User login

MARQUIS Highlights Need for Improved Medication Reconciliation

What is the best possible medication history? How is it done? Who should do it? When should it be done during a patient’s journey in and out of the hospital? What medication discrepancies—and potential adverse drug events—are most likely?

Those are questions veteran hospitalist Jason Stein, MD, tried to answer during an HM13 breakout session on medication reconciliation at the Gaylord National Resort and Conference Center in National Harbor, Md.

“How do you know as the discharging provider if the medication list you’re looking at is gold or garbage?” said Dr. Stein, associate director for quality improvement (QI) at Emory University in Atlanta and a mentor for SHM’s Multi-Center Medication Reconciliation Quality Improvement Study (MARQUIS) quality-research initiative.

“Sometimes it’s impossible to know what the patient was or wasn’t taking, but it doesn’t mean you don’t do your best,” he said, adding that hospitalists should attempt to get at least one reliable, corroborating source of information for a patient’s medical history.

Sometimes it is necessary to speak to family members or the community pharmacy, Dr. Schnipper said, because many patients can’t remember all of the drugs they are taking. Trying to do medication reconciliation at the time of discharge when BPMH has not been done can lead to more work for the provider, medication errors, or rehospitalizations. Ideally, knowledge of what the patient was taking before admission, as well as the patient’s health literacy and adherence history, should be gathered and documented once, early, and well during the hospitalization by a trained provider, according to Dr. Schnipper.

An SHM survey, however, showed 50% to 70% percent of front-line providers have never received BPMH training, and 60% say they are not given the time.1

“Not knowing means a diligent provider would need to take a BPMH at discharge, which is a waste,” Dr. Stein said. It would be nice to tell from the electronic health record whether a true BPMH had been taken for every hospitalized patient—or at least every high-risk patient—but this goal is not well-supported by current information technology, MARQUIS investigators said they have learned.

The MARQUIS program was launched in 2011 with a grant from the federal Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. It began with a thorough review of the literature on medication reconciliation and the development of a toolkit of best practices. In 2012, six pilot sites were offered a menu of 11 MARQUIS medication-reconciliation interventions to choose from and help in implementing them from an SHM mentor, with expertise in both QI and medication safety.

Listen to more of our interview with MARQUIS principal investigator Jeffrey Schnipper, MD, MPH, FHM.

Participating sites have mobilized high-level hospital leadership and utilize a local champion, usually a hospitalist, tools for assessing high-risk patients, medication-reconciliation assistants or counselors, and pharmacist involvement. Different sites have employed different professional staff to take medication histories.

Dr. Schnipper said he expects another round of MARQUIS-mentored implementation, probably in 2014, after data from the first round have been analyzed. The program is tracking such outcomes as the number of potentially harmful, unintentional medication discrepancies per patient at participating sites.

The MARQUIS toolkit is available on the SHM website. TH

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in San Francisco.

Reference

1. Schnipper JL, Mueller SK, Salanitro AH, Stein J. Got Med Wreck? Targeted Repairs from the Multi-Center Medication Reconciliation Quality Improvement Study (MARQUIS). PowerPoint presentation at Society of Hospital Medicine annual meeting, May 16-19, 2013, National Harbor, Md.

What is the best possible medication history? How is it done? Who should do it? When should it be done during a patient’s journey in and out of the hospital? What medication discrepancies—and potential adverse drug events—are most likely?

Those are questions veteran hospitalist Jason Stein, MD, tried to answer during an HM13 breakout session on medication reconciliation at the Gaylord National Resort and Conference Center in National Harbor, Md.

“How do you know as the discharging provider if the medication list you’re looking at is gold or garbage?” said Dr. Stein, associate director for quality improvement (QI) at Emory University in Atlanta and a mentor for SHM’s Multi-Center Medication Reconciliation Quality Improvement Study (MARQUIS) quality-research initiative.

“Sometimes it’s impossible to know what the patient was or wasn’t taking, but it doesn’t mean you don’t do your best,” he said, adding that hospitalists should attempt to get at least one reliable, corroborating source of information for a patient’s medical history.

Sometimes it is necessary to speak to family members or the community pharmacy, Dr. Schnipper said, because many patients can’t remember all of the drugs they are taking. Trying to do medication reconciliation at the time of discharge when BPMH has not been done can lead to more work for the provider, medication errors, or rehospitalizations. Ideally, knowledge of what the patient was taking before admission, as well as the patient’s health literacy and adherence history, should be gathered and documented once, early, and well during the hospitalization by a trained provider, according to Dr. Schnipper.

An SHM survey, however, showed 50% to 70% percent of front-line providers have never received BPMH training, and 60% say they are not given the time.1

“Not knowing means a diligent provider would need to take a BPMH at discharge, which is a waste,” Dr. Stein said. It would be nice to tell from the electronic health record whether a true BPMH had been taken for every hospitalized patient—or at least every high-risk patient—but this goal is not well-supported by current information technology, MARQUIS investigators said they have learned.

The MARQUIS program was launched in 2011 with a grant from the federal Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. It began with a thorough review of the literature on medication reconciliation and the development of a toolkit of best practices. In 2012, six pilot sites were offered a menu of 11 MARQUIS medication-reconciliation interventions to choose from and help in implementing them from an SHM mentor, with expertise in both QI and medication safety.

Listen to more of our interview with MARQUIS principal investigator Jeffrey Schnipper, MD, MPH, FHM.

Participating sites have mobilized high-level hospital leadership and utilize a local champion, usually a hospitalist, tools for assessing high-risk patients, medication-reconciliation assistants or counselors, and pharmacist involvement. Different sites have employed different professional staff to take medication histories.

Dr. Schnipper said he expects another round of MARQUIS-mentored implementation, probably in 2014, after data from the first round have been analyzed. The program is tracking such outcomes as the number of potentially harmful, unintentional medication discrepancies per patient at participating sites.

The MARQUIS toolkit is available on the SHM website. TH

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in San Francisco.

Reference

1. Schnipper JL, Mueller SK, Salanitro AH, Stein J. Got Med Wreck? Targeted Repairs from the Multi-Center Medication Reconciliation Quality Improvement Study (MARQUIS). PowerPoint presentation at Society of Hospital Medicine annual meeting, May 16-19, 2013, National Harbor, Md.

What is the best possible medication history? How is it done? Who should do it? When should it be done during a patient’s journey in and out of the hospital? What medication discrepancies—and potential adverse drug events—are most likely?

Those are questions veteran hospitalist Jason Stein, MD, tried to answer during an HM13 breakout session on medication reconciliation at the Gaylord National Resort and Conference Center in National Harbor, Md.

“How do you know as the discharging provider if the medication list you’re looking at is gold or garbage?” said Dr. Stein, associate director for quality improvement (QI) at Emory University in Atlanta and a mentor for SHM’s Multi-Center Medication Reconciliation Quality Improvement Study (MARQUIS) quality-research initiative.

“Sometimes it’s impossible to know what the patient was or wasn’t taking, but it doesn’t mean you don’t do your best,” he said, adding that hospitalists should attempt to get at least one reliable, corroborating source of information for a patient’s medical history.

Sometimes it is necessary to speak to family members or the community pharmacy, Dr. Schnipper said, because many patients can’t remember all of the drugs they are taking. Trying to do medication reconciliation at the time of discharge when BPMH has not been done can lead to more work for the provider, medication errors, or rehospitalizations. Ideally, knowledge of what the patient was taking before admission, as well as the patient’s health literacy and adherence history, should be gathered and documented once, early, and well during the hospitalization by a trained provider, according to Dr. Schnipper.

An SHM survey, however, showed 50% to 70% percent of front-line providers have never received BPMH training, and 60% say they are not given the time.1

“Not knowing means a diligent provider would need to take a BPMH at discharge, which is a waste,” Dr. Stein said. It would be nice to tell from the electronic health record whether a true BPMH had been taken for every hospitalized patient—or at least every high-risk patient—but this goal is not well-supported by current information technology, MARQUIS investigators said they have learned.

