User login

FDA grants marketing clearance for chlamydia and gonorrhea extragenital tests

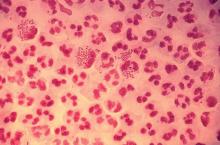

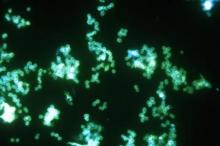

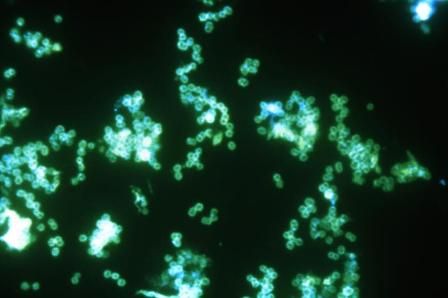

The new tests, the Aptima Combo 2 Assay and Xpert CT/NG, use samples from the throat and rectum to test for chlamydia and gonorrhea, according to a statement from the FDA.

“It is best for patients if both [chlamydia and gonorrhea] are caught and treated right away, as significant complications can occur if left untreated,” noted Tim Stenzel, MD, in the statement.

“Today’s clearances provide a mechanism for more easily diagnosing these infections,” said Dr. Stenzel, director of the Office of In Vitro Diagnostics and Radiological Health in the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health.

The two tests were reviewed through the premarket notification – or 510(k) – pathway, which seeks to demonstrate to the FDA that the device to be marketed is equivalent or better in safety and effectiveness to the legally marketed device.

In the FDA’s evaluation of the tests, it reviewed clinical data from a multisite study of more than 2,500 patients. This study evaluated the diagnostic accuracy of multiple commercially available nucleic acid amplification tests for detection of Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis from throat and rectal sites. The results of this study and other information reviewed by the FDA demonstrated that the two tests “are safe and effective for extragenital testing for chlamydia and gonorrhea,” according to the statement.

The data were collected through a cross-sectional study coordinated by the Antibacterial Resistance Leadership Group, which is funded and supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

The FDA granted marketing clearance to Hologic and Cepheid for the Aptima Combo 2 Assay and the Xpert CT/NG, respectively.

The new tests, the Aptima Combo 2 Assay and Xpert CT/NG, use samples from the throat and rectum to test for chlamydia and gonorrhea, according to a statement from the FDA.

“It is best for patients if both [chlamydia and gonorrhea] are caught and treated right away, as significant complications can occur if left untreated,” noted Tim Stenzel, MD, in the statement.

“Today’s clearances provide a mechanism for more easily diagnosing these infections,” said Dr. Stenzel, director of the Office of In Vitro Diagnostics and Radiological Health in the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health.

The two tests were reviewed through the premarket notification – or 510(k) – pathway, which seeks to demonstrate to the FDA that the device to be marketed is equivalent or better in safety and effectiveness to the legally marketed device.

In the FDA’s evaluation of the tests, it reviewed clinical data from a multisite study of more than 2,500 patients. This study evaluated the diagnostic accuracy of multiple commercially available nucleic acid amplification tests for detection of Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis from throat and rectal sites. The results of this study and other information reviewed by the FDA demonstrated that the two tests “are safe and effective for extragenital testing for chlamydia and gonorrhea,” according to the statement.

The data were collected through a cross-sectional study coordinated by the Antibacterial Resistance Leadership Group, which is funded and supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

The FDA granted marketing clearance to Hologic and Cepheid for the Aptima Combo 2 Assay and the Xpert CT/NG, respectively.

The new tests, the Aptima Combo 2 Assay and Xpert CT/NG, use samples from the throat and rectum to test for chlamydia and gonorrhea, according to a statement from the FDA.

“It is best for patients if both [chlamydia and gonorrhea] are caught and treated right away, as significant complications can occur if left untreated,” noted Tim Stenzel, MD, in the statement.

“Today’s clearances provide a mechanism for more easily diagnosing these infections,” said Dr. Stenzel, director of the Office of In Vitro Diagnostics and Radiological Health in the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health.

The two tests were reviewed through the premarket notification – or 510(k) – pathway, which seeks to demonstrate to the FDA that the device to be marketed is equivalent or better in safety and effectiveness to the legally marketed device.

In the FDA’s evaluation of the tests, it reviewed clinical data from a multisite study of more than 2,500 patients. This study evaluated the diagnostic accuracy of multiple commercially available nucleic acid amplification tests for detection of Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis from throat and rectal sites. The results of this study and other information reviewed by the FDA demonstrated that the two tests “are safe and effective for extragenital testing for chlamydia and gonorrhea,” according to the statement.

The data were collected through a cross-sectional study coordinated by the Antibacterial Resistance Leadership Group, which is funded and supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

The FDA granted marketing clearance to Hologic and Cepheid for the Aptima Combo 2 Assay and the Xpert CT/NG, respectively.

Flu vaccine visits reveal missed opportunities for HPV vaccination

BALTIMORE – according to a study.

“Overall in preventive visits, missed opportunities were much higher for HPV, compared to the other two vaccines” recommended for adolescents, MenACWY (meningococcal conjugate vaccine) and Tdap, Mary Kate Kelly, MPH, of Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, told attendees at the Pediatric Academic Societies annual meeting. “In order to increase vaccination rates, it’s essential to implement efforts to reduce missed opportunities.”

According to 2018 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data, Ms. Kelly said, vaccine coverage for the HPV vaccine is approximately 66%, compared with 85% for the MenACWY vaccine and 89% for the Tdap vaccine.

Ms. Kelly and her colleagues investigated how often children or adolescents missed an opportunity to get an HPV vaccine when they received an influenza vaccine during an office visit. This study was part of the larger STOP HPV trial funded by the National Institutes of Health and aimed at implementing evidence-based interventions to reduce missed opportunities for HPV vaccination in primary care.

The researchers retrospectively reviewed EHRs from 2015 to 2018 for 48 pediatric practices across 19 states. All practices were part of the American Academy of Pediatrics’ Pediatric Research in Office Settings (PROS) national pediatric primary care network. The researchers isolated all visits for patients aged 11-17 years who received their flu vaccine and were eligible to receive the HPV vaccine.

The investigators defined a missed opportunity as one in which a patient was due for the HPV vaccine but did not receive one at the visit when they received their flu vaccine.

The study involved 40,129 patients who received the flu vaccine at 52,818 visits when they also were eligible to receive the HPV vaccine. The median age of patients was 12 years old, and 47% were female.

In 68% of visits, the patient could have received an HPV vaccine but did not – even though they were due and eligible for one. The rate was the same for boys and for girls. By contrast, only 38% of visits involved a missed opportunity for the MenACWY vaccines and 39% for the Tdap vaccine.

Rates of missed opportunities for HPV vaccination ranged among individual practices from 22% to 81% of overall visits. Patients were more than twice as likely to miss the opportunity for an HPV vaccine dose if it would have been their first dose – 70% of missed opportunities – versus being a second or third dose, which comprised 30% of missed opportunities (adjusted relative risk, 2.48; P less than .001)).

“However, missed opportunities were also common for subsequent HPV doses when vaccine hesitancy is less likely to be an issue,” Ms. Kelly added.

It also was much more likely that missed opportunities occurred during nurse visits or visits for an acute or chronic condition rather than preventive visits, which made up about half (51%) of all visits analyzed. While 48% of preventive visits involved a missed opportunity, 93% of nurse visits (aRR compared with preventive, 2.18; P less than.001) and 89% of acute or chronic visits (aRR, 2.11; P less than .001) did.

Percentages of missed opportunities were similarly high for the MenACWY and Tdap vaccines at nurse visits and acute/chronic visits, but much lower at preventive visits for the MenACWY (12%) and Tdap (15%) vaccines.

“Increasing simultaneous administration of HPV and other adolescent vaccines with the influenza vaccine may help to improve coverage,” Ms. Kelly concluded.

