necessary amount already. If you start giving kids pills to help them sleep, then they start to have a pill problem, causing another issue,” Dr. Breus added.

“Most children’s falling asleep and staying sleep issues can be treated with behavioral measures like cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia,” he said.

The study had no specific funding. Dr. Cohen has received research support from Consumers Union and PEW Charitable Trusts and royalties from UptoDate. Dr. Breus disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA

How safe is the blackout rage gallon drinking trend?

This discussion was recorded on April 6, 2023. This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Robert D. Glatter, MD: Welcome. I’m Dr. Robert Glatter, medical adviser for Medscape Emergency Medicine. Joining us today is Dr. Lewis Nelson, professor and chair of emergency medicine at Rutgers New Jersey Medical School and a certified medical toxicologist.

Today, we will be discussing an important and disturbing Gen Z trend circulating on social media, known as blackout rage gallon, or BORG.

Welcome, Lewis.

Lewis S. Nelson, MD: Thanks for having me.

Dr. Glatter: Thanks so much for joining us. This trend that’s been circulating on social media is really disturbing. It has elements that focus on binge drinking: Talking about taking a jug; emptying half of it out; and putting one fifth of vodka and some electrolytes, caffeine, or other things too is just incredibly disturbing. Teens and parents are looking at this. I’ll let you jump into the discussion.

Dr. Nelson: You’re totally right, it is disturbing. Binge drinking is a huge problem in this country in general. It’s a particular problem with young people – teenagers and young adults. I don’t think people appreciate the dangers associated with binge drinking, such as the amount of alcohol they consume and some of the unintended consequences of doing that.

To frame things quickly, we think there are probably around six people a day in the United States who die of alcohol poisoning. Alcohol poisoning basically is binge drinking to such an extent that you die of the alcohol itself. You’re not dying of a car crash or doing something that injures you. You’re dying of the alcohol. You’re drinking so much that your breathing slows, it stops, you have heart rhythm disturbances, and so on. It totals about 2,200 people a year in the United States.

Dr. Glatter: That’s alarming. For this trend, their argument is that half of the gallon is water. Therefore, I’m fine. I can drink it over 8-12 hours and it’s not an issue. How would you respond to that?

Dr. Nelson: Well, alcohol is alcohol. It’s all about how much you take in over what time period. I guess, in concept, it could be safer if you do it right. That’s not the way it’s been, so to speak, marketed on the various social media platforms. It’s meant to be a way to protect yourself from having your drink spiked or eating or ingesting contaminants from other people’s mouths when you share glasses or dip cups into communal pots like jungle juice or something.

Clearly, if you’re going to drink a large amount of alcohol over a short or long period of time, you do run the risk of having significant consequences, including bad decision-making if you’re just a little drunk all the way down to that of the complications you described about alcohol poisoning.

Dr. Glatter: There has been a comment made that this could be a form of harm reduction. The point of harm reduction is that we run trials, we validate it, and we test it. This, certainly in my mind, is no form of true harm reduction. I think you would agree.

Dr. Nelson: Many things that are marketed as harm reduction aren’t. There could be some aspects of this that could be considered harm reduction. You may believe – and there’s no reason not to – that protecting your drink is a good idea. If you’re at a bar and you leave your glass open and somebody put something in it, you can be drugged. Drug-facilitated sexual assault, for example, is a big issue. That means you have to leave your glass unattended. If you tend to your glass, it’s probably fine. One of the ways of harm reduction they mention is that by having a cap and having this bottle with you at all times, that can’t happen.

Now, in fairness, by far the drug most commonly associated with sexual assault is alcohol. It’s not gamma-hydroxybutyrate or ketamine. It’s not the other things that people are concerned about. Those happen, but those are small problems in the big picture. It’s drinking too much.

A form of harm reduction that you can comment on perhaps is that you make this drink concoction yourself, so you know what is in there. You can take that bottle, pour out half the water, and fill up the other half with water and nobody’s going to know. More likely, the way they say you should do it is you take your gallon jug, you pour it out, and you fill it up with one fifth of vodka.

One fifth of vodka is the same amount of volume as a bottle of wine. At 750 mL, that’s a huge amount of alcohol. If you measure the number of shots in that bottle, it’s about 17 shots. Even if you drink that over 6 hours, that’s still several shots an hour. That’s a large amount of alcohol. You might do two or three shots once and then not drink for a few hours. To sit and drink two or three shots an hour for 6 hours, that’s just an exceptional amount of alcohol.

They flavorize it and add caffeine, which only adds to the risk. It doesn’t make it in any way safer. With the volume, 1 gal of water or equivalent over a short period of time in and of itself could be a problem. There’s a large amount of mismessaging here. Whether something’s harm reduction, it could flip around to be easily construed or understood as being harmful.

Not to mention, the idea that when you make something safer, one of the unintended consequences of harm reduction is what we call risk compensation. This is best probably described as what’s called the Peltzman effect. The way that we think about airbags and seatbelts is that they’re going to reduce car crash deaths; and they do, but people drive faster and more recklessly because they know they’re safe.

This is a well-described problem in epidemiology: You expect a certain amount of harm reduction through some implemented process, but you don’t meet that because people take increased risks.

Dr. Glatter: Right. The idea of not developing a hangover is common among many teens and 20-somethings, thinking that because there’s hydration there, because half of it is water, it’s just not going to happen. There’s your “harm reduction,” but your judgment’s impaired. It’s day drinking at its best, all day long. Then someone has the idea to get behind the wheel. These are the disastrous consequences that we all fear.

