User login

HPV vaccination remains below Healthy People goals despite increases

and vary widely across states based on data from a nested cohort study including more than 7 million children.

“Understanding regional and temporal variations in HPV vaccination coverage may help improve HPV vaccination uptake by informing public health policy,” Szu-Ta Chen, MD, of Harvard University, Boston, and colleagues wrote in Pediatrics.

To identify trends in one-dose and two-dose human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination coverage, the researchers reviewed data from the MarketScan health care database between January 2003 and December 2017 that included 7,837,480 children and 19,843,737 person-years. The children were followed starting at age 9, when HPV vaccination could begin, and ending at one of the following: the first or second vaccination, insurance disenrollment, December 2017, or the end of the year in which they turned 17.

Overall, the proportion of 15-year-old girls and boys with at least a one-dose HPV vaccination increased from 38% and 5%, respectively, in 2011 to 57% and 51%, respectively, in 2017. The comparable proportions of girls and boys with at least a two-dose vaccination increased from 30% and 2%, respectively, in 2011 to 46% and 39%, respectively, in 2017.

Coverage lacks consistency across states

However, the vaccination coverage varied widely across states; two-dose HPV vaccination coverage ranged from 80% of girls in the District of Columbia to 15% of boys in Mississippi. In general, states with more HPV vaccine interventions had higher levels of vaccination, the researchers noted.

Legislation to improve vaccination education showed the strongest association with coverage; an 8.8% increase in coverage for girls and an 8.7% increase for boys. Pediatrician availability also was a factor associated with a 1.1% increase in coverage estimated for every pediatrician per 10,000 children.

Cumulative HPV vaccinations seen among children continuously enrolled in the study were similar to the primary analysis, the Dr. Chen and associates said. “After the initial HPV vaccination, 87% of girls and 82% of boys received a second dose by age 17 in the most recent cohorts.”

However, the HPV vaccination coverage remains below the Healthy People 2020 goal of 80% of children vaccinated by age 15 years, the researchers said. Barriers to vaccination may include a lack of routine clinical encounters in adolescents aged 11-17 years. HPV vaccination coverage was higher in urban populations, compared with rural, which may be related to a lack of providers in rural areas.

“Thus, measures beyond recommending routine vaccination at annual check-ups might be necessary to attain sufficient HPV vaccine coverage, and the optimal strategy may differ by state characteristics,” they wrote.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the use of data from only commercially-insured children and lack of data on vaccines received outside of insurance, the researchers noted.

However, the results were strengthened by the large, population-based sample, and support the need for increased efforts in HPV vaccination. “Most states will not achieve the Healthy People 2020 goal of 80% coverage with at least two HPV vaccine doses by 2020,” Dr. Chen and associates concluded.

Vaccination goals are possible with effort in the right places

The fact of below-target vaccination for HPV in the United States may be old news, but the current study offers new insights on HPV uptake, Amanda F. Dempsey, MD, PhD, of the University of Colorado at Denver, in Aurora, wrote in an accompanying editorial.

“A unique feature of this study is the ability of its researchers to study individuals over time, particularly at a national scope,” which yielded two key messages, she said.

The longitudinal examination of vaccination levels among birth cohorts showed that similar vaccination levels were achieved more quickly each year.

“For example, among the birth cohort from the year 2000, representing 17-year-olds at the time data were abstracted for the study, 40% vaccination coverage was achieved when this group was 14 years old. In contrast, among the birth cohort from the year 2005, representing 12-year-olds at the time of data abstraction, 40% vaccination coverage was reached at the age of 12,” Dr. Dempsey explained.

In addition, the study design allowed the researchers to model future vaccine coverage based on current trends, said Dr. Dempsey. “The authors estimate that, by the year 2022, the 2012 birth cohort will have reached 80% coverage for the first dose in the HPV vaccine series.”

Dr. Dempsey said she was surprised that the models did not support the hypothesis that school mandates for vaccination would increase coverage; however, there were few states in this category.

Although the findings were limited by the lack of data on uninsured children and those insured by Medicaid, the state-by-state results show that the achievement of national vaccination goals is possible, Dr. Dempsey said. In addition, the findings “warrant close consideration by policy makers and the medical community at large regarding vaccination policies and workforce,” she emphasized.The study received no outside funding. Dr. Chen had no financial conflicts to disclose. Several coauthors reported research grants to their institutions from pharmaceutical companies or being consultants to such companies. Dr. Dempsey disclosed serving on the advisory boards for Merck, Pfizer, and Sanofi Pasteur.

SOURCE: Chen S-T et al. Pediatrics. 2020 Sep 14. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-3557.

and vary widely across states based on data from a nested cohort study including more than 7 million children.

“Understanding regional and temporal variations in HPV vaccination coverage may help improve HPV vaccination uptake by informing public health policy,” Szu-Ta Chen, MD, of Harvard University, Boston, and colleagues wrote in Pediatrics.

To identify trends in one-dose and two-dose human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination coverage, the researchers reviewed data from the MarketScan health care database between January 2003 and December 2017 that included 7,837,480 children and 19,843,737 person-years. The children were followed starting at age 9, when HPV vaccination could begin, and ending at one of the following: the first or second vaccination, insurance disenrollment, December 2017, or the end of the year in which they turned 17.

Overall, the proportion of 15-year-old girls and boys with at least a one-dose HPV vaccination increased from 38% and 5%, respectively, in 2011 to 57% and 51%, respectively, in 2017. The comparable proportions of girls and boys with at least a two-dose vaccination increased from 30% and 2%, respectively, in 2011 to 46% and 39%, respectively, in 2017.

Coverage lacks consistency across states

However, the vaccination coverage varied widely across states; two-dose HPV vaccination coverage ranged from 80% of girls in the District of Columbia to 15% of boys in Mississippi. In general, states with more HPV vaccine interventions had higher levels of vaccination, the researchers noted.

Legislation to improve vaccination education showed the strongest association with coverage; an 8.8% increase in coverage for girls and an 8.7% increase for boys. Pediatrician availability also was a factor associated with a 1.1% increase in coverage estimated for every pediatrician per 10,000 children.

Cumulative HPV vaccinations seen among children continuously enrolled in the study were similar to the primary analysis, the Dr. Chen and associates said. “After the initial HPV vaccination, 87% of girls and 82% of boys received a second dose by age 17 in the most recent cohorts.”

However, the HPV vaccination coverage remains below the Healthy People 2020 goal of 80% of children vaccinated by age 15 years, the researchers said. Barriers to vaccination may include a lack of routine clinical encounters in adolescents aged 11-17 years. HPV vaccination coverage was higher in urban populations, compared with rural, which may be related to a lack of providers in rural areas.

“Thus, measures beyond recommending routine vaccination at annual check-ups might be necessary to attain sufficient HPV vaccine coverage, and the optimal strategy may differ by state characteristics,” they wrote.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the use of data from only commercially-insured children and lack of data on vaccines received outside of insurance, the researchers noted.

However, the results were strengthened by the large, population-based sample, and support the need for increased efforts in HPV vaccination. “Most states will not achieve the Healthy People 2020 goal of 80% coverage with at least two HPV vaccine doses by 2020,” Dr. Chen and associates concluded.

Vaccination goals are possible with effort in the right places

The fact of below-target vaccination for HPV in the United States may be old news, but the current study offers new insights on HPV uptake, Amanda F. Dempsey, MD, PhD, of the University of Colorado at Denver, in Aurora, wrote in an accompanying editorial.

“A unique feature of this study is the ability of its researchers to study individuals over time, particularly at a national scope,” which yielded two key messages, she said.

The longitudinal examination of vaccination levels among birth cohorts showed that similar vaccination levels were achieved more quickly each year.

“For example, among the birth cohort from the year 2000, representing 17-year-olds at the time data were abstracted for the study, 40% vaccination coverage was achieved when this group was 14 years old. In contrast, among the birth cohort from the year 2005, representing 12-year-olds at the time of data abstraction, 40% vaccination coverage was reached at the age of 12,” Dr. Dempsey explained.

In addition, the study design allowed the researchers to model future vaccine coverage based on current trends, said Dr. Dempsey. “The authors estimate that, by the year 2022, the 2012 birth cohort will have reached 80% coverage for the first dose in the HPV vaccine series.”

Dr. Dempsey said she was surprised that the models did not support the hypothesis that school mandates for vaccination would increase coverage; however, there were few states in this category.

Although the findings were limited by the lack of data on uninsured children and those insured by Medicaid, the state-by-state results show that the achievement of national vaccination goals is possible, Dr. Dempsey said. In addition, the findings “warrant close consideration by policy makers and the medical community at large regarding vaccination policies and workforce,” she emphasized.The study received no outside funding. Dr. Chen had no financial conflicts to disclose. Several coauthors reported research grants to their institutions from pharmaceutical companies or being consultants to such companies. Dr. Dempsey disclosed serving on the advisory boards for Merck, Pfizer, and Sanofi Pasteur.

SOURCE: Chen S-T et al. Pediatrics. 2020 Sep 14. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-3557.

and vary widely across states based on data from a nested cohort study including more than 7 million children.

“Understanding regional and temporal variations in HPV vaccination coverage may help improve HPV vaccination uptake by informing public health policy,” Szu-Ta Chen, MD, of Harvard University, Boston, and colleagues wrote in Pediatrics.

To identify trends in one-dose and two-dose human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination coverage, the researchers reviewed data from the MarketScan health care database between January 2003 and December 2017 that included 7,837,480 children and 19,843,737 person-years. The children were followed starting at age 9, when HPV vaccination could begin, and ending at one of the following: the first or second vaccination, insurance disenrollment, December 2017, or the end of the year in which they turned 17.

Overall, the proportion of 15-year-old girls and boys with at least a one-dose HPV vaccination increased from 38% and 5%, respectively, in 2011 to 57% and 51%, respectively, in 2017. The comparable proportions of girls and boys with at least a two-dose vaccination increased from 30% and 2%, respectively, in 2011 to 46% and 39%, respectively, in 2017.