The study was limited by its use of a convenience sample from practices that were interested in participating and willing to stock the HPV vaccine. Additionally, the researchers could not detect or adjust for EHR errors or inaccurate or incomplete vaccine histories, and they were unable to look at vaccine hesitancy or refusal with the EHRs.

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health, the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, and the National Research Network to Improve Children’s Health. The authors reported no relevant financial disclosures.

BALTIMORE – according to a study.

“Overall in preventive visits, missed opportunities were much higher for HPV, compared to the other two vaccines” recommended for adolescents, MenACWY (meningococcal conjugate vaccine) and Tdap, Mary Kate Kelly, MPH, of Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, told attendees at the Pediatric Academic Societies annual meeting. “In order to increase vaccination rates, it’s essential to implement efforts to reduce missed opportunities.”

According to 2018 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data, Ms. Kelly said, vaccine coverage for the HPV vaccine is approximately 66%, compared with 85% for the MenACWY vaccine and 89% for the Tdap vaccine.

Ms. Kelly and her colleagues investigated how often children or adolescents missed an opportunity to get an HPV vaccine when they received an influenza vaccine during an office visit. This study was part of the larger STOP HPV trial funded by the National Institutes of Health and aimed at implementing evidence-based interventions to reduce missed opportunities for HPV vaccination in primary care.

The researchers retrospectively reviewed EHRs from 2015 to 2018 for 48 pediatric practices across 19 states. All practices were part of the American Academy of Pediatrics’ Pediatric Research in Office Settings (PROS) national pediatric primary care network. The researchers isolated all visits for patients aged 11-17 years who received their flu vaccine and were eligible to receive the HPV vaccine.

The investigators defined a missed opportunity as one in which a patient was due for the HPV vaccine but did not receive one at the visit when they received their flu vaccine.

The study involved 40,129 patients who received the flu vaccine at 52,818 visits when they also were eligible to receive the HPV vaccine. The median age of patients was 12 years old, and 47% were female.

In 68% of visits, the patient could have received an HPV vaccine but did not – even though they were due and eligible for one. The rate was the same for boys and for girls. By contrast, only 38% of visits involved a missed opportunity for the MenACWY vaccines and 39% for the Tdap vaccine.

Rates of missed opportunities for HPV vaccination ranged among individual practices from 22% to 81% of overall visits. Patients were more than twice as likely to miss the opportunity for an HPV vaccine dose if it would have been their first dose – 70% of missed opportunities – versus being a second or third dose, which comprised 30% of missed opportunities (adjusted relative risk, 2.48; P less than .001)).

“However, missed opportunities were also common for subsequent HPV doses when vaccine hesitancy is less likely to be an issue,” Ms. Kelly added.

It also was much more likely that missed opportunities occurred during nurse visits or visits for an acute or chronic condition rather than preventive visits, which made up about half (51%) of all visits analyzed. While 48% of preventive visits involved a missed opportunity, 93% of nurse visits (aRR compared with preventive, 2.18; P less than.001) and 89% of acute or chronic visits (aRR, 2.11; P less than .001) did.

Percentages of missed opportunities were similarly high for the MenACWY and Tdap vaccines at nurse visits and acute/chronic visits, but much lower at preventive visits for the MenACWY (12%) and Tdap (15%) vaccines.

“Increasing simultaneous administration of HPV and other adolescent vaccines with the influenza vaccine may help to improve coverage,” Ms. Kelly concluded.

The study was limited by its use of a convenience sample from practices that were interested in participating and willing to stock the HPV vaccine. Additionally, the researchers could not detect or adjust for EHR errors or inaccurate or incomplete vaccine histories, and they were unable to look at vaccine hesitancy or refusal with the EHRs.

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health, the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, and the National Research Network to Improve Children’s Health. The authors reported no relevant financial disclosures.

BALTIMORE – according to a study.

“Overall in preventive visits, missed opportunities were much higher for HPV, compared to the other two vaccines” recommended for adolescents, MenACWY (meningococcal conjugate vaccine) and Tdap, Mary Kate Kelly, MPH, of Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, told attendees at the Pediatric Academic Societies annual meeting. “In order to increase vaccination rates, it’s essential to implement efforts to reduce missed opportunities.”

According to 2018 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data, Ms. Kelly said, vaccine coverage for the HPV vaccine is approximately 66%, compared with 85% for the MenACWY vaccine and 89% for the Tdap vaccine.

Ms. Kelly and her colleagues investigated how often children or adolescents missed an opportunity to get an HPV vaccine when they received an influenza vaccine during an office visit. This study was part of the larger STOP HPV trial funded by the National Institutes of Health and aimed at implementing evidence-based interventions to reduce missed opportunities for HPV vaccination in primary care.

The researchers retrospectively reviewed EHRs from 2015 to 2018 for 48 pediatric practices across 19 states. All practices were part of the American Academy of Pediatrics’ Pediatric Research in Office Settings (PROS) national pediatric primary care network. The researchers isolated all visits for patients aged 11-17 years who received their flu vaccine and were eligible to receive the HPV vaccine.

The investigators defined a missed opportunity as one in which a patient was due for the HPV vaccine but did not receive one at the visit when they received their flu vaccine.

The study involved 40,129 patients who received the flu vaccine at 52,818 visits when they also were eligible to receive the HPV vaccine. The median age of patients was 12 years old, and 47% were female.

In 68% of visits, the patient could have received an HPV vaccine but did not – even though they were due and eligible for one. The rate was the same for boys and for girls. By contrast, only 38% of visits involved a missed opportunity for the MenACWY vaccines and 39% for the Tdap vaccine.

Rates of missed opportunities for HPV vaccination ranged among individual practices from 22% to 81% of overall visits. Patients were more than twice as likely to miss the opportunity for an HPV vaccine dose if it would have been their first dose – 70% of missed opportunities – versus being a second or third dose, which comprised 30% of missed opportunities (adjusted relative risk, 2.48; P less than .001)).

“However, missed opportunities were also common for subsequent HPV doses when vaccine hesitancy is less likely to be an issue,” Ms. Kelly added.

It also was much more likely that missed opportunities occurred during nurse visits or visits for an acute or chronic condition rather than preventive visits, which made up about half (51%) of all visits analyzed. While 48% of preventive visits involved a missed opportunity, 93% of nurse visits (aRR compared with preventive, 2.18; P less than.001) and 89% of acute or chronic visits (aRR, 2.11; P less than .001) did.

Percentages of missed opportunities were similarly high for the MenACWY and Tdap vaccines at nurse visits and acute/chronic visits, but much lower at preventive visits for the MenACWY (12%) and Tdap (15%) vaccines.

“Increasing simultaneous administration of HPV and other adolescent vaccines with the influenza vaccine may help to improve coverage,” Ms. Kelly concluded.

The study was limited by its use of a convenience sample from practices that were interested in participating and willing to stock the HPV vaccine. Additionally, the researchers could not detect or adjust for EHR errors or inaccurate or incomplete vaccine histories, and they were unable to look at vaccine hesitancy or refusal with the EHRs.

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health, the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, and the National Research Network to Improve Children’s Health. The authors reported no relevant financial disclosures.

REPORTING FROM PAS 2019

Understanding the terminology of gender identity

Use vocabulary to reduce barriers

TRANSforming Gynecology is a column about the ways in which ob.gyns. can become leaders in addressing the needs of the transgender/gender-nonconforming population. We hope to provide readers with some basic tools to help open the door to this marginalized population. We will lay the groundwork with an article on terminology and the importance of language before moving onto more focused discussions of topics that intersect with medical care of gender-nonconforming individuals. Transgender individuals experience among the worst health care outcomes of any demographic, and we hope that this column can be a starting point for providers to continue affirming the needs of marginalized populations in their everyday practice.