Dr. Nelson: There is a great example, perhaps of an unintended consequence of harm reduction. By putting caffeine in it, depending on how much caffeine you put in, some of these mixtures can have up to 1,000 mg of caffeine. Remember, a cup of coffee is about 1-200 mg, so you’re talking about several cups of coffee. The idea is that you will not be able to sense, as you normally do, how drunk you are. You’re not going to be a sleepy drunk, you’re going to be an awake drunk.

The idea that you’re going to have to drive so you’re going to drink a strong cup of black coffee before you go driving, you’re not going to drive any better. I can assure you that. You’re going to be more awake, perhaps, and not fall asleep at the wheel, but you’re still going to have psychomotor impairment. Your judgment is going to be impaired. There’s nothing good that comes with adding caffeine except that you’re going to be awake.

From a hangover perspective, there are many things that we’ve guessed at or suggested as either prevention or cures for hangovers. I don’t doubt that you’re going to have some volume depletion if you drink a large amount of alcohol. Alcohol’s a diuretic, so you’re going to lose more volume than you bring in.

Hydrating is probably always a good idea, but there is hydrating and then there’s overhydrating. We don’t need volumes like that. If you drink a cup or two of water, you’re probably fine. You don’t need to drink half a gallon of water. That can lead to problems like delusional hyponatremia, and so forth. There’s not any clear benefit to doing it.

If you want to prevent a hangover, one of the ways you might do it is by using vodka. There are nice data that show that clear alcohols typically, particularly vodka, don’t have many of the congeners that make the specific forms of alcohol what they are. Bourbon smells and tastes like bourbon because of these little molecules, these alkalis and ketones and amino acids and things that make it taste and smell the way it does. That’s true for all the other alcohols.

Vodka has the least amount of that. Even wine and beer have those in them, but vodka is basically alcohol mixed with water. It’s probably the least hangover-prone of all the alcohols; but still, if you drink a lot of vodka, you’re going to have a hangover. It’s just a dose-response curve to how much alcohol you drink, to how drunk you get, and to how much of a hangover you’re going to have.

Dr. Glatter: The hangover is really what it’s about because people want to be functional the next day. There are many companies out there that market hangover remedies, but people are using this as the hangover remedy in a way that’s socially accepted. That’s a good point you make.

The question is how do we get the message out to parents and teens? What’s the best way you feel to really sound the alarm here?

Dr. Nelson: These are challenging issues. We face this all the time with all the sorts of social media in particular. Most parents are not as savvy on social media as their kids are. You have to know what your children are doing. You should know what they’re listening to and watching. You do have to pay attention to the media directed at parents that will inform you a little bit about what your kids are doing. You have to talk with your kids and make sure they understand what it is that they’re doing.

We do this with our kids for some things. Hopefully, we talk about drinking, smoking, sex, and other things with our children (like driving if they get to that stage) and make sure they understand what the risks are and how to mitigate those risks. Being an attentive parent is part of it.

Sometimes you need outside messengers to do it. We’d like to believe that these social media companies are able to police themselves – at least they pay lip service to the fact they do. They have warnings that they’ll take things down that aren’t socially appropriate. Whether they do or not, I don’t know, because you keep seeing things about BORG on these media sites. If they are doing it, they’re not doing it efficiently or quickly enough.

Dr. Glatter: There has to be some censorship. These are young persons who are impressionable, who have developing brains, who are looking at this, thinking that if it’s out there on social media, such as TikTok or Instagram, then it’s okay to do so. That message has to be driven home.

Dr. Nelson: That’s a great point, and it’s tough. We know there’s been debate over the liability of social media or what they post, and whether or not they should be held liable like a more conventional media company or not. That’s politics and philosophy, and we’re probably not going to solve it here.

All these things wind up going viral and there’s probably got to be some filter on things that go viral. Maybe they need to have a bit more attentiveness to that when those things start happening. Now, clearly not every one of these is viral. When you think about some of the challenges we’ve seen in the past, such as the Tide Pod challenge and cinnamon challenge, some of these things could be quickly figured out to be dangerous.

I remember that the ice bucket challenge for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis was pretty benign. You pour a bucket of water over your head, and people aren’t really getting hurt. That’s fun and good, and let people go out and do that. That could pass through the filter. When you start to see people drinking excessive amounts of alcohol, it doesn’t take an emergency physician to know that’s not a good thing. Any parent should know that if my kid drinks half a bottle or a bottle of vodka over a short period of time, that just can’t be okay.

Dr. Glatter: It’s a public health issue. That’s what we need to elevate it to because ultimately that’s what it impacts: welfare and safety.

Speaking of buckets, there’s a new bucket challenge, wherein unsuspecting people have a bucket put on their head, can’t breathe, and then pass out. There’s been a number of these reported and actually filmed on social media. Here’s another example of dangerous types of behavior that essentially are a form of assault. Unsuspecting people suffer injuries from young children and teens trying to play pranks.

Again, had there not been this medium, we wouldn’t necessarily see the extent of the injuries. I guess going forward, the next step would be to send a message to colleges that there should be some form of warning if this trend is seen, at least from a public health standpoint.

Dr. Nelson: Education is a necessary thing to do, but it’s almost never the real solution to a problem. We can educate people as best we can that they need to do things right. At some point, we’re going to need to regulate it or manage it somehow.

Whether it’s through a carrot or a stick approach, or whether you want to give people kudos for doing the right thing or punish them for doing something wrong, that’s a tough decision to make and one that is going to be made by a parent or guardian, a school official, or law enforcement. Somehow, we have to figure out how to make this happen.

