User login

D-dimer thresholds rule out PE in meta-analysis

In a patient suspected to have a PE, “diagnosis is made radiographically, usually with CT pulmonary angiogram, or V/Q scan,” Suman Pal, MD, of the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, said in an interview.

“Validated clinical decision tools such as Wells’ score or Geneva score may be used to identify patients at low pretest probability of PE who may initially get a D-dimer level check, followed by imaging only if D-dimer level is elevated,” explained Dr. Pal, who was not involved with the new research, which was published in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

According to the authors of the new paper, while current diagnostic strategies in patients with suspected PE include use of a validated clinical decision rule (CDR) and D-dimer testing to rule out PE without imaging tests, the effectiveness of D-dimer tests in older patients, inpatients, cancer patients, and other high-risk groups has not been well-studied.

Lead author of the paper, Milou A.M. Stals, MD, and colleagues said their goal was to evaluate the safety and efficiency of the Wells rule and revised Geneva score in combination with D-dimer tests, and also the YEARS algorithm for D-dimer thresholds, in their paper.

Dr. Stals, of Leiden (the Netherlands) University Medical Center, and the coinvestigators conducted an international systemic review and individual patient data meta-analysis that included 16 studies and 20,553 patients, with all studies having been published between Jan. 1, 1995, and Jan. 1, 2021. Their primary outcomes were the safety and efficiency of each of these three strategies.

In the review, the researchers defined safety as the 3-month incidence of venous thromboembolism after PE was ruled out without imaging at baseline. They defined efficiency as the proportion patients for whom PE was ruled out based on D-dimer thresholds without imaging.

Overall, efficiency was highest in the subset of patients aged younger than 40 years, ranging from 47% to 68% in this group. Efficiency was lowest in patients aged 80 years and older (6.0%-23%), and in patients with cancer (9.6%-26%).

The efficiency was higher when D-dimer thresholds based on pretest probability were used, compared with when fixed or age-adjusted D-dimer thresholds were used.

The key finding was the significant variability in performance of the diagnostic strategies, the researchers said.

“The predicted failure rate was generally highest for strategies incorporating adapted D-dimer thresholds. However, at the same time, predicted overall efficiency was substantially higher with these strategies versus strategies with a fixed D-dimer threshold as well,” they said. Given that the benefits of each of the three diagnostic strategies depends on their correct application, the researchers recommended that an individual hospitalist choose one strategy for their institution.

“Whether clinicians should rely on the Wells rule, the YEARS algorithm, or the revised Geneva score becomes a matter of local preference and experience,” Dr. Stals and colleagues wrote.

The study findings were limited by several factors including between-study differences in scoring predictors and D-dimer assays. Another limitation was that differential verification biases for classifying fatal events and PE may have contributed to overestimation of failure rates of the adapted D-dimer thresholds.

Strengths of the study included its large sample size and original data on pretest probability, and that data support the use of any of the three strategies for ruling out PE in the identified subgroups without the need for imaging tests, the authors wrote.

“Pending the results of ongoing diagnostic randomized trials, physicians and guideline committees should balance the interlink between safety and efficiency of available diagnostic strategies,” they concluded.

Adapted D-dimer benefits some patients

“Clearly, increasing the D-dimer cutoff will lower the number of patients who require radiographic imaging (improved specificity), but this comes with a risk for missing PE (lower sensitivity). Is this risk worth taking?” Daniel J. Brotman, MD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, asked in an editorial accompanying the new study.

Dr. Brotman was not surprised by the study findings.

“Conditions that predispose to thrombosis through activated hemostasis – such as advanced age, cancer, inflammation, prolonged hospitalization, and trauma – drive D-dimer levels higher independent of the presence or absence of radiographically apparent thrombosis,” he said. However, these patients are unlikely to have normal D-dimer levels regardless of the cutoff used.

Adapted D-dimer cutoffs may benefit some patients, including those with contraindications or limited access to imaging, said Dr. Brotman. D-dimer may be used for risk stratification regardless of PE, since patients with marginally elevated D-dimers have better prognoses than those with higher D-dimer elevations, even if a small PE is missed.

Dr. Brotman wrote that increasing D-dimer cutoffs for high-risk patients in the subgroups analyzed may spare some patients radiographic testing, but doing so carries an increased risk for diagnostic failure. Overall, “the important work by Stals and colleagues offers reassurance that modifying D-dimer thresholds according to age or pretest probability is safe enough for widespread practice, even in high-risk groups.”

Focus on single strategy ‘based on local needs’

“Several validated clinical decision tools, along with age or pretest probability adjusted D-dimer threshold are currently in use as diagnostic strategies for ruling out pulmonary embolism,” Dr. Pal said in an interview.

The current study is important because of limited data on the performance of these strategies in specific subgroups of patients whose risk of PE may differ from the overall patient population, he noted.

“Different diagnostic strategies for PE have a variable performance in patients with differences of age, active cancer, and history of VTE,” said Dr. Pal. “However, in this study, no clear preference for one strategy over others could be established for these subgroups, and clinicians should continue to follow institution-specific guidance.

“A single strategy should be adopted at each institution based on local needs and used as the standard of care until further data are available,” he said.

“The use of D-dimer to rule out PE, either with fixed threshold or age-adjusted thresholds, can be confounded in clinical settings by other comorbid conditions such as sepsis, recent surgery, and more recently, COVID-19,” he said.

“Since the findings of this study do not show a clear benefit of one diagnostic strategy over others in the analyzed subgroups of patients, further prospective head-to-head comparison among the subgroups of interest would be helpful to guide clinical decision making,” Dr. Pal added.

YEARS-specific study supports D-dimer safety and value

A recent paper published in JAMA supported the results of the meta-analysis. In that study, Yonathan Freund, MD, of Sorbonne Université, Paris, and colleagues focused on the YEARS strategy combined with age-adjusted D-dimer thresholds as a way to rule out PE in PERC-positive ED patients.

The authors of this paper randomized 18 EDs to either a protocol of intervention followed by control, or control followed by intervention. The study population included 726 patients in the intervention group and 688 in the control group.

The intervention strategy to rule out PE consisted of assessing the YEARS criteria and D-dimer testing. PE was ruled out in patients with no YEARS criteria and a D-dimer level below 1,000 ng/mL and in patients with one or more YEARS criteria and D-dimers below an age-adjusted threshold (defined as age times 10 ng/mL in patients aged 50 years and older).

The control strategy consisted of D-dimer testing for all patients with the threshold at age-adjusted levels; D-dimers about these levels prompted chest imaging.

Overall, the risk of a missed VTE at 3 months was noninferior between the groups (0.15% in the intervention group and 0.80% in the controls).

“The intervention was associated with a statistically significant reduction in chest imaging use,” the researchers wrote.

This study’s findings were limited by randomization at the center level, rather than the patient level, and the use of imaging on some patients despite negative D-dimer tests, the researchers wrote. However, their findings support those of previous studies and especially support the safety of the intervention, in an emergency medicine setting, as no PEs occurred in patients with a YEARS score of zero who underwent the intervention.

Downsides to applying algorithms to every patient explained

In an editorial accompanying the JAMA study, Marcel Levi, MD, and Nick van Es, MD, of Amsterdam University Medical Center, emphasized the challenges of diagnosing PE given that many patients present with nonspecific clinical manifestations and without typical signs and symptoms. High-resolution CT pulmonary angiography allows for a fast and easy diagnosis in an emergency setting. However, efforts are ongoing to develop alternative strategies that avoid unnecessary scanning for potential PE patients, many of whom have alternative diagnoses such as pulmonary infections, cardiac conditions, pleural disease, or musculoskeletal problems.

On review of the JAMA study using the YEARS rule with adjusted D-dimer thresholds, the editorialists noted that the data were robust and indicated a 10% reduction in chest imaging. They also emphasized the potential to overwhelm busy clinicians with more algorithms.

“Blindly applying algorithms to every patient may be less appropriate or even undesirable in specific situations in which deviation from the rules on clinical grounds is indicated,” but a complex imaging approach may be time consuming and challenging in the acute setting, and a simple algorithm may be safe and efficient in many cases, they wrote. “From a patient perspective, a negative diagnostic algorithm for pulmonary embolism does not diminish the physician’s obligation to consider other diagnoses that explain the symptoms, for which chest CT scans may still be needed and helpful.”