We live in a society in which most people’s gender identities are congruent with the sex they were assigned at birth based on physical characteristics. Transgender and gender-nonconforming people – often referred to as trans people, broadly – feel that their gender identity does not match their sex assigned at birth. This gender nonconformity, or the extent to which someone’s gender identity or expression differs from the cultural norm assigned to people with certain sexual organs, is in fact a matter of diversity, not pathology.

To truly provide sensitive care to trans patients, medical providers must first gain familiarity with the terminology used when discussing gender diversity. Gender identity, for starters, refers to an individual’s own personal and internal experience of themselves as a man, woman, some of both, or neither gender.1 It is only possible to learn a person’s gender identity through direct communication because gender identity is not always signaled by a certain gender expression. Gender expression is an external display usually through clothing, attitudes, or body language, that may or may not fit into socially recognized masculine or feminine categories.1 A separate aspect of the human experience is sexuality, such as gay, straight, bisexual, lesbian, etc. Sexuality should not be confused with sexual practices, which can sometimes deviate from a person’s sexuality. Gender identity is distinct from sexuality and sexual practices because people of any gender identity can hold any sexuality and engage in any sexual practices. Tied up in all of these categories is sex assigned at birth, which is a process by which health care providers categorize babies into two buckets based on the appearance of the external genitalia at the time of birth. It bears mentioning that the assignment of sex based on the appearance of external genitalia at the time of birth is a biologically inconsistent method that can lead to the exclusion of and nonconsensual mutilation of intersex people, who are individuals born with ambiguous genitalia and/or discrepancies between sex chromosome genotype and phenotype (stay tuned for more on people who are intersex in a future article).

A simplified way of remembering the distinctions between these concepts is that gender identity is who you go to bed as; gender expression is what you were wearing before you went to bed; sexuality is whom you tell others/yourself you go to bed with; sexual practice is whom you actually go to bed with; and sex assigned at birth is what you have between your legs when you are born (generally in a bed).

While cisgender persons feel that their experience of gender – their gender identity – agrees with the cultural norms surrounding their sex assigned at birth, transgender/gender-nonconforming (GNC) persons feel that their experience of gender is incongruent with their sex assigned at birth.1 Specifically, a transgender man is a person born with a vagina and therefore assigned female at birth who experiences himself as a man. A transgender woman is a person born with a penis and therefore assigned male at birth who experiences herself as a woman. A gender nonbinary person is someone with any sexual assignment at birth whose gender experience cannot be described using a binary that includes only male and female concepts, and a gender fluid person is someone whose internal experience of gender can oscillate.1 While these examples represent only a few of the many facets of gender diversity, the general terms trans and gender nonconforming (GNC) are widely accepted as inclusive, umbrella terms to describe all persons whose experience of gender is not congruent with their sex assigned at birth.

It is pivotal that medical providers understand that a person’s sex assigned at birth, gender identity, gender expression, sexuality, sexual practice, and romantic attraction can vary widely along a spectrum in each distinct category.2 For example, the current social norm dictates that someone born with a penis and assigned male at birth (AMAB) will feel that he is male, dress in a masculine fashion, and be both sexually and romantically attracted to someone born with a vagina who was assigned female at birth (AFAB), feels that she is female, dresses femininely, and likewise is sexually and romantically attracted to him. One possible alternative reality is a person who was born with a vagina that was therefore AFAB that experiences a masculine gender identity while engaging in a feminine gender expression in order to conform to social norms. In addition, they may be sexually attracted to people whom they perceive to be feminine while engaging in sexual activity with people who were AMAB. Informed medical care for trans persons starts with the basic understanding that an individual’s gender identity may not necessarily align with their gender expression, sex assigned at birth, sexual attraction, or romantic attraction.

As obstetrician-gynecologists, we are tasked by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists to provide nondiscriminatory care to all patients, regardless of gender identity.3 We must be careful not to assume that all of our patients are cisgender women who use “she/hers/her” pronouns. By simply asking patients what names or pronouns they would like us to use before initiating care, we become more sensitive to variations in gender identity. Many providers may feel uncertain about how to initiate or respond to this line of questioning. One way that health care practices can begin to respectfully access information around gender identity is to create intake forms that include more than two options for gender or to alter their office visit note templates to include a section that prompts the provider to include a discussion surrounding gender identity. By offering these opportunities for inclusion, we become more welcoming of gender minorities like transgender men seeking cervical cancer screening.

There are a number of reasons that trans persons have limited access to the health care system, but the greatest barrier reported by transgender patients is the paucity of knowledgeable providers.4 to an already marginalized patient population. Familiarity with this terminology normalizes the idea of gender diversity and subsequently reduces the risk of providers making assumptions about patients that contributes to suboptimal care.

Dr. Joyner is an assistant professor at Emory University, Atlanta, and is the director of gynecologic services in the Gender Center at Grady Memorial Hospital in Atlanta. Dr. Joyner identifies as a cisgender female and uses she/hers/her as her personal pronouns. Dr. Joey Bahng is a PGY-1 resident physician in Emory University’s gynecology & obstetrics residency program. Dr. Bahng identifies as nonbinary and uses they/them/their as their personal pronouns. Dr. Joyner and Dr. Bahng reported no financial disclosures.

1. Lancet. 2016 Jul 23;388(10042):390-400.

2. www.genderbread.org/resource/genderbread-person-v4-0.

3. Obstet Gynecol. 2011 Dec;118(6):1454-8.

4. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2016 Apr 1;23(2):168-71.

Use vocabulary to reduce barriers

Use vocabulary to reduce barriers

TRANSforming Gynecology is a column about the ways in which ob.gyns. can become leaders in addressing the needs of the transgender/gender-nonconforming population. We hope to provide readers with some basic tools to help open the door to this marginalized population. We will lay the groundwork with an article on terminology and the importance of language before moving onto more focused discussions of topics that intersect with medical care of gender-nonconforming individuals. Transgender individuals experience among the worst health care outcomes of any demographic, and we hope that this column can be a starting point for providers to continue affirming the needs of marginalized populations in their everyday practice.

We live in a society in which most people’s gender identities are congruent with the sex they were assigned at birth based on physical characteristics. Transgender and gender-nonconforming people – often referred to as trans people, broadly – feel that their gender identity does not match their sex assigned at birth. This gender nonconformity, or the extent to which someone’s gender identity or expression differs from the cultural norm assigned to people with certain sexual organs, is in fact a matter of diversity, not pathology.

To truly provide sensitive care to trans patients, medical providers must first gain familiarity with the terminology used when discussing gender diversity. Gender identity, for starters, refers to an individual’s own personal and internal experience of themselves as a man, woman, some of both, or neither gender.1 It is only possible to learn a person’s gender identity through direct communication because gender identity is not always signaled by a certain gender expression. Gender expression is an external display usually through clothing, attitudes, or body language, that may or may not fit into socially recognized masculine or feminine categories.1 A separate aspect of the human experience is sexuality, such as gay, straight, bisexual, lesbian, etc. Sexuality should not be confused with sexual practices, which can sometimes deviate from a person’s sexuality. Gender identity is distinct from sexuality and sexual practices because people of any gender identity can hold any sexuality and engage in any sexual practices. Tied up in all of these categories is sex assigned at birth, which is a process by which health care providers categorize babies into two buckets based on the appearance of the external genitalia at the time of birth. It bears mentioning that the assignment of sex based on the appearance of external genitalia at the time of birth is a biologically inconsistent method that can lead to the exclusion of and nonconsensual mutilation of intersex people, who are individuals born with ambiguous genitalia and/or discrepancies between sex chromosome genotype and phenotype (stay tuned for more on people who are intersex in a future article).

A simplified way of remembering the distinctions between these concepts is that gender identity is who you go to bed as; gender expression is what you were wearing before you went to bed; sexuality is whom you tell others/yourself you go to bed with; sexual practice is whom you actually go to bed with; and sex assigned at birth is what you have between your legs when you are born (generally in a bed).