Coverage lacks consistency across states

However, the vaccination coverage varied widely across states; two-dose HPV vaccination coverage ranged from 80% of girls in the District of Columbia to 15% of boys in Mississippi. In general, states with more HPV vaccine interventions had higher levels of vaccination, the researchers noted.

Legislation to improve vaccination education showed the strongest association with coverage; an 8.8% increase in coverage for girls and an 8.7% increase for boys. Pediatrician availability also was a factor associated with a 1.1% increase in coverage estimated for every pediatrician per 10,000 children.

Cumulative HPV vaccinations seen among children continuously enrolled in the study were similar to the primary analysis, the Dr. Chen and associates said. “After the initial HPV vaccination, 87% of girls and 82% of boys received a second dose by age 17 in the most recent cohorts.”

However, the HPV vaccination coverage remains below the Healthy People 2020 goal of 80% of children vaccinated by age 15 years, the researchers said. Barriers to vaccination may include a lack of routine clinical encounters in adolescents aged 11-17 years. HPV vaccination coverage was higher in urban populations, compared with rural, which may be related to a lack of providers in rural areas.

“Thus, measures beyond recommending routine vaccination at annual check-ups might be necessary to attain sufficient HPV vaccine coverage, and the optimal strategy may differ by state characteristics,” they wrote.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the use of data from only commercially-insured children and lack of data on vaccines received outside of insurance, the researchers noted.

However, the results were strengthened by the large, population-based sample, and support the need for increased efforts in HPV vaccination. “Most states will not achieve the Healthy People 2020 goal of 80% coverage with at least two HPV vaccine doses by 2020,” Dr. Chen and associates concluded.

Vaccination goals are possible with effort in the right places

The fact of below-target vaccination for HPV in the United States may be old news, but the current study offers new insights on HPV uptake, Amanda F. Dempsey, MD, PhD, of the University of Colorado at Denver, in Aurora, wrote in an accompanying editorial.

“A unique feature of this study is the ability of its researchers to study individuals over time, particularly at a national scope,” which yielded two key messages, she said.

The longitudinal examination of vaccination levels among birth cohorts showed that similar vaccination levels were achieved more quickly each year.

“For example, among the birth cohort from the year 2000, representing 17-year-olds at the time data were abstracted for the study, 40% vaccination coverage was achieved when this group was 14 years old. In contrast, among the birth cohort from the year 2005, representing 12-year-olds at the time of data abstraction, 40% vaccination coverage was reached at the age of 12,” Dr. Dempsey explained.

In addition, the study design allowed the researchers to model future vaccine coverage based on current trends, said Dr. Dempsey. “The authors estimate that, by the year 2022, the 2012 birth cohort will have reached 80% coverage for the first dose in the HPV vaccine series.”

Dr. Dempsey said she was surprised that the models did not support the hypothesis that school mandates for vaccination would increase coverage; however, there were few states in this category.

Although the findings were limited by the lack of data on uninsured children and those insured by Medicaid, the state-by-state results show that the achievement of national vaccination goals is possible, Dr. Dempsey said. In addition, the findings “warrant close consideration by policy makers and the medical community at large regarding vaccination policies and workforce,” she emphasized.The study received no outside funding. Dr. Chen had no financial conflicts to disclose. Several coauthors reported research grants to their institutions from pharmaceutical companies or being consultants to such companies. Dr. Dempsey disclosed serving on the advisory boards for Merck, Pfizer, and Sanofi Pasteur.

SOURCE: Chen S-T et al. Pediatrics. 2020 Sep 14. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-3557.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Prospects and challenges for the upcoming influenza season

The 2020-2021 influenza season is shaping up to be challenging. Its likely concurrence with the ongoing severe acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus 2 (SARS-coV-2) pandemic (COVID-19) will pose diagnostic and therapeutic dilemmas and could overload the hospital system. But there could also be potential synergies in preventing morbidity and mortality from each disease.

A consistent pattern overthe past few influenza seasons

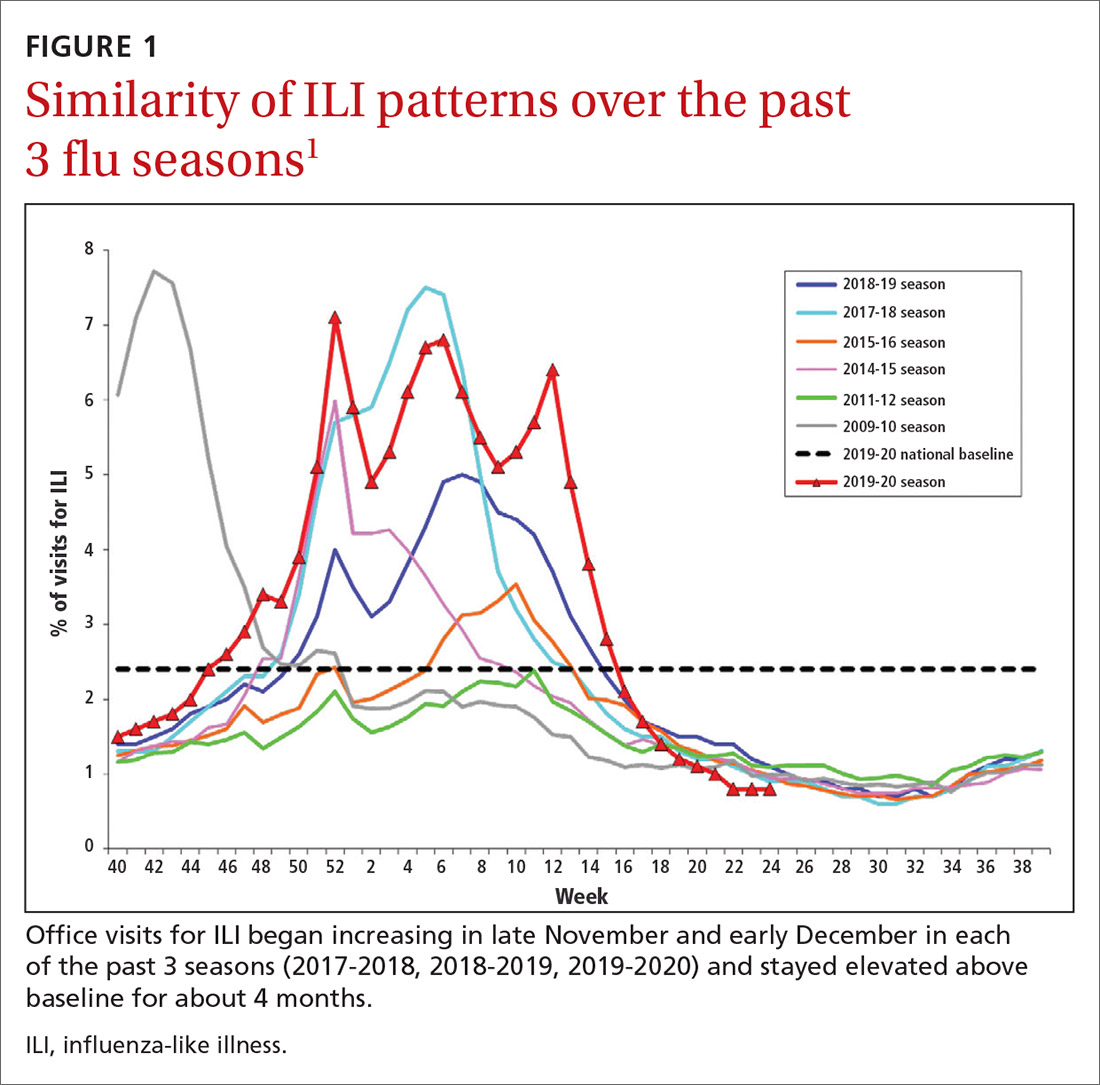

During the 2019-2020 flu season, there were an estimated 410,000 to 740,000 hospitalizations and 24,000 to 62,000 deaths attributed to influenza.1 As seen in FIGURE 1, office visits for influenza-like illness (ILI) began to increase in late November and early December in each of the last 3 years (2017-2018, 2018-2019, 2019-2020) and stayed elevated above baseline for about 4 months each season.1

