User login

Clinical Guidelines Hub only

Implications of cholesterol guidelines for cardiology practices

CHICAGO – Cardiologists certainly have their work cut out in order to bring their patients into concordance with the 2013 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association cholesterol guidelines, according to Dr. Thomas M. Maddox.

An analysis of nearly 1.2 million patients in U.S. outpatient cardiology practices showed that one in three who appeared to have an indication for statin therapy under the latest guidelines weren’t on a statin as of 2012. That constitutes a sizable “statin gap” that cardiologists need to address, he said at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

Dr. Maddox presented an analysis of 1,174,535 adult patients under cardiologists’ care during 2008-2012 in more than 100 U.S. outpatient cardiology practices participating in the voluntary National Cardiovascular Data Registry’s Practice Innovation and Clinical Excellence Registry (NCDR PINNACLE). Under this national office-based quality improvement program sponsored by the ACC, patient electronic medical record (EMR) data gets uploaded to the registry nightly.

The 2013 ACC/AHA cholesterol guidelines in some ways greatly simplified patient management. The guidelines redefined the risk groups warranting treatment: basically, patients with known atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD), diabetes, an off-treatment LDL of 190 mg/dL or more, or a 10-year ASCVD risk of 7.5% or greater using the risk calculator incorporated in the guidelines (Circulation 2014; 129:S1-45). Also, physicians were advised to use fixed-dose statins and no longer to treat to an LDL target, thereby making repeated LDL testing unnecessary.

The purposes of this new NCDR PINNACLE study were to evaluate the potential impact of the new guidelines on current cardiology practice through an assessment of current treatment and testing patterns, and to make a determination of the scope of changes necessary under the 2013 guidelines, explained Dr. Maddox, a cardiologist at the Veterans Affairs Eastern Colorado Health Care System and the University of Colorado at Denver.

Under the new guidelines, 1,129,205 adult cardiology patients, or 96% of the study population, appeared to be candidates for statin therapy, most often because they had known ASCVD, as was the case in 88%, or diabetes without known ASCVD, accounting for another 6%.

Among the statin-eligible patients, 29% were not on any lipid-lowering therapy, and another 3% were on nonstatin lipid-lowering agents only, which is not recommended in the guidelines. Thus, 32% of the cardiologists’ patients for whom statin therapy appeared to be indicated under the 2013 guidelines weren’t on it.

In addition, 29% of statin-eligible patients were on combined lipid-lowering therapy with a statin plus a nonstatin, such as niacin, a fibrate, or ezetimibe. The guidelines don’t recommend the use of nonstatins because of the lack of evidence of clinical benefit, so cardiologists will want to reconsider their use of combination therapy in this sizable group. The major caveat here is that the guidelines are likely to be revised to embrace the selective use of a moderate-intensity statin plus ezetimibe on the basis of the positive findings of the IMPROVE-IT trial, also presented at the AHA meeting, Dr. Maddox noted.

The registry analysis also pointed to a need to reduce repeated LDL testing, which the guidelines characterize as costly, inconvenient, and unnecessary. Nearly 21% of subjects had at least two LDL assessments during the 4-year period, and 7% had more than four. And those figures probably underestimate the true rate of LDL testing, since many patients may have also had LDL measurements taken in primary care settings.

Several audience members rose to decry the one-in-three-patient statin gap as evidence of widespread substandard care by cardiologists, especially given that 28% of the patients with known ASCVD and 36% with diabetes were not receiving any lipid-lowering therapy, contrary to recommendations both in the current ACC/AHA guidelines and the guidelines in place in 2012. There is good evidence to show that putting such patients on statin therapy would result in roughly a 25% reduction in cardiovascular events.

But Dr. Maddox took a more sanguine view of the statin gap. Although it’s likely there is some heterogeneity in clinical practice that needs to be corrected, he cautioned that the limitations of an analysis based upon EMR data must be borne in mind. Some cardiologists probably didn’t record the use of statins at every visit, and they may not have always reliably documented patients’ intolerance of statins in the EMR.

The NCDR PINNACLE Registry is supported by the American College of Cardiology Foundation. Dr. Maddox reported having no relevant financial conflicts of interest.

CHICAGO – Cardiologists certainly have their work cut out in order to bring their patients into concordance with the 2013 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association cholesterol guidelines, according to Dr. Thomas M. Maddox.

An analysis of nearly 1.2 million patients in U.S. outpatient cardiology practices showed that one in three who appeared to have an indication for statin therapy under the latest guidelines weren’t on a statin as of 2012. That constitutes a sizable “statin gap” that cardiologists need to address, he said at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

Dr. Maddox presented an analysis of 1,174,535 adult patients under cardiologists’ care during 2008-2012 in more than 100 U.S. outpatient cardiology practices participating in the voluntary National Cardiovascular Data Registry’s Practice Innovation and Clinical Excellence Registry (NCDR PINNACLE). Under this national office-based quality improvement program sponsored by the ACC, patient electronic medical record (EMR) data gets uploaded to the registry nightly.

The 2013 ACC/AHA cholesterol guidelines in some ways greatly simplified patient management. The guidelines redefined the risk groups warranting treatment: basically, patients with known atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD), diabetes, an off-treatment LDL of 190 mg/dL or more, or a 10-year ASCVD risk of 7.5% or greater using the risk calculator incorporated in the guidelines (Circulation 2014; 129:S1-45). Also, physicians were advised to use fixed-dose statins and no longer to treat to an LDL target, thereby making repeated LDL testing unnecessary.

The purposes of this new NCDR PINNACLE study were to evaluate the potential impact of the new guidelines on current cardiology practice through an assessment of current treatment and testing patterns, and to make a determination of the scope of changes necessary under the 2013 guidelines, explained Dr. Maddox, a cardiologist at the Veterans Affairs Eastern Colorado Health Care System and the University of Colorado at Denver.

Under the new guidelines, 1,129,205 adult cardiology patients, or 96% of the study population, appeared to be candidates for statin therapy, most often because they had known ASCVD, as was the case in 88%, or diabetes without known ASCVD, accounting for another 6%.

Among the statin-eligible patients, 29% were not on any lipid-lowering therapy, and another 3% were on nonstatin lipid-lowering agents only, which is not recommended in the guidelines. Thus, 32% of the cardiologists’ patients for whom statin therapy appeared to be indicated under the 2013 guidelines weren’t on it.

In addition, 29% of statin-eligible patients were on combined lipid-lowering therapy with a statin plus a nonstatin, such as niacin, a fibrate, or ezetimibe. The guidelines don’t recommend the use of nonstatins because of the lack of evidence of clinical benefit, so cardiologists will want to reconsider their use of combination therapy in this sizable group. The major caveat here is that the guidelines are likely to be revised to embrace the selective use of a moderate-intensity statin plus ezetimibe on the basis of the positive findings of the IMPROVE-IT trial, also presented at the AHA meeting, Dr. Maddox noted.

The registry analysis also pointed to a need to reduce repeated LDL testing, which the guidelines characterize as costly, inconvenient, and unnecessary. Nearly 21% of subjects had at least two LDL assessments during the 4-year period, and 7% had more than four. And those figures probably underestimate the true rate of LDL testing, since many patients may have also had LDL measurements taken in primary care settings.

Several audience members rose to decry the one-in-three-patient statin gap as evidence of widespread substandard care by cardiologists, especially given that 28% of the patients with known ASCVD and 36% with diabetes were not receiving any lipid-lowering therapy, contrary to recommendations both in the current ACC/AHA guidelines and the guidelines in place in 2012. There is good evidence to show that putting such patients on statin therapy would result in roughly a 25% reduction in cardiovascular events.

But Dr. Maddox took a more sanguine view of the statin gap. Although it’s likely there is some heterogeneity in clinical practice that needs to be corrected, he cautioned that the limitations of an analysis based upon EMR data must be borne in mind. Some cardiologists probably didn’t record the use of statins at every visit, and they may not have always reliably documented patients’ intolerance of statins in the EMR.

The NCDR PINNACLE Registry is supported by the American College of Cardiology Foundation. Dr. Maddox reported having no relevant financial conflicts of interest.

CHICAGO – Cardiologists certainly have their work cut out in order to bring their patients into concordance with the 2013 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association cholesterol guidelines, according to Dr. Thomas M. Maddox.