There’s not going to be a single size that fits all for this. At some level, we have to do something to educate and regulate. The balance between those two things is going to be political and philosophical in nature.

Dr. Glatter: Right, and the element of peer pressure and conformity in this is really part of the element. If we try to remove that aspect of it, then often these trends would go away. That aspect of conformity and peer pressure is instrumental in fueling these trends. Maybe we can make a full gallon of water be the trend without any alcohol in there.

Dr. Nelson: We say water is only water, but as a medical toxicologist, I can tell you that one of the foundations in medical toxicology is that everything is toxic. It’s just the dose that determines the toxicity. Oxygen is toxic, water is toxic. Everything’s toxic if you take enough of it.

We know that whether it’s psychogenic or intentional, polydipsia by drinking excessive amounts of water, especially without electrolytes, is one of the reasons they say you should add electrolytes. That’s all relative as well, because depending on the electrolyte and how much you put in and things like that, that could also become dangerous. Drinking excessive amounts of water like they’re suggesting, which sounds like a good thing to prevent hangover and so on, can in and of itself be a problem too.

Dr. Glatter: Right, and we know that there’s no magic bullet for a hangover. Obviously, abstinence is the only thing that truly works.

Dr. Nelson: Or moderation.

Dr. Glatter: Until research proves further.

Thank you so much. You’ve made some really important points. Thank you for talking about the BORG phenomenon, how it relates to society in general, and what we can do to try to change people’s perception of alcohol and the bigger picture of binge drinking. I really appreciate it.

Dr. Nelson: Thanks, Rob, for having me. It’s an important topic and hopefully we can get a handle on this. I appreciate your time.

Dr. Glatter is an attending physician at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York City and assistant professor of emergency medicine at Hofstra University, Hempstead, N.Y. Dr. Nelson is professor and chair of the department of emergency medicine and chief of the division of medical toxicology at Rutgers New Jersey Medical School, Newark. He is a member of the board of directors of the American Board of Emergency Medicine, the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education, and Association of Academic Chairs in Emergency Medicine and is past-president of the American College of Medical Toxicology. Dr. Glatter and Dr. Nelson disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

This discussion was recorded on April 6, 2023. This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Robert D. Glatter, MD: Welcome. I’m Dr. Robert Glatter, medical adviser for Medscape Emergency Medicine. Joining us today is Dr. Lewis Nelson, professor and chair of emergency medicine at Rutgers New Jersey Medical School and a certified medical toxicologist.

Today, we will be discussing an important and disturbing Gen Z trend circulating on social media, known as blackout rage gallon, or BORG.

Welcome, Lewis.

Lewis S. Nelson, MD: Thanks for having me.

Dr. Glatter: Thanks so much for joining us. This trend that’s been circulating on social media is really disturbing. It has elements that focus on binge drinking: Talking about taking a jug; emptying half of it out; and putting one fifth of vodka and some electrolytes, caffeine, or other things too is just incredibly disturbing. Teens and parents are looking at this. I’ll let you jump into the discussion.

Dr. Nelson: You’re totally right, it is disturbing. Binge drinking is a huge problem in this country in general. It’s a particular problem with young people – teenagers and young adults. I don’t think people appreciate the dangers associated with binge drinking, such as the amount of alcohol they consume and some of the unintended consequences of doing that.

To frame things quickly, we think there are probably around six people a day in the United States who die of alcohol poisoning. Alcohol poisoning basically is binge drinking to such an extent that you die of the alcohol itself. You’re not dying of a car crash or doing something that injures you. You’re dying of the alcohol. You’re drinking so much that your breathing slows, it stops, you have heart rhythm disturbances, and so on. It totals about 2,200 people a year in the United States.

Dr. Glatter: That’s alarming. For this trend, their argument is that half of the gallon is water. Therefore, I’m fine. I can drink it over 8-12 hours and it’s not an issue. How would you respond to that?

Dr. Nelson: Well, alcohol is alcohol. It’s all about how much you take in over what time period. I guess, in concept, it could be safer if you do it right. That’s not the way it’s been, so to speak, marketed on the various social media platforms. It’s meant to be a way to protect yourself from having your drink spiked or eating or ingesting contaminants from other people’s mouths when you share glasses or dip cups into communal pots like jungle juice or something.

Clearly, if you’re going to drink a large amount of alcohol over a short or long period of time, you do run the risk of having significant consequences, including bad decision-making if you’re just a little drunk all the way down to that of the complications you described about alcohol poisoning.

Dr. Glatter: There has been a comment made that this could be a form of harm reduction. The point of harm reduction is that we run trials, we validate it, and we test it. This, certainly in my mind, is no form of true harm reduction. I think you would agree.

Dr. Nelson: Many things that are marketed as harm reduction aren’t. There could be some aspects of this that could be considered harm reduction. You may believe – and there’s no reason not to – that protecting your drink is a good idea. If you’re at a bar and you leave your glass open and somebody put something in it, you can be drugged. Drug-facilitated sexual assault, for example, is a big issue. That means you have to leave your glass unattended. If you tend to your glass, it’s probably fine. One of the ways of harm reduction they mention is that by having a cap and having this bottle with you at all times, that can’t happen.

Now, in fairness, by far the drug most commonly associated with sexual assault is alcohol. It’s not gamma-hydroxybutyrate or ketamine. It’s not the other things that people are concerned about. Those happen, but those are small problems in the big picture. It’s drinking too much.

