User login

Arthritis drugs ‘impressive’ for severe COVID but not ‘magic cure’

New findings suggest that monoclonal antibodies used to treat RA could improve severe COVID-19 outcomes, including risk for death.

Given within 24 hours of critical illness, tocilizumab (Actemra) was associated with a median of 10 days free of respiratory and cardiovascular support up to day 21, the primary outcome. Similarly, sarilumab (Kevzara) was linked to a median of 11 days. In contrast, the usual care control group experienced zero such days in the hospital.

However, the Randomized, Embedded, Multifactorial Adaptive Platform Trial for Community-Acquired Pneumonia (REMAP-CAP) trial comes with a caveat. The preprint findings have not yet been peer reviewed and “should not be used to guide clinical practice,” the authors stated.

The results were published online Jan. 7 in MedRxiv.

Nevertheless, the trial also revealed a mortality benefit associated with the two interleukin-6 antagonists. The hospital mortality rate was 22% with sarilumab, 28% with tocilizumab, and almost 36% with usual care.

“That’s a big change in survival. They are both lifesaving drugs,” lead coinvestigator Anthony Gordon, an Imperial College London professor of anesthesia and critical care, commented in a recent story by Reuters.

Consider the big picture

“What I think is important is ... this is one of many trials,” Paul Auwaerter, MD, MBA, said in an interview. Many other studies looking at monoclonal antibody therapy for people with COVID-19 were halted because they did not show improvement.

One exception is the EMPACTA trial, which suggested that tocilizumab was effective if given before a person becomes ill enough to be placed on a ventilator, said Dr. Auwaerter, clinical director of the division of infectious diseases at Johns Hopkins Medicine and a contributor to this news organization. “It appeared to reduce the need for mechanical ventilation or death.”

“These two trials are the first randomized, prospective trials that show a benefit on a background of others which have not,” Dr. Auwaerter added.

Interim findings

The REMAP-CAP investigators randomly assigned adults within 24 hours of critical care for COVID-19 to 8 mg/kg tocilizumab, 400 mg sarilumab, or usual care at 113 sites in six countries. There were 353 participants in the tocilizumab arm, 48 in the sarilumab group, and 402 in the control group.

Compared with the control group, the 10 days free of organ support in the tocilizumab cohort was associated with an adjusted odds ratio of 1.64 (95% confidence interval, 1.25-2.14). The 11 days free of organ support in the sarilumab cohort was likewise superior to control (adjusted odds ratio, 1.76; 95% CI, 1.17-2.91).

“All secondary outcomes and analyses supported efficacy of these IL-6 receptor antagonists,” the authors note. These endpoints included 90-day survival, time to intensive care unit discharge, and hospital discharge.

Cautious optimism?

“The results were quite impressive – having 10 or 11 fewer days in the ICU, compared to standard of care,” Deepa Gotur, MD, said in an interview. “Choosing the right patient population and providing the anti-IL-6 treatment at the right time would be the key here.”

In addition to not yet receiving peer review, an open-label design, a relatively short follow-up of 21 days, and steroids becoming standard of care about halfway through the trial are potential limitations, said Dr. Gotur, an intensivist at Houston Methodist Hospital and associate professor of clinical medicine at Weill Cornell Medicine, New York.

“This is an interesting study,” Carl J. Fichtenbaum, MD, professor of clinical medicine at the University of Cincinnati, said in a comment.

Additional detail on how many participants in each group received steroids is warranted, Dr. Fichtenbaum said. “The analysis did not carefully adjust for the use of steroids that might have influenced outcomes.”

Dr. Fichtenbaum said it’s important to look at what is distinctive about REMAP-CAP because “there are several other studies showing opposite results.”

Dr. Gotur was an investigator on a previous study evaluating tocilizumab for patients already on mechanical ventilation. “One of the key differences between this and other studies is that they included more of the ICU population,” she said. “They also included patients within 24 hours of requiring organ support, cardiac, as well as respiratory support.” Some other research included less-acute patients, including all comers into the ED who required oxygen and received tocilizumab.

The prior studies also evaluated cytokine or inflammatory markers. In contrast, REMAP-CAP researchers “looked at organ failure itself ... which I think makes sense,” Dr. Gotur said.

Cytokine release syndrome can cause organ damage or organ failure, she added, “but these markers are all over the place. I’ve seen patients who are very, very sick despite having a low [C-reactive protein] or IL-6 level.”

Backing from the British

Citing the combined 24% decrease in the risk for death associated with these agents in the REMAP-CAP trial, the U.K. government announced Jan. 7 it will work to make tocilizumab and sarilumab available to citizens with severe COVID-19.

Experts in the United Kingdom shared their perspectives on the REMAP-CAP interim findings through the U.K. Science Media Centre.

“There are few treatments for severe COVID-19,” said Robin Ferner, MD, honorary professor of clinical pharmacology at the University of Birmingham (England) and honorary consultant physician at City Hospital Birmingham. “If the published data from REMAP-CAP are supported by further studies, this suggests that two IL-6 receptor antagonists can reduce the death rate in the most severely ill patients.”

Dr. Ferner added that the findings are not a “magic cure,” however. He pointed out that of 401 patients given the drugs, 109 died, and with standard treatment, 144 out of 402 died.

Peter Horby, MD, PhD, was more optimistic. “It is great to see a positive result at a time that we really need good news and more tools to fight COVID. This is great achievement for REMAP-CAP,” he said.

“We hope to soon have results from RECOVERY on the effect of tocilizumab in less severely ill patients in the hospital,” said Dr. Horby, cochief investigator of the RECOVERY trial and professor of emerging infectious diseases at the Centre for Tropical Medicine and Global Health at the University of Oxford (England).

Stephen Evans, BA, MSc, FRCP, professor of pharmacoepidemiology at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, said, “This is a high-quality trial, and although published as a preprint, is of much higher quality than many non–peer-reviewed papers.”

Dr. Evans also noted the addition of steroid therapy for many participants. “Partway through the trial, the RECOVERY trial findings showed that the corticosteroid drug dexamethasone had notable mortality benefits. Consequently, quite a number of the patients in this trial had also received a corticosteroid.”

“It does look as though these drugs give some additional benefit beyond that given by dexamethasone,” he added.

Awaiting peer review

“We need to wait for the final results and ensure it was adequately powered with enough observations to make us confident in the results,” Dr. Fichtenbaum said.

“We in the United States have to step back and look at the entire set of studies and also, for this particular one, REMAP-CAP, to be in a peer-reviewed publication,” Dr. Auwaerter said. Preprints are often released “in the setting of the pandemic, where there may be important findings, especially if they impact mortality or severity of illness.”

“We need to make sure these findings, as outlined, hold up,” he said.

In the meantime, Dr. Auwaerter added, “Exactly how this will fit in is unclear. But it’s important to me as another potential drug that can help our critically ill patients.”

The REMAP-CAP study is ongoing and updated results will be provided online.

Dr. Auwaerter disclosed that he is a consultant for EMD Serono and a member of the data monitoring safety board for Humanigen. Dr. Gotur, Dr. Fichtenbaum, Dr. Ferner, and Dr. Evans disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Horby reported that Oxford University receives funding for the RECOVERY trial from U.K. Research and Innovation and the National Institute for Health Research. Roche Products and Sanofi supported REMAP-CAP through provision of tocilizumab and sarilumab in the United Kingdom.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

New findings suggest that monoclonal antibodies used to treat RA could improve severe COVID-19 outcomes, including risk for death.

Given within 24 hours of critical illness, tocilizumab (Actemra) was associated with a median of 10 days free of respiratory and cardiovascular support up to day 21, the primary outcome. Similarly, sarilumab (Kevzara) was linked to a median of 11 days. In contrast, the usual care control group experienced zero such days in the hospital.