The Annals of Internal Medicine study was supported by the Dutch Research Council. The JAMA study was supported by the French Health Ministry. Dr. Stals, Dr. Freund, Dr. Pal, Dr. Levi, and Dr. van Es had no financial conflicts to disclose.

In a patient suspected to have a PE, “diagnosis is made radiographically, usually with CT pulmonary angiogram, or V/Q scan,” Suman Pal, MD, of the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, said in an interview.

“Validated clinical decision tools such as Wells’ score or Geneva score may be used to identify patients at low pretest probability of PE who may initially get a D-dimer level check, followed by imaging only if D-dimer level is elevated,” explained Dr. Pal, who was not involved with the new research, which was published in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

According to the authors of the new paper, while current diagnostic strategies in patients with suspected PE include use of a validated clinical decision rule (CDR) and D-dimer testing to rule out PE without imaging tests, the effectiveness of D-dimer tests in older patients, inpatients, cancer patients, and other high-risk groups has not been well-studied.

Lead author of the paper, Milou A.M. Stals, MD, and colleagues said their goal was to evaluate the safety and efficiency of the Wells rule and revised Geneva score in combination with D-dimer tests, and also the YEARS algorithm for D-dimer thresholds, in their paper.

Dr. Stals, of Leiden (the Netherlands) University Medical Center, and the coinvestigators conducted an international systemic review and individual patient data meta-analysis that included 16 studies and 20,553 patients, with all studies having been published between Jan. 1, 1995, and Jan. 1, 2021. Their primary outcomes were the safety and efficiency of each of these three strategies.

In the review, the researchers defined safety as the 3-month incidence of venous thromboembolism after PE was ruled out without imaging at baseline. They defined efficiency as the proportion patients for whom PE was ruled out based on D-dimer thresholds without imaging.

Overall, efficiency was highest in the subset of patients aged younger than 40 years, ranging from 47% to 68% in this group. Efficiency was lowest in patients aged 80 years and older (6.0%-23%), and in patients with cancer (9.6%-26%).

The efficiency was higher when D-dimer thresholds based on pretest probability were used, compared with when fixed or age-adjusted D-dimer thresholds were used.

The key finding was the significant variability in performance of the diagnostic strategies, the researchers said.

“The predicted failure rate was generally highest for strategies incorporating adapted D-dimer thresholds. However, at the same time, predicted overall efficiency was substantially higher with these strategies versus strategies with a fixed D-dimer threshold as well,” they said. Given that the benefits of each of the three diagnostic strategies depends on their correct application, the researchers recommended that an individual hospitalist choose one strategy for their institution.

“Whether clinicians should rely on the Wells rule, the YEARS algorithm, or the revised Geneva score becomes a matter of local preference and experience,” Dr. Stals and colleagues wrote.

The study findings were limited by several factors including between-study differences in scoring predictors and D-dimer assays. Another limitation was that differential verification biases for classifying fatal events and PE may have contributed to overestimation of failure rates of the adapted D-dimer thresholds.

Strengths of the study included its large sample size and original data on pretest probability, and that data support the use of any of the three strategies for ruling out PE in the identified subgroups without the need for imaging tests, the authors wrote.

“Pending the results of ongoing diagnostic randomized trials, physicians and guideline committees should balance the interlink between safety and efficiency of available diagnostic strategies,” they concluded.

Adapted D-dimer benefits some patients

“Clearly, increasing the D-dimer cutoff will lower the number of patients who require radiographic imaging (improved specificity), but this comes with a risk for missing PE (lower sensitivity). Is this risk worth taking?” Daniel J. Brotman, MD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, asked in an editorial accompanying the new study.

Dr. Brotman was not surprised by the study findings.

“Conditions that predispose to thrombosis through activated hemostasis – such as advanced age, cancer, inflammation, prolonged hospitalization, and trauma – drive D-dimer levels higher independent of the presence or absence of radiographically apparent thrombosis,” he said. However, these patients are unlikely to have normal D-dimer levels regardless of the cutoff used.

Adapted D-dimer cutoffs may benefit some patients, including those with contraindications or limited access to imaging, said Dr. Brotman. D-dimer may be used for risk stratification regardless of PE, since patients with marginally elevated D-dimers have better prognoses than those with higher D-dimer elevations, even if a small PE is missed.

Dr. Brotman wrote that increasing D-dimer cutoffs for high-risk patients in the subgroups analyzed may spare some patients radiographic testing, but doing so carries an increased risk for diagnostic failure. Overall, “the important work by Stals and colleagues offers reassurance that modifying D-dimer thresholds according to age or pretest probability is safe enough for widespread practice, even in high-risk groups.”

Focus on single strategy ‘based on local needs’

“Several validated clinical decision tools, along with age or pretest probability adjusted D-dimer threshold are currently in use as diagnostic strategies for ruling out pulmonary embolism,” Dr. Pal said in an interview.

The current study is important because of limited data on the performance of these strategies in specific subgroups of patients whose risk of PE may differ from the overall patient population, he noted.

“Different diagnostic strategies for PE have a variable performance in patients with differences of age, active cancer, and history of VTE,” said Dr. Pal. “However, in this study, no clear preference for one strategy over others could be established for these subgroups, and clinicians should continue to follow institution-specific guidance.

“A single strategy should be adopted at each institution based on local needs and used as the standard of care until further data are available,” he said.

“The use of D-dimer to rule out PE, either with fixed threshold or age-adjusted thresholds, can be confounded in clinical settings by other comorbid conditions such as sepsis, recent surgery, and more recently, COVID-19,” he said.

“Since the findings of this study do not show a clear benefit of one diagnostic strategy over others in the analyzed subgroups of patients, further prospective head-to-head comparison among the subgroups of interest would be helpful to guide clinical decision making,” Dr. Pal added.

YEARS-specific study supports D-dimer safety and value

A recent paper published in JAMA supported the results of the meta-analysis. In that study, Yonathan Freund, MD, of Sorbonne Université, Paris, and colleagues focused on the YEARS strategy combined with age-adjusted D-dimer thresholds as a way to rule out PE in PERC-positive ED patients.

The authors of this paper randomized 18 EDs to either a protocol of intervention followed by control, or control followed by intervention. The study population included 726 patients in the intervention group and 688 in the control group.

The intervention strategy to rule out PE consisted of assessing the YEARS criteria and D-dimer testing. PE was ruled out in patients with no YEARS criteria and a D-dimer level below 1,000 ng/mL and in patients with one or more YEARS criteria and D-dimers below an age-adjusted threshold (defined as age times 10 ng/mL in patients aged 50 years and older).

The control strategy consisted of D-dimer testing for all patients with the threshold at age-adjusted levels; D-dimers about these levels prompted chest imaging.

Overall, the risk of a missed VTE at 3 months was noninferior between the groups (0.15% in the intervention group and 0.80% in the controls).

“The intervention was associated with a statistically significant reduction in chest imaging use,” the researchers wrote.

This study’s findings were limited by randomization at the center level, rather than the patient level, and the use of imaging on some patients despite negative D-dimer tests, the researchers wrote. However, their findings support those of previous studies and especially support the safety of the intervention, in an emergency medicine setting, as no PEs occurred in patients with a YEARS score of zero who underwent the intervention.

Downsides to applying algorithms to every patient explained

In an editorial accompanying the JAMA study, Marcel Levi, MD, and Nick van Es, MD, of Amsterdam University Medical Center, emphasized the challenges of diagnosing PE given that many patients present with nonspecific clinical manifestations and without typical signs and symptoms. High-resolution CT pulmonary angiography allows for a fast and easy diagnosis in an emergency setting. However, efforts are ongoing to develop alternative strategies that avoid unnecessary scanning for potential PE patients, many of whom have alternative diagnoses such as pulmonary infections, cardiac conditions, pleural disease, or musculoskeletal problems.

On review of the JAMA study using the YEARS rule with adjusted D-dimer thresholds, the editorialists noted that the data were robust and indicated a 10% reduction in chest imaging. They also emphasized the potential to overwhelm busy clinicians with more algorithms.