The MARQUIS program was launched in 2011 with a grant from the federal Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. It began with a thorough review of the literature on medication reconciliation and the development of a toolkit of best practices. In 2012, six pilot sites were offered a menu of 11 MARQUIS medication-reconciliation interventions to choose from and help in implementing them from an SHM mentor, with expertise in both QI and medication safety.

Listen to more of our interview with MARQUIS principal investigator Jeffrey Schnipper, MD, MPH, FHM.

Participating sites have mobilized high-level hospital leadership and utilize a local champion, usually a hospitalist, tools for assessing high-risk patients, medication-reconciliation assistants or counselors, and pharmacist involvement. Different sites have employed different professional staff to take medication histories.

Dr. Schnipper said he expects another round of MARQUIS-mentored implementation, probably in 2014, after data from the first round have been analyzed. The program is tracking such outcomes as the number of potentially harmful, unintentional medication discrepancies per patient at participating sites.

The MARQUIS toolkit is available on the SHM website. TH

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in San Francisco.

Reference

1. Schnipper JL, Mueller SK, Salanitro AH, Stein J. Got Med Wreck? Targeted Repairs from the Multi-Center Medication Reconciliation Quality Improvement Study (MARQUIS). PowerPoint presentation at Society of Hospital Medicine annual meeting, May 16-19, 2013, National Harbor, Md.

Society of Hospital Medicine’s MARQUIS Initiative Highlights Need For Improved Medication Reconciliation

–Jeffrey Schnipper, MD, MPH, FHM

What is the best possible medication history? How is it done? Who should do it? When should it be done during a patient’s journey in and out of the hospital? What medication discrepancies—and potential adverse drug events—are most likely?

Those are questions veteran hospitalist Jason Stein, MD, tried to answer during an HM13 breakout session on medication reconciliation at the Gaylord National Resort and Conference Center in National Harbor, Md.

“How do you know as the discharging provider if the medication list you’re looking at is gold or garbage?” said Dr. Stein, associate director for quality improvement (QI) at Emory University in Atlanta and a mentor for SHM’s Multi-Center Medication Reconciliation Quality Improvement Study (MARQUIS) quality-research initiative.

The concept of the “best possible medication history” (BPMH) originated with patient-safety expert Edward Etchells, MD, MSc, at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre in Toronto. The concept is outlined on a pocket reminder card for MARQUIS participants, explained co-presenter and principal investigator Jeffrey Schnipper MD, MPH, FHM, a hospitalist at Brigham & Women’s Hospital in Boston.

“Sometimes it’s impossible to know what the patient was or wasn’t taking, but it doesn’t mean you don’t do your best,” he said, adding that hospitalists should attempt to get at least one reliable, corroborating source of information for a patient’s medical history.

Sometimes it is necessary to speak to family members or the community pharmacy, Dr. Schnipper said, because many patients can’t remember all of the drugs they are taking. Trying to do medication reconciliation at the time of discharge when BPMH has not been done can lead to more work for the provider, medication errors, or rehospitalizations. Ideally, knowledge of what the patient was taking before admission, as well as the patient’s health literacy and adherence history, should be gathered and documented once, early, and well during the hospitalization by a trained provider, according to Dr. Schnipper.

An SHM survey, however, showed 50% to 70% percent of front-line providers have never received BPMH training, and 60% say they are not given the time.

“Not knowing means a diligent provider would need to take a BPMH at discharge, which is a waste,” Dr. Stein said. It would be nice to tell from the electronic health record whether a true BPMH had been taken for every hospitalized patient—or at least every high-risk patient—but this goal is not well-supported by current information technology, MARQUIS investigators said they have learned.

The MARQUIS program was launched in 2011 with a grant from the federal Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. It began with a thorough review of the literature on medication reconciliation and the development of a toolkit of best practices. In 2012, six pilot sites were offered a menu of 11 MARQUIS medication-reconciliation interventions to choose from and help in implementing them from an SHM mentor, with expertise in both QI and medication safety.

Participating sites have mobilized high-level hospital leadership and utilize a local champion, usually a hospitalist, tools for assessing high-risk patients, medication-reconciliation assistants or counselors, and pharmacist involvement. Different sites have employed different professional staff to take medication histories.

Dr. Schnipper said he expects another round of MARQUIS-mentored implementation, probably in 2014, after data from the first round have been analyzed. The program is tracking such outcomes as the number of potentially harmful, unintentional medication discrepancies per patient at participating sites.

The MARQUIS toolkit is available on the SHM website at www.hospitalmedicine.org/marquis.

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in San Francisco.

–Jeffrey Schnipper, MD, MPH, FHM

What is the best possible medication history? How is it done? Who should do it? When should it be done during a patient’s journey in and out of the hospital? What medication discrepancies—and potential adverse drug events—are most likely?

Those are questions veteran hospitalist Jason Stein, MD, tried to answer during an HM13 breakout session on medication reconciliation at the Gaylord National Resort and Conference Center in National Harbor, Md.

“How do you know as the discharging provider if the medication list you’re looking at is gold or garbage?” said Dr. Stein, associate director for quality improvement (QI) at Emory University in Atlanta and a mentor for SHM’s Multi-Center Medication Reconciliation Quality Improvement Study (MARQUIS) quality-research initiative.

The concept of the “best possible medication history” (BPMH) originated with patient-safety expert Edward Etchells, MD, MSc, at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre in Toronto. The concept is outlined on a pocket reminder card for MARQUIS participants, explained co-presenter and principal investigator Jeffrey Schnipper MD, MPH, FHM, a hospitalist at Brigham & Women’s Hospital in Boston.

“Sometimes it’s impossible to know what the patient was or wasn’t taking, but it doesn’t mean you don’t do your best,” he said, adding that hospitalists should attempt to get at least one reliable, corroborating source of information for a patient’s medical history.

Sometimes it is necessary to speak to family members or the community pharmacy, Dr. Schnipper said, because many patients can’t remember all of the drugs they are taking. Trying to do medication reconciliation at the time of discharge when BPMH has not been done can lead to more work for the provider, medication errors, or rehospitalizations. Ideally, knowledge of what the patient was taking before admission, as well as the patient’s health literacy and adherence history, should be gathered and documented once, early, and well during the hospitalization by a trained provider, according to Dr. Schnipper.

An SHM survey, however, showed 50% to 70% percent of front-line providers have never received BPMH training, and 60% say they are not given the time.

“Not knowing means a diligent provider would need to take a BPMH at discharge, which is a waste,” Dr. Stein said. It would be nice to tell from the electronic health record whether a true BPMH had been taken for every hospitalized patient—or at least every high-risk patient—but this goal is not well-supported by current information technology, MARQUIS investigators said they have learned.

The MARQUIS program was launched in 2011 with a grant from the federal Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. It began with a thorough review of the literature on medication reconciliation and the development of a toolkit of best practices. In 2012, six pilot sites were offered a menu of 11 MARQUIS medication-reconciliation interventions to choose from and help in implementing them from an SHM mentor, with expertise in both QI and medication safety.

Participating sites have mobilized high-level hospital leadership and utilize a local champion, usually a hospitalist, tools for assessing high-risk patients, medication-reconciliation assistants or counselors, and pharmacist involvement. Different sites have employed different professional staff to take medication histories.

Dr. Schnipper said he expects another round of MARQUIS-mentored implementation, probably in 2014, after data from the first round have been analyzed. The program is tracking such outcomes as the number of potentially harmful, unintentional medication discrepancies per patient at participating sites.

The MARQUIS toolkit is available on the SHM website at www.hospitalmedicine.org/marquis.

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in San Francisco.