An analysis of nearly 1.2 million patients in U.S. outpatient cardiology practices showed that one in three who appeared to have an indication for statin therapy under the latest guidelines weren’t on a statin as of 2012. That constitutes a sizable “statin gap” that cardiologists need to address, he said at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

Dr. Maddox presented an analysis of 1,174,535 adult patients under cardiologists’ care during 2008-2012 in more than 100 U.S. outpatient cardiology practices participating in the voluntary National Cardiovascular Data Registry’s Practice Innovation and Clinical Excellence Registry (NCDR PINNACLE). Under this national office-based quality improvement program sponsored by the ACC, patient electronic medical record (EMR) data gets uploaded to the registry nightly.

The 2013 ACC/AHA cholesterol guidelines in some ways greatly simplified patient management. The guidelines redefined the risk groups warranting treatment: basically, patients with known atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD), diabetes, an off-treatment LDL of 190 mg/dL or more, or a 10-year ASCVD risk of 7.5% or greater using the risk calculator incorporated in the guidelines (Circulation 2014; 129:S1-45). Also, physicians were advised to use fixed-dose statins and no longer to treat to an LDL target, thereby making repeated LDL testing unnecessary.

The purposes of this new NCDR PINNACLE study were to evaluate the potential impact of the new guidelines on current cardiology practice through an assessment of current treatment and testing patterns, and to make a determination of the scope of changes necessary under the 2013 guidelines, explained Dr. Maddox, a cardiologist at the Veterans Affairs Eastern Colorado Health Care System and the University of Colorado at Denver.

Under the new guidelines, 1,129,205 adult cardiology patients, or 96% of the study population, appeared to be candidates for statin therapy, most often because they had known ASCVD, as was the case in 88%, or diabetes without known ASCVD, accounting for another 6%.

Among the statin-eligible patients, 29% were not on any lipid-lowering therapy, and another 3% were on nonstatin lipid-lowering agents only, which is not recommended in the guidelines. Thus, 32% of the cardiologists’ patients for whom statin therapy appeared to be indicated under the 2013 guidelines weren’t on it.

In addition, 29% of statin-eligible patients were on combined lipid-lowering therapy with a statin plus a nonstatin, such as niacin, a fibrate, or ezetimibe. The guidelines don’t recommend the use of nonstatins because of the lack of evidence of clinical benefit, so cardiologists will want to reconsider their use of combination therapy in this sizable group. The major caveat here is that the guidelines are likely to be revised to embrace the selective use of a moderate-intensity statin plus ezetimibe on the basis of the positive findings of the IMPROVE-IT trial, also presented at the AHA meeting, Dr. Maddox noted.

The registry analysis also pointed to a need to reduce repeated LDL testing, which the guidelines characterize as costly, inconvenient, and unnecessary. Nearly 21% of subjects had at least two LDL assessments during the 4-year period, and 7% had more than four. And those figures probably underestimate the true rate of LDL testing, since many patients may have also had LDL measurements taken in primary care settings.

Several audience members rose to decry the one-in-three-patient statin gap as evidence of widespread substandard care by cardiologists, especially given that 28% of the patients with known ASCVD and 36% with diabetes were not receiving any lipid-lowering therapy, contrary to recommendations both in the current ACC/AHA guidelines and the guidelines in place in 2012. There is good evidence to show that putting such patients on statin therapy would result in roughly a 25% reduction in cardiovascular events.

But Dr. Maddox took a more sanguine view of the statin gap. Although it’s likely there is some heterogeneity in clinical practice that needs to be corrected, he cautioned that the limitations of an analysis based upon EMR data must be borne in mind. Some cardiologists probably didn’t record the use of statins at every visit, and they may not have always reliably documented patients’ intolerance of statins in the EMR.

The NCDR PINNACLE Registry is supported by the American College of Cardiology Foundation. Dr. Maddox reported having no relevant financial conflicts of interest.

AT THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Key clinical point: As U.S. cardiologists increasingly “get with the guidelines” regarding cholesterol lowering, expect to see large increases in statin use, much less prescribing of nonstatin therapies, and a lot less repeat LDL testing.

Major finding: Nearly one in three U.S. patients under a cardiologist’s care who appear to have an indication for statin therapy under the 2013 ACC/AHA cholesterol guidelines weren’t on a statin as of 2012.

Data source: An analysis of nearly 1.2 million patients in an ongoing nationwide voluntary prospective registry aimed at improving the quality of cardiovascular care.

Disclosures: The NCDR PINNACLE Registry is supported by the American College of Cardiology Foundation. The presenter reported having no relevant financial conflicts.

Preventing, treating HBV reactivation during immunosuppressive therapy

Patients who are to undergo immunosuppressive therapy but are at high risk for reactivation of hepatitis B infection should receive antiviral prophylaxis, rather than being monitored for reactivation and treated only if it develops, according to a new guideline published online in Gastroenterology.

The American Gastroenterological Association conducted a rigorous review of the available evidence and compiled seven recommendations to guide clinicians and researchers in preventing HBV reactivation before patients initiate immunosuppressive therapy and in treating reactivated HBV if it arises during immunosuppressive therapy. “Despite the large number of published studies, in most cases our recommendations are weak because either (1) the quality of the available data and/or the baseline risk of HBV reactivation is low or uncertain, and/or (2) the balance of risks and benefits for a particular strategy does not overwhelmingly support its use,” said Dr. K. Rajender Reddy, lead writer of the guideline and professor of gastroenterology and hepatology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and his associates.

In contrast, the data supporting the recommendation to provide prophylaxis for high-risk patients are moderately robust, so that recommendation is strong, they noted.

Patients’ level of risk is based on their HBV serologic status and the type of immunosuppression they require. For example, patients are considered at high risk for HBV reactivation if they are hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) positive/anti–hepatitis B core (HBc) positive or are HBsAg negative/anti-HBc positive and are to be treated with B-cell–depleting agents such as rituximab or ofatumumab. Also at high risk are HBsAg-positive/anti-HBc–positive patients to be treated with anthracycline derivatives such as doxorubicin or epirubicin, and HBsAg-positive/anti-HBc–positive patients to be treated with moderate- or high-dose corticosteroids for 4 weeks or longer.

In these high-risk patients, antiviral prophylaxis is definitely warranted, and it should extend for at least 6 months after the immunosuppressive therapy is completed, according to the guideline. In contrast, antiviral prophylaxis is “suggested” for moderate-risk patients, but those who place a higher value on avoiding antivirals and a lower value on avoiding HBV reactivation “may reasonably select no prophylaxis over antiviral prophylaxis,” Dr. Reddy and his associates said.

In contrast, routine antiviral prophylaxis is not recommended for patients undergoing immunosuppressive therapy who are at low risk for HBV reactivation.

Other recommendations in the new guideline concern which antiviral agents are preferred in different situations. The AGA strongly recommends antivirals that have a high barrier to resistance, in preference to lamivudine, in most patients. But it acknowledges that the evidence comparing various antivirals is weak, and that the drugs vary considerably in price. “Patients who put a higher value on cost and a lower value on avoiding the potentially small risk of resistance development may reasonably select the least expensive antiviral hepatitis B medication over more expensive antiviral drugs with a higher barrier to resistance,” Dr. Reddy and his associates said (Gastroenterol. 2014 [doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2014.10.039]).

The evidence regarding patient monitoring for HBV reactivation instead of prophylaxis is so sparse that the AGA makes no recommendation for or against this strategy at present. Most studies of the issue are of poor quality, use different definitions of HBV reactivation, have inconsistent reporting of patient outcomes, and disagree about the best methods and frequency of HBV DNA monitoring. Moreover, frequent monitoring requires “considerable” personnel resources, and the methods used in clinical studies may not even be adaptable to real world practice, the investigators said.

Patients who are to undergo immunosuppressive therapy but are at high risk for reactivation of hepatitis B infection should receive antiviral prophylaxis, rather than being monitored for reactivation and treated only if it develops, according to a new guideline published online in Gastroenterology.