“Blindly applying algorithms to every patient may be less appropriate or even undesirable in specific situations in which deviation from the rules on clinical grounds is indicated,” but a complex imaging approach may be time consuming and challenging in the acute setting, and a simple algorithm may be safe and efficient in many cases, they wrote. “From a patient perspective, a negative diagnostic algorithm for pulmonary embolism does not diminish the physician’s obligation to consider other diagnoses that explain the symptoms, for which chest CT scans may still be needed and helpful.”

The Annals of Internal Medicine study was supported by the Dutch Research Council. The JAMA study was supported by the French Health Ministry. Dr. Stals, Dr. Freund, Dr. Pal, Dr. Levi, and Dr. van Es had no financial conflicts to disclose.

In a patient suspected to have a PE, “diagnosis is made radiographically, usually with CT pulmonary angiogram, or V/Q scan,” Suman Pal, MD, of the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, said in an interview.

“Validated clinical decision tools such as Wells’ score or Geneva score may be used to identify patients at low pretest probability of PE who may initially get a D-dimer level check, followed by imaging only if D-dimer level is elevated,” explained Dr. Pal, who was not involved with the new research, which was published in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

According to the authors of the new paper, while current diagnostic strategies in patients with suspected PE include use of a validated clinical decision rule (CDR) and D-dimer testing to rule out PE without imaging tests, the effectiveness of D-dimer tests in older patients, inpatients, cancer patients, and other high-risk groups has not been well-studied.

Lead author of the paper, Milou A.M. Stals, MD, and colleagues said their goal was to evaluate the safety and efficiency of the Wells rule and revised Geneva score in combination with D-dimer tests, and also the YEARS algorithm for D-dimer thresholds, in their paper.

Dr. Stals, of Leiden (the Netherlands) University Medical Center, and the coinvestigators conducted an international systemic review and individual patient data meta-analysis that included 16 studies and 20,553 patients, with all studies having been published between Jan. 1, 1995, and Jan. 1, 2021. Their primary outcomes were the safety and efficiency of each of these three strategies.

In the review, the researchers defined safety as the 3-month incidence of venous thromboembolism after PE was ruled out without imaging at baseline. They defined efficiency as the proportion patients for whom PE was ruled out based on D-dimer thresholds without imaging.

Overall, efficiency was highest in the subset of patients aged younger than 40 years, ranging from 47% to 68% in this group. Efficiency was lowest in patients aged 80 years and older (6.0%-23%), and in patients with cancer (9.6%-26%).

The efficiency was higher when D-dimer thresholds based on pretest probability were used, compared with when fixed or age-adjusted D-dimer thresholds were used.

The key finding was the significant variability in performance of the diagnostic strategies, the researchers said.

“The predicted failure rate was generally highest for strategies incorporating adapted D-dimer thresholds. However, at the same time, predicted overall efficiency was substantially higher with these strategies versus strategies with a fixed D-dimer threshold as well,” they said. Given that the benefits of each of the three diagnostic strategies depends on their correct application, the researchers recommended that an individual hospitalist choose one strategy for their institution.

“Whether clinicians should rely on the Wells rule, the YEARS algorithm, or the revised Geneva score becomes a matter of local preference and experience,” Dr. Stals and colleagues wrote.

The study findings were limited by several factors including between-study differences in scoring predictors and D-dimer assays. Another limitation was that differential verification biases for classifying fatal events and PE may have contributed to overestimation of failure rates of the adapted D-dimer thresholds.

Strengths of the study included its large sample size and original data on pretest probability, and that data support the use of any of the three strategies for ruling out PE in the identified subgroups without the need for imaging tests, the authors wrote.

“Pending the results of ongoing diagnostic randomized trials, physicians and guideline committees should balance the interlink between safety and efficiency of available diagnostic strategies,” they concluded.

Adapted D-dimer benefits some patients

“Clearly, increasing the D-dimer cutoff will lower the number of patients who require radiographic imaging (improved specificity), but this comes with a risk for missing PE (lower sensitivity). Is this risk worth taking?” Daniel J. Brotman, MD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, asked in an editorial accompanying the new study.

Dr. Brotman was not surprised by the study findings.

“Conditions that predispose to thrombosis through activated hemostasis – such as advanced age, cancer, inflammation, prolonged hospitalization, and trauma – drive D-dimer levels higher independent of the presence or absence of radiographically apparent thrombosis,” he said. However, these patients are unlikely to have normal D-dimer levels regardless of the cutoff used.

Adapted D-dimer cutoffs may benefit some patients, including those with contraindications or limited access to imaging, said Dr. Brotman. D-dimer may be used for risk stratification regardless of PE, since patients with marginally elevated D-dimers have better prognoses than those with higher D-dimer elevations, even if a small PE is missed.

Dr. Brotman wrote that increasing D-dimer cutoffs for high-risk patients in the subgroups analyzed may spare some patients radiographic testing, but doing so carries an increased risk for diagnostic failure. Overall, “the important work by Stals and colleagues offers reassurance that modifying D-dimer thresholds according to age or pretest probability is safe enough for widespread practice, even in high-risk groups.”

Focus on single strategy ‘based on local needs’

“Several validated clinical decision tools, along with age or pretest probability adjusted D-dimer threshold are currently in use as diagnostic strategies for ruling out pulmonary embolism,” Dr. Pal said in an interview.

The current study is important because of limited data on the performance of these strategies in specific subgroups of patients whose risk of PE may differ from the overall patient population, he noted.

“Different diagnostic strategies for PE have a variable performance in patients with differences of age, active cancer, and history of VTE,” said Dr. Pal. “However, in this study, no clear preference for one strategy over others could be established for these subgroups, and clinicians should continue to follow institution-specific guidance.

“A single strategy should be adopted at each institution based on local needs and used as the standard of care until further data are available,” he said.

“The use of D-dimer to rule out PE, either with fixed threshold or age-adjusted thresholds, can be confounded in clinical settings by other comorbid conditions such as sepsis, recent surgery, and more recently, COVID-19,” he said.

“Since the findings of this study do not show a clear benefit of one diagnostic strategy over others in the analyzed subgroups of patients, further prospective head-to-head comparison among the subgroups of interest would be helpful to guide clinical decision making,” Dr. Pal added.

YEARS-specific study supports D-dimer safety and value

A recent paper published in JAMA supported the results of the meta-analysis. In that study, Yonathan Freund, MD, of Sorbonne Université, Paris, and colleagues focused on the YEARS strategy combined with age-adjusted D-dimer thresholds as a way to rule out PE in PERC-positive ED patients.

The authors of this paper randomized 18 EDs to either a protocol of intervention followed by control, or control followed by intervention. The study population included 726 patients in the intervention group and 688 in the control group.

The intervention strategy to rule out PE consisted of assessing the YEARS criteria and D-dimer testing. PE was ruled out in patients with no YEARS criteria and a D-dimer level below 1,000 ng/mL and in patients with one or more YEARS criteria and D-dimers below an age-adjusted threshold (defined as age times 10 ng/mL in patients aged 50 years and older).

The control strategy consisted of D-dimer testing for all patients with the threshold at age-adjusted levels; D-dimers about these levels prompted chest imaging.

Overall, the risk of a missed VTE at 3 months was noninferior between the groups (0.15% in the intervention group and 0.80% in the controls).

“The intervention was associated with a statistically significant reduction in chest imaging use,” the researchers wrote.

This study’s findings were limited by randomization at the center level, rather than the patient level, and the use of imaging on some patients despite negative D-dimer tests, the researchers wrote. However, their findings support those of previous studies and especially support the safety of the intervention, in an emergency medicine setting, as no PEs occurred in patients with a YEARS score of zero who underwent the intervention.

Downsides to applying algorithms to every patient explained

In an editorial accompanying the JAMA study, Marcel Levi, MD, and Nick van Es, MD, of Amsterdam University Medical Center, emphasized the challenges of diagnosing PE given that many patients present with nonspecific clinical manifestations and without typical signs and symptoms. High-resolution CT pulmonary angiography allows for a fast and easy diagnosis in an emergency setting. However, efforts are ongoing to develop alternative strategies that avoid unnecessary scanning for potential PE patients, many of whom have alternative diagnoses such as pulmonary infections, cardiac conditions, pleural disease, or musculoskeletal problems.

