User login

Borderline personality disorder: 6 studies of biological interventions

FIRST OF 2 PARTS

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) is marked by an ongoing pattern of mood instability, cognitive distortions, problems with self-image, and impulsive behavior, often resulting in problems in relationships. BPD is associated with serious impairment in psychosocial functioning.1 Patients with BPD tend to use more mental health services than patients with other personality disorders or those with major depressive disorder (MDD).2 However, there has been little consensus on the best treatment(s) for this serious and debilitating disorder, and some clinicians view BPD as difficult to treat.

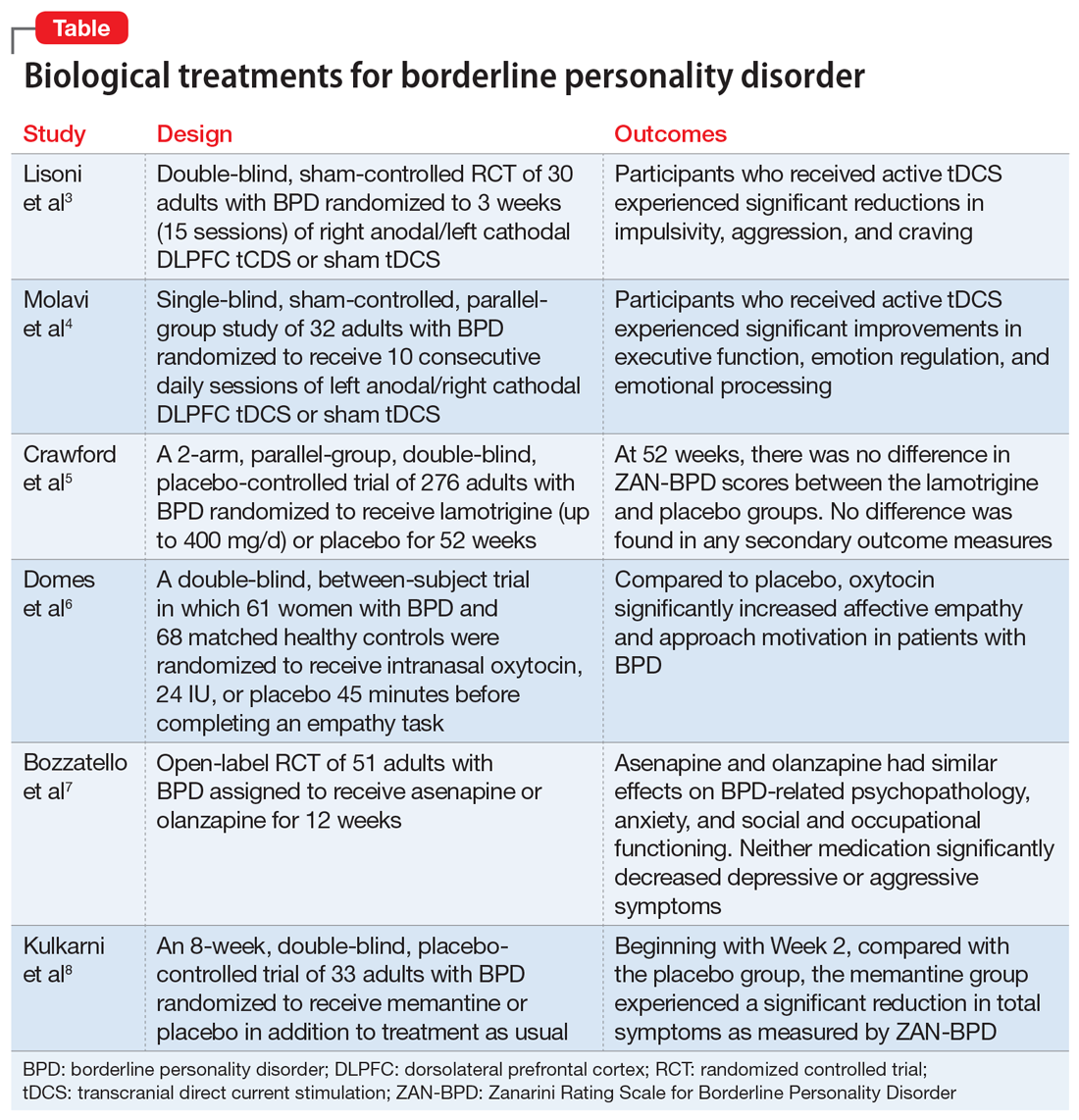

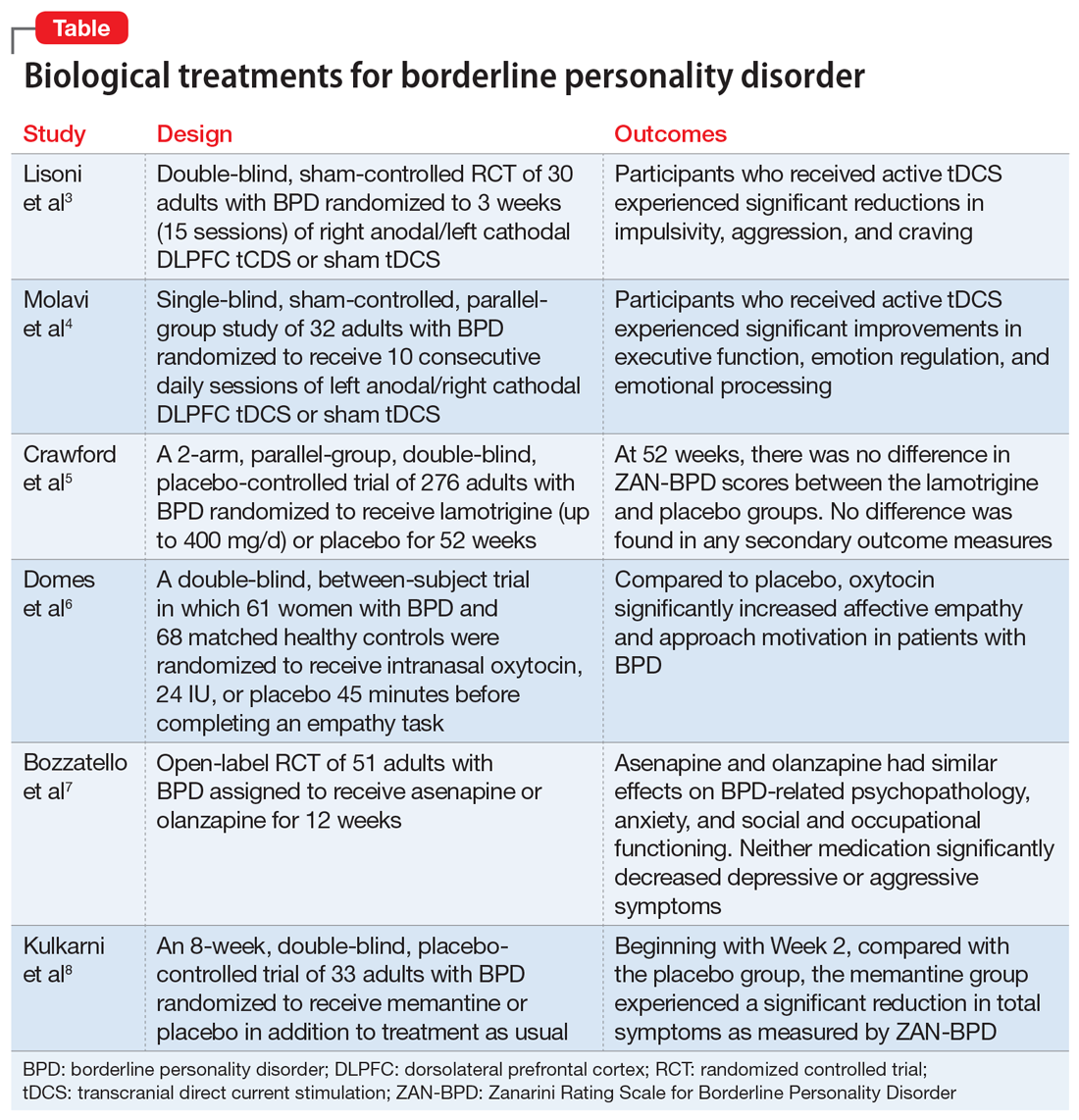

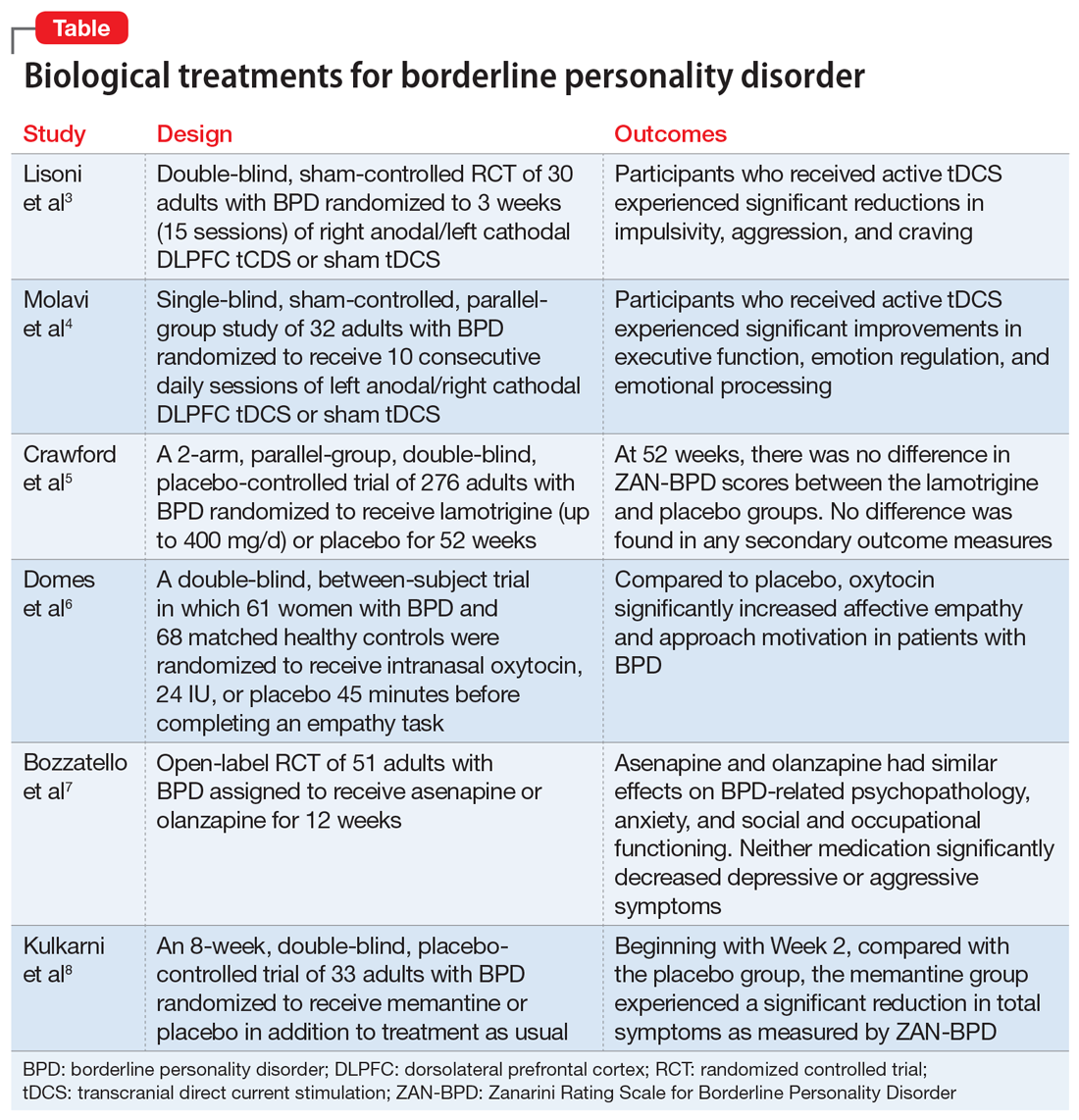

Current treatments for BPD include psychological and pharmacological interventions. Neuromodulation techniques, such as repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation, may also positively affect BPD symptomatology. In recent years, there have been some promising findings in the treatment of BPD. In this 2-part article, we focus on current (within the last 5 years) findings from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of BPD treatments. Here in Part 1, we focus on 6 studies that evaluated biological interventions (Table,3-8). In Part 2, we will focus on RCTs that investigated psychological interventions.

1. Lisoni J, Miotto P, Barlati S, et al. Change in core symptoms of borderline personality disorder by tDCS: a pilot study. Psychiatry Res. 2020;291:113261. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113261

Impulsivity has been described as the core feature of BPD that best explains its behavioral, cognitive, and clinical manifestations. Studies have repeatedly demonstrated the role of the prefrontal cortex in modulating impulsivity. Dysfunction of the

Continue to: Study design...

Study design

- In a double-blind, sham-controlled trial, adults who met DSM-IV-TR criteria for BPD were randomized to 3 weeks (15 sessions) of right anodal/left cathodal DLPFC tCDS (n = 15) or sham tDCS (n = 15). This study included patients with comorbid psychiatric disorders, including substance use disorders. Discontinuation or alteration of existing medications was not allowed.

- The presence, severity, and change over time of BPD core symptoms was assessed at baseline and after 3 weeks using several clinical scales, self-questionnaires, and neuropsychological tests, including the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale-11 (BIS-11), Buss-Perry Aggression Questionnaire (BP-AQ), Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS), Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D), Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A), Irritability-Depression Anxiety Scale (IDA), Visual Analog Scales (VAS), and Iowa Gambling Task.

Outcomes

- Participants in the active tDCS group experienced significant reductions in impulsivity, aggression, and craving as measured by the BIS-11, BP-AQ, and VAS.

- Compared to the sham group, the active tDCS group had greater reductions in HAM-D and BDI scores.

- HAM-A and IDA scores were improved in both groups, although the active tDCS group showed greater reductions in IDA scores compared with the sham group.

- As measured by DERS, active tDCS did not improve affective dysregulation more than sham tDCS.

Conclusions/limitations

- Bilateral tDCS targeting the right DLPFC with anodal stimulation is a safe, well-tolerated technique that may modulate core dimensions of BPD, including impulsivity, aggression, and craving.

- Excitatory anodal stimulation of the right DLFPC coupled with inhibitory cathodal stimulation on the left DLPFC may be an effective montage for targeting impulsivity in patients with BPD.

- Study limitations include a small sample size, use of targeted questionnaires only, inclusion of patients with BPD who also had certain comorbid psychiatric disorders, lack of analysis of the contributions of medications, lack of functional neuroimaging, and lack of a follow-up phase.

2. Molavi P, Aziziaram S, Basharpoor S, et al. Repeated transcranial direct current stimulation of dorsolateral-prefrontal cortex improves executive functions, cognitive reappraisal emotion regulation, and control over emotional processing in borderline personality disorder: a randomized, sham-controlled, parallel-group study. J Affect Disord. 2020;274:93-102. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.05.007