A form of harm reduction that you can comment on perhaps is that you make this drink concoction yourself, so you know what is in there. You can take that bottle, pour out half the water, and fill up the other half with water and nobody’s going to know. More likely, the way they say you should do it is you take your gallon jug, you pour it out, and you fill it up with one fifth of vodka.

One fifth of vodka is the same amount of volume as a bottle of wine. At 750 mL, that’s a huge amount of alcohol. If you measure the number of shots in that bottle, it’s about 17 shots. Even if you drink that over 6 hours, that’s still several shots an hour. That’s a large amount of alcohol. You might do two or three shots once and then not drink for a few hours. To sit and drink two or three shots an hour for 6 hours, that’s just an exceptional amount of alcohol.

They flavorize it and add caffeine, which only adds to the risk. It doesn’t make it in any way safer. With the volume, 1 gal of water or equivalent over a short period of time in and of itself could be a problem. There’s a large amount of mismessaging here. Whether something’s harm reduction, it could flip around to be easily construed or understood as being harmful.

Not to mention, the idea that when you make something safer, one of the unintended consequences of harm reduction is what we call risk compensation. This is best probably described as what’s called the Peltzman effect. The way that we think about airbags and seatbelts is that they’re going to reduce car crash deaths; and they do, but people drive faster and more recklessly because they know they’re safe.

This is a well-described problem in epidemiology: You expect a certain amount of harm reduction through some implemented process, but you don’t meet that because people take increased risks.

Dr. Glatter: Right. The idea of not developing a hangover is common among many teens and 20-somethings, thinking that because there’s hydration there, because half of it is water, it’s just not going to happen. There’s your “harm reduction,” but your judgment’s impaired. It’s day drinking at its best, all day long. Then someone has the idea to get behind the wheel. These are the disastrous consequences that we all fear.

Dr. Nelson: There is a great example, perhaps of an unintended consequence of harm reduction. By putting caffeine in it, depending on how much caffeine you put in, some of these mixtures can have up to 1,000 mg of caffeine. Remember, a cup of coffee is about 1-200 mg, so you’re talking about several cups of coffee. The idea is that you will not be able to sense, as you normally do, how drunk you are. You’re not going to be a sleepy drunk, you’re going to be an awake drunk.

The idea that you’re going to have to drive so you’re going to drink a strong cup of black coffee before you go driving, you’re not going to drive any better. I can assure you that. You’re going to be more awake, perhaps, and not fall asleep at the wheel, but you’re still going to have psychomotor impairment. Your judgment is going to be impaired. There’s nothing good that comes with adding caffeine except that you’re going to be awake.

From a hangover perspective, there are many things that we’ve guessed at or suggested as either prevention or cures for hangovers. I don’t doubt that you’re going to have some volume depletion if you drink a large amount of alcohol. Alcohol’s a diuretic, so you’re going to lose more volume than you bring in.

Hydrating is probably always a good idea, but there is hydrating and then there’s overhydrating. We don’t need volumes like that. If you drink a cup or two of water, you’re probably fine. You don’t need to drink half a gallon of water. That can lead to problems like delusional hyponatremia, and so forth. There’s not any clear benefit to doing it.

If you want to prevent a hangover, one of the ways you might do it is by using vodka. There are nice data that show that clear alcohols typically, particularly vodka, don’t have many of the congeners that make the specific forms of alcohol what they are. Bourbon smells and tastes like bourbon because of these little molecules, these alkalis and ketones and amino acids and things that make it taste and smell the way it does. That’s true for all the other alcohols.

Vodka has the least amount of that. Even wine and beer have those in them, but vodka is basically alcohol mixed with water. It’s probably the least hangover-prone of all the alcohols; but still, if you drink a lot of vodka, you’re going to have a hangover. It’s just a dose-response curve to how much alcohol you drink, to how drunk you get, and to how much of a hangover you’re going to have.

Dr. Glatter: The hangover is really what it’s about because people want to be functional the next day. There are many companies out there that market hangover remedies, but people are using this as the hangover remedy in a way that’s socially accepted. That’s a good point you make.

The question is how do we get the message out to parents and teens? What’s the best way you feel to really sound the alarm here?

Dr. Nelson: These are challenging issues. We face this all the time with all the sorts of social media in particular. Most parents are not as savvy on social media as their kids are. You have to know what your children are doing. You should know what they’re listening to and watching. You do have to pay attention to the media directed at parents that will inform you a little bit about what your kids are doing. You have to talk with your kids and make sure they understand what it is that they’re doing.

We do this with our kids for some things. Hopefully, we talk about drinking, smoking, sex, and other things with our children (like driving if they get to that stage) and make sure they understand what the risks are and how to mitigate those risks. Being an attentive parent is part of it.

Sometimes you need outside messengers to do it. We’d like to believe that these social media companies are able to police themselves – at least they pay lip service to the fact they do. They have warnings that they’ll take things down that aren’t socially appropriate. Whether they do or not, I don’t know, because you keep seeing things about BORG on these media sites. If they are doing it, they’re not doing it efficiently or quickly enough.

Dr. Glatter: There has to be some censorship. These are young persons who are impressionable, who have developing brains, who are looking at this, thinking that if it’s out there on social media, such as TikTok or Instagram, then it’s okay to do so. That message has to be driven home.

Dr. Nelson: That’s a great point, and it’s tough. We know there’s been debate over the liability of social media or what they post, and whether or not they should be held liable like a more conventional media company or not. That’s politics and philosophy, and we’re probably not going to solve it here.

