User login

Aaron Beck: An appreciation

He always dressed the same at conferences: dark suit, white shirt, bright red bow tie.

For all his fame, he was very kind, warmly greeting those who wanted to see him and immediately turning attention toward their research rather than his own. Aaron Beck actually didn’t lecture much; he preferred to roleplay cognitive therapy with an audience member acting as the patient. He would engage in what he called Socratic questioning, or more formally, cognitive restructuring, with warmth and true curiosity:

- What might be another explanation or viewpoint?

- What are the effects of thinking this way?

- Can you think of any evidence that supports the opposite view?

The audience member/patient would benefit not only from thinking about things differently, but also from the captivating interaction with the man, Aaron Temkin Beck, MD, (who went by Tim), youngest child of Jewish immigrants from the Ukraine.

When written up in treatment manuals, cognitive restructuring can seem cold and overly logical, but in person, Dr. Beck made it come to life. This ability to nurture curiosity was a special talent; his friend and fellow cognitive psychologist Donald Meichenbaum, PhD, recalls that even over lunch, he never stopped asking questions, personal and professional, on a wide range of topics.

It is widely accepted that Dr. Beck, who died Nov. 1 at the age of 100 in suburban Philadelphia, was the most important figure in the field of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT).

He didn’t invent the field. Behaviorism predated him by generations, founded by figures such as John Watson and B.F. Skinner. Those psychologists set up behaviorism as an alternative to the reigning power of Freudian psychoanalysis, but they ran a distant second.

It wasn’t until Dr. Beck added a new approach, cognitive therapy, to the behavioristic movement that the new mélange, CBT, began to gain traction with clinicians and researchers. Dr. Beck, who had trained in psychiatry, developed his ideas in the 1960s while observing what he believed were limitations in the classic Freudian methods. He recognized that patients had “automatic thoughts,” not just unconscious emotions, when they engaged in Freudian free association, saying whatever came to their minds.

These thoughts often distorted reality, he observed; they were “maladaptive beliefs,” and when they changed, patients’ emotional states improved.

Dr. Beck wasn’t alone. The psychologist Albert Ellis, PhD, in New York, had come to similar conclusions a decade earlier, though with a more coldly logical and challenging style. The prominent British psychologist Hans Eysenck, PhD, had argued strongly that Freudian psychoanalysis was ineffective and that behavioral approaches were better.

Dr. Beck turned the Freudian equation around: Instead of emotion as cause and thought as effect, it was thought which affected emotion, for better or worse. Once you connected behavior as the outcome, you had the essence of CBT: thought, emotion, and behavior – each affecting the other, with thought being the strongest axis of change.

The process wasn’t bloodless. Behaviorists defended their turf against cognitivists, just as much as Freudians rejected both. At one point the behaviorists in the Association for the Advancement of Behavior Therapy tried to expel the advocates of a cognitive approach. Dr. Beck responded by leading the cognitivists in creating a new journal; he emphasized the importance of research being the main mechanism to decide what treatments worked the best.

Putting these ideas out in the 1960s and 1970s, Dr. Beck garnered support from researchers when he manualized the approach. Freudian psychoanalysis was idiosyncratic; it was almost impossible to study empirically, because the therapist would be responding to the unpredictable dreams and memories of patients engaged in free association. Each case was unique.

But CBT was systematic: The same general approach was taken to all patients; the same negative cognitions were found in depression, for instance, like all-or-nothing thinking or overgeneralization. Once manualized, CBT became the standard method of psychotherapy studied with the newly developed method of randomized controlled trials (RCTs).

By the 1980s, RCTs had proven the efficacy of CBT in depression, and the approach took off.

Dr. Beck already had developed a series of rating scales: the Beck Depression Inventory, the Beck Scale for Suicidal Ideation, the Beck Anxiety Inventory, the Beck Hopelessness Scale. Widely used, these scales extended his influence enormously. Copyrighted, they created a new industry of psychological research.

Dr. Beck’s own work was mainly in depression, but his followers extended it everywhere else: anxiety disorders and phobias, eating disorders, substance abuse, bipolar illness, even schizophrenia. Meanwhile, Freudian psychoanalysis fell into a steep decline from which it never recovered.

Some argued that it was abetted by insurance restrictions on psychotherapy, which favored shorter-term CBT; others that its research was biased in its favor because psychotherapy treatments, unlike medications, cannot be blinded; others that its efficacy could not be shown to be specific to its theory, as opposed to the interpersonal relationship between therapist and client.

Still, CBT has transformed psychotherapy and continues to expand its influence. Computer-based CBT has been proven effective, and digital CBT has become a standard approach in many smartphone applications and is central to the claims of multiple new biotechnology companies advocating for digital psychotherapy.

Aaron Beck continued publishing scientific articles to age 98. His last papers reviewed his life’s work. He characteristically gave credit to others, calmly recollected how he traveled away from psychoanalysis, described how his work started and ended in schizophrenia, and noted that the “working relationship with the therapist” remained a key factor for the success of CBT.

That parting comment reminds us that behind all the technology and research stands the kindly man in the dark suit, white shirt, and bright red bow tie, looking at you warmly, asking about your thoughts, and curiously wondering what might be another explanation or viewpoint you hadn’t considered.

Nassir Ghaemi, MD, MPH, is a professor of psychiatry at Tufts Medical Center and a lecturer in psychiatry at Harvard Medical School. He is the author of several general-interest books on psychiatry. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

He always dressed the same at conferences: dark suit, white shirt, bright red bow tie.

For all his fame, he was very kind, warmly greeting those who wanted to see him and immediately turning attention toward their research rather than his own. Aaron Beck actually didn’t lecture much; he preferred to roleplay cognitive therapy with an audience member acting as the patient. He would engage in what he called Socratic questioning, or more formally, cognitive restructuring, with warmth and true curiosity:

- What might be another explanation or viewpoint?

- What are the effects of thinking this way?

- Can you think of any evidence that supports the opposite view?

The audience member/patient would benefit not only from thinking about things differently, but also from the captivating interaction with the man, Aaron Temkin Beck, MD, (who went by Tim), youngest child of Jewish immigrants from the Ukraine.

When written up in treatment manuals, cognitive restructuring can seem cold and overly logical, but in person, Dr. Beck made it come to life. This ability to nurture curiosity was a special talent; his friend and fellow cognitive psychologist Donald Meichenbaum, PhD, recalls that even over lunch, he never stopped asking questions, personal and professional, on a wide range of topics.

It is widely accepted that Dr. Beck, who died Nov. 1 at the age of 100 in suburban Philadelphia, was the most important figure in the field of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT).

He didn’t invent the field. Behaviorism predated him by generations, founded by figures such as John Watson and B.F. Skinner. Those psychologists set up behaviorism as an alternative to the reigning power of Freudian psychoanalysis, but they ran a distant second.

It wasn’t until Dr. Beck added a new approach, cognitive therapy, to the behavioristic movement that the new mélange, CBT, began to gain traction with clinicians and researchers. Dr. Beck, who had trained in psychiatry, developed his ideas in the 1960s while observing what he believed were limitations in the classic Freudian methods. He recognized that patients had “automatic thoughts,” not just unconscious emotions, when they engaged in Freudian free association, saying whatever came to their minds.

These thoughts often distorted reality, he observed; they were “maladaptive beliefs,” and when they changed, patients’ emotional states improved.

Dr. Beck wasn’t alone. The psychologist Albert Ellis, PhD, in New York, had come to similar conclusions a decade earlier, though with a more coldly logical and challenging style. The prominent British psychologist Hans Eysenck, PhD, had argued strongly that Freudian psychoanalysis was ineffective and that behavioral approaches were better.

Dr. Beck turned the Freudian equation around: Instead of emotion as cause and thought as effect, it was thought which affected emotion, for better or worse. Once you connected behavior as the outcome, you had the essence of CBT: thought, emotion, and behavior – each affecting the other, with thought being the strongest axis of change.

The process wasn’t bloodless. Behaviorists defended their turf against cognitivists, just as much as Freudians rejected both. At one point the behaviorists in the Association for the Advancement of Behavior Therapy tried to expel the advocates of a cognitive approach. Dr. Beck responded by leading the cognitivists in creating a new journal; he emphasized the importance of research being the main mechanism to decide what treatments worked the best.