The American Gastroenterological Association conducted a rigorous review of the available evidence and compiled seven recommendations to guide clinicians and researchers in preventing HBV reactivation before patients initiate immunosuppressive therapy and in treating reactivated HBV if it arises during immunosuppressive therapy. “Despite the large number of published studies, in most cases our recommendations are weak because either (1) the quality of the available data and/or the baseline risk of HBV reactivation is low or uncertain, and/or (2) the balance of risks and benefits for a particular strategy does not overwhelmingly support its use,” said Dr. K. Rajender Reddy, lead writer of the guideline and professor of gastroenterology and hepatology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and his associates.

In contrast, the data supporting the recommendation to provide prophylaxis for high-risk patients are moderately robust, so that recommendation is strong, they noted.

Patients’ level of risk is based on their HBV serologic status and the type of immunosuppression they require. For example, patients are considered at high risk for HBV reactivation if they are hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) positive/anti–hepatitis B core (HBc) positive or are HBsAg negative/anti-HBc positive and are to be treated with B-cell–depleting agents such as rituximab or ofatumumab. Also at high risk are HBsAg-positive/anti-HBc–positive patients to be treated with anthracycline derivatives such as doxorubicin or epirubicin, and HBsAg-positive/anti-HBc–positive patients to be treated with moderate- or high-dose corticosteroids for 4 weeks or longer.

In these high-risk patients, antiviral prophylaxis is definitely warranted, and it should extend for at least 6 months after the immunosuppressive therapy is completed, according to the guideline. In contrast, antiviral prophylaxis is “suggested” for moderate-risk patients, but those who place a higher value on avoiding antivirals and a lower value on avoiding HBV reactivation “may reasonably select no prophylaxis over antiviral prophylaxis,” Dr. Reddy and his associates said.

In contrast, routine antiviral prophylaxis is not recommended for patients undergoing immunosuppressive therapy who are at low risk for HBV reactivation.

Other recommendations in the new guideline concern which antiviral agents are preferred in different situations. The AGA strongly recommends antivirals that have a high barrier to resistance, in preference to lamivudine, in most patients. But it acknowledges that the evidence comparing various antivirals is weak, and that the drugs vary considerably in price. “Patients who put a higher value on cost and a lower value on avoiding the potentially small risk of resistance development may reasonably select the least expensive antiviral hepatitis B medication over more expensive antiviral drugs with a higher barrier to resistance,” Dr. Reddy and his associates said (Gastroenterol. 2014 [doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2014.10.039]).

The evidence regarding patient monitoring for HBV reactivation instead of prophylaxis is so sparse that the AGA makes no recommendation for or against this strategy at present. Most studies of the issue are of poor quality, use different definitions of HBV reactivation, have inconsistent reporting of patient outcomes, and disagree about the best methods and frequency of HBV DNA monitoring. Moreover, frequent monitoring requires “considerable” personnel resources, and the methods used in clinical studies may not even be adaptable to real world practice, the investigators said.

Patients who are to undergo immunosuppressive therapy but are at high risk for reactivation of hepatitis B infection should receive antiviral prophylaxis, rather than being monitored for reactivation and treated only if it develops, according to a new guideline published online in Gastroenterology.

The American Gastroenterological Association conducted a rigorous review of the available evidence and compiled seven recommendations to guide clinicians and researchers in preventing HBV reactivation before patients initiate immunosuppressive therapy and in treating reactivated HBV if it arises during immunosuppressive therapy. “Despite the large number of published studies, in most cases our recommendations are weak because either (1) the quality of the available data and/or the baseline risk of HBV reactivation is low or uncertain, and/or (2) the balance of risks and benefits for a particular strategy does not overwhelmingly support its use,” said Dr. K. Rajender Reddy, lead writer of the guideline and professor of gastroenterology and hepatology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and his associates.

In contrast, the data supporting the recommendation to provide prophylaxis for high-risk patients are moderately robust, so that recommendation is strong, they noted.

Patients’ level of risk is based on their HBV serologic status and the type of immunosuppression they require. For example, patients are considered at high risk for HBV reactivation if they are hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) positive/anti–hepatitis B core (HBc) positive or are HBsAg negative/anti-HBc positive and are to be treated with B-cell–depleting agents such as rituximab or ofatumumab. Also at high risk are HBsAg-positive/anti-HBc–positive patients to be treated with anthracycline derivatives such as doxorubicin or epirubicin, and HBsAg-positive/anti-HBc–positive patients to be treated with moderate- or high-dose corticosteroids for 4 weeks or longer.

In these high-risk patients, antiviral prophylaxis is definitely warranted, and it should extend for at least 6 months after the immunosuppressive therapy is completed, according to the guideline. In contrast, antiviral prophylaxis is “suggested” for moderate-risk patients, but those who place a higher value on avoiding antivirals and a lower value on avoiding HBV reactivation “may reasonably select no prophylaxis over antiviral prophylaxis,” Dr. Reddy and his associates said.

In contrast, routine antiviral prophylaxis is not recommended for patients undergoing immunosuppressive therapy who are at low risk for HBV reactivation.

Other recommendations in the new guideline concern which antiviral agents are preferred in different situations. The AGA strongly recommends antivirals that have a high barrier to resistance, in preference to lamivudine, in most patients. But it acknowledges that the evidence comparing various antivirals is weak, and that the drugs vary considerably in price. “Patients who put a higher value on cost and a lower value on avoiding the potentially small risk of resistance development may reasonably select the least expensive antiviral hepatitis B medication over more expensive antiviral drugs with a higher barrier to resistance,” Dr. Reddy and his associates said (Gastroenterol. 2014 [doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2014.10.039]).

The evidence regarding patient monitoring for HBV reactivation instead of prophylaxis is so sparse that the AGA makes no recommendation for or against this strategy at present. Most studies of the issue are of poor quality, use different definitions of HBV reactivation, have inconsistent reporting of patient outcomes, and disagree about the best methods and frequency of HBV DNA monitoring. Moreover, frequent monitoring requires “considerable” personnel resources, and the methods used in clinical studies may not even be adaptable to real world practice, the investigators said.

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY

Key clinical point: The American Gastroenterological Association published a guideline for preventing the reactivation of HBV in patients who need immunosuppressive therapy and for treating reactivated HBV when it develops in patients undergoing immunosuppression.

Major finding: Robust evidence supports the recommendation that antiviral prophylaxis is warranted in patients at high risk for HBV reactivation, “suggested” for patients at moderate risk, and not recommended for patients at low risk.

Data source: A rigorous review and summary of the available evidence regarding prevention and treatment of HBV reactivation, and a compilation of recommendations for clinicians and researchers.

Disclosures: Dr. Reddy and his associates’ disclosure statements are available at the American Gastroenterological Association, Bethesda, Md. .

New evidence suggests 2014 hypertension guidelines could backfire

CHICAGO – Nearly one in seven patients in U.S. ambulatory cardiology practices who would have been recommended for initiation or intensification of antihypertensive drug therapy under the 2003 Seventh Joint National Committee guidelines are no longer treatment candidates under the 2014 expert panel recommendations.

These patients who no longer qualify for antihypertensive therapy under the 2014 guidelines turn out to have a disturbingly high average estimated 10-year risk of cardiovascular events. As a result, widespread adoption of the 2014 expert panel recommendations could have major adverse consequences for cardiovascular health, Dr. William B. Borden cautioned at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

“Given the size and underlying cardiovascular risk of the population affected by the changes in the 2014 panel recommendations, close monitoring will be required to assess changes in practice patterns, blood pressure control, and – importantly – any changes in cardiovascular morbidity and mortality,” said Dr. Borden, a cardiologist at George Washington University in Washington.

Because the 2014 expert panel guidelines represent a major shift in hypertension management, Dr. Borden and coinvestigators sought to quantify the potential cardiovascular health impact of this more lenient treatment approach. For this purpose they turned to the National Cardiovascular Data Registry Practice Innovation and Clinical Excellence (NCDR PINNACLE) Registry, a voluntary quality improvement project involving outpatient cardiology practices.