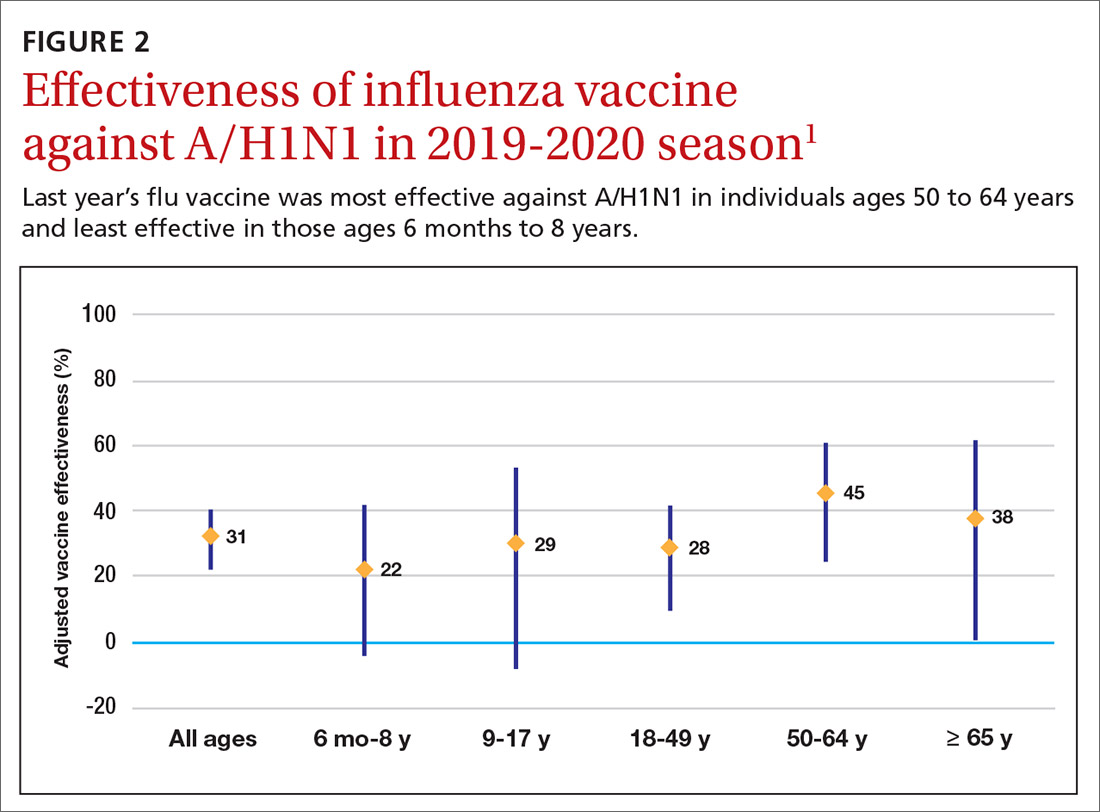

The effectiveness of influenza vaccine during the 2019-2020 season is being estimated using the US Flu Vaccine Effectiveness Network, which has close to 9000 enrollees. Overall, it appears the vaccine was 39% effective against medically attended influenza, with a higher effectiveness against influenza B (44%) than against A/H1N1 (31%). Effectiveness against influenza B was similar in all age groups, but effectiveness against A/H1N1 was highest for those ages 50 to 64 years (45%) and lowest for those ages 6 months through 8 years (22%), although 95% confidence intervals overlapped for all age groups (FIGURE 2). These preliminary effectiveness rates were presented at the summer meeting of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP).1

Influenza vaccine safety data for 2019-2020 were based on the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS), a passive surveillance system, and on the Vaccine Safety Datalink (VSD) system, an active surveillance system involving close to 6 million doses administered at VSD sites. No safety concerns were identified for any of the different vaccine types. Both the VAERS and VSD surveillance systems have been described in more detail in a previous Practice Alert.2

Recommendations for 2020-2021

The composition of the influenza vaccines for this year’s flu season will be different for 3 of the 4 antigens: A/H1N1, A/H2N2 and B/Victoria.3 The antigens included in the influenza vaccines each year are decided on in the spring, based on surveillance of circulating strains around the world. The effectiveness of the vaccine each year largely depends on how well the strains included in the vaccine match those circulating in the United States during the influenza season.

The main immunization recommendation for preventing morbidity and mortality from influenza has not changed: All individuals ages 6 months and older without a contraindication should receive an influenza vaccine.4 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends that patients receive the vaccine by the end of October.4 This includes the second dose for those children younger than 9 years who need 2 doses—ie, those who have received fewer than 2 doses of influenza vaccine prior to July 2020. Vaccination should continue through the end of the season for anyone who has not received a 2020-2021 influenza vaccine.

Two new influenza vaccine products are available for use in those ages 65 years and older: Fluzone high-dose quadrivalent and Fluad Quadrivalent (adjuvanted).4 Both of these products were available last year as trivalent options. Currently no specific vaccine product is listed as preferred by ACIP for those ages 65 and older.

Continue to: New vaccine contraindications

New vaccine contraindications. Four medical conditions have been added to the list of contraindications for quadrivalent live, attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV4): cochlear implant, cerebrospinal fluid leak, asplenia (anatomic and functional), and sickle cell anemia.4 In addition, those who receive LAIV4 should not be prescribed an influenza antiviral until 2 weeks after receiving the vaccine. And the vaccine should not be administered for 48 hours after receipt of oseltamivir or zanamivir, 5 days after peramivir, and 17 days after baloxavir marboxil.4 This is to prevent possible antiviral inactivation of the live attenuated influenza viruses in the vaccine.

For those who have a history of severe allergic reaction to eggs, there are now 2 egg-free options: cell-culture-based inactivated vaccine (ccIIV4) and recombinant influenza vaccine (RIV4).3,4 Urticaria alone is not considered a severe reaction. If neither of these egg-free options is available, a vaccine may still be administered in a medical setting supervised by a provider who is able to manage a severe allergic reaction (which rarely occurs).

All vaccine products available for the upcoming influenza season are listed and described on the CDC Web site, as is a summary of related recommendations.4 Particular attention should be paid to the dose of vaccine administered, as it differs by product for those ages 6 through 35 months of age and those ages 65 years and older.

Use of antiviral medications

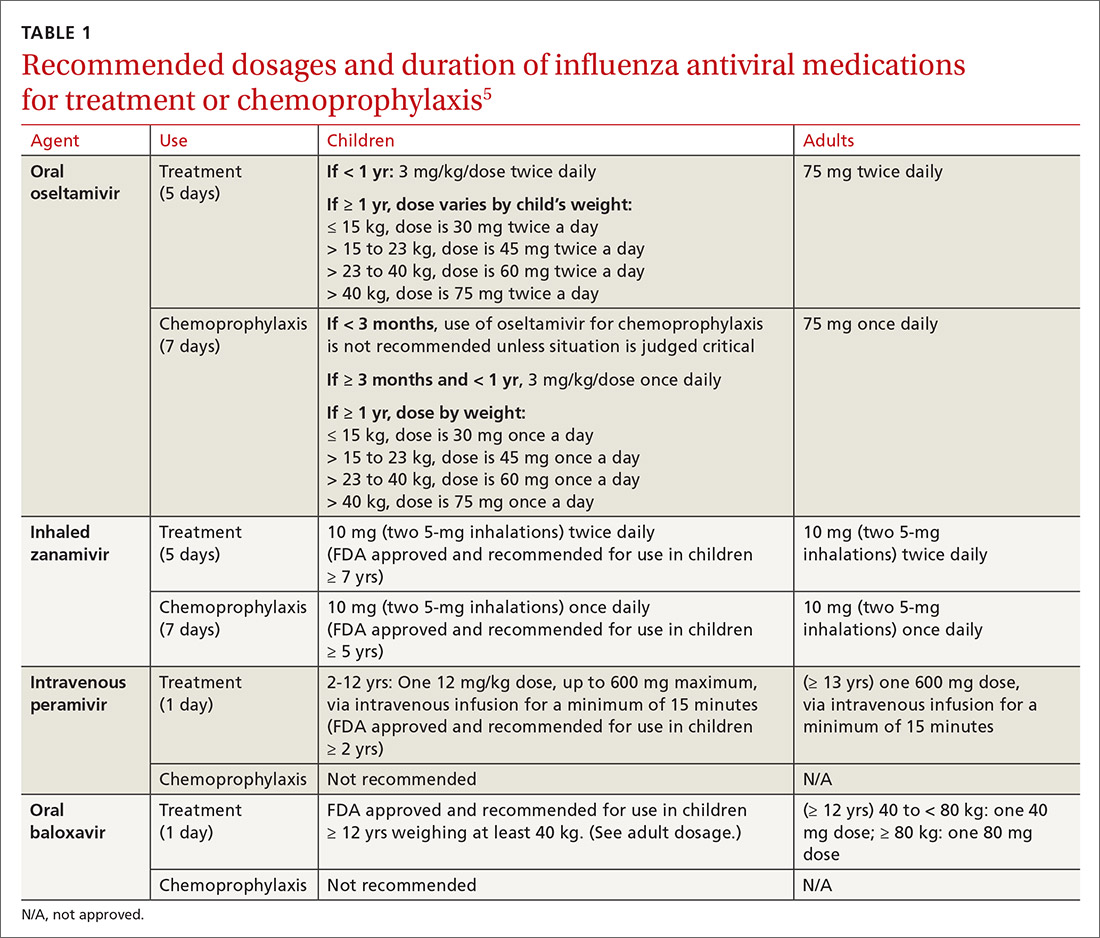

Four antiviral medications are now available for treating influenza (3 neuraminidase inhibitors and 1 endonuclease inhibitor), and there are 2 agents for preventing influenza, both neuraminidase inhibitors (TABLE 1).5 The CDC recommends treating with antivirals as soon as possible if individuals with confirmed or suspected influenza require hospitalization; have severe, complicated, or progressive illness; or are at high risk for complications. Use antivirals based on clinical judgment if previously healthy individuals do not have severe complications and are not at increased risk for complications, and only if the medication can be started within 48 hours of symptom onset.

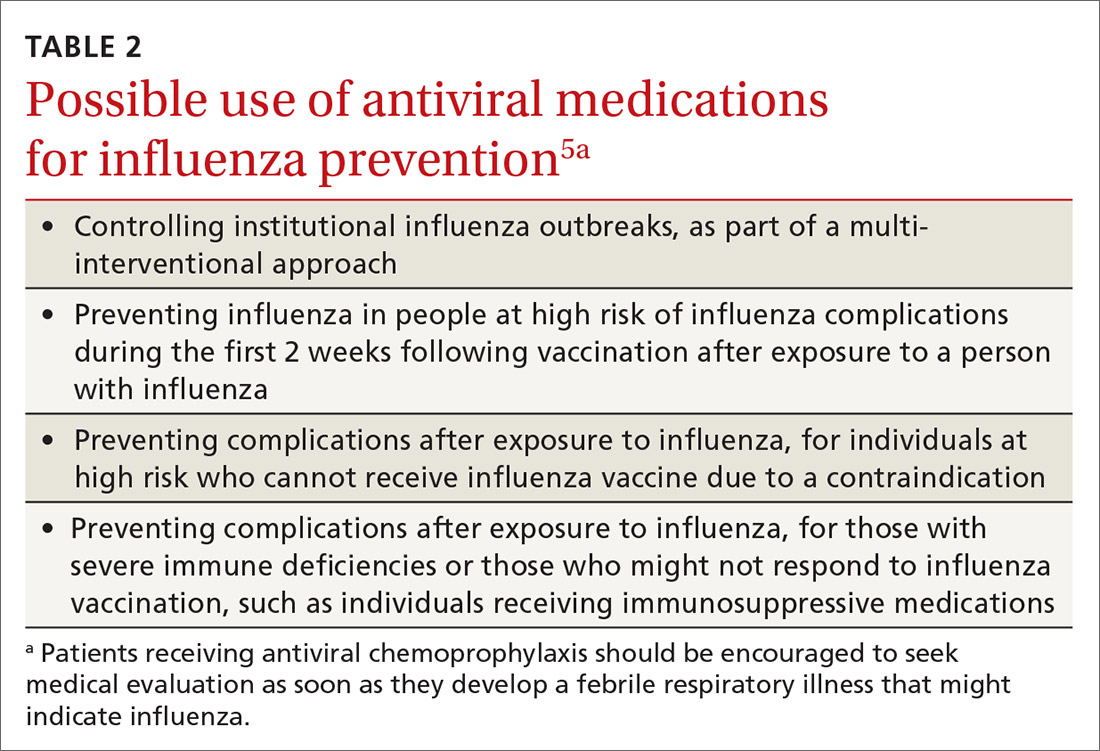

The CDC discourages widespread use of antivirals to prevent influenza, either pre- or postexposure, although it specifies certain situations in which usage would be acceptable (TABLE 2).5 There is some concern that widespread use could lead to the emergence of drug-resistant strains and that using postexposure dosing could lead to suboptimal treatment if influenza infection occurred before the start of prophylaxis. If postexposure antivirals are prescribed, they should be started within 48 hours of exposure and continued for 7 days after the last exposure.