On review of the JAMA study using the YEARS rule with adjusted D-dimer thresholds, the editorialists noted that the data were robust and indicated a 10% reduction in chest imaging. They also emphasized the potential to overwhelm busy clinicians with more algorithms.

“Blindly applying algorithms to every patient may be less appropriate or even undesirable in specific situations in which deviation from the rules on clinical grounds is indicated,” but a complex imaging approach may be time consuming and challenging in the acute setting, and a simple algorithm may be safe and efficient in many cases, they wrote. “From a patient perspective, a negative diagnostic algorithm for pulmonary embolism does not diminish the physician’s obligation to consider other diagnoses that explain the symptoms, for which chest CT scans may still be needed and helpful.”

The Annals of Internal Medicine study was supported by the Dutch Research Council. The JAMA study was supported by the French Health Ministry. Dr. Stals, Dr. Freund, Dr. Pal, Dr. Levi, and Dr. van Es had no financial conflicts to disclose.

FROM THE ANNALS OF INTERNAL MEDICINE

Exercise reduces arm and shoulder problems after breast cancer surgery

However, according to a U.K. study published by The BMJ on Nov. 10, women who exercised shortly after having nonreconstructive breast cancer surgery experienced less pain and regained better shoulder and arm mobility at 1 year than those who did not exercise.

“Hospitals should consider training physiotherapists in the PROSPER program to offer this structured, prescribed exercise program to women undergoing axillary clearance surgery and those having radiotherapy to the axilla,” said lead author Julie Bruce, PhD, a specialist in surgical epidemiology with the University of Warwick, Coventry, England.

Up to one-third of women experience adverse effects to their lymphatic and musculoskeletal systems after breast cancer surgery and radiotherapy targeting the axilla. A study of 2,411 women in Denmark found that pain remained for up to 7 years after breast cancer treatment. U.K. guidelines for the management of breast cancer recommend referral to physical therapy if such problems develop, but the best timing and intensity along with the safety of postoperative exercise remain uncertain. A review of the literature in 2019 found a lack of adequate evidence to support the use of postoperative exercise after breast cancer surgery. Moreover, concerns with such exercise have been reported, such as increased risks of postoperative wound complications and lymphedema.

“The study was conducted to address uncertainty whether early postoperative exercise after women at high risk of shoulder and arm problems after nonreconstructive surgery was safe, clinically, and cost-effective. Previous studies were small, and no large high-quality randomized controlled trials had been undertaken with this patient population in the U.K.,” Dr. Bruce said.

In UK PROSPER, a multicenter, randomized controlled trial, researchers investigated the effects of an exercise program compared with usual care for 392 women (mean age 58) undergoing breast cancer surgery at 17 National Health Service (NHS) cancer centers. The women were randomly assigned to usual care with structured exercise or usual care alone. Structured exercise, introduced 7-10 days postoperatively, consisted of a physical therapy–led exercise program comprising stretching, strengthening, and physical activity, along with behavioral change techniques to support exercise adherence. Two further appointments were offered 1 and 3 months later. Outcomes included upper limb function, as measured by the Disability of Arm, Hand, and Shoulder (DASH) questionnaire at 12 months, complications, health related quality of life, and cost effectiveness.

At 12 months, women in the exercise group showed improved upper limb function compared with those who received usual care (mean DASH 16.3 for exercise, 23.7 for usual care; adjusted mean difference 7.81, 95% confidence interval, 3.17-12.44; P = .001). Compared with the usual care group, women in the exercise group reported lower pain intensity, fewer arm disability symptoms, and better health related quality of life.

“We found that arm function, measured using the DASH scale, improved over time and found surprisingly, these differences between treatment groups persisted at 12 months,” Dr. Bruce said. “There was no increased risk of neuropathic pain or lymphedema, so we concluded that the structured exercise program introduced from the seventh postoperative day was safe. Strengthening exercises were introduced from 1 month postoperatively.”

While the authors noted that the study was limited as participants and physical therapists knew which treatment they were receiving, they stressed that the study included a larger sample size than that of previous trials, along with a long follow-up period.

“We know that some women develop late lymphedema. Our findings are based on follow-up at 12 months. We hope to undertake longer-term follow up of our patient sample in the future,” Dr. Bruce said.

The authors declared support from the UK National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Technology Assessment Programme.

However, according to a U.K. study published by The BMJ on Nov. 10, women who exercised shortly after having nonreconstructive breast cancer surgery experienced less pain and regained better shoulder and arm mobility at 1 year than those who did not exercise.

“Hospitals should consider training physiotherapists in the PROSPER program to offer this structured, prescribed exercise program to women undergoing axillary clearance surgery and those having radiotherapy to the axilla,” said lead author Julie Bruce, PhD, a specialist in surgical epidemiology with the University of Warwick, Coventry, England.

Up to one-third of women experience adverse effects to their lymphatic and musculoskeletal systems after breast cancer surgery and radiotherapy targeting the axilla. A study of 2,411 women in Denmark found that pain remained for up to 7 years after breast cancer treatment. U.K. guidelines for the management of breast cancer recommend referral to physical therapy if such problems develop, but the best timing and intensity along with the safety of postoperative exercise remain uncertain. A review of the literature in 2019 found a lack of adequate evidence to support the use of postoperative exercise after breast cancer surgery. Moreover, concerns with such exercise have been reported, such as increased risks of postoperative wound complications and lymphedema.

“The study was conducted to address uncertainty whether early postoperative exercise after women at high risk of shoulder and arm problems after nonreconstructive surgery was safe, clinically, and cost-effective. Previous studies were small, and no large high-quality randomized controlled trials had been undertaken with this patient population in the U.K.,” Dr. Bruce said.

In UK PROSPER, a multicenter, randomized controlled trial, researchers investigated the effects of an exercise program compared with usual care for 392 women (mean age 58) undergoing breast cancer surgery at 17 National Health Service (NHS) cancer centers. The women were randomly assigned to usual care with structured exercise or usual care alone. Structured exercise, introduced 7-10 days postoperatively, consisted of a physical therapy–led exercise program comprising stretching, strengthening, and physical activity, along with behavioral change techniques to support exercise adherence. Two further appointments were offered 1 and 3 months later. Outcomes included upper limb function, as measured by the Disability of Arm, Hand, and Shoulder (DASH) questionnaire at 12 months, complications, health related quality of life, and cost effectiveness.

At 12 months, women in the exercise group showed improved upper limb function compared with those who received usual care (mean DASH 16.3 for exercise, 23.7 for usual care; adjusted mean difference 7.81, 95% confidence interval, 3.17-12.44; P = .001). Compared with the usual care group, women in the exercise group reported lower pain intensity, fewer arm disability symptoms, and better health related quality of life.

“We found that arm function, measured using the DASH scale, improved over time and found surprisingly, these differences between treatment groups persisted at 12 months,” Dr. Bruce said. “There was no increased risk of neuropathic pain or lymphedema, so we concluded that the structured exercise program introduced from the seventh postoperative day was safe. Strengthening exercises were introduced from 1 month postoperatively.”

While the authors noted that the study was limited as participants and physical therapists knew which treatment they were receiving, they stressed that the study included a larger sample size than that of previous trials, along with a long follow-up period.

“We know that some women develop late lymphedema. Our findings are based on follow-up at 12 months. We hope to undertake longer-term follow up of our patient sample in the future,” Dr. Bruce said.

The authors declared support from the UK National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Technology Assessment Programme.

However, according to a U.K. study published by The BMJ on Nov. 10, women who exercised shortly after having nonreconstructive breast cancer surgery experienced less pain and regained better shoulder and arm mobility at 1 year than those who did not exercise.

“Hospitals should consider training physiotherapists in the PROSPER program to offer this structured, prescribed exercise program to women undergoing axillary clearance surgery and those having radiotherapy to the axilla,” said lead author Julie Bruce, PhD, a specialist in surgical epidemiology with the University of Warwick, Coventry, England.