However, the Randomized, Embedded, Multifactorial Adaptive Platform Trial for Community-Acquired Pneumonia (REMAP-CAP) trial comes with a caveat. The preprint findings have not yet been peer reviewed and “should not be used to guide clinical practice,” the authors stated.

The results were published online Jan. 7 in MedRxiv.

Nevertheless, the trial also revealed a mortality benefit associated with the two interleukin-6 antagonists. The hospital mortality rate was 22% with sarilumab, 28% with tocilizumab, and almost 36% with usual care.

“That’s a big change in survival. They are both lifesaving drugs,” lead coinvestigator Anthony Gordon, an Imperial College London professor of anesthesia and critical care, commented in a recent story by Reuters.

Consider the big picture

“What I think is important is ... this is one of many trials,” Paul Auwaerter, MD, MBA, said in an interview. Many other studies looking at monoclonal antibody therapy for people with COVID-19 were halted because they did not show improvement.

One exception is the EMPACTA trial, which suggested that tocilizumab was effective if given before a person becomes ill enough to be placed on a ventilator, said Dr. Auwaerter, clinical director of the division of infectious diseases at Johns Hopkins Medicine and a contributor to this news organization. “It appeared to reduce the need for mechanical ventilation or death.”

“These two trials are the first randomized, prospective trials that show a benefit on a background of others which have not,” Dr. Auwaerter added.

Interim findings

The REMAP-CAP investigators randomly assigned adults within 24 hours of critical care for COVID-19 to 8 mg/kg tocilizumab, 400 mg sarilumab, or usual care at 113 sites in six countries. There were 353 participants in the tocilizumab arm, 48 in the sarilumab group, and 402 in the control group.

Compared with the control group, the 10 days free of organ support in the tocilizumab cohort was associated with an adjusted odds ratio of 1.64 (95% confidence interval, 1.25-2.14). The 11 days free of organ support in the sarilumab cohort was likewise superior to control (adjusted odds ratio, 1.76; 95% CI, 1.17-2.91).

“All secondary outcomes and analyses supported efficacy of these IL-6 receptor antagonists,” the authors note. These endpoints included 90-day survival, time to intensive care unit discharge, and hospital discharge.

Cautious optimism?

“The results were quite impressive – having 10 or 11 fewer days in the ICU, compared to standard of care,” Deepa Gotur, MD, said in an interview. “Choosing the right patient population and providing the anti-IL-6 treatment at the right time would be the key here.”

In addition to not yet receiving peer review, an open-label design, a relatively short follow-up of 21 days, and steroids becoming standard of care about halfway through the trial are potential limitations, said Dr. Gotur, an intensivist at Houston Methodist Hospital and associate professor of clinical medicine at Weill Cornell Medicine, New York.

“This is an interesting study,” Carl J. Fichtenbaum, MD, professor of clinical medicine at the University of Cincinnati, said in a comment.

Additional detail on how many participants in each group received steroids is warranted, Dr. Fichtenbaum said. “The analysis did not carefully adjust for the use of steroids that might have influenced outcomes.”

Dr. Fichtenbaum said it’s important to look at what is distinctive about REMAP-CAP because “there are several other studies showing opposite results.”

Dr. Gotur was an investigator on a previous study evaluating tocilizumab for patients already on mechanical ventilation. “One of the key differences between this and other studies is that they included more of the ICU population,” she said. “They also included patients within 24 hours of requiring organ support, cardiac, as well as respiratory support.” Some other research included less-acute patients, including all comers into the ED who required oxygen and received tocilizumab.

The prior studies also evaluated cytokine or inflammatory markers. In contrast, REMAP-CAP researchers “looked at organ failure itself ... which I think makes sense,” Dr. Gotur said.

Cytokine release syndrome can cause organ damage or organ failure, she added, “but these markers are all over the place. I’ve seen patients who are very, very sick despite having a low [C-reactive protein] or IL-6 level.”

Backing from the British

Citing the combined 24% decrease in the risk for death associated with these agents in the REMAP-CAP trial, the U.K. government announced Jan. 7 it will work to make tocilizumab and sarilumab available to citizens with severe COVID-19.

Experts in the United Kingdom shared their perspectives on the REMAP-CAP interim findings through the U.K. Science Media Centre.

“There are few treatments for severe COVID-19,” said Robin Ferner, MD, honorary professor of clinical pharmacology at the University of Birmingham (England) and honorary consultant physician at City Hospital Birmingham. “If the published data from REMAP-CAP are supported by further studies, this suggests that two IL-6 receptor antagonists can reduce the death rate in the most severely ill patients.”

Dr. Ferner added that the findings are not a “magic cure,” however. He pointed out that of 401 patients given the drugs, 109 died, and with standard treatment, 144 out of 402 died.

Peter Horby, MD, PhD, was more optimistic. “It is great to see a positive result at a time that we really need good news and more tools to fight COVID. This is great achievement for REMAP-CAP,” he said.

“We hope to soon have results from RECOVERY on the effect of tocilizumab in less severely ill patients in the hospital,” said Dr. Horby, cochief investigator of the RECOVERY trial and professor of emerging infectious diseases at the Centre for Tropical Medicine and Global Health at the University of Oxford (England).

Stephen Evans, BA, MSc, FRCP, professor of pharmacoepidemiology at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, said, “This is a high-quality trial, and although published as a preprint, is of much higher quality than many non–peer-reviewed papers.”

Dr. Evans also noted the addition of steroid therapy for many participants. “Partway through the trial, the RECOVERY trial findings showed that the corticosteroid drug dexamethasone had notable mortality benefits. Consequently, quite a number of the patients in this trial had also received a corticosteroid.”

“It does look as though these drugs give some additional benefit beyond that given by dexamethasone,” he added.

Awaiting peer review

“We need to wait for the final results and ensure it was adequately powered with enough observations to make us confident in the results,” Dr. Fichtenbaum said.

“We in the United States have to step back and look at the entire set of studies and also, for this particular one, REMAP-CAP, to be in a peer-reviewed publication,” Dr. Auwaerter said. Preprints are often released “in the setting of the pandemic, where there may be important findings, especially if they impact mortality or severity of illness.”

“We need to make sure these findings, as outlined, hold up,” he said.

In the meantime, Dr. Auwaerter added, “Exactly how this will fit in is unclear. But it’s important to me as another potential drug that can help our critically ill patients.”

The REMAP-CAP study is ongoing and updated results will be provided online.

Dr. Auwaerter disclosed that he is a consultant for EMD Serono and a member of the data monitoring safety board for Humanigen. Dr. Gotur, Dr. Fichtenbaum, Dr. Ferner, and Dr. Evans disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Horby reported that Oxford University receives funding for the RECOVERY trial from U.K. Research and Innovation and the National Institute for Health Research. Roche Products and Sanofi supported REMAP-CAP through provision of tocilizumab and sarilumab in the United Kingdom.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

New findings suggest that monoclonal antibodies used to treat RA could improve severe COVID-19 outcomes, including risk for death.

Given within 24 hours of critical illness, tocilizumab (Actemra) was associated with a median of 10 days free of respiratory and cardiovascular support up to day 21, the primary outcome. Similarly, sarilumab (Kevzara) was linked to a median of 11 days. In contrast, the usual care control group experienced zero such days in the hospital.

However, the Randomized, Embedded, Multifactorial Adaptive Platform Trial for Community-Acquired Pneumonia (REMAP-CAP) trial comes with a caveat. The preprint findings have not yet been peer reviewed and “should not be used to guide clinical practice,” the authors stated.

The results were published online Jan. 7 in MedRxiv.

Nevertheless, the trial also revealed a mortality benefit associated with the two interleukin-6 antagonists. The hospital mortality rate was 22% with sarilumab, 28% with tocilizumab, and almost 36% with usual care.