–Jeffrey Schnipper, MD, MPH, FHM

What is the best possible medication history? How is it done? Who should do it? When should it be done during a patient’s journey in and out of the hospital? What medication discrepancies—and potential adverse drug events—are most likely?

Those are questions veteran hospitalist Jason Stein, MD, tried to answer during an HM13 breakout session on medication reconciliation at the Gaylord National Resort and Conference Center in National Harbor, Md.

“How do you know as the discharging provider if the medication list you’re looking at is gold or garbage?” said Dr. Stein, associate director for quality improvement (QI) at Emory University in Atlanta and a mentor for SHM’s Multi-Center Medication Reconciliation Quality Improvement Study (MARQUIS) quality-research initiative.

The concept of the “best possible medication history” (BPMH) originated with patient-safety expert Edward Etchells, MD, MSc, at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre in Toronto. The concept is outlined on a pocket reminder card for MARQUIS participants, explained co-presenter and principal investigator Jeffrey Schnipper MD, MPH, FHM, a hospitalist at Brigham & Women’s Hospital in Boston.

“Sometimes it’s impossible to know what the patient was or wasn’t taking, but it doesn’t mean you don’t do your best,” he said, adding that hospitalists should attempt to get at least one reliable, corroborating source of information for a patient’s medical history.

Sometimes it is necessary to speak to family members or the community pharmacy, Dr. Schnipper said, because many patients can’t remember all of the drugs they are taking. Trying to do medication reconciliation at the time of discharge when BPMH has not been done can lead to more work for the provider, medication errors, or rehospitalizations. Ideally, knowledge of what the patient was taking before admission, as well as the patient’s health literacy and adherence history, should be gathered and documented once, early, and well during the hospitalization by a trained provider, according to Dr. Schnipper.

An SHM survey, however, showed 50% to 70% percent of front-line providers have never received BPMH training, and 60% say they are not given the time.

“Not knowing means a diligent provider would need to take a BPMH at discharge, which is a waste,” Dr. Stein said. It would be nice to tell from the electronic health record whether a true BPMH had been taken for every hospitalized patient—or at least every high-risk patient—but this goal is not well-supported by current information technology, MARQUIS investigators said they have learned.

The MARQUIS program was launched in 2011 with a grant from the federal Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. It began with a thorough review of the literature on medication reconciliation and the development of a toolkit of best practices. In 2012, six pilot sites were offered a menu of 11 MARQUIS medication-reconciliation interventions to choose from and help in implementing them from an SHM mentor, with expertise in both QI and medication safety.

Participating sites have mobilized high-level hospital leadership and utilize a local champion, usually a hospitalist, tools for assessing high-risk patients, medication-reconciliation assistants or counselors, and pharmacist involvement. Different sites have employed different professional staff to take medication histories.

Dr. Schnipper said he expects another round of MARQUIS-mentored implementation, probably in 2014, after data from the first round have been analyzed. The program is tracking such outcomes as the number of potentially harmful, unintentional medication discrepancies per patient at participating sites.

The MARQUIS toolkit is available on the SHM website at www.hospitalmedicine.org/marquis.

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in San Francisco.

Drive Change in an ACO

From informal polls I’ve recently conducted of hospitalists, many are not even aware they are part of an accountable-care organization (ACO). And if they are aware, they might not be engaging in meaningful dialogue with ACO leaders about their role in these organizations. But, in the long term, ACOs will need to bring hospitalists to the table in order to be successful.

Are You Part of an ACO?

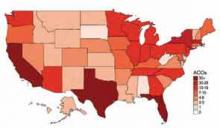

David Muhlestein, who blogs for Health Affairs, tracks the growth of ACOs around the country. He states that, as of Jan. 31, there were 428 ACOs in the U.S. (see Figure 1).1 In terms of numbers, Florida, Texas, and California lead the nation with 42, 33, and 46 ACOs, respectively. So it is likely that you are part of an ACO. If you are unsure, ask your chief medical officer or president of the medical staff.

How ACOs Work

All ACOs seek to manage a group, or population, of patients as efficiently as possible while maintaining or improving quality of care. For Medicare ACOs, the goal is to bring together hospitals and physicians in order to share savings derived from efficiencies in care. But before any savings can be shared, the Medicare ACO must demonstrate that it achieved high-quality care across four domains, totaling 33 individual quality measures. (see Table 1)

Main Flavors of ACOs

There are two types of ACOs: private ACOs and Medicare ACOs. Prior to Medicare ACOs, which were launched in January 2012, there were 150 private-sector ACOs, and this number continues to grow. Private ACOs represent a heterogeneous group in terms of reimbursement model. Some operate under shared savings programs; others use full or partial capitation, bundled payments, and/or other types of arrangements. But nearly all ACOs operate under the premise that the incentives used to make care more efficient and less costly can only be applied if measurable quality is maintained or improved. ACOs do not pay doctors or hospitals more unless high quality is demonstrated.

ACO Quality Measures and Hospitalists

Most of the 33 quality measures required by Medicare ACOs are based in ambulatory practice. These include measures related to blood pressure, immunizations, cancer, and fall-risk screening, and measures for diabetics, such as lipids and hemoglobin A1C. However, there are a few measures for which hospitalists should share in accountability, including:

- All-cause hospital readmission rate—risk-standardized;

- Ambulatory sensitive condition hospital admission rates (CHF, COPD); and

- Medication reconciliation after discharge from an inpatient facility.

Four Key Actions for Hospitalists

Hospitalists make a significant contribution to the quality and the financial performance of ACOs. In addition to the quality metrics cited above, hospitalists impact the inpatient portion of the overall population’s cost of care. Furthermore, hospitalists are vital partners in the care coordination required for an ACO to be successful.

Here are four actions I suggest taking in order for your hospitalist group to be effective as participants in an ACO:

- Have a representative from your group participate in ACO committees that address hospital utilization and related matters, such as care coordination impacting pre- and post-hospital care.

- Learn how to work with ACO case managers on care transitions, including post-discharge follow-up and information transfer.

- Understand an ACO’s approach to engagement of and coordination with post-acute-care facilities. The ability of a post-acute facility, such a skilled nursing facility, to accept patients who have complex care needs, to manage changes in condition in the facility when appropriate, and to send complete information upon transfer to the hospital are important strategies for an ACO’s success.

- Understand how an ACO reports quality and cost performance and how savings will be shared among participants.

Mindset Change

If hospitalists are part of the chain of ACO physicians and providers held accountable for the health of a population of patients, we must work more closely with the medical home/neighborhood, post-acute-care facilities, and home-care providers. The change in mindset will occur only if we have a set of tools to get the job done, such as case managers and information technology, and the appropriate incentives to support better care coordination. I encourage my fellow hospitalists to make things happen, instead of taking a passive role in this monumental transformation.

Reference

Dr. Whitcomb is medical director of healthcare quality at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass. He is a co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at wfwhit@comcast.net.

From informal polls I’ve recently conducted of hospitalists, many are not even aware they are part of an accountable-care organization (ACO). And if they are aware, they might not be engaging in meaningful dialogue with ACO leaders about their role in these organizations. But, in the long term, ACOs will need to bring hospitalists to the table in order to be successful.

Are You Part of an ACO?

David Muhlestein, who blogs for Health Affairs, tracks the growth of ACOs around the country. He states that, as of Jan. 31, there were 428 ACOs in the U.S. (see Figure 1).1 In terms of numbers, Florida, Texas, and California lead the nation with 42, 33, and 46 ACOs, respectively. So it is likely that you are part of an ACO. If you are unsure, ask your chief medical officer or president of the medical staff.

