User login

Mupirocin plus chlorhexidine halved Mohs surgical-site infections

SYDNEY – All patients undergoing Mohs surgery should be treated with intranasal mupirocin and a chlorhexidine body wash for 5 days before surgery, without any requirement for a nasal swab positive for Staphylococcus aureus, according to Dr. Harvey Smith.

He presented data from a randomized, controlled trial investigating the prevention of surgical-site infection in 1,002 patients undergoing Mohs surgery who had a negative nasal swab result for S. aureus. Patients were randomized to intranasal mupirocin ointment twice daily and chlorhexidine body wash daily for the 5 days before surgery, or no intervention, said Dr. Smith, a dermatologist in group practice in Perth, Australia.

The results add to earlier studies by the same group. The first study – Staph 1 – showed that swab-positive nasal carriage of S. aureus was a greater risk factor for surgical-site infections in Mohs surgery than the Wright criteria, and that decolonization with intranasal mupirocin and chlorhexidine body wash for a few days before surgery reduced the risk of infection in these patients from 12% to 4%.

The second previous study – Staph 2 – showed that using mupirocin and chlorhexidine before surgery was actually superior to the recommended treatment of stat oral cephalexin in reducing the risk of surgical-site infection.

“So, our third paper has been wondering what to do about the silent majority: These are the two-thirds of patients on whom we operate who have a negative swab for S. aureus,” Dr. Harvey said.

A negative nasal swab was not significant, he said, because skin microbiome studies had already demonstrated that humans carry S. aureus in several places, particularly the feet and buttocks.

“What we’re basically saying is we don’t think you need to swab people, because they’ve got it somewhere,” Dr. Harvey said in an interview. “We don’t think risk stratification is useful anymore, because we’ve shown it’s a benefit to everybody.”

The strategy of treating all patients with mupirocin and chlorhexidine, regardless of nasal carriage, rather than using the broad-spectrum cephalexin, fits with the World Health Organization’s global action plan on antimicrobial resistance, Dr. Harvey explained.

While there had been cases of mupirocin resistance in the past, Dr. Harvey said these had been seen in places where the drug had previously been available over the counter, such as New Zealand. However, there was no evidence of resistance developing for such a short course of use as employed in this setting, he said.

An audience member asked about whether there were any side effects from the mupirocin or chlorhexidine. Dr. Harvey said the main potential adverse event from the treatment was the risk of chlorhexidine toxicity to the cornea. However, he said that patients were told not to get the wash near their eyes.

Apart from one or two patients with eczema who could not tolerate the full 5 days of the chlorhexidine, Dr. Harvey said they had now treated more than 4,000 patients with no other side effects observed.

The study was supported by the Australasian College of Dermatologists. No conflicts of interest were declared.

SYDNEY – All patients undergoing Mohs surgery should be treated with intranasal mupirocin and a chlorhexidine body wash for 5 days before surgery, without any requirement for a nasal swab positive for Staphylococcus aureus, according to Dr. Harvey Smith.

He presented data from a randomized, controlled trial investigating the prevention of surgical-site infection in 1,002 patients undergoing Mohs surgery who had a negative nasal swab result for S. aureus. Patients were randomized to intranasal mupirocin ointment twice daily and chlorhexidine body wash daily for the 5 days before surgery, or no intervention, said Dr. Smith, a dermatologist in group practice in Perth, Australia.

The results add to earlier studies by the same group. The first study – Staph 1 – showed that swab-positive nasal carriage of S. aureus was a greater risk factor for surgical-site infections in Mohs surgery than the Wright criteria, and that decolonization with intranasal mupirocin and chlorhexidine body wash for a few days before surgery reduced the risk of infection in these patients from 12% to 4%.

The second previous study – Staph 2 – showed that using mupirocin and chlorhexidine before surgery was actually superior to the recommended treatment of stat oral cephalexin in reducing the risk of surgical-site infection.

“So, our third paper has been wondering what to do about the silent majority: These are the two-thirds of patients on whom we operate who have a negative swab for S. aureus,” Dr. Harvey said.

A negative nasal swab was not significant, he said, because skin microbiome studies had already demonstrated that humans carry S. aureus in several places, particularly the feet and buttocks.

“What we’re basically saying is we don’t think you need to swab people, because they’ve got it somewhere,” Dr. Harvey said in an interview. “We don’t think risk stratification is useful anymore, because we’ve shown it’s a benefit to everybody.”

The strategy of treating all patients with mupirocin and chlorhexidine, regardless of nasal carriage, rather than using the broad-spectrum cephalexin, fits with the World Health Organization’s global action plan on antimicrobial resistance, Dr. Harvey explained.

While there had been cases of mupirocin resistance in the past, Dr. Harvey said these had been seen in places where the drug had previously been available over the counter, such as New Zealand. However, there was no evidence of resistance developing for such a short course of use as employed in this setting, he said.

An audience member asked about whether there were any side effects from the mupirocin or chlorhexidine. Dr. Harvey said the main potential adverse event from the treatment was the risk of chlorhexidine toxicity to the cornea. However, he said that patients were told not to get the wash near their eyes.

Apart from one or two patients with eczema who could not tolerate the full 5 days of the chlorhexidine, Dr. Harvey said they had now treated more than 4,000 patients with no other side effects observed.

The study was supported by the Australasian College of Dermatologists. No conflicts of interest were declared.

SYDNEY – All patients undergoing Mohs surgery should be treated with intranasal mupirocin and a chlorhexidine body wash for 5 days before surgery, without any requirement for a nasal swab positive for Staphylococcus aureus, according to Dr. Harvey Smith.

He presented data from a randomized, controlled trial investigating the prevention of surgical-site infection in 1,002 patients undergoing Mohs surgery who had a negative nasal swab result for S. aureus. Patients were randomized to intranasal mupirocin ointment twice daily and chlorhexidine body wash daily for the 5 days before surgery, or no intervention, said Dr. Smith, a dermatologist in group practice in Perth, Australia.

The results add to earlier studies by the same group. The first study – Staph 1 – showed that swab-positive nasal carriage of S. aureus was a greater risk factor for surgical-site infections in Mohs surgery than the Wright criteria, and that decolonization with intranasal mupirocin and chlorhexidine body wash for a few days before surgery reduced the risk of infection in these patients from 12% to 4%.

The second previous study – Staph 2 – showed that using mupirocin and chlorhexidine before surgery was actually superior to the recommended treatment of stat oral cephalexin in reducing the risk of surgical-site infection.

“So, our third paper has been wondering what to do about the silent majority: These are the two-thirds of patients on whom we operate who have a negative swab for S. aureus,” Dr. Harvey said.

A negative nasal swab was not significant, he said, because skin microbiome studies had already demonstrated that humans carry S. aureus in several places, particularly the feet and buttocks.

“What we’re basically saying is we don’t think you need to swab people, because they’ve got it somewhere,” Dr. Harvey said in an interview. “We don’t think risk stratification is useful anymore, because we’ve shown it’s a benefit to everybody.”

The strategy of treating all patients with mupirocin and chlorhexidine, regardless of nasal carriage, rather than using the broad-spectrum cephalexin, fits with the World Health Organization’s global action plan on antimicrobial resistance, Dr. Harvey explained.

While there had been cases of mupirocin resistance in the past, Dr. Harvey said these had been seen in places where the drug had previously been available over the counter, such as New Zealand. However, there was no evidence of resistance developing for such a short course of use as employed in this setting, he said.

An audience member asked about whether there were any side effects from the mupirocin or chlorhexidine. Dr. Harvey said the main potential adverse event from the treatment was the risk of chlorhexidine toxicity to the cornea. However, he said that patients were told not to get the wash near their eyes.

Apart from one or two patients with eczema who could not tolerate the full 5 days of the chlorhexidine, Dr. Harvey said they had now treated more than 4,000 patients with no other side effects observed.

The study was supported by the Australasian College of Dermatologists. No conflicts of interest were declared.

Key clinical point: Treat all patients undergoing Mohs surgery with intranasal mupirocin and a chlorhexidine body wash for 5 days before surgery, without the need for a nasal swab for Staphylococcus aureus.

Major finding: Treating patients undergoing Mohs surgery with intranasal mupirocin and a chlorhexidine body wash for 5 days before surgery halved the risk of surgical-site infections, even if the patients did not have a positive nasal swab for S. aureus.

Data source: A randomized, controlled trial in 1,002 patients with a negative nasal swab for S. aureus undergoing Mohs surgery.

Disclosures: The study was partly supported by the Australasian College of Dermatologists. No conflicts of interest were declared.

Skin cancer risk similar for liver and kidney transplant recipients

SYDNEY – The risk of developing nonmelanoma skin cancer among liver transplant recipients is similar to that among kidney transplant recipients, but the former tend to have more skin cancer risk factors at baseline, according to a longitudinal cohort study reported at the annual meeting of the Australasian College of Dermatologists.

Liver transplant recipients have been thought to be at a lower risk of developing nonmelanoma skin cancers than are other solid organ transplant recipients, said Ludi Ge, MD, of the department of dermatology at the University of Sydney and Royal Prince Alfred Hospital, Sydney. However, data from a longitudinal cohort study of 230 kidney or liver transplant patients suggest the risk of nonmelanoma skin cancer is similar – if not greater – among liver transplant recipients, compared with kidney transplant recipients.

Over a 5-year period, 47% of liver transplant recipients developed at least one nonmelanoma skin cancer, compared with 33% of renal transplant recipients, representing a 78% greater risk among liver transplant recipients. However, Dr. Ge said the confidence intervals were wide, and the difference lost statistical significance in the multivariate analysis.

The researchers also noted that the liver transplant recipients in the study tended to be older at baseline, with a history of more sun exposure and more previous skin cancers, and were more likely to have a high risk skin type that sunburns easily.

In an interview, Dr. Ge said the findings had implications for the screening and follow-up of liver transplant recipients.

“Previously, we always thought that liver transplant recipients were at lower risk, and, possibly, they’re not screened as much so not followed up as much,” she said. “I think they really should be thought ... as high risk as renal transplant patients and the heart and lung transplant patients.”

The study showed that, while the renal transplant patients developed fewer skin cancers, they developed 1.9 lesions per year on average, compared with liver transplant patients, who developed 1.4 lesions per year.

The majority of skin cancers in both groups were squamous cell carcinomas and basal cell carcinomas, with a small number of keratoacanthomas. There was a similar ratio of squamous cell carcinomas to basal cell carcinomas between the two groups of transplant recipients – 1.7:1 in renal transplant recipients and 1.6:1 in liver recipients – which differed from the previously reported ratios of about 3:1, Dr. Ge said at the meeting.

She noted that this may have been because not every squamous cell carcinoma in situ was biopsied because of the sheer number of tumors, so many were treated empirically and, therefore, not entered into the clinic database.

Dr. Ge also pointed out that the evidence for the 3:1 ratio was around 10 years old.

“I think there’s been quite a change in the immunosuppressants that are used by transplant physicians, so, more and more, we’re seeing the use of sirolimus and everolimus, which are antiangiogenic,” she said.

Dr. Ge also strongly recommended that dermatology clinics specifically manage organ transplant recipients and commented that this could revolutionize the management of these patients, who tend to get lost to follow-up in standard dermatology clinics. “They’re very difficult to look after, they develop innumerable skin cancers that can result in death, and you need to intervene quite early,” she said in the interview.

No conflicts of interest were declared.

SYDNEY – The risk of developing nonmelanoma skin cancer among liver transplant recipients is similar to that among kidney transplant recipients, but the former tend to have more skin cancer risk factors at baseline, according to a longitudinal cohort study reported at the annual meeting of the Australasian College of Dermatologists.