Continue to: A potential perfect storm

A potential perfect storm: Concurrence of influenza and SARS-coV-19

While we have vaccines and antivirals to prevent influenza, and have effective antivirals for treatment, no prevention or treatment options exist for COVID-19, except, possibly, dexamethasone to reduce mortality among those seriously ill.6 The concurrence of influenza and COVID-19 will present unique challenges for the health care system.

Action steps. Keep abreast of the incidences of circulating SARS-coV-19 and influenza viruses in your community. The similar signs and symptoms of these 2 infectious agents will complicate diagnosis. Rapid, or point-of-care, tests for influenza are widely available, but their accuracy varies and not all tests detect both influenza A and B. The CDC lists approved point-of-care tests at www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/diagnosis/table-ridt.html and advises on how to interpret these test results when influenza is and is not circulating in the community, at www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/diagnosis/clinician_guidance_ridt.htm.

Clinical practice advice for both conditions should be implemented when any patient presents with ILI:7

- Most patients who are not seriously ill and have no conditions that place them at high risk for adverse outcomes can be treated symptomatically at home.

- Those with ILI should be tested for both influenza virus and SARS-CoV-2 if testing is available. It is possible to be co-infected.

- Sick patients should self-isolate at home for the duration of their symptoms.

- If others live in the house, the sick person should stay in a separate room and wear a mask. Everyone in the house should cover coughs and sneezes (if not wearing a mask), dispose of used tissues in a trash can (rather than leaving them on night stands and countertops), and wash hands frequently.

- All household members should be vaccinated against influenza. Those who are unvaccinated, and those at high risk who have been recently vaccinated, can consider influenza antiviral prophylaxis. If the sick family member is confirmed to have COVID-19, with no co-existing influenza, anti-influenza antiviral prophylaxis may be discontinued.

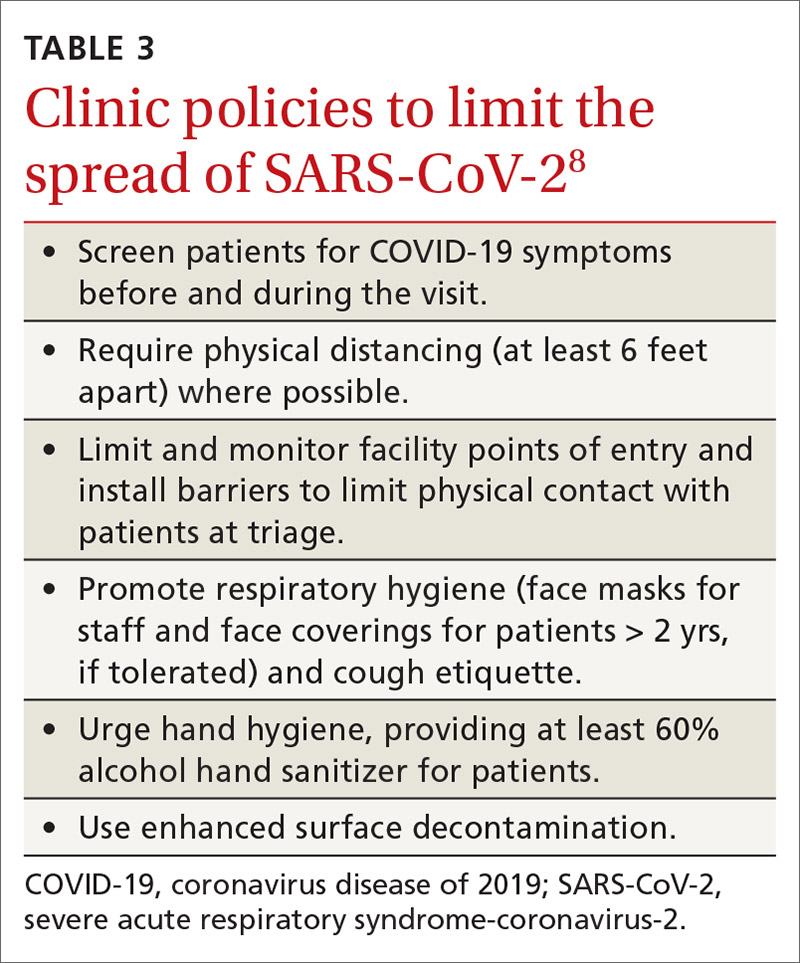

- Clinical infection control practices should be the same for anyone presenting with ILI.7 Enhanced clinic-based infection control practices to prevent spread of SARS-CoV-2 are listed in TABLE 3.8

Since there currently are no preventive medications proven to work for COVID-19, the main clinical decision physicians will have to make when a patient presents with ILI is whether to use antivirals to treat those who are at risk for complications based on the result of rapid, on-site influenza testing, or clinical presentation, or both. In this situation, knowledge of which viruses are circulating at high rates in the community could be valuable.

Milder season or perfect storm? The society-wide interventions that have been encouraged (although not mandated everywhere) to prevent community spread of SARS-CoV-2 should help prevent the community spread of influenza as well, and, if adhered to, may lead to a milder influenza season than would otherwise have occurred. However, given the uncertainties, the combination of influenza and coronavirus could present a perfect storm for the health care system and result in higher-than-normal morbidity and mortality from ILI and pneumonia overall.

Continue to: The possibility that one or more vaccines...

The possibility that one or more vaccines to prevent COVID-19 may be available in late 2020 or early 2021 offers hope. However, in current testing, the vaccine is not being given simultaneously with the influenza vaccine. If the potential for adverse interaction exists between the vaccines, it is important that influenza vaccine be given by mid- to late-October to avoid such an interaction if and when the new SARS-CoV-2 vaccine becomes available. Individuals who have symptoms of COVID-19 should not be vaccinated with influenza vaccine until they are considered noninfectious.

Encourage influenza vaccination. The COVID-19 pandemic may make it difficult to achieve desired community influenza vaccine levels because of decreased visits to medical facilities for preventive care, possible lower insurance coverage due to loss of employment, and a decrease in worksite mass vaccination programs. This makes it important for family physicians to encourage and offer influenza vaccines at their clinical sites.

Several evidence-based practices have been shown to improve vaccine uptake. Examples of such practices include patient reminder and recall systems that provide feedback to clinicians about rates of vaccination among patients, and establishing standing orders for vaccine administration that allow other health care providers to assess a patient’s immunization status and administer vaccinations according to a protocol.9 Finally, the CDC provides a video on how to recommend influenza vaccine to those who may be resistant (www.cdc.gov/vaccines/howirecommend/adult-vacc-videos.html).

SIDEBAR

CDC influenza resources

Point-of-care tests that detect both influenza A and B viruses approved by the CDC

www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/diagnosis/table-ridt.html

Advice on how to interpret the test results

www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/diagnosis/clinician_guidance_ridt.htm

How to recommend influenza vaccine to reluctant patients

www.cdc.gov/vaccines/howirecommend/adult-vacc-videos.html

CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

1. Grohskopf L. Influenza work groups: updates, considerations, and proposed recommendations for the 2020-2021 season. Presented at the ACIP meeting June 24, 2020. www.youtube.com/watch?v=W1SV2DSJsaQ&list=PLvrp9iOILTQb6D9e1YZWpbUvzfptNMKx2&index=8&t=0s. [Time stamp: 1:26:48] Accessed Septemeber 29, 2020.

2. Campos-Outcalt D. Facts to help you keep pace with the vaccine conversation. J Fam Pract. 2019;68:341-346.

3. Grohskopf L, Alyanak E, Broder KR, et al. Prevention and control of seasonal influenza with vaccines: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, 2020-21 Influenza Season. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2020;69:1-24.

4. Prevention and Control of Seasonal Influenza with Vaccines: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP)—United States, 2020-21 Summary of Recommendations. www.cdc.gov/flu/pdf/professionals/acip/acip-2020-21-summary-of-recommendations.pdf. Accessed September 29, 2020.

5. CDC. Influenza antiviral medications: summary for clinicians. www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/antivirals/summary-clinicians.htm. Accessed September 29, 2020.

6. NIH. COVID-19 treatment guidelines. Corticosteroids. www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/immune-based-therapy/immunomodulators/corticosteroids/. Accessed September 29, 2020.

7. CDC. Infection control. www.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol/. Accessed September 29, 2020.

8. CDC. Interim infection prevention and control recommendations for healthcare personnel during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/infection-control.html. Accessed September 29, 2020.

9. HHS. CPSTF findings for increasing vaccination. www.thecommunityguide.org/content/task-force-findings-increasing-vaccination. Accessed September 29, 2020.

The 2020-2021 influenza season is shaping up to be challenging. Its likely concurrence with the ongoing severe acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus 2 (SARS-coV-2) pandemic (COVID-19) will pose diagnostic and therapeutic dilemmas and could overload the hospital system. But there could also be potential synergies in preventing morbidity and mortality from each disease.