How ACOs Work

All ACOs seek to manage a group, or population, of patients as efficiently as possible while maintaining or improving quality of care. For Medicare ACOs, the goal is to bring together hospitals and physicians in order to share savings derived from efficiencies in care. But before any savings can be shared, the Medicare ACO must demonstrate that it achieved high-quality care across four domains, totaling 33 individual quality measures. (see Table 1)

Main Flavors of ACOs

There are two types of ACOs: private ACOs and Medicare ACOs. Prior to Medicare ACOs, which were launched in January 2012, there were 150 private-sector ACOs, and this number continues to grow. Private ACOs represent a heterogeneous group in terms of reimbursement model. Some operate under shared savings programs; others use full or partial capitation, bundled payments, and/or other types of arrangements. But nearly all ACOs operate under the premise that the incentives used to make care more efficient and less costly can only be applied if measurable quality is maintained or improved. ACOs do not pay doctors or hospitals more unless high quality is demonstrated.

ACO Quality Measures and Hospitalists

Most of the 33 quality measures required by Medicare ACOs are based in ambulatory practice. These include measures related to blood pressure, immunizations, cancer, and fall-risk screening, and measures for diabetics, such as lipids and hemoglobin A1C. However, there are a few measures for which hospitalists should share in accountability, including:

- All-cause hospital readmission rate—risk-standardized;

- Ambulatory sensitive condition hospital admission rates (CHF, COPD); and

- Medication reconciliation after discharge from an inpatient facility.

Four Key Actions for Hospitalists

Hospitalists make a significant contribution to the quality and the financial performance of ACOs. In addition to the quality metrics cited above, hospitalists impact the inpatient portion of the overall population’s cost of care. Furthermore, hospitalists are vital partners in the care coordination required for an ACO to be successful.

Here are four actions I suggest taking in order for your hospitalist group to be effective as participants in an ACO:

- Have a representative from your group participate in ACO committees that address hospital utilization and related matters, such as care coordination impacting pre- and post-hospital care.

- Learn how to work with ACO case managers on care transitions, including post-discharge follow-up and information transfer.

- Understand an ACO’s approach to engagement of and coordination with post-acute-care facilities. The ability of a post-acute facility, such a skilled nursing facility, to accept patients who have complex care needs, to manage changes in condition in the facility when appropriate, and to send complete information upon transfer to the hospital are important strategies for an ACO’s success.

- Understand how an ACO reports quality and cost performance and how savings will be shared among participants.

Mindset Change

If hospitalists are part of the chain of ACO physicians and providers held accountable for the health of a population of patients, we must work more closely with the medical home/neighborhood, post-acute-care facilities, and home-care providers. The change in mindset will occur only if we have a set of tools to get the job done, such as case managers and information technology, and the appropriate incentives to support better care coordination. I encourage my fellow hospitalists to make things happen, instead of taking a passive role in this monumental transformation.

Reference

Dr. Whitcomb is medical director of healthcare quality at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass. He is a co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at wfwhit@comcast.net.

From informal polls I’ve recently conducted of hospitalists, many are not even aware they are part of an accountable-care organization (ACO). And if they are aware, they might not be engaging in meaningful dialogue with ACO leaders about their role in these organizations. But, in the long term, ACOs will need to bring hospitalists to the table in order to be successful.

Are You Part of an ACO?

David Muhlestein, who blogs for Health Affairs, tracks the growth of ACOs around the country. He states that, as of Jan. 31, there were 428 ACOs in the U.S. (see Figure 1).1 In terms of numbers, Florida, Texas, and California lead the nation with 42, 33, and 46 ACOs, respectively. So it is likely that you are part of an ACO. If you are unsure, ask your chief medical officer or president of the medical staff.

How ACOs Work

All ACOs seek to manage a group, or population, of patients as efficiently as possible while maintaining or improving quality of care. For Medicare ACOs, the goal is to bring together hospitals and physicians in order to share savings derived from efficiencies in care. But before any savings can be shared, the Medicare ACO must demonstrate that it achieved high-quality care across four domains, totaling 33 individual quality measures. (see Table 1)

Main Flavors of ACOs

There are two types of ACOs: private ACOs and Medicare ACOs. Prior to Medicare ACOs, which were launched in January 2012, there were 150 private-sector ACOs, and this number continues to grow. Private ACOs represent a heterogeneous group in terms of reimbursement model. Some operate under shared savings programs; others use full or partial capitation, bundled payments, and/or other types of arrangements. But nearly all ACOs operate under the premise that the incentives used to make care more efficient and less costly can only be applied if measurable quality is maintained or improved. ACOs do not pay doctors or hospitals more unless high quality is demonstrated.

ACO Quality Measures and Hospitalists

Most of the 33 quality measures required by Medicare ACOs are based in ambulatory practice. These include measures related to blood pressure, immunizations, cancer, and fall-risk screening, and measures for diabetics, such as lipids and hemoglobin A1C. However, there are a few measures for which hospitalists should share in accountability, including:

- All-cause hospital readmission rate—risk-standardized;

- Ambulatory sensitive condition hospital admission rates (CHF, COPD); and

- Medication reconciliation after discharge from an inpatient facility.

Four Key Actions for Hospitalists

Hospitalists make a significant contribution to the quality and the financial performance of ACOs. In addition to the quality metrics cited above, hospitalists impact the inpatient portion of the overall population’s cost of care. Furthermore, hospitalists are vital partners in the care coordination required for an ACO to be successful.

Here are four actions I suggest taking in order for your hospitalist group to be effective as participants in an ACO:

- Have a representative from your group participate in ACO committees that address hospital utilization and related matters, such as care coordination impacting pre- and post-hospital care.

- Learn how to work with ACO case managers on care transitions, including post-discharge follow-up and information transfer.

- Understand an ACO’s approach to engagement of and coordination with post-acute-care facilities. The ability of a post-acute facility, such a skilled nursing facility, to accept patients who have complex care needs, to manage changes in condition in the facility when appropriate, and to send complete information upon transfer to the hospital are important strategies for an ACO’s success.

- Understand how an ACO reports quality and cost performance and how savings will be shared among participants.

Mindset Change

If hospitalists are part of the chain of ACO physicians and providers held accountable for the health of a population of patients, we must work more closely with the medical home/neighborhood, post-acute-care facilities, and home-care providers. The change in mindset will occur only if we have a set of tools to get the job done, such as case managers and information technology, and the appropriate incentives to support better care coordination. I encourage my fellow hospitalists to make things happen, instead of taking a passive role in this monumental transformation.

Reference

Dr. Whitcomb is medical director of healthcare quality at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass. He is a co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at wfwhit@comcast.net.

Consider Patient Safety, Outcomes Risk before Prescribing Off-Label Drugs

Consider Patient Safety, Outcomes Risk before Prescribing “Off-Label”

What is the story with off-label drug use? I have seen some other physicians in my group use dabigatran for VTE prophylaxis, which I know it is not an approved indication. Am I taking on risk by continuing this treatment?

—Fabian Harris, Tuscaloosa, Ala.

Dr. Hospitalist responds:

Our friends at the FDA are in the business of approving drugs for use, but they do not regulate medical practice. So the short answer to your question is that off-label drug use is perfectly acceptable. Once a drug has been approved for use, if, in your clinical judgment, there are other indications for which it could be beneficial, then you are well within your rights to prescribe it. The FDA does not dictate how you practice medicine.

However, you will still be held to the community standard when it comes to your medical practice. As an example, gabapentin is used all the time for neuropathic pain syndromes, though technically it is only approved for seizures and post-herpetic neuralgia. Although the FDA won’t restrict your prescribing, it does prohibit pharmaceutical companies from marketing their drugs for anything other than their approved indications. In fact, Pfizer settled a case in 2004 on this very drug due to the promotion of prescribing it for nonapproved indications. I think at this point it’s fairly well accepted that lots of physicians use gabapentin for neuropathic pain, so you would not be too far out on a limb in prescribing it yourself in this manner.

