User login

HPV vaccination rates continue to climb among young adults in U.S.

Although vaccination rates against the human papillomavirus remain low for young adults across the United States, the number of self-reported HPV vaccinations among women and men aged between 18 and 21 years has markedly increased since 2010, according to new research findings.

The findings were published online April 27, 2021, as a research letter in JAMA.

In 2006, the Food and Drug Administration approved the HPV vaccine for the prevention of cervical cancer and genital warts in female patients. Three years later, the FDA approved the vaccine for the prevention of anogenital cancer and warts in male patients.

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommend two doses of the HPV vaccine for children aged 11-12 years. Adolescents and young adults may need three doses over the course of 6 months if they start their vaccine series on or following their 15th birthday.

For persons who have not previously received the HPV vaccine or who did not receive adequate doses, the HPV vaccine is recommended through age 26. Data on the rates of vaccination among young adults between 18 and 21 years of age in the United States are sparse, and it is not known how well vaccination programs are progressing in the country.

In the recently published JAMA research letter, investigators from the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, examined data for the period 2010-2018 from the cross-sectional National Health Interview Survey. Respondents included in the analysis were aged 18-21 years. They were asked whether they had received the HPV vaccine before age 18 and at what age they had been vaccinated against the virus.

The researchers also assessed whether the respondents had received any HPV vaccine dose between the ages of 18 and 21 years. The findings were limited to self-reported vaccination status.

In total, 6,606 women and 6,038 men were included in the analysis. Approximately 42% of women and 16% of men said they had received at least one HPV vaccine dose at any age. The proportion of female patients who reported receiving an HPV vaccine dose significantly increased from 32% in 2010 to 55% in 2018 (P =.001). Similarly, among men, the percentage significantly increased from 2% in 2010 to 34% in 2018 (P <.001).

Approximately 4% of the female respondents and 3% of the male respondents reported that they had received an HPV vaccine between the ages of 18 and 21 years; 46% of women and 29% of men who received the vaccine between these ages completed the recommended vaccination series.

Findings from the study highlight the continual need for improving vaccination rates among vulnerable populations. Lead study author Michelle Chen, MD, MHS, a professor in the department of otolaryngology–head and neck surgery at the University of Michigan, explained in an interview that there are multiple barriers to HPV vaccination among young adults. “These barriers to vaccination among young adults primarily include cost, lack of knowledge and awareness, missed opportunities for vaccination, rapidly changing guidelines, and initial gender-based guidelines,” said Dr. Chen.

Clinicians play a large role in improving vaccination rates among young adults, who may lack awareness of the overall importance of inoculation against the potentially debilitating and deadly virus. Dr. Chen noted that clinicians can lead the way by increasing gender-inclusive awareness of HPV-associated diseases and HPV vaccination, by performing routine vaccine eligibility assessments for young adults regardless of sex, by developing robust reminder and recall strategies to improve series completion rates, and by offering patients resources regarding assistance programs to address cost barriers for uninsured patients.

“Young adult men are particularly vulnerable [to HPV], because they start to age out of pediatric health practices,” added Dr. Chen. “Thus, a multilevel gender-inclusive approach is needed to target clinicians, patients, parents, and community-based organizations.”

Gypsyamber D’Souza, PhD, professor of epidemiology at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, said in an interview that the initial uptake of HPV vaccination was slow in the United States but that progress has been made in recent years among persons in the targeted age range of 11-12 years. “However, catch-up vaccination has lagged behind, and sadly, we’re still seeing low uptake in those older ages that are still eligible and where we know there still is tremendous benefit,” she said.

Dr. D’Souza is a lead investigator in the MOUTH trial, which is currently enrolling patients. That trial will examine potential biomarkers for oropharyngeal cancer risk among people with known risk factors for HPV who came of age prior to the rollout of the vaccine.

She explained that many parents want their children to be vaccinated for HPV after they hear about the vaccine, but because the health care system in the United States is an “opt-in” system, rather than an “opt-out” one, parents need to actively seek out vaccination. Children then move toward adulthood without having received the recommended vaccine course. “There are individuals who did not get vaccinated at the ages of 11 and 12 and then forget to ask about it later, or the provider asks about it and the patients don’t have enough information,” Dr. D’Souza said.

She noted that one reason why HPV vaccination rates remain low among young adults is that the vaccine is not often kept in stock other than in pediatric clinics. “Because vaccines expire and clinics don’t have a lot of people in that age group getting vaccinated, they may not have it regularly in stock, making this one reason it might be hard for someone to get vaccinated.”

The HPV vaccine is not effective for clearing HPV once a patient acquires the infection, she added. “So young adulthood is a critical time where we have individuals who still can benefit from being vaccinated, but if we wait too long, they’ll age out of those ages where we see the highest efficacy.”

Ultimately, said Dr. D’Souza, clinicians need to catch people at multiple time points and work to remove barriers to vaccination, including letting patients know that HPV vaccination is covered by insurance. “There’s a lot of opportunity to prevent future cancers in young adults by having care providers for that age group talk about the vaccine and remember to offer it.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Although vaccination rates against the human papillomavirus remain low for young adults across the United States, the number of self-reported HPV vaccinations among women and men aged between 18 and 21 years has markedly increased since 2010, according to new research findings.

The findings were published online April 27, 2021, as a research letter in JAMA.

In 2006, the Food and Drug Administration approved the HPV vaccine for the prevention of cervical cancer and genital warts in female patients. Three years later, the FDA approved the vaccine for the prevention of anogenital cancer and warts in male patients.

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommend two doses of the HPV vaccine for children aged 11-12 years. Adolescents and young adults may need three doses over the course of 6 months if they start their vaccine series on or following their 15th birthday.

For persons who have not previously received the HPV vaccine or who did not receive adequate doses, the HPV vaccine is recommended through age 26. Data on the rates of vaccination among young adults between 18 and 21 years of age in the United States are sparse, and it is not known how well vaccination programs are progressing in the country.

In the recently published JAMA research letter, investigators from the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, examined data for the period 2010-2018 from the cross-sectional National Health Interview Survey. Respondents included in the analysis were aged 18-21 years. They were asked whether they had received the HPV vaccine before age 18 and at what age they had been vaccinated against the virus.

The researchers also assessed whether the respondents had received any HPV vaccine dose between the ages of 18 and 21 years. The findings were limited to self-reported vaccination status.

In total, 6,606 women and 6,038 men were included in the analysis. Approximately 42% of women and 16% of men said they had received at least one HPV vaccine dose at any age. The proportion of female patients who reported receiving an HPV vaccine dose significantly increased from 32% in 2010 to 55% in 2018 (P =.001). Similarly, among men, the percentage significantly increased from 2% in 2010 to 34% in 2018 (P <.001).

Approximately 4% of the female respondents and 3% of the male respondents reported that they had received an HPV vaccine between the ages of 18 and 21 years; 46% of women and 29% of men who received the vaccine between these ages completed the recommended vaccination series.

Findings from the study highlight the continual need for improving vaccination rates among vulnerable populations. Lead study author Michelle Chen, MD, MHS, a professor in the department of otolaryngology–head and neck surgery at the University of Michigan, explained in an interview that there are multiple barriers to HPV vaccination among young adults. “These barriers to vaccination among young adults primarily include cost, lack of knowledge and awareness, missed opportunities for vaccination, rapidly changing guidelines, and initial gender-based guidelines,” said Dr. Chen.

Clinicians play a large role in improving vaccination rates among young adults, who may lack awareness of the overall importance of inoculation against the potentially debilitating and deadly virus. Dr. Chen noted that clinicians can lead the way by increasing gender-inclusive awareness of HPV-associated diseases and HPV vaccination, by performing routine vaccine eligibility assessments for young adults regardless of sex, by developing robust reminder and recall strategies to improve series completion rates, and by offering patients resources regarding assistance programs to address cost barriers for uninsured patients.