Putting these ideas out in the 1960s and 1970s, Dr. Beck garnered support from researchers when he manualized the approach. Freudian psychoanalysis was idiosyncratic; it was almost impossible to study empirically, because the therapist would be responding to the unpredictable dreams and memories of patients engaged in free association. Each case was unique.

But CBT was systematic: The same general approach was taken to all patients; the same negative cognitions were found in depression, for instance, like all-or-nothing thinking or overgeneralization. Once manualized, CBT became the standard method of psychotherapy studied with the newly developed method of randomized controlled trials (RCTs).

By the 1980s, RCTs had proven the efficacy of CBT in depression, and the approach took off.

Dr. Beck already had developed a series of rating scales: the Beck Depression Inventory, the Beck Scale for Suicidal Ideation, the Beck Anxiety Inventory, the Beck Hopelessness Scale. Widely used, these scales extended his influence enormously. Copyrighted, they created a new industry of psychological research.

Dr. Beck’s own work was mainly in depression, but his followers extended it everywhere else: anxiety disorders and phobias, eating disorders, substance abuse, bipolar illness, even schizophrenia. Meanwhile, Freudian psychoanalysis fell into a steep decline from which it never recovered.

Some argued that it was abetted by insurance restrictions on psychotherapy, which favored shorter-term CBT; others that its research was biased in its favor because psychotherapy treatments, unlike medications, cannot be blinded; others that its efficacy could not be shown to be specific to its theory, as opposed to the interpersonal relationship between therapist and client.

Still, CBT has transformed psychotherapy and continues to expand its influence. Computer-based CBT has been proven effective, and digital CBT has become a standard approach in many smartphone applications and is central to the claims of multiple new biotechnology companies advocating for digital psychotherapy.

Aaron Beck continued publishing scientific articles to age 98. His last papers reviewed his life’s work. He characteristically gave credit to others, calmly recollected how he traveled away from psychoanalysis, described how his work started and ended in schizophrenia, and noted that the “working relationship with the therapist” remained a key factor for the success of CBT.

That parting comment reminds us that behind all the technology and research stands the kindly man in the dark suit, white shirt, and bright red bow tie, looking at you warmly, asking about your thoughts, and curiously wondering what might be another explanation or viewpoint you hadn’t considered.

Nassir Ghaemi, MD, MPH, is a professor of psychiatry at Tufts Medical Center and a lecturer in psychiatry at Harvard Medical School. He is the author of several general-interest books on psychiatry. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

He always dressed the same at conferences: dark suit, white shirt, bright red bow tie.

For all his fame, he was very kind, warmly greeting those who wanted to see him and immediately turning attention toward their research rather than his own. Aaron Beck actually didn’t lecture much; he preferred to roleplay cognitive therapy with an audience member acting as the patient. He would engage in what he called Socratic questioning, or more formally, cognitive restructuring, with warmth and true curiosity:

- What might be another explanation or viewpoint?

- What are the effects of thinking this way?

- Can you think of any evidence that supports the opposite view?

The audience member/patient would benefit not only from thinking about things differently, but also from the captivating interaction with the man, Aaron Temkin Beck, MD, (who went by Tim), youngest child of Jewish immigrants from the Ukraine.

When written up in treatment manuals, cognitive restructuring can seem cold and overly logical, but in person, Dr. Beck made it come to life. This ability to nurture curiosity was a special talent; his friend and fellow cognitive psychologist Donald Meichenbaum, PhD, recalls that even over lunch, he never stopped asking questions, personal and professional, on a wide range of topics.

It is widely accepted that Dr. Beck, who died Nov. 1 at the age of 100 in suburban Philadelphia, was the most important figure in the field of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT).

He didn’t invent the field. Behaviorism predated him by generations, founded by figures such as John Watson and B.F. Skinner. Those psychologists set up behaviorism as an alternative to the reigning power of Freudian psychoanalysis, but they ran a distant second.

It wasn’t until Dr. Beck added a new approach, cognitive therapy, to the behavioristic movement that the new mélange, CBT, began to gain traction with clinicians and researchers. Dr. Beck, who had trained in psychiatry, developed his ideas in the 1960s while observing what he believed were limitations in the classic Freudian methods. He recognized that patients had “automatic thoughts,” not just unconscious emotions, when they engaged in Freudian free association, saying whatever came to their minds.

These thoughts often distorted reality, he observed; they were “maladaptive beliefs,” and when they changed, patients’ emotional states improved.

Dr. Beck wasn’t alone. The psychologist Albert Ellis, PhD, in New York, had come to similar conclusions a decade earlier, though with a more coldly logical and challenging style. The prominent British psychologist Hans Eysenck, PhD, had argued strongly that Freudian psychoanalysis was ineffective and that behavioral approaches were better.

Dr. Beck turned the Freudian equation around: Instead of emotion as cause and thought as effect, it was thought which affected emotion, for better or worse. Once you connected behavior as the outcome, you had the essence of CBT: thought, emotion, and behavior – each affecting the other, with thought being the strongest axis of change.

The process wasn’t bloodless. Behaviorists defended their turf against cognitivists, just as much as Freudians rejected both. At one point the behaviorists in the Association for the Advancement of Behavior Therapy tried to expel the advocates of a cognitive approach. Dr. Beck responded by leading the cognitivists in creating a new journal; he emphasized the importance of research being the main mechanism to decide what treatments worked the best.

Putting these ideas out in the 1960s and 1970s, Dr. Beck garnered support from researchers when he manualized the approach. Freudian psychoanalysis was idiosyncratic; it was almost impossible to study empirically, because the therapist would be responding to the unpredictable dreams and memories of patients engaged in free association. Each case was unique.

But CBT was systematic: The same general approach was taken to all patients; the same negative cognitions were found in depression, for instance, like all-or-nothing thinking or overgeneralization. Once manualized, CBT became the standard method of psychotherapy studied with the newly developed method of randomized controlled trials (RCTs).

By the 1980s, RCTs had proven the efficacy of CBT in depression, and the approach took off.

Dr. Beck already had developed a series of rating scales: the Beck Depression Inventory, the Beck Scale for Suicidal Ideation, the Beck Anxiety Inventory, the Beck Hopelessness Scale. Widely used, these scales extended his influence enormously. Copyrighted, they created a new industry of psychological research.

Dr. Beck’s own work was mainly in depression, but his followers extended it everywhere else: anxiety disorders and phobias, eating disorders, substance abuse, bipolar illness, even schizophrenia. Meanwhile, Freudian psychoanalysis fell into a steep decline from which it never recovered.

Some argued that it was abetted by insurance restrictions on psychotherapy, which favored shorter-term CBT; others that its research was biased in its favor because psychotherapy treatments, unlike medications, cannot be blinded; others that its efficacy could not be shown to be specific to its theory, as opposed to the interpersonal relationship between therapist and client.

Still, CBT has transformed psychotherapy and continues to expand its influence. Computer-based CBT has been proven effective, and digital CBT has become a standard approach in many smartphone applications and is central to the claims of multiple new biotechnology companies advocating for digital psychotherapy.

Aaron Beck continued publishing scientific articles to age 98. His last papers reviewed his life’s work. He characteristically gave credit to others, calmly recollected how he traveled away from psychoanalysis, described how his work started and ended in schizophrenia, and noted that the “working relationship with the therapist” remained a key factor for the success of CBT.

That parting comment reminds us that behind all the technology and research stands the kindly man in the dark suit, white shirt, and bright red bow tie, looking at you warmly, asking about your thoughts, and curiously wondering what might be another explanation or viewpoint you hadn’t considered.

Nassir Ghaemi, MD, MPH, is a professor of psychiatry at Tufts Medical Center and a lecturer in psychiatry at Harvard Medical School. He is the author of several general-interest books on psychiatry. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

City or country life? Genetic risk for mental illness may decide

Individuals with a genetic predisposition to schizophrenia, bipolar disorder (BD), autism spectrum disorder (ASD), or anorexia nervosa (AN) are significantly more likely to move from a rural to an urban setting, whereas those at high genetic risk for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder were more likely to do the opposite.