For newer drugs, I might proceed with a little more caution. Anyone out there remember trovofloxacin (Trovan)? It was a new antibiotic approved in the late 1990s, with a coverage spectrum similar to levofloxacin, but with even more weight toward the gram positives. A wonder drug! Oral! As a result, it got prescribed like water, but not for the serious infections it was designed for: It got prescribed “off label” for common URIs and sinusitis. Unfortunately, it also caused a fair amount of liver failure and was summarily pulled from the market.

Does this mean dabigatran is a bad drug? No, but we don’t have much history with it, either. So while it might seem to be an innocuous extension to prescribe it for VTE prevention when it has already been approved for stroke prevention in afib, I think you carry some risk by doing this. In addition, some insurers will not cover a drug being prescribed in this manner, so you might be exposing your patient to added costs as well. Additionally, there’s nothing about off-label prescribing that says you have to tell the patient that’s what you’re doing. However, if you put together the factors of not informing a patient about an off-label use, and a patient having to pay out of pocket for that medicine, with an adverse outcome ... well, let’s just say that might not end too well.

Ultimately, I think you will need to consider the safety profile of the drug, the risk for an adverse outcome, your own risk tolerance, and the current state of medical practice before you consistently agree to use a drug “off label.” Given the slow-moving jungle of FDA approval, I can understand the desire to use a newer drug in an off-label manner, but it’s probably best to stop and think about the alternatives before proceeding. If you’re practicing in a group, then it’s just as important to come to a consensus with your partners about which drugs you will comfortably use off-label and which ones you won’t, especially as newer drugs come into the marketplace.

Consider Patient Safety, Outcomes Risk before Prescribing “Off-Label”

What is the story with off-label drug use? I have seen some other physicians in my group use dabigatran for VTE prophylaxis, which I know it is not an approved indication. Am I taking on risk by continuing this treatment?

—Fabian Harris, Tuscaloosa, Ala.

Dr. Hospitalist responds:

Our friends at the FDA are in the business of approving drugs for use, but they do not regulate medical practice. So the short answer to your question is that off-label drug use is perfectly acceptable. Once a drug has been approved for use, if, in your clinical judgment, there are other indications for which it could be beneficial, then you are well within your rights to prescribe it. The FDA does not dictate how you practice medicine.

However, you will still be held to the community standard when it comes to your medical practice. As an example, gabapentin is used all the time for neuropathic pain syndromes, though technically it is only approved for seizures and post-herpetic neuralgia. Although the FDA won’t restrict your prescribing, it does prohibit pharmaceutical companies from marketing their drugs for anything other than their approved indications. In fact, Pfizer settled a case in 2004 on this very drug due to the promotion of prescribing it for nonapproved indications. I think at this point it’s fairly well accepted that lots of physicians use gabapentin for neuropathic pain, so you would not be too far out on a limb in prescribing it yourself in this manner.

For newer drugs, I might proceed with a little more caution. Anyone out there remember trovofloxacin (Trovan)? It was a new antibiotic approved in the late 1990s, with a coverage spectrum similar to levofloxacin, but with even more weight toward the gram positives. A wonder drug! Oral! As a result, it got prescribed like water, but not for the serious infections it was designed for: It got prescribed “off label” for common URIs and sinusitis. Unfortunately, it also caused a fair amount of liver failure and was summarily pulled from the market.

Does this mean dabigatran is a bad drug? No, but we don’t have much history with it, either. So while it might seem to be an innocuous extension to prescribe it for VTE prevention when it has already been approved for stroke prevention in afib, I think you carry some risk by doing this. In addition, some insurers will not cover a drug being prescribed in this manner, so you might be exposing your patient to added costs as well. Additionally, there’s nothing about off-label prescribing that says you have to tell the patient that’s what you’re doing. However, if you put together the factors of not informing a patient about an off-label use, and a patient having to pay out of pocket for that medicine, with an adverse outcome ... well, let’s just say that might not end too well.

Ultimately, I think you will need to consider the safety profile of the drug, the risk for an adverse outcome, your own risk tolerance, and the current state of medical practice before you consistently agree to use a drug “off label.” Given the slow-moving jungle of FDA approval, I can understand the desire to use a newer drug in an off-label manner, but it’s probably best to stop and think about the alternatives before proceeding. If you’re practicing in a group, then it’s just as important to come to a consensus with your partners about which drugs you will comfortably use off-label and which ones you won’t, especially as newer drugs come into the marketplace.

Consider Patient Safety, Outcomes Risk before Prescribing “Off-Label”

What is the story with off-label drug use? I have seen some other physicians in my group use dabigatran for VTE prophylaxis, which I know it is not an approved indication. Am I taking on risk by continuing this treatment?

—Fabian Harris, Tuscaloosa, Ala.

Dr. Hospitalist responds:

Our friends at the FDA are in the business of approving drugs for use, but they do not regulate medical practice. So the short answer to your question is that off-label drug use is perfectly acceptable. Once a drug has been approved for use, if, in your clinical judgment, there are other indications for which it could be beneficial, then you are well within your rights to prescribe it. The FDA does not dictate how you practice medicine.

However, you will still be held to the community standard when it comes to your medical practice. As an example, gabapentin is used all the time for neuropathic pain syndromes, though technically it is only approved for seizures and post-herpetic neuralgia. Although the FDA won’t restrict your prescribing, it does prohibit pharmaceutical companies from marketing their drugs for anything other than their approved indications. In fact, Pfizer settled a case in 2004 on this very drug due to the promotion of prescribing it for nonapproved indications. I think at this point it’s fairly well accepted that lots of physicians use gabapentin for neuropathic pain, so you would not be too far out on a limb in prescribing it yourself in this manner.

For newer drugs, I might proceed with a little more caution. Anyone out there remember trovofloxacin (Trovan)? It was a new antibiotic approved in the late 1990s, with a coverage spectrum similar to levofloxacin, but with even more weight toward the gram positives. A wonder drug! Oral! As a result, it got prescribed like water, but not for the serious infections it was designed for: It got prescribed “off label” for common URIs and sinusitis. Unfortunately, it also caused a fair amount of liver failure and was summarily pulled from the market.

Does this mean dabigatran is a bad drug? No, but we don’t have much history with it, either. So while it might seem to be an innocuous extension to prescribe it for VTE prevention when it has already been approved for stroke prevention in afib, I think you carry some risk by doing this. In addition, some insurers will not cover a drug being prescribed in this manner, so you might be exposing your patient to added costs as well. Additionally, there’s nothing about off-label prescribing that says you have to tell the patient that’s what you’re doing. However, if you put together the factors of not informing a patient about an off-label use, and a patient having to pay out of pocket for that medicine, with an adverse outcome ... well, let’s just say that might not end too well.

Ultimately, I think you will need to consider the safety profile of the drug, the risk for an adverse outcome, your own risk tolerance, and the current state of medical practice before you consistently agree to use a drug “off label.” Given the slow-moving jungle of FDA approval, I can understand the desire to use a newer drug in an off-label manner, but it’s probably best to stop and think about the alternatives before proceeding. If you’re practicing in a group, then it’s just as important to come to a consensus with your partners about which drugs you will comfortably use off-label and which ones you won’t, especially as newer drugs come into the marketplace.

Study: Collaborative Approach to Med Rec Effective, Cost-Efficient

A paper published in the May/June issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine shows that a collaborative approach to medication reconciliation ("med rec") appears to both prevent adverse drug events and pay for itself.

The paper, "Nurse-Pharmacist Collaboration on Medication Reconciliation Prevents Potential Harm," found that 225 of 500 surveyed patients had at least one unintended discrepancy in their house medication list (HML) on admission or discharge. And 162 of those patients had a discrepancy ranked on the upper end of the study's risk scale.

However, having nurses and pharmacists work together "allowed many discrepancies to be reconciled before causing harm," the study concluded.

"It absolutely supports the idea that we need to approach medicine as a team game," says hospitalist and lead author Lenny Feldman, MD, FACP, FAAP, SFHM, of John Hopkins School of Medicine in Baltimore. "We can't do this alone, and patients don't do better when we do this alone."