“Young adult men are particularly vulnerable [to HPV], because they start to age out of pediatric health practices,” added Dr. Chen. “Thus, a multilevel gender-inclusive approach is needed to target clinicians, patients, parents, and community-based organizations.”

Gypsyamber D’Souza, PhD, professor of epidemiology at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, said in an interview that the initial uptake of HPV vaccination was slow in the United States but that progress has been made in recent years among persons in the targeted age range of 11-12 years. “However, catch-up vaccination has lagged behind, and sadly, we’re still seeing low uptake in those older ages that are still eligible and where we know there still is tremendous benefit,” she said.

Dr. D’Souza is a lead investigator in the MOUTH trial, which is currently enrolling patients. That trial will examine potential biomarkers for oropharyngeal cancer risk among people with known risk factors for HPV who came of age prior to the rollout of the vaccine.

She explained that many parents want their children to be vaccinated for HPV after they hear about the vaccine, but because the health care system in the United States is an “opt-in” system, rather than an “opt-out” one, parents need to actively seek out vaccination. Children then move toward adulthood without having received the recommended vaccine course. “There are individuals who did not get vaccinated at the ages of 11 and 12 and then forget to ask about it later, or the provider asks about it and the patients don’t have enough information,” Dr. D’Souza said.

She noted that one reason why HPV vaccination rates remain low among young adults is that the vaccine is not often kept in stock other than in pediatric clinics. “Because vaccines expire and clinics don’t have a lot of people in that age group getting vaccinated, they may not have it regularly in stock, making this one reason it might be hard for someone to get vaccinated.”

The HPV vaccine is not effective for clearing HPV once a patient acquires the infection, she added. “So young adulthood is a critical time where we have individuals who still can benefit from being vaccinated, but if we wait too long, they’ll age out of those ages where we see the highest efficacy.”

Ultimately, said Dr. D’Souza, clinicians need to catch people at multiple time points and work to remove barriers to vaccination, including letting patients know that HPV vaccination is covered by insurance. “There’s a lot of opportunity to prevent future cancers in young adults by having care providers for that age group talk about the vaccine and remember to offer it.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Although vaccination rates against the human papillomavirus remain low for young adults across the United States, the number of self-reported HPV vaccinations among women and men aged between 18 and 21 years has markedly increased since 2010, according to new research findings.

The findings were published online April 27, 2021, as a research letter in JAMA.

In 2006, the Food and Drug Administration approved the HPV vaccine for the prevention of cervical cancer and genital warts in female patients. Three years later, the FDA approved the vaccine for the prevention of anogenital cancer and warts in male patients.

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommend two doses of the HPV vaccine for children aged 11-12 years. Adolescents and young adults may need three doses over the course of 6 months if they start their vaccine series on or following their 15th birthday.

For persons who have not previously received the HPV vaccine or who did not receive adequate doses, the HPV vaccine is recommended through age 26. Data on the rates of vaccination among young adults between 18 and 21 years of age in the United States are sparse, and it is not known how well vaccination programs are progressing in the country.

In the recently published JAMA research letter, investigators from the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, examined data for the period 2010-2018 from the cross-sectional National Health Interview Survey. Respondents included in the analysis were aged 18-21 years. They were asked whether they had received the HPV vaccine before age 18 and at what age they had been vaccinated against the virus.

The researchers also assessed whether the respondents had received any HPV vaccine dose between the ages of 18 and 21 years. The findings were limited to self-reported vaccination status.

In total, 6,606 women and 6,038 men were included in the analysis. Approximately 42% of women and 16% of men said they had received at least one HPV vaccine dose at any age. The proportion of female patients who reported receiving an HPV vaccine dose significantly increased from 32% in 2010 to 55% in 2018 (P =.001). Similarly, among men, the percentage significantly increased from 2% in 2010 to 34% in 2018 (P <.001).

Approximately 4% of the female respondents and 3% of the male respondents reported that they had received an HPV vaccine between the ages of 18 and 21 years; 46% of women and 29% of men who received the vaccine between these ages completed the recommended vaccination series.

Findings from the study highlight the continual need for improving vaccination rates among vulnerable populations. Lead study author Michelle Chen, MD, MHS, a professor in the department of otolaryngology–head and neck surgery at the University of Michigan, explained in an interview that there are multiple barriers to HPV vaccination among young adults. “These barriers to vaccination among young adults primarily include cost, lack of knowledge and awareness, missed opportunities for vaccination, rapidly changing guidelines, and initial gender-based guidelines,” said Dr. Chen.

Clinicians play a large role in improving vaccination rates among young adults, who may lack awareness of the overall importance of inoculation against the potentially debilitating and deadly virus. Dr. Chen noted that clinicians can lead the way by increasing gender-inclusive awareness of HPV-associated diseases and HPV vaccination, by performing routine vaccine eligibility assessments for young adults regardless of sex, by developing robust reminder and recall strategies to improve series completion rates, and by offering patients resources regarding assistance programs to address cost barriers for uninsured patients.

“Young adult men are particularly vulnerable [to HPV], because they start to age out of pediatric health practices,” added Dr. Chen. “Thus, a multilevel gender-inclusive approach is needed to target clinicians, patients, parents, and community-based organizations.”

Gypsyamber D’Souza, PhD, professor of epidemiology at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, said in an interview that the initial uptake of HPV vaccination was slow in the United States but that progress has been made in recent years among persons in the targeted age range of 11-12 years. “However, catch-up vaccination has lagged behind, and sadly, we’re still seeing low uptake in those older ages that are still eligible and where we know there still is tremendous benefit,” she said.

Dr. D’Souza is a lead investigator in the MOUTH trial, which is currently enrolling patients. That trial will examine potential biomarkers for oropharyngeal cancer risk among people with known risk factors for HPV who came of age prior to the rollout of the vaccine.

She explained that many parents want their children to be vaccinated for HPV after they hear about the vaccine, but because the health care system in the United States is an “opt-in” system, rather than an “opt-out” one, parents need to actively seek out vaccination. Children then move toward adulthood without having received the recommended vaccine course. “There are individuals who did not get vaccinated at the ages of 11 and 12 and then forget to ask about it later, or the provider asks about it and the patients don’t have enough information,” Dr. D’Souza said.

She noted that one reason why HPV vaccination rates remain low among young adults is that the vaccine is not often kept in stock other than in pediatric clinics. “Because vaccines expire and clinics don’t have a lot of people in that age group getting vaccinated, they may not have it regularly in stock, making this one reason it might be hard for someone to get vaccinated.”

The HPV vaccine is not effective for clearing HPV once a patient acquires the infection, she added. “So young adulthood is a critical time where we have individuals who still can benefit from being vaccinated, but if we wait too long, they’ll age out of those ages where we see the highest efficacy.”

Ultimately, said Dr. D’Souza, clinicians need to catch people at multiple time points and work to remove barriers to vaccination, including letting patients know that HPV vaccination is covered by insurance. “There’s a lot of opportunity to prevent future cancers in young adults by having care providers for that age group talk about the vaccine and remember to offer it.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

STD Prevention: We’ve Come Far, but not Far Enough

On any given day in 2018, one in five people had a sexually transmitted infection (STI), according to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) recently released Sexually Transmitted Disease (STD) Surveillance Report, 2018. There were nearly 68 million infections in the US—and 26 million STIs were acquired in that year.

“The CDC report is an important reminder that infectious diseases continue to do what they do best, which is to cause illness and spread from person to person,” says David Aronoff, MD, director, Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Medicine, Vanderbilt University Medical Center. “Sexually transmitted infections are persistent threats to human health.”

Most of the infections on the CDC’s watchlist were due to the human papillomavirus (HPV), herpes simplex virus-2 (HSV-2), and trichomoniasis. Chlamydia, gonorrhea, HIV, hepatitis B virus, and syphilis followed. Although lower on the list, gonorrhea and syphilis numbers are on the rise to a disquieting degree. Since 2014, gonorrhea cases have increased 63% and syphilis cases, 71%.