The findings held even in those at high genetic risk who had never been diagnosed with a psychiatric disorder, highlighting a genetic factor that previous research linking urban living to mental illness has not explored.

“It’s not as simple as saying that urban environment is responsible for schizophrenia and everyone should move out of urban environments and they will be safe,” study investigator Evangelos Vassos, MD, PhD, senior clinical research fellow at King’s College London, and a consulting psychiatrist, said in an interview. “If you are genetically predisposed to schizophrenia, you will still be predisposed to schizophrenia even if you move.”

The study was published online in JAMA Psychiatry.

Genetic influence

The study results don’t rule out environmental influence, but offer evidence that the migration pattern researchers have tracked for years may have a multifactorial explanation.

“Our research shows that, at some level, an individual’s genes select their environment and that the relationship between environmental and genetic influences on mental health is interrelated,” Jessye Maxwell, MSc, lead author and a PhD candidate in psychiatry at King’s College, said in a statement. “This overlap needs to be considered when developing models to predict the risk of people developing mental health conditions in the future.”

For the study, the investigators calculated polygenic risk scores (PRS) of different psychiatric illnesses for 385,793 U.K. Biobank participants aged 37-73. PRS analyzes genetic information across a person’s entire genome, rather than by individual genes.

They used address history and U.K. census records from 1931 to 2011 to map population density over time.

PRS analyses showed significant associations with higher population density throughout adulthood, reaching highest significance between age 45 and 55 years for schizophrenia (88 people/km2; 95% confidence interval, 65-98 people/km2), BD (44 people/km2; 95%CI, 34-54 people/km2), AN (36 people/km2; 95%CI, 22-50 people/km2), and ASD (35 people/km2; 95%CI, 25-45 people/km2).

When they compared those who were born and stayed in rural or suburban areas to their counterparts who moved from those areas to cities, they found the odds of moving to urban areas ranged from 5% among people at high genetic risk for schizophrenia to 13% of those with a high risk for BD. Only people at high risk for ADHD were more likely to move to rural areas.

However, the study is not without its limitations. Only people of European descent were included, family medical history was unavailable for some participants, and only about 50,000 people had a lifetime diagnosis of mental illness, which is not representative of the general population.

‘Convincing evidence’

Still, the research adds another piece of the puzzle scientists seek to solve about where people live and mental illness risk, said Jordan DeVylder, PhD, associate professor of social work at Fordham University, New York, who commented on the study for this news organization.

Dr. DeVylder, who has also published research on the topic but was not part of the current study, noted that urban living has long been thought to be among the most consistent environmental risk factors for psychosis. However, he noted, “this association can also be explained by genetic selection, in which the same genes that predispose one to schizophrenia also predispose one to choose urban living.”

“This study presents the most convincing evidence to date that genetics have a major role in this association, at least in the countries where this association between urban living and psychosis exists,” he said.

The study was funded by National Institute for Health Research, Biomedical Research Centre at South London and Maudsley National Health Service Foundation Trust and King’s College London. The authors and Dr. DeVylder have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Individuals with a genetic predisposition to schizophrenia, bipolar disorder (BD), autism spectrum disorder (ASD), or anorexia nervosa (AN) are significantly more likely to move from a rural to an urban setting, whereas those at high genetic risk for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder were more likely to do the opposite.

The findings held even in those at high genetic risk who had never been diagnosed with a psychiatric disorder, highlighting a genetic factor that previous research linking urban living to mental illness has not explored.

“It’s not as simple as saying that urban environment is responsible for schizophrenia and everyone should move out of urban environments and they will be safe,” study investigator Evangelos Vassos, MD, PhD, senior clinical research fellow at King’s College London, and a consulting psychiatrist, said in an interview. “If you are genetically predisposed to schizophrenia, you will still be predisposed to schizophrenia even if you move.”

The study was published online in JAMA Psychiatry.

Genetic influence

The study results don’t rule out environmental influence, but offer evidence that the migration pattern researchers have tracked for years may have a multifactorial explanation.

“Our research shows that, at some level, an individual’s genes select their environment and that the relationship between environmental and genetic influences on mental health is interrelated,” Jessye Maxwell, MSc, lead author and a PhD candidate in psychiatry at King’s College, said in a statement. “This overlap needs to be considered when developing models to predict the risk of people developing mental health conditions in the future.”

For the study, the investigators calculated polygenic risk scores (PRS) of different psychiatric illnesses for 385,793 U.K. Biobank participants aged 37-73. PRS analyzes genetic information across a person’s entire genome, rather than by individual genes.

They used address history and U.K. census records from 1931 to 2011 to map population density over time.

PRS analyses showed significant associations with higher population density throughout adulthood, reaching highest significance between age 45 and 55 years for schizophrenia (88 people/km2; 95% confidence interval, 65-98 people/km2), BD (44 people/km2; 95%CI, 34-54 people/km2), AN (36 people/km2; 95%CI, 22-50 people/km2), and ASD (35 people/km2; 95%CI, 25-45 people/km2).

When they compared those who were born and stayed in rural or suburban areas to their counterparts who moved from those areas to cities, they found the odds of moving to urban areas ranged from 5% among people at high genetic risk for schizophrenia to 13% of those with a high risk for BD. Only people at high risk for ADHD were more likely to move to rural areas.

However, the study is not without its limitations. Only people of European descent were included, family medical history was unavailable for some participants, and only about 50,000 people had a lifetime diagnosis of mental illness, which is not representative of the general population.

‘Convincing evidence’

Still, the research adds another piece of the puzzle scientists seek to solve about where people live and mental illness risk, said Jordan DeVylder, PhD, associate professor of social work at Fordham University, New York, who commented on the study for this news organization.

Dr. DeVylder, who has also published research on the topic but was not part of the current study, noted that urban living has long been thought to be among the most consistent environmental risk factors for psychosis. However, he noted, “this association can also be explained by genetic selection, in which the same genes that predispose one to schizophrenia also predispose one to choose urban living.”

“This study presents the most convincing evidence to date that genetics have a major role in this association, at least in the countries where this association between urban living and psychosis exists,” he said.

The study was funded by National Institute for Health Research, Biomedical Research Centre at South London and Maudsley National Health Service Foundation Trust and King’s College London. The authors and Dr. DeVylder have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Individuals with a genetic predisposition to schizophrenia, bipolar disorder (BD), autism spectrum disorder (ASD), or anorexia nervosa (AN) are significantly more likely to move from a rural to an urban setting, whereas those at high genetic risk for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder were more likely to do the opposite.

The findings held even in those at high genetic risk who had never been diagnosed with a psychiatric disorder, highlighting a genetic factor that previous research linking urban living to mental illness has not explored.

“It’s not as simple as saying that urban environment is responsible for schizophrenia and everyone should move out of urban environments and they will be safe,” study investigator Evangelos Vassos, MD, PhD, senior clinical research fellow at King’s College London, and a consulting psychiatrist, said in an interview. “If you are genetically predisposed to schizophrenia, you will still be predisposed to schizophrenia even if you move.”

The study was published online in JAMA Psychiatry.

Genetic influence

The study results don’t rule out environmental influence, but offer evidence that the migration pattern researchers have tracked for years may have a multifactorial explanation.

“Our research shows that, at some level, an individual’s genes select their environment and that the relationship between environmental and genetic influences on mental health is interrelated,” Jessye Maxwell, MSc, lead author and a PhD candidate in psychiatry at King’s College, said in a statement. “This overlap needs to be considered when developing models to predict the risk of people developing mental health conditions in the future.”

For the study, the investigators calculated polygenic risk scores (PRS) of different psychiatric illnesses for 385,793 U.K. Biobank participants aged 37-73. PRS analyzes genetic information across a person’s entire genome, rather than by individual genes.

They used address history and U.K. census records from 1931 to 2011 to map population density over time.