Liver transplant recipients have been thought to be at a lower risk of developing nonmelanoma skin cancers than are other solid organ transplant recipients, said Ludi Ge, MD, of the department of dermatology at the University of Sydney and Royal Prince Alfred Hospital, Sydney. However, data from a longitudinal cohort study of 230 kidney or liver transplant patients suggest the risk of nonmelanoma skin cancer is similar – if not greater – among liver transplant recipients, compared with kidney transplant recipients.

Over a 5-year period, 47% of liver transplant recipients developed at least one nonmelanoma skin cancer, compared with 33% of renal transplant recipients, representing a 78% greater risk among liver transplant recipients. However, Dr. Ge said the confidence intervals were wide, and the difference lost statistical significance in the multivariate analysis.

The researchers also noted that the liver transplant recipients in the study tended to be older at baseline, with a history of more sun exposure and more previous skin cancers, and were more likely to have a high risk skin type that sunburns easily.

In an interview, Dr. Ge said the findings had implications for the screening and follow-up of liver transplant recipients.

“Previously, we always thought that liver transplant recipients were at lower risk, and, possibly, they’re not screened as much so not followed up as much,” she said. “I think they really should be thought ... as high risk as renal transplant patients and the heart and lung transplant patients.”

The study showed that, while the renal transplant patients developed fewer skin cancers, they developed 1.9 lesions per year on average, compared with liver transplant patients, who developed 1.4 lesions per year.

The majority of skin cancers in both groups were squamous cell carcinomas and basal cell carcinomas, with a small number of keratoacanthomas. There was a similar ratio of squamous cell carcinomas to basal cell carcinomas between the two groups of transplant recipients – 1.7:1 in renal transplant recipients and 1.6:1 in liver recipients – which differed from the previously reported ratios of about 3:1, Dr. Ge said at the meeting.

She noted that this may have been because not every squamous cell carcinoma in situ was biopsied because of the sheer number of tumors, so many were treated empirically and, therefore, not entered into the clinic database.

Dr. Ge also pointed out that the evidence for the 3:1 ratio was around 10 years old.

“I think there’s been quite a change in the immunosuppressants that are used by transplant physicians, so, more and more, we’re seeing the use of sirolimus and everolimus, which are antiangiogenic,” she said.

Dr. Ge also strongly recommended that dermatology clinics specifically manage organ transplant recipients and commented that this could revolutionize the management of these patients, who tend to get lost to follow-up in standard dermatology clinics. “They’re very difficult to look after, they develop innumerable skin cancers that can result in death, and you need to intervene quite early,” she said in the interview.

No conflicts of interest were declared.

SYDNEY – The risk of developing nonmelanoma skin cancer among liver transplant recipients is similar to that among kidney transplant recipients, but the former tend to have more skin cancer risk factors at baseline, according to a longitudinal cohort study reported at the annual meeting of the Australasian College of Dermatologists.

Liver transplant recipients have been thought to be at a lower risk of developing nonmelanoma skin cancers than are other solid organ transplant recipients, said Ludi Ge, MD, of the department of dermatology at the University of Sydney and Royal Prince Alfred Hospital, Sydney. However, data from a longitudinal cohort study of 230 kidney or liver transplant patients suggest the risk of nonmelanoma skin cancer is similar – if not greater – among liver transplant recipients, compared with kidney transplant recipients.

Over a 5-year period, 47% of liver transplant recipients developed at least one nonmelanoma skin cancer, compared with 33% of renal transplant recipients, representing a 78% greater risk among liver transplant recipients. However, Dr. Ge said the confidence intervals were wide, and the difference lost statistical significance in the multivariate analysis.

The researchers also noted that the liver transplant recipients in the study tended to be older at baseline, with a history of more sun exposure and more previous skin cancers, and were more likely to have a high risk skin type that sunburns easily.

In an interview, Dr. Ge said the findings had implications for the screening and follow-up of liver transplant recipients.

“Previously, we always thought that liver transplant recipients were at lower risk, and, possibly, they’re not screened as much so not followed up as much,” she said. “I think they really should be thought ... as high risk as renal transplant patients and the heart and lung transplant patients.”

The study showed that, while the renal transplant patients developed fewer skin cancers, they developed 1.9 lesions per year on average, compared with liver transplant patients, who developed 1.4 lesions per year.

The majority of skin cancers in both groups were squamous cell carcinomas and basal cell carcinomas, with a small number of keratoacanthomas. There was a similar ratio of squamous cell carcinomas to basal cell carcinomas between the two groups of transplant recipients – 1.7:1 in renal transplant recipients and 1.6:1 in liver recipients – which differed from the previously reported ratios of about 3:1, Dr. Ge said at the meeting.

She noted that this may have been because not every squamous cell carcinoma in situ was biopsied because of the sheer number of tumors, so many were treated empirically and, therefore, not entered into the clinic database.

Dr. Ge also pointed out that the evidence for the 3:1 ratio was around 10 years old.

“I think there’s been quite a change in the immunosuppressants that are used by transplant physicians, so, more and more, we’re seeing the use of sirolimus and everolimus, which are antiangiogenic,” she said.

Dr. Ge also strongly recommended that dermatology clinics specifically manage organ transplant recipients and commented that this could revolutionize the management of these patients, who tend to get lost to follow-up in standard dermatology clinics. “They’re very difficult to look after, they develop innumerable skin cancers that can result in death, and you need to intervene quite early,” she said in the interview.

No conflicts of interest were declared.

AT ACDASM 2017

Key clinical point: Liver transplant recipients should be screened and followed for the development of nonmelanoma skin cancers as closely as are kidney transplant recipients.

Major finding: Over 5 years, 47% of liver transplant recipients developed at least one nonmelanoma skin cancer, compared with 33% of renal transplant recipients, a difference that was not statistically significant after a multivariate analysis was done.

Data source: A longitudinal cohort study of 230 kidney or liver transplant recipients attending a dermatology clinic affiliated with an organ transplant unit.

Disclosures: No conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Chemoprevention: Thinking outside the box

WAILEA, HAWAII – Nicotinamide is one of the rare proposed agents for skin cancer chemoprevention distinguished by dirt cheap cost combined with a highly reassuring safety profile plus evidence of efficacy – which, together, make it a reasonable option in high risk patients, according to Daniel M. Siegel, MD.

Other agents that fit into that category include the tropical rainforest fern Polypodium leucotomos and milk thistle, added Dr. Siegel, a dermatologist at the State University of New York, Brooklyn.

“That’s a really interesting one. I don’t know if, 5 years from now, we’ll all be taking low-dose rapamycin as an antiaging drug, but we might, especially if someone figures out the ideal dose,” he said at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Research Foundation.

Nicotinamide

In the case of nicotinamide, the efficacy is actually supported by published level 1 evidence in the form of a highly positive 1-year, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled phase III clinical trial.

“You can Google ‘nicotinamide’ and find it at places like Costco and Trader Joe’s for less than 6 cents per day. That makes for a really good risk/benefit ratio. A nickel a day: That’s a cheap one. That’s one where I’d say, ‘Why not?’ It seems to be safe,” Dr. Siegel said.

In the phase III ONTRAC trial, Australian investigators randomized 386 patients who averaged roughly eight nonmelanoma skin cancers in the past 5 years to either 500 mg of oral nicotinamide twice daily or matched placebo for 12 months. During the study period, the nicotinamide group had a statistically significant and clinically meaningful 23% reduction in new nonmelanoma skin cancers, compared with the control group. They also had 13% fewer actinic keratoses at 12 months than controls. And the side effect profile mirrored that of placebo (N Engl J Med. 2015 Oct 22;373[17]:1618-26).

“Nicotinamide is vitamin B3. It’s not niacin. It doesn’t cause flushing and other vasodilatory effects. It’s actually pretty innocuous,” Dr. Siegel said.

In laboratory studies, nicotinamide has been shown to enhance DNA repair following UV exposure, as well as curb UV-induced immunosuppression.

Polypodium leucotomos Samambaia

This plant, commonly known as calaguala in the Spanish-speaking tropics and samambaia in Brazil, has a centuries-long tradition of safe medicinal use. It is commercially available over-the-counter (OTC) as a standardized product called Heliocare, designed to avoid the guesswork involved in topical sunscreen application. Each capsule contains 240 mg of an extract of P. leucotomos. Dr. Siegel said he takes it daily when he’s in a sunny locale, such as Hawaii.

Milk thistle

This plant, known as Silybum marianum, has silymarin as its bioactive compound. Dermatologist Haines Ely, MD, of the University of California, Davis, has reported therapeutic success using it in porphyria cutanea tarda and other conditions. It has been shown to inhibit photocarcinogenesis in animal studies.

Dr. Siegel said that, while Dr. Ely has told him his preferred preparation is a German OTC product, milk thistle seeds can be found in health food stores, ground to a powder using a coffee bean grinder, and used as a food supplement. Like Polypodium leucotomos and nicotinamide, milk thistle is nontoxic.

Rapamycin

This macrolide compound is produced by the bacterium Streptomyces hygroscopicus. Rapamycin is an immunosuppressant used to coat coronary stents and prevent rejection of transplanted organs. It is an mechanistic target of rapamycin signaling pathway inhibitor being studied as a cancer prevention and antiaging agent.

Science magazine called the discovery that rapamycin increased the lifespan of mice one of the top scientific breakthroughs of 2009. Subsequent animal studies have established that the extended lifespan wasn’t solely the result of rapamycin’s antineoplastic effects but of across-the-board delayed onset of all the major age-related diseases. Thus, rapamycin could turn out to be a true antiaging agent, in Dr. Siegel’s view.

Studies in humans are underway. Researchers at Novartis have reported that a rapamycin-related compound curbed the typical decline in immune function that accompanies aging as reflected in a 20% enhancement in the response to influenza vaccine in elderly volunteers (Sci Transl Med. 2014 Dec 24;6[268]:268ra179).

Dr. Siegel reported serving as a consultant to Ferndale, which markets Heliocare. The SDEF and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

WAILEA, HAWAII – Nicotinamide is one of the rare proposed agents for skin cancer chemoprevention distinguished by dirt cheap cost combined with a highly reassuring safety profile plus evidence of efficacy – which, together, make it a reasonable option in high risk patients, according to Daniel M. Siegel, MD.

Other agents that fit into that category include the tropical rainforest fern Polypodium leucotomos and milk thistle, added Dr. Siegel, a dermatologist at the State University of New York, Brooklyn.

“That’s a really interesting one. I don’t know if, 5 years from now, we’ll all be taking low-dose rapamycin as an antiaging drug, but we might, especially if someone figures out the ideal dose,” he said at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Research Foundation.

Nicotinamide

In the case of nicotinamide, the efficacy is actually supported by published level 1 evidence in the form of a highly positive 1-year, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled phase III clinical trial.

“You can Google ‘nicotinamide’ and find it at places like Costco and Trader Joe’s for less than 6 cents per day. That makes for a really good risk/benefit ratio. A nickel a day: That’s a cheap one. That’s one where I’d say, ‘Why not?’ It seems to be safe,” Dr. Siegel said.

In the phase III ONTRAC trial, Australian investigators randomized 386 patients who averaged roughly eight nonmelanoma skin cancers in the past 5 years to either 500 mg of oral nicotinamide twice daily or matched placebo for 12 months. During the study period, the nicotinamide group had a statistically significant and clinically meaningful 23% reduction in new nonmelanoma skin cancers, compared with the control group. They also had 13% fewer actinic keratoses at 12 months than controls. And the side effect profile mirrored that of placebo (N Engl J Med. 2015 Oct 22;373[17]:1618-26).

“Nicotinamide is vitamin B3. It’s not niacin. It doesn’t cause flushing and other vasodilatory effects. It’s actually pretty innocuous,” Dr. Siegel said.