Syphilis is still treatable with penicillin. But “the tragedy of poor STI [sexually transmitted infection] control is compounded by the fact that many of the germs that cause STIs are gradually developing more and more resistance to available treatments,” Dr. Aronoff says.

The rise in gonorrhea cases is particularly concerning to many health care providers. “There’s a very limited pipeline of new antibiotics to use if we’re confronted with antibiotic-resistant STIs,” says Ina Park, MD, assistant professor at University of California San Francisco School of Medicine; medical director, California Prevention Training Center; and author of Strange Bedfellows: Adventures in the Science, History and Surprising Secrets of STDs. In the case of gonorrhea, she warns, we’re down to one class of antibiotics. When all conventional therapies fail in cases of multidrug-resistant gonorrhea, patients have to be hospitalized and treated with broad-spectrum IV antibiotics, such as ertapenem. “We really don’t want to have to resort to that for an infection as common as gonorrhea,” she says.

Syphilis’ resurgence in new populations also is a concern. In the ’80s, says Michelle Collins-Ogle, MD, there was an epidemic of syphilis in pregnant women and newborns. Then it “sort of quieted down,” she says, in part because obstetricians and gynecologists and other health care providers did a better job of screening, diagnosing, and treating in that demographic. The latest resurgence is in young men of color who have sex with men—“we didn’t see that coming.”

Women and babies are still vulnerable, though. In one year, according to the CDC, syphilis cases among women of childbearing age leaped 36%. And, alarmingly, since 2014, cases of congenital syphilis have increased 185%. Between 2017 and 2018 alone, newborn deaths due to syphilis increased 22%—a “startling” number, says Gail Bolan, MD, the CDC director of STD prevention, in a release about the surveillance report. “Too many babies are needlessly dying. Every single instance of congenital syphilis is one too many when we have the tools to prevent it.”

Can all STIs be prevented? Can the rising tides be turned? Dr. Aronoff says, “As with the COVID-19 pandemic, STIs provide an important opportunity for us to understand how multiple factors can contribute to their spread and difficulty controlling.” Drug use, poverty, unstable housing, and stigma can all reduce access to STD prevention and care, he says. “And, as we’ve seen with COVID-19, under-resourced public health programs can also foster epidemics and pandemics of STIs.” Moreover, he adds, many public health programs at the state and local level have been subjected to budget cuts, which translates into less control of disease.

Some STI rates have been reduced with, for instance, antiretrovirals for HIV/AIDS and the HPV vaccine. But there’s still ground to cover, and new patient groups to protect. Nearly half of all new infections in 2018 were in young people aged 15 to 24 years. Not only is it another dangerous trend, it is an expensive one. Chlamydia, gonorrhea, and syphilis combined accounted for $1.1 billion in direct medical costs in 2018, the CDC report says, and care for young people aged 15 to 24 made up about 60% of those costs.

“Low or decreasing rates of condom use among vulnerable groups, including young people and gay and bisexual men, play important roles in driving ongoing STI rates,” Aronoff says. In part, that’s due to lack of comprehensive sex education, a lack that’s taking a huge toll.

“Remember now, we basically cut out a lot of the sex education. It doesn’t exist,” says Dr. Collins-Ogle. She has run clinics for several decades, and says she continually sees young male patients who don’t know how to use a condom. We know more now, though, she points out. “Back in the ‘80s, we didn’t have a direct correlation between STIs and AIDS. Now we know that having syphilis, for example, predisposes you to HIV acquisition. We also know that having HSV2, for example, predisposes you to HIV.”

It’s an ongoing battle, though, with each new generation of pathogens—and people. And as the CDC report shows, it’s like fighting a Hydra: When one infection is wrestled to the ground, another rears its head. There’s no time to rest on laurels. “Having highly contagious infections caused by difficult or impossible-to-treat microbes,” says David Aronoff, “is not a future I would wish on anyone

On any given day in 2018, one in five people had a sexually transmitted infection (STI), according to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) recently released Sexually Transmitted Disease (STD) Surveillance Report, 2018. There were nearly 68 million infections in the US—and 26 million STIs were acquired in that year.

“The CDC report is an important reminder that infectious diseases continue to do what they do best, which is to cause illness and spread from person to person,” says David Aronoff, MD, director, Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Medicine, Vanderbilt University Medical Center. “Sexually transmitted infections are persistent threats to human health.”

Most of the infections on the CDC’s watchlist were due to the human papillomavirus (HPV), herpes simplex virus-2 (HSV-2), and trichomoniasis. Chlamydia, gonorrhea, HIV, hepatitis B virus, and syphilis followed. Although lower on the list, gonorrhea and syphilis numbers are on the rise to a disquieting degree. Since 2014, gonorrhea cases have increased 63% and syphilis cases, 71%.

Syphilis is still treatable with penicillin. But “the tragedy of poor STI [sexually transmitted infection] control is compounded by the fact that many of the germs that cause STIs are gradually developing more and more resistance to available treatments,” Dr. Aronoff says.

The rise in gonorrhea cases is particularly concerning to many health care providers. “There’s a very limited pipeline of new antibiotics to use if we’re confronted with antibiotic-resistant STIs,” says Ina Park, MD, assistant professor at University of California San Francisco School of Medicine; medical director, California Prevention Training Center; and author of Strange Bedfellows: Adventures in the Science, History and Surprising Secrets of STDs. In the case of gonorrhea, she warns, we’re down to one class of antibiotics. When all conventional therapies fail in cases of multidrug-resistant gonorrhea, patients have to be hospitalized and treated with broad-spectrum IV antibiotics, such as ertapenem. “We really don’t want to have to resort to that for an infection as common as gonorrhea,” she says.

Syphilis’ resurgence in new populations also is a concern. In the ’80s, says Michelle Collins-Ogle, MD, there was an epidemic of syphilis in pregnant women and newborns. Then it “sort of quieted down,” she says, in part because obstetricians and gynecologists and other health care providers did a better job of screening, diagnosing, and treating in that demographic. The latest resurgence is in young men of color who have sex with men—“we didn’t see that coming.”

Women and babies are still vulnerable, though. In one year, according to the CDC, syphilis cases among women of childbearing age leaped 36%. And, alarmingly, since 2014, cases of congenital syphilis have increased 185%. Between 2017 and 2018 alone, newborn deaths due to syphilis increased 22%—a “startling” number, says Gail Bolan, MD, the CDC director of STD prevention, in a release about the surveillance report. “Too many babies are needlessly dying. Every single instance of congenital syphilis is one too many when we have the tools to prevent it.”

Can all STIs be prevented? Can the rising tides be turned? Dr. Aronoff says, “As with the COVID-19 pandemic, STIs provide an important opportunity for us to understand how multiple factors can contribute to their spread and difficulty controlling.” Drug use, poverty, unstable housing, and stigma can all reduce access to STD prevention and care, he says. “And, as we’ve seen with COVID-19, under-resourced public health programs can also foster epidemics and pandemics of STIs.” Moreover, he adds, many public health programs at the state and local level have been subjected to budget cuts, which translates into less control of disease.

Some STI rates have been reduced with, for instance, antiretrovirals for HIV/AIDS and the HPV vaccine. But there’s still ground to cover, and new patient groups to protect. Nearly half of all new infections in 2018 were in young people aged 15 to 24 years. Not only is it another dangerous trend, it is an expensive one. Chlamydia, gonorrhea, and syphilis combined accounted for $1.1 billion in direct medical costs in 2018, the CDC report says, and care for young people aged 15 to 24 made up about 60% of those costs.

“Low or decreasing rates of condom use among vulnerable groups, including young people and gay and bisexual men, play important roles in driving ongoing STI rates,” Aronoff says. In part, that’s due to lack of comprehensive sex education, a lack that’s taking a huge toll.

“Remember now, we basically cut out a lot of the sex education. It doesn’t exist,” says Dr. Collins-Ogle. She has run clinics for several decades, and says she continually sees young male patients who don’t know how to use a condom. We know more now, though, she points out. “Back in the ‘80s, we didn’t have a direct correlation between STIs and AIDS. Now we know that having syphilis, for example, predisposes you to HIV acquisition. We also know that having HSV2, for example, predisposes you to HIV.”