“That’s a big change in survival. They are both lifesaving drugs,” lead coinvestigator Anthony Gordon, an Imperial College London professor of anesthesia and critical care, commented in a recent story by Reuters.

Consider the big picture

“What I think is important is ... this is one of many trials,” Paul Auwaerter, MD, MBA, said in an interview. Many other studies looking at monoclonal antibody therapy for people with COVID-19 were halted because they did not show improvement.

One exception is the EMPACTA trial, which suggested that tocilizumab was effective if given before a person becomes ill enough to be placed on a ventilator, said Dr. Auwaerter, clinical director of the division of infectious diseases at Johns Hopkins Medicine and a contributor to this news organization. “It appeared to reduce the need for mechanical ventilation or death.”

“These two trials are the first randomized, prospective trials that show a benefit on a background of others which have not,” Dr. Auwaerter added.

Interim findings

The REMAP-CAP investigators randomly assigned adults within 24 hours of critical care for COVID-19 to 8 mg/kg tocilizumab, 400 mg sarilumab, or usual care at 113 sites in six countries. There were 353 participants in the tocilizumab arm, 48 in the sarilumab group, and 402 in the control group.

Compared with the control group, the 10 days free of organ support in the tocilizumab cohort was associated with an adjusted odds ratio of 1.64 (95% confidence interval, 1.25-2.14). The 11 days free of organ support in the sarilumab cohort was likewise superior to control (adjusted odds ratio, 1.76; 95% CI, 1.17-2.91).

“All secondary outcomes and analyses supported efficacy of these IL-6 receptor antagonists,” the authors note. These endpoints included 90-day survival, time to intensive care unit discharge, and hospital discharge.

Cautious optimism?

“The results were quite impressive – having 10 or 11 fewer days in the ICU, compared to standard of care,” Deepa Gotur, MD, said in an interview. “Choosing the right patient population and providing the anti-IL-6 treatment at the right time would be the key here.”

In addition to not yet receiving peer review, an open-label design, a relatively short follow-up of 21 days, and steroids becoming standard of care about halfway through the trial are potential limitations, said Dr. Gotur, an intensivist at Houston Methodist Hospital and associate professor of clinical medicine at Weill Cornell Medicine, New York.

“This is an interesting study,” Carl J. Fichtenbaum, MD, professor of clinical medicine at the University of Cincinnati, said in a comment.

Additional detail on how many participants in each group received steroids is warranted, Dr. Fichtenbaum said. “The analysis did not carefully adjust for the use of steroids that might have influenced outcomes.”

Dr. Fichtenbaum said it’s important to look at what is distinctive about REMAP-CAP because “there are several other studies showing opposite results.”

Dr. Gotur was an investigator on a previous study evaluating tocilizumab for patients already on mechanical ventilation. “One of the key differences between this and other studies is that they included more of the ICU population,” she said. “They also included patients within 24 hours of requiring organ support, cardiac, as well as respiratory support.” Some other research included less-acute patients, including all comers into the ED who required oxygen and received tocilizumab.

The prior studies also evaluated cytokine or inflammatory markers. In contrast, REMAP-CAP researchers “looked at organ failure itself ... which I think makes sense,” Dr. Gotur said.

Cytokine release syndrome can cause organ damage or organ failure, she added, “but these markers are all over the place. I’ve seen patients who are very, very sick despite having a low [C-reactive protein] or IL-6 level.”

Backing from the British

Citing the combined 24% decrease in the risk for death associated with these agents in the REMAP-CAP trial, the U.K. government announced Jan. 7 it will work to make tocilizumab and sarilumab available to citizens with severe COVID-19.

Experts in the United Kingdom shared their perspectives on the REMAP-CAP interim findings through the U.K. Science Media Centre.

“There are few treatments for severe COVID-19,” said Robin Ferner, MD, honorary professor of clinical pharmacology at the University of Birmingham (England) and honorary consultant physician at City Hospital Birmingham. “If the published data from REMAP-CAP are supported by further studies, this suggests that two IL-6 receptor antagonists can reduce the death rate in the most severely ill patients.”

Dr. Ferner added that the findings are not a “magic cure,” however. He pointed out that of 401 patients given the drugs, 109 died, and with standard treatment, 144 out of 402 died.

Peter Horby, MD, PhD, was more optimistic. “It is great to see a positive result at a time that we really need good news and more tools to fight COVID. This is great achievement for REMAP-CAP,” he said.

“We hope to soon have results from RECOVERY on the effect of tocilizumab in less severely ill patients in the hospital,” said Dr. Horby, cochief investigator of the RECOVERY trial and professor of emerging infectious diseases at the Centre for Tropical Medicine and Global Health at the University of Oxford (England).

Stephen Evans, BA, MSc, FRCP, professor of pharmacoepidemiology at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, said, “This is a high-quality trial, and although published as a preprint, is of much higher quality than many non–peer-reviewed papers.”

Dr. Evans also noted the addition of steroid therapy for many participants. “Partway through the trial, the RECOVERY trial findings showed that the corticosteroid drug dexamethasone had notable mortality benefits. Consequently, quite a number of the patients in this trial had also received a corticosteroid.”

“It does look as though these drugs give some additional benefit beyond that given by dexamethasone,” he added.

Awaiting peer review

“We need to wait for the final results and ensure it was adequately powered with enough observations to make us confident in the results,” Dr. Fichtenbaum said.

“We in the United States have to step back and look at the entire set of studies and also, for this particular one, REMAP-CAP, to be in a peer-reviewed publication,” Dr. Auwaerter said. Preprints are often released “in the setting of the pandemic, where there may be important findings, especially if they impact mortality or severity of illness.”

“We need to make sure these findings, as outlined, hold up,” he said.

In the meantime, Dr. Auwaerter added, “Exactly how this will fit in is unclear. But it’s important to me as another potential drug that can help our critically ill patients.”

The REMAP-CAP study is ongoing and updated results will be provided online.

Dr. Auwaerter disclosed that he is a consultant for EMD Serono and a member of the data monitoring safety board for Humanigen. Dr. Gotur, Dr. Fichtenbaum, Dr. Ferner, and Dr. Evans disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Horby reported that Oxford University receives funding for the RECOVERY trial from U.K. Research and Innovation and the National Institute for Health Research. Roche Products and Sanofi supported REMAP-CAP through provision of tocilizumab and sarilumab in the United Kingdom.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Pityriasis rosea carries few risks for pregnant women

according to a review of 33 patients.

“Though generally considered benign, PR may be associated with an increased risk of birth complications if acquired during pregnancy,” and previous studies have shown increased rates of complications including miscarriage and neonatal hypotonia in these patients, wrote Julian Stashower of the University of Virginia, Charlottesville, and colleagues.