Emotional dysregulation is considered a core feature of BPD psychopathology and is closely associated with executive dysfunction and cognitive control. Manifestations of executive dysfunction include aggressiveness, impulsive decision-making, disinhibition, and self-destructive behaviors. Neuroimaging of patients with BPD has shown enhanced activity in the insula, posterior cingulate cortex, and amygdala, with reduced activity in the medial PFC, subgenual anterior cingulate cortex, and DLPFC. Molavi et al4 postulated that increasing DLPFC activation with left anodal tDCS would result in improved executive functioning and emotion dysregulation in patients with BPD.

Study design

- In this single-blind, sham-controlled, parallel-group study, adults who met DSM-5 criteria for BPD were randomized to receive 10 consecutive daily sessions of left anodal/right cathodal DLPFC tDCS (n = 16) or sham tDCS (n = 16).

- The effect of tDCS on executive dysfunction, emotion dysregulation, and emotional processing was measured using the Executive Skills Questionnaire for Adults (ESQ), Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (ERQ), and Emotional Processing Scale (EPS). Measurements occurred at baseline and after 10 sessions of active or sham tDCS.

Outcomes

- Participants who received active tDCS experienced significant improvements in ESQ overall score and most of the executive function domains measured by the ESQ.

- Those in the active tDCS group also experienced significant improvement in emotion regulation as measured by the cognitive reappraisal subscale (but not the expressive suppression subscale) of the ERQ after the intervention.

- Overall emotional processing as measured by the EPS was significantly improved in the active tDCS group following the intervention.

Conclusions/limitations

- Repeated bilateral left anodal/right cathodal tDCS stimulation of the DLPFC significantly improved executive functioning and aspects of emotion regulation and emotional processing in patients with BPD. This improvement was presumed to be the result of increased activity of left DLPFC.

- Study limitations include a single-blind design, lack of follow-up to assess durability and stability of response over time, reliance on self-report measures, lack of functional neuroimaging, and limited focality of tDCS.

3. Crawford MJ, Sanatinia R, Barrett B, et al; LABILE study team. The clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of lamotrigine in borderline personality disorder: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(8):756-764. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2018.17091006

One of the hallmark symptoms of BPD is mood dysregulation. Current treatment guidelines recommend the use of mood stabilizers for BPD despite limited quality evidence of effectiveness and a lack of FDA-approved medications with this indication. In this RCT, Crawford et al5 examined whether lamotrigine is a clinically effective and cost-effective treatment for people with BPD.

Continue to: Study design...

Study design

- In this 2-arm, parallel-group, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, 276 adults who met DSM-IV criteria for BPD were randomized to receive lamotrigine (up to 400 mg/d) or placebo for 52 weeks.

- The primary outcome was the score on the Zanarini Rating Scale for Borderline Personality Disorder (ZAN-BPD) at 52 weeks. Secondary outcomes included depressive symptoms, deliberate self-harm, social functioning, health-related quality of life, resource use and costs, treatment adverse effects, and adverse events. These were assessed using the BDI; Acts of Deliberate Self-Harm Inventory; Social Functioning Questionnaire; Alcohol, Smoking, and Substance Involvement Screening Test; and the EQ-5D-3L.

Outcomes

- Mean ZAN-BPD score decreased at 12 weeks in both groups, after which time the score remained stable.

- There was no difference in ZAN-BPD scores at 52 weeks between treatment arms. No difference was found in any secondary outcome measures.

- Difference in costs between groups was not significant.

Conclusions/limitations

- There was no evidence that lamotrigine led to clinical improvements in BPD symptomatology, social functioning, health-related quality of life, or substance use.

- Lamotrigine is neither clinically effective nor a cost-effective use of resources in the treatment of BPD.

- Limitations include a low level of adherence.

4. Domes G, Ower N, von Dawans B, et al. Effects of intranasal oxytocin administration on empathy and approach motivation in women with borderline personality disorder: a randomized controlled trial. Transl Psychiatry. 2019;9(1):328. doi: 10.1038/s41398-019-0658-4

A core feature of BPD is impairment in empathy; adequate empathy is required for intact social functioning. Oxytocin is a neuropeptide that helps regulate complex social cognition and behavior. Prior research has found that oxytocin administration enhances emotion regulation and empathy. Women with BPD have been observed to have lower levels of oxytocin. Domes et al6 conducted an RCT to see if oxytocin could have a beneficial effect on social approach and social cognition in women with BPD.