A consistent pattern overthe past few influenza seasons

During the 2019-2020 flu season, there were an estimated 410,000 to 740,000 hospitalizations and 24,000 to 62,000 deaths attributed to influenza.1 As seen in FIGURE 1, office visits for influenza-like illness (ILI) began to increase in late November and early December in each of the last 3 years (2017-2018, 2018-2019, 2019-2020) and stayed elevated above baseline for about 4 months each season.1

The effectiveness of influenza vaccine during the 2019-2020 season is being estimated using the US Flu Vaccine Effectiveness Network, which has close to 9000 enrollees. Overall, it appears the vaccine was 39% effective against medically attended influenza, with a higher effectiveness against influenza B (44%) than against A/H1N1 (31%). Effectiveness against influenza B was similar in all age groups, but effectiveness against A/H1N1 was highest for those ages 50 to 64 years (45%) and lowest for those ages 6 months through 8 years (22%), although 95% confidence intervals overlapped for all age groups (FIGURE 2). These preliminary effectiveness rates were presented at the summer meeting of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP).1

Influenza vaccine safety data for 2019-2020 were based on the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS), a passive surveillance system, and on the Vaccine Safety Datalink (VSD) system, an active surveillance system involving close to 6 million doses administered at VSD sites. No safety concerns were identified for any of the different vaccine types. Both the VAERS and VSD surveillance systems have been described in more detail in a previous Practice Alert.2

Recommendations for 2020-2021

The composition of the influenza vaccines for this year’s flu season will be different for 3 of the 4 antigens: A/H1N1, A/H2N2 and B/Victoria.3 The antigens included in the influenza vaccines each year are decided on in the spring, based on surveillance of circulating strains around the world. The effectiveness of the vaccine each year largely depends on how well the strains included in the vaccine match those circulating in the United States during the influenza season.

The main immunization recommendation for preventing morbidity and mortality from influenza has not changed: All individuals ages 6 months and older without a contraindication should receive an influenza vaccine.4 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends that patients receive the vaccine by the end of October.4 This includes the second dose for those children younger than 9 years who need 2 doses—ie, those who have received fewer than 2 doses of influenza vaccine prior to July 2020. Vaccination should continue through the end of the season for anyone who has not received a 2020-2021 influenza vaccine.

Two new influenza vaccine products are available for use in those ages 65 years and older: Fluzone high-dose quadrivalent and Fluad Quadrivalent (adjuvanted).4 Both of these products were available last year as trivalent options. Currently no specific vaccine product is listed as preferred by ACIP for those ages 65 and older.

Continue to: New vaccine contraindications

New vaccine contraindications. Four medical conditions have been added to the list of contraindications for quadrivalent live, attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV4): cochlear implant, cerebrospinal fluid leak, asplenia (anatomic and functional), and sickle cell anemia.4 In addition, those who receive LAIV4 should not be prescribed an influenza antiviral until 2 weeks after receiving the vaccine. And the vaccine should not be administered for 48 hours after receipt of oseltamivir or zanamivir, 5 days after peramivir, and 17 days after baloxavir marboxil.4 This is to prevent possible antiviral inactivation of the live attenuated influenza viruses in the vaccine.

For those who have a history of severe allergic reaction to eggs, there are now 2 egg-free options: cell-culture-based inactivated vaccine (ccIIV4) and recombinant influenza vaccine (RIV4).3,4 Urticaria alone is not considered a severe reaction. If neither of these egg-free options is available, a vaccine may still be administered in a medical setting supervised by a provider who is able to manage a severe allergic reaction (which rarely occurs).

All vaccine products available for the upcoming influenza season are listed and described on the CDC Web site, as is a summary of related recommendations.4 Particular attention should be paid to the dose of vaccine administered, as it differs by product for those ages 6 through 35 months of age and those ages 65 years and older.

Use of antiviral medications

Four antiviral medications are now available for treating influenza (3 neuraminidase inhibitors and 1 endonuclease inhibitor), and there are 2 agents for preventing influenza, both neuraminidase inhibitors (TABLE 1).5 The CDC recommends treating with antivirals as soon as possible if individuals with confirmed or suspected influenza require hospitalization; have severe, complicated, or progressive illness; or are at high risk for complications. Use antivirals based on clinical judgment if previously healthy individuals do not have severe complications and are not at increased risk for complications, and only if the medication can be started within 48 hours of symptom onset.

The CDC discourages widespread use of antivirals to prevent influenza, either pre- or postexposure, although it specifies certain situations in which usage would be acceptable (TABLE 2).5 There is some concern that widespread use could lead to the emergence of drug-resistant strains and that using postexposure dosing could lead to suboptimal treatment if influenza infection occurred before the start of prophylaxis. If postexposure antivirals are prescribed, they should be started within 48 hours of exposure and continued for 7 days after the last exposure.

Continue to: A potential perfect storm

A potential perfect storm: Concurrence of influenza and SARS-coV-19

While we have vaccines and antivirals to prevent influenza, and have effective antivirals for treatment, no prevention or treatment options exist for COVID-19, except, possibly, dexamethasone to reduce mortality among those seriously ill.6 The concurrence of influenza and COVID-19 will present unique challenges for the health care system.

Action steps. Keep abreast of the incidences of circulating SARS-coV-19 and influenza viruses in your community. The similar signs and symptoms of these 2 infectious agents will complicate diagnosis. Rapid, or point-of-care, tests for influenza are widely available, but their accuracy varies and not all tests detect both influenza A and B. The CDC lists approved point-of-care tests at www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/diagnosis/table-ridt.html and advises on how to interpret these test results when influenza is and is not circulating in the community, at www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/diagnosis/clinician_guidance_ridt.htm.

Clinical practice advice for both conditions should be implemented when any patient presents with ILI:7

- Most patients who are not seriously ill and have no conditions that place them at high risk for adverse outcomes can be treated symptomatically at home.

- Those with ILI should be tested for both influenza virus and SARS-CoV-2 if testing is available. It is possible to be co-infected.

- Sick patients should self-isolate at home for the duration of their symptoms.

- If others live in the house, the sick person should stay in a separate room and wear a mask. Everyone in the house should cover coughs and sneezes (if not wearing a mask), dispose of used tissues in a trash can (rather than leaving them on night stands and countertops), and wash hands frequently.

- All household members should be vaccinated against influenza. Those who are unvaccinated, and those at high risk who have been recently vaccinated, can consider influenza antiviral prophylaxis. If the sick family member is confirmed to have COVID-19, with no co-existing influenza, anti-influenza antiviral prophylaxis may be discontinued.

- Clinical infection control practices should be the same for anyone presenting with ILI.7 Enhanced clinic-based infection control practices to prevent spread of SARS-CoV-2 are listed in TABLE 3.8

Since there currently are no preventive medications proven to work for COVID-19, the main clinical decision physicians will have to make when a patient presents with ILI is whether to use antivirals to treat those who are at risk for complications based on the result of rapid, on-site influenza testing, or clinical presentation, or both. In this situation, knowledge of which viruses are circulating at high rates in the community could be valuable.

Milder season or perfect storm? The society-wide interventions that have been encouraged (although not mandated everywhere) to prevent community spread of SARS-CoV-2 should help prevent the community spread of influenza as well, and, if adhered to, may lead to a milder influenza season than would otherwise have occurred. However, given the uncertainties, the combination of influenza and coronavirus could present a perfect storm for the health care system and result in higher-than-normal morbidity and mortality from ILI and pneumonia overall.

Continue to: The possibility that one or more vaccines...

The possibility that one or more vaccines to prevent COVID-19 may be available in late 2020 or early 2021 offers hope. However, in current testing, the vaccine is not being given simultaneously with the influenza vaccine. If the potential for adverse interaction exists between the vaccines, it is important that influenza vaccine be given by mid- to late-October to avoid such an interaction if and when the new SARS-CoV-2 vaccine becomes available. Individuals who have symptoms of COVID-19 should not be vaccinated with influenza vaccine until they are considered noninfectious.

Encourage influenza vaccination. The COVID-19 pandemic may make it difficult to achieve desired community influenza vaccine levels because of decreased visits to medical facilities for preventive care, possible lower insurance coverage due to loss of employment, and a decrease in worksite mass vaccination programs. This makes it important for family physicians to encourage and offer influenza vaccines at their clinical sites.

Several evidence-based practices have been shown to improve vaccine uptake. Examples of such practices include patient reminder and recall systems that provide feedback to clinicians about rates of vaccination among patients, and establishing standing orders for vaccine administration that allow other health care providers to assess a patient’s immunization status and administer vaccinations according to a protocol.9 Finally, the CDC provides a video on how to recommend influenza vaccine to those who may be resistant (www.cdc.gov/vaccines/howirecommend/adult-vacc-videos.html).

SIDEBAR

CDC influenza resources

Point-of-care tests that detect both influenza A and B viruses approved by the CDC

www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/diagnosis/table-ridt.html

Advice on how to interpret the test results

www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/diagnosis/clinician_guidance_ridt.htm

How to recommend influenza vaccine to reluctant patients

www.cdc.gov/vaccines/howirecommend/adult-vacc-videos.html

CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The 2020-2021 influenza season is shaping up to be challenging. Its likely concurrence with the ongoing severe acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus 2 (SARS-coV-2) pandemic (COVID-19) will pose diagnostic and therapeutic dilemmas and could overload the hospital system. But there could also be potential synergies in preventing morbidity and mortality from each disease.