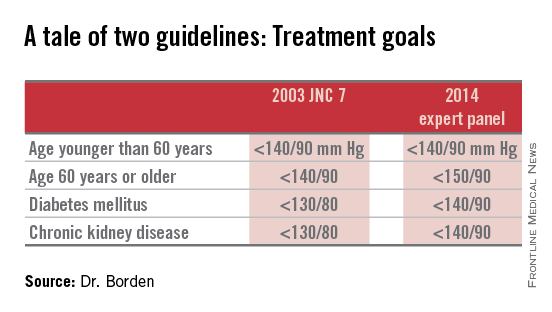

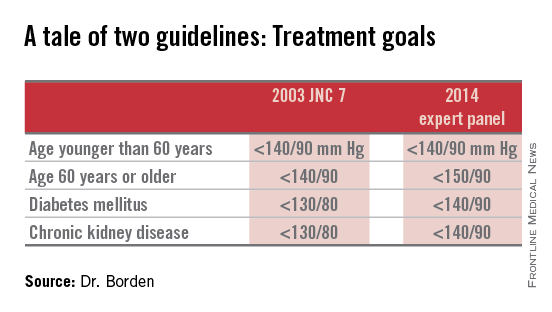

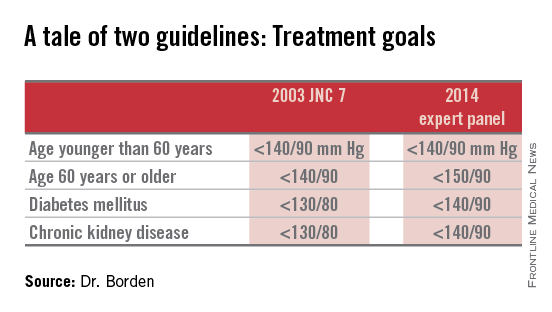

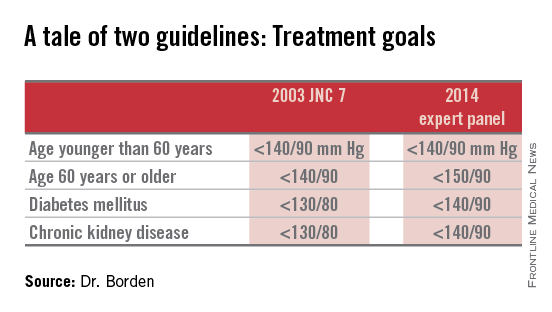

Of 1,185,253 patients with hypertension as identified in their chart by a recorded diagnosis or notation of blood pressure greater than 140/90 mm Hg, 60% met the 2003 JNC 7 goals (JAMA 2003;289:2560-72), meaning the other 40% were candidates for initiation or intensification of antihypertensive therapy in order to achieve those goals (see chart). In contrast, 74% of hypertensive patients in U.S. cardiology practices met the less aggressive targets recommended in the 2014 expert panel report (JAMA 2014;311:502-20).

Thus, fewer than two-thirds of hypertensive patients in outpatient cardiology practices met the 2003 JNC 7 blood pressure targets, while three-quarters met the liberalized 2014 targets.

Dr. Borden and coworkers zeroed in on the 15% of hypertensive patients – that’s fully 173,519 individuals in cardiology practices participating in the PINNACLE Registry – who would have been eligible for treatment under the JNC 7 recommendations but not the 2014 expert panel guidelines. Interestingly, that 15% figure was closely similar to the 17% rate reported by Dr. Michael D. Miedema of the Minneapolis Heart Institute in an analysis of a more primary care population of older patients in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study he presented in the same session.

Dr. Borden and coinvestigators determined from medical records that the PINNACLE Registry group whose antihypertensive therapy treatment status changed between the two guidelines was at substantial baseline cardiovascular risk: Nearly two-thirds had been diagnosed with CAD, 54% had diabetes, 27% had a history of heart failure, 25% had a prior MI, and 23% had a prior transient ischemic attack or stroke.

This large group of patients who fell through the cracks between two conflicting sets of guidelines turned out to have a mean 10-year Framingham Risk Score of 8.5%. Upon incorporating the patients’ stroke risk using the atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) risk score embedded in the 2013 ACC/AHA cholesterol management guidelines, their 10-year risk shot up to 28%.

The investigators then conducted a modeling exercise aimed at estimating the clinical impact of lowering systolic blood pressure in the elderly from about 150 mm Hg, as recommended in the 2014 expert panel guidelines, to about 140 mm Hg, as was the goal in JNC 7. To do so they extrapolated from the results of two randomized controlled clinical trials: the Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program (SHEP) and the Hypertension in the Very Elderly Trial (HYVET).

The result? Extrapolating from SHEP data, the 10-year ASCVD risk in these real-world elderly hypertensive patients caught between two conflicting sets of guidelines would drop from 28% to 19%. Using HYVET data, the average 10-year ASCVD risk would fall to 18.4%.

“This is equivalent to a number-needed-to-treat of 10-11 patients for 10 years in order to prevent one cardiovascular event,” according to Dr. Borden.

For the more than 80,000 patients over age 60 in the study population, that works out to roughly 8,000 cardiovascular events averted over the course of 10 years, he added.

The 2014 expert panel recommendations were based on a strict evidence-based review of published randomized controlled trials. The guidelines are new enough that it remains unclear if they will be embraced by clinicians or incorporated into performance measures and value-based health care purchasing programs.

The 2014 guidelines are considered highly controversial. The guideline committee comprising some of the nation’s top hypertension researchers was initially convened to come up with what was intended to be the long-awaited JNC 8 report; however, in the midst of the process the sponsoring National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute declared it was getting out of the guideline-writing business altogether. As a result, the guidelines ultimately published carried the imprimatur of “the 2014 expert panel,” rather than the more prestigious official stamp of JNC 8.

Indeed, five members of the guideline panel felt strongly enough to break away and issued a minority report (Ann. Intern. Med. 2014;160:499-503) in which they argued there is insufficient evidence of harm stemming from the JNC 7 goal of 140/90 mm Hg in patients over age 60 to justify revising the target to 150/90. They warned that this step could reverse the impressive reductions in cardiovascular and cerebrovascular morbidity and mortality realized in recent decades. And they concluded that the burden of proof should be on those who advocate raising the treatment threshold to 150/90 mm Hg to demonstrate that it has benefit in patients over age 60, which they haven’t done.

“I’m very concerned about the [2014 expert panel] guidelines. Older individuals have the highest prevalence of hypertension, they’re the least adequately controlled, and based on the available data I’m concerned that if people follow the new guidelines there’s going to be an increase in cardiovascular events,” said Dr. Wilbert F. Aronow of New York Medical College, Valhalla, who chaired the writing committee for the first-ever ACC/AHA clinical guidelines for controlling high blood pressure in the elderly (J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2011;57:2037-114).

The NCDR PINNACLE Registry and this study were supported by the American College of Cardiology Foundation. Dr. Borden and Dr. Aronow reported having no financial conflicts.

CHICAGO – Nearly one in seven patients in U.S. ambulatory cardiology practices who would have been recommended for initiation or intensification of antihypertensive drug therapy under the 2003 Seventh Joint National Committee guidelines are no longer treatment candidates under the 2014 expert panel recommendations.

These patients who no longer qualify for antihypertensive therapy under the 2014 guidelines turn out to have a disturbingly high average estimated 10-year risk of cardiovascular events. As a result, widespread adoption of the 2014 expert panel recommendations could have major adverse consequences for cardiovascular health, Dr. William B. Borden cautioned at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

“Given the size and underlying cardiovascular risk of the population affected by the changes in the 2014 panel recommendations, close monitoring will be required to assess changes in practice patterns, blood pressure control, and – importantly – any changes in cardiovascular morbidity and mortality,” said Dr. Borden, a cardiologist at George Washington University in Washington.

Because the 2014 expert panel guidelines represent a major shift in hypertension management, Dr. Borden and coinvestigators sought to quantify the potential cardiovascular health impact of this more lenient treatment approach. For this purpose they turned to the National Cardiovascular Data Registry Practice Innovation and Clinical Excellence (NCDR PINNACLE) Registry, a voluntary quality improvement project involving outpatient cardiology practices.

Of 1,185,253 patients with hypertension as identified in their chart by a recorded diagnosis or notation of blood pressure greater than 140/90 mm Hg, 60% met the 2003 JNC 7 goals (JAMA 2003;289:2560-72), meaning the other 40% were candidates for initiation or intensification of antihypertensive therapy in order to achieve those goals (see chart). In contrast, 74% of hypertensive patients in U.S. cardiology practices met the less aggressive targets recommended in the 2014 expert panel report (JAMA 2014;311:502-20).