All these things wind up going viral and there’s probably got to be some filter on things that go viral. Maybe they need to have a bit more attentiveness to that when those things start happening. Now, clearly not every one of these is viral. When you think about some of the challenges we’ve seen in the past, such as the Tide Pod challenge and cinnamon challenge, some of these things could be quickly figured out to be dangerous.

I remember that the ice bucket challenge for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis was pretty benign. You pour a bucket of water over your head, and people aren’t really getting hurt. That’s fun and good, and let people go out and do that. That could pass through the filter. When you start to see people drinking excessive amounts of alcohol, it doesn’t take an emergency physician to know that’s not a good thing. Any parent should know that if my kid drinks half a bottle or a bottle of vodka over a short period of time, that just can’t be okay.

Dr. Glatter: It’s a public health issue. That’s what we need to elevate it to because ultimately that’s what it impacts: welfare and safety.

Speaking of buckets, there’s a new bucket challenge, wherein unsuspecting people have a bucket put on their head, can’t breathe, and then pass out. There’s been a number of these reported and actually filmed on social media. Here’s another example of dangerous types of behavior that essentially are a form of assault. Unsuspecting people suffer injuries from young children and teens trying to play pranks.

Again, had there not been this medium, we wouldn’t necessarily see the extent of the injuries. I guess going forward, the next step would be to send a message to colleges that there should be some form of warning if this trend is seen, at least from a public health standpoint.

Dr. Nelson: Education is a necessary thing to do, but it’s almost never the real solution to a problem. We can educate people as best we can that they need to do things right. At some point, we’re going to need to regulate it or manage it somehow.

Whether it’s through a carrot or a stick approach, or whether you want to give people kudos for doing the right thing or punish them for doing something wrong, that’s a tough decision to make and one that is going to be made by a parent or guardian, a school official, or law enforcement. Somehow, we have to figure out how to make this happen.

There’s not going to be a single size that fits all for this. At some level, we have to do something to educate and regulate. The balance between those two things is going to be political and philosophical in nature.

Dr. Glatter: Right, and the element of peer pressure and conformity in this is really part of the element. If we try to remove that aspect of it, then often these trends would go away. That aspect of conformity and peer pressure is instrumental in fueling these trends. Maybe we can make a full gallon of water be the trend without any alcohol in there.

Dr. Nelson: We say water is only water, but as a medical toxicologist, I can tell you that one of the foundations in medical toxicology is that everything is toxic. It’s just the dose that determines the toxicity. Oxygen is toxic, water is toxic. Everything’s toxic if you take enough of it.

We know that whether it’s psychogenic or intentional, polydipsia by drinking excessive amounts of water, especially without electrolytes, is one of the reasons they say you should add electrolytes. That’s all relative as well, because depending on the electrolyte and how much you put in and things like that, that could also become dangerous. Drinking excessive amounts of water like they’re suggesting, which sounds like a good thing to prevent hangover and so on, can in and of itself be a problem too.

Dr. Glatter: Right, and we know that there’s no magic bullet for a hangover. Obviously, abstinence is the only thing that truly works.

Dr. Nelson: Or moderation.

Dr. Glatter: Until research proves further.

Thank you so much. You’ve made some really important points. Thank you for talking about the BORG phenomenon, how it relates to society in general, and what we can do to try to change people’s perception of alcohol and the bigger picture of binge drinking. I really appreciate it.

Dr. Nelson: Thanks, Rob, for having me. It’s an important topic and hopefully we can get a handle on this. I appreciate your time.

Dr. Glatter is an attending physician at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York City and assistant professor of emergency medicine at Hofstra University, Hempstead, N.Y. Dr. Nelson is professor and chair of the department of emergency medicine and chief of the division of medical toxicology at Rutgers New Jersey Medical School, Newark. He is a member of the board of directors of the American Board of Emergency Medicine, the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education, and Association of Academic Chairs in Emergency Medicine and is past-president of the American College of Medical Toxicology. Dr. Glatter and Dr. Nelson disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

This discussion was recorded on April 6, 2023. This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Robert D. Glatter, MD: Welcome. I’m Dr. Robert Glatter, medical adviser for Medscape Emergency Medicine. Joining us today is Dr. Lewis Nelson, professor and chair of emergency medicine at Rutgers New Jersey Medical School and a certified medical toxicologist.

Today, we will be discussing an important and disturbing Gen Z trend circulating on social media, known as blackout rage gallon, or BORG.

Welcome, Lewis.

Lewis S. Nelson, MD: Thanks for having me.

Dr. Glatter: Thanks so much for joining us. This trend that’s been circulating on social media is really disturbing. It has elements that focus on binge drinking: Talking about taking a jug; emptying half of it out; and putting one fifth of vodka and some electrolytes, caffeine, or other things too is just incredibly disturbing. Teens and parents are looking at this. I’ll let you jump into the discussion.

Dr. Nelson: You’re totally right, it is disturbing. Binge drinking is a huge problem in this country in general. It’s a particular problem with young people – teenagers and young adults. I don’t think people appreciate the dangers associated with binge drinking, such as the amount of alcohol they consume and some of the unintended consequences of doing that.

To frame things quickly, we think there are probably around six people a day in the United States who die of alcohol poisoning. Alcohol poisoning basically is binge drinking to such an extent that you die of the alcohol itself. You’re not dying of a car crash or doing something that injures you. You’re dying of the alcohol. You’re drinking so much that your breathing slows, it stops, you have heart rhythm disturbances, and so on. It totals about 2,200 people a year in the United States.

Dr. Glatter: That’s alarming. For this trend, their argument is that half of the gallon is water. Therefore, I’m fine. I can drink it over 8-12 hours and it’s not an issue. How would you respond to that?