A consistent pattern overthe past few influenza seasons

During the 2019-2020 flu season, there were an estimated 410,000 to 740,000 hospitalizations and 24,000 to 62,000 deaths attributed to influenza.1 As seen in FIGURE 1, office visits for influenza-like illness (ILI) began to increase in late November and early December in each of the last 3 years (2017-2018, 2018-2019, 2019-2020) and stayed elevated above baseline for about 4 months each season.1

The effectiveness of influenza vaccine during the 2019-2020 season is being estimated using the US Flu Vaccine Effectiveness Network, which has close to 9000 enrollees. Overall, it appears the vaccine was 39% effective against medically attended influenza, with a higher effectiveness against influenza B (44%) than against A/H1N1 (31%). Effectiveness against influenza B was similar in all age groups, but effectiveness against A/H1N1 was highest for those ages 50 to 64 years (45%) and lowest for those ages 6 months through 8 years (22%), although 95% confidence intervals overlapped for all age groups (FIGURE 2). These preliminary effectiveness rates were presented at the summer meeting of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP).1

Influenza vaccine safety data for 2019-2020 were based on the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS), a passive surveillance system, and on the Vaccine Safety Datalink (VSD) system, an active surveillance system involving close to 6 million doses administered at VSD sites. No safety concerns were identified for any of the different vaccine types. Both the VAERS and VSD surveillance systems have been described in more detail in a previous Practice Alert.2

Recommendations for 2020-2021

The composition of the influenza vaccines for this year’s flu season will be different for 3 of the 4 antigens: A/H1N1, A/H2N2 and B/Victoria.3 The antigens included in the influenza vaccines each year are decided on in the spring, based on surveillance of circulating strains around the world. The effectiveness of the vaccine each year largely depends on how well the strains included in the vaccine match those circulating in the United States during the influenza season.

The main immunization recommendation for preventing morbidity and mortality from influenza has not changed: All individuals ages 6 months and older without a contraindication should receive an influenza vaccine.4 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends that patients receive the vaccine by the end of October.4 This includes the second dose for those children younger than 9 years who need 2 doses—ie, those who have received fewer than 2 doses of influenza vaccine prior to July 2020. Vaccination should continue through the end of the season for anyone who has not received a 2020-2021 influenza vaccine.

Two new influenza vaccine products are available for use in those ages 65 years and older: Fluzone high-dose quadrivalent and Fluad Quadrivalent (adjuvanted).4 Both of these products were available last year as trivalent options. Currently no specific vaccine product is listed as preferred by ACIP for those ages 65 and older.

Continue to: New vaccine contraindications

New vaccine contraindications. Four medical conditions have been added to the list of contraindications for quadrivalent live, attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV4): cochlear implant, cerebrospinal fluid leak, asplenia (anatomic and functional), and sickle cell anemia.4 In addition, those who receive LAIV4 should not be prescribed an influenza antiviral until 2 weeks after receiving the vaccine. And the vaccine should not be administered for 48 hours after receipt of oseltamivir or zanamivir, 5 days after peramivir, and 17 days after baloxavir marboxil.4 This is to prevent possible antiviral inactivation of the live attenuated influenza viruses in the vaccine.

For those who have a history of severe allergic reaction to eggs, there are now 2 egg-free options: cell-culture-based inactivated vaccine (ccIIV4) and recombinant influenza vaccine (RIV4).3,4 Urticaria alone is not considered a severe reaction. If neither of these egg-free options is available, a vaccine may still be administered in a medical setting supervised by a provider who is able to manage a severe allergic reaction (which rarely occurs).

All vaccine products available for the upcoming influenza season are listed and described on the CDC Web site, as is a summary of related recommendations.4 Particular attention should be paid to the dose of vaccine administered, as it differs by product for those ages 6 through 35 months of age and those ages 65 years and older.

Use of antiviral medications

Four antiviral medications are now available for treating influenza (3 neuraminidase inhibitors and 1 endonuclease inhibitor), and there are 2 agents for preventing influenza, both neuraminidase inhibitors (TABLE 1).5 The CDC recommends treating with antivirals as soon as possible if individuals with confirmed or suspected influenza require hospitalization; have severe, complicated, or progressive illness; or are at high risk for complications. Use antivirals based on clinical judgment if previously healthy individuals do not have severe complications and are not at increased risk for complications, and only if the medication can be started within 48 hours of symptom onset.

The CDC discourages widespread use of antivirals to prevent influenza, either pre- or postexposure, although it specifies certain situations in which usage would be acceptable (TABLE 2).5 There is some concern that widespread use could lead to the emergence of drug-resistant strains and that using postexposure dosing could lead to suboptimal treatment if influenza infection occurred before the start of prophylaxis. If postexposure antivirals are prescribed, they should be started within 48 hours of exposure and continued for 7 days after the last exposure.

Continue to: A potential perfect storm

A potential perfect storm: Concurrence of influenza and SARS-coV-19

While we have vaccines and antivirals to prevent influenza, and have effective antivirals for treatment, no prevention or treatment options exist for COVID-19, except, possibly, dexamethasone to reduce mortality among those seriously ill.6 The concurrence of influenza and COVID-19 will present unique challenges for the health care system.

Action steps. Keep abreast of the incidences of circulating SARS-coV-19 and influenza viruses in your community. The similar signs and symptoms of these 2 infectious agents will complicate diagnosis. Rapid, or point-of-care, tests for influenza are widely available, but their accuracy varies and not all tests detect both influenza A and B. The CDC lists approved point-of-care tests at www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/diagnosis/table-ridt.html and advises on how to interpret these test results when influenza is and is not circulating in the community, at www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/diagnosis/clinician_guidance_ridt.htm.

Clinical practice advice for both conditions should be implemented when any patient presents with ILI:7

- Most patients who are not seriously ill and have no conditions that place them at high risk for adverse outcomes can be treated symptomatically at home.

- Those with ILI should be tested for both influenza virus and SARS-CoV-2 if testing is available. It is possible to be co-infected.

- Sick patients should self-isolate at home for the duration of their symptoms.

- If others live in the house, the sick person should stay in a separate room and wear a mask. Everyone in the house should cover coughs and sneezes (if not wearing a mask), dispose of used tissues in a trash can (rather than leaving them on night stands and countertops), and wash hands frequently.

- All household members should be vaccinated against influenza. Those who are unvaccinated, and those at high risk who have been recently vaccinated, can consider influenza antiviral prophylaxis. If the sick family member is confirmed to have COVID-19, with no co-existing influenza, anti-influenza antiviral prophylaxis may be discontinued.

- Clinical infection control practices should be the same for anyone presenting with ILI.7 Enhanced clinic-based infection control practices to prevent spread of SARS-CoV-2 are listed in TABLE 3.8

Since there currently are no preventive medications proven to work for COVID-19, the main clinical decision physicians will have to make when a patient presents with ILI is whether to use antivirals to treat those who are at risk for complications based on the result of rapid, on-site influenza testing, or clinical presentation, or both. In this situation, knowledge of which viruses are circulating at high rates in the community could be valuable.

Milder season or perfect storm? The society-wide interventions that have been encouraged (although not mandated everywhere) to prevent community spread of SARS-CoV-2 should help prevent the community spread of influenza as well, and, if adhered to, may lead to a milder influenza season than would otherwise have occurred. However, given the uncertainties, the combination of influenza and coronavirus could present a perfect storm for the health care system and result in higher-than-normal morbidity and mortality from ILI and pneumonia overall.

Continue to: The possibility that one or more vaccines...

The possibility that one or more vaccines to prevent COVID-19 may be available in late 2020 or early 2021 offers hope. However, in current testing, the vaccine is not being given simultaneously with the influenza vaccine. If the potential for adverse interaction exists between the vaccines, it is important that influenza vaccine be given by mid- to late-October to avoid such an interaction if and when the new SARS-CoV-2 vaccine becomes available. Individuals who have symptoms of COVID-19 should not be vaccinated with influenza vaccine until they are considered noninfectious.

Encourage influenza vaccination. The COVID-19 pandemic may make it difficult to achieve desired community influenza vaccine levels because of decreased visits to medical facilities for preventive care, possible lower insurance coverage due to loss of employment, and a decrease in worksite mass vaccination programs. This makes it important for family physicians to encourage and offer influenza vaccines at their clinical sites.

Several evidence-based practices have been shown to improve vaccine uptake. Examples of such practices include patient reminder and recall systems that provide feedback to clinicians about rates of vaccination among patients, and establishing standing orders for vaccine administration that allow other health care providers to assess a patient’s immunization status and administer vaccinations according to a protocol.9 Finally, the CDC provides a video on how to recommend influenza vaccine to those who may be resistant (www.cdc.gov/vaccines/howirecommend/adult-vacc-videos.html).

SIDEBAR

CDC influenza resources

Point-of-care tests that detect both influenza A and B viruses approved by the CDC

www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/diagnosis/table-ridt.html

Advice on how to interpret the test results

www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/diagnosis/clinician_guidance_ridt.htm

How to recommend influenza vaccine to reluctant patients

www.cdc.gov/vaccines/howirecommend/adult-vacc-videos.html

CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

1. Grohskopf L. Influenza work groups: updates, considerations, and proposed recommendations for the 2020-2021 season. Presented at the ACIP meeting June 24, 2020. www.youtube.com/watch?v=W1SV2DSJsaQ&list=PLvrp9iOILTQb6D9e1YZWpbUvzfptNMKx2&index=8&t=0s. [Time stamp: 1:26:48] Accessed Septemeber 29, 2020.

2. Campos-Outcalt D. Facts to help you keep pace with the vaccine conversation. J Fam Pract. 2019;68:341-346.

3. Grohskopf L, Alyanak E, Broder KR, et al. Prevention and control of seasonal influenza with vaccines: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, 2020-21 Influenza Season. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2020;69:1-24.

4. Prevention and Control of Seasonal Influenza with Vaccines: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP)—United States, 2020-21 Summary of Recommendations. www.cdc.gov/flu/pdf/professionals/acip/acip-2020-21-summary-of-recommendations.pdf. Accessed September 29, 2020.

5. CDC. Influenza antiviral medications: summary for clinicians. www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/antivirals/summary-clinicians.htm. Accessed September 29, 2020.

6. NIH. COVID-19 treatment guidelines. Corticosteroids. www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/immune-based-therapy/immunomodulators/corticosteroids/. Accessed September 29, 2020.

7. CDC. Infection control. www.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol/. Accessed September 29, 2020.

8. CDC. Interim infection prevention and control recommendations for healthcare personnel during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/infection-control.html. Accessed September 29, 2020.