The study noted that it cost $113.64 to find one potentially harmful medication discrepancy. To offset those costs, an institution would have to prevent one discrepancy for every 290 patient encounters. The Johns Hopkins team averted 81 such events, but Dr. Feldman notes that without a control group, it’s difficult to say how many of those potential issues would have been caught at some other point in a patient's stay.

Still, he says, part of the value of a multidisciplinary approach to med rec is that it can help hospitalists improve patient care. By having nurses, physicians, and pharmacists working together, more potential adverse drug events could be prevented, Dr. Feldman says.

"That data-gathering is difficult and time-consuming, and it is not something hospitalists need do on their own," he adds.

A paper published in the May/June issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine shows that a collaborative approach to medication reconciliation ("med rec") appears to both prevent adverse drug events and pay for itself.

The paper, "Nurse-Pharmacist Collaboration on Medication Reconciliation Prevents Potential Harm," found that 225 of 500 surveyed patients had at least one unintended discrepancy in their house medication list (HML) on admission or discharge. And 162 of those patients had a discrepancy ranked on the upper end of the study's risk scale.

However, having nurses and pharmacists work together "allowed many discrepancies to be reconciled before causing harm," the study concluded.

"It absolutely supports the idea that we need to approach medicine as a team game," says hospitalist and lead author Lenny Feldman, MD, FACP, FAAP, SFHM, of John Hopkins School of Medicine in Baltimore. "We can't do this alone, and patients don't do better when we do this alone."

The study noted that it cost $113.64 to find one potentially harmful medication discrepancy. To offset those costs, an institution would have to prevent one discrepancy for every 290 patient encounters. The Johns Hopkins team averted 81 such events, but Dr. Feldman notes that without a control group, it’s difficult to say how many of those potential issues would have been caught at some other point in a patient's stay.

Still, he says, part of the value of a multidisciplinary approach to med rec is that it can help hospitalists improve patient care. By having nurses, physicians, and pharmacists working together, more potential adverse drug events could be prevented, Dr. Feldman says.

"That data-gathering is difficult and time-consuming, and it is not something hospitalists need do on their own," he adds.

A paper published in the May/June issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine shows that a collaborative approach to medication reconciliation ("med rec") appears to both prevent adverse drug events and pay for itself.

The paper, "Nurse-Pharmacist Collaboration on Medication Reconciliation Prevents Potential Harm," found that 225 of 500 surveyed patients had at least one unintended discrepancy in their house medication list (HML) on admission or discharge. And 162 of those patients had a discrepancy ranked on the upper end of the study's risk scale.

However, having nurses and pharmacists work together "allowed many discrepancies to be reconciled before causing harm," the study concluded.

"It absolutely supports the idea that we need to approach medicine as a team game," says hospitalist and lead author Lenny Feldman, MD, FACP, FAAP, SFHM, of John Hopkins School of Medicine in Baltimore. "We can't do this alone, and patients don't do better when we do this alone."

The study noted that it cost $113.64 to find one potentially harmful medication discrepancy. To offset those costs, an institution would have to prevent one discrepancy for every 290 patient encounters. The Johns Hopkins team averted 81 such events, but Dr. Feldman notes that without a control group, it’s difficult to say how many of those potential issues would have been caught at some other point in a patient's stay.

Still, he says, part of the value of a multidisciplinary approach to med rec is that it can help hospitalists improve patient care. By having nurses, physicians, and pharmacists working together, more potential adverse drug events could be prevented, Dr. Feldman says.

"That data-gathering is difficult and time-consuming, and it is not something hospitalists need do on their own," he adds.

Report: Pharmacist-Led Interventions Don’t Reduce Medication Errors Post-Discharge

At first blush, some hospitalists might see it as bad news that a recent report found a pharmacist-assisted medication reconciliation ("med rec") intervention did not significantly reduce clinically important medication errors after discharge. But a deeper reading of the study tells a different story, says a hospitalist who worked on the report.

"This is the latest in our growing understanding of the roles of certain interventions on transitions of care," says Jeffrey Schnipper, MD, MPH, FHM, director of clinical research and an associate physician in the general medicine division at Brigham and Women's Hospitalist Service in Boston, and co-author of the study "Effect of a Pharmacist Intervention on Clinically Important Medication Errors after Hospital Discharge." "What I don't want to have happen is for people to read this article ... and say, 'Oh, pharmacists don't make a difference.' They absolutely make a difference. This is a more nuanced issue of who do they have the biggest impact with, and 'On top of what other interventions are you doing this?'"

The researchers set out to determine whether a pharmacist-delivered intervention on patients with low health literacy (including a post-discharge telephone call) would lower adverse drug events and other clinically important medication errors. They concluded that it did not (unadjusted incidence rate ratio, 0.92 [95% CI, 0.77 to 1.10]).

Dr. Schnipper says the impact was likely muted because the patients studied had higher health-literacy levels than researchers expected. Also, because most follow-up phone calls occurred within a few days of discharge, the intervention failed to capture any events that happened in the 30 days after discharge.

He also notes that the institutions that participated in the study have already implemented multiple med-rec interventions over the past few years. Hospitals that have not focused intently on the issue could find much larger gains from implementing pharmacist-led programs.

"If you're a hospital that has not been fixated on improving medication safety and transitions of care, I think pharmacists are huge," Dr. Schnipper says. "The key, then, is to focus them on the highest-risk patients."

At first blush, some hospitalists might see it as bad news that a recent report found a pharmacist-assisted medication reconciliation ("med rec") intervention did not significantly reduce clinically important medication errors after discharge. But a deeper reading of the study tells a different story, says a hospitalist who worked on the report.

"This is the latest in our growing understanding of the roles of certain interventions on transitions of care," says Jeffrey Schnipper, MD, MPH, FHM, director of clinical research and an associate physician in the general medicine division at Brigham and Women's Hospitalist Service in Boston, and co-author of the study "Effect of a Pharmacist Intervention on Clinically Important Medication Errors after Hospital Discharge." "What I don't want to have happen is for people to read this article ... and say, 'Oh, pharmacists don't make a difference.' They absolutely make a difference. This is a more nuanced issue of who do they have the biggest impact with, and 'On top of what other interventions are you doing this?'"

The researchers set out to determine whether a pharmacist-delivered intervention on patients with low health literacy (including a post-discharge telephone call) would lower adverse drug events and other clinically important medication errors. They concluded that it did not (unadjusted incidence rate ratio, 0.92 [95% CI, 0.77 to 1.10]).

Dr. Schnipper says the impact was likely muted because the patients studied had higher health-literacy levels than researchers expected. Also, because most follow-up phone calls occurred within a few days of discharge, the intervention failed to capture any events that happened in the 30 days after discharge.

He also notes that the institutions that participated in the study have already implemented multiple med-rec interventions over the past few years. Hospitals that have not focused intently on the issue could find much larger gains from implementing pharmacist-led programs.

"If you're a hospital that has not been fixated on improving medication safety and transitions of care, I think pharmacists are huge," Dr. Schnipper says. "The key, then, is to focus them on the highest-risk patients."

At first blush, some hospitalists might see it as bad news that a recent report found a pharmacist-assisted medication reconciliation ("med rec") intervention did not significantly reduce clinically important medication errors after discharge. But a deeper reading of the study tells a different story, says a hospitalist who worked on the report.

"This is the latest in our growing understanding of the roles of certain interventions on transitions of care," says Jeffrey Schnipper, MD, MPH, FHM, director of clinical research and an associate physician in the general medicine division at Brigham and Women's Hospitalist Service in Boston, and co-author of the study "Effect of a Pharmacist Intervention on Clinically Important Medication Errors after Hospital Discharge." "What I don't want to have happen is for people to read this article ... and say, 'Oh, pharmacists don't make a difference.' They absolutely make a difference. This is a more nuanced issue of who do they have the biggest impact with, and 'On top of what other interventions are you doing this?'"