While cisgender persons feel that their experience of gender – their gender identity – agrees with the cultural norms surrounding their sex assigned at birth, transgender/gender-nonconforming (GNC) persons feel that their experience of gender is incongruent with their sex assigned at birth.1 Specifically, a transgender man is a person born with a vagina and therefore assigned female at birth who experiences himself as a man. A transgender woman is a person born with a penis and therefore assigned male at birth who experiences herself as a woman. A gender nonbinary person is someone with any sexual assignment at birth whose gender experience cannot be described using a binary that includes only male and female concepts, and a gender fluid person is someone whose internal experience of gender can oscillate.1 While these examples represent only a few of the many facets of gender diversity, the general terms trans and gender nonconforming (GNC) are widely accepted as inclusive, umbrella terms to describe all persons whose experience of gender is not congruent with their sex assigned at birth.

It is pivotal that medical providers understand that a person’s sex assigned at birth, gender identity, gender expression, sexuality, sexual practice, and romantic attraction can vary widely along a spectrum in each distinct category.2 For example, the current social norm dictates that someone born with a penis and assigned male at birth (AMAB) will feel that he is male, dress in a masculine fashion, and be both sexually and romantically attracted to someone born with a vagina who was assigned female at birth (AFAB), feels that she is female, dresses femininely, and likewise is sexually and romantically attracted to him. One possible alternative reality is a person who was born with a vagina that was therefore AFAB that experiences a masculine gender identity while engaging in a feminine gender expression in order to conform to social norms. In addition, they may be sexually attracted to people whom they perceive to be feminine while engaging in sexual activity with people who were AMAB. Informed medical care for trans persons starts with the basic understanding that an individual’s gender identity may not necessarily align with their gender expression, sex assigned at birth, sexual attraction, or romantic attraction.

As obstetrician-gynecologists, we are tasked by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists to provide nondiscriminatory care to all patients, regardless of gender identity.3 We must be careful not to assume that all of our patients are cisgender women who use “she/hers/her” pronouns. By simply asking patients what names or pronouns they would like us to use before initiating care, we become more sensitive to variations in gender identity. Many providers may feel uncertain about how to initiate or respond to this line of questioning. One way that health care practices can begin to respectfully access information around gender identity is to create intake forms that include more than two options for gender or to alter their office visit note templates to include a section that prompts the provider to include a discussion surrounding gender identity. By offering these opportunities for inclusion, we become more welcoming of gender minorities like transgender men seeking cervical cancer screening.

There are a number of reasons that trans persons have limited access to the health care system, but the greatest barrier reported by transgender patients is the paucity of knowledgeable providers.4 to an already marginalized patient population. Familiarity with this terminology normalizes the idea of gender diversity and subsequently reduces the risk of providers making assumptions about patients that contributes to suboptimal care.

Dr. Joyner is an assistant professor at Emory University, Atlanta, and is the director of gynecologic services in the Gender Center at Grady Memorial Hospital in Atlanta. Dr. Joyner identifies as a cisgender female and uses she/hers/her as her personal pronouns. Dr. Joey Bahng is a PGY-1 resident physician in Emory University’s gynecology & obstetrics residency program. Dr. Bahng identifies as nonbinary and uses they/them/their as their personal pronouns. Dr. Joyner and Dr. Bahng reported no financial disclosures.

1. Lancet. 2016 Jul 23;388(10042):390-400.

2. www.genderbread.org/resource/genderbread-person-v4-0.

3. Obstet Gynecol. 2011 Dec;118(6):1454-8.

4. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2016 Apr 1;23(2):168-71.

TRANSforming Gynecology is a column about the ways in which ob.gyns. can become leaders in addressing the needs of the transgender/gender-nonconforming population. We hope to provide readers with some basic tools to help open the door to this marginalized population. We will lay the groundwork with an article on terminology and the importance of language before moving onto more focused discussions of topics that intersect with medical care of gender-nonconforming individuals. Transgender individuals experience among the worst health care outcomes of any demographic, and we hope that this column can be a starting point for providers to continue affirming the needs of marginalized populations in their everyday practice.

We live in a society in which most people’s gender identities are congruent with the sex they were assigned at birth based on physical characteristics. Transgender and gender-nonconforming people – often referred to as trans people, broadly – feel that their gender identity does not match their sex assigned at birth. This gender nonconformity, or the extent to which someone’s gender identity or expression differs from the cultural norm assigned to people with certain sexual organs, is in fact a matter of diversity, not pathology.

To truly provide sensitive care to trans patients, medical providers must first gain familiarity with the terminology used when discussing gender diversity. Gender identity, for starters, refers to an individual’s own personal and internal experience of themselves as a man, woman, some of both, or neither gender.1 It is only possible to learn a person’s gender identity through direct communication because gender identity is not always signaled by a certain gender expression. Gender expression is an external display usually through clothing, attitudes, or body language, that may or may not fit into socially recognized masculine or feminine categories.1 A separate aspect of the human experience is sexuality, such as gay, straight, bisexual, lesbian, etc. Sexuality should not be confused with sexual practices, which can sometimes deviate from a person’s sexuality. Gender identity is distinct from sexuality and sexual practices because people of any gender identity can hold any sexuality and engage in any sexual practices. Tied up in all of these categories is sex assigned at birth, which is a process by which health care providers categorize babies into two buckets based on the appearance of the external genitalia at the time of birth. It bears mentioning that the assignment of sex based on the appearance of external genitalia at the time of birth is a biologically inconsistent method that can lead to the exclusion of and nonconsensual mutilation of intersex people, who are individuals born with ambiguous genitalia and/or discrepancies between sex chromosome genotype and phenotype (stay tuned for more on people who are intersex in a future article).

A simplified way of remembering the distinctions between these concepts is that gender identity is who you go to bed as; gender expression is what you were wearing before you went to bed; sexuality is whom you tell others/yourself you go to bed with; sexual practice is whom you actually go to bed with; and sex assigned at birth is what you have between your legs when you are born (generally in a bed).

While cisgender persons feel that their experience of gender – their gender identity – agrees with the cultural norms surrounding their sex assigned at birth, transgender/gender-nonconforming (GNC) persons feel that their experience of gender is incongruent with their sex assigned at birth.1 Specifically, a transgender man is a person born with a vagina and therefore assigned female at birth who experiences himself as a man. A transgender woman is a person born with a penis and therefore assigned male at birth who experiences herself as a woman. A gender nonbinary person is someone with any sexual assignment at birth whose gender experience cannot be described using a binary that includes only male and female concepts, and a gender fluid person is someone whose internal experience of gender can oscillate.1 While these examples represent only a few of the many facets of gender diversity, the general terms trans and gender nonconforming (GNC) are widely accepted as inclusive, umbrella terms to describe all persons whose experience of gender is not congruent with their sex assigned at birth.

It is pivotal that medical providers understand that a person’s sex assigned at birth, gender identity, gender expression, sexuality, sexual practice, and romantic attraction can vary widely along a spectrum in each distinct category.2 For example, the current social norm dictates that someone born with a penis and assigned male at birth (AMAB) will feel that he is male, dress in a masculine fashion, and be both sexually and romantically attracted to someone born with a vagina who was assigned female at birth (AFAB), feels that she is female, dresses femininely, and likewise is sexually and romantically attracted to him. One possible alternative reality is a person who was born with a vagina that was therefore AFAB that experiences a masculine gender identity while engaging in a feminine gender expression in order to conform to social norms. In addition, they may be sexually attracted to people whom they perceive to be feminine while engaging in sexual activity with people who were AMAB. Informed medical care for trans persons starts with the basic understanding that an individual’s gender identity may not necessarily align with their gender expression, sex assigned at birth, sexual attraction, or romantic attraction.