In laboratory studies, nicotinamide has been shown to enhance DNA repair following UV exposure, as well as curb UV-induced immunosuppression.

Polypodium leucotomos Samambaia

This plant, commonly known as calaguala in the Spanish-speaking tropics and samambaia in Brazil, has a centuries-long tradition of safe medicinal use. It is commercially available over-the-counter (OTC) as a standardized product called Heliocare, designed to avoid the guesswork involved in topical sunscreen application. Each capsule contains 240 mg of an extract of P. leucotomos. Dr. Siegel said he takes it daily when he’s in a sunny locale, such as Hawaii.

Milk thistle

This plant, known as Silybum marianum, has silymarin as its bioactive compound. Dermatologist Haines Ely, MD, of the University of California, Davis, has reported therapeutic success using it in porphyria cutanea tarda and other conditions. It has been shown to inhibit photocarcinogenesis in animal studies.

Dr. Siegel said that, while Dr. Ely has told him his preferred preparation is a German OTC product, milk thistle seeds can be found in health food stores, ground to a powder using a coffee bean grinder, and used as a food supplement. Like Polypodium leucotomos and nicotinamide, milk thistle is nontoxic.

Rapamycin

This macrolide compound is produced by the bacterium Streptomyces hygroscopicus. Rapamycin is an immunosuppressant used to coat coronary stents and prevent rejection of transplanted organs. It is an mechanistic target of rapamycin signaling pathway inhibitor being studied as a cancer prevention and antiaging agent.

Science magazine called the discovery that rapamycin increased the lifespan of mice one of the top scientific breakthroughs of 2009. Subsequent animal studies have established that the extended lifespan wasn’t solely the result of rapamycin’s antineoplastic effects but of across-the-board delayed onset of all the major age-related diseases. Thus, rapamycin could turn out to be a true antiaging agent, in Dr. Siegel’s view.

Studies in humans are underway. Researchers at Novartis have reported that a rapamycin-related compound curbed the typical decline in immune function that accompanies aging as reflected in a 20% enhancement in the response to influenza vaccine in elderly volunteers (Sci Transl Med. 2014 Dec 24;6[268]:268ra179).

Dr. Siegel reported serving as a consultant to Ferndale, which markets Heliocare. The SDEF and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

WAILEA, HAWAII – Nicotinamide is one of the rare proposed agents for skin cancer chemoprevention distinguished by dirt cheap cost combined with a highly reassuring safety profile plus evidence of efficacy – which, together, make it a reasonable option in high risk patients, according to Daniel M. Siegel, MD.

Other agents that fit into that category include the tropical rainforest fern Polypodium leucotomos and milk thistle, added Dr. Siegel, a dermatologist at the State University of New York, Brooklyn.

“That’s a really interesting one. I don’t know if, 5 years from now, we’ll all be taking low-dose rapamycin as an antiaging drug, but we might, especially if someone figures out the ideal dose,” he said at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Research Foundation.

Nicotinamide

In the case of nicotinamide, the efficacy is actually supported by published level 1 evidence in the form of a highly positive 1-year, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled phase III clinical trial.

“You can Google ‘nicotinamide’ and find it at places like Costco and Trader Joe’s for less than 6 cents per day. That makes for a really good risk/benefit ratio. A nickel a day: That’s a cheap one. That’s one where I’d say, ‘Why not?’ It seems to be safe,” Dr. Siegel said.

In the phase III ONTRAC trial, Australian investigators randomized 386 patients who averaged roughly eight nonmelanoma skin cancers in the past 5 years to either 500 mg of oral nicotinamide twice daily or matched placebo for 12 months. During the study period, the nicotinamide group had a statistically significant and clinically meaningful 23% reduction in new nonmelanoma skin cancers, compared with the control group. They also had 13% fewer actinic keratoses at 12 months than controls. And the side effect profile mirrored that of placebo (N Engl J Med. 2015 Oct 22;373[17]:1618-26).

“Nicotinamide is vitamin B3. It’s not niacin. It doesn’t cause flushing and other vasodilatory effects. It’s actually pretty innocuous,” Dr. Siegel said.

In laboratory studies, nicotinamide has been shown to enhance DNA repair following UV exposure, as well as curb UV-induced immunosuppression.

Polypodium leucotomos Samambaia

This plant, commonly known as calaguala in the Spanish-speaking tropics and samambaia in Brazil, has a centuries-long tradition of safe medicinal use. It is commercially available over-the-counter (OTC) as a standardized product called Heliocare, designed to avoid the guesswork involved in topical sunscreen application. Each capsule contains 240 mg of an extract of P. leucotomos. Dr. Siegel said he takes it daily when he’s in a sunny locale, such as Hawaii.

Milk thistle

This plant, known as Silybum marianum, has silymarin as its bioactive compound. Dermatologist Haines Ely, MD, of the University of California, Davis, has reported therapeutic success using it in porphyria cutanea tarda and other conditions. It has been shown to inhibit photocarcinogenesis in animal studies.

Dr. Siegel said that, while Dr. Ely has told him his preferred preparation is a German OTC product, milk thistle seeds can be found in health food stores, ground to a powder using a coffee bean grinder, and used as a food supplement. Like Polypodium leucotomos and nicotinamide, milk thistle is nontoxic.

Rapamycin

This macrolide compound is produced by the bacterium Streptomyces hygroscopicus. Rapamycin is an immunosuppressant used to coat coronary stents and prevent rejection of transplanted organs. It is an mechanistic target of rapamycin signaling pathway inhibitor being studied as a cancer prevention and antiaging agent.

Science magazine called the discovery that rapamycin increased the lifespan of mice one of the top scientific breakthroughs of 2009. Subsequent animal studies have established that the extended lifespan wasn’t solely the result of rapamycin’s antineoplastic effects but of across-the-board delayed onset of all the major age-related diseases. Thus, rapamycin could turn out to be a true antiaging agent, in Dr. Siegel’s view.

Studies in humans are underway. Researchers at Novartis have reported that a rapamycin-related compound curbed the typical decline in immune function that accompanies aging as reflected in a 20% enhancement in the response to influenza vaccine in elderly volunteers (Sci Transl Med. 2014 Dec 24;6[268]:268ra179).

Dr. Siegel reported serving as a consultant to Ferndale, which markets Heliocare. The SDEF and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM SDEF HAWAII DERMATOLOGY SEMINAR

Study links photosensitizing antihypertensives to SCC

PORTLAND, ORE. – Patients prescribed photosensitizing antihypertensive drugs had a 16% increase in risk of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC) in a large retrospective cohort study.

These drugs include alpha-2 receptor agonists and loop diuretics, potassium-sparing diuretics, thiazide diuretics, and combination diuretics, Katherine Levandoski said in an oral presentation at the annual meeting of the Society for Investigative Dermatology.

Furthermore, taking antihypertensive drugs of unknown photosensitizing potential conferred a 10% increase in risk of cSCC in the study, she added. Such medications include angiotensin–converting enzyme inhibitors, calcium channel blockers, and vasodilators, she said.

More than 50 million Americans take antihypertensive drugs, many of which are photosensitizing, noted Ms. Levandoski, a research assistant in the Patient Oriented Research on the Epidemiology of Skin Diseases Unit in the department of dermatology, Massachusetts General Hospital, and the department of population medicine, Harvard University, Boston. However, few studies have explored the oncogenic effects of exposure to these drugs, and those that have done so were subject to confounding, small sample sizes, missing data, lack of pathologic verification, and reliance on self-reported medication history, she added.

To help fill this knowledge gap, she and her associates studied 28,357 non-Hispanic whites diagnosed with hypertension and treated at Kaiser Permanente Northern California between 1997 and 2012. They limited the cohort to non-Hispanic whites because they represent the group with most cases of cSCC.

During follow-up, 3,010 patients were diagnosed with new-onset, pathologically verified cSCC, Ms. Levandoski said. Compared with nonusers of antihypertensives, users of photosensitizing antihypertensives had about a 16% increase in the rate of cSCC (hazard ratio, 1.16; 95% confidence interval, 1.06-1.27), even after accounting for age, sex, smoking, comorbidities, health care utilization, skin cancer history, length of health plan membership, and prior exposure to photosensitizing medications.

Strikingly, patients who used antihypertensives of unknown photosensitizing effect had a 10% increase in risk of incident cSCC (RR, 1.10; 95% CI, 1.02-1.19). Some antihypertensive drugs that are classified as unknown photosensitizers “may actually have photosensitizing properties,” Ms. Levandoski commented. Patients taking antihypertensives of known or unknown photosensitizing potential “should be educated on safe sun practices and may benefit from closer screening for cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma,” she added.

The risk of cSCC was not increased among users of nonphotosensitizing antihypertensives (HR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.91-1.07), including alpha-blockers, beta-blockers, central agonists, and angiotensin receptor blockers, Ms. Levandoski reported.

Patients in the study cohort averaged aged 60 years (standard deviation, 10.6 years), and 56% were female. In all, 1,530 had never been prescribed antihypertensives, while about 17,000-19,000 had been prescribed unknown, known, or nonphotosensitizing antihypertensives.

The work was funded by the National Institutes of Health, a travel award from the Society for Investigative Dermatology, and a Massachusetts General Hospital Medical Student Award. Ms. Levandoski had no conflicts of interest.

PORTLAND, ORE. – Patients prescribed photosensitizing antihypertensive drugs had a 16% increase in risk of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC) in a large retrospective cohort study.

These drugs include alpha-2 receptor agonists and loop diuretics, potassium-sparing diuretics, thiazide diuretics, and combination diuretics, Katherine Levandoski said in an oral presentation at the annual meeting of the Society for Investigative Dermatology.

Furthermore, taking antihypertensive drugs of unknown photosensitizing potential conferred a 10% increase in risk of cSCC in the study, she added. Such medications include angiotensin–converting enzyme inhibitors, calcium channel blockers, and vasodilators, she said.

More than 50 million Americans take antihypertensive drugs, many of which are photosensitizing, noted Ms. Levandoski, a research assistant in the Patient Oriented Research on the Epidemiology of Skin Diseases Unit in the department of dermatology, Massachusetts General Hospital, and the department of population medicine, Harvard University, Boston. However, few studies have explored the oncogenic effects of exposure to these drugs, and those that have done so were subject to confounding, small sample sizes, missing data, lack of pathologic verification, and reliance on self-reported medication history, she added.

To help fill this knowledge gap, she and her associates studied 28,357 non-Hispanic whites diagnosed with hypertension and treated at Kaiser Permanente Northern California between 1997 and 2012. They limited the cohort to non-Hispanic whites because they represent the group with most cases of cSCC.

During follow-up, 3,010 patients were diagnosed with new-onset, pathologically verified cSCC, Ms. Levandoski said. Compared with nonusers of antihypertensives, users of photosensitizing antihypertensives had about a 16% increase in the rate of cSCC (hazard ratio, 1.16; 95% confidence interval, 1.06-1.27), even after accounting for age, sex, smoking, comorbidities, health care utilization, skin cancer history, length of health plan membership, and prior exposure to photosensitizing medications.

Strikingly, patients who used antihypertensives of unknown photosensitizing effect had a 10% increase in risk of incident cSCC (RR, 1.10; 95% CI, 1.02-1.19). Some antihypertensive drugs that are classified as unknown photosensitizers “may actually have photosensitizing properties,” Ms. Levandoski commented. Patients taking antihypertensives of known or unknown photosensitizing potential “should be educated on safe sun practices and may benefit from closer screening for cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma,” she added.

The risk of cSCC was not increased among users of nonphotosensitizing antihypertensives (HR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.91-1.07), including alpha-blockers, beta-blockers, central agonists, and angiotensin receptor blockers, Ms. Levandoski reported.

Patients in the study cohort averaged aged 60 years (standard deviation, 10.6 years), and 56% were female. In all, 1,530 had never been prescribed antihypertensives, while about 17,000-19,000 had been prescribed unknown, known, or nonphotosensitizing antihypertensives.

The work was funded by the National Institutes of Health, a travel award from the Society for Investigative Dermatology, and a Massachusetts General Hospital Medical Student Award. Ms. Levandoski had no conflicts of interest.

PORTLAND, ORE. – Patients prescribed photosensitizing antihypertensive drugs had a 16% increase in risk of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC) in a large retrospective cohort study.

These drugs include alpha-2 receptor agonists and loop diuretics, potassium-sparing diuretics, thiazide diuretics, and combination diuretics, Katherine Levandoski said in an oral presentation at the annual meeting of the Society for Investigative Dermatology.

Furthermore, taking antihypertensive drugs of unknown photosensitizing potential conferred a 10% increase in risk of cSCC in the study, she added. Such medications include angiotensin–converting enzyme inhibitors, calcium channel blockers, and vasodilators, she said.

More than 50 million Americans take antihypertensive drugs, many of which are photosensitizing, noted Ms. Levandoski, a research assistant in the Patient Oriented Research on the Epidemiology of Skin Diseases Unit in the department of dermatology, Massachusetts General Hospital, and the department of population medicine, Harvard University, Boston. However, few studies have explored the oncogenic effects of exposure to these drugs, and those that have done so were subject to confounding, small sample sizes, missing data, lack of pathologic verification, and reliance on self-reported medication history, she added.

To help fill this knowledge gap, she and her associates studied 28,357 non-Hispanic whites diagnosed with hypertension and treated at Kaiser Permanente Northern California between 1997 and 2012. They limited the cohort to non-Hispanic whites because they represent the group with most cases of cSCC.

During follow-up, 3,010 patients were diagnosed with new-onset, pathologically verified cSCC, Ms. Levandoski said. Compared with nonusers of antihypertensives, users of photosensitizing antihypertensives had about a 16% increase in the rate of cSCC (hazard ratio, 1.16; 95% confidence interval, 1.06-1.27), even after accounting for age, sex, smoking, comorbidities, health care utilization, skin cancer history, length of health plan membership, and prior exposure to photosensitizing medications.

Strikingly, patients who used antihypertensives of unknown photosensitizing effect had a 10% increase in risk of incident cSCC (RR, 1.10; 95% CI, 1.02-1.19). Some antihypertensive drugs that are classified as unknown photosensitizers “may actually have photosensitizing properties,” Ms. Levandoski commented. Patients taking antihypertensives of known or unknown photosensitizing potential “should be educated on safe sun practices and may benefit from closer screening for cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma,” she added.

The risk of cSCC was not increased among users of nonphotosensitizing antihypertensives (HR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.91-1.07), including alpha-blockers, beta-blockers, central agonists, and angiotensin receptor blockers, Ms. Levandoski reported.

Patients in the study cohort averaged aged 60 years (standard deviation, 10.6 years), and 56% were female. In all, 1,530 had never been prescribed antihypertensives, while about 17,000-19,000 had been prescribed unknown, known, or nonphotosensitizing antihypertensives.

The work was funded by the National Institutes of Health, a travel award from the Society for Investigative Dermatology, and a Massachusetts General Hospital Medical Student Award. Ms. Levandoski had no conflicts of interest.

AT SID 2017

Key clinical point: Consider skin cancer screening for patients who are taking antihypertensives of known or unknown photosensitizing potential.

Major finding: The risk of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma associated with photosensitizing antihypertensives was about 16% .

Data source: A retrospective cohort study of 28,357 non-Hispanic whites with hypertension.

Disclosures: The work was funded by the National Institutes of Health, a travel award from the Society for Investigative Dermatology, and a Massachusetts General Hospital Medical Student Award. Ms. Levandoski had no conflicts of interest.

Chronic GVHD linked to fivefold increase in squamous cell skin carcinomas

PORTLAND – Chronic graft versus host disease (GVHD) was associated with a fivefold increase in risk of squamous cell carcinoma and a nearly twofold rise in the rate of basal cell carcinoma, based on a meta-analysis of eight studies.

Acute GVHD was not tied to an increase in secondary nonmelanoma skin cancers, Pooja H. Rambhia and her associates reported in a poster presented at the annual meeting of the Society for Investigative Dermatology. The findings highlight the need for multidisciplinary consults to distinguish malignancies from the cutaneous manifestations of chronic GVHD and for vigorous surveillance for skin cancer even years after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

GVHS has been linked to secondary nonmelanoma skin cancers in previous studies, but few have quantified the risk, according to the reviewers, who are from the department of dermatology and dermatopathology at the Cleveland Clinic Foundation. The increased risk may be related to the heavy immunosuppression needed to treat chronic GVHD.

For the meta-analysis, the researchers identified 1,411 studies recorded in academic databases and reviewed those that reported both cases of skin cancers and GVHD. Seven retrospective, and one prospective, studies published between 1997 and 2012 measured both variables in all patients.

The studies included more than 56,000 patients followed for up to 36 years after undergoing allogeneic or syngeneic transplantation, the reviewers reported. During follow-up, between 17% and 73% of patients developed chronic GVHD, and 29% to 67% developed acute GVHD. There were 98 cases of basal cell carcinoma, 49 cases of squamous cell carcinoma, and 34 cases of malignant melanoma. Chronic GVHD was significantly associated with both squamous cell carcinoma (risk ratio, 5.3; 95% confidence interval, 2.4-11.8; P less than .001) and basal cell carcinoma (RR, 2.0; 95% CI, 1.3-3.0; P = .002). In contrast, chronic GVHD showed a nonsignificant trend toward an inverse correlation with the risk of secondary melanoma. Acute GVHD was not linked with squamous cell carcinoma, basal cell carcinoma, or melanoma.

GVHD develops, up to half the time, after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and often becomes chronic, the reviewers noted. Catching skin cancer early is crucial, and transplant patients should undergo regular skin checks with multidisciplinary consults to promptly, accurately distinguish malignancies from the cutaneous manifestations of GVHD, they added.

The researchers did not report external funding sources. They had no relevant financial conflicts of interest.

PORTLAND – Chronic graft versus host disease (GVHD) was associated with a fivefold increase in risk of squamous cell carcinoma and a nearly twofold rise in the rate of basal cell carcinoma, based on a meta-analysis of eight studies.

Acute GVHD was not tied to an increase in secondary nonmelanoma skin cancers, Pooja H. Rambhia and her associates reported in a poster presented at the annual meeting of the Society for Investigative Dermatology. The findings highlight the need for multidisciplinary consults to distinguish malignancies from the cutaneous manifestations of chronic GVHD and for vigorous surveillance for skin cancer even years after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

GVHS has been linked to secondary nonmelanoma skin cancers in previous studies, but few have quantified the risk, according to the reviewers, who are from the department of dermatology and dermatopathology at the Cleveland Clinic Foundation. The increased risk may be related to the heavy immunosuppression needed to treat chronic GVHD.

For the meta-analysis, the researchers identified 1,411 studies recorded in academic databases and reviewed those that reported both cases of skin cancers and GVHD. Seven retrospective, and one prospective, studies published between 1997 and 2012 measured both variables in all patients.

The studies included more than 56,000 patients followed for up to 36 years after undergoing allogeneic or syngeneic transplantation, the reviewers reported. During follow-up, between 17% and 73% of patients developed chronic GVHD, and 29% to 67% developed acute GVHD. There were 98 cases of basal cell carcinoma, 49 cases of squamous cell carcinoma, and 34 cases of malignant melanoma. Chronic GVHD was significantly associated with both squamous cell carcinoma (risk ratio, 5.3; 95% confidence interval, 2.4-11.8; P less than .001) and basal cell carcinoma (RR, 2.0; 95% CI, 1.3-3.0; P = .002). In contrast, chronic GVHD showed a nonsignificant trend toward an inverse correlation with the risk of secondary melanoma. Acute GVHD was not linked with squamous cell carcinoma, basal cell carcinoma, or melanoma.

GVHD develops, up to half the time, after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and often becomes chronic, the reviewers noted. Catching skin cancer early is crucial, and transplant patients should undergo regular skin checks with multidisciplinary consults to promptly, accurately distinguish malignancies from the cutaneous manifestations of GVHD, they added.

The researchers did not report external funding sources. They had no relevant financial conflicts of interest.

PORTLAND – Chronic graft versus host disease (GVHD) was associated with a fivefold increase in risk of squamous cell carcinoma and a nearly twofold rise in the rate of basal cell carcinoma, based on a meta-analysis of eight studies.

Acute GVHD was not tied to an increase in secondary nonmelanoma skin cancers, Pooja H. Rambhia and her associates reported in a poster presented at the annual meeting of the Society for Investigative Dermatology. The findings highlight the need for multidisciplinary consults to distinguish malignancies from the cutaneous manifestations of chronic GVHD and for vigorous surveillance for skin cancer even years after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

GVHS has been linked to secondary nonmelanoma skin cancers in previous studies, but few have quantified the risk, according to the reviewers, who are from the department of dermatology and dermatopathology at the Cleveland Clinic Foundation. The increased risk may be related to the heavy immunosuppression needed to treat chronic GVHD.

For the meta-analysis, the researchers identified 1,411 studies recorded in academic databases and reviewed those that reported both cases of skin cancers and GVHD. Seven retrospective, and one prospective, studies published between 1997 and 2012 measured both variables in all patients.

The studies included more than 56,000 patients followed for up to 36 years after undergoing allogeneic or syngeneic transplantation, the reviewers reported. During follow-up, between 17% and 73% of patients developed chronic GVHD, and 29% to 67% developed acute GVHD. There were 98 cases of basal cell carcinoma, 49 cases of squamous cell carcinoma, and 34 cases of malignant melanoma. Chronic GVHD was significantly associated with both squamous cell carcinoma (risk ratio, 5.3; 95% confidence interval, 2.4-11.8; P less than .001) and basal cell carcinoma (RR, 2.0; 95% CI, 1.3-3.0; P = .002). In contrast, chronic GVHD showed a nonsignificant trend toward an inverse correlation with the risk of secondary melanoma. Acute GVHD was not linked with squamous cell carcinoma, basal cell carcinoma, or melanoma.

GVHD develops, up to half the time, after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and often becomes chronic, the reviewers noted. Catching skin cancer early is crucial, and transplant patients should undergo regular skin checks with multidisciplinary consults to promptly, accurately distinguish malignancies from the cutaneous manifestations of GVHD, they added.

The researchers did not report external funding sources. They had no relevant financial conflicts of interest.

AT SID 2017

Key clinical point: Chronic graft versus host disease was associated with a significantly increased risk of squamous cell and basal cell carcinomas.

Major finding: Chronic GVHD was associated with a fivefold increase in squamous cell carcinoma (risk ratio, 5.3; 95% confidence interval, 2.4 to 11.8; P less than .001).

Data source: A meta-analysis of eight cohort studies of 56,000 patients who underwent hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

Disclosures: The researchers did not report external funding sources. They had no conflicts of interest.

Tattoo artist survey finds almost half agree to tattoo skin with lesions

The importance of educating tattoo artists on identifying and being careful around skin with melanocytic nevi and other lesions was highlighted by the results of a survey of tattoo artists, according to a study from the University of Pittsburgh.

“While most of those surveyed reported deliberately avoiding nevi, a similar proportion reported either tattooing over them or simply deferring to the client’s preference,” wrote Westley S. Mori and his associates in the department of dermatology at the University of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. “This is concerning because few clients specifically ask tattoo artists to avoid skin lesions,” they added.

They surveyed 42 tattoo artists in July and August 2016 regarding their encounters with clients with skin lesions and their personal knowledge or experiences they may have had with skin cancer. Of those surveyed, 23 (55%) said they had declined to tattoo skin with a rash or lesion (JAMA Dermatology. 2017;153[4]:328-30).When asked about their reasoning for declining a client’s request, 21 (50%) of respondents said they did so because of a poor cosmetic outcome, while the next highest answer, a concern of potential skin cancer, was only cited by 12 (29%).

Most (74%) said there was no official store policy about tattooing over moles or other skin lesions. When asked about their approaches to tattooing skin with moles or other lesions, many said they choose to tattoo around the lesion (41%), tattoo over the lesion (19%), or defer to the client’s preferences (24%). However, with regards to deferring to a client, 29 artists (69%) reported never being asked to avoid a lesion.

Investigators noted that 12 respondents reported that they had identified a possible cancerous lesion on a client, followed by the same number of respondents reporting having recommended that a client see a dermatologist.

Tattoo artists who had seen a dermatologist for a skin examination were significantly more likely to refuse to tattoo a client with a lesion (P = .01) and recommend that the client see a dermatologist (P less than .001) when they had a lesion. Based on this response, the authors said that they believed that educating both clients and tattoo artists may be the best way to get tattoo artists to engage clients. “Our study highlights an opportunity for dermatologists to educate tattoo artists about skin cancer, particularly melanoma, to help reduce the incidence of skin cancers hidden in tattoos and to encourage appropriate referral to dermatologists for suspicious lesions on clients,” they concluded.

“When you perform a total body skin examination, it’s a little difficult to kind of tease out if a lesion looks suspicious or not if it’s surrounded by ink,” Mr. Mori, a medical student at the university, said in an interview. “Tattoos are becoming more and more common, especially among younger people, and incidence of melanoma has increased in younger populations as well. ... It is very concerning that skin cancers could be hidden in tattoos.”

In fact, Mr. Mori pointed out, there are opportunities for dermatologists to reach out to the tattoo artist community and start the communication process. “Tattoo artists have national conferences where they get together and discuss the state of the industry, and that represents one opportunity where dermatologists could talk about the effects of skin cancer,” he said.

The study was funded by the University of Pittsburgh. The authors reported no relevant financial disclosures.

ezimmerman@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @eaztweets

The importance of educating tattoo artists on identifying and being careful around skin with melanocytic nevi and other lesions was highlighted by the results of a survey of tattoo artists, according to a study from the University of Pittsburgh.

“While most of those surveyed reported deliberately avoiding nevi, a similar proportion reported either tattooing over them or simply deferring to the client’s preference,” wrote Westley S. Mori and his associates in the department of dermatology at the University of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. “This is concerning because few clients specifically ask tattoo artists to avoid skin lesions,” they added.

They surveyed 42 tattoo artists in July and August 2016 regarding their encounters with clients with skin lesions and their personal knowledge or experiences they may have had with skin cancer. Of those surveyed, 23 (55%) said they had declined to tattoo skin with a rash or lesion (JAMA Dermatology. 2017;153[4]:328-30).When asked about their reasoning for declining a client’s request, 21 (50%) of respondents said they did so because of a poor cosmetic outcome, while the next highest answer, a concern of potential skin cancer, was only cited by 12 (29%).

Most (74%) said there was no official store policy about tattooing over moles or other skin lesions. When asked about their approaches to tattooing skin with moles or other lesions, many said they choose to tattoo around the lesion (41%), tattoo over the lesion (19%), or defer to the client’s preferences (24%). However, with regards to deferring to a client, 29 artists (69%) reported never being asked to avoid a lesion.

Investigators noted that 12 respondents reported that they had identified a possible cancerous lesion on a client, followed by the same number of respondents reporting having recommended that a client see a dermatologist.

Tattoo artists who had seen a dermatologist for a skin examination were significantly more likely to refuse to tattoo a client with a lesion (P = .01) and recommend that the client see a dermatologist (P less than .001) when they had a lesion. Based on this response, the authors said that they believed that educating both clients and tattoo artists may be the best way to get tattoo artists to engage clients. “Our study highlights an opportunity for dermatologists to educate tattoo artists about skin cancer, particularly melanoma, to help reduce the incidence of skin cancers hidden in tattoos and to encourage appropriate referral to dermatologists for suspicious lesions on clients,” they concluded.

“When you perform a total body skin examination, it’s a little difficult to kind of tease out if a lesion looks suspicious or not if it’s surrounded by ink,” Mr. Mori, a medical student at the university, said in an interview. “Tattoos are becoming more and more common, especially among younger people, and incidence of melanoma has increased in younger populations as well. ... It is very concerning that skin cancers could be hidden in tattoos.”

In fact, Mr. Mori pointed out, there are opportunities for dermatologists to reach out to the tattoo artist community and start the communication process. “Tattoo artists have national conferences where they get together and discuss the state of the industry, and that represents one opportunity where dermatologists could talk about the effects of skin cancer,” he said.

The study was funded by the University of Pittsburgh. The authors reported no relevant financial disclosures.

ezimmerman@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @eaztweets

The importance of educating tattoo artists on identifying and being careful around skin with melanocytic nevi and other lesions was highlighted by the results of a survey of tattoo artists, according to a study from the University of Pittsburgh.

“While most of those surveyed reported deliberately avoiding nevi, a similar proportion reported either tattooing over them or simply deferring to the client’s preference,” wrote Westley S. Mori and his associates in the department of dermatology at the University of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. “This is concerning because few clients specifically ask tattoo artists to avoid skin lesions,” they added.

They surveyed 42 tattoo artists in July and August 2016 regarding their encounters with clients with skin lesions and their personal knowledge or experiences they may have had with skin cancer. Of those surveyed, 23 (55%) said they had declined to tattoo skin with a rash or lesion (JAMA Dermatology. 2017;153[4]:328-30).When asked about their reasoning for declining a client’s request, 21 (50%) of respondents said they did so because of a poor cosmetic outcome, while the next highest answer, a concern of potential skin cancer, was only cited by 12 (29%).

Most (74%) said there was no official store policy about tattooing over moles or other skin lesions. When asked about their approaches to tattooing skin with moles or other lesions, many said they choose to tattoo around the lesion (41%), tattoo over the lesion (19%), or defer to the client’s preferences (24%). However, with regards to deferring to a client, 29 artists (69%) reported never being asked to avoid a lesion.

Investigators noted that 12 respondents reported that they had identified a possible cancerous lesion on a client, followed by the same number of respondents reporting having recommended that a client see a dermatologist.

Tattoo artists who had seen a dermatologist for a skin examination were significantly more likely to refuse to tattoo a client with a lesion (P = .01) and recommend that the client see a dermatologist (P less than .001) when they had a lesion. Based on this response, the authors said that they believed that educating both clients and tattoo artists may be the best way to get tattoo artists to engage clients. “Our study highlights an opportunity for dermatologists to educate tattoo artists about skin cancer, particularly melanoma, to help reduce the incidence of skin cancers hidden in tattoos and to encourage appropriate referral to dermatologists for suspicious lesions on clients,” they concluded.

“When you perform a total body skin examination, it’s a little difficult to kind of tease out if a lesion looks suspicious or not if it’s surrounded by ink,” Mr. Mori, a medical student at the university, said in an interview. “Tattoos are becoming more and more common, especially among younger people, and incidence of melanoma has increased in younger populations as well. ... It is very concerning that skin cancers could be hidden in tattoos.”

In fact, Mr. Mori pointed out, there are opportunities for dermatologists to reach out to the tattoo artist community and start the communication process. “Tattoo artists have national conferences where they get together and discuss the state of the industry, and that represents one opportunity where dermatologists could talk about the effects of skin cancer,” he said.

The study was funded by the University of Pittsburgh. The authors reported no relevant financial disclosures.

ezimmerman@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @eaztweets

Key clinical point: Dermatologists can educate tattoo artists about avoiding tattoos around moles and other skin lesions.

Major finding: Of 42 tattoo artists who were surveyed, 19 (45%) reported never declining a client’s request to tattoo skin with a lesion, and 31 (74%) reporting having no official store policy on tattooing over lesions.

Data source: An anonymous survey of 42 tattoo artists conducted in July and August 2016.

Disclosures: This study was funded by the University of Pittsburgh. Investigators reported no relevant disclosures.

Acquired Epidermodysplasia Verruciformis Occurring in a Renal Transplant Recipient

Acquired epidermodysplasia verruciformis (EDV) is a rare disorder occurring in patients with depressed cellular immunity, particularly individuals with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Rare cases of acquired EDV have been reported in stem cell or solid organ transplant recipients. Weakened cellular immunity predisposes the patient to human papillomavirus (HPV) infections, with 92% of renal transplant recipients developing warts within 5 years posttransplantation.1 Specific EDV-HPV subtypes have been isolated from lesions in several immunosuppressed individuals, with HPV-5 and HPV-8 being the most commonly isolated subtypes.2,3 Herein, we present the clinical findings of a renal transplant recipient who presented for evaluation of multiple skin lesions characteristic of EDV 5 years following transplantation and initiation of immunosuppressive therapy. Additionally, we review the current diagnostic findings, management, and treatment of acquired EDV.

A 44-year-old white woman presented for evaluation of several pruritic cutaneous lesions that had developed on the chest and neck of 1 month’s duration. The patient had been on the immunosuppressant medications cyclosporine and mycophenolate mofetil for more than 5 years following renal transplantation 7 years prior to the current presentation. She also was on low-dose prednisone for chronic systemic lupus erythematosus. Her family history was negative for any pertinent skin conditions.

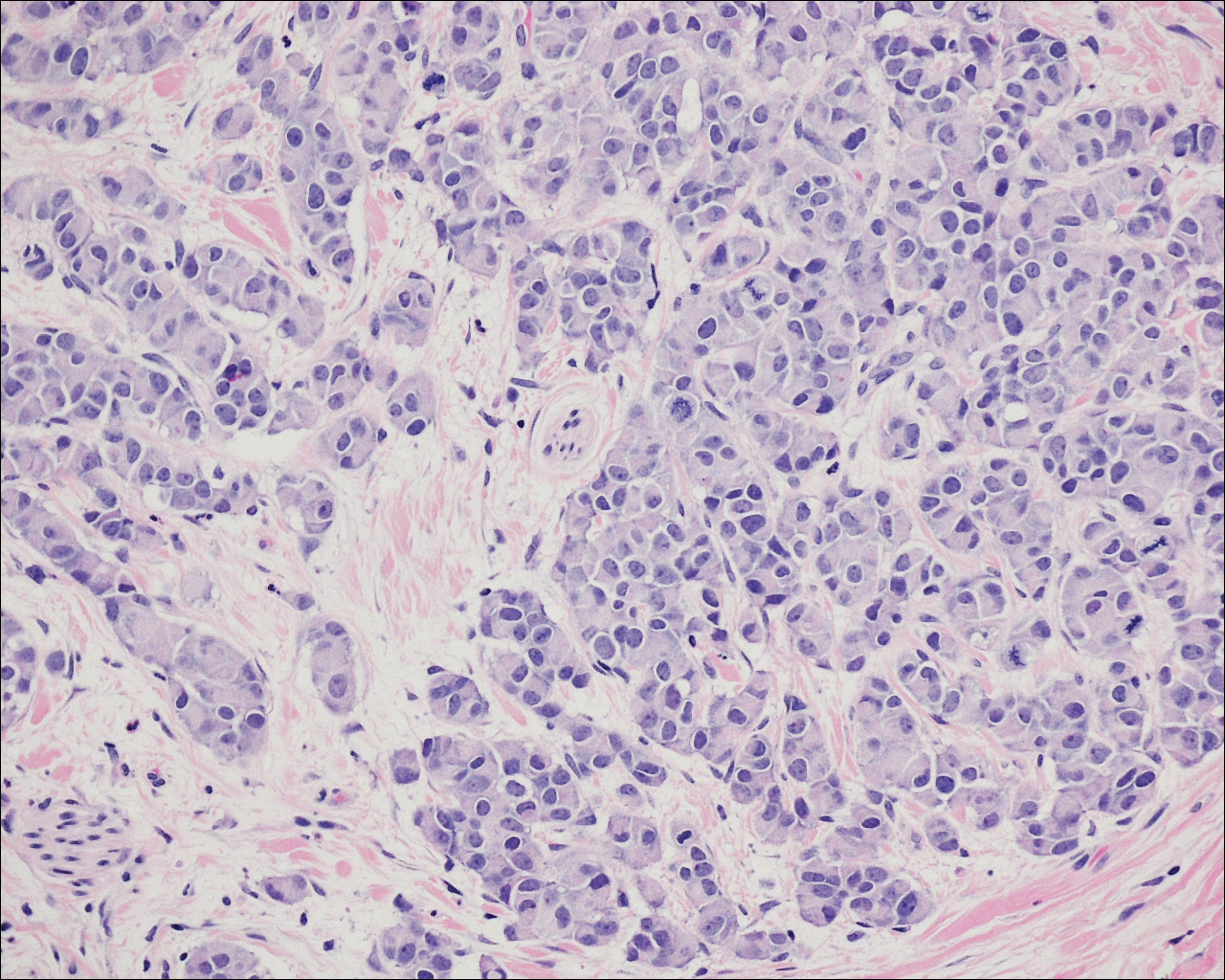

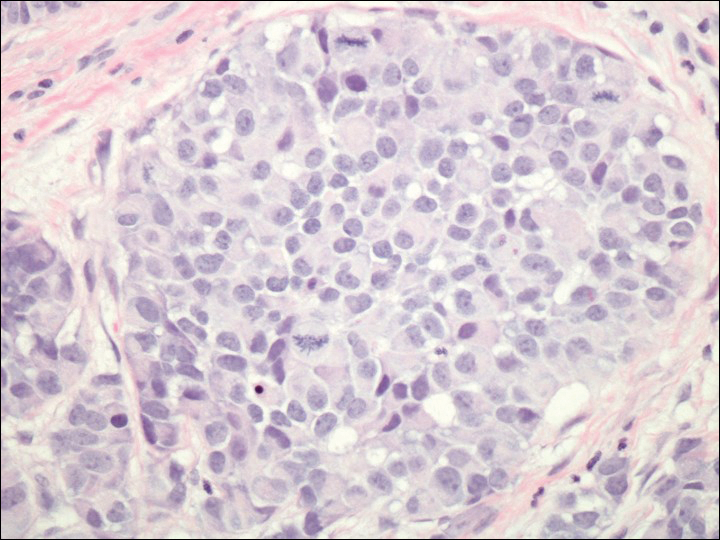

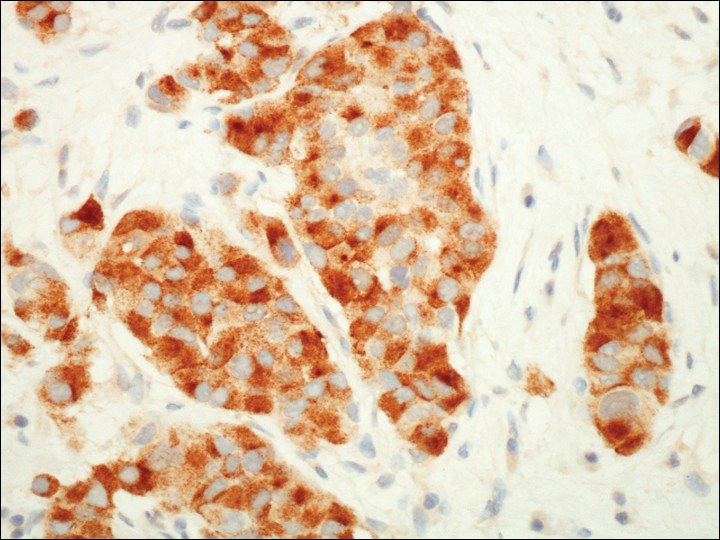

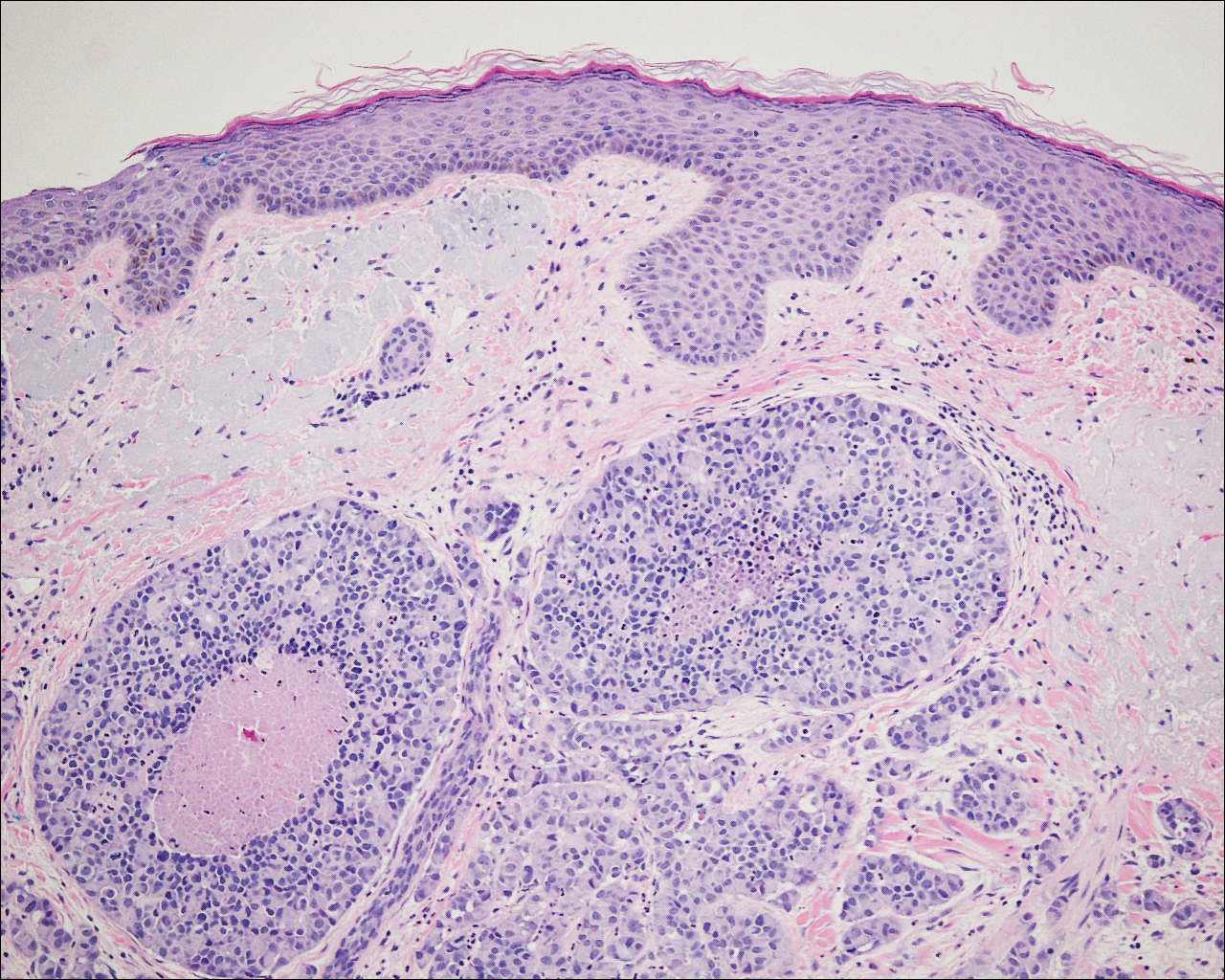

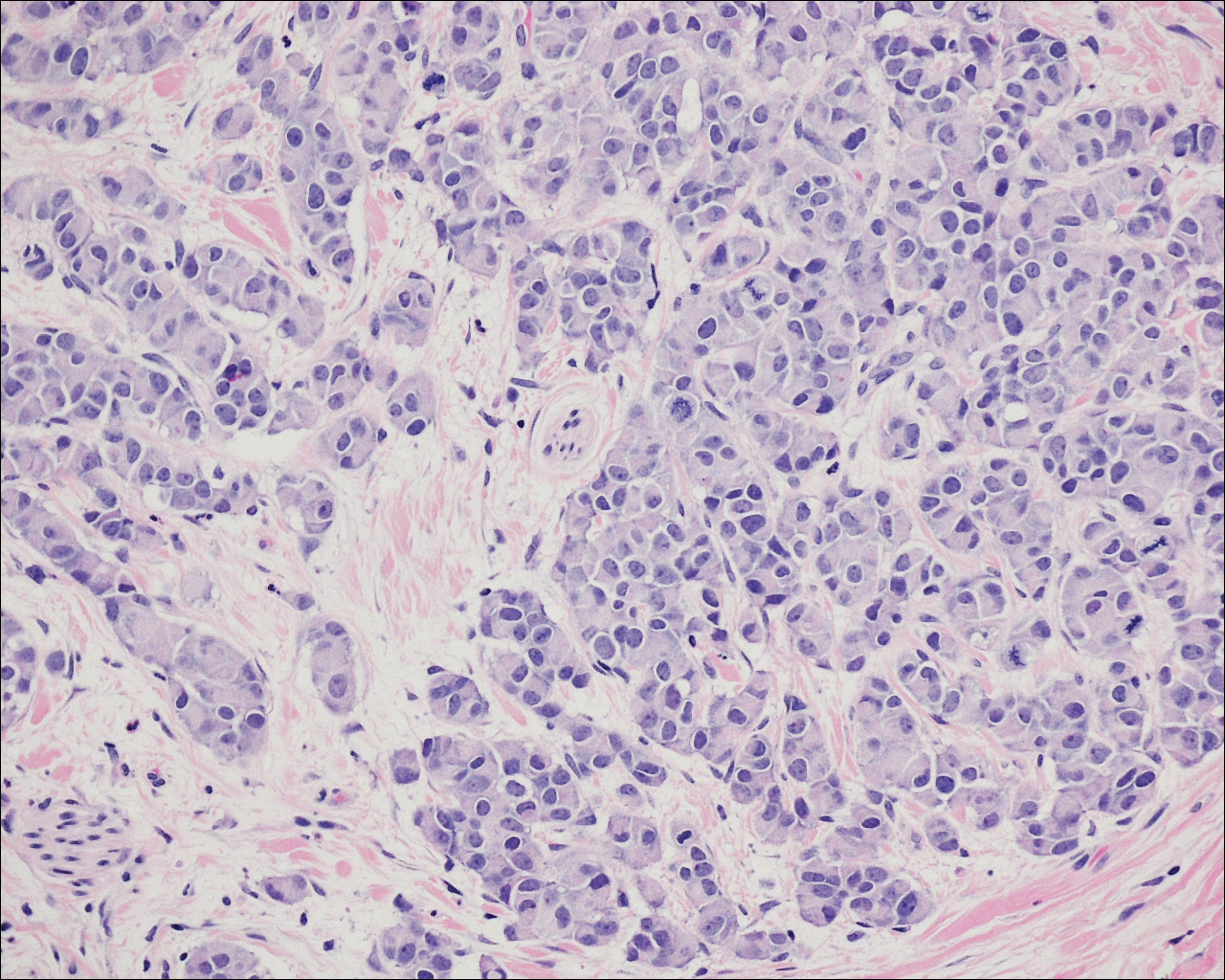

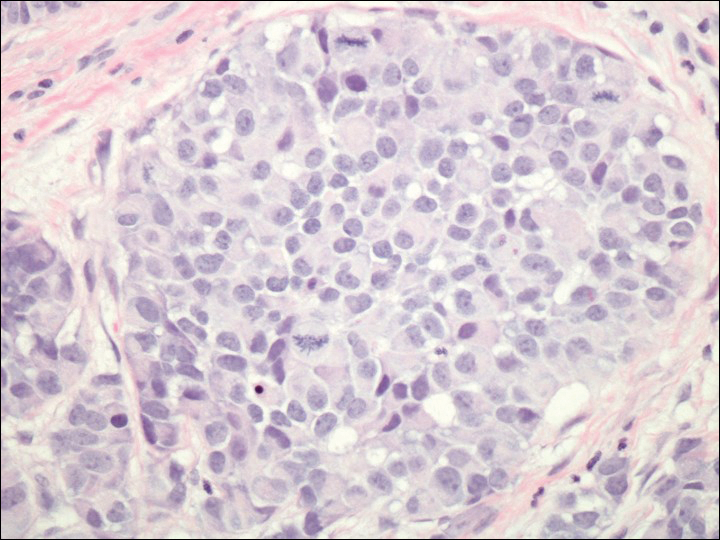

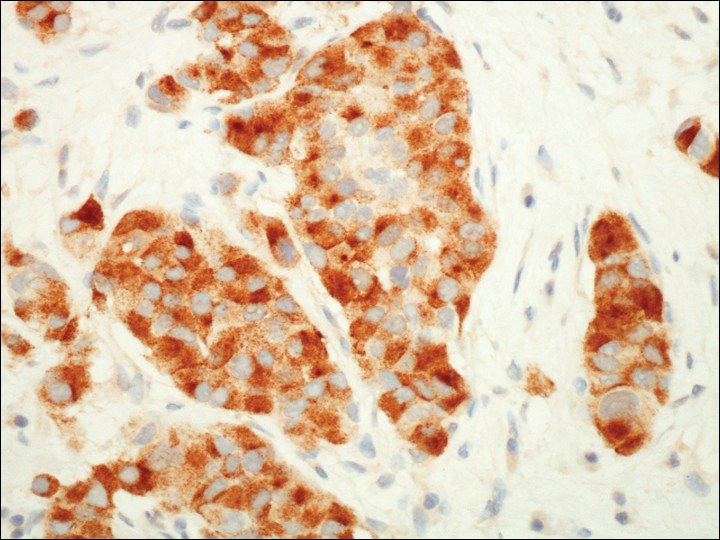

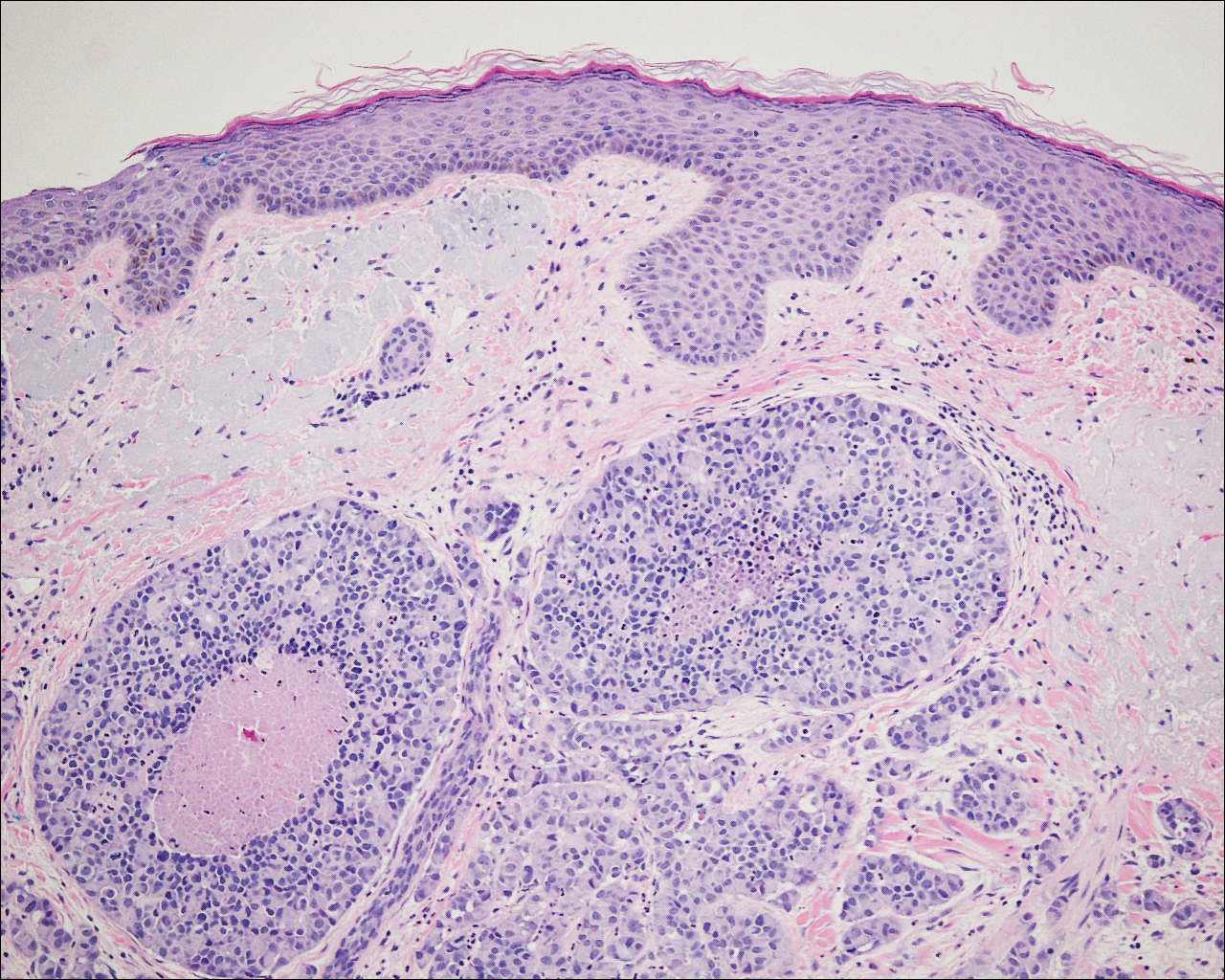

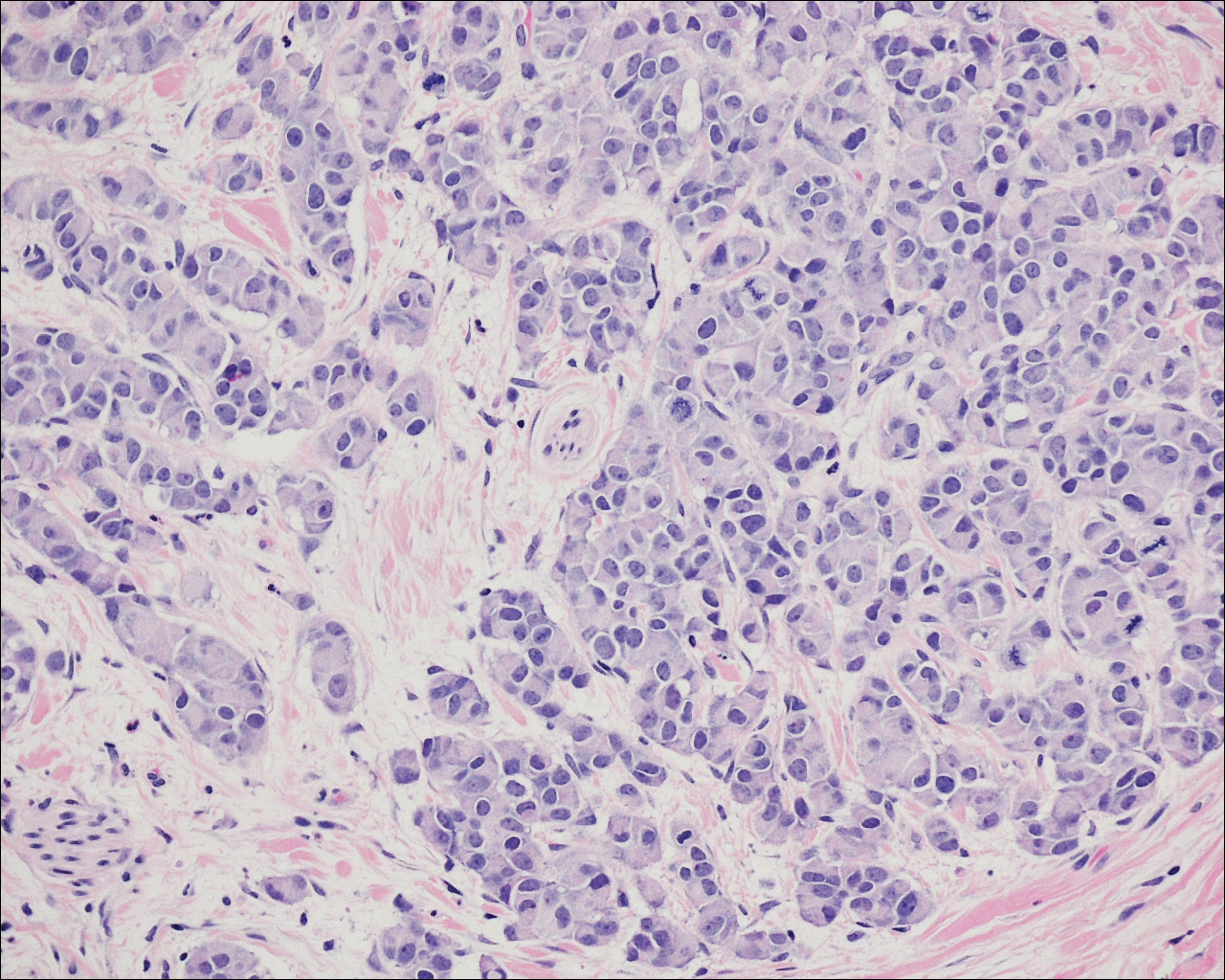

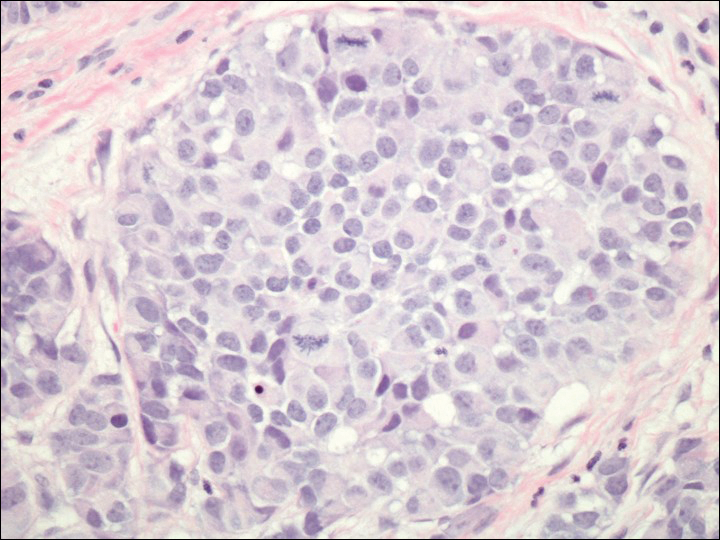

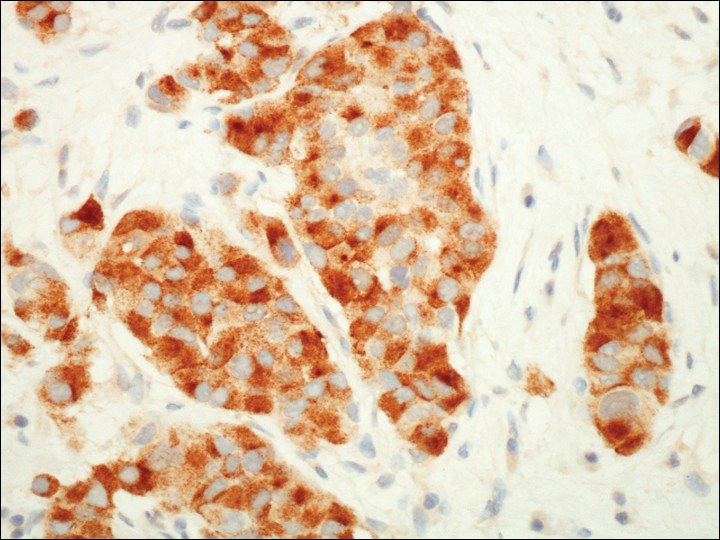

On physical examination the patient exhibited several grouped 0.5-cm, shiny, pink lichenoid macules located on the upper mid chest, anterior neck, and left leg clinically resembling the lesions of pityriasis versicolor (Figure 1). A shave biopsy was taken from one of the newest lesions on the left leg. Histopathology revealed viral epidermal cytopathic changes, blue cytoplasm, and coarse hypergranulosis characteristic of EDV (Figure 2). A diagnosis of acquired EDV was made based on the clinical and histopathologic findings.

The patient’s skin lesions became more widespread despite several different treatment regimens, including cryosurgery; tazarotene cream 0.05% nightly; imiquimod cream 5% once weekly; and intermittent short courses of 5-fluorouracil cream 5%, which provided the best response. At her most recent clinic visit 8 years after initial presentation, she continued to have more widespread lesions on the trunk, arms, and legs, but no evidence of malignant transformation.

Comment

Epidermodysplasia verruciformis was first recognized as an inherited condition, most commonly inherited in an autosomal-dominant fashion; however, X-linked recessive cases have been reported.4,5 Patients with the inherited forms of this condition are prone to recurrent HPV infections secondary to a missense mutation in the epidermodysplasia verruciformis 1 and 2 genes, EVER1 and EVER2, on the EV1 locus located on chromosome 17q25.6 Because of this mutation, the patient’s cellular immunity becomes weakened. Cellular presentation of the EDV-HPV antigen to T lymphocytes becomes impaired, thereby inhibiting the body’s ability to successfully clear itself of the virus.5,6 The most commonly isolated EDV-HPV subtypes are HPV-5 and HPV-8, but HPV types 9, 12, 14, 15, 17, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, and 50 also have been associated with EDV.1,3,7

Patients who have suppressed cellular immunity, such as transplant recipients on long-term immunosuppressant medications and individuals with HIV, graft-vs-host disease, systemic lupus erythematosus, and hematologic malignancies, are susceptible to EDV, as well as patients with atopic dermatitis being treated with topical calcineurin inhibitors.2,3,8-15 These patients acquire depressed cellular immunity and become increasingly susceptible to infections with the EDV-HPV subtypes. When clinical and histopathologic findings are consistent with EDV, a diagnosis of acquired EDV is given, which was further confirmed in a study conducted by Harwood et al.16 They found immunocompromised patients carry more EDV-HPV subtypes in skin lesions analyzed by polymerase chain reaction than immunocompetent individuals.16 Additionally, there is a positive correlation between the length of immunosuppression and the development of HPV lesions, with a majority of patients developing lesions within 5 years following initial immunosuppression.1,7,10,17

Epidermodysplasia verruciformis commonly presents with multiple hypopigmented to red macules that may coalesce into patches with a fine scale, clinically resembling the lesions of pityriasis versicolor.2,3,8-15 Epidermodysplasia verruciformis also may present as multiple flesh-colored, flat-topped, verrucous papules that clinically resemble the lesions of verruca plana on sun-exposed areas such as the face, arms, and legs.9 The characteristic histopathologic findings are enlarged keratinocytes with perinuclear halos and blue-gray cytoplasm as well as hypergranulosis.18 Immunocompromised hosts infected with EDV-HPV histologically tend to display more severe dysplasia than immunocompetent individuals.19 The differential diagnosis includes pityriasis versicolor, squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), and verruca plana. Tissue cultures and potassium hydroxide scrapings for microorganisms should be negative.

The specific EDV-HPV strains 5, 8, and 41 carry the highest oncogenic potential, with more than 60% of inherited EDV patients developing SCC by the fourth and fifth decades of life.16 Unlike inherited EDV, the clinical course of acquired EDV is less well known; however, UV light is thought to act synergistically with the EDV-HPV in oncogenic transformation of the lesions, as most of the SCCs develop on sun-exposed areas, and darker-skinned patients seem to have a decreased risk for malignant transformation of EDV lesions.4,9,20,21 Preventative measures such as strict sun protection and annual surveillance of lesions can help to prevent oncogenic progression of the lesions; however, several single- and multiple-agent regimens have been used in the treatment of EDV with variable results. Topical imiquimod, 5-fluorouracil, tretinoin, and tazarotene have been used with variable success. Acitretin alone and in combination with interferon alfa-2a also has been used.22,23 Highly active antiretroviral therapy in patients with HIV has effectively decreased the number of lesions in a subset of patients.24 We (anecdotal) and others25 also have had success using photodynamic therapy. Squamous cell carcinoma arising in patients with EDV can be managed by excision or by Mohs micrographic surgery.

Conclusion

We report a rare case of acquired EDV in a solid organ transplant recipient. Epidermodysplasia verruciformis can be acquired in immunosuppressed patients such as ours, and these patients should be followed closely due to the potential for malignant transformation. More studies regarding the anticipated clinical course of skin lesions in patients with acquired EDV are needed to better predict the time frame for malignant transformation.

- Dyall-Smith D, Trowell H, Dyall-Smith ML. Benign human papillomavirus infection in renal transplant recipients. Int J Dermatol. 1991;30:785-789.

- Lutzner MA, Orth G, Dutronquay V, et al. Detection of human papillomavirus type 5 DNA in skin cancers of an immunosuppressed renal allograft recipient. Lancet. 1983;2:422-424.

- Lutzner M, Croissant O, Ducasse MF, et al. A potentially oncogenic human papillomavirus (HPV-5) found in two renal allograft recipients. J Invest Dermatol. 1980;75:353-356.

- Androphy EJ, Dvoretzky I, Lowy DR. X-linked inheritance of epidermodysplasia verruciformis. genetic and virologic studies of a kindred. Arch Dermatol. 1985;121:864-868.

- Lutzner MA. Epidermodysplasia verruciformis. an autosomal recessive disease characterized by viral warts and skin cancer. a model for viral oncogenesis. Bull Cancer. 1978;65:169-182.

- Ramoz N, Rueda LA, Bouadjar B, et al. Mutations in two adjacent novel genes are associated with epidermodysplasia verruciformis. Nat Genet. 2002;32:579-581.

- Rüdlinger R, Smith IW, Bunney MH, et al. Human papillomavirus infections in a group of renal transplant recipients. Br J Dermatol. 1986;115:681-692.

- Kawai K, Egawa N, Kiyono T, et al. Epidermodysplasia-verruciformis-like eruption associated with gamma-papillomavirus infection in a patient with adult T-cell leukemia. Dermatology. 2009;219:274-278.

- Barr BB, Benton EC, McLaren K, et al. Human papilloma virus infection and skin cancer in renal allograft recipients. Lancet. 1989;1:124-129.

- Tanigaki T, Kanda R, Sato K. Epidermodysplasia verruciformis (L-L, 1922) in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arch Dermatol Res. 1986;278:247-248.

- Holmes C, Chong AH, Tabrizi SN, et al. Epidermodysplasia verruciformis-like syndrome in association with systemic lupus erythematosus. Australas J Dermatol. 2009;50:44-47.

- Gross G, Ellinger K, Roussaki A, et al. Epidermodysplasia verruciformis in a patient with Hodgkin’s disease: characterization of a new papillomavirus type and interferon treatment. J Invest Dermatol. 1988;91:43-48.

- Fernandez KH, Rady P, Tyring S, et al. Acquired epidermodysplasia verruciformis in a child with atopic dermatitis [published online September 3, 2012]. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31:400-402.

- Hultgren TL, Srinivasan SK, DiMaio DJ. Epidermodysplasia verruciformis occurring in a patient with human immunodeficiency virus: a case report. Cutis. 2007;79:307-311.

- Kunishige JH, Hymes SR, Madkan V, et al. Epidermodysplasia verruciformis in the setting of graft-versus-host disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57(5 suppl):S78-S80.

- Harwood CA, Surentheran T, McGregor JM, et al. Human papillomavirus infection and non-melanoma skin cancer in immunosuppressed and immunocompetent individuals. J Med Virol. 2000;61:289-297.

- Moloney FJ, Keane S, O’Kelly P, et al. The impact of skin disease following renal transplantation on quality of life. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:574-578.

- Tanigaki T, Endo H. A case of epidermodysplasia verruciformis (Lewandowsky-Lutz, 1922) with skin cancer: histopathology of malignant cutaneous changes. Dermatologica. 1984;169:97-101.

- Morrison C, Eliezri Y, Magro C, et al. The histologic spectrum of epidermodysplasia verruciformis in transplant and AIDS patients. J Cutan Pathol. 2002;29:480-489.

- Majewski S, Jabło´nska S. Epidermodysplasia verruciformis as a model of human papillomavirus-induced genetic cancer of the skin. Arch Dermatol. 1995;131:1312-1318.

- Jacyk WK, De Villiers EM. Epidermodysplasia verruciformis in Africans. Int J Dermatol. 1993;32:806-810.

- Gubinelli E, Posteraro P, Cocuroccia B, et al. Epidermodysplasia verruciformis with multiple mucosal carcinomas treated with pegylated interferon alfa and acitretin. J Dermatolog Treat. 2003;14:184-188.

- Anadolu R, Oskay T, Erdem C, et al. Treatment of epidermodysplasia verruciformis with a combination of acitretin and interferon alfa-2a. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:296-299.

- Haas N, Fuchs PG, Hermes B, et al. Remission of epidermodysplasia verruciformis-like skin eruption after highly active antiretroviral therapy in a human immunodeficiency virus-positive patient. Br J Dermatol. 2001;145:669-670.

- Karrer S, Szeimies RM, Abels C, et al. Epidermo-dysplasia verruciformis treated using topical 5-aminolaevulinic acid photodynamic therapy. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:935-938.

Acquired epidermodysplasia verruciformis (EDV) is a rare disorder occurring in patients with depressed cellular immunity, particularly individuals with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Rare cases of acquired EDV have been reported in stem cell or solid organ transplant recipients. Weakened cellular immunity predisposes the patient to human papillomavirus (HPV) infections, with 92% of renal transplant recipients developing warts within 5 years posttransplantation.1 Specific EDV-HPV subtypes have been isolated from lesions in several immunosuppressed individuals, with HPV-5 and HPV-8 being the most commonly isolated subtypes.2,3 Herein, we present the clinical findings of a renal transplant recipient who presented for evaluation of multiple skin lesions characteristic of EDV 5 years following transplantation and initiation of immunosuppressive therapy. Additionally, we review the current diagnostic findings, management, and treatment of acquired EDV.