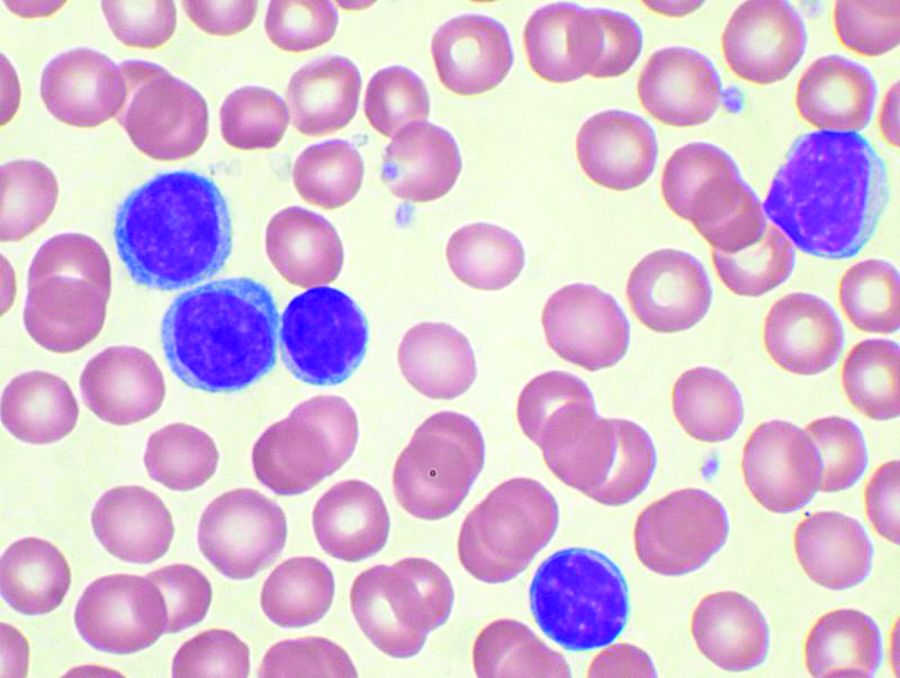

In a retrospective study published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, the researchers assessed pregnancy outcomes in women who developed PR during pregnancy. They were identified from medical records at three institutions between September 2010 and June 2020. Diagnosis of PR, a papulosquamous skin eruption associated with human herpesvirus (HHV)–6/7 reactivation, was based on history and physical examination.

Overall, 8 of the 33 women (24%) had birth complications; the rates of preterm delivery, spontaneous pregnancy loss in clinically detectable pregnancies, and oligohydramnios were 6%, 0%, and 3%, respectively. The average onset of PR during pregnancy was earlier among women with complications, compared with those without complications (10.75 weeks’ gestation vs. 15.21 weeks’ gestation), but the difference was not statistically significant.

The researchers noted that their findings differed from the most recent study of PR in pregnancy, which included 60 patients and found a notably higher incidence of overall birth complications (50%), as well as higher incidence of neonatal hypotonia (25%), and miscarriage (13%).

The previous study also showed an increased risk of birth complications when PR onset occurred prior to 15 weeks’ gestation, but the current study did not reflect that finding, they wrote.

The current study findings were limited by several factors including the small sample size, retrospective design, and lack of confirmation of PR with HHV-6/7 testing, as well as lack of exclusion of atypical PR cases, the researchers noted. However, the results suggest that birth complications associated with PR may be lower than previously reported. “Further research is needed to guide future care and fully elucidate this possible association, which has important implications for both pregnant women with PR and their providers.”

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflict to disclose.

according to a review of 33 patients.

“Though generally considered benign, PR may be associated with an increased risk of birth complications if acquired during pregnancy,” and previous studies have shown increased rates of complications including miscarriage and neonatal hypotonia in these patients, wrote Julian Stashower of the University of Virginia, Charlottesville, and colleagues.

In a retrospective study published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, the researchers assessed pregnancy outcomes in women who developed PR during pregnancy. They were identified from medical records at three institutions between September 2010 and June 2020. Diagnosis of PR, a papulosquamous skin eruption associated with human herpesvirus (HHV)–6/7 reactivation, was based on history and physical examination.

Overall, 8 of the 33 women (24%) had birth complications; the rates of preterm delivery, spontaneous pregnancy loss in clinically detectable pregnancies, and oligohydramnios were 6%, 0%, and 3%, respectively. The average onset of PR during pregnancy was earlier among women with complications, compared with those without complications (10.75 weeks’ gestation vs. 15.21 weeks’ gestation), but the difference was not statistically significant.

The researchers noted that their findings differed from the most recent study of PR in pregnancy, which included 60 patients and found a notably higher incidence of overall birth complications (50%), as well as higher incidence of neonatal hypotonia (25%), and miscarriage (13%).

The previous study also showed an increased risk of birth complications when PR onset occurred prior to 15 weeks’ gestation, but the current study did not reflect that finding, they wrote.

The current study findings were limited by several factors including the small sample size, retrospective design, and lack of confirmation of PR with HHV-6/7 testing, as well as lack of exclusion of atypical PR cases, the researchers noted. However, the results suggest that birth complications associated with PR may be lower than previously reported. “Further research is needed to guide future care and fully elucidate this possible association, which has important implications for both pregnant women with PR and their providers.”

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflict to disclose.

according to a review of 33 patients.

“Though generally considered benign, PR may be associated with an increased risk of birth complications if acquired during pregnancy,” and previous studies have shown increased rates of complications including miscarriage and neonatal hypotonia in these patients, wrote Julian Stashower of the University of Virginia, Charlottesville, and colleagues.

In a retrospective study published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, the researchers assessed pregnancy outcomes in women who developed PR during pregnancy. They were identified from medical records at three institutions between September 2010 and June 2020. Diagnosis of PR, a papulosquamous skin eruption associated with human herpesvirus (HHV)–6/7 reactivation, was based on history and physical examination.

Overall, 8 of the 33 women (24%) had birth complications; the rates of preterm delivery, spontaneous pregnancy loss in clinically detectable pregnancies, and oligohydramnios were 6%, 0%, and 3%, respectively. The average onset of PR during pregnancy was earlier among women with complications, compared with those without complications (10.75 weeks’ gestation vs. 15.21 weeks’ gestation), but the difference was not statistically significant.

The researchers noted that their findings differed from the most recent study of PR in pregnancy, which included 60 patients and found a notably higher incidence of overall birth complications (50%), as well as higher incidence of neonatal hypotonia (25%), and miscarriage (13%).

The previous study also showed an increased risk of birth complications when PR onset occurred prior to 15 weeks’ gestation, but the current study did not reflect that finding, they wrote.

The current study findings were limited by several factors including the small sample size, retrospective design, and lack of confirmation of PR with HHV-6/7 testing, as well as lack of exclusion of atypical PR cases, the researchers noted. However, the results suggest that birth complications associated with PR may be lower than previously reported. “Further research is needed to guide future care and fully elucidate this possible association, which has important implications for both pregnant women with PR and their providers.”

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflict to disclose.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF DERMATOLOGY

Eliminating hepatitis by 2030: HHS releases new strategic plan

In an effort to counteract alarming trends in rising hepatitis infections, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services has developed and released its Viral Hepatitis National Strategic Plan 2021-2025, which aims to eliminate viral hepatitis infection in the United States by 2030.

An estimated 3.3 million people in the United States were chronically infected with hepatitis B (HBV) and hepatitis C (HCV) as of 2016. In addition, the country “is currently facing unprecedented hepatitis A (HAV) outbreaks, while progress in preventing hepatitis B has stalled, and hepatitis C rates nearly tripled from 2011 to 2018,” according to the HHS.

The new plan, “A Roadmap to Elimination for the United States,” builds upon previous initiatives the HHS has made to tackle the diseases and was coordinated by the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health through the Office of Infectious Disease and HIV/AIDS Policy.

The plan focuses on HAV, HBV, and HCV, which have the largest impact on the health of the nation, according to the HHS. The plan addresses populations with the highest burden of viral hepatitis based on nationwide data so that resources can be focused there to achieve the greatest impact. Persons who inject drugs are a priority population for all three hepatitis viruses. HAV efforts will also include a focus on the homeless population. HBV efforts will also focus on Asian and Pacific Islander and the Black, non-Hispanic populations, while HCV efforts will include a focus on Black, non-Hispanic people, people born during 1945-1965, people with HIV, and the American Indian/Alaska Native population.

Goal-setting

There are five main goals outlined in the plan, according to the HHS:

- Prevent new hepatitis infections.

- Improve hepatitis-related health outcomes of people with viral hepatitis.

- Reduce hepatitis-related disparities and health inequities.

- Improve hepatitis surveillance and data use.

- Achieve integrated, coordinated efforts that address the viral hepatitis epidemics among all partners and stakeholders.