Thus, fewer than two-thirds of hypertensive patients in outpatient cardiology practices met the 2003 JNC 7 blood pressure targets, while three-quarters met the liberalized 2014 targets.

Dr. Borden and coworkers zeroed in on the 15% of hypertensive patients – that’s fully 173,519 individuals in cardiology practices participating in the PINNACLE Registry – who would have been eligible for treatment under the JNC 7 recommendations but not the 2014 expert panel guidelines. Interestingly, that 15% figure was closely similar to the 17% rate reported by Dr. Michael D. Miedema of the Minneapolis Heart Institute in an analysis of a more primary care population of older patients in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study he presented in the same session.

Dr. Borden and coinvestigators determined from medical records that the PINNACLE Registry group whose antihypertensive therapy treatment status changed between the two guidelines was at substantial baseline cardiovascular risk: Nearly two-thirds had been diagnosed with CAD, 54% had diabetes, 27% had a history of heart failure, 25% had a prior MI, and 23% had a prior transient ischemic attack or stroke.

This large group of patients who fell through the cracks between two conflicting sets of guidelines turned out to have a mean 10-year Framingham Risk Score of 8.5%. Upon incorporating the patients’ stroke risk using the atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) risk score embedded in the 2013 ACC/AHA cholesterol management guidelines, their 10-year risk shot up to 28%.

The investigators then conducted a modeling exercise aimed at estimating the clinical impact of lowering systolic blood pressure in the elderly from about 150 mm Hg, as recommended in the 2014 expert panel guidelines, to about 140 mm Hg, as was the goal in JNC 7. To do so they extrapolated from the results of two randomized controlled clinical trials: the Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program (SHEP) and the Hypertension in the Very Elderly Trial (HYVET).

The result? Extrapolating from SHEP data, the 10-year ASCVD risk in these real-world elderly hypertensive patients caught between two conflicting sets of guidelines would drop from 28% to 19%. Using HYVET data, the average 10-year ASCVD risk would fall to 18.4%.

“This is equivalent to a number-needed-to-treat of 10-11 patients for 10 years in order to prevent one cardiovascular event,” according to Dr. Borden.

For the more than 80,000 patients over age 60 in the study population, that works out to roughly 8,000 cardiovascular events averted over the course of 10 years, he added.

The 2014 expert panel recommendations were based on a strict evidence-based review of published randomized controlled trials. The guidelines are new enough that it remains unclear if they will be embraced by clinicians or incorporated into performance measures and value-based health care purchasing programs.

The 2014 guidelines are considered highly controversial. The guideline committee comprising some of the nation’s top hypertension researchers was initially convened to come up with what was intended to be the long-awaited JNC 8 report; however, in the midst of the process the sponsoring National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute declared it was getting out of the guideline-writing business altogether. As a result, the guidelines ultimately published carried the imprimatur of “the 2014 expert panel,” rather than the more prestigious official stamp of JNC 8.

Indeed, five members of the guideline panel felt strongly enough to break away and issued a minority report (Ann. Intern. Med. 2014;160:499-503) in which they argued there is insufficient evidence of harm stemming from the JNC 7 goal of 140/90 mm Hg in patients over age 60 to justify revising the target to 150/90. They warned that this step could reverse the impressive reductions in cardiovascular and cerebrovascular morbidity and mortality realized in recent decades. And they concluded that the burden of proof should be on those who advocate raising the treatment threshold to 150/90 mm Hg to demonstrate that it has benefit in patients over age 60, which they haven’t done.

“I’m very concerned about the [2014 expert panel] guidelines. Older individuals have the highest prevalence of hypertension, they’re the least adequately controlled, and based on the available data I’m concerned that if people follow the new guidelines there’s going to be an increase in cardiovascular events,” said Dr. Wilbert F. Aronow of New York Medical College, Valhalla, who chaired the writing committee for the first-ever ACC/AHA clinical guidelines for controlling high blood pressure in the elderly (J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2011;57:2037-114).

The NCDR PINNACLE Registry and this study were supported by the American College of Cardiology Foundation. Dr. Borden and Dr. Aronow reported having no financial conflicts.

CHICAGO – Nearly one in seven patients in U.S. ambulatory cardiology practices who would have been recommended for initiation or intensification of antihypertensive drug therapy under the 2003 Seventh Joint National Committee guidelines are no longer treatment candidates under the 2014 expert panel recommendations.

These patients who no longer qualify for antihypertensive therapy under the 2014 guidelines turn out to have a disturbingly high average estimated 10-year risk of cardiovascular events. As a result, widespread adoption of the 2014 expert panel recommendations could have major adverse consequences for cardiovascular health, Dr. William B. Borden cautioned at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

“Given the size and underlying cardiovascular risk of the population affected by the changes in the 2014 panel recommendations, close monitoring will be required to assess changes in practice patterns, blood pressure control, and – importantly – any changes in cardiovascular morbidity and mortality,” said Dr. Borden, a cardiologist at George Washington University in Washington.

Because the 2014 expert panel guidelines represent a major shift in hypertension management, Dr. Borden and coinvestigators sought to quantify the potential cardiovascular health impact of this more lenient treatment approach. For this purpose they turned to the National Cardiovascular Data Registry Practice Innovation and Clinical Excellence (NCDR PINNACLE) Registry, a voluntary quality improvement project involving outpatient cardiology practices.

Of 1,185,253 patients with hypertension as identified in their chart by a recorded diagnosis or notation of blood pressure greater than 140/90 mm Hg, 60% met the 2003 JNC 7 goals (JAMA 2003;289:2560-72), meaning the other 40% were candidates for initiation or intensification of antihypertensive therapy in order to achieve those goals (see chart). In contrast, 74% of hypertensive patients in U.S. cardiology practices met the less aggressive targets recommended in the 2014 expert panel report (JAMA 2014;311:502-20).

Thus, fewer than two-thirds of hypertensive patients in outpatient cardiology practices met the 2003 JNC 7 blood pressure targets, while three-quarters met the liberalized 2014 targets.

Dr. Borden and coworkers zeroed in on the 15% of hypertensive patients – that’s fully 173,519 individuals in cardiology practices participating in the PINNACLE Registry – who would have been eligible for treatment under the JNC 7 recommendations but not the 2014 expert panel guidelines. Interestingly, that 15% figure was closely similar to the 17% rate reported by Dr. Michael D. Miedema of the Minneapolis Heart Institute in an analysis of a more primary care population of older patients in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study he presented in the same session.

Dr. Borden and coinvestigators determined from medical records that the PINNACLE Registry group whose antihypertensive therapy treatment status changed between the two guidelines was at substantial baseline cardiovascular risk: Nearly two-thirds had been diagnosed with CAD, 54% had diabetes, 27% had a history of heart failure, 25% had a prior MI, and 23% had a prior transient ischemic attack or stroke.

This large group of patients who fell through the cracks between two conflicting sets of guidelines turned out to have a mean 10-year Framingham Risk Score of 8.5%. Upon incorporating the patients’ stroke risk using the atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) risk score embedded in the 2013 ACC/AHA cholesterol management guidelines, their 10-year risk shot up to 28%.

The investigators then conducted a modeling exercise aimed at estimating the clinical impact of lowering systolic blood pressure in the elderly from about 150 mm Hg, as recommended in the 2014 expert panel guidelines, to about 140 mm Hg, as was the goal in JNC 7. To do so they extrapolated from the results of two randomized controlled clinical trials: the Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program (SHEP) and the Hypertension in the Very Elderly Trial (HYVET).

The result? Extrapolating from SHEP data, the 10-year ASCVD risk in these real-world elderly hypertensive patients caught between two conflicting sets of guidelines would drop from 28% to 19%. Using HYVET data, the average 10-year ASCVD risk would fall to 18.4%.

“This is equivalent to a number-needed-to-treat of 10-11 patients for 10 years in order to prevent one cardiovascular event,” according to Dr. Borden.

For the more than 80,000 patients over age 60 in the study population, that works out to roughly 8,000 cardiovascular events averted over the course of 10 years, he added.

The 2014 expert panel recommendations were based on a strict evidence-based review of published randomized controlled trials. The guidelines are new enough that it remains unclear if they will be embraced by clinicians or incorporated into performance measures and value-based health care purchasing programs.