Dr. Nelson: Well, alcohol is alcohol. It’s all about how much you take in over what time period. I guess, in concept, it could be safer if you do it right. That’s not the way it’s been, so to speak, marketed on the various social media platforms. It’s meant to be a way to protect yourself from having your drink spiked or eating or ingesting contaminants from other people’s mouths when you share glasses or dip cups into communal pots like jungle juice or something.

Clearly, if you’re going to drink a large amount of alcohol over a short or long period of time, you do run the risk of having significant consequences, including bad decision-making if you’re just a little drunk all the way down to that of the complications you described about alcohol poisoning.

Dr. Glatter: There has been a comment made that this could be a form of harm reduction. The point of harm reduction is that we run trials, we validate it, and we test it. This, certainly in my mind, is no form of true harm reduction. I think you would agree.

Dr. Nelson: Many things that are marketed as harm reduction aren’t. There could be some aspects of this that could be considered harm reduction. You may believe – and there’s no reason not to – that protecting your drink is a good idea. If you’re at a bar and you leave your glass open and somebody put something in it, you can be drugged. Drug-facilitated sexual assault, for example, is a big issue. That means you have to leave your glass unattended. If you tend to your glass, it’s probably fine. One of the ways of harm reduction they mention is that by having a cap and having this bottle with you at all times, that can’t happen.

Now, in fairness, by far the drug most commonly associated with sexual assault is alcohol. It’s not gamma-hydroxybutyrate or ketamine. It’s not the other things that people are concerned about. Those happen, but those are small problems in the big picture. It’s drinking too much.

A form of harm reduction that you can comment on perhaps is that you make this drink concoction yourself, so you know what is in there. You can take that bottle, pour out half the water, and fill up the other half with water and nobody’s going to know. More likely, the way they say you should do it is you take your gallon jug, you pour it out, and you fill it up with one fifth of vodka.

One fifth of vodka is the same amount of volume as a bottle of wine. At 750 mL, that’s a huge amount of alcohol. If you measure the number of shots in that bottle, it’s about 17 shots. Even if you drink that over 6 hours, that’s still several shots an hour. That’s a large amount of alcohol. You might do two or three shots once and then not drink for a few hours. To sit and drink two or three shots an hour for 6 hours, that’s just an exceptional amount of alcohol.

They flavorize it and add caffeine, which only adds to the risk. It doesn’t make it in any way safer. With the volume, 1 gal of water or equivalent over a short period of time in and of itself could be a problem. There’s a large amount of mismessaging here. Whether something’s harm reduction, it could flip around to be easily construed or understood as being harmful.

Not to mention, the idea that when you make something safer, one of the unintended consequences of harm reduction is what we call risk compensation. This is best probably described as what’s called the Peltzman effect. The way that we think about airbags and seatbelts is that they’re going to reduce car crash deaths; and they do, but people drive faster and more recklessly because they know they’re safe.

This is a well-described problem in epidemiology: You expect a certain amount of harm reduction through some implemented process, but you don’t meet that because people take increased risks.

Dr. Glatter: Right. The idea of not developing a hangover is common among many teens and 20-somethings, thinking that because there’s hydration there, because half of it is water, it’s just not going to happen. There’s your “harm reduction,” but your judgment’s impaired. It’s day drinking at its best, all day long. Then someone has the idea to get behind the wheel. These are the disastrous consequences that we all fear.

Dr. Nelson: There is a great example, perhaps of an unintended consequence of harm reduction. By putting caffeine in it, depending on how much caffeine you put in, some of these mixtures can have up to 1,000 mg of caffeine. Remember, a cup of coffee is about 1-200 mg, so you’re talking about several cups of coffee. The idea is that you will not be able to sense, as you normally do, how drunk you are. You’re not going to be a sleepy drunk, you’re going to be an awake drunk.

The idea that you’re going to have to drive so you’re going to drink a strong cup of black coffee before you go driving, you’re not going to drive any better. I can assure you that. You’re going to be more awake, perhaps, and not fall asleep at the wheel, but you’re still going to have psychomotor impairment. Your judgment is going to be impaired. There’s nothing good that comes with adding caffeine except that you’re going to be awake.

From a hangover perspective, there are many things that we’ve guessed at or suggested as either prevention or cures for hangovers. I don’t doubt that you’re going to have some volume depletion if you drink a large amount of alcohol. Alcohol’s a diuretic, so you’re going to lose more volume than you bring in.

Hydrating is probably always a good idea, but there is hydrating and then there’s overhydrating. We don’t need volumes like that. If you drink a cup or two of water, you’re probably fine. You don’t need to drink half a gallon of water. That can lead to problems like delusional hyponatremia, and so forth. There’s not any clear benefit to doing it.

If you want to prevent a hangover, one of the ways you might do it is by using vodka. There are nice data that show that clear alcohols typically, particularly vodka, don’t have many of the congeners that make the specific forms of alcohol what they are. Bourbon smells and tastes like bourbon because of these little molecules, these alkalis and ketones and amino acids and things that make it taste and smell the way it does. That’s true for all the other alcohols.

Vodka has the least amount of that. Even wine and beer have those in them, but vodka is basically alcohol mixed with water. It’s probably the least hangover-prone of all the alcohols; but still, if you drink a lot of vodka, you’re going to have a hangover. It’s just a dose-response curve to how much alcohol you drink, to how drunk you get, and to how much of a hangover you’re going to have.

Dr. Glatter: The hangover is really what it’s about because people want to be functional the next day. There are many companies out there that market hangover remedies, but people are using this as the hangover remedy in a way that’s socially accepted. That’s a good point you make.