PRS analyses showed significant associations with higher population density throughout adulthood, reaching highest significance between age 45 and 55 years for schizophrenia (88 people/km2; 95% confidence interval, 65-98 people/km2), BD (44 people/km2; 95%CI, 34-54 people/km2), AN (36 people/km2; 95%CI, 22-50 people/km2), and ASD (35 people/km2; 95%CI, 25-45 people/km2).

When they compared those who were born and stayed in rural or suburban areas to their counterparts who moved from those areas to cities, they found the odds of moving to urban areas ranged from 5% among people at high genetic risk for schizophrenia to 13% of those with a high risk for BD. Only people at high risk for ADHD were more likely to move to rural areas.

However, the study is not without its limitations. Only people of European descent were included, family medical history was unavailable for some participants, and only about 50,000 people had a lifetime diagnosis of mental illness, which is not representative of the general population.

‘Convincing evidence’

Still, the research adds another piece of the puzzle scientists seek to solve about where people live and mental illness risk, said Jordan DeVylder, PhD, associate professor of social work at Fordham University, New York, who commented on the study for this news organization.

Dr. DeVylder, who has also published research on the topic but was not part of the current study, noted that urban living has long been thought to be among the most consistent environmental risk factors for psychosis. However, he noted, “this association can also be explained by genetic selection, in which the same genes that predispose one to schizophrenia also predispose one to choose urban living.”

“This study presents the most convincing evidence to date that genetics have a major role in this association, at least in the countries where this association between urban living and psychosis exists,” he said.

The study was funded by National Institute for Health Research, Biomedical Research Centre at South London and Maudsley National Health Service Foundation Trust and King’s College London. The authors and Dr. DeVylder have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA PSYCHIATRY

FDA not recognizing efficacy of psychopharmacologic therapies

Many years ago, drug development in psychiatry turned to control of specific symptoms across disorders rather than within disorders, but regulatory agencies are still not yet on board, according to an expert psychopharmacologist outlining the ongoing evolution at the virtual Psychopharmacology Update presented by Current Psychiatry and the American Academy of Clinical Psychiatrists, sponsored by Medscape Live.

If this reorientation is going to lead to the broad indications the newer drugs likely deserve, which is control of specific types of symptoms regardless of the diagnosis, “we have to move the [Food and Drug Administration] along,” said Stephen M. Stahl, MD, PhD, chairman of the Neuroscience Institute and an adjunct professor of psychiatry at the University of California, San Diego.

On the side of drug development and clinical practice, the reorientation has already taken place. Dr. Stahl described numerous brain circuits known to produce symptoms when function is altered that are now treatment targets. This includes the ventral medial prefrontal cortex where deficient information processing leads to depression and the orbital frontal cortex where altered function leads to impulsivity.

“It is not like each part of the brain does a little bit of everything. Rather, each part of the brain has an assignment and duty and function,” Dr. Stahl explained. By addressing the disturbed signaling in brain circuits that lead to depression, impulsivity, agitation, or other symptoms, there is an opportunity for control, regardless of the psychiatric diagnosis with which the symptom is associated.

For example, Dr. Stahl predicted that pimavanserin, a highly selective 5-HT2A inverse agonist that is already approved for psychosis in Parkinson’s disease, is now likely to be approved for psychosis associated with other conditions on the basis of recent positive clinical studies in these other disorders.

Brexpiprazole, a serotonin-dopamine activity modulator already known to be useful for control of the agitation characteristic of schizophrenia, is now showing the same type of activity against agitation when it is associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Again, Dr. Stahl thinks this drug is on course for an indication across diseases once studies are conducted in each disease individually.

Another drug being evaluated for agitation, the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonist dextromethorphan bupropion, is also being tested for treatment of symptoms across multiple disorders, he reported.

However, the FDA has so far taken the position that each drug must be tested separately for a given symptom in each disorder for which it is being considered despite the underlying premise that it is the symptom, not the disease, that is important.

Unlike physiological diseases where symptoms, like a fever or abdominal cramps, are the product of a disease, psychiatric symptoms are the disease and a fundamental target – regardless of the DSM-based diagnosis.

To some degree, the symptoms of psychiatric disorders have always been the focus of treatment, but a pivot toward developing therapies that will control a symptom regardless of the underlying diagnosis is an important conceptual change. It is being made possible by advances in the detail with which the neuropathology of these symptoms is understood .

“By my count, 79 symptoms are described in DSM-5, but they are spread across hundreds of syndromes because they are grouped together in different ways,” Dr. Stahl observed.

He noted that clinicians make a diagnosis on the basis symptom groupings, but their interventions are selected to address the manifestations of the disease, not the disease itself.

“If you are a real psychopharmacologist treating real patients, you are treating the specific symptoms of the specific patient,” according to Dr. Stahl.

So far, the FDA has not made this leap, insisting on trials in these categorical disorders rather than permitting trial designs that allow benefit to be demonstrated against a symptom regardless of the syndrome with which it is associated.

Of egregious examples, Dr. Stahl recounted a recent trial of a 5-HT2 antagonist that looked so promising against psychosis in Alzheimer’s disease that the trialists enrolled patients with psychosis regardless of type of dementia, such as vascular dementia and Lewy body disease. The efficacy was impressive.

“It worked so well that they stopped the trial, but the FDA declined to approve it,” Dr. Stahl recounted. Despite clear evidence of benefit, the regulators insisted that the investigators needed to show a significant benefit in each condition individually.

While the trial investigators acknowledged that there was not enough power in the trial to show a statistically significant benefit in each category, they argued that the overall benefit and the consistent response across categories required them to stop the trial for ethical reasons.

“That’s your problem, the FDA said to the investigators,” according to Dr. Stahl.

The failure of the FDA to recognize the efficacy of psychopharmacologic therapies across symptoms regardless of the associated disease is a failure to stay current with an important evolution in medicine, Dr. Stahl indicated.

“What we have come to understand is the neurobiology of any given symptom is likely to be the same across disorders,” he said.

Agency’s arbitrary decisions cited

“I completely agree with Dr. Stahl,” said Henry A. Nasrallah, MD, professor of psychiatry, neurology, and neuroscience, University of Cincinnati.

In addition to the fact that symptoms are present across multiple categories, many patients manifest multiple symptoms at one time, Dr. Nasrallah pointed out. For neurodegenerative disorders associated with psychosis, depression, anxiety, aggression, and other symptoms, it is already well known that the heterogeneous symptoms “cannot be treated with a single drug,” he said. Rather different drugs targeting each symptom individually is essential for effective management.

Dr. Nasrallah, who chaired the Psychopharmacology Update meeting, has made this point many times in the past, including in his role as the editor of Current Psychiatry. In one editorial 10 years ago, he wrote that “it makes little sense for the FDA to mandate that a drug must work for a DSM diagnosis instead of specific symptoms.”

“The FDA must update its old policy, which has led to the widespread off-label use of psychiatric drugs, an artificial concept, simply because the FDA arbitrarily decided a long time ago that new drugs must be approved for a specific DSM diagnosis,” Dr. Nasrallah said.

Dr. Stahl reported financial relationships with more than 20 pharmaceutical companies, including those that are involved in the development of drugs included in his talk. Medscape Live and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

Many years ago, drug development in psychiatry turned to control of specific symptoms across disorders rather than within disorders, but regulatory agencies are still not yet on board, according to an expert psychopharmacologist outlining the ongoing evolution at the virtual Psychopharmacology Update presented by Current Psychiatry and the American Academy of Clinical Psychiatrists, sponsored by Medscape Live.

If this reorientation is going to lead to the broad indications the newer drugs likely deserve, which is control of specific types of symptoms regardless of the diagnosis, “we have to move the [Food and Drug Administration] along,” said Stephen M. Stahl, MD, PhD, chairman of the Neuroscience Institute and an adjunct professor of psychiatry at the University of California, San Diego.

On the side of drug development and clinical practice, the reorientation has already taken place. Dr. Stahl described numerous brain circuits known to produce symptoms when function is altered that are now treatment targets. This includes the ventral medial prefrontal cortex where deficient information processing leads to depression and the orbital frontal cortex where altered function leads to impulsivity.