The 2014 guidelines are considered highly controversial. The guideline committee comprising some of the nation’s top hypertension researchers was initially convened to come up with what was intended to be the long-awaited JNC 8 report; however, in the midst of the process the sponsoring National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute declared it was getting out of the guideline-writing business altogether. As a result, the guidelines ultimately published carried the imprimatur of “the 2014 expert panel,” rather than the more prestigious official stamp of JNC 8.

Indeed, five members of the guideline panel felt strongly enough to break away and issued a minority report (Ann. Intern. Med. 2014;160:499-503) in which they argued there is insufficient evidence of harm stemming from the JNC 7 goal of 140/90 mm Hg in patients over age 60 to justify revising the target to 150/90. They warned that this step could reverse the impressive reductions in cardiovascular and cerebrovascular morbidity and mortality realized in recent decades. And they concluded that the burden of proof should be on those who advocate raising the treatment threshold to 150/90 mm Hg to demonstrate that it has benefit in patients over age 60, which they haven’t done.

“I’m very concerned about the [2014 expert panel] guidelines. Older individuals have the highest prevalence of hypertension, they’re the least adequately controlled, and based on the available data I’m concerned that if people follow the new guidelines there’s going to be an increase in cardiovascular events,” said Dr. Wilbert F. Aronow of New York Medical College, Valhalla, who chaired the writing committee for the first-ever ACC/AHA clinical guidelines for controlling high blood pressure in the elderly (J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2011;57:2037-114).

The NCDR PINNACLE Registry and this study were supported by the American College of Cardiology Foundation. Dr. Borden and Dr. Aronow reported having no financial conflicts.

AT THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Key clinical point: Adoption of the less aggressive blood pressure goal of 150/90 mm Hg for patients age 60 and older as recommended in the 2014 expert panel guidelines could result in significantly more harm than good.

Major finding: Patients in cardiology practices who qualified for antihypertensive therapy under the 2003 JNC 7 guidelines but not under the 2014 expert panel guidelines have a baseline 10-year 28% risk of cardiovascular events or stroke using the risk calculator included in the 2013 ACC/AHA cholesterol management guidelines.

Data source: An analysis of 1,185,253 patients in U.S. ambulatory cardiology practices.

Disclosures: The NCDR PINNACLE Registry is supported by the American College of Cardiology Foundation. The presenter reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

USPSTF: Not enough evidence for vitamin D screening

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force made no recommendation for or against primary care physicians screening asymptomatic adults for vitamin D deficiency, because the current evidence is insufficient to adequately assess the benefits and harms of doing so, according to a report published online Nov. 24 in Annals of Internal Medicine.

The USPSTF reviewed the evidence on screening and treatment for vitamin D deficiency, because the condition may contribute to fractures, falls, functional limitations, cancer, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, depression, and excess mortality.

In addition, testing of vitamin D levels has increased markedly in recent years. One national survey showed the annual rate of outpatient visits with a diagnosis code for vitamin D deficiency more than tripled between 2008 and 2010, and a 2009 survey of clinical laboratories reported that the testing increased by at least half in the space of just 1 year, said Dr. Michael L. LeFevre, chair of the task force and professor of family medicine at the University of Missouri, Columbia, and his associates.

The organization is a voluntary expert group tasked with making recommendations about specific preventive care services, devices, and medications for asymptomatic people, with a view to improving Americans’ general health.

The task force reviewed the evidence presented in 16 randomized trials, as well as nested case-control studies using data from the Women’s Health Initiative. They found that no study has directly examined the effects of vitamin D screening, compared with no screening, on clinical outcomes. There isn’t even any consensus about what constitutes vitamin D deficiency, or what the optimal circulating level of 25-hydroxyvitamin D is.

Many testing methods are available, including competitive protein binding, immunoassay, high-performance liquid chromatography, and mass spectrometry. But the sensitivity and specificity of these tests remains unknown, because there is no internationally recognized reference standard. Moreover, the USPSTF found that test results vary not just by which test is used, but even between laboratories using the same test.

Symptomatic vitamin D deficiency is known to affect health adversely, as is asymptomatic vitamin D deficiency in certain patient populations. But the evidence that deficiency contributes to adverse health outcomes in asymptomatic adults is inadequate. The evidence that screening for such deficiency and treating “low” vitamin D levels prevents adverse outcomes or simply improves general health also is inadequate, Dr. LeFevre and his associates said.

Similarly, no studies to date have directly examined possible harms of screening for and treating vitamin D deficiency. Although there are concerns that vitamin D supplements may lead to hypercalcemia, kidney stones, or gastrointestinal symptoms, there is no evidence of such effects in the asymptomatic patient population.

The USPSTF concluded that the harms of screening for and treating vitamin D deficiency are likely “small to none,” but it still is not possible to determine whether the benefits outweigh even that small amount of harm.

At present, no national primary care professional organization recommends screening of the general adult population for vitamin D deficiency. The American Academy of Family Physicians, the Endocrine Society, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the American Geriatrics Society, and the National Osteoporosis Foundation all recommend screening for patients at risk for fractures or falls only. The Institute of Medicine has no formal guidelines regarding vitamin D screening, Dr. LeFevre and his associates noted.

The USPSTF summary report and the review of the evidence are available at www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org.

The USPSTF is focused on providing a firm evidential base for early detection and prevention of disease, noted Dr. Robert P. Heaney and Dr. Laura A. G. Armas in an accompanying editorial. But perhaps clinicians should have a different focus: full nutrient repletion in their patients, to optimize their health.

A strict disease-avoidance approach is too simplistic with regard to micronutrients, because they don’t directly cause the effects often attributed to them. Instead, when supplies of micronutrients are inadequate, cellular responses are blunted, Dr. Heaney and Dr. Armas noted. That is dysfunction, but not clinically manifest disease.

Such dysfunction may indeed lead ultimately to various diseases, they added, but disease prevention is a dull tool for discerning the defect. And a disease-prevention approach clearly doesn’t show whether there is enough of the nutrient present to enable appropriate physiological responses.

Dr. Heaney and Dr. Armas are at Creighton University in Omaha, Neb. Their remarks are drawn from an editorial accompanying the USPSTF reports.

The USPSTF is focused on providing a firm evidential base for early detection and prevention of disease, noted Dr. Robert P. Heaney and Dr. Laura A. G. Armas in an accompanying editorial. But perhaps clinicians should have a different focus: full nutrient repletion in their patients, to optimize their health.

A strict disease-avoidance approach is too simplistic with regard to micronutrients, because they don’t directly cause the effects often attributed to them. Instead, when supplies of micronutrients are inadequate, cellular responses are blunted, Dr. Heaney and Dr. Armas noted. That is dysfunction, but not clinically manifest disease.

Such dysfunction may indeed lead ultimately to various diseases, they added, but disease prevention is a dull tool for discerning the defect. And a disease-prevention approach clearly doesn’t show whether there is enough of the nutrient present to enable appropriate physiological responses.

Dr. Heaney and Dr. Armas are at Creighton University in Omaha, Neb. Their remarks are drawn from an editorial accompanying the USPSTF reports.

The USPSTF is focused on providing a firm evidential base for early detection and prevention of disease, noted Dr. Robert P. Heaney and Dr. Laura A. G. Armas in an accompanying editorial. But perhaps clinicians should have a different focus: full nutrient repletion in their patients, to optimize their health.

A strict disease-avoidance approach is too simplistic with regard to micronutrients, because they don’t directly cause the effects often attributed to them. Instead, when supplies of micronutrients are inadequate, cellular responses are blunted, Dr. Heaney and Dr. Armas noted. That is dysfunction, but not clinically manifest disease.

Such dysfunction may indeed lead ultimately to various diseases, they added, but disease prevention is a dull tool for discerning the defect. And a disease-prevention approach clearly doesn’t show whether there is enough of the nutrient present to enable appropriate physiological responses.

Dr. Heaney and Dr. Armas are at Creighton University in Omaha, Neb. Their remarks are drawn from an editorial accompanying the USPSTF reports.

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force made no recommendation for or against primary care physicians screening asymptomatic adults for vitamin D deficiency, because the current evidence is insufficient to adequately assess the benefits and harms of doing so, according to a report published online Nov. 24 in Annals of Internal Medicine.

The USPSTF reviewed the evidence on screening and treatment for vitamin D deficiency, because the condition may contribute to fractures, falls, functional limitations, cancer, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, depression, and excess mortality.