The question is how do we get the message out to parents and teens? What’s the best way you feel to really sound the alarm here?

Dr. Nelson: These are challenging issues. We face this all the time with all the sorts of social media in particular. Most parents are not as savvy on social media as their kids are. You have to know what your children are doing. You should know what they’re listening to and watching. You do have to pay attention to the media directed at parents that will inform you a little bit about what your kids are doing. You have to talk with your kids and make sure they understand what it is that they’re doing.

We do this with our kids for some things. Hopefully, we talk about drinking, smoking, sex, and other things with our children (like driving if they get to that stage) and make sure they understand what the risks are and how to mitigate those risks. Being an attentive parent is part of it.

Sometimes you need outside messengers to do it. We’d like to believe that these social media companies are able to police themselves – at least they pay lip service to the fact they do. They have warnings that they’ll take things down that aren’t socially appropriate. Whether they do or not, I don’t know, because you keep seeing things about BORG on these media sites. If they are doing it, they’re not doing it efficiently or quickly enough.

Dr. Glatter: There has to be some censorship. These are young persons who are impressionable, who have developing brains, who are looking at this, thinking that if it’s out there on social media, such as TikTok or Instagram, then it’s okay to do so. That message has to be driven home.

Dr. Nelson: That’s a great point, and it’s tough. We know there’s been debate over the liability of social media or what they post, and whether or not they should be held liable like a more conventional media company or not. That’s politics and philosophy, and we’re probably not going to solve it here.

All these things wind up going viral and there’s probably got to be some filter on things that go viral. Maybe they need to have a bit more attentiveness to that when those things start happening. Now, clearly not every one of these is viral. When you think about some of the challenges we’ve seen in the past, such as the Tide Pod challenge and cinnamon challenge, some of these things could be quickly figured out to be dangerous.

I remember that the ice bucket challenge for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis was pretty benign. You pour a bucket of water over your head, and people aren’t really getting hurt. That’s fun and good, and let people go out and do that. That could pass through the filter. When you start to see people drinking excessive amounts of alcohol, it doesn’t take an emergency physician to know that’s not a good thing. Any parent should know that if my kid drinks half a bottle or a bottle of vodka over a short period of time, that just can’t be okay.

Dr. Glatter: It’s a public health issue. That’s what we need to elevate it to because ultimately that’s what it impacts: welfare and safety.

Speaking of buckets, there’s a new bucket challenge, wherein unsuspecting people have a bucket put on their head, can’t breathe, and then pass out. There’s been a number of these reported and actually filmed on social media. Here’s another example of dangerous types of behavior that essentially are a form of assault. Unsuspecting people suffer injuries from young children and teens trying to play pranks.

Again, had there not been this medium, we wouldn’t necessarily see the extent of the injuries. I guess going forward, the next step would be to send a message to colleges that there should be some form of warning if this trend is seen, at least from a public health standpoint.

Dr. Nelson: Education is a necessary thing to do, but it’s almost never the real solution to a problem. We can educate people as best we can that they need to do things right. At some point, we’re going to need to regulate it or manage it somehow.

Whether it’s through a carrot or a stick approach, or whether you want to give people kudos for doing the right thing or punish them for doing something wrong, that’s a tough decision to make and one that is going to be made by a parent or guardian, a school official, or law enforcement. Somehow, we have to figure out how to make this happen.

There’s not going to be a single size that fits all for this. At some level, we have to do something to educate and regulate. The balance between those two things is going to be political and philosophical in nature.

Dr. Glatter: Right, and the element of peer pressure and conformity in this is really part of the element. If we try to remove that aspect of it, then often these trends would go away. That aspect of conformity and peer pressure is instrumental in fueling these trends. Maybe we can make a full gallon of water be the trend without any alcohol in there.

Dr. Nelson: We say water is only water, but as a medical toxicologist, I can tell you that one of the foundations in medical toxicology is that everything is toxic. It’s just the dose that determines the toxicity. Oxygen is toxic, water is toxic. Everything’s toxic if you take enough of it.

We know that whether it’s psychogenic or intentional, polydipsia by drinking excessive amounts of water, especially without electrolytes, is one of the reasons they say you should add electrolytes. That’s all relative as well, because depending on the electrolyte and how much you put in and things like that, that could also become dangerous. Drinking excessive amounts of water like they’re suggesting, which sounds like a good thing to prevent hangover and so on, can in and of itself be a problem too.

Dr. Glatter: Right, and we know that there’s no magic bullet for a hangover. Obviously, abstinence is the only thing that truly works.

Dr. Nelson: Or moderation.

Dr. Glatter: Until research proves further.

Thank you so much. You’ve made some really important points. Thank you for talking about the BORG phenomenon, how it relates to society in general, and what we can do to try to change people’s perception of alcohol and the bigger picture of binge drinking. I really appreciate it.

Dr. Nelson: Thanks, Rob, for having me. It’s an important topic and hopefully we can get a handle on this. I appreciate your time.

Dr. Glatter is an attending physician at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York City and assistant professor of emergency medicine at Hofstra University, Hempstead, N.Y. Dr. Nelson is professor and chair of the department of emergency medicine and chief of the division of medical toxicology at Rutgers New Jersey Medical School, Newark. He is a member of the board of directors of the American Board of Emergency Medicine, the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education, and Association of Academic Chairs in Emergency Medicine and is past-president of the American College of Medical Toxicology. Dr. Glatter and Dr. Nelson disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Tranq-contaminated fentanyl now in 48 states, DEA warns

The DEA warning comes on the heels of a Food and Drug Administration announcement that it would begin more closely monitoring imports of the raw materials and bulk shipments of xylazine, also known as “tranq” and “zombie drug.”