Study design

- In a double-blind, placebo-controlled, between-subject trial, 61 women who met DSM-IV criteria for BPD and 68 matched healthy controls were randomized to receive intranasal oxytocin, 24 IU, or placebo 45 minutes before completing an empathy task.

- An extended version of the Multifaceted Empathy Test was used to assess empathy and approach motivation.

Outcomes

- For cognitive empathy, patients with BPD exhibited significantly lower overall performance compared to controls. There was no effect of oxytocin on this performance in either group.

- Patients with BPD had significantly lower affective empathy compared with controls. After oxytocin administration, patients with BPD had significantly higher affective empathy than those with BPD who received placebo, reaching the level of healthy controls who received placebo.

- For positive stimuli, patients with BPD showed lower affective empathy than controls. Oxytocin treatment increased affective empathy in both groups.

- For negative stimuli, oxytocin increased affective empathy more in patients with BPD than in controls.

- Patients with BPD demonstrated less approach motivation than controls. Oxytocin increased approach motivation more in patients with BPD than in controls. For approach motivation toward positive stimuli, oxytocin had a significant effect on patients with BPD.

Continue to: Conclusions/limitations...

Conclusions/limitations

- Patients with BPD showed reduced cognitive and affective empathy and less approach behavior motivation than healthy controls.

- Patients with BPD who received oxytocin attained a level of affective empathy and approach motivation similar to that of healthy controls who received placebo. For positive stimuli, both groups exhibited comparable improvements from oxytocin. For negative stimuli, patients with BPD patients showed significant improvement with oxytocin, whereas healthy controls received no such benefit.

- Limitations include the use of self-report scales, lack of a control group, and inclusion of patients using psychotherapeutic medications. The study lacks generalizability because only women were included; the effect of exogenous oxytocin on men may differ.

5. Bozzatello P, Rocca P, Uscinska M, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of asenapine compared with olanzapine in borderline personality disorder: an open-label randomized controlled trial. CNS Drugs. 2017;31(9):809-819. doi: 10.1007/s40263-017-0458-4

The last decade has seen a noticeable shift in clinical practice from the use of antidepressants to mood stabilizers and second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) in the treatment of BPD. Studies have demonstrated therapeutic effects of antipsychotic drugs across a wide range of BPD symptoms. Among SGAs, olanzapine is the most extensively studied across case reports, open-label studies, and RCTs of patients with BPD. In an RCT, Bozzatello et al7 compared the efficacy and tolerability of asenapine to olanzapine.

Study design

- In this open-label RCT, adults who met DSM-5 criteria for BPD were assigned to receive asenapine (n = 25) or olanzapine (n = 26) for 12 weeks.

- Study measurements included the Clinical Global Impression Scale, Severity item, HAM-D, HAM-A, Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale, Borderline Personality Disorder Severity Index (BPDSI), BIS-11, Modified Overt Aggression Scale, and Dosage Record Treatment Emergent Symptom Scale.

Outcomes

- Asenapine and olanzapine had similar effects on BPD-related psychopathology, anxiety, and social and occupational functioning.

- Neither medication significantly decreased depressive or aggressive symptoms.

- Asenapine was superior to olanzapine in reducing the affective instability score of the BPDSI.

- Akathisia and restlessness/anxiety were more common with asenapine, and somnolence and fatigue were more common with olanzapine.

Conclusions/limitations

- The overall efficacy of asenapine was not different from olanzapine, and both medications were well-tolerated.

- Neither medication led to an improvement in depression or aggression, but asenapine was superior to olanzapine in reducing the severity of affective instability.

- Limitations include an open-label design, lack of placebo group, small sample size, high drop-out rate, exclusion of participants with co-occurring MDD and substance abuse/dependence, lack of data on prior pharmacotherapies and psychotherapies, and lack of power to detect a difference on the dissociation/paranoid ideation item of BPDSI.

6. Kulkarni J, Thomas N, Hudaib AR, et al. Effect of the glutamate NMDA receptor antagonist memantine as adjunctive treatment in borderline personality disorder: an exploratory, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. CNS Drugs. 2018;32(2):179-187. doi: 10.1007/s40263-018-0506-8

It has been hypothesized that glutamate dysregulation and excitotoxicity are crucial to the development of the cognitive disturbances that underlie BPD. As such, glutamate modulators such as memantine hold promise for the treatment of BPD. In this RCT, Kulkarni et al8 examined the efficacy and tolerability of memantine compared with treatment as usual in patients with BPD.

Continue to: Study design...

Study design

- In an 8-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, adults diagnosed with BPD according to the Diagnostic Interview for Borderline Patients were randomized to receive memantine (n = 17) or placebo (n = 16) in addition to treatment as usual. Treatment as usual included the use of antidepressants, mood stabilizers, and antipsychotics as well as psychotherapy and other psychosocial interventions.

- Patients were initiated on placebo or memantine, 10 mg/d. Memantine was increased to 20 mg/d after 7 days.

- ZAN-BPD score was the primary outcome and was measured at baseline and 2, 4, 6, and 8 weeks. An adverse effects questionnaire was administered every 2 weeks to assess tolerability.

Outcomes

- During the first 2 weeks of treatment, there were no significant improvements in ZAN-BPD score in the memantine group compared with the placebo group.

- Beginning with Week 2, compared with the placebo group, the memantine group experienced a significant reduction in total symptoms as measured by ZAN-BPD.

- There were no statistically significant differences in adverse events between groups.

Conclusions/limitations

- Memantine appears to be a well-tolerated treatment option for patients with BPD and merits further study.

- Limitations include a small sample size, and an inability to reach plateau of ZAN-BPD total score in either group. Also, there is considerable individual variability in memantine steady-state plasma concentrations, but plasma levels were not measured in this study.

Bottom Line

Findings from small randomized controlled trials suggest that transcranial direct current stimulation, oxytocin, asenapine, olanzapine, and memantine may have beneficial effects on some core symptoms of borderline personality disorder. These findings need to be replicated in larger studies.

1. Skodol AE, Gunderson JG, McGlashan TM, et al. Functional impairment in patients with schizotypal, borderline, avoidant, or obsessive-compulsive personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2002; 159:276-283.

2. Bender DS, Dolan RT, Skodol AE, et al. Treatment utilization by patients with personality disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:295-302.

3. Lisoni J, Miotto P, Barlati S, et al. Change in core symptoms of borderline personality disorder by tDCS: a pilot study. Psychiatry Res. 2020;291:113261. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113261

4. Molavi P, Aziziaram S, Basharpoor S, et al. Repeated transcranial direct current stimulation of dorsolateral-prefrontal cortex improves executive functions, cognitive reappraisal emotion regulation, and control over emotional processing in borderline personality disorder: a randomized, sham-controlled, parallel-group study. J Affect Disord. 2020;274:93-102. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.05.007

5. Crawford MJ, Sanatinia R, Barrett B, et al; LABILE study team. The clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of lamotrigine in borderline personality disorder: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(8):756-764. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2018.17091006

6. Domes G, Ower N, von Dawans B, et al. Effects of intranasal oxytocin administration on empathy and approach motivation in women with borderline personality disorder: a randomized controlled trial. Transl Psychiatry. 2019;9(1):328. doi: 10.1038/s41398-019-0658-4

7. Bozzatello P, Rocca P, Uscinska M, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of asenapine compared with olanzapine in borderline personality disorder: an open-label randomized controlled trial. CNS Drugs. 2017;31(9):809-819. doi: 10.1007/s40263-017-0458-4

8. Kulkarni J, Thomas N, Hudaib AR, et al. Effect of the glutamate NMDA receptor antagonist memantine as adjunctive treatment in borderline personality disorder: an exploratory, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. CNS Drugs. 2018;32(2):179-187. doi: 10.1007/s40263-018-0506-8

FIRST OF 2 PARTS

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) is marked by an ongoing pattern of mood instability, cognitive distortions, problems with self-image, and impulsive behavior, often resulting in problems in relationships. BPD is associated with serious impairment in psychosocial functioning.1 Patients with BPD tend to use more mental health services than patients with other personality disorders or those with major depressive disorder (MDD).2 However, there has been little consensus on the best treatment(s) for this serious and debilitating disorder, and some clinicians view BPD as difficult to treat.

Current treatments for BPD include psychological and pharmacological interventions. Neuromodulation techniques, such as repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation, may also positively affect BPD symptomatology. In recent years, there have been some promising findings in the treatment of BPD. In this 2-part article, we focus on current (within the last 5 years) findings from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of BPD treatments. Here in Part 1, we focus on 6 studies that evaluated biological interventions (Table,3-8). In Part 2, we will focus on RCTs that investigated psychological interventions.

1. Lisoni J, Miotto P, Barlati S, et al. Change in core symptoms of borderline personality disorder by tDCS: a pilot study. Psychiatry Res. 2020;291:113261. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113261

Impulsivity has been described as the core feature of BPD that best explains its behavioral, cognitive, and clinical manifestations. Studies have repeatedly demonstrated the role of the prefrontal cortex in modulating impulsivity. Dysfunction of the

Continue to: Study design...

Study design

- In a double-blind, sham-controlled trial, adults who met DSM-IV-TR criteria for BPD were randomized to 3 weeks (15 sessions) of right anodal/left cathodal DLPFC tCDS (n = 15) or sham tDCS (n = 15). This study included patients with comorbid psychiatric disorders, including substance use disorders. Discontinuation or alteration of existing medications was not allowed.