Up to one-third of women experience adverse effects to their lymphatic and musculoskeletal systems after breast cancer surgery and radiotherapy targeting the axilla. A study of 2,411 women in Denmark found that pain remained for up to 7 years after breast cancer treatment. U.K. guidelines for the management of breast cancer recommend referral to physical therapy if such problems develop, but the best timing and intensity along with the safety of postoperative exercise remain uncertain. A review of the literature in 2019 found a lack of adequate evidence to support the use of postoperative exercise after breast cancer surgery. Moreover, concerns with such exercise have been reported, such as increased risks of postoperative wound complications and lymphedema.

“The study was conducted to address uncertainty whether early postoperative exercise after women at high risk of shoulder and arm problems after nonreconstructive surgery was safe, clinically, and cost-effective. Previous studies were small, and no large high-quality randomized controlled trials had been undertaken with this patient population in the U.K.,” Dr. Bruce said.

In UK PROSPER, a multicenter, randomized controlled trial, researchers investigated the effects of an exercise program compared with usual care for 392 women (mean age 58) undergoing breast cancer surgery at 17 National Health Service (NHS) cancer centers. The women were randomly assigned to usual care with structured exercise or usual care alone. Structured exercise, introduced 7-10 days postoperatively, consisted of a physical therapy–led exercise program comprising stretching, strengthening, and physical activity, along with behavioral change techniques to support exercise adherence. Two further appointments were offered 1 and 3 months later. Outcomes included upper limb function, as measured by the Disability of Arm, Hand, and Shoulder (DASH) questionnaire at 12 months, complications, health related quality of life, and cost effectiveness.

At 12 months, women in the exercise group showed improved upper limb function compared with those who received usual care (mean DASH 16.3 for exercise, 23.7 for usual care; adjusted mean difference 7.81, 95% confidence interval, 3.17-12.44; P = .001). Compared with the usual care group, women in the exercise group reported lower pain intensity, fewer arm disability symptoms, and better health related quality of life.

“We found that arm function, measured using the DASH scale, improved over time and found surprisingly, these differences between treatment groups persisted at 12 months,” Dr. Bruce said. “There was no increased risk of neuropathic pain or lymphedema, so we concluded that the structured exercise program introduced from the seventh postoperative day was safe. Strengthening exercises were introduced from 1 month postoperatively.”

While the authors noted that the study was limited as participants and physical therapists knew which treatment they were receiving, they stressed that the study included a larger sample size than that of previous trials, along with a long follow-up period.

“We know that some women develop late lymphedema. Our findings are based on follow-up at 12 months. We hope to undertake longer-term follow up of our patient sample in the future,” Dr. Bruce said.

The authors declared support from the UK National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Technology Assessment Programme.

FROM THE BMJ

Fully endovascular mitral valve replacement a limited success in feasibility study

It remains early days for transcatheter mitral-valve replacement (TMVR) as a minimally invasive way to treat severe, mitral regurgitation (MR), but it’s even earlier days for TMVR as an endovascular procedure. Most of the technique’s limited experience with a dedicated mitral prosthesis has involved transapical delivery.

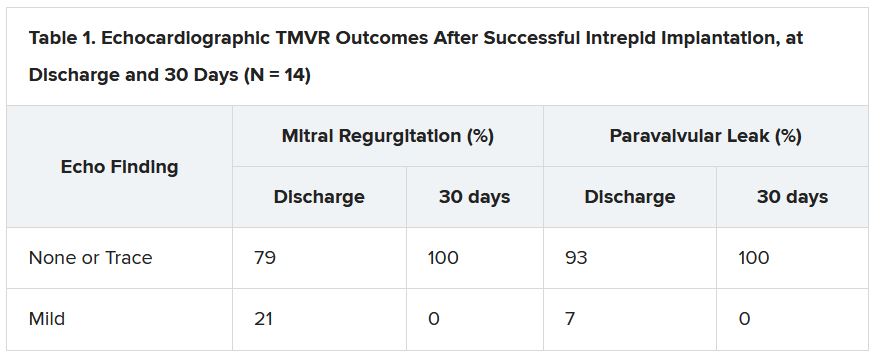

But now a 15-patient study of transfemoral, transeptal TMVR – with a prosthesis designed for the mitral position and previously tested only transapically – has shown good 30-day results in that MR was essentially abolished with virtually no paravalvular leakage.

Nor were there adverse clinical events such as death, stroke, reintervention, or new need for a pacemaker in any of the high-surgical-risk patients with MR in this feasibility study of the transfemoral Intrepid TMVR System (Medtronic). Implantation failed, however, in one patient who then received a surgical valve via sternotomy.

The current cohort is part of a larger ongoing trial that will track whether patients implanted transfemorally with the Intrepid also show reverse remodeling and good clinical outcomes over at least a year. That study, called APOLLO, is one of several exploring dedicated TMVR valves from different companies, with names like SUMMIT, MISCEND, and TIARA-2.

Currently, TMVR is approved in the United States only using one device designed for the aortic position and only for treating failed surgical mitral bioprostheses in high-risk patients.

If the Intrepid transfemoral system has an Achilles’ heel, at least in the current iteration, it might be its 35 F catheter delivery system that requires surgical access to the femoral vein. Seven of the patients in the small series experienced major bleeding events, including six at the femoral access site, listed as major vascular complications.

Overall, the study’s patients “were extremely sick with a lot of comorbidity. A lot of them had atrial fibrillation, a lot of them were on anticoagulation to start with,” observed Firas Zahr, MD, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, as part of his presentation of the study at Transcatheter Cardiovascular Therapeutics (TCT) 2021, held virtually as well as onsite in Orlando, Florida.

All had moderate-to-severe, usually primary MR; two thirds of the cohort had been in NYHA class III or IV at baseline, and 40% had been hospitalized for heart failure within the past year. Eight had a history of cardiovascular surgery, and eight had diabetes. Their mean Society of Thoracic Surgeons Predicted Risk of Mortality (STS-PROM) score was 4.7, Dr. Zahr reported.

“At 30 days, there was a significant improvement in their heart failure classification; the vast majority of the patients were [NYHA] class I and class II,” said Dr. Zahr, who is also lead author on the study’s Nov. 6 publication in JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions.

Observers of the study at TCT 2021 seemed enthusiastic about the study’s results but recognized that TMVR in its current form still has formidable limitations.

“This is clearly an exciting look into the future and very reassuring to a degree, aside from the complications, which are somewhat expected as we go with 30-plus French devices,” Rajiv Tayal, MD, MPH, said at a press conference on the Intrepid study held before Dr. Zahr’s formal presentation. Dr. Tayal is an interventional cardiologist with Valley Health System, Ridgewood, New Jersey, and New York Medical College, Valhalla.

“I think we’ve all learned that transapical [access] is just not a viable procedure for a lot of these patients, and so we’ve got to get to transfemoral,” Susheel K. Kodali, MD, interventional cardiologist at New York-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center, said at the same forum.

A 35 F device “is going to be too big,” he said. However, “it is the first step to iterate to a smaller device.” Dr. Kodali said his center contributed a patient to the study, and he is listed as a coauthor on the publication.

The delivery system’s large profile is only part of the vascular complication issue. Not only did the procedure require surgical cutdown for venous access, but “we were fairly aggressive in anticoagulating these patients with the fear of thrombus formation,” Dr. Zahr said in the discussion following his presentation.

“A postprocedure anticoagulation regimen is recommended within the protocol, but ultimate therapy was left to the discretion of the treating site physician,” the published report states, noting that all 14 patients with successful TMVR were discharged on warfarin. They included 12 who were also put on a single antiplatelet and one given dual antiplatelet therapy on top of the oral anticoagulant.

“One thing that we learned is that we probably should standardize our approach to perioperative anticoagulation,” Dr. Zahr observed. Also, a 29 F sheath for the system is in the works, “and we’re hoping that with smaller sheath size, and hopefully going even to percutaneous, might have an impact on lowering the vascular complications.”

Explanations for the “higher-than-expected vascular complication rate” remains somewhat unclear, agreed an editorial accompanying the study’s publication, “but may include a learning curve with the system, the large introducer sheath, the need for surgical cutdown, and postprocedural anticoagulation.”