“It is not like each part of the brain does a little bit of everything. Rather, each part of the brain has an assignment and duty and function,” Dr. Stahl explained. By addressing the disturbed signaling in brain circuits that lead to depression, impulsivity, agitation, or other symptoms, there is an opportunity for control, regardless of the psychiatric diagnosis with which the symptom is associated.

For example, Dr. Stahl predicted that pimavanserin, a highly selective 5-HT2A inverse agonist that is already approved for psychosis in Parkinson’s disease, is now likely to be approved for psychosis associated with other conditions on the basis of recent positive clinical studies in these other disorders.

Brexpiprazole, a serotonin-dopamine activity modulator already known to be useful for control of the agitation characteristic of schizophrenia, is now showing the same type of activity against agitation when it is associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Again, Dr. Stahl thinks this drug is on course for an indication across diseases once studies are conducted in each disease individually.

Another drug being evaluated for agitation, the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonist dextromethorphan bupropion, is also being tested for treatment of symptoms across multiple disorders, he reported.

However, the FDA has so far taken the position that each drug must be tested separately for a given symptom in each disorder for which it is being considered despite the underlying premise that it is the symptom, not the disease, that is important.

Unlike physiological diseases where symptoms, like a fever or abdominal cramps, are the product of a disease, psychiatric symptoms are the disease and a fundamental target – regardless of the DSM-based diagnosis.

To some degree, the symptoms of psychiatric disorders have always been the focus of treatment, but a pivot toward developing therapies that will control a symptom regardless of the underlying diagnosis is an important conceptual change. It is being made possible by advances in the detail with which the neuropathology of these symptoms is understood .

“By my count, 79 symptoms are described in DSM-5, but they are spread across hundreds of syndromes because they are grouped together in different ways,” Dr. Stahl observed.

He noted that clinicians make a diagnosis on the basis symptom groupings, but their interventions are selected to address the manifestations of the disease, not the disease itself.

“If you are a real psychopharmacologist treating real patients, you are treating the specific symptoms of the specific patient,” according to Dr. Stahl.

So far, the FDA has not made this leap, insisting on trials in these categorical disorders rather than permitting trial designs that allow benefit to be demonstrated against a symptom regardless of the syndrome with which it is associated.

Of egregious examples, Dr. Stahl recounted a recent trial of a 5-HT2 antagonist that looked so promising against psychosis in Alzheimer’s disease that the trialists enrolled patients with psychosis regardless of type of dementia, such as vascular dementia and Lewy body disease. The efficacy was impressive.

“It worked so well that they stopped the trial, but the FDA declined to approve it,” Dr. Stahl recounted. Despite clear evidence of benefit, the regulators insisted that the investigators needed to show a significant benefit in each condition individually.

While the trial investigators acknowledged that there was not enough power in the trial to show a statistically significant benefit in each category, they argued that the overall benefit and the consistent response across categories required them to stop the trial for ethical reasons.

“That’s your problem, the FDA said to the investigators,” according to Dr. Stahl.

The failure of the FDA to recognize the efficacy of psychopharmacologic therapies across symptoms regardless of the associated disease is a failure to stay current with an important evolution in medicine, Dr. Stahl indicated.

“What we have come to understand is the neurobiology of any given symptom is likely to be the same across disorders,” he said.

Agency’s arbitrary decisions cited

“I completely agree with Dr. Stahl,” said Henry A. Nasrallah, MD, professor of psychiatry, neurology, and neuroscience, University of Cincinnati.

In addition to the fact that symptoms are present across multiple categories, many patients manifest multiple symptoms at one time, Dr. Nasrallah pointed out. For neurodegenerative disorders associated with psychosis, depression, anxiety, aggression, and other symptoms, it is already well known that the heterogeneous symptoms “cannot be treated with a single drug,” he said. Rather different drugs targeting each symptom individually is essential for effective management.

Dr. Nasrallah, who chaired the Psychopharmacology Update meeting, has made this point many times in the past, including in his role as the editor of Current Psychiatry. In one editorial 10 years ago, he wrote that “it makes little sense for the FDA to mandate that a drug must work for a DSM diagnosis instead of specific symptoms.”

“The FDA must update its old policy, which has led to the widespread off-label use of psychiatric drugs, an artificial concept, simply because the FDA arbitrarily decided a long time ago that new drugs must be approved for a specific DSM diagnosis,” Dr. Nasrallah said.

Dr. Stahl reported financial relationships with more than 20 pharmaceutical companies, including those that are involved in the development of drugs included in his talk. Medscape Live and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

Many years ago, drug development in psychiatry turned to control of specific symptoms across disorders rather than within disorders, but regulatory agencies are still not yet on board, according to an expert psychopharmacologist outlining the ongoing evolution at the virtual Psychopharmacology Update presented by Current Psychiatry and the American Academy of Clinical Psychiatrists, sponsored by Medscape Live.

If this reorientation is going to lead to the broad indications the newer drugs likely deserve, which is control of specific types of symptoms regardless of the diagnosis, “we have to move the [Food and Drug Administration] along,” said Stephen M. Stahl, MD, PhD, chairman of the Neuroscience Institute and an adjunct professor of psychiatry at the University of California, San Diego.

On the side of drug development and clinical practice, the reorientation has already taken place. Dr. Stahl described numerous brain circuits known to produce symptoms when function is altered that are now treatment targets. This includes the ventral medial prefrontal cortex where deficient information processing leads to depression and the orbital frontal cortex where altered function leads to impulsivity.

“It is not like each part of the brain does a little bit of everything. Rather, each part of the brain has an assignment and duty and function,” Dr. Stahl explained. By addressing the disturbed signaling in brain circuits that lead to depression, impulsivity, agitation, or other symptoms, there is an opportunity for control, regardless of the psychiatric diagnosis with which the symptom is associated.

For example, Dr. Stahl predicted that pimavanserin, a highly selective 5-HT2A inverse agonist that is already approved for psychosis in Parkinson’s disease, is now likely to be approved for psychosis associated with other conditions on the basis of recent positive clinical studies in these other disorders.

Brexpiprazole, a serotonin-dopamine activity modulator already known to be useful for control of the agitation characteristic of schizophrenia, is now showing the same type of activity against agitation when it is associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Again, Dr. Stahl thinks this drug is on course for an indication across diseases once studies are conducted in each disease individually.

Another drug being evaluated for agitation, the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonist dextromethorphan bupropion, is also being tested for treatment of symptoms across multiple disorders, he reported.

However, the FDA has so far taken the position that each drug must be tested separately for a given symptom in each disorder for which it is being considered despite the underlying premise that it is the symptom, not the disease, that is important.

Unlike physiological diseases where symptoms, like a fever or abdominal cramps, are the product of a disease, psychiatric symptoms are the disease and a fundamental target – regardless of the DSM-based diagnosis.

To some degree, the symptoms of psychiatric disorders have always been the focus of treatment, but a pivot toward developing therapies that will control a symptom regardless of the underlying diagnosis is an important conceptual change. It is being made possible by advances in the detail with which the neuropathology of these symptoms is understood .

“By my count, 79 symptoms are described in DSM-5, but they are spread across hundreds of syndromes because they are grouped together in different ways,” Dr. Stahl observed.

He noted that clinicians make a diagnosis on the basis symptom groupings, but their interventions are selected to address the manifestations of the disease, not the disease itself.

“If you are a real psychopharmacologist treating real patients, you are treating the specific symptoms of the specific patient,” according to Dr. Stahl.

So far, the FDA has not made this leap, insisting on trials in these categorical disorders rather than permitting trial designs that allow benefit to be demonstrated against a symptom regardless of the syndrome with which it is associated.

Of egregious examples, Dr. Stahl recounted a recent trial of a 5-HT2 antagonist that looked so promising against psychosis in Alzheimer’s disease that the trialists enrolled patients with psychosis regardless of type of dementia, such as vascular dementia and Lewy body disease. The efficacy was impressive.

“It worked so well that they stopped the trial, but the FDA declined to approve it,” Dr. Stahl recounted. Despite clear evidence of benefit, the regulators insisted that the investigators needed to show a significant benefit in each condition individually.

While the trial investigators acknowledged that there was not enough power in the trial to show a statistically significant benefit in each category, they argued that the overall benefit and the consistent response across categories required them to stop the trial for ethical reasons.