- The presence, severity, and change over time of BPD core symptoms was assessed at baseline and after 3 weeks using several clinical scales, self-questionnaires, and neuropsychological tests, including the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale-11 (BIS-11), Buss-Perry Aggression Questionnaire (BP-AQ), Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS), Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D), Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A), Irritability-Depression Anxiety Scale (IDA), Visual Analog Scales (VAS), and Iowa Gambling Task.

Outcomes

- Participants in the active tDCS group experienced significant reductions in impulsivity, aggression, and craving as measured by the BIS-11, BP-AQ, and VAS.

- Compared to the sham group, the active tDCS group had greater reductions in HAM-D and BDI scores.

- HAM-A and IDA scores were improved in both groups, although the active tDCS group showed greater reductions in IDA scores compared with the sham group.

- As measured by DERS, active tDCS did not improve affective dysregulation more than sham tDCS.

Conclusions/limitations

- Bilateral tDCS targeting the right DLPFC with anodal stimulation is a safe, well-tolerated technique that may modulate core dimensions of BPD, including impulsivity, aggression, and craving.

- Excitatory anodal stimulation of the right DLFPC coupled with inhibitory cathodal stimulation on the left DLPFC may be an effective montage for targeting impulsivity in patients with BPD.

- Study limitations include a small sample size, use of targeted questionnaires only, inclusion of patients with BPD who also had certain comorbid psychiatric disorders, lack of analysis of the contributions of medications, lack of functional neuroimaging, and lack of a follow-up phase.

2. Molavi P, Aziziaram S, Basharpoor S, et al. Repeated transcranial direct current stimulation of dorsolateral-prefrontal cortex improves executive functions, cognitive reappraisal emotion regulation, and control over emotional processing in borderline personality disorder: a randomized, sham-controlled, parallel-group study. J Affect Disord. 2020;274:93-102. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.05.007

Emotional dysregulation is considered a core feature of BPD psychopathology and is closely associated with executive dysfunction and cognitive control. Manifestations of executive dysfunction include aggressiveness, impulsive decision-making, disinhibition, and self-destructive behaviors. Neuroimaging of patients with BPD has shown enhanced activity in the insula, posterior cingulate cortex, and amygdala, with reduced activity in the medial PFC, subgenual anterior cingulate cortex, and DLPFC. Molavi et al4 postulated that increasing DLPFC activation with left anodal tDCS would result in improved executive functioning and emotion dysregulation in patients with BPD.

Study design

- In this single-blind, sham-controlled, parallel-group study, adults who met DSM-5 criteria for BPD were randomized to receive 10 consecutive daily sessions of left anodal/right cathodal DLPFC tDCS (n = 16) or sham tDCS (n = 16).

- The effect of tDCS on executive dysfunction, emotion dysregulation, and emotional processing was measured using the Executive Skills Questionnaire for Adults (ESQ), Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (ERQ), and Emotional Processing Scale (EPS). Measurements occurred at baseline and after 10 sessions of active or sham tDCS.

Outcomes

- Participants who received active tDCS experienced significant improvements in ESQ overall score and most of the executive function domains measured by the ESQ.

- Those in the active tDCS group also experienced significant improvement in emotion regulation as measured by the cognitive reappraisal subscale (but not the expressive suppression subscale) of the ERQ after the intervention.

- Overall emotional processing as measured by the EPS was significantly improved in the active tDCS group following the intervention.

Conclusions/limitations

- Repeated bilateral left anodal/right cathodal tDCS stimulation of the DLPFC significantly improved executive functioning and aspects of emotion regulation and emotional processing in patients with BPD. This improvement was presumed to be the result of increased activity of left DLPFC.

- Study limitations include a single-blind design, lack of follow-up to assess durability and stability of response over time, reliance on self-report measures, lack of functional neuroimaging, and limited focality of tDCS.

3. Crawford MJ, Sanatinia R, Barrett B, et al; LABILE study team. The clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of lamotrigine in borderline personality disorder: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(8):756-764. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2018.17091006

One of the hallmark symptoms of BPD is mood dysregulation. Current treatment guidelines recommend the use of mood stabilizers for BPD despite limited quality evidence of effectiveness and a lack of FDA-approved medications with this indication. In this RCT, Crawford et al5 examined whether lamotrigine is a clinically effective and cost-effective treatment for people with BPD.

Continue to: Study design...

Study design

- In this 2-arm, parallel-group, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, 276 adults who met DSM-IV criteria for BPD were randomized to receive lamotrigine (up to 400 mg/d) or placebo for 52 weeks.

- The primary outcome was the score on the Zanarini Rating Scale for Borderline Personality Disorder (ZAN-BPD) at 52 weeks. Secondary outcomes included depressive symptoms, deliberate self-harm, social functioning, health-related quality of life, resource use and costs, treatment adverse effects, and adverse events. These were assessed using the BDI; Acts of Deliberate Self-Harm Inventory; Social Functioning Questionnaire; Alcohol, Smoking, and Substance Involvement Screening Test; and the EQ-5D-3L.

Outcomes

- Mean ZAN-BPD score decreased at 12 weeks in both groups, after which time the score remained stable.

- There was no difference in ZAN-BPD scores at 52 weeks between treatment arms. No difference was found in any secondary outcome measures.

- Difference in costs between groups was not significant.

Conclusions/limitations

- There was no evidence that lamotrigine led to clinical improvements in BPD symptomatology, social functioning, health-related quality of life, or substance use.

- Lamotrigine is neither clinically effective nor a cost-effective use of resources in the treatment of BPD.

- Limitations include a low level of adherence.

4. Domes G, Ower N, von Dawans B, et al. Effects of intranasal oxytocin administration on empathy and approach motivation in women with borderline personality disorder: a randomized controlled trial. Transl Psychiatry. 2019;9(1):328. doi: 10.1038/s41398-019-0658-4

A core feature of BPD is impairment in empathy; adequate empathy is required for intact social functioning. Oxytocin is a neuropeptide that helps regulate complex social cognition and behavior. Prior research has found that oxytocin administration enhances emotion regulation and empathy. Women with BPD have been observed to have lower levels of oxytocin. Domes et al6 conducted an RCT to see if oxytocin could have a beneficial effect on social approach and social cognition in women with BPD.

Study design

- In a double-blind, placebo-controlled, between-subject trial, 61 women who met DSM-IV criteria for BPD and 68 matched healthy controls were randomized to receive intranasal oxytocin, 24 IU, or placebo 45 minutes before completing an empathy task.

- An extended version of the Multifaceted Empathy Test was used to assess empathy and approach motivation.

Outcomes

- For cognitive empathy, patients with BPD exhibited significantly lower overall performance compared to controls. There was no effect of oxytocin on this performance in either group.

- Patients with BPD had significantly lower affective empathy compared with controls. After oxytocin administration, patients with BPD had significantly higher affective empathy than those with BPD who received placebo, reaching the level of healthy controls who received placebo.

- For positive stimuli, patients with BPD showed lower affective empathy than controls. Oxytocin treatment increased affective empathy in both groups.

- For negative stimuli, oxytocin increased affective empathy more in patients with BPD than in controls.

- Patients with BPD demonstrated less approach motivation than controls. Oxytocin increased approach motivation more in patients with BPD than in controls. For approach motivation toward positive stimuli, oxytocin had a significant effect on patients with BPD.

Continue to: Conclusions/limitations...

Conclusions/limitations

- Patients with BPD showed reduced cognitive and affective empathy and less approach behavior motivation than healthy controls.

- Patients with BPD who received oxytocin attained a level of affective empathy and approach motivation similar to that of healthy controls who received placebo. For positive stimuli, both groups exhibited comparable improvements from oxytocin. For negative stimuli, patients with BPD patients showed significant improvement with oxytocin, whereas healthy controls received no such benefit.

- Limitations include the use of self-report scales, lack of a control group, and inclusion of patients using psychotherapeutic medications. The study lacks generalizability because only women were included; the effect of exogenous oxytocin on men may differ.

5. Bozzatello P, Rocca P, Uscinska M, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of asenapine compared with olanzapine in borderline personality disorder: an open-label randomized controlled trial. CNS Drugs. 2017;31(9):809-819. doi: 10.1007/s40263-017-0458-4

The last decade has seen a noticeable shift in clinical practice from the use of antidepressants to mood stabilizers and second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) in the treatment of BPD. Studies have demonstrated therapeutic effects of antipsychotic drugs across a wide range of BPD symptoms. Among SGAs, olanzapine is the most extensively studied across case reports, open-label studies, and RCTs of patients with BPD. In an RCT, Bozzatello et al7 compared the efficacy and tolerability of asenapine to olanzapine.

Study design

- In this open-label RCT, adults who met DSM-5 criteria for BPD were assigned to receive asenapine (n = 25) or olanzapine (n = 26) for 12 weeks.

- Study measurements included the Clinical Global Impression Scale, Severity item, HAM-D, HAM-A, Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale, Borderline Personality Disorder Severity Index (BPDSI), BIS-11, Modified Overt Aggression Scale, and Dosage Record Treatment Emergent Symptom Scale.

Outcomes

- Asenapine and olanzapine had similar effects on BPD-related psychopathology, anxiety, and social and occupational functioning.

- Neither medication significantly decreased depressive or aggressive symptoms.

- Asenapine was superior to olanzapine in reducing the affective instability score of the BPDSI.

- Akathisia and restlessness/anxiety were more common with asenapine, and somnolence and fatigue were more common with olanzapine.