For trans-septal TMVR to become a default approach, “venous access will need to be achieved percutaneously and vascular complications need to be infrequent,” contends the editorial, with lead author Mohamad Alkhouli, MD, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

“These data provide a glimpse into the future of TMVR. The excellent short-term safety and effectiveness of this still very early-stage procedure represent a major step forward in the field,” they write.

“The main question that the Intrepid early feasibility data raise is whether transfemoral, trans-septal TMVR will evolve to become the preferred strategy over transapical TMVR,” as occurred with transcatheter aortic-valve replacement (TAVR), the editorial states. “The answer is likely yes, but a few matters specific to trans-septal route will need be addressed first.”

Among those matters: The 35 F catheter leaves behind a considerable atrial septal defect (ASD). At operator discretion in this series, 11 patients received an ASD closure device.

None of the remaining four patients “developed significant heart failure or right ventricular dysfunction,” Dr. Zahr observed. “So, it seems like those patients who had their ASD left open tolerated it fairly well, at least until 30 days.”

But “we still need to learn what to do with those ASDs,” he said. “What is an acceptable residual shunt and what is an acceptable ASD size is to be determined.”

In general, the editorial notes, “the TMVR population has a high prevalence of cardiomyopathy, and a large residual iatrogenic ASD may lead to worsening volume overload and heart failure decompensation in some patients.”

Insertion of a closure device has its own issues, it continues. “Closure of the ASD might impede future access to the left atrium, which could impact life-long management of this high-risk population. A large septal occluder may hinder potentially needed procedures such as paravalvular leak closure, left atrial appendage closure, or pulmonary vein isolation.”

Patients like those in the current series, Dr. Kodali observed, will face “a lifetime of management challenges, and you want to make sure you don’t take away other options.”

The study was funded by Medtronic. Dr. Zahr reported institutional grant support from Edwards Lifesciences and Medtronic. Dr. Kodali disclosed consultant fees from Admedus and Dura Biotech; equity in Dura Biotech, Microinterventional Devices, Thubrika Aortic Valve, Supira, Admedus, TriFlo, and Anona; and institutional grant support from Edwards Lifesciences, Medtronic, Abbott Vascular, Boston Scientific, and JenaValve. The editorial writers have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Tayal disclosed consultant fees or honoraria from or serving on a speakers bureau for Abiomed, Edwards Lifesciences, Abbott Vascular, and Shockwave Medical.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

It remains early days for transcatheter mitral-valve replacement (TMVR) as a minimally invasive way to treat severe, mitral regurgitation (MR), but it’s even earlier days for TMVR as an endovascular procedure. Most of the technique’s limited experience with a dedicated mitral prosthesis has involved transapical delivery.

But now a 15-patient study of transfemoral, transeptal TMVR – with a prosthesis designed for the mitral position and previously tested only transapically – has shown good 30-day results in that MR was essentially abolished with virtually no paravalvular leakage.

Nor were there adverse clinical events such as death, stroke, reintervention, or new need for a pacemaker in any of the high-surgical-risk patients with MR in this feasibility study of the transfemoral Intrepid TMVR System (Medtronic). Implantation failed, however, in one patient who then received a surgical valve via sternotomy.

The current cohort is part of a larger ongoing trial that will track whether patients implanted transfemorally with the Intrepid also show reverse remodeling and good clinical outcomes over at least a year. That study, called APOLLO, is one of several exploring dedicated TMVR valves from different companies, with names like SUMMIT, MISCEND, and TIARA-2.

Currently, TMVR is approved in the United States only using one device designed for the aortic position and only for treating failed surgical mitral bioprostheses in high-risk patients.

If the Intrepid transfemoral system has an Achilles’ heel, at least in the current iteration, it might be its 35 F catheter delivery system that requires surgical access to the femoral vein. Seven of the patients in the small series experienced major bleeding events, including six at the femoral access site, listed as major vascular complications.

Overall, the study’s patients “were extremely sick with a lot of comorbidity. A lot of them had atrial fibrillation, a lot of them were on anticoagulation to start with,” observed Firas Zahr, MD, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, as part of his presentation of the study at Transcatheter Cardiovascular Therapeutics (TCT) 2021, held virtually as well as onsite in Orlando, Florida.

All had moderate-to-severe, usually primary MR; two thirds of the cohort had been in NYHA class III or IV at baseline, and 40% had been hospitalized for heart failure within the past year. Eight had a history of cardiovascular surgery, and eight had diabetes. Their mean Society of Thoracic Surgeons Predicted Risk of Mortality (STS-PROM) score was 4.7, Dr. Zahr reported.

“At 30 days, there was a significant improvement in their heart failure classification; the vast majority of the patients were [NYHA] class I and class II,” said Dr. Zahr, who is also lead author on the study’s Nov. 6 publication in JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions.

Observers of the study at TCT 2021 seemed enthusiastic about the study’s results but recognized that TMVR in its current form still has formidable limitations.

“This is clearly an exciting look into the future and very reassuring to a degree, aside from the complications, which are somewhat expected as we go with 30-plus French devices,” Rajiv Tayal, MD, MPH, said at a press conference on the Intrepid study held before Dr. Zahr’s formal presentation. Dr. Tayal is an interventional cardiologist with Valley Health System, Ridgewood, New Jersey, and New York Medical College, Valhalla.

“I think we’ve all learned that transapical [access] is just not a viable procedure for a lot of these patients, and so we’ve got to get to transfemoral,” Susheel K. Kodali, MD, interventional cardiologist at New York-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center, said at the same forum.

A 35 F device “is going to be too big,” he said. However, “it is the first step to iterate to a smaller device.” Dr. Kodali said his center contributed a patient to the study, and he is listed as a coauthor on the publication.

The delivery system’s large profile is only part of the vascular complication issue. Not only did the procedure require surgical cutdown for venous access, but “we were fairly aggressive in anticoagulating these patients with the fear of thrombus formation,” Dr. Zahr said in the discussion following his presentation.

“A postprocedure anticoagulation regimen is recommended within the protocol, but ultimate therapy was left to the discretion of the treating site physician,” the published report states, noting that all 14 patients with successful TMVR were discharged on warfarin. They included 12 who were also put on a single antiplatelet and one given dual antiplatelet therapy on top of the oral anticoagulant.

“One thing that we learned is that we probably should standardize our approach to perioperative anticoagulation,” Dr. Zahr observed. Also, a 29 F sheath for the system is in the works, “and we’re hoping that with smaller sheath size, and hopefully going even to percutaneous, might have an impact on lowering the vascular complications.”

Explanations for the “higher-than-expected vascular complication rate” remains somewhat unclear, agreed an editorial accompanying the study’s publication, “but may include a learning curve with the system, the large introducer sheath, the need for surgical cutdown, and postprocedural anticoagulation.”

For trans-septal TMVR to become a default approach, “venous access will need to be achieved percutaneously and vascular complications need to be infrequent,” contends the editorial, with lead author Mohamad Alkhouli, MD, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

“These data provide a glimpse into the future of TMVR. The excellent short-term safety and effectiveness of this still very early-stage procedure represent a major step forward in the field,” they write.

“The main question that the Intrepid early feasibility data raise is whether transfemoral, trans-septal TMVR will evolve to become the preferred strategy over transapical TMVR,” as occurred with transcatheter aortic-valve replacement (TAVR), the editorial states. “The answer is likely yes, but a few matters specific to trans-septal route will need be addressed first.”

Among those matters: The 35 F catheter leaves behind a considerable atrial septal defect (ASD). At operator discretion in this series, 11 patients received an ASD closure device.

None of the remaining four patients “developed significant heart failure or right ventricular dysfunction,” Dr. Zahr observed. “So, it seems like those patients who had their ASD left open tolerated it fairly well, at least until 30 days.”

But “we still need to learn what to do with those ASDs,” he said. “What is an acceptable residual shunt and what is an acceptable ASD size is to be determined.”

In general, the editorial notes, “the TMVR population has a high prevalence of cardiomyopathy, and a large residual iatrogenic ASD may lead to worsening volume overload and heart failure decompensation in some patients.”