As obstetrician-gynecologists, we are tasked by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists to provide nondiscriminatory care to all patients, regardless of gender identity.3 We must be careful not to assume that all of our patients are cisgender women who use “she/hers/her” pronouns. By simply asking patients what names or pronouns they would like us to use before initiating care, we become more sensitive to variations in gender identity. Many providers may feel uncertain about how to initiate or respond to this line of questioning. One way that health care practices can begin to respectfully access information around gender identity is to create intake forms that include more than two options for gender or to alter their office visit note templates to include a section that prompts the provider to include a discussion surrounding gender identity. By offering these opportunities for inclusion, we become more welcoming of gender minorities like transgender men seeking cervical cancer screening.

There are a number of reasons that trans persons have limited access to the health care system, but the greatest barrier reported by transgender patients is the paucity of knowledgeable providers.4 to an already marginalized patient population. Familiarity with this terminology normalizes the idea of gender diversity and subsequently reduces the risk of providers making assumptions about patients that contributes to suboptimal care.

Dr. Joyner is an assistant professor at Emory University, Atlanta, and is the director of gynecologic services in the Gender Center at Grady Memorial Hospital in Atlanta. Dr. Joyner identifies as a cisgender female and uses she/hers/her as her personal pronouns. Dr. Joey Bahng is a PGY-1 resident physician in Emory University’s gynecology & obstetrics residency program. Dr. Bahng identifies as nonbinary and uses they/them/their as their personal pronouns. Dr. Joyner and Dr. Bahng reported no financial disclosures.

1. Lancet. 2016 Jul 23;388(10042):390-400.

2. www.genderbread.org/resource/genderbread-person-v4-0.

3. Obstet Gynecol. 2011 Dec;118(6):1454-8.

4. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2016 Apr 1;23(2):168-71.

Female Veterans’ Experiences With VHA Treatment for Military Sexual Trauma

Females are the fastest growing population to seek care at the Veterans Health Administration (VHA).1 Based on a 2014 study examining prevalence of military sexual trauma (MST), it is estimated that about one-third of females in the military screen positive for MST, and the rates are higher for younger veterans.2 Military sexual trauma includes both rape and any sexual activity that occurred without consent; offensive sexual remarks or advances can also represent MST. The issue of MST, therefore, is an important one to address adequately, especially for female veterans who are screened through the VHA system.

Since 1992, the VHA has been required to provide services for MST, defined as “sexual harassment that is threatening in character or physical assault of a sexual nature that occurred while the victim was in the military.”3 Despite this mandate, it has taken many years for all VHA hospitals to adopt recommended screening tools to identify survivors of MST and give them proper resources. Only half of VHA hospitals adopted screening 6 years after the policy change.4 In addition, the environment in which the survivors receive MST care may trigger posttraumatic stress symptoms as many of the other patients seeking care at the VHA hospital resemble the perpetrators.5 Thus, up to half of females who report a history of MST do not receive care for their MST through the VHA.6

Having a history of MST significantly increases the risks of developing mental health disorders, including posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), major depressive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, and suicidal ideation.2 This group also has overall decreased quality of life (QOL). Female veterans have increased sexual dysfunction and dissatisfaction, which is heightened with a history of MST.7 Addressing MST requires treatment of all aspects of life affected by MST, such as mental health, sexual function, and QOL. The quality of treatment for MST through VHA hospitals deserves attention and likely still requires improvement with better incorporation of the patient’s perspective.

Qualitative research allows for incorporation of the patient’s perspective and is useful for exploring new ideas and themes.8 Current qualitative research using individual interviews of MST survivors focuses more on mental health treatment modalities through the VHA system and how resources are used within the system.9,10 While it is important to understand the quantity of these resources, their quality also should be explored. Research has identified unique gender-specific concerns such as female-only mental health groups.10 However, there has been less focus on how to improve current therapies and the treatment modalities (regardless of whether it is a community service or at the VHA system) females find most helpful. There is a gap in understanding the patient’s perspective and assessment of current MST treatments as well as the unmet needs both within and outside of the VHA system. Therefore, the purpose of this study is 2-fold: (1) examine the utilization of VHA services for MST, as well as outside services, through focusgroup sessions; and (2) to offer specific recommendations for improving MST treatment for female veterans from the patient’s perspective.

Methods

After obtaining institutional review board approval (16-H192), females who screened positive for a history of MST, using the validated MST screening questionnaire, were recruited from the Women’s Continuity Clinic, Urology clinic, and via a research flyer placed within key locations at the New Mexico Veterans Affairs (VA) Health Care System (NMVAHCS).11 Inclusion criteria were veterans aged > 18 years who could speak and understand English. Those who agreed to participate attended any 1 of 5 focus groups. Prior to initiation of the focus groups, the investigators generated a focus-group script, including specific questions or probes to explore treatment, unmet needs (such as other health conditions the veteran associated with MST that were not being addressed), and recommendations for care improvement.

Subjects granted consent privately prior to conduction of the focus group. Each participant completed a basic demographic (age, race, ethnicity) and clinical history (including pain conditions and therapy received for MST). These characteristics were evaluated with descriptive statistics, including means and frequencies.

The focus groups took place on the NM VAHCS Raymond G. Murphy VA Medical Center campus in a private conference room and were moderated by nonmedical research personnel experienced in focus-group moderation. Focus groups were recorded and transcribed. An iterative process was used with revisions to the script and probe questions as needed. Focus groups were planned for 2 hours but were allowed to continue at the participants’ discretion.

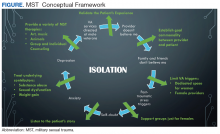

The de-identified transcripts were uploaded to the web-based qualitative engine Dedoose 6.2.21 software (Los Angeles, CA) and coded. Using grounded theory, the codes were grouped into themes and subsequently organized into emergent concepts.8,12 Following constant comparative methodology, ideas were compared and combined between each focus group.8,13 After completion of the focus groups, the generated ideas were organized and refined to create a conceptual framework that represented the collective ideas from the focus groups.

Results

Between January and June 2017, 5 focus groups with 17 participants were conducted; each session lasted about 3 hours. The average age was 52 ± 8.3 years, and were from a diverse racial and ethnic background. Most reported that > 20 years had passed since the first MST, and care-seeking for the first time was > 11 years after the trauma, although symptoms related to the MST most frequently began within 1 year of the trauma (Table 1).

Preliminary Themes

The Trauma

Focus-group participants noted improved therapies offered by the VA but challenges obtaining health care:

“…because I’m really trying to deal with it and just be happy and get my joy back and deal with the isolation.”

“Another way that the memories affected me was barricading myself in my own house, starting from the front door.”

Male-Dominated VA

Participants also noted that, along with screening improving the system, dedicated female staff and service connection are important:

“The Womens Clinic is nice, and it’s nice to know that I can go there and I’m not having to discuss everything with men all over the place.”

“The other thing... that would be really good for survivors of MST, is help with disability.”

While the focus-group participants found dedicated women’s clinics helpful and providing improved care, the overall VA environment remains male-dominated:

“Because it’s really hard to relax and be vulnerable and be in your body and in your emotions if there‘s a bunch of penises around. When I saw these guys on the floor I’m like, I ain’t going in there.”

This male-dominated sense also incorporated a feeling of being misunderstood by a system that has traditionally cared for male veterans:

“People don‘t understand. They think, oh, you‘re overreacting, but they don’t know what it feels like to be inside.”

“I wouldn’t say they treat you like a second citizen, but it’s like almost every appointment I go to that’s not in the Women’s Clinic, the secretaries or whatever will be like ‘Oh, are you looking for somebody, or...’

Assumption Females Are Not Veterans

“There was an older gentleman behind me, they were like ‘Are you checking him in?’ I said, ‘I’m sure he’ll check himself in, but I’m checking myself in.’”

Participants also reported that there is an assumption that you’re not a veteran when you’re female:

“All of the care should be geared to be the same. And we know we need to recognize that men have their issues, and women will have their issues. But we don’t need to just say ‘all women have this issue, throw them over there.’”