“That’s your problem, the FDA said to the investigators,” according to Dr. Stahl.

The failure of the FDA to recognize the efficacy of psychopharmacologic therapies across symptoms regardless of the associated disease is a failure to stay current with an important evolution in medicine, Dr. Stahl indicated.

“What we have come to understand is the neurobiology of any given symptom is likely to be the same across disorders,” he said.

Agency’s arbitrary decisions cited

“I completely agree with Dr. Stahl,” said Henry A. Nasrallah, MD, professor of psychiatry, neurology, and neuroscience, University of Cincinnati.

In addition to the fact that symptoms are present across multiple categories, many patients manifest multiple symptoms at one time, Dr. Nasrallah pointed out. For neurodegenerative disorders associated with psychosis, depression, anxiety, aggression, and other symptoms, it is already well known that the heterogeneous symptoms “cannot be treated with a single drug,” he said. Rather different drugs targeting each symptom individually is essential for effective management.

Dr. Nasrallah, who chaired the Psychopharmacology Update meeting, has made this point many times in the past, including in his role as the editor of Current Psychiatry. In one editorial 10 years ago, he wrote that “it makes little sense for the FDA to mandate that a drug must work for a DSM diagnosis instead of specific symptoms.”

“The FDA must update its old policy, which has led to the widespread off-label use of psychiatric drugs, an artificial concept, simply because the FDA arbitrarily decided a long time ago that new drugs must be approved for a specific DSM diagnosis,” Dr. Nasrallah said.

Dr. Stahl reported financial relationships with more than 20 pharmaceutical companies, including those that are involved in the development of drugs included in his talk. Medscape Live and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

FROM PSYCHOPHARMACOLOGY UPDATE

Open notes: Big benefits, few harms in psychiatry, experts say

There are multiple benefits and few harms from sharing clinical notes in patients with mental illness, results of a poll of international experts show.

As of April 5, 2021, new federal rules in the United States mandate that all patients are offered online access to their electronic health record.

“Given that sharing notes in psychiatry is likely to be more complicated than in some other specialties, we were unsure whether experts would consider the practice more harmful than beneficial,” Charlotte Blease, PhD, of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, told this news organization.

“However, the results of our poll suggest clinicians’ anxieties about sharing mental health notes with patients may be misplaced. We found clear consensus among experts that the benefits of online access to clinical notes could outweigh the risks,” Dr. Blease said in a news release.

The study was published online in PLOS ONE.

Empowering patients

Investigators used an online Delphi poll, an established methodology used to investigate emerging health care policy – including in psychiatry – to solicit the views of an international panel of experts on the mental health effects of sharing clinical notes.

The panel included clinicians, chief medical information officers, patient advocates, and informatics experts with extensive experience and research knowledge about patient access to mental health notes.

There was consensus among the panel that offering online access to mental health notes could enhance patients’ understanding about their diagnosis, care plan, and rationale for treatments.

There was also consensus that access to clinical notes could enhance patient recall about what was communicated and improve mental health patients’ sense of control over their health care.

The panel also agreed that blocking mental health notes could lead to greater harms including increased feelings of stigmatization.

Confirmatory findings

The poll results support an earlier study by Dr. Blease and colleagues that evaluated the experiences of patients in accessing their online clinical notes.

Among these patients with major depressive disorder, schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or bipolar-related disorder, “access helped to clarify why medications had been prescribed, improved understanding about side effects, and 20% of patients reported doing a better job taking their meds as prescribed,” said Dr. Blease.

However, the expert panel in the Delphi poll predicted that with “open notes” some patients might demand changes to their clinical notes, and that mental health clinicians might be less detailed/accurate in documenting negative aspects of the patient relationship, details about patients’ personalities, or symptoms of paranoia in patients.

“If some patients feel more judged or offended by what they read, this may undermine the therapeutic relationship. ,” she added.

“In some clinical cases where there is more focus on emergency care than in forming a therapeutic relationship, for example emergency department visits, we know almost nothing about the risks and benefits associated with OpenNotes,” senior author John Torous, MD, with Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Harvard Medical School, said in an interview.

“One thing is clear,” Dr. Blease said. “Patient access to their online medical records is now mainstream, and we need more clinician education on how to write notes that patients will read, and more guidance among patients on the benefits and risks of accessing their notes.”

Support for this research was provided by a J. F. Keane Scholar Award and a Swedish Research Council on Health, Working Life, and Welfare grant. The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

There are multiple benefits and few harms from sharing clinical notes in patients with mental illness, results of a poll of international experts show.

As of April 5, 2021, new federal rules in the United States mandate that all patients are offered online access to their electronic health record.

“Given that sharing notes in psychiatry is likely to be more complicated than in some other specialties, we were unsure whether experts would consider the practice more harmful than beneficial,” Charlotte Blease, PhD, of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, told this news organization.

“However, the results of our poll suggest clinicians’ anxieties about sharing mental health notes with patients may be misplaced. We found clear consensus among experts that the benefits of online access to clinical notes could outweigh the risks,” Dr. Blease said in a news release.

The study was published online in PLOS ONE.

Empowering patients

Investigators used an online Delphi poll, an established methodology used to investigate emerging health care policy – including in psychiatry – to solicit the views of an international panel of experts on the mental health effects of sharing clinical notes.

The panel included clinicians, chief medical information officers, patient advocates, and informatics experts with extensive experience and research knowledge about patient access to mental health notes.

There was consensus among the panel that offering online access to mental health notes could enhance patients’ understanding about their diagnosis, care plan, and rationale for treatments.

There was also consensus that access to clinical notes could enhance patient recall about what was communicated and improve mental health patients’ sense of control over their health care.

The panel also agreed that blocking mental health notes could lead to greater harms including increased feelings of stigmatization.

Confirmatory findings

The poll results support an earlier study by Dr. Blease and colleagues that evaluated the experiences of patients in accessing their online clinical notes.

Among these patients with major depressive disorder, schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or bipolar-related disorder, “access helped to clarify why medications had been prescribed, improved understanding about side effects, and 20% of patients reported doing a better job taking their meds as prescribed,” said Dr. Blease.

However, the expert panel in the Delphi poll predicted that with “open notes” some patients might demand changes to their clinical notes, and that mental health clinicians might be less detailed/accurate in documenting negative aspects of the patient relationship, details about patients’ personalities, or symptoms of paranoia in patients.

“If some patients feel more judged or offended by what they read, this may undermine the therapeutic relationship. ,” she added.

“In some clinical cases where there is more focus on emergency care than in forming a therapeutic relationship, for example emergency department visits, we know almost nothing about the risks and benefits associated with OpenNotes,” senior author John Torous, MD, with Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Harvard Medical School, said in an interview.

“One thing is clear,” Dr. Blease said. “Patient access to their online medical records is now mainstream, and we need more clinician education on how to write notes that patients will read, and more guidance among patients on the benefits and risks of accessing their notes.”

Support for this research was provided by a J. F. Keane Scholar Award and a Swedish Research Council on Health, Working Life, and Welfare grant. The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

There are multiple benefits and few harms from sharing clinical notes in patients with mental illness, results of a poll of international experts show.

As of April 5, 2021, new federal rules in the United States mandate that all patients are offered online access to their electronic health record.

“Given that sharing notes in psychiatry is likely to be more complicated than in some other specialties, we were unsure whether experts would consider the practice more harmful than beneficial,” Charlotte Blease, PhD, of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, told this news organization.

“However, the results of our poll suggest clinicians’ anxieties about sharing mental health notes with patients may be misplaced. We found clear consensus among experts that the benefits of online access to clinical notes could outweigh the risks,” Dr. Blease said in a news release.

The study was published online in PLOS ONE.

Empowering patients

Investigators used an online Delphi poll, an established methodology used to investigate emerging health care policy – including in psychiatry – to solicit the views of an international panel of experts on the mental health effects of sharing clinical notes.

The panel included clinicians, chief medical information officers, patient advocates, and informatics experts with extensive experience and research knowledge about patient access to mental health notes.