Insertion of a closure device has its own issues, it continues. “Closure of the ASD might impede future access to the left atrium, which could impact life-long management of this high-risk population. A large septal occluder may hinder potentially needed procedures such as paravalvular leak closure, left atrial appendage closure, or pulmonary vein isolation.”

Patients like those in the current series, Dr. Kodali observed, will face “a lifetime of management challenges, and you want to make sure you don’t take away other options.”

The study was funded by Medtronic. Dr. Zahr reported institutional grant support from Edwards Lifesciences and Medtronic. Dr. Kodali disclosed consultant fees from Admedus and Dura Biotech; equity in Dura Biotech, Microinterventional Devices, Thubrika Aortic Valve, Supira, Admedus, TriFlo, and Anona; and institutional grant support from Edwards Lifesciences, Medtronic, Abbott Vascular, Boston Scientific, and JenaValve. The editorial writers have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Tayal disclosed consultant fees or honoraria from or serving on a speakers bureau for Abiomed, Edwards Lifesciences, Abbott Vascular, and Shockwave Medical.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

It remains early days for transcatheter mitral-valve replacement (TMVR) as a minimally invasive way to treat severe, mitral regurgitation (MR), but it’s even earlier days for TMVR as an endovascular procedure. Most of the technique’s limited experience with a dedicated mitral prosthesis has involved transapical delivery.

But now a 15-patient study of transfemoral, transeptal TMVR – with a prosthesis designed for the mitral position and previously tested only transapically – has shown good 30-day results in that MR was essentially abolished with virtually no paravalvular leakage.

Nor were there adverse clinical events such as death, stroke, reintervention, or new need for a pacemaker in any of the high-surgical-risk patients with MR in this feasibility study of the transfemoral Intrepid TMVR System (Medtronic). Implantation failed, however, in one patient who then received a surgical valve via sternotomy.

The current cohort is part of a larger ongoing trial that will track whether patients implanted transfemorally with the Intrepid also show reverse remodeling and good clinical outcomes over at least a year. That study, called APOLLO, is one of several exploring dedicated TMVR valves from different companies, with names like SUMMIT, MISCEND, and TIARA-2.

Currently, TMVR is approved in the United States only using one device designed for the aortic position and only for treating failed surgical mitral bioprostheses in high-risk patients.

If the Intrepid transfemoral system has an Achilles’ heel, at least in the current iteration, it might be its 35 F catheter delivery system that requires surgical access to the femoral vein. Seven of the patients in the small series experienced major bleeding events, including six at the femoral access site, listed as major vascular complications.

Overall, the study’s patients “were extremely sick with a lot of comorbidity. A lot of them had atrial fibrillation, a lot of them were on anticoagulation to start with,” observed Firas Zahr, MD, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, as part of his presentation of the study at Transcatheter Cardiovascular Therapeutics (TCT) 2021, held virtually as well as onsite in Orlando, Florida.

All had moderate-to-severe, usually primary MR; two thirds of the cohort had been in NYHA class III or IV at baseline, and 40% had been hospitalized for heart failure within the past year. Eight had a history of cardiovascular surgery, and eight had diabetes. Their mean Society of Thoracic Surgeons Predicted Risk of Mortality (STS-PROM) score was 4.7, Dr. Zahr reported.

“At 30 days, there was a significant improvement in their heart failure classification; the vast majority of the patients were [NYHA] class I and class II,” said Dr. Zahr, who is also lead author on the study’s Nov. 6 publication in JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions.

Observers of the study at TCT 2021 seemed enthusiastic about the study’s results but recognized that TMVR in its current form still has formidable limitations.

“This is clearly an exciting look into the future and very reassuring to a degree, aside from the complications, which are somewhat expected as we go with 30-plus French devices,” Rajiv Tayal, MD, MPH, said at a press conference on the Intrepid study held before Dr. Zahr’s formal presentation. Dr. Tayal is an interventional cardiologist with Valley Health System, Ridgewood, New Jersey, and New York Medical College, Valhalla.

“I think we’ve all learned that transapical [access] is just not a viable procedure for a lot of these patients, and so we’ve got to get to transfemoral,” Susheel K. Kodali, MD, interventional cardiologist at New York-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center, said at the same forum.

A 35 F device “is going to be too big,” he said. However, “it is the first step to iterate to a smaller device.” Dr. Kodali said his center contributed a patient to the study, and he is listed as a coauthor on the publication.

The delivery system’s large profile is only part of the vascular complication issue. Not only did the procedure require surgical cutdown for venous access, but “we were fairly aggressive in anticoagulating these patients with the fear of thrombus formation,” Dr. Zahr said in the discussion following his presentation.

“A postprocedure anticoagulation regimen is recommended within the protocol, but ultimate therapy was left to the discretion of the treating site physician,” the published report states, noting that all 14 patients with successful TMVR were discharged on warfarin. They included 12 who were also put on a single antiplatelet and one given dual antiplatelet therapy on top of the oral anticoagulant.

“One thing that we learned is that we probably should standardize our approach to perioperative anticoagulation,” Dr. Zahr observed. Also, a 29 F sheath for the system is in the works, “and we’re hoping that with smaller sheath size, and hopefully going even to percutaneous, might have an impact on lowering the vascular complications.”

Explanations for the “higher-than-expected vascular complication rate” remains somewhat unclear, agreed an editorial accompanying the study’s publication, “but may include a learning curve with the system, the large introducer sheath, the need for surgical cutdown, and postprocedural anticoagulation.”

For trans-septal TMVR to become a default approach, “venous access will need to be achieved percutaneously and vascular complications need to be infrequent,” contends the editorial, with lead author Mohamad Alkhouli, MD, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

“These data provide a glimpse into the future of TMVR. The excellent short-term safety and effectiveness of this still very early-stage procedure represent a major step forward in the field,” they write.

“The main question that the Intrepid early feasibility data raise is whether transfemoral, trans-septal TMVR will evolve to become the preferred strategy over transapical TMVR,” as occurred with transcatheter aortic-valve replacement (TAVR), the editorial states. “The answer is likely yes, but a few matters specific to trans-septal route will need be addressed first.”

Among those matters: The 35 F catheter leaves behind a considerable atrial septal defect (ASD). At operator discretion in this series, 11 patients received an ASD closure device.

None of the remaining four patients “developed significant heart failure or right ventricular dysfunction,” Dr. Zahr observed. “So, it seems like those patients who had their ASD left open tolerated it fairly well, at least until 30 days.”

But “we still need to learn what to do with those ASDs,” he said. “What is an acceptable residual shunt and what is an acceptable ASD size is to be determined.”

In general, the editorial notes, “the TMVR population has a high prevalence of cardiomyopathy, and a large residual iatrogenic ASD may lead to worsening volume overload and heart failure decompensation in some patients.”

Insertion of a closure device has its own issues, it continues. “Closure of the ASD might impede future access to the left atrium, which could impact life-long management of this high-risk population. A large septal occluder may hinder potentially needed procedures such as paravalvular leak closure, left atrial appendage closure, or pulmonary vein isolation.”

Patients like those in the current series, Dr. Kodali observed, will face “a lifetime of management challenges, and you want to make sure you don’t take away other options.”

The study was funded by Medtronic. Dr. Zahr reported institutional grant support from Edwards Lifesciences and Medtronic. Dr. Kodali disclosed consultant fees from Admedus and Dura Biotech; equity in Dura Biotech, Microinterventional Devices, Thubrika Aortic Valve, Supira, Admedus, TriFlo, and Anona; and institutional grant support from Edwards Lifesciences, Medtronic, Abbott Vascular, Boston Scientific, and JenaValve. The editorial writers have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Tayal disclosed consultant fees or honoraria from or serving on a speakers bureau for Abiomed, Edwards Lifesciences, Abbott Vascular, and Shockwave Medical.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

AHA 2021 puts scientific dialogue, health equity center stage

Virtual platforms democratized scientific meetings during the COVID-19 pandemic but, as any meeting-goer will tell you, it’s the questions from the floor and the back-and-forth of an expert panel that often reveal the importance of and/or problems with a presentation. It’s the scrutiny that makes the science resonate, especially in this postfactual era.