Xylazine was first approved by the FDA in 1972 as a sedative and analgesic for use only in animals, but is increasingly being detected in illicit street drugs, and is often mixed with fentanyl, cocaine, and methamphetamine.

The FDA warned in November that naloxone (Narcan) would not reverse xylazine-related overdoses because the tranquilizer is not an opioid. It does suppress respiration and repeated exposures may lead to dependence and withdrawal, said the agency. Users are also experiencing severe necrosis at injection sites.

“Xylazine is making the deadliest drug threat our country has ever faced, fentanyl, even deadlier,” said DEA Administrator Anne Milgram in a statement. “The DEA Laboratory System is reporting that in 2022 approximately 23% of fentanyl powder and 7% of fentanyl pills seized by the DEA contained xylazine.”

Xylazine use has spread quickly, from its start in the Philadelphia area to the Northeast, the South, and most recently the West.

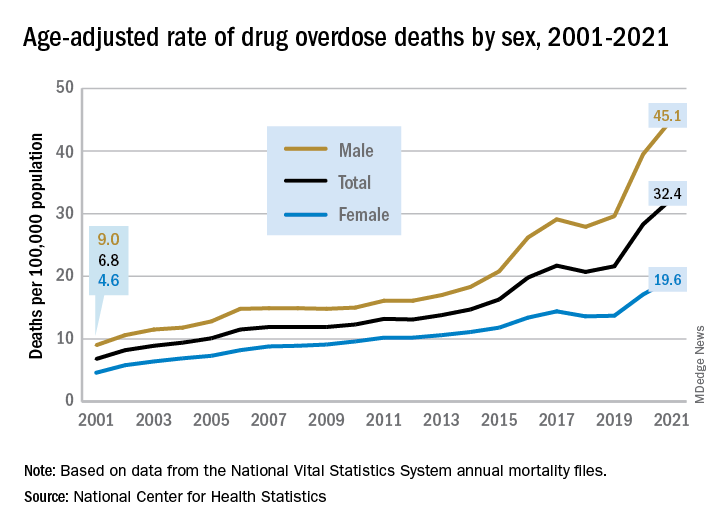

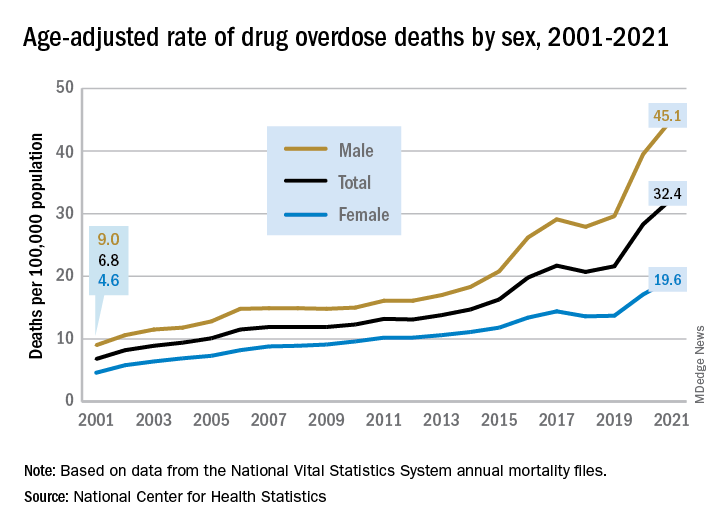

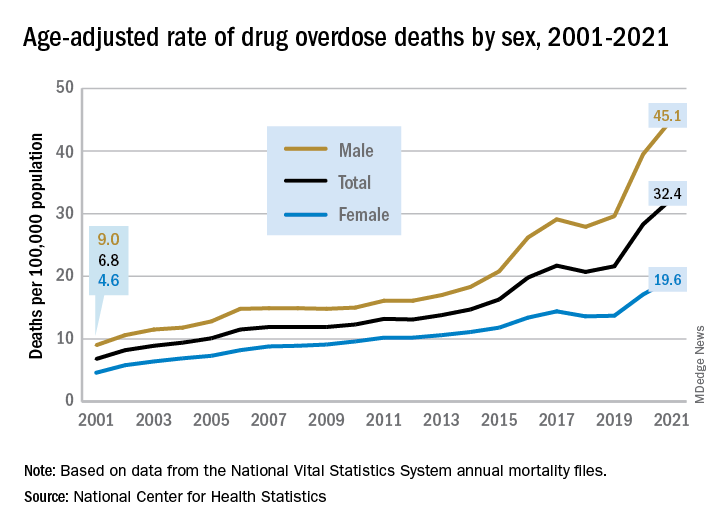

Citing data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the DEA said that 66% of the 107,735 overdose deaths for the year ending August 2022 involved synthetic opioids such as fentanyl. The DEA said that the Sinaloa Cartel and Jalisco Cartel in Mexico, using chemicals sourced from China, are primarily responsible for trafficking fentanyl in the United States.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

The DEA warning comes on the heels of a Food and Drug Administration announcement that it would begin more closely monitoring imports of the raw materials and bulk shipments of xylazine, also known as “tranq” and “zombie drug.”

Xylazine was first approved by the FDA in 1972 as a sedative and analgesic for use only in animals, but is increasingly being detected in illicit street drugs, and is often mixed with fentanyl, cocaine, and methamphetamine.