Self-Doubt

“The world doesn’t validate rape, you asked for it, it was what you were wearing, it was what you said.”

Ongoing efforts to have female-only spaces, therapy groups, and support networks were encouraged by all 5 focus groups. These themes, provided the foundation for emergent concepts regarding patients’ perceptions of their treatment for MST: (1) Improvement has been slow but measurable; (2) VA cares more about male veterans; (3) The isolation from MST is pervasive; (4) It’s hard to navigate the VA system or any health care when you’re traumatized; and (5) Sexual assault leaves lasting self-doubt that providers need to address.

Isolation

Because there are barriers to seeking care the overarching method for coping with the effects of MST was isolation.

Overcoming the isolation was essential to seeking any care. Participants reported years of living alone, avoiding social situations and contexts, and difficulty with basic tasks because of the isolation.

“That the coping skills, that the isolation is a coping skill and all these things, and that I had to do that to survive.”

Lack of family and provider support and the VHA’s perceived focus on male veterans perpetuated this sense of isolation. Additionally, feeding the isolation were other maladaptive behaviors, such as alcoholism, weight gain, and anger.

“I was always an athlete until my MST, and I still find myself drinking whisky and wanting to smoke pot. It’s not that I want to, I guess it gives me a sense of relief, because my MST made me an alcoholic.”

Participants reported that successful treatment of MST must include treatment of other maladaptive behaviors and specific provider-behavior changes.

At times, providers contribute to female MST survivors’ feeling undervalued:

“I had an hour session and she kept looking at her watch and blowing me off, and I finally said, okay, I’m done, good-bye, after 45 minutes.”

Validation

Participants’ suggestions to improve MST treatment, including goal sharing, validation, knowledge, and support:

“They should have staff awareness groups, or focus groups to teach them the same thing that the patients are receiving as far as how to handle yourself, how to interact with others. Don’t bring your sh** from home into your job. You’re an employee, don’t take it personal.” (

The need for provider-level support and validation likely stems from the sense that many females expressed that MST was their fault. As one participant said,

“It wasn’t violent for me. I froze. So that’s another reason that I feel guilty because it’s like I didn’t fight. I just froze and put up with it, so I feel like jeez it was my fault. I didn’t... Somehow I am responsible for this.”

Thus, the groups concluded that the most powerful support was provider validation:

“The most important for me was that I was told it was not my fault. Over and over and over. That is the most important thing that us females need to know. Because that is such a relief and that opened up so much more.”

At all of the focus groups, female veterans reported that physician validation of the assault was essential to healing. When providers communicated validation, the women experienced the most improvement in symptoms.

Therapies for MST

A variety of modalities was recommended as helpful in coping with symptoms associated with MST. One female noted her therapy dog allowed her to get her first Papanicolaou (Pap) smear in years:

“Pelvic exams are like the seventh circle of hell. Like, God, you’d think I was being abducted by aliens or something. Last time, up here, they let me bring my little dog, which was extraordinarily helpful for me.”

For others, more traditional therapy such as prolonged exposure therapy or cognitive behavioral therapy, was helpful.

“After my prolonged exposure therapy; it saved my life. I’m not suicidal, and the only thing that’s really, really affected is sometimes I still have to sleep with a night light. Over 80% of the symptoms that I had and the problems that I had were alleviated with the therapy.”

Other veterans noted alternative therapies as beneficial for overcoming trauma:

“Yoga has really helped me with dealing with chronic pain and letting go of things that no longer serve me, and remembering about the inhale, the exhale, there’s a pause between the exhale and an inhale, where that’s where I make my choices, my thoughts, catch it, check it, change it, challenge my thoughts, that’s really, really helped me.”

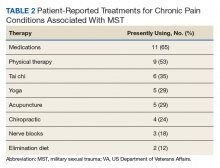

From these concepts, and the specific suggestions female veterans provided for improvement in care,

Discussion

This qualitative study of the quality of MST treatment with specific suggestions for improvement shows that the underlying force impacting health care in female survivors of MST is isolation. In turn, that isolation is perpetuated by personal beliefs, mental health, lack of support, and the VHA culture. While there was improvement in VHA care noted, female veterans offered many specific suggestions—simple ones that could be rapidly implemented—to enhance care. Many of these suggestions were targeted at provider-level behaviors such as validation, goal setting, knowledge (both about the military and about MST), and support.

Previous work showed that tangible (ie, words, being present) support rather than broad social support only generally helps reduces posttraumatic stress symptoms.15 These researchers found that tangible support moderated the relationship between number of lifetime traumas and PTSD. Schumm and colleagues also found that high social support predicted lower PTSD severity for inner-city women who experienced both child abuse and adult rape.16 A prior meta-analysis found social support was the strongest correlate of PTSD (effect size = 0.4).17

Our finding that female MST survivors desire verbal support from physicians may point to the inherent sense that validation helps healing, demonstrated by this meta-analysis. Importantly, the focus group participants did not specify the type of physician (psychiatrist, primary care provider, gynecologist, surgeon, etc) who needed to provide this support. Thus, we believe this suggestion is applicable to all physician interactions when the history of MST comes up. Physicians may be unaware of their profound impact in helping women recover from MST. This validation may also apply to survivors of other types of sexual trauma.

A second simple suggestion that arose from the focus groups was the need for broader options for MST therapy. Current data on the locations female veterans are treated for MST include specialty MST clinics, specialty PTSD clinics, psychosocial rehabilitation, and substance use disorder clinics, showing a wide range of settings.18 But female veterans are also asking for more services, including animal therapy, art therapy, yoga, and tai chi. While it may not be possible to offer every resource at every VHA facility, partnering with community services may help fulfill this veteran need.

The focus groups’ third suggestion for improvement in MST was better treatment for the health problems associated with sexual trauma, such as chronic pelvic pain, sexual dysfunction, and weight gain. It is important to note that the female veterans provided this list of associated health conditions from the broader facilitator question “What health problems do you think you have because of MST?” Females correctly identified common sequelae of sexual abuse, including pelvic pain and sexual dysfunction.14,19 Weight gain and obesity have been associated with childhood sexual trauma and abuse, but they are not well studied in MST and may be worth further exploration.20,21

Limitations

There are several inherent weaknesses in this study. The female veterans who agreed to participate in the focus group may not be representative of the entire population, particularly as survivors may be reluctant to talk about their MST experience. The participants in our focus groups were most commonly 2 decades past the MST and their experience with therapy may differ from that of women more recently traumatized and engaged in therapy. However, the fact that many of these females were still receiving some form of therapy 20 years after the traumatic event deserves attention.

Recall bias may have affected how female veterans described their experiences with MST treatment.

Strengths of the study included the inherent patient-centered approach and ability to analyze data not readily extracted from patient records or validated questionnaires. Additionally, this qualitative approach allows for the discovery of patient-driven ideas and concerns. Our focus groups also contained a majority of minority females (including Hispanic and American Indian) populations that are frequently underrepresented in research.

Conclusion

Our data show there is still substantial room for improvement in the therapies and in the physician-level care for MST. While each treatment experience was unique, the collective agreement was that multimodal therapy was beneficial. However, the isolation that often comes from MST makes accessing care and treatment challenging. A crucial component to combating this isolation is provider validation and support for the female’s experience with MST. The simple act of hearing “I believe you” from the provider can make a huge impact on continuing to seek care and overcoming the consequences of MST.

1. Rossiter AG, Smith S. The invisible wounds of war: caring for women veterans who have experienced military sexual trauma. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract. 2014;26(7):364-369.

2. Klingensmith K, Tsai J, Mota N, et al. Military sexual trauma in US veterans: results from the national health and resilience in veterans study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2014;75(10):e1133-e1139.