“The United States will be a place where new viral hepatitis infections are prevented, every person knows their status, and every person with viral hepatitis has high-quality health care and treatment and lives free from stigma and discrimination. This vision includes all people, regardless of age, sex, gender identity, sexual orientation, race, ethnicity, religion, disability, geographic location, or socioeconomic circumstance,” according to the HHS vision statement.

In an effort to counteract alarming trends in rising hepatitis infections, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services has developed and released its Viral Hepatitis National Strategic Plan 2021-2025, which aims to eliminate viral hepatitis infection in the United States by 2030.

An estimated 3.3 million people in the United States were chronically infected with hepatitis B (HBV) and hepatitis C (HCV) as of 2016. In addition, the country “is currently facing unprecedented hepatitis A (HAV) outbreaks, while progress in preventing hepatitis B has stalled, and hepatitis C rates nearly tripled from 2011 to 2018,” according to the HHS.

The new plan, “A Roadmap to Elimination for the United States,” builds upon previous initiatives the HHS has made to tackle the diseases and was coordinated by the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health through the Office of Infectious Disease and HIV/AIDS Policy.

The plan focuses on HAV, HBV, and HCV, which have the largest impact on the health of the nation, according to the HHS. The plan addresses populations with the highest burden of viral hepatitis based on nationwide data so that resources can be focused there to achieve the greatest impact. Persons who inject drugs are a priority population for all three hepatitis viruses. HAV efforts will also include a focus on the homeless population. HBV efforts will also focus on Asian and Pacific Islander and the Black, non-Hispanic populations, while HCV efforts will include a focus on Black, non-Hispanic people, people born during 1945-1965, people with HIV, and the American Indian/Alaska Native population.

Goal-setting

There are five main goals outlined in the plan, according to the HHS:

- Prevent new hepatitis infections.

- Improve hepatitis-related health outcomes of people with viral hepatitis.

- Reduce hepatitis-related disparities and health inequities.

- Improve hepatitis surveillance and data use.

- Achieve integrated, coordinated efforts that address the viral hepatitis epidemics among all partners and stakeholders.

“The United States will be a place where new viral hepatitis infections are prevented, every person knows their status, and every person with viral hepatitis has high-quality health care and treatment and lives free from stigma and discrimination. This vision includes all people, regardless of age, sex, gender identity, sexual orientation, race, ethnicity, religion, disability, geographic location, or socioeconomic circumstance,” according to the HHS vision statement.

In an effort to counteract alarming trends in rising hepatitis infections, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services has developed and released its Viral Hepatitis National Strategic Plan 2021-2025, which aims to eliminate viral hepatitis infection in the United States by 2030.

An estimated 3.3 million people in the United States were chronically infected with hepatitis B (HBV) and hepatitis C (HCV) as of 2016. In addition, the country “is currently facing unprecedented hepatitis A (HAV) outbreaks, while progress in preventing hepatitis B has stalled, and hepatitis C rates nearly tripled from 2011 to 2018,” according to the HHS.

The new plan, “A Roadmap to Elimination for the United States,” builds upon previous initiatives the HHS has made to tackle the diseases and was coordinated by the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health through the Office of Infectious Disease and HIV/AIDS Policy.

The plan focuses on HAV, HBV, and HCV, which have the largest impact on the health of the nation, according to the HHS. The plan addresses populations with the highest burden of viral hepatitis based on nationwide data so that resources can be focused there to achieve the greatest impact. Persons who inject drugs are a priority population for all three hepatitis viruses. HAV efforts will also include a focus on the homeless population. HBV efforts will also focus on Asian and Pacific Islander and the Black, non-Hispanic populations, while HCV efforts will include a focus on Black, non-Hispanic people, people born during 1945-1965, people with HIV, and the American Indian/Alaska Native population.

Goal-setting

There are five main goals outlined in the plan, according to the HHS:

- Prevent new hepatitis infections.

- Improve hepatitis-related health outcomes of people with viral hepatitis.

- Reduce hepatitis-related disparities and health inequities.

- Improve hepatitis surveillance and data use.

- Achieve integrated, coordinated efforts that address the viral hepatitis epidemics among all partners and stakeholders.

“The United States will be a place where new viral hepatitis infections are prevented, every person knows their status, and every person with viral hepatitis has high-quality health care and treatment and lives free from stigma and discrimination. This vision includes all people, regardless of age, sex, gender identity, sexual orientation, race, ethnicity, religion, disability, geographic location, or socioeconomic circumstance,” according to the HHS vision statement.

Family physicians can help achieve national goals on STIs

Among these are the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ first “Sexually Transmitted Infections (STIs) National Strategic Plan for the United States,” which has a strong encompassing vision.

“The United States will be a place where sexually transmitted infections are prevented and where every person has high-quality STI prevention care, and treatment while living free from stigma and discrimination. The vision includes all people, regardless of age, sex, gender identity, sexual orientation, race, ethnicity, religion, disability, geographic location, or socioeconomic circumstance,” the new HHS plan states.1

Family physicians can and should play important roles in helping our country meet this plan’s goals particularly by following two important updated clinical guidelines, one from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) and another from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

This strategic plan includes the following five overarching goals with associated objectives:

- Prevent New STIs.

- Improve the health of people by reducing adverse outcomes of STIs.

- Accelerate progress in STI research, technology, and innovation.

- Reduce STI-related health disparities and health inequities.

- Achieve integrated, coordinated efforts that address the STI epidemic.1

In my opinion, family physicians have important roles to play in order for each of these goals to be achieved.Unfortunately, there are approximately 20 million new cases of STIs each year, and the U.S. has seen increases in the rates of STIs in the past decade.

“Sexually transmitted infections are frequently asymptomatic, which may delay diagnosis and treatment and lead persons to unknowingly transmit STIs to others,” according to a new recommendation statement from the USPSTF.2 STIs may lead to serious health consequences for patients, cause harms to a mother and infant during pregnancy, and lead to cases of cancer among other concerning outcomes. As such, following the HHS new national strategic plan is critical for us to address the needs of our communities.

Preventing new STIs

Family physicians can be vital in achieving the first goal of the plan by helping to prevent new STIs. In August 2020, the USPSTF updated its guideline on behavioral counseling interventions to prevent STIs. In my opinion, the USPSTF offers some practical improvements from the earlier version of this guideline.

The task force provides a grade B recommendation that all sexually active adolescents and adults at increased risk for STIs be provided with behavioral counseling to prevent STIs. The guideline indicates that behavioral counseling interventions reduce the likelihood of those at increased risk for acquiring STIs.2

The 2014 guideline had recommended intensive interventions with a minimum of 30 minutes of counseling. Many family physicians may have found this previous recommendation impractical to implement. These updated recommendations now include a variety of interventions, such as those that take less than 30 minutes.

Although interventions with more than 120 minutes of contact time had the most effect, those with less than 30 minutes still demonstrated statistically significant fewer acquisitions of STIs during follow-up. These options include in-person counseling, and providing written materials, websites, videos, and telephone and text support to patients. These interventions can be delivered directly by the family physician, or patients may be referred to other settings or the media interventions.

The task force’s updated recommendation statement refers to a variety of resources that can be used to identify these interventions. Many of the studies reviewed for this guideline were conducted in STI clinics, and the guideline authors recommended further studies in primary care as opportunities for more generalizability.

In addition to behavioral counseling for STI prevention, family physicians can help prevent STIs in their patients through HPV vaccination and HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP provision) within their practices. As the first contact for health care for many patients, we have an opportunity to significantly impact this first goal of prevention.

Treating STIs

Within the second goal of the national strategic plan is treatment of STIs, which family physicians should include in their practices as well as the diagnosis of STIs.