It’s an ongoing battle, though, with each new generation of pathogens—and people. And as the CDC report shows, it’s like fighting a Hydra: When one infection is wrestled to the ground, another rears its head. There’s no time to rest on laurels. “Having highly contagious infections caused by difficult or impossible-to-treat microbes,” says David Aronoff, “is not a future I would wish on anyone

On any given day in 2018, one in five people had a sexually transmitted infection (STI), according to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) recently released Sexually Transmitted Disease (STD) Surveillance Report, 2018. There were nearly 68 million infections in the US—and 26 million STIs were acquired in that year.

“The CDC report is an important reminder that infectious diseases continue to do what they do best, which is to cause illness and spread from person to person,” says David Aronoff, MD, director, Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Medicine, Vanderbilt University Medical Center. “Sexually transmitted infections are persistent threats to human health.”

Most of the infections on the CDC’s watchlist were due to the human papillomavirus (HPV), herpes simplex virus-2 (HSV-2), and trichomoniasis. Chlamydia, gonorrhea, HIV, hepatitis B virus, and syphilis followed. Although lower on the list, gonorrhea and syphilis numbers are on the rise to a disquieting degree. Since 2014, gonorrhea cases have increased 63% and syphilis cases, 71%.

Syphilis is still treatable with penicillin. But “the tragedy of poor STI [sexually transmitted infection] control is compounded by the fact that many of the germs that cause STIs are gradually developing more and more resistance to available treatments,” Dr. Aronoff says.

The rise in gonorrhea cases is particularly concerning to many health care providers. “There’s a very limited pipeline of new antibiotics to use if we’re confronted with antibiotic-resistant STIs,” says Ina Park, MD, assistant professor at University of California San Francisco School of Medicine; medical director, California Prevention Training Center; and author of Strange Bedfellows: Adventures in the Science, History and Surprising Secrets of STDs. In the case of gonorrhea, she warns, we’re down to one class of antibiotics. When all conventional therapies fail in cases of multidrug-resistant gonorrhea, patients have to be hospitalized and treated with broad-spectrum IV antibiotics, such as ertapenem. “We really don’t want to have to resort to that for an infection as common as gonorrhea,” she says.

Syphilis’ resurgence in new populations also is a concern. In the ’80s, says Michelle Collins-Ogle, MD, there was an epidemic of syphilis in pregnant women and newborns. Then it “sort of quieted down,” she says, in part because obstetricians and gynecologists and other health care providers did a better job of screening, diagnosing, and treating in that demographic. The latest resurgence is in young men of color who have sex with men—“we didn’t see that coming.”

Women and babies are still vulnerable, though. In one year, according to the CDC, syphilis cases among women of childbearing age leaped 36%. And, alarmingly, since 2014, cases of congenital syphilis have increased 185%. Between 2017 and 2018 alone, newborn deaths due to syphilis increased 22%—a “startling” number, says Gail Bolan, MD, the CDC director of STD prevention, in a release about the surveillance report. “Too many babies are needlessly dying. Every single instance of congenital syphilis is one too many when we have the tools to prevent it.”

Can all STIs be prevented? Can the rising tides be turned? Dr. Aronoff says, “As with the COVID-19 pandemic, STIs provide an important opportunity for us to understand how multiple factors can contribute to their spread and difficulty controlling.” Drug use, poverty, unstable housing, and stigma can all reduce access to STD prevention and care, he says. “And, as we’ve seen with COVID-19, under-resourced public health programs can also foster epidemics and pandemics of STIs.” Moreover, he adds, many public health programs at the state and local level have been subjected to budget cuts, which translates into less control of disease.

Some STI rates have been reduced with, for instance, antiretrovirals for HIV/AIDS and the HPV vaccine. But there’s still ground to cover, and new patient groups to protect. Nearly half of all new infections in 2018 were in young people aged 15 to 24 years. Not only is it another dangerous trend, it is an expensive one. Chlamydia, gonorrhea, and syphilis combined accounted for $1.1 billion in direct medical costs in 2018, the CDC report says, and care for young people aged 15 to 24 made up about 60% of those costs.

“Low or decreasing rates of condom use among vulnerable groups, including young people and gay and bisexual men, play important roles in driving ongoing STI rates,” Aronoff says. In part, that’s due to lack of comprehensive sex education, a lack that’s taking a huge toll.

“Remember now, we basically cut out a lot of the sex education. It doesn’t exist,” says Dr. Collins-Ogle. She has run clinics for several decades, and says she continually sees young male patients who don’t know how to use a condom. We know more now, though, she points out. “Back in the ‘80s, we didn’t have a direct correlation between STIs and AIDS. Now we know that having syphilis, for example, predisposes you to HIV acquisition. We also know that having HSV2, for example, predisposes you to HIV.”

It’s an ongoing battle, though, with each new generation of pathogens—and people. And as the CDC report shows, it’s like fighting a Hydra: When one infection is wrestled to the ground, another rears its head. There’s no time to rest on laurels. “Having highly contagious infections caused by difficult or impossible-to-treat microbes,” says David Aronoff, “is not a future I would wish on anyone

Preliminary Evaluation of an Order Template to Improve Diagnosis and Testosterone Therapy of Hypogonadism in Veterans

Testosterone treatment is clinically indicated when a patient presents with symptoms and signs and biochemical evidence of testosterone deficiency, ie, male hypogonadism. Laboratory confirmation of hypogonadism requires repeatedly low serum testosterone concentrations; between 8

Recent studies have reported an increase in testosterone prescriptions and raised concerns regarding health care provider (HCP) prescribing practices despite current clinical practice guidelines from major societies, such as the Endocrine Society. In the US from 2001 to 2011, testosterone use among men aged ≥ 40 years increased more than 3-fold in all age groups.3 Subsequently in the years from 2013 to 2016, prescription rates declined perhaps due to the cardiovascular and stroke concerns.4

In the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), new testosterone prescriptions across VA medical centers increased from 20,437 in fiscal year (FY) 2009 to 36,394 in FY 2012. Yet only 3.1% of men who received testosterone therapy had 2 or more low morning total or free testosterone concentrations measured; LH and/or FSH levels assessed; and presence of contraindications to therapy documented. Remarkably, 16.5% of these veterans did not have a testosterone level tested prior to being prescribed testosterone. Among veterans who were prescribed testosterone, 1.4% had a diagnosis of prostate cancer, 7.6% had a diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), and 3.5% had elevated hematocrit at baseline.5 These findings raised concerns of whether the diagnosis and etiology of hypogonadism were appropriately established and risks were considered before testosterone treatment was initiated.5,6

To further understand VA prescribing practices of testosterone therapy, a 2018 VA Office of the Inspector General (OIG) report evaluated the initiation and follow-up of testosterone replacement therapy. The OIG randomly sampled and reviewed 1,091 male patients who filled at least 1 outpatient testosterone prescription from VA in FY 2014 and who did not have a prior testosterone prescription in FY 2013. Patients were followed through September 30, 2015. Within 1 year prior to initiating testosterone, only 1.5% had clinical signs and symptoms of testosterone deficiency documented prior to testosterone testing (76% within 18 months of starting testosterone); only 9.1% of veterans had the recommended measurements of 2 low morning testosterone levels; and only 12% had LH and FSH levels measured. Within 3 to 6 months after starting testosterone therapy, only 24% of veterans were assessed for symptom improvement, and 29% to 33% were evaluated for adverse effects, hematocrit levels and adherence to the therapy. The OIG report concluded that VA HCPs were not adhering to guidelines (referencing the Endocrine Society guidelines) when evaluating and treating veterans with testosterone deficiency.7

Considering the OIG recommendations and need to improve current practices among providers, VA Puget Sound Health Care System (VAPSHCS) in Washington established a multidisciplinary workgroup consisting of an endocrinologist, geriatrician, primary care provider (PCP), pharmacists, VA information technology (IT) specialist, and health products support (HPS) clinical team in the spring of 2019 to assess and improve testosterone prescribing practices.