3. US. Department of Veterans Affairs, Veteran Health Administration. Military sexual trauma. https://www.publichealth.va.gov/docs/vhi/military_sexual_trauma.pdf. Published January 2004. Accessed July 16, 2018.

4. Suris AM, Davis LL, Kashner TM, et al. A survey of sexual trauma treatment provided by VA medical centers. Psychiatr Serv. 1998;49(3):382-384.

5. Gilmore AK, Davis MT, Grubaugh A, et al. “Do you expect me to receive PTSD care in a setting where most of the other patients remind me of the perpetrator?”: home-based telemedicine to address barriers to care unique to military sexual trauma and veterans affairs hospitals. Contemp Clin Trials. 2016;48:59-64.

6. Calhoun PS, Schry AR, Dennis PA, et al. The association between military sexual trauma and use of VA and non-VA health care services among female veterans with military service in Iraq or Afghanistan. J Interpers Violence. 2018;33(15):2439-2464.

7. Rosebrock L, Carroll R. Sexual function in female veterans: a review. J Sex Marital Ther. 2017;43(3):228-245.

8. Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The Discovery of Grounded Theory. Strategies for Qualitative Research. http://www.sxf.uevora.pt/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/Glaser_1967.pdf. Published 1999. Accessed July 16, 2018.

9. Kelly MM, Vogt DS, Scheiderer EM, et al. Effects of military trauma exposure on women veterans’ use and perceptions of Veterans Health Administration care. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(6):741-747.

10. Kehle-Forbes SM, Harwood EM, Spoont MR, et al. Experiences with VHA care: a qualitative study of U.S. women veterans with self-reported trauma histories. BMC Women Health. 2017;17(1):38.

11. McIntyre LM, Butterfield MI, Nanda K. Validation of trauma questionnaire in Veteran women. J Gen Int Med;1999;14(3):186-189.

12. Pope C, Ziebland S, Mays N. Analysing qualitative data. BMJ. 2000;320:114-116.

13. Maykut PMR. Beginning Qualitative Research. A Philosophic and Practical Guide. London, England: The Falmer Press; 1994.

14. Cichowski SB, Rogers RG, Clark EA, et al. Military sexual trauma in female veterans is associated with chronic pain conditions. Mil Med. 2017;182(9):e1895-e1899.

15. Glass N, Perrin N, Campbell JC, Soeken K. The protective role of tangible support on post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms in urban women survivors of violence. Res Nurs Health. 2007;30(5):558-568.

16. Schumm JA, Briggs-Phillips M, Hobfoll SE. Cumulative interpersonal traumas and social support as risk and resiliency factors in predicting PTSD and depression among Inner-city women. J Trauma Stress. 2006;19(6):825-836.

17. Ozer EJ, Best SR, Lipsey TL, Weiss DS. Predictors of posttraumatic stress disorder and symptoms in adults: a meta-analysis. Psychol Bull. 2003;129(1):52-73.

18. Valdez C, Kimerling R, Hyun JK, et al. Veterans Health Administration mental health treatment settings of patients who report military sexual trauma. J Trauma Dissociation. 2011;12(3):232-243.

19. Maseroli E, Scavello I, Cipriani S, et al. Psychobiological correlates of vaginismus: an exploratory analysis. J Sex Med. 2017;14(11):1392-1402.

20. Imperatori C, Innamorati M, Lamis DA, et al. Childhood trauma in obese and overweight women with food addiction and clinical-level of binge eating. Child Abuse Negl. 2016;58:180-190.

21. Williamson DF, Thompson TJ, Anda RF, Dietz WH, Felitti V. Body weight and obesity in adults and self-reported abuse in childhood. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2002;26(8):1075-1082.

Females are the fastest growing population to seek care at the Veterans Health Administration (VHA).1 Based on a 2014 study examining prevalence of military sexual trauma (MST), it is estimated that about one-third of females in the military screen positive for MST, and the rates are higher for younger veterans.2 Military sexual trauma includes both rape and any sexual activity that occurred without consent; offensive sexual remarks or advances can also represent MST. The issue of MST, therefore, is an important one to address adequately, especially for female veterans who are screened through the VHA system.

Since 1992, the VHA has been required to provide services for MST, defined as “sexual harassment that is threatening in character or physical assault of a sexual nature that occurred while the victim was in the military.”3 Despite this mandate, it has taken many years for all VHA hospitals to adopt recommended screening tools to identify survivors of MST and give them proper resources. Only half of VHA hospitals adopted screening 6 years after the policy change.4 In addition, the environment in which the survivors receive MST care may trigger posttraumatic stress symptoms as many of the other patients seeking care at the VHA hospital resemble the perpetrators.5 Thus, up to half of females who report a history of MST do not receive care for their MST through the VHA.6

Having a history of MST significantly increases the risks of developing mental health disorders, including posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), major depressive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, and suicidal ideation.2 This group also has overall decreased quality of life (QOL). Female veterans have increased sexual dysfunction and dissatisfaction, which is heightened with a history of MST.7 Addressing MST requires treatment of all aspects of life affected by MST, such as mental health, sexual function, and QOL. The quality of treatment for MST through VHA hospitals deserves attention and likely still requires improvement with better incorporation of the patient’s perspective.

Qualitative research allows for incorporation of the patient’s perspective and is useful for exploring new ideas and themes.8 Current qualitative research using individual interviews of MST survivors focuses more on mental health treatment modalities through the VHA system and how resources are used within the system.9,10 While it is important to understand the quantity of these resources, their quality also should be explored. Research has identified unique gender-specific concerns such as female-only mental health groups.10 However, there has been less focus on how to improve current therapies and the treatment modalities (regardless of whether it is a community service or at the VHA system) females find most helpful. There is a gap in understanding the patient’s perspective and assessment of current MST treatments as well as the unmet needs both within and outside of the VHA system. Therefore, the purpose of this study is 2-fold: (1) examine the utilization of VHA services for MST, as well as outside services, through focusgroup sessions; and (2) to offer specific recommendations for improving MST treatment for female veterans from the patient’s perspective.

Methods

After obtaining institutional review board approval (16-H192), females who screened positive for a history of MST, using the validated MST screening questionnaire, were recruited from the Women’s Continuity Clinic, Urology clinic, and via a research flyer placed within key locations at the New Mexico Veterans Affairs (VA) Health Care System (NMVAHCS).11 Inclusion criteria were veterans aged > 18 years who could speak and understand English. Those who agreed to participate attended any 1 of 5 focus groups. Prior to initiation of the focus groups, the investigators generated a focus-group script, including specific questions or probes to explore treatment, unmet needs (such as other health conditions the veteran associated with MST that were not being addressed), and recommendations for care improvement.

Subjects granted consent privately prior to conduction of the focus group. Each participant completed a basic demographic (age, race, ethnicity) and clinical history (including pain conditions and therapy received for MST). These characteristics were evaluated with descriptive statistics, including means and frequencies.

The focus groups took place on the NM VAHCS Raymond G. Murphy VA Medical Center campus in a private conference room and were moderated by nonmedical research personnel experienced in focus-group moderation. Focus groups were recorded and transcribed. An iterative process was used with revisions to the script and probe questions as needed. Focus groups were planned for 2 hours but were allowed to continue at the participants’ discretion.

The de-identified transcripts were uploaded to the web-based qualitative engine Dedoose 6.2.21 software (Los Angeles, CA) and coded. Using grounded theory, the codes were grouped into themes and subsequently organized into emergent concepts.8,12 Following constant comparative methodology, ideas were compared and combined between each focus group.8,13 After completion of the focus groups, the generated ideas were organized and refined to create a conceptual framework that represented the collective ideas from the focus groups.

Results

Between January and June 2017, 5 focus groups with 17 participants were conducted; each session lasted about 3 hours. The average age was 52 ± 8.3 years, and were from a diverse racial and ethnic background. Most reported that > 20 years had passed since the first MST, and care-seeking for the first time was > 11 years after the trauma, although symptoms related to the MST most frequently began within 1 year of the trauma (Table 1).