Conclusions/limitations

- The overall efficacy of asenapine was not different from olanzapine, and both medications were well-tolerated.

- Neither medication led to an improvement in depression or aggression, but asenapine was superior to olanzapine in reducing the severity of affective instability.

- Limitations include an open-label design, lack of placebo group, small sample size, high drop-out rate, exclusion of participants with co-occurring MDD and substance abuse/dependence, lack of data on prior pharmacotherapies and psychotherapies, and lack of power to detect a difference on the dissociation/paranoid ideation item of BPDSI.

6. Kulkarni J, Thomas N, Hudaib AR, et al. Effect of the glutamate NMDA receptor antagonist memantine as adjunctive treatment in borderline personality disorder: an exploratory, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. CNS Drugs. 2018;32(2):179-187. doi: 10.1007/s40263-018-0506-8

It has been hypothesized that glutamate dysregulation and excitotoxicity are crucial to the development of the cognitive disturbances that underlie BPD. As such, glutamate modulators such as memantine hold promise for the treatment of BPD. In this RCT, Kulkarni et al8 examined the efficacy and tolerability of memantine compared with treatment as usual in patients with BPD.

Continue to: Study design...

Study design

- In an 8-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, adults diagnosed with BPD according to the Diagnostic Interview for Borderline Patients were randomized to receive memantine (n = 17) or placebo (n = 16) in addition to treatment as usual. Treatment as usual included the use of antidepressants, mood stabilizers, and antipsychotics as well as psychotherapy and other psychosocial interventions.

- Patients were initiated on placebo or memantine, 10 mg/d. Memantine was increased to 20 mg/d after 7 days.

- ZAN-BPD score was the primary outcome and was measured at baseline and 2, 4, 6, and 8 weeks. An adverse effects questionnaire was administered every 2 weeks to assess tolerability.

Outcomes

- During the first 2 weeks of treatment, there were no significant improvements in ZAN-BPD score in the memantine group compared with the placebo group.

- Beginning with Week 2, compared with the placebo group, the memantine group experienced a significant reduction in total symptoms as measured by ZAN-BPD.

- There were no statistically significant differences in adverse events between groups.

Conclusions/limitations

- Memantine appears to be a well-tolerated treatment option for patients with BPD and merits further study.

- Limitations include a small sample size, and an inability to reach plateau of ZAN-BPD total score in either group. Also, there is considerable individual variability in memantine steady-state plasma concentrations, but plasma levels were not measured in this study.

Bottom Line

Findings from small randomized controlled trials suggest that transcranial direct current stimulation, oxytocin, asenapine, olanzapine, and memantine may have beneficial effects on some core symptoms of borderline personality disorder. These findings need to be replicated in larger studies.

FIRST OF 2 PARTS

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) is marked by an ongoing pattern of mood instability, cognitive distortions, problems with self-image, and impulsive behavior, often resulting in problems in relationships. BPD is associated with serious impairment in psychosocial functioning.1 Patients with BPD tend to use more mental health services than patients with other personality disorders or those with major depressive disorder (MDD).2 However, there has been little consensus on the best treatment(s) for this serious and debilitating disorder, and some clinicians view BPD as difficult to treat.

Current treatments for BPD include psychological and pharmacological interventions. Neuromodulation techniques, such as repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation, may also positively affect BPD symptomatology. In recent years, there have been some promising findings in the treatment of BPD. In this 2-part article, we focus on current (within the last 5 years) findings from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of BPD treatments. Here in Part 1, we focus on 6 studies that evaluated biological interventions (Table,3-8). In Part 2, we will focus on RCTs that investigated psychological interventions.

1. Lisoni J, Miotto P, Barlati S, et al. Change in core symptoms of borderline personality disorder by tDCS: a pilot study. Psychiatry Res. 2020;291:113261. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113261

Impulsivity has been described as the core feature of BPD that best explains its behavioral, cognitive, and clinical manifestations. Studies have repeatedly demonstrated the role of the prefrontal cortex in modulating impulsivity. Dysfunction of the

Continue to: Study design...

Study design

- In a double-blind, sham-controlled trial, adults who met DSM-IV-TR criteria for BPD were randomized to 3 weeks (15 sessions) of right anodal/left cathodal DLPFC tCDS (n = 15) or sham tDCS (n = 15). This study included patients with comorbid psychiatric disorders, including substance use disorders. Discontinuation or alteration of existing medications was not allowed.

- The presence, severity, and change over time of BPD core symptoms was assessed at baseline and after 3 weeks using several clinical scales, self-questionnaires, and neuropsychological tests, including the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale-11 (BIS-11), Buss-Perry Aggression Questionnaire (BP-AQ), Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS), Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D), Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A), Irritability-Depression Anxiety Scale (IDA), Visual Analog Scales (VAS), and Iowa Gambling Task.

Outcomes

- Participants in the active tDCS group experienced significant reductions in impulsivity, aggression, and craving as measured by the BIS-11, BP-AQ, and VAS.

- Compared to the sham group, the active tDCS group had greater reductions in HAM-D and BDI scores.

- HAM-A and IDA scores were improved in both groups, although the active tDCS group showed greater reductions in IDA scores compared with the sham group.

- As measured by DERS, active tDCS did not improve affective dysregulation more than sham tDCS.

Conclusions/limitations

- Bilateral tDCS targeting the right DLPFC with anodal stimulation is a safe, well-tolerated technique that may modulate core dimensions of BPD, including impulsivity, aggression, and craving.

- Excitatory anodal stimulation of the right DLFPC coupled with inhibitory cathodal stimulation on the left DLPFC may be an effective montage for targeting impulsivity in patients with BPD.

- Study limitations include a small sample size, use of targeted questionnaires only, inclusion of patients with BPD who also had certain comorbid psychiatric disorders, lack of analysis of the contributions of medications, lack of functional neuroimaging, and lack of a follow-up phase.

2. Molavi P, Aziziaram S, Basharpoor S, et al. Repeated transcranial direct current stimulation of dorsolateral-prefrontal cortex improves executive functions, cognitive reappraisal emotion regulation, and control over emotional processing in borderline personality disorder: a randomized, sham-controlled, parallel-group study. J Affect Disord. 2020;274:93-102. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.05.007

Emotional dysregulation is considered a core feature of BPD psychopathology and is closely associated with executive dysfunction and cognitive control. Manifestations of executive dysfunction include aggressiveness, impulsive decision-making, disinhibition, and self-destructive behaviors. Neuroimaging of patients with BPD has shown enhanced activity in the insula, posterior cingulate cortex, and amygdala, with reduced activity in the medial PFC, subgenual anterior cingulate cortex, and DLPFC. Molavi et al4 postulated that increasing DLPFC activation with left anodal tDCS would result in improved executive functioning and emotion dysregulation in patients with BPD.

Study design

- In this single-blind, sham-controlled, parallel-group study, adults who met DSM-5 criteria for BPD were randomized to receive 10 consecutive daily sessions of left anodal/right cathodal DLPFC tDCS (n = 16) or sham tDCS (n = 16).

- The effect of tDCS on executive dysfunction, emotion dysregulation, and emotional processing was measured using the Executive Skills Questionnaire for Adults (ESQ), Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (ERQ), and Emotional Processing Scale (EPS). Measurements occurred at baseline and after 10 sessions of active or sham tDCS.

Outcomes

- Participants who received active tDCS experienced significant improvements in ESQ overall score and most of the executive function domains measured by the ESQ.

- Those in the active tDCS group also experienced significant improvement in emotion regulation as measured by the cognitive reappraisal subscale (but not the expressive suppression subscale) of the ERQ after the intervention.

- Overall emotional processing as measured by the EPS was significantly improved in the active tDCS group following the intervention.

Conclusions/limitations

- Repeated bilateral left anodal/right cathodal tDCS stimulation of the DLPFC significantly improved executive functioning and aspects of emotion regulation and emotional processing in patients with BPD. This improvement was presumed to be the result of increased activity of left DLPFC.

- Study limitations include a single-blind design, lack of follow-up to assess durability and stability of response over time, reliance on self-report measures, lack of functional neuroimaging, and limited focality of tDCS.

3. Crawford MJ, Sanatinia R, Barrett B, et al; LABILE study team. The clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of lamotrigine in borderline personality disorder: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(8):756-764. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2018.17091006

One of the hallmark symptoms of BPD is mood dysregulation. Current treatment guidelines recommend the use of mood stabilizers for BPD despite limited quality evidence of effectiveness and a lack of FDA-approved medications with this indication. In this RCT, Crawford et al5 examined whether lamotrigine is a clinically effective and cost-effective treatment for people with BPD.

Continue to: Study design...

Study design

- In this 2-arm, parallel-group, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, 276 adults who met DSM-IV criteria for BPD were randomized to receive lamotrigine (up to 400 mg/d) or placebo for 52 weeks.

- The primary outcome was the score on the Zanarini Rating Scale for Borderline Personality Disorder (ZAN-BPD) at 52 weeks. Secondary outcomes included depressive symptoms, deliberate self-harm, social functioning, health-related quality of life, resource use and costs, treatment adverse effects, and adverse events. These were assessed using the BDI; Acts of Deliberate Self-Harm Inventory; Social Functioning Questionnaire; Alcohol, Smoking, and Substance Involvement Screening Test; and the EQ-5D-3L.

Outcomes

- Mean ZAN-BPD score decreased at 12 weeks in both groups, after which time the score remained stable.

- There was no difference in ZAN-BPD scores at 52 weeks between treatment arms. No difference was found in any secondary outcome measures.

- Difference in costs between groups was not significant.

Conclusions/limitations

- There was no evidence that lamotrigine led to clinical improvements in BPD symptomatology, social functioning, health-related quality of life, or substance use.