Methods

A testosterone order template was developed, approved by VAPSHCS Pharmacy and Therapeutics Committee, and implemented on July 1, 2019, at VAPSHCS, a 1a medical facility caring for more than 112,000 veterans. Given its potential risks and the propensity for varied prescribing practices, testosterone was designated as a restricted drug requiring a prior authorization drug request (PADR) and required completion of the testosterone order template in the Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS).

Testosterone Order Template

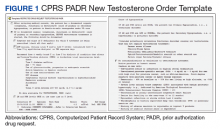

The testosterone order template had 2 components. Completion of the template for new testosterone orders was required to initiate treatment unless the patient had known organic hypogonadism or was a transgender male. The template ensured documentation of defined symptoms and signs of testosterone deficiency; low serum testosterone levels on at least 2 occasions and LH and FSH concentrations; no contraindications to testosterone treatment; discussion of risks and benefits of therapy; and baseline hematocrit (Figure 1). Relevant educational content (eg, risks and benefits of testosterone) was incorporated in the template. The second template was required for the first renewal of testosterone to document adherence to or reason for discontinuation of testosterone; improvement of symptoms and signs; and confirm monitoring hematocrit and testosterone levels during treatment.

Prior to implementation, the PADR template was introduced to HCPs at 2 chief-of-medicine rounds on the diagnosis and evaluation of hypogonadism by a pharmacist and endocrinologist. These educational sessions used case examples and discussions to teach the appropriate use of testosterone therapy in men with hypogonadism. The target audience was PCPs, residents, and other specialists who might prescribe testosterone.

Retrospective Chart Review

To assess the impact of the new testosterone order template on adherence to OIG recommendations, a retrospective chart review was completed comparing the appropriateness of initiating testosterone replacement therapy pretemplate period (July 1 to December 31, 2018) vs posttemplate period (July 1 to December 31, 2019). Inclusion and exclusion criteria were modeled after the 2018 OIG report to allow for comparison with the OIG study population. Eligible veterans in each time period included males who received a new testosterone prescription without having been prescribed testosterone in the previous 12 months. Exclusion criteria included community care network prescriptions (CCNRx); current testosterone prescription from a different VA site; clinic administration of testosterone in the previous 12 months; an organic hypogonadism (ie, Klinefelter syndrome) or gender dysphoria diagnosis; and whether the testosterone prescription was never dispensed (PADR was denied or veteran never had the prescription filled). Veterans who met the inclusion criteria in CPRS were identified by an algorithm developed by the VAPSHCS pharmacoeconomist.

Determining the appropriateness of testosterone prescribing, such as symptoms and laboratory measurements to confirm the diagnosis of hypogonadism, was based on the OIG report and Endocrine Society guidelines. A chart review of the 12 months before testosterone prescribing was completed for each veteran, assessing for documentation of symptoms of testosterone deficiency and laboratory measurements of serum testosterone, LH, and FSH. Also, documentation of a discussion of risks and benefits of testosterone therapy in the 3 months before prescribing was assessed, which matched the timeframe in the VA OIG report.

Interim Analysis

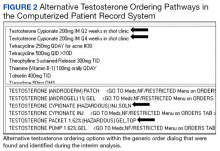

After initial template implementation, the multidisciplinary workgroup reconvened for a preplanned interim analysis in November 2019. The evaluation at this meeting revealed multiple order pathways in CPRS that were not linked to the PADR testosterone order template. Testosterone could be ordered in the generic order dialog, medications by drug class, and medications by alphabet, and endocrinology specialty menus without prompting to complete the testosterone order template or redirection to the restricted drug menu (Figure 2). These alternative testosterone ordering pathways were removed in early December 2019 and additional data collection was conducted for 3 months after discontinuation of alternative order pathways, the posttemplate/no alternative ordering pathways period, from December 7, 2019 to February 29, 2020.

Exclusion of Previous Testosterone Prescriptions Predating Chart Review Period, Subgroup Analysis

In the OIG report and the initial retrospective chart review, only veterans without a testosterone prescription in the previous 12 months were evaluated. To assess whether a previous testosterone prescription influenced completion of the PADR and order template, a further subgroup analysis was conducted that excluded veterans who had a previous testosterone prescription at any time before the chart review periods. Therefore, “new testosterone prescription” refers to a veteran who never had a history of being on testosterone vs “former testosterone prescription,” meaning a patient could have had a previous testosterone prescription > 1 year prior to a new VA testosterone prescription.

Results

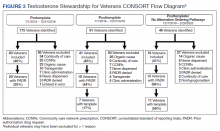

One hundred seventy-five veterans with a new testosterone prescription were identified in the pretemplate period; of these 80 (46%) met eligibility criteria; only 20 eligible veterans (25%) had a completed PADR (Figure 3). Ninety-one veterans with a new testosterone prescription were identified in the posttemplate period of which 41 (46%) veterans were eligible; 18 eligible veterans (44%) had a completed PADR, but only 7 (17%) had a completed testosterone order template.

After excluding veterans who had alternative ordering pathways for testosterone, 46 veterans were identified in the posttemplate/no alternative ordering pathways period of which 19 (41%) veterans were eligible. Compared with the posttemplate period, a higher proportion of eligible veterans, 68% (13) had a completed PADR, and 58% (11) had a testosterone order template during the posttemplate/no alternative ordering pathways period.

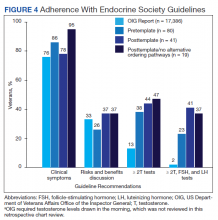

Compared with the OIG report findings, a similar percentage of veterans at VAPSHCS in the pretemplate period had documented clinical symptoms of testosterone deficiency and documented discussion of risks and benefits of testosterone therapy (Figure 4). However, a higher percentage of veterans had biochemical confirmation of testosterone deficiency with ≥ 2 low testosterone levels and evaluation of LH and FSH levels in the pretemplate period (23%) vs that in the OIG report (2%).

Compared with the pretemplate period, activation of the testosterone ordering template in the posttemplate period (Figure 4) had little effect on documented clinical symptoms and discussion of risks and benefits of testosterone treatment. However, the percentage of veterans who had ≥ 2 low testosterone levels and gonadotropins tested was higher in the posttemplate period (41%) vs both the pretemplate period and OIG report.

After removing alternative ordering pathways of testosterone, the percentages of veterans who had documented clinical symptoms, discussion of risks and benefits of testosterone, and ≥ 2 low testosterone levels and gonadotropin tests performed were similar in the posttemplate/no alternative ordering pathways vs posttemplate period.

Excluding veterans who had previously received a former testosterone prescription at any time prior to chart review periods, this subgroup analysis resulted in greater adherence to Endocrine Society guidelines for testosterone treatment with introduction of the testosterone order template, particularly after removal of alternative ordering pathway (Figure 5). With the exclusion of veterans who formerly received testosterone prescriptions, the percentages of veterans who had documented clinical symptoms, discussion of risks and benefits, and ≥ 2 low testosterone levels with gonadotropin tests were higher (100%, 57%, and 71%, respectively) in the posttemplate/no alternative ordering pathways period, compared with the pretemplate period (86%, 30%, and 32%, respectively).

Discussion

The 2018 OIG report found that VA practitioners demonstrated poor adherence to evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for testosterone treatment in men with hypogonadism. Based on OIG recommendations, we developed a PADR testosterone ordering template to help HCPs improve practice by better adherence to guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of hypogonadism in veterans. Before implementation of the PADR template, the percentage of veterans at VAPSHCS who had biochemical confirmation of hypogonadism was higher than that in the OIG report. Activation of the PADR testosterone ordering template (with or without removal of options for alternative ordering pathways of testosterone) resulted only in an improvement of laboratory confirmation and evaluation of etiology of hypogonadism. This is when we reasoned that clinicians may have access to prior records and laboratory testing beyond just the past year, and this information may have influenced their use of the PADR template. Subsequently, with exclusion of veterans who were previously prescribed testosterone, implementation of the PADR testosterone order template improved documentation of symptoms of testosterone deficiency, discussion of risks and benefits of testosterone therapy, and biochemical diagnosis and evaluation of hypogonadism relative to the period before implementation.