9. HHS. CPSTF findings for increasing vaccination. www.thecommunityguide.org/content/task-force-findings-increasing-vaccination. Accessed September 29, 2020.

1. Grohskopf L. Influenza work groups: updates, considerations, and proposed recommendations for the 2020-2021 season. Presented at the ACIP meeting June 24, 2020. www.youtube.com/watch?v=W1SV2DSJsaQ&list=PLvrp9iOILTQb6D9e1YZWpbUvzfptNMKx2&index=8&t=0s. [Time stamp: 1:26:48] Accessed Septemeber 29, 2020.

2. Campos-Outcalt D. Facts to help you keep pace with the vaccine conversation. J Fam Pract. 2019;68:341-346.

3. Grohskopf L, Alyanak E, Broder KR, et al. Prevention and control of seasonal influenza with vaccines: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, 2020-21 Influenza Season. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2020;69:1-24.

4. Prevention and Control of Seasonal Influenza with Vaccines: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP)—United States, 2020-21 Summary of Recommendations. www.cdc.gov/flu/pdf/professionals/acip/acip-2020-21-summary-of-recommendations.pdf. Accessed September 29, 2020.

5. CDC. Influenza antiviral medications: summary for clinicians. www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/antivirals/summary-clinicians.htm. Accessed September 29, 2020.

6. NIH. COVID-19 treatment guidelines. Corticosteroids. www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/immune-based-therapy/immunomodulators/corticosteroids/. Accessed September 29, 2020.

7. CDC. Infection control. www.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol/. Accessed September 29, 2020.

8. CDC. Interim infection prevention and control recommendations for healthcare personnel during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/infection-control.html. Accessed September 29, 2020.

9. HHS. CPSTF findings for increasing vaccination. www.thecommunityguide.org/content/task-force-findings-increasing-vaccination. Accessed September 29, 2020.

Choosing Wisely: 10 practices to stop—or adopt—to reduce overuse in health care

When medical care is based on consistent, good-quality evidence, most physicians adopt it. However, not all care is well supported by the literature and may, in fact, be overused without offering benefit to patients. Choosing Wisely, at www.choosingwisely.org, is a health care initiative that highlights screening and testing recommendations from specialty societies in an effort to encourage patients and clinicians to talk about how to make high-value, effective health care decisions and avoid overuse. (See “Test and Tx overutilization: A bigger problem than you might think"1-3).

SIDEBAR

Test and Tx overutilization: A bigger problem than you might think

Care that isn’t backed up by the medical literature is adopted by some physicians and not adopted by others, leading to practice variations. Some variation is to be expected, since no 2 patients require exactly the same care, but substantial variations may be a clue to overuse.

A 2006 analysis of inpatient lab studies found that doctors ordered an average of 2.96 studies per patient per day, but only 29% of these tests (0.95 test/patient/day) contributed to management.1 A 2016 systematic review found more than 800 studies on overuse were published in a single year.2 One study of thyroid nodules followed almost 1000 patients with nodules as they underwent routine follow-up imaging. At the end of the study, 7 were found to have cancer, but of those, only 3 had enlarging or changing nodules that would have been detected with the follow-up imaging being studied. Three of the cancers were stable in size and 1 was found incidentally.3

Enabling physician and patient dialogue. The initiative began in 2010 when the American Board of Internal Medicine convened a panel of experts to identify low-value tests and therapies. Their list took the form of a “Top Five Things” that may not be high value in patient care, and it used language tailored to patients and physicians so that they could converse meaningfully. Physicians could use the evidence to make a clinical decision, and patients could feel empowered to ask informed questions about recommendations they received. The initiative has now expanded to include ways that health care systems can reduce low-value interventions.

Scope of participation. Since the first Choosing Wisely recommendations were published in 2013, more than 80 professional associations have contributed lists of their own. Professional societies participate voluntarily. The American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP), Society of General Internal Medicine, and American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) have contributed lists relevant to primary care. All Choosing Wisely recommendations can be searched or sorted by specialty organization. Recommendations are reviewed and revised regularly. If the evidence becomes conflicted or contradictory, recommendations are withdrawn.

Making meaningful improvements by Choosing Wisely

Several studies have shown that health care systems can implement Choosing Wisely recommendations to reduce overuse of unnecessary tests. A 2015 study examined the effect of applying a Choosing Wisely recommendation to reduce the use of continuous pulse oximetry in pediatric inpatients with asthma, wheezing, or bronchiolitis. The recommendation, from the Society of Hospital Medicine–Pediatric Hospital Medicine, advises against continuous pulse oximetry in children with acute respiratory illnesses unless the child is using supplemental oxygen.4 This study, done at the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, found that within 3 months of initiating a protocol on all general pediatrics floors, the average time on pulse oximetry after meeting clinical goals decreased from 10.7 hours to 3.1 hours. In addition, the percentage of patients who had their continuous pulse oximetry stopped within 2 hours of clinical stability (a goal time) increased from 25% to 46%.5

Patients are important drivers of health care utilization. A 2003 study showed that physicians are more likely to order referrals, tests, and prescriptions when patients ask for them, and that nearly 1 in 4 patients did so.6 A 2002 study found that physicians granted all but 3% of patient’s requests for orders or tests, and that fulfilling requests correlated with patient satisfaction in the specialty office studied (cardiology) but not in the primary care (internal medicine) office.7

From its inception, Choosing Wisely has considered patients as full partners in conversations about health care utilization. Choosing Wisely partners with Consumer Reports to create and disseminate plain-language summaries of recommendations. Community groups and physician organizations have also participated in implementation efforts. In 2018, Choosing Wisely secured a grant to expand outreach to diverse or underserved communities.

Choosing Wisely recommendations are not guidelines or mandates. They are intended to be evidence-based advice from a specialty society to its members and to patients about care that is often unnecessary. The goal is to create a conversation and not to eliminate these services from ever being offered or used.

Continue to: Improve your practice with these 10 primary care recommendations

Improve your practice with these 10 primary care recommendations

1 Avoid imaging studies in early acute low back pain without red flags.

Both the AAFP and the American Society of Anesthesiologists recommend against routine X-rays, magnetic resonance imaging, and computed tomography (CT) scans in the first 6 weeks of acute low back pain (LBP).8,9 The American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) recommends against routine lumbar spine imaging for emergency department (ED) patients.10 In all cases, imaging is indicated if the patient has any signs or symptoms of neurologic deficits or other indications, such as signs of spinal infection or fracture. However, as ACEP notes, diagnostic imaging does not typically help identify the cause of acute LBP, and when it does, it does not reduce the time to symptom improvement.10

2 Prescribe oral contraceptives on the basis of a medical history and a blood pressure measurement. No routine pelvic exam or other physical exam is necessary.

This AAFP recommendation11 is based on clinical practice guidelines from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and other research.12 The ACOG practice guideline supports provision of hormonal contraception without a pelvic exam, cervical cancer (Pap) testing, urine pregnancy testing, or testing for sexually transmitted infections. ACOG guidelines also support over-the-counter provision of hormonal contraceptives, including combined oral contraceptives.12

3 Stop recommending daily self-glucose monitoring for patients with diabetes who are not using insulin.

Both the AAFP and the Society for General Internal Medicine recommend against daily blood sugar checks for people who do not use insulin.13,14 A Cochrane review of 9 trials (3300 patients) found that after 6 months, hemoglobin A1C was reduced by 0.3% in people who checked their sugar daily compared with those who did not, but this difference was not significant after a year.15 Hypoglycemic episodes were more common in the “checking” group, and there were no differences in quality of life. A qualitative study found that blood sugar results had little impact on patients’ motivation to change behavior.16

4 Don’t screen for herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection in asymptomatic adults, even those who are pregnant.

This AAFP recommendation17 comes from a US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) Grade D recommendation.18 Most people with positive HSV-2 serology have had an outbreak; even those who do not think they have had one will realize that they had the symptoms once they hear them described.18 With available tests, 1 in 2 positive results for HSV-2 among asymptomatic people will be a false-positive.18

There is no known cure, intervention, or reduction in transmission for infected patients who do not have symptoms.18 Also, serologically detected HSV-2 does not reliably predict genital herpes; and HSV-1 has been found to cause an increasing percentage of genital infection cases.18

Continue to: 5 Don't screen for testicular cancer in asymptomatic individuals

5 Don’t screen for testicular cancer in asymptomatic individuals.

This AAFP recommendation19 also comes from a USPSTF Grade D recommendation.20 A 2010 systematic review found no evidence to support screening of asymptomatic people with a physical exam or ultrasound. All available studies involved symptomatic patients.20

6 Stop recommending cough and cold medicines for children younger than 4 years.

The AAP recommends that clinicians discourage the use of any cough or cold medicine for children in this age-group.21 A 2008 study found that more than 7000 children annually presented to EDs for adverse events from cough and cold medicines.22 Previous studies found no benefit in reducing symptoms.23 In children older than 12 months, a Cochrane review found that honey has a modest benefit for cough in single-night trials.24

7 Avoid performing serum allergy panels.

The American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology discourages the use of serum panel testing when patients present with allergy symptoms.25 A patient can have a strong positive immunoglobulin E (IgE) serum result to an allergen and have no clinical allergic symptoms or can have a weak positive serum result and a strong clinical reaction. Targeted skin or serum IgE testing—for example, testing for cashew allergy in a patient known to have had a reaction after eating one—is reasonable.26

8 Avoid routine electroencephalography (EEG), head CT, and carotid ultrasound as initial work-up for simple syncope in adults.