- Lamotrigine is neither clinically effective nor a cost-effective use of resources in the treatment of BPD.

- Limitations include a low level of adherence.

4. Domes G, Ower N, von Dawans B, et al. Effects of intranasal oxytocin administration on empathy and approach motivation in women with borderline personality disorder: a randomized controlled trial. Transl Psychiatry. 2019;9(1):328. doi: 10.1038/s41398-019-0658-4

A core feature of BPD is impairment in empathy; adequate empathy is required for intact social functioning. Oxytocin is a neuropeptide that helps regulate complex social cognition and behavior. Prior research has found that oxytocin administration enhances emotion regulation and empathy. Women with BPD have been observed to have lower levels of oxytocin. Domes et al6 conducted an RCT to see if oxytocin could have a beneficial effect on social approach and social cognition in women with BPD.

Study design

- In a double-blind, placebo-controlled, between-subject trial, 61 women who met DSM-IV criteria for BPD and 68 matched healthy controls were randomized to receive intranasal oxytocin, 24 IU, or placebo 45 minutes before completing an empathy task.

- An extended version of the Multifaceted Empathy Test was used to assess empathy and approach motivation.

Outcomes

- For cognitive empathy, patients with BPD exhibited significantly lower overall performance compared to controls. There was no effect of oxytocin on this performance in either group.

- Patients with BPD had significantly lower affective empathy compared with controls. After oxytocin administration, patients with BPD had significantly higher affective empathy than those with BPD who received placebo, reaching the level of healthy controls who received placebo.

- For positive stimuli, patients with BPD showed lower affective empathy than controls. Oxytocin treatment increased affective empathy in both groups.

- For negative stimuli, oxytocin increased affective empathy more in patients with BPD than in controls.

- Patients with BPD demonstrated less approach motivation than controls. Oxytocin increased approach motivation more in patients with BPD than in controls. For approach motivation toward positive stimuli, oxytocin had a significant effect on patients with BPD.

Continue to: Conclusions/limitations...

Conclusions/limitations

- Patients with BPD showed reduced cognitive and affective empathy and less approach behavior motivation than healthy controls.

- Patients with BPD who received oxytocin attained a level of affective empathy and approach motivation similar to that of healthy controls who received placebo. For positive stimuli, both groups exhibited comparable improvements from oxytocin. For negative stimuli, patients with BPD patients showed significant improvement with oxytocin, whereas healthy controls received no such benefit.

- Limitations include the use of self-report scales, lack of a control group, and inclusion of patients using psychotherapeutic medications. The study lacks generalizability because only women were included; the effect of exogenous oxytocin on men may differ.

5. Bozzatello P, Rocca P, Uscinska M, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of asenapine compared with olanzapine in borderline personality disorder: an open-label randomized controlled trial. CNS Drugs. 2017;31(9):809-819. doi: 10.1007/s40263-017-0458-4

The last decade has seen a noticeable shift in clinical practice from the use of antidepressants to mood stabilizers and second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) in the treatment of BPD. Studies have demonstrated therapeutic effects of antipsychotic drugs across a wide range of BPD symptoms. Among SGAs, olanzapine is the most extensively studied across case reports, open-label studies, and RCTs of patients with BPD. In an RCT, Bozzatello et al7 compared the efficacy and tolerability of asenapine to olanzapine.

Study design

- In this open-label RCT, adults who met DSM-5 criteria for BPD were assigned to receive asenapine (n = 25) or olanzapine (n = 26) for 12 weeks.

- Study measurements included the Clinical Global Impression Scale, Severity item, HAM-D, HAM-A, Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale, Borderline Personality Disorder Severity Index (BPDSI), BIS-11, Modified Overt Aggression Scale, and Dosage Record Treatment Emergent Symptom Scale.

Outcomes

- Asenapine and olanzapine had similar effects on BPD-related psychopathology, anxiety, and social and occupational functioning.

- Neither medication significantly decreased depressive or aggressive symptoms.

- Asenapine was superior to olanzapine in reducing the affective instability score of the BPDSI.

- Akathisia and restlessness/anxiety were more common with asenapine, and somnolence and fatigue were more common with olanzapine.

Conclusions/limitations

- The overall efficacy of asenapine was not different from olanzapine, and both medications were well-tolerated.

- Neither medication led to an improvement in depression or aggression, but asenapine was superior to olanzapine in reducing the severity of affective instability.

- Limitations include an open-label design, lack of placebo group, small sample size, high drop-out rate, exclusion of participants with co-occurring MDD and substance abuse/dependence, lack of data on prior pharmacotherapies and psychotherapies, and lack of power to detect a difference on the dissociation/paranoid ideation item of BPDSI.

6. Kulkarni J, Thomas N, Hudaib AR, et al. Effect of the glutamate NMDA receptor antagonist memantine as adjunctive treatment in borderline personality disorder: an exploratory, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. CNS Drugs. 2018;32(2):179-187. doi: 10.1007/s40263-018-0506-8

It has been hypothesized that glutamate dysregulation and excitotoxicity are crucial to the development of the cognitive disturbances that underlie BPD. As such, glutamate modulators such as memantine hold promise for the treatment of BPD. In this RCT, Kulkarni et al8 examined the efficacy and tolerability of memantine compared with treatment as usual in patients with BPD.

Continue to: Study design...

Study design

- In an 8-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, adults diagnosed with BPD according to the Diagnostic Interview for Borderline Patients were randomized to receive memantine (n = 17) or placebo (n = 16) in addition to treatment as usual. Treatment as usual included the use of antidepressants, mood stabilizers, and antipsychotics as well as psychotherapy and other psychosocial interventions.

- Patients were initiated on placebo or memantine, 10 mg/d. Memantine was increased to 20 mg/d after 7 days.

- ZAN-BPD score was the primary outcome and was measured at baseline and 2, 4, 6, and 8 weeks. An adverse effects questionnaire was administered every 2 weeks to assess tolerability.

Outcomes

- During the first 2 weeks of treatment, there were no significant improvements in ZAN-BPD score in the memantine group compared with the placebo group.

- Beginning with Week 2, compared with the placebo group, the memantine group experienced a significant reduction in total symptoms as measured by ZAN-BPD.

- There were no statistically significant differences in adverse events between groups.

Conclusions/limitations

- Memantine appears to be a well-tolerated treatment option for patients with BPD and merits further study.

- Limitations include a small sample size, and an inability to reach plateau of ZAN-BPD total score in either group. Also, there is considerable individual variability in memantine steady-state plasma concentrations, but plasma levels were not measured in this study.

Bottom Line

Findings from small randomized controlled trials suggest that transcranial direct current stimulation, oxytocin, asenapine, olanzapine, and memantine may have beneficial effects on some core symptoms of borderline personality disorder. These findings need to be replicated in larger studies.

1. Skodol AE, Gunderson JG, McGlashan TM, et al. Functional impairment in patients with schizotypal, borderline, avoidant, or obsessive-compulsive personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2002; 159:276-283.

2. Bender DS, Dolan RT, Skodol AE, et al. Treatment utilization by patients with personality disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:295-302.

3. Lisoni J, Miotto P, Barlati S, et al. Change in core symptoms of borderline personality disorder by tDCS: a pilot study. Psychiatry Res. 2020;291:113261. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113261

4. Molavi P, Aziziaram S, Basharpoor S, et al. Repeated transcranial direct current stimulation of dorsolateral-prefrontal cortex improves executive functions, cognitive reappraisal emotion regulation, and control over emotional processing in borderline personality disorder: a randomized, sham-controlled, parallel-group study. J Affect Disord. 2020;274:93-102. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.05.007

5. Crawford MJ, Sanatinia R, Barrett B, et al; LABILE study team. The clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of lamotrigine in borderline personality disorder: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(8):756-764. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2018.17091006

6. Domes G, Ower N, von Dawans B, et al. Effects of intranasal oxytocin administration on empathy and approach motivation in women with borderline personality disorder: a randomized controlled trial. Transl Psychiatry. 2019;9(1):328. doi: 10.1038/s41398-019-0658-4

7. Bozzatello P, Rocca P, Uscinska M, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of asenapine compared with olanzapine in borderline personality disorder: an open-label randomized controlled trial. CNS Drugs. 2017;31(9):809-819. doi: 10.1007/s40263-017-0458-4

8. Kulkarni J, Thomas N, Hudaib AR, et al. Effect of the glutamate NMDA receptor antagonist memantine as adjunctive treatment in borderline personality disorder: an exploratory, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. CNS Drugs. 2018;32(2):179-187. doi: 10.1007/s40263-018-0506-8

1. Skodol AE, Gunderson JG, McGlashan TM, et al. Functional impairment in patients with schizotypal, borderline, avoidant, or obsessive-compulsive personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2002; 159:276-283.

2. Bender DS, Dolan RT, Skodol AE, et al. Treatment utilization by patients with personality disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:295-302.