The lack of effects of implementing the testosterone order template on documentation of symptoms of testosterone deficiency and discussion of risks and benefits of testosterone therapy may be due to local expertise resulting in the relatively high adherence to these guideline recommendations at VAPSHCS before activation of the template vs that in the OIG report. The template improved documentation of the diagnosis and evaluation of hypogonadism for genuinely new testosterone prescriptions in veterans without a history of testosterone prescriptions; while those with a previous prescription had limited improvement. It is possible that in veterans who had testosterone prescribed previously, HCPs may have assumed or had bias that the diagnosis and evaluation of hypogonadism originally made was adequate. This finding underscores the need to develop strategies for reviewing PADR requests where there is historical testosterone use. Perhaps a clinical team member, such as a clinical pharmacist, with the background and training in guidelines for the evaluation of hypogonadism could review PADR requests in veterans with previous testosterone use.

Removal of alternative ordering pathways for testosterone increased the completion rate of PADR requests and the testosterone ordering template, although the latter was not completed in one-third of veterans. Possible reasons for HCPs’ suboptimal completion of the testosterone template despite the PADR initiation include clinicians’ lack of willingness to read the PADR completely and familiarize themselves with the clinical guidelines due to workload demands of PCPs. In addition there maybe pressure from patients to receive testosterone for age-related symptoms due to heavy marketing. In addition, there may have been pharmacists who reviewed the PADR and approved the incomplete testosterone template. At VAPSHCS there were up to 40 pharmacists during different periods reviewing the testosterone PADRs. Likely, not everyone was completely familiar with this implementation process, and a possible future consideration would be further education to staff pharmacists who are verifying these prescriptions. There were several advantages to using this new testosterone order template when HCPs attempted to order a prescription. First, they were prompted to complete the PADR. Subsequently, a pharmacist reviewed the template and approved or rejected the prescription if the template was incomplete. The completed template served as documentation in the electronic health record for the prescribing HCP. The template was constructed to populate the required laboratory tests for ease of use and documentation. In addition, educational information regarding the symptoms and signs of testosterone deficiency, laboratory tests needed to confirm and evaluate hypogonadism, contraindications to testosterone treatment, and risks and benefits of therapy were incorporated into the template to assist HCPs in understanding the requirements for a complete diagnosis and evaluation. Finally, on completion of the template, HCPs were able to order testosterone via link to various testosterone formulations.

Before its implementation, the PADR testosterone order template was introduced to PCPs and internal medicine residents at 2 case-based conferences aimed at the diagnosis and treatment of male hypogonadism. These conferences were well received and helped launch the testosterone PADR template at VAPSHCS. Similar outreach to HCPs who prescribe testosterone is highly recommended in other VA facilities before implementation of the testosterone ordering template. It is possible that more targeted education to other HCPs would have resulted in greater use of the testosterone ordering template and adherence to clinical practice guidelines.

The VAPSHCS multidisciplinary workgroup was essential for the development, implementation, evaluation, and revision of the PADR and testosterone ordering template. The workgroup met routinely to follow up on the ease of installation in CPRS and discuss technical corrections that were needed. This was an essential for quality improvement, as loopholes in CPRS were identified where the HCP could order testosterone without being prompted to use the new PADR testosterone order template (alternative ordering pathways). The workgroup swiftly informed the IT specialist and HPS team to remove alternative ordering pathways of testosterone. Continuous quality improvement evaluations are highly recommended during implementation of the template in other facilities to accommodate specific local modifications that might be needed.

After February 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the National VA Pharmacy and Medication Board halted PADR requirements. As a result, further evaluation of the New Testosterone Order template and planned initial assessment of First Renewal Testosterone Order template could not be performed. In addition, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, there was restricted in-person outpatient visits and reduced adjustments to prescribing practices. To address recommendations made in the OIG report, the VAPSHCS testosterone order template was modified into a clinical reminder dialog format by a VA National IT Specialist and HPS team, tested for usability at several VA test sites and approved by the National Clinical Template Workgroup for implementation nationally across all VAs. The National Endocrinology Ambulatory Council Workgroup will ensure that this template is adopted in a similar format when the new electronic health record system Cerner is introduced to the VA.

Conclusions

The creation and implementation of a PADR testosterone order template may be a beneficial approach to improve the diagnosis of hypogonadism and facilitate appropriate use of testosterone therapy in veterans in accordance with established clinical practice guidelines, particularly in veterans without any prior testosterone use. Key future strategies to improve testosterone prescribing should focus on identifying clinical team members, such as a local clinical pharmacist, to review and steward PADR requests to ensure that testosterone is indicated, and treatment is appropriately monitored.

1. Bhasin S, Cunningham GR, Hayes FJ, Matsumoto AM, Snyder PJ, Swerdloff RS, Montori VM; Task Force, Endocrine Society. Testosterone therapy in men with androgen deficiency syndromes: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(6):2536-2559. doi:10.1210/jc.2009-2354

2. Grossmann M, Matsumoto AM. A perspective on middle-aged and older men with functional hypogonadism: focus on holistic management. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102(3):1067-1075. doi:10.1210/jc.2016-3580

3. Baillargeon J, Urban RJ, Kuo YF, et al. Screening and monitoring in men prescribed testosterone therapy in the US, 2001-2010. Public Health Rep. 2015;130(2):143-152. doi:10.1177/003335491513000207

4. Baillargeon J, Kuo Y, Westra JR, Urban RJ, Goodwin JS. Testosterone prescribing in the United States, 2002-2016. JAMA. 2018;320(2):200-202. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.7999

5. Jasuja GK, Bhasin S, Reisman JI, Berlowitz DR, Rose AJ. Ascertainment of testosterone prescribing practices in the VA. Med Care. 2015;53(9):746-52. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000000398

6. Jasuja GK, Bhasin S, Rose AJ. Patterns of testosterone prescription overuse. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2017;24(3):240-245. doi:10.1097/MED.0000000000000336

7. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Inspector General. Office of Healthcare Inspections. Report No. 15-03215-154. Published April 11, 2018. Accessed February 24, 2021. https://www.va.gov/oig/pubs/VAOIG-15-03215-154.pdf

Testosterone treatment is clinically indicated when a patient presents with symptoms and signs and biochemical evidence of testosterone deficiency, ie, male hypogonadism. Laboratory confirmation of hypogonadism requires repeatedly low serum testosterone concentrations; between 8

Recent studies have reported an increase in testosterone prescriptions and raised concerns regarding health care provider (HCP) prescribing practices despite current clinical practice guidelines from major societies, such as the Endocrine Society. In the US from 2001 to 2011, testosterone use among men aged ≥ 40 years increased more than 3-fold in all age groups.3 Subsequently in the years from 2013 to 2016, prescription rates declined perhaps due to the cardiovascular and stroke concerns.4

In the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), new testosterone prescriptions across VA medical centers increased from 20,437 in fiscal year (FY) 2009 to 36,394 in FY 2012. Yet only 3.1% of men who received testosterone therapy had 2 or more low morning total or free testosterone concentrations measured; LH and/or FSH levels assessed; and presence of contraindications to therapy documented. Remarkably, 16.5% of these veterans did not have a testosterone level tested prior to being prescribed testosterone. Among veterans who were prescribed testosterone, 1.4% had a diagnosis of prostate cancer, 7.6% had a diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), and 3.5% had elevated hematocrit at baseline.5 These findings raised concerns of whether the diagnosis and etiology of hypogonadism were appropriately established and risks were considered before testosterone treatment was initiated.5,6