The researchers set out to determine whether a pharmacist-delivered intervention on patients with low health literacy (including a post-discharge telephone call) would lower adverse drug events and other clinically important medication errors. They concluded that it did not (unadjusted incidence rate ratio, 0.92 [95% CI, 0.77 to 1.10]).

Dr. Schnipper says the impact was likely muted because the patients studied had higher health-literacy levels than researchers expected. Also, because most follow-up phone calls occurred within a few days of discharge, the intervention failed to capture any events that happened in the 30 days after discharge.

He also notes that the institutions that participated in the study have already implemented multiple med-rec interventions over the past few years. Hospitals that have not focused intently on the issue could find much larger gains from implementing pharmacist-led programs.

"If you're a hospital that has not been fixated on improving medication safety and transitions of care, I think pharmacists are huge," Dr. Schnipper says. "The key, then, is to focus them on the highest-risk patients."

Collaboration Prevents Identification Band Errors

Clinical question: Can a quality-improvement (QI) collaborative decrease patient identification (ID) band errors?

Background: ID band errors often result in medication errors and unsafe care. Consequently, correct patient identification, through the use of at least two identifiers, has been an ongoing Joint Commission National Patient Safety Goal. Although individual sites have demonstrated improvement in accuracy of patient identification, there have not been reports of dissemination of successful practices.

Study design: Collaborative quality-improvement initiative.

Setting: Six hospitals.

Synopsis: ID band audits in 11,377 patients were performed in the learning collaborative’s six participating hospitals.

The audits were organized primarily around monthly conference calls. The hospital settings were diverse: community hospitals, hospitals within an academic medical center, and freestanding children’s hospitals. The aim of the collaborative was to reduce ID band errors by 50% within a one-year time frame across the collective sites.

Key interventions included transparent data collection and reporting; engagement of staff, families and leadership; voluntary event reporting; and auditing of failures. The mean combined ID band failure rate decreased to 4% from 22% within 13 months, representing a 77% relative reduction (P<0.001).

QI collaboratives are not designed to specifically result in generalizable knowledge, yet they might produce widespread improvement, as this effort demonstrates. The careful documentation of iterative factors implemented across sites in this initiative provides a blueprint for hospitals looking to replicate this success. Additionally, the interventions represent feasible and logical concepts within the basic constructs of improvement science methodology.

Bottom line: A QI collaborative might result in rapid and significant reductions in ID band errors.

Citation: Phillips SC, Saysana M, Worley S, Hain PD. Reduction in pediatric identification band errors: a quality collaborative. Pediatrics. 2012;129(6):e1587-e1593.

Reviewed by Pediatric Editor Mark Shen, MD, SFHM, medical director of hospital medicine at Dell Children's Medical Center, Austin, Texas.

Clinical question: Can a quality-improvement (QI) collaborative decrease patient identification (ID) band errors?

Background: ID band errors often result in medication errors and unsafe care. Consequently, correct patient identification, through the use of at least two identifiers, has been an ongoing Joint Commission National Patient Safety Goal. Although individual sites have demonstrated improvement in accuracy of patient identification, there have not been reports of dissemination of successful practices.

Study design: Collaborative quality-improvement initiative.

Setting: Six hospitals.

Synopsis: ID band audits in 11,377 patients were performed in the learning collaborative’s six participating hospitals.

The audits were organized primarily around monthly conference calls. The hospital settings were diverse: community hospitals, hospitals within an academic medical center, and freestanding children’s hospitals. The aim of the collaborative was to reduce ID band errors by 50% within a one-year time frame across the collective sites.

Key interventions included transparent data collection and reporting; engagement of staff, families and leadership; voluntary event reporting; and auditing of failures. The mean combined ID band failure rate decreased to 4% from 22% within 13 months, representing a 77% relative reduction (P<0.001).

QI collaboratives are not designed to specifically result in generalizable knowledge, yet they might produce widespread improvement, as this effort demonstrates. The careful documentation of iterative factors implemented across sites in this initiative provides a blueprint for hospitals looking to replicate this success. Additionally, the interventions represent feasible and logical concepts within the basic constructs of improvement science methodology.

Bottom line: A QI collaborative might result in rapid and significant reductions in ID band errors.

Citation: Phillips SC, Saysana M, Worley S, Hain PD. Reduction in pediatric identification band errors: a quality collaborative. Pediatrics. 2012;129(6):e1587-e1593.

Reviewed by Pediatric Editor Mark Shen, MD, SFHM, medical director of hospital medicine at Dell Children's Medical Center, Austin, Texas.

Clinical question: Can a quality-improvement (QI) collaborative decrease patient identification (ID) band errors?

Background: ID band errors often result in medication errors and unsafe care. Consequently, correct patient identification, through the use of at least two identifiers, has been an ongoing Joint Commission National Patient Safety Goal. Although individual sites have demonstrated improvement in accuracy of patient identification, there have not been reports of dissemination of successful practices.

Study design: Collaborative quality-improvement initiative.

Setting: Six hospitals.

Synopsis: ID band audits in 11,377 patients were performed in the learning collaborative’s six participating hospitals.

The audits were organized primarily around monthly conference calls. The hospital settings were diverse: community hospitals, hospitals within an academic medical center, and freestanding children’s hospitals. The aim of the collaborative was to reduce ID band errors by 50% within a one-year time frame across the collective sites.

Key interventions included transparent data collection and reporting; engagement of staff, families and leadership; voluntary event reporting; and auditing of failures. The mean combined ID band failure rate decreased to 4% from 22% within 13 months, representing a 77% relative reduction (P<0.001).

QI collaboratives are not designed to specifically result in generalizable knowledge, yet they might produce widespread improvement, as this effort demonstrates. The careful documentation of iterative factors implemented across sites in this initiative provides a blueprint for hospitals looking to replicate this success. Additionally, the interventions represent feasible and logical concepts within the basic constructs of improvement science methodology.

Bottom line: A QI collaborative might result in rapid and significant reductions in ID band errors.

Citation: Phillips SC, Saysana M, Worley S, Hain PD. Reduction in pediatric identification band errors: a quality collaborative. Pediatrics. 2012;129(6):e1587-e1593.

Reviewed by Pediatric Editor Mark Shen, MD, SFHM, medical director of hospital medicine at Dell Children's Medical Center, Austin, Texas.

Reconciliation Act

Pharmacist Kristine M. Gleason, RPh, got the chance to personally test her ability to help ED providers with medication reconciliation—known by most in healthcare as “med rec”—when she broke her leg a couple of years ago. No problem, she thought: “I’ve been involved in med-rec efforts for eight-plus years.”

But when asked to provide her current medications, Gleason, who is the clinical quality leader in the department of clinical quality and analytics at Northwestern Memorial Hospital in Chicago, says she was in pain and overwhelmed. “I couldn’t even remember my children’s names, let alone the names and dosages of my aspirin and my thyroid medication,” she says. Moreover, she didn’t carry a list in her wallet because “I’m a pharmacist and I do med rec,” she says.

Gleason’s experience highlights why, six years after The Joint Commission introduced medication reconciliation as National Patient Safety Goal (NPSG) No. 8, hospitals and providers still struggle with the process.1 As a younger patient, Gleason took few medications. But for the majority of elderly inpatients with comorbid conditions, just establishing the patient’s medication list can bring the whole process to a halt; without that foundational list, reconciling other medications becomes problematic.