In addition, testing of vitamin D levels has increased markedly in recent years. One national survey showed the annual rate of outpatient visits with a diagnosis code for vitamin D deficiency more than tripled between 2008 and 2010, and a 2009 survey of clinical laboratories reported that the testing increased by at least half in the space of just 1 year, said Dr. Michael L. LeFevre, chair of the task force and professor of family medicine at the University of Missouri, Columbia, and his associates.

The organization is a voluntary expert group tasked with making recommendations about specific preventive care services, devices, and medications for asymptomatic people, with a view to improving Americans’ general health.

The task force reviewed the evidence presented in 16 randomized trials, as well as nested case-control studies using data from the Women’s Health Initiative. They found that no study has directly examined the effects of vitamin D screening, compared with no screening, on clinical outcomes. There isn’t even any consensus about what constitutes vitamin D deficiency, or what the optimal circulating level of 25-hydroxyvitamin D is.

Many testing methods are available, including competitive protein binding, immunoassay, high-performance liquid chromatography, and mass spectrometry. But the sensitivity and specificity of these tests remains unknown, because there is no internationally recognized reference standard. Moreover, the USPSTF found that test results vary not just by which test is used, but even between laboratories using the same test.

Symptomatic vitamin D deficiency is known to affect health adversely, as is asymptomatic vitamin D deficiency in certain patient populations. But the evidence that deficiency contributes to adverse health outcomes in asymptomatic adults is inadequate. The evidence that screening for such deficiency and treating “low” vitamin D levels prevents adverse outcomes or simply improves general health also is inadequate, Dr. LeFevre and his associates said.

Similarly, no studies to date have directly examined possible harms of screening for and treating vitamin D deficiency. Although there are concerns that vitamin D supplements may lead to hypercalcemia, kidney stones, or gastrointestinal symptoms, there is no evidence of such effects in the asymptomatic patient population.

The USPSTF concluded that the harms of screening for and treating vitamin D deficiency are likely “small to none,” but it still is not possible to determine whether the benefits outweigh even that small amount of harm.

At present, no national primary care professional organization recommends screening of the general adult population for vitamin D deficiency. The American Academy of Family Physicians, the Endocrine Society, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the American Geriatrics Society, and the National Osteoporosis Foundation all recommend screening for patients at risk for fractures or falls only. The Institute of Medicine has no formal guidelines regarding vitamin D screening, Dr. LeFevre and his associates noted.

The USPSTF summary report and the review of the evidence are available at www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org.

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force made no recommendation for or against primary care physicians screening asymptomatic adults for vitamin D deficiency, because the current evidence is insufficient to adequately assess the benefits and harms of doing so, according to a report published online Nov. 24 in Annals of Internal Medicine.

The USPSTF reviewed the evidence on screening and treatment for vitamin D deficiency, because the condition may contribute to fractures, falls, functional limitations, cancer, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, depression, and excess mortality.

In addition, testing of vitamin D levels has increased markedly in recent years. One national survey showed the annual rate of outpatient visits with a diagnosis code for vitamin D deficiency more than tripled between 2008 and 2010, and a 2009 survey of clinical laboratories reported that the testing increased by at least half in the space of just 1 year, said Dr. Michael L. LeFevre, chair of the task force and professor of family medicine at the University of Missouri, Columbia, and his associates.

The organization is a voluntary expert group tasked with making recommendations about specific preventive care services, devices, and medications for asymptomatic people, with a view to improving Americans’ general health.

The task force reviewed the evidence presented in 16 randomized trials, as well as nested case-control studies using data from the Women’s Health Initiative. They found that no study has directly examined the effects of vitamin D screening, compared with no screening, on clinical outcomes. There isn’t even any consensus about what constitutes vitamin D deficiency, or what the optimal circulating level of 25-hydroxyvitamin D is.

Many testing methods are available, including competitive protein binding, immunoassay, high-performance liquid chromatography, and mass spectrometry. But the sensitivity and specificity of these tests remains unknown, because there is no internationally recognized reference standard. Moreover, the USPSTF found that test results vary not just by which test is used, but even between laboratories using the same test.

Symptomatic vitamin D deficiency is known to affect health adversely, as is asymptomatic vitamin D deficiency in certain patient populations. But the evidence that deficiency contributes to adverse health outcomes in asymptomatic adults is inadequate. The evidence that screening for such deficiency and treating “low” vitamin D levels prevents adverse outcomes or simply improves general health also is inadequate, Dr. LeFevre and his associates said.

Similarly, no studies to date have directly examined possible harms of screening for and treating vitamin D deficiency. Although there are concerns that vitamin D supplements may lead to hypercalcemia, kidney stones, or gastrointestinal symptoms, there is no evidence of such effects in the asymptomatic patient population.

The USPSTF concluded that the harms of screening for and treating vitamin D deficiency are likely “small to none,” but it still is not possible to determine whether the benefits outweigh even that small amount of harm.

At present, no national primary care professional organization recommends screening of the general adult population for vitamin D deficiency. The American Academy of Family Physicians, the Endocrine Society, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the American Geriatrics Society, and the National Osteoporosis Foundation all recommend screening for patients at risk for fractures or falls only. The Institute of Medicine has no formal guidelines regarding vitamin D screening, Dr. LeFevre and his associates noted.

The USPSTF summary report and the review of the evidence are available at www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org.

FROM ANNALS OF INTERNAL MEDICINE

Key clinical point: The USPSTF makes no recommendation for or against screening and treating asymptomatic adults for vitamin D deficiency, because the evidence regarding the benefits and harms is insufficient.

Major finding: Testing of vitamin D levels has increased markedly, with one national survey showing the annual rate of outpatient visits with a diagnosis code for vitamin D deficiency more than tripled between 2008 and 2010, and a 2009 survey of clinical laboratories reporting that the testing increased by at least half in the space of just 1 year.

Data source: A detailed review of the evidence and an expert consensus regarding screening asymptomatic adults for vitamin D deficiency to prevent fractures, cancer, CVD, and other adverse outcomes.

Disclosures: The USPSTF is an independent, voluntary group supported by the U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality to improve Americans’ health by making recommendations concerning preventive services such as screenings and medications. Dr. LeFevre and his associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Axial spondyloarthropathy guidelines: NSAIDs and PT first

BOSTON – A nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug and exercise may be enough to control active axial spondyloarthritis in some patients, suggest authors of draft guidelines on the management of patients with the condition.

The guidelines, not ready for prime time, have yet to be reviewed or endorsed by the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) and the Spondylitis Association of America, or the SpondyloArthritis Research and Treatment Network (SPARTAN), and are subject to change, emphasized Dr. Michael M. Ward, senior investigator at the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS).

With that caveat in mind, Dr. Ward presented a sneak peek at the guidelines to a standing-room only crowd at the ACR annual meeting in Boston.

Some definitions

The guidelines offer recommendations on the management of patients with active and stable ankylosing spondylitis (AS) and axial spondyloarthropathies (axSpA) that are symptomatic but without radiographic evidence (nonradiographic, or nr-axSpA).

Active AS is defined as disease that causes symptoms at an unacceptably burdensome level as reported by the patient that are judged by the examining clinician to be caused by AS. The same definition also applies to nr-axSpA.

Stable disease is defined as either an asymptomatic state or symptoms that were previously bothersome but are currently at an acceptable level as reported by the patient. The patient had to have had bothersome symptoms for at least 6 months before entering the stable disease state. This definition is also applicable to stable nr-axSpA.

The investigators considered the best available evidence on the use of NSAIDs (running the gamut from aspirin to tolmetin), slow-acting antirheumatic agents such as methotrexate, glucocorticoids (prednisone and others), tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors, such as adalimumab, etanercept, and others), and non-TNF biologic agents (abatacept, rituximab, tocilizumab, and others).

Active AS

Dr. Ward presented a management flow tree for patients with active AS, starting with a strong recommendation for an NSAID, conditionally recommended to be used continuously. The authors felt, however, that there was not enough evidence to support the use of one NSAID over another. They also strongly recommended physical therapy, with less robust recommendations for active than for passive exercise and for exercises performed in water rather than on land. The latter recommendation is based on the fact that, although water-based exercises have been shown to be as good as or better than dry land exercises for relieving symptoms, water-based exercise may be impractical for many patients, Dr. Ward noted.