To further understand VA prescribing practices of testosterone therapy, a 2018 VA Office of the Inspector General (OIG) report evaluated the initiation and follow-up of testosterone replacement therapy. The OIG randomly sampled and reviewed 1,091 male patients who filled at least 1 outpatient testosterone prescription from VA in FY 2014 and who did not have a prior testosterone prescription in FY 2013. Patients were followed through September 30, 2015. Within 1 year prior to initiating testosterone, only 1.5% had clinical signs and symptoms of testosterone deficiency documented prior to testosterone testing (76% within 18 months of starting testosterone); only 9.1% of veterans had the recommended measurements of 2 low morning testosterone levels; and only 12% had LH and FSH levels measured. Within 3 to 6 months after starting testosterone therapy, only 24% of veterans were assessed for symptom improvement, and 29% to 33% were evaluated for adverse effects, hematocrit levels and adherence to the therapy. The OIG report concluded that VA HCPs were not adhering to guidelines (referencing the Endocrine Society guidelines) when evaluating and treating veterans with testosterone deficiency.7

Considering the OIG recommendations and need to improve current practices among providers, VA Puget Sound Health Care System (VAPSHCS) in Washington established a multidisciplinary workgroup consisting of an endocrinologist, geriatrician, primary care provider (PCP), pharmacists, VA information technology (IT) specialist, and health products support (HPS) clinical team in the spring of 2019 to assess and improve testosterone prescribing practices.

Methods

A testosterone order template was developed, approved by VAPSHCS Pharmacy and Therapeutics Committee, and implemented on July 1, 2019, at VAPSHCS, a 1a medical facility caring for more than 112,000 veterans. Given its potential risks and the propensity for varied prescribing practices, testosterone was designated as a restricted drug requiring a prior authorization drug request (PADR) and required completion of the testosterone order template in the Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS).

Testosterone Order Template

The testosterone order template had 2 components. Completion of the template for new testosterone orders was required to initiate treatment unless the patient had known organic hypogonadism or was a transgender male. The template ensured documentation of defined symptoms and signs of testosterone deficiency; low serum testosterone levels on at least 2 occasions and LH and FSH concentrations; no contraindications to testosterone treatment; discussion of risks and benefits of therapy; and baseline hematocrit (Figure 1). Relevant educational content (eg, risks and benefits of testosterone) was incorporated in the template. The second template was required for the first renewal of testosterone to document adherence to or reason for discontinuation of testosterone; improvement of symptoms and signs; and confirm monitoring hematocrit and testosterone levels during treatment.

Prior to implementation, the PADR template was introduced to HCPs at 2 chief-of-medicine rounds on the diagnosis and evaluation of hypogonadism by a pharmacist and endocrinologist. These educational sessions used case examples and discussions to teach the appropriate use of testosterone therapy in men with hypogonadism. The target audience was PCPs, residents, and other specialists who might prescribe testosterone.

Retrospective Chart Review

To assess the impact of the new testosterone order template on adherence to OIG recommendations, a retrospective chart review was completed comparing the appropriateness of initiating testosterone replacement therapy pretemplate period (July 1 to December 31, 2018) vs posttemplate period (July 1 to December 31, 2019). Inclusion and exclusion criteria were modeled after the 2018 OIG report to allow for comparison with the OIG study population. Eligible veterans in each time period included males who received a new testosterone prescription without having been prescribed testosterone in the previous 12 months. Exclusion criteria included community care network prescriptions (CCNRx); current testosterone prescription from a different VA site; clinic administration of testosterone in the previous 12 months; an organic hypogonadism (ie, Klinefelter syndrome) or gender dysphoria diagnosis; and whether the testosterone prescription was never dispensed (PADR was denied or veteran never had the prescription filled). Veterans who met the inclusion criteria in CPRS were identified by an algorithm developed by the VAPSHCS pharmacoeconomist.

Determining the appropriateness of testosterone prescribing, such as symptoms and laboratory measurements to confirm the diagnosis of hypogonadism, was based on the OIG report and Endocrine Society guidelines. A chart review of the 12 months before testosterone prescribing was completed for each veteran, assessing for documentation of symptoms of testosterone deficiency and laboratory measurements of serum testosterone, LH, and FSH. Also, documentation of a discussion of risks and benefits of testosterone therapy in the 3 months before prescribing was assessed, which matched the timeframe in the VA OIG report.

Interim Analysis

After initial template implementation, the multidisciplinary workgroup reconvened for a preplanned interim analysis in November 2019. The evaluation at this meeting revealed multiple order pathways in CPRS that were not linked to the PADR testosterone order template. Testosterone could be ordered in the generic order dialog, medications by drug class, and medications by alphabet, and endocrinology specialty menus without prompting to complete the testosterone order template or redirection to the restricted drug menu (Figure 2). These alternative testosterone ordering pathways were removed in early December 2019 and additional data collection was conducted for 3 months after discontinuation of alternative order pathways, the posttemplate/no alternative ordering pathways period, from December 7, 2019 to February 29, 2020.

Exclusion of Previous Testosterone Prescriptions Predating Chart Review Period, Subgroup Analysis

In the OIG report and the initial retrospective chart review, only veterans without a testosterone prescription in the previous 12 months were evaluated. To assess whether a previous testosterone prescription influenced completion of the PADR and order template, a further subgroup analysis was conducted that excluded veterans who had a previous testosterone prescription at any time before the chart review periods. Therefore, “new testosterone prescription” refers to a veteran who never had a history of being on testosterone vs “former testosterone prescription,” meaning a patient could have had a previous testosterone prescription > 1 year prior to a new VA testosterone prescription.

Results

One hundred seventy-five veterans with a new testosterone prescription were identified in the pretemplate period; of these 80 (46%) met eligibility criteria; only 20 eligible veterans (25%) had a completed PADR (Figure 3). Ninety-one veterans with a new testosterone prescription were identified in the posttemplate period of which 41 (46%) veterans were eligible; 18 eligible veterans (44%) had a completed PADR, but only 7 (17%) had a completed testosterone order template.

After excluding veterans who had alternative ordering pathways for testosterone, 46 veterans were identified in the posttemplate/no alternative ordering pathways period of which 19 (41%) veterans were eligible. Compared with the posttemplate period, a higher proportion of eligible veterans, 68% (13) had a completed PADR, and 58% (11) had a testosterone order template during the posttemplate/no alternative ordering pathways period.

Compared with the OIG report findings, a similar percentage of veterans at VAPSHCS in the pretemplate period had documented clinical symptoms of testosterone deficiency and documented discussion of risks and benefits of testosterone therapy (Figure 4). However, a higher percentage of veterans had biochemical confirmation of testosterone deficiency with ≥ 2 low testosterone levels and evaluation of LH and FSH levels in the pretemplate period (23%) vs that in the OIG report (2%).

Compared with the pretemplate period, activation of the testosterone ordering template in the posttemplate period (Figure 4) had little effect on documented clinical symptoms and discussion of risks and benefits of testosterone treatment. However, the percentage of veterans who had ≥ 2 low testosterone levels and gonadotropins tested was higher in the posttemplate period (41%) vs both the pretemplate period and OIG report.

After removing alternative ordering pathways of testosterone, the percentages of veterans who had documented clinical symptoms, discussion of risks and benefits of testosterone, and ≥ 2 low testosterone levels and gonadotropin tests performed were similar in the posttemplate/no alternative ordering pathways vs posttemplate period.

Excluding veterans who had previously received a former testosterone prescription at any time prior to chart review periods, this subgroup analysis resulted in greater adherence to Endocrine Society guidelines for testosterone treatment with introduction of the testosterone order template, particularly after removal of alternative ordering pathway (Figure 5). With the exclusion of veterans who formerly received testosterone prescriptions, the percentages of veterans who had documented clinical symptoms, discussion of risks and benefits, and ≥ 2 low testosterone levels with gonadotropin tests were higher (100%, 57%, and 71%, respectively) in the posttemplate/no alternative ordering pathways period, compared with the pretemplate period (86%, 30%, and 32%, respectively).