3. Lisoni J, Miotto P, Barlati S, et al. Change in core symptoms of borderline personality disorder by tDCS: a pilot study. Psychiatry Res. 2020;291:113261. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113261

4. Molavi P, Aziziaram S, Basharpoor S, et al. Repeated transcranial direct current stimulation of dorsolateral-prefrontal cortex improves executive functions, cognitive reappraisal emotion regulation, and control over emotional processing in borderline personality disorder: a randomized, sham-controlled, parallel-group study. J Affect Disord. 2020;274:93-102. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.05.007

5. Crawford MJ, Sanatinia R, Barrett B, et al; LABILE study team. The clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of lamotrigine in borderline personality disorder: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(8):756-764. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2018.17091006

6. Domes G, Ower N, von Dawans B, et al. Effects of intranasal oxytocin administration on empathy and approach motivation in women with borderline personality disorder: a randomized controlled trial. Transl Psychiatry. 2019;9(1):328. doi: 10.1038/s41398-019-0658-4

7. Bozzatello P, Rocca P, Uscinska M, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of asenapine compared with olanzapine in borderline personality disorder: an open-label randomized controlled trial. CNS Drugs. 2017;31(9):809-819. doi: 10.1007/s40263-017-0458-4

8. Kulkarni J, Thomas N, Hudaib AR, et al. Effect of the glutamate NMDA receptor antagonist memantine as adjunctive treatment in borderline personality disorder: an exploratory, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. CNS Drugs. 2018;32(2):179-187. doi: 10.1007/s40263-018-0506-8

Residency programs need greater focus on BPD treatment

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) has suffered from underdiagnosis, in part because not enough clinicians know how to handle patients with BPD. “They don’t have the tools to know how to manage these situations effectively,” Lois W. Choi-Kain, MEd, MD, director of the Gunderson Personality Disorders Institute, McLean Hospital, Belmont, Mass., said in an interview.

As a result, the clinician avoids the BPD patient, who feels demeaned and never finds the capacity to get better.

Psychiatry training in residency tends to emphasize biomedical treatments and does not focus enough on learning psychotherapy and other psychosocial treatments, according to Eric M. Plakun, MD, DLFAPA, FACPsych, medical director/CEO of the Austen Riggs Center in Stockbridge, Mass.

“This is where I see the need for a greater psychotherapy teaching focus in residency, along with teaching of general principles for working with patients with BPD,” said Dr. Plakun.

In his last phase of his career, BPD pioneer John G. Gunderson, MD, worked with Dr. Choi-Kain to train clinicians on general psychiatric management (GPM), which employs a sensitive, nonattacking approach to diffuse and calm situations with BPD patients.

As interest grows in combining GPM with manual treatments, GPM alone offers a more accessible approach for therapist and patient, said Dr. Choi-Kain, who has been trying to promote its use and do research on its techniques.

“It’s trying to boil it down to make it simple,” she said. As much as evidence-based, manualized approaches have advanced the field, they’re just not that widely available, she said.

Orchestrating treatments such as dialectical behavior therapy and mentalization-based therapy takes a lot of specialization, noted Dr. Choi-Kain. “And because of the amount of work that it involves for both the clinician and the patient, it decreases the capacity that clinicians and systems have to offer treatment to a wider number of patients.”

Learning a manualized treatment for BPD is asking a lot from residents, agreed Dr. Plakun. “Those who want more immersion in treating these patients can pursue further training in residency electives, in postresidency graduate medical education programs or through psychoanalytic training.”

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) has suffered from underdiagnosis, in part because not enough clinicians know how to handle patients with BPD. “They don’t have the tools to know how to manage these situations effectively,” Lois W. Choi-Kain, MEd, MD, director of the Gunderson Personality Disorders Institute, McLean Hospital, Belmont, Mass., said in an interview.

As a result, the clinician avoids the BPD patient, who feels demeaned and never finds the capacity to get better.

Psychiatry training in residency tends to emphasize biomedical treatments and does not focus enough on learning psychotherapy and other psychosocial treatments, according to Eric M. Plakun, MD, DLFAPA, FACPsych, medical director/CEO of the Austen Riggs Center in Stockbridge, Mass.

“This is where I see the need for a greater psychotherapy teaching focus in residency, along with teaching of general principles for working with patients with BPD,” said Dr. Plakun.

In his last phase of his career, BPD pioneer John G. Gunderson, MD, worked with Dr. Choi-Kain to train clinicians on general psychiatric management (GPM), which employs a sensitive, nonattacking approach to diffuse and calm situations with BPD patients.

As interest grows in combining GPM with manual treatments, GPM alone offers a more accessible approach for therapist and patient, said Dr. Choi-Kain, who has been trying to promote its use and do research on its techniques.

“It’s trying to boil it down to make it simple,” she said. As much as evidence-based, manualized approaches have advanced the field, they’re just not that widely available, she said.

Orchestrating treatments such as dialectical behavior therapy and mentalization-based therapy takes a lot of specialization, noted Dr. Choi-Kain. “And because of the amount of work that it involves for both the clinician and the patient, it decreases the capacity that clinicians and systems have to offer treatment to a wider number of patients.”

Learning a manualized treatment for BPD is asking a lot from residents, agreed Dr. Plakun. “Those who want more immersion in treating these patients can pursue further training in residency electives, in postresidency graduate medical education programs or through psychoanalytic training.”

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) has suffered from underdiagnosis, in part because not enough clinicians know how to handle patients with BPD. “They don’t have the tools to know how to manage these situations effectively,” Lois W. Choi-Kain, MEd, MD, director of the Gunderson Personality Disorders Institute, McLean Hospital, Belmont, Mass., said in an interview.

As a result, the clinician avoids the BPD patient, who feels demeaned and never finds the capacity to get better.

Psychiatry training in residency tends to emphasize biomedical treatments and does not focus enough on learning psychotherapy and other psychosocial treatments, according to Eric M. Plakun, MD, DLFAPA, FACPsych, medical director/CEO of the Austen Riggs Center in Stockbridge, Mass.

“This is where I see the need for a greater psychotherapy teaching focus in residency, along with teaching of general principles for working with patients with BPD,” said Dr. Plakun.

In his last phase of his career, BPD pioneer John G. Gunderson, MD, worked with Dr. Choi-Kain to train clinicians on general psychiatric management (GPM), which employs a sensitive, nonattacking approach to diffuse and calm situations with BPD patients.

As interest grows in combining GPM with manual treatments, GPM alone offers a more accessible approach for therapist and patient, said Dr. Choi-Kain, who has been trying to promote its use and do research on its techniques.

“It’s trying to boil it down to make it simple,” she said. As much as evidence-based, manualized approaches have advanced the field, they’re just not that widely available, she said.

Orchestrating treatments such as dialectical behavior therapy and mentalization-based therapy takes a lot of specialization, noted Dr. Choi-Kain. “And because of the amount of work that it involves for both the clinician and the patient, it decreases the capacity that clinicians and systems have to offer treatment to a wider number of patients.”

Learning a manualized treatment for BPD is asking a lot from residents, agreed Dr. Plakun. “Those who want more immersion in treating these patients can pursue further training in residency electives, in postresidency graduate medical education programs or through psychoanalytic training.”

A new name for BPD?

Michael A. Cummings, MD, has never liked the term “borderline personality disorder” (BPD). In his view, it’s a misnomer and needs to be changed.

“What is it bordering on? It’s not bordering on something, it’s a disorder on its own,” said Dr. Cummings of the department of psychiatry at the University of California, Riverside, and a psychopharmacology consultant with the California Department of State Hospitals’ Psychopharmacology Resource Network.

BPD grew out of the concept that patients were bordering on something, perhaps becoming bipolar. “In many ways, I don’t think it is even a personality disorder. It appears to be an inherent temperament that evolves into an inability to regulate mood.”

In his view, this puts it in the category of a mood dysregulation disorder.

Changing the label would not necessarily improve treatment, he added. However, transitioning from a pejorative to a more neutral label could make it easier for people to say, “this is just a type of mood disorder. It’s not necessarily easy, but it’s workable,” said Dr. Cummings.

Others in the field contend that the term fits the condition. BPD “describes how it encompasses a lot of complex psychological difficulties, undermining functioning of patients in a specific way,” said Lois W. Choi-Kain, MD, MEd, director of the Gunderson Personality Disorders Institute, McLean Hospital, Belmont, Mass. The disorder was identified because of its relationship with other known psychiatric disorders, said Dr. Choi-Kain. “There’s an element of BPD that borders on mood disorders because moods are so unstable with BPD. It also borders on trauma-related disorders. It borders on psychotic disorders because there’s sometimes stress-induced experiences of losing contact with realistic thinking.”

If anything needs to change, it’s the attitude toward the disorder, not the name. “I don’t think the term itself is pejorative. But I think that associations with the term have been very stigmatizing. For a long time, there was an attitude that these patients could not be treated or had negative therapeutic reactions.”

Data suggest that these patients are highly prevalent in clinical settings. “And I interpret that as them seeking the care that they need rather than resisting care or not responding to care,” said Dr. Choi-Kain.

Michael A. Cummings, MD, has never liked the term “borderline personality disorder” (BPD). In his view, it’s a misnomer and needs to be changed.

“What is it bordering on? It’s not bordering on something, it’s a disorder on its own,” said Dr. Cummings of the department of psychiatry at the University of California, Riverside, and a psychopharmacology consultant with the California Department of State Hospitals’ Psychopharmacology Resource Network.

BPD grew out of the concept that patients were bordering on something, perhaps becoming bipolar. “In many ways, I don’t think it is even a personality disorder. It appears to be an inherent temperament that evolves into an inability to regulate mood.”

In his view, this puts it in the category of a mood dysregulation disorder.

Changing the label would not necessarily improve treatment, he added. However, transitioning from a pejorative to a more neutral label could make it easier for people to say, “this is just a type of mood disorder. It’s not necessarily easy, but it’s workable,” said Dr. Cummings.

Others in the field contend that the term fits the condition. BPD “describes how it encompasses a lot of complex psychological difficulties, undermining functioning of patients in a specific way,” said Lois W. Choi-Kain, MD, MEd, director of the Gunderson Personality Disorders Institute, McLean Hospital, Belmont, Mass. The disorder was identified because of its relationship with other known psychiatric disorders, said Dr. Choi-Kain. “There’s an element of BPD that borders on mood disorders because moods are so unstable with BPD. It also borders on trauma-related disorders. It borders on psychotic disorders because there’s sometimes stress-induced experiences of losing contact with realistic thinking.”