In December 2020, an update to the CDC’s treatment guideline for gonococcal infection was released. Prior to the publishing of this updated recommendation, the CDC recommended combination therapy of 250 mg intramuscular (IM) dose of ceftriaxone and either doxycycline or azithromycin. This recommendation has been changed to a single 500-mg IM dose of ceftriaxone for uncomplicated urogenital, anorectal, and pharyngeal gonorrhea. If chlamydia cannot be excluded, then the addition of oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 7 days is recommended for nonpregnant persons, and 1 g oral azithromycin for pregnant persons. The previous treatment was recommended based on a concern for gonococcal resistance.

This updated guideline reflects increasing concerns for antimicrobial stewardship and emerging azithromycin resistance. It does not recommend a test-of-cure for urogenital or rectal gonorrhea, though did recommend a test-of-cure 7-14 days after treatment of pharyngeal gonorrhea. The guideline also recommends testing for reinfection 3-12 months after treatment as the rate of reinfection ranges from 7% to 12% among those previously treated.3

For some offices, the provision of the IM injection may be challenging, though having this medication in stock with the possibility of provision can greatly improve access and ease of treatment for patients. Family physicians can incorporate these updated recommendations along with those for other STIs such as chlamydia and syphilis with standing orders for treatment and testing within their offices.

Accelerating progress in STI research

Family physicians can also support the national strategic plan by participating in studies looking at the impact of behavioral counseling in the primary care office as opposed to in STI clinics. In addition, by following the STI treatment and screening guidelines, family physicians will contribute to the body of knowledge of prevalence, treatment failure, and reinfection rates of STIs. We can also help advance the research by providing feedback on interventions that have success within our practices.

Reducing STI-related health disparities and inequities

Family physicians are also in important places to support the strategic plan’s fourth goal of reducing health disparities and health inequities.

If we continue to ask the questions to identify those at high risk and ensure that we are offering appropriate STI prevention, care, and treatment services within our clinics, we can expand access to all who need services and improve equity. By offering these services within the primary care office, we may be able to decrease the stigma some may feel going to an STI clinic for services.

By incorporating additional screening and counseling in our practices we may identify some patients who were not aware that they were at risk for an STI and offer them preventive services.

Achieving integrated and coordinated efforts

Finally, as many family physicians have integrated practices, we are uniquely poised to support the fifth goal of the strategic plan of achieving integrated and coordinated efforts addressing the STI epidemic. In our practices we can participate in, lead, and refer to programs for substance use disorders, viral hepatitis, STIs, and HIV as part of full scope primary care.

Family physicians and other primary care providers should work to support the entire strategic plan to ensure that we are fully caring for our patients and communities and stopping the past decade’s increase in STIs. We have an opportunity to use this strategy and make a large impact in our communities.

Dr. Wheat is a family physician at Erie Family Health Center in Chicago. She is program director of Northwestern’s McGaw Family Medicine residency program at Humboldt Park, Chicago. Dr. Wheat serves on the editorial advisory board of Family Practice News. You can contact her at fpnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2020. Sexually Transmitted Infections National Strategic Plan for the United States: 2021-2025. Washington.

2. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Behavioral counseling interventions to prevent sexually transmitted infections: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2020;324(7):674-81. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.13095.

3. St. Cyr S et al. Update to CDC’s Treatment Guideline for Gonococcal Infection, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69:1911-6. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6950a6external_icon.

Among these are the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ first “Sexually Transmitted Infections (STIs) National Strategic Plan for the United States,” which has a strong encompassing vision.

“The United States will be a place where sexually transmitted infections are prevented and where every person has high-quality STI prevention care, and treatment while living free from stigma and discrimination. The vision includes all people, regardless of age, sex, gender identity, sexual orientation, race, ethnicity, religion, disability, geographic location, or socioeconomic circumstance,” the new HHS plan states.1

Family physicians can and should play important roles in helping our country meet this plan’s goals particularly by following two important updated clinical guidelines, one from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) and another from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

This strategic plan includes the following five overarching goals with associated objectives:

- Prevent New STIs.

- Improve the health of people by reducing adverse outcomes of STIs.

- Accelerate progress in STI research, technology, and innovation.

- Reduce STI-related health disparities and health inequities.

- Achieve integrated, coordinated efforts that address the STI epidemic.1

In my opinion, family physicians have important roles to play in order for each of these goals to be achieved.Unfortunately, there are approximately 20 million new cases of STIs each year, and the U.S. has seen increases in the rates of STIs in the past decade.

“Sexually transmitted infections are frequently asymptomatic, which may delay diagnosis and treatment and lead persons to unknowingly transmit STIs to others,” according to a new recommendation statement from the USPSTF.2 STIs may lead to serious health consequences for patients, cause harms to a mother and infant during pregnancy, and lead to cases of cancer among other concerning outcomes. As such, following the HHS new national strategic plan is critical for us to address the needs of our communities.

Preventing new STIs

Family physicians can be vital in achieving the first goal of the plan by helping to prevent new STIs. In August 2020, the USPSTF updated its guideline on behavioral counseling interventions to prevent STIs. In my opinion, the USPSTF offers some practical improvements from the earlier version of this guideline.

The task force provides a grade B recommendation that all sexually active adolescents and adults at increased risk for STIs be provided with behavioral counseling to prevent STIs. The guideline indicates that behavioral counseling interventions reduce the likelihood of those at increased risk for acquiring STIs.2

The 2014 guideline had recommended intensive interventions with a minimum of 30 minutes of counseling. Many family physicians may have found this previous recommendation impractical to implement. These updated recommendations now include a variety of interventions, such as those that take less than 30 minutes.

Although interventions with more than 120 minutes of contact time had the most effect, those with less than 30 minutes still demonstrated statistically significant fewer acquisitions of STIs during follow-up. These options include in-person counseling, and providing written materials, websites, videos, and telephone and text support to patients. These interventions can be delivered directly by the family physician, or patients may be referred to other settings or the media interventions.

The task force’s updated recommendation statement refers to a variety of resources that can be used to identify these interventions. Many of the studies reviewed for this guideline were conducted in STI clinics, and the guideline authors recommended further studies in primary care as opportunities for more generalizability.

In addition to behavioral counseling for STI prevention, family physicians can help prevent STIs in their patients through HPV vaccination and HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP provision) within their practices. As the first contact for health care for many patients, we have an opportunity to significantly impact this first goal of prevention.

Treating STIs

Within the second goal of the national strategic plan is treatment of STIs, which family physicians should include in their practices as well as the diagnosis of STIs.

In December 2020, an update to the CDC’s treatment guideline for gonococcal infection was released. Prior to the publishing of this updated recommendation, the CDC recommended combination therapy of 250 mg intramuscular (IM) dose of ceftriaxone and either doxycycline or azithromycin. This recommendation has been changed to a single 500-mg IM dose of ceftriaxone for uncomplicated urogenital, anorectal, and pharyngeal gonorrhea. If chlamydia cannot be excluded, then the addition of oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 7 days is recommended for nonpregnant persons, and 1 g oral azithromycin for pregnant persons. The previous treatment was recommended based on a concern for gonococcal resistance.

This updated guideline reflects increasing concerns for antimicrobial stewardship and emerging azithromycin resistance. It does not recommend a test-of-cure for urogenital or rectal gonorrhea, though did recommend a test-of-cure 7-14 days after treatment of pharyngeal gonorrhea. The guideline also recommends testing for reinfection 3-12 months after treatment as the rate of reinfection ranges from 7% to 12% among those previously treated.3

For some offices, the provision of the IM injection may be challenging, though having this medication in stock with the possibility of provision can greatly improve access and ease of treatment for patients. Family physicians can incorporate these updated recommendations along with those for other STIs such as chlamydia and syphilis with standing orders for treatment and testing within their offices.

Accelerating progress in STI research

Family physicians can also support the national strategic plan by participating in studies looking at the impact of behavioral counseling in the primary care office as opposed to in STI clinics. In addition, by following the STI treatment and screening guidelines, family physicians will contribute to the body of knowledge of prevalence, treatment failure, and reinfection rates of STIs. We can also help advance the research by providing feedback on interventions that have success within our practices.