Discussion

The 2018 OIG report found that VA practitioners demonstrated poor adherence to evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for testosterone treatment in men with hypogonadism. Based on OIG recommendations, we developed a PADR testosterone ordering template to help HCPs improve practice by better adherence to guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of hypogonadism in veterans. Before implementation of the PADR template, the percentage of veterans at VAPSHCS who had biochemical confirmation of hypogonadism was higher than that in the OIG report. Activation of the PADR testosterone ordering template (with or without removal of options for alternative ordering pathways of testosterone) resulted only in an improvement of laboratory confirmation and evaluation of etiology of hypogonadism. This is when we reasoned that clinicians may have access to prior records and laboratory testing beyond just the past year, and this information may have influenced their use of the PADR template. Subsequently, with exclusion of veterans who were previously prescribed testosterone, implementation of the PADR testosterone order template improved documentation of symptoms of testosterone deficiency, discussion of risks and benefits of testosterone therapy, and biochemical diagnosis and evaluation of hypogonadism relative to the period before implementation.

The lack of effects of implementing the testosterone order template on documentation of symptoms of testosterone deficiency and discussion of risks and benefits of testosterone therapy may be due to local expertise resulting in the relatively high adherence to these guideline recommendations at VAPSHCS before activation of the template vs that in the OIG report. The template improved documentation of the diagnosis and evaluation of hypogonadism for genuinely new testosterone prescriptions in veterans without a history of testosterone prescriptions; while those with a previous prescription had limited improvement. It is possible that in veterans who had testosterone prescribed previously, HCPs may have assumed or had bias that the diagnosis and evaluation of hypogonadism originally made was adequate. This finding underscores the need to develop strategies for reviewing PADR requests where there is historical testosterone use. Perhaps a clinical team member, such as a clinical pharmacist, with the background and training in guidelines for the evaluation of hypogonadism could review PADR requests in veterans with previous testosterone use.

Removal of alternative ordering pathways for testosterone increased the completion rate of PADR requests and the testosterone ordering template, although the latter was not completed in one-third of veterans. Possible reasons for HCPs’ suboptimal completion of the testosterone template despite the PADR initiation include clinicians’ lack of willingness to read the PADR completely and familiarize themselves with the clinical guidelines due to workload demands of PCPs. In addition there maybe pressure from patients to receive testosterone for age-related symptoms due to heavy marketing. In addition, there may have been pharmacists who reviewed the PADR and approved the incomplete testosterone template. At VAPSHCS there were up to 40 pharmacists during different periods reviewing the testosterone PADRs. Likely, not everyone was completely familiar with this implementation process, and a possible future consideration would be further education to staff pharmacists who are verifying these prescriptions. There were several advantages to using this new testosterone order template when HCPs attempted to order a prescription. First, they were prompted to complete the PADR. Subsequently, a pharmacist reviewed the template and approved or rejected the prescription if the template was incomplete. The completed template served as documentation in the electronic health record for the prescribing HCP. The template was constructed to populate the required laboratory tests for ease of use and documentation. In addition, educational information regarding the symptoms and signs of testosterone deficiency, laboratory tests needed to confirm and evaluate hypogonadism, contraindications to testosterone treatment, and risks and benefits of therapy were incorporated into the template to assist HCPs in understanding the requirements for a complete diagnosis and evaluation. Finally, on completion of the template, HCPs were able to order testosterone via link to various testosterone formulations.

Before its implementation, the PADR testosterone order template was introduced to PCPs and internal medicine residents at 2 case-based conferences aimed at the diagnosis and treatment of male hypogonadism. These conferences were well received and helped launch the testosterone PADR template at VAPSHCS. Similar outreach to HCPs who prescribe testosterone is highly recommended in other VA facilities before implementation of the testosterone ordering template. It is possible that more targeted education to other HCPs would have resulted in greater use of the testosterone ordering template and adherence to clinical practice guidelines.

The VAPSHCS multidisciplinary workgroup was essential for the development, implementation, evaluation, and revision of the PADR and testosterone ordering template. The workgroup met routinely to follow up on the ease of installation in CPRS and discuss technical corrections that were needed. This was an essential for quality improvement, as loopholes in CPRS were identified where the HCP could order testosterone without being prompted to use the new PADR testosterone order template (alternative ordering pathways). The workgroup swiftly informed the IT specialist and HPS team to remove alternative ordering pathways of testosterone. Continuous quality improvement evaluations are highly recommended during implementation of the template in other facilities to accommodate specific local modifications that might be needed.

After February 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the National VA Pharmacy and Medication Board halted PADR requirements. As a result, further evaluation of the New Testosterone Order template and planned initial assessment of First Renewal Testosterone Order template could not be performed. In addition, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, there was restricted in-person outpatient visits and reduced adjustments to prescribing practices. To address recommendations made in the OIG report, the VAPSHCS testosterone order template was modified into a clinical reminder dialog format by a VA National IT Specialist and HPS team, tested for usability at several VA test sites and approved by the National Clinical Template Workgroup for implementation nationally across all VAs. The National Endocrinology Ambulatory Council Workgroup will ensure that this template is adopted in a similar format when the new electronic health record system Cerner is introduced to the VA.

Conclusions

The creation and implementation of a PADR testosterone order template may be a beneficial approach to improve the diagnosis of hypogonadism and facilitate appropriate use of testosterone therapy in veterans in accordance with established clinical practice guidelines, particularly in veterans without any prior testosterone use. Key future strategies to improve testosterone prescribing should focus on identifying clinical team members, such as a local clinical pharmacist, to review and steward PADR requests to ensure that testosterone is indicated, and treatment is appropriately monitored.

Testosterone treatment is clinically indicated when a patient presents with symptoms and signs and biochemical evidence of testosterone deficiency, ie, male hypogonadism. Laboratory confirmation of hypogonadism requires repeatedly low serum testosterone concentrations; between 8

Recent studies have reported an increase in testosterone prescriptions and raised concerns regarding health care provider (HCP) prescribing practices despite current clinical practice guidelines from major societies, such as the Endocrine Society. In the US from 2001 to 2011, testosterone use among men aged ≥ 40 years increased more than 3-fold in all age groups.3 Subsequently in the years from 2013 to 2016, prescription rates declined perhaps due to the cardiovascular and stroke concerns.4

In the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), new testosterone prescriptions across VA medical centers increased from 20,437 in fiscal year (FY) 2009 to 36,394 in FY 2012. Yet only 3.1% of men who received testosterone therapy had 2 or more low morning total or free testosterone concentrations measured; LH and/or FSH levels assessed; and presence of contraindications to therapy documented. Remarkably, 16.5% of these veterans did not have a testosterone level tested prior to being prescribed testosterone. Among veterans who were prescribed testosterone, 1.4% had a diagnosis of prostate cancer, 7.6% had a diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), and 3.5% had elevated hematocrit at baseline.5 These findings raised concerns of whether the diagnosis and etiology of hypogonadism were appropriately established and risks were considered before testosterone treatment was initiated.5,6

To further understand VA prescribing practices of testosterone therapy, a 2018 VA Office of the Inspector General (OIG) report evaluated the initiation and follow-up of testosterone replacement therapy. The OIG randomly sampled and reviewed 1,091 male patients who filled at least 1 outpatient testosterone prescription from VA in FY 2014 and who did not have a prior testosterone prescription in FY 2013. Patients were followed through September 30, 2015. Within 1 year prior to initiating testosterone, only 1.5% had clinical signs and symptoms of testosterone deficiency documented prior to testosterone testing (76% within 18 months of starting testosterone); only 9.1% of veterans had the recommended measurements of 2 low morning testosterone levels; and only 12% had LH and FSH levels measured. Within 3 to 6 months after starting testosterone therapy, only 24% of veterans were assessed for symptom improvement, and 29% to 33% were evaluated for adverse effects, hematocrit levels and adherence to the therapy. The OIG report concluded that VA HCPs were not adhering to guidelines (referencing the Endocrine Society guidelines) when evaluating and treating veterans with testosterone deficiency.7