The all-virtual American Heart Association Scientific Sessions 2021 is looking to recreate the engagement of an in-person meeting by offering more live interactive events. They range from seven late-breaking science (LBS) sessions to Saturday’s fireside chat on the Pfizer and Moderna COVID-19 vaccines and Monday’s dive into the controversial new AHA/American College of Cardiology Chest Pain guidelines.

To help digest the latest science, attendees will be able to have their questions answered in real-time via Slido, meet with the trialists, and hear live commentary from key opinion leaders after the live events. A networking function will also allow attendees and exhibitors to chat or meet virtually.

“In this day and age, many people pretty quickly can get access to the science but it’s what I call the IC sort of phenomenon – the presentation of the information, the context of the information, putting it into how I’m going to use it in my practice, and then the critical appraisal – that’s what most people want at the Scientific Sessions,” program committee chair Manesh R. Patel, MD, of Duke University School of Medicine, said in an interview. “We’re all craving ways in which we can interact with one another to put things in context.”

Plans for a hybrid in-person meeting in Boston were scuttled in September because of the Delta variant surge, but the theme of the meeting remained: “One World. Together for Science.” Attendees will be able to access more than 500 live and on-demand sessions including 117 oral abstracts, 286 poster sessions, 59 moderated digital posters, and over a dozen sessions focused on strategies to promote health equity.

“Last year there was a Presidential Session and a statement on structural racism, so we wanted to take the next step and say, What are the ways in which people are starting to interact and do things to make a difference?” explained Dr. Patel. “So, this year, you’ll see different versions of that from the Main Event session, which has some case vignettes and a panel discussion, to other health equity sessions that describe not just COVID care, but blood pressure care, maternal-fetal medicine, and congenital kids. Wherever we can, we’ve tried to infuse it throughout the sessions and will continue to.”

Late-breaking science

The LBS sessions kick off at 9:30 a.m. ET Saturday with AVATAR, a randomized trial of aortic valve replacement vs. watchful waiting in severe aortic stenosis proved asymptomatic through exercise testing.

“The findings of that trial, depending on what they are, could certainly impact clinical practice because it’s a very common scenario in which we have elderly patients with aortic valve stenosis that might be severe but they may not be symptomatic,” he said.

It’s followed by a randomized trial from the Cardiothoracic Surgical Trials Network, examining whether tricuspid repair at the time of mitral valve surgery leads to beneficial outcomes. “I think it’s a pretty important study,” Dr. Patel said, “because it’ll again affect how we think about our clinical practice.”

Rounding out the LBS.01 session is RAPID CABG, comparing early vs. delayed coronary bypass graft surgery (CABG) in patients with acute coronary syndromes on ticagrelor, and the pivotal U.S. VEST trial of an external support device already approved in Europe for saphenous vein grafts during CABG.

Saturday’s LBS.02 at 3:00 p.m. ET is devoted to hypertension and looks at how the COVID-19 pandemic affected blood pressure control. There’s also a study of remotely delivered hypertension and lipid management in 10,000 patients across the Partners Healthcare System and a cluster randomized trial of a village doctor–led blood pressure intervention in rural China.

Sunday’s LBS.03 at 8:00 a.m. ET is focused on atrial arrhythmias, starting with the CRAVE trial examining the effect of caffeine consumption on cardiac ectopy burden in 108 patients using an N-of-1 design and 2-day blocks on and off caffeine. “There’s an ability to identify a dose response that you get arrhythmias when you increase the amount of coffee you drink vs. not in an individual, so I think that will be likely discussed a lot and worth paying attention to,” Dr. Patel said.

The session also includes GIRAF, a comparison of cognitive outcomes with dabigatran (Pradaxa) vs. warfarin (Coumadin) in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (AF); PALACS, a randomized trial examining whether left-sided pericardiotomy prevents AF after cardiac surgery; and AMAZE, which study sponsor AtriCure revealed missed its primary efficacy endpoint of freedom from AF with the LARIAT suture delivery device for left atrial appendage closure plus pulmonary vein isolation.

LBS.04 at 3:30 p.m. ET Sunday takes on digital health, with results from the nonrandomized Fitbit Heart Study on AF notifications from 450,000 participants wearing a single-lead ECG patch. “A lot of technologies claim that they can detect things, and we should ask that people go through the rigorous evaluation to see if they in fact do. So, in that respect, I think it›s an important step,” observed Dr. Patel.

Also on tap is I-STOP-AFib, another N-of-1 study using mobile apps and the AliveCor device to identify individual AF triggers; and REVeAL-HF, a 4,000-patient study examining whether electronic alerts that provide clinicians with prognostic information on their heart failure (HF) patients will reduce mortality and 30-day HF hospitalizations.

LBS.05 at 5:00 p.m. ET provides new information from EMPEROR-Preserved in HF with preserved ejection fraction and main results from EMPULSE, also using the sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor empagliflozin (Jardiance) in 530 patients hospitalized for acute HF.

The session also features CHIEF-HF, a randomized trial leveraging mobile technologies to test whether 12 weeks of another SGLT2 inhibitor, canagliflozin (Invokana), is superior to placebo for improving HF symptoms; and DREAM-HF, a comparison of transendocardial delivery of allogeneic mesenchymal precursor cells vs. a sham comparator in chronic HF as a result of left ventricular systolic dysfunction.

Monday’s LBS.06 at 8:00 a.m. ET details the safety and cholesterol-lowering efficacy of MK-0616, an investigational oral PCSK9 inhibitor. “It’s just a phase 2 [trial], but there’s interest in an oral PCSK9 inhibitor, given that the current ones are subcutaneous,” Dr. Patel said.

Results will also be presented from PREPARE-IT 2, which tested icosapent ethyl vs. placebo in outpatients with COVID-19. In the recently reported PREPARE-IT 1, a loading dose of icosapent ethyl failed to reduce the risk of hospitalization with SARS-CoV-2 infection among at-risk individuals.

LBS.07 at 11:00 a.m. Monday completes the late-breakers with new results from ASCEND, this time examining the effect of aspirin on dementia and cognitive impairment in patients with diabetes.

Next up is a look at the effectiveness of P2Y12 inhibitors in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in the adaptive ACTIV-4a trial, followed by results of the pivotal phase 3 REVERSE-IT trial of bentracimab, a recombinant human monoclonal antibody antigen fragment designed to reverse the antiplatelet activity of ticagrelor in the event of major bleeding or when urgent surgery is needed.

Closing out the session is AXIOMATIC-TKR, a double-blind comparison of the safety and efficacy of the investigational oral factor XI anticoagulant JNJ-70033093 vs. subcutaneous enoxaparin (Lovenox) in elective total knee replacement.

For those searching for more AHA-related science online, the Resuscitation Science Symposium (ReSS) will run from this Friday through Sunday and the Quality of Care and Outcomes Research (QCOR) Scientific Sessions will take the stage next Monday, Nov. 15.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Virtual platforms democratized scientific meetings during the COVID-19 pandemic but, as any meeting-goer will tell you, it’s the questions from the floor and the back-and-forth of an expert panel that often reveal the importance of and/or problems with a presentation. It’s the scrutiny that makes the science resonate, especially in this postfactual era.

The all-virtual American Heart Association Scientific Sessions 2021 is looking to recreate the engagement of an in-person meeting by offering more live interactive events. They range from seven late-breaking science (LBS) sessions to Saturday’s fireside chat on the Pfizer and Moderna COVID-19 vaccines and Monday’s dive into the controversial new AHA/American College of Cardiology Chest Pain guidelines.

To help digest the latest science, attendees will be able to have their questions answered in real-time via Slido, meet with the trialists, and hear live commentary from key opinion leaders after the live events. A networking function will also allow attendees and exhibitors to chat or meet virtually.

“In this day and age, many people pretty quickly can get access to the science but it’s what I call the IC sort of phenomenon – the presentation of the information, the context of the information, putting it into how I’m going to use it in my practice, and then the critical appraisal – that’s what most people want at the Scientific Sessions,” program committee chair Manesh R. Patel, MD, of Duke University School of Medicine, said in an interview. “We’re all craving ways in which we can interact with one another to put things in context.”