There was consensus among the panel that offering online access to mental health notes could enhance patients’ understanding about their diagnosis, care plan, and rationale for treatments.

There was also consensus that access to clinical notes could enhance patient recall about what was communicated and improve mental health patients’ sense of control over their health care.

The panel also agreed that blocking mental health notes could lead to greater harms including increased feelings of stigmatization.

Confirmatory findings

The poll results support an earlier study by Dr. Blease and colleagues that evaluated the experiences of patients in accessing their online clinical notes.

Among these patients with major depressive disorder, schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or bipolar-related disorder, “access helped to clarify why medications had been prescribed, improved understanding about side effects, and 20% of patients reported doing a better job taking their meds as prescribed,” said Dr. Blease.

However, the expert panel in the Delphi poll predicted that with “open notes” some patients might demand changes to their clinical notes, and that mental health clinicians might be less detailed/accurate in documenting negative aspects of the patient relationship, details about patients’ personalities, or symptoms of paranoia in patients.

“If some patients feel more judged or offended by what they read, this may undermine the therapeutic relationship. ,” she added.

“In some clinical cases where there is more focus on emergency care than in forming a therapeutic relationship, for example emergency department visits, we know almost nothing about the risks and benefits associated with OpenNotes,” senior author John Torous, MD, with Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Harvard Medical School, said in an interview.

“One thing is clear,” Dr. Blease said. “Patient access to their online medical records is now mainstream, and we need more clinician education on how to write notes that patients will read, and more guidance among patients on the benefits and risks of accessing their notes.”

Support for this research was provided by a J. F. Keane Scholar Award and a Swedish Research Council on Health, Working Life, and Welfare grant. The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

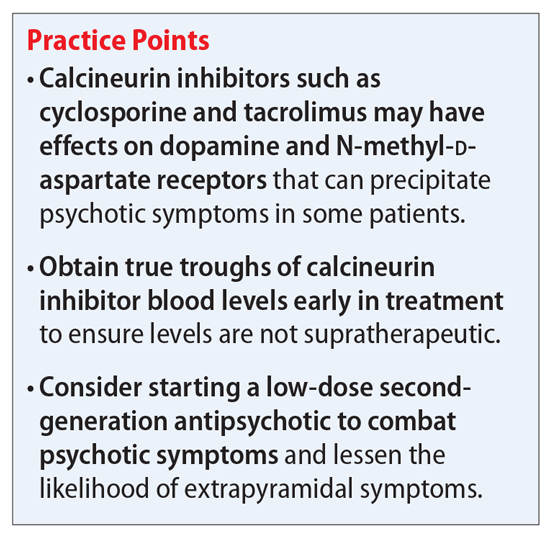

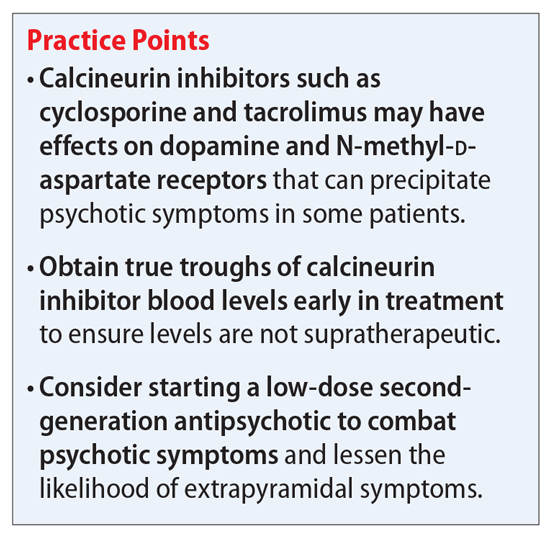

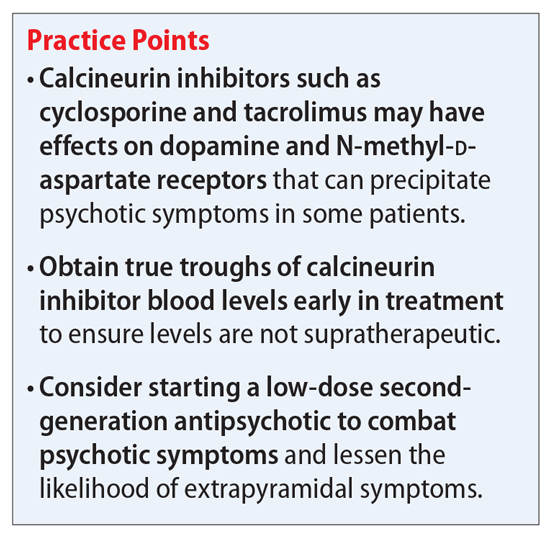

Calcineurin inhibitor–induced psychosis

Mrs. C, age 68, is experiencing worsening paranoid delusions. She believes that because she lied about her income when she was younger, the FBI is tracking her and wants to poison her food and spray dangerous fumes in her house. Her paranoia has made it hard for her to sleep, eat, or feel safe in her home.

Mrs. C’s daughter reports that her mother’s delusions started 3 years ago and have worsened in recent months. Mrs. C has no psychiatric history. Her medical history is significant for renal transplant in 2015, type 2 diabetes, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, and hypothyroidism. She is currently normotensive. Mrs. C’s home medications include cyclosporine, which is a calcineurin inhibitor, 125 mg twice daily (trough level = 138 mcg/L); mycophenolate mofetil, 500 mg twice daily; cinacalcet, 30 mg 3 times a week; metformin, 500 mg twice daily; amlodipine, 5 mg twice daily; levothyroxine, 112 mcg/d; and atorvastatin, 40 mg at bedtime.

As you review her medications, you wonder if the cyclosporine she began receiving after her kidney transplant could be causing or contributing to her worsening paranoid delusions.

Kidney transplantation has become an ideal treatment for patients with end-stage renal disease. In 2020, 22,817 kidney transplants were performed in the United States.1 Compared with dialysis, kidney transplant allows patients the chance to return to a satisfactory quality of life.2 However, to ensure a successful and long-lasting transplant, patients must be started and maintained on lifelong immunosuppressant agents that have potential adverse effects, including nephrotoxicity and hypertension. Further, immunosuppressant agents—particularly calcineurin inhibitors—are associated with potential adverse effects on mental health. The most commonly documented mental health-related adverse effects include insomnia, anxiety, depression, and confusion.3 In this article, we discuss the risk of severe psychosis associated with the use of calcineurin inhibitors.

Calcineurin inhibitors and psychiatric symptoms

Cyclosporine and tacrolimus are calcineurin inhibitors that are commonly used as immunosuppressant agents after kidney transplantation. They primarily work by specifically and competitively binding to and inhibiting the calcineurin protein to reduce the transcriptional activation of cytokine genes for interleukin-2, tumor necrosis factor-alpha, interleukin-3, interleukin-4, CD40L (CD40 ligand), granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, and interferon-gamma.4,5 The ultimate downstream effect is reduced proliferation of T lymphocytes and thereby an immunosuppressed state that will protect against organ rejection. However, this is not the only downstream effect that can occur from inhibiting calcineurin. Cyclosporine and tacrolimus may modulate the activity of dopamine and N-methyl-

An increased effect of dopamine in the mesocortical dopaminergic pathway has long been a suspected cause for psychotic symptoms. A study conducted in rodents suggested that tacrolimus selectively modifies the responsivity and sensitivity of postsynaptic dopamine-2 (D2) and dopamine-3 (D3) receptors.9 These receptors are important when discussing psychosis because antipsychotic medications work primarily by blocking dopamine D2, while many also block the D3 receptor. We hypothesize that modifying the responsivity and sensitivity of these 2 receptors could increase the risk of a person developing psychosis. It may also provide insight into how to best treat a psychotic episode.