Reducing STI-related health disparities and inequities

Family physicians are also in important places to support the strategic plan’s fourth goal of reducing health disparities and health inequities.

If we continue to ask the questions to identify those at high risk and ensure that we are offering appropriate STI prevention, care, and treatment services within our clinics, we can expand access to all who need services and improve equity. By offering these services within the primary care office, we may be able to decrease the stigma some may feel going to an STI clinic for services.

By incorporating additional screening and counseling in our practices we may identify some patients who were not aware that they were at risk for an STI and offer them preventive services.

Achieving integrated and coordinated efforts

Finally, as many family physicians have integrated practices, we are uniquely poised to support the fifth goal of the strategic plan of achieving integrated and coordinated efforts addressing the STI epidemic. In our practices we can participate in, lead, and refer to programs for substance use disorders, viral hepatitis, STIs, and HIV as part of full scope primary care.

Family physicians and other primary care providers should work to support the entire strategic plan to ensure that we are fully caring for our patients and communities and stopping the past decade’s increase in STIs. We have an opportunity to use this strategy and make a large impact in our communities.

Dr. Wheat is a family physician at Erie Family Health Center in Chicago. She is program director of Northwestern’s McGaw Family Medicine residency program at Humboldt Park, Chicago. Dr. Wheat serves on the editorial advisory board of Family Practice News. You can contact her at fpnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2020. Sexually Transmitted Infections National Strategic Plan for the United States: 2021-2025. Washington.

2. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Behavioral counseling interventions to prevent sexually transmitted infections: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2020;324(7):674-81. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.13095.

3. St. Cyr S et al. Update to CDC’s Treatment Guideline for Gonococcal Infection, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69:1911-6. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6950a6external_icon.

Among these are the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ first “Sexually Transmitted Infections (STIs) National Strategic Plan for the United States,” which has a strong encompassing vision.

“The United States will be a place where sexually transmitted infections are prevented and where every person has high-quality STI prevention care, and treatment while living free from stigma and discrimination. The vision includes all people, regardless of age, sex, gender identity, sexual orientation, race, ethnicity, religion, disability, geographic location, or socioeconomic circumstance,” the new HHS plan states.1

Family physicians can and should play important roles in helping our country meet this plan’s goals particularly by following two important updated clinical guidelines, one from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) and another from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

This strategic plan includes the following five overarching goals with associated objectives:

- Prevent New STIs.

- Improve the health of people by reducing adverse outcomes of STIs.

- Accelerate progress in STI research, technology, and innovation.

- Reduce STI-related health disparities and health inequities.

- Achieve integrated, coordinated efforts that address the STI epidemic.1

In my opinion, family physicians have important roles to play in order for each of these goals to be achieved.Unfortunately, there are approximately 20 million new cases of STIs each year, and the U.S. has seen increases in the rates of STIs in the past decade.

“Sexually transmitted infections are frequently asymptomatic, which may delay diagnosis and treatment and lead persons to unknowingly transmit STIs to others,” according to a new recommendation statement from the USPSTF.2 STIs may lead to serious health consequences for patients, cause harms to a mother and infant during pregnancy, and lead to cases of cancer among other concerning outcomes. As such, following the HHS new national strategic plan is critical for us to address the needs of our communities.

Preventing new STIs

Family physicians can be vital in achieving the first goal of the plan by helping to prevent new STIs. In August 2020, the USPSTF updated its guideline on behavioral counseling interventions to prevent STIs. In my opinion, the USPSTF offers some practical improvements from the earlier version of this guideline.

The task force provides a grade B recommendation that all sexually active adolescents and adults at increased risk for STIs be provided with behavioral counseling to prevent STIs. The guideline indicates that behavioral counseling interventions reduce the likelihood of those at increased risk for acquiring STIs.2

The 2014 guideline had recommended intensive interventions with a minimum of 30 minutes of counseling. Many family physicians may have found this previous recommendation impractical to implement. These updated recommendations now include a variety of interventions, such as those that take less than 30 minutes.

Although interventions with more than 120 minutes of contact time had the most effect, those with less than 30 minutes still demonstrated statistically significant fewer acquisitions of STIs during follow-up. These options include in-person counseling, and providing written materials, websites, videos, and telephone and text support to patients. These interventions can be delivered directly by the family physician, or patients may be referred to other settings or the media interventions.

The task force’s updated recommendation statement refers to a variety of resources that can be used to identify these interventions. Many of the studies reviewed for this guideline were conducted in STI clinics, and the guideline authors recommended further studies in primary care as opportunities for more generalizability.

In addition to behavioral counseling for STI prevention, family physicians can help prevent STIs in their patients through HPV vaccination and HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP provision) within their practices. As the first contact for health care for many patients, we have an opportunity to significantly impact this first goal of prevention.

Treating STIs

Within the second goal of the national strategic plan is treatment of STIs, which family physicians should include in their practices as well as the diagnosis of STIs.

In December 2020, an update to the CDC’s treatment guideline for gonococcal infection was released. Prior to the publishing of this updated recommendation, the CDC recommended combination therapy of 250 mg intramuscular (IM) dose of ceftriaxone and either doxycycline or azithromycin. This recommendation has been changed to a single 500-mg IM dose of ceftriaxone for uncomplicated urogenital, anorectal, and pharyngeal gonorrhea. If chlamydia cannot be excluded, then the addition of oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 7 days is recommended for nonpregnant persons, and 1 g oral azithromycin for pregnant persons. The previous treatment was recommended based on a concern for gonococcal resistance.

This updated guideline reflects increasing concerns for antimicrobial stewardship and emerging azithromycin resistance. It does not recommend a test-of-cure for urogenital or rectal gonorrhea, though did recommend a test-of-cure 7-14 days after treatment of pharyngeal gonorrhea. The guideline also recommends testing for reinfection 3-12 months after treatment as the rate of reinfection ranges from 7% to 12% among those previously treated.3

For some offices, the provision of the IM injection may be challenging, though having this medication in stock with the possibility of provision can greatly improve access and ease of treatment for patients. Family physicians can incorporate these updated recommendations along with those for other STIs such as chlamydia and syphilis with standing orders for treatment and testing within their offices.

Accelerating progress in STI research

Family physicians can also support the national strategic plan by participating in studies looking at the impact of behavioral counseling in the primary care office as opposed to in STI clinics. In addition, by following the STI treatment and screening guidelines, family physicians will contribute to the body of knowledge of prevalence, treatment failure, and reinfection rates of STIs. We can also help advance the research by providing feedback on interventions that have success within our practices.

Reducing STI-related health disparities and inequities

Family physicians are also in important places to support the strategic plan’s fourth goal of reducing health disparities and health inequities.

If we continue to ask the questions to identify those at high risk and ensure that we are offering appropriate STI prevention, care, and treatment services within our clinics, we can expand access to all who need services and improve equity. By offering these services within the primary care office, we may be able to decrease the stigma some may feel going to an STI clinic for services.

By incorporating additional screening and counseling in our practices we may identify some patients who were not aware that they were at risk for an STI and offer them preventive services.

Achieving integrated and coordinated efforts

Finally, as many family physicians have integrated practices, we are uniquely poised to support the fifth goal of the strategic plan of achieving integrated and coordinated efforts addressing the STI epidemic. In our practices we can participate in, lead, and refer to programs for substance use disorders, viral hepatitis, STIs, and HIV as part of full scope primary care.

Family physicians and other primary care providers should work to support the entire strategic plan to ensure that we are fully caring for our patients and communities and stopping the past decade’s increase in STIs. We have an opportunity to use this strategy and make a large impact in our communities.