For patients whose disease remains active despite NSAIDs and exercise, the committee strongly recommends use of a tumor necrosis factor inhibitor (TNFi) (no specific agent preferred). If a patient on a TNFi has recurrent iritis, the guidelines have a conditional recommendation for the use of infliximab or adalimumab. For patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), the authors conditionally recommend a TNFi monoclonal antibody as opposed to etanercept.

If the disease remains active on a TNFi, an alternative TNFi can be considered.

“For patients who have contraindications to TNF inhibitors, we considered the choice between adding a slow-acting drug such as sulfasalazine or pamidronate or treating with a non-TNF biologic. Of course, there are no head-to-head trials between those two options, so based on the indirect evidence that’s available, the committee voted for a conditional recommendation against the use of a non-TNF biologic in favor of a slow-acting drug in that setting,” Dr. Ward said.

If there are no contraindications to a TNF inhibitor, however, the committee strongly favored the use of a TNF inhibitor over a slow-acting agent, he emphasized.

For patients who have isolated sacroiliitis, peripheral arthritis, or enthesis, the committee provisionally recommends local injection of a glucocorticoid, with cautions to use infrequently and only if two or fewer joints are involved in peripheral arthritis, and avoidance of injection of the Achilles, patellar, or quadriceps tendons in patients with enthesitis.

For all patients, the guidelines half-heartedly recommend monitoring validated axSpA disease activity measures and C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR). The group also conditionally supported unsupervised back exercises, formal group or individual self-management education, and fall evaluation and counseling.

Committee members strongly felt that systemic glucocorticoids should not be used in patients with active axSpA, except in cases where a short-term course with quick taper may be helpful, such as in patients with peripheral flare, or during pregnancy or a concomitant IBD flare.

Stable AS

“For patients with stable ankylosing spondylitis who are on combination therapy, either combination therapy with NSAIDs and a TNF inhibitor, or a slow-acting drug and a TNF inhibitor, the committee voted against continuation of a combination in favor of TNF monotherapy. It’s a conditional recommendation, so there certainly would be situations where one would not want to do that, but in general the committee thought that was the preferable approach, balancing the benefits and potential risks of combination therapy against monotherapy in patients with stable AS,” Dr. Ward said.

The committee members strongly supported physical therapy in patients with stable AS and gave a conditional nod to monitoring, back exercises, group support, and fall counseling.

For patients with stable AS and advanced hip arthritis, hip replacement is strongly recommended. Recommendations for and against other special conditions include severe kyphosis (strongly against elective spine osteotomy except in specialized centers), acute iritis (strong support for an ophthalmology consultant), recurrent iritis (conditional support for at home use of a topical glucocorticoid under the supervision of an eye care provider, and use of infliximab or adalimumab over etanercept), and IBD (strong recommendation for TNFi monoclonals over etanercept and conditional endorsement of no preferred NSAID).

Active nr-axSpA

Recommendations for the treatment of nr-axSpA are essentially identical to those for treating active AS, Dr. Ward noted, except that in contrast to active AS, where the recommendation is strongly in favor of TNF inhibitors, the committee gave only a conditional recommendation for the use of a TNF inhibitor in this clinical situation.

Stable nr-axSpA

For patients with stable nr-axSpA, the recommendations are strongly in favor of NSAID use, with a conditional suggestion to use on demand. The recommendations also are conditionally against combination therapy with either an NSAID or slow-acting agent plus a TNF inhibitor, with a conditional approval for TNF inhibitor monotherapy instead. The committee strongly supported physical therapy for these patients and gave a lukewarm embrace of monitoring for disease activity, CRP, or ESR.

Dr. Ward noted that the guidelines are designed to help clinicians with treatment decisions for the typical patient with AS or nr-axSpA, and do not address the needs of all populations or all clinical circumstances or contingencies.

He also noted that for many of the questions the committee members tried to address, high-quality evidence was limited.

Dr. Ward did not mention a projected publication date for the guidelines. He had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

BOSTON – A nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug and exercise may be enough to control active axial spondyloarthritis in some patients, suggest authors of draft guidelines on the management of patients with the condition.

The guidelines, not ready for prime time, have yet to be reviewed or endorsed by the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) and the Spondylitis Association of America, or the SpondyloArthritis Research and Treatment Network (SPARTAN), and are subject to change, emphasized Dr. Michael M. Ward, senior investigator at the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS).

With that caveat in mind, Dr. Ward presented a sneak peek at the guidelines to a standing-room only crowd at the ACR annual meeting in Boston.

Some definitions

The guidelines offer recommendations on the management of patients with active and stable ankylosing spondylitis (AS) and axial spondyloarthropathies (axSpA) that are symptomatic but without radiographic evidence (nonradiographic, or nr-axSpA).

Active AS is defined as disease that causes symptoms at an unacceptably burdensome level as reported by the patient that are judged by the examining clinician to be caused by AS. The same definition also applies to nr-axSpA.

Stable disease is defined as either an asymptomatic state or symptoms that were previously bothersome but are currently at an acceptable level as reported by the patient. The patient had to have had bothersome symptoms for at least 6 months before entering the stable disease state. This definition is also applicable to stable nr-axSpA.

The investigators considered the best available evidence on the use of NSAIDs (running the gamut from aspirin to tolmetin), slow-acting antirheumatic agents such as methotrexate, glucocorticoids (prednisone and others), tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors, such as adalimumab, etanercept, and others), and non-TNF biologic agents (abatacept, rituximab, tocilizumab, and others).

Active AS

Dr. Ward presented a management flow tree for patients with active AS, starting with a strong recommendation for an NSAID, conditionally recommended to be used continuously. The authors felt, however, that there was not enough evidence to support the use of one NSAID over another. They also strongly recommended physical therapy, with less robust recommendations for active than for passive exercise and for exercises performed in water rather than on land. The latter recommendation is based on the fact that, although water-based exercises have been shown to be as good as or better than dry land exercises for relieving symptoms, water-based exercise may be impractical for many patients, Dr. Ward noted.

For patients whose disease remains active despite NSAIDs and exercise, the committee strongly recommends use of a tumor necrosis factor inhibitor (TNFi) (no specific agent preferred). If a patient on a TNFi has recurrent iritis, the guidelines have a conditional recommendation for the use of infliximab or adalimumab. For patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), the authors conditionally recommend a TNFi monoclonal antibody as opposed to etanercept.

If the disease remains active on a TNFi, an alternative TNFi can be considered.

“For patients who have contraindications to TNF inhibitors, we considered the choice between adding a slow-acting drug such as sulfasalazine or pamidronate or treating with a non-TNF biologic. Of course, there are no head-to-head trials between those two options, so based on the indirect evidence that’s available, the committee voted for a conditional recommendation against the use of a non-TNF biologic in favor of a slow-acting drug in that setting,” Dr. Ward said.

If there are no contraindications to a TNF inhibitor, however, the committee strongly favored the use of a TNF inhibitor over a slow-acting agent, he emphasized.

For patients who have isolated sacroiliitis, peripheral arthritis, or enthesis, the committee provisionally recommends local injection of a glucocorticoid, with cautions to use infrequently and only if two or fewer joints are involved in peripheral arthritis, and avoidance of injection of the Achilles, patellar, or quadriceps tendons in patients with enthesitis.

For all patients, the guidelines half-heartedly recommend monitoring validated axSpA disease activity measures and C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR). The group also conditionally supported unsupervised back exercises, formal group or individual self-management education, and fall evaluation and counseling.

Committee members strongly felt that systemic glucocorticoids should not be used in patients with active axSpA, except in cases where a short-term course with quick taper may be helpful, such as in patients with peripheral flare, or during pregnancy or a concomitant IBD flare.

Stable AS

“For patients with stable ankylosing spondylitis who are on combination therapy, either combination therapy with NSAIDs and a TNF inhibitor, or a slow-acting drug and a TNF inhibitor, the committee voted against continuation of a combination in favor of TNF monotherapy. It’s a conditional recommendation, so there certainly would be situations where one would not want to do that, but in general the committee thought that was the preferable approach, balancing the benefits and potential risks of combination therapy against monotherapy in patients with stable AS,” Dr. Ward said.