If anything needs to change, it’s the attitude toward the disorder, not the name. “I don’t think the term itself is pejorative. But I think that associations with the term have been very stigmatizing. For a long time, there was an attitude that these patients could not be treated or had negative therapeutic reactions.”

Data suggest that these patients are highly prevalent in clinical settings. “And I interpret that as them seeking the care that they need rather than resisting care or not responding to care,” said Dr. Choi-Kain.

Michael A. Cummings, MD, has never liked the term “borderline personality disorder” (BPD). In his view, it’s a misnomer and needs to be changed.

“What is it bordering on? It’s not bordering on something, it’s a disorder on its own,” said Dr. Cummings of the department of psychiatry at the University of California, Riverside, and a psychopharmacology consultant with the California Department of State Hospitals’ Psychopharmacology Resource Network.

BPD grew out of the concept that patients were bordering on something, perhaps becoming bipolar. “In many ways, I don’t think it is even a personality disorder. It appears to be an inherent temperament that evolves into an inability to regulate mood.”

In his view, this puts it in the category of a mood dysregulation disorder.

Changing the label would not necessarily improve treatment, he added. However, transitioning from a pejorative to a more neutral label could make it easier for people to say, “this is just a type of mood disorder. It’s not necessarily easy, but it’s workable,” said Dr. Cummings.

Others in the field contend that the term fits the condition. BPD “describes how it encompasses a lot of complex psychological difficulties, undermining functioning of patients in a specific way,” said Lois W. Choi-Kain, MD, MEd, director of the Gunderson Personality Disorders Institute, McLean Hospital, Belmont, Mass. The disorder was identified because of its relationship with other known psychiatric disorders, said Dr. Choi-Kain. “There’s an element of BPD that borders on mood disorders because moods are so unstable with BPD. It also borders on trauma-related disorders. It borders on psychotic disorders because there’s sometimes stress-induced experiences of losing contact with realistic thinking.”

If anything needs to change, it’s the attitude toward the disorder, not the name. “I don’t think the term itself is pejorative. But I think that associations with the term have been very stigmatizing. For a long time, there was an attitude that these patients could not be treated or had negative therapeutic reactions.”

Data suggest that these patients are highly prevalent in clinical settings. “And I interpret that as them seeking the care that they need rather than resisting care or not responding to care,” said Dr. Choi-Kain.

Trust is key in treating borderline personality disorder

Difficulties associated with treating borderline personality disorder (BPD) make for an uneasy alliance between patient and clinician. Deep-seated anxiety and trust issues often lead to patients skipping visits or raging at those who treat them, leaving clinicians frustrated and ready to give up or relying on a pill to make the patient better.

John M. Oldham, MD, MS, recalls one patient he almost lost, a woman who was struggling with aggressive behavior. Initially cooperative and punctual, the patient gradually became distrustful, grilling Dr. Oldham on his training and credentials. “As the questions continued, she slipped from being very cooperative to being enraged and attacking me,” said Dr. Oldham, Distinguished Emeritus Professor in the Menninger department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Baylor College in Houston.

Dr. Oldham eventually drew her back in by earning her trust. “There’s no magic to this,” he acknowledged. “You try to be as alert and informed and vigilant for anything you say that produces a negative or concerning reaction in the patient.”

This interactive approach to BPD treatment has been gaining traction in a profession that often looks to medications to alleviate specific symptoms. It’s so effective that it sometimes even surprises the patient, Dr. Oldham noted. “When you approach them like this, they can begin to settle down,” which was the case with the female patient he once treated.

About 1.4% of the U.S. population has BPD, according to the National Institute of Mental Health. Conceptualized by the late John G. Gunderson, MD, BPD initially was seen as floating on the borderline between psychosis and neurosis. Clinicians now understand that this isn’t the case. The patients need, as Dr. Gunderson once pointed out, constant vigilance because of attachment issues and childhood trauma.

A stable therapeutic alliance between patient and physician, sometimes in combination with evidence-based therapies, is a formula for success, some experts say.

A misunderstood condition

Although there is some degree of heritable risk, BPD patients are often the product of an invalidating environment in childhood. “As kids, we’re guided and nurtured by caring adults to provide models of reasonable, trustworthy behavior. If those role models are missing or just so inconsistent and unpredictable, the patient doesn’t end up with a sturdy self-image. Instead, they’re adrift, trying to figure out who will be helpful and be a meaningful, trustworthy companion and adviser,” Dr. Oldham said.

Emotional or affective instability and impulsivity, sometimes impulsive aggression, often characterize their condition. “Brain-imaging studies have revealed that certain nerve pathways that are necessary to regulate emotions are impoverished in patients with BPD,” Dr. Oldham said.

An analogy is a car going too fast, with a runaway engine that’s running too hot – and the brakes don’t work, he added.

“People think these patients are trying to create big drama, that they’re putting on a big show. That’s not accurate,” he continued. These patients don’t have the ability to stop the trigger that leads to their emotional storms. They also don’t have the ability to regulate themselves. “We may say, it’s a beautiful day outside, but I still have to go to work. Someone with BPD may say: It’s a beautiful day; I’m going to the beach,” Dr. Oldham explained.

A person with BPD might sound coherent when arguing with someone else. But their words are driven by the storm they can’t turn off.

This can lead to their own efforts to turn off the intensity. They might become self-injurious or push other people away. It’s one of the ironies of this condition because BPD patients desperately want to trust others but are scared to do so. “They look for any little signal – that someone else will hurt, disappoint, or leave them. Eventually their relationships unravel,” Dr. Oldham saod.

For some, suicide is sometimes a final solution.

Those traits make it difficult for a therapist to connect with a patient. “This is a very difficult group of people to treat and to establish treatment,” said Michael A. Cummings, MD, of the department of psychiatry at University of California, Riverside, and a psychopharmacology consultant with the California Department of State Hospitals’ Psychopharmacology Resource Network.

BPD patients tend to idealize people who are attempting to help them. When they become frustrated or disappointed in some way, “they then devalue the caregiver or the treatment and not infrequently, fall out of treatment,” Dr. Cummings said. It can be a very taxing experience, particularly for younger, less experienced therapists.

Medication only goes so far

Psychiatrists tend to look at BPD patients as receptor sites for molecules, assessing symptoms they can prescribe for, Eric M. Plakun, MD, DLFAPA, FACPsych, medical director/CEO of the Austen Riggs Center in Stockbridge, Mass., said in an interview.

Yet, BPD is not a molecular problem, principally. It’s an interpersonal disorder. When BPD is a co-occurring disorder, as is often the case, the depressive, anxiety, or other disorder can mask the BPD, he added, citing his 2018 paper on tensions in psychiatry between the biomedical and biopsychosocial models (Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2018 Jun;41[2]:237-48).

In one longitudinal study (J Pers Disord. 2005 Oct;19[5]:487-504), the presence of BPD strongly predicted the persistence of depression. BPD comorbid with depression is often a recipe for treatment-resistant depression, which results in higher costs, more utilization of resources, and higher suicide rates. Too often, psychiatrists diagnose the depression but miss the BPD. They keep trying molecular approaches with prescription drugs – even though it’s really the interpersonal issues of BPD that need to be addressed, said Dr. Plakun, who is a member of the Group for the Advancement of Psychiatry’s Psychotherapy Committee, and founder and past leader of the American Psychiatric Association’s Psychotherapy Caucus.

Medication can be helpful as a short-term adjunctive therapy. Long term, it’s not a sustainable approach, said Dr. Oldham. “If a patient is in a particularly stressful period, in the middle of a stormy breakup or having a depressive episode or talking about suicide, a time-limited course of an antidepressant may be helpful,” he said. They could also benefit from an anxiety-related drug or medication to help them sleep.

What you don’t want is for the patient to start relying on medications to help them feel better. The problem is, many are suffering so much that they’ll go to their primary care doctor and say, “I’m suffering from anxiety,” and get an antianxiety drug. Or they’re depressed or in pain and end up with a cocktail of medications. “And that’s just going to make matters worse,” Dr. Oldham said.

Psychotherapy as a first-line approach

APA practice guidelines and others worldwide have all come to the same conclusion about BPD. , who chaired an APA committee that developed an evidence-based practice guideline for patients with BPD.

Psychotherapy keeps the patient from firing you, he asserted. “Because of the lack of trust, they push away. They’re very scared, and this fear also applies to therapist. The goal is to help the patient learn to trust you. To do that, you need to develop a strong therapeutic alliance.”

In crafting the APA’s practice guideline, Dr. Oldham and his colleagues studied a variety of approaches, including mentalization-based therapy (MBT) and dialectical behavior therapy (DBT), which was developed by Marsha Linehan, PhD. Since then, other approaches have demonstrated efficacy in randomized clinical trials, including schema-based therapy (SBT), cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), and transference-focused psychotherapy (TFP).

Those treatments might complement the broader goal of establishing a strong alliance with the patient, Dr. Oldham said. Manualized approaches can help prepackage a program that allows clinicians and patients to look at their problems in an objective, nonpejorative way, Lois W. Choi-Kain, MD, MEd, director of the Gunderson Personality Disorders Institute at McLean Hospital in Belmont, Mass., said in an interview. DBT, for example, focuses on emotion dysregulation. MBT addresses how the patient sees themselves through others and their interactions with others. “It destigmatizes a problem as a clinical entity rather than an interpersonal problem between the patient and the clinician,” Dr. Choi-Kain said.