These recommendations, from the American Epilepsy Society,27 ACEP,28 American College of Physicians,29 and American Academy of Neurology (AAN),30 emphasize the low yield of routine work-ups for patients with simple syncope. The AAN notes that 40% of people will experience syncope during adulthood and most will not have carotid disease, which generally manifests with stroke-like symptoms rather than syncope. One study found that approximately 1 in 8 patients referred to an epilepsy clinic had neurocardiogenic syncope rather than epilepsy.31

EEGs have high false-negative and false-positive rates, and history-taking is a better tool with which to make a diagnosis. CT scans performed in the ED were found to contribute to the diagnosis of simple syncope in fewer than 2% of cases of syncope, compared with orthostatic blood pressure (25% of cases).32

Continue to: 9 Wait to refer children with umbilical hernias to pediatric surgery until they are 4 to 5 years of age

9 Wait to refer children with umbilical hernias to pediatric surgery until they are 4 to 5 years of age.

The AAP Section on Surgery offers evidence that the risk-benefit analysis strongly favors waiting on intervention.33 About 1 in 4 children will have an umbilical hernia, and about 85% of cases will resolve by age 5. The strangulation rate with umbilical hernias is very low, and although the risk of infection with surgery is likewise low, the risk of recurrence following surgery before the age of 4 is as high as 2.4%.34 The AAP Section on Surgery recommends against strapping or restraining the hernia, as well.

10 Avoid using appetite stimulants, such as megesterol, and high-calorie nutritional supplements to treat anorexia and cachexia in older adults.

Instead, the American Geriatrics Society recommends that physicians encourage caregivers to serve appealing food, provide support with eating, and remove barriers to appetite and nutrition.35 A Cochrane review showed that high-calorie supplements, such as Boost or Ensure, are associated with very modest weight gain—about 2% of weight—but are not associated with an increased life expectancy or improved quality of life.36

Prescription appetite stimulants are associated with adverse effects and yield inconsistent benefits in older adults. Megesterol, for example, was associated with headache, gastrointestinal adverse effects, insomnia, weakness, and fatigue. Mirtazapine is associated with sedation and fatigue.37

CORRESPONDENCE

Kathleen Rowland, MD, MS, Rush Copley Family Medicine Residency, Rush Medical College, 600 South Paulina, Kidston House Room 605, Chicago IL 60612; kathleen_rowland@rush.edu.

1. Miyakis S, Karamanof G, Liontos M, et al. Factors contributing to inappropriate ordering of tests in an academic medical department and the effect of an educational feedback strategy. Postgrad Med J. 2006;82:823-829.

2. Morgan DJ, Dhruva SS, Wright SM, et al. Update on medical overuse: a systematic review. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176:1687-1692.

3. Durante C, Costante G, Lucisano G, et al. The natural history of benign thyroid nodules. JAMA. 2015;313:926-935.

4. Choosing Wisely. Society of Hospital Medicine—Pediatric hospital medicine. Don’t use continuous pulse oximetry routinely in children with acute respiratory illness unless they are on supplemental oxygen. www.choosingwisely.org/clinician-lists/society-hospital-medicine-pediatric-continuous-pulse-oximetry-in-children-with-acute-respiratory-illness/. Accessed September 28, 2020.

5. Schondelmeyer AC, Simmons JM, Statile AM, et al. Using quality improvement to reduce continuous pulse oximetry use in children with wheezing. Pediatrics. 2015;135:e1044-e1051.

6. Kravitz RL, Bell RA, Azari R, et al. Direct observation of requests for clinical services in office practice: what do patients want and do they get it? Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:1673-1681.

7. Kravitz RL, Bell RA, Franz CE, et al. Characterizing patient requests and physician responses in office practice. Health Serv Res. 2002;37:217-238.

8. Choosing Wisely. American Academy of Family Physicians. Don’t do imaging for low back pain within the first six weeks, unless red flags are present. www.choosingwisely.org/clinician-lists/american-academy-family-physicians-imaging-low-back-pain/. Accessed September 28, 2020.

9. Choosing Wisely. American Society of Anesthesiologists–Pain Medicine. Avoid imaging studies (MRI, CT or X-rays) for acute low back pain without specific indications. www.choosingwisely.org/clinician-lists/american-society-anesthesiologists-imaging-studies-for-acute-low-back-pain/. Accessed September 28, 2020.

10. Choosing Wisely. American College of Emergency Physicians. Avoid lumbar spine imaging in the emergency department for adults with non-traumatic back pain unless the patient has severe or progressive neurologic deficits or is suspected of having a serious underlying condition (such as vertebral infection, cauda equina syndrome, or cancer with bony metastasis). www.choosingwisely.org/clinician-lists/acep-lumbar-spine-imaging-in-the-ed/. Accessed September 28, 2020.

11. Choosing Wisely. American Academy of Family Physicians. Don’t require a pelvic exam or other physical exam to prescribe oral contraceptive medications. www.choosingwisely.org/clinician-lists/american-academy-family-physicians-pelvic-or-physical-exams-to-prescribe-oral-contraceptives/. Accessed September 28, 2020.

12. Over-the-counter access to hormonal contraception. ACOG Committee Opinion, Number 788. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;134:e96-e105. https://journals.lww.com/greenjournal/Fulltext/2019/10000/Over_the_Counter_Access_to_Hormonal_Contraception_.46.aspx. Accessed September 28, 2020.

13. Choosing Wisely. American Academy of Family Physicians. Don’t routinely recommend daily home glucose monitoring for patients who have Type 2 diabetes mellitus and are not using insulin. www.choosingwisely.org/clinician-lists/aafp-daily-home-glucose-monitoring-for-patients-with-type-2-diabetes. Accessed September 28, 2020.

14. Choosing Wisely. Society of General Internal Medicine. Don’t recommend daily home finger glucose testing in patients with Type 2 diabetes mellitus not using insulin. www.choosingwisely.org/clinician-lists/society-general-internal-medicine-daily-home-finger-glucose-testing-type-2-diabetes-mellitus/. Accessed September 28, 2020.

15. Malanda UL, Welschen LM, Riphagen II, et al. Self‐monitoring of blood glucose in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus who are not using insulin. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012(1):CD005060.

16. Peel E, Douglas M, Lawton J. Self monitoring of blood glucose in type 2 diabetes: longitudinal qualitative study of patients’ perspectives. BMJ. 2007;335:493.

17. Choosing Wisely. American Academy of Family Physicians. Don’t screen for genital herpes simplex virus infection (HSV) in asymptomatic adults, including pregnant women. www.choosingwisely.org/clinician-lists/aafp-genital-herpes-screening-in-asymptomatic-adults/. Accessed September 28, 2020.

18. Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, Curry SJ, et al. Serologic screening for genital herpes infection: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2016;316:2525-2530.

19. Choosing Wisely. American Academy of Family Physicians. Don’t screen for testicular cancer in asymptomatic adolescent and adult males. www.choosingwisely.org/clinician-lists/aafp-testicular-cancer-screening-in-asymptomatic-adolescent-and-adult-men/. Accessed September 28, 2020.

20. Lin K, Sharangpani R. Screening for testicular cancer: an evidence review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153:396-399.

21. Choosing Wisely. American Academy of Pediatrics. Cough and cold medicines should not be prescribed, recommended or used for respiratory illnesses in young children. www.choosingwisely.org/clinician-lists/american-academy-pediatrics-cough-and-cold-medicines-for-children-under-four/. Accessed September 28, 2020.

22. Schaefer MK, Shehab N, Cohen AL, et al. Adverse events from cough and cold medications in children. Pediatrics. 2008;121:783-787.

23. Carr BC. Efficacy, abuse, and toxicity of over-the-counter cough and cold medicines in the pediatric population. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2006;18:184-188.

24. Oduwole O, Udoh EE, Oyo‐Ita A, et al. Honey for acute cough in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018(4):CD007094.

25. Choosing Wisely. American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology. Don’t perform unproven diagnostic tests, such as immunoglobulin G(lgG) testing or an indiscriminate battery of immunoglobulin E(lgE) tests, in the evaluation of allergy. www.choosingwisely.org/clinician-lists/american-academy-allergy-asthma-immunology-diagnostic-tests-for-allergy-evaluation/. Accessed September 28, 2020.

26. Cox L, Williams B, Sicherer S, et al. Pearls and pitfalls of allergy diagnostic testing: report from the American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology Specific IgE Test Task Force. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2008;101:580-592.

27. Choosing Wisely. American Epilepsy Society. Do not routinely order electroencephalogram (EEG) as part of initial syncope work-up. www.choosingwisely.org/clinician-lists/aes-eeg-as-part-of-initial-syncope-work-up/. Accessed September 28, 2020.

28. Choosing Wisely. American College of Emergency Physicians. Avoid CT of the head in asymptomatic adult patients in the emergency department with syncope, insignificant trauma and a normal neurological evaluation. www.choosingwisely.org/clinician-lists/acep-avoid-head-ct-for-asymptomatic-adults-with-syncope/. Accessed September 28, 2020.

29. Choosing Wisely. American College of Physicians. In the evaluation of simple syncope and a normal neurological examination, don’t obtain brain imaging studies (CT or MRI). www.choosingwisely.org/clinician-lists/american-college-physicians-brain-imaging-to-evaluate-simple-syncope/. Accessed September 28, 2020.

30. Choosing Wisely. American Academy of Neurology. Don’t perform imaging of the carotid arteries for simple syncope without other neurologic symptoms. www.choosingwisely.org/clinician-lists/american-academy-neurology-carotid-artery-imaging-for-simple-syncope/. Accessed September 28, 2020.

31. Josephson CB, Rahey S, Sadler RM. Neurocardiogenic syncope: frequency and consequences of its misdiagnosis as epilepsy. Can J Neurol Sci. 2007;34:221-224.

32. Mendu ML, McAvay G, Lampert R, et al. Yield of diagnostic tests in evaluating syncopal episodes in older patients. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:1299-1305.

33. Choosing Wisely. American Academy of Pediatrics–Section on Surgery. Avoid referring most children with umbilical hernias to a pediatric surgeon until around age 4-5 years. www.choosingwisely.org/clinician-lists/aap-sosu-avoid-surgery-referral-for-umbilical-hernias-until-age-4-5/. Accessed September 28, 2020.

34. Antonoff MB, Kreykes NS, Saltzman DA, et al. American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Surgery hernia survey revisited. J Pediatr Surg. 2005;40:1009-1014.