Preliminary Themes

The Trauma

Focus-group participants noted improved therapies offered by the VA but challenges obtaining health care:

“…because I’m really trying to deal with it and just be happy and get my joy back and deal with the isolation.”

“Another way that the memories affected me was barricading myself in my own house, starting from the front door.”

Male-Dominated VA

Participants also noted that, along with screening improving the system, dedicated female staff and service connection are important:

“The Womens Clinic is nice, and it’s nice to know that I can go there and I’m not having to discuss everything with men all over the place.”

“The other thing... that would be really good for survivors of MST, is help with disability.”

While the focus-group participants found dedicated women’s clinics helpful and providing improved care, the overall VA environment remains male-dominated:

“Because it’s really hard to relax and be vulnerable and be in your body and in your emotions if there‘s a bunch of penises around. When I saw these guys on the floor I’m like, I ain’t going in there.”

This male-dominated sense also incorporated a feeling of being misunderstood by a system that has traditionally cared for male veterans:

“People don‘t understand. They think, oh, you‘re overreacting, but they don’t know what it feels like to be inside.”

“I wouldn’t say they treat you like a second citizen, but it’s like almost every appointment I go to that’s not in the Women’s Clinic, the secretaries or whatever will be like ‘Oh, are you looking for somebody, or...’

Assumption Females Are Not Veterans

“There was an older gentleman behind me, they were like ‘Are you checking him in?’ I said, ‘I’m sure he’ll check himself in, but I’m checking myself in.’”

Participants also reported that there is an assumption that you’re not a veteran when you’re female:

“All of the care should be geared to be the same. And we know we need to recognize that men have their issues, and women will have their issues. But we don’t need to just say ‘all women have this issue, throw them over there.’”

Self-Doubt

“The world doesn’t validate rape, you asked for it, it was what you were wearing, it was what you said.”

Ongoing efforts to have female-only spaces, therapy groups, and support networks were encouraged by all 5 focus groups. These themes, provided the foundation for emergent concepts regarding patients’ perceptions of their treatment for MST: (1) Improvement has been slow but measurable; (2) VA cares more about male veterans; (3) The isolation from MST is pervasive; (4) It’s hard to navigate the VA system or any health care when you’re traumatized; and (5) Sexual assault leaves lasting self-doubt that providers need to address.

Isolation

Because there are barriers to seeking care the overarching method for coping with the effects of MST was isolation.

Overcoming the isolation was essential to seeking any care. Participants reported years of living alone, avoiding social situations and contexts, and difficulty with basic tasks because of the isolation.

“That the coping skills, that the isolation is a coping skill and all these things, and that I had to do that to survive.”

Lack of family and provider support and the VHA’s perceived focus on male veterans perpetuated this sense of isolation. Additionally, feeding the isolation were other maladaptive behaviors, such as alcoholism, weight gain, and anger.

“I was always an athlete until my MST, and I still find myself drinking whisky and wanting to smoke pot. It’s not that I want to, I guess it gives me a sense of relief, because my MST made me an alcoholic.”

Participants reported that successful treatment of MST must include treatment of other maladaptive behaviors and specific provider-behavior changes.

At times, providers contribute to female MST survivors’ feeling undervalued:

“I had an hour session and she kept looking at her watch and blowing me off, and I finally said, okay, I’m done, good-bye, after 45 minutes.”

Validation

Participants’ suggestions to improve MST treatment, including goal sharing, validation, knowledge, and support:

“They should have staff awareness groups, or focus groups to teach them the same thing that the patients are receiving as far as how to handle yourself, how to interact with others. Don’t bring your sh** from home into your job. You’re an employee, don’t take it personal.” (

The need for provider-level support and validation likely stems from the sense that many females expressed that MST was their fault. As one participant said,

“It wasn’t violent for me. I froze. So that’s another reason that I feel guilty because it’s like I didn’t fight. I just froze and put up with it, so I feel like jeez it was my fault. I didn’t... Somehow I am responsible for this.”

Thus, the groups concluded that the most powerful support was provider validation:

“The most important for me was that I was told it was not my fault. Over and over and over. That is the most important thing that us females need to know. Because that is such a relief and that opened up so much more.”

At all of the focus groups, female veterans reported that physician validation of the assault was essential to healing. When providers communicated validation, the women experienced the most improvement in symptoms.

Therapies for MST

A variety of modalities was recommended as helpful in coping with symptoms associated with MST. One female noted her therapy dog allowed her to get her first Papanicolaou (Pap) smear in years:

“Pelvic exams are like the seventh circle of hell. Like, God, you’d think I was being abducted by aliens or something. Last time, up here, they let me bring my little dog, which was extraordinarily helpful for me.”

For others, more traditional therapy such as prolonged exposure therapy or cognitive behavioral therapy, was helpful.

“After my prolonged exposure therapy; it saved my life. I’m not suicidal, and the only thing that’s really, really affected is sometimes I still have to sleep with a night light. Over 80% of the symptoms that I had and the problems that I had were alleviated with the therapy.”

Other veterans noted alternative therapies as beneficial for overcoming trauma:

“Yoga has really helped me with dealing with chronic pain and letting go of things that no longer serve me, and remembering about the inhale, the exhale, there’s a pause between the exhale and an inhale, where that’s where I make my choices, my thoughts, catch it, check it, change it, challenge my thoughts, that’s really, really helped me.”

From these concepts, and the specific suggestions female veterans provided for improvement in care,

Discussion

This qualitative study of the quality of MST treatment with specific suggestions for improvement shows that the underlying force impacting health care in female survivors of MST is isolation. In turn, that isolation is perpetuated by personal beliefs, mental health, lack of support, and the VHA culture. While there was improvement in VHA care noted, female veterans offered many specific suggestions—simple ones that could be rapidly implemented—to enhance care. Many of these suggestions were targeted at provider-level behaviors such as validation, goal setting, knowledge (both about the military and about MST), and support.

Previous work showed that tangible (ie, words, being present) support rather than broad social support only generally helps reduces posttraumatic stress symptoms.15 These researchers found that tangible support moderated the relationship between number of lifetime traumas and PTSD. Schumm and colleagues also found that high social support predicted lower PTSD severity for inner-city women who experienced both child abuse and adult rape.16 A prior meta-analysis found social support was the strongest correlate of PTSD (effect size = 0.4).17

Our finding that female MST survivors desire verbal support from physicians may point to the inherent sense that validation helps healing, demonstrated by this meta-analysis. Importantly, the focus group participants did not specify the type of physician (psychiatrist, primary care provider, gynecologist, surgeon, etc) who needed to provide this support. Thus, we believe this suggestion is applicable to all physician interactions when the history of MST comes up. Physicians may be unaware of their profound impact in helping women recover from MST. This validation may also apply to survivors of other types of sexual trauma.

A second simple suggestion that arose from the focus groups was the need for broader options for MST therapy. Current data on the locations female veterans are treated for MST include specialty MST clinics, specialty PTSD clinics, psychosocial rehabilitation, and substance use disorder clinics, showing a wide range of settings.18 But female veterans are also asking for more services, including animal therapy, art therapy, yoga, and tai chi. While it may not be possible to offer every resource at every VHA facility, partnering with community services may help fulfill this veteran need.

The focus groups’ third suggestion for improvement in MST was better treatment for the health problems associated with sexual trauma, such as chronic pelvic pain, sexual dysfunction, and weight gain. It is important to note that the female veterans provided this list of associated health conditions from the broader facilitator question “What health problems do you think you have because of MST?” Females correctly identified common sequelae of sexual abuse, including pelvic pain and sexual dysfunction.14,19 Weight gain and obesity have been associated with childhood sexual trauma and abuse, but they are not well studied in MST and may be worth further exploration.20,21

Limitations