Tacrolimus has been shown to elicit inhibition of NMDA-induced neurotransmitter release and augmentation of depolarization-induced neurotransmitter release.10 In theory, this potential inhibition at the NMDA receptors may lead to a compensatory and excessive release of glutamate. Elevated glutamate levels in the brain could lead to psychiatric symptoms, including psychosis. This is supported by the psychosis caused by many NMDA receptor antagonists, such as phencyclidine (PCP) and ketamine. Furthermore, a study examining calcineurin in knockout mice showed that the spectrum of behavioral abnormalities was strikingly similar to those in schizophrenia models.11 These mice displayed impaired working memory, impaired attentional function, social withdrawal, and psychomotor agitation. This further supports the idea that calcineurin inhibition can play a significant role in causing psychiatric symptoms by affecting both dopamine and NMDA receptors.

Continue to: How to address calcineurin inhibitor–induced psychosis...

How to address calcineurin inhibitor–induced psychosis

Here we outline a potential treatment strategy to combat psychosis secondary to calcineurin inhibitors. First, evaluate the patient’s calcineurin inhibitor level (either cyclosporine or tacrolimus). Levels should be drawn as a true trough and doses adjusted if necessary via appropriate consultation with a transplant specialist. Because many of the adverse effects associated with these agents are dose-dependent, we suspect that the risk of psychosis and other mental health–related adverse effects may also follow this trend.

Assuming that the calcineurin inhibitor cannot be stopped, changed to a different agent, or subject to a dose decrease, we recommend initiating an antipsychotic medication to control psychotic symptoms. Given the potential effect of calcineurin inhibitors on dopamine, we suggest trialing a second-generation antipsychotic with relatively high affinity for dopamine D2 receptors, such as risperidone or paliperidone. However, compared with patients with schizophrenia, patients receiving a calcineurin inhibitor may be more likely to develop extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS). Therefore, to avoid potential adverse effects, consider using a lower starting dose or an antipsychotic medication with less dopamine D2 affinity, such as quetiapine, olanzapine, or aripiprazole. Furthermore, because post-transplant patients may be at a higher risk for depression, which may be secondary to medication adverse effects, we suggest avoiding first-generation antipsychotics (FGAs) such as haloperidol because FGAs may worsen depressive symptoms.

We recommend initiating risperidone, 1 mg twice a day, for patients with psychosis secondary to a calcineurin inhibitor. If the patient develops EPS, consider switching to an antipsychotic medication with a less potent dopamine D2 blockade, such as quetiapine, olanzapine, or aripiprazole. We recommend an antipsychotic switch rather than adding benztropine or diphenhydramine to the regimen because many transplant recipients may be older patients, and adding anticholinergic medications can be problematic for this population. However, if the patient is younger or has responded particularly well to risperidone, the benefit of adding an anticholinergic medication may outweigh the risks. This decision should be made on an individual basis and may include other options, such as a switch to quetiapine, olanzapine, or aripiprazole. While these agents may not block the D2 receptor as strongly as risperidone, they all are effective and approved for adjunct therapy in major depressive disorder. We recommend quetiapine and olanzapine as second-line agents because of their potential for sedation and significant weight gain. While aripiprazole has a great metabolic adverse effect profile, its mechanism of action as a partial D2 agonist may make it difficult to control psychotic symptoms in this patient population compared with true D2 antagonists.

Continue to: CASE CONTINUED...

CASE CONTINUED

Mrs. C is admitted to the inpatient psychiatric unit and started on risperidone, 1 mg twice daily. Initially, she complains of lightheadedness at night due to the risperidone, so her dose is changed to 2 mg at bedtime. Gradually, she begins to show mild improvement. Previously, she reported feeling frightened of staff members, but after a few days she reports that she feels safe at the hospital. However, her delusions of being monitored by the FBI persist.

After 9 days of hospitalization, Mrs. C is discharged home to the care of her daughter. At first, she does well, but unfortunately she begins to refuse to take her medication and returns to her baseline.

Related Resources

- Gok F, Eroglu MZ. Acute psychotic disorder associated with immunosuppressive agent use after renal transplantation: a case report. Psychiatry and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2017;3:314-316.

- Bersani G, Marino P, Valerani G, et al. Manic-like psychosis associated with elevated trough tacrolimus blood concentrations 17 years after kidney transplant. Case Rep Psychiatry. 2013;2013:926395. doi: 10.1155/2013/926395

Drug Brand Names

Amlodipine • Norvasc

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Atorvastatin • Lipitor

Benztropine • Cogentin

Cinacalcet • Sensipar

Cyclosporine • Gengraf

Haloperidol • Haldol

Ketamine • Ketalar

Levothyroxine • Synthroid

Metformin • Glucophage

Mycophenolate mofetil • CellCept

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Paliperidone • Invega

Risperidone • Risperdal

Tacrolimus • Prograf

1. Health Resources & Services Administration. US Government Information on Organ Donor Transplantation. Organ Donation Statistics. Updated October 1, 2020. Accessed October 8, 2021. https://www.organdonor.gov/learn/organ-donation-statistics/detailed-description#fig1

2. De Pasquale C, Veroux M, Indelicato L, et al. Psychopathological aspects of kidney transplantation: efficacy of a multidisciplinary team. World J Transplant. 2014;4(4):267-275.

3. Gengraf capsules [package insert]. North Chicago, IL: AbbVie Inc; 2017.

4. Wiederrecht G, Lam E, Hung S, et al. The mechanism of action of FK-506 and cyclosporin A. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1993;696:9-19.

5. Schreiber SL, Crabtree GR. The mechanism of action of cyclosporin A and FK506. Immunol Today. 1992;13(4):136-142.

6. Scherrer U, Vissing SF, Morgan BJ, et al. Cyclosporine-induced sympathetic activation and hypertension after heart transplantation. N Engl J Med. 1990;323(11):693-699.

7. Fulya G, Meliha ZE. Acute psychotic disorder associated with immunosuppressive agent use after renal transplantation: a case report. Psychiatry and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2017;27(3):314-316.

8. Tan TC, Robinson PJ. Mechanisms of calcineurin inhibitor-induced neurotoxicity. Transplant Rev. 2006;20(1):49-60.

9. Masatsuna S, Norio M, Nori Takei, et al. Tacrolimus, a specific inhibitor of calcineurin, modifies the locomotor activity of quinpirole, but not that of SKF82958, in male rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 2002;438(1-2):93-97.

10. Gold BG. FK506 and the role of immunophilins in nerve regeneration. Mol Neurobiol. 1997;15(3):285-306.

11. Miyakawa T, Leiter LM, Gerber DJ. Conditional calcineurin knockout mice exhibit multiple abnormal behaviors related to schizophrenia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(15): 8987-8992.

Mrs. C, age 68, is experiencing worsening paranoid delusions. She believes that because she lied about her income when she was younger, the FBI is tracking her and wants to poison her food and spray dangerous fumes in her house. Her paranoia has made it hard for her to sleep, eat, or feel safe in her home.

Mrs. C’s daughter reports that her mother’s delusions started 3 years ago and have worsened in recent months. Mrs. C has no psychiatric history. Her medical history is significant for renal transplant in 2015, type 2 diabetes, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, and hypothyroidism. She is currently normotensive. Mrs. C’s home medications include cyclosporine, which is a calcineurin inhibitor, 125 mg twice daily (trough level = 138 mcg/L); mycophenolate mofetil, 500 mg twice daily; cinacalcet, 30 mg 3 times a week; metformin, 500 mg twice daily; amlodipine, 5 mg twice daily; levothyroxine, 112 mcg/d; and atorvastatin, 40 mg at bedtime.

As you review her medications, you wonder if the cyclosporine she began receiving after her kidney transplant could be causing or contributing to her worsening paranoid delusions.

Kidney transplantation has become an ideal treatment for patients with end-stage renal disease. In 2020, 22,817 kidney transplants were performed in the United States.1 Compared with dialysis, kidney transplant allows patients the chance to return to a satisfactory quality of life.2 However, to ensure a successful and long-lasting transplant, patients must be started and maintained on lifelong immunosuppressant agents that have potential adverse effects, including nephrotoxicity and hypertension. Further, immunosuppressant agents—particularly calcineurin inhibitors—are associated with potential adverse effects on mental health. The most commonly documented mental health-related adverse effects include insomnia, anxiety, depression, and confusion.3 In this article, we discuss the risk of severe psychosis associated with the use of calcineurin inhibitors.

Calcineurin inhibitors and psychiatric symptoms