Dr. Wheat is a family physician at Erie Family Health Center in Chicago. She is program director of Northwestern’s McGaw Family Medicine residency program at Humboldt Park, Chicago. Dr. Wheat serves on the editorial advisory board of Family Practice News. You can contact her at fpnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2020. Sexually Transmitted Infections National Strategic Plan for the United States: 2021-2025. Washington.

2. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Behavioral counseling interventions to prevent sexually transmitted infections: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2020;324(7):674-81. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.13095.

3. St. Cyr S et al. Update to CDC’s Treatment Guideline for Gonococcal Infection, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69:1911-6. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6950a6external_icon.

Coping with vaccine refusal

Do you accept new families into your practice who have already chosen to not have their children immunized? What about families who have been in your practice for several months or years? In 2016 the American Academy of Pediatrics published a clinical report in which it stated that, under some circumstances, dismissing families who refuse to vaccinate is permissible. Have you felt sufficiently supported by that statement and dismissed any families after multiple attempts at education on your part?

In a Pediatrics Perspective article in the December issue of Pediatrics, two philosophers and a physician make the argument that, while in some situations dismissing a family who refuses vaccines may be “an ethically acceptable option” refusing to accept a family with the same philosophy is not. It is an interesting paper and worth reading regardless of whether or not you already accept and continue to tolerate vaccine deniers in your practice.

The Pediatrics Perspective is certainly not the last word on the ethics of caring for families who deny their children care that we believe is critical to their health and the welfare of the community at large. There has been a lot of discussion about the issue but little has been written about how we as the physicians on the front line are coping emotionally with what the authors of the paper call the “burdens associated with treating” families who refuse to follow our guidance.

It is hard not to feel angry when a family you have invested valuable office time in discussing the benefits and safety of vaccines continues to disregard what you see as the facts. The time you have spent with them is not just income-generating time for your practice, it is time stolen from other families who are more willing to follow your recommendations. In how many visits will you continue to raise the issue? Unless I saw a glimmer of hope I would usually stop after two wasted encounters. But, the issue would still linger as the elephant in the examination room for as long as I continued to see the patient.

How have you expressed your anger? Have you been argumentative or rude? You may have been able maintain your composure and remain civil and appear caring, but I suspect the anger is still gnawing at you. And, there is still the frustration and feeling of impotence. You may have questioned your ability as an educator. You should get over that notion quickly. There is ample evidence that most vaccine deniers are not going to be convinced by even the most carefully presented information. I suggest you leave it to others to try their hands at education. Let them invest their time while you tend to the needs of your other patients. You can try being a fear monger and, while fear can be effective, you have better ways to spend your office day than telling horror stories.

If vaccine denial makes you feel powerless, you should get over that pretty quickly as well and accept the fact that you are simply an advisor. If you believe that most of the families in your practice are following your recommendations as though you had presented them on stone tablets, it is time for a wakeup call.

Finally, there is the most troubling emotion associated with vaccine refusal and that is fear, the fear of being sued. Establishing a relationship with a family is one that requires mutual trust and certainly vaccine refusal will put that trust in question, particularly if you have done a less than adequate job of hiding your anger and frustration with their unfortunate decision.

For now, vaccine refusal is just another one of those crosses that those of us in primary care must bear together wearing the best face we can put forward. That doesn’t mean we can’t share those emotions with our peers. Misery does love company.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

Do you accept new families into your practice who have already chosen to not have their children immunized? What about families who have been in your practice for several months or years? In 2016 the American Academy of Pediatrics published a clinical report in which it stated that, under some circumstances, dismissing families who refuse to vaccinate is permissible. Have you felt sufficiently supported by that statement and dismissed any families after multiple attempts at education on your part?

In a Pediatrics Perspective article in the December issue of Pediatrics, two philosophers and a physician make the argument that, while in some situations dismissing a family who refuses vaccines may be “an ethically acceptable option” refusing to accept a family with the same philosophy is not. It is an interesting paper and worth reading regardless of whether or not you already accept and continue to tolerate vaccine deniers in your practice.

The Pediatrics Perspective is certainly not the last word on the ethics of caring for families who deny their children care that we believe is critical to their health and the welfare of the community at large. There has been a lot of discussion about the issue but little has been written about how we as the physicians on the front line are coping emotionally with what the authors of the paper call the “burdens associated with treating” families who refuse to follow our guidance.

It is hard not to feel angry when a family you have invested valuable office time in discussing the benefits and safety of vaccines continues to disregard what you see as the facts. The time you have spent with them is not just income-generating time for your practice, it is time stolen from other families who are more willing to follow your recommendations. In how many visits will you continue to raise the issue? Unless I saw a glimmer of hope I would usually stop after two wasted encounters. But, the issue would still linger as the elephant in the examination room for as long as I continued to see the patient.

How have you expressed your anger? Have you been argumentative or rude? You may have been able maintain your composure and remain civil and appear caring, but I suspect the anger is still gnawing at you. And, there is still the frustration and feeling of impotence. You may have questioned your ability as an educator. You should get over that notion quickly. There is ample evidence that most vaccine deniers are not going to be convinced by even the most carefully presented information. I suggest you leave it to others to try their hands at education. Let them invest their time while you tend to the needs of your other patients. You can try being a fear monger and, while fear can be effective, you have better ways to spend your office day than telling horror stories.

If vaccine denial makes you feel powerless, you should get over that pretty quickly as well and accept the fact that you are simply an advisor. If you believe that most of the families in your practice are following your recommendations as though you had presented them on stone tablets, it is time for a wakeup call.

Finally, there is the most troubling emotion associated with vaccine refusal and that is fear, the fear of being sued. Establishing a relationship with a family is one that requires mutual trust and certainly vaccine refusal will put that trust in question, particularly if you have done a less than adequate job of hiding your anger and frustration with their unfortunate decision.

For now, vaccine refusal is just another one of those crosses that those of us in primary care must bear together wearing the best face we can put forward. That doesn’t mean we can’t share those emotions with our peers. Misery does love company.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

Do you accept new families into your practice who have already chosen to not have their children immunized? What about families who have been in your practice for several months or years? In 2016 the American Academy of Pediatrics published a clinical report in which it stated that, under some circumstances, dismissing families who refuse to vaccinate is permissible. Have you felt sufficiently supported by that statement and dismissed any families after multiple attempts at education on your part?

In a Pediatrics Perspective article in the December issue of Pediatrics, two philosophers and a physician make the argument that, while in some situations dismissing a family who refuses vaccines may be “an ethically acceptable option” refusing to accept a family with the same philosophy is not. It is an interesting paper and worth reading regardless of whether or not you already accept and continue to tolerate vaccine deniers in your practice.

The Pediatrics Perspective is certainly not the last word on the ethics of caring for families who deny their children care that we believe is critical to their health and the welfare of the community at large. There has been a lot of discussion about the issue but little has been written about how we as the physicians on the front line are coping emotionally with what the authors of the paper call the “burdens associated with treating” families who refuse to follow our guidance.

It is hard not to feel angry when a family you have invested valuable office time in discussing the benefits and safety of vaccines continues to disregard what you see as the facts. The time you have spent with them is not just income-generating time for your practice, it is time stolen from other families who are more willing to follow your recommendations. In how many visits will you continue to raise the issue? Unless I saw a glimmer of hope I would usually stop after two wasted encounters. But, the issue would still linger as the elephant in the examination room for as long as I continued to see the patient.

How have you expressed your anger? Have you been argumentative or rude? You may have been able maintain your composure and remain civil and appear caring, but I suspect the anger is still gnawing at you. And, there is still the frustration and feeling of impotence. You may have questioned your ability as an educator. You should get over that notion quickly. There is ample evidence that most vaccine deniers are not going to be convinced by even the most carefully presented information. I suggest you leave it to others to try their hands at education. Let them invest their time while you tend to the needs of your other patients. You can try being a fear monger and, while fear can be effective, you have better ways to spend your office day than telling horror stories.