Although the commission has taken the goals under review and has, since July 1, required compliance with the revised NPSG 03.06.01 (see “Additional Resources,”), hospitalization-associated adverse drug events continue to mount. A recent Canadian study caused a ripple this summer with its findings that patients discharged from acute-care hospitals were at higher risk for unintentional discontinuation of their medications prescribed for chronic diseases than control groups, and those who had an ICU stay are at even higher risk.2

There’s been no shortage of med-rec initiatives in recent years. Medication reconciliation was at the top of the list for ways to prevent errors when the Institute for Healthcare Improvement launched its “5 Million Lives Campaign” in December 2006. SHM weighed in on the issue in 2010 with a consensus statement on key principles and necessary first steps in med rec.3

“This isn’t a new problem,” Gleason says. “Med rec has become more heightened because we have many more medications and complex therapies, more care providers, more specialists—more players, if you will.”

The March launch of the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program, part of the Centers for Medicaid & Medicare Services’ (CMS) Inpatient Prospective Payment System, will again shine the spotlight on med rec’s role in the prevention of 30-day readmissions. The Hospitalist talked with researchers, pharmacists, and hospitalists about the reasons behind medication discrepancies, and their strategies for addressing mismatches.

Why So Difficult?

The goal of medication reconciliation is to generate and maintain an accurate and coherent record of patients’ medications across all transitions of care, which sounds straightforward enough. But the process involves much more than just checking items off a list, says Jeffrey Schnipper, MD, MPH, FHM, currently the principal investigator for the $1.5 million study funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) to research and implement best practices in med rec, dubbed MARQUIS (Multicenter Medication Reconciliation Quality Improvement Study). Those immersed in med rec know that it’s nonlinear, multilayered, and surprisingly complex, requiring partnerships among diverse providers across many domains of care.

“Medication reconciliation gets right at all the weaknesses of our healthcare system,” says Dr. Schnipper, a hospitalist and director of clinical research for the HM service at Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH) and assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, both in Boston. “We have an excellent healthcare system in so many ways, but what we do not do such a good job of is coordination of care across settings, easy transfer of information, and having one person who is responsible for the accuracy of a patient’s health information.”

Dr. Schnipper’s studies attest to the common occurrence of unintentional medical discrepancies, pointing to the need for accurate medication histories, identifying high-risk patients for intensive interventions, and careful med rec at time of discharge.4

Other factors might come into play, says Ted Tsomides, MD, PhD, an attending physician on the HM service at WakeMed Hospital and assistant professor of medicine at the University of North Carolina’s School of Medicine in Raleigh, N.C. For example, he surmises that a “fatigue factor” sets in for some providers. “After five years of working on any initiative, people get worn out and push it to the back burner, unless they are really incentivized to stay on it,” he says.

List Capture

Medication reconciliation is a multifaceted process, and the first step is to gather the history of medications the patient has been taking. Hospitalist Blake J. Lesselroth, MD, MBI, assistant professor of medicine and medical informatics and director of the Portland Patient Safety Center of Inquiry at the Portland VA Medical Center in Oregon, points out that “the initial exposure to the patient is like a pencil sketch. You start to realize that med rec involves iterative loops of communication between you, the patient, and other knowledge resources (see Figure 1). As you start to pull in more information, you begin to complete your narrative. At the end of hospitalization, you’ve got a vibrant portrait with much more nuance to it. So it can’t be a linear process.”

—Kristine M. Gleason, RPh, clinical quality leader, department of clinical quality and analytics, Northwestern Memorial Hospital, Chicago

The list is dynamic, especially in the ICU setting, says Gleason, where it represents only one point in time.

In a closed system, such as the Veterans Administration or Kaiser Permanente, it’s often easier to establish a patient’s ongoing medications. With an integrated electronic health record (EHR), providers can call up the patient’s list of medications during admittance to the hospital. Verifying those medications remains critical: The health record lists patients’ prescriptions, but that doesn’t always mean they have actually filled or are taking those medications.

At the Kaiser Permanente Southern California site in Santa Clarita, Calif., where hospitalist David W. Wong, MD, works, pharmacists review their medications with patients when they are admitted, provide any needed consultation, then repeat the process at discharge. “So far,” Dr. Wong says, “this has resulted in the best medication reconciliation that we’ve seen.”

Pharmacy Is Key

In 2006, Kenneth Boockvar, MD, of the James J. Peters VA Medical Center in Bronx, N.Y., found in a pre- and post-intervention study that using pharmacists to ferret out and communicate prescribing discrepancies to physicians resulted in lower risk of adverse drug events (ADEs) for patients transferred between the hospital and the nursing home.5 Likewise, Dr. Schnipper and his colleagues found that using pharmacists to conduct medication reviews, counsel patients at discharge, and make follow-up telephone calls to patients was associated with a lower rate of preventable ADEs 30 days after hospital discharge.6

At United Hospital System’s (UHS) Kenosha Medical Center campus in Kenosha, Wis., pharmacists play a key role in generating medication lists for incoming patients. Hospitalist Corey Black, MD, regional medical director for Cogent HMG, says many patients do not recall their medications or the dosages, so UHS utilizes a team approach: If patients come in during evenings or weekends, pharmacists start calling local pharmacies to track down patients’ medication lists. “We also try to have family members bring in any medication containers they can find,” he adds. Due to a Wisconsin state law mandating nursing homes to send medication lists along with patients, generating a list is much easier.

Dr. Tsomides is a physician sponsor of a new med-rec initiative at WakeMed. With a steering committee that includes representatives from stakeholder services (medicine, nursing, pharmacy, administration, etc.), the group plans to hire and train pharmacy techs who will take home medication lists in the ED, lifting that responsibility from physicians’ task lists.

Is IT the Answer?

Would many of the barriers to med rec go away with universal EHR? So far, the literature has not borne out the superiority of using EHR to facilitate better med rec.

Peter Kaboli and colleagues found that the computerized medication record reflected what patients were actually taking for only 5.3% of the 493 VA patients enrolled in a study at the Iowa City VA.7 Kenneth Boockvar and colleagues at the Bronx VA found no difference in the overall incidence of ADEs caused by medication discrepancies between VA patients with an EHR and non-VA patients without an EHR.8 A group of researchers with Partners HealthCare in Boston evaluated a secure, Web-based patient portal to produce more accurate medication lists. The patients using this system had just as many discrepancies between medication lists and self-reporting as those who did not.9

Dr. Lesselroth, who has devised a patient kiosk touch-screen tool for reconciling patients’ medication lists and has faced barriers when implementing said technology, says med rec is much more “organic” than strictly mechanical. “It invokes theories of learning from the cognitive sciences,” he says. “We haven’t actually built tools that help people with their problem representation, with understanding not just how medications reconcile with the prior setting of care, but whether they make clinical sense within the new context of care. That requires a quantum leap in thinking.”

Re-Brand the Message

Drs. Schnipper and Tsomides believe that when The Joint Committee first coined the term “medication reconciliation” and advanced it as a mandate, most providers associated it with a regulatory requirement, and understandably so. Dr. Schnipper says med rec could be improved if providers think about it in the context of accurate orders that translate to greater patient safety. “After all,” he says, “hospitalists are ultimately responsible for the medication orders written for their patients.

“This is not about regulatory requirements,” he continues. “This is about medication safety and transitions of care. You can spend an hour on deciding what dose of Lasix you want to send this patient home on, but if the patient then takes the wrong dose of Lasix because they don’t know what they were supposed to be taking, then all that good medical care is undone.”

The med rec conversation has come full circle, then, as being truly an issue of delivering patient-centered care. (For more on this topic, visit the-hospitalist.org to read “Patient Engagement Critical.”) Rather than focusing on the sometimes-befuddling term of medication reconciliation, providers should see med rec as part of an integrated medication management process that aims to take better care of patients through prevention and treatment, Gleason says.

The med rec issue is about effective communication at every transition of care. And that’s why, says Dr. Schnipper, “Hospitalists should own this process. We don’t have to do the process entirely by ourselves—and shouldn’t. But we are responsible for errors that happen during transitions in care and